Project Gutenberg's Popular Technology, Vol. I (of 2), by Edward Hazen

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Popular Technology, Vol. I (of 2)

or, Professions and Trades

Author: Edward Hazen

Release Date: May 18, 2012 [EBook #39721]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POPULAR TECHNOLOGY, VOL. I (OF 2) ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, JoAnn Greenwood, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The following work has been written for the use of schools and families, as well as for miscellaneous readers. It embraces a class of subjects in which every individual is deeply interested, and with which, as a mere philosophical inspector of the affairs of men, he should become acquainted.

They, however, challenge attention by considerations of greater moment than mere curiosity; for, in the present age, a great proportion of mankind pursue some kind of business as means of subsistence or distinction; and in this country especially, such pursuit is deemed honorable and, in fact, indispensable to a reputable position in the community.

Nevertheless, it is a fact that cannot have escaped the attention of persons of observation, that many individuals mistake their appropriate calling, and engage in employments for which they have neither mental nor physical adaptation; some learn a trade who should have studied a profession; others study a profession who should have learned a trade. Hence arise, in a great measure, the ill success and discontent which so frequently attend the pursuits of men.

For these reasons, parents should be particularly cautious in the choice of permanent employments for their children; and, in every case, capacity should be especially regarded, without paying much attention to the comparative favor in which the several employments may be held; for a successful prosecution of an humble business is far more honorable than inferiority or failure in one which may be greatly esteemed.

To determine the particular genius of children, parents should give them, at least, a superficial knowledge of the several trades and professions. To do this effectually, a systematic course of instruction[viii] should be given, not only at the family fireside and in the schoolroom, but also at places where practical exhibitions of the several employments may be seen. These means, together with a competent literary education, and some tools and other facilities for mechanical operations, can scarcely fail of furnishing clear indications of intellectual bias.

The course just proposed is not only necessary to a judicious choice of a trade or profession, but also as means of intellectual improvement; and as such it should be pursued, at all events, even though the choice of an employment were not in view.

We are endowed with a nature composed of many faculties both of the intellectual and the animal kinds, and the reasoning faculties were originally designed by the Creator to have the ascendency. In the present moral condition of man, however, they do not commonly maintain their right of precedence. This failure arises from imbecility, originating, in part, from a deficiency in judicious cultivation, and from the superior strength of the passions.

This condition is particularly conspicuous in youth, and shows itself in disobedience to parents, and in various other aberrations from moral duty. If, therefore, parents would have their children act a reasonable part, while in their minority, and, also, after they have assumed their stations in manhood, they must pursue a course of early instruction, calculated to secure the ascendency of the reasoning faculties.

The subjects for instruction best adapted to the cultivation of the young mind are the common things with which we are surrounded. This is evident from the fact, that it uniformly expands with great rapidity under their influence during the first three or four years of life; for, it is from them, children obtain all their ideas, as well as a knowledge of the language by which they are expressed.

The rapid progress of young children in the acquisition of knowledge often excites the surprise of parents of observation, and the fact that their improvement is almost imperceptible, after they have attained[ix] to the age of four or five years, is equally surprising. Why, it is often asked, do not children continue to advance in knowledge with equal and increased rapidity, especially, as their capabilities increase with age?

The solution of this question is not difficult. Children continue to improve, while they have the means of doing so; but, having acquired a knowledge of the objects within their reach, at least, so far as they may be capable at the time, their advancement must consequently cease. It is hardly necessary to remark, that the march of mind might be continued with increased celerity, were new objects or subjects continually presented.

In supplying subjects for mental improvement, as they may be needed at the several stages of advancement, there can be but little difficulty, since we are surrounded by works both of nature and of art. In fact, the same subjects may be presented several times, and, at each presentation, instructions might be given adapted to the particular state of improvement in the pupil.

Instructions of this nature need never interfere injuriously with those on the elementary branches of education, although the latter would undoubtedly be considered of minor importance. Had they been always regarded in this light, our schools would now present a far more favorable aspect, and we should have been farther removed from the ignorance and the barbarism of the middle ages.

Were this view of education generally adopted, teachers would soon find, that the business of communicating instructions to the young has been changed from an irksome to a pleasant task, since their pupils will have become studious and intellectual, and, consequently, more capable of comprehending explanations upon every subject. Such a course would also be attended with the incidental advantage of good conduct on the part of pupils, inasmuch as the elevation of the understanding over the passions uniformly tends to this result.

For carrying into practice a system of intellectual[x] education, the following work supplies as great an amount of materials as can be embodied in the same compass. Every article may be made the foundation of one lecture or more, which might have reference not only to the particular subject on which it treats, but also to the meaning and application of the words.

The articles have been concisely written, as must necessarily be the case in all works embracing so great a variety of subjects. This particular trait, however, need not be considered objectionable, since all who may desire to read more extensively on any particular subject, can easily obtain works which are exclusively devoted to it.

Prolix descriptions of machinery and of mechanical operations have been studiously avoided; for it has been presumed, that all who might have perseverance enough to read such details, would feel curiosity sufficient to visit the shops and manufactories, and see the machines and operations themselves. Nevertheless, enough has been said, in all cases, to give a general idea of the business, and to guide in the researches of those who may wish to obtain information by the impressive method of actual inspection.

A great proportion of the whole work is occupied in recounting historical facts, connected with the invention and progress of the arts. The author was induced to pay especial attention to this branch of history, from the consideration, that it furnishes very clear indications of the real state of society in past ages, as well as at the present time, and also that it would supply the reader with data, by which he might, in some measure, determine the vast capabilities of man.

This kind of historical information will be especially beneficial to the youthful mind, by inducing a habit of investigation and antiquarian research. In addition to this, a knowledge of the origin and progress of the various employments which are in active operation all around, will throw upon the busy world an aspect exceedingly interesting.

It may be well, however, to caution the reader[xi] against expecting too much information of this kind, in regard to most of the trades practised in very ancient times. Many of the most useful inventions were effected, before any permanent means of record had been devised; and, in after ages, among the Greeks and Romans, the useful arts were practised almost exclusively by slaves. The latter circumstance led to their general neglect by the writers among these distinguished people.

The information which may be obtained from this work, especially when accompanied by the inspection of the operations which it describes, may be daily applied to some useful purpose. It will be particularly valuable in furnishing subjects for conversation, and in preventing the mind from continuing in, or from sinking into, a state of indifference in regard to the busy scenes of this world.

In the composition of this work, all puerile expressions have been avoided, not only because they would be offensive to adult individuals of taste, but because they are at least useless, if not positively injurious, to younger persons. What parent of reflection would suffer his children to peruse a book calculated to induce or confirm a manner of speaking or writing, which he would not have them use after having arrived to manhood? Every sentence may be rendered perfectly plain by appropriate explanations and illustrations.

No formal classification of the professions and trades has been adopted, although those articles which treat of kindred subjects have been placed near each other, and in that order which seemed to be the most natural. The paragraphs of the several articles have been numbered for the especial accommodation of classes in schools, but this particular feature of the work need meet with no serious objection from miscellaneous readers, as it has no other effect, in reference to its use by them, than to give it the aspect of a school-book.

While writing the articles on the different subjects, the author consulted several works which embraced[xii] the arts and sciences generally, as well as many which were more circumscribed in their objects. He, however, relied more upon them for historical facts than for a knowledge of the operations and processes which he had occasion to detail. For this he depended, as far as practicable, upon his own personal researches, although in the employment of appropriate phraseology, he acknowledges his obligations to predecessors.

