The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lord Montagu's Page, by G. P. R. James

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Lord Montagu's Page

An Historical Romance

Author: G. P. R. James

Release Date: July 22, 2012 [EBook #40295]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LORD MONTAGU'S PAGE ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Jane Robins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

PHILADELPHIA

CHILDS AND PETERSON,

602 ARCH STREET.

1858.

I. WATY

AN

HISTORICAL ROMANCE

OF THE

Seventeenth Century.

By

G. P. R. JAMES,

Author of

"RICHELIEU," "DARNLEY," "MARY OF BURGUNDY," "OLD DOMINION," ETC.

PHILADELPHIA:

CHILDS & PETERSON, 602 ARCH ST.

1858.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH.

Prefatory Dedication.

LORD MONTAGU'S PAGE.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHAPTER XXIX.

CHAPTER XXX.

CHAPTER XXXI.

CHAPTER XXXII.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

CHAPTER XXXIV.

CHAPTER XXXV.

CHAPTER XXXVI.

CHAPTER XXXVII.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

CHAPTER XXXIX.

CHAPTER XL.

CHAPTER XLI.

CHAPTER XLII.

CHAPTER XLIII.

CHAPTER XLIV.

CHAPTER XLV.

CHAPTER XLVI.

CHAPTER XLVII.

CHAPTER XLVIII.

CHAPTER XLIX.

CHAPTER L.

CHAPTER LI.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1858, by

CHILDS & PETERSON,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States in and

for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

STEREOTYPED BY L. JOHNSON & CO.

PHILADELPHIA.

PRINTED BY DEACON & PETERSON.

[From Allibone's forthcoming Dictionary of Authors.]

George Payne Rainsford James was born in London about the year 1800, and commenced his literary career at an early age by anonymous contributions to the journals and reviews which catered to the literary taste of "a discerning public." Some of these juvenile effusions fell under the notice of Washington Irving, and this gentleman, with his usual kindness of heart, encouraged the young author to venture upon something of a more important character than the fugitive essays which had hitherto employed his pen. Thus strengthened in his literary proclivity, the young aspirant nibbed his "gray-goose quill," commenced author in earnest, and gave to the world in 1822 his first work,—a Life of Edward the Black Prince. Mr. James now turned his attention to a field which had recently been cultivated with eminent success,—historical romance,—and completed in 1825 his novel of Richelieu, which, having received the favorable verdict of Sir Walter Scott, made its appearance in 1829. This was followed in the next year by Darnley and De L'Orme.

Richelieu was so fortunate as to secure the favor of the formidable Christopher North of Blackwood; but this invaluable commendation was withheld from Darnley:—

"Mr. Colburn has lately given us two books of a very different character, Richelieu and Darnley. Richelieu is one of the most spirited, amusing, and interesting romances I ever read; characters well drawn—incidents well managed—story perpetually progressive—catastrophe at once natural and unexpected—moral good, but not goody—and the whole felt, in every chapter, to be the work of a—Gentleman."—Noctes Ambrosianæ, April, 1830; Blackw. Mag., xxvii. 688, q.v.

From this time to the present Mr. James has been no idler in the Republic of Letters, as the following alphabetical list of his writings amply proves:—

1. Adra, or the Peruvians; a Poem, 1 vol. 2. Agincourt, 1844, 3 vols. 3. Agnes Sorrel, 1853, 3 vols. 4. Arabella Stuart, 1853, 3 vols. 5. Arrah Neil, 1845, 3 vols. 6. Attila, 1837, 3 vols. 7. Beauchamp, 1848, 3 vols. 8. Blanche of Navarre; a Play, 1839, 1 vol. 9. Book of the Passions, 1838, 1 vol. 10. Cameralzaman; a Fairy Drama, 1848,1 vol. 11. Castelneau; or, The Ancient Régime, 1841, 3 vols. 12. Castle of Ehrenstein, 1847, 3 vols. 13. Charles Tyrrell, 1839, 2 vols. 14. City of the Silent; a Poem, 1 vol. 15. Commissioner; or, De Lunatico Inquirendo, 1842, 1 vol. 16. Convict, 1847, 3 vols. 17. Corse de Leon, the Brigand, 1841, 3 vols. 18. Dark Scenes of History, 1849, 3 vols. 19. Darnley, 1830, 3 vols. 20. Delaware, 3 vols; subsequently published under the title of Thirty Years Since, 1848, 1 vol. 21. De L'Orme, 1830, 3 vols. 22. Desultory Man, 3 vols. 23. Educational Institutions of Germany, 1 vol. 24. Eva St. Clair, and other Tales, 1843, 2 vols. 25. False Heir, [2] 1843, 3 vols. 26. Fate, 1851, 3 vols. 27. Fight of the Fiddlers, 1848, 1 vol. 28. Forest Days, 1843, 3 vols. 29. Forgery; or, Best Intentions, 1848, 3 vols. 30. Gentleman of the Old School, 1839, 3 vols. 31. Gipsy, 1835, 3 vols. 32. Gowrie; or, The King's Plot, 1 vol. 33. Heidelberg, 1846, 3 vols. 34. Henry Masterton, 1832, 3 vols. 35. Henry Smeaton, 1850, 3 vols. 36. Henry of Guise, 1839, 3 vols. 37. History of Charlemagne, 1832, 1 vol. 38. History of Chivalry, 1 vol. 39. History of Louis XIV., 1838, 4 vols. 40. History of Richard Cœur de Lion, 1841-42, 4 vols. 41. Huguenot, 1838, 3 vols. 42. Jacquerie, 1841, 3 vols. 43. John Jones's Tales from English History, for Little John Joneses, 1849, 2 vols. 44. John Marston Hall, 1834, 3 vols; subsequently published under the title of Little Ball o' Fire, 1847, 1 vol. 45. King's Highway, 1840, 3 vols. 46. Last of the Fairies, 1847, 1 vol. 47. Life of Edward the Black Prince, 1822, 2 vols. 48. Life of Henry IV. of France, 1847, 3 vols. 49. Life of Vicissitudes, 1 vol. 50. Man-at-Arms, 1840, 3 vols. 51. Margaret Graham, 1847, 2 vols. 52. Mary of Burgundy, 1833, 3 vols. 53. Memoirs of Great Commanders, 1832, 3 vols. 54. Morley Ernstein, 1842, 3 vols. 55. My Aunt Pontypool, 3 vols. 56. Old Dominion; or, The Southampton Massacre, 1856, 3 vols. 57. Old Oak Chest, 3 vols. 58. One in a Thousand, 1835, 3 vols. 59. Pequinillo, 1852, 3 vols. 60. Philip Augustus, 1831, 3 vols. 61. Prince Life, 1855, 1 vol. 62. Revenge, 1851, 3 vols; so styled by the bookseller, without the author's consent. It was originally published in papers under a different name. 63. Richelieu, 1829, 3 vols. 64. Robber, 1838, 3 vols. 65. Rose D'Albret, 1840, 3 vols. 66. Russell, 1847, 3 vols. 67. Sir Theodore Broughton, 1847, 3 vols. 68. Smuggler, 1845, 3 vols. 69. Stepmother, 1846, 3 vols. 70. Story without a Name, 1852, 1 vol. 71. String of Pearls, 1849, 2 vols. 72. Ticonderoga; or, The Black Eagle, 1854, 3 vols. 73. Whim and its Consequences, 1847, 3 vols. 74. Woodman, 1847, 3 vols.

It will be seen that the above list presents a total of 188 vols.,—viz: 51 works in 3 vols. each, 2 in 4 vols. each, 6 in 2 vols. each, and 15 in 1 vol. each. Almost all of these volumes are of the post-octavo size. Mr. James is also the editor of the Vernon Letters, illustrative of the times of William III., 1841, 3 vols. 8vo; and of Wm. Henry Ireland's historical romance of David Rizzio, 1849, 3 vols. p. 8vo; and was associated with Dr. E. E. Crowe in the Lives of the Most Eminent Foreign Statesmen, 1832-38, 5 vols. p. 8vo, (4 vols. were Mr. James's, and 1 vol. Dr. Crowe's,) and with Mr. Maunsell B. Field in the composition of Adrian, or The Clouds of the Mind, 1852, 2 vols. p. 8vo.

