Transcriber's Note: This e-text contains Unicode characters that

may not display properly in your browser or font, such as the sharp music

symbol and box drawings. A mouse-hover

description of these symbols has been provided, e.g.: C♯, └─┘.

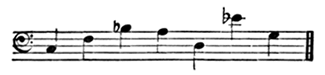

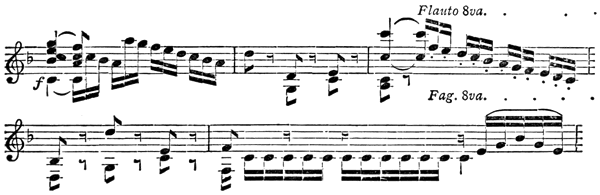

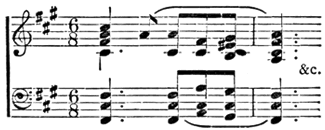

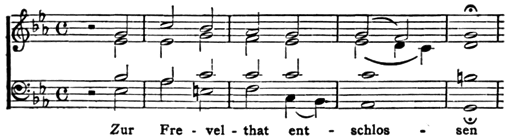

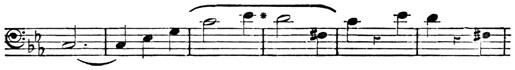

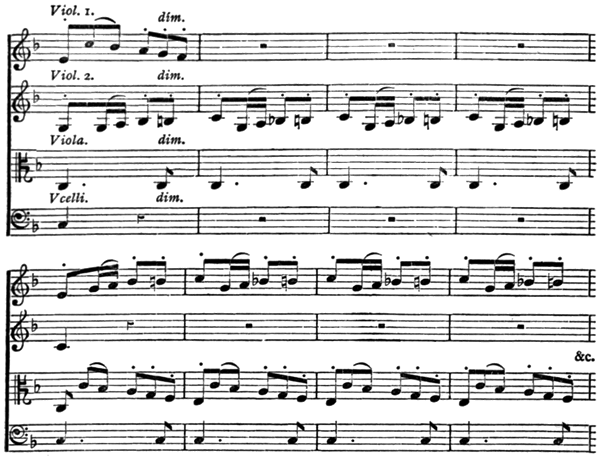

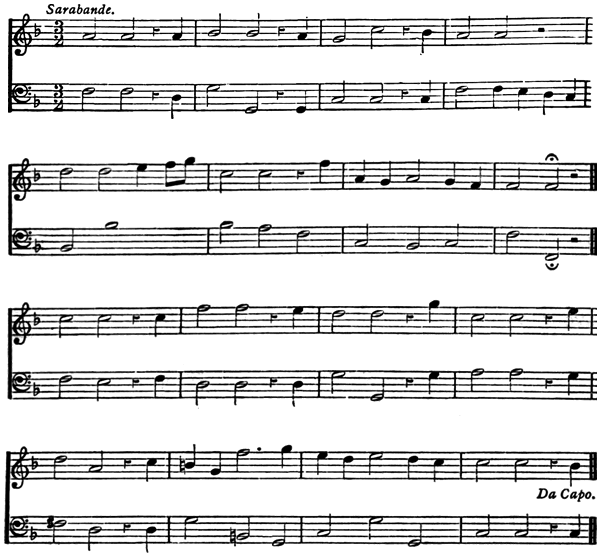

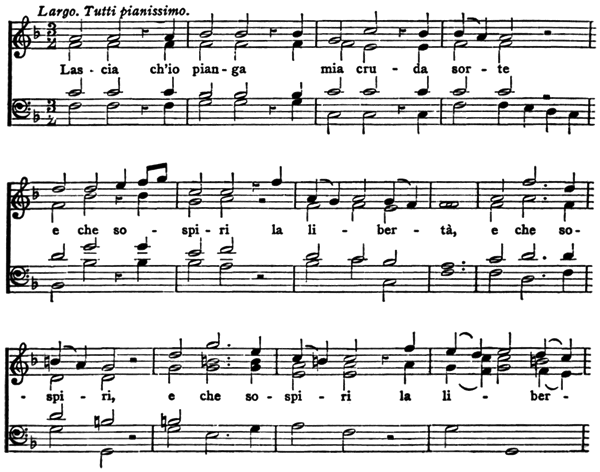

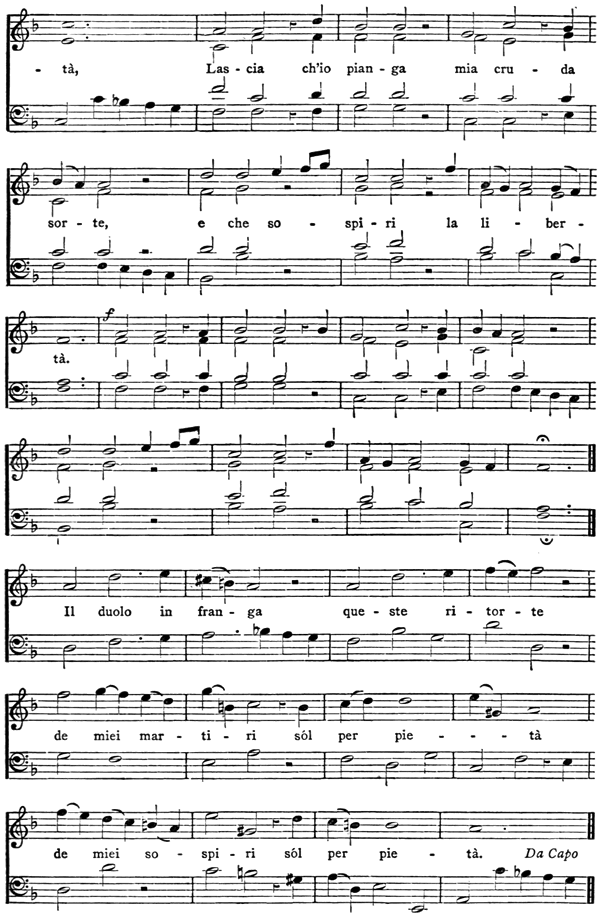

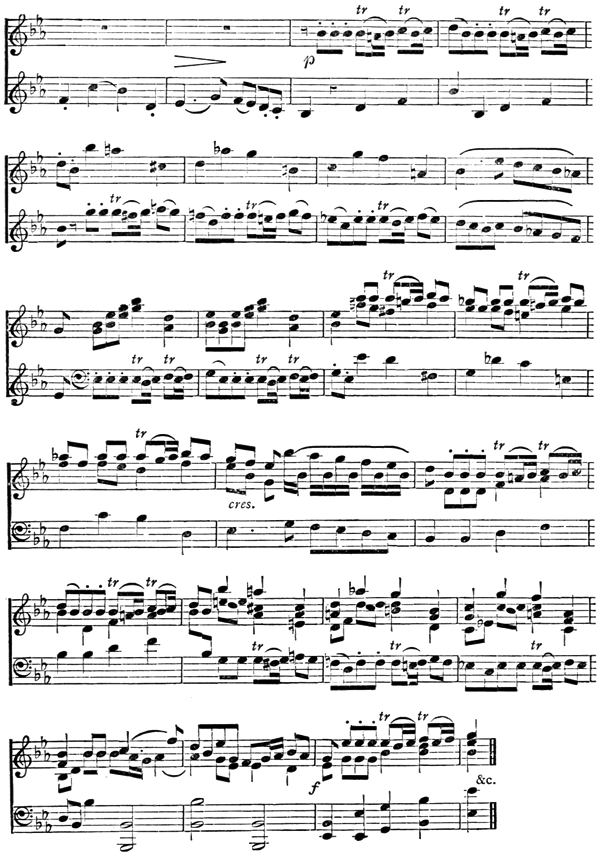

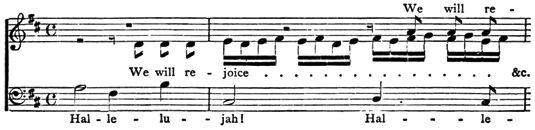

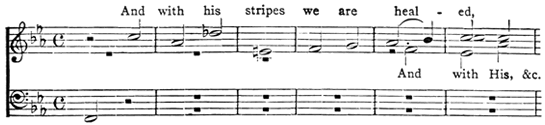

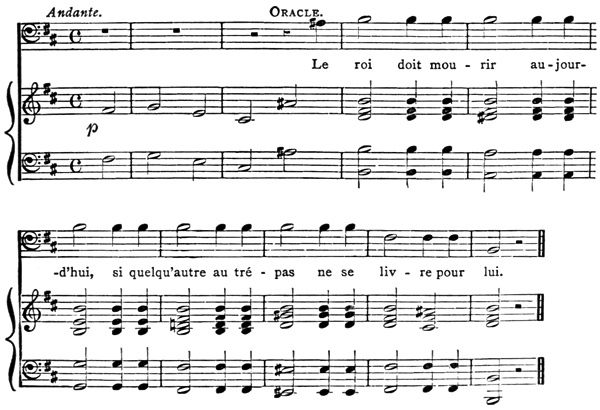

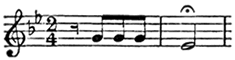

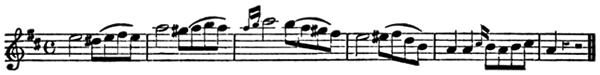

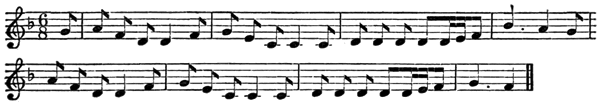

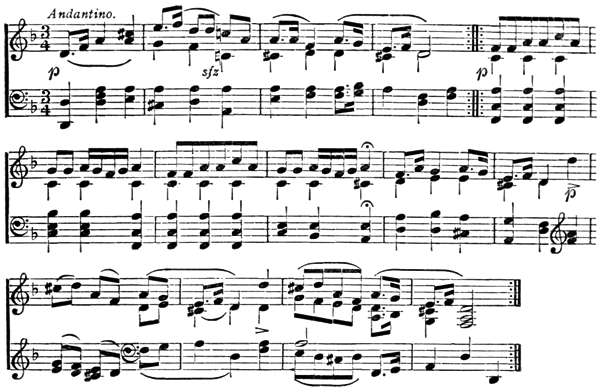

Many musical excerpts appear throughout the book, along with links to midi

files [Listen] directly below each excerpt. If the excerpt has lyrics,

they appear below the music and the link to the midi file.

