The Project Gutenberg EBook of Empires and Emperors of Russia, China,

Korea, and Japan, by Péter Vay

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Empires and Emperors of Russia, China, Korea, and Japan

Notes and Recollections by Monsignor Count Vay de Vaya and Luskod

Author: Péter Vay

Release Date: January 6, 2012 [EBook #38508]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EMPIRES AND EMPERORS ***

Produced by Meredith Bach, Eric Skeet and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY

1906

[Page v]

As the name of the author of this book may not be so well known to some English readers as it is on the Continent, I have, at his request, undertaken to write a few lines of introduction and preface.

Count Vay de Vaya and Luskod is a member of one of the oldest and most distinguished families of Hungary. Ever since his ancestor took part with King Stephen in the foundation of the Hungarian Kingdom, nine hundred years ago, the members of his family, in succeeding generations, have been eminent in the service of that state.

The Count studied at various European universities, and was destined for the diplomatic service, but early in life he decided to take Holy Orders and devote himself to the work of the Church.

In this capacity he attended the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1897 as one of the envoys of Pope Leo XIII.

The chief enterprise of his life, however, has been to study the work of the Roman Catholic[vi] Church in all parts of the world—her missions, charitable institutions, schools, and organizations of all kinds.

Few men have travelled so far and into such remote quarters as the Count Vay de Vaya has, with this object. His position has secured for him access to the leading and most accomplished circles wherever he has been, and his linguistic attainments, as well as his wide personal experience of men and affairs in every quarter of the globe, give him an almost unique opportunity of describing and commenting on the countries which he has visited—their people, rulers, and institutions.

Seldom has any region been subjected to such complete and revolutionary changes as have the countries which he describes in the following pages.

Russia has been compelled to relax that grip on the Far East which seemed to be permanently tightening and closing: at home she has been subjected to a social upheaval which at one time threatened the existing form of government and the throne itself. And for the first time we have witnessed the triumph of an Asiatic race over one of the leading Powers of Europe.

The substance of this volume was written in 1902 and the following year, before any of these events had occurred, or were dreamed of, and this may cause some of the details of the[vii] record to be a little out of date historically; but the change, far from diminishing, has, on the whole, probably increased its value to all thoughtful readers.

A few passages of comment and forecast have been added since the occurrence of the war, but in the main the narrative remains as it was originally written.

Japan, Korea, Manchuria, and the Siberian Railway have been described over and over again, both during and since the war, but descriptions of them on the eve of the outbreak may come with some freshness and enable readers to compare what was yesterday with what is today.

And what has been changed in the "Unchanging East" bears but a very small proportion to what remains the same in spite of wars and revolutions.

I hope, therefore, that these first impressions of countries which, in name at any rate, are far more familiar to the British public than they were four or five years ago, may prove of great interest to many readers in England and America.

The chapters on The Tsar of all the Russias, The Reception at the Summer Palace, The Audience of the Emperor of Korea, and The Mikado and the Empress, appeared in "Pearson's Magazine," and thanks are due to the Editor for[viii] kind permission to reprint them. The chapters on Manchuria under Russian Rule first appeared in the "Revue des deux Mondes," and those on Japan and China in the Twentieth Century in the "Deutsche Rundschau," but none of these have been translated into English before. The whole has been carefully revised, and considerable additions have been made.

JOHN MURRAY.

[ix]

General situation—Eve of the war—Political outlook in Russia—Characteristics of the two capitals—Siberia and Siberians—Conquest of Manchuria—Position of China and the Powers—Korea's difficulties—Racial tendencies

Page xvii

I

THE TSAR AND TSARINA AT THEIR HOME

OF PETERHOF

The Baltic station of St. Petersburg—The Imperial "Special"—Through the suburbs of the capital—Peterhof—Sentries and passwords—The Imperial Family's favourite home—Alexandrovsky—A homely interior—The Empress and her tastes—Mother and wife—H.M. Nicholas II—A conversation on different topics

Page 1

II

TO THE

FAR EAST BY THE TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY

Main characteristics—The Emperor's kind hospitality—Prince Chilkoff, Minister of Communications—Last days at St. Petersburg—The metropolis of incoherence—Typical Russian departure—On the way to Moscow—The agricultural districts—A short visit to Pienza—Conversations on board the Trans-Siberian express—Political and economical appreciations—Crossing the Volga—In the land of the Baskirs—The Ural range—Western Siberia—The colonization of the uninhabited regions—Growing townships—Central Siberia—Unlimited pastures and endless forests—The Altai range—Irkutsk—The Siberian Paris—Arrival—Luggage difficulties—Civility and kindness—The luxuries of the Hôtel du Métropole—Plush and gold, but[x] no air and no water—A gloomy evening and a bright morning—The life and the lights of the city—Lake Baikal—The islands of dwarfs and fairies—The large fairy coat—Myssowa a new mining centre—Petrovsk, the town of inferno—Trans-Baikalia—Buriats and their pilgrimages to Tibet—The Amur region—On the frontier of Manchuria

Page 16

III

MANCHURIA UNDER RUSSIAN RULE

The Manchurian frontier—Russian soldiers and officials—Public safety—Trains provided with military escort—The Eastern Chinese Railway Company—The system of construction—On the borders of the desert of Gobi—The travel by goods trains—My special car my home—The railway stations: what they looked like—Geographical beauty and ethnological features—Tsi-tsi-kar, the capital of Northern Manchuria—Customs and habits—Primitive modes of living—Kharbin (Harbin), the junction of the eastern Asiatic railway lines—The news of the bridge by Liaoyang carried away by floods—The centre of mobilization—Harbin's part in case of war—Pleasant surprises—At last a new start—Central Manchuria—The mineral wealth of this region—Kirin, a picturesque city—Fine scenery—A dull dawn—Station and station-master—The hunt for a vehicle—A typical Chinese cart—The horrors of a night's journey—Manchurian highroads—Exchanging the cart with a mule—A beautiful bridge—How-di and Poo-how—The fantastic aspect of the scenery—The comforts of little Li-Hu—In a marauders' inn—Lugubrious den and its keepers—In midst of Chunchuses—The bargain with Li-Hu for his charge—Chinese diplomacy and Western art save my purse—Farewell from my companions—A fine daybreak, and the sun throws a veil of obligation over the misery of the night

Page 63

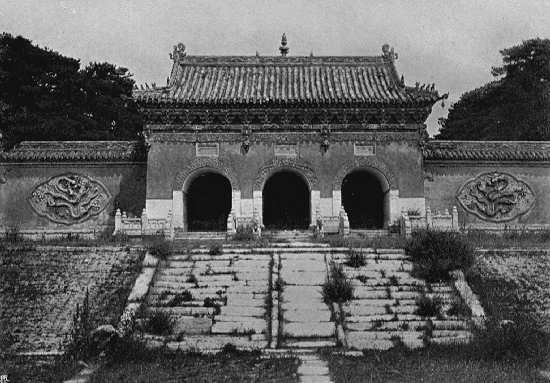

First view of Mukden—The streets, shops, and inhabitants—Public buildings—The Palace—The Russian occupation—Friendliness of Russians and Manchus—Administrative divisions of Manchuria—Official reception by the Governor—A luncheon party—Manchus and Hungarians—Visit to the Imperial Tombs—A magnificent arch—The[xi] Great Ancestor—Outbreak of cholera—Dinner with the Russian Resident—Russian hospitality—Return journey to the station—An adventurous drive—Across country—Chunchuses—Safe arrival at the station

Page 88

V

PORT ARTHUR, DALNY, NIU-CHWANG, TIEN-TSIN

Chinese agriculture—Friendliness between Russians and Chinese—Rebuilding a bridge at Liaoyang—Difficulties of crossing—Arrival at Port Arthur—The staff at Port Arthur—Essentially a military port—Dalny—Niu-chwang—Official journal description—Trade—Niu-chwang a real Chinese town—Description—Future of Niu-chwang—The Catholic Mission—Official transfer of the railway to the Chinese Governor-General or Manchuria—The famous Chinese wall—Hankan-chang—Dinner with the English Commander—Li Hung-Chang—His weakness for speculation—Taku—Tien-tsin—The home of the Progressive Party—The Boxer rising, 1900—Drawing near Pekin—Wonderful sunset—First Impressions

Page 119

VI

PEKIN

I: Gloomy arrival—The first disappointment—Incoherent impressions of the following day—Yamen of the Legation—How the city appeared on my round of exploration.

II: Appreciations after the first month's stay—Contradictions of the Yellow metropolis—Plan and outline—Light and shadow.

