The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pike's Peak Rush, by Edwin L. Sabin

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Pike's Peak Rush

Terry in the New Gold Fields

Author: Edwin L. Sabin

Release Date: November 6, 2011 [EBook #37943]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIKE'S PEAK RUSH ***

Produced by Beth and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

"These mountains are supposed to contain minerals, precious stones and gold and silver ore. It is but late that they have taken the name Rocky Mountains; by all the old travelers they are called the Shining Mountains, from an infinite number of crystal stones of an amazing size, with which they are covered, and which, when the sun shines full upon them, sparkle so as to be seen at a great distance."

—From a Geography One Hundred Years Ago.

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1917,

By THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY.

| Terry Richards | Off to the Gold Fields |

| Mr. and Mrs. Richards | His Parents |

| Harry Revere | His Partner |

| George Stanton | A Tender-foot |

| Virgie Stanton | Also a Tender-foot |

| Mr. and Mrs. Stanton | Their Parents |

| Sol Judy | A "Forty-niner" |

| Pine Knot Ike | Not so Tough After All |

| Thunder Horse | Bad Medicine |

| Shep | Ready for Anything |

| Duke the Half-Buffalo} | Queer Wagon Mates |

| Jenny the Yellow Mule} |

| The Sick Boy | Who Shows His Gratitude |

| Pat Casey | With a Taste for Pie |

| Little Raven | White Man's Friend |

| Left Hand | Official Interpreter |

| Horace Greeley | New York Tribune Editor |

| Journalist Richardson | Boston Journal Reporter |

| Journalist Villard | The Cincinnati Reporter |

| Green Russell} | The Original "Boomers" |

| John Gregory } | |

| McGrew the Wheel-Barrow Man | Who "Pushed" Across |

And Certain Others of the Busy Folk That Thronged the Gulches and the Young Denver City.

Place and Time: The Pike's Peak Country of the Rocky Mountains, 1859.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | To the Mountains of Gold | 1 |

| II. | The "Pike's Peak Limited" | 15 |

| III. | Duke on a Rampage | 29 |

| IV. | The Trail Grows Lonesome | 39 |

| V. | Tough Luck for the Limited | 53 |

| VI. | Just in Time | 65 |

| VII. | Shep Does His Duty | 75 |

| VIII. | The Trail Grows Lively | 91 |

| IX. | Now Where Is the "Elephant"? | 103 |

| X. | "Forward March" to Gregory Gulch | 116 |

| XI. | "Rich at Last!" | 126 |

| XII. | Panning the "Golden Prize" | 138 |

| XIII. | Ready for Big Business, But * * * | 147 |

| XIV. | Pat Casey Helps Out | 161 |

| XV. | Horace Greeley Comes to Town | 171 |

| XVI. | Two Tenderfeet Arrive | 180 |

| XVII. | Another Call for Hustle | 192 |

| XVIII. | Never Say Die! | 201 |

| XIX. | To the Pound-a-Day | 211 |

| XX. | Millions in Sight | 224 |

| XXI. | Terry Makes a Deal | 233 |

| XXII. | The "Virginia Consolidated" | 241 |

"Twenty-five thousand people—and more on the way! Think of that!" exclaimed Mr. Richards, Terry's father.

It was an evening in early April, 1859, and spring had come to the Richards ranch, up the Valley of the Big Blue, Kansas Territory. Excitement had come, too, for Harry (Harry Revere, that is, the clever, boyish Virginia school-teacher who was a regular member of the family) had been down to the town of Manhattan, south on the Kansas River and the emigrant trail there, and had brought back some Kansas City and St. Louis papers. They were brimming with the news of a tremendous throng of gold-seekers swarming to cross the plains for the new gold fields, discovered only last year, in the Pike's Peak country of the Rocky Mountains.

"Do you suppose it's true, Ralph? So many?" appealed Mrs. Richards, doubting.

"Whew!" gasped Terry—the third man in the family. At least, he worked as hard as any man.

"I believe it," asserted Harry. "Manhattan's jammed and the trail in both directions is a sight!"

"So are Kansas City and Leavenworth, according to the dispatches," laughed Terry's father. "People from the east are flocking across Iowa, to the Missouri River, and the steamboats up from St. Louis are loaded to the guards—everybody bound for the Pike's Peak country and the Cherry Creek diggin's there. It beats the California rush of Forty-nine and Fifty."

"But twenty-five thousand, Ralph!" Mother Richards protested.

"Yes, and the papers say there'll be a hundred thousand before summer's over."

"Oh, Pa! Can't we go?" pleaded Terry.

"And quit the ranch?"

"But if we don't go now all the gold will be found."

"I think it would be sinful to leave this good ranch and go clear out there, with nothing certain," voiced his mother, anxiously. "You know it almost killed your father. He'd never have got home, if it hadn't been for you."

"That was when he was coming back, and we wouldn't need to come back," argued Terry. "And he fetched some gold, too, didn't he?"

"And hasn't recovered yet!" triumphed Mother Richards. "He couldn't possibly stand another long overland trip—and I don't want to stand it, either. Why, we're just nicely settled, all together again, on our own farm."

"Well, some of us ought to go," persisted Terry. "I'd a heap rather dig gold than plant it.'

"I notice you aren't extra fond of digging potatoes, though," slily remarked Harry. "You say it makes your back ache!"

"Digging gold's different," retorted Terry. "Besides, we've a gold mine already, haven't we? The one dad discovered. If we don't get there soon somebody else will dig everything out of it and we'll have only a hole."

"That will be a cellar for us, anyway, to put a house over," mused Harry, who always saw opportunities.

"I don't lay much store on that claim of mine," confessed Terry's father. "The country'll be over-run, and if the spot was worth anything it's probably jumped, or will be jumped very quickly. And I don't remember where it is."

"But what a rush!" faltered Mrs. Richards, glancing through the paper. "The news does say twenty-five thousand people about to cross the plains and more coming. I do declare! I'm sure some of them will suffer dreadfully."

"Yes; they'll earn their way, all right," agreed Father Richards. "It's a tough region, yonder at the mountains—and the more people, the tighter the living, till they raise other crops than gold."

"Then that's the reason why we ought to be starting—so as to get in ahead," persisted Terry. "This ranching's awful slow, and it's toler'ble hard work, too. Putting stuff in and taking it out again."

"You can't expect to 'take stuff out' unless you do put some in, first, can you?" demanded his father. "That's the law of life. But if you think you can dodge hard work, go on and try."

"Where?" blurted Terry.

"Anywhere. To the Pike's Peak country. You have my permission." And his father's blue eyes twinkled.

"Oh, Ralph!" protested Terry's mother, aghast. "Don't joke about it."

"Aw, I can't go alone," stammered Terry, taken aback.

"I'm not joking," asserted Father Richards. "But he'll have to find his own outfit, like other gold-seekers. Then he can go, and we'll follow when we can."

Mother Richards dropped the paper.

"Ralph! Have you the fever again? Oh, dear!"

Gold-fever she meant, of course. Father Richards smiled, and rubbed his hair where it showed a white streak over the wound received when on their road out from the Missouri River, a year ago, to settle on the ranch, he had been knocked off his horse in fording Wildcat Creek, and had disappeared for months. Only by great good fortune had Terry found him, wandering in, through a blizzard, from the Pike's Peak gold fields; and had brought him home in time for a merry Christmas.

"Not 'again.' Don't know as I'd call it gold-fever, exactly. But I feel a bit like Terry does—I want to join the crowd. It was the same way, in coming to Kansas. We thought this was to be the West; and now there's another West. This ranch can be made to pay—I'm certain it can if we're able to hold on long enough and weather the droughts and grasshoppers and low prices. But——"

"Harry and Terry and I made it pay," reminded Mother Richards, with a flash of pride.

"Yes, you all did bravely. But you managed it by cutting and selling the timber. The timber won't last forever, and the grasshoppers may! This is rather a lonely life, for you, yet, up in here. Out at the mountains, though, they've founded those two towns, Denver and Auraria, and probably others; and I believe opportunities will be more there than here."

"Do you intend to sell the ranch?" asked Mrs. Richards, a little pale. She loved the ranch, which she had helped to make.

"We'll talk that over. I wouldn't sell unless you consented. It's your place; you and Terry and Harry've done most of the work."

"But you said I could go right away, Pa; didn't you?" enthused Terry. "Then I'll take the wagon and Buck and Spot, and Shep—and Harry; and——"

"Hold on," bade his father. "Not quite so fast. I said you're to find your own outfit. If we sell the ranch, you'll have to leave part of it as a sample to show to customers. Those oxen are valuable. Oxen'll be as good as gold, in this country. The rush across the plains will sweep up every kind of work critter. If you take Buck and Spot, how'll anybody on this ranch do the ploughing? And if you take the wagon, what'll become of the hauling?"

"And if you take Harry, who'll help your father and me?" chimed in his mother.

