The Project Gutenberg EBook of Miss Dividends, by Archibald Clavering Gunter

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Miss Dividends

A Novel

Author: Archibald Clavering Gunter

Release Date: May 27, 2012 [EBook #39824]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MISS DIVIDENDS ***

Produced by Robert Cicconetti, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

NEW YORK

THE HOME PUBLISHING COMPANY

3 East Fourteenth Street

1892

Copyright, 1892,

By A. C. GUNTER.

All rights reserved.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

Astor Place, New York

| I.— | Mr. West | 7 |

| II.— | Miss East | 17 |

| III.— | Her Father's Friend | 30 |

| IV.— | Mr. Ferdie begins his Western Investigations | 38 |

| V.— | The Grand Island Eating-House | 54 |

| VI.— | Mr. Ferdie Discovers a Vigilante | 66 |

| VII.— | What Manner of Man is This? | 77 |

| VIII.— | The City of Saints | 101 |

| IX.— | The Ball in Salt Lake | 115 |

| X.— | "Papa!" | 135 |

| XI.— | "For Business Purposes" | 153 |

| XII.— | A Daughter of the Church | 166 |

| XIII.— | The Love of a Bishop | 179 |

| XIV.— | A Rare Club Story | 197 |

| XV.— | The Snow-Bound Pullman | 217 |

| XVI.— | "To the Girl I Love!" | 233 |

| XVII.— | A Voice in the Night | 240 |

| XVIII.— | The Last of the Danites | 251 |

| XIX.— | Orange Blossoms among the Snow | 264 |

"Five minutes behind your appointment," remarks Mr. Whitehouse Southmead in kindly severity; then he laughs and continues: "You see, your oysters are cold."

"As they should be, covered up with ice," returns Captain Harry Storey Lawrence. A moment after, however, he adds more seriously, "I had a good excuse."

"An excuse for keeping this waiting?" And Whitehouse pours out lovingly a glass of Château Yquem.

"Yes, and the best in the world, though probably not one that would be considered good by a lawyer."

"Aha! a woman?" rejoins Mr. Southmead.

"The most beautiful I have ever seen!" cries Lawrence, the enthusiasm of youth beaming in his handsome dark eyes.

"Pooh!" returns the other, "you have only been from the Far West for three days."

"True," remarks Lawrence. "Three days ago I was incompetent, but am not now. You see, I have been living in a mining camp in Southern Utah for the last year, where all women are scarce and none beautiful. For my first three days in New York, every woman I met on the streets seemed to me a houri. Now, however, I am beginning to discriminate. My taste has become normal, and I pronounce the young lady whose fan I picked up on the stairs a few moments ago, just what I have called her. Wouldn't you, if she had eyes——"

"Oh, leave the eyes and devote yourself to the oysters," interjects the more practical Southmead. "You cannot have fallen in love with a girl while picking up her fan; besides, I have business to talk to you about this evening,—business upon which the success of your present transaction may depend."

"You do not think the financial effort France is making to pay its war indemnity to Germany will stop the sale of my mine?" says the young man hurriedly, seating himself opposite his companion, and the two begin to discuss the charming petit souper, such as one bachelor gave to another in old Delmonico's on Fourteenth Street and Fifth Avenue before canvas-back ducks had become quite as expensive as they now are, and terrapin had become so scarce that mud-turtles frequently masquerade for diamond-backs, even in our most expensive restaurants. For this conversation and this supper took place in the autumn of 1871, before fashionable New York had moved above Twenty-third Street, when Neilson was about to enter into the glory of her first season at the Academy, when Capoul was to be the idol of the ladies, and dear little Duval was getting ready to charm the public by her polonaise in "Mignon."

This year, 1871, had marked several changes in the business of these United States of America. During the War of the Confederacy, speculators, under the guise of Government contractors, had stolen great sums from Uncle Sam. In 1865 the Government changed its policy, and began to make presents of fortunes to speculators, thus saving them the trouble of robbing it.

In 1868 it had just finished presenting a syndicate of Boston capitalists with the Union Pacific Railway, many millions of dollars in solid cash, and every alternate section of Government land for twenty miles on each side of their thousand miles of track. It had, also, been equally generous to five small Sacramento capitalists, and had presented them with the Central Pacific Railway, the same amount of Government land, and some fifty-five millions of dollars, and had received in return for all this—not even thanks.

The opening of these railroads, however, had brought the West and East in much more intimate connection. Mines had been developed in Utah and Colorado, and the Western speculator, with his indomitable energy, had opened up a promising market for various silver properties in the West, not only in New York and other Eastern cities, but in Europe itself.

One of the results of this is the appearance in New York of the young man, Captain Harry Storey Lawrence, who has come to complete the negotiations for the sale of a silver property in which he is interested, to an English syndicate, the lawyer representing the same in America being Mr. Whitehouse Southmead, who is now seated opposite to him.

As the two men discuss their oysters, champagne, partridges and salad, their appearances are strikingly dissimilar. Southmead, who is perhaps fifty, is slightly gray and slightly bald, and has the characteristics of an easy-going family lawyer,—one to whom family secrets, wealth and investments, might be implicitly trusted, though he is distinctly not that kind of advocate one would choose to fight a desperate criminal case before a jury, where it was either emotional insanity or murder.

The man opposite to him, however, were he a lawyer, would have been just the one for the latter case, for the most marked characteristic in Harry Storey Lawrence's bearing, demeanor and appearance is that of resolution, unflinching, indomitable,—not the resolution of a stubborn man, but one whose fixed purpose is dominated by reason and directed by wisdom.

He has a broad, intellectual forehead, a resolute chin and lower lip. These would be perhaps too stern did not his dark, flashing eyes have in them intelligence as well as passion, humanity as well as firmness. His hair is of a dark brown, for this man is a brunette, not of the Spanish type, but of the Anglo-Saxon. His mustache, which is long and drooping, conceals a delicate upper lip, which together with the eyes give softness and humanity to a countenance that but for them would look too combative. His figure, considerably over the middle height, has that peculiar activity which is produced only by training in open air,—not the exercise of the athlete, but that of the soldier, the pioneer, the adventurer; for Harry Lawrence has had a great deal of this kind of life in his twenty-nine years of existence.

Leaving his engineering studies at college, he had entered the army as a lieutenant at the opening of the rebellion, and in two years had found himself the captain of an Iowa battery—the only command which gives to a young officer that independence which makes him plan as well as act. But, having fought for his country and not for a career, as soon as the rebellion had finished, this citizen soldier had resigned, and until 1868 had been one of the division engineers of the Union Pacific Railway. On the completion of that great road, he had found himself at Ogden, and had devoted himself to mining in Utah.

Altogether, he looks like a man who could win a woman's heart and take very good care of it; though, perhaps his appearance would hardly please one of the strong-minded sisterhood, for there is an indication of command and domination in his manner, doubtless arising from his military experience.

As the two gentlemen discuss their supper, their conversation first turns on business; though, from Lawrence's remarks it is apparent there is a conflicting interest in his mind, that of the young lady whom he has just seen down-stairs.

"You don't think that milliard going to the Germans will affect the sale of the Mineral Hill Mine," asks Harry, earnestly, opening the conversation.

"Not at all," replies the lawyer. "No fluctuation in funds can affect the capital the English company is about to invest, and has already deposited in the bank for that purpose."

"Then what more do they want? The mine has already been reported upon favorably by their experts and engineers."

"They insist, however, upon a title without contest," returns Southmead.

"Why, you yourself have stated that our title to the Mineral Hill was without flaw," interjects the young man hastily.

"Certainly," answers the lawyer; "but not without contest. I have to-day received a letter from Utah, stating that there is apt to be litigation in regard to your property. If so, it must certainly delay its sale."

"Oh, I know what you mean," cries Harry, a determined expression coming into his eyes. "It is those infernal Mormons! When we made the locations in Tintic, there was not a stake driven in the District, but now word has been given out by Father Brigham to his followers that as it is impossible to stop the entry of Gentiles into Utah for the purpose of mining, the Latter-Day Saints had best claim all the mines they can under prior locations and get these properties for themselves, as far as possible. Consequently, a Mormon company has been started, who have put in a claim of prior location to a portion of one of our mines, without any more right to it than I have to this restaurant. And what do you think the beggars call themselves? Why, Zion's Co-operative Mining Company." Here he laughs a little bitterly and continues: "It was Zion's Co-operative Commercial Institutions, and now it is Zion's Co-operative Mining Companies. Those fellows drag in the Lord to help them in every iniquitous scheme for despoiling the Gentile."

