The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Silent Readers, by

William D. Lewis and Albert Lindsay Rowland and Ethel J. Maltby Gehres

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Silent Readers

Sixth Reader

Author: William D. Lewis

Albert Lindsay Rowland

Ethel J. Maltby Gehres

Illustrator: Frederick Richardson

Edwin J. Prittie

Release Date: July 29, 2012 [EBook #40369]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SILENT READERS ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Douglas L. Alley, III and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

FORMERLY DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT, DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

DIRECTOR BUREAU OF TEACHER TRAINING AND CERTIFICATION, DEPARTMENT OF

PUBLIC INSTRUCTION, COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

CO-AUTHOR OF THE WINSTON READERS

| CHICAGO SAN FRANCISCO |

PHILADELPHIA | DALLAS TORONTO, CAN. |

Copyright, 1920, by

The John C. Winston Company

Copyright in Great Britain and the

British Dominions and Possessions

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A.

The purpose of this series. This series of readers is definitely designed to provide working material for the development of efficient "silent reading". It is not planned to compete with the many excellent series of readers now available. The authors believe that it will efficiently supplement the well-nigh universal school practice of conducting all reading lessons aloud.

Oral reading not sufficient. In the majority of classes the pupils are all supplied with the same text. One pupil reads aloud while the others are supposed to follow his reading silently. When he has finished his portion of the text, the teacher or the pupils make corrections of his pronunciation or phrasing, and the teacher may ask questions or add comments or explanations. This incentive to adequate expression by the reader is lacking because his classmates all have the text before them; it is natural for the hearers to read on ahead of the oral reader if the material is of interest; and it is perfectly easy for them to gaze absently at the book while employing their minds with matters wholly unrelated to the class exercise. Perhaps most important of all, reading aloud is an experience of rare occurrence outside the classroom, while silent reading is a universal daily experience for all but the illiterate.

The mechanics of reading are fairly well mastered in the third—some authorities say the second—grade. Some oral reading is doubtless desirable beyond these grades, but the relative amount should diminish rapidly.

Experts have recognized the importance of silent reading for many years. Briggs and Coffman showed its value in their book, "Reading in Public Schools," published in 1908. Studies in this field have been made by Gray, Starch, Judd, Courtis, Monroe, Kelly, and many others. They have made no attempt to deny that oral reading has a place in the curriculum, but have merely pointed out that from the third grade[Pg iv] on its place is less and less important in comparison with silent reading.

Reading to get the thought quickly. Once the mechanics of reading are mastered, the problem becomes one of speed and accuracy in thought-getting. Upon these two qualities depends the pupil's progress in school and his use of the deluge of ideas that appeal only through the printed page. If he reads and understands, if he quickly grasps the important idea from a mass of details, if he arranges the relations of the ideas presented, we say that he is good in geography, history, science, or mathematics. If he comprehends only slowly or fails to understand, he is a dullard or a defective.

Speed usually goes with comprehension. At first glance it would seem that comprehension would be inversely proportional to speed; that is, the greater the speed the poorer the comprehension and vice versa. The standard tests of Gray, Courtis, Kelly, and Monroe, however, which have been given to thousands of children, prove exactly the reverse. The rapid silent readers have almost invariably shown the best understanding of the matter read. It would thus seem that concentrated effort on either speed or comprehension would tend to improve the other factor. It is necessary, however, to test speed results carefully to insure conscientious reading of the text.

The material in these books. In selecting the material for these books the authors have purposely avoided the established paths of literary reputation, and have selected from a wide variety of sources interesting material representative of the printed matter the child will inevitably read. Every effort has been made to avoid the necessity of explanation by the teacher to elucidate the text. In general, the exercises have been under- rather than over-graded, as the pupil should read for content and should be as far as possible relieved from technical grammatical or vocabulary difficulties. Occasionally, however, in each book exercises somewhat more difficult or of a more or less unusual nature have been included,[Pg v] because everyone, old or young, is called upon to read a variety of material, and pupils should have some experience with selections that require special effort.

Why we read. Most of the reading which we do has one of three purposes: we read for information; we read for instruction; we read for appreciation or entertainment. These purposes are somewhat determined by the nature of the material read. Rarely do we read an encyclopedia article for appreciation. On the other hand, we lose ourselves in the quiet humor of Rip Van Winkle merely for entertainment through appreciation. Contrasted with this would be our reading of a biography of Irving in order to find out who were his American contemporaries. The boy who reads an explanation of how to make a rabbit trap with the purpose of making one is reading for instruction, while his father who scans the evening paper to see how his representative in Congress or the State Legislature voted on a bill is reading purely for information.

The Pedagogical Editing. The authors have kept constantly in mind the purposes of each selection in the directions they have given to the pupils. They have also had clearly in mind certain fundamental things that they wish pupils to learn and certain habits which they wish them to form by the use of these books. A perusal of the directions given before and after any given selection will suffice to make this purpose clear. For example, much attention is given to the writing of headings for certain parts of a selection or to the statement of the most important thought in a given paragraph. With increasing emphasis in the upper grades this type of exercise is developed into the complete outline. The authors believe that practice of this kind will develop in pupils the habit of looking for the important thought and of grouping around it related subordinate ideas. This is perhaps the habit most essential to good reading for instruction or information. On the other hand, selections which are of a purely literary character and which should be read for appreciation and entertainment are given without exhaustive notes or questions,[Pg vi] because minute discussion of this kind of reading would detract from its value.

Method of handling the books. Many teachers will prefer to keep the books in the class room, distributing them at the time of the silent reading lesson and collecting them again at its conclusion. In this way the material will remain fresh, and the drill exercises will always be under the control of the teacher.

In many places, however, text books are not supplied by the school authorities, but are purchased by the pupils directly. Inasmuch as this series of books contains all the necessary instruction for the use of each exercise, they become peculiarly helpful where the pupil is thrown upon his own resources. He is able to test his own speed and comprehension and his ability to analyze or outline any of the material by the plain directions that are given for handling the books. Although the instructions accompanying various selections are addressed to the pupils, they contain suggestions for the teacher. It is, therefore, important that the teacher read in advance of the lesson such instructions or comments as appear before or after the text or the particular exercise to be read.

Speed drills. As much of the value of teaching silent reading lies in the development of speed, a number of exercises are designated as speed drills. For these drills it is suggested that the teacher prepare, on the mimeograph if possible, a considerable number of slips to be filled out arranged as follows:

| 10/4/22 | 5A | G. P. W. | |||

| Date | Grade | Teacher's Initials or Room Number. |

| Name of Exercise | Page |

| Pupils | Time in Minutes |

| Brown, Mary | 5½ |

| Carmalt, Joseph | 3 |

| Derr, Jane | 4 |

| Eldridge, Henry[Pg vii] | 5 |

| Fisher, Mary | 5½ |

| Green, Alice | 6 |

| Hunt, Roy | 8½ |

| Knowlton, William | 5 |

| Manly, Rose | 4 |

| Morris, Mary | 4½ |

| Newton, George | 5 |

| Newton, Thomas | 4½ |

| Orr, Robert | 5 |

| Pierce, Helen | 6 |

| Porter, Clara | 5 |

| Roberts, John | 4 |

| Rowe, Gertrude | 6 |

| Smith, Fred | 5 |

| Vaughn, Lee | 6 |

| Wilson, Alice | 3½ |

1-3, 1-3½, 3-4, 2-4½, 6-5, 2-5½, 4-6, 1-8½.

Class median 5 Class mode 5

For a speed drill the teacher should have one of these slips and a watch with a second hand. A stop watch would be valuable. Directions should be given for all the pupils to begin reading at the same moment and raise their hands as a signal to the teacher when they have finished. The teacher should give the signal for them to begin as the second hand of her watch reaches sixty. As each pupil raises his hand indicating that he has finished, the teacher should note the time in half minutes opposite that pupil's name on the drill sheet. Any pupil's time should be indicated at the nearest half minute space. For example, a pupil who finishes at two minutes ten seconds should be marked as two minutes; one who finishes at two minutes twenty seconds, at two and one-half.

