The Project Gutenberg EBook of The White Blackbird, by Hudson Douglas This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The White Blackbird Author: Hudson Douglas Release Date: March 8, 2012 [EBook #39066] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WHITE BLACKBIRD *** Produced by David Clarke, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1912

Copyright, 1912,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved, including those of translation into

foreign languages, including the Scandinavian

Published, September, 1912

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. SIMONDS & CO., BOSTON, U. S. A.

FOR

ISOBEL MY WIFE

AND

OUR DAUGHTER ISOBEL

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Tropical Discussion | 1 |

| II. | "Dutch Courage" | 11 |

| III. | El Farish | 18 |

| IV. | The Masque of Death | 28 |

| V. | Afloat and Ashore | 38 |

| VI. | Hobson's Choice | 51 |

| VII. | The White Blackbird | 64 |

| VIII. | Unmasked | 80 |

| IX. | An Overdraft on the Future | 91 |

| X. | The Goddess of Chance | 107 |

| XI. | A Fool and his Fortune | 119 |

| XII. | The Price of Freedom | 130 |

| XIII. | A Masterstroke | 143 |

| XIV. | "Sallie Harris" | 156 |

| XV. | The Law—and the Profits | 169 |

| XVI. | "Pleasures and Palaces" | 184 |

| XVII. | The Man in Possession | 195 |

| XVIII. | The Loser | 205 |

| XIX. | The Winner | 217 |

| XX. | Beggar-My-Neighbour | 232 |

| XXI. | The Jura Succession | 243 |

| XXII. | The Party of the First Part | 259 |

| XXIII. | A New Idea | 271 |

| XXIV. | By Right of Purchase | 280 |

| XXV. | The White Lady | 295 |

| XXVI. | A Matter of Life and Death | 306 |

| XXVII. | Debit and Credit | 320 |

| XXVIII. | Ishmael's Heritage | 332 |

| XXIX. | Pride's Price | 342 |

| XXX. | The Tenth Earl | 350 |

| XXXI. | "At the End of the Passage" | 358 |

"I'd far rather beg in the gutter than marry you, Jasper!" flashed the girl, at last goaded past all patience. Her clouded, indignant eyes expressed both contempt and aversion for the young man leaning over the deck-rail beside her.

He was still a young man as years go and in spite of the grey streaks in his dark hair, the crow's-feet above his cheek-bones; more than passably good-looking, too, with his regular profile and straight, spare, athletic figure, though his sleepy eyes were a trifle close-set and more than a trifle untrustworthy, though the black moustache he was twirling with a long, thin, almost womanish hand hid a cruel, selfish mouth.

In his smart white yachting-suit and panama, lounging over the sun-dried teak taffrail with his knees crossed, he seemed to be neither oppressed by the tropical heat nor impressed at all by anything that his companion could say.

"I'd far rather beg in the gutter," she repeated, as if to settle the matter. And the emphasis with which she spoke showed that she meant what she said.

"But—that doesn't make any difference, my dear Sallie," he once more answered, displaying his white, even teeth in a slight, amused smile. "You're going to marry me just the same. And you may as well make up your mind right away—that it will pay you best to be pleasant about it.

"Captain Dove has come to the point at last," he went on to explain condescendingly, in the same cool, careless, conversational tone, a tone which, however, could not quite hide the ugly determination behind it. "You've upset him for good and all this time. He's aching to get rid of you now. In fact, he's cursing himself that he didn't—when he might have made more out of the deal. And, anyhow, he's promised you to me."

The girl's slim, shapely body had suddenly stiffened. She started up and away from him with a gesture of blind repulsion. Her pure, proud, sensitive face showed the struggle that was going on in her mind—between fear and hope; quick fear that what he had just said might be true, slow hope that he had been lying to her again.

He had turned on one elbow with a lazy air of inexhaustible tolerance, that he might the more conveniently follow her with his greedy glance. He was apparently quite sure of himself—and her. At any rate, he was openly gloating over her beauty in her distress while she stood gazing in dire dismay about the shabby, unkempt little steamer which was all the home she had in the world, all the home she had ever had except for a few forgotten years of her childhood.

Its name, on a life-buoy triced to the rusty netting between the rails, was the Olive Branch, but its port of registry had been painted out. It rode deep although it was decked after the old-fashioned switchback design and had no cargo on board. Its squat, inconspicuous smokestack helped to give it a somewhat nefarious air.

About its ill-kept, untidy decks there were very few signs of life and none at all of luxury. Under a tattered canvas sun-screen on the fo'c'sle-head a ragged deck hand was on the look-out, his scorched face expressive of anything but contentment with his circumstances. He shifted frequently from one bare, blistered foot to the other; it was impossible to stand still for long, with the deck-plates as hot as any frying-pan on a brisk fire.

On the bridge, the officer of the watch was pacing to and fro. Every time he turned on his beat beneath the dirty, weather-worn awning he paused to dart a suspicious, expectant glance at the double hatchway which led to the crew's quarters, forward. The open wheel-house behind him was occupied only by the quartermaster on duty. The remainder of the watch on deck were nowhere visible.

Through the heat-haze to starboard the blurred outline of the low-lying African coast was dimly discernible. Seaward, ahead, and astern, the long, oily swell that the North-east Trades never reach blazed like molten metal under the almost vertical afternoon sun. Except for the lonely little grey steamer wallowing sluggishly northward through it, the world of water was empty to the horizon.

A poignant sense of her own no less forlorn plight there stirred the girl to glance round at her companion, as if in helpless appeal.

"You don't really mean—what you said, do you, Jasper?" she asked, with a very pitiful inflection in her low, musical voice.

"Every word," he answered her promptly. "If you don't believe me, go down and ask Captain Dove."

She turned away from him again, to hide the effect of his curt reply. But her drooping shoulders no doubt betrayed that to him. He pulled out a cigar-case and, having lighted a rank cheroot with languid deliberation, puffed that contemplatively.

"I will go down and ask Captain Dove," she said to herself at length, with tremulous courage, and was moving toward the companion-hatch when she heard from the other end of the ship a sudden ominous discord, a sound such as might have come from a nest of hornets about to swarm. There seemed to be something wrong forward; and she faced about again, instantly.

Peering through the hurtful sunshine with anxious eyes, her scarlet lips compressed and resolute, she saw that the look-out had turned on his half-baked feet to stare from the fo'c'sle into the well-deck behind him. The officer of the watch had ceased his regular march and countermarch, and was also gazing downward in that direction. Even her self-confident companion had started up from his idle posture, in obvious alarm.

A figure darted up one of the two ladders which led to the bridge. The officer of the watch had left his post by the other at the same moment, as if to avoid the new-comer, and was making his way aft, unhurriedly, yet at speed. He did not look back, but she was aware of other figures which also had appeared in a moment from nowhere, and were following him on tiptoe, under cover where it could be had. Once, a flash, as of flame, amidships, almost forced from her lips a wild cry of warning, but that was only a glint of sun on a gun-barrel where the browning had worn away and left the steel bright. And he, seemingly unaware of the danger behind him, reached the poop unharmed, a big, fair, bluff-looking, broad-shouldered man in shabby blue sea-uniform.

At the foot of the narrow stairway by which alone access could be had to the poop, he called softly up to the girl at the rail above, "They'll be at our throats in a minute, Sallie. Get you away below, quick—and warn the Old Man."

At the top of the steps he stopped, and turned, and stayed there, blocking the stairway with his great body. And the armed ruffians swarming aft in his wake slackened their pace, then hung back about the hatch on the deck below. But each had a finger crooked on the trigger of a ready rifle. The simplest word or motion misplaced at that first moment of crisis must have precipitated the murder that was to be.

The girl had obeyed him promptly, if without appearance of haste and, once out of sight of the mutineers, there was no need to study her steps. She darted across the dim, daintily appointed saloon below and, having knocked imperatively at one of the two doors on that side of the ship entered, without waiting for any permission, the stateroom it opened into.

"The men have broken out, Captain Dove," she cried, breathless a little, her bosom heaving. "They're coming aft—there isn't a moment to spare. What are we to do?"

In the berth behind the curtains some one was moving. The room was practically in darkness, since the open port was also screened, to shut out the searching sun. But, in spite of all such precautions, the heat was almost unbearable.