"Shucks!" bemoaned Terry. "There's the old mare, and the colt—and a cow—and——"

"And a half-buffalo, and a tame turkey, and a yellow mule twenty years of age if she's a day," completed his father. "Buck and Spot beat the lot of them put together. No, sir; I'll not spare those oxen, for any wild-goose chase across to the mountains. But I'll tell you what you can do. You can have Harry, and find the rest of your come-along."

"Hum!" murmured Harry, who had been scratching his nose and looking wise. "That sounds like a dare. Let's go outside, Terry."

He rose. Terry wonderingly followed him. Within, Mother Richards gazed dubiously upon Father Richards.

"Are you really in earnest, Ralph?"

"Yes; after a fashion. Terry can't make such a trip alone; he's too young; but he'd be safe with Harry. Enough cultivating's done on the ranch so I can manage for the next few months. That would give you and me a chance to dispose of the place when we were ready—and it will sell better with the crops showing. And besides, I agree with you that I'm not quite in shape yet to stand the trip. By the time we were free to go, those two boys would have the country yonder pretty well spied out, and they'd send us back reliable information. Harry has a level head."

"And maybe they'd be so disappointed they'd want to come back, themselves!" hopefully asserted Mrs. Richards. "Terry'd be cured of his gold-seeking fever. Anyway, they haven't gone, yet. They can't have the oxen, and they can't have my cow, and if they took the old mare how'd I ever visit my neighbors, and if they took the colt he's not heavy enough for hard work, and the yellow mule won't pull alone, and Duke won't pull at all, and you've refused them the wagon—and I sha'n't let them walk. So I don't believe I'll worry."

"Um—m!" muttered Father Richards, rubbing his hair. "I won't be positive about all that. What Terry doesn't cook up, Harry will. They're both of them too uncommon smart. I reckon they're into some scheme already."

And so they were. He resumed his reading of the papers. Mrs. Richards proceeded to finish the evening housework. Suddenly they were interrupted. Outside welled a frantic chorus of shouting and cheering and barking and clattering.

"For goodness' sake!" ejaculated Mrs. Richards; and they sprang to the door.

Harry, who walked with a slight limp because when a boy down in Virginia he had hurt his foot, had beckoned Terry on, around the hen-house, out of ear-shot of the cabin. Here he had paused, and scratched his long nose again—a sure sign of mischief. Slender and smooth-faced and young was Harry, but stronger than anybody'd think. The way he could ride bareback, and could fell timber—whew! And that long head of his was a mine in itself.

"Shall we go?" he queried.

"Will you, Harry? Do you want to go?"

"Yes, I reckon I do. I always knew I was cut out for a miner instead of a schoolmaster or a farmer."

"How'll we go, then?" demanded Terry. "Thunder! We've nothing to start with, 'cept our feet. Dad says we'll have to find our own outfit."

"And one of the feet's a bad one," commented Harry. "I suppose we could walk, and carry our stuff—or carry part of it and come back for the rest."

"Five hundred miles?" cried Terry. "Aw, jiminy! We'd be the last in, if we tried to carry stuff on our backs."

"And we'd be the first out, if we didn't carry stuff," returned Harry. "We'd be frozen out and starved out, both. Now, let's see." He scratched his nose, and was solemn—save that his pointed chin twitched, and his wide brown eyes laughed. "We can't have the oxen; and we mustn't take the old mare or the colt, because they're a part of the ranch; or the brindled cow, because she belongs to Mother Richards' butter and milk department; or Pete the turkey, because he can't swim; so that leaves us Jenny and Duke."

"That old yellow mule, and a half-buffalo!" yapped Terry. "But they're a part of the ranch stock, too, and besides——"

"No, they're ours," corrected Harry. "Jenny's mine, and I'm hers. I brought her in here—or, rather, she brought me in; in fact, we brought each other. And Duke is yours. You rescued him from a life among the wild buffalo—a rough, low life, the ungrateful brute!—and his mother's disowned him since he learned to eat grass and hay, and nobody else wants him. Jenny works for her keep, but he doesn't do a thing except bawl and eat and sleep and pick quarrels with his betters. He's only an idle good-for-nothing."

"What do you aim to do, then?" questioned Terry, staring open-mouthed. "Ride 'em? We can't have the wagon. You going to ride Jenny and make me ride Duke? We'd both of us be split in two! I'd rather walk. I'd make great time, wouldn't I, on that buffalo—and Jenny mostly moves up and down in one spot! Your saddle's falling to pieces. It's just tied with rope."

"Hum!" mused Harry. "We'll hitch them."

"What to?"

"A wagon. I know where there are two wheels and an axle."

"Where?"

"In an old mud-hole. The front end traveled on, but the hind end stayed."

"Jenny won't pull single, and Duke won't pull at all."

"Make 'em pull together, then."

"What'll we do for the rest of the wagon?"

"Make it."

"Huh!" reflected Terry, trying to be convinced. "That'll be a great outfit. Where'll we get our supplies?"

"Maybe somebody'll grub-stake us, on shares. But no matter about that. We'll learn not to eat when we haven't anything to eat. If," continued Harry, "a couple of fellows our size, with a yellow mule and a half-buffalo and two wagon-wheels, can't get through to the mountains, I'd like to know who can! So it's high time we started. Come on."

"What are you going to do first?" demanded Terry, bewildered by Harry's sudden movement.

"Educate Duke, of course. We'll put him and Jenny to the drag and give them their first lesson. You be driving Duke in and I'll talk with Jenny."

Away hustled Harry, at his rapid limp, for a halter and Jenny, where in a stall she was munching a feed of hay as reward after her trip to town. With the interested Shep (shaggy black dog) at his heels, prepared to help, Terry hastened into the pasture and rounded up Duke, the half-buffalo, from amidst the other animals. Duke was now a yearling—grown to be a sturdy, stocky youngster since Terry had captured him and his brindled cow mother during the buffalo hunt with the Delaware Indians last summer.

Knowing Terry well, and tamed to everything except work, Duke submitted to being driven out. In the ranch yard Harry was waiting with big, gaunt Jenny, already attached by collar and traces to the drag. The drag was only an old rail, heavy and spike-studded, used to uproot the brush when the ranch land was cleared.

It required considerable maneuvering to fit an ox-bow around Duke's short neck, and yoke him to the drag. He seemed dumbly astonished. Jenny laid back her long ears in disgust with her strange mate.

"Be patient with him, Jenny," pleaded Harry. "He's only a boy, and part Indian, while you're a cultured lady. I think," he said, to Terry, "that I'll do the driving, for the first spell on this Pike's Peak trail." Holding the lines attached to Jenny's bit (but Duke, ox-fashion, had no lines), he fell a few paces to rear. "No," he added, "that won't answer. You drive Duke and I'll drive Jenny. Get your whip."

Terry stationed himself with the ox-whip at Duke's flank. Harry stepped upon the drag, and balanced.

"Gid-dap, Jenny!" he bade.

"G'lang, Duke!" bade Terry.

Jenny, sidling as far as she could in the traces, her ears flat, started. Duke stayed. Consequently, Jenny did not get very far.

"Duke! G'lang, Duke!" implored Terry, desperately, cracking his whip.

"Pull, Jenny! Pull!" encouraged Harry, balancing on the drag now askew.

Up went Jenny's heels, down went Duke's head, away went Harry on the drag and Terry on the run. Shep, thinking it great sport, barked gaily.

"Whoa, Jenny! Whoa now!"

"Haw, Duke! Whoa-haw! Gee! Whoa!"

And from the cabin doorway Father Richards clapped and shouted, and Mother Richards called warnings.

Harry was speedily thrown from the bouncing drag, but he clung to the lines. Having careered, plunging and tugging and side-stepping, until she was astraddle of the outside trace, Jenny stopped. Duke, who had been bawling and galloping, half hauled, half frightened, stopped likewise, the yoke crooked on his neck; and all stood heaving.

"This'll never do," panted Harry. "Jenny's too fast for him—either her legs are too long or his are too short. We'll have to train them singly and hitch them tandem. That's it: tandem."

"You mean one in front of the other?" wheezed Terry.

"Yes."

"Which where, then?"

"Oh, Jenny for the wheel team and Duke for the lead team, I think," decided Harry. "By rights, Jenny ought to have the lead, because she's faster; and Duke ought to have the pole, because he's heavier. But Jenny is quick-tempered with her heels, you know, and Duke is quick-tempered with his head, so we'd best keep their tempers separated. We can teach Duke to 'haw' and 'gee,' but Jenny's main accomplishment is simply to 'haw-haw.'"

"Here comes George," announced Terry. "Now he'll 'haw-haw,' too."

Through the gloaming another boy was loping in, on a spotted pony. He was a wiry, black-eyed boy—George Stanton, from the Stanton ranch some two miles down the valley.

"Whoop-ee! Which way you going?" he challenged. "What is it—a show?"

"Going to Pike's Peak," retorted Terry.

"Tonight? With that team? Aw——!"

