The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 13, Slice 7, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 13, Slice 7

"Horticulture" to "Hudson Bay"

Author: Various

Release Date: March 2, 2012 [EBook #39029]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

HORTICULTURE (Lat. hortus, a garden), the art and science of the cultivation of garden plants, whether for utilitarian or for decorative purposes. The subject naturally divides itself into two sections, which we here propose to treat separately, commencing with the science, and passing on to the practice of the cultivation of flowers, fruits and vegetables as applicable to the home garden. The point of view taken is necessarily, as a rule, that of a British gardener.

Part I.—Principles or Science of Horticulture

Horticulture, apart from the mechanical details connected with the maintenance of a garden and its appurtenances, may be considered as the application of the principles of plant physiology to the cultivation of plants from all parts of the globe, and from various altitudes, soils and situations. The lessons derived from the abstract principles enunciated by the physiologist, the chemist and the physicist require, however, to be modified to suit the special circumstances of plants under cultivation. The necessity for this modification arises from the fact that such plants are subjected to conditions more or less unnatural to them, and that they are grown for special purposes which are at variance, in degree at any rate, with their natural requirements.

The life of the plant (see Plants) makes itself manifest in the processes of growth, development and reproduction. By growth is here meant mere increase in bulk, and by development the series of gradual modifications by which a plant, originally simple in its structure and conformation, becomes eventually complicated, and endowed with distinct parts or organs. The reproduction of the higher plants takes place either asexually by the formation of buds or organs answering thereto, or sexually by the production of an embryo plant within the seed. The conditions requisite for the growth, development and reproduction of plants are, in general terms, exposure, at the proper time, to suitable amounts of light, heat and moisture, and a due supply of appropriate food. The various amounts of these needed in different cases have to be adjusted by the gardener, according to the nature of the plant, its “habit” or general mode of growth in its native country, and the influence to which it is there subjected, as also in accordance with the purposes for which it is to be cultivated, &c. It is but rarely that direct information on all these points can be obtained; but inference from previous experience, especially with regard to allied forms, will go far to supply such deficiencies. Moreover, it must be remembered that the conditions most favourable to plants are not always those to which they are subjected in nature, for, owing to the competition of other forms in the struggle for existence, liability to injury from insects, and other adverse circumstances, plants may actually be excluded from the localities best suited for their development. The gardener therefore may, and does, by modifying, improve upon the conditions under which a plant naturally exists. Thus it frequently happens that in our gardens flowers have a beauty 742 and a fragrance, and fruits a size and savour denied to them in their native haunts. It behooves the judicious gardener, then, not to be too slavish in his attempts to imitate natural conditions, and to bear in mind that such attempts sometimes end in failure. The most successful gardening is that which turns to the best account the plastic organization of the plant, and enables it to develop and multiply as perfectly as possible. Experience, coupled with observation and reflection, as well as the more indirect teachings of tradition, are therefore of primary importance to the practical gardener.

We propose here to notice briefly the several parts of a flowering plant, and to point out the rationale of the cultural procedures connected with them (see the references to separate articles at the end of article on Botany).

The Root.—The root, though not precluded from access of air, is not directly dependent for its growth on the agency of light. The efficiency of drainage, digging, hoeing and like operations is accounted for by the manner in which they promote aeration of the soil, raise its temperature and remove its stagnant water. Owing to their growth in length at, or rather in the immediate vicinity of, their tips, roots are enabled to traverse long distances by surmounting some obstacles, penetrating others, and insinuating themselves into narrow crevices. As they have no power of absorbing solid materials, their food must be of a liquid or gaseous character. It is taken up from the interstices between the particles of soil exclusively by the finest subdivisions of the fibrils, and in many cases by the extremely delicate thread-like cells which project from them and which are known as root-hairs. The importance of the root-fibres, or “feeding roots” justifies the care which is taken by every good gardener to secure their fullest development, and to prevent as far as possible any injury to them in digging, potting and transplanting, such operations being therefore least prejudicial at seasons when the plant is in a state of comparative rest.

Root-Pruning and Lifting.—In apparent disregard of the general rule just enunciated is the practice of root-pruning fruit trees, when, from the formation of wood being more active than that of fruit, they bear badly. The contrariety is more apparent than real, as the operation consists in the removal of the coarser roots, a process which results in the development of a mass of fine feeding roots. Moreover, there is a generally recognised quasi-antagonism between the vegetative and reproductive processes, so that, other things being equal, anything that checks the one helps forward the other.

Watering.—So far as practical gardening is concerned, feeding by the roots after they have been placed in suitable soil is confined principally to the administration of water and, under certain circumstances, of liquid or chemical manure; and no operations demand more judicious management. The amount of water required, and the times when it should be applied, vary greatly according to the kind of plant and the object for which it is grown, the season, the supply of heat and light, and numerous other conditions, the influence of which is to be learnt by experience only. The same may be said with respect to the application of manures. The watering of pot-plants requires especial care. Water should as a rule be used at a temperature not lower than that of the surrounding atmosphere, and preferably after exposure for some time to the air.

Bottom-Heat.—The “optimum” temperature, or that best suited to promote the general activity of roots, and indeed of all vegetable organs, necessarily varies very much with the nature of the plant, and the circumstances in which it is placed, and is ascertained by practical experience. Artificial heat applied to the roots, called by gardeners “bottom-heat,” is supplied by fermenting materials such as stable manure, leaves, &c., or by hot-water pipes. In winter the temperature of the soil, out of doors, beyond a certain depth is usually higher than that of the atmosphere, so that the roots are in a warmer and more uniform medium than are the upper parts of the plant. Often the escape of heat from the soil is prevented by “mulching,” i.e. by depositing on it a layer of litter, straw, dead leaves and the like.

The Stem and its subdivisions or branches raise to the light and air the leaves and flowers, serve as channels for the passage to them of fluids from the roots, and act as reservoirs for nutritive substances. Their functions in annual, biennial and herbaceous perennial plants cease after the ripening of the seed, whilst in plants of longer duration layer after layer of strong woody tissue is formed, which enables them to bear the strains which the weight of foliage and the exposure to wind entail. The gardener aims usually at producing stout, robust, short-jointed stems, instead of long lanky growths defective in woody tissue. To secure these conditions free exposure to light and air is requisite; but in the case of coppices and woods, or where long straight spars are needed by the forester, plants are allowed to grow thickly so as to ensure development in an upward rather than in a lateral direction. This and like matters will, however, be more fitly considered in dealing hereafter with the buds and their treatment.

Leaves.—The work of the leaves may briefly be stated to consist of the processes of nutrition, respiration and transpiration. Nutri tion (assimilation) by the leaves includes the inhalation of air, and the interaction under the influence of light and in the presence of chlorophyll of the carbon dioxide of the air with the water received from the root, to form carbonaceous food. Respiration in plants, as in other organisms, is a process that goes on by night as well as by day and consists in plants in the breaking up of the complex carbonaceous substances formed by assimilation into less complex and more transportable substances. This process, which is as yet imperfectly understood, is attended by the consumption of oxygen, the liberation of energy in the form of heat, and the exhalation of carbon dioxide and water vapour. Transpiration is loss of water by the plant by evaporation, chiefly from the minute pores or stomata on the leaves. In xerophytic plants (e.g. cacti, euphorbias, &c.) from hot, dry and almost waterless regions where evaporation would be excessive, the leaf surface, and consequently the number of stomata, are reduced to a minimum, as it would be fatal to such plants to exhale vapour as freely in those regions as the broad-leaved plants that grow in places where there is abundance of moisture. Although transpiration is a necessary accompaniment of nutrition, it may easily become excessive, especially where the plant cannot readily recoup itself. In these circumstances “syringing” and “damping down” are of value in cooling the temperature of the air in hothouses and greenhouses and increasing its humidity, thereby checking excessive transpiration. Shading the glass with canvas or washes during the summer months has the same object in view. Syringing is also beneficial in washing away dirt and insects.

