The Project Gutenberg EBook of The History of the Nineteenth Century in

Caricature, by Arthur Bartlett Maurice and Frederic Taber Cooper

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The History of the Nineteenth Century in Caricature

Author: Arthur Bartlett Maurice

Frederic Taber Cooper

Release Date: October 3, 2011 [EBook #37603]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HISTORY OF THE ***

Produced by Bryan Ness, Christine P. Travers and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected. Hyphenation and accentuation have been standardised, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

BY

ARTHUR BARTLETT MAURICE

and

FREDERIC TABER COOPER

PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED

LONDON

GRANT RICHARDS

1904

Copyright, 1903, 1904

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

BURR PRINTING HOUSE

NEW YORK

PART I. THE NAPOLEONIC ERA

PART II. FROM WATERLOO THROUGH THE CRIMEAN WAR

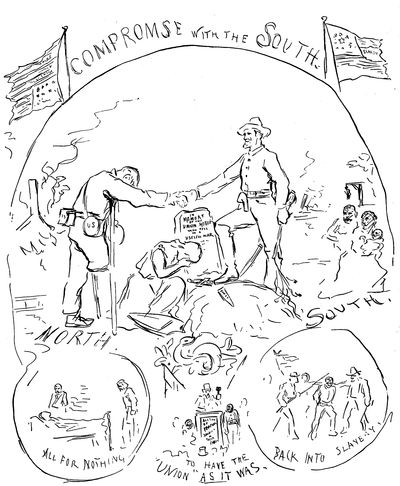

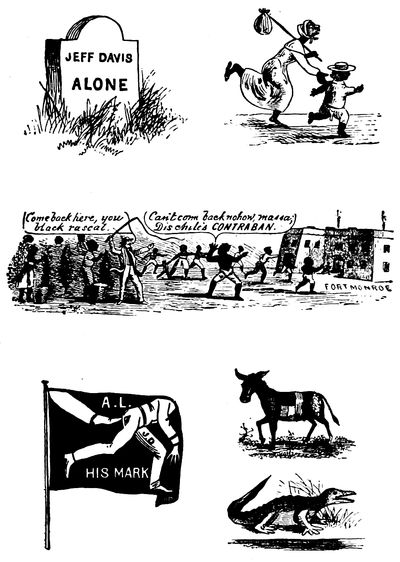

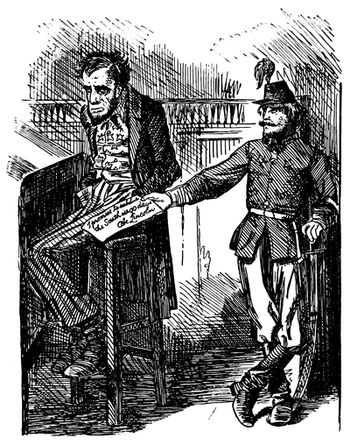

PART III. THE CIVIL AND FRANCO-PRUSSIAN WARS

(p. viii) PART IV. THE END OF THE CENTURY

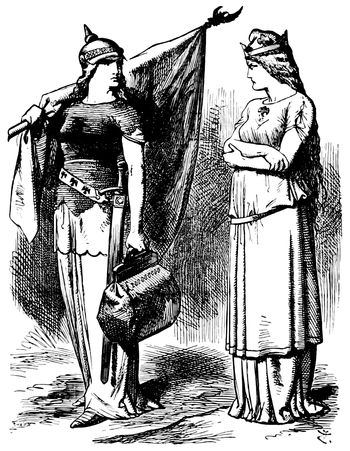

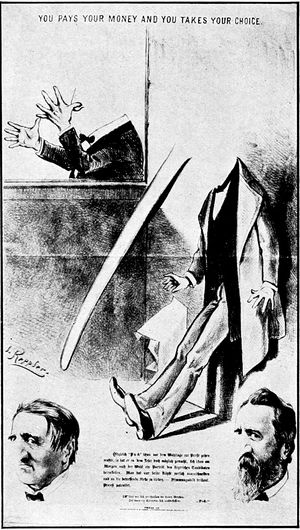

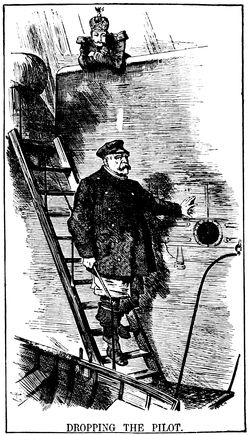

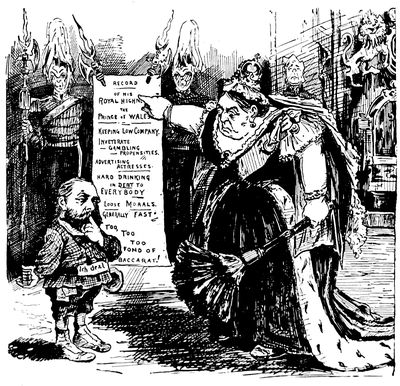

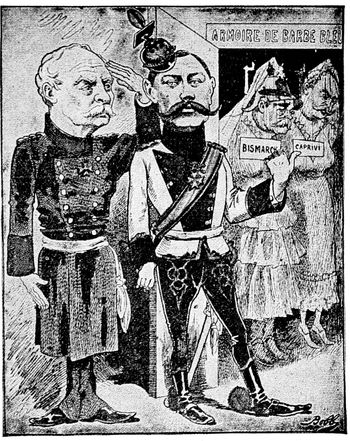

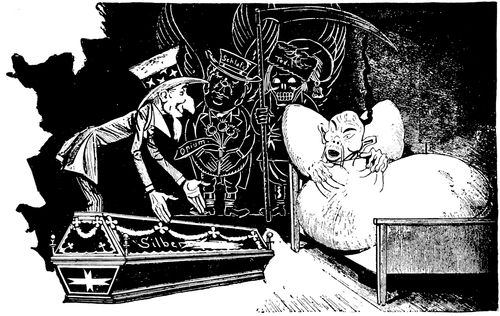

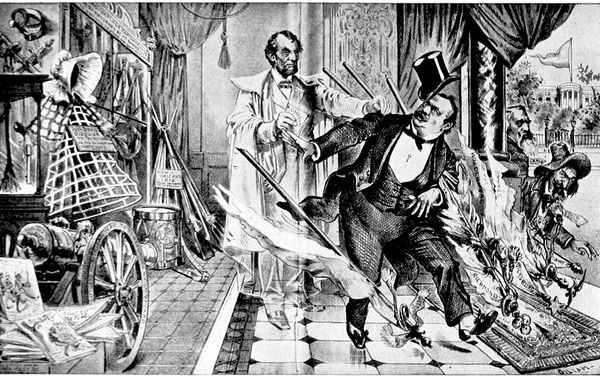

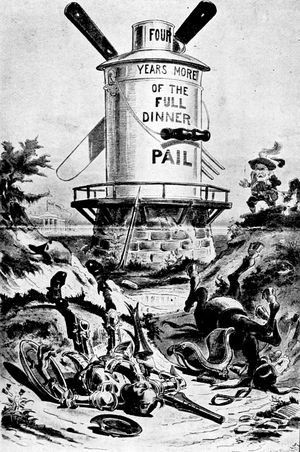

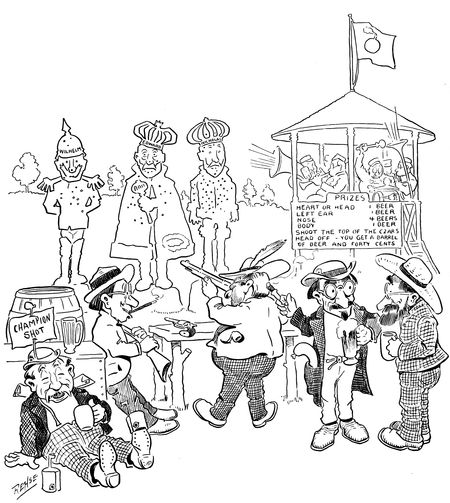

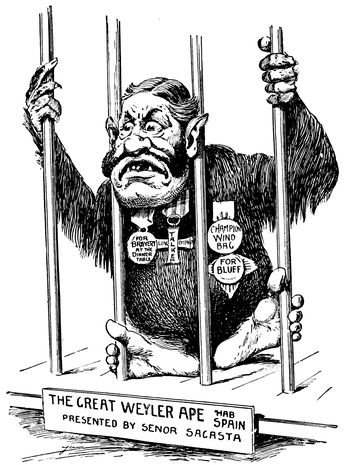

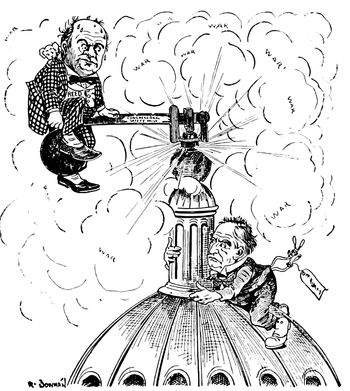

While the impulse to satirize public men in picture is probably as old as satiric verse, if not older, the political cartoon, as an effective agent in molding public opinion, is essentially a product of modern conditions and methods. As with the campaign song, its success depends upon its timeliness, upon the ability to seize upon a critical moment, a burning question of the hour, and anticipate the outcome while public excitement is still at a white heat. But unlike satiric verse, it is dependent upon ink and paper. It cannot be transmitted orally. The doggerel verses of the Roman legions passed from camp to camp with the mysterious swiftness of an epidemic, and found their way even into the sober history of Suetonius. The topical songs and parodies of the Middle Ages migrated from town to town with the strolling minstrels, as readily as did the cycles of heroic poetry. But with caricature the case was very different. It may be that the man of the Stone Age, whom Mr. Opper has lately utilized so cleverly in a series of caricatures, (p. 2) was the first to draw rude and distorted likenesses of some unpopular chieftain, just as the Roman soldier of 79 A. D. scratched on the wall of his barracks in Pompeii an unflattering portrait of some martinet centurion which the ashes of Vesuvius have preserved until to-day. It is certain that the Greeks and Romans appreciated the power of ridicule latent in satiric pictures; but until the era of the printing press, the caricaturist was as one crying in a wilderness. And it is only with the modern co-operation of printing and photography that caricature has come into its full inheritance. The best and most telling cartoons are those which do not merely reflect current public opinion, but guide it. In looking back over a century of caricature, we are apt to overlook this distinction. A cartoon which cleverly illustrates some important historical event, and throws light upon the contemporary attitude of the public, is equally interesting to-day, whether it anticipated the event or was published a month afterward. But in order to influence public opinion, caricature must contain a certain element of prophecy. It must suggest a danger or point an interrogation. As an example, we may compare two famous cartoons by the English artist Gillray, "A Connoisseur Examining a Cooper" and the "King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver." In the latter, George III., in the guise of a giant, is curiously examining through his magnifying glass a Lilliputian Napoleon. There is no element of prophecy about the cartoon. It simply reflects the contemptuous attitude of the time toward Napoleon, and underestimates the danger. The other cartoon, which appeared several years earlier, shows the King anxiously examining the features of Cooper's well-known miniature of Cromwell, the great overthrower of kings. Public sentiment at that time suggested the imminence of another revolution, (p. 4) and the cartoon suggests a momentous question: "Will the fate of Charles I. be repeated?" In the light of history, the Gulliver cartoon is to-day undoubtedly the more interesting, but at the time of its appearance it could not have produced anything approaching the sensation of that of "a Connoisseur."

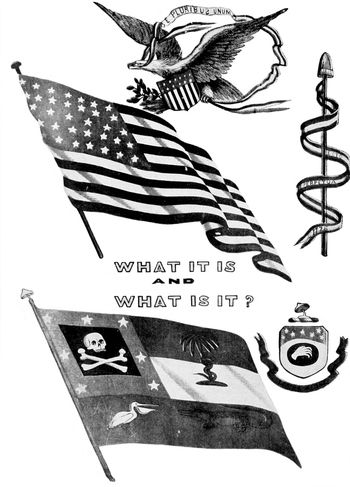

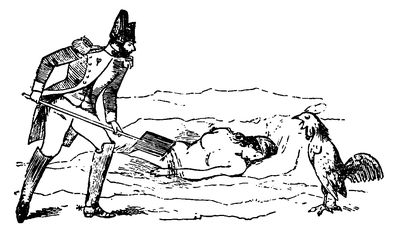

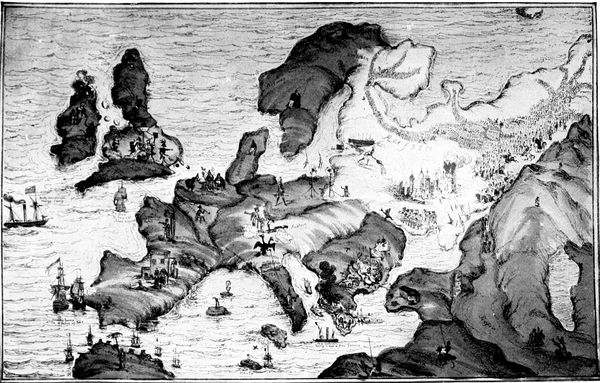

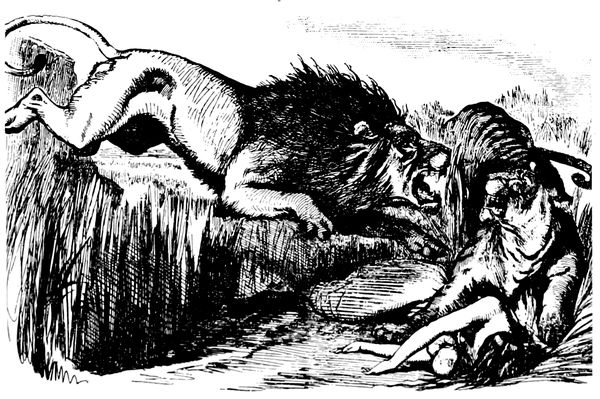

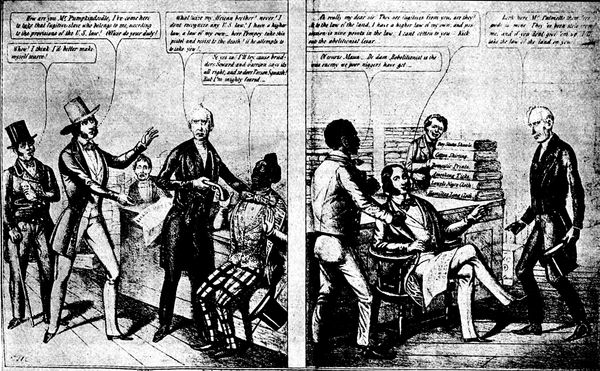

Gillray's Conception of the French Invasion of England.

The necessity of getting a caricature swiftly before the public has always been felt, and has given rise to some curious devices and makeshifts. In the example which we have noted as having come down from Roman times, a patriotic citizen of Pompeii could find no better medium for giving his cartoon of an important local event to the world than by scratching it upon the wall of his dwelling-house after the fashion of the modern advertisement. There was a time in the seventeenth century when packs of political playing-cards enjoyed an extended vogue. The fashion of printing cartoons upon ladies' fans and other articles of similarly intimate character was a transitory fad in England a century ago. Mr. Ackermann, a famous printer of his generation, and publisher of the greater part of Rowlandson's cartoons, adopted as an expedient for spreading political news a small balloon with an attached mechanism, which, when liberated, would drop news bulletins at intervals as it passed over field and village. In this country many people of the older generation will still remember the widespread popularity of the patriotic caricature-envelopes that were circulated during the Civil War. To-day we are so used to the daily newspaper cartoon that we do not stop to think how seriously handicapped the cartoonists of a century ago found themselves. The more important cartoons of Gillray and Rowlandson appeared either in monthly periodicals, such as the Westminster Magazine and the Oxford Magazine, or in separate sheets that sold at the prohibitive (p. 6) price of several shillings. In times of great public excitement, as during the later years of the Napoleonic wars, such cartoons were bought up greedily, the City vying with the aristocratic West End in their patriotic demand for them. But such times were exceptional, and the older caricaturists were obliged to let pass many interesting crises because the situations would have become already stale before the day of publication of the monthly magazines came round. With the advent of the illustrated weeklies the situation was improved, but it is only in recent times that the ideal condition has been reached, when the cabled news of yesterday is interpreted in the cartoon of to-day.

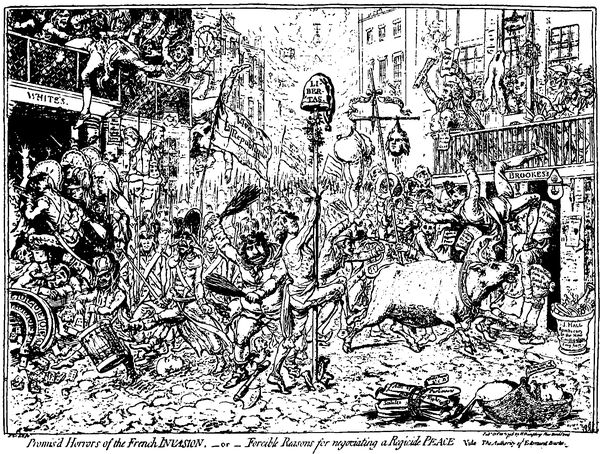

Nelson at the Battle of the Nile.

