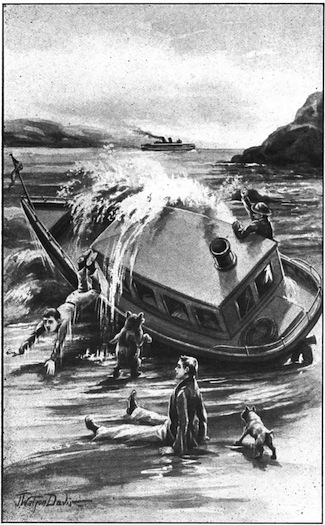

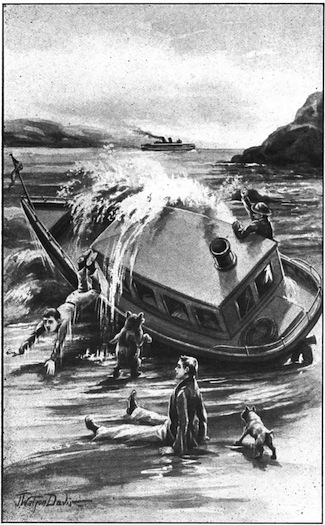

The wave caught the Rambler broadside, and in an instant she was beached high and dry on the bar.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The River Motor Boat Boys on the St.

Lawrence, by Harry Gordon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The River Motor Boat Boys on the St. Lawrence

The Lost Channel

Author: Harry Gordon

Release Date: December 31, 2011 [EBook #38450]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RIVER MOTOR BOAT BOYS ON ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

The wave caught the Rambler broadside, and in an instant she was beached high and dry on the bar.

THE SIX RIVER MOTOR BOAT

BOYS ON THE ST. LAWRENCE

OR

THE LOST CHANNEL

By HARRY GORDON

Author of

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Mississippi”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Colorado”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Amazon”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Columbia”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Ohio”

A. L. BURT COMPANY

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1913

By A. L. Burt Company

THE SIX RIVER MOTOR BOYS ON THE ST. LAWRENCE

CONTENTS

THE SIX RIVER MOTOR BOYS ON THE ST. LAWRENCE.

It was dark on the St. Lawrence River at nine o’clock that August night. There would be a moon later, but the clouds drifting in from the bay might or might not hold the landscape in darkness until morning. The tide was running in, and with it came a faint fog from the distant coast of Newfoundland.

Only one light showed on the dark surface of the river in the vicinity of St. Luce, and this came from the deck of a motor boat, anchored well out from the landing on the south side of the stream, fifty miles or more from Point des Montes, which is where the St. Lawrence widens out to the north to form the upper part of the bay of the same name.

The light on the motor boat came from an electric lamp set at the prow, six feet above the deck. It showed as trim and powerful a craft as ever pushed her nose into those waters.

Those who have followed the adventures of the Six River Motor Boat Boys will not need to be told here of the strength, speed and perfect equipment of the Rambler. The motors were suitable for a sea-going tug, and the boat had all the conveniences known to modern shipbuilders. She had carried her present crew in safety up the Amazon to its source, down the Columbia from its headwaters, through the Colorado to the Grand Canyon, and down the Mississippi from its source to the Gulf of Mexico.

All these trips had been crowded with adventure, but both the boys and the boat had proved equal to every emergency. At the conclusion of the Mississippi journey, the boys of the Six River Motor Boat Club had decided to explore the St. Lawrence river from the Gulf to Lake Ontario.

The Rambler had been shipped by rail to a point on the coast of New Brunswick, and the remainder of the journey to St. Luce had been made by water along the treacherous coasts of New Brunswick and Quebec. A fresh supply of gasoline had been taken on just before night fell, and on the approach of daylight the boys would be on their way up the stream.

Although it was early August, the night was decidedly cold, and Clayton Emmett, Alex Smithwick, Julian Shafer, and Cornelius Witters, the four boys who had embarked on the trip, were sitting snugly around a coal fire in the cabin. They were sturdy, healthy, merry-hearted lads of about sixteen, all from Chicago, and all without family ties of any kind so far as they knew. They had been reared in the streets of the big city, and had become possessed of the Rambler by a series of adventures which the readers of the previous volumes of this series will readily recall.

The night grew darker as it grew older, and a strong wind came up from the bay, bobbing the Rambler about drunkenly. Clayton Emmett—always just “Clay” to his chums—arose from his chair after a particularly fierce blast from the wind and approached the cabin door.

“Don’t open that door!” shouted Alex Smithwick. “We’ll be sent smashing through the back wall if you do. This night makes me think of a smiling summer day in Chicago harbor,—it’s so different!”

“Company!” Clay answered, excitedly, “We’re going to have company. Listen!”

“Yes,” laughed Jule Shafer, “I’ve got a flashlight of any one rowing out to us to-night. The river is too rough for a rowboat.”

“Now you look here, Captain Joe,” Clay went on, “don’t you go start anything!”

This last remark was made to a white bulldog of sinister aspect which had arisen from a rug in a corner of the cabin and now stood at Clay’s side, growling threateningly. Joe wagged a stumpy tail in acknowledgment of the advice, but dashed out, snarling, as Clay opened the door and gained the deck.

“All right; go to it!” Alex laughed, as the door closed behind the two. “Stick out on deck a spell and the wind will do the rest.”

Case Witters—he was never anything but “Case” to his friends—went to the door and looked out through the blurred glass, wiping the inside of the panel with his sleeve in order to get a clearer view.

“What’s coming off?” demanded Jule.

“I hope we’ll be able to get away on one trip without some one butting in,” suggested Case.

“Say, now, look at Teddy,” cried Jule, springing to his feet.

“Teddy” was a quarter-grown grizzly bear. He had been captured on the Columbia river, and had been a great pet of the boys ever since. He now rose from the rug which he had occupied in company with Captain Joe, the white bulldog, and shambled over to the door, against which he lifted a pair of capable paws in an effort to get a view of the deck.

“Rubberneck!” called Alex, digging the cub in the ribs.

“You know what you’ll come to if you talk slang!” Jule grinned. “You’ll have to wash dishes for a week. We all agreed to that, you know,” he added as Alex wrinkled a freckled nose and pointed to the bear cub still trying to look out.

“Why don’t you let him out?” he asked. “If the wind blows his hide off, we’ll make a rug of it. What is Clay doing?”

Case did not reply to the question. Instead, he opened the door, swinging it back with a bang, and both boy and bear ran out on deck. The first thing Teddy did was to sit up on his hind legs and box at the wind, which rumpled his fur and brought moisture to his little round eyes. Boxing was one of the accomplishments taught him by the boys, and he took great pride in it.

Alex closed the door and, with Jule at his side, stood looking out on deck. Clay, Case and the two pets stood at the prow, gazing down on the river.

Directly the top of a worn fur cap made its appearance above the gunwale of the boat, followed almost immediately by the head and shoulders of a man. Then Alex and Jule both rushed out of the cabin.

“He must be a peach, whoever he is, to come off to us in a canoe over that rough water to-night!” Alex cried. “I want to see that boat of his.”

The boat in which the stranger had put off was rocking viciously in the stream, and it was some seconds before he could secure a footing which promised a successful leap for the deck. When at last he came over the rail, the boys saw a heavily-built man with thin whiskers growing out of a dark face. His eyes were keen and black, and the hair hanging low down on his wide shoulders, was black, too, and straight.

Holding his boat line in one hand, in order that the craft might not drift away, he searched with the other hand in the interior pockets of a rough Jersey jacket for a second, and then brought forth a sealed package which he handed to Clay. As the boy took the package, the man who had delivered it sprang, without speaking a word, to the railing, hung for a moment with his feet in the air above the bobbing canoe, dropped, and was almost instantly lost in the darkness.

Leaning over the railing of the boat, wide-eyed and amazed, the four boys stood for a moment trying to pierce the line of darkness beyond the round circle of the prow light. Nothing was to be seen. The boat had come and gone in the darkness. The packet in Clay’s hands was the only evidence that it had ever existed. Alex was the first to speak.

“What do you know about that?” he shouted.

“They must have fine mail facilities on the St. Lawrence!” commented Case.

“That was only a ghost!” Jule asserted, with a wink at Alex. “That letter will go sailing up in the air in a minute.”

