Late on a September afternoon, in the year 1913, two boys returned to Friar's Court by way of the woods. Each carried a gun under his arm, and a well-bred Irish water-spaniel followed close upon their heels. They were of about the same age, though it would have been apparent, even to the most casual observer, that they stood to one another in the relation of master to man.

The one, Henry Urquhart, home for his holidays from Eton, was the nephew of Mr. Langton, the retired West African judge, who owned Friar's Court. The other was Jim Braid, the son of Mr. Langton's head-gamekeeper, who had already donned the corduroys and the moleskin waistcoat of his father's trade. Though to some extent a social gap divided them, a friendship had already sprung up between these two which was destined to ripen as the years went on, carrying both to the uttermost parts of the world, through the forests of the Cameroons, across the inhospitable hills west of the Cameroon Peak, even to the great plains of the Sahara.

Harry was a boy of the open air. He was never happier than when on horseback, or when he carried a shot-gun and a pocketful of cartridges. As for Jim, he was no rider, but there were few boys of his age who could hit a bolting rabbit or a rocketing pheasant with such surety of aim.

The Judge himself was much given to study, and was said to be a recognized authority on the primitive races of Africa and the East. For hours at a time he would shut himself up in the little bungalow he had built in the woods, where, undisturbed, he could carry out his researches. He was fond of his nephew, not the less so because Harry was a boy well able to amuse himself; and where there were rabbits to be shot and ditches to be jumped, young Urquhart was in his element.

In Jim Braid, the schoolboy found one who had kindred tastes, who was a better shot than himself, who could manage ferrets, and who, on one occasion, had even had the privilege of assisting his father in the capture of a poacher. Constant companionship engendered a friendship which in time grew into feelings of mutual admiration. In the young gamekeeper's eyes Harry was all that a gentleman should be; whereas the schoolboy knew that in Jim Braid he had found a companion after his heart.

The path they followed led them past the bungalow. As they drew near they saw there was a light in the window, and within was Mr. Langton, a tall, grey-haired man, who sat at his writing-desk, poring over his books and papers.

"My uncle works too hard," said Harry. "For the last week he has done nothing else. Every morning he has left the house directly after breakfast to come here. I think there's something on his mind; he seldom speaks at meals."

"I suppose," said Braid, "in a big estate like this there must be a good deal of business to be done?"

"I don't think that takes him much time," said the other. "He keeps his accounts and his cashbox in the bungalow, it is true, but he is much more interested in the ancient histories of India and Asia than in Friar's Court. He's a member of the Royal Society, you know, and that's a very great honour."

"He's a fine gentleman!" said Braid, as if that clinched the matter once and for all.

They walked on in silence for some minutes, and presently came to the drive. It was then that they heard the sound of the wheels of a dog-cart driving towards the house.

"That's Captain von Hardenberg," said Braid.

"I expect so," said the other. "His train must have been late. There'll be three of us to shoot to-morrow."

Braid did not answer. Harry glanced at him quickly.

"You don't seem pleased," he said.

"To tell the truth, sir," said Braid, after a brief pause, "I'm not. Captain von Hardenberg and I don't get on very well together."

"How's that?"

Jim hesitated.

"I hardly like to say, sir," said he, after a pause.

"I don't mind," said Harry. "To tell the truth, my cousin and I have never been friends. I can't think whatever possessed an aunt of mine to marry a German—and a Prussian at that. He's a military attaché, you know, at the German Embassy in London."

The dog-cart came into sight round a bend in the drive. They stepped aside to let it pass. There was just sufficient light to enable them to see clearly the features of the young man who was seated by the side of the coachman. He was about twenty-three years of age, with a very dark and somewhat sallow complexion, sharp, aquiline features, and piercing eyes. Upon his upper lip was a small, black moustache. He wore a heavy ulster, into the pockets of which his hands were thrust.

"Well, sir," said Jim, when the dog-cart had passed, "we've had a good time together, what with shooting and the ferrets, but I'm afraid it's all ended, now that the captain's come."

"Ended!" said Harry. "Why should it be ended?"

"Because I can never be the same with that gentleman as I am with you. Last time he was here he struck me."

"Struck you! What for?"

"There was a shooting-party at the Court," the young gamekeeper went on, "and I was helping my father. A pheasant broke covert midway between Captain von Hardenberg and another gentleman, and they both fired. Both claimed the bird, and appealed to me. I knew the captain had fired first and missed, and I told him so. He said nothing at the time, though he got very red in the face. That evening he came up to me and asked me what I meant by it. I said I had spoken the truth, and he told me not to be insolent. I don't know what I said to that, sir; but, at any rate, he struck me. I clenched my fists, and as near as a touch did I knock him down. I remembered in time that he was the Judge's nephew, the same as yourself, and I'd lose my place if I did it. So I just jammed both my fists in my trousers pockets, and walked away, holding myself in, as it were, and cursing my luck."

"You did right, Jim," said the other, after a pause. "You deserve to be congratulated."

"It was pretty difficult," Braid added. "I could have knocked him into a cocked hat, and near as a touch I did it."

"Though he's my cousin," said Harry, "I'm afraid he's a bad lot. He's very unpopular in the diplomatic club in London to which he belongs. When I went back to school last term I happened to travel in the same carriage as two men who had known him well in Germany, and who talked about him the whole way. It appears that he's sowing his wild oats right and left, that he's always gambling and is already heavily in debt."

"I fancy," said Braid, "that a gamekeeper soon learns to know a rogue when he sees one. You see, sir, we're always after foxes or poachers or weasels; and the first time as ever I set eyes on Captain von Hardenberg, I said to myself: 'That man's one of them that try to live by their wits.'"

"I think," said Harry, "we had better talk about something else. In point of fact, Jim, I had no right to discuss my cousin at all. But I was carried away by my feelings when you told me he had struck you."

"I understand, sir," said the young gamekeeper, with a nod.

"At all events, we must make the best of him. We're to have him here for a month."

"As long as he doesn't cross my path," said Jim Braid, "I'll not meddle with him."

Soon after that they parted, Harry going towards the house, Jim taking the path that led to his father's cottage.

In the hall Harry found his cousin, who had already taken off his hat and overcoat, and was now seated before a roaring fire, with a cigarette in one hand and an empty wine glass in the other.

"Hallo!" said von Hardenberg, who spoke English perfectly. "Didn't know I was to have the pleasure of your company. Where's my uncle?"

"In the bungalow," said Harry. "During the last few days he's been extremely hard at work."

"How do you like school?" asked the young Prussian.

His manner was particularly domineering. With his sleek, black hair, carefully parted in the middle, and his neatly trimmed moustache, he had the appearance of a very superior person. Moreover, he did not attempt to disguise the fact that he looked upon his schoolboy cousin barely with toleration, if not with actual contempt.

"I like it tremendously!" said Harry, brightening up at once. "I suppose you know I got into the Cricket Eleven, and took four wickets against Harrow?"

He said this with frank, boyish enthusiasm. There was nothing boastful about it. Von Hardenberg, raising his eyebrows, flicked some cigarette-ash from his trousers.

"Himmel!" he observed. "You don't suppose I take the least interest in what you do against Harrow. The whole of your nation appears to think of nothing but play. As for us Germans, we have something better to think of!"

Harry looked at his cousin. For a moment a spirit of mischief rose within him, and he had half a mind to ask whether von Hardenberg had forgotten his gambling debts. However, he thought better of it, and went upstairs to dress for dinner.

The Judge came late from the bungalow, bursting into the dining-room as his two nephews were seating themselves at the table, saying that he had no time to change.

"Boys," he cried, rubbing his hands together, "I've made the greatest discovery of my life! I've hit upon a thing that will set the whole world talking for a month! I've discovered the Sunstone! I've solved its mystery! As you, Carl, would say, the whole thing's colossal!"

"The Sunstone!" cried Harry. "What is that?"

"The Sunstone," said the Judge, "has been known to exist for centuries. It is the key to the storehouse of one of the greatest treasures the world contains. It has been in my possession for nine years, and not till this evening did I dream that I possessed it."

"Come!" cried Harry. "You must tell us all about it!"