Mode and Median. In the illustration above, the sheet has[Pg viii] been filled with names and scores of a supposed fifth grade class of twenty pupils. On this sheet three minutes occurs once, three and one-half minutes once, four minutes three times, four and one-half minutes twice, five minutes six times, five and one-half minutes twice, six minutes four times and eight and one-half minutes once. The number occurring the largest number of times is five.

This number is called the "mode".

If all the scores are arranged in order with the highest score at the top and the lowest score at the bottom, the middle score in this series is called the "median" and is in this case also "five".

Individual scores. The class median or mode is, however, not so significant as the individual scores. The class score is always determined by the ease or difficulty as well as by the length of the particular exercise read. This makes comparison with other exercises almost valueless. The only significant comparison in this case is between individuals of the same class, and between the score of this class and of other classes of parallel grade who have read the same exercise.

Important facts for G. P. W., the class teacher, in this case are the individual scores and their relative standing. Roy Hunt, who took eight and one-half minutes to read this exercise, is the slowest reader on this occasion. Is this true of other occasions? If so, Roy needs special help and training. It is also clear that Joseph Carmalt and Alice Wilson are rapid readers and it is important to see that their comprehension of the exercise is also adequate. Thus, for the class teacher the important facts are the relative scores of the pupils both in comparison with other pupils and with the former scores of the same pupils.

Scale of approximate speed. The following scale of speeds by grades is based roughly on the Courtis standard tests and may be somewhat helpful to the teacher who may desire such norms.

| Grade | Words per minute |

| 4 | 140-180 |

| 5 | 160-200 |

| 6 | 180-220 |

| 7 | 190-230 |

| 8 | 200-240 |

Of course it must be recognized that no standard speeds are possible without also standardizing the material. To be absolutely accurate, each separate exercise should be its own speed standard. This, although possible, would be a device so cumbersome as to defeat its own purpose. Every bit of reading presents its peculiar difficulties, its slow spots, its points of interest, its urge to hurry on. These in turn vary with the apperception of the reader, with his peculiarities, his interests, and his motives. These largely determine his speed. The authors have thought it unwise in the vast majority of cases to indicate with any degree of definiteness the time required for various exercises. Their experience in trying out these exercises with different classes showed so wide a variation that it was thought that specific statements would tend only to mislead the teacher.

Testing Comprehension. It is, however, equally important that the teacher know that the pupils are understanding what they read. As each pupil is reading silently, there is no guarantee of comprehension without some form of check. This may be as simple a device as watching the expression of the children's faces to see registered there appreciation of the exercise read; or it may be as complex as a dramatic reproduction of the incidents.

Devices for checking comprehension are suggested in connection with each exercise. The more usual and effective methods of teaching comprehension are dramatization, reproduction, writing of headlines, development of outlines, expression of opinion based upon facts read, topical analysis, the naming of characters and statements of their relationships, and appreciation of ethical or artistic appeal.

The test material. The drill exercise, although modeled in some cases upon the standard reading and intelligence tests, expressly disclaim any attempt to displace or supersede these tests. The function of the two is wholly different. The material in the readers is for drill and improvement in speed and comprehension. The standard tests are for the measurement of achievement. No devices can be used as a measure until it has been standardized by application in thousands of concrete cases without substantial variation.

Standard Tests. This is the case with a number of standard tests now in general use. In the field of reading the most notable are the Courtis Standard Tests devised by S. A. Courtis, Director of Instruction, Teacher Training and Research, and Dean of Teachers College, Detroit, Michigan, and Walter S. Monroe, Professor of Education and Director of the Bureau of Educational Research, University of Illinois. The necessary instructions, record blanks and test sheets giving these tests may be obtained as follows:

Directions for Ordering Standardized Tests

| Test. | How many tests to order. | How many directions, record sheets, and other accessories to order. | Used in what grades. | Publisher. | Price. |

| Monroe's Standardized Silent Reading Tests | One copy of the test for each pupil. | All directions are printed on either the test or on the class record sheet. One record sheet is furnished with each 25 copies of the test. Additional copies may be ordered if desired. | 3 to 8 | Public School Publicity Co., Bloomington, Illinois. | Including complete directions and record sheets, 60c per 100 copies; postage extra, 9c per 100. |

| Courtis's Silent Reading Test No. 2 | One copy of the test for each pupil. | Folder B, Series R, contains detailed directions for giving the test and for scoring by the pupils. One copy is needed for each person giving the test. Folder D, Series R, contains detailed directions for completing the scoring, for recording the scores, and for calculating class scores. One copy is needed for each person giving the test. A class record sheet for recording the scores of a class is needed for each class. A school record and graph sheet for Silent Reading No. 2 is needed for each school. | 2 to 6 | S. A. Courtis. | Test only, $1.80 per 100; Folder B, 5c; Folder D, 5c; Class Record Sheet, 1½c each; Record Sheet No. 3 and Graph Sheet 1½c each. |

These tests should be given at least once a year and if possible semi-annually in order to determine progress in speed and comprehension in silent reading, as well as to measure the pupils by a well established standard.

Topical recitation. Particular emphasis, especially in the later grades, should be placed upon the complete presentation of a topic by a pupil standing in front of the class and making the group understand what he has to say without questions by the teacher. More and more this is coming to be emphasized as a means of good teaching everywhere; and pupils are being trained to stand before a group of their classmates and give an intelligent account of anything of which they have adequate knowledge without the painful tooth-pulling process of extracting ideas.

The philosophy of study. One of the most important results of efficient teaching of silent reading is the contribution which it makes to the whole problem of study in the school. Briggs says that the primary purpose of the school is to teach people to do better the desirable things that they are likely to do anyway. One of the desirable things that school children are not only likely but certain to have to do is to study. A large portion of the studying that the child as well as the adult does consists in the acquirement of information from the printed page. It is essentially silent reading. Much of the difficulty teachers now meet in the inability of their pupils to study will be dispelled by effective teaching of silent reading. Probably no use of the same amount of time would yield more definite and valuable results than will thorough instruction in the process of thought getting from a printed page—in other words—silent reading.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following authors and publishers for their courtesy in allowing the use of the copyrighted material in this volume: to J. Russell Smith for "The Eskimo" and "Otelne, the Indian of the Great North Woods"; to A. and C. Black for five selections from the series "Peeps at Many Lands"; to Augustus R. Keller and Company for Oscar Wilde's "The Happy Prince"; to J. Berg Esenwein for two selections from "Stories for Children and How to Tell Them"; to W. F. Quarrie and Company for four selections from "The World Book"; to The Youth's Companion for John Clair Minot's "Pietro's Adventure", and "Noblesse Oblige"; to the J. B. Lippincott Company for "The Mole Awakes" from Dr. S. C. Schmucker's "Under the Open Sky", and "A Trip to the Moon" from Charles R. Gibson's "The Stars and Their Mysteries"; to D. Appleton and Company for two selections from the "Boy Scouts' Year Book"; to the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia for C. A. Sienkiewicz's "The Safest Place"; to the Association Press for "The First Potter" and "The Fire Spirit" from Hanford M. Burr's "Around the Fire"; to Boys' Life, the Boy Scouts' Magazine, for "The Ghost of Terrible Terry"; to Longmans, Green and Company for "The Boyhood of a Painter", from Andrew Lang's "The Strange Story Book"; and to the Public Ledger of Philadelphia for "General Pershing's Welcome Home". Henry W. Longfellow's "The Skeleton in Armor" is used by permission of, and under arrangement with, Houghton Mifflin Company, authorized publishers.

