The Project Gutenberg EBook of Copyright: Its History and Its Law, by Richard Rogers Bowker This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Copyright: Its History and Its Law Author: Richard Rogers Bowker Release Date: April 21, 2012 [EBook #39502] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK COPYRIGHT: ITS HISTORY AND ITS LAW *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Carol Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.)

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY R. R. BOWKER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

FOR ALL COUNTRIES

Published March 1912

Copyright progress

The American copyright code of 1909, comprehensively replacing all previous laws, a gratifying advance in legislation despite its serious restrictions and minor defects, places American copyright practice on a new basis. The new British code, brought before Parliament in 1910, and finally adopted in December, 1911, to be effective July 1, 1912, marks a like forward step for the British Empire, enabling the mother country and its colonies to participate in the Berlin convention. Among the self-governing Dominions made free to accept the British code or legislate independently, Australia had already adopted in 1905 a complete new code, and Canada is following its example in the measure proposed in 1911, which will probably be conformed to the new British code for passage in 1912. Portugal has already in 1911 joined the family of nations by adherence to the Berlin convention, Russia has shaped and Holland is shaping domestic legislation to the same end, and even China in 1910 decreed copyright protection throughout its vast empire of ancient and reviving letters. The Berlin convention of 1908 strengthened and broadened the bond of the International Copyright Union, and the Buenos Aires convention of 1910, which the United States has already ratified, made a new basis for copyright protection throughout the Pan American Union, both freeing authors from formalities beyond those required in the country of origin. Thus the American dream of 1838 of "a universal republic of letters whose foundation shall be one just law" is well on the way toward realization.

Field for the present treatise

In this new stage of copyright development, a comprehensive work on copyright seemed desirable, especially with reference to the new American code. Neither Eaton S. Drone nor George Haven Putnam were disposed to enter upon the task, which has therefore fallen to the present writer. He hopes that his participation for the last twenty-five years in copyright development,—during which, as editor of the Publishers' Weekly and of the Library Journal, he has had occasion to keep watch of copyright progress, and as vice-president of the American (Authors) Copyright League, he has taken part in the copyright conferences and hearings and in the drafting of the new code,—will serve to make the present volume of use to his fellow members of the Authors Club and to like craftsmen, as well as to publishers and others, and aid in clarifying relations and preventing the waste and cost of litigation among the coördinating factors in the making of books and other forms of intellectual property.

Authorities and acknowledgments

The present work includes some of the historical material of the Bowker-Solberg volume of 1886, "Copyright, its law and its literature." This material has been verified, extended and brought up to date, especially in the somewhat detailed sketch of the copyright discussions and legislation resulting in the "international copyright amendment" of 1891 and the code of 1909. The volume is in this respect practically, and in other respects entirely new. It has had the advantage of the cordial co-operation of the copyright authorities at Washington, especially the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, and the Register of Copyrights, Thorvald Solberg; also of helpful courtesy from the Canadian Minister of Agriculture in the recent Laurier administration, Sidney Fisher, and the Canadian Registrar of Copyrights, P. E. Ritchie, and of Prof. Ernest Röthlisberger, editor of the Droit d'Auteur, and one of the best authorities on international copyright. This acknowledgment of obligation is not to be taken as assuming for the work official sanction and authority, though so far as practicable, it reflects the opinions of the best authorities. The writer has also consulted freely—but it is hoped always within the limits of "fair use"—the best law book writers, especially Drone, Copinger, Colles and Hardy, and MacGillivray, to whom acknowledgment is made in the several chapters. Acknowledgment is also made for the courtesies of Sir Frederick Macmillan, G. Herbert Thring, secretary of the British Society of Authors, and others numerous beyond naming. But most of all the writer is indebted to the intelligent and capable helpfulness of Carl L. Jellinghaus, who as private secretary, has been both right hand and eyes to the writer, and besides participating in the work of research, is largely responsible for the index and other "equipment" of the volume.

Method and form

Copyright law is exceptionally confused and confusing, and even the new American and British codes are not without such defects. Specific subjects are so interdependent that it has been difficult to make clear lines of division among the several chapters, and there is necessarily repetition; it has been the endeavor to concentrate the main discussion in one place, designated in the index by black face figures, with subordinate references in other chapters. Ambiguities in the text of this volume often reflect ambiguities in the laws, particularly of foreign countries. Where acts, decisions, etc., are quoted in the text or given in the appendix, spelling, capitalization, punctuation, headings, etc., follow usually the respective forms, thus involving apparent inconsistencies. Side-headings in the appendix follow usually the official form, unless shortened to prevent displacement. Translations of foreign conventions follow usually the official text of the translation, but have been corrected or conformed in case of evident error or variance. Citation of cases is confined for the most part to ruling or recent cases or those of historic importance or interest. Though it has not been practicable to verify statements from the copyright laws of so many countries in divers languages, a fairly comprehensive and accurate statement of the status of copyright throughout the world is here presented. The present work, originally planned for publication in 1910, has been held back and alterations and insertions made to bring the record of legislation to the close of 1911. For those who wish to keep their copyright knowledge up to date, the Publishers' Weekly will endeavor to present information as to the English speaking world, and the monthly issues of the Droit d'Auteur of Berne, under the editorship of Prof. Röthlisberger, will be found a comprehensive and adequate guide.

Advocates of authors' rights

The preparation of this work brings a recurring sense of the losses which the copyright cause has suffered during the long campaign for copyright reform, beginning in the American Copyright League, under the presidency of James Russell Lowell, and continued under that of Edmund Clarence Stedman, both of whom have passed over to the majority. Bronson Howard, always active in the counsels of the League as a vice-president, and the foremost advocate of dramatic copyright as president of the American Dramatists Club, failed, like Stedman, to see the fulfillment of his labors in the passage of the act of 1909. George Parsons Lathrop, Edward Eggleston, Richard Watson Gilder, "Mark Twain" and other ardent advocates of the rights of the author, gave large share of enthusiasm and effort to the cause. Happily the two men who for the last twenty years and more have labored at the working oar for the Authors League and for the Publishers League, are still active in the good work, ready to defend the code against attack and eager to forward every betterment that can be made; to Robert Underwood Johnson, the successor of the lamented Gilder as editor of the Century, and to George Haven Putnam, the head of the firm which still bears the name of his honored father, authors the world over owe in great measure the progress which has been made in America toward a higher ideal for the protection of authors' rights.

Copyright evolution

It may be noted that while throughout the British Empire English precedent is naturally followed, the more restrictive American copyright system has unfortunately influenced legislation in Canada and Newfoundland, and in Australia. France, open-handed to authors of other countries, has afforded precedent for the widest international protection and for the international term; while Spain, with the longest term and most liberal arrangements otherwise, has been followed largely by Latin American countries. The International Copyright Union has reached in the Berlin convention almost the ideal of copyright legislation, and this has been closely followed in the Buenos Aires convention of the Pan American Union. The world over, there seems to have been a general evolution of copyright protection from the rude and imperfect recognition of intellectual property as cognate to other property, for a term indefinite and in a sense perpetual, almost impossible of enforcement in the lack of statutory protection and penalties. Systems of legislation, at first of very limited term and of restricted scope, have led up to the comprehensive codes giving wide and definite protection for all classes of intellectual property for a term of years extending beyond life, with the least possible formalities compatible with the necessities of legal procedure. Unfortunately in the United States of America the forward movement which produced the "international copyright amendment" of 1891 and the code of 1909, conspicuously excellent despite defects of detail, was in some measure offset by retrogression, as in the manufacturing restrictions. Until this policy, which still remains a blot on the 'scutcheon, is abandoned, as the friends of copyright hope may ultimately be the case, the United States of America cannot enter on even terms the family of nations and become part of the United States of the world.

R. R. Bowker.

December, 1911.

Postscript. Since this book has been passing through the press, Cuba has been added to the countries in reciprocal relations with the United States with respect to mechanical music by the President's proclamation of November 27, 1911; Russia has made with France its first copyright treaty, in conformity with the new Russian code of 1911; and the new British code, referred to on p. 33, having passed the House of Commons August 17, passed the House of Lords December 6, and after concurrence by the House of Commons in minor amendments, mostly verbal, became law by Crown approval, December 16, 1911, as noted on p. 374. The text of the act in the appendix follows the official text as it now stands on the English statute books; the summary (pp. 374-80) describes the act as it became law—and the earlier references are in accordance therewith, with a few exceptions. These exceptions mostly concern immaterial changes, made in the House of Lords. Within January, 1912, Brazil has adopted a new measure for international copyright, and a treaty has been signed between the United States and Hungary, the twenty-fifth nation in reciprocal relations with this country.

Under the names of countries are given dates of the basic and latest amendatory laws. International relations are shown by the name in small caps of the convention city when a country is a party to the International Copyright Union or the Pan American conventions, and by the names of countries with which there are specific treaties, excepting those within the union or conventions. The general term of duration is entered, without specification of special terms for specific classes. Places of registration and deposit are indicated by R and D when these are not the same. The number of copies required and in some cases period after publication within which deposit is required are given in parentheses. Notice of copyright or of reservation is indicated. Special exceptions or conditions are noted so far as practicable under remarks. An asterisk indicates that specific exceptions exist.

