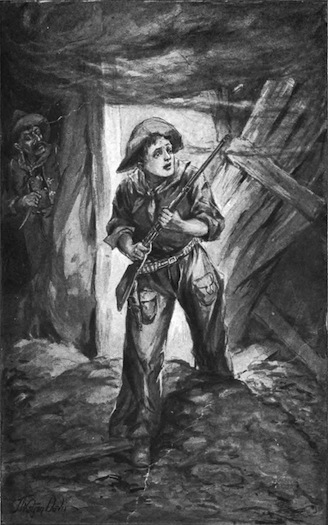

PULLING HIMSELF TOGETHER AND GRASPING HIS MARLIN FIRMLY, ADRIAN STEPPED CAUTIOUSLY TOWARD THE BROKEN DOOR.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Broncho Rider Boys with the Texas Rangers

The Capture of the Smugglers on the Rio Grande

Author: Frank Fowler

Release Date: April 30, 2012 [eBook #39577]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BRONCHO RIDER BOYS WITH THE TEXAS RANGERS***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through the HathiTrust Digital Library. See http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433082303128 |

CONTENTS

PULLING HIMSELF TOGETHER AND GRASPING HIS MARLIN FIRMLY, ADRIAN STEPPED CAUTIOUSLY TOWARD THE BROKEN DOOR.

THE BRONCHO RIDER BOYS WITH THE TEXAS RANGERS

or

The Capture of the Smugglers On the Rio Grande

By Frank Fowler

Author Of

“The Broncho Rider Boys At Keystone Ranch.”

“The Broncho Rider Boys In Arizona.”

“The Broncho Rider Boys Along The Border.”

“The Broncho Rider Boys On The Wyoming Trail.”

A. L. BURT COMPANY

NEW YORK.

Copyright, 1915

By A. L. Burt Company

THE BRONCHO RIDER BOYS WITH THE TEXAS RANGERS

“Crack!” went Broncho Billie’s revolver and the silver dollar which had been tossed into the air as a target went spinning into the yellow waters of the Rio Grande as a result of Billie’s unerring aim.

“Not a bad shot, Ad,” remarked Billie with a laugh as he ejected the shell from the cylinder and shoved a fresh cartridge into the empty chamber of the revolver. “I don’t miss ’em very often now, and this time the river is a dollar in.”

“Yes,” replied Adrian, a bit crestfallen, “and I’m a dollar out.”

“Didn’t think I’d hit it, eh?” and Billie’s round face broadened till it looked like a full moon.

“Well, I didn’t know but you might, but I hadn’t stopped to think what would happen to the dollar if you did. The river didn’t look so near.”

Billie chuckled to himself good-naturedly as he returned his six-shooter to its holster, while Adrian continued:

“I’ll make a better guess at distances before I try it again. I can’t afford to be losing dollars like that.”

“Oh, that’s all right, Ad!” and Billie shoved his hand down into his pocket. “Here’s one to take its place.”

Adrian shook his head and made no move to take the proffered coin.

“Go on, take it!” insisted Billie. “I don’t want to make you lose your last dollar.”

“That’s all right about my last dollar,” replied Adrian. “I guess I know where to get another, and the lesson is worth a peso.”

“Well, if you go broke because of it, don’t be afraid to tell me,” was Billie’s joking reply; “but what can be keeping Donald, I wonder. It’s high time we were getting back over the river,” and Billie cast his eye toward the mountains some miles in the distance to see how close to their tops the sun was getting.

“He’ll surely be here in a few minutes,” said Adrian. “He knows how long it will take us to get to town as well as we do.”

And while the boys are awaiting the arrival of their companion, it might be well to explain to any reader who has not had the pleasure of reading the preceding volumes of the Broncho Rider Boys series something about the trio of young Americans whose names have been mentioned.

Adrian Sherwood, who had so recklessly risked his silver dollar as a target for his companion to shoot at, was the owner of a ranch in Wyoming, which he had but recently inherited and come into possession of through a series of most exciting adventures as told in a preceding volume of this series, entitled “The Broncho Rider Boys on the Wyoming Trail.” He was a youth of much wisdom and judgment for one of his years and a close chum of Billie, who had been christened William Stonewall Jackson Winkle.

Because of the exciting adventures through which Adrian, Billie and Donald had passed and because they had practically lived in the saddle for the past year and a half, they had become known to the cowboys and rough riders of three states as “The Broncho Rider Boys.” Born in the south, but having spent most of his boyhood in New York State, Billie had come west nearly two years previous to find health and to rid himself of the superfluous weight which some good-natured doctor had said was the cause of his trouble. Months in the saddle had made very little difference in his weight and if there were a more healthy chap in the country than he, such a one would be hard to find.

When Billie first came west, he was a veritable tenderfoot. He was always creating fun for those with whom he was thrown and was invariably in some sort of trouble. The number of times he had been thrown from the back of his broncho could hardly be enumerated, and more in fun than because he was a daring rider, he had been rechristened Broncho Billie by his cowboy friends.

But Billie had developed rapidly. Of the three there was not one who could ride or shoot better than he. His only weak spot was in throwing the lariat. He never seemed to get just the proper hang and his attempts to use the rope almost invariably resulted in disaster to himself or his friends. As is usually the case with fat people, Billie fairly bubbled over with good humor, being a fine example of Tony Lumpkin’s famous advice to “laugh and grow fat.”

Donald Mackay, Billie’s cousin, whom he had come west to visit, was the son of the owner of a big ranch, known as Keystone Ranch. He was one of those steady, reliable boys whom we have all met and who can always be depended upon in any emergency to do the right thing, although at times he may be slower than some others in the manner in which he works. Taken all in all they were a well-balanced trio, as their actions under many trying conditions and in many hazardous adventures had justly proved. They had thwarted an unscrupulous syndicate from robbing Donald’s father of valuable property. They had protected an inoffensive tribe of Indians against the designs of a band of sharpers, and they had straightened out affairs at Adrian’s ranch in a manner which would have been a credit to much older heads.

After their adventures in Wyoming, as told in a preceding volume, they had started to return to Arizona by a two months’ ride through Colorado and New Mexico; but, when they reached Albuquerque, they had received a letter from Billie’s father, saying that he was going on a vacation trip to El Paso, Texas, and asking if it were possible for Billie to meet him there.

“Of course I can,” exclaimed Billie aloud, as he read the letter.

“Of course you can what?” queried Donald.

“Meet father in El Paso,” was the reply.

“What, and leave us to go home all alone?” said Adrian.

“There’s two of you, isn’t there?” retorted Billie, forgetting his grammar entirely.

“Of course there are two of us; but that’s hardly a company, while, as everybody knows, three make a crowd,” and Adrian laughed almost sadly. “Who’d take care of Jupiter?”

Now Jupiter was the broncho which Billie’s uncle had given him when he first came West, and a terrible time Billie had had in breaking him. He hadn’t thought about him.

“You could lead him, couldn’t you?” asked Billie.

“We’re driving two pack mules now. How would you expect us to take care of Jupiter?”

Billie shook his head slowly. “I don’t know,” he said.

“I’ll tell you what,” suddenly exclaimed Donald, “we’ll all go to El Paso. We’ll ride there. It isn’t so many days out of our way, and we’ll see something of the country. We might even get a look at President Madero, of Mexico.”

Donald’s suggestion met with immediate approval by the others, and so, instead of going southwest from Albuquerque, they headed south. Because of the lay of the land, they had traveled farther south than was really necessary, but had figured it out that it would be better riding in the valley of the Rio Grande than to climb over the range of mountains that forms the watershed of the Pecos River. Striking the Rio Grande near Langtry, they had slowly ridden up stream toward El Paso, first on one side of the river and then on the other, until this afternoon found them approaching the mouth of the Concho river, which empties into the Rio Grande from the Mexican side.

Two hours previous they had halted in the chaparral for a bite to eat and a short siesta. While they were lounging about, Donald had announced his intention of going to a little hamlet, the adobe houses of which could be seen a couple of miles away, to see if he could not buy a riata, as a rope for leading horses is called.

“Why not wait until we reach Presidio?” queried Adrian. “We should reach there by dark.”