"Pretty soon, though. We're practising."

"Watch us, and you'll see us drive to the corral," invited Harry. "Let's turn 'em around, Terry. Easy, now. I'll hold Jenny back and you hurry Duke."

"I'll help," proffered the obliging George. "Gwan, Duke."

"Duke! Gwan!" ordered Terry.

"Whoa, Jenny! Steady, Jenny!" cautioned Harry.

With Harry hauling on the lines, George, pony-back, pressing against Duke's shoulder, and Terry urging him at the flank, they all managed to achieve a half circle. Duke, his eyes bulging with rage and alarm, occasionally balked; Jenny flattened her ears and shook her scarred head; but finally the corral bars were really reached. It seemed like quite a victory.

"First lesson ended," decreed Harry. "Too dark, and we're tired if they aren't. We'll put 'em in together and they can talk it over."

Released into the corral, neither Jenny nor Duke appeared to be in very good humor. Duke rumbled and pawed, flinging the dirt; Jenny laid her ears and bared her teeth. Suddenly Duke charged; whereat Jenny nimbly whirled, and met him with both hind hoofs. Aside staggered Duke, to stand a moment, glaring at her and rumbling; then he turned and stalked stiffly to the other end of the enclosure. Jenny "hee-hawed" shrill and derisive, and kneeling down, rolled and kicked; scrambled up, shook herself, and began to nose about for husks.

"Now they understand each other," remarked Harry. "They've agreed to pull singly."

"Say—are you fellows really going to Pike's Peak?" asked George. "With that team?"

"Yes, sir-ee. We're in training, aren't we, Terry?" responded Harry.

"That's right. Dad said if we'd find our own outfit we could strike out."

"We've got the fever, too, sort of, down at our house," confessed George. "That's what I rode up about. Now I guess I'd better go back and tell the folks. Maybe I can join you," he added, waxing excited.

"The more the merrier. That will make twenty-five thousand and three," laughed Harry.

"If I can't, I'll be coming later," called back George.

"We'll locate a claim for you," promised Terry, grandly—as if he and Harry were already on the way.

"I'll tell you what I'll do," spoke Terry's father, finally. "I'll lend you $100—'grub-stake' you, as they say, from the dust that I fetched back last winter. That's half. And I'm to have half interest in whatever you find."

"Hum! This sounds like a good business proposition, if you mean it," accepted Harry, scratching his nose.

"Do you mean it, Dad?" cried Terry, overjoyed. "Supposing we find your mine. Do we get half of that?"

"That's part yours, anyway. But I don't think you'll find it unoccupied. Doubt if you find it at all. You'll likely meet up with some of the Russell brothers out there, though. You might ask Green Russell or Oliver or the doctor if they have any recollection of my being along with 'em, one of their Fifty-eighters, by name of Jones, and if they remember where I got the dust. Yes, I mean it: you and Harry'll need supplies, and you ought to have a little cash in hand besides."

"But we can go to digging gold, the first day we get there, can't we?" argued Terry.

"You might be a bit awkward and break a pick or shovel, and want a new one," remarked his father, drily.

Anyway, the $100 was not to be sneezed at. To be sure, Harry, with Terry assisting, had proceeded right ahead making ready. He was a wonder, was Harry. He had brought the two wagon-wheels from the mud-hole, and (Terry helping) had constructed a two-wheeled cart: had fitted a shallow body on the axle-tree and attached a pair of long heavy shafts. Jenny was to haul in the shafts, and the chains of Duke were to be run back to stout eye-bolts.

"You see," reasoned Harry, "some days when Jenny is tired and wishes to stop, Duke will be pulling the cart and she'll have to come along whether or no."

Jenny's collar and Duke's wooden bow and single yoke (manufactured to suit the case, from cast-off materials) were rough and ready, but no worse than the rest of the harness. However, on the whole Harry was rather proud of his work, and Terry was rather proud of Harry. Just now they were engaged in stretching a canvas hood over the cart.

As for Jenny, the yellow mule, and Duke, the half-buffalo—their days, of late, had been exciting ones. While they were being trained to haul tandem the ranch yard had resembled a circus-ring, much to the alarm of Terry's mother, and to the entertainment of Terry's father and the Stantons.

George and Virgie (who was his little sister) came up, whenever they could, to watch the preparation; and Mr. Stanton was considerably interested, himself. But George was more than interested; he was roundly sceptical—also, as anybody might see, envious.

"Aw, you don't think you're ever going to get there with that contraption, do you?" he challenged. "A rickety old cart, and an old mule and a half-buffalo! You'll bust down."

"I'd rather bust down than bust up," retorted Terry.

"It'll take you a year. Look at how your wheels wobble." And George added, somewhat oddly: "Wish I was going."

"If it'll take us a year, you might as well wait and come on with your own folks later," reminded Harry. "You'll probably travel in style, and pass us."

"That's right," hopefully answered George. "We'll pass you during the summer. You see if we don't."

"Said the hare to the tortoise," gibed Harry. "Terry and Jenny and Duke and I may be slow, but we're powerful sure—if our wheels keep turning."

He picked up a tar-pot and a stick, and stepped to the cart, on which the hood at last had been stretched.

"What you going to do now?"

"Don't hurry me," drawled Harry. "This isn't a hurry outfit." On the canvas he drew a letter. "What's that, Virgie?"

"'P'!"

"Right. And what's this?"

"'I'!"

"You're a smart girl—a smarter girl than your brother," praised Harry. "Next?"

"'K'!"

"Next?"

"'E'!"

"Next?"

"A—comma!" declared Virgie.

"Oh, pshaw!" deplored Harry. "You go to the foot." And he finished the word: "PIKE'S." He stepped back to admire the result.

"Pike's Peak or Bust! That's what you ought to put on," yelped George. "Pike's Peak or Bust! There was a wagon went down the valley yesterday with that on it. And it had four wheels instead of two."

"'Pike's Peak and No Bust,' is our motto," corrected Harry. He daubed rapidly, until the words stood: "PIKE'S PEAK LIMITED."

"I guess you're 'limited,'" sniggered George. "Anyway," he confessed, loyally, "wish I was going with you. I'll trade you my pistol for a share in your mine if you find one."

"That old pistol with a wooden hammer?" scoffed Terry. "You come on out and we'll give you a whole mine, maybe, if we have more than we can work!"

"I'll cook for you," piped Virgie.

"All right, Virgie," quoth Harry. "George can shoot buffalo with his pistol, and you can cook all he gets! You be ready tomorrow early, and we'll take you aboard on our way down."

"Do you start tomorrow?" blurted George.

"Sure thing," asserted Terry. "Stop at Manhattan, is all, to get supplies. Then we hit the trail for the land of gold."

The painting of "PIKE'S PEAK LIMITED" had indeed been the final touch. The start was set for the next morning immediately after breakfast. That evening in the cabin they all tried to be merry and hopeful, but Terry went to bed in the loft, where he and Harry slept, with a lump in his throat after his mother's goodnight hug and kiss; and although he dreamed exciting dreams of a marvelously quick trip and a row of mountains blotched with precious yellow, he awakened to the same curious lump.

But Harry hustled about briskly, before breakfast, to feed and water Jenny and Duke. Harry was always the first out.

he declaimed. "Eh, Jenny? Or should I say:

So Terry aided by carrying the stuff out, to be stowed in the cart. After breakfast there was no delay. Presently Jenny and Duke stood harnessed tandem, and rather wondering at the decisive manner with which they were handled. They little knew that six hundred miles lay before them.

"All aboard for Pike's Peak!" announced Harry. "You're to walk behind, Terry, for a piece, and pick up the wheels if they drop off. I'll encourage Duke and Jenny not to look back. Good-bye, folks."

"Good-bye, Mother. Good-bye, Father," repeated Terry. "Come on, Shep. You're going. Of course!"

Shep gamboled and barked. He was going and he did not care where, if only he went.

"We'll follow, in a month or two—as soon as we sell the place," called Father Richards. "We and the Stantons, too, I guess. Get posted on the country, and be careful. Good luck. Look up the Russells."

"Yes, be very careful," enjoined Mother Richards. "Don't get lost, and don't sleep in wet clothes, and don't fail to send word back often, and, Terry, don't disobey Harry, and, Harry, don't you try to perform all the work, and, both of you, don't have any disputes or quarrel with anybody, and don't omit to eat hearty meals——"

"Oh, Mother Richards!" laughed Harry. "This is a Do concern, not a Don't. But we'll remember. You'll find us ready to trade you our gold dust for a pan of good corn-bread. Good-bye. Gee-up, Duke! Step ahead, Jenny! Whoop-ee! G'lang!"

"Whoop-ee!" cheered Terry, stanchly, as now he trudged in the wake of the creaking, lurching cart. "Hooray for the Pike's Peak Limited to the gold mines!"

