The Project Gutenberg EBook of True Tales of Arctic Heroism in the New World, by Adolphus W. Greely This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: True Tales of Arctic Heroism in the New World Author: Adolphus W. Greely Release Date: March 11, 2012 [EBook #39108] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRUE TALES OF ARCTIC HEROISM *** Produced by Henry Flower, Greg Bergquist and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

MAJOR-GENERAL A. W. GREELY, U. S. ARMY

GOLD-MEDALLIST ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY AND OF SOCIÉTÉ DE GÉOGRAPHIE

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Copyright, 1912, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Printed in the United States of America

From the dawn of history great deeds and heroic actions have ever fed the flame of noble thought. Horace tells us that

The peace-aspiring twentieth century tends toward phases of heroism apart from either wars or kings, and so the heroic strains of the "True Tales" appear in the unwarlike environment of uncommercial explorations.

One object of this volume is to recall in part the geographic evolution of North America and of its adjacent isles. The heroic-loving American youth is not always familiar with the deeds of daring, the devotion to duty, and the self-abnegation which have so often illumined the stirring annals of exploration in arctic America.

Notable exemplars of heroic conduct have already been inscribed on the polar scroll of immortals, among whom are Franklin and McClintock, of England; Kane, of America; Rae, of Scotland; and Mylius-Erichsen, of Denmark. Less known to the world are the names Brönlund, Egerton and Rawson, Holm, Hegemann, Jarvis and Bertholf, Kalutunah, Parr, Petitot, Pim, Richardson, Ross, Schwatka and Gilder, Sonntag, Staffe, Tyson and Woon, whose deeds appear herein. As to the representative women, Lady Jane Franklin is faintly associated in men's minds with arctic heroism, while Merkut, the Inuit, has been only mentioned incidentally. Yet all these minor actors have displayed similar qualities of courage and of self-sacrifice which are scarcely less striking than those shown in the lives of others who are recognized as arctic heroes.

The "True Tales" are neither figments of the fancy nor embellished exaggerations of ordinary occurrences. They are exact accounts of unusual episodes of arctic service, drawn from official relations and other absolutely accurate sources. Some of these heroic actions involve dramatic situations, which offer strong temptations for thrilling and picturesque enlargements. The writer has sedulously avoided such methods, preferring to follow the course quaintly and delightfully set forth by the unsurpassed French essayist of the sixteenth century.

Montaigne says: "For I make others to relate (not after mine own fantasy, but as it best falleth out) what I cannot so well express, either through unskill of language or want of judgment. I number not my borrowings, but I weigh them. And if I would have made their number to prevail I would have had twice as many. They are all, or almost all, of so famous and ancient names that methinks they sufficiently name themselves without me."

The "Tale" of Merkut, the daughter of Shung-hu, is the only entirely original sketch. The main incident therein has been drawn from an unpublished arctic journal that has been in the writer's possession for a quarter of a century. This character—a primitive woman, an unspoiled child of the stone age—is not alone of human interest but of special historic value. For her lovely heroic life indicates that the men and women of ages many thousands of years remote were very like in character and in nature to those of the present period.

A. W. Greely.

Washington, D. C., August, 1912.

| PAGE | |

| The Loyalty of Philip Staffe to Henry Hudson | 1 |

| Franklin's Crossing of the Barren Grounds | 13 |

| The Retreat of Ross from the Victory | 37 |

| The Discovery of the Northwest Passage | 55 |

| The Timely Sledge Journey of Bedford Pim | 71 |

| Kane's Rescue of His Freezing Shipmates | 91 |

| How Woon Won Promotion | 105 |

| The Angekok Kalutunah and the Starving Whites | 119 |

| Dr. Rae and the Franklin Mystery | 137 |

| Sonntag's Fatal Sledge Journey | 155 |

| The Heroic Devotion of Lady Jane Franklin | 169 |

| The Marvellous Ice-Drift of Captain Tyson | 187 |

| The Saving of Petersen | 213 |

| [iv]Life on an East Greenland Ice-Pack | 231 |

| Parr's Lonely March from the Great Frozen Sea | 251 |

| Relief of American Whalers at Point Barrow | 269 |

| The Missionary's Arctic Trail | 293 |

| Schwatka's Summer Search | 311 |

| The Inuit Survivors of the Stone Age | 329 |

| The Fidelity of Eskimo Brönlund | 347 |

| The Wifely Heroism of Mertuk, the Daughter of Shung-Hu | 367 |

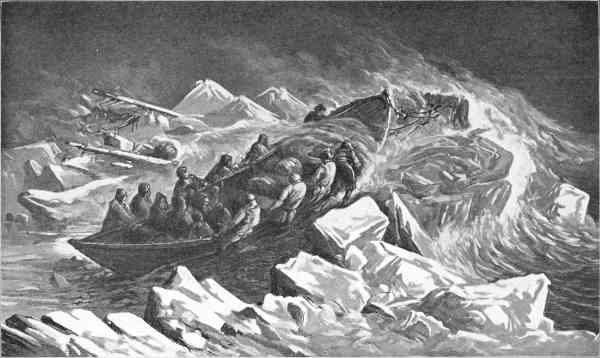

| Dr. Kane's Men Hauling Their Boat Over Rough Ice | Frontispiece |

| From a sketch by Dr. Kane. | |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Henry Hudson's Last Voyage | 4 |

| From the painting by the Hon. John Collier. | |

| "We Were Nearly Carried Off, Boat and All, Many Times during This Dreadful Night" | 208 |

| From Tyson's Arctic Experiences. | |

| A Group of the Eskimo Inuits | 334 |

| PAGE | |

| The Arctic Regions of the New World | 2 |

| Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait | 5 |

| Barren Grounds of Northwestern Canada | 16 |

| Boothia Peninsula and North Somerset | 41 |

| Franklin's Route on Northwest Passage | 58 |

| Route of Pim's Sledge Journey | 75 |

| Smith Sound and West Greenland | 95 |

| Boothia and Melville Peninsulas | 141 |

| King William Land | 177 |

| Robeson Channel and Lady Franklin Bay | 217 |

| Southeastern Greenland | 235 |

| Great Frozen Sea and Robeson Channel | 255 |

| Northwestern Alaska | 273 |

| Liverpool Bay Region | 297 |

| Amdrup and Hazen Lands, Greenland | 351 |

On the walls of the great Tate Gallery in London are many famous pictures, but few draw more attention from the masses or excite a livelier human interest among the travelled than does "The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson." While the artist dwells most on the courage of Henry Hudson, he recalls the loyalty of Philip Staffe and thus unites high human qualities ever admired.

Consider that in barely four years Hudson made search for both the northeast and northwest passages, laid the foundations for the settlement of New York, opened up Hudson Bay, and in a north-polar voyage reached the then farthest north—a world record that was unsurpassed for nearly two centuries. Few explorers in career, in success, and in world influence have equalled Hudson, and among those few are Columbus, Magellan, Vasco da Gama, and Livingston.

Thus Hudson's life was not merely an adventurous tale to be told, whether in the golden words of a great[4] chronicle or in magic colors through the brush of a great artist. It appeals to the imagination and so impresses succeeding generations throughout the passing centuries.

For such reasons the materialistic twentieth century acclaimed loudly the fame of this unknown man—mysterious in his humanity though great as a navigator. So in 1909 the deeds and life of Henry Hudson were commemorated by the most wonderful celebration of the western hemisphere, whether judged by its two millions of spectators, its unsurpassed electric displays with six hundred thousand lights, or its parade of great war-ships from eight admiring nations.

Great were his deeds; but what was the manner of this man who won that greatest love from Philip Staffe, who in stress lay down life for his master? There was religious duty done, for Purchas tells that "Anno, 1607, April the nineteenth, at Saint Ethelburge, in Bishops-gate Street, did communicate these persons, seamen, purposing to go to sea in four days after, to discover a passage by the north pole to Japan and China. First, Henry Hudson, master.... Twelfthly, John Hudson, a boy." Hence we have faith that Hudson was sound and true.