There is another and less specific reason why caricature had to await the advent of printing and the wider dissemination of knowledge which resulted. The successful political (p. 7) cartoon presupposes a certain average degree of intelligence in a nation, an awakened civic conscience, a sense of responsibility for the nation's welfare. The cleverest cartoonist would waste his time appealing to a nation of feudal vassals; he could not expect to influence a people to whom the ballot box was closed. Caricature flourishes best in an atmosphere of democracy; there is an eternal incompatibility between its audacious irreverence and the doctrine of the divine right of kings.

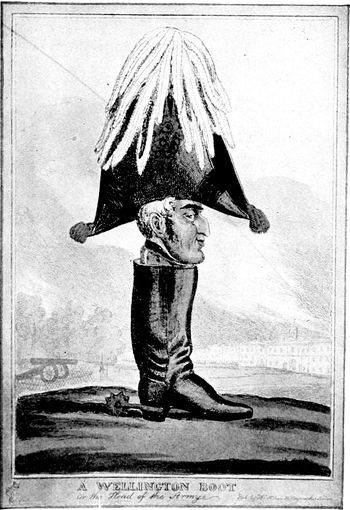

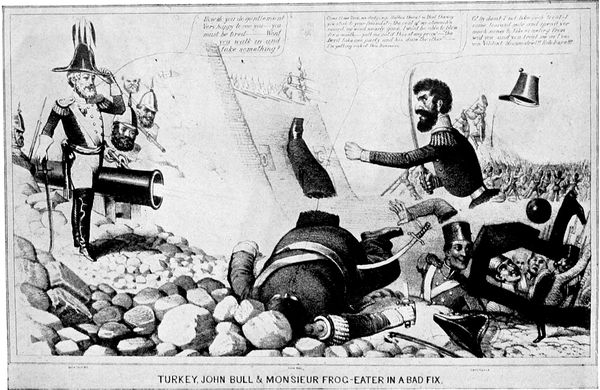

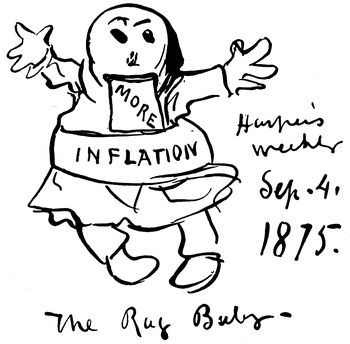

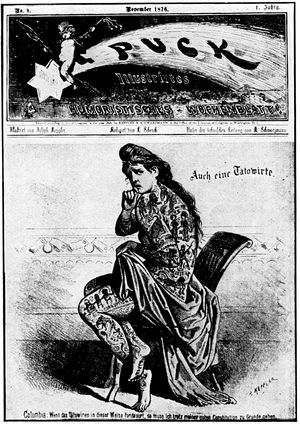

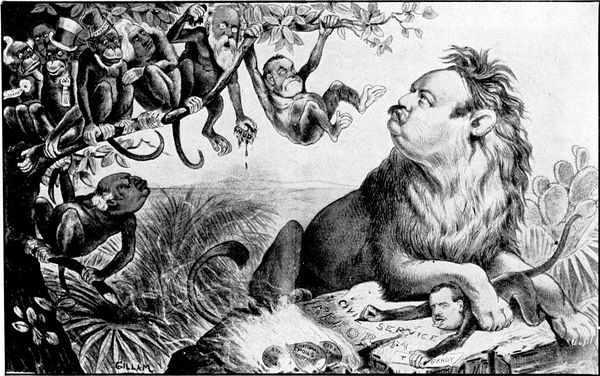

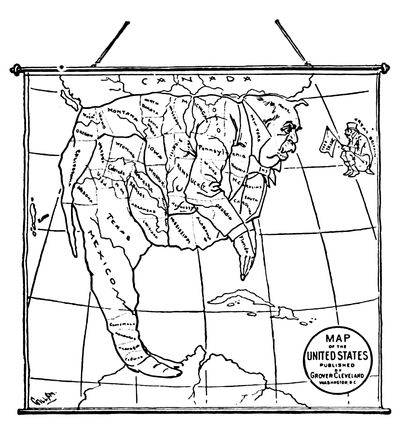

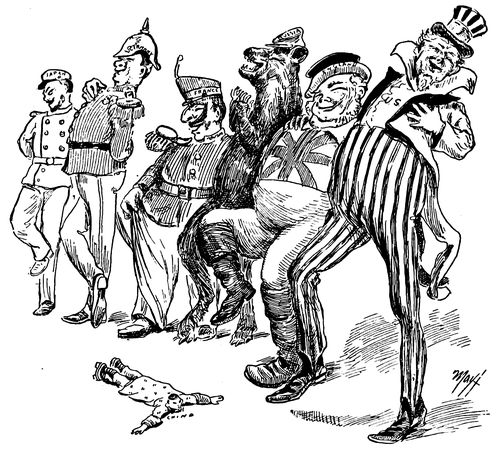

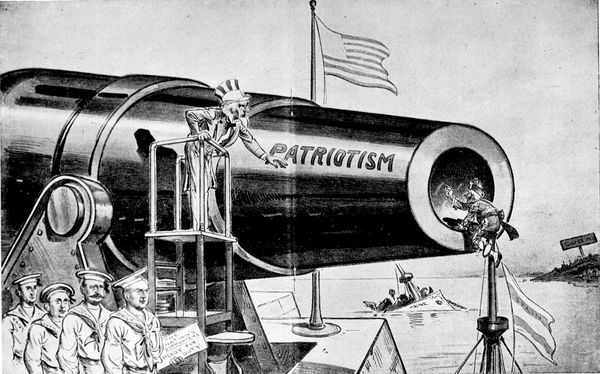

And yet the best type of caricature should not require a high degree of intelligence. Many clever cartoonists over-reach themselves by an excess of cleverness, appealing at best to a limited audience. Of this type are the cartoons whose point lies in parodying some famous painting or a masterpiece of literature, which, as a result, necessarily remains caviare to the general. There is a type of portrait caricature so cultured and subtle that it often produces likenesses truer to the man we know in real life than a photograph would be. A good example of this type is the familiar work of William Nicholson, whose portrait of the late Queen of England is said to have been recognized by her as one of the most characteristic pictures she had ever had taken. What appeals to the public, however, is a coarser type, a gross exaggeration of prominent features, a willful distortion, resulting in ridicule or glorification. Oftentimes the caricature degenerates into a mere symbol. We have outgrown the puerility of the pictorial pun which flourished in England at the close of the seventeenth century, when cartoonists of Gillray's rank were content to represent Lord Bute as a pair of boots, Lord North as Boreas, the north wind, and the elder Fox with the head and tail of the animal suggested by his name. Yet personification of one kind and another, and notably the personification (p. 9) of the nations in the shape of John Bull and Uncle Sam and the Russian Bear, forms the very alphabet of political caricature of the present day. Some of the most memorable series that have ever appeared were founded upon a chance resemblance of the subject of them to some natural object. Notable instances are Daumier's famous series of Louis Philippe represented as a pear, and Nast's equally clever, but more local, caricatures of Tweed as a money-bag. It would be interesting, if the material were accessible, to trace the development of the different personifications of England, France, and Russia, and the rest, from their first appearance in caricature, but unfortunately their earlier development cannot be fully traced. The underlying idea of representing the different nations as individuals, and depicting the great international crises in a series of allegories or parables or animal stories—a sort of pictorial Æsop's fables—dates back to the very beginning of caricature. In one of the earliest cartoons that have been preserved, England, France, and a number of minor principalities which have since disappeared from the map of Europe, are represented as playing a game of cards with some disputed island possessions as the stakes. In this case the several nations are indicated merely by heraldic emblems. The conception of John Bull was not to be evolved until a couple of centuries later. This cartoon, like the others of that time, originated in France under Louis XII. The further development of the art was decisively checked under the despotic reign of Louis XIV., and the few caricaturists of that time who had the courage to use their pencil against the king were driven to the expedient of publishing their works in Holland.

An impressive illustration of the advantage which the (p. 10) satirical poet has over the cartoonist lies in the fact that some of the cleverest political satire ever written, as well as the best examples of the application of the animal fable to politics, were produced in France at this very time in the fables of La Fontaine.

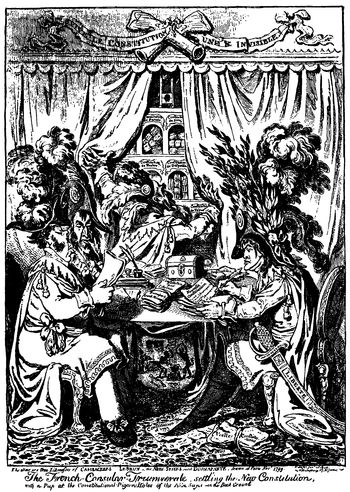

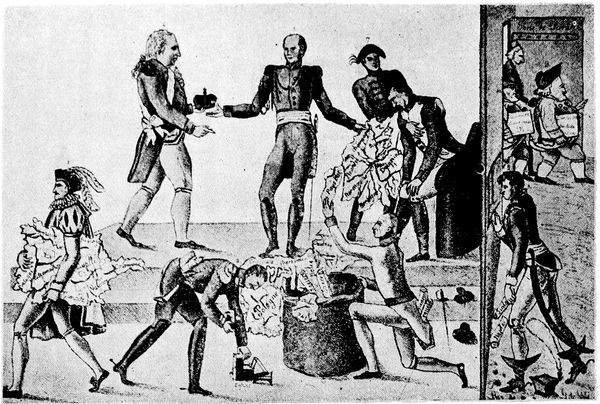

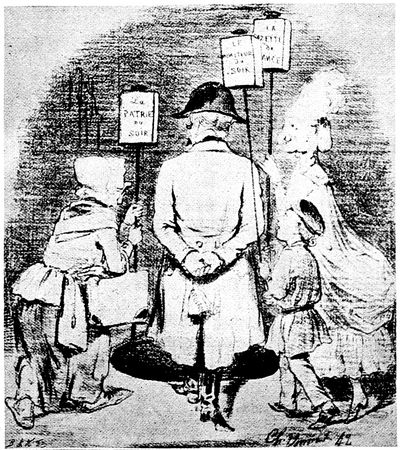

The French Consular Triumvirate.

From Holland caricature migrated to Great Britain in the closing years of the seventeenth century—a natural result of the attention which Dutch cartoonists had bestowed upon the revolution of 1688—and there it found a fertile and congenial soil. The English had not had time to forget that they had once put the divine right of kings to the test of the executioner's block, and what little reverence still survived was not likely to afford protection for a race of imported monarchs. Moreover, as it happened, the development of English caricature was destined to be guided by the giant genius of two men, Hogarth and Gillray; and however far apart these two men were in their moral and artistic standards, they had one thing in common, a perennial scorn for the House of Hanover. Hogarth's contemptuous satire of George II. was more than echoed in Gillray's merciless attacks upon George III. The well-known cartoons of "Farmer George," and "George the Button-Maker," were but two of the countless ways in which he avenged himself upon the dull-witted king who had once acknowledged that he could not see the point of Gillray's caricatures.

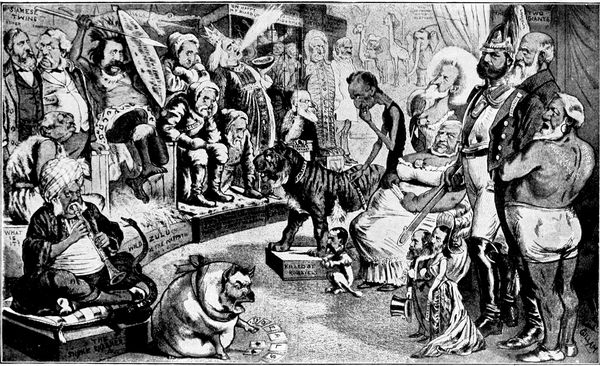

Although Hogarth antedates the period covered by the present articles by fully half a century, he is much too commanding a figure in the history of comic art to be summarily dismissed. The year 1720 marks the era of the so-called "bubble mania," the era of unprecedented inflation, of the (p. 13) South Sea Company in London, and the equally notorious Mississippi schemes of John Law in France. Popular excitement found vent in a veritable deluge of cartoons, many of which originated in Amsterdam and were reprinted in London, often with the addition of explanatory satiric verses in English. In one, Fortune is represented riding in a car driven by Folly, and drawn by personifications of the different companies responsible for the disastrous epidemic of speculation: the Mississippi, limping along on a wooden leg; the South Sea, with its foot in splints, etc. In another, we have an imaginary map of the Southern seas, representing "the very famous island of Madhead, situated in Share Sea, and inhabited by all kinds of people, to which is given the general name of Shareholders." John Law came in for a major share of the caricaturist's attention. In one picture he is represented as assisting Atlas to bear up immense globes of wind; in another, he is a "wind-monopolist," declaring, "The wind is my treasure, cushion, and foundation. Master of the wind, I am master of life, and my wind monopoly becomes straightway the object of idolatry." The windy character of the share-business is the dominant note in the cartoons of the period. Bubbles, windmills, flying kites, play a prominent part in the detail with which the background of the typical Dutch caricature was always crowded. These cartoons, displayed conspicuously in London shop windows, were not only seen by Hogarth, but influenced him vitally. His earliest known essay in political caricature is an adaptation of one of these Dutch prints, representing the wheel of Fortune, bearing the luckless and infatuated speculators high aloft. His latest work still shows the influence of Holland in the endless wealth of minute detail, the painstaking elaboration of his backgrounds, in which the most patient (p. 15) examination is ever finding something new. With Hogarth, the overcharged method of the Dutch school became a medium for irrepressible genius. At the hands of his followers and imitators, it became a source of obscurity and confusion.

"The Capture of the Danish Ships."

While Hogarth is rightly recognized as the father of English caricature, it must be remembered that his best work was done on the social rather than on the political side. Even his most famous political series, that of "The Elections," is broadly generalized. It is not in any sense campaign literature, but an exposition of contemporary manners. And this was always Hogarth's aim. He was by instinct a realist, endowed with a keen sense of humor—a quality in which many a modern realist is deficient. He satirized life as he saw it, the good and the bad together, with a frankness which at times was somewhat brutal, like the frankness of Fielding and of Smollett the frankness of the age they lived in. It was essentially an outspoken age, robust and rather gross; a red-blooded age, nurtured on English beef and beer; a jovial age that shook its sides over many a broad jest, and saw no shame in open allusion to the obvious and elemental facts of physical life. Judged by the standards of his day, there is little offense in Hogarth's work; even when measured by our own, he is not deliberately licentious. On the contrary, he set an example of moderation which his successors would have done well to imitate. He realized, as the later caricaturists of his century did not, that the great strength of pictorial satire lies in ridicule rather than in invective; that the subtlest irony often lies in a close adherence to truth, where riotous and unrestrained exaggeration defeats its own end. Just as in the case of "Joseph Andrews," Fielding's creative instinct got the upper hand of the parodist, so in much of (p. 17) Hogarth's work one feels that the caricaturist is forced to yield place to the realistic artist, the student of human life, carried away by the interest of the story he has to tell. His chief gift to caricature is his unprecedented development of the narrative quality in pictorial art. He pointed a road along which his imitators could follow him only at a distance.

"Bonaparte and his English Friends—The Broad Bottom Administration."

With the second half of the eighteenth century there began an era of great license in the political press, an era of bitter vituperation and vile personal abuse. Hogarth was one of the chief sufferers. After holding aloof from partisan politics for nearly half a century, he published, in 1762, his well-known cartoon attacking the ex-minister, Pitt. All Europe is represented in flames, which are spreading to Great Britain in spite of the efforts of Lord Bute, aided by his Highlanders, to extinguish them. Pitt is blowing upon the flames, which are being fed by the Duke of Newcastle from a barrow full of Monitors and North Britons, two scurrilous papers of the day. The bitterness with which Hogarth was attacked in retaliation and the persistence of his persecutors resulted, as was generally believed at the time, in a broken heart and his death in 1764.

An amazing increase in the number of caricatures followed the entry of Lord Bute's ministry into power. They were distinguished chiefly by their poor execution and gross indecency. As early as 1762, the Gentleman's Magazine, itself none too immaculate, complains that "Many of the representations that have lately appeared in the shops are not only reproachful to the government, but offensive to common-sense; they discover a tendency to inflame, without a spark of fire to light their own combustion." The state of society in England was at this time notoriously immoral and licentious. It was a period of hard living and hard drinking. (p. 18) The well-known habits of such public figures as Sheridan and Fox are eminent examples. The spirit of gambling had become a mania, and women had caught the contagion as well as men. Nowhere was the profligacy of the times more clearly shown than in the looseness of public social functions, such as the notorious masquerade balls, which a contemporary journal, the Westminster Magazine, seriously decried as "subversive of virtue and every noble and domestic point of honor." The low standards of morals and want of delicacy are revealed in the extravagance of women's dress, the looseness of their speech. It was an age when women of rank, such as Lady Buckingham and Lady Archer, were publicly threatened by an eminent judge with exposure on the pillory for having systematically enticed young men and robbed them at their faro tables, and afterward found themselves exposed in the pillory of popular opinion in scurrilous cartoons from shop windows all over London.

