The Project Gutenberg EBook of Two Little Waifs, by Mrs. Molesworth This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Two Little Waifs Author: Mrs. Molesworth Illustrator: Walter Crane Release Date: April 29, 2012 [EBook #39567] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TWO LITTLE WAIFS *** Produced by Annie McGuire.This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print archive.

AUTHOR OF 'CARROTS,' 'CUCKOO CLOCK,' 'TELL ME A STORY'

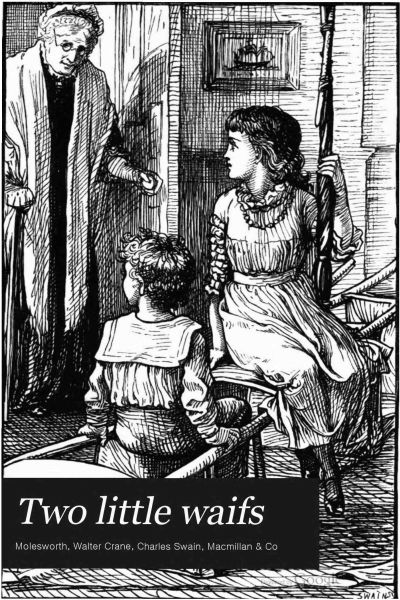

Two small figures, hurrying along hand-in-hand, caught the attention of several people.—Page 166.

Two small figures, hurrying along hand-in-hand, caught the attention of several people.—Page 166.

| CHAPTER I. | Papa has sent for us |

| CHAPTER II. | Poor Mrs. Lacy |

| CHAPTER III. | A pretty Kettle of Fish |

| CHAPTER IV. | "What is to be Done?" |

| CHAPTER V. | In the Rue Verte |

| CHAPTER VI. | Among the Sofas and Chairs |

| CHAPTER VII. | The kind-looking Gentleman |

| CHAPTER VIII. | A Fall Downstairs |

| CHAPTER IX. | From Bad to Worse |

| CHAPTER X. | "Avenue Gérard, No. 9" |

| CHAPTER XI. | Walter's Tea-Party |

| CHAPTER XII. | Papa at Last |

"It would both have excited your pity, and have done your heart good, to have seen how these two little ones were so fond of each other, and how hand-in-hand they trotted along."

The Renowned History of Goody Two-Shoes.

"It's what comes in our heads when we

Play at 'Let's-make-believe,'

And when we play at 'Guessing.'"

Charles Lamb.

It was their favourite play. Gladys had invented it, as she invented most of their plays, and Roger was even more ready to play at it than at any other, ready though he always was to do anything Gladys liked or wanted. Many children would have made it different—instead of "going over the sea to Papa," they would have played at what they would do when Papa should come over the sea to them. But that was not what they had learnt to look forward to, somehow—they were like two little swallows, always dreaming of a sunny fairyland they knew not where, only "over the sea," and in these dreams and plays they found the brightness and happiness which they were still too[Pg 2] young to feel should have been in their everyday baby life.

For "Mamma" was a word that had no real meaning to them. They thought of her as of a far-away beautiful angel—beautiful, but a little frightening too; cold and white like the marble angels in church, whose wings looked so soft, till one day Roger touched them, and found them, to his strange surprise, hard and icy, which made him tell Gladys that he thought hens much prettier than angels. Gladys looked a little shocked at this, and whispered to remind him that he should not say that: had he forgotten that the angels lived up in heaven, and were always good, and that Mamma was an angel? No, Roger had not forgotten, and that was what made him think about angels; but they weren't pretty and soft like Snowball, the little white hen, and he was sure he would never like them as much. Gladys said no more to him, for she knew by the tone of his voice that it would not take very much to make him cry, and when Roger got "that way," as she called it, she used to try to make him forget what had troubled him.

"Let's play at going to Papa," she said; "I've thought of such a good way of making a ship with[Pg 3] the chairs, half of them upside down and half long-ways—like that, see, Roger; and with our hoop-sticks tied on to the top of Miss Susan's umbrella—I found it in the passage—we can make such a great high pole in the middle. What is it they call a pole in the middle of a ship? I can't remember the name?"

Nor could Roger; but he was greatly delighted with the new kind of ship, and forgot all about the disappointment of the angels in helping Gladys to make it, and when it was made, sailing away, away to Papa, "over the sea, over the sea," as Gladys sang in her little soft thin voice, as she rocked Roger gently up and down, making believe it was the waves.

Some slight misgiving as to what Miss Susan would say to the borrowing of her umbrella was the only thing that interfered with their enjoyment, and made them jump up hastily with a "Oh, Miss Susan," as the beginning of an apology, ready on Gladys's lips when the door opened rather suddenly.

But it was not Miss Susan who came in. A little to their relief and a good deal to their surprise it was Susan's aunt, old Mrs. Lacy, who seldom—for she was lame and rheumatic—managed to get as far as the nursery. She was kind and gentle, though rather[Pg 4] deaf, so that the children were in no way afraid of her.

"Well, dears," she said, "and what are you playing at?"

"Over the sea, Mrs. Lacy," said Gladys. "Over the sea," repeated Roger, who spoke very plainly for his age. "Going over the sea to Papa; that's what we're playing at, and we like it the best of all our games. This is the ship, you see, and that's the big stick in the middle that all ships have—what is it they call it? I can't remember?"

"The mast," suggested Mrs. Lacy.

"Oh yes, the mast," said Gladys in a satisfied tone; "well, you see, we've made the mast with our hoop-sticks and Miss Susan's umbrella—you don't think Miss Susan will mind, do you?" with an anxious glance of her bright brown eyes; "isn't it high, the—the mart?"

"Mast," corrected Mrs. Lacy; "yes, it's taller than you, little Gladys, though you are beginning to grow very fast! What a little body you were when you came here first," and the old lady gave a sigh, which made Roger look up at her.

"Has you got a sore troat?" he inquired.

"No, my dear; what makes you think so?"

"'Cos, when my troat was sore I was always breaving out loud like that," said Roger sympathisingly.

"No, my throat's not sore, dear, thank you," said the old lady. "Sometimes people 'breathe' like that when they're feeling a little sad."

"And are you feeling a little sad, poor Mrs. Lacy?" said Gladys. "It's not 'cos Miss Susan's going to be married, is it? I think we shall be very happy when Miss Susan's married, only p'raps it wouldn't be very polite to say so to her, would it?"

"No, it wouldn't be kind, certainly," said the old lady, with a little glance of alarm. Evidently Miss Susan kept her as well as the children in good order. "You must be careful never to say anything like that, for you know Susan has been very good to you and taken great care of you."

"I know," said Gladys; "but still I like you best, Mrs. Lacy."

"And you would be sorry to leave me, just a little sorry; I should not want you to be very sorry," said the gentle old lady.

Gladys glanced up with a curious expression in her eyes.

"Do you mean—is it that you are sad about?—has[Pg 6] it come at last? Has Papa sent for us, Mrs. Lacy? Oh Roger, listen! Of course we should be sorry to leave you and—and Miss Susan. But is it true, can it be true that Papa has sent for us?"

"Yes, dears, it is true; though I never thought you would have guessed it so quickly, Gladys. You are to go to him in a very few weeks. I will tell you all about it as soon as it is settled. There will be a great deal to do with Susan's marriage, too, so soon, and I wouldn't like you to go away without your things being in perfect order."

"I think they are in very nice order already," said Gladys. "I don't think there'll be much to do. I can tell you over all my frocks and Roger's coats if you like, and then you can think what new ones we'll need. Our stockings are getting rather bad, but Miss Susan thought they'd do till we got our new winter ones, and Roger's second-best house shoes are——"

"Yes, dear," said Mrs. Lacy, smiling, though a little sadly, at the child's business-like tone; "I must go over them all with Susan. But not to-day. I am tired and rather upset by this news."

"Poor Mrs. Lacy," said Gladys again. "But can't you tell us just a very little? What does Papa say?[Pg 7] Where are we to go to? Not all the way to where he is?"

"No, dear. He is coming home, sooner than he expected, for he has not been well, and you are to meet him somewhere—he has not quite fixed where—in Italy perhaps, and to stay there through the winter. It is a good thing, as it had to be, that he can have you before Susan leaves me, for I am getting too old, dears, to take care of you as I should like—as I took care of him long ago."

