The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Crooked Mile, by Oliver Onions This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: A Crooked Mile Author: Oliver Onions Release Date: October 1, 2011 [EBook #37584] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A CROOKED MILE *** Produced by Judith Wirawan, Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

| PART I | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | The Witan | 1 |

| II | The Pond-Room | 17 |

| III | The "Novum" | 33 |

| IV | The Stone Wall | 51 |

| V | Three Ships | 76 |

| VI | Policy | 98 |

| PART II | ||

| I | The Pigeon Pair | 119 |

| II | The 'Vert | 132 |

| III | The Imperialists | 148 |

| IV | The Outsiders | 171 |

| V | "House Full" | 189 |

| VI | The Soul Storm | 210 |

| PART III | ||

| I | Litmus | 239 |

| II | By the Way | 254 |

| III | De Trop | 274 |

| IV | Grey Youth | 285 |

| Tailpiece | 307 |

Lady Tasker had missed her way in the Tube. She had been on, or rather under known ground on the Piccadilly Railway as far as Leicester Square, but after that she had not heard, or else had forgotten, that in order to get to Hampstead by the train into which she had stepped she must change at Camden Town. Or perhaps she had merely wondered what Camden Town supposed itself to be that she should put herself to the trouble of changing there. With the newspaper held at arm's length, and a little figure-8-shaped gold glass moving slightly between her puckered old eyes and the page, she was reading the "By the Way" column of the "Globe."—"All change," called the man at Highgate; and, still unconscious of her mistake, Lady Tasker left the train. She was the last to enter the lift. But for an unhurried raising of the little locket-shaped glass as the attendant fidgeted at the half-closed gate she might have been the first to enter the next lift.

Only from the policeman outside Highgate Station[Pg 2] did she learn that she must either take the Tube back again to Camden Town or else walk across the Heath.

Now Lady Tasker was seventy, and, with the exception of the Zoo, a place she visited from time to time with troops of turbulent great-nephews, the whole of North London was a sort of Camden Town to her, that is to say, she had no objection to its existence so long as it wasn't troublesome. It was half-past three when she said as much to the Highgate policeman, who up to that time had been an ordinary easy-going Conservative; by five-and-twenty minutes to four she had made of him a fuming Radical. He was saying something about South Square and Merton Lane. Lady Tasker addressed the bracing Highgate air in one of those expressionless and semi-ventriloquial asides that, especially in a mixed company, always made her ladyship very well worth sitting next to.

"Merton Lane! Does the man suppose that conveys anything to me?.... I want to know how to get to Hampstead, not the names of the objects of interest on the way!"

The newly-made Radical told her that there might be a taxi on the rank, and turned away to cuff the ears of an urchin who was tampering with an automatic machine. It was a wonder that Lady Tasker's glare, focussed through the gold-rimmed glass on a point between his shoulder-blades, did not burn a hole in his tunic.

Taxis at eightpence a mile, indeed, with the house at Ludlow already full of those children of Churchill's, and three of Tony's little girls eating[Pg 3] their way through the larder in Cromwell Gardens, and young Tommy, Emily's boy, who had just "pulled" his captaincy, arriving at Southampton in the "Seringapatam" on Saturday with another batch for her to take under her wing! Did people suppose she was made of money?...

The policeman's tunic was just beginning to scorch when Lady Tasker, dropping the glass, turned away and set out for Hampstead on foot.

She might very well have been excused had she omitted to return Mrs. Cosimo Pratt's call. Indeed she had vowed that very morning that nothing should drag her up to Hampstead that day. But for twenty times that Lady Tasker said "I will not," nineteen she repented and went, taking out the small change of her magnanimity when she got there. And after all, she would be killing two birds with one stone, for her niece Dorothy also lived somewhere in this northern Great Karroo, and unless she got these things over before the "Seringapatam" dropped anchor on Saturday there was no knowing when next she would have an hour to call her own. As she turned (after a brush with a second policeman, who summed her up quite wrongly on the strength of her antiquated pelisse and trailing old Victorian hat) down Merton Lane to the ponds, she told herself again that she was a foolish old woman to have come at all.

