Project Gutenberg's Ocean to Ocean on Horseback, by Willard Glazier

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Ocean to Ocean on Horseback

Being the Story of a Tour in the Saddle from the Atlantic

to the Pacific; with Especial Reference to the Early History

and Devel

Author: Willard Glazier

Release Date: October 4, 2011 [EBook #37615]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OCEAN TO OCEAN ON HORSEBACK ***

Produced by Julia Miller, Julia Neufeld and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

| I. | Three years in the Federal Cavalry. |

| II. | Capture, Prison-Pen and Escape. |

| III. | Battles for the Union. |

| IV. | Heroes of Three Wars. |

| V. | Peculiarities of American Cities. |

| VI. | Down the Great River. |

| VII. | Headwaters of the Mississippi. |

| VIII. | Ocean to Ocean on Horseback. |

Captain Glazier's works are growing more and more popular every day. Their delineations of social, military and frontier life, constantly varying scenes, and deeply interesting stories, combine to place their writer in the front rank of American authors.

It was the intention of the writer to publish a narrative descriptive of his overland tour from the Atlantic to the Pacific soon after returning from California in 1876, and his excuse for the delay in publication is that a variety of circumstances compelled him to postpone for a time the duty of arranging the contents of his journal until other pressing matters had been satisfactorily attended to. Again, considerable unfinished literary work, set aside when he began preparation for crossing the Continent, had to be resumed, and for these reasons the story of his journey from "Ocean to Ocean on Horseback" is only now ready for the printer. In view of this delay in going to press, the author will endeavor to show a due regard for the changes time has wrought along his line of march, and[viii] while noting the incidents of his long ride from day to day, it has been his aim so far as possible to discuss the regions traversed, the growth of cities and the development of their industries from the standpoint of the present.

Albany, New York,

August 22, 1895.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTORY.

Boyhood Longings—Confronted by Obstacles—Trapping Along the Oswegatchie—Enter Gouverneur Wesleyan Seminary—Appointed to State Normal College—Straitened Circumstances—Teach School in Rensselaer County—War of the Rebellion—Enlist in a Cavalry Regiment—Taken Prisoner—Fourteen Months in Southern Prisons—Escape from Columbia—Recaptured—Escape from Sylvania, Georgia—Re-enter the Army—Close of the War—Publish "Capture, Prison-Pen and Escape" and Other Books—Decide to Cross the Continent—Preparation for Journey—Ocean to Ocean on Horseback 25

CHAPTER II.

BOSTON AND ITS ENVIRONS.

Early History and Development—Situation of the Metropolis of New England—Boston Harbor—The Cradle of Liberty—Old South Church—Migrations of the Post Office—Patriots of the Revolution—The Boston Tea Party—Bunker Hill Monument—Visit of Lafayette—The Public Library—House where Franklin was Born—The Back Bay—Public Gardens—Streets of Boston—Soldiers' Monument—The Old Elm—Commonwealth Avenue—State Capitol—Tremont Temple—Edward Everett—Wendell Phillips—William Loyd Garrison—Phillips Brooks—Harvard University—Wellesley College—Holmes, Parkman—Prescott, Lowell, Longfellow—Boston's Claims to Greatness 32

CHAPTER III.

LECTURE AT TREMONT TEMPLE.

Subject of Lecture—Objects Contemplated—Grand Army of the[x] Republic—Introduction by Captain Theodore L. Kelly—Reference to Army and Prison Experiences—Newspaper Comment—Proceeds of Lecture Given to Posts 7 and 15—Letter to Adjutant-General of Department 70

CHAPTER IV.

BOSTON TO ALBANY.

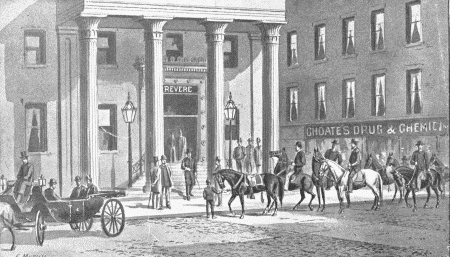

First Day of Journey—Start from the Revere House—Escorted to Brighton by G. A. R. Comrades—Dinner at Cattle Fair Hotel—South Framingham—Second Day—Boston and Albany Turnpike—Riding in a Rain-storm—Arrival at Worcester—Lecture in Opera House—Pioneer History—Rapid Growth of Worcester—Lincoln Park—The Old Common—Third and Fourth Days—The Ride to Springfield—Met by Wife and Daughter—Lecture at Haynes Opera House—Fifth Day—Ride to Russell—The Berkshire Hills—Sixth Day—Journey to Becket—Rainbow Reflections—Seventh Day—Over the Hoosac Mountains—Eighth Day—Arrival at Pittsfield—Among the Lebanon Shakers—Ninth Day—Reach Nassau, New York 81

CHAPTER V.

FOUR DAYS AT ALBANY.

Nassau to Albany—Among Old Friends in Rensselaer County—Thoughts of Rip Van Winkle—Crossing the Hudson—Albany as Seen from the River—Schoolday Associations—Early History—Settled by the Dutch—Henry Hudson—Killian Van Rensselaer—Fort Orange—Peter Schuyler and Robert Livingstone—Lecture at Tweddle Hall—Call at the Capitol—Meet Army Comrades. 110

CHAPTER VI.

ALBANY TO SYRACUSE.

Fourteenth Day—On the Schenectady Turnpike—Riding between Showers—Talk with Peter Lansing—Reach Schenectady—Lecture at Union Hall under G. A. R. Auspices—Fifteenth and Sixteenth Days—Go over to Troy—Lecture at Harmony Hall—Visit Old Friends—Seventeenth Day—Return to Schenectady—Eighteenth Day—In the Mohawk Valley—Halt at Amsterdam—Reach Fonda—Nineteenth Day—Saint Johnsville—Twentieth Day—Little Falls—Twenty-first Day—Utica—Twenty-second Day—Rome—Twenty-third Day—Chittenango 118

CHAPTER VII.

TWO DAYS AT SYRACUSE.

Walks and Talks with the People—Early History—Lake Onondaga—Father Le Moyne—Discovery of Salt Springs—Major Danforth—Joshua Forman—James Geddes—The Erie Canal—Visit of La Fayette—Syracuse University—Lecture at Shakespeare Hall. 132

CHAPTER VIII.

SYRACUSE TO ROCHESTER.

Twenty-sixth Day—Grand Army Friends—General Sniper—Captain Auer—Stopped by a Thunder-shower—An Unpleasant Predicament—Twenty-Seventh Day—Jordan, New York—Lake Skaneateles—Twenty-eighth Day—Photographed—Entertained at Port Byron—Montezuma Swamp—Twenty-ninth Day—Newark, New York—Journey Continued Along the New York Central Railway—Another Adventure with Paul—Thirtieth Day—Fairport—Riding in the Cool of the Day 141

CHAPTER IX.

FOUR DAYS AT ROCHESTER.

Rainstorm Anticipated—Friends of the Horse—Seven-Sealed Wonder—Newspaper Controversy—Lecture at Corinthian Hall—Colonel J. A. Reynolds—Pioneer History—Colonel Nathaniel Rochester—William Fitzhugh—Charles Carroll—Rapid Growth of City—Sam Patch—Genesee Falls—The Erie Canal—Mount Hope—Lake Ontario—Fruit Nurseries 147

CHAPTER X.

ROCHESTER TO BUFFALO.

Thirty-fifth Day—Churchville—Cordiality of the People—Dinner at Chili—Thirty-sixth Day—Bergen Corners—Byron Centre—Rev. Edwin Allen—Thirty-seventh Day—Batavia—Meet a Comrade of the Harris Light Cavalry—Thirty-eighth Day—"Croft's"—More Trouble with Mosquitoes—Amusing Episode—Thirty-ninth Day—Crittenden—Rural Reminiscences—Fortieth Day—Lancaster—Lectured in Methodist Church—Captain Remington 158

CHAPTER XI.

THREE DAYS AT BUFFALO.

"Queen City" of the Lakes—Arrival at the Tift House—Lecture at St. James Hall—Major Farquhar—Aboriginal History—The Eries—Iroquois—"Cats"—La Hontan—Lake Erie—Black Rock—War of 1812—The Erie Canal—Buffalo River—Grosvenor Library—Historical Society—Red Jacket—Forest Lawn—Predictions for the Future 171

CHAPTER XII.

BUFFALO TO CLEVELAND.

Forty-fourth Day—On the Shore of Lake Erie—Forty-fifth Day—Again on the Shore of Erie—Bracing Air—Enchanting Scenery—Angola—Big Sister Creek—Forty-sixth Day—Angola to Dunkirk—Forty-eighth Day—Dunkirk to Westfield—Fruit and Vegetable Farms—Fredonia—Forty-ninth Day—Westfield to North East—Cordial Reception—Fiftieth Day—North East to Erie—Oliver Hazzard Perry—Fifty-first Day—Erie to Swanville—Fifty-second Day—Talk with Early Settlers—John Joseph Swan—Fifty-third Day—Swanville to Girard—Greeted by Girard Band—Lecture at Town Hall—Fifty-fourth Day—Girard to Ashtabula—Lecture Postponed—Fifty-fifth Day—Ashtabula to Painesville—The Centennial Fourth—Halt at Farm House—Fifty-sixth Day—Reach Willoughby—Guest of the Lloyds 183

CHAPTER XIII.

FIVE DAYS AT CLEVELAND.

An Early Start—School Girls—"Do you Like Apples, Mister?"—Mentor—Home of Garfield—Dismount at Euclid—Rumors of the Custer Massacre—Reach the "Forest City"—Met by Comrades of the G. A. R.—Lecture at Garrett Hall—Lake Erie—Cuyahoga River—Early History—Moses Cleveland—Connecticut Land Company—Job Stiles—The Ohio Canal—God of Lake Erie—"Ohio City"—West Side Boat Building—"The Pilot"—Levi Johnson-Visit of Lorenzo Dow—Monument Square—Commodore Perry—Public Buildings—Euclid Avenue—"The Flats"—Standard Oil Company 206

CHAPTER XIV.

CLEVELAND TO TOLEDO.

Sixty-first Day—Again in the Saddle—Call on Major Hessler—Donate Proceeds of Lecture to Soldiers' Monument Fund—Letters from General James Barnett and Rev. William Earnshaw—Stop for Night at Black River—Sixty-second Day—Mounted at Nine A.M.—Halted at Vermillion for Dinner—Lake Shore Road—More Mosquitoes—Reach Huron Late at Night—Sixty-third Day—Huron to Sandusky—Traces of the Red Man—Ottawas and Wyandots—Johnson's Island—Lecture in Union Hall—Captain Culver—Sixty-fourth Day—Ride to Castalia—A Remarkable Spring—Sixty-fifth Day—Reach Fremont—Home of President Hayes—Sixty-sixth Day—Reach Elmore, Ohio—Comparison of Hotels 221

CHAPTER XV.

