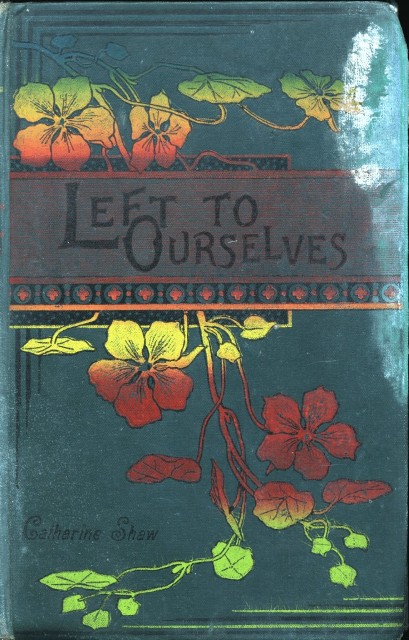

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Left to Ourselves, by Catharine Shaw

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Left to Ourselves

or, John Headley's Promise.

Author: Catharine Shaw

Release Date: October 3, 2011 [EBook #37606]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LEFT TO OURSELVES ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Mark Young, Lindy Walsh and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

OR

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE FIVE | 9 |

| II. | A PACKET | 14 |

| III. | THE DARK CAVERN: AN ALLEGORY | 19 |

| IV. | RESCUED | 27 |

| V. | NEW ROBES | 33 |

| VI. | AT LAST | 37 |

| VII. | LAST DAYS | 43 |

| VIII. | ONE INJUNCTION | 52 |

| IX. | THE FIRST SUNDAY ALONE | 65 |

| X. | THE GOLDEN OIL: AN ALLEGORY | 74 |

| XI. | A CUPBOARD OF RUBBISH | 85 |

| XII. | JOHN'S PROMISE | 92 |

| XIII. | HUGH'S PROMISE | 101 |

| XIV. | CHRISTMAS-DAY | 109 |

| XV. | WHERE ONE PUDDING WENT | 118 |

| XVI. | THE RAG CUSHION | 128 |

| XVII. | THE LAST PUDDING | 136 |

| XVIII. | NEW YEAR'S EVE | 142 |

| XIX. | WORRIED | 151 |

| XX. | A SURPRISE | 158 |

| XXI. | THE MAGIC OF LOVE | 169 |

| XXII. | MINNIE'S SECRET | 177 |

| XXIII. | THE END OF THE JOURNEY | 185 |

other, I'm sure you may trust me!"

"My child, I trust you for all that you know; but there are things which no one but a mother can know."

"Of course there are. Oh, I don't for a moment mean that I shall do as well as you, mother, only——"

"Yes," answered Mrs. Headley, thoughtfully, "you see, Agnes, your dear grandmother in America is pronounced to be failing very fast. I have not seen her for twenty years, and if I do not go now I may never see her again in this world."[ 10]

"And father's having to go there on business now makes it so easy."

"Easy all but leaving you children."

"But I am nineteen now, mother—quite old enough to be trusted; besides, grandmama and aunt Phyllis live next door, and if anything happened I could run in to them."

Mrs. Headley smiled, looking half convinced.

"Who is it you are afraid to leave?" asked Agnes coaxingly. "Is it me, mother?"

"You?" echoed Mrs. Headley, stroking her face tenderly. "No, not you, dear."

"Then it is John."

"No, no; John is a good boy, he will help you I am sure."

"Then is it Hugh?"

"No; Hugh is steady, and very fond of his lessons; and he will be sure to do as you wish him, if he promises beforehand."

"Then is it Alice?"

Mrs. Headley shook her head.

"Then it must be Minnie, for there's no one else. And as to Minnie, you know I love her exactly as if she were my own child."

Mrs. Headley laughed a little, though bright tears filled her eyes and fell down into her lap.

"Don't you think I do?" asked Agnes soberly—not half liking the little laugh, or the tears either for that matter.[ 11]

"You love her as much as you possibly can, dearest, but that does not give you my experience. No, Agnes, it is not Minnie or any one in particular, but it is the five of you all together that I'm afraid to leave. I am so afraid they might get tired of doing as you said."

"They never have yet, mother. You ask them, and see."

Mrs. Headley looked thoughtfully into the fire, and was silent for a long time. So was Agnes, till at last she roused up suddenly and put her hand into her mother's.

"There's one Friend I shall always have near, nearer than next door; always at hand to help and counsel—eh, mother dear? We had not forgotten Him, only we did not say anything actually about Him."

"Yes, my child, I do not forget; and if I were more trustful I should not be so afraid."

Mrs. Headley rose and left the room just as the door opened, and John came in.

"Holloa, Agnes, all alone in the dark," he exclaimed, stumbling over the stools and chairs. "Why don't you have a light?"

"Mother and I were talking, and we did not want any."

"About America? Don't I wish it was me instead of her, that's all!"

"But, you see, that is not the question," said Agnes, watching her brother lean back against the[ 12] mantelpiece with nervous eyes. "John, you'll knock something down."

"Not I. Of course it isn't the question; but why doesn't mother want to go?"

"She does want to go; only, you see, John, she's afraid we shall not all get on together."

"Is she afraid we shall quarrel?"

Agnes nodded.

"I shan't."

"Perhaps not."

"But Hugh will?" he asked, smiling.

"Hugh and John together," answered Agnes, smiling too.

"Very likely."

"Do you think you will?" asked his sister, drawing back.

"What a frightened question! Agnes, look here; I'll promise you——"

"What?"

"It takes two to make a quarrel, doesn't it?"

"Yes."

"Then I'll promise you to walk out of the room at the first indication of a squabble. Will that make things straight?"

"If you will not forget."

"If I do, you look at me, and I'll fly, or be 'mum'!"

"All right, I will," answered Agnes soberly. "John, I believe mother thinks she ought to go, and so I am sure we ought to make it easy."[ 13]

"I mean to."

Agnes kissed him gratefully, but did not speak, yet John understood, and when she had gone out of the room he fancied he felt a tear left on his coat.

He roused himself up, and turned round to poke the fire into a blaze.

"My eye!" he ejaculated, half audibly, "it will be a go to do without mother for three months."

other, here is a nice little square packet come for you by post!" said Minnie as Mrs. Headley entered the dining-room the next morning.

"Yes; Minnie has been turning it, and twisting it, and weighing it, and smelling it—doing everything except open it," said John, laughing.

"I do wish to know what it is though!" said Minnie shyly, "and I believe John wants to see just as much as I do."

"I will open it presently," answered their mother, smiling, while she seated herself at the head of the table.

"Minnie is always rather curious," observed Hugh, looking up from a lesson he had been conning over.

"This is something which will rouse your curiosity, and I will see who can tell me the meaning of it," answered Mrs. Headley.[ 15]

"Then you know what it is, mother?" asked Minnie.

Her mother assented; and when they had finished breakfast, and their father had gone off to his business, Mrs. Headley took up the little package and began untying the knots.

"Cut it," said Alice.

"Catch mother cutting a knot if she can undo it," laughed Hugh, gathering his books together.

"It's a good thing it is Saturday," said John, "or we couldn't wait, however curious we might be."

"There, it is undone!" said Minnie, pressing nearer. As she spoke the paper fell open, and two dozen little square books came tumbling out.

The children were going to seize upon them, when Mrs. Headley placed her hand over them, taking up one at the same moment, saying. "What is this, now?"

"A little book," said John.

"Has it reading in it?"

She opened the first page, and to their astonishment there was nothing but a page of black to be seen.

"What a strange book!" said Hugh. "It would not be much trouble to learn a page of that!"

"It is a great trouble to learn that black page, though," said his mother.

Hugh peeped closer. "Let me read the outside, mother; perhaps it explains."[ 16]

"Perhaps it does," said his mother, still showing only the black page.

"Well, what next? as we can't make that out," said Alice, who was looking on with her arms twined round her sister Agnes.

Mrs. Headley opened the next leaf, and they found it deep red.

"How strange," said Hugh; "is this difficult to learn, mother?"

Mrs. Headley smiled thoughtfully, and answered. "Not so hard as the other; oh, not half so hard—for us!"

"And the next?" said Agnes, with a tender light in her gentle eyes.

"Pure white!" exclaimed Alice; "and I believe Agnes guesses."