Clay opened the packet so strangely delivered and unfolded a crude map of a country enclosed between two rivers. These rivers, after running close together for a long distance, spread apart, like the two arms of a pair of tongs, at their mouths, making an egg-shaped peninsula which extended far into the main river. Back from the river shore, on this rude drawing, a narrow creek cut through the territory between the two rivers, making the peninsula an island.

Below this rude drawing of the rivers and the peninsula was another of an old-fashioned safe resting high up in a niche in a rocky wall. The face of the wall was cross-hatched, to show that it was in the shadows.

Below the drawing of the safe, were these words:

“At last! Follow instructions. Success is certain. Map enclosed. Point straight to the north.”

The boys gathered closely around Clay, standing under the brilliant prow light, and examined the paper, passing it from one to another with questioning glances.

“I guess,” Alex said, “that we are drawing somebody else’s cards.”

“Well,” Case suggested, “that’s a queer kind of a hand to come out of the night.”

“Perhaps,” Jule observed, “they present travelers on the St. Lawrence with these little souvenirs just to excite interest.”

“Point straight to the north,” repeated Clay. “I wonder what that means.”

“I’d like to know what any of it means,” Alex asserted. “It looks to me like some one was butting in.”

“Well,” Case remarked, “we have started out on every trip with a mystery to unravel, and here we go again, loaded up with another.”

“You bet we have!” laughed Alex. “We harvested gold on the Amazon, caught murderers on the Columbia, found a secret treasure in the Grand Canyon, and chased pirates on the Mississippi, but this is the only real Captain Kidd mystery we have struck yet.”

“What shall we do with it?” asked Clay, rattling the paper.

“Throw it in the river and be on our way,” proposed Case.

“Suppose,” Alex grinned, “there should be a barrel of money in that safe they’ve made a drawing of. If there is, we want to get it.”

“I think we’d better be going on, just the same,” Case said. “I’m for dumping this map thing into the river and forgetting all about it.”

“Aw,” Alex cut in, “that would be throwing away all the fun. I want to go to this ‘North,’ wherever it is. There may be something funny doing there.”

Captain Joe, who had been sitting at the prow, watching the boys with an intelligent interest, now passed back to the cabin, leaped upon the low roof, and bounded to the after deck. The boys heard him growling threateningly for a moment, and then he came back.

Teddy, the cub, arose from the place where he had been lying, sniffed at the gunwale of the boat for an instant, and walked into the cabin.

“What’s the matter with our menagerie to-night,” demanded Alex. “There seems to be something in the air.”

“What do you see, Captain Joe?” asked Clay. “If it’s a man, and he’s got a letter, you go get it. Some other fellow may be wanting us to go South, or East, or West.”

As Clay ceased speaking, the splash of a paddle came faintly from the darkness to the West.

“Here comes R. F. D. postman number two,” shouted Alex.

As the boys listened, the splashings of the paddle came louder for a moment, then ceased entirely.

“Hello, the boat!” Alex cried. “Have you got a letter for us?”

No answer came back. There was now a break in the clouds, and the moon shone sharply down upon the swirling river, but only for an instant.

“There he comes!” cried Jule.

But the moonlight was gone, and the sound of the paddle was gone, and just at the edge of the circle of light which came from the prow, an Indian canoe glided, phantom-like, down the stream and disappeared.

“Do you suppose that is the fellow Captain Joe caught prowling around the stem of the boat?” asked Jule as the canoe disappeared down the river.

Captain Joe answered the question by trotting up to the prow and snarling at the disappearing canoe.

“Now, what do you think he wanted here, anyway?” asked Alex.

“Possibly he just dropped down to see if we were ready to start north,” Case observed with a yawn.

“It looks to me,” Alex said, “that we have struck a storm center of some kind, and I’m going to bed and think it over.

“I’m glad you’re going to bed,” Clay laughed, “for you get lost whenever we leave you on watch.”

“But I always find myself!” answered Alex, with a provoking grin.

It was finally arranged that Case should stand guard that night, and the others prepared for sleep. The bunks were let down in the cabin, the prow light was switched off, and directly all was dark, save when the moon broke out from a bank of wandering clouds.

Sitting well wrapped at the door of the cabin, shortly before midnight, Clay once more heard the sweep of a paddle or an oar. He arose and went to the prow.

Off to the right, on a point of land below St. Luce, a column of flame was beckoning in the gale from the gulf. Only the flame was to be seen. There was neither habitation nor human figure in sight under its light. While the boy watched, a signal shot came from the east.

Then an answering light came from the north, and a ship’s boat, four-oared and sturdy, passed for an instant under the light of the moon and was lost in the darkness.

The rowboat had passed so close to the Rambler that the watching boy could have seen the faces of the occupants if they had not been turned away. For a moment he had feared that it was the intention of the rowers to board the Rambler, but they had passed on apparently without noticing the boat at all.

After following the boat with his eyes for an instant, he switched on the prow light and turned to the cabin to awaken his chums. Here was a new feature of the night which must be considered.

As he turned toward the cabin, a white package lying upon the deck caught his eye. It had not been there a moment before, so the boy naturally concluded that it had been thrown from the row boat. He lifted it and, going back under the prow light, opened the envelope and read.

“Don’t interfere with what doesn’t concern you. Go on about your business, if you have any. Life is sweet to the young. Do you understand? Be warned. Others have tried and lost.”

The puzzled boy dashed into the cabin with the paper in his hand.

“Look here, fellows!” he shouted, pulling away at the first sleeping figure he came upon, “R. F. D. postman number two has arrived. Here’s the letter he brought.”

He read the message aloud to the three wondering boys, sitting wide-eyed on their bunks, and handed the paper to Clay.

“What about it?” he asked.

“I reckon,” Alex observed with a grin, “that we’re going to be arrested for opening some one else’s mail.”

“Don’t you ever think this letter wasn’t intended for us,” Jule declared.

“And now,” Case said, “I suppose we’ll have to give up following the orders given in the first letter. We’re ordered off the premises. See?”

“Not for mine,” Alex cried. “You can’t win me on any sawed-off mystery! I want to know what this means.”

After a time the boys switched off the prow light, turned on the small lamp in the cabin, and sat down to consider seriously the events of the night. While they talked, the clouds drifted away, and the whole surface of the river was flooded with moonlight. The flame on the south bank was seen no more. It had evidently been built as a beacon for the men in the ship’s boat.

After a time, Captain Joe, who had been sitting in the middle of the deliberative circle in the cabin, raced out to the deck. The boys heard him growling, heard a conciliatory human voice, and then a quick fall.

When the boys switched on the prow light and gained the deck, they found Captain Joe standing guard over a slender youth who had evidently fallen to the deck to escape being tumbled down by the dog. They gathered about waiting for him to speak—waiting for some explanation of his sudden appearance on the motor boat. Captain Joe seemed proud of his capture, and remained with threatening teeth within an inch of the boy’s throat.

“Say, you!” shouted Alex. “Did you come by parcel post? We’ve been getting letters all right, but no such packages as this.”

“Looks to me like he must have come in a parachute,” Jule suggested. “Where’s your boat, kid?” he added.

The visitor smiled brightly and sprang alertly to his feet. He looked from face to face for a moment, smiling at each in turn, and then pointed to a light canoe bumping against the hull of the Rambler.

He was a lad of, perhaps, eighteen, slender, lithe, dark. His clothing was rough and not too clean. His manner was intended to be ingratiating, but was only insincere.

“What about you?” demanded Alex. “Do you think this is a passenger boat?”

“A long time ago,” replied the visitor, speaking excellent English, “I read of the Rambler and her boy crew in the Quebec newspapers. When I saw the boat here to-night, I ran away from my employer and came out to you. I want to go with you wherever you are going.”

“You’ve got your nerve!” Alex cried.

“Oh, let him alone,” Case interposed. “We’ve had a stranger with us on every trip, so why not take him along?”

Alex took the speaker by the arm and walked with him back to the cabin.

“Say,” he said then, “this fellow may be all right, but I don’t like the looks of his map.”

“You’ll wash dishes a week for that,” Case announced. “You’re getting so you talk too much slang. Anyway, you shouldn’t say ‘map’—that’s common. Say you don’t like his dial.”

“Oh, I guess I’ll have plenty of help washing dishes,” Alex grunted. “But what are we going to do with this boy?” he added.