To this list may be added Norfolk and Hereford, (in a collection entitled Seven Tales by Seven Authors,) and enough articles in various periodicals to fill eight or ten volumes. Perhaps we should not omit to notice that a work entitled A Brief History of the United States Boundary Question, drawn up from official papers, published in London, 1839, 8vo, and ascribed to Mr. James, is not his production; nor had he any share (further than writing a preface, or something of that kind) in another work often credited to him,—Memoirs of Celebrated Women, 1837, 2 vols. p. 8vo. During the reign of William IV. the author received the appointment of historiographer of Great Britain; but this post was resigned by him many years since.

There have been new editions of many of Mr. James's novels, and some or all of them have appeared in Bentley's Series of Standard Novels. There has been also a Parlor-Library Edition. A collective edition was published by Smith, Elder & Co., commencing in June, 1844, and continued by Parry, and by Simpkin, Marshall & Co. In America they have been very popular and published in large quantities.

About 1850 Mr. James, with his family, removed permanently to the United States, and resided for two or three years in Berkshire county, Massachusetts. Since 1852 he has been British Consul at Richmond, Virginia. The space which we have occupied by a recital of the titles only of Mr. James's volumes necessarily restricts the quotation of criticisms upon the merits or demerits of their contents. It has fallen to the lot of few authors to be so much read, and at the same time so much abused, as the owner of the fertile pen which claims the long list of novels commencing with Richelieu in 1829 and extending to the Old Dominion in 1856. That there should be a family likeness in this numerous race—where so many, too, are nearly of an age—can be no matter of surprise. The mind, like any other artisan, can only construct from materials which lie within its range; and, when no time is allowed for the accumulation and renewal of these, it is vain to hope that variety of architecture will conceal the identity of substance. Yet, after all, the champion of this popular author will probably argue that this objection against the writings of Mr. James is greatly overstated and extravagantly overestimated. The novelist can draw only from the experience of human life in its different phases, and these admit not of such variety as the inordinate appetite of the modern Athenians unreasonably demands. A new series of catastrophes and perplexities, of mortifications and triumphs, of joys and sorrows, cannot be evoked for the benefit of the reader of each new novel. Again, Mr. James's admirer insists that this charge of sameness so often urged against our novelist's writings is perhaps overstated. Where one author, as is frequently the case, gains the reputation of versatility of talent by writing one or two volumes, it is not to be believed that Mr. James exhibits less in one or two hundred. He who composes a library is not to be judged by the same standard as he who writes but one book. And even if the charge of "sameness" be admitted to its full extent, yet many will cordially concur with the grateful and graceful acknowledgment of one of the most eminent of modern critics:—

"I hail every fresh publication of James, though I half know what he is going to do with his lady, and his gentleman, and his landscape, and his mystery, and his orthodoxy, and his criminal trial. But I am charmed with the new amusement which he brings out of old materials. I look on him as I look on a musician famous for 'variations.' I am grateful for his vein of cheerfulness, for his singularly varied and vivid landscapes, for his power of painting women at once ladylike and loving, (a rare talent,) for making lovers to match, at once beautiful and well-bred, and for the solace which all this has afforded me, sometimes over and over again, in illness and in convalescence, when I required interest without violence, and entertainment at once animated and mild."—Leigh Hunt.

Two of the severest criticisms to which Mr. James's novels have been subjected are, the one in the London Athenæum for April 11, 1846, and the one in the North American Review, by E. P. Whipple, for April, 1844.

We have spoken of Mr. James's champions and admirers; and such are by no means fabulous personages, notwithstanding the severe censures to which we have alluded. A brief quotation from one of these eulogies will be another evidence added to the many in this volume of a wide dissimilarity in critical opinions:—

"His pen is prolific enough to keep the imagination constantly nourished; and of him, more than of any modern writer, it may be said, that he has improved his style by the mere dint of constant and abundant practice. For, although so agreeable a novelist, it must not be forgotten that he stands infinitely higher as an historian.... The most fantastic and beautiful coruscations which the skies can exhibit to the eyes of mankind dart as if in play from the huge volumes that roll out from the crater of the volcano.... The recreation of an enlarged intellect is ever more valuable than the highest efforts of a confined one. Hence we find in the works before us, [Corse de Leon, the Ancient Régime, and The Jacquerie,] lightly as they have been thrown off, the traces of study,—the footsteps of a powerful and vigorous understanding."—Dublin University Magazine, March, 1842.

The Edinburgh Review concludes some comments upon our author with the remark,

"Our readers will perceive from these general observations that we estimate Mr. James's abilities, as a romance-writer, highly: his works are lively and interesting, and animated by a spirit of sound and healthy morality in feeling, and of natural delineation in character, which, we think, will secure for them a calm popularity which will last beyond the present day."

We have before us more than thirty (to be exact, just thirty-two) commendatory notices of our author, but brief extracts from two of these is all for which we can find space.

"He belongs to the historical school of fiction, and, like the masters of the art, takes up a real person or a real event, and, pursuing the course of history, makes out the intentions of nature by adding circumstances and heightening character, till, like a statue in the hands of the sculptor, the whole is in fair proportion, truth of sentiment, and character. For this he has high qualities,—an excellent taste, extensive knowledge of history, a right feeling of the chivalrous, and a heroic and a ready eye for the picturesque: his proprieties are admirable; his sympathy with whatever is high-souled and noble is deep and impressive. His best works are Richelieu and Mary of Burgundy."—Allan Cunningham: Biographical and Critical History of the Literature of the Last Fifty Years, 1833.

The critic next to be quoted, whilst coinciding in the objections prominently urged against Mr. James as an author,—repetition, tediousness, and deficiency of terseness,—yet urges on his behalf that

"There is a constant appeal in his brilliant pages not only to the pure and generous, but to the elevated and noble sentiments; he is imbued with the very soul of chivalry; and all his stories turn on the final triumph of those who are influenced by such feelings over such as are swayed by selfish or base desires. He possesses great pictorial powers, and a remarkable facility of turning his graphic pen at will to the delineation of the most distant and opposite scenes, manners, and social customs.... Not a word or a thought which can give pain to the purest heart ever escapes from his pen; and the mind wearied with the cares and grieved at the selfishness of the world reverts with pleasure to his varied compositions, which carry it back, as it were, to former days, and portray, perhaps in too brilliant colors, the ideas and manners of the olden time."—Sir Archibald Alison: Hist. of Europe, 1815-52, chap, v., 1853. See also Alison's Essays, 1850, iii. 545-546; North British Review, Feb. 1857, art, on Modern Style.

My dear Sir:—

In dedicating to you the following pages, I am moved not more by private friendship and regard, than by esteem for your abilities, and respect for your many and varied acquirements. It might seem somewhat presumptuous in me to call for your acceptance or seek your approbation of this work, when not only your general acquaintance with, but your profound knowledge of, almost every branch of modern and ancient literature qualify and might be expected to prompt you to minute and severe criticism. But I have always found, in regard to my own works at least, that those who were best fitted to judge were the most inclined to be lenient, and that men of high talent and deep learning condescended to tolerate, if not to approve, that which was assailed by very small critics, or scoffed at by men who, calling themselves humorists, omitted the word "bad" before the appellation in which they gloried.

To your good humor, then, I leave the work, and will only add a few words in regard to the object and construction of the story.

We have in the present day romances of many various kinds; and I really know not how to class my present effort. It is not a love-story, for any thing like that which was the great moving power of young energies—at least in less material days than these—has very little part in the book. I cannot call it a novel without a hero, because it is altogether dedicated to the adventures of one man. [6] I cannot call it a romance without a heroine, because there is a woman in it, and a woman with whom I am myself very much in love. I cannot call it absolutely a historical romance, because there are several characters which are not historical, and I am afraid I have taken a few little liberties with Chronology which, were she as prudish a dame as some of the middle-aged ladies whom I could mention, would either earn me a box of the ear, or produce so much scandal that my good name would be lost forever. Plague take the months and the days! they are always getting in one's way. But I do believe I have been very reverent and respectful to their grandmothers the years, and, with due regard for precedence and the Court Guide, have not put any of the latter out of her proper place.