For Mrs. Lacy was a very, very old friend of the children's father. She had taken care of him as a boy, and years after, when his children came to be left much as he had been, without a mother, and their father obliged to be far away from them, she had, for love of her adopted son, as she sometimes called him, taken his children and done her best to make them happy. But she was old and feeble, sometimes for days together too ill to see Gladys and Roger, and her niece Susan, who kept house for her, though a very active and clever young lady, did not like children. So, though the children were well taken care of as far as regarded their health, and were always neatly dressed, and had a nice nursery and a pleasant garden to play in, they were, though they were not old enough[Pg 8] to understand it, rather lonely and solitary little creatures. Poor old Mrs. Lacy saw that it was so, but felt that she could do no more; and just when the unexpected letter from their father came, she was on the point of writing to tell him that she thought, especially as her niece was going to be married, some new home must be found for his two little waifs, as he sometimes called them.

Before Mrs. Lacy had time to tell them any more about the great news Miss Susan came in. She looked surprised to see her aunt in the nursery.

"You will knock yourself up if you don't take care," she said rather sharply, though not unkindly. "And my umbrella—my best umbrella! I declare it's too bad—the moment one's back is turned."

"It's the mast, Miss Susan," said Gladys eagerly. "We thought you wouldn't mind. It's the mast of the ship that's going to take us over the sea to Papa."

Some softer feeling came over Susan as she glanced at Gladys's flushed, half-frightened face.

"Poor little things!" she said to herself gently. "Well, be sure to put it back in its place when you've done with it. And now, aunt, come downstairs with me, I have ever so many things to say to you."

Mrs. Lacy obeyed meekly.

"You haven't told them yet, have you, aunt?" said Susan, as soon as they were alone.

"Yes, I told them a little," said the old lady. "Somehow I could not help it. I went upstairs and found them playing at the very thing—it seemed to come so naturally. I know you will think it foolish of me, Susan, but I can't help feeling their going, even though it is better for them."

"It's quite natural you should feel it," said Susan in a not unkindly tone. "But still it is a very good thing it has happened just now. For you know, aunt, we have quite decided that you must live with us——"

"You are very good, I know," said Mrs. Lacy, who was really very dependent on her niece's care.

"And yet I could not have asked Mr. Rexford to have taken the children, who, after all, are no relations, you know."

"No," said Mrs. Lacy.

"And then to give them up to their own father is quite different from sending them away to strangers."

"Yes, of course," said the old lady, more briskly this time.

"On the whole," Miss Susan proceeded to sum up, "it could not have happened better, and the[Pg 10] sooner the good-byings and all the bustle of the going are over, the better for you and for me, and for all concerned, indeed. And this leads me to what I wanted to tell you. Things happen so strangely sometimes. This very morning I have heard of such a capital escort for them."

Mrs. Lacy looked up with startled eyes.

"An escort," she repeated. "But not yet, Susan. They are not going yet. Wilfred speaks of 'some weeks hence' in his letter."

"Yes; but his letter was written three weeks ago, and, of course, I am not proposing to send them away to-day or to-morrow. The opportunity I have heard of will be about a fortnight hence. Plenty of time to telegraph, even to write, to Captain Bertram to ensure there being no mistake. But anyway we need not decide just yet. He says he will write again by the next mail, so we shall have another letter by Saturday."

"And what is the escort you have heard of?" asked Mrs. Lacy.

"It is a married niece of the Murrays, who is going to India in about a fortnight. They start from here, as they are coming here on a visit the last thing. They go straight to Marseilles."

"But would they like to be troubled with children?"

"They know Captain Bertram, that is how we came to speak of it. And Mrs. Murray is sure they would be glad to do anything to oblige him."

"Ah, well," said Mrs. Lacy. "It sounds very nice. And it is certainly not every day that we should find any one going to France from a little place like this." For Mrs. Lacy's home was in a rather remote and out-of-the-way part of the country. "It would save expense too, for, as they have no longer a regular nurse, I have no one to send even as far as London with them."

"And young Mrs. ——, I forget her name—her maid would look after them on the journey. I asked about that," said Susan, who was certainly not thoughtless.

"Well, well, we must just wait for Saturday's letter," said Mrs. Lacy.

"And in the meantime the less said about it the better, I think," said Susan.

"Perhaps so; I daresay you are right," agreed Mrs. Lacy.

She hardly saw the children again that day. Susan, who seemed to be in an unusually gracious[Pg 12] mood, took them out herself in the afternoon, and was very kind. But they were so little used to talk to her, for she had never tried to gain their confidence, that it did not occur to either Gladys or Roger to chatter about what nevertheless their little heads and hearts were full of. They had also, I think, a vague childish notion of loyalty to their old friend in not mentioning the subject, even though she had not told them not to do so. So they trotted along demurely, pleased at having their best things on, and proud of the honour of a walk with Miss Susan, even while not a little afraid of doing anything to displease her.

"They are good little things after all," thought Susan, when she had brought them home without any misfortune of any kind having marred the harmony of the afternoon. And the colour rushed into Gladys's face when Miss Susan sent them up to the nursery with the promise of strawberry jam for tea, as they had been very good.

"I don't mind so much about the strawberry jam," Gladys confided to Roger, "though it is very nice. But I do like when any one says we've been very good, don't you?"

"Yes," said Roger; adding, however, with his usual[Pg 13] honesty: "I like bofe, being praised and jam, you know, Gladdie."

"'Cos," Gladys continued, "if we are good, you see, Roger, and I really think we must be so if she says so, it will be very nice for Papa, won't it? It matters more now, you see, what we are, 'cos of going to him. When people have people of their own they should be gooder even than when they haven't any one that cares much."

"Should they?" said Roger, a little bewildered. "But Mrs. Lacy cares," he added. Roger was great at second thoughts.

"Ye—s," said Gladys, "she cares, but not dreadfully much. She's getting old, you know. And sometimes—don't say so to anybody, Roger—sometimes I think p'raps she'll soon have to be going to heaven. I think she thinks so. That's another reason, you see," reverting to the central idea round which her busy brain had done nothing but revolve all day, "why it's such a good thing Papa's sent for us now."

"I don't like about people going to heaven," said Roger, with a little shiver. "Why can't God let them stay here, or go over the sea to where it's so pretty. I don't want ever to go to heaven."

"Oh, Roger!" said Gladys, shocked. "Papa wouldn't like you to say that."

"Wouldn't he?" said Roger; "then I won't. It's because of the angels, you know, Gladdie. Oh, do you think," he went on, his ideas following the next link in the chain, "do you think we can take Snowball with us when we go?"

"I don't know," said Gladys; and just then Mrs. Lacy's housemaid, who had taken care of them since their nurse had had to leave them some months before, happening to bring in their tea, the little girl turned to her with some vague idea of taking her into their confidence. To have no one but Roger to talk to about so absorbing a matter was almost too much. But Ellen was either quite ignorant of the great news, or too discreet to allow that she had heard it. In answer to Gladys's "feeler" as to how hens travelled, and if one might take them in the carriage with one, she replied matter-of-factly that she believed there were places on purpose for all sorts of live things on the railway, but that Miss Gladys had better ask Miss Susan, who had travelled a great deal more than she, Ellen.

"Yes," replied Gladys disappointedly, "perhaps she has; but most likely not with hens. But have[Pg 15] you stayed at home all your life, Ellen? Have you never left your father and mother till you came here?"

Whereupon Ellen, who was a kindly good girl, only a little too much in awe of Miss Susan to yield to her natural love of children, feeling herself on safe ground, launched out into a somewhat rose-coloured description of her home and belongings, and of her visits as a child to the neighbouring market-town, which much amused and interested her little hearers, besides serving for the time to distract their thoughts from the one idea, which was, I daresay, a good thing. For in this life it is not well to think too much or feel too sure of any hoped-for happiness. The doing so of itself leads to disappointment, for we unconsciously paint our pictures with colours impossibly bright, so that the real cannot but fall short of the imaginary.

But baby Gladys—poor little girl!—at seven it is early days to learn these useful but hard lessons.

She and Roger made up for their silence when they went to bed, and you, children, can better imagine than I can tell the whispered chatter that went on between the two little cots that stood close[Pg 16] together side by side. And still more the lovely confusion of happy dreams that flitted that night through the two curly heads on the two little pillows.

"For the last time—words of too sad a tone."

An Old Story and other Poems.

Saturday brought the expected letter, which both Mrs. Lacy and Susan anxiously expected, though with different feelings. Susan hoped that nothing would interfere with the plan she had made for the children's leaving; Mrs. Lacy, even though she owned that it seemed a good plan, could not help wishing that something would happen to defer the parting with the two little creatures whom she had learnt to love as much as if they had been her own grandchildren.