The curtains parted slightly and from their opening a face peered out at her, the blandly benevolent face of a mild-looking, white-haired old man who, at a casual glance, might perhaps have passed for a clergyman or a missionary.

But in an instant a most disconcerting change came over his features. Some dormant devil seemed to have wakened within him and was glaring out at the girl from behind evil, red-rimmed eyes. His appearance then might have frightened a man away. But she stood her ground undismayed.

No less suddenly he broke into a torrent of fierce abuse, freely interspersed with blood-curdling, old-fashioned oaths. And that was only stemmed by a frantic paroxysm of coughing which left a crimson froth about the white stubble upon his chin. He fell back into the gloom behind the curtains, as if he would choke.

The girl hurriedly filled a glass with water from a carafe on a rack at one side of the room, pulled the curtains apart, and held it to the sick man's lips. He sipped at it and then struck it away so that most of its contents spilled on her skirts.

"Would you poison me now, you witch!" he gasped, and then, regaining his voice a little, "Ambrizette," he called weakly, with a quavering imprecation, "brandy. Bring me the bottle. Your mistress has poisoned me."

A coloured woman, stunted, misshapen, almost inconceivably ugly, came shambling in with a bottle, which he snatched eagerly from her and set to his lips, while she made off again, in very evident dread of him. The colour came back to his face, and at last he laid it aside, with a sigh of relief.

"The men have broken out, have they?" he muttered, half to himself. "And you come to me to ask what's to be done!" He glowered down at one of his arms which lay across his chest in a sling and tightly bandaged. His voice once more became venomous. "It's your fault that I'm lying here," he snarled. "You and your bully Yoxall have taken charge of my ship between you. Why don't the two of you tackle them? What the Seven Stars d'ye think I care now whether you sink or swim!"

She turned away from him with a little, tired, hopeless gesture.

"I don't care very much, either, now," she answered, dully, "what happens to me. But—it's you they're after, Captain Dove, and there isn't a moment to spare. They've got the guns up already."

The old man was plucking with feverish fingers at the fine lace counterpane which covered him. He made an effort to rise, but lay back again with a groan.

"They've got the guns up, have they!" he growled, deep down in his throat, with a most horrid effect. "Then one of the mates at least must be standing in with them—the mutinous dogs! And since it's come to settling old scores, I'm ready; I'll settle all with them before we go any farther." His eyes were sunken with sickness and he was so weak that he could scarcely move, but his spirit seemed to be altogether unquenchable.

"I'm going to settle with them now," he declared, "and—don't you interfere again, Sallie. I've stood all I'm going to stand from you, too. You've got to fancy yourself far too much, my girl! Listen here! Next time I have to talk to you, it'll be with that,"—he pointed to a heavy kourbash of hippopotamus-hide hanging from a hook on the panelling,—"and, by all that's holy! if I've to begin, I'll lace you from head to heel with it—as I should have done long ago."

The girl shrank as if he had actually struck her with it. She knew he was even capable of carrying out that threat.

"Where's Jasper Slyne?" he demanded, in a low whisper, almost exhausted.

"On deck, above, with Reuben Yoxall," she told him.

"Send him down here to me. I must get up out o' this. To-day's Sunday, isn't it? What was our position at noon?"

She told him exactly, at once, and he seemed content to rely on her nautical knowledge. He nodded, as if satisfied.

"That's all right. Off you go now. And don't forget what I've said to you. Tell Slyne to look sharp—and stand the men off somehow till I get on deck," he snapped, as she hurried away.

She did not know what might have happened overhead while she had been below, and heaved a heartfelt sigh of relief as, gaining the open air again, she saw that the two men she had left there were still at the rail, unharmed. Only one of them looked round as she approached, and it was to him she spoke.

"Captain Dove wants you in a hurry, Jasper," she said, and he went below in his turn, not altogether unwillingly.

As he disappeared behind her, she glanced down at the main-deck alive with armed men, as evil-looking a crowd as could be recruited from the purlieus of Hell's Kitchen or crimped from the Hole-in-the-Wall. The flush on her face died away.

"What are they waiting for, Rube?" she whispered to the big man at the top of the steps, whose steady glance seemed to have such a repressive effect on them.

"Sunset, I suppose," he answered in a low tone. "If no one crosses them, they'll maybe wait till it's dark before they begin. Better go below again, Sallie."

She shook her head and said "No," aloud, since he was not looking at her. And he did not urge that precaution. The sun was already nearing the steamy horizon.

The sullen, lowering looks of the ill-favoured assemblage about the hatch foretold the fate which threatened her and him.

"But they won't shoot you, Sallie," he said, giving voice to his only fear in a shaky whisper, his soul in his honest eyes as he glanced wretchedly round at her.

She laid a clenched hand on the rail and opened it slightly. "Don't worry about me, Rube," she whispered back, very matter of fact, while he gazed as if fascinated at the thin blue phial, with its red danger-label, resting in her rosy palm. "I always carry a key that will unlock the last gate of all. So there's no need to worry about me. I just wish you'd say you forgive me all the trouble I've brought on you."

"There's nothing to forgive, lass," he asserted stolidly, and, looking away again as though her appealing regard had hurt him, was taken with a gulping in the throat.

Two or three of the mutineers had begun to knock loose the wedges securing the tarpaulin cover of the after-hatch, through which alone access to the ship's magazine was to be had.

"There's no use in trying to stop them at that," he said, as if to himself. "It's only a matter of minutes now, I suppose. And—"

"Dutch courage is cheap enough," said a contemptuous, sneering voice in the background, and the sound of shuffling footsteps succeeded it. The men on the main-deck were gazing past him, handling their rifles, muttering hoarsely, moving to get more elbow-room. The girl beside him had turned at the words, but he kept his eyes steadfastly on the foremost of the fermenting, murderous rabble below.

Captain Dove had come up on deck, and was standing by the companion-hatch, drawing difficult breaths, swaying to the rise and sink of the ship on the long, slow, ceaseless swell.

He had only a greatcoat secured by a single button about his shoulders over his night-dress, and on his feet an old pair of carpet slippers. Sallie darted a blazing glance of indignation at Jasper Slyne who, instead of helping the sick old man, seemed only bent on aggravating him with his evil tongue.

"You coward!" she cried at that immaculate gentleman, and would have gone to the old man's aid but that he angrily waved her also aside as he tottered forward, changing his scowl by the way to that sleek, benevolent smile which he could always assume at his pleasure.

A slow silence followed on the low, suspicious rumble of voices with which the mutineers had greeted his most unexpected appearance. They had, of course, supposed him physically incapable of further interference with them and their plans. But, as it was, he did not look very dangerous in his grotesque dishabille.

As he reached the rail, Reuben Yoxall stepped to one side, touching his cap in his customary salute. Slyne had halted a couple of paces behind, and Sallie, too, had drawn back. Captain Dove stood alone at the top of the stairway, in the forefront of the little group there, and looked contemplatively down at the men who, he knew very well, would listen to no appeal of his for his life. From his placid, benign demeanour then he might have been inspecting a Sunday-school.

His features were in themselves of an unctuous cast, smooth, flat, snub-nosed, clean-shaven as a rule, except for a straggling fringe of whisker. His white hair and weak, winking eyes added to his smugly sanctimonious expression. He was squat of build, unduly short in the legs and long of arm. And, altogether, he cut no very dashing figure in his ridiculous garments, one sleeve of his coat hanging limp and empty, the arm that should have filled it lying across his chest in a sling, his chin disfigured by a week's growth of stubble, his whiskers all unkempt.

But it had never been by his gallant presence that he had held to heel the cut-throats who composed his crew, and, even then, when they had him before them helpless, a certain target for their loaded rifles, not one of them seized the immediate opportunity.

He steadied himself with his free hand on the rail of the narrow stairway, and so stepped downward among them. Still no one else moved. It may have been that his almost inhuman daring daunted them in spite of themselves. But Sallie, in the background, was holding her breath. She knew he was courting a bloody death, and feared he would meet it there, before her shrinking eyes. That tragedy and all its unspeakable consequences were literally hanging on a hair-trigger.