They were on their way; they were real gold-seekers, bound for the Pike's Peak country. In his cow-hide boots and red flannel shirt and slouch hat, Terry felt that no one should make fun of their rough-and-ready outfit. A half-buffalo, and a yellow mule, and a two-wheeled cart with a regular prairie-schooner hood, and a tar-pot hanging to the axle, indicated serious purpose.

Black Shep loped happily from side to side, hunting through the weeds. At the "near" or left of Jenny strode Harry, with a slight limp, a willow pole in his hand to serve for occasionally touching up Duke. Harry also wore cow-hide boots, trousers tucked in, and a battered slouch hat, but a gray shirt instead of blue or red. However, a red 'kerchief for a tie gave him a natty appearance.

"Duke! Hi! Step along!" he urged. And—"Not so fast, Jenny!" he cautioned. Duke pulled steadily, keeping the chains fairly tight; Jenny, her ears wobbling, but now and then laid back in protest at one thing or another, slothfully dragged her long legs. Together they easily twitched the lightly laden cart over the rutted road.

George and Virgie were waiting in front of the Stanton ranch, to see the gold-seekers pass. Mrs. Stanton waved from the ranch-house door, and Mr. Stanton from the potato field.

"Where are your guns?" demanded George, first crack, much as if he had expected to see them heavily armed on this peaceful trail down to Manhattan.

"Got a shot-gun in the cart," answered Terry.

"How'll you fight Injuns, then? Where are your mining tools—picks and spades and things?"

"Get 'em later."

"Coming, Virgie?" hailed Harry.

Her finger in her mouth, Virgie shook her head in its pink sunbonnet.

"I can't. My mother needs me."

"All right. Sorry. We need a cook. Duke! What are you stopping for? Gwan! Hump along, Jenny!" And to creak of top and jangle of fry-pan and tin plates and cups, and water bucket clashing with tar pot, the Pike's Peak Limited pressed on.

"We'll see you later, though," promised George, gazing after wistfully. "Good-bye."

"Good-bye, George."

All down the valley people called and waved good-bye, for the word that the "Richards boys" were going to Pike's Peak had traveled ahead. And many a joke was leveled at Duke and Jenny and the two-wheeled cart bearing its Pike's Peak sign. But who cared? Everybody seemed bent upon following as soon as possible; and as Harry remarked: "We're doing instead of talking!"

Manhattan town was a day and a half, at walking gait.

"No ranch house for us tonight," quoth Harry. "We'll start right in making our own camp. And we'll have to start in with a system, too. First we'll noon, for an hour, to rest the animals—not to mention ourselves. My feet are about one hundred and ten degrees hot, already. And we'll make camp every evening at six o'clock. If we don't travel by system we'll wear out. There's nothing like regularity."

So they nooned beside a creek; had lunch and let Duke and Jenny drink and graze. That evening, promptly, they camped, near water. Harry had elected to do the cooking and dish-washing, Terry was to forage for fuel and tend to the animals.

Jenny was staked out for fear that she would take the notion to amble back to the ranch. Duke, who appeared to think much more of her than she did of him, could be depended upon to stay wherever she stayed. Harry boiled coffee, and fried bacon, and there was the batch of bread that Mother Richards had baked for the first stages of the journey.

When everything had been tidied up and the camp was ship-shape, in the dusk they "bedded down," each to his coverings. Whew, but it felt good to shed those hot boots! They also removed their trousers, and used them and their coats for pillows.

Harry sighed with luxury.

"First camp—twelve miles from home," he said.

"Wonder how many camps we'll make before we get there," proposed Terry.

"Some forty, I reckon," murmured Harry. "Six hundred miles at an average of fifteen miles a day—and there you are. But we have to make only one camp at a time."

"Hello!" cried a voice, through the dusk.

Shep growled, where he was curled, but instantly flopped his tail, and with a quick look in the direction of the voice, Harry called, gladly:

"Hello yourself. Come in."

"Hello, Sol," welcomed Terry.

They sat up in their blankets. A horseman approached along the back trail, and halted. He was a lean, well-built man, with long hair and full beard, and sat erect upon a small but active horse. He wore a peaked, silver-bound sombrero or Mexican hat, a black velvet Mexican jacket half revealed under a gaily striped blanket over his shoulders, tight black velvet trousers slashed with a white strip, and on his heels jingling spurs. The saddle was enormous, and the bridle jingly and silver-mounted. But he was no Mexican; he was Sol Judy, the American horse-trader, who had been in California and on the plains, and was counted as almost the very first friend made by Terry and his mother when they had started in to "ranch it," a year ago, while waiting for Mr. Richards to come home. And a very good friend Sol Judy had remained.

"How's the Pike's Peak Limited by this time?" he queried, with a smile, as he sat looking down. "On the way to the elephant, are you, and as snug as a bug in a rug?"

"'Light, 'light," bade Harry. "Have a cup of coffee, Sol. Wait till I put on my pants."

"No, no; thank you," declined Sol. "I've eaten and I'm going on through." It seemed as though Sol was always bound somewhere else. "I passed the ranch and stopped off a minute, and they told me you'd gone. So I knew I'd probably catch you. I'm on my way, myself."

"To the mines, Sol?"

"Yes, sir-ee. Just got back; been in Leavenworth a short spell, and am headed west again, for more of the elephant."

"What elephant?"

Sol laughed.

"The big show. 'Seeing the elephant,' they call it, now, when they set out for the Pike's Peak diggin's—because there are folks who don't believe there is any such critter."

"Did you see him, Sol?"

"Well, you know we've seen a goose-quill or two containing a few freckles from his hide."

"What trail's the best?" queried Harry.

"I went out by the Santy Fee Trail and came back by the Platte government trail. But those are too long for you. I hear tell a lot of people are going to try the trail straight west, up the Smoky Hill. If I were you, though, I wouldn't tackle that. The water peters out. You'd do better to cut northwest from Riley or Junction City, over the divide between the Solomon and the Republican, and strike the Republican. Jones and Russell, the Leavenworth freighters, are going to put on a line of stages by that route, and they know what they're about. They've surveyed a route already, and I shouldn't wonder if you'd find some of their stakes. Anyway, the stages'll overtake you, and then you'll have their tracks and stations. On the divide you'll keep to the high ground and head the creeks and save a lot of trouble. Always travel high; that's my notion. The fellows that try to follow the brush river-bottoms are the ones who get stuck. You may have to make one or two dry marches, but you can keep your water cask full."

"What's doing out at the mines, Sol?"

"Doing? There were about two hundred people there when I left. They'd had a nice mild winter; only one cold snap at Christmas. They're all collected at Cherry Creek; they've started two towns opposite each other, near where the creek joins the Platte. The one on the west side the creek they've called Auraria; the one on the east side was St. Charles for a time, but now it's named Denver, after Governor Denver of Kansas Territory. Auraria's the bigger, to date. What it'll be in a month or two, can't tell. That's where they're all living, anyhow: in Auraria and Denver. S'pose you've read in the papers that last fall they held a meeting and set off the Pike's Peak country as 'Arapahoe County' of Kansas, elected a delegate to the Kansas legislature, and another to go to Washington and get the government to let 'em be organized as a new separate Territory. He hasn't done much, though. Congress won't listen to him. It's all too sudden. Proof of the elephant hadn't reached there yet."

"Are they digging lots of gold, Sol?" asked Terry, eagerly.

"You could put all the gold I saw in two hands," declared Sol. "It's mostly color, and flake gold washed from the creeks. They haven't got down to real mining, and some of the people who counted on an easy time at getting rich quick are plumb disgusted. What's been done since I left I can't say. But the gold's in the mountains, and it'll take work to dig it out."

"How far are the mountains from the towns? How far's Pike's Peak, Sol?" demanded Terry.

"The real mountains are about forty miles, I judge; and that Pike's Peak we're all hearing of is near a hundred. 'Cherry Creek' diggin's is a heap better name for the place than 'Pike's Peak.' Pike's Peak is away down south and there aren't any mines there, yet. Well, how's your outfit behaving? Does the mule pull with the buffalo?"

"First-rate," answered Harry. "They're used to each other."

"That's good. Usually a mule's got no love for a buffalo. You want to watch out when you get into the buffalo country or you'll have trouble, sure, with one or the other of your critters. And I'd advise you to peg along as fast as you can and keep ahead of the crowd or there won't be a piece of fuel left as large as a match, to cook with."

"Jiminy! That sounds like a rush," exclaimed Harry. "Then what the papers say is true—about twenty-five thousand people."

"Twenty-five thousand!" laughed Sol. "I've been at Leavenworth, and Kansas City too, and every steamer from the south is loaded to the stacks. You can't see the steamers for the people! Those two cities are regular camps—streets jammed, merchants selling tons of supplies, wagons and critters hardly to be bought for love or money, and the country around white with wagons and tents of folks making ready—waiting for a start. Same way up at Council Bluffs, where the crossing is from Iowa into Nebraska to strike the Platte River Trail. In a month the Platte Trail will be so thick you can walk clear from the Missouri to the mountains on the tops of the prairie schooners. So you do well to peg along early. The rush is begun." Sol reined up his horse, preparing to leave. "Good luck to you, boys. I'll see you at the mines."