But the letter was all in favour of Susan's ideas. Captain Bertram wrote much more decidedly than he had done before. He named the date at which he was leaving, a very few days after his letter, the date at which he expected to be at Marseilles, and went[Pg 18] on to say that if Mrs. Lacy could possibly arrange to have the children taken over to Paris within a certain time, he would undertake to meet them there at any hour of any day of the week she named. The sooner the better for him, he said, as he would be anxious to get back to the south and settle himself there for the winter, the doctor having warned him to run no risks in exposing himself to cold, though with care he quite hoped to be all right again by the spring. As to a maid for the children—Mrs. Lacy having told him that they had had no regular nurse for some time—he thought it would be a good plan to have a French one, and as he had friends in Paris who understood very well about such things he would look out for one immediately he got there, if Mrs. Lacy could find one to take them over and stay a few days, or if she, perhaps, could spare one of her servants for the time. And he begged her, when she had made her plans, to telegraph, or write if there were time, to him at a certain hotel at Marseilles, "to wait his arrival."

Susan's face had brightened considerably while reading the letter; for Mrs. Lacy, after trying to do so, had given it up, and begged her niece to read it aloud.

"My sight is very bad this morning," she said,[Pg 19] and her voice trembled as she spoke, "and Wilfred's writing was never very clear."

Susan looked at her rather anxiously—for some time past it had seemed to her that her aunt was much less well than usual—but she took the letter and read it aloud in her firm distinct voice, only stopping now and then to exclaim: "Could anything have happened better? It is really most fortunate." Only at the part where Captain Bertram spoke of engaging a maid for the journey, or lending one of theirs, her face darkened a little. "Quite unnecessary—foolish expense. Hope aunt won't speak of it to Ellen," she said to herself in too low a voice for Mrs. Lacy to hear.

"Well, aunt?" she said aloud, when she had finished the letter, but rather to her surprise Mrs. Lacy did not at once reply. She was lying on her couch, and her soft old face looked very white against the cushions. She had closed her eyes, but her lips seemed to be gently moving. What were the unheard words they were saying? A prayer perhaps for the two little fledglings about to be taken from her wing for ever. She knew it was for ever.

"I shall never see them again," she said, loud[Pg 20] enough for Susan to hear, but Susan thought it better not to hear.

"Well, aunt," she repeated, rather impatiently, but the impatience was partly caused by real anxiety; "won't you say what you think of it? could anything have happened better than the Murrays' escort? Just the right time and all."

"Yes, my dear. It seems to have happened wonderfully well. I am sure you will arrange it all perfectly. Can you write to Wilfred at once? And perhaps you had better see Mrs. Murray again. I don't feel able to do anything, but I trust it all to you, Susan. You are so practical and sensible."

"Certainly," replied Susan, agreeably surprised to find her aunt of the same opinion as herself; "I will arrange it all. Don't trouble about it in the least. I will see the Murrays again this afternoon or to-morrow. But in the meantime I think it is better to say nothing more to the children."

"Perhaps so," said Mrs. Lacy. Something in her voice made Susan look round. She was leaving the room at the moment. "Aunt, what is the matter?" she said.

Mrs. Lacy tried to smile, but there were tears in her eyes.

"It is nothing, my dear," she said. "I am a foolish old woman, I know. I was only thinking"—and here her voice broke again—"it would have been a great pleasure to me," she went on, "if he could have managed it. If Wilfred could have come all the way himself, and I could have given the children up into his own hands. It would not have seemed quite so—so sad a parting, and I should have liked to see him again."

"But you will see him again, dear aunt," said Susan; "in the spring he is sure to come to England, to settle probably, perhaps not far from us. He has spoken of it in his letters."

"Yes, I know," said Mrs. Lacy, "but——"

"But what?"

"I don't want to be foolish; but you know, my dear, by the spring I may not be here."

"Oh, aunt!" said Susan reproachfully.

"It is true, my dear; but do not think any more of what I said."

But Susan, who was well-principled, though not of a very tender or sympathising nature, turned again, still with her hand on the door-handle.

"Aunt," she said, "you have a right to be consulted—even to be fanciful if you choose. You have[Pg 22] been very good to me, very good to Gladys and Roger, and I have no doubt you were very good to their father long ago. If it would be a comfort to you, let me do it—let me write to Wilfred Bertram and ask him to come here, as you say, to fetch the children himself."

Mrs. Lacy reflected a moment. Then, as had been her habit all her life, she decided on self-denial.

"No, my dear Susan," she said firmly. "Thank you for proposing it, but it is better not. Wilfred has not thought of it, or perhaps he has thought of it and decided against it. It would be additional expense for him, and he has to think of that—then it would give you much more to do, and you have enough."

"I don't mind about that," said Susan.

"And then, too," went on Mrs. Lacy, "there is his health. Evidently it will be better for him not to come so far north so late in the year."

"Yes," said Susan, "that is true."

"So think no more about it, my dear, and thank you for your patience with a silly old woman."

Susan stooped and kissed her aunt, which from her meant a good deal. Then, her conscience quite at rest, she got ready to go to see Mrs. Murray at once.

"There is no use losing the chance through any foolish delay," she said to herself.

Two days later she was able to tell her aunt that all was settled. Mrs. Murray had written to her niece, Mrs. Marton, and had already got her answer. She and her husband would gladly take charge of the children as far as Paris, and her maid, a very nice French girl, who adored little people, would look after them in every way—not the slightest need to engage a nurse for them for the journey, as they would be met by their father on their arrival. The Martons were to spend two days, the last two days of their stay in England, with Mrs. Murray, and meant to leave on the Thursday of the week during which Captain Bertram had said he could meet the children at any day and any hour. Everything seemed to suit capitally.

"They will cross on Friday," said Susan; "that is the Indian mail day, of course. And it is better than earlier in the week, as it gives Captain Bertram two or three days' grace in case of any possible delay."

"And will you write, or telegraph—which is it?" asked Mrs. Lacy timidly, for these sudden arrangements had confused her—"at once, then?"

"Telegraph, aunt? No, of course not," said Susan a little sharply, "he will have left ——pore several[Pg 24] days ago, you know, and there is no use telegraphing to Marseilles. I will write to-morrow—there is plenty of time—a letter to wait his arrival, as he himself proposed. Then when he arrives he will telegraph to us to say he has got the letter, and that it is all right. You quite understand, aunt?"

"Oh yes, quite. I am very stupid, I know, my dear," said the old lady meekly.

A few days passed. Gladys had got accustomed by this time to the idea of leaving, and no longer felt bewildered and almost oppressed by the rush of questions and wonderings in her mind. But her busy little brain nevertheless was constantly at work. She had talked it all over with Roger so often that he, poor little boy, no longer knew what he thought or did not think about it. He had vague visions of a ship about the size of Mrs. Lacy's drawing-room, with a person whom he fancied his father—a tall man with very black whiskers, something like Mrs. Murray's butler, whom Miss Susan had one day spoken of as quite "soldier-like"—and Roger's Papa was of course a soldier—standing in the middle to hold the mast steady, and Gladys and he with new ulsters on—Gladys had talked a great deal about new ulsters for the journey—waving flags at each side. Flags were[Pg 25] hopelessly confused with ships in Roger's mind; he thought they had something to do with making boats go quicker. But he did not quite like to say so to Gladys, as she sometimes told him he was really too silly for a big boy of nearly five.

So the two had become rather silent on the subject. Roger had almost left off thinking about it. His little everyday life of getting up and going to bed, saying his prayers and learning his small lessons for the daily governess who came for an hour every morning, eating his breakfast and dinner and tea, and playing with his toy-horses, was enough for him. He could not for long together have kept his thoughts on the strain of far-away and unfamiliar things, and so long as he knew that he had Gladys at hand, and that nobody (which meant Miss Susan in particular) was vexed with him, he asked no more of fate! And when Gladys saw that he was much more interested in trying to catch sight of an imaginary little mouse which was supposed to have been nibbling at the tail of his favourite horse in the toy-cupboard, than in listening to her wonderings whether Papa had written again, and when Miss Susan was going to see about their new ulsters, she gave up talking to him in despair.

