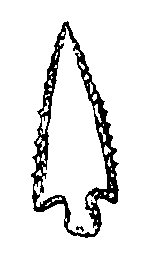

Fig. 1 (202-8369). Chipped Point made of Chalcedony. From

the surface, near the head of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.

Fig. 1 (202-8369). Chipped Point made of Chalcedony. From

the surface, near the head of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Archaeology of the Yakima Valley, by Harlan Ingersoll Smith This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Archaeology of the Yakima Valley Author: Harlan Ingersoll Smith Release Date: July 8, 2012 [EBook #40167] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK YAKIMA VALLEY *** Produced by Pat McCoy, Julia Miller, Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

NEW YORK:

Published by Order of the Trustees.

June, 1910.

[Pg 1]

Plates.

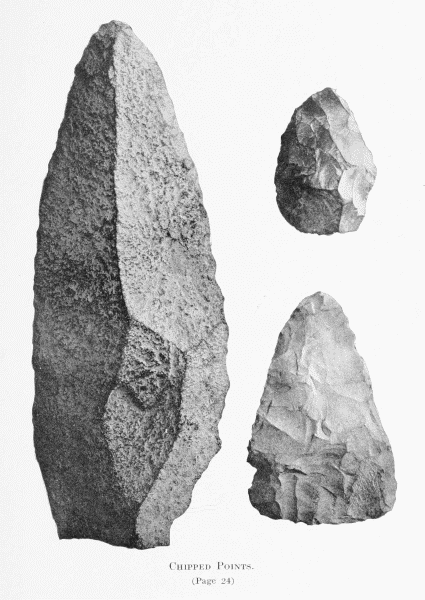

| I. | Chipped Points. Fig. 1 (Museum No. 202-8333), length 21 cm.; Fig. 2 (202-8338); Fig. 3 (202-8334). |

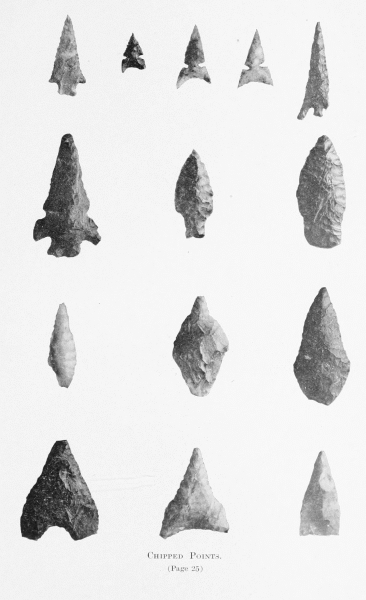

| II. | Chipped Points. Fig. 1 (Museum No. 202-8115), length 3.8 cm.; Fig. 2 (202-8169 A); |

| Fig. 3 (202-8196 A); Fig. 4 (202-8196 B); Fig. 5 (202-8142); Fig. 6 (202-8397); Fig. 7 (202-8366); | |

| Fig. 8 (202-8363); Fig. 9 (202-8368); Fig. 10 (202-8361); Fig. 11 (202-8359); Fig. 12 (202-8222); | |

| Fig. 13 (202-8203): Fig. 14 (202-8360). | |

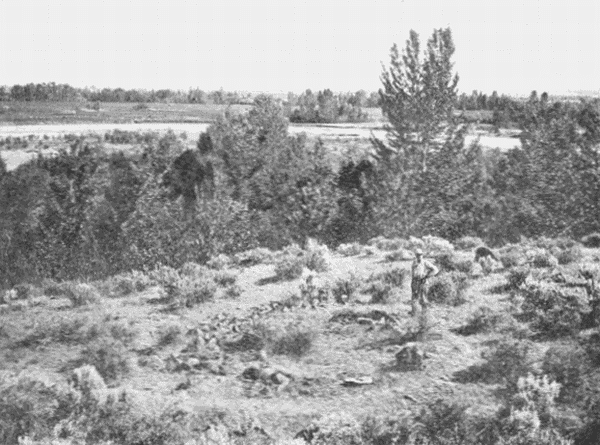

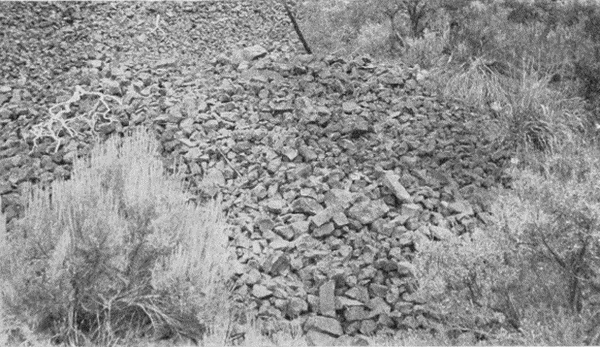

| III. | Quarry near Naches River. |

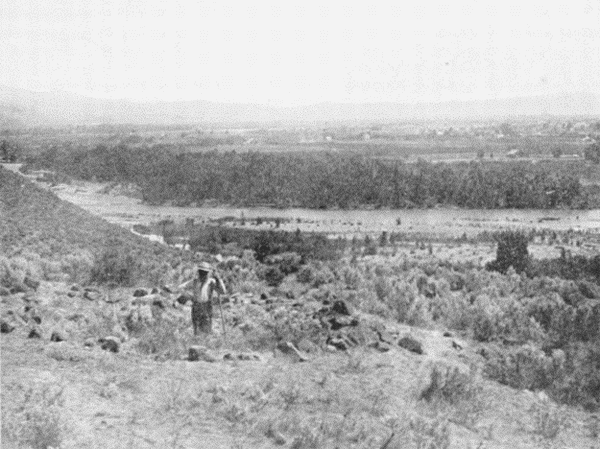

| House Site near Naches River. | |

| IV. | House Sites near Naches River. |

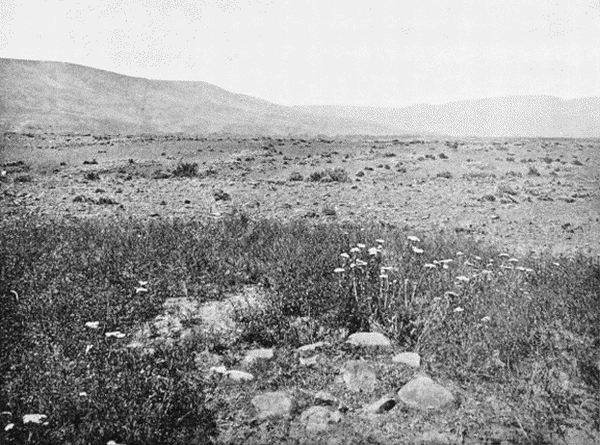

| V. | Camp Sites near Sentinal Bluffs. |

| VI. | Fort near Rock Creek. |

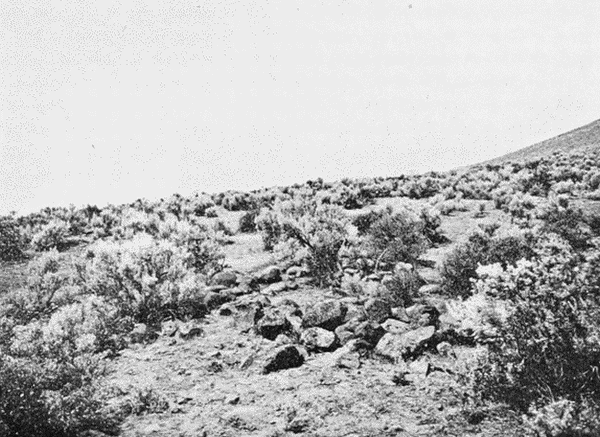

| Rock-Slide Grave on Yakima Ridge. | |

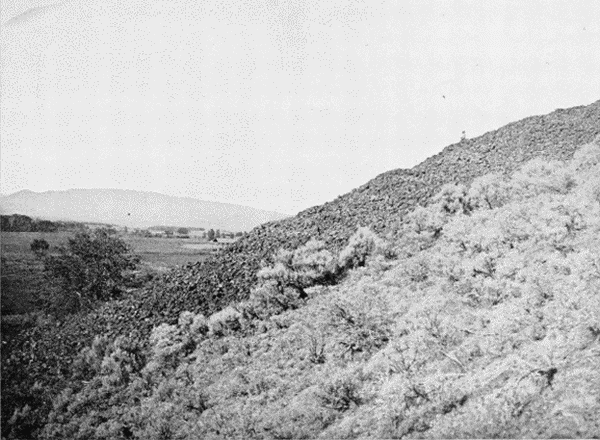

| VII. | Terraced Rock-Slide on Yakima Ridge. |

| VIII. | Rock-Slide Graves on Yakima Ridge. |

| IX. | Cremation Circle near Mouth of Naches River. |

| Grave in Dome of Volcanic Ash near Tampico. | |

| X. | Opened Grave in Dome of Volcanic Ash near Tampico. |

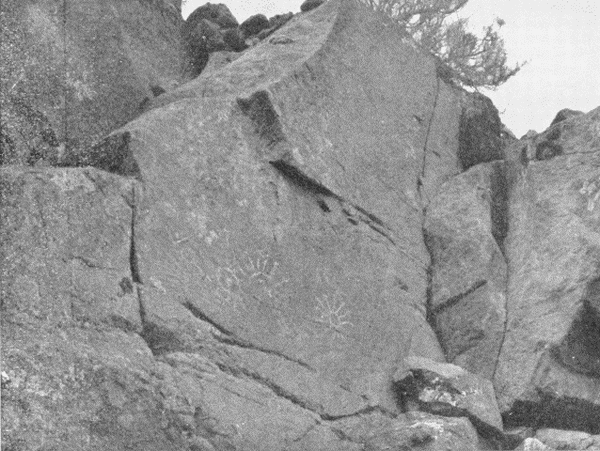

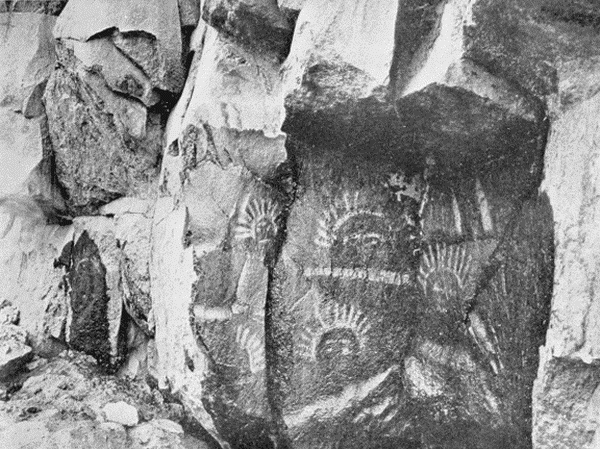

| XI. | Petroglyphs near Sentinal Bluffs. |

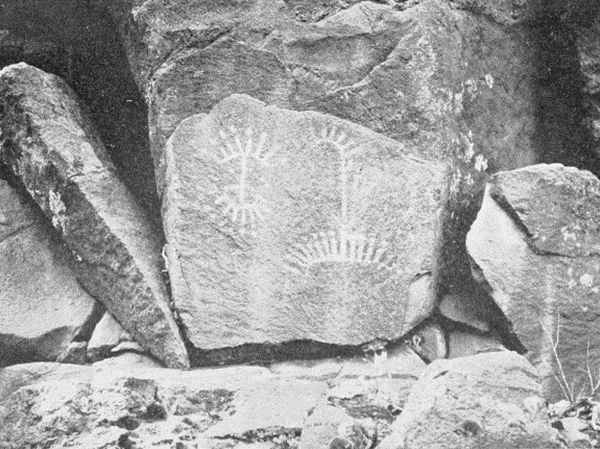

| XII. | Petroglyphs in Selah Canon. |

| XIII. | Petroglyph in Selah Canon. |

| Petroglyph near Wallula Junction. | |

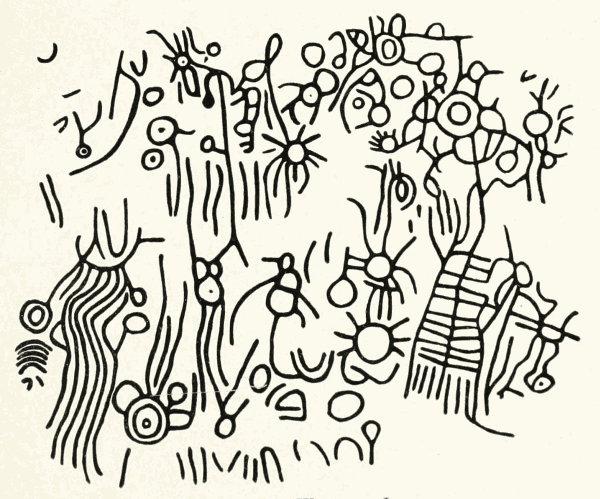

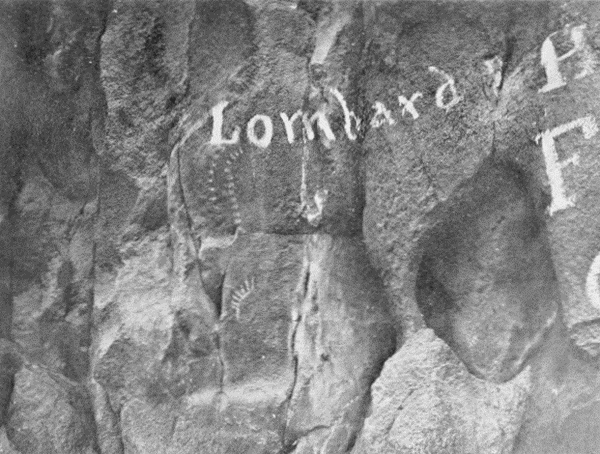

| XIV. | Pictographs at Mouth of Cowiche Creek. |

| XV. | Pictographs at Mouth of Cowiche Creek. |

| XVI. | Pictographs at Mouth of Cowiche Creek. |

Text Figures.