FIVE DAYS AT TOLEDO.

Ride from Elmore—Lecture at Lyceum Hall—Forsyth Post, G. A. R.—Doctor J. T. Woods—Concerning General Custer—Pioneer History—Battle of Fallen Timbers—Mad Anthony Wayne—Miami and Wabash Indians—The Toledo War—Unpleasant Complications—Governor Lucas—Strategy of General Vanfleet— Milbourn Wagon Works—Visited by a Detroit Friend 231

CHAPTER XVI.

TOLEDO TO DETROIT.

Seventy-second Day—Leave Toledo—Change of Route—Ride to Erie, Michigan—Paul Shows His Mettle—Seventy-third Day—Sunday —Go to Church—Rev. E. P. Willard—Solicitude of Friends— Seventy-fourth Day—Ride to Monroe—Greeted with Music—Hail Columbia—Star-Spangled Banner—Home of Custer—Meet Custer Family—Custer Monument Association—Received at City Hall—Great Enthusiasm—River Rasin—Indian Massacre—General Winchester— Battle of the Thames—Death of Tecumseh—Monroe Monitor—Seventy-seventh Day—Lecture at City Hall—Personal Recollections of Custer—Incidents of His School Life—Seventy-eighth Day—Leave Monroe—Huron River—Traces of the Mound Builders—Rockwood—Seventy-ninth Day—Along the Detroit River—Wyandotte—Ecorse—Eightieth Day—Letter from Judge Wing—Indorsement of Custer Monument Association 243

CHAPTER XVII.

FOUR DAYS AT DETROIT.

Leave Ecorse—Met at Fort Wayne—Sad News—Reach Detroit— Met by General Throop and Others—at Russell House—Lecture at St. Andrew's Hall—General Trowbridge—Meet Captain Hampton—Army and Prison Reminiscences—Pioneer History of Detroit— La Motte Cadillac—Miamies and Pottawattomies—Fort Ponchartrain— Plot of Pontiac—Major Gladwyn—Fort Shelby—War of 1812—General Brock and Tecumseh Advance on Detroit—Surrender of General Hull—British Compelled to Evacuate 265

CHAPTER XVIII.

DETROIT TO CHICAGO.

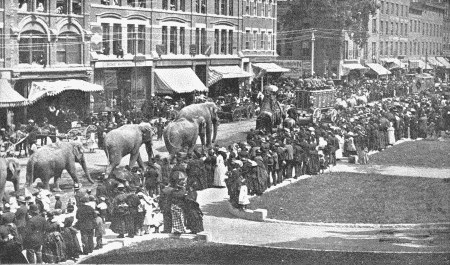

Eighty-fifth Day—Leave Detroit Reluctantly—Paul in Good Spirits —Reach Inkster—Eighty-sixth Day—Lowering Clouds—Take Shelter under Trees and in a Woodshed—Meet War Veterans[xiv]— Ypsilanti—Eighty-seventh Day—Lecture at Union Hall—Incidents of the Late War—Eighty-eighth Day—An Early Start—Ann Arbor —Michigan University—Dinner at Dexter—Eighty-ninth Day—Dinner at Grass Lake—Reach Jackson—Ninetieth Day—Comment of Jackson Citizen—Coal Fields—Grand River—Ninety-first Day—A Circus in Town—Parma—Ninety-second Day—"Wolverines"—Ninety-third Day—Ride to Battle Creek—Lecture at Stuart's Hall—Ninety-fourth Day—Go to Church—Goguac Lake—Ninety-fifth Day—Arrive at Kalamazoo—Sketch of the "Big Village"—Ninety-sixth Day—Return to Albion and Lecture in Opera House—Ninety-seventh Day—Lecture at Wayne Hall, Marshall—Ninety-eighth Day—Calhoun County—Ninety-ninth Day—Letter to Custer Monument Association—One Hundredth Day—Colonel Curtenius—One Hundred and First Day—Paw Paw—One Hundred and Second Day—South Bend, Indiana—Hon. Schuyler Colfax—One Hundred and Third Day—Grand Rapids—Speak in Luce's Hall—One Hundred and Fourth Day—Return to Decatur—One Hundred and Fifth Day—Again in Paw Paw—One Hundred and Sixth Day—Lecture at Niles—One Hundred and Seventh Day—Go to La Porte by Rail—One Hundred and Eighth Day—Return to Michigan City—One Hundred and Ninth Day—Go Back to Decatur, Michigan—One Hundred and Tenth to One Hundred and Twenty-second Day—Dowagiac—Buchanan—Rolling Prairie 279

CHAPTER XIX.

THREE DAYS AT CHICAGO.

Register at the Grand Pacific Hotel—Lecture at Farwell Hall—Visit McVicker's Theatre—See John T. Raymond in "Mulberry Sellers"—The Chicago Exposition—Site of City—Origin of Name—Father Marquette—First Dwelling—Death of Marquette—Lake Michigan—Fort Dearborn—First Settlement Destroyed by Indians—Chicago as a Commercial City—The Great Fire—An Unparalleled Conflagration—Rises from her Ashes—Financial Reorganization—Greater than Before—Schools and Colleges—Historical Society—The Palmer House—Spirit of the People—One Hundred and Twenty-sixth Day—Again at Michigan City—Attend a Political Meeting—Hon. Daniel W. Voorhees—"Blue Jeans" Williams—One Hundred and Twenty-eighth Day—Leave Michigan City—Hobart—"Hoosierdum"—One Hundred and Twenty-ninth Day—Weather Much Cooler 333

CHAPTER XX.

CHICAGO TO DAVENPORT.

One Hundred and Thirtieth Day—Followed by Prairie Wolves—Reach Joliet, Illinois—Lecture at Werner Hall—One Hundred and Thirty-first Day—Ride on Tow Path of Michigan Canal—Morris—One Hundred and Thirty-second Day—Corn and Hogs—Arrive at Ottawa—One Hundred and Thirty-third Day—Reach La Salle—One Hundred and Thirty-fourth Day—Colonel Stephens—One Hundred and Thirty-fifth Day—Visit Peru—One Hundred and Thirty-sixth Day—Mistaken for a Highwayman—One Hundred and Thirty-seventh Day—Fine Stock Farms—Wyanet—One Hundred and Thirty-eighth Day—Annawan—Commendatory Letter—One Hundred and Thirty-ninth Day—A Woman Farmer—One Hundred and Fortieth Day—Reach Milan, Illinois 354

CHAPTER XXI.

FOUR DAYS AT DAVENPORT.

Cross the Mississippi—Lecture at Moore's Hall—Colonel Russell—General Sanders—Early History of the City—Colonel George Davenport—Antoine Le Claire—Griswold College—Rock Island—Fort Armstrong—Rock Island Arsenal—General Rodman—Colonel Flagler—Rock Island City—Sac and Fox Indians—Black Hawk War—Jefferson Davis—Abraham Lincoln—Defeat of Black Hawk—Rock River—Indian Legends 372

CHAPTER XXII.

DAVENPORT TO DES MOINES.

One Hundred and Forty-fifth Day—Leave Davenport—Stop over Night at Farm House—One Hundred and Forty-sixth Day—Reach Moscow, Iowa—Rolling Prairies—One Hundred and Forty-seventh Day—Weather Cold and Stormy—Iowa City—One Hundred and Forty-eighth Day—Description of City—One Hundred and Forty-ninth Day—Lectured at Ham's Hall—Hon. G. B. Edmunds—One Hundred and Fiftieth Day—Reach Tiffin—Guests of the Tiffin House—One Hundred and Fifty-first Day—Marengo—One Hundred and Fifty-second Day—Halt for the Night at Brooklyn—One Hundred and Fifty-third Day—Ride to Kellogg—Stop at a School House—Talk with Boys—One Hundred and Fifty-fourth Day—Reach Colfax—One Hundred and Fifty-fifth Day—Arrive at Des Moines—Capital of Iowa—Description of City—Professor Bowen—Meet an Army Comrade 386

CHAPTER XXIII.

DES MOINES TO OMAHA.

One Hundred and Fifty-seventh Day—Leave Des Moines with Pleasant Reflections—Reach Adel—Dallas County—Raccoon River—One Hundred and Fifty-eighth Day—Ride through Redfield—Reach Dale City—Talk Politics with Farmers—One Hundred and Fifty-ninth Day—A Night with Coyotes—Re-enforced by a Friendly Dog—One Hundred and Sixtieth Day—Cold Winds from the Northwest—All Day on the Prairies—One Hundred and Sixty-first Day—Halt at Avoca—One Hundred and Sixty-second Day—Riding in the Rain—Reach Neola—One Hundred and Sixty-third Day—Roads in Bad Condition—Ride through Council Bluffs—Arrive at Omaha 401

CHAPTER XXIV.

A HALT AT OMAHA.

The Metropolis of Nebraska—First Impressions—Peculiarity of the Streets—Hanscom Park—Poor House Farm—Prospect Cemetery—Douglas County Fair Grounds—Omaha Driving Park—Fort Omaha—Creighton College—Father Marquette—The Mormons—"Winter Quarters"—Lone Tree Ferry—Nebraska Ferry Company—Old State House—First Territorial Legislature—Governor Cummings—Omaha in the Civil War—Rapid Development of the "Gate City" 409

CHAPTER XXV.

OMAHA TO CHEYENNE.

Leave Paul in Omaha—Purchase a Mustang—Use Mexican Saddle—Over the Great Plains—Surface of Nebraska—Extensive Beds of Peat—Salt Basins—The Platte River—High Winds—Dry Climate—Fertile Soil—Lincoln—Nebraska City—Fremont—Grand Island—Plum Creek—McPherson—Sheep Raising—Elk Horn River—In Wyoming Territory—Reach Cheyenne—Description of Wyoming "Magic City"—Vigilance Committee—Rocky Mountains—Laramie Plains—Union Pacific Railroad 420

CHAPTER XXVI.

CAPTURED BY INDIANS.

Leave Cheyenne—Arrange to Journey with Herders—Additional Notes on Territory—Yellowstone National Park—Sherman—Skull Rocks—Laramie Plains—Encounter Indians—Friendly Signals—Surrounded by Arrapahoes—One Indian Killed—Taken Prisoners—Carried toward Deadwood—Indians Propose to Kill[xvii] their Captives—Herder Tortured at the Stake—Move toward Black Hills—Escape from Guards—Pursued by the Arrapahoes—Take Refuge in a Gulch—Reach a Cattle Ranch—Secure a Mustang and Continue Journey 435

CHAPTER XXVII.

AMONG THE MORMONS.