Buds.—The recognition of the various forms of buds and their modes of disposition in different plants is a matter of the first consequence in the operations of pruning and training. Flower-buds are produced either on the old wood, i.e. the shoots of the past year’s growth, or on a shoot of the present year. The peach, horse-chestnut, lilac, morello cherry, black currant, rhododendron and many other trees and shrubs develop flower-buds for the next season speedily after blossoming, and these may be stimulated into premature growth. The peculiar short, stunted branches or “spurs” which bear the flower-buds of the pear, apple, plum, sweet cherry, red currant, laburnum, &c., deserve special attention. In the rose, passion-flower, clematis, honeysuckle, &c., in which the flower-buds are developed at the ends of the young shoot of the year, we have examples of plants destitute of flower-buds during the winter.

Propagation by Buds.—The detached leaf-buds (gemmae or bulbils), of some plants are capable under favourable conditions of forming new plants. The edges of the leaves of Bryophyllum calycinum and of Cardamine pratensis, and the growths in the axils of the leaves of Lilium bulbiferum, as well as the fronds of certain ferns (e.g. Asplenium bulbiferum), produce buds of this character. It is a matter of familiar observation that the ends of the shoots of brambles take root when bent down to the ground. In some instances buds form on the roots, and may be used for purposes of propagation, as in the Japan quince, the globe thistle, the sea holly, some sea lavenders, Bocconia, Acanthus, &c. Of the tendency in buds to assume an independent existence gardeners avail themselves in the operations of striking “cuttings,” and making “layers” and “pipings,” as also in budding and grafting. In taking a slip or cutting the gardener removes from the parent plant a shoot having one or more buds or “eyes,” in the case of the vine one only, and places it in a moist and sufficiently warm situation, where, as previously mentioned, undue evaporation from the surface is prevented. For some cuttings, pots filled with light soil, with the protection of the propagating-house and of bell-glasses, are requisite; but for many of our hardy deciduous trees and shrubs no such precautions are necessary, and the insertion of a short shoot about half its length into moist and gritty ground at the proper season suffices to ensure its growth. In the case of the more delicate plants, the formation of roots is preceded by the production from the cambium of the cuttings of a succulent mass of tissue, the callus. It is important in some cases, e.g. zonal pelargoniums, fuchsias, shrubby calceolarias, dahlias, carnations, &c., to retain on the cutting some of its leaves, so as to supply the requisite food for storage in the callus. In other cases, where the buds themselves contain a sufficiency of nutritive matter for the young growths, the retention of leaves is not necessary. The most successful mode of forming roots is to place the cuttings in a mild bottom-heat, which expedites their growth, even in the case of many hardy plants whose cuttings strike roots in the open soil. With some hard-wooded trees, as the common white-thorn, roots cannot be obtained without bottom-heat. It is a general rule throughout plant culture that the activity of the roots shall be in advance of that of the leaves. Cuttings of deciduous trees and shrubs succeed best if planted early in autumn while the soil still retains the solar heat absorbed during summer. For evergreens August or September, and for greenhouse and stove-plants the spring and summer months, are the times most suitable for propagation by cuttings.

Layering consists simply in bending down a branch and keeping it in contact with or buried to a small depth in the soil until roots are formed; the connexion with the parent plant may then be 743 severed. Many plants can be far more easily propagated thus than by cuttings.

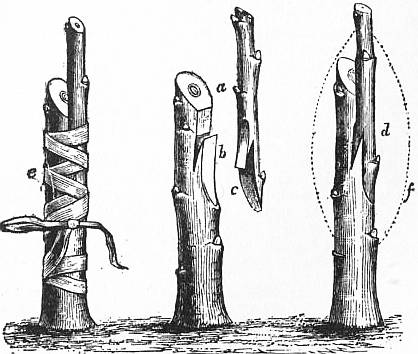

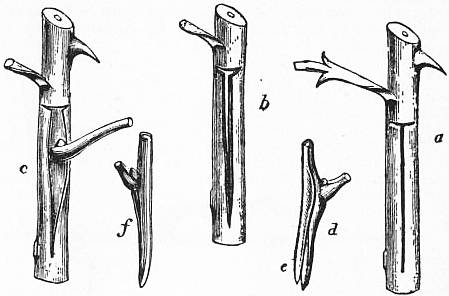

Grafting or “working” consists in the transfer of a branch, the “graft” or “scion,” from one plant to another, which latter is termed the “stock.” The operation must be so performed that the growing tissues, or cambium-layer of the scion, may fit accurately to the corresponding layer of the stock. In budding, as with roses and peaches, a single bud only is implanted. Inarching is essentially the promotion of the union of a shoot of one plant to that of another of the same or allied species or variety. The outer bark of each being removed, the two shoots are kept in contact by ligature until union is established, when the scion is completely severed from its original attachments. This operation is varied in detail according to the kind of plant to be propagated, but it is essential in all cases that the affinity between the two plants be near, that the union be neatly effected, and that the ratio as well as the season of growth of stock and scion be similar.

The selection of suitable stocks is a matter still requiring much scientific experiment. The object of grafting is to expedite and increase the formation of flowers and fruit. Strong-growing pears, for instance, are grafted on the quince stock in order to restrict their tendency to form “gross” shoots and a superabundance of wood in place of flowers and fruit. Apples, for the same reason, are “worked” on the “paradise” or “doucin” stocks, which from their influence on the scion are known as dwarfing stocks. Scions from a tree which is weakly, or liable to injury by frosts, are strengthened by engrafting on robust stocks. Lindley has pointed out that, while in Persia, its native country, the peach is probably best grafted on the peach, or on its wild type the almond, in England, where the summer temperature of the soil is much lower than that of Persia, it might be expected, as experience has proved, to be most successful on stocks of the native plum.

The soil in which the stock grows is a point demanding attention. From a careful series of experiments made in the Horticultural Society’s Garden at Chiswick, it was found that where the soil is loamy, or light and slightly enriched with decayed vegetable matter, the apple succeeds best on the doucin stock, and the pear on the quince; and where it is chalky it is preferable to graft the apple on the crab, and the pear on the wild pear. For the plum on loamy soils the plum, and on chalky and light soils the almond, are the most desirable stocks, and for the cherry on loamy or light rich soils the wild cherry, and on chalk the “mahaleb” stock.

The form and especially the quality of fruit is more or less affected by the stock upon which it is grown. The Stanwick nectarine, so apt to crack and not to ripen when worked in the ordinary way, is said to be cured of these propensities by being first budded close to the ground, on a very strong-growing Magnum Bonum plum, worked on a Brussels stock, and by then budding the nectarine on the Magnum Bonum about a foot from the ground. The fruit of the pear is of a higher colour and smaller on the quince stock than on the wild pear; still more so on the medlar. On the mountain ash the pear becomes earlier.

The effects produced by stock on scion, and more particularly by scion on stock, are as a rule with difficulty appreciable. Nevertheless, in exceptional cases modified growths, termed “graft-hybrids,” have been obtained which have been attributed to the commingling of the characteristics of stock and scion (see Hybridism). Of these the most remarkable example is Cytisus Adami, a tree which year after year produces some shoots, foliage and flowers like those of the common laburnum, others like those of the very different looking dwarf shrub C. purpureus, and others again intermediate between these. We may hence infer that C. purpureus was grafted or budded on the common laburnum, and that the intermediate forms are the result of graft-hybridization. Numerous similar facts have been recorded. Among gardeners the general opinion is against the possibility of graft-hybridization. The wonder, however, seems to be that it does not occur more frequently, seeing that fluids must pass from stock to scion, and matter elaborated in the leaves of the scion must certainly to some extent enter the stock. It is clear, nevertheless, from examination that as a rule the wood of the stock and the wood of the scion retain their external characters year by year without change. Still, as in the laburnum just mentioned, in the variegated jasmine and in Abutilon Darwinii, in the copper beech and in the horse-chestnut, the influence of a variegated scion has occasionally shown itself in the production from the stock of variegated shoots. At a meeting of the Scottish Horticultural Association (see Gard. Chron., Jan. 10, 1880, figs. 12-14) specimens of a small roundish pear, the “Aston Town,” and of the elongated kind known as “Beurré Clairgeau,” were exhibited. Two more dissimilar pears hardly exist. The result of working the Beurré Clairgeau upon the Aston Town was the production of fruits precisely intermediate in size, form, colour, speckling of rind and other characteristics. Similar, though less marked, intermediate characters were obvious in the foliage and flowers.

