Project Gutenberg's Cathedral Cities of Spain, by William Wiehe Collins This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Cathedral Cities of Spain Author: William Wiehe Collins Release Date: July 27, 2012 [EBook #40356] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CATHEDRAL CITIES OF SPAIN *** Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

CATHEDRAL CITIES

OF SPAIN

| UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME |

CATHEDRAL CITIES OF ENGLAND. By GEORGE GILBERT. With 60 reproductions from water-colours by W.W. Collins, R.I. Demy 8vo, 16s. net. |

CATHEDRAL CITIES OF FRANCE. By HERBERT and HESTER MARSHALL. With 60 reproductions from water-colours by HERBERT MARSHALL, R.W.S. Demy 8vo, 16s. net. Also large paper edition, £2 2s. net. |

| BOOKS ILLUSTRATED BY JOSEPH PENNELL |

ITALIAN HOURS. By HENRY JAMES. With 32 plates in colour and numerous illustrations in black and white by JOSEPH PENNELL. Large crown 4to. Price 20s. net. |

A LITTLE TOUR IN FRANCE. By HENRY JAMES. With 94 illustrations by JOSEPH PENNELL. Pott 4to. Price 10s. net. |

ENGLISH HOURS. By HENRY JAMES. With 94 illustrations by Joseph Pennell. Pott 4to. Price 10s. net. |

ITALIAN JOURNEYS. By W.D. Howells. With 103 illustrations by Joseph Pennell. Pott 4to. Price 10s. net. |

CASTILIAN DAYS. By the Hon. JOHN HAY. With 111 illustrations by JOSEPH PENNELL. Pott 4to. Price 10s. net. |

| London: WILLIAM HEINEMANN 21 Bedford Street, W.C. |

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED

BY

W. W. COLLINS, R.I.

LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

NEW YORK: DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1909

All rights reserved

Copyright, London, 1909, by William Heinemann and

Washington, U.S.A., by Dodd, Mead & Co

SPAIN, the country of contrasts, of races differing from one another in habits, customs, and language, has one great thing that welds it into a homogeneous nation, and this is its Religion. Wherever one's footsteps wander, be it in the progressive provinces of the north, the mediævalism of the Great Plain, or in that still eastern portion of the south, Andalusia, this one thing is ever omnipresent and stamps itself on the memory as the great living force throughout the Peninsula.

In her Cathedrals and Churches, her ruined Monasteries and Convents, there is more than abundant evidence of the vitality of her Faith; and we can see how, after the expulsion of the Moor, the wealth of the nation poured into the coffers of the Church and there centralised the life of the nation.

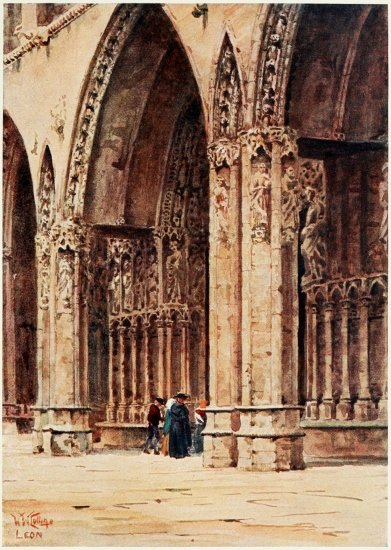

In the mountain fastnesses of Asturias the churches of Santa Maria de Naranco and San Miguel de Lino, dating from the ninth century and contemporary with San Pablo and Santa Cristina, in Barcelona, are the earliest Christian buildings in Spain. As the Moor was pushed further south, a new style followed his retreating steps; and the Romanesque, introduced from over the Pyrenees, became the adopted form of architecture in the more or less settled parts of the country. Creeping south through Leon, where San Isidoro is well worth mention, we find the finest examples of the period in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, at Segovia, Avila, and the grand Catedral Vieja of Salamanca.

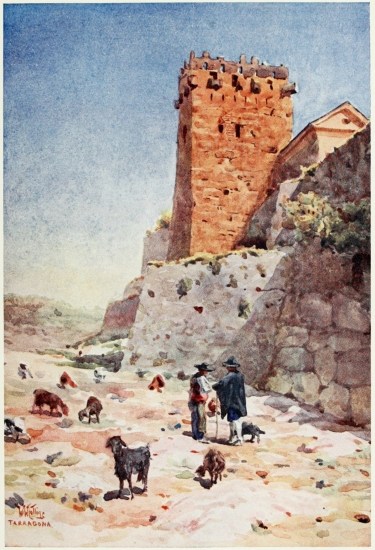

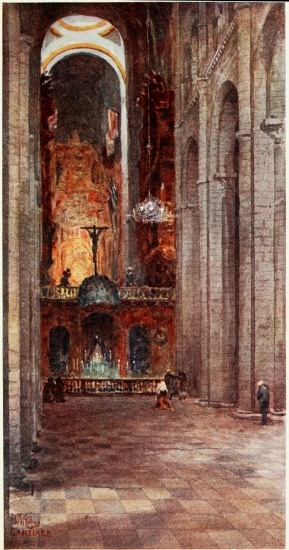

Spain sought help from France to expel the Moor, and it is but natural that the more advanced nation should leave her mark somewhere and in some way in the country she pacifically invaded. Before the spread of this influence became general, we find at least one great monument of native genius rise up at Tarragona. The Transition Cathedral there can lay claim to be entirely Spanish. It is the epitome and outcome of a yearning for the display of Spain's own talent, and is one of the most interesting and beautiful in the whole country.

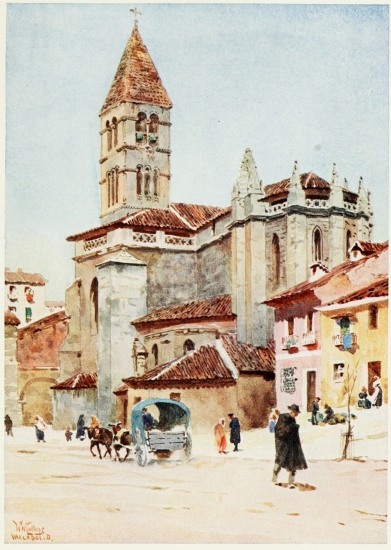

Toledo, Leon, and Burgos are the three Cathedrals known as the "French" Cathedrals of Spain. They are Gothic and the first named is the finest of all. Spanish Gothic is best exemplified in the Cathedral of Barcelona. For late-Gothic, we must go to the huge structures of Salamanca, Segovia, and the Cathedral at Seville which almost overwhelms in the grandeur of its scale.

After the close of the fifteenth century Italian or Renaissance influence began to be felt, and the decoration of the Plateresque style became the vogue. San Marcos at Leon, the University of Salamanca, and the Casa de Ayuntamiento at Seville are among the best examples of this. The influence of Churriguera, who evolved the Churrigueresque style, is to be met with in almost every Cathedral in the country. He it is who was responsible for those great gilded altars with their enormous twisted pillars so familiar to travellers in Spain; and which, though no doubt a tribute to the glory of God, one feels are more a vulgar display of wealth than a tasteful or artistic addition to her architecture. The finest of the Renaissance Cathedrals is that of Granada, and the most obtrusive piece of Churrigueresque is the Cartuja in the same city.

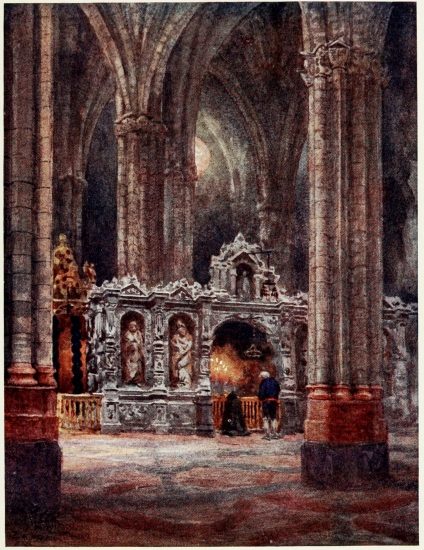

Taking the Cathedrals as a whole the two most unfamiliar and notable features are the Coros or Choirs, and the Retablos. These latter—gorgeous backings to the High Altar, generally ill-lit, with a superabundance of carving sometimes coloured and gilded, sometimes of plain stone—are of Low-country or Flemish origin. The former, with one exception at Oviedo, are placed in the nave west of the crossing, and enclose, as a rule, two or more bays in this direction. Every Cathedral is a museum of art, and these two features are the most worth study.

NOTE.—Since the revolution in Catalonia of July-August 1909, the King has decreed that no one can secure exemption from military service by the payment of a sum of money.

AT one time the greatest port in the world—"Where are thy glories now, oh, Cadiz?" She is still a White City lying embosomed on a sea of emerald and topaz. Her streets are still full of the colour of the East, but alas! Seville has robbed her of her trade, and in the hustle of modern life she is too far from the busy centre, too much on the outskirts of everything, to be anything more than a port of call for American tourists and a point from whence the emigrant leaves his native country.

This isolation is one of her great charms, and the recollections I have carried away of her quiet clean streets, her white or pink washed houses with their flat roofs and miradores, her brilliant sun and blue sea, can never be effaced by Time's subtle hand.