The International Copyright Union includes (A) under the Berlin convention, 1908 (a) without reservation Germany, Belgium, Luxemburg, Switzerland, Spain, Monaco, Liberia, Haiti, Portugal, and (b) with reservation France, Norway, Tunis, Japan; (B) under the Berne convention, 1886, and the Paris additional act and interpretative declaration, 1896, Denmark, Italy; (C) under the Berne convention, 1886, and the Paris additional act, 1896, Great Britain; (D) under the Berne convention, 1886, and the Paris interpretative declaration, 1896, Sweden. The Pan American conventions agreed on at Mexico City, 1902, Rio de Janeiro, 1906, and Buenos Aires, 1910, have not been ratified except that of Mexico by the United States and by Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Salvador, and doubtfully by Cuba and Dominican Republic; that of Rio by a few states insufficient to make it anywhere operative; and that of Buenos Aires by the United States. The South American convention of Montevideo, 1889, has been accepted by Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay, Peru and Bolivia, and has the adherence (in relation with Argentina and Paraguay only) of Belgium, France, Italy and Spain. The five Central American states have a mutual convention through their Washington treaty of peace of 1907.

| Countries Dates of laws |

International relations |

Duration | Registration and Deposit |

Notice | Remarks |

| North America: English | |||||

| North America (English-speaking) |

|||||

| United States 1909 |

Mexico, B.

Aires, Gt. Brit., Belg., China, Den., Fr., Ger., It., Jap., Lux., Nor., Sp., Swe., Switz., Aust., Hol., Port., Chile, Costa R., Cuba, Mex. |

28 + 28 | Library of Congress (2 "promptly") | "Copyright, 19—, by A. B." or statutory equivalent | Manufacture within U. S. for books, etc. |

| Canada 1875-1908 [1912 ?] |

See Gt. Brit.* (Aus.-Hung. excepted) | 28 + 14 | Dept. of Agriculture: Copyright Branch (3) | "Copyright, Canada 19—, by A. B." or signature of artist | Printing and publ. within Canada.* |

| Newfoundland 1890-1899 |

See Gt. Brit. | 28 + 14 | Colonial Sec. (2) | "Entered, Newf.... by A. B." etc. or signature of artist | Printing and publ. within Newf.* |

| Canal Zone (U. S.) | See U. S. | ||||

| Porto Rico (U. S.) | See U. S. | ||||

| Jamaica (Br.) 1887 |

See Gt. Brit. | Life + 7 or 42* | (3 or 1* within mo.) | None | |

| Trinidad (Br.) 1888 |

See Gt. Brit. | Life + 7 or 42* | Registrar of copyright (3 within mo.) | None | |

| Europe: English | |||||

| Europe | |||||

| Great Britain & Ireland D 1842-1906 I 1844-1886 [1911] |

Berne-Paris A U. S., Aus.-Hung.* |

Life + 7 or 42* [Life + 50*] |

R Stationers Hall (before suit)* D British Museum (1) + 4 library copies (on demand)* |

None* [None] [No registration] |

First or simultaneous publication [In effect 1912] |

| Isle of Man 1907 |

See Gt. Brit. | ||||

| Channel Isles | See Gt. Brit. | ||||

| French | |||||

| France 1793-1910 |

Berlin* Montv.* U. S., Aus-Hung., Hol., Port., Mont., Roum., Lat. Amer. | Life + 50* | D Ministry of Interior or prefecture (2 before suit)* | None | |

| Belgium 1886 |

Berlin, Montv.* U. S., Aus., Hol., Port., Roum., Mex. |

Life + 50 | None* | None* | |

| Luxemburg 1898 |

Berlin U. S. |

Life + 50* | None* | None* (res. playr.) | |

| Holland 1881 [1912?] |

U. S., Belg., Fr. | 50 or life* | Dept. of Justice (2 within mo.) | None* (res. trans. playr.) |

Printing within Holland |

| German | |||||

| Germany 1901-1910 |

Berlin U. S., Aus.-Hung. |

Life + 30* | None* | None* | |

| Austria 1895, 1907 |

Hung., U. S., Gt. Brit.,* Belg. Den, Fr., Ger., It., Roum., Swed. | Life + 30* | None* | None* (res. trans. photos, mus.) | |

| Hungary 1884 |

Aust., Gt. Brit.,*Fr., Ger., It. | Life + 50* | None* | None* (res. trans. photos) | |

| Scandinavian | |||||

| Switzerland 1874, 1883 |

Berlin U. S. |

Life + 30* | R. Office of Intel. Prop. optional* | None* (res. playr.) | |

| Denmark 1865-1911 |

Berne-Paris U. S., Aus. |

Life + 50* | None* | None* (photos,res. music) | |

| Iceland (Den.) 1905 |

See Denmark | As in Denmark | |||

| Norway 1877-1910 |

Berlin* U. S. |

Life + 50* | None* | None* (photos, res. music) | |

| Sweden 1897-1908 |

Berne-Paris D U. S., Aus. |

Life + 50* | None | None* (photos, res. playr.) | |

| Russian | |||||

| Russia 1911 |

France | Life + 50* | None* (photos,res. trans.mus.) |

||

| Finland 1880 | None | Life + 50* | None* | None* | |

| Southern | |||||

| Spain 1879-1896 |

Berlin, Montv.* U. S., Port., Lat. Amer. |

Life + 80* | Register of Intel. Prop. (3 within one year*) | None* | Special provisions |

| Portugal 1867, 1886 |

Berlin U. S., It., Sp., Bra. |

Life + 50* | Pub. Lib.* (2 before pub.) | None | |

| Italy 1882, 1889, 1910 |

Berne-Paris Montv.* U. S., Aus.-Hung., Mont., Port., Roum., San. Mar., Lat. Amer. |

Life or 40* + 40* | Prefecture (3 within 3 months)* | None* (res. trans.) |

Added 40 yrs. on royalty of 5 p. c. |

| Europe: Minor States | |||||

| San Marino | See Italy | As in Italy | |||

| Monaco 1889, 1896 |

Berlin | Life + 50* | None | None* | |

| Greece 1833-1910 |

None | 15 + * | D (4 within10 days*) | ||

| Malta, Cyprus, etc. (Br.) | See Gt. Brit. | Life + 7 or 42* | D (3 within mo.) | ||

| Balkan States | |||||

| Montenegro | Fr., It. | Uncertain protection | |||

| Bulgaria 1896? |

Uncertain protection | ||||

| Servia | No protection | ||||

| Roumania 1862-1904 |

Aus., Belg., Fr., It. | Life + 10 | R. Min. of Instruc. | ||

| Turkey 1910 | None | Life + 30* | Min. of Pub. Instruc. (3)* | None. | |

| Asia | |||||

| Asia | |||||

| Japan 1899, 1910 |

Berlin* U. S.,* China |

Life + 30* | R. Ministry of Int. (before suit) | None* | |

| Korea 1908 |

See Japan | As in Japan | |||

| China 1910 |

U. S.,* Japan | Life + 30* | Ministry of Int. (2) | ||

| Hong Kong (Br.) | See Gt. Brit. | Life + 7 or 42* | D (3 within mo.) | ||

| Philippines (U. S.) | See U. S. | ||||

| India, British 1847, 1867 |

See Gt. Brit. | Life + 7 or 42* | D (3 within mo.) | Printer's and publisher's name on work | |

| Ceylon, etc. (Br.) | See Gt. Brit. | Life + 7 or 42* | D (3 within mo.) (4 within yr.) | ||

| Siam 1901 |

None | Life + 7 or 42* | |||

| Persia | None | No protection | |||

| Africa | |||||

| Africa | |||||

| Egypt | None | Indefinite | Court protection | ||

| Tunis 1889 |

Berlin* | Life + 50* | As in France | ||

| Algeria (Fr.) | See France | ||||

| Sierra Leone, etc. (Br.) 1887 |

See Gt. Brit. | Life + 7 or 42* | D (3)* | ||

| Liberia | Berlin | Indefinite | Without specific law | ||

| Congo Free State | Belg., Fr. (extradition) | Punishes fraud only | |||

| So. Africa (Br.) | See Gr. Brit.* Aus.-Hung., excepted | ||||

| Cape Colony 1873-1895 |

Life + 5 or 30* | Registrar of Deeds D (4 within mo.)* | |||

| Natal 1895-1898 |

Life + 7 or 42* | Colonial Sec., D (2 within 3 mos.)* | |||

| Transvaal, etc. 1887 |

50 or life* | Registrator D (3 within 2 mos.)* | Reserv. of playr. and trans. | Printing within colony* | |