Clay now joined the two boys in the cabin and asked the same question.

“It is my idea,” he said, “that the appearance of this lad is in some way connected with the other events of the night.”

“What did you find out about him?” asked Clay.

“He says his name is Max Michel, and that he lives at St. Luce,” was the reply.

“Well,” Clay decided, “we can’t send him away to-night, so we’ll give him a bunk and settle the matter to-morrow.”

“I just believe,” Alex interposed, “that this boy Max could tell us something about those two boats if he wanted to.”

“I notice,” Case put in, “that he’s paying a good deal of attention to what is going on in the cabin just now. He may be all right, but he doesn’t look good to me.”

Clay beckoned to Jule, and the two boys entered the cabin together, closely followed by Captain Joe, who seemed determined to keep close watch on the strange visitor.

“How long ago did you leave St. Luce?” asked Clay of the boy.

“An hour ago,” was the answer. “I rowed up the river near the shore where the current is not so strong and then drifted down to the motor boat. I called out to you before I landed, but I guess you did not hear.”

Alex, standing at the boy’s back and looking over his head, wrinkled a freckled nose at Clay and said by his expression that he did not believe what the boy was saying.

“Did you see a light on the point below St. Luce not long ago?” continued Clay.

The boy shook his head.

“There are often lights there at night,” he said. “Wreckers and fishermen build them for signals. But I saw none there to-night.”

“What about the four-oared boat that left St. Luce not long ago?” Clay asked. “Do you know the men who were in it?”

“I didn’t see any such boat,” was the reply.

“Well, crawl into a bunk here,” Clay finally said, “and we’ll tell you in the morning what we are going to do.”

The boy did as instructed, and was, apparently, soon sound asleep. Then the boys went out to the deck again and sat in the brilliant moonlight watching the settlement on the right bank.

There is a railway station at St. Luce, and while they watched and talked, the shrill challenge of a locomotive came to their ears, followed by the low rumbling of a heavy train.

The prow light was out, and the cabin light was out, and the cabin was dark now, because when the boys had sought their bunks, a heavy curtain had been drawn across the glass panel of the door. From where the boys sat, therefore, they could see nothing of the interior of the cabin.

Five minutes after the door closed on the stranger, he left his bunk and moved toward the rear of the cabin. Against the back wall, stood a square wooden table, and upon this table stood an electric coil used for cooking. Above the table, was a small window opening on the after deck.

The catch which held the sash in place was on the inside and was easily released. The boy opened it, drew the swinging sash in, passed through the opening, and sprang down to the deck.

Reaching the deck, the visitor, as though familiar with the situation, ran his hand carefully about his feet feeling for a closed hatch. He found it at last and, lifting it, peered into the space set aside for the electric batteries and the extra gasoline tanks.

Reaching far under the planking, he found what he sought—the wire connecting the electric batteries with the motors. Listening for a moment to make sure that his motions were not being observed, he drew a pair of wire clippers from a pocket and cut the supply wire. Only for the fact that the lights on the boat were all out, this villainous act would at once have been discovered. As it was, the boys remained at the prow believing the visitor was still asleep in his bunk.

This act of vandalism accomplished, the boy dropped softly over the stern into his canoe, still trailing in the rear of the motor boat. Once in the canoe, he laid the paddle within easy reach and propelled the boat along the hull of the Rambler, toward the prow with his hands. Once or twice discovery seemed to the boy to be certain, for Captain Joe came to the gunwale of the boat and sniffed suspiciously over the rail.

Once, Clay left his place at the prow and looked over into the stream, but the moon was in the south and a heavy shadow lay over the water on the north side, so the dark object slipping like a snake to do an act of mischief reached the prow unseen.

At that moment the boys left the prow and moved toward the cabin door. In another instant they would have entered and noted the absence of their guest, but Alex paused and pointed to lights moving in the village of St. Luce.

“There’s something going on over there,” he said “and I believe it has something to do with what we’ve been bumping against. There’s the letter from the canoe, and the warning from the boat, and the boy dropping out of the darkness on deck, and the signal lights, and now the stir in the village. Some one who wishes us ill is running the scenes to-night, all right.”

While the boys stood watching the lights of St. Luce, Max caught the manila cable which held the motor boat and drew his canoe up to it. Cutting the cable, strand by strand, so as to cause no jar or sudden lurching of the boat, he left it slashed nearly through and, leaving the strain of the current to do the rest, worked back through the shadow and struck out up stream.

Standing in the door of the cabin, the boys felt the boat sway violently under their feet, then they knew from the shifting lights in the village that they were drifting swiftly down with the current. Clay sprang to the motors, but they refused to turn.

Case hastened to the prow and lifted the end of the cable. There was no doubt that it had been cut. Clay made a quick examination of the motors and saw that the electrical connection had been broken. Then Jule called out in alarm that they were drifting directly upon a rocky island.

The Rambler, drifting broadside to the current, threatened to strike full upon a rocky promontory projecting from the island which lay in the course of the boat. In vain Case tugged at the tiller ropes. There was no steerage way, and the boat was beyond control.

“It looks like the last of the Rambler!” Case cried as the boat drifted down. “The rock ahead will cut her in two if we strike it.”

But there was a current crossing the rocky point from north to south, and the boat, catching it, was drawn away, so that in time, she came, stern first, to the curve of a little channel into which the waters drew. For a moment, the prow swung out, and the possibility of a continuation of the vagrant journey was imminent.

However, before the sweep of water turned the prow fairly around, Alex was over the gunwale, clinging with all his might to the broken cable. Clay and Jule were at his side in a moment and, half swimming, half stumbling, quite up to their chins in the cold water, they held the boat until the current swept it farther over on the sandy beach that bordered the cove.

“There you are!” shouted Alex, wading, dripping, from the river. “The next time I take a trip on the Rambler, I’m going to wear a diving suit. I’m dead tired of getting wet.”

“You’re lucky not to be at the bottom of the river!” Clay announced.

The rowboat, which lay upon the roof of the cabin, was now brought down, a cable was taken out of the store room, and the Rambler firmly secured to a great rock which towered above the slope of the cove.

The boys stood for a moment looking over the surface of the river, still bathed in moonlight, then Alex rushed into the cabin and brought out a field glass.

“What I want to know just now, is who cut that cable,” he said.

“That’s easy,” Jule replied. “It was the innocent little boy who had read all about the Rambler in the Quebec newspaper.”

Alex swept the river with the glass for a time and then passed it to Clay.

“There he goes,” he said, “away up the river, heading for St. Luce! That’s the boy who disconnected the electricity and cut the cable. That’s the boy who we will even up with when we catch him, too.”

“And you’re the boy who’ll wash dishes for a week for talking slang!” Jule taunted.

“I’d wash dishes for a month if I could get hold of that rat,” answered Alex, angrily. “He came near wrecking the Rambler!”

“Well,” Clay said, “we may as well be getting the motors into shape. We can’t stay on this island long.”

“If we do, there’s no knowing what will happen,” Jule suggested. “We’ve had two letters and a runaway to-night and the next thing is likely to be a stick of dynamite.”

“Say, suppose we repair the electric apparatus and get away from this vicinity right now,” suggested Case, “I don’t like the looks of things.”

“Now, look here,” Alex cut in, “I’m ready to get out of this section, but do you mind what the first letter said about going north? Now that means something. If the first letter hadn’t told us to go north, and the men who threw the second letter hadn’t believed that we were obeying instructions, we wouldn’t have been interfered with. Now, there’s a friendly force here, and a hostile force. The friendly people may be mistaken in our identity, but that doesn’t alter the fact that the hostile element is out to do us a mischief.

“I’d like to find out what it is the friendly force expects us to do. If we can learn that, we’ll know why the hostile force is opposing us. And so, it looks to me that instead of running away, we would better find out what is wanted of us. How does that strike you, fellows? Isn’t that deduction worthy of Sherlock Holmes?”

“All right,” Clay declared, “I’m willing to investigate, but we mustn’t spend all our time looking into one mystery, for if we have the same luck we had on other trips, we are likely to come across several more before we go back to Chicago.”

“I’d like to know,” Case said, as they brought up an extra anchor and a new cable, “why we were dumped on this island.”

“To get us out of the way, probably,” Jule commented. “They undoubtedly expected to steal or wreck the Rambler.”