He reached the level below, still smiling blandly, and, letting go the rail, shuffled forward, slowly but steadily enough, his slippers flapping at his heels with ludicrous effect. Two or three of the men confronting him stepped to one side, gave him free passage into the throng, and closed in again behind him. He took no notice of anyone, but held on his way till he reached the ladder which led from the break of the poop to the quarter-deck.

He climbed that at his leisure, panting a little, his back toward them. They had faced about and were following his every movement with malevolent eyes. A single shot would have made a quick end of him, but no shot was fired. And, at the top of the ladder, he turned to speak.

"I'll send Mr. Hobson aft to issue your ammunition," he said, in a voice without any tremor of weakness. "Get two full bandoliers, each of you, and then file forward again while the others come aft for theirs."

And with that, leaving them to their own reflections, agape, absolutely dumfounded by his audacity, he made his way up on to the bridge, the skirts of his night-dress fluttering from under the shorter length of his heavy coat.

They fell to whispering among themselves, excited and distrustful. They had only a few loose rounds for their rifles, and Captain Dove alone knew how the ship's magazine might safely be entered. It would undoubtedly have cost some of them their lives to force that secret. No one of them would be willing to sacrifice himself for the common cause, and Captain Dove's unlooked-for concession of their chief need had no doubt mystified them altogether.

Hobson, the second mate, came aft a few minutes later, a beetle-browed, foxy-looking fellow, with a furtive smile of encouragement for his accomplices. At a sign from him they unshipped the hatches. He disappeared into the hold, a bunch of keys dangling from one wrist, and presently shouted up some order, in terms much more polite than he had lately been in the habit of using, to them at least. A chain of living links was promptly formed from the magazine, and packed bandoliers, passed rapidly from hand to hand, soon reached its farther end. The men grinned meaningly at each other as they slung the web belts crosswise over their shoulders. For with these they were still more absolutely masters of the situation.

Reuben Yoxall, back at his dangerous post by the stairway, was watching them no less narrowly than before. It seemed the sheerest madness on Captain Dove's part to have disclosed to their ringleader the secret of the magazine, and no one could tell at what moment they might now assume the offensive. The sun was already dipping behind the sea-rim.

"We've changed our course," Sallie said to him in a puzzled whisper, and he nodded silently. The Olive Branch was heading inshore. The outline of the coast had grown clearer under the last of the evening light. Here and there against its smudgy-brown background showed dark green blots that were mangroves or clumps of palm. A thin, white ribbon of surf was distinctly visible on the distant beach.

Captain Dove was at the starboard extremity of the bridge, his binoculars at his eyes. He laid them down, and pointed out to the third mate, at his elbow, some landmark directly ahead. Then he climbed carefully down to the quarter-deck and began to make his way aft again. Behind him, rifles in hand, came creeping another strong contingent of his strangely numerous crew. Half a dozen of those nearest him had drawn and fixed the long sword-bayonet each wore at his hip.

The old man in greatcoat and slippers paused at the after-rail of the quarter-deck. The bayonets were almost at his shoulder blades. But the three anxious onlookers aft could not even warn him of that additional danger, to which he seemed quite oblivious.

The crowd at the open hatch looked round at him, as of one accord, and the bulk turned on their heels towards him, but a few remained facing the three still, silent figures on the poop. Sunset and the final instant of crisis had come together.

From among the men grouped about the hatch one stepped forward, as if to speak. Captain Dove held up his hand and the fellow hesitated, with bent brows. A quick, angry growl arose from among his neighbours. But Captain Dove was not to be hurried. He cleared his throat and spat indifferently into the scuppers.

"I've a little job ashore for you lads to-night," he said then, in a tone audible to all, "a job that'll fill our empty pockets properly—if it's properly carried out. We haven't been so lucky of late that we can afford to lay off just yet. What money there is on board means no more than a few dollars apiece, share and share alike. I know where I can lay my hands on a thousand at least for each of us. If you think that's worth your while, get away forward now to your supper; the others are coming aft for their ammunition."

He ceased abruptly, and for a moment no one answered him or made any move. He had succeeded in raising their curiosity, and so gained some trifling respite at least for himself. They were turning over in their dense minds, however suspiciously, this new and plausible suggestion of his.

It was no news that there was very little money on board, and—they were of a class which always can be led to grasp at the shadow if that looks larger to them than the substance itself. They hesitated—and they were lost. Captain Dove had descended among them, and as if the subject were closed, was pushing his way through the gathering with a good-humoured, masterful, "Get forward. Get away forward, now."

And they gave way again before him, apparently forgetful of their purpose there, quite willing, since they held the power securely in their own hands, to await the outcome of one more night. In the morning, and rich, as he promised, or no worse off if his promise failed, they could just as conveniently close their account with him. As the others came crowding aft, those already possessed of bandoliers began to file forward, exchanging rough jokes with their fellows.

Captain Dove addressed a parting remark to them from the poop. "We won't be going ashore till midnight," said he, "and I must get some sleep or I won't be fit for the work we've to do there. I'm sick enough as it is. Get that hatch-cover on again as soon as you can, and keep to your own end of the ship till the time comes. I'll send you forward a hogshead of rum to help it along."

"Ay, ay, sir," a voice answered him cheerily from out of the gathering darkness, and Sallie saw that he almost smiled to himself as he staggered toward the companion-hatch.

There he would have fallen, spent, but that she, at his shoulder, caught hold of him and held him up till Slyne came to her assistance. And they together got him safely below.

"Gimme brandy," he gasped, as he lay limply back in the chair on which they had set him. His lips were white. His overworked heart had almost failed him under the strain he had put on it.

The stimulant still served its purpose, however. He sat up again, revived.

"But that was an uncommon close call!" he commented, half to himself. "I felt blind-sure I'd have a bayonet through my back before I could play my last card. And I didn't believe I'd win out even with that. But here I am, and—" He turned to the girl at his side.

"Don't stand there idling, Sallie," he ordered querulously, "when there's so much to be done. Tell Ambrizette to bring me a bull's-eye lantern. Go up and see if the decks are clear yet. Send Reuben Yoxall down to me as soon as they are. And then get ready for going ashore. You'll have to wear something that won't be seen—but take a couple of Arab cloaks in a bundle with you as well."

At that Jasper Slyne spoke, divided between doubt and anger.

"What devilment have you in your mind now, Dove?" he demanded. "You surely don't mean to—You told me yourself that there's nothing but dangerous desert ashore here."

"Never you mind what I mean to do, Mister Slyne," Captain Dove answered him with a gratified grin, picking up the brandy bottle again. "When I want any advice from you, I'll let you know. And, if I ever ask you again to help me into my clothes, you'll maybe be more obliging next time.

"Dutch courage is cheap enough, Mister Slyne," said the old man tauntingly. "So I'm going ashore,—into the dangerous desert,—in a few minutes, with Sallie. But there's nothing you need be afraid of, for you're going to stay safe on board."

On the stealthy-looking little grey steamship at anchor under the obscure stars not even a riding-light was visible. But she was close to the desolate coast, well out of the way of all respectable traffic. And a solitary figure, squatted in the bows, pipe in mouth, pannikin of rum within easy reach, was keeping a perfunctory anchor-watch, staring idly seaward so that he saw nothing of a tiny light which flashed three times from the shore in belated response to a similar signal from a screened port in the poop-cabin.

But for him, the decks were deserted. From the crew's quarters came frequent outbursts of ribald talk and uproarious laughter, the odour of food, the clank and clatter of tin-ware empty or full. The crew were at supper and satisfied for the present.

From the companion-hatch on the poop four soundless shadows emerged. Two of them were carrying cautiously a long, flat fabric which they in a moment or two converted into a fourteen-foot canvas boat. These two lowered that overside. One of the others, a bundle in hand, slipped easily down into it by means of a rope made fast to a stanchion. The last, cursing under his breath, was helped over the rail, with one foot in a loop of the same line, by the two remaining on deck.

Sallie, safely seated in the cockleshell below, laid a pair of muffled oars in the rowlocks and pushed quietly off from under the dripping overhang of the ship. Captain Dove, crouching in its stern, whispered curt directions to her. She could just see Reuben Yoxall and Jasper Slyne standing side by side at the steamer's taffrail, and then the black bulk of the Olive Branch became merged in the blacker water.