"All the same," replies the lawyer, "if you wish to make the sale of your property to the English company that I represent, you had better compromise the matter with them. I sharn't permit my clients to buy a lawsuit."

"Compromise? Never!" answers the other impulsively. Then he goes on more contemplatively: "And yet I wish to make the sale more than ever. You see, the price we name for the property is an honest one. It is worth every dollar of the five hundred thousand we ask for it."

"Then, why not work it yourself?" asks the lawyer.

"Simply because I have got tired of living the life of a barbarian—surrounded by barbarians. It was well enough to spend four years of early manhood in camps and battles, three others in building a big railroad, and three more in the excitement of mining, away from the convenances and graces of life that only come with the presence of refined women; but now I am tired of it, more so than ever since I have seen that young lady down-stairs."

"Ah! still going back to Miss Travenion?" laughs the lawyer.

"You know her name then?" cries the captain, suddenly.

"Yes," says the other. "I happened to be impatient for your coming. The evening was sultry. I walked out of the room, looked down the stairs and saw your act of gallantry."

"Ah, since you know her name, you must know her!"

"Quite well; I am her trustee."

"Her trustee!" cries Harry Lawrence impulsively. "Her guardian? You will introduce me to her? This is luck," and before the old gentleman can interrupt him, the Westerner has seized his hand and given it a squeeze which he remembers for some five minutes.

"I said her trustee; not her guardian," answers the lawyer cautiously. "If, as your manner rather indicates, you have designs upon the young lady's heart, you had better get a reply from her father."

"Her father is living then?"

"Certainly. Last January you could have seen him any afternoon in the windows of the Unity Club looking at the ladies promenading on the Avenue, just as he used to do when he lived here, and was a man about town, and club habitué and heavy swell. Ralph Travenion has gone West again, however, but I have not heard of his death."

"Then for what reason does his daughter need a trustee?"

"Well, if you will listen to me and smoke your cigar in silence," says Southmead, for they have arrived at that stage of the meal. "Erma Lucille Travenion——"

"Erma—Lucille—Travenion!" mutters the young man, turning the words over very tenderly as if they were sweet morsels on his tongue. "Erma—Lucille—Travenion,—what a beautiful name."

"Hang it, don't interrupt me and don't look romantic," laughs the lawyer.

But here a soft-treading waiter knocks upon the door and says: "Mr. Ferdinand Rives Chauncey would like to see you half a minute, Mr. Southmead."

And with the words, the young gentleman announced, a dapper boy of about nineteen, faultlessly clad in the evening dress of that period, enters hastily and says: "My dear Mr. Southmead, Mrs. Livingston has commissioned me to ask you if you won't come down and join her for a few moments. Oh, I beg pardon—" He pauses and gives a look expectant of introduction towards Harry Lawrence. The lawyer, following his glance, presents the two young men, and after acknowledging it, Chauncey proceeds glibly, "Awful sorry to have interrupted you."

"Won't you sit down and have a glass of wine and a cigar?" says Southmead hospitably.

"Yes, just one glass and one cigar—a baby cigar—they remind me of cigarettes. I have not more than a moment to deliver my message. You see, Mrs. Ogden Livingston has just come back from Newport, and to-night gave a little theatre party: Daly's 'Divorce,' Clara Morris, Fanny Davenport, Louis James and James Lewis, etc. Have you seen Lewis's Templeton Jitt? It is immense. That muff, Oliver, actually giggled," babbles this youth, commonly called by his intimates Ferdie.

"So, Mr. Oliver Livingston laughed? It must have been very funny," remarks Whitehouse affably.

"Didn't he, when Jitt, the lawyer, got his ears boxed instead of the husband he was suing for divorce. You want to see that play, Southmead; it might give you points in your next application for alimony."

"I am not a divorce lawyer," cries the attorney rather savagely.

"Oh, no telling what might happen in your swell clientele, some day," giggles Ferdie. "But Ollie was scandalized at the placing of a minister on the stage—an Episcopal minister, too."

"Does he expect to use an Episcopal minister soon?" asks the lawyer, suggestively.

"Not very soon, judging by the young lady," grins Ferdie. "The only time Miss Dividends——"

"What the dickens do you call Miss Travenion Miss Dividends for?" interrupts Whitehouse testily.

"You ought to know best; you're her trustee," returns the youth. "Besides, every one called her that at Newport this season, especially the other girls, she is so stunning and they envied her so. Lots of money, lots of beaux and more of beauty. If she didn't have a level head, it would be turned."

"Yes, she has got a brain like her father. Besides, Mrs. Livingston keeps a very sharp eye on her," remarks Southmead.

"Don't she though?" chimes in Mr. Chauncey. "Look at to-night. The widow invited your humble servant to take care of the Amory girl, so that Ollie could have full swing with Miss Dividends—I mean Erma. We are all having supper in the Chinese-room. Mrs. Livingston wishes to see you for a moment on business; Miss Travenion on more important business. They chanced to mention it, and knowing your habits, I thought it very probable you were at supper here. I told them I could find you if you were in the building. I roamed through the café and inquired of Rimmer, and he suggested you were up-stairs. The head waiter in the restaurant corroborated him. It won't keep you long. Miss Travenion and Mrs. Livingston wish to see you particularly. They are very busy."

"Busy!" cries the lawyer. "What have those two birds of Paradise to do with business?"

"They are packing. They wish to know if you can possibly call on them to-morrow afternoon."

"To-morrow afternoon, Captain Lawrence's business compels my attention."

"Ah, then, to-morrow evening."

"Unfortunately I have promised to deliver an address at the Bar Association Dinner."

"Very well, to-morrow morning."

"Still this young gentleman's business," remarks Mr. Southmead. "It is important and immediate."

"Oh, very well, then," returns Ferdie; "suppose you come down to our supper party now! I know what Mrs. Livingston wants to say to you, won't take over three minutes, and Miss Travenion won't occupy you five. Come down and join us? We are pretty well finished."

"But this young gentleman," remarks Whitehouse, smiling at Lawrence.

"Oh, bring Captain Lawrence down with you," and before Southmead can reply to this request, which is given in an off-hand, snappy kind of a way, Ferdie finds his hand grasped warmly in a set of bronzed maniples and Harry Storey Lawrence looking into his eyes with a face full of gratitude, and saying to him, "Certainly! I will run down with you with the greatest pleasure."

"But—" interjects Southmead.

"Oh, it will not inconvenience me in the slightest. It will be rather a pleasure," cries the Westerner.

And before he can urge any further objection to Mr. Ferdinand Chauncey's proposed move, the two younger men have left the room and are walking down-stairs, and the lawyer has nothing to do but to follow after them as rapidly as possible.

The door of the Chinese-room is opened for Mr. Chauncey. As he looks in one thought strikes the mind of the mining man, and that is,—If you would thoroughly appreciate the beauty of women, be without their society for a few months. Then you will know why men rave about them, why men die for them.

No prettier sight has ever come before the eyes of this young Westerner,—who has still the fire of youth in his veins, but whose life has kept him away from nearly all such scenes as this,—than this one he gazes on with beaming eyes, flushed face, a slight trembling of his stalwart limbs. This room, made bright by Chinese decorations and Oriental color, illuminated by the soft wax lights of the supper table, and made radiant by the presence of lovely women—one of whom—the one his eyes seek—the like of which he has never seen before—Erma Travenion.

The girl stands in an easy, but vivacious, attitude. She has just been telling some story, and growing excited, has got to acting it, to the derangement but beauty of her toilet, as a little bonnet made all of pansies has fallen, and hanging by two light blue ribbons, adorns her white neck instead of her fair hair, which, disordered by her enthusiasm, has become wavy, floating and gold in the light, and red bronze in the shadow.

The party having left the supper table with its fruit, flowers, crystal, silverware and decorated china, are grouped about, looking at her.

The chaperon, Mrs. Livingston, standing near the door, is a widow and forty-five, though still comely to look upon, and the girl behind her is interesting in her own peculiar style, being piquant and pretty. Though it is late in September the weather is still quite warm, and dressed in the light summer costumes of 1871, which gave as charming glimpses of white necks and dazzling arms as those of to-day, either lady would attract the eyes of men: but the glorious beauty of Erma Travenion still holds the Westerner's gaze.