“But the Rambler,” Alex laughed, “has the luck of the Irish, so she’s still able to travel.”

The island upon which the boat had been cast, lay only a short distance from the south shore of the river. In fact, at low water, when the tide was out, it might have been possible to pass to the mainland on dry ground.

Its location was not more than two miles below the little landing at St. Luce. In fact, as the boys afterwards decided, it must have been from this island that the signal flame had burned early in the evening.

Working busily on the repairs, the boys did not notice the arrival upon the island of two roughly dressed fellows, who landed from a small boat and who took great pains to keep rocky elevations between themselves and the cove where the boat lay.

“I wonder,” Jule asked, sitting down on the prow after a struggle with the new cable, “whether the stories I have read about wreckers along the St. Lawrence are true.”

While the boys discussed the possibility of wreckers working along the stream, one of the two men clambered to an elevation which was in turn hidden from the cove by a higher one and waved a red and blue handkerchief toward the shore.

The tide was now running out, and the channel between the island and the mainland swirled like a mill-race. This, however, did not prevent the launching of a boat from the shore, the same being manned by four men. They edged along the shore and then, passing boldly into the current, landed on the island at a point east of the cove. There they secreted their boat and moved on toward the place where the boys, all unconscious of their presence, were repairing the damages wrought by their treacherous guest.

It was Captain Joe who gave the first intimation of the presence of others on the island. He sprang from the boat, paddled through the shallow water between the hull and the shore, and set out for the elevation where the man who had signaled had been standing.

The boys heard a cry of pain, a shout of anger and a pistol shot, and then Captain Joe came running back to where the Rambler lay.

“What was it you said about wreckers?” Case asked with a startled look. “No beast or bird fired that shot!”

“I was only wondering,” Jule answered, “whether there are really wreckers at work along the river. That’s the answer!”

“Well,” Clay said, “we’ll get on the boat to talk it over! In the meantime, we’ll be putting space between the Rambler and this island. If ever a wrecker’s beacon told where to lure a boat to be plundered, that flame we saw on the island told our sneaking guest when to cut the Rambler loose!”

The boys hastened on board and Clay ran to the motors. At that instant, four men made their appearance on the ledge above the cove, beckoning with their hands and calling out to the boys that they had something of importance to say to them.

“They look to me like triple-plated thieves,” Alex commented, “and I wouldn’t be caught on an island with them for a farm.”

Captain Joe seemed to approve of this decision, for he stood with his feet braced, growling furiously at the beckoning men.

“Boat ahoy!” one of the men cried. “We have a message for you.”

“All right,” Case answered, “you may send it by wireless.”

“But it is important!” came from the man.

During this brief conversation, the motors were slowly drawing the Rambler out of the sandy cove, the electric connection having been made, and the men were rapidly approaching the shore. The boat moved slowly, for the keel was dragging slightly in the sand, and the wreckers, if such they were, stood at the water’s edge before the craft was more than a dozen yards away.

Directly, all appearance of friendship ceased, and the men stood threatening the boys with automatic guns.

“Run back!” one of the men cried, “or we’ll pick you off like pigeons!”

The boys had already taken their automatic revolvers from the cabin, and now, instead of obeying the command of the outlaws, they dropped down behind the gunwale and sent forth a volley not intended to injure, but only to frighten.

Apparently undismayed by the shots, the outlaws passed boldly down the shore line seeking to keep pace with the motor boat as she drew out of the cove. Every moment the motors were gaining speed. In another minute, the Rambler would be entirely beyond the reach of the outlaws.

Apparently hopeless of coercing the boys into a return, the outlaws now began shooting. Bullets pinged against the gunwale and imbedded themselves in the walls of the cabin but did no damage.

A tinge of color was now showing in the east. Birds were astir in the moving currents of the air, and lights flashed dimly forth from the distant houses of St. Luce. Against the ruddy glow of the sky, a river steamer lifted its column of smoke. Observing the approach of the vessel, the outlaws redoubled their efforts to frighten the boys into instant submission.

However, the Rambler was gaining speed, and the incident would have been closed in a moment if the connection made between the batteries and the motors had not become disarranged. In the haste of making the repairs, the work had not been properly done.

The propeller ceased its revolutions and the boat dropped back toward the cove. Evidently guessing what had taken place on board, the outlaws gathered at the point where it seemed certain that she would become beached.

Understanding what would take place if the motor boat dropped back, the boys fired volley after volley in order to attract the attention of those on the steamer. There came a jangling of bells from the advancing craft, and she slowed down and headed for the point. The outlaws fired a parting volley and disappeared among the rocks.

The steamer continued on her course toward the little island, but paused a few yards away and the boys saw a rowboat dropped to the river. The Rambler continued to drift toward the beach she had so recently left and the rowboat headed for that point.

Fearful that the boat would again come within reach of the outlaws, Clay and Case now rushed to the prow, and threw the supply anchor over just in time to prevent a collision between a nest of rocks and the stern of the boat.

The outlaws were now out of sight, and the boys felt secure in the protection of the steamer, but directly the situation was changed, for a show of arms was seen on board the rowboat, and the boys were suddenly ordered to throw up their hands.

“You fellows are nicely rigged out—fine motor boat, and all that,” one of the men in the boat shouted, “but the days of river pirates on the St. Lawrence are over. You are all under arrest.”

“Gee whiz!” shouted Alex. “Is this what you call a pinch?”

“It is what we call a clean-up,” replied one of the men in the boat, rowing up to the Rambler. “We’ve been watching for you fellows, and now we’ve got you.”

“And what are you going to do with us?” asked Clay restraining his anger and indignation with difficulty.

“We’re going to take you up to Quebec and put you on trial for piracy!”

“That’ll be fine!” Jule commented.

The boys tried to smile and make light of the situation as the four men from the steamer boarded the Rambler, but they all understood that it was a very serious proposition that they were facing.

The men from the steamer took possession of the Rambler impudently, acting like ignorant men clothed with small authority. The boys were ordered to the cabin and the door locked.

“We left our manacles on board the Sybil,” one of the men announced, “or we’d rig you out with some of the King’s jewelry.”

“We’ll overlook the slight for the present,” Case flared back, “but you be sure and bring the jewels at the first opportunity.”

“You’ll get them quick enough,” snarled one of the men. “Three days ago we received notice that you were coming, and we’ve been watching for you ever since. You came along just in time to be nicely trapped.”

“Do you mean that you were watching for the Rambler?” asked Clay, lifting his voice in order that he might be heard through the glass panel of the door. “I’d like to have you tell me about that.”

“No one knew the shape you would come in,” was the gruff reply. “We only knew that a band of pirates and wreckers who had been luring vessels on the rocks along the bay was preparing to visit the St. Lawrence. Perhaps you will tell me where you stole this fine boat?”

“They must have a big foolish house in this province,” Alex taunted, “if all the King’s officers are as crazy in the cupola as you are.”

“Let them alone,” urged Clay. “No use in talking to men of their stripe. Wait until we get to the captain of the steamer.”

The sailors continued to question the boys, resorting now and then to insulting epithets, but the lads sat dumbly in the cabin until the arrival of Captain Morgan, in charge of the steamer Sybil. To express it mildly, they were all very much elated at the appearance of Captain Morgan, who unlocked the cabin door, called them out on deck and greeted them pleasantly. They all wanted to shake hands with him.

“It seems,” Clay said to the captain, as the latter motioned to the sailors to move up to the prow, “that your men have captured a band of bold, bad men. It was a daring thing for them to do!”

The captain laughed until his sides shook, and the men, gathered on the forward part of the deck, scowled fiercely, to which the captain paid no attention at all.

“Perhaps there is an excuse for the men,” Captain Morgan finally said, suppressing his laughter. “We heard firing as we came up the river, and wreckers are known to be about.”

“If you have any doubt as to the presence of wreckers,” Clay explained, “just send your ruffians over on the island. The men who did most of the shooting are there. They may also be able to find the ashes of the signal fire the outlaws lighted.”

“That will be good exercise for them,” Jule cut in, “and perhaps they won’t be so brave when they find they haven’t boys to deal with.”

“Do you mean to tell me that the wreckers are now on the island?” asked the captain. “If they are, we may yet be able to make a capture.”

“They were on the island just before you came up,” Clay answered, “and I presume they are there yet. We’ll help you take them.”