Once out of earshot of the ship, she set to rowing in earnest, a strong, steady stroke, like one well accustomed to that exercise; and Captain Dove, with an eye cocked at a helpful star twinkling dimly through the heat-haze, kept her heading straight for the shore. The boom of the breakers soon began to grow louder, but, even when it had become almost deafening, she did not look round. They had got into broken water and it was taking her all her time to handle the oars.

She was breathless and all but exhausted before they at length shot dizzily out of the wild turmoil of the surf into a tranquil, land-locked lagoon, concealed from seaward by a long sand-spit, which served it as a breakwater in such smooth weather.

"Way enough," said the old man gruffly, and, as Sallie shipped her oars, the light craft lost speed. Presently, its prow took the sand, and at last they were free of the ominous, phosphorescent black fins which had followed them from where they had left the ship.

"Strike a match," ordered Captain Dove, and held out a stump of candle. "Light this and stick it on the gunwale. Now, on with your cloak and hood—and lend me a hand with mine."

The tiny flame at her elbow burned steadily enough in the still night, while Sallie was slipping on over her dark dress the white robe he had bidden her bring with her. As soon as she had hooded her head and drawn the veil well over her features, she turned to help him. She was smoothing the crumpled burnous about his shoulders while he tugged irritably at it with his only available hand, grumbling at her in a low monotone, when she heard a sudden splashing behind her and, glancing round, saw a number of other white-robed figures wading out through the shallows towards the boat and its flickering light. Captain Dove took their coming as a matter of course, and she sat down again silently, though that cost her a great effort. It was unspeakably eerie there, in the very heart of a darkness that seemed to be whispering hints of such horrors as only exist in the dark.

The old man exchanged a few low words in doggerel Arabic with the strangers. Two of them, tall, brown, fierce-faced fellows, slung over their shoulders the long guns with which they were armed, stooped and lifted Sallie lightly up, carried her to the shore dry-shod. She was still shivering nervously when two more deposited Captain Dove at her side, and then the canvas boat was brought high and dry. At a curt remark from him a makeshift litter was formed of four rifles and, seated on that, he was carried away as if he had been a mere featherweight, Sallie following close behind on foot, uncomfortably conscious of the shadows at her own shoulders.

It was hard work for her in the darkness and ankle-deep in the soft, loose sand at every step, although his bearers made little enough of their burden. But farther on the footing grew firmer, and then they came to a rough, trodden path.

That led them to the still darker mouth of a narrow defile between two low, rocky bluffs, and from the summit of one of these there suddenly rang a harsh challenge. It was answered at once by their escort, and they went on without pause through that pitch-black, crooked passage with its invisible, whispering guard, until, emerging at an unexpected turn from its landward outlet, a most astonishing panorama presented itself to the girl's startled eyes.

Within a titanic natural amphitheatre formed by the rock-ridge which, except for the cleft they had entered by, enclosed it completely, there had been pitched an encampment that occupied its entire arena. Everywhere there were dry desert fires, burning redly, with little flame, and the vault of heaven overhead was like some vast crimson dome reflecting a light whose effect was weird and unreal to the last degree. Sallie, gazing about her with lips a little apart behind her veil, could scarcely convince herself that she was not dreaming.

In the foreground, on one side of the wide way which led straight to the heart of the camp, there were picketed rows upon rows of whinnying horses, and on the other almost as many restless mehari camels, among which a number of negroes, presumably slaves, were briskly at work. Past these was a wide, open space, at whose other edge stood a flagpole from which a great green flag with a golden harp on it fluttered and flapped in the red firelight on the first of the evening breeze. Under that was a group of men, all in flowing garments, one seated in state, the others standing about him. A dozen paces behind them a white pavilion that seemed rose-pink, with a heavily curtained porch, occupied a roomy, level expanse by itself. Surrounding and encircling it on three sides, but at a respectful distance, stretching as far back as the foot of the steep rock-rampart which hemmed them in, was ranged an orderly assemblage of horsehair tents, whose inhabitants, loose-robed men, swart women, and half-naked children, were all very busy about them in the open air. Everywhere there was life and bustle....

Beneath the searching rays of the sun it would all, no doubt, have appeared travel-stained and sordid and tawdry to a degree. But the desert night and the dim stars brooding above it had imbued it with all their own magic and mystery.

Captain Dove's carriers strode forward with him and set him carefully on his feet before the green flag, under which, on a great gilt chair, sat one who was evidently their chief, a man in the very prime of life and still younger yet than his years. Sallie eyed him over her veil with anxious interest. The group behind his chair was regarding her with no less curiosity. The attention of the multitude among the tents had been attracted to the new arrivals, and many inquisitive onlookers, more women than men, were beginning to gather about the boundaries of the area sacred to their Emir and his officers.

That dignitary got hastily up and came forward. He was tall and stalwart on foot, a fine figure of a man even in his loose, shapeless garments, with a bronzed, hook-nosed, handsome face of his own, a heavy moustache, the brooding, patient, predatory eyes of a desert vulture. And, as he confronted Captain Dove, over whom he seemed to tower threateningly, the hood of the selham slipped on to his shoulders, disclosing a flaming shock of red hair.

"At last!" he said, after a long time, in the difficult voice of one amazed almost beyond words. The muscles of his lean, brown face were working visibly. His eyes had become inflamed, his fingers were twitching.

"At last!" he said again, as if finally convinced in spite of himself, and licked his lips.

But Captain Dove met his wickedest glance unwinkingly, and made him no answer at all.

For a moment longer they two stood gazing thus at each other, the onlookers silent and still. And then the big man's blazing eyes shifted to the face of the girl at Captain Dove's elbow. Sallie's veil had slipped to her chin, but she had been unconscious of that till then. She pulled it up across the bridge of her nose again hastily. The red-haired Emir's scowl had relaxed; he was scanning her with a very different expression to that he had shown Captain Dove, but one which alarmed her no less.

He turned to the group behind him and, at a word, it melted away. The onlookers in the distance also went about their own business again. A black slave-boy came staggering forward with a heavy chair, and set that down side by side with the other there. Captain Dove seated himself at once, without ceremony.

The Emir, biting his lip, followed suit, and sat for a time sunk in his own reflections. He seemed to have mastered for the moment his first almost overwhelming impulse at sight of that venerable-looking adventurer, and had evidently some other and much more pleasant idea in his mind.

"That's a high-stepping filly you've brought with you," said he at length in a puzzled tone, and glanced round at Sallie again. She was standing at Captain Dove's other shoulder, her head bent, her hands clasped before her, in helpless, patient suspense. Captain Dove had gruffly informed her, before they had left the ship, that she would be perfectly safe in his company, but even his own safety seemed to be hanging on a very slender thread.

"I wonder, now," the Emir went on, "if it's to seek trade that you've come ashore here again—after all these years." His face once more darkened, as if over some recollection that rankled sorely, but which he was doing his best to dismiss from his thoughts in the meantime.

"I've some trifles in hand that might interest you if it is trade you're after," said he, speaking amicably with an effort, "such truck as gold-dust, and jewels, and silk—and ivory, too, galore."

The black boy had come back with an unwieldy tray of a dull yellow metal on which were set two cool, moist, earthenware chatties and a couple of uncouth drinking-cups. Captain Dove, with unerring instinct, laid his hand on the flagon which held strong drink, poured out for himself a liberal helping of the sticky magia it contained, and swallowed that off without a word. After the Emir had also helped himself the boy would have carried the tray away, but Captain Dove bade him set it down and dealt him an indignant cuff, so that he fled empty-handed, with an anguished yelp.

"It wasn't exactly to pay you a polite call that I came ashore to this God-forsaken hole, Farish," the old man at last remarked, with uncompromising frankness. "The fact of the matter is—I'm in a bit of a bog just now. And I've come to get you to give me a hand out of it—if your price isn't too high for me to pay."

The Emir stared at him, open-mouthed.

"You were always the bold one, Captain Brown," said he, reminiscently, after a lengthy interval, "but this beats all! And it's to the man you set ashore here, alone, long years ago, to die in the desert like a mad dog, that you come demanding a hand to get you out of a bit of a bog! You've surely forgotten—"

"I'm not one who forgets," Captain Dove interrupted sourly. "And you'll maybe remember, since you think it's worth while to hark back to such old stories, that I didn't shoot you down at once, as I might have done—for disobedience of orders. I gave you a chance for your life, anyhow. And you've made a very good thing out of it. You've risen in the world, Farish, since you were the second mate of the old Fer de Lance—and I was Captain John Bunyan Brown. I'm Captain Dove now, by the way."

