The Project Gutenberg EBook of Homes of American Statesmen, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Homes of American Statesmen

With Anecdotical, Personal, and Descriptive Sketches

Author: Various

Release Date: November 2, 2011 [EBook #37910]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOMES OF AMERICAN STATESMEN ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Steven Brown and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Birthplace of Henry Clay

HARTFORD.

Marshfield, Residence of Daniel Webster

WITH

Anecdotical,

Personal, and Descriptive Sketches,

BY VARIOUS WRITERS.

ILLUSTRATED WITH ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD, FROM DRAWINGS BY DÖPLER

AND DAGUERREOTYPES: AND FAC-SIMILES OF AUTOGRAPH LETTERS.

HARTFORD:

PUBLISHED BY O.D. CASE & CO.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, SON & CO.

M.DCCC.LVI.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1854,

by O.D. CASE & CO.,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, for the

District of Connecticut.

We need hardly commend to the American public this attempt to describe and familiarize the habitual dwelling-places of some of the more eminent of our Statesmen. In bringing together such particulars as we could gather, of the homes of the men to whom we owe our own, we feel that we have performed an acceptable and not unnecessary service. The generation who were too well acquainted with these intimate personal circumstances to think of recording them, is fast passing away; and their successors, while acknowledging a vast debt of gratitude, might still forget to preserve and cherish the individual and private memories of the benefactors of our country and race. We therefore present our contribution to the national annals with confidence, hoping that in all respects the present volume will be found no unworthy or unwelcome successor of the "Homes of American Authors."[ iv ]

Dr. R.W. Griswold having been prevented by ill health from contributing an original paper on Marshall, we have availed ourselves, with his kind permission, of the sketch which he prepared for the "Prose Writers of America." All the other papers in the present volume have been written expressly for it: and the best acknowledgments of the publishers are due to the several contributors for the zealous interest and ability to which these sketches bear witness.

For several of the original letters which we have copied in fac-simile, we are indebted to the kindness of the Rev. Dr. Sprague of Albany.

The drawing of the residence of the "Washington Family," and a few of the smaller cuts, have been copied, with some variations, from Mr. Lossing's very valuable work, "The Field-Book of the Revolution." Most of the other illustrations have been engraved from original drawings, or daguerreotypes taken for the purpose.

| Page. | ||

| WASHINGTON | Mrs. C.M. Kirkland | 1 |

| FRANKLIN | C.F. Briggs | 63 |

| JEFFERSON | Parke Godwin | 77 |

| HANCOCK | Richard Hildreth | 95 |

| JOHN ADAMS | Clarence Cook | 123 |

| PATRICK HENRY | Edward W. Johnston | 151 |

| MADISON | Edward W. Johnston | 179 |

| JAY | William S. Thayer | 197 |

| HAMILTON | James C. Carter | 231 |

| MARSHALL | R.W. Griswold, D.D. | 261 |

| AMES | James B. Thayer | 275 |

| JOHN QUINCY ADAMS | David Lee Child | 299 |

| JACKSON | Parke Godwin | 339 |

| RUFUS KING | Charles King, L.L.D. | 353 |

| CLAY | Horace Greeley | 369 |

| CALHOUN | Parke Godwin | 395 |

| CLINTON | T. Romeyn Beck, M.D. | 413 |

| STORY | Francis Howland | 425 |

| WHEATON | 447 | |

| WEBSTER | Henry C. Deming | 471 |

| Page. | |

| Washington. | 2 |

| Franklin. | 64 |

| Jefferson. | 78 |

| Hancock. | 96 |

| John Adams. | 124 |

| Patrick Henry. | 152 |

| Madison. | 180 |

| John Jay. | 198 |

| Marshall. | 262 |

| Ames. | 276 |

| John Quincy Adams. | 300 |

| Jackson. | 340 |

| Rufus King. | 354 |

| Henry Clay. | 370 |

| Calhoun. | 396 |

| Dewitt Clinton. | 414 |

| Story. | 426 |

| Wheaton. | 448 |

| Webster. | 472 |

Site of Washingtons Birthplace

To see great men at home is often more pleasant to the visitor than advantageous to the hero. Men's lives are two-fold, and the life of habit and instinct is not often, on superficial view, strictly consistent with the other—the more deliberate, intentional and principled one, which taxes only the higher powers. Yet, perhaps, if our rules of judgment were more humane and more sincere, we should find less discrepancy than it has been usual to imagine, and what there is would be more indulgently accounted for. The most common-place[4] man has an inner and an outer life, which, if displayed separately, might never be expected to belong to the same individual; and it would be impossible for him to introduce his dearest friend into the sanctum, where, as in a spiritual laboratory, his words and actions originate and are prepared for use. Yet we could accuse him of no hypocrisy on this ground. The thing is so because Nature says it should be so, and we must be content with her truth and harmony, even if they be not ours. So with regard to public and domestic life. If we pursue our hero to his home, it should be in a home-spirit—a spirit of affection, not of impertinent intrusion or ungenerous cavil. If we lift the purple curtains of the tent in which our weary knight reposes, when he has laid aside his heavy armor and put on his gown of ease, it is not as malicious servants may pry into the privacy of their superiors, but as friends love to penetrate the charmed circle within which disguises and defences are not needed, and personal interest may properly take the place of distant admiration and respect. In no other temper is it lawful, or even decent, to follow the great actors on life's stage to their retirement; and if they be benefactors, the greater the shame if we coolly criticize what was never meant for any but loving eyes.

The private life of him who is supereminently the hero of every true American heart, is happily sacred from disrespectful scrutiny, but less happily closed to the devout approach of those who would look upon it with more than filial reverence. This is less remarkable than it may at first sight appear to us who know his merit. The George Washington of early times was a splendid youth, but his modesty was equal to his other great qualities, and his neighbors could not be expected to [5] foresee the noon of such a morning. And when the first stirring time was over, and the young soldier settled himself quietly at Mount Vernon, as a country gentleman, a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, a vigorous farmer and tobacco planter, a churchwarden in two parishes, and a staid married man with two step-children, to whom he was an active and faithful guardian, no one thought of recording his life and doings, any more than those of his brother planters on the Potomac, all landed men, deer and fox-hunters and zealous fishermen, who visited each other in the hospitable Southern fashion, and lived in rustic luxury, very much within themselves. Few, indeed, compared with the longings of our admiration, are the particulars that have come down to us of Washington's Home—the home of his natural affections; but he had many homes of duty, and these the annals of his country will ever keep in grateful memory. Through these our present design is to trace his career, succinctly and imperfectly indeed, and with the diffidence which a character so august naturally inspires. Happily, many deficiencies in our sketch will be supplied by the intimate knowledge and the inborn reverence of a large proportion of our readers.

It seems to be a conceded point that ours is not the age of reverence, nor our country its home. While the masses were nothing and individuals every thing, gods or demigods were the natural product of every public emergency and relief. Mankind in general, ignorant, and of course indolent, only too happy to be spared the labor of thought and the responsibility of action, looked up to the great and the fortunate till their eyes were dazzled, and they saw characters and exploits through a glorious golden mist, which precluded criticism. It [6]was easy, then, to be a hero, for a single success or a happy chance sufficed. Altars sprang up in every bye-road, and incense fumed without stint or question.

To-day the case is widely different. We give nothing for nothing. Whatever esteem or praise we accord, must be justified, inch by inch, by facts tangible and productive, successes undimmed by any after failure, and qualities which owe nothing to imagination or passion in the observer. No aureole is allowed about any head unless it emanate from it. Our Apollo must actually have sent the shaft, and to the mark, too, or we sneer at the attitude of triumph. If we erect a statue, no robe is confessed to be proper drapery but the soiled and threadbare one of every-day life and toil. No illusion—no poetry! is the American maxim of our time. Bald, staring, naked literality for us! He is the true philosopher who can

Peep

and botanize

Upon his

mother's grave

if the flowers required by science happen to grow there.