The cross-referencing links included between the two volumes of this text

worked at the time of posting. However, these links may become broken if

adjustments are made to the Project Gutenberg site.

For

additional Transcriber's Notes, click here.

MUSICAL

BY

——————

LONDON: [All rights reserved.] |

NOVELLO, EWER AND CO.,

TYPOGRAPHICAL MUSIC AND GENERAL PRINTERS,

1, BERNERS STREET, LONDON.

An idealized portrait of Beethoven, representing him as, in the opinion of many of his admirers, he must have looked in his moments of inspiration, would undoubtedly have made a handsomer frontispiece to this little work, than his figure roughly sketched by an artist who happened to see the composer rambling through the fields in the vicinity of Vienna.

The faithful sketch from life, however, indicates precisely the chief object of the present contribution to musical literature, which is simply to set forth the truth.

Whatever may be the short-comings of the essays, they will be of some use should they impress upon musical pedants the truth of Göthe's dictum:

"Grau, theurer Freund, ist alle Theorie,

Und grün des Lebens goldner Baum."

For the sake of correctness, one or two statements occurring in this volume require a word of explanation.

On page 5, the comprehensive 'Encyclopædia of Music,' by J. W. Moore, Boston, United States, 1854, should perhaps not have been left unnoticed; it is, however, too superficial a compilation to be of essential use for reference. Dr. Stainer's 'Dictionary of Musical Terms' was not published until the sheet containing page 5 had gone through the press.

The poem, on page 175, ascribed to Shakespeare, "If music and sweet poetry agree," is by some recent inquirers claimed for Richard Barnfield, a contemporary of Shakespeare.

On page 218, Sovter Liedekens, the title of a Dutch book published in the year 1556, is incorrectly translated. Sovter, an obsolete Dutch word, means "Psalter," just like the English Sauter mentioned in Halliwell's 'Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words.' Liedekens should have been rendered "Little Songs."

In Volume II., the compositions of Henry Purcell noticed on page 202 form only a small portion of the works of this distinguished English musician. The Prospectus issued by the 'Purcell Society,' which has recently been founded for the purpose of publishing all his works, enumerates forty-five Operas and Dramas, besides many Odes, Hymns, Anthems, and other sacred music, instrumental pieces, &c., most of which exist only in manuscript, and which ought long since to have been in the hands of the lovers of music.

Should the reader disapprove of the easy tone in which the Myths are told, he will perhaps derive some satisfaction from the carefulness with which I have endeavoured to state the Facts.

CARL ENGEL.

Kensington.

————————

| PAGE | |||||

| A Musical Library | 1 | ||||

| Elsass-Lothringen | 8 | ||||

| Music and Ethnology | 23 | ||||

| Collections of Musical Instruments | 32 | ||||

| Musical Myths and Folk-lore | 74 | ||||

| PAGE | PAGE | ||||

| Curious Coincidences | 77 | The Wild Huntsman | 85 | ||

| Hindu Traditions | 79 | The Bold German Baron | 87 | ||

| Celestial Quarrels | 80 | Prophetic Calls of Birds | 89 | ||

| Al-Farabi | 82 | Whistling | 91 | ||

| Trusty Ferdinand | 84 | ||||

| The Studies of our Great Composers | 94 | ||||

| Superstitions concerning Bells | 129 | ||||

| PAGE | PAGE | ||||

| Protective Bell-ringing | 130 |

The Church Bells banishing the Mountain Dwarfs |

|||

| Significant Sounds of Bells | 131 | 137 | |||

| Baptised Bells | 134 |

The Expulsion of Paganism in Sweden |

|||

| Inscriptions on Church Bells | 136 | 139 | |||

| Curiosities in Musical Literature | 141 | ||||

| The English Instrumentalists | 166 | ||||

| [Pg viii]Musical Fairies and their Kinsfolk | 187 | ||||

| PAGE | PAGE | ||||

| The Fairies of the Maories | 187 | Linus, the King's Son | 197 | ||

| Adventures in the Highlands | 189 | Necks | 202 | ||

| The Importunate Elves | 191 | The Christian Neck | 204 | ||

| Bad Spirits | 192 | Maurice Connor | 205 | ||

| The Musician and the Dwarfs | 193 | Water Lilies | 206 | ||

| The Little Folks | 195 | Ignis Fatuus | 207 | ||

| Macruimean's Bagpipe | 196 |

The Fairy Music of our Composers |

|||

| The Gygur Family | 197 | 208 | |||

| Sacred Songs of Christian Sects | 210 | ||||

If we cast a retrospective glance at the cultivation of music in England during the last twenty or thirty years, we cannot but be struck with the extraordinary progress which, during this short period, has been made in the diffusion of musical knowledge. The prosperity of England facilitates grand and expensive performances of the best musical works, and is continually drawing the most accomplished artists from all parts of the world to this country. The foreign musicians, in combination with some distinguished native talent, have achieved so much, that there are now, perhaps, more excellent performances of excellent music to be heard in England than in any other country.

Taking these facts into consideration, it appears surprising that England does not yet possess a musical library adequate to the wealth and love for music of the nation. True, there is in the British Museum a musical library, the catalogue of which comprises above one hundred thick folio volumes; but anyone expecting to find in this library the necessary aids to the study of some particular branch of music is almost sure to be disappointed. The plan observed in the construction of the catalogue is the same as that of the new General Catalogue of the Library in the British Museum. The titles of the works are written on slips of thin paper, and fastened, at a considerable distance from each other, down the pages, so that space is reserved for future entries. The musical catalogue contains only two entries upon the one side of a leaf and three upon the other. Each volume has about one hundred and ten leaves. The whole catalogue contains about 60,000 titles of musical compositions and literary works on the subject of music. The British Museum possesses, besides, a collection of musical[Pg 2] compositions and treatises in manuscript, of which a small catalogue was printed in the year 1842. It contains about 250 different works, some of which are valuable.

Even a hasty inspection of the written catalogue must convince the student that it contains principally entries of compositions possessing no value whatever. Every quadrille, ballad, and polka which has been published in England during the last fifty years appears to have a place here, and occupies just as ample space as Gluck's 'Alceste,' or Burney's 'History of Music.' This is perhaps unavoidable. If works of merit only were to find admission, who would be competent to draw the line between these and such as ought to be rejected? In no other art, perhaps, do the opinions of connoisseurs respecting the merit of any work differ so much as in music. Since music appeals more directly and more exclusively to the heart than other arts, its beauties are less capable of demonstration, and, in fact, do not exist for those who have no feeling for them. There are even at the present day musicians who cannot appreciate the compositions of J. Sebastian Bach. Forkel, the well-known musical historian, has written a long dissertation, in which he endeavours to prove that Gluck's operas are execrable.[1] Again, among the adherents of a certain modern school despising distinctness of form and melody may be found men who speak with enthusiasm of the works of Handel, Gluck, Mozart, and other classical composers, although these works are especially characterised by clearness of form and melodious expression. Besides, it must be borne in mind that even our classical composers have now and then produced works of inferior merit, which are nevertheless interesting, inasmuch as they afford us an insight into the gradual development of their powers.

In short, in a musical library for the use of a nation, every musical composition which has been published ought necessarily to be included. In the Musical Library of the British Museum it unfortunately happens, however, that many of those works are wanting which are almost universally[Pg 3] acknowledged to be of importance. Indeed, it would require far less space to enumerate the works of this kind which it contains than those which it does not, but ought to, contain.

Again, the student must be prepared for disappointment, should he have to consult any of our scientific treatises on music. However, there may be more works relating to the science of music in the Library of the British Museum than would appear from the catalogue of music. Several have evidently been entered in the new General Catalogue. Would it not be advisable to have all the books relating to music entered in the musical catalogue? Even the most important dissertations on musical subjects which are found in various scientific works might with advantage be noticed in this catalogue. Take, for instance, the essays in the 'Asiatic Researches,' in the works of Sir W. Jones and Sir W. Ouseley, in 'Description de l'Egypte,' in the 'Philosophical Transactions.'

Thus much respecting the Musical Library in the British Museum. Let us now consider how a national musical library ought to be constituted. Premising that it is intended as much for the use of musical people who resort to it for reference, as for those who are engaged in a continued study of some particular branch of the art, the following kinds of works ought to form, it would appear, the basis of its constitution.

1. The Scores of the Classical Operas, Oratorios, and similar Vocal Compositions, with Orchestral Accompaniments.—Many of these scores have not appeared in print, but are obtainable in carefully revised manuscript copies.