"We've got one waiting for us, maybe, you know, Sol," reminded Terry. "And—"

"All right," answered Harry. "We'll see you in the land of the elephant, anyway. So long."

And Sol galloped south, into the darkness.

Before noon of the next day Harry, in the advance guiding Jenny and Duke, swung his hat and cheered.

"Did you ever see the like!" he cried. "The rush has begun, all right."

"I should say!" gasped Terry.

They had arrived in sight of the town of Manhattan, just above the mouth of the Big Blue, on the Kansas River emigrant trail from the east. The prairie for half a mile around was alive with campers; the smoke from a host of dinner fires drifted upon the clear air, and a great chorus arose—shouts of men, cries of children, bawling of cows and oxen, barking of dogs.

"And this is only one trail from the Missouri," said Harry. "Hurrah! Gwan, Duke, Jenny! Gwan!"

As they proceeded down the valley road, for the town, presently they struck the overflow of the encampment, and began to be greeted from every side. Duke and Jenny apparently attracted much attention.

"Whar you think you're goin', boys?"

"Why don't you get astraddle an' ride?"

"Is that a genuyine buff'lo?"

"Who invented that rig?"

"I'll trade you a cow for your mule, strangers."

"When do you give your show?"

And so forth, and so forth. Men laughed, women and children stared, dogs barked, and Shep, bristling, took refuge under the cart. To all the sallies Harry, and sometimes Terry, made good-natured reply, for this was a good-natured crowd.

Many wagons besides theirs bore signs. There were several with "Pike's Peak or Bust," which evidently was popular. "To the Land of Gold" was another favorite scrawl. One wagon announced: "Mind Your Own Business." Another proclaimed: "From Pike County for Pike's Peak." And another: "We're Going to See the Elephant—Are You?"

As they entered the main road they turned in just ahead of a rickety farm wagon with flimsy makeshift cotton hood, containing a strange medley of children, women, household furniture, what-not. It was drawn by a cow and a gaunt horse, a goat was led at the rear, a dusty, sallow man trudged alongside. The wagon-hood said: "Noah's Ark."

"How'll you swap outfits, strangers?" sung the man.

"Nary swap," laughed Harry.

"Whar you from?"

"Up the Blue."

"We're from Injianny," quavered one of the women, on the front seat. "It's a powerful long way to the gold fields, isn't it?"

"You've hardly started yet," replied Harry. "But just keep a-going." And—"Whoa, Duke! Look out, there! Gee! Gee-up!" He thwacked Duke smartly on the shoulder with the willow pole, and ran to his head. The road before and behind was thronged with the travelers, and Duke, not accustomed to so much confusion, had been waxing restive. He snorted, his eyes bulged, his little tail jerked, and he made a side-ways jump at an annoying dog. Out flew Shep, rolled the dog over and over until he fled yelping, while with rapid commands Harry quieted Duke. Even Jenny the yellow mule was showing symptoms of rebellion.

"We'll never get into town, this way," panted Harry. "Let's drive around and on to the river and unspan for noon. Then you watch Duke, and I'll ride Jenny back in for supplies."

So, picking their path, they began to circuit the little town. To do this was considerable of an undertaking, for the tents and wagons and people were scattered everywhere over the prairie, and Duke much resented the shouts and laughter and smoke and barking dogs and the incessant orders from Harry. His eyes bulged, he rumbled indignantly, he shook his head, the froth dripped from his lips.

On a sudden a mean little cur darted from one side and nipped him in his heel—and this was the last straw. With a lunge and a kick away he bolted, dragging the surprised Jenny until she also lost her temper, and together they dragged the cart.

Harry ran, shouting. Terry ran. Shep yapped excitedly.

"Stampede!"

"Look out for the buffalo!"

"Hi! Hi!"

"Head 'em off!"

Women hastily clutched children, men waved their arms and hats.

"Duke! Jenny! Whoa! Whoa!" vainly yelled Harry and Terry, following at best speed in the wake of the lurching cart.

Through among the camps galloped Duke and Jenny—Duke cavorting, Jenny plunging, the cart bounding and skidding, the pails and cooking utensils rattling, people scampering from the path; and Harry and Terry, in their heavy boots, pursuing, wild with alarm. Something serious was likely to result.

There! A dinner group was shattered—away rolled the pot, and the fire flew. There—down collapsed a tent, as the cart struck the guy-ropes! Into a clearing burst the two animals—but straight for a wagon and ox team facing them, beyond! The wagon had no hood, and its principal occupants were a black-bearded, black-hatted, red-shirted man on the seat and a large barrel in the box.

Duke must have been seeing red, by this time. His head down, he charged at the wagon, or oxen, or both. The man on the seat yelled; swung his arm at Duke; swung his whip at his own team—tried to turn them; and then, in a great panic, with a mighty leap landed asprawl and losing his hat, legged for safety, his boot-tags flopping and his shaggy hair tossing.

"Ha, ha!" roared the spectators. And the man did indeed look funny.

The yoke of oxen suddenly awakened to the danger, and sharply veered. Duke just missed them, at an angle—he and Jenny both, but the cart struck the rear of the wagon, tilted it, tilted the barrel, and there stayed, locking wheels with it, while Duke and Jenny were brought to a quick stand.

Up raced Harry and Terry, to investigate damages. At the same time back clumped the man, aglare with rage.

"Oh, crickity!" gasped Terry. "It's Pine Knot Ike!"

"Hyar!" he bellowed. He searched for his precious hat and clapped it on his ragged locks. Now his hair and whiskers stood out all around his face. "Hyar! I want to ask what you mean by rampagin' through a peaceful collection o' citizens an' endangerin' the life an' property of a man in pursuit of his lawful okkipation? I air mild, strangers; I kin stan' a good deal, but now I air after blood. My name is Ike Chubbers, but most people call me Pine Knot Ike, 'cause I air so plaguey hard to chaw. That thar air your buffler, air it? Waal, I will now perceed to eat him."

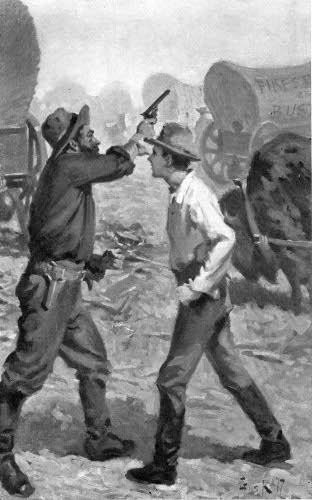

With that, Ike whipped a huge revolver from his belt—and instantly Harry sprang like a cat for him—grabbed the arm—"None of that, Pine Knot Ike!"—bang went the gun, and the bullet plinked somewhere, but not into Duke.

"None of that, Mr. Ike Chubbers!" repeated Harry, stoutly forcing the muzzle upward. "You can't shoot any animal of ours. Besides, no damage had been done."

"Yes; you can't go shooting promiscuous through a camp like this, friend," spoke somebody in the crowd that had gathered. "Those boys aren't to blame for their stampede. Put your gun where it belongs."

"Why didn't you stay with your wagon?" demanded somebody else.

Pine Knot Ike slowly relaxed. Harry released his grip on the revolver, and Ike glared around. His fierce black eyes came back to Harry, who stood breathless but ready.

"We have met before, stranger," he growled. "You air the schoolmaster who nigh murdered me in this hyar very town. You know me, I reckon?"

"I am the schoolmaster who made you dance, with your own revolver, after you'd threatened to kill me if I didn't drink liquor for you," retorted Harry. "Yes, I know you for a big bulldozer."

And Terry well remembered the first encounter, last summer, between Harry and Pine Knot Ike, when Harry not only had refused to drink but had cleverly snatched Ike's gun and ordered him to dance as a penalty. Yet Ike was as large in body as two Harry Reveres.

"Haw, haw!" laughed the crowd.

Ike glared around again.

"I cherish no bad feelin's," he alleged. "I air a man o' peace. I air so peaceful that I hain't bit a nail in two for nigh a full week. I mostly drink milk." His breath did not smell milky! "I air so peaceful that I gener'ly lay down an' let folks walk on me. But I would ask if a peaceful man pursuin' a lawful okkipation, on his way to build up a civi-li-zation in them Rocky Mountings air to be run over by two boys an' a wild buffler an' a yaller mule?"

"Hey! Your whiskey's leakin'!" called a voice.

And that was so. Pine Knot Ike exclaimed and leaped for his wagon. The odor in the air had not been entirely from his breath. The bullet intended for Duke had punctured the barrel near the top; and now the wagon was dripping.

Ike hastily clambered in. First he tried to stop the hole with his thumb; next with his hat; and while the crowd hooted he shamelessly stooped and glued his lips to the spot!