I do not altogether wish to call this a book of character; for I do not exactly understand that word as the public has lately been taught to understand it. There is no peasant, or cobbler, or brick-layer's apprentice, in the whole book, endowed with superhuman qualities, moral and physical. There is no personage in high station—given as the type of a class—imbued with intense selfishness or demoniac passions, wicked without motive, heartless against common sense, and utterly degraded from that noble humanity, God's best and holiest gift to mankind. There is no meek, poor, puling, suffering lover, who condescends humbly to be bamboozled and befooled through three volumes, or Heaven knows how many numbers, for the sake of marrying the heroine in the end. I therefore cannot properly, in the present day, call it a work of character.

I might call it, perhaps,—although the hero is an Englishman,—a picture of the times of Louis XIII; but, alas! I have not ventured to give a full picture of these times. We have become so uncommonly cleanly and decorous in our own days, that a mere allusion to the dirt and indecency of the age of our great-grandmothers is not to be tolerated. In order, indeed, to preserve something like verisimilitude, I have been obliged to glance, in one chapter, at the freedom of manners of the days to which I refer; but it has been a mere glance, and given in such a manner that the cheek of one who understands it, in the sense in which one of those very days would understand it, must have lost the power of blushing. At all events, it can never sully [7] or offend the pure, nor lead the impure any further wrong.

There are a great many explanations and comments, in illustration of the times, which I should like to give for the benefit of that part of my readers who have put on the right of knowing all things at the same time that the third change was made in their dress, and I would have done so, in notes; but, unfortunately, I do not write Greek; and a little incident prevented me from writing those notes in Latin. A work—a most interesting work—was published a few years ago in London, called the Bernstein Hexe, or Amber Witch. More than one translation appeared; and one of these had the original notes,—some written in Latin where they were peculiarly anatomical and indecent; but, to my surprise, I found that several ladies were fully versed in that sort of Latinity. I cannot flatter myself with having a sufficient command of the Roman tongue to be enabled to veil the meaning more completely from the unlearned.

Only in the case of two personages have I attempted to elaborate character,—in regard to my hero, and in regard to the Cardinal de Richelieu. The former, though not altogether fictitious, must go with very little comment. I wished to show how a young heart may be hardened by circumstances, and how it may be softened and its better feelings evolved by a propitious change. The latter, I will confess, I have labored much; because I think the world in general, and I myself also, have done some injustice to one of the greatest men that ever lived. Very early in life I depicted him when he had reached old age,—that is to say, his old age; for he had not, at the time of his death, numbered as many years as are now upon my own head. He had then been tried in the fire of the most terrible circumstances which perhaps ever assayed a human heart; not only tried, but hardened; and even then, upon his death-bed, his burst of tenderness to his old friend, Bois Robert, his delight in the arts, and passion for flowers, showed that the tenderer and—may I not say more noble?—feelings of the man had not been swallowed up by the hard duties of the statesman, or the galling cares of the politician. I now present him to the reader at a much earlier period of life,—young, vigorous, successful, happy,—when the germs of all those qualities for which men have reproached or applauded him were certainly developed, [8] were growing to maturity; when the severity which afterwards characterized him, and the gentleness which he as certainly displayed, had both been exercised; but when the briers and thorns had not fully grown up, and before the soft grass of the heart had been trampled under foot.

All men have mixed characters. I do not believe in perfect evil or in perfect goodness on this earth; but at various times of life the worse or the better spirit predominates, according to the nourishment and encouragement it receives. How far Richelieu changed, and when and how he changed, would require a longer discussion than can be here afforded. But one thing is to be always remembered,—that he was generally painted by his enemies; and, where they admit high qualities and generous feelings, we may be sure that it was done with even a niggard hand, and add something to the tribute of the unwilling witness.

In regard to critics, it may be supposed that I have spoken, a few pages back, somewhat irreverently: I do not mean to do so in the least. Amongst them are some most admirable men,—some who have done great, real, tangible service to the public,—who have guided, if not formed, public taste; and for them I have the greatest possible respect. I speak not of the contributors to our greater and more pretentious Reviews,—although, perhaps, a mass of deeper learning, more close and acute investigation, and purer critical taste, cannot be found in the literature of the world than that contained in their pages; but I speak of the whole body of contemporary critics, many of whose minor articles are full of astute perception and sound judgment. But there are others for whom, though I have the most profound contempt, I have a most humble fear. It is useless in Southern climates, such as that which I inhabit, to attempt to prevent oneself from being stung by mosquitos or to keep one's ears closed against their musical but venomous song. The only plan which presents any chance of success—at least, it is as good as any other—is to go down upon your knees and humbly to beseech them to spare you. I therefore most reverently beseech the moral mosquitos, who are accustomed to whistle and sing about my lowly path, to forbear as much as possible; and, although their critical virulence may be aroused to the highest pitch by seeing a man walk quietly on for thirty years along the only [9] firm path he can find amongst the bogs and quagmires of literature, to spare at least those parts which are left naked by his tailor and his shoemaker; to remember, in other words, that, besides the faults and errors for which I am myself clearly responsible, there is some allowance to be made for the faults of my amanuensis and for the errors of my printer. I admit that I am the worst corrector in the whole world; but I do hope that the liberality of criticism will not think fit to see, as has been lately done, errors of mind in errors clearly of the printer; especially in works which, by some arrangement between Mr. Newby and the Atlantic, I never by any means see till the book has passed through the press. But, should they still be determined to lay the whole blame upon the poor author's shoulders, I may as well furnish them with some excuse for so doing. The best that I know is to be found in the following little anecdote:—

When I was quite a young boy, there was a painter in Edinburgh, of the name of Skirven, celebrated both for his taste and genius, and his minute accuracy in portrait-painting. A very beautiful lady of my acquaintance sat to him for her portrait in a falling collar of rich and beautiful lace. Unfortunately, there was a hole in the lace. As usual, he did not suffer her to see the portrait till it was completed; and, when she did see it, there was a portrait of the hole as well as herself. "Well, Mr. Skirven," she said, "I think you need not have painted the hole."

"Well, madam," answered the painter, "then you should have mended it first."

G. P. R. James.

Ashland, Virginia,

December, 1857.

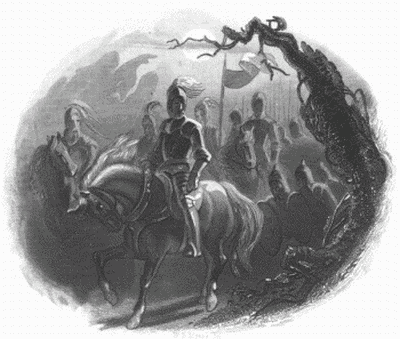

It was a dark and stormy night,—a very dark night indeed. No dog's mouth, whether terrier, mastiff, or Newfoundland, was ever so dark as that night. The hatches had been battened down, and every aperture but one, by which any of the great, curly-pated, leaping waves could jump into the vessel, had been closed.

What vessel? the reader may perhaps inquire. Well, that being a piece of reasonable curiosity,—although I do wish, as a general thing, that readers would not be so impatient,—I will gratify it, and answer the inquirer's question; and, indeed, would have told him all about it in five minutes if he would but have given me time.

What vessel? asks the reader. Why, a little, heavy-looking, fore-and-aft, one-masted ship, somewhat tubbish in form, which had battled with a not very favorable gale during a long stormy day, and had, as the sun went down, approached the coast of France, it might be somewhat too close for safety. The atmosphere in the cabin below was hot and oppressive. How indeed could it be otherwise, when not one breath of air, notwithstanding all the bullying and roaring of Boreas, had been able to get in during the whole day? But such being the case, and respiration in the little den being difficult, the only altogether terrestrial animal—sailors are, of course, amphibious—which that vessel contained had forced his way up to the deck through the only narrow outlet which had been left open.

The amphibia have always a considerable dislike and some degree of contempt for all land-animals, and the five sailors, with their skipper, who formed all the crew so small a craft required, would probably have driven below the intruder upon their labors, had they had time, leisure, or light to notice him at all. But for near two hours he stood at the stern on the weather side of the ship, holding on by the bulwarks, wet to the skin, with his hat blown off and probably swimming back toward Old England, and his hands numbed with cold and with hard grasping.