Eyes draw eyes, and the young lady returns his glance for a second.

Then Mrs. Livingston speaks: "Why, Chauncey," she says, "I thought you were going to bring Mr. Southmead."

"And I have brought his client," laughs Ferdie. "Mr. Southmead will be here in a minute. He was engaged with Captain Lawrence and could not leave him. So I took the liberty and persuaded Captain Lawrence to join us also. But permit me," and he presents his companion in due form to the hostess of the evening.

While Harry is making his bow, Mr. Southmead enters.

"Ah, Chauncey," he says laughingly, "you have made the introduction, I see. But still, Mrs. Livingston, I think I can give you some information about Captain Lawrence which Ferdinand does not possess. He is a rara avis. He has not opened his mouth to a beautiful woman for eight months."

"Excuse me," interposes Lawrence gallantly. "That was before I had spoken to Mrs. Livingston."

This happy shot makes the widow his friend at once. She says: "Not spoken to a beautiful woman for eight months! Surely there could be no beautiful women about," and her eyes emphasize her words as she looks with admiration on the athletic symmetry the young Western man displays under his broadcloth evening dress.

"Not spoken to a beautiful woman for eight months!" This is an astonished echo from the two young ladies.

"Yes," replies Southmead laughing. "He has been in southern Utah. He only stopped over night in Salt Lake City on his trip to New York; he comes from the wilds of the Rocky Mountains."

"The Rocky Mountains?" cries Erma, whose eyes seem to take sudden interest at the locality mentioned.

A moment after, Mrs. Livingston hastily presents the Western engineer. "Miss Amory—Miss Travenion: Captain Lawrence."

"Not heard the voice of beauty for eight months? That is severe for a military man, Captain Lawrence," laughs Miss Amory, her eyes growing bright, for she is in the habit of going to West Point, to graduating exercises, and loving cadets and brass buttons generally and awfully.

"I was once Captain of an Iowa battery," answers Harry; "for some years after that I was a civil engineer on the Union Pacific Railway, and for the last three I have been a mining engineer in Utah."

"On the Union Pacific Railway," says Miss Travenion, her eyes growing more interested. "Then perhaps you know my father. Won't you sit beside me? I should like to ask you a few questions. But let me present Mr. Oliver Ogden Livingston, Captain Lawrence." She introduces in the easy manner of one accustomed to society the Westerner to a gentleman who has arisen from beside her.

This being remarks, "Awh! delighted," with a slight English affectation of manner, which in 1871 was very uncommon in America, and reseats himself beside Miss Travenion.

"There is another chair on my other hand," says the young lady, indicating the article in question, and looking rather sneeringly at Mr. Oliver for his by no means civil performance.

Consequently, a moment after the young man finds himself beside Miss Travenion, though Mr. Livingston has destroyed a tête-à-tête by sitting upon the other hand of the beauty.

Ferdie has grouped himself with Miss Amory and is entering into some society small talk or gossip that apparently interests her greatly, as she gives out every now and then excited giggles and exclamations at the young man's flippant sentences.

Mrs. Livingston is occupied with Mr. Southmead, who has just said: "You brought Louise with you from Newport?"

"Of course," answers the widow. "We have left there for the season." Then noticing that the gentleman's glance is wandering about the room, she continues: "You need not hope to find Louise here. She is only sixteen—too young for theatre parties. The child is in bed and asleep." A moment after their voices are lowered, apparently discussing some business matter.

During this, Erma Travenion appears to be considering some proposition in her mind. This gives Lawrence a chance to contemplate her more minutely than when he picked up her fan on the staircase or as he entered the room. He repeats the inspection, with the same decision intensified: she is the most beautiful woman he has ever seen; but, dominating even her beauty, is that peculiar and radiant thing we call the charm of manner.

Seated in a languid, careless, dreamy way, as if her thoughts were far from this brilliant supper-room, the unstudied pose of her attitude, gives additional femininity to her graceful figure; for, when self-conscious, Miss Travenion has an appearance of coldness, even hauteur; but there is none of this now.

Her well-proportioned head, supported by a neck of enchanting whiteness, is lighted by two eyes which would be sapphires, were they not made dazzling by the soul that shines through them, reflecting each emotion of her vivacious yet brilliant mind. Her forehead has that peculiar breadth, which denotes that intellect would always dominate passion, were it not for her lips that indicate when she loves, she will love with her whole heart. Her figure, betwixt girlhood and womanhood, retains the graces of one and the contours of the other. The dress she wears brings all this out with wonderful distinctness, for it is jet black, even to its laces,—a color which segregates her from the more brilliant decorations of the room, outlining her exquisite arms, shoulders and bust, in a way that would make her seem a statue of ebony and ivory, were it not for the delicate pink of her lips and nostrils as she softly breathes, the slight compression of her brows, and the nervous tapping of her little foot that just shows itself in dainty boot beneath the laces of her robe. These indicate that youthful and enthusiastic life will in a moment make this dreaming figure a vivacious woman.

As Lawrence thinks this, action comes to her. She says impulsively: "You must let me thank you again for the attention you showed me on the stairway."

"What attention?" asks Mr. Oliver Livingston, waking up also.

"Something you were too occupied with yourself to notice," smiles the young lady. "I dropped my fan as we entered this evening, and this gentleman, though he did not know me, was kind enough to pick it up. But," she continues suddenly, "Captain Lawrence, you can do me a much greater favor."

"Indeed! How?" is Harry's eager answer.

"You say that you have been an engineer upon the Union Pacific Railway. What portion of it?"

"From Green River to Ogden, though I was employed as assistant at one time at Cheyenne."

"From Green River to Ogden! Then you must have met my father, Ralph Harriman Travenion."

"No, I never had that pleasure," answers the young man, after a moment's consideration.

"But you must have!" cries the girl impulsively. "He was one of the largest contractors on that portion of the road."

"Your father—a railroad contractor?" answers Harry, opening his eyes, which appear to the young lady very large, earnest, and flashing compared to the rather effeminate ones of Mr. Livingston.

"Not in New York," laughs Ollie, waving his white hands. "When here, Mr. Travenion is one of our leading fashionables. Did you see any one dance more gracefully than your father did last winter, Miss Erma?—though I believe he did have something to do with the building of the railway out there."

"I don't see how that was possible," suggests Lawrence. "I and my assistants figured all the cross-sectionings of that portion of the work, and I know that none were accredited to Ralph Travenion. Our largest contractors were Little & Co., Tranyon & Co., Amos Jennings, George H. Smith, and Brigham Young—nearly all Mormons."

"You are sure?" says the young lady, knitting her brows as if in thought.

"Certainly!"

"This is very curious. Why, I have even had letters from him on Union Pacific paper."

"Perhaps he was a silent partner in one of the companies," suggests Lawrence, who is very much astonished to find a girl in New York's most exclusive set, as Miss Travenion evidently is, connected so intimately with one of the builders of a railway in the Far West.

"Perhaps you are right," says the young lady contemplatively. "However, I will know all about it myself in a few weeks."

"He is coming to visit you, I presume?"

"No, but I am going to take a trip to California with Mrs. Livingston and her party," remarks Erma, "and en route I expect to meet him—my dear father, whom I haven't seen for half a year!" and the girl's eyes light up with sudden tenderness and pleasure. "Apropos of the trip—excuse me." Here she rises suddenly and passes to the family lawyer.

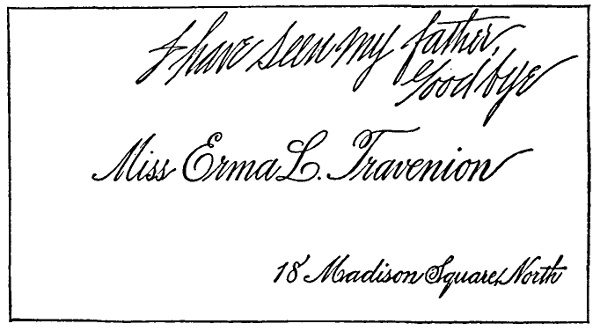

At his side she says: "Mr. Southmead, if you have finished your business with Mrs. Livingston, I have some for you. I want to inform you that Mrs. Livingston, her daughter Miss Louise, her son Mr. Chauncey, and myself, intend to take a trip to California, and to ask you, as my trustee, if you have any objection to the same. I presume that it is a mere form, as you are not my guardian."