2. The Scores of Symphonies, Overtures, and similar Orchestral Compositions.—The editions which have been revised by the composers themselves are the most desirable. The same remark applies to the scores of operas, oratorios, etc.

3. Vocal Music in Score.—The sacred compositions Alla Cappella, and the madrigals of the old Flemish, Italian, and other continental schools, as well as those of the celebrated old English composers. The choruses of the Greek Church in Russia, etc.[Pg 4]

4. Quartets, Quintets, and similar Compositions in Score.—The study of these works of our great masters is so essential to the musician, that special care should be taken to secure the best editions. The classical trios for pianoforte, violin, and violoncello, and some other compositions of this kind, originally published in parts, have more recently been issued in score. The latter editions are greatly preferable to those in which the part for each instrument is only printed separately. The same remark applies to the concertos of Mozart, Beethoven, and other masters, which have been published with the orchestral accompaniment in score, as well as with the orchestral accompaniment arranged for the pianoforte or for some other instruments.

5. Sonatas, Fantasias, Fugues, etc.—Of all the classical works composed for a single instrument, the original editions, generally revised by the composers themselves, are indispensable. Besides these, the most important subsequent editions of the same works would be required. Beethoven's pianoforte sonatas, for instance, have been re-edited by several eminent pianists. It is instructive to examine the readings of these musicians, which differ in many points from each other.

6. Arrangements.—Those of operas, oratorios, masses, and other elaborate compositions with orchestral accompaniment, must necessarily be confined to the instrumental portion, otherwise they are useless either for study or reference. Those arrangements are greatly preferable which have been made by the composers themselves, or under their superintendence.

7. National Music.—All the collections of national songs and dances which have been published in different countries. The advantage which the musician might derive from a careful study of them is not yet so fully appreciated as it deserves; but it would probably soon be better understood, if these treasures were made more easily accessible.

8. Books of Instruction for Vocal and Instrumental Practice.—The best books for every instrument, as well as for the voice, which have been published in different countries and languages.[Pg 5]

9. Works on the Theory and History of Music.—All the standard works ought to be found in the library, not only in the languages in which they were originally written, but also in translations, if any such exist. Many of the latter are valuable, on account of the explanations and other additions by the translators. This is, for instance, the case with some English books which have been translated into German; as Brown's 'Dissertation on the Rise, Union, and Power of Music,' translated by Eschenburg; 'Handel's Life,' by Mainwaring, translated by Mattheson, etc. It need scarcely be added that the biographies of celebrated musicians ought also to be included among the desirable requisites.

10. Works on Sciences intimately connected with the Theory of Music.—Treatises on acoustics, on the construction of musical instruments, on æsthetics, etc.

11. Musical Journals.—All the principal ones published in different countries and languages. To these might advantageously be added the most important literary journals containing critical and other dissertations on music.

12. Dictionaries, Catalogues, etc.—The English language possesses no musical dictionary, technical, biographical, or bibliographical, similar to the French and German works by Fétis, Schilling, Gerber, Koch, Rousseau, and others, which are indispensable for the library. With these may be classed the useful works on the Literature of Music compiled by Forkel, Lichtenthal, and Becker, as well as Hofmeister's comprehensive 'Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur.' The collection of catalogues should comprise all those of the principal public musical libraries on the Continent and in England; those of large and valuable private libraries, several of which have appeared in print,—as, for instance, Kiesewetter's 'Sammlung alter Musik,' Becker's 'Tonwerke des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts,' and others; those of the principal music-publishers, and those of important musical libraries which have been disposed of at public auctions.

There is no necessity for extending this list any further, as it will suffice to indicate the plan which, in my opinion,[Pg 6] ought to be pursued in the formation of a national musical library. I shall therefore only observe further that there are, besides the above mentioned, several kinds of works which can scarcely be considered as of secondary importance, such as musical travels, novels, and entertaining as well as instructive musical essays; librettos of operas, and the poetry of other elaborate vocal compositions; drawings illustrating the construction of musical instruments,—as, for instance, of the most celebrated organs, of the various improvements in the pianoforte, etc.; engravings from the best portraits of celebrated musicians; faithful sketches from sculptures and paintings of nations of antiquity in which musical instruments and performances are represented, etc.

There remains yet another point which requires a moment's consideration,—namely, the daily increasing difficulty of forming such a library as has just been planned. The interest in the study of classical works relating to music is no longer confined to the professional musician, but is spreading among amateurs and men of science. Their libraries now absorb many of the old and scarce works which formerly were almost exclusively in the hands of musicians. Moreover, the English colonies have already drawn upon our limited supply of the old standard works, and there is every reason to suppose that the demand for them will continue to increase. Many of these works have evidently been published in an edition of only a small number of copies. Still it is not likely that they will be republished. In a few instances where a new edition has been made, it has not apparently affected the price of the original edition, because the latter is justly considered preferable. To note one instance: the new edition of Hawkins' 'History of Music' has not lessened the value of the first edition, the price of which is still, as formerly, on a par with the price of Burney's 'History of Music' of which no new edition has been published. About ten years ago it was possible to procure the original scores of our old classical operas, and other works of the kind, at half the price which they fetch now, and there is a probability that they will become every year more expensive. Indeed, whatever may be the[Pg 7] intrinsic value of any such work, the circumstance of its being old and scarce seems sufficient, at least in England, to ensure it a high price.

If, therefore, the acquisition of such a national musical library as I have endeavoured to sketch is thought desirable, no time ought to be lost in commencing its formation.

Whatever may be thought of the value of the well-known aphorism, "Let me make a nation's Ballads; who will may make their Laws"—it can hardly be denied that through the popular songs of a country we ascertain to a great extent the characteristic views and sentiments of the inhabitants.

The villagers of Alsace recently may not have been in the mood for singing their old cherished songs; otherwise the German soldiers must have been struck by recognizing among the ditties old familiar friends slightly disguised by the peculiar dialect of the district. Take, for instance, the cradle songs, or initiatory lessons as they might be called. Here is one as sung by the countrywomen of Alsace:—

"Schlof, Kindele, schlof!

Dien Vadder hied die Schof,

Dien

Muedder hied die Lämmele,

Drum schlof du guldi's Engele;

Schlof,

Kindele, schlof!"

(Sleep, darling, sleep!

Thy father tends the sheep,

Thy mother

tends the lambkins dear,

Sleep then, my precious angel, here;

Sleep, darling, sleep!)

And another:—

"Aie Bubbaie was rasselt im Stroh?

D'Gänsle gehn baarfuesz, sie han

keen Schueh;

Der Schuester het's Leder, keen Leiste derzue."

(Hush-a-bye baby, what rustles the straw?

Poor goslings go barefoot,

they have not a shoe;

The souter has leather, no last that will do.)

Making allowance for the pronunciation of the words, which sounds odd to the North-German ear, these are the identical lullabies with which the mothers in the villages[Pg 9] near Hanover sing their babies to sleep. Some of the old ballads, legends, fairy-tales, and proverbs, popular in Alsace, are current throughout almost the whole of Germany. Then we have the old-fashioned invitation to the wedding feast, stiff and formal, as it is observed especially in Lower Alsace, and likewise in the villages of Hanover and other districts of North Germany. In Alsace the weddings take place on a Tuesday, because, they say, we read in the Bible: "And the third day there was a marriage in Cana of Galilee." In sacred poetry Alsace can pride herself upon having produced some of the most distinguished German writers. The oldest known of these is Ottfried von Weissenburg, who lived about the middle of the ninth century. Gottfried von Strassburg, in the beginning of the thirteenth century, was renowned as a writer of hymns as well as of Minnelieder. The first sacred songs of a popular character recorded in Alsace date from about the middle of the fourteenth century. But it is especially since the time of the Reformation that this branch of sacred poetry has been much cultivated here as in other parts of Germany. The authors of sacred poetry were generally either theologians or musicians. The latter often composed the words as well as the airs. Music and poetry were not cultivated so separately as is the case in our day. Of the musicians, deserves to be mentioned Wolfgang Dachstein, who, in the beginning of the sixteenth century, was organist in Strassburg, first at the Cathedral, and afterwards, when he become a Protestant, at the Thomas Church. His hymn An Wasserflüssen Babylon is still to be found in most chorale books of the German Protestants.

The secular songs of the villagers are not all in the peculiar dialect of the province. Some are in High German, and there are several in which High German is mixed with the dialect. Occasionally we meet with a word which has become obsolete in other German districts; for instance, Pfiffholder for "Schmetterling," Low German "Buttervogel," English "butterfly;" Irten (Old German Urt, Uirthe) for "Zeche," English "score." Of the lyric poets of the present century, Hebel is, perhaps, the most popular in Alsace.[Pg 10] His "Allemannische Gedichte" used to be sung especially in the southern district, which, until recently, formed the French department of Haut-Rhin. The people of this district have a less soft pronunciation than those of Bas-Rhin.

As regards the popular songs of Lorraine, those which have been collected and published are, almost all of them, from the French districts of the province.

The Société d'Archéologie Lorraine has published a collection, entitled 'Poésies populaires de la Lorraine, Nancy, 1854;' and R. Grosjean, organist of the Cathedral of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, has edited a number of old Christmas Carols, arranged for the organ or harmonium, and published under the title of 'Air des Noëls Lorrains, Saint-Dié, 1862.' In the German villages we meet with songs in a peculiar dialect, not unfrequently interspersed with French words. The following example is from the neighbourhood of Saarlouis:—

"Of de Bam senge de Viglen bei Daa ond Naat,

D'Männtcher peife hibsch

on rufe: ti-ti-pi-pi,

On d'Weibcher saan: pi-pi-zi-zi.