"What next, mother?" asked Hugh; "for I suppose you do not mean to tell us the meaning yet?"

"Gold!" exclaimed Minnie. "How lovely it looks! Is this difficult to learn, mother?"

"Ah no!" said Mrs. Headley, "that is the easiest page of all—nothing but glory."

"Glory?" asked Hugh, "you have told us the meaning of the last first. Now, what is it, mother?"

"What does the black remind you of, dears?" she asked, in answer to their eager look.

"Night," "discomfort," "blindness," "being lost," suggested several of them.

"Yes," said Mrs. Headley; "but anything else?"[ 17]

"Is it sin, mother?" asked Agnes, in a low tone.

"Yes, my dear children, it is sin. The black is sin; 'hopeless night,' 'discomfort,' 'blindness,' 'being lost'—all you have said summed up in that one dark page—sin."

"Now I guess," exclaimed John hastily, "the red is Blood. Oh, I guess now!"

"The Blood of Jesus, the Son of God. Nothing else can take the black sin away. But that can; yes, the blood is easier to read than the sin, isn't it, dears?"

"I don't see why," said Hugh, looking puzzled.

"Do you not think it is hard to feel that we are utterly black and sinful, no good in us at all?"

"Oh, mother!"

"But turn over the page, and the Blood shuts out all remembrance of the sin. The Lamb of God, who taketh away the sin of the world."

"How beautiful!" said Agnes.

Their mother turned to the next page, and went on.

"Then, when the Blood has cleansed us, what are we?"

"Whiter than snow," said Minnie reverently.

"That is right, little Minnie; and I think the white reminds us of two or three things. Can you suggest them, children?"

"How pure we ought to be?" asked Agnes.

"Yes, and how pure He is," answered her mother.

"'These are they that have washed their robes,[ 18] and made them white in the blood of the Lamb,'" said Alice. "That was our text last Sunday."

"So it was, and the end of it introduces us to our final page, and that lasts for ever."

"Gold," said Minnie.

"Glory," said Hugh.

"Everlasting glory, all joy and light for evermore. All purchased for us by that one page which cost Him His life's blood. Now, dear children, repeat over to me the lessons of this little book, that we may all remember them together—

Black—Red—White—Gold.

The childrena repeated the words as their mother turned the pages, and then she added:

Sin—Blood—Righteousness—Glory.

Mrs. Headley then passed a book to each of them, saying in a low tone, with an earnestness which impressed her young hearers, "May all of you fly from the first, take refuge in the second, be covered by the third, and share the last."

When their mother had left them Minnie stood looking long and lovingly at her little treasure, as if she would read its wordless leaves if she could.

"I think this book has a whole story on each page," said Agnes thoughtfully.

"I wish you could tell us one," answered Minnie, looking up wistfully.

"Perhaps I will next Sunday," replied Agnes.

ou promised to tell us a story of the 'Wordless pages,' Agnes," said Minnie on Sunday afternoon, when the children had left their parents to a few moments' quiet, and were gathered in the drawing-room to spend the hour in which Agnes generally read to them.

"I have not forgotten," answered Agnes, "but, as mother said, the first page is very hard to read, and the second page—"

"Well?" said John.

"You will see," answered Agnes. "Come on my lap, Minnie; you will not be afraid if I describe something very dreadful?"

"I don't think so," said Minnie wondering; "but is it dreadful, Agnes?"

"Don't you think that first page looks dreadful? So black and hopeless!"

"Oh, yes, so it does."[ 20]

"Then listen:

Black—Sin.

I seemed to be dreaming, and in my dream I beheld a rocky country stretched out before me.

On all sides were rugged stones, underneath which grew ferns and mosses, while short brushwood, growing luxuriantly, gave the place a wild, unfrequented appearance.

By-and-by I heard the sound of voices approaching, and two boys came in view, who seemed to be travelling through this mountainous country.

They were jumping lightly from stone to stone, or pushing their way through the bushes in the more open parts, talking gaily as they came towards me."

"I have heard that there are some wonderful caverns somewhere about here, and I have determined to try and find them out," said one.

"The Guide-book says they are most perilous," answered the other, opening his knapsack and looking in a book he carried there.

"Oh, those old Guide-books always call everything dangerous," answered the other contemptuously, "and I am not going to be turned from my purpose by any such nonsense. Look here!"

As he spoke he too opened his knapsack, and proceeded to pull out two candles triumphantly.

"With these we shall do perfectly well," he added, laughing, "and shall prove the Guide-book to have been written for people with less sense."[ 21]

"I should like to see the caverns," said the younger boy hesitatingly, "but——"

"No 'buts' for me," sneered the other, jumping up; "I am off to explore the mysteries. It is because you are afraid, I believe."

I thought that the younger boy seemed not to like being called afraid, for he got up reluctantly and followed his companion somewhat slowly; not at all as he had bounded over the rocks a few minutes before.

A call from the other announced that he had discovered the opening, and the colour flushed into the younger boy's face as he hastened on.

In my dream I seemed permitted to follow them unseen, and saw before me the mouth of the caverns, large and wide.

The boys laughed gaily, but I was not sure if I were right in imagining an uneasiness in their merriment.

They eagerly traversed the outer caves, which were quite light, and chose one of the many winding turnings.

"You will want your candle soon, Edred," said the younger.

"So I shall, and I mean to have it too, and see all the beauties of which I have heard."

They stopped to light the tapers, and I could not help wondering whether they would last long enough to guide them safely out again; but as I knew nothing of these dangerous caves, I could[ 22] only follow silently, with an anxiety which increased as I perceived how headstrong Edred appeared to be.

They wandered on and on, the light from their tapers illuminating the wonderful caverns, and the boys were full of interest and enjoyment, while my eyes watched the quickly-lessening candles.

"You told me the Guide-book spoke of evil beasts," said Edred mockingly, "but I don't see a sign of them, and this place is like a fairy palace."

"I wish we were going out towards the light," said Alwin; "we have been going inwards so long, and I am sure we shall lose our way, there are such numbers of turnings."

"No fear," answered the other, "I can tell which way we are going; you have not a grain of sense. Alwin!"

Alwin sighed, "I'm afraid I am stupid, but I did hear a noise just now, and I have seen several shadows that I can't account for."

Did Edred look round nervously, or was it my fancy? The lights burned lower still, but the boys were too intent to notice.

"I am tired," said Alwin, "let us rest."

Edred glanced at him, and seemed to consider. "Well," he said, "I dare say we shall reach the end the sooner for a little rest; and I want to look right down the abyss which they say is to be found there; so let us sit down here."

Alwin willingly consented, but he suddenly[ 23] started from his seat again. "They say," he exclaimed, "that there is a mysterious drowsiness which creeps over people in this cavern. Can we be falling into that, think you?"

"Nonsense," answered Edred, "this is only ordinary fatigue, five minutes' sleep will revive us, and we shall be as fresh as ever."

Already they had set down their candles near them; and as they leaned back against the rocky sides of the cavern a strain of music, soft and dreamy, filled the air, and they slept.

Long I watched, and would willingly have waked them, but that I found myself spell-bound. I was unable to speak or move. I could only look; and as I looked, the weird, dreamy music continued to lull them into deeper slumber, while their little lights burned lower and lower, and then slowly flickered out, and they were left in dense darkness.

Then the music seemed to change into a new key, and my fancy made me think it sounded like the distant cries of some in dire distress. The miserable moan seemed to disturb the sleepers, for I heard an exclamation of dismay, and Alwin's voice said, in a tone of horror, "Edred! Edred! where are we? our lights are gone out!" Edred seemed to be only half awake, and he grumbled an impatient answer; but Alwin shook him with a despairing cry.[ 24]

"What is it?" said Edred, now thoroughly roused.

"We are in darkness; we shall never find our way out. Oh, what shall we do, Edred?"

"I do not know, I am sure," said Edred; "but we had better turn the way we came."

"But which way?" said the other.

"This, to be sure," said Edred, beginning to grope his way along.

"But there were numbers of turnings, Edred," said Alwin reproachfully; "and the Guide-book——"

"Stop that!" called Edred, with fierce anger, "we shall come all right; but let's have a truce to your whining."

Alwin was silent after this rebuke; but the caverns were by no means silent, for now the unearthly sounds seemed to increase, and the boys clung to each other in terror. Louder and louder grew the roar, and I heard one of them exclaim. "There is something coming towards us. Oh, see! what is it? what can it be?"