"And how did you know who it was would be here to-night?" the soi-disant Emir demanded, turning it all over in his own mind.

"The Spaniards at the Rio de Oro told me, when I called in there the other day, that they were expecting the Emir El Farish shortly, from this direction, and, of course, I pricked up my ears at the name. I asked a few simple questions about him, and it didn't take a great deal of brain-power to figure out that the famous Emir was just my old second mate turned land pirate on his own account. They wanted me to wait on the chance of a cargo from your caravan, but—I had other fish to fry at the time.

"Then, coming up the coast, I caught sight of your smoke from the steamer's bridge—at least I judged it would be yours. I reckoned you'd be camping here, you see, and, when you answered my signal, I was quite sure. So—I'm in a bit of a bog, as I told you. And it'll pay you to give me a hand out of it—if your price isn't too high."

"The price that you'll have to pay for my help you can guess now without my telling you," returned the Emir in a muffled whisper, and nodded meaningly over his shoulder. "And you'll find me a fair man to deal with, so long as you deal fairly by me."

Captain Dove signified his comprehension by means of a non-committal grunt. He stooped down and helped himself awkwardly to another drink before making any other answer.

"But—you've got a wife already," he whispered back, at a shrewd guess, as he sat up again, smiling blandly.

"I won't have her long, poor thing!" said the other, some tinge of real regret in his tone. "And I'll miss her, too, when she's gone, let me tell you." He sat silent for a moment, musing, and then, "'Twas a notable revenge that I took on them-all!" he muttered darkly. "But I'll miss her for herself as well—after all these years."

"It's the desert has killed her," he said, pulling at his moustache. "I've had a doctor-fellow with her for a while past—I saved him out of an exploring party we cut up near Jebado. 'Twas nearly three weeks ago he told me she hadn't a month to live. The sand's got into her lungs, he says—and I've promised to shovel him into a sand-pit alive the day she dies, to see how he likes the sand in his own lungs, the useless scum!"

He sighed stormily, and then seemed to bethink himself again of the girl listening behind. In answer to a call of his, in a caressing voice, there came from the big tent in the background a woman, veiled as Sallie was but clad in silk instead of cotton, who bowed submissively to what he had to say to her and then held out a slender, bloodless, burning hand to Sallie.

"Go with her," ordered Captain Dove. "You'll be all right. I'll shout for you when I want you again."

And Sallie, glad so to escape from the Emir's glance, went willingly enough. It would not have helped her in any way then to disobey Captain Dove. But her hand, within the other woman's, was as cold as ice.

They passed together through the curtained porch of the pavilion, and Sallie looked about her with blinking eyes as the Emir's wife led her toward a long, low, cushioned divan, with a tall screen of black carved ebony behind it, which stood in one of the corners formed by the partitions within.

The entire interior of the tent was brilliantly lighted by many lamps of a dull yellow metal, swung from under the billowy silken ceiling. Underfoot were carpets and rugs of the most costly, chosen with taste. The inner divisions seemed almost solid behind their heavy hangings of embroidery and filigree work. About the couch in the corner were grouped a number of languorous women slaves, all very richly dressed. The whole effect was one of barbaric splendour and luxury.

Her women crossed their arms on their breasts and bowed before the Emir's wife, their golden bangles jingling. She drew Sallie down on the couch beside her and waved them away. They backed into another corner with heads still bent, but stealing furtive glances at the fair stranger. Sallie had let her veil fall; the heat was stifling.

The Emir's wife laid a hand on her heart and panted, as if she had been running. A hectic flush had coloured her sunken cheeks. Sallie saw that she must once have been a very good-looking girl.

"How did you come to our camp?" she asked, suppressing with a great effort the cough her labouring chest could scarcely contain. "Is there another caravan near, or—a ship?"

"A ship," Sallie answered gently, forgetting all her own urgent troubles in quick compassion for that poor soul. And the dying girl's feverish eyes grew suddenly eager.

"A ship!" she repeated breathlessly, and for a moment or two seemed to be searching Sallie's expressively pitiful features for some further information, which she found there. The anxiety in her eyes changed to appeal, and then certainty.

"You'll help—me," she whispered. "I know you will." And she began to cough.

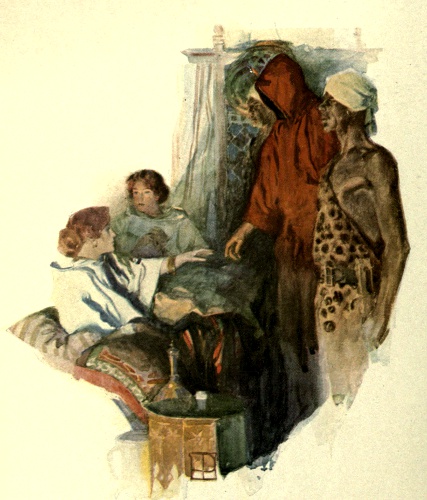

Two or three of her women came running forward to offer her such first aid as lay in their power. Another had hurried off through a curtained doorway which led inward, and promptly returned, followed by two enormous negroes, vile-looking rascals, each wearing a scanty tunic of leopard-skins which hung from one shoulder and did not reach to his knees, with a broad waist-belt which also served to contain a short, heavy scimitar, in a metal scabbard. Between them walked a man, a white man to judge by his hands, since his head was completely masked in a hood of coarse scarlet cotton, with only a couple of careless eyelet-holes and a rough round mouth cut in it. He was dressed in a worn drill tunic and riding-breeches and pigskin puttees, and carried himself, a thin, limber, muscular figure, with careless ease.

Sallie took him to be that doctor of whom the Emir had spoken, and shuddered at thought of the dreadful death with which the Emir had threatened him. His guards' cruel faces grew still more watchful and grim as he hastened, limping a little, toward the couch, while they were still saluting its occupant.

Sallie had risen from it and was standing with one arm about the other girl's heaving shoulders, adjusting her veil. The cough had ceased again, but its victim had not yet recovered her voice. The man in the mask glanced most unhappily at her and then at Sallie. But it was not concern on his own account that his steady grey eyes expressed.

He was about to speak, when the Emir's wife held up a thin, transparent hand. "Wait," she begged weakly. "There is so little time—and my strength—"

He pulled a glass tube from one of his pockets and gave her a tabloid. She swallowed it down, with a mouthful of water, indifferently, but it soon did her good. She signed her women aside, and looked imploringly up at Sallie.

"I can't live through another night," she said, "and—neither will this man, unless you help me to help him. You will do that, won't you? He's an Englishman—a doctor—he has done all he possibly could for me—and I cannot die while I know that his life hangs on mine. It's too horrible—"

Sallie sat down again and clasped the wasted, writhing body closely to her in her strong, young arms.

"I'll do all I possibly can to help him," she promised in a quick whisper. The grey eyes behind the horrible scarlet hood had seemed to say that they would not hold her responsible for any promise given to lighten that poor creature's last hours. And the Emir's wife lay back against her shoulder with an exhausted sob of relief.

"I'm really an American," said a pleasant and very grateful voice from behind the mask which was gazing down at them so inscrutably now, "and no doctor at all." He was speaking to Sallie; the Emir's wife was still gasping for breath. "But—you can see for yourself how very harmful this nervous excitement must be to her."

"We must humour her—whatever may happen," his glance seemed to add, and Sallie nodded in quick understanding and sympathy.

She had been wondering what she, so helpless and uncertain herself, could possibly do to reassure the dying girl and help the man who was doomed.

"If I could get back on board the ship," she said somewhat uncertainly, in answer to the appealing look with which the Emir's wife was once more regarding her, "I would bring or send a boat ashore—"

The other girl's wan face displayed renewed life and animation.

"Soon after midnight," she whispered eagerly. "You must give me till then to do my part. But soon after midnight he will be waiting beyond the outermost of the guards at the shore-end of the ravine which leads from our camp. He'll be wearing that woman's cloak and veil, and carrying a bucket—I sometimes send her to the beach for sea-water to bathe my feet." She pointed to one of her slaves, but at that the man in the mask intervened.

