FEMALE ARTISTE (SINGS REFRAIN).

FEMALE ARTISTE (SINGS REFRAIN).

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Voces Populi, by F. Anstey This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Voces Populi Author: F. Anstey Release Date: October 2, 2011 [EBook #37597] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK VOCES POPULI *** Produced by David Clarke, Katie Hernandez and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

FEMALE ARTISTE (SINGS REFRAIN).

FEMALE ARTISTE (SINGS REFRAIN).

WITH TWENTY-FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS

BY J. BERNARD PARTRIDGE

SECOND EDITION

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

AND NEW YORK: 15 EAST 16th STREET

1892

[All rights reserved]

Richard Clay and Sons, Limited,

LONDON AND BUNGAY.

| PAGE | |

| AN EVENING WITH A CONJUROR | 1 |

| AT THE TUDOR EXHIBITION | 7 |

| IN AN OMNIBUS | 13 |

| AT A SALE OF HIGH-CLASS SCULPTURE | 19 |

| AT THE GUELPH EXHIBITION | 26 |

| AT THE ROYAL ACADEMY | 32 |

| AT THE HORSE SHOW | 38 |

| AT A DANCE | 44 |

| AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM | 50 |

| THE TRAVELLING MENAGERIE | 57 |

| AT THE REGENT STREET TUSSAUD'S | 62 |

| AT THE MILITARY EXHIBITION | 67 |

| AT THE FRENCH EXHIBITION | 73 |

| IN THE MALL ON DRAWING-ROOM DAY | 80 |

| AT A PARISIAN CAFÉ CHANTANT | 85 |

| AT A GARDEN PARTY | 90 |

| AT THE MILITARY TOURNAMENT | 95 |

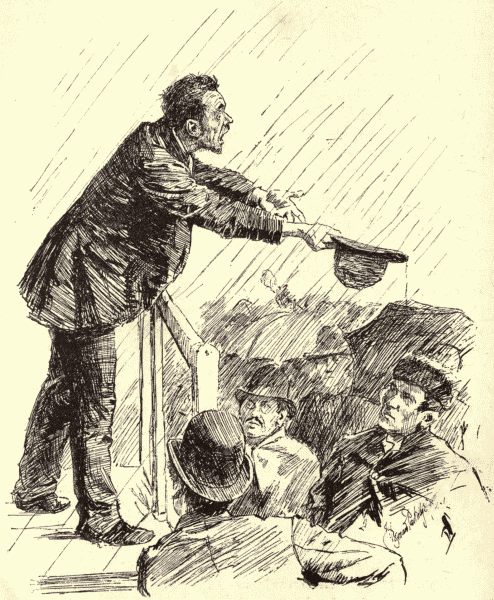

| FREE SPEECH | 99 |

| THE RIDING-CLASS | 104 |

| THE IMPROMPTU CHARADE-PARTY | 110 |

| A CHRISTMAS ROMP | 115 |

| ON THE ICE | 121 |

| IN A FOG | 127 |

| BRICKS WITHOUT STRAW | 131 |

| AT A MUSIC HALL | 136 |

| A RECITATION UNDER DIFFICULTIES | 142 |

| BANK HOLIDAY | 147 |

| A ROW IN THE PIT; OR, THE OBSTRUCTIVE HAT | 153 |

| PAGE | |

| "LED ME SEE—I SEEM TO REMEMBER YOUR FACE SOME'OW." | 3 |

| "WHAT ARE YOU DOIN' THEM C'RECT GUIDES AT, OLE MAN? A SHILLIN'? | |

| NOT me!" | |

| "GO 'OME, DIRTY DICK!" | 17 |

| "FIGGERS 'ere, GEN'L'M'N!" | 20 |

| "PETS! DON'T YOU love THEM?" | 27 |

| "CAPTURED BY A DESULTORY ENTHUSIAST" | 34 |

| "HE EXPECTED THERE WOULD HAVE BEEN MORE TO SEE" | 42 |

| "ER"—(CONSULTS SOME HIEROGLYPHICS ON HIS CUFF STEALTHILY) | 46 |

| "H'M; THAT MAY BE MITHRAS'S NOTION OF MAKING A CLEAN JOB OF IT, BUT | |

| IT AIN'T mine!" | 51 |

| "I SEZ AS THAT UN'S A FAWKS, AN' I'M READY TO PROVE IT ON ANNY MAN" | 60 |

| "THAT'S PLAY-ACTIN', THAT IS—AND I DON'T 'OLD WITH IT NO HOW!" | 64 |

| "GO IN, JIM! YOU GOT YER MARKIN'-PAPER READY ANYHOW" | 71 |

| "COME AN LOOK! ALAHA-BA-LI-BOO!" | 74 |

| "OW 'E SMOILED AT ME THROUGH THE BRORNCHES!" | 81 |

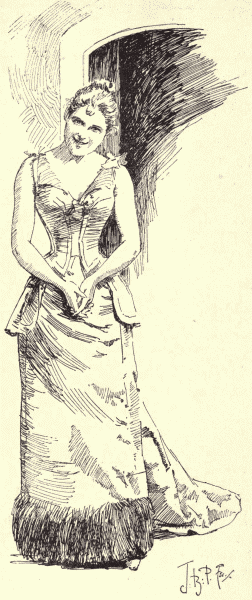

| FEMALE ARTISTE (SINGS REFRAIN) | 86 |

| "SHOW IT NOW, BY PUTTING MONEY IN THIS 'AT!" | 102 |

| "YOU AIN'T NO MORE 'OLD ON THAT SADDLE THAN A STAMP WITH THE GUM | |

| LICKED OFF!" | 105 |

| "Warm, SIR? I am WARM—AND SOMETHING MORE!" | 119 |

| "SNAY PAS FACILE QUAND VOUS AVEZ LES SKATES TOUTES SUR UN CÔTÉ—COMME | |

| moi!" | 123 |

| "GO IT, OLE FRANKY, MY SON!" | 125 |

| RECOGNISES WITH DISMAY A VIEW OF THE GRAND CANAL | 134 |

| THE SISTERS SILVERTWANG | 137 |

| "I AM ONLY A COWBOY" | 143 |

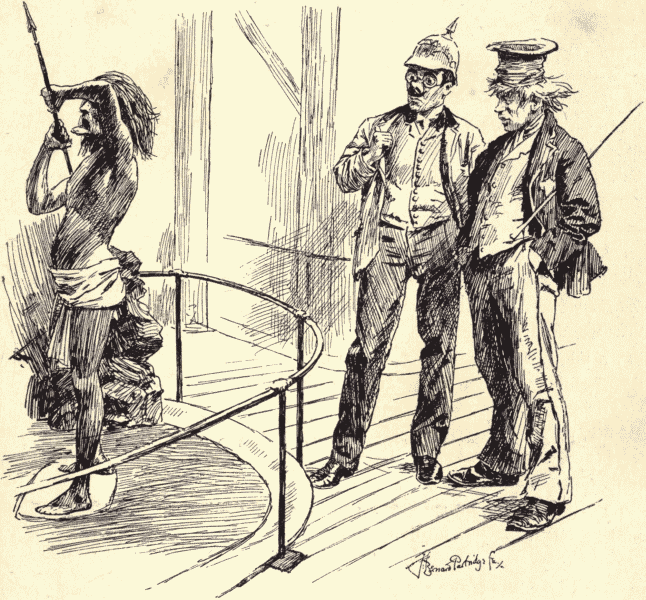

| "RUM THE SIGHTS THESE 'ERE SAVIDGES MAKE O' THEIRSELVES" | 149 |

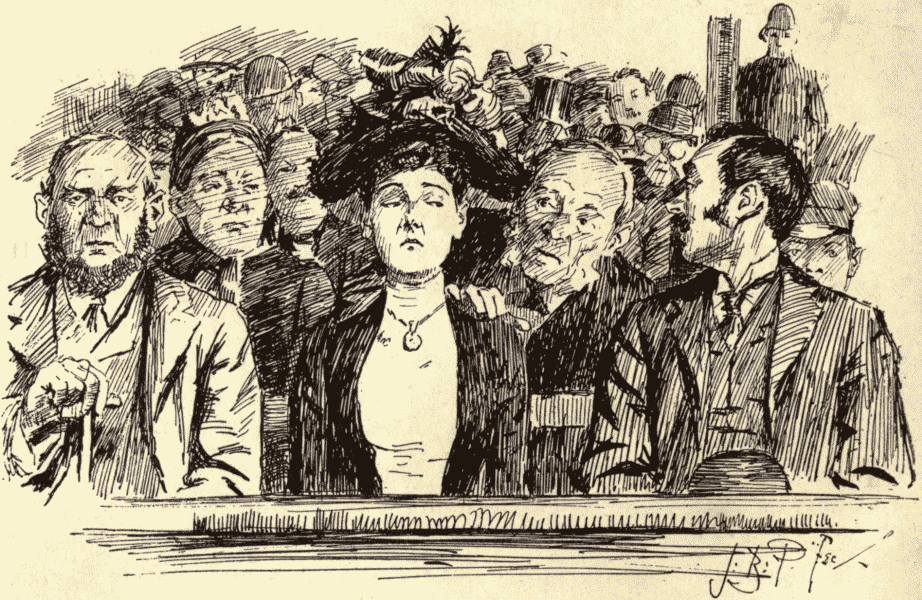

| THE OWNER OF THE HAT DEIGNS NO REPLY | 154 |

Scene—A Suburban Hall. The Performance has not yet begun. The Audience is limited and low-spirited, and may perhaps number—including the Attendants—eighteen. The only people in the front seats are a man in full evening dress, which he tries to conceal under a caped coat, and two Ladies in plush opera-cloaks. Fog is hanging about in the rafters, and the gas-stars sing a melancholy dirge. Each casual cough arouses dismal echoes. Enter an intending Spectator, who is conducted to a seat in the middle of an empty row. After removing his hat and coat, he suddenly thinks better—or worse—of it, puts them on again, and vanishes hurriedly.