All this may be very wise and knowing, yet as long as the machine called man has something within it which is not exactly a subject for mathematical measurement, there will remain some little doubt of the expediency of thus stripping life of its poetry, and bringing all that is inspiring to the test of line and plummet. Just now, however, there is no hearing for any argument on this side.

Greenough's Statue of Washington

What shall we think, then, of a character which, in a single [7] half century, has begun, even among us, to wear something of a mythical splendor? What must the man have been, whom an age like this deliberately deifies? Who but Washington has, in any age, secured for himself such a place in the universal esteem and reverence of his countrymen, that simple description of him is all that can be tolerated, the public sense of his merits being such as makes praise impertinent, and blame impious?

Washington! It were almost enough to grace our page and our volume with this honored and beloved name. The commentary upon it is written in every heart. It is true the most anxious curiosity has been able to find but a small part of what it would fain know of the first man of all the earth, yet no doubt remains as to what he was, in every relation of life. The minutiæ may not be full, but the outline, in which resides the expression, is perfect. It were too curious to inquire how much of Washington would have been lost had the rural life of which he was so fond, bounded his field of action. Providence made the stage ready for the performer, as the performer for the stage. In his public character, he was not the man of the time, but for the time, bearing in his very looks the seal of a grand mission, and seeming, from his surprising dignity, to have no private domestic side. Greenough's marble statue of him, that sits unmoved under all the vicissitudes of storm and calm, gazing with unwinking eyes at the Capitol, is not more impassive or immovable than the Washington of our imaginations. Yet we know there must have been another side to this grand figure, less grand, perhaps, but not less symmetrical, and wonderfully free from those lowering discrepancies which bring nearer to our own level all other great, conspicuous men.

Houdon's Statue of Washington.

We ought to know more of him; but, besides the other reasons we have alluded to for our dearth of intelligence, his was not a writing age on this side the water. Doing, not describing, was the business of the day. "Our own correspondent" was not born yet; desperate tourists had not yet forced their way into gentlemen's drawing-rooms, to steal portraits by pen and pencil, to inquire into dates and antecedents, and repay enforced hospitality by holding the most sacred personalities up to the comments of the curious. It would, indeed, be delightful to possess this kind of knowledge; to ascertain how George Washington of Fairfax [9] appeared to the sturdy country gentlemen, his neighbors; what the "troublesome man" he speaks of in one of his letters thought of the rich planter he was annoying; whether Mr. Payne was proud or ashamed when he remembered that he had knocked down the Father of his Country in a public court-room; what amount of influence, not to say rule, Mrs. Martha Custis, with her large fortune, exercised over the Commander-in-chief of the armies of the United States. But rarer than all it would have been to see Washington himself deal with one of those gentry, who should have called at Mount Vernon with a view of favoring the world with such particulars. How he treated poachers of another sort we know; he mounted his horse, and dashing into the water, rode directly up to the muzzle of a loaded musket, which he wrenched from the astounded intruder, and then, drawing the canoe to land, belabored the scamp soundly with his riding whip. How he would have faced a loaded pen, and received its owner, we can but conjecture. We have heard an old gentleman, who had lived in the neighborhood of Mount Vernon in his boyhood, say that when the General found any stranger shooting in his grounds, his practice was to take the gun without a word, and, passing the barrel through the fence, with one effort of his powerful arm, bend it so as to render it useless, returning it afterwards very quietly, perhaps observing that his rules were very well known. The whole neighborhood, our old friend said, feared the General, not because of any caprice or injustice in his character, but only for his inflexibility, which must have had its own trials on a Southern plantation at that early day.

Chantrey's Statue of Washington.

Painting and sculpture have done what they could to give us an

accurate and satisfying idea of the outward appearance of the Father of

our Country, and a surpassing dignity has been the aim if not the

result, of all these efforts. The statue by Chantrey, which graces the

State House at Boston, is perhaps as successful as any in this respect,

and white marble is of all substances the most appropriate for the

purpose. From all, collectively, we derive the impression, or something

more, that in Washington we have one of the few examples on record of a

complete and splendid union and consent of personal and mental

qualifications for greatness

[11]

in the same individual; unsurpassed

symmetry and amplitude of mind and body for once contributing to the

efficiency of a single being, to whom, also, opportunities for

development and action proved no less propitious than nature. In the

birth, nurture and destiny of this man, so blest in all good gifts,

Providence seems to have intended the realization of Milton's ideal

type of glorious manhood:

A creature who, endued

With sanctity of reason, might erect

His stature, and, upright with front

serene

Govern the rest, self-knowing; and from

thence

Magnanimous, to correspond with Heaven;

But, grateful to acknowledge whence his

good

Descends, thither, with heart voice and

eyes,

Directed in devotion, to adore

And worship God supreme, who made him

chief

Of all his works.

We may the more naturally think this because Washington was so little indebted to school learning for his mental power. Born in a plain farm-house near the Potomac—a hallowed spot now marked only by a memorial stone and a clump of decaying fig-trees, probably coeval with the dwelling; none but the simplest elements of knowledge were within his reach, for although his father was a gentleman of large landed estate, the country was thinly settled and means of education were few. To these he applied himself with a force and steadiness even then remarkable, though with no view more ambitious than to prepare himself for the agricultural pursuits to which he was destined, by a widowed mother, eminent for common sense and high integrity. His mother, [12] characteristically enough, for she was much more practical than imaginative, always spoke of him as a docile and diligent boy, passionately fond of athletic exercises, rather than as a brilliant or ambitious one. In after years, when La Fayette was recounting to her, in florid phrase, but with the generous enthusiasm which did him so much honor, the glorious services and successes of her son, she replied—"I am not surprised; George was always a good boy!" and this simple phrase from a mother who never uttered a superfluous word, throws a clear light on his early history. Then we have, besides, remnants of his school-exercises in arithmetic and geometry, beautiful in neatness, accuracy and method. At thirteen his mathematical turn had begun to discover itself, and the precision and elegance of his handwriting were already remarkable. His precocious wisdom would seem at that early age to have cast its horoscope, for we have thirty pages of forms for the transaction of important business, all copied out beautifully; and joined to this direct preparation for his future career are "Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation," to the number of one hundred and ten, all pointing distinctly at self-control and respect for the rights of others, rather than at a Chesterfieldian polish or policy, and these he learned so well that he practised them unfailingly all his life after.

Residence of the Washington Family.

A farm in Stafford County on the Rappahannoc, where his father had lived for several years before his death, was his share of the paternal estate, and on this he lived with his mother, till he had completed his sixteenth year. He desired to enter the British Navy, as a path to honorable distinction, and one of his half brothers, many years older than himself, had succeeded in obtaining a warrant for him; but the mother's reluctance to part with her eldest boy induced him to relinquish this advantage, and to embrace instead the laborious and trying life of a surveyor, in those rude, early days of Virginia exposed to extraordinary hazards. Upon this he entered immediately, accepting employment offered him by Lord Fairfax, who had come from England to ascertain the value of an immense tract of land which he had inherited, lying between the Potomac and Rappahannoc rivers, and extending beyond the Alleghanies. The surveying party was accompanied by William Fairfax, a distant relative of his lordship, but the boy of sixteen was evidently the most important member of the party. When the hardships of this undertaking became too exhausting, he returned to the more settled regions, and employed himself in laying out private tracts and farms, but he spent the greater part of three years in the [14] wilderness, learning the value of lands, becoming acquainted with the habits and character of the wild Indian tribes, then so troublesome in the forests, and fitting himself by labor, study, the endurance of personal hardships and the exercise of vigilance and systematic effort, for the arduous path before him.