The anguish of those words I shall never forget.

Before them along one of the many passages, a faint light seemed to shine; it came apparently from the eyes of a fierce beast who was approaching. The light was not sufficient to discern his shape, but from the lurid glare cast upwards from his eyes I could see three letters traced on his brow—S-I-N. They were incomprehensible to me, but[ 25] I think the boys understood them; for, as they confronted those mysterious letters, they fell back appalled. Well indeed they might, for such a dreadful creature as bore them I never before beheld. He approached nearer and nearer, while the boys shrank back against the rocks. The fiend looked as if he would devour them; but yet, as he came near, I perceived his intention was to torture them for a while first. He came close up to them, and seemed almost to enfold them in his embrace. He whispered to them, and as his eyes cast a light on their faces, I could see the misery and despair depicted there. The fiend then gave a growl of awful meaning, and set himself down at a little distance from them, as if to take some sleep.

"What did he say?" whispered Alwin mournfully.

"That he would never let us go," answered Edred in a despairing tone.

"Let us try to get away," again whispered Alwin; "will no one save us?"

"No one is so strong as he," said Edred hoarsely. "What fools we were, Alwin!"

"What shall we do? Do let us try to escape."

They crept forward a few steps, but the ground was noisome mire after the passage of this creature, and the boys were covered with filth at every step they took.

It was all in vain, however, for they knew not which way to go; and once, when a slight sound[ 26] roused the attention of the fierce fiend, he turned as if to spring on them, uttering a deep growl.

"What did he say?" again whispered Alwin.

"That it is of no use our trying to escape," groaned Edred. "He says there is no return from this pit of darkness."

Then I awoke from my dream.

Agnes paused, and the children remained silent, till Minnie broke forth with passionate earnestness—

"But oh, Agnes, there is a way out! Oh, why were they left there to perish?"

"That was all I saw in that dream," said Agnes; "and when I woke these words were ringing in my ears, 'The wages of sin is death.'"

"But," said John, with kindling eyes, "there is a bit more to the end of that verse, Agnes."

"Not if we keep only to the first page of the 'Wordless Book,'" answered Agnes.

"But we need not keep to the first page, need we?" said Minnie, looking rather sorrowful.

"Oh, no, thank God! For Hugh shall finish that twenty-third verse of the sixth of Romans which begins so sadly."

So Hugh repeated: "'The wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.'"

nother Sunday came round, and the brothers and sisters again claimed Agnes's promise to continue the story of the "Wordless" pages. They had several times in the week asked if she could do so then; but she had always answered. "Wait till Sunday."

"Now Agnes," said John, "let us have the rest of that dream."

"I did describe to you all that dream," answered Agnes. "What I have to tell you to-day is another dream—a new page as it were; not black, but red."

"I thought it was to be a continuation," said Alice.

"Yes, it is; but you will not let me begin."

"Oh! yes we will," said Minnie. "Now then. Agnes."[ 28]

Red—Blood.

Again I dreamed, and found myself in the same cavern where I had before been such a terrified spectator. Should I be able to see the dismal end of those miserable boys? I asked myself. At first the darkness seemed impenetrable, and as there was no sound to break the stillness, I feared that already the fierce beast had devoured those whom he had captured.

But hark! was not that a sobbing sigh from some one?

Again it met my ear, and I thought I could distinguish Alwin's voice, saying in a low, pleading tone:

"Edred, I am sure I read something in the Guide-book about the King's Son, who lives in that Palace we saw over the Hills there, being willing to rescue travellers, if they were in distress."

"Hush!" said Edred, in a frightened voice, "the fiend will hear you, and will spring upon us if he thinks we are meditating escape—however futile it may be," he added bitterly.

"He is half asleep over there," answered Alwin in a low tone; "see how he rests, and his eyes are shut. Oh, Edred, our position is so dreadful that it is worth a desperate effort to get free."

"No effort is of any avail," said Edred hopelessly. "If you only look at yonder monster, with his awful name shining on his forehead, you will know that he will never let us enter the King's[ 29] Palace; he told us just now that his wages are death, and that we shall not escape."

"I know," said Alwin, "but all the same I have read enough of the Guide-book to believe there is some way of deliverance; do, Edred, try to recall what it was."

"I never read it," said Edred, "and to consult it now, when we are in this dire distress, seems like mocking the King who ordered it to be written."

He sighed heavily, and as I grew accustomed to the darkness, I could faintly perceive the two boys crouching down in a corner, watching the evil beast, never taking their wearied eyes from him for a moment.

Alwin seemed unable to let go his last hope, and began again imploringly, "Edred, I know it said if people got into these caverns they were to call to the King; do let us try."

"Call and wake the monster?" asked Edred, mockingly. "Besides, who could hear?"

"I shall try," whispered Alwin, "for I feel I shall soon have no strength left."

Edred made a gesture as if to reply, when the enemy roused himself suddenly, and before either of them had time to speak or move, he had sprung across the cavern. I saw the two boys disappear beneath his awful form.

A fearful cry rent the air, a cry of agony, but a cry too which seemed to expect an answer.

The fiend grappled with them both, and gave[ 30] them blow after blow. Still spell-bound I watched, feeling myself turned to stone with horror.

But what did I hear? Surely above the cruel strokes which resounded on the bodies of these captive boys, surely above their cries for help, and moans of anguish, I heard another sound—a sound of rescue, coming nearer and nearer?

Did the evil creature hear it too? Did he not strike the faster, that there might be no deliverance; that the deliverance might be too late?

A strange light approached along one of the passages, and all at once One entered the cavern, and dealt a swift blow at the fiend, which made him relax his hold, only to tighten it more painfully. "I have come to deliver those that are appointed to die," said a voice of heavenly sweetness; but the fiend turned on Him with blows, fiercer and deadlier than those he had given the boys, and there ensued such a terrible combat that my very heart failed me.

By-and-by I found that the fiend seemed to grow weaker and weaker, and the Deliverer, though wounded and bleeding, was a Conqueror. The evil creature at last sank down in the mire, motionless, his grasp loosened from the poor boys, and the Conqueror came up to them and raised them from the ground.

Alwin had just sufficient strength left to clasp the feet of his Deliverer with a cry of love, but Edred neither spoke nor moved.[ 31]

"Edred," said the tender voice, "I have fought, and he who held thee is conquered; wilt thou come with Me?"

Edred groaned.

"Thou wilt not stay here, Edred?" again said the loving tone reproachfully.

"I am not worthy," moaned Edred, "I disobeyed——"

"Nay, nay, thou art not worthy; but I have loved thee, and have done it all for thee. Edred, wilt thou refuse?"

Then I heard a broken cry of grateful acquiescence, and the two lost, hopeless boys were clasped to that bosom of love.

And Alwin whispered, "Thou hast been wounded in the sore fight, for I can feel Thy blood flowing upon me!"

"That was the price at which I rescued thee," answered the Deliverer, "and thou shalt find when we come into the Light that the Blood of the King's Son worketh marvels for thee."

"Art Thou the King's Son?" asked Edred as they moved forward from this cavern of Death.

"Didst thou not know?" answered his Deliverer with a radiant smile, "no one else is 'Mighty to save.'"

When Agnes ceased the relation of her dream, she turned over the leaves of her Bible which lay[ 32] on her knee, her brothers and sisters waiting to see if there were any more of the story.

At last she looked up, and said earnestly, "You all like allegories, but they can only teach one side of a truth at once, and the Lord Jesus has done so much more than anything I can say for us. I have not told you half that Red page means, but you can seek it out for yourselves, dears. Think of all the love which brought Him down to redeem us, and what it cost Him, and let the Red page of the 'Wordless Book' impress this upon your hearts, never to be forgotten, 'Without shedding of blood is no remission;' 'God commendeth His love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners. Christ died for us.'"

ave you another dream to tell us?" asked Minnie on the following Sunday.

"It is the end of the same dream, but it has a different page in the 'Wordless Book' as its suggestion," answered Agnes.

"Yes, the White page," said John.

White—Righteousness.

Then the boys passed out towards the Light, leaning on Him who had delivered them. I followed silently, still allowed to watch and listen.

"Dost Thou say that Thou wilt present us to the King?" asked Alwin hesitatingly.