For the Cosimo Pratts were not bosom friends of hers. True, they had been, until six months ago, her neighbours at Ludlow, and for that matter she had known young Cosimo's people for the greater[Pg 4] part of her life: but she had not forgotten the hearty blackguarding the young couple had got, any time this last two years, from the rest of the country-side. Small wonder. What else did they expect, after the way in which they had made farm-labour too big for its jacket and beaters hardly to be had for love or money? Not that Lady Tasker herself had seen very much of their antics. Great-nieces and nephews had kept her too busy for that, and she was moreover wise enough not to believe all she heard. And even were it true, that, she now told herself, had been in the country. They would have to behave differently now that they had let the Shropshire house and had come to live in town. They could hardly dance barefoot round a maypole in Hampstead, or stage-manage the yearly Hiring-Fair for the sake of the "Daily Speculum" photographer (as they had done in Ludlow), or group themselves picturesquely about the feet of the oldest inhabitant while that shocking old reprobate with the splendid head recited (at five shillings an hour) the stories of old, unhappy, far-off things he had learned by heart from the booklets they had printed at the Village Press. No: in London they would almost certainly have to do as other people did, and Shropshire, after its three years of social and artistic awakening, would no doubt forget all about the æsthetic revival and would sink back into a well-earned rest.

It was a Thursday afternoon in September, warm for the time of the year, and a half-day closing for the shops. Had Lady Tasker remembered[Pg 5] the half-holiday she certainly would not have come. She hated crowds, and, if you would believe her, had no illusions whatever about the sanctity of our common nature and the brotherhood of man. She would tell you roundly that there was far too much aimless good-nature in the world, and that every sob wasted over a sinner was something taken away from the man who, if he was a sinner too, had at least the decency to keep up appearances. And so much for brotherhood. Great-nephewship, of course, was another matter. Somebody had to look after all those youngsters, and if her sister Eliza, the one at Spurrs, went into a tantrum about every bud that was picked in the gardens and every chair-leg that was an inch out of its place in the house, so much the worse for Lady Tasker, who must walk because she had something else to do with her money than to waste it on taxis.

She had been told by her niece Dorothy to look out for a clump of tall willows and an ivied chimney; that was where the Pratts lived; but Dorothy had spoken of the approach from the Hampstead side, not from Highgate way. Lady Tasker got lost. She was almost dropping for want of a cup of tea, and the Heath seemed all willows, and all the wrong ones. No policeman, Radical or Conservative, was to be seen. Walking across an apparently empty space, well away (as she thought) from a horde of shouting boys, the old lady suddenly found herself enveloped in a game of football. This completed her exhaustion. Near[Pg 6] by, one of Messrs. Libertys' carts was ascending a steep road at a slow walk; somehow or other Lady Tasker managed to get her hand on the tail of it; and the car gave her a tow. She was seventy after all.

As it happened, that was her first piece of luck in a luckless afternoon. The cart drew on to the left; Lady Tasker trailed after it; and suddenly it stopped before a high privet hedge with a closed green door in the middle of it. Lady Tasker did not look for the ivied chimney. On the door was painted in white letters "The Witan." She was where she wanted to be.

Ordinarily Lady Tasker would have approved of the height of the privet hedge, which was seven or eight feet; that was a nice, reassuring, anti-social height for a hedge; but as it was she could not even put up her hand to the bell. The carter rang it for the pair of them. Over the hedge came the low murmur of voices and the clink of cups and saucers, and then the door was opened. It was opened by the mistress of the house. No doubt Mrs. Pratt had expected the cart, had heard its drawing up, and had not waited for a maid to come. Her eyes sought the carman, who had stepped aside. She spoke with some asperity.

"It's Libertys', isn't it?" she said. "Well, I've a very good mind to make you take it back. It was promised for yesterday."

"Can't say, I'm sure, m'm."

"It's always the same. Every time I——"

Then she saw her visitor, and gave a little start.[Pg 7]

"Why, it's Lady Tasker! How delightful! Do come in! And do just excuse me—I shan't be a minute.... Why didn't this come yesterday? It was promised faithfully——"

She stepped outside to scold the carman, leaving Lady Tasker standing just within the green door.

The altercation was plainly audible:

"Very sorry, m'm. You see——"

"I will see, if it occurs again——"

"The orders is taken as they come, m'm——"

"They said the first delivery——"

"We wasn't loaded till one o'clock——"

"That's none of my business——"

"Very sorry, m'm——"

"Well, the next time it occurs——"

And so forth.