There is something in the very act of holding on tight which increases the natural tenacity of purpose that exists in some minds, and, if I may use a very vulgar figure, thickens the glue. At the end of the two hours, one of the sailors, who had something to do at the stern in a great hurry, ran up to the spot where the only passenger was clinging and nearly tumbled over him. Then, of course, he cursed him, as men in a hurry are wont to, and exclaimed, "Get down below! What the devil are you doing up here, where you are in everybody's way? Get down, I say!"

"I will not," was the reply, in a quiet, and even sweet, but very resolute, voice.

"Then I'll knock you overboard, by ——!" said the seaman, adding an oath which did not much strengthen the threat in the ears to which it was addressed.

"You cannot, and you dare not try," answered the other. But then the voice of the skipper, who had been working hard at the tiller, was heard exclaiming, "Let him alone, Tom;" and he beneficently called down condemnation not only upon the eyes but upon all the members of his subordinate. "Mind your own work, and let him alone."

Now, it may be worth while to ask what sort of a personage was this, whom the somewhat irascible Master Tom threatened to knock overboard, and who replied with so little reverence for the threat. He could not be a very formidable person, at least in appearance,—a very necessary qualification of the assertion; for I have known very formidable snakes the most pitiful-looking reptiles I ever beheld; and some of the most [13] dangerous men ever seen, either on the same stage of life where we are playing our parts with them, or on the wider boards of history, have been the least impressive in person, and the meanest-looking of creatures. But, as I was saying,—for it is too late to finish that sentence now,—the single passenger could not be very formidable in appearance; for Tom was probably too wise and too experienced to engage in what he considered even an equal struggle on so dark a night, while the wind was blowing a gale, and the little craft heeling gunwale to. Yet he could not be one without some powers, internally if not externally, which rendered him fully as careless of consequences as the other. Well, he was only a lad of some five feet eight or nine in height, slight-looking in form, and dressed in a common sailor's jacket. But in a leathern belt round his waist was a large caseknife, on the handle or hilt of which, while he continued to hold on to the rail of the bulwark with his left hand, he clasped the fingers of his right in a very resolute and uncompromising manner. We all know that bowie-knives, in one land at least, are very useful companions, and in all lands very formidable weapons. Now, the knife in the lad's black leather belt was not at all unlike a bowie-knife, and not in the least less formidable. There was the slight insinuating curve, the heavy haft, the tremendously long blade, the razor-like edge, and the sharp, unfailing point; so that it is not improbable that the youth's confidence was mightily strengthened by the companionship of such a serviceable friend, although he was not half the size of his adversary and not above a third of his weight. Boys, however, are always daring; and he could not at the utmost have passed much more than seventeen years on the surface of this cold earth.

Now, all this account would have been spared the beloved reader had not a trait of character at the outset of the career of any personage, in a poem, novel, romance, or tale, been worth half a volume of description afterward. It would have been spared, indeed, simply because the little incident ended just where we have left it. Tom, the sailor, though a reckless, ill-conditioned fellow, was obedient to the voice of his [14] commander, and, after having boused the boom a little to the one side or the other of the vessel,—which side I neither know nor care,—he returned to the bow, muttering a few objurgations of the youth, implying that if it had not been for him they would never have come upon that d——d voyage at all, and that probably they all would go to the bottom for having such a Jonah on board.

The truth is, Tom had left his sweetheart at Plymouth.

As soon as he was gone, the skipper called the lad a little nearer and said, "Tom says true enough, Master Ned. You were better below on every account. I don't see what you want to come up for on such a night as this."

"Because I do not want to be smothered, Captain Tinly," replied Master Ned. "I had rather be frozen than stewed; rather be melted by the water like a piece of salt or sugar than baked like a pasty. Besides, what harm do I do here? I am in no one's way, and that sea-dog could do his work as well with me here as without me. But I'll tell you what, captain, we are getting into smoother water. Some land is giving us a lee. We ought soon to see a light."

"Why, were you ever here before, youngster?" asked the master.

"Ay, twice," said the boy; "and I know that when the sea smooths down as it is now doing, we cannot be far from the island; and you will soon see the lantern."

"Well, keep a sharp look-out, then," was the reply: "you can see better where you stand than I can, and it's so dark those fellows forward may miss it. A minute or two to-night may save or sink us."

"It matters not much which," answered the young man. A strange thought for one at the age when life is brightest! but there are cases when the disappointment of all early hopes—when the first grasp of misfortune's iron hand has been so hard that it seems to have crushed the butterfly of the heart even unto death,—when it is not alone the gay colors have been brushed off, the soft down swept away, but when Hope's own life seems extinguished.

Happily, it is but for a time. There is immortality in Hope. [15] She cannot die; The fabled Phœnix of the ancients was but an emblem, like every other myth; and, if the painting of Cupid burning a butterfly over a flame was the image of love tormenting the soul, the Phœnix rising from her ashes was surely a figure of the constant resurrection of Hope. Ay, from her very ashes does she rise to brighter and still brighter existence, till, soaring over the cold Lethe of the grave, she spreads her wings afar to the Elysian fields beyond!

It is an old axiom, never to say "die;" and though there be those who say it, ay, and in a momentary madness give the word the form of action, did they but wait, they themselves would find that, though circumstances remained unchanged, the prospect as rugged or the night as dark, the sunshine of Hope would break forth again to cheer, or her star twinkle through the gloom to guide.

The boy felt what he said at the time, but it was only for the time; and there were years before him in which he never felt so again.

"Captain, there is a light surely toward the southwest," said the lad: "that must be the light at St. Martin's-on-Re. It seems very far off. We must be hugging the main shore too close."

"I don't see it," answered the skipper; "but there is one due east, or half a point north. What the devil is that?"

The boy ran across the deck nearly at the risk of his life; for though the sea and wind had both fallen, the little craft still pitched and heeled so much that he lost his footing and had wellnigh gone overboard. He held on, however, was up in a moment, and exclaimed, "Marans! The light in Maran's church! You'll be on the sands in ten minutes! Put about, put about, if you would save the ship!"

A great deal of hurry and confusion succeeded; and there was much unnecessary noise, and still more unnecessary swearing. The youth who had discovered the danger was the most silent of the party; but he was not inactive, aiding the captain with more strength than he seemed to possess, to bring the ship's head as near to the wind as possible. And the manœuvre was just in time; for the lead at one time showed [16] that they were just up the very verge of the sands at the moment when, answering the helm better than she did at first, she made way toward the west, and the danger was past. In half an hour—for their progress was slow—the light upon the Isle de Re could be distinctly seen, and one by one other lights and landmarks appeared, rendering the rest of the voyage comparatively safe.

Still the lad kept his place upon the deck, addressing hardly a word to any one, but watching with a keen eye the eastern line of shore, which was every now and then visible notwithstanding the darkness. The moon, too, began to give some light, though she could not be seen; for the clouds were still thick, and their rapid race across the sky told that, though the sea under the lea of the Isle de Re had lost all its fierceness, the gale was blowing with unabated fury.

The lad quitted his hold of the bulwarks and walked slowly to the captain's side, as if to speak to him; but the skipper spoke first. His professional vanity was somewhat mortified, or perhaps he was afraid that his professional reputation might suffer by the lad's report in the ears of those whose approbation was valuable to him; and consequently he was inclined to put a little bit of defensive armor on a spot where he fancied himself vulnerable.

"We had a narrow squeak of it just now, Master Ned," he said. "However, it was no fault of mine. I could not help it. It is twenty years since I was last at this d——d place, and the chart they gave me is a mighty bad one. Besides, those beastly gales we have had ever since Ushant might puzzle the devil,—and this dark night, too!"

"You've saved the ship, captain," answered the lad: "that is all we have to do with;" and then, perhaps thinking he might as well add something to help the good skipper's palliatives for wellnigh running the ship ashore, he added, "Besides, there is a strong current running,—what between the sands of Oleron and the point of Re, and the Pertuis d'Antioche—I do not know very well how it is; but I was so told by one of the men last time I was here."

"Ay, 'tis so, I dare say," answered the captain. "Indeed, it must [17] be so; for we could never have got so far to the eastward without one of those currents. I wish to heaven some one would put them all down, for one can't keep them all in one's head, anyhow. You tell the duke, when you see him again, about the currents, Master Ned."