Double grafting (French, greffe sur greffe) is sufficiently explained by its name. By means of it a variety may often be propagated, or its fruit improved in a way not found practicable under ordinary circumstances. For its successful prosecution prolonged experiments in different localities and in gardens devoted to the purpose are requisite.

Planting.—By removal from one place to another the growth of every plant receives a check. How this check can be obviated or reduced, with regard to the season, the state of atmosphere, and the condition and circumstances of the plant generally, is a matter to be considered by the practical gardener.

As to season, it is now admitted with respect to deciduous trees and shrubs that the earlier in autumn planting is performed the better; although some extend it from the period when the leaves fall to the first part of spring, before the sap begins to move. If feasible, the operation should be completed by the end of November, whilst the soil is still warm with the heat absorbed during summer. Attention to this rule is specially important in the case of rare and delicate plants. Early autumn planting enables wounded parts of roots to be healed over, and to form fibrils, which will be ready in spring, when it is most required, to collect food for the plant. Planting late in spring should, as far as possible, be avoided, for the buds then begin to awaken into active life, and the draught upon the roots becomes great. It has been supposed that because the surface of the young leaves is small transpiration is correspondingly feeble; but it must be remembered, not only that their newly-formed tissue is unable without an abundant supply of sap from the roots to resist the excessive drying action of the atmosphere, but that, in spring, the lowness of the temperature at that season in Great Britain prevents the free circulation of the sap. The comparative dryness of the atmosphere in spring also causes a greater amount of transpiration then than in autumn and winter. Another fact in favour of autumnal planting is the production of roots in winter.

The best way of performing transplantation depends greatly on the size of the trees, the soil in which they grow, and the mechanical appliances made use of in lifting and transporting them. The smaller the tree the more successfully can it be removed. The more argillaceous and the less siliceous the soil the more readily can balls of earth be retained about the roots. All planters lay great stress on the preservation of the fibrils; the point principally disputed is to what extent they can with safety be allowed to be cut off in transplantation. Trees and shrubs in thick plantations, or in sheltered warm places, are ill fitted for planting in bleak and cold situations. During their removal it is important that the roots be covered, if only to prevent desiccation by the air. Damp days are therefore the best for the operation; the dryest months are the most unfavourable. Though success in transplanting depends much on the humidity of the atmosphere, the most important requisite is warmth in the soil; humidity can be supplied artificially, but heat cannot.

Pruning, or the removal of superfluous growths, is practised in order to equalize the development of the different parts of trees, or to promote it in particular directions so as to secure a certain form, and, by checking undue luxuriance, to promote enhanced fertility. In the rose-bush, for instance, in which, as we have seen, the flower-buds are formed on the new wood of the year, pruning causes the old wood to “break,” i.e. to put forth a number of new buds, some of which will produce flowers at their extremities. The manner and the time in which pruning should be accomplished, and its extent, vary with the plant, the objects of the operation, i.e. whether for the production of timber or fruit, the season and various other circumstances. So much judgment and experience does the operation call for that it is a truism to say that bad pruning is worse than none. The removal of weakly, sickly, overcrowded and gross infertile shoots is usually, however, a matter about which there can be few mistakes when once the habit of growth and the form and arrangement of the buds are known. Winter pruning is effected when the tree is comparatively at rest, and is therefore less liable to “bleeding” or outpouring of sap. Summer pruning or pinching off the tips of such of the younger shoots as are not required for the extension of the tree, when not carried to too great an extent, is preferable to the coarser more reckless style of pruning. The injury inflicted is less and not so concentrated; the wounds are smaller, and have time to heal before winter sets in. The effects of badly-executed pruning, or rather hacking, are most noticeable in the case of forest trees, the mutilation of which often results in rotting, canker and other diseases. Judicious and timely thinning so as to allow the trees room to grow, and to give them sufficiency of light and air, will generally obviate the need of the pruning-saw, except to a relatively small extent.

Training is a procedure adopted when it is required to grow plants in a limited area, or in a particular shape, as in the case of many plants of trailing habit. Judicious training also may be of importance as encouraging the formation of flowers and fruit. Growth in length is mainly in a vertical direction, or at least at the ends of the shoots; and this should be encouraged, in the case of a timber tree, or of a climbing plant which it is desired should cover a wall quickly; but where flowers or fruit are specially desired, then, when the wood required is formed, the lateral shoots may often be trained more or less downward to induce fertility. The refinements of training, as of pruning, may, however, be carried too far; and not unfrequently the symmetrically trained trees of the French excite admiration in every respect save fertility.

Sports or Bud Variations.—Here we may conveniently mention certain variations from the normal condition in the size, form or 744 disposition of buds or shoots on a given plant. An inferior variety of pear, for instance, may suddenly produce a shoot bearing fruit of superior quality; a beech tree, without obvious cause, a shoot with finely divided foliage; or a camellia an unwontedly fine flower. When removed from the plant and treated as cuttings or grafts, such sports may be perpetuated. Many garden varieties of flowers and fruits have thus originated. The cause of their production is very obscure.

Formation of Flowers.—Flowers, whether for their own sake or as the necessary precursors of the fruit and seed, are objects of the greatest concern to the gardener. As a rule they are not formed until the plant has arrived at a certain degree of vigour, or until a sufficient supply of nourishment has been stored in the tissues of the plant. The reproductive process of which the formation of the flower is the first stage being an exhaustive one, it is necessary that the plant, as gardeners say, should get “established” before it flowers. Moreover, although the green portions of the flower do indeed perform the same office as the leaves, the more highly coloured and more specialized portions, which are further removed from the typical leaf-form, do not carry on those processes for which the presence of chlorophyll is essential; and the floral organs may, therefore, in a rough sense, be said to be parasitic upon the green parts. A check or arrest of growth in the vegetative organs seems to be a necessary preliminary to the development of the flower.

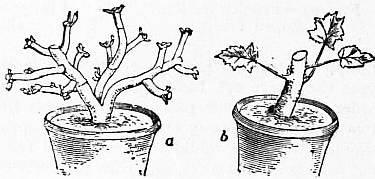

A diminished supply of water at the root is requisite, so as to check energy of growth, or rather to divert it from leaf-making. Partial starvation will sometimes effect this; hence the grafting of free-growing fruit trees upon dwarfing stocks, as before alluded to, and also the “ringing” or girdling of fruit trees, i.e. the removal from the branch of a ring of bark, or the application of a tight cincture, in consequence of which the growth of the fruits above the wound or the obstruction is enhanced. On the same principle the use of small pots to confine the roots, root-pruning and lifting the roots, and exposing them to the sun, as is done in the case of the vine in some countries, are resorted to. A higher temperature, especially with deficiency of moisture, will tend to throw a plant into a flowering condition. This is exemplified by the fact that the temperature of the climate of Great Britain is too low for the flowering, though sufficiently high for the growth of many plants. Thus the Jerusalem artichoke, though able to produce stems and tubers abundantly, only flowers in exceptionally hot seasons.

Forcing.—The operation of forcing is based upon the facts just mentioned. By subjecting a plant to a gradually increasing temperature, and supplying water in proportion, its growth may be accelerated; its season of development may be, as it were, anticipated; it is roused from a dormant to an active state. Forcing therefore demands the most careful adjustment of temperature and supplies of moisture and light.

Deficiency of light is less injurious than might at first be expected, because the plant to be forced has stored up in its tissues, and available for use, a reserve stock of material formed through the agency of light in former seasons. The intensity of the colour of flowers and the richness of flavour of fruit are, however, deficient where there is feebleness of light. Recent experiments show that the influence of electric light on chlorophyll is similar to that of sunlight, and that deficiencies of natural light may to some extent be made good by its use. The employment of that light for forcing purposes would seem to be in part a question of expense. The advantage hitherto obtained from its use has consisted in the rapidity with which flowers have been formed and fruits ripened under its influence, circumstances which go towards compensating for the extra cost of production.