"You have written to your father?" asks Whitehouse hastily.

"No," laughs the girl. "I intend it to be a surprise to papa."

"Then, let me suggest," answers the lawyer, something of a shade passing over his brow, "that you write to Mr. Travenion first."

"Impossible! We have not time! We leave in three days! Fancy—in a little over a week I shall see my father. You wouldn't deprive me of that pleasure, would you, Mr. Southmead?"

"No! but I would suggest that you telegraph him."

"I can't. I have not heard from papa for two weeks, and I do not know his address. Besides, it will be such a surprise!" Miss Travenion has thrown away contemplation from her, and is all brightness and gayety.

"Of course I can have no objections," says Whitehouse.

"Then you don't think it wise?" mutters the girl, with a pout.

"I don't say that. I have no doubt it is all right, and I know your father will be pleased to see you."

"I should think so! The idea of anything else! You know I am the apple of his eye!"

"Yes, I know that," remarks Southmead decidedly.

"Very well, then," returns Miss Travenion; "will you be kind enough to get me a letter of credit on California and the West for—for twenty thousand dollars."

This amount for a two or three months' pleasure trip makes Lawrence open his eyes, and the lawyer gives a little deprecating shrug of the shoulders.

"Oh, I don't mean to spend it all," cries Erma. "I am not so extravagant as that. Still, it might be convenient. I might want to buy something in the West. Please get it by to-morrow for me."

"Not later, any way, than the day after," interjects Mrs. Livingston. "It is impossible to put off our trip."

"Oh, it had all been decided before you saw me?" laughs Southmead.

"Certainly. We didn't propose to have any objection made to our taking Erma with us on our trip," says Mrs. Livingston, leaving Mr. Ferdie and Miss Amory, and placing a plump arm round Miss Travenion's waist.

The party have all now risen, apparently ready to leave, and Lawrence and Southmead are compelled to say "Good evening."

As he departs, however, Harry astonishes Miss Travenion. She is a little in advance of her party, and offers him her hand cordially, saying, "Were we not in disorder on account of our preparations for departure, I should ask you to come and see me, Captain Lawrence."

"As it is," answers the young man, "I hope to see you in the West."

"Ah, you expect to be there?"

"Yes; my headquarters must be in Salt Lake for the next month or two."

"Why, we shall be there also," cries Erma. "You shall show me over your city."

"Excuse me, I am not a Mormon!" answers Lawrence grimly, biting the end of his moustache.

"Oh, of course not! I—I beg your pardon. Yes; I remember now—that awful sect live there—" stammers Miss Travenion. "You'll forgive my ignorance, won't you?" Her eyes have a playful pleading in them that makes her judge very mild.

"On one condition!" he answers eagerly: "that you surely come to Salt Lake."

"Certainly," answers Miss Penitent; "it is there or in Ogden or somewhere about the Rocky Mountains I hope to meet my father."

"I also hope to meet your father some day," replies Harry, in a tone that astonishes the girl, for her beautiful eyes have made him forget he has only met her ten minutes.

She raises these to his inquiringly, and what she sees makes her cheeks grow red. A cordial grip upon her fingers is emphasizing this rapid gentleman's speech.

Miss Travenion draws her hand hastily from his; then says with thoroughbred coldness and hauteur, "Perhaps. Good evening!" turns her pretty back upon him and begins to converse with Mrs. Livingston and her party as if no such being as Harry Storey Lawrence existed upon this earth.

A moment after the Westerner finds himself beside Southmead strolling up Fifth Avenue, en route for his hotel.

"I'll go with you as far as the Fifth Avenue," remarks the lawyer. "There may be some telegrams awaiting you on your mining business."

"Delighted," says the young man. Then he breaks out hurriedly: "How the dickens does Miss Travenion, who is apparently a butterfly of New York fashion, have a father who, she says, was a contractor on the Union Pacific Railway? You, as her trustee, ought to know."

"Yes—I know!" returns Southmead. Then after a second's pause of contemplation he continues: "And I'll tell you—it may save you getting a wild idea in your head, young man. Only don't look romantic, because the young lady we are discussing is half-way engaged to another, Mr. Oliver Ogden Livingston."

"Half-way engaged," ejaculates Harry with a sigh. Then he says suddenly, a look of determination coming into his eyes: "Half-way is sometimes a long distance from the winning post," and lapses into silence, smoking his cigar in a nervous but savage manner, while the lawyer continues his conversation.

"Miss Erma Travenion's history is rather a curious one. Her father is an old friend of mine. Her mother was an old friend of mine." This last with a slight sigh of recollection. "Both came of families who have from colonial times occupied leading positions in Manhattan society. Nearly twenty-five years ago, Ralph Harriman Travenion married Ella Travers Schuyler, one of the prettiest girls in the Manhattan set of New York society. Four years after, the young lady we are discussing came into the world. When she was about ten, her mother died, and her father concentrated his affection, apparently, on his only daughter. He was a man of very large fortune, a member of the leading clubs, on the governing committee of one or two of them, a man about town and a swell among swells.—But perhaps to forget his wife, whom I know he loved; during the sea of speculation that came with the Rebellion, he entered largely into dealing in stocks and gold, in an easy-going sybaritic kind of a way—and Wall Street made almost a wreck of what had once been a very fine fortune. This blow to his pocket was a blow to his pride. He could not endure to live in diminished style among the people who had known him as millionnaire, aristocrat, and bon vivant. Shortly after he sold his horses, yacht, villa in Newport, house in town, in short, his whole extensive establishment, and placing his daughter, who was about fourteen years of age at that time, at Miss Hines' Fashionable Academy, in Gramercy Park, he went West.

"When he did so, I thought it was wholly from pride. Now I have become satisfied that it was in the hope of making another fortune, so that when she arrived at young ladyhood, Erma Travenion could assume the position in New York society to which she had been born."

"What makes you think this?" asks Lawrence hurriedly.

"Her father's actions since that time. You see, the Travenions and Livingstons had always been great friends, second cousins in fact, and it had been a kind of family matter and understanding that when Erma grew up, she should marry Mr. Oliver Ogden Livingston, who was then but a boy."

"A—ah! He is the son of the lady we met this evening!"

"Of course!" says the lawyer sharply. "It had been mutually understood between the fathers of the two children that each should settle what was considered in those days a most enormous sum upon their children, that is, one million dollars. The two fathers fondly hoped and expected in those days of smaller fortunes that this would put the young couple on the very top of New York society. When Travenion went West, Oliver's father was still alive. What the interview between the two men was, I do not know; but shortly afterwards, Livingston settled his one million dollars upon his son, and during the succeeding year died. As Mrs. Livingston was very ambitious for her son to make what is called a grand match, it was generally supposed the compact would come to nothing, when, some three years later, in 1868, Mr. Travenion returned from the West and settled on his daughter three hundred thousand dollars, making the Union Trust Company of New York and myself co-trustees. One year after that he again made his appearance here and settled two hundred thousand dollars more, and only eight months ago he once more returned and deposited five hundred thousand in addition, completing the sum of one million dollars, which the Union Trust Company and myself hold as co-trustees for his daughter. One half of the income from this is to be paid to Erma Travenion until she is twenty-five or her marriage. In case of her marriage before that time or upon her arrival at the age of twenty-five, we are to pay the full dividends of this one million dollar investment to the young lady, and at the age of thirty, we are to make the principal over to her, subject to her sole control, use and bequest."

"I am sorry you told me this," says Harry, a trace of agitation in his eyes, and a slight tremble on his moustachioed lip.

"Sorry? Why?" asks the lawyer, turning and looking at the young man.

The answer he gets astonishes him.

"Because I mean to marry her," says the Westerner determinedly, "and I would sooner have a fortune equal to that of my bride; perhaps sooner have her with nothing."

"You are a very extraordinary young man, then," comments Southmead. "But I think her father would not care about her marrying any one except Oliver Ogden Livingston."

"I don't imagine any father would care about seeing his daughter marry that young man I saw at supper," remarks Lawrence, contemplatively, between puffs of his cigar.

"And why not?"

"Because I do not think he is a man, anyway."

"Still, I think Ralph Travenion wishes his daughter to marry Oliver Livingston, because he has settled his million on her."

Here Harry astonishes the lawyer again. He says shortly: "Might not Ralph Travenion have some other reason for settling the million dollars on his daughter?"