"Well," said the Judge, pushing aside the plate of soup which he had hardly tasted, "I don't know whether or not the story will interest you. It ought to, because it's romantic, and also melodramatic—that is to say, it is concerned with death. It came into my possession nine years ago, when I was presiding judge at Sierra Leone. I remember being informed by the police that a native from the region of Lake Chad had come into the country with several Arabs on his track. He had fled for his life from the hills; he had gone as far south as the Congo, and had then cut back on his tracks; and all this time, over thousands of miles of almost impenetrable country, the Arabs—slave-traders by repute—had clung to his heels like bloodhounds. In Sierra Leone he turned upon his tormentors and killed two of them. He was brought before me on a charge of murder, and I had no option but to sentence him to death. The day before he was hanged he wished to see me, and I visited him in prison. He gave into my hands a large, circular piece of jade, and I have kept it ever since, always looking upon it merely as a curiosity and a memento of a very unpleasant duty. Never for a moment did I dream it was the Sunstone itself.

"Now, before you can understand the whole story, you must know something of Zoroaster. Zoroaster was the preacher, or prophet, who was responsible for the most ancient religion in the world. He was the first of the Magi, or the Wise Men of the East, and it was he who framed the famous laws of the Medes and Persians. He is supposed to have lived more than six thousand years before Christ.

"The doctrine of Zoroaster is concerned with the worship of the sun; hence the name of the Sunstone. This religion was adopted by the Persians, who conquered Egypt, and thus spread their influence across the Red Sea into Africa. To-day, among the hills that surround Lake Chad, there exists a tribe of which little is known, except that they are called the Maziris, and are believed still to follow the religion of Zoroaster.

"In the days when Zoroaster preached, it was the custom of his followers and admirers to present the sage with jewels and precious stones. These were first given as alms, to enable him to live; but, as his fame extended, the treasure became so great that it far exceeded his needs.

"One rumour has it that Zoroaster died in the Himalayas; another that his body was embalmed in Egypt and conveyed by a party of Ethiopians into the very heart of the Dark Continent, where it was buried in a cave with all his treasure.

"The Sunstone is referred to by many ancient Persian writers. I have known of it for years as the key to the treasure of Zoroaster. As I have said, it is a circular piece of jade, bright yellow in colour, and of about the size of a saucer. On both sides of the stone various signs and symbols have been cut. On one side, from the centre, nine radii divide the circumference into nine equal arcs. In each arc is a distinct cuneiform character, similar to those which have been found upon the stone monuments of Persia and Arabia.

"The Arabs are in many ways the most wonderful people in the world. Their vitality as a race is amazing. For centuries—possibly for thousands of years—they have terrorized northern and central Africa. They were feared by the ancient Egyptians, who built walls around their cities to protect them from the Bedouins—the ancestors of the men who to-day lead their caravans to Erzerum, Zanzibar, and Timbuctoo.

"So far as I can discover, the Maziris are an Arab tribe who have given up their old nomad life. Somewhere in the Maziri country is a group of caves which no European has ever entered. They are known as the 'Caves of Zoroaster', for it is here that the sage is supposed to have been buried. The bones of Zoroaster, as well as the jewels, are said to lie in a vault cut in the living rock; and the Sunstone is the key which opens the entrance to that vault. The man, whom in my capacity as a judge I was obliged to sentence to death, had no doubt stolen it, and had been pursued across the continent by the Maziri chieftains, who desired to recover the Sunstone.

"There is the whole story. A week ago I came across a description of the Sunstone in the writings of a Persian historian, and that description led me to suspect that the very thing was in my own possession. I followed up clue after clue, and this evening I put the matter beyond all doubt."

Mr. Langton's two nephews had listened in breathless interest. Harry was leaning forward with his elbows on the table and his chin upon a hand. Von Hardenberg lay back in a chair, his arms folded, his dark eyes fixed upon his uncle.

"Then," said he, "you have but to get into these so-called 'Caves of Zoroaster' to possess yourself of the jewels?"

The Judge smiled, and shook his head.

"And to get into the caves," he answered, "is just the very thing that, for the present, it is almost impossible for any European to do. The Maziri are a wild and lawless tribe. They are indeed so bloodthirsty, their country so mountainous, and their valleys so infertile, that hitherto no one has ever interfered with their affairs. Like all the Arabs, they are a nation of robbers and cut-throats, who lived in the past by means of the slave-trade, and to-day exist by cattle-stealing and robbery. The man who tries to enter the 'Caves of Zoroaster' will have his work cut out."

"Will you let us see the Sunstone?" asked Harry.

"Certainly, my boy," said Mr. Langton. "I'll take you both down to the bungalow to-morrow morning, or—if you cannot wait till then—we can go to-night."

"Isn't it rather risky," asked von Hardenberg, "to keep such a valuable thing out of the house?"

"The bungalow is always locked," said Mr. Langton, "and I keep the Sunstone in a cabinet. Moreover, you must remember that nobody knows of its value. No thief would ever dream of stealing it. It is, to all appearances, only an inferior piece of jade."

"But you have money there as well?" said von Hardenberg.

"Not much," answered the Judge. "Since I do my accounts there it is convenient to have my cashbox at hand. But it seldom contains more than twenty pounds—the amount of money I require to pay the men employed on the estate."

"What an extraordinary thing," said Harry, still thinking of the treasure of Zoroaster, "that it should have existed for all these years and never have been plundered."

"Not so extraordinary," said Mr. Langton, "when you know the Arabs. The Maziris, as I have told you, are of Arab descent, though they are not followers of the Prophet. The sun-worshippers are extremely devout. No priest of Zoroaster would think of stealing the treasure; that would be to plunge his soul into eternal punishment."

"And no one else," asked von Hardenberg, "no Mohammedan or heathen, has ever been able to enter the vault?"

"Never," said Mr. Langton, "because the Sunstone is the secret. That is why, when the Sunstone was stolen, they were so anxious to run the thief to earth."

Von Hardenberg knit his brows. He was silent for a moment, and appeared to be thinking.

"And you believe you have solved the mystery?" he asked.

"I know I have," said the Judge. "If at this moment I suddenly found myself in the Caves of Zoroaster, with the Sunstone in my hand, I could gain access to the vault."

Von Hardenberg bit his lip quickly, and then looked sharply at his uncle. When he spoke, it was in the voice of a man who took little or no interest in the subject under discussion.

"I should rather like to see it," he remarked.

Accordingly, as soon as dinner was finished, they put on their overcoats, and conducted by the Judge, who carried a lantern, they followed a path through the woods until they came to the bungalow.

Mr. Langton unlocked the door and put the key into his pocket. Then he lit an oil lamp, which presently burned up and illumined the room. They found themselves in what to all intents and purposes was a library. The four walls were stacked with books, but the overflow of these was so great that many were piled upon chairs and in odd corners of the room. In the centre of the floor-space was a large writing-desk, and near this a cabinet with several drawers. Lying open on the writing-desk was a fair-sized cash-box, in which several golden sovereigns glittered in the light.

"How careless, to be sure!" exclaimed the Judge. "I had no business to leave my cash-box open. The truth is, I was so excited about this discovery that I forgot to put it away."

"And where's the Sunstone?" asked von Hardenberg.

"I keep it here," said Mr. Langton.

Going to the cabinet, and unlocking the third drawer from the top, he took out a large stone and laid it on the table in the light of the lamp. His two nephews, one on either side of him, leaned forward to examine this extraordinary relic.

On one side of the Sunstone were the cuneiform characters already mentioned by the Judge. On the other was a great deal of writing in the same primitive language, scratched upon the face of the jade, but so faint as to be barely legible.

"It was only with the greatest difficulty," observed the Judge, "that I managed to decipher and translate this writing. It is in no known language. Indeed, I would never have been able to make head or tail of it had I not been a scholar of Sanskrit. This writing is nothing more nor less than the definite instructions for using the Sunstone for the purpose of entering the vaults of Zoroaster."

"What does it say?" asked von Hardenberg.

"You are told to begin with a certain character and take the others in a circle 'in the way of the sun'—that is to say, from left to right, as with the hands of a clock. Before the main vault is a large lock, which works on the same principle as the modern Bramah lock—a very ancient device. It consists of nine enormous wheels. The outside, or tyre, of each of these wheels is adorned with hundreds of cuneiform characters, all of them quite different. Each wheel must be turned until the characters visible along a given line correspond with those upon the Sunstone. Not otherwise can the vault be opened."