“We may not, and we need it to tether the pack mules. The one on Bray is worn out, and first thing we know he’ll wander away and we’ll waste a whole day looking for him.”

“Well, hurry up, then,” said Billie. “We don’t want to be waiting around here all the afternoon.”

Without more words Donald had mounted Wireless, for so his mount was named, and ridden away in the direction of the houses, while Billie and Adrian had strolled up the bank of the river, killing time. It was during this stroll that Billie had offered to show his skill with a six-shooter by hitting a silver dollar thrown into the air.

They had hardly been out of sight of the halting place during their stroll, but, upon their return, instead of finding Donald, they found old Bray, one of the pack mules, missing, just as Donald had predicted.

“He cannot have gone far,” declared Adrian. “He hasn’t had time.”

“That’s certain,” was Billie’s reassuring comment, and, feeling sure that a few minutes’ search of the chaparral would reveal the missing animal, they started out hastily, on foot, not deeming it necessary even to mount their steeds.

For the next ten minutes they tramped through the chaparral, calling to each other as they went, but no sign of the mule could be found. Then they returned to the camp and mounted their horses, but, although this enabled them to see over the tops of the mesquite bushes that spread out for miles up and down the river, they could see nothing of the missing animal.

“There comes Don,” Billie at last sung out, as he caught sight of the returning horseman. “Maybe he can give us some advice.”

But Donald had no advice to give, except to scatter and search.

“I hate to say 'I told you so,’” laughed Donald, “because it was really my fault that I didn’t get a new riata before. I reckon now we might as well decide to stop here all right, for I can see we have our afternoon’s work cut out.”

Half an hour’s riding having revealed no sign of Bray, the boys again met at the camp.

“Haven’t you seen anything at all?” called out Adrian, as the boys came within hailing distance of each other.

“Yes,” replied Billie, “I saw a hacienda about three miles up the river. I knew Don spoke a little Mexican, so I came back to tell him, and ask if you didn’t think it would be a good thing to apply to the owner for help. Maybe some of the peons have run across Bray and driven him home.”

“Good idea,” said Adrian. “You fellows go up to the hacienda and I’ll stay here and look after the other mule and the camp. I’m glad Bray didn’t have his pack on, or we’d stand a chance of going hungry tonight.”

“Don’t mention such a thing,” laughed Billie. “The very thought of it fills me with despair.”

The hacienda which Billie had discovered in his search for the lost pack mule was located about a mile from the Rio Grande on the Mexican side of the river, and appeared to be part of an estate of considerable size. The house itself was a good-sized dwelling, built in true Mexican style, with a great wall surrounding it, and the yard, or patio, as it is called, inside the walls. It was of dazzling whiteness, and, situated upon a little knoll that rose almost abruptly out of the otherwise level plain, made quite a pretentious appearance.

“Looks as though it might belong to people of quality,” remarked Donald, as the boys approached it, after a sharp gallop of twenty minutes.

“Yes, or a fort of some kind, with that high wall all around it.”

“The wall, as you call it, is part of the house,” explained Donald. “However, it serves the purpose of a fortification. Father told me they got into the habit of building their houses in this way during the days when revolutions were of almost daily occurrence.”

“A habit from which they haven’t yet recovered,” laughed Billie.

Riding up to the great front door, or gate, which they found closed, they knocked loudly. A sharp-eyed Mexican lad answered the summons and ushered them into the patio, where they sat quietly upon their horses until the owner appeared. He was a little, weazened old man—Don Pablo Ojeda, by name, as the boys afterward learned—but he received them with a great show of friendliness.

“Welcome, strangers,” he said, by way of greeting. “What can I do for you today?”

“We are travelers,” replied Donald, “and one of our pack mules strayed away. Being unable to find it, we thought perhaps some of your servants might have come across it, and, not knowing to whom it belonged, have driven it to this place.”

“Quite possible,” replied the old man. “I will summon them and inquire.”

This he did. In response to his summons, half a dozen peons put in an appearance, but all denied any knowledge of the mule.

“He has probably gone down the river in the direction from which you came,” said Don Pablo, after the servants had gone back to their work. “That would be the most natural thing.”

“Quite likely,” was Donald’s reply. “We will look for him in that direction. We are much obliged to you for your trouble.”

“No hay de que,” meaning, there is no occasion for thanks, was the Mexican’s answer, and, without more ado, the boys took their departure.

“The old hypocrite,” exclaimed Donald, as soon as the boys were out of earshot. “I actually believe he found the mule himself, and knows where he is at this very minute.”

“I thought that myself,” commented Billie, “although I could understand very little of what was being said. But he was altogether too gracious.”

“What most aroused my suspicions,” said Donald, “was a side remark I heard him whisper to that big dark peon. I didn’t get the whole of it, but it was something about removing the livestock to another pasture. But he can’t fool me, if ever I get sight of old Bray, for he had the Keystone brand.”

The boys walked their horses slowly along, talking the matter over, undecided what to do next; but, as they at last emerged from behind a long row of cactus, which formed a hedge around one side of the hacienda, Billie uttered a sudden exclamation.

“Look!” he almost shouted, and pointed away to the left, where, about a mile distant, could be seen a couple of men on horseback, driving before them a dozen or more horses and mules. “I believe that big mule a little to the side is old Bray.”

“I’m sure of it,” replied Donald. “It’s a long ways too far to see the brand, but he’s got a peculiar stride that I recognize as soon as I set eyes on him.”

“What had we better do?” queried Billie. “We’re perfect strangers here, you know.”

“I don’t care if we are,” was the emphatic response. “No thieving hypocrite can get away with my mule as long as my name is Donald Mackay. Follow me,” and, putting spurs to Wireless, he dashed off in the direction of the drove, closely followed by Billie.

From the direction in which the men were driving the animals it was very evident they were headed for the mountains, some seven or eight miles away, and it was plain to the boys that, if they ever expected to get old Bray, they would have to overtake the drove before it reached the foothills. A small stream flowed across the plain and emptied into the Concho some miles farther west, and it was necessary for the men with the drove to cross this stream before they could make a direct line for the place they wished.

The boys were unfamiliar with the lay of the land, but they made up their mind that they could cross the stream higher up and thus get between the men and the mountains. They did not know that the only ford was the one toward which the men were driving the horses, and accordingly, instead of following the direct trail, they struck off diagonally across the plain.

The men saw the boys as soon as they appeared upon the scene, and immediately put the drove on a full run for the ford.

While the stream toward which both the pursued and the pursuers were heading was not a large one, it was quite a torrent because of the heavy rains of the past two or three days—the rainy season having already begun. The natives were well aware of this, and thought it impossible for anyone to cross it except at the ford in question. Being fully a mile in advance, they had no fear of being overtaken, as they felt certain that when the boys reached the river they would have to turn down stream for more than half a mile before they could cross. This would give the thieves another good mile the advantage.

Wireless and Jupiter seemed to know what was expected of them, and fairly flew over the ground. The natives were also well mounted, and the chase would have been a fruitless one, had conditions been as they supposed. But they did not know the kind of boys they had to deal with, nor the mettle of the horses they rode.

After ten minutes of hard riding, it became evident that the boys were gaining, and as the thieves and their booty plunged into the ford, the boys were rapidly approaching the river at the place they had picked out to cross.

Then for the first time the pursuers saw why it was that the thieves had chosen a crossing so far downstream.

For just a moment they drew rein, seeing which the natives gave a shout of derision as they, too, slackened their pace and rode more leisurely toward the mountains.

But again the thieves had reckoned without their host, for, in another minute the boys put spurs to their horses and dashed toward the stream, even higher up than they had first aimed. Billie had discovered a narrow place, and had made a suggestion to Donald, which they determined to carry out.

At the spot which Billie had discovered the stream was about thirty feet from bank to bank. Billie’s suggestion was that they make the horses jump it.

It was a dangerous suggestion, because the very narrowness of the stream made the current at this point exceedingly swift. How deep it was neither of the boys had the slightest idea; they did know, however, that it was necessarily the deepest spot on the whole plain. But this did not deter them. They had made up their minds to head off the thieves, and such a small thing as a thirty-foot leap over a raging torrent of water was not to be considered.