Se senge

luschtig on peife du haut en bas.

Berjer, Buwe on Baure

d'iwrall her,

Die plassire sich recht à leur aise.

Se senge ensemble hibsch on fein.

D'gröscht Pläsirn hot

mer van de Welt

Dat mer saan kann am grine Bam;

Dat esch wohr,

dat esch keen Dram."

(On the tree sing the birds by day and night,

They pipe and call,

ti-ti-pi-pi;

Their mates reply, pi-pi-zi-zi.

They cheerfully

chirp du haut en bas,

High life and low life, from all around,

Placent themselves quite à leur aise.

They sing ensemble

sweet and fine.

No greater plaisir earth can give

Than

the sight of a greenwood tree;

That's truth, no idle dream.)

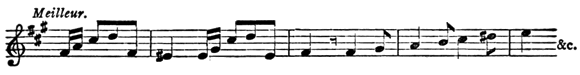

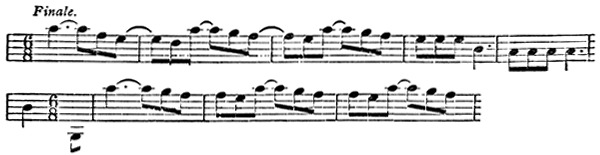

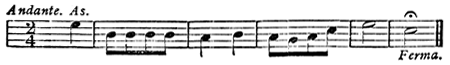

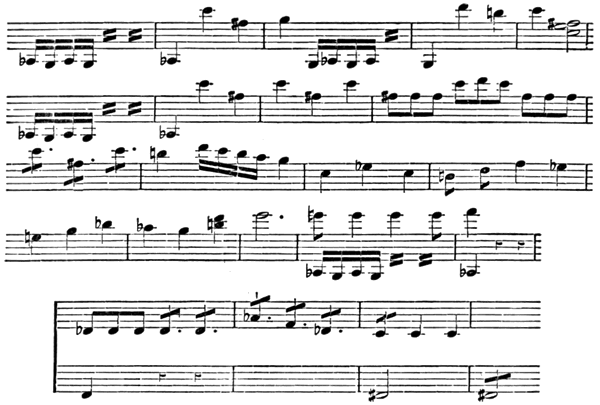

Thus much about the words of the popular songs. As regards the airs, those which have been traditionally preserved[Pg 11] by the villagers of Alsace exhibit the characteristics of the German national music. That the construction of the airs has not altered much in the course of a century is evident from the specimens of songs and dance-tunes which Laborde gives in his 'Essai sur la Musique,' published in the year 1780. Still earlier, about two hundred years ago, the French composers adopted from Alsace a German tune of a peculiar construction, the Allemande. This happened at the time of the invention of the Suite, a composition which consists of a series of short pieces written in the style of popular tunes of various countries. The Allemande, which generally formed the introductory movement to the series, is more dignified than the sprightly Courante, Gavotte, and Bourrée, originally obtained from different provinces of France.

Particularly interesting is the music of the peasant of Kochersberg. The mountain called Kochersberg is situated in the vicinity of the town of Zabern in Upper Alsace. The district immediately surrounding the mountain is also called Kochersberg. The villagers of this district are considered by the French as rather rude in manner, but as honest, straightforward, and trustworthy. They have several old favourite dances, as for instance, Der Scharrer ("The Scraper"), Der Zäuner ("The Fence Dance"), Der Morisken (evidently the "Morrice" or Moorish Dance, formerly also popular in England, and originally derived from the Moors in Spain), Der Hahnentanz ("The Cock Dance"). The last-named dance, which is also popular in other districts of Alsace, and, with some modifications, in the Black Forest of Germany, is generally performed in a large barn. On a cross-beam is affixed a dish, in which is placed a fine large cock (called Guller). The cock is ornamented with ribands of various colours. Near the dish hangs a tallow-candle, through which a string is drawn horizontally. To one end of the string is attached a leaden ball. The dancers arrange themselves in pairs, one behind the other. As soon as the musicians strike up, the candle is lighted, and the first pair receive a nosegay, which they have to hold as long as they continue dancing. When they are tired, and stop to rest,[Pg 12] they must give the nosegay to the next following pair, and so on. The pair which have possession of the nosegay at the moment when the candle burns the string, and the ball falls into the dish, win the cock. The Hammeltanz of the Kochersberg peasants is likewise known in Baden. In this dance a fat wether is the prize of the lucky pair who happen to be dancing when a glass suspended by a burning match-cord becomes detached and falls to the ground. Some of the dancers are accompanied with singing; for instance, the Bloue Storken, in which the song begins with the words:—

"Hon err de bloue Storken nit g'sähn?"

(Have you not seen the blue

storks?)

The Bloue Storken is one of the oldest national dances of the Alsatian peasants. It is danced by one person only. At the commencement his performance resembles that of the slow and grave minuet; after awhile it becomes more animated.

However, in a musical point of view, the most interesting of these dances is the Kochersberger Tanz, which is mentioned by Reicha and other musical theorists on account of its peculiar rhythm. According to Reicha's notation it is in 5/8 time. Perhaps it would have been as correctly written in 3/8 and 2/8 alternately, like Der Zwiefache, or Gerad und Ungerad ("Even and Uneven"), of the villagers in the Upper Palatinate of Bavaria, to which it bears altogether a strong resemblance. The musical bands attending the villagers at dances and other rural pastimes are, as might be expected, very simple—a clarionet and one or two brass instruments generally constituting the whole orchestra.

In Alsace a certain musical instrument is still to be found which, about three centuries ago, was popular in Germany. Some of the works on music published in the beginning of the seventeenth century contain drawings of it. Its German name is Scheidholt, and its French name is bûche. It consists of an oblong square box of wood, upon which are stretched about half-a-dozen wire-strings. Some of the strings run over a finger-board provided with iron frets. These strings are used for playing the melody. The others are at the[Pg 13] side of the finger-board, and serve for the accompaniment. The strings are twanged with a plectrum. The Scheidholt may be considered as the prototype of the horizontal cither which, in the present century, has come much in vogue in Bavaria and Austria, and which has recently been introduced also into England.

Formerly, the professional musicians of Alsace formed a guild, the origin of which dates from the time of the Minnesänger, when players on musical instruments wandered from castle to castle to entertain the knights with their minstrelsy. In the year 1400 a Roman imperial diploma was granted to Count Rappoltstein constituting him protector of the guild. The musicians were called Pfeiffer, and Count Rappoltstein and his successors had the title of Pfeiffer-König ("King of the Pipers"). In the seventeenth century the Pfeiffer held annually a musical festival at Bischweiler, a small town near Strassburg. Having gradually fallen into decay, this old guild died out in the year 1789.

Considering the influence which the principal town of a country usually exercises upon the taste of the rural population, a few remarks relating to the cultivation of music in Strassburg may find here a place. Strassburg possesses, indeed, valuable relics illustrative of the history of music as well as of the other fine arts. Unfortunately, several of these treasures were injured at the recent bombardment. The town library, which was burnt, contained some valuable musical manuscripts; for instance, the Gesellschaftsbuch der Meistersänger from the year 1490 to 1768, and an historic treatise on the music and the Meistersänger of Strassburg written in the year 1598, by M. Cyriacus Spangenberg. To antiquarians who deplore the loss of these relics it may afford consolation to know that the town library of Colmar, in Alsace, possesses a manuscript collection of more than 1,000 old Minne-songs and Meister-songs, which originally belonged to the guild of shoemakers of Colmar. It must be remembered that in the beginning of the fourteenth century, after the Minnesänger of the Middle Ages, like the old chivalry with which they were associated, had become obsolete, there sprang up in Germany a corporation of poets and singers[Pg 14] constituted of citizens, and known as the Meistersänger. Strassburg was one of the first among the German towns in which the Meistersänger flourished. An old sculpture of a Meistersänger, life-size, placed under the celebrated organ of the cathedral, testifies to the popular esteem enjoyed by this corporation. The town library possessed two curious oil-paintings on panel, dating from about the year 1600, which belonged to the Meistersänger of Strassburg, who used to place them one at each side of the entrance to their hall of assembly. A collection of antiquated musical instruments, which, probably, originally belonged to the Meistersänger, was formerly in a public building called Pfenningthurm, from which, in the year 1745, it was removed to the town library, where it was reduced to ashes.