III: Sights of Pekin—Chinese, Tartar, Imperial, Purple, Inner, and Sacred cities—Winter and Summer Palaces—Neighbourhood and western hills—Pagodas—Temples—Shrines—Bell and Drum Towers—Chinese city—Commercial life and shops— Pei-tang—International quarter of Legations

Page 141

VII

THE DOWAGER EMPRESS AND THE EMPEROR OF

CHINA AT THE SUMMER PALACE

Pekin in the early morning—En route to the Summer Palace—Varied modes of locomotion—On the highway—Prince Ching, Minister of Foreign Affairs—The pageant of the Dragon—The Imperial residence—Princes and[xii] mandarins—The splendour of the Court—Picturesque uniforms and artistic decorations—Her Majesty the Empress Regent—A striking personality—The Manchu fashions—Reception of the diplomatic body—The doyen's complimentary speech, and the Regent's sarcastic answer—The Emperor—The wonderland of the state banquet of hundred dainties—Supper at the Pei-tang Orphanage

Page 175

VIII

KOREA OF BYGONE DAYS AND ON THE EVE OF THE WAR

Glimpses of the past and present—Geographical features—Topography—Soil—Mineral Wealth—Mountains and valleys—Rivers and bays—Climate and natural advantages—The flora and fauna—Minerals—Ethnological—The Korean race: Its origin—Physical and moral characteristics—The ancient Korea—Early myth of the land—First history—Foundation of the present dynasty—Chinese policy—Internal troubles—Home and foreign affairs—The administration of the country—The defence—Justice—Torture—The criminal court—Public education—Examination system—Language—The present dynasty—The Emperor—Tai-Wen-Kun—The Royal Prince—Social and public existence—Daily life—The rôle of men and women—Korean children—Marriage—General occupations—Agriculture—Trades—Domestic routine—Spinning—Weaving—Sewing—Ironing—Cooking—Recreations—Music—Theatricals—Singing—National dances—Old customs—Dwellings—Food—Dress—Games—Sports—The awakening of Korea—International treaties—Commerce and shipping—Mining concessions—Means of locomotion—Pedlars' Guild—Railways—Electric tramways—Changes in the last quarter of a century—Korea's open ports—Foreign influences—Antagonistic movements—Apathy and fermentation—Puzzles and problems of the present—Korea's future

Page 189

IX

SEOUL, THE CAPITAL OF KOREA

Late arrival—Moonlight impressions—General effects—A fairy city—The dawn—Military display—The Korean sons of Mars—My first walk through the town—Street life—Shops and booths—A battle-royal—The Emperor's commemoration[xiii] hall—The old palace yard—Korean vehicles—Servants and liveries—A noble wedding—Quaint customs—The dowry—Korean T. Atkins—Native school—Master and pupils—The R.C. Mission—The new cathedral—Sunset—Barracks—Toy hussars—Canine street police—Faithful guardians—Glorious evening—Princely funeral—The catafalques and cortège—Danse macabre—Some reflections

Page 240

X

THE EMPEROR OF KOREA AT THE NEW PALACE

The capital in a state of revolution—Imperial invitation—My sedan-chairs—The little suite of Kisos and Mapus—The New Palace—An incoherent tout ensemble—Court dignitaries—Elaborate uniforms—The Imperial apartments—Court etiquette—The Emperor—A thousand questions—The Crown Prince—State robes—The chief eunuch—Farewell—Y.-Yung-Yk the favourite

Page 263

XI

TOKIO

First surprises—The Japanese capital on a dreary winter morning—General aspect of the city—Artistic disappointments—Sights of Yeddo—The famous Shogun graves—"Tories" and pagodas—Natural beauties of the capital—Artistic qualities—The Katsura-no-Rikyu Palace—The school of the æsthetics—The world seen from the Tsuki-mi-dai—Actual characteristics—Numbers and activity—Railways—Shipping—Electric companies—Telegraphs and telephones—Modern institutions—Schools—University—Public library—Printing offices—Students and their work—Brain power and technical skill—Commercial museum—The capital at work

Page 275

XII

THE EMPEROR AND EMPRESS OF JAPAN AT THE YEDDO PALACE

Tokio buried in snow—Black and white effects—The Imperial grounds—Avenues of cryptomerea—The Yeddo Palace—The home of the Mikado—Disappointments—Modern transformations—Western comfort and Japanese art—Private apartments—The Mikado—His Majesty's appearance—A[xiv] long conversation—The Empress—A sincere interest in European topics—Education and charitable work—The Japanese woman—Her sense of duty—The virtue of self-abnegation—The great halls—A Lilliputian garden—National taste and æsthetics

Page 300

XIII

JAPAN AND CHINA ON THE THRESHOLD OF

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

I: Japan. The Yellow Peril—Power of assimilation in discipline—Bushido—Dr. Nitobe's description of its origin: its great principles, justice, courage and honour—Hara-kiri—Kataki-ushi—The conventional smile—Sanctity of the Mikado—Reverence for the sword—National influence of Bushido—The Soul of the Nation—Christianity and Shintoism—Western veneer.

II: China. Contrast to Japan—The Chinese Coolie—Resourcefulness—Feeling against Chinese labour—Trustworthy traders—Guilds and clubs—Music—Culture—Art—Chan-chi-tung—His work and writings—Chinese views of Western ideas—Government and public opinion—China and European politics—Dissimilarity of Chinese and Japanese—Europe and the yellow races—Transformation in Japan—Chinese national inclinations—The progressive party—Yuan-chi-kai—Fashions and home-life—Chinese Christians—Education—The Chinaman's ideal—Ignorance and prejudice

Page 313

XIV

CONCLUSION

After the war—Peace negotiations of Portsmouth—M. de Witte and Komura—National feelings—Japanese diplomatic triumph

Page 381

Page 391

[xv]