The captain laughed and looked critically at the slender, well-dressed youngsters, then his eyes turned to the white bulldog and the bear, now sniffing suspiciously at his legs.

“It seems to me,” he said, “that I have heard of this outfit before! When I came aboard I thought I recognized the name of the Rambler. This menagerie of yours settles the point. You brought Captain Joe, the dog, from Para, on the Amazon and Teddy, the cub, from British Columbia.”

“You’ve got it,” Alex cried, “but how did you come to know so much about us? We rather expected to get away from our damaged reputations up here,” he added with a wink and a grin.

“You have long been famous in these parts,” the captain answered, “Ever since the Rambler came riding up to the Newfoundland coast on a flat car. It is a wonder that my men did not recognize you.”

“I don’t believe they can read,” laughed Alex. “Suppose you send them over on the island to see if they can recognize some of the outlaws.”

One of the sailors approached Captain Morgan, saluted, and pointed to the narrow channel between the island and the mainland. The sun was now shining brightly in the sky, and the whole landscape lay bright under its strong and rosy light. Half way across the channel, its rays glinted on splashing oars, and from the shore came hoarse commands.

“There are men leaving the island, sir,” the sailor said. “Perhaps we did get hold of the wrong fellows.”

“I should think you did,” laughed the captain, “but there may be time to correct the error. Signal to the steamer for more men, and drift down in your boats. You may be able to capture some of those outlaws, and,” he added with a smile as the sailor turned away, “don’t forget that there is a reward offered for every one of them.”

“Perhaps we’d better go with the men,” suggested Case. “We aren’t anxious to get where there’s shooting going on, but we need the money.”

“I prefer,” the captain replied, “that you come on board the Sybil with me. I’ll have the cook get up a fine breakfast, and you boys can tell me all about your river trips. I have always been interested in such journeys and have long planned to take one myself.”

The boys readily agreed to this arrangement, Alex declaring that it would save the washing of at least one mess of dishes, and all were soon seated in the captain’s cosy room.

“I’ll wait here an hour,” Captain Morgan said, “to give my men a chance to gather in some of the rewards, but after that I must be on my way. We shall be late now, on account of this delay.”

The boys briefly described their river trips on the Amazon, the Columbia, the Colorado and the Mississippi, and were rewarded with a breakfast which Alex admitted was almost as good as he could cook himself.

“And now,” Clay said, as they all stood on the deck, watching the sailors returning empty-handed from their quest of the outlaws, “I wish you would tell me what all this rural free delivery business we’ve encountered means. We’ve been puzzling over it all night.”

As he spoke he handed the first letter—the one delivered by the mysterious canoeist—to the captain, who smiled as he looked at it.

“I’ll tell you about that,” he said. “There is a man over in Quebec who claims that he owns about half of the province under a grant of land made to Jacques Cartier in 1541 by Francis I. of France. This grant, or charter, he claims, was confirmed to his family, the Fontenelles, in 1603 by Samuel de Champlain, who was sent to Canada by de Chaste, upon whom King Louis XIII. had generously bestowed about half of the new world.

“Fontenelle claims that all the kings and presidents of France from 1541 down to the present time have confirmed this grant so far as certain mineral and timber properties are concerned. For years Fontenelle has been trying to gain possession of the original charter brought to this country by Cartier, but has never succeeded.”

“Would he secure a large amount of property if he found it?” asked Alex. “How did it ever become lost?”

“It disappeared from Cartier’s hands,” was the reply. “It is believed that the recovery of the original charter would make the Fontenelles very wealthy, especially as the family jewels, worth millions of francs, are said to have been lost with the important document.”

“I think they had their nerve to send family jewels to America in 1541,” Case cut in. “Might have known they would be lost.”

“You must remember,” Captain Morgan replied, “that for years during and following the reign of Francis I. the protestant persecutions kept France in a turmoil. It was hinted that the Fontenelles did not favor these persecutions and that the jewels were shipped to the new world for greater safety. What I am telling you now, remember, is only tradition, and not history. To be frank with you, I will say that I don’t believe it myself. It is too misty.”

“It is interesting, anyway,” Clay declared, “and I’d like to hear more about it, but tell me this—why should the Fontenelles, or their agents, send this letter to us? And why should they send it, if at all, in so mysterious a manner?”

“I have heard,” Captain Morgan replied, “that an expedition for the recovery of this original charter was being fitted out at Quebec. Your boat may have been mistaken for the one carrying the searchers.”

“Searching in this wild country?” questioned Alex. “Where do they think this blooming charter is, I’d like to know?”

Captain Morgan took the crude map into his hands and pointed to an egg-shaped peninsula reaching out into the St. Lawrence between the mouths of two rivers.

“There is said to be a lost channel somewhere in that vicinity,” he said, “and tradition has it that the papers and the jewels were hidden on its shore. The searchers, for years, have been in the hope of finding this lost channel. They have never succeeded.”

“Then we’re almost on the ground,” cried Jule. “Where do we go to reach this peninsula? We might be lucky enough to find this channel.”

“It doesn’t exist,” smiled Captain Morgan. “Every inch of that country has been gone over with a microscope, almost, and there is no lost channel there. At least, it can’t be found.”

“There is one on the map, anyway,” Alex observed.

“Well,” Clay laughed, “we have been mixed up with some one else’s affairs on every one of our river trips, and we may as well keep up the record, so I propose that we spend a few days looking for this lost charter and these family jewels.”

The boys all agreed to the proposition, and even Captain Morgan seemed to gain enthusiasm as they talked over their plans.

“I wouldn’t mind being with you,” the captain said, “but of course, I can’t go. However, if you keep on across the river, straight to the north, you’ll come to the egg-shaped peninsula. Keep to the right of it, and you’ll enter a broad river. This map shows you where the lost channel is claimed to have existed. Go to it, kids, and good luck go with you!”

“Now then that point is settled,” Clay smiled, taking the second letter from his pocket, “tell us what this means.”

Captain Morgan looked over the paper carefully before making any reply. His face clouded and an expression of anger came to his eyes.

“The fact of the matter is,” he said, “that for two hundred years the Fontenelles have met with opposition in their search for the lost channel. Some of the land claimed under the charter is now held by innocent purchasers who believe their title to be perfect.

“There is no doubt that such might come to a fair understanding with the Fontenelles if the charter should ever be found, but it is alleged that an association has been formed by the wealthier persons who are interested to defeat any attempt made to discover the charter. They claim, of course, that with the charter in their possession the Fontenelles would be able to make their own exorbitant terms.”

“I knew it!” Alex cried. “We are in between two hostile interests again! It always happens that way. But we like it!”

“I have been thinking,” Captain Morgan went on, “that the men who attempted to wreck the Rambler are not river pirates at all, but men sent here to obstruct, as far as possible, those in search of the lost channel. It certainly looks that way.”

“Well,” Clay remarked, “they haven’t got any motor boat, and we’ve got one that can almost beat the sun around the earth, so we’ll just run away from them. In an hour after you leave here, we’ll be in the east river looking for the channel which is said to have connected it in past years with the one paralleling it on the west.”

The sailors who had been searching now reported to the captain that no strangers had been seen by them on the island, and it was agreed that the outlaws, whether wreckers or men employed to obstruct the search for the lost channel, had taken to the south shore. Captain Morgan shook the boys warmly by the hand as they parted.

“If you say any more about your plans,” he said, “I’ll be going with you. Already I can sense the smoke of your campfire, and smell the odor of the summer woods. There are fine fish up in those rivers, boys, great shiny, gamy things that fight like the dickens in the stream and melt like butter in the mouth.”

“We’ll send you out some,” promised Clay, and the steamer’s boat carried the boys back to the Rambler.

The needed repairs were soon accomplished, and when night fell the motor boat lay under a roof of leaves in a deep cove on one of the rivers behind the egg-shaped peninsula. Just above the anchorage the water tumbled, from a high ledge. The boys had no idea of remaining on board that night, so they built a roaring campfire on shore and stretched hammocks from the trees.

“Right here,” Clay said as the moon rose, “right about where we are sitting, there may be a lost channel!”

“That’s all right,” grinned Alex, “but I don’t see myself getting very wet sitting on it.”

“I don’t blame any old channel for getting lost in this wild country,” Case contributed. “We’ll be lucky if we don’t get lost ourselves. Hear the owls laughing at us!”