First Sardonic Attendant (at doorway). Reg'lar turnin' em away to-night, we are!

Second Sardonic Attendant. He come up to me afore he goes to the pay-box, and sez he—"Is there a seat left?" he sez. And I sez to 'im, "Well, I think we can manage to squeeze you in somewhere." Like that, I sez.

[The Orchestra, consisting of two thin-armed little girls, with pigtails, enter, and perform a stumbling Overture upon a cracked piano. Herr Von Kamberwohl, the Conjuror, appears on platform, amidst loud clapping from two obvious Confederates in a back row.[ 2]

Herr V. K. (in a mixed accent). Lyties and Shentilmans, pefoor I co-mence viz my hillusions zis hevenin' I 'ave most hemphadically to repoodiate hall assistance from hany spirrids or soopernatural beins vatsohever. All I shall 'ave ze honour of showing you will be perform by simple Sloight of 'and or Ledger-dee-Mang! (He invites any member of the Audience to step up and assist him, but the spectators remain coy.) I see zat I 'ave not to night so larsh an orjence to select from as usual, still I 'ope—(Here one of the obvious Confederates slouches up, and joins him on the platform.) Ah, zat is goot! I am vair much oblige to you, Sare. (The Confederate grins sheepishly.) Led me see—I seem to remember your face some'ow. (Broader grin from Confederate.) Hah you vos 'ere last night?—zat exblains it! But you 'ave nevaire assist me befoor, eh? (Reckless shake of the head from Confederate.) I thought nod. Vair vell. You 'ave nevaire done any dricks mit carts—no? Bot you will dry? You never dell vat you gan do till you dry, as ze ole sow said ven she learn ze halphabet. (He pauses for a laugh—which doesn't come.) Now, Sare, you know a cart ven you see 'im? Ah, zat is somtings alretty! Now I vill ask you to choose any cart or carts out of zis back. (The Confederate fumbles.) I don't vish to 'urry you—but I vant you to mike 'aste—&c., &c.

The Man in Evening Dress. I remember giving Bimbo, the Wizard of the West, a guinea once to teach me that trick—there was nothing in it.

First Lady in Plush Cloak. And can you do it?

The M. in E. D. (guardedly). Well, I don't know that I could exactly do it now—but I know how it's done.

[He explains elaborately how it is done.

Herr V. K. (stamping, as a signal that the Orchestra may leave off). Next I shall show you my zelebrated hillusion of ze inexhaustible 'At, to gonclude viz the Invisible 'En. And I shall be moch oblige if any shentilmans vill kindly favour me viz 'is 'at for ze purpose of my exberiment.

The M. in E. D. Here's mine—it's quite at your service. [To his companions.] This is a stale old trick, he merely—(explains as before). But you wait and see how I'll score off him over it![ 3]

"LED ME SEE—I SEEM TO REMEMBER YOUR FACE SOME'OW."

"LED ME SEE—I SEEM TO REMEMBER YOUR FACE SOME'OW."

Herr V. K. (to the M. in E. D.). You are gvide sure, Sare, you leaf nossing insoide of your 'at?

The M. in E. D. (with a wink to his neighbours). On the contrary, there are several little things there belonging to me, which I'll thank you to give me back by-and-by.

Herr V. K. (diving into the hat). So? Vat 'ave we 'ere? A bonch of flowairs! Anozzer bonch of flowairs? Anozzer—and anozzer! Ha, do you alvays garry flowairs insoide your 'at, Sare?

The M. in E. D. Invariably—to keep my head cool; so hand them over, please; I want them.

[His Companions titter, and declare "it really is too bad of him!"

Herr V. K. Bresently, Sare,—zere is somtings ailse, it feels loike—yes, it ees—a mahouse-drap. Your haid is drouble vid moice, Sare, yes? Bot zere is none 'ere in ze 'at!

The M. in E. D. (with rather feeble indignation). I never said there were.

Herr V. K. No, zere is no mahouse—bot—[diving again]—ha! a leedle vide rad! Anozzer vide rad! And again a vide rad—and one, two, dree more vide rads! You vind zey keep your haid noice and cool, Sare? May I drouble you to com and dake zem avay? I don't loike the vide rads myself, it is madder of daste. [The Audience snigger.] Oh, bot vait—zis is a most gonvenient 'at—[extracting a large feeding-bottle and a complete set of baby-linen]—ze shentelman is vairy domestic I see. And zere is more yet, he is goot business man, he knows ow von must hadvertise in zese' ere toimes. 'E 'as 'elp me, so I vill 'elp 'im by distributing some of his cairculars for 'im.

[He showers cards, commending somebody's self-adjusting trousers amongst the Audience, each person receiving about two dozen—chiefly in the eye—until the air is dark, and the floor thick with them.

The M. in E. D. (much annoyed). Infernal liberty! Confounded impudence! Shouldn't have had my hat if I'd known he was going to play the fool with it like this![ 5]

First Lady in Plush Cloak. But I thought you knew what was coming?

The M. in E. D. So I did—but this fellow does it differently.

[Herr Von K. is preparing to fire a marked half-crown from a blunderbuss into a crystal casket.

A Lady with Nerves (to her husband). John, I'm sure he's going to let that thing off!

John (a Brute). Well, I shouldn't be surprised if he is. I can't help it.

The L. with N. You could if you liked—you could tell him my nerves won't stand it—the trick will be every bit as good if he only pretends to fire, I'm sure.

John. Oh, nonsense!—You can stand it very well if you like.

The L. with N. I can't, John.... There, he's raising it to his shoulder. John, I must go out. I shall scream if I sit here, I know I shall!

John. No, no—what's the use? He'll have fired long before you get to the door. Much better stay where you are, and do your screaming sitting down. (The Conjuror fires.) There, you see, you didn't scream, after all!

The L. with N. I screamed to myself—which is ever so much worse for me; but you never will understand me till it's too late!

[Herr Von K. performs another trick.

First Lady in Plush Cloak. That was very clever, wasn't it? I can't imagine how it was done!

The M. in E. D. (in whom the memory of his desecrated hat is still rankling). Oh, can't you? Simplest thing in the world—any child could do it!

Second Lady. What, find the rabbit inside those boxes, when they were all corded up, and sealed!

The M. in E. D. You don't mean to say you were taken in by that! Why, it was another rabbit, of course!

First Lady. But even if it was another rabbit, it was wearing the borrowed watch round its neck.[ 6]

The M. in E. D. Easy enough to slip the watch in, if all the boxes have false bottoms.

Second L. Yes, but he passed the boxes round for us to examine.

The M. in E. D. Boxes—but not those boxes.

First L. But how could he slip the watch in when somebody was holding it all the time in a paper bag?

The M. in E. D. Ah, I saw how it was done—but it would take too long to explain it now. I have seen it so well performed that you couldn't spot it. But this chap's a regular duffer!

Herr V. K. (who finds this sort of thing rather disturbing). Lyties and Shentilmans, I see zere is von among us who is a brofessional like myself, and knows how all my leedle dricks is done. Now—[suddenly abandoning his accent]—I am always griteful for hanythink that will distrack the attention of the orjence from what is going on upon the Stige; naterally so, because it prevents you from follerin' my actions too closely, and so I now call upon this gentleman in the hevenin' dress jest to speak hup a very little louder than what he 'as been doin', so that you will be enabled to 'ear hevery word of 'is hexplanation more puffickly than what some of you in the back benches have done itherto. Now, Sir, if you'll kindly repeat your very hinteresting remarks in a more haudible tone, I can go on between like. [Murmurs of "No no!" "Shut up!" "We don't want to hear him!" from various places; The Man in Evening Dress subsides into a crimson taciturnity, which continues during the remainder of the performance.[ 7]

IN THE CENTRAL HALL.

The usual Jocose 'Arry (who has come here with 'Arriet, for no very obvious reason, as they neither of them know or care about any history but their own). Well, I s'pose as we are 'ere, we'd better go in a buster for a book o' the words, eh? (To Commissionaire.) What are yer doin' them c'rect guides at, ole man? A shillin'? Not me! 'Ere, 'Arriet, we'll make it out for ourselves.

A Young Man (who has dropped in for five minutes—"just to say he's been, don't you know"). 'Jove—my Aunt! Nip out before she spots me.... Stop, though, suppose she has spotted me? Never can tell with giglamps ... better not risk it. [Is "spotted" while hesitating.

His Aunt. I didn't recognise you till just this moment, John, my boy. I was just wishing I had some one to read out all the extracts in the Catalogue for me; now we can go round together.

[John affects a dutiful delight at this suggestion, and wonders mentally if he can get away in time to go to afternoon tea with those pretty Chesterton Girls.

An Uncle (who has taken Master Tommy out for the afternoon). This is the way to make your English History real to you, my boy!

[Tommy, who had cherished hopes of Covent Garden Circus, privately thinks that English History is a sufficiently unpleasant reality as it is, and conceives a bitter prejudice against the entire Tudor Period on the spot.

The Intelligent Person. Ha! armour of the period, you see![ 8]

"WHAT ARE YOU DOIN' THEM C'RECT GUIDES AT, OLE MAN? A SHILLIN'? NOT me!"

"WHAT ARE YOU DOIN' THEM C'RECT GUIDES AT, OLE MAN? A SHILLIN'? NOT me!"

(Feels bound to make an intelligent remark.) 'Stonishing how the whole art of war has been transformed since then, eh? Now—to me—(as if he was conscious of being singular in this respect)—to me, all this is most interesting. Coming as I do, fresh from Froude—

His Companion (a Flippant Person). Don't speak so loud. If they know you've come in here fresh, you'll get turned out!

Patronising Persons (inspecting magnificent suit of russet and gilt armour). 'Pon my word, no idea they turned out such good work in those times—very creditable to them, really.

BEFORE THE PORTRAITS.

