This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Satan Sanderson

Author: Hallie Erminie Rives

Release Date: May 13, 2012 [eBook #39689]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SATAN SANDERSON***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/satansanderson00riverich |

SATAN SANDERSON

A FURNACE OF EARTH

HEARTS COURAGEOUS

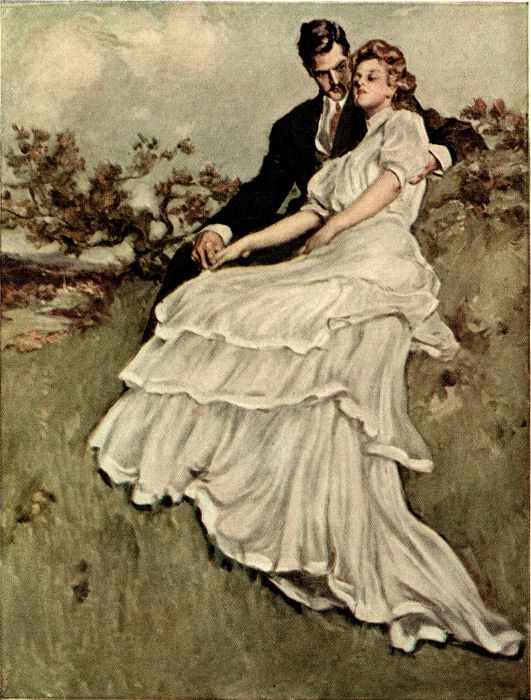

Illustrated by A. B. Wenzell

THE CASTAWAY

Illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy

TALES FROM DICKENS

Illustrated by Reginald B. Birch

SATAN SANDERSON

Illustrated by A. B. Wenzell

Author of

The Castaway, Hearts Courageous, etc.

With Illustrations by

A. B. WENZELL

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright 1907

The Bobbs-Merrill Company

——

August

PRESS OF

BRAUNWORTH & CO.

BOOKBINDERS AND PRINTERS

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | As a Man Sows | 1 |

| II | Doctor Moreau | 15 |

| III | The Coming of a Prodigal | 20 |

| IV | The Lane That Had No Turning | 32 |

| V | The Bishop Speaks | 47 |

| VI | What Came of a Wedding | 50 |

| VII | Out of the Dark | 60 |

| VIII | Am I My Brother's Keeper? | 68 |

| IX | After a Year | 75 |

| X | The Game | 85 |

| XI | Hallelujah Jones Takes a Hand | 95 |

| XII | The Fall of the Curtain | 105 |

| XIII | The Closed Door | 108 |

| XIV | The Woman Who Remembered | 115 |

| XV | The Man Who Had Forgotten | 125 |

| XVI | The Awakening | 137 |

| XVII | At the Turn of the Trail | 147 |

| XVIII | The Strength of the Weak | 155 |

| XIX | The Evil Eye | 160 |

| XX | Mrs. Halloran Tells a Story | 167 |

| XXI | A Visit and a Violin | 171 |

| XXII | The Passing of Prendergast | 179 |

| XXIII | A Race With Death | 187 |

| XXIV | On Smoky Mountain | 198 |

| XXV | The Open Window | 210 |

| XXVI | Like a Thief in the Night | 222 |

| XXVII | Into the Golden Sunset | 229 |

| XXVIII | The Tenantless House | 238 |

| XXIX | The Call of Love | 250 |

| XXX | In a Forest of Arden | 259 |

| XXXI | The Revelation of Hallelujah Jones | 269 |

| XXXII | The White Horse Skin | 277 |

| XXXIII | The Renegade | 282 |

| XXXIV | The Temptation | 289 |

| XXXV | Felder Takes a Case | 302 |

| XXXVI | The Hand at the Door | 305 |

| XXXVII | The Penitent Thief | 311 |

| XXXVIII | A Day for the State | 319 |

| XXXIX | The Unsummoned Witness | 331 |

| XL | Fate's Way | 335 |

| XLI | Felder Walks With Doctor Brent | 339 |

| XLII | The Reckoning | 344 |

| XLIII | The Little Gold Cross | 353 |

| XLIV | The Impostor | 360 |

| XLV | An Appeal to Cæsar | 369 |

| XLVI | Face to Face | 376 |

| XLVII | Between the Millstones | 384 |

| XLVIII | The Verdict | 390 |

| XLIX | The Crimson Disk | 395 |

| L | When Dreams Come True | 397 |

SATAN SANDERSON

SATAN SANDERSON

"To my son Hugh, in return for the care and sorrow he has caused me all the days of his life, for his dissolute career and his desertion, I do give and bequeath the sum of one thousand dollars and the memory of his misspent youth."

It was very quiet in the wide, richly furnished library. The May night was still, but a faint suspiration, heavy with the fragrance of jasmin flowers, stirred the Venetian blind before the open window and rustled the moon-silvered leaves of the aspens outside. As the incisive professional pronouncement of the judge cut through the lamp-lighted silence, the grim, furrowed face with its sunken eyes and gray military mustaches on the pillow of the wheel-chair set more grimly; a girl seated in the damask shadow of the fire-screen caught her breath; and from across the polished table the Reverend Henry Sanderson turned his handsome, clean-shaven face and looked at the old man.

A peevish misogynist the neighborhood labeled the latter, with the parish chapel for hobby, and for thorn-in-the-flesh this only son Hugh, a black sheep whose open breaches of decorum the town had borne as best it might, till the tradition of his forebears took him off to an eastern university. A reckless life there and three wastrel years abroad, had sent him back to resume his peccadilloes on a larger scale, to quarrel bitterly with his father, and to leave his home in anger. In what rough business of life was Hugh now chewing the cud of his folly? Harry Sanderson was wondering.

"Wait," came the querulous voice from the chair. "Write in 'graceless' before the word 'desertion'."

"For his dissolute career and his—graceless—desertion," repeated the lawyer, the parchment crackling under his pen.

The stubborn antagonism that was a part of David Stires' nature flared under the bushy eyebrows. "As a man sows!" he said, a kind of bitter jocularity in the tone. "That should be the text, if this sermon of mine needed any, Sanderson! It won't have as large an audience as your discourses draw, but it will be remembered by one of its hearers, at least."

Judge Conwell glanced curiously at Harry Sanderson as he blotted the emendation. He knew the liking[Pg 3] of the cross-grained and taciturn old invalid—St. James' richest parishioner—for this young man of twenty-five who had come to the parish only two months before, fresh from his theological studies, to fill a place temporarily vacant—and had stayed by sheer force of personality. He wondered if, aside from natural magnetic qualities, this liking had not been due first of all to the curious resemblance between the young minister and the absent son whom David Stires was disinheriting. For, as far as mold of feature went, the young minister and the ne'er-do-well might have been twin brothers; yet a totally different manner and coloring made this likeness rather suggestive than striking.

No one, perhaps, had ever interested the community more than had Harry Sanderson. He had entered upon his duties with the marks of youth, good looks, self-possession and an ample income thick upon him, and had brought with him a peculiar charm of manner and an apparent incapacity for doing things in a hackneyed way. Convention sat lightly upon Harry Sanderson. He recognized few precedents, either in the new methods and millinery with which he had invested the service, or in his personal habits. Instead of attending the meeting of St. Andrew's Guild, after the constant custom of his predecessor, he was apt to be found [Pg 4]playing his violin (a passion with him) in the smart study that adjoined the Gothic chapel where he shepherded his fashionable flock, or tramping across the country with a briar pipe in his mouth and his brown spaniel "Rummy" nosing at his heels. His athletic frame and clean-chiselled features made him a rare figure for the reading-desk, as his violin practice, the cut of his golf-flannels, the immaculate elegance of his motor-car—even the white carnation he affected in his buttonhole—made him for the younger men a goodly pattern of the cloth; and it had speedily grown to be the fashion to hear the brilliant young minister, to memorize his classical aphorisms or to look up his latest quotation from Keats or Walter Pater. So that Harry Sanderson, whose innovations had at first disturbed and ruffled the sensibilities of those who would have preferred a fogy, in the end had drifted, apparently without special effort, into a far wider popularity than that which bowed to the whim of the old invalid in the white house in the aspens.

Something of all this was in the lawyer's mind as he paused—a perfunctory pause—before he continued:

"... I do give and bequeath the sum of one thousand dollars, and the memory of his misspent youth."