| America, Latin: Mexico Central America | |||||

| Latin America | |||||

| Mexico 1871, 1884 |

U. S., Dom. Rep., Ecu., Belg., Fr., It., Sp. | Perpetuity* | R. Min. Pub. Instruc. D (2)* | None* (res. trans.) | |

| Costa Rica 1880-1896 |

Mexico U. S., Sp., Fr. Guat., Sal., Hon. |

Life + 50* | Office of Pub. Libs. (3)* within yr.* | None | |

| Guatemala 1879 |

Mexico Sp., Fr., Costa R. |

Perpetuity | Min. of Pub. Educ. (4)* | (res. trans.) | |

| Honduras 1894, 1898 |

Mexico Costa R. |

Indefinite | No specific law | ||

| Nicaragua 1904 |

Mexico It. |

Perpetuity* | Min. of Agric. (6*) | (res. trans.) | |

| Salvador 1886, 1900 |

Mexico Sp., Fr., Costa R. |

Life + 25* | D Min. of Agric. (1 before pub.) | None | Publication within country |

| Panama 1904 | None | Life + 80 | As in Colombia | ||

| West Indies | |||||

| Cuba 1879-1909 |

Mexico? U. S., It. |

Life +80* | Dept. of State (3) | None | |

| Haiti 1885 |

Berlin | Life + * | D Dept. of Int., (5 within yr.) | None | |

| Dominican Rep. 1896 |

Mexico? Mex. | Uncertain | |||

| South America | |||||

| Brazil 1891-1901 |

Portugal | 50* from the 1st Jan. of yr. of pub. | Nat. Lib. (1 within 2 yrs.) | None* (res. playr.) | |

| Argentina 1910 |

Montevideo Belg., Sp., Fr., It. |

Life + 10* | Nat. Lib. (2 within 15 or 30 days) | None* | |

| Uruguay 1868 |

Montevideo | Indefinite | No specific law | ||

| Paraguay 1870, 1881, 1910 |

Montevideo Belg., Sp., Fr., It. |

Public registries | Under penal code | ||

| Chile 1833-1874 |

U. S. | Life + 5* | D Nat. Pub. Lib. (3)* | None | |

| Peru 1849, 1860 |

Montevideo | Life + 20* | D Pub. Lib. (1) + Dept. Pref. (1) | None | |

| Bolivia 1834, 1909 |

Montevideo Fr. |

Life + 30* | R Min. of Pub. Instruc. D Pub. Lib. (1 within yr.) | ||

| Ecuador, 1884, 1887 |

Sp., Fr., Mex. | Life + 50* | Min. of Pub. Educ. (3 within 6 mos.)* | None* (res. playr.) | |

| Colombia 1886, 1890 |

Sp., It. | Life + 80* | Min. of Pub. Educ. (3 within yr.)* | None | |

| Venezuela 1894, 1897 |

None. | Perpetuity | Registry (6) | Notice of patent | |

| Australasia | |||||

| Australasia | |||||

| Australia (Br.) 1905 |

See Gt. Brit.* Aus.-Hung. excepted | Life + 7 or 42* | Commonwealth Copyr. Office D (2) | Reserv. performing right | |

| New Zealand (Br.) 1842-1903 |

See Gt. Brit. | 28 or life* | R Registrar of Coprs.* D libr. of Gen. Assem. (for plays only) | ||

| Hawaii (U. S.) | See U. S. | ||||

| CONTENTS | ||

|---|---|---|

| PART I | ||

| Nature and Development of Copyright | ||

| I. | The Nature and Origin of Copyright | 1-7 |

| Copyright meaning, 1—Its two senses, 1—Blackstone, 2—Property by creation, 3—Property in unpublished works, 4—The question of publication, 5—Inherent right, 5—Statutory penalties, 6—Statute of Anne, 6—Supersedure of common law right, 7. | ||

| II. | The Early History of Copyright | 8-23 |

| In classic times, 8—Roman law, 8—Monastic copyists, 8—St. Columba and Finnian, 9—University protection, 9—Invention of printing, 10—In Germany, 10—In Italy: Venice, 13—Florence, 17—Control of Church, 17—In France, 17—In England, 19—The Stationers' Company, 21—Statutory provisions, 22. | ||

| III. | The Development of Statutory Copyright in England | 24-34 |

| The Statute of Anne as foundation, 24—Its relations to common law, 24—The crucial case, 25—The Judges' opinions, 25—The Lords' decision, 26—Protests, 26—Supplementary legislation, 26—Georgian period, 27—Legislation under William IV, 28—Victorian act of 1842, 28—Protection of designs, 29—Subsequent acts, 29—Royal Commission report of 1878, 30—Later legislation, 31—International copyright, 31—Musical copyright, 31—Conference reports, 1909, 32—Act of 1911, 32—Design patents, 33—Common law rights, 34. | ||

| IV. | The History of Copyright in the United States | 35-41 |

| Constitutional provision, 35—Early state legislation, 35—Act of 1790, 35—1802-1867, 36—Revised act of 1870, 37—1874-1882, 37—International copyright legislation, 1891, 37—Private copyright acts, 38—American possessions, 38—American code of 1909, 39—State protection of playright, 39—Trade-Mark act, 40—Common law relations, 40. | ||

| PART II | ||

| Literary and General Copyright | ||

| V. | Scope of Copyright: Rights and Extent | 42-62 |

| General scope, 42—American provisions, 42—Oral addresses, 42—Dramas, 42—Music, 43—Previous American law, 43—Unpublished works, 43—Common law scope, 44—Common law in U. S. practice, 44—Statutory limitations, 44—General rights, 45—Inferential rights, 46—Differentiated rights, 46—Court protection, 46—Division of rights, 46—Analysis of property rights, 47—Broad interpretation, 48—Limits of protection, 48—Differentiated contracts, 48—Enforcement in limited grants, 49—Copyright as monopoly, 50—Altered theory of copyright, 52—Publishing, 52—What constitutes publishing, 53—"Privately printed" works, 53—Copying, 53—Vending, 54—Control of sale, 54—Macy cases, 55—Bobbs-Merrill case, 56—Scribner case, 56—English underselling case, 57—Suits under state law, 57—Translating, 58—"Other version," 58—Translating term, 58—Oral delivery, 59—"Publicly and for profit," 59—Material and immaterial property, 60—Schemes not copyrightable, 61—New British code, 61—Foreign statutes, 62—International provisions, 62. | ||

| VI. | Subject-Matter of Copyright: What may be Copyrighted | 63-94 |

| Subject-matter in general, 63—Classification, 63—Prints and labels excluded, 64—All the writings of an author, 64—Component parts, 64—Compilations, new editions, etc., 64—Non-copyrightable works, 65—Government use, 65—"Author" and "writing" definitions, 66—Interpretation by Congress and courts, 66—Supreme Court decisions, 67—Originality and merit, 68—"Book" definitions, 68—Blank books, 72—Combinations and arrangements, 73—Advertisements, 73—New editions, 75—Copyright comprehensive, 76—Non-copyrightable parts excepted, 76—Book illustrations, 77—Translations, 77—Translator's rights, 78—English practice, 79—Translations in international relations, 79—Foreign translators, 79—Abridgments, 80—Compilations, 81—Collections, 81—Titles, 82—Changed titles, 82—Titles as trade-marks, 83—"Chatterbox" cases, 84—Projected titles, 85—Projected works not copyrightable, 86—Immoral works, 86—Periodicals, 87—Definition of periodicals, 87—Periodicals under manufacturing clause, 88—Periodicals copyrightable by numbers, 88—News, 89—British periodicals, 90—Oral works, 90—Newspaper reports, 91—Lectures in England, 91—Letters, 91—Designs patentable, 93—Foreign practice, 94—International definition, 94. | ||

| VII. | Ownership of Copyright: Who may secure Copyright | 95-113 |

| Persons named, 95—The author primarily, 95—Claimant's right to register, 96—Employer as author, 97—Implied ownership, 98—Protection outside of copyright, 98—Work in cyclopædias, 99—Association of author's name, 100—Added material and alteration, 100—Separate registration of contributions, 100—Anonymous works, 101—Joint authorship, 101—Corporate bodies, 102—Posthumous works, 102—Peary cases, 102—Renewal rights, 104—Assignments, 104—Assignment record, 105—Substitution of name, 105—Witnesses, 106—"Outrights" and renewal, 106—Proof of proprietorship, 107—Foreign citizens, 107—Earlier provisions, 108—Residence, 108—Intending citizens, 109—Time of first publication, 109—Non-qualified authors, 110—Foreign ownership, 111—"Proclaimed" countries, 111—Buenos Aires convention, 113—New British code, 113—Foreign practice, 113. | ||

| VIII. | Duration of Copyright: Term and Renewal | 114-124 |

| Historic precedent, 114—Previous American practice, 114—Term in code of 1909, 115—Renewal, 115—Extension of subsisting copyrights, 116—Assignee of unpublished manuscripts, 116—Extension of subsisting renewals, 117—Publishers' equities, 117—Estoppel of renewal, 118—Life term and beyond, 118—Unpublished works, 119—Publication as date of copyright, 119—Serial publication, 120—Joint authorship, 120—Forfeiture, 121—Abandonment, 121—In England, 121—New British code, 122—Perpetual copyright, 123—Other countries, 124—International standard term, 124—Special categories, 124. | ||