So surprised were the men whom they were pursuing, that for the time they forgot their herd and riveted their attention upon the boys, not for a moment expecting them to try to cross when once they approached near enough to the stream to know the actual condition.

But, never flagging, almost neck and neck, Wireless and Jupiter dashed toward the narrow spot.

As they drew nearer, both boys saw that the stream was wider than they had thought, and swerved just a moment from their course.

Again the natives uttered a shout of derision, expecting to see them pull up; but on they came.

“Can we make it?” shouted Billie.

“Sure,” replied Donald, who was better acquainted with the latent ability of his horse than his eastern-bred cousin. “Give Jupiter his head and just a touch of the spur, and over we go!”

They were right on the brink, and suiting the action to the word, they gave their horses their heads for the leap.

Into the air they rose like a couple of soaring birds, and for one brief moment were flying over the rushing water. The shout of derision died on the lips of the now thoroughly frightened natives, as both the thoroughbred beauties landed fairly on the opposite bank and sped on their way, as though they had but jumped a ditch.

By their daring feat the boys had so gained upon the thieves that they were now not more than a quarter of a mile behind and gaining rapidly. Seeing that they could not escape with their booty, the thieves turned suddenly to the left, deserting their herd, and rode as fast as their horses could carry them directly toward the chaparral that skirted the Rio Grande.

At this the boys would have drawn rein, seeing that old Bray was now within their grasp, but their attention was attracted by a shout from the opposite side of the stream which they had just crossed.

Turning their heads to see whence came the noise, they beheld a body of a dozen or more horsemen headed toward the ford at full speed.

“Don’t let them escape! Don’t let them escape!” shouted the leader of the band, and, without stopping to think why they should obey such an order, but feeling that there was good reason for it, the boys again took up the chase.

As they espied the horsemen on the opposite bank, and realizing that there was but one way to escape, the thieves turned in their saddles and simultaneously fired a shot at their boy pursuers.

The balls whistled by the boys’ heads, but did not stop their furious gallop. Again the thieves fired, and again the balls whistled harmlessly by their heads.

But they had no chance to fire again, for the lads were right upon them. Suddenly Donald’s hand shot forward, and his lariat sung out with lightning speed. True to its aim, it fell over the shoulders of the nearest Mexican. Wireless stopped as though he had been suddenly rooted to the spot; the Mexican’s horse dashed on riderless, and his master lay senseless upon the ground.

At the same moment Billie’s revolver cracked and the horse of the other fleeing Mexican pitched headlong to the earth, carrying his rider with him. Before he could recover himself, Billie had pulled up beside him, and, leaping to the ground, quickly bound him with his own lariat.

The boys had hardly regained their breath, when a loud cheer announced the arrival of the other horsemen.

“Good for you, young fellows,” exclaimed the leader of the band, as he, too, sprang from his saddle. “You’ve made an important capture. We’ve been trying to get evidence against these cutthroats for weeks. I surely owe you one.”

“That’s good,” laughed Billie. “It’s mighty nice to have something coming. But who are you?”

“Oh, me,” was the good-natured rejoinder. “I’m Captain June Peak, of the Texas Rangers, and these are part of my company.”

Of course both Donald and Billie had heard of the Texas Rangers, that daring body of the Texas militia which has done so much in maintaining law and order along the Mexican frontier, as well as in the lawless communities farther interior. This, however, was their first introduction to the rangers, and they gazed at the riders with considerable astonishment, their appearance not being such as would give a stranger a very good opinion of their law-abiding character.

“Texas Rangers,” finally exclaimed Donald, in a tone that indicated some doubt. “Then what are you doing this side of the Rio Grande?”

“Well, I declare,” responded Captain Peak, looking around at his men with a twinkle in his eye, “we must have crossed the river without seeing it. We’d better get back just as fast as we can.”

“That’s right, Cap.,” replied one of the men, “but you wouldn’t think of leaving these poor fellows lying on the ground, would you?”

“Sure not. Just pick them up, some of you, and we’ll get right back to our own side of the river.”

The words were no sooner spoken than several of the men sprang to the ground. The two Mexicans were quickly thrown across the backs of a couple of horses, and the rangers prepared to return.

The boys had heard the words of the captain, and watched the proceedings without a word, realizing by the captain’s manner that the affair was more serious than he let on. As the men again resumed their saddles, and the captain was about to mount, Donald thought it high time to ask further questions; but he hadn’t decided just what to say before Captain Peak asked:

“How did you boys happen to be chasing these greasers?”

“They were stealing our mule—that big one there,” replied Donald, pointing to old Bray. “You can see he has the Keystone brand, the same as our horses,” and he indicated the marks upon Jupiter and Wireless.

“Then you’d better cut him out and come along with us,” said Captain Peak. “This won’t be a very healthy place for you much longer.”

“No?” And the boys looked at the captain inquiringly.

“No; there’s going to be trouble along the border, and it may break out any minute. That’s why these horse-thieves are so bold; and that’s why we are on this side the river, where we really have no business. But these fellows have become such a nuisance that when we saw them leaving the casa a little while ago we couldn’t resist the chance of getting them. We shall turn them over to the Mexican authorities at the first opportunity, and I hope you boys will be on hand to give your testimony against them.”

“If they are really horse-thieves,” replied Donald, “we shall be glad to help bring them to justice; but we are only travelers, and don’t wish to be delayed on our journey any longer than necessary. We have a companion and another mule back there in the chaparral.”

“All right,” replied Captain Peak, “we’ll ride back that way and see that no one disturbs you. Then we’ll all get into town as soon as possible. It’s only six or seven miles.”

Acting upon Captain Peak’s advice, the boys cut old Bray out from the rest of the drove, and in company with the rangers, galloped back toward the place where they had left Adrian. It is hard to say which was the greater, his pleasure at seeing his companions with old Bray in their possession, or his surprise at the numerous company that was with them.

As they rode leisurely toward Presidio, after crossing to the American shore, Donald explained to Captain Peak how they happened to be so far from home. He was much interested in their story, and when they reached town introduced them to the officials, both civil and military. The captured horse-thieves were locked up in jail and the boys went home with Captain Peak, who invited them to spend the night with him at the hotel.

“I tell you,” exclaimed Billie, as they sat on the porch that evening after supper, “a woman’s cooking surely does taste good! Why, just think, we haven’t had a bite for most a month that we didn’t cook ourselves.”

The following morning the boys were awakened by a big commotion outside, and, looking down the street toward the jail, saw that it was surrounded by a great crowd. They hastily dressed themselves and rushed out of the hotel. Almost the first man they met was Captain Peak.

“What’s the matter?” asked Billie.

“There has been an attempt to rescue the prisoners, but it did not succeed.”

“Who did it?” queried Adrian.

“We are not exactly sure, as the rescuers mounted their horses as soon as they were discovered, and managed to get away. Some of the rangers are after them, however, and I hope will get a trace of them.”

“They must have been pretty bold to come into a town as big as this,” said Donald.

“So they are; but, as I told you yesterday, there is likely to be a lot of trouble the other side of the river, and the authorities are having their hands full looking after possible revolutionists. As a result lesser culprits go free.”

“That must make a lot of trouble on this side,” suggested Adrian.

“It does, for, in addition to watching for horse and cattle thieves, we have to keep our eyes open for gun runners.”

“What do you mean?” asked Billie. “What are gun runners?”

“Would-be revolutionists, who smuggle quantities of arms into Mexico without the knowledge of the Mexican officials.”

“I didn’t know it was our business to stop that. I thought anybody could buy arms to sell in Mexico?” said Adrian.

“So they can; but these arms would not be for sale. They would be for arming bands of men to overturn the government. We are under no obligation to stop it, but, as we want law and order along the border, we always try to help the Mexican authorities,” explained Captain Peak.

“But there come my men now,” he continued, as several horsemen turned into the main street.

The boys crowded around with others to hear the result of the chase, which the men reported to have been fruitless.

“If we could only have chased them over the river we could have captured them,” declared the sergeant in charge, “but, after the little raid yesterday, we thought we’d better not try it.”

Seeing that there was likely to be no more excitement, the crowd dispersed and the boys went into the hotel for breakfast; but when they came out they found Captain Peak waiting for them.

“How would you boys like to do a little scout duty for me over the river?” he asked.