Retardation.—The art of retarding the period of flowering in certain plants consists, in principle, in the artificial application of cold temperatures whereby the resting condition induced by low winter temperature is prolonged. For commercial purposes, crowns of lily of the valley, tulip and other bulbs, and such deciduous woody plants as lilac and deciduous species of rhododendron, while in a state of rest, are packed in wet moss and introduced into cold-storage chambers, where they may be kept in a state of quiescence, it desired, throughout the following summer. The temperature of the cold chamber is varied from the freezing-point of water, to a few degrees lower, according to the needs of the plants under treatment. When required for use they are removed to cool sheds to thaw, and are then gradually inured to higher temperatures. The chief advantages of retarded plants are:—(a) they may be flowered almost at will; (b) they are readily induced to flower at those times when unretarded plants refuse to respond to forcing. Cold-storage chambers form a part of the equipment of most of the leading establishments where flowers are grown for market.

Double Flowers.—The taste of the day demands that “double flowers” should be largely grown. Though in many instances, as in hyacinths, they are less beautiful than single ones, they always present the advantage of being less evanescent. Under the vague term “double” many very different morphological changes are included. The flower of a double dahlia, e.g. offers a totally different condition of structure from that of a rose or a hyacinth. The double poinsettia, again, owes its so-called double condition merely to the increased number of its scarlet involucral leaves, which are not parts of the flower at all. It is reasonable, therefore, to infer that the causes leading to the production of double flowers are varied. A good deal of difference of opinion exists as to whether they are the result of arrested growth or of exuberant development, and accordingly whether restricted food or abundant supplies of nourishment are the more necessary for their production. It must suffice here to say that double flowers are most commonly the result of the substitution of brightly-coloured petals for stamens or pistils or both, and that a perfectly double flower where all the stamens and pistils are thus metamorphosed is necessarily barren. Such a plant must needs be propagated by cuttings. It rarely happens, however, that the change is quite complete throughout the flower, and so a few seeds may be formed, some of which may be expected to reproduce the double-blossomed plants. By continuous selection of seed from the best varieties, and “roguing” or eliminating plants of the ordinary type, a “strain” or race of double flowers is gradually produced.

Formation of Seed—Fertilization.—In fertilization—the influence in flowering plants of the male-cell in the pollen tube upon the egg-cell in the ovule (see Botany)—there are many circumstances of importance horticulturally, to which, therefore, brief reference must be made. Flowers, generally speaking, are either self-fertilized, cross-fertilized or hybridized. Self-fertilization occurs when the pollen of a given flower affects the egg-cell of the same individual flower. Cross-fertilization varies both in manner and degree. In the simplest instances the pollen of one flower fertilizes the ovules of another on the same plant, owing to the stamens arriving at maturity in any one flower earlier or later than the pistils.

Cross-fertilization must of necessity occur when the flowers are structurally unisexual, as in the hazel, in which the male and female flowers are monoecious, or separate on the same plant, and in the willow, in which they are dioecious, or on different plants. A conspicuous example of a dioecious plant is the common aucuba, of which for years only the female plant was known in Britain. When, through the introduction of the male plant from Japan, its fertilization was rendered possible, ripe berries, before unknown, became common ornaments of the shrub.

The conveyance of pollen from one flower to another in cross-fertilization is effected naturally by the wind, or by the agency of insects and other creatures. Flowers that require the aid of insects usually offer some attraction to their visitors in the shape of bright colour, fragrance or sweet juices. The colour and markings of a flower often serve to guide the insects to the honey, in the obtaining of which they are compelled either to remove or to deposit pollen. The reciprocal adaptations of insects and flowers demand attentive observation on the part of the gardener concerned with the growing of grapes, cucumbers, melons and strawberries, or with the raising of new and improved varieties of plants. In wind-fertilized plants the flowers are comparatively inconspicuous and devoid of much attraction for insects; and their pollen is smoother and smaller, and better adapted for transport by the wind, than that of insect-fertilized plants, the roughness of which adapts it for attachment to the bodies of insects.

It is very probable that the same flower at certain times and seasons is self-fertilizing, and at others not so. The defects which cause gardeners to speak of certain vines as “shy setters,” and of certain strawberries as “blind,” may be due either to unsuitable conditions of external temperature, or to the non-accomplishment, from some cause or other, of cross-fertilization. In a vinery, tomato-house or a peach-house it is often good practice at the time of flowering to tap the branches smartly with a stick so as to ensure the dispersal of the pollen. Sometimes more delicate and direct manipulation is required, and the gardener has himself to convey the pollen from one flower to another, for which purpose a small camel’s-hair pencil is generally suitable. The degree of fertility varies greatly according to external conditions, the structural and functional arrangements just alluded to, and other causes which may roughly be called constitutional. Thus, it often happens that an apparently very slight change in climate alters the degree of fertility. In a particular country or at certain seasons one flower will be self-sterile or nearly so, and another just the opposite.

Hybridization.—Some of the most interesting results and many of the gardener’s greatest triumphs have been obtained by hybridization, i.e. the crossing of two individuals not of the same but of two distinct species of plants, as, for instance, two species of rhododendron or two species of orchid (see Hybridism). It is obvious that hybridization differs more in degree than in kind from cross-fertilization. The occurrence of hybrids in nature explains the difficulty experienced by botanists in deciding on what is a species, and the widely different limitations of the term adopted by different observers in the case of willows, roses, brambles, &c. The artificial process is practically the same in hybridization as in cross-fertilization, but usually requires more care. To prevent self-fertilization, or the access of insects, it is advisable to remove the stamens and even the corolla from the flower to be impregnated, as its own pollen or that of a flower of the same species is often found to be “prepotent.” There are, however, cases, e.g. some passion-flowers and rhododendrons, in which a flower is more or less sterile with its own, but fertile with foreign pollen, even when this is from a distinct species. It is a singular circumstance that reciprocal crosses are not always or even often possible; thus, one rhododendron may 745 afford pollen perfectly potent on the stigma of another kind, by the pollen of which latter its own stigma is unaffected.

The object of the hybridizer is to obtain varieties exhibiting improvements in hardihood, vigour, size, shape, colour, fruitfulness, resistance to disease or other attributes. His success depends not alone on skill and judgment, for some seasons, or days even, are found more propitious than others. Although promiscuous and hap-hazard procedures no doubt meet with a measure of success, the best results are those which are attained by systematic work with a definite aim.

Hybrids are sometimes less fertile than pure-bred species, and are occasionally quite sterile. Some hybrids, however, are as fertile as pure-bred plants. Hybrid plants may be again crossed, or even re-hybridized, so as to produce a progeny of very mixed parentage. This is the case with many of our roses, dahlias, begonias, pelargoniums, orchids and other long or widely cultivated garden plants.

Reversion.—In modified forms of plants there is frequently a tendency to “sport” or revert to parental or ancestral characteristics. So markedly is this the case with hybrids that in a few generations all traces of a hybrid origin may disappear. The dissociation of the hybrid element in a plant must be obviated by careful selection. The researches of Gregor Johann Mendel (1822-1884), abbot of the Augustinian monastery at Brünn, in connexion with peas and other plants, apparently indicate that there is a definite natural law at work in the production of hybrids. Having crossed yellow and green seeded peas both ways, he found that the progeny resulted in all yellow coloured seeds. These gave rise in due course to a second generation in which there were three yellows to one green. In the third generation the yellows from the second generation gave the proportion of one pure yellow, two impure yellows, and one green; while the green seed of the second generation threw only green seeds in the third, fourth and fifth generations. The pure yellow in the third generation also threw pure yellows in the fourth and fifth and succeeding generations. The impure yellows, however, in the next generation gave rise to one pure yellow, one pure green, to two impure yellows, and so on from generation to generation. Accordingly as the green or the yellow predominated in the progeny it was termed “dominant,” while the colour that disappeared was called “recessive.” It happened, however, that a recessive colour in one generation becomes the dominant in a succeeding one.