Their Deliverer assented; for Edred immediately answered, "We are not fit to appear before Him! Thy power has indeed saved us from the destruction we merited; but we are so soiled and filthy from contact with the mire in this awful Cavern, that we[ 34] could not appear before any one, least of all before the Great King." He spoke eagerly and half proudly.

"Dost thou not remember what I told thee? That My Blood, which has been shed for thee, with which thou hast been covered, will work—nay, has already worked, marvels; and when the Light shines upon thee, thou wilt see. Fear nothing, only believe what I tell thee."

They were silent after this, and were quickly approaching the end of the darkness. Then the boys could look upon their Deliverer, and could see the terrible wounds that He had sustained in His conflict with the foul fiend. And when they looked they wept—wept for sorrow that He should so have suffered for them—wept for joy that they were safe from the dreadful destruction.

They thought not of themselves; but when I could unfasten my eyes from the lovely face of the Deliverer, I was amazed to find that the boys were no longer arrayed in their former clothes, for in that mysterious passage from Darkness to Light all these had been changed, and they were now clad in a spotless robe of pure white.

By-and-by they perceived it themselves, or rather their Guide pointed it out to them.

"See," He said tenderly, "what My deliverance has done for you; now you can meet the King without fear. Covered by this robe, you will be accepted even in His eyes, because when He sees[ 35] it He will remember that I have fought for you and prevailed; and He will count My merits yours."

He led them now swiftly, it seemed to me, towards a spot which He told them would be the Meeting-place, but for the first time I was unable to follow them. A thin cloud seemed to obscure my vision for a while.

When I saw the boys again their Guide had left them, and they were walking along the road towards the Palace of the King, which lay at the end of the journey.

They were busily engaged in perusing the Guide-book, which Edred had before so despised; but now his face bent over it with a look which was both inquiring and trustful.

"What does it mean, Alwin, when it says, 'Needeth not save to wash his feet?'"

"Does it not mean that we, who have been cleansed from all that filth by the wonderful efficacy of our Deliverer's Blood, still may get defilements in our path, and that these will need constant washing away?"

"I suppose it does," said Edred hesitatingly and looking round; "but where——?"

"Our Deliverer told us—do you not remember it?—that by our road we should find a cleansing stream, dyed by His Blood, to which we must needs constantly repair."

"He did, but I had well-nigh forgotten it; but[ 36] see, Alwin, the end of the journey is not so very far off; just beyond those Hills, where the radiance is; there will be nothing to defile us there."

Alwin looked towards the Hills in silence, with a rapt face, on which the glory seemed reflected. Then he added suddenly, "Our Deliverer said that He might fetch us Himself, instead of our travelling so far; that would be better still, Edred."

"Indeed it would," answered Edred earnestly. "I hope He will."

Then I awoke from my dream.

"And this text has been running in my head while I have been pondering over my dream," added Agnes, "'The blood of Jesus Christ His Son cleanseth us from all sin'—and—'He hath made us accepted in the Beloved.'"

am sorry we have come to the Gold page," said Alice, with a sigh, folding her hands together as she seated herself in the bow-window seat on the Sunday before their parents were to sail for America.

"Sorry!" echoed Minnie, "why, I am very glad indeed!"

"Because it is the last, I mean," answered Alice; "we shall miss our Sunday afternoon story dreadfully."

"I propose that Agnes tells us one every Sunday," said John.

Agnes shook her head, but answered, half-smiling. "Sometimes, perhaps, I may, but you know they cannot be all allegories."

"Oh, no!" said Hugh; "but let us begin our last page now."[ 38]

Gold—Glory.

Once again I dreamed, and once again I saw the boys in whom I took so much interest.

This time they were nearing the Hills, above which the radiance shone.

The country was still of the same mountainous description, and I thought I could see beneath the steep ascent before me a River winding in and out.

The golden light seemed to shine down on some parts of the River, but generally it was dark and sombre.

Just now the boys were standing near it, and Edred was gazing down into its depths.

"It is rather dreadful, Alwin," he exclaimed, turning round and glancing in his companion's face, "to think of having to cross this before we reach the Palace of the King."

"Yes," answered Alwin, "and when we look down into it, instead of looking up at the Glory, we do get depressed. But, you know, Edred, our Deliverer has promised to bear us safely through."

"Of course He has. He would not leave those whom He has delivered at such a price to perish in the final water, Alwin. No; I will not look down into the River any longer, but rather, as you say, to the Glory beyond. But I wish I knew more of its delights."

"The Guide-book tells us a great deal about it; and often since we have neared this River, I have[ 39] had to turn to the description of it to cheer my fainting courage."

"I wish I were acquainted with the Guide-book as you are, Alwin; but I do love it much more than I used—I love it dearly! What does it say?"

"Shall I read it to you?"

"Yes, do," answered Edred, throwing himself down on the grass by the side of the water, and settling himself into an attitude of expectancy.

Alwin once more drew from his knapsack the Guide-book, which had seen much service since my eyes had first fallen upon it, and with one glance upwards at the radiance over the Hills, he turned towards his companion and read in a thrilling tone from the book in his hand, words which seemed familiar to me, though I could not tell in my dream where I heard them:

"And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea. And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away. Then came unto me one of the seven angels..., and he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and showed me that great city, the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God, having the glory of God: and her light[ 40] was like unto a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal. And I saw no temple therein: for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are the temple of it. And the city had no need of the sun, neither of the moon to shine in it: for the glory of God did lighten it, and the Lamb is the light thereof. And the nations of them which are saved shall walk in the light of it: and the kings of the earth do bring their glory and honour into it. And the gates of it shall not be shut at all by day: for there shall be no night there. And they shall bring the glory and the honour of the nations into it. And there shall in no wise enter into it anything that defileth, neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a lie: but they which are written in the Lamb's book of life. And there shall be no more curse: but the throne of God and of the Lamb shall be in it; and His servants shall serve Him: and they shall see His face; and His name shall be in their foreheads. And there shall be no night there; and they need no candle, neither light of the sun; for the Lord God giveth them light: and they shall reign for ever and ever."

Alwin ceased reading, and Edred, whose eyes, from being turned on his friend's face at first, had been latterly directed upwards, now rose from the ground with a new light shining in them.

"Alwin," he said solemnly, "I always have dreaded this River, but I do not any longer. I[ 41] have long known that I should soon have to pass through it. Ever since we were in that Cavern of Death I have known it, but now I fear it no longer. The words of the Guide-book have taken away my terror. See, I shall soon be where the light will never fade away."

As he spoke a touch of golden light which had for a moment illumined the dark river passed away from it, and the gloom grew deeper.

But Edred thought not of it, his eyes were fixed on the Light beyond.

"You are not going to leave me alone?" said the younger boy yearningly.

"I must; I have been sent for by the King. He told me some little time ago that it would be soon."

"Oh, Edred!" murmured Alwin.

"He will bear you through too," answered Edred kindly. "I could not have believed that His words would have cheered me so. I am quite joyful in going now. I only long to cross."

As he spoke he stepped into the River, which looked to me so dark and drear.

Now a mist brooded over the River, between those standing on the bank and the Shore beyond, and so Edred was lost to my sight.

Alwin stood long looking after him, with tear-dimmed eyes; but by-and-by he turned once more to the Book in his hand, and as he read it I noticed that the sorrow passed away from his face.[ 42]

"A little while," he murmured to himself, and turned to go on his journey.

But I saw that his road lay close to the River; and, or ever I was aware, I found he too had entered the water, and was actually crossing over to the bright Land.

As the waters got deeper and deeper, his face only grew the more radiant, and when the mist almost hid him from my view, I heard a triumphant voice exclaiming, "Thanks be unto God for His unspeakable Gift."

Minnie's little head was laid on Agnes's lap during the narration of this dream, and she now raised it with an earnest look.

"And that is all?" she said, sighing.

"All, except that there is no end to the Glory," replied Agnes.

"No," said John, "I often think that is the best of Heaven—there will be no 'leaving-off' there."

"That is just it," answered Agnes, "and the summing-up of all these Wordless pages—of Sin—Blood—Righteousness—Glory—seems to me to be expressed in these words, 'That ye might walk worthy of the Lord unto all pleasing.... Who hath made us meet to be partakers of the inheritance of the saints in light.'"

sn't it awfully cold for you and mother to travel at this time of year, father?" asked Hugh as he buttoned up his warm great coat to set out for school for the last time before the Christmas holidays.