There followed a silence of several moments. The Judge's discovery seemed so romantic and so astonishing that it was almost impossible to believe it was true. After a while, it was von Hardenberg who spoke.

"And now that you have made this discovery," he asked, "what do you propose to do?"

"I don't know," said the Judge. "I have no desire to pillage a sacred shrine. For the present I propose to keep the affair a secret whilst I continue my researches. There are several points upon which the historical world desires to be enlightened. Very little is known concerning the life of Zoroaster."

"But surely," exclaimed von Hardenberg, "you don't intend to keep this to yourself!"

"When I have the whole facts of the case at my finger-tips," said the Judge, "I will make the result of my investigations known to the authorities of the British Museum."

Soon after that they left the bungalow. Before they went to bed that night von Hardenberg took his cousin aside and looked at him intently.

"What do you make of it?" he asked.

"Of the Sunstone?" asked Harry.

"Yes," said the other. "It seems to me, if the old gentleman wanted to, he could make himself a millionaire."

Harry laughed.

"I don't think Uncle Jack cares much about money," said he. "He looks at the whole matter from a scientific point of view."

"No doubt," exclaimed the Prussian. "No doubt. I dare say he does."

And at that he turned and went slowly up the stairs.

Some hours after sunset, on the evening of the following day, Jim Braid was stationed in the woods, on the look-out for poachers. His father, John Braid, the head-gamekeeper, was also out that night, keeping watch in a different part of the estate. A well-known gang of poachers had been reported in the district, and, the week before, several shots had been heard as late as twelve o'clock, for which the gamekeepers could not account.

The night was cold and foggy, and Jim wore the collar of his coat turned up, and carried his gun under his arm, with his hands thrust deep into his breeches pockets.

He was moving along the edge of the coverts, which lay between Mr. Langton's bungalow and the house, when suddenly he became conscious of footsteps approaching stealthily through the woods. Without a moment's thought he dropped flat upon his face, and lay close as a hare, concealed in a clump of bracken. From this position he was able to see the path by which the intruder approached; he could also command a view of the windows of Friar's Court, several of which were illumined.

The dark figure of a man came from among the trees. Jim, taking his whistle from his pocket, put it to his lips, and was about to sound the alarm which would bring his father and the other keepers to the spot, when he was arrested by the man's singular appearance.

This was no common poacher. He wore a heavy fur overcoat, and carried in his hand—not a gun—but no more formidable a weapon than an umbrella. On his head, tilted at an angle, was a white bowler hat.

Jim Braid was in two minds what to do, and was even about to show himself to the stranger and ask his business, when the front door of the house opened, and he made out the figure of Captain von Hardenberg silhouetted against the light in the hall. Jim had no particular desire to eavesdrop. Still, as we know, he disliked and mistrusted the Prussian; and, besides, the secretive manner in which the stranger was careful to keep in the shadow of the trees had already aroused his suspicions.

When the man with the white hat saw von Hardenberg, he whistled softly, and went forward a little towards him. They met a few yards from where Jim Braid was hiding. The stranger at once held out a hand. Von Hardenberg refused to take it.

"I knew you'd come here," said he. "Can't you leave me alone?"

"You're four months overdue, Captain von Hardenberg," answered the other. "My interest is increasing day by day. You owe me nearly four thousand pounds!"

"Well, I can't pay," said von Hardenberg. "And there's an end of it."

"Captain von Hardenberg," said the man, who spoke English with a strong German accent. "I am sick of you. In a word, I have found you out. You desire the services of a spy—one who has access to valuable information—and you come to me, Peter Klein, even myself, who as the butler of a cabinet minister have many opportunities of reading letters and overhearing the consultations of those who are suppose to govern these sleepy, fog-begotten islands. You are paid from Berlin, and you are paid to pay me. And what do you do with the money? Gamble. In a word, you play cards and lose money which by right is mine, which I—not you—have earned. Then you beseech me to hold my tongue, promising me that you will repay me with interest as soon as ever you have inherited your uncle's estates. This, I find, is a lie. Your uncle has another nephew, just as likely to inherit his capital as you. You play with me. But I hold you in the hollow of my hand. Remember, I have only to report you to Berlin, and you are ruined, once and for all."

Von Hardenberg was silent for some moments. Then he spoke in a quick, jerky voice.

"Look here," said he; "it's no good. This very evening, knowing that you were coming, I made a clean breast of it to my uncle. I told him that I was four thousand pounds in debt to a money-lender, and that, if I couldn't pay, you would come down upon me. I suppose you don't mind that. I couldn't tell him you were a Government spy disguised as a butler in a private house. And what do you think he said?"

"I have not the least idea," said the other.

"He told me," said von Hardenberg, "that he would cut me off with a shilling!"

Mr. Peter Klein was heard to gasp. Thrusting his hat well back upon his head, he threw out his hands and gesticulated wildly.

"Then, you're a thief!" he cried. "What it comes to is this: you have embezzled Government money. I have given the Wilhelmstrasse valuable information, and I have never received a penny."

"Do what you like," answered von Hardenberg. "I cannot pay."

"I'll have you court-martialled!" the other cried. "The Wilhelmstrasse will be on my side. You have made a fool of me."

Von Hardenberg grasped the man by the wrist.

"Listen here," said he. "Can you wait a week?"

"Yes. I can. But why?"

"Because I know how I can get hold of the money, though it will take some getting. You had better go back to London. I promise to call at your office within a few days, and then I shall have something to tell you."

Peter Klein turned the matter over in his mind. As long as there remained a chance of getting his money he thought it worth while to take it. For all his threats, he knew enough of the Secret Service department in the Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin to know that in a fight against a Prussian military attaché he would stand but a poor chance. However, he was cunning enough to point out to von Hardenberg that the Wilhelmstrasse might think that the services of Peter Klein might possibly be valuable in the future. Then, he went his way, walking quickly through the woods in the direction of the railway station. As for von Hardenberg, he returned to the house; and no sooner was he gone than Jim Braid got to his feet.

The young gamekeeper had been able to understand only a third of what had been said, for they had lapsed from German into English, and back to German again. But, that night—or, rather, early the following morning—when he went to bed, he thought over the matter for some time, and had half a mind to tell his father. However, in the end he came to the conclusion that it was no business of his, and slept the sleep of the just.

The following afternoon he was engaged in driving into the ground a series of hurdles to keep the cattle from the pheasant coverts, when he was approached by Mr. Langton.

"Hard at work, Jim?" asked the Judge.

"Yes, sir," said Jim, touching his cap. "These are the old hurdles we brought up from Boot's Hollow."

"That's a useful weapon, anyhow," said the Judge, indicating the crowbar with which Jim was working.

"Yes, sir, it's a handy tool, and sharp in the bargain."

At that the Judge wished the boy "Good-night!" and went his way towards the house. Hardly had he departed than Captain von Hardenberg brushed his way through some thickets near at hand, and approached the young gamekeeper. He must certainly have overheard the conversation that had passed between Jim Braid and the Judge.

"Braid," said he, "would you mind lending me that crowbar?"

"I've finished with it to-night, sir," said Braid, "but I shall want it to-morrow morning."

"I'll let you have it back by then," said the other. And taking the unwieldy tool from Jim's hands, he walked with it towards the house.

No sooner was he out of sight, however, than he dropped down upon a knee and looked furtively about him, as if to satisfy himself that he was not observed. Then he thrust the crowbar down a rabbit-hole, the mouth of which he covered over with several fronds of bracken. That done, he walked quickly towards the house.

That night, towards midnight, when everyone else in Friar's Court was sound asleep, Captain Carl von Hardenberg sat, fully dressed, at the foot of his bed with a cigar between his lips. He had taken off his dress-coat and put on an old Norfolk jacket. On his feet he wore long gum-boots, into which he had tucked his trousers. He sat looking at the clock, which was but dimly visible upon the mantelpiece through the clouds of tobacco-smoke with which the room was filled.