Harry Sanderson's eyes had wandered from the chair to the slim figure of the girl who sat by the screen. This was Jessica Holme, the orphaned daughter of a friend of the old man's early years, who had recently come to the house in the aspens to fill the void left by Hugh's departure. Harry could see the contour of throat and wrists, the wild-rose mesh of the skin against the Romney-blue gown, the plenteous red-bronze hair uncoiled and falling in a single braid, and the shadowy pathos of her eyes. Clear hazel eyes they were, wide and full, but there was in them no depth of expression—for Jessica Holme was blind. As the crisp deliberate accent pointed the judicial period, as with a subterranean echo of irrefutable condemnation, Harry saw her under lip indrawn, her hands clasp tightly, then unclasp in her lap. Pliant, graceful hands, he thought, which even blindness could not make maladroit. In the chapel porch stood the figure of an angel which she had modelled solely by the wonderful touch in the finger-tips.

"Go on," rasped the old man.

"The residue of my estate, real and personal, I do give and bequeath to my ward, Jessica Holme, to be and become—"

He broke off suddenly, for the girl was kneeling by the chair, groping for the restless hand that wandered[Pg 6] on the afghan, and crying in a strained, agitated voice: "No ... no ... you must not! Please, please! I never could bear it!"

"Why not?" The old man's irritant query was belligerent. "Why not? What is there for you to bear, I'd like to know!"

"He is your son!"

"In the eyes of the law, yes. But not otherwise!" His voice rose. "What has he done to deserve anything from me? What has he had all his life but kindness? And how has he repaid it? By being a waster and a prodigal. By setting me in contempt, and finally by forsaking me in my old age for his own paths of ribaldry."

The girl shook her head. "You don't know where he is now, or what he is doing. Oh, he was wild and reckless, I have no doubt. But when he quarrelled and left you, wasn't it perhaps because he was too quick-tempered? And if he hasn't come back, isn't it perhaps because he is too proud? Why, he wouldn't be your son if he weren't proud! No matter how sorry he might be, it would make no difference then. I could give him the money you had given me, but I couldn't change the fact. You, his own father, would have disowned him, disinherited him, taken away his birthright!"

"And richly he'd deserve it!" he snapped, his bent[Pg 7] fingers plucking angrily at the wool of the afghan. "He doesn't want a father or a home. He wants his own way and a freedom that is license! I know him. You don't; you never saw him."

"I never saw you either," she said, a little sadly.

"Come," he answered a shade more gently. "I didn't mean your eyes, my dear! I mean that you never met him in your life. He had shaken off the dust of his feet against this house before you came to brighten it, Jessica. I've not forgiven him seven times; I've forgiven him seventy times seven. But he doesn't want forgiveness. To him I am only 'the old man' who refused to 'put up' longer for his fopperies and extravagances! When he left this house six months ago, he declared he would never enter it again. Very well—let him stay away! He shan't come back when I am in my grave, to play ducks and drakes with the money he misuses! And I've fixed it so that you won't be able to give it away either, Jessica. Give me the pen," he said to the judge, "and, Sanderson, will you ring? We shall need the butler to witness with you."

As Harry Sanderson rose to his feet the girl, still kneeling, turned half about with a hopeless gesture. "Oh, won't you help me?" she said. She spoke more to herself, it seemed, than to either of the men who waited.[Pg 8] Harry's face was in the shadow. The lawyer with careful deliberation was putting a new pen into the holder.

"Sanderson," said the old man with bitter fierceness, lifting his hand, "I dare say you think I am hard; but I tell you there has never been a day since Hugh was born when I wouldn't have laid down my life for him! You are so like! When I look at you, I seem to see him as he might have been but for his own wayward choice! If he were only as like you in other things as he is in feature! You are nearly the same age; you went to the same college, I believe; you have had the same advantages and the same temptations. Yet you, an orphan, come out a divinity student, and Hugh—my son!—comes out a roisterer with gambling debts, a member of the 'fast set,' one of a dissolute fraternity known as 'The Saints,' whose very existence, no doubt, was a shame to the institution!"

Harry Sanderson turned slowly to the light. A strange panorama in that moment had flashed through his brain—kaleidoscopic pictures of an earlier reckless era when he had not been known as the "Reverend Henry Sanderson." An odd, sensitive flush burned his forehead. The hand he had outstretched to the bell-cord dropped to his side, and he said, with painful steadiness:[Pg 9]

"I think I ought to say that I was the founder, and at the time you speak of, the Abbot of The Saints."

The pen rattled against the mahogany, as the man of law leaned back to regard the speaker with a stare of surprise whetted with a keen edge of satiric amusement. The old man sat silent, and the girl crouched by the chair with parted lips. The look in Harry's face was not now that of the decorative young churchman of the Sabbath surplice. It held a keen electric sense of the sharp contrasts of life, touched with a wakeful pain of conscience.

"I was in the same year with Hugh," Harry went on. "We sowed our wild oats together—a tidy crop, I fancy, for us both. That page of my life is pasted down. I speak of it now because it would be cowardly not to. I have not seen Hugh since college closed four years ago. But then I was all you have called him—a waster and a prodigal. And I was more; for while others followed, I led. At college I was known as 'Satan Sanderson'."

He stopped. The old man cleared his throat, but did not speak. He was looking at Harry fixedly. In the pause the girl found his gnarled hand and laid her cheek against it. Harry leaned an elbow upon the mantelpiece as he continued, in a low voice:

"Colleges are not moral strait-jackets. Men have[Pg 10] there to cast about, try themselves and find their bearings. They are in hand-touch with temptation, and out of earshot of the warnings of experience. The mental and moral machine lacks a governor. Slips of the cog then may or may not count seriously to character in the end. They sometimes signify only a phase. They may be mere idiosyncrasy. I have thought that it stood in this case," he added with the glimmer of a smile, "with Satan Sanderson; he seems to me from this focus to be quite another individual from the present rector of St. James."

"It is only the Hugh of the present that I am dealing with," interposed the old man. For David Stires was just and he was feeling a grim respect for Harry's honesty.

Harry acknowledged the brusque kindliness of the tone with a little motion of the hand. As he spoke he had been feeling his way through a maze of contradictory impulses. For a moment he had been back in that old irresponsible time; the Hugh he had known then had sprung to his mind's eye—an imitative idler, with a certain grace and brilliancy of manner that made him hail-fellow-well-met, but withal shallow, foppish and incorrigible, a cheap and shabby imitator of the outward manner, not the inner graces, of [Pg 11]good-fellowship. Yet Hugh had been one of his own "fast set"; they had called him "Satan's shadow," a tribute to the actual resemblance as well as to the palpable imitation he affected. Harry shivered a little. The situation seemed, in antic irony, to be reversing itself. It was as if not alone Hugh, but he, Harry Sanderson, in the person of that past of his, was now brought to bar for judgment in that room. For the instant he forgot how utterly characterless Hugh had shown himself of old, how devoid of all desire for rehabilitation his present reputation in the town argued him. At that moment it seemed as if in saving Hugh from this condemnation, he was pleading for himself as he had been—for the further chance which he, but for circumstances, perhaps, had needed, too. His mind, working swiftly, told him that no appeal to mere sentiment would suffice—he must touch another note. As he paused, his eyes wandered to an oil portrait on the wall, and suddenly he saw his way.

"You," he said, "have lived a life of just and balanced action. It is bred in the bone. You hate all loose conduct, and rightly. You hate it most in Hugh for the simple reason that he is your son. The very relation makes it more impossible to countenance. He should be like you—of temperate and prudent habit.[Pg 12] But did you and he start on equal terms? Your grandfather was a Standish; your ancestry was undiluted Puritan. Did Hugh have all your fund of resistance?"

The old man's gaze for the first time left Harry's face. It lifted for an instant to the portrait at which Harry had glanced—a picture of Hugh's dark gipsy-like mother, painted in the month of her marriage, and the year of her death—and in that instant the stern lines about the mouth relaxed a little. Harry had laid his finger on the deepest cord of feeling in the old man's gruff nature. The glow that had smoldered in the cavernous eyes faded and a troubled cloud came to belie their former wrath.

"'As a man sows,' you say, and you deny him another seeding and it may be a better harvest. You shut the door;—and if you shut it, it may not swing open again! With me it was the turning of a long lane. Hugh perhaps has not turned—yet." A breath of that past life had swept anew over Harry, the old shuddering recoil again had rushed upon him. It gave his voice a curious energy as he ended: "And I have seen how far a man may go and yet—come back!"

There was a pause. The judge had an inspiration. He folded the parchment, and rose.