The following pages contain the results of archaeological investigations carried on by the writer for the American Museum of Natural History from May to August, 1903,[1] in the Yakima Valley between Clealum of the forested eastern slope of the Cascade Mountains and Kennewick, between the mouths of the Yakima and Snake Rivers in the treeless arid region, and in the Columbia Valley in the vicinity of Priest Rapids. My preliminary notes on the archaeology of this region were published in Science.[2] Definite age cannot be assigned to the archaeological finds, since here, as to the north, the remains are found at no great depth or in soil the surface of which is frequently shifted. Some of the graves are known to be of modern Indians, but many of them antedate the advent of the white race in this region or at least contain no objects of European manufacture, such as glass beads or iron knives. On the other hand, there was found no positive evidence of the great antiquity of any of the skeletons, artifacts or structures found in the area. The greater part of the area was formerly inhabited by Sahaptian speaking people, including the Yakima, Atanum, Topinish, Chamnapum, and Wanapum, while the northern part of it was occupied by the Piskwans or Winatshmpui of the Salish linguistic stock.[3]

Near North Yakima we examined graves in the rock-slides along the Yakima and Naches Rivers; a site, where material, possibly boulders, suitable for chipped implements had been dug and broken with pebble hammers, on the north side of the Naches about one mile above its mouth; pictographs on the basaltic columns on the south side of the Naches River to the west of the mouth of Cowiche Creek; petroglyphs pecked into basaltic columns in Selah Canon; ancient house sites on the north side of the Naches River near its mouth, and on the north side of the Yakima River below the mouth of the Naches; remains of human cremations, each surrounded by a circle of rocks on the point to the northwest of the junction of the Naches [Pg 8]and Yakima Rivers; recent rock-slide graves on the eastern side of the Yakima River above Union Gap below Old Yakima (Old Town); the surface along the eastern side of the Yakima River, as far as the vicinity of Sunnyside; graves in the domes of volcanic ash in the Ahtanum Valley near Tampico; and rock-slide graves in the Cowiche Valley.

We then moved our base about thirty miles up the Yakima River to Ellensburg, Mr. Albert A. Argyle examining the surface along the western side, en route. From Ellensburg, rock-slide graves and human remains, surrounded by circles of rocks, as well as a village site upon the lowland, were examined near the mouth of Cherry Creek. A day spent at Clealum failed to develop anything of archaeological interest in that vicinity, except that a human skeleton had been removed in the sinking of a shaft for a coal mine.

From Ellensburg we went to Fort Simcoe by way of North Yakima and near the Indian Agency observed circles of rocks, like those around the cremated human remains near North Yakima, and a circular hole surrounded by a ridge, the remains of an underground house. Crossing the divide from Ellensburg and going down to Priest Rapids in the Columbia Valley, no archaeological remains were observed except chips of stone suitable for chipped implements which were found on the eastern slope of the divide near the top and apparently marked the place where material for such implements, probably float quartz, had been quarried. On the western side of the Columbia, on the flat between Sentinal Bluffs and the river at the head of Priest Rapids, considerable material was found. This was on the surface of the beach opposite the bluffs and on a village site near the head of Priest Rapids. Graves in the rock-slides, back from the river about opposite this site, were also examined. Some modern graves were noticed in a low ridge near the river, a short distance above the village site. Crossing the Columbia, some material was found on the surface of the beach and further up, petroglyphs pecked in the basaltic rocks at the base of Sentinal Bluffs were photographed.

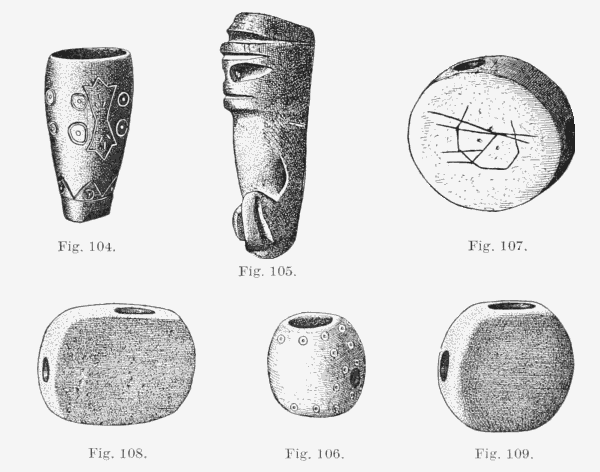

The writer wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness to Mr. D. W. Owen of Kennewick for information, for permission to examine his collection, to make notes and sketches of specimens in it, and for presenting certain specimens;[4] to Mr. Frank N. McCandless of Tacoma for permission to study and photograph the specimens[5] in his collection containing part of the York collection in the Ferry Museum, City Hall, Tacoma; to Mr. Louis O. Janeck of 415 North 2nd. St., North Yakima for information and for per[Pg 9]mission to study and photograph the specimens[6] in his collection as well as for supplementary information since received from him; to Hon. Austin Mires of Ellensburg for information and permission to study and photograph specimens[7] in his collection; to Mrs. O. Hinman of Ellensburg for permission to photograph specimens[8] in her collection; to Mrs. J. B. Davidson of Ellensburg for information and permission to study her collection and to make drawings of specimens[9] in it, and for the pipe shown in Fig. 106; to Mr. W. H. Spalding of Ellensburg for permission to photograph specimens[10] in his collection; to Mrs. Jay Lynch of Fort Simcoe, for information and permission to photograph specimens[11] in her collection; to Mr. W. Z. York of Old Yakima for permission to sketch and study specimens[12] in his collection, and to others credited specifically in the following pages. The accompanying drawings are by Mr. R. Weber and the photographs are by the author, unless otherwise credited.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] A brief report of the operations of this expedition appeared in the American Museum Journal, Vol. IV, No. 1, pp. 12-14, January, 1904. It was slightly revised and appeared in Science N. S. Vol. XIX, No. 484, pp. 579-580, April 8, 1904, and Records of the Past, Vol. IV, Part 4, pp. 119-127, April 1905.

[2] N. S. Vol. XXIII, No. 588, p. 551-555, April 6, 1906. Reprinted in the Seattle Post Intelligencer for March, 1906, the Scientific American Supplement, Vol. LXII, No. 1602, September 15, 1906, and in the Washington Magazine, Vol. I, No. 4, June 1906. Abstracted in the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, May, 1906.

[3] Mooney, Plate LXXXVIII

Clealum is situated on the Yakima River, at a point on the Northern Pacific Railway, 122 miles east of the humid, heavily forested coast at Puget Sound. Although situated not over 154 miles from Copalis, on the ocean at the western edge or furthest limit of the temperate humid coast country, the summers are hot and dry and the winters severe. It is 1909 feet above the sea level and far enough towards the summit of the Cascade Mountains, that marks the line between the humid coast and the arid almost treeless interior, to find considerable moisture and many trees.

Ellensburg is situated near the eastern side of the Yakima River, 25 miles below Clealum, at an altitude of 1512 feet above the sea level and in the wide somewhat flat Kittitas Valley which was, in former geologic times, a lake bottom. The river flows rapidly and its low banks at places are high enough to form gravel bluffs. The surrounding country is arid and there is no natural forest growth.

Cherry Creek, one of a number of small streams on this side of the river, flows through the eastern part of this valley, and empties into the Yakima [Pg 10]River about one mile below Thrall on Section 31, Town 17, North of Range 19 East. Here, the river enters Yakima Canon which cuts through Umptanum Ridge and the western foothills of Saddle Mountains. There are some pines in this canon.

Selah Creek flows through Selah Canon from the east and empties into the Yakima, about one mile above Selah at the northwest corner of Section 16, Town 14, north of Range 19 East. This is in a broad valley below Yakima Canon. At the time of our visit, however, the lower portion of this creek was dry. Wenas Creek empties into the Yakima from the west, nearly opposite Selah.

North Yakima is on the western side of the Yakima River, about two miles below the mouth of the Naches, which empties into the Yakima from the west, immediately below where the latter breaks through Yakima Ridge. This break is called the Gap or the Upper Gap. North Yakima is at an altitude of 1067 feet above the sea level. The soil of the valley is made up of a rich volcanic ash and the region is arid and practically treeless except on the banks of the rivers and creeks or where irrigation has been successfully practised. The climate in most respects resembles that of the southern interior of British Columbia, lying to the north, but in general, there is less vegetation except on irrigated land.

Cowiche Creek flows from the southwest and empties into the south side of the Naches, at a point about three miles above its mouth.

Tampico is situated on Section 17, Town 12, north of Range 16 East, on the north side of Ahtanum Creek, which flows nearly east along the base of the north side of Rattlesnake Range and empties into the Yakima at Union Gap or Lower Gap, below Old Yakima.

Fort Simcoe is located in a cluster of live oak trees, on one of the branches of Simcoe Creek, which flows in an easterly direction and empties into the Toppenish River, a western feeder of the Yakima. This place is at an altitude of 937 feet above the sea level and is surrounded by 'scab' land. Going west from Fort Simcoe, up the slopes of the Cascade Mountains, a mile or so, one notices timber in the valleys, and as one proceeds still further up the mountains, the timber becomes thicker and of greater size. This is the beginning of the forest, which at the west side of the Cascades becomes so remarkably dense. To the east of Fort Simcoe, however, no trees are seen, except in the bottoms along the streams, while on the lower reaches of the Yakima and on the banks of the Columbia, east of here, there are absolutely no trees.

Kennewick is located on the western side of the Columbia River about six miles below the mouth of the Yakima. It is opposite Pasco, which is about three miles above the mouth of Snake River. The place is only 366[Pg 11] feet above the sea level and except where irrigation has been practised, there are no trees in sight, the vegetation being that typical of the desert among which are sagebrush, grease-wood and cactus. Lewis and Clark, when here on their way to the Pacific Coast, October 17, 1805,[13] saw the Indians drying salmon on scaffolds for food and fuel. Captain Clark said, "I do not think [it] at all improbable that those people make use of Dried fish as fuel. The number of dead Salmon on the Shores & floating in the river is incrediable to say ... how far they have to raft their timber they make their scaffolds of I could not learn; but there is no timber of any sort except Small willow bushes in sight in any direction."

Sentinal Bluffs is the name given to both sides of the gap where the Columbia River breaks through Saddle Mountains. It is a short distance above the head of Priest Rapids. Crab Creek empties into the Columbia from the east on the north side of these mountains. On the western side of the river, between the Bluffs and the head of Priest Rapids, there is a flat place of considerable area, portions of which the Columbia floods during the winter. Going northwest from here to Ellensburg, the trail leads up a small valley in which are several springs surrounded by some small trees. One ascends about 2000 feet to the top of the divide and then descends perhaps 1000 feet into the Kittitas Valley.

FOOTNOTES:

[13] Lewis and Clark, III, p. 124.

At Clealum, we found no archaeological remains, except a single human skeleton unearthed in the sinking of a shaft for a coal mine. Here, however, our examination of the vicinity was limited to one day, and it is possible that a more thorough search might bring to light archaeological sites. Specimens from the vicinity of Clealum are unknown to the writer, although there are a number of collections from the vicinity of Ellensburg, Priest Rapids, Kennewick and other places lower down. The abundance of specimens on the surface near Priest Rapids and Kennewick in proportion to those found near North Yakima and Ellensburg, suggests that the high parts of the valley were less densely inhabited and that the mountains were perhaps only occasionally visited. It would seem possible that the prehistoric people of the Yakima Valley had their permanent homes on the Columbia, and possibly in the lower parts of the Yakima region. This is indicated by the remains of underground houses, some of which are as far up as Ellensburg. These remains are similar to those found in the Thompson River region, where such [Pg 12]houses were inhabited in the winter. The people of the Yakima area probably seldom went up to the higher valleys and the mountains, except on hunting expeditions or to gather berries, roots and wood for their scaffolds, canoes and other manufactures. If this be correct, it would account for the scarcity of specimens upon the surface along the higher streams, since all the hunting parties, berry, root and wood-gathering expeditions were not likely to leave behind them so much material as would be lost or discarded in the vicinity of the permanent villages. Spinden states[14] that in the Nez Perce region to the east of the Yakima country, permanent villages were not built in the uplands, although in a few places where camas and kouse were abundant, temporary summer camps were constructed.

In the vicinity of Ellensburg, we found no archaeological specimens except the chipped point mentioned on page 163, but this may be due in part to the modern cultivation of the soil and to the fact that the irrigated crops, such as are grown here, hide so much of the surface of the ground. A search along portions of the level country west of the town and even in such places as those where the river cuts the bank, failed to reveal signs of house or village sites. In Ellensburg, I saw a summer lodge, made up of a conical framework of poles covered with cloth and inhabited by an old blind Indian and his wife. East of the city, near the little stream below the City Reservoir was another summer lodge made similarly, but among the covering cloths was some matting of native manufacture. The remains of an underground house, possibly 30 feet in diameter were seen to the east of the Northern Pacific Railway, between Ellensburg and Thrall.