"By Jove!" ejaculates Southmead in astonishment. "What do you mean?"

"I don't mean anything except the suggestion," remarks the young man. "But here we are in the Fifth Avenue," and the two stride into that great hostelry together, and go to the office, where the clerk says, "Captain Lawrence, a telegram for you." After a glance at its address Harry tears it open, and with a suppressed exclamation passes the despatch to his companion.

"Aha, as I thought," remarks Southmead, glancing over the message. "The Zion's Co-operative Mining Institution has brought suit for part of your Mineral Hill property. Unless you compromise, this will delay the English sale."

"Yes, this takes me back to Utah at once," says the young man. Then he adds with a laughing sigh: "I need that five hundred thousand dollars, or rather my share of it, as soon as possible."

"Ah! But why this hurry?"

"Because I'm impatient to make Erma Travenion my wife," says the young man determinedly; "but I must go up-stairs to pack my trunk, so as to get off by the morning train." Then, after a few minutes' hurried conversation on the details of the business, he bids Southmead good-bye, adding: "Telegraph me any further information at the Sherman House, Chicago."

"You are going to Utah to compromise this matter?" asks the lawyer, shaking the young man's hand.

"Never!" says Lawrence. "But, for all that, I am going to have a try for the girl."

With that he steps into the elevator of the Fifth Avenue Hotel, leaving Whitehouse Southmead to saunter to the Unity Club and cards in rather a contemplative, though by no means legal, mood, for he chuckles to himself: "Jove! If that rapid Mr. West should capture rich and lovely Miss East? wouldn't it make Mrs. Livingston wild?"

"Mr. Kruger, how do you do?" says Miss Erma Travenion, some three days after; turning suddenly from the Cerberus who stands at the gate leading to the out-going trains of the Hudson River Railroad, in the Grand Central Depot, New York, waiting to punch her ticket. Then she calls again with the bright, fresh voice of youth: "Mr. Kruger! Mr. Kruger! Don't you recognize me?" and drawing up her dainty white skirts to give her pretty feet room for rapid movement, pursues a gentleman who, in the rush of the great station, apparently does not notice her.

The ticket puncher looks astonished for a moment, and then promptly and savagely cries, "Next!"

But the "Next!" is Mr. Oliver Ogden Livingston, who has also turned from the entrance, and is gazing after Miss Travenion, an occupation his eyes have become quite used to in the last few months, since her father had finished settling his million upon her.

Livingston, after a second's pause of consideration, says hurriedly to the lady who comes immediately behind him, "Mother, you and Louise had better go to our car. Ferdie will escort you. I will wait for Miss Travenion and see her on board before the train starts."

To this, Mrs. Livingston, who, though fair, plump and forty-five, is of a nervous tendency, cries out, "My Heaven! She's running out of the depot—she is so impulsive—if anything happens to Erma, what shall I say to her father?" And the chaperon casts anxious glances on her charge, who is still moving in pursuit of the abstracted Mr. Kruger, who is apparently looking for somebody himself.

"Next!" cries the ticket man savagely. "Don't block the way!"

"Ferdie, take us in," whispers Miss Livingston, who is immediately behind her mother, and is sixteen, pretty and snippy. "That gateman looks impatient."

"Quick, Louise, or the ticket puncher 'll mistake my head for a ticket," laughs the young man. Then he cries, "Come along, auntie. Don't be frightened. You don't suppose Oliver will ever lose sight of Miss Dividends?" And with a passing wink of inborn knowledge to Ollie, which is returned by a stare prim and savage, Ferdie rushes his aunt and Miss Louise past the portals, towards a private Pullman car, the last of an express train standing ready to move out to Chicago, on a bright September day, of the year of our Lord 1871.

Livingston, relieved of the care of the other ladies of his party, watches his valet, assisted by two maid-servants in caps, carrying the hand-satchels, shawls, and minor baggage of the party to the car, then turns his glance towards Miss Travenion. The savageness leaves his eyes, and a little soft passion takes its place. They follow the movements of the girl with prim rapture, as well they may.

Miss Travenion is just overtaking the man she is pursuing; her eyes, intent upon her chase, sparkle as blue diamonds. From her well-shaped head float, after the fashion of that day, two long curls of hair that would be golden, did not the sun seem to claim them as his own, and permeating them with his fire, make each hair as brilliant as his own bright rays. Above the curls, a summer hat, beneath this, waving locks that crown a marble forehead, perhaps too broad for ancient sculptors' taste, but ideal for modern artists, who love soul in woman; cheeks rosy with health, lips red and moist as coral washed by sea-spray, the upper one laughing, the under one eager; a chin that tells of resolution, a figure light as a fairy's, but with the contours of a Venus; clothed in a travelling gown that does not disguise the graces that it robes; one eager hand outstretched towards the flitting Kruger, the other grasping firmly, yet lightly, the skirt and draping it about her, plucking its laces and broideries from out the dust, and showing as she trips along a foot and ankle that a lover would rave about—a sculptor mould.

This is what makes Ollie Livingston's little heart beat one or two pats to the second more rapidly than normal, showing how small his soul, how puny his manhood, for no more charming girl has ever been looked upon than Erma Travenion, as she lays her well-gloved patrician hand upon Lot Kruger's big Western arm, even amid the crowds of this great railroad station of New York, where beauties—American beauties at that—have given forth to admiring humanity each glance and gesture, grace and tone, that allure and conquer mankind.

Mr. Kruger, also in pursuit of some one, has just found his man, and thus Erma is enabled to overtake him. As she comes up he is in such earnest conversation with a small, weazened-face, ferret-like individual that he does not note the approaching beauty.

Were Miss Travenion intent upon anything but speaking to the Westerner she could hardly avoid appreciating the peculiarity of the interview she is breaking in upon—Kruger all command, the other answering with a docility unusual among Americans, and at times saluting in almost a cringing manner the man addressing him. As Erma stands for a moment behind Kruger, she hears him say tersely and sharply to his companion: "Jenkins, there are four hundred more coming on the Scotia, due to-morrow, and three hundred here now. We have contracted with the Central for the U. P. to take them at forty dollars a head. The other crowd I will wait for."

Mr. Jenkins's reply Miss Travenion does not catch, as she places her hand on Lot Kruger's arm and he swings around suddenly and quickly to see who interrupts him. His face for a moment has a startled and annoyed, perhaps an angry, expression upon it, but as he turns and gazes upon Erma, smiles chase sternness away from his features, even as they did upon Livingston's flaccid face; the young lady's beauty seeming to have a similar effect upon both men, though Kruger's virile passion is ten times as strong as that of the prim New Yorker.

Miss Travenion says hurriedly: "Mr. Kruger, I saw you here. I couldn't help following you. You have just come from the West—you have seen my father lately? Tell me, is he well? I haven't had a letter from him for a fortnight."

He cries, "Miss Ermie, I am mighty glad your daddy hain't written, for if he had, I guess I shouldn't have heard your pretty voice, unless I hunted you up at your boarding-school."

"Oh, you wouldn't have found me there. I have not been at Miss Hines' for nearly ten months."

"Ah, I see: graduated in all the arts and sciences and music and etceteras," remarks Kruger, his eyes, piercing, though gray, looking over the exquisite girl before him, and growing red and inflamed with some potent emotion, as he concludes rather huskily: "I might have seen you have left school. You have developed as be-uti-fu-l-ly as one of the lambs of Zion," though, even as he says this, Lot Kruger seems to repress himself and from this time on to keep a tight rein upon some peculiarity that is strong within him.

"But papa, papa; you haven't told me of him," exclaims the young lady, who seems little interested in Mr. Kruger's remarks, and only intent upon information as to her absent loved one, for as she speaks of her father, the girl's voice grows soft, and tender tears come into her eyes.

"Oh, your dad's all right, Sissy," goes on Kruger, in his easy Western way. "You needn't water his grave yit. Reckon your pap has had too much railroad and mine on his hands to be able to even eat for the last month. I know, for I am interested in the mine a leetle." Then he tells her quite shortly that her father has so many big enterprises beyond the Rockies that he is an "uncommon busy man."

As he does so, Erma is gazing at him and thinking what an extraordinary individual her father has found for a partner, beyond the Rocky Mountains; for Lot Kruger, as he stands before her, would be a striking figure, even in Western America, which produces curious types and more curious individuals.