Landing from a coasting-boat from Gibraltar, I began my travels through Spain at Cadiz; and it was with intense regret, so pleasant was the change from the grey skies and cold winds of England, that I took my final stroll along the broad Alameda bordered with palms of all sorts, and lined with other exotic growth—that I bid good-bye to the Parque de Genoves where many a pleasant hour had been spent in the grateful shade of its trees. I shall probably never again lean idly over the sea-washed walls and watch the graceful barques with their cargoes of salt, spread their sails to the breeze and glide away on the long voyage to South America.

Looking out eastwards over the marshes I was at first much puzzled to know what were the white pyramids that stood in rows like the tents of an invading host. Then I was told. Shallow pans are dug out in the marsh and the sea let in. After evaporation this is repeated again and again, until the saline deposit is thick enough to be scraped and by degrees grows into a pyramid. Every pan is named after a saint from whom good luck is implored. No, I doubt if ever my eyes will wander again over the blue waters to the marsh lands of San Fernando.

Life is short and I can hardly hope that Fate will carry me back to those sea walls and once more permit me as the sun goes down to speculate on the catch of the fishing-fleet as each boat makes for its haven in the short twilight of a southern clime. I cannot but regret that all this is of the past, but I shall never regret that at Cadiz, the most enchanting of Spain's seaports, began my acquaintance with her many glorious cities.

In ancient times Cadiz was the chief mart for the tin of the Cassiterides and the amber of the Baltic. Founded by the Tyrians as far back as 1100 B.C., it was the Gadir (fortress) of the Phœnicians. Later on Hamilcar and Hannibal equipped their armies and built their fleets here. The Romans named the city Gades, and it became second only to Padua and Rome. After the discovery of America, Cadiz became once more a busy port, the great silver fleets discharged their precious cargoes in its harbour and from the estuary sailed many a man whose descendants have created the great Spain over the water.

The loss of the Spanish colonies ruined Cadiz and it has never regained the place in the world it once held. Huge quays are about to be constructed and the present King has just laid the first stone of these, in the hopes that trade may once more be brought to a city that sleeps.

There are two Cathedrals in Cadiz. The Catedral Nueva is a modern structure commenced in 1722 and finished in 1838 by the bishop whose statue faces the rather imposing west façade. Built of limestone and Jérez sandstone, it is white—dazzling white, and rich ochre brown. There is very little of interest in the interior. The silleria del coro (choir stalls) were given by Queen Isabel, and came originally from a suppressed Carthusian Convent near Seville. The exterior can claim a certain grandeur, especially when seen from the sea. The drum of the cimborio with the great yellow dome above, and the towers of the west façade give it from a distance somewhat the appearance of a mosque.

The Catedral Vieja, built in the thirteenth century, was originally Gothic, but being almost entirely destroyed during Lord Essex's siege in 1596, was rebuilt in its present unpretentious Renaissance form.

Cadiz possesses an Académia de Bellas Artes where Zurbaran, Murillo and Alfonso Cano are represented by second-rate paintings. To the suppressed convent of San Francisco is attached the melancholy interest of Murillo's fatal fall from the scaffolding while at work on the Marriage of St. Catherine. The picture was finished by his apt pupil Meneses Osorio. Another work by the master, a San Francisco, quite in his best style also hangs here.

The churches of Cadiz contain nothing to attract one, indeed if it were not for the fine setting of the city surrounded by water, and the semi-eastern atmosphere that pervades the place, there is but little to hold the ordinary tourist. The Mercado, or market-place, is a busy scene and full of colour; the Fish Market, too, abounds in varieties of finny inhabitants of the deep and compares favourably in this respect with that of Bergen in far away Norway. The sole attraction in this City of the Past—in fact, I might say in the Past of Spain as far as it concerns Cadiz—lies on the stretch of water into which the rivers Guadalete and San Pedro empty themselves. From the very earliest days down to the time when Columbus sailed on his voyage which altered the face of the then known globe, and so on to our own day, it is in the Bahia de Cadiz that her history has been written.

SEVILLE, the "Sephela" of the Phœnicians, "Hispalis" of the Romans, and "Ishbilyah" of the Moors, is by far the largest and most interesting city of Southern Spain. In Visigothic times Seville was the capital of the Silingi until Leovigild moved his court to Toledo. It was captured by Julius Cæsar in 45 B.C., but during the Roman occupation was overshadowed by Italica, the birthplace of the Emperors Trajan, Adrian, and Theodosius, and the greatest of Rome's cities in Hispania. This once magnificent place is now a desolate ruin, plundered of its glories and the haunt of gipsies.

Under the Moors, who ruled it for five hundred and thirty-six years, Seville was second only to Cordova, to which city it became subject when Abdurrhaman established the Western Kalifate there in the year 756.

San Ferdinand, King of Leon and Castile, pushed his conquests far south and Seville succumbed to the force of his arms in 1248.

Seville is the most fascinating city in Spain. It is still Moorish in a way. Its houses are built on the Eastern plan with patios, their roofs are flat and many have that charming accessory, the miradore. Its streets are narrow and winding, pushed out from a common centre with no particular plan. It is Andalusian and behind the times. Triana, the gipsy suburb, is full of interest. The Cathedral, though of late and therefore not particularly good Gothic, is, on account of its great size, the most impressive in the whole country. The Alcázar, once more a royal residence, vies with Granada's Alhambra in beauty; and as a mercantile port, sixty miles from the estuary, Seville ranks second to none in Southern Spain.

The Cathedral stands third in point of size if the ground space is alone considered, after St. Peter's at Rome and the Mesquita at Cordova. The proportions of the lofty nave, one hundred feet in height, are so good that it appears really much higher. The columns of the double aisles break up the two hundred and sixty feet of its width and add much to the solemn dignity of the vast interior, enhanced greatly by the height of the vaulting above the spectator. Standing anywhere in the Cathedral I felt that there was a roof above my head, but it seemed lost in space. And this is the great characteristic of Seville's Cathedral, i.e., space.

The coro is railed off from the crossing by a simple iron-gilt reja. The silleria, by Sanchez, Dancart, and Guillier are very fine and took seventy years to execute. Between the coro and Capilla Mayor, in Holy Week the great bronze candlestick, twenty-five feet high, a fine specimen of sixteenth-century work, is placed alight. When the Misere is chanted during service, twelve of its thirteen candles are put out, one by one, indicating the desertion of Christ by his apostles. The thirteenth left burning symbolises the Virgin, faithful to the end. From this single light all the other candles in the Cathedral are lit.

The reja of the Capilla Mayor is a grand example of an iron-gilt screen, and with those to the north and south, is due to the talent of the Dominican, Francisco de Salamanca.

The fine Gothic retablo of the High Altar surpasses all others in Spain in size and elaboration of detail. It was designed by Dancart and many artists were employed in its execution. When the sun finds his way through the magnificent coloured glass of the windows between noon and three o'clock, and glints across it, few "interior" subjects surpass the beautiful effect on this fine piece of work.

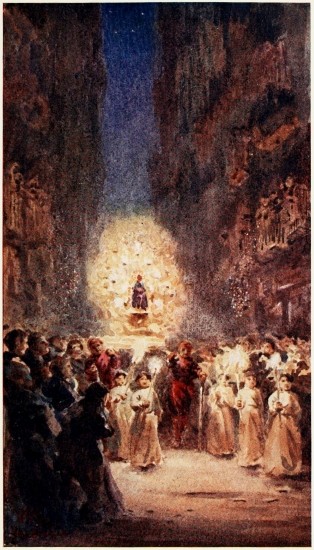

In front of the High Altar at the feast of Corpus Christi and on three other occasions, the Seises's dance takes place. This strange ceremony is performed by chorister boys who dance a sort of minuet with castanets. Their costume is of the time of Philip III., i.e., 1630, and they wear plumed hats. Of the numerous chapels the most interesting is the Capilla Real. It possesses a staff of clergy all to itself. Begun in 1514 by Martin de Gainza, it was finished fifty years later. Over the High Altar is the almost life-size figure of the Virgin de los Reyes, given by St. Louis of France to San Ferdinand. Its hair is of spun gold and its numerous vestments are marvellous examples of early embroidery. The throne on which the Virgin is seated is a thirteenth-century piece of silver work, with the arms of Castile and Leon, San Ferdinand's two kingdoms. Before it lies the King himself in a silver shrine. Three times a year, in May, August and November, a great military Mass takes place before this royal shrine, when the garrison of Seville marches through the chapel and colours are lowered in front of the altar. In the vault beneath are the coffins of Pedro the Cruel and Maria Padilla his mistress, the only living being who was humanly treated by this scourge of Spain. Their three sons rest close to them.

On the north and south sides of this remarkable chapel, within arched recesses, are the sarcophagi of Beatrice of Swabia and Alfonso the Learned. They are covered with cloth of gold emblazoned with coats-of-arms. A crown and sceptre rest on the cushion which lies on each tomb. In the dim light, high above and beyond mortal reach rest these two—it is very impressive.