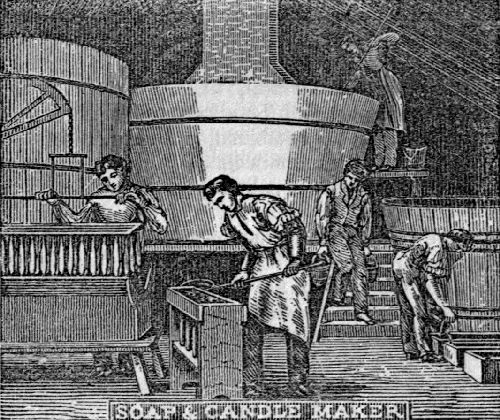

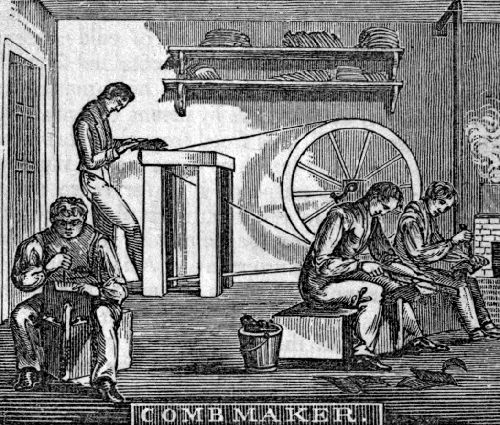

With the preceding remarks, the author submits his work to the public, in the confident expectation, that the subjects which it embraces, that the care which has been taken in its composition, and that the skill of the artists employed in its embellishment, will secure to it an abundant and liberal patronage.

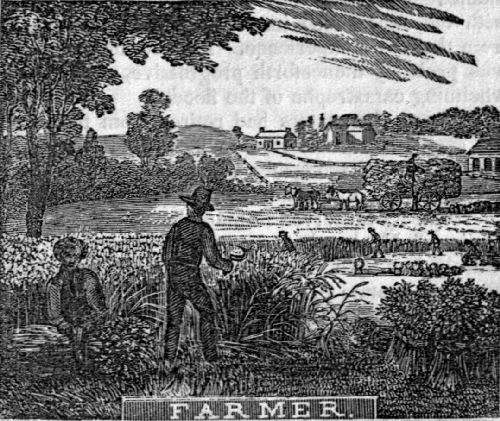

1. Agriculture embraces, in its broad application, whatever relates to the cultivation of the fields, with the view of producing food for man and those animals which he may have brought into a state of domestication.

2. If we carry our observations so far back as to reach the antediluvian history of the earth, we shall find, from the authority of Scripture, that the cultivation of the soil was the first employment of man, after his expulsion from the garden of Eden, when he was commanded to till the ground from which he had been taken. We shall also learn from the same source of information, that "Cain was a husbandman," and that "Abel was a keeper of sheep." Hence it may be inferred, that Adam instructed his sons[14] in the art of husbandry; and that they, in turn, communicated the knowledge to their posterity, together with the superadded information which had resulted from their own experience. Improvement in this art was probably thenceforth progressive, until the overwhelming catastrophe of the flood.

3. After the waters had retired from the face of the earth, Noah resorted to husbandry, as the certain means of procuring the necessaries and comforts of life. The art of cultivating the soil was uninterruptedly preserved in many branches of the great family of Noah; but, in others, it was at length entirely lost. In the latter case, the people, having sunk into a state of barbarism, depended for subsistence on the natural productions of the earth, and on such animals as they could contrive to capture by hunting and fishing. Many of these degenerate tribes did not emerge from this condition for several succeeding ages; while others have not done so to the present day.

4. Notwithstanding the great antiquity of agriculture, the husbandmen, for several centuries immediately succeeding the deluge, seem to have been but little acquainted with any proper method of restoring fertility to exhausted soils; for we find them frequently changing their residence, as their flocks and herds required fresh pasturage, or as their tillage land became unproductive. As men, however, became more numerous, and as their flocks increased, this practice became inconvenient and, in some cases, impracticable. They were, therefore, compelled, by degrees, to confine their flocks and herds, and their farming operations, to lands of more narrow and specified limits.

5. The Chaldeans were probably the people who first adopted the important measure of retaining perpetual possession of the soil which they had cultivated; and, consequently, were among the first who became[15] skilful in agriculture. But all the great nations of antiquity held this art in the highest estimation, and usually attributed its invention to superhuman agency. The Egyptians even worshipped the image of the ox in gratitude for the services of the living animal in the labours of the field.

6. The reader of ancient history can form some idea of the extent to which this art was cultivated in those days, from the warlike operations of different nations; for, from no other source, could the great armies which were then brought into the field, have been supplied with the necessary provisions. The Greeks and the Romans, who were more celebrated than any other people for their military enterprise, were also most attentive to the proper cultivation of the soil; and many of their distinguished men, especially among the Romans, were practical husbandmen.

7. Nor was agriculture neglected by the learned men of antiquity. Several works on this subject, by Greek and Latin authors, have descended to our times; and the correctness of many of the principles which they inculcate, has been confirmed by modern experience.

8. Throughout the extensive empire of Rome, agriculture maintained a respectable standing, until the commencement of those formidable invasions of the northern hordes, which, finally, nearly extinguished the arts and sciences in every part of Europe. During the long period of anarchy which succeeded the settlement of these barbarians in their newly-acquired possessions, pasturage was, in most cases, preferred to tillage, as being better suited to their state of civilization, and as affording facilities of removal, in cases of alarm from invading enemies. But, when permanent governments had been again established, and when the nations enjoyed comparative peace, the regular cultivation of the soil once more revived.[16]

9. The art of husbandry was at a low ebb in England, until the fourteenth century, when it began to be practised with considerable success in the midland and south-western parts of the island; yet, it does not seem to have been cultivated as a science, until the latter end of the sixteenth century. The first book on husbandry, printed and published in the English language, appeared in 1534. It was written by Sir A. Fitzherbert, a judge of the Common Pleas, who had studied the laws of vegetation, and the nature of soils, with philosophical accuracy.

10. Very little improvement was made on the theory of this author, for upwards of a hundred years, when Sir Hugh Platt discovered and brought into use several kinds of substances for fertilizing and restoring exhausted soils.

11. Agriculture again received a new impulse, about the middle of the eighteenth century; and, in 1793, a Board of Agriculture was established by an act of Parliament, at the suggestion of Sir John Sinclair, who was elected its first president. Through the influence of this board, a great number of agricultural societies have been formed in the kingdom, and much valuable information on rural economy has been communicated to the public, through the medium of a voluminous periodical under its superintendence.

12. After the example of Great Britain, agricultural societies have been formed, and periodical journals published, in various parts of the continent of Europe, as well as in the United States. The principal publications devoted to this subject in this country, are the American Farmer, at Baltimore; the New-England Farmer, at Boston; and the Cultivator, at Albany.

13. The modern improvements in husbandry consist, principally, in the proper application of manures,[17] in the mixture of different kinds of earths, in the use of plaster and lime, in the rotation of crops, in adapting the crop to the soil, in the introduction of new kinds of grain, roots, grasses, and fruits, as well as in improvements in the breeds of domestic animals, and in the implements with which the various operations of the art are performed.

14. For many of the improved processes which relate to the amelioration of the soil, we are indebted to chemistry. Before this science was brought to the aid of the art, the cultivators of the soil were chiefly guided by the precept and example of their predecessors, which were often inapplicable. By the aid of chemical analysis, it is easy to discover the constituent parts of different soils; and, when this has been done, there is but little difficulty in determining the best mode of improving them, or in applying the most suitable crops.

15. In the large extent of territory embraced within the United States, there is great variation of soil and climate; but, in each state, or district, the attention of the cultivators is directed to the production of those articles which, under the circumstances, promise to be the most profitable. In the northern portions of our country, the cultivators of the soil are called farmers. They direct their attention chiefly to the production of wheat, rye, corn, oats, barley, peas, beans, potatoes, pumpkins, and flax, together with grasses and fruits of various kinds. The same class of men, in the Southern states, are usually denominated planters, who confine themselves principally to tobacco, rice, cotton, sugar-cane, or hemp. In some parts of that portion of our country, however, rye, wheat, oats, and sweet potatoes, are extensively cultivated; and, in almost every part, corn is a favourite article.

16. The process of cultivating most of the productions[18] which have been mentioned, is nearly the same. In general, with the occasional exception of new lands, the plough is used to prepare the ground for the reception of the seed. Wheat, rye, barley, oats, peas, and the seeds of hemp and flax, are scattered with the hand, and covered in the earth with the harrow. In Great Britain, such seeds are sown in drills; and this method is thought to be better than ours, as it admits of the use of the hoe, while the vegetable is growing.

17. Corn, beans, potatoes, and pumpkins, are covered in the earth with the hoe. The ground is ploughed several times during the summer, to make it loose, and to keep down the weeds. The hoe is also used in accomplishing the same objects, and in depositing fresh earth around the growing vegetable.