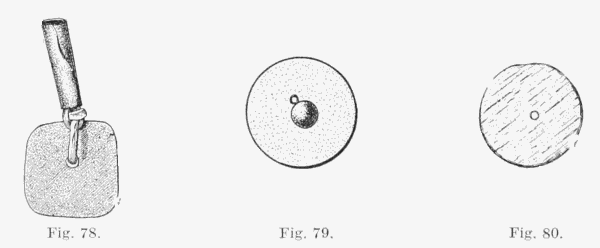

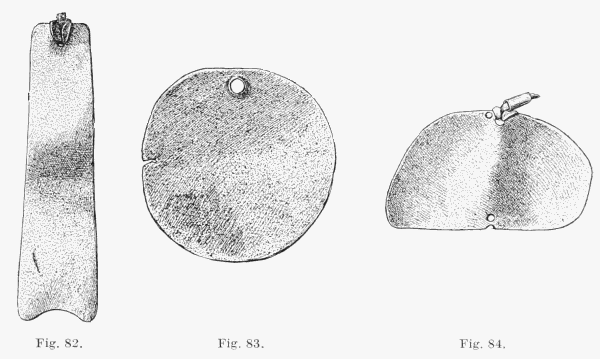

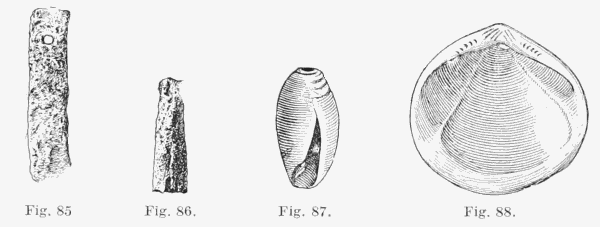

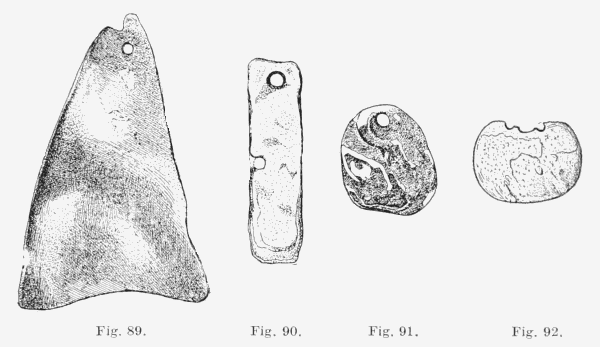

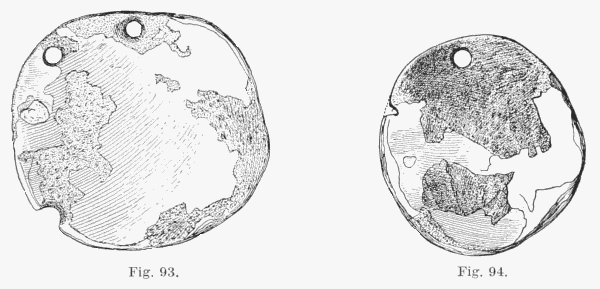

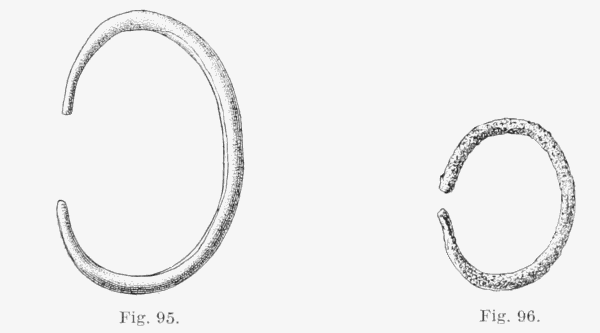

On the little bottom land along the western side of Cherry Creek, near its mouth, at the upper end of Yakima Canon, we found objects which show that the place had been a camping ground. This is immediately south of where an east and west road crosses the creek on the farm of Mr. Bull. On this village site were found the specimens catalogued under numbers 202-8213 to 8222, of which two are shown in Plate II, Fig. 12, and Fig. 52. The opposite side of this stream strikes one of the foothills of the uplands, the western extension of Saddle Mountains. On the top of this foothill, which overlooks the above mentioned village site, were a number of burials marked by circles of rocks.[15] In the rock-slide on the side of this hill, between these circles and the village site below, were a number of graves which are described in detail under numbers 99-4326-4332 and 202-8223-8258 on pages 164 to 166. Some of the objects found, many of which are recent and show contact with the white race, are shown in Figs. 71a, 72, 74, 78, 80, 82-86, 90, 92, 95, and 96.

On the western side of the Yakima, about opposite the above mentioned village site, a rock-slide appears at the head of Yakima Canon. In it are a number of rock-slide graves marked by sticks.

In Selah Canon, on the north side of Selah Creek, about a mile and a half above where it empties into the Yakima are three groups of petroglyphs pecked into the vertical surface of the low basaltic cliffs of the canon wall. Two of these groups (Plate XII) are upon eastern faces of the rock, while the one shown in Fig. 1, Plate XIII, is upon a southern exposure. In the rock-slide on the south side of Selah Canon, about three quarters of a mile above the Yakima or about half way between these petroglyphs and the Yakima, were found a number of graves, one of them marked by a much weathered twig. These were the only archaeological remains seen by us in Selah Canon, although we examined it for at least two miles from its mouth.

On the north slope of Yakima Ridge, near its base, at a point where the Moxee Canal and the river road turn and run west along the base of the ridge or about southeast of the largest ranch there, possibly two miles northeasterly from the Gap, were a number of scattered graves covered with rock-slide material. About one quarter of a mile west from here, a little west of south of the ranch, was a large rock-slide, covering a short northerly spur of the ridge. This is shown from the southwest in Plate VII. It is about three quarters of a mile northeast from where the Yakima River, after flowing through bottom lands, strikes the base of the Yakima Ridge. In this slide were a large number of shallow parallel nearly horizontal ditches below each of which is a low ridge or terrace of the angular slide-rock. Among these terraces, as shown in Fig. 2 of the plate, were a few pits surrounded by a low ridge, made up of jagged slide-rock, apparently from out of the pits. It was naturally larger at the side of the pit towards the bottom of the slide. In none of these did we find human remains or specimens. Some of them are larger than similar pits that we found to be rock-slide graves. Their close resemblance to graves found to have been disturbed, part of their remains being scattered near by and to other graves, as they appeared after our excavations, suggests that these pits are the remains of such rock-slide graves from which the bodies have been removed by the Indians possibly since the land became the property of the United States Government. On the other hand, these pits remind us of rifle pits, though it does not seem probable that they would be built in such a place for that purpose and there is no local account of the site having been used for such pits. This rock-slide is particularly interesting because of the terraces into which most of its surface had been formed. The character of the rock-slide material is such that one may walk over these for some little time without noticing them, but once having been noticed, they always force themselves upon the attention. Standing near the top[Pg 14] of the slide, they remind one of rows of seats in a theatre. Each terrace begins at the edge of the slide and runs horizontally out around its convex surface to the opposite side. Some of them are wider than others. They resemble the more or less horizontal and parallel terraces formed by horses and cattle while feeding on steep slopes. The Yakima Ridge has been so terraced by stock in many places and over large areas. However, there is no vegetation on the rock-slide to entice stock and the difficulty of walking over the cruelly sharp rocks as well as the presence of rattlesnakes would seem sufficient to cause both cattle and horses to pass either below or above it. The outer edge of each terrace is probably little lower than the inner edge, but viewed from the slope it seems so, and this suggests that these terraces may have been entrenchments, though it would seem that they would be useless for such a purpose since one can easily reach the land above from either side. Moreover, it would not seem necessary to make parallel entrenchments down the entire slope. That they were made to facilitate the carrying of the dead to the rock-slide graves is possible but not probable. It seems unlikely that they could have been made for the seating of spectators to overlook games or ceremonies; for the sharpness of the rocks would make them very uncomfortable.

There is a much higher rock-slide on the east side of a small steep ravine near where the Yakima River flows close to the base of the ridge, about a mile northeast of the Naches River or Upper Gap. Near the top of this slide, possibly three hundred feet above the river, were similar pits larger than those just described. Two or three of these were bounded along the edge towards the top of the slide by an unusually wide terrace. Near the bottom of this slide were graves[16] (Nos. 1 and 2) which are described in detail on page 153. Grave No. 1 was in the base of the rock-slide as shown in the figure and was indicated by a cedar stick projecting from a slight depression in the top of the heap of rock-slide material covering it. It was on a slight terrace about eighty feet above the river, and commanded a view over the valley of the Yakima to the north. The presence of the brass tube shown in Fig. 75 suggests that this grave is not of great antiquity. Grave No. 2 was in the same rock-slide about fifty feet down the ravine or to the north, and about forty feet above the Moxee flume. It was indicated by a hole in a pile of rock, like an old well. It was found to contain nothing, the remains having been removed. On the south side of the Yakima Ridge, near the bridge over the Yakima, at the Upper Gap, rock-slide graves are said to have been disturbed during the construction of the flume which carries the waters of the Moxee ditch around the western end of the Yakima Ridge, and [Pg 15]during the gathering of stone on this point for commercial purposes. Some of these graves are said to have been above the flume.

Here and there, near the base of the ridge from this point easterly for about a mile, were found small pits, such as one shown in Fig. 1, Plate VIII. Apparently, these were rock-slide graves from which the human remains had been removed, either by the Indians in early times or more recently by visitors from the neighboring town of North Yakima. Possibly some of them are old cache holes. One of these graves near the top of a small rock-slide above the flume contained a human skeleton and is shown in Fig. 2, Plate VIII. Below these graves, on the narrow flat between the base of the ridge and the Yakima River at a point about three quarters of a mile below the Upper Gap at the mouth of the Naches River, were discovered a number of small pits each surrounded by a low ridge of earth which were probably the remains of cache holes made by the Indians during the last twenty years. On this flat, close to the river were two pits surrounded by a circular ridge which indicated ancient semi-subterranean house sites, further described on page 51.

It is said, that above the flume at a point about a mile and a half below the Upper Gap, rock-slide graves, some of which were marked by pieces of canoes were excavated by school boys. The writer was also informed by small boys that near the top of the ridge immediately above here, they frequently found chipped points for arrows but on examination discovered only chips of stone suitable for such points, the boys either having mistaken the chips for points or having collected so many of the points that they were scarce.

On the west side of the Yakima, at the Upper Gap, there is a raised flat top or terrace that overlooks the mouth of the Naches River to the southeast. Here were a number of circles made up of angular rocks. Within each we found the remains of human cremations. Unburned fragments of the bones of several individuals with shell ornaments were often present in a single circle.[17]

Continuing westward, along the slope of the ridge, cut along its southern base by the Naches River, at a point about one and a quarter miles west of the mouth of the river, a small ravine cuts down from the top of the ridge. This has formed a little flat through the middle of which it has again cut down towards the river. East of this ravine on the flat is a circle of angular rocks such as are found scattered over the ridge. This circle no doubt marks a house site, the interior having been cleared of stone and the circle of rocks probably having been used to hold down the lodge covering.[18] To [Pg 16]the west of the ravine, where the flat is somewhat higher than to the east, there are the remains of two semi-subterranean houses. Each of these is represented by a pit surrounded by a ridge of earth, and on the top, are large angular rocks.[19] At a point where the ridge meets this flat, close to the western side of the ravine was a slight depression in a small rock-slide which marked what seemed to be a grave, but which, on excavation, revealed nothing. Still further westward at a point probably two miles above the mouth of the Naches River and overlooking the stream at an altitude of perhaps 250 feet, we found scattered over the ground along the eastern summit of a deep ravine, the first one west of the house sites above mentioned, numerous small chips of material suitable for chipped implements. These became more numerous as we proceeded northward up the eastern side of the ravine for a distance of about a quarter of a mile. Here we came upon the small quarry in the volcanic soil, shown in Fig. 1, Plate III. Immediately to the west of the pit was a pile of earth, apparently excavated from it.

On the top of this heap of soil and among the broken rock to the south and east of it, were found several water-worn pebbles, used as hammers in breaking up the rock, as indicated by the battered condition of their ends (p. 58). We saw no other water-worn pebbles on the surface of the ridge, but they were numerous in the gravel of the bottom-lands subject to the overflow of the rivers. It would seem that these pebbles were brought up from the river below for use as hammers. Scattered to the south of the pit were found large fragments of float quartz material containing small pieces of stone suitable for chipped implements but made up mainly of stone which was badly disintegrated. Lying on the slope of the ravine were many small fragments of this same stone which were clear of flaws.

It would seem that a mass of float quartz much of which was suitable for chipped implements had been found here. It had been excavated, leaving the pile of earth and then broken up with the river pebbles which were left behind with the waste. Probably there were fairly large pieces of the material, suitable for chipped implements; that were carried away while small pieces were left lying about a pile of unsuitable material. In other words, it would seem that these specimens mark a place for the roughing out of material for chipped implements.[20] On the same side of the river, on the side of a rather low ridge or table-land overlooking it, at a point about twelve miles above its mouth, are some rock-slides. Here it is said that graves have been found. They were probably typical rock-slide graves. On a point of land perhaps fifty feet above these and a few hundred feet to [Pg 17]the north, Master James McWhirter pointed out a grave on his farm. It was then surrounded by a ring made up of water-worn pebbles, apparently brought up from the river. He stated that an attempt had been made to excavate it which possibly accounts for the pebbles being in a circle rather than a heap over the grave. This grave was found to contain a slab of wood, shell ornaments, probably modern, and an adult skeleton, No. 12 (7), 99-4320, p. 156.

There are a number of painted pictographs on the vertical faces of the basaltic columns, facing north on the south side of the Naches River, immediately to the west of the mouth of Cowiche Creek. These are below the flume and may be reached from the top of the talus slope which has been added to by the blasting away of the rock above, during the construction of the flume. In fact, debris from this blasting has covered part of the pictographs. Some of the pictures are in red, others in white and there are combinations of the two colors.[21] Local merchants have defaced these pictographs with advertisements.

In the Cowiche Valley, there are several rock-slide graves, but these seem to have been rifled. Northeast of the fair grounds at North Yakima, the remains of an underground house are said to exist. A short distance east of Tampico, about 18 miles above the mouth of the Ahtanum, on the north side of the river and east of the road from the north where it meets the river road and immediately across it from the house of Mr. Sherman Eglin, was a grave located in a volcanic dome left by the wind, which Mr. Eglin pointed out to us. The site is about 600 feet north of the north branch of the Ahtanum and about fifteen feet above the level of the river. A pile of rocks about eight feet in diameter covered this grave, No. 25, p. 160. On the land of Mr. A. D. Eglin, between the above-mentioned grave and Tampico on the north side of the road were seen the signs of two graves, destroyed by plowing. Near here, an oblong mound six or eight inches high and ten feet wide by eight feet long, supposedly covering a grave, marked by a stone on the level at each side and each end, 12 and 16 feet apart respectively was reported by Mr. Eglin's son. A little distance further north and up the slope of the land, were a number of volcanic ash heaps left by the wind. The surrounding land is what is locally known as "scab land." In some of these knolls, graves have been found and one which has been explored is shown in Fig. 2, Plate IX. It is located near the pasture gate, and was marked by a circle of stones as shown in the figure. On excavating, nothing was found. It is possible that the remains were entirely disintegrated. Graves in rock-slides on hill sides, and a village site near this place were [Pg 18]reported by Mr. Eglin's son. Along the north side of Ahtanum Creek between Ahtanum and Tampico, below the rim rock of the uplands parallel to the creek are a number of rock-slide graves.