"Perhaps it would be as well," he said in a [Pg 13]matter-of-fact way, "if the signing be left open for the present. Last testaments, whatever their provisions, are more or less serious matters, and in your case,"—he nodded toward the occupant of the chair—"there is not the element of necessitous haste. Of course," he added tentatively, "I am at your service at any time."

He rose as he spoke, and laid the document on the table.

For a moment David Stires sat in silence. Then he said, with a glint of the old ironic fire: "You should have been a special pleader, Sanderson. There's no client too bad for them to make out a case for! Well ... well ... we won't sign to-night. I will read it over again when I am more equal to it."

His visitors made their adieux, and as the door closed upon them, the girl came to the wheel-chair and wistfully drew the parchment from his hands.

"You're a good girl, Jessica," he said, "too good to a rascal you've never known. But there—go to your room, child. I can ring for Blake when I want anything."

For long the old man sat alone, musing in his chair, his eyes on the painted portrait on the wall. The image there was just as young and fair and joyous as though yesterday she had stood in bridal white beside him,[Pg 14] instead of so long ago—so long ago! His lips moved. "In return for the care and sorrow," he muttered, "all the days of his life!"

At length he sighed and took up a magazine. He was thinking of Harry Sanderson.

"How like!" he said aloud. "So Sanderson sowed his wild oats, too!... When he stood there, with the light on his face—when he talked—I—I could almost have thought it was Hugh!"

Harry Sanderson and the judge parted at the gate, and Harry walked slowly home in the moonlight.

The youthful follies that he had resurrected when he had called himself his old nickname of "Satan Sanderson" he had left so far behind him, had buried so deep, that the ironic turn of circumstance that had dragged them into view, sorry skeletons, seemed intrusive and malicious. Not that he was desirous of sailing under false colors; he had brought into his new career more than a soupçon of the old indifference to popular estimation, the old propensity to go his own way and to care very little what others thought of him. The sting was a nearer one; it was his own present of fair example and good repute that recoiled with a fastidious sense of abasement from the recollection.

As he stood in the library, his hand on the mantelpiece, he had been painfully conscious of detail. He remembered vividly the half amused smile of the lawyer, the silent, listening attitude of the girl crouched[Pg 16] by the wheel-chair. He had seen Jessica Holme scarcely a half-dozen times, then only at service, or driving behind the Stires bays. That moment when she had thrown herself beside the old man's chair to plead for the son she had never seen—an instant revelation wrought by the strenuous agitation of the moment—had been illuminative; it had given him a lightning-like glimpse into the unplummeted deeps of womanly unselfishness and sympathy. He flushed suddenly. He had not realized that she was so beautiful.

What a tragedy to be blind, for a woman with temperament, talent and heart! To be sightless to the beauty of such a perfect night, with that silver bridge of stars, those far hills rising like purple tulips—an alluring night for those who saw! The picture she had made, kneeling with the lamplight rosying in her hair, hung before him. The flower-scent with which the room had been full was in his nostrils, and verses flashed into his mind:

Under his thought the lines repeated themselves in a mystical monotone.

He had saved an old college-mate from possible disinheritance and the grind of poverty, for David Stires' health was precarious. He thought of this with a tinge of satisfaction. The least of that peculiar clan, one who had held his place, not by likable qualities but by a versatile talent for entertainment, Hugh Stires yet deserved thus much. Harry Sanderson had never shirked an obligation. "As a man sows"—the old man's words recurred to him. Did any man reap what he sowed, after all? Was he, the "Satan Sanderson" that was, getting his deserts?

"If there is a Providence that parcels out our earthly rewards and penalties," he said to himself, "it has missed me! If there is any virtue in example, I ought to be the black sheep. Hugh never influenced anybody; he was a natural camp-follower. I was in the van. All I said was a sneer, all I did a challenge to respectability. Yet here I am, a shepherd of the faithful, a brother of Aaron!"

Harry stepped more briskly along the gas-lighted square, nodding now and then to an acquaintance, and bowing on a crossing to a carriage that bowled by with the wife of the Very Reverend, the Bishop of the Diocese. As he passed a darkened entrance, a door with a small barred window in its upper panel opened, and a[Pg 18] man came into the street—a man light and fair with watery blue eyes and a drooping, blond mustache. He lifted his silk hat with a faded, Chesterfieldian grace as he came down the steps with outstretched hand.

"My dear Sanderson!" he said effusively. "In the interest of sweetness and light, where did you stumble on your new chauffeur? His style is the admiration of the town. Next to having your gift of eloquence, I can think of nothing so splendid as possessing such a tonneau! The city is in your debt; you have shown it that even a cleric can be 'fast' without reproach!"

Harry Sanderson saw the weak features and ingratiating smile, the clayey, dry-lined skin and restless eyes, but he did not seem to see the extended hand. He did not smile at the badinage as he replied evenly:

"My chauffeur, Doctor, is a Finn; and his style is his own. I see, however, that I must decrease his speed-limit."

Doctor Moreau stood a moment looking after him, his womanish hands clenching and his cynical glance full of an evil light.

"The university prig!" he said under his breath. "Doesn't he take himself for the whole thing, with his money and his buttonhole bouquet, and his smug self-righteousness! He thinks I'm hardly fit to speak to[Pg 19] since I've had to quit the hospital! I'd like to take him down a peg!"

He watched the alert, ministerial figure till it rounded the corner. He looked up and down the street, hesitating; then, shrugging his shoulders, he turned and reëntered the door with the narrow barred window.

The later night was very still and the moon, lifting like a paper lantern over the aspen tops, silvered all the landscape. In its placid radiance the white house loomed in a ghostly pallor. The windows of one side were blank, but behind the library shade the bulbous lamp still drowsed like a monster glow-worm. From the shadowy side of the building stretched a narrow L, its front covered by a rose-trellis, whose pale blossoms in the soft night air mingled their delicate fragrance with that of the jasmin.

Save for the one bright pane, there seemed now no life or movement in the house. But outside, in the moonlight, a lurching, shabbily-clothed figure moved, making his uncertain way with the deliberation of composed inebriety. The sash of the window was raised a few inches and he nodded sagely at the yellow shade.

"Gay old silver-top!" he hiccoughed; "see you in the morning!"

He capsized against an althea bush and shook his[Pg 21] head with owlish gravity as he disentangled himself. Then he staggered serenely to the rose-trellis, and, choosing its angle with an assurance that betrayed ancient practice, climbed to the upper window, shot its bolt with a knife, and let himself in. He painstakingly closed both windows and inner blinds, before he turned on an electric light.

In the room in which he now stood he had stored his boyish treasures and shirked his maturer tasks. It should have had deeper human associations, too, for once, before the house had been enlarged to its present proportions, that chamber had been his mother's. The Maréchal Niel rose that clambered to the window-sill had been planted by her hand. In that room he had been born. And in it had occurred that sharp, corrosive quarrel with his father on the night he had flung himself from the house vowing never to return.

As Hugh Stires stood looking about him, it seemed for an instant to his clouded senses that the past six months of wandering and unsavory adventure were a dream. There was his bed, with its clean linen sheets and soft pillows. How he would like to lie down just as he was and sleep a full round of the clock! Last night he had slept—where had he slept? He had forgotten for the moment. He looked longingly at the spotless[Pg 22] coverlid. No; some one might appear, and it would not do to be seen in his present condition. It was scarcely ten. Time enough for that afterward.

He drew out the drawer of a chiffonier, opened a closet and gloated over the order and plenty of their contents. He made difficult selection from these, and, steadying his progress by wall and chair, opened the door of an adjoining bath-room. It contained a circular bath with a needle shower. Without removing his clothing, he climbed into this, balancing himself with an effort, found and turned the cold faucet, and let the icy water, chilled from artesian depths, trickle over him in a hundred stinging needle-points.

It was a very different figure that reëntered the larger room a half-hour later, from the slinking mud-lark that had climbed the rose-trellis. The old Hugh lay, a heap of soiled and sodden garments; the new stood forth shaven, fragrant with fresh linen and clean and fit apparel. The maudlin had vanished, the gaze was unvexed and bright, the whole man seemed to have settled into himself, to have grown trim, nonchalant, debonair. He held up his hand, palm outward, between the electric globe and his eye—there was not a tremor of nerve or muscle. He smiled. No headache, no fever, no [Pg 23]uncertain feet or trembling hands or swollen tongue, after more than a week of deep potations. He could still "sober-up" as he used to do (with Blake the butler to help him) when it had been a mere matter of an evening's tipsiness! And how fine it felt to be decently clad again!