The Uncle. Now, Tommy, you remember what became of Katherine of Aragon, I'm sure? No, no—tut—tut—she wasn't executed! I'm afraid you're getting rather rusty with these long holidays. Remind me to speak to your mother about setting you a chapter or so of history to read every day when we get home, will you?

Tommy (to himself). It is hard lines on a chap having a Sneak for an Uncle! Catch me swotting to please him!

'Arry. There's old 'Enery the Eighth, you see—that's 'im right enough; him as 'ad all those wives, and cut every one of their 'eds off!

'Arriet (admiringly). Ah, I knew we shouldn't want a Catalogue.

The Int. P. Wonderfully Holbein's caught the character of the man—the—er—curious compound of obstinacy, violence, good-humour, sensuality, and—and so on. No mistaking a Holbein—you can tell him at once by the extraordinary finish of all the accessories. Now look at that girdle—isn't that Holbein all over?

Flippant P. Not quite all over, old fellow. Catalogue says it's painted by Paris Bordone.

The Int. P. Possibly—but it's Holbein's manner, and, looking at these portraits, you see at once how right Froude's estimate was of the King.

F. P. Does Froude say how he got that nasty one on the side of his nose?

A Visitor. Looks overfed, don't he?[ 10]

Second V. (sympathetically). Oh, he fed himself very well; you can see that.

The Aunt. Wait a bit, John—don't read so fast. I haven't made out the middle background yet. And where's the figure of St. Michael rising above the gilt tent, lined with fleurs-de-lis on a blue ground? Would this be Guisnes, or Ardres, now? Oh, Ardres on the right—so that's Ardres—yes, yes; and now tell me what it says about the two gold fountains, and that dragon up in the sky.

[John calculates that, at this rate, he has a very poor chance of getting away before the Gallery closes.

The Patronising Persons. 'Um! Holbein again, you see—very curious their ideas of painting in those days. Ah, well, Art has made great progress since then—like everything else!

Miss Fisher. So that's the beautiful Queen Mary! I wonder if it is really true that people have got better-looking since those days?

[Glances appealingly at Phlegmatic Fiancé.

Her Phlegmatic Fiancé. I wonder.

Miss F. You hardly ever see such small hands now, do you? With those lovely long fingers, too!

The Phl. F. No, never.

Miss F. Perhaps people in some other century will wonder how anybody ever saw anything to admire in us?

The Phl. F. Shouldn't be surprised.

[Miss F. does wish secretly that Charles had more conversation.

The Aunt. John, just find out who No. 222 is.

John (sulkily). Sir George Penruddocke, Knight.

His Aunt (with enthusiasm). Of course—how interesting this is, isn't it?—seeing all these celebrated persons exactly as they were in life! Now read who he was, John, please.

The Int. Person. Froude tells a curious incident about—

Flippant P. I tell you what it is, old chap, if you read so much history, you'll end by believing it!

The Int. P. (pausing before the Shakspeare portraits). "He was not for an age, but for all time."[ 11]

The Fl. P. I suppose that's why they've painted none of them alike.

A Person with a talent for Comparison. Mary, come here a moment. Do look at this—"Elizabeth, Lady Hoby"—did you ever see such a likeness?

Mary. Well, dear, I don't quite—

The Person with, &c. It's her living image! Do you mean to say you really don't recognise it?—Why, Cook, of course!

Mary. Ah! (apologetically)—but I've never seen her dressed to go out, you know.

The Uncle. "No. 13, Sir Rowland Hill, Lord Mayor, died 1561"—

Tommy (anxious to escape the threatened chapters if possible). I know about him, Uncle, he invented postage stamps!

OVER THE CASES.

First Patronising P. "A Tooth of Queen Katherine Parr." Dear me! very quaint.

Second P. P. (tolerantly). And not at all a bad tooth, either.

'Arriet (comes to a case containing a hat labelled as formerly belonging to Henry the Eighth). 'Arry, look 'ere; fancy a king going about in a thing like that—pink with a green feather! Why, I wouldn't be seen in it myself!

'Arry. Ah, but that was ole 'Enery all over, that was; he wasn't one for show. He liked a quiet, unassumin' style of 'at, he did. "None of yer loud pot 'ats for Me!" he'd tell the Royal 'atters; "find me a tile as won't attract people's notice, or you won't want a tile yerselves in another minute!" An' you may take yer oath they served him pretty sharp, too!

'Arriet (giggling). It's a pity they didn't ask you to write their Catalogue for 'em.

The Aunt. John, you're not really looking at that needlework—it's Queen Elizabeth's own work, John. Only look how wonderfully fine the stitches are. Ah, she was a truly great woman! I could spend hours over this case alone. What, closing are they, already? We must have another day at this together, John—just you and I.[ 12]

John. Yes, Aunt. And now—(thinks there is just time to call on the Chestertons, if he goes soon)—can I get you a cab, or put you into a 'bus or anything?

His Aunt. Not just yet; you must take me somewhere where I can get a bun and a cup of tea first, and then we can go over the Catalogue together, and mark all the things we missed, you know.

[John resigns himself to the inevitable rather than offend his wealthy relative; the Intelligent Person comes out, saying he has had "an intellectual treat" and intends to "run through Froude again" that evening. 'Arry and 'Arriet, depart to the "Ocean Wave" at Hengler's. Gallery gradually clears as Scene closes in.[ 13]

The majority of the inside passengers, as usual, sit in solemn silence, and gaze past their opposite neighbours into vacancy. A couple of Matrons converse in wheezy whispers.

First Matron. Well, I must say a bus is pleasanter riding than what they used to be not many years back, and then so much cheaper, too. Why you can go all the way right from here to Mile End Road for threepence!

Second Matron. What, all that way for threepence—(with an impulse of vague humanity). The poor 'orses!

First Matron. Ah, well, my dear, it's Competition, you know,—it don't do to think too much of it.

Conductor (stopping the bus). Orchard Street, Lady!

[To Second Matron, who had desired to be put down there.

Second Matron (to Conductor). Just move on a few doors further, opposite the boot-shop. (To First Matron.) It will save us walking.

Conductor. Cert'inly, Mum, we'll drive in and wait while you're tryin' 'em on, if you like—we ain't in no 'urry!

[The Matrons get out, and their places are taken by two young girls, who are in the middle of a conversation of thrilling interest.

First Girl. I never liked her myself—ever since the way she behaved at his Mother's that Sunday.

Second Girl. How did she behave?

[A faint curiosity is discernible amongst the other passengers to learn how she—whoever she is—behaved that Sunday.[ 14]

First Girl. Why, it was you told me! You remember. That night Joe let out about her and the automatic scent fountain.

Second Girl. Oh, yes, I remember now. (General disappointment.) I couldn't help laughing myself. Joe didn't ought to have told—but she needn't have got into such a state over it, need she?

First Girl. That was Eliza all over. If George had been sensible, he'd have broken it off then and there—but no, he wouldn't hear a word against her, not at that time—it was the button-hook opened his eyes!

[The other passengers strive to dissemble a frantic desire to know how and why this delicate operation was performed.

Second Girl (mysteriously). And enough too! But what put George off most was her keeping that bag so quiet.

[The general imagination is once more stirred to its depths by this mysterious allusion.

First Girl. Yes, he did feel that, I know, he used to come and go on about it to me by the hour together. "I shouldn't have minded so much," he told me over and over again, with the tears standing in his eyes,—"if it hadn't been that the bottles was all silver-mounted!"

Second Girl. Silver-mounted? I never heard of that before—no wonder he felt hurt!

First Girl (impressively). Silver tops to every one of them—and that girl to turn round as she did, and her with an Uncle in the oil and colour line, too—it nearly broke George's 'art!

Second Girl. He's such a one to take on about things—but, as I said to him, "George," I says, "You must remember it might have been worse. Suppose you'd been married to that girl, and then found out about Alf and the Jubilee sixpence—how would that have been?"

First Girl (unconsciously acting as the mouthpiece of the other passengers). And what did he say to that?

Second Girl. Oh, nothing—there was nothing he could say, but I could see he was struck. She behaved very mean to the last—she wouldn't send back the German concertina.[ 15]

First Girl. You don't say so! Well, I wouldn't have thought that of her, bad as she is.

Second Girl. No, she stuck to it that it wasn't like a regular present, being got through a grocer, and as she couldn't send him back the tea, being drunk,—but did you hear how she treated Emma over the crinoline 'at she got for her?

First Girl (to the immense relief of the rest). No, what was that?

Second Girl. Well, I had it from Emma her own self. Eliza wrote up to her and says, in a postscript like,—Why, this is Tottenham Court Road, I get out here. Good-bye, dear, I must tell you the rest another day.

[Gets out, leaving the tantalised audience inconsolable, and longing for courage to question her companion as to the precise details of Eliza's heartless behaviour to George. The companion, however, relapses into a stony reserve. Enter a Chatty Old Gentleman who has no secrets from anybody, and of course selects as the first recipient of his confidence the one person who hates to be talked to in an omnibus.

The Chatty O. G. I've just been having a talk with the policeman at the corner there—what do you think I said to him?

His Opposite Neighbour. I—I really don't know.

THE C. O. G. Well, I told him he was a rich man compared to me. He said "I only get thirty shillings a week, Sir." "Ah," I said, "but look at your expenses, compared to mine. What would you do if you had to spend eight hundred a year on your children's education?" I spend that—every penny of it, Sir.

His Opp. N. (utterly uninterested). Do you indeed?—dear me!