On the western side of Union Gap, through which the Yakima River flows, below the mouth of Ahtanum Creek, a short distance below Old Yakima, on a little flat or terrace projecting from the south side of Rattle Snake Range is a modern Indian cemetery surrounded by a fence. To the east of Union Gap, on the northwestern slope of Rattle Snake Range, we examined some rock-slide graves which had been made since the advent of objects of white manufacture. A mile or so south of Union Gap not far from the uplands to the east of the river was a ridge of earth extending north and south nearly parallel with the river road. This, however, I believe may be the remains of some early irrigation project. On the west side of the Yakima River about two miles south of Union Gap was seen a summer lodge made by covering a conical framework with mats.

At Fort Simcoe, immediately south of the Indian agency, on the north edge of the "scab land," overlooking a small ravine, is a large pit surrounded by an embankment of earth, the remains of a semi-subterranean house. Perhaps an eighth of a mile south of this, on higher "scab land" was a rather low long mound upon which were several piles of stone that probably marked graves. This mound was lower and more oblong than the usual dome in which such graves were made. Mrs. Lynch, who pointed these out has excavated similar piles at this place and found them to mark graves. We were informed that chipped implements were frequently found along the Yakima River at a point near Prosser. Above Kennewick, while digging a flume, a number of graves were discovered, from which Mr. Sonderman made his collection. Some of these graves contained modern material (p. 111).

On the surface of the western beach of the Columbia at Kennewick and on the flat land back of it we found chips of material suitable for making chipped implements, and a large pebble, probably a net sinker.[22] These, together with the fact that Mr. D. W. Owen has also frequently found specimens here, suggest that this place was an ancient camping ground. That Lewis and Clark saw Indians here and in the vicinity, as well as that the Indians still camp here on the beach of the river, sheltered from the wind by the bank and depending upon the river driftwood for their fuel, strengthens this suggestion. Specimens have been found on the large island in the Columbia at the mouth of the Yakima. (See p. 64.) At a point four miles below Kennewick or perhaps a mile below a point opposite the mouth [Pg 19]of the Snake, a grave which contained material of white manufacture is said to have been discovered by a man while hauling water up the bank of the Columbia.

Schoolcraft states[23] that there was an earthwork on the left bank of the Lower Yakima on the edge of a terrace about fifteen feet high a short distance from the water. This terrace was banked on either side by a gully. This consisted of two concentric circles of earth about eighty yards in diameter by three feet high, with a ditch between. Within were about twenty "cellars", situated without apparent design, except economy of room. They were some thirty feet across, and three feet deep. A guide stated that it was unique and made very long ago by an unknown people. Outside, but near by, were other "cellars" in no way differing from the remains of villages of the region. What may be an earthwork near by is described by Schoolcraft[24] as follows: "The Indians also pointed out, near by, a low hill or spur, which in form might be supposed to resemble an inverted canoe, and which he had said was a ship." Schoolcraft suggests a possible relation of this to the mounds of the Sacramento Valley and continues:—

"In this connection may also be mentioned a couple of modern fortifications, erected by the Yakamas upon the Sunkive fork. They are situated between two small branches, upon the summits of a narrow ridge some two hundred yards long, and thirty feet in height, and are about twenty-five yards apart. The first is a square with rounded corners, formed by an earthen embankment capped with stones; the interstices between which served for loop-holes, and without any ditch. It is about thirty feet on the sides, and the wall three feet high. The other is built of adobes, in the form of a rectangle, twenty by thirty-four feet, the walls three feet high, and twelve to eighteen inches thick, with loop-holes six feet apart. Both are commanded within rifle-shot by neighboring hills. They were erected in 1847 by Skloo, as a defence against the Cayuse. We did not hear whether they were successfully maintained, accounts varying greatly in this respect. In the same neighborhood Captain M'Clellan's party noticed small piles of stones raised by the Indians on the edges of the basaltic walls which enclose these valleys, but were informed that they had no purpose; they were put up through idleness. Similar piles are, however, sometimes erected to mark the fork of a trail. At points on these walls there were also many graves, generally made in regular form, covered with loose stones to protect them from the cayotes, and marked by poles decorated with tin cups, powder-horns, and articles of dress. During the summer the Indians for the most part live in the small valleys lying well into the foot of the mountains. These are, however, uninhabitable during the winter, and they move further down, or to more sheltered situations. The mission which, in summer, is maintained in the A-tį-nam valley, is transferred into that of the main river."[25]

[Pg 20]After passing the top of the divide, to the left of the trail from Ellensburg to Priest Rapids, chips and fragments of variegated float quartz suitable for chipped implements were found. This apparently marked a place where a fragment of float rock had been broken up, but fine fragments were hardly numerous enough to indicate that the place had been a shop site, or at least a large one. The quantity of material broken up, judging from the amount of refuse, was small. On the western side of the Columbia, at the base of the basaltic rocks where they meet the bottom-land, perhaps a mile from the river were rock-slide graves in the talus slope. At the head of Priest Rapids, the river turns towards the west and then southward, flowing close to the southern end of this escarpment. On the flat, at the very head of Priest Rapids, the river, during high water had washed out the remains of a village or camp site, where pestles and animal bones were numerous. A short distance above this, in a low ridge near the river were some modern graves some of which were marked with sticks at the head and foot. The bodies, judging from the mounds of earth, were laid full length and many, if not all of them, judging from the size of the head and foot sticks, were placed with the feet towards the east. Perhaps a mile above here near the home of Mr. Britain Everette Craig, several large and deep pits, the sites of ancient semi-subterranean houses were seen. Above and near his house, the river had washed out what was apparently a village site, and perhaps a few graves. Here was found the small fresh water shell heap, shown in Fig. 1, Plate V, and the pile of flat oval pebbles which probably marked a cooking place, shown in Fig. 2. On the west beach of the Columbia at Sentinal Bluffs perhaps another mile further up the river, notched sinkers and other indications of a camp or fishing ground were found.

On the eastern side of the river near the head of Priest Rapids some material was found on the surface of the beach where the floods of the river had uncovered it. A mile or more above here, pecked on the basaltic columns of Sentinal Bluffs, which may be seen in both figures of Plate V were a number of petroglyphs, shown in Plate XI and described on page 121. Those shown in Fig. 1, photographed from the west, are on the columns to the east of the road, blasted through the rocks at this point, and perhaps fifteen feet from the river. Those in Fig. 2, photographed from the north, are to the west of the road on the columns which rise abruptly from the river. Some specimens and indications of habitation were found scattered between this point and the mouth of Crab Creek, the bed of which was dry in most places when we visited it.

FOOTNOTES:

[14] Spinden, p. 178.

[15] See 99-4325, page 163.

[16] See Fig. 3, Plate VI from the north of west.

[17] See p. 142 and Fig. 1, Plate IX.

[18] See p. 15 and Fig. 1, Plate IV.

[19] See p. 52 and Fig. 2, Plate IV.

[23] Schoolcraft, VI. p. 612.

[24] Schoolcraft, VI. p. 613.

[25] Cf. also Bancroft, IV. p. 736; Stevens, pp. 232-3; Gibbs, (a), pp. 408-9.

The resources of the prehistoric people of the Yakima Valley, as indicated by the specimens found in the graves and about the village sites, were chiefly of stone, copper, shell, bone, antler, horn, feathers, skin, tule stalks, birch bark and wood. They employed extensively various kinds of stone for making a variety of objects. Obsidian,[26] glassy basalt or trap, petrified wood, agate, chalcedonic quartz with opaline intrusions, chert and jasper were used for chipping into various kinds of points, such as those used for arrows, spears, knives, drills and scrapers. According to Spinden,[27] obsidian was used in the Nez Perce region to the east where it was obtained from the John Day River and in the mountains to the east, possibly in the vicinity of the Yellowstone National Park. The people of the Yakima Valley may have secured it from the Nez Perce. As on the coast, objects made of glassy basalt were rare here, although it will be remembered that they were the most common among chipped objects in the Thompson River region.[28] Mr. James Teit believes that glassy basalt is scarce in the Yakima region and that this is the reason why the prehistoric people there did not use it extensively. Some agate, chalcedony and similar materials were used in the Thompson River region, but while there is a great quantity of the raw material of these substances there, the Indians say that the black basalt was easier to work and quite as effective when finished. Several small quarries of float quartz had been excavated and broken up to be flaked at adjacent work shops, p. 16. River pebbles were made into net sinkers, pestles, mortars, hammerstones, scrapers, clubs, slave killers, sculptures, and similar objects, and were also used for covering some of the graves in the knolls. Serpentine was used for celts and clubs; lava for sculptures. Slate was used for ornamental or ceremonial tablets steatite for ornaments and pipes, though rarely for pestles and other objects; and impure limestone for pipes. Fragments of basaltic rock were used for covering graves in the rock-slides and in some of the knolls. Places on the basaltic columns and cliffs served as backgrounds upon which pictures were made, some being pecked,[29] others painted.[30] No objects made of mica or nephrite were found. Siliceous sandstone was made into pestles, pipes and smoothers for arrow-shafts, but the last were rare. Copper clay, white earth and red ochre were not found, but red and white [Pg 22]paint were seen on the basaltic cliffs and Mrs. Lynch reports blue paint from a grave near Fort Simcoe (p. 117).

Copper was used for beads, pendants and bracelets. While all of this copper may have been obtained by barter from the whites, yet some of it may have been native. Copper, according to Spinden, was probably not known to the Nez Perce before the articles of civilization had reached that region, but he states that large quantities of copper have been taken from graves and that the edges of some of the specimens are uneven, such as would be more likely to result from beating out a nugget than from working a piece of cut sheet copper.[31] The glass beads, iron bracelets,[32] and bangles,[33] the brass rolled beads,[34] brass pendant[35] and the white metal inlay,[36] which we found, all came from trade with the white race during recent times and do not belong to the old culture.

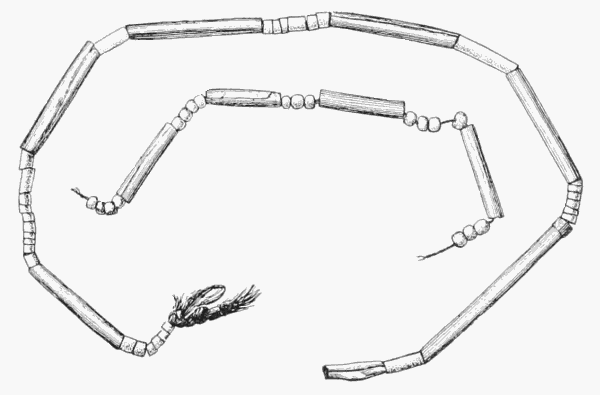

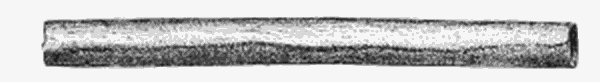

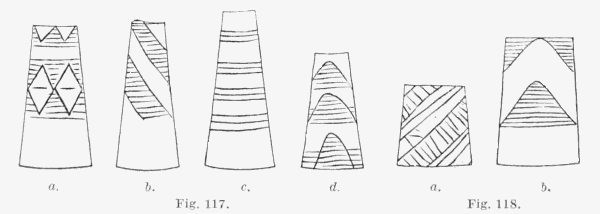

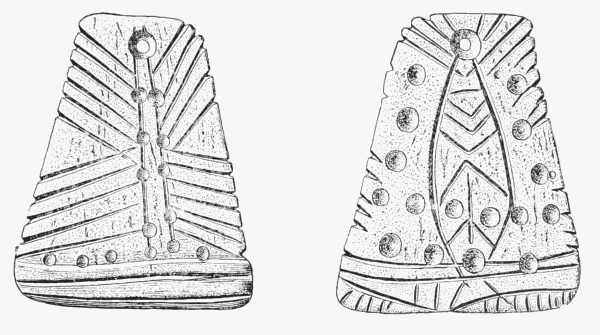

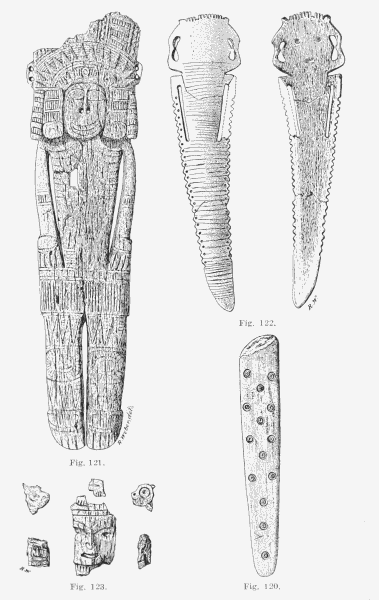

Shells of the fresh water unio, in a bed five or six feet in diameter and two or three inches thick, at the Priest Rapids village site and described on p. 34 indicate that this animal had been used for food. Shells of the little salt water clam (Pectunculus 202-8388, Fig. 88), haliotis (202-8234b, 8252, 8255, 8386, Figs. 89-92), dentalium (202-8178, 8156, 8163, 8173, 8177-9, 8184, 8186-89, 8192-3, 8233, 8241, 8253, 8389, Figs. 74, 117, and 118) olivella (202-8393, Fig. 87), and oyster (202-8170, Fig. 94) which were made into various ornaments must have been obtained from the coast. No shells of Pecten caurinus were found.

Deer bones were seen in great numbers in the earth of a village site at the head of Priest Rapids where they probably are the remains of cooking. Animal bones were made into points for arrows or harpoon barbs, awls and tubes that were probably used in gambling. Fish bones (202-8387) found in the village sites suggest that fish were used for food. No bones of the whale were found.

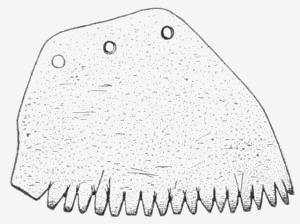

Antler was used for wedges, combs and as material upon which to carve. Horns of the Rocky Mountain sheep were used for digging-stick handles. Mountain sheep horns were secured by the Nez Perce who lived to the east of the Yakima region, and were traded with Indians westward as far as the Lower Columbia.[37] No objects made of teeth were found although a piece of a beaver tooth (202-8189) was seen in grave No. 21, and Mrs. Lynch reports elk teeth from a grave near Fort Simcoe (p. 119). Pieces of [Pg 23]thong, skin, fur, and feathers of the woodpecker, all of which were probably used as articles of wearing apparel, were found in the graves preserved by the action of copper salts or the dryness of the climate.