| Monsignor the Count Vay de Vaya and Luskod |

|

| TO FACE PAGE | |

| Le Palais Anglais | 4 |

| H.I.M. The Empress of Russia | 6 |

| H.I.M. Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia | 12 |

| Marsanka | 28 |

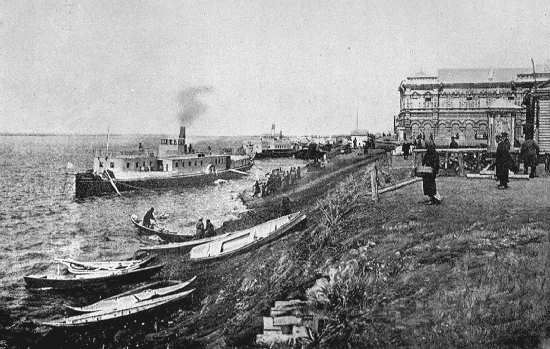

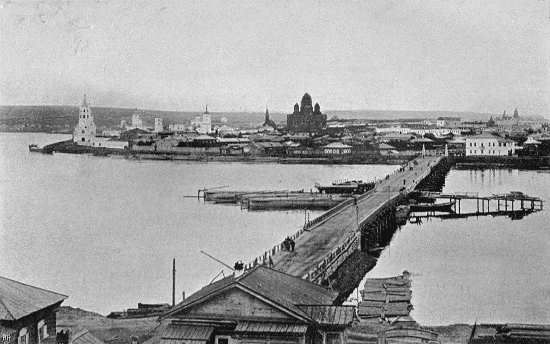

| Samara | 30 |

| On the Volga | 32 |

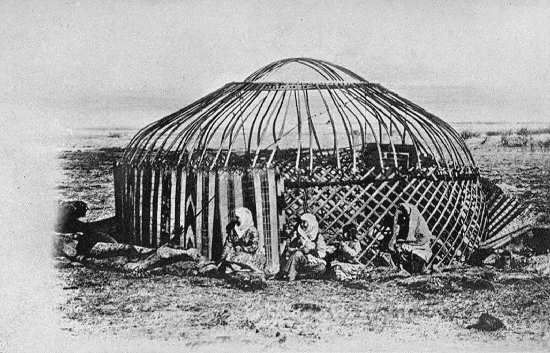

| Siberian Home | 34 |

| A Siberian Town | 36 |

| Railway Church Service | 38 |

| M. de Plehve | 40 |

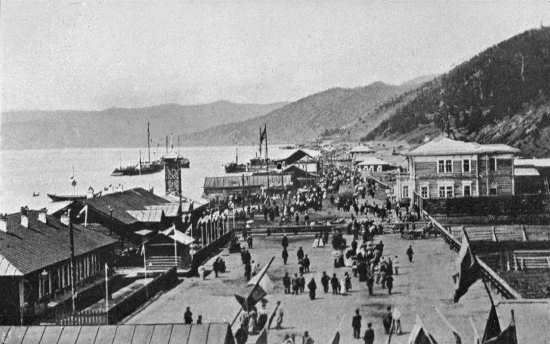

| Irkutsk | 48 |

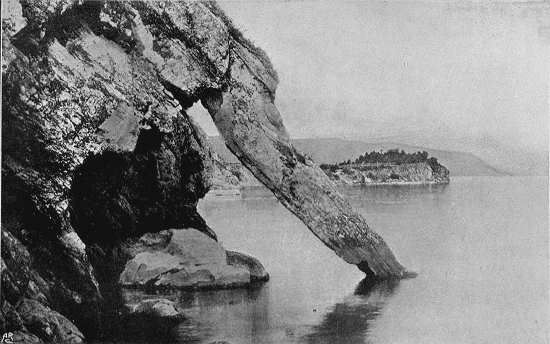

| Lake Baikal | 52 |

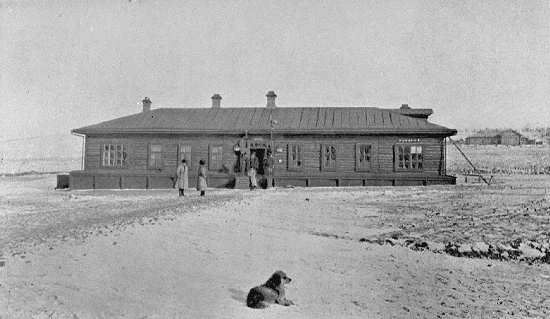

| The Station of Manchury | 60 |

| Tsi-Tsi-Kar | 68 |

| Kharbin | 70 |

| A Street in Kharbin | 76 |

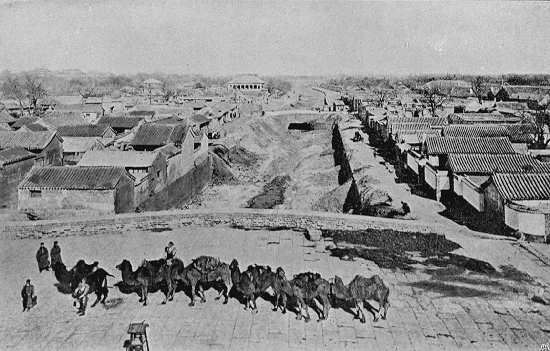

| From Mukden Flats on to the Town | 80 |

| The Entrance to the Imperial Tombs | 104 |

| General Kuropatkin | 124 |

| The Legation Quarter | 152 |

| Entrance to the Forbidden City | 158 |

| Triumphal Arch | 162 |

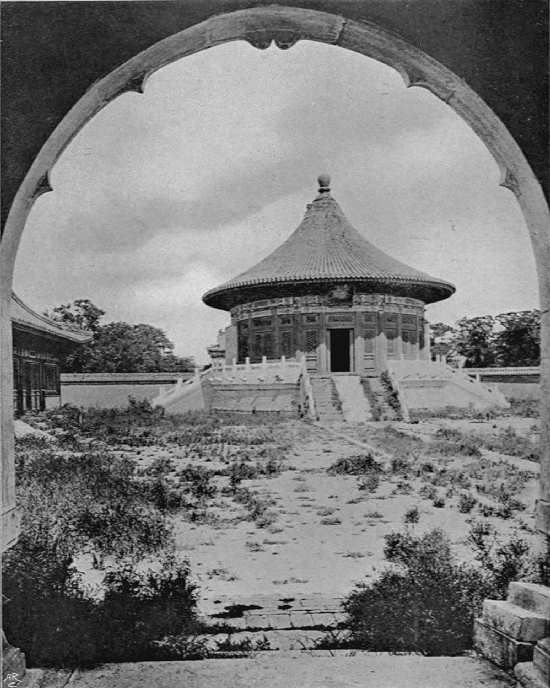

| The Temple of Heaven | 172 |

| The Empress Dowager of China | 184 |

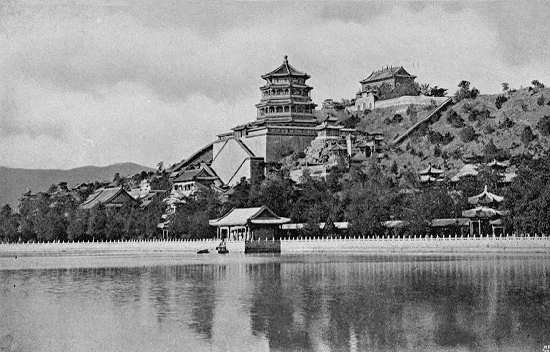

| The Summer Palace | 188 |

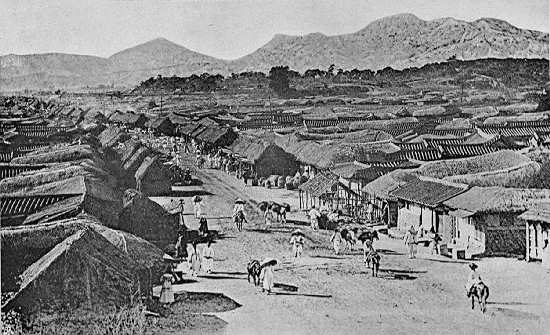

| Seoul | 240 |

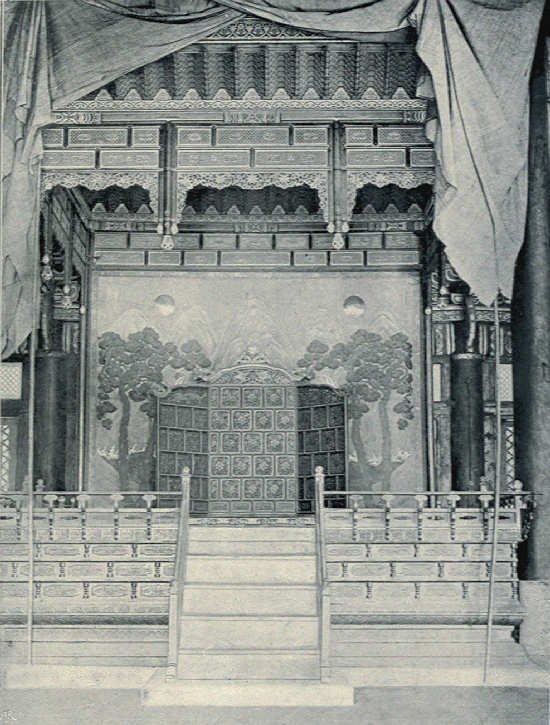

| The Emperor's Throne in the Old Palace | 248 |

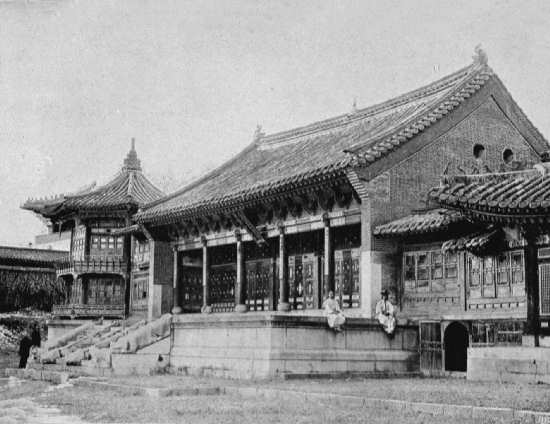

| The Imperial Library in Seoul | 252 |

| The Throne Room | 268 |

| The Emperor of Korea | 270 |

| The State Examination Hall at Pekin | 292 |

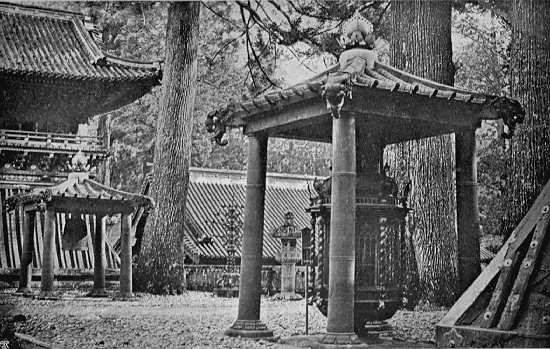

| Shrines at Nikko | 296 |

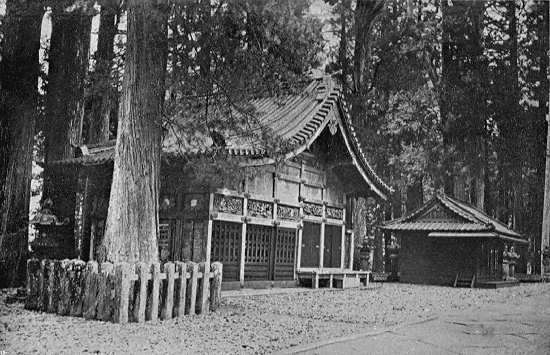

| Delightful Scenery | 298 |

| Street in Japan | 300 |

| The Tokaïdo | 304 |

| A Typical Nippon Building | 312 |

| Marshal Oyama | 322 |

| On the Yang-Tze-Kiang | 340 |

| In the Flowery Land | 344 |

| Count Witte | 384 |

[xvii]

During my prolonged stay in the Far East, I promised to send home notes whenever I came across anything interesting, or whenever I had time to do so. This is how it happened that the story of my visits to the different cities of interest, of receptions graciously granted by the various Emperors of Eastern Asia, and the chief impressions received when crossing their empires, came to be jotted down.

Naturally in these pages, written often under considerable pressure and in spare moments, I was at the mercy of circumstances, and could not dwell on all the points at such length as I should have liked to do. In short, in these narratives, destined to be confided to couriers and post offices, I was compelled to leave out much that might have been more sensational.

Some of the papers have already appeared in periodicals, and the appreciation that has kindly been shown to them, and the favourable criticism they have received, have been due to the sincerity and the absolute lack of pretension with which I have tried to treat the different subjects.

My intention was simply to note what was[xviii] striking at the moment and what impressed me most vividly. I have tried to be as objective as possible, and to deal with things as they are, not as I could have wished to find them. Even in the most attractive books that have dealt with these far-off countries, there has sometimes been a tendency to adopt the tone of a mentor and to judge everything from a superior standpoint, as if the complete difference between those remote lands and peoples and our own had been forgotten, and as if the Westerner wished to ignore a civilization which, though different from, is not less serious than his own; in short, as though this mysterious Far East, with its almost incomprehensible masses, did not possess anything at all of a higher nature and lacked a mind altogether.

Certainly it is difficult, almost impossible, for an alien to perceive their inner qualities and mental powers; at the same time we shall have opportunities in our everyday lives of noting explanatory manifestations. It is from living in the same atmosphere and from continual intercourse with all classes, high and low, that it will be given us to understand a little of what is called the soul of a land and its inhabitants.

Thus, while describing events in their simplicity, we may succeed in giving something of the local atmosphere too. This is the reason[xix] why we always read with pleasure memoirs of past generations or correspondences from far-away countries or of days gone by; and why all the best descriptions in books dealing with the Far East are those unassuming and faded letters from merchants or missionaries; and why the narrative of Marco Polo, with all its naïveté, will remain for all ages a standard work.

