THE BIRTH-HOUSE OF NAPOLEON.

THE BIRTH-HOUSE OF NAPOLEON.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 15, August, 1851, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 15, August, 1851 Author: Various Release Date: December 25, 2011 [EBook #38409] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY *** Produced by David Kline, Henry Gardiner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The island of Corsica, sublimely picturesque with its wild ravines and rugged mountains, emerges from the bosom of the Mediterranean Sea, about one hundred miles from the coast of France. It was formerly a province of Italy, and was Italian in its language, sympathies, and customs. In the year 1767 it was invaded by a French army, and after several most sanguinary conflicts, the inhabitants were compelled to yield to superior power, and Corsica was annexed to the empire of the Bourbons.

At the time of this invasion there was a young lawyer, of Italian extraction, residing upon the island, whose name was Charles Bonaparte. He was endowed with commanding beauty of person, great vigor of mind, and his remote lineage was illustrious, but the opulence of the noble house had passed away, and the descendant of a family, whose line could be traced far back into the twilight of the dark ages, was under the fortunate necessity of being dependent for his support upon the energies of his own mind. He had married Letitia Raniolini, one of the most beautiful and accomplished of the young ladies of Corsica. Of thirteen children born to them eight survived to attain maturity. As a successful lawyer the father of this large family was able to provide them with an ample competence. His illustrious descent gave him an elevated position in society, and the energies of his mind, ever in vigorous action, invested him with powerful influence.

The family occupied a town house, an ample stone mansion, in Ajaccio, the principal city of the island. They also enjoyed a very delightful country retreat near the sea-shore, a few miles from Ajaccio. This rural home was the favorite resort of the children during the heats of summer. When the French invaded Corsica, Charles Bonaparte, then quite a young man, having been married but a few years, abandoned the peaceful profession of the law, and grasping his sword, united with his countrymen, under the banner of General Paoli, to resist the invaders. His wife, Letitia, had then but one child, Joseph. She was expecting soon to give birth to another. Civil war was desolating the little island. Paoli and his band of patriots, defeated again and again, were retreating before their victorious foes into the fastnesses of the mountains. Letitia followed the fortunes of her husband, and, notwithstanding the embarrassment of her condition, accompanied him on horseback in these perilous and fatiguing expeditions. The conflict, however, was short, and, by the energies of the sword, Corsica became a province of France, and the Italians who inhabited the island became the unwilling subjects of the Bourbon throne. On the 15th of August, 1769, in anticipation of her confinement, Letitia had taken refuge in her town house at Ajaccio. On the morning of that day she attended church, but, during the service, admonished by approaching pains, she was obliged suddenly to return home, and throwing herself upon a couch, covered with an ancient piece of tapestry, upon which was embroidered the battles and the heroes of the Illiad, she gave birth to her second son, Napoleon Bonaparte. Had the young Napoleon seen the light two months earlier he would have been by birth an Italian, not a Frenchman, for but eight weeks had then elapsed since the island had been transferred to the dominion of France.

The father of Napoleon died not many years after the birth of that child whose subsequent renown has filled the world. He is said to have appreciated the remarkable powers of his son, and, in the delirium which preceded his death, he was calling upon Napoleon to help him. Madame Bonaparte, by this event, was left a widow with eight children, Joseph, Napoleon, Lucien, Jerome, Eliza, Pauline, and Caroline. Her means were limited, but her mental endowments were commensurate with the weighty responsibilities which devolved upon her. Her children all appreciated the superiority of her character, and yielded, with perfect and unquestioning submission, to her authority. Napoleon in particular ever regarded his mother with the most profound respect and affection. He repeatedly declared that the family were entirely indebted to her for that physical, intellectual, and moral training, which prepared them to ascend the lofty summits of power to which they finally attained. He was so deeply impressed with the sense of these obligations that he often said, "My opinion is that the future good or bad conduct of a child, depends entirely upon its mother." One of his first acts, on attaining power, was to surround his mother with every luxury which wealth could furnish. And when placed at the head of the government of France, he immediately and energetically established schools for female education, remarking that France needed nothing so much to promote its regeneration as good mothers. 290

Madame Bonaparte after the death of her husband, resided with her children in their country house. It was a retired residence, approached by an avenue overarched by lofty trees and bordered by flowering shrubs. A smooth, sunny lawn, which extended in front of the house, lured these children, so unconscious of the high destinies which awaited them, to their infantile sports. They chased the butterfly; they played in the little pools of water with their naked feet; in childish gambols they rode upon the back of the faithful dog, as happy as if their brows were never to ache beneath the burden of a crown. How mysterious the designs of that inscrutable Providence, which, in the island of Corsica, under the sunny skies of the Mediterranean, was thus rearing a Napoleon, and far away, beneath the burning sun of the tropics, under the shade of the cocoa groves and orange-trees of the West Indies, was moulding the person and ennobling the affections of the beautiful and lovely Josephine. It was by a guidance, which neither of these children sought, that they were conducted from their widely separated and obscure homes to the metropolis of France. There, by their united energies, which had been fostered in solitary studies and deepest musings they won for themselves the proudest throne upon which the sun has ever risen; a throne which in power and splendor eclipsed all that had been told of Roman, or Persian, or Egyptian greatness.

THE BIRTH-HOUSE OF NAPOLEON.

THE BIRTH-HOUSE OF NAPOLEON.

The dilapidated villa in Corsica, where Napoleon passed his infantile years, still exists, and the thoughtful tourist loses himself in pensive reverie as he wanders over the lawn where those children have played—as he passes through the vegetable garden in the rear of the house, which enticed them to toil with their tiny hoes and spades, and as he struggles through the wilderness of shrubbery, now running to wild waste, in the midst of which once could have been heard the merry shouts of these infantile kings and queens. Their voices are now hushed in death. But the records of earth can not show a more eventful drama than that enacted by these young Bonapartes between the cradle and the grave.

There is, in a sequestered and romantic spot upon the ground, an isolated granite rock, of wild and rugged form, in the fissures of which there is something resembling a cave, which still retains the name of "Napoleon's Grotto." This solitary rock was the favorite resort of the pensive and meditative child, even in his earliest years. When his brothers and sisters were in most happy companionship in the garden, or on the lawn, and the air resounded with their mirthful voices, Napoleon would steal away alone to his loved retreat. There, in the long and sunny afternoons, with a book in his hand, he would repose, in a recumbent posture, for hours, gazing upon the broad expanse of the Mediterranean, spread out before him, and upon the blue sky, which overarched his head. Who can imagine the visions which in those hours arose before the expanding energies of that wonderful mind?

Napoleon could not be called an amiable child. He was silent and retiring in his disposition, melancholy and irritable in his temperament, and impatient of restraint. He was not fond of companionship nor of play. He had no natural joyousness or buoyancy of spirit, no frankness of disposition. His brothers and sisters were not fond of him, though they admitted his superiority. "Joseph," said an uncle at that time, 291 "is the eldest of the family, but Napoleon is its head." His passionate energy and decision of character were such that his brother Joseph, who was a mild, amiable, and unassuming boy, was quite in subjection to his will. It was observed that his proud spirit was unrelenting under any severity of punishment. With stoical firmness, and without the shedding of a tear, he would endure any inflictions. At one time he was unjustly accused of a fault which another had committed. He silently endured the punishment and submitted to the disgrace, and to the subsistence for three days on the coarsest fare, rather than betray his companion; and he did this, not from any special friendship for the one in the wrong, but from an innate pride and firmness of spirit. Impulsive in his disposition, his anger was easily and violently aroused, and as rapidly passed away. There were no tendencies to cruelty in his nature, and no malignant passion could long hold him in subjection.