Each of the remaining twenty-nine chapels contains something of interest. In the Capilla de Santiago is a beautiful painted window of the conversion of St. Paul. The retablo in the Capilla de San Pedro contains pictures by Zurbaran. In the north transept in a small chapel is a good Virgin and Child by Alonso Cano; in the south is the Altar de la Gamba, over which hangs the celebrated La Generacion of Louis de Vargas, known as La Gamba from the well-drawn leg of Adam. On the other side of this transept is the Altar de la Santa Cruz and between these two altars is the monument to Christopher Columbus. Erected in Havana it was brought to Spain after the late war and put up here.

Murillo's work outshines all other's in the Cathedral. The grand San Antonio de Padua, in the second chapel west of the north aisle, is difficult to see. The window which lights it is covered by a curtain, which, however, the silver key will pull aside. Over the Altar of Nuestra Señora del Consuelo is a beautiful Guardian Angel from the same brush. Close by is another, Santa Dorotea, a very choice little picture. In the Sacristy are two more, S.S. Isidore and Leander. In the Sala Capitular a Conception and a Mater Dolorosa in the small sacristy attached to the Capilla Real complete the list.

Besides these fine pictures there are others which one can include in the same category by Cano, Zurbaran, Morales, Vargas, Pedro Campaña and the Flemish painter Sturm, a veritable gallery! And when I went into the Treasury and saw the priceless relics which belong to Seville's Cathedral, priceless in value and interest, and priceless from my own art point of view, "Surely," thought I, "not only is it a picture gallery, it is a museum as well."

The original mosque of Abu Yusuf Yakub was used as a Cathedral until 1401, when it was pulled down, the present building, which took its place, being finished in 1506. The dome of this collapsed five years later and was re-erected by Juan Gil de Hontañon. Earthquake shocks and "jerry-building" were responsible for a second collapse in the August of 1888. The restoration has since been completed in a most satisfactory manner—let us hope it will last.

The exterior of the Cathedral is a very irregular mass of towers, domes, pinnacles and flying buttresses, which give no clue to the almost over-powering solemnity within the walls. Three doorways occupy the west façade, which is of modern construction, and there are three also on the north side of the Cathedral, one of which opens into the Segrario, another into the Patio de los Naranjos and the third into the arcade of the same patio. This last retains the horse-shoe arch of the old mosque. In the porch hangs the stuffed crocodile which was sent by the Sultan of Egypt to Alfonso el Sabio with a request for the hand of his daughter. On the south is one huge door seldom opened. On the east there are two more, that of La Puerta de los Palos being under the shadow of the great Giralda Tower.

This magnificent relic of the Moslem's rule rears its height far above everything else in Seville. Erected at the close of the twelfth century by order of Abu Yusuf Yakub, it belongs to the second and best period of Moorish architecture.

On its summit at the four corners rested four brazen balls of enormous size overthrown by one of the numerous earthquakes which have shaken Seville in days gone by. The belfry above the Moorish portion of the tower, which ends where the solid walls stop, was put up in 1568, and has a second rectangular stage of smaller dimensions above. Both these are in keeping with the Moorish work below and in no way detract from its beauty. On top of the small cupola which caps the whole is the world-famed figure of Faith. Cast in bronze, with the banner of Constantine spread out to the winds of heaven, this, the Giraldilla, or weather-cock, moves to the slightest breeze. It is thirteen feet high, and weighs one and a quarter tons. Over three hundred feet above the ground, the wonder is—how did it get there? and how has it preserved its equipoise these last three hundred years?

It is difficult to find a point from which one can see the Giralda Tower, in fact the only street from which it is visible from base to summit is the one in which I made my sketch. Even this view does not really convey its marvellous elegance and beauty.

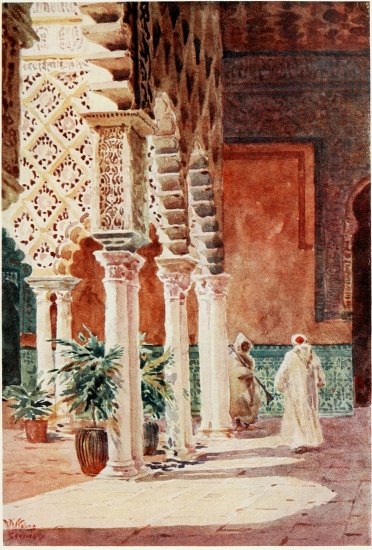

Next to the Cathedral the Alcázar is the most famous building in Seville. It is now a royal residence in the early part of the year, and when the King and Queen are there, no stranger under any pretext whatever is admitted.

Its courtyards and gardens are its glory. The scent of orange blossom perfumes the air, the fountains splash and play, all is still within these fascinating courts save the tinkle of the water and cooing of doves. Of its orange trees, one was pointed out to me which Pedro the Cruel planted! and many others are known to be over two hundred years old.

SEVILLE. IN THE ALCÁZAR, THE PATIO DE LAS DONCELLAS

Of all its courts, the Patio de las Doncellas is the most perfect. Fifty-two marble columns support the closed gallery and rooms above, and the walls of the arcade are rich with glazed tiles.

Of all its chambers, the Hall of Ambassadors is the finest and is certainly the architectural gem of the Alcázar. Its dome is a marvel of Media Naranja form, and the frieze of window-shaped niches but adds to its beauty.

Very little remains of the first Alcázar, which, by the way, is a derivation of Al-Kasr or house of Cæsar, and the present building as it now stands was due to Pedro the Cruel, Henry II., Charles V. and Philip V. The first named employed Moorish workmen from Granada, who emulated, under his directions, the newly finished Palace of the Alhambra. Many a treacherous deed has taken place within these walls, and none more loathsome than those credited to Pedro the Cruel. However, one thing can be put to his credit and that is this fairy Palace, this flower from the East, by the possession of which Seville is the gainer.

To the east of the Alcázar is the old Jewish quarter, the most puzzling in plan, if plan it has, and the oldest part of Seville.

The balconies of the houses opposite one another almost touch; there certainly, in some cases, would be no difficulty in getting across the street by using them as steps, and if a laden donkey essayed the passage below I doubt if he could get through. Poking about in these narrow alley-ways one day, I fell into conversation with a guardia municipal who entertained me greatly with his own version of Seville's history, which ended, as he melodramatically pointed down the lane in which we were standing—"And here, señor, one man with a sword could keep an army at bay, and"—this in confidence, whispered—"I should not like to be the first man of the army"!

In almost every quarter of the city fine old houses are to be found amidst most squalid and dirty surroundings. You may wander down some mean calle, where children in dozens are playing on the uneven pavement, their mothers sit about in the doorways shouting to one another across the street. Suddenly a wall, windowless save for a row of small openings under the roof, is met. A huge portal, above which is a sculptured coat-of-arms, with some old knight's helmet betokening a noble owner, is let into this, look inside, as you pass by—behind the iron grille is a deliciously cool patio, full of palms and shrubs. A Moorish arcade runs round supporting the glazed galleries of the first floor. A man in livery sits in a rocking chair dosing with the eternal cigarette between his lips. Beyond the first patio you can see another, a bigger one, which the sun is lighting up. The life in this house is as different to the life of its next door neighbours as Park Lane is to Shoreditch. One of these great houses—owned by the Duke of Medinaceli—the Casa del Pilatos, has a large Moorish court, very similar to those of the Alcázar. They will tell you in Seville, that Pilate was a Spaniard, a lawyer, and failing to win the case for Christ, left the Holy Land, where he had a good practice, and returned to Spain to assist Ferdinand to drive out the Moors. "Yes, señor, he settled here and built this fine house about five hundred years ago."

As a rule, in the better-class houses a porch opens into the street. On the inner side of this there is always a strong iron gate with a grille around to prevent any entry. These gates served a purpose in the days of the Inquisition, when none knew if the Holy Office might not suddenly descend upon and raid the house. Seville suffered terribly from the horrors of those dark times; even now—when a ring at the bell calls forth: "Who is there?" from the servant in the balcony above, before she pulls the handle which connects with the catch that releases the lock of the gate—the answer often is: "People of Peace." Some houses have interior walls six feet thick and more, which being hollow contain hiding-places with access from the roof by a rope.

In the heat of summer—and Seville is called the "frying-pan of Europe"—when the temperature in the shade of the streets rises to over 115° Fahr. family life is spent below in the cool patio. A real house moving takes place as the heat comes on. The upper rooms, which are always inhabited in the winter, the kitchen, servants' rooms and all are deserted, every one migrates with the furniture to the lower floors. The upper windows are closed, shutters put up and a great awning drawn across the top of the courtyard. Despite the great heat, summer is a perfectly healthy period. No one dreams of going out in the daytime, and all Seville begins life towards five o'clock in the afternoon; 2 A.M. to 4 A.M. being the time to retire for the night! Seville can be very gay, and Sevillanos worship the Torrero or bull-fighter (Toreador is a word unknown to the Spaniard). If a favourite Torrero, who has done well in the ring during the afternoon, enters the dining-room of a hotel or goes into a café it is not unusual for every one at table to rise and salute him.

There is another life in Seville, the life of the roofs. In early spring before the great heat comes, and in autumn before the cold winds arrive, the life of the roofs fascinated me. Up on the roofs in the dry atmosphere, Seville's washing hangs out to air, and up on the roofs, in the warm sun, with the hum of the streets far below, you will hear the quaint song—so Arabian in character—of the lavandera, as she pegs out the damp linen in rows. In the evening the click-a-click-click of the castanets and the sound of the guitar, broken by merry laughter, tells one that perhaps the Sevillano has fathomed the mystery of knowing how best to live. And as sundown approaches what lovely colour effects creep o'er this city in the air! The light below fades from housetop and miradore, pinnacle and dome, until the last rays of the departing majesty touch the vane of the Giralda, that superb symbol of Faith,—and all is steely grey.