18. When ripe, wheat, barley, oats, and peas, are cut down with the sickle, cradle, or scythe; while hemp and flax are pulled up by the roots. The seeds are separated from the other parts of the plants with the flail, or by means of horses or oxen driven round upon them. Of late, threshing machines are used to effect the same object. Chaff, and extraneous matter generally, are separated from the grain, or seeds, by means of a fanning-mill, or with a large fan made of the twigs of the willow. The same thing was formerly, and is yet sometimes, effected by the aid of a current of air.

19. When the corn, or maize, has become ripe, the ears, with the husks, and sometimes the stalks, are deposited in large heaps. To assist in stripping the husks from the ears, it is customary to call together the neighbours. In such cases, the owner of the corn provides for them a supper, together with some means of merriment and good cheer.

20. This custom is most prevalent, where the greater part of the labour is performed by slaves. The blacks, when assembled for a husking match, choose[19] a captain, whose business it is to lead the song, while the rest join in chorus. Sometimes, they divide the corn as nearly as possible into two equal heaps, and apportion the hands accordingly, with a captain to each division. This is done to produce a contest for the most speedy execution of the task. Should the owner of the corn be sparing of his refreshments, his want of generosity is sure to be published in song at every similar frolic in the neighborhood.

21. Maize, or Indian corn, and potatoes of all kinds, were unknown in the eastern continent, until the discovery of America. Their origin is, therefore, known with certainty; but some of the other productions which have been mentioned, cannot be so satisfactorily traced. This is particularly the case with regard to those which have been extensively cultivated for many centuries.

22. The grasses have ever been valuable to man, as affording a supply of food for domestic animals. Many portions of our country are particularly adapted to grazing. Where this is the case, the farmers usually turn their attention to raising live stock, and to making butter and cheese. Grass reserved in meadows, as a supply of food for the winter, is cut at maturity with a scythe, dried in the sun, and stored in barns, or heaped in stacks.

23. Rice was first cultivated in the eastern parts of Asia, and, from the earliest ages, has been the principal article of food among the Chinese and Hindoos. To this grain may be attributed, in a great measure, the early civilization of those nations; and its adaptation to marshy grounds caused many districts to become populous, which would otherwise have remained irreclaimable and desolate.

24. Rice was long known in the east, before it was introduced into Egypt and Greece, whence it spread over Africa generally, and the southern parts of Europe.[20] It is now cultivated in all the warm parts of the globe, chiefly on grounds subject to periodical inundations. The Chinese obtain two crops a year from the same ground, and cultivate it in this way from generation to generation, without applying any manure, except the stubble of the preceding crop, and the mud deposited from the water overflowing it.

25. Soon after the waters of the inundation have retired, a spot is inclosed with an embankment, lightly ploughed and harrowed, and then sown very thickly with the grain. Immediately, a thin sheet of water is brought over it, either by a stream or some hydraulic machinery. When the plants have grown to the height of six or seven inches, they are transplanted in furrows; and again water is brought over them, and kept on, until the crop begins to ripen, when it is withheld.

26. The crop is cut with a sickle, threshed with a flail, or by the treading of cattle; and the husks, which adhere closely to the kernel, are beaten off in a stone mortar, or by passing the grain through a mill, similar to our corn-mills. The mode of cultivating rice in any part of the world, varies but little from the foregoing process. The point which requires the greatest attention, is keeping the ground properly covered with water.

27. Rice was introduced into the Carolinas in 1697, where it is now produced in greater perfection than in any other part of the world. The seeds are dropped along, from the small end of a gourd, into drills made with one corner of the hoe. The plants, when partly grown, are not transferred to another place, as in Asia, but are suffered to grow and ripen in the original drills. The crop is secured like wheat, and the husks are forced from the grain by a machine, which leaves the kernels more perfect than the methods adopted in other countries.[21]

28. Cotton is cultivated in the East and West Indies, North and South America, Egypt, and in many other parts of the world, where the climate is sufficiently warm for the purpose. There are several species of this plant; of which three kinds are cultivated in the southern states of the Union—the nankeen cotton, the green seed cotton, and the black seed, or sea island cotton. The first two, which grow in the middle and upland countries, are denominated short staple cotton: the last is cultivated in the lower country, near the sea, and on the islands near the main land, and is of a fine quality, and of a long staple.

29. The plants are propagated annually from seeds, which are sown very thickly in ridges made with the plough or hoe. After they have grown to the height of three or four inches, part of them are pulled up, in order that the rest, while coming to maturity, may stand about four inches apart. It is henceforth managed, until fully grown, like Indian corn.

30. The cotton is inclosed in pods, which open as fast as their contents become fit to be gathered. In Georgia, about eighty pounds of upland cotton can be gathered by a single hand in a day; but in Alabama and Mississippi, where the plant thrives better, two hundred pounds are frequently collected in the same time.

31. The seeds adhere closely to the cotton, when picked from the pods; but they are properly separated by machines called gins; of which there are two kinds,—the roller-gin, and the saw-gin. The essential parts of the former are two cylinders, which are placed nearly in contact with each other. By their revolving motion, the cotton is drawn between them, while the size of the seeds prevents their passage. This machine, being of small size, is worked by hand.

32. The saw-gin is much larger, and is moved by animal, steam, or water power. It consists of a receiver,[22] having one side covered with strong wires, placed in a parallel direction about an eighth of an inch apart, and a number of circular saws, which revolve on a common axis. The saws pass between these wires, and entangle in their teeth the cotton, which is thereby drawn through the grating, while the seeds, from their size, are forced to remain on the other side.

33. Before the invention of the saw-gin, the seeds were separated from the upland cottons by hand,—a method so extremely tedious, that their cultivation was attended with but little profit to the planter. This machine was invented in Georgia by Eli Whitney, of Massachusetts. It was undertaken at the request of several planters of the former state, and was there put in operation in 1792.

34. In the preceding year, the whole crop of cotton in the United States was only sixty-four bales; but, in 1834, it amounted to 1,000,617. The vast increase in the production of this article has arisen, in part, from the increased demand for it in Europe, and in the Northern states, but, chiefly, from the use of the invaluable machine just mentioned.

35. Sugar-cane was cultivated by the Chinese, at a very early period, probably two thousand years before it was known in Europe; but sugar, in a candied form, was used in small quantities by the Greeks and Romans in the days of their prosperity. It was probably brought from Bengal, Siam, or some of the East India Islands, as it is supposed, that it grew nowhere else at that time.

36. In the thirteenth century, soon after the merchants of the West began to traffic in Indian articles of commerce, the plant was introduced into Arabia Felix, and thence into Egypt, Nubia, Ethiopia, and Morocco. The Spaniards obtained it from the Moors, and, in the fifteenth century, introduced it into the[23] Canary Islands. It was brought to America, and to the West India Islands, by the Spaniards and Portuguese. It is now cultivated in the United States, below the thirty-first degree of latitude, and in the warm parts of the globe generally.

37. Previous to the year 1466, sugar was known in England chiefly, as a medicine; and, although the sugar-cane was cultivated, at that time, in several places on the Mediterranean, it was not more extensively used on the continent. Now, in extent of cultivation, it ranks next to wheat and rice, and first in maritime commerce.

38. The cultivators of sugar-cane propagate the plant by means of cuttings from the lower end of the stalks, which are planted in the spring or autumn, in drills, or in furrows. The new plants spring from the joints of the cuttings, and are fit to be gathered for use in eight, ten, twelve, or fourteen months. While growing, sugar-cane is managed much like Indian corn.

39. When ripe, the cane is cut and brought to the sugar-mill, where the juice is expressed between iron or stone cylinders, moved by steam, water, or animal power. The juice thus obtained is evaporated in large boilers to a syrup, which is afterwards removed to coolers, where it is agitated with wooden instruments called stirrers. To accelerate its cooling, it is next poured into casks, and, when yet warm, is conveyed to barrels, placed in an upright position over a cistern, and pierced in the bottom in several places. The holes being partially stopped with canes, the part which still remains in the form of syrup, filters through them into the cistern beneath, while the rest is left in the form of sugar, in the state called muscovado.