Ride Across Utah—Chief Occupation of the People—Description of Territory—Great Salt Lake—Mormon Settlements—Brigham Young—Peculiar Views of the Latter Day Saints—"Celestial Marriages"—Joseph Smith, the Founder of Mormonism—The Book of Mormon—City of Ogden—Pioneer History—Peter Skeen Ogden—Weber and Ogden Rivers—Heber C. Kimball—Echo Canyon—Enterprise of the Mormons—Rapid Development of the Territory 446

CHAPTER XXVIII.

OVER THE SIERRAS.

The Word Sierra—At Kelton, Utah—Ride to Terrace—Wells, Nevada—The Sierra Nevada—Lake Tahoe—Silver Mines—The Comstock Lode—Stock Raising—Camp Halleck—Humboldt River—Mineral Springs—Reach Palisade—Reese River Mountain—Golconda—Winnemucca—Lovelocks—Wadsworth—Cross Truckee River—In California 458

CHAPTER XXIX.

ALONG THE SACRAMENTO.

Colfax—Auburn—Summit—Reach Sacramento—California Boundaries—Pacific Ocean—Coast Range Mountains—The Sacramento Valley—Inhabitants of California—John A. Sutter—Sutter's Fort—A Saw-mill—James Wilson Marshall—Discovery of Gold—"Boys, I believe I have found a Gold Mine"—The Secret Out—First Days of Sacramento—A "City of Tents"—Capital of California 465

CHAPTER XXX.

SAN FRANCISCO AND END OF JOURNEY.

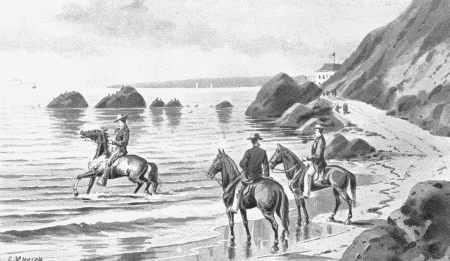

Metropolis of the Pacific Coast—Largest Gold Fields in the World—The Jesuits—Captain Sutter—Argonauts of "49"—Great Excitement—Discovery of Upper California—Sir Francis Drake—John P. Lease—The Founding of San Francisco—The "Golden Age"—Story of Kit Carson—The Golden Gate—San Francisco Deserted—The Cholera Plague—California Admitted to the Union—Crandall's Stage—Wonderful Development of San Francisco—United States Mint—Handsome Buildings—Trade with China, Japan, India and Australia—Go Out to the Cliff House—Ride into the Pacific—End of Journey 476