"What is the use of telling him any thing at all but that we got safe to Rochelle?" asked the lad. "If we get there—as there is now no doubt—he will ask no questions how; and if we don't, anybody may blame us who likes: it will make little difference to you or me."

The skipper was about to answer; but just at that moment a light broke suddenly out upon that longish point of land which a boat that keeps under the western shore of France has to double—as the reader very well recollects—before it can make the port of La Rochelle; and the boy as suddenly laid his hand on the captain's arm, saying, "Make for that light as near as you can, captain; keep the lead going; drop your anchor as close as you can, and send me ashore in a boat."

"Why, Master Ned, I was told to land you at Rochelle," replied the other.

"You were told to do as I bade you," answered the lad, as stoutly as if he had been a captain of horse,—adding the saving clause, "in every thing except the navigation of your vessel. I must be put ashore where you see that light. So send down for my bags, have the boat all ready, and when I am landed go on to Rochelle and wait till you hear more."

The captain of the vessel did not hesitate to obey. The ship ran speedily for the shore and approached perhaps nearer than was altogether safe; the boat was lowered to the water, and the lad sprang in without bidding adieu to any one. There was a heavy sea running upon the coast, and it required no slight skill and strength on the part of the two stout rowers to land him in safety; but he showed neither fear nor hesitation, though probably he knew the extent of the danger and the service better than any one; for, when he sprang out into the shallow water where the boat grounded, he gave each of the men a gold-piece, and then watched them with somewhat anxious eyes till they had got their boat through the surf into the open sea.

What an extraordinary world it is! Men in general are mere shellfish, unapproachable except at certain tender points; such as the eyes of the crab, or the soft yellow skin under an alligator's gullet,—Achilles' heels which have been neglected by the mothers of those sapient reptiles when they were dipped in Styx. But perhaps it is as well as it is; for if a man were tender all over, and once began to think of all the misery that is going on around him, the faces he would make would be horrible to see. Reader, at this very moment there are thousands dying in agony, there are many starving for lack of food, there is a whole host of gentle hearts watching the expiring lamp of life in the eyes of those most dearly loved, there are multitudes of noble spirits and mighty minds struggling in doubt for to-morrow's daily crust, there is crime, folly, sorrow, anguish, shame, remorse, despair, around us on every side; and yet we are as merry as a grasshopper unless somebody snaps off one of our own legs. There is not an instant of time that does not bring with it a thousand waves of agony over the stormy sea of human existence; and yet every man's light boat dances on, and the mariner sings, till one of the many billows overwhelms him. It is quite as well as it is.

Some, however, are blessed—or cursed, as it may be—with a faculty of feeling for others; and that boy, as he took his way up from the shore toward the little hillock of sand on which a bonfire of pine logs was blazing,—with two heavy bags on his arms, and the rain dashed by the fierce wind in his face,—could not help thinking of the roofless heads and chilled hearts he knew were in the world.

"Poor souls!" he thought; "in an hour I shall be warm and dry and comfortable, and to-morrow all this will be forgotten; but for them there is no comfort, no better to-morrow."

Stay a minute, my lad! Do not go too fast and reckon without your [19] host, either for yourself or others. Joy may light up the dim eye, hope fan the aching brow; and you,—after all you have seen and undergone even in your short life,—how dare you count upon the events of the next hour,—nay, of the next moment?

He climbed the hill stoutly but slowly; for it was steep, and his bags were heavy. The wicked wind, too, fought with him all the way up, and the rain, which had lately begun to fall, came loaded with small particles of hail, as if it sought to aid the wind in keeping him back till their united force could put out the beacon-fire. But the pine was full of resin, and it burned on, with the flame and the smoke whirled about by the wind but never extinguished, until at length he stood on the windward side of the fire and looked round, as if expecting to see the man who lighted it.

There was no one there, however; and the youth, who, it must be acknowledged, was of a somewhat eager and impatient temper and apt to come to hasty conclusions, fancied for a moment or two that those he should have found there had grown weary of waiting in that boisterous night, and had left him to enjoy its pleasures or its terrors by himself. A moment after, however, as the flame swayed a little more to the westward, he caught a glimpse of the ground on the other side of the hill sinking rapidly down into a little dell where some less arid soil seemed to have settled,—enough at least to bear some scanty herbage, a few low bushes, and some thin pines; and there, amongst the latter, appeared a small fixed light. It might be a candle in a cottage-window, and probably was; for it was too red for a jack-o'lantern.

"Ah! I can at least find out where I am," thought the lad; "but I dare say the men are there, taking care of their own skins and little caring about mine."

Thus thinking, he began to descend, and had not proceeded far when a voice hailed him in French. The lad made no answer, but went on; for, to say sooth, he was somewhat moody with all the events of the last three or four days.

"Is that you, Master Ned, I say?" repeated the voice, in English, but with a very strong foreign accent.

"Ay, ay!" replied the youth; "but how the devil did you expect me to find you if you did not stay by the fire?"

"Oh, we kept a good look-out," answered a stout man of some five-and-thirty years of age, who was advancing to meet him. "We have waited for you by the fire long enough these two last nights; and, as we could see any one who came across the blaze, there was no use of our getting frozen, or melted, or blown away on the top of the hill. But what has made you so long behind? You were to have been here on Tuesday night: so the letters said. What kept you?"

"Head-winds all the way from Ushant," replied the boy. "But let us go on, Jargeau, for we must be far from the town, and time enough has been lost already."

"Well, come down to the cottage," said the other, in a musing sort of tone. "You want something to refresh you while the horses are being saddled. Here; let me carry your bags." And as he spoke he laid his hand upon one of the large leather-covered cases.

"Not that one," said the boy, sharply, pushing away his hand: "here; you may take this." The man laughed, saying, "Ay, as sharp as ever!" and they descended to the pines, where the light still glimmered behind one of the few remaining panes of glass in the window of a dilapidated cottage, on the leeward side of which stood three horses, tethered but without their saddles.

The interior of the building offered no very cheerful aspect; but, seeing that the boy had not eaten any thing for the last twelve hours, that he was weary, wet, and cold, the sight of a very tolerable supply of viands on the floor,—for there was furniture of no kind within,—and a large black bottle fitted to hold at least a gallon, was very consolatory.

The only other objects which the cottage contained were the rosin candle fixed into a split log, and a lean but apparently strong man of perhaps forty, whose face had evidently had at least a ten years' intimacy with the brandy-flask. He was stretched out at length upon the ground, but with his head and arm within reach of the viands and bottle; and though, in answer to some observations of his comrade of the watch, he swore [21] manfully that he had touched neither, yet he wiped his mouth upon the sleeve of his coat, as if he felt that something might be clinging to his lips which would contradict him.

"Ah, Master Ned!" he exclaimed, in French, but without moving from where he lay, "I am right glad you have come, for my throat is as dry as an ear of rye, and Jargeau there would not have the cold meat touched nor the bottle broached till you came."

"By the Lord, you have broached it, though!" exclaimed the other, who had been stooping down: "the neck is quite wet, you vagabond; and, if we did not need you, I would give you a touch of my knife for disobeying my orders. But come, Master Ned, sit down on the floor and eat. There is enough left in the bottle for you, at all events; and, on my soul, he shall not have another drop till both you and I have finished."

The other man only laughed, and the boy applied himself to the food with a good will. When he had eaten silently for some ten minutes, he stretched out his hand, saying, "Give me the bottle, Jargeau: I will have one draught of wine, and then I am ready. Pierrot, get up and put the saddles on the horses."

"No wine will you get here," replied Jargeau; "but this is better for you, wet as you are,—as good eau-de-vie as ever came from Tonnay Charente. Take a good drink: you will need it."

"Get up and saddle the horses," said the boy before he drank, addressing somewhat sharply the lean gentleman on the ground. "Have you forgotten St. Martin's, good Pierrot?"

"I will have my drink first," answered the other, grinning. "I brought the bottle here; and drop for drop all round is fair play."

As the quickest mode of ending all dispute, the youth drank and gave the bottle to Pierrot; but it remained so long at his lips that Jargeau snatched it angrily from him, swearing he would not leave a drop. He seemed loath to part with it, but at length raised his long limbs from the floor, and, lighting another rosin candle, went forth to perform his task.