"Very; but you see, my boy, urgent business calls me; and urgent necessity calls your mother."

"Oh, yes! but I wish it were summer. Are you really going on Saturday?"

"Yes, God willing."

Hugh went into the hall, where he found his brother brushing his hat.

"I wonder why father always adds 'God willing,'" he said in an undertone, "so few people do. Do you care about it, John?"

"Well, I can't say that I've come to doing it myself," answered John candidly; "but I do feel this, Hugh, that when they're out on the Atlantic I'd rather know they had felt it was 'God willing,' than that they should have acted on their own responsibility."[ 44]

Hugh whistled. "You ain't getting preachified I suppose, are you, John?"

"No; but, all the same, I know when I think a thing's right."

"So do I; leastways I know when I'm in the right, and that's generally!"

"Or you think so."

"Of course; comes to the same thing."

Hugh had a pleasantly good opinion of himself, which often roused the ridicule and annoyance of his brother and sisters; and so before John was aware he found himself caught in an argument which was beginning to rasp his temper.

"Well, I'm off," he said, abruptly turning on his heel, thinking within himself that if his promise to Agnes was to be kept during his parents' absence it would be well to begin at once.

"Beaten off the field?" asked Hugh, laughing, while he turned round to give his mother a passing kiss.

"Teasing again, my boy," she said gently.

"Only on the surface, mother," he answered lightly.

"Do you not think that the surface of a mirror sometimes gets scratched, and cannot reflect back the same perfect image it should?"

Hugh shook his head. "Mother, I shall be late," he said, turning the handle of the door, and wishing to escape.

She smiled archly. "Next week there will be no[ 45] mother to run away from, so listen, Hugh. Can't you invent some remedy for that tongue of yours?"

"I wasn't doing a bit of harm, mother, then."

"But if you could you would be 'able to bridle the whole body.' Think of that, Hugh! Can you not make up your mind to try?"

"All right, mother, I'll see about it."

"Not in your own strength though, dear."

He nodded, and seeing that he was let off, he darted through the door and was gone in a moment.

Mrs. Headley turned back with a momentary look of pain, then, as if those words were whispered in her ear she heard:

"In the morning sow thy seed, and in the evening withhold not thine hand; for thou knowest not whether shall prosper, either this or that, or whether they both shall be alike good." And at that word she went into the dining-room with a smile on her face, and seated herself at her preparations with peace in her heart.

"What are you going to do for poor people this Christmas, mother?" said Minnie, throwing her arms round her mother's neck in her warm-hearted little way.

Mrs. Headley looked up from the close embrace with a smile, and answered, "We shall not be able to do very much this year, Minnie; but I have not forgotten."

"I did not think you had, only I do like to know."

At this moment Agnes entered the room, bearing[ 46] in her arms a heap of garments, which she deposited on the table, saying to her mother, "This is all I can find, and they will need a good many stitches."

"I dare say they will," said Mrs. Headley; "but we must all help."

Minnie peered curiously at the assortment of clothes, and exclaimed, "Why, there's my old frock, Agnes! Whatever are you going to do with that?"

"This is part of what we are going to do for Christmas," said her mother.

Minnie looked incredulous, and turned over her brother's worn jacket with the tips of her rosy fingers rather disdainfully.

Agnes already had seated herself at the table, and was proceeding to examine each garment with critical eyes.

Mrs. Headley glanced at the little face opposite her, but made no remark as she leaned over to reach the old dress, which Minnie thought so useless.

"This wants a button, Minnie; get the box, and see if there is one like the others there."

Minnie sprang up to get it, and was soon engaged in searching for the button. "What's it for?" she asked.

"Some little girl who has a worse one than this."

"Are there any? I thought this was so very shabby."[ 47]

"Plenty, I am sorry to think; but if we get this ready for some one, there will be one less needing a frock."

"Why is Agnes helping?" asked Minnie, drawing nearer.

"Because she wants to do something to make Christmas happy to others."

"Will this make any one happy?" asked Minnie again, her puzzled little face gradually assuming a more contented look.

"Should you not think so, if you had a little bare frock just drawn together with a crooked pin, and hardly covering your shivering little shoulders?"

"Oh, yes, indeed," said Minnie, now quite convinced, eyeing her warm though cast-off frock with fresh interest. "Could I do anything to help make it ready?"

"You can put on the button, and fasten this little bit of hem."

"Why do you mend all these things? Could not their mothers do it?"

Mrs. Headley did not answer, so Minnie sat down; and while she put on the button she pondered the question.

Meanwhile Mrs. Headley with rapid fingers was darning and patching, aided by Agnes, who sat industriously stitching away, silently buried in her own thoughts.

At last Minnie exclaimed, "Is this all you are going to do, mother?"[ 48]

"No, my dear, we are making some puddings for three or four families."

"Oh, yes, of course! I knew you would; I do love Christmas."

"I wonder if Minnie knows or thinks about why we do it?"

"Because we love the Lord Jesus, I suppose," answered Minnie, looking up from her work with her tender little face.

"Not only that, dear, though that is one reason. Do you remember what we were reading the other day about dealing our bread to the hungry?"

"I think I do."

"And about visiting 'the fatherless and widows in their affliction'?" added Agnes.

"Oh, yes! but, then, this isn't visiting the fatherless and widows; this is making things at home."

"Should you like to help me take them when they are done, Minnie?" asked Agnes, looking up.

"That I should, if I might."

"You may, then," said her mother; "and I think you will understand their value better after you have been."

Just then John and Hugh came in from school, and guessing what their mother and sisters were engaged in, they suddenly disappeared; at which Mrs. Headley did not look surprised, nor did she either when they re-entered with her rag-bag, a large cardboard box, and a small parcel.

Minnie threw down her work and jumped up to[ 49] examine this new marvel; but John, who liked to tease her, kept his intentions to himself, and taking a pair of scissors, bent down his head into the box, and was soon absorbed.

Hugh, who was less particular, opened the parcel, and drew out a piece of bright-patterned cretonne.

"Oh, how lovely!" exclaimed his little sister, leaning over the table. "What are you going to do, Hugh?"

Agnes glanced up, and reminded Minnie of her own work; but she was too busy in conjecturing what Hugh was about to heed.

He laid the piece out on the table, folded it in half, and proceeded to thread himself a needle.

"Are you going to work, Hugh?" asked the never-satisfied little maiden.

Hugh nodded, nowise disconcerted at her surprised tone, and soon he had begun to sew up the sides, clumsily enough perhaps, but still effectually.

Minnie found work was to be "the order of the day," so she relapsed into silence.

After an hour's close application, during which time Minnie had watched with curious eyes John's hand diving in and out of the rag-bag, Hugh pronounced his contribution done, and went over to his brother and asked him if his were ready. A whispered consultation ensued behind the cardboard box, and then there was some mysterious pushing and man[oe]uvring, which raised[ 50] Minnie's expectation to the last extent. Her brothers, however, enjoyed keeping up the joke, and there was a fine laugh when they laid a neatly-finished cushion on the table in front of the inquisitive little girl.

"What is in it?" she asked, pinching and pulling it about.

"Only mother's woollen rags snipped up in tiny pieces," said Hugh.

"You should not have told her," remarked John; "but I say, don't my fingers ache! and isn't there a blister on my thumb?"

"Did you cut all that to-day?"

"No, we have been at the snipping business all the week, off and on, and I declare old Mrs. Hales will not have a bad pillow after all."

"Where is Alice?" said Hugh.

"She is doing her part," answered Mrs. Headley; "this is a busy time for cook, and Alice is helping her to make the puddings."

"When shall we go round, Agnes?" asked Minnie.

"On Christmas Eve, mother thinks."

"I wish it were here, then."

"I do not, for we must finish all this heap of mending first."

"You'll tell us who you give it to, Agnes, and all about your visits," said John, who loved a story as much as anyone. "It will make us 'good boys' when they are gone."[ 51]

"Oh, yes," answered Agnes.

"Then we will wait patiently till then; and if you can think of anything we can help in, we are ready, mother, now it is holiday time."

"I will consider it," she answered, "but while we plan to do something for those in need, let us remember, my dears, one thing."