| PAGE | |

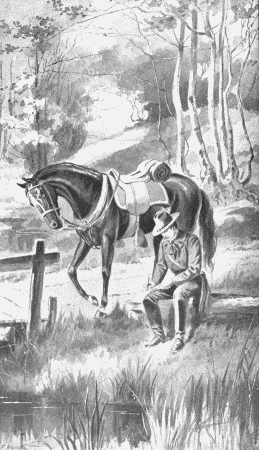

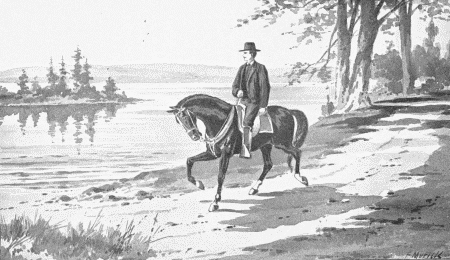

| Wayside Notes | Frontispiece |

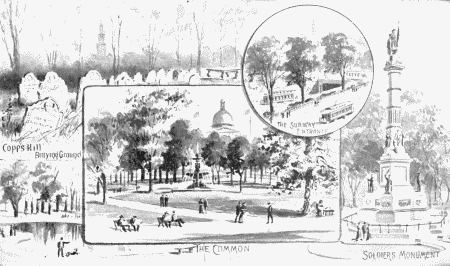

| Views in Boston | 33 |

| Scenes in Boston | 39 |

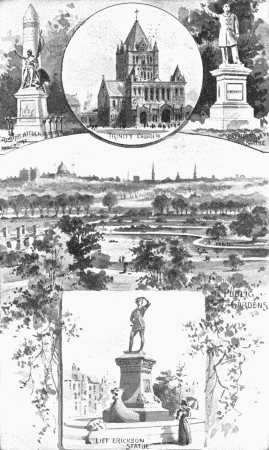

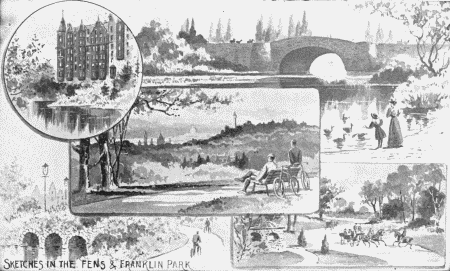

| Boston and Environs | 49 |

| Commonwealth Avenue, Boston | 57 |

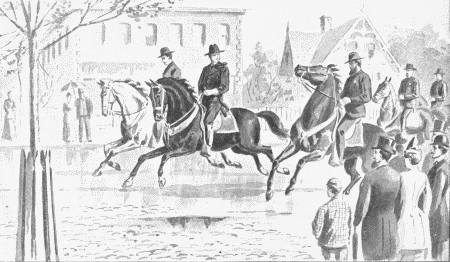

| Leaving the Revere House, Boston | 71 |

| Riding Through Cambridge | 77 |

| View in Worcester, Mass. | 81 |

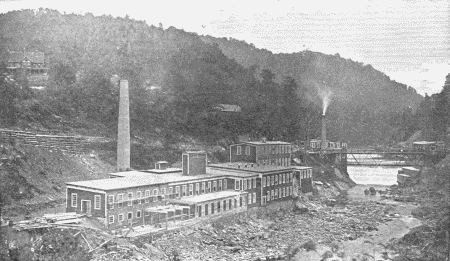

| A New England Paper Mill | 85 |

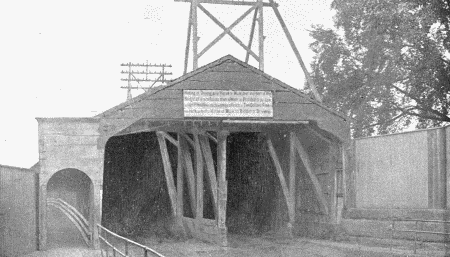

| Old Toll-Bridge at Springfield | 91 |

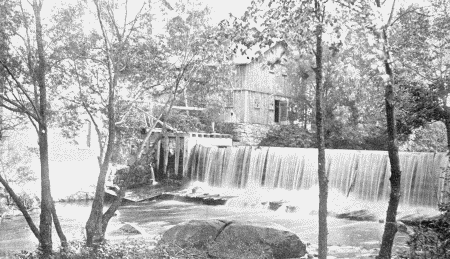

| A Massachusetts Mill Stream | 95 |

| The Springfield Armory | 99 |

| A Mill in the Berkshire Hills | 103 |

| A Hamlet in Berkshire Hills | 107 |

| Suburb of Pittsfield | 111 |

| A Scene in the Berkshire Hills | 115 |

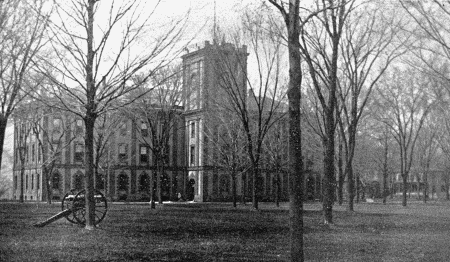

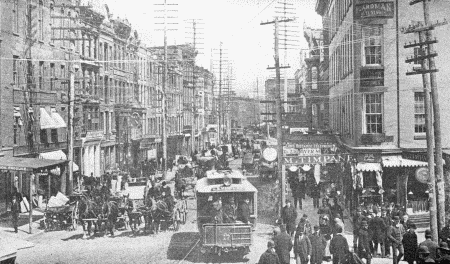

| State Street and Capitol, Albany, N. Y. | 125 |

| River Street, Troy, N. Y. | 129 |

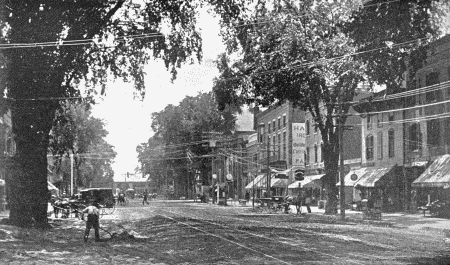

| View in Schenectady, N. Y. | 133 |

| View in Mohawk Valley | 143 |

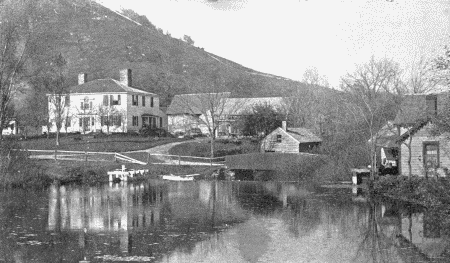

| A Mill Stream in Mohawk Valley | 139 |

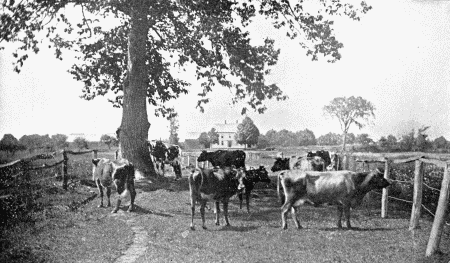

| A Flourishing Farm | 157 |

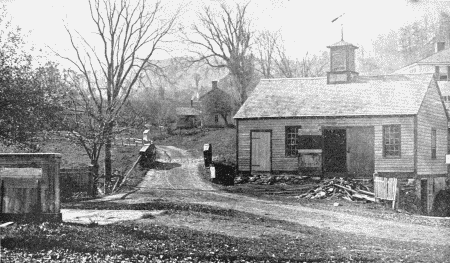

| An Old Landmark | 161 |

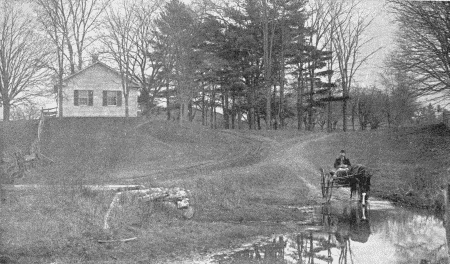

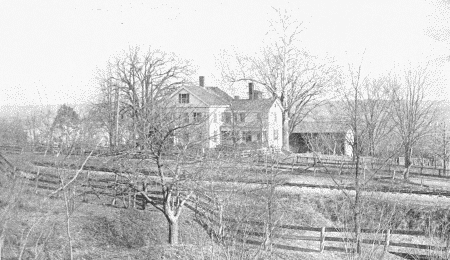

| The Road to Albany | 121 |

| View of Rochester | 171 |

| The District School-House | 177 |

| Rural Scene in Central New York | 183 |

| The Road to Buffalo | 189 |

| Juvenile Picnic | 205 |

| A Cottage on the Hillside | 211 |

| Haying in Northern Ohio | 221 |

| Just Out of Cleveland | 225 |

| On the Shore of Lake Erie | 235 |

| Sunday at the Farm | 241 |

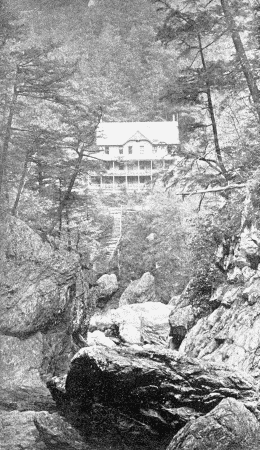

| A Home in the Woods | 245 |

| Country Store and Post Office | 255 |

| An Ohio Farm | 265 |

| Outskirts of a City | 279 |

| A Summer Afternoon | 303 |

| The Country Peddler | 313 |

| A Mill in the Forest | 321 |

| No Rooms To Let | 335 |

| Rural Scene in Michigan | 341 |

| Spinning Yarns by a Tavern Fire | 345 |

| A Hoosier Cabin | 355 |

| A Circus in Town | 359 |

| A Country Road in Illinois | 381 |

| An Illinois Home | 385 |

| A Happy Family | 395 |

| An Illinois Village | 399 |

| The Road to the Church | 404 |

| An Iowa Village | 419 |

| On the Way to Mill | 427 |

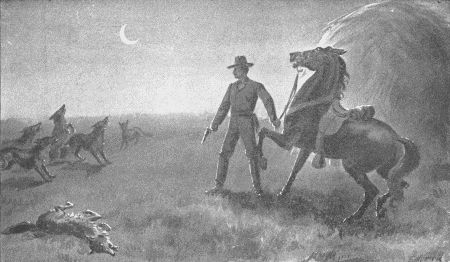

| A Night Among the Coyotes | 431 |

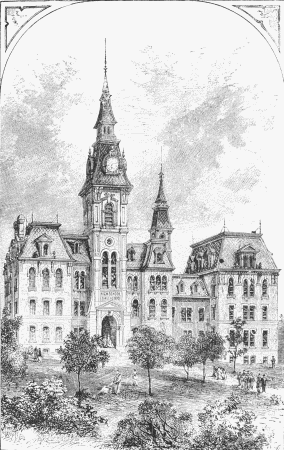

| High School, Omaha, Neb. | 441 |

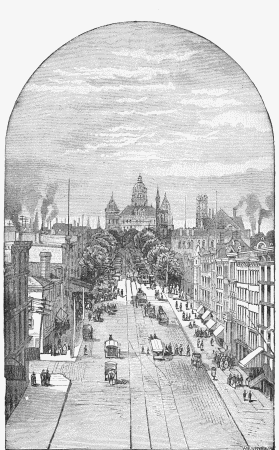

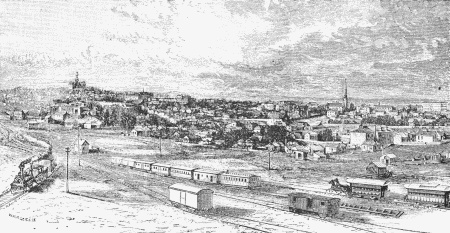

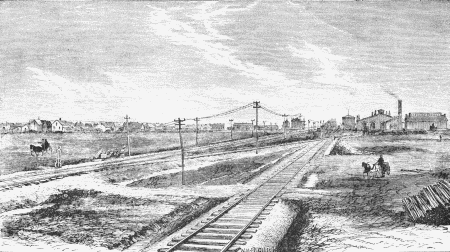

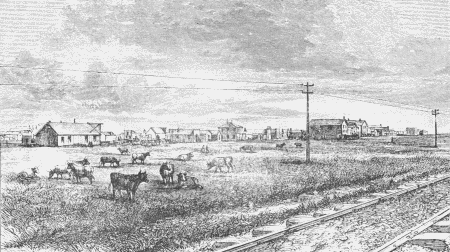

| Omaha, Neb., in 1876 | 437 |

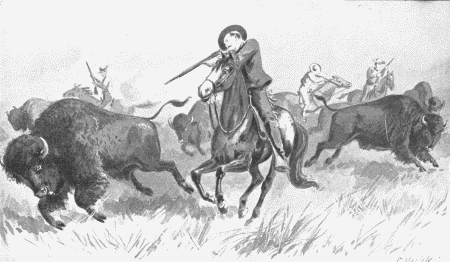

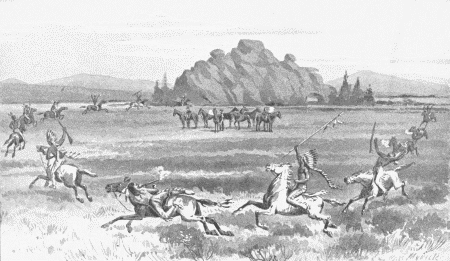

| Sport on the Plains | 449 |

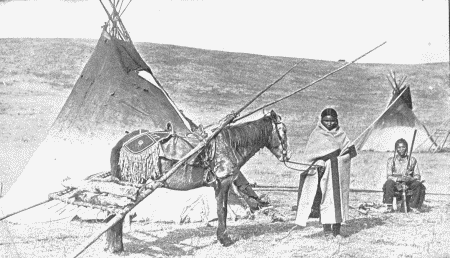

| Pawnee Indians, Neb. | 453 |

| North Platte, Neb. | 457 |

| Plum Creek, Neb. | 463 |

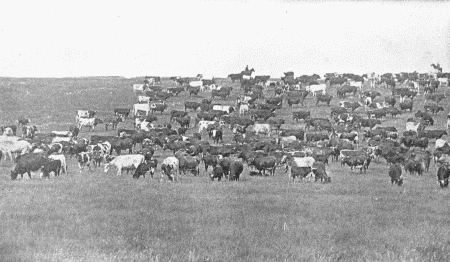

| Cattle Ranch in Nebraska | 467 |

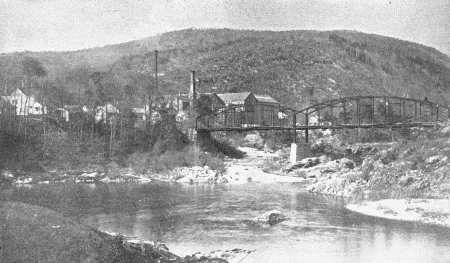

| A Mountain Village | 471 |

| Captured by the Indians | 477 |

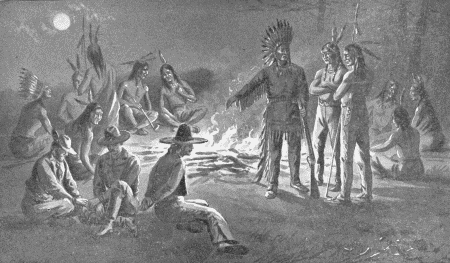

| Deciding the Fate of the Captives | 481 |

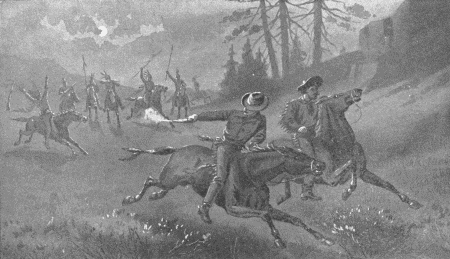

| Escape from the Arrapahoes | 487 |

| An Indian Encampment, Wyoming | 495 |

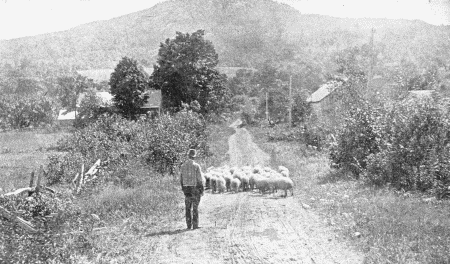

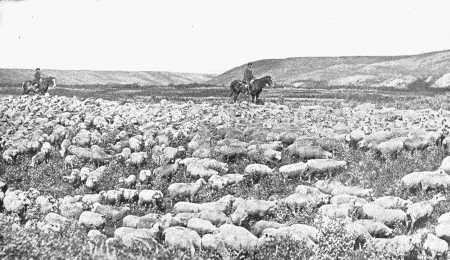

| Sheep Ranch in Wyoming | 503 |

| Mining Camp in Nevada | 507 |

| A Rocky Mountain River | 513 |

| A Lake in the Sierra Nevadas | 517 |

| A Cascade by the Roadside | 525 |

| View in Woodward's Garden, San Francisco | 533 |

| The Pacific Ocean, End of Journey | 541 |

From earliest boyhood it had been my earnest desire to see and learn from personal observation all that was possible of the wonderful land of my birth. Passing from the schoolroom to the War of the Rebellion and thence back to the employments of peace, the old longing to make a series of journeys over the American Continent again took possession of me and was the controlling incentive of all my ambitions and struggles for many years.

To see New England—the home of my ancestors; to visit the Middle and Western States; to look upon the majestic Mississippi; to cross the Great Plains; to scale the mountains and to look through the Golden Gate upon the far-off Pacific were among the cherished desires through which my fancy wandered before leaving the Old Home and village school in Northern New York.

The want of an education and the want of money were two serious obstacles which confronted me for a time. Without the former I could not prosecute my journeys intelligently and for want of the latter I could not even attempt them.

Aspiring to an academic and collegiate course of study, but being at that period entirely without means for the accomplishment of my purpose, I left the district school of my native town and sought to raise the necessary funds by trapping for mink and other fur-bearing animals along the Oswegatchie and its tributary streams. This venture proving successful I entered the academy at Gouverneur in August, 1857, from which institution I was appointed to the State Normal College at Albany in the fall of 1859.

I had been in Albany but six weeks when it became apparent that if I continued at the Normal I would soon be compelled to part with my last dollar for board and clothing.

The years 1859-60 were spent alternately at Albany as student and in the village schools of Rensselaer County as teacher—the latter course being resorted to whenever money was needed with which to meet current expenses at the Normal School.

Then came our great Civil Conflict overriding every other consideration. Books were thrown aside and the pursuits of the student and teacher supplanted by the sterner and more arduous duties of the soldier.