If she could have given up thinking so much about what was to come, it would have been better, I daresay. But still it was not to be wondered at that she found it difficult to give her mind to anything else. The governess could not make out why Gladys had become so absent and inattentive all of a sudden, for though the little girl's head was so full of the absorbing thought, she never dreamt of speaking of it to any one but Roger. Mrs. Lacy had not told her she must not do so, but somehow Gladys, with a child's quick delicate instinct of honour, often so little understood, had taken for granted that she was not to do so.

"Everything comes to him that has patience to wait," says the Eastern proverb, and in her own way Gladys had been patient, when one morning, about a week after the day on which Susan had told her aunt that everything was settled, Miss Fern, the daily governess, at the close of lessons, told her to go down to the drawing-room, as Mrs. Lacy wanted her.

"And Roger too?" asked Gladys, her heart beating fast, though she spoke quietly.

"Yes, I suppose so," said Miss Fern, as she tied her bonnet-strings.

The children had noticed that she had come into the schoolroom a little later than usual that morning,[Pg 27] and that her eyes were red. But in answer to Roger's tender though very frank inquiries, she had murmured something about a cold.

"That was a story, then, what she said about her eyes," thought sharp-witted Gladys. "She's been crying; I'm sure she has." But then a feeling of pity came into her mind. "Poor Miss Fern; I suppose she's sorry to go away, and I daresay Mrs. Lacy said she wasn't to say anything about it to us." So she kissed Miss Fern very nicely, and stopped the rest of the remarks which she saw Roger was preparing.

"Go and wash your hands quick, Roger," she said, "for we must go downstairs. Mine are quite clean, but your middle fingers are all over ink."

"Washing doesn't take it away," said Roger reluctantly. There were not many excuses he would have hesitated to use to avoid washing his hands!

"Never mind. It makes them clean anyway," said Gladys decidedly, and five minutes later two very spruce little pinafored figures stood tapping at the drawing-room door.

"Come in, dears," said Mrs. Lacy's faint gentle voice. She was lying on her sofa, and the children went up and kissed her.

"You has got a cold too—like Miss Fern," said[Pg 28] Roger, whose grammar was sometimes at fault, though he pronounced his words so clearly.

"Roger," whispered Gladys, tugging at her little brother under his holland blouse. But Mrs. Lacy caught the word.

"Never mind, dear," she said, with a little smile, which showed that she saw that Gladys understood. "Let him say whatever comes into his head, dear little man."

Something in the words, simple as they were, or more perhaps in the tone, made little Gladys suddenly turn away. A lump came into her throat, and she felt as if she were going to cry.

"I wonder why I feel so strange," she thought, "just when we're going to hear about going to Papa? I think it is that Mrs. Lacy's eyes look so sad, 'cos she's been crying. It's much worse than Miss Fern's. I don't care so much for her as for Mrs. Lacy," and all these feelings surging up in her heart made her not hear when their old friend began to speak. She had already said some words when Gladys's thoughts wandered back again.

"It came this morning," the old lady was saying. "See, dears, can you read what your Papa says?" And she held out a pinky-coloured little sheet of[Pg 29] paper, not at all like a letter. Gladys knew what it was, but Roger did not; he had never seen a telegram before.

"Is that Papa's writing?" he said. "It's very messy-looking. I couldn't read it, I don't think."

"But I can," said Gladys, spelling out the words. "'Ar—arrived safe. Will meet children as you prop—' What is the last word, please, Mrs. Lacy?"

"Propose," said the old lady, "as you propose." And then she went on to explain that this telegram was in answer to a letter from Miss Susan to their father, telling him all she had settled about the journey. "This telegram is from Marseilles," she said; "that is the town by the sea in France, where your dear Papa has arrived. It is quite in the south, but he will come up by the railway to meet you at Paris, where Mr. and Mrs. Marton—Mrs. Marton is Mrs. Murray's niece, Gladys—will take you to."

It was a little confusing to understand, but Mrs. Lacy went over it all again most patiently, for she felt it right that the children, Gladys especially, should understand all the plans before starting away with Mr. and Mrs. Marton, who, however kind, were still quite strangers to them.

Gladys listened attentively.

"Yes," she said; "I understand now. But how will Papa know us, Mrs. Lacy? We have grown so, and——" she went on, rather reluctantly, "I am not quite sure that I should know him, not just at the very first minute."

Mrs. Lacy smiled.

"No, dear, of course you could not, after more than four years! But Mr. Marton knows your Papa."

Gladys's face cleared.

"Oh, that is all right," she said. "That is a very good thing. But"—and Gladys looked round hesitatingly—"isn't anybody else going with us? I wish—I wish nurse wasn't married; don't you, Mrs. Lacy?"

The sort of appeal in the child's voice went to the old lady's heart.

"Yes, dear," she said. "But Susan thinks it will be quite nice for you with Léonie, young Mrs. Marton's maid, for your Papa will have a new nurse all ready. She wrote to tell him that we would not send any nurse with you."

Gladys gave a little sigh. It took some of the bloom off the delight of "going to Papa" to have to begin the journey alone among strangers, and she saw that Mrs. Lacy sympathised with her.

"It will save a good deal of expense too," the old lady added, more as if thinking aloud, and half forgetting to whom she was speaking.

"Will it?" said Gladys quickly. "Oh, then, I won't mind. We won't mind, will we, Roger?" she repeated, turning to her little brother.

"No, we won't," answered Roger solemnly, though without a very clear idea of what he was talking about, for he was quite bewildered by all he had heard, and knew and understood nothing but that he and Gladys were going somewhere with somebody to see Papa.

"That's right," said Mrs. Lacy cheerfully. "You are a sensible little body, my Gladys."

"I know Papa isn't very rich," said Gladys, encouraged by this approval, "and he'll have a great lot more to pay now that Roger and I are going to be with him, won't he?"

"You have such very big appetites, do you think?"

"I don't know," said Gladys. "But there are such lots of things to buy, aren't there? All our frocks and hats and boots. But oh!" she suddenly broke off, "won't we have to be getting our things ready? and do you think we should have new ulsters?"

"They are ordered," said Mrs. Lacy. "Indeed,[Pg 32] everything you will need is ordered. Susan has been very busy, but everything will be ready."

"When are we to go?" asked Gladys, suddenly remembering this important question.

The sad look came into Mrs. Lacy's eyes again, and her voice trembled as she replied: "Next Thursday, my darling."

"Next Thursday," repeated Gladys; and then catching sight of the tears which were slowly welling up into Mrs. Lacy's kind eyes—it is so sad to see an aged person cry!—she suddenly threw her arms around her old friend's neck, and, bursting out sobbing, exclaimed again: "Next Thursday. Oh, dear Mrs. Lacy, next Thursday!"

And Roger stood by, fumbling to get out his pocket-handkerchief, not quite sure if he should also cry or not. It seemed to him strange that Gladys should cry just when what she had wanted so much had come—just when it was all settled about going to Papa!

"The cab-wheels made a dreamy thunder

In their half-awakened ears;

And then they felt a dreamy wonder

Amid their dream-like fears."

Lavender Lady.

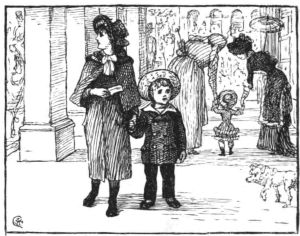

Gladys said something of the same kind to herself when, looking round her in the railway carriage on that same Thursday morning, she realised that the long, long looked-forward-to day had come. She and Roger had actually started on their journey to Papa! Yet her eyes were red and her face was pale. Little Roger, too, looked subdued and sober. It had never been so in their plays; in their pretence goings to Papa they were always full of fun and high spirits. It was always a beautiful sunny day to begin with, and to-day, the real day, was sadly dull and dreary, and cold too; the children, even though the new[Pg 34] ulsters were in all their glory, shivered a little and drew closer together. The rain was falling so fast that there was no use trying to look out of the window, when fields and trees and farmhouses all seem to fly past in a misty confusion. Mr. Marton was deep in his Times; Mrs. Marton, after settling the children in the most comfortable places and doing all she could think of, had drawn a book out of her travelling-bag and was also busy reading. Roger, after a while, grew sleepy, and nodded his head, and then Mrs. Marton made a pillow for him on the arm of the seat, and covered him up with her rug. But Gladys, who was not at all sleepy, sat staring before her with wide open eyes, and thinking it was all very strange, and, above all, not the very least bit like what she had thought it would be. The tears came back into her eyes again when she thought of the parting with Mrs. Lacy. She and Roger had hardly seen their kind old friend the last few days, for she was ill, much more ill than usual, and Susan had looked grave and troubled. But the evening before, she had sent for them to say good-bye, and this was the recollection that made the tears rush back to the little girl's eyes. Dear Mrs. Lacy, how very white and ill she looked, propped up by pillows on the old-fashioned sofa in[Pg 35] her room—every article in which was old-fashioned too, and could have told many a long-ago tender little story of the days when their owner was a merry blooming girl; or, farther back still, a tiny child like Gladys herself! For much of Mrs. Lacy's life had been spent in the same house and among the same things. She had gone from there when she was married, and she had come back there a widow and childless, and there she had brought up these children's father, Wilfred, as she often called him even in speaking to them, the son of her dearest friend. All this Gladys knew, for sometimes when they were alone together, Mrs. Lacy would tell her little stories of the past, which left their memory with the child, even though at the time hardly understood; and now that she and Roger were quite gone from the old house and the old life, the thought of them hung about Gladys with a strange solemn kind of mystery.