He stands six feet two in his stockings, and has proportionate shoulders and limbs, which are covered with ample black broadcloth, after the Sunday-best-clothes Southern and Western fashion of the year 1871; the coat of Prince Albert style, open and unbuttoned and falling below the knees of his trousers, that are cut in what was then called the "peg-top" pattern; his shirt front as ample as his coat is large, crumpled and protruding from out a low-cut vest and adorned by a splash or two of tobacco juice; his hat a stove-pipe, its plush rumpled and brushed against the grain,—all make him a man of mark. From off his broad shoulders rises a neck strong as that of a buffalo, and supporting a massive head covered with long red hair, and a face from the nose up that of a good-natured Newfoundland, but below the jaws and teeth of a bull-dog; the eyes gray as a grizzly's, and steely when in anger; while, thrown over all this is a kind of indescribable, semi-Puritanical, semi-theological air that makes one wonder, "Is this man a backwoods preacher turned mining speculator, or a reformed cowboy made into a missionary?"

At present, as he gazes at Miss Travenion, Lot Kruger's face is nearly all that of the Newfoundland dog; and Erma, though she thinks him a curious associate for her father, with his Eastern breeding and education and New York manners, still considers Mr. Kruger, though crude, very good-natured and rather meek.

Oh, these judgments of women, whose instinct never mistakes character,—where one out of ten women guesses the villain at sight and brags of it forever, the other nine mistaken sisters are swindled and perchance undone, and say nothing about woman's unfailing intuition, but still keep on guessing wrong until the crack of doom.

As Erma gazes on Kruger he continues: "Bound for a summer jaunt, I guess,—some watering place where the boys and gals will have a high time—Nar-regani-set or Newport or Sarietogy, Miss Ermie. Your dad is very liberal to you, I understand,—puts up the greenbacks in wads."

"My father is generosity itself to me," returns Miss Travenion rather haughtily, for she is by no means pleased with the freedom of Mr. Kruger's remarks. "But the Newport season is finished, and I have accepted Mrs. Ogden Livingston's invitation to be one of her party. Under her charge I am going to take a run across the continent, and en route for California I shall drop in upon papa, and astonish and enrapture him."

"Wh—e—w!" This would be a prolonged whistle, did not Kruger check it savagely, and cut it off in the middle. Then he goes on stammeringly, but eagerly:—"Your dad doesn't know of—of your intention?" an amazed expression lighting up his honest gray eyes, which is forced down by his set, calm, repressive lower face.

"No, he doesn't guess that I'm coming. Won't it be a surprise to dear papa when I step lightly into his office, and say: 'Behold your daughter!'" laughs Erma.

"Yes,—I—reckon it will be a—sockdolager!" mutters her father's friend contemplatively. Then says suddenly, "You haven't telegraphed him?"

"Certainly not; I wish to surprise him. Besides, I shall be with him almost as soon as a telegram, now that this wonderful Pacific Railway is finished," babbles the girl. "It will only take seven days to far-off California, and Ogden is two days this side of San Francisco, I understand."

"Yes, your time-table's all right," returns Mr. Kruger. Then he asks quietly, "Who's in your party?"

"Oh, Mrs. Livingston, of course; her daughter, Louise; Mr. Ferdinand Chauncey, her nephew, and her son, who is now just beside me. Mr. Livingston, Mr. Lot Kruger, my father's friend."

The two men acknowledge this introduction; then Livingston says hastily, "Miss Travenion, excuse me interrupting your conversation, but the train leaves in five minutes, and I presume my mother is even now anxious—perhaps already hysterical."

"Very well, then," returns Erma. "Good-bye, Mr. Kruger. I am so glad to hear that papa is all right. Shall we see you in the West? We shall be in California two months, and perhaps on our return—" And she extends a gracious hand to the Westerner.

But Lot laughs: "You'll see me before then. I'm going on the same train. You needn't have run after me, if you had known that I go out on the Chicago express also." With this, he gives the little gloved hand that is already in his a hearty squeeze, that makes the blood fly out of the girl's fingers into her face, and turns hurriedly to the man he had previously addressed, who has been waiting for him just out of ear-shot.

A moment after, Miss Travenion is conducted by her escort through the crowd of the great station, past the ticket man at the gate, and on board the train, where Mrs. Livingston is already in a state of animated nervous rhapsody, muttering, "The cars are moving! They are left behind! What'll I say to that girl's father?" and other exclamations indicative of approaching spasms.

"Forgive me, dear Mrs. Livingston," says Erma, apologetically. "I couldn't help asking about my father. I haven't seen him for so long, and have had no letter for two weeks."

"He's a rather curious creature, that friend of papa," remarks Ollie superciliously.

"Very," answers Erma. "But my father, in his railroad enterprises, must be thrown among men of all ranks, grades and conditions."

"Oh, certainly," assents Oliver. "You remember that individual with the free and easy manners who invited himself to mother's supper party the other night."

"If you mean Captain Lawrence," remarks Ferdie, tossing himself into the conversation, "I can tell you he didn't invite himself—I did that part of the business myself. And as to his manners being free and easy, I think, considering he hadn't spoken to a pretty woman for a year, he did very well—under the circumstances. If I'd been in his place I'd have probably kissed the ladies all round."

This assertion is greeted by a very horrified "Oh, Ferdinand!" from Mrs. Livingston, and screams of laughter from Louise.

Miss Travenion, who remembers Captain Lawrence's last glance and hand squeeze and words, grows slightly red about her cheeks and sinks upon a seat and gazes out of an open car window.

As for Mr. Kruger, the moment he has left Erma Travenion, he has dropped all the laziness of a Newfoundland dog, and assumes the activity of a terrier. He has said hurriedly but determinedly to his satellite, "Jenkins, you stay and wait for the four hundred coming on the Scotia. Forward the other three hundred by Davis, who came from Wales with them."

"But—" Jenkins is about to interrupt.

"No time to discuss this 'ere matter," says Kruger with a snap. "I must go West on this train. It's somethin' you can't understand, but more important than all the Welsh cows that we've brought over these ten years—you do as I tell ye."

"Yes, Bishop," answers the man humbly and goes away, as Mr. Kruger, whose plans the sudden meeting with Miss Travenion seems to have changed, produces a pass from the New York Central Railway, hurries to the sleeping-car office, buys a ticket to Chicago, and boards the train almost as it begins to move out for the West, and placing himself in a smoking compartment, goes to chewing tobacco in a meditative but seemingly contented manner, as after a little time he remarks to himself, "How things seem to be coming to Lot Kruger and Zion together."

The train rattles out of New York, and crossing the Harlem, skirts that pretty little salt water river; as Miss Travenion settles herself lazily in her seat, with a graceful ease peculiar to her, for the girl has a curious blending of both style and beauty, giving her a patrician elegance of manner that makes gracious even the slight tendency to hauteur in her manner and voice.

The sun shines upon her face, and she turns it from the morning beams, and gazing towards the West, thinks of her father. Her eyes grow gentle, her mobile features expectant with hope, and tender with love; and Oliver Livingston, who is reading a New York journal, glances up from it, and noting Erma's face thinks, "She really does love me, dear girl, though she is so cold, which is much better form till we are regularly engaged," and decides to give her a chance to admit her affection to him formally before the end of their summer tour, for this prim gentleman actually adores the young lady he is looking at as much as his diminutive soul can love anything, except himself.

At present he does not know how small his soul is, but rather thinks it is large and noble and very magnanimous. He has had no occasion so far to test its dimensions, his life up to this time having been quite narrow; and though he has travelled, it has not brought much into his brain, save some strong, high church notions he has imported from Oxford, to which university this young gentleman had been sent to complete his education after Harvard; his mother having an idea it might get him into English society, and perhaps permit him to make a great European match. This was before Erma's father had made his million dollar settlement upon her; Mrs. Livingston having been one of the first of those pioneers from New York who passed over to England and replaced the social chains of the Mother Country upon her,—those her grandfather and other American patriots had fought to throw off, together with the political ones of George the Third, his Majesty of glorious memory.

Upon his return to New York, Mr. Ollie had signalized his advent by dragging his mother and sister to Saint Agnes's from their old pew at Grace Church, the ritual of that place not being sufficiently Puseyitic for his views; his father, the elder Livingston, who had no religion to mention save certain maxims of business and the rules of his club, being, fortunately for his son's high church movement, dead.