Strange adventures, depicted in brilliant hues and by an exaggerated imagination, seldom help our general knowledge. Instead of adding to what we see and encumbering real facts with more or less imaginary occurrences, it is more useful to omit unnecessary details, just as the important thing in painting a landscape is to know what to leave out, so as to make the general character of the scenery clearer. This it is that constitutes the difference between the very best photograph or chromo-lithograph and a rough artistic study or water-colour sketch. In short, one ought to strive to treat this land as its painters do their sketches, always bearing in mind their design of giving in a masterly manner general impressions more than worthless details, so as to get hold of something more than can be seen—something of abstract value in the life they are endeavouring to render.

It was life with its everyday occupations that brought me into contact with all social phases, and rendered my journey and stay of interest,[xx] and made it possible for me to see the country and people in a stronger light than if I had been an ordinary traveller. I was investigating the civilizing, charitable, and spiritual work carried on by the Catholic Church under different conditions, amongst various races. These matters I have dealt with in another volume; but even the subjects that I treated of in those unassuming pages may have acquired a certain local colour, as having been seen by one who had interests and ties with the places he wrote from, and the people he lived amongst.

During the year I passed in the countries bordering on the Yellow Sea, I had an opportunity of making the acquaintance of the greater number of those eminent persons whose names have lately been so often in the mouths of all the world. It was most interesting to listen to them and to hear their views. Though there may have been great diversity in their opinions, they were none the less instructive for that.

My departure from St. Petersburg presented the first glimpse into Orientalism. The splendour of the Imperial City, and the patriarchal condition of the lower classes, gave it a different character from the usual European capitals, and the network of interests in the metropolis differs even more. I had to stay rather longer than I had expected, and this prolongation gave me the best chance of making the amplest preparations,[xxi] and acquiring the necessary preliminary knowledge for my journey across the empire.

Moreover, since as an ecclesiastic I had to obtain special permission even to get to Russia, it was therefore natural that I should have expected to find the greatest difficulties and complications thrown in the way of the accomplishment of my future journey.

Thanks to the kindness of the Tsar himself, however, all possible obstacles were smoothed over. He was personally acquainted with the journey that awaited me, but with this difference, that he made it before the railway was completed, and travelled by post. It was interesting to listen to the narrative of the sovereign, giving his impressions of the remotest portions of his empire, where he could not but come into contact with all classes of his subjects, and where he was obliged to share the vicissitudes of "inflexible circumstance," as we so often read in official ukases.

His Majesty evidently took the liveliest interest in everything he saw, and gave charming accounts of his personal experiences. As in all royal tours, everything was naturally shown to him in as favourable a light as possible, and yet, apparently, the shadows had not altogether escaped his observation. Being heir to all this enormous territory, he probably traversed it[xxii] full of hope of being able one day to ameliorate the general condition of his country, and to prove a true and loving "Little Father" to his folk. It is indeed a melancholy reflection that those who are generally supposed to be blindly obeyed, to have all their wishes accomplished, and whose will is imagined to be absolutely autocratic, are those who are most tied by the force majeur.

The little hermitage of Alexandrovsky, nestling in pine woods, with its home-like character, stands, like an oasis, in the midst of Peterhof, that town of palaces and splendour. The simplicity of the Imperial family is in striking contrast with the luxury of the so-called Court circle. All that one hears of the ostentation and extravagance of Russian Court life entirely disappears when one comes to know the home of the Tsar and Tsaritsa.

Elsewhere there is undoubtedly much pomp and glitter, for the luxury and lavishness of Russian officialism is too well known to need mention here. Indeed, there is hardly a country where things are done more elaborately, and the Exchequer seems to be inexhaustible. If the administration leaves much to be desired and cannot be criticized too severely, we must allow that the officials themselves are the most accomplished men we could wish to know. Whether an official be a minister of State, with all the[xxiii] polish of the old régime of the eighteenth century, or a simple tchinovnik, a tram conductor or a railway guard, it is equally pleasant to have dealings with him.

A stay of a few weeks in St. Petersburg, filled with receptions at the residences of the various members of the Imperial family, calls at the Embassies, official visits, sight-seeing, and business of all sorts, certainly gives one ample opportunity to gain a better insight into local matters than the study of whole volumes.

It was on the eve of the war that I was there. The atmosphere was full of gunpowder, and yet nobody seemed to believe that such a thing could happen; or, even if it really came to pass, that it could have greater consequences than the annihilation of that far-away island folk, of whom the Russian world seemed to know very little. For just as they are so well informed and interested in Western affairs, that one might fancy oneself in a suburb of Paris, so they are supremely indifferent to, and have very hazy ideas of what they call the "Barbarous East."

Such was public opinion and such the tone adopted by the newspapers. M. de Witte was the only man who seemed to be of another conviction. He was just then on his way back from Port Arthur and Dalny. He had been on the spot and realized the situation. He had[xxiv] planned and built Dalny with a view to having a great commercial stronghold to command the Far East, in opposition to his neighbour, Kuropatkin, who commanded the fortifications of Port Arthur. He believed that the best foundation for Russia's supremacy lay in industrial development; Kuropatkin trusted in the sword. Witte was dismissed—the rest we know.

Moscow, my next stoppage, revealed another side of the empire. The holy Moscow, the Mother of Cities, exhibited other features of interest illustrative of the mystical Slavonic soul. The Kremlin, with its gilt cupolas, is not only a monument unique of its kind, but also the expression of a nation's sentiment.

The history of the past, the aspirations of the future, are equally manifested. The glory of arms, of arts, of thought, is expressed in this Valhalla. It is the embodiment of the word "Muscovite," which means all that is characteristic of Russia. Light and shadow, brightness and gloom, virtues and vices, are equally perceptible in this marvellous city, and what is not visible is even more impressive.

All the transcendental tendencies, the shadowy mysticism, peculiar to this strange population, all that is abstract, finds new and unexpected expression within these venerable walls. Patriotism and anarchy, faith and superstition, walk side by side. Churches, shrines, and[xxv] ikons are met at every corner, and before them all, large groups are on their knees, prostrated in devotion. In this same city the most terrible crimes are committed, and the same populace that seemed so repentant and contrite, perpetrates the most cruel and bloody outrages.

In fact, Moscow is an inexhaustible field of study, and not only for historical research, but also for a more certain knowledge of this paradoxical race, full as it is of inexplicable contrasts and incessant surprises.

Siberia was another mine of contrasts and surprises, and the longer I was there the more I began to comprehend the vast possibilities of this formidable stretch of country. It is a continent in itself, with all the natural advantages to enable it to become rich and prosperous. Her future development has the same chance as that of Canada, and her wealth is even larger. To say nothing of Siberia's inexhaustible mines, the land is better watered, and the timber-forests even more extensive.

The population is still slumbering in its cradle. The life they lead is archaic in the extreme. They dwell mostly in tents, lead a nomadic life, and provide their own clothing and food themselves.

They are uneducated, but not unintelligent. In fact, after having visited different camps, I was most struck with their open expression and[xxvi] self-reliance. But it must not be forgotten that, in contradistinction to the Slavs of Russia proper, the various tribes of the Ural-Altai race have never been serfs. They have always led a wandering, independent existence under their Hetmans.

The Baskirs and the Kirghiz are the most interesting, and are the finest specimens of Mid-Asiatic types. The Kalmuks and Ostiaks represent a more Mongolian stock. The farther we go to the East the more they resemble the Yellow race, and the Buriats and Tunguses of Trans-Baikalia are hardly to be distinguished from the Chinese.

What tremendous force is dormant in this world of Tartars! and what a shock their awakening will cause one day!

Towns like Tomsk, Omsk, Tobolsk, and particularly Irkutsk, show us the country from another side. Commercial enterprises, trade, and general progress, have taken root. They are so-called centres of civilization, but I fear that they might more fitly be called places of exploitation.

Certainly these growing towns are not wanting in praiseworthy attempts at culture, and I was especially struck by the philanthropic and charitable institutions. Unfortunately, the moral tone of this agglomerate population is deplorable, and money is spent in a reckless way.

Men, banished from their homes to such[xxvii] distant regions, allow themselves to be dragged down and brought to contempt, instead of trying to dominate the mass by superior character.

Manchuria was entirely under Russian rule in those days. The famous railway was in the hands of the Cossacks, although it ostensibly bore the name of the "Eastern Chinese Line," and barracks for Muscovite soldiers were dotted all over the country. The larger towns had quartered on them Russian officials under various designations, such as consuls, railway directors, bank managers, and so forth. Their influence and domination were uncontested, although apparently they were on the best of terms with the local officials. The Russo-Chinese Bank had branches everywhere, and evidently the least services rendered them were amply recompensed. This Asiatic method of colonization was not wanting in interest to the observer. Its demoralizing effect was very sad, and could not fail to bring retribution later on. For after all, political life, like that of individuals, has a moral code, by which any criminal actions are bound to find their punishment.

After crossing the Great Wall and staying in China proper, I still found the preponderating Muscovite influence. This was especially the case in Pekin, where the success of M. Lessar, Resident Minister, and M. Pocadiloff, Manager of the Russian Bank, was at its zenith. The[xxviii] influence of St. Petersburg, which had succeeded in gaining over Li Hung-Chang, was still in full swing, and Yung Lu was a not less useful partisan. He was the man of the moment, and knew how to secure, even to a greater extent than his predecessor, the sympathy and favour of the Empress Dowager.