C. O. G. Not that I grudge it—a good education is a fortune in itself, and as I've always told my boys, they must make the best of it, for it's all they'll get. They're good enough lads, but I've had a deal of trouble with them one way and another—a deal of trouble. (Pauses for some expression of sympathy—which does not come—and he continues:) There are my two eldest sons—what must they do but fall in love with the same lady—the same lady, Sir! (No one seems to care much for these domestic revelations—possibly because they are too[ 16] obviously addressed to the general ear). And, to make matters worse, she was a married woman—(his principal hearer looks another way uneasily)—the wife of a godson of mine, which made it all the more awkward, y'know. (His Opposite Neighbour giving no sign, the C. O. G. tries one Passenger after another.) Well, I went to him—(here he fixes an old Lady, who immediately passes up coppers out of her glove to the Conductor)—I went to him, and said—(addressing a smartly dressed young Lady with a parcel who giggles)—I said, "You're a man of the world—so am I. Don't you take any notice," I told him—(this to a callow young man, who blushes)—"they're a couple of young fools," I said, "but you tell your dear wife from me not to mind those boys of mine—they'll soon get tired of it if they're only let alone." And so they would have, long ago, it's my belief, if they'd met with no encouragement—but what can I do—it's a heavy trial to a father, you know. Then there's my third son—he must needs go and marry—(to a Lady at his side with a reticule, who gasps faintly)—some young woman who dances at a Music-hall—nice daughter-in-law that for a man in my position, eh? I've forbidden him the house of course, and told his mother not to have any communication with him—but I know, Sir,—(violently, to a Man on his other side, who coughs in much embarrassment)—I know she meets him once a week under the eagle in Orme Square, and I can't stop her! Then I'm worried about my daughters—one of 'em gave me no peace till I let her have some painting lessons—of course, I naturally thought the drawing-master would be an elderly man—whereas, as things turned out,——

A QUIET MAN IN A CORNER. I 'ope you told all this to the Policeman, Sir?

The C. O. G. (flaming unexpectedly). No, Sir, I did not. I am not in the habit—whatever you may be—of discussing my private affairs with strangers. I consider your remark highly impertinent, Sir.

[Fumes in silence for the rest of the journey.

The Young Lady with the Parcel (to her friend—for the sake of vindicating her gentility). Oh, my dear, I do feel so funny, carrying a great brown-paper parcel, in a bus, too! Any one would take me for a shop-girl![ 17]

"GO 'OME, DIRTY DICK!"

"GO 'OME, DIRTY DICK!"

A Grim Old Lady Opposite. And I only hope, my dear, you'll never be taken for any one less respectable.

[Collapse of Genteel Y.L.

First Humorous 'Arry (recognising a friend on entering). Excuse me stoppin' your kerridge, old man, but I thought you wouldn't mind givin' me a lift, as you was goin' my way.

Second H. 'A. Quite welcome, old chap, so long as you give my man a bit when you git down, yer know.

First H. 'A. Oh, o' course—that's expected between gentlemen.

(Both look round to see if their facetiousness is appreciated, find it is not and subside.)

The Conductor. Benk, benk! (he means "Bank") 'Oborn, benk! 'Igher up there, Bill, can't you?

A Dingy Man smoking, in a van. Want to block up the ole o' the road, eh? That's right!

The Conductor (roused to personality). Go 'ome, Dirty Dick! syme old soign, I see,—"Monkey an' Poipe!" (To Coachman of smart brougham which is pressing rather closely behind.) I say old man, don't you race after my bus like this—you'll only tire your 'orse.

[The Coachman affects not to have heard.

The Conductor (addressing the brougham horse, whose head is almost through the door of the omnibus). 'Ere, 'ang it all!—step insoide, if yer want to!

[Brougham falls to rear—triumph of Conductor as Scene closes.[ 19]

Scene—An upper floor in a City Warehouse; a low whitewashed room, dimly lighted by dusty windows and two gas-burners in wire cages. Around the walls are ranged several statues of meek aspect, securely confined in barred wooden cases, like a sort of marble menagerie. In the centre, a labyrinthine grove of pedestals, surmounted by busts, groups, and statuettes by modern Italian masters. About these pedestals a small crowd—consisting of Elderly Merchants on the look out for a "neat thing in statuary" for the conservatory at Croydon or Muswell Hill, Young City Men who have dropped in after lunch, Disinterested Dealers, Upholsterers' Buyers, Obliging Brokers, and Grubby and Mysterious men—is cautiously circulating.

Obliging Broker (to Amiable Spectator, who has come in out of curiosity, and without the remotest intention of purchasing sculpture). No Catlog, Sir? 'Ere, allow me to orfer you mine—that's my name in pencil on the top of it, Sir; and, if you should 'appen to see any lot that takes your fancy, you jest ketch my eye. (Reassuringly.) I sha'n't be fur off. Or look 'ere, gimme a nudge—I shall know what it means.

[The A. S. thanks him profusely, and edges away with an inward vow to avoid his and the Auctioneer's eyes, as he would those of a basilisk.

Auctioneer (from desk, with the usual perfunctory fervour). Lot 13, Gentlemen, very charming pair of subjects from child life—"The Pricked Finger" and "The Scratched Toe"—by Bimbi.

A Stolid Assistant (in shirtsleeves). Figgers 'ere, Gen'lm'n!

[Languid surge of crowd towards them.[ 20]

"FIGGERS 'ere, GEN'L'M'N!"

"FIGGERS 'ere, GEN'L'M'N!"

A Facetious Bidder. Which of 'em's the finger and which the toe?

Auct. (coldly). I should have thought it was easy to identify by the attitude. Now, Gentlemen, give me a bidding for these very finely-executed works by Bimbi. Make any offer. What will you give me for 'em? Both very sweet things, Gentlemen. Shall we say ten guineas?

A Grubby Man. Give yer five.

Auct. (with grieved resignation). Very well, start 'em at five. Any advance on five? (To Assist.) Turn 'em round, to show the back view. And a 'arf! Six! And a 'arf! Only six and a 'arf bid for this beautiful pair of figures, done direct from nature by Bimbi. Come, Gentlemen, come! Seven! Was that you, Mr. Grimes? (The Grubby Man admits the soft impeachment.) Seven and a 'arf. Eight! It's against you.

Mr. Grimes (with a supreme effort). Two-and-six!

[Mops his brow with a red cotton handkerchief.

Auct. (in a tone of gratitude for the smallest mercies). Eight-ten-six. All done at eight-ten-six? Going ... gone! Grimes, Eight, ten, six. Take money for 'em. Now we come to a very 'andsome work by Piffalini—"The Ocarina Player," one of this great artist's masterpieces, and an exceedingly choice and high-class work, as you will all agree directly you see it. (To Assist.) Now, then, Lot 14, there—look sharp!

Stolid Assist. "Hocarina Plier" eyn't arrived, Sir.

Auct. Oh, hasn't it? Very well, then. Lot 15. "The Pretty Pill-taker," by Antonio Bilio—a really magnificent work of Art, Gentlemen. ("Pill-taker, 'ere.!" from the S. A.) What'll you give me for her? Come, make me an offer. (Bidding proceeds till the "Pill-taker" is knocked down for twenty-three-and-a-half guineas.) Lot 16, "The Mixture as Before," by same artist—make a charming and suitable companion to the last lot. What do you say, Mr. Middleman—take it at the same bidding? (Mr. M. assents, with the end of one eyebrow.) Any advance on twenty-three and a 'arf? None? Then,—Middleman, Twenty-four, thirteen, six.

Mr. Middleman (to the Amiable Spectator, who has been vaguely inspecting the "Pill-taker"). Don't know if you noticed it, Sir, but I got that last couple very cheap—on'y forty-seven guineas the pair, and they are worth eighty, I solemnly declare to you. I could get forty a piece for[ 22] 'em to-morrow, upon my word and honour, I could. Ah, and I know who'd give it me for 'em, too!

The A. S. (sympathetically). Dear me, then you've done very well over it.

Mr. M. Ah, well ain't the word—and those two aren't the only lots I've got either. That "Sandwich-Man" over there is mine—look at the work in those boards, and the nature in his clay pipe; and "The Boot-Black," that's mine, too—all worth twice what I got 'em for—and lovely things, too, ain't they?

The A. S. Oh, very nice, very clever—congratulate you, I'm sure.

Mr. M. I can see you've took a fancy to 'em, Sir, and, when I come across a gentleman that's a connysewer, I'm always sorry to stand in his light; so, see here, you can have any one you like out o' my little lot, or all on 'em, with all the pleasure in the wide world, Sir, and I'll on'y charge you five per cent. on what I gave for 'em, and be exceedingly obliged to you, into the bargain, Sir. (The A. S. feebly disclaims any desire to take advantage of this magnanimous offer.) Don't say No, if you mean Yes, Sir. Will you 'ave "The Pill-taker," Sir?

The A. S. (politely). Thank you very much, but—er—I think not.

Mr. M. Then perhaps you could do with "The Little Boot-Black," or "The Sandwich-Man," Sir?

The A. S. Perhaps—but I could do still better without them.

[He moves to another part of the room.

The Obl. Broker (whispering beerily in his ear). Seen anythink yet as takes your fancy, Sir; 'cos, if so—

[The A. S. escapes to a dark corner—where he is warmly welcomed by Mr. Middleman.

Mr. M. Knew you'd think better on it, Sir. Now which is it to be—the "Boot-Black," or "Mixture as Before"?

Auct. Now we come to Lot 19. Massive fluted column in coral marble with revolving-top—a column, Gentlemen, which will speak for itself.

The Facetious Bidder (after a scrutiny). Then it may as well mention, while it's about it, that it's got a bit out of its back![ 23]

Auct. Flaw in the marble, that's all. (To Assist.) Nothing the matter with the column, is there?

Assist. (with reluctant candour). Well, it 'as got a little chipped, Sir.

Auct. (easily). Oh, very well then, we'll sell it "A. F." Very glad it was found out in time, I'm sure. [Bidding proceeds.

First Dealer to Second (in a husky whisper). Talkin' o' Old Masters, I put young 'Anway up to a good thing the other day.

Second D. (without surprise—probably from a knowledge of his friend's noble unselfish nature). Ah—'ow was that?