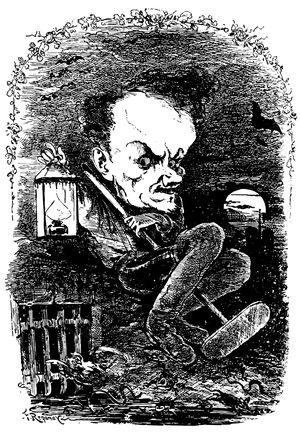

At a time when cheap abuse took the place of technical skill, and vulgarity passed for wit, a man of unlimited audacity, who was also a consummate master of his pencil, easily took precedence. Such a man was James Gillray, unquestionably the leading cartoonist of the reign of George III. Yet of the many who are to-day familiar with the name of Gillray and the important part he played in influencing public opinion during the struggle with Napoleon, very few have an understanding of the dominant qualities of his work. A large part of it, and probably the most representative part, is characterized by a foulness and an obscenity which the present generation cannot countenance. There is a whole series of cartoons bearing his name which it would not only be absolutely out of the question to reproduce, but the very nature of which can be indicated only in the most guarded manner. Imagine the works of Rabelais shamelessly illustrated by a master hand! Try to conceive of the nature of the pictures which Panurge chalked up on the walls of old Paris. It was not merely the fault of the times, as in the case of Hogarth. Public taste was sufficiently depraved already; but Gillray deliberately prostituted his genius to the level of a procurer, to debauch it further. From first to last his drawings impress one as emanating from a mind not only unclean, but unbalanced as well—a mind over which there hung, even at the beginning, the furtive shadow of that madness which at last overtook (p. 22) and blighted him. There is but one of the hallmarks of great caricature in the work of Gillray, and that is the lasting impression which they make. They refuse to be forgotten; they remain imprinted on the brain, like the obsession of a nightmare. While in one sense they stand as a pitiless indictment of the generation that tolerated them, they are not a reflection of the life that Gillray saw, except in the sense that their physical deformity symbolizes the moral foulness of the age. Grace and charm and physical beauty, which Hogarth could use effectively, are unknown quantities to Gillray. There is an element of monstrosity about all his figures, distorted and repellent. Foul, bloated faces; twisted, swollen limbs; unshapely figures whose protuberant flesh suggests a tumefied and fungoid growth—such is the brood begotten by Gillray's pencil, like the malignant spawn of some forgotten circle of the lower inferno.

It would be idle to dispute the far-reaching power of Gillray's genius, perverted though it was. Throughout the Napoleonic wars, caricature and the name of Gillray are convertible terms; for, even after he was forced to lay down his pencil, his brilliant contemporaries and successors, Rowlandson and Cruikshank, found themselves unable to throw off the fetters of his influence. No history of Napoleon is quite complete which fails to recognize Gillray as a potent factor in crystallizing public opinion in England. His long series of cartoons aimed at "little Boney" are the culminating work of his life. Their power lay, not in intellectual subtlety or brilliant scintillation of wit, but in the bitterness of their invective, the appeal they make to elemental passions. They spoke a language which the roughest of London mobs could understand—the language of the gutter. They were, many of them, masterpieces of pictorial Billingsgate.

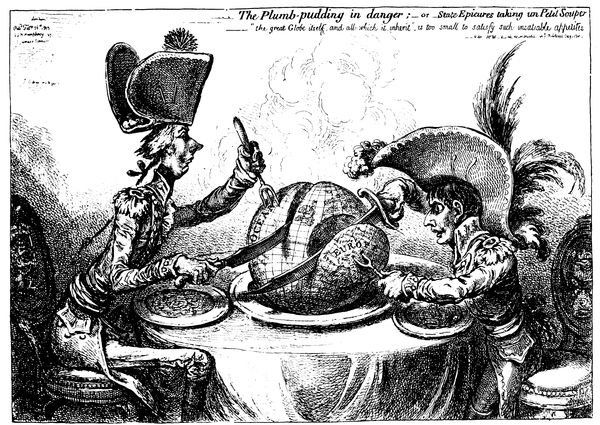

"Napoleon and Pitt dividing the World between Them."

(p. 24) There is rancor, there is venom, there is the inevitable inheritance of the warfare of centuries, in these caricatures of Gillray, but above all there is fear—fear of Napoleon, of his genius, of his star. It has been very easy for Englishmen of later days to say that the French never could have crossed the Channel, that there was never any reason for disquiet; it was another matter in the days when troops were actually massing by thousands on the hills behind Boulogne. You can find this fear voiced everywhere in Gillray, in the discordance between the drawings and the text. John Bull is the ox, Bonaparte the contemptible frog; but it is usually the ox who is bellowing out defiance, daring the other to "come on," flinging down insult at the diminutive foe. "Let 'em come, damme!" shouts the bold Briton in the pictures of the time. "Damme! where are the French bugaboos? Single-handed I'll beat forty of 'em, damme!" Every means was used to rouse the spirit of the English nation, and to stimulate hatred of the French and their leader. In one picture, Boney and his family are in rags, and are gnawing raw bones in a rude Corsican hut; in another we find him with a hookah and turban, having adopted the Mahometan religion; in a third we see him murdering the sick at Joppa. In the caricatures of Gillray, Napoleon is always a monster, a fiend in human shape, craven and murderous; but when dealing with the question of this fiend's power for evil, Gillray made no attempt at consistency. This ogre, who through one series of pictures was represented as kicked about from boot to boot, kicked by the Spaniards, the Turks, the Austrians, the Prussians, the Russians, in another is depicted as being very dangerous indeed. A curious example of this inconsistency will be found in placing side by side the two cartoons considered by many to be Gillray's best: "The King of Brobdingnag (p. 26) and Gulliver," already referred to, and "Tiddy-Doll, the great French gingerbread Maker, Drawing out a new Batch of Kings." The "pernicious, little, odious reptile" whom George the Third is holding so contemptuously in the hollow of his hand, in the first caricature, is in the second concededly of European importance.

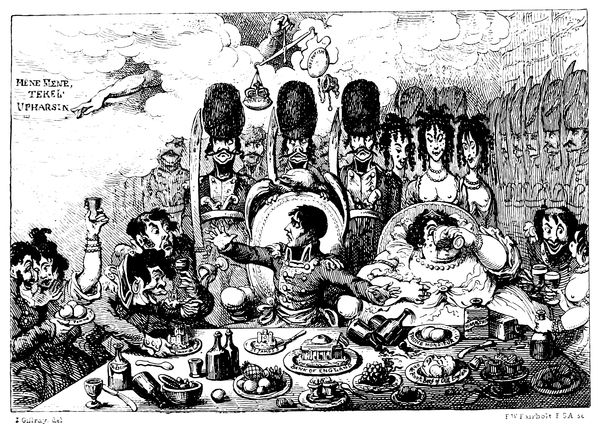

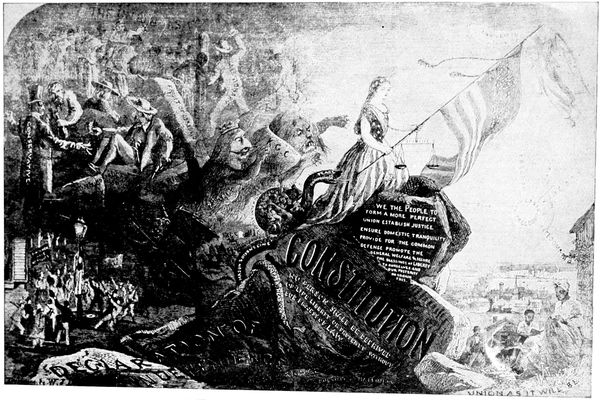

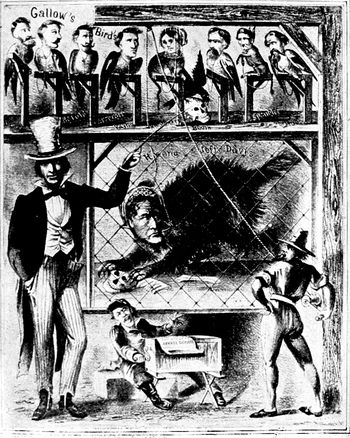

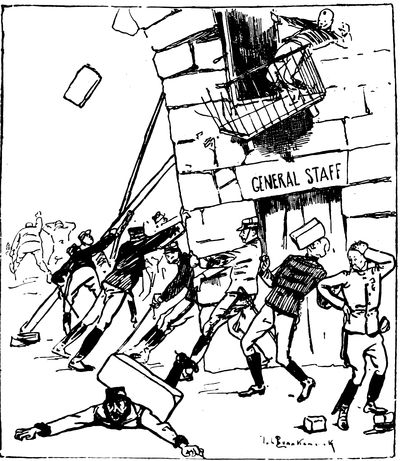

"The Handwriting on the Wall."

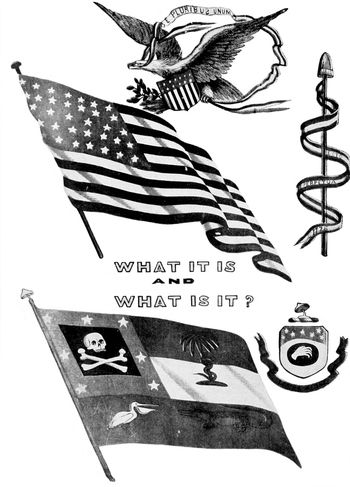

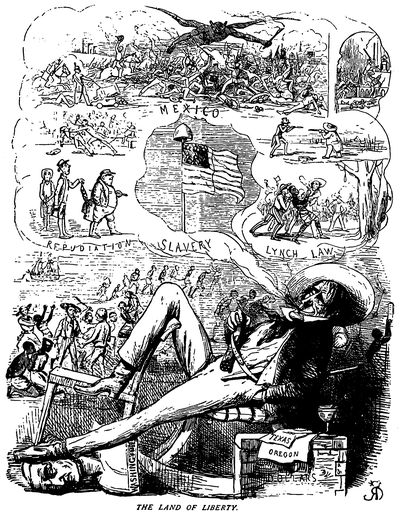

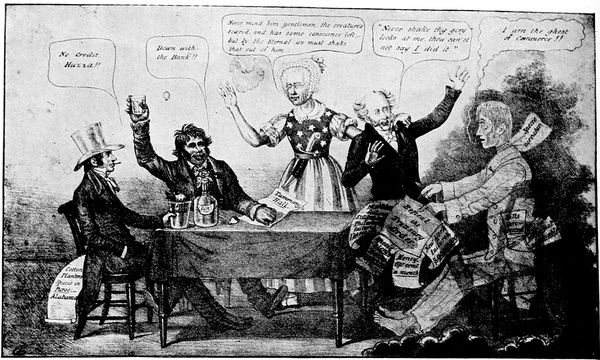

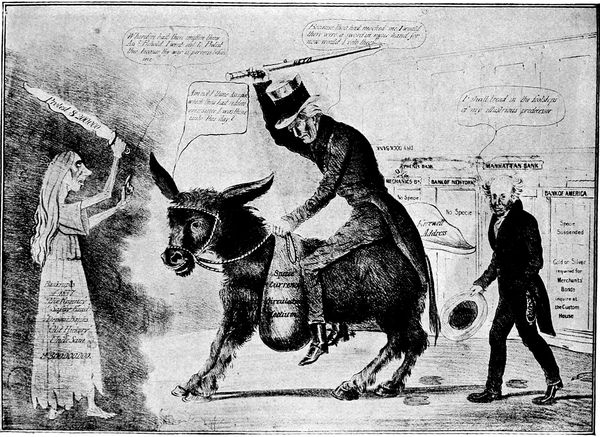

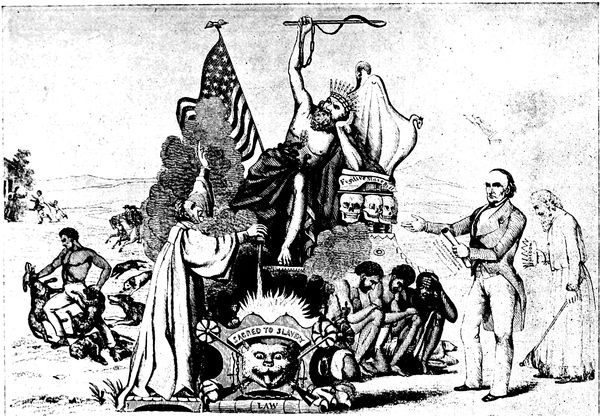

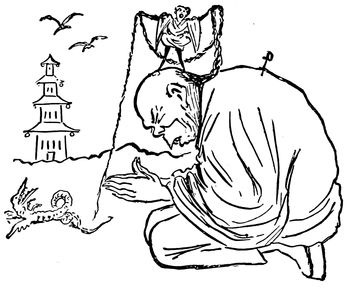

For the first decade of the nineteenth century there was but one important source of caricature, and one all-important subject—England and Bonaparte. America at this time counted for little in international politics. The revolutionary period closed definitely with the death of Washington, the one figure in our national politics who stood for something definite in the eyes of Europe. Our incipient naval war with France, which for a moment threatened to assign us a part in the general struggle of the Powers, was amicably concluded before the close of the eighteenth century. Throughout the Jeffersonian period, national and local satire and burlesque flourished, atoning in quantity for what it lacked in wit and artistic skill. Mr. Parton, in his "Caricature and Other Comic Art," finds but one cartoon which he thinks it worth while to cite—Jefferson kneeling before a pillar labeled "Altar of Gallic Despotism," upon which are Paine's "Age of Reason," and the works of Rousseau, Voltaire, and Helvetius, with the demon of the French Revolution crouching behind it, and the American Eagle soaring to the sky bearing away the Constitution and the independence of the United States, and he adds: "Pictures of that nature, of great size, crowded with objects, emblems, and sentences—an elaborate blending of burlesque, allegory, and enigma—were so much valued by that generation that some of them were engraved upon copper."

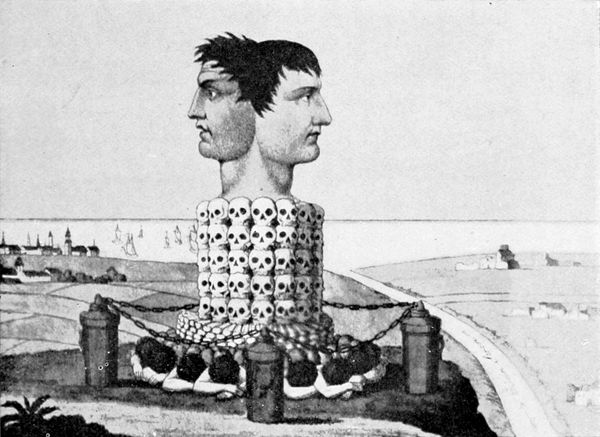

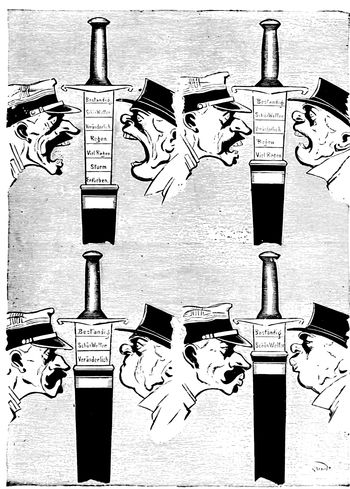

"The Double-Faced Napoleon."

From the collection of John Leonard Dudley, Jr.

France, on the contrary, the central stage of the great (p. 29) drama of nations, might at this time have produced a school of caricaturists worthy of their opportunity—a school that would have offset with its Gallic wit the heavier school of British invective, and might have furnished Napoleon with a strong weapon against his most persistent enemies, had he not, with questionable wisdom, sternly repressed pictorial satire of a political nature. As the century opens, the drama of the ensuing fourteen years becomes clearly defined; the prologue has been played; Napoleon's ambition in the East has been checked, first by the Battle of the Nile, and then definitely at Aboukir. Henceforth he is to limit his schemes of conquest to Europe, and John Bull is the only national figure who seems likely to attempt to check him. The Battle of the Nile was commemorated by Gillray, who depicted (p. 30) Nelson's victory in a cartoon entitled "Extirpation of the Plagues of Egypt, Destruction of the Revolutionary Crocodiles, or the British Hero Cleansing the Mouth of the Nile." Here Nelson is shown dispersing the French fleet treated as crocodiles. He has destroyed numbers with his cudgel of British oak; he is beating down others; a whole bevy, with hooks through their noses, are attached by strings to the iron hook which replaced his lost forearm. In the distance a crocodile is bursting and casting fire and ruin on all sides. This is an allusion to the destruction of the Orient, the flagship of the Republican Admiral, the heroic Brueys, who declined to quit his post when literally cut to pieces.

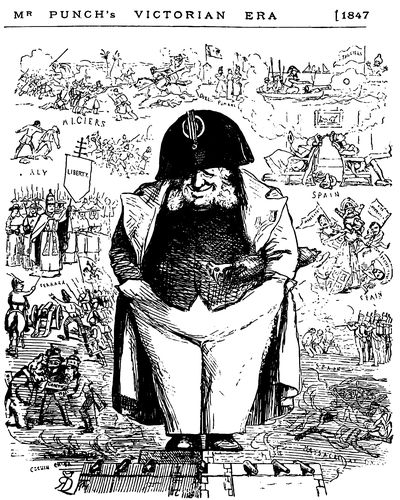

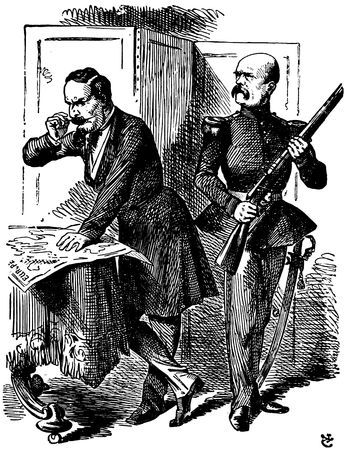

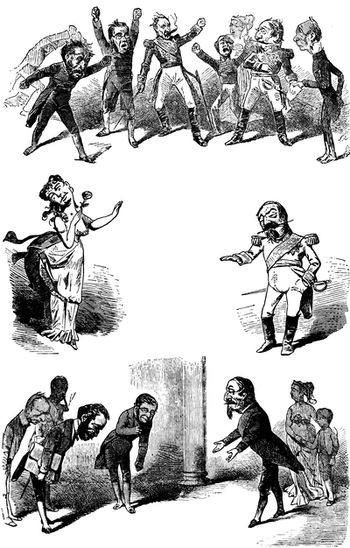

Another cartoon by Gillray which belongs to this period is "The French Consular Triumvirate Settling the New Constitution." It introduces the figures of Napoleon and his fellow-consuls, Cambacérès and Lebrun, who replaced the very authors of the new instrument, Sièyes and Ducos, quietly deposed by Napoleon within the year. The second and third consuls are provided with blank sheets of paper, for mere form—they have only to bite their pens. The Corsican is compiling a constitution in accordance with his own views. A band of imps is beneath the table, forging new chains for France and for Europe.