The authors of The Silent Readers wish to acknowledge the careful and efficient assistance of Miss Mabel Dodge Holmes of the William Penn High School of Philadelphia, and of Superintendent Sidney V. Rowland of Radnor Township, Pa.

| Page | ||

| Silent Reading | 1 | |

| The Eskimo | J. Russell Smith | 2 |

| Scottish Border Warfare | Elizabeth Grierson | 9 |

| The New Wonderland | Mabel Dodge Holmes | 11 |

| Bristol | 16 | |

| On the Frontier | 18 | |

| The Happy Prince | Oscar Wilde | 19 |

| Can You Follow Directions? | 29 | |

| Feeding French Children | 30 | |

| Genevieve's Letter | 34 | |

| Travel | Robert Louis Stevenson | 35 |

| How the Wish Came True | 36 | |

| Rules for Using the Eyes | 37 | |

| Acting for the Movies | 38 | |

| Clear Thinking | 40 | |

| The Land of Equal Chance | 41 | |

| The Broken Flower-Pot | Bulwer-Lytton | 46 |

| Saint George and the Dragon | 51 | |

| Nonsense Test | 56 | |

| Turning Out the Intruder | 57 | |

| Roosevelt's Favorite Study | William Draper Lewis | 58 |

| What a Chimney Is | 61 | |

| Is It True? | 62 | |

| Franklin Writes for the Newspaper | 63 | |

| Yes or No? | 64 | |

| How to Make a Sun-Dial | 65[Pg xiv] | |

| Putting Words Where They Belong | 67 | |

| An Indian Buffalo Hunt | 68 | |

| Indian Life and Customs | 76 | |

| Can You Understand Relationship? | 89 | |

| Opening the Great West | 90 | |

| Turning Out the Intruder | 96 | |

| The Training of a Boy King | H. E. Marshall | 97 |

| "Some Ugly Old Lawyer" | 103 | |

| Adding the Right Words | 104 | |

| The Desert Indians' "Fire Bed" | 105 | |

| Yes or No? | 105 | |

| Pietro's Adventure | John Clair Minot | 106 |

| Some Patriotic Mine Workers | 111 | |

| Father Domino | 112 | |

| The Good Giant Wins His Fortune | 116 | |

| The Mole Awakes | S. C. Schmucker | 117 |

| The Count and the Robbers | Beatrix Jungman | 119 |

| What the Earliest Men Did for Us | Smith Burnham | 124 |

| Try This | 136 | |

| Putting Words Where They Belong | 137 | |

| Making Money Earn Money | 138 | |

| Heroes of History | Mabel Dodge Holmes | 139 |

| The Skeleton in Armor | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | 149 |

| Acting for the Movies | 156 | |

| The Safest Place | Casimir A. Sienkiewicz | 158 |

| Unpatriotic Carelessness | 167 | |

| A Memory Test | 169 | |

| Caliph for One Day | 170 | |

| The First Potter | Hanford M. Burr | 180 |

| Finding Opposites | 187[Pg xv] | |

| "It's Quite True!" | Hans Christian Andersen | 188 |

| Tangled Sentences | 191 | |

| How Sella Lost Her Slippers | Mabel Dodge Holmes | 192 |

| The Ghost of Terrible Terry | 198 | |

| Roast Chicken | 203 | |

| Why the Echo Answers | Mabel Dodge Holmes | 204 |

| The Fight with the Sea | Beatrix Jungman | 207 |

| Agriculture | 210 | |

| Can You Do this One? | 215 | |

| The Inchcape Rock | Robert Southey | 216 |

| Some Definitions | 218 | |

| The Battle of Morgarten | John Finnemore | 219 |

| Finding Opposites | 222 | |

| What Mekolka Knows | 223 | |

| The Bear's Night | 228 | |

| Is It the Same Bear? | 231 | |

| The Chinese New Year's Day | Lena E. Johnston | 232 |

| Adding the Right Words | 235 | |

| The Good Citizen—How He Uses Matches | 236 | |

| Noblesse Oblige | 242 | |

| The Magic Horse | 243 | |

| Thinking | 255 | |

| What is a Boy Scout? | 256 | |

| The Scout and the Knight | 258 | |

| The Fire Spirit | Hanford M. Burr | 259 |

| The Boyhood of a Painter | Andrew Lang | 273 |

| Civil Death | 277 | |

| Otelne, The Indian of the Great North Woods | J. Russell Smith | 278 |

| Which is Right? | 288[Pg xvi] | |

| "Verdun Belle" | 290 | |

| Another Nonsense Test | 296 | |

| Can You Understand Relationship? | 297 | |

| Charades | 298 | |

| General Pershing's Welcome Home | 299 | |

| The Fairies on the Gump | Mabel Quiller-Couch | 303 |

| Thinking and Doing | 312 | |

| A Trip to the Moon | Charles R. Gibson | 312 |

The book which you are now beginning is, as its title tells you, a silent reader; that is, a reader that you are to read to yourself, silently. It is much more interesting to read silently than to read aloud, and it is also much faster. With all the wonderful books and valuable articles that are being printed every day, it is important that you learn to read rapidly as well as to understand.

The purpose of this book is to help you to read fast and to understand clearly what you read. You will find all sorts of reading; animal stories, poems, fairy tales, problems, descriptions of strange places, puzzles, war stories, and lots of other things. We think you will find it very interesting, but the important thing is to use all this material to make yourself a rapid and at the same time a careful reader.

Of course you are much too old to move your lips when you read. If you have this habit you must break it at once, for you will never read rapidly as long as you continue to pronounce words even to yourself. It takes just as long to pronounce a word to yourself as to read it aloud. You must learn not to do so, if you are to gain speed in reading.

Your teacher is going to help you in every possible way and will frequently time you when you read and then test you to see if you have understood what you have read. But you will have to do the most yourself if you are really to learn to read rapidly and well.

You will be able to remember what you read and to tell about it much better if you form the habit of making a brief outline as you go along. You can learn to make this outline without writing anything down, but in the beginning it would be a good plan to write down the topics as you come to them.

At the end of this selection you will find suggestions for making an outline.

Suppose there was no grocery where you could get bread or flour or potatoes, no meat shop, no milk dealer. Make it worse and suppose there was no place where you could buy clothes, shoes, coal or wood, balls or bats, sleds or knives. Suppose you had to go without all these things unless your father and mother or brothers and sisters helped you to make them. You would all have to work very hard and even then be poor, and often hungry, cold, and wet. You could not live in town because there is not ground enough there to raise potatoes and other things to eat. You would have to live in the country, where there is more land near each home. Your father would have to learn how to build a house, how to make shoes, how to make his tools, and how to do many things which the people you know never need to think about now. Your mother would have to make even the cloth for your clothes and to prepare all the food you had. That is, your family would have to make everything that you had in your home, or that you ate, or wore, or played with, or used in the garden. They would be busy all the time. Every family would have to have more businesses or trades than you can find in some small towns, and many of the things you have now they could not make at all, so you would not have them. For a long time, a very long time, that is the way people[Pg 3] used to live all over the world. It was a hard life. There are even yet many places where people do not use machines and where every family makes everything for its own use.

The Eskimos live that way. Their country is far away to the north. It is a very poor, cold country, where very few things will grow, so there are not many Eskimos. Robinson Crusoe tried living all by himself for a while, but he had a lot of tools from the ship, and his island was rich in food and wood. He found goats there that gave milk; he found good wild grapes and other fruits; but he said he had to work very hard, even though he did not have any family to support. The Eskimo country is much poorer than Crusoe's island. It is away up north where the winter is very long and cold, and the summer is so short that no trees grow, and there are not many other plants. The Eskimo has no animals to give milk; he never heard of potatoes or bread, to say nothing of cake.

It is hard to get the things you need in such a country. For a winter house the Eskimo often builds a little hut of snow. Many boys and girls in the cooler parts of the United States and Canada have built a little snow house for sport, but the Eskimo finds it the warmest house he can get. If it has a window, you cannot see through it, for it is a piece of fish skin that looks like dirty glass. To keep the cold out he makes the doorway so low that people must crawl in. Then he builds a long tunnel outside the door to keep the wind out, and puts a chunk of snow in the outer end of the tunnel for a door. Along the sides of the house inside is a bank of snow covered with skins. This is both chair and bed.

If he made the room as warm as we make our houses, the roof would melt and drip down his neck. But he does not have enough fire to warm it much anyhow. The little fire he has for cooking is made by burning the fat of animals in an oil lamp.