At nineteen Washington had made so favorable an impression that he was appointed, by the government of Virginia, Adjutant-General with the rank of Major, and charged with the duty of assembling and exercising the militia, in preparation for expected or present difficulties on the frontier. He had always shown a turn for military affairs, beginning with his school-days, when his favorite play was drilling troops of boys, he himself always taking command; and noticeable again in his early manhood, when he studied tactics, and learned the manual exercise and the use of the sword. It was not long before the talent thus cultivated was called into action. Governor Dinwiddie sent Major Washington as commissioner to confer with the officer commanding the French forces, making the delicate inquiry by what authority he presumed to invade the dominions of his Majesty King George III., and what were his designs. A winter journey of seven hundred and fifty miles, at least half of which lay through an unbroken wilderness, haunted by wild beasts, and more formidable savages, was the first duty of the youthful Major under this commission, and it occupied six weeks, marked by many hardships and some adventures. The famous one of the raft on a half-frozen river, in which Washington narrowly escaped drowning, and the other of a malcontent Indian's firing on him, occurred during this journey; but he reached [15] the French post in safety, and had an amicable, though not very satisfactory conference, with the Sieur St. Pierre, a courteous gentleman, but a wily old soldier. Governor Dinwiddie caused Major Washington's account of the expedition to be published, and when a little army was formed for the protection of the frontier, Washington received a command, with the rank of Colonel, at twenty-two years of age. Advancing at once into the wilderness, he encountered a French detachment, which he took prisoners, with their commander, and so proceeded during the remainder of the season, with general success. The next year, serving as a volunteer, it was his painful lot, when just recovering from a severe illness, to witness Braddock's defeat, a misfortune which, it is unanimously conceded, might have been avoided, if General Braddock had not been too proud to take his young friend's prudent counsel. All that an almost frantic bravery could do to retrieve the fortunes of this disastrous day, Washington, whom we are in the habit of thinking immovable, and who was at this time weak from the effects of fever, is reported to have done; and the fact that he had two horses shot under him, and his coat well riddled with rifle balls, shows how unsparingly he exposed himself to the enemy's sharp-shooters. A spectator says—"I saw him take hold of a brass field-piece as if it had been a stick. He looked like a fury; he tore the sheet lead from the touch-hole; he pulled with this and pushed with that; and wheeled it round as if it had been nothing. The powder-monkey rushed up with the fire, and then the cannon began to bark, and the Indians came down." Nothing but defeat and disgrace was the result of this unhappy encounter, except to Washington, who in that instance, as in so many [16]others, stood out, individual and conspicuous, by qualities so much in advance of those of all the men with whom he acted, that no misfortune or disaster ever caused him to be confounded with them, or included in the most hasty general censure. It is most instructive as well as interesting to observe that his mind, never considered brilliant, was yet recognized from the beginning as almost infallible in its judgments, a tower of strength for the weak, a terror to the selfish and dishonest. The uneasiness of Governor Dinwiddie under Washington's superiority is accounted for only by the fact that that superiority was unquestionable.

Mount Vernon.

After Braddock's defeat, Washington retired to Mount [17] Vernon,—which had fallen to him by the will of his half-brother Lawrence—to recoup his mind and body, after a wasting fever and the distressing scenes he had been forced to witness. The country rang with his praises, and even the pulpit could not withhold its tribute. The Reverend Samuel Davies hardly deserves the reputation of a prophet for saying, in the course of a eulogy on the bravery of the Virginian troops,—"As a remarkable instance of this, I may point out that heroic youth, Colonel Washington, whom I cannot but hope Providence has hitherto preserved in so signal a manner for some important service to his country."

When another army was to be raised for frontier service, the command was given to Washington, who stipulated for a voice in choosing his officers, a better system of military regulations, more promptness in paying the troops, and a thorough reform in the system of procuring supplies. All these were granted, with the addition of an aid-de-camp and secretary, to the young colonel of twenty-three. But he nevertheless had to encounter the evils of insubordination, inactivity, perverseness and disunion among the troops, with the further vexation of deficient support on the part of the government, while the terrors and real dangers and sufferings of the inhabitants of the outer settlements wrung his heart with anguish. In one of his many expostulatory letters to the timid and time-serving Governor Dinwiddie, his feelings burst their usual guarded bounds: "I am too little acquainted, sir, with pathetic language, to attempt a description of the people's distresses; but I have a generous soul, sensible of wrongs and swelling for redress. But what can I do? I see their situation, know [18] their danger and participate in their sufferings, without having it in my power to give them further relief than uncertain promises. In short, I see inevitable destruction in so clear a light, that unless vigorous measures are taken by the Assembly, and speedy assistance sent from below, the poor inhabitants that are now in forts must unavoidably fall, while the remainder are flying before a barbarous foe. In fine, the melancholy situation of the people, the little prospect of assistance, the gross and scandalous abuse cast upon the officers in general, which reflects upon me in particular for suffering misconduct of such extraordinary kinds, and the distant prospect, if any, of gaining honor and reputation in the service, cause me to lament the hour that gave me a commission, and would induce me, at any other time than this of imminent danger, to resign, without one hesitating moment, a command from which I never expect to reap either honor or benefit; but, on the contrary, have almost an absolute certainty of incurring displeasure below, while the murder of helpless families may be laid to my account here. The supplicating tears of the women and moving petitions of the men melt me into such deadly sorrow, that I solemnly declare, if I know my own mind, I could offer myself a willing sacrifice to the butchering enemy, provided that would contribute to the people's ease."

Tomb of Washington's Mother.

This extract is given as being very characteristic;

full of

that fire whose volcanic intensity was so carefully covered under the

snow of caution in after life; and also as a specimen of Washington's

style of writing, clear, earnest, commanding and business-like, but

deficient in all express graces, and valuable rather for substance than

form. We see in his general tone of expression something of that

resolute mother, who, when her son, already the first man in public

estimation, urged her to make Mount Vernon her home for the rest of her

days, tersely replied——"I thank you for your affectionate and dutiful

offers, but my wants are few in this world, and I feel perfectly

[20]

competent to take care of myself." Directness is the leading trait in

the style of both mother and son; if either used circumlocution, it was

rather through deliberateness than for diplomacy. Indeed, the alleged

indebtedness of great sons to strong mothers, can hardly find a more

prominent support than in this case. What a Roman pair they were! If

her heart failed her a little, sometimes, as what mother's heart must

not, in view of toils, sacrifices, and dangers like his; if she argued

towards the softer side, how he answered her, appealing to her stronger

self:

"Honored Madam,

"If it is in my power to avoid going to the Ohio again, I shall; but if the command is passed upon me by the general voice of the country, and offered upon such terms as cannot be objected against, it would reflect dishonor upon me to refuse it; and that, I am sure, must, or ought to, give you greater uneasiness than my going in an honorable command. Upon no other terms will I accept of it. At present I have no proposals made to me, nor have I advice of such an intention, except from private hands.