"I never thought about leaving Mrs. Lacy when we used to play at going," she said to herself. "I never even thought of leaving the house and our own little beds and everything, and even Miss Susan. And Ellen was very kind. I wish she could have come with us, just till we get to Papa," and then, at the thought of this unknown Papa, a little tremor came[Pg 36] over the child, though she would not have owned it to any one. "I wonder if it would have cost a very great deal for Ellen to come with us just for a few days. I would have given my money-box money, and so would Roger, I am sure. I have fifteen and sixpence, and he has seven shillings and fourpence. It could not have cost more than all that," and then she set to work to count up how much her money and Roger's added together would be. It would not come twice together to the same sum somehow, and Gladys went on counting it up over and over again confusedly till at last it all got into a confusion together, for she too, tired out with excitement and the awakening of so many strange feelings, had fallen asleep like poor little Roger.

They both slept a good while, and Mr. and Mrs. Marton congratulated themselves on having such very quiet and peaceable small fellow-travellers.

"They are no trouble at all," said young Mrs. Marton. "But on the boat we must of course have Léonie with us, in case of a bad passage."

"Yes, certainly," said her husband; "indeed I think she had better be with us from London. They will be getting tired by then."

"They are tired already, poor pets," said Mrs.[Pg 37] Marton, who was little more than a girl herself. "They don't look very strong, do they, Phillip?"

Mr. Marton took the cigarette he had just been preparing to enjoy out of his mouth, and turned towards the children, examining them critically.

"The boy looks sturdy enough, though he's small. He's like Bertram. The girl seems delicate; she's so thin too."

"Yes," agreed Mrs. Marton. "I don't mind, and no more does Léonie; but I think it was rather hard-hearted of Susan Lacy to have sent them off like that without a nurse of their own. If she had not been so worried about Mrs. Lacy's illness, I think I would have said something about it to her, even at the last. Somehow, till I saw the children, I did not think they were so tiny."

"It'll be all right once we get to Paris and we give them over to their father," said Mr. Marton, who was of a philosophical turn of mind, puffing away again at his cigarette. "It will have saved some expense, and that's a consideration too."

The children slept for some time. When they awoke they were not so very far from London. They felt less tired and better able to look about them and ask a few modest little questions. And when they got[Pg 38] to London they enjoyed the nice hot cup of tea they had in the refreshment room, and by degrees they began to make friends with Léonie, who was very bright and merry, so that they were pleased to hear she was to be in the same carriage with them for the rest of the journey.

"Till you see your dear Papa," said Léonie, who had heard all the particulars from her young mistress.

"Yes," said Gladys quietly—by this time they were settled again in another railway carriage—"our Papa's to be at the station to meet us."

"And we're to have a new nurse," added Roger, who was in a communicative humour. "Do you think she'll be kind to us?"

"I'm sure she will," said Léonie, whose heart was already won.

"She's to teach us French," said Gladys.

"That will be very nice," said Léonie. "It is a very good thing to know many languages."

"Can you speak French?" asked Roger.

Léonie laughed, "Of course I can," she replied, "French is my tongue."

Roger sat straight up, with an appearance of great interest.

"Your tongue," he repeated. "Please let me see[Pg 39] it," and he stared hard at Léonie's half-opened mouth. "Is it not like our tongues then?"

Léonie stared too, then she burst out laughing.

"Oh, I don't mean tongue like that," she said, "I mean talking—language. When I was little like you I could talk nothing but French, just like you now, who can talk only English."

"And can't everybody in France talk English too?" asked Gladys, opening her eyes.

"Oh dear no!" said Léonie.

Gladys and Roger looked at each other. This was quite a new and rather an alarming idea.

"It is a very good thing," Gladys remarked at last, "that Papa is to be at the station. If we got lost over there," she went on, nodding her head in the direction of an imaginary France, "it would be even worse than in London."

"But you're not going to get lost anywhere," said Léonie, smiling. "We'll take better care of you than that."

And then she went on to tell them a little story of how once, when she was a very little girl, she had got lost—not in Paris, but in a much smaller town—and how frightened she was, and how at last an old peasant woman on her way home from market had[Pg 40] found her crying under a hedge, and had brought her home again to her mother. This thrilling adventure was listened to with the greatest interest.

"How pleased your mother must have been to see you again!" said Gladys. "Does she still live in that queer old town? Doesn't she mind you going away from her?"

"Alas!" said Léonie, and the tears twinkled in her bright eyes, "my mother is no longer of this world. She went away from me several years ago. I shall not see her again till in heaven."

"That's like us," said Gladys. "We've no Mamma. Did you know?"

"But you've a good Papa," said Léonie.

"Yes," said Gladys, rather doubtfully, for somehow the idea of a real flesh-and-blood Papa seemed to be getting more instead of less indistinct now that they were soon to see him. "But he's been away such a very long time."

"Poor darlings," said Léonie.

"And have you no Papa, no little brothers, not any one like that?" inquired Gladys.

"I have some cousins—very good people," said Léonie. "They live in Paris, where we are now going. If there had been time I should have liked to go to[Pg 41] see them. But we shall stay no time in Paris—just run from one station to the other."

"But the luggage?" said Gladys. "Mrs. Marton has a lot of boxes. I don't see how you can run if you have them to carry. I think it would be better to take a cab, even if it does cost a little more. But perhaps there are no cabs in Paris. Is that why you talk of running to the station?"

Léonie had burst out laughing half-way through this speech, and though she knew it was not very polite, she really could not help it. The more she tried to stop, the more she laughed.

"What is the matter?" said Gladys at last, a little offended.

"I beg your pardon," said Léonie; "I know it is rude. But, Mademoiselle, the idea"—and here she began to laugh again—"of Monsieur and Madame and me all running with the boxes! It was too amusing!"

Gladys laughed herself now, and so did Roger.

"Then there are cabs in Paris," she said in a tone of relief. "I am glad of that. Papa will have one all ready for us, I suppose. What time do we get there, Léonie?"

Léonie shook her head.

"A very disagreeable time," she said, "quite, quite early in the morning, before anybody seems quite awake. And the mornings are already so cold. I am afraid you will not like Paris very much at first."

"Oh yes, they will," said Mrs. Marton, who had overheard the last part of the conversation. "Think how nice it will be to see their Papa waiting for them, and to go to a nice warm house and have breakfast; chocolate, most likely. Do you like chocolate?"

"Yes, very much," said Gladys and Roger.

"I think it is not you to be pitied, anyway," Mrs. Marton went on, for the half-appealing, half-frightened look of the little things touched her. "It's much worse for us three, poor things, travelling on all the way to Marseilles."

"That's where Papa's been. Mrs. Lacy showed it me on the map. What a long way! Poor Mrs. Marton. Wouldn't Mr. Marton let you stay at Paris with us till you'd had a rest?"

"We'd give you some of our chocolate," said Roger hospitably.

"And let poor Phillip, that's Mr. Marton," replied the young lady, "go all the way to India alone?"

The children looked doubtful.

"You could go after him," suggested Roger.

"But Léonie and I wouldn't like to go so far alone. It's nicer to have a man to take care of you when you travel. You're getting to be a man, you see, Roger, already—learning to take care of your sister."

"I have growed a good big piece on the nursery door since my birthday," agreed Roger complacently. "But when Papa's there he'll take care of us both till I'm quite big."