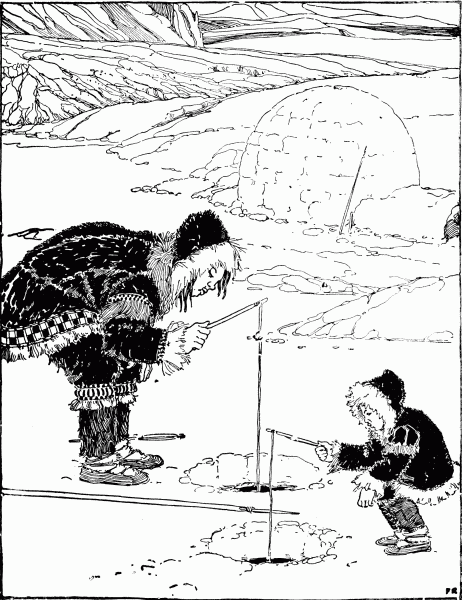

The Eskimo Boy and His Father Fishing

Not long ago a man named Rasmussen, whose father[Pg 5] was a missionary in Greenland and whose mother was an Eskimo, made a long journey through Eskimo land. At one place he found a dead whale on the seashore and the Eskimos there felt as rich as we should if a carload of coal or fire-wood were dumped down in the yard. They were busy tearing off strips of the fat, called blubber, that lies under the whale's skin. Some of them were hauling it two days' journey on their sleds. Some of the people Rasmussen saw had never even heard of white men or of any of the things the white man makes. They themselves had to make everything they had.

Their boats (or kyaks) were of seal skins sewed into a water-tight sheet and stretched over a frame-work of whale rib bones and long walrus tusks, tied together with sinews and strips of leather. In these tiny boats they paddle around in the sea and catch seals with spears.

Nearly all the Eskimos live along the seashore where they can catch fish, seals and walrus. The seal is the greatest wealth the Eskimo has. The seal eats fish and keeps warm in the ice-cold water because he has a coat of soft, fine, water-proof fur, and under his skin a thick layer of fat. Seal meat is bread to the Eskimo. He cooks with seal fat and makes clothes, boats, and tents of the sealskin.

In winter the Eskimo wears two suits of fur, one with the fur inside and the other with the fur outside. In summer one suit is enough.

When spring comes and the snow house begins to melt, the Eskimo moves into his sealskin tent or into a stone hut chinked with dirt. Some of these stone huts are hundreds of years old. Toward the end of summer there are some[Pg 6] berries that get ripe on low-growing bushes, and many bright flowers bloom in the northland. Then the Eskimos sometimes make trips inland. They eat berries, rabbit meat, birds, and wild reindeer. Wild ducks and many other birds are there in summer, but they fly away to warm lands when cold weather comes, and the people go back to the seashore to lay in their winter supply of seal meat.

The wild animals that live here all the time do not seem to mind the cold. They have warm fur, and the rabbit changes his color to keep from getting caught. He is snow white in winter so that the fox cannot see him on the snow, but in summer his coat is brown so that the fox cannot see him on the ground.

The Eskimo has one helper, the dog that pulls his sled. We call him the "huskie". This dog has a thick, warm coat so that he can curl up in the dry snow, put his four feet and his nose into a little bunch, lay his bushy tail over them, and sleep through a blinding snow storm that would freeze a white man to death. Sometimes the snow covers him entirely as he sleeps and he has to dig himself out when he wakes up.

When Admiral Peary went over the ice to the North Pole, in 1909, Eskimo dogs pulled the sleds that carried his food and tents, and Eskimo men helped him. He found them to be honest, brave men, trusty helpers, and good friends.

The Eskimos are very fond of games. They play football and several kinds of shinny, using long bones for shinny sticks. Sometimes they skate on new smooth ice, using bone skates tied fast to their soft shoes. As they do not go to school and have no books, the days must seem long in bad weather, for they have nothing to do but sit around the little fire in the dark smoky little snow house. They have many indoor games. The house is too small to play[Pg 7] tag or run around, so they have sitting down games. There are as many as fifty kinds of string games something like our cat's cradle.

This is the simplest kind of living to be found anywhere in the world. Every family in the world needs a certain amount of food, clothes, fuel, shelter, tools, and playthings. In different countries there are different ways of getting these things, depending on the weather, on the things that will grow, and the things that man finds in the ground, or in the woods, or in the sea. Each Eskimo family must make or get all these things for itself.

The Eskimos do not need money because they do not buy nor sell. If two Eskimos should meet and want to trade two dogs for a sled, they would just trade as two schoolboys swap knives. The Eskimos would be much more comfortable if they could trade some of their sealskins for lumber to build houses and for flour and dried fruit to eat with their never ending meat. We cannot trade with them because they are too far away for us to build railroads to their land, and the sea is so full of ice that ships cannot get through it Perhaps the aeroplane will let us see more of the Eskimo.

Questions

Glance quickly at the first paragraph. How would this do as a title or topic for it: "Doing things for yourself"?

The second paragraph connects the idea that it is very hard to do everything for yourself with the various things told about the Eskimo in the rest of the story. So that you may understand better, the Eskimo is compared with Robinson Crusoe, who had to do everything for himself but had a better chance because of the country in which he lived. A topic for the[Pg 8] second paragraph might be, "The Eskimo's life compared with Robinson Crusoe's".

Beginning with the third paragraph, the author tells how the Eskimo lives. It is not necessary to make a topic for every paragraph. We can make a general heading under which some of his ways of living can be grouped. Arrange the heading and the sub-headings as follows:

How the Eskimo manages to live.

(a) His house.

(b) His food,

(c) His clothing.

Now look through the rest of the story, and you will see that it can be included under the following headings:

The Eskimo dog.

Eskimo games.

Why the Eskimo does not buy and sell.

In making an outline it is not necessary to put in every single idea in the piece you are outlining.

Now, after going through the selection to see how the outline is made, you can easily answer the following questions:

1. How does it happen that you do not have to depend on your own family for the things you eat and wear and use? Make a list of the people who help you to get the things necessary for every-day life. Your list might begin with the baker, the milk-man, and the shoemaker.

2. Try to draw a picture of the outside of the Eskimo's winter house as it is described here.

3. Make a list of the things you think an Eskimo boy or girl about your age would do from morning to night—his day's program, you may call it.

4. Do you think the Eskimo is glad when summer comes? Why?

5. Tell a story that a "huskie" might tell of his experiences.

6. Make a list of raw materials, such as wood, that would make the life of the Eskimo more comfortable.

From your study of the way to make an outline of "The Eskimo", you will be able to make an outline of "Scottish Border Warfare" yourself.

Read the selection through, and then go back and write topics that cover the main points.

Legends of the Scottish borders tell the exciting stories of a warfare that went on for a hundred years, in the days before England and Scotland were united. The "Borders" consisted of that part of the country in the South of Scotland where the boundary was not properly fixed. The King of England might claim a piece of land that the King of Scotland thought was his, and the King of Scotland might do the same by the King of England. And so, because things were never really settled in these parts, and men thought they could do pretty much as they liked, a constant warfare sprang up between the families who lived on the English side of the border and those who lived on the Scottish side. These families formed great clans, almost like the Highland clans, and every man in the clan rose in arms at the bidding of his chief.

The warfare which they carried on was not honest fighting so much as something that sounds to us very much like stealing; only in these old plundering, or "reiving" days, as they were called, people were not very particular about other people's property, and right was often decided by might. So when these old Border chieftains found that their larders were getting empty, they sent messages around the countryside to their retainers, telling them to meet them that night at some secret trysting-place, and ride with them into England to steal some English yeoman's flock of sheep.

In the darkness, groups of men, mounted on rough, shaggy ponies, would assemble at some lonely spot among the hills and ride stealthily into Cumberland or Northumberland, and surround some Englishman's little flock of sheep, or herd of cattle, and drive them off, setting fire, perhaps, to his cottage and haystacks at the same time.

The Englishman might be unable to retaliate at the moment, but no sooner were the reivers' backs turned than he betook himself with all haste to his chieftain, who, in his turn, gathered his men together, and rode over into Scotland to take vengeance, and, if possible, bring back with him a larger drove of sheep and cattle than had been stolen, or "lifted", by the Scotch.