The "Last Voyage" was in the Discovery, fifty-five tons only, during which Hudson, in search of the northwest passage, explored and wintered in Hudson Bay. The journal of Abacuck Prickett, the fullest known, gives a human touch to the voyage. He tells of a bear, "which from one ice-floe to another came toward us, till she was ready to come aboard the ship. But when she saw us look at her, she cast her head between her hind legs, and then dived under the ice, and so from piece to piece, till she was out of our reach."

Some strange-appearing Indian caches were found, of

which he relates: "We saw some round hills of stone,[5]

[6]

like to grass cocks, which at first I took to be the work

of some Christian. We went unto them, turned off the

uppermost stone, and found them hollow within, and

full of fowls hanged by their necks." Later he adds:

"We were desirous to know how the savages killed

their fowl, which was thus: They take a long pole with

a snare or (noose) at the end, which they put about the

fowl's neck, and so pluck them down."

Hudson unwisely decided to remain in the bay through the winter and put the Discovery into quarters in James Bay, an unfortunate though possibly inevitable anchorage. Knowing as we do the terrible cold of the winters in the Hudson Bay region, it is certain that the illy provided crew must have suffered excessively during the winter. Besides, the ship was provisioned only for six months and must be absent nearly a year. Sensible of the situation, Hudson encouraged systematic hunting and promised a reward for every one who "killed either beast, or fish, or fowl." The surrounding forests and barren hills were scoured for reindeer-moss or any other vegetable matter that could be eaten, while the activity of the hunters was such that in three winter months they obtained more than twelve hundred ptarmigan. Nevertheless, they were in straits for food despite efforts at sea and on land.

They had sailed a few days only on their homeward voyage when the discontent and insubordination, engendered the preceding winter, had swollen into mutiny. Alleging that there had been unfairness in the distribu[7]tion of food, Henry Greene, a dissipated youth who owed his position to Hudson's kindness, incited his fellows to depose Hudson and cast him adrift. That this was a mere suspicion is clear from the cruel and inhuman treatment of their sick and helpless shipmates, who also suffered Hudson's fate.

Prickett relates that Hudson was brought bound from his cabin, and "Then was the shallop hauled up to the ship's side, and the poor, sick, and lame men were called on to get them out of their cabins into the shallop." Two of the seamen, Lodlo and Bute, railed at the mutineers and were at once ordered into the boat.

Philip Staffe, the former carpenter, now mate, took a decided stand against the mutineers, but they decided that he should remain on the ship owing to his value as a skilled workman. He heroically refused to share their lot, but would go with the master, saying, "As for himself, he would not stay in the ship unless they would force him."

The private log of Prickett, though favoring always the mutineers with whom he returned to England, clearly shows that Philip Staffe was a man of parts although unable to either read or write. His high character and unfailing loyalty appear from his decision. He was steadfast in encouraging those inclined to despair, and also discouraged grumbling discontent which was so prevalent in the ship. He was one of the men sent to select the location of winter quarters on the desolate shores of James Bay. Faithful to his sense of duty, he knew how and when to stand for his dignity[8] and rights. He displayed spirit and resolution when Hudson, in untimely season and in an abusive manner, ordered him in a fit of anger to build a house under unsuitable conditions ashore. Staffe asserted his rights as a ship's carpenter, and declined to compromise himself ashore.

His quick eye and prompt acts indicated his fitness for a ship's officer. He first saw and gave warning, unheeded, of a ledge of rocks on which the Discovery grounded. Again in a crisis, by watchful care and quick action, he saved the ship's cable by cutting it when the main anchor was lost. But in critical matters he stood fast by the choleric Hudson, who recognized his merit and fidelity by making him mate when obliged to make a change. This caused feeling, as Prickett records. "For that the master (Hudson) loved him and made him mate, whereat they (the crew) did grudge, because he could neither read nor write."

Even in the last extremity Staffe kept his head, exerted his personal influence with the mutineers for the good of the eight men who were to be cast adrift with the master. Declining the proferred chance of personal safety, he asked the mutineers to give means of prolonging life in the wild. He thus secured his tools, pikes, a pot, some meal, a musket with powder and shot. Then he quietly went down into the boat. Wilson, a mutineer, testified that "Philip Staffe might have staid still in the ship, but he would voluntarily go into the shallop for love of the master (Hudson)."

Rather than cast in his life with mutineers, thus in[9]suring present comfort with prolonged life, this plain, illiterate English sailor stood fast by his commander, and faced a lingering death while caring for his sick and helpless comrades in a desolate, far-off land. Death with unstained honor among his distressed shipmates was to Philip Staffe preferable to a life of shame and dishonor among the mutineers of the Discovery. Surely he belongs to those described by the Bishop of Exeter:

The heroic loyalty of Philip Staffe was fittingly embalmed in quaint historic prose by the incomparable English chronicler of the principal voyages of famous navigators. Purchas, in "His Pilgrimage," relates: "But see what sincerity can do in the most desperate trials. One Philip Staffe, an Ipswich man, who, according to his name, had been a principal staff and stay to the weaker and more enfeebled courages of his companions in the whole action, lightening and unlightening their drooping darkened spirits, with sparks from his own resolution; their best purveyor, with his piece on shore, and both a skilful carpenter and lusty mariner on board; when he could by no persuasions, seasoned with tears, divert them from their devilish designs, notwithstanding they entreated him to stay with them, yet chose rather to commit himself to God's mercy in the forlorn shallop than with such villains to accept of likelier hopes."

The mutineers, having deposed and marooned the[10] great navigator Hudson, looked forward to a homeward voyage of plenty and of comfort. But under the rash and untrained directions of Henry Greene, William Wilson, and Robert Juet, the wretched, luckless seamen were in turn harried by hostile savages and distressed by deadly famine.

Prickett relates that a party landed near Cape Diggs, at the mouth of Hudson Strait, to barter with the natives for provisions, and adds: "I cast up my head, and saw a savage with a knife in his hands, who stroke at my breast over my head: I cast up my right arm to save my breast, he wounded my arm and stroke me in the body under the right pap. He stroke a second blow, which I met with my left hand, and then he stroke me in the right thigh, and had like to cut off my little finger of the left hand. I sought for somewhat wherewith to strike him (not remembering my dagger at my side), but looking down I saw it, and therewith stroke him into the body and the throat.

"Whiles I was thus assaulted in the boat, our men were set upon on the shore. John Thomas and William Wilson had their bowels cut, and Michael Perse and Henry Greene, being mortally wounded, came tumbling into the boat together....

"The savages betook them to their bows and arrows, which they sent amongst us, wherewith Henry Greene was slain outright, and Michael Perse received many wounds, and so did the rest. In turning the boat I received a cruel wound in my back with an arrow. But there died there that day William Wilson, swearing[11] and cursing in most fearful manner. Michael Perse lived two days and then died."

Of their final sufferings Prickett records: "Towards Ireland we now stood, with prosperous winds for many days together. Then was all our meal spent, and our fowl [birds from Hudson Bay] restie [rusty?] and dry; but, being no remedy, we were content with salt broth for dinner and the half-fowl for supper. Now went our candles to wrack, and Bennet, our cook, made a mess of meat of the bones of the fowl, frying them with candle grease. Our vinegar was shared, and to every man a pound of candles delivered for a week, as a great dainty....

"Our men became so faint that they could not stand at the helm, but were fain to sit. Then Robert Juet died for mere want, and all our men were in despair, ... and our last fowl were in the steep tub.... Now in this extremity it pleased God to give us sight of land."

As to Hudson, with loyal Staffe and their sick comrades, the record runs: "They stood out of the ice, the shallop being fast to the stern, and so they cut her head fast.... We saw not the shallop, or ever after." Thus perished Henry Hudson, the man who laid the foundations of the metropolis of the western hemisphere, who indirectly enriched the world by hundreds of millions of dollars by giving to it the fisheries of Spitzbergen and the fur trade of Hudson Bay. To the day of his death he followed the noble rule of life set forth in his own words: "To achieve what they have undertaken,[12] or else to give reason wherefore it will not be." In geography and in navigation, in history and in romance, his name and his deeds stand forever recorded.