“Scout duty?” repeated Donald. “I don’t think I understand.”

“Draw up some chairs,” replied the captain, “and I’ll explain.”

The boys did as directed, and the captain continued:

“I’ve been interested a whole lot in the adventures you boys have had, and I can see you are a smart bunch. You said you were willing to stay and help convict the cattle thieves, but we can’t arrange to turn them over to the Mexican officials and have their trial before tomorrow, no matter how fast we act. The Mexican always wants to wait till tomorrow.”

“Now, as long as you will be here a day or two, anyway, I thought maybe you would like to take a little excursion across the Rio Grande, and see how people live on that side. If you kept your eyes open, you might see something that would be useful to me.”

“In what way?” queried Adrian.

Captain Peak drew his chair a bit nearer and looked all around to be sure no one was listening.

“It is like this,” he continued. “President Madero has discovered that there is a real plot on foot to start another revolution and overthrow his government. Arms for the revolutionists would have to come from this side of the river. As a revolution is unlawful, carrying arms across the Rio Grande to help a revolution is unlawful, and he has asked Uncle Sam and the State of Texas to prevent any guns or ammunition from going into Mexico which do not go through the Mexican custom house.”

“It looks to me,” broke in Billie, “as though that was the business of the Mexican government.”

“So it is,” replied Captain Peak, “but as long as Mexico is a friendly nation it is also our business to prevent filibustering—and that is what gun running amounts to.

“There is also another reason for helping to prevent this sort of smuggling. We frequently have to ask the Mexican government to aid us in running down outlaws who escape into that country. If we don’t help them, they won’t help us. So you can see, if we can learn anything about this revolutionary movement, it will be a good thing. You boys, because you are strangers and travelers, are just the ones to help. What do you say?”

For several moments the boys said nothing, but finally Donald replied that if the captain would give them a few minutes to talk the matter over between themselves, they would be able to let him know.

“All right,” was the reply, “I’ve an appointment with the mayor, which will give you all the time you need,” and he left the hotel to keep his appointment.

“Well,” remarked Billie, as the captain disappeared around the corner, “what do you think of that?”

“I don’t think anything of it,” replied Donald. “I’ve no liking for that kind of work.”

“Why not?” queried Adrian.

“I don’t know. I just haven’t, that’s all.”

“You’d like to prevent war, wouldn’t you?”

“Sure,” was Donald’s emphatic rejoinder; “but I can’t see how this trip can prevent war.”

“I don’t know as it would,” said Adrian, “but, if we could do anything which would keep a lot of dissatisfied peons from getting guns and going out and killing people, it seems to me we would be doing a good deed.”

“That’s just the way it seems to me,” declared Billie. “The average Mexican who wants to start a revolution looks to me a good deal like the fellows who stole our mule.”

“Not necessarily,” replied Adrian. “Sometimes revolutions are started by men to overthrow a bad government. But my mother has always taught me there was a better way to right a wrong than to go to war over it. That’s why I am in favor of doing all we can to help those who want to prevent trouble.”

“Of course if you put it that way,” said Donald, “I’ve no objection to the excursion, as the captain calls it.”

When Captain Peak returned, they unanimously announced their readiness for the trip, and, half an hour later, fully instructed as to what was expected of them, they were across the Rio Grande, engaged upon what proved to be the most important adventure of their career.

“This is certainly a funny excursion,” laughed Billie, after the boys had ridden along in silence for some minutes. “It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

“How so?” queried Donald.

“Well, isn’t it? This big country is the haystack, and the bunch of gun runners is the needle. I see mighty little chance of finding them.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” replied Donald. “We never started out to find anything yet that we didn’t locate it—even old Bray,” he added as an afterthought.

“That’s right,” chimed in Adrian. “There is nothing like having your luck with you.”

“Huh,” grunted Billie, “I’m not sure but the greatest luck we could have would be not to find anything.”

Adrian looked at the speaker in surprise.

“It’s the first time I ever knew you to show the white feather,” he said.

“Who’s showing the white feather?” demanded Billie, with much spirit. “I’m just as anxious as anyone to put a stop to lawlessness; but you wouldn’t call any man a coward, would you, because he wouldn’t deliberately stick his head in a hornet’s nest?” And he gave his horse a vicious dig with his spurs.

“Oh, don’t get mad about it,” said Adrian. “I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings.”

“Well, then, don’t be accusing me of showing the white feather. There’s a whole lot of difference, in my mind, between being a coward and using a little common sense.”

“He has the best of you there, Ad.,” remarked Donald; “when it comes to doing things, Billie will be on the job.”

Donald’s words were like oil on the troubled waters, and after a few minutes Billie continued in a voice entirely free from any irritation:

“The thing I can’t understand is this: If somebody has so much information as to what is to be done, why don’t they have some little knowledge of those who propose to do it? The whole thing looks fishy to me.”

“I believe you’re right,” assented Adrian, after turning the matter over in his mind for several minutes. “There is something kind of mysterious about it.”

“I don’t see it,” declared Donald, “but, even if there is, all we have to do is to keep our eyes and ears open. We have the law on our side.”

“Looks like mighty little law to me,” replied Billie, who, for some reason or other insisted upon looking on the dark side. “But, to change the subject, what do you call that?” and he pointed away to the south, where a cloud of dust was to be seen.

“Looks as though it might be a herd of cattle.” said Donald, after a moment’s inspection. “Although,” he added, after further observation, “it would be a mighty small one.”

“They certainly make a lot of dust,” was Adrian’s comment, followed in a moment with: “Look! Look! It’s a race! It’s a race!”

A race it certainly was, in which something less than half a dozen horsemen were engaged, and the boys drew rein to watch it.

At the first glance it did not appear to be very exciting, as one of the riders was so far in advance that there seemed very little chance for any of the others. But, as the boys watched the flying horsemen, it slowly dawned upon Donald that there was something wrong.

“By George!” he suddenly exclaimed, “I don’t believe it’s a race at all. It looks to me as though there were three trying to catch one, and I don’t think it’s for any good purpose.”

“I believe you’re right, Don; and, look,” exclaimed Adrian, “they’re headed this way!”

That the boys were right was fully evidenced as the flying horsemen approached. The pursuers seemed to be men, while the fugitive was a lad of about the same age as our travelers.

All at once the boy espied the Broncho Rider Boys, and, digging his spurs into his horse, turned abruptly and rode directly toward them.

“Socorre mi! Socorre mi!” he called, as he came within hailing distance.

“What does he say?” asked Billie.

“He’s crying for help,” replied Donald. “What had we better do?”

“Help him, of course,” replied Billie.

“And get ourselves into a lot of trouble for our pains,” declared Donald.

“Who cares! Three to one is more than I can stand,” and Billie yanked his Marlin from its sheath at his saddle girth.

Seeing that Billie intended to interfere, even if he had to go it alone, Don and Adrian followed his example, and, spurring their horses forward, interposed between the boy and his pursuers.

“What’s all the trouble?” asked Donald in Spanish, as soon as the pursuing horsemen had come to a halt.

“He is running away from home,” replied one who seemed to be the leader, “and his uncle sent us to bring him back.”

“It isn’t so,” declared the lad, who had stopped his flight and had come up behind the boys. “Do not believe him, señores!”

Adrian turned at the sound of the lad’s voice. “Which are we to believe?” he asked.

“Believe me,” exclaimed the lad imploringly. “If you let them take me, I do not know what they will do with me.”

“Why are they chasing you?” asked Don.

“I don’t know, unless it is because they do not like my father.”

“Who is your father?”

“General Sanchez, of President Madero’s staff.”

“Who are these?” and Don pointed to the waiting horsemen.

“I don’t know who that man is,” replied the lad, pointing to the leader, “but the others are peons on my uncle’s hacienda.”

“Is this true?” asked Don, turning to the pursuers, while Billie and Adrian tenderly fondled their rifles.

“Partly,” replied the leader. “But you heard him say he did not know who I am. Well, I am one of his uncle’s closest friends. I learned this morning that Pedro,” and he pointed at the boy, “was getting into bad company, and so came out to look for him. I found him in bad company and told him he must come home with me. He refused and rode away. I then started after him. If I were not his uncle’s friend, do you think I would have his uncle’s peons with me?”