When the object for which he had undertaken the

campaign—viz.:

the undisturbed possession of the Ohio River—was accomplished,

Washington resigned his commission, after five years of active and

severe service, his health much broken and his private affairs not a

little disordered. The resignation took effect in December, 1758, and

in January, 1759, he was married, and, as he supposed, finally settled

at Mount Vernon—or, [21]

as he expresses it in his quiet way—"Fixed at this

seat, with an agreeable partner for life, I hope to find more happiness

in retirement than I ever experienced amidst the wide and bustling

world." And in liberal and elegant improvements, and the exercise of a

generous hospitality, the young couple spent the following fifteen

years; the husband attending to his duties as citizen and planter, with

ample time and inclination for fox-hunting and duck-shooting, and the

wife, a kind, comely, thrifty dame, looking well to the ways of her

household, superintending fifteen domestic spinning-wheels, and

presiding at a bountiful table, to the great satisfaction of her

husband and his numerous guests. When the spirit of the people began to

rise against the exactions of the mother country, Washington was among

the foremost to sympathize with the feeling of indignation, and the

desire to resist, peaceably, if possible, forcibly if necessary. Of

this, his letters afford ample proof. When armed resistance was

threatened, Washington was immediately thought of as the Virginia

leader. When Congress began, in earnest, preparations for defence,

Washington was chairman of all the committees on the state of the

country. When the very delicate business of appointing a

commander-in-chief of the American armies was under consideration,

Washington was the man whose name was on every tongue, and who was

unanimously chosen, and that by the direct instrumentality of a son of

Massachusetts, though that noble State, having commenced the struggle,

might well have claimed the honor of furnishing a leader for it. What

generosity of patriotism there was, in the men of those days, and how a

common indignation and a common danger seem to have raised them above

the petty jealousies and heart-burnings

[22]

that so disfigure public doings

in time of peace and prosperity! How the greatness of the great man

blazed forth on this new field! What an attitude he took before the

country, when he said, on accepting the position, "I beg leave to

assure the Congress that as no pecuniary consideration could have

tempted me to accept this arduous employment, at the expense of my

domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any profit from it.

I will keep an exact account of my expenses. These, I doubt not they

will discharge, and that is all I desire." There was a natural,

unconscious sovereignty in thus assuming to be the judge of what it

might be proper to expend, in concerns the most momentous, extensive,

and novel, as well as in taking the entire risk, both of payment and of

public approbation,—in a direction in which he had already found the

sensitiveness of the popular mind,—that equals any boldness of

Napoleon's. We can hardly wonder that, in after times, common men

instinctively desired and expected to make him a king.

The battle of Bunker Hill had taken place in the time that intervened between Washington's consent and the receipt of his commission, so that he set out for Cambridge, with no lingering doubt as to the nature, meaning, or result of the service in which he had pledged all. He writes to his brother, "I am embarked on a wide ocean, boundless in its prospect, and in which, perhaps, no safe harbor is to be found." His residence at Cambridge, a fine old mansion, still stands, and in worthy occupancy. Here it was that he undertook the intolerable duty of organizing a young army, without clothes, tents, ammunition, or money, with a rich, bitter and disciplined enemy in sight, and boiling blood on both sides. Here [23] it was that General Gage, with whom he had fought, side by side, twenty years before, on the Monongahela, so exasperated him by insolent replies to his remonstrances against the cruel treatment of American prisoners, that he gave directions for retaliation upon any of the enemy that might fall into American hands.

Washington's Headquarters, Cambridge, 1775.

He was, however, Washington still, even

though burning with a holy anger; and, ere the order could reach its

destination, it was countermanded, and a charge given to all concerned

that the prisoners should be allowed parole, and that [24]

every other

proper indulgence and civility should be shown them. His letters to

General Gage are models of that kind of writing. In writing to Lord

Dartmouth afterwards, the British commander, who had been rebuked with

such cutting and deserved severity, observes with great significance,

"The trials we have had, show the rebels are not the despicable rabble

we have supposed them to be."

Washington was not without a stern kind of wit, on certain occasions. When the rock was struck hard, it failed not in fire. The jealousy of military domination was so great as to cause him terrible solicitudes at this time, and a month's enlistments brought only five thousand men, while murmurs were heard on all sides against poor pay and bad living. Thinking of this, at a later day, when a member of the Convention for forming the Constitution, desired to introduce a clause limiting the standing army to five thousand men, Washington observed that he should have no objection to such a clause, "if it were so amended as to provide that no enemy should presume to invade the United States with more than three thousand."

Amid all the discouragements of that heavy time, the resolution of the commander-in-chief suffered no abatement. "My situation is so irksome to me at times," he says after enumerating his difficulties in a few forcible words, "that if I did not consult the public good more than my own tranquillity, I should long ere this have put every thing on the cast of a die." But he goes on to say, in a tone more habitual with him—"If every man was of my mind, the ministers of Great Britain should know, in a few words, upon what issue the cause should be put. I would not be deceived by artful declarations, nor specious pretences, nor would I be amused by unmeaning propositions, but, in open, undisguised and manly terms, proclaim our wrongs, and our resolution to be redressed. I would tell them that we had borne much, that we had long and ardently sought for reconciliation upon honorable terms; that it had been denied us; that all our attempts after peace had proved abortive, and had been grossly misrepresented; that we had done every thing that could be expected from the best of subjects; that the spirit of freedom rises too high in us to submit to slavery. This I would tell them, not under covert, but in words as clear as the sun in its meridian brightness."[25]

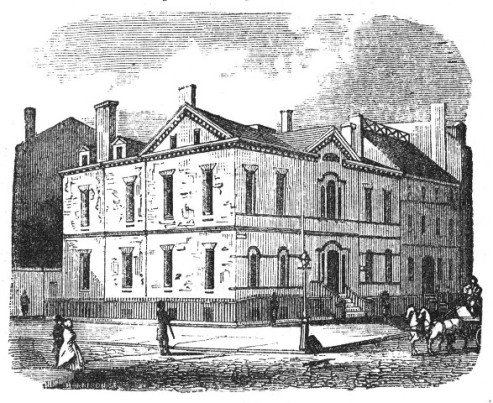

Washington's Headquarters, 180 Pearl

street, New-York. 1776.

House No. 1 Broadway.

The house No. 1 Broadway, opposite the Bowling-green, remained unaltered until within a year or two in the shape here presented, in which it had become familiar to all New-Yorkers. It was built by Captain Kennedy of the Royal Navy, in April, 1765. There Lee, Washington, and afterwards Sir Henry Clinton, Robertson, Carleton, and other British officers were quartered, and here André wrote his letter to Arnold.—Lossing. It was afterwards occupied by Aaron Burr. Very recently, this interesting house, which in New-York may be termed ancient, has been metamorphosed by the [26] addition of two or three stories, and it is now reduced to be the Washington Hotel.

When the British evacuated Boston, Congress voted Washington a gold medal, with abundant thanks and praises; and, thus compensated for the cruel anxieties of the winter, he proceeded with unwavering courage to New-York, where new labors awaited him, and the mortifying defeat at Gowanus, turned into almost triumph by the admirable retreat Afterwards.

The movement from New-York city to Harlem Heights should have been another glory, and nothing on the part of the Commander-in-Chief was wanting to make it such, but a panic seized two brigades of militia, who ran away, sans façon, causing Washington to lose, for a moment, some portion of the power over his own emotions for which he is so justly celebrated. He dashed in among the flying rout, shouting, shaming them, riding exposed within a few yards of the enemy; and, finding this of no avail, drew his sword and threatened to "run them through," and cocked and snapped his pistol in their faces. But all would not do, and General Greene says, in a letter to a friend, "He was so vexed at the [27] infamous conduct of the troops, that he sought death rather than life." Washington, the "man of marble," would have preferred a thousand deaths to dishonor.