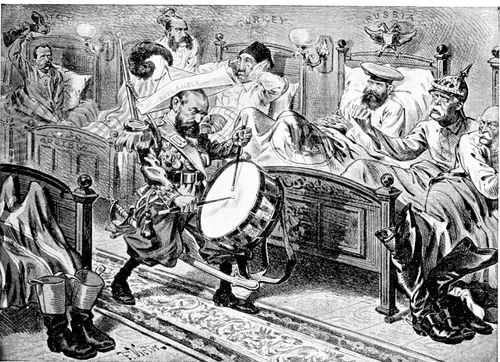

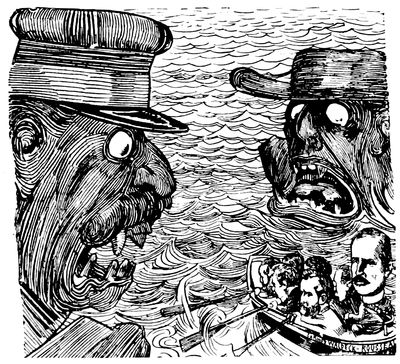

"The Two Kings of Terror."

After a cartoon by Rowlandson

In England, the Addington ministry, which in 1801 replaced that of William Pitt, and are represented in caricature as "Lilliputian substitutes" lost in the depths of Mr. Pitt's jack-boots, set out as a peace ministry and entered into the negotiations with Napoleon which, in the following March, resulted in the Peace of Amiens. Gillray anticipated this peace with several alarmist cartoons: "Preliminaries of Peace," representing John Bull being led by the nose across the channel over a rotten plank, while Britannia's shield and (p. 31) several valuable possessions have been cast aside into the water; and "Britannia's Death Warrant," in which Britannia is seen being dragged away to the guillotine by the Corsican marauder. The peace at first gave genuine satisfaction in England, but toward the end of 1802 there were growing signs of popular discontent, which Gillray voiced in "The Nursery, with Britannia Reposing in Peace." Britannia is here portrayed as an overgrown baby in her cradle and fed upon French principles by Addington, Lord Hawkesbury, and Fox. Still more famous was his next cartoon, "The First Kiss this Ten Years; or, the Meeting of Britannia and Citizen Francois." Britannia, grown enormously stout, her shield and spear idly reposing against the wall, is blushing deeply at his warm embrace and ardent expressions of joy: "Madame, permit me to pay my profound esteem to your engaging person, and to seal on your divine lips my everlasting attachment!!!" She replies: "Monsieur, you are truly a well-bred gentleman; and though you make me blush, (p. 32) yet you kiss so delicately that I cannot refuse you, though I was sure you would deceive me again." In the background the portraits of King George and Bonaparte scowl fiercely at each other upon the wall. This is said to be one of the very few caricatures which Napoleon himself heartily enjoyed.

From now on, the cartoons take on a more caustic tone. Britannia is being robbed of her cherished possessions, even Malta being on the point of being wrested from her; while the bugaboo of an invading army looms large upon the horizon. In one picture Britannia, unexpectedly attacked by Napoleon's fleet, is awakening from a trance of fancied peace, and praying that her "angels and ministers of disgrace defend her!" In another, John Bull, having waded across the water, is taunting little Boney, whose head just shows above the wall of his fortress:

If you mean to invade us, why make such a rout?

I say, little Boney, why don't you come out?

Yes, d—— you, why don't you come out?

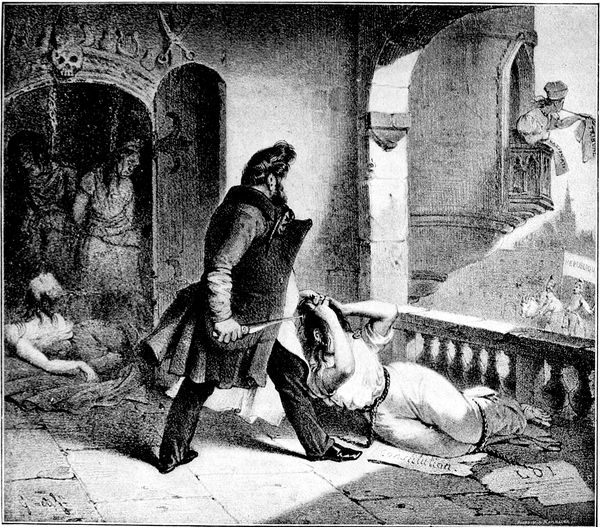

In his cartoon called "Promised Horrors of the French Invasion; or, Forcible Reasons for Negotiating a Regicide Peace," Gillray painted the imaginary landing of the French in England. The ferocious legions are pouring from St. James's Palace, which is in flames, and they are marching past the clubs. The practice of patronizing democracy in the countries they had conquered has been carried out by handing over the Tories, the constitution, and the crown to the Foxite reformers and the Whig party. The chief hostility of the French troops is directed against the aristocratic clubs. An indiscriminate massacre of the members of White's is proceeding in the doorways, on the balconies, and wherever the republican levies have penetrated. The royal princes are stabbed and thrown into the street. A rivulet of blood is (p. 34) running. In the center of the picture is a tree of liberty. To this tree Pitt is bound, while Fox is lashing him.

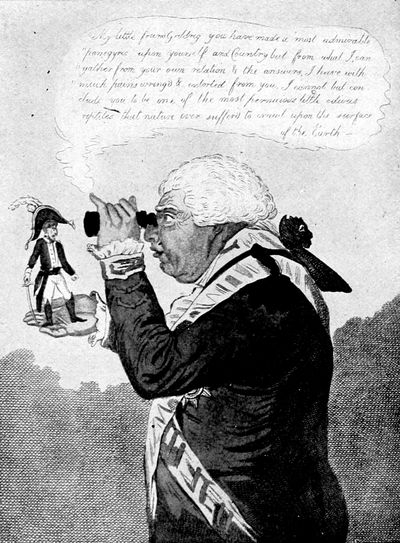

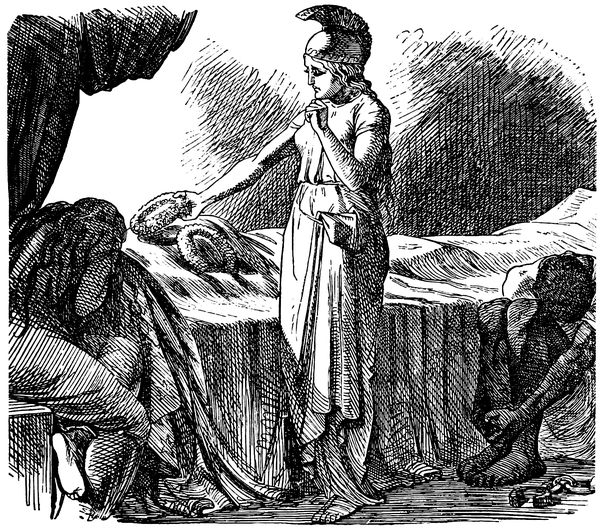

The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver.

"You may have seen Gillray's famous print of him—in the old wig, in the stout, old, hideous Windsor uniform—as the King of Brobdingnag, peering at a little Gulliver, whom he holds up in his hand, whilst in the other he has an opera-glass, through which he surveys the pygmy? Our fathers chose to set up George as the type of a great king; and the little Gulliver was the great Napoleon."—Thackeray's "Four Georges".

The increasing venom of the English cartoons, and their frequent coarse personalities, caused no little uneasiness to Bonaparte, until they culminated in a famous cartoon by Gillray, "The Handwriting on the Wall," a broad satire on Belshazzar's feast, which was published August 24, 1803. The First Consul, his wife Josephine, and the members of the court are seated at table, consuming the good things of Old England. The palace of St. James, transfixed upon Napoleon's fork; the tower of London, which one of the convives is swallowing whole; the head of King George on a platter inscribed: "Oh, de beef of Old England!" A hand above holds out the scales of Justice, in which the legitimate crown of France weighs down the red cap with its attached chain—despotism misnamed liberty.

For the next year parliamentary strife at home, fostered by Pitt's quarrel with the Addington ministry on the one hand and his opposition to Fox on the other, kept the cartoonists busy. They found time, however, to celebrate the coronation of Napoleon as Emperor in December, 1804. Gillray anticipated the event with a cartoon entitled "The Genius of France Nursing her Darling," in which the genius, depicted as a lady with blood-stained garments and a reeking spear, tosses an infant Napoleon, armed with a scepter, and vainly tries to check his cries with a rattle surmounted by a crown.

Rowlandson, Gillray's clever and more artistic contemporary, commemorated the event itself in a clever cartoon, "The Death of Madame République," published December 14, 1804. The moribund République lies stretched upon her death-bed, her nightcap adorned with the tricolored cockade. The Abbé Sièyes, in the rôle of doctor, is exhibiting the Emperor, portrayed as a newborn infant in long clothes. John Bull, spectacles on nose, is regarding the altered conditions with visible astonishment. "Pray, Mr. Abbé Sièyes, what was the cause of the poor lady's death? She seemed at one time in a tolerable thriving way." "She died in childbed, Mr. Bull, after giving birth to this little Emperor!"

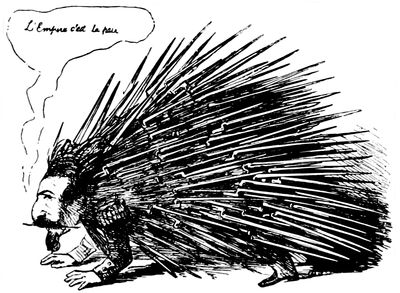

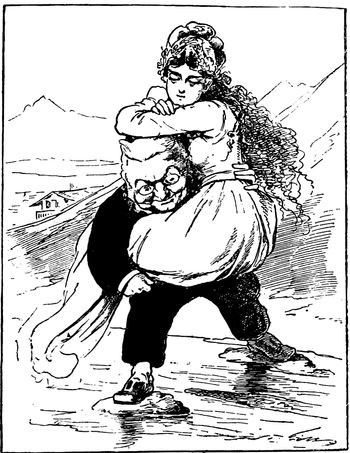

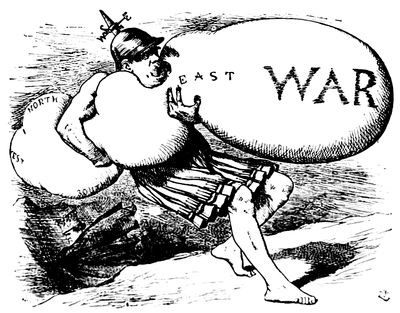

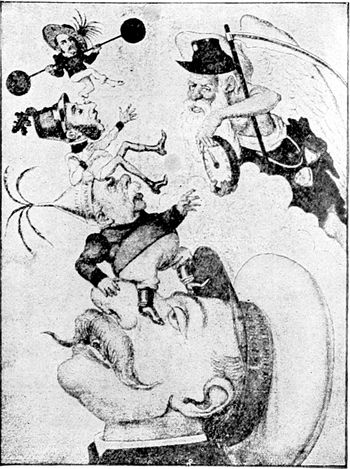

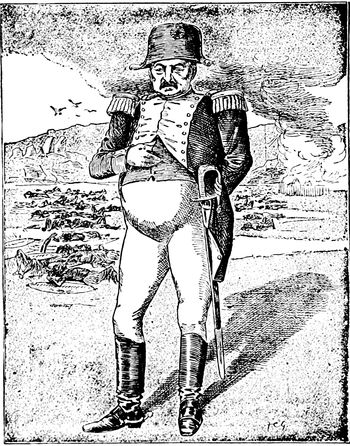

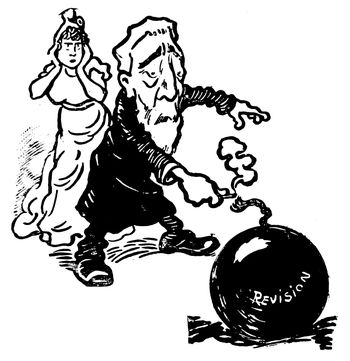

Napoleon's Burden.

From a German cartoon of the period.

This was followed on the 1st of January by a large satirical print by Gillray, of "The Grand Coronation Procession," (p. 36) in which the feature that gave special offense was the group of three princesses, the Princess Borghese, the Princess Louise, and the Princess Joseph Bonaparte, arrayed in garments of indecent scantiness, and heading the procession as the "three imperial Graces." The English caricatures of this period relating to the new Emperor and Empress are as a rule not only libelous, but grossly coarse. At the same time, the political conditions of the times are cleverly hit off in "The Plum Pudding in Danger; or, State Epicures Taking on Petit Souper," published February 26, 1805, which depicts the rival pretensions of Napoleon and Pitt. They are seated at opposite sides of the table, the only dish between them (p. 37) being the Globe, served up on a shallow plate and resembling a plum pudding. Napoleon's sword has sliced off the continent—France, Holland, Spain, Italy, Prussia—and his fork is dug spitefully into Hanover, which was then an appanage of the British crown. Pitt's trident is stuck in the ocean, and his carver is modestly dividing the Globe down the middle.

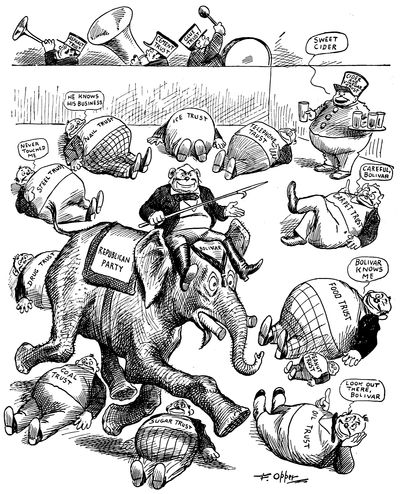

During the summer of 1805 the third coalition against France was completed, its chief factors being Great Britain, Russia, and Austria. A contemporary print entitled "Tom Thumb at Bay" commemorates the new armament. Napoleon, dropping crown and scepter in his flight, is evading the Austrian eagle, the Russian bear, and the Westphalian pig, only to run at last pell-mell into the gaping jaws of the British lion. It is somewhat curious that the momentous events of the new war—the annihilation of the French fleet at Trafalgar, the equally decisive French victory at Austerlitz—were scarcely noticed in caricature, and a few exceptions have little merit. But in the following January, 1806, when Napoleon had entered upon an epoch of king-making, with his kings of Wurtemburg and Bavaria, Gillray produced one of his most famous prints. It was published the 23d of January (the day that Pitt breathed his last), and was entitled "Tiddy-Doll, the Great French Gingerbread Baker, Drawing out a new Batch of Kings, His Man, 'Hopping Talley,' Mixing up the Dough." The great gilt gingerbread baker is shown at work at his new French oven for imperial gingerbread. He is just drawing from the oven's mouth a fresh batch of kings. The fuel is shown in the form of cannon-balls. Holland, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Venice and Spain are following the fate of the French Republic. On top of the chest of drawers, labeled respectively "kings and queens," "crowns and scepters," "suns and (p. 38) moons" is arranged a gay parcel of little dough viceroys intended for the next batch. Among them are the figures of Fox, Sheridan, Derby, and others of the Whig party in England.

The French Gingerbread Baker.

In the comprehensive and ill-assorted Coalition ministry which was formed soon after Pitt's death, the caricaturists found a congenial topic for their pencils. They ridiculed it unmercifully under the title "All the Talents," and the "Board Bottomed" ministry. A composite picture by Rowlandson shows the ministry as a spectacled ape in the wig of a learned justice, with episcopal mitre and Catholic crozier. He wears a lawyer's coat and ragged breeches, with a shoe on one foot and a French jack-boot on the other. He is dancing on a funeral pyre of papers, the results of the administration, its endless negotiations with France, its sinecures and patronages, which are blazing away. The creature's foot is discharging a gun, which produces signal mischief in the rear (p. 39) and brings down two heavy folios, the Magna Charta and the Coronation Oath, upon its head.

"The Devil and Napoleon."

From an anonymous French caricature.