In the Homeric centuries Hudson might well have been deified, and even in this age he has become in a manner mythological among the sea-rovers as graphically depicted by Kipling:

Strange as it may now seem, a century since the entire northern coasts of North America were wholly unknown, save at two isolated and widely separated points—the mouth of the Coppermine and the delta of the Mackenzie. The mouth of the Coppermine was a seriously doubted geographical point, as Hearne's discovery thereof in 1771 was made without astronomical observations; though he did reach the sea we now know that he placed the mouth of the Coppermine nearly two hundred and fifty miles too far to the north. Mackenzie's journey to the delta of the great river that bears his name was accepted as accurate.

In the renewed efforts of Great Britain to discover the northwest passage and outline the continental coasts of North America, it was deemed important to supplement the efforts being made by Parry at sea with a land expedition. For this purpose it selected neither a civilian nor a soldier, but a sailor known to the world in history as a famous arctic explorer—Sir[16] John Franklin—who was to attain enduring fame at the price of his life.

Franklin had served as signal officer with Nelson at Trafalgar, was wounded while engaged under Packenham at the battle of New Orleans, and had commanded an arctic ship under Buchan in the Spitzbergen seas. The vicissitudes of Franklin and his companions while on exploring duty in Canada, especially while crossing the barren grounds, are told in this tale.

A dangerous voyage by ship through Hudson Straits brought Franklin and his companions, Dr. Richardson, Midshipmen Hood and Back, and Seaman Hepburn to York Factory, Hudson Bay, at the end of August, 1819.[17] Contrary to the advice of the local agents, he started northward, and after a hazardous journey in the opening winter—involving a trip of seven hundred miles of marches, canoeing, and portages—reached Cumberland House.

With unreasonable ambition this indomitable man of iron pushed northward in mid-winter with Back and Hepburn, on a journey to Fort Chipewyan, Athabasca Lake, of eight hundred and fifty-seven miles, during which the whole party barely failed of destruction. While dogs hauled the food and camp gear, the men travelling on snow-shoes were pushed to keep up with the dogs. Being mangeurs de lard (novices or tenderfeet), they suffered intolerable pain in their swollen feet, besides suffering horribly from the blizzards and extreme cold, the temperature at times failing to ninety degrees below the freezing-point.

The sledges were of the Hudson Bay pattern, differing from those used elsewhere. They are made of two or three boards, the front curving upward, fastened by transverse cleats above. They are so thin that a heavily laden sledge undulates with the irregularities of the snow. Less than two feet wide as a rule, they are about nine feet long, and have around the edges a lacing by which the load is secured.

By a journey of fifteen hundred and twenty miles Franklin verified Hearne's discovery of the Coppermine, though finding its latitude and longitude very far out, and later he built and wintered at Fort Enterprise. It is interesting to note that the only complaint that[18] he makes of his summer journey were the insect pests—the bull-dog fly that carries off a bit of flesh at each attack, the irritating sand-fly, and the mosquito. Of the latter he says: "They swarmed under our blankets, goring us with their envenomed trunks and steeping our clothes in blood. The wound is infinitely painful, and when multiplied an hundred-fold for many successive days becomes an evil of such magnitude that cold, famine, and every other concomitant of an inhospitable climate must yield pre-eminence to it. The mosquito, irritating to madness, drives the buffalo to the plains and the reindeer to the sea-shore."

In the summer of 1821 Franklin descended the Coppermine River, and in a canoe voyage of five hundred and fifty miles to the eastward discovered the waters and bordering lands of Bathurst Inlet, Coronation Gulf, and as far as Dease Inlet. The very day that he was forced by failing food to turn back, Captain Parry, R.N., in the Fury, sailed out of Repulse Bay five hundred and forty miles to the east.

With the utmost reluctance Franklin saw the necessity for a speedy return. It was now the 22d of August, the nights were fast lengthening, the deer were already migrating, and the air was full of honking wild geese flying in long lines to the south. Both canoes were badly damaged, one having fifteen timbers broken. The other was so racked and warped that repairs were impracticable, the birch bark being in danger of separating from the gunwales at any severe shock.

One man had frozen his thighs, and the others,[19] shaken in mind and worn in body, unaccustomed to the sea, were in such a demoralized state that two of them threw away deer meat, sadly needed, to lighten the boats. Sudden cold set in with snow, a fierce blizzard blew up a high sea, and the inland pools froze over. Return by sea was clearly impossible, and the only chance of saving their lives was to ascend Hood River and reach Fort Enterprise by a land journey across the barren grounds, so dreaded and avoided by the Indians and the Eskimos.

With the subsiding gale they put to sea along the coast, and in three days entered Hood River, though at times with utmost difficulty escaping foundering, as says Franklin: "The waves were so high that the masthead of our canoe was often hid from the other, though it was sailing within hail."

Once landed on the river bank, the mercurial voyageurs, unmindful of the difficult and dangerous march before them, were in most joyful mood. They spent a gay evening before a large camp-fire, bursting into song, reciting the novel perils of the sea now past, and exaggerating with quaint humor every little incident.

With the vigor of famishing men they scoured the country for game, and nets were skilfully set under cascade falls, which yielded the first morning a dozen trout and white-fish. On these they made a delicious meal, seasoned by abundant berries, for in this country there remain on the bushes throughout the winter cranberries and red whortleberries.

The voyageurs were quite worn out poling their boats[20] up the rapids of Hood River. At times it was even needful to take out the loads and, wading knee-deep in the ice-cold waters, drag the boats across the many shoals. One day Franklin was dismayed, though the men were quite indifferent, at coming to impassable rapids. They proved to be the lower section of a series of wonderful cascades which could be passed neither by traversing nor by portage. For the distance of a mile the river was enclosed by solid, perpendicular walls of sandstone, shutting the stream into a canyon that was in places only a few yards wide. In this single mile the stream fell two hundred and fifty feet, forming two high falls and a number of successive rapids. A survey of the upper river proved its unnavigability even had a portage been possible. The crossing of the barren grounds was thus lengthened far beyond Franklin's expectations.

Franklin, meantime, determining by astronomical observations the location of his camp on Hood River, informed the men that they were only one hundred and fifty miles from Point Lake, which was opposite Fort Enterprise, their starting-point the previous spring. The voyageurs received this news with great joy, thinking it to be a short journey, as they had had no experience with the barren region. Franklin was not so cheerful, as accounts of the desolation from various sources had made him alive to the certain hardships and possible dangers of the march. He decided to omit no precaution that would relieve or obviate the hardships.

Besides the five Englishmen, there were fifteen voyageurs,[21] of whom two were Eskimo hunters, two interpreters, an Italian, an Iroquois Indian, and nine Canadian half-breeds. All were men inured to hard service and familiar with frontier life.

The large boats were taken apart, and from this material were built two small portable canoes which were fit to carry three men across any stream that might be discovered in this trackless and unexplored desert. Such books, clothing, supplies, and equipment as were not absolutely necessary for the journey were cached so as to reduce the loads to be carried in the men's packs. The tanned skins that had been brought along for the purpose of replacing worn-out moccasins were equally divided, and strong extra foot-gear was made up with great care. Each one was given two pairs of flannel socks and other warm clothing, for freezing weather had come to stay. One tent was taken for the men and another for the officers.

On the last day of August the party started in Indian file, each man carrying ninety pounds, and the officers according to their strength. The luggage consisted of their little stock of pemmican, tents, ammunition, fishing-nets, hatchets, instruments, extra clothing, sleeping and cooking gear. Each officer had a gun, his field journals, instruments, etc., and two men were told off daily to carry the cumbersome and hated canoe. They were so heavily laden that they made only a mile an hour, including frequent rests. The voyageurs complained from the first at taking two canoes, and were but half convinced when the raging Hood[22] River was speedily crossed by lashing the two canoes together.