However, the most interesting musical instrument in Strassburg is the organ of the cathedral made by Andreas Silbermann. Notwithstanding the care exercised by the beleaguerers to prevent damage to the cathedral, a shell found its way right through the centre of the organ, and must have greatly injured this work of art. Andreas Silbermann was no mere handicraftman, but an artist like Amati or Stradivari. He was born in Saxony, settled in Strassburg in the year 1701, and built the organ of the cathedral in 1715. His brother, Gottfried Silbermann of Saxony, was likewise a distinguished maker, not only of organs, but also of clavichords, and an improver of the pianoforte soon after its invention, in the beginning of the eighteenth century. Almost all the organs built during the eighteenth century for the churches of Strassburg are by Andreas Silbermann and his sons. Among the latter, Johann Andreas is noteworthy on account of his antiquarian pursuits. He wrote, besides other works, a 'History of the Town of Strassburg,' which was published in folio, with engravings, in the year 1775. His collection of sketches drawn by himself of the most remarkable scenery, and of old castles and other interesting buildings of Alsace, and likewise his collection of the old coins of Strassburg, were preserved in the town library, and are, it is to be feared, now lost. As even the catalogue of the library has, it is said, been burnt, it may be worth while[Pg 15] to notice some of the losses. With the irreparable ones must be recorded a copy of the first hymn book of the Protestant Church, of which no other copy is known to be extant. It was published at Erfurt in the year 1524, and contains twenty-five songs, eighteen of which are by Luther. Its title is Enchiridion, oder eyn Handbuchlein eynem yetzlichen Christen fast nutzlich bey sich zu haben, zur stetter vbung vnd trachtung geystlicher gesenge und Psalmen, Rechtschaffen vnd Kunstlich vertheutscht. ("Enchiridion, or a little Hand-book, very useful for a Christian at the present time to have by him for the constant practice and contemplation of spiritual songs and psalms, judiciously and carefully put into German.") The musical notation is given with the words. It is believed that Luther gave the manuscript of his own songs, and most likely also of the other songs, and of the musical notation, into the hands of the publisher;—that, in fact, the "Enchiridion" emanated directly from Luther. A fac-simile of this book was published in Erfurt in the year 1848. Only three chorales are known with certainty to be of Luther's composition.

With the musical relics of the olden time preserved in Strassburg must be classed the so-called Astronomic Clock. This curious piece of mechanism, which is in the cathedral, was, in the year 1570, substituted for one which dated from the year 1354. Having been out of repair since the year 1789, it was restored about thirty years ago. The cylinders of the old mechanism of 1354, which act upon a carillon of ten bells, have been retained. The old tonal system exhibited in the arrangement of the cylinders, which produce hymn tunes, cannot but be interesting to musical antiquarians. Also, the wonderful mechanical cock, which, at the end of a tune, flapped its wings, stretched out its neck, and crowed twice—a relic of the work of 1354—is still extant; but whether it continues to perform its functions, I cannot say.

Let us now refer for a moment to the theatrical performances patronised by the burghers. Some interesting records relating to the history of the opera in Strassburg have been published by G. F. Lobstein, in his 'Beiträge zur[Pg 16] Geschichte der Musik im Elsass, Strassburg, 1840.' The oldest theatrical representations in Strassburg are of the sixteenth century. They consisted of sacred and historical pieces, and likewise of dramas of the Greek and Latin classics. The actors were scholars, or academicians, and the performances were called Dramata theatralia, Actiones comicae or tragicae, Comoediae academicae. About the year 1600 also the Meistersänger occasionally engaged in dramatic performances, or, as they called it, in Comödien von Glück und Unglück ("Comedies treating of Happiness and Unhappiness") and they continued to act such pieces in public until towards the end of the seventeenth century. In the year 1601 we find, the first time, mention made of the English comedians who, like the Meistersänger, evidently introduced music into their dramatic performances. Respecting the companies of English comedians who visited Germany at the time of Shakespeare, much has been written by Shakespearean scholars; but little attention has, however, been given by them to the musical accomplishments of these strollers. The old records which have recently been brought to light in Germany relating to the history of the theatres of the principal German towns, contain some interesting notices of "English instrumentalists" who formed part of the companies of English comedians. Indeed, most of the so-called English comedians appear to have been musicians and dancers (or rather tumblers) as well as actors. Probably it was more the novelty of their performances than any superiority of skill which rendered these odd foreigners temporarily attractive in Germany. Howbeit, to the musical historian they are interesting.

The invention of the opera, it must be remembered, dates from the year 1580, when, at Florence, the Count of Vernio formed at his palace a society for the revival of the ancient Greek musical declamation in the drama. This endeavour resulted in the production of the operas 'Dafne' and 'Orfeo ed Euridice,' composed by Peri and Caccini. The first German opera was performed in Dresden, in the year 1627. It was the libretto of 'Dafne,' just mentioned, written by Rinuccini, which was translated into German, and anew set[Pg 17] to music by Heinrich von Schütz, Kapellmeister of the Elector of Saxony. In France the first composer of an opera was Robert Cambert, in the year 1647. He called his production 'La Pastorale, première comédie française en musique.' This composition was, however, performed only at Court. The first public performance of an opera in France occurred not earlier than the year 1671.[2] However, before the invention of the opera, strolling actors, such as the English comedians, and the Italian companies, which were popular in Strassburg, used to intersperse their performances with songs, accompanied by musical instruments such as the lute, theorbo, viol, etc. The first operatic representations, properly so called, in Strassburg, took place in the year 1701, and the operas were German, performed by German companies. Later, Italian companies made their appearance, and still later, French ones. In the year 1750 the French comic opera 'Le Devin du Village,' by J. J. Rousseau, was much admired. However, even during the eighteenth century the German operas and dramas enjoyed greater popularity in Strassburg than the French, notwithstanding the protection which the French companies received from the Government officials of the town. Indeed, the theatrical taste of the burghers has never become thoroughly French, if we may rely on G. F. Lobstein, who says, "The diminished interest evinced by the inhabitants of Strassburg at the present day" [about the year 1840] "in theatrical performances dates from the time when the French melodramas and vaudevilles made their appearance. The hideous melodramatic exhibitions, and the frivolous subjects, unsuitable for our town, and often incomprehensible to us—depicting Parisian daily occurrences and habits not unfrequently highly indecent—have, since their introduction on our stage, scared away those families which formerly visited the theatre regularly. They now come only occasionally, when something better is offered."

As regards the musical institutions and periodical concerts of Strassburg, suffice it to state that the local government[Pg 18] has always encouraged the cultivation of music; it is, therefore, not surprising, considering the love for music evinced by the Alsatians, that Strassburg has been during the last three centuries one of the chief nurseries of this art on the Continent. Until the year 1681, when Strassburg was ceded to France, it possessed an institution called Collegium Musicum, which enjoyed the special patronage of the local government. An Académie de Musique, instituted in the year 1731 by the French Governor of the town, was dissolved, after twenty years' existence, in 1751. At the present day the musical societies are not less numerous in Strassburg than in most large towns of Germany. An enumeration of the various kinds of concerts would perhaps only interest some musicians.

But Pleyel's Republican Hymn of the year 1792 is too characteristic of French taste at the time of the great events which it was intended to celebrate to be left unnoticed. Ignaz Pleyel, the well-known musician, was born in a village near Vienna, in the year 1757. On visiting Strassburg, after a sojourn in Italy, in the year 1789, he was made Kapellmeister of the cathedral. Unfortunately for him, soon his political opinions were regarded with suspicion by the National Assembly, especially from his being a native of Austria. He found himself in peril of losing his liberty, if not his life. Anxious to save himself, he conceived the happy idea of writing a brilliant musical composition in glorification of the Revolution. He communicated his intention to the National Assembly; it found approval, and he was ordered to write, under the surveillance of a gendarme, a grand vocal and orchestral piece, entitled 'La Révolution du 10 Août (1792) ou le Tocsin allégorique.' The manuscript score of this singular composition was, until recently, preserved in Strassburg, but has now probably perished. A short analysis of its construction will convince the reader that the monster orchestra which Hector Berlioz has planned for the music of the future, and of which he says in prophetic raptures: "Its repose would be majestic as the slumber of the ocean; its agitation would recall the tempest of the tropics; its explosions, the outbursts of[Pg 19] volcanoes," was already anticipated by Pleyel nearly a hundred years ago. Pleyel required for his orchestra not only a number of large field-guns, but also several alarm-bells. The financial condition of France at that period, and the abolition of divine worship, induced the National Assembly to decree the delivering up of all the church-bells in Alsace. About 900 bells were consequently sent to Strassburg. Pleyel selected from them seven for the performance of his work; and all the others were either converted into cannon, or coined into money—mostly one-sol and two-sol pieces.

The Introduzione of Pleyel's composition is intended to depict the rising of the people. The stringed instruments begin piano. After a little while a low murmuring noise mingles with the soft strains, sounding at first as if from a great distance, and approaching gradually nearer and nearer. Now the wind-instruments fall in, and soon the blowing is as furious as if it were intended to represent the most terrific storm. It is, however, meant to represent the storming of the Tuileries. Fortunately the awful noise soon passes over, and only some sharp skirmishes are occasionally heard. After about a hundred bars of this descriptive fiddling and blowing, the alarm-bells begin—first one, then another, and now all in rapid succession. Suddenly they are silenced by a loud trumpet signal, responded to by a number of drums and fifes. The fanfare leads to a new confusion, through which the melody of some old French military march is faintly discernible. The excitement gradually subsides, and after awhile the stringed instruments alone are engaged, softly expressing the sighs of the wounded and dying. Presently the Royalists make themselves heard with the song, "O Richard, ô mon roi" (from 'Richard Cœur de Lion') which, after some more confusion, is followed by the air, "Où peut-on être mieux?" at the end of which discharges of cannon commence. Another general confusion, depicted by the whole orchestra with the addition of cannon and alarm-bells. Suddenly a flourish of trumpets, with kettle-drums, announces victory, and forms the introduction to a jubilant chorus with full orchestral accompaniment: "La victoire est[Pg 20] à nous, le peuple est sauvé!" This again, after some more instrumental interluding, is followed by a chorus with orchestral accompaniment founded on the tune "Ça ira, ça ira," a patriotic song which was, during the time of the Revolution, very popular with the French soldiers. The remaining portion of the composition consists of a few songs for single voices alternating with choruses. As the words are not only musically but also historically interesting, they may find a place here.