Now in reading what happened the next moment you must remember that Lady Tasker was very, very tired. Had she been less tired she might have wondered why one of the two maids she saw crossing to the tea-table under the copper beech had not been allowed to take in Mrs. Cosimo Pratt's parcel. And she would certainly have thought it extraordinary that she should be left standing alone while Mrs. Cosimo Pratt scolded the carrier, and wanted to know why the parcel had not been brought yesterday. But, tired as she was, her eyes had already rested on something that had momentarily galvanized even the weariness out of her. It was this:—

Seven or eight people sat in basket-chairs or stood talking; and, under the copper beech, as if[Pg 8] Mrs. Pratt had just slid out of it, a hammock of coloured string still moved, slung from the beech to a sycamore beyond. Lady Tasker saw these things at once; she did not at once see what it was that stood just beyond the hammock.

Then it moved, and Lady Tasker raised her glass.

No doubt you have seen the cover of Mr. Wells's "Invisible Man." It will be remembered that all that can be seen of that afflicted person is his clothes; and all that Lady Tasker at first saw of the Invisible Man by the copper beech was his clothes. These were of light yellow tussore, with a white double collar and a small red tie, sharp-edged white cuffs and highly polished brown boots. At collar and cuffs the man ended.

And yet he did not end, for the lenses of a pair of spectacles made lurking lights in the shadow of the beech, a few inches above the white collar.

The phantom wore no hat.

Then Lady Tasker, suddenly pale, dropped her glass. Between the collar and the spectacles a white gash of teeth had appeared. The Invisible Man had smiled, and at the same moment there had shown round the bole of the beech a second smoky shape, this one without teeth, but with white and mobile eyes instead.

Lady Tasker was in the presence of two Hindoos.

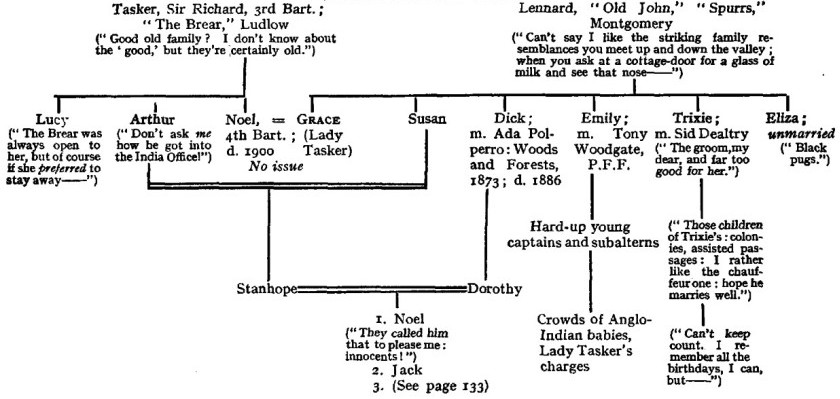

Now all her life, and long before her life for that matter, Lady Tasker had been accustomed ... but no: that is not the way to put it. The following table will save many words:

You see how it was, and had to be. Not only was Lady Tasker insular, arrogant, and of opinion that Saint Paul made the mistake of his life when he set out to preach the Gospel to all nations, but she made a virtue of her narrowness and defect. Show her a finger-nail with a purple half-moon, and you no longer saw a charming if acid-tongued old English lady, who cut timber in order to pay for governesses for those grandchildren of Emily's and sent, under guise of birthday gifts, useful little cheques to the descendants of her brother-in-law the groom. Babu or Brahmin, all were the same to her. No defence is offered of an attitude so indefensible. Such people do still exist. Let us sigh for their narrowness of mind, and pass on.

The smile of the first Hindoo was for Mrs. Pratt, who had got her row with the carman over and had reappeared behind Lady Tasker and closed the door of The Witan again. Her face, pretty and finished as a miniature, and the great chestnut-red helm of her hair, showed over the slant of the box in her arms. "Do excuse me, just one moment!" she said, smiling at Lady Tasker as she passed; and she ran off into the house, her mistletoe-berry white robe with its stencilling of grey-green whipping about her heels as she did so. And fortunately, as she ran in at the door, Cosimo Pratt came out of the French window, saw Lady Tasker, and strode to her. He broke into rapid and hearty speech.