Presently the clock struck twelve, and at that von Hardenberg rose to his feet and went on tiptoe to the door. Without a sound he passed out, walked quickly down the passage, and descended the back stairs to the kitchen. With nervous hands he opened the scullery door, and then paused to listen. Hearing no sound, he stepped quickly into the yard.

He walked rapidly past the lawns which lie between Friar's Court and the woods. Once inside the woods, he immediately sought out the path that led straight to the bungalow. He had some difficulty in finding the rabbit-hole in which he had hidden the crowbar, and only succeeded in doing so with the aid of a lighted match. It was the flare of this match that attracted Jim Braid, who was again on duty in this part of the estate.

Von Hardenberg, the crowbar in his hand, approached the bungalow. With all his strength he drove the crowbar between the door and the jamb, and with one wrench broke open the lock.

In his uncle's study he lit the oil lamp that stood upon the central table. He was surprised to see that the Judge had again left his cash-box on the desk. The cash-box, however, was not his business; he was determined to possess himself of the Sunstone.

He had provided himself with a bunch of skeleton keys. Those whose business it is to employ Government spies are not infrequently provided with such things. After several futile attempts he succeeded in opening the third drawer in the cabinet. Then, with the precious stone in his hand, he rushed to the lamp and examined the Sunstone in the light.

"Now," he cried—he was so excited that he spoke aloud—"now for the German Cameroons!"

And scarcely had he said the words than he looked up, and there in the doorway was Jim Braid, the gamekeeper's son.

"Hands up!" cried Braid, bringing his gun to his shoulder.

Captain von Hardenberg looked about him like a hunted beast.

"Don't be a fool!" he exclaimed. "You know who I am!"

"Yes, I do," said Braid; "and you're up to no good. Hands up, I say!"

Von Hardenberg held up his hands, and then tried to laugh it off.

"You're mad!" said he more quietly. "Surely you don't imagine I'm a thief?"

"I'm not given much to imagining things," said Braid. "All I know is, you broke in here by force."

As he was speaking, before the last words had left his mouth, von Hardenberg, with a quick and desperate action, had seized the gun by the barrel. There followed a struggle, during which the gun went off.

There was a loud report and a piercing cry, and Jim Braid fell forward on his face. Even as he rolled over upon the ground, a black pool of blood spread slowly across the floor.

The Prussian went to the door and listened. He saw lights appear in the windows of the house, and one or two were thrown open. Near at hand he heard the strong voice of John Braid, the keeper, shouting to his son. On the other side of the bungalow, an under-gamekeeper was hurrying to the place.

Von Hardenberg's face was ashen white. His hands were shaking, his lips moving with strange, convulsive jerks.

He went quickly to the body of the unconscious boy, and, kneeling down, felt Braid's heart.

"Thank Heaven," said he, "he is not killed."

And then a new fear possessed him. If Jim Braid was not dead, he would live to accuse von Hardenberg of the theft. The Prussian stood bolt upright, his teeth fastened on his under lip. The voices without were nearer to the house than before. He had not ten seconds in which to act.

Seizing the cash-box, he laid it on the ground and dealt it a shivering blow with the crowbar. The lid flew open, and the contents—a score of sovereigns—were scattered on the floor. These he gathered together and thrust into the pockets of the unconscious boy. Then he took the crowbar and closed Jim's fingers about it. It was at that moment that John Braid, the gamekeeper, burst into the room.

"What's this?" he cried.

"I regret to tell you," said Captain von Hardenberg, "that your son is a thief. I caught him red-handed."

In less than a minute the bungalow was crowded. Close upon the head-gamekeeper's heels came one of his assistants, and after him Mr. Langton himself and Harry, followed by several servants from the house.

When John Braid heard von Hardenberg's words, accusing his son of theft, it was as if a blow had been struck him. He looked about him like a man dazed, and then carried a hand across his eyes. Then, without a word, he went down upon his knees at his son's side and examined the wounded boy.

"He's not dead," said he in a husky voice. "I can feel his heart distinctly."

It was at this moment that the Judge rushed into the room. His bare feet were encased in bedroom slippers; he was dressed in a shirt and a pair of trousers.

"Whatever has happened?" he exclaimed.

He repeated the question several times before anyone answered, and by then the room was full. The chauffeur was sent back post-haste to the stables, with orders to drive for a doctor.

"How did it happen, John?" repeated Mr. Langton.

But the gamekeeper shook his head. He had the look of a man who is not completely master of his senses.

The Judge regarded his nephew.

"Carl," said he, "can you explain how this—accident occurred?"

"Certainly!" said von Hardenberg, who now realized, that to save himself, all his presence of mind was necessary.

"Then," said the Judge, "be so good as to do so."

"After my yesterday's interview with you," von Hardenberg began, in tones of complete assurance, "as you may imagine, I had several letters to write, and to-night I did not think of getting into bed till nearly twelve o'clock. Before I began to undress I went to the window and opened it. As I did so I saw a man cross the lawn and enter the woods. As his conduct was suspicious, I took him for a poacher. As quickly as possible I left the house and walked in the direction I knew the man had taken."

"Why did not you wake any of us?" asked the Judge, who was in his own element, and might have been examining a witness in the box.

Von Hardenberg, however, did not appear to be the least alarmed. He answered his uncle slowly, but without the slightest hesitation.

"For the very simple reason," said he, "that I did not wish to make a fool of myself. I half expected that the man would prove to be a gamekeeper."

"Then why did you follow him?"

"For two reasons. First, because I wanted to satisfy myself as to who he was, and, secondly, because a man who has just learnt he is to remain a pauper for life does not, as a rule, feel inclined for sleep. I wanted to go out into the air."

"Well," asked the Judge, "and then what happened?"

"I was unable to find the man in the woods, until I heard a noise in the direction of the bungalow. To the bungalow, accordingly I went, as quickly as I could. I got there in time to see him break open the door with a crowbar. There is the crowbar in his hand."

Everyone in the room caught his breath. Such an accusation against Jim Braid was almost incomprehensible. The boy was believed to be perfectly honest and trustworthy; and yet, as Captain von Hardenberg had said, there was the crowbar in his hand.

"And then?" prompted the judge.

"And then," the Prussian continued, "I watched him enter the room. I could see him through the window. He went straight to your desk, took the cash-box, and burst it open with the crowbar. There is the box lying on the floor. If you examine it, you will see that I speak the truth."

The judge picked up the box and looked at it.

"You are prepared to swear to this?" he asked.

"In a court of law," said the other—and never flinched.

It was the Judge himself who emptied Jim's pockets, and there sure enough he found the sovereigns which had been taken from the cash-box.

"I would never have believed it!" he exclaimed. "It's terrible to think that one of my own servants should have treated me thus!"

It was then that Harry Urquhart spoke for the first time. He could not stand by and see his old friend so basely accused and not offer a word in his defence.

"It's a lie!" he cried, his indignation rising in a flood. "A base, unmitigated lie! Uncle," he pleaded, "you don't believe it, surely?"

The Judge shook his head.

"It would be very foolish for me," said he, "to give an opinion one way or the other, before the boy has had a chance to speak in his own defence. I must admit, however, that the evidence is very strong against him."

A hurdle was fetched, upon which a mattress was laid; and upon this the wounded boy was carried to the house, which was nearer to the bungalow than his father's cottage. By a strange coincidence, it was one of the very hurdles that Jim had been setting up that afternoon.

The doctor, who lived at some distance, did not arrive for an hour. After a short examination of the patient he was able to give a satisfactory report. The gun had gone off at too close a range to allow the shot to scatter, and only about a quarter of the pellets had entered the boy's side, the rest tearing a great hole in his coat and waistcoat. The wound was large and gaping, but no artery was touched, and before they reached the house, and Jim had been laid upon the bed in Harry's room, the patient had recovered consciousness.

For all that, it was several days before the doctor would allow him to see anyone. He was to be kept perfectly quiet, and not excited in any way. During that time he was attended with the greatest care, not only by the housekeeper and Harry Urquhart, but by Mr. Langton himself.

At the end of a week, a naturally strong constitution, and the good health resulting from a life that is lived in the open air, had done their work, and Jim was allowed to get up. It was soon after that that the Judge heard the case in his dining-room, where, seated at the head of the table, pen in hand, he might have been back in his old place in the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone.