This ministry's futile negotiations for peace with France are frequently burlesqued. Gillray published on April 5 "Pacific Overtures; or, a Flight from St. Cloud's 'over the water to Charley,'" in which the negotiations are described as "a new dramatic peace, now rehearsing." In this cartoon King George has left the state box—where the play-book of "I Know You All" still remains open—to approach nearer to little Boney, who, elevated on the clouds, is directing attention to his proposed treaty. "Terms of Peace: Acknowledge me as Emperor; dismantle your fleet, reduce your armies; abandon Malta and Gibraltar; renounce all continental connection; your colonies I will take at a valuation; engage to pay to the Great Nation for seven years annually one million pounds; and place in my hands as hostages the Princess Charlotte of Wales, with others of the late administration (p. 40) whom I shall name." King George replies: "Very amusing terms, indeed, and might do vastly well with some of the new-made little gingerbread kings; but we are not in the habit of giving up either ships or commerce or colonies merely because little Boney is in a pet to have them." This cartoon introduces among others Talleyrand, O'Conor, Fox, Lord Ellenborough, the Duke of Bedford, Lord Moira, Lord Lauderdale, Addington, Lord Henry Petty, Lord Derby, and Mrs. Fitzherbert.

Shortly afterward, on July 21, 1806, Rowlandson voices the current feeling of distrust of Fox in "Experiments at Dover; or, Master Charley's Magic Lantern." Fox is depicted at Dover, training the rays of his magic lantern on the cliffs of Calais. John Bull, watching him, is not satisfied. "Yes, yes, it be all very fine, if it be true; but I can't forget that d—d Omnium last week.... I will tell thee what, Charley, since thee hast become a great man, I think in my heart thee beest always conjuring."

The cartoon entitled "Westminster Conscripts under the Training Act" appeared September 1, 1806. Napoleon, the drill sergeant, is elevated on a pile of cannon-balls; he is giving his authoritative order to "Ground arms." The invalided Fox has been wheeled to the ground in his armchair; the Prince of Wales' plume appears on the back of his seat. Other figures in the cartoon are Lord Lauderdale, Lord Grenville, Lord Howick, Lord Holland, Lord Robert Spencer, Lord Ellenborough, the Duke of Clarence, Lord Moira, Lord Chancellor Erskine, Colonel Hanger, and Talleyrand.

Gillray has left a cartoon commemorating the arrival of the Danish squadron, under the title of "British Tars Towing the Danish Fleet into Harbor; the Broad Bottom (p. 43) Leviathan trying to swamp Billy's Old Boat; and the Little Corsican Tottering on the Clouds of Ambition." This cartoon was issued October 1, 1807. Lords Liverpool and Castlereagh are lustily rowing the Billy Pitt; Canning, seated in the stern, is towing the captured fleet into Sheerness, with the Union Jack flying over the forts. Copenhagen, smoking from the recent bombardment, may be distinguished in the distance. In Sheerness harbor the sign of "Good Old George" is hung out at John Bull's Tavern; John Bull is seated at the door, a pot of porter in his hand, waving his hat and shouting: "Rule Britannia! Britannia Rules the Waves!" That the expedition did not escape censure is shown by the figure of a three-headed porpoise which is savagely assailing the successful crew. This monster bears the heads of Lord Howick, shouting "Detraction!" Lord St. Vincent tilled with "Envy," and discharging a watery broadside; and Lord Grenville, who is raising his "Opposition Clamor" to confuse their course.

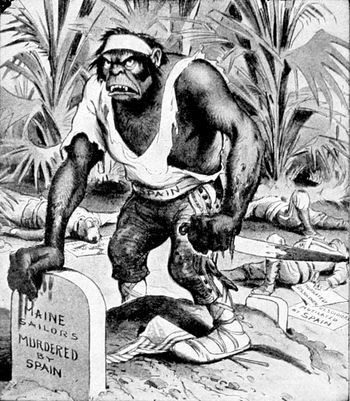

No period of the Napoleonic wars gave better opportunity for satire than Napoleon's disastrous occupation of Spain and his invasion of Portugal. The titles alone of the cartoons would fill a volume. The sanguine hopes of success cherished by the English government are expressed by Gillray in a print published April 10, 1808. "Delicious Dreams! Castles in the Air! Glorious Prospects!" It depicts the ministers sunken in a drunken sleep and visited by glorious visions of Britannia and her lion occupying a triumphal car formed from the hull of a British ship, drawn by an Irish bull and led by an English tar. She is dragging captive to the Tower little Boney and the Russian Bear, both loaded with chains.

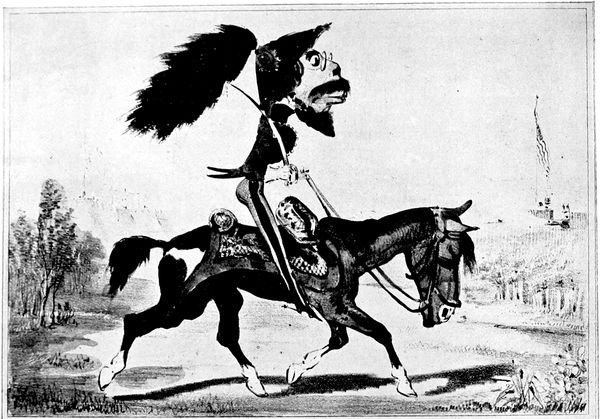

"The Corsican Top in Full Flight."

From a colored stamp of the period.

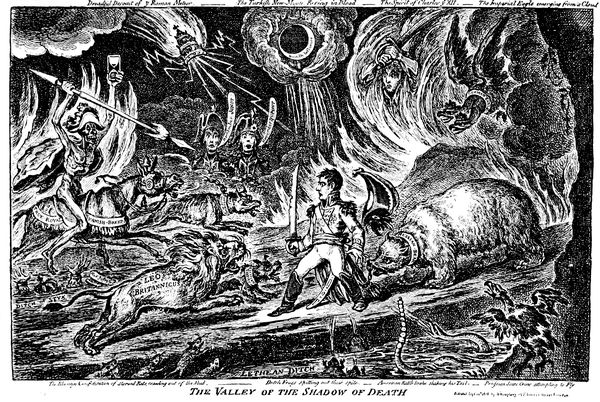

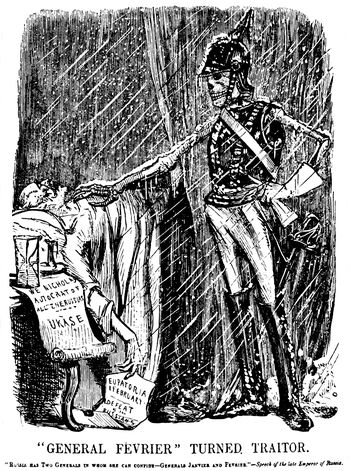

The dangers which threatened Napoleon at this period were shown by Gillray in one of the most striking of all his cartoons, the "Valley of the Shadow of Death," which was issued September 24, 1808. The valley is the valley of Bunyan's allegory. The Emperor is proceeding timorously down a treacherous path, bounded on either side by the waters of Styx and hemmed in by a circle of flame. From every side horrors are springing up to assail him. The British lion, raging and furious, is springing at his throat. The Portuguese wolf has broken his chain. King Death, mounted on a mule of "True Royal Spanish Breed," has cleared at a bound the body of the ex-King Joseph, which has been thrown into the "Ditch of Styx." Death is poising his spear with fatal (p. 46) aim, warningly holding up at the same time his hour-glass with the sand exhausted; flames follow in his course. From the smoke rise the figures of Junot and Dupont, the beaten generals. The papal tiara is descending as a "Roman meteor," charged with lightnings to blast the Corsican. The "Turkish New Moon" is seen rising in blood. The "Spirit of Charles XII." rises from the flames to avenge the wrongs of Sweden. The "Imperial German Eagle" is emerging from a cloud; the Prussian bird appears as a scarecrow, making desperate efforts to fly and screaming revenge. From the "Lethean Ditch" the "American Rattlesnake" is thrusting forth a poisoned tongue. The "Dutch Frogs" are spitting out their spite; and the Rhenish Confederation is personified as a herd of starved "Rats," ready to feast on the Corsican. The great "Russian Bear," the only ally Napoleon has secured, is shaking his chain and growling—a formidable enemy in the rear.

Gillray's caricature entitled "John Bull Taking a Luncheon; or, British Cooks Cramming Old Grumble-Gizzard with Bonne Chère," shows the strange-appearing John of the caricature of that day sitting at a table, overwhelmed by the zealous attentions of his cooks, foremost among whom is the hero of the Nile, who is offering him a "Fricassée à la Nelson," a large dish of battered French ships of the line. John is swallowing a frigate at a mouthful. Through the window we see Fox and Sheridan, representative of the Broad Bottom administration, running away in dismay at John Bull's voracity.

Napoleon in the Valley of the Shadow of Death.

From James Gillray's caricature.

As Gillray retires from the field several other clever artists stand ready to take his place, and chief among them Rowlandson. The latter had a distinct advantage over Gillray in his superior artistic training. He was educated in the French (p. 48) schools, where he gave especial attention to studies from the nude. In the opinion of such capable judges as Reynolds, West, and Lawrence, his gifts might have won him a high place among English artists, if he had not turned, through sheer perversity, to satire and burlesque. Rowlandson's Napoleonic cartoons began in July, 1808. These initial efforts are neither especially characteristic nor especially clever, but they certainly were duly appreciated by the public. Joseph Grego, in his interesting and comprehensive work upon Rowlandson, says of them:

The Spider's Web.

From a German caricature commemorating German success in 1814.

"It is certain that the caricaturist's travesties of the little Emperor, his burlesques of his great actions and grandiose declarations, his figurative displays of the mean origin of the (p. 49) imperial family, with the cowardice and depravity of its members, won popular applause ... And when disasters began to cloud the career of Napoleon, as army after army melted away, ... the artist bent his skill to interpret the delight of the public. The City competed with the West End in buying every caricature, in loyal contest to prove their national enmity for Bonaparte. In too many cases, the incentive was to gratify the hatred of the Corsican rather than any remarkable merit that could be discovered in the caricatures. Very few of these mock-heroic sallies imprint themselves upon (p. 50) the recollection by sheer force of their own brilliancy, as was the case with Gillray, and frequently with John Tenniel. Rowlandson and Cruikshank are risible, but not inspired."

On July 8 Rowlandson began his series with "The Corsican Tiger at Bay." Napoleon is depicted as a savage tiger, rending four "Royal Greyhounds," quite at his mercy. But a fresh pack appears in the background and prepares for a fierce charge. The Russian bear and Austrian eagle are securely bound with heavy fetters, but the eagle is asking: "Now, Brother Bruin, is it time to break our fetters?"

"The Chief of the Grand Army in a Sad Plight."

From a French cartoon of the period.

"The Beast as Described in the Revelations" followed within two weeks. The beast, of Corsican origin, is represented with seven heads, and the names of Austria, Naples, Holland, Denmark, Prussia, and Russia are inscribed on their respective crowns. Napoleon's head, severed from the trunk, vomits forth flames. In the distance, cities are blazing, showing the destruction wrought by the beast. Spain is represented as the champion who alone dares to stand against the monster.

"The Political Butcher" bears date September 12 of (p. 51) the same year. In this print the Spanish Don, in the garb of a butcher, is cutting up Bonaparte for the benefit of his neighbors. The body of the late Corsican lies before him and is being cut up with professional zeal. The Don holds up his enemy's heart and calls upon the other Powers to take their share. The double-headed eagle of Austria is swooping upon Napoleon's head: "I have long wished to strike my talons into that diabolical head-piece"; the British bulldog has been enjoying portions of the joints, and thinks that he would "like to have the picking of that head." The Russian bear is luxuriously licking Napoleon's boots, and remarks, "This licking is giving me a mortal inclination to pick a bone."

The final failure of the Spanish campaign is signalized, September 20, in a cartoon labeled "Napoleon the Little in a Rage with his Great French Eagle." The Emperor, with drawn sword and bristling with rage, threatens the French imperial eagle, larger than himself. The bird's head and one leg are tied up—the result of damage inflicted by the Spaniards. "Confusion and destruction!" thunders Napoleon, "what is this I see? Did I not command you not to return until you had spread your wing of victory over the whole of Spain?" "Aye, it's fine talking," rejoins the bird, "but if you had been there, you would not much have liked it. The Spanish cormorants pursued me in such a manner that they set me molting in a terrible way. I wonder that I have not lost my feathers. Besides, it got so hot I could not bear it any longer."

"The Signature Symbol of Abdication."

From a caricature in color by George Cruikshank.

In August, 1809, Rowlandson published "The Rising Sun." Bonaparte is surrounded by the Continental powers, and is busy rocking to sleep in a cradle the Russian bear, securely muzzled with French promises. But the dawn of a (p. 53) new era is breaking: the sun of Spain and Portugal is rising with threatening import. The Emperor is disturbed by the new light: "This rising sun has set me upon thorns." The Prussian eagle is trussed; Denmark is snuffed out. But Austria has once more taken heart: "Tyrant, I defy thee and thy cursed crew!"

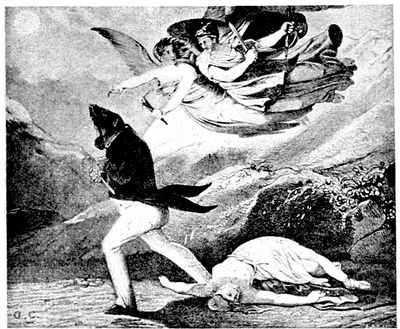

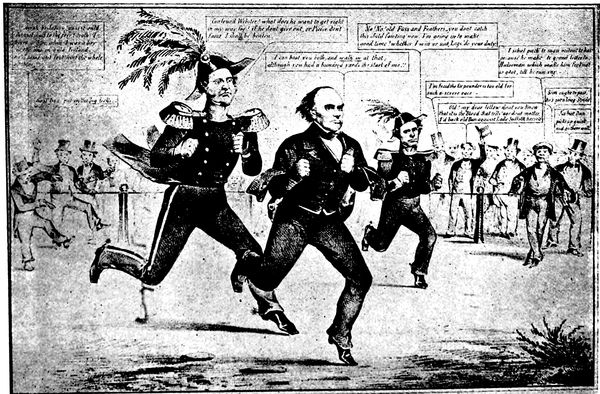

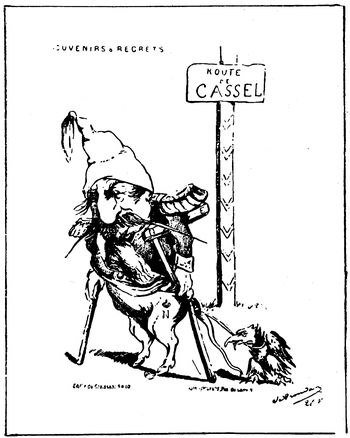

The victories of the Peninsular war, and later of the disastrous Russian campaign, called forth an ever-increasing number of cartoons, which showed little mercy or consideration to a fallen foe. A sample of the titles of this period show the general tendency; he is the "Corsican Bloodhound," the "Carcass-Butcher"; he is a jail-bird doing the "Rogues' March to the Island of Elba." An analysis of a few of the more striking cartoons will serve to close the survey of the Napoleonic period. "Death and Bonaparte" is a grewsome cartoon by Rowlandson, dated January 1, 1814. Napoleon is seated on a drum with his head clasped between his hands, staring into the face of a skeleton Death, who is watching the baffled general, face to face. Death mockingly parodies Napoleon's attitude. A broken eagle, the imperial standard, lies at his bony feet. In the background the Russian, Prussian, Austrian, and other allied armies are streaming past in unbroken ranks, routing the dismayed legions of France.

"Bloody Boney, the Corsican Butcher, Left off Trade and Retiring to Scarecrow Island" is the title of still another of Rowlandson's characteristic cartoons. In it Napoleon is represented as riding on a rough-coated donkey and wearing a fool's cap in place of a crown. His only provision is a bag of brown bread. His consort is riding on the same beast, which is being unmercifully flogged with a stick labeled "Bâton Maréchal."

"The Oven of the Allies."

From an anonymous French cartoon.

(p. 55) Napoleon's escape from Elba was commemorated by Rowlandson in "The Flight of Bonaparte from Hell Bay." In it the foul fiend is amusing himself by letting his captive loose, to work fresh mischief in the world above. He has mounted the Corsican upon a bubble and sends him careering upward back to earth, while hissing dragons pour forth furious blasts to waft the bubble onward.

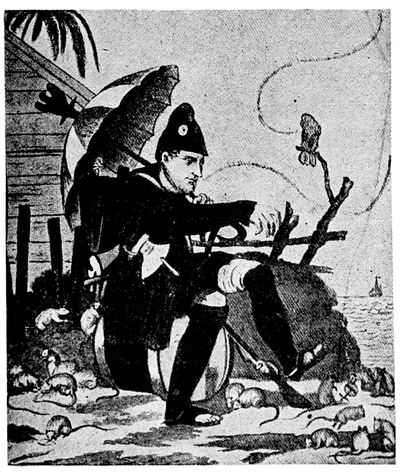

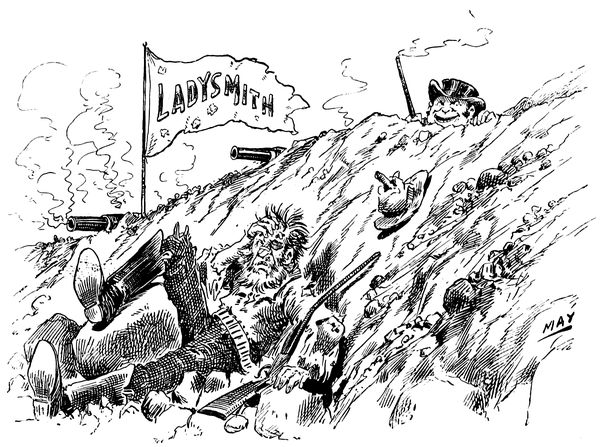

"The New Robinson Crusoe."