There is still preserved upon the island of Corsica, as an interesting relic, a small brass cannon, weighing about thirty pounds, which was the early and favorite plaything of Napoleon. Its loud report was music to his childish ears. In imaginary battle he saw whole squadrons mown down by the discharges of his formidable piece of artillery. Napoleon was the favorite child of his father, and had often sat upon his knee; and, with a throbbing heart, a heaving bosom, and a tearful eye, listened to his recital of those bloody battles in which the patriots of Corsica had been compelled to yield to the victorious French. Napoleon hated the French. He fought those battles over again. He delighted, in fancy, to sweep away the embattled host with his discharges of grape-shot; to see the routed foe, flying over the plain, and to witness the dying and the dead covering the ground. He left the bat and the ball, the kite and the hoop for others, and in this strange divertisement found exhilarating joy.

He loved to hear, from his mother's lips, the story of her hardships and sufferings, as, with her husband and the vanquished Corsicans, she fled from village to village, and from fastness to fastness before their conquering enemies. The mother was probably but little aware of the warlike spirit she was thus nurturing in the bosom of her son, but with her own high mental endowments, she could not be insensible of the extraordinary capacities which had been conferred upon the silent, thoughtful, pensive listener. There were no mirthful tendencies in the character of Napoleon; no tendencies in childhood, youth, or manhood to frivolous amusements or fashionable dissipation. "My mother," said Napoleon, at St. Helena, "loves me. She is capable of selling every thing for me, even to her last article of clothing." This distinguished lady died at Marseilles in the year 1822, about a year after the death of her illustrious son upon the island of St. Helena. Seven of her children were still living, to each of whom she bequeathed nearly two millions of dollars; while to her brother, Cardinal Fesch, she left a superb palace, embellished with the most magnificent decorations of furniture, paintings, and sculpture which Europe could furnish. The son, who had conferred all this wealth—to whom the family was indebted for all this greatness, and who had filled the world with his renown, died a prisoner in a dilapidated stable, upon the most bleak and barren isle of the ocean. The dignified character of this exalted lady is illustrated by the following anecdote: Soon after Napoleon's assumption of the imperial purple, he happened to meet his mother in the gardens of St. Cloud. The Emperor was surrounded with his courtiers, and half playfully extended his hand for her to kiss. "Not so, my son," she gravely replied, at the same time presenting her hand in return, "it is your duty to kiss the hand of her who gave you life."

"Left without guide, without support," says Napoleon, "my mother was obliged to take the direction of affairs upon herself. But the task was not above her strength. She managed every thing, provided for every thing with a prudence which could neither have been expected from her sex nor from her age. Ah, what a woman! where shall we look for her equal? She watched over us with a solicitude unexampled. Every low sentiment, every ungenerous affection was discouraged and discarded. She suffered nothing but that which was grand and elevated to take root in our youthful understandings. She abhorred falsehood, and would not tolerate the slightest act of disobedience. None of our faults were overlooked. Losses, privations, fatigue had no effect upon her. She endured all, braved all. She had the energy of a man, combined with the gentleness and delicacy of a woman."

A bachelor uncle owned the rural retreat where the family resided. He was very wealthy, but very parsimonious. The young Bonapartes, though living in the abundant enjoyment of all the necessaries of life, could obtain but little money for the purchase of those thousand little conveniences and luxuries which every boy covets. Whenever they ventured to ask their uncle for coppers, he invariably pleaded poverty, assuring them that though he had lands and vineyards, goats and poultry, he had no money. At last the boys discovered a bag of doubloons secreted upon a shelf. They formed a conspiracy, and, by the aid of Pauline, who was too young to understand the share which she had in the mischief, they contrived, on a certain occasion, when the uncle was pleading poverty, to draw down the bag, and the glittering gold rolled over the floor. The boys burst into shouts of laughter, while the good old man was almost choked with indignation. Just at that moment Madame Bonaparte came in. Her presence immediately silenced the merriment. She severely reprimanded her sons for their improper behavior, and ordered them to collect again the scattered doubloons.

When the island of Corsica was surrendered to the French, Count Marbœuf was appointed, 292 by the Court at Paris, as its governor. The beauty of Madame Bonaparte, and her rich intellectual endowments, attracted his admiration, and they frequently met in the small but aristocratic circle of society, which the island afforded. He became a warm friend of the family, and manifested much interest in the welfare of the little Napoleon. The gravity of the child, his air of pensive thoughtfulness, the oracular style of his remarks, which characterized even that early period of life, strongly attracted the attention of the governor, and he predicted that Napoleon would create for himself a path through life of more than ordinary splendor.

THE HOME OF NAPOLEON'S CHILDHOOD.

THE HOME OF NAPOLEON'S CHILDHOOD.

When Napoleon was but five or six years of age, he was placed in a school with a number of other children. There a fair-haired little maiden won his youthful heart. It was Napoleon's first love. His impetuous nature was all engrossed by this new passion, and he inspired as ardent an affection in the bosom of his loved companion as that which she had enkindled in his own. He walked to and from school, holding the hand of Giacominetta. He abandoned all the plays and companionship of the other children to talk and muse with her. The older boys and girls made themselves very merry with the display of affection which the loving couple exhibited. Their mirth, however, exerted not the slightest influence to abash Napoleon, though often his anger would be so aroused by their insulting ridicule, that, regardless of the number or the size of his adversaries, with sticks, stones, and every other implement which came in his way, he would rush into their midst and attack them with such a recklessness of consequences, that they were generally put to flight. Then, with the pride of a conqueror, he would take the hand of his infantile friend. The little Napoleon was, at this period of his life, very careless in his dress, and almost invariably appeared with his stockings slipped down about his heels. Some witty boy formed a couplet, which was often shouted upon the play-ground, not a little to the annoyance of the young lover.

When Napoleon was about ten years of age, Count Marbœuf obtained for him admission to the military school at Brienne, near Paris. Forty years afterward Napoleon remarked that he never could forget the pangs which he then felt, when parting from his mother. Stoic as he was, his stoicism then forsook him, and he wept like any other child. His journey led him through Italy, and crossing France, he entered Paris. Little did the young Corsican then imagine as he gazed awe-stricken upon the splendors of the metropolis, that all those thronged streets were yet to resound with his name, and that in those gorgeous palaces the proudest kings and queens of Europe were to bow obsequiously before his unrivaled power. The ardent and studious boy was soon established in school. His companions regarded him as a foreigner, as he spoke the Italian language, and the French was to him almost an unknown tongue. He found that his associates were composed mostly of the sons of the proud and wealthy nobility of France. Their pockets were filled with money, and they indulged in the most extravagant expenditures. The haughtiness with which these worthless sons of imperious but debauched and enervated 293 sires, affected to look down upon the solitary and unfriended alien, produced an impression upon his mind which was never effaced. The revolutionary struggle, that long and lurid day of storms and desolation was just beginning darkly to dawn; the portentous rumblings of that approaching earthquake, which soon uphove both altar and throne, and overthrew all of the most sacred institutions of France in chaotic ruin, fell heavily upon the ear. The young noblemen at Brienne taunted Napoleon with being the son of a Corsican lawyer; for in that day of aristocratic domination the nobility regarded all with contempt who were dependent upon any exertions of their own for support. They sneered at the plainness of Napoleon's dress, and at the emptiness of his purse. His proud spirit was stung to the quick by these indignities, and his temper was roused by that disdain to which he was compelled to submit, and from which he could find no refuge. Then it was that there was implanted in his mind that hostility which he ever afterward so signally manifested to rank founded not upon merit but upon the accident of birth. He thus early espoused this prominent principle of republicanism: "I hate those French," said he, in an hour of bitterness, "and I will do them all the mischief in my power."

Thirty years after this Napoleon said, "Called to the throne by the voice of the people, my maxim has always been, 'A career open to talent,' without distinction of birth."

NAPOLEON AT BRIENNE.

NAPOLEON AT BRIENNE.