First D. Well, there was a picter as I 'appened to know could be got in for a deal under what it ought—in good 'ands, mind yer—to fetch. It was a Morlan'—leastwise, it was so like you couldn't ha' told the difference, if you understand my meanin'. (The other nods with complete intelligence.) Well, I 'adn't no openin' for it myself just then, so I sez to young 'Anway, "You might do worse than go and 'ave a look at it," I told him. And I run against him yesterday, Wardour Street way, and I sez, "Did yer go and see that picter?" "Yes," sez he, "and what's more, I got it at pretty much my own figger, too!" "Well," sez I, "and ain't yer goin' to shake 'ands with me over it?"

Second D. (interested). And did he?

First D. Yes, he did—he beyaved very fair over the matter, I will say that for him.

Second D. Oh, 'Anway's a very decent little feller—now.

Auct. (hopefully). Now, Gentlemen, this next lot'll tempt you, I'm sure! Lot 33, a magnificent and very finely executed dramatic group out of the "Merchant of Venice," Othello in the act of smothering Desdemona, both nearly life-size. (Assist., with a sardonic inflection. "Group 'ere, Gen'lm'n!") What shall we say for this great work by Roccocippi, Gentlemen? A hundred guineas, just to start us?

The F. B. Can't you put the two figgers up separate?

Auct. You know better than that—being a group, Sir. Come, come, any one give me a hundred for this magnificent marble group! The figure of Othello very finely finished, Gentlemen.[ 24]

The F. B. I should ha' thought it was her who was the finely finished one of the two.

Auct. (pained by this levity). Really, Gentlemen, do 'ave more appreciation of a 'igh-class work like this!... Twenty-five guineas?... Nonsense! I can't put it up at that.

[Bidding languishes. Lot withdrawn.

Second Disinterested Dealer (to First D. D., in an undertone). I wouldn't tell every one, but I shouldn't like to see you stay 'ere and waste your time; so, in case you was thinking of waiting for that last lot, I may just as well mention—

[Whispers.

First D. D. Ah, it's that way, is it? Much obliged to you for the 'int. But I'd do the same for you any day.

Second D. D. I'm sure yer would!

[They watch one another suspiciously.

Auct. Now 'ere's a tasteful thing, Gentlemen. Lot. 41. "Nymph eating Oysters" ("Nymph 'ere, Gen'lm'n!"), by the celebrated Italian artist Vabene, one of the finest works of Art in this room, and they're all exceedingly fine works of Art; but this is a truly work of Art, Gentlemen. What shall we say for her, eh? (Silence.) Why, Gentlemen, no more appreciation than that? Come, don't be afraid of it. Make a beginning. (Bidding starts.) Forty-five guineas. Forty-six—pounds. Forty-six pounds only, this remarkable specimen of modern Italian Art. Forty-six and a 'arf. Only forty-six ten bid for it. Give character to any gentleman's collection, a figure like this would. Forty-seven pounds—guineas! and a 'arf.... Forty-seven and a 'arf guineas.... For the last time! Bidding with you, Sir. Forty-seven guineas and a 'arf—Gone! Name, Sir, if you please. Oh, money? Very well. Thank you.

Proud Purchaser (to Friend, in excuse for his extravagance). You see, I must have something for that grotto I've got in the grounds.

His Friend. If she was mine, I should put her in the hall, and have a gaslight fitted in the oyster-shell.

P. P. (thoughtfully). Not a bad idea. But electric light would be more suitable, and easier to fix too. Yes—we'll see.[ 25]

The Obl. Broker (pursuing the Am. Spect.). I 'ope, Sir, you'll remember me, next time you're this way.

The Am. Spect. (who has only ransomed himself by taking over an odd lot, consisting of imitation marble fruit, a model, under crystal, of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and three busts of Italian celebrities of whom he has never heard). I'm afraid I sh'an't have very much chance of forgetting you. Good afternoon!

[Exit hurriedly, dropping the fruit, as Scene closes.[ 26]

IN THE CENTRAL HALL.

A Thrifty Visitor (on entering). Catalogue? No. What's the use of a Catalogue? Miserable thing, the size of a tract, that tells you nothing you don't know!

His Wife (indicating a pile of Catalogues on table). Aren't these big enough for you?

The Thr. V. Those? Why they're big enough for the London Directory! Think I'm going to drag a thing like that about the place? You don't really want a Catalogue—it's all your fancy!

Mr. Prattler (to Miss Ammerson). Oh, do stop and look at these sweet goldfish! Pets! Don't you love them? Aren't they tame?

Miss Ammerson. Wouldn't do to have them wild—might jump out and bite people, you know!

Mr. P. It's too horrid of you to make fun of my poor little enthusiasms! But really,—couldn't we get something and feed them?—Do let's!

Miss A. I dare say you could get ham-sandwiches in the Restaurant—or chocolates.

Mr. P. How unkind you are to me! But I don't care. (Wilfully.) I shall come here all by myself, and bring biscuits. Great big ones! Are you determined to take me into that big room with all the Portraits? Well you must tell me who they all are, then, and which are the Guelphiest ones.[ 27]

"PETS! DON'T YOU love THEM? Aren't THEY TAME?"

"PETS! DON'T YOU love THEM? Aren't THEY TAME?"

Considerate Niece (to Uncle). They seem mostly Portraits here. You're sure you don't mind looking at them, Uncle? I know so many people do object to Portraits.

Uncle (with the air of a Christian Martyr). No, my dear, no; I don't mind 'em. Stay here as long as you like. I'll sit down and look at the people till you've done.

First Critical Visitor (examining a View of St. James's Park). I wonder where that was taken. In Scotland, I expect—there's two Highlanders there, you see.

Second C. V. Shouldn't wonder—lot o' work in that, all those different colours, and so many dresses. [Admires, thoughtfully.

A Well-read Woman. That's Queen Charlotte, that is. George the Third's wife, you know—her that was so domestic.

Her Companion. Wasn't that the one that was shut up in the Tower, or something?

The W. W. In the Tower? Lor, my dear, no, I never 'eard of it. You're thinking of the Tudors, or some o' that lot, I expect!

Her Comp. Am I? I dare say. I never could remember 'Istry. Why, if you'll believe me, I always have to stop and think which of the Georges came first!

More Critical Visitors (before Portraits). He's rather pleasant-looking, don't you think? I don't like her face at all. So peculiar. And what a hideous dress—like a tea-gown without any upper part—frightful!

A Sceptical V. They all seem to have had such thin lips in those days. Somehow, I can't bring myself to believe in such very thin lips—can you, dear?

Her Friend. I always think it's a sign of meanness, myself.

The S. V. No; but I mean—I can't believe every one had them in the eighteenth century.

Her Friend. Oh, I don't know. If it was the fashion![ 29]

ABOUT THE CASES.

Visitor (admiring an embroidered waistcoat of the time of George the Second—a highly popular exhibit). What lovely work! Why, it looks as if it was done yesterday!

Her Companion (who is not in the habit of allowing his enthusiasm to run away with him). Um—yes, it's not bad. But, of course, they wouldn't send a thing like that here without having it washed and done up first!

An Old Lady. "Teapot used by the Duke of Wellington during his campaigns." So he drank tea, did he? Dear me! Do you know, my dear, I think I must have my old tea-pot engraved. It will make it so much more interesting some day!

IN THE SOUTH GALLERY.

Mr. Prattler (before a portrait of Lady Hamilton by Romney). There! Isn't she too charming? I do call her a perfect duck!

Miss Ammerson. Yes, you mustn't forget her when you bring those biscuits.

An Amurrcan Girl. Father, see up there; there's Byron. Did you erver see such a purrfectly beautiful face?

Her Father (solemnly). He was a beautiful Man—a beautiful Poet.

The A. G. I know—but the expression, it's real saint-like!

Father (slowly). Well, I guess if he'd had any different kind of expression, he wouldn't have written the things he did write, and that's a fact!

A Moralising Old Lady (at Case O). No. 1260. "Ball of Worsted wound by William Cowper, the poet, for Mrs. Unwin." No. 1261. "Netting done by William Cowper, the poet." How very nice, and what a difference in the habit of literary persons nowadays, my dear![ 30]

IN THE CENTRAL HALL.

Mr. Whiterose, a Jacobite fin de siècle, is seated on a Bench beside a Seedy Stranger.

The S. S. (half to himself). Har, well, there's one comfort, these 'ere Guelphs'll get notice to quit afore we're much older!

Mr. Whiterose (surprised). You say so? Then you too are of the Young England Party! I am rejoiced to hear it. You cheer me; it is a sign that the good Cause is advancing.

The S. S. Advancin'? I believe yer. Why, I know a dozen and more as are workin' 'art and soul for it!

Mr. W. You do? We are making strides, indeed! Our England has suffered these usurpers too long.

The S. S. Yer right. But we'll chuck 'em out afore long, and it'll be "Over goes the Show" with the lot, eh?

Mr. W. I had no idea that the—er—intelligent artisan classes were so heartily with us. We must talk more of this. Come and see me. Bring your friends—all you can depend upon. Here is my card.

The S. S. (putting the card in the lining of his hat). Right, Guv'nor; we'll come. I wish there was more gents like yer, I do!

Mr. W. We are united by a common bond. We both detest—do we not?—the Hanoverian interlopers. We are both pledged never to rest until we have brought back to the throne of our beloved England, her lawful sovereign lady—(uncovering)—our gracious Mary of Austria-Este, the legitimate descendant of Charles the Blessed Martyr!

The S. S. 'Old on, Guv'nor! Me and my friends are with yer so fur as doing away with these 'ere hidle Guelphs; but blow yer Mary of Orstria, yer know. Blow 'er!

Mr. W. (horrified). Hush—this is rank treason! Remember—she is the lineal descendant of the House of Stuart!

The S. S. What of it? There won't be no lineal descendants when we git hour way, 'cause there won't be nothing to descend to nobody. The honly suv'rin we mean to 'ave is the People—the Democrisy.[ 31] But there, you're young, me and my friends'll soon tork you over to hour way o' thinking. I dessay we 'aint fur apart, as it is. I got yer address, and we'll drop in on yer some night—never fear. No hevenin' dress, o' course?