Their important vegetable food, berries, failed a few miles from the river, and as very little game was seen they were obliged to eat the last of their pemmican on September 4. As a blizzard sprang up the next morning, the party was storm-bound for two days—passed without food or fire, their usual fuel, moss, failing, as it was covered with snow and ice. The temperature fell to twenty degrees and the wet tents and damp blankets were frozen in solid masses. On breaking camp Franklin fainted from exhaustion, cold, and hunger. Dr. Richardson revived him, against his protest, with a bit of portable soup which, with a little arrow-root for sickness, was the only remaining food.

The snow was now a foot deep and travel lay across swamps where the new, thin ice constantly broke, plunging the wretched men up to their knees in ice-cold water. To add to their misfortunes, Benoit, to Franklin's distress, fell and broke the larger of the canoes into pieces; worst of all, he was suspected of doing so maliciously, having threatened to destroy the canoe whenever it should be his turn to carry it. Franklin chose to ignore this mutinous conduct and resourcefully utilized the accident. Halting the march and causing a fire to be made of the birch bark and the timbers, he ordered the men to cook and distribute the last of the portable soup and the arrow-root. Though a scanty meal, it cheered them all up, being the first food after three days of fasting.

After a march of two days along the river bank, they struck across the barren grounds, taking a direct compass course for Point Lake. The country was already covered with snow and high winds also impeded their progress. In many places the ground was found to have on its surface numberless small, rolling stones, which often caused the heavily burdened voyageurs to stumble and fall, so that much damage was done to loads, especially to the frail canoe. As the only foot-gear consisted of moccasins made of soft, pliant moose-skin, the men soon suffered great pain from frequent stone-bruises, which delayed the march as the cripples could only limp along.

The barren grounds soon justified their name, for, though an occasional animal was seen and killed, the men more often went hungry. The deep snow and the level country obliged Franklin to adopt special methods to avoid wandering from the direct compass route, and the party travelled in single file, Indian fashion. The voyageurs took turns breaking the path through the snow, and to this leader was indicated a distant object toward which he travelled as directly as possible. Midshipman Hood followed far enough in the rear to be able to correct the course of the trail-breaker, to whom were pointed out from time to time new objects. This method of travel was followed during the whole journey, meeting with great success.

In time they reached a hilly region, most barren to the eye but where most fortunately were found on the large rocks edible lichens of the genus gyrophora, which[24] were locally known to the voyageurs as tripe de roche (rock-tripe). Ten partridges had been shot during the day's march, half a bird to a man, and with the abundant lichens a palatable mess was made over a fire of bits of the arctic willow dug up from beneath the snow. Franklin that night, which was unusually cold, adopted the plan, now common among arctic sledgemen, of sleeping with his wet socks and moccasins under him, thus by the heat of the body drying them in part, and above all preventing them from freezing hard.

Coming to a rapid-flowing river, they were obliged to follow it up to find a possible crossing. They were fortunate to find a grove of small willows, which enabled them to make a fire and thus apply gum to the very much damaged canoe. Though the operation was a very ticklish one, three of the voyageurs under Saint Germain, the interpreter, managed the canoe with such dexterity as to ferry over one passenger at a time, causing him to lie flat in the canoe, a most uncomfortable situation owing to the cold water that steadily seeped into the boat.

Starvation meals on an occasional grouse, with the usual tripe de roche, caused great rejoicing when, after long stalking, the hunters killed a musk-cow. The ravenous condition of the voyageurs was evident from Franklin's statement that "the contents of its stomach were devoured on the spot and the raw intestines, which were next attacked, were pronounced by the most delicate of us to be excellent. This was the sixth day since we had had a good meal; the tripe de roche, even[25] when we got enough, only served to allay hunger a short time."

Suffering continual privations from hunger, they reached Rum Lake, where the supper for twenty men was a single partridge with some excellent berries. There was still tripe de roche to be had, but "this unpalatable weed was now quite nauseous to the whole party, and in several cases it produced bowel complaints."

Franklin considered that the safety of the men could now be insured through the lake fishing, as most of the voyageurs were experts with the net from having long lived at points where they depended on fish for their food. His consternation almost gave way to despair when he discovered the fatal improvidence of the voyageurs, who, to lessen their burdens by a few pounds, had thrown away the fishing-nets and burned the floats. "They knew [says Franklin] we had brought them to procure subsistence for the party, when the animals should fail, and we could scarcely believe the fact of their having deprived themselves of this resource," which eventually caused the death of the majority of the party.

Franklin at once lightened the loads of his sadly weakened men by abandoning everything save astronomical instruments, without which he could not determine correctly their route. Under these disheartening circumstances, the captain's heart was cheered beyond measure by an act of heroic generosity on the part of one of his starving men. As they were starting[26] on the march Perrault came forward and gave to each officer a bit of meat that he had saved from his own allowance. Franklin says: "It was received with great thankfulness, and such an act of self-denial and kindness, being entirely unexpected in a Canadian voyageur, filled our eyes with tears."

A short time after, Credit, one of the hunters, came in with the grateful news that he had killed a deer.

The same day there was a striking display of courage, skill, and endurance on the part of one of the men indicative of the mettle of these uncultured voyageurs. In crossing a river the first boat-load consisted of Saint Germain, Solomon Belanger, and Franklin. Driven by a strong current to the edge of a dangerous rapid, Belanger lost his balance and upset the canoe in the rapid. All held fast to the frail craft and were carried to a point where they touched a rock and gained their footing, although up to their waists in the stream. Emptying the canoe of water, Belanger held the boat steady whilst Saint Germain placed Franklin in it and embarked himself in a dexterous manner. As it was impossible to get Belanger in the boat, they started down the river and after another submersion reached the opposite shore.

Belanger's position was one of extreme danger and his sufferings were extreme. He was immersed to his waist in water near the freezing-point, and, worse yet, his upper body, clothed with wet garments, was exposed to a high wind of a temperature not much above zero. Two voyageurs tried vainly in turn to reach him with[27] the canoe, but the current was too strong. A quick-witted voyageur caused the slings to be stripped from the men's packs and sent out the line toward Belanger, but just as he was about to catch it the line broke and the slings were carried away. Fortunately there was at hand a small, strong cord attached to a fishing-net. When Belanger's strength was about gone the canoe reached him with this cord and he was dragged quite senseless to the shore. Dr. Richardson had him stripped instantly, wrapped him up in dry blankets, and two men taking off their clothes aided by their bodily heat in bringing the sufferer to consciousness an hour or so later.

Meantime the distracted Franklin was watching this desperate struggle from the farther bank, where with drenched and freezing clothes he was without musket, blankets, hatchet, or any means of making a fire. If this betossed canoe was lost the intrepid commander and all the men would have perished. It is to be noted, as characteristic of the man, that in his journal Franklin makes no mention of his sufferings, but dwells on his anxiety for the safety of Belanger, while deploring also the loss of his field journal and the scientific records.

The loss of all their pack-slings in rescuing Belanger somewhat delayed their march, but with the skill and resourcefulness gained by life in the wilds, the voyageurs made quite serviceable substitute slings from their clothing and sleeping-gear.

Conditions grew harder from day to day, and soon the only endurable situation was on the march, for[28] then they were at least warm. The usual joy of the trapper's life was gone—the evening camp with its hours of quiet rest, its blazing fire, the full pipe, the good meal, and the tales of personal prowess or adventure. Now, with either no supper or a scanty bit of food, the camp was a place of gloom and discomfort. Of the routine Franklin writes: "The first operation after camping was to thaw out our frozen shoes, if a fire could be made, and put on dry ones. Each wrote his daily notes and evening prayers were read. Supper if any was eaten generally in the dark. Then to bed, where a cheerful conversation was kept up until our blankets were thawed by the heat of our bodies and we were warm enough to go to sleep. Many nights there was not enough fire to dry our shoes; we durst not venture to pull them off lest they should freeze so hard as to be unfit to put on in the morning."

Game so utterly failed that the hunters rarely brought in anything but a partridge. Often they were days without food, and at times, faint and exhausted, the men could scarcely stagger through the deep snow. Midshipman Hood became so weak that Dr. Richardson had to replace him as the second man in the marching file, who kept the path-breaking leader straight on the compass course. The voyageurs were in such a state of frenzy that they would have thrown away their packs and deserted Franklin, but they were unable to decide on a course that would insure their safe arrival at Fort Enterprise.