"Ah, yes, that will be best of all," said Mrs. Marton, smiling. "I do hope Papa will be there all right, poor little souls," she added to herself. For, though young, Mrs. Marton was not thoughtless, and she belonged to a happy and prosperous family where since infancy every care had been lavished on the children, and somehow since she had seen and talked to Gladys and Roger their innocence and loneliness had struck her sharply, and once or twice a misgiving had come over her that in her anxiety to get rid of the children, and to waste no money, Susan Lacy had acted rather hastily. "Captain Bertram should have telegraphed again," she reflected. "It is nearly a week since he did so. I wish I had[Pg 44] made Phillip telegraph yesterday to be sure all was right. The Lacys need not have known anything about it."

But they were at Dover now, and all these fears and reflections were put out of her head by the bustle of embarking and settling themselves comfortably, and devoutly hoping they would have a good passage. The words meant nothing to Gladys and Roger. They had never been on the sea since they were little babies, and had no fears. And, fortunately, nothing disturbed their happy ignorance, for, though cold, the sea was very smooth. They were disappointed at the voyage being made in the dark, as they had counted on all sorts of investigations into the machinery of the "ship," and Roger had quite expected that his services would be required to help to make it go faster, whereas it seemed to them only as if they were taken into a queer sort of drawing-room and made to lie down on red sofas, and covered up with shawls, and that then there came a booming noise something like the threshing machine at the farm where they sometimes went to fetch butter and eggs, and then—and then—they fell asleep, and when they woke they were being bundled into another railway carriage! Léonie was carrying[Pg 45] Roger, and Gladys, as she found to her great disgust—she thought herself far too big for anything of the kind—was in Mr. Marton's arms, where she struggled so that the poor man thought she was having an attack of nightmare, and began to soothe her as if she were about two, which did not improve matters.

"Hush, hush, my dear. You shall go to sleep again in a moment," he said. "But what a little vixen she is!" he added, when he had at last got Gladys, red and indignant, deposited in a corner.

"I'm too big to be carried," she burst out, half sobbing. "I wouldn't even let Papa carry me."

But kind Mrs. Marton, though she could hardly help laughing, soon put matters right by assuring Gladys that lots of people, even quite big grown-up ladies, were often lifted in and out of ships. When it was rough only the sailors could keep their footing. So Gladys, who was beginning to calm down and to feel a little ashamed, took it for granted that it had been very rough, and told Mr. Marton she was very sorry—she had not understood. The railway carriage was warm and comfortable, so after a while the children again did the best thing they could under the circumstances—they went to sleep. And so, I think, did their three grown-up friends.

Gladys was the first to wake. She looked round her in the dim morning light—all the others were still asleep. It felt chilly, and her poor little legs were stiff and numb. She drew them up on to the seat to try to warm them, and looked out of the window. Nothing to be seen but damp flat fields, and trees with a few late leaves still clinging to them, and here and there a little cottage or farmhouse looking, like everything else, desolate and dreary. Gladys withdrew her eyes from the prospect.

"I don't like travelling," she decided. "I wonder if the sun never shines in this country."

A little voice beside her made her look round.

"Gladdie," it said, "are we near that place? Are you sure Papa will be there? I'm so tired of these railways, Gladdie."

"So am I," said Gladys sympathisingly. "I should think we'll soon be there. But I'm sure I shan't like Paris, Roger. I'll ask Papa to take us back to Mrs. Lacy's again."

Roger gave a little shiver.

"It's such a long way to go," he said. "I wouldn't mind if only Ellen had come with us, and if we had chocolate for breakfast."

But their voices, low as they were, awakened[Pg 47] Léonie, who was beside them. And then Mrs. Marton awoke, and at last Mr. Marton, who looked at his watch, and finding they were within ten minutes of Paris, jumped up and began fussing away at the rugs and shawls and bags, strapping them together, and generally unsettling everybody.

"We must get everything ready," he said. "I shall want to be free to see Bertram at once."

"But there's never a crowd inside the station here," said his wife. "They won't let people in without special leave. We shall easily catch sight of Captain Bertram if he has managed to get inside."

"He's sure to have done so," said Mr. Marton, and in his anxiety to catch the first glimpse of his friend, Mr. Marton spent the next ten minutes with his head and half his body stretched out of the window long before the train entered the station, though even when it arrived there the dim light would have made it difficult to recognise any one.

Had there been any one to recognise! But there was not. The train came to a stand at last. Mr. Marton had eagerly examined the faces of the two or three men, not railway officials, standing on the platform, but there was no one whom by any possibility he could for a second have taken for Captain[Pg 48] Bertram. Mrs. Marton sat patiently in her place, hoping every instant that "Phillip" would turn round with a cheery "all right, here he is. Here, children!" and oh, what a weight—a weight that all through the long night journey had been mysteriously increasing—would have been lifted off the kind young lady's heart had he done so! But no; when Mr. Marton at last drew in his head there was a disappointed and perplexed look on his good-natured face.

"He's not here—not on the platform, I mean," he said, hastily correcting himself. "He must be waiting outside; we'll find him where we give up the tickets. It's a pity he didn't manage to get inside. However, we must jump out. Here, Léonie, you take Mrs. Marton's bag, I'll shoulder the rugs. Hallo there," to a porter, "that's all right. You give him the things, Léonie. Omnibus, does he say? Bless me, how can I tell? Bertram's got a cab engaged most likely, and we don't want an omnibus for us three. You explain to him, Léonie."

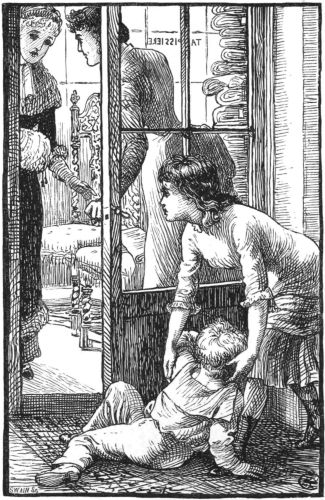

Which Léonie did, and in another moment the little party was making its way through the station, among the crowd of their fellow-passengers. Mr. Marton first, with the rugs, then his wife holding[Pg 49] Gladys by the hand, then Léonie and Roger, followed by the porter bringing up the rear. Mrs. Marton's heart was not beating fast by this time; it was almost standing still with apprehension. But she said nothing. On they went through the little gate where the tickets were given up, on the other side of which stood with eager faces the few expectant friends who had been devoted enough to get up at five o'clock to meet their belongings who were crossing by the night mail. Mr. Marton's eyes ran round them, then glanced behind, first to one side and then to the other as if Captain Bertram could jump up from some corner like a jack-in-the-box. His face grew graver and graver, but he did not speak. He led his wife and the children and Léonie to the most comfortable corner of the dreary waiting-room, and saying shortly, "I'm going to look after the luggage and to hunt up Bertram. He must have overslept himself if he's not here yet. You all wait here quietly till I come back," disappeared in the direction of the luggage-room.

Mrs. Marton did not speak either. She drew Gladys nearer her, and put her arm round the little girl as if to protect her against the disappointment which she felt was coming. Gladys sat perfectly silent. What she was expecting, or fearing, or even[Pg 50] thinking, I don't believe she could have told. She had only one feeling that she could have put into words, "Everything is quite different from what I thought. It isn't at all like going to Papa."

But poor little Roger tugged at Léonie, who was next him.

"What are we waiting here in this ugly house for?" he said. "Can't we go to Papa and have our chocolate?"

Léonie stooped down and said something to soothe him, and after a while he grew drowsy again, and his little head dropped on to her shoulder. And so they sat for what seemed a terribly long time. It was more than half an hour, till at last Mr. Marton appeared again.

"I've only just got out that luggage," he said. "What a detestable plan that registering it is! And now I've got it I don't know what to do with it, for——"

"Has he not come?" interrupted his wife.

Mr. Marton glanced at Gladys. She did not seem to be listening.

"Not a bit of him," he replied. "I've hunted right through the station half a dozen times, and it's an hour and a half since the train was due. It cannot[Pg 51] be some little delay. It's a pretty kettle of fish and no mistake."

Mrs. Marton's blue eyes gazed up in her husband's face with a look of the deepest anxiety.

"What is to be done?" she said.

"That is the question."

Hamlet.

Yes, "what was to be done?" That was certainly the question. Mr. Marton looked at his wife for a moment or two without replying. Then he seemed to take a sudden resolution.

"We can't stay here all the morning, that's about all I can say at present," he said. "Come along, we'd better go to the nearest hotel and think over matters."