In consequence of this state of feeling, he secluded himself almost entirely from his fellow-students, and buried himself in the midst of his books and his maps. While they were wasting their time in dissipation and in frivolous amusements, he consecrated his days and his nights with untiring assiduity to study. He almost immediately elevated himself above his companions, and, by his superiority, commanded their respect. Soon he was regarded as the brightest ornament of the institution, and Napoleon exulted in his conscious strength and his undisputed exaltation. In all mathematical studies he became highly distinguished. All books upon history, upon government, upon the practical sciences he devoured with the utmost avidity. The poetry of Homer and of Ossian he read and re-read with great delight. His mind combined the poetical and the practical in most harmonious blending. In a letter written to his mother at this time, he says, "With my sword by my side, and Homer in my pocket, I hope to carve my way through the world." Many of his companions regarded him as morose and moody, and though they could not but respect him, they still disliked his recluse habits and his refusal to participate in their amusements. He was seldom seen upon the play-ground, but every leisure hour found him in the library. The Lives of Plutarch he studied so thoroughly, and with such profound admiration, that his whole soul became imbued with the spirit of these illustrious men. All the thrilling scenes of Grecian and Roman story, the rise and fall of empires, and deeds of heroic daring absorbed his contemplation. Even at this early period of his life, and in all subsequent years, he expressed utter contempt for those enervating tales of fiction, with which so many of the readers of the present day are squandering their time and enfeebling their energies. It may be doubted whether he ever wasted an hour upon such worthless reading. When afterward seated 294 upon the throne of France, he would not allow a novel to be brought into the palace; and has been known to take such a book from the hands of a maid of honor, and after giving her a severe reprimand to throw it into the fire. So great was his ardor for intellectual improvement, that he considered every day as lost in which he had not made perceptible progress in knowledge. By this rigid mental discipline he acquired that wonderful power of concentration by which he was ever enabled to simplify subjects the most difficult and complicated.

He made no efforts to conciliate the good-will of his fellow-students; and he was so stern in his morals and so unceremonious in his manners that he was familiarly called the Spartan. At this time he was distinguished by his Italian complexion, a piercing eagle eye, and by that energy of conversational expression which, through life, gave such an oracular import to all his utterances. His unremitting application to study, probably impaired his growth, for his fine head was developed disproportionately with his small stature. Though stubborn and self-willed in his intercourse with his equals, he was a firm friend of strict discipline, and gave his support to established authority. This trait of character, added to his diligence and brilliant attainments, made him a great favorite with the professors. There was, however, one exception. Napoleon took no interest in the study of the German language. The German teacher, consequently, entertained a very contemptible opinion of the talents of his pupil. It chanced that upon one occasion Napoleon was absent from the class. M. Bouer, upon inquiring, ascertained that he was employed that hour in the class of engineers. "Oh! he does learn something, then," said the teacher, ironically. "Why, sir!" a pupil rejoined; "he is esteemed the very first mathematician in the school." "Truly," the irritated German replied, "I have always heard it remarked, and have uniformly believed, that any fool, and none but a fool, could learn mathematics." Napoleon afterward relating this anecdote, laughingly said, "It would be curious to ascertain whether M. Bouer lived long enough to learn my real character, and enjoy the fruits of his own judgment."

Each student at Brienne had a small portion of land allotted to him, which he might cultivate, or not, as he pleased. Napoleon converted his little field into a garden. To prevent intrusion, he surrounded it with palisades, and planted it thickly with trees. In the centre of this, his fortified camp, he constructed a pleasant bower, which became to him a substitute for the beloved grotto he had left in Corsica. To this grotto he was wont to repair to study and to meditate, where he was exposed to no annoyances from his frivolous fellow-students. In those trumpet-toned proclamations which subsequently so often electrified Europe, one can see the influence of these hours of unremitting mental application.

At that time he had few thoughts of any glory but military glory. Young men were taught that the only path to renown was to be found through fields of blood. All the peaceful arts of life, which tend to embellish the world with competence and refinement, were despised. He only was the chivalric gentleman, whose career was marked by conflagrations and smouldering ruins, by the despair of the maiden, the tears and woe of widows and orphans, and by the shrieks of the wounded and the dying. Such was the school in which Napoleon was trained. The writings of Voltaire and Rousseau had taught France, that the religion of Jesus Christ was but a fable; that the idea of accountability at the bar of God was a foolish superstition; that death was a sleep from which there was no awaking; that life itself, aimless and objectless, was so worthless a thing that it was a matter of most trivial importance how soon its vapor should pass away. These peculiarities in the education of Napoleon must be taken into account in forming a correct estimate of his character. It could hardly be said that he was educated in a Christian land. France renounced Christianity and plunged into the blackest of Pagan darkness, without any religion, and without a God. Though the altars of religion were not, at this time, entirely swept away, they were thoroughly undermined by that torrent of infidelity which, in crested billows, was surging over the land. Napoleon had but little regard for the lives of others and still less for his own. He never commanded the meanest soldier to go where he was not willing to lead him. Having never been taught any correct ideas of probation or retribution, the question whether a few thousand illiterate peasants, should eat, drink, and sleep for a few years more or less, was in his view of little importance compared with those great measures of political wisdom which should meliorate the condition of Europe for ages. It is Christianity alone which stamps importance upon each individual life, and which invests the apparent trivialities of time with the sublimities of eternity. It is, indeed, strange that Napoleon, graduating at the schools of infidelity and of war, should have cherished so much of the spirit of humanity, and should have formed so many just conceptions of right and wrong. It is, indeed, strange that surrounded by so many allurements to entice him to voluptuous indulgence and self-abandonment, he should have retained a character, so immeasurably superior in all moral worth, to that of nearly all the crowned heads who occupied the thrones around him.

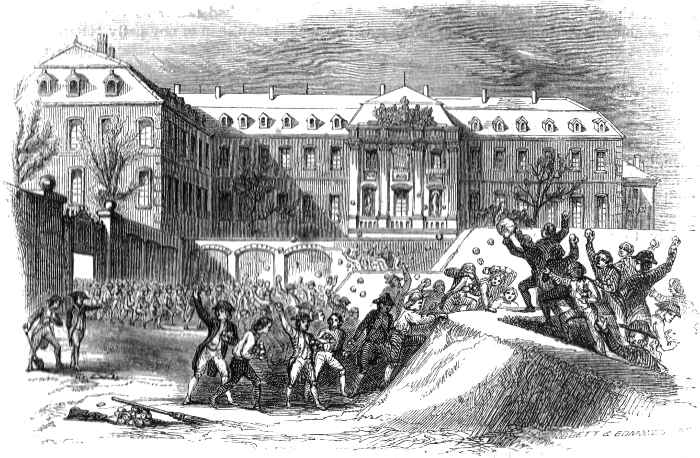

The winter of 1784 was one of unusual severity. Large quantities of snow fell, which so completely blocked up the walks, that the students at Brienne could find but little amusement without doors. Napoleon proposed, that to beguile the weary hours, they should erect an extensive fortification of snow, with intrenchments and bastions, parapets, ravelins, and horn-works. He had studied the science of fortification with the utmost diligence, and, under his superintendence the works were conceived and executed according to the strictest rules of art. The power 295 of his mind now displayed itself. No one thought of questioning the authority of Napoleon. He planned and directed while a hundred busy hands, with unquestioning alacrity, obeyed his will. The works rapidly rose, and in such perfection of science, as to attract crowds of the inhabitants of Brienne for their inspection. Napoleon divided the school into two armies, one being intrusted with the defense of the works, while the other composed the host of the besiegers. He took upon himself the command of both bodies, now heading the besiegers in the desperate assault, and now animating the besieged to an equally vigorous defense. For several weeks this mimic warfare continued, during which time many severe wounds were received on each side. In the heat of the battle, when the bullets of snow were flying thick and fast, one of the subordinate officers, venturing to disobey the commands of his general, Napoleon felled him to the earth, inflicting a wound which left a scar for life.

THE SNOW FORT.

THE SNOW FORT.

In justice to Napoleon it must be related that when he had attained the highest pitch of grandeur, this unfortunate school-boy, who had thus experienced the rigor of Napoleon's military discipline, sought to obtain an audience with the Emperor. Calamities had darkened the path of the unfortunate man, and he was in poverty and obscurity. Napoleon, not immediately recalling his name to mind, inquired if the applicant could designate some incident of boyhood which would bring him to his recollection. "Sire!" replied the courtier; "he has a deep scar upon his forehead which he says was inflicted by your hand." "Ah!" rejoined Napoleon, smiling; "I know the meaning of that scar perfectly well. It was caused by an ice bullet which I hurled at his head. Bid him enter." The poor man made his appearance, and immediately obtained from Napoleon every thing that he requested.