"You here! How delightful!—Amory!—I didn't hear you come! So kind of you!—Amory,[Pg 11] where are you?—How are you? Do let me get you some tea!—Amory!——"

Lady Tasker spoke faintly.—"I should like," she said, "to go into the house."

"Rather! Hang on to my arm.—Amory! Where is that girl?—Sure you won't have tea outside? I can find you a nice shady place under the beech——"

Lady Tasker closed her eyes.—"Please take me in."

"Tube headache? I hate the beastly thing. I thought you were in Ludlow. Charming of you——"

And he led Lady Tasker into the house.

This was a low building of stucco, with slatted window-shuts which, like the sashes of the slightly bowed French window and of the two windows beyond, were newly painted green. This painting seemed rather to emphasize than to mitigate a certain dogseared look the place had, not amounting to dilapidation, but enough to make it probable that Cosimo Pratt had taken it on a repairing lease. The copper beech, the high privet hedge and the willows beyond it, shut out both light and air. The fan-lighted door had two electric bell buttons, with little brass plates. The upper plate read, "Mr. Cosimo Pratt"; the lower one "Miss Amory Towers (Studio)."

But Lady Tasker noticed none of these things. In the hall she sank into the first chair she came to. "Tea, please," she said faintly; and Cosimo dashed out to get it. He returned, and began to[Pg 12] murmur something sympathetic, but Lady Tasker made a little movement with her hand. She didn't want him to "send Amory." She only wanted to rest her tired legs and to collect her dispersed thoughts.

An eight-foot hedge, not to shut the populace out, but to shut Indians in! And she, Lady Tasker, had been kept standing while some parcel or other had been taken into the house—standing, and watching a still-moving hammock with a smiling Invisible Man bending over it! Was this England, or a Durbar?... And even yet her hostess didn't come to ask her if she felt better!... Not that Lady Tasker was greatly surprised at that. She knew that Mrs. Pratt was quite capable of reasoning that the greatest respect is shown to a tired old lady when no fuss is made about her tiredness. The Pratts were like that—full of delicacies so subtle that plain folk never noticed them, but jumped instead to the conclusion that they were bad-mannered. And it would not in the least surprise Lady Tasker if, presently, Mrs. Pratt allowed her to leave without a word about her indisposition. Of course: Lady Tasker had a little forgotten the Pratts at Ludlow. That would be it: "Good-bye—and do come again!" She could see Mrs. Pratt's pretty brook-brown eyes did anybody (say a Japanese or an Ethiopian) point out this so-called omission to her. She could see the surprise in them. She could hear her earnest voice: "Say these things!... Why, does she suppose I was glad then?"...[Pg 13]

Yes, Lady Tasker had a little forgotten her Pratts.

It was an odd little hall in which she sat. It appeared to be an approach to the studio of which the electric bell gave notice, for it was continued by a narrower passage that led to a garden at the back; and either the studio "properties" were gradually thrusting the hatstand and hall table out of the fan-lighted front door, or else these latter ordinary and necessary objects were fighting as it were for admission. Thus, the chair on which Lady Tasker sat was of oak, but it had a Faust-like look; beyond it stood a glass-fronted cupboard of bric-à-brac, with a trophy of Abyssinian armour hanging over it; and the whole of the wall facing Lady Tasker was hung with a tapestry which, if it had been the only one of its kind in existence, would no doubt have been very valuable. And two other objects not commonly to be seen in ordinary halls were there. One of these stood on the narrow gilt console table next to Lady Tasker's cup of tea. It was a plaster cast, taken from the life, of a female foot. The other hung on the wall above it. This also was a plaster cast, of the whole of a female arm and shoulder, ending with a portion of the side of the neck and the entire breast—of its kind an exquisite specimen. Many artists make or buy such things, but Brucciani has nothing half so beautiful.

It was as Lady Tasker finished her tea that her gaze fell on the two casts. Half negligently she raised her glass and inspected, first the foot, and then the other piece. It is probable that her first[Pg 14] remark, uttered in a casual undertone to the air about her, was prompted by mere association of ideas; it was "Hm! I wonder if Mrs. Pratt nursed those twins herself!" Any other reflection that might have followed it was cut short by a sudden darkening of the doorway by which she had entered. Mrs. Pratt stood there. Lady Tasker had been wrong. She had come to ask if she felt better. She did ask her, gathering up long swathes of some newly unpacked white material she carried over her arm as she did so.