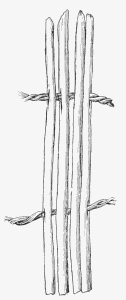

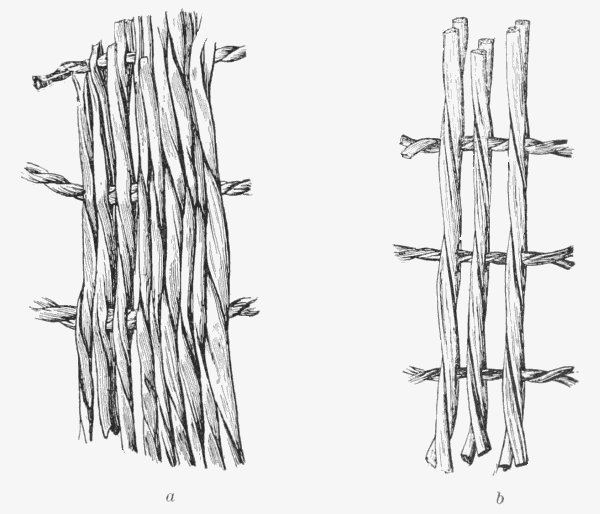

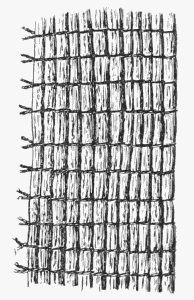

Wood was used as the hearth of a fire drill[38] and for a bow, a fragment of which is shown in Fig. 114. Sticks which had not decayed in this dry climate, marked some of the graves in the rock-slides (p. 140). Charcoal was also found in the graves and village sites. A fragment of birch bark, tightly rolled (202-8392) was found in a grave; roots were woven into baskets;[39] rushes were stitched and woven into mats.[40]

FOOTNOTES:

[27] Spinden, p. 184.

[28] Smith, (d) p. 132 and 135 (c) p. 407.

[31] Spinden, p. 190.

[37] Spinden, p. 223.

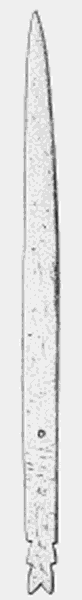

Fig. 1 (202-8369). Chipped Point made of Chalcedony. From

the surface, near the head of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.

Fig. 1 (202-8369). Chipped Point made of Chalcedony. From

the surface, near the head of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.

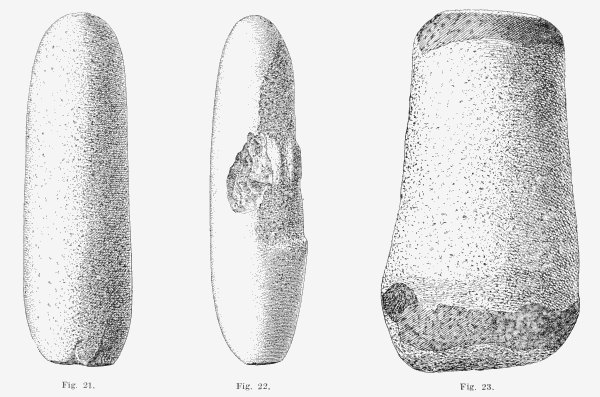

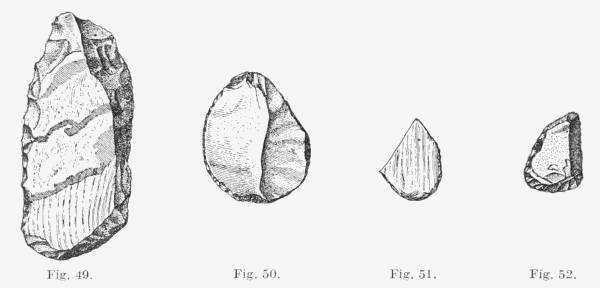

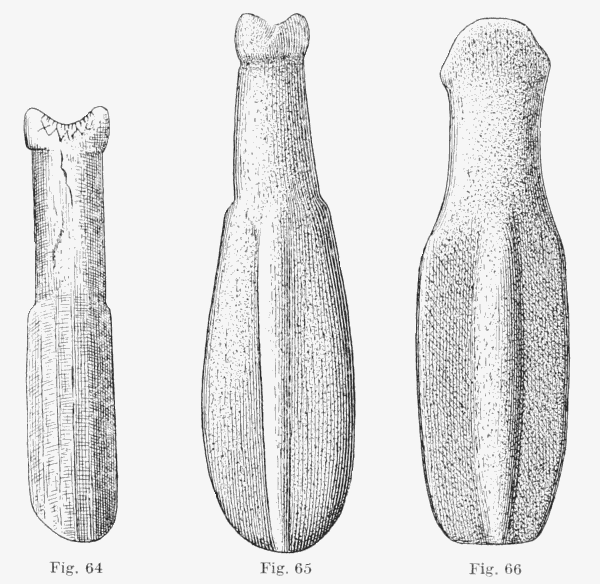

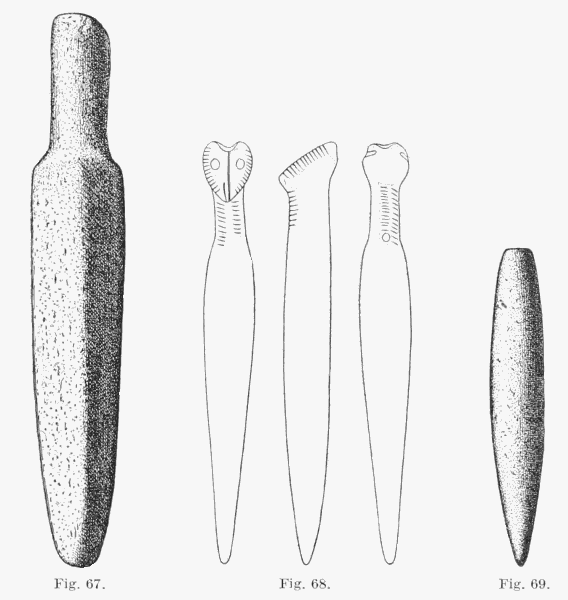

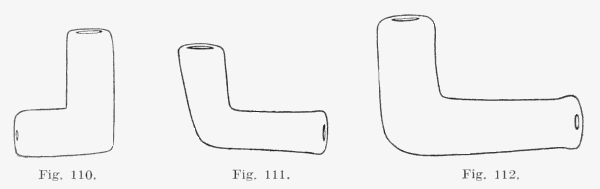

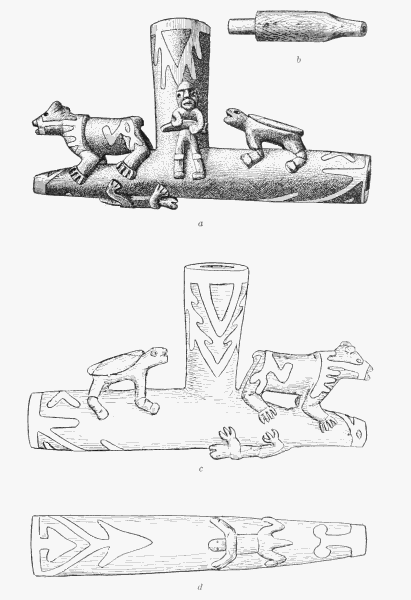

Points Chipped out of Stone. Many implements used in procuring food were found. In general, they are similar in character to those found in the Thompson River Region.[41] The most numerous perhaps, were points of various sizes and shapes, made by chipping and flaking, for arrows, knives and spears. Many of these are small and finely wrought and most of them are of bright colored agates, chalcedonies and similar stones. As before mentioned, several small quarries of such material with adjacent workshops were found. A very few specimens were made of glassy basalt, and it will be remembered (p. 21) that this was the prevailing material for chipped implements in the Thompson River region to the north, where there was perhaps not such a great variety of material used.[42] In the Nez Perce region to the east, according to Spinden, a great variety of forms of arrow points chipped from stone of many kinds is found,[43] and the extreme minuteness of some of them is noteworthy. The war spear sometimes had a point of stone, usually lance-shaped, but sometimes barbed.[44] He further states that iron supplanted flint and obsidian at an early date, for the manufacture of arrow-heads.[45]

No caches of chipped implements were found in the Yakima region. Judging from the collections which I have seen, I am under the impression that chipped points are not nearly so numerous in this region as they are near The Dalles and in the Columbia Valley immediately south of this area, [Pg 24]and perhaps not even as numerous as in the Thompson River country to the north. We found no fantastic forms such as were rather common in the Thompson River country.[46] It will be remembered[47] that the art of chipping stone was not extensively practised on the coast of British Columbia or Washington, no specimens having been found in that area north of Vancouver Island except at Bella Coola, where only two were discovered. They were frequent at Saanich and in the Fraser Delta and became still more common as one approached the mouth of the Columbia on the west coast of Washington where, on the whole, they seem to resemble, especially in the general character of the material, the chipped points of the Columbia River Valley in the general region from Portland to The Dalles.

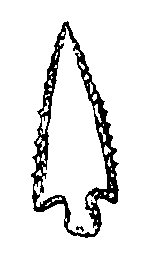

Fig. 2 (202-8364). Chipped Point made of Chalcedony. From the surface, near the

head of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.

Fig. 2 (202-8364). Chipped Point made of Chalcedony. From the surface, near the

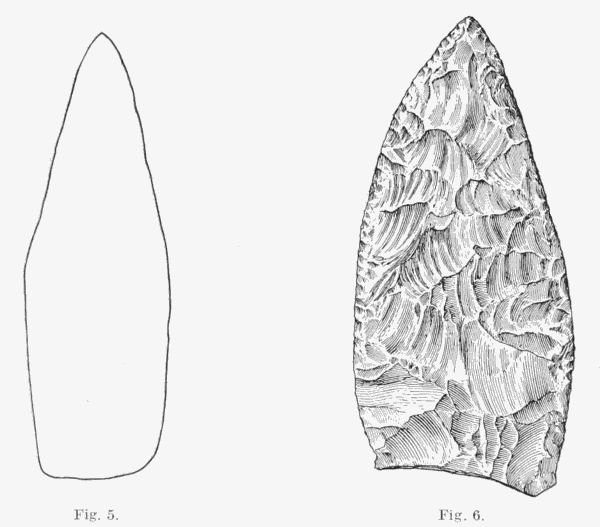

head of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.The range of forms and sizes is well shown in Figs. 1 to 6 and in Plates I and II.[48] The specimen shown in Fig. 1 is very small, apparently made from a thin flake of chalcedony that has not been much chipped. Its edges are slightly serrated and it was found on the surface near the head of Priest Rapids. Deeply serrated points are found in the Nez Perce region to the east, but they are unusual.[49] The one shown in Fig. 2 is also made of chalcedony and is from the same place. It is larger and the barbs are not so deep. The specimen shown in Fig. 3, chipped from white chalcedony was found at the same place and may be considered as a knife point rather than as an arrow point. The one shown in Fig. 4 is made of petrified wood and has serrated edges. It was found at Priest Rapids and is in the collection of Mr. Mires. Fig. 5 illustrates a point with a straight base chipped from obsidian, one of the few made of this material that have been found in the whole region. This is also from Priest Rapids in the collection of Mr. Mires. The straight based arrow-head is very common in the Nez Perce region.[50] The specimen shown in Fig. 6 is leaf shaped, the base being broken off. It is made of chert, was collected at Wallula near the Columbia River in Oregon by Judge James Kennedy in 1882 and is in the James Terry collection of this Museum. Plate I shows a rather large and crudely chipped point made of basalt, from the surface near the head of Priest Rapids on the bank of the Columbia River. The second is made of red jasper and the third of white chert. They were found near the head of Priest Rapids, the latter also on [Pg 25] the bank of the river. These three specimens may be considered as finished or unfinished spear or knife points. The specimens shown in Plate II are more nearly of the average size. The first is made of buff jasper and was found on the surface at Kennewick. It is slightly serrated. The second is made of brownish fissile jasper and was found in grave No. 10 (5) in a rock-slide near the mouth of the Naches River. The third, chipped from mottled quartz was found in grave No. 28 (21) near the skull in a rock-slide about three miles west of the mouth of Cowiche Creek. The fourth of white quartzite is also from grave No. 28 (21) near the skull. The breadth of the base of these last two specimens and the notches would facilitate their being fastened very securely in an arrow-shaft, while the basal points would probably project far enough beyond the shaft to make serviceable barbs. The fifth specimen, chipped from brown chert was found among the refuse of a fire in grave No. 1, in a rock-slide of the Yakima Ridge. The sixth is made of glassy basalt and is remarkable for having two sets of notches. It is rather large, which suggests that it may have served as a knife point. It is from the head of Priest Rapids and was collected and presented by Mrs. J. B. Davidson. Double notched arrow points are found in the Nez Perce region.[51] The seventh is chipped from pale fulvous chalcedony and is from the surface at the same place. The eighth is chipped from similar material and was found near by. The ninth is made of opaline whitish chalcedony and is from the same place. The tenth is chipped from yellow agate, and somewhat resembles a drill, while the eleventh is of brown horn stone, both of them being from the surface near the head of Priest Rapids.

The twelfth which is chipped from clove brown jasper was found on the surface of the Cherry Creek camp site near Ellensburg. The thirteenth is made of reddish white chert and was found on the surface near the mouth of Wenas Creek. The fourteenth is of pale yellow chalcedony and comes from the surface near the head of Priest Rapids. Most of these specimens seem to be suitable for arrow points, although some of them probably served for use as knives.