From a German caricature.

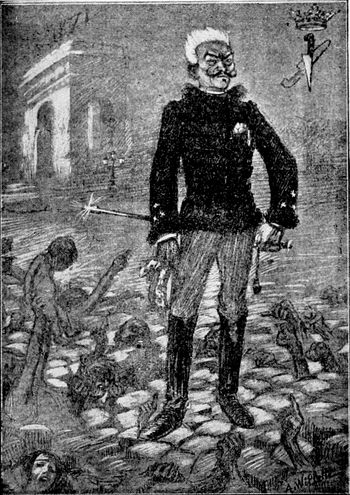

"Hell Hounds Rallying around the Idol of France" is the title of still another of Rowlandson's designs, which appeared in April, 1815. The head and bust of the Emperor drawn on a colossal scale, a hangman's noose around his throat, is mounted on a vast pyramid of human heads, his decapitated victims. Demons are flying through the air to place upon his brow a crown of blazing pitch, while a ring of other excited fiends, whose features represent Maréchal Ney, Lefebre, Davoust (p. 56) and others, with horns, hoofs, and tails, are dancing in triumph around the idol they have replaced. Closely resembling this cartoon of Rowlandson is the German cartoon, which is reproduced in these pages, showing a double-faced Napoleon topping a monument built of skulls. Rowlandson's "Hell Hounds Rallying around the Idol of France" was the last English cartoon directed against Napoleon when he was at the head of France. Two months later the Emperor's power was finally broken at Waterloo.

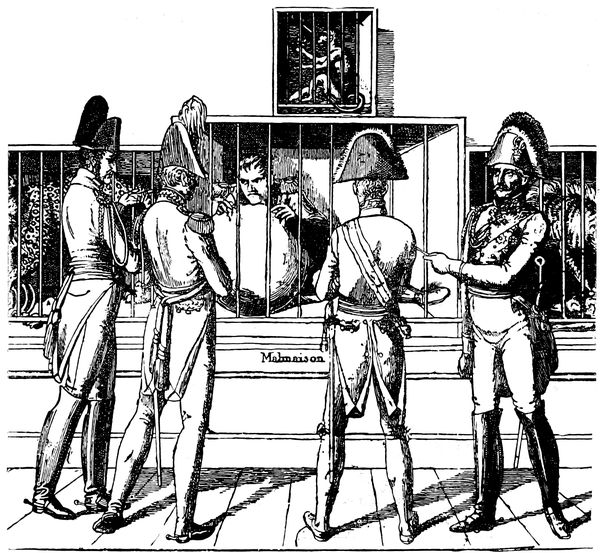

"Napoleon caged by the Allies."

From a French cartoon of the period.

"Restitution: Or, to Each his Share."

From a colored stamp of the period.

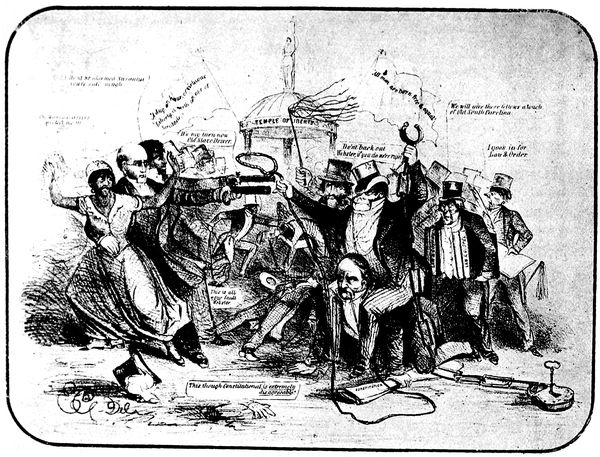

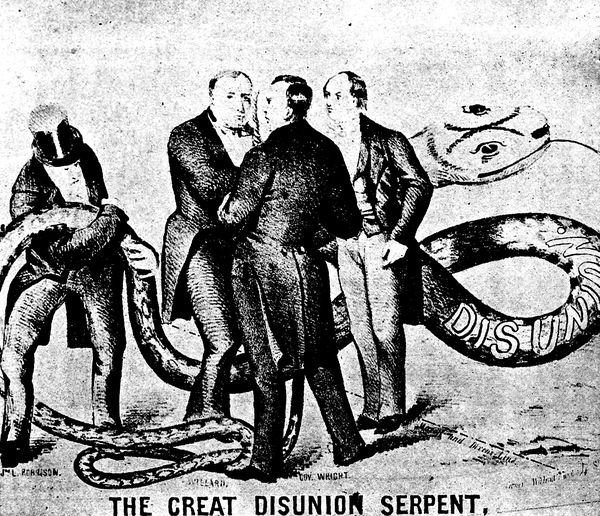

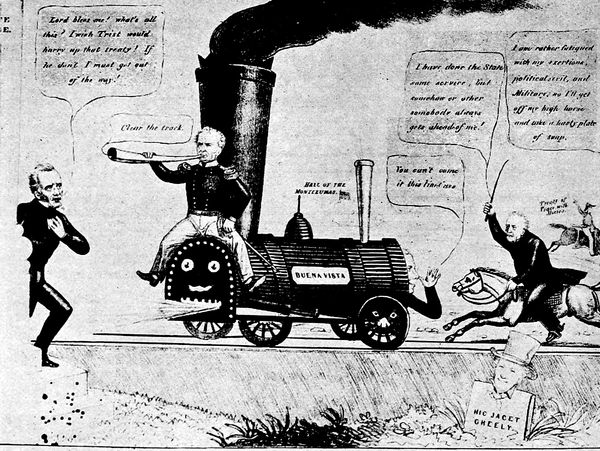

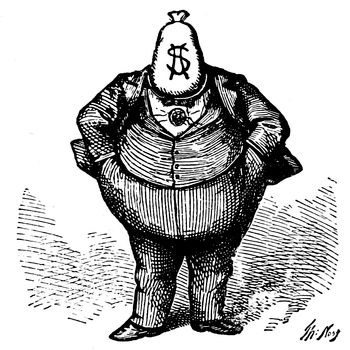

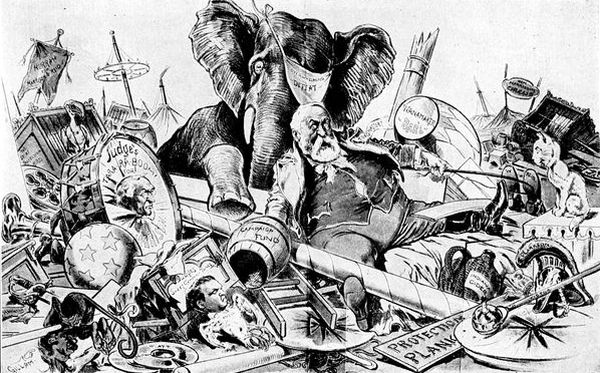

With the downfall of Napoleon the Gillray school of caricature came to an abrupt and very natural close. It was a school born of fear and nurtured upon rancor—a school that indulged freely in obscenity and sacrilege, and did not hesitate to stoop to kick the fallen hero, to heap insult and ignominy upon Napoleon in his exile. Only during a great world crisis, a death struggle of nations, could popular opinion have tolerated such wanton disregard for decency. And when the crisis was passed it came to an end like some malignant growth, strangled by its own virulence. The truth is that Gillray and Rowlandson led caricature into an impasse; they deliberately perverted its true function, which is, to advance an argument with the cogent force of a clever orator, to sum up a political issue in terms so simple that a child may read, and not merely to echo back the blatant rancor of the mob. In the hands of a master of the art it becomes an incisive weapon, like the blade with which the matador gives his coup-de-grace. Gillray's conception of its office seems to have been that of the red rag to be flapped tauntingly in the face of John Bull; and John Bull obediently bellowed in (p. 59) response. It would be idle to deny that for the purpose of spurring on public opinion, the Napoleonic cartoons exercised a potent influence. They kept popular excitement at fever heat; they added fuel to the general hatred. But when the crisis was passed, when the public pulse was beating normally once more, when virulent attacks upon a helpless exile had ceased to seem amusing, there really remained no material upon which caricature of the Gillray type could exercise its offensive ingenuity. What seemed justifiable license when directed against the arch-enemy of European peace would have been insufferable when applied to British statesmen and to the milder problems of local political issues. Another and quite practical reason helps to explain the dearth of political caricature in England for a full generation after the battle of Waterloo, and that is the question of expense. A public which freely gave shillings and even pounds to see its hatred of "Little Boney" interpreted with Gillray's vindictive malice hesitated to expend even pennies for a cartoon on the corn laws or the latest ministerial changes. In England, as well as on the Continent, caricature as an effective factor in politics remained in abeyance until the advent of an essentially modern type of periodical, the comic weekly, of which La Caricature, the London Punch, the Fliegende Blätter, and in this country Puck and Judge, are the most famous examples. The progress of lithography made such a periodical possible in France as early as 1830, when La Caricature was founded by the famous Philipon; but the oppressive laws of censorship throughout Europe prevented any wide development of this class of journalism until after the general political upheaval of 1848.

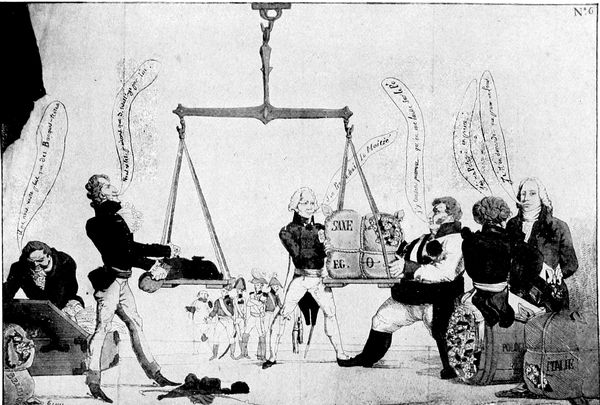

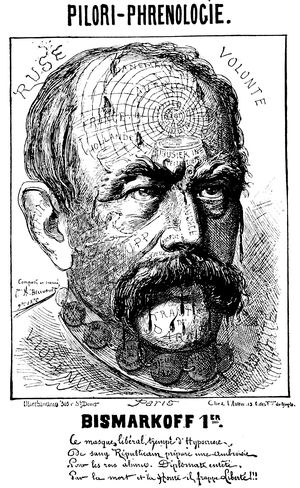

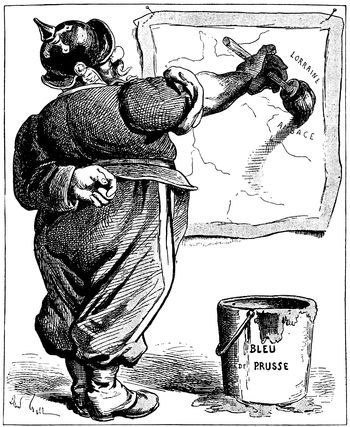

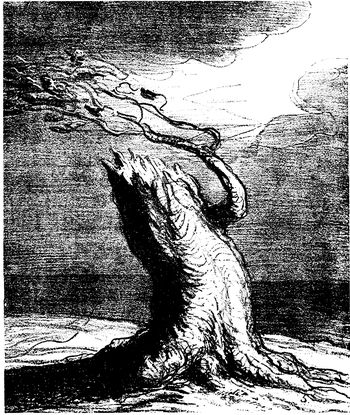

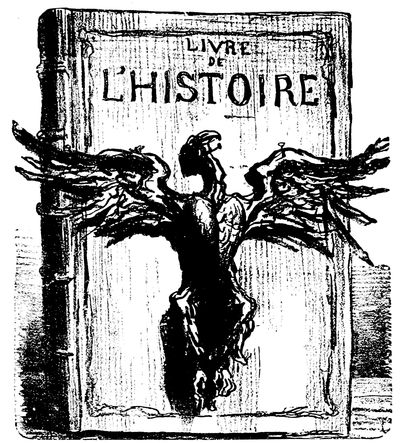

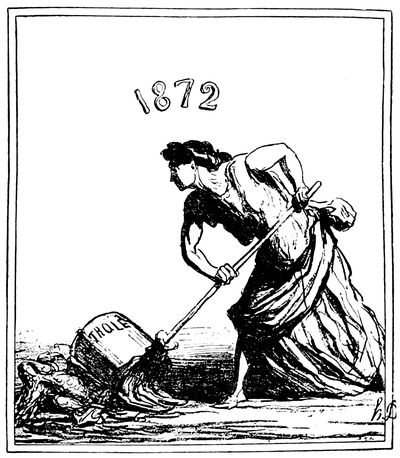

Adjusting the Balance of Power after Napoleon.

It would be idle, however, to deny that Gillray exerted a (p. 61) lasting influence upon all future caricature. His license, his vulgarity, his repulsive perversion of the human face and form, have found no disciples in later generations; but his effective assemblage of many figures, the crowded significance of minor details, the dramatic unity of the whole conception which he inherited from Hogarth, have been passed on down the line and still continue to influence the leading cartoonists of to-day in England, Germany, and the United States, although to a much less degree in France. Even at the time of Napoleon's downfall the few cartoons which appeared in Paris were far less extreme than their English models, while the German caricaturists, on the contrary, were extremely virulent, notably the Berliner, Schadow, who openly acknowledged his indebtedness to the Englishman by signing himself the Parisian Gillray; and Volz, author of the famous "true portrait of Napoleon"—a portrait in which Napoleon's face, upon closer inspection, is seen made up of a head of inextricably tangled dead bodies, his head surmounted by a bird of prey, his breast a map of Europe overspread by a vast spider web, in which the different national capitals are entangled like so many luckless flies. Had there been more liberty of the press, an interesting school of political cartoonists might have arisen at this time in Germany. But they met with such scanty encouragement that little of real interest is to be gleaned from this source until after the advent of the Berlin Kladderadatsch in 1848, and the Fliegende Blätter, but a short time earlier.

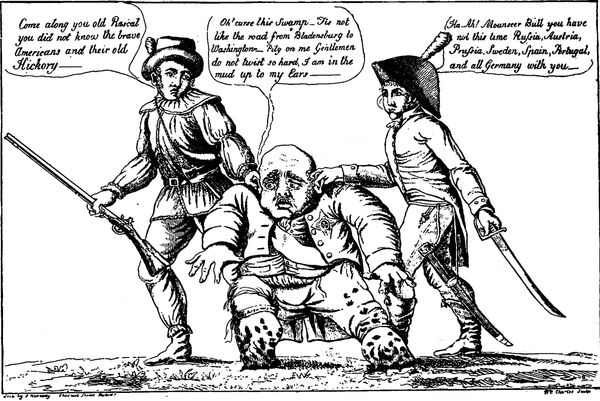

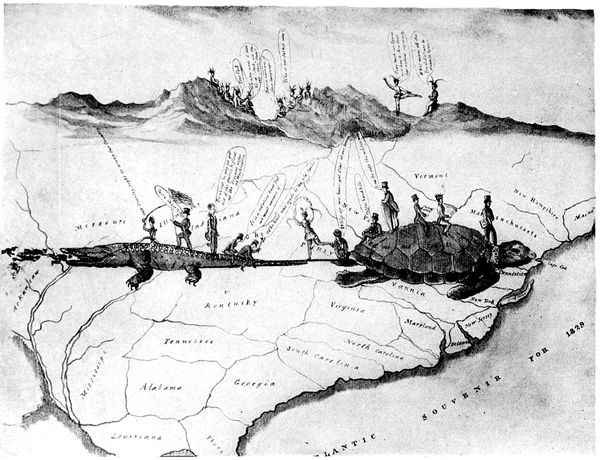

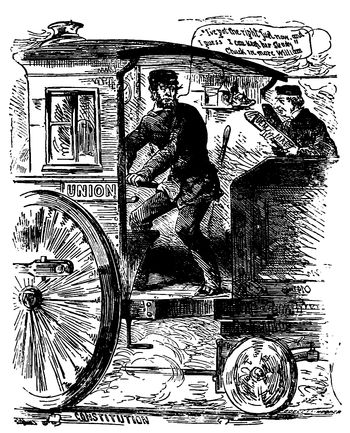

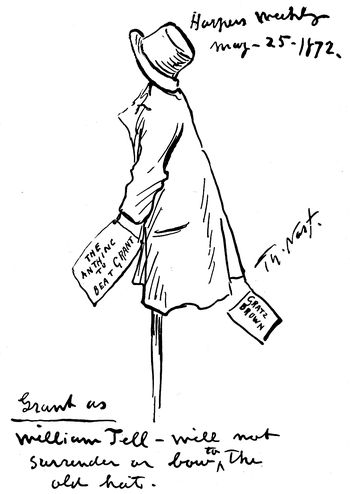

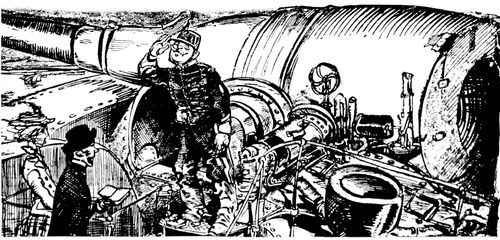

John Bull making a new Batch of Ships to send to the Lakes.

This cartoon by William Charles, a Scotchman who was forced to leave Great Britain, and who came to the United States, and wielded his pencil against his renounced country, is in many ways an imitator of Gillray's famous "Tiddy Do, the Great French Gingerbread-Baker, making a new Batch of Kings."