Jim Braid—who, in very truth, was the prisoner in the dock—was seated on a chair, facing the Judge. On either side of the table were those whom Mr. Langton proposed to call as witnesses—namely, Captain von Hardenberg, John Braid, and the under-gamekeeper.

The face of the prisoner in the dock was white as a sheet. Harry Urquhart stood behind his uncle's chair, regarding his old friend with commiseration in his eyes and a deep sympathy in his heart.

Von Hardenberg's evidence differed in no material points from what he had said before. Indeed, he played his cards with almost fiendish cunning. The circumstantial evidence was all against the boy. The Judge had not yet discovered that the Sunstone was missing. There was no doubt that both the door of the bungalow and the cash-box had been broken open by the crowbar—moreover, the very crowbar which the Judge himself had seen in Jim's hands on the afternoon of the crime. Neither John Braid nor any other gamekeeper could do anything but bear out the testimony of von Hardenberg. When they entered the bungalow the boy's guilt had seemed manifest.

In his own defence Jim could state as much of the truth as he knew. He said that he had seen von Hardenberg break into the bungalow; he swore that he had lent him the crowbar that very day. Asked why he supposed the Judge's nephew had become a burglar, he was unable to give an answer. From his position he had not been able to see into the room; he had not the slightest idea what von Hardenberg did immediately after entering.

All this the Judge flatly refused to believe. He protested that it was ridiculous to suppose that a young man of von Hardenberg's position would rifle a cash-box, containing about twenty pounds. In Mr. Langton's opinion, the case was proved against the boy; he could not doubt that he was guilty. He said that he would refrain from prosecuting, since John Braid had served him faithfully for many years, but he was unwilling any longer to employ Jim on the estate.

When Mr. Langton had finished, John Braid asked for permission to speak, and then turned upon his son with a savage fierceness that was terrible to see. He disowned him; he was no longer a son of his. He pointed out the benefits Jim had received at the hands of Mr. Langton, and swore that he had never dreamed that such ingratitude was possible. As far as he was concerned, he had done with his son, once and for all. He would blot out his memory. Henceforward Jim could fend for himself.

Still weak from his wounds, and with a far greater pain in his heart than ever came from physical hurt, the boy rose to his feet and slowly and in silence left the room. He went to his father's cottage, and there saw his mother, from whom he parted in tears. Then, shouldering the few belongings he possessed, done up in a bundle that he proposed to carry on the end of a stick, he went his way down the drive of Friar's Court.

He had not gone far before he heard footsteps approaching, and, turning, beheld Harry Urquhart, running forward in haste. The boy waited until his friend had come up with him. He tried to speak, but found that impossible. Something rose in his throat and choked his power of utterance.

"You believe in me?" said he at last.

"I do," cried Harry, "and I always will! I know that you are innocent!"

"Thank you for that, sir!" said Jim. "I can go my way with a lighter heart."

"Where are you going?" asked Harry.

"I don't know, sir, and I don't think I care. Anywhere, so long as I can get away from this place where I am suspected and despised!"

"Have you any money?" asked Harry.

Jim shook his head.

"Here you are. Take this. It's all I have." And Harry thrust into his friend's hand a five-pound note.

Jim hesitated to take it; but in the end he did so, folding it carefully and putting it into his waistcoat pocket.

"God bless you, sir!" said he.

"I'll make it my life's work," cried Harry, "to prove your innocence. I'm confident I will succeed in the end. For the present, good-bye!"

"Good-bye!" said the other. He dared not look young Urquhart in the face, for his eyes were filling fast with tears.

Then he went his way, throwing himself upon the mercy of the world, with life before him to be started all anew. Under his own name, and with his old surroundings, he was disinherited, disowned, and dishonoured. He must find some new employment. He must endeavour to forget and to live down the past.

At the gate of the drive he came into the highroad, and, turning his face towards London, set forward, walking as quickly as he could.

The following day Captain von Hardenberg left Friar's Court. He had more reasons than one to be anxious to return to London.

The robbery and the outrage at the bungalow had sadly interrupted Mr. Langton's studies. Nearly a month elapsed before the Judge took up his old researches, and then it was that for the first time he discovered that the Sunstone was missing. Search where he might, he could find it nowhere. The evidence was against Jim Braid, and there was no one to speak up on his behalf, for by then Harry Urquhart had returned to school. On the night Braid was wounded, only his coat pockets had been emptied, and, since the whole of the money had been recovered, no further search had been made. The Judge had little doubt in his mind that, as well as the contents of the cash-box, the boy had stolen the Sunstone, though poor Jim could have had no idea as to its value.

Mr. Langton was determined to recover the relic at all costs. He spent a great deal of money on advertisements, and gave a full description of Braid to the police; but no trace of the boy could be found. It was not until Christmas had come, and Harry Urquhart was again at Friar's Court, that the Judge told his nephew of his suspicions.

And though Harry was sure of Braid's innocence, he could not convince the Judge. Mr. Langton's mind was the mind of a lawyer; he based his conclusions upon the testimony of facts, and never allowed his personal opinions to influence him in the least.

Though the police had failed to discover any trace of Braid, Harry was determined to find him. Since he had now left school, he obtained permission from his uncle to go to London. He felt perfectly certain that Braid was somewhere in the great city where it is possible for a man to hide himself from the eyes of the world, even to bury his identity.

In the meantime, Captain von Hardenberg had presented himself before Peter Klein, the informer, and a long interview had taken place between them.

Peter listened to the whole story of the Sunstone, doubted it one moment, believed it the next; and fingered the strange jade ornament, first with reverence, and then almost with suspicion. He examined it through a magnifying-glass, shook his head, shrugged his shoulders, and found it impossible to make up his mind. Von Hardenberg made no secret of the fact that he was determined to undertake a journey through the German colonial territory of the Cameroons to the Caves of Zoroaster, to recover the jewels that were hidden in the vault. With the treasure once in his possession, he swore that he would pay Klein, not only the full amount that was due to him, but ten per cent of the total profits.

Now, Peter Klein was a usurer—as well as a butler and a spy—one who drove a hard bargain, who was relentless to his victims. He said that he himself was tired of cities, that the suspicions of the British police authorities had already been aroused in regard to his occupation, and that therefore he also would like to travel. He would accompany von Hardenberg to the West Coast, which was once called the White-Man's Grave; he would penetrate the bush to the Cameroon peaks, even to the Caves of Zoroaster. But he would require more than ten per cent: they would share and share alike.

Von Hardenberg was in no position to refuse. This man had him in his clutches. Klein knew well that the Prussian was ruined for life if ever his conduct was made known to the departmental heads of the German Secret Service. And, moreover, in a few days Klein had gained the whip hand by enlisting in his services an Arab whom he found starving in the vicinity of the docks.

This man, though he was poor, in rags, and well-nigh perishing in the cold, was learned in many things. Like all his race, he was a nomad—a man who had roamed the world throughout his life, who had even been all-powerful in his day. He had sold ivory in Zanzibar; he had stolen cattle in the neighbourhood of Lake Chad, and driven his capture across the great plains to the east; he had hunted for slaves in the Upper Congo and the Aruwimi. Though he was starving, he boasted that he was a sheik, and said that his name was Bayram. He said he had been to the Cameroons River, and that he despised the Negro from Loango to Zanzibar. He was confident that, provided he was rewarded, he could render invaluable services to his employer. He had never before heard of the Sunstone, but, from rumours he had heard, there was a treasure hidden somewhere in the mist-shrouded mountains that guard Lake Chad to the east.

To return to Jim Braid. All these winter months he wandered the streets of London. He found the greatest difficulty in getting work. He had no trade but that of a gamekeeper, and such business was at a discount in the midst of the great, seething city. He was out of work for some weeks; then he obtained work in the docks; after which he was again unemployed for nearly a month. By that time he had got to the end of his money, and was obliged to pawn his clothes. He thanked Heaven when the snow came; for, though the frost was severe, and his clothes in rags, he saw employment in sweeping the pavements and the roads.

Then the thaw followed, and he was starving again. One night he found himself in Jermyn Street. He had had no food that day. A taxi-cab drew up before a doorway, upon which was a brass plate bearing the name "Peter Klein".