He crossed to a cheval-glass. The dark handsome face that looked out at him was clean-cut and aristocratic, perfect save for one blemish—a pale line that slanted across the right brow, a birth-mark, resembling a scar. All his life this mark had been an eyesore to its owner. It had a trick of turning an evil red under the stress of anger or emotion.

On the features, young and vigorous as they were, subtle lines of self-indulgence had already set themselves, and beneath their expression, cavalier and caressing, lay the unmistakable stigmata of inherited weakness. But these the gazer did not see. He regarded himself with egotistic complacency. Here he was, just as sound as ever. He had had his fling, and taught "the Governor" that he could get along well enough without any paternal help if he chose. Needs must when the devil drives, but his father should never guess the coarse and desperate expediences that had sickened him of his bargain, or the stringent calculation of his return. He[Pg 24] was no milksop, either, to come sneaking to him with his hat in his hand. When he saw him now, he would be dressed as the gentleman he was!

He attentively surveyed the room. It was clean and dusted—evidently it had been carefully tended. He might have stepped out of it yesterday. There in a corner was his banjo. On the edge of a silver tray was a half-consumed cigar. It crumbled between his fingers. He had been smoking that cigar when his father had entered the room on that last night. There, too, was the deck of cards he had angrily flung on to the table when he left. Not a thing had been disturbed—yes, one thing. His portrait, that had hung over his bed, was not in its place. A momentary sense of trepidation rushed through him. Could his father really have meant all he had said in his rage? Did he really mean to disown him?

For an instant he faced the hall door with clenched hands. Somewhere in the house, unconscious of his presence, was that ward of whose coming he had learned. Moreau was a good friend to have warned him! Was she part of a plan of reprisal—her presence there a tentative threat to him? Could his father mean to adopt her? Might that great house, those grounds, the bulk of his wealth, go to her, and he, the son, be left in[Pg 25] the cold? He shivered. Perhaps he had stayed away too long!

As he turned again, he heard a sound in the hall. He listened. A light step was approaching—the swish of a gown. With a sudden impulse he stepped into the embrasure of the window, as the figure of a girl paused at the door. He felt his face flush; she had thrown a crimson kimono over her white night-gown, and the apparition seemed to part the dusk of the doorway like the red breast of a robin. She held in her hands a bunch of the pale Maréchal Niel roses, and his eye caught the long rebellious sweep of her bronze hair, and the rosy tint of bare feet through the worsted meshes of her night-slippers.

To his wonder the sight of the lighted room seemed to cause her no surprise. For an instant she stood still as though listening, then entered and placed the roses in a vase on a reading-stand by the bedside.

Hugh gasped. To reach the stand the girl had passed the spot where he stood, but she had taken no note of him. Her gaze had gone by him as if he had been empty air. Then he realized the truth; Jessica Holme was blind! Moreau's letter had given him no inkling of that. So this was the girl with whom his father now threatened him! Was she counting on his not coming[Pg 26] back, waiting for the windfall? She was blind—but she was beautiful! Suppose he were to turn the tables on the old man, not only climb back into his good graces through her, but even—

The thin line on his brow sprang suddenly scarlet. What a supple, graceful arm she had! How adroit her fingers as they arranged the rose-stems! Was he already wholly blackened in her opinion? What did she think of him? Why did she bring those flowers to that empty room? Could it have been she who had kept it clean and fresh and unaltered against his return? A confident, daring look grew in his eyes; he wished she could see him in that purple tie and velvet smoking-jacket! What an opportunity for a romantic self-justification! Should he speak? Suppose it should frighten her?

Chance answered him. His respiration had conveyed to her the knowledge of a presence in the room. He heard her draw a quick breath. "Some one is here!" she whispered.

He started forward. "Wait! wait!" he said in a loud whisper, as she sprang back. But the voice seemed to startle her the more, and before he could reach her side she was gone. He heard her flying steps descend the stair, and the opening and closing of a door.

The sudden flight jarred Hugh's pleasurable sense of[Pg 27] novelty. He thrust his hands deep into his pockets. Now he was in for it! She would alarm the house, rouse the servants—he should have a staring, domestic audience for the imminent reconciliation his sobered sense told him was so necessary. Why could he not slip back into the old rut, he thought sullenly, without such a boring, perfunctory ceremony? He had intended to postpone this, if possible, until a night's sleep had fortified him. But now the sooner the ordeal was over, the better! Shrugging his shoulders, he went quickly down the stair to the library.

He had known exactly what he should see there—the vivid girl with the hue of fright in her cheeks, the shaded lamp, the wheel-chair, and the feeble old man with his furrowed face and gray mustaches. What he himself should say he had not had time to reflect.

The figure in the chair looked up as the door opened. "Hugh!" he cried, and half lifted himself from his seat. Then he settled back, and the sunken, indomitable eyes fastened themselves on his son's face.

Hugh was melodramatic—cheaply so. He saw the girl start at the name, saw her hands catch at the kimono to draw its folds over the bare white throat, saw the rich color that flooded her brow. He saw himself suddenly the moving hero of the stagery, the[Pg 28] tractive force of the situation. Real tears came to his eyes—tears of insincere feeling, due partly to the cheap whisky he had drunk that day, whose outward consequences he had so drastically banished, and partly to sheer nervous excitation.

"Father!" he said, and came and caught the gaunt hand that shook against the chair.

Then the deeps of the old man's heart were suddenly broken up. "My son!" he cried, and threw his arms about him. "Hugh—my boy, my boy!"

Jessica waited to hear no more. Thrilling with gladness, and flushing with the sudden recollection of her bare throat and feet, she slipped away to her room to creep into bed and lie wide-eyed and thinking.

What did he look like? Of his face she had never seen even a counterfeit presentment. Through what adventures had he passed? Now that he had come home, forgiving and forgiven, would he stay? He had been in his room when she entered it with the roses—must have guessed, if he had not already known, that she was blind. Would he guess that she had cared for that room, had placed fresh flowers there often and often?

Since she had come to the house in the aspens Jessica had found the imagined figure of Hugh a dominant[Pg 29] presence in a horizon lightened with a throng of new impressions. The direful catastrophe of her blindness—it had been the sudden result of an accident—had fallen like a thunderbolt upon a nature elastic and joyous. It had brought her face to face with a revelation of mental agony, made her feel herself the hapless martyr of that curt thing called Chance; one moment seeing a universe unfolding before her in line and hue, the next feeling it thrust rudely behind a gruesome blank of darkness. The two years that followed had been a period when despair had covered her; when specialists had peered with cunning instruments into her darkened eyes, to utter hopeful platitudes—and to counsel not at all. Then into her own painful self-absorption had intruded her father's death, and the very hurt of this, perhaps, had been a salving one. It had of necessity changed her whole course of living. In her new surroundings she had taken up life once more. Her alert imagination had begun to stir, to turn diffidently to new channels of exploration and interest. She had always lived largely in books and pictures, and her world was still full of ideals and of brave adventures. Gratitude had made her love the morose old invalid with his crabbed tempers; and the wandering son, choosing for pride's sake a resourceless battle with the world[Pg 30]—the very mystery of his whereabouts—had taken strong hold of her imagination. Of the quarrel which had preceded Hugh's departure, she had made her own version. That he should have come back on this very night, when the disinheritance she had dreaded had been so nearly consummated, seemed now to have an especial and an appealing significance.

Presently she rose, slipped on the red kimono, and, taking a key from the pocket of her gown, stole from the room. She ascended a stairway and unlocked the door of a wide, bare attic where the moonlight poured through a skylight in the roof upon an unfinished statue. In this statue she had begun to fashion, in the imagined figure of Hugh, her conception of the Prodigal Son; not the battered and husk-filled wayfarer of the parable, but a figure of character and pathos, erring through youthful pride and spirit. The unfinished clay no eyes had seen, for those walls bounded her especial domain.

Carefully, one by one, she unwound the wet cloths that swathed the figure. In the streaming radiance of the night, the clay looked white as snow and she a crimson ghost. She passed her fingers lightly over the features. Was the real Hugh's face like that? One day, perhaps, her own eyes would tell her, and she would finish it. Then she might show it to him, but not now.

She replaced the coverings, relocked the door, and went softly down to her bed.