From the collection of the New York Public Library.

Russia as Mediator between the United States and Great Britain.

From the collection of the New York Public Library.

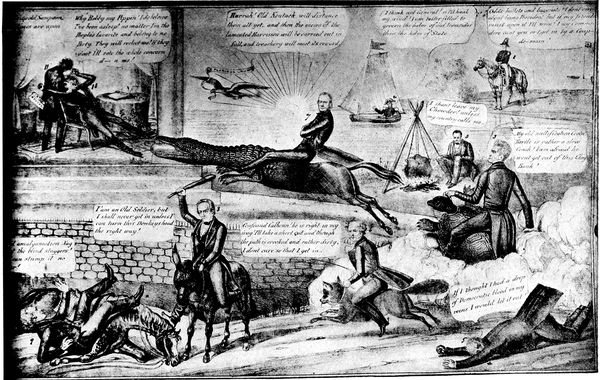

The Cossack Bite.

An american cartoon of the war of 1812.

John Bull's Troubles.

A caricature of the war of 1812.

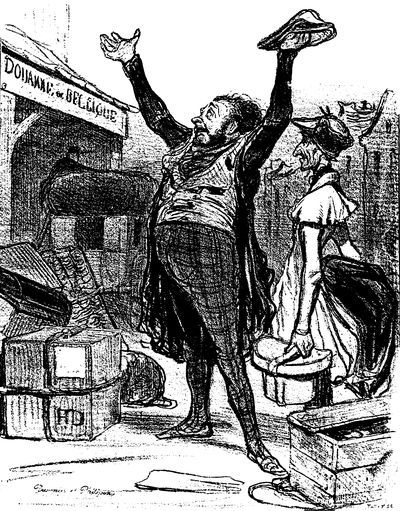

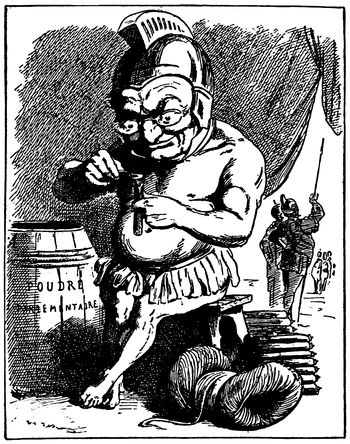

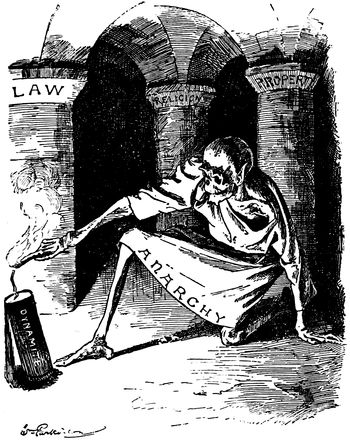

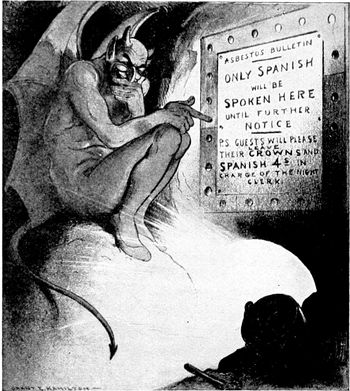

From the collection of the New York Public Library.

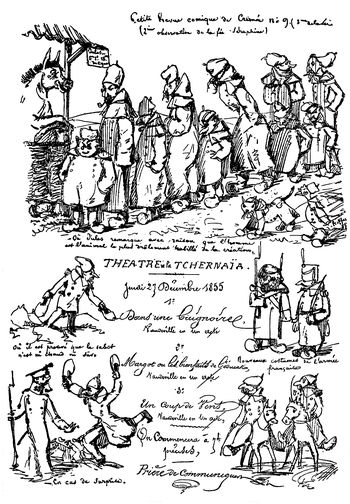

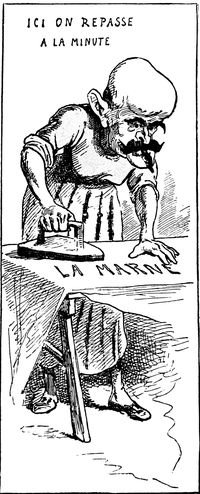

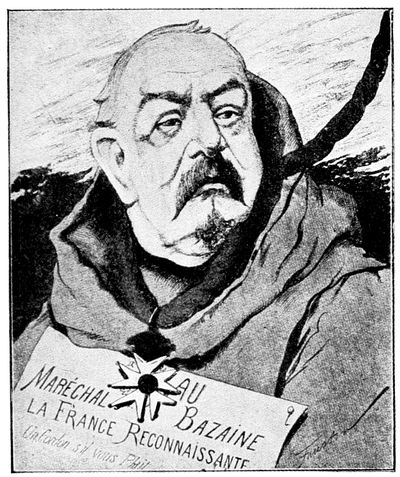

Throughout the Napoleonic period England practically had a monopoly in caricature. During the second period, down to the year 1848, France is the center of interest. Prior to 1830, French political cartoons were neither numerous nor especially significant. Indeed they present a simplicity of imagination rather amusing as compared with the complicated English caricatures. A hate of the Jesuits, a mingling of liberalism, touched with Bonapartism, and the war of newspapers furnished the theme. The two symbols constantly recurring are the girouette, or weather-cock, and the éteignoir, or extinguisher. Many of the French statesmen who played a prominent part during the French Empire and after the Restoration changed their political creed with such surprising rapidity that it was difficult to keep track of their changes. They were accordingly symbolized by a number of weathercocks proportioned to the number of their political conversions, Talleyrand leading the procession, with not less than seven to his credit. The éteignoir was constantly used in satire directed against the priesthood, the most famous instance appearing in the Minerva in 1819. It took for the text a refrain from a song of Beranger. In this cartoon the Church is personified by the figure of the Pope holding in one hand a sabre, and, in the other, a paper with the words Bulls, crusades, Sicilian vespers, St. Bartholomew. Beside the figure of the Church, torch in hand, is the demon (p. 66) of discord. From the smoke of the torch of the demon various horrors are escaping. We read "the restoration of feudal rights," "feudal privileges," "division of families." Monks are trying to snuff out the memory of Fénelon, Buffon, Voltaire, Rousseau, Montaigne, and other philosophers and thinkers. For ten years the caricaturists played with this theme. A feeble forerunner of La Caricature, entitled Le Nain Jaune, depended largely for its wit upon the variations it could improvise upon the girouette and upon the éteignoir.

Yet it would be a mistake to suppose that French art was quite destitute of humorists at the beginning of the century. M. Armand Dayot, in a monograph upon French caricature, mentions among others the names of Isabey, Boilly, and Carle Vernet as rivaling the English cartoonists in the ingenuity of their designs, and surpassing them in artistic finish and harmony of color. "But," he adds, "they were never able to go below the surface in their satire. It would be a mistake to enroll in the hirsute cohort of caricaturists these witty and charming artists, who were more concerned in depicting the pleasures of mundane life than in castigating its vices and irregularities." The 4th of November, 1830, is a momentous date in the history of French caricature. Prior to that time, French cartoons, such as there were, were studiously, even painfully, impersonal. Thackeray, in his delightful essay upon "Caricatures and Lithography," in the "Paris Sketch Book," describes the conditions of this period with the following whimsical allegory:

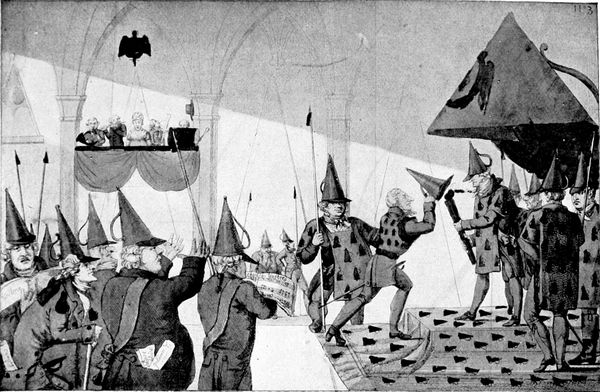

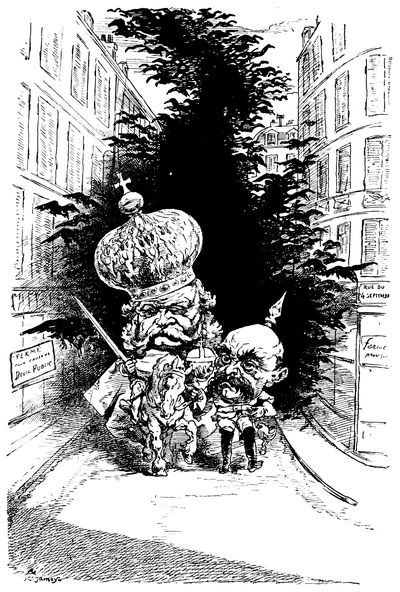

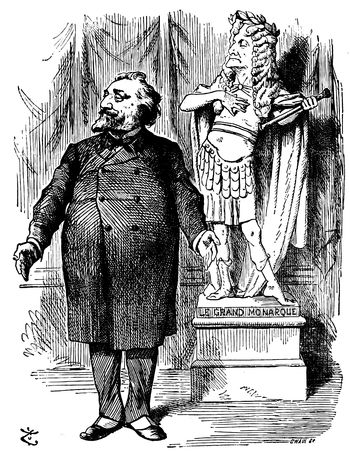

The Order of the Extinguishers.

A typical French cartoon of the Restoration.

"As for poor caricature and freedom of the press, they, like the rightful princess in a fairy tale, with the merry fantastic dwarf, her attendant, were entirely in the power of the giant who rules the land. The Princess, the press, was so (p. 68) closely watched and guarded (with some little show, nevertheless, of respect for her rank) that she dared not utter a word of her own thoughts; and, as for poor Caricature, he was gagged and put out of the way altogether."

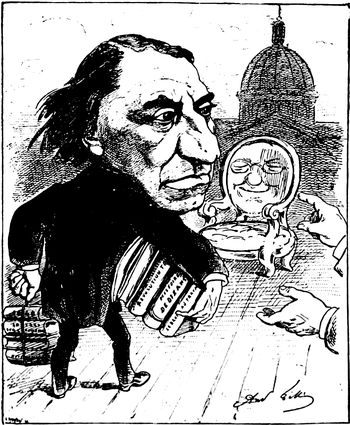

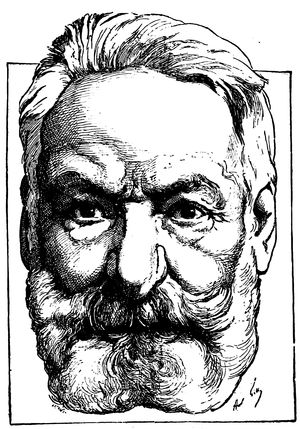

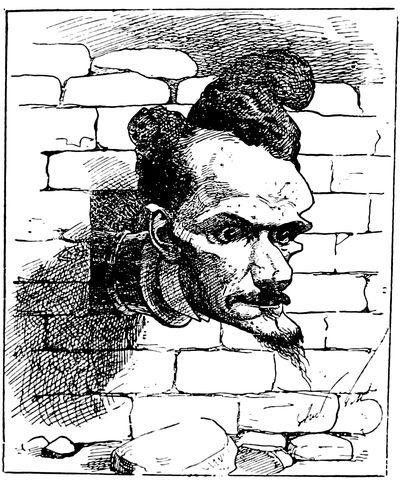

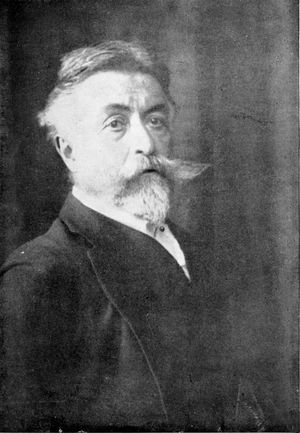

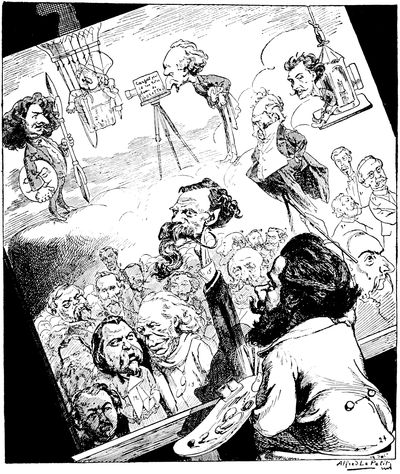

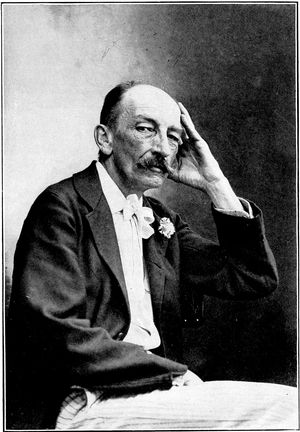

Proudhon.

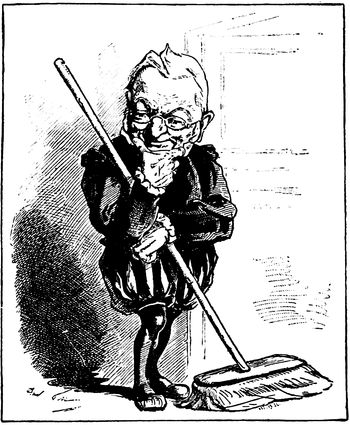

Digging the Grave.

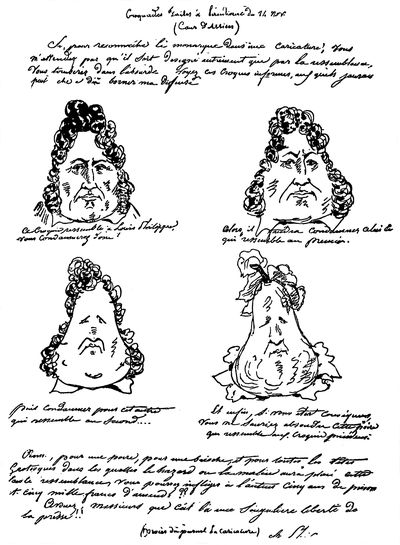

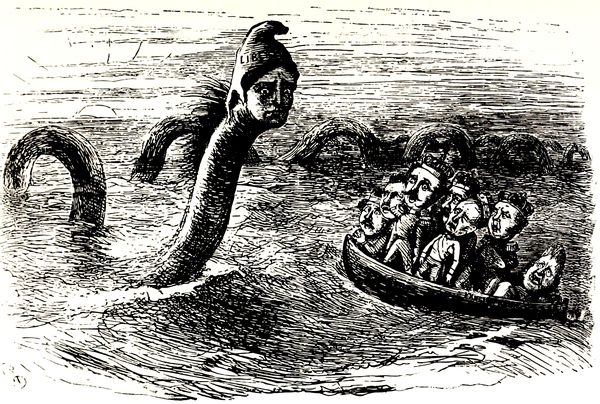

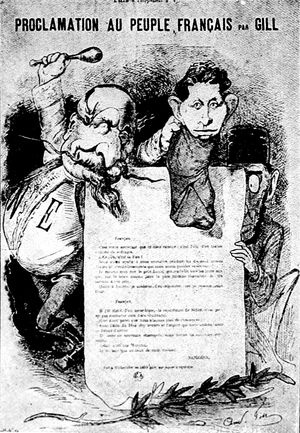

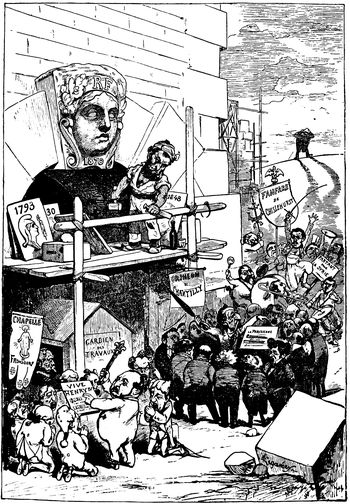

On this famous 4th of November, however, there appeared the initial number of Philipon's La Caricature, which was destined to usher in a new era of comic art, and which proved the most efficacious weapon which the Republicans found to use against Louis Philippe—a weapon as redoubtable as La Lanterne of Henri Rochefort became under the Second Empire. Like several of his most famous collaborators, Charles Philipon was a Meridional. He was born in (p. 69) Lyons at the opening of the century. He studied art in the atelier of Gros. He married into the family of an eminent publisher of prints, M. Aubert, and was himself successively the editor of the three most famous comic papers that France has had, La Caricature, Charivari, and the Journal pour Rire. The first of these was a weekly paper. The Charivari appeared daily, and at first its cartoons were almost exclusively political. Philipon had gathered around him a group of artists, men like Daumier, Gavarni, Henry Monnier, and Traviès, whose names afterward became famous, and they united in a veritable crusade of merciless ridicule against the king, his family, and his supporters. Their satire took the form of bitter personal attacks, and a very curious contest ensued between the government and the editorial staff of the Charivari. As Thackeray sums it up, it was a struggle between "half a dozen poor artists on the one side and His Majesty Louis Philippe, his august family, and the numberless placemen and supporters of the monarchy on the other; it was something like Thersites girding at Ajax." Time after time were Philipon and his dauntless aids arrested. More than a dozen times they lost their cause before a jury, yet each defeat was equivalent to a victory, bringing them new sympathy, and each time they returned to the attack with cartoons (p. 71) which, if more covert in their meaning, were even more offensive. Perhaps the most famous of all the cartoons which originated in Philipon's fertile brain is that of the "Pear," which did so much to turn the countenance of Louis Philippe to ridicule—a ridicule which did more than anything else to cause him to be driven from the French throne. The "Pear" was reproduced in various forms in La Caricature, and afterward in Le Charivari. By inferior artists the "Pear" was chalked up on walls all over Paris. The most politically important of the "Poire" series was produced when Philipon was obliged to appear before a jury to answer for the crime of provoking contempt against the King's person by giving such a ludicrous version of his face. In his own defense Philipon took up a sheet of paper and drew a large Burgundy pear, in the lower parts round and capacious, narrower near the stalk, and crowned with two or three careless leaves. "Is there any treason in that?" he asked the jury. Then he drew a second pear like the first, except that one or two lines were scrawled in the midst of it, which bore somehow an odd resemblance to the features of a celebrated personage; and, lastly, he produced the exact portrait of Louis Philippe; the well-known toupet, the ample whiskers—nothing was extenuated or set down maliciously. "Gentlemen of the jury," said Philipon, "can I help it if His Majesty's face is like a pear?" Thackeray, in giving an account of this amusing trial, makes the curious error of supposing that Philipon's naïve defense carried conviction with the jury. On the contrary, Philipon was condemned and fined, and immediately took vengeance upon the judge and jury by arranging their portraits upon the front page of Charivari in the form of a "Pear." In a hundred different ways his artists rang the changes upon the "pear," and each new attack was the forerunner of a new (p. 72) arrest and trial. One day La Caricature published a design representing a gigantic pear surmounting the pedestal in the Place de la Concorde, and bearing the legend, "Le monument expia-poire." This regicidal pleasantry brought Philipon once more into court. "The prosecution sees in this a provocation to murder!" cried the accused. "It would be at most a provocation to make marmalade." Finally, after a picture of a monkey stealing a pear proved to be an indictable offense, the subject was abandoned as being altogether too expensive a luxury.