| IX. | Formalities of Copyright: Publication, Notice, Registration and Deposit | 125-152 |

| General principles, 125—Previous American requirements, 125—Present American basis, 126—Provisions of 1909, 126—Publication, 126—Copyright notice, 127—Previous statutory form, 128—Exact phraseology required, 128—Name, 129—Date, 129—Accidental omission, 130—Place of notice, 131—One notice sufficient, 131—Separate volumes, 132—Different dates, 133—Extraterritorial notice, 133—Successive editions, 134—False copyright notice, 134—Ad interim protection, 135—Substitution of name, 135—Registration, 136—Rules and regulations, 136—Application, 136—Certificate, 136—Application requirements, 137—Illustrations, 138—Periodicals, 138—Application cards, 139—Certificate cards, 140—Fees, 141—Deposit, 142—Fragment not depositable, 143—Typewriting publication and deposit, 143—Legal provisions, 143—Failure to deposit, 144—Forfeiture by false affidavit, 144—Works not reproduced, 144—Second registration, 145—Free transportation in mail, 145—Loss in mail, 145—Foreign works, 146—Ad interim deposit, 146—Completion of ad interim copyright, 147—Omission of copyright notice, 148—Books only ad interim, 148—Exact conformity required, 149—Expunging from registry, 150—British formalities, 150—New British code, 151—Other countries, 151—International provisions, 152. | ||

| X. | The American Manufacturing Provisions | 153-161 |

| Manufacturing provision of 1891, 153—Text in 1909 code, 153—Scope and exceptions, 154—Changes, 1891-1909, 154—German-American instances, 155—Dramas excepted, 155—Exception of foreign original texts, 156—Exception of foreign illustrative subjects, 156—Affidavit requirement, 156—Avoidance of errors, 157—Forfeiture by false affidavit, 158—Exact compliance necessary, 158—Importation questions, 159—Foreign manufacturing provisions, 160—English patent proviso, 161. | ||

| PART III | ||

| Dramatic, Musical and Artistic Copyright | ||

| XI. | Dramatic and Musical Copyright, Including Playright | 162-201 |

| Dramatists' and composers' rights, 162—American provisions, 162—Rights assured, 163—Dramatic rights, 163—Musical rights, 164—Excepted performance, 164—Performance "for profit," 165—Works not reproduced, 166—Copyright notice, 166—Dramatico-musical works protected from mechanical reproduction, 166—Dramatic and musical works excepted from manufacturing provisions, 167—British colonial practice, 168—Entry under proper class, 168—Application and certificates, 168—Right of dramatization, 169—Dramatization term, 169—Musical arrangements, 169—Transposition, 170—Works in the public domain, 170—Dramatization right protected, 170—English law and practice, 171—Infringement cases, 172—Substantial quotations, 173—Specific scenes or situations, 174—What is a dramatic composition, 174—Judge Blatchford's opinion, 175—Judicial definitions, 175—Moving pictures, 176—Literary merit not requisite, 177—What is a dramatico-musical composition, 177—Protection of playright, 178—Protection of unpublished work, 179—Indeterminate protection, 180—Printing and performance, 180—Specific English provisions, 182—Publication prior to performance, 183—British international protection, 184—What is public performance, 185—Manuscript rights, 186—Unpublished orchestral score, 187—Dramatic work by employee, 188—Copyright term, 188—Registration, 189—Assignment, 189—Parody, 190—Infringement by single situation, 191—Protection of title, 191—Names of characters, 192—Persons liable for infringement, 193—Protection against "fly by night" companies, 194—State legislation, 194—Remedies under present law, 195—Musical protection in England, 195—Acts of 1902-1906, 196—Playright in other countries, 197—International provisions, 197—Foreign protection of arrangements, 197—International definitions, 198—National formalities, 199—Specific reservations and conditions, 200—Pan American Union, 201. | ||

| XII. | Mechanical Music Provisions | 202-221 |

| "Canned music" contest, 202—Mechanical music provisos, 202—Compulsory license, 203—Damages, 203—Public performance, 204—The compromise result, 204—Judicial construction, 205—Punishment of infringement, 206—Notice of intention to use, 206—Constitutional question, 207—English law, 208—Berne situation, 1886, 209—Paris, 1896, 209—Berlin provision, 1908, 209—German precedents, 210—Law of 1910, 211—Germany and the United States, 212—French precedents, 212—Belgian precedents, 213—Italian precedents, 213—Other countries, 214—Argument for inclusion, 214—Inscribed writings, 215—Direct sound-writings, 216—Music transmissal, 216—Music notation, 217—The law prior to 1909, 218—Manuscript and copies, 218—Protection of the inventor, 219—The counter argument, 220—Complete protection, 221. | ||

| XIII. | Artistic Copyright | 222-250 |

| Threefold value in art works, 222—American provisions, 223—Copyright Office classification definitions, 223—The question of exhibition, 224—Protection of unpublished work, 225—Copyright notice, 225—Deposit, 226—Summary of requirements, 227—Material and immaterial properties distinct, 228—Manufacturing clause, 228—German post cards, 229—Artistic merit, unimportant, 229—Application forms, 229—Certificates, 230—Term in unpublished work, 230—Date not required, 230—Re-copyright objectionable, 231—Exhibition right transfer, 231—Early English decision, 232—The Werckmeister leading case, 233—Unrestricted exhibition hazardous, 234—Reservation on sale, 234—Publication construed, 234—Danger of forfeiture, 235—Limited use and license, 236—Character, not method of use, 237—Illustration, 237—Description of artistic work, 238—Portraits, 238—Right of employer, 239—Photographs, 240—Tableaux vivants and moving pictures, 241—Architectural works, 242—Copy of a copy, 243—Alterations, 243, 244—Remedies, 245—Artistic copyright term, 245—British practice, 246—Sculpture provisions, 247—Engraving provisions, 247—New British code, 247—Foreign countries, 248—Berne convention, 1886, 248—Paris declaration, 1896, 249—Berlin convention, 1908, 250—Exhibition not publication, 250—Pan American Union, 250. | ||

| PART IV | ||

| Copyright Protection and Procedure | ||

| XIV. | Infringement of Copyright: Piracy, "Fair Use" and "Unfair Competition" | 251-264 |

| Piracy, 251—Test of piracy, 251—Infringement in specific meaning, 252—Questions of fact and intent, 253—"Fair use," 253—Principle of infringement, 254—Infringement by indirect copying, 254—Exceptions from infringement, 255—Infringement by abridgment and compilation, 255—Abridged compilations, 256—Separation of infringing parts, 256—Law digests, 257—Proof from common errors, 257—Infringement in part, 258—No infringement of piracies or frauds, 258—Quotation, 259—Private use, 259—"Unfair competition," 260—Deceptive intent, 260—"Chatterbox" cases, 261—Encyclopædia Britannica cases, 261—Webster Dictionary cases, 261—"Old Sleuth" cases, 262—Other title decisions, 262—Rebound copies, 263—Kipling case, 263—Burlesqued title, 264—Drummond case, 264—New British code, 264. | ||

| XV. | Remedies and Procedure | 265-277 |

| Protection and procedure, 265—Injunction, 265—Damages, 265—One suit sufficing, 266—Deposit of infringing articles, 266—Remedies specified, 267—Impounding, 268—Supreme court rules, 268—Court jurisdiction, 268—Limitation, 269—Text of procedure provisions, 270—Proceedings united in one action, 270—Jurisdiction, 270—Injunction provisions, 270—Appeal, 271—No criminal proceedings, after three years, 271—Strict compliance requisite, 271—Damage not penalty, 272—Other procedure decisions, 273—Preventive action, 274—Party in suit, 274—Willful case, 275—Penal provisions, 275—False notice of copyright, 276—Allowance of costs, 276—New British code, 277. | ||

| XVI. | Importation of Copyrighted Works | 278-296 |

| Copyright and importation, 278—Fundamental right of exclusion, 278—General prohibitions, 279—Exceptions permitted, 279—Text provisions, 280—Prohibition of piratical copies, 280—Permitted importations, 280—Library importations, 281—Seizure, 282—Return of importations, 282—Rules against unlawful importation, 282—Supersedure of previous provisions, 283—Manufacturing clause affects earlier copyrights, 283—Importation of foreign texts, 284—Printing within country, 285—Innocent importation, 286—Books not claiming copyright, 286—Periodicals, 286—Composite books, 286—Rebinding abroad, 287—Importation of non-copyright translation, 288—Books dutiable, 288—Books on free list, 289—Library free importation, 290—Copyrights and the free list, 291—The duty on books, 291—British prohibition of importation, 292—Foreign reprints, 293—Divided market, 293—New British code, 293—Canadian practice, 294—Australian provision, 295—Foreign practice, 295—International practice, 296. | ||