At one time the students at Brienne got up a private theatre for their entertainment. The wife of the porter of the school, who sold the boys cakes and apples, presented herself at the door of the theatre to obtain admission to see the play, of the death of Cæsar, which was to be performed that evening. Napoleon's sense of decorum was shocked at the idea of the presence of a female among such a host of young men, and he indignantly exclaimed, in characteristic language, "Remove that woman, who brings here the license of camps."

Napoleon remained in the school at Brienne for five years, from 1779 till 1784. His vacations were usually spent in Corsica. He was enthusiastically attached to his native island, and enjoyed exceedingly rambling over its mountains, and through its valleys, and listening at humble firesides to those traditions of violence and crime with which every peasant was familiar. He was a great admirer of Paoli, the friend of his father and the hero of Corsica. At Brienne the students were invited to dine, by turns, with the principal of the school. One day when Napoleon was at the table, one of the professors, knowing his young pupil's admiration for Paoli, spoke disrespectfully of the distinguished general, that he might tease the sensitive lad. Napoleon promptly and energetically replied, "Paoli, sir, was a great man! He loved his country; and I never shall forgive my father, for consenting to the union of Corsica with France. He ought to have followed Paoli's fortunes and to have fallen with him."

Paoli, who upon the conquest of Corsica had fled to England, was afterward permitted to return 296 to his native island. Napoleon, though in years but a boy, was, in mind a full-grown man. He sought the acquaintance of Paoli, and they became intimate friends. The veteran general and the manly boy took many excursions together over the island; and Paoli pointed out to his intensely-interested companion, the fields where sanguinary battles had been fought, and the positions which the little army of Corsicans had occupied in the struggle for independence. The energy and decision of character displayed by Napoleon produced such an impression upon the mind of this illustrious man, that he at one time exclaimed, "Oh, Napoleon! you do not at all resemble the moderns. You belong only to the heroes of Plutarch."

Pichegru, who afterward became so celebrated as the conqueror of Holland and who came to so melancholy a death, was a member of the school at Brienne at the same time with Napoleon. Being several years older than the young Corsican, he instructed him in mathematics. The commanding talents and firm character of his pupil deeply impressed the mind of Pichegru. Many years after, when Napoleon was rising rapidly to power, the Bourbons proposed to Pichegru, who had espoused the royalist cause, to sound Napoleon and ascertain if he could be purchased to advocate their claims. "It will be but lost time to attempt it," said Pichegru: "I knew him in his youth. His character is inflexible. He has taken his side, and he will not change it."

One of the ladies of Brienne, occasionally invited some of the school-boys to sup with her at her chateau. Napoleon was once passing the evening with this lady, and, in the course of conversation, she remarked, "Turenne was certainly a very great man; but I should have liked him better had he not burned the Palatinate." "What signifies that," was Napoleon's characteristic remark, "if the burning was necessary to the object he had in view?"[1] This sentiment, uttered in childhood, is a key to the character of Napoleon. It was his great moral defect. To attain an end which he deemed important, he would ride over every obstacle. He was not a cruel man. He was not a malignant man. It was his great ambition to make himself illustrious by making France the most powerful, enlightened, and happy empire upon the surface of the globe. If, to attain this end, it was necessary to sacrifice a million of lives, he would not shrink from the sacrifice. Had he been educated in the school of Christianity, he might have learned that the end will not sanctify the means. Napoleon was not a Christian.

[1] Turenne was a marshal of France, and a distinguished military leader in the reign of Louis XIV. He marched an invading army into the Palatinate, a province of Germany, on the Rhine, and spread devastation every where around him. From the top of his castle at Manheim, the Elector of the Palatinate, at one time saw two of his cities and twenty five of his villages in flames.

His character for integrity and honor ever stood very high. At Brienne he was a great favorite with the younger boys, whose rights he defended against the invasions of the older. The indignation which Napoleon felt at this time, in view of the arrogance of the young nobility, produced an impression upon his character, the traces of which never passed away. When his alliance with the royal house of Austria was proposed, the Emperor Francis, whom Napoleon very irreverently called "an old granny,"[2] was extremely anxious to prove the illustrious descent of his prospective son-in-law.

[2] Some one repeated, to Maria Louisa, this remark of Napoleon. She did not understand its meaning, and went to Talleyrand, inquiring, "What does that mean, Monsieur, an old granny, what does it mean?" "It means," the accomplished courtier replied, with one of his most profound bows, "it means a venerable sage."

He accordingly employed many persons to make researches among the records of genealogy, to trace out the grandeur of his ancestral line. Napoleon refused to have the account published, remarking, "I had rather be the descendant of an honest man than of any petty tyrant of Italy. I wish my nobility to commence with myself, and to derive all my titles from the French people. I am the Rodolph of Hapsburg of my family. My patent of nobility dates from the battle of Montenotte."[3]

[3] Rodolph of Hapsburg, was a gentleman, who by his own energies had elevated himself to the imperial throne of Germany; and became the founder of the house of Hapsburg. He was the ancestor to whom the Austrian kings looked back with the loftiest pride.

Upon the occasion of this marriage, the Pope, in order to render the pedigree of Napoleon more illustrious, proposed the canonization of a poor monk, by the name of Bonaparte, who for centuries had been quietly reposing in his grave. "Holy Father!" exclaimed Napoleon, "I beseech you, spare me the ridicule of that step. You being in my power, all the world will say that I forced you to create a saint out of my family." To some remonstrances which were made against this marriage Napoleon coolly replied, "I certainly should not enter into this alliance, if I were not aware of the origin of Maria Louise being equally as noble as my own."

Still Napoleon was by no means regardless of that mysterious influence which illustrious descent invariably exerts over the human mind. Through his life one can trace the struggles of those conflicting sentiments. The marshals of France, and the distinguished generals who surrounded his throne, were raised from the rank and file of the army, by their own merit; but he divorced his faithful Josephine, and married a daughter of the Cæsars, that by an illustrious alliance he might avail himself of this universal and innate prejudice. No power of reasoning can induce one to look with the same interest upon the child of Cæsar and the child of the beggar.

Near the close of Napoleon's career, while Europe in arms was crowding upon him, the Emperor found himself in desperate and hopeless conflict on that very plain at Brienne, where in childhood he had reared his fortification of snow. He sought an interview with the old woman, whom he had ejected from the theatre, and from whom he had often purchased milk and fruit. 297

"Do you remember a boy by the name of Bonaparte," inquired Napoleon, "who formerly attended this school?" "Yes! very well," was the answer. "Did he always pay you for what he bought?" "Yes;" replied the old woman, "and he often compelled the other boys to pay, when they wished to defraud me." "Perhaps he may have forgotten a few sous," said Napoleon, "and here is a purse of gold to discharge any outstanding debt which may remain between us." At this same time he pointed out to his companion a tree, under which, with unbounded delight, he read, when a boy, Jerusalem Delivered, and where, in the warm summer evenings, with indescribable luxury of emotion, he listened to the tolling of the bells on the distant village-church spires. To such impressions his sensibilities were peculiarly alive. The monarch then turned away sadly from these reminiscenses of childhood, to plunge, seeking death, into the smoke and the carnage of his last and despairing conflicts.

It was a noble trait in the character of Napoleon, that in his day of power he so generously remembered even the casual acquaintances of his early years. He ever wrote an exceedingly illegible hand, as his impetuous and restless spirit was such that he could not drive his pen with sufficient rapidity over his paper. The poor writing-master at Brienne was in utter despair, and could do nothing with his pupil. Years after, Napoleon was sitting one day with Josephine, in his cabinet at St. Cloud, when a poor man, with threadbare coat, was ushered into his presence. Trembling before his former pupil, he announced himself as the writing-master of Brienne, and solicited a pension from the Emperor. Napoleon affected anger, and said, "Yes, you were my writing-master, were you? and a pretty chirographist you made of me, too. Ask Josephine, there, what she thinks of my handwriting!" The Empress, with that amiable tact, which made her the most lovely of women, smilingly replied, "I assure you, sir, his letters are perfectly delightful." The Emperor laughed cordially at the well-timed compliment, and made the poor old man comfortable for the rest of his days.