Germination.—The length of the period during which seeds remain dormant after their formation is very variable. The conditions for germination are much the same as for growth in general. Access to light is not required, because the seed contains a sufficiency of stored-up food. The temperature necessary varies according to the nature and source of the seed. Some seeds require prolonged immersion in water to soften their shells; others are of so delicate a texture that they would dry up and perish if not kept constantly in a moist atmosphere. Seeds buried too deeply receive a deficient supply of air. As a rule, seeds require to be sown more deeply in proportion to their size and the lightness of the soil.

The time required for germination in the most favourable circumstances varies very greatly, even in the same species, and in seeds taken from one pod. Thus the seeds of Primula japonica, though sown under precisely similar conditions, yet come up at very irregular intervals of time. Germination is often slower where there is a store of available food in the perisperm, or in the endosperm, or in the embryo itself, than where this is scanty or wanting. In the latter case the seedling has early to shift for itself, and to form roots and leaves for the supply of its needs.

Selection.—Supposing seedlings to have been developed, it is found that a large number of them present considerable variations, some being especially robust, others peculiar in size or form. Those most suitable for the purpose of the gardener are carefully selected for propagation, while others not so desirable are destroyed; and thus after a few generations a fixed variety, race or strain superior to the original form is obtained. Many garden plants have originated solely by selection; and much has been done to improve our breeds of vegetables, flowers and fruit by systematic selection.

Large and well-formed seeds are to be preferred for harvesting. The seeds should be kept in sacks or bags in a dry place, and if from plants which are rare, or liable to lose their vitality, they are advantageously packed for transmission to a distance in hermetically sealed bottles or jars filled with earth or moss, without the addition of moisture.

It will have been gathered from what has been said that seeds cannot always be depended on to reproduce exactly the characteristics of the plant which yielded them; for instance, seeds of the greengage plum or of the Ribston pippin will produce a plum or an apple, but not these particular varieties, to perpetuate which grafts or buds must be employed.

Part II.—The Practice of Horticulture

The details of horticultural practice naturally range under the three heads of flowers, fruits and vegetables (see also Fruit and Flower Farming). There are, however, certain general aspects of the subject which will be more conveniently noticed apart, since they apply alike to each department. We shall therefore first treat of these under four headings: formation and preparation of the garden, garden structures and edifices, garden materials and appliances, and garden operations.

I. Formation and Preparation of the Garden.

Site.—The site chosen for the mansion will more or less determine that of the garden, the pleasure grounds and flower garden being placed so as to surround or lie contiguous to it, while the fruit and vegetable gardens, either together or separate, should be placed on one side or in the rear, according to fitness as regards the nature of the soil and subsoil, the slope of the surface or the general features of the park scenery. In the case of villa gardens there is usually little choice: the land to be occupied is cut up into plots, usually rectangular, and of greater or less breadth, and in laying out these plots there is generally a smaller space left in the front of the villa residence and a larger one behind, the front plot being usually devoted to approaches, shrubbery and plantations, flower beds being added if space permits, while the back or more private plot has a piece of lawn grass with flower beds next the house, and a space for vegetables and fruit trees at the far end, this latter being shut off from the lawn by an intervening screen of evergreens or other plants. Between these two classes of gardens there are many gradations, but our remarks will chiefly apply to those of larger extent.

The almost universal practice is to have the fruit and vegetable gardens combined; and the flower garden may sometimes be conveniently placed in juxtaposition with them. When the fruit and vegetable gardens are combined, the smaller and choicer fruit trees only should be admitted, such larger-growing hardy fruits as apples, pears, plums, cherries, &c., being relegated to the orchard.

Ground possessing a gentle inclination towards the south is desirable for a garden. On such a slope effectual draining is easily accomplished, and the greatest possible benefit is derived from the sun’s rays. It is well also to have an open exposure towards the east and west, so that the garden may enjoy the full benefit of the morning and evening sun, especially the latter; but shelter is desirable on the north and north-east, or in any direction in which the particular locality may happen to be exposed. In some places the south-western gales are so severe that a belt of trees is useful as a break wind and shelter.

Soil and Subsoil.—A hazel-coloured loam, moderately light in texture, is well adapted for most garden crops, whether of fruits or vegetables, especially a good warm deep loam resting upon chalk; and if such a soil occurs naturally in the selected site, but little will be required in the way of preparation. If the soil is not moderately good and of fair depth, it is not so favourable for gardening purposes. Wherever the soil is not quite suitable, but is capable of being made so, it is best to remedy the defect at the outset by trenching it all over to a depth of 2 or 3 ft., incorporating plenty of manure with it. A heavy soil, although at first requiring more labour, generally gives far better results when worked than a light soil. The latter is not sufficiently retentive of moisture and gets too hot in summer and requires large quantities of organic manures to keep it in good condition. It is advantageous to possess a variety of soils; and if the garden be on a slope it will often be practicable to render the upper part light and dry, while the lower remains of a heavier and damper nature.

Natural soils consist of substances derived from the decomposition of various kinds of rocks, the bulk consisting of clay, silica and lime, in various proportions. As regards preparation, draining is of course of the utmost importance. The ground should also be trenched to the depth of 3 ft. at least, and the deeper the better so as to bring up the subsoil—whether it be clay, sand, gravel, marl, &c.—for exposure to the weather and thus convert it from a sterile mass into a living soil teeming with bacteria. In this operation all stones larger than a man’s fist must be taken out, and all roots of trees and of 746 perennial weeds carefully cleared away. When the whole ground has been thus treated, a moderate liming will, in general, be useful, especially on heavy clay soils. After this, supposing the work to have occupied most of the summer, the whole may be laid up in ridges, to expose as great a surface as possible to the action of the winter’s frost.

Argillaceous or clay soils are those which contain a large percentage (45-50) of clay, and a small percentage (5 or less) of lime. These are unfitted for garden purposes until improved by draining, liming, trenching and the addition of porous materials, such as ashes, burnt ballast or sand, but when thoroughly improved they are very fertile and less liable to become exhausted than most other soils. Loamy soils contain a considerable quantity (30-45%) of clay, and smaller quantities of lime, humus and sand. Such soils properly drained and prepared are very suitable for orchards, and when the proportion of clay is smaller (20-30%) they form excellent garden soils, in which the better sort of fruit trees luxuriate. Marly soils are those which contain a considerable percentage (10-20) of lime, and are called clay marls, loamy marls and sandy marls, according as these several ingredients preponderate. The clay marls are, like clay soils, too stiff for garden purposes until well worked and heavily manured; but loamy marls are fertile and well suited to fruit trees, and sandy marls are adapted for producing early crops. Calcareous soils, which may also be heavy, intermediate or light, are those which contain more than 20% of lime, their fertility depending on the proportions of clay and sand which enter into their composition; they are generally cold and wet. Vegetable soils or moulds, or humus soils, contain a considerable percentage (more than 5) of humus, and embrace both the rich productive garden moulds and those known as peaty soils.

The nature of the subsoil is of scarcely less importance than that of the surface soil. Many gardeners are still afraid to disturb an unsuitable subsoil, but experienced growers have proved that by bringing it up to the surface and placing plenty of manure in the bottoms of the various trenches, the very best results are attained in the course of a season or so. An uneven subsoil, especially if retentive, is most undesirable, as water is apt to collect in the hollows, and thus affect the upper soil. The remedy is to make the plane of its surface agree with that of the ground. When there is a hard pan this should be broken up with the spade or the fork, and have plenty of manure mixed with it. When there is an injurious preponderance of metallic oxides or other deleterious substances, the roots of trees would be affected by them, and they must therefore be removed. When the subsoil is too compact to be pervious to water, effectual drainage must be resorted to; when it is very loose, so that it drains away the fertile ingredients of the soil as well as those which are artificially supplied, the compactness of the stratum should be increased by the addition of clay, marl or loam. The best of all subsoils is a dry bed of clay overlying sandstone.

Plan.—In laying out the garden, the plan should be prepared in minute detail before commencing operations. The form of the kitchen and fruit garden should be square or oblong, rather than curvilinear, since the working and cropping of the ground can thus be more easily carried out. The whole should be compactly arranged, so as to facilitate working, and to afford convenient access for the carting of the heavy materials. This access is especially desirable as regards the store-yards and framing ground, where fermenting manures and tree leaves for making up hot beds, coals or wood for fuel and ingredients for composts, together with flower-pots and the many necessaries of garden culture, have to be accommodated. In the case of villas or picturesque residences, gardens of irregular form may be permitted; when adapted to the conditions of the locality, they associate better with surrounding objects, but in such gardens wall space is usually limited.