"I couldn't do that. Your husband would—"

She held up a hand again, and he said no more, only shaking his head. He seemed to have forgotten that she was not to be contradicted.

"The woman is mine," said the Emir's wife, "and my husband will not hurt a hair of her head while she obeys me. He has sworn that on the Cross. He will keep his oath—and you have my word as well that she shall come to no harm. You need have no scruples, then!"

She looked impatiently up at the scarlet mask bending over her, not to be satisfied until it bowed in submission to her authority there. But Sallie could read in the steadfast grey eyes behind it a dumb determination that the slave girl should run no such risk, and she did not think it needful at that moment to say anything about the other difficulties to be overcome. She had promised that she would do all she possibly could to help the man in the mask, and believed she could help him best in the meantime by keeping her own troubles to herself.

She did not even know as yet what Captain Dove's immediate intentions toward her were, or whether she herself would ever see the Olive Branch again. But—she would know before very long, and it would be time enough then to explain her own plight.

"Feel my pulse now, before you go," the pseudo-doctor's patient commanded, and he did so, drawing out his watch, while she continued to plan for his flight.

"I'll send for you again before midnight," she said rapidly, for his guards had begun to show signs of unrest as his visit grew more prolonged, "and you must bring your—your—" She tapped her chest, very tenderly, with her free hand.

"Stethoscope?" he suggested, and she nodded quickly.

"You'll come in your cloak—it will be cold then. My women will draw a screen about us. As soon as you are safely behind it, slip off your shoes and gaiters while they are changing your cloak and hood. There will not be a moment to spare. And now—you must go."

He released her wrist and stood upright again.

"I shall come whenever you send for me, of course," he assured her soothingly, although his eyes, meeting Sallie's for an instant, betrayed the stubborn will behind them. "And I'm far more grateful than I can express for your good-will toward me. So now you'll rest quietly, won't you? And try not to worry needlessly about—anything at all. You're not afraid, I know. And neither am I."

He bowed to them both in his hideous hood, and went back to his scowling guards.

The Emir's dying wife lay very quietly in Sallie's arms for some time after he had gone. She was quite exhausted again. Her women, in a group at a little distance, were watching with jealous eyes the fair stranger who had supplanted them with such ease. The only sounds that broke the silence were the sick girl's laboured breathing, the occasional hoarse, angry rumble of Captain Dove's voice outside. Sallie was listening anxiously for that. She could hear no word of what he said, but—she wanted to be quite sure that he was still there. It was not her own fate alone that now depended on what these strangely dragging minutes should bring to pass.

"Lay me back on the cushions now," begged the girl in her arms. "I feel better—in every way. And—tell me how you came here, in the nick of time. I'm so thankful—but you know that, and I mustn't talk too much, I have so little strength left, and—

"Who is that shouting?"

"It's Captain Dove," Sallie answered in haste. "He brought me here. I must go to him now, but I'll come back before—" She had no time to say more, for Captain Dove had called her again, in a very angry voice.

He was shaking his only available fist impotently at the high heavens when she stepped timidly out from under the curtained porch of the tent.

She hesitated, but for no more than a moment, and then, drawing her veil closer, went on across the sand, with beating heart.

"You called me, Captain Dove?" she said, as she stopped at the old man's shoulder. And he ceased blaspheming to glare round at her as though she had been some intrusive stranger, his face very puffed and repulsive in the red firelight.

He did not answer at once, but reached again for the earthenware flagon. It was lying on its side empty, for she had tipped it over with a stealthy foot.

His angry glance grew darker with suspicion, but her eyes were downcast.

"Come round in front," he ordered harshly, and she had once more to submit herself to the Emir's appraising glance.

He and Captain Dove had still much to say to each other, too, while she stood patiently there, like a slave for sale. They fell to arguing with much heat some point in dispute between them, an argument she could not follow since they were speaking some jargon of Arabic strange to her. But she knew very well that it was about her they were wrangling, and a cold fear clutched cruelly at her heart.

At last, however, the Emir appeared to give in to his visitor, and Captain Dove, after a final ineffectual snatch at the flagon, got on to his feet, since even that hint seemed to be thrown away on his host.

"We'll get off to the ship again," he said in English, and Sallie could almost have cried aloud in relief from such sore suspense.

"May I go back to the tent—just for a minute—to say good-bye?" she begged in a breathless whisper, and turned and ran.

The Emir's wife glanced eagerly up at her as she reappeared.

"I'm going back on board now," Sallie told her with shining eyes, which suddenly grew dim as she thought of the other girl's loneliness there. She sank on her knees beside the couch, and the Emir's wife, leaning forward, slipped a frail arm about her neck; and so they two, sisters in trouble, kissed each other good-bye for all time.

"You'll be sure to send the boat—soon after midnight?" the other asked, but with no shadow of doubt in her low, weak tones.

"I'll come myself, if I possibly can," Sallie promised, "and, if not, I'll send a safe friend—soon after midnight."

As she was rising, she saw on her bosom a little locket which hung from a thin gold chain. She lifted a hand to it, and hesitated uncertainly.

"It's all I have in the world that's my own," said the Emir's wife in a pleading whisper, "all I can offer you but my empty thanks. I'd like to think to-night that you will sometimes remember me. Will you not keep it, for my sake?"

"I'll wear it always—I'll never forget you—and oh! I'm so sorry that I must go," cried Sallie, sorely distressed, and had to hurry away without more words. Captain Dove had twice called her. There were tears in her eyes as she ran back across the sand to where, under the green flag, he was wrathfully waiting for her, and she scarcely heard his harsh order to hurry up.

Some of the Emir's men had come forward with a couple of litters. She seated herself in one, although she would much rather have walked, and, as soon as Captain Dove was ready, they were carried off, the Emir shouting a valedictory message to the old man.

"You keep your bargain and I'll keep mine," Captain Dove called back, and snorted contemptuously.

"That damned fellow talks to me as if I had been his second mate!" he commented, and snorted again.

From the mouth of the dark defile which led toward the shore, Sallie looked back over one shoulder, almost as an escaped prisoner might, at the bizarre, fantastic scene the still camp made in that strange crimson light. And the big, red-haired Emir standing motionless under his great green flag, whose fluttering folds seen from that distance seemed of the colour of blood, waved a hand to her ere she disappeared.

She shivered, instinctively. She had been dumbly afraid of the man, and that although she was possessed of a courage such as could look grim death itself in the empty eye-holes and smile. She was correspondingly thankful when, the gorge and its sentinels safely behind her, she found herself once more facing the open sea.

Captain Dove's carriers set him down alongside the boat, lying high and dry on the sands where they had left it. Having set it afloat, they lifted him carefully into it, and her also. A few shallow yards from the shore, she slipped off her white cloak and head-covering at an order from the old man, and so set to rowing again.

Once, one of her oars touched some invisible body swimming parallel with the boat, and a lightning-like flash of phosphorus showed a curved black fin that darted to a little distance and then turned back toward them. It was risky work crossing the bar, but both she and Captain Dove knew just what they were about, and presently they shot free of the surf into comparative safety.

"Starboard a little," he told her then, and ten or twelve minutes' pulling took them back to the Olive Branch, which he must have found by sheer instinct, since the ship was showing no lights.

They approached it almost soundlessly from astern, so that the sleepy look-out on the fo'c'sle-head neither heard nor saw them. For even the stars were invisible then through the curtain of vapour overhanging the coast.

Reuben Yoxall, the mate, was awaiting them at the poop-rail. He threw Sallie a line, and running to the companion-hatch, called Jasper Slyne up from the little saloon below. The two of them hoisted Captain Dove up the side, and after him Sallie, as light and agile as any boy. The canvas boat was easily got to the rail, folded flat and returned to its hiding-place.

Sallie stayed on deck, and Yoxall was not long in rejoining her there. Slyne and Captain Dove had sat down to a leisurely supper below. The plup! of a cork popping in the saloon broke the silence just before seven bells struck. They had half an hour yet till midnight.

"Who's that, Rube?—there, by the hatch," whispered Sallie, and pointed to where a pair of white eyeballs had been uncannily visible for a moment and then disappeared. She was nervous and overwrought in the midst of so many uncertainties.