“It hardly seems so,” replied Donald; “but, if you are such a good friend of his uncle, it’s a wonder he does not know you. How about that, Pedro,” and he again turned to the boy.

“It’s all a lie,” was the emphatic reply. “I was out watching the men at work at the foot of the mountains this morning, when this man rode up. He told me to come with him. Never having seen him, I refused, whereupon he threatened to flog me. I jumped on my horse and rode away. A few minutes later he came after me, making all sorts of threats. Then he summoned the peons and chased me. They seem to do everything he tells them, but I do not know why.”

“It sure is a queer mix-up,” said Donald to his companions, in English, “and I don’t know what to do.”

“I’ll tell you what,” exclaimed Billie, after the matter had been fully explained to him, “let’s all ride back to his uncle’s, wherever that is, and see what he says.”

“Why, sure,” said Donald. “Billie, you’ll make a judge some day. We’ll go at once.”

When the proposed plan was explained to the Mexicans, both sides to the controversy quickly acquiesced, and, turning their horses about, the combined parties started toward the mountains, Pedro leading the way.

The road ran along the bank of the Concho for a couple of miles, and then turned abruptly toward the foothills. It was a beautiful valley, and the Broncho Rider Boys were much interested in the scenery. They passed several small groups of adobe houses, which Pedro explained were on his uncle’s estate, which seemed very large.

“There is the house,” Pedro at length explained, pointing to a fine appearing place on the top of a small hill. “It’s only a couple of miles farther.”

So interested had the boys become in what Pedro was telling them that they had paid very little attention to the rest of the company, until, as they rounded a turn in the now rocky road, Adrian discovered that the man who had made all the trouble had disappeared. Adrian quickly turned and rode back a few rods to where he could get an unobstructed view of the road behind, and there was Mr. Mexican riding away as fast as his horse could carry him.

“What shall we do?” queried Adrian, as soon as he had called the others back.

“Nothing, I should say,” was Donald’s advice. “It looks like the question of who was right and who wrong had settled itself. I say good riddance. What do you say, Pedro?”

“I say let him go. I don’t want him; but I should like to know who he is.” Then to the peons: “Do you know who he is?”

The peons looked stupidly at each other, but made no reply.

“Why don’t you answer?” asked Donald sharply. “Who is that man?”

“Quien sabe!” was the exasperating answer, as the men shrugged their shoulders in a manner which reminded Billie so much of a vaudeville act that he burst into a hearty laugh.

“Quien sabe!” he repeated. “Well, I know enough Spanish to understand that they don’t know. But why don’t they know?”

“It’s too deep for me,” replied Adrian. “The whole affair is too mysterious for anyone but a Sherlock Holmes to ferret out; but there is certainly no need of our going any farther in this direction, and I move that we start back.”

“You won’t have any trouble in getting home now, will you?” he asked, turning to Pedro.

“Oh, no; and are you going back to the Rio Brava?”

“To the what?” asked Donald.

“The Rio Brava.”

“He means the Rio Grande,” explained Adrian. “The Mexicans call it the Rio Brava, and that is the way it is on their maps. I saw one of their geographies once.”

“Then we’re going back to the Rio Brava,” laughed Billie, “and I hope we get there before it begins to rain.”

Whereupon, bidding good-by to Pedro, who was most profound in his thanks, they started on their return ride.

They had not been riding more than half an hour before the clouds, which had been getting blacker and blacker, became so angry-looking that they determined to seek shelter, and turned their horses’ heads toward one of the little cluster of houses they had passed earlier in the day.

By the time the boys reached the little cluster of adobe buildings, the rain was descending in torrents, and, in spite of the tropical surroundings, the air was much too cold to be comfortable. As they approached the first house on the outskirts of the hamlet, the door opened and a blanketed peon, preceded by half a dozen dogs of all kinds and conditions, made his appearance. Rushing at the horses, the dogs made the neighborhood hideous with their barking, but they made no attempt to do more.

“What do you want?” called out the man, speaking in Spanish.

“Call off your dogs,” replied Donald, “so we can talk with you.”

The man did as requested, and the animals grouped themselves around him in the doorway.

“We want a place to get in out of the rain and something to eat,” Donald continued, as soon as the barking had ceased.

“There is no place here,” replied the peon.

“What is this building?” and Donald pointed at a small hut at one side, which was covered with a thatched roof.

“It’s the kitchen.”

“What does he say?” asked Billie, who hadn’t been able to gain the faintest idea of the conversation.

“He says that’s the kitchen,” replied Adrian.

“Huh!” grunted Billie, “looks more like a pigpen.”

“What’s the matter with our going in there until it stops raining?” continued Donald, pressing his inquiries.

“You can go in there, if you want to, but there is nothing for you to eat.”

“No eggs?”

“No.”

“No tortillas?”

“No.”

“No frijolles?”

“No.”

“We will pay you well,” added Donald.

The peon’s manner underwent a remarkable change.

“Perhaps the señora has a few tortillas,” he said. “I’ll go and see.”

He turned and quickly entered the house, returning in a minute to say that there were both tortillas—corn cakes—and beans, and inviting the boys to alight.

“There is no room in my casa,” he said, “but, if the young señores will be satisfied to go into the kitchen, I will make a fire and the señora will get them something to eat.”

The boys needed no second bidding, and, quickly dismounting, they threw their bridle-reins over some cactus growing about, and went inside.

“I’d rather eat out of doors,” declared Billie, after looking the place over.

“So would I,” said Adrian, “if it were not for the rain.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” ventured Donald philosophically, “I’ve seen worse places than this. Do you remember the Zunis?”

“It was always dry there,” declared Billie.

“Yes, and there were always plenty of snakes,” laughed Adrian, who never had forgotten Billie’s aversion to reptiles since his visit to the snake dancers.

Their conversation was interrupted by the appearance of the peon’s wife, who proceeded to make a fire in the Mexican range, as the boys called the few bricks set up on edge. From a little earthen dish she produced a few thin corn cakes, which she toasted over the fire. When they were properly done, she put them on a dish and poured over them a couple of spoonfuls of black beans. These she offered to the boys to eat.

Billie looked at it askance.

“I thought I was glad to eat a woman’s cooking at Presidio last night,” he said. “If this is a sample of Mexican women’s cooking, I’d rather get my own meals.”

However, they were all hungry, and the beans and tortillas soon disappeared.

“How much are you going to pay him for this, Don?” queried Adrian. “You said you would pay him well.”

“I don’t know. Do you think fifty cents is enough?”

“Try him and see.”

Donald took a silver half dollar from his pocket and held it out toward the man, who had been watching the boys in silence. He looked stupidly at it, but made no move to take it.

“Don’t you want it?” asked Donald.

“No, señor; it is too much.”

“How much do you want?”

“A real is plenty.”

A real is worth in American money about seven cents.

“Oh, take it,” urged Donald in Spanish, “although I think a real is all it’s worth,” he added in English, which the peon could not understand.

Thus urged the man took the coin and bowed low with many expressions of thanks. The coin also seemed to have loosened his tongue, and he urged the boys to make themselves perfectly at home.

“My poor house is yours,” he declared, “as long as you will honor it with your presence. I will go and give your horses some straw.”

Suiting the action to the word, he hastily left the hut, and, looking through the door, the boys saw him leading the animals to a little corral a short distance from the kitchen.

The rain continued to descend almost in sheets.

“This must be the way it rained in the days of Noah,” Billie suggested.

“Yes,” replied Adrian, “and it looks as though it might continue for forty days. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“What had we better do?” asked Billie, thinking about the ride back to Presidio.

“What can we do?” echoed Donald. “We never could find our way back to the Rio Grande in this rain, and, if we did, we would find it so full of water we couldn’t get across. The only thing we can do is to stay right here till it stops raining.”

And stay they did.

The afternoon passed and darkness fell. The peon brought in a candle stuck into a most unique candlestick, which must have been the property of some ancient Don. The boys wondered where he got it, but did not think it wise to inquire. They knew too little Spanish to engage in anything like a general conversation with the man, but they did manage to get enough out of him to discover that he was much dissatisfied. Why, they could not make out.