During my three years of camping and campaigning with the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac I was enabled to gratify to some extent my desire for travel and to see much of interest as the shifting scenes of war led Bayard, Stoneman, Pleasonton, Gregg, Custer,[23] Davies and Kilpatrick and their followers over the hills and through the valleys of Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Being captured in a cavalry battle between Kilpatrick and Stuart in October, 1863, I was imprisoned successively at Richmond, Danville, Macon, Savannah, Charleston and Columbia, from which last prison I escaped in November, 1864; was recaptured and escaped a second and third time, traversing the States of South Carolina and Georgia in my long tramp from Columbia to Savannah.

The marches, raids, battles, captures and escapes of those days seem to have increased rather than diminished my ardor for travel and adventure and hence it is possibly not strange that on leaving the army I still looked forward to more extended journeys in the East and exploratory tours beyond the Mississippi.

With the close of the war and mustering out of service came new duties and responsibilities which I had hardly contemplated during my school days. The question of ways and means again confronted me. I desired first to continue the course of study which had been interrupted by my enlistment, and secondly to carry out my cherished plans for exploration. Having a journal kept during my incarceration in and escapes from Southern prisons, I was advised and decided to amplify and publish it if possible with a view to promoting these projects.

Going to New York, I at once sought the leading publishers. My manuscript was submitted to the Harpers, Appletons, Scribners, and some others, but as I was entirely unknown, few cared to undertake the publication and none seemed disposed to allow[24] a royalty which to me at least seemed consistent with the time and labor expended in preparation. I had now spent my last dollar in the Metropolis in pursuit of a publisher, and in this dilemma it was thought best to return to Albany, where I had friends and perhaps some credit, and endeavor to bring out the book by subscription. This course would compel me to assume the cost of production, but if successful would prove much more lucrative than if issued in the usual way through the trade.

Fully resolved upon retracing my steps to Albany, I was most fortunate in meeting an old comrade and friend to whom I frankly stated my plans and circumstances. He immediately loaned me twenty dollars with which to continue my search for a publisher and to meet in the meantime necessary current expenses.

On reaching Albany an attic room and meals were secured for a trifling sum, arrangements made with a publisher, and the work of getting out the book begun. While the printer was engaged in composing, stereotyping, printing and binding the work, I employed my spare time in a door-to-door canvass of the city for subscriptions, promising to deliver on the orders as soon as the books came from the press. In this way the start was made and before the close of the year hundreds of agencies were established throughout the country.

The venture proved successful beyond my most sanguine expectations, and where I had expected to dispose of two or three editions and to realize a few hundred dollars from the sale of "Capture, Prison-Pen and Escape," the book had a sale of over 400,000 copies and netted me $75,000, This remarkable success,[25] rivalling in its financial results even "Uncle Tom's Cabin," which had just had a run of 300,000 copies, was most gratifying and led to the publication, at intervals, of "Three Years in the Federal Cavalry," "Battles for the Union," and "Heroes of Three Wars."

The temptation to make the most of my literary ventures lured me on from year to year until 1875, when I laid down the pen and began preparation for my long contemplated and oft deferred journey across the Continent. Being now possessed of ample means, I proposed to ride at leisure on a tour of observation from OCEAN TO OCEAN ON HORSEBACK.

My preference for an equestrian journey was in a great measure due to early associations with the horse, in jaunts along country highways and over the hills after the cows, as well as numerous boyhood adventures in which this noblest of animals frequently played a conspicuous part. Then, too, my experience in the cavalry largely influenced me to adopt the saddle as the best suited to my purpose.

Reflecting further upon the various modes of travel, I was led to conclude as the result of much experience that he who looks at the country from the windows of a railway car, can at best have only an imperfect idea of the many objects of interest which are constantly brought to his notice. Again, a journey in the saddle, wherein the rider mounts and dismounts at will as he jogs along over the highway, chatting with an occasional farmer, talking with the people in town and gazing upon rural scenes at his pleasure, presents many attractive features to the student and tourist who wishes to view the landscape, to commune with nature,[26] to see men and note the products of their toil and to learn something of their manners and customs.

Having therefore decided to make my journey in the saddle, I at once set about to secure such a horse as was likely to meet the requirements of my undertaking. As soon as my purpose was known, horses of every grade, weight and shade were thrust upon my attention and after some three weeks spent in advertising, talks with horse fanciers and in the livery and sale stables of Boston, my choice fell upon a Kentucky Black Hawk, one of the finest animals I had ever seen and, as was subsequently established, just the horse I wanted for my long ride from sea to sea.

His color was coal black, with a white star in the forehead and four white feet; long mane and tail; height fifteen hands; weight between ten and eleven hundred pounds, with an easy and graceful movement under the saddle; his make-up was all that could be desired for the objects I had in view. The price asked for this beautiful animal was promptly paid, and it was generally conceded that I had shown excellent judgment in the selection of my equine companion.

A few days after my purchase I learned that my four-legged friend had been but a short time before the property of an ex-governor of Massachusetts and that the reason he had but recently found his way into a livery stable on Portland street, was that he had acquired the very bad habit of running away whenever he saw a railway train or anything else, in short, that tended to disturb his naturally excitable nature. This information led to no regrets, however, nor did it even lessen my regard for the noble animal which was destined[27] soon to be my sole companion in many a lonely ride and adventure.

The unsavory reputation he had made, and possibly of which he was very proud, of running away upon the slightest provocation, smashing up vehicles and scattering their occupants to the four winds, was considered by his new master a virtue rather than a fault, so long as he ran in the direction of San Francisco, and did not precipitate him from his position in the saddle.

As soon as I was in possession of my horse the question of a suitable name arose and it was agreed after some discussion among friends that he should be christened Paul Revere, after that stirring patriot of the Revolution who won undying fame by his ride from Boston and appeals to the yeomanry the night before the Battle of Lexington.

The month of April, 1876, found myself and horse fully equipped and ready to leave Boston, but I will not ride away from the metropolis of New England without some reference to its early history and remarkable development, nor without telling the reader of my lecture at Tremont Temple and other contemplated lectures in the leading cities and towns along my route.

Boston, standing on her three hills with the torch of learning in her hand for the illumination of North, South, East and West, is not one of your ordinary every-day cities, to be approached without due introduction. Like some ancient dame of historic lineage, her truest hospitality and friendliest face are for those who know her story and properly appreciate her greatness, past and present. Before visiting her, therefore, I recalled to memory those facts which touch us no more nearly than a dream on the pages of written history, but when studied from the living models and relics gain much life, color and verisimilitude.

Boston Harbor, with its waters lying in azure[29] placidity over the buried boxes of tea which the hasty hands of the angered patriots hurled to a watery grave; Boston Common, whose turf grows velvet-green over ground once blackened by the fires of the grim colonial days of witch-burning, and again trampled down by innumerable soldierly feet in Revolutionary times; the Old State House, from whose east window the governor's haughty command, "Disperse, ye rebels!" sounded on the occasion of the "Boston Massacre," the first shedding of American blood by the British military; and the monument of Bunker Hill—these, with a thousand and one other reminders of the city's brilliant historical record, compose the Old Boston which I was prepared to see. The first vision, however, of that many-sided city was almost bewilderingly different from the mental picture. Where was the quaint Puritan town of the colonial romances? Where were its crooked, winding streets, its plain uncompromising meeting-houses, darkened with time, its curious gabled houses, stooping with age? Around me everything was shining with newness—the smooth wide streets, beautifully paved, the splendid examples of fin de siècle architecture in churches, public buildings, school houses and dwellings.

Afterwards I realized that there was a New Boston, risen Phoenix-like from the ashes of its many conflagrations, and an Old Boston, whose "outward and visible signs" are best studied in that picturesque, shabby stronghold of ancient story, now rapidly degenerating into a "slum" district—the North End.

Boston, viewed without regard to its history, is indeed "Hamlet presented without the part of[30] Hamlet." It would be interesting to conjecture what the city's present place and condition might be, had Governor Winthrop's and Deputy-Governor Dudley's plan of making "New-towne"—the Cambridge of to-day—the Bay Colony's principal settlement, been executed. Instead, and fortunately, Governor Winthrop became convinced of the superiority of Boston as an embryo "county seat." "Trimountain," as it was first called, was bought in 1630 from Rev. William Blackstone, who dwelt somewhere between the Charles River and what is now Louisburg Square, and held the proprietary right of the entire Boston Peninsula—a sort of American Selkirk, "monarch of all he surveyed, and whose right there was none to dispute." He was "bought off," however, for the modest sum of £30, and retired to what was then the wilderness, on the banks of the Blackstone River—named after him—and left "Trimountain" to the settlers. Then Boston began to grow, almost with the quickness of Jack's fabled beanstalk. Always one of the most important of colonial towns, it conducted itself in sturdy Puritan style, fearing God, honoring the King—with reservations—burning witches and Quakers, waxing prosperous on codfish, and placing education above every earthly thing in value, until the exciting events of the Revolution, which has left behind it relics which make Boston a veritable "old curiosity shop" for the antiquarian, or indeed the ordinary loyal American, who can spend a happy day, or week, or month, prowling around the picturesque narrow streets, crooked as the proverbial ram's horn, of Old Boston.

He will perhaps turn first, as I did, to the[31] "cradle of Liberty"—Faneuil Hall. A slight shock will await him, possibly, in the discovery that under the ancient structure, round which hover so many imperishable memories of America's early struggles for freedom, is a market-house, where thrifty housewives and still more thrifty farmers chaffer, chat and drive bargains the year round, and which brings into the city a comfortable annual income of $20,000. But the presence of the money-changers in the temple of Freedom does not disturb the "solid men of Boston," who are practical as well as public-spirited. The market itself is as old as the hall, which was erected by the city in 1762, to take the place of the old market-house, which Peter Faneuil had built at his own expense and presented to the city in 1742, and which was burned down in 1761.

The building is an unpretending but substantial structure, plainly showing its age both in the exterior and the interior. Its size—seventy-four feet long by seventy-five feet wide—is apparently increased by the lack of seats on the main floor and even in the gallery, where only a few of these indispensable adjuncts to the comfort of a later luxurious generation are provided. The hall is granted rent free for such public or political meetings as the city authorities may approve, and probably is only used for gatherings where, as in the old days, the participants bring with them such an excess of effervescent enthusiasm as would make them unwilling to keep their seats if they had any. The walls are embellished by portraits of Hancock, Washington, Adams, Everett, Lincoln, and other great personages, and by Healy's immense painting—sixteen by thirty feet—of "Webster Replying to Hayne."

For a short time Faneuil Hall was occupied by the Boston Post Office, while that institution, whose early days were somewhat restless ones, was seeking a more permanent home. For thirty years after the Revolution, it was moved about from pillar to post, occupying at one time a building on the site of Boston's first meeting-house, and at another the Merchants' Exchange Building, whence it was driven by the great fire of 1872. Faneuil Hall was next selected as the temporary headquarters, next the Old South Church, after which the Post Office—a veritable Wandering Jew among Boston public institutions—was finally and suitably housed under its own roof-tree, the present fine building on Post Office Square.