Now and then there were gleams of encouragement—a[29] deer or a few ptarmigan; and once they thought they had a treasure-trove in a large plot of iceland moss. Though nutritious when boiled, it was so acrid and bitter that only a few could eat more than a mouthful or two.

After six days of cloudy weather, Franklin got the sun and found by observation that he was six miles south of the place where he was to strike Point Lake, the error being due to their ignorance of the local deviation of the compass by which they had laid out their route. When the course was changed the suspicious voyageurs thought that they were lost, and gave little credit to Franklin's assurances that they were within sixty miles of Fort Enterprise. Dr. Richardson was now so weak that he had to abandon his beloved plants and precious mineral specimens.

Their misfortunes culminated when the remaining canoe was badly broken, and the men, despite entreaties and commands, refused to carry it farther. Franklin says: "My anguish was beyond my power to describe it. The men seemed to have lost all hope, and all arguments failed to stimulate them to the least exertion."

When Lieutenant Back and the Eskimo hunters started ahead to search for game, the Canadians burst into a rage, alleged an intended desertion, threw down their packs, and announced that it was now to be every one for himself. Partly by entreaties and partly by threats, for the officers were all armed (and in view of the fact that Franklin sent the fleetest runner of the[30] party to recall the hunters), the voyageurs finally consented to hold together as a party.

Death by starvation appeared inevitable, but with his commanding presence and heroic courage the captain was able to instil into the men some of his own spirit of hope and effort. As they were now on the summer pasturage grounds of large game, they were fortunate enough to find here and there scattered horns and bones of reindeer—refuse abandoned even by the wolves. These were eagerly gathered up, and after being made friable by fire were ravenously devoured to prolong life, as were scraps of leather and the remnants of their worn-out moose-skin moccasins.

September 26 brought them, in the last stages of life, to the banks of the Coppermine, within forty miles of their destination. The misguided voyageurs then declared themselves safe, as for once they were warm and full of food, for the hunters had killed five deer and they came across a willow grove which gave them a glorious camp-fire. But the seeds of disloyalty and selfishness now blossomed into demoralization. After gorging on their own meat two of the voyageurs stole part of the meat set aside for the officers.

The question of crossing the Coppermine, a broad stream full of rapids, was now one of life or death. With remorse nearly bordering on desperation, the Canadians now saw that the despised and abandoned canoe was their real ark of safety. Following the banks for miles, no ford could be found despite the closest search. Franklin fixed on two plans for crossing,[31] either by a raft of willows, which grew in quantities near by, or by a canvas boat to be made by stretching over a willow framework parts of tents still in hand. The voyageurs arrogantly scouted both expedients, but after wasting three precious days wrangling they built a willow raft. When done its buoyancy was so slight that only one man could be supported by it. It was thought, however, that a crossing could be made by getting a line across the river by which the raft could be pulled to and fro. As an incitement to exertion, Franklin offered to the voyageur who should take a line across the sum of three hundred livres (sixty dollars), a large amount for any of these men. Two of the strongest men failed in their efforts to work the raft across, the stream being rapid and one hundred and thirty yards across. The single paddle, brought by Richardson all these weary miles from the sea-shore, was too feeble, and two tent-poles lashed together were not long enough to reach bottom a short distance from the shore. Repeated failures demoralized the voyageurs, who cried out with common accord that they were lost.

Dr. Richardson now felt that the time had come to venture his life for the safety of the party, and so offered to swim across the Coppermine with a line by which the raft could be hauled over. As he stripped his gaunt frame looked rather like a skeleton than a living man. At the sight the Canadians all cried out at once, "Ah! que nous sommes maigres!" ("Oh! how thin we are!"). As the doctor was entering the[32] river he stepped on a dagger which had been carelessly left on the ground. It cut him to the bone, but he did not draw back for a second. Pain was nothing to the lives of his comrades.

With the line fastened around his waist, he plunged into the stream. Before he reached the middle of the river his arms were so benumbed by the cold water, which was only six degrees above the freezing-point, that he could no longer use them in swimming. Some of the men cried out that he was gone, but the doctor was not at the end of his resources, and turning on his back he swam on in that way. His comrades watched him with renewed anxiety. Could he succeed or must he fail? Were they to be saved or not? The swimmer's progress became slower and slower, but still he moved on. When almost within reaching distance of the other bank his legs failed also, and to the intense alarm of the Canadians he sank. The voyageurs instantly hauled on the line, which brought him to the surface, and he was drawn to the shore in an unconscious and almost lifeless condition. He was rubbed dry, his limbs chafed, and, still unconscious, was rolled up in blankets and placed before a very hot fire. In their zeal the men nearly caused the death of the doctor, for he was put so near the fire that the intense heat scorched his left side so badly that it remained deprived of most sensation for several months. Fortunately he regained consciousness in time to give some slight directions about his proper treatment.

Apart from the failure of Richardson to cross the[33] river, the spirits of the party were more cast down by the loss of Junius, the best hunter of the party. Taking the field as usual, the Eskimo failed to return, and no traces could be found of him.

As a final resort they adopted a plan first advanced by Franklin, and the ingenious interpreter, Saint Germain, offered to make a canvas boat by stretching across a willow framework the painted, water-proof canvas in which the bedding was wrapped. Meanwhile the general body of the voyageurs was in such depths of indifference that they even preferred to go without food rather than to make the least exertion, and they refused to pick the tripe de roche on which the party now existed. Franklin records that "the sense of hunger was no longer felt by any of us, yet we were scarcely able to converse on any other subject than the pleasures of eating."

Finally the canoe was finished on October 4, and, proving water-tight, the whole party was ferried safely across, one at a time. The week lost by ignoring Franklin's orders proved the destruction of the party as a whole.

This was not the view of the voyageurs, who were now as joyful that they were within forty miles of the station as they had been downcast the day before crossing, when one of them stole a partridge given Hood, whose stomach refused the lichens. Of this mercurial change Franklin says: "Their spirits immediately revived, each shook the officers by the hand, declared the worst of their difficulties over,[34] and did not doubt reaching Fort Enterprise in a few days."

Franklin at once sent Back with three men ahead for assistance from Fort Enterprise, as previous arrangements had been made with a Hudson Bay agent to supply the station with provisions and to have Indians there as hunters.

The rear guard following slowly found no food save lichens, and so began to eat their shoes and bits of their bedding robes. On the third march two voyageurs fell exhausted on the trail, and despite the encouraging efforts of their comrades thus perished. To give aid to the failing men, to relieve the packs from the weight of the tent, and to enable Franklin to go ahead unencumbered by the weakest, Dr. Richardson asked that he be left with Hood and Hepburn at such place as fuel and tripe de roche were plentiful, which was done, relief to be sent to them from the station as soon as possible. Of this Franklin says: "Distressed beyond description at leaving them in such a dangerous situation, I long combated their proposal, and reluctantly acceded when they strenuously urged that this step afforded the only chance of safety for the party. After we had united in thanksgiving and prayers to Almighty God, I separated from my companions deeply afflicted. Dr. Richardson was influenced in his resolution to remain by the desire which influenced his character of devoting himself to the succor of the weak and Hepburn by the zealous attachment toward his officers."

The nine other voyageurs given their choice went for[35]ward with Franklin, but Michel Teroahaute, the Iroquois Indian, and two Canadians returned next day to Richardson's camp.

On his arrival at Fort Enterprise on October 14, Franklin for the first time lost heart, the station being unprovisioned and desolate. A note from the indefatigable Back told that he was seeking aid from roving Indians or at the nearest Hudson Bay post.

Franklin says: "It would be impossible to describe our sensations after discovering how we had been neglected. The whole party shed tears, not for our own fate, but for that of our friends in the rear, whose lives depended entirely on our sending immediate relief."

On October 29 Richardson came in with the horrible news that two voyageurs had died on the trail, that the Iroquois Indian, Michel, had murdered Hood, and that in self-defence he had been obliged to shoot Michel.