| "Chorus. | ||

|

"Nous t'offrons les débris d'un trône, Sur ces autels, ô Sainte Liberté! De l'éternelle vérité. Ce jour enfin, qui nous environne, Rend tout ce peuple à la félicité; Par sa vertu, par sa fierté, Il conquiert l'égalité. Parmis nos héros la foudre qui tonne L'annonce au loin à l'humanité. |

||

| "A Woman. (Solo.) | ||

|

"Mon fils vient d'expirer, Mais je n'ai plus de rois! |

||

| "Romance. | ||

|

"Il fut à son pays avant que d'être à moi, Et j'étais citoyenne avant que d'être mère. Mon fils! par tes vertus j'honore ta poussière. |

||

| "Chorus. | ||

| "Nous t'offrons les débris d'un trône, etc., etc. | ||

| "Solo. (Soprano.) | ||

|

"Ah! périsse l'idolatrie Qu'on voue à la royauté. Terre ne sois qu'une patrie, Qu'un seul temple à l'humanité, Que l'homme venge son injure Brise, en bravant, le faux devoir, Et le piédestal du pouvoir Et les autels de l'imposture, |

{ |

Repeated by the Chorus. |

|

Rois, pontifs! ô ligue impure Dans ton impuissant désespoir Contemple aux pieds de la nature Le diadème et l'encensoir! Versailles et la fourbe Rome Ont perdu leurs adulateurs. Les vertus seront les grandeurs, Les palais sont les toits de chaume. |

{ |

Repeated by the Chorus. |

| "Solo. (Tenore.) | ||

|

"Les Français qu'on forme à la guerre Appellent contre les tyrans Les représailles de la terre, Du haut des palais fumans. Des bords du Gange à ceux du Tibre Dieu! rends bientôt selon nos vœux Tout homme un citoyen heureux, Le genre humain un peuple libre. |

{ |

Repeated by the Chorus. |

| "Solo Recit. (Basso.) | ||

|

"Nous finirons son esclavage Ce grand jour en est le présage! |

||

| "Chorus (concluding with a brilliant orchestral Coda). | ||

| "Nous t'offrons les débris d'un trône," etc., etc. | ||

This curious composition was performed in the Cathedral of Strassburg, and created great sensation. Everyone declared that only an ardent patriot could have produced such a stirring work. Nevertheless Pleyel, after having been set free, thought it advisable to leave Strassburg for London as soon as possible.

Besides those already mentioned, several other distinguished musicians could be named who were born or who lived in Strassburg. Ottomarus Luscinius, a priest, whose proper German name was Nachtigall, published in the year 1536, in Strassburg, his 'Musurgia, seu Praxis Musicæ,' a work much coveted by musical antiquarians. Sebastian Brossard, who, about the year 1700, was Kapellmeister at the Strassburg Cathedral, is the author of a well-known musical dictionary. Sebastian Erard, the inventor of the repetition-action and other improvements in the pianoforte, as well as of the double-action in the harp, was born at Strassburg in the year 1752.

In short, Elsass-Lothringen has been the cradle of many men distinguished in arts and sciences. The prominent feature of the national character of the inhabitants, revealed in their popular songs and usages, is a staidness which is[Pg 22] not conspicuous among the pleasant qualities of the French. This innate staidness accounts for the reluctance recently shown by them to being separated from France, just as it accounts for their former disinclination to become French subjects. Moreover it will probably, now that they are reunited to their kinsmen, gradually make them as patriotic Germans as they originally were. That they require time to transfer their attachment redounds to their honour.

The following scheme devised for obtaining accurate information respecting the music of different nations is probably without precedent.

In the year 1874 the British Association for the Advancement of Science resolved to issue a book of instructions for the guidance of travellers and residents in uncivilized countries, to enable them to collect such information as might be of use to those who make special study of the various subjects enumerated in the book.[3] The subjects relate to manners and customs, arts, sciences, religion, war, social life,—in fact, to everything which throws light upon the stage of civilization attained by the people, and which the ethnologist may desire to ascertain. The book is for this purpose divided into a number of sections, each on a certain subject, on which it contains a number of questions. These are preceded by a short note explanatory of the subject. In order to render the questions as effective as possible, especial care has been taken that they should enter into all necessary details.[4][Pg 24]

Having been requested to undertake the section headed "Music," and to draw up a list of numbered questions in accordance with the plan adopted by the committee, I have endeavoured to direct the attention of those for whom the book is intended to the musical investigations which, in my opinion, are especially desirable; and I have occasionally interspersed among the questions a hint which may assist the investigator. It appeared to me unnecessary to give definitions of musical terms made use of in the questions—such as interval, melody, harmony, etc.—which are to be found in every dictionary of the English language. Some terms, however, required an explanation to render them fully intelligible to those travellers who are but little acquainted with music. Of this kind are, for instance, the names of the different musical scales. The English missionaries, traders, merchants, consuls, and other residents in foreign countries, seldom possess any available knowledge of music. Still, among the questions here submitted to them are many which they may be able to answer satisfactorily; while, on the other hand, it must be admitted, not a few can be properly replied to only by men of musical education and experience. However, what one person is unable to investigate another may do; and thus, perhaps, we may hope, in the course of time, to be supplied with reliable and instructive answers to most of the questions from different parts of the world.

Some of the questions may appear, at a first glance, to be of but little importance; it is, however, just those facts to which they refer which ought to be clearly ascertained before we can expect to discern exactly the characteristics of the music of a nation or tribe.

It will be observed that certain questions pre-suppose a somewhat advanced state of civilization—as, for instance, those referring to musical notation, instruction, literature, etc. There are several extra-European nations—as the Japanese, Chinese, Hindus, etc.—which have advanced so far in the cultivation of music as to render these questions necessary; and it would be very desirable to possess more detailed information concerning the method pursued by these[Pg 25] nations in the cultivation of the art than is at present available.

The present scheme is quite as interesting to the musician, or even more so, than it is to the ethnologist. Professional musicians in general are, however, not likely to become acquainted with the instructions for musical researches published together with various other scientific inquiries by the British Association. It is for this reason that they are here inserted, since the present work has a better chance of coming into the hands of professional musicians than the anthropological publication. Howbeit, years must elapse before it leads to a practical result. The originator of the questions may never enjoy the advantage of receiving the answers; but he has, at least, the pleasure of preparing the way for an accumulation of well-ascertained facts which intelligent musicians of a future generation will know how to turn to good account.

"(Section LXVIII.) Music.

"The music of every nation has certain characteristics of its own. The progressions of intervals, the modulations, embellishments, rhythmical effects, etc., occurring in the music of extra-European nations, are not unfrequently too peculiar to be accurately indicated by means of our musical notation. Some additional explanation is, therefore, required with the notation. In writing down the popular tunes of foreign countries, on hearing them sung or played by the natives, no attempt should be made to rectify anything which may appear incorrect to the European ear. The more faithfully the apparent defects are preserved the more valuable is the notation. Collections of popular tunes (with the words of the airs) are very desirable. Likewise, drawings of musical instruments with explanations respecting the construction, dimensions, capabilities, and employment of the instruments represented.

"Vocal Music:—

"1. Are the people fond of music?[Pg 26]

"2. Is their ear acute for discerning small musical intervals?

"3. Can they easily hit a tone which is sung or played to them?

"4. Is their voice flexible?

"5. What is the quality of the voice? is it loud or soft, clear or rough, steady or tremulous?

"6. What is the usual compass of the voice?

"7. Which is the prevailing male voice—tenor, baritone or bass?

"8. Which is the prevailing female voice—soprano or alto?

"9. Do the people generally sing without instrumental accompaniment?

"10. Have they songs performed in chorus by men only, or by women only, or by both sexes together?

"11. When they sing together, do they sing in unison, or in harmony, or with the occasional introduction of some drone accompaniment of the voice?

"12. Is their singing in regular time, or does it partake of the character of the recitative?

"13. Have they songs for solo and chorus,—or, with an air for a single voice, and a burden (or refrain) for a number of voices?

"14. Describe the different kinds of songs which they have (such as sacred songs, war-songs, love-songs, nursery-songs, etc.), with remarks on the poetry.

"Instruments:—

"15. What are their instruments of percussion (such as drums, castanets, rattles, cymbals, gongs, bells, etc.)?

"16. Have they instruments of percussion containing sonorous plates of wood, glass, stone, metal, etc., upon which tunes can be played? and if so, write down in notation, or in letters, the tones emitted by the slabs.

"17. Have they drums with cords, or some other contrivance by means of which the parchment can be tightened or slackened at pleasure?[Pg 27]

"18. Have they drums with definite tones (like our kettle-drums)? and, if so, what are the tones in which they are tuned when two or more are played together?

"19. Any open hand-drums with one parchment only (like our tambourine)?

"20. Are the drums beaten with sticks or with the hands?

"21. What wind-instruments (trumpets, flutes, etc.) have they?

"22. Any trumpets with sliding tubes (like the trombone)?

"23. How are the flutes sounded? is there a plug in the mouth-hole?

"24. Any nose-flutes?

"25. What is the number and the position of the finger-holes on the flutes?

"26. What tones do the flutes yield if the finger-holes are closed in regular succession upwards or downwards?

"27. If the people have the syrinx (or Pandean pipe), ascertain the series of musical intervals yielded by its tubes.

"28. Do the people construct wind-instruments with a vibrating reed, or some similar contrivance, inserted in the mouth-hole?