The Court had only just returned from their flight. They had scarcely settled down again in that marvellous Palace which they had expected never to revisit. In fact, who could ever have imagined, after all the outrages against Christian Powers, that those Powers themselves should have brought back again the very people against whom they had fought only a few months before?

The diplomatic talent of the Dowager Empress must incontestably be of a high order. She was herself a foreigner—a simple Manchu girl. No less remarkable than her achievement in raising herself step by step to the highest pinnacle of power is the manner in which she maintains her position. The way in which she deals with her own provinces, and plays them off one against the other, is most skilful. It will therefore not be astonishing if she sometimes uses the same methods in foreign difficulties.

The victory of the Western Powers was complete, and yet, with the exception of Russia, they did not reap any apparent advantage from[xxix] it. They could come to no agreement among themselves as to the partition of the spoil, and the disappointment of Japan at seeing the territory she had formerly conquered pass into the hands of her rivals, was only too justly founded.

The situation was most interesting, the general tension being extreme. At the same time it was just this atmosphere of excitement which rendered my stay so instructive and intercourse with leading men of such great interest. Every one gained in importance at this critical moment.

Men like Prince Ching, the Foreign Minister of China and a near relative of the Emperor; his interpreter, Mr. Lee, who has such thorough knowledge of European countries; Yan-Tsi-Kai, who represents the Chinese military spirit and believes in introducing Western methods; and Chang-Tsi-Tung, the great sage and strict disciple of Confucius—are fine specimens of the children of this vast and unknown empire.

After all, among so many interesting points in the Far East, the most interesting is man. Situations may change, war and peace, power and decadence, follow each other at intervals, but the essential characteristics of this population will remain in their main tendencies more or less the same as long as the race endures. The expressions of national sentiment that surround us, great and small, whether apparently[xxx] superficial or really striking, are human documents which must be considered with earnestness and attention, for after all it is they, more than political treatises, diplomatic achievements, or victories of armies, which will direct the natural tendencies and the relentless march of progress in and development of nations in the future. It is when observing, in all its phases, the life that surrounds us, that we can gain an approximate idea of the possibilities of the Far East.

I arrived in the Land of the Morning Calm, which might more suitably be called the Land of Continual Upheaval, when a revolution was in progress. Y-yung-Ik, Minister of Finance, was being attacked by those who sympathized with Japan. The capital was divided into two camps. Skirmishes took place in the open street. Everybody was excited, and anarchy reigned supreme.

Y-yung-Ik, whose views were favoured at the Palace, and who, on the occasion of the last riots, had saved the Emperor's life, carrying him on his back to the Russian Legation, where he remained for over a year, was in concealment in the Palace, and the mob was raging vociferously before the Imperial abode. It was a typical situation, throwing a strong light on the condition of the country.

The nation was divided into two factions.[xxxi] There were pro-Russians and pro-Japanese, but no pro-Koreans. This fine country, instead of constituting a guarantee of the peace of the Far East, was a prey to rivalry. Once suzerain of China, then under Japanese influence, during my stay she seemed to be at the mercy of the Slav.

It seemed to be the last flicker of the candle of Russian preponderance in the Far East. Their hegemony was not only apparent at Court and in the Ministries, but even began to be established all over the country. As in Manchuria, so in Korea, Russian soldiers and sailors, who were billeted on the country for various reasons, made themselves quite at home.

Between the Russians and Koreans there did not appear to be the same difference which separates Europeans from Orientals. The uncultured children of the Steppes amalgamated naturally with the native population. It was striking, particularly in Manchuria, to notice how the so-called conquerors began to be conquered in their turn by the land they occupied, which, indeed, in the long run, has always absorbed those who dreamed of dominating her, whether Mongol, Tartar, or Manchu. Probably what happened to the descendants of the famous Genghis Khan would have happened to the victorious Muscovite.

Arms cannot solve problems of a higher[xxxii] order. In spite of their superiority of military equipment, the new invaders of the Eastern Asiatic continent, the new masters of Manchuria, did not seem to be conscious of their moral duty towards their lately acquired subjects.

Instead of attempting to raise the population among whom they had settled, to a higher degree of civilization, and to inculcate nobler ideals, they were on the point of slipping down to the level of the so-called conquered barbarians.

The life and the mode of thought of the camps were low, and the moral dangers of every kind that surrounded the soldiers and officials were too great for people who, in many cases, had only a veneer of culture themselves and very little practical experience of civilizing and ennobling work, to struggle against.

After all, a state has only the right to conquer when, instead of oppressing, they strengthen and educate those weaker and more primitive than themselves. Conquest can only bear ripe fruit when it is for the general welfare.

Nations, like individuals, have their moral codes, and vocations. Nemesis must always overtake evil of every kind, and to the virtuous alone is granted the palm of final victory.

THE TSAR AND TSARINA AT THEIR HOME OF PETERHOF

It is half-past nine in the morning, as I start on my journey to Peterhof, having been honoured by the Tsar with an invitation thither. It is yet cold and chilly. The great metropolis is covered with a veil of fog. One would imagine that winter had already begun, and it is difficult to realize that according to the calendar it is the month of August. The street leading to the Baltic station, St. Petersburg, is still half deserted.

There Switzers begin to sweep the doorways, and detachments of soldiers hurry to take up their different posts. There are a few milk-carts that rattle to and fro, and one or two private vehicles occupied by people in full dress and uniforms covered with decorations, throwing into sharp contrast the dreary surroundings of the humble suburb. In fact, contrasts are the most striking feature of the capital of the vast Russian Empire—contrasts in light and shadow, splendour and humility, and I dare say contrasts in everything that is characteristic of[2] the West and the East.

The railway station, where I arrive at last, is certainly one of the most interesting illustrations of what I have just pointed out—the very link and meeting-place of the West with the East. It is crowded with people: their countenances are so different, their dress so picturesque, their behaviour so unconventional, yet so characteristic, that I forget that I am on a railway platform, and imagine myself amidst the picturesqueness of a great caravanserai.

Perfect order is kept. The train is already at the platform, ready to start, and I am shown without delay into my compartment. There are a great many officials, all of them in striking uniforms. In fact, there are nearly as many railway employés as travellers, and together they form incoherent groups of Oriental brightness.

The train winds through colourless and uninteresting suburbs for some time. Here and there we have a glimpse of the white Neva, arched by beautiful bridges and skirted with magnificent palaces. We pass near many small villages full of summer-houses, all built of wood. Each house is painted in different colours, and has its own pretty garden. There are some red, some green, and some blue, making a polychromatic mosaic on the green fields. They are all summer residences of the official or semi-official[3] world, who are obliged to pass the summer near town. Indeed, the great charm of St. Petersburg consists in its neighbourhood. These attractive retreats, or, as they are called, Datshas, are on the riverside or on the seashore, or hidden in a quiet neighbourhood like the magnificent Imperial residences, Tsarskoe Selo, Pavlovsk, and Gatschina.

But among them all, Peterhof is the most famous—the Versailles of the North. I think Peterhof undoubtedly deserves the first place. There is not only splendour, but there is real beauty too. Art and nature contribute to make it one of the loveliest spots on earth. There is, in fact, only one royal residence, I think, that can compare with it, and that is the castle of Pena on the high peaks overlooking the ocean near Lisbon.

To get an idea of Peterhof we must imagine a luxuriant forest overshadowing the blue waters of the Baltic. Buried in the woods are summer-houses, gardens, fountains, Greek temples, and triumphal arches. The palace itself stands on a hill that has been cut into terraces—terraces that are surrounded by balustrades and ornamented by statues and flower-vases. Then as a centre there is a magnificent cascade looking like a crystal staircase leading up to a golden palace; it spreads out its waters into a silver carpet covering the pathway and flowing[4] in a broad canal to the sea, bordered by an avenue of rippling fountains.

And when we get tired of the golden palace, of its silver carpet and its dazzling brightness, we return to some of the smaller residences, of which there are many scattered about in the grounds. Some are little French châteaux, some others imitate Dutch farms or Roman villas. They are all different in style and taste, but they are all charming, and contain priceless collections of art. Each has interesting annals; each has some historical connexion and a past of romantic or tragic memory. Wars have been declared, treaties ratified, peace re-established in its lofty halls and gilded salons, every one the scene of important events. Peter the Great's many schemes were born within these walls; and from these groves Catharine II ruled with her iron sceptre.

LE PALAIS ANGLAIS

"The great charm of Petersburg is its neighbourhood"

[To face page 4]

The present Tsar selected for his home one of the smaller châteaux, called Alexandrovsky.

Alexandrovsky is indeed a modest house. It has no lofty cupolas, no magnificent gates, no stately cour d'honneur. It is a simple villa such as is seen in the neighbourhood of well-to-do commercial towns. It might be somewhere near Birmingham or Queenstown. It is built of bright red bricks, has some friendly bow windows, and is ornamented by some little turrets.

Its charm consists in its homeliness. Its beauty[5] is its situation.

It stands in the centre of a green lawn on the border of the sea. It is surrounded by a little flower-garden, where, instead of magnificent fountains and marble statues, there are masses of bloom full of colour and scent; borders of lilies, hollyhocks, poppies, and sweet peas form a natural fence of many hues against the sombre background of the wood. It is a garden which you can realize is tended with affection.