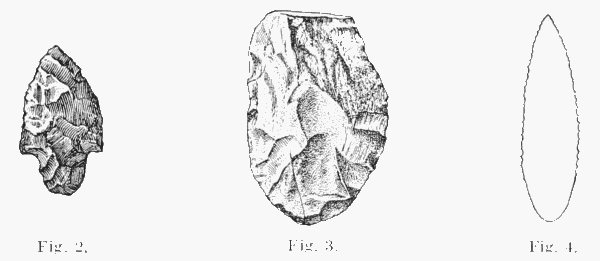

Fig. 5. Chipped Point made of Obsidian. From Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size. (Drawn

from a sketch. Original in the collection of Mr. Mires.)

Fig. 5. Chipped Point made of Obsidian. From Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size. (Drawn

from a sketch. Original in the collection of Mr. Mires.)Points Rubbed out of Stone. No points rubbed out of stone have been found in this region, although it will be remembered that two such points were found in the Thompson River region[52] and were thought to represent an intrusion from the coast where they were common as in the Fraser Delta[53] at both Port Hammond and Eburne where they are more than one half as numerous as the chipped points, and at Comox[54] where at least seven of this [Pg 27]type to three chipped from stone were found. They were also found at Saanich,[55] where they were in proportion of nineteen to twenty-four, near Victoria[56] and on the San Juan Islands.[57]

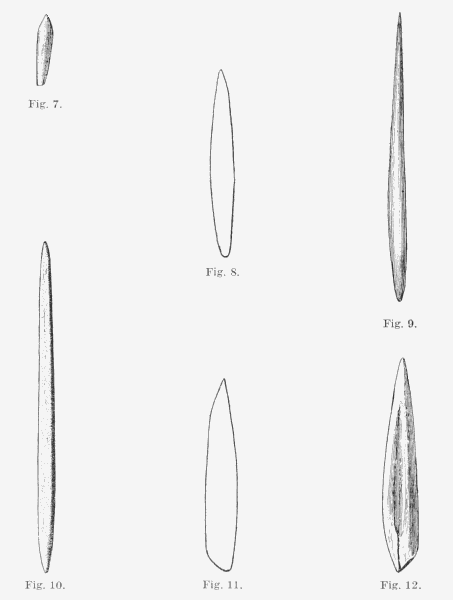

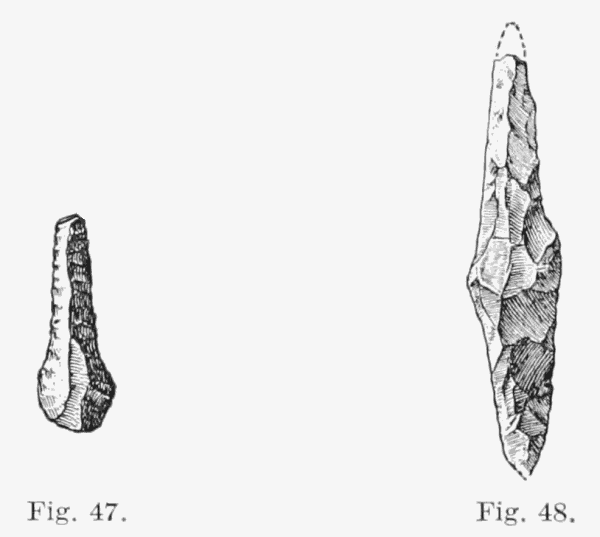

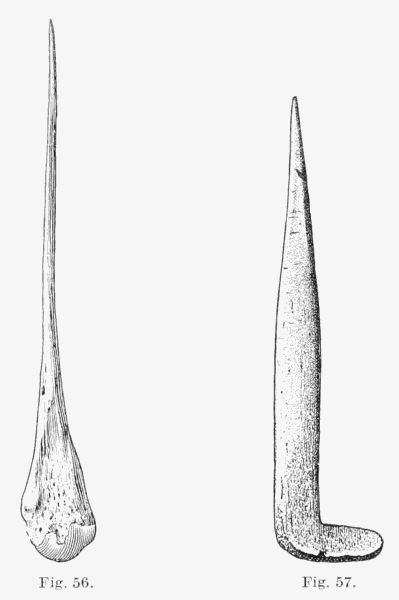

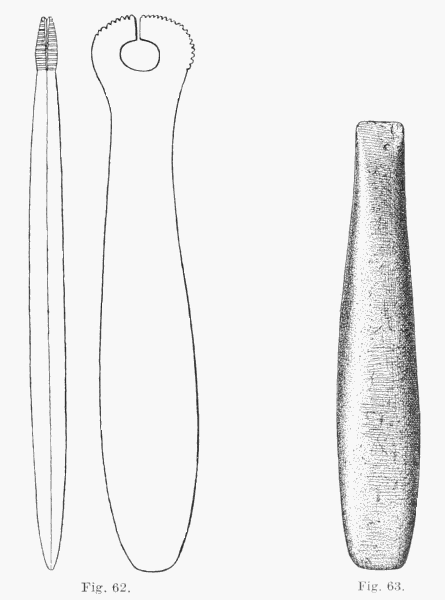

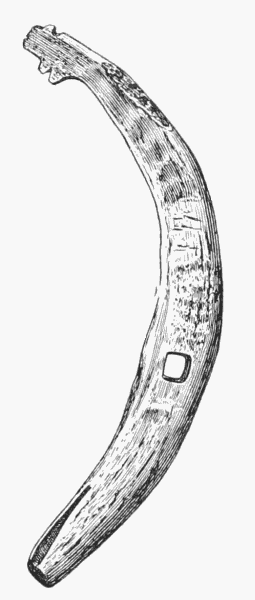

Points Rubbed out of Bone. Points rubbed out of bone which were so common on the coast everywhere, but rare in the Thompson River country are still more scarce here. Only ten specimens from the whole region can be identified as clearly intended for the points or barbs of arrows, harpoon heads or spears. The types are shown in Figs. 7 to 12. The first was found in the west, northwest part of grave No. 10 (5) in a rock-slide about a half mile above the mouth of the Naches River. It is nearly circular in cross section, 31 mm. long with a point only 6 mm. in length and was apparently intended for a salmon harpoon head, similar to those used in the Thompson River region[58] both in ancient and modern times but which are much more common on the coast. The specimen shown in Fig. 8 is circular in cross section and was seen in the collection of Mrs. Davidson. It is from Kennewick and is of the shape of one of the most frequent types of bone points found in the Fraser Delta.[59] The specimen shown in Fig. 9 was found with three others in grave No. 1 in a rock-slide of the Yakima Ridge. This and two of the others were scorched. They are circular in cross section and sharp at both ends but the upper end is much the more slender. The point shown in Fig. 10 somewhat resembles these, but it is slightly larger and tends to be rectangular in cross section except at the base. It was found with a similar specimen in a grave on the Snake River, five miles above its mouth, and was collected and presented by Mr. Owen who still has the other specimen. Diagonal striations may still be seen on its much weathered brown surface. These were probably caused by rubbing it on a stone in its manufacture. A slightly different type of bone point is shown in Figs. 11 and 12. These seem to be barbs for fish spears such as were found in the Thompson River region,[60] among both ancient and modern specimens. The one shown in Fig. 11 has traces of the marrow canal on the reverse. It was found in the Yakima Valley below Prosser and is in the collection of Mr. Spalding. While the specimen shown in Fig. 12 is from the surface near the head of Priest Rapids.

Fig. 7 (202-8165). Point made of Bone. From the W., N. W. part of grave No. 10 (5)

in a rock-slide about half a mile above the mouth of Naches River. ½ nat. size.

Fig. 7 (202-8165). Point made of Bone. From the W., N. W. part of grave No. 10 (5)

in a rock-slide about half a mile above the mouth of Naches River. ½ nat. size.Bone points and barbs were used in the Nez Perce region to the east, where three types of spears with bone points were known, two of them at least being similar to those found in the Thompson River region to the[Pg 29] north.[61] The war spears sometimes had a point of bone, usually lance-shaped, but sometimes barbed.[62]

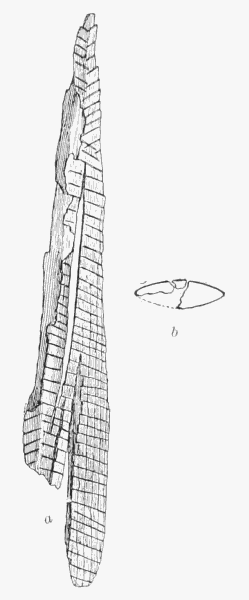

Bows. The only information which we have regarding bows is from the specimen shown in Fig. 114. The object seems to be a fragment of a bow which was lenticular in cross section although rather flat. It is slightly bent and the concave side bears transverse incisions. (p. 125.) The specimen was found in grave No. 10 (5) in a rock-slide about one hundred and fifty feet up the slope on the north side of the Naches River, about half a mile above its mouth. The presence of several perishable objects in the grave suggest it to be modern, but no objects of white manufacture were found. This is the only object indicating the sort of bow used in this region and with the exception of the chipped points previously described, some of which were undoubtedly for arrows, is the only archaeological object tending to prove the use of the bow. It will be remembered[63] that fragments of a bow of lenticular cross section ornamented with parallel irregularly arranged cuneiform incisions, were found in a grave near Nicola Lake in the Thompson River region and that pieces of wood, some of which may have been part of a bow, were found in a grave at the mouth of Nicola Lake; also that pieces of wood found at Kamloops resemble a bow of the type shown in Fig. 220 of Mr. Teit's paper on the present Thompson Indians.[64]

In the Nez Perce region to the east, war clubs with heads made of unworked river boulders, according to Spinden,[65] were sometimes used in killing game and such may have been the case in this region.

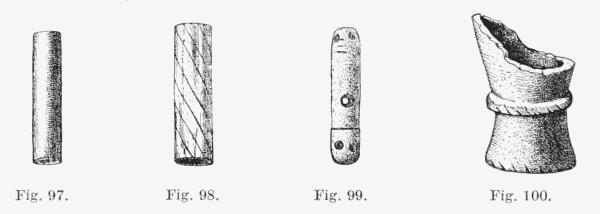

Snares. Fragments of thongs, skin, fur and woodpecker feathers merely suggest methods of hunting or trapping which are not proven by any of our finds. It is barely possible although not probable that the bone tubes considered to have been used in gambling and illustrated in Figs. 97 and 98 and also the perforated cylinder of serpentine shown in Fig. 99 may be portions of snares. Traps and snares of various kinds were common among the Indians of the larger plateau area of which this is a part.[66]

Mr. J. S. Cotton informs me that in the vicinity of Mr. Turner's home, Section 6, Town north 18, Range 40 east, on Rock Creek, about six miles below Rock Lake, and in the vicinity of the graves described on p. 140 and the so-called fort mentioned on p. 82, there is a long line of stones running from Rock Creek in a southeasterly direction across the coule to a small draw on the other side. This chain of rocks is about five miles long. The stones [Pg 30]have evidently sunk into the ground and show signs of having been there a long time. They have been in the same condition since about 1874 when first seen by the whites, even the oldest Indians claiming to know nothing about them. According to Lewis, game was surrounded and driven in by a large number of hunters or was run down by horses, in the great area of which this is part.[67] It seems altogether probable that a line of stone heaps may have been made to serve either as a line of scarecrows, possibly to support flags or similar objects, which would have the effect of a fence to direct the flight of the game or as a guide to enable the hunters to drive the game towards a precipice where it would be killed, or a corral where it would be impounded.

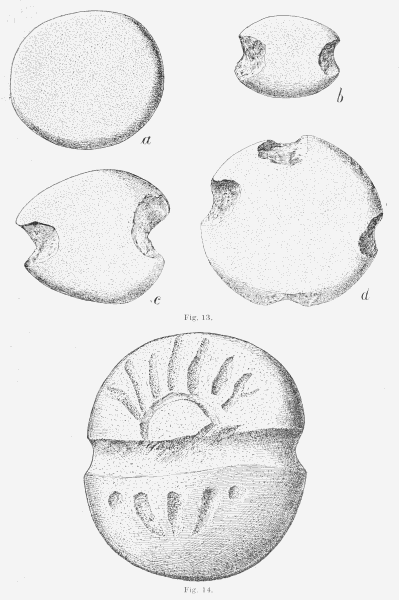

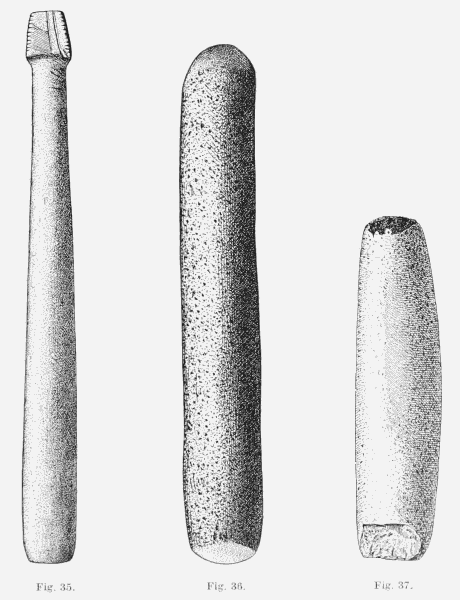

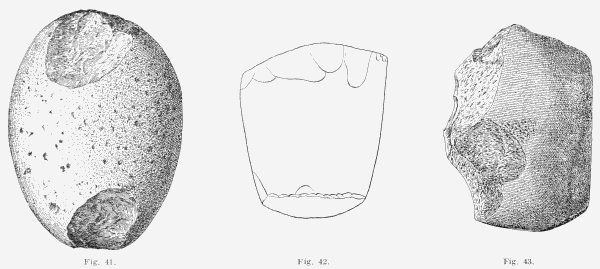

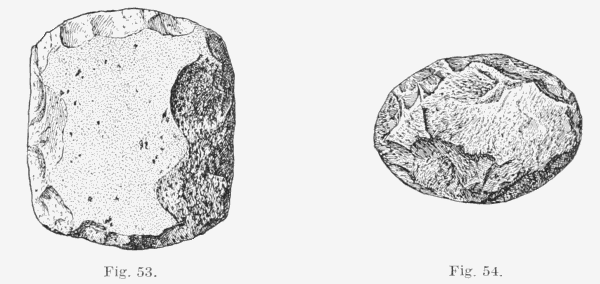

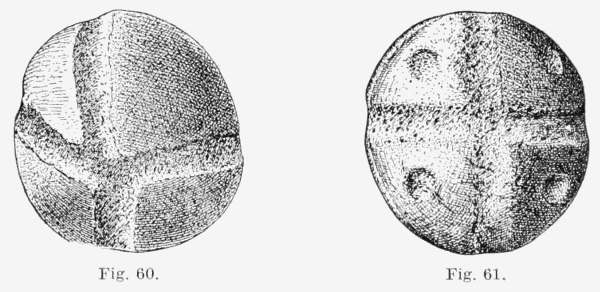

Notched Sinkers. Sinkers for fish nets or lines were made of disk-shaped river pebbles. A pebble and the different types of sinkers are shown in Fig. 13. These were numerous on the surface of the beach of the Columbia River near the head of Priest Rapids. They have two or four notches chipped from each side in the edges. When there are two, the notches are usually at each end; when there are four, they are at the end and side edges. Sometimes, the notches are so crudely made that the edge of the pebble is simply roughened so that a string tied about it at this place would hold. One of these sinkers from Priest Rapids was seen in Mr. Mires' collection.