40. This sugar is of a yellow colour, being yet in a crude, or raw state. It is further purified by various[24] processes, such as redissolving it in water, and again boiling it with lime and bullocks' blood, or with animal charcoal, and passing the syrup through several canvas filters.

41. Loaf-sugar is manufactured by pouring the syrup, after it has been purified, and reduced to a certain thickness by evaporation, into unglazed earthen vessels of a conical shape. The cones have a hole at their apex, through which may filter the syrup which separates from the sugar above. Most of the sugar is imported in a raw or crude state, and is afterward refined in the cities in sugar-houses.

42. Molasses is far less free from extraneous substances than sugar, as it is nothing more than the drainings from the latter. Rum is distilled from inferior molasses, and other saccharine matter of the cane, which will answer for no other purpose.

43. Sugar is also manufactured from the sap of the sugar-maple, in considerable quantities, in the northern parts of the United States, and in the Canadas. The sap is obtained by cutting a notch, or boring a hole, in the tree, and applying a spout to conduct it to a receiver, which is either a rude trough, or a cheap vessel made by a cooper. This operation is performed late in the winter, or early in the spring, when the weather is freezing at night, and thawing in the day.

44. The liquid in which the saccharine matter is suspended, is evaporated by heat, as in the case of the juice of the cane. During the process of evaporation, slices of pork are kept in the kettle, to prevent the sap or syrup from boiling over.

45. When a sufficient quantity of syrup, of a certain thickness, has been obtained, it is passed through a strainer, and, having been again placed over the fire, it is clarified with eggs and milk, the scum, as it rises, being carefully removed with a skimmer.[25] When sufficiently reduced, it is usually poured into tin pans, or basins, in which, as it cools, it consolidates into hard cakes of sugar.

46. Most of the lands in a state of nature, are covered with forest trees. This is especially the case in North America. When this division of our continent was first visited by Europeans, it was nearly one vast wilderness, throughout its entire extent; and even now, after a lapse of three centuries, a great portion of it remains in the same condition. The industrious settlers, however, are rapidly clearing away the natural encumbrances of the soil; and, before a similar period shall have passed away, we may expect, that civilized men will have occupied every portion of this vast territory, which may be worthy of cultivation.

47. The mode of clearing land, as it is termed, varies in different parts of the United States. In Pennsylvania, and in neighborhoods settled by people from that state, the large trees are deadened by girdling them, and the small ones, together with the underbrush, are felled and burned. This mode is very objectionable, for the reason, that the limbs on the standing trees, when they have become rotten, sometimes peril the lives of persons and animals underneath. It seems, however, that those who pursue this method, prefer risking life in this way to wearing it out in wielding the axe, and in rolling logs.

48. A very different plan is pursued by settlers from New-England. The underbrush is first cut down, and piled in heaps. The large trees are then felled, to serve as foundations for log-heaps; and the smaller ones are cut so as to fall as nearly parallel to these as practicable. The smaller trees, as well as the limbs of the larger ones, are cut into lengths of twelve or fifteen feet.

49. At a proper season of the year, when the brush[26] has become dry enough, fire is applied, which consumes much of the small stuff. The logs are next hauled together with oxen or horses, and rolled into heaps with handspikes. The small stuff which has escaped the first burning, is thrown upon the heaps, and, fire being applied, the whole is consumed together.

50. In the Northern, Middle, and Western states, where a great proportion of the timber is beech, maple, and elm, great quantities of ashes are obtained in this mode of clearing land. From these ashes are extracted the pot and pearl ashes of commerce, which have been, and which still are, among the principal exports of the United States.

51. The usual process of making potash is as follows: the crude ashes are put into large tubs, or leeches, with a small quantity of salt and lime. The strength of this mixture is extracted by pouring upon it hot water, which passes through it into a reservoir. The water thus saturated is called black ley, which is evaporated in large kettles. The residuum is called black salts, which are converted into potash by applying to the kettle an intense heat.

52. The process of making pearlash is the same, until the ley has been reduced to black salts, except that no lime or salt is used. The salts are baked in large ovens, heated by a blazing fire, which proceeds from an arch below. Having been thus scorched, the salts are dissolved in hot water. The solution is allowed to be at rest, until all extraneous substances have settled to the bottom, when it is drawn off and evaporated as before. The residuum is called white salts. Another baking, like the former, completes the process.

53. Very few of the settlers have an ashery, as it is called, in which the whole process of making either pot or pearl ash is performed. They usually sell the[27] black salts to the store-keepers in their neighborhood, who complete the process of the manufacture.

54. The trade in ashes is often profitable to the settlers; some of them even pay, in this way, the whole expense of clearing their land. Pot and pearl ashes are packed in strong barrels, and sent to the cities, where, previous to sale, they are inspected, and branded according to their quality.

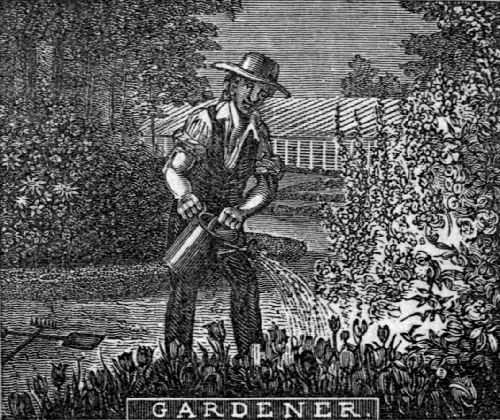

1. The Creator of the Universe, having formed man from the dust of the ground, provided a magnificent garden for his residence, and commanded him "to dress it and to keep it:" but, having transgressed the commandment of his lawful Sovereign, he was driven from this delightful paradise, thenceforth to gain a subsistence from the earth at large, which had been cursed with barrenness, thorns, thistles, and briars.

2. Scripture does not inform us, that Adam turned his attention to gardening; nor have we any means of determining the state of this art, in the centuries previous to the flood; but it is highly probable, that it had arrived to considerable perfection, before the advent of this destructive visitation from Heaven.[29]

3. Gardens, for useful purposes, were probably made, soon after the waters had subsided; and the statement in Scripture, that "Noah planted a vineyard," may, perhaps, be regarded as evidence sufficient to establish it as a fact. If this were the case, the art, doubtless, continued progressive among those descendants of Noah, who did not sink into a state of barbarism, after the confusion of tongues.

4. Among savage nations, one of the first indications of advancement towards a state of civilization, is the cultivation of a little spot of ground for raising vegetables; and the degree of refinement among the inhabitants of any country, may be determined, with tolerable certainty, by the taste and skill exhibited in their gardens.

5. Ornamental gardening is never attended to, in any country, until the arts in general have advanced to a considerable degree of perfection; and it uniformly declines with other fine or ornamental arts. Accordingly, we do not read of splendid gardens among the Babylonians, Egyptians, Jews, Greeks, Romans, and other nations of antiquity, until they had reached an exalted state of refinement; and when these nations descended from this condition, or were overthrown by barbarians, this art declined or disappeared.

6. During the period of mental darkness, which prevailed between the eighth and thirteenth centuries, the practice of ornamental gardening had fallen into such general disuse, that it was confined exclusively to the monks. After this period, it began again to spread among the people generally. It revived in Italy, Germany, Holland, and France, long before any attention was paid to it in England.

7. In the latter country, but few culinary vegetables were consumed before the beginning of the sixteenth century, and most of these were brought from[30] Holland; nor was gardening introduced there, as a source of profit, until about one hundred years after that period. Peaches, pears, plums, nectarines, apricots, grapes, cherries, strawberries, and melons, were luxuries but little enjoyed in England, until near the middle of the seventeenth century. The first hot and ice houses known on the island, were built by Charles II., who ascended the British throne in 1660, and soon after introduced French gardening at Hampton Court, Carlton, and Marlborough.

8. About the beginning of the eighteenth century, this art attracted the attention of some of the first characters in Great Britain, who gave it a new impulse in that country. But the style which they imitated was objectionable, inasmuch as the mode of laying out the gardens, and of planting and trimming the trees, was too formal and fantastical.