Jim was conscious of the fact that he had heard the name before, he could not remember where. Just then, starvation, ill-health, and the misery in his heart had broken the boy completely; it was as if his senses were numbed. All that interested him was the taxi, by the side of which he remained, in the hope of earning a copper by opening the door. Presently a manservant came from the house, carrying a box. Jim volunteered to help him, and the man agreed. Together they put the box upon the taxi-cab, and Jim noticed that it bore the same name, "Peter Klein", and several steamship labels, upon each of which was written the word "Old Calabar". Jim Braid saw these things like one who is half-dazed, without understanding what they meant.

There were several other boxes to be put on to the cab, and when the work was finished, and the driver had strapped them securely together, two men came from the house, followed by one who wore a turban, and shivered from the cold.

Jim's attention was attracted by the native. He was very tall and thin. He had a great black beard, and his eyes were like those of a bird of prey. They were cruel, bloodshot, and passionate.

One of the Europeans, who wore a fur coat, got into the cab. The other paused with his foot upon the step and looked Jim Braid in the face. Near by a street lamp flared and flickered, and in the light Jim recognized the features of Captain von Hardenberg, the man who had been his accuser.

He stared at him in amazement. He had not the power to speak. He thought, at first, that he, too, would be recognized. He did not know that misfortune had so changed him that his own mother would not have known him. He was thin and haggard-looking; his rags hung loosely upon his gaunt form; his hair was so long that it extended over his ears.

"Are you the man," said von Hardenberg in his old, insolent way, "who helped to carry the boxes?"

"Yes," said Jim, "I am."

"There you are, then. There's sixpence, and don't spend it on drink."

At that the Prussian jumped into the taxi, telling the driver to go to Charing Cross. The Arab followed, closing the door, and a few seconds later the taxi was driving down the street.

Jim Braid stood on the pavement under the street lamp, regarding the sixpence in his hand. He was starving; his bones ached from physical exhaustion; his head throbbed in a kind of fever. He knew not where he would sleep. This sixpence to him was wealth.

For a moment he was tempted, but not for longer. With a quick, spasmodic action he hurled the coin into the gutter, and walked away quickly in the direction of the Haymarket.

He knew not where he was going. The streets were crowded. People were going to the theatre. Outside a fashionable restaurant a lady with a gorgeous opera-cloak brushed against him, and uttered an exclamation of disgust. He walked on more rapidly than before, and came presently to Trafalgar Square, and before he knew where he was he found himself on the Embankment. Slowly he walked up the steps towards the Hungerford footbridge; and there, pausing, with his folded arms upon the rails, he looked down into the water.

At that moment the sound of footsteps attracted his attention. He looked up into a face that he recognized at once. It was that of Harry Urquhart, his only friend, the only person in the world who had believed him innocent.

"Jim!" cried Harry.

So astonished was he that he reeled backward as though he had been struck.

"My poor, old friend," said Harry. "I have searched for you everywhere, and had almost given up hope of finding you. I don't know what led my footsteps to the bridge."

At that Jim Braid burst into tears.

"It was the work of God," said he.

Harry said nothing, but pressed Jim's arm. At the bottom of Northumberland Avenue he hailed a taxi, and the driver looked somewhat astonished when this ragged pauper got into the cab and seated himself at the side of his well-dressed companion.

Harry had rooms in Davies Street, where he thrust Jim into an arm-chair before the fire, upon which he heaped more coals. Braid, leaning forward, held out his hands before the cheerful blaze. As Harry looked at him, a great feeling of pity arose in his heart. The boy looked so miserable and wretched that he appeared barely to cling to life.

Harry would not allow him to speak, until he had eaten a meal. Braid fell upon his food like a wolf. He had had absolutely nothing to eat for two days.

It is not wise to feed a starving man to repletion. But perhaps in Braid's case this made little or no difference, since the boy was on the verge of double pneumonia. Within twenty-four hours he was in a raging fever, and for days afterwards the doctor despaired of saving his life. Starvation, cold, dirt, to say nothing of his wound, had done their work; but a strong heart and youth pulled him through.

It was nearly three months afterwards, when the spring was well advanced, that one afternoon the two friends talked the whole matter out.

Harry looked at Jim Braid and smiled.

"You're a different fellow now," said he. "It was a near thing though. One night the doctor gave you up. He actually left the house believing you were dead."

Jim tried to thank his benefactor, but his heart was too full to speak.

"Come," said Harry, "tell me what has happened since you left Friar's Court."

"There is nothing to tell," said the other. "I tramped to London, sometimes sleeping in the open air, sometimes—when the weather was bad—lodging at wayside inns. At first, I was glad to get here. In a great city like this I felt I could not be recognized and pointed out as a thief. Oh," he burst forth, "you know that I am innocent!"

"I was always sure of it," said Harry. "I can't think how my uncle can believe you guilty."

"Everything was against me," said Jim. "That man, to shield himself, laid a trap for me from which I could not escape. Had I known why he went to the bungalow that night, my story might have been believed."

"I know why he went," said Harry. "I am sure of it. It was to steal the Sunstone."

"The Sunstone!" said Braid. "What's that?"

"It is a very valuable relic that originally came from Persia. No one knows of its value but my uncle, von Hardenberg, and myself. There can be no doubt that my cousin took it."

Jim Braid sighed.

"I could not prove my innocence," said he.

"Jim, old friend," said Harry, "I promise you shall not remain under this cloud for the rest of your life. I know my cousin to be guilty; I will not rest until I have proved him to be so. He has the Sunstone in his possession, and I intend to do my best to recover it!"

"You will not succeed," said the other, shaking his head.

"Why not?"

"Because he left England weeks ago."

"Left England!" echoed the other.

"Yes. He went away with a man called Peter Klein and a native who wore a turban. They took the boat train from Charing Cross. It was I who carried their boxes on to the taxi. They were going to Old Calabar."

"The West Coast!" cried Harry, jumping to his feet.

Braid was as mystified as ever. Before he knew what was happening, Harry had seized him by the shoulders, and was shaking him as a terrier shakes a rat.

"Don't you see," cried Urquhart, "your innocence is practically proved already. If they have not got the Sunstone, why should they want to go to Africa? They are after the treasure of which the Sunstone is the key. I don't know who the native is, but he is probably some interpreter or guide whom they have hired for the journey. Jim, when my uncle hears of this, I promise you he will take a very different view of the question."

"Then," said Braid, "has this Sunstone got something to do with Africa?"

"Everything!" exclaimed the other. "Here, in Europe, it is valueless; but in certain caves which are situated upon the watershed on the southern side of the Sahara, the thing is worth thousands of pounds. To-morrow morning I will return to my uncle, to Friar's Court, and tell him what you have told me. I will ask him to allow me to follow von Hardenberg to the West Coast, to keep upon his tracks, to run him to ground and accuse him to his face. You will come with me. My uncle will supply us with funds. He would be willing to spend his entire fortune in order to recover the Sunstone."

Harry was so excited that he could scarcely talk coherently. He paced up and down the little sitting-room—three steps this way and three steps that—and every now and again laid his hands upon Jim Braid and shook him violently to emphasize his words.

When Jim awoke the following morning, he was informed that Mr. Urquhart had left early to go back to Friar's Court. He had promised to return the following day. In the meantime, Harry had given instructions that his landlady was to look after his guest. If he wanted anything, he had only to ring the bell.

On the afternoon of the second day Harry returned to London.

"My uncle," he explained, "is inclined to withdraw his verdict, though he will not say openly that he has been guilty of a great injustice. In any case he intends to do everything in his power to get the Sunstone back. He has given me leave to fit out an expedition. Preparations, however, will take some little time. I am to be supplied with letters of introduction to several influential persons on the West Coast. He even said he would come with us himself, were it not that his strength is failing, and he feels he is getting old. Jim, there's hope yet, my lad. You and I together will see this matter through."

Braid held out his hand.

"I can't thank you sufficiently, sir," said he, "for what you have done! You have saved my life twice, and now you mean to save my reputation."

"Don't speak of it," said Harry. "You and I have a great task in front of us; we must stick to each other through thick and thin. I am impatient to be off."

And he had more need of his patience than he thought; for, before they could start upon their journey, war descended upon Europe like a thunderbolt, finding England wholly unprepared.