Along about nine o’clock, the peon and his wife betook themselves off to the other hut, which served as their main house, and the boys, piling their saddles in the doorway, to keep out any stray dog that might be prowling about, rolled themselves up in their blankets, stretched themselves out on the floor, and were soon asleep.

How long he had slept, Billie could not tell, when he was awakened by a most unusual noise. The rain was still falling, although not in such torrents. At first Billie thought that the noise was caused by the rain on the thatched roof; but he soon became convinced that such was not the case. Finally he reached over and shook the sleeper nearest to him. It happened to be Adrian.

“What’s the matter?” queried that young gentleman, sitting up and peering into the darkness.

“I don’t know,” whispered Billie, “but it sounds as though some one were trying to get in.”

“Where?”

“That’s what I can’t make out.”

Adrian pulled his saddle-bag toward him and took out his electric torch. Slowly he pointed it in every direction, but he could see nothing unusual, although the strange noise continued.

“Funny, isn’t it?” he said, and then he arose to his feet.

As he did so, Billie glanced up at the speaker, and what he saw caused a broad grin to overspread his rotund countenance.

“Look!” he exclaimed, and pointed toward the roof.

Adrian did as he was told, and burst into a hearty laugh, which aroused Donald.

“What is it?” he exclaimed, also springing to his feet.

“Goats,” laughed Billy. “They’re climbing all over the roof.”

And sure enough they were, for what Billie had seen was the hoof of one of them sticking through the roof.

“They’ll all be coming through, first thing you know,” said Billie.

“I’m not so much afraid of that as that they will make holes for the rain to come through,” declared Adrian. “We must scare them off. Shoo!”

But he might as well have cried shoo at the moon.

“Wait a minute,” exclaimed Billie, “I’ll fix them.”

He crawled over to the other side of the kitchen, where a great dry cactus stem was leaned up against the side of the wall. It was as thick as a man’s leg, about six or eight feet long, and almost as light as cork. Waiting until he was satisfied by the sound that a goat was directly over his head, he gave a great thrust with the cactus log.

His aim was a good one. With a loud bleat, that was almost a wail, the goat went tumbling off the roof, and in a minute the boys heard it pattering away as fast as it could scamper. Twice during the night was the feat repeated, the only inconvenience it caused being that the boys did not sleep as soundly as they otherwise would.

After the last interruption Billie did not return to sleep, but lay awake thinking about the strange experiences of the past two days. As a result he saw daylight slowly breaking, and finding himself so wide awake, he determined to go and tend to the horses.

Removing the saddles from the doorway, he went out. The rain had ceased and there was every indication of a fine day. After taking a critical survey of the landscape, he went to the corral and examined the horses, to see that they were all right, after which he led them to a pool some distance away to water.

The whole proceeding consumed some fifteen or twenty minutes, so that, by the time he was ready to return to the hut, the sun was just rising above the horizon.

Giving the horses an armful of straw, which he found under a little shed, he started back to awaken his companions, when, to his surprise, he found himself confronted by the whole pack of wolfish dogs, who not only refused to let him advance, but threatened to attack him.

He uttered a loud “Halloo,” but no one seemed to hear him.

“Get out of my way,” he shouted, but his words only seemed to make the animals more furious.

Again he uttered a loud “Halloo,” and again no one replied.

By this time the dogs had become more courageous, and it began to look like a very serious situation, so that Billie, in order to defend himself, drew his six-shooter, determined to use it on the first of the dogs who should make up his mind to attack him.

Once more, however, he called aloud, and in response to the shout Donald appeared at the door, just as Billie was taking aim at a big gaunt hound which seemed determined to spring upon him.

“Don’t do it,” called Donald. “Don’t shoot unless you want to get us into all sorts of trouble.”

“Why not?” asked Billie. “I’m not going to be made dog meat.”

“You’ll be made worse than that if you kill one of the peon’s dogs.”

Just what might have been the outcome of the situation is hard to tell, had not a voice of authority suddenly rang out from the direction of the house:

“Vaya te, perros! Vaya te!”1

The dogs ceased their angry barking, and slunk hastily away, while Billie, looking in the direction from which the voice proceeded, saw Pedro riding around the kitchen.

“By George!” exclaimed Billie, as he advanced to meet Pedro, “you surely did come right in the nick of time. I thought I’d have to become dog-meat, just to keep the others out of trouble, and I was going to do it.”

“I don’t think that would have been necessary,” declared Donald, as he came out from the kitchen, followed by Adrian. “But I’m glad you got out of the trouble without killing the peon’s dog. I know how much the peons think of their dogs—more than their wives.”

“I’m very sorry,” said Pedro, “that you should have had so much trouble, and that I did not take you home with me yesterday. My uncle says I was very rude not to have brought you home to breakfast.”

“Breakfast!” exclaimed Billie. “How could you have taken us home to breakfast? It was after eleven o’clock when we met you.”

Donald laughed.

“You don’t understand,” he said; “in Mexico they call the meal that we name breakfast simply coffee, as that is all they have to break their morning fast. From eleven to half-past twelve they have what they call almuerzo, or breakfast. Along about five o’clock they have cena, or supper, and dinner comes anywhere from seven to ten o’clock. This they call comida.”

Billie’s round face expanded into a broad smile.

“Four meals a day!” he finally exclaimed. “Fine! I think I’d like to live in Mexico.”

“I’m sure we’d like to have you,” laughed Pedro, “and now that I have found you again, you must come with me and have coffee. Then my uncle will send someone with you to show you the short way back to the Rio Brava.”

The Broncho Rider Boys looked at each other knowingly as Adrian explained that they were not at all anxious to find a short road back, as they wished to see as much of the country as possible.

“That’s fine,” was Pedro’s exultant exclamation, “for, if you are in no hurry, you can stay with us several days, and I can take you up the Concho. I surely want to do something to show you how much I appreciate what you did for me yesterday. My uncle thinks I was in great danger.”

“How so?” asked Donald.

“Get onto your horses, and I’ll tell you as you ride along,” replied Pedro. “Here, Fillipe!” he called, “come and saddle the horses.”

Not only Fillipe, but several other peons, who had made their appearance while the boys were talking, hastened to obey Pedro’s command, and in a very few minutes the four boys were jogging along toward the Hacienda del Rio, for so the estate of Pedro’s uncle was called.

“Now for the story,” laughed Billie, “and I wish you would tell it in English so I can understand.”

“If you won’t laugh at my English,” said Pedro, “I’ll try.”

“What, do you speak English?” asked Adrian.

“A little. My sister, Guadalupe, speaks it well, as does my uncle; but they call me the lazy one, because I have never tried very hard. I’m sorry now I didn’t try harder.”

“Well, try now,” insisted Billie. “We have so many foreigners in the United States and so many speak poor English that we can understand most anything.”

Pedro laughed heartily.

“I hope I can do as well as some; so, to begin with, I must tell you something about my home. We live on a large hacienda, in the State of Michoa-can, and our house is built only a little ways from the shore of a small lake, Tiasca by name. On the other side of this lake are mountains, very much like these across the Concho,” and he pointed across the river to the west.

“On the shore of the lake, nearest the mountains, is a little village of fisher-folk, but they are a bad lot. They are lazy and dishonest. They steal at every opportunity. Hardly a week passes that some of them do not cross the lake and steal chickens, pigs, goats, and even cattle. We call them pirates, because they come over in little boats. They have always been bad, but since they became Zapatists they are worse than ever.”

“What do you mean by Zapatists?” asked Adrian.

“Followers of the robber, Zapata. You must have heard about him.”

“Now that you explain, I believe I have. So these men are followers of Zapata?”

“Yes; and before the days of President Madero they were a part of what was known as the Las Cruces robbers.

“Well, ever since my father was a young officer he has always had trouble with these pirates.”

“Do they ever try to break into your house?” queried Billie.

“They did once, and that is part of the story. It happened when Guadalupe was a baby and I was only a little more. My father was away at the time with almost all the rurales in the district, and the robbers must have known that there were only a few peons left to guard the house.

“Three of them came to the gate and demanded that my mother give them five hundred dollars. She refused, and they threatened to come and get it. Mother was not much afraid, as our house is very strongly built of stone; but still she took every precaution to see that they could not break in; but that night about twenty-five of them surrounded the house and sat down to a regular siege.”