"Sorry you were done up," she remarked. "Won't you have some more tea?"

Already Lady Tasker was rising.—"No more, thank you.—I was just looking at these. What are they?" She indicated the casts.

The gesture that Mrs. Pratt gave she could probably no more have helped giving than an eye can help winking when it is threatened with a blow. Within one mistletoe-white sleeve an arm moved ever so slightly; very likely a foot also moved within a curiously-toed Saxon-looking white slipper; and she gave a confused and conscious and apologetic little laugh.

"Oh, those silly things!" she said deprecatingly. "I really must move them. But the studio is so full.... Do you know, it's a most horrid feeling having them done—first the cold plaster poured on, and then, when they take it off again—the mould—you know——"

Lady Tasker plainly did not understand. Perhaps she did not yet even apprehend.—"But—but—,"[Pg 15] she said, "they're from a statue, aren't they?"

Again Mrs. Pratt gave the pleased bashful little laugh. It was almost as if she said it was very good of Lady Tasker to say so.

"No, they're from life," she said. "As a matter of fact they're me, but I really must move them; they aren't so remarkable as all that.... Oh, you're not going, are you?——"

For Lady Tasker had given a jump, and a movement as sudden and sprightly as if she had only that moment got freshly out of her bed. Nervously she put out her hand, while her hostess looked politely disappointed.

"Oh, and I was hoping you'd come and join us in the garden! We've Brimby there, the novelist, you know—and Wilkinson, the young Member—and Mr. Strong, of the 'Novum'—and I should so much like to introduce Mr. Suwarree Prang to you——"

"Oh, thank you so much—," sprang as effusively from Lady Tasker's lips as if she had been a schoolgirl allowed for the first time to come down to dinner, "—it's so good of you, but really I half hoped you'd be out when I called—I only meant to leave cards—I'm going on to see my niece, and really haven't a moment——"

"Oh, I'm sure Dorothy'd excuse you for once!——," Mrs. Pratt pressed her.

"Oh, she wouldn't—I'm quite sure she wouldn't—she'd never forgive me if she knew I'd been so near and hadn't called," said Lady Tasker feverishly....[Pg 16] "How do I get to Dorothy's from here?"

"Oh, Mr. Wilkinson will take you, or Mr. Prang; but are you sure you won't stay?"

Lady Tasker was so far from staying that she was already out of the hall and walking quickly towards the green door in the eight-foot hedge. "Thank you, thank you so much," she was murmuring hurriedly. "I don't see your husband anywhere about—never mind—so good of you—good-bye——"

"Come again soon, won't you?"

"Yes, yes—oh, yes!... No, no, please don't!" (Mrs. Pratt had made a half-turn towards the hammock and the copper beech). "Straight across the Heath you said, didn't you? I shall find it quite easily! Don't come any further—good-bye——"

And, touching Mrs. Cosimo Pratt's extended fingers as timorously as she might have touched those of the cast itself, she fairly broke into a run. The door of The Witan closed behind her.

The truth was not very far to seek: Lady Tasker was too old for these things. Nobody could have expressed this more effectively than Mrs. Cosimo Pratt herself, had it entered the mind of Mrs. Pratt to conceive that any human soul could be so benighted as the soul of Lady Tasker was. "Those casts!" Mrs. Pratt might have cried in amazement—or rather Miss Amory Towers might have cried, for there is nothing in the Wedding Service about making over to your husband, along with your love and obedience, the valuable goodwill of a professional name. "Those poor casts!... Of course they may not be very beautiful—," here the original of the casts might have modestly dropped her eyes, "—but such as they are—goodness me! How can people be so prurient, Cosimo? Don't they see that what they really prove has nothing at all to do with the casts, but—ahem!—a good deal to do with their own imaginations? I don't want to use the word 'morbid,' but really!... Well, thank goodness Corin and Bonniebell won't grow up like that! Afraid of the beautiful, innocent human form!... Now that's what I've always claimed, Cosimo—that[Pg 18] that's the type of mind that's made all the mischief we've got to set right to-day."