Mr. W. Of course. I—I'll look out for you. But I'm seldom in—hardly ever, in fact.

The S. S. Don't you fret about that. Me and my friends ain't nothing partickler to do just now. We'll wait for yer. I should like yer to know ole Bill Gabb. You should 'ear that feller goin' on agin the Guelphs when he's 'ad a little booze—it 'ud do your 'art good. Well, I on'y come in 'ere as a deligate like, to report, and I seen enough. So 'ere's good-day to yer.

Mr W. (alone). I shall have to change my rooms—and I was so comfortable! Well, well,—another sacrifice to the Cause![ 32]

IN THE VESTIBULE.

Visitors ascending staircase, full of enthusiasm and energetic determination not to miss a single Picture, encounter people descending in various stages of mental and physical exhaustion. At the turnstiles two Friends meet unexpectedly; both being shy men, who, with timely notice, would have preferred to avoid one another, their greetings are marked by an unnatural effusion and followed by embarrassed silence.

First Shy Man (to break the spell). Odd, our running up against one another like this, eh?

Second Shy Man. Oh, very odd. (Looks about him irresolutely, and wonders if it would be decent to pass on. Decides it will hardly do.) Great place for meeting, the Academy, though.

First S. M. Yes; sure to come across somebody, sooner or later.

[Laughs nervously, and wishes the other would go.

Second S. M. (seeing that his friend lingers). This your first visit here?

First S. M. Yes. Couldn't very well get away before, you know.

[Feels apologetic, without exactly knowing why.

Second S. M. It's my first visit, too. (Sees no escape, and resigns himself.) Er—we may as well go round together, eh?

First S. M. (who was afraid this was coming—heartily). Good! By the way, I always think, on a first visit, it's best to take a single room, and do that thoroughly. [This has only just occurred to him.[ 33]

Second S. M. (who had been intending to follow that plan himself). Oh, do you? Now, for my part, I don't attempt to see anything thoroughly the first time. Just scamper through, glance at the things one oughtn't to miss, get a general impression, and come away. Then, if I don't happen to come again, I've always done it, you see. But (considerately), look here. Don't let me drag you about, if you'd rather not!

First S. M. Oh, but I shouldn't like to feel I was any tie on you. Don't you mind about me. I shall potter about in here—for hours, I dare say.

Second S. M. Ah, well (with vague consolation), I shall always know where to find you, I suppose.

First S. M. (brightening visibly). Oh dear, yes; I sha'n't be far away.

[They part with mutual relief, only tempered by the necessity of following the course they have respectively prescribed for themselves. Nemesis overtakes the Second S. M. in the next Gallery, when he is captured by a Desultory Enthusiast, who insists upon dragging him all over the place to see obscure "bits" and "gems," which are only to be appreciated by ricking the neck or stooping painfully.

A Suburban Lady (to Female Friend). Oh dear, how stupid of me! I quite forgot to bring a pencil! Oh, thank you, dear, that will do beautifully. It's just a little blunt; but so long as I can mark with it, you know. You don't think we should avoid the crush if we began at the end room? Well, perhaps it is less confusing to begin at the beginning, and work steadily through.

IN GALLERY NO. I.

A small group has collected before Mr. Wyllie's "Davy Jones's Locker," which they inspect solemnly for some time before venturing to commit themselves to any opinion.

First Visitor (after devoting his whole mind to the subject). Why, it's the Bottom of the Sea—at least (more cautiously), that's what it seems to be intended for.

Second V. Ah, and very well done, too. I wonder, now, how he managed to stay down long enough to paint all that?[ 34]

"CAPTURED BY A DESULTORY ENTHUSIAST."

"CAPTURED BY A DESULTORY ENTHUSIAST."

Third V. Practice, I suppose. I've seen writing done under water myself. But that was a tank!

Fourth V. (presumably in profound allusion to the fishes and sea-anemones). Well, they seem to be 'aving it all their own way down there, don't they?

[The Group, feeling that this remark sums up the situation, disperses.

The Suburban Lady (her pencil in full play). No. 93. Now what's that about? Oh, "Forbidden Sweets,"—yes, to be sure. Isn't that charming? Those two dear little tots having their tea, and the kitten with its head stuck in the jam-pot, and the label and all, and the sticky spoon on the nursery table-cloth—so natural! I really must mark that. (Awards this distinction.) 97. "Going up Top." Yes, of course. Look, Lucy dear, that little fellow has just answered a question, and his master tells him he may go to the top of the class, do you see? And the big boy looking so sulky, he's wishing he had learnt his lesson better. I do think it's so clever—all the different expressions. Yes, I shall certainly mark that!

IN GALLERY NO. II.

The S. L. (doubtfully). H'm, No. 156. "Cloud Chariots"? Not very like chariots, though, are they?

Her Friend. I expect it's one of those sort of pictures that you have to look at a long time, and then things gradually come out of it, you know.

The S. L. It may be. (Tries the experiment.) No, I can't make anything come out—only just clouds and their reflections. (Struggling between good-nature and conscientiousness.) I don't think I can mark that.

IN GALLERY NO. III.

A Matron (before Mr. Dicksee's "Tannhäuser"). "Venus and Tannhäuser"—ah, and is that Venus on the stretcher? Oh, that's her all on fire in the background. Then which is Tannhäuser, and what are they all supposed to be doing? [In a tone of irritation.

Her Nephew. Oh, it tells you all about it in the Catalogue—he meets her funeral, you know, and leaves grow on his stick.[ 36]

The Matron (pursing her lips). Oh, a dead person.

[Repulses the Catalogue severely and passes on.

First Person, with an "Eye for Art" (before "Psyche's Bath," by the President). Not bad, eh?

Second Person, &c. No, I rather like it. (Feels that he is growing too lenient). He doesn't give you a very good idea of marble, though.

First P. &c. No—that's not marble, and he always puts too many folds in his drapery to suit me.

First P. &c. Just what I always say. It's not natural, you know.

[They pass on, much pleased with themselves and one another.

A Fiancé (halting before a sea-scape, by Mr. Henry Moore, to Fiancée). Here, I say, hold on a bit—what's this one?

Fiancée (who doesn't mean to waste the whole afternoon over pictures). Why, it's only a lot of waves—come on!

The Suburban L. Lucy, this is rather nice. "Breakfasts for the Porth!" (Pondering). I think there must be a mistake in the Catalogue—I don't see any breakfast things—they're cleaning fish, and what's a "Porth!" Would you mark that—or not?

Her Comp. Oh, I think so.

The S. L. I don't know. I've marked such a quantity already and the lead won't hold out much longer. Oh, it's by Hook, R.A. Then I suppose it's sure to be all right. I've marked it, dear.

Duet by Two Dreadfully Severe Young Ladies, who paint a little on China. Oh, my dear, look at that. Did you ever see such a thing? Isn't it too perfectly awful? And there's a thing! Do come and look at this horror over here. A "Study," indeed. I should just think it was! Oh, Maggie, don't be so satirical, or I shall die! No, but do just see this—isn't it killing? They get worse and worse every year, I declare!

[And so on.

IN GALLERY NO. V.

Two Prosaic Persons come upon a little picture, by Mr. Swan, of a boy lying on a rock, piping to fishes.

First P. P. That's a rum thing![ 37]

Second P. P. Yes, I wasn't aware myself that fishes were so partial to music.

First P. P. They may be—out there—(perceiving that the boy is unclad)—but it's peculiar altogether—they look like herrings to me.

Second P. P. Yes—or mackerel. But (tolerantly) I suppose it's a fancy subject.

[They consider that this absolves them from taking any further interest in it, and pass on.

IN GALLERY NO. XI.

An Old Lady (who judges Art from a purely Moral Standpoint, halts approvingly before a picture of a female orphan). Now that really is a nice picture, my dear—a plain black dress and white cuffs—just what I like to see in a young person!

The S. L. (her enthusiasm greatly on the wane, and her temper slightly affected). Lucy, I wish you wouldn't worry so—it's quite impossible to stop and look at everything. If you wanted your tea as badly as I do! Mark that one? What, when they neither of them have a single thing on! Never, Lucy,—and I'm surprised at your suggesting it! Oh, you meant the next one? h'm—no, I can't say I care for it. Well, if I do mark it, I shall only put a tick—for it really is not worth a cross!

COMING OUT.

The Man who always makes the Right Remark. H'm. Haven't seen anything I could carry away with me.

His Flippant Friend. Too many people about, eh? Never mind, old chap, you may manage to sneak an umbrella down stairs—I won't say anything!

[Disgust of his companion, who descends stairs in offended silence, as scene closes.[ 38]

Time—About 3.30. Leaping Competition about to begin. The Competitors are ranged in a line at the upper end of the Hall while the attendants place the hedges in position. Amongst the Spectators in the Area are—a Saturnine Stableman from the country; a Cockney Groom; a Morbid Man; a Man who is apparently under the impression that he is the only person gifted with sight; a Critic who is extremely severe upon other people's seats; a Judge of Horseflesh; and Two Women who can't see as well as they could wish.

The Descriptive Man. They've got both the fences up now, d'ye see? There's the judges going to start the jumping; each rider's got a ticket with his number on his back. See? The first man's horse don't seem to care about jumping this afternoon—see how he's dancing about. Now he's going at it—there, he's cleared it! Now he'll have to jump the next one!

[Keeps up a running fire of these instructive and valuable observations throughout the proceedings.

The Judge of Horseflesh. Rare good shoulders that one has.

The Severe Critic (taking the remark to apply to the horse's rider). H'm, yes—rather—pity he sticks his elbows out quite so much, though.

[His Friend regards him in silent astonishment. Another Competitor clears a fence, but exhibits a considerable amount of daylight.

The Saturnine Stableman (encouragingly). You'll 'ev to set back a bit next journey, Guv'nor![ 39]

The Cockney Groom. 'Orses 'ud jump better if the fences was a bit 'igher.