A new army was now to be raised, the term of the last enlistment having expired; and, to form a just opinion of Washington's character and talents, every letter of his, to Congress and others during this period, should be studied. Such wisdom, such indignation, such patience, such manly firmness, such disappointment! every thing but despair; the watchfulness, the forethought, the perseverance displayed in those letters, give a truer idea of the man than all his battles.

Take a single passage from one of his letters:—"I am wearied almost to death with the retrograde motion of things, and I solemnly protest, that a pecuniary reward of twenty thousand pounds a year would not induce me to undergo what I do; and after all, perhaps, to lose my character, as it is impossible, under such a variety of distressing circumstances, to conduct matters agreeably to public expectation, or even to the expectation of those who employ me, as they will not make proper allowances for the difficulties their own errors have occasioned."

And besides that which came upon him daily, in the regular line of duty, the yet more difficult work of bearing up the hearts of others, whose threats of abandoning the service were the running bass that made worse the din of war. "I am sorry to find," writes the Chief to General Schuyler, "that both you and General Montgomery incline to quit the service. Let me ask you, sir, what is the time for brave men to exert themselves in the cause of liberty and their country, if this is not? God knows there is not a difficulty that you [28] both very justly complain of, which I have not in an eminent degree experienced, that I am not every day experiencing. But we must bear up against them, and make the best of mankind as they are, since we cannot have them as we wish." In studying the career of Washington, nothing strikes one more frequently than that no fame came to him fortuitously, not only did he borrow none, usurp none, fall heir to none that belonged to others; he earned every tittle that has ever been awarded to him, and evidently contributed very much, by his secret advice and caution to officers placed in difficult positions, to enhance the measure of praise bestowed on his companions in arms.

Washington's

Headquarters, Morristown, New Jersey. 1779.

Dark as these times were, Washington's peculiar merits were every day becoming more and more evident; indeed the [29] darkest hours were his opportunities. He might well say, after the loss of Fort Washington, which had been held contrary to his judgment,—"No person ever had a greater choice of difficulties to contend with than I have;" yet he carried the war into New Jersey with all the resolution and courage of a victor. Never without a party, too often a very large one, ready to disparage his military skill, and throw doubts upon his energy in the conduct of the war, he pursued his plans without swerving a hair's breadth to court the popular gale, though a natural and honorable love of reputation was one of the ruling passions of his soul. It was impossible to make the people believe that a series of daring encounters would have cost the Commander-in-chief far less than the "Fabian policy," so scorned at the time; but Washington saw then, in the very heat of the contest, what the result has now made evident enough to all, that England must carry on a war on the other side of the globe under an immense disadvantage, and that considering the general spirit of the American people, the expense to an invading power must be greater than even the richest nation on earth could long sustain. That the necessity for delay was intensely mortifying to him, we have a thousand proofs; and it was not the least bitter drop in his cup, that in order to conceal from the enemy the deficiencies occasioned by the delay of Congress to meet his most strenuous requisitions, he was obliged to magnify his numbers and resources, in a way which could not but increase the public doubts of his promptness. No one can read his letters, incessant under these circumstances, without an intense personal sympathy, that almost forgets the warrior and the patriot in the man.

His being invested with what was in reality a military [30] dictatorship, did not help to render him more popular, although he used his power with his accustomed moderation, conscientiousness and judgment. In this, as in other cases, he took the whole responsibility and odium, while he allowed others to reap the credit of particular efforts; giving to every man at least his due, and content if the country was served, even though he himself seemed to be doing nothing. This we gather as much from the letters of others to him as from his own writings.

The celebrated passage of the Delaware, on Christmas-day, 1776,—so lifelike represented in Leutze's great picture,—flashed a cheering light over the prospects of the contest, and lifted up the hearts of the desponding, if it did not silence the cavils of the disaffected. The intense cold was as discouraging here as the killing heat had been at Gowanus. Two men were found frozen to death, and the whole army suffered terribly; but the success was splendid, and the enemy's line along the Delaware was broken. The British opened their eyes very wide at this daring deed of the rebel chief, and sent the veteran Cornwallis to chastise his insolence. But Washington was not waiting for him. He had marched to Princeton, harassing the enemy, and throwing their lines still more into confusion. New Jersey was almost completely relieved, and the spirits of the country raised to martial pitch before the campaign closed. Those who had hastily condemned Washington as half a traitor to the cause, now began to call him the Saviour of his Country. Success has wondrous power in illuminating merit, that may yet have been transparent without it. But even now, when he thought proper to administer to all the oath of allegiance to the United States, granting leave to the disaffected to retire within the enemy's lines, a new clamor was raised against him, as assuming undue and dangerous power. It was said there were no "United States," and the Legislature of New Jersey censured the order as interfering with their prerogative. But Washington made no change. The dangers of pretended neutrality had become sufficiently apparent to him; and he chose, as he always did, to defer his personal popularity to the safety of the great cause. And again he took occasion, though the treatment of General Lee was in question, to argue against retaliation of the sufferings of prisoners, in a manly letter, which would serve as a text in similar cases for all time.

What a blessing was Lafayette's arrival! not only to the struggling States, but in particular to Washington. The spirit of the generous young Frenchman was to the harassed chief as cold water to the thirsty soul. No jealousies, no fault-finding, no selfish emulation; but pure, high, uncalculating enthusiasm, and a devotion to the character and person of Washington that melted the strong man, and opened those springs of tenderness which cares and duties had well-nigh choked up. It is not difficult to believe that Lafayette had even more to do with the success of the war than we are accustomed to think. Whatever kept up the chief's heart up-bore the army and the country; for it is plain that, without derogation from the ability or faithfulness of any of the heroic contributors to the final triumph, Washington was in a peculiar manner the life and soul,—the main-spring and the balance-wheel,—the spur and the rein, of the whole movement and its result. Blessings, then, on Lafayette, the helper and [32] consoler of the chosen father of his heart, through so many trials! His name goes down to posterity on the same breath that is destined for ever to proclaim the glory of Washington.

Washington's

Headquarters, Chad's Ford, 1777.

Chad's Ford, in Delaware, was the scene of another of those disasters which it was Washington's happy fortune to turn into benefits. The American army retreated from a much superior force, and retreated in such disorder as could seem, even to its well-wishers, little better than a flight. But when, after encamping at Germantown, it was found that the General meant to give battle again, with a barefooted army, exhausted by forced marches, in a country which Washington himself says, was "to a man, disaffected," dismay itself became buoyant, and the opinion spread, not only throughout America, but even as far as France, that the leader of our armies [33] was indeed invincible. A heavy rain and an impenetrable fog defeated our brave troops; the attempt cost a thousand men. Washington says, solemnly, "It was a bloody day." Yet the Count de Vergennes, on whose impressions of America so much depended at that time, told our Commissioners in Paris that nothing in the course of our struggle had struck him so much as General Washington's venturing to attack the veteran army of Sir William Howe, with troops raised within the year. The leader's glory was never obscured for a moment, to the view of those who were so placed as to see it in its true light. Providence seems to have determined that the effective power of this great instrument should be independent of the glitter of victory.

Washington's

Headquarters, White Marsh, 1777.

Encamped at Whitemarsh, fourteen miles from Philadelphia, Washington, with his half-clad and half-fed troops, awaited an attack from General Howe who had marched in [34] that direction with twelve thousand effective men. But both commanders were wary—the British not choosing to attack his adversary on his own ground, and the American not to be decoyed from his chosen position to one less favorable. Some severe skirmishing was therefore all that ensued, and General Howe retreated, rather ingloriously, to Philadelphia.

Washington's

Headquarters, Valley Forge, 1777.