This performance of the heir of the house had made his mother think him a saint; as, indeed, to do the young man justice, he wished to be; and had Ollie Livingston elected to follow any profession, he would doubtless have turned to the ministry; but his million of dollars perhaps dulled his incentive for work, and after his return from England, the young man had done nothing; but as Ferdie had irreverently expressed it, "had done that nothing Grandly."

And why should he work? He had money enough to command any ordinary luxury of life. As for position, was he not a Livingston, and could he add additional honor to that old Knickerbocker name? thought his mother.

There was only one trouble in all their family affairs, and that was removed by the settlement Mr. Travenion had made upon Ollie's fiancée, for as such Mrs. Livingston already regarded Erma. In order to make the settlement upon his son, the elder Livingston had culled his best securities and most gilded collaterals; those left for the support of his widow and daughter, not being so stable, had depreciated in the last few years, and Mrs. Livingston's income had dwindled until it was not what she considered it should be for a lady of her station. Now, of course, if Ollie married a very rich wife, he could be very liberal to his mother and sister, and that point had been happily settled by the million-dollar settlement upon Miss Travenion.

It is some thought of this that is in Erma's mind once or twice in her first day's journey towards the West. The girl loves Mrs. Livingston, who had been a companion of Erma's mother, and had been very kind to the child even after her father's reverses, and had frequently visited Miss Hines' Academy in Gramercy Park, and had the little Erma, now wholly orphaned by her mother's death and father's absence, to her great house on Madison Square, where she had been regaled en princess and sent back to the boarding school made happy with good things to eat and presents that make children's hearts glad.

This, Miss Travenion does not forget, now that her father's settlements upon her have made her probably as great an heiress in her own right as any girl of her circle in Manhattan society.

This peculiar position of Mrs. Livingston had been pretty well known to Erma, and it seemed to compel her to make no protest when the widow had taken her from the seclusion of Miss Hines' Academy at the beginning of the winter and brought her out, with much blowing of social trumpets and flowers and fiddling at Mrs. Livingston's Madison Square mansion—and also had chaperoned her at Newport.

Therefore, she has rather grown to consider herself set apart for Oliver's wife, and as such has turned a deaf ear to the many men who, on slight encouragement, would be more than happy and more than ready to woo a young lady who has gorgeous beauty, a million of dollars of her own and a father of indefinite Western wealth, which, magnified by distance, has increased to such Monte Cristo proportions, that it has gained for her the title, among her set, of "Miss Dividends."

Besides any notion of gratitude to Mrs. Livingston, Erma knows that this match with Ollie is her father's wish. On one of his visits to New York, she had once hinted her desire to visit and live with him in the West, and had been promptly refused in terms as stern as Ralph Travenion could bring himself to use to his daughter, for whom he seemed to have a very tender love, and in doing so he had indicated that his wishes were that she fulfil the arrangement he had made with his old-time friend, the elder Livingston.

"Marry Oliver," he had said. "He is in your rank—the position to which you were born, Erma. Live in the East. The West is, perhaps, the best place to make money, but New York is par excellence the place to enjoy it. Some day—perhaps sooner than you expect, I shall join you here, and settle down to my old life as club man again," and Ralph Travenion looks towards the Unity Club, upon whose lists his name still stands, and of whose smoking-room he is still an habitué on his visits to Manhattan, rather longingly from his parlor in the Brevoort House, at which hotel he always stopped, in contradistinction to most of his comrades from the Plains, who are more apt to register at the Fifth Avenue or the Hoffman.

It was on one of these visits at the Brevoort that Erma had chanced to meet Mr. Lot Kruger, and circumstances compelling the same, had received introduction to him.

"Ha! a new convert to Zion!" the Westerner had cried out, looking rather curiously at the beautiful girl of nineteen, who had entered unannounced into Ralph Travenion's apartments.

But her father had simply said: "My daughter, Miss Erma, let me present Mr. Kruger, a business associate of mine," and had so dismissed the affair, though several times afterward the Westerner had chanced to be at Travenion's apartments when Erma called, and once or twice he had appeared at Miss Hines' Academy, bearer, as he said, of news from her father to Miss Travenion, to the amusement, astonishment and giggles of her fellow-pupils and the dismay of the schoolmistress, who thought Mr. Kruger a species of Western border ruffian or bandit.

However, as she sits and meditates, the thought that she is drawing nearer and nearer to her loved father, drives all else out of Erma Travenion's head, and she watches the wave-washed banks of the beautiful Hudson, and as they pass by says, "One more tree nearer papa—one more island nearer papa—one more town nearer papa," and later in the day, they having got off the New York Central, she murmurs "One more railroad nearer papa," and grows happier and happier as the cars bear her on.

So the day passes. Her companions have settled down to their journey, and are passing their time in cards or novel reading, and Miss Travenion has plenty of opportunity for reflection, for Ollie notices that the girl seems to wish to be left to herself, and only ventures occasional remarks when passing objects demand them.

Mr. Kruger, awed perhaps by the private car, which was much more of a rarity and luxury in 1871 than it is to-day, does not intrude upon the young lady or her party, though Erma notices when she gets off at the large stations for exercise that Lot's eyes seem to follow her about, as if he were interested in her for her father's sake.

Thus the night comes and goes, and during the next day, the 1st of October, the party pass through Chicago, just then waiting to be burned in order that it may become great.

So, running over the prairies two days and a few hours after leaving New York, they arrive at Council Bluffs, and take ferry across the Missouri River, no bridge at this time crossing that great but uncertain and shifting stream.

During this two days' journey from New York to the Missouri, a considerable change has taken place in the minds of some of the members of the party as to their proposed jaunt to the Rocky Mountains and beyond. This has chiefly been brought about by Mr. Ferdie, who, having purchased a book entitled "Facts About the Far West," has been regaling himself with the same, and devoting a considerable portion of his time explaining and elucidating the knowledge he thinks he has gained from it to Mrs. Livingston, producing a very distressing effect upon that plump lady's nervous system.

These "Facts About the West" consist chiefly of anecdotes of the border ruffian kind, descriptions of various atrocities, Indian massacres, Mormon outrages and vigilance committees, and are of such a very highly colored and blood-curdling description that Mr. Chauncey himself remarks, as he finishes the volume: "If these are facts about the West, I think the fiction will be too rich for my blood!" Though half-believing the same, this young gentleman imagines he has acquired in his two days between New York and Council Bluffs, considerable knowledge of the manners of the Western frontiersman, border-ruffians, stage-drivers, Indians, Mormons, and buffaloes.

A number of the more blood-curdling anecdotes he has detailed to Mrs. Livingston at odd times, enjoying her shudderings at such stories as that of the waiter in the New Mexico hotel, who shot the Chicago drummer to death because he declined to eat the eggs and said they were incipient chickens; also, a few of the more cruel exploits of celebrated Johnnie Slade, the murderous superintendent of a division of the Ben Holliday's stage line, together with a full, true and accurate account of the atrocious butchery of one hundred and thirty three men, women and children by the notorious John D. Lee, of Utah, the Mormon bishop, and a portion of the Mormon militia, disguised as Indians, that occurred in 1857, and now known under the head of the Mountain Meadow Massacre; "The Last Shot of Joaquin, the California Bandit," etc., etc.

These revelations of Western atrocity Mr. Ferdinand is delighted to see produce upon the nerves of Mrs. Livingston effects more demoralizing than the morphine habit. And he would continue his narrations, with much gusto, to the agitated Mrs. Livingston, did not Erma, who has been listening indifferently to his tales of blood, suddenly, at her first opportunity, lead the chuckling Ferdie aside, and, placing two flaming eyes upon him, whisper: "Not another of your Western horrors to your aunt!" Then her voice grows pathetic, and she mutters: "Would you frighten her so that she retreats from her journey and takes me back to New York, and deprives me of seeing my father—the joy I am looking forward to minute by minute, and hour by hour."

This oration, emphasized by savage glances and made pathetic by flashing eyes, has a great effect on Mr. Ferdinand, and he promises silence, remarking to himself: "What a stunner that Erma is, and only out of boarding school ten months."