The S. S. They'll be plenty 'oigh enough fur some on 'em.

The Severe Critic. Ugly seat that fellow has—all anyhow when the horse jumps.

Judge of Horseflesh. Has he? I didn't notice—I was looking at the horse. [Severe Critic feels snubbed.

The S. S. (soothingly, as the Competitor with the loose seat comes round again). That's not good, Guv'nor!

The Cockney Groom. 'Ere's a little bit o' fashion coming down next—why, there's quite a boy on his back.

The S. S. 'E won't be on 'im long if he don't look out. Cup an ball I call it!

The Morbid Man. I suppose there's always a accident o' some sort before they've finished.

First Woman. Oh, don't, for goodness' sake, talk like that—I'm sure I don't want to see nothing 'appen.

Second Woman. Well, you may make your mind easy—for you won't see nothing here; you would have it this was the best place to come to!

First Woman. I only said there was no sense in paying extra for the balcony, when you can go in the area for nothing.

Second Woman (snorting). Area, indeed! It might be a good deal airier than what it is, I'm sure—I shall melt if I stay here much longer.

The Morbid Man, There's one thing about being so close to the jump as this—if the 'orse jumps sideways—as 'osses will do every now and then—he'll be right in among us before we know where we are, and then there'll be a pretty how-de-do!

Second Woman (to her Friend). Oh, come away, do—it's bad enough to see nothing, let alone having a great 'orse coming down atop of us, and me coming out in my best bonnet, too—come away! [They leave.

The Descriptive Man. Now, they're going to make 'em do some in-and-out jumping, see? they're putting the fences close[ 40] together—that'll puzzle some of them—ah, he's over both of 'em; very clean that one jumps! Over again! He's got to do it all twice, you see.

The Judge of Horseflesh. Temperate horse, that chestnut.

The Severe Critic. Is he, though?—but I suppose they have to be here, eh? Not allowed champagne or whiskey or anything before they go in—like they are on a race-course?

The J. of H. No, they insist on every horse taking the pledge before they'll enter him.

The Descriptive Man. Each of 'em's had a turn at the in-and-out jump now. What's coming next? Oh, the five-barred gate—they're going over that now, and the stone wall—see them putting the bricks on top? That's to raise it.

The Morbid Man. None of 'em been off yet; but (hopefully) there'll be a nasty fall or two over this business—there's been many a neck broke over a lower gate than that.

[A Competitor clears the gate easily, holding the reins casually in his right hand.

The J. of H. That man can ride.

The Severe Critic. Pretty well—not what I call business, though—going over a gate with one hand, like that.

The J. of H. Didn't know you were such an authority.

The S. C. (modestly). Oh, I can tell when a fellow has a good seat. I used to ride a good deal at one time. Don't get the chance much now—worse luck!

The J. of H. Well, I can give you a chance, as it happens. (Severe Critic accepts with enthusiasm, and the inward reflection that the chance is much less likely to come off than he is himself.) You wait till the show is over, and they let the horses in for exercise. I know a man who's got a cob here—regular little devil to go—bucks a bit at times—but you won't mind that. I'll take you round to the stall and get my friend to let you try him on the tan. How will that do you, eh?

The Severe Critic (almost speechless with gratitude). Oh—er—it[ 41] will do me right enough—capital! That is—it would, if I hadn't an appointment, and had my riding things on, and wasn't feeling rather out of sorts, and hadn't promised to go home and take my wife in the Park, and it's her birthday, too, and, then, I've long made it a rule never to mount a strange horse, and—er—so you understand how it is don't you?

The J. of H. Quite, my dear fellow. (As, for that matter, he has done from the first.)

The Cockney Groom (alluding to a man who is riding at the gate). 'Ere's a rough 'un this bloke's on! (Horse rises at gate; his rider shouts "Hoo, over!" and the gate falls amidst general derision.) Over? Ah, I should just think it was over!

The Saturnine Stableman (as horseman passes). Yer needn't ha' "Hoo'd" for that much!

[The Small Boy, precariously perched on an immense animal, follows; his horse, becoming unmanageable, declines the gate, and leaps the hurdle at the side.

The S. S. Ah, you're a artful lad, you are—thought you'd take it where it was easiest, eh?—you'll 'ev to goo back and try agen you will.

Chorus of Sympathetic Bystanders. Take him at it again, boy; you're all right!... Hold him in tighter, my lad.... Let out your reins a bit! Lor, they didn't ought to let a boy like that ride.... He ain't no more 'old on that big 'orse than if he was a fly on him!... Keep his 'ed straighter next time.... Enough to try a boy's nerve! &c., &c.

[The Boy takes the horse back, and eventually clears the gate amidst immense and well-deserved applause.

The Morbid Man (disappointed). Well, I fully expected to see 'im took off on a shutter.

The Descriptive Man. It's the water-jump next—see; that's it in the middle; there's the water, underneath the hedge; they'll have to clear the 'ole of that—or else fall in and get a wetting. They've taken all the[ 42] horses round to the other entrance—they'll come in from that side directly.

"HE EXPECTED THERE WOULD HAVE BEEN MORE TO SEE."

"HE EXPECTED THERE WOULD HAVE BEEN MORE TO SEE."

[One of the Judges holds up his stick as a signal; wild shouts of "Hoy-hoy! Whorr-oosh!" from within, as a Competitor dashes out and clears hedge and ditch by a foot or two. Deafening applause. A second horseman rides at it, and lands—if the word is allowable—neatly in the water. Roars of laughter as he scrambles out.

The Morbid Man. Call that a brook! It ain't a couple of inches deep—it's more mud than water! No fear (he means "no hope") of any on 'em getting a ducking over that!

[And so it turns out; the horses take the jump with more or less success, but without a single saddle being vacated. The proceedings terminate for the afternoon amidst demonstrations of hearty satisfaction from all but The Morbid Man, who had expected there would have been "more to see."

The Hostess is receiving her Guests at the head of the staircase; a Conscientiously Literal Man presents himself.

Hostess (with a gracious smile, and her eyes directed to the people immediately behind him). So glad you were able to come—how do you do?

The Conscientiously Literal Man. Well, if you had asked me that question this afternoon, I should have said I was in for a severe attack of malarial fever—I had all the symptoms—but, about seven o'clock this evening, they suddenly passed off, and—

[Perceives, to his surprise, that his Hostess's attention is wandering, and decides to tell her the rest later in the evening.

Mr. Clumpsole. How do you do, Miss Thistledown? Can you give me a dance?

Miss Thistledown (who has danced with him before—once). With pleasure—let me see, the third extra after supper? Don't forget.

Miss Bruskleigh (to Major Erser). Afraid I can't give you anything just now—but if you see me standing about later on, you can come and ask me again, you know.

Mr. Boldover (glancing eagerly round the room as he enters, and soliloquising mentally). She ought to be here by this time, if she's coming—can't see her though—she's certainly not dancing. There's her sister over there with the mother. She hasn't come, or she'd be with them. Poor-looking lot of girls here to-night—don't think much of this music—get away as soon as I can, no go about the thing!... Hooray! There she is, after all! Jolly waltz this is they're playing! How pretty she's looking—how pretty all the girls are looking! If I can only get her to[ 45] give me one dance, and sit out most of it somewhere! I feel as if I could talk to her to-night. By Jove, I'll try it!

[Watches his opportunity, and is cautiously making his way towards his divinity, when he is intercepted.

Mrs. Grappleton. Mr. Boldover, I do believe you were going to cut me! (Mr. B. protests and apologises.) Well, I forgive you. I've been wanting to have another talk with you for ever so long. I've been thinking so much of what you said that evening about Browning's relation to Science and the Supernatural. Suppose you take me down stairs for an ice or something, and we can have it out comfortably together.

[Dismay of Mr. B., who has entirely forgotten any theories he may have advanced on the subject, but has no option but to comply; as he leaves the room with Mrs. Grappleton on his arm, he has a torturing glimpse of Miss Roundarm, apparently absorbed in her partner's conversation.

Mr. Senior Roppe (as he waltzes). Oh, you needn't feel convicted of extraordinary ignorance, I assure you, Miss Featherhead. You would be surprised if you knew how many really clever persons have found that simple little problem of nought divided by one too much for them. Would you have supposed, by the way, that there is a reservoir in Pennsylvania containing a sufficient number of gallons to supply all London for eighteen months? You don't quite realize it, I see. "How many gallons is that?" Well, let me calculate roughly—taking the population of London at four millions, and the average daily consumption for each individual at—no, I can't work it out with sufficient accuracy while I am dancing; suppose we sit down, and I'll do it for you on my shirt-cuff—oh, very well; then I'll work it out when I get home, and send you the result to-morrow, if you will allow me.

Mr. Culdersack (who has provided himself beforehand with a set of topics for conversation—to his partner, as they halt for a moment). Er—(consults some hieroglyphics on his cuff stealthily)—have you read Stanley's book yet?

Miss Tabula Raiser. No, I haven't. Is it interesting?

Mr. Culdersack. I can't say. I've not seen it myself. Shall we—er—?

[They take another turn.[ 46]

"ER—" (CONSULTS SOME HIEROGLYPHICS ON HIS CUFF STEALTHILY).

"ER—" (CONSULTS SOME HIEROGLYPHICS ON HIS CUFF STEALTHILY).

Mr. C. I suppose you have—er—been to the (hesitates between the Academy and the Military Exhibition—decides on latter topic as fresher) Military Exhibition?

Miss T. R. No—not yet. What do you think of it?

Mr. C. Oh—I haven't been either. Er—do you care to—?

[They take another turn.

Mr. C. (after third halt). Er—do you take any interest in politics?

Miss T. R. Not a bit.

Mr. C. (much relieved). No more do I. (Considers that he has satisfied all mental requirements.) Er—let me take you down stairs for an ice.

[They go.