"29. If they have a reed wind-instrument, observe whether the reed is single (like that of the clarionet) or double (like that of the oboe.)

"30. Have they a kind of bagpipe?

"31. What musical instruments have they which are not used by them in musical performances, but merely for conveying signals and for such like purposes?

"32. Have they stringed instruments the strings of which are sounded by being twanged with the fingers?

"33. Any stringed instruments twanged with a plectrum?

"34. Any stringed instruments beaten with sticks or hammers (like the dulcimer)?

"35. Any stringed instruments played with a bow?

"36. If there are stringed instruments with frets on the neck (as is the case with our guitar), note down the intervals produced by the frets in regular succession.[Pg 28]

"37. What are the substances of which the strings are made?

"38. Is there any peculiar contrivance on some of the instruments in the arrangement and situation of the strings?

"39. Are there stringed instruments with sympathetic strings (i.e., strings placed under those strings which are played upon. The sympathetic strings merely serve to increase the sonorousness)?

"40. What are the musical intervals in which the stringed instruments are tuned?

"41. Do the people possess any musical instrument of a very peculiar construction? If so, describe it minutely.

"42. Give the name of each instrument in the language of the country.

"43. Describe each instrument, and give illustrations, if possible.

"44. Give some account of the makers of musical instruments; of the woods, metals, hide, gut, hair, and other materials they use; of their tools, etc.

"45. What are the usual adornments and appendages of the musical instruments?

"Compositions:—

"46. On what order of intervals is the music of the people founded? Is it the Diatonic Major Scale (like c, d, e, f, g, a, b, c)? Or the Diatonic Minor Scale (in which the third is flat; like c, d, e flat, f, g, a, b, c)? Or the Pentatonic Scale (in which the fourth and the seventh are omitted, thus c, d, e, g, a, c)? Or some other order of intervals?

"47. Is the seventh used sharp (c-b), or flat (c-b flat)?

"48. Does the superfluous second occur in the scale?

| (In the example c, d, e flat, f sharp, g, a flat, b, c, |

| └──┘ └─┘ |

| the steps from the third to the fourth, and from the sixth to the seventh, are superfluous seconds.) |

"49. Does the music contain progressions in semitones, or chromatic intervals?

"50. Are there smaller intervals than semitones, such as 1/3 tones, 1/4 tones?

"51. Are there peculiar progressions in certain intervals[Pg 29] which are of frequent occurrence in the tunes? If so, what are they?

"52. Do the tunes usually conclude on the tonic (the key-note, or the first interval of the scale), or, if not, on what other interval?

"53. Do the tunes contain modulations from one key into another? If so, describe the usual modulations.

"54. Are there certain rhythmical peculiarities predominant in the music? If so, what are they?

"55. Is the time of the music generally common time, triple time, or irregular?

"56. Are there phrases or passages in the melodies which are of frequent re-occurrence?

"57. Have the airs of the songs re-occurrences of musical phrases which are traceable to the form of the poetry?

"58. Have the people musical compositions which they regard as very old? and do these compositions exhibit the same characteristics which are found in the modern ones?

"59. Are the compositions generally lively or grave?

"60. Describe the form of the various kinds of musical compositions.

"Performances:—

"61. Have the people musical bands or orchestras?

"62. Which are the instruments generally used in combination?

"63. Which are the instruments commonly used singly?

"64. What is the number of performers in a properly constituted band?

"65. Is there a leader of the band? How does he direct the performers?

"66. Does the band play in unison or in harmony?

"67. If vocal music is combined with instrumental music performed by the band, is the instrumental accompaniment in unison (or in octaves) with the voice, or has it something of its own?

"68. Is the tempo generally fast or slow?

"69. Are there sudden or gradual changes in the tempo?

"70. Are there changes in the degree of loudness?[Pg 30]

"71. Do the musicians, on repeating a piece, introduce alterations, or variations of the theme?

"72. Do they introduce embellishments ad libitum?

"73. Mention the occasions (religious ceremonies, social and public amusements, celebrations, processions, etc.) on which musical performances take place.

"74. Are there military bands? and how are they constituted?

"75. Is music employed to facilitate manual labour?

"76. Are there songs or instrumental compositions appertaining to particular occupations or trades?

"77. Have the people a national hymn or an instrumental composition which they perform in honour of their sovereign or in commemoration of some political event?

"78. Describe minutely the musical performances in religious worship, if there are any.

"79. Have they sacred dances performed in religious ceremonies, at funerals, etc.?

"80. Any war-dances, dances of defiance, etc.?

"81. Any dances in which they imitate the peculiar movements and habits of certain animals?

"82. Are there dances accompanied by musical instruments, by singing, or merely by rhythmical sounds such as clapping of hands, snapping of fingers, reiterated vociferation, etc.?

"83. Give a list of all the dances.

"84. Endeavour to ascertain whether the rhythm of the music accompanying the dance is suggested by the steps of the dancers, or vice versâ.

"Cultivation:—

"85. Do the people easily learn a melody by ear?

"86. Have they a good musical memory?

"87. Are the children taught music? and if so, how is it done?

"88. Are there professional musicians?

"89. Any performers who evince much talent?

"90. Any minstrels, bards, reciters of old ballads?

"91. Any professional improvisators?[Pg 31]

"92. Are there professional musicians of different grades?

"93. Who composes the music?

"94. Do the musicians follow other professions besides music?

"95. Are the ministers of religion also musicians and medical men?

"96. Have the people some kind of musical notation?

"97. Have they written signs for raising or lowering the voice in singing, for giving emphasis to certain words or phrases, or for similar purposes? If so, describe the signs.

"98. Do they possess treatises on the history, theory, etc., of music; instruction books for singing, and for playing musical instruments, etc.? If so, give a detailed account of their musical literature.

"99. Have they musical institutions? Give an account of them.

"100. How do the people appreciate their own music?

"101. What impression does the music of foreign nations produce upon them?

"Traditions:—

"102. Are there popular traditions respecting the origin of music?

"103. Any myths about a musical deity, or some superhuman musician?

"104. Any legends or fairy-tales in which allusion to music is made? If so, what are they?

"105. Any tradition about the invention of certain favourite musical instruments?

"106. Any tradition or historical record respecting the antiquity of stringed instruments played with a bow?

"107. Any records respecting their sacred music?

"108. Is music believed to possess the power of curing certain illnesses?

"109. The power of enticing and taming wild animals?

"110. Are there popular tunes, or certain rhythmical figures in the tunes, which, according to tradition, have been suggested by the songs of birds?

"111. If there is anything noteworthy about music which has not been alluded to in the preceding questions, notice it."

In Thibet, and other Asiatic countries in which the Buddhist religion is established, variously-constructed musical instruments are generally deposited in a certain part of the temple, to be at hand for the priests when required in ceremonies and processions. In examining the Assyrian bas-reliefs in the British Museum, we are led to surmise that a similar custom prevailed in Western Asia before the Christian era. At any rate, it appears probable that the various instruments represented in the hands of musicians who assisted in religious rites observed by the king were usually deposited in a room appropriated to their reception. The same appears to have been the case in the Temple of Jerusalem. King David had, it is recorded, musical instruments made of a wood called berosh, which afterwards, under the reign of Solomon, were made of algum, or almug, a more precious wood imported from foreign districts. King Solomon, being in possession of superior instruments, probably preserved the inferior ones of his father as venerated memorials; and the kinnor upon which David played before Saul may have been as carefully guarded by King Solomon as the Emperor of Germany guards in his cabinet of curiosities the flute of Frederick the Great.

Howbeit, Josephus records that Solomon had made for the musical performances at the dedication of the Temple a large number of stringed instruments and trumpets, all of which were kept together in the Temple with the treasures. It is not likely that at so early a period collections of antiquated instruments were formed for any scientific purpose; the art of music was too much in its infancy to suggest the preservation of evidences elucidating its gradual development.[Pg 33]

The collections of ancient and scarce musical instruments which, in modern time, have been made in several European countries are very interesting to the lover of music, although they have, in most instances, evidently been formed less with the object of illustrating the history of the art of music than for the purpose of preserving curious and tasteful relics of bygone time, or of exhibiting characteristic contrivances of foreign nations.

In Italy some of the Conservatories of Music possess antiquated instruments of great rarity. Curious old spinets, lutes, mandolines, and guitars, are said to be found dispersed among private families and in convents, especially in Naples and its vicinity. In the Liceo Comunale di Musica, at Bologna, are deposited above fifty instruments, among which are an Italian cither (cetera) of the beginning of the sixteenth century; an archlute by "Hieronymus Brensius, Bonon" (Bologna); a chitarrone, by "Matteo Selles, alla Corona in Venetia, 1639;" a chitarrone inscribed "In Padova Uvendelio Veneto, 1609;" a theorbo by "Hans Frei in Bologna, 1597;" a lute by "Magno Stegher in Venetia." A lute, "Magno Dieffopruchar a Venetia, 1612." This lute has fourteen strings arranged in seven pairs, each pair being tuned in unison. Several marine trumpets, one of which bears the inscription, "Pieter Rombouts, Amsterdam, 17." A viola da gamba, inscribed "Antonius Bononiensis." A sordino, or pochette, by "Baptista Bressano," supposed to date from the end of the fifteenth century. Its shape is peculiar, somewhat resembling that of the Portuguese machête, representing a fish. A viola d'amore, with the inscription "Mattias Grieser, Lauten and Geigenmacher in Insbrugg, Anno 1727;" two curious old harps; an old tenor flute, measuring in length about three feet; some curious double flutes; cornetti, or zinken, of different dimensions. An archicembalo. This is a kind of harpsichord with four rows of keys, made after the invention of Nicolo Vicentino, and described in his work "L'Antica Musica ridotta alla moderna prattica. Rome, 1555." The compass of this archicembalo comprises only four octaves; but each octave is divided into thirty-one intervals, forming[Pg 34] in all one hundred and twenty-five keys. It was made by Vito Trasuntino, a Venetian, who lived towards the end of the sixteenth century, and who added a tetracordo to it, to facilitate the tuning of its minute intervals. However, the archicembalo was probably not the first instrument of the harpsichord kind which contained an enharmonic arrangement of intervals. The clavicymbalum perfectum, or Universal-clavicymbel, which Prætorius states he saw in Prague, and which was likewise made in the sixteenth century, was of a similar construction. One of the most singular instruments in the collection of the Liceo Comunale de Musica at Bologna is the cornamusa, which consists of five pipes inserted into a cross-tube, through which they are sounded. Four of the pipes serve as drones; and the fifth, which is the largest, is provided with finger-holes, like the chanter of a bagpipe. The instrument has, however, no bag, although it is probably the predecessor of the species of bagpipe called cornamusa.