Over the Guadalquiver lies Triana, and as I crossed the bridge for the first time the remains of an old tower were pointed out to me on the river bank. The subterranean passage through which the victims of the Inquisition found their exit to another world in the dark waters below is exposed to view, the walls having fallen away. It was therefore with something akin to relief I reached the gipsy quarter in this quaint, dirty suburb and feasted my eyes on the colours worn by its dark-skinned people. The potteries of Triana are world-renowned, and still bear traces in their output of Moorish tradition and design.

Seville's quays are the busiest part of the city, and the constant dredging of the river permits of vessels of four thousand tons making this a port of call.

Next to the Prado in Madrid, the Museum of Seville is more full of interest than any other. It is here that Murillo is seen at his best. The building was at one time the Convento de la Mercede founded by San Ferdinand. The exhibits in the archæological portion nearly all come from that ruin, the wonderful city of Italica. Among the best of Murillo's work are St. Thomas de Villa Nueva Distributing Alms, Saint Felix of Cantalicio and a Saint Anthony of Padua. A large collection of Zurbaran's works also hangs in the gallery, but his big composition of the Apotheosis of Saint Anthony, is not so good as his single-figure subjects, and none of these approach in quality the fine Monk in the possession of the Bankes family at Kingston Lacy in Dorset.

Seville is the home of bull-fights. The first ever recorded took place in 1405, in the Plaza del Triunfo, in honour of the birth of a son to Henry II. of Castile. The world of Fashion takes the air every evening in the beautiful Paseo de las Delicias. The humbler members of society throng the walks watching their wealthier sisters drive down its fine avenues—this daily drive being the only exercise the ladies of Seville permit themselves to take.

It is a pretty sight to watch the carriages coming home as twilight begins, and the last rays of the sun light up the Torre del Oro. Built by the Almohades this Moorish octagon stood at the river extremity of Moslem Seville. The golden yellow of the stone no doubt gave it the name of "Borju-d-dahab," "the tower of gold," which has stuck to it under Christian rule. But "how are the mighty fallen," and one of the glories of the Moor debased. It is now an office used by clerks of the Port, and, instead of the dignified tread of the sentinel, resounds to the scribble of pens.

IT is hard to realise that the Cordova of to-day was, under the rule of the Moor, a city famous all the world over and second only to the great Damascus. Long before the Moor's beneficent advent, in the far-off days of Carthage, Cordova was known as "the gem of the south." Its position on the mighty Guadalquiver, backed by mountains on the north, always seems to have attracted the best of those who conquered. In the time of the Romans, Marcellus peopled it with poor Patricians from Rome, and Cordova became Colonia Patricia, the capital of Hispania Ulterior. But it was left to the Infidel to make it what is now so difficult to realise—the first city in Western Europe.

The zenith of its fame was reached during the tenth century, when the mighty Abderrhaman III., ruler of the Omayyades reigned, and did not begin to decrease until the death of Almanzor at the beginning of the next century. If we are to believe the historian Almakkari, Cordova contained at one time a million inhabitants, for whose worship were provided three hundred Mosques, and for whose ablutions nine hundred baths were no more than was necessary. (The arch-destroyer of all things Infidel, Philip II., demolished these.) It was the centre of art and literature, students from all parts flocked hither, its wealth increased and its fame spread, riches and their concomitant luxury made it the most famous place in Western Europe. Nothing could exceed the grace and elegance of its life, the courtly manners of its people, nor the magnificence of its buildings.

From the years 711 to 1295, when Ferdinand drove him out, the cultivated Moslem reigned in this his second Mecca. And now?—under Christian rule it has dwindled down to what one finds it to-day—a quiet, partly ruinous town. Of all its great buildings nothing remains to remind one of the past but the ruins of the Alcázar—now a prison, a portion of its walls, and the much mutilated Mesquita—the Cathedral.

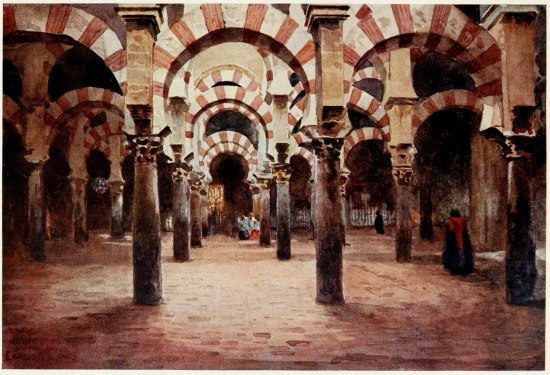

CORDOVA. INTERIOR OF THE MESQUITA

I could not at first entry grasp the size of this the second largest church of any in existence. Coming suddenly into the cool shade of its many pillared avenues, I felt as if transplanted into the silent depths of a great forest. In every direction I looked the trunks of huge trees apparently rose upwards in ordered array. The light here and there filtered through gaps on to the red-tiled floor, which only made the deception greater by its resemblance to the needles of a pine-wood or the dead leaves of autumn. Then the organ boomed out a note and the deep bass of a priest in the coro shattered the illusion.

The first Mosque built on the site of Leovigild's Visigothic Cathedral, occupied one-fifth of the present Mesquita. It was "Ceca" or House of Purification, and a pilgrimage to it was equivalent to a visit to Mecca. It contained ten rows of columns, and is that portion which occupies the north-west corner ending at the south-east extremity where the present coro begins. This space soon became insufficient for the population, and the Mosque was extended as far as the present Capilla de Nuestra Señora de Villavicosia.

Subsequent additions were made by different rulers. The Caliph Al-Hakim II., who followed Abderrhaman III., expanded its size by building southwards as far as the inclination of the sloping ground would allow. To him is due the third Mihrâb, or Holy of Holies, the pavement of which is worn by the knees of the devout who went thus round the Mihrâb seven times. This Mihrâb is the most beautiful chamber I came across in all Spain. The Byzantine Mosaics which adorn it are among the most superb that exist, the domed ceiling of the recess is hewn out of a solid block of marble, and its walls, which Leo the Emperor of Constantinople sent a Greek artist and skilled workmen to put up, are chiselled in marble arabesques and moulded in stucco. The entrance archway to this gem of the East, an intricate and well-proportioned feature, rests on two green and two dark coloured columns. Close by is the private door of the Sultan which led from the Alcázar to the Mesquita.

The last addition of all nearly doubled the size of the Mosque. Building to the south was impracticable on account of the fall in the land towards the river. Eastwards was the only way out of the difficulty unless the beautiful Court of the Oranges was to be enclosed. Eastwards, therefore, did Almanzor extend his building, and the whole space in this direction from the transepts or Crucero of the present church, in a line north and south, was due to his initiative.

The Mesquita at one time contained twelve hundred and ninety columns. Sixty eight were removed to make room for the Coro, Crucero and Capilla Major, which is the portion reserved for service now. In the coro, the extremely fine silleria, are some of the best in Spain. The Lectern is very good Flemish work in brass of the sixteenth century. The choir books are beautifully illuminated missals, especially those of the "Crucifixion" and the "Calling of the Apostles." All this does not, however, compensate for the partial destruction of the Mosque. So thought the people of Cordova, who petitioned Charles V. in vain against the alterations which have destroyed the harmony of the wonderful building. When passing through the city at a later date and viewing the mischief that had been done, the King rebuked the chapter thus: "You have built here what you, or any one, might have built anywhere else; but you have destroyed what was unique in the world."

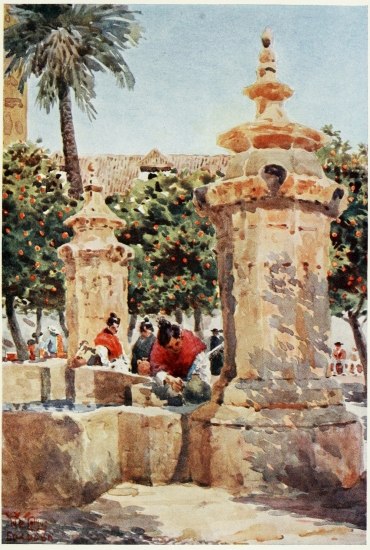

Eight hundred and fifty columns now remain out of the above number. The odd four hundred and forty occupied the place where now stand the rows of orange trees in the courtyard, one time covered in, which is known as the Patio de los Naranjos, or Court of the Oranges. The fountain used for the ablutions of the Holy still runs with a crystal stream of pure water, and is to-day the meeting place of all the gossips in Cordova.

Of the five gates to this enchanting court, that of the Puerta del Perdon, over which rises the great Tower, el Campanario, is the most important. It is only opened on state occasions. Erected in 1377 by Henry II. it is an imitation of Moorish design. The immense doors are plated with copper arabesques.

The exterior of the Mesquita is still Moorish despite the great church which has been thrust through the centre and rises high above the flat roof of the remainder of the Mosque. A massive terraced wall with flame-shaped battlements encircles the whole, the view of which from the bridge over the river is more Eastern than anything else I saw in Spain.