| XVII. | Copyright Office: Methods and Practice | 297-310 |

| History of Copyright Office, 297—Routine of registration, 297—Treatment of deposits, 298—Destruction of useless material, 299—Register of Copyrights, 299—Catalogues and indexes, 300—Entry cards, 301—Text provisions, 302—Copyright records, 302—Register and assistant register, 302—Deposit and report of fees, 302—Bond, 303—Annual report, 303—Seal, 303—Rules, 303—Record books, 303—Certificate, 303—Receipt for deposits, 304—Catalogue and index provision, 304—Distribution and subscriptions, 305—Records open to inspection, 305—Preservation of deposits, 305—Disposal of deposits, 306—Fees, 307—Only one registration required, 307—Present organization, 308—Efficiency of methods, 308—Registration, 1909-1910, 309—Certificates for court use, 309—Searches, 309—Patent Office registry for labels, 309—Foreign practice, 310. | ||

| PART V | ||

| International and Foreign Copyright | ||

| XVIII. | International Copyright Conventions and Arrangements | 311-340 |

| International protection of property, 311—Early copyright protection, 311—English protection, 311—Effect of Berne convention, 313—International literary congresses, 314—Fundamental proposition, 314—Preliminary official conference, 1883, 314—Propositions of 1883, 315—First official conference, 1884, 316—Second official conference, 1885, 317—Third official conference, 1886, 318—Berne convention, 1886, 318—Authors and terms, 318—"Literary and artistic works" defined, 318—Performing rights, 319—Other provisions, 319—Final protocol, 320—Ratification in 1887, 320—Paris conference, 1896, 321—Paris Additional Act, 321—Paris Interpretative Declaration, 322—Ratification in 1897, 322—Berlin conference, 1908, 323—United States' position, 324—Welcome of non-unionist countries, 325—Death of Sir Henry Bergne, 325—Berlin convention, 1908, 326—"Literary and artistic works" defined, 326—Authors' rights, 326—"Country of origin," 327—Broadened international protection, 327—Term, 328—Performing rights, 328—Other provisions, 329—National powers reserved, 329—Organization provisions, 329—Ratification in 1910, 330—Official organ, 330—Montevideo congress, 1889, 331—Pan American conferences, 331—Mexico City conference, 1902, 332—Mexico convention, 1902, 332—Indispensable condition, 333—Special provisions, 333—Ratification, 334—Rio de Janeiro conference, 1906, 334—Rio provisions, 335—Ratification, 336—Buenos Aires conference and convention, 1910, 336—Attorney General's opinion on ratification, 337—Relation with importation provisions, 338—United States international relations, 339—"Proclaimed" countries, 339—Mechanical music reciprocity, 340. | ||

| XIX. | The International Copyright Movement in America | 341-372 |

| Initial endeavor in America, 1837, 341—The British address, 341—Henry Clay report, 1837, 344—Prophecy of world union, 344—Clay bills, 1837-42, 346—Palmerston invitation, 1838, 346—Efforts, 1840-48, 346—Everett treaty, 1853, 347—Morris bills, 1858-60, 348—International Copyright Association, 1868, 348—Baldwin bill and report, 1868, 348—Clarendon treaty, 1870, 349—Cox bill and resolution, 1871, 349—The Appleton proposal, 1872, 350—Philadelphia protest, 1872, 351—The Bristed proposal, 1872, 351—Kelley resolution, 1872, 352—Congressional hearings, 352—Beck-Sherman bill, 1872, 352—Morrill report, 1873, 353—Banning Bill, 1874, 353—The Harper proposal and draft, 1878, 353—Granville negotiations, 1880, 355—Robinson and Collins bills, 1882-83, 356—American Copyright League, 356—Dorsheimer bill, 1884, 356—American publishers' sentiment, 357—Hawley bill, 1885, 358—Chace bill, 1886, 358—Congressional hearings, 1886, 359—Mr. Lowell's epigram, 359—President Cleveland's second message, 1886, 360—Campaign of 1887, 360—Senate passage of Chace bill, 1888, 361,—Bryce bill, 1888, 361—President Harrison's message, 1889, 361—Simonds bill and report, 1890, 362—Senate debate, 1891, 363—Act of March 4, 1891, 363—Review of the publishing situation, 364—Lack of unified policy, 365—Compromise of 1891, 365—Need of general revision, 366—Ad interim copyright act, 1905, 366—Copyright conferences, 1905-06, 367—President Roosevelt's message, 1905, 368—Congressional hearings, 1906-08, 369—Kittredge-Currier reports, 1907, 369—Smoot-Currier Kittredge-Barchfeld bills, 1907-08, 370—Washburn, Sulzer, McCall, Currier bills, 1908, 370—Fourth Congressional hearing, 1909, 371—Act of March 4, 1909, 371—Hopes of future progress, 372. | ||

| XX. | Copyright throughout the British Empire | 373-397 |

| English and American systems, 373—First publication and residence, 373—Variations in copyright terms, 374—New British code, 374—Scope and extent, 375—Publication, 376—Definition of copyright, 376—Infringement, 376—Term, 377—Ownership, 377—Deposit copies, 378—Importation, 378—Remedies, 378—General relations, 379—Acts repealed, 379—Changes from original bill, 379—Isle of Man, 380—Channel Islands, 381—International relations, 381—Colonial relations, 381—Local legislation, 382—Canadian copyright history, 383—Dominion of Canada: early acts, 383—Acts of 1875, 384—License acts disallowed, 385—Fisher Act, 1900, 385—Minor acts, 386—Short form of notice, 386—Proposed Canadian copyright code, 1911, 386—Imperial and Canadian copyright, 388—Requisites for domestic copyright, 388—Imperial and local protection, 388—Additional local protection, 389—Application for copyright, 389—Newfoundland, 390—British West Indies, etc., 391—Australian code of 1905, 391—General provisions, 392—Dramatic and musical works, 393—Performing right, 393—Registration and license, 394—New Zealand, 394—Australasia otherwise, 395—British India, 395—South Africa, 396—West coast colonies, 397—Mediterranean islands, 397. | ||

| XXI. | Copyright in Other Countries | 398-429 |

| France, 398—Belgium, 400—Luxemburg, 400—Holland, 401—Germany, 402—Austria-Hungary, 405—Switzerland, 406—Scandinavian countries, 407—Russia, 409—Finland, 409—Spain, 410—Portugal, 411—Italy, 412—San Marino, 413—Monaco, 413—Greece, 414—Montenegro, 414—Balkan states, 414—Turkey, 415—Japan, 415—Korea, 416—China, 417—Siam, 417—Asia otherwise, 418—Tunis, etc., 418—Egypt, 418—Liberia, 419—Africa otherwise, 419—Latin America, 419—Mexico, 420—Central American states, 421—Interstate and international relations, 422—Panama, 423—Cuba, 423—Haiti, 424—Dominican Republic, 424—West Indian colonies, 425—Brazil, 425—Argentina, 425—Paraguay and Uruguay, 426—Chile, 427—Peru, 427—Bolivia, 427—Ecuador, 428—Colombia, 429—Venezuela, 429. | ||

| PART VI | ||

| Business Relations and Literature | ||

| XXII. | Business Relations of Copyright: Author and Publisher | 430-452 |

| Copyrights in business relations, 430—German publishing law of 1901, 430—The publisher as merchant, 434—"Outright" transfer, 434—"Joint adventure," 435—Risk and profit, 435—Long price and "net" price, 436—Equities, 436—The literary agent, 436—Usual American contract, 437—Publishers' obligations, 437—Reversion of contract, 438—Scope of contract, 438—Other works of author, 439—Standard contract, 439—Serial rights, 439—Republication of periodical articles, 440—Foreign markets, 440—Contract to do work, 440—Contract not to write, 441—Implied obligations, 442—Contract personal and mutual, 442—Author's transfer to other publishers, 445—Proprietary name, 445—Copies remaining unsold, 446—Renewal term, 447—License not assignment, 447—Author's and publisher's profits, 447—The publisher's share, 448—"Author's editions," 449—Printer's lien, 449—Compulsory license system, 449—License payments, 450—Saving through single publisher, 451—Copyrights in bankruptcy, 451—Copyrights in taxation, 452. | ||

| XXIII. | The Literature of Copyright | 453-462 |

| Bibliographical materials, 453—Early history, 453—Early American contributions, 454—Later American pamphleteers, 454—American treatises, 455—Copyright Office publications, 455—Labor report, 456—English contributions about 1840, 456—Later English contributions, 457—English legal treatises, 457—Birrell's lectures, 458—MacGillivray's works, 458—English special treatises, 459—Parliamentary and Commission reports, 459—Cyclopædias and digests, 460—French works, 460—German works, 460—Italian works, 461—Spanish compendium, 461—International compilations, 462. | ||