9. Several eminent writers, among whom were Pope and Addison, ridiculed this Dutch mode of gardening, as it was called, and endeavoured to introduce another, more consistent with genuine taste. Their views were, at length, seconded by practical horticulturists; and those principles of the art which they advocated, were adopted in every part of Great Britain. The English mode has been followed and emulated by the refined nations of the Eastern continent and by many opulent individuals in the United States.

10. Since the beginning of the present century horticultural societies have been formed in every kingdom of Europe. In Great Britain alone, there are no less than fifty; and, it is satisfactory to add, that there are also several of these institutions in the United States. The objects of the persons who compose these societies are, to collect and disseminate information on this interesting art, especially in regard to the introduction of new and valuable articles of cultivation.[31]

11. The authors who have written upon scientific and practical gardening, at different periods, and in different countries, are very numerous. Among the ancient Greek writers, were Hesiod, Theophrastus, Xenophon, and Ælian. Among the Latins, Varo was the first; to whom succeeded, Cato, Pliny the elder, Columella, and Palladius.

12. Since the revival of literature, horticulture, in common with agriculture, has shared largely in the labours of the learned; and many works, on this important branch of rural economy, have been published in every language of Europe. But the publications on this subject, which attract the greatest attention, are the periodicals under the superintendence of the great horticultural societies. Those of London and Paris, are particularly distinguished.

13. It is impossible to draw a distinct line between horticulture and agriculture; since so many articles of cultivation are common to both, and since a well-regulated farm approaches very nearly to a garden.

14. The divisions of a complete garden, usually adopted by writers on this subject, are the following: 1st. the culinary garden; 2d. the flower garden; 3d. the orchard, embracing different kinds of fruits; 4th. the vineyard; 5th. the seminary, for raising seeds; 6th. the nursery, for raising trees to be transplanted; 7th. the botanical garden, for raising various kinds of plants; 8th. the arboretum of ornamental trees; and, 9th. the picturesque, or landscape garden. To become skilful in the management of even one or two of these branches, requires much attention; but to become proficient in all, would require years of the closest application.

15. In Europe, the professed gardeners constitute a large class of the population. They are employed either in their own gardens, or in those of the wealthy, who engage them by the day or year. There are[32] many in this country who devote their attention to this business; but they are chiefly from the other side of the Atlantic. In our Southern states, the rich assign one of their slaves to the garden.

16. In the United States, almost every family in the country, and in the villages, has its garden for the production of vegetables, in which are also usually reared, a few flowers, ornamental shrubs, and fruit-trees: but horticulture, as a science, is studied and practised here by very few, especially that branch of it called picturesque, or landscape. To produce a pleasing effect, in a garden of this kind, from twenty to one hundred acres are necessary, according to the manner in which the ground may be situated. In an area of that extent, every branch of this pleasing art can be advantageously embraced.

17. Delicate exotic plants, which will not bear exposure to the open air during the winter, are preserved from the effects of the cold in hot or green houses, which may be warmed by artificial heat. A hot-house is exhibited in the representation of a garden, at the head of this article. It is composed chiefly of window-glass set in sashes of wood. A green-house is usually larger; and is designed for the preservation of those plants requiring less heat.

18. The vegetables commonly cultivated in gardens for the table, are,—corn, potatoes, tomatoes, peas, beans, squashes, cucumbers, melons, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries, currants, beets, parsnips, carrots, onions, radishes, cabbages, asparagus, lettuce, grapes, and various kinds of fruits. The flowers, ornamental shrubs, and trees, are very numerous, and are becoming more so by accessions from the forests, and from foreign countries.

19. The scientific horticulturist, in laying off his garden, endeavours to unite beauty and utility, locating the flowers, ornamental shrubs, and trees, where[33] they will be most conspicuous, and those vegetables less pleasing to the eye, in more retired situations, yet, in a soil and exposure adapted to their constitution. In improving the soil of his garden, he brings to his aid the science of chemistry, together with the experience of practical men. He is also careful in the choice of his fruit-trees, and in increasing the variety of their products by engrafting, and by inoculation.

1. The Miller belongs to that class of employments which relates to the preparation of food and drinks for man. His business consists, chiefly, in reducing the farinaceous grains to a suitable degree of fineness.

2. The simplest method by which grain can be reduced to meal, or flour, is rubbing or pounding it between two stones; and this was probably the one first practised in all primitive conditions of society, as it is still pursued among some tribes of uncivilized men.

3. The first machine for comminuting grain, of which we have any knowledge, was a simple hand-mill, composed of a nether stone fixed in a horizontal position, and an upper stone, which was put in motion[35] with the hand by means of a peg. This simple contrivance is still used in India, as well as in some sequestered parts of Scotland, and on many of the plantations in the Southern states of our Union. But, in general, where large quantities of grain are to be ground, it has been entirely superseded by mills not moved by manual power.

4. The modern corn and flour mill differs from the primitive hand-mill in the size of the stones, in the addition of an apparatus for separating the hulls and bran from the farinaceous part of the grain, and in the power applied for putting it in motion.

5. The grinding surfaces of the stones have channels, or furrows, cut in them, which proceed obliquely from the centre to the circumference. The furrows are cut slantwise on one side, and perpendicular on the other; so that each of the ridges which they form, has a sharp edge; and, when the upper stone is in motion, these edges pass one another, like the blades of a pair of scissors, and cut the grain the more easily, as it falls upon the furrows.

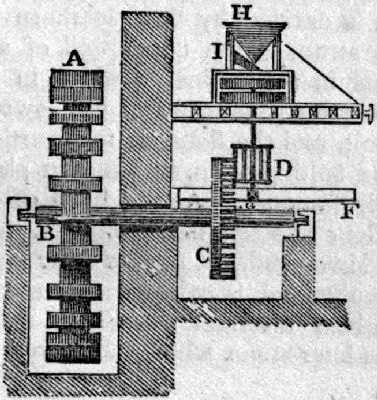

6. By a careful inspection of the following picture, the whole machinery of a common mill may be understood.

A represents the water-wheel; B, the shaft to which is attached the cog-wheel C, which acts on the trundle-head, D; and this, in turn, acts on the moveable stone. The spindle, trundle-head, and upper stone, all rest entirely on the beam, F, which can be elevated or depressed, at pleasure, by a simple apparatus; so that the distance between the stones can be easily regulated, to grind either fine or coarse. The grain about to be submitted to the action of the mill, is thrown into the hopper, H, whence it passes by the shoe, or spout I, through a hole in the upper stone, and then between them both.

7. The upper stone is a little convex, and the other a little concave. There is a little difference, however, between the convexity and the concavity of the two stones: this difference causes the space between them to become less and less towards their edges; and the grain, being admitted between them, is, consequently, ground finer and finer, as it passes out in that direction, in which it is impelled by the centrifugal power of the moving stone.

8. If the flour, or meal, is not to be separated from the bran, the simple grinding completes the operation; but, when this separation is to be made, the comminuted grain, as it is thrown out from between the stones, is carried, by little leathern buckets fastened to a strap, to the upper end of an octagonal sieve, placed in an inclined position in a large box. The coarse bran passes out at the lower end of the sieve, or bolt, and the flour, or fine particles of bran, through the bolting-cloth, at different places, according to their fineness. At the head of the bolt, the superfine flour passes; in the middle, the fine flour; and at the lower end, the coarse flour and fine bran; which, when mixed, is called canel, or shorts.

9. The best material of which mill-stones are made, is the burr-stone, which is brought from France[37] in small pieces, weighing from ten to one hundred pounds. These are cemented together with plaster of Paris, and closely bound around the circumference with hoops made of bar iron. For grinding corn or rye, those made of sienite, or granite rock, are frequently used.

10. A mill, exclusively employed in grinding grain, consumed by the inhabitants of the neighborhood, is called a grist or custom mill; and a portion of the grist is allowed to the miller, in payment for his services. The proportion is regulated by law; and, in our own country, it varies according to the legislation of the different states.

11. Mills in which flour is manufactured, and packed in barrels for sale, are called merchant mills. Here, the wheat is purchased by the miller, or by the owner of the mill, who relies upon the difference between the original cost of the grain, and the probable amount of its several products, when sold, to remunerate him for the manufacture, and his investments of capital. In Virginia, and, perhaps, in some of the other states, it is a common practice among the farmers, to deliver to the millers their wheat, for which they receive a specified quantity of flour.