So off they all set again—Mr. Marton and the rugs, Mrs. Marton and Gladys, Léonie and Roger—another porter being got hold of to bring such of the bags, etc., as were not left at the station with the big luggage. Gladys walked along as if in a dream; she did not even wake up to notice the great wide street and all the carriages, and omnibuses, and carts,[Pg 53] and people as they crossed to the hotel in front of the station. She hardly even noticed that all the voices about her were talking in a language she did not understand—she was completely dazed—the only words which remained clearly in her brain were the strange ones which Mr. Marton had made use of—"a pretty kettle of fish and no mistake." "No mistake," that must mean that Papa's not coming to the station was not a mistake, but that there was some reason for it. But "a kettle of fish," what could that have to do with it all? She completely lost herself in puzzling about it. Why she did not simply ask Mrs. Marton to explain it I cannot tell. Perhaps the distressed anxious expression on that young lady's own face had something to do with her not doing so.

Arrived at the hotel, and before a good fire in a large dining-room at that early hour quite empty, a slight look of relief came over all the faces. It was something to get warmed at least! And Mr. Marton ordered the hot chocolate for which Roger had been pining, before he said anything else. It came almost at once, and Léonie established the children at one of the little tables, drinking her own coffee standing, that she might attend to them and join in[Pg 54] the talking of her master and mistress if they wished it.

Roger began to feel pretty comfortable. He had not the least idea where he was—he had never before in his life been at a hotel, and would not have known what it meant—but to find himself warmed and fed and Gladys beside him was enough for the moment; and even Gladys herself began to feel a very little less stupefied and confused. Mr. and Mrs. Marton, at another table, talked gravely and in a low voice. At last Mr. Marton called Léonie.

"Come here a minute," he said, "and see if you can throw any light on the matter. You are more at home in Paris than we are. Mrs. Marton and I are at our wits' end. If we had a few days to spare it would not be so bad, but we have not. Our berths are taken, and we cannot afford to lose three passages."

"Mine too, sir," said Léonie. "Is mine taken too?"

"Of course it is. You didn't suppose you were going as cabin-boy, did you?" said Mr. Marton rather crossly, though I don't think his being a little cross was to be wondered at. Poor Léonie looked very snubbed.

"I was only wondering," she said meekly, "if I[Pg 55] could have stayed behind with the poor children till——"

"Impossible," said Mr. Marton; "lose your passage for a day or two's delay in their father's fetching them. If I thought it was more than that I would send them back to England," he added, turning to his wife.

"And poor Mrs. Lacy so ill! Oh no, that would never do," she said.

"And there's much more involved than our passages," he went on. "It's as much as my appointment is worth to miss this mail. It's just this—Captain Bertram is either here, or has been detained at Marseilles. If he's still there, we can look him up when we get there to-morrow; if he's in Paris, and has made some stupid mistake, we must get his address at Marseilles, he's sure to have left it at the hotel there for letters following him, and telegraph back to him here. I never did know anything so senseless as Susan Lacy's not making him give a Paris address," he added.

"He was only to arrive here yesterday or the day before," said Mrs. Marton.

"But the friends who were to have a nurse ready for the children? We should have had some address."

"Yes," said Mrs. Marton self-reproachfully. "I[Pg 56] wish I had thought of it. But Susan was so sure all would be right. And certainly, in case of anything preventing Captain Bertram's coming, it was only natural to suppose he would have telegraphed, or sent some one else, or done something."

"Well—all things considered," said Mr. Marton, "it seems to me the best thing to do is to leave the children here, even if we had a choice, which I must say I don't see! For I don't know how I could send them back to England, nor what their friends there might find to say if I did—nor can we——"

"Take them on to Marseilles with us?" interrupted Mrs. Marton. "Oh, Phillip, would not that be better?"

"And find that their father had just started for Paris?" replied her husband. "And then think of the expense. Here, they are much nearer at hand if they have to be fetched back to England."

Mrs. Marton was silent. Suddenly another idea struck her. She started up.

"Supposing Captain Bertram has come to the station since we left," she exclaimed. "He may be there now."

Mr. Marton gave a little laugh.

"No fear," he said "Every official in the place[Pg 57] knows the whole story. I managed to explain it, and told them to send him over here."

"And what are you thinking of doing, then? Where can we leave them?"

Mr. Marton looked at his watch.

"That's just the point," he said. "We've only three hours unless we put off till the night express, and that is running it too fine. Any little detention and we might miss the boat."

"We've run it too fine already, I fear," said Mrs. Marton dolefully. "It's been my fault, Phillip—the wanting to stay in England till the last minute."

"It's Susan Lacy's fault, or Bertram's fault, or both our faults for being too good-natured," said Mr. Marton gloomily. "But that's not the question now. I don't think we should put off going, for—another reason—it would leave us no time to look up Bertram at Marseilles. Only if we had had a few hours, I could have found some decent people to leave the children with here, some good 'pension,' or——"

"But such places are all so dear, and we have to consider the money too."

"Yes," said Mr. Marton, "we have literally to do so. I've only just in cash what we need for ourselves, and I couldn't cash a cheque here all in a minute,[Pg 58] for my name is not known. But something must be fixed, and at once. I wonder if it would be any good if I were to consult the manager of this hotel? I——"

"Pardon," said Léonie, suddenly interrupting. "I have an idea. My aunt—she is really my cousin, but I call her aunt—you know her by name, Madame?" she went on, turning to Mrs. Marton. "My mother often spoke of her"—for Mrs. Marton's family had known Léonie's mother long ago when she had been a nurse in England—"Madame Nestor. They are upholsterers in the Rue Verte, not very far from here, quite in the centre of Paris. They are very good people—of course, quite in a little way; but honest and good. They would do their best, just for a few days! It would be better than leaving the dear babies with those we knew nothing of. I think I could persuade them, if I start at once!" She began drawing her gloves on while she was speaking. And she had spoken so fast and confusedly that for a moment or two both Mr. and Mrs. Marton stared at her, not clearly taking in what she meant.

"Shall I go, Madame?" she said, with a little impatience. "There is no time to lose. Of course if you do not like the idea—I would not have thought of it except that all is so difficult, so unexpected."

"Not like it?" said Mr. Marton; "on the contrary I think it's a capital idea. The children would be in safe hands, and at worst it can't be for more than a couple of days. If Captain Bertram has been detained at Marseilles by illness or anything——"

"That's not likely," interrupted Mrs. Marton, "he would have written or telegraphed."

"Well, then, if it's some stupid mistake about the day, he'll come off at once when we tell him where they are. I was only going to say that, at worst, if he is ill, or anything wrong, we'll telegraph to Susan Lacy from Marseilles and she'll send over for them somehow."

"Should we not telegraph to her at once from here?"

Mr. Marton considered.

"I don't see the use," he said at last. "We can tell her nothing certain, nothing that she should act on yet. And it would only worry the old lady for nothing."

"I'm afraid she's too ill to be told anything about it," said Mrs. Marton.

"Then the more reason for waiting. But here we are losing the precious minutes, and Léonie all ready to start. Off with you, Léonie, as fast as ever you[Pg 60] can, and see what you can do. Take a cab and make him drive fast," he called after her, for she had started off almost with his first words. "She's a very good sort of a girl," he added, turning to his wife.

"Yes, she always has her wits about her in an emergency," agreed Mrs. Marton. "I do hope," she went on, "that what we are doing will turn out for the best. I really never did know anything so unfortunate, and——"

"Is it all because of the kettle of fish? Did Papa tumble over it? Oh, I wish you'd tell me!" said a pathetic little voice at her side, and turning round Mrs. Marton caught sight of Gladys, her hands clasped, her small white face and dark eyes gazing up beseechingly. It had grown too much for her at last, the bewilderment and the strangeness, and the not understanding. And the change from the cramped-up railway carriage and the warm breakfast had refreshed her a little, so that gradually her ideas were growing less confused. She had sat on patiently at the table long after she had finished her chocolate, though Roger was still occupied in feeding himself by tiny spoonfuls. He had never had anything in the way of food more interesting than this chocolate, for it was still hot, and whenever he left it for a moment a skin[Pg 61] grew over the top, which it was quite a business to clear away—catching now and then snatches of the eager anxious talk that was going on among the big people. And at last when Léonie hurried out of the room, evidently sent on a message, Gladys felt that she must find out what was the matter and what it all meant. But the topmost idea in her poor little brain was still the kettle of fish.

"If Papa has hurt himself," Gladys went on, "I think it would be better to tell me. I'd so much rather know. I'm not so very little, Mrs. Marton, Mrs. Lacy used to tell me things."

Mrs. Marton stooped down and put her arms round the pathetic little figure.