And so things went merrily on, with raids and counter-raids, and fierce little encounters, and brave men slain. You can read the accounts of many of these raids in Sir Walter Scott's "Border Minstrelsy"—about "Kinmont Willie," "Dick o' the Cow," "Jamie Telfer of the Fair Dodhead," "Johnnie Armstrong," and "the Raid of the Reidswire"—and if you ever chance to be traveling between Hawick and Carlisle you can look out of the window, as the train carries you swiftly down Liddesdale, and people the hillsides, in your imagination, with companies of reivers setting out to harry their "auld enemies", the English.

Questions

1. What were the "Borders"?

2. From the way they are used, tell what you think the following words mean: "reiving," larders, retainers, clan, trysting-place, yeoman, retaliate, "lifted," harry.

You have probably, like Betty, the little girl in this story, read "Alice in Wonderland". If you haven't, you will find out, before you have read very far on this page, when Alice lived. Glance at the first part of the story and see.

Alice, in the book that Betty had been reading, had wonderful adventures in a strange country, where rabbits and caterpillars talked, and where certain kinds of cake made you grow taller or shorter, and where people put pepper in tea. Anybody would think a country like that was a Wonderland; but you will see that Alice found our everyday, twentieth-century world is a Wonderland, too. See if you can tell why she thought so.

Betty laid down her book with a sigh. It had been a lovely book, and she was sorry it was finished. "Such a humdrum old world!" she said discontentedly. "I wish I had a chance to go to Wonderland, like Alice."

"Why," said a voice from the doorway, "isn't this Wonderland, then?"

Betty looked up, startled. She saw a little girl of about her own age, with long, light, straight hair hanging to her waist, with wide, wondering blue eyes, and dressed in the simplest, most old-fashioned of little white frocks.

"Who are you?" inquired Betty.

"Why, don't you know me? I'm Alice," said the quaint little girl.

"How did you get here? I thought you lived a long time ago, in 1850 or so."

"Oh, yes, I did begin to live then; but you see I've been traveling in Wonderland so long that I've never had time to grow up."

"Aren't you sorry to have come back to real life, and begin to do lessons, and mind what the older people say, and all?"

"Oh, but I haven't! Of course, I suppose the people in Wonderland don't know they are queer, and so that's why you don't know you live there."

"Well," said Betty scornfully, "I'm sure I don't see anything to wonder at in this old place—" Just then a bell rang sharply, and Betty hurried to answer the telephone. It was her father speaking. She took his message and returned to her guest.

"What in the world," said Alice, "made you talk into that little black cup?"

"Why, that's the telephone."

"What's a telephone? We didn't have them in my time, I'm sure."

"Oh, everybody has one now. It lets you talk to somebody 'way off, over an electric wire."

"Of course, we read about Franklin and his kite and all that. Let me try it." But when the operator's voice saying "Number, please?" came to Alice's ear, she was so frightened that she dropped the receiver.

"I can show you lots more things we do with electricity," said Betty, beginning to understand that things which were commonplace to her were wonders to her visitor. "You see it's getting dark? Now watch." Going to the push-button in the wall she snapped on the light; Alice jumped at its suddenness.

"Why, at home we had to find matches and light a lamp," she said in amazement.

"That's nothing," said Betty. "Come along." She led her new friend into the dining room, and showed her how, by pressing a button, the rack could be heated for toasting bread, or heat supplied for the coffee pot. Then they went on into the kitchen, and she showed Alice the gas stove, where a flame sprang into life at the turning of a handle; and the washing-machine, where the pressing of another button set the clothes to churning up and down in the suds; and the electric iron, heated by the pressing of still another button.

Betty Showed Her the Victrola

"Why, nobody needs to do any work at all," said Alice[Pg 14] admiringly, while Betty began to feel that after all she had a great many remarkable things in her house, which she had never thought much about because they had always been there. As they walked back into the hall, they heard a click-clicking sound.

"What's that?" said Alice.

"Oh, it's just my big brother's wireless apparatus catching a message. If he were here he could tell us what it says."

"What's a wireless?"

"Why, you don't know anything much, do you?" Betty explained as well as she could about the wireless telegraph.

"Goodness! That's like real magic. You must feel as if you were living in a fairy story."

Betty had never thought of life in that way, and was about to tell Alice how really dull a time she had, when a sound of music interrupted them.

"Oh, how lovely! Somebody's singing!"

"No, you little goose, that's only the victrola," answered Betty.

"What's a victrola?"

Betty tried to explain that it was a machine that caught and imprisoned somebody's voice or the music of some instrument. But Alice couldn't understand. Even when Betty showed her the victrola, and the record, she could hardly believe that a real singer wasn't hidden somewhere making fun of her.

While she was still unpersuaded, Betty heard her father's[Pg 15] key in the lock. She knew the car must still be before the door.

"Father, father," she cried, "this is Alice—from Wonderland, you know. Won't you take us for a ride?"

"A little one," said Betty's father. Alice clapped her hands, for she loved to go driving. But when the two little girls were safely seated in the back seat, she began to wonder again.

"Where are the horses?" she inquired.

"Horses! Why, it's an automobile."

"What's an automobile?"

"Why, a carriage that runs of itself." The car started, and Alice understood without further explaining. She couldn't ask any more questions, because the rapid motion quite took away her breath.

Betty asked Alice to spend the night with her, and promised that next morning she would take her to town and show her some more of the sights of the New Wonderland. She went to sleep feeling that after all it wasn't such a humdrum world, and that she had taken for granted a great many things that, when you came to think of it, really made life a fairy tale, and the world Wonderland.

Questions

1. Alice was no more surprised than any little girl of 1850 would be. What has happened in the world since that time to make it a Wonderland?

2. Why was the telephone a wonder to Alice?

3. Make a list of the wonders Betty showed Alice. Add to this list any similar wonders that you could show her in your house.

4. Can you think of some of the wonders that Betty showed Alice in their trip to the city?

Here is an account of the City of Bristol taken from an encyclopedia. Without reading the whole account, find as quickly as possible the answer to each of the following questions, in order.

1. Where is Bristol?

2. Is it an attractive city?

3. Is it an industrial city?

4. Is it a healthy city?

5. Are there many public buildings there?

6. If you had children could they be well educated there?

7. Has it had any famous citizens?

8. Is it a seaport or an inland city?

9. Is it a large city?

Bristol, a cathedral city of England, situated partly in Gloucestershire, partly in Somersetshire, but forming a county in itself. In 1911 it had a population of 357,059. It stands at the confluence of the rivers Avon and Frome, which unite within the city whence the combined stream (the Avon) pursues a course of nearly seven miles to the Bristol Channel. The Avon is a navigable river, and the tides rise in it to a great height. The town is built partly on low grounds, partly on eminences, and has some fine suburban districts, such as Clifton, on the opposite side of the Avon, connected with Bristol by a suspension bridge 703 feet long and 245 feet above high-water mark. The public buildings are numerous and handsome, and the number of places of worship very great. The most notable of these are the cathedral, founded in 1142, exhibiting various styles of architecture, and recently restored and enlarged; St. Mary Redcliff, said to have been founded in 1293, and perhaps the finest parish church in the kingdom. Among modern buildings are the exchange,[Pg 17] the guild-hall, the council house, the post office, the new grammar school, the fine arts academy, the West of England, and other banks, insurance offices, etc. The charities are exceedingly numerous, the most important being Ashley Down Orphanage, for the orphans of Protestant parents, founded and still managed by the Rev. George Müller, which may almost be described as a village of orphans. Among the educational institutions are the University College, the Theological Colleges of the Baptists and Independents, Clifton College, and the Philosophical Institute. There is a school of art, and also a public library. Bristol has glassworks, potteries, soap works, tanneries, sugar refineries, and chemical works, shipbuilding and machinery yards. Coal is worked extensively within the limits of the borough. The export and import trade is large and varied, it being one of the leading English ports in the foreign trade. Regular navigation across the Atlantic was first established here, and the Great Western, the pioneer steamship in this route, was built here. There is a harbor in the city itself, and the construction of new docks at Avonmouth and Portishead has given a fresh impetus to the port. The construction of very large new docks was begun in 1902. Bristol is one of the healthiest of the large towns of the kingdom. It has an excellent water supply chiefly obtained from the Mendip Hills.—In old Celtic chronicles we find the name Caer Oder, or "the City of the Chasm", given to a place in this neighborhood, a name peculiarly appropriate to the situation of Bristol, or rather of its suburb Clifton. The Saxons called it Bricgstow, "bridge-place". In 1373 it was constituted a county of itself by Edward III. It was made the seat of a bisphoric by Henry VIII in 1542 (now united with Gloucester). Sebastian Cabot, Chatterton, and Southey were natives of Bristol.