This fine bridge, erected by the Infidel on Roman foundations, is approached at the city end by a Doric gateway, built by Herrera in the reign of Philip II., that Philip who married Mary of England. It consists of sixteen arches and is guarded at its southern extremity by the Calahorra or Moorish Tower, round which the road passes instead of through a gateway, thus giving additional security to the defence.

The mills of the Moslem's day still work, both above and below bridge, and the patient angler sits in the sun with his bamboo rod, while the wheels of these relics groan and hum as they did in days gone by. More cunning is Isaac Walton's disciple who fishes from the bridge itself. A dozen rods with heavily weighted lines, for the Guadalquiver runs swift beneath the arches, and a small bell attached to the end of each rod is his armament. And when the unwary fish impales himself on the hook and the bell gives warning of a bite, the excitement is great. Greater still when a peal begins as three or four rods bend!

The beggars of Cordova were the most importunate that fate sent across my path in the whole of Spain. I found it impossible to sit in the streets where I would gladly have planted my easel, and it was only by standing with my back to the wall that I was able to make my sketch of the Campanario. These streets are tortuous and narrow, and the houses, built on the Moorish plan with a beautiful patio inside, are low. At many a corner I came across marble columns, some with Roman inscriptions, probably from Italica, placed against the house to prevent undue wear and tear. In the narrowest ways I noticed how the load borne by the patient ass had scooped out a regular track on either wall about three or four feet from the ground. Wherever I went, to the oldest quarters of the town in the south-east corner or the modern in the north-west, I could never rid myself of the feeling that Cordova was a city of the past. Her life is more Eastern than that of Seville, and her people bear more traces of the Moor. Decay and ruin are apparent at every turn, but how picturesque it all is!—the rags, the squalor, and the ruin. How I anathematised those beggars with no legs, or minus arms, when I tried to begin a street sketch! The patience of Job would not have helped me, it was the loathsomeness of these cripples that drove me away. Begging is prohibited in Seville and Madrid and in one or two other towns, would that it were so in Cordova.

Away up in the southern slopes of the Sierra de Cordoba stands the Convento de San Jerónimo, now a lunatic asylum. Built out of the ruins of the once magnificent Medînat-az-zahrâ, the Palace that Abderrhaman III. erected, its situation is perfect. In the old days this palace surpassed all others in the wonders of its art and luxury. The plough still turns up ornaments of rare workmanship, but like so many things in Spain its glories have departed.

Yes, Cordova has seen its grandest days, the birthplace of Seneca, Lucan, Averroes, Juan de Mena—the Spanish Chaucer—Morales, and many another who became famous, can now boast at best with regard to human celebrities as being the Government establishment for breaking in horses for the cavalry. Certainly the men employed in this are fine dashing specimens of humanity, and they wear a very picturesque dress. But Cordova like her world-famed sons, sleeps—and who can say that it would be better now if her sleep were broken?

CORDOVA. FOUNTAIN IN THE COURT OF ORANGES

SPREAD out on the edge of a fertile plain at the base of the Sierra Nevada, Granada basks in the sun; and though the wind blows cold with an icy nip from the snows of the highest peaks in Spain, I cannot but think that this, the last stronghold of the Moors, is the most ideal situation of any place I have been in.

The city is divided into three distinct districts, each with its own peculiar characteristics. The Albaicin, Antequeruela, and Alhambra. The first named covers the low ground and the hills on the bank of the Darro, a gold-bearing stream which rushes below the Alhambra hill on the north. The second occupies the lower portion of the city which slopes on to the plain, and the Alhambra rises above both, a well-nigh demolished citadel, brooding over past glories of the civilised Moor, the most fascinating spot in all Spain.

The Albaicin district is practically the rebuilt Moorish town, where the aristocrats of Seville and Cordova settled when driven out of those cities by St. Ferdinand in the thirteenth century. Many traces remain to remind one of their occupation in the tortuous streets which wind up the steep hill sides, and the wall which they built for greater security is still the boundary of the city on the north. The Albaicin is a grand place to wander in and lose oneself hunting for relics and little bits of architecture. At every turn of the intricate maze I came across something of interest, either Moorish or Mediæval. A mean looking house with a fine coat-of-arms over the door had evidently been built by a knight with the collector's craze. He had specialised in millstones; a round dozen or more were utilised in the lower portions of the wall and looked strange with stones set in the plaster between them. A delicious patio, now given over to pigs and fowls, with a broken-down fountain in the centre of its ruined arcaded court, recalled the luxuries of the Infidel. The terraced gardens standing behind and above many a blank wall carried me back to those days of old when the opulence of the East pervaded every dwelling in this Mayfair of Granada. Of all these the Casa del Chapiz, though degraded into a low-class dwelling, is with its beautiful garden the most perfect remnant of the exotic Moor.

In the Carrera de Darro, just opposite the spot where once a handsome Moorish arch spanned the stream, stands a house wherein is a Moorish bath surrounded by horseshoe arcades. The bath is 18 ft. square, and in the vaulted recess beyond is one of smaller dimensions commanding more privacy for the cleanly Eastern whose day was never complete without many ablutions.

Not far away up the hillside, in cave-dwellings amidst an almost impenetrable thicket of prickly pears, live the gitanos. I fear they now exist on the charity of the tourist, and make a peseta or two by fortune-telling or in the exercise of a more reprehensible cleverness, a light-fingered dexterity which is generally only discovered by those who "must go to the gipsy quarter" on their return to the hotel. These gipsies no longer wander in the summer months and lie up for the winter as they did of yore. They are not the Romanies of old times, and a nomadic life holds no charm for them now. They make enough out of the tourist to eke out a lazy existence throughout the year, and are fast losing all the character of a wandering tribe and the lively splendour of their race.

Higher up, the banks of the Darro are lined with more cave-dwellings, a great many of which, to judge by their present inaccessibility, are undoubtedly of prehistoric origin. Those that I took to be of later date have a sort of level platform in front of the entrance, from which the approach of a stranger could be seen and due warning taken by those inside of any hostile intent.

The Antequeruela quarter, called thus from the remnant of Moorish refugees who driven from Antequera found here a home, extends from the base of Monte Mauro to some distance below the confluence of the Darro and Genil, Granada's other river. It is the most modern quarter and busiest part of the city.

The life of an ordinary Spanish town passes in front of me as I sit in the sun sharing a seat with an old man wrapped closely in a capa. It is April. We are in the Alameda, a broad promenade which leads to the gardens of the Paseo de Salòn and de la Bomba. On either side are many coloured houses with green shutters. They are very French, and to this day I try to recall the town in France where I had seen them before. How often this happens when we travel abroad!—a face, a scent, a sound. Memory racks the tortuous channels of half-forgotten things stored away somewhere in the brain, and for days with an irritating restlessness we wander fruitlessly amid the paths of long ago.

I turned to my companion on the seat, he looked chilled despite the warmth of an April sun. "Tell me, sir, to whom does all the fine country of the Vega belong?" "Absent landlords, señor; they take their rents and they live in Madrid, and the poor man has no one to care for him." "But surely he begs and does not wish to work or to be cared for. The beggars in Granada are more numerous than in any place I know." "That is true, señor," and with a shake he relapsed into silence, drawing his capa closer around him. The turn the conversation had taken was not worth pursuing.

New buildings are superseding the old in Antequeruela, and poverty and squalor pushed further out of the sight of El Caballero, his Highness the tourist. Æsthetically we appreciate the picturesque side of poverty, the tumble-down houses, the rags, the graceful attitudes of the patient poor for ever shifting in the patches of sunlight as the great life-giver moves round. Dinner will be ready for us at 7 o'clock in the hotel, there would be no call to leave home if every town we came to was clean and its people prosperous. "But what about Los Pobres, the beggars?" you ask. "Are they really deserving of charity, or only lazy scoundrels?" I cannot answer you. I can only tell you that I have never seen such terrible emaciated bundles of rags as those I saw in Granada.

In Seville, though it is forbidden to beg, it was the one-eyed that predominated; in Cordova he of no legs, who having marked down his prey, displayed great agility as he scuttled across the street with the help of little wooden hand-rests; but here not only were both combined, but various horrors of crippled and disfigured humanity with open sores and loathsome disease thrust themselves before me wherever I went. It was disgusting—but oh! how picturesque! If only, my good Pobres, you would not come so close to me!

They say Spain is the one unspoilt country in Europe. Personally I think she is the one country that wants regenerating. Her girls are women at sixteen, old at thirty, and aged ten years later. Her men take life as it comes with very little initiative to better themselves. Very few display any energy. Their chief thoughts are woman, and how to pass the day at ease. Luckily for the country, at the age when good food and clean living helps to make men, her youth is invigorated by army service. True it is not popular. In the late war they died like flies through fever and ill-feeding, and many were the sad tales I heard of José and Pedro returning from the front with health ruined for life. It was a sad blow to Spain, that war. Her navy demolished and her colonies lost. It may be the regeneration of the nation, her well-wishers hope so, but it is a difficult thing to change the leopard's spots. The beggar being hungry begs, and well-nigh starves, his children follow his example and probably his great grandchildren will be in the same line of business a hundred years hence—Quien sabe? who knows?