This brings us to the terrible winter at Valley Forge, the sufferings of which can need no recapitulation for our readers. Washington felt them with sufficient keenness, yet his invariable respect for the rights of property extended to that of the disaffected, and in no extremity was he willing to resort to coercive measures, to remedy evils which distressed his very soul, and which he shared with the meanest soldier. His testimony to the patience and fortitude of the men is emphatic: "Naked and starving as they are, we cannot enough admire the incomparable patience and fidelity of the soldiery, that [35] they have not been, ere this, excited by their sufferings to a general mutiny and dispersion." And while this evil was present, and for the time irremediable, he writes to Congress on the subject of a suggestion which had been made of a winter campaign, "I can assure those gentlemen, that it is a much easier and less distressing thing to draw remonstrances, in a comfortable room, by a good fireside, than to occupy a cold bleak hill, and sleep under frost and snow, without clothes or blankets. However, although they seem to have little feeling for the naked and distrest soldiers, I feel super-abundantly for them, and from my soul I pity those miseries which it is neither in my power to relieve nor prevent."

It was during this period of perplexity and distress on public accounts, that the discovery of secret cabals against himself, was added to Washington's burthens. But whatever was personal was never more than secondary with him. When the treachery of pretended friends was disclosed, he showed none of the warmth which attends his statement of the soldiers' grievances. "My enemies take an ungenerous advantage of me," he said, "they know the delicacy of my situation, and that motives of policy deprive me of the defence I might otherwise make against their insidious attacks. They know I cannot combat their insinuations, however injurious, without disclosing secrets which it is of the utmost moment to conceal." * * * "My chief concern arises from an apprehension of the dangerous consequences which intestine dissensions may produce to the common cause."

General Howe made no attempt on the camp during the winter, but his foraging parties were watched and often severely handled by the Americans. When Dr. Franklin, who [36] was in Paris, was told that General Howe had taken Philadelphia, "Say rather," he replied, "that Philadelphia has taken General Howe," and the advantage was certainly a problematical one. Philadelphia was evacuated by the British on the 18th of June, 1776, General Clinton having superseded General Howe, who returned to England in the spring. Washington followed in the footsteps of the retreating army, and, contrary to the opinion of General Lee, decided to attack them. At Monmouth occurred the scene so often cited as proving that Washington could lose his temper—a testimony to his habitual self-command which no art of praise could enhance. Finding General Lee with his five thousand men in full retreat when they should have been rushing on the enemy, the commander-in-chief addressed the recreant with words of severe reproof, and a look and manner still more cutting. Receiving in return a most insolent reply, Washington proceeded, himself, by rapid manœuvres, to array the troops for battle, and when intelligence arrived that the British were within fifteen minutes march, he said to General Lee, who had followed him, deeply mortified,—"Will you command on this ground, or not?" "It is equal with me where I command," was the answer. "Then I expect you to take proper measures for checking the enemy," said the General, much incensed at the offensive manner of Lee. "Your orders shall be obeyed," said that officer, "and I will not be the first to leave the field." And his bravery made it evident that an uncontrolled temper was the fault for which he afterwards suffered so severely. During the action Washington exposed himself to every danger, animating and cheering on the men under the burning sun; and when night came, he lay down in [37] his cloak at the foot of a tree, hoping for a general action the next day. But in the morning Sir Henry Clinton was gone, too far for pursuit under such killing heat—the thermometer at 96°. Many on both sides had perished without a wound, from fatigue and thirst.

Washington's

Headquarters, Tappan, 1778.

The headquarters at Tappan will always have a sad interest from the fact that Major André, whose fine private qualities have almost made the world forget that he was a spy, there met his unhappy fate. That General Washington suffered severely under the necessity which obliged him, by the rules of war, to sanction the decision of the court-martial in this case, we have ample testimony; and an eye-witness still living observed, that when the windows of the town were thronged with gazers at the stern procession as it passed, those of the commander-in-chief were entirely closed, and his house without sign of life except the two sentinels at the door.[38]

The revolt of a part of the Pennsylvania line, which occurred in January, 1781, afforded a new occasion for the exercise of Washington's pacific wisdom. He had felt the grievances of the army too warmly to be surprised when any portion of it lost patience, and his prudent and humane suggestions, with the good management of General Wayne, proved effectual in averting the great danger which now threatened. But when the troops of New Jersey, emboldened by this mild treatment, attempted to imitate their Pennsylvania neighbors, they found Washington prepared, and six hundred men in arms ready to crush the revolt by force—a catastrophe prevented only by the unconditional submission of the mutineers, who were obliged to lay down their arms, make concessions to their officers, and promise obedience.

As we are not giving here a sketch of the Revolutionary War, we pass at once to the siege and surrender at Yorktown, an event which shook the country like that heaviest clap of thunder, herald of the departing storm. All felt that brighter skies were preparing, and the universal joy did not wait the sanction of a deliberate treaty of peace. The great game of chess which had been so warily played, on one side at least, was now in check, if not closed by a final check-mate; and people on the winning side were fain to unknit their weary brows, and indulge the repose they had earned. Congress and the country felt as if the decisive blow had been struck, as if the long agony was over. Thanks were lavished on the commanders, on the officers, on the troops. Two stands of the enemy's colors were presented to the Commander-in-Chief, and to Counts Rochambeau and De Grasse each a piece of British field ordnance as a trophy. A commemorative column at [39] Yorktown was decreed, to carry down to posterity the events of the glorious 17th of October, 1781. There was, in short, a kind of wildness in the national joy, showing how deep had been the previous despondency. Watchmen woke the citizens of Philadelphia at one in the morning, crying "Cornwallis is taken!" Sober, Puritan America was almost startled from her habitual coolness; almost forgot the still possible danger. The chief alone, on whom had fallen the heaviest stress of the long contest, was impelled to new care and forecast by the victory. He feared the negligence of triumph, and reminded the government and the nation that all might yet be lost, without vigilance. "I cannot but flatter myself," he says, "that the States, rather than relax in their exertions, will be stimulated to the most vigorous preparations, for another active, glorious, and decisive campaign." And Congress responded wisely to the appeal, and called on the States to keep up the military establishment, and to complete their several quotas of troops at an early day. With his characteristic modesty and courage, Washington wrote to Congress a letter of advice on the occasion, of which one sentence may be taken as a specimen. "Although we cannot, by the best concerted plans, absolutely command success; although the race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong; yet, without presumptuously waiting for miracles to be wrought in our favor, it is an indispensable duty, with the deepest gratitude to Heaven for the past, and humble confidence in its smiles on our future operations, to make use of all the means in our power for our defence and security."

It was this man, pure, devoted, and indefatigable in the cause of his country and her liberties, that some shortsighted [40] malcontents, judging his virtue by their own, would now have persuaded to finish the struggle for liberty by becoming a king. The discontent of the officers and soldiers, with the slowness of their pay, had long been a cause of ferment in the army, and gave to the hasty and the selfish an excuse for desiring a change in the form of government. The king's troops had been well fed, well clothed, and well paid, and were sure of half-pay after the war should be finished, while the continentals, suffering real personal destitution, were always in arrear, drawing on their private resources, and with no provision whatever for any permanent pecuniary recompense. As to the half-pay, Washington had long before expressed his opinion of the justice as well as policy of such a provision. "I am ready to declare," he says, "that I do most religiously believe the salvation of the cause depends upon it, and without it your officers will moulder to nothing, or be composed of low and illiterate men, void of capacity for this or any other business. * * * Personally, as an officer, I have no interest in the decision; because I have declared, and I now repeat it, that I never will receive the smallest benefit from the half-pay establishment." But the deep-seated jealousy of the army, which haunted Congress and the country, like a Banshee, throughout the whole course of the war, was too powerful for even Washington's representations. All that could be effected was an unsatisfactory compromise, and some of the officers saw or affected to see, in the reluctance of the government to provide properly for its defenders, a sign of fatal weakness, which but little recommended the republican form. Under these circumstances, a well written letter was sent to the Commander-in-Chief, proposing to him the establishment of a "mixed government," in which the supreme position was to be given, as of right, to the man who had been the instrument of Providence in saving the country, in "difficulties apparently insurmountable by human power," the dignity to be accompanied with the title of king. Of this daring proposition a colonel of good standing was made the organ. Washington's reply may be well known, but it will bear many repetitions.[41]

Washington's

Headquarters, Newburgh, N.Y.