12. The power most commonly employed to put heavy machinery in operation, is that supplied by water. This is especially the case with regard to mills for grinding grain; but, when this cannot be had, a substitute is found in steam, or animal strength. The wind is also rendered subservient to this purpose. The wind-mill was invented in the time of Augustus Cæsar. During the reign of this emperor, and probably long before, mules and asses were employed by both the Greeks and Romans in turning their mills. The period at which water-mills began to be used cannot be certainly determined. Some writers place it as far back as the Christian era.[38]

13. Wheat flour is one of the staple commodities of the United States, and there are mills for its manufacture in almost every part of the country, where wheat is extensively cultivated; but our most celebrated flour-mills are on the Brandywine Creek, Del., at Rochester, N. Y., and at Richmond, Va.

14. In our Southern states, hommony is a favorite article of food. It consists of the flinty portions of Indian corn, which have been separated from the hulls and eyes of the grain. To effect this separation, the corn is sometimes ground very coarsely in a mill; but the most usual method is that of pounding it in a mortar.

15. The mortar is excavated from a log of hard wood, between twelve and eighteen inches in diameter. The form of the excavation is similar to that of a common iron mortar, except that it is less flat at the bottom, to prevent the corn from being reduced to meal during the operation. The pestle is usually made by confining an iron wedge in the split end of a round stick, by means of an iron ring.

16. The white flint corn is the kind usually chosen for hommony; although any kind, possessing the requisite solidity, will do. Having been poured into the mortar, it is moistened with hot water, and immediately beaten with the pestle, until the eyes and hulls are forced from the flinty portions of the grain. The part of the corn which has been reduced to meal by the foregoing process, is removed by means of a sieve, and the hulls, by the aid of the wind.

17. Hommony is prepared for the table by boiling it in water for twelve hours with about one fourth of its quantity of white beans, and some fat bacon. It is eaten while yet warm, with milk or butter; or, if suffered to get cold, is again warmed with lard or some other fat substance, before it is brought to the table.

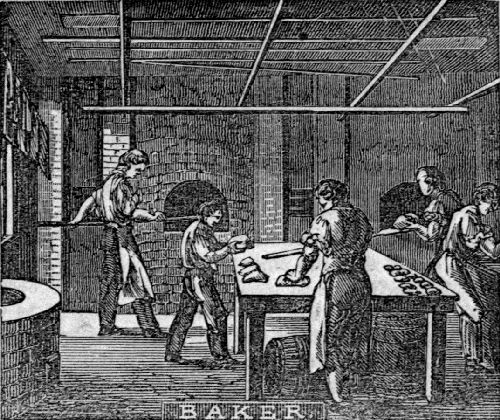

1. The business of the Baker consists in making bread, rolls, biscuits, and crackers, and in baking various kinds of provisions.

2. Man appears to be designed by nature, to eat all substances capable of affording nourishment to his system; but, being more inclined to vegetable than to animal food, he has, from the earliest times, used farinaceous grains, as his principal means of sustenance. As these, however, cannot be eaten in their native state without difficulty, means have been contrived for extracting their farinaceous part, and for converting it into an agreeable and wholesome aliment.

3. Those who are accustomed to enjoy all the advantages of the most useful inventions, without reflecting[40] on the labour expended in their completion, may fancy that there is nothing more easy than to grind grain, to make it into paste, and to bake it in an oven; but it must have been a long time, before men discovered any better method of preparing their grain, than roasting it in the fire, or boiling it in water, and forming it into viscous cakes. Accident, probably, at length furnished some observing person a hint, by which good and wholesome bread could be made by means of fermentation.

4. Before the invention of the oven, bread was exclusively baked in the embers, or ashes, or before the fire. These methods, with sometimes a little variation, are still practised, more or less, in all parts of the world. In England, the poor class of people place the loaf on the heated hearth, and invert over it an iron pot or kettle, which they surround with embers or coals.

5. The invention of the oven must have added much to the conveniences and comforts of the ancients; but it cannot be determined, at what period, or by whom, it was contrived. During that period of remote antiquity, in which the people were generally erratic in their habits, the ovens were made of clay, and hardened by fire, like earthenware; and, being small, they could be easily transported from place to place, like our iron bake-ovens. Such ovens are still in use in some parts of Asia.

6. There are few nations that do not use bread, or a substitute for it. Its general use arises from a law of our economy, which requires a mixture of the animal fluids, in every stage of the process of digestion. The saliva is, therefore, essential; and the mastication of dry food is required, to bring it forth from the glands of the mouth.

7. The farinaceous grains most usually employed in making bread, are,—wheat, rye, barley, maize, and[41] oats. The flour or meal of two of these are often mixed; and wheat flour is sometimes advantageously combined with rice, peas, beans, or potatoes.

8. The component parts of wheat, rye, and barley flour, are,—fecula, or starch, gluten, and saccharine mucilage. Fecula is the most nutritive part of grain. It is found in all seeds, and is especially abundant in the potato. Gluten is necessary to the production of light bread; and wheat flour, containing it in the greatest proportion, answers the purpose better than any other. The saccharine mucilage is equally necessary, as this is the substance on which yeast and leaven act, in producing the internal commotion in the particles of dough during fermentation.

9. There are three general methods of making bread; 1st. by mixing meal or flour with water, or with water and milk; 2d. by adding to the foregoing materials a small quantity of sour dough, or leaven, to serve as a fermenting agent; and, 3d. by using yeast, to produce the same general effect.

10. The theory of making light bread, is not difficult to be understood. The leaven or yeast acts upon the saccharine mucilage of the dough, and, by the aid of heat and moisture, disengages carbonaceous matter, which, uniting with oxygen, forms carbonic acid gas. This, being prevented from escaping by the gluten of the dough, causes the mass to become light and spongy. During the process of baking, the increased heat disengages more of the fixed air, which is further prevented from escaping by the formation of the crust. The superfluous moisture having been expelled, the substance becomes firm, and retains that spongy hollowness which distinguishes good bread.

11. Many other substances contain fermenting qualities, and are, therefore, sometimes used as substitutes for yeast and leaven. The waters of several mineral springs, both in Europe and America, being[42] impregnated with carbonic acid gas, are occasionally employed in making light bread.

12. The three general methods of making bread, and the great number of materials employed, admit of a great variety in this essential article of food; so much so, that we cannot enter into details, as regards the particular modes of manufacture adopted by different nations, or people. There are, comparatively, but few people on the globe, among whom this art is not practised in some way or other.

13. It is impossible to ascertain, at what period of time the process of baking bread became a particular profession. It is supposed, that the first bakers in Rome came from Greece, about two hundred years before the Christian era; and that these, together with some freemen of the city, were incorporated into a college, or company, from which neither they nor their children were permitted to withdraw. They held their effects in common, without possessing any individual power of parting with them.

14. Each bake-house had a patron, or superintendent; and one of the patrons had the management of the rest, and the care of the college. So respectable was this class of men in Rome, that one of the body was occasionally admitted, as a member of the senate; and all, on account of their peculiar corporate association, and the public utility of their employment, were exempted from the performance of the civil duties to which other citizens were liable.

15. In many of the large cities of Europe, the price and weight of bread sold by bakers, are regulated by law. The weight of the loaves of different sizes must be always the same; but the price may vary, according to the current cost of the chief materials. The law was such in the city of London, a few years ago, that if a loaf fell short in weight a single ounce, the baker was liable to be put in the[43] pillory; but now, he is subject only to a fine, varying from one to five shillings, according to the will of the magistrate before whom he may be indicted.

16. In this country, laws of a character somewhat similar have been enacted by the legislatures of several states, and by city authorities, with a view to protect the community against impositions; but whether there is a law or not, the bakers regulate the weight, price, and quality of their loaves by the general principles of trade.

17. There is, perhaps, no business more laborious than that of the baker of loaf bread, who has a regular set of customers to be supplied every morning. The twenty-four hours of the day are systematically appropriated to the performance of certain labours, and to rest.