"And now, Master Ned," said Jargeau, "I have news for you which [22] you may be will not like. You are not going to La Rochelle to-night. There is no one there whom you want to see."

"I must go," said the boy, thoughtfully, as if speaking to himself. "I must go."

"But just listen, Master Ned," said Jargeau. "I know you are somewhat hard-headed; but what is the use of going to a place where there is no one to deal with? Now, the Prince de Soubise and the Duc de Rohan are both at the Chateau of Mauzé; and with them are all the people you want to see."

The lad paused and mused for several minutes without making any answer, and Jargeau pressed him to take some more of the brandy, saying that he would have a ride of thirty miles. But still he replied nothing, till at length, awaking from his reverie, he asked, "Who is to guide me? I do not know the way to Mauzé."

"Oh, Pierrot is here for the very purpose," answered Jargeau: "he will guide you, and though, by one way or another, he will find means to make all you leave of the brandy disappear, you know he is never drunk enough not to find his way."

Master Ned, as they called him, again fell into thought for a moment or two, and then answered, "It would be better for you to go yourself. But perhaps you are wanted in Rochelle?"

"No," answered the other, in an indifferent tone; "I have got to go to Fontenay, where some of our friends—you understand?—are to have a meeting to-morrow night."

"Then you must be there, of course," replied Master Ned; "but, if Pierrot is to ride thirty miles with me, the poor devil had better have some food. He has tasted nothing but the brandy."

"That is enough for him," answered Jargeau: "he cares nothing for meat when he can get drink."

"Well, then, let him have enough of what he likes best," answered the lad; "and in the mean time I will get a cloak out of the bag, for we shall have a wet ride as well as a long one." Thus saying, he rose, took the bags into the farther corner of the cabin, and certainly took a cloak out of one of them. Whether he brought forth any thing else I do [23] not say; but the cloak was soon over his shoulders, and a moment after Pierrot appeared at the door, saying that the beasts were saddled.

"Here, Pierrot," exclaimed the lad; "come in and devour that chicken, and then you shall have some more of the devil's drops."

"Take some more yourself, Ned," said Jargeau: "'tis the only way to prevent catching the fever."

The lad assented, and, taking the bottle with both hands, put it to his lips; but whether any of its contents passed beyond them I am doubtful, seeing that the throat, which was fully exposed by his falling collar, showed no signs of deglutition. He then handed the liquor to Pierrot, who by this time had torn a large fat fowl to pieces and swallowed one-half of it. The brandy fared still worse; for, although Jargeau frowned upon him fiercely while he drank, the bottle, whatever remained of the contents when he put it to his mouth, left that organ quite empty.

"You drunken beast, you have swallowed it all!" said Jargeau.

"True," answered Pierrot, with a watery and somewhat swimming eye: "my mouth is not large, but it is deep. I wish the Pertuis d'Antioche could be filled with the same stuff and my mouth be laid at the other end. There would be only one current then, Monsieur Jargeau."

The lad and the elderman both eyed him keenly as he spoke; but, strange to say, the sight seemed to please the former more than the latter, and, as they issued forth to mount, Jargeau drew Pierrot aside and said something to him in a low but angry voice.

The lad took not the slightest notice of this little interlude, but, advancing to where the horses stood with bent heads, not liking the rain at all, he selected the one which seemed to him the strongest and best, without asking consent of any one, placed his bags, tied together with a strong leathern thong, over the pommel of the saddle, and then sprang into his seat. "Come on, Pierrot!" he cried; "we have far to ride, it seems, and but little time." Jargeau advanced to his side and said, in a whisper, "That beast is half drunk. Take care of him. You remember it is the Chateau of Mauzé you are going to. He may turn refractory."

"Oh, no fear," replied Master Ned. "I can drive him as well as any other ass. I have driven him before. Mauzé?—that is upon the road to Niort, is it not?"

"Yes," answered the other. "Where the road forks, keep to the right, and then straight on: you cannot miss it. I think the moon will get the better of the clouds and shine out."

"Good!" said the youth. "We want a little light."

Thus saying, he struck the horse with his heel, and the beast started forward. Pierrot, who by this time had contrived to mount, followed, and Jargeau returned to the cottage, as he said, to put out the light.

There had been something a little peculiar in the way in which Master Ned had pronounced the words, "We want a little light," which, if Jargeau had remarked the curl of his lip as they were uttered, might have induced him to turn his horse's head toward Rochelle instead of Fontenay; for in truth the lad spoke of other than moonlight. Ned rode on in silence, however, for some minutes, along a small road, or rather path, which led from the old cottage, first to a small straggling village, such as is still to be seen in the Bocage and its neighborhood, and then to a place of junction with the highroad running from Marans to Mauzé. It was called a highroad then, God wot; but it has fallen into a second-class way now, and was in all but name a very low road always.

Pierrot was silent too,—not that he had not a strong impulse toward eloquence upon him, but that he felt a certain confusion of thought which did not permit of seeing distinctly which was the head, which the tail, of a subject. The last draught of brandy had been a deep one. Yet Pierrot was practised in all the various phases of drunkenness, and in general knew how to carry his liquor discreetly; but this was in fact the reason that he abstained from using his tongue, feeling an [25] intense conviction that it would either speak some gross nonsense, or betray some secret, or commit some other of those lamentable blunders in which drunken men's tongues are wont to indulge, if he once opened his mouth.

It was not an easy task to keep quiet, it is true; and, had he not been a very experienced man, he could not have accomplished it. But the struggle was soon brought to a conclusion; for, when they had ridden about half a mile, Master Ned turned sharp upon him, and asked, abruptly, "What was that Jargeau said to you, just as we were coming away, Pierrot?"

"Oh, nothing," answered Pierrot, in a muddled voice, "but to lead you right."

"Where?" demanded the lad, sternly.

"Why, to Mauzé, to-be-sure," replied Pierrot.

"What a pity he gave himself such unnecessary trouble!" answered the lad, in a quiet tone: "neither you nor I go to Mauzé to-night, Pierrot."

"Then where, in Satan's name, are you going?" demanded his companion, checking his horse.

"To Rochelle," replied Master Ned. "Jog on, Maître Pierrot. It is the next turn on the right we take, I think. Jog on, I say. Why do you stop?"

"Because I ought to go back and tell Jargeau, and ask him what I am to do," answered the other, half bewildered with drink and astonishment.

"You are to do what I tell you, and to do it at once," replied the lad; "and, if you do not, I have got a persuader here which will convince you sooner than any other argument I can use." And as he spoke he drew one of the large horse-pistols of that day from beneath his cloak and pointed it straight at Pierrot's head. "It is the same argument that stopped your running away and leaving us in the enemy's teeth at St. Martin's-in-Rhé," he said.

"You young devil, the ball is in my leg still," answered Pierrot. "But this is not fair, Master Ned. You might be right enough then, for you thought I was going to betray you; though, on my life and soul, I was only afraid. Now you want me to disobey those I am bound to serve, [26] and do not even give me a reason."

"I will give you a reason, though I have not much time, for fear the powder in the pan should get damp," replied the boy; "but my reason is that I was told to go to Rochelle and see Maître Clement Tournon; and therefore I am going. Now, in the Isle de Rhé I did not think you were going to betray us, and knew quite well it was mere fear; but at present I do think Jargeau is seeking to betray me,—or mislead me, which is as bad. At all events, you have got to go with me to Rochelle, or have the lead in your head, Pierrot: so choose quickly, because you know I do not wait long for any one."

"Well, I vow you are too hard upon me, Master Ned," said Pierrot, in a whimpering tone. "You take the very bread out of my mouth and give me over to the vengeance of that cold-blooded devil Jargeau."

"You will find me a worse devil still," replied Master Ned, coldly; but even as he spoke he fell into a fit of thought, and then added, "Listen to me, Pierrot, if the brandy has left you any brains, or ears either. I want a man like you to go with me a long way, perhaps. It will not be I who pay you, for I have got little enough, as you know; but I will be your surety that you shall be well paid as long as you serve well. I know you to the bottom. You are honest at heart, whether you are drunk or sober; though liquor has not the same effect upon you as upon most men. You are brave enough when you are sober, but a terrible coward when you are drunk. Now, if you like to go with me, you shall have enough to live on, and to get drunk on, when I choose to let you get drunk."