Yoxall had stepped quickly in front of her. He caught sight of a shadow crawling away in the dark on the deck below.

"One of the niggers," he told her, and turned. "He's come scouting aft more than once while you were ashore. Most of the men are asleep, I suppose, but there are sure to be some standing guard—they won't run any risk of being caught napping by Captain Dove."

She fell into step with him again, and presently, pacing the poop at his side, slipped an arm into one of his. He shivered a little.

"Aren't you feeling all right?" she asked anxiously. "You're not going to have fever, are you?"

"No, lass," he answered at once. "Not much! I'm all right, of course. It would never do for me to fall sick now, would it?"

"It would be the last straw!" she agreed, and shivered also. For she was counting on him in case the worst should come to the worst.

"I don't know what I'd do without you, Rube," she said. And the big Englishman blushed like any boy as she peered up into his face. "You're the only real friend I have in the world. If it weren't for you—I'd be quite desperate; I'm so unhappy here now."

Reuben Yoxall pressed the arm that lay within his, and gulped. "Then why won't you come away out of it, Sallie?" he asked in a husky voice he could scarcely control. "It wouldn't be so very difficult—if Captain Dove just manages to keep the men in hand till we make some port. And we must call somewhere soon, for we're short of coal.

"I have some money laid by—I'll work harder than ever for you. There's a snug little farm in Cumberland that one of these days will be mine, and till then the old folk would make you and me more than welcome there." He was speaking very quickly, bent on making the most of that unusual opportunity.

"I'm not much of a man, I know," he went on, "but—such as I am, I'm yours. And I'll always be yours, to do whatever you like with. You might come to care more for me, Sallie, if you knew me better. Will you not try? Just give me the chance, and I'll soon have you safely out of the Old Man's clutches. But—so long as you insist on sticking to him, I can't do any more for you than I'm doing."

Her eyes grew dim as she thought of the dog-like devotion which he had shown her, although she had so often told him that she could never repay it as he would have liked.

"I wish I could, Rube," she assured him again, "but—I can't. I'm not ungrateful, and I hate to hurt you, but—I just can't. And you wouldn't want me to sell myself—even for a home and a husband, would you, Rube? I'll never marry anyone. Jasper Slyne says that Captain Dove's going to give me to him—but he doesn't know.... And—I'm not afraid."

Reuben Yoxall sighed, very softly. But she heard, and her own heart grew heavier. Life had become so difficult, and there was still so much to be done, so many troubles to think about, while she did not even know yet what Captain Dove was going to do next.

She had just finished telling Yoxall about the man in the scarlet mask and what she had promised to do for him, when sounds of stealthy bustle from forward told her that the mutineers were once more mustering on deck. She called down to Captain Dove, and he shortly came up from the saloon, followed by Jasper Slyne in a neutral-tinted, workmanlike semi-uniform, at whose belt hung a heavy-calibre Colt revolver.

Under the sharp spur of necessity, Captain Dove appeared to have quite overcome the physical weakness by which he had been oppressed. He stepped briskly to the stair-head rail and thence looked down on the shadowy, moving mass of armed men who had by that time gathered at the after-hatch again. Aware of his presence, they ceased to shuffle about. A tense silence ensued, and Captain Dove cleared his throat.

"Are all hands aft?" he asked sharply, and "Ay, ay, sir," a voice answered. "All hands but the engine-room crew. D'ye want them too?"

"I do not," he declared, and Sallie felt dumbly thankful that the engineers and their underlings were still, apparently, loyal to him.

"Where's Mr. Hobson—and the third mate?" he demanded, and, "Here," answered simultaneously two other very sullen, suspicious voices.

"Listen, then, all of you," ordered Captain Dove, bristling in the dark at that traitorous pair, and, raising his voice again, "I've got a fine plum ripe for your picking to-night, lads!" cried he at his heartiest. "There's a caravan camped ashore here, on its way to the Rio de Oro, with close on a hundred camel-loads of such things as silk and ivory—and jewels—and gold—and girls. I got a word of it from a friend of mine at the Rio when we were in there, and—now's our chance! You can see the flare of the camp-fires on the sky beyond the beach. I've been in here before and I know the place. If you follow me now as you've followed me in the past, I'll guarantee that you'll open your eyes at what's waiting for you ashore."

Slyne, safe in the background, listening, laughed furtively to himself.

"But—if you're going back on me now, I give it up. Strike a light and put a bullet through me right away, if you feel like that. I've only one hand—I won't lift even that against you. And my share of what little money there is on board you can divide among you."

A general murmur of approval greeted this blatant speech. And not even the two malcontent mates could pick any hole in that proposal. A faint crimson glow amid the darkness beyond the surf on the shore served to corroborate his statement in part. That he meant to accompany them was his strongest guarantee of good faith. They were evidently ready and willing, for such a prospect as he had held out to them, to follow him wherever he liked to lead them. The two mates began to tell the men off to the boats and get these swung outboard. A temporary atmosphere of peace and good-will prevailed.

Captain Dove turned to Reuben Yoxall. "You'll stay on board," he whispered very brusquely, "in charge of the ship. I'll tell the chief engineer to lend you two or three men, and you'll see to it that they don't lay their hands on any more guns.

"You'll stick by me," he told Slyne, in the background, and Slyne merely shrugged his shoulders impatiently as the old man passed on to where Sallie was waiting to hear what her part was to be. She did not know in the least what to make of his newly-declared intentions.

"Am I to go with you?" she asked on the spur of the moment. And Captain Dove stared at her.

"No, you are not," he declared emphatically. "D'you want to be shot—or kidnapped—or what! Get away down below, girl, and stay there till I come aboard again. You must be mad!"

She turned obediently toward the companion-hatch, and stopped there. He went forward then, the men making way for him readily, and disappeared into the engine-room. When he climbed carefully back on deck through the fiddley-hatch in the skylight, he found all the boats afloat and only one boat's crew remaining on board, under charge of the second mate, Hobson, with the evident aim of making sure that he did not somehow give them the slip or otherwise take any advantage of them. In response to a shout from him, Jasper Slyne went jauntily forward, and, with commendable promptitude, let himself down the falls overside. One of these, unhooked, served Captain Dove for a sling, and he was soon seated at the boat's tiller. The men followed swiftly, and the second mate went last, no doubt satisfied by then that all would be well.

"Give way, lads!" cried Captain Dove to those at the sweeps, "and we'll show the others the short road ashore. I'm in no end of a hurry to get what's coming to me from that caravan."

Midnight lay very black on the bight where the Olive Branch was riding easily to a single anchor; as the dark hours sped they seemed to grow always darker. The boats which had just put off from her were almost instantly hidden from Sallie's sight. She stepped quietly out on deck beside Reuben Yoxall.

"Rube," she said in a low, determined voice. "I must be going too, now. Will you help me to get out the canvas boat?"

He stared at her, as Captain Dove had done, and swallowed down a lump in his throat.

"It's madness now!" he declared. "But—I'll go myself. You must stay where you are. It would be worse than madness for you—"

She was smiling very gratefully up into his unhappy, stubborn face.

"We'll go together, Rube," she said, "or not at all. And, even although it does seem hopeless, I know you wouldn't want me to break my promise. So you get the boat launched while I go and tell Mr. Brasse."

She turned and ran lightly down the steps and along the main-deck, leaving the mate, sorely perturbed and uncertain, to carry out her instructions or not, as he chose. As she reached the engine-room skylight on the quarter-deck an unobtrusive shadow emerged from it and would have passed her with a nod on its way toward the bridge.

"Mr. Brasse," she said appealingly, and it halted to peer at her through a single eye-glass, after touching its cap in a very precise salute.

"Miss Sallie?" it answered in a surprised but courteous tone which told that the speaker was, or had once been, a gentleman.

"I'm going ashore," she went on in a hurry, "and Mr. Yoxall is going with me. Will you look after things for him until we get back? Every one else has gone already."

"I have Captain Dove's orders to be on the bridge—for another purpose," the chief engineer of the Olive Branch informed her, "and I'll do my best, of course, to make sure that nothing goes wrong in the chief mate's absence. But—is it safe for you—"

"Quite safe," she assured him. "And—Mr. Brasse, if I bring—I'm going ashore to try to save a man—a white man the Arabs mean to murder to-night. If I manage to bring him on board, will you help me to hide him?—so that Captain Dove won't know?"