It was not so with the Germans. Peter Klein and birds of a like feather had been employed for years in every country liable to prove hostile to the Fatherland. Germany had for long intended war, and these rascals—paid in proportion to the information they obtained—were living by the score under the protection of the British flag, within sound of Big Ben, in every colony, dependency, and dominion. Moreover, it has since been proved that the great German Empire did not scruple to employ even her consular and diplomatic servants either as spies themselves or as agents for the purpose of engaging and rewarding informers.

Small wonder, when preparations had been so complete, that Germany had the whip hand at the start, that Belgium, Poland, and Serbia were overrun, and Paris herself saved only at the eleventh hour.

During those early, anxious days, Harry Urquhart was in two minds what to do. He was wishful to serve his country, and could without difficulty have secured a commission within a few weeks of the declaration of war. Braid was also willing to enlist. On talking the matter out, however, with Mr. Langton, it was decided that the quest of the Sunstone was as patriotic a cause as any man could wish for; since, if von Hardenberg succeeded in reaching the Caves of Zoroaster, the wealth that they contained would ultimately find its way to the Fatherland.

But, since there was fighting both in Togoland and the Cameroons, their departure had to be postponed whilst Mr. Langton obtained permission from the War Office authorities for his two protégés to visit the West African scene of operations. All this took time; and it was not until the beginning of October that young Urquhart and Jim Braid found themselves sitting together in a first-class railway compartment on their way to Southampton.

A few hours afterwards, on a dark windy night, they were on board a ship that rolled and pitched upon its way to Ushant. The Lizard light flashed good-bye from England, and the dark sea, as they knew quite well, contained hidden dangers in the shape of submarines and mines, but the quest of the Sunstone had begun.

They experienced rough weather in the Bay of Biscay, where the ship pitched and rolled in a confused sea, and the wind howled round Finisterre, which was wrapped in an impenetrable fog.

Two days afterwards they found the blue waters that bound the Morocco coast, after which the heat became excessive.

The ship was bound first for Sierra Leone, and thence to Old Calabar, from which place they intended to strike inland through the bush, after engaging the services of a party of Kru boys to act as carriers.

On these still tropic seas, dazzling in the sunshine, there was no sign of war, except an occasional torpedo-boat destroyer which flew past them at a speed of thirty knots an hour.

At Sierra Leone, Harry betook himself to a certain gentleman holding an influential position in the Civil Service, to whom he had a letter of introduction from his uncle, and who received the boy with courtesy and kindness. It was from that Harry learned that the Germans had been driven back in Togoland, and that active operations were in progress in the valley of the Cameroon River. He himself had travelled far in the interior; and in consequence he was able to give the boy invaluable advice concerning the kit and equipment he would need to take with him upon his expedition. He advised him to strike into the bush from Old Calabar, where he could procure servants and guides; if he went to Victoria he would find his hands tied by those in command of the Expeditionary Force, who had no liking for civilians at the front.

"All the same," he added, "I strongly advise you not to endeavour to enter Maziriland."

Harry smiled.

"I am afraid, sir," said he, "I have no option. My duty takes me there."

"Of course," said the other, "I don't know what this duty may be, but I tell you frankly the country is by no means safe. All the natives are in arms, some purchased by rum by the Germans, others loyal to us. In the old days the Cameroon kings implored the British Government to take the country under its protection. In their own words, they wanted English laws. But the Government took no notice of them until it was too late, until the Germans had forestalled us and taken possession of the country, by buying over the chiefs. If you go into the bush, you run into a thousand dangers: yellow fever, malaria, even starvation, and the natives you encounter may sell you as prisoners to the Germans. Some of them will do anything for drink."

Harry explained that he was prepared to take the gravest risks, since the object of his journey was of more than vital importance, and shortly afterwards took his leave, returning to the ship.

They had brought with them all they needed in the way of provisions, clothing, arms and ammunition; and at Old Calabar they purchased a canoe and engaged the services of six stalwart Kru boys. Harry's idea was to travel up-river, crossing the Cameroon frontier west of Bamenda, and thence striking inland towards the mountains in northern German territory, beyond which the Caves of Zoroaster were said to be. They also interviewed an interpreter, a half-caste Spaniard from Fernando Po, who assured them he could speak every native dialect of the Hinterland, from Lagos to the Congo, as well as English and German. This proved to be no exaggeration. Urquhart was assured that the man was indeed a wonderful linguist, and, moreover, that he could be trusted implicitly as a guide—the more so since he hated the Germans, who had destroyed his 'factory' to make room for a house for a Prussian Governor, who had hoped to rule the West Coast native with the iron discipline of Potsdam.

This man—who called himself "Fernando" after the place of his birth—said that he would never venture across the Cameroons to Maziriland unless his brother was engaged to come with him.

He explained that this brother of his was younger and more agile than himself. Before they became traders they had been hunters, in the old days when the West Coast was practically unexplored, and they had worked together hand-in-glove.

Accordingly, it was agreed that both brothers should join the expedition; and when they presented themselves before Harry Urquhart, the young Englishman could hardly refrain from smiling at their personal appearance.

They were plainly half-castes, and, like most such, considered themselves Europeans, though neither had ever set eyes upon the northern continent. Though they were almost as black of skin as a Kru boy, they wore large pith helmets, suits of white ducks and blue puttees, being dressed to a button exactly the same. Both wore brown leather belts from which depended revolver holsters and cartridge pouches. The one was robust, wrinkled, broad of chest, and upright; the other, stooping, tall, and abnormally thin. There was a business-like air about them both that appealed to Harry; and this favourable impression was by no means dispelled when the brothers, in quite tolerable English, raved against the Germans, who, they swore, had bought the Cameroons with rum, in order to manage the country to their own profit without regard to the welfare of the natives. It was owing to the German occupation of the Cameroons that Fernando and his brother—who went by the name of Cortes—had been ruined by the State-aided German factories that had sprung up as if by magic in the early 'nineties. Later, they had been accused of inciting the natives to rebellion, heavily fined, and banished from the country.

This increase in numbers necessitated the purchase of a second canoe. Before leaving Calabar they supplemented their commissariat with a new supply of provisions; and, a few days after, it was a small but well-equipped and dauntless expedition that set forth up-river in the sweltering heat, making straight for the heart of the great West African bush and the very stronghold of the enemy's position.

Three weeks later they camped on the river bank not many miles from the German frontier. The heat was terribly oppressive. Thousands of insects droned about their ears. A thick mist hung upon the river like a poison-cloud. They were in the very depths of the great White Man's Grave.

Four days afterwards Fernando deemed it advisable to leave the river valley, and unloading the canoes—which they hid in a mangrove swamp—they began their journey through the bush.

It would be tedious to describe in detail the long weeks that followed or the hardships they had to undergo. One by one the Kru boys deserted them, to find their own way back to the coast. But both Cortes and Fernando proved loyal to the hilt, and eventually the party came out from the jungle upon the high ground in the central part of the colony.

The country here was savage, inhospitable, and bleak. There was little vegetation save rank mountain grass and withered shrubs in sheltered places. Day by day they advanced with the utmost caution, giving native villages a wide berth and always on the look-out for an ambuscade.

Fernando proved himself to be an excellent cook, whereas his younger brother prided himself upon his skill as a runner. It was his custom on the line of march to jump fallen trees and brooks.

In these higher altitudes there was a plenitude of game, whereas in the bush they had been near to starving, and one morning they were crossing a spur of a great cloud-wrapped mountain when Cortes, who had been walking about fifty yards in advance of Harry and Jim, dropped suddenly upon his face, and motioned the two boys to do the same. They had no idea as to what had happened, and suspected that the guide had sighted a party of the enemy.

Crawling on hands and knees, they drew level with the man.

"Goat," said he, pointing towards the mountain.

And there, sure enough, was a species of mountain goat with his great horns branching from the crown of his shaggy head.

"Come," said the man to Harry; "you shoot."

They could not afford to let the beast escape. The flesh of all the wild goats, though perhaps not so good as that of the wild sheep, is by no means unwelcome when one must journey far from civilization in the wilds of the African hills.