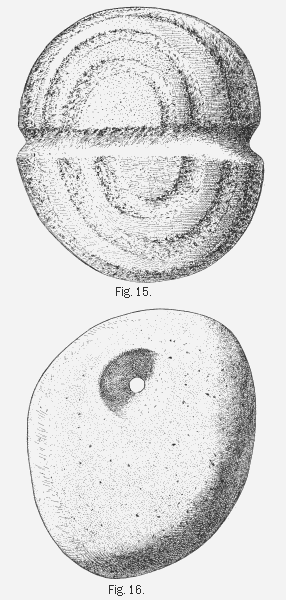

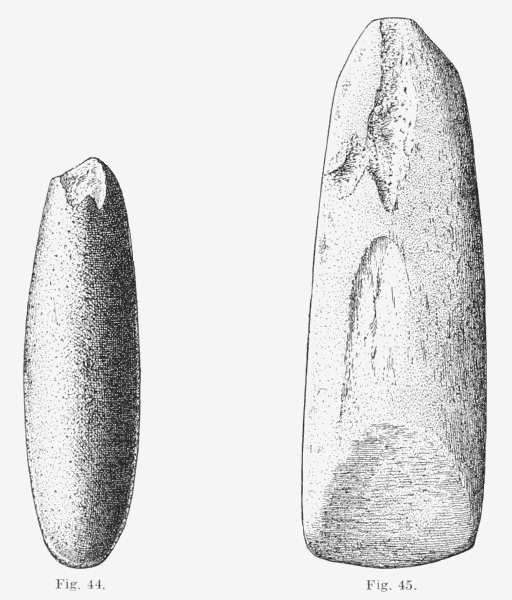

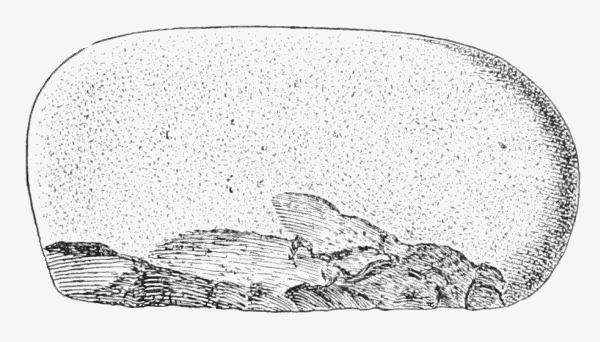

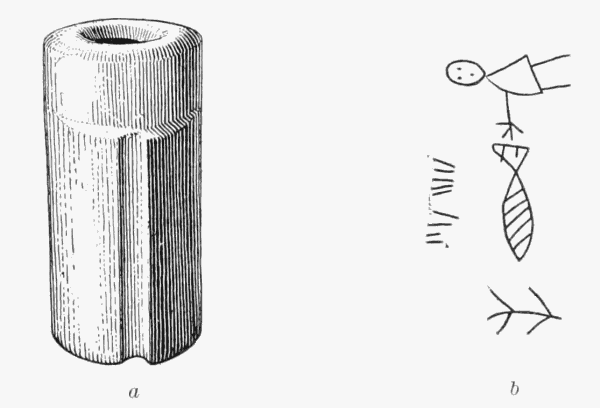

Grooved Sinkers. Some large thick pebbles have grooves pecked around

their shortest circumference. They may have been used as canoe smashers

or anchors, but seem more likely to be net sinkers. Two of these are shown

in Figs. 14 and 15. They are from Priest Rapids and are in the collection

of Mr. Mires. Both are battered along the lower edge, from the groove on

the left to within a very short distance of it on the right and over a considerable

portion of the edge of the top. In the second specimen, this battering

forms a considerable groove on the lower edge, but a groove only the size of

those shown in the illustration on the upper edge. This battering suggests

that they may have been used as hammers, but the battered ends of hammers

are not often grooved. There are certain grooves pecked on one side of each

which seem to be of a decorative or ceremonial significance and are consequently

discussed on p. 132 under the section devoted to art. The first

specimen is made of granite or yellow quartzite with mica, the second is of

granite or yellowish gray quartz with augite and feldspar. One specimen

similar to these two, but without any decoration or grooving (202-8116) was

found by us on the beach at Kennewick as was also a large pebble grooved

nearly around the shortest circumference (202-8332) at Priest Rapids.

One object of this type made of a boulder but grooved around the longest

[Pg 31]

[Pg 32]

circumference was seen in Mr. Owen's collection. It was found on the bank

of the Columbia River two miles below Pasco. The specimen described on

p. 60 which has a notch pecked in each side edge and is battered slightly

on one end may have been used as a net sinker, although it has been considered

a hammer. This specimen (202-8214) in a way resembles the small

flat notched sinkers except that the notch is pecked instead of chipped and

that it is larger and thicker in proportion. Other specimens which are

considered as net sinkers, anchors or "canoe smashers" instead of being

grooved, are perforated by a hole which tapers from each side and has

apparently been made by pecking. Sometimes this hole is in the center,

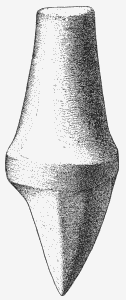

while in other cases it passes through one end. Fig. 16 illustrates such a

specimen. It was found at Priest Rapids and is in the collection of Mr.

Mires. It is made from a river pebble of yellowish-gray volcanic rock.

The perforation is in the broadest end. A similar specimen perforated near

one end and one pierced near the middle were seen in Mr. Owen's collection.

He believes that these were used for killing fish, an Indian having told him

that such stones were thrown at the fish and retrieved with a cord which was

tied through the hole. Probably all of these were sinkers for nets or at least

anchors for the ends of nets, set lines or for small boats.

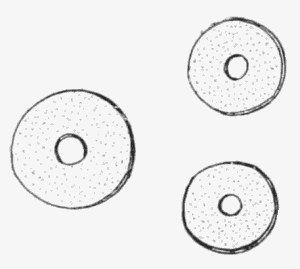

Fig. 13 a (202-8296), b (202-8318), c (202-8313), d (202-8330). Pebble and Net

Sinkers made of Pebbles. From the surface of the bank of Columbia River, near the head

of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.

Fig. 13 a (202-8296), b (202-8318), c (202-8313), d (202-8330). Pebble and Net

Sinkers made of Pebbles. From the surface of the bank of Columbia River, near the head

of Priest Rapids. ½ nat. size.Sinkers were not seen by us among archaeological finds in the Thompson

River region but Mr. James Teit has informed the writer of their use there

on both nets and lines, particularly on the former. Nets, excepting the bag

net, were very little used in the Kamloops-Lytton region along the Thompson

River and that may account for a scarcity of sinkers among archaeological

finds. Nets were more extensively used on the Fraser River, but were very

much used near large lakes and consequently one would expect to find sinkers

in the vicinity of such places as Kamloops, Shushwap, Anderson, Seaton,

Lillooet, Nicola, Kootenay and Arrow Lakes. Now, as the Shushwap generally

made little bags of netting in which they put their sinkers to attach

them to nets, this would greatly militate against the finding of grooved,

notched or perforated sinkers in the Shushwap part of this region. They

probably thought this method was more effective or took up less time than

notching, grooving or perforating stones, and attaching lines to them. It is

unknown which of these methods is the most primitive. Unworked pebbles,

chosen for their special adaptation in shape, and others grooved or perforated

were used in some parts of the interior of British Columbia for sinkers

which were not enclosed in netting. Unworked pebbles attached to

lines have been seen in use among the Thompson River Indians by Mr.

Teit who sent a specimen of one to the Museum.[68] These were of various

[Pg 33]

[Pg 34]

shapes, some of them being egg-shaped. A deeply notched oval pebble

was found on the site of an old semi-subterranean winter house on the west

side of Fraser River at the month of Churn Creek in the country of the

Fraser River division of the Shushwap. The Thompson Indians said it

had been intended for a war ax and accordingly one of them mounted it in a

handle. It is now cat. No. 16-9073 in this Museum. Mr. Teit believes the

stone to be too heavy for a war club of any kind and that possibly it may

originally have been a sinker, although it is chipped more than necessary

for the latter. In 1908, he saw a perforated sinker found near the outlet of

Kootenay Lake, on the borders of the Lake division of the Colville tribe and

the Flat-bow or Kootenay Lake branch of the Kootenay tribe. It was

made of a smooth flat water-worn beach pebble 132 mm. long by 75 mm. wide

and 25 mm. thick. The perforation was drilled from both sides near the

slightly narrower end and a groove extended from it over the nearest end

where it formed a notch somewhat deeper than the groove. Mr. Teit heard

that several such sinkers had been picked up around Kootenay Lake and

also along the Arrow Lakes of the Columbia River on the borders of the

Shushwap and Lake divisions of the Colville tribe.

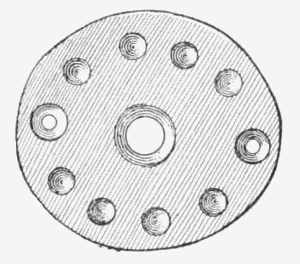

Fig. 15. Sinker, a Grooved Boulder bearing a Design in Intaglio. From Priest Rapids.

½ nat. size. (Drawn from photograph 44536, 9-2. Original in the collection of Mr. Mires.)

Fig. 15. Sinker, a Grooved Boulder bearing a Design in Intaglio. From Priest Rapids.

½ nat. size. (Drawn from photograph 44536, 9-2. Original in the collection of Mr. Mires.)In the Nez Perce region[69] to the east, no sinkers were used with fish lines, but roughly grooved river boulders were employed as net sinkers.[70] A grooved sinker has been found at Comox, grooved stones which may have been used as sinkers occur at Saanich, on the west coast of Washington and the lower Columbia. On the coast of Washington some of them have a second groove at right angles to the first which in some cases extends only half way around; that is, from the first groove over one end to meet the groove on the opposite side. One of the specimens found at Saanich was of this general type. Perforated specimens have been found in the Fraser Delta,[71] at Comox,[72] at Saanich,[72] Point Gray,[72] Marietta,[72] at Gray's Harbor and in the Lower Columbia Valley. On the whole, however, sinkers are much more numerous in the Yakima region than on the Coast. The fish bones which were found, as mentioned under resources, tend to corroborate the theory that the notched, grooved and perforated pebbles were net sinkers and that the bone barbs were for harpoons used in fishing.

Shell Heaps. Small heaps of fresh water clam shells, as before mentioned among the resources of the region on p. 22, were seen; but these being only about five feet in diameter and two or three inches thick are hardly comparable to the immense shell heaps of the coast. These fresh water [Pg 35]shells were probably secured from the river near by, where such mollusks now live. Shell fish probably formed only a small part of the diet of the people although dried sea clams may have been secured from the coast by bartering. The objects made of sea shell mentioned among the resources of this region as probably secured from the coast through channels of trade, suggest that the same method was employed for obtaining certain food products from a distance. In fact, Lewis and Clark inform us that the tribes of this general region carried on considerable trade with those of the lower Columbia. Shell heaps of this character, however, are found in the Nez Perce region. Spinden[73] states that no shell heaps except of very small size are found, but occasionally those of a cubic foot or more in size are seen in the loamy banks of the rivers, noting a few near the junction of the South and Middle forks of Clearwater River, and also near the confluence of the North fork with the Clearwater. These seem to be the remains of single meals that had been buried or cast into holes.

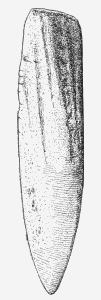

Digging Sticks. The gathering of roots is suggested by the presence of digging stick handles. One of these (Fig. 126) is made of the horn of a rocky mountain sheep and was secured from an Indian woman living near Union Gap below Old Yakima. The perforation, near the middle of one side for the reception of the end of the digging stick, is nearly square but has bulging sides and rounded corners. The smaller end of the object is carved, apparently to represent the head of an animal. Similar handles, some of them of wood, others of antler and with perforations of the same shape, were seen in Mr. Janeck's collection. It will be remembered that such digging stick handles made of antler were found in the Thompson River region among both archaeological finds and living natives,[74] the archaeological specimens being of antler, the modern handles of wood or horn.

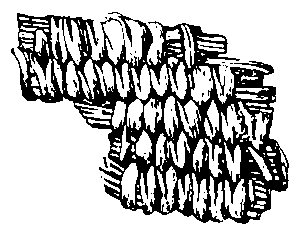

Fig. 17 (202-8161). Fragment of Coiled Basket

of Splint Foundation and Bifurcated Stitch. From grave No. 10 (5) in

a rock-slide about half a mile above the mouth of

Naches River. ½ nat. size.

Fig. 17 (202-8161). Fragment of Coiled Basket

of Splint Foundation and Bifurcated Stitch. From grave No. 10 (5) in

a rock-slide about half a mile above the mouth of

Naches River. ½ nat. size.

The digging stick was one of the most necessary and characteristic implements of the Nez Perce region to the east, the handle consisting of a piece of bone or horn perforated in the middle for the reception of the end of the digging stick, or, according to Spinden, an oblong stone with a transverse groove in the middle lashed at right angles to the stick.[75] No archaeological specimens which are certainly digging stick handles were found on the coast.