VIEWS IN BOSTON.

VIEWS IN BOSTON.

To the Old South Church itself, the sightseer next turns, if still bent on historical pilgrimages. This venerable building of unadorned brick, whose name figures so prominently in Revolutionary annals, stands at the corner of Washington and Milk streets. Rows of business structures, some of them new and clean as a whistle and almost impertinently eloquent of the importance of this world and its goods, cluster around the old church and hem it in, but are unable to jostle it out of the quiet dignity with which it holds its place, its heavenward-pointing spire preaching the sermons against worldliness which are no longer heard within its ancient walls. To every window the fanciful mind can summon a ghost—that of Benjamin Franklin, who was baptized and attended service here; Whitfield, who here delivered some of the soul-searching, soul-reaching sermons, which swept America like a Pentecostal flame; Warren, who here uttered his famous words on the anniversary of the[35] Boston Massacre; of the patriot-orators of the Revolution and the organizers of the Boston Tea-Party, which first took place as a definite scheme within these walls. Here and there a red-coated figure would be faintly outlined—one of the lawless troop of British soldiers who in 1775 desecrated the church by using it as a riding-school.

At present the church is used as a museum, where antique curiosities and historical relics are on exhibition to the public, and the Old South Preservation Committee is making strenuous efforts to save the building from the iconoclastic hand of Progress, which has dealt blows in so many directions in Boston, destroying a large number of interesting landmarks. Its congregation left it long ago, in obedience to that inexorable law of change and removal, which leaves so many old churches stranded amid the business sections of so many of our prominent cities, and settled in the "New Old South Church" at Dartmouth and Boylston streets.

It is curious and in its way disappointing to us visitors from other cities to see what "a clean sweep" the broom of improvement has been permitted in a city so intensely and justly proud of its historical associations as Boston. Year by year the old landmarks disappear and fine new buildings rise in their places and Boston is apparently satisfied that all is for the best. The historic Beacon, for which Beacon Hill was named and which was erected in 1634 to give alarm to the country round about in case of invasion, is not only gone, but the very mound where it stood has been levelled, this step having been taken in 1811. The Beacon had disappeared ten years before and a shaft[36] sixty feet high, dedicated to the fallen heroes of Bunker Hill, had been erected on the spot and of course removed when the mound was levelled. The site of Washington's old lodgings at Court and Hanover street—a fine colonial mansion, later occupied by Daniel Webster and by Harrison Gray Otis, the celebrated lawyer—is now taken up by an immense wholesale and retail grocery store; the splendid Hancock mansion, where the Revolutionary patriot entertained Lafayette, D'Estaing, and many other notabilities of the day, was torn down in 1863, despite the protests of antiquarian enthusiasts. The double house, in one part of which Lafayette lived in 1825, is still standing; the other half of it was occupied during his lifetime by a distinguished member of that unsurpassed group of literati who helped win for Boston so much of her intellectual pre-eminence—George Ticknor, the Spanish historian, the friend of Holmes, Lowell, Whittier and Longfellow, from whom the latter is supposed to have drawn his portrait of the "Historian" in his "Tales of a Wayside Inn." The Boston Public Library, that magnificent institution, which has done so much to spread "sweetness and light," to use Matthew Arnolds' celebrated definition of culture, among the people of the "Hub," counts Mr. Ticknor among the most generous of its benefactors.

One interesting spot for the historical pilgrim is the oldest inn in Boston, the "Hancock House," near Faneuil Hall, which sheltered Talleyrand and Louis Philippe during the French reign of terror.

In addition to the fever for improvement, Boston owes the loss of many of her time-hallowed buildings[37] to a more disastrous agency—that of the conflagrations which have visited her with strange frequency. A fire in 1811, which swept away the little house on Milk street where Franklin was born—and which is now occupied by the Boston Post—another in 1874, in which more than one hundred buildings were destroyed; and the "Great Boston Fire" of 1872, followed by conflagrations in 1873, 1874, 1877 and 1878, seemed to indicate that the fire fiend had selected Boston as his especial prey. To the terrible fire of 1872 many precious lives, property valued at eighty millions of dollars, and the entire section of the city enclosed by Summer, Washington, Milk and Broad streets were sacrificed. The scene was one a witness never could forget. Mingled with the alarum of the fire-bells and the screams and shouts of a fear-stricken people came the sound of terrific explosions, those of the buildings which were blown up in the hope of thus "starving out" the fire by making gaps which it could not overstep, and to still further complete the desolation, the gas was shut off, leaving the city in a horror of darkness; but the flames swept on like a pursuing Fury, wrapping the doomed city still closer in her embrace of death, and who was not satisfied until she had left the business centre of Boston a charred and blackened ruin.

This same district is to-day, however, the most prosperous and architecturally prepossessing of the business sections of the city, practically illustrating another phase of that same spirit of improvement and civic pride which has overturned so many ancient idols and to-day threatens others. Indeed, it would be a churlish disposition which would lament the disappearance[38] of the old edifices, the straightening of the thoroughfares, the alterations without number which have taken place, and which have resulted in the Boston of to-day, one of the most beautiful, prosperous and public-spirited cities in the world. The intelligence and local loyalty, for which her citizens are renowned, have been set to work to attain one object—the modest goal of perfection. Obstacles which some cities might have contentedly accepted as unavoidable have been swept away; advantages with which other cities might have been satisfied have been still further extended and improved. The 783 acres originally purchased by the settlers of Boston from William Blaxton for £30 has been increased over thirty times, until the city limits comprise 23,661 acres; this not by magic as it would seem, but by annexation of adjoining boroughs—Roxbury, Dorchester, Charlestown, and others—and by reclamation of the seemingly hopeless marshy land to the north and south of the city. The "Back-Bay" district, the very centre of Boston's wealth, fashion and refinement, the handsomest residence quarter in America, is built upon this "made land," which it cost the city about $1,750,000 to fill in and otherwise render solid.

SCENES IN BOSTON.

SCENES IN BOSTON.

All good Bostonians, like the rest of their countrymen, may wish to go to Paris when they die—that point cannot be settled; but it is certain that they all wish to go to the Back-Bay while they live. And who can wonder? To drive at night down Commonwealth avenue, the most aristocratic street in this aristocratic quarter, is to view a scene from fairyland. "The Avenue" itself is 250 feet wide from house to house[41] and 175 feet wide from curb to curb, and in the centre a picturesque strip of parkland, adorned with statues and bordered with ornamental trees and shrubs, follows its entire length. On either side of the street stand palatial hotels and magnificent private residences, from whose innumerable windows twinkle innumerable lights, which, mingling with the quadruple row of gas-lamps which look like a winding ribbon of light, make the vista perfectly dazzling in its beauty. By day, when the Back Bay Park, the Public Garden, the fine bridge over the park water-way extension and the handsome surrounding and intersecting streets can be seen, the view is even more attractive.

In the newer parts of Boston the reproach of crooked streets, which has given her sister cities opportunity for so much good-natured "chaff," is removed, and the thoroughfares are laid out with such precision that "the wayfaring man, though a fool," can hardly "err therein." In the business district much money has been spent on the straightening process, a fact whose knowledge prompts the bewildered stranger to exclaim, "Were they ever worse than this?" Stories aimed at this little peculiarity of the "Hub" are innumerable, the visitor being told with perfect gravity that if he follows a street in a straight line he will find himself at his original starting-point—a statement the writer's experience can pretty nearly verify. The best, if not the most credible, of these tales relates how a puzzled pedestrian, becoming "mixed up in his tracks," endeavored to overtake a man who was walking ahead of him, and inquire his way. The faster he walked, however, the faster the other man walked, until it became a regular chase, and the now thoroughly confused[42] stranger had but one idea—to catch his fellow-pedestrian by the coat-tails, if need be, and demand to be set on his homeward way. Finally, by making a frantic forward lurch, he succeeded—and discovered that the coat-tails he was grasping were his own!

The true Bostonian is secretly rather proud, however, of this distinguished trait of his beloved city, and is willing to go "all around Robin Hood's barn" to get to his destination.

But the thing of which the Bostonian is proudest of all is his famous Common, whose green turf and noble shade-trees have formed a stage and background for so many of the most exciting scenes of Colonial and Revolutionary history. Among the troops which have been mustered and drilled upon it were a portion of the forces which captured Quebec and Louisburg; and the rehearsals for the grim drama of war, which later was partly performed on the same ground by red-coat and continental, took place here. It was at the Common's foot that the hated "lobster-backs" assembled before embarking for Lexington; on the Common that they marshalled their forces for the conflict at Bunker Hill. It has been covered with white tents during the British occupation of Boston; dotted with earthworks behind which the enemy crouched, expecting an attack by Washington upon their stronghold. It was on Boston Common that the school-boys constructed their snowmen, whose destruction by the insolent red-coats sent an indignant deputation of young Bostonians to complain to General Gage, who, stunned by what the young Bostonian of to-day would designate as "the cheek of the thing," promised them redress, and[43] exclaimed, "These boys seem to take in the love of liberty with the very air they breathe."

There are other interesting historical incidents, recorded in connection with the Common, but space forbids their narration. I would rather describe it as it first appeared to me, a beautiful surprise, a gracious spot of greenness and of silvery waters and splendid shade-trees, in the heart of the busy brick-bound city. Here the children play and coast, as they did in the days of General Gage; here the lovers walk, on the five beautiful broad pathways, the Tremont street, Park street, Beacon street, Charles street and Boylston street malls. Here the invalids and old folks rest on the numerous benches; here the people congregate on summer evenings to enjoy the free open-air concerts, which are given from the band-stand. "Frog Pond," a pretty lakelet, near Flagstaff Hill, and a fine deer-park in the vicinity of the Boylston street mall, are great attractions. The Common covers forty-eight acres, with 1000 stately old shade-trees, and the iron fence by which it is inclosed measures 5932 feet.

In addition to its natural beauties, the Common has two fine pieces of statuary, the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument on Flagstaff Hill, and the Brener Fountain. The former was erected in 1871 at a cost of $75,000. It is a majestic granite shaft in the Roman-Doric style, seventy feet high, surmounted by a bronze figure of the Genius of America, eleven feet in height. At the base of the shaft are grouped alto-relievo figures representing the North, the South, the East, and the West. Four other bronze figures, representing Peace, History, the Army and the Navy, stand on projecting pedestals around the foundation. The monument, which was[44] executed by Martin Milmore, was Boston's tribute to her fallen heroes of the Civil War. The Brener Fountain is a beautiful bronze casting designed by Lienard, of Paris, with bronze figures representing Neptune, Amphitrite, Acis, and Galatea grouped round the base. The late Gardner Brener presented it to the city in 1868.