When Hugh went shamefacedly up the stair from the library, the artificial glow that had tingled to his finger-tips had faded. The poise of mind, the certitude of all the faculties of eye and hand that his icy bath had given him, were yielding. The penalties he had dislodged were returning reinforced. He was rapidly becoming drunk.

He groped his way to his room, turned out the light, threw himself fully dressed upon the bed, and slept the deep sleep of deferred intoxication.

On a June day a month later, Harry Sanderson sat in his study, looking out of the window across the dim summer haze of heat, negligently smoking. On the distant hill overlooking the town was the cemetery, flanked by fields of growing corn where sulky, round-shouldered crows quarrelled and pilfered. He could see the long white marl road, bending in a broad curve between clover-stippled meadows, to skirt the willow-green bluff above the river. There, miles away, on the high bank, he could distinguish the railroad bridge, a long black skeleton spanning "the hole," a deep, fish-haunted pool, the deepest spot in the river for fifty miles. From the nearer, elm-shaded streets came the muffled clack of trade and the discordant treble of a huckster, somewhere a trolley-bell was buzzing angrily, and the impudent scream of a blue jay sheared across the monotone. Harry's gaze went past the streets—past the open square, with its chapel spire lifting from a beryl sea of foliage—to a white colonial porch, peering from between aspens that quivered in the tremulous sunlight.

The dog on the rug rose, stretching, and came to thrust an eager insinuating muzzle into its master's lap. Rummy whined, the stubby tail wagged, but his master paid no heed, and with dejected ears, he slunk out into the sunshine. Harry was looking, with brows gathered to a frown, at the far-away porch. The look was full of a troubled question, a vague misgiving, an interrogative anxiety. He was thinking of a night when he had saved the son of that house from the calamity of disinheritance—to what end?

For since that moonlighted evening of the will-making Harry had learned that the long lane had had no true turning for Hugh. He had sifted him through and through. At college he had put him down for a weakling—unballasted, misdemeanant. Now he knew him for what he really was—a moral mollusk, a scamp in embryo, a decadent, realizing an ugly propensity to a deplorable finale. A consistent career of loose living had carried Hugh far since those college days when he had been dubbed "Satan's Shadow." While to Harry Sanderson the eccentric and agnostical had then been, as it were, the mask through which his temperament looked at life, to Hugh it had spelled shipwreck. Harry Sanderson had done broadly as he pleased. He had entertained whom he listed; had gone "slumming"; had[Pg 34] once boxed to a finish, for a wager, a local pugilist whose acquaintance he affected, known as "Gentleman Jim." He had been both the hardest hitter and the hardest drinker in his class, yet withal its most brilliant student. Native character had enabled him to persist, as the exasperating function of success which dissipation declined to eliminate. But the same natural gravitation which in spite of all aberration had given Harry Sanderson classical honors, had brought Hugh Stires to the imminent brink of expulsion. And since that time, without the character which belonged to Harry as a possession, Hugh had continued to drift aimlessly on down the broad lax way of profligacy.

The conditions he found upon his return, however, had opened Hugh's eyes to the perilous strait in which he stood. He was a materialist, and the taste he had had of deprivation had sickened him. In the first revulsion, when the contrast between recent famine and present plenty was strong upon him, he had been at anxious pains to make himself secure with his father—and with Jessica Holme. Harry's mental sight—keen as the hunter's sight on the rifle-barrel—was sharpened by his knowledge of the old Hugh, an intuitive knowledge gained in a significant formative period. He saw more clearly than the townfolk who, in a general way, had[Pg 35] known Hugh Stires all their lives. Week by week Harry had seen him regain lost ground in his father's esteem; day by day he had seen him making studious appeal to all that was romantic in Jessica, climbing to the favor of each on the ladder of the other's regard. Hugh was naturally a poseur, with a keen sense of effect. He could be brilliant at will, could play a little on piano, banjo and violin, could sing a little, and had himself well in hand. And feeling the unconscious cord of romance vibrate to his touch, he had played upon it with no unskilful fingers.

Jessica was comparatively free from that coquetry by means of which a woman's instinct experiments in emotion. Although she had been artist enough before the cloistered years of her blindness to know that she was comely, she had never employed that beauty in the ordinary blandishments of girlish fascination. But steadily and unconsciously she had turned in her darkness more and more to the bright and tender air with which Hugh clothed all their intercourse. Her blindness had been of too short duration to have developed that fine sense-perception with which nature seeks to supplement the darkened vision. The ineradicable marks which ill-governed living had set in Hugh's face—the self-indulgence and egotism—she could not see. She mistook impulse for [Pg 36]instinct. She read him by the untrustworthy light of a colorful imagination. She deemed him high-spirited and debonair, a Prince Charming, whose prideful rebellion had been atoned for by a touching and manly surrender.

All this Harry had watched with a painful sense of impotence, and this feeling was upon him to-day as he stared out from the study toward the white porch, glistening in the sun.

At length, with a little gesture expressive at once of helplessness and puzzle, he turned from the window, took his violin and began to play. He began a barcarole, but the music wandered away, through insensible variations, into a moving minor, a composition of his own.

It broke off suddenly at a dog's fierce snarl from the yard, and the rattle of a thrown pebble. Immediately a knock came at the door, and a man entered.

"Don't stop," said the new-comer. "I've dropped in for only a minute! That's an ill-tempered little brute of yours! If I were you, I'd get rid of him."

Harry Sanderson laid the violin carefully in its case and shut the lid before he answered. "Rummy is impulsive," he said dryly. "How is your father to-day, Hugh?"

The other tapped the toe of his shining patent-leather with his cane as he said with a look of ill-humor:

"About as well as usual. He's planning now to put me in business, and expects me to become a staid pillar of society—'like Sanderson,' as he says forty times a week. How do you do it, Harry? There isn't an old lady in town who thinks her parlor carpet half good enough for you to walk on! You're only a month older than I am, yet you can wind the whole vestry, and the bishop to boot, around your finger!"

"I wasn't aware of the idolatry." Harry laughed a little—a distant laugh. "You are observant, Hugh."

"Oh, anybody can see it. I'd like to know how you do it. It was always so with you, even at college. You could do pretty much as you liked, and yet be popular, too. Why, there was never a jamboree complete without you and your violin at the head of the table."

"That is a long time ago," said Harry.

"More than four years. Four years and a month to-morrow, since that last evening of college. Yet I imagine it will be longer before we forget it! I think of it still, sometimes, in the night—" Hugh went on more slowly,—"that last dinner of The Saints, and poor Archie singing with that wobbly smilax wreath over one eye and the claret spilled down his shirt-front—then the sudden silence like a wet blanket! I can see him yet, when his head dropped. He seemed to shrivel right[Pg 38] up in his chair. How horrible to die like that! I didn't touch a drink for a month afterward!" He shivered slightly, and walked to the window.

Harry did not speak. The words had torn the network of the past as sheet-lightning tears the summer dusk; had called up a ghost that he had labored hard to lay—a memory-specter of a select coterie whose wild days and nights had once revolved about him as its central sun. The sharp tragedy of that long-ago evening had been the awakening. The swift, appalling catastrophe had crashed into his career at the pivotal moment. It had shocked him from his orbit and set him to the right-about-face. And the moral bouleversement had carried him, in abrupt recoil, into the ministry.

An odd confusion blurred his vision. Perhaps to cover this, he crossed the room to a small private safe which stood open in the corner, in which he kept his tithes and his charities. When Hugh, shrugging his shoulders as if to dismiss the unwelcome picture he had painted, turned again, Harry was putting into it some papers from his pocket. Hugh saw the action; his eyes fastened on the safe avidly.

"I say," he said after a moment's pause, as Harry made to shut its door, "can you loan me another fifty?[Pg 39] I'm flat on my uppers again, and the old man has been tight as nails with me since I came back. I'm sure to be able to return it with the rest, in a week or two."

Harry stretched his hand again toward the safe—then drew it back with compressed lips. He had met Hugh with persistent courtesy, and the other had found him sufficiently obliging with loans. Of late, however, his nerves had been on edge. The patent calculation of Hugh's course had sickened, and his flippant cynicism had jarred and disconcerted him. A growing sense of security, too, had made Hugh less circumspect. More than once during the past month Harry had seen him issue from the shadowed door whose upper panel held the little barred window—the door at which Doctor Moreau had entrance, though decent doors were closed in his face.

Hugh's lowered gaze saw the arrested movement and his cheek flushed.

"Oh, if it's inconvenient, I won't trouble you for the accommodation," he said. "I dare say I can raise it."