“Couldn’t you shoot them from the windows?” asked Billie.

“I suppose we could, but mother didn’t wish to do that. So she just kept everything shut tight, expecting every hour that my father would return.

“After they had been there three days, one of our peons, Jose Gonzales, who had been away to Morelia on an errand, came home. He said that, as he came up the shore of the lake, he heard a group of the pirates saying that they were getting afraid to stay longer, and that they were going back across the lake. Sure enough, they did, and my mother was so relieved, especially to have Jose home, for he was considered above the ordinary run of peons, that she ceased her watchfulness and turned the care of the place over to Jose.

“Along about midnight my sister was taken sick, and my mother was obliged to get up to take care of her. As she came out into the rotunda and cast her eyes across the patio toward the great front gate, she saw a sight which frightened her nearly to death. Jose was standing in the half-open gate, talking to men whom my mother knew must be the pirates. She realized at once that he was a traitor, and, drawing quickly back into her room, she barred the door as best she could, and waited to see what would happen.

“She didn’t have long to wait, as the robbers soon attempted to get in; but for a long time the bar held. Then Jose brought a great hammer and the door finally yielded.”

“The villain!” exclaimed Billie, whose fighting blood was stirred by the recital of such treachery.

“It is even worse than you think,” continued Pedro, “for, as the pirates rushed in, Jose called out, as he pointed to my father’s strong box: 'There is the silver. You can have that, but the señora is mine.’

“At this he seized my mother, and started to carry her out of the door; but, as he turned, he saw a sight which caused him to loose his hold and draw his knife, for there in the door stood my father, his drawn saber in his hand and death in his eye. He took a step forward and aimed a blow at Jose, but as he struck, my mother, overcome with joy, seized him around the knees and spoiled his aim. Instead of cleaving Jose’s skull, he struck a glancing blow and cut off his left ear. We found the ear later.”

“Good for your father!” exclaimed all the boys. “But then what happened?” and they drew their horses down to a walk, so interested had they become in the story.

“Well, for a moment the robbers were surprised by the attack, but when they saw my father was alone, they all turned upon him and he would undoubtedly have been killed, but that his men, who had by this time overpowered the robbers in the patio, came to his aid. The bandits were soon secured, but in the fight and darkness, Jose escaped. We afterwards learned that he had been an accomplice of the bandits for years and had planned this attack for the sole purpose of stealing my mother. His aim was to become a gentleman and live in the City of Mexico, and for a while he did. Later my father learned of his whereabouts and his arrest was ordered, but again he managed to escape.

“During the Madero revolution he tried to win the good graces of President Madero, but his record was too bad and President Madero ordered him out of the city. Since that time he has threatened vengeance on the President and all his friends. It is even said he is trying to start a new revolution. He is none too good, I can tell you.”

“But what has all this to do with your great danger?” asked Adrian.

“Why, my uncle thinks Jose is the man from whom you rescued me yesterday.”

“What!” exclaimed all the boys in chorus. “That man!”

“That’s what my uncle thinks. He has been reported in this vicinity. He has changed his name to Rafael Solis and I heard one of the peons yesterday address him as Don Rafael.”

“I didn’t notice that he had lost an ear,” said Donald.

“No,” said Billie, “but you noticed that he wore his hair unusually long, didn’t you? I expect he does that to hide the missing ear.”

“That’s it exactly!” exclaimed Donald. “I knew there was something strange about his appearance, but for the life of me I couldn’t tell what it was.”

“Well, that’s it,” replied Billie, “and if I ever get my eye on you again, Mr. Don Rafael, I’ll know you.”

“You mustn’t say Mr. Don Rafael,” explained Pedro. “Don means Mr. If you want to, you can call him Don Rafael; but as for me I shall think of him always as Jose the traitor.

“But here we are at my uncle’s house and he will be more than glad to see you.”

As the little cavalcade drew up in front of the great white house, a peon opened the big gate and the quartette rode into the patio. Other servants quickly took their horses and led them to the stable, while Pedro escorted the boys up a broad flight of stairs to the second floor, on which were located the parlors, library and dining room. It was a beautiful home and our boys felt just a little bit awkward on coming into such a sumptuous house dressed in their travel-stained riding garments. But if they had any sense of being out of place, they were quickly put at their ease by a kindly faced gentleman of middle age, who advanced to the head of the stairs and greeted them pleasantly.

“These are the brave Americans who gave me such unexpected assistance yesterday,” said Pedro by way of introduction.

“I guessed as much,” replied his uncle.

“And this is my uncle, Don Antonio Sanchez,” said Pedro to the boys, “he is just as glad to see you and to have you here as I am. And uncle,” he continued without stopping to catch his breath, “they are going to stay with me several days, aren’t you?” to the boys.

“I don’t think we promised, did we?” replied Donald, “but we will stay today, anyway. We shall be pleased to see something of the Concho valley.”

Don Antonio lead the way to the dining room, where the boys were introduced to Pedro’s aunt and to his sister, Guadalupe.

If the boys had been embarrassed upon meeting Don Antonio, they were more so upon meeting Guadalupe, who was something different from any girl they had ever met. When she was introduced to Billie and called him Don Guillermo, he turned as red as a turkey gobbler and wished he was somewhere else; but, after a few minutes, he forgot his embarrassment in his morning meal—for when it came to eating, there was nothing could interfere with the business of the moment.

Don Antonio and his wife were much pleased with the boys and asked Donald and Adrian many questions about the big ranches from which they came. Both were able to give him all the information he wanted and he insisted that after breakfast all should ride over his hacienda and see the American improvements he had put upon it.

A member of Don Antonio’s household who attracted much attention from the boys was a great Newfoundland dog, by the name of Tanto. He was Guadalupe’s special property, and at first eyed the boys with a good deal of suspicion. But, when he discovered that they were friends of the family, he became quite as friendly as any of the others.

“He seems very fond of you,” said Billie to Guadalupe, in an attempt to make himself agreeable to the beautiful señorita.

“Yes, indeed,” she replied. “I raised him from a puppy. Are you fond of dogs, Don Guillermo?”

“Oh, yes,” interrupted Adrian, who overheard the remark, “Don Guillermo is very fond of dogs. If you could have seen him playing with them, about daylight this morning, you would have thought so,” at which remark all the boys laughed heartily, and Billie had to explain his adventure.

“Well, I think it was too bad that you should be caught in such a place; but Tanto will never do a thing like that. Will you, Tanto?” and she patted the dog’s head.

“Come on,” called Pedro from the patio, “if we’re going to look over the hacienda, let’s get started before it gets any warmer.”

Accompanied by Don Antonio, the boys rode from place to place over the great farm, along the eastern border of which the Concho river wound its way, while on the other side the mountains rose abruptly to several hundred feet. At the southern extremity the river approached almost to the foot of the mountains, making a narrow neck of land. Still farther south the river broadened out into quite a lake, upon which were a number of small boats.

As the boys turned to retrace their path, Adrian lingered a moment to watch the flight of a flock of water-fowl, and, as he did so, his attention was attracted to the movements of a boat, which had put out from the mountain-side, and which had started the flight of the water-fowl. It contained three men, and, as it slipped silently out of the shadows of the overhanging trees, there was something about the appearance of the man at the stern which seemed most familiar, although he had his blanket thrown over his shoulder in such a manner as to conceal his face.

At first Adrian started to call his companions, but upon second thought he decided to do a little reconnoitering on his own hook. He accordingly dismounted from his horse, and walked slowly around the trees which obscured his view. At his left was a little point of land, extending out into the water, and he slowly and cautiously made his way thither. From this point of vantage he obtained a good view of the river for quite a distance, and could see the boat without being seen.

It was very evident that the boat had come out of a little inlet about a hundred yards from the point upon which Adrian was standing, which appeared to be the mouth of a small brook. On the other side of the point, around which the boat was slowly being rowed, was a steep rock, at least three times the length of an ordinary skiff, beyond which it was impossible for Adrian to see. The boat headed directly for the rock, and a moment later disappeared behind it; but that one look was sufficient to convince Adrian that the man who had attracted his attention was the same who had tried to steal Pedro.