Facsimile of the Famous Defense presented by Philipon when on Trial for Libeling the King.

"Is it my fault, gentlemen of the jury, if his Majesty's face looks like a pear?"

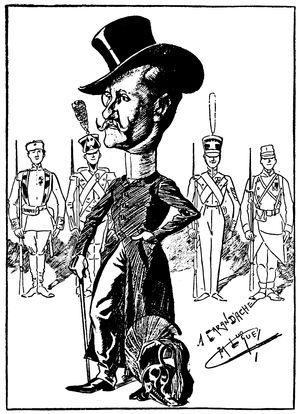

The Pious Monarch. Caricature of Charles X.

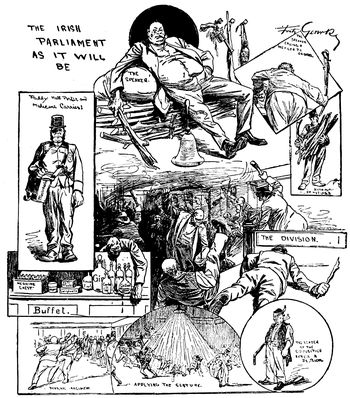

But although the "Pear" was forced to disappear, Philipon continued to harass the government, until Louis Philippe, who had gained his crown largely by his championship of the freedom of the press, was driven in desperation to sanction the famous September laws, which virtually strangled its liberty. Yet, in spite of the obstacles thrown in their way, the work of Philipon and of the remarkable corps of satirical geniuses which he gathered round him, forms a pictorial record in which the intimate history of France, from Charles X.'s famous coup d'état down to the revolution of 1848, may be read like an open book. The adversaries of the government of 1830 were of two kinds. One kind, of which Admiral Carrel was a type, resorted to passionate argument, to indignant eloquence. The other kind resorted to the methods of the Fronde; they made war by pin-pricks, by bursts of laughter, with all the resources of French gayety and wit. In this method the leading spirit was Philipon, who understood clearly the power that would result from the closest alliance between la presse et l'image. Even before La Caricature was founded the features of the last of the Bourbons became a familiar subject in cartoons. Invariably the same features are emphasized; a tall, lank figure, frequently contorted like the "india-rubber man" of the dime museums; a narrow, vacuous countenance, a high, receding forehead, over which sparse locks of hair are straggling; a salient jaw, the lips drawn back in a mirthless grin, revealing (p. 75) huge, ungainly teeth, projecting like the incisors of a horse. In one memorable cartoon he is expending the full crushing power of these teeth upon the famous "charter" of 1830, but is finding it a nut quite too hard to crack.

Charles X. In the Rôle of the "Great Nutcracker."

In this caricature Charles X. is attempting to break with his teeth a billiard ball on which is written the word "Charter." The cartoon is entitled "The Great Nutcracker of July 25th, or the Impotent Horse-jaw" (ganache)—a play upon words.

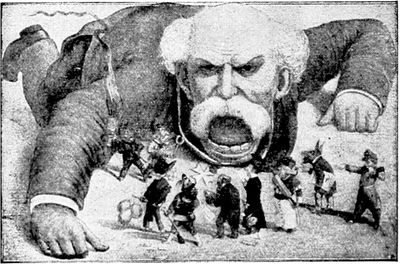

From the very beginning La Caricature assumed an attitude of hostile suspicion toward Louis Philippe, the pretended champion of the bourgeoisie, whose veneer of expedient republicanism never went deeper than to send his children to the (p. 76) public schools, and to exhibit himself parading the streets of Paris, umbrella in hand. Two cartoons which appeared in the early days of his reign, and are labeled respectively "Ne vous y frottez pas" and "Il va bon train, le Ministère!" admirably illustrate the public lack of confidence. The first of these, an eloquent lithograph by Daumier, represents a powerfully built and resolute young journeyman printer standing with hands clinched, ready to defend the liberty of the press. In the background are two groups. In the one Charles X., already worsted in an encounter, lies prone upon the earth; in the other Louis Philippe, waving his ubiquitous umbrella, is with difficulty restrained from assuming the aggressive. The second of these cartoons is more sweeping in its indictment. It represents the sovereign and his ministers in their "chariot of state," one and all lashing the horses into a mad gallop toward a bottomless abyss. General Soult, the Minister of War, is flourishing and snapping a military flag, in place of a whip. At the back of the chariot a Jesuit has succeeded in securing foothold upon the baggage, and is adding his voice to hasten the forward march, all symbolic of the violent momentum of the reactionary movement.

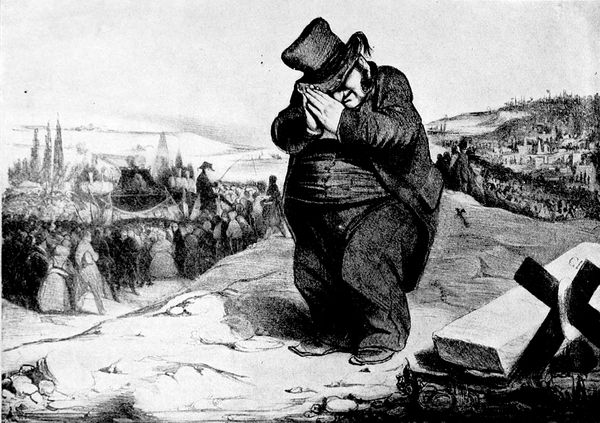

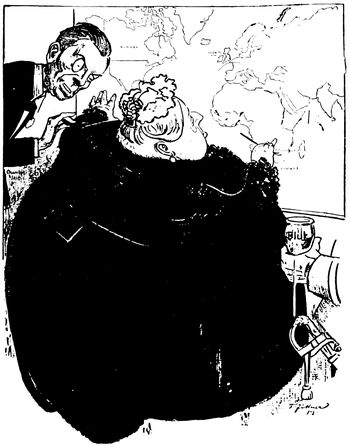

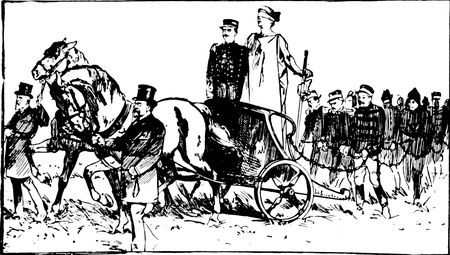

Louis Philippe at the Funeral of Lafayette.

"Enfoncé Lafayette!... Attrapé, mon vieux!"

The Ship of State in Peril—Its Sailors know not to what Saints to commend Themselves.

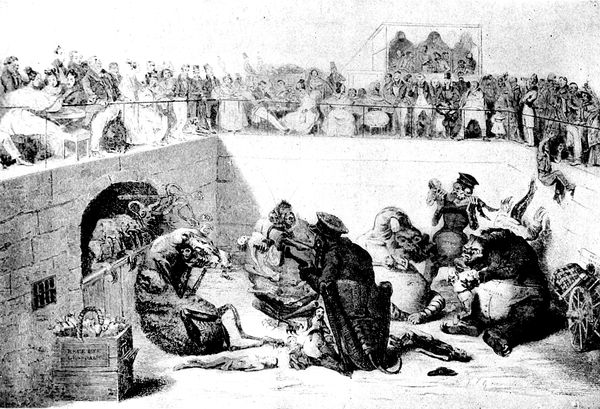

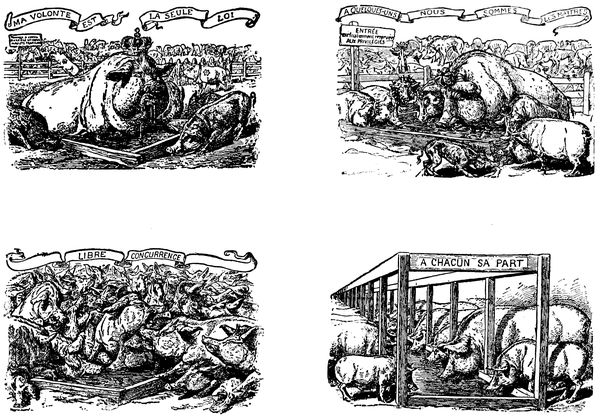

The People thrown into the Pit held by the Monsters of Various Taxes.

"Once more, Madame, do you wish divorce, or do you not wish divorce? You are perfectly free to choose?"

It was not likely that the part which Louis Philippe played in the revolution of 1789, his share in the republican victories of Jemappes and of Valmy, would be forgotten by those who saw in him only a pseudo-republican, a "citizen king" in name only, and who seized eagerly upon the opportunity of mocking at his youthful espousal of republicanism. The names of these battles recur again and again in the caricature of the period, in the legends, in maps conspicuously hung upon the walls of the background. An anonymous cut represents the public gazing eagerly into a magic lantern, the old "Poire" officiating as showman: "You have before you (p. 78) the conqueror of Jemappes and of Valmy. You see him surrounded by his nobles, his generals, and his family, all ready to die in his defense. See how the jolly rascals fight. They are not the ones to be driven in disgrace from their kingdom. Oh, no!" Of all the cartoons touching upon Louis Philippe's insincerity, probably the most famous is that of Daumier commemorating the death of Lafayette. The persistent popularity of this veteran statesman had steadily become more and more embarrassing to a government whose reactionary doctrines he repudiated, and whose political corruption he despised. "Enfoncé Lafayette!... Attrapé, mon vieux!" is the legend inscribed beneath what is unquestionably one of the most extraordinary of all the caricatures of Honoré Daumier. It represents Louis Philippe watching the funeral cortège of Lafayette, his hands raised to his face in the pretense of grief, but the face behind distorted into a hideous leer of gratification. M. Arsène Alexandre, in his remarkable work on Daumier, describes this splendid drawing in the following terms: "Under a grey sky, against the somber and broken background of a cemetery, rises on a little hillock the fat and black figure of an undertaker's man. Below him on a winding road is proceeding a long funeral procession. It is the crowd that has thronged to the obsequies of the illustrious patriot. Through the leafage of the weeping willows may be seen the white tombstones. The whole scene bears the mark of a profound sadness, in which the principal figure seems to join, if one is to judge by his sorrowful attitude and his clasped hands. But look closer. If this undertaker's man, with the features of Louis Philippe, is clasping his hands, it is simply to rub them together with joy; and through his fingers, half hiding his countenance, one may detect a sly grin." The obsequious attitude of the members (p. 80) of Parliament came in for its share of satirical abuse. "This is not a Chamber, it is a Kennel," is the title of a spirited lithograph by Grandville, representing the French statesmen as a pack of hounds fawning beneath the lash of their imperious keeper, Casimir Périer. Another characteristic cartoon of Grandville's represents the legislature as an "Infernal laboratory for extracting the quintessence of politics"—a composition which, in its crowded detail, its grim and uncanny suggestiveness, and above all its bizarre distortions of the human face and form, shows more plainly than the work of any other French caricaturist the influence of Gillray. A collection of grinning skulls are labeled "Analysis of Human Thought"; state documents of Louis Philippe are being cut and weighed and triturated, while in the foreground a legislator with distended cheeks is wasting an infinite lot of breath upon a blowpipe in his effort to distill the much-sought-for quintessence from a retort filled with fragments of the words "Bonapartism," "anarchy," "equality," "republic," etc. One of the palpable results of the "political quintessence" of Louis Philippe's government took the form of heavy imposts, and these also afforded a subject for Grandville's graphic pencil. "The Public Thrown to the Imposts in the Great Pit of the Budget" first appeared in La Caricature. It represented the various taxes under which France was suffering in the guise of strange and unearthly animals congregated in a sort of bear pit, somewhat similar to the one which attracts the attention of all visitors to the city of Berne. The spectacle is one given by the government in power for the amusement of all those connected in any way with public office: in other words, the salaried officials who draw their livelihood from the taxes imposed upon the people. It is for their entertainment that the tax-paying public is being hurled (p. 82) to the monsters below—monsters more uncouth and fantastic than even Mr. H. G. Wells's fertile brain conceived in his "War of the Worlds," or "First Men in the Moon." Daumier in his turn had to have his fling at the ministerial benches of the government of July—the "prostituted Chamber of 1834." At the present day, when the very names of the men whom he attacked are half forgotten, his famous cartoon, "Le Ventre Législatif," is still interesting; yet it is impossible to realize the impression it must have made in the days when every one of those "ventrigoulus," those rotund, somnolent, inanely smiling old men, with the word "bourgeoisie" plainly written all over them, were familiar figures in the political world, and Daumier's presentment of them, one and all, a masterly indictment of complacent incapacity. As between Daumier and Grandville, the two leading lights of La Caricature, there is little question that the former was the greater. Balzac, who was at one time one of the editors of La Caricature, writing under pseudonym of "Comte Alexandre de B.," and was the source of inspiration of one of its leading features, the curious Etudes de Genre, once said of Daumier: "Ce gaillard-là, mes enfants, a du Michel-Ange sous la peau." Balzac took Daumier under his protection from the beginning. His first counsel to him was: "If you wish to become a great artist, faites des dettes!" Grandville has been defined by later French critics as un névrosé, a bitter and pessimistic soul. It was he who produced the cruelest compositions that ever appeared in La Caricature. He had, however, some admirable pages to his credit, among others his interpretation of Sebastian's famous "L'Ordre règne à Varsovie." Fearfully sinister is the field of carnage, with the Cossack, with bloody pique, mounting guard, smoking his pipe tranquilly, on his face the horrible expression (p. 84) of satisfaction over a work well done. Grandville also conceived the idea, worthy of a great cartoonist, of Processions and Cortèges. These enabled him to have pass before the eye, under costumes, each conveying some subtle irony or allusion, all the political men in favor. Every occasion was good. A religious procession, and the men of the day appeared as choir boys, as acolytes, etc. Un vote de budget, and then it was une marche de bœuf gras, with savages, musketeers, clowns forming the escort of "M. Gros, gras et bête." It is easy to guess who was the personage so designated. (p. 87) Nothing is more amusing than these pages, full of a verve, soutenue de pince sans rire.

The Resuscitation of the French Censorship.

By Grandville.

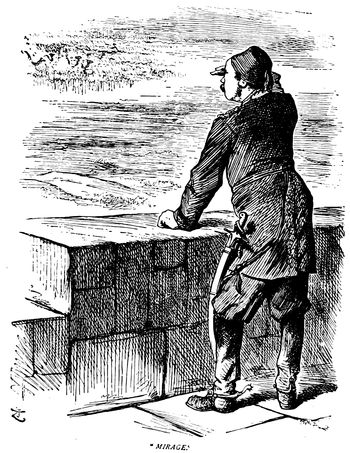

Louis Philippe as Bluebeard.

"Sister Press, do you see anything?"

"Nothing, but the July sun beating on the dusty road."

"Sister Press, do you see anything?"

"Two Cavaliers, urging their horses across the plain, and bearing a

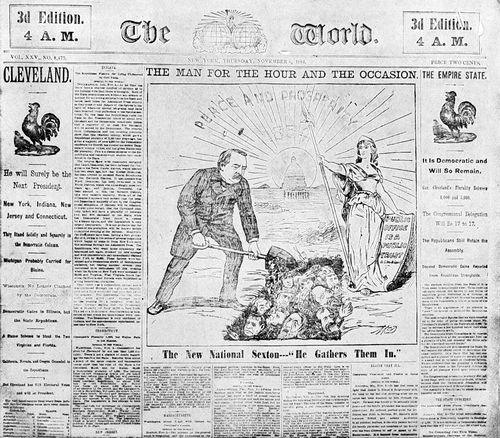

banner."