To forget the Old Elm in describing the Common, would be rank disrespect to that hoary "oldest inhabitant," albeit nothing remains of it now but its memory. An iron fence surrounds the spot where once it stood, and a vigorous young sapling has providentially sprung up in its place, as a successor. The Old Elm was ancient in 1630, when the town was settled, and was one of its most interesting landmarks up to 1876, when it was blown down.

The Public Garden, from which the beautiful Commonwealth avenue begins, the Back-Bay Park, which cost a million of dollars, and the Arnold Arboretum, where Harvard University has planted and maintained a fine horticultural collection for the pleasure of the public, are lovely spots on whose beauty the mind would fain linger, but whose descriptions must be omitted, for all Boston's splendid public buildings wait in stately array their share of attention. Nowhere has the skilled artist-architect been so freely permitted to carry out his designs unhampered by stupidity and stinginess as in Boston, and the result has been a collection of public buildings unsurpassed by those of any modern city. The Boston State House comes first, of course—did not the "Autocrat of the Breakfast Table" term it, with loving exaggeration, the "Hub of the Solar System?" From Beacon Hill, the most prominent[45] coign of vantage which could be selected for it, its gilded dome rises majestically against the blue sky and imperiously beckons the visitor to come and pay his respects to this most venerated of Boston institutions. The State House stands, at a height of 110 feet, at the junction of Beacon and Mt. Vernon streets and Hancock avenue, on a lot which Governor Hancock once used for pasturing his cows, and was erected in 1795, beginning its existence in a blaze of glory, with the corner-stone laid by Paul Revere, then Grand Master of the Masons, and an oration by Samuel Adams. The building contains Doric Hall, which is approached by a fine series of stone terraces from Beacon street; Hall of Representatives, the Senate Chamber, the Government Room, and the State Library.

It abounds in relics, among which are the tattered shreds of flags brought back by Massachusetts soldiers from Southern battle-fields—a sight which must stir every loyal heart, to whatsoever State it owes allegiance; the guns carried by the Concord minute-men in the Revolutionary conflict; and duplicates of the gift to the State by Charles Sumner, of the memorial tablets of the Washington family in England. Doric Hall contains busts of Sumner, Adams, Lincoln, and other great men, and several fine statues—one of Washington, by Chantrey, and one by Thomas Ball; a speaking likeness in marble of John A. Andrew, the indomitable old War Governor of Massachusetts.

On the handsome terraces in front of the building stand two superb bronzes, one is the Horace Mann statue, by Emma Stebbins, which was erected in 1865, and paid for by contributions from teachers and school children all over Massachusetts; the other Hiram Powers'[46] statue of Daniel Webster, which cost $10,000. It was erected in 1859, and was the second statue of Webster which the famous sculptor wrought, the first, the product of so much toil and pains and the embodiment of so much genius, having been lost at sea.

Last, but very far from least in importance, may be mentioned the historic codfish, which hangs from the ceiling of Assembly Hall, dangling before the eyes of the legislators in perpetual reminder of the source of Massachusetts' present greatness, for the codfish might by a stretch of Hibernian rhetoric be described as the patron saint of the Bay State.

I must confess to having been one of the 50,000 curious ones who, it is computed, annually ascend into the gilded cupola and "view the landscape o'er." The spectacle unrolled panorama-like before the sight is indeed a feast to the eyes.

The Old State House of 1748, built on the site of Boston's earliest town hall, is now used as a historical museum under the auspices of the Bostonian Society. Careful restoration has perpetuated many of the old associations which hallow the ancient fane, sacred to loyalty and to liberty. The old council-chambers have been given much of their original appearance, and the great carving of the Lion and the Unicorn, which savored of offence to patriotic nostrils and so was taken down from its gables in Revolutionary times, has been replaced. To visit this building is a liberal education in local history.

The Boston Post Office, of whose migrations I have spoken earlier, is now settled for good and all in a magnificent structure of Cape Ann granite, built in Renaissance style, whose corner-stone was laid in 1871[47] and which was just ready for the addition of the roof when the Great Fire of 1872 descended upon it and beat upon it so fiercely that even to-day the traces of the intense heat are visible on parts of the edifice. Damage to the amount of $175,000 was done. The Sub-Treasury, the United States courts, the pension and internal revenue offices are domiciled here, and it is considered the handsomest public building in all New England, having cost $6,000,000. The interior furnishings are sumptuous in the extreme, the doors and windows in the Sub-Treasury apartments being of solid mahogany, beautifully polished. The "marble cash-room" is a splendid hall, decorated in Greek style, with wall-slabbing of dark and light shades of Sienna marble and graceful pilasters of Sicilian marble.

The City Hall, on School street, is the seat of the municipal housekeeping. Here the departments of streets, water, lighting, police, and public printing have their offices, and Common Council sits in august assemblage. It is a commanding structure of granite, fireproof, and in the Renaissance style. Its cost was $500,000. Two fine bronze statues, one by Greenough, of Franklin, one by Ball, of Josiah Quincy, ornament the grassy square in front of the building.

No picture of Boston would be complete without that old landmark, Tremont Temple. It occupies the former site of the Tremont Theatre and contains one of the largest halls in the city. The building itself, however, sinks into insignificance before the crowd of associations that stir the blood at its very name. For years it has been the rallying point of Boston's most notable gatherings—political, intellectual, and religious. If, instead of colorless words, we could[48] photograph upon this page the pictures those old walls have looked upon, we might revel in a gallery of famous portraits such as the world has rarely seen. Edward Everett, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Joseph Cook, Phillips Brooks, and other master-spirits of the age, would be there. And there, too, would be a sprinkling of that other sex, no longer handicapped by the epithet "gentler."

But, could we press the phonograph as well as the camera into our service, and hear again the thunders of stormy oratory, the clash of political warfare, and the pleading tenderness of religious eloquence that has often resounded under that old roof, then indeed we might well forget the world of to-day in the fascination of this drama of the past.

Architecturally, Boston combines in the happiest way all that is beautiful and dignified in the classic models and all that is fresh and original in modern canons of building. A magnificent group of buildings, in the vicinity of Boylston and Huntingdon streets and Copley Square, fairly takes the breath away with its beauty. Trinity Church and the Museum of Fine Arts, the "New Old South Church" and the new Boston Public Library, form such a quartet of splendid edifices as even the travelled eye seldom sees. The Public Library is an embodied Triumph—the symbol of that great heritage of culture which the city pours out on her denizens as lavishly and as freely as water, and which, like "the gentle dew from heaven, blesseth him that gives and him that takes," returning to enrich the community with its diffused presence, like the showers which return to the bosom of the river, the moisture the sun only borrowed for a space. Bostonians have always been proud of their Public[51] Library, from its foundation in 1852. By 1885, the Boylston street building, with accommodations for 250,000 volumes, was too contracted a space to hold the largest public library in the world, and with characteristic promptness the city rose to the occasion and embodied its thought that "nothing can be too good for the people" in the beautiful new library in Copley Square, which cost the royal sum of $2,600,000.

BOSTON AND ENVIRONS.

BOSTON AND ENVIRONS.

The long chapter of description which this splendid enterprise merits must be reluctantly crowded into a few lines. Nothing, however, save personal observation, can give an adequate perception of its outward loveliness; its exterior of soft cream-gray granite, with a succession of noble arched windows ranged along its fine façades; its arches, pillars and floorings of rare marbles, and its mosaics, panels and carvings. The grand staircase of splendid Sienna marble, opposite the main entrance, is one of the finest in the world; and scholar or philosopher could ask no more attractive spot for thoughtful promenade than the beautiful open court, with its marble basin and MacMonnies fountain in the centre, the soft green of its surrounding turf affording grateful rest to book-wearied eyes, and the pensive beauty of the cloister-like colonnade forming an ideal retreat.

The foremost artists of the world are represented in the interior decoration. The famous St. Gaudens seal, designed by Kenyon Cox and executed by Augustus St. Gaudens, ornaments the central arch of the main vestibule; the bronze doors are by Daniel G. French; the splendid marble lions in the staircase hall—erected as memorials to their martyred comrades by two regiments of Massachusetts volunteers—are by Louis St.[52] Gaudens; and Puvis de Chavannes, James McNeil Whistler, Edwin A. Abbey and John S. Sargent are among the celebrated artists who have contributed to the mural decorations, friezes and ceiling frescoes.

Six hundred and fifty thousand volumes at present constitute the stock of the library—a vast treasure-house of information, instruction and pleasure to which any citizen of Boston can have access by simply registering his name, and which among other valuable special collections includes the Brown musical library of 12,000 volumes and rare autograph manuscripts; the Barton Shaksperian library, one of the finest collections of Shakesperiana extant, valued at $250,000; the Bowditch mathematical library and the splendid Chamberlain collection of autographs, which is worth $60,000 and represents a lifetime of work on the part of the donor. The wonderful pneumatic and electric system of tubes and railways which connects the delivery and stackrooms and keeps this vast collection of books, pamphlets and magazines in circulation, smacks almost of the conjurer's craft. Whatever else must be crowded out of a visit to Boston, the Public Library assuredly should not be passed by.

Trinity Church stands within hailing distance of the Public Library, on Boylston and Clarendon streets—an imposing and beautiful edifice of granite and freestone, built in French Romanesque style, with a tower 211 feet high. Far outside of Boston has the fame of Trinity Church penetrated, owing not to the fact that it is one of the most splendid, costly and fashionable churches in the country, but to its ever-revered and ever-mourned rector, the late Phillips Brooks, Bishop of Massachusetts, whose massive figure[53] will stand out against the horizon for many a year as the most striking speaker and deeply spiritual thinker America has ever known.

From Copley Square, not far from Trinity, rise the spires of the "New Old South" Church, a superb structure in North Italian Gothic style, rich in beautiful stone-work, carvings and stained glass. It was erected at a cost of over half a million of dollars to take the place of the disused "Old South" on Washington street. Another prominent church is the First Church, at Marlborough and Berkeley streets, the lineal descendant of the humble little mud-walled meeting-house which was the first consecrated roof under which the good folk of Boston gathered for divine worship. The congregation of that day could scarce believe their sober Puritan eyes could they behold the $325,000 church which was built in 1868 to continue the succession which had begun with the little mud meeting-house of 1632.