In the days of his prosperity, amidst all the cares of empire, Napoleon remembered the poor Corsican woman, who was the kind nurse of his infancy, and settled upon her a pension of two hundred dollars a year. Though far advanced in life, the good woman was determined to see her little nursling, in the glory of whose exaltation her heart so abundantly shared. With this object in view she made a journey to Paris. The Emperor received her most kindly, and transported the happy woman home again with her pension doubled.

In one of Napoleon's composition exercises at Brienne, he gave rather free utterance to his republican sentiments, and condemned the conduct of the royal family. The professor of rhetoric rebuked the young republican severely for the offensive passage, and to add to the severity of the rebuke, compelled him to throw the paper into the fire. Long afterward, the professor was commanded to attend a levee of the First Consul to receive Napoleon's younger brother Jerome as a pupil. Napoleon received him with great kindness, but at the close of the business, very good-humoredly reminded him that times were very considerably changed since the burning of that paper.

Napoleon remained in the school of Brienne for five years, from 1779 till 1784. He had just entered his fifteenth year, when he was promoted to the military school at Paris. Annually, three of the best scholars, from each of the twelve provincial military schools of France, were promoted to the military school at Paris. This promotion, at the earliest possible period in which his age would allow his admission, shows the high rank, as a scholar, which Napoleon sustained. The records of the Minister of War contain the following interesting entry:

"State of the king's scholars eligible to enter into service, or to pass to the school at Paris. Monsieur de Bonaparte (Napoleon), born 15th August, 1769; in height five feet six and a half inches; has finished his fourth season; of a good constitution, health excellent, character mild, honest, and grateful; conduct exemplary; has always distinguished himself by application to mathematics; understands history and geography tolerably well; is indifferently skilled in merely ornamental studies, and in Latin, in which he has only finished his fourth course; would make an excellent sailor; deserves to be passed to the school at Paris."

The military school at Paris, which Napoleon now entered, was furnished with all the appliances of aristocratic luxury. It had been founded for the sons of the nobility, who had been accustomed to every indulgence. Each of the three hundred young men assembled in this school had a servant to groom his horse, to polish his weapons, to brush his boots, and to perform all other necessary menial services. The cadet reposed on a luxurious bed, and was fed with sumptuous viands. There are few lads of fifteen who would not have been delighted with the dignity, the ease, and the independence of this style of living. Napoleon, however, immediately saw that this was by no means the training requisite to prepare officers for the toils and the hardships of war. He addressed an energetic memorial to the governor, urging the banishment of this effeminacy and voluptuousness from the military school. He argued that the students should learn to groom their own horses, to clean their armor, and to perform all those services, and to inure themselves to those privations which would prepare them for the exposure and the toils of actual service. No incident in the childhood or in the life of Napoleon shows more decisively than this his energetic, self-reliant, commanding character. The wisdom, the fortitude, and the foresight, not only of mature years, but of the mature years of the most powerful intellect, were here exhibited. The military school which he 298 afterward established at Fontainebleau, and which obtained such world-wide celebrity, was founded upon the model of this youthful memorial. And one distinguishing cause of the extraordinary popularity which Napoleon afterward secured, was to be found in the fact, that through life he called upon no one to encounter perils, or to endure hardships which he was not perfectly ready himself to encounter or to endure.

At Paris the elevation of his character, his untiring devotion to study, his peculiar conversational energy, and the almost boundless information he had acquired, attracted much attention. His solitary and recluse habits, and his total want of sympathy with most of his fellow students in their idleness, and in their frivolous amusements, rendered him far from popular with the multitude. His great superiority was, however, universally recognized. He pressed on in his studies with as much vehemence as if he had been forewarned of the extraordinary career before him, and that but a few months were left in which to garner up those stores of knowledge with which he was to remodel the institutions of Europe, and almost change the face of the world.

About this time he was at Marseilles on some day of public festivity. A large party of young gentlemen and ladies were amusing themselves with dancing. Napoleon was rallied upon his want of gallantry in declining to participate in the amusements of the evening. He replied, "It is not by playing and dancing that a man is to be formed." Indeed he never, from childhood, took any pleasure in fashionable dissipation. He had not a very high opinion of men or women in general. He was perfectly willing to provide amusements which he thought adapted to the capacities of the masculine and feminine minions flitting about the court; but his own expanded mind was so engrossed with vast projects of utility and renown, that he found no moments to spare in cards and billiards, and he was at the furthest possible remove from what may be called a lady's man.

On one occasion a mathematical problem of great difficulty having been proposed to the class, Napoleon, in order to solve it, secluded himself in his room for seventy-two hours; and he solved the problem. This extraordinary faculty of intense and continuous exertion both of mind and body, was his distinguishing characteristic through life. Napoleon did not blunder into renown. His triumphs were not casualties; his achievements were not accidents; his grand conceptions were not the brilliant flashes of unthinking and unpremeditated genius. Never did man prepare the way for greatness by more untiring devotion to the acquisition of all useful knowledge, and to the attainment of the highest possible degree of mental discipline. That he possessed native powers of mind, of extraordinary vigor it is true; but those powers were expanded and energized by Herculean study. His mighty genius impelled to the sacrifice of every indulgence, and to sleepless toil.

The vigor of Napoleon's mind, so conspicuous in conversation, was equally remarkable in his exercises in composition. His professor of Belles-Lettres remarked that Napoleon's amplifications ever reminded him of "flaming missiles ejected from a volcano." While in the military school at Paris the Abbé Raynal became so forcibly impressed with his astonishing mental acquirements, and the extent of his capacities, that he frequently invited him, though Napoleon was then but a lad of sixteen, to breakfast at his table with other illustrious guests. His mind was at that time characterized by great logical accuracy, united with the most brilliant powers of masculine imagination. His conversation, laconic, graphic, oracular, arrested every mind. Had the vicissitudes of life so ordered his lot, he would undoubtedly have been as distinguished in the walks of literature and in the halls of science, as he became in the field and in the cabinet. That he was one of the profoundest of thinkers all admit; and his trumpet-toned proclamations resounded through Europe, rousing the army to almost a frenzy of enthusiasm, and electrifying alike the peasant and the prince. Napoleon had that comprehensive genius which would have been pre-eminent in any pursuit to which he had devoted the energies of his mind. Great as were his military victories, they were by no means the greatest of his achievements.

In September, 1785, Napoleon, then but sixteen years of age, was examined to receive an appointment in the army. The mathematical branch of the examination was conducted by the celebrated La Place. Napoleon passed the ordeal triumphantly. In history he had made very extensive attainments. His proclamations, his public addresses, his private conferences with his ministers in his cabinet, all attest the philosophical discrimination with which he had pondered the records of the past, and had studied the causes of the rise and fall of empires. At the close of his examination in history, the historical professor, Monsieur Keruglion, wrote opposite to the signature of Napoleon, "A Corsican by character and by birth. This young man will distinguish himself in the world if favored by fortune." This professor was very strongly attached to his brilliant pupil. He often invited him to dinner, and cultivated his confidence. Napoleon in after years did not forget this kindness, and many years after, upon the death of the professor, settled a very handsome pension upon his widow. Napoleon, as the result of this examination, was appointed second lieutenant in a regiment of artillery. He was exceedingly gratified in becoming thus early in life an officer in the army. To a boy of sixteen it must have appeared the attainment of a very high degree of human grandeur.