The Empress herself takes an interest in it, and, surrounded by her daughters, passes in this charming retreat many quiet hours of the long summer afternoons. Undoubtedly, this must remind her of lovely Wolfsgarten, hidden in the Hessian forests, where she passed the merry days of her childhood, where she returns so faithfully nearly every year, and where she is so beloved by all the villagers.

Her Majesty is tall, has a fine presence, and is extremely graceful in all her movements. She is refined in the highest degree and very artistic in her disposition. Her leisure hours are mainly occupied in drawing, painting, and music. She is an ardent supporter of all the artistic societies in the capital, and gives a great impetus to literary training in all the different schools which are under her patronage. There are a large number of these schools in St. Petersburg, and she pays personal visits to them frequently.[6]

Her greatest interest, however, is concentrated in her children, and she finds her chief happiness in her own home. Her domestic virtues are those which make her respected by the whole nation. Coming as she did from a far-away country, and being a foreigner, it must have been no easy matter to be at once understood. For refined and retiring natures it is specially difficult to become at once popular. It is only in time, and by having opportunities to show deeper qualities, that sympathy can be awakened. By kind actions, by benevolence towards those she came in contact with, and by unbounded charity, the love of the nation was secured. But how she won the hearts of all was by being an ideal mother.

Copyright, Nops Ltd.

H.I.M. THE EMPRESS OF RUSSIA

[To face page 6]

The Empress is a devoted mother. She attends to her children, as much as possible, personally, and with the greatest care supervises the education of her four little daughters.

The nurseries are established entirely on the English system. There is great simplicity in the furniture, but plenty of fresh air and a good water supply.

The nursery governess is an English lady, and the rules of this little world are strictly observed and precisely carried out, Her Majesty herself having been brought up, as a grandchild of Queen Victoria, on the same principles. Method[7] and punctuality are strictly observed, and the little Princesses must attend to their duties most scrupulously; lessons, recreation, exercises—everything is timed and planned in advance. There is a great deal to be done in the twenty-four hours, lessons and all sorts of small duties of many kinds.

The simplicity of everything might serve as a model to many households.

The food they partake of is of the plainest kind, healthy, but nothing elaborate, consisting mainly of porridge, bread and butter, milk and vegetables, and a little meat or fish. So it is with their attire; generally they are dressed in scrupulously neat white cotton, but it is devoid of all ornament. They pass many hours of the day on the seashore, and as they are running about, laughing, building castles in the sand, or clasping their beloved mother round the neck, they make a perfect picture of happiness.

I reach Peterhof at half-past ten by the special train which daily conveys the Tsar's guests and visitors. Officials, Court dignitaries, aides-de-camp, and others of those who are on duty, have hurried to the large platform, which, covered with red carpet, presents the appearance of a reception-hall. There is great animation at the Peterhof station all the time the Court is there, as the greater part of the suite live in town.[8]

Before the station is a long row of carriages belonging to the Imperial household; peculiar-shaped victorias are there, horsed by enormous black Orloff stallions with great arching necks and flowing manes and tails, looking very much as if they had stepped from one of the pictures of Wouvermans or Velasquez. Lackeys, with three-cornered hats, gaiters, and heavy scarlet coats covered with gold lace, usher each guest to his vehicle, and each starts in a different direction to the many palaces and offices. Rattling over gravelled roadways, I first fully realize that in a few moments I shall be in the presence of the mighty Tsar of all the Russias, the ruler over the greater part of the enormous Asiatic continent, the autocratic head of millions of human beings.

My request is a very modest one—simply permission to get to my destination in the Far East through Siberia. There was some difficulty at the Russian frontier about my further journey, and I was advised to get the obstacles removed by His Majesty himself. He very likely knew that I am only interested in the spiritual and philanthropic institutions established in the Far East, my desire being to get through to my objective as soon as possible.

We drive for quite a quarter of an hour through woods, and here and there as we pass[9] by different residences meet sentries marching up and down. We pass through several gates, all of them made of plain wooden bars—they might almost be in Leicestershire—each opened and closed by a Cossack. As we get nearer there are more sentries, and several times the password is given by the groom.

Alexandrovsky stands isolated in a quiet corner of the vast domain. Its home grounds are surrounded by walls and a kind of palisade. At last, having passed the last sentry and the last gate, the carriage stops at the private garden entrance.

I am received by an officer who shows me immediately into the palace—I ought to say villa. Villa indeed it is in every respect, and the entrance-hall is so small that it scarcely holds the few servants who are in attendance. The staircase is very narrow, too, and winds in exactly the same way as in small old-fashioned English houses.

The drawing-room gives the same impression of comfort and cheerfulness—the privileges of English homes. It is small, and with a rather low ceiling. The furniture is extremely plain. The few sofas and armchairs are covered with bright material, and the woodwork is lacquered white. The walls are covered with watercolours, sketches, and photographs. In one corner there stands a piano with music, and in[10] the window a desk, apparently both much in use. The main feature of this room is the quantity of flowers. Tables, brackets, and furniture, are laden with jars, vases, and bowls filled with fresh-cut, sweet-smelling flowers.

But I have no time for further observations or to analyze more minutely this bright, homely abode in all its detail, giving as it does such a good insight into the private life of its owners. Simple, bright, unassuming, it is a sincere illustration of domestic happiness; and with its writing-desk littered with papers, its piano covered with music, and tiny jars and vases full of sweet-smelling blossoms, it is a human document in itself.

The door opens and an imposing A.D.C. enters and announces that His Majesty is ready to receive me. He is one of the Grand Dukes on duty at the palace for the day. He is a first cousin of the Emperor, an officer in the Russian army, and a most accomplished linguist. He narrated to me many interesting details of his yachting tour in far-distant seas. He had just returned from India, and seemed much impressed by the beauties of that wonderful land.

A bell begins to ring, a signal that the Emperor is ready to receive me. I am shown into the next room, which is even smaller and simpler than the one which I have just left. In its extreme modesty the furniture seems to be reduced[11] to a few chairs, a lounge, and a large writing-table which occupies the greater part of the room.

This is His Majesty's study.

But if the interior is so very unassuming, the view out of the windows is simply magnificent; it looks straight on to the sea—a grey and shining mirror, crowned by the dark battlements of majestic Kronstadt. The famous citadel floats like a mirage in the blue haze of the distance, looking even finer than usual as I see it from one of the Tsar's windows.

The room is so small that there is no space to make the obligatory three bows. I have scarcely stepped into the room when His Majesty gets up and meets me himself with his well-known affability. Nicholas II wears the undress uniform of a Russian general—dark blue and green, with a very little gold lace, and a single medal on his breast—a modest garment, subdued in colouring, suited very well in every respect to its owner.

The portraits of the Emperor are well enough known to make it unnecessary for me to go into minute details. He is not tall, and of rather delicate frame, but healthy, and with a good complexion. What strikes one at the first moment is his open and kind-hearted expression. The two main features that impressed me at the first glance are the turquoise-blue[12] colour of his eyes and their open gaze. Those eyes, which are the chief feature of his countenance, and seem to be a family inheritance, can hardly fail to arouse deep sympathy in the beholder. A very great likeness exists in this respect to the heir to the English throne.

Photo, Levinsky

Copyright, Nops Ltd.

H.I.M. NICHOLAS II, EMPEROR OF RUSSIA

[To face page 12]

His Majesty seemed to be much interested in my proposed journey across Siberia, and wanted to know how long I intended to stay in those regions. He spoke in an interesting way about his own experiences; he knows the whole length of the country in fact, as Tsarevitch he turned the first sod for the railway about twelve years ago in Vladivostok, and now the line runs from one end to the other, linking two continents. But he himself has travelled over the greater part of the route in the simple Russian tarantas.

He gave me with great vivacity many of his innumerable reminiscences and impressions. He was interested in every question, and tried to see everything as much as possible for himself. He stopped at each place of any importance and investigated the situation in detail. Besides his official engagements, he was keenly interested in the purely historical and scientific sides of these unknown regions. The knowledge he gathered during his journey is unique in value, and of the greatest importance to students of the Asiatic races, their origin, life, and future development. Undoubtedly there has been no[13] other ruler of this enormous empire who ever before ventured to enter these remote districts.

He told me what never-failing interest it was to him to come across the different races in his Asiatic dominions, and to see the nomadic tribes there leading their own primitive life. It was a pleasure to listen, not only to his world-wide experiences, but to all his different impressions, gathered with the fresh conception of a young man, and to realize the keen interest which every sentence so eloquently expressed.

He spoke with such benevolence about his subjects, with such love about all those with whom he came in contact throughout his endless wanderings, that there should be no doubt that the Tsar of all the Russias really loves his subjects tenderly, and that their welfare is the highest aim of his life.

And he spoke further of his hopes of improving their condition, of witnessing their advancement, and of his earnest wish to have peace during his reign all over his territory. When he spoke about the great blessing of universal peace his voice vibrated with an emotion that carried the conviction, that so long as the fate of his vast empire depended entirely on his personal desire, there would be no cruel wars, but calm peace and prosperity over all his possessions. In replying I ventured to remark, "What could prevent the mighty Tsar of all the Russias[14] carrying out his wishes?" He only answered, with a never-to-be-forgotten expression, "I see you are yet a new-comer in this country."

His Majesty showed the greatest care in making my journey through his vast empire, across Siberia, not only possible, but also in insuring that I should see as much as possible—that I should be able to observe and learn as much as would be useful to my endeavour.

His Majesty's permission was extended to embrace such hospitality as I would not have sought. I took the liberty of saying I would prefer to proceed as a humble missionary to my destination.