As it is, when Ferdie first looks upon the Missouri River and utters, "The West is now before me. I feel as if I knew it very well from my guide-book," tapping his blood-curdling volume. "Now for a practical experience of the same," adding to this one or two attempts at Indian war-whoops, the effect of his narratives has been so great on Mrs. Livingston that she puts her plump hands over her pale blue eyes and shudderingly mutters: "The West—shall I ever live to come out of it?" and would take train immediately for Eastern civilization, were it not that she fears the laughter of her daughter, Louise, and the sneers of Oliver, her son, who has several times pooh-poohed Ferdie's anecdotes of Rocky Mountain life, and once or twice, during his more atrocious recitals, has ejaculated "Bosh!"

As she descends from her car at Council Bluffs, she lays one trembling hand on her son's arm, and makes one half-hearted expostulation, "Don't you think, since we are compelled to leave our private car here, we had better end the trip and return to New York immediately?"

This Mr. Oliver silences by a stern "What! Our tickets already bought for San Francisco? Besides that, Van Wyke Stuyvesant has just come back with his mother and sisters, and pronounces the trip delightful, and I don't wish Van Wyke, who is something of a braggart, to be able to talk of the Yosemite and Big-trees and I be unable to say I have been there also. Besides, Erma is looking forward to meeting her father."

Thus compelled, Mrs. Livingston nervously accepts her son's escort to the ferry boat, and the party cross the Missouri River to take cars at Omaha on the Union Pacific Railway—Mr. Oliver, calmly indifferent to his mother's feelings, and only intent upon using some of the chances of the journey for making his romantic declaration to Miss Travenion.

It will give that young lady, he imagines, the opportunity she is anxiously awaiting, to accept his distinguished name, large fortune and small heart; though did he but guess it, Miss Travenion has but one thought in her soul—fifteen hundred miles nearer papa!

Mr. Chauncey, however, is very anxious for the wonders of the border land he has read about, crazy to see a herd of buffaloes, and determined to investigate Western matters for himself generally, in order to have some rare stories of frontier life with which to make his Eastern college chums open their eyes over social spreads at the "D. K. E.," for this young gentleman will enter Harvard as freshman next term. An Alma Mater of which he is already very proud in futuro, and in which he is very anxious to distinguish himself, not as a reading man, but as a Harvard man—a being, who, this young gentleman fondly imagines, has the beauty of an Adonis, the muscle of a Sullivan, the pluck of a bull-terrier, the brain of a Macchiavelli, and the morals of a Don Juan, disguised by the demeanor and bearing of a Lord Chesterfield.

So the young man springs eagerly ashore on the Nebraska side of the Missouri, and cries out in a laughing voice: "Omaha! All aboard for the Rockies and buffaloes and Indians and scalpings!" exclamations which make the widow's nerves tingle and the widow's plump hands shake a little, as her son assists her across the gang-plank.

Then, his mother being landed, Ollie turns to offer the same attention to Erma, but to his astonishment he is anticipated in his act of gallantry by the Western Mr. Kruger.

This gentleman, apparently, near his native heath, has grown bolder, and as he expresses it to himself, "has been do'en the perlite" to Miss Travenion, indicating to her the various points of interest in Omaha as seen from the river, together with the Union Pacific Railway bridge, which is at this time in process of construction.

"Your daddy and I once spent four hours in winter trying to get across this river, Sissy, and were mighty nigh froze to death doing it, and if it had not been for my U. S. blanket overcoat that I picked up when Johnston was out thar invadin' us"—he checks himself shortly here and mumbles: "I reckon your old man would have given in. But here we air—Permit the hand of fellowship over the step-off!"

This allusion to her father is received by a grateful "thank you" from the young lady, who, if she has read of Albert Sydney Johnston's campaign in Utah has forgotten the same, and she accepts Mr. Kruger's aid across the gang-plank in so easy and affable a manner that Lot proffers his further escort to the omnibus waiting to bear this young lady up the hill toward what is called the railroad depot in Omaha. Having assisted her into the 'bus with rather effusive gallantry, and noting during his attentions a ravishing ankle in silken hose that makes his fatherly eyes grow red and watery, he remarks with a chuckle to himself as he sees the New York beauty drive off: "If Miss High-Fallutin' should come to Zion in the Far West, oh Saints of Melchisedec!" and is so overcome by his emotions that he almost misses the last transfer omnibus.

So, it comes to pass that in the course of a few minutes they all find themselves at that ramshackle affair that was, and is now, for that matter, termed the Western Union Depot in Omaha. Here the train is drawn up, ready for its race towards the West. Attached to it are two Pullman cars, in one of which Erma's party have engaged their accommodations, which consist of a rear stateroom, occupied by Mrs. Livingston and her daughter, a forward stateroom, which has been engaged for Miss Travenion and her maid. The section next his mother's being occupied entirely by Oliver, that young man always looking after his own comfort and luxury very thoroughly; while a section in the forward end of the car, next Miss Travenion's stateroom, has been set apart for Mr. Ferdinand Chauncey in order that he may be situated so as to give Erma any masculine assistance or protection she may require.

Of course, this is by no means so convenient for the New York party as the private car, which had been placed at their service by a relative of Mrs. Livingston, one of the magnates of the Pennsylvania Railway, but it had been considered by Mr. Oliver best to submit to the more contracted accommodations found upon a general sleeping car than to the exorbitant charges of the Western railways.

Miss Travenion has already made herself comfortable in her stateroom by the aid of her maid, a pretty French girl, who is about as useless a one as could have been selected for this trip, save in the matter of feminine toilet; when glancing into the open portion of the sleeping car, Erma gets a little surprise. She sees Captain Harry Storey Lawrence entering the same, and placing his impedimenta in the section opposite Ferdie's, which from its location is also next to her stateroom. She gives the young man a slight bow, which he acknowledges with military courtesy, a little red showing under the tan of the sun upon his hardy cheeks; but thinks only passingly of the matter, judging it a mere chance of travel, she having already heard the gentleman state that he was returning to Utah.

She would probably pay more attention to the affair did she know that what she considers a mere accident of travel, has been brought about on the part of the young man by deliberate design.

Lawrence having finished his business in Chicago, and his telegrams from Southmead received at the Sherman House indicating that there was no immediate hurry for his presence in Salt Lake, that young gentleman had said to himself, "Why not travel with her? Three days in a Pullman sleeper are equal to a voyage at sea. Before my arrival at Salt Lake, she shall have better acquaintance with me than a few words in a Delmonico supper room can produce." Actuated by this idea, the captain had journeyed leisurely to Omaha, and discovering the location of Erma's stateroom, had promptly selected the section next to it for the trip to the West.

Very shortly after this, with much ringing of bell and much blowing of whistle, the train gets into motion, and passing out of the Omaha depot, in a few minutes is climbing a little ascent over which it will pass into the valley of the Platte, to run along endless plains till the snowy summits of the Rocky Mountains come into view on the Western horizon.

To the south, a low range of hills is bordering the river; to the north prairies, nothing but prairies; to the west nothing but prairies, save two long lines of rails that run straight as an arrow towards the setting sun till they seem to come together and be one.

Gazing at these, her eyes full of expectant happiness and hope, Miss Travenion murmurs, "At the end of these, one thousand and odd miles away, my father," and the green prairies of Nebraska grow very beautiful to her, and the soft southern wind, as it enters the car windows, seems very pleasant to her, and the rays of the setting sun make the green grass lands and the long reaches of the Platte River flowing over its yellow quicksands and dotted with its little cottonwood islands seem like a landscape of Heaven to her.

Then Ferdie comes in, looking eagerly out of the car window, and whispers: "Do you see any buffaloes yet? I have got a revolver and a sporting rifle to kill them." A second after he ejaculates, "What's that!"

And Erma starts and echoes "What's that?"

For it is a sound these two have never heard the like of before—the shriek of the Western train book agent—not the pitiful note of the puny Eastern vender, but the wild whoop of the genuine transcontinental fiend, who in the earlier seventies went bellowing through a car like a calliope on a Mississippi River boat.

"Bre-own's prize candies! Twenty-five cents a box, warranted fresh and something that'll make you feel pleased and slick in every one of 'em—Bre-own's prize candies."

Being of a speculative turn of mind, Ferdie invests in one or two of these, and he and Erma open them together and laugh at their bad luck, for Ferdie has won a Jew's harp, worth about a cent, and she is the happy possessor of a brass thimble, and the candies, apparently, have been manufactured before Noah's Ark put to sea. While joking about this, a new idea seems to strike Ferdie.

The news-boy, who has gathered up his packages after making his trades on the sharpest of business principles, is leaving the car. Mr. Chauncey asks him if he has any Western literature.