| APPENDIX | |||

| I. | United States of America: Copyright Provisions | 465-516 | |

| 1. | United States Copyright Code of 1909, 465. | ||

| 2. | President's Proclamations, 489. | ||

| 3. | United States Supreme Court Rules, 491. | ||

| 4. | United States Copyright Office Regulations, 495. | ||

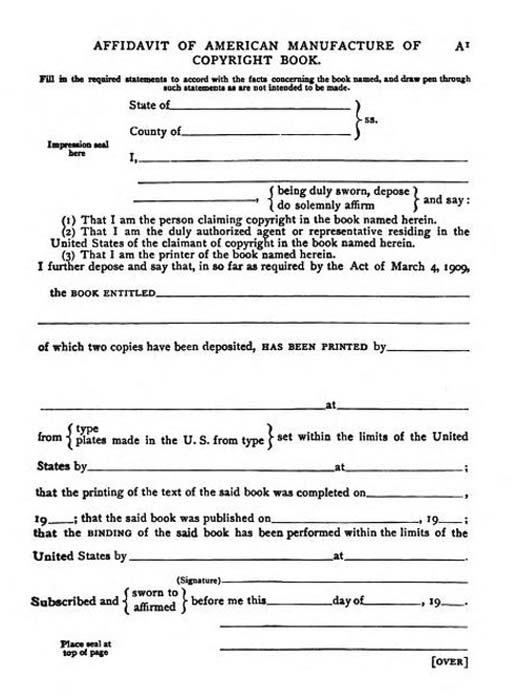

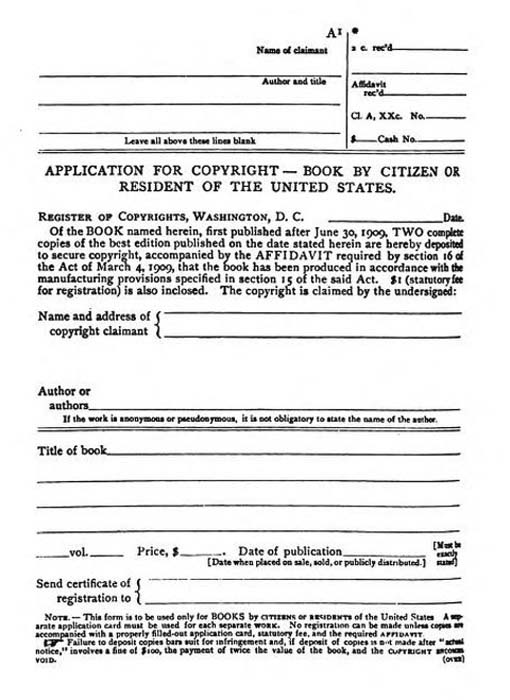

| Application for copyright, with affidavit form, 511. | |||

| 5. | U. S. Treasury and Post Office Regulations, 513. | ||

| II. | British Empire: Copyright Provisions | 517-602 | |

| 6. | British Copyright Act, 1911, 517. | ||

| 6a. | Fine Arts Copyright Act, 1862, 548. | ||

| 6b. | Musical (Summary Proceedings) Copyright Act, 1902, 550. | ||

| 6c. | Musical Copyright Act, 1906, 552. | ||

| 7. | Canadian Copyright Measure, 1911, 555. | ||

| 8. | Australian Copyright Act, 1905, 580. | ||

| III. | International Copyright Union: Conventions | 603-632 | |

| 9. | Berne-Paris Conventions, 1886, 1896, 603. | ||

| 10. | Berlin Convention, 1908, 603. | ||

| IV. | Pan American Union: Conventions | 633-652 | |

| 11. | Montevideo Convention, 1889, 633. | ||

| 12. | Mexico City Convention, 1902, 637. | ||

| 13. | Rio de Janeiro Convention, 1906, 642. | ||

| 14. | Buenos Aires Convention, 1910, 649. | ||

| Chronological Table of Laws and Cases, English and American | 653-675 | ||

| Index | 677-709 | ||

| Conspectus of Copyright by Countries | precedes Contents | ||

Copyright (from the Latin copia, plenty) means, in general, the right to copy, to make plenty. In its specific application it means the right to multiply copies of those products of the human brain known as literature and art.

There is another legal sense of the word "copyright" much emphasized by several English justices. Through the low Latin use of the word copia, our word "copy" has a secondary and reversed meaning, as the pattern to be copied or made plenty, in which sense the schoolboy copies from the "copy" set in his copy-book, and the modern printer calls for the author's "copy."

Copyright, accordingly, may also mean the right in copy made (whether the original work or a duplication of it), as well as the right to make copies, which by no means goes with the work or any duplicate of it. Said Lord St. Leonards in the case of Jefferys v. Boosey in 1854: "When we are talking of the right of an author we must distinguish between the mere right to his manuscript, and to any copy which he may choose to make of it, as his property, just like any other personal chattel, and the right to multiply copies to the exclusion of every other person. Nothing can be more distinct than these two [Pg 2]things. The common law does give a man who has composed a work a right to that composition, just as he has a right to any other part of his personal property; but the question of the right of excluding all the world from copying, and of himself claiming the exclusive right of forever copying his own composition after he has published it to the world, is a totally different thing." Baron Parke, in the same case, pointed out expressly these two different legal senses of the word copyright, the right in copy, a right of possession, always fully protected by the common law, and the right to copy, a right of multiplication, which alone has been the subject of special statutory protection.

Blackstone in his Commentaries of 1767, in which the word copyright seems to have been first used, lays down the fundamental principles of copyright as follows: "When a man, by the exertion of his rational powers, has produced an original work, he seems to have clearly a right to dispose of that identical work as he pleases, and any attempt to vary the disposition he has made of it appears to be an invasion of that right. Now the identity of a literary composition consists entirely in the sentiment and the language; the same conceptions, clothed in the same words, must necessarily be the same composition; and whatever method be taken of exhibiting that composition to the ear or the eye of another, by recital, by writing, or by printing, in any number of copies, or at any period of time, it is always the identical work of the author which is so exhibited; and no other man (it hath been thought) can have a right to exhibit it, especially for profit, without the author's consent. This consent may, perhaps, be tacitly given to all mankind, when an author suffers his work to be published by another hand, without any claim or reserve [Pg 3]of right, and without stamping on it any marks of ownership; it being then a present to the public, like building a church or bridge, or laying out a new highway."

There is nothing which may more rightfully be called property than the creation of the individual brain. For property (from the Latin proprius, own) means a man's very own, and there is nothing more his own than the thought, created, made out of no material thing (unless the nerve-food which the brain consumes in the act of thinking be so counted), which uses material things only for its record or manifestation. The best proof of own-ership is that if this individual man or woman had not thought this individual thought, realized in writing or in music or in marble, it would not exist. Or if the individual thinking it had put it aside without such record, it would not, in any practical sense, exist. We cannot know what "might have beens" of untold value have been lost to the world where thinkers, such as inventors, have had no inducement or opportunity thus to materialize their thoughts.

Are thoughts created?

It is sometimes said, as a bar to this idea of property, that no thought is new—that every thinker is dependent upon the gifts of nature and the thoughts of other thinkers before him, as every tiller of the soil is dependent upon the land as given by nature and improved by the men who have toiled and tilled before him,—a view of which Henry C. Carey has been the chief exponent in this country. But there is no real analogy—aside from the question whether the denial of individual property in land would not be setting back the hands of progress. If Farmer Jones does not raise potatoes from a piece of land, Farmer Smith can; but Shakespeare cannot write "Paradise lost" nor Milton "Much ado," though before both [Pg 4]Dante dreamed and Boccaccio told his tales. It was because of Milton and Shakespeare writing, not because of Dante and Boccaccio who had written, that these immortal works are treasures of the English tongue. It was the very self of each, in propria persona, that gave these form and worth, though they used words that had come down from generations as the common heritage of English-speaking men. Property in a stream of water, as has been pointed out, is not in the atoms of the water but in the flow of the stream.

Property right in unpublished works has never been effectively questioned—a fact which in itself confirms the view that intellectual property is a natural inherent right. The author has "supreme control" over an unpublished work, and his manuscript cannot be utilized by creditors as assets without his consent. "If he lends a copy to another," says Baron Parke, "his right is not gone; if he sends it to another under an implied undertaking that he is not to part with it or publish it, he has a right to enforce that undertaking." The receiver of a letter, to whom the paper containing the writing has undoubtedly been given, has no right to publish or otherwise use the letter without the writer's consent. The theory that by permitting copies to be made, an author dedicates his writing to the public, as an owner of land dedicates a road to the public by permitting public use of it for twenty-one years, overlooks the fact that in so doing the author only conveys to each holder of his book the right to individual use, and not the right to multiply copies, as though the landowner should not give but sell permission to individuals to pass over his road, without any permission to them to sell tickets for the same privilege to other people. The owner of a right does not forfeit a right by selling a privilege.

[Pg 5]It is at the moment of publication that the undisputed possessory right passes over into the much disputed right to multiply copies, and that the vexed question of the true theory of copyright property arises. The broad view of literary property holds that the one kind of copyright is involved in the other. The right to have is the right to use. An author cannot use—that is, get beneficial results from—his work, without offering copies for sale. He would be otherwise like the owner of a loaf of bread who was told that the bread was his until he wanted to eat it. That sale would seem to contain "an implied undertaking" that the buyer has liberty to use his copy, but not to multiply it. Peculiarly in this kind of property the right of ownership consists in the right to prevent use of one's property by others without the owner's consent. The right of exclusion seems to be indeed a part of ownership. In the case of land the owner is entitled to prevent trespass, to the extent of a shot-gun, and in the same way the law recognizes the right to use violence, even to the extreme, in preventing others from possession of one's own property of any kind. The owner of a literary property has, however, no physical means of defence or redress; the very act of publication by which he gets a market for his productions opens him to the danger of wider multiplication and publication without his consent. There is, therefore, no kind of property which is so dependent on the help of the law for the protection of the real owner.