The faces were turned affectionately towards the mother, who so anxiously watched over her children, while she said gently, "It is not only that we are to 'visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction,' but we are 'to keep ourselves unspotted from the world.'"

"That's almost harder than the other," said Hugh thoughtfully.

"Except by 'looking off unto Jesus,'" said Mrs. Headley; "'I can do all things, through Christ which strengtheneth me.'"

cannot leave you a great number of injunctions," exclaimed Mrs. Headley tearfully, on that last morning when all was ready for departure, and the day for the sailing of the steamer had really come.

"I think you have, mother," said Hugh, trying to hide his feeling under a joke.

"No, not to you, dear; to Agnes I may have."

"Yes, to me" said Hugh. "I am to mind Agnes, and not to mind John; and to mind I am kind to Minnie; and to keep in mind that Alice is younger than I; and to——"

"Shut up," said John; "we don't want to hear your gabble to the last moment!"

"I was going to say," resumed their mother gently, "that there was one thing I did want you to think of."

"Tell us then, mother," said Alice, putting her[ 53] arm round her fondly, "we'll keep it as the most important of all."

There was a momentary silence, and then Mrs. Headley turned to her husband with a mute appeal. "Tell them," she said brokenly, "what we were saying this morning."

"We want you all to think of one thing. In any difficulty, in every difficulty, in all circumstances, say to yourselves, 'Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?' If you wait and hear the answer, it will help you in everything."

"People generally do wait to hear the answer to their question, don't they, father?" asked John.

"Not always; especially when they are speaking to God. But you be wiser, my children. In the waiting-time for the answer an extra blessing often comes."

The children looked thoughtful; and then their father took from a paper a large painted card in an oak frame, which he proceeded to hang up on a nail ready prepared for it.

On the card were letters in crimson and gold and blue, and the children read:

"Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?"

Then the sound of wheels suddenly reminded them that the parting had come. With a close embrace to each from their mother, and with an earnest "God bless you" to each from their father, the travellers turned to the door, followed by John[ 54] and Hugh, who were to accompany them to the railway station.

When the last bit of the cab had disappeared. Agnes turned round to her younger sisters and put her arms round them both lovingly. "We'll be ever so happy together when we once get settled in," she said, choking down her own emotion, and bending down to kiss them in turn.

"Oh, yes," answered Alice with a sob, trying to look up bravely.

But Minnie could not look up. Her mother was her all, and her mother had gone. She threw herself into Agnes's arms in a passion of misery.

Agnes sat down and tried to make her comfortable on her lap; but the child wailed and sobbed, and gave way to such violent grief that the elder sister was almost frightened, and looked towards the window with a momentary thought of whether it would be possible to recall her mother.

It was only momentary, for how could she? Then her eyes fell on the new text, and her heart, with a throb of joy, realized that the Lord was with her.

"Always," she said to herself; "so that must mean to-day. 'Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?'"

She bent her head over the little golden one, and clasped her arms tighter round the trembling little form, and then she said softly:[ 55]

"Minnie, have you read our text since father and mother went?"

Minnie listened, but only for an instant, then she sobbed louder than ever.

"Minnie," again pursued Agnes, "do you think you are carrying out what He would have you do?"

Minnie stopped a little, and clung more lovingly than before to her sister's waist.

"We must be sorry they are gone; we can't help it, and I don't think Jesus wants us to help it; but we ought not to give way to such grief as to seem rebellious to what He has ordered."

"Do you think I am?" asked the child brokenly.

"What do you think yourself?"

"I don't know," hesitating.

"Well, think about it for a moment. Look here. Minnie, I want to put up these things that are scattered about, so I will lay you on the sofa and cover you up warm; then you can think about it while you watch me. Come, Alice dear, you and I shall soon make things look brighter if we try."

Alice had been standing gazing rather forlornly at Minnie, but now turned round with alacrity. To do something would divert her sorrowful thoughts.

By-and-by a heavy sigh from Minnie made her sisters look at her. There she lay like a picture, her long curls tossed about over the sofa cushion like a halo, her dark eyelashes resting on her flushed cheeks, where the tears were hardly dry, asleep.[ 56]

"What a good thing," said Alice in a low tone. "I thought she would cry herself ill."

"Yes, I am glad," answered Agnes, looking down upon her. "But, Alice, the boys will be back before we have done if we stand talking."

"Then we won't. Agnes, did not aunt Phyllis say she would come in early?"

"Yes; but I hope she will not till we have put away everything. Just take up that heap and come upstairs with me, Alice; and then run down for that one, will you? You don't mind?"

"I'm not going to 'mind' anything, as Hugh says," answered Alice earnestly, a tear just sparkling in the corner of her eye.

"That's a dear girl; it will make everything so much easier if you do that."

"I mean to try."

They left the room, closing the door after them, and went up with their loads—papers, string, packing-canvas, cardboard boxes, rubbish, shawls, and what not.

Agnes placed the various things in their places, while Alice watched and handed them to her, and at last all was done and the girls ran down, just as a double rap sounded through the hall.

"That's auntie's knock, I shall open it," exclaimed Alice, and in a moment she admitted a little lady, whose pale delicate face and stooping attitude betokened constant ill health.

"Well, my dears," she said cheerfully, "I knew[ 57] you would have a few things to do after such an early starting, so I waited for a little time. Are the boys back yet?"

"No; we expect them every moment," answered Agnes, leading her aunt into the now orderly dining-room, and placing her in an arm-chair.

Miss Headley's eyes wandered round in search of little Minnie, and soon she saw the sleeping child.

"Not ill?" she asked, reassuring herself with her eyes before Agnes answered:

"She was tired with excitement, I think, and grief. I am so glad she is asleep."

"The best thing for her. And they got off well?"

"Oh, yes; but I hardly knew how utterly dreadful it would be to feel I could not call them back!"

Agnes turned away; she could not say any more. While the responsibility rested on her alone she had been brave, but now with her aunt's sympathy so near she began to feel as if she must break down.

"I know," said the soft voice, "do not mind me, my child; come here and let me comfort you."

Agnes knelt down and laid her head on her aunt's shoulder, while one or two convulsive sobs relieved her burdened heart.

"There will often be moments when you would give anything to have them here, my child; but the Lord knows just that, and has sent forth[ 58] strength for thee to meet it all. We never know how very dear and precious He can be till we've got no one else."

"I shall learn it soon," whispered Agnes.

"Yes, my child; and it is such a mercy to know that He suits our discipline to our exact need. The other day I was on a visit in the country, and had to go to an instrument-maker there to do something for my back. He told me he could not help me at all, for my case was so very peculiar, and he had nothing to suit me. But that's not like the Lord, my child. He knows us too intimately for that. He does not think our case too peculiar for His skill, but holds in His tender hand just the support, just the strengthening, just the treatment we want, and He gives us what will be the very best for us."

Agnes and Alice knew to what their aunt referred. An accident when she was a beautiful young woman of twenty had caused her life-long suffering, and obliged her to wear a heavy instrument which often gave her great pain and weariness.

Her niece raised her hand at those gentle words, and stroked her aunt's face lovingly.

"It is resting to know He understands perfectly, my child, isn't it?"

"Very. But oh, auntie, I wish you hadn't to suffer so!"

"Don't wish that, my dear, but rejoice that, in[ 59] every trial that has ever come to me, I can say, 'His grace has been sufficient for me.'"

Agnes knelt on in silence; and aunt Phyllis did not attempt to disturb the quiet till some hasty footsteps were heard along the pavement, which came springing up the steps, and in another moment the two boys, fresh from their walk, came bursting into the room; but not before Agnes had sprung up and seated herself at the table with her work.

"Hulloa, Agnes! Why, auntie, is that you? So you've come to look after the forsaken nest, have you?"

"How did they get off, John?" Agnes asked, looking up as quietly as if she had been sitting there for an hour.

"Very well; mother was cheerful to the last."

"And they had a foot-warmer?"

"Your humble servant saw to that."

"And you got them something to read?"

"Wouldn't have anything."

"And they did not leave any more messages?"

"None whatever. Now, Hugh, as Agnes has pumped me dry, let Alice take a turn at you!"

Alice, till her brothers came in, had been leaning over the fire, deeply buried in a book and now turned round to it again, as if she would very much rather read than do anything else.