But for all that Lady Tasker was too old. Invisible Men in the garden (or, if not actually invisible, at any rate as hard to be seen against the leaves of the copper beech as a new penny would have been)—and in the hall those extraordinary replicas! In the hall—the very forefront of the house! It was to be presumed that Mrs. Pratt's foreign friends, who were permitted to lean over her hammock, would not be denied The Witan itself, and, for all Lady Tasker knew, the rest of Mrs. Pratt might be reduplicated in plaster in the dining-room, the drawing-room, and elsewhere....

Had she not said it herself, Lady Tasker would never have believed it....

What a—what a—what an extraordinary thing!——

Lady Tasker had fled from The Witan still under the influence of that access of effusive schoolgirlishness in which she had told Mrs. Pratt that she really must go; nor did she grow up again all at once. But little by little, as she walked, she began to resume the burden of her years. She became eighteen, twenty-five, thirty again. By the time she reached the lower pond Arthur had just got that billet in the India Office, and her brother Dick, of the Department of Woods and Forests, had married Ada Polperro, daughter of old Polperro of Delhi fame, and her sister Emily had got engaged to Tony Woodgate, of the Piffers. (But those casts!)... Then as she took the path[Pg 19] between the ponds she remembered the children at Ludlow, the three little girls at Cromwell Gardens, and the arrival on Saturday of the "Seringapatam." (But those natives!)... The thought of the children settled it. Her curious lapse into juvenescence was over. By the time she rang Dorothy's bell she was the same Lady Tasker who changed the political opinions of policemen and deprecated the wanderings of Saint Paul.

Dorothy's flat was as different as it could well be from that other house which (Lady Tasker had already decided) had something odd and furtive about it—stagnant yet busy, segregated yet too wide open. The flat had one really brilliant room. This room did not merely overlook the pond in front of it; it seemed actually to have asked the pond to come inside. A large triple window occupied the whole of one end of it; this window faced west; and not only did the September sun shine brightly in, but the inverted sun in the water shone in also, doubling (yet also halving) all shadows, illumining the ceiling, and setting the cream walls a-ripple with the dancing of the wavelets outside. Sprightly chintzes looked as if they also might begin to dance at any moment; the china in Dorothy's cupboards surprised the eye that had not expected this altered light; and presently, to complete the complexity, the shadow of the sycamore in the little garden below would move round, so that you would hardly be able to tell whether the ceaseless creeping on the cream walls was glitter of ripples, pattern of leaves, or both.[Pg 20]

Dorothy sat in her accordion-pleats by the window, surrounded by letters. And pray do not think it mere coincidence in this story that her letters were Indian letters. Some interests that the home-amateur takes up as he might take up poker-work or the diversion of jig-saw hold a large part of the hearts and lives of others, and so Dorothy, as she did more or less every week, had been reading her cousin Churchill's letter, and that of her little niece and namesake Dot, up in Murree, and Eva Woodgate's, who had sent her a parcel from Kohat, and others. She rose slowly as her aunt was announced, and put her finger on the bell as she passed.

"How are you, auntie?" she said, kissing Lady Tasker on both cheeks. "Give me your things. Somehow I thought you might come to-day, but I'd almost given you up. Do look what Eva's sent me! Really, with her own to look after, I don't know how she finds the time! Aren't they sweet!——"

And she held them up.

Now Lady Tasker knew perfectly well the meaning of her niece's accordion-pleating; but she was seventy and worldly-wise again now. Therefore as she looked at the things she remarked off-handedly, "But they're far too small."

"Too small!" Dorothy exclaimed. "Of course they aren't. Why, Noel was only nine, and that's pretty big, and Jackie only just over eight-and-a-half, though he put on weight while you watched him. They're just right."[Pg 21]

Lady Tasker reached for a chair. "But they are for Jackie, aren't they?"

Dorothy's blue eyes were as big as the plates in her cupboards.—"Jackie! Good gracious, auntie!——"

"Eh?" said Lady Tasker, sitting down. "Not Jackie? Dear me. How stupid of me. Of course, I did hear, but I've so many other things to think of, and nobody'd suppose, to look at you——"

Dorothy ran to her aunt and gave her a kiss and a hug, a loud kiss and a hug like two.