The inherent right of authors is a right at what is called common law—that is, natural or customary law. The common law, says Kent, "includes those principles, usages, and rules of action applicable to the government and security of person and property which do not rest for their authority upon [Pg 6]any express and positive declaration of the will of the legislature." "The common law or lex non scripta," says Blackstone, "depends upon its having been used time out of mind; or, in the solemnity of our legal phrase, time whereof the memory of man runneth not to the contrary." So far as concerns the undisputed rights before publication, the copyright laws are auxiliary merely to common law. Rights exist before remedies; remedies are merely invented to enforce rights. "The seeking for the law of the right of property in the law of procedure relating to the remedies," says Copinger in his standard English work on "The law of copyright," "is a mistake similar to supposing that the mark on the ear of an animal is the cause, instead of the consequence, of property therein."

After the invention of printing it became evident that new methods of procedure must be devised to enforce common law rights. Copyright became, therefore, the subject of statute law, by the passage of laws imposing penalties for a theft which, without such laws, could not be punished.

Statute of Anne

Supersedure of common law right

These laws, covering naturally only the country of the author, and specifying a time during which the penalties could be enforced, and providing means of registration by which authors could register their property rights, as the title to a house is registered when it is sold, had an unexpected result. The statute of Anne, which is the foundation of present English copyright law, intended to protect authors' rights by providing penalties against their violation, had the effect of limiting those rights. It was doubtless the intention of those who framed the statute of Anne to establish, for the benefit of authors, specific means of redress. Overlooking apparently the fact that law and equity, as their principles were then [Pg 7]established, enabled authors to use the same means of redress, so far as they held good, which persons suffering wrongs as to other property had, the law was so drawn that in 1774 the English House of Lords (against, however, the weight of one half of English judicial opinion) decided that, instead of giving additional sanction to a formerly existing right, the statute of Anne had substituted a new and lesser right to the exclusion of what the majority of English judges held to have been an old and greater right. Literary and like property to this extent lost the character of copy-right, and became the subject of copy-privilege, depending on legal enactment for the security of the private owner. American courts, wont to follow English precedent, have rather taken for granted this view of the law of literary property, and our Constitution, in authorizing Congress to secure "for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries," was evidently drawn from the same point of view, though it does not in itself deny or withdraw the natural rights of the author at common law.

Our traditions of the blind Homer, singing his Iliad in the multitudinous places of his protean nativity, do not vouchsafe us any information as to the status of authors in his day. There seems indeed to be no indication of author's rights or literary property in Greek or earlier literatures. But there is mention in Roman literature of the sale of playright by the dramatic authors, as Terence; and Rome had booksellers who sold copies of poems written out by slaves, and who seem to have been protected by some kind of "courtesy of the trade," since Martial names certain booksellers who had specific poems of his for sale. Horace complains that the Sosius brothers, his publishers, got gold while he got only fame—but this may have been a classic "author's grumble." Cicero in his letters indicates that there was some notion of literary property, and it is probable that some kind of payment was made to authors.

The Roman jurist Gaius, probably of the second century, held that where an artist had painted upon a tabula, his was the superior right. And this opinion was adopted by Tribonian, chief editor of the code of Justinian, in the sixth century, and was applied in a modern question in respect to John Leech's drawings upon wood.

Monastic copyists

St. Columba and Finnian

In the early Christian centuries, the monasteries became the seats of learning, and the scriptorium or writing room, in connection with the librarium or armarium,—the armory in which the weapons of the [Pg 9]faith were kept,—was the work-shop of the monkish copyists, sometimes working as a publishing staff under the direction of the librarius or armarius as chief scribe. The first record of a copyright case is that of Finnian v. Columba in 567, chronicled by Adamnan fifty years later and cited by Montalembert in "The monks of the West." St. Columba, in his pre-saintly days, surreptitiously made a copy of a psalter in possession of his teacher Finnian, and the copy was reclaimed, so the tradition relates, under the decision of King Dermott, in the Halls of Tara: "To every cow her calf." The authenticity of the tradition is questioned by other writers, but the phrase gives the pith of the common law doctrine of literary property and indicates that in those early centuries there was a sense of copyright. Monks from other monasteries came to a noted scriptorium where a specially authentic or valuable manuscript could be copied, and the privilege of copying sometimes became the basis of an exchange of copies or of a commercial charge. Finally different texts of the same work were compared to obtain a certain or standard text, and the multiplication of such copies became the basis of a publishing and bookselling trade, in secular as well as sacerdotal hands, the development of which is traced in detail by George Haven Putnam in "Books and their makers in the Middle Ages."

This development is illustrated in the statutes of 1223 of the University of Paris, providing that the "booksellers of the University" should produce duplicate copies of the texts authorized for the use of the University, and there is indication that payment was made by the University to scholars for the annotation and proof-reading of such texts. In fact, there existed in France in those days a kind of guild of [Pg 10]libraires jurés or legalized booksellers, under regulation of the University, as a body of publishers and writers having jurisdiction over the copying and censorship of manuscripts. "Letters of patent" of Charles V, 1368, specified fourteen libraires and eleven écrivains as registered in Paris, and four chief libraires had jurisdiction over the calling of the librarius and the stationarius. The certificate of the correctness of a copy, and perhaps of the right to copy or sell it, may be considered the primitive form of copyright certificate.

The invention of printing, prior to 1450, made protection of literary property a question of rapidly increasing importance. The new art raised, of course, many new questions wherever the guardians of the law were set to their chronic task of applying old ideas of right to new conditions. The earliest copyright certificate, if it may be so called, in a printed book was that in the reissue of the tractate of Peter Nigrus printed in 1475, at Esslingen, in which the Bishop of Ratisbon certified the correctness of the copy and his approval. At first "privileges" were granted chiefly to printers, for the reproduction of classic or patristic works, but possibly in some cases as the representatives of living writers; and there are early instances of direct grants to authors, the earliest known being in 1486 in Venice to Sabellico.

In Germany, the cradle of the art of printing, whence come the earliest incunabula or cradle-books, printing privileges were developed some decades later than in Italy. Koberger, the early Nuremberg printer, whose imprint dates back to 1473, relied rather on the "courtesy of the trade," and indeed made an agreement in 1495 with Kessler of Basel to respect each other's rights. Yet a suit brought in 1480 by Schöffer, who with Fust had established the first [Pg 11]publishing and bookselling business, brought in connection with Fust's heirs against Inkus of Frankfort for the infringement of property rights in certain books, and the issue of a preliminary injunction by a court at Basel, indicated some definite legal status.

The first recorded privilege in Germany was issued by the imperial Aulic Council in 1501, to the Rhenish Celtic Sodalitas for the printing of dramas of the nun-poet, Hroswitha, who had been dead for 600 years, as prepared by Celtes of Nuremberg. The imperial privilege covered only the imperial domain, and Celtes in the same year obtained a similar privilege from the magistracy of Frankfort, then the seat of the book-fair, organized there about 1500, afterwards superseded by that at Leipzig. Later, imperial privileges were issued by the Imperial Chancellor in the name of the Emperor, as one in 1510 to the printer Johann Schott of the "Lectura aurea." In 1512 Maximilian I granted to the historiographer Johann Stab in Lintz a privilege covering "all works" which he "might cause to be printed," under which he issued licenses on particular books for ten years or less. This grant, however, some authorities consider not a privilege or copyright, but an authorization to license, possibly similar to that which had been granted in 1455 by Frederick III and confirmed later by Maximilian I to Dr. Jacob Össler at Strasburg, perhaps the earliest centre of printing and bookselling, as imperial supervisor of literature and superintendent of printing. In 1512 also, copies or imitations or engravings by Albert Dürer, with forged signature, were ordered confiscated by the magistrates of Nuremberg, though perhaps on grounds of fraud rather than of copyright. But in 1528 Dürer's widow obtained from the Nuremberg authorities exclusive privilege for his works, and in [Pg 12]that year the magistrates went so far in protecting Dürer's "Proportion" as to restrain another work of the same title and subject, presumably though mistakenly inferred to be an adaptation or imitation, until after the completion and sale of the original work. In 1532 reëngravings of some of Dürer's works were restrained, and when a Latin edition of his "Perspective," printed in Paris, found its way to Nuremberg, the magistrates called the booksellers together, warned them against keeping or selling the unauthorized edition, and sent letters to the magistracy of Strasburg, Frankfort, Leipzig and Antwerp, requesting similar action. Luther in his reforming zeal was the first protestant against authors' wrongs, and in a letter of 1528 complained that "there are many now busying themselves with the spoiling of books through misprinting them," and pleaded for legislation to protect literary producers. In 1531 the city council of Basel enjoined all booksellers from reprinting the books of each other for three years from publication under penalty of one hundred gulden, which illustrates the nature of local legislation, privileging printers as well as other guilds within a city. The protection was usually for short terms and sometimes covered the subject as well as the book, as indicated in the Dürer case.