The chief engineer of the Olive Branch was obviously much perplexed. But he was also obviously much better disposed toward Sallie than to Captain Dove.

"If he's willing to work in the stokehold," he stipulated, "I don't think Captain Dove would ever know he's on board the ship. And then he can slip ashore at the first safe port we manage to make."

Sallie's lower lip trembled a little. She did not quite know how to thank the punctilious engineer who had proved himself such a friend in need. And time was passing.

"You're always very good to me, Mr. Brasse," she said timidly.

"Not at all," he returned with formal politeness, and, having saluted again, went on his own way toward the bridge.

When Sallie got back to the poop she found Reuben Yoxall awaiting her there and the canvas boat already afloat. The mate, however slow-witted, was smart enough in all his movements once he had made up his mind. He helped her over the side without any more words, and was soon driving the light boat along a straight, swift line for the landing-place.

Sallie's sense of direction enabled her to show him that, and also brought them safely across the bar into the lagoon where the other boats from the Olive Branch were lying empty, afloat. The third mate and some of the men had seemingly been left there in charge of them. Sallie caught sight of the former's sullen, furtive features in the sudden, foolhardy light of a match he was holding over the pipe whose bowl his hands hid. And there were shapes moving about him. She laid a shaky hand on one of Yoxall's, and the oar in his, dipping, shifted their course.

The boom of the breakers, behind them, killed all other sound. But she lifted a finger to her lips, and he proved sufficiently quick-witted then. Between them, they beached their own boat in the dark a couple of hundred yards nearer the camp, and waded ashore with it, and left it there, up-side down on the sand.

The same magnetic instinct which had brought them safely across the bar to the beach led her almost straight to the mouth of the narrow ravine through which Captain Dove and she had reached the red-haired Emir's camp. And Reuben Yoxall followed her, blind, through the night.

"It was here that he was to meet us," she whispered breathlessly, her heart in her mouth. They had met no one at all by the way, and there seemed to be no one there.

Yoxall scowled about him, unseeingly, and bit his lip, in helpless dissatisfaction with everybody and everything. Then he sniffed inquiringly, and in an instant all his relaxed muscles were taut again. A faint whiff of tobacco-smoke had reached his nostrils on the hot, humid night-air.

Sallie was aware of it too, and had snatched at his hand, to draw him on tiptoe toward the base of the great rock-wall that cropped up out of the sand there. They reached its shelter unseen and unheard as a harsh, suppressed voice spoke from round the corner, within the velvet-black mouth of the gorge. It was Hobson's, the second mate's.

"Put out that pipe," it ordered furiously, and was answered by a low, mocking laugh. There followed the sound of a smashing blow, and a short, sharp struggle that was interrupted by a muffled shout from high overhead. "Hobson ahoy!"

It was Captain Dove who had called cautiously down from the summit of the ridge at one side of the ravine, and the second mate panted a quick response.

"You can get a move on now," cried the old man above the roar of the surf. "The others will all be in position by the time you've pushed through. Open fire as soon as ever you sight the camp. D'ye hear?"

"Ay, ay, sir," answered the second mate, the habit of years still strong upon him, and went on to issue his own commands in the curt growl of custom. The fellow who had lighted a pipe in defiance of him was apparently quelled.

It seemed that he meant to leave some of his men to guard that end of the gorge. "And you'll keep a sharp look-out," he instructed them very threateningly. "If we're trapped in this damned tunnel there will be all hell to pay—and you'll pay it!

"Move on now, in front. Feel your way with your bayonets. And don't fire so long as cold steel will serve."

The two listeners could hear the dull clink and shuffle of the advance. That soon died away. The men who had been left behind began a low, intermittent grumbling over their own hard lot; they did not believe for a moment that their comrades would share the loot fairly with them. Hobson was a coward at heart, said one, or why, otherwise, would they be wasting their time there? They were all smoking by then.

"The whole thing's a cinch," declared the same speaker more loudly. "I'll swear there isn't an Arab outside the ring-fence we've drawn round 'em, and—I'm going on along inside, to get what I want for myself. I'm not afraid of Mr. Blasted Hobson!"

He came out into the open and stood for a moment or two listening intently, within a few feet of where Sallie and Reuben Yoxall were crouching, their backs toward him. But the ceaseless crash and rumble of the breakers was all there was to be heard.

He turned back, and tramped off into the gorge, with two of the others for company. But three remained.

Sallie felt Reuben Yoxall tug at her sleeve and began to move softly away after him. From somewhere in the distance a shot suddenly rang out. More followed, in quick succession. The irregular crackle of independent rifle-fire soon made it clear that the concentric attack on the camp had begun. The three men in the mouth of the gorge were shouting excitedly to each other.

"We must get away back on board—at once," Yoxall whispered peremptorily. "We can't search the whole Sahara, blind, for a man you wouldn't even know if you saw him. You've done all you can, Sallie. You've kept your promise. Come away, now."

She suppressed a hopeless sob with an effort. It seemed so inexpressibly hard that they should have gained nothing at all by the grave risk they were still running. But hope had failed her, too.

"We'll wait by the boat—just for a little, Rube," she begged none the less. "It may be that—"

"Come on, then," he urged again. "Let's get to the boat,—and, if you'll stay by it, I'll scout round a bit before we put off again."

"More this way," she directed him, as he moved on, impatient to get her back into at least comparative safety. And, under her guidance, they soon reached the rough, trodden path that led toward the lagoon where the boats were lying.

A hundred yards further on, he stopped her abruptly, and dropped to the ground, to set an anxious ear to it. He was up again in a second or two.

"There's a whole army coming this way," he declared in a tone of stricken dismay, "and horses with them too!

"We must make for the soft sand and lie down and burrow as deep as we can."

He turned toward the sea, one arm about her, and almost carried her across the deep, undulating drifts that clutched at her ankles like a dry quicksand. His own strength soon failed against them. He stumbled and fell on his face at the brink of a slope, and slipped on into its hollow and lay there, quite still. But he had let go his hold of her, so that she had not lost her feet: and she was soon cowering beside him, face downward also. They had both heard the nearness of those other feet—very many of them—which had seemingly crossed from the pathway to intercept them.

A hoarse murmur was audible behind them. Some one had ordered a halt. They could hear the heavy breathing of men and the restless movements of horses hock-deep in the drift. They could almost see the ghostly shapes of the white-cloaked riders, but only the leader's horse was even very dimly discernible—because it also was white. Its bridle was jingling a little, too, as none of the others' were.

He uttered a short, sharp order, and Sallie set her teeth to choke back the cry of despair which had almost escaped her. For it was the Emir himself into whose hands they seemed fated to fall, and his tone told the temper he was in.

From among his horsemen a number of men on foot seemed to have emerged, and he was speaking to one of them, in English.

"Are you there, my fine doctor?" he asked evilly, and leaned from his saddle as though he could see through the dark.

"I'm here," a level voice replied, and Sallie covered her face with her hands in helpless horror.

"You're here, you say! And here you'll stay, say I—as was promised you," hissed the Emir. "'Tis not right that the likes of you should be still drawing breath—and her-you-know-of already cold. You're quick yet, and she's dead, my fine doctor—but yours is the funeral that comes first. And you're standing over your own grave now—hell's waiting for you beneath your feet. Stand to one side, and let my men dig down to it."

There was more movement about him, and then a quick shovelling of sand.

"If it's all the same to you, I'll tell them to help you in head first," said the Emir venomously. But the man in the scarlet mask answered nothing at all to that.

Sallie had made an effort to rise, but her knees had utterly failed her, and Reuben Yoxall had laid a heavy arm across her shoulders. The ceaseless uproar from within the camp had suddenly increased.

The Emir was standing up in his stirrups to listen. He sank into his saddle again, and issued some further orders, in Arabic. Most of his force on foot in the rear made off at a staggering run. The horses of his body-guard began to paw and curvet to free their feet as the loose reins tightened on their necks.

"I must be going now, my fine doctor," said the Emir most reluctantly, "but I'll leave you company enough for the few minutes you've left, although you're but a dumb dog!

"And you'll maybe think of me when you're swallowing your first mouthful. Till then you can mourn her-you-know-of."