I still sit in the sun rolling cigarettes; it is extraordinary how soon the custom becomes a habit, and think of all this. A string of donkeys passes with baskets stuffed tight with half a dozen large long-funnelled water cans. They have come in with fresh drinking water from the spring up the Darro under the Alhambra hill, and a little later the water-sellers will be offering glasses of the refreshingly cool contents of their cans. Granada is a city running with water, but the pollution from the drains and the never-ending ranks of women on their knees wrinsing clothes in its two streams, into which, by the way, all dead refuse is thrown, makes that which is fit to drink a purchasable quantity only.

I watch the peasants from the Vega, who come in with empty panniers slung across their donkeys, scraping up the dirt of the streets which they take away to fertilise their cottage gardens. Herds of goats go by muzzled until milking is over. They make for that bit of blank wall opposite, and stand licking the saline moisture which oozes from the plaster in the shade. The goats of Granada are reckoned the finest in Spain, and, as is the custom throughout Andalusia, graze in the early spring on the tender shoots of the young corn. This not only keeps them in food, but improves the quality of that part of the crop which reaches maturity. I could sit all day here if only the sun stood still. My companion removed himself half an hour ago and it is getting chilly in the shade, so up and on to the Cathedral.

What a huge Renaissance pile it is. Built on the Gothic plans of Diego de Siloe it is undoubtedly the most imposing edifice of this style in Spain. Fergusson considers its plan makes it one of the finest churches in Europe. The western façade was erected by Alonso Cano and José Granados, and does not follow Siloe's original design. The name of the sculptor-painter is writ in big letters throughout the building. To him are due the colossal heads of Adam and Eve, let into recesses above the High Altar, and the seven pictures of the Annunciation, Conception, Presentation in the Temple, Visitation, Purification and Assumption in the Capilla Mayor. The two very fine colossal figures, bronze gilt, which stand above the over-elaborated pulpits; a couple of beautiful miniatures on copper in the Capilla de la Trinidad; a fine Christ bearing the Cross and a head of S. Pedro over the altar of Jesus Nazareno, are also by Cano. Many other examples from his carving tools and brush are to be found in the Cathedral, of which he was made a "Racione" or minor Canon, after fleeing from Valladolid when accused of the murder of his wife. The little room he used as a workshop in the Great Tower may still be visited and his remains lie tranquilly beneath the floor of the coro.

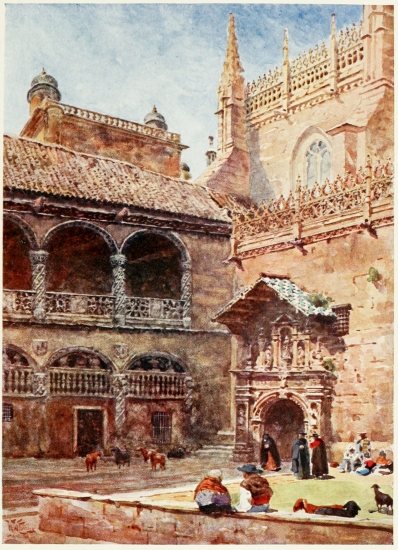

GRANADA. EXTERIOR OF THE CATHEDRAL

In the Capilla de la Antigua there is that curious little image which, found in a cave, served Ferdinand as a battle banner; and also contemporary (?) portraits of the King and his Queen.

To me the thing of surpassing interest, which ought to be the most revered building in all Spain, was the Capilla Real and its contents. The reja, which separates the choir from the rest of the chapel, is a magnificent piece of work, coloured and gilded, by Bartolomé. As the verger unlocked the great gate he drew my attention to the box containing the lock with its three beautifully wrought little iron figures and intricate pattern. We passed in, the gate swung to with a click, the lock was as good as if it had but recently been placed there. These rejas throughout the country are all in splendid condition. A dry climate no doubt preserves them as it has preserved everything else, and I very seldom detected rust on any iron work. The humidity of the winter atmosphere is insufficient, I suppose, to set up much decay in metal, and certainly the only decay in Spain is where inferior material has been used in construction, or the negligence of man has left things to rot.

With the gate locked behind me I stood in front of the two marble monuments, the one of the recumbent figures of Ferdinand and Isabella, the other of Philip and Juana la Loca—crazy Jane. Beyond rose the steps up to the High Altar, close at my side those—a short flight—that led to the crypt where the coffins of these four rest. I felt surrounded by the Great of this Earth, and certainly a feeling of awe took hold of me as their deeds passed through my mind and I realised that here lay the remains of those who had turned out the Moor, bidden God-speed to Columbus, and instituted the Inquisition.

They are wonderful tombs these two. Ferdinand wears the order of St. George, the ribbon of the Garter, Isabella that of the Cross of Santiago, Philip and his wife the Insignia of the order of the Golden Fleece. Four doctors of the church occupy the corners of the first tomb, with the twelve Apostles at the sides. The other has figures of SS. Michael, Andrew, and John the Baptist, and the Evangelist. Both tombs are elaborately carved, the medallions in alto-relievo being of very delicate work. Next to that magnificent tomb in the Cartuja de Miraflores at Burgos, these are the finest monuments in all Spain.

Above the High Altar is a florid Retablo with not much artistic merit. My interest was entirely centred in the two portrait figures of Ferdinand and Isabella. They each kneel at a Prie-Dieu facing one another on either side of the altar—the King to the north, the Queen to the south. Below them in double sections are four wooden panels in bas-relief, to which I turned after a long examination of these authentic and contemporary portraits. These panels are unsurpassed as records of the costume of the day and a faithful representation of their subject. On the left is the mournful figure of Boabdil giving up the key of the Alhambra to Cardinal Mendoza, who seated on his mule between the King and Queen, alone wears gloves. Surrounding them are knights, courtiers and the victorious soldiery. In the background are the towers of the Alhambra. To the right is seen the wholesale conversion by Baptism of the Infidel, the principal figures being monks who are very busy over their work, inducing the reluctant Moor to enter an alien Faith.

There is something very impressive about these panels, they render so well and in such a naïve manner the history they record. The surrender of the Moor after 750 years' rule, the end of his dreams, the final triumph of the King and Queen, who devoted the first portion of their reign to driving him out of the country, and the great church receiving the token of submission at the end of last act, they are all here.—The verger touched my arm, my reverie of those stirring times was broken, he had other things to show and noon was fast approaching. Pointing to three iron plates let into the floor of the chapel, he inquired if I would like to see the spot where rest the coffins of these great makers of history. Certainly; I could not leave the Cathedral without a silent homage to those who placed Spain first among the nations. He lifted the plates, and lighting a small taper which he thrust into the end of a long pole, disappeared down the steps, with a warning to mind my head for the entry was very low. I followed, stooping. At the bottom of the steps was a small opening heavily barred. The verger pushed his lighted taper and pole through the bars, and beckoned to me to look. I peered into the dark chamber, there resting on a marble slab were the rough iron-bound coffins of the "Catholic Kings." The taper flickered and cast long shadows in the gloom, discovering the coffins of Philip and Juana. It was all very eerie, a fitting climax in its simplicity to the magnificent monuments above and to the history writ on the walls of the Capilla Real. I shall never forget it.

In the sacristy I was shown the identical banner which floated from the Torre de la Vela when the Alhambra had surrendered. Isabella herself had worked this for the very object to which it was put. Next to it hangs Ferdinand's sword, with a remarkably small handle. I had thought, from the kneeling effigy in the Capilla Real, that both he and Isabella must have been small-made and this verified my guess. Many other personal relics of the two were shown me. The Queen's own missal, a beautiful embroidered chasuble from her industrious fingers, an exquisitely enamelled viril, &c. Time was short, my verger wanted his dinner, and I had seen enough for one morning. He let me out through the closed door into the Placeta de la Lonja and in a sort of dream I carried away all I had seen.

The next morning I returned to the Placeta and stood in the doorway of the old Royal Palace, now used as a drapery warehouse, and commenced the drawing figured in the illustration. The rich late Gothic ornament of the exterior of the Capilla Real is well balanced by the Lonja which backs on to the sacristy. Here Pradas's work has been much mutilated and the lower stage of the arcading built up. The twisted columns of the gallery and its original wooden roof remain to tell us what this fine façade once was.

There is a great deal of interest in this huge Cathedral, which to the tourist is quite overshadowed by the Alhambra. In the north-west corner of the Segrario which adjoins the building on the south, is the Capilla de Pulgar. Herman Perez del Pulgar was a knight serving under Ferdinand's banner. Filled with holy zeal, he entered Granada one stormy night in December 1490 by the Darro conduit, and making his way to the Mosque which then stood where the Segrario now is, pinned a scroll bearing the words Ave Maria to its principal door with his dagger. This daring deed was not discovered until the next morning, by which time the intrepid knight was safe back in camp. His courage was rewarded by a seat in the coro of the Cathedral, and at his death his body was interred in the chapel which bears his name.

Nearly all the churches of Granada occupy the sites of Mosques. Santa Anna, like San Nicolás, has a most beautiful wooden roof. San Juan de los Reyes contains portraits of Ferdinand and Isabella; its tower is the minaret of what was once a Mosque.