"Haw, haw! There's his 'lawful okkipation'!"

"That's his idee of 'civi-li-zation,' is it?"

"Pity the hole isn't at the bottom instead of near the top," remarked Harry, disgusted. "Come on, Terry."

With a little help they freed the cart from the Chubbers wagon; and driving the now quieted Duke and Jenny, proceeded on their way. Behind, they heard Pine Knot Ike haranguing the crowd, proclaiming that he was a "ruined man." But he seemed to get scant sympathy.

Without more adventure they completed the half circuit of Manhattan town, crossed the main road and between the road and the Kansas River found a shady spot where they might noon comfortably. Duke was tied by a fore-leg to a tree (they knew better than to tie him by the horns, for he was strong enough to break any rope, that way); and after lunch Harry rode Jenny bareback, down to town, for supplies.

The road up-river was one line of outfits toiling onward under a cloud of dust. They were interesting to watch. Was the whole United States moving westward for the mountains? The constant procession passed—wagons of all descriptions, men horseback and muleback, men, women and children afoot; a party of men accompanying a push-cart hauled by two of them in the shafts. The "Noah's Ark" wagon passed. And Pine Knot Ike's wagon, with Ike swaying tipsily on the seat. And now a man wheeling a wheel-barrow. But he did not pass, after all. He turned aside, and deposited his laden barrow and himself under a tree near Terry.

He ate his lunch, and eyed Terry, Shep and Duke.

"How'll you trade?" he asked. That was the customary challenge.

"No trade," answered Terry, promptly. "Are you going clear to Pike's Peak with a wheel-barrow?"

"Yes, sir. I'll push across. I've got the best outfit of anybody. Only my own mouth to feed, and don't need to look for grass. When I make a dry camp I'm the only sufferer. I can set my own gait, too—can cover twenty miles a day. Well, my name's McGrew. What's your name? Where you from, where'd you get that buffalo, who's with you, and what trail do you calculate on taking?"

He seemed to be a very cheerful, plucky man, and Terry replied in fashion as friendly.

"My name's Terry Richards. My partner's Harry Revere—he's the same as a brother. We're from up the Big Blue. This buffalo is half cow; I caught him when I was hunting with the Delawares; his name is Duke. We're thinking of taking the Republican trail."

"Oh, you're the boys from the Big Blue, are you? I might have guessed. I've heard about you."

"Have you?" responded Terry, curious.

"Yes. Sol Judy rode through last night and told me to keep an eye out for you; but you seem able to take care of yourselves, all right, judging from your little set-to with that whiskey peddler. I only wish the shot had gone lower, but the chances are he'll empty his barrel himself before he gets to the diggin's."

"Which trail do you think you'll follow?" asked Terry, in turn.

The wheel-barrow man scratched his head.

"I travel light. Believe I'll tackle the Smoky Hill route, straight west from Riley. It's shortest. Sol favors the Republican, on account of the stages. The majority of the people are going by the Smoky, though, or by the Santa Fe Trail—except those who are already striking the Republican farther to the north of us. The California and Oregon Trail, up along the Platte, of course will be the main trail."

Harry returned with a sack of flour, a side of salt pork or sow-belly, some sugar and coffee and beans, matches, a hatchet, and a few other articles. His arms were filled, and Jenny was almost covered, much to her disgust. She hee-hawed at Duke, and Duke stared wonderingly through his matted forelock.

"Best I could do," hailed Harry. "Never saw such a mob. The stores are near cleaned out. I couldn't get picks or spades for love or money, but I reckon we can find them at the other end, or maybe at Junction City beyond Riley."

"Well, I'll see you boys at the diggin's," spoke the wheel-barrow man, rising and grasping the handles of his barrow. And away he trudged, to skirt the procession on the dust-enveloped road.

"He says he's going to try the Smoky Hill trail," informed Terry, "because it's shorter."

"It may do for him," answered Harry. "But the more haste the less speed, for some of the rest of us. I believe we'd better take Sol's advice, and break our trail across to the Republican until the stages catch up with us."

Fort Riley was fifteen miles west. Progress was slow, on the crowded road, and at six o'clock the "Pike's Peak Limited" was glad to draw aside out of the dust and camp for the night near to a wagon labeled "Litening Express." The owner was a heavy, round-faced German, with a family of buxom wife, and of six girls ranging from big to little. He had a chicken coop, a large cook stove set up for the evening meal, a feather mattress, and an enormous bale of gunny-sacks that formed a seat for him while he watched the supper-getting.

Harry and Terry called easy greeting, and pretty soon he strolled over.

"Iss dat a wild boof'lo?" he queried.

"He was wild once, but he's tame now."

"You are de boys who made dot man loose his whiskey, mebbe."

"I guess we are," laughed Harry. It was astonishing, the speed with which news traveled among the overlanders.

"Dot was a goot t'ing. How far you say to dose gold mines, already?"

"'Bout six hundred miles. What are you doing with all those sacks?"

"I t'ink I poot my gold in dem, an' bring it back home."

"That'll be quite a load, won't it?" smiled Harry. "You know gold weighs mighty heavy."

"I haf a goot team," replied the German, not at all worried. "I fill my sacks, an' poot dem in my wagon, an' I come home in time for winter, an' den I am rich. I will be one of de richest men in Illinois. Mebbe next year I do it over."

"A very fine plan," remarked Harry, gravely. And the German returned to his own fire, much satisfied.

"Jiminy! Is that the way?" blurted Terry, suddenly excited again. "We ought to've brought sacks."

"We've a sack of oats and a sack of flour, and I wouldn't trade 'em for his sacks of gold—yet," retorted Harry.

This night the flickering camp-fires of the other gold-seekers twinkled all along the road. Fiddles were tuned up, to play "Monkey Musk," "My Old Kentucky Home," "Yankee Doodle," and other tunes, and voices joined in. What with the playing and singing, the barking of dogs and the noises from cattle, sleep was difficult except for persons as tired as were the "boys from the Big Blue."

At Fort Riley, which was a new army post, with massive stone buildings, near the juncture of the Smoky Hill River from the west and the Republican River from the north, here forming the Kansas River, the number of outfits lessened. Some struck north, some took a short cut south for the Santa Fe Trail at the Arkansas River.

At Junction City, beyond, the last of the white settlements, the route of the remaining "Pike's Peak Pilgrims" again split. The main portion of the travelers seemed to favor the new trail straight westward, up along the Smoky Hill River, and on they toiled, to "get rich in a hurry." It was the common report that the Smoky Hill River could be followed clear to the mountains, but this, as Harry and Terry afterward heard, proved untrue.

Another portion turned off southward, for the Santa Fe Trail again. A good government road led down to it. Only a few had decided upon attempting the newest trail of all: that to the northwest, for the Republican by way of the divide between the Solomon River on the left and the Republican, far on the right.

"We're on our way," tersely remarked Harry, as the "Pike's Peak Limited" left Junction City for the unknown. "It's liable to be lonesome, till the stages come."

However, several wagons had preceded; and this first night camp was made at a creek, and close to another party also camped.

"Whar you boys from?" That was the first question.

"Do you calkilate to get thar with a buffalo and a yaller mule?" That was the second question.

"How'll you swap dogs?" That was the third question.

And—"Do you figger on diggin' out your pound of gold a day?" was the fourth question. For Eastern papers had asserted that this was the regular output of the Pike's Peak country: a pound of gold a day to each miner!

"Half a pound a day will suit us," responded Harry.

"Dearie me!" sighed the woman—a nice, motherly woman, the sight of whom imbued Terry with a little sense of homesickness. "We all count on a pound a day for one hundred days, so as to buy a farm back in Missouri. Maybe, if the children and I dig, we can raise it to two pounds a day. That'll be two hundred pounds, which is a right smart amount of money."

Junction City having been put behind, now there was not even a cabin to be seen. The high plain between the valley of the Solomon on the south and the valley of the Republican on the north stretched wide and unoccupied save by the squads of antelope, the scant trees marking the creek courses, and the scattered white-canvased wagons ambling on.

It was a go-as-you-please march. Outfits wandered aside, seeking better trail or better camping-spot. Occasionally one had broken down, and was halted for repairs or rest. Already the chosen route was dotted with cast-off articles, abandoned to lighten the loads. Bedsteads, trunks, mattresses, chairs—and Harry, pointing, cried:

"There's the 'Lightning Express' stove!"

For the German's heavy cook-stove reposed, by itself, on the prairie—and odd enough it looked, too.

"Wish we'd come to his feather tick, some evening," quoth Terry.

Fuel, even buffalo chips (which were the dried deposits left by the buffalo, and burned hotly) were scarce. The "Limited" aimed to camp each evening at a creek, if possible, where trees might be found; but most of the dead wood had been used by other travelers, or by Indians, and the green willow and ash smudged. The sage and greasewood burned well, but burned out very quickly.