"How often will that be?" asked Pierrot, interrupting him.

"I will make no bargain," answered the lad; "but this much I will say: you may drink whenever I do not tell you I have important business on hand. When I do tell you that, you shall taste nothing stronger than water."

"Good! good!" said Pierrot: "strong water you mean, of course."

"Well-water," said the lad, sharply. "But, remember, I am not to be trifled with. As to Jargeau, I will take care he does nothing to injure [27] you. If it be as I think, I have got his head under my belt, and he will soon know that it is so. Now choose quickly, for we have stood here too long."

"Well, I'll go," said Pierrot; "but I am terribly afraid of that Jargeau. However, your pistol is nearest; and so I'll go. I know you are not to be trifled with, well enough; but I must find some way of letting Jargeau know I have left him. It would be a shame to go without telling him, you know, Master Ned."

"We shall find means enough in Rochelle of sending him word," answered the lad, putting up his pistol and resuming his journey.

Pierrot followed with sundry half-articulate grunts; but he appeared soon to recover both good humor and spirits, for ere they had gone half a mile he burst forth into song, broken and irregular indeed, now a scrap from one lay, now from another; but, at all events, the music seemed to show that no very heavy thing was resting on his mind. His rambling scraps of old ditties ran somewhat as follows:—

"By my life, the moon is beginning to break through,—though how she will manage it I don't know; for there is mud enough in yonder sky to swallow up the tallest horse I ever rode.

"She has got behind the cloud again. Moons and maidens don't know their own minds.

The concluding stanzas, if they were neither very excellent nor very tender, were at least an indication that his mind was settling down into a calmer state than when he began. They were connected, at all events; and continuity of thought is a great approach to reason, which dwelleth not in the brains of any man together with much brandy. The finer spirit was, therefore, apparently getting the better of the coarser; and Master Ned thought the time was come for him to take advantage of the change of dynasty and see whether he could not obtain some advantage from the new ruler.

"Well, Pierrot," he said, "this is a very pretty business you have been engaged in. After having had the honor of serving the King of England and fighting for the liberty of the Protestants of France, you have been persuaded to aid in trying to betray me into the hands of the enemy, though you did not know that I might not be the bearer of important messages to your own people."

"Whew!" cried Pierrot, with a long whistle. Now, whistles mean all kinds of things, from the ostracism of a play-house gallery to the signal of love or housebreaking; but the whistle of good Pierrot was decidedly a whistle of astonishment, and so Master Ned interpreted it.

"Do not affect ignorance or surprise, Pierrot," he said: "that will not do with me. Jargeau is a traitor: that is clear."

"Well, well, Master Ned," interposed his companion, "you are a mighty sharp lad, beyond question; but sometimes you ride your horse too fast, notwithstanding. Just stop a bit till my head gets a little—a very little bit—clearer, and I'll set you right. As you think the matter worse than it is, I may as well show you it is better. I don't mean to say they did not want to trick you; but not the way you fancy."

"Why, are not all the towns round in the hands of the Papists?" asked the lad. "We have had that news in England for the last four months."

"No, no, no," answered Pierrot: "the Papists may have the upper hand in most of them, it is true; but stop a bit, and I'll tell you all clearly. Your long pistol half sobered me; and when I can get to a spring and put my head in, that will wash out the rest of the brandy. It is of no use giving you a muddled tale."

"Take care you do not make one up," answered Master Ned. "I shall find you out in five minutes."

Pierrot laughed. "I'd as soon try to cheat the devil," he said. "But let us ride on. There is a well just where the roads cross, and it will serve my turn. Brandy is a fine thing, but a mighty poor counsellor."

The lad followed the suggestion, for he did not wish to give his companion too much time to think, and, urging their horses on, in about five minutes they reached the spot where two highways crossed, and where a large stone trough received the waters of a beautiful and plentiful spring, affording solace to many a weary and thirsty horse in those days of saddle-travelling. There Pierrot dismounted, slowly and deliberately, for he could not precisely ascertain to what extent he retained a balancing power till his feet touched the ground. With more directness of purpose, however, than could have been expected, he made his way to the trough, and, kneeling down, plunged his head once or twice into the cool water. He then rose, with his long rugged black hair still streaming; and, after the horses had been suffered to drink, the two travellers resumed their way. The moon by this time had completely scattered the clouds; glimpses of dark-blue sky appeared between the [30] broken masses, and the keen eye of the young lad could mark every change in the expression of Pierrot's face as he went on.

"Now, Master Ned," he said, "I think my noddle has got clear enough of the fumes to let you know something of what people have been about here, which you do not know rightly, I can see. Rochelle is going to be taken by the Catholics: that's clear to me."

"Unless the great Duke of Buckingham drive the Catholics beyond the Loire, it must be taken," answered the lad. "You can never stand against all France. But what makes you give up hope, Pierrot?"

"First, the King of France, and his devil of a Cardinal, are drawing together a great army all around us," answered Pierrot,—"a greater army than ever approached Rochelle before. That we could manage to resist, perhaps. But then they are going very coolly to work fortifying every town and well-pitched village of the Papists within fifty miles of the city, and filling them with soldiers, so that every egg that comes to market will have to be fought for. Well, that we could perhaps manage too, for we could get supplies from England. But look here, Master Ned: there are two parties in Rochelle. Our best lords and wisest citizens, our chief generals and captains, know well that our only hope is in the support of England; but there is a more numerous, if not a stronger, party, who do not like your great duke, would have nothing to do with your good country, and would have us stand alone and fight it out by ourselves. One of their chief men is Jargeau."

"I see," said the lad. "But what did he seek by trying to entrap me to go to Mauzé?"

"First, your letters were likely either to fall into the hands of the Catholics, and, by showing how firmly Rochelle could count upon English help, frighten them and make them reasonable," answered Pierrot, "or, secondly, they might fall into the hands of Miguet and his other friends, who would take care they should never reach their destination. That was the plan, Master Ned."

"And not a bad plan, either," answered the other, thoughtfully, "supposing I had any letters. But, as you say, Rochelle is in a bad [31] way; for, if her leaders are afraid to let each other know their exact position and what they may count upon, she is a house divided against herself, and cannot stand. But what made Jargeau think I had letters? Nobody told him so, I think."

"No; but they told him you would have messages for our principal people," answered Pierrot,—adding, not unwilling, perhaps, to show a little scorn for one whose strong will had exercised what may be called an unnatural ascendency over him more than once, "and Jargeau never believed that they would trust messages to such a young boy as you."

"He must have thought my memory very bad," replied the lad, "not to be able to carry a message from England to France. But my memory is not so bad, good Pierrot, as he may find some day. At all events, if Rochelle is to be lost by the intrigues of a man who does not choose his comrades to know where succor lies when they like to seek it, all the world shall know who ruined a good cause. But I suppose, Pierrot, all he told me of the meeting of the Reformed leaders at Mauzé was a mere lure."

"No, no; it is all true," answered Pierrot. "The prince is there, and Rohan, and a dozen of others; and if you could have got safe through without the loss of your bags, you would have found some of those you want; but I suppose he had provided against that. I don't know: he never told me; but it is likely."

"Very likely," replied Master Ned; "but you say 'some of those I want.' I only want one person; and him I must see if it be possible. Is Maître Clement Tournon in the city?"

"He is not with those in the Chateau of Mauzé," replied Pierrot. "I know little of him. He is a goldsmith,—a very quiet man?"

"Probably," answered the lad: "quiet men are the best friends in this world. So, on to Rochelle! Will they let us pass the gates at night?"

"'Tis a hard question to answer," said Pierrot. "Sometimes they are very strict, sometimes lax enough. But it is somewhat late, young lad, and, [32] if none of the guard is in love with moonlight, we shall find them all asleep."

"Asleep in such times as these!" exclaimed the young man.

"Why, either the Papists are trying to throw us off our guard," said Pierrot, "or they are too busy cutting off each others' heads to mind ours. They have not troubled us much as yet. True, they have taken a town or two, and stopped some of our parties into the country, and begun what they call lines; but not a man of their armies has come within cannon-shot. And there is not much more strictness than in the times of the little war which has been going on for the last fifty years. But the people in the town vary from time to time. When one man commands, the very nose of a Catholic will be fired at; and, when another is on duty, the gates will be opened to Schomberg, or the devil, or any one else who comes in a civil manner. But there is Rochelle peeping over the trees yonder, just as if she had come out to see the moon shine."