The distribution of paths must be governed by circumstances. Generally speaking, the main paths for cartage should be 8 ft. wide, made up of 9 in. hard core covered by 4 in. of gravel or ash, with a gentle rise to centre to throw off surface water. The smaller paths, not intended for cartage, should be 4 ft. to 6 ft. wide, according to circumstances, made up of 6 in. hard core and 3 in. of gravel or ash, and should be slightly raised at centre.

A considerable portion of the north wall is usually covered in front with the glazed structures called forcing-houses, and to these the houses for ornamental plants are sometimes attached; but a more appropriate site for the latter is the flower garden, when that forms a separate department. It is well, however, that everything connected with the forcing of fruits or flowers should be concentrated in one place. The frame ground, including melon and pine pits, should occupy some well-sheltered spot in the slips, or on one side of the garden, and adjoining to this may be found a suitable site for the compost ground, in which the various kinds of soils are kept in store, and in which also composts may be prepared.

As walls afford valuable space for the growth of the choicer kinds of hardy fruits, the direction in which they are built is of considerable importance. In the warmer parts of the country the wall on the north side of the garden should be so placed as to face the sun at about an hour before noon, or a little to the east of south; in less favoured localities it should be made to face direct south, and in still more unfavourable districts it should face the sun an hour after noon, or a little west of south. The east and west walls should run parallel to each other, and at right angles to that on the north side, in all the most favoured localities; but in colder or later ones, though parallel, they should be so far removed from a right angle as to get the sun by eleven o’clock. On the whole, the form of a parallelogram with its longest sides in the proportion of about five to three of the shorter, and running east and west, may be considered the best form, since it affords a greater extent of south wall than any other.

|

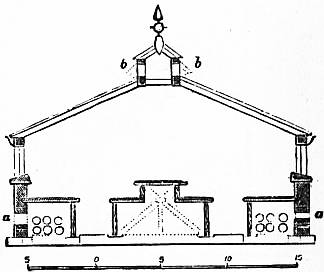

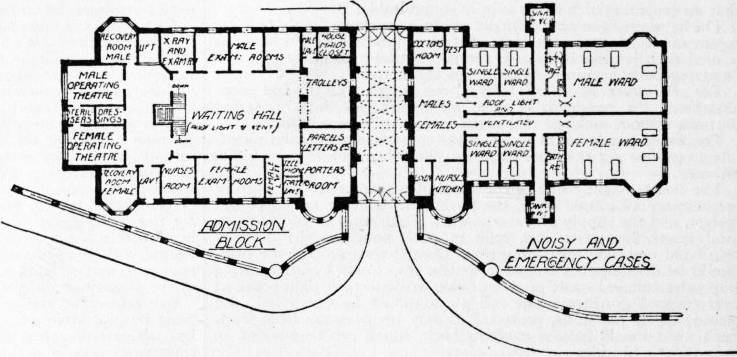

| Fig. 1.—Plan of Garden an acre in area. |

Fig. 1 represents a garden of one acre and admits of nearly double the number of trees on the south aspect as compared with the east and west; it allows a greater number of espalier or pyramid trees to face the south; and it admits of being divided into equal principal compartments, each of which forms nearly a square. The size of course can be increased to any requisite extent. That of the royal gardens at Frogmore, 760 ft. from east to west and 440 ft. from north to south, is nearly of the same proportions.

The spaces between the walls and the outer fence are called “slips.” A considerable extent is sometimes thus enclosed, and utilized for the growth of such vegetables as potatoes, winter greens and sea-kale, for the small bush fruits, and for strawberries. The slips are also convenient as affording a variety of aspects, and thus helping to prolong the season of particular vegetable crops.

Shelter.—A screen of some kind to temper the fury of the blast is absolutely necessary. If the situation is not naturally well sheltered, the defect may be remedied by masses of forest trees disposed at a considerable distance so as not to shade the walls or fruit trees. They should not be nearer than, say, 50 yds., and may vary from that to 100 or 150 yds. distance according to circumstances, regard being had especially to peculiarities occasioned by the configuration of the country, as for instance to aerial currents from adjacent eminences. Care should be taken, however, not to hem in the garden by crowded plantations, shelter from the prevailing strong winds being all that is required, while the more open it is in other directions the better. The trees employed for screens should include both those of deciduous and of evergreen habit, and should suit the peculiarities of local soil and climate. Of deciduous trees the sycamore, wych-elm, horse-chestnut, beech, lime, plane and poplar may be used,—the abele or white poplar, Populus alba, being one of the most rapid-growing of all trees, and, like other poplars, well suited for nursing other choicer subjects; while of evergreens, the holm oak, holly, laurel (both common and Portugal), and such conifers as the Scotch, Weymouth and Austrian pines, with spruce and 747 silver firs and yews, are suitable. The conifers make the most effective screens.

Extensive gardens in exposed situations are often divided into compartments by hedges, so disposed as to break the force of high winds. Where these are required to be narrow as well as lofty, holly, yew or beech is to be preferred; but, if there is sufficient space, the beautiful laurel and the bay may be employed where they will thrive. Smaller hedges may be formed of evergreen privet or of tree-box. These subordinate divisions furnish, not only shelter but also shade, which, at certain seasons, is peculiarly valuable.

Belts of shrubbery may be placed round the slips outside the walls; and these may in many cases, or in certain parts, be of sufficient breadth to furnish pleasant retired promenades, at the same time that they serve to mask the formality of the walled gardens, and are made to harmonize with the picturesque scenery of the pleasure ground.

Water Supply.—Although water is one of the most important elements in plant life, we do not find one garden in twenty where even ordinary precautions have been taken to secure a competent supply. Rain-water is the best, next to that river or pond water, and last of all that from springs; but a chemical analysis should be made of the last before introducing it, as some spring waters contain mineral ingredients injurious to vegetation. Iron pipes are the best conductors; they should lead to a capacious open reservoir placed outside the garden, and at the highest convenient level, in order to secure sufficient pressure for effective distribution, and so that the wall trees also may be effectually washed. Stand-pipes should be placed at intervals beside the walks and in other convenient places, from which water may at all times be drawn; and to which a garden hose can be attached, so as to permit of the whole garden being readily watered. The mains should be placed under the walks for safety, and also that they may be easily reached when repairs are required. Pipes should also be laid having a connexion with all the various greenhouses and forcing-houses, each of which should be provided with a cistern for aerating the daily supplies. In fact, every part of the garden, including the working sheds and offices, should have water supplied without stint.

Fence.—Gardens of large extent should be encircled by an outer boundary, which is often formed by a sunk wall or ha-ha surrounded by an invisible wire fence to exclude ground game, or consists of a hedge with low wire fence on its inner side. Occasionally this sunk wall is placed on the exterior of the screen plantations, and walks lead through the trees, so that views are obtained of the adjacent country. Although the interior garden receives its form from the walls, the ring fence and plantations may be adapted to the shape and surface of the ground. In smaller country gardens the enclosure or outer fence is often a hedge, and there is possibly no space enclosed by walls, but some divisional wall having a suitable aspect is utilized for the growth of peaches, apricots, &c., and the hedge merely separates the garden from a paddock used for grazing. The still smaller gardens of villas are generally bounded by a wall or wood fence, the inner side of which is appropriated to fruit trees. For the latter walls are much more convenient and suitable than a boarded fence, but in general these are too low to be of much value as aids to cultivation, and they are best covered with bush fruits or with ornamental plants of limited growth.

Walks.—The best material for the construction of garden walks is good binding gravel. The ground should be excavated to the depth of a foot or more—the bottom being made firm and slightly concave, so that it may slope to the centre, where a drain should be introduced; or the bottom may be made convex and the water allowed to drain away at the sides. The bottom 9 in. should be filled in compactly with hard, coarse materials, such as stones, brickbats, clinkers, burned clay, &c., on which should be laid 2 or 3 in. of coarse gravel, and then 1 or 2 in. of firm binding gravel on the surface. The surface of the walks should be kept well rolled, for nothing contributes more to their elegance and durability.