The Setting for an Act in a Play

Your teacher will give the word when you are to begin. She will keep track of the time and will ask you to stop reading in thirty seconds. Then she will ask you, without looking back at the paragraph, to write answers to the questions at the end.

It is a blockhouse in a Kentucky clearing, at one of the outposts of civilization to be found all along the frontier of the United States at the close of the eighteenth century. The sun is about to rise and objects are only dimly seen through the early morning haze. The building itself is at the left. It is made of rough hewn logs. A closed door of heavy planks is shown in the front wall. The windows are narrow loop-holes through which can be seen from time to time the blue barrels of flint-lock rifles. The second story of the blockhouse projects over the first, so that anyone approaching the wall would be subjected to rifle fire from the floor above. A cleared space in front contains the stumps of several large trees, behind one of which may be seen a crouching Indian, invisible to the blockhouse but easily seen by the audience. Well back and at the right is a small stream. Beyond both right and back the forest extends indefinitely. Shadowy figures are moving among the trees.

Write answers to the following questions. Remember, that if you are really a good sport and play the game fairly, you will not look back at the paragraph you have just read.

1. Does the scene show a time of danger or of peace?

2. Are people within the blockhouse?

3. What means of defense has the blockhouse?

4. What time of day is it?

5. On which side of the stage is the blockhouse? the stream?

Here is a story of a golden statue and a little bird, both of whom sacrificed a great deal for the sake of others. As you read, see if you can tell which sacrificed more, and decide whether you are sorry for them because they gave up so much.

High above the city, on a tall column, stood the statue of the Happy Prince. He was gilded all over with thin leaves of fine gold, for eyes he had two bright sapphires, and a large red ruby glowed on his sword-hilt.

One night, there flew over the city a little Swallow. His friends had gone away to Egypt six weeks before, but he had stayed behind, for he was in love with the most beautiful Reed. He had met her early in the spring as he was flying down the river after a big yellow moth, and had been so attracted by her slender waist that he had stopped to talk to her.

After the other swallows had gone he felt lonely, and began to tire of his lady-love. "She has no conversation," he said, "and I am afraid that she is a coquette, for she is always flirting with the wind." And certainly, whenever the wind blew, the Reed made the most graceful curtsies. "I admit that she is domestic," he continued, "but I love traveling, and my wife, consequently, should love traveling also."

"Will you come away with me?" he said finally to her; but the Reed shook her head, she was so attached to her home.

"You have been trifling with me," he cried. "I am off to the Pyramids. Good-bye!" and he flew away.

All day long he flew, and at night-time he arrived at the city. "Where shall I put up?" he said. "I hope the town has made preparations."

Then he saw the statue on the tall column. "I will put up there," he cried; "it is a fine position, with plenty of fresh air." So he alighted just between the feet of the Happy Prince.

"I have a golden bedroom," he said softly to himself as he looked round, and he prepared to go to sleep; but just as he was putting his head under his wing a large drop of water fell on him.

"What a curious thing!" he cried, "there is not a single cloud in the sky, the stars are quite clear and bright, and yet it is raining. The climate in the north of Europe is really dreadful. The Reed used to like the rain, but that was merely her selfishness."

Then another drop fell.

"What is the use of a statue if it cannot keep the rain off?" he said; "I must look for a good chimney-pot," and he determined to fly away.

But before he had opened his wings, a third drop fell, and he looked up, and saw—Ah! what did he see?

The eyes of the Happy Prince were filled with tears, and tears were running down his golden cheeks. His face was so beautiful in the moonlight that the little Swallow was filled with pity.

"Who are you?" he said.

"I am the Happy Prince."

"Why are you weeping then?" asked the swallow; "you have quite drenched me."

"When I was alive and had a human heart," answered the statue, "I did not know what tears were, for I lived in the Palace of Sans-Souci (without care), where sorrow is not allowed to enter. In the daytime I played with my companions in the garden, and in the evening I led the dance in the Great Hall. Round the garden ran a very lofty wall, but I never cared to ask what lay beyond it, everything about me was so beautiful. My courtiers called me the Happy Prince, and happy indeed I was, if pleasure be happiness. So I lived, and so I died. And now that I am dead they have set me up here so high that I can see all the ugliness and all the misery of my city, and though my heart is made of lead yet I cannot choose but weep."

"Little Swallow, Will You Not Stay with Me for One Night?"

"What, is he not of solid gold?" said the Swallow to[Pg 22] himself. He was too polite to make any personal remarks out loud.

"Far away," continued the statue in a low musical voice, "far away in a little street there is a poor house. One of the windows is open, and through it I can see a woman seated at the table. Her face is thin and worn, and she has coarse, red hands, all pricked by the needle, for she is a seamstress. She is embroidering passion-flowers on a satin gown for the loveliest of the Queen's maids-of-honor to wear at the next Court-ball. In a bed in the corner of the room her little boy is lying ill. He has a fever, and is asking for oranges. His mother has nothing to give him but river water, so he is crying. Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow, will you not bring her the ruby out of my sword hilt? My feet are fastened to this pedestal and I cannot move."

"I am waited for in Egypt," said the Swallow. "My friends are flying up and down the Nile and talking to the large lotus-flowers. Soon they will go to sleep in the tomb of the great King. The King is there himself in his painted coffin. He is wrapped in yellow linen, and embalmed with spices. Round his neck is a chain of pale green jade, and his hands are like withered leaves."

"Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow," said the Prince, "will you not stay with me for one night, and be my[Pg 23] messenger? The boy is so thirsty and the mother is so sad."

"I don't think I like boys," answered the Swallow. "Last summer, when I was staying on the river, there were two rude boys, the miller's sons, who were always throwing stones at me. They never hit me, of course; we swallows fly far too well for that, and besides, I come of a family famous for its agility; but still, it was a mark of disrespect."

But the Happy Prince looked so sad that the little Swallow was sorry. "It is very cold here," he said; "but I will stay with you for one night, and be your messenger."

"Thank you, little Swallow," said the Prince.

So the Swallow picked out the ruby from the Prince's sword, and flew away with it in his beak over the roofs of the town.

He passed by the cathedral tower, where the white marble angels were sculptured. He passed by the palace and heard the sound of dancing. A beautiful girl came out on the balcony with her lover. "How wonderful the stars are," he said to her, "and how wonderful is the power of love!" "I hope my dress will be ready in time for the State-ball," she answered; "I have ordered passion-flowers to be embroidered on it; but the seamstresses are so lazy."

He passed over the river, and saw the lanterns hanging to the masts of the ships. At last he came to the poor house and looked in. The boy was tossing feverishly on his bed, and the mother had fallen asleep, she was so tired. In he hopped, and laid the great ruby on the table beside the woman's thimble. Then he flew gently round the bed, fanning the boy's forehead with his wings. "How cool I feel," said the boy, "I must be getting better;" and he sank into a delicious slumber.

Then the Swallow flew back to the Happy Prince, and[Pg 24] told him what he had done. "It is curious," he remarked, "but I feel quite warm now, although it is so cold."

"That is because you have done a good action," said the Prince. And the little Swallow began to think, and then fell asleep. Thinking always made him sleepy.

When day broke he flew down to the river and had a bath. "To-night I go to Egypt," he said, and he was in high spirits at the prospect. He visited all the public monuments, and sat a long time on top of the church steeple. Wherever he went sparrows chirruped, and said to each other, "What a distinguished stranger!" so he enjoyed himself very much.