[Pg 36]No sap scrapers such as were collected in the Thompson River region[76] were identified and they have not been recognized among specimens from the coast.

Basketry. The gathering of berries as well as of roots is suggested by fragments of baskets which have been found. One of these is shown in Fig. 17. It was found in grave No. 10 (5) in a rock-slide about a half mile above the mouth of the Naches River. It is coiled with splint foundation and bifurcated stitch. Judging from other baskets of the same kind, it was probably once imbricated. This type of basketry is widely distributed towards the north and with grass foundation is even found in Siberia.[77] Commonly the coiled basketry in the Nez Perce region to the east was made with bifurcated stitch,[78] by means of a sharpened awl which was the only instrument used in weaving it. Some were imbricated, although this style has not been made for many years, and only a few of the older natives remember women who could make them.[79] Some similar basketry of a finer technique was found with this fragment.

FOOTNOTES:

[41] Smith, (d) p. 135; and (c) p. 408.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Cf. Spinden, Figs. 10-22, Plate VII.

[44] Spinden, p. 227.

[45] Spinden, p. 190.

[46] Smith, (d) p. 136; and (c) p. 409.

[47] Smith, (b) p. 437; (a) p. 190; (e) p. 564; and (f), p. 359.

[48] Photographs by Mr. Wm. C. Orchard.

[49] Cf. Spinden, Fig. 16, Plate VII.

[50] Cf. Spinden, Fig. 14, Plate VII.

[51] Cf. Spinden, Fig. 15, Plate VII.

[52] Smith, (c), p. 409.

[53] Smith, (a), pp. 141 and 143.

[54] Smith, (b), p. 308.

[55] Smith, (b), p. 332.

[56] P. 357 and 358, ibid.

[57] P. 380, ibid.

[58] Smith, (c), p. 410; Teit, (a), Fig. 231.

[59] Cf. Smith, (a), Fig. 13h.

[60] Smith, (c), p. 410; Teit, (a), Fig. 232.

[61] Spinden, p. 189 and Fig. 5s, 10, 11.

[62] Spinden, p. 227.

[63] Smith, (c), p. 411.

[64] Teit, (a), Fig. 216.

[65] Spinden, p. 188 and 227, also Fig. 55.

[66] Lewis, p. 182.

[67] Lewis, p. 182; Ross, (a), p. 316; De Smet III, p. 1026; Lewis and Clark, IV, p. 371.

[68] Teit, (a), Fig. 234.

[69] Spinden, p. 210.

[70] Spinden, pp. 188 and 211.

[71] Smith, (a), Fig. 22.

[72] Smith, (b), p. 311, 338, 362, 369.

[73] Spinden, p. 177.

[74] Smith, (d), p. 137; (c), p. 411; Teit, (a), p. 231.

[75] Spinden, p. 200. Fig. 33, Plate VII.

[76] Smith, (c), p. 411.

[77] Jochelson, p. 632.

[79] Spinden, p. 193.

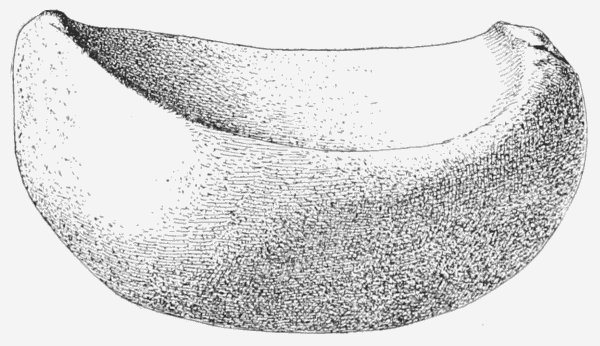

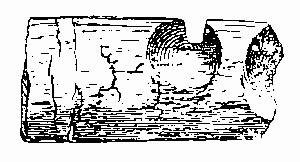

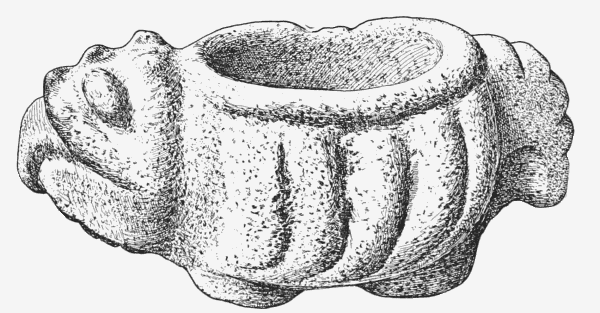

Fig. 18 (202-8394). Fragment of a Mortar made of Stone. From among covering boulders

of grave No. 42 (4) of adult in sand at the western edge of Columbia River about twelve miles

above the head of Priest Rapids. ¼ nat. size.

Fig. 18 (202-8394). Fragment of a Mortar made of Stone. From among covering boulders

of grave No. 42 (4) of adult in sand at the western edge of Columbia River about twelve miles

above the head of Priest Rapids. ¼ nat. size.

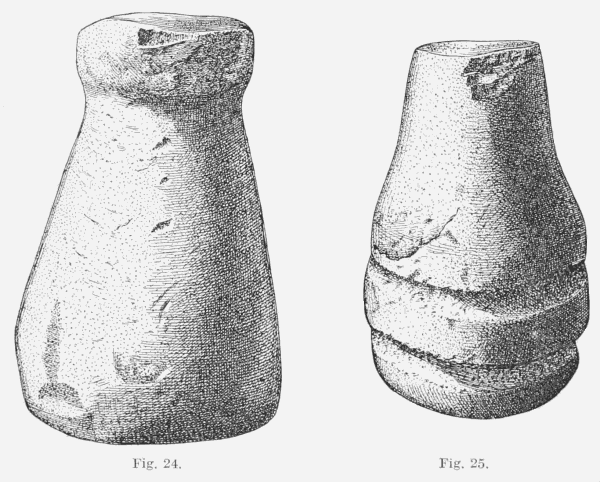

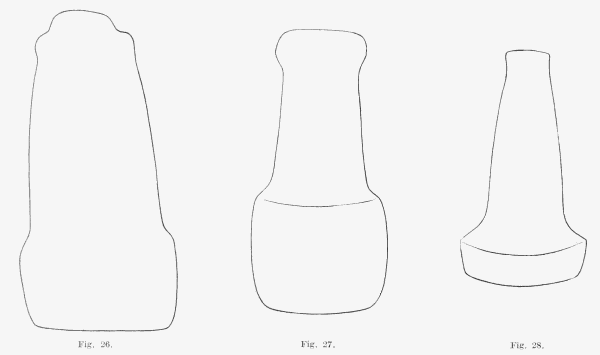

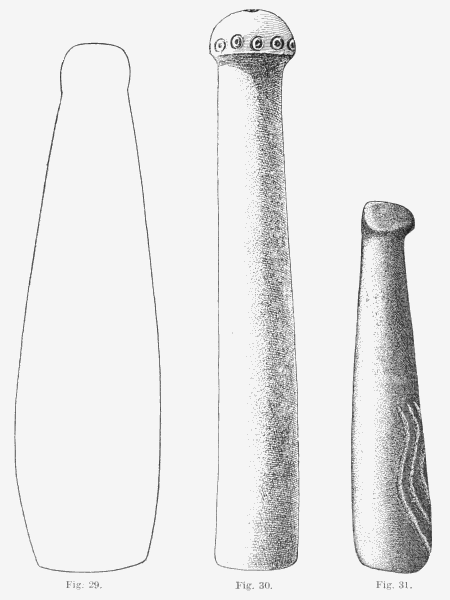

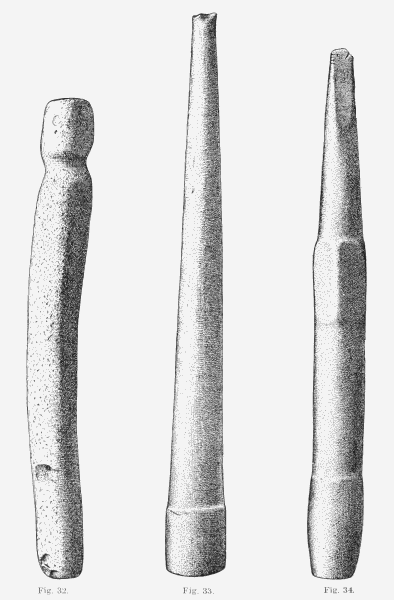

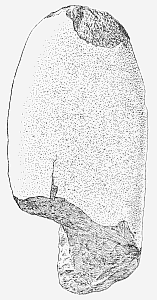

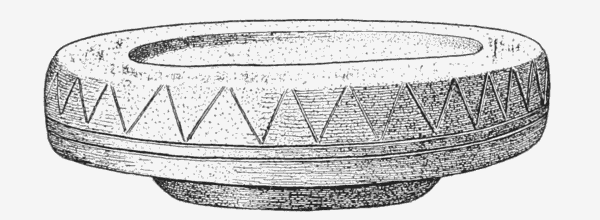

Mortars. Mortars made of stone for crushing food, such as dried salmon, other meat and berries, were not uncommon in this region and pestles of the same material were numerous. Flat oval pebbles were found scattered on [Pg 37]the surface of a village site on the west bank of the Columbia at the head of Priest Rapids, and were probably used as lap stones or as objects upon which to crush food. A somewhat circular one (202-8295) about 230 mm. in diameter has a notch, formed by chipping from one side, opposite one naturally water-worn, which suggests that it may have been used as a sinker; but it seems more likely that it was simply an anvil or lap stone. Similar pebbles were used in the Thompson River region,[80] some of them having indications of pecking or a slight pecked depression in the middle of one or both sides. In the Nez Perce region to the east, basketry funnels were used in connection with flat stones for mortars. These funnels were of rather crude coil technique.[81] Another specimen (202-8292b) found at the same place is merely a water-worn boulder somewhat thinner at one end than at the other, the surface of which apparently has been rubbed from use as a mortar or milling stone. A few large chips have been broken from the thinner edge. Still another specimen (202-8294) from here is a fragment of a pebble only 120 mm. in diameter with a saucer-shaped depression about 10 mm. deep, in the top.

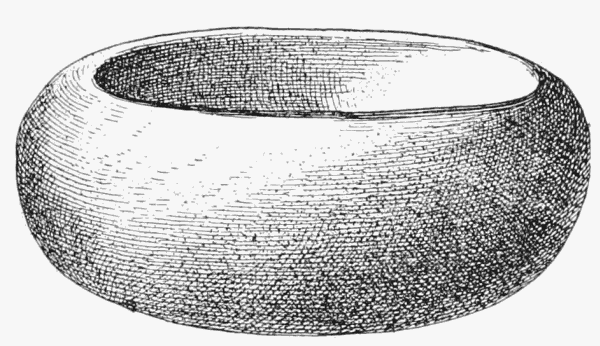

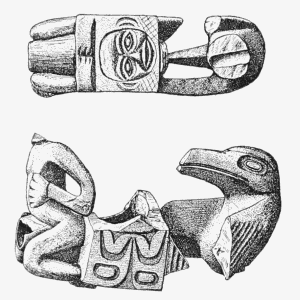

Fig. 19. Mortar made of Stone. From the Yakima Reservation near Union Gap. ½ nat.

size. (Drawn from photograph 44455, 2-4. Original in the collection of Mr. Janeck.)

Fig. 19. Mortar made of Stone. From the Yakima Reservation near Union Gap. ½ nat.

size. (Drawn from photograph 44455, 2-4. Original in the collection of Mr. Janeck.)

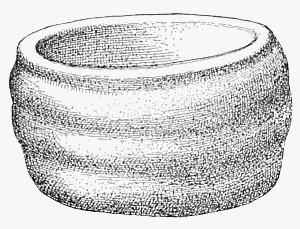

A somewhat disk-shaped pebble of gray lava 295 mm. in diameter with a saucer-shaped depression in the top and a large pecked pit in the bottom (20.0-3344) was collected at Fort Simcoe by Dr. H. J. Spinden. A fragment of a mortar about 190 mm. in diameter with a nearly flat or slightly convex base and a depression 50 mm. deep in the top (202-8293) was found on the surface near the head of Priest Rapids and another fragment nearly twice as large, the base of which is concave over most of its surface and shows marks of pecking, apparently the result of an attempt to make it either quite flat or concave like many other mortars that have a concavity in each side, is shown in Fig. 18. It was found among the covering boulders of the grave [Pg 38]of an adult, No. 42(4), in the sand at the western edge of the Columbia River about twelve miles above the head of Priest Rapids. The mortar shown in Fig. 19, is hollowed in the top of a symmetrical, nearly circular pebble and has a convex base. It was found on the Yakima Reservation near Union Gap and is in the collection of Mr. Janeck.[82] This reminds us of a similar mortar found in the Thompson River region,[83] but such simple mortars made from pebbles are rarely found in the Nez Perce region to the east.[84] The mortar shown in Fig. 20 also from the same place and in the same collection has a nearly flat base and three encircling grooves.[85] These grooves find their counterpart in four encircling incisions on the little mortar found in the Thompson River region.[86]

Fig. 20. Mortar made of Stone. From the Yakima Reservation near Union

Gap. ½ nat. size. (Drawn from photograph 44455, 2-4. Original in the collection

of Mr. Janeck.)

Fig. 20. Mortar made of Stone. From the Yakima Reservation near Union

Gap. ½ nat. size. (Drawn from photograph 44455, 2-4. Original in the collection

of Mr. Janeck.)

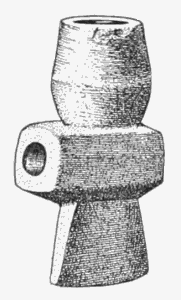

The specimen shown in Fig. 116, which may be considered as a dish rather than a mortar, was seen in the collection of Mrs. Hinman who obtained it from Priest Rapids. It is apparently of sandstone, 150 mm. in diameter, 50 mm. high, the upper part being 38 mm. high and of disk shape with slightly bulging sides which are decorated with incised lines,[87] the lower part being also roughly disk shaped 64 mm. by 76 mm. in diameter by about 12 mm. high with slightly convex bottom and edges curved out to the base of the upper part. There is a disk shaped dish in the top 100 mm. in diameter by 12 mm. in depth.[88]