“I’ve been listening to the owls,” Clay said, “and I have concluded that they are fake owls. If you’ll listen, you will hear signals.”

The boys listened for a long time, and then above the rush of the river and the murmur of the leaves in the wind, came a long, low call which seemed to them to be a very bad imitation of owl talk.

“There is one sure thing,” Clay said, as the boys listened, “and that is that we have got to watch the Rambler to-night. I propose that we take down the hammocks and go back to our bunks.”

“It’s a shame to sleep in that little cabin,” Alex protested, “when we’ve got the whole wide world to snore in. Suppose you boys remain here on shore, and let me stand guard on the boat.”

“That will be nice!” Jule laughed. “Alex always gets his soundest sleep when he’s on guard.”

“Don’t you worry about me,” Alex said, “I’ll keep awake, all right. Besides, I want to hear the owls talk.”

“I think we would better all go back to the Rambler,” Clay advised. “We can anchor her farther out in the stream, leave one on guard, and so pass a quiet night. It looks risky to leave the boat where she is.”

“Perhaps that’s what we ought to do,” Alex agreed, giving Jule a nudge in the ribs with his elbow. “Who’s going to stand watch?”

“I will,” Case offered. “I’ll sit up until daylight, and then you boys can get up and catch fish for breakfast.”

“I want a fish for breakfast two feet long,” Alex declared. “I’ll catch it and cook it in Indian style. That will be fine!”

“How do you cook fish a la Indian?” asked Case.

“Aw, you know,” Alex replied. “First, you get your fish; then you dig a deep hole in the ground and fill it full of stones. Then you build a roaring fire on the stones. Then you wrap your fish up in leaves and put it on the hot stones and cover it up. Then, if you want it to cook quick, you must build a fire on top. They sell fish cooked in that way at two dollars an order in Chicago.”

“Cook it any way you want to,” Clay said, “only don’t muff it the way Case does when he tries to make biscuits. We’ll be hungry.”

Taking down the hammocks, the boys moved back to the Rambler. Clay, Alex, and Jule, after listening in vain for a time for more signals from the woods, finally went to their bunks, leaving Case sitting on the deck, across which a great tree on the east bank threw a long blur of shade.

Clay and Jule were soon sound asleep, but Alex lay awake listening. There was a notion at the back of his brain that the signals heard had been treated too lightly. He knew that Clay, always active and ready for any emergency, considered the party secure in midstream, but he was by no means satisfied that the best steps for the protection of the boat had been taken.

After a time he arose, dressed himself, and softly slipped out on deck, leaving the rest sleeping in the cabin.

“It isn’t morning yet,” Case said, speaking out of the shadow. “Why don’t you go back to bed? You’ll be sleepy to-morrow.”

“Have you heard any more owl talk?” asked Alex.

“Not a line,” replied Case. “Go on back to bed.”

Alex did go back to bed, but could not sleep. Presently the long-expected owl-call came from the north, and then Teddy rubbed his soft nose against the boy’s hand.

“What do you want, old man?” whispered Alex. “Does that hooting warn you of danger, too?”

The cub put his paws upon the edge of the bunk and tried to answer in bear talk that it did.

“All right,” Alex said, “I’ll just go out and see about it.”

When he reached the deck for the second time, Case stood at the gunwale listening. The call came again from the woods.

“Now you hear it, don’t you?” asked Alex, scornfully. “I reckon you fellows would sit around here and let those wops carry off the boat.”

“Well, haven’t they got to show up before we can do anything to them?” asked Case reproachfully. “I guess they have.”

“I’d like to know what they are doing,” Alex wondered, “and I just believe I could sneak out and learn something about it. It makes me nervous, waiting here for them to get in the first blow.”

“If I had a house and lot for every time you’ve been lost on our river trips,” Case grinned, “I’d own the biggest city in the world. You go back to bed, or I’ll get Clay out here to tie you up.”

Teddy now came sniffing where the two boys stood, and, lifting his paws to the gunwale, looked over in the forest.

“See that!” Alex exclaimed. “Even the bear knows there is something wrong on! If you’ll keep that twirler of yours still for a little while, I’ll go and see what it is.”

“You’re the wise little sleuth!” Case declared. “Go on back to bed and dream that you’re Nick of the Woods.”

“Tell you what,” Alex said, “we’ll tie a line to the rowboat, and I’ll row ashore, then you pull the boat back, and I’ll creep out in the thicket and see what I can discover. I believe those outlaws will gather around the campfire. Anyway, they’re foolish if they don’t.”

“If you take my advice,” Case said, “you won’t go, but if you insist on it, I’ll draw the boat back, for our own protection.”

Very reluctantly, then, Case assisted in getting the boat into the river, found a long line to attach to the prow, and helped the boy away on his journey. He felt guilty for aiding in the adventure.

Alex landed in a thicket almost straight west of the Rambler, and at once secreted himself. No signals had been heard for some moments, and the boy believed that he had reached the shore without attracting attention. Case drew the boat back and sat waiting.

Alex remained perfectly still in his hiding-place for some moments. There was only the noises of river and forest. To the west, the embers of the campfire made a faint red glow in the moonlight.

Just as the boy was about to move out of the thicket, he heard a heavy splash in the river, followed by words of command and entreaty from Case. The splashing continued, and presently the bushes at the edge of the stream were moved by an entering body.

“That’s Captain Joe!” thought Alex. “He’s always ready for a run in the woods. I suppose I ought to send him back.”

But it was not Captain Joe that thrust a wet nose into Alex’s hand. It was Teddy, the bear cub, and his greeting was so friendly and sincere that all thoughts of sending him back to the boat vanished from the boy’s mind. Teddy shook the water from his coat like a great dog, and cuddled up to the boy as if thanking him.

“You’re a runaway bear,” Alex whispered to the cub, “and I ought to send you back, but I’ll just see if you know how to behave in the kind of society I am going to mix with. Will you be good?”

Teddy declared in his best bear talk that he would be good, and the boy and the cub lay in the thicket, still listening, for a long time before moving. Then Alex crept toward the campfire.

When he came to a considerable rise in the center of the ground between the two streams, he found that the ground was broken and rocky. It seemed to him that a great crag had formerly risen where he stood, and that some distant convulsion of nature had shattered it.

To the south, between the rivers and at no great distance from the egg-shaped peninsula, ran a long, rocky ridge. Making his way to this, he secreted himself in the shadow of a boulder and settled down to watch and listen.

After a time Teddy grew impatient at the inactivity thus forced upon him, and began moving restlessly about.

“Bear!” warned Alex, “if you make any more racket here, I’ll send you back to the boat. We’re supposed to be sleuthing!”

Teddy evidently did not like the idea of being sent back to the boat, or of keeping still either, so he almost immediately disappeared, notwithstanding Alex’s efforts to detain him by main force. The boy called to him in vain.

“Now,” thought Alex, “the cub has gone and done it! He’ll thrash around in the woods and scare my outlaws away. I wish I had tied him up on the boat. I might have known he would make trouble.”

The boy waited a long time, but the cub did not return. Now and then he could hear him moving about in the thicket.

“He’s just laughing in his sleeve at me!” complained the boy. “I wish I had hold of him!”

Directly a sound other than that made by the bear came to the ears of the listening boy. Some one was creeping towards his shelter. He could see no one, for the shadows were thick at the point from which the sounds proceeded, but presently, he heard a voice.

“They went back to the boat,” some one said gruffly.

“That’s all the better for us,” another spoke.

“I don’t know about that,” the first speaker said.

“Why, we’ll just cut her out and take boys and boat and all.”

“That’s easier said than done,” was the reply. “Those boys are no spring chickens. They have guns and they know how to use them.”

“Well,” the other chided, “it isn’t my fault that they went back to the boat. If you hadn’t been giving your confounded signals, they would have slept by the fire and everything would have been easy.”

Alex listened with his heart beating anxiously. There was no longer any doubt that the right construction had been placed on the signals which had been heard. The outlaws who had attacked them in the cove were now on the peninsula, ready to make trouble.

While the boy listened for further conversation, a rustling in the thicket at the base of the cliff told him that Teddy, the cub, was still in that vicinity. He chuckled at the thought which came to him.