Hugh seeing this, advanced a step nearer, and his eyes looked mischievous.[ 60]

"Well, Alice, don't perfectly smother a body with questions. One at a time. What's the first?"

"I don't know; I haven't any to ask."

"You mean you're too busy?"

"No," answered Alice, half vexed.

"Perhaps you're cold, you're such a long way off from that tiny fire!"

"I'm not cold," said Alice, putting her hand up to her glowing face.

"Not? Now I really thought——"

But a gentle voice interrupted what was becoming too hot for poor Alice's temper, and aunt Phyllis said:

"Grandmama invites you all to dinner to-day, my dears, at two o'clock; will you come?"

At the word dinner Agnes started. "Oh dear, auntie, I forgot it was my duty now to see after dinner! I do not believe I should have thought of it for ever so long."

"Cook would have reminded you, I dare say," said her aunt, smiling.

"What are you boys going to do this morning?" asked Agnes.

"I'm going to my room to have a general turn out for the holidays, and shall not be visible again till five minutes to two."

"That's a good thing," said Agnes, laughing.

"Your politeness is only exceeded by your truth," said John, giving his aunt a kiss, and disappearing[ 61] through the door before Agnes could give him back an answer, had she wished it.

"And what is Hugh going to do?" asked Miss Headley, turning to him.

"Tease Alice," said Hugh, nodding towards the crouching figure by the fire.

"I was going to say that I have to go to see a woman in Earl Street, and wanted you to carry my basket for me, Hugh. Can you spare time, do you think?"

"All right, auntie."

"Where's Hugh going?" said Minnie, sleepily, opening her eyes.

"He is going out with me, darling; would you like to go too?"

"I don't know; I think I 'm going to sleep again."

She turned her back on the room, and vouchsafed no further notice of her aunt, nor of anyone else. Agnes gave a glance of apology, but Miss Headley answered by a look that it was not needed, and in a few moments took her leave, followed by her nephew, who ran in next door for the basket, and caught her up before she had reached the corner of the street.

Agnes left the room, and Alice woke up from her book to find herself alone.

She was just going to stoop again over it, when her eyes caught the unaccustomed frame upon the wall, and she could not but see the words, "Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?"[ 62]

"I've nothing to do but this now," she said, drawing her shoulders nearer to the blaze. "It's holiday time, and I have not lessons or duties of any kind; I may do as I like."

But though she tried to read, she could not forget that question. At first she determined to shake it off, but by-and-by her book fell closed on to her lap, and she looked up straight at the words, thoughtfully.

"This is the first way I am keeping my resolves; a pretty way!"

"Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?"

Then she waited, as her father had said—waited, looking at the words as if they would shine out with an answer. And so they did; for as her eyes rested on the last word, she suddenly started up.

"Do," she said, half aloud. "I don't suppose He likes me to sit here idling my time. I wonder if Agnes wants me? Or if not, I promised mother to practise a whole hour every day, and as I am going out to dinner I shall have to do that first."

Then her eyes met Minnie's wondering ones shining out from among the golden curls and crimson sofa cushion, and she heard a little voice say:

"Who wants you to 'do'?"

Alice pointed with her finger towards the text.

"Oh!" said Minnie, comprehending.

"But I didn't remember you were there, or I should not have spoken aloud."[ 63]

"I forgot what Agnes said, because I went to sleep; but——"

"Yes," answered Alice, waiting for what the little pet sister wanted to say.

"I don't think He would have liked me to cry so much, if I had asked Him first."

And with another little sob she rushed past her sister and flew up the stairs.

At five minutes to two o'clock, John opened his bedroom door and called Agnes.

She was just coming out on the landing, with her hat on, followed by Minnie and Alice.

"Come and see my arrangements," he said, opening the door wider.

"I don't see anything particu——Oh!" with a start, "why, John, where did you get that?"

"Out of these two hands of mine, to be sure, and these eyes, and that paint box, and that cardboard."

On the wall hung the same text that their father had prepared with such care downstairs, only that John's was not framed, but put up with four small nails.

"I thought I should see it more up here than downstairs."

"And he thought," added Hugh slyly, "that I should have the benefit of it here."

"I never thought of you at all," said John.

"It is very nice," said Agnes, coming in to examine it.[ 64]

The others went down stairs, and the brother and sister were left alone.

"I've been thinking a lot, Agnes," said John, turning his back to her, as he busied himself at one of his drawers, "and I've made up my mind while I've been tracing the words of that text."

"What about?" asked Agnes, with a feeling that there was something unusual in his tone.

"I've determined to take it as my life text."

"John!"

"Yes. It seemed so horrid without mother, and I've been thinking about it, on and off, for a year past; and to-day, as I painted those words. I thought——"

Agnes was standing behind him, her soft cheek resting against the back of his shoulder.

"Yes," she whispered.

"He seemed to say to me, that the first thing I had to do was to come to Him."

"I'm sure it is."

"So now you know," said John huskily.

"And you did come?" asked Agnes, feeling as if she wanted to understand all before she could rejoice.

"Of course," answered John, turning round astonished; "I should not have said a word if that had not been the end of it!"

he next morning dawned bright and clear, and Agnes was the first awake.

She slipped on her dressing-gown, and went across to her brothers' door and tapped gently.

"It is time to get up," she called.

"All right, mother," answered a very sleepy voice, and there was a comfortable sound of smothering bedclothes, and then silence.

"Hugh and John, do wake," exclaimed shivering Agnes; "we shall be late for church, if you go to sleep again."

She tapped louder this time, and then John's voice responded:

"All right, old woman; I'm awake now."

"Really, John?" asked Agnes.

"Really," said John; and she heard a bump on the floor, and a pattering across the room.

She flew back, for if those feet were by chance[ 66] Hugh's, a wet sponge would probably be trickling down her neck before she had time to escape.

She had waked with the heartache, but her brothers' cheerful laughter had turned her thoughts, and as she dressed, though she considered soberly her responsibility as head of the house, yet it was trustfully too, and the remembrance of the great joy which John's words yesterday had brought her, made her so glad, that she felt ashamed of being dull or mopish because her parents were gone.

So she went downstairs, looking as bright as if no weight of care overshadowed her.

"This is our first day alone," she remarked as they sat at breakfast, "for I do not count yesterday anything, because we went out to dinner."

"I like going to grandmama's," said Hugh, "for she always makes us jolly comfortable."

"That's Hugh's idea of bliss," said Alice mischievously, "nothing to do—and plenty to eat."

"Oh, Alice!" exclaimed Agnes, shocked.

Hugh was not disconcerted, as it happened, but answered:

"Well, what if it is? We're all in the same boat it strikes me. One likes one sort of ease, and another sort; but there isn't much to choose between us."

"Thank you," laughed Alice, who was a little ashamed of her home truth; "but my idea of comfort isn't like yours, Hugh."

"What is yours, Alice?" asked John.[ 67]

"A warm fire and an interesting book," said Alice promptly.

"Like yesterday," said Hugh, whose memory was often inconvenient.

"Like yesterday," assented Alice soberly, remembering something about that which Hugh knew nothing of.

"I hope you will all be ready in time for church," said John, "for I mean to start whether you are or not. Agnes will be sure to be ready."

Agnes acknowledged the compliment with a smile, but candour forced her to add, "I'm afraid I'm not always ready."

Then they rose from the table, and Agnes stood hesitating for a moment, while the colour mounted into her face.

"John," she whispered, "could you take prayers, do you think?"

John shook his head.

"I thought, perhaps, since yesterday——"

"Oh, Agnes," he returned, "you'll do it twice as well; and the servants, and all—you will not mind. You were going to, weren't you?"

"Yes, I was; and if you would rather I did——"

"Much rather—of course I would. You need not be nervous."

The whispered conversation was unheeded by the others, who had gathered round the fire looking at their mother's bullfinch taking his morning bath on the mantelshelf.[ 68]

"I hope you won't forget his royal highness," said Hugh to Alice.

"I do not suppose I shall."

"If you do I'll remind you," said Minnie.

"When it is starved to death," answered Hugh.

Minnie looked distressed, and Alice rather defiant. "I mean to attend to him every morning before I taste my own breakfast."

"Oh, I am sure we shall think of him," said Agnes, joining the circle, while her hand pulled the bell for the servants, "we are so used to giving him his bath that his food will be sure to be remembered."