That evening, arrayed in his new uniform, with epaulets and the enormous boots which at that time were worn by the artillery, in an exuberant glow of spirits, he called upon a female friend, Mademoiselle Permon, who afterward became Duchess of Abrantes, and who was regarded 299 as one of the most brilliant wits of the imperial court. A younger sister of this lady, who had just returned from a boarding-school, was so much struck with the comical appearance of Napoleon, whose feminine proportions so little accorded with this military costume, that she burst into an immoderate fit of laughter, declaring that he resembled nothing so much as "Puss in Boots." The raillery was too just not to be felt. Napoleon struggled against his sense of mortification, and soon regained his accustomed equanimity. A few days after, to prove that he cherished no rancorous recollection of the occurrence, he presented the mirthful maiden with an elegantly bound copy of Puss in Boots.

LIEUTENANT BONAPARTE.

LIEUTENANT BONAPARTE.

Napoleon soon, exulting in his new commission, repaired to Valence to join his regiment. His excessive devotion to study had impeded the full development of his physical frame. Though exceedingly thin and fragile in figure, there was a girlish gracefulness and beauty in his form; and his noble brow and piercing eye attracted attention and commanded respect. One of the most distinguished ladies of the place, Madame du Colombier, became much interested in the young lieutenant, and he was frequently invited to her house. He was there introduced to much intelligent and genteel society. In after life he frequently spoke with gratitude of the advantages he derived from this early introduction to refined and polished associates. Napoleon formed a strong attachment for a daughter of Madame du Colombier, a young lady of about his own age and possessed of many accomplishments. They frequently enjoyed morning and evening rambles through the pleasant walks in the environs of Valence. Napoleon subsequently speaking of this youthful attachment said, "We were the most innocent creatures imaginable. We contrived short interviews together. I well remember one which took place, on a midsummer's morning, just as the light began to dawn. It will scarcely be credited that all our felicity consisted in eating cherries together." The vicissitudes of life soon separated these young friends from each other, and they met not again for ten years. Napoleon, then Emperor of France, was, with a magnificent retinue, passing through Lyons, when this young lady, who had since been married, and who had encountered many misfortunes, with some difficulty gained access to him, environed as he was with all the etiquette of royalty. Napoleon instantly recognized his former friend and inquired minutely respecting all her joys and griefs. He immediately assigned to her husband a post which secured for him an ample competence, and conferred upon her the situation of a maid of honor to one of his sisters.

From Valence Napoleon went to Lyons, having been ordered, with his regiment, to that place in consequence of some disturbances which had broken out there. His pay as lieutenant was quite inadequate to support him in the rank of a gentleman. His widowed mother, with six children younger than Napoleon, who was then but seventeen years of age, was quite unable to supply him with funds. This pecuniary embarrassment often exposed the high-spirited young officer to the keenest mortification. It did not, however, in the slightest degree, impair his energies or weaken his confidence in that peculiar consciousness, which from childhood he had cherished, that he was endowed with extraordinary powers, and that he was born to an exalted destiny. He secluded himself from his brother officers, and, keeping aloof from all the haunts of 300 amusement and dissipation, cloistered himself in his study, and with indefatigable energy devoted himself anew to the acquisition of knowledge, laying up those inexhaustible stores of information and gaining that mental discipline which proved of such incalculable advantage to him in the brilliant career upon which he subsequently entered.

While at Lyons, Napoleon, friendless and poor, was taken sick. He had a small room in the attic of an hotel, where, alone, he lingered through the weary hours of hunger and pain. A lady from Geneva, visiting some friends at Lyons, happened to learn that a young officer was sick in the hotel. She could only ascertain, respecting him, that he was quite young—that his name was Bonaparte—then an unknown name; and that his purse was very scantily provided. Her benevolent feelings impelled her to his bedside. She immediately felt the fascination with which Napoleon could ever charm those who approached him. With unremitting kindness she nursed him, and had the gratification of seeing him so far restored as to be able to rejoin his regiment. Napoleon took his leave of the benevolent lady with many expressions of gratitude for the kindness he had experienced.

After the lapse of years when Napoleon had been crowned Emperor, he received a letter from this lady, congratulating him upon the eminence he had attained, and informing him that disastrous days had darkened around her. Napoleon immediately returned an answer, containing two thousand dollars, and expressing the most friendly assurances of his immediate attention to any favors she might in future solicit.

The Academy at Lyons offered a prize for the best dissertation upon the question: "What are the institutions most likely to contribute to human happiness?" Napoleon wrote upon the subject, and though there were many competitors, the prize was awarded to him. Many years afterward, when seated upon the throne, his Minister Talleyrand sent a courier to Lyons and obtained the manuscript. Thinking it would please the Emperor, he, one day, when they were alone, put the essay into Napoleon's hands, asking him if he knew the author. Napoleon immediately recognizing the writing, threw it into the flames, saying at the same time, that it was a boyish production full of visionary and impracticable schemes. He also, in these hours of unceasing study, wrote a History of Corsica, which he was preparing to publish, when the rising storms of the times led him to lay aside his pen for the sword.

Two great parties, the Royalists and the Republicans, were now throughout France contending for the supremacy. Napoleon joined the Republican side. Most of the officers in the army being sons of the Old Nobility, were of the opposite party; and this made him very unpopular with them. He, however, with great firmness, openly avowed his sentiments, and eagerly watched the progress of those events, which he thought would open to him a career of fame and fortune. He still continued to prosecute his studies with untiring diligence. He was, at this period of his life, considered proud, haughty, and irascible, though he was loved with great enthusiasm by the few whose friendship he chose to cultivate. His friends appreciated his distinguished character and attainments, and predicted his future eminence. His remarkable logical accuracy of mind, his lucid and energetic expressions, his immense information upon all points of history and upon every subject of practical importance, his extensive scientific attainments, and his thorough accomplishments as an officer, rendered him an object of general observation, and secured for him the respect even of the idlers who disliked his unsocial habits.

About this time, in consequence of some popular tumults at Auxonne, Napoleon, with his regiment, was ordered to that place. He, with some subaltern officers, was quartered at the house of a barber. Napoleon, as usual, immediately, when off of duty, cloistered himself in his room with his law books, his scientific treatises, his histories, and his mathematics. His associate officers loitered through the listless days, coquetting with the pretty wife of the barber, smoking cigars in the shop, and listening to the petty gossip of the place. The barber's wife was quite annoyed at receiving no attentions from the handsome, distinguished, but ungallant young lieutenant. She accordingly disliked him exceedingly. A few years after as Napoleon, then commander of the army of Italy, was on his way to Marengo, he passed through Auxonne. He stopped at the door of the barber's shop and asked his former hostess, if she remembered a young officer by the name of Bonaparte, who was once quartered in her family. "Indeed, I do," was the pettish reply, "and a very disagreeable inmate he was. He was always either shut up in his room or, if he walked out, he never condescended to speak to any one." "Ah! my good woman," Napoleon rejoined; "had I passed my time as you wished to have me, I should not now have been in command of the army of Italy."

The higher nobility and most of the officers in the army were in favor of Royalty. The common soldiers and the great mass of the people were advocates of Republicanism. Napoleon's fearless avowal, under all circumstances, of his hostility to monarchy and his approval of popular liberty, often exposed him to serious embarrassments. He has himself given a very glowing account of an interview at one of the fashionable residences at Auxonne, where he had been invited to meet an aristocratic circle. The revolution was just breaking out in all its terror, and the excitement was intense throughout France. In the course of conversation Napoleon gave free utterance to his sentiments. They all instantly assailed him, gentlemen and ladies, pell-mell. Napoleon was not a man to retreat. His condensed sentences fell like hot shot among the crowd of antagonists who surrounded him. The battle waxed warmer and warmer. There was no one to utter a word in favor of Napoleon. 301 He was a young man of nineteen, surrounded by veteran generals and distinguished nobles. Like Wellington at Waterloo he was wishing that some "Blucher or night were come." Suddenly the door was opened, and the mayor of the city was announced. Napoleon began to flatter himself that a rescue was at hand, when the little great man in pompous dignity joined the assailants and belabored the young officer at bay, more mercilessly than all the rest. At last the lady of the house took compassion upon her defenseless guest, and interposed to shield him from the blows which he was receiving in the unequal contest.