Pending the relief of the party, which was on November 7, the members existed on Labrador tea (an infusion from a plant thus used by the Indians), on lichens, and the refuse of deer killed the year before. The deerskins gathered up in the neighborhood were singed of their hair and then roasted, while the horns and bones were either roasted or used in soup. Two of the Canadians died on this diet. Of a partridge shot and divided into six portions Franklin says: "I and my companions ravenously devoured our shares, as it was the first morsel of flesh any of us had tasted for thirty-one days."

The praiseworthy conduct of Franklin and of his[36] companions in prosecuting the work of outlining the arctic coasts of North America is not to be measured alone by the fortitude and courage shown in crossing the barren grounds. An unusual sense of duty, akin to heroism, could alone have inspired Franklin and Richardson to attempt the exploration under the adverse conditions then prevailing in that country. A warfare, practically of extermination, was then in progress between the Hudson Bay Company and the Northwestern Company. This struggle, under the instigation of misguided agents, aroused the worst passions of both half-breeds and of Indians, who were demoralized by the distribution of spirits. By diversions of hunters many people were starved, while others were murdered outright. Franklin's sad experiences in the public service at Fort Enterprise were duplicated by the starvation and deaths of innocent people at other remote points through commercial cupidity or rivalry.

Disastrous and lamentable as was the outcome of the journey across the barren lands, it indicated in a striking manner the superior staying powers of the English as pitted against the hardy voyageurs—Canadians, Eskimos, Indians, and half-breeds. Five of the fifteen voyageurs perished and one of the English. Doubtless the latter survived largely through their powers of will, acts of energy and of heroic devotion to the interests of the party—one and all.

Among the many notable voyages in search of the northwest passage, although less spectacular in phases of adventurous exploration than some others, there is none which deserves more careful examination than that of Sir John Ross in the Victory. Not only did this voyage make most important contributions to the various branches of science, but it was unequalled for its duration and unsurpassed in variety of experiences. It was fitted out as a private expedition, largely at the expense of Felix Booth, sheriff of London, was absent from 1829 to 1833, and was the first arctic expedition to use steam as a motive power.

Sailing in the small paddle-wheel steamer Victory, Ross passed through Baffin Bay into Lancaster Sound, whence he shaped his course to the south. Discovering the eastern shores of North Somerset and of Boothia, he put his ship into winter quarters at Felix Harbor, which became his base of operations. Rarely have such valuable explorations been made without disaster or even serious hardships. Boothia was found to be the most northerly apex of the continent of North America,[40] while to its west King William Land and other extended areas were discovered.

Of surpassing interest and importance was the magnetic work done by James Clark Ross, a nephew of Sir John. Many persons do not realize that the place to which constantly points the north end of the needle of the magnetic compass is not the north geographic pole. The locality to which the compass turns is, in fact, nearly fourteen hundred miles to the south of the north pole. With this expedition in 1830, James Clark Ross by his many observations proved that the north magnetic pole, to which the needle of the compass points, was then very near Cape Adelaide, in 70° 05′ north latitude, 96° 44′ west longitude.[1]

The adventures of the crew in their retreat from Boothia Land by boat and sledge are recorded in this sketch.

Captain Ross failing to free his ship from the ice the second summer, it was clear to him that the Victory must be abandoned the coming spring. It was true salmon were so abundant in the lakes of Boothia that five thousand were caught in one fishing trip, which netted six tons of dressed fish, but bread and salt meat, the usual and favorite food of the crew, were so short that it had become necessary to reduce the daily issues. Fuel was so reduced that none remained save for cooking, and the deck had to be strewn with a thick coating[41] of gravel, for warmth, before the usual covering of snow was spread over the ship. Creatures of habit, the seamen now showed signs of depression bordering on discontent if not of despair.

There were two routes of retreat open to Ross, one being toward the south, attractive as being warmer and possibly more ice-free. He chose, however, the way to the north, which, desolate as it might be, was known to him both as to its food supplies and also as to the chances of meeting a ship. Every year the daring Scotch whalers were fishing in Lancaster Sound, and at Fury Beach, on the line by which he would travel, were large quantities of food, boats, and other[42] needful articles—landed from the wreck of Parry's ship Fury in 1825.

Ross did not plan his abandonment of the Victory any too early, for in January Seaman Dixon died and his mate Buck lost his eyesight from epilepsy. Signs of the dreaded arctic horror, scurvy, were not lacking, as the foolish seamen were averse to the antiscorbutic lime juice and refused to take the fresh salmon-oil ordered by the doctor. Ross was also affected, his old wounds breaking out afresh, reminders of the day when as a lieutenant he had aided in cutting out a Spanish ship under the batteries of Bilbao.

Knowing that the Victory would be plundered by the natives after its abandonment, Ross provided for a possible contingency of falling back on her for another winter, and so constructed a cave inshore in which were cached scientific instruments, ship's logs, accounts, ammunition, etc. Sledge-building began in January, and the dismantling of the ship proceeded as fast as the weakness of the crew permitted.

It was impossible to reach the open water of Prince Regent Inlet without establishing advance depots of provisions and of boats, as the conditions at Fury Beach were unknown. Floe-travel was so bad, and the loads hauled by the enfeebled men so small, that it took the entire month of April to move a distance of thirty miles two boats and food for five weeks, while open water was not to be expected within three hundred miles.

On May 29, 1832, the British colors were hoisted,[43] nailed to the mast, duly saluted, and the Victory abandoned. With the true military spirit Ross was the last to quit his ship, his first experience in forty-two years' service in thirty-six ships.

The prospects were dismal enough, with heavily laden sledges moving less than a mile an hour, while the party were encumbered by helpless men: these were moved with comfort by rigging up overhead canvas canopies for the sledge on which a man could be carried in his sleeping-bag.

The midsummer month of June opened with the sea ice stretching like solid marble as far north as the eye could reach. The change from forecastle to tent, from warm hammocks and hot meals to frozen blankets and lukewarm food, told severely on the worn-out sledgemen whose thirst even could be but rarely quenched until later the snow of the land began to melt. Now and then a lucky hunter killed a hare, or later a duck, still in its snowy winter coat, which gave an ounce or two of fresh meat to flavor the canned-meat stew.

Six days out the seamen, demoralized at their slow progress, sent a delegation asking the captain to abandon boats and food so that travelling light they might the earlier reach the Fury Beach depot. Ross with firmness reprimanded the spokesman and ordered the men to take up the line of march. He knew that food could not be thus wasted without imperilling the fate of the party, and that boats were absolutely essential. While striving to the utmost with the crew, coming a week later to a safe place he cached both boats, and[44] taking all the food sent his nephew ahead to learn whether the boats at Fury Beach were serviceable. After a journey in which young Ross displayed his usual heroic energy and ability, he brought the glad news that although a violent gale had carried off the three boats and seriously damaged one, yet he had secured all so that the boats of the Victory could be left behind.

July 1 brought the party to Fury Beach, where despite orders and cautions some of the hungry seamen gorged themselves sick. But the ice was still solid. Ross therefore built a house of canvas stretched over a wooden frame, and named the habitation Somerset House, as it was on North Somerset Land. Work was pushed on the boats, which were in bad shape, and as they were of mahogany they were sure to lack the fine flotation qualities of those left behind. Ross fitted his two boats with mutton sails, while the nephew put in sprit-sails.

Fortunately the food at Fury Beach had escaped the ravages of arctic animals, though the clever sharp-nosed foxes had scented the tallow candles, gnawed holes through the boxes, and made way with them all.