All the principal lines of walk should be broad enough to allow at least three persons to walk abreast; the others may be narrower, but a multitude of narrow walks has a puny effect. Much of the neatness of walks depends upon the material of which they are made. Gravel from an inland pit is to be preferred; though occasionally very excellent varieties are found upon the sea-coast. Gravel walks must be kept free from weeds, either by hand weeding, or by the use of one of the many weed killers now on the market. In some parts of the country the available material does not bind to form a close, even surface, and such walks are kept clean by hoeing.

Grass walks were common in English gardens during the prevalence of the Dutch taste, but, owing to the frequent humidity of the climate, they have in a great measure been discarded. Grass walks are made in the same way as grass lawns. When the space to be thus occupied is prepared, a thin layer of sand or poor earth is laid upon the surface and over this a similar layer of good soil. This arrangement is adopted in order to prevent excessive luxuriance in the grass. In many modern gardens pathways made of old paving stones lead from the house to different parts. They give an old-fashioned and restful appearance to a garden, and in the interstices charming little plants like thyme, Ionopsidium acaule, &c., are allowed to grow.

Edgings.—Walks are separated from the adjoining beds and borders in a variety of ways. If a living edging is adopted, by far the best is afforded by the dwarf box planted closely in line. It is of extremely neat growth, and when annually clipped will remain in good order for many years. Very good edgings, but of a less durable character, are formed by thrift (Armeria vulgaris), double daisy (Bellis perennis), gentianella (Gentiana acaulis) and London pride (Saxifraga umbrosa), Cerastium tomentosum, Stachys lavata and the beautiful evergreen Veronica rupestris with sheets of bright blue flowers close to the ground, or by some of the finer grasses very carefully selected, such as the sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina) or its glaucous-leaved variety. Indeed, any low-growing herbaceous plant, susceptible of minute division, is suitable for an edging. Amongst shrubby plants suitable for edgings are the evergreen candytuft (Iberis sempervirens), Euonymus radicans variegata, ivy, and Euonymus microphyllus—a charming little evergreen with small serrated leaves. Edgings may also be formed of narrow slips of sandstone flag, slate, tiles or bricks. One advantage of using edgings of this kind, especially in kitchen gardens, is that they do not harbour slugs and similar vermin, which all live edgings do, and often to a serious extent, if they are left to grow large. In shrubberies and large flower-plots, verges of grass-turf, from 1 to 3 ft. in breadth, according to the size of the border and width of the walk, make a very handsome edging, but they should not be allowed to rise more than an inch and a half above the gravel, the grass being kept short by repeated mowings, and the edges kept trim and well-defined by frequently clipping with shears and cutting once or twice a year with an edging iron.

II. Garden Structures.

Walls.—The position to be given to the garden walls has been already referred to. The shelter afforded by a wall, and the increased temperature secured by its presence, are indispensable in the climate of Great Britain, for the production of all the finer kinds of outdoor fruits; and hence the inner side of a north wall, having a southern aspect, is appropriated to the more tender kinds. It is, indeed, estimated that such positions enjoy an increased temperature equal to 7° of latitude—that is to say, the mean temperature within a few inches of the wall is equal to the mean temperature of the open plain 7° farther south. The eastern and western aspects are set apart for fruits of a somewhat hardier character.

Where the inclination of the ground is considerable, and the presence of high walls would be objectionable, the latter may be replaced by sunk walls. These should not rise more than 3 ft. above the level of the ground behind them. As dryness is favourable to an increase of heat, such walls should be either built hollow or packed behind to the thickness of 3 or 4 ft. 748 with rubble stones, flints, brickbats or similar material, thoroughly drained at bottom. For mere purposes of shelter a height of 6 or 7 ft. will generally be sufficient for the walls of a garden, but for the training of fruit trees it is found that an average height of 12 ft. is more suitable. In gardens of large size the northern or principal wall may be 14 ft., and the side walls 12 ft. in height; while smaller areas of an acre or so should have the principal walls 12 and the side walls 10 ft. in height. As brick is more easily built hollow than stone, it is to be preferred for garden walls. A 14-in. hollow wall will take in its construction 12,800 bricks, while a solid 9-in. one, with piers, will take 11,000; but the hollow wall, while thus only a little more costly, will be greatly superior, being drier and warmer, as well as more substantial. Bricks cannot be too well burnt for garden walls; the harder they are the less moisture will they absorb. Many excellent walls are built of stone. The best is dark-coloured whinstone, because it absorbs very little moisture, or in Scotland Caithness pavement 4 in. thick. The stones can be cut (in the quarries) to any required length, and built in regular courses. Stone walls should always be built with thin courses for convenience of training over their surface. Concrete walls, properly coped and provided with a trellis, may in some places be cheapest, and they are very durable. Common rubble walls are the worst of all.

The coping of garden walls is important, both for the preservation of the walls and for throwing the rain-water off their surfaces. It should not project less than from 2 to 2½ in., but in wet districts may be extended to 6 in. Stone copings are best, but they are costly, and Portland cement is sometimes substituted. Temporary copings of wood, which may be fixed by means of permanent iron brackets just below the stone coping, are extremely useful in spring for the protection of the blossoms of fruit trees. They should be 9 in. or 1 ft. wide, and should be put on during spring before the blossom buds begin to expand; they should have attached to them scrim cloth (a sort of thin canvas), which admits light pretty freely, yet is sufficient to ward off ordinary frosts; this canvas is to be let down towards evening and drawn up again in the morning. These copings should be removed when they are of no further utility as protectors, so that the foliage may have the full benefit of rain and dew. Any contrivance that serves to interrupt radiation, though it may not keep the temperature much above freezing, will be found sufficient. Standard fruit trees must be left to take their chance; and, indeed from the lateness of their flowering, they are generally more injured by blight, and by drenching rains, which wash away the pollen of the flowers, than by the direct effects of cold.

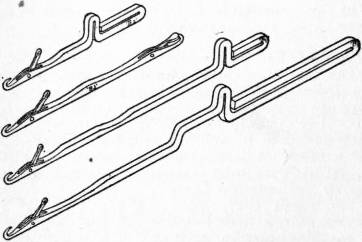

Espalier Rails.—Subsidiary to walls as a means of training fruit trees, espalier rails were formerly much employed, and are still used in many gardens. In their simplest form, they are merely a row of slender stakes of larch or other wood driven into the ground, and connected by a slight rod or fillet at top. The use of iron rails has now been almost wholly discontinued on account of metallic substances acting as powerful conductors of both heat and cold in equal extremes. Standards from which galvanized wire is tightly strained from one end to the other are preferable and very convenient. Trees trained to them are easily got at for all cultural operations, space is saved, and the fruit, while freely exposed to sun and air, is tolerably secure against wind. They form, moreover, neat enclosures for the vegetable quarters, and, provided excess of growth from the centre is successfully grappled with, they are productive in soils and situations which are suitable.

Plant Houses.—These include all those structures which are more intimately associated with the growth of ornamental plants and flowers, and comprise conservatory, plant stove, greenhouse and the subsidiary pits and frames. They should be so erected as to present the smallest extent of opaque surface consistent with stability. With this object in view, the early improvers of hot-house architecture substituted metal for wood in the construction of the roofs, and for the most part dispensed with back walls; but the conducting power of the metal caused a great irregularity of temperature, which it was found difficult to control; and, notwithstanding the elegance of metallic houses, this circumstance, together with their greater cost, has induced most recent authorities to give the preference to wood. The combination of the two, however, shows clearly that, without much variation of heat or loss of light, any extent of space may be covered, and houses of any altitude constructed.