"You dear old thing!—Really, I'd begun to hate all the horrid kind people who asked me how I felt to-day and whether I shouldn't be glad when it was over! What business is it of theirs? I nearly made Stan sack Ruth last week, she looked so, and I positively refuse to have a young girl anywhere near me!... But wasn't it sweet of Eva? I'll give you some tea and then read you her letter. Indian or China?"

"China," Lady Tasker remarked.

"China, Ruth, and I'll have some more too. I don't know whether His Impudence is coming in or not; he's gadding off somewhere, I expect.... But you weren't only pretending just now, were you, auntie?——"

She put the plug of the spirit-kettle into the wall.

"Well, how are the Bits?" Lady Tasker asked....

(Perhaps "His Impudence" and "The Bits" require explanation. Both expressions Dorothy[Pg 22] had from her "maid," Ruth Mossop. "Maid" is thus written because Ruth was a young widow, who, after a series of disciplinary knockings-about by the late Mr. Mossop, was not over-troubled with maternal anxiety for the four children he had left her with. When asked by Dorothy whether she would prefer to be called Mrs. Mossop or Ruth, Mrs. Mossop had chosen the latter name, giving as her reason that it had been like Mr. Mossop's impudence to ask her to accept the other name at all; and very many other memories also, brooded on and gloomily loved, including the four children, had been bits of Mr. Mossop's impudence. Stan had adopted the phrase, finding in it chuckles of his own; and so His Impudence he had become, and Noel and Jackie the fruits thereof.)

Dorothy put her fair head on one side, as if she considered the absent Bits critically and dispassionately, and really thought that on the whole she might venture to approve of them.

"Ra-ther little dears; but oh, Heaven, how are we going to manage with a third!"

Her aunt dissociated herself from the problem with a shrug.—"Well—if Stan will persist in thinking that his dressing-room is merely a room for him to dress in——"

"So I tell him," Dorothy murmured, with great meekness. "But—but flats aren't made for children. We did manage to seize the estate agent's little office for a nursery when all the flats were let, but when Stan brings a man home we have to sleep him in the dressing-room as it is—,"[Pg 23] (Lady Tasker shook her head, but the words "Wrong man" were hardly audible), "—and a house will mean stair-carpets, and hall furniture, and I don't know what else. Besides, Stan hasn't time to look for one——"

"No?" said Lady Tasker drily.

"He really hasn't, poor boy," Dorothy protested. "And he's after something really good this time—Fortune and Brooks, the what-d'-you-call-'ems, in Pall Mall——"

"What about them?"

"Well, Stan's been told that they pay awfully good commissions, for introductions, new accounts, you know; Stan dines out, say, and makes himself nice to somebody with whole stacks of money, and mentions Fortune & Brooks's chutney and pickled peaches and things, and—and——"

"I know," remarked Lady Tasker, with not much more expression than if she had been a talking doll and somebody had pulled the string that worked the speaking apparatus. She did know these dazzling schemes of her smart and helpless nephew's—his club secretaryships, his projects for journals that should combine the various desirable features of the "Field" and "Country Life" and the "Sporting Times" and "Punch," his pony deals, and his other innumerable attempts to make of his saunters down Bond Street to St. James's and back viâ the Junior Carlton and Regent Street a source of income. Perhaps she knew, too, that Dorothy knew of her knowledge, for she went on, "Well, well—let's hope there's more in[Pg 24] it than there was in the fishing-flies—now tell me what Eva's got fresh."

"Oh, yes!" cried Dorothy, plunging her hand into her letters. "Eva sent the things, but here's Dot's first—look at the darling's writing!——"

And from a sheet of paper with a regimental heading Dorothy began to read:

"Dearest Aunt Dorothy,—

"were in murree and we got a servant that wigles his toes when we speak to him and he loves baba and makes noises like him and there are squiboos in the tres—"

—(she means squirrels)—

"—and ive got a parrot uncle tony bought me and uncle tony says the monsoon will praps fale and the peple wont have anything to eat but weve lots and i like this better than kohat the shops are lovely but there are lots of flees and they bite baba and he cries this is a long letter how are Jackie and noel i got the photograf—"

—(that's the new one on the mantelpiece)—

"—were going to tifin at major hirsts little girls one is called marjorie and were great friends——"

"Where's the other page got to? It was here——"

She found the other page, and continued the reading of the child's letter.[Pg 25]

Suddenly Lady Tasker interrupted her.