The attempt at nonchalance cost him a palpable effort. Comparatively small as the amount was, he needed it. He was in sore straits. By hook or crook he must stave off an evil day whose approach he knew not how to meet.

"It isn't that it is inconvenient, Hugh," said Harry. "It's that I can't approve your manner of living lately, and—I don't know where the fifty is going."

The mark on Hugh's brow reddened. "I wasn't aware that I was expected to render you an accounting," he said sulkily, "if I do borrow a dollar or two now and then! What if I play cards, and drink a little when I'm dry? I've got to have a bit of amusement once in a while between prayers. You liked it yourself well enough, before you discovered a sudden talent for preaching!"

"Some men hide their talents under a napkin," said Harry. "You drown yours—in a bottle. You have been steadily going downhill. You are deceiving your father—and others—with a pretended reform which isn't skin-deep! You have made them believe you are living straight, when you are carousing; that you keep respectable company, when you have taken up with a besotted and discredited gambler!"

"I suppose you mean Doctor Moreau," returned Hugh. "There are plenty of people in town who are worse than he is."

"He is a quack—dropped from the hospital staff for addiction to drugs, and expelled from his club for cheating at cards."

"He's down and out," said Hugh sullenly, "and any cur can bite him. He never cheated me, and I find him better company than your sanctimonious, psalm-singing sort. I'm not going to give him the cold shoulder because everybody else does. I never went back on a friend yet. I'm not that sort!"

A steely look had come to Harry Sanderson's eyes; he was thinking of the house in the aspens. While he talked, shooting pictures had been flashing through his mind. Now, at the boast of this eager protester of loyalty, this recreant who "never went back on a friend," his face set like a flint.

"You never had a friend, Hugh," he said steadily. "You never really loved anybody or anything but yourself. You are utterly selfish. You are deliberately lying, every hour you live, to those who love you. You are playing a part—for your own ends! You were only a good imitation of a good fellow at college. You are a poor imitation of a man of honor now."

Hugh rose to his feet, as he answered hotly: "And what are you, I'd like to know? Just because I take my pleasure as I please, while you choose to make a stained-glass cherub of yourself, is no reason why I'm not just as good as you! I knew you well enough before you set up for such a pattern. You didn't go in much[Pg 42] then for a theological diet. Pshaw!" he went on, snapping his fingers toward the well-stocked book-shelves. "I wonder how much of all that you really believe!"

Harry passed the insolence of the remark. He flecked a bit of dust from his sleeve before he answered, smiling a little disdainfully:

"And how much do you believe, Hugh?"

"I believe in running my own affairs, and letting other people run theirs! I don't believe in talking cant, and posing as a little-tin-god-on-wheels! If I lived in a glass-house, I'd be precious careful not to throw stones!"

Harry Sanderson was staring at him curiously now—a stare of singular inquiry. This shallow witness of his youthful misconduct, then, judged him by himself; deemed him a mere masquerader in the domino of decorous life, carrying the reckless and vicious humors of his nonage into the wider issues of living, and clothing an arrant hypocrisy under the habit of one of God's ministers!

The elastic weight of air in the study seemed suddenly grown suffocating. He reached and flung open the chapel door, and stood looking across the choir, through the mellow light of the duskily tinted nave, solemn as with the hush of past prayer. On this [Pg 43]interior had been lavished the special love of the invalid, who had given of his riches that this place for the comfort of souls might be. It was an expanse of dim colors and dark woodwork. At its eastern end was the high altar, with tall flowers in stately gilt vases on either side, and a brass lectern glimmered near-by. In the western wall was set a great rose-window of rich stained glass—a picture of the eternal tragedy of Calvary. As Harry stood gazing into the mellow light, Hugh paced moodily up and down behind him. Suddenly he caught Harry's arm and pointed.

Harry turned and looked.

Above the mantel was set a mirror, and from where they stood, this reflected Hugh's face. It startled Harry, for some trick of the atmosphere, or the sunlight falling through the painted glass, lightening the sallow face and leaving the hair in deeper shade—as a cunning painter by a single line will alter a whole physiognomy—had for the instant wiped out all superficial unresemblance and left a weird likeness. As Hugh's mocking countenance looked from the oval frame, Harry had a queer sensation as if he were looking at his own face, with some indefinable smear of attaint upon it—the trail of evil. As he drew away from the other's touch, his eye followed the bar of[Pg 44] amber light to the rose-window in the chapel; it was falling through the face of the unrepentant thief.

The movement broke the spell. When he looked again the eerie impression of identity was gone.

Hugh had felt the recoil. "Not complimented, eh?" he said with a half-sneer. "Too bad the prodigal should resemble Satan Sanderson, the fashionable parish rector who waves his arms so gracefully in the pulpit, and preaches such nice little sermons! You didn't mind it so much in the old days! Pardon me," he added with malice, "I forgot. It's the 'Reverend Henry' at present, of course! I imagine your friends don't call you 'Satan' now."

"No," returned Harry quietly. "They don't call me 'Satan' now!"

He went back to the safe.

The movement set Hugh instantly to regretting his hasty tongue. If he had only assumed penitence, instead of flying into a passion, he might have had the money he wanted just as well as not!

"There's no sense in us two quarrelling," he said hastily. "We've been friends a long time. I'm sure I didn't intend to when I came in. I suppose you're right about some things, and probably dropping Moreau wouldn't hurt me any. I'm sorry I said all I did.[Pg 45] Only—the money seemed such a little thing, and I—I needed it."

Harry stood an instant with his hand on the knob, then instead of closing the door, he drew out a little drawer. He lifted a packet of crisp yellow-backs and slowly counted out one hundred dollars. "I'm trying to believe you mean what you say, Hugh," he said.

Hugh's fingers closed eagerly over the crackling notes. "Now that's white of you, after everything I said! You're a good fellow, Harry, after all, and I'll always say so. I wish Old Gooseberry was half as decent in a money way. He seems to think fifty dollars a week is plenty till I marry and settle down. He talks of retiring then, and I suppose he'll come down handsomely, and give me a chance to look my debts in the face." He pocketed the money with an air of relief and picked up his hat and cane.

Just then from the dusty street came the sound of carriage-wheels and the click of the gate-latch.

"It's Bishop Ludlow," he said, glancing through the window. "He's coming in. I think I'll slip out the side way. Thanks for the loan and—I'll think over what you've said!"

Avoiding the bishop, Hugh stepped toward the gate. The money was in his pocket. Well, one of these days[Pg 46] he would not have to grovel for a paltry fifty dollars! He would be his own master, and could afford to let Harry Sanderson and everybody else think what they liked.

"So I'm playing a part, am I!" he said to himself. "Why should your Holiness trouble yourself over it, if I am! Not because you're so careful of the Governor's feelings; not by a long shot! It's because you choose to think Jessica Holme is too good for me! That's where the shoe pinches! Perhaps you'd like to play at that game yourself, eh?"

He walked jauntily up the street—toward the door with the little barred window.

"The old man is fond of her. He thinks I mean to settle down and let the moss grow over my ears, and he'll do the proper thing. It'll be a good way to put my head above water and keep it there. It must be soon, though!" A smile came to his face, a pretentious, boastful smile, and his shining patent-leathers stepped more confidently. "She's the finest-looking girl in this town, even without her eyes. She may get back her sight sometime. But even if she doesn't, blindness in a wife might not be such a bad thing, after all!"

Inside the study, meanwhile, the bishop was greeting Harry Sanderson. He had officiated at his ordination and liked him. His eyes took in the simple order of the room, lingering with a light tinge of disapproval upon the violin case in the corner, and with a deeper shade of question upon the jewel on the other's finger—a pigeon-blood ruby in a setting curiously twisted of the two initial letters of his name.

There came to his mind for an instant a whisper of early prodigalities and wildnesses which he had heard. For the lawyer who had listened to Harry Sanderson's recital on the night of the making of the will had not considered it a professional disclosure. He had thought it a "good story," and had told it at his club, whence it had percolated at leisure through the heavier strata of town-talk. The tale, however, had seemed rather to increase than to discourage popular interest in Harry Sanderson. The bishop knew that those whose approval had been withheld were in the hopeless minority, and that even these could not have denied that he possessed [Pg 48]desirable qualities—a manner by turns sparkling and grave, picturesqueness in the pulpit, and the unteachable tone of blood—and had infused new life into a generally sleepy parish. He had dismissed the whisper with a smile, but oddly enough it recurred to him now at sight of the ruby ring.