His Majesty kindly insisted:

"If you will not accept it for yourself, accept it for the satisfaction of your mother. She must be very anxious. I know from my own travels how hard it is for parents to be separated from their children by thousands of miles. I sent a telegram every day, but, even then, I knew what their sufferings were. It will give your mother some relief to know that while you are in this empire you are under my protection...."

*****

Time seems to have flown. On my way back I write with difficulty in my solitary compartment, by the rays of a single light. My day at Peterhof has seemed to vanish as a moment,[15] but it has been so full of interesting incidents that to look back upon it is as if a month had been crowded into a day. I have no time to go into details in my diary, so to be correct I limit myself to generalities, and if I cannot put down in extenso all that was of interest—I might say of importance—I want to fix the main outlines of the picture.

TO THE FAR EAST BY THE TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY

I

FROM PETERSBURG TO MANCHURIA

Is it really possible to get to the Far East by land? Is the Siberian Railway open to the public? Is it comfortable? Those were the universal questions that everybody without exception addressed to me on my arrival. As for the first: yes, it is possible. With reference to the second, we must make distinctions. It is well known that to get through Russia everybody must be provided with a passport signed by the local Russian consul. It is different for priests and other church dignitaries who do not belong to the Greek denomination; these require a special permission granted by the Tsar himself. About comfort! The express trains are not only comfortable, but luxurious. In my many travels I do not remember having seen anything better fitted up, or affording to the traveller greater facilities for forgetting the long strain of the journey. The Trans-Siberian Railway is undoubtedly a marvellous piece of[17] engineering. It may have defects, and it may need several alterations, but as a whole it deserves full admiration. Besides its commercial and strategical importance, as a mere civilizing influence it might become incalculable.

Another question which is constantly addressed to me is: Is not the journey very monotonous? Is it not a most uninteresting and flat country? Are not the natives of a very low type? The answer to these questions depends entirely on what the wanderer is interested in. If he looks for variety and excitement, the journey may be to a certain extent uneventful. For those who are in search of Swiss scenery and Alpine grandeur, it may seem flat and colourless. As for social intercourse and pleasure, naturally, these cannot be expected. But to anybody who is interested in land and folk—I mean those whose emotions are awakened by the deeper characteristics of the different countries and their inhabitants—the journey across the Asiatic continent cannot fail to offer a series of continuous revelations. From a geographical point of view, I admit it is in part very flat, and sometimes for days the train pursues its way in an unbroken line through green pastures or the denseness of virgin forests. The people one meets at different hamlets are certainly rough-looking, children of the Steppes; but it is exactly the untouched state of those regions, and the originality of their[18] inhabitants, that render it all of the greatest value to the student of history and folk-lore. The land may be hilly or flat; its greatest interests are not dependent upon its mere external features, and the attractive points of a race do not consist purely in the state of its advancement. They may still be very primitive, living in tents, wearing skins, leading nomadic lives, unaffected, and yet give us an insight into their characteristics and capabilities. When untouched and unaffected by outside influences, they afford even better material for psychological observation, and present us human documents of exceptional interest in regard to the possibilities of their future.

But what compensates largely for the lack of panoramic effects is the vastness of the scenery. Grand it is in every respect. Undulating steppes like the wave-beaten ocean; never-ending, densely wooded regions which seem to extend without limit. Its chief beauty—if beauty it may be called—is the sentiment. The charm of these northern regions of Asia vibrates in their atmosphere. Sentiment and atmosphere! These are the two features of that strange land which impressed me most during the endless hours I looked from the balcony of my railway car, or when I stopped at one or other of the various townships; or, again, when I was visiting some of the native encampments. Among[19] all I noticed that was new and striking, the most surprising thing was undoubtedly the "unseen"—what one might call the moral or metaphysical sides; the impression of unseen strength, exuberant vitality, primeval power, which forces itself on the traveller indirectly again and again in endless forms and aspects. We see it in the soil and in the people. It is equally expressed in the inanimate and animate nature. We perceive it in the yet unploughed fields, and we feel it among the unawakened humanity. It is more an instinctive sensation than the absolute reality which gives us revelations as to the future of this part of the globe.

I proceeded slowly, stopping at every place of interest, and made a short halt wherever there was anything that appealed to me. And when my journey was ended, I regretted it had been so short, and I was sorry the time was too limited to permit me to penetrate deeper into the matter. But I did not fail to put down my impressions from day to day. I made a short note of everything that was interesting, new, or striking, just as it presented itself to me—just as I saw it at the moment.

At present, when the general interest towards the Far East is widening, and people seem to wish to know a little more about Asiatic nations and their different races, and when every year will see more travellers and students trying[20] to make the link between West and East stronger, I hope a few extracts from my diary may strengthen their wish, and help them to realize and put their intentions into execution. There are great openings for activity, and scope for intelligence; and there is a great deal to be done from commercial, scientific, and humanitarian points of view, for the benefit of the whole civilized world and the greater glory of the Almighty.

II

FROM PETERSBURG TO MOSCOW

The Tsar very kindly consented to all the concessions necessary to traverse his extensive empire, and, after my leave-taking, an official brought me all the requisite papers, which had been signed by the Minister of Railways. What an interesting man Prince Chilkoff is! and such an enthusiast too! He lives literally in the midst of his locomotives, rails, and sleepers. I think his favourite abode is the extensive railway workshops of the metropolis. Looking at him, you would think he was born in Chicago; he speaks perfect English, but with a slight American intonation. He is American moreover in his keen sense of business and boundless energy. To hear him talk about the[21] land, new tracks, almost impracticable tunnels, and steel bridges crossing the large rivers, is like a most descriptive geographical lecture; and when he starts on his favourite theories on locomotives, boilers, and pumps, one regrets not knowing more about the mysteries and fascinations of mechanics.

Prince Chilkoff[1] went through a very thorough mechanical training, and has been studying the matter in the United States for many years. He worked there himself, and got initiated into all the secrets of railway communication. He returned finally to his own country, where he hoped to devote his knowledge and qualifications to the benefit of his countrymen. But every post of any importance seemed to be occupied. I hear he was told there was only a subordinate vacancy in the mechanical department. "Give it to me," was his answer, and he is today Minister of all the Russian State Railways, and controller of nearly 25,000 miles of railway and other means of communication.

[1] It is needless to add that since this was written Prince Chilkoff has earned a world-wide reputation by his management of the railway transport during the Russo-Japanese war.

His study is a large room in the Ministry of Railways, which is a country-like residence, standing in extensive grounds. In the centre of his famous office are two large tables, covered, as are also the walls, with books, plans,[22] and railway charts; and as he kindly explains the route I shall take, he gets up and points it out on a geographical map opposite his writing-table. What an enormous territory this Asiatic continent is! I look at it with a kind of amazement and a sort of fear. Shall I really get across it in a comfortable railway carriage, as you would go on a trip into the country? My host seems to divine my thoughts, and with a smile assures me that from one end to another the line is entirely under the same central management, and a telegraph apparatus from the head office brings him unbroken news throughout the entire length. "I quite understand it might seem strange and unusual to other countries, but you must not forget our tendencies and our force consist in centralization." He has made the Siberian journey again and again, and gives me most valuable information respecting what to see, and where to stop, and what is really of interest. It is a grand work, and, considering the space of time in which it was achieved, and its extent, it seems nearly incredible. Including the branch lines, the Siberian Railway is over ten thousand kilometres long, and its construction was begun only twelve years ago. Prince Chilkoff has, moreover, under his management, 10,400 post offices, and over 100,000 miles of telegraph line.

I leave his house charged with valuable hints[23] and a packet of letters and recommendations; and Prince Chilkoff, with a cordial hand-shake, repeats, "Good luck! and don't forget to let me know if anything should prove unsatisfactory."

My last day at St. Petersburg is even more crowded than the rest of the week has been. Calls of farewell, final preparations, leaving cards and inscribing my name in visiting-books, occupy the greater part of it. But this going to and fro gives me opportunity of seeing it again from end to end in all its immensity before I leave. What an extraordinary idea to build a town in the midst of a marsh! to dig canals where one cannot build roads, and to be surrounded with a plain as flat as a table. Peter the Great must have been very much impressed by Amsterdam! There are corners in St. Petersburg drenched and misty as on the borders of the Zuyder Zee. But if it has reminiscences of quiet, home-like Holland, again there are brilliant thoroughfares like a Parisian boulevard. The Nevsky Prospect, in its bustle and traffic, full of colour and of life, is unique. Nevsky is the main artery of the capital—palaces belonging to the Imperial family and the grandees, public buildings, bazaars, workshops, and every edifice you can think of. And each is of different style, each of different height, and each is painted in a different hue of the rainbow. Its main feature—I[24] dare say attraction—is its incoherence.

During this last week the Russian metropolis presented itself to me from a thousand different sides, and in how many different lights too! Trying to remember them all before I depart for good, I do so with preference for what was pleasant, instructive, and good. Besides, I do not come to criticize, I merely come to pass through, and so I prefer to put down in my diary what might prove instructive. I fully understand the great attraction which St. Petersburg always has for foreigners. I admit it also, though I should not choose it for my residence or for my sphere of labour. The polish is perfect, and of course, if one does not belong to a country, as a passing visitor one scarcely requires more. The conditions of life—at least, for the well-to-do—are most agreeable; manners all that can be desired; refinement exquisite. I do not think you can come in contact anywhere with better informed and more richly equipped people than here. Some of the scientific institutions, like the Naval Academy and the Public Library, are quite remarkable; and the new Polytechnic School—a regular town in itself, with its five faculties and its laboratories—stands alone. Then the museums and galleries contain the most celebrated art treasures. The famous Hermitage, large as it is, can scarcely hold them all. Antiques, gems, jewels, weapons,[25] vases, engravings, and pictures, all of the first order; and I must say they appreciate what they do possess, and the arrangements of the museums are excellent. Unquestionably there is a highly intellectual current, or, if you would prefer to call it so, undercurrent, which comes to brilliant manifestations here and there; sometimes most unexpectedly, amid squalor and débris.