When the moon rose he flew back and said to the Happy Prince: "Have you any commissions for Egypt? I am just starting."

"Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow," said the Prince, "will you not stay with me one night longer? Far away across the city I see a young man in a garret. He is leaning over a desk covered with papers, and in a tumbler by his side there is a bunch of withered violets. His hair is brown and crisp and his lips are red as a pomegranate, and he has large and dreamy eyes. He is trying to finish a play for the Director of the Theatre, but he is too cold to write any more. There is no fire in the grate, and hunger has made him faint."

"I will wait one night longer," said the Swallow, who had a good heart. "Shall I take him another ruby?"

"Alas! I have no ruby now," said the Prince; "my eyes are all that I have left. They are made of rare sapphires which were brought out of India a thousand years ago. Pluck out one of them and take it to him. He will sell it to the jeweller, and buy food and firewood, and finish his play."

"Dear Prince," said the Swallow, "I cannot do that"; and he began to weep.

"Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow," said the Prince, "do as I command you."

So the Swallow plucked out the Prince's eye, and flew away to the student's garret. It was easy enough to get in, as there was a hole in the roof. Through this he darted, and came into the room. The young man had his head buried in his hands, so he did not hear the flutter of the bird's wings, and when he looked up he found the beautiful sapphire lying on the withered violets.

"I am beginning to be appreciated," he cried; "this is from some great admirer. Now I can finish my play," and he looked quite happy.

The next day the Swallow flew down to the harbor. He sat on the mast of a large vessel and watched the sailors hauling big chests out of the hold with ropes. "I am going to Egypt!" cried the Swallow, but nobody minded, and when the moon rose he flew back to the Happy Prince.

"I am come to bid you good-bye," he cried.

"Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow," said the Prince, "will you not stay with me one night longer?"

"It is winter," answered the Swallow, "and the chill snow will soon be here. In Egypt the sun is warm on the green palm-trees, and the crocodiles lie in the mud and look lazily about them."

"In the square below," said the Happy Prince, "there stands a little match-girl. She has let her matches fall in the gutter, and they are all spoiled. Her father will beat her if she does not bring home some money, and she is crying. She has no shoes or stockings, and her little head is bare. Pluck out my other eye, and give it to her, and her father will not beat her."

"I will stay with you one night longer," said the Swallow, "but I cannot pluck out your eye. You would be quite blind then."

"Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow," said the Prince, "do as I command you."

So he plucked out the Prince's other eye, and darted down with it. He swooped past the match-girl, and slipped the jewel into the palm of her hand. "What a lovely bit of glass," cried the little girl; and she ran home laughing.

Then the Swallow came back to the Prince. "You are blind now," he said, "so I will stay with you always."

"No, little Swallow," said the poor Prince, "you must go away to Egypt."

"I will stay with you always," said the Swallow, and he slept at the Prince's feet.

Next day the Swallow flew over the great city, and saw the rich making merry in their beautiful houses, while the beggars were sitting at the gates. He flew into dark lanes, and saw the white faces of starving children looking out listlessly at the black streets. Under the archway of a bridge two little boys were lying in one another's arms to try and keep themselves warm.

Then he flew back and told the Prince what he had seen.

"I am covered with fine gold," said the Prince, "you must take it off leaf by leaf, and give it to my poor; the living always think that gold can make them happy."

Leaf after leaf of the fine gold the Swallow picked off, till the Happy Prince looked quite dull and grey. Leaf after leaf of the fine gold he brought to the poor, and the children's faces grew rosier, and they laughed and played games in the street. "We have bread now!" they cried.

Then the snow came, and after the snow came the frost. The streets looked as if they were made of silver, they[Pg 27] were so bright and glistening; long icicles like crystal daggers hung down from the eaves of the houses, everybody went about in furs, and the little boys wore scarlet caps and skated on the ice.

The poor little Swallow grew colder and colder, but he would not leave the Prince, for he loved him too well. He picked up crumbs outside the baker's door, and tried to keep himself warm by flapping his wings.

But at last he knew that he was going to die. He had just enough strength to fly up to the Prince's shoulder once more. "Good-bye, dear Prince!" he murmured, "will you let me kiss your hand?"

"I am glad that you are going to Egypt at last, little Swallow," said the Prince, "you have stayed too long here; but you must kiss me on the lips, for I love you."

"It is not to Egypt that I am going," said the Swallow. "I am going to the House of Death. Death is the brother of Sleep, is he not?"

And he kissed the Happy Prince on the lips, and fell down dead at his feet.

At that moment a curious crack sounded inside the statue as if something had broken. The fact is that the leaden heart had snapped right in two. It certainly was a dreadfully hard frost.

Early the next morning the Mayor was walking in the square below in company with the Town Councillors. As they passed the column he looked up at the statue: "Dear me! how shabby the Happy Prince looks!" he said.

"How shabby indeed!" cried the Town Councillors, who always agreed with the Mayor; and they went up to look at it.

"The ruby has fallen out of his sword, his eyes are gone,[Pg 28] and he is golden no longer," said the Mayor; "in fact he is little better than a beggar."

"Little better than a beggar," said the Town Councillors.

"And here is actually a dead bird at his feet!" continued the Mayor. "We must really issue a proclamation that birds are not to be allowed to die here." And the Town Clerk made a note of the suggestion.

So they pulled down the statue of the Happy Prince. "As he is no longer beautiful he is no longer useful," said the Art Professor at the University.

Then they melted the statue in a furnace and the Mayor held a meeting of the Corporation to decide what was to be done with the metal. "We must have another statue, of course," he said, "and it shall be a statue of myself."

"Of myself," said each of the Town Councillors, and they quarreled. When I last heard of them they were quarreling still.

"What a strange thing!" said the overseer at the foundry. "This broken lead heart will not melt in the furnace. We must throw it away." So they threw it on a dust heap where the dead swallow was also lying.

"Bring me the two most precious things in the city," said God to one of His Angels; and the Angel brought Him the leaden heart and the dead bird.

"You have rightly chosen," said God, "for in my garden of Paradise this little bird shall sing for evermore, and in my city of gold the Happy Prince shall praise me."

It would be too bad to mar this beautiful story by asking questions about it. This is a story to tell. Your teacher, or perhaps the class, will decide who is to come to the front of the room and tell the story. It would be a good Christmas story.

This exercise is given to see if you can follow directions. Follow each direction as you read it. Do not wait for others to start, but begin now.

1. Arrange your paper with your name on the first line and your grade on the second. At the left hand side of your paper number the next ten lines from number 1 to number 10.

2. The words name is a John boy's do not make a good sentence, but if the words are arranged in order they form a good sentence: John is a boy's name. This sentence is true. In the same way, the words books made iron of are, in this order do not make a good sentence, but arranged in the right order they form a good sentence: Books are made of iron. This sentence is not true.

3. Here are ten groups of words which can be rearranged into good sentences. When they are rearranged in their right order, some will be true and some will be false. Look at the first set of words. Do not write the words in their right order, but see what they would say if rearranged. If what they would say is true, write the word true after figure 1 on your paper; but if what they would say is not true, write the word false after figure 1. Do this with each group of words.

1. shepherd the his good sheep cares for.

2. Pigeons carry frequently used war to were messages.

3. usually elected kings for are four years.

4. from get caterpillar we called a silk-worm the silk.

5. live the far-away Eskimos sandy hot in deserts the.

6. and coal mined the cotton south are in.

7. sail Spain three set Columbus from great steamships with.

8. chief of England the city Philadelphia is.

9. our days long summer and hot are.

10. noted California trees is big its for.

You should all begin reading at the same moment. Your teacher will time you and tell you how long it takes you to read this selection. But do not hurry, for you will be asked to tell the class the things you remember best.

Maybe you had a big brother or sister or cousin or aunt or uncle who, during the great war, worked under the Red Cross in France. If you did, he or she may have written home just such letters as this one, which a big sister wrote to her little brothers in America. As you read, see if you do not think she must be a very pleasant, friendly big sister, not only to her own little brothers, but also to the little French children.