“I wish I had the little rascal here,” he mused. “I think he might be able to do something in the line of giving those fellows exercise! I wish I could get over to him.”

The boy started in the direction of the sound, but paused when he heard one of the men saying:

“Where are the others?”

“Down on the river shore,” was the reply.

“Then what is all that noise?” demanded the other.

“I don’t hear any noise,” was the surly reply.

“There is some one moving in the bushes.”

“Then it must be one of the boys,” Alex heard, “and I think we had better investigate. It would be luck to catch one of them.”

“It wouldn’t be any luck for me to be caught,” thought Alex, “and so I’ll just make a sneak back to the boat. I’ve learned all I wanted to know, anyway.”

He started away, but almost at his first motion a stone became detached from the ledge at his side and went thundering down toward the spot from which the voices had proceeded.

“There!” one of the men cried, “I told you there was some one here.”

Together the men immediately rushed to the spot where Alex lay hidden. They rustled through the bushes without any attempt at concealment, scrambling up the acclivity with the use of both hands and feet.

As they advanced another rustling came from the left, and Alex saw Teddy on the way back to his side. The moon, creeping farther to the south, found an opening in the dense foliage above the ledge, and threw a long shaft of light upon the exact spot where Alex lay, revolver in hand, waiting for the expected attack.

He moved out of this natural limelight hastily, but as he did so another figure entered it. Advancing swiftly, the men who had discovered the location of the boy, saw him disappear and saw the new figure which came upon the scene. They stopped instantly.

To their excited imaginations Teddy, standing somewhat above their heads, seemed to be at least nine feet high! Evidently trying to propitiate Alex for running away from him, the cub set about practicing all the stunts the boys had been teaching him for months.

Standing upon his hind legs, he extended his paws in a boxing attitude and pranced about, as he had been taught to do, in all the attitudes of the prize ring. The hair on his neck and back seemed to bristle with anger. His little round eyes, bright in the moonlight, twinkled viciously!

The men who were watching this trained exhibition, held their breaths in terror. They expected to be attacked by the animal immediately. Directly, they began backing slowly away. Then Teddy broke into his pet amusement, a whirling half-dance and they turned and ran, stumbling down the declivity, brushing through the briars and clinging vines of the thicket, and finally disappearing in the shadows farther upstream!

It did not take Alex long to find his way to the cub.

“You certainly are enough to scare the life out of a stranger,” he said, addressing the bear. “If you don’t mind, now, we’ll go back to the boat. We’ve got news for the boys, at any rate.”

But Teddy was not inclined to go back to the close cabin. He wanted a longer run in the woods. Before Alex could seize the collar which had been placed about his neck, he was away again. Alex pursued him for some distance, and then turned back toward the boat.

When he reached the shore and called softly to Case to row the boat over to him, there was no answer from the craft, as the rush of the river drowned his voice, but a most unexpected one came from the shore back of him. He turned quickly to see the barrel of a gun shining in the moonlight. He reached for his own weapon, but a hand caught his wrist and held it, as if in a grasp of iron.

“All right, kid,” a harsh voice said, “if they don’t want you on your boat, we’ll give you a home on ours. We’ve got the snuggest little craft upstream you ever saw. You’re welcome to it, only it may be dangerous for you to try to get away or make any noise!”

Case waited patiently a long time for the return of his chum. When it came near midnight he decided to awaken Clay and inform him of the situation. The latter was out of his bed instantly.

“He shouldn’t have gone,” the boy said, anxiously. “There is no doubt that he is in trouble of some kind. I’m sorry for this!”

“Well, he would go,” Case urged, “and he promised to go only to the shore and look around. Just after he left, Teddy splashed off the boat and ran into the thicket. I presume the two are together.”

“Of course they’re together,” said Clay, “That is, if Teddy hasn’t been discovered and shot. That is likely to happen.”

“What shall we do?” asked Case anxiously.

“It isn’t much use to go into the thicket after him,” Clay decided. “There is plenty of moonlight here, it is true, but the foliage must make it very dark in the forest. It would be like looking for a special pebble on the beach to try to find him now. We’ll have to wait.”

“Perhaps Teddy will come and bring us news,” suggested Case. “I have known him to do such things. He’s a wise little bear.”

There was no more sleep on board the Rambler that night. With the first flush of dawn Clay and Jule were abroad in the forest, leaving Case on watch. Although they searched patiently for a long time, no trace of the missing boy could be discovered.

Here and there were tracks which must have been made by Teddy, but it was not certain that the two had been together. After a time the boys returned to the bank of the river just above the location of the Rambler. There they found where a boat had been drawn up to the bank.

“I don’t see how they ever got a boat by us,” Clay argued, “but they certainly did, for they couldn’t have got here first. They must have sneaked up the east shore in the shadows and landed above the Rambler. Are you sure that no boat passed down after Alex left?” he asked of Case. “One might have drifted down without making much noise.”

“I was awake every minute of the time,” Case insisted, “and no boat passed down. When the moon swung around to the south, the whole river was illuminated. I would have seen any craft that passed.”

“Then it is certain that the intruders are still up river, perhaps above the falls, and I am afraid that Alex is where they are. That little rascal is always getting lost! He should have remained on board.”

“Yes, he gets lost,” admitted Case, loyally, “but he always comes out on top in the end. There wouldn’t be any fun if Alex and Teddy were not always getting into trouble. It sort of keeps things moving!”

“Well,” Clay concluded, “the place to look for the boy is, as I said before, upstream. Now, the question is, shall we take the Rambler up?”

“I am afraid the motors would declare our presence,” Case observed, speaking from the deck of the boat, “and, besides, we couldn’t go very far on account of the falls, so, perhaps, we would better go up as far as we can in the rowboat, making as little noise as possible.”

“And what’s the matter with putting Captain Joe on shore?” asked Jule. “He may be able to point out the spot where the men left the river. Anyhow, it won’t do any harm to try.”

“That’s a good idea,” declared Clay, “and I’ll go along with him.”

“I’m afraid you’ll find it pretty rough walking along that bank,” Case suggested, “for the country is rocky and leads up to the plateau above the falls, and small streams may run in from the peninsula. You might have to swim when you wasn’t climbing hills.”

“I’ll try it a short distance, anyway,” Clay answered, “and you, Case, remain on board and let Jule row up in the boat.”

This arrangement was carried out, and in a short time, the little boat was moving upstream, with Jule pulling cautiously at the oars. Clay found the bank a difficult one to ascend. He was obliged to wade through small creeks and climb rocky heights, but he kept steadily on his way, with Captain Joe at his heels.

At last, they came to a creek which ran into the river at the foot of the falls. On the south side of this creek, for some distance in, was a level, grassy plateau, and here Captain Joe picked up the scent they were looking for. The south bank showed that a boat had recently been drawn up there.

Disregarding, for the time being, all commands from the boy, the dog raced up the small stream, and finally disappeared in a thicket.

Clay hesitated, undecided as to whether he ought to follow the dog at once or return to notify Jule of his discovery and secure his assistance.

He had already lost sight of the dog, so he concluded that he might as well return to Jule. This he did, and in a short time, the boat was anchored at the mouth of the creek, and the boys were pressing on into the thicket. Captain Joe was nowhere in sight.

“They certainly are on this side of the creek,” Clay reasoned, “for they couldn’t very well make progress on the other side unless they traveled in an aeroplane.”

There were no tracks to follow, no indications of any one having passed that way recently, but the boys kept pluckily on, listening now and then for some sign from the dog.

“If he finds Alex,” Jule declared, “he’ll make a note of it, and we’ll hear a racket fit to wake the dead.”

“And that will warn the outlaws of our approach,” said Clay in a discouraged tone of voice. “Perhaps we did wrong to bring the dog.”

“You may be sure Captain Joe will give a good account of himself,” Jule said confidently. “He may make a racket, but it’s dollars to apples that they won’t catch him.”

In a short time the clamor the boys had been expecting came from the forest beyond. Captain Joe was barking and growling and, judging from the commotion in the copse, was evidently threshing about.

“That’s a scrap,” Jule declared. “Perhaps he has caught one of the men. If he has, I hope he’s got him by the throat.”

Pressing into the interior of the forest, the level grassy plateau having long since disappeared, the boys finally came to a small cleared glade and discovered the cause of Captain Joe’s enthusiasm.