The huge electric globes cast a cold and glaring light over the gloomy square in front of the Moscow station. A dense crowd invades passages, halls, and waiting-rooms, and, like the swelling tide, groans, surges, and finally overflows the platforms. Travelling in Russia has a different meaning altogether from that which it possesses elsewhere—it really means a removal: a regular déplacement. Then, people seem to leave for ever: all their belongings appear to follow them, so enormous and so diverse is their kit. From simple boxes and knapsacks to kitchen utensils and even furniture, it embraces everything one could desire in one's own abode. And afterwards, when they take leave, their shaking of hands, embracing, and tears, give the impression that they never are to meet again. And this is only the local train, taking me as far as Moscow. What will it be there, at the Siberian terminus?

The journey lasts only one night, across the[26] famous wheat-growing plains, and to-morrow, in the early hours of the morn, I hope to reach the ancient capital of the Tsars. I want to break my journey to see the ancient metropolis of the mighty rulers, to revisit all the famous scenes where so many important chapters of eastern history were once displayed to view. I want to see again the towering Kremlin, with its mosaic basilicas and treasure-houses, slumbering at present in quiet dreams of the past under their golden domes. And I want to get prepared and acclimatized to a certain extent for Siberia; for Moscow belongs altogether to the other continent; it is really the capital of Asia.

III

THROUGH EUROPEAN RUSSIA

The fading disc of the sinking sun disappears slowly beneath the horizon of the waving corn-fields. The first day of the journey is over. It was uneventful, calm, but it has not lacked interest. We have ploughed through endless fields of rich land, with a peaceful agricultural aspect. Here and there a few scattered villages of dark mud huts, and large white churches. Sometimes there is a country seat of some landed gentleman, buildings which remind me very[27] much of an Indian bungalow. They are very long and of only one storey high, half hidden by ancient trees. On the high roads peasants are just returning in endless streams, with carts and kettles, from their daily work. However far off they may have been working, they always return home for the night, for Russian peasants seldom live on their farms. The whole picture speaks of such perfect peace: the slowly moving and singing workmen, and the little villages bathed in the afterglow, express such simple happiness, that I can scarcely realize that some of those very districts have been the scene of violence and cruel outrages. It is indeed difficult to believe the reports of the latest troubles and dissatisfaction which have burst forth in the midst of the quietest of mujiks. How difficult it is to understand the inner feelings of these quaint folk! Sleepy as they may look, uncultured, and a couple of centuries behind the rest of the world, they can yet occasionally awaken; and when they awake, their passions burst out like as a stream of lava without restraint.

During the day we stop at many smaller and larger places, nearly all insignificant, and generally very far from the station—sometimes so far that I can scarcely understand the reason of our stopping. For miles and miles around there is no human habitation, and we wonder[28] by whose hands all those fields are worked. The most important township seemed to be Marsanka. It is a typical Russian country town, with its wooden houses, each surrounded by a flower-garden, and each garden fenced by lattice-work. The houses and gates are all painted in bright colours. A river encloses the entire place like a loop, and beyond the river are low-lying hills. The main feature of the place is given by innumerable windmills, of all sizes and of every imaginable construction—all equally conspicuous, equally high, and equally equipped with gigantic sails. They all whirl—they all work as if they would never stop. I do not think I ever saw so many windmills within view at one time; I counted more than a hundred. What a fertile country it must be, to keep so many busy!

MARSANKA

After a Water Colour Drawing by the Author

"The main feature of the place is given by innumerable windmills"

[To face page 28]

It is night as we arrive at Pienza, and we can see nothing except the railway station; but, as I hear, this is the main sight of the place. A fine building, though constructed of wood. I must also add that the stations all along the line are fine and convenient. They are well kept, a great many have restaurants, abundantly stocked, with richly laid out tables, and fair attendance. Prices are high, but this is to be expected, considering the distance from which they sometimes procure their provisions. Here at Pienza I find even luxury. Grapes and[29] peaches from the Crimea, wine from Germany and France, and all kinds of American and English conserves; and, as ornamentation, fine old French candelabra, derived probably from some ruined noble's residence.

The station is animated. A great many officers and a great many officials, all dressed in uniform. Some are travellers, some have just come from the town for mere amusement. The great express has not yet lost its novelty, and twice a week is the object of universal admiration. Our train consists of two first-class and three second-class carriages, a dining-car, luggage-van, tender, and engine. A long corridor leads from one end to the other, and affords a convenient walk for daily exercise. The compartments are nicely fitted up; the one I occupy, a so-called saloon, affords me a comfortable home during the journey. The dining-car is fitted up in American style; and, as I see, all the seats are taken from morning till night. To my fellow-passengers their meals seem to be their only occupation, for if the train stops, and there is a restaurant, they alight and commence each time a fresh meal. Indeed, my fellow-passengers are great eaters and great talkers; they seem to speak about everything with the same ease and unreserve. Especially when they start on their own countrymen and government, there is no end to their sarcasm and witty remarks.[30] To any one liking to hear about the local conditions, the Siberian journey gives an exceptional opportunity. People soon become acquainted, and if so they are delighted to find somebody to whom to grumble. Before twenty-four hours had passed I learnt more about the corn-fields and little villages we skirted; about Russian agricultural and industrial aspirations; about agrarian Plehve and M. de Witte's commercial enterprises than I ever should have expected.

SAMARA

"I shall make a short stay at Samara"

[To face page 30]

It seems that Russia is at present passing through a serious crisis which affects everybody, rich and poor—especially the latter. The conditions of the peasantry are often very hard, though the reports we read are generally exaggerated. Education and moral training might do a great deal to lift them out of their stagnant state, to inspire self-reliance, and awaken sound ambitions; but this is exactly what appears to be lacking, and where so much good could be done. And the people deserve education, for these Russian peasants, as a whole, are a fine stock—strong and healthy, easy to lead, and not difficult to improve. Even more, they have generally an unspoilt heart, and are capable of gratitude. What I hear unanimously abused is the local administration. If I were to believe half what I heard about the unworthiness of the official employés, their untruthfulness and[31] bribery, it would be bad enough, and would easily explain the reason of the continuous outbreaks. The antagonism between the so-called Progressives and Conservatives is becoming more intolerant, and strivings for reform on a smaller or larger scale seem to be universal. Some are hopeful, some pessimistic; some see Russia's future secured on the same old patriarchal and primitive foundations, others believe in commercial prosperity, trade, and advance. It is a great problem, and it is equally interesting to listen to the advocate of one or other theory. Yet I am afraid that in their sanguine anticipations they are equally far from what will prove to be the reality.

All the talk I listen to serves as a description of, or comment on, the uninterrupted panorama which unfolds itself without ceasing before us as we glide swiftly along. It is a kind of prologue to the epic of this land which we shall soon leave altogether.

To-morrow we shall cross the Volga by the famous steel bridge of nearly a mile. I shall make a short stay at Samara, and shall visit its well-known orphanages, asylums, and other charitable establishments which the town is so proud of; and, somewhat farther towards the east, the train will wind along the Ural Mountains to Siberia.

At half-past nine in the morning we cross the boundary of the two continents. We are in Asia. A kind of mysterious feeling impresses itself on my mind. New sensations infuse themselves into me. Encouraging hopes awaken, which I trust will give me endurance to carry out my work and aims.

Asia! What a field for exploration! What an unlimited area for higher aspirations! Modest as our endeavours may be, the result may prove incalculable in the future. From a commercial, civilizing, or spiritual point of view, there is an equally vast field for action.

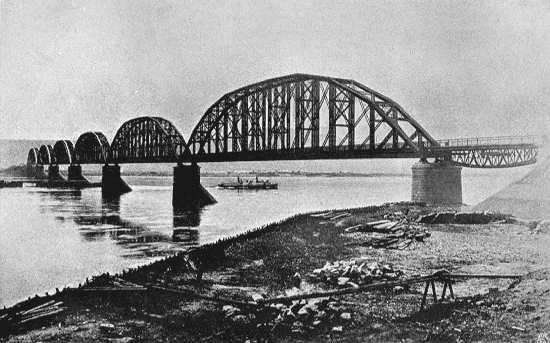

ON THE VOLGA

"The famous steel bridge of nearly a mile"

[To face page 32]

Our last day in Europe passed on the Baskir land—a high plateau, a severe and cold region, covered with rich pasture and inhabited by a semi-nomadic race of the same name. Fine people they are, of heavy countenance and magnificent frame; very conservative in their habits, very clannish in their intimacies, and even today living from preference in tents. They wear sheepskins; cover their heads, like Eskimos, with furs; and, instead of boots, roll round their feet and legs skins fastened like a classic sandal with endless straps of leather. They look uncouth, but picturesque. Their movements are[33] unquestionably plastic. This race is one of the finest of the Tartar stock, and I am sorry to learn that they are slowly dying out.