Instruments played with a bow of the celebrated Cremona makers are at the present day more likely to be met with in England than in Italy. In the beginning of the present century Luigi Tarisio, an Italian by birth, and a great connoisseur and collector of old violins, hunted over all Italy and other European countries for old fiddles. To avoid the high custom dues which he would have had to pay on the old instruments, he took them all to pieces, as small as possible, and carried the bits about him in his pockets and in a bag under his arm. So thoroughly was he acquainted with his acquisitions that, having arrived at the place of his destination, he soon restored them to their former condition, assigning to each fragment its original position. Tarisio made his first appearance in Paris, in the year 1827, with a bag full of valuable débris from Italy; and he continued his searches for nearly thirty years. During this time he imported into France most of the beautiful violins by Antonius Stradiuarius, Joseph Guarnerius, Bergonzi, Montagnana, and Ruggeri, which are of highest repute, and the greater number of which have afterwards found their way into England.[Pg 35]

In Germany we meet with several collections of interest. The Museum of Antiquities, at Berlin, contains, among other musical curiosities, well-preserved lyres which have been found in tombs of the ancient Egyptians. The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde ("Society of Lovers of Music"), at Vienna, possesses a collection of antiquated instruments, among which are noteworthy: a viola di bardone by Jacobus Stainer, 1660; a viola di bardone by Magnus Feldlen, Vienna, 1556; a viola di bardone by H. Kramer, Vienna, 1717; a viola d'amore by Weigert, Linz, 1721; a viola d'amore by Joannes Schorn, Salzburg, 1699; a tromba marina (marine trumpet) by J. Fischer, Landshut, 1722; a lute by Leonardo Tieffenbrucker, Padua, 1587; a theorbo by Wenger, Padua, 1622; a theorbo by Bassiano, Rome, 1666; a Polish cither by J. Schorn, Salzburg, 1696; a large flute made in the year 1501; an old German schalmey (English shalm or shawm) by Sebastian Koch; an old German trumpet by Schnitzer, Nürnberg, 1598; an oboe d'amore, made about the year 1770, etc.

A curious assemblage of scarce relics of this kind is also to be found in the Museum of the Germanic Society at Nürnberg. The most noteworthy specimens in this collection are: two marine trumpets, fifteenth century; a German cither with a double neck (bijuga-cither) sixteenth century; a German dulcimer (hackbret), sixteenth century; a lute by Michael Harton, Padua, 1602; a viola da gamba by Paul Hiltz, Nürnberg, 1656; a viola d'amore, with five catgut strings, and eight sympathetic wire strings, seventeenth century; an arpanetta (harpanetta, German spitzharfe) mounted on one side with brass wire, and on the opposite side with steel wire, sixteenth century; a clavecin with finely painted cover, by Martinus van der Biest, Antwerp, 1580; two German zinken (cornetti) sixteenth century; two specimens of the bombardo, viz., a German alt-pommer and tenor-pommer, by J. C. Denner, seventeenth century; some specimens of the cormorne (German krummhorn) of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; a trumpet made by J. C. Kodisch, Nürnberg, anno 1690; a splendid brass trombone (German bass-posaune) ornamented with the[Pg 36] German eagle and imperial crown, made by Friedrich Ehe, in Nürnberg, anno 1612; a Polish bagpipe, seventeenth century; a syrinx of reeds covered with black leather, sixteenth century; eight military pipes, made by H. F. Kynsker, in Nürnberg, seventeenth century; a small portable organ (regal) with two rows of keys, sixteenth century. The regal has become very scarce. There are only a few specimens known to be in existence; one, of the sixteenth century, is in the possession of the Chanoinesses de Berlaimont, at Brussels; another, made about the middle of the seventeenth century, belongs to the Duke of Athol, and is at Blair Athol, in Scotland; another, which belongs to Mr. Wyndham S. Portal, Malshanger, Basingstoke, is in the shape of a book, and its pipes have reeds, or vibrating tongues of metal. This regal, which probably dates from the sixteenth century, is of the kind which was called in German Bibelregal, because it resembles a Bible in appearance.

Old musical instruments are generally so fragile, and were formerly thought so little of when they came out of use, that it is perhaps not surprising to find of those dating from a period earlier than the sixteenth century very few specimens, and these have generally been altered, and it is seldom that they have been properly restored to their original condition. As an instance how valuable specimens are gradually becoming more and more scarce, may be mentioned the interesting collection of obsolete German harps, pipes, and trumpets, dating from a period anterior to the year 1600, which was preserved in the Town Library of Strassburg, and which, at the recent bombardment of the town, was reduced to ashes. It contained, among other curiosities: a cornetto curvo; some specimens of the cornetto dritto; a flauto dolce. Several specimens of the bombardone, the predecessor of the bassoon; a dulcinum fagotto; two specimens of the cormorne, an oddly-shaped wind instrument belonging to the shalm or oboe family. An arpanetta. This instrument, called in German spitzharfe or drathharfe, is especially interesting, inasmuch as it resembles the old Irish harp called keirnine, which was of a similar form, and which was also strung[Pg 37] with wire instead of catgut. There is such a harp extant in the museum of the Society of Lovers of Music, at Vienna, before-mentioned.

If the lumber-rooms of old castles and mansions in Germany were ransacked for the purpose, some interesting relics of the kind would probably be brought to light. In the year 1872 Dr. E. Schebeck, of Prague, was requested by Prince Moriz Lobkowitz to examine the musical instruments preserved in Eisenberg, a castle of the Prince, situated at the foot of the Erzgebirge, in Bohemia. Most of them had formerly been used in the private orchestra kept by Prince Josef Franz Maximilian Lobkowitz, the well-known patron of Beethoven, to whom the composer has dedicated some of his great works. The present Prince Lobkowitz, who seems to have inherited his parent's love for music, wished to have an examination of the instruments, with the object of making a selection of the most interesting ones for the great Vienna Exhibition in 1873. Dr. Schebeck found, among other rarities, violins by Gaspar di Salo, Amati, Grancino, Techler, Stainer, and Albani; a violoncello by Andreas Guarnerius; a scarce specimen of a double-bass by Jacobus Stainer; two precious old lutes by Laux Maler, who lived at Bologna during the first half of the fifteenth century; a lute, highly finished, and apparently as old as those of Laux Maler, with the inscription in the inside "Marx Unverdorben a Venetia;" a lute, with the inscription "Magno Dieffoprukhar a Venetia, 1607." There can be no doubt that we have here the Italianised name of the German Magnus Tieffenbrucker, who lived in Italy.[5]

Fortunately for musical antiquarians the collection of rare instruments in the Conservatoire de Musique at Paris has been preserved uninjured during the recent disasters in that city. Among the instruments may be noticed, a small and beautiful musette with drones of ivory and gold, which belonged to Louis XIII.; a German regal, or portable organ, sixteenth century; a pochette by Stradiuarius; a courtaud, an early kind of bassoon, dating from the fifteenth[Pg 38] century; several bass-flutes, and other rare old wind instruments; Boïeldieu's pianoforte; Grétry's clavichord; a "Trumpet of Honour," which was made by order of Napoleon I., and which has the name of "T. Harper" engraven on its silver rim. M. Victor Schœlcher has presented to the Conservatoire de Musique about twenty rather primitive instruments of uncivilised nations obtained by him during his travels in Western Africa and South America, among which may be noted several Negro contrivances of the harp and guitar kind.

An interesting catalogue of the instruments in the Musée du Conservatoire National de Musique has recently been published by Gustave Chouquet, the curator of the museum. It comprises 630 instruments, or portions of instruments, each fiddle-bow, mute, etc., being separately numbered. On the whole, the Paris collection, though large, is far less valuable than that of the South Kensington Museum.

One of the most valuable private collections ever formed of ancient musical instruments was that of M. Louis Clapisson in Paris. During a course of more than twenty years M. Louis Clapisson succeeded in procuring a considerable number of scarce and highly decorated specimens of instruments of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The collection has been dispersed since the death of its owner; a large portion of it is now incorporated with the collection of the Conservatoire de Musique at Paris, and some of its most valuable specimens were secured for the South Kensington Museum. It was, however, so unique that the following short survey of its contents will probably be welcome to the archæological musician.