"I looked in to tell you a bit of news," said the bishop. "I've just come from David Stires—he has a letter from Van Lennap, the great eye-surgeon of Vienna. He disagrees with the rest of them—thinks Jessica's case may not be hopeless."

The cloud that Hugh's call had left on Harry's countenance lifted.

"Thank God!" he said. "Will she go to him?"

The bishop looked at him curiously, for the exclamation seemed to hold more than a conventional relief.

"He is to be in America next month. He will come here then to examine, and perhaps to operate. An exceptional girl," went on the bishop, "with a remarkable talent! The angel in the chapel porch, I suppose you know, is her modelling, though that isn't just masculine enough in feature to suit me. The Scriptures are silent on the subject of woman-angels in Heaven; though, mind you, I don't say they're not common on earth!" The bishop chuckled mildly at his own epigram.

"Poor child!" he continued more soberly. "It will be a terrible thing for her if this last hope fails her, too! Especially now, when she and Hugh are to make a match of it."

Harry's face was turned away, or the bishop would have seen it suddenly startled. "To make a match of it!" To hide the flush he felt staining his cheek, Harry bent to close the safe. A something that had darkled in some obscure depth of his being, whose existence he had not guessed, was throbbing now to a painful resentment. Jessica was to marry Hugh!

"A handsome fellow—Hugh!" said the bishop. "He seems to have returned with a new heart—a brand plucked from the burning. You had the same alma mater, I think you told me. Your influence has done the boy good, Sanderson!" He laid his hand kindly on the other's shoulder. "The fact that you were in college together makes him look up to you—as the whole parish does," he added.

Harry was setting the combination, and did not answer. But through the turmoil in his brain a satiric voice kept repeating:

"No, they don't call me 'Satan' now!"

The white house in the aspens was in gala attire. Flowers—great banks of bloom—were massed in the hall, along the stairway and in the window-seats, and wreaths of delicate fern trembled on the prim-hung chandeliers. Over all breathed the sweet fragrance of jasmin. Musicians sat behind a screen of palms in a corridor, and a long scarlet carpet strip ran down the front steps to the driveway, up which passed bravely dressed folk, arriving in carriages and on foot, to witness the completion of a much-booted romance.

For a fortnight this afternoon's event had been the chat of the town, for David Stires, who to-day retired from active business, was its magnate, the owner of its finest single estate and of its most important bank. From his scapegrace boyhood Hugh Stires had made himself the subject of uncomfortable discussion. His sudden disappearance after the rumored quarrel with his father, and the advent of Jessica Holme, had furnished the community sufficient material for gossip. The[Pg 51] wedding had capped this gossip with an appropriate climax. Tongues had wagged over its pros and cons—for Hugh's past had induced a wholesome skepticism of his future. But the carping were willing to let bygones be bygones, and the wiseacres, to whose experience marriage stood as a sedative for the harum-scarum, augured well.

There was an additional element of romance, too, in the situation; for Jessica, who had never yet seen her lover, would see her husband. The great surgeon on whose prognostication she had built so much, had arrived and had operated. He was not alone an eminent consultant in diagnosis, but an operator of masterly precision, whose daring of scalpel had made him well-nigh a last resort in the delicate adventurings of eye surgery. The experiment had been completely successful, and Jessica's hope of vision had become a sure and certain promise.

To see once again! To walk free and careless! To mold the plastic clay into the shapes that thronged her brain! To finish the statue which she had never yet shown to any one, in the great sky-lighted attic! To see flowers, and the sunset, the new green of the trees in spring, and the sparkle of the snow in winter, and people's faces!—to see Hugh! That had been at the[Pg 52] core of her thought when it reeled dizzily back from the merciful oblivion of the anesthetic, to touch the strange gauze wrappings on her eyes—the tight bandage that must stay for so long, while nature plied her silent medicaments of healing.

Meanwhile the accepted lover had become the importunate one. The operation over, there had remained many days before the bandages could be removed—before Jessica could be given her first glimpse of the world for nearly three years. Hugh had urged against delay. If he had stringent reasons of his own, he was silent concerning them. And Jessica, steeped in the delicious wonder of new and inchoate sensations, had yielded.

So it had come about that the wedding was to be on this hot August afternoon, although it would be yet some time before the eye-bandages might be laid aside, save in a darkened room. In her girlish, passionate ideality, Jessica had offered a sacrifice to her sentiment. She had promised herself that the first form her new sight should behold should be, not her lover, but her husband! The idea pleased her sense of romance. So, hugging the fancy, she had denied herself. She was to see Hugh for the first time in a shaded room, after the glare and nervous excitement of the ceremony.

Gossip had heard and had seized upon this tidbit with[Pg 53] relish. The blind marriage—a bride with hoodwinked eyes, who had never seen the man she was to marry—the moment's imperfect vision of him, a poor dole for memory to carry into the honeymoon—these ingredients had given the occasion a titillating sense of the extraordinary and romantic, and sharpened the buzz of the waiting guests, as they whiled away the irksome minutes.

It was a sweltering afternoon, and in the wide east parlor, limp handkerchiefs and energetic fans fought vainly against the intolerable heat. There, as the clock struck six, a hundred pairs of eyes galloped between two centers of interest: the door at which the bride would enter, and the raised platform at the other end of the room where, prayer-book in hand, in his wide robes and flowing sleeves, Harry Sanderson had just taken his stand. Perhaps more looked at Harry than at the door.

He seemed his usual magnetic self as he stood there, backed by the flowers, his waving brown hair unsmoothed, the ruby-ring glowing dull-red against the dark leather of the book he held. Few felt it much a matter of regret that the humdrum and less personable Bishop of the Diocese should be away at convocation, since the young rector furnished the final esthetic touch to a perfectly appointed function. But Harry Sanderson was far from feeling the grave, alien, figure he [Pg 54]appeared. In the past weeks he had waged a silent warfare with himself, bitterer because repressed. The strange new thing that had sprung up in him he had trampled mercilessly under. From the thought that he loved the promised wife of another, a quick, fastidious sense in him recoiled abashed. This painful struggle had been sharpened by his sense of Hugh's utter worthlessness. To that rustling assemblage, the man who was to make those solemn promises was David Stires' son, who had had his fling, turned over his new leaf becomingly, and was now offering substantial hostages to good repute. To him, Harry Sanderson, he was a flâneur, a marginless gambler in the futures of his father's favor and a woman's heart. He had shrunk from the ceremony, but circumstances had constrained him. There had been choice only between an evasion—to which he would not stoop—and a flat refusal, the result of which would have been a footless scandal—ugly town-talk—a sneer at himself and his motives—a quietus, possibly, to his whole career.

So now he stood to face a task which was doubly painful, but which he would go through with to the bitter end!

Only a moment Harry stood waiting; then the palm-screened musicians began the march, and Hugh took his place, animated and assured, looking the flushed and [Pg 55]expectant bridegroom. At the same instant the chattering and hubbub ceased; Jessica, on the arm of the old man, erect but walking feebly with his cane, was advancing down the roped lane.

She was in simple white, the point-lace on the frock an heirloom. Her bronze hair was drawn low, hiding much of the disfiguring bandage, under which her lips were parted in a half-smile, human, intimate and eager, full of the hope and intoxication of living.

Harry's eyes dropped to the opened book, though he knew the office by heart. He spoke the time-worn adjuration with clear enunciation, with almost perfunctory distinctness. He did not look at Hugh.

"If any man can show just cause why they may not lawfully be joined together, let him speak, or else hereafter for ever hold his peace." In the pause—the slightest pause—that turned the page, he felt an insane prompting to tear off his robes, to proclaim to this roomful of heated, gaping, fan-fluttering humanity, that he himself, a minister of the gospel, the celebrant of the rite, knew "just cause"!

The choking impulse passed. The periods rolled on—the long white glove was slipped from the hand, the ring put on the finger, and the pair, whom God and Harry Sanderson had joined together, were kneeling on[Pg 56] the white satin prie-dieu with bowed heads under the final invocation. As they knelt, choir voices rose:

Then, while the music lingered, the hush of the room broke in a confused murmur; the white ribbon-wound ropes were let down, and a voluble wave of congratulators swept over the spot. In a moment more Harry found himself laying off his robes in the next room.