The Cathedral itself is so crowded in by other buildings, that no comprehensive view of the fabric is possible. Unfortunately this is the case, with one or two notable exceptions, throughout the country. Its fine proportions are thus lost, and it is only the interior with its great length and breath, its lofty arches and fine Corinthian pilasters that serve to dignify this House of God.

Taking a morning off, I walked out to the Cartuja Convent. The Gran Capitan, Gonzalo de Cordoba, at one time granted an estate to the Carthusians and on it they erected the convent to which I turned my steps. The Order about this time was immensely wealthy and they spent money with reckless lavishness on the interior of their church. Mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, ebony and cedar-wood entered largely into their decorations, as well as ivory and silver. But perhaps the marbles in the church are the most remarkable part of their scheme. These were chosen for the wonderful patterns of the sections, and with a little stretch of the imagination I could trace well-composed landscapes, human and animal forms in a great many of the slabs. The overdone chirrugueresque work, to which add these fantastic wall decorations, makes this interior positively scream. It is nothing more nor less than a vulgar display of wealth. The cloisters of the convent also attest the bad taste of the Carthusians, they contain a series of pictures which represent the most repugnant and bloodthirsty scenes of persecutions and martyrdoms of the Order.

In another convent, San Gerónimo, was buried the Gran Capitan. A slab marks the spot, but his poor bones were exhumed and carried off to Madrid in 1868 to form the nucleus of a Spanish Pantheon. Needless to say, like so many other great ideas in Spain, nothing further was done, and Gonzalo's remains still await a last resting-place.

One more fact before I reach the Alhambra. In the church of San Juan de Dios you may see the cage in which the founder, Juan de Robles, was shut up as a lunatic. What do you think his lunacy was? Having the infirm and the poor always before him, this tender-hearted man went about preaching the necessity of hospitals to alleviate their distress. Aye, he was a hundred years and more before his time, so they shut him up in a cage and there let him rot and die. Those that came after in more enlightened days valued the good man's crusade at its proper price, and he was eventually canonised, and his supposed remains now rest in an urna.

Up a toilsome approach, splashing through the mud, I drove on the night I reached Granada. As the horses slowed up, I put my head out of the carriage window, we were passing under an archway and I knew that at last one of the dreams of my life was realised. I was in the Alhambra. I became conscious of rows and rows of tall trees swaying in the wind. I smelt the delicious scent of damp earth, and could just distinguish, as the carriage crawled up the steep ascent, in the lulls of the storm, the sound of running water. It was fairyland, it was peace. After that long, tedious journey and the glare of the electric lit streets I had just passed through, I sank back on the cushions and felt my reward had come.

How is it possible to describe the Alhambra? It has been done so often and so well. Every one has read Washington Irving, and most of us know Victor Hugo's eulogy. I had better begin at the beginning, which is the gateway erected by Charles V. under which I passed with such a happy consciousness. Further up the hill, through which only pedestrians can go, is the Gate of Judgment, the first gateway into the Moorish fortress. Above it is the Torre de Justicia erected by Yusuf I. in 1348. On the external keystone is cut a hand, on the inner a key. Much controversy rages round these two signs and I leave it to others to find a solution. In old days the Kadi sat in this gateway dispensing justice. The massive doors still turn on their vertical pivots, the spear rests of the Moorish guard are still attached to the wall, and you must enter, as the Moors did, by the three turns in the dark passage beyond the gate. A narrow lane leads to the Plaza de las Algibes, under the level of which are the old Moorish cisterns. To the right is the Torre del Vino, and on the left the Acazaba.

Come with me up the short flight of steps into the little strip of garden. Let us lean over the wall and look out on to the Vega. Is there anywhere so grand and varied an outline of plain and mountain? Do you wonder at the tears that suffused the eyes of Boabdil as he turned for a last look at this incomparable spot? The brown roofs of Granada lie at our feet. Far away through the levels of the green plain, the Vega, I can see the winding of many silver streams. Beyond those rugged peaks to the south lies the Alpujarras district, the last abiding place of the conquered Moor. Further on the mass of the Sierra Aburijara bounds the horizon, west of it is the town of Loja, thirty miles away, buried in the dip towards Antequerra. To the north is Mount Parapanda, the barometer of the Vega, always covered with mist when rain is at hand. Nearer in is the Sierra de Elvira, spread out below which are the dark woods of the Duke of Wellington's property—he is known in Spain as Duque de Ciudad Rodriguez. It is clear enough for us to see the blue haze of the mountains round Jaen, and the rocky defile of Mochin. The Torre de la Vela shuts out the rest of the view. There is a bell hanging in this tower which can be heard as far away as Loja. Now turn and look behind. Right up into the blue sky rise the snow peaks of the Sierra Nevada. Mulhacen, the highest point in all Spain, is not visible, but we can see Veleta which is but a few feet lower. The whole range glistens in the afternoon sun, but it is the evening hour that brings such wonderful changes of colour over these great snowfields, and, after the sun is down, such a pale mother-of-pearl grey silhouetted against the purple sky.

The entrance into what we call the Alhambra is hidden away behind the unfinished Palace of Charles V. The low door admits us directly in the Patio de los Arrayanes, or court of the Myrtles. Running north and south it gets more sun than any other court of the Alhambra. What a revelation it is! In the centre is an oblong tank full of golden carp. The neatly kept myrtle hedges encircle this, reflected in the clear water they add refreshing charm to a first impression of the Moorish Palace. On the north rises the Torre de Comares, the approach to which is through a beautifully proportioned chamber, the roof of which was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 1890. The whole of the ground-floor of this tower is known as the Hall of the Ambassadors. The monarch's throne occupied a space opposite the entrance and it was here that the last meeting to consider the surrender was held by Boabdil. The elaborate domed roof of this magnificent chamber is of larch wood, but the semi-darkness prevents one realising to the full extent its beauties. From the windows, which almost form small rooms, so thick are the walls of the Tower of Comares, fine views over the roofs of the city and the Albaicin hill are obtained.

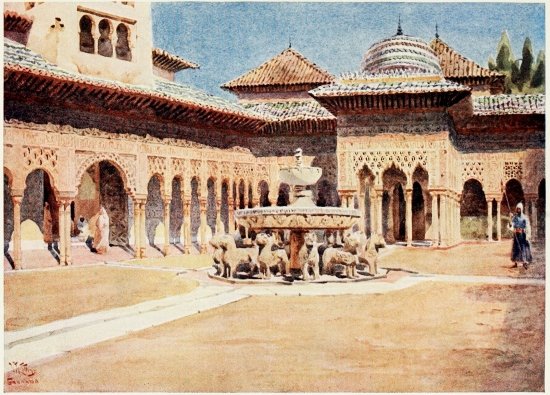

The Court of the Lions, so called from the central fountain upheld by marble representations of the kingly beast, is surrounded by a beautiful arcade. At either end this is thrown out, forming a couple of extremely elegant pavilions. Fairy columns support a massive roof, the woodwork of which is carved with the pomegranate of Granada. Intricate fret-work is arranged to break the monotony of strong sunlight on a flat surface. Arabesques and inscriptions, stamped with an iron mould on the wet clay, repeat themselves all round the frieze. Orange trees at one time adorned the court and cast gracious shade on its surface. The fountain threw up jets of splashing water, the musical sound harmonising with the wonderful arrangement of light and shade. I tried to picture all this as I sat making my sketch, but even in April, though hot in the sun, I required an overcoat in the shadow, and I must own that the ever-present tourist with his kodak sadly disturbed all mental attempts at the reconstruction of Moorish life.

GRANADA. THE ALHAMBRA, COURT OF LIONS

On the south side of the court is the hall of the Abencerrages, named after that noble family. The massive wooden doors, which shut it off from the arcade, are of most beautiful design. The hall is rectangular and has a fine star-shaped stalactite dome. The azulejos, or tiles, are the oldest that remain in the Alhambra. A passage leads to what was once the Royal Sepulchral Chamber.

On the east side is the so-called Sala de la Justicia divided into several recesses and running the whole length of this portion of the court. The central recess was used by Ferdinand and Isabella when they held the first Mass after the surrender of the Moors. The chief interest of the Sala I found to be in a study of the paintings on the semicircular domed roofs. They portray the Moor of the period. The middle one, that in the chapel-recess, no doubt contains portraits of Granada's rulers in council. The other two represent hunting scenes and deeds of chivalry. It is supposed that the Koran forbids the delineation of any living thing. The Moor got over this difficulty by portraying animal life in as grotesque a manner as possible, or by employing foreign captives to do this for him. One theory of the origin of the Lion Fountain is that a captive Christian carved the lions and gave his best—or his worst—as the price of his liberation. Personally I think they are of Phœnician origin. Animals and birds in decoration reached the Moor from Persia, where from unknown ages they had always been employed in this way; and the Môsil style of hammered metal work is replete with this feature.

On the north side of the court lies the Room of the Two Sisters, with others opening out from it, which seems to point to the probability that this was the suite occupied by the Sultana herself. Moorish art has here reached its highest phase. The honeycomb roof contains nearly five thousand cells, all are different, yet all combine to form a marvellously symmetrical whole. Fancy ran free with the architect who piled one tiny cell upon another and on these supported a third. Pendant pyramids cluster everywhere and hang suspended apparently from nothing. In the fertility of his imagination the designer surpassed anything of the kind that went before or has since been attempted. Truly the verses of a poem copied on to the azulejos are well set. "Look well at my elegance, and reap the benefit of a commentary on decoration. Here are columns ornamented with every perfection, the beauty of which has become proverbial."