And then they sat down for their first prayers without their parents; and Agnes read with a voice that trembled nervously at first, but as she proceeded she took courage. Their text flashed across her, and she felt that what He wished her to do now was just this, and the thought made her wonderfully happy.

When they sat at dinner—Agnes taking the top of the table and John the bottom—Hugh exclaimed:

"How awfully funny it is without father and mother!"

Minnie looked up quickly, and then looked down, and her knife and fork fell from her fingers.

John turned towards her kindly. "Why, Minnie," he said, "think how much good the change may[ 69] do them; and if it were you, you would want to see your own mother, wouldn't you, after twenty years?"

This roused Minnie's sympathy. She had never thought such a thing possible before as being separated from her mother for so long; so she swallowed down her tears and began her dinner, which, in spite of her woe-begone feelings, tasted very nice.

"What shall you do with yourself after dinner. John?" asked Hugh.

"I shall look out some texts I have to do, and enter them into my book."

"What book?"

John hesitated. "One I began some little time ago."

"What for?"

"To enter special subjects in that I am interested about."

"What sort of subjects?" asked Alice.

"Scripture subjects; or any others that seem to me to belong to that sort of thing."

Hugh gave a little shrug of his shoulders.

"What time are you going to read to us, Agnes?" asked Minnie.

"A little before four, I think. Hugh and Alice, you have your scripture questions to do for father, haven't you?"

"Yes," they answered.

"Then, John, can you come in the drawing-room[ 70] to do your writing? Minnie and I shall not disturb you."

He got up and followed her upstairs, smiling as he went.

Turning round on the first landing she saw the smile, and enquired:

"Well?"

"You're a good general," he said.

"Why?"

"Take care to separate your different regiments in case——"

"John!"

"Now, don't you?"

"Not exactly——"

"I know you!"

"Well, come along; you cannot say that my generalship has not made you comfortable, anyhow."

"I don't wish to. What a glorious fire, Agnes; and what a nice arm-chair; and what a jolly little table; and what a nice inkstand; and——"

"There, John, leave off, or our afternoon will be gone; and those children will be up before we have had a moment's quiet."

She seated herself on the sofa, at one side of the fire, Minnie curling herself up by her with her book, and Agnes opening her Bible and bending over it.

Silence reigned for an hour; while John's pen scratched, and the leaves of his concordance turned[ 71] over; and Agnes's eyes were fixed on one page, from which she hardly raised them, except to give Minnie an occasional caress, or to whisper something to her about her book.

At last there was a stir downstairs. Chairs were pushed back; careful Alice put on some coal, that the fire might not be out when they returned to it; and then there was a rush, and the two came tearing up the stairs.

"How jolly comfortable you look!" exclaimed Hugh.

"We are," said John, preparing to close his book.

"Any room on the sofa for a fellow?" asked Hugh.

"Oh, yes! plenty."

"Sit next me," said Minnie.

"All right. I say, Agnes, how strange it will seem to have Christmas Day without them!"

"Yes; but we can make it happy if we try," said Agnes.

"How?"

"By being happy."

"That's all very well," said Hugh; "but then, you know, Agnes, being made happy depends on outward things."

"Of course it does; and on inward things too. If we have got a well of happiness inside us, it will make everything round us seem bright and beautiful."

"What do you call a 'well of happiness'?"[ 72]

"I know what Agnes means," said Minnie.

"I was thinking then of the day father came home from America—last time; and we had received the telegram that he had landed at Liverpool. How we all went about singing and happy; how we never thought of quarrelling, but hastened to get everything ready for him."

"I remember that day," said Alice; "it was one of the nicest I ever spent."

"So that is what I mean by a 'well of happiness;' something which gives us joy, independently of anything else."

"And what's your Christmas 'well of joy' for this year, Agnes?" asked John with a smile.

Agnes gave an answering smile. "Oh, John, it is that we are His; that, through the coming of the dear Saviour, we have been given all other blessings—happiness and peace here, everlasting joy hereafter."

"And you think that ought to make up for all other deficiencies?" asked Hugh.

"If we have got it," said Alice thoughtfully; "but sometimes I wonder——" she looked down, and tears glittered in her eyes.

Agnes heard the quiver in the tone, and put her arm lovingly round her sister. "Is it so difficult to know?"

Alice shook her head.

"He gives the Holy Spirit to them that ask Him."[ 73]

The little party were silent; Alice's unusual feeling startled them. The Sunday afternoon was drawing in, and the light fading.

Presently Agnes said, "I have thought of a little allegory; would you like to hear it? It might help us to understand Alice's difficulty."

The question did not need repeating, and she began:

fell asleep and dreamed. Before me spread out verdant fields, picturesque villages, valleys of peace and plenty, cities of care and toil, the wide ocean restlessly tossing, the mountain bare and rugged.

At first my eyes seemed heavy with sleep, but after a time I began to see things more clearly, and in all these varied scenes I perceived there were children moving to and fro.

I was apparently at a great distance from them, and could not well understand what they did, nor could I hear what they said.

They appeared to be very busy, often eagerly running or walking; talking together in twos and threes; playing with the trifles which seemed to lie everywhere for their amusement; sometimes two quarrelling loudly over these same trifles, and crying pitifully if they could not have what they wanted.[ 75]

In my dream I seemed to be drawing nearer and nearer to them, and I began to perceive the differences in their countenances and dress, and to find that there was only one point of resemblance in them all; and this one thing caused me great surprise.

Some were robed in dresses whose sheen, reflecting the rays of the morning sun, dazzled my eyes; again, others had garments of the dullest hue; and the clothes of others were so covered with mud and dirt, that I could not have told what they once were. But, whether gaily decked or dressed in sombre attire, each child had fastened round it a curiously-fashioned girdle, to which hung a small pitcher. The pitchers appeared to be all of one shape and size, but the materials of which they were made seemed to differ widely.

On some of the children, whose dress was of gayest hue, the pitcher, strange to say, appeared to be made of commonest material, for it looked dull and dark; while at the girdle of some who were most plainly attired hung vessels of brightest gold. This also was incomprehensible to me.

Presently my dream seemed to bring me so near that I could see what they were doing and hear a little of what they said.

A group of them were sitting on a bank of flowers, resting in the shade, and as they talked I drew near to listen.

"I do not believe it," said a sturdy little boy,[ 76] as he threw a ball of flowers into the lap of a little maiden opposite.

"What do you not believe?" asked a grave-looking girl who was seated near.

"That there is any hurry to get the pitchers filled."

"Did any one say there was?" asked the girl, glancing thoughtfully at the vessel hanging at her side, while I perceived that it had the look of being neglected and soiled.

"Yes, there was a proclamation this morning that the pitchers might be needed this very day, and that all who had not the Golden Oil should, without delay, repair to the place whence it could be obtained."

"So there is every day," exclaimed a tall youth who was lying on the grass at their feet. "That is nothing new: it is the duty of the Herald to proclaim, and it is our duty to hear, but——"

"No one ever thinks of obeying," laughed the roguish boy, weaving his flowers as if all his life were centred in doing that only.

But the thoughtful girl looked up with a deep flush at those careless words. "I do not think every one does that, Ashton; for Esther here——"

She pointed to a child at a little distance who was threading daisies together wherewith to deck a tiny brother, who sat watching her little fingers with absorbed interest.[ 77]

Now that my attention was directed to this little girl, I took note of her for the first time. Her dress was of some white material, her eyes clear as the deep summer azure, her face full of sunshine, while close to her heart a golden pitcher gleamed in the light, as her happy little figure turned backwards and forwards in her task.

"Oh, Esther always obeys!" said the youth from the grass, "and is the happiest little mortal in doing so; but that would not suit every one."

He turned round restlessly, and any one who cared might see that his pitcher was empty enough as it lay on the ground under his arm.

Esther was all unconscious that the eyes of the party were fixed upon her. When she had completed her chain of daisies, she took her little brother's hand in hers.

"Now, darling," she said softly, "you promised me you would go at once to get your little pitcher filled."

He nodded and trotted off by her side, while she continued, "It would be so sad not to have any Oil when night comes on, wouldn't it?"

"But you could lend me some," answered the child, confident in her love.

"You know I can't; I must not; no one can lend. So that is why I want you to get some for yourself."