The earliest notice we have of such structures is given in the Latin writers of the 1st century (Mart. Epigr. viii. 14 and 68); the Ἀδὠνιδος κῆποι, to which allusion is made by various Greek authors, have no claim to be mentioned in this connexion. Columella (xi. 3, 51, 52) and Pliny (H.N. xix. 23) both refer to their use in Italy for the cultivation of the rarer and more delicate sorts of plants and trees. Seneca has given us a description of the application of hot water for securing the necessary temperature. The botanist Jungermann had plant houses at Altdorf in Switzerland; those of Loader, a London merchant, and the conservatory in the Apothecaries’ Botanic Garden at Chelsea, were among the first structures of the kind erected in British gardens. These were, however, ill adapted for the growth of plants, as they consisted of little else than a huge chamber of masonry, having large windows in front, with the roof invariably opaque. The next step was taken when it became fashionable to have conservatories attached to mansions, instead of having them in the pleasure grounds. This arrangement brought them within the province of architects, and for nearly a century utility and fitness for the cultivation of plants were sacrificed, as still is often the case, to the unity of architectural expression between the conservatory and the mansion.

|

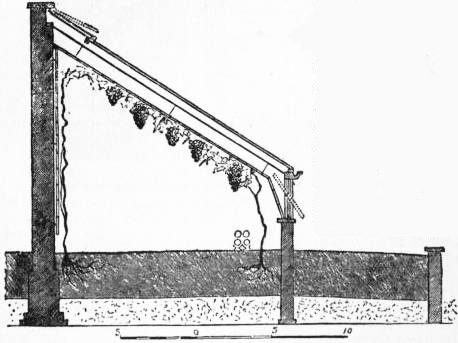

| Fig. 2.—Lean-to Plant House. |

Plant houses must be as far as possible impervious to wet and cold air from the exterior, provision at the same time being made for ventilation, while the escape of warm air from the interior must also be under control. The most important part of the enclosing material is necessarily glass. But as the rays of light, even in passing through transparent glass, lose much of their energy, which is further weakened in proportion to the distance it has to travel, the nearer the plant can be placed to the glass the more perfectly will its functions be performed; hence the importance of constructing the roofs at such an angle as will admit the most light, especially sunlight, at the time it is most required. Plants in glass houses require for their fullest development more solar light probably than even our best hot-houses transmit—certainly much more than is transmitted through the roofs of houses as generally constructed.

Plant houses constructed of the best Baltic pine timber are very durable, but the whole of the parts should be kept as light as possible. In many houses, especially those where ornament is of no consequence, the rafters are now omitted, or only used at wide intervals, somewhat stouter sash-bars being adopted, and stout panes of glass (usually called 21-oz.) 12 to 18 in. wide, made use of. Such houses are very light; being also very close, they require careful ventilation. The glass roof is commonly designed so as to form a uniform plane or slope from back to front in lean-to houses (fig. 2), and from centre to sides in span-roofed houses. To secure the greatest possible influx of light, some horticulturists recommend curvilinear roofs; but the superiority of these is largely due to the absence of rafters, which may also be dispensed with in plain roofs. They are very expensive to build and maintain. Span and ridge-and-furrow roofs, the forms now mostly preferred, are exceedingly well adapted for the admission of light, especially when they are glazed to within a few inches 749 of the ground. They can be made, too, to cover in any extent of area without sustaining walls. Indeed, it has been proposed to support such roofs to a great extent upon suspension principles, the internal columns of support being utilized for conducting the rain-water off the roof to underground drains or reservoirs. The lean-to is the least desirable form, since it scarcely admits of elegance of design, but it is necessarily adopted in many cases.

In glazing, the greater the surface of glass, and the less space occupied by rafters and astragals as well as overlaps, the greater the admission of light. Some prefer that the sash-bars should be grooved instead of rebated, and this plan exposes less putty to the action of the weather. The simple bedding of the glass, without the use of over putty, seems to be widely approved; but the glass may be fixed in a variety of other ways, some of which are patented.

The Conservatory is often built in connexion with the mansion, so as to be entered from the drawing-room or boudoir. But when so situated it is apt to suffer from the shade of the building, and is objectionable on account of admitting damp to the drawing-room. Where circumstances will admit, it is better to place it at some distance from the house, and to form a connexion by means of a glass corridor. In order that the conservatory may be kept gay with flowers, there should be a subsidiary structure to receive the plants as they go out of bloom. The conservatory may also with great propriety be placed in the flower garden, where it may occupy an elevated terrace, and form the termination of one of the more important walks.

Great variety of design is admissible in the conservatory, but it ought always to be adapted to the style of the mansion of which it is a prominent appendage. Some very pleasing examples are to be met with which have the form of a parallelogram with a lightly-rounded roof; others of appropriate character are square or nearly so, with a ridge-and-furrow roof. Whatever the form, there must be light in abundance; and the shade both of buildings and of trees must be avoided. A southern aspect, or one varying to south-east or south-west, is preferable; if these aspects cannot be secured, the plants selected must be adapted to the position. The central part of the house may be devoted to permanent plants; the side stages and open spaces in the permanent beds should be reserved for the temporary plants.

|

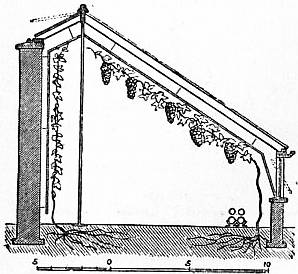

| Fig. 3.—Section of Greenhouse. |

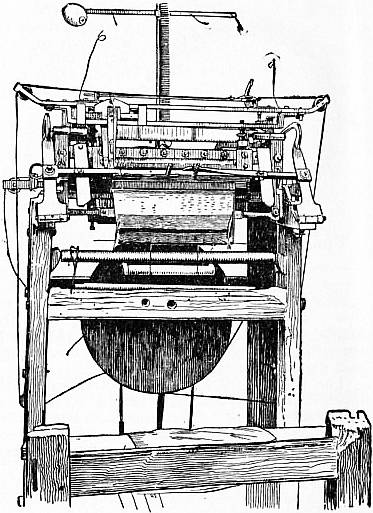

The Greenhouse is a structure designed for the growth of such exotic plants as require to be kept during winter in a temperature considerably above the freezing-point. The best form is the span-roofed, a single span being better even than a series of spans such as form the ridge-and-furrow roof. For plant culture, houses at a comparatively low pitch are better than higher ones where the plants have to stand at a greater distance from the glass, and therefore in greater gloom. Fig. 3 represents a convenient form of greenhouse. It is 20 ft. wide and 12 ft. high, and may be of any convenient length. The side walls are surmounted by short upright sashes which open outwards by machinery a, and the roof is provided with sliding upper sashes for top ventilation. The upper sashes may also be made to lift, and are in many respects more convenient to operate. In the centre is a two-tier stage 6 ft. wide, for plants, with a pathway on each side 3 ft. wide, and a side stage 4 ft. wide, the side stages being flat, and the centre stage having the middle portion one-third of the width elevated 1 ft. above the rest so as to lift up the middle row of plants nearer the light. Span-roofed houses of this character should run north and south so as to secure an equalization of light, and should be warmed by two flow, and one or two return 4-in. hot-water pipes, carried under the side stages along each side and across each end. Where it is desired to cultivate a large number of plants, it is much better to increase the number of such houses than to provide larger structures. The smaller houses are far better for cultural purposes, while the plants can be classified, and the little details of management more conveniently attended to. Pelargoniums, cinerarias, calceolarias, cyclamens, camellias, heaths, roses and other specialities might thus have to themselves either a whole house or part of a house, the conditions of which could then be more accurately fitted to the wants of the inmates.

The lean-to house is in most respects inferior to the span-roofed; one of the latter could be converted into two of the former of opposite aspects by a divisional wall along the centre. Except where space does not permit a span-roofed building to be introduced, a lean-to is not to be recommended; but a house of this class may often be greatly improved by adopting a half-span or hipped roof—that is, one with a short slope behind and a longer in front.

|

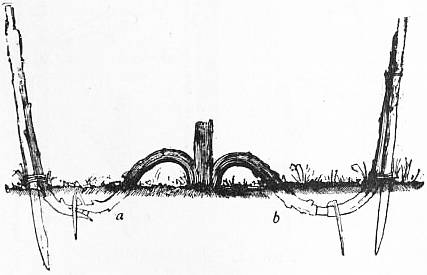

| Fig. 4.—Section of Plant Stove. |