"Well, then, mark me, good Pierrot," said Master Ned, "I expect you to do all you can to make them open the gates to us. You understand what that means, I suppose?"

"That I shall have a shot in my other leg or through my head if I do not, I presume," answered Pierrot. "But don't be afraid. When you have given me a crown, I shall have taken service with you; and then you know, or ought to know, I will serve you well."

The lad, it would seem, had some reason to judge that the estimate which his companion put upon such a bond was just. Indeed, in those days the act of taking service, confirmed by earnest-money, implied much more than it does in our more enlightened times. Then a man who had thus bound himself thought himself obliged to let nobody cheat his master but himself, to feel a personal interest in his purposes and in his safety. Now, alas! we hire a man to rob us himself and help all others to rob us,—to brush our coats in the evening, and cut our throats in the morning if we have too many silver spoons. However, Master Ned put his hand into his pocket and pulled out a piece of money, which he held out to Pierrot, who seemed for a moment to hesitate to take it. "I wish I had told Jargeau I was going to quit him," he said: "not that he ever [33] gave me a sol, but plenty of promises. How much is it, Master Ned?"

"A spur rial," replied the boy,—"worth a number of your French crowns."

"Lead us not into temptation!" cried Pierrot, taking and pocketing the money. "And now tell me what I am to do."

"All you can to make them open the gates," answered Master Ned. "You have got the word, of course?"

"Nay, 'faith, not I," replied Pierrot: "Jargeau got it this evening, but I did not think of asking. Never mind, however: all the people in Rochelle know me, and I will get in if any one can."

He was destined to be disappointed, however. In the little suburb, just before the gate, he and his companion passed a little tavern where lights were burning and people singing and making a good deal of noise; but it was in vain that Pierrot knocked at the large heavy door or shouted through a small barred aperture. No one could be made to hear; and he and Master Ned were forced to retreat to one of the cabarets of the faubourg and await the coming of daylight.

"Who is that boy?" said one of the early shopkeepers of Rochelle, speaking to his neighbor, who was engaged in the same laudable occupation as himself,—namely, that of opening his shop for the business of the day. At the same time he pointed out a handsome lad, well but plainly dressed, who was walking along somewhat slowly toward the better part of the city. "Who is that boy, I wonder?"

"He's a stranger, by that cloak with the silver lace," replied the other: "most likely come over in the ship that nearly ran upon the pier last night. He carries a sword, too. Those English make monkeys even of their children; but he is a good-looking youth nevertheless, and bears [34] himself manly. Ah! there is that worthless vagabond, Pierrot la Grange, speaking to him. And now Master Pierrot is coming here. I will have naught to do with him or his." And, so saying, he turned into his shop.

The other tradesman waited without, proposing in his own mind to ask Pierrot sundry questions regarding his young companion; for, although he had no curiosity, as he frequently assured his neighbors, yet he always liked to know who every-body was, and what was his business.

Pierrot, however, had only had time to cross over from the other corner of the street and ask, in a civil, and even sober, tone, where the dwelling of Monsieur Clement Tournon could be found, when the good tradesman exclaimed, "My life! what is that?" and instantly darted across the street as fast as a somewhat short pair of legs could carry him.

Now, the street there was not very wide; but it was crossed by one much broader within fifty yards of the spot where the shopkeeper was standing, called in that day "Rue de l'Horloge." It may have gone by a hundred names since. The street was quite vacant, too, when Pierrot addressed the tradesman; but the moment after, two sailors came up the Rue de l'Horloge, and one of them, as soon as he set eyes on Master Ned, who was standing with his back to the new-comers, laid his hand upon his shoulder and said something in a tone apparently not the most civil, for the lad instantly shook himself free, turned round, and put his hand upon the hilt of the short sword he carried. It seemed to the good shopkeeper that he made an effort to draw it; but whether it fitted too close, or it had got somewhat rusted to the scabbard during the previous rainy night, it would not come forth; and in the mean time the sailor struck him a thundering blow on the head with a stick he carried. The youth fell to the ground at once, but he did not get up again, and the two tradesmen ran up, crying, "Shame! shame! Seize the fellow!"

"You've killed him, Tom, by the Lord!" cried the other sailor. "You deserve hanging; but get back to the ship if you would escape it. Quick! quick! or they will stop you."

"He was drawing his sword on me!" cried our friend Tom, whose quarrel—not the first one—with Master Ned we have already seen as the ship neared the Isle of Rhé. But, not quite confident in the availability of his excuse, he took his companion's advice and began to run, turning the corner of the Rue de l'Horloge. One of the tradesmen pursued him, however, shouting, "Stop him! stop him!" and the malevolent scoundrel had not run thirty yards, when he was seized by a strong, middle-aged man, who was walking up the street with an elderly companion and was followed by two common men dressed as porters.

The sailor made a struggle to get free, but it was in vain; and the shopkeeper, who was pursuing, soon made the whole affair known to his captors.

The elderly man with the white beard put one or two questions to the prisoner, to which he received no reply; for since that untoward event of the Tower of Babel the world is no longer of one speech, and Tom was master of no other than his own.

"Take him to the prison," said the old man, addressing the two men who had been following him. "Do not use him roughly, but see that he does not escape."

"He shall not get away, Master Syndic," replied one of the porters; and, while the syndic was speaking a few whispered words to his companion, Tom was carried off to durance vile.

The two gentlemen then walked on with the tradesman by their side, and were soon on the spot where the assault had been committed. By this time a good many people had gathered round poor Master Ned; and the other English sailor had lifted the lad's head upon his knee, while Pierrot was pouring some water on his face. The shopkeeper, to whom the latter had been speaking when the misadventure had occurred, was trying to stanch the blood which flowed from a severe cut on the head; but the moment he saw the syndic approach he exclaimed, "Ah, Monsieur Clement Tournon, this poor lad was inquiring for you when that brute felled him."

"Indeed!" said the old man, with less appearance of interest than might perhaps have been expected. "Leave stopping the blood: its flow will do [36] him good; and some one carry him to my house, where he shall be well tended."

Pierrot had risen from his knee as the syndic spoke, and now whispered a word in his ear, which he evidently thought of much consequence; but the old man remained unmoved, merely saying, "Not quite so close, my friend! I tell you he shall be well tended. Neighbor Gasson, for charity, call two or three of your lads and let them carry the poor lad up to my dwelling."

At this moment the younger and stouter man who had seized and held Master Ned's brutal assailant suggested that it would be better to take the boy to his dwelling, as it was next door but one to the house of the famous physician Cavillac.

"Nay, nay, Guiton," replied the syndic, "my poor place is hard by; and yours," he added, in a lower tone, "may be too noisy. You go and send down the doctor,—though I think the lad is but stunned, and will soon be well again. Pierrot la Grange, follow us up, if you be, as you say, his servant,—though how he happened to hire such a drunken fellow I know not. Yes, I know you, Master Pierrot, though you have forgotten me." Thus saying, he drew the personage whom he had called Guiton aside and spoke to him during a few moments in a whisper. In the mean time, two or three stout apprentices had been called forth from the neighboring houses; and the youth, being raised in their arms, was being carried along the Rue de l'Horloge. Clement Tournon followed quickly, leaving his friend Guiton at the corner; and at the tenth door on the left-hand side the party stopped and entered the passage of a tall house standing somewhat back from the general line of the street. It was rather a gloomy-looking edifice, with small windows and heavy doors plated on the inner side with iron; but whether sad or cheerful mattered little to poor Master Ned, for the state of stupor in which he lay was not affected by the act of bearing him thither, nor by the still more troublesome task of carrying him up a narrow stairs. That he was not dead his heavy breathing showed; but that was almost the only sign of life which could be discovered by a casual observer.

"Carry him into the small room behind the saloon," said Clement Tournon, [37] who was at this time following close; and in another minute the lad was laid upon a bed in a room situated in the back of the house, where little noise could penetrate, and which was cheerful and airy enough.

"Thank you, lads; thank you!" said the syndic, speaking to the apprentices. "Now leave us. You, Pierrot la Grange, stay here: undress him and get him between the sheets."