Everything was arranged for a long sea trip, each boat being loaded with food for sixty days and had assigned thereto an officer and seven seamen. The ice opening suddenly and unexpectedly, they started north on August 1, moving by oar-power, as the water lanes were too narrow and irregular for the use of sails. On the water once more, the crew thought their retreat[45] secure. They had hardly gone eight miles before they were driven to shore by the moving pack, and were barely able to draw up their boats when the floes drove violently against the rocks, throwing up great pressure-ridges of heavy ice and nearly destroying the boats. The men had scarcely begun to congratulate themselves on their escape from death in the pack when they realized that they were under conditions of great peril. They found themselves on a rocky beach, only a few yards in width, which was a talus of loose, rolling rocks at the base of perpendicular cliffs nearly five hundred feet high. As the ice which cemented the disintegrating upper cliffs melted, the least wind loosened stones, which fell in numbers around them, one heavy rock striking a boat's mast. Unable to escape by land, hemmed in by the closely crowding pack, they passed nine days unable to protect themselves, and fearing death at any moment from some of the falling stones, which at times came in showers. They were tantalized by the presence of numerous foxes and flocks of game birds, but they did not dare to fire at them, fearing that the concussion from the firing would increase the number of the falling rocks.

With barely room for their tents under the disintegrating precipice, with decreasing food, in freezing weather, without fuel, and with the short summer going day by day, they suffered agonies of mind and of body. Fortunately the ice opened a trifle to the southward so that they were able to launch the lightest boat, which went back to Fury Beach and obtained[46] food for three weeks. Driven ashore by the ice-pack on its return, the crew from Fury Beach managed with difficulty to rejoin the main party on foot. In this as in other instances they had very great difficulty in hauling up their heavy mahogany boats, it being possible to handle the heaviest only by tackle.

Through the opening ice they made very slow progress, being often driven to shore. Most rarely did anything laughable occur, but one experience gave rise to much fun. One morning the cook was up early to celebrate a departure from their usually simple meal. The day before the hunters had killed three hares, and the cook now intended to make a toothsome sea-pie, for which he was celebrated among the men. Half-awake, he groped around for his foot-gear, but could find only one boot. Rubbing his eyes and looking around him, he was astonished to see a white fox near the door of the tent calmly gnawing at the missing boot. Seizing the nearest loose article, he threw it at the animal, expecting that he would drop the boot. The half-famished fox had no mind to lose his breakfast, and holding fast to the boot fled up the hill, to the disgust of the cook and to the amusement of his comrades. To add to the fun they named the place Boot Bight, though some said that there was more than one bite in the lost boot.

A strong gale opening the sea, they improved the occasion by crossing Batty Bay, when the heavy mahogany boat of Ross was nearly swamped. She took in so much water that the crew were wet up to their knees, and it required lively work and good seamanship to save her.

After more than seven weeks of such terrible struggles with the ice, the three boats reached the junction of Prince Regent Inlet and Lancaster Sound, only to find the sea covered with continuous, impenetrable ice-floes. Ross cached his instruments, records, specimens, etc., for the following year, so as to return light to Somerset House.

There were objections to returning south on the part of some of the crew, who suggested that under the command of young Ross (and apparently with his approval) the stronger members should "take a certain amount of provisions from each boat and attempt to obtain a passage over the ice." This meant not only the division of the party, but almost certainly would have resulted in the death of all. For the crossing party, of the strongest men, would have reached a barren land, while the sick and helpless would have perished in trying to return alone to Somerset House (Fury Beach). Ross wisely held fast to this opinion, and the return trip began.

The delay caused by differences of opinion nearly proved fatal, owing to the rapidly forming new ice through which the boats were only moved by rolling them. The illy clad men now suffered terribly from the cold, as the temperature was often at zero or below. It was so horrible to sleep in the open, crowded boats that they sought the shore whenever possible. Generally there was neither time nor was there fit snow to put up a snow-hut, and then the men followed another plan to lessen their terrible sufferings and sleepless[48] nights. Each of the seamen had a single blanket, which had been turned into a sack-shaped sleeping-bag so that their feet should not become exposed and freeze while they were asleep. Each of the three messes dug a trench, in a convenient snow-drift, long enough and wide enough to hold the seven sleeping-bags when arranged close together. Thrown over and covering the trench was a canvas sail or tent, and the canvas was then overlaid with thick layers of snow, which thus prevented any of the heat of the men from escaping. Very carefully brushing off any particles of snow on their outer garments, the men carefully wormed themselves into their sleeping-bags, and by huddling together were generally able to gain such collective heat as made it possible for them to drop off to sleep.

Whenever practicable they supplemented their now reduced rations by the hunt, but got little except foxes and hares. The audacity of the white arctic foxes was always striking and at times amusing. Once a thievish fox crept slyly into a tent where the men were quietly awaiting the return of a comrade for whose convenience a candle was kept lighted. The candle smelt and looked good to Master Fox, who evidently had never seen such a thing as fire before. Running up to the candle, he boldly snapped at it, when his whiskers were so sorely singed that he departed in hot haste. All laughed and thought that was the end of the affair. But a few minutes later, discomfited but not discouraged, Master Fox, with his scorched head-fur, appeared again in the tent. He had learned his lesson, for avoiding[49] the candle he snapped up the sou'wester of the engineer and made off with it though a watching sailor threw a candlestick at him.

The weather soon became most bitterly cold, and as they sailed or rowed toward Fury Beach the sea-water often froze as it fell in driblets on their garments. Food was reduced a third, as Ross knew that a return in boats was now doubtful. A gale drove them to a wretched spot, a rocky beach six feet wide beneath frowning cliffs many hundreds of feet high. Their food was now cut off one-half, and the daily hunt brought little—a few foxes and sea-gulls, with an occasional duck from the southward-flying flocks.

Near Batty Bay they were caught in the ice-pack two miles from land and their fate was for a time doubtful. Only by almost superhuman efforts did they effect their release. The cargo was carried ashore by hand, and by using the masts as rollers under the hulls of the boats—though often discouraged by their breaking through the new, thin ice—they managed at last to get the boats safe on shore. It might be thought that three years of arctic service would have taught the men prudence, but here one of the sailors in zero weather rolled a bread-cask along the shore with bare hands, which caused him to lose the tips of his fingers and obliged other men to do his duty.

It was now necessary to make the rest of the journey to Fury Beach overland. Fortunately there were some empty bread-casks out of which the carpenter made shift to build three sledges. The party left everything[50] behind for the journey of the next spring, taking only tentage, food, needful tools, and instruments. The way lay along the base of precipitous cliffs, with deep drifts of loose snow on the one hand, and on the other rough ridges of heavy ice pushed up from the sea. Hard as were the conditions of travel for the worn-out seamen, they were much worse for the crippled mate, Taylor, who could not walk with his crutches, and who suffered agony by frequent falls from the overturning sled on which he had to be hauled. The first day broke one sledge, and with zero temperatures the spirits of the men were most gloomy. Being obliged to make double trips to carry their baggage, some of the sailors complained when told off to return for the crippled mate. Ross shamed them into quiet by telling them how much better was their case to be able to haul a shipmate than was that of the wretched mate dependent on others for life and comfort.

How closely the party was pressed by fate is shown by their eating the last morsel of their food the day they reached Somerset House. As they approached a white fox fled from the house, but though dirty, cold, hungry, and exhausted, they were happy to reach this desolate spot which they now called home.

Apart from the death of the carpenter, the winter passed without any distressing events, though some of the men failed somewhat in strength. It was a matter of rejoicing that in the early spring they obtained fresh meat by killing two bears. The carcass of one of them was set up as a decoy, and one of the seamen stuck a[51] piece of iron hoop into it as a tail. Soon frozen solid, it attracted another bear, who rushed at it and after capsizing it was killed by a volley from sailors lying in wait.

Careful plans were made for the summer campaign. Stoves were reduced to one-fourth of their original weight and sledges were shod from ice-saws. The three sledges were fitted with four uprights, with a canvas mat hauled out to each corner. On this upper mat the sick and helpless men were laid in their sleeping-bags, and thus could make with comparative comfort any sledge journeys that might be necessary. It was deemed advisable to provide for travel either by land or by sea.