18. After breakfast, the yeast is prepared, and the oven-wood provided: at two or three o'clock, the sponge is set: the hours from three to eight or nine o'clock, are appropriated to rest. The baking commences at nine or ten o'clock at night; and, in large bakeries, continues until five o'clock in the morning. From that time until the breakfast hour, the hands are engaged in distributing the bread to customers. For seven months in the year, and, in some cases, during the whole of it, part of the hands are employed, from eleven to one o'clock, in baking pies, puddings, and different kinds of meats, sent to them from neighboring families.

19. In large cities, the bakers usually confine their attention to particular branches of the business. Some bake light loaf bread only; others bake unleavened bread, such as crackers, sea-biscuit, and cakes for people of the Jewish faith. Some, again, unite several branches together; and this is especially the case in small cities and towns, where the demand for different kinds of bread is more limited.

1. The Confectioner makes liquid and dry confects, jellies, marmalades, pastes, conserves, sugar-plums, ice-creams, candies, and cakes of various kinds.

2. Many of the articles just enumerated, are prepared in families for domestic use; but, as their preparation requires skill and practice, and is likewise attended with some trouble, it is sometimes better to purchase them of the confectioner.

3. Liquid and dry confects are preserves made of various kinds of fruits and berries, the principal of which are,—peaches, apricots, pears, quinces, apples, plums, cherries, grapes, strawberries, gooseberries, currants, and raspberries. The fruit, of whatever kind it may be, is confected by boiling it in a thick clarified syrup of sugar, until it is about half cooked.[45] Dry confects are made by boiling the fruit a little in syrup, and then drying it with a moderate heat in an oven. The ancients confected with honey; but, at present, sugar is deemed more suitable for this purpose, and is almost exclusively employed.

4. Jellies resemble a thin transparent glue, or size. They are made by mixing the juice of the fruits mentioned in the preceding paragraph, with a due proportion of sugar, and then boiling the composition down to a proper consistence. Jellies are also made of the flesh of animals; but such preparations cannot be long kept, as they soon become corrupt.

5. Marmalades are thin pastes, usually made of the pulp of fruits that have some consistence, and about an equal weight of sugar. Pastes are similar to marmalades, in their materials, and mode of preparation. The difference consists only in their being reduced by evaporation to a consistence, which renders them capable of retaining a form, when put into moulds, and dried in an oven.

6. Conserves are a species of dry confects, compounded of sugar and flowers. The flowers usually employed, are,—roses, mallows, rosemary, orange, violets, jessamine, pistachoes, citrons, and sloes. Orange-peel is also used for the same purpose.

7. Candies are made of clarified sugar, reduced by evaporation to a suitable degree of consistence. They receive their name from the essence, or substance, employed in giving them the required flavour.

8. Sugar-plums are small fruits, seeds, little pieces of bark, or odoriferous and aromatic roots, incrusted with hard sugar. These trifles are variously denominated; but, in most cases, according to the name of the substance inclosed by the incrustation.

9. Ice-cream is an article of agreeable refreshment in hot weather. It is sold in confectionary shops, as well as at the public gardens, and other places of temporary[46] resort in cities. It is composed, chiefly, of milk or cream, fruit, and lemon-juice. It is prepared by beating the materials well together, and rubbing them through a fine hair sieve. The congelation is effected by placing the containing vessel in one which is somewhat larger, and filling the surrounding vacancy with a mixture of salt and fine ice.

10. Cakes are made of a great variety of ingredients; the principal of which are, flour, butter, eggs, sugar, water, milk, cream, yeast, wine, brandy, raisins, currants, caraway, lemon, orange, almonds, cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, cloves, and ginger. The different combinations of these materials, produce so great a variety of cakes, that it would be tedious to detail even their names.

11. The confectioner, in addition to those articles which may be considered peculiar to his business, deals in various kinds of fruits and nuts, which grow in different climates. He also sells a variety of pickles, which he usually procures from those who make it a business to prepare them.

12. Soda-water is likewise often sold by the confectioner. This agreeable drink is merely water, impregnated with carbonic acid gas, by means of a forcing-pump. The confectioners, however, in large cities, seldom prepare it themselves, as they can procure it at less expense, and with less trouble, ready made.

13. Sometimes, the business of the pastry-cook is united with that of the confectioner, especially with that branch of it which relates to making cakes. Pies and tarts consist of paste, which, in baking, becomes a crust, and some kind of fruit or meat, or both, with suitable seasoning. The art of making pies and tarts is practised, more or less, in every family: it is not, therefore, essential to be particular in naming the materials employed, or the manner in which they are combined.

1. Brewing is the art of preparing a liquor, which has received the general denomination of beer. This beverage can be brewed from any kind of farinaceous grain; but, on various accounts, barley is usually preferred. It is prepared for the brewer's use by converting it into malt, which is effected by the following process.

2. The grain is soaked in a cistern of water about two days, or until it is completely saturated with that fluid. It is then taken out, and spread upon a floor in a layer nearly two feet thick. When the inside of this heap begins to grow warm, and the kernels to germinate, the maltster checks the rapid growth of the grain in that situation by changing it to the outside.[48] This operation is continued, until the saccharine matter in the barley has been sufficiently evolved by the natural process of germination.

3. The grain is next transferred to the kiln, which is an iron or tile floor, perforated with small holes, and moderately heated beneath with a fire of coke or stone coal. Here, the grain is thoroughly dried, and the principle of germination completely destroyed. The malt thus made is prepared for being brewed, by crushing it in a common mill, or between rollers. Malting, in Great Britain, and in some other parts of Europe, is a business distinct from brewing; but, in the United States, the brewers generally make their own malt.

4. The first part of the process of brewing is called mashing. This is performed in a large tub, or tun, having two bottoms. The upper one, consisting of several moveable pieces, is perforated with a great number of small holes; the other, though tight and immoveable at the edges, has several large holes, furnished with ducts, which lead to a cistern beneath.

5. The malt, designed for one mashing, is spread in an even layer on the upper bottom, and thoroughly saturated and incorporated with water nearly boiling, by means of iron rakes, which are made to revolve and move round in the tub by the aid of machinery. The water, together with the soluble parts of the malt, at length passes off, through the holes before mentioned, into the reservoir beneath.

6. The malt requires to be mashed two or three times in succession with fresh quantities of water; and the product of each mashing is appropriated to making liquors of different degrees of strength.

7. The product of the mashing-tun is called wort, which, being transferred to a large copper kettle, is boiled for a considerable time with a quantity of hops, and then drawn off into large shallow cisterns,[49] called coolers. When the mixture has become cool enough to be submitted to fermentation, it is drawn off into the working tun.

8. The fermentation is effected with yeast, which, acting on the saccharine matter, disengages carbonic acid gas. This part of the process requires from eighteen to forty-eight hours, according to the degree of heat which may be in the atmosphere.

9. The beer is then drawn off into casks of different dimensions, in which it undergoes a still further fermentation, sometimes called the brewer's cleansing. During this fermentation, the froth, or yeast, works out at the bung-hole, and is received in a trough, on the edges of which the casks have been placed. The froth thus discharged from the beer, is the yeast used by the brewers.

10. The products of the brewery are denominated beer, ale, and porter. The difference between these liquors arises, chiefly, from the manner in which the malt has been prepared, the relative strength imparted to each, and the extent to which the fermentation has been carried.

11. There are several kinds of beer; such as table beer, half and half, and strong beer. They are adapted to use soon after being brewed, and differ from each other but little, except in the degree of their strength.

12. Ale and porter are called stock liquors; because, not being designed for immediate consumption, they are kept for a considerable time, that they may improve in quality. Porter is usually prepared for consumption by putting it into bottles. This is done either at the brewery, or in bottling establishments. In the latter case, the liquor is purchased in large quantities from the brewer by persons who make it their business to supply retailers and private families.

13. We have evidence that fermented liquor was[50] in use three thousand years ago. It was first used in Egypt, whence it passed into adjacent countries, and afterward into Spain, France, and England. It was sometimes called the wine of barley; and one kind of it was denominated Pelusian drink, from the city Pelusium, where it was first made.

14. Among the nations of modern times, the English are the most celebrated for brewing good liquors. London porter is especially in great repute, not only in that city, but in distant countries. Much fermented liquor of the different kinds, is consumed in the United States, where it is also made in considerable perfection.