Beyond this entrancing suite of rooms is the Miradoro de Daraxa with three tall windows overlooking that little gem of a garden the Patio de Daraxa. It was here that Washington Irving lodged when dreaming away those delicious days in the Alhambra.

The old Council Chamber of the Moors, the Meshwâr, is reached through the Patio de Mexuar. Charles V. turned this chamber into a chapel, and the hideous decorations he put up are still extant. An underground passage, which leads to the baths, ran from the patio and gave access to the battlements and galleries of the fortress as well as forming a connecting link between each tower.

The baths are most interesting, but to me were pervaded by a deadly chill. I felt sorry for the guardian who spends his days down in such damp, icy quarters. A remark I made to him inquiring how long his duty kept him in so cold a spot, called forth so terrible a fit of coughing that I got no reply. I was told afterwards that he was only placed there as he was too ill for other duty, and it was expected he would not live much longer! There are two baths of full size and one for children. The azulejos in them are very beautiful, as they also are in the disrobing room and chamber for rest.

An open corridor leads from the Hall of the Ambassadors to the Torre del Peinador which Yusuf I. built. The small Tocador de la Reina, or Queen's dressing-room, with its quaint frescoes, was modernised by Charles V. Let into the floor is a marble slab drilled with holes, through which perfumes found their way from a room below while the Queen was dressing.

The glamour of the East clings to every corner of the Alhambra, and the wonder of it all increased as I began to grow familiar with its courtyards and halls, the slender columns of its arcades, with their tracery and oft-repeated verses forming ornament and decoration, and the well thought-out balance of light and shade. What must it all have been like when the sedate Moor glided noiselessly through the cool corridors, or the clang of arms resounded through the now silent halls! It is difficult to imagine. The inner chambers were then lined with matchless carpets and rugs and the walls were covered with subtly coloured azulejos.

Many are the changes since those days of the Infidel who cultivated the art of living as it has never been cultivated since. Restoration is judiciously but slowly going on, and every courtesy is shown to the visitor. A small charge might be levied, however, to assist the Government, even in a slight degree, with restoration, and I am sure no one would grudge paying for the privilege of sauntering through the most interesting remains of the Moorish days of Spain.

The unfinished Palace of Charles V. occupies a large space, to clear which a great deal of the Moorish Palace was demolished. The interior is extremely graceful. The double arcades, the lower of which is Doric and the upper Ionic, run round a circular court which for good proportion it would be hard to beat.

On the Corre de Sol, a little way out of the Alhambra and situated above it, is the Generalife. It belongs to the Pallavicini family of Genoa, but on the death of the present representative becomes the property of the Spanish Government. A stately cypress avenue leads to the entrance doorway, through which one enters an oblong court full of exotic growth and even in April a blaze of colour. Through a tank down the centre runs a delicious stream of clear water. At the further end of this captivating court are a series of rooms, one of which contains badly painted portraits of the Spanish Sovereigns since the days of Ferdinand and Isabella.

Up some steps is another garden court with another tank, shaded by more cypress trees. One huge patriarch is over six hundred years old, and it is supposed that under it Boabdil's wife clandestinely met Hamet the Abencerrage.

Space will not permit me to tell of the many entrancing excursions I made to the foot-hills of the Sierra Nevada and up the two rivers. I can only add that the valleys disclosed to the pedestrian are a wealth of rare botanical specimens, and if time permits will well repay a lengthened sojourn in the last stronghold of the Moors in Spain.

MALAGA disputes with Cadiz the honour of being the oldest seaport in the country. In early days the Phœnicians had a settlement here, and in after times both the Carthagenians and Romans utilised "Malacca" as their principal port on the Mediterranean littoral of Spain. In 571 the Goths under their redoubtable King, Leovigild, wrested the town from the Byzantines. Once more it was captured, by Tarik, in the year 710 and remained a Moorish stronghold until Ferdinand took it after a long siege in 1487.

It is said that gunpowder was first used in Spain at this siege, when the "seven sisters of Ximenes," guns planted in the Gibralfaro, belched forth fire and smoke.

In the year 709 the Berber Tarif entered into an alliance with Julian, Governor of Ceuta, who held that place for Witiza the Gothic King of Spain. With four ships and five hundred men he crossed the narrow and dangerous straits to reconnoitre the European coast, having secretly in view an independent kingdom for himself on the Iberian peninsula. He landed at Cape Tarifa.

This expedition was so far successful that in two years' time another Berber, of a name almost similar, Tarík to wit, was sent over with twelve thousand men and landed near the rock which received the name of Jabal-Tarík, or mountain of Tarík, the present Gibraltar.

Witiza in the meantime died and was succeeded by Roderic, who, hearing of the invasion of this Moorish host, hastened south from Toledo and met his death in the first decisive battle between Christian and Infidel on the banks of the Guadalete near Cadiz. Tarík then commenced his victorious march, which ended in less than three years with the subjugation of the whole country as far as the foot of the Pyrenees—Pelayo, in his cave at Covadonga near Oviedo, alone holding out with a mere remnant against the all-conquering Moor.

If you ask me, "What is Malaga to-day?" I can reply with truth, "The noisiest town in Spain." Like all places in the south it is a babel of street-cries, only a little more so than any of the others. The seranos, or night-watchmen, disturb one's rest as they call out the hour of the night, or whistle at the street corners to their comrades. A breeze makes hideous the hours of darkness by the banging to and fro of unsecured shutters. The early arrival of herds of goats with tinkling bells heralds the dawn, which is soon followed by the discordant clatter of all those, cracked and otherwise, which hang in the church belfries. The noisiest town I visited, most certainly, but for all that a very enchanting place. In a way not unlike Naples, for the Malagueno is the Spanish prototype of the Neapolitan. Lazy, lighthearted, good-natured, but quick to take affront, he gets through the day doing nothing in a manner that won my sincere admiration. "Why work, señor, when you have the sun? I do not know why the English travellers are always in such a hurry. And the North American, he is far worse. I earned two pesetas yesterday. To-day I have no wants, I do not work. To-morrow? Yes, perhaps to-morrow I work, but to-day I sit here in the sun, I smoke my cigarette, I am content to watch others, that is life!"—and who can say that the Malagueno is far wrong? Not I.

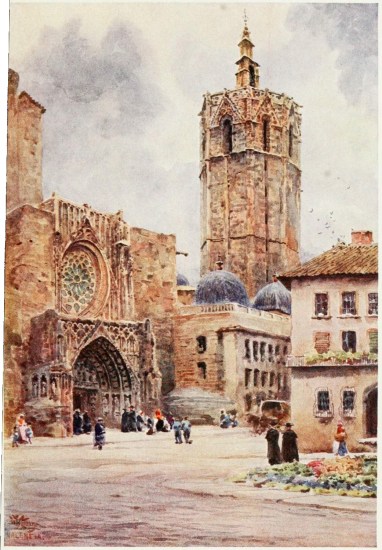

Malaga's Cathedral, an imposing building of a very mixed Corinthian character, occupies the site of a Moorish mosque which was converted into a church. Of this early church of the Incarnation, the Gothic portal of the Segragrio is the only portion remaining. The present edifice was begun in 1538 from the plans of that great architect Diego de Siloe, but being partially destroyed by an earthquake in 1680, was not completed until 1719. It cannot be called complete even now, and the long period over which its construction has been spread accounts for the very many inconsistencies in a building which is full of architectural defects.

The west façade is flanked by two Towers, only one of which has been finished; this is drawn out in three stages like the tower of La Seo at Saragossa, and has a dome with lantern above. The doors of the north and south Transepts are also flanked by towers, but they do not rise beyond the cornice line. The interior, reminding one of Granada's Cathedral, is seemingly immense. The proportions are massive and decidedly good. It was in his proportions that Siloe excelled. The length of this is three hundred and seventy-five feet, the width two hundred and forty, and the height one hundred and thirty feet. The columns which support the heavy roof consist of two rows of pillars one above the other. The vaulting is of round arches.

A picture by Alonso Cano in the chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary, and one of a Virgin and Child, in that of San Francisco, by Morales, were the only two objects that I could say interested me, besides the magnificently carved silleria del coro, the work of many hands, but chiefly those of Pedro de Mena, a pupil of Cano.

With all its architectural incongruities it is an impressive fabric, and rises high above the surrounding roofs, like a great Liner with a crowd of smaller boats lying around her. So it struck me as I sat on the quayside of the Malagueta making my sketch, sadly interfered with by an unpleasant throng of idling loafers.

Beyond Malagueta lies Caleta, and on the hill above them is the Castilla de Gibralfaro, from which when the sky is clear the African mountains near Ceuta can be seen. Below the Gibralfaro and between it and the Cathedral, lies the most ancient part of the city, the Alcazába, the glorious castle and town of Moorish days. And now?—like so many of Spain's departed glories, it is not much more than a ruined conglomeration of huts and houses of a low and very insanitary order.

At the other end of Malaga is the Mercado, and close by is the old Moorish sea gateway, the Puerta del Mar, washed by the waters of the blue Mediterranean in their day, but at the present time well away from the sea and surrounded by houses.