Duke and Jenny footed steadily, making their twelve and fifteen miles a day, up and down, into draws and out again, and the "Limited" seemed to be gradually forging ahead. For a time, each night camp might be established (a very simple matter) in company with other pilgrims; and the spectacle of the half-buffalo and the yellow mule pulling in, or already waiting, invariably excited the one conversation.

"How far to Pike's Peak, strangers?"

"Five hundred miles or so, yet, I guess," would answer Harry, politely.

"It's an awful long trail, this way, ain't it? How far to the Republican?"

"That I can't say."

Then the outfits would exchange travel notes and personal history.

But the trail was petering out, as Harry expressed, more and more, as the creeks were being headed, and anxious gold-seekers swerved aside looking for the Republican Valley and better water.

About noon one day a giant, solitary tree waited before. Several wagon-tracks led for it, and Duke and Jenny followed of their own accord. It was a big cottonwood, with half the bark stripped from its trunk by lightning.

"A store of good wood, there," remarked Harry. "Wonder why nobody's chopped it down."

"It's got a sign on it," exclaimed Terry. "See?" And—"'Pike's Peak Post Office,'" he read, aloud.

The sign was plain; and presently the reason of the sign was plain. On the white surface of the peeled trunk was scrawled a number of names and other words.

"Pike's Peak or Bust!"

Underneath: "Busted! No wood, no water, no gold. Boston Party."

Also:

"Keep to the north."

"Climb this tree and you won't see anything."

"The jumping-off place."

"The Peoria wagon. All well."

"Bound for the Peak, are you?"

"'Litening Express'!" announced Harry. "Our German friend is still ahead."

"'Mr. Ike Chubbers'!" spelled out Terry, with difficulty. "Aw, shucks! He's this far already."

"Yes, and there he went!" laughed Harry, gleefully. "Those are sure his tracks. He's sampling his barrel."

And by token of a weaving, wobbling, sort of drunken pair of wagon-wheel tracks that made a wide swing for the north, Pine Knot Ike evidently had continued in a new direction.

"He's hunting the Republican," agreed Terry. "Hope we don't run into him."

"Nope," declared Harry. "Once is enough. Hurrah!" he uttered. And he read: "'Stage line here. Sol Judy.'"

"That's so." And Terry peered. "But I don't see the line. Wonder which way he went. There's a double arrow, pointing both ways. Wonder if it's his. Wonder when he wrote here. If somebody hadn't written on top of him with charcoal, a fellow might tell."

"Anyway, we won't turn off yet," declared Harry. "And if we stand here 'wondering' we won't get anywhere at all. He said to keep northwest by the high ground. Maybe that wagon track ahead is the Lightning Express. We'll keep going. Gwan, Duke! Jenny!"

"Sort of wish we'd gone by the Smoky Hill, don't you?" ventured Terry. "We'd had more company."

"When we strike the Republican we'll find plenty company," asserted Harry. "This is getting rather lonesome, I must confess."

Not a moving object was in sight. The "Pike's Peak Post Office" tree stood here all by itself, as if waiting for the stages. And yet, Terry well knew (unless the sights at Manhattan had been a dream), north and south of them thousands of people were trooping, trooping westward in long, human rivers of creaking wagons.

He and Harry gave a last look behind and on either side, searching the brushy expanse for other outfits; then they left the friendly cottonwood and headed westward again, in the tracks of the wagon before. But suddenly Harry stopped.

"Pshaw! We forgot." And he limped hastily back to the tree. With his pencil he wrote on it. Of course! Terry returned to see.

"The Pike's Peak Limited. April 20, 1859. All well," announced this latest inscription.

"Somebody will read it," quoth Harry. "It'll show we got this far ourselves." And they returned, better satisfied, to the cart.

"There's one thing sure," continued Harry: "The less company we have, the more fuel and forage we'll find. We're getting into the buffalo country, too. See?"

For the surface of the ground was cut deeply by narrow trails like cattle trails, but made by buffalo wending probably from water to water. Some of the trails had been freshly trodden.

"That means we'll have to look sharp after Duke and Jenny," warned Terry.

They proceeded.

"Well, here come a party," remarked Harry. "But they're going the wrong way."

"Maybe it's some of the stage line surveyors."

The party, of three men, two of them horseback and one of them muleback, drew on at trot and rapid walk. The men were bearded, roughly dressed, and well armed with revolvers and rifles. Meeting the Pike's Peak Limited, they halted. So Harry and Terry halted.

"Howdy?"

"Howdy yourselves. Where you bound?"

"For the land of gold," cheerfully answered Harry.

"Land o' nothin'!" rebuffed the spokesman of the party. "Turn back, turn back, 'fore you starve to death."

"Why? Are you from the Pike's Peak mines?"

"We're from the Cherry Creek diggin's, young feller, but we didn't see any mines there nor nowheres else. It's all a fake, and we're on our way to tell the people so and save 'em their bacon."

"Aren't you bringing any gold?" exclaimed Terry. "Have you been there long?"

"Long! Gold!" And he turned his pocket inside out. "That's the size of your elephant. We've been there since last November, sonny, and the gold is in your eye. That Pike's Peak craze is the biggest hoax ever invented. It's just a scheme of a few rascals to sell off town lots. They want to get people to come out yonder; and gold is the only thing that'll persuade 'em into the barrenest, porest country on the face of the 'arth. We've been thar, so we know. We couldn't get out, in the winter; but everybody's leavin' now, to tell the folks along all the trails to face back and go home."

Terry felt a sinking of the heart. Harry also seemed to sober.

"What gold is it that's been sent out of there, then?" he asked.

"Californy gold! Fetched through from Californy. Never was taken out of that Pike's Peak country at all. Californy gold, used to fool the people with, back in the States."

"But my father brought home two hundred dollars in gold, and he found it there somewhere, himself—near Pike's Peak," argued Terry, with sudden thought. "We've already got a mine!"

"He did, did he? Waal, if he did he was lucky, and he was luckier to get out with it. Thar may be a little gold—thar's gold to be washed from 'most any mountain stream, but you can't eat gold. Yon country's a freezin' country and a starvation country and an Injun country, fit for neither civilized man nor beast. The government'll need to step in and forbid people goin' to it. The hull of it ain't wuth an east Kansas acre."

"All right. Much obliged," said Harry. "So long."

"Goin' on?"

"We'll try a piece farther," said Harry. "How's the trail ahead? Did you see any stage line stakes?"

"Stage line stakes! What you dreamin' of? That stage idee is another hoax. You'll find that out, together with a few other things. But if you're set on bein' a pair of young fools, go on. We haven't more time to waste with you."

And forthwith the party spurred on its eastward way.

"Look out for Injuns," called one, over his shoulder.

"Humph!" mused Harry. "Doesn't sound very encouraging, but we can't believe everything we hear, for and against, both. If we did, we'd never know what to do. A fellow has to act on his own hook, sometimes, until he can judge by his own experience, where he can't depend on the experience of others. That party may have secret reasons for talking so." He eyed Terry. "Shall we go on, clear through? I don't think a few discouragements will turn the wheel-barrow man back."

"I don't, either!" declared Terry, bracing. "Let's go on."

"Duke! Jenny! Hep with you!" responded Harry. "Hurrah for the Pike's Peak Limited, and maybe the Lightning Express, too! But no German with a wife and six girls and a feather bed shall beat this outfit. We're liable to come on a stake, any time. And the next will be only a few miles, and the next another few miles, and at that rate we'll hit the Republican River smack."

But to Terry, surveying the monotonous, empty landscape, single stakes planted maybe days' journeys apart seemed rather small landmarks.

In mid-afternoon they did indeed overtake the "Litening Express." It was halted beside a small, stagnant water-hole, as if making early camp. The wife and the six girls were sitting around, in disconsolate manner, and the German himself was soaking his naked feet in the water.

"What's the matter here?" hailed the cheerful Harry. "Broken down? You're pointing the wrong way."

For that was so. The one wagon track beyond had doubled, and the wagon, from which the team had been unspanned, was heading east instead of west.

"Yah," stolidly answered the German. "We go back. Dere iss no elephant. Now we go back again home quick. We haf met some men who haf told us."

"Oh, pshaw!" uttered Harry. "You're half-way. Better go the rest of the way and see for yourself. You mustn't let a few wild rumors stop you."

"Don't you intend to fill your sacks?" added Terry.

"Dere iss no gold, so dey say; an' notting else," insisted the German.

"Once you believed there was, and now you believe there isn't," laughed Harry. "You might as well believe the first as the second, as far as you know."

"And there is gold, because we've got a mine," encouraged Terry.

"Nein." And the German shook his head. "I set out to fill my sacks; dose men say I cannot fill dem. So I go home. I t'ink you better go home, too. You camp here with us, an' I fix my feet, an' we haf a goot supper, an' den in mornin' we travel togedder."

"Nope, we're bound through," replied Harry. "This is no time of day for us to camp." And Terry was relieved to hear him say so, for the stagnant pool, with the German's feet in it, did not look very inviting. "What did you find ahead?"