The ice of Prince Regent Inlet held fast far into the summer, and at times there stole into the minds of even the most hopeful and courageous a fear lest it should not break up at all. Birds and game were fairly plentiful, far more so than in the preceding year, but all hope, care, and interest centred in the coming boat journey. No one could look forward to the possibility of passing a fifth year in the arctic regions without most dismal forebodings as to the sufferings and fatalities that must result therefrom. The highest cliffs that commanded a view of the inlet to the north were occupied by eager watchers of the ice horizon. Day after day and week after week passed without the faintest signs of water spots, which mark the disintegrating pack and give hopes of its coming disruption. Would the pack ever break? Could that vast, unbroken extent of ice ever waste away so that boats could pass? A thousand[52] times this or similar questions were asked, and no answer came.

Midsummer was far past when, by one of those sudden and almost instantaneous changes of which the polar pack is possible, a favorable wind and fortunate current dissipated the ice-covering of the inlet, and alongshore, stretching far to the north, an ice-free channel appeared.

With the utmost haste the boats were loaded, the selected stores having long been ready, and with hearts full of hope they started toward the north. Ross and his officers fully realized that this was their sole and final chance of life, and that failure to reach the whalers of Barrow Strait or Baffin Bay meant ultimate death by starvation.

Amid the alternations during their voyage, of open water, of the dangerous navigation of various ice streams, and of the tantalizing land delays, when the violent insetting pack drove them to the cliff-bounded beaches of North Somerset, even the feeblest worked with desperate energy, for all knew that their lives depended on concerted, persistent, intelligent action.

The ice conditions improved as they worked to the north end of Prince Regent Inlet, and finally the pack was so disrupted and wasted that they crossed to Baffin Land without difficulty.

Skirting the northern coast of that desolate land, they sailed to the eastward, hoping almost against hope to see a friendly sail, for the season was passing and the nights had begun to lengthen rapidly.

On the morning of August 25, 1833, their feelings were raised to an intense pitch of excitement by the sight of a sail, which failed to detect in turn the forlorn castaways. Though some fell into deep despair as the ship stood away, the more rational men felt assured of their final safety, since whalers were actually in the strait. A few hours later they were fortunate enough to fall in with and to be picked up by the whaler Isabella, a remarkable incident from the fact that she was the arctic ship which Sir John Ross had commanded in his expedition of 1818 to Baffin Bay.

When Ross answered the hail from the astonished captain of the Isabella, it was a unique and startling greeting that he received. For when answering that he was Captain John Ross, the captain of the whaler blurted out, "Why, Captain Ross has been dead two years," which was indeed the general belief.

After investigating the affairs of the expedition, a committee of Parliament reported "that a great public service had been performed [with] deeds of daring enterprise and patient endurance of hardships." They added that Captain John Ross "had the merit of maintaining both health and discipline in a remarkable degree ... under circumstances the most trying to which British seamen were perhaps ever subjected."

Through daily duty well done, by fidelity to work in hand, and by unfailing courage in dire extremities, Sir John Ross and his expeditionary force won their country's praise for heroic conduct.

Few persons realize the accompaniments of the prolonged search by England for the northwest passage, whether in its wealth of venturesome daring, in its development of the greatest maritime nation of the world, or in its material contributions to the wealth of the nations. Through three and a half centuries the British Government never lost sight of it, from the voyage of Sebastian Cabot, in 1498, to the completion of the discovery by Franklin in 1846-7. It became a part of the maritime life of England when Sir Martin Frobisher brought to bear on the search "all the most eminent interests of England—political and aristocratic, scientific and commercial." To the search are due the fur-trade of Hudson Bay, the discovery of continental America, the cod-fishery of Newfoundland, and the whale-fishery of Baffin Bay. For the discovery of the northwest passage various parliaments offered a reward of twenty thousand pounds sterling.

An enterprise that so vitally affected the maritime policy of England, and in which the historic explorer,[58] Henry Hudson, and the great navigator, James Cook, met their deaths, involved many heroic adventures, among which none has engaged more attention than the fateful voyage of Sir John Franklin and his men, by which the problem was solved.

Among the many notable and interesting paintings in the Tate Gallery, one of the famous collections of pictures in London, is one by Sir John Millais, entitled "The Northwest Passage." A young girl is reading tales of arctic travel and of bold adventure to her listening father, whose tightly closed right hand she affectionately[59] fondles as the thrilling story reaches its climax. On the table is an outspread map of North America, consulted often by the attentive readers, whereon blank spaces denote regions as yet unknown to man. The tale done, the old, grizzled, weather-beaten sailor, whose clinched hands and fixed eyes betray his strong emotion, cries out: "It can be done, and England should do it!" Few pictures, in title and in subject, have more forcibly portrayed that pride of achievement which is the glory of Britain.

The tale of the northwest passage in its last phase of discovery cannot anywhere be found in a distinct and connected form. As a record of man's heroic endeavor and of successful accomplishment at the cost of life itself, it should be retold from time to time. For it vividly illustrates an eagerness for adventurous daring for honor's sake that seems to be growing rarer and rarer under the influences of a luxurious and materialistic century.

When in 1845 the British Government decided to send out an expedition for the northwest passage, all thoughts turned to Franklin. Notable among the naval giants of his day through deeds done at sea and on land, in battle and on civic duty, he was an honored type of the brave and able captains of the royal navy. Following the glorious day of Trafalgar came six years of arctic service—whose arduous demands appear in the sketch, "Crossing the Barren Grounds"—followed by seven years of duty as governor of Tasmania. But these exacting duties had not tamed the adventurous[60] spirit of this heroic Englishman. Deeming it a high honor, he would not ask for the command of this squadron, for the expedition was a notable public enterprise whereon England should send its ablest commander.

When tendered the command the public awaited eagerly for his reply. He was in his sixtieth year, and through forty-one degrees of longitude—from 107° W. to 148° W.—he had traced the coast of North America, thus outlining far the greater extent of the passage. But his arctic work had been done under such conditions of hardship and at such eminent peril of life as would have deterred most men from ever again accepting such hazardous duty save under imperative orders.

Franklin's manly character stood forth in his answer: "No service is dearer to my heart than the completion of the survey of the northern coast of North America and the accomplishment of the northwest passage."

Going with him on this dangerous duty were other heroic souls, officers and men, old in polar service, defiantly familiar with its perils and scornful of its hardships. Among these were Crozier and Gore, who, the first in five and the last in two voyages, had sailed into both the ice-packs of northern seas and among the wondrous ice islands of the antarctic world.

Sailing May 26, 1845, with one hundred and twenty-nine souls in the Erebus and the Terror, Franklin's ships were last seen by Captain Dennett, of the whaler Prince of Wales, on July 26, 1845. Then moored to an iceberg, they awaited an opening in the middle pack through which to cross Baffin Bay and enter Lancaster Sound.

Franklin's orders directed that from Cape Walker, Barrow Strait, he should "endeavor to penetrate to the southward and to the westward, in a course as direct to Bering Strait as the position and extent of the ice, or the existence of the land at present unknown, may admit."

His progress to the west being barred by heavy ice, he sailed up the open channel to the west of Cornwallis Land, reaching 77° N., the nearest approach to the north pole in the western hemisphere that had been reached in three centuries, and exceeded alone by Baffin in 1616, who sailed forty-five miles nearer. Returning to the southward, the squadron went into winter quarters at Beechey Island, 74° 42′ N., 91° 32′ W.

Knowing the virtue of labor, the captain set up an observatory on shore, built a workshop for sledge-making and for repairs, and surely must have tested the strength and spirit of his crews by journeys of exploration to the north and to the east. It is more than probable that the energy and experiences of this master of arctic exploration sent the flag of England far to the north of Wellington Channel.

Affairs looked dark the next spring, for three of the men had died, while the main floe of the straits was holding fast later than usual. As summer came on care was given to the making of a little garden, while the seaman's sense of order was seen in the decorative garden border made of scores of empty meat-cans in lieu of more fitting material.

They had built a canvas-covered stone hut, made wind-proof by having its cracks calked, sailor-fashion, by bunches of long, reddish mosses. This was the sleeping or rest room of the magnetic and other scientific observers, who cooked their simple meals in a stone fireplace built to the leeward of the main hut. Here with hunter's skill were roasted and served the sweet-meated arctic grouse savored with wild sorrel and scurvy grass from the near-by ravines.[2]