King's Chapel, with its ancient burying-ground, is one of the most famous churches in Boston, having been the chapel of the royal governor, officers of the army and navy, and other official representatives of the "principalities and powers" of the mother country. Massive, almost sombre, in its exterior, and quaint and picturesque within, the old church stands, with few changes, as erected in 1749, with its old-fashioned pulpit and sounding-board, prim, straight pillars, and antique high-backed pews which recall the remark of the little girl, that when she went to church she "went into a cupboard and climbed up on the shelf." Its burying-ground is believed to be the oldest in the city. Christ Church, built in 1723, is the oldest church[54] edifice in the city. Its age-mellowed chime of bells was the first ever brought into this country, and the first American Sunday-school was established there in 1816. To-day its tall steeple, which on the eve of Lexington's conflict bore the signal lanterns of Paul Revere, is the most conspicuous object in the North End, where the old-time aristocrats who worshipped in Christ Church have given place to a poverty-stricken foreign population to whom the church is little and its traditions less. Churches which well deserve more extended mention, could space permit, are the beautiful Gothic Cathedral of the Holy Cross, with its fine organ and splendid high-altar of onyx and marble; Tremont Temple, whose hall is the largest in Boston; and the South Congregational Church, presided over by Rev. Edward Everett Hale, author of "The Man without a Country" and other world-famous literary productions, and originator of the equally famous "Ten Times One" clubs.

Boston's religious history is most interesting, although almost kaleidoscopic in its changes. From being the stronghold of Puritan orthodoxy it has become the headquarters of liberal Unitarianism. King's Chapel is a curious instance; originally an Episcopal church and congregation, it became Unitarian in 1787, retaining the Episcopal liturgy with necessary changes, and now doctrines are preached over the tombs of the dead dignitaries interred beneath the church floor, diametrically opposed to those in which they lived, died and were buried. Though all denominations of course flourish within her walls, Boston is still strongly Congregational in her leanings.

From the churches to the schools is a natural transition.[55] The founders of Boston's greatness placed the two influences side by side in importance, and their wisdom in doing so has had its justification. The current "poking of fun" at the "Boston school-ma'am," her glasses, her learning and her devotion to Browning; and the Boston infant, who converses in polysyllables almost from his birth, has its foundation in the fact, everywhere admitted, that nowhere are intelligence and culture so widely diffused in all ranks of life as in Boston. The free-school system, an experiment which she was the first American city to inaugurate, is considered by educators to lead the world. The city's annual expenditures for her public schools, of which there are over 500, amount to about $2,000,000, and from the kindergarten to the High School, where the pupils can be prepared for college, the youth of the city are carefully watched, trained, instructed, and all that is best in them drawn out. Even in summer, "vacation schools" are held, where the children who would otherwise be running wild in the streets can learn sewing, box-making, cooking and other useful branches.

The English High and Latin School is the largest free public school building in the world, being 423 feet long by 220 feet wide. It is a fine structure in Renaissance style, with every advantage and improvement looking to health and convenience that even the progressive Boston mind could think of. It would be a sluggish soul indeed that would not be thrilled by the sight of the entire school-battalion going through its exercises in the immense drill-room, and realize the hopeful future for this vast army of coming citizens,[56] who are thus early and thus admirably taught the priceless lesson of discipline.

The Boston Normal School, the Girls' High School and the Public Latin School for girls, fully cover the demand for the higher education of women. The latter institution is the fruit of the efforts of the Society for the University Education of Women, and its graduates enter the female colleges with ease. Wellesley, the "College Beautiful," as its students have fondly christened it, is situated close to Boston in the beautiful village of Wellesley, where feminine education is conducted almost on ideal lines. No woman's college in the world has so many students, or so beautiful a home in which to shelter the fair heads, inwardly crammed and running over with knowledge, and outwardly adorned, either in fact or in prospective, with the scholastic cap of learning. Since its opening in 1875, Wellesley has almost created a new era in woman's education, and its curriculum is the same as those of the most advanced male colleges. The College Aid Society, which at an annual cost of from $6000 to $7000 helps ambitious girlhood, for whom straitened means would otherwise render a university education impossible, is an interesting feature of the college.

COMMONWEALTH AVENUE, BOSTON.

COMMONWEALTH AVENUE, BOSTON.

What Wellesley has for twenty years been to American girlhood, Harvard University has for 150 years been to American young manhood, and though its chief departments are located at Cambridge, it may still be fairly ranked with Bostonian institutions. The tie which connects the Cambridge University and the capital of Massachusetts is closer than that existing between mere neighbors—it is a veritable bond of kinship.[59] It might be said that from the opening of the University in 1638, Boston made Harvard and Harvard Boston. Its illustrious founder, John Harvard, was a resident of Charlestown, now a part of Boston—and his monument, erected by subscriptions of Harvard graduates, is one of the principal "sights" of that district, where it stands near the Old State Prison. To its classic groves Boston has sent, and from them received again, the noblest of her sons; and three of her departments, the Bussey Institution of Agriculture, the Medical School and the Dental School, are situated within the limits of Boston proper. Harvard University at present owns property valued at $6,000,000, and accommodates nearly 2000 pupils. In addition to the departments already mentioned and which are located in Boston, the principal sections are Harvard College, the Jefferson Laboratory, the Lawrence Scientific School, the new Law School, the Divinity School, the Harvard Library, Botanical Gardens, Observatory, Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, Peabody Museum of Archæology and Ethnology, Agassiz Museum, Hemenway Gymnasium and Memorial Hall. To wander through its ancient halls, the oldest of which dates back to 1720, and which have been used by Congress, is to visit the cradle of university education in America.

Boston University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the best scientific colleges on the continent, Tufts College and the celebrated Chauncy Hall School, are among the finest of Boston's many admirable educational institutions.

Mention has been made of the Harvard Monument, but not of the others among the scores of fine examples[60] of the sculptor's art which are scattered throughout the city in generous profusion for the delight and the education of the public eye. The famous Bunker Hill Monument was naturally one of the first objects sought out by the writer on the occasion of his first visit to Boston. This splendid shaft of granite was dedicated to the fallen patriots of Bunker Hill in 1841, the corner-stone having been laid in 1825 by General Lafayette—Daniel Webster delivering the orations on both occasions. Its site, on Monument Square, Breed's Hill, is the spot where the Americans threw up the redoubt on the night before the memorable battle, and a tablet at its foot marks the place where the illustrious Warren fell.

The monument is 221-1/6 feet high—a fact fully realized only by climbing the 259 steps of the spiral staircase of stone in the interior of the shaft which leads to a small chamber near the apex, from which four windows look out upon the surrounding country—a superb vista. The cost of this monument was $150,000.

In the Public Gardens, in the Back Bay district, across from Commonwealth avenue, may be seen one of the largest pieces of statuary in America, and, according to some connoisseurs, the handsomest in Boston. This is Ball's huge statue of Washington, which measures twenty-two feet in height. The statue was unveiled in 1869, and it is said that not a stroke of work was laid upon it by any hand of artisan or artist outside of Massachusetts. The Beacon street side of the Public Gardens contains another famous statue—that of Edward Everett, by W. W. Story. Other great citizens whose memory has been perpetuated in[61] life-like marble are Samuel Adams, William Lloyd Garrison and Colonel William Prescott. The Emancipation Group is a duplicate of the "Freedman's Memorial" statue in Washington. The soldiers' monuments in Dorchester, Charlestown, Roxbury, West Roxbury and Brighton commemorate the unnamed, uncounted, but not unhonored dead who laid down their lives on the battlefields of the Civil War.

An interesting object is the Ether Monument on the Arlington street side of the Public Gardens erected in recognition of the fact that it was in the Massachusetts General Hospital—in the face of terrible opposition and coldness and discouragement, as history tells us, though the marble does not—that Dr. Sims first gave the world his wonderful discovery of the power of ether to cause insensibility to pain.

That there should be so many of these fine pieces in Boston's parks and public places is matter for congratulation but scarcely for surprise. As a patron of music, literature, art and all the external graces of civilization she has so long and so easily held her supremacy that one is half inclined to believe that at least a delegation of the Muses, if not the whole sisterhood, had exchanged the lonely and unappreciated grandeur of Parnassus for a seat on one of Boston's three hills. The Handel and Haydn Society, the oldest musical society in the United States; the Harvard Musical Association; the famous Boston[62] Symphony Orchestra and the Orpheus Club, speak—and right musically—of Boston's love for the art of which Cecilia was patron saint. Music Hall, an immense edifice near Tremont street, is the home of music in Boston. Here the symphony concerts are held weekly, and here all the musical "stars" whose orbit includes Boston make their first appearance before a critical "Hub" audience. Its great organ, with over 5,000 pipes, is one of the largest ever made.

The idea of a national university of music—sneered at and scouted when a few enthusiasts first talked and dreamed of it—took shape in 1867 in the now famous New England Conservatory of Music, founded by Eben Tourjée. It is a magnificent school in a magnificent home—the old St. James' Hotel on Franklin Square—with a hundred teachers from the very foremost rank of their profession. The conservatory has possibly done more for New England culture than any other influence save Harvard University.

The literary life of Boston needs neither chronicler nor comment. Such men as Thomas Bailey Aldrich, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Francis Parkman, Prescott, the historian, Longfellow, Lowell and countless others who, living, have made the city their home, or, dead, sleep in its chambers of Peace, have cast a glamour of books and bookmen and book-life around her until her title of "The Athens of America" has passed from jest to earnest. The earliest newspaper in America was the Boston News Letter; and to-day its many newspapers maintain the highest standard of "up-to-date" journalism in the dignified, not the degrading sense of the word. Boston is indeed a "bookworm's paradise," with its splendid free lending library and[63] low-priced book-stores, making access to the best authors possible to the poorest. The Atlantic Monthly, which for so many years has occupied a place unique and unapproachable among American magazines, is published here.

Art is represented by the magnificent Museum of Fine Arts, with its beautiful exterior and interior decorations and fine collection of antiques and art objects; the Art Club, the Sketch and the Paint and Clay clubs, as well as by the innumerable paintings and statues appearing in public places; by the Athenæum, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Boston Society of Natural History, the Warren Museum and the Lowell Institute free lectures.

To draw this brief study of Boston to a close without mentioning her countless charities would be a grave omission, since these form so large a part of the city's life and activities. As is always the case in great towns, two hands are ever outstretched—that of Lazarus, pleading, demanding, and that of Dives—more unselfish now than in the days of the parable—giving again and yet again. Boston's philanthropists flatter themselves that there the giving is rather more judicious, as well as generous, than is frequently the case; and that "the pauperizing of the poor," that consummation devoutly to be avoided, is a minimized danger. The "Central Charity Bureau" and the "Associated Charities" systematize the work of relief, prevent imposture and duplication of charity, and do an invaluable service to the different organizations. Private subscriptions of citizens maintain the work, which is carried on in three fine buildings of brick and stone on Chardon street, one of which is used as a[64] temporary home for destitute women and children. The Massachusetts General Hospital—which, save for the Pennsylvania Hospital, is the oldest in the country—the Boston City Hospital, the New England Hospital for Women and Children, and a number of other finely-organized institutions care efficiently for the city's sick and suffering. Orphan asylums, reform schools, missions of various sorts, and retreats for the aged and indigent, are numerous.