"Notting an' nobody," grumbled the German. "All joost like dis." And he swept his arm around to indicate the bare stretch of plains. "Purty soon you see where I turn to go home, an' den you be all by yourself. I do not like it. I like peoples. So I go home."

"You didn't see any stake, did you?" queried Terry.

"What stake?"

"To mark the stage line."

"What for would dey poot any stage line where dey ain't peoples?" demanded the German.

"All right: how'll you sell your mining tools?" asked Harry, with alert mind. "You've no use for them."

"Mebbe I dig garden. But I sell dem to you for one dollar an' half—de whole lot."

"Done!" cried Harry. "And how about those sacks?"

"Dey iss goot potato sacks. But what will you gif me for dose sacks?"

"Four bits."

"Well, I guess you take dem. You t'ink to poot potatoes in dem? Nein, nein; you iss crazy. It iss as crazy as to t'ink to poot gold in dem."

When they left the German, who had resumed the soaking of his sore feet in the general pool, they were possessed of two new picks, two new spades, a cask of sauerkraut, and the bale of sacks.

"What'll we ever do with the sacks?" inquired Terry.

Harry scratched his long nose.

"Blamed if I know, yet," he admitted. "But you never can tell."

In about an hour they passed the place where the "Litening Express" had turned about. Now there was no trail at all, except the endless buffalo trails. Somewhere they had lost even the hoof-prints of the three horsemen.

They made late and solitary evening camp on the farther side of a deep creek bed, whose banks had been broken down by crossing buffalo. There was so little water that Terry had to dig a hole, in order to get a pailful for supper and breakfast. But in wandering about searching for buffalo chips in the gloaming, he shouted gladly:

"Here's a stake—a new one! It says: 'Station 11'!"

Harry limped to inspect.

"Bully!" he enthused. "We don't care where the other ten are. This shows we're on the right road. Well, Mr. Station Master, I want supper and beds for two, and a guide to the next station. What's the tariff, and what'll you trade for sauerkraut and gunny-sacks? But I wish your company'd make your stations a little bigger, for this is a powerful big country."

However, tiny as it was, the stake appealed as a human token. There were signs, also, of an old camp, near the creek; and from the stake hoof-marks led away westward, as if to the next stake.

"I suppose," reflectively drawled Harry, in the morning at breakfast, "that by the looks of things we're in for a dry march or two before we strike the creeks on the other side. Anyway, we'd better fill the water keg, sure. And I opine you're to go ahead, to keep those horse tracks, while I follow with the cart."

"Pike's Peak or Bust," responded Terry.

They started early, to push on at best speed. Duke grunted, Jenny sighed, the cart creaked, Harry whistled, Shep scouted before and on either hand, sniffing at the buffalo trails and charging the prairie dogs and little brown birds, and Terry, trudging in the advance, faithfully kept to the hoof-prints.

Perhaps the Pike's Peak pilgrims who had turned off had been wise, for the water certainly was failing. Now there were only a few shallow washes, and these were dry as a bone, showing that the top of the low prairie divide was being crossed. Still, with a full water keg, which would give several good drinks to all, and with the horse tracks to follow, and the Republican side of the divide somewhere ahead, there was no cause for worry.

Duke and Jenny stepped valiantly. Terry felt a pride in the thought that the Pike's Peak Limited was the first overland outfit on the new stage trail. He wondered if they would beat the wheel-barrow man in to the diggin's. Maybe they would! He wondered when they would sight the mountains. Tomorrow? No, scarcely tomorrow. The horizon ahead was a complete half-circle, broken by never an up-lift. In fact, 'twas hard to believe that any mountains at all lay in that direction.

At noon Harry guessed that they had covered ten miles, and he figured on covering another ten miles before evening camp. He was anxious to reach the next water. The cart was not much of a drag, and both Duke and Jenny were strong. So at the noon camp everybody had a little drink, and Duke and Jenny had a little grass, and a little doze. Shep snored. A good dog, Shep.

"It's queer how little game we've seen, except measley rabbits," observed Harry, that evening. "Only some antelope, and one old buffalo bull at a distance."

"And no Indians, either," added Terry.

"Well, expect the Indians are with the buffalo or else begging along the main trails," reasoned Harry. "But we'd better hobble both animals short, anyway, so they won't stray off looking for water."

The sun had set gloriously in a clear and golden west. While camp was being located in the open, the broad expanse of rolling plain quickly empurpled; and in the twilight Terry staked out Duke, by a rope and a strap around his fore-leg, and Jenny by a rope around her neck. When supper was finished, and the dishes scoured with twigs to save the water, the first stars had appeared in the sky.

Just before closing his eyes to sleep, Terry from his buffalo robe gazed up and sighed contentedly. It was a fine night.

The coyotes and the larger wolves seemed unusually busy. Their yaps and howls sounded frequently. Several times during the night Terry was conscious that Shep growled, and that Duke and Jenny were uneasy; he heard also a low rumble, as of distant thunder, but he was too sleepy to sit up and look about. When he did unclose his eyes, to blink for a moment, he saw that the stars were still vivid in the blue-black sky overhead.

This was the last thought—and next he awakened with a start, to pink dawn and Harry's ringing shout:

"Buffalo! Great Scott! Look at the buffalo!"

Harry was up, standing near the cart and gazing to the east. Up sprang Terry, too, and gazed. The rumble was distinct. A miracle had occurred between darkness and dawn—all the plain to the east was black with a living mass which had flowed upon it during the night.

Buffalo!

"I should say!" gasped Terry.

"Must be ten thousand of them," called Harry.

"Look out for Jenny and Duke!"

Jenny was snorting, as the morning breeze bore the reek of the vast herd to her nostrils. No, mules did not like buffalo. Duke's head was high, as he stared. Harry had partially dressed; now he hurried to quiet the team. Terry drew on his trousers and boots and hastened after.

The buffalo were grazing, and seemed to be drifting slowly this way. The hither fringe was not a quarter of a mile from the camp. Bulls bellowed and pawed and rolled, calves gamboled and breakfasted, and around the mass prowled great gray buffalo wolves, waiting their chances. All was wondrously clear in the first rays of the rising sun.

Harry led the restive Jenny to the wagon and tied her short.

"I think we'd better get right out of here," he announced, as he helped Terry and Shep drive the equally restive Duke in. "The coast ahead is clear. But if we wait for breakfast or anything, that herd's liable to be on top of us."

"Let's hustle, then," agreed Terry. "They're coming this way, sure. I heard 'em, in the night, but I didn't know what it was."

"Same here," confessed Harry, as they hustled to put Duke and Jenny to the cart, and pitch the camp stuff inside. "Funny where such a mob rose from. Reckon something set 'em traveling."

Jenny was quite ready to leave, but Duke was more reluctant. However, on started the Pike's Peak Limited again.

"We'll stop for breakfast when we're at a safer distance," quoth Harry. "Hope we reach water tonight."

Yes, the great herd was perceptibly nearer when they pulled out. But at the rate it was moving it could be left behind while it peacefully grazed. The thin brush was a-sparkle with scant dew, soon dried by the bright sun. The hoof-prints of the second horseman party showed plainly in the sod and sandy gravel. Terry acted as guide, Harry, following with the cart, urged on Duke and Jenny.

"Reckon we'll come to another stake today," called back Terry.

"Reckon we will," answered Harry.

The rumble of the herd gradually died. The sun mounted higher, and Terry was thinking upon breakfast, when a sudden hail from Harry halted him.

"Wait! Listen!"

Harry had stopped.

"Whoa!" And Duke and Jenny stopped, not at all unwillingly.

Terry stopped, poised. Another dull rumble! More buffalo? Nothing was in sight before or on either hand. The rumble came from behind—and yonder, against the sun, welled a cloud of dust.

"They've stampeded!" he cried.

"Sounds like it. And the question is, which way are they going?"

That was speedily answered.

"Gee whillikens!" exclaimed Terry. "They're coming this way!"

A swell of the prairie had concealed all save the dust; but now atop the swell had appeared black dots, succeeded instantly by a long wave of solid black, as over and down surged the whole herd, covering the back trail and pouring on with astonishing, not to say alarming rapidity. The flanks extended widely; there was no time for escaping to one side or the other. In fact, the cart seemed to be right in the middle of the broad path.

Harry acted quickly.

"Watch the animals!" he ordered. "I'll tend to this end. Don't lose your head, Terry. We can split 'em."

He limped to the rear of the wagon. Terry ran back to Duke—and saw that Harry had jerked the shot-gun from where it was stowed, and was posted out behind the wagon. The crowded ranks of the buffalo were so close that the earth trembled. Jenny trembled, also, and Duke was pawing and staring side-ways. Shep, barking wildly, took refuge underneath the wagon.

Terry seized the whip, dropped by Harry, and threatened Duke from before.

"Steady, Duke! Jenny! Whoa! Whoa, now!"