“I wonder what he is doing around here, anyway?” soliloquized Adrian. “No good, I’m sure. The best thing I can do is to hurry after the rest of them and tell them what I have seen. They’ll be wondering where I am.”

Hastily he scrambled up the bank to where he had left his horse, when, just as he raised his head above the edge, he felt a hand grasp his right foot, and he was pulled violently downward. For just a minute he clung to the shrubbery about him, and then, gaining his wits, he suddenly relaxed his hold and, turning half way round, push himself backward.

It was an old trick he had learned at school, and the result was that he came down on top, instead of underneath, the man who had grasped his ankle.

In another moment he was engaged in a rough-and-tumble fight, which proved of short duration, for Adrian was much more than a match for his assailant. Almost as soon as it takes to tell it, Adrian was sitting on top of a white-shirted peon, whose only weapon was a great stone, with which he had doubtless intended to intimidate, rather than hit, the boy.

“Well,” exclaimed Adrian, as soon as he had gained his breath sufficiently to speak, “what do you mean by dragging me down like this?”

At the sound of Adrian’s voice the peon turned his head and looked up at his captor in the greatest surprise.

“Pardon me,” he whined. “It was a mistake. I thought you were someone else.”

“Who did you think I was?”

“El niño de Sanchez”—meaning the Sanchez boy—whined the peon.

“Oh, you did, eh?” exclaimed Adrian. “Well, you come with me and let Don Antonio question you. I think he is looking for you.”

Adrian did not have to lead his captive far, for, when he reached the place where his horse was waiting for him, he saw the others returning. They had become concerned at his delay, and had come back to look for him.

“What’s the matter?” called Donald, as soon as he was within speaking distance.

“I’ve had a fight,” was the response, “and this is the result,” pushing the peon forward.

“Fight!” exclaimed Billie. “What were you fighting about?”

“Oh, nothing. This man tried to capture me, and I turned the tables, that’s all.”

“Explain,” said Don Antonio, looking first at Adrian and then at the peon.

“This man mistook me for Pedro, he says, and tried to drag me into the river, or somewhere.”

Don Antonio turned upon the peon fiercely.

“Is this true?” he demanded sternly.

“Forgive me, señor,” whined the peon, “I was ordered to do it.”

“Ordered!” thundered Don Antonio. “By whom?”

“Don Rafael.”

“Asi!” exclaimed Don Antonio, and his face grew even more stern. “So it is that scoundrel who put you up to this? Where is he?”

The peon remained silent.

“Where is he, I say?” repeated Don Antonio.

“I can’t tell.”

“Why not?”

“He would kill me, señor.”

“Have no fear. If you will tell me why you tried to take Pedro and where we can catch Don Rafael, as you call him, I will give you ample protection.”

Thus encouraged, the peon said that Don Rafael was hiding in the mountains a short distance from the river. He said that he had gathered about him a band of more than fifty men, and that he had told them they were to be part of a new army to overthrow President Madero and make Porfirio Diaz again president. In order to protect themselves, he told them they must make a captive of General Sanchez’s son, Pedro.

“I see,” exclaimed Don Antonio. “They want to hold Pedro as a hostage, in case any of them get into the hands of the law. Isn’t that it?”

“Si, señor,” said the peon, nodding his head emphatically. If this proved to be true then Donald’s guess had been along correct lines. This little fact seemed like a good omen to begin with. Now, if it turned out that this further prediction regarding the limited number of the rustlers also came to pass, and they could only catch them off their guard before dawn arrived, it would not be strange if they turned the trick, daring as their plans might appear.

“Now, first of all we’ve got to muffle our ponies’ heads so they can’t betray us by neighing,” announced Donald.

“A good idea, I say,” Adrian went on to remark, approvingly. “I’ve known the best trained cayuse going to let out a neigh when it scented some of its own kind near by. That’s a thing they just can’t help, seems like. So, the sooner we get their muzzles tied up the better.”

“You’ll have to show me how,” said Billie; “because that’s where my education’s been sorter neglected, so to speak. But I want to know, just stick a pin in that, please.”

He soon learned just how this could be accomplished by the aid of their blankets. The horses objected to such treatment, but had to submit in the end. And when the job had been completed they were so muzzled that they could not have whinnied, no matter how hard they tried.

Mounting them again the three boys moved cautiously ahead. It was their purpose to cover a cer- [Transcriber's note: missing line(s) of text at this place in original printed text.] can get away. The rurales can take care of the fifty others later on.“

“That is good advice,” declared Don Antonio. “Let us hasten back and send a messenger to Presidio del Norte, and then we can return and watch for Don Rafael.”

“I don’t see any use of all of us returning to the house,” declared Billie. “I’ll stay here and watch the river.”

“And I’ll stay with you,” declared Adrian.

“Suppose we fix it this way,” said Don Antonio: “Pedro and one of you return to the house and send the messenger, and I and two others will stay and watch the river, as Don Guillermo says.”

“If Don Guillermo’s willing,” replied Adrian, with a laugh at Billie’s Mexican name.

“Sure I’m willing,” said Billie, “and tell the rurales to hurry up or we’ll capture the whole bunch.”

The matter having been thus decided, Pedro and Donald returned to the house, taking the captured peon with them, while the other three hitched their horses and proceeded to the little point of land from which Adrian made his observation.

The morning was now far spent, and the sun was rapidly approaching the meridian; but for once Billie seemed to have forgotten that it was dinnertime. In fact, so interested was he in the adventure, that he seemed utterly oblivious of the sun itself, which beat down fiercely upon the trio, and made the shade almost a necessity. So interested was he, in fact, that he ventured to the very edge of the point, and peered eagerly in the direction of the great rock.

“I could almost swim around there,” he said to himself. “I’ve a great notion to do it.”

For a minute he stood undecided.

“If it wasn’t for my Marlin I would,” he mused. “As it is, I guess I’d better go around.”

He walked back toward the place where he had left the others, all the time looking for a place where he could get around behind the big rock.

“What are you looking after?” queried Adrian, as Billie passed the spot where he sat with his eyes glued on the river.

“I want to see what is the other side of that rock.”

“What good’ll that do? We can see way up the river from here.”

“I don’t know,” was Billie’s response, “but I’ve got a hunch to take a look.”

“Well, go ahead. Don Antonio and I will stay here. If you see anything, call.”

Slowly Billie forced his way through the fringe of bushes that lined the bank, and, little by little, climbed to the top of the big rock, from which he could gain just as good a view of the mountainous country at the side as he could of the river. What he saw caused him to drop hastily to the ground and crawl a step or two backward, for directly in front of him, not a hundred yards away, was a score or more men grouped around Don Rafael, who was addressing them earnestly.

Waiting to see whether or not he had been observed, and judging from the fact that there was no commotion from below that he had not, Billie cautiously peered through the foliage.

The spot upon which the men were gathered was right at the mouth of the little stream before mentioned. A boat, evidently the one in which Adrian had seen Don Rafael and his two companions, was tied to the bank.

So far as Billie could see, only three or four of the men were armed. They seemed a peaceable lot.

“I wonder what he is telling them?” mused Billie in a partly audible voice—a habit of talking with himself of which he seemed totally unconscious. “I wish I could get near enough to hear.”

Cautiously he crept nearer the edge of the rock, in the meantime straining every nerve to catch a word. Once he did catch the sound of Don Rafael’s voice, but he could not understand.

“The trouble is,” explained Billie to himself, “he is talking Spanish, and I’m not familiar enough with the lingo to distinguish the sounds. I wish he would talk English.”

Again he advanced his position a couple of feet.

The voice was more distinct, and, as Don Rafael became somewhat excited, Billie caught the words, “carbina” and “macheté,” which he knew referred to arms.

“By George!” suddenly exclaimed Billie, in a voice loud enough for anyone near him to have heard, “I’ll bet they’re talking about running guns into the country. I’ll bet we’ve stumbled onto the very thing we came out to find. I must hurry back and tell Ad.”

Unmindful of the men below, he jumped up from his recumbent position and started to leave the rock the way he had come. In his haste, he did not notice that the spot upon which he had been reclining was covered with moss, and, as he took his first step forward, his foot slipped; he grasped frantically at the surrounding bushes, to save himself, failed in his attempt, and the next moment pitched head first off the rock.