Harry adjusted his sights to six hundred yards, and then, drawing in a deep breath, took long and careful aim. Gently he pressed the trigger, the rifle kicked, there came a sharp report, and the bullet sped upon its way. On the instant the beast was seen galloping at breakneck speed down what seemed an almost perpendicular cliff.

"Missed!" cried Harry.

"No," said Cortes. "He's hit—he's wounded. He will not go far."

For a few minutes the members of the party held a hurried consultation. Finally it was decided that Fernando should go on ahead with the camp kit and cooking-utensils, whilst the younger brother accompanied Harry and Jim in pursuit of the wounded goat. They agreed to meet at nightfall at a place known to the brothers.

It took them nearly an hour to scramble across the valley, to reach the place where the animal had been wounded. There, as the guide had predicted, there were drops of blood upon the stones. All that morning they followed the spoor, and about two o'clock in the afternoon they sighted the wounded beast, lying down in the open.

He was still well out of range, and, unfortunately for them, on the windward side. That meant they would have to make a detour of several miles in order to come within range.

For three hours they climbed round the wind, all the time being careful not to show themselves, for the eyes of the wild goat are like those of the eagle. With its wonderful eyesight, its still more wonderful sense of smell, and its ability to travel at the pace of a galloping horse across rugged cliffs and valleys, it is a prize that is not easily gained. When they last saw the animal it was lying down in the same place. They were then at right angles to the wind, about two miles up the valley.

From this point, on the advice of Cortes, they passed into another valley to the west. Here there was no chance of being seen or winded by the beast; and, since it was now possible to walk in an upright position, they progressed more rapidly.

When they had arrived at the spot which the guide judged was immediately above the wounded animal they climbed stealthily up the hill. On the crest-line they sought cover behind great boulders, which lay scattered about in all directions as if they had been hurled down from the skies. Lying on their faces, side by side, Harry with his field-glasses to his eyes, they scanned the valley where they had left their quarry.

Not a sign of it was to be seen. The thing had disappeared as mysteriously as if it had been spirited away.

"He's gone!" said Harry, with a feeling of bitter disappointment.

He was about to rise to his feet, but the half-caste held him down by force.

"Don't get up;" he cried. "Lie still! There are men in the valley yonder."

"Men! Have you seen them?"

"No, I have not seen them," said Cortes. "But the beast saw them, or got their wind. Otherwise he would not have gone."

"It's von Hardenberg, perhaps!" said Harry, turning to Braid, the wish being father to the thought.

Both looked at their guide.

"It is either the man you want," said the guide, "or else it is the Germans."

The wounded animal was now forgotten. They were face to face with the reality of their situation. They had either overtaken von Hardenberg and Peter Klein or else the Germans had received news of their having reached the frontier.

"We'll have to cross the valley," said Harry, "to get back to camp."

"That is the worst of it," said Cortes; "we must rejoin my brother. He will be awaiting us."

He had learnt his English on the Coast. He spoke the language well, but with the strange, clipped words used by the natives themselves, though the man was half a Spaniard.

"How are we to get there?" asked Jim.

The guide looked at the sun.

"It is too late," said he, "to go by a roundabout way. We must walk straight there. There are many things which cause me to believe that danger is close at hand."

"What else?" asked Harry, who already was conscious that his heart was beating quickly.

"Late last night I saw smoke on the mountains. This morning, before we started, my brother thought he heard a shot, far in the distance. Also," he added, "during the last three days we have seen very little game. Something has scared them away."

"Come," said Harry. "We waste time in words. As it is, we have barely time to get back before nightfall."

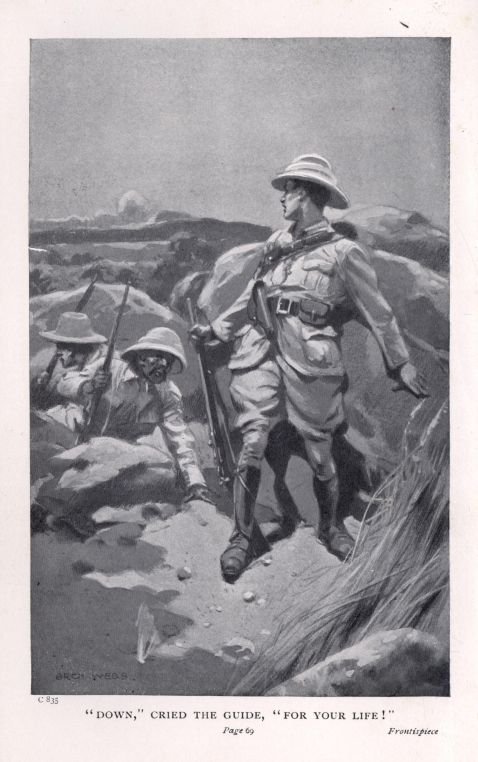

As he said this he rose to his feet, and the moment he did so there came the double report of a rifle from far away in the hills, and a bullet cut past him and buried itself in the ground, not fifteen paces from his feet.

"Down," cried the guide, "for your life!"

Harry was not slow to obey. He fell flat upon his face, whilst a second bullet whistled over his head.

"Come," said Cortes; "we must escape."

As he uttered these words, he turned upon his heel and ran down the hill, followed by the two boys. The man held himself in a crouching position until he was well over the crest-line. Then he stopped and waited for his companions.

"Who is it?" asked Braid, already out of breath as much from excitement as from running.

"The Germans. They are on our track."

"You are sure of that?" asked Harry.

"Master," said Cortes, "it is not possible to mistake a German bullet. In this part of the world only those natives carry rifles who are paid by Kaiser Wilhelm."

Indeed, for weeks already, they had been in the heart of the enemy's country. The elder guide was some miles away, and, since they could not cross the valley, they would have to make a detour; which meant that they could not possibly rejoin Fernando before nightfall. By then, for all they knew, they might find him lying in his own blood, their provisions and their reserve ammunition stolen.

Harry looked at Cortes, who seemed to be thinking, standing at his full height, his fingers playing with his chin.

"We must not desert your brother," said the boy.

"I am thinking," said the guide, "it will be easier for him to reach us than for you and your friend to go to him. My brother and I are hunters; we can pass through the bush in silence; we can travel amid the rocks like snakes. I could cross that valley crawling on my face, and the eye of an eagle would not see me. As for you, you are Englishmen; you have not lived your lives in the mountains and the bush; you do not understand these things."

He said this with some scorn in his voice. There was something about the man—despite his European clothes—that was fully in keeping with the aspect of their surroundings, which were savage, relentless, and cruel. He went on in a calm voice, speaking very slowly:

"In this valley we are safe," said he. "I know the country well. Yonder," and he pointed to the north, "there is a forest that lies upon the hill-side like a mantle. I will guide you. It will take us about two hours to get there. Then I will leave you. You will be quite safe; for many of the trunks of the trees are hollow, and should the Germans come, you can hide. I will go alone to my brother and bring him back with me."

They set forward without delay, sometimes climbing, sometimes walking, on the mountain-side. About four o'clock in the afternoon they sighted the forest of which the man had spoken. It opened out into a mangrove swamp, thousands of feet below them, where the heat hung like a fog.

Among the trees they found themselves in a kind of twilight. By then the sun was setting; but as the daylight dwindled a great moon arose. Cortes led them to a place, on the verge of a deep ravine, where there was an old tree with a hollow trunk that looked as if it had been struck by lightning.

"You and your friend will remain here," said the man to Harry. "I will be as quick as I can, but in any case I cannot be back until midnight. If I do not return by then, you will know that I am dead; then—if you are wise—you will go back to Calabar. If the Germans come, you will hide." And he pointed to the hollow tree.

Without another word he set forward on his way, gliding down the face of the living rock like some gigantic lizard.

The two boys found themselves in a place romantic but terrible. On every side they were surrounded by the impenetrable hills. The trees of the forest stood forth in the semi-darkness like great, ghostly giants. Somewhere near at hand a mountain stream roared and thundered over the rocks. The breeze brought to their nostrils the smell of the swamp lower down the valley. The hollow tree stood on the edge of the bush. A few yards away was the ravine, the bottom of which was wide and bare and stony.

Throughout the earlier part of the night they possessed their souls in patience. It was stiflingly hot after the cool mountain air.