Mrs. Grappleton (re-entering with Mr. Boldover, after a discussion that has outlasted two ices and a plate of strawberries). Well, I thought you would have explained my difficulties better than that—oh, what a delicious waltz! Doesn't it set you longing to dance?

Mr. B. (who sees Miss Roundarm in the distance, disengaged). Yes, I really think I must—. [Preparing to escape.

Mrs. Grappleton. I'm getting such an old thing, that really I oughtn't to—but well, just this once, as my husband isn't here.

[Mr. Boldover resigns himself to necessity once more.

First Chaperon (to second ditto). How sweet it is of your eldest girl to dance with that absurd Mr. Clumpsole! It's really too bad of him to make such an exhibition of her—one can't help smiling at them!

Second Ch. Oh, Ethel never can bear to hurt any one's feelings—so different from some girls! By the way, I've not seen your daughter dancing to-night—men who dance are so scarce nowadays—I suppose they think they have the right to be a little fastidious.

First Ch. Bella has been out so much this week, that she doesn't care to dance except with a really first-rate partner. She is not so easily pleased as your Ethel, I'm afraid.

Second Ch. Ethel is young, you see, and, when one is pressed so much to dance, one can hardly refuse, can one? When she has had as many seasons as Bella, she will be less energetic, I dare say.[ 48]

[Mr. Boldover has at last succeeded in approaching Miss Roundarm, and even in inducing her to sit out a dance with him; but, having led her to a convenient alcove, he finds himself totally unable to give any adequate expression to the rapture he feels at being by her side.

Mr. B. (determined to lead up to it somehow). I—I was rather thinking—(he meant to say, "devoutly hoping," but, to his own bitter disgust, it comes out like this)—I should meet you here to-night.

Miss R. Were you? Why?

Mr. B. (with a sudden dread of going too far just yet). Oh (carelessly), you know how one does wonder who will be at a place, and who won't.

Miss R. No, indeed, I don't—how does one wonder?

Mr. B. (with a vague notion of implying a complimentary exception in her case). Oh, well, generally—(with the fatal tendency of a shy man to a sweeping statement)—one may be pretty sure of meeting just the people one least wants to see, you know.

Miss R. And so you thought you would probably meet me. I see.

Mr. B. (overwhelmed with confusion, and not in the least knowing what he says). No, no, I didn't think that—I hoped you mightn't—I mean, I was afraid you might—

[Stops short, oppressed by the impossibility of explaining.

Miss R. You are not very complimentary to-night, are you?

Mr. B. I can't pay compliments—to you—I don't know how it is, but I never can talk to you as I can to other people!

Miss R. Are you amusing when you are with other people?

Mr. B. At all events I can find things to say to them.

Enter Another Man.

Another Man (to Miss R.). Our dance, I think?

Miss R. (who had intended to get out of it). I was wondering if you ever meant to come for it. (To Mr. B., as they rise.) Now I sha'n't feel I am depriving the other people! (Perceives the speechless agony in his expression, and relents.) Well, you can have the next after this if you care[ 49] about it—only do try to think of something in the meantime! (As she goes off.) You will—won't you?

Mr. B. (to himself). She's given me another chance! If only I can rise to it. Let me see—what shall I begin with? I know—Supper! She hasn't been down yet.

His Hostess. Oh, Mr. Boldover, you're not dancing this—do be good and take some one down to supper—those poor Chaperons are dying for some food.

[Mr. B. takes down a Matron whose repast is protracted through three waltzes and a set of Lancers—he comes up to find Miss Roundarm gone, and the Musicians putting up their instruments.

Coachman at Door (to Linkman, as Mr. B. goes down the steps). That's the lot, Jim!

[Mr. B. walks home, wishing the Park Gates were not shut, so as to render the Serpentine inaccessible.[ 50]

IN THE SCULPTURE GALLERIES.

Sightseers discovered drifting languidly along in a state of depression, only tempered by the occasional exercise of the right of every free-born Briton to criticize whenever he fails to understand. The general tone is that of faintly amused and patronizing superiority.

A Burly Sightseer with a red face (inspecting group representing "Mithras Sacrificing a Bull"). H'm; that may be Mithras's notion of making a clean job of it, but it ain't mine!

A Woman (examining a fragment from base of sculptured column with a puzzled expression as she reads the inscription). "Lower portion of female figure—probably a Bacchante." Well, how they know who it's intended for, when there ain't more than a bit of her skirt left, beats me!

Her Companion. Oh, I s'pose they've got to put a name to it o' some sort.

An Intelligent Artisan (out for the day with his FIANCÉE—reading from pedestal). "Part of a group of As—Astrala—no, Astraga—lizontes"—that's what they are, yer see.

Fiancée. But who were they?

The I. A. Well, I can't tell yer—not for certain; but I expect they'd be the people who in'abited Astragalizontia.

Fiancée. Was that what they used to call Ostralia before it was discovered? (They come to the Clytie bust.) Why, if that isn't the same[ 51] [ 52] head Mrs. Meggles has under a glass shade in her front window, only smaller—and hers is alabaster, too! But fancy them going and copying it, and I dare say without so much as a "by your leave," or a "thank you!"

"H'M; THAT MAY BE MITHRAS'S NOTION OF MAKING A CLEAN JOB OF IT,

BUT IT AIN'T mine!"

"H'M; THAT MAY BE MITHRAS'S NOTION OF MAKING A CLEAN JOB OF IT,

BUT IT AIN'T mine!"

The I. A. (reading). "Portrait of Antonia, sister-in-law of the Emperor Tiberius, in the character of Clytie turning into a sunflower."

Fiancée. Lor! They did queer things in those days, didn't they? (Stopping before another bust.) Who's that?

The I. A. 'Ed of Ariadne.

Fiancée (slightly surprised). What!—not young Adney down our street? I didn't know as he'd been took in stone.

The I. A. How do you suppose they'd 'ave young Adney in among this lot—why, that's antique!

Fiancée. Well, I was thinking it looked more like a female. But if it's meant for old Mr. Teak the shipbuilder's daughter, it flatters her up considerable; and, besides, I always understood as her name was Betsy.

The I. A. No, no; what a girl you are for getting things wrong! that 'ed was cut out years and years ago!

Fiancée. Well, she's gone off since, that's all; but I wonder at old Mr. Teak letting it go out of the family, instead of putting it on his mantelpiece along with the lustres, and the two chiny dogs.

The A. I. (with ungallant candour). 'Ark at you! Why you 'ain't much more sense nor a chiny dog yourself!

Moralizing Matron (before the Venus of Ostia). And to think of the poor ignorant Greeks worshipping a shameless hussey like that! It's a pity they hadn't some one to teach them more respectable notions! Well, well! it ought to make us thankful we don't live in those benighted times, that it ought!

A Connoisseur (after staring at a colossal Greek lion). A lion, eh? Well, it's another proof to my mind that the ancients hadn't got very far in the statuary line. Now, if you want to see a stone lion done true to Nature, you've only to walk any day along the Euston Road.

A Practical Man. I dessay it's a fine collection, enough, but it's[ 53] a pity the things ain't more perfect. I should ha' thought, with so many odds and ends and rubbish lying about as is no use to nobody at present they might ha' used it up in mending some that only requires a 'arm 'ere or a leg there, or a 'ed and what not, to make 'em as good as ever. But ketch them (he means the Officials) taking any extra trouble if they can help it!

His Companion. Ah, but yer see it ain't so easy fitting on bits that belonged to something different. You've got to look at it that way.

The P. M. I don't see no difficulty about it. Why, any stonemason could cut down the odd pieces to fit well enough, and they wouldn't have such a neglected appearance as they do now.

A Group has collected round a Gigantic Arm in red granite.

First Sightseer. There's a arm for yer!

Second S. (a humourist). Yes; 'ow would yer like to 'ave that come a punching your 'ed?

Third S. (thoughtfully). I expect they've put it up 'ere as a sarmple like.

The Moralizing Matron. How it makes one realize that there were giants in those days!

Her Friend. But surely the size must be a little exaggerated, don't you think? Oh, is this the God Ptah?

[The M. M. says nothing, but clicks her tongue to express a grieved pity, after which she passes on.

The Intelligent Artisan and his Fiancée have entered the Nineveh Gallery, and are regarding an immense human-headed, winged bull.

The I. A. (indulgently). Rum-looking sort o' beast that 'ere.

Fiancée. Ye-es—I wonder if it's a likeness of some animal they used to 'ave then?

The I. A. I did think you was wider than that!—it's only imaginative. What 'ud be the good o' wings to a bull?

Fiancée (on her defence). You think you know so much—but it's[ 54] got a man's 'ed, ain't it? and I know there used to be 'orses with 'alf a man where the 'ed ought to be, because I've seen their pictures—so there!

The I. A. I dunno what you've got where your 'ed ought to be, torking such rot!

IN THE UPPER GALLERIES; ETHNOGRAPHICAL COLLECTION.

The Grim Governess (directing a scared small boy's attention to a particularly hideous mask). See, Henry, that's the kind of mask worn by savages!

Henry. Always—or only on the fifth of November, Miss Goole?

[He records a mental vow never to visit a Savage Island on Guy Fawkes's Day, and makes a prolonged study of the mask, with a view to future nightmares.

A Kind, but Dense Uncle (to Niece). All these curious things were made by cannibals, Ethel—savages who eat one another, you know.

Ethel (suggestively). But, I suppose, Uncle, they wouldn't eat one another if they had any one to give them buns, would they?

[Her Uncle discusses the suggestion elaborately, but without appreciating the hint; the Governess has caught sight of a huge and hideous Hawaiian Idol, with a furry orange-coloured head, big mother-o'-pearl eyes, with black balls for the pupils, and a grinning mouth picked out with shark's teeth, to which she introduces the horrified Henry.

Miss Goole. Now, Henry, you see the kind of idol the poor savages say their prayers to.

Harry (tremulously). But n—not just before they go to bed, do they, Miss Goole?

AMONG THE MUMMIES.

The Uncle. That's King Rameses' mummy, Ethel.