The Project Gutenberg EBook of English Book-Illustration of To-day, by

Rose Esther Dorothea Sketchley

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: English Book-Illustration of To-day

Appreciations of the Work of Living English Illustrators

With Lists of Their Books

Author: Rose Esther Dorothea Sketchley

Contributor: Alfred W. Pollard

Release Date: November 29, 2011 [EBook #38164]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENGLISH BOOK-ILLUSTRATION ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Diane Monico, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

APPRECIATIONS OF THE WORK OF LIVING

ENGLISH ILLUSTRATORS WITH

LISTS OF THEIR BOOKS

By R. E. D. SKETCHLEY

WITH AN INTRODUCTION

By ALFRED W. POLLARD

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRÜBNER AND CO., Ltd.

PATERNOSTER HOUSE, CHARING CROSS ROAD, W.C.

1903

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

The four articles and bibliographies contained in this volume originally appeared in "The Library."

In connection with the bibliographies, I desire to express cordial thanks to the authorities and attendants of the British Museum, without whose courtesy and aid, extending over many weeks, it would have been impossible to bring together the particulars. Most of the artists, too, have kindly checked and supplemented the entries relating to their work, but even with the help given me I cannot hope to have produced exhaustive lists. My thanks are due to the publishers with whom arrangements have been made for the use of blocks.

| PAGE | |

| Note | v |

| Introduction | xi |

| I. Some Decorative Illustrators | 1 |

| II. Some Open-Air Illustrators | 30 |

| III. Some Character Illustrators | 56 |

| IV. Some Children's-Books Illustrators | 94 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHIES. | |

|---|---|

| I. Some Decorative Illustrators | 121 |

| II. Some Open-Air Illustrators | 132 |

| II. III. Some Character Illustrators | 144 |

| II. IV. Some Children's Books Illustrators | 158 |

| Index of Artists | 174 |

| FROM | PAGE | |

| "Les Quinze Joies de Mariage" | xii | |

| The "Dialogus Creaturarum" | xiii | |

| A Venetian Chapbook | xvii | |

| The "Rappresentazione di un Miracolo del Corpo di Gesù" | xviii | |

| The "Rappresentazione di S. Cristina" | xix | |

| "La Nencia da Barberino" | xxi | |

| The "Storia di Ippolito Buondelmonti e Dianora Bardi" | xxii | |

| Ingold's "Guldin Spiel" | xxiv | |

| The Malermi Bible | xxv | |

| A French Book of Hours | xxvii | |

| FROM | BY | |

| "A Farm in Fairyland." | Laurence Housman | xxx |

| Grimm's "Household Stories." | Walter Crane | 5 |

| "Undine." | Heywood Sumner | 7 |

| "Keats' Poems." | R. Anning Bell | 9 |

| "Stories and Fairy Tales." | A. J. Gaskin | 11 |

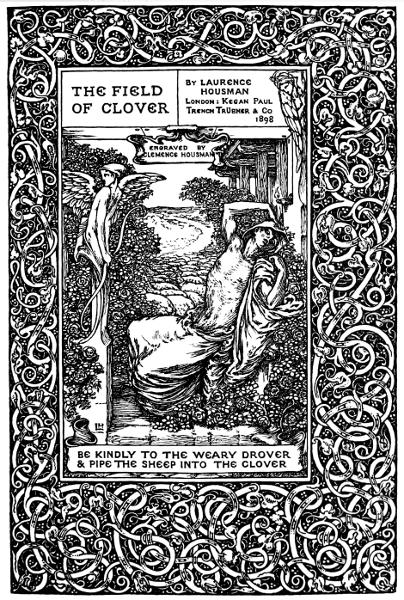

| "The Field of Clover." | Laurence Housman | 20 and 21 |

| "Cupide and Psyches." | Charles Ricketts | 22 |

| "Daphnis and Chloe." | Charles Ricketts and C. H. Shannon | 23 |

| "The Centaur." | T. Sturge Moore | 25 |

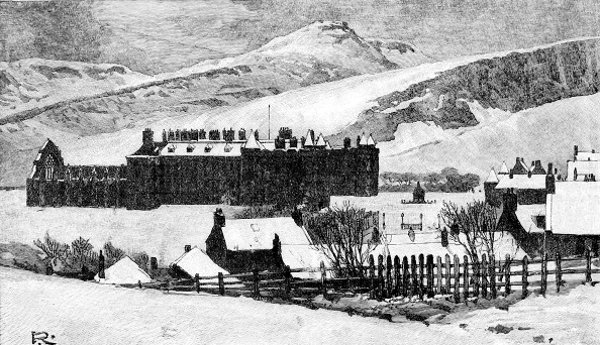

| "Royal Edinburgh." | Sir George Reid | facing 35 |

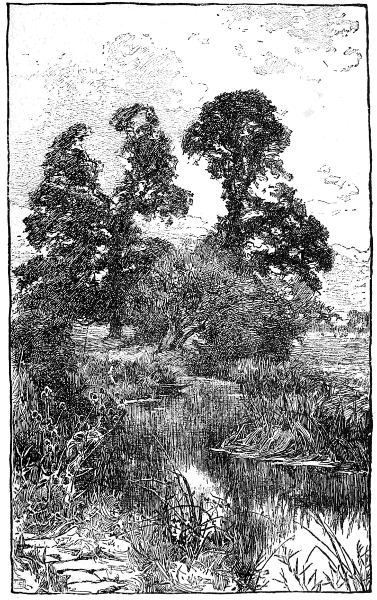

| "The Warwickshire Avon." | Alfred Parsons | 37 |

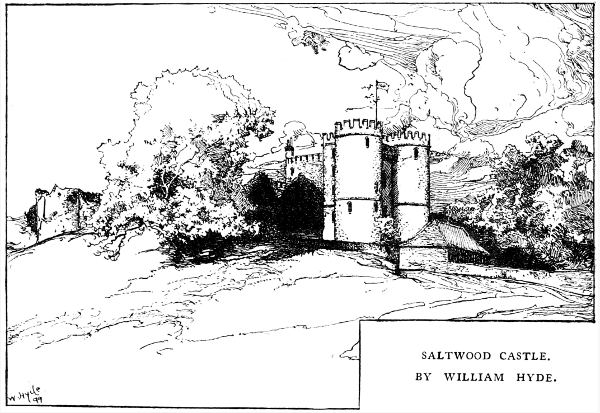

| "The Cinque Ports." | William Hyde | 42 |

| "Italian Journeys." | Joseph Pennell | facing 45 |

| "The Holyhead Road." | C. G. Harper | 49 |

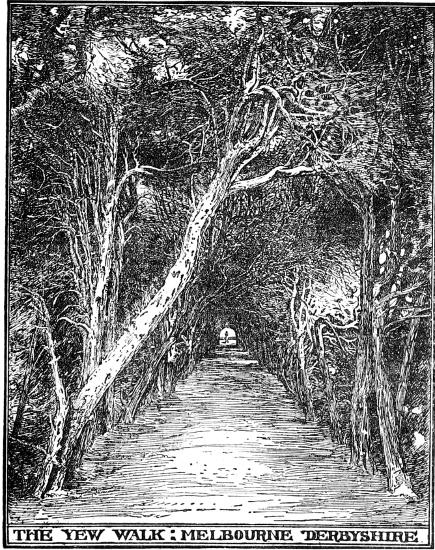

| "The Formal Garden." | F. Inigo Thomas | 51 |

| "The Natural History of Selborne." | E. H. New | 53 |

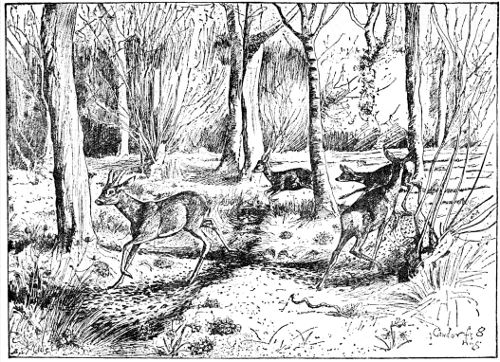

| "British Deer and their Horns." | J. G. Millais | 55 |

| "Death and the Ploughman's Wife." | William Strang | 61 |

| "The Bride of Lammermoor." | Fred Pegram | 71 |

| "Shirley." | F. H. Townsend | 73 |

| "The Heart of Midlothian." | Claude A. Shepperson | 75 |

| "The School for Scandal." | E. J. Sullivan | 78 |

| "The Ballad of Beau Brocade." | Hugh Thomson | 82 |

| "The Essays of Elia." | C. E. Brock | 85 |

| "The Talk of the Town." | Sir Harry Furniss | 89 |

| "Hermy." | Lewis Baumer | 100 |

| "To tell the King the Sky is falling." | Alice B. Woodward | 105 |

| "Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm." | Arthur Rackham | 109 |

| "Indian Fairy Tales." | J. D. Batten | 111 |

| "The Pink Fairy Book." | H. J. Ford | 113 |

| "Fairy Tales by Q." | H. R. Millar | 115 |

SOME PRESENT-DAY LESSONS FROM OLD WOODCUTS.

By Alfred W. Pollard.

SOME explanation seems needed for the intrusion of a talk about the woodcuts of the fifteenth century into a book dealing with the work of the illustrators of our own day, and the explanation, though no doubt discreditable, is simple enough. It was to a mere bibliographer that the idea occurred that lists of contemporary illustrated books, with estimates of the work found in them, might form a useful record of the state of English book-illustration at the end of a century in which for the first time (if we stretch the century a little so as to include Bewick) it had competed on equal terms with the work of foreign artists. Fortunately the bibliographer's scanty leisure was already heavily mortgaged, and so the idea was transferred to a special student of the subject, much better equipped for the task. But partly for the pleasure of keeping a finger in an interesting pie, partly because there was a fine hobby-horse waiting to be mounted, the bibliographer bargained that he should be allowed to write an introduction in which his hobby should have free play, and the reader, who has got a much better book than he was intended to have, must acquiesce in this meddling, or resort to his natural rights and skip.

It is well to ride a hobby with at least a semblance of moderation, and the thesis which this introduction is written to maintain does not assert that the woodcuts of the fifteenth century are better than the illustrations of the present day, only that our modern artists, if they will condescend, may learn some useful lessons from them. At the outset it may frankly be owned that the range of the earliest illustrators was limited. They had no landscape art, no such out-of-door illustrations as those which furnish the subject for one of Miss Sketchley's most interesting chapters. Again, they had little humour, at least of the voluntary kind, though this was hardly their own fault, for as the admission is made the thought at once follows it that of all the many deficiencies[Pg xiv] of fifteenth-century literature the lack of humour is one of the most striking. The rough horseplay of the Life of Aesop prefixed to editions of the Fables can hardly be counted an exception; the wit combats of Solomon and Marcolphus produced no more than a title-cut showing king and clown, and outside the 'Dialogus Creaturarum' I can think of only a single valid exception, itself rather satirical than funny, this curious picture of a family on the move from a French treatise on the Joys of Marriage. On the 'Dialogus' itself it seems fair to lay some stress, for surely the picture here shown of the Lion and the Hare who applied for the post of his secretary may well encourage us to believe that in two other departments of illustration from which also they were shut out, those of Caricature (for which we must go back to thirteenth-century prayer-books) and Christmas Books for Children, the fifteenth-century artist would have made no mean mark. It is, indeed, our Children's Gift-Books that come nearest both to his feeling and his style.

What remains for us here to consider is the achievement of the early designers and woodcutters in the field of Decorative and Character Illustrations with which Miss Sketchley deals in her first and third chapters. Here the first point to be made is that by an invention of the last twenty years they are brought nearer to the possible work of our own day than to that of any previous time. It has been often enough pointed out that, not from preference, but from inability to devise any better plan, the art of woodcut illustration began on wholly wrong lines. Starting, as was inevitable, from the colour-work of illuminated[Pg xv] manuscripts, the illustrators could think of no other means of simplification than the reduction of pictures to their outlines. With a piece of plank cut, not across the grain of the wood, but with it, as his material, and a sharp knife and, perhaps, a gouge as his only tools, the woodcutter had to reproduce these outlines as best he could, and it is little to be wondered at if his lines were often scratchy and angular, and many a good design was deplorably ill handled. After a time, soft metal, presumably pewter, was used as an alternative to wood, and perhaps, though probably slower, was a little easier to work successfully. But save in some Florentine pictures and a few designs by Geoffroy Tory, the craftsman's work was not to cut the lines which the artist had drawn, but to cut away everything else. This inverted method of work continued after the invention of crosshatching to represent shading, and was undoubtedly the cause of the rapid supersession of woodcuts by copper engravings during the sixteenth century, the more natural method of work compensating for the trouble caused when the illustrations no longer stood in relief like the type, but had to be printed as incised plates, either on separate leaves, or by passing the sheet through a different press. The eighteenth-century invention of wood-engraving as opposed to woodcutting once again caused pictures and text to be printed together, and the amazing dexterity of successive schools of wood-engravers enabled them to produce, though at the cost of immense labour, work which seemed to compete on equal terms with engravings on copper. At its best the wood-engraving[Pg xvi] of the nineteenth century was almost miraculously good; at its worst, in the wood-engravings of commerce—the wood-engravings of the weekly papers, for which the artist's drawing might come in on a Tuesday, to be cut up into little squares and worked on all night as well as all day, in the engravers' shops—it was unequivocally and deplorably, but hardly surprisingly, bad.

Upon this strange medley of the miraculously good and the excusably horrid came the invention of the process line-block, and the problem which had baffled so many fifteenth-century woodcutters, of how to preserve the beauty of simple outlines was solved at a single stroke. Have our modern artists made anything like adequate use of this excellent invention? My own answer would be that they have used it, skilfully enough, to save themselves trouble, but that its artistic possibilities have been allowed to remain almost unexplored. As for the trouble-saving—and trouble-saving is not only legitimate but commendable—the photographer's camera is the most obliging of craftsmen. Only leave your work fairly open and you may draw on as large a scale and with as coarse lines as you please, and the camera will photograph it down for you to the exact space the illustration has to fill and will win you undeserved credit for delicacy and fineness of touch as well. Thus to save trouble is well, but to produce beautiful work is better, and what use has been made of the fidelity with which beautiful and gracious line can now be reproduced? The caricaturists, it is true, have seen their opportunity. Cleverness could hardly be carried further than it is[Pg xvii] by Mr. Phil May, and a caricaturist of another sort, the late Mr. Aubrey Beardsley, degenerate and despicable as was almost every figure he drew, yet saw and used the possibilities which artists of happier temperament have neglected. With all the disadvantages under which they laboured in the reproduction of fine line the craftsmen of Venice and Florence essayed and achieved more than this. Witness the fine rendering into pure line of a picture by Gentile Bellini of a tall preacher preceded by his little crossbearer in the 'Doctrina' of Lorenzo Giustiniano printed at Venice in 1494, or again the impressiveness, surviving even its little touch of the grotesque, of this armed warrior kneeling at the feet[Pg xviii] of a pope, which I have unearthed from a favourite volume of Venetian chapbooks at the British Museum. A Florentine picture of Jacopone da Todi on his knees before a vision of the Blessed Virgin (from Bonacorsi's edition of his 'Laude,' 1490) gives another instance of what can be done by simple line in a different style. We have yet other examples in many of the illustrations to the famous romance, the 'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili,' printed at Venice in 1499. Of similar cuts on a much smaller scale, a specimen will be given later. Here, lest anyone should despise these fifteenth-century efforts, I would once more recall the fact that at the time they were made the execution of such woodcuts required the greatest possible dexterity,[Pg xix] in cutting away on each side so as to leave the line as the artist drew it with any semblance of its original grace. In many illustrated books which have come down to us what must have been beautiful designs have been completely spoilt, rendered even grotesque, by the fine curves of the drawing being translated into scratchy angularities. But draw he never so finely no artist nowadays need fear that his work will be made scratchy or angular by photographic process. It is only when he crowds lines together, from inability to work simply, that the process block aggravates his defects.

I pass on to another point as to which I think the Florentine woodcutters have something to teach us. If we put pictures into our books, why should not the pictures be framed? A hard single line round the edge of a woodcut is a poor set-off to it, often conflicting with the lines in the picture itself, and sometimes insufficiently emphatic as a frame to make us acquiesce in what seems a mere cutting away a portion from a larger whole. Our Florentine friends knew better. Here (pp. xiv-xv), for instance, are two scenes, from some unidentified romance, which in 1572 and 1555 respectively (by which time they must have been about fifty and sixty years old) appeared in Florentine religious chapbooks, with which they have nothing to do. The little borders are simple enough, but they are sufficiently heavy to carry off the blacks which the artist (according to what is the true method of woodcutting) has left in his picture, and we are much less inclined to grumble at the window being cut in two than we should be if the cut were made by a simple line[Pg xx] instead of quite firmly and with determination by a frame.

I have given these two Florentine cuts, much the worse for wear though they be, with peculiar pleasure, because I take them to be the exact equivalents of the pictures in our illustrated novels of the present day of which Miss Sketchley gives several examples in her third paper. They are good[Pg xxi] examples of what may be called the diffused characterization in which our modern illustrators excel. Every single figure is good and has its own individuality, but there is no attempt to illustrate a central character at a decisive moment. Decisive moments, it may be objected, do not occur (except for epicures) at polite dinner parties, or during the 'mauvais[Pg xxii] quart d'heure,' which might very well be the subject of our first picture. But it seems to me that modern illustrators often deliberately shun decisive moments, preferring to illustrate their characters in more ordinary moods, and perhaps the Florentines did this also. Where the illustrator is not a great artist the discretion is no doubt a wise one. What for instance could be more charming, more completely successful than this little picture of a messenger bringing a lady a flower, no doubt with a pleasing message with it? In our next cut the artist has been much more ambitious. Preceded by soldiers with their long spears, followed by the hideously masked 'Battuti' who ministered to the condemned, Ippolito is being led to execution. As he passes her door, Dianora flings herself on him in a last embrace. The lady's attitude is good, but the woodcutter, alas, has made the lover look merely bored. In book-illustration, as in life, who would avoid failure must know his limitations.

Whatever shortcomings these Florentine pictures may have in themselves, or whatever they may lose when examined by eyes only accustomed to modern work, I hope that it will be conceded that as character-illustrations they are far from being despicable. Nevertheless the true home of character-illustration in the fifteenth century was rather in Germany than in Italy. Inferior to the Italian craftsmen in delicacy and in producing a general impression of grace (partly, perhaps, because their work was intended to be printed in conjunction with far heavier type) the German artists and woodcutters often showed extraordinary power in rendering facial expression.[Pg xxiii] My favourite example of this is a little picture from the 'De Claris Mulieribus' of Boccaccio printed at Ulm in 1473, on one side of which the Roman general Scipio is shown with uplifted finger bidding the craven Massinissa put away his Carthaginian wife, while on the other Sophonisba is watched by a horror-stricken messenger as she drains the poison her husband sends her. But there is a naïveté about the figure of Scipio which has frequently provoked laughter from audiences at lantern-lectures, so my readers must look up this illustration for themselves[Pg xxiv] at the British Museum, or elsewhere. I fall back on a picture of a card-party from a 'Guldin Spiel' printed at Augsburg in 1472, in which the hesitation of the woman whose turn it is to play, the rather supercilious interest of her vis-à-vis, and the calm confidence of the third hand, not only ready to play his best, but sure that his best will be good enough, are all shown with absolute simplicity, but in a really masterly manner. Facial expression such as this in modern work seems entirely confined to children's books and caricature, but one would sacrifice a good deal of our modern prettiness for a few more touches of it.

The last point to which I would draw attention is that a good deal more use might be made of quite small illustrations. The full-pagers are, no doubt, impressive and dignified, but I always seem to see written on the back of them the artist's contract to supply so many drawings of such and such size at[Pg xxv] so many guineas apiece, and to hear him groaning as he runs through his text trying to pick out the full complement of subjects. The little sketch is more popular in France than in England, and there is a suggestion of joyous freedom about it which is very captivating. Such small pictures did not suit the rather heavy touch of the German woodcutters; in Italy they were much more popular. At Venice a whole series of large folio books were illustrated in this way in the last decade of the fifteenth century, two editions of Malermi's translation of the Bible, Lives of the Saints, an Italian Livy, the Decamerone of Boccaccio, the Novels of Masuccio, and other works, all in the vernacular. At Ferrara, under Venetian influence, an edition of the Epistles of S. Jerome was printed in 1497, with upwards of one hundred and eighty such little cuts, many of them illustrating incidents of monastic life. Both at Venice and Ferrara the cuts are mainly in outline, and when they are well cut and two or three come together on a page the effect is delightful. In France the vogue of the small cut took a very special form. By far the most famous series of early French illustrated books is that of the Hours of the Blessed Virgin (with which went other devotions, making fairly complete prayer-books for lay use), which were at their best for some fifteen years reckoning from 1488. These Hour-Books usually contained some fifteen large illustrations, but their most notable features are to be found in the borders which surround every page. On the outer and lower margins these borders are as a rule about an inch broad, sometimes more, so that they can hold four[Pg xxvi] or five little pictures of about an inch by an inch and a half on the outer margin, and one rather larger one at the foot of the page. The variety of the pictures designed to fill these spaces is almost endless. Figures of the Saints and their emblems and illustrations of the games or occupations suited to each month fill the margins of the Calendar. To surround the text of the book there is a long series of pictures of incidents in the life of Christ, with parallel scenes from the Old Testament, scenes from the lives of Joseph and Job, representations of the Virtues, the Deadly Sins being overcome by the contrary graces, the Dance of Death, and for pleasant relief woodland and pastoral scenes and even grotesques. The popularity of these prayer-books was enormous, new editions being printed almost every month, with the result that the illustrations were soon worn out and had frequently to be replaced. I have often wished, if only for the sake of small children in sermon time, that our English prayer-books could be similarly illustrated. An attempt to do this was made in the middle of the last century, but it was pretentious and unsuccessful. The great difficulty in the way of a new essay lies in the popularity of very small prayer-books, with so little margin and printed on such thin paper as hardly to admit of border cuts. The difficulty is real, but should not be insuperable, and I hope that some bold illustrator may soon try his hand afresh.

I should not be candid if I closed this paper without admitting that my fifteenth-century friends anticipated modern publishers in one of their worst faults, the dragging in illustrations where they are[Pg xxvii] not wanted. In the fifteenth century the same cuts were repeated over and over again in the same book to serve for different subjects. Modern publishers are not so simple-hearted as this, but they add to the cost of their books by unpleasant half-tone reproductions of unnecessary portraits and views, and I do not think that book-buyers are in the least grateful to them. Miss Sketchley, I am glad to see, has not concerned herself with illustrators whose designs require to be produced by the half-tone process. To condemn this process unreservedly would be absurd. It gives us illustrations which are really needed for the understanding of the text when they could hardly be produced in any other way, and while it does this it must be tolerated. But by necessitating the use of heavily-loaded paper—unpleasant to the touch, heavy in the hand, doomed, unless all the chemists are wrong, speedily to rot—it is the greatest danger to the excellence of our English book-work which has at present to be faced, while by wearying readers with endless mechanically produced pictures it is injurious also to the best interests of artistic illustration.

OF the famous 'Poems by Alfred Tennyson,' published in 1857 by Edward Moxon, Mr. Gleeson White wrote in 1897: 'The whole modern school of decorative illustrators regard it, rightly enough, as the genesis of the modern movement.' The statement may need some modification to touch exact truth, for the 'modern movement' is no single-file, straightforward movement. 'Kelmscott,' 'Japan,' the 'Yellow Book,' black-and-white art in Germany, in France, in Spain, in America, the influence of Blake, the style of artists such as Walter Crane, have affected the present form of decorative book-illustration. Such perfect unanimity of opinion as is here ascribed to a large and rather indefinitely related body of men hardly exists among even the smallest and most derided body of artists. Still, allowing for the impossibility of telling the whole truth about any modern and eclectic form of art in one sentence, there is here a statement of fact. What Rossetti and Millais and Holman Hunt achieved in the drawings to the 'Tennyson' of 1857, was a vital change in the intention of English illustrative art,[Pg 2] and whatever form decorative illustration may assume, their ideal is effective while a personal interpretation of the spirit of the text is the creative impulse. The influence of technical mastery is strong and enduring enough. It is constantly in sight and constantly in mind. But it is in discovering and making evident a principle in art that the influence of spirit on spirit becomes one of the illimitable powers.

To Rossetti the illustration of literature meant giving beautiful form to the expression of delight, of penetration, that had kindled his imagination as he read. He illustrated the 'Palace of Art' in the spirit that stirred him to rhythmic translation into words of the still music in Giorgione's 'Pastoral,' or of the unpassing movement of Mantegna's 'Parnassus.' Not the words of the text, nor those things precisely affirmed by the writer, but the spell of significance and of beauty that held his mind to the exclusion of other images, gave him inspiration for his drawings. As Mr. William Michael Rossetti says: 'He drew just what he chose, taking from his author's text nothing more than a hint and an opportunity.' It is said, indeed, that Tennyson could never see what the St. Cecily drawing had to do with his poem. And that is strange enough to be true.

It is clear that such an ideal of illustration is for the attainment of a few only. The ordinary illustrator, making drawings for cheap reproduction in the ordinary book, can no more work in this mood than the journalist can model his style on the prose of Milton. But journalism is not literature, and[Pg 3] pictured matter-of-fact is not illustration, though it is convenient and customary to call it so. However, here one need not consider this, for the decorative illustrator has usually literature to illustrate, and a commission to be beautiful and imaginative in his work. He has the opportunity of Rossetti, the opportunity for significant art.

The 'Classics' and children's books give greatest opportunity to decorative illustrators. Those who have illustrated children's books chiefly, or whose best work has been for the playful classics of literature, it is convenient to consider in a separate chapter, though there are instances where the division is not maintainable: Walter Crane, for example, whose influence on a school of decorative design makes his position at the head of his following imperative.

Representing the 'architectural' sense in the decoration of books, many years before the supreme achievements of William Morris added that ideal to generally recognized motives of book-decoration, Walter Crane is the precursor of a large and prolific school of decorative illustrators. Many factors, as he himself tells, have gone to the shaping of his art. Born in 1846 at Liverpool, he came to London in 1857, and there after two years was 'apprenticed' to Mr. W. J. Linton, the well-known wood-engraver. His work began with 'the sixties,' in contact with the enthusiasm and inspiration those years brought into English art. The illustrated 'Tennyson,' and Ruskin's 'Elements of Drawing,' were in his thoughts before he entered Mr. Linton's workshop, and the 'Once a Week' school had[Pg 4] a strong influence on his early contributions to 'Good Words,' 'Once a Week,' and other famous magazines. In 1865 Messrs. Warne published the first toy-book, and by 1869-70 the 'Walter Crane Toy-book' was a fact in art. The sight of some Japanese colour-prints during these years suggested a finer decorative quality to be obtained with tint and outline, and in the use of black, as well as in a more delicate simplicity of colour, the later toy-books show the first effect of Japanese art on the decorative art of England. Italian art in England and Italy, the prints of Dürer, the Parthenon sculptures, these were influences that affected him strongly. 'The Baby's Opera' (1877) and 'The Baby's Bouquet' (1879) are classics almost impossible to criticise, classics familiar from cover to cover before one was aware of any art but the art on their pages. So that if these delightful designs seem less expressive of the Greece, Germany, and Italy of the supreme artists than of the 'Crane' countries by whose coasts ships 'from over the sea' go sailing by with strange cargoes and strange crews, it is not in their dispraise. As a decorative draughtsman Mr. Crane is at his best when the use of colour gives clearness to the composition, but some of his most 'serious' work is in the black-and-white pages of 'The Sirens Three,' of 'The Shepheardes Calendar,' and especially of 'The Faerie Queene.' The number of books he has illustrated—upwards of seventy—makes a detailed account impossible. Nursery rhyme and fairy books, children's stories, Spenser, Shakespeare, the myths of Greece, 'pageant books' such as 'Flora's Feast' or 'Queen Summer,' or the just published 'Masque of Days,' his own writings, serious or gay, have given him subjects, as the great art of all times has touched the ideals of his art.

But whatever the subject, how strong soever his artistic admirations, he is always Walter Crane, unmistakable at a glance. Knights and ladies, fairies and fairy people, allegorical figures, nursery and school-room children, fulfil his decorative purpose without swerving, though not always without injury to their comfort and freedom and the life in their limbs. An individual apprehension that sees every situation as a conventional 'arrangement' is occasionally beside the mark in rendering real life. But when his theme touches imagination, and is not a supreme expression of it—for then, as in the illustrations to 'The Faerie Queene,' an unusual sense of subservience appears to dull his spirit—his humorous fancy knows no weariness nor sameness of device.

The work of most of Mr. Crane's followers belongs to 'the nineties,' when the 'Arts and Crafts' movement, the 'Century Guild,' the Birmingham and other schools had attracted or produced artists working according to the canons of Kelmscott. Mr. Heywood Sumner was earlier in the field. The drawings to 'Sintram' (1883) and to 'Undine' (1888) show his art as an illustrator. Undine—spirit of wind and water, flower-like in gladness—seeking to win an immortal soul by submission to the forms of life, is realized in the gracefully designed figures of frontispiece and title-page. Where Mr. Sumner illustrates incident he is 'factual'[Pg 7] without being matter-of-fact. The small drawing reproduced is hardly representative of his art, but most of his work is adapted to a squarer page than this, and has had to be rejected on that account. Some of the most apt decorations in 'The English Illustrated' were by Mr. Sumner, and during the time when art was represented in the magazine Mr. Ryland and Mr. Louis Davis were also frequent contributors. The graceful figures of Mr. Ryland, uninterested in activity, a garden-world set with statues around them, and the carol-like grace of Mr. Davis's designs in that magazine, represent them better than the one or two books they have illustrated.

Among those associated with the 'Arts and Crafts' who have given more of their art to book-decoration, Mr. Anning Bell is first. He has gained the approval even of the most exigent of critics as an artist who understands drawing for process. Since 1895, when the 'Midsummer Night's Dream' appeared, his winning[Pg 8] art has been praised with discrimination and without discrimination, but always praised. Trained in an architect's office, widely known as the recreator of coloured relief for architectural decoration, Mr. Anning Bell's illustrations show constructive power no less than that fairy gift of seeming to improvise without labour and without hesitancy, which is one of its especial charms. In feeling, and in many of his decorative forms, his drawings recall the art of Florentine bas-relief, when Agostino di Duccio, or Rossellino or Mino da Fiesole, created shapes of delicate sweetness, pure, graceful—so graceful that their power is hardly realized. The fairy by-play of the 'Midsummer Night's Dream' is exactly to Mr. Anning Bell's fancy. He knows better than to go about to expound this dream, and it is not likely that a more delightful edition will ever be put into the hands of children, or of anyone, than this in the white and gold cover devised by the artist.

Of his illustrations to the 'Poems by John Keats' (1897), and to the 'English Lyrics from Spenser to Milton' of the following year—as illustrations—not quite so much can be said, distinguished and felicitous as many of them are. The simple profile, the demure type of beauty that he affects, hardly suit with Isabella when she hears that Lorenzo has gone from her, with Lamia by the clear pool

or with Madeline, 'St. Agnes' charmëd maid.' Mr.[Pg 9] Anning Bell's drawings to 'The Pilgrim's Progress' (1898) reveal him in a different mood, as do those in 'The Christian Year' of three years earlier. His vision is hardly energetic enough, his energy of belief sufficient, to make him a strong illustrator of Bunyan, with his many moods, his great mood. A little these designs suggest Howard Pyle, and Anning Bell is better in a way of beauty not Gothic.

So if Mr. Anning Bell represents the 'Arts and Crafts' movement in the variety of decorative arts he has practised, and in the architectural sense underlying all his art, his work does not agree with the form in which the influence of William Morris on decorative illustration has chiefly shown itself. That form, of course, is Gothic, as the ideal of Kelmscott was Gothic. The work of the 'Century Guild' artists as decorative illustrators is[Pg 10] chiefly in the pages of 'The Hobby Horse.' Mr. Selwyn Image and Mr. Herbert Horne can hardly be included among book illustrators, so in this connection one may not stop to consider the decorative strength of their ideal in art. The Birmingham school represents Gothic ideals with determination and rigidity. Morris addressed the students of the school and prefaced the edition of 'Good King Wenceslas,' decorated and engraved and printed by Mr. A. J. Gaskin 'at the press of the Guild of Handicraft in the City of Birmingham,' with cordial words of appreciation for the pictures. These illustrations are among the best Mr. Gaskin has done. The commission for twelve full-page drawings to 'The Shepheardes Calendar' (Kelmscott Press, 1896) marks Morris's pleasure in Mr. Gaskin's work—especially in the illustrations to Andersen's 'Stories and Fairy Tales.' If not quite in tune with Spenser's Elizabethan idyllism, these drawings are distinctive of the definite convictions of the artist.

These convictions represent a splendid tradition. They are expressive, in their regard for the unity of the page, for harmony between type and decoration, of the universal truth in all fine bookmaking. Only at times, Birmingham work seems rather heavy in spirit, rather too rigid for development. Still, judging by results, a code that would appear to be against individual expression is inspiring individual artists. Some of these—as Mr. E. H. New—have turned their attention to architectural and 'open-air' illustration, in which connection their work will be considered, and many[Pg 12] have illustrated children's books. Their quaint and naïve fancy has there, at times, produced a portentous embodiment of the 'old-fashioned' child of fiction. Mr. Gere, though he has done little book-illustration, is one of the strongest artists of the school. His original wood engravings show unmistakably his decorative power and his craftsmanship. With Mr. K. Fairfax Muckley he was responsible for 'The Quest' (1894-96). Mr. Fairfax Muckley has illustrated and decorated a three-volume edition of 'The Faerie Queene' (1897), wherein the forest branches and winding ways of woodland and of plain are more happily conventionalized than are Spenser's figures. Some of the headpieces are especially successful. The artist uses the 'mixed convention' of solid black and line with less confusion than many modern draughtsmen. Once its dangers must have been evident, but now the puzzle pattern, with solid blacks in the foreground, background, and mid-distance—only there is no distance in these drawings—is a common form of black and white.

Miss Celia Levetus, Mr. Henry Payne, Mr. F. Mason, and Mr. Bernard Sleigh, are also to the credit of the school. Miss Levetus, in her later work, shows that an inclination towards a more flexible style is not incompatible with the training in Gothic convention. Mr. Mason's illustrations to ancient romances of chivalry give evidence of conscientious craftsmanship, and of a spirit sympathetic to themes such as 'Renaud of Montauban.' Mr. Bernard Sleigh's original wood-engravings are well known and justly appreciated. Strong in tradition[Pg 13] and logic as is the work of these designers, it is, for many, too consistent with convention to be delightful. Perhaps the best result of the Birmingham school will hardly be achieved until the formal effect of its training is less patent.

The 'sixties' might have been void of art, so far as these designers are concerned, save that in those days Morris and Burne-Jones and Walter Crane, as well as Millais and Houghton and Sandys, were about their work. Far other is the case with artists such as Mr. Byam Shaw, or with the many draughtsmen, including Messrs. P. V. Woodroffe, Henry Ospovat, Philip Connard, and Herbert Cole, whose art derives its form and intention from the sixties. Differing in technical power and fineness of invention, in all that distinguishes good from less good, they have this in common—that the form of their art would have been quite other if the illustrated books of that period were among things unseen. Mr. Byam Shaw began his work as an illustrator in 1897 with a volume of 'Browning's Poems,' edited by Dr. Garnett. He proved himself in these drawings, as in his pictures and later illustrations, an artist with a definite memory for the forms, and a genuine sympathy with the aims of pre-Raphaelite art. Evidently, too, he admires the black-and-white of Mr. Abbey. He has the gift of dramatic conception, sees a situation at high pitch, and has a pleasant way of giving side-lights, pictorial asides, by means of decorative head and tailpieces. His illustrations to the little green and gold volumes of the 'Chiswick Shakespeare' are more emphatic than his earlier work, and in the decorations his[Pg 14] power of summarizing the chief motive is put to good use. There is no need of his signature to distinguish the work of Byam Shaw, though he shows himself under the influence of various masters. Probably he is only an illustrator of books by the way, but in the meantime, as the 'Boccaccio,' 'Browning,' and 'Shakespeare' drawings show, he works in black and white with vigorous intention.

Mr. Ospovat's illustrations to 'Shakespeare's Sonnets' and to 'Matthew Arnold's Poems' are interesting, if not very markedly his own. He illustrates the Sonnets as a celebration of a poet's passion for his mistress. As in these, so in the Matthew Arnold drawings, he shows some genuine creative power and an aptitude for illustrative decoration. Mr. Philip Connard has made spirited and well-realized illustrations in somewhat the same kind; Miss Amelia Bauerle, and Mr. Bulcock, who began by illustrating 'The Blessed Damozel' in memory of Rossetti, have made appearance in the 'Flowers of Parnassus' series, and Mr. Herbert Cole, with three of these little green volumes, prepared one for more important work in 'Gulliver's Travels' (1900).

The work of Mr. Woodroffe was, I think, first seen in the 'Quarto'—the organ of the Slade School—where also Mr. A. Garth Jones, Mr. Cyril Goldie, and Mr. Robert Spence, gave unmistakable evidence of individuality. Mr. Woodroffe's wood-engravings in the 'Quarto' showed strength, which is apparent, too, in the delicately characterized figures to 'Songs from Shakespeare's Plays' (1898), with their borders of lightly-strung field flowers.[Pg 15] His drawings to 'The Confessions of S. Augustine,' engraved by Miss Clemence Housman, are in keeping with the text, not impertinent. Mr. A. Garth Jones in the 'Quarto' seemed much influenced by Japanese grotesques; but in illustrations to Milton's 'Minor Poems' (1898) he has shown development towards the expression of beauty more austere, classical, controlled to the presentment of Milton's high thought. His recent 'Essays of Elia' remind one of the forcible work of Mr. E. J. Sullivan in 'Sartor Resartus.' Mr. Sullivan's 'Sartor' and 'Dream of Fair Women' must be mentioned. His mastery over an assertive use of line and solid black, the unity of his effects, the humour and imagination of his decorative designs, are not likely to be forgotten, though the balance of his work in illustrations to Sheridan, Marryat, Sir Walter Scott, obliges one to class him with "character" illustrators, and so to leave a blank in this article.

Mr. Laurence Housman stands alone among modern illustrators, though one may, if one will, speak of him as representing the succession of the sixties, or as connected with the group of artists whose noteworthy development dates from the publication of 'The Dial' by Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon in 1889. To look at Mr. Housman's art in either connection, or to record the effect of Dürer, of Blake, of Edward Calvert, on his technique, is only to come back to appreciation of all that is his own. As an illustrator he has hardly surpassed the spirit of the 'forty-four designs, drawn and written by Laurence Housman,' that express his idea of George Meredith's 'Jump[Pg 16] to Glory Jane' (1890). These designs were the result of the appreciation which the editor, Mr. Harry Quilter, felt for Mr. Housman's drawings to 'The Green Gaffer' in 'The Universal Review.' Jane—the village woman with 'wistful eyes in a touching but bony face,' leaping with countenance composed, arms and feet 'like those who hang,' leaping in crude expression of the unity of soul and body, making her converts, failing to move the bishop, dying at last, though not ingloriously, by the wayside—this most difficult conception has no 'burlesque outline' in Mr. Housman's work, inexperienced and unacademic as is the drawing.

'Weird Tales from Northern Seas,' by Jonas Lie, was the next book illustrated by Mr. Housman. Christina Rossetti's 'Goblin Market' (1893), offered greater scope for freakish imagination than did 'Jane.' The goblins, pale-eyed, mole and rat and weasel-faced; the sisters, whose simple life they surround with hideous fantasy, are realized in harmony with the unique effect of the poem—an effect of simplicity, of naïve imagination, of power, of things stranger than are told in the cry of the goblin merchants, as at evening time they invade quiet places to traffic with their evil fruits for the souls of maidens. The frail-bodied elves of 'The End of Elfin Town,' moving and sleeping among the white mushrooms and slender stalks of field flowers, are of another land than that of the goblin merchant-folk. Illustrations to 'The Imitation of Christ,' to 'The Sensitive Plant,' and drawings to 'The Were-Wolf,' by Miss Clemence Housman,[Pg 17] complete the list of Mr. Housman's illustrations to writings not his own, with the exception of frontispiece drawings to several books.

To explain Mr. Housman's vision of 'The Sensitive Plant' would be as superfluous as it would be ineffectual. In a note on the illustrations he has told how the formal beauty, the exquisite ministrations, the sounds and fragrance and sweet winds of the garden enclosed, seem to him as 'a form of beauty that springs out of modes and fashions,' too graceful to endure. In his pictures he has realized the perfect ensemble of the garden, its sunny lawns and rose-trellises, its fountains, statues, and flower-sweet ways; realized, too, the spirit of the Sensitive Plant, the lady of the garden, and Pan, the great god who never dies, who waits only without the garden, till in a little while he enters, 'effacing and replacing with his own image and superscription, the parenthetic grace ... of the garden deity.'

Of a talent that treats always of enchanted places, where 'reality' is a long day's journey down a dusty road, it is difficult to speak without suggesting that it is all just a charming dalliance with pretty fancies, lacking strength. Of the strength of Mr. Housman's imagination, however, his work speaks. His illustrations to his own writings, fairy tales, and poems, cannot with any force be discussed by themselves. The words belong to the pictures, the pictures to the words. The drawings to 'The Field of Clover' are seen to full advantage in the wood-engravings of Miss Housman. Only so, or in reproduction by photogravure,[Pg 18] is the full intention of Mr. Housman's pen-drawings apparent.

THE FIELD OF CLOVER By Laurence Housman,

Engraved by Clemence Housman

THE FIELD OF CLOVER By Laurence Housman,

Engraved by Clemence HousmanOne may group the names of Charles Ricketts, C. H. Shannon, T. Sturge Moore, Lucien Pissarro, and Reginald Savage together in memory of 'The Dial,' where the activity of five original artists first became evident, though, save in the case of Mr. Ricketts and Mr. Shannon, no continuance of the classification is possible. The first number of 'The Dial' (1889) had a cover design cut on wood by Mr. C. H. Shannon—afterwards replaced by the design of Mr. Ricketts. Twelve designs by Mr. Ricketts may be said to represent the transitional—or a transitional—phase of his art, from the earlier work in magazines, which he disregards, to the reticent expression of 'Vale Press' illustrations. In 1891 the first book decorated by these artists appeared, 'The House of Pomegranates,' by Oscar Wilde. There was, however, nothing in this book to suggest the form their joint talent was to take. Many delightful designs by Mr. Ricketts, somewhat marred by heaviness of line, and full-page illustrations by Mr. Shannon, printed in an almost invisible, nondescript colour, contained no suggestion of 'Daphnis and Chloe.'

The second 'Dial'(1892) contained Mr. Ricketts' first work as his own wood-engraver, and in the following year the result of eleven months' joint work by Mr. Ricketts and Mr. Shannon was shown in the publication of 'Daphnis and Chloe,' with thirty-seven woodcuts by the artists. Fifteen of the pictures were sketched by Mr. Shannon and revised and drawn on the wood by Mr. Ricketts,[Pg 19] who also engraved the initials. It is a complete achievement of individuality subordinated to an ideal. Here and there one can affirm that Mr. Shannon drew this figure, composed this scene, Mr. Ricketts that; but generally the hand is not to be known. The ideal of their inspiration—the immortal 'Hypnerotomachia'—seems equally theirs, equally potent over their individuality. Speaking with diffidence, it would seem as though Mr. Shannon's idea of the idyll were more naïve and humorous. Incidents beside the main theme of the pastoral loves of young Daphnis and Chloe—the household animals, other shepherds—are touched with humorous intent. Mr. Ricketts shows more suavity, and, as in the charming double-page design of the marriage feast, a more lyrical realization of delight and shepherd joys.

The 'Hero and Leander' of 1894 is a less elaborate, and, on the whole, a finer production. I must speak of the illustrations only, lest consideration of Vale Press publications should fill the remaining space at my disposal. Obviously the attenuated type of these figures shows Mr. Ricketts' ideal of the human form as a decoration for a page of type. The severe reticence he imposes on himself is in order to maintain the balance between illustrations and text. One has only to turn to illustrations to Lord de Tabley's 'Poems,' published in 1893, to see with what eager imagination he realizes a subject, how strong a gift he has for dramatic expression. That a more persuasive beauty of form was once his wont, much of his early and transitional work attests. But I do[Pg 22] not think his power to achieve beauty need be defended. After the publication of 'Hero and Leander,' Mr. Shannon practically ceased wood-engraving for the illustration of books, though, as the series of roundel designs in the recent exhibition of his work proved, he has not abandoned nor ceased to go forward in the art.

OF THE APPARITION OF THE THREE NYMPHS TO DAPHNIS

IN A DREAM.

OF THE APPARITION OF THE THREE NYMPHS TO DAPHNIS

IN A DREAM.'The Sphinx,' a poem by Oscar Wilde, 'built, decorated and bound' by Mr. Ricketts—but without woodcuts—was published in 1894, just after 'Hero and Leander,' and designs for a magnificent edition of 'The King's Quhair' were begun.[Pg 24] Some of these are in 'The Dial,' as are also designs for William Adlington's translation of 'Cupide and Psyches' in 'The Pageant,' 'The Dial,' and 'The Magazine of Art.' The edition of the work published by the new Vale Press in 1897, is not that projected at this time. It contains roundel designs in place of the square designs first intended. These roundels are, I think, the finest achievement of Mr. Ricketts as an original wood-engraver. The engraving reproduced shows of what quality are both line and form, how successful is the placing of the figure within the circle. On the page they are what the artist would have them be. With the beginning of the sequence of later Vale Press books—books printed from founts designed by Mr. Ricketts—a consecutive account is impossible, but the frontispiece to the 'Milton' and the borders and initials designed by Mr. Ricketts, must be mentioned. As a designer of book-covers only one failure is set down to Mr. Ricketts, and that was ten years ago, in the cover to 'The House of Pomegranates.'

Mr. Reginald Savage's illustrations to some tales from Wagner lack the force of designs in 'The Pageant,' and of woodcuts in Essex House publications. Of M. Lucien Pissarro, in an article overcrowded with English illustrators, I cannot speak. His fame is in France as the forerunner of his art, and we in England know his coloured wood-engravings, his designs for 'The Book of Ruth and Esther' and for 'The Queen of the Fishes,' printed at his press at Epping, but included among Vale Press books.

'The Centaur,' 'The Bacchant,' 'The Metamorphoses of Pan,' 'Siegfried'—young Siegfried, wood-nurtured, untamed, setting his lusty strength against the strength of the brutes, hearing the bird-call then, and following the white bird to issues remote from savage life—these are subjects realized by the imagination of Mr. T. Sturge Moore. There are few artists illustrating books to-day whose work is more unified, imaginatively and technically. It is some years since first Mr. Moore's wood-engravings attracted notice in 'The Dial' and 'The Pageant,' and the latest work from his graver—finer, more rhythmic in composition though it be—shows no change in ideals, in the direction of his talent. He has said, I think, that the easiest line for the artist is the true basis of that artist's[Pg 26] work, and it would seem as though much deliberation in finding that line for himself had preceded any of the work by which he is known. The wood-engraving of Mr. Sturge Moore is of some importance. Always the true understanding of his material, the unhesitating realization of his subject, combine to produce the effect of inevitable line and form, of an inevitable setting down of forms in expression of the thought within. Only that gives the idea of formality, and Mr. Moore's art handles the strong impulse of the wild creatures of earth, of the solitary creatures, mighty and terrible, haunting the desert places and fearing the order men make for safety. Designs to Wordsworth's 'Poems,' not yet published, represent with innate perception the earth-spirit as Wordsworth knew it, when the great mood of 'impassioned contemplation' came upon his careful spirit, when his heart leapt up, or when, wandering beneath the wind-driven clouds of March, at sight of daffodils, he lost his loneliness.

'The Evergreen,' that 'Northern Seasonal,' represented the pictorial outlook of an interesting group of artists—Robert Burns, Andrew K. Womrath, John Duncan, and James Cadenhead, for example—and the racial element, as well as their own individuality, distinguishes the work of Mr. W. B. Macdougall and Mr. J. J. Guthrie of 'The Elf.' Mr. Macdougall has been known as a book-illustrator since 1896, when 'The Book of Ruth,' with decorated borders showing the fertility of his designing power, and illustrations that were no less representative of a unique use of material, appeared.[Pg 27] The conventionalized landscape backgrounds, the long, straightly-draped women, seemed strange enough as a reading of the Hebrew pastoral, with its close kinship to the natural life of the free children of earth. Their unimpassioned faces, unspontaneous gestures, the artificiality of the whole impression, were undoubtedly a new reading of the ancient charm of the story. Two books in 1897, and 'Isabella' and 'The Shadow of Love,' 1898, showed beyond doubt that the manner was not assumed, that it was the expression of Mr. Macdougall's sense of beauty. The decorations to 'Isabella' are more elaborate than to 'Ruth,' and inventive handling of natural forms is as marked. Again, the faces are de-characterized in accordance with the desire to make the whole figure the symbol of passion, and that without emphasis. Mr. J. J. Guthrie is hardly among book-illustrators, since 'Wedding Bells' of 1895 does not represent Mr. Guthrie, nor does the child's book of the following year, while the illustrations to Edgar Allan Poe's 'Poems' are still, I think, being issued from the Pear Tree Press in single numbers. His treatment of landscape is inventive, his rhythmic arrangements, his effects of white line on black, are based on a real sense of the beauty of earth, of tall trees and wooded hills, of mysterious moon-brightness and shade in the leafy depths of the woodlands.

Mr. Granville Fell made his name known in 1896 by his illustrations to 'The Book of Job.' In careful detail, drawn with fidelity, never obtrusive, his art is pre-Raphaelite. He touches[Pg 28] Japanese ideals in the rendering of flower-growth and animals, but the whole effect of his decorative illustrations is far enough away from the art of Japan. In the 'Book of Job' he had a subject sufficient to dwarf a very vital imaginative sense by its grandeur. In the opinion of competent critics Mr. Granville Fell proved more than the technical distinction of his work by the manner in which he fulfilled his purpose. The solid black and white, the definite line of these drawings, were laid aside for the sympathetic medium of pencil in 'The Song of Solomon' (1897). Again, his conception is invariably dramatic, and never crudely dramatic, robust, with no trace of morbid or sentimental thought about it. The garden, the wealth of vineyard and of royal pleasure ground, is used as a background to comely and gracious figures. His other work, illustrative of children's books and of legend, the cover and title-page to Mr. W. B. Yeats's 'Poems,' shows the same definite yet restrained imagination.

Mr. Patten Wilson is somewhat akin to Mr. Granville Fell in the energy and soundness of his conceptions. Each of these artists is, as we know, a colourist, delighting in brilliant and iridescent colour-schemes, yet in black and white they do not seek to suggest colour. Mr. Patten Wilson's illustrations to Coleridge's 'Poems' have the careful fulness of drawings well thought out, and worked upon with the whole idea realised in the imagination. He has observed life carefully for the purposes of his art. But it is rather in rendering the circumstance of poems, such as 'The Ancient[Pg 29] Mariner,' or, in a Chaucer illustration—Constance on the lonely ship—that he shows his grasp of the subject, than by any expression of the spiritual terror or loneliness of the one living man among the dead, the solitary woman on strange seas.

Few decorative artists habitually use 'wash' rather than line. Among these, however, is Mr. Weguelin, who has illustrated Anacreon in a manner to earn the appreciation of Greek scholars, and his illustrations to Hans Andersen have had a wider and not less appreciative reception. His drawings have movement and atmosphere. Mr. W. E. F. Britten also uses this medium with fluency, as is shown by his successful illustrations to Mr. Swinburne's 'Carols of the Year' in the 'Magazine of Art' in 1892-3. Since that time his version of 'Undine,' and illustrations to Tennyson's 'Early Poems,' have shown the same power of graceful composition and sympathy with his subject.

OPEN-AIR illustration is less influenced by the tradition of Rossetti and of the romanticists of 'the sixties' than any other branch of illustrative art. The reason is obvious. Of all illustrators, the illustrator of open-air books has least concern with the interpretation of literature, and is most concerned with recording facts from observation. It is true that usually he follows where a writer goes, and studies garden, village or city, according to another man's inclination. But the road they take, the cities and wayside places, are as obvious to the one as to the other. The artist has not to realize the personal significance of beauty conceived by another mind; he has to set down in black and white the aspect of indisputable cities and palaces and churches, of the actual highways and gardens of earth. No fugitive light, but the light of common day shows him his subject. So, although Stevenson's words, that reaching romantic art one becomes conscious of the background, are completely true in application to the drawings of Rossetti, of Millais, Sandys and Houghton, these 'backgrounds' have had no[Pg 31] traceable effect on modern open-air illustration. Nor are the landscape drawings in works such as 'Wayside Poesies,' or 'Pictures of English Landscape,' at the beginning of the style or styles—formal or picturesque—most in vogue at present. Birket Foster has no followers; the pensive landscape is not suited to holiday excursion books; and, though Mr. J. W. North is among artists of to-day, as a book-illustrator he has unfortunately added little to his fine record of landscape drawings made between 1864 and 1867. One cannot include his work in a study of contemporary illustration, though it is a pleasure passed over to leave unconsidered drawings that in 'colour,' in effects of winter-weather, of leaf-thrown light and shade amid summer woods and over the green lanes of English country, are delightfully remote from obvious and paragraphic habits of rendering facts.

With few exceptions the open-air illustrators of to-day began their work and took their place in public favour, and in the estimation of critics, after 1890. Mr. Joseph Pennell, it is true, had been making sketches in England, in France, and in Italy for some years; Mr. Railton had made some preliminary illustrations; Mr. Alfred Parsons illustrated 'Old Songs' with Mr. Abbey in 1889; and Mr. Fulleylove contributed to 'The Picturesque Mediterranean,' and published his 'Oxford' drawings, in the same year. Still, with a little elasticity, 'the nineties' covers the past activity of these men. The only important exception is Sir George Reid, President of the Royal Scottish Academy, much of whose illustrative[Pg 32] work belongs to the years prior to 1890. The one subject for regret in connection with Sir George Reid's landscape illustrations is that the chapter is closed. He makes no more drawings with pen-and-ink, and the more one is content with those he has made, the less does the quantity seem sufficient. Those who know only the portraits on which Sir George Reid's reputation is firmly based will find in his landscape illustrations a new side to his art. Here, as in portraiture, he sees distinctly and records without prejudice the characteristics of his subject. He renders what he sees, and he knows how to see. His conception being clear to himself, he avoids vagueness and obscurity, finding, with apparent ease, plain modes of expression. A straight observer of men and of the country-side, there is this directness and perspicuity about his work, whether he paints a portrait, or makes pen-drawings of the village worthies of 'Pyketillim' parish, or draws Pyketillim Kirk, small and white and plain, with the sparse trees beside it, or great river or city of his native land.

But in these pen-stroke landscapes, while the same clear-headed survey, the same logical record of facts, is to be observed as in his work as a portrait painter, there is besides a charm of manner that brings the indefinable element into one's appreciation of excellent work. Of course this is not to estimate these drawings above the portraits of Sir George Reid. That would be absurd. But he draws a country known to him all his life, and unconsciously, from intimate memory, he suggests more than actual observation would discover.[Pg 33] This identification of past knowledge with the special scrutiny of a subject to be rendered is not usually possible in portraiture. The 'portrait in-time' is a question of occasion as well as of genius.

The first book in which his inimitable pen-drawing of landscape can be properly studied is the illustrated edition of 'Johnny Gibb of Gushetneuk, in the Parish of Pyketillim,' published in 1880. Here the illustrations are facsimile reproductions by Amand-Durand's heliogravure process, and their delicacy is perfectly seen. These drawings are of the Aberdeenshire country-folk and country, the native land of the artist; though, as a lad in Aberdeen, practising lithography by day, and seizing opportunities for independent art when work was over, the affairs and doings of Gushetneuk, of Smiddyward, of Pyketillim, or the quiet of Benachie when the snow lies untrodden on its slopes, were things outside the city of work.

It is as difficult to praise these drawings intelligibly to those who have not seen them, as it is unnecessary to enforce their charm on those who have. Unfortunately, a reproduction of one of them is not possible, and admirable as is the drawing from 'Royal Edinburgh,' it is in subject and in treatment distinct from the 'Gushetneuk' and 'North of Scotland' illustrations. The 'Twelve Sketches of Scenery and Antiquities on the Great North of Scotland Railway,' issued in 1883, were made in 1881, and have the same characteristics as the 'Gushetneuk' landscapes. The original drawings for the engraved illustrations in 'The Life of a Scotch Naturalist,' belonging to 1876—drawings[Pg 34] made because the artist was 'greatly interested' in the story of Thomas Edward—must have been of the same delicate force, and the splendid volumes of plates illustrating the 'River Clyde,' and the 'River Tweed,' issued by the Royal Association for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Scotland, contain more of his fine work. It was this society, that, in the difficult days following the artist's abandonment of Aberdeen and lithography for Edinburgh and painting, gave him the opportunity, by the purchase of two of his early landscapes, for study in Holland and in Paris. There is something of Bosboom in a rendering of a church interior such as 'The West Kirk,' but of Israels, who was his master at the Hague, there is nothing to be seen in Sir George Reid's illustrations. They are never merely picturesque, and when too many men are 'freakish' in their rendering of architecture, the drawings of North of Scotland castles—well founded to endure weather and rough times of war—seem as real and true to Scottish romance as the "pleasant seat," the martlet-haunted masonry of Macbeth's castle set among the brooding wildness of Inverness by the fine words of Duncan and Banquo.

The print-black of naked boughs against pale sky, a snow-covered country where roofs are white, and the shelter of the woods is thin after the passing of the autumn winds—this black and white is the black and white of most of Sir George Reid's studies of northern landscape. To call it black and white is to stretch the octave and omit all the notes of the scale. Pure white of plastered masonry, or of snow-covered roof or field in the bleak winter[Pg 35] light, pure black in some deep-set window, in the figure of a passer-by, or in the bare trees, are used with the finesse of a colourist. Look at the 'Pyketillim Kirk' drawing in 'Johnny Gibb.' Between the white of the long church wall, and the black of the little groups of village folk in the churchyard, how quiet and easy is the transition, and how true to colour is the result. Of the Edinburgh drawings the same may be said; but, except in facsimile reproduction, one has to know the scale of tone used by Sir George Reid in order to see the original effect where the printed page shows unmodified black and white. In 'Holyrood Castle' the values are fairly well kept, and the rendering of the ancient building in the deep snow, without false emphasis, yet losing nothing of emphatic effect, shows the dominant intellectual quality of the artist's work.

HOLYROOD CASTLE. BY SIR GEORGE REID. FROM MRS. OLIPHANT'S "ROYAL EDINBURGH."

HOLYROOD CASTLE. BY SIR GEORGE REID. FROM MRS. OLIPHANT'S "ROYAL EDINBURGH."It does not seem as though Sir George Reid as an illustrator had any followers. He could hardly have imitators. If a man had delicacy and patience of observation and hand to produce drawings in this 'style,' his style would be his own and not an imitation. The number of artists in black and white who cannot plausibly be imitated is a small number. Sir George Reid is one, Mr. Alfred Parsons is another. Inevitably there are points of similarity in the work of artists, the foundation of whose black and white is colour, and who render the country-side with the understanding of the native, the understanding that is beyond knowledge. The difference between them only proves the essential similarity in the elements of their art;[Pg 36] but that, like most paradoxes, is a truism. Mr. Parsons is, of course, thoroughly English in his art. He has the particularity of English nature-poets. Pastoral country is dear to him, and homesteads and flowering orchards, or villages with church tower half hidden by the elms, are part of his home country, the country he draws best. It is interesting to compare his drawings for 'The Warwickshire Avon' with the Scottish artist's drawings of the northern rivers. The drawings of Shakespeare's river show spring trees in a mist of green, leafy summer trees, meadowsweet and hayfields, green earth and blue sky, and a river of pleasure watering a pleasant country. If a man can draw English summer-time in colour with black and white, he must rank high as a landscape pen-draughtsman. Mr. Alfred Parsons has illustrated about a dozen books, and his work is to be found in 'Harper's Magazine,' and 'The English Illustrated' in early days. Two books, the 'Old Songs' and 'The Quiet Life,' published in 1887 and 1890, were illustrated by E. A. Abbey and Alfred Parsons. The drawings of landscape, of fruit and flowers, by Mr. Parsons, the Chippendale people and rooms of Mr. Abbey, fill two charming volumes with pictures whose pleasantness and happy art accord with the dainty verses of eighteenth-century sentiment. 'The Warwickshire Avon,' and another river book, 'The Danube from the Black Forest to the Sea,' illustrated in collaboration with the author, Mr. F. D. Millet, belong to 1892. The slight sketches—passing-by sketches—in these books, are among fortunate examples of a[Pg 38] briefness that few men find compatible with grace and significance. Sketches, mostly in wash, of a farther and more decorated country—'Japan, the Far East, the Land of Flowers and of the Rising Sun, the country which for years it had been my dream to see and paint'—illustrate the artist's 'Notes in Japan,' 1895. In the written notes are memoranda of actual colour, of the green harmony of the Japanese summer—harmony culminating in the vivid tint of the rice fields—of sunset and butterflies, of delicate masses of azalea and drifts of cherry-blossom and wisteria, while in the drawings are all the flowers, the green hills and gray hamlets, and the temples, shrines and bridges, that make unspoilt Japan one of the perpetual motives of decorative art. Illustrations to Wordsworth—to a selected Wordsworth—gave the artist fortunate opportunities to render the England of English descriptive verse.

ELMS BY BIDFORD GRANGE. BY ALFRED PARSONS.

REPRODUCED FROM QUILLER COUCH'S 'THE WARWICKSHIRE

AVON.'

ELMS BY BIDFORD GRANGE. BY ALFRED PARSONS.

REPRODUCED FROM QUILLER COUCH'S 'THE WARWICKSHIRE

AVON.'It is convenient to speak first of these painter-illustrators, because, in a sense, they stand alone among illustrative artists. Obviously, that is not to say that their work is worth more than the work of illustrators, who, conforming to the laws of 'process,' make their drawings with brain and hand that know how to win profit by concession. But popularisers of an effective topographical or architectural style are indirectly responsible for a large amount of work besides their own. In one sense a leader does not stand alone, and cannot be considered alone. Before, then, passing on to a draughtsman such as Mr. Joseph Pennell, again, to Mr. Railton, or to Mr. New, whose successful and[Pg 39] unforgettable works have inspired many drawings in the books whereby authors pay for their holiday journeys, other artists, whose style is no convenience to the industrious imitator, may be considered. Another painter, known for his work in black and white, is Mr. John Fulleylove, whose 'Pictures of Classic Greek Landscape,' and drawings of 'Oxford,' show him to be one of the few men who see architecture steadily and whole, and who draw beautiful buildings as part of the earth which they help to beautify. Compare the Greek drawings with ordinary archæological renderings of pillared temples, and the difference in beauty and interest is apparent. In Mr. Fulleylove's drawings, the relation between landscape and architecture is never forgotten, and he draws both with the structural knowledge of a landscape painter, who is also by training an architect. In aim, his work is in accord with classical traditions; he discerns the classical spirit that built temples and carved statues in the beautiful places of the open-air, a spirit which has nothing of the museum setting about it. The 'Oxford' drawings show that Mr. Fulleylove can draw Gothic.

Though not a painter, Mr. William Hyde works 'to colour' in his illustrations, and is generally successful in rendering both colour and atmosphere. He has done little with the pen, and it is in wash drawings, reproduced by photogravure, that he is best to be studied. Of his early training as an engraver there is little to be seen in his work, though his appreciation of the range of tone existing between black and white may have developed from working within restrictions of monotone, when the colour[Pg 40] sense was growing strong in him. At all events he can gradate from black to white with remarkable minuteness and ease. His earliest work of any importance after giving up engraving, was in illustration of 'L'Allegro' and 'Il Penseroso,' 1895, and shows his talent already well controlled. There are thirteen illustrations, and the opportunities for rendering aspects of light, from the moment of the lark's morning flight against the dappled skies of dawn, to the passing of whispering night-winds over the darkened country, given in the verse of a poet sensitive as none before him to the gradations of lightness and dark, are realized. So are the hawthorns in the dale, and the towered cities. But it is as an illustrator of another towered city than that imagined by Milton, that some of Mr. Hyde's most individual work has been produced. In the etchings and pictures in photogravure published with Mrs. Meynell's 'London Impressions,' London beneath the strange great sky that smoke and weather make over the gray roofs, London when the dawn is low in the sky, or when the glow of lamps and lamp-lit windows turns the street darkness to golden haze, is drawn by a man who has seen for himself how beautiful the great city is in 'between lights.' His other work is superficially in contrast with these studies of city light and darkness; but the same love for 'big' skies, for the larger aspects of changing lights and cloud movements, are expressed in the drawings of the wide country that is around and beyond the Cinque Ports, and in the illustrations to Mr. George Meredith's 'Nature Poems.' The reproduction is[Pg 41] from a pen drawing in Mr. Hueffer's book, 'The Cinque Ports.' There is no pettiness about it, and the 'phrasing' of castle, trees and sky shows the artist.

SALTWOOD CASTLE.

BY WILLIAM HYDE.

SALTWOOD CASTLE.

BY WILLIAM HYDE.Mr. D. Y. Cameron has illustrated a book or two with etchings—notably White's 'Selborne' 1902,—but to consider him as a book-illustrator would be to stretch a point. A few of his etchings are to be seen in books, and one would like to make them the text for the consideration of other etchings by him, but it would be a digression. He is not among painter-illustrators, but among painters who have illustrated, and that would bring more names into this chapter than it could hold except in catalogue arrangement.

Coming to artists who are illustrators, not on occasion but always, there is no question with whom to begin. It is true that Mr. Pennell is American, but he is such an important figure in English illustration that to leave him out would be impossible. He has been illustrating Europe for more than fifteen years, and the forcible fashion of his work, and all that he represents, have influenced black-and-white artists in this country, as his master Rico influenced him. In range and facility, and in getting to the point and keeping there, there is no open-air illustrator to put beside Mr. Pennell. Always interested and always interesting, he is apparently never bewildered, always ready and able to draw. Surely there was never a mind with a greater faculty for quick study; and he can apply this power to the realization of an architectural detail, or of a cathedral, of miles of country with[Pg 43] river curves and castles, trees, and hills and fields, and a stretch of sky over all; or of a great city-street crowded with traffic, of new or old buildings, of Tuscany or of the Stock Exchange, with equal ease. To attempt a record of Mr. Pennell's work would leave no room for appreciation of it. As far as the English public is concerned, it began in 1885 with the publication of 'A Canterbury Pilgrimage,' and since then each year has added to Mr. Pennell's notes of the world at the rate of two or three volumes. The highways and byways of England—east, west, south and north—France from Normandy to Provence, the cities and spaces of Italy, the Saone and the Thames, the 'real' Alps and the New Zealand Alps, London and Paris, the Cathedrals of Europe, the gipsy encampment and the Ghetto, Chelsea and the Alhambra—Mr. Pennell has been everywhere and seen most things as he went, and one can see it in his drawings.

He draws architecture without missing anything tangible, and his buildings belong to cities that have life—and an individual life—in their streets. But where he is unapproachable, or at all events unapproached among pen-draughtsmen, is in drawing a great scheme of country from a height. If one could reproduce a drawing such as that of the country of Le Puy in Mr. Wickham Flower's 'Aquitaine,' or, better still, the etching of the same amazing country, one need say no more about Mr. Pennell's art in this kind. Unluckily the page is too small. This strange and lovely landscape, where curving road and river and tree-bordered[Pg 44] fields are dominated by two image-crowned rocks, built about with close-set houses, looks like a design from a dream fantasy worked out by a master of definite imagination. One knows it is not. Mr. Pennell is concerned to give facts in picturesque order, and here he has a theme that affects us poetically, however it may have affected Mr. Pennell. His eye measures a landscape that seems outside the measure of observation, and his ability to grasp and render the characteristics of actuality serves him as ever. It is an unforgettable drawing, though the skill displayed in the simplification and relation of facts is no greater than in other drawings by the artist. That power hardly ever fails him. The 'Devils of Notre Dame' again stands out in memory, when one thinks generally of Mr. Pennell's drawings. And again, though it seems as if he were working above his usual pitch of conception, it is only that he is using his keenness of sight, his logical grasp of form and power of expression, on matter that is expressive of mental passion. The man who carved the devils, like those who crowned the rocks of Le Puy with the haloed figures, created facts. The outrageous passion that made these evil things made them in stone. You can measure them. They are matter-of-fact. Mr. Pennell has drawn them as they are, with so much trenchancy, such assertion of their hideous decorativeness, their isolation over modern Paris, that no drawings could be better, and any others would be superfluous. It is impossible to enumerate all that Mr. Pennell has done and can do in black-and-white. He is a master of so many methods. From the sheer black[Pg 45] ink and white paper of the 'Devils,' to the light broken line that suggests Moorish fantastic architecture under a hot sun in the 'Alhambra' drawings, there is nothing he cannot do with a pen. Nor is it only with a pen that he can do what he likes and what we must admire. He covers the whole field of black-and-white drawing.

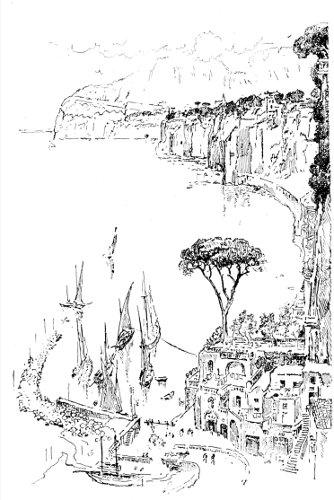

THE HARBOUR, SORRENTO. BY JOSEPH PENNELL.

FROM HOWELL'S "ITALIAN JOURNEYS."

THE HARBOUR, SORRENTO. BY JOSEPH PENNELL.