"Oh, I wish I could take you with me all the way. Oh! I'm so sorry for you, my poor little pet," she exclaimed girlishly. "But indeed we are not keeping anything from you. I only wish we had anything to tell. We don't know ourselves; we have no idea why your father has not come."

"But the kettle of fish?" repeated Gladys.

Mrs. Marton stared at her a moment, and then looked up at her husband. He grew a little red.

"It must have been I that said it," he explained. "It is only an expression; a way of speaking, little[Pg 62] Gladys. It means when—when people are rather bothered, you know—and can't tell what to do. I suppose it comes from somebody once upon a time having had more fish than there was room for in their kettle, and not knowing what to do with them."

"Then we're the fish—Roger and I—I suppose, that you don't know what to do with?" said Gladys, her countenance clearing a little. "I'm very sorry. But I think Papa'll come soon; don't you?"

"Yes, I do," replied Mr. Marton. "Something must have kept him at Marseilles, or else he's mistaken the day after all."

"I thought you said it was 'no mistake!'" said Gladys.

Mr. Marton gave a little groan.

"Oh, you're a dreadful little person and no—there, I was just going to say it again! That's only an expression too, Gladys. It means, 'to be sure,' or 'no doubt about it,' though I suppose it is a little what one calls 'slang.' But you don't know anything about that, do you?"

"No," said Gladys simply, "I don't know what it means."

"And I haven't time to tell you, for we must explain to you what we're thinking of doing. You[Pg 63] tell her, Lilly. I'm going about the luggage," he added, turning to his wife, for he was dreadfully tender-hearted, though he was such a big strong young man, and he was afraid of poor Gladys beginning to cry or clinging to them and begging them not to leave her and Roger alone in Paris, when she understood what was intended.

But Gladys was not the kind of child to do so. She listened attentively, and seemed proud of being treated like a big girl, and almost before Mrs. Marton had done speaking she had her sensible little answer ready.

"Yes, I see," she said. "It is much better for us to stay here, for Papa might come very soon, mightn't he? Only, supposing he came this afternoon he wouldn't know where we were?"

"Mr. Marton will give the address at the station, in case your Papa inquires there, as he very likely would, if a lady and gentleman and two children arrived there from England this morning. And he will also leave the address here, for so many people come here from the station. And when we get to Marseilles, we will at once go to the hotel where he was—where he is still, perhaps; if he has left, he is pretty sure to have given an address."

"And if he's not there—if you can't find him—what will you do then?" said Gladys, opening wide her eyes and gazing up in her friend's face.

Mrs. Marton hesitated.

"I suppose if we really could not find your father at once, we should have to write or telegraph to Miss Susan."

Gladys looked more distressed than she had yet done.

"Don't do that, please," she said, clasping her hands together in the way she sometimes did. "I'd much rather stay here a little longer till Papa comes. It would be such a trouble to Miss Susan—I know she did think we were a great trouble sometimes—and it would make Mrs. Lacy cry perhaps to have to say good-bye again, and she's so ill."

"Yes, I know she is," said Mrs. Marton, surprised at the little girl's thoughtfulness. "But you know, dear, we'd have to let them know, and then most likely they'd send over for you."

"But Papa's sure to come," said Gladys. "It would only be waiting a little, and I don't mind much, and I don't think Roger will, not if I'm with him. Will they be kind to us, do you think, those friends of Léonie's?"

"I'm sure they will; otherwise you know, dear, we wouldn't leave you with them. Of course it will only be for a day or two, for they are quite plain people, with quite a little house."

"I don't mind, not if they're kind to us," said Gladys. "But, oh! I do wish you weren't going away."

"So do I," said Mrs. Marton, who felt really very nearly breaking down herself. The sort of quiet resignation about Gladys was very touching, much more so than if she had burst out into sobs and tears. It was perhaps as well that just at that moment Mr. Marton came back, and saying something in a low voice to his wife, drew her out of the room, where in the passage stood Léonie.

"Back already," exclaimed Mrs. Marton in surprise.

"Oh yes," Léonie replied, "it was not far, and the coachman drove fast. But I thought it better not to speak before the children. It is a very little place, Madame. I wonder if it will do." She seemed anxious and a little afraid of what she had proposed.

"But can they take them? That is the principal question," said Mr. Marton.

"Oh yes," said Léonie. "My aunt is goodness[Pg 66] itself. She understands it all quite well, and would do her best; and it would certainly be better than to leave them with strangers, and would cost much less; only—the poor children!—all is so small and so cramped. Just two or three little rooms behind the shop; and they have been used to an English nursery, and all so nice."

"I don't think they have been spoilt in some ways," said Mrs. Marton. "Poor little Gladys seems to mind nothing if she is sure of kindness. Besides, what else can we do? And it is very kind of your aunt to consent, Léonie."

"Yes, Madame. It is not for gain that she does it. Indeed it will not be gain, for she must find a room for her son, and arrange his room for the dear children. They have little beds among the furniture, so that will be easy; and all is very clean—my aunt is a good manager—but only——"

Léonie looked very anxious.

"Oh I'm sure it will be all right," said Mr. Marton. "I think we had better take them at once—I've got the luggage out—and then we can see for ourselves."

The children were soon ready. Gladys had been employing the time in trying to explain to poor little[Pg 67] Roger the new change that was before them. He did not find it easy to understand, but, as Gladys had said, he did not seem to mind anything so long as he was sure he was not to be separated from his sister.

A few minutes' drive brought them to the Rue Verte. It was a narrow street—narrow, at least in comparison with the wide new ones of the present day, for it was in an old-fashioned part of Paris, in the very centre of one of the busiest quarters of the town; but it was quite respectable, and the people one saw were all well-dressed and well-to-do looking. Still Mr. Marton looked about him uneasily.

"Dreadfully crowded place," he said; "must be very stuffy in warm weather. I'm glad it isn't summer; we couldn't have left them here in that case."

And when the cab stopped before a low door leading into a long narrow shop, filled with sofas and chairs, and great rolls of stuffs for making curtains and beds and mattresses in the background, Mr. Marton's face did not grow any brighter. But it did brighten up, and so did his wife's, when from the farther end of the shop, a glass door, evidently leading into a little sitting-room, opened, and an elderly woman, with a white frilled cap and a bright healthy[Pg 68] face, with the kindliest expression in the world, came forward eagerly.

"Pardon," she said in French, "I had not thought the ladies would be here so soon. But all will be ready directly. And are these the dear children?" she went on, her pleasant face growing still pleasanter.

"Yes," said Mrs. Marton, who held Gladys by one hand and Roger by the other, "these are the two little strangers you are going to be so kind as to take care of for a day or two. It is very kind of you, Madame Nestor, and I hope it will not give you much trouble. Léonie has explained all to you?"

"Oh yes," replied Madame Nestor, "poor darlings! What a disappointment to them not to have been met by their dear Papa! But he will come soon, and they will not be too unhappy with us."

Mrs. Marton turned to the children.

"What does she say? Is she the new nurse?" whispered Roger, whose ideas, notwithstanding Gladys's explanations, were still very confused. It was not a very bad guess, for Madame Nestor's good-humoured face and clean cap gave her very much the look of a nurse of the old-fashioned kind. Mrs. Marton stooped down and kissed the little puzzled face.

"No, dear," she said, "she's not your nurse. She[Pg 69] is Léonie's aunt, and she's going to take care of you for a few days till your Papa comes. And she says she will be very, very kind to you."

But Roger looked doubtful.

"Why doesn't she talk p'operly?" he said, drawing back.

Mrs. Marton looked rather distressed. In the hurry and confusion she had not thought of this other difficulty—that the children would not understand what their new friends said to them! Gladys seemed to feel by instinct what Mrs. Marton was thinking.

"I'll try to learn French," she said softly, "and then I can tell Roger."

Léonie pressed forward.

"Is she not a dear child?" she said, and then she quickly explained to her aunt what Gladys had whispered. The old lady seemed greatly pleased.

"My son speaks a little English," she said, with evident pride. "He is not at home now, but in the evening, when he is not busy, he must talk with our little demoiselle."

"That's a good thing," exclaimed Mr. Marton, who felt the greatest sympathy with Roger, for his own French would have been sadly at fault had he had to say more than two or three words in it.

Then Madame Nestor took Mrs. Marton to see the little room she was preparing for her little guests. It was already undergoing a good cleaning, so its appearance was not very tempting, but it would not have done to seem anything but pleased.