One evening, in the year 1790, there was a very brilliant party in the drawing-rooms of M. Neckar, the celebrated financier. The Bastile had just been demolished. The people, exulting in newly found power, and dimly discerning long-defrauded rights, were trampling beneath their feet, indiscriminately, all institutions, good and bad, upon which ages had left their sanction. The gay and fickle Parisians, notwithstanding the portentous approachings of a storm, the most fearful earth has ever witnessed, were pleased with change, and with reckless curiosity awaited the result of the appalling phenomenon exhibited around them. Many of the higher nobility, terrified at the violence, daily growing more resistless and extended, had sought personal safety in emigration. The tone of society in the metropolis had, however, become decidedly improved by the greater commingling, in all the large parties, of men eminent in talents and in public services, as well as of those illustrious in rank.

The entertainments given by M. Neckar, embellished by the presence, as the presiding genius, of his distinguished daughter, Madame de Staël,[4] were brilliant in the extreme, assembling all the noted gentlemen and ladies of the metropolis. On the occasion to which we refer, the magnificent saloon was filled with men who had attained the highest eminence in literature and science, or who, in those troubled times, had ascended to posts of influence and honor in the state. Mirabeau was there,[5] with his lofty brow and thunder tones, proud of his very ugliness. Talleyrand[6] moved majestically through the halls, conspicuous for his gigantic proportions and courtly bearing. La Fayette, rendered glorious as the friend of Washington and his companion in arms, had gathered around him a group of congenial spirits. In the embrasure of a window sat Madame de Staël. By the brilliance of her conversational powers she had attracted to her side St. Just, who afterward obtained such sanguinary notoriety; Malesherbes, the eloquent and intrepid advocate of royalty; Lalande, the venerable astronomer; Marmontel and Lagrange, illustrious mathematicians, and others, whose fame was circulating through Europe.

[4] Napoleon, at St. Helena, gave the following graphic and most discriminating sketch of the character of Madame de Staël. "She was a woman of considerable talent and great ambition; but so extremely intriguing and restless, as to give rise to the observation, that she would throw her friends into the sea, that, at the moment of drowning, she might have an opportunity of saving them. Shortly after my return from the conquest of Italy, I was accosted by her in a large company, though at that time I avoided going out much in public. She followed me every where, and stuck so close that I could not shake her off. At last she asked me, 'Who is at this moment the first woman in the world?' intending to pay a compliment to me, and thinking that I would return it. I looked at her, and replied, 'She, madame, who has borne the greatest number of children,' an answer which greatly confused her." From this hour she became the unrelenting enemy of Napoleon.

[5] "Few persons," said Mirabeau, "comprehend the power of my ugliness." "If you would form an idea of my looks," he wrote to a lady who had never seen him, "you must imagine a tiger who has had the small-pox." "The life of Mirabeau," says Sydney Smith, "should embrace all the talents and all the vices, every merit and every defect, every glory and every disgrace. He was student, voluptuary, soldier, prisoner, author, diplomatist, exile, pauper, courtier, democrat, orator, statesman, traitor. He has seen more, suffered more, learned more, felt more, done more, than any man of his own or any other age."

[6] Talleyrand, one of the most distinguished diplomatists, was afterward elevated by the Emperor Napoleon to be Grand Chamberlain of the Empire. He was celebrated for his witticisms. One day Mirabeau was recounting the qualities which, in those difficult times, one should possess to be minister of state. He was evidently describing his own character, when, to the great mirth of all present, Talleyrand archly interrupted him with the inquiry, "He should also be pitted with the small-pox, should he not?"

In one corner stood the celebrated Alfieri, reciting with almost maniacal gesticulation his own poetry to a group of ladies. The grave and philosophical Neckar was the centre of another group of careworn statesmen, discussing the rising perils of the times. It was an assemblage of all which Paris could afford of brilliance in rank, talent, or station. About the middle of the evening, Josephine, the beautiful, but then neglected wife of M. Beauharnais, was announced, accompanied by her little son Eugène. Madame de Genlis, soon made her appearance, attended by the brother of the king; and, conscious of her intellectual dignity, floated through that sea of brilliance, recognized wherever she approached, by the abundance of perfumery which her dress exhaled. Madame Campan, the friend and companion of Maria Antoinette, and other ladies and gentlemen of the Court were introduced, and the party now consisted of a truly remarkable assemblage of distinguished men and women. Parisian gayety seemed to banish all thoughts of the troubles of the times, and the hours were surrendered to unrestrained hilarity. Servants were gliding through the throng, bearing a profusion of refreshments consisting of delicacies gathered from all quarters of the globe.

As the hour of midnight approached there was a lull in the buzz of conversation, and the guests gathered in silent groups to listen to a musical entertainment. Madame de Staël took her seat at the piano, while Josephine prepared to accompany her with the harp. They both were performers of singular excellence, and the whole assembly was hushed in expectation. Just as they had commenced the first notes of a charming 302 duet the door of the saloon was thrown open, and two new guests entered the apartment. The one was an elderly gentleman, of very venerable aspect, and dressed in the extreme of simplicity. The other was a young man, very small, pale, and slender. The elderly gentleman was immediately recognized by all as the Abbé Raynal, one of the most distinguished philosophers of France; but no one knew the pale, slender, fragile youth who accompanied him. They both, that they might not interrupt the music, silently took seats near the door. As soon as the performance was ended, and the ladies had received those compliments which their skill and taste elicited, the Abbé approached Madame de Staël, accompanied by his young protégé, and introduced him as Monsieur Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte! that name which has since filled the world, was then plebeian and unknown, and upon its utterance many of the proud aristocrats in that assembly shrugged their shoulders, and turned contemptuously away to their conversation and amusement.

Madame de Staël had almost an instinctive perception of the presence of genius. Her attention was instantly arrested by the few remarks with which Napoleon addressed her. They were soon engaged in very animated conversation. Josephine and several other ladies joined them. The group grew larger and larger as the gentlemen began to gather around the increasing circle. "Who is that young man who thus suddenly has gathered such a group around him?" the proud Alfieri condescended to ask of the Abbé Raynal. "He is," replied the Abbé, "a protégé of mine, and a young man of very extraordinary talent. He is very industrious, well read, and has made remarkable attainments in history, mathematics, and all military science." Mirabeau came stalking across the room, lured by curiosity to see what could be the source of the general attraction. "Come here! come here!" said Madame de Staël, with a smile, and in an under tone. "We have found a little great man. I will introduce him to you, for I know that you are fond of men of genius."

Mirabeau very graciously shook hands with Napoleon, and entered into conversation with the untitled young man, without assuming any airs of superiority. A group of distinguished men now gathered round them, and the conversation became in some degree general. The Bishop of Autun commended Fox and Sheridan for having asserted that the French army, by refusing to obey the orders of their superiors to fire upon the populace, had set a glorious example to all the armies of Europe; because, by so doing, they had shown that men by becoming soldiers did not cease to be citizens.

"Excuse me, my lord," exclaimed Napoleon, in tones of earnestness which arrested general attention, "if I venture to interrupt you; but as I am an officer I must claim the privilege of expressing my sentiments. It is true that I am very young, and it may appear presumptuous in me to address so many distinguished men; but during the last three years I have paid intense attention to our political troubles. I see with sorrow the state of our country, and I will incur censure rather than pass unnoticed principles which are not only unsound but which are subversive of all government. As much as any one I desire to see all abuses, antiquated privileges, and usurped rights annulled. Nay! as I am at the commencement of my career, it will be my best policy as well as my duty to support the progress of popular institutions, and to promote reform in every branch of the public administration. But as in the last twelve months I have witnessed repeated alarming popular disturbances, and have seen our best men divided into factions which threaten to be irreconcilable, I sincerely believe that now more than ever, a strict discipline in the army is absolutely necessary for the safety of our constitutional government and for the maintenance of order. Nay! if our troops are not compelled unhesitatingly to obey the commands of the executive, we shall be exposed to the blind fury of democratic passions, which will render France the most miserable country on the globe. The ministry may be assured that if the daily increasing arrogance of the Parisian mob is not repressed by a strong arm, and social order rigidly maintained, we shall see not only this capital, but every other city in France, thrown into a state of indescribable anarchy, while the real friends of liberty, the enlightened patriots, now working for the best good of our country, will sink beneath a set of demagogues, who, with louder outcries for freedom on their tongues, will be in reality but a horde of savages worse than the Neros of old."