Do you wish you had been born in France and that your names were Jean, and René, and Etienne instead of Bill and George Albert and Ben? And do you wish you wore black sateen aprons instead of woolly blue sweaters?

The reason I began to write you this letter is that yesterday afternoon I put on my hat and coat when I ought to have been working, and went to visit some French schools. I went with twenty fine people who all wore Red Cross uniforms.

The reason I went is very interesting. For three years, while all the men and the big boys in France have been fighting, their mothers and sisters and all the children whom they had to leave behind them have been getting poorer and thinner and hungrier. You see, since the men have gone to war there haven't been enough of them left to grow the wheat and run the machinery which makes the bread. Well, as I said, the mothers and the little children got thinner and poorer and hungrier, but the last thing of all that they gave up was a luncheon they served in the afternoon in the schools to the smallest and poorest children. It was such a little luncheon that they called it "the taste",[Pg 31] but finally they had to give up even that; and then when the time came to eat, the children, who were just as brave as soldiers, had to pretend they weren't hungry at all. They went without that luncheon for a number of months, and then an American doctor decided that the boys and girls in that part of Paris must have that luncheon again. So the doctor rented a bakeshop and he got a ton of nice white American flour, and hundreds and hundreds of cans of American condensed milk, and a very great deal of sugar and some other things, and went to work making buns. And the reason I went to the schools yesterday was to help give out the buns and chocolate for the children's "taste".

I suppose you think that one bun and one piece of chocolate wasn't much—and we thought so too when we saw all those hungry little faces, and their little legs that looked quite hollow—but the children thought it was fine. They were so polite, boys! When we marched into their classrooms they all stood up and saluted us as if they had been soldiers. They showed us their copy books and told us what the lesson was. In one class the master himself was quite scared because he wanted to speak English to make us feel at home. But he made us a fine speech, saying how thankful they all were to their American friends for being so generous to them. He thanked us especially for thinking of the children and for trying to help them when their fathers were away fighting. Then he asked the boys whose fathers or brothers were in the war to raise their hands, and, do you know, almost every boy could raise his hand. They were proud to do it, too. Their hands went up quickly and some of them waved—as you do when you especially want the teacher to pay attention to you. The master asked the boys whose fathers would never come back to raise their hands, and there[Pg 32] were so many of them that we could hardly bear to count them; and this time the hands went up very slowly and their faces were very, very sober.

In the first school we went to, the big hall was decorated with a long string of American flags. Every one was drawn very carefully, and then colored with crayons by the littlest children. There were paper chains, too, made out of red, white, and blue paper; and finally, when the buns came in, the baskets were all decorated with the American flag because the American people had given the bread.

The boys all marched into the hall in a long, long line, and, Bill and Junior and Ben, I was so afraid that there wouldn't be enough buns to go around! They marched up to the baskets, their little wooden shoes making a terrible clatter on the stone floor; and every boy got a bun in one hand and a bar of chocolate in the other, and every boy said "Thank you" in French, very politely. I don't think even the smallest forgot that, though some of them were so excited that they couldn't march straight and some of them couldn't talk at all plainly, even in French. There was one time when I got very much excited myself. That was when one little boy, in a blue soldier suit just like his father's, said "Thank you" in English. I nearly dropped all the buns I had in my two hands, I was so surprised.

The Mayor of the district, who probably seemed like the President of the United States to most of the children, made a speech and told them how sorry the Americans had been that they couldn't have their lunch in the afternoon, and how the Americans wanted them to be strong and well and happy and had given them the buns and the chocolate to help, and he talked to them in such a pleasant voice and in such a loving sort of way, that when he said he wanted them to shout, "Vive l'Amerique!" which means, "Hurrah for[Pg 33] the United States of America!" they shouted—really and truly shouted—just as if they'd been little American boys.

At the next school, we went to the building where the tiniest children of all learned their kindergarten games. They marched for us, and sang a little song about the good "Saint Christopher", who was kind to little children; and a little boy who had lost his mother and father in the war and who was really too little to understand, said a very polite speech to us and promised us that he and his little friends would always remember how kind the Americans had been to them. He was so tiny that he hid his head in the teacher's apron when he had finished.

Finally we went to the biggest school of all, and there we found a great hall filled with classes of little girls, all dressed in black, all looking so pale and thin and sad that we were glad to think that perhaps the buns and chocolates we had brought would—in a month or two—bring some color into their poor little faces, and perhaps even put some fat on their wrists and hands that were so thin they seemed like birds' claws. One of the older girls had made a fine big panel picture here showing the children eating their buns and chocolates and capering up and down just as I've seen somebody caper a bit when he was going to have—was it ice cream for Sunday dinner?

At the end, the nice old Mayor made another speech, in which he told us a little bit of how brave the children had been when they were hungry, and how glad he was that they were now going to have the American food, and then he thanked us all over again. So, then, one of the American doctors said that when we came over here to France with our men, our food, and our love, we weren't making gifts, we were just trying to pay the debt that America had owed to France since Lafayette and his men came across the sea[Pg 34] to help us in our war. Then the doctor told us how the Arabs believe that people who once eat even a tiny piece of bread together will always be friends, so the little children and their teachers, and the nice old Mayor, and all the Americans from the Red Cross ate some of the American buns and—that is the end of the story!

Here is part of a letter written by a nine-year-old French girl to girls of the William Penn High School, Philadelphia, who had "adopted" her as their "war orphan". After you read it, tell what kind of little girl you think she is.

Dear Sisters: I have just received your letter. I am much touched by your kindness to me, and for your generous hearts. I am contented to find among you so many devoted new sisters for the poor orphan of this unfortunate war, which has killed all our fathers. Dear Sisters, I don't want you to see a like war with you, for it is too frightful and too sad. I shall not speak any more about it; that gives too much trouble.

You ask me of what I have the greatest need; indeed, that will be a dress if that is possible for you; for mamma does not want us to abuse your good hearts. The dress, I should like to see it dark blue, for up to now I have always worn black and white. Mamma permits me now to wear blue, and I think that will be becoming.

Mamma has made little economies of money. She is going to have my photograph taken, and I am going to send them. I think that will give you pleasure, and I will write to you often. I do not forget you in my morning and evening prayers. Once again, thanks, all these sisters whom I do not know. But if I have the good fortune to grow up, I will see you all with pleasure.

If you have a strong imagination and have read and have liked your geography and, perhaps, some books of travel, you will enjoy this poem. As you read see how many different places are hinted at. Read the poem through; close your book, and make a list of all you can remember.

Not every child who plans how some day he is going to travel has a chance to carry out his plans. But Robert Louis Stevenson travelled far enough to see nearly all the places he dreamed of. He did not travel just for pleasure, however; his health was so poor that he wandered all over the world to find a climate where he could live. The place he found was an island in the Southern Pacific, one of a group called Samoa, where he spent all the last years of his life. Stevenson was a man who made friends wherever he went. In Samoa the natives loved him dearly. Their name for him was Tusitala, "the Teller of Tales," because he wrote such wonderful stories.

Read the following rules through once; then cover the page with a sheet of paper, and answer the questions.

1. When reading, writing, or doing other close work, be sure to have good, clear light, preferably over the left shoulder if writing, and not directly in the eyes nor reflected sharply from the paper.

2. Do not hold your work less than 12 inches from your eyes.

3. Do not use the eyes too long continuously—rest them a few minutes occasionally by closing them or by looking into the distance to relax them. One should do this at least every hour, especially if reading fine type or doing intense, delicate work.

4. Keep away from places where stone chips, sparks, or emery dust is flying. If you have to work where such dangers exist, wear goggles.

5. If strong light bothers you, wear slightly brown non-magnifying glasses outdoors, with a broad-brimmed hat.

6. Avoid the common towel and do not rub the eyes with dirty hands. Contagious eye disease is spread in these two ways.

Questions

1. Give two rules about the right use of light for reading, writing, etc.

2. How far from your eyes should you hold your book?

3. Give the rule for resting the eyes.

4. How can you avoid danger from sparks, emery dust and stone chips?