"Had Jack to borrow money to send them up there?"

"To Murree? I really don't know. Perhaps he had. But as adjutant of the Railway Volunteers he'd have his saloon."

"H'm!... Anyway, the child oughtn't to be there at all. India's no place for children."

"I know, auntie; but what can one do? They do come."

"H'm!... They didn't to me. Thank goodness I've done with love and babies." (Dorothy laughed, perhaps at a mental vision of the houses in Ludlow and Cromwell Gardens.) "Anyway, now they are here somebody's got to look after them. They may as well be healthy...."

She mused, and Dorothy reached for other letters.

Lady Tasker's additions to her responsibilities usually began in this way. Dorothy had very little doubt that presently little Dot also would be handed like a parcel to some man or other coming home on leave, and Lady Tasker would send to the makers for yet another cot.... Therefore, pushing aside her last letter, she exclaimed almost crossly, "I do think it's selfish of Aunt Eliza! There she is, with Spurrs all to herself, and she never once thinks that Jack might like to send Dot to England!"

"Neither would I if I had my time over again," said Lady Tasker resolutely. "You needn't look like that—I wouldn't. Cromwell Gardens is past[Pg 26] praying for, and in another year there won't be a stick at the Brear that's fit to be seen. The next batch I certainly intend to charge for. I'm on the brink of the poorhouse as it is."

This time it was Dorothy who mused. She was a calculating young woman; the wife of His Impudence had to be; and she was far too shrewd to suppose for a moment that her aunt could ever escape her destiny, which was to be imposed upon by her own flesh and blood while hardening her heart against the rest of the world. Dorothy, and not Stan, had had to keep that flat going, and the flat before it; unless Fortune & Brooks turned up trumps—a rather remote contingency—she would have to continue to do so; and she was quite casuistical enough to argue that, while Aunt Eliza might keep her old Spurrs, Aunt Grace might properly be victimized because Dorothy loved Aunt Grace. Therefore there were musings in Dorothy's wide-angle blue eyes ... musings that only the sound of a key in the outer lock interrupted.

"Hallo, that's His Impudence," Dorothy exclaimed. "I do hope he hasn't brought anybody. I shall simply rush out if he has."

Stan hadn't. He came in at the door drawing off a pair of lemon-yellow gloves, said "Hallo, Aunt Grace," and rang the bell. He next said, "Hallo, Dot! Been out? Beastly smelly in town. No, I've not had tea. Look here, you've eaten all the hot cakes; never mind; bread and butter'll do, if you've got some jam—no, honey.[Pg 27] Got an invitation for you, Dot, to lunch, with Ferrers on Monday; can't you buck up and manage it?... Well, Aunt Grace, what brings you up here? Bit off your beat, isn't it? Awfully rude of me, I know, but it is a long way. Glad I came in."

"I've been to see the Cosimo Pratts," said Lady Tasker.

Dorothy looked suddenly up.

"Oh, auntie, you didn't tell me that!" she exclaimed.

A grin lighted up Stan's good-looking face.

"Oh? How many annas to the rupee are they to-day? By Jove, they are a rum lot up there! Any new prime cuts?"

"Stan, you mustn't!" said Dorothy, peremptorily. "Please don't! Don't listen to him, auntie; he's outrageous."

But His Impudence went on, with his mouth full of bread and butter.

"I've only seen the fore-quarter and the trotter, but you see I haven't been over the house. Did they show you the Bluebeard's Chamber? What is there there? By Jove, it's like Jezebel and the dogs.... But I don't suppose they'll have me up again. There was some chap there, and I got him by himself and told him he didn't know what he was talking about; rotten of me, I know, but you should have heard him! Anarchist—Votes for Women—all the lot; whew!... More tea, Ruth, please——"

Lady Tasker felt the years beginning to ebb[Pg 28] away from her again. She had remembered the hammock and the Invisible Men.

"I hope he was—English?" she murmured.

"Who?"

"The man you say you were rude to."

"English? Yes. Why? English? Rather! No end of gas about the Empire. Said it was on a wrong basis or something. Why do you ask?"

"I only wondered."

But Stