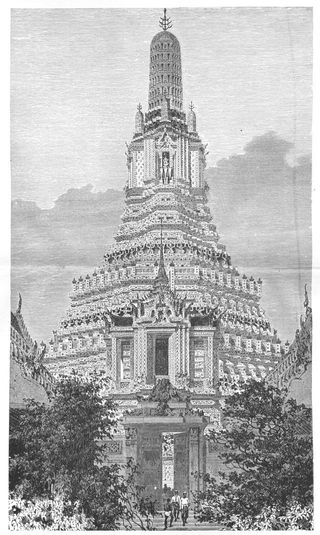

GREAT PAGODA WAT CHANG.

GREAT PAGODA WAT CHANG.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Siam, by George B. Bacon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Siam

The Land of the White Elephant as it Was and Is

Author: George B. Bacon

Editor: Frederick Wells Williams

Release Date: November 27, 2011 [EBook #38078]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIAM ***

Produced by Hunter Monroe, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY

REVISED BY

Copyright, 1881, 1892, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

TROW DIRECTORY

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY

NEW YORK

The present editor's aim in revising this little volume has been to leave untouched, so far as possible, Mr. Bacon's compilation, omitting only such portions as were inaccurate or obsolete, and adding rather sparingly from the narratives of a few recent travellers. The authoritative history and description of Siam has yet to be written, and until this work appears the accounts of Pallegoix, of Bowring, and of Mouhot convey as satisfactory and accurate impressions of the country as those of later writers. Though the wonderful ruins at Angkor are now technically within the confines of Siam, their consideration still belongs to a treatise on Cambodia, and this as a separate country could not fairly be joined to Siam in carrying out the plan of the series. In other respects, without attempting to be exhaustive, the reviser's endeavor has been to neglect no important part or feature of the kingdom.

The regeneration effected in Siam during the past half century presents a suggestive contrast to that ebullition of new life which has within an even briefer period transformed despotic Japan into a free and ambitious state. Here, as there, the stranger is impressed with those outward symbols of nineteenth-century life, the agencies of steam, gas, and electricity that appear in many busy centres in whimsical incongruity to their Oriental setting; but these are the adjuncts rather than the essentials of that Western civilization which both countries are striving to imitate. In Siam, it must be confessed, there is no such evidence of popular awakening as now directs the world's attention to the Mikado's empire. The languor and content of life in the tropics disposes the people to seek new ideals and accept new institutions less eagerly than under Northern skies. Siam's policy of gradual progress toward a condition of higher enlightenment is in admirable accordance with her needs, and promises to achieve its purpose with no such risks of reaction or shipwreck as beset the course of more ambitious states in the East.

F. W. W.

CONTENTS | |

| Page | |

CHAPTER I. | |

| Early Intercourse with Siam—Relations with Other Countries | 1 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| Geography of Siam | 10 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| Old Siam—Its History | 17 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Stories of Two Adventurers | 36 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| Modern Siam | 65 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| First Impressions | 73 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| A Royal Gentleman | 86 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Phrabat Somdetch Phra Paramendr Maha Mongkut | 104 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| Ayuthia | 121 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| Phrabat and Patawi | 130 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| From Bangkok to Chantaboun—A Missionary Journey

in 1835 | 146 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| Chantaboun and the Gulf | 170 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Mouhot in the Hill-country of Chantaboun | 183 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Pechaburi or P'ripp'ree | 200 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Tribes of Northern Siam | 216 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Siamese Life and Customs | 234 |

CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Natural Productions of Siam | 258 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Christian Missions in Siam—The Outlook for The

Future | 270 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Bangkok and the New Siam | 277 |

The acquaintance of the Christian world with the kingdom and people of Siam dates from the beginning of the sixteenth century, and is due to the adventurous and enterprising spirit of the Portuguese. It is difficult for us, in these days when Portugal occupies a position so inconsiderable, and plays a part so insignificant, among the peoples of the earth, to realize what great achievements were wrought in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by the peaceful victories of the early navigators and discoverers from that country, or by the military conquests which not seldom followed in the track of their explorations. It was while Alphonso d'Albuquerque was occupied with a military expedition in Malacca, that he seized the occasion to open diplomatic intercourse with Siam. A lieutenant under his command, who was fitted for the service by an experience of captivity during which he had acquired the Malay language, was selected for the mission. He was well received by the king, and came back to his general, bringing royal presents and proposals to assist in the siege of Malacca. So cordial a response to the overtures of the Portuguese led to the more formal establishment of diplomatic and commercial intercourse. And before the middle of the sixteenth century a considerable number of Portuguese had settled, some of them in the neighborhood of the capital (Ayuthia), and some of them in the provinces of the peninsula of Malacca, at that time belonging to the kingdom of Siam. One or two adventurers, such as De Seixas and De Mello, rose to positions of great power and dignity under the Siamese king. And for almost a century the Portuguese maintained, if not an exclusive, certainly a pre-eminent, right to the commercial and diplomatic intercourse which they had inaugurated.

As in other parts of the East Indies, however, the Dutch presently began to dispute the supremacy of their rivals, and, partly by the injudicious and presumptuous arrogance of the Portuguese themselves, succeeded in supplanting them. The cool and mercenary cunning of the greedy Hollanders was more than a match for the proud temper of the hot-blooded Dons. And as, in the case of Japan, the story of Simabara lives in history to witness what shameless and unscrupulous wickedness commercial rivalry could lead to; so in Siam there is for fifty years a story of intrigue and greed, over-reaching itself first on one side, and then on the other. First, the Portuguese were crowded out of their exclusive privileges. And then in turn the Dutch were obliged to surrender theirs. To-day there are still visible in the jungle, near the mouth of the Meinam River, the ruins of the Amsterdam which grew up between the years 1672 and 1725, under the enterprise of the Dutch East India Company, protected and fostered by the Siamese Government. And to-day, also, the descendants of the Portuguese, easy to be recognized, notwithstanding the mixture of blood for many generations, hold insignificant or menial offices about the capital and court.

As a result of Portuguese intercourse with Siam, there came the introduction of the Christian religion by Jesuit missionaries, who, as in China and Japan, were quick to follow in the steps of the first explorers. No hindrance was put in the way of the unmolested exercise of religious rites by the foreign settlers. Two churches were built; and the ecclesiastics in charge of the church at Ayuthia had begun to acquire some of that political influence which is so irresistible a temptation to the Roman Catholic missionary, and so dangerous a possession when he has once acquired it. It is probable enough (although the evidence does not distinctly appear) that this tendency of religious zeal toward political intrigue inflamed the animosity of the Dutch traders, and afforded them a convenient occasion for undermining the supremacy of their rivals. However this may be, the Christian religion did not make any great headway among the Siamese people. And while they conceded to the foreigners religious liberty, they showed no eagerness to receive from them the gift of a new religion.

In the year 1604 the Siamese king sent an ambas[Pg 4]sador to the Dutch colony at Bantam, in the island of Java. And in 1608 the same ambassador extended his journey to Holland, expressing "much surprise at finding that the Dutch actually possessed a country of their own, and were not a nation of pirates, as the Portuguese had always insinuated." The history of this period of the intercourse between Siam and the European nations, abundantly proves that shrewdness, enterprise, and diplomatic skill were not on one side only.

Between Siam and France there was no considerable intercourse until the reign of Louis XIV., when an embassy of a curiously characteristic sort was sent out by the French monarch. The embassy was ostentatiously splendid, and made great profession of a religious purpose no less important than the conversion of the Siamese king to Christianity. The origin of the mission was strangely interesting, and the record of it, even after the lapse of nearly two hundred years, is so lively and instructive that it deserves to be reproduced, in part, in another chapter of this volume. The enterprise was a failure. The king refused to be converted, and was able to give some dignified and substantial reasons for distrusting the religious interest which his "esteemed friend, the king of France," had taken "in an affair which seems to belong to God, and which the Divine Being appears to have left entirely to our discretion." Commercially and diplomatically, also, as well as religiously, the embassy was a failure. The Siamese prime minister (a Greek by birth, a Roman Catholic by religion), at whose instigation the French king[Pg 5] had acted, soon after was deposed from his office, and came to his death by violence. The Jesuit priests were put under restraint and detained as hostages, and the military force which accompanied the mission met with an inglorious fate. A scheme which seemed at first to promise the establishment of a great dominion tributary to the throne of France, perished in its very conception.

The Government of Spain had early relations with Siam, through the Spanish colony in the Philippine Islands; and on one or more occasions there was an interchange of courtesies and good offices between Manilla and Ayuthia. But the Spanish never had a foothold in the kingdom, and the occasional and unimportant intercourse referred to ceased almost wholly until, during the last fifty years, and even the last twenty, a new era of commercial activity has brought the nations of Europe and America into close and familiar relations with the Land of the White Elephant.

The relations of the kingdom of Siam with its immediate neighbors have been full of the vicissitudes of peace and war. There still remains some trace of a remote period of partial vassalage to the Chinese Empire, in the custom of sending gifts—which were originally understood, by the recipients at least, if not by the givers, to be tribute to Peking. With Burmah and Pegu on the one side, and with Cambodia and Cochin China on the other, there has existed from time immemorial a state of jealous hostility. The boundaries of Siam, eastward and westward, have fluctuated with the successes or defeats of the Siam[Pg 6]ese arms. Southward the deep gulf shuts off the country from any neighbors, whether good or bad, and for more than three centuries this has been the highway of a commerce of unequal importance, sometimes very active and remunerative, but never wholly interrupted even in the period of the most complete reactionary seclusion of the kingdom.

The new era in Siam may be properly dated from the year 1854, when the existing treaties between Siam on the one part, and Great Britain and the United States on the other part, were successfully negotiated. But before this time, various influences had been quietly at work to produce a change of such singular interest and importance. The change is indeed a part of that great movement by which the whole Oriental world has been re-discovered in our day; by which China has been started on a new course of development and progress; by which Japan and Corea have been made to lay aside their policy of hostile seclusion. It is hard to fix the precise date of a movement which is the result of tendencies so various and so numerous, and which is evidently, as yet, only at the beginning of its history. But the treaty negotiated by Sir John Bowring, as the ambassador of Great Britain, and that negotiated by the Honorable Townsend Harris, as the ambassador of the United States, served to call public attention in those two countries to a land which was previously almost unheard of except by geographical students. There was no popular narrative of travel and exploration. Indeed, there had been no travel and exploration much beyond the walls of Bangkok or the ruins of[Pg 7] Ayuthia. The German, Mandelslohe, is the earliest traveller who has left a record of what he saw and heard. His visit to Ayuthia, to which he gave the name which subsequent travellers have agreed in bestowing on Bangkok, the present capital—"The Venice of the East"—was made in 1537. The Portuguese, Mendez Pinto, whose visit was made in the course of the same century, has also left a record of his travels, which is evidently faithful and trustworthy. We have also the records of various embassies, and the narratives of missionaries (both the Roman Catholic and, during the present century, the American Protestant missionaries), who have found time, amid their arduous and discouraging labors, to furnish to the Christian world much valuable information concerning the people among whom they have chosen to dwell.

Of these missionary records, by far the most complete and the most valuable is the work of Bishop Pallegoix (published in French in the year 1854), entitled "Description du Royaume Thai ou Siam." The long residence of the excellent Bishop in the country of which he wrote, and in which, not many years afterward (in 1862) he died, sincerely lamented and honored, fitted him to speak with intelligent authority; and his book was of especial value at the time when it was published, because the Western Powers were engaged that very year in the successful attempt to renew and to enlarge their treaties with Siam. To Bishop Pallegoix the English envoy, Sir John Bowring, is largely indebted, as he does not fail to confess, for a knowledge of the[Pg 8] history, manners, and customs of the realm, which helped to make the work of his embassy more easy, and also for much of the material which gives the work of Bowring himself ("The Kingdom and People of Siam," London, 1857) its value.

Since Sir John Bowring's time the interior of Siam has been largely explored, and especially by one adventurous traveller, Henry Mouhot, who lost his life in the jungles of Laos while engaged in his work of exploration. With him begins our real knowledge of the interior of Siam, and its partly dependent neighbors Laos and Cambodia. The scientific results of his travel are unfortunately not presented in such orderly completeness as would have been given to them had Mouhot lived to arrange and to supplement the details of his fragmentary and outlined journal. But notwithstanding these necessary defects, Mouhot's book deserves a high place, as giving the most adventurous exploration of a country which appears more interesting the more and better it is known. The great ruins of Angkor (or Angeor) Wat, for example, near the boundary which separates Siam from Cambodia, were by him for the first time examined, measured, and reported with some approach to scientific exactness.

Among more recent and easily accessible works on the country, from some of which we have borrowed, may be mentioned, F. Vincent's, "Land of the White Elephant," 1874, A. Gréhan's, "Royaume de Siam," fourth edition, Paris, 1878, "Siam and Laos, as seen by our American Missionaries," Philadelphia, 1884, Carl Bock's "Temples and Elephants," London, 1884,[Pg 9] A. R. Colquhoun's, "Among the Shans," 1885, L. de Carné's, "Travels in Indo-China, etc.," 1872, Miss M. L. Cort's, "Siam, or the Heart of Farther India," 1886, and John Anderson's, "English Intercourse with Siam," 1890. The most authoritative map of Siam is that published in the "Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society," London, 1888, by Mr. J. McCarthy, Superintendent of Surveys in Siam.

The following description of the country is quoted with some emendations from Mr. Carl Bock's "Temples and Elephants."

The European name for this land has been derived from the Malay word Sayam (or sajam) meaning "brown," but this is a conjecture. The natives call themselves Thai, i.e., "free," and their country Muang Thai, "the kingdom of the free."

Including its dependencies, the Lao states in the north, and the Malay states in the south, Siam extends from latitude 20° 20' N. to exactly 4° S., while, with its Cambodian provinces, its extreme breadth is from longitude 97° E. to about 108° E. The northern frontier of the Lao dependencies has not been defined, but it may be said, roughly, to lie north of the twentieth parallel, beyond the great bend of the Mekong River, the high range to the east of which separates Siam from Annam. To the south lie Cambodia and the Gulf of Siam, stretching a long arm down into the Malay Peninsula. On the west it abuts on Upper and Lower Burma, both now British possessions.

Through Siam and Lao run two great mountain chains, both radiating from Yunnan through the[Pg 11] Shan states. The eastern chain stretches in a S.S.E. direction from Kiang Tsen right down to Cambodia, while the western chain extends in a southerly direction through the Malay Peninsula. Their height rises sometimes to 9,000 feet, but it does not often seem to exceed 5,000; limestone, gneiss, and granite appear to form the main composition of the rocks.

Between these two mountain-chains, with their ramifications, lies the great alluvial plain of the Meinam, a magnificent river, of which the Portuguese poet Camoens sings (Lusiad X. cxxv.):

in which statement, however, the bard was misinformed, the source being a mountain stream on the border of the Shan states, but within Lao territory, and not, as is generally marked on charts, in Yunnan. Near Rahang the main stream is joined by the Mei Wang, flowing S.W. from Lakon, the larger river being called above this junction the Mei Ping. The other great tributary, the Pak-nam-po, also called the Meinam Yome, joins it in latitude 15° 45', after flowing also in a S.W. direction.

To the annual inundation of the Meinam and its tributaries the fertility of the soil is due. Even as far up as in the Lao states the water rises from eight to ten feet during the rainy season. A failure of these inundations would be fatal to the rice crop, so that Siam is almost as much as Egypt a single river valley, upon whose alluvial deposits the welfare of millions depends. In this broad valley are to be[Pg 12] found the forty-one political divisions which make up Siam proper.

The second great river of importance is the Bang-Pa Kong, which has its source in a barrier range of irregular mountains, separating the elevated plateau of Korat from the alluvial plains extending to the head of the Gulf of Siam. The river meanders through the extensive paddy-lands and richly cultivated districts of the northeast provinces, and falls into the sea twenty miles east of the Meinam. Another considerable river is the Meklong, which falls into the sea about the same distance to the west of Bangkok; at its mouth is a large and thriving village of the same name. This is the great rice district, and from Meklong all up the river to Kanburi a large number of the population are Chinese. In this valley are salt-pits, on which the whole kingdom depends for its supply. The Meklong is connected with the Meinam by means of a canal, which affords a short cut to Bangkok, avoiding the sea passage.

A third river system, that of the Mekong, much the largest of all the rivers in Indo-China, drains the extreme north and east of Siam. This huge stream, which is also mentioned in Camoens' Lusiad, takes its rise near the sources of the Yangtse Kiang in Eastern Thibet, and belongs in nearly half its course to China. It was partly explored by M. Mouhot, and later (in 1868) by Lagrée's expedition, who found it, in spite of the great body of water, impracticable for navigation. M. de Carné, one of the exploration party, thus sums up the results of the search for a new trade route into Southern China: "The difficulties[Pg 13] the river offers begin at first, starting from the Cambodian frontier, and they are very serious, if not insurmountable. If it were attempted to use steam on this part of the Mekong the return would be most dangerous. At Khong an absolutely impassable barrier, as things are, stands in the way. Between Khong and Bassac the waters are unbroken and deep, but the channel is again obstructed a short distance from the latter. From the mouth of the river Ubone the Mekong is nothing more than an impetuous torrent, whose waters rush along a channel more than a hundred yards deep by hardly sixty across. Steamers can never plough the Mekong as they do the Amazon or the Mississippi, and Saigon can never be united to the western provinces of China by this immense waterway, whose waters make it mighty indeed, but which seems after all to be a work unfinished."

Of the tributary states, the Laos, who occupy the Mekong valley and spread themselves among the wilds between Tongking, China, and Siam, are probably the least known. In physique and speech they are akin to the Siamese, and are regarded by some writers as being the primitive stock of that race. They have some claims as a people of historical importance, constituting an ancient and powerful kingdom whose capital Vein-shan, was destroyed by Siam in 1828. Since then they have remained subject to Siam, being governed partly by native hereditary princes, duly invested with gold dish, betel-box, spittoon, and teapot sent from Bangkok, and partly by officers appointed by the Siamese government.[Pg 14] Their besetting sin is slave-hunting, which was until recently pursued with the acquiescence of the Siam authorities, to the terror of the hill-tribes within their reach and to their own demoralization. Apart from the passions associated with this infamous trade the Laos are for the most part an inoffensive, unwarlike race, fond of music, and living chiefly on a diet of rice, vegetables, fruits, fish, and poultry. Pure and mixed, they number altogether perhaps some one million five hundred thousand.

The most important of the Malay states is Quedha, in Siamese Muang Sai. Its population of half a million Malays is increased by some twenty thousand Chinese and perhaps five thousand of other races. The country is level land covered with fine forests, where elephants, tigers, and rhinoceroses abound. A high range of mountains separates Quedha from the provinces of Patani (noted for its production of rice and tin) and Songkhla. These again are divided from the province of Kalantan by the Banara River, and from Tringann by the Batut River. In Ligor province, called in Siamese Lakhon, three-fourths of the population are Siamese. The gold and silver-smiths of Ligor have a considerable reputation for their vessels of the precious metals inlaid with a black enamel.

As to the Cambodian provinces under Siamese rule the following particulars are extracted from a paper by M. Victor Berthier:

The most important provinces are those lying to the west, Battambang and Korat. The former of these is situated on the west of the Grand Lake (Tonle[Pg 15] Sap), and supports a population of about seventy thousand, producing salt, fish, rice, wax, and cardamoms, besides animals found in the forests. Two days' march from Battambang is the village of Angkor Borey (the royal town), the great centre of the beeswax industry, of which 24,000 pounds are sent yearly to Siam. Thirty miles from this place is situated the auriferous country of Tu'k Cho, where two Chinese companies have bought the monopoly of the mines. The metal is obtained by washing the sand extracted from wells about twenty feet deep, at which depth auriferous quartz is usually met, but working as they do the miners have no means of getting ore from the hard stone.

Korat is the largest province and is peopled almost entirely by Cambodians. Besides its chief town of the same name it contains a great number of villages with more than eleven district centres, and contains a population estimated at fifty thousand or sixty thousand. Angkor, the most noted of the Cambodian provinces, is now of little importance, being thinly populated and chiefly renowned for the splendor of its ancient capital, whose remarkable ruins are the silent witnesses of a glorious past. The present capital is Siem Rap, a few miles south of which is the hill called Phnom Krom (Inferior Mount), which becomes an island during the annual inundation. The other Cambodian provinces now ruled by Siam are almost totally unknown by Europeans.

The population of Siam has never been officially counted, but is approximately estimated by Europeans at from six to twelve millions. According to Mr.[Pg 16] Archibald Colquhoun, however, this is based upon an entirely erroneous calculation. "Prince Prisdang assured me," he says,[A] "that Sir John Bowring had made a great mistake in taking the list of those who were liable to be called out for military service as the gross population of the kingdom; and that if that list were multiplied by five, it would give a nearer approximation to the population. M. Mouhot says that a few years before 1862 the native registers showed for the male sex (those who were inscribed), 2,000,000 Siamese, 1,000,000 Laotians (or Shans), 1,000,000 Malays, 1,500,000 Chinese, 350,000 Cambodians, 50,000 Peguans, and a like number composed of various tribes inhabiting the mountain-ranges. Taking these statistics and multiplying them by five, which Bishop Pallegoix allows is a fair way of computing from them, we should have a population of 29,950,000. To this would have to be added the Chinese and Peguans who had not been born in the country, and were therefore not among the inscribed; also the hill tribes that were merely tributary and therefore merely paid by the village, as well as about one-seventh of the above total for the ruling classes, their families and slaves. This total would give at least 35,000,000 inhabitants for Siam Proper, to which would have to be added about 3,000,000 for its dependencies, Zimmé (Cheung Mai), Luang Prabang, and Kiang Tsen,—a gross population, therefore, of about 38,000,000 for the year 1860." On the other hand, Mr. McCarthy, a competent judge, considers the government estimate of ten million too high.

The date at which any coherent and trustworthy history of Siam must commence is the founding of the sacred city of Ayuthia (the former capital of the kingdom), in the year 1350 of the Christian era. Tradition, more or less obscure and fabulous, does indeed reach back into the remote past so far as the fifth century, B.C. According to the carefully arranged chronology of Bishop Pallegoix, gathered from the Siamese annals, which annals, however, are declared by His Majesty the late King to be "all full of fable, and are not in satisfaction for believe," the origin of the nation can be traced back, if not into indefinite space of time, at least into the vague and uncertain "woods," and ran on this wise:

"There were two Brahminical recluses dwelling in the woods, named Sătxănalăi and Sîtthĭongkŏn, coeval with Plua Khôdŏm (the Buddha), and one hundred and fifty years of age, who having called their numerous posterity together, counselled them to build a city having seven walls, and then departed to the woods to pass their lives as hermits.

"But their posterity, under the leadership of Bathămăràt, erected the city Săvănthe vălôk, or[Pg 18] Sangkhălôk, about the year 300 of the era of Phra Khôdŏm (B.C. about 243).

"Bathămăràt founded three other cities, over which he placed his three sons. The first he appointed ruler in the city of Hărĭpunxăi, the second in Kamphôxă năkhon, the third in Phětxăbun. These four sovereignties enjoyed, for five hundred years or more, the uttermost peace and harmony under the rule of the monarchs of this dynasty."

The places named in this chronicle are all in the valley of the upper Meinam, in the "north country," and the fact of most historical value which the chronicle indicates is that the Siamese came from the north and from the west, bringing with them the government and the religion which they still possess. The most conspicuous personage in these ancient annals is one Phra Ruàng, "whose advent and glorious reign had been announced by a communication from Gaudama himself, and who possessed, in consequence of his merits, a white elephant with black tusks;" he introduced the Thai alphabet, ordained a new era which is still in vogue, married the daughter of the emperor of China, and consolidated the petty princedoms of the north country into one sovereignty. His birth was fabulous and his departure from the world mysterious. He is the mythic author of the Siamese History. Born of a queen of the Nakhae (a fabulous race dwelling under the earth), who came in the way of his father, the King of Hărĭpunxăi, one day when the king had "retired to a mountain for the purpose of meditation, he was discovered accidentally by a huntsman,[Pg 19] and was recognized by the royal ring which his father had given to the lady from the underworld. When he had grown up he entered the court of his father, and the palace trembled. He was acknowledged as the heir, and his great career proceeded with uninterrupted glory. At last he went one day to the river and disappeared." It was thought he had rejoined his mother, the Queen of the Nakhae, and would pass the remainder of his life in the realms beneath. The date of Phra Ruàng's reign is given as the middle of the fifth century of the Christian era.

After him there came successive dynasties of kings, ending with Phăja Uthong, who reigned seven years in Northern Cambodia, but being driven from his kingdom by a severe pestilence, or having voluntarily abandoned it (as another account asserts), in consequence of explorations which had discovered "the southern country," and found it extremely fertile and abundant in fish, he emigrated with his people and arrived at a certain island in the Meinam, where he "founded a new city, Krŭng thèph măhá năkhon Síajŭthăja—a great town impregnable against angels: Siamese era 711, A.D. 1349."

Here, at last, we touch firm historic ground, although there is still in the annals a sufficient admixture of what the late king happily designates as "fable." The foundations of Ayuthia, the new city, were laid with extraordinary care. The soothsayers were consulted, and decided that "in the 712th year of the Siamese era, on the sixth day of the waning moon, the fifth month, at ten minutes before[Pg 20] four o'clock, the foundation should be laid. Three palaces were erected in honor of the king; and vast countries, among which were Malacca, Tennasserim, Java, and many others whose position cannot now be defined, were claimed as tributary states." King Uthong assumed the title Phra-Rama-thi-bodi, and after a reign of about twenty years in his new capital handed down to his son and to a long line of successors, a large, opulent, and consolidated realm. The word Phra, which appears in his title and in that of almost all his successors to the present day, is said by Sir John Bowring to be "probably either derived from or of common origin with the Pharaoh of antiquity." But the resemblance between the words is simply accidental, and the connection which he seeks to establish is not for a moment to be admitted.

His Majesty the late King of Siam, a man of remarkable character and history, was probably, while he lived, the best-informed authority on all matters relating to the history of his kingdom. Fortunately, being a man of scholarly habits and literary tastes, he has left on record a concise and readable historical sketch, from which we cannot do better than to make large quotations, supplementing it when necessary with details gathered from other sources. The narrative begins with the foundation of the royal city, Ayuthia, of which an account has already been given on a previous page. The method of writing the proper names is that adopted by the king himself, who was exact, even to a pedantic extent, in regard to such matters. The king's English, however,[Pg 21] which was often droll and sometimes unintelligible, has in this instance been corrected by the missionary under whose auspices the sketch was first published.[A]

"Ayuthia when founded was gradually improved and became more and more populous by natural increase, and the settlement there of families of Laos, Kambujans, Peguans, people from Yunnán in China, who had been brought there as captives, and by Chinese and Mussulmans from India, who came for the purposes of trade. Here reigned fifteen kings of one dynasty, successors of and belonging to the family of U-T'ong Rámá-thi-bodi, who, after his death, was honorably designated as Phra Chetha Bida—i.e., 'Royal Elder Brother Father.' This line was interrupted by one interloping usurper between the thirteenth and fourteenth. The last king was Mahíntrá-thi-ràt. During his reign the renowned king of Pegu, named Chamna-dischop, gathered an immense army, consisting of Peguans, Birmese, and inhabitants of northern Siam, and made an attack upon Ayuthia. The ruler of northern Siam was Mahá-thamma rájá related to the fourteenth king as son-in-law, and to the last as brother-in-law.

"After a siege of three months the Peguans took Ayuthia, but did not destroy it or its inhabitants, the Peguan monarch contenting himself with capturing the king and royal family, to take with him as[Pg 22] trophies to Pegu, and delivered the country over to be governed by Mahá-thamma rájá, as a dependency. The king of Pegu also took back with him the oldest son of Mahá-thamma rájá as a hostage; his name was Phra Náret. This conquest of Ayuthia by the king of Pegu took place A. D. 1556.

[A] No attempt at uniformity in this respect has been made by the editor of this volume; but, in passages quoted from different authors, the proper names are written and accented according to the various methods of those authors.

"This state of dependence and tribute continued but a few years. The king of Pegu died, and in the confusion incident to the elevation of his son as successor Prince Náret escaped with his family, and, attended by many Peguans of influence, commenced his return to his native land. The new king on hearing of his escape despatched an army to seize and bring him back. They followed him till he had crossed the Si-thong (Birman Sit-thaung) River, where he turned against the Peguan army, shot the commander, who fell from his elephant dead, and then proceeded in safety to Ayuthia.

"War with Pegu followed, and Siam again became independent. On the demise of Mahá-thamma rájá, Prince Náret succeeded to the throne, and became one of the mightiest and most renowned rulers Siam ever had. In his wars with Pegu, he was accompanied by his younger brother, Eká-tassa-rot, who succeeded Náret on the throne, but on account of mental derangement was soon removed, and Phra-Siri Sin Ni-montham was called by the nobles from the priesthood to the throne."

With the accession of this last-mentioned sovereign begins a new dynasty. But before reproducing the chronicles of it we may add a few words concerning that which preceded.[Pg 23]

This dynasty had lasted from the founding of Ayuthia, A.D. 1350, until A.D. 1602, a period of two hundred years. Its record shows, on the whole, a remarkable regularity of succession, with perhaps no more intrigues, illegitimacies, murders, and assassinations than are to be found in the records of Christian dynasties. Temples and palaces were built, and among other works a gold image of Buddha is said to have been cast (in the city of Pichai, in the year A.D. 1380), "which weighed fifty-three thousand catties, or one hundred and forty-one thousand pounds, which would represent the almost incredible value (at seventy shillings per ounce) of nearly six millions sterling. The gold for the garments weighed two hundred and eighty-six catties." Another great image of Buddha, in a sitting posture, was cast from gold, silver, and copper, the height of which was fifty cubits.

One curious tradition is on record, the date of which is at the beginning of the fifteenth century. On the death of King Intharaxa, the sixth of the dynasty, his two eldest sons, who were rulers of smaller provinces, hastened, each one from his home, to seize their father's vacant throne. Mounted on elephants they hastened to Ayuthia, and by strange chance arrived at the same moment at a bridge, crossing in opposite directions. The princes were at no loss to understand the motive each of his brother's journey. A contest ensued upon the bridge—a contest so furious and desperate that both fell, killed by each other's hands. One result of this tragedy was to make easy the way of the youngest and surviving[Pg 24] brother, who, coming by an undisputed title to the throne, reigned long and prosperously.

During some of the wars between Pegu and Siam, the hostile kings availed themselves of the services of Portuguese, who had begun, by the middle of the sixteenth century, to settle in considerable numbers in both kingdoms. And there are still extant the narratives of several historians, who describe with characteristic pomposity and extravagance, the magnificence of the military operations in which they bore a part. One of these wars seems to have originated in the jealousy of the king of Pegu, who had learned, to his great disgust, that his neighbor of Siam was the fortunate possessor of no less than seven white elephants, and was prospering mightily in consequence. Accordingly he sent an embassy of five hundred persons to request that two of the seven sacred beasts might be transferred as a mark of honor to himself. After some diplomacy the Siamese king declined—not that he loved his neighbor of Pegu less, but that he loved the elephants more, and that the Peguans were (as they had themselves acknowledged) uninstructed in the management of white elephants, and had on a former occasion almost been the death of two of the animals of which they had been the owners, and had been obliged to send them to Siam to save their lives. The king of Pegu, however, was so far from regarding this excuse as satisfactory that he waged furious and victorious war, and carried off not two but four of the white elephants which had been the casus belli. It seems to have been in a campaign about[Pg 25] this time that, when the king of Siam was disabled by the ignominious flight of the war elephant on which he was mounted, his queen, "clad in the royal robes, with manly spirit fights in her husband's stead, until she expires on her elephant from the loss of an arm."

It is related of the illustrious Phra Náret, of whom the royal author, in the passage quoted on a previous page, speaks with so much admiration, that being greatly offended by the perfidious conduct of his neighbor, the king of Cambodia, he bound himself by an oath to wash his feet in the blood of that monarch. "So, immediately on finding himself freed from other enemies, he assailed Cambodia, and besieged the royal city of Lăvĭk, having captured which, he ordered the king to be slain, and his blood having been collected in a golden ewer he washed his feet therein, in the presence of his courtiers, amid the clang of trumpets."

The founder of the second dynasty is famous in Siamese history as the king in whose reign was discovered and consecrated the celebrated footstep of Buddha, Phra Bàt, at the base of a famous mountain to the eastward of Ayuthia. Concerning him the late king, in his historical sketch, remarks:

"He had been very popular as a learned and religious teacher, and commanded the respect of all the public counsellors; but he was not of the royal family. His coronation took place A.D. 1602. There had preceded him a race of nineteen kings, excepting one usurper. The new king submitted all authority in government to a descendant of the former line of[Pg 26] kings, and to him also he intrusted his sons for education, reposing confidence in him as capable of maintaining the royal authority over all the tributary provinces. This officer thus became possessed of the highest dignity and power. His master had been raised to the throne at an advanced age. During the twenty-six years he was on the throne he had three sons, born under the royal canopy—i.e., the great white umbrella, one of the insignia of royalty.

"After the demise of the king, at an extreme old age, the personage whom he had appointed as regent, in full council of the nobles, raised his eldest son, then sixteen years old, to the throne. A short time after, the regent caused the second son to be slain, under the pretext of a rebellion against his elder brother. Those who were envious of the regent excited the king to revenge his brother's death as causeless, and plan the regent's assassination; but he, being seasonably apprised of it, called a council of the nobles and dethroned him after one year's reign, and then raised his youngest brother, the third son, to the throne.

"He was only eleven years old. His extreme youth and fondness for play, rather than politics or government, soon created discontent. Men of office saw that it was exposing their country to contempt, and sought for some one who might fill the place with dignity. The regent was long accustomed to all the duties of the government, and had enjoyed the confidence of their late venerable king; so, with one voice, the child was dethroned and the regent[Pg 27] exalted under the title of Phra Chan Pra Sath-thong. This event occurred A.D. 1630," and forms the commencement of the third dynasty.

"The king was said to have been connected with the former dynasty, both paternally and maternally; but the connection must have been quite remote and obscure. Under the reign of the priest-king he bore the title Raja Suriwong, as indicating a remote connection with the royal family. From him descended a line of ten kings, who reigned at Ayuthia and Lopha-buri—Louvô of French writers. This line was once interrupted by an usurper between the fourth and fifth reigns. This usurper was the foster-father of an unacknowledged though real son of the fourth king, Chau Nárái. During his reign many European merchants established themselves and their trade in the country, among whom was Constantine Phaulkon (Faulkon). He became a great favorite through his skill in business, his suggestions and superintendence of public works after European models, and by his presents of many articles regarded by the people of those days as great curiosities, such as telescopes, etc.

"King Nárái, the most distinguished of all Siamese rulers, before or since, being highly pleased with the services of Constantine, conferred on him the title of Chau Phyá Wicha-yentrá-thé-bodi, under which title there devolved on him the management of the government in all the northern provinces of the country. He suggested to the king the plan of erecting a fort on European principles as a protection to the capital. This was so acceptable a proposal,[Pg 28] that at the king's direction he was authorized to select the location and construct the fort.

"He selected a territory which was then employed as garden-ground, but is now the territory of Bangkok. On the west bank, near the mouth of a canal, now called Báng-luang, he constructed a fort, which bears the name of Wichayeiw Fort to this day. It is close to the residence of his Royal Highness Chau-fà-noi Kromma Khun Isaret rangsan. This fort and circumjacent territory was called Thana-buri. A wall was erected, enclosing a space of about one hundred yards square. Another fort was built on the east side of the river, where the walled city of Bangkok now stands. The ancient name Bángkok was in use when the whole region was a garden.[A] The above-mentioned fort was erected about the year A.D. 1675.

"This extraordinary European also induced his grateful sovereign King Nárái to repair the old city of Lopha-buri (Louvô), and construct there an extensive royal palace on the principles of European architecture. On the north of this palace Constantine erected an extensive and beautiful collection of buildings for his own residence. Here also he built a Romish church. The ruins of these edifices and their walls are still to be seen, and are said to be a great curiosity. It is moreover stated that he planned the construction of canals, with reservoirs at intervals for bringing water from the mountains on the northeast to the city Lopha-buri, and conveying[Pg 29] it through earthen and copper pipes and siphons, so as to supply the city in the dry season on the same principle as that adopted in Europe. He commenced also a canal, with embankments, to the holy place called Phra-Bat, about twenty-five miles southwest from the city. He made an artificial pond on the summit of Phra-Bat Mountain, and thence, by means of copper tubes and stop-cocks, conveyed abundance of water to the kitchen and bath-rooms of the royal residence at the foot of the mountain. His works were not completed when misfortune overtook him.

[A] Such names abound now, as Bang-cha, Bang-phra, Bang-pla-soi, etc.; Bang signifying a small stream or canal, such as is seen in gardens.

"After the demise of Nárái, his unacknowledged son, born of a princess of Yunnan or Chiang-Mai, and intrusted for training to the care of Phya Petcha raja, slew Nárái's son and heir, and constituted his foster-father king, himself acting as prime-minister till the death of his foster-father, fifteen years after; he then assumed the royal state himself. He is ordinarily spoken of as Nai Dua. Two of his sons and two of his grandsons subsequently reigned at Ayuthia. The youngest of these grandsons reigned only a short time, and then surrendered the royal authority to his brother and entered the priesthood. While this brother reigned, in the year 1759, the Birman king, Meng-luang Alaung Barah-gyi, came with an immense army, marching in three divisions on as many distinct routes, and combined at last in the siege of Aynthia.

"The Siamese king, Chaufa Ekadwat Anurak Moutri, made no resolute effort of resistance. His great officers disagreed in their measures. The in[Pg 30]habitants of all the smaller towns were indeed called behind the walls of the city, and ordered to defend it to their utmost ability; but jealousy and dissension rendered all their bravery useless. Sallies and skirmishes were frequent, in which the Birmese were generally the victorious party. The siege was continued for two years. The Birmese commander-in-chief, Mahá Nōratha, died, but his principal officers elected another in his place. At the end of the two years the Birmese, favored by the dry season, when the waters were shallow, crossed in safety, battered the walls, broke down the gates, and entered without resistance. The provisions of the Siamese were exhausted, confusion reigned, and the Birmese fired the city and public buildings. The king, badly wounded, escaped with his flying subjects, but soon died alone of his wounds and his sorrows. He was subsequently discovered and buried.

"His brother, who was in the priesthood, and now the most important personage in the country, was captured by the Birmans, to be conveyed in triumph to Birmah. They perceived that the country was too remote from their own to be governed by them; they therefore freely plundered the inhabitants, beating, wounding, and even killing many families, to induce them to disclose treasures which they supposed were hidden by them. By these measures the Birmese officers enriched themselves with most of the wealth of the country. After two or three months spent in plunder they appointed a person of Mon or Peguan origin as ruler over Siam, and withdrew with numerous captives, leaving this Peguan officer to gather[Pg 31] fugitives and property to convey to Birmah at some subsequent opportunity. This officer was named Phrá Nái Kong, and made his headquarters about three miles north of the city, at a place called Phō Sam-ton, i.e., 'the three Sacred Fig-trees.' One account relates that the last king mentioned above, when he fled from the city, wounded, was apprehended by a party of travellers and brought into the presence of Phyá Nái Kong in a state of great exhaustion and illness; that he was kindly received and respectfully treated, as though he was still the sovereign, and that Phyá Nái Kong promised to confirm him again as a ruler of Siam, but his strength failed and he died a few days after his apprehension.

"The conquest by Birmah, the destruction of Ayuthia, and appointment of Phyá Nái Kong took place in March, A.D. 1767. This date is unquestionable. The period between the foundation of Ayuthia and its overthrow by the Birmans embraces four hundred and seventeen years, during which there were thirty-three kings of three distinct dynasties, of which the first dynasty had nineteen kings with one usurper; the second had three kings, and the third had nine kings and one usurper.

"When Ayuthia was conquered by the Birmese, in March, 1767, there remained in the country many bands of robbers associated under brave men as their leaders. These parties had continued their depredations since the first appearance of the Birman army, and during about two years had lived by plundering the quiet inhabitants, having no government to fear.[Pg 32]

On the return of the Birman troops to their own country, these parties of robbers had various skirmishes with each other during the year 1767.

"The first king established at Bangkok was an extraordinary man, of Chinese origin, named Pin Tat. He was called by the Chinese, Tia Sin Tat, or Tuat. He was born at a village called Bánták, in Northern Siam, in latitude 16° N. The date of his birth was in March, 1734. At the capture of Ayuthia he was thirty-three years old. Previous to that time he had obtained the office of second governor of his own township, Tak, and he next obtained the office of governor of his own town, under the dignified title of Phyá Ták, which name he bears to the present day. During the reign of the last king of Ayuthia, he was promoted to the office and dignity of governor of the city Kam-Cheng-philet, which from times of antiquity was called the capital of the western province of Northern Siam. He obtained this office by bribing the high minister of the king, Chaufá Ekadwat Anurak Moutri; and being a brave warrior he was called to Ayuthia on the arrival of the Birman troops as a member of the council. But when sent to resist the Birman troops, who were harassing the eastern side of the city, perceiving that the Ayuthian government was unable to resist the enemy, he, with his followers, fled to Chantaburi (Chantaboun), a town on the eastern shore of the Gulf of Siam, in latitude 12-1/2° N. and longitude 102° 10' E. There he united with many brave men, who were robbers and pirates, and subsisted by robbing the villages and merchant-vessels. In this way he be[Pg 33]came the great military leader of the district and had a force of more than ten thousand men. He soon formed a treaty of peace with the headman of Bángplásoi, a district on the north, and with Kambuja and Annam (or Cochin China) on the southeast."

With the fall of Ayuthia and the disasters inflicted by the Burman army ended the third dynasty in the year 1767. So complete was the victory of the Burmese, and so utter the overthrow of the kingdom of Siam, that it was only after some years of disorder and partial lawlessness that the realm became reorganized under strong centralized authority. The great military leader, to whom the royal chronicle from which we have been quoting refers, seems to have been pre-eminently the man for the hour. By his patient sagacity, joined with bravery and qualities of leadership which are not often found in the annals of Oriental warfare, he succeeded in expelling the Burmese from the capital, and in reconquering the provinces which, during the period of anarchy consequent on the Burmese invasion, had asserted separate sovereignty and independence. The war which about this time broke out between Burmah and China made this task of throwing off the foreign yoke more easy. And his own good sense and judicious admixture of mildness with severity conciliated and settled the disturbed and disorganized provinces. Notably was this the case in the province of Ligor, on the peninsula, where an alliance with the beautiful daughter of the captive king, and presently the birth of a son from the princess, made it easy to[Pg 34] attach the government of that province (and incidentally of the adjoining provinces), by ties of the strongest allegiance to the new dynasty.

Joined with Phyá Ták, in his adventures and successes as his confidential friend and helper, was a man of noble birth and vigorous character, who was, indeed, scarcely the inferior of the great general in ability. This man, closely associated with Phyá Ták, became at last his successor. For, at the close of his career, and after his great work of reconstructing the kingdom was fully accomplished, Phyá Ták became insane. The bonzes (or priests of Buddha), notwithstanding all that he had done to enrich the temples of the new capital (especially in bringing from Laos "the emerald Buddha which is the pride and glory of Bangkok at the present day"), turned against him, declaring that he aspired to the divine honor of Buddha himself. His exactions of money from his rich subjects and his deeds of cruelty and arbitrary power toward all classes became so intolerable, that a revolt took place in the city, and the king fled for safety to a neighboring pagoda and declared himself a member of the priesthood. For a while his refuge in the monastery availed to save his life. But presently his favorite general, either in response to an invitation from the nobles or else prompted by his own ambition, assumed the sovereignty and put his friend and predecessor to a violent death. The accession of the new king (who seems to have shared the dignity and responsibility of government with his brother), was the commencement of the present dynasty, to the history of which a new chapter may[Pg 35] properly be devoted. But before proceeding with the history we interrupt the narrative to give sketches of two European adventurers whose exploits in Siam are among the most romantic and suggestive in her annals.[Pg 36]

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, that golden age of discovery and adventure, did not fail to find in the Indo-Chinese peninsula brilliant opportunities for the exercise of those qualities which made their times so remarkable in the history of the world. Marco Polo, the greatest of Asiatic travellers, dismisses Siam in a few words as a "country called Locac; a country good and rich, with a king of its own. The people are idolaters and have a peculiar language, and pay tribute to nobody, for their country is so situated that no one can enter it to do them ill. Indeed, if it were possible to get at it the Great Kaan [of China] would soon bring them under subjection to him. In this country the brazil which we make use of grows in great plenty; and they also have gold in incredible quantity. They have elephants likewise, and much game. In this kingdom too are gathered all the porcelain shells which are used for small change in all those regions, as I have told you before. There is nothing else to mention except that this is a very wild region, visited by few people; nor does the king desire that any strangers should frequent the country and so find out about his treasures and other resources."[Pg 37]

The Venetian's account, though probably obtained from his Chinese sailors, is essentially correct, and applies without much doubt to the region now known as Siam. Sir Henry Yule derives Locac either from the Chinese name Lo-hoh, pronounced Lo-kok by Polo's Fokien mariners, or from Lawék, which the late King of Siam tells us was an ancient Cambodian city occupying the site of Ayuthia, "whose inhabitants then possessed Southern Siam or Western Cambodia."

Nearly three centuries after Polo, when the far East had become a common hunting-ground for European adventurers, Siam was visited by one of the most extraordinary men of this type who ever told his thrilling tales. The famous Portuguese, Mendez Pinto, passed twenty-one years in various parts of Asia (1537-1558), as merchant, pirate, soldier, sailor, and slave, during which period he was sold sixteen times and shipwrecked five, but happily lived to end his life peacefully in Portugal, where his published "Peregrinacao" earned the fate of Marco Polo's book, and its author was stamped as a liar of the first magnitude. Though mistaken in many of its inferences and details Pinto's account bears surprisingly well the examination of modern critical scholars. When we consider the character of the man and the fact that he must have composed his memoirs entirely from recollection, the wonder really is that he should have erred so little. The value of his story lies in the fact that we get from it, as Professor Vambery suggests, "a picture, however incomplete and defective, of the power and authority of Asia, then still unbroken. In[Pg 38] this picture, so full of instructive details, we perceive more than one thing fully worthy of the attention of the latter-day reader. Above all we see the fact that the traveller from the west, although obliged to endure unspeakable hardships, privation, pain, and danger, at least had not to suffer on account of his nationality and religion, as has been the case in recent times since the all-puissance of Europe has thrown its threatening shadow on the interior of Asia, and the appearance of the European is considered the foreboding of material decay and national downfall. How utterly different it was to travel in mediæval Asia from what it is at present is clearly seen from the fact that in those days missionaries, merchants, and political agents from Europe could, even in time of war, traverse any distances in Asiatic lands without molestation in their personal liberty or property, just as any Asiatic traveller of Moslem or Buddhist persuasion."

Pinto seems to have gone to Siam hoping there to repair his fortunes, which had suffered shipwreck for the fourth time and left him in extreme destitution. Soon after he joined in Odiaa (Ayuthia) the Portuguese colony, which he found to be one hundred and thirty strong, he was induced with his countrymen to serve among the King's body-guards on an expedition made against the rebellious Shan states in the north. The campaign progressed favorably and ended in the subjection of the "King of Chiammay" and his allies, but a scheming queen, desirous of putting her paramour on the throne, poisoned the conqueror upon his return to Odiaa in 1545. "But whereas heaven never leaves wicked actions unpunished, the[Pg 39] year after, 1546, and on January 15th, they were both slain by Oyaa Passilico and the King of Cambaya at a certain banquet which these princes made in a temple." The usurpers were thus promptly despatched, but the consequences of their infamy were fateful to Siam, as Pinto informs us at some length.

"The Empire of Siam remaining without a lawfull successor, those two great lords of the Kingdom, namely, Oyaa Passilico, and the King of Cambaya, together with four or five men of the trustiest that were left, and which had been confederated with them, thought fit to chuse for King a certain religious man named Pretiem, in regard he was the naturall brother of the deceased prince, husband to that wicked queen of whom I have spoken; whereupon this religious man, who was a Talagrepo of a Pagode, called Quiay Mitran, from whence he had not budged for the space of thirty years, was the day after drawn forth of it by Oyaa Passilico, who brought him on January 17th, into the city of Odiaa, where on the 19th he was crowned King with a new kind of ceremony, and a world of magnificence, which (to avoid prolixity) I will not make mention of here, having formerly treated of such like things. Withall passing by all that further arrived in the Kingdom of Siam, I will content myself with reporting such things as I imagine will be most agreeable to the curious. It happened then that the King of Bramaa (Burmah), who at that time reigned tyrannically in Pegu, being advertised of the deplorable estate whereunto the Empire of Sornau (Siam) was reduced, and of the death of the greatest lords of the country, as also that[Pg 40] the new king of this monarchy was a religious man, who had no knowledge either of arms or war, and, withall of a cowardly disposition, a tyrant, and ill beloved of his subjects, he fell to consult thereupon with his lords in the town of Anapleu, where at that time he kept his court."

The decision in favor of seizing this favorable opportunity for acquiring his neighbor's territory was practically unanimous, and the tyrant of Pegu accordingly assembled an army of 800,000 men, 100,000 of whom were "strangers," i.e., mercenary troops, and among these we find 1,000 Portuguese, commanded by one Diego Suarez d'Albergaria, nicknamed Galego. So the Portuguese, as we shall see, played important parts on both sides of the great war that followed. After capturing the frontier defences, the Burmans marched across the country through the forests "that were cut down by three-score thousand pioneers, whom the King had sent before to plane the passages and wayes," and sat down before the devoted capital. "During the first five days that the King of Bramaa had been before the city of Odiaa, he had bestowed labour and pains enough, as well in making of trenches and pallisadoes, as in the providing all things necessary for the siege; in all which time the besieged never offered to stir, whereof Diego Suarez, the marshall of the camp, resolved to execute the design for which he came; to which effect, of the most part of the men which he had under his command, he made two separated squadrons, in each of which there were six battalions of six thousand a piece. After this manner he[Pg 41] marched in battell array, at the sound of many instruments, towards the two poynts which the city made on the south side, because the entrance there seemed more facile to him than any other where. So upon the 19th day of June, in the year 1548, an hour before day, all these men of war, having set up above a thousand ladders against the walls, endeavoured to mount up on them; but the besieged opposed them so valiently, that in less than half an hour there remained dead on the place above ten thousand on either part. In the mean time the King, who incouraged his souldiers, seeing the ill success of this fight, commanded these to retreat, and then made the wall to be assaulted afresh, making use for that effect of five thousand elephants of war which he had brought thither and divided into twenty troops of two hundred and fifty apiece, upon whom there were twenty thousand Moens and Chaleus, choice men and that had double pay. The wall was then assaulted by these forces with so terrible an impetuosity as I want words to express it. For whereas all the elephants carried wooden castles on their backs, from whence they shot with muskets, brass culverins, and a great number of harquebuses a crock, each of them ten or twelve spans long, these guns made such an havock of the besieged that in less than a quarter of an hour the most of them were beaten down; the elephants withall setting their trunks to the target fences, which served as battlements, and wherewith they within defended themselves, tore them down in such sort as not one of them remained entire; so that by this means the wall was abandoned of all defence, no man[Pg 42] daring to shew himself above. In this sort was the entry into the city very easy to the assailants, who being invited by so good success to make their profit of so favourable an occasion, set up their ladders again which they had quitted, and mounting up by them to the top of the wall with a world of cries and acclamations, they planted thereon in sign of victory a number of banners and ensigns. Now because the Turks (Arabs?) desired to have therein a better share than the rest, they besought the King to do them so much favour as to give them the vantguard, which the King easily granted them, and that by the counsell of Diego Suarez, who desired nothing more than to see their number lessened, always gave them the most dangerous imployments. They in the mean time extraordinarily contented, whither more rash or more infortunate than the rest, sliding down by a pane of the wall, descended through a bulwark into a place which was below, with an intent to open a gate and give an entrance unto the King, to the end that they might rightly boast that they all alone had delivered to him the capital city of Siam; for he had before promised to give unto whomsoever should deliver up the city unto him, a thousand bisses of gold, which in value are five hundred thousand ducates of our money. These Turks being gotten down, as I have said, laboured to break open a gate with two rams which they had brought with them for that purpose; but as they were occupied about it they saw themselves suddenly charged by three thousand Jaos, all resolute souldiers, who fell upon them with such fury, as in little more than a quarter of an hour there was not[Pg 43] so much as one Turk left alive in the place, wherewith not contented, they mounted up immediately to the top of the wall, and so flesht as they were and covered over with the blood of the Turks, they set upon the Bramaa's men which they found there, so valiently that most of them were slain and the rest tumbled down over the wall.

"The King of Bramaa redoubling his courage would not for all that give over this assault, so as imagining that those elephants alone would be able to give him an entry into the city, he caused them once again to approach unto the wall. At the noise hereof Oyaa Passilico, captain general of the city, ran in all haste to this part of the wall, and caused the gate to be opened through which the Bramaa pretended to enter, and then sent him word that whereas he was given to understand how his Highness had promised to give a thousand bisses of gold, he had now performed it so that he might enter if he would make good his word and send him the gold, which he stayed there to receive. The King of Bramaa having received this jear, would not vouchsafe to give an answer, but instantly commanded the city to be assaulted. The fight began so terrible as it was a dreadfull thing to behold, the rather for that the violence of it lasted above three whole hours, during the which time the gate was twice forced open, and twice the assailants got an entrance into the city, which the King of Siam no sooner perceived, and that all was in danger to be lost, but he ran speedily to oppose them with his followers, the best souldiers that were in all the city: whereupon the conflict grew[Pg 44] much hotter than before, and continued half an hour and better, during the which I do not know what passed, nor can say any other thing save that we saw streams of bloud running every where and the air all of a light fire; there was also on either part such a tumult and noise, as one would have said the earth had been tottering; for it was a most dreadful thing to hear the discord and jarring of those barbarous instruments, as bells, drums, and trumpets, intermingled with the noise of the great ordnance and smaller shot, and the dreadful yelling of six thousand elephants, whence ensued so great a terrour that it took from them that heard it both courage and strength. Diego Suarez then, seeing their forces quite repulsed out of the city, the most part of the elephants hurt, and the rest so scared with the noise of the great ordnance, as it was impossible to make them return unto the wall, counselled the King to sound a retreat, whereunto the King yielded, though much against his will, because he observed that both he and the most part of the Portugals were wounded."

The king's wound took seventeen days to heal, a breathing space which we can imagine both sides accepted with satisfaction. Nothing daunted by the failure of his first onset, he attacked the city again and again during the four months of the siege, employing against it the machines and devices of a Greek engineer in his service, and achieving prodigies of valor. At length, upon the suggestion of his Portuguese captain, he began "with bavins and green turf to erect a kind of platform higher than the walls, and thereon mounted good store of great ord[Pg 45]nance, wherewith the principal fortifications of the city should be battered." Considering the exhausted state of the defenders it is likely that this elaborate effort would have succeeded, but before the critical moment arrived word came from home that the "Xemindoo being risen up in Pegu had cut fifteen thousand Bramaas there in pieces, and had withal seized on the principal places of the country. At these news the King was so troubled, that without further delay he raised the siege and imbarqued himself on a river called Pacarau, where he stayed but that night and the day following, which he imployed in retiring his great ordnance and ammunition. Then having set fire on all the pallisadoes and lodgings of the camp, he parted away on Tuesday the 15th of October, 1548, for to go to the town of Martabano." So was Ayuthia honorably saved, but Pinto, we fear, followed with his countryman Diego in the Bramaa's train, for he has much to say henceforth of the civil disturbance in Burma and the Xemindoo's final suppression, but of Siam, excepting a brief description of the country, he tells us nothing more.

About a century after Pinto's stay in Siam another adventurer found his way thither while seeking his fortune in the golden Orient and encountered there such vicissitudes of experience as to rival in picturesqueness and wonder the tales of the Arabian Nights. This was the Greek sailor, Constantine Phaulcon, whose story, even when stripped of the extravagant embellishments with which the devout priest, his biographer, has adorned it, is marvellous enough to deserve a place in the annals of travel and[Pg 46] adventure. His strange life has been woven into a romance, "Phaulcon the Adventurer," by William Dalton, but the following sketch of his career, condensed from Sir John Bowring's translation of Père d'Orléans' "Histoire de M. Constance," printed in Tours in 1690, is a better authority for our purpose.

Constantine Phaulcon, or Falcon, born in Cephalonia, was the son of a Venetian nobleman and a Greek lady of rank. Owing to his parents' poverty, however, he left home when a mere boy to shift for himself, and presently drifted into the employ of the English East India Company. After several years passed in this service he accumulated money enough to buy a ship and embark in speculations of his own, but three shipwrecks following in rapid succession brought him at length into a desperate plight of poverty and debt. Being cast in his third misadventure upon the Malabar coast, he there found a fellow sufferer, the sole survivor of a like catastrophe, who proved to be the Siamese ambassador to Persia returning from his mission. Phaulcon was able with the little money saved in his belt to assist the ambassador to Ayuthia, where that officer in gratitude recommended him to the Baraclan (prime-minister) and the king, both of whom were delighted with his ability and determined to make use of him. He was first taken into favor, it is said, from the address with which he supplanted the Moors in the employment, which seemed to have been made over to them, of preparing the splendid entertainments and pageants that were the king's chief pride. Reforms[Pg 47] introduced into this office resulted in the production of much more effective spectacles at a smaller expense to the treasury, for the Moors had indulged in some knavish practices, and when their dishonesty was discovered by the Greek his high place in the sovereign's estimation was fully assured.

At this time his prosperity was interrupted by a severe illness that well-nigh proved fatal to the new favorite, but was turned to good account by Father Antoine Thomas, a Flemish Jesuit, who was passing through Siam on his way to join the Portuguese missions in China and Japan. Thoroughly alive to the importance of securing so powerful a man to the Roman Church, the good father adroitly converted the invalid, and at last had the satisfaction of receiving from Phaulcon abjuration of his errors and heresies and numbering him among the faithful. By the priest's advice, also, "he married, a few days afterward, a young Japanese lady of good family, distinguished not only by rank, but also by the blood of the martyrs from whom she was descended and whose virtues she imitates." It is an interesting episode in the history of Siam that for about a generation near the beginning of the seventeenth century there existed, besides the free intercourse with Western nations, an active exchange of commodities between this part of Cochin China and Japan, many of whose merchants found good employments under Phra Narain, the Siamese king. They proved themselves, however, to be such profound schemers as finally to earn the hatred of the natives, who drove them out in 1632. Soon after this date[Pg 48] Japan adopted a policy of complete exclusion and we hear no more of her subjects in any foreign country.

"If, as a man of talent," continues Père d'Orléans, "Phaulcon knew how to avail himself of the royal favor to establish his own fortune, he used it no less faithfully for the glory of his master and the good of the state; still more, as a true Christian, for the advancement of religion. Up to this time he had aimed chiefly to increase commerce, which occupies the attention of Oriental sovereigns far more than politics, and had succeeded so well that the king of Siam was now one of the richest monarchs in Asia; but he considered that, having enriched, he should now endeavor to render his Sovereign illustrious by making known to foreign nations the noble qualities which distinguished him; and his chief aim being the establishment of Christianity in Siam, he resolved to engage his master to form treaties of friendship with those European monarchs who were most capable of advancing this object."

We must be cautious, however, in accepting all his motives from his Jesuit biographer, who doubtless does him too much honor. According to the Dutch historian Kämpfer, Phaulcon had the fate of all his kind ever before his eyes, and the better to secure himself in his exalted position, "he thought it necessary to secure it by some foreign power, of which he judged the French nation to be the most proper for seconding his designs, which appeared even to aim at the royal dignity. In order to do this he made his sovereign believe that by the assistance of the said[Pg 49] nation he might polish his subjects and put his dominion into a flourishing condition."

Whatever his intentions, it is certain that Phaulcon carried his point, and an embassy was sent to the court of Louis XIV. In return the Chevalier de Chaumont, accompanied by a considerable retinue, and bearing royal gifts and letters, was despatched to Siam, where he arrived in September, 1685, and was splendidly received. Phaulcon was, of course, foremost among the dignitaries; the shipwrecked adventurer, who had risen from the position of common sailor to the post of premier in a rich and thriving realm, found himself receiving on terms of equality and in a style of magnificence that, even to European eyes, seemed admirable, the ambassador of the most illustrious king in Europe. Whether his loyalty to the sovereign whom he was bound to serve was always quite above the suspicion of intrigue with the French is more than doubtful. He greatly desired on his own behalf to effect the conversion of the king to Catholicism, and did what he could to support the arguments of the French envoy to this end. But the king, who was a shrewd man, refused to abandon the religion of his ancestors for that of these designing foreigners.

"Phaulcon had long thought," says the Père d'Orléans, "of bringing to Siam Jesuits who, like those in China, might introduce the Gospel at court through the mathematical sciences, especially astronomy. Six Jesuits having profited by so good an occasion as that of the embassy of the Chevalier de Chaumont to stop in Siam on their way to China, M. Constance upon[Pg 50] seeing them begged that some might be sent to him from France; and for this especial object Father Tachard, one of the six, was requested to return to Europe." This was really the first step in Phaulcon's ruin; for, aware that his master could not in this way encourage the Christians without incurring the hatred of both the Buddhists and Mohammedans in the kingdom, he conceived the plan of begging Louis for some French troops ostensibly to accompany and support the missionaries, but practically to sustain his influence by force, and in the event of defeat to hand the country over to France. Three officers returned with M. de Chaumont and effected a treaty whereby Louis promised to send some troops to the Siamese king, "not only to instruct his own in our discipline, but also to be at his disposal according as he should need them for the security of his person, or for that of his kingdom. In the mean time the king of Siam would appoint the French soldiers to guard two places where they would be commanded by their own officers under the authority of this monarch." The troops and a dozen missionaries set out under Father Tachard's charge in 1686.