These emphatic sentences uttered by Napoleon, with an air of authority which seemed natural to the youthful speaker, caused a profound sensation. For a moment there was perfect silence in the group, and every eye was riveted upon the pale and marble cheek of Napoleon. Neckar and La Fayette listened with evident uneasiness to his bold and weighty sentiments, as if conscious of the perils which his words so forcibly portrayed. Mirabeau nodded once or twice significantly to Tallyrand, seeming thus to say "that is exactly the truth." Some turned upon their heels, exasperated at this fearless avowal of hostility to democratic progress. Alfieri, one of the proudest of aristocrats, could hardly restrain his delight, and gazed with amazement upon the intrepid young man. "Condorcet," says an eye witness, "nearly made me cry out, by the squeezes which he gave my hand at every sentence uttered by the pale, slender, youthful speaker."

As soon as Napoleon had concluded, Madame de Staël, turning to the Abbé Raynal, cordially thanked him for having introduced her to the acquaintance of one, cherishing views as a statesman so profound, and so essential to present emergencies. Then turning to her father and his colleagues, she said, with her accustomed air of dignity and authority, "Gentlemen, I hope 303 that you will heed the important truths which you have now heard uttered." The young Napoleon, then but nineteen years of age, thus suddenly became the most prominent individual in that whole assembly. Wherever he moved many eyes followed him. He had none of the airs of a man of fashion. He made no attempts at displays of gallantry. A peaceful melancholy seemed to overshadow him, as, with an abstracted air, he moved through the glittering throng, without being in the slightest degree dazzled by its brilliance. The good old Abbé Raynal appeared quite enraptured in witnessing this triumph of his young protégé.

Soon after this, in September, 1791, Napoleon, then twenty years of age, on furlough, visited his native island. He had recently been promoted to a first-lieutenancy. Upon returning to the home of his childhood, to spend a few months in rural leisure, the first object of his attention was to prepare for himself a study, where he could be secluded from all interruption. For this purpose he selected a room in the attic of the house, where he would be removed from all the noise of the family. Here, with his books spread out before him, he passed days and nights of the most incessant mental toil. He sought no recreation; he seldom went out; he seldom saw any company. Had some guardian angel informed him of the immense drafts which, in the future, were to be made upon his mind, he could not have consecrated himself with more sleepless energy, to prepare for the emergency. The life of Napoleon presents the most striking illustration of the truth of the sentiment,

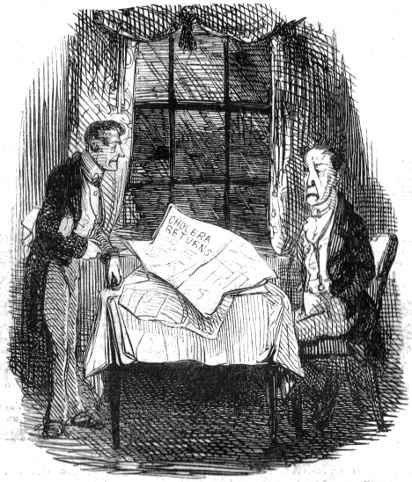

THE WATER-EXCURSION.

THE WATER-EXCURSION.

One cloudless morning, just after the sun had risen, he was sauntering along by the sea-shore, in solitary musings, when he chanced to meet a brother officer, who reproached him with his unsocial habits, and urged him to indulge, for once, in a pleasure excursion. Napoleon, who had, for some time, been desirous of taking a survey of the harbor, and of examining some heights, upon the opposite side of the gulf, which, in his view, commanded the town of Ajaccio, consented to the proposal, upon the condition that his friend should accompany him upon the water. They made a signal to some sailors on board a vessel riding at anchor, at some distance from the shore, and were soon in a boat propelled by vigorous rowers. Napoleon seated himself at the stern, and taking from his pocket a ball of pack-thread, one end of which he had fastened upon the shore, commenced the accurate measurement of the width of the gulf. His companion, feeling no interest in the survey, and seeking only listless pleasure, was not a little annoyed in having his amusement thus converted into a study for which he had no relish. When they arrived at the opposite side of the bay, Napoleon insisted upon climbing the heights. Regardless of the remonstrances of his associate, who complained of hunger, and of absence from the warm breakfast which was in readiness for him, Napoleon persisted in exploring the ground. Napoleon in describing the scene says: "My companion, quite uninterested in researches of this kind, begged me to desist. I strove to divert him, and to gain time to accomplish my purpose, but appetite made him deaf. If I spoke to him of the width of the bay, he replied that he was hungry, and that his warm 304 breakfast was cooling. If I pointed out to him a church steeple or a house, which I could reach with my bomb-shells, he replied, "Yes, but I have not breakfasted." At length, late in the morning, we returned, but the friends with whom he was expecting to breakfast, tired of the delay, had finished their repast, so that, on his arrival he found neither guests nor banquet. He resolved to be more cautious in future as to the companion he would choose, and the hour in which he would set out, on an excursion of pleasure."

Subsequently the English surmounted these very heights by a redoubt, and then Napoleon had occasion to avail himself very efficiently of the information acquired upon this occasion.

About twelve months ago Andrè Folitton, horticulturist and herbalist of St. Cloud, a young man of worth and respectability, was united in marriage to Julienne, daughter of an apothecary of the same place. Andrè and Julienne had long loved each other, and congeniality of disposition, parity of years, and health and strength, as well as a tolerably comfortable setout in the world, seemed to promise for them many years of happiness. Supremely contented, and equally disposed to render life as pleasant and blithe as possible, the future seemed spread before them, a long vista of peace and pleasantness, and bright were the auguries which rose around them during the early days of their espousal.

Though he loved mirth and fun as much as any one, Andrè was extremely regular in his habits, and every engagement he made was pretty sure of being punctually attended to. Julienne quickly discovered that thrice every week, precisely at seven o'clock in the evening, her husband left his home, to which he returned generally after the lapse of two hours. Whither he went she did not know, nor could she find out.

Andrè always parried her little inquisitions with jokes and laughter. She perceived, however, that his excursions might be connected with business in some way or other, for he never expended money, as he would had he gone to a café or estaminet. Julienne's speculations went no further than this. As to the husband and wife, had they been left to themselves, not the slightest interruption of mutual good-feeling would ever have arisen out of this matter.

But it is a long lane which has no turning, and a very slight circumstance gave an unhappy twist to the path which had promised such a direct and pleasant voyage through life. Julienne had almost ceased to puzzle herself about her husband's periodical absences, indeed had ceased to joke when he returned from them, having easily learned—the good-tempered little woman—to consider them as nothing more than some engagement connected with the ordinary course of business. One night, however, a neighbor, Madame Margot, stepped into the bowery cottage of the young pair to have a chat and a cup of coffee with Madame Folitton. Madame Margot, though she had more words than Julienne, and could keep the conversation going at a more rattling pace, had by no means so sweet and gracious a presence. Her sharp eye and thin lips were true indices to a prying and somewhat ill-natured disposition; and the fact is, that Madame Margot, having several times seen Andrè pass her house alone in the evening, as if taking a walk by himself, had been seized with a strong desire to know "how things were going on" between him and his wife. Madame Margot had never joined other folks in their profuse prophesies of future happiness when Andrè and Julienne were wedded. She was not the woman to do it; her temper had spread her own bed, and her husband's too, with thorns and briars, and so she declared that the happiness of wedded life was something worse than a mauvaise plaisanterie. "Eh, bien!" she exclaimed, when folks spoke of Andrè and his wife. "I wish them well, but I have lived too long to suppose that such a beginning as theirs can hold on long! We shall hear different tales by and by!" So Madame Margot, with her sharp eye and thin lips, eager to verify her prognostications, had visited Andrè's house to reconnoitre.

"M. Folitton? he is not here?" said she, in the course of conversation.