With a sigh of relief, he stepped through the wide French window into the garden, fresh with the scent of growing things and the humid odors of the soil. The twitter and bustle he had left came painfully out to him, and a whiff of evening coolness breathed through the oppressive air. The strain over, he longed for the solitude of his study. But David Stires had asked him to remain for a final word, since bride and groom were to leave on an early evening train; the old man was to accompany them a part of the journey, and "the Stires place" was to be closed for an indefinite period. Harry found a bench and sat down, where camelias dropped like blood.

What would Jessica suffer in the inevitable awakening, when the tinted petals of her dreams were shattered[Pg 57] and strewn? For the first time he looked down through his sore sense of outrage and protest to deeps in himself—as a diver peers through a water-glass to the depths of a river troubled and opaque, dimly descrying vague shapes of ill. Poetry, passion and dreams had been his also, but he had dreamed too late!

It was not long before the sound of gay voices and of carriage-wheels came around the corner of the house, for the reception was to be curtailed. There had been neither bridesmaids nor groomsmen, and there was no skylarking on the cards; the guests, who on lesser occasions would have lingered to throw rice and old shoes, departed from the house in the aspens with primness and dignity.

One by one he heard the carriages roll down the graveled driveway. A bicycle careened across the lawn from a side-gate, carrying a bank messenger—the last shaft of commerce before old David Stires washed his tenacious mind of business. A few moments later the messenger reappeared and rode away whistling. A last chime of voices talking together—Harry could distinguish Hugh's voice now—and at length quiet told him the last of the guests were gone. Thinking that he would now see his old friends for a last farewell, he rose and went slowly back through the French window.

The east room was empty, save for servants who were gathering some of the cut flowers for themselves. He stood aimlessly for a few moments looking about him. A white carnation lay at the foot of the dais, fallen from Jessica's shower-bouquet. He picked this up, abstractedly smelled its perfume, and drew the stem through his buttonhole. Then, passing into the next room, he found his robes leisurely and laid them by—he had now only to embellish the sham with his best wishes!

All at once he heard voices in the library. He opened the door and entered.

Harry Sanderson stopped stock-still. In the room sat old David Stires in his wheel-chair opposite his son. He was deadly pale, and his fierce eyes blazed like fire in tinder. And what a Hugh! Not the indolently gay prodigal Harry had known in the past, nor the flushed bridegroom of a half-hour ago! It was a cringing, a hang-dog Hugh now; with a slinking dread in the face—a trembling of the hands—a tense expectation in the posture. The thin line across his brow was a livid pallor. His eyes lifted to Harry's for an instant, then returned in a kind of fascination to a slip of paper on the desk, on which his father's forefinger rested, like a nail transfixing an animate infamy.

"Sanderson," said the old man in a low, hoarse, unnatural voice, "come in and shut the door. God forgive us—we have married Jessica to a common thief! Hugh—my son, my only child, whom I have forgiven beyond all reckoning—has forged my name to a draft for five thousand dollars!"

For a moment there was dead silence in the room. In the hall the tall clock struck ponderously, and a porch blind slammed beneath a caretaker's hand. Harry's breath caught in his throat, and the old man's eye again impaled his hapless son.

Hugh threw up his head with an attempt at jauntiness, but with furtive apprehension in every muscle—for he could not solve the look he saw on his father's face—and said:

"You act as if it were a cool million! I'm no worse than a lot who have better luck than I. Suppose I did draw the five thousand?—you were going to give me ten for a wedding present. I had to have the money then, and you wouldn't have given it to me. You know that as well as I do. Besides, I was going to take it up myself and you would never have been the wiser. He promised to hold it—it's a low trick for him to round on me like this. I'll pay him off for it sometime! I don't see that it's anybody else's business but[Pg 61] ours, anyway," he continued, with a surly glance at Harry.

Harry had been staring at him, but with a vision turned curiously backward—a vision that seemed to see Hugh standing at a carpeted dais in a flower-hung room, while his own voice said out of a lurid shadow: "Wilt thou have this man to be thy wedded husband...."

"Stay, Sanderson," said the old man; then turning to Hugh: "Who advanced you money on this and promised to 'hold it'?"

"Doctor Moreau."

"He profited by it?"

"He got his margin," said Hugh sullenly.

"How much margin did he get?"

"A thousand."

"Where is the rest?" David Stires' voice was like a whip of steel.

Hugh hesitated a moment. He had still a few hundreds in pocket, but he did not mention them.

"I used most of it. I—had a few debts."

"Debts of honor, I presume!"

Hugh's sensibility quivered at the fierce, grating irony of the inquiry.

"If you'd been more decent with spending-money," he said with a flare of the old effrontery, "I'd have been[Pg 62] all right! Ever since I came home you've kept me strapped. I was ashamed to stick up any more of my friends. And of course I couldn't borrow from Jessica."

"Ashamed!" exclaimed the old man with harsh sternness. "You are without the decency of shame! If you were capable of feeling it, you would not mention her name now!"

Hugh thought he saw a glimmer through the storm-cloud. Jessica was his anchor to windward. What hurt him, would hurt her. He would pull through!

"Well," he said, "it's done, and there's no good making such a row about it. She's my wife and she'll stand by me, if nobody else does!"

No one had ever seen such a look on David Stires' face as came to it now—a sudden blaze of fury and righteous scorn, that burned it like a brand.

"You impudent blackguard! You drag my name in the gutter and then try to trade on my self-respect and Jessica's affection. You thought you would take it up yourself—and I would be none the wiser! And if I did find it out, you counted on my love for the poor deluded girl you have married, to make me condone your criminality—to perjure myself—to admit the signature and shield you from the consequences. You imagine because you are my son, that you can do this thing and all still[Pg 63] go on as before! Do you suppose I don't consider Jessica? Do you think because you have fooled and cheated her—and me—and married her, that I will give her now to a caught thief—a common jailbird?"

Hugh started. A sickly pallor came to his sallow cheek. That salient chin, that mouth close-gripped—those words, vengeful, vindictive, the utterance of a wrath so mighty in the feeble frame as to seem almost uncouth—smote him with a mastering terror.

A jailbird! That was what his father called him! Did he mean to give him up, then? To have him arrested—tried—put in prison? When he had canvassed the risks of discovery, he had imagined a scene, bitter anger—perhaps even disinheritance. His marriage to Jessica, he had reckoned, would cover that extremity. But he had never thought of something worse. Now, for the first time, he saw himself in the grip of that impersonal thing known as the law—handcuffs on his wrists, riding through the streets in the "Black-Maria"—standing at the dock an outcast, gazed at with contempt by all the town—at length sitting in a cell somewhere, no more pleasures or gaming, or fine linen, but dressed in convict's dress, loose, ill-shapen, hanging on him like bags, with broad black-and-white stripes. He had been through the penetentiary once. He remembered the [Pg 64]sullen, stolid faces, the rough, hobnailed shoes, the cropped heads! His mind turned from the picture with fear and loathing.

In the thoughts that were darting through Hugh's mind, there was none now of regret or of pity for Jessica. His fear was the fear of the trapped spoiler, who discerns capture and its consequent penalties in the patrolling bull's-eye flashed upon him. He studied his father with hunted, calculating eyes, as the old man turned to Harry Sanderson.

"Sanderson," said David Stires, once more in his even, deadly voice, "Jessica is waiting in the room above this. She will not understand the delay. Will you go to her? Make some excuse—any you can think of—till I come."

Harry nodded and left the room, shutting the door carefully behind him, carrying with him the cowering helpless look with which Hugh saw himself left alone with his implacable judge. What to say to her? How to say it?

As he passed the hall, the haste of demolition had already begun. Florists' assistants were carrying the plants from the east room, and through the open door a man was rolling up the red carpet. The cluttered emptiness struck him with a sense of fateful symbolism—as though it shadowed forth the shattering of [Pg 65]Jessica's ordered dream of happiness. He mounted the stair as if a pack swung from his shoulders. He paused a moment at the door, then knocked, turned the knob, and entered.

There, in the middle of the blue-hung room, in her wedding-dress, with her bandaged eyes, and her bridal bouquet on the table, stood Jessica. Twilight was near, but even so, all the shutters were drawn save one, through which a last glow of refracted sunlight sifted to fall upon his face. Her hands were clasped before her, he could hear her breathing—the full hurried respiration of expectancy.

Then, while his hand closed the door behind him, a thing unexpected, anomalous, happened—a thing that took him as utterly by surprise as if the solid floor had yawned before him. Slim fingers tore away the broad encircling bandage. She started forward. Her arms were flung about his neck.

"Hugh!... Hugh!" she cried. "My husband!"