Teddy, the cub, was standing with his back to the hole of a giant tree inviting the dog to a boxing match. Captain Joe’s clamor indicated only delight at the meeting with his friend.

Before showing themselves in the glade, the boys looked in every direction for some indication of the outlaws, but there was no sign of human life anywhere near them. No noise, save the cries of the creatures of the air and the jungle.

“You’re a fine old scout, Captain Joe,” whispered Clay as he finally advanced into the glade. “You notify everybody within a mile of us as to our location, but you don’t do a thing to help us find Alex.”

At mention of the lost boy’s name, Teddy dropped down from his antagonistic attitude, and, thrusting a soft muzzle against Clay’s hand, moved away to the west.

“The cub has more sense than the dog,” Jule exclaimed. “Captain Joe makes a noise, and Teddy does the piloting. Do you suppose he knows where Alex is?” he added.

“It seems to me that he is trying to tell us something,” Clay replied. “Anyway, we may as well follow him.”

Teddy, who was an especial favorite of Alex’s, and never lost an opportunity of following him about, appeared to know exactly where he was going, for he maintained a steady pace for half an hour or more, keeping to the south shore of the creek for a time and then crossing on a fallen tree to the opposite bank.

“Now,” said Clay, “we ought not to follow close behind the cub. He makes as much noise as a freight train going up a steep grade, and we’ll be sure to be seen if the outlaws are anywhere about.”

“Perhaps he will go on alone,” Jule suggested.

“In that case, we can skirt his track and remain hidden. That ought not to be very difficult in this broken country.”

Teddy turned about with an inquiring glance as the boys left his side, but soon proceeded on his course. Fearful that Captain Joe would indulge in another demonstration of some kind, the boys kept him with them, Jule keeping a close hold on his collar.

“This doesn’t seem much like a river trip to me,” Jule grinned as they passed over rocks, sneaked through miniature canyons and threaded thickets alive with briers and clinging vines. “Seems more like an overland expedition to the north star.”

“There is one compensation,” Clay added humorously. “Alex will get good and hungry—and serve him right at that.”

“Huh!” Jule declared, “Alex is always hungry anyway.”

Teddy now quickened his pace so that the boys had great difficulty in following him. He ran with his nose to the rough ground, his short ears tipped forward, for all the world like a hound on a scent.

“Look at the beast!” Jule laughed. “Acts like he was a hound after foxes. That’s some bear, Clay.”

“So far as I know,” Clay answered, “he’s the only cub that ever did a stunt like that. Still, he’s only exhibiting the advantages of an early education, for he has long been trained to follow us.”

After a short time the boys, advancing up a ledge and then into a little gully, came upon Teddy lying flat on the ground, his nose pointing straight ahead. When they came to him Captain Joe pulled fiercely to get away, his nose pointing straight to the north.

“I guess,” Jule panted, holding to the dog with all his strength, “that they have located Alex. If you’ll take charge of this obstreperous animal for a while, I’ll sneak ahead and have a look.”

Clay finally succeeded in quieting the dog, and Jule pushed on up the gully. At the very end, where the depression terminated in a wall of rock, he saw a faint column of smoke. A closer approach revealed a small fire of dry sticks with something cooking in a tin pail over the coals.

Jule stopped and considered the situation seriously.

“Now, I wonder,” he thought, “why Teddy didn’t make a fool of himself by rushing right up to Alex. I don’t believe he’s scared of the men, and, to tell the truth, I don’t see any men to be frightened at. Alex seems to be there alone. Wonder why he doesn’t run.”

The reason why Alex didn’t run was disclosed in a moment. The boy’s hands were tightly bound across his breast and a strong rope encircled his ankles. For a moment there was no one in sight save the boy, then a roughly dressed man came into view carrying an armful of dry wood for the fire. Jule heard both the dog and the cub protesting at being kept away from the fellow, and saw the man turn sharply about.

Then there came another revelation. With bound arms swinging out, and bound feet kicking violently, Alex was ordering the two animals away. Well trained as they were, they protested while they obeyed.

“Is that that bear of yours, again?” Jule heard the man asking. “If I wasn’t afraid of attracting attention, I’d put a bullet into him. Call him up here and keep him quiet while I gather more dry wood. The boys will be here in an hour or so and will want breakfast.”

“That settles it,” whispered Jule. “If the boys are so far away that they won’t be back in an hour or more, they won’t find any cook when they return. If I have my way, the cook will be tied up.”

“All right,” Alex said in reply to the fellow’s order, “I’ll call him up and keep him quiet after you go away. He’s been used to polite society and doesn’t like you!”

The man snarled out some surly reply and disappeared. Jule was at his chum’s side in a moment. The ropes were cut, and the two boys were speeding back to where Clay had been left.

There was a little scene of congratulation, and then Captain Joe, growling fiercely, leaped forward. The man who had gone in search of wood must have heard the noisy greetings of the boys, for he came running back to the fire. The boys saw him throw a hand back for a weapon, heard an exclamation of anger, and knew that the dog was springing at his throat.

The struggle was a short one, for the man who had been attacked had not succeeded in reaching his revolver. When the boys reached the scene the man was black in the face and the dog was shaking him viciously by the neck.

“Captain Joe seems to know who his friends are!” Alex shouted.

“If we don’t break his hold in a minute, the man will be dead,” Jule exclaimed, dancing excitedly about, “and we’re not out to commit murder.”

When the clutch of the dog was finally released, the man lay back, panting, on the ground. An examination of his injury showed that it was not serious, his throat having been compressed rather than torn.

In a moment the man sat up and glared about with murder in his protruding eyes. Seeing the dog still watching him, he gave him a vicious kick and came near inviting a repetition of the attack.

“I’ll kill that dog!” he shouted.

“No, you won’t!” laughed Alex. “We’re going to take that dog out of this blooming country. We’re going to tie you up so you won’t over-exert yourself while in your present weakened condition, and streak it for the motor boat. We’ve had enough of this blooming election precinct.”

This program was carried out so far as moving back toward the motor boat was concerned, but when, after a long, hard journey, they came to the place in the river where the Rambler had been left, it was nowhere to be seen. Satisfied that Case had not proceeded up the river—the falls would have prevented a long run up—they all entered the rowboat and passed on down toward the St. Lawrence.

“Talk about getting lost!” grinned Alex. “Case has gone and lost the boat!”

As may well be imagined, Case was waiting impatiently on board the Rambler while the events described in the last chapter were taking place in the forest. It is one thing to face a desperate situation in the company of helpful friends. It is quite another to consider a grave peril alone, especially when chums are in danger.

Several hours passed, and Case heard nothing from the wanderers in the forest. Then an unexpected visitor arrived. The boy saw an Indian canoe paddled swiftly up the river.

He had not had a good chance to observe the visitor who had cut the cable, thus bring about the meeting with the steamer people, but it was his opinion that the canoeist was none other than the boy who had given his name as Max Michel. He anxiously awaited the arrival of the craft.

“If that is Max,” he thought, “he certainly has a well-developed nerve to come back to the Rambler after doing what he did.”

In a short time the canoe, coming steadily upstream, touched the hull of the motor boat, and its occupant clambered alertly to the deck. Case stood for a moment regarding him with disapproval, no welcome at all in his face. The boy approached with a confident smile.

“What are you doing here?” demanded Case.

“I came,” was the quick reply, “because I have news which may interest you. I know you have good reason to doubt my friendship, but I hope you will listen to me. It will be in your interest to do so.”

“News of my friends?” asked Case quickly, forgetting in the impulse of the moment that the boy’s information was more than likely to be misleading. “Have you seen any of the boys to-day?”

“No,” was the slow reply, “but I have heard from them. They crossed the peninsula early this morning, were lured into a boat passing down a parallel stream, and must now be somewhere on or near the St. Lawrence.”

“How do you know all this?” demanded Case half-angrily.

“Ever since the night I cut your cable,” Max began, “I have been more than ashamed of myself. I was ordered to do the work, and believed that there was nothing else for me to do except to obey. I was not far from St. Luce yesterday when you boys went aboard the Sybil. The steamer touched at St. Luce and I afterwards heard the captain telling a friend of meeting you. Then I decided to return to you, if you were still in this vicinity.”

“And so you come here and tell me a fairy tale about my chums?” Case exclaimed. “You don’t expect me to believe a word you say, do you?”