The coördinate jurisdiction of imperial and local authority continued into the seventeenth century, and besides a special protection of official publications, including church texts and school books, there developed a differentiation between privileged books and protected authors. The imperial city of Frankfort in 1660 passed an ordinance for the protection of "bücher" and "autores" and an imperial patent of 1685 made the curious distinction between "privileged" and "unprivileged" works, which Pütter, [Pg 13]reputed the German apostle of the modern theory of property in literary productions, writing in 1764, explains as meaning respectively "non-individual" and "individual" (eigenthümlich) works, the former those issued under printers' privileges, the latter the works of contemporary authors, copyrightable in our modern sense. At the close of the seventeenth century, the book-fair at Leipzig began to assume dominating importance, and the privileges from the Commission of the Elector of Saxony became more authoritative, perhaps, than the imperial privileges issued from Frankfort.

Venice, among whose chief glories were to be the master printers Aldus, was the first and foremost of the Italian states to encourage the new art. The first privilege granted by her Senate, in 1469, indeed ante-dated the first in Germany by thirty-two years, the first in France by thirty-four years, and the first in England by forty-nine years. This was to John of Speyer, a German printer, for a monopoly for printing in Venice for five years, with prohibition of importation of works printed elsewhere, which he did not live to enjoy. The first known author's copyright was granted September 1, 1486, to Antonio Sabellico, historian to the Republic, of the sole right to publish or authorize the publication of his "Decade of Venetian affairs," not limited in time, with a penalty of five hundred ducats for infringement. In 1491 the Senate gave to the publicist Peter of Ravenna and the publisher of his choice the sole right, without mention of term, to print and sell his "Phœnix," usually cited as the first instance of copyright. In 1493 one Barbaro was granted a privilege for ten years in the work of his deceased brother, and in the same year an editor's copyright was granted to Joannes Nigro for his edition of "Haliabas," his application [Pg 14] being accompanied by a certificate from learned doctors of Padua of its value for the community, and a publisher's copyright to Benaliis on Giustiniani's "Origin of the city of Venice," both apparently without term. In 1494 a privilege to Codeca contained the condition of fair price, and another privilege required publication within a year or at the rate of a folio a day. In 1496 Aldus himself was given the privilege for twenty years of printing any Greek texts, and in 1501, another for ten years of printing in cursive or italic characters, an invention of his own modeled on the handwriting of Boccaccio, a quasi patent right; and rights for other languages were granted to other printers.

From 1505 renewals were granted for good cause, as in 1508 to Crasso for his edition of the works of Polifilo, because the wars had prevented due return. The privilege dated sometimes from application, sometimes from publication, and varied in term from one year up, averaging perhaps ten years at the beginning and twenty years toward the close of the sixteenth century. Many of the privileges were conditioned on printing within Venice. Copyright to authors became frequent, as in 1515 on his "Orlando" for his lifetime, to Ariosto, on whose poems an extra term for ten years was granted, in 1535, to his heirs. In 1521 Castellazzo obtained a copyright for his engravings illustrating the Pentateuch and for others which he had in plan; and many musical works were also copyrighted.

It will be seen that before or early in the sixteenth century most of the copyright conditions of later legislation, even in the American code of 1909, had been prophesied in Venice. But the privileges had become so complicated and perplexing that in 1517 the Venetian Senate abolished all printing privileges [Pg 15] previously granted and decreed that privileges should thereafter be granted only by two-thirds vote and for a new work (opus novum) "never published before," or works hitherto unprivileged. This attempt at reform proved inadequate and indefinite, and in 1533 the first real copyright code was decreed, under which printing was required within Venice, and publication within a year—later modified for larger works to a folio a day. No publisher could apply twice for the same copyright, and a maximum price was fixed from an advance copy by the Bureau of Arts and Industries. Under the restriction of competition, Venetian printers, once the best in the world, fell into "the ruinous and disgraceful practice," according to a decree of 1537, "for the sake of gain" of using "vile paper that would not hold the ink" or permit marginal notes; and the use of good paper that could be written upon without blotting was required, except for works priced under 10 soldi, on penalty of forfeiture of copyright and a fine of 100 ducats. Under the earlier privileges publishers had printed books without consent of the authors or against their will, but in 1545 it was decreed that no copyright should issue unless documentary evidence of the consent of the author or his representatives had been submitted to the Rifformatori, the commission from the University of Padua, appointed the year before as censors upon non-theological works, not covered by the ecclesiastical censors.

A decree in 1548 established a guild of printers and publishers, antedating the charter granted by Queen Mary to the Stationers' Company in London, though later than the organization of the book-fair of Frankfort and of the libraires jurés in France; and its regulations, aiding the censorship, incidentally defined literary property and protected copyrights. [Pg 16]About 1566 there was a provision that works should be registered before publication without charge, and a complete registry of published works was kept in Venice. In 1569 as many as 117 copyright entries were made in Venice, and so few, after the plague years, as seven in 1599. Only two applications are recorded as refused by the Senate. The one recorded instance of punishment for piracy was that on the work of Pappa Alesio of Corfu, wherein the infringer was fined 200 ducats, besides ten ducats for each unauthorized copy printed, and was forbidden to print for ten years.

About 1600 the exodus of printers from Venice was checked by legislation, and in 1603 an elaborate decree provided copyright for twenty years on books first published in Venice, for ten years on books first published in Italy but registered in Venice, or on books not printed in Venice within the previous twenty years, and for five years on books not printed within ten years previous, and also a fine of twenty-five ducats for the false use of "Venetia" in the imprint. Later, as is evidenced by complaints in 1671, deposit copies were required for the libraries of St. Mark and of Padua. By the close of the seventeenth century the provisions for copyright in Venice had become so complicated, according to Putnam, following Brown's historical study of "The Venetian printing press," as to require the following processes, most of them involving a fee: "testamur from the ducal secretary; certificate from the Rifformatori of the University of Padua; imprimatur from the Chiefs of the Ten; revision by the Superintendent of the Press; revision by the public proof-reader; collation of the original text with the text as printed, by the secretary to the Rifformatori; certificate from the librarian of St. Mark that a copy had been deposited in the [Pg 17]library; examination by experts appointed by the Proveditori to establish the market price of the book."

Florence was second only to Venice in the production of books and the protection of authors, and the records of Florentine printing show that in the sixteenth century international privileges were sought and obtained. Thus the printer of a Florentine edition of the Pandects, in 1553, obtained privileges also in Spain, France and the two Sicilies, possibly through a Papal grant.

By 1515, under Leo X, patron of art and letters, the Holy See had asserted its jurisdiction over copyrights and privileges, not only in its own territory, but throughout Italy and Germany, and elsewhere, under pain of spiritual punishments. Fra Felice of Prato, a converted Jew, had obtained from the Pope a privilege for certain Hebrew works valid throughout all Europe, the denial or infringement of which was punishable by excommunication; but he took the precaution to obtain a privilege also from the Venetian authorities. There is other evidence of a compromise policy involving approval from the Church before a secular privilege was granted, especially of theological works. Throughout Catholic countries the index expurgatorius banned for the most part the printing of forbidden books; and this made Holland later the chief centre of printing, since the placing of a work in the index invited prompt reprint by Dutch publishers. It was perhaps a survival of a requirement for deposit of such books that Holland so long remained the only nation in Europe conditioning copyright on deposit of a copy printed within the country.

In France, after the invention of printing, the functions of the libraires jurés, under the authority given by the King through the University of Paris, naturally [Pg 18] came to include books, and this relation was continued until the Revolution of 1789. Copyrights throughout this period seem to have been in perpetuity. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, in the times of Louis XII, "letters of the King" forbade booksellers, printers and other persons to "introduce foreign impressions" of the books to which such letters were appended. They were usually issued to printers. In 1537, under Francis I, a work had first to secure "the King's approval given through the royal librarian," a copy must be deposited in the library of the royal château of Blois, and the selling of foreign works was permitted only after approval as worthy of a place in the royal library,—but for these last the library was to pay the usual price. In 1556 a general ordinance of Henry II defined literary property, and publication of condemned books was declared treason. In 1566 the "Ordinance de Moulins" of Charles IX made further definition; and letters patent of Henry III, in 1576, referred back to these earlier ordinances. Infringement of such privileges was punished with especial severity in France, for, as quoted by Lowndes, such conduct was thought "worse than to enter a neighbor's house and steal his goods: for negligence might be imputed to him for permitting the thief to enter: but in the case of piracy of copyright, it was stealing a thing confided to the public honor." Louis XIV in 1682 visited it with corporal punishment, and for a second offence decreed in 1686 also that the offender should be forever disabled from exercising his trade of bookseller or printer.

Copyrights continued in perpetuity until all royal privileges were abolished in 1789 by the National Assembly, after which in July, 1793, a general copyright law was passed, granting copyright to an author for his life and to his heirs for ten years thereafter.