"Sir,

"With a mixture of great surprise and astonishment, I have read with attention the sentiments you submitted to my perusal. Be assured, Sir, no occurrence in the course of the war has given me more painful sensations than your information, of there being such ideas existing in the army as you have expressed, and I must view with abhorrence, and reprehend with severity. For the present, the communication of them will rest in my own bosom, unless some further agitation of the matter shall make a disclosure necessary.

"I am much at a loss to conceive what part of my conduct could have given encouragement to an address, which, to me, seems big with the greatest mischiefs that can befall my country. If I am not deceived in the knowledge of myself, you could not have found a person to whom your schemes are more disagreeable. At the same time, in justice to my own feelings, I must add that no man possesses a more sincere wish to see ample justice done to the army than I do; and as far as my powers and influence, in a constitutional way, extend, they shall be employed to the utmost of my abilities to effect it, should there be any occasion. Let me conjure you, then, if you have any regard for your country, concern for yourself or [42] posterity, or respect for me, to banish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate, as from yourself or any one else, a sentiment of the like nature.

This letter is extremely characteristic, not only because it

declines the glittering bait, for that is hardly worth noticing where

Washington is in question, but for the cool and quiet tone of rebuke,

in a case in which most other men would have been disposed to be at

least dramatically indignant. The perfectly respectful way in which he

could show a man that he despised him, is remarkable. He does not even

admit that there has been injustice done to the army, though the fact

had cost him such loads of anxious and ingenious remonstrance; but only

promises to see to it, "should there be any occasion." It would have

been easier for him, at that very moment, at the head of a victorious

army, and with the heart of the nation at his feet, to make himself a

king, than to induce Congress to do justice to the troops and their

brave officers; but identifying himself with his army, he considered

that his own private affair, and would accept no offer of partnership,

however specious. Happily the name of the "very respectable" colonel

has never been disclosed; an instance of mercy not the least noticeable

among the features of this remarkable transaction.

During the negotiations for peace which so soon followed the surrender at Yorktown, the discontent of the army reached a height which became alarming. Meetings of officers were called, for the purpose of preparing threatening resolutions, since called "the Newburgh addresses," to be offered to Congress. [43] The alternative proposed was a relinquishment of the service in a body, if the war continued, or remaining under arms, in time of peace, until justice could be obtained from Congress. Washington, having timely notice of this danger, came forward with his usual decision, wisdom, and kindliness, to the rescue of the public interest and peace. While he took occasion, in a general order, to censure the disorderly and anonymous form proposed, he himself called a meeting of officers, taking care to converse in private beforehand with many of them, acknowledging the justice of their complaints, but inculcating moderation and an honorable mode of obtaining what they desired. It is said that many of the gentlemen were in tears when they left the presence of the Commander-in-Chief. When they assembled, he addressed them in the most impressive manner, imploring them not to tarnish their hard-won laurels, by selfish passion, in a case in which the vital interests of the country were concerned. He insisted on the good faith of Congress, and the certainty that, before the army should be disbanded, all claims would be satisfactorily adjusted.

His remonstrance proved irresistible. The officers, left to themselves,—for the General withdrew after he had given utterance to the advice made so potent by his character and services,—passed resolutions thanking him for his wise interference, and expressing their love and respect for him, and their determination to abide by his counsel. In this emergency Washington may almost have been said to have saved his country a second time, but in his letters written at the time he sinks all mention of his own paramount share in restoring tranquillity, speaking merely of "measures taken to postpone the meeting," and "the good sense of the officers" having terminated the affair [44] "in a manner which reflects the greatest glory on themselves." His own remonstrances with Congress were immediately renewed, setting forth the just claims of those who "had so long, so patiently, and so cheerfully, fought under his direction," so forcibly, that in a very short time all was conceded, and general harmony and satisfaction established.

His military labors thus finished,—for the adjudication of the army claims by Congress was almost simultaneous with the news of the signing of the treaty at Paris,—Washington might, without impropriety, have given himself up to the private occupations and enjoyments so religiously renounced for eight years,—the proclamation of peace to the army having been made, April 19, 1783, precisely eight years from the day of the first bloodshedding at Lexington. But the feelings of a father were too strong within him, and his solicitudes brooded over the land of his love with that unfailing anxiety for its best good which had characterized him from the beginning. Yet he modestly observes, in a letter on the subject to Col. Hamilton, "How far any further essay by me might be productive of the wished-for end, or appear to arrogate more than belongs to me, depends so much upon popular opinion, and the temper and dispositions of the people, that it is not easy to decide." He wrote a circular letter to the Governors of the several States, full of wisdom, dignity, and kindness, dwelling principally on four great points—an indissoluble union of the States; a sacred regard to public justice; the adoption of a proper military peace establishment; and a pacific and friendly disposition among the people of the States, which should induce them to forget local prejudices, and incline them to mutual concessions. This address is masterly in all respects, and [45] was felt to be particularly well-timed, the calm and honoured voice of Washington being at that moment the only one which could hope to be heard above the din of party, and amid the confusion natural during the first excitement of joy and triumph.

Washington's

Headquarters, Rocky Hill, N.J., 1783

Congress was not too proud to ask the counsel of its brave and faithful servant, in making arrangements for peace and settling the new affairs of the country. Washington was invited to Princeton, where Congress was then sitting, and introduced into the Chamber, where he was addressed by the President, and congratulated on the success of the war, to which he had so much contributed. Washington replied with his usual self-respect and modesty, and retired. A house had been prepared for him at Rocky Hill, near Princeton, where he resided for some time, holding conference with committees and members, and giving counsel on public affairs; and where he wrote that [46] admirable farewell to his army, perhaps as full of his own peculiar spirit as any of his public papers. His thanks to officers and soldiers for their devotion during the war have no perfunctory coldness in them, but speak the full heart of a brave and noble captain, reviewing a most trying period, and recalling with warm gratitude the co-operation of those on whom he relied. Then, for their future, his cautions and persuasions, the motives he urges, and the virtues he recommends, all form a curious contrast with those of Napoleon's addresses to his troops. "Let it be known and remembered," he says, "that the reputation of the federal armies is established beyond the reach of malevolence; and let a consciousness of their achievements and fame still incite the men who composed them to honorable actions; under the persuasion that the private virtues of economy, prudence, and industry, will not be less amiable in civil life, than the more splendid qualities of valor, perseverance and enterprise were in the field." Thus consistent to the last he honored all the virtues; showing that while those of the field were not misplaced in the farm, those of the farm might well be counted among the best friends of the field—his own life of planter and soldier forming a glorious commentary on his doctrines.