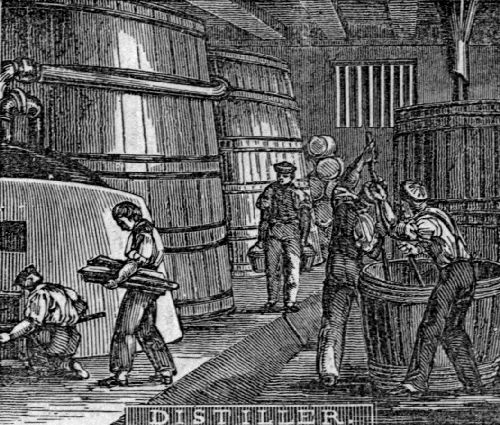

1. Although alcohol can be extracted from any substance containing saccharine matter, yet sugar-cane, grapes, apples, peaches, rye, corn, and rice, on account of their abundance, and superior adaptation to the purpose, are more commonly used than any other. As whiskey is the chief article of this kind, manufactured in the United States, it will be selected to illustrate the general principles of distillation.

2. Corn and rye are the materials from which this liquor is mostly extracted; and these are used either together or separately, at the option of the distiller. The meal is scalded and mashed in a large tub: it is then permitted to stand, until it has become a little sweet, when more water is poured upon it, and, at a suitable temperature, a quantity of yeast is added. To aid in producing rapid fermentation, a little malt is sprinkled on the top.

3. After an adequate fermentation has taken place, the beer, as it is called, is transferred to a large close tub, from the top of which leads a tube extending to the worm in another tub filled with cold water. The[51] worm is a long pewter tube, twisted spirally, that it may occupy a small space.

4. The beer is heated in the close tub, by means of steam, which is conveyed to it, from a large kettle or boiler, by a copper or iron pipe. The heat causes the alcoholic particles to rise like vapour, and pass into the worm, where they are condensed into a watery fluid, which passes out into a receiver.

5. At first, pure alcohol distils from the worm; but the produce becomes gradually weaker, until, at length, the spirit in the beer being exhausted, it consists only of water condensed from steam. The remains of the beer are given as feed to hogs and cattle.

6. Brandy is distilled from grapes, rum from sugar-cane, arrack from rice, whiskey from various kinds of grain, peach-brandy from peaches, and cider-brandy from apples.

7. The great variety of articles employed in the productions of different kinds of ardent spirits, must necessarily vary the process of distillation in some particulars; but, in all cases, fermentation and heat are necessary to disengage the alcoholic properties of the saccharine matter, and also an apparatus for condensing the same from a gaseous to a liquid form. In some countries, the alembic is used as a condenser, instead of a worm. The form of this instrument is much like that of the retort; and when applied, it is screwed upon the top of the boiler.

8. Spirits, which come to market in a crude state, are sometimes distilled for the purpose of improving their quality, or for disguising them with drugs and colouring substances, that they may resemble superior liquors. The process by which they are thus changed, or improved, is called rectification. Many distilleries in large cities, are employed in this branch of business.[52]

9. There is, perhaps, no kind of merchandise in which the public is more deceived, than in the quality of ardent spirits and wines. To illustrate this, it is only necessary to observe, that Holland gin is made by distilling French brandy with juniper-berries; but most of the spirits which are vended under that name, consist only of rum or whiskey, flavoured with the oil of turpentine. Genuine French brandy is distilled from grapes; but the article usually sold under that denomination, is whiskey or rum coloured with treacle or scorched sugar, and flavoured with the oil of wine, or some kind of drug.

10. The ancient Greeks and Romans were acquainted with an instrument for distillation, which they denominated ambix. This was adopted, a long time afterward, by the Arabian alchemists, for making their chemical experiments; but they made some improvements in its construction, and changed its name to alembic.

11. The ancients, however, knew nothing of alcohol. The method of extracting this intoxicating substance, was probably discovered some time in the twelfth or thirteenth century; but, for many ages after the discovery, it was used only as a medicine, and was kept for sale exclusively in apothecary shops. It is now used as a common article of stimulation, in almost every quarter of the globe.

12. But the opinion is becoming general, among all civilized people, that the use of alcohol, for this purpose, is destructive of health, and the primary cause of most of the crimes and pauperism in all places, where its consumption is common. The formation of Temperance Societies, and the publication of their reports, together with the extensive circulation of periodical papers, devoted to the cause of temperance, have already diminished, to a very great extent, the use of spirituous liquors.[53]

13. Although the ancients knew nothing of distilling alcohol, yet they were well versed in the art of making wine. We read of the vineyard, as far back as the time of Noah, the second father of nations; and, from that period to the present, the grape has been the object of careful cultivation, in all civilized nations, where the climate and soil were adapted to the purpose.

14. The general process of making wine from grapes, is as follows. The grapes, when gathered, are crushed by treading them with the feet, and rubbing them in the hands, or by some other means, with the view to press out the juice. The whole is then suffered to stand in the vat, until it has passed through what is termed the vinous fermentation, when the juice, which, in this state, is termed must, is drawn off into open vessels, where it remains until the pressing of the husks is finished.

15. The husks are submitted, in hair bags, to the press; and the must which is the result of this operation, is mixed with that drawn from the vat. The whole is then put into casks, where it undergoes another fermentation, called the spirituous, which occupies from six to twelve days. The casks are then bunged up, and suffered to stand a few weeks, when the wine is racked off from the lees, and again returned to the same casks, after they have been perfectly cleansed. Two such rackings generally render the wine clear and brilliant.

16. In many cases, sugar, brandy, and flavouring substances, are necessary, to render the wine palatable; but the best kinds of grapes seldom require any of these additions. Wine-merchants often adulterate their wines in various ways, and afterwards sell them for those which are genuine. To correct acidity, and some other unpleasant qualities, lead, copper, antimony, and corrosive sublimate, are often used[54] by the dealers in wine; though the practice is attended with deleterious effects to the health of the consumers.

17. The wines most usually met with in this country, are known by the following denominations, viz., Madeira and Teneriffe, from islands of the same names; Port, from Portugal; Sherry and Malaga, from Spain; Champagne, Burgundy, and Claret, from France; and Hock, from Germany.

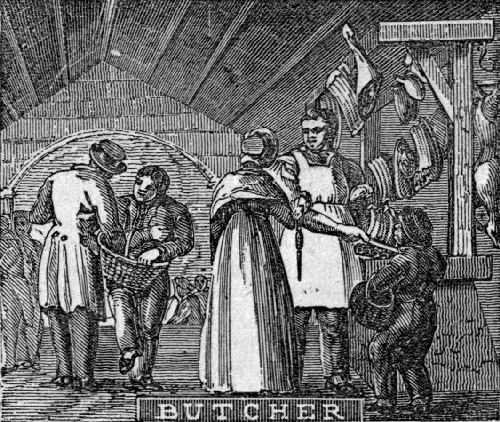

1. Man is designed by nature, to subsist on vegetable and animal food. This is obvious, from the structure of his organs of mastication and digestion. It does not follow, however, that animal food is, in all cases, positively required. In some countries, the mass of the people subsist chiefly or entirely on vegetables. This is especially the case in the East Indies, where rice and fruits are the chief articles of food.

2. On the other hand, the people who live in the higher latitudes subsist principally on the flesh of animals. This is preferred, not only because it is better suited to brace the system against the rigours of the climate, but because it is most easily provided.[56] In temperate climates, a due proportion of both animal and vegetable substances is consumed.

3. Although the skins of beasts were used for the purpose of clothing, soon after the fall of man, we have no intimation from the Scriptures, that their flesh, or that of any other animal, was used, until after the flood. The Divine permission was then given to Noah and his posterity, to use, for this purpose, "every moving thing that liveth." But in the law of Moses, delivered several centuries after this period, many exceptions are to be found, which were intended to apply only to the Jewish people. These restrictions were removed, on the introduction of Christianity. The unbelieving Jews, however, still adhere to their ancient law.

4. The doctrine of transmigration has had a great influence in diminishing the consumption of animal food. This absurd notion arose somewhere in Central Asia, and, at a very early period, it spread into Egypt, Greece, Italy, and finally among the remote countries of the ancient world. It is still entertained by the heathen nations of Eastern Asia, by the tribes in the vicinity of Mount Caucasus, and by some of the American savages, and African negroes.