The evacuation of New-York by the British was a grand affair, General Washington and Governor George Clinton riding in at the head of the American troops that came from the northward to take possession, while Sir Guy Carleton and his legions embarked at the lower end of the city. The immense cavalcade of the victors embraced both military and civil authorities, and was closed by a great throng of citizens. This absolute finale of the war brought on the Commander-in-Chief [47] one of those duties at once sweet and painful—taking leave of his companions in arms; partners in toil and triumph, in danger and victory. "I cannot come to each of you to take my leave," he said, as he stood, trembling with emotion, "but I shall be obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand." General Knox, the warm-hearted, stood forward and received the first embrace; then the rest in succession, silently and with universal tears. Without another word the General walked from the room, passed through lines of soldiery to the barge which awaited him, then, turning, waved his hat, and bade to friends and comrades a silent, heartfelt adieu, which was responded to in the same solemn spirit. All felt that it was not the hour nor the man for noisy cheers; the spirit of Washington presided there, as ever, where honorable and high-minded men were concerned.

The journey southward was a triumphal march. Addresses, processions, delegations from religious and civil bodies, awaited him at every pause. When he reached Philadelphia he appeared before Congress to resign his commission, and no royal abdication was ever so rich in dignity. All the human life that the house would hold came together to hear him, and the words, few and simple, wise and kind, that fell from the lips of the revered chief, proved worthy to be engraved on every heart. In conclusion he said:—"Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action; and, bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body, under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life." He said afterwards to a friend:—"I feel now as I conceive a wearied traveller must do, who, after treading many a step [48] with a heavy burden on his shoulders, is eased of the latter, having reached the haven to which all the former were directed, and from his house-top is looking back, and tracing with an eager eye the meanders by which he escaped the quicksands and mire which lay in his way, and into which none but the all-powerful Guide and Dispenser of human events could have prevented his falling." And to Lafayette, he says:—"I am not only retired from all public employments, but I am retiring within myself, and shall be able to view the solitary walk, and tread the paths of private life with a heartfelt satisfaction. Envious of none, I am determined to be pleased with all; and this, my dear friend, being the order of my march, I will move gently down the stream of life until I sleep with my fathers."

That the public did not anticipate for him the repose and retirement he so much desired, we may gather from the instructions sent, at the time he resigned his commission, by the State of Pennsylvania, to her representatives in Congress, saying that "his illustrious actions and virtues render his character so splendid and venerable that it is highly probable the world may make his life in a considerable degree public;" and that "his very services to his country may therefore subject him to expenses, unless he permits her gratitude to interpose." "We are perfectly acquainted," says the paper, "with the disinterestedness and generosity of his soul. He thinks himself amply rewarded for all his labors and cares, by the love and prosperity of his fellow-citizens. It is true no rewards they can bestow can be equal to his merits, but they ought not to suffer those merits to be burdensome to him. * * * We are aware of the delicacy with which such a subject must be treated. But, relying in the good sense of Congress, we wish it may engage their early attention."

The delegates, on receipt of these instructions, very wisely [49] bethought themselves of submitting the matter to the person most concerned before they brought it before Congress, and he, as might have been expected, entirely declined the intended favor, and put an end to the project altogether. If he could have been induced to accept pecuniary compensation, there is no doubt a grateful nation would gladly have made it ample. But Washington, born to be an example in so many respects, had provided against all the dangers and temptations of money, by making himself independent as to his private fortune; having neglected no opportunity of enlarging it by honorable labor or judicious management, while he subjected the expenses of his family to the strictest scrutiny of economy.

Mount

Vernon (rear view).

His first care, on arriving at Mount Vernon, was to ascertain [50] the condition of his private affairs; his next to make a tour of more than six hundred miles through the western country, with the double purpose of inspecting some lands of his, and of ascertaining the practicability of a communication between the head waters of the great rivers flowing east and west of the Alleghanies. He travelled entirely on horseback, in military style, and kept a minute journal of each day's observations, the result of which he communicated, on his return, in a letter to the Governor of Virginia, which Mr. Sparks declares to be "one of the ablest, most sagacious, and most important productions of his pen," and "the first suggestion of the great system of internal improvements which has since been pursued in the United States." On a previous tour, through the northern part of the State of New-York, he had observed the possibility of a water communication between the Hudson and the Great Lakes, and appreciated its advantages, thus foreshowing, at that early date, the existence of the Erie Canal. In 1784, Washington had a final visit from Lafayette, from whom he parted at Annapolis, with manifestations of a deeper tenderness than the weak can even know. Arrived at home, he sat down at once to say yet another word to the beloved: "In the moment of our separation, upon the road as I travelled, and every hour since," (mark the specification from this man of exact truth,) "I have felt all that love, respect and attachment for you, with which length of years, close connection, and your merits have inspired me. I often asked myself, as our carriages separated, whether that was the last sight I should ever have of you? And though I wished to say No! my fears answered Yes!" He was right; they never met again, but they loved each other always. Lafayette's letters to [51] Washington are lover-like; they are alone sufficient to show how capable of the softest feeling was the great heart to which they were addressed.

Space fails us for even the baldest enumeration of the instances of care for the public good with which the life of Washington abounded, when he fancied himself "in retirement," for we have unconsciously dwelt, with the reverence of affection, upon the picture of his character during the Revolution, and felt impelled to illustrate it, where we could, by quotations from his own weighty words; weighty, because, to him, words were things indeed, and we feel that he never used one thoughtlessly or untruly. Brevity must now be our chief aim, and we pass, at once, over all the labor and anxiety which attended the settlement of the Constitution, to mention the election of Washington to the Presidency of the States so newly united, by bonds which, however willingly assumed, were as yet but ill fitted to the wearers. The unaffected reluctance with which he accepted the trust appears in every word and action of the time; and it is evident that, as far as selfish feelings went, he was much more afraid of losing the honor he had gained than of acquiring new. The heart of the nation was with him, however, even more than he knew; and the "mind oppressed with more anxious and painful sensations" than he had words to express at the outset, was soon calmed, not only by the suggestions of duty, but by the marks of unbounded love and confidence lavished on him at every step of his way by a grateful people. The Inaugural Oath was taken, before an immense concourse of people, on the balcony of Federal Hall, New-York, April 30, 1789, and the President afterwards delivered his first Address, in the Senate Chamber of the same building, [52] now no longer standing, but not very satisfactorily replaced by that magnificent Grecian temple wherein the United States Government collects the Customs of New-York.

House of the First Presidential Levee, Cherry street.

The house in which the first

Presidential levee was held will always be a point of interest, and the

consultations between Washington and the great officers of state about

the simple ceremonial of these public receptions, are extremely

curious, as showing the manners and ideas of the times, and the

struggle between the old-country associations natural to gentlemen of

that day, and the recognized necessity of accommodating even court

regulations to the feelings of a people to whom the least shadow of

aristocratic form was necessarily hateful. We must not condemn the

popular scrupulousness of 1789 as puerile and foolish, until we too

have perilled life and fortune in the cause of liberty and equality.

A dangerous illness brought Washington near the grave, [53] during his first Presidential summer, and he is said never to have regained his full strength. In August his mother died, venerable for years and wisdom, and always honored by her son in a spirit that would have satisfied a Roman matron. She maintained her simple habits to the last, and is said never to have exhibited surprise or elation, at her son's greatest glory, or the highest honors that could be paid him. Her remains rest under an unfinished monument, near Fredericksburgh, Virginia.

Of the wife of the illustrious Chief, it is often said that little is known, and there is felt almost a spite against her memory because she destroyed before her death every letter of her husband to herself, save only one, written when he accepted the post of Commander-in-Chief. But, to our thinking, one single letter of hers, written to Mrs. Warren, after the President's return from a tour through the eastern States, tells the whole story of her character and tastes, a story by no means discreditable to the choice of the wisest of mankind. Mr. Sparks gives the letter entire, as we would gladly do if it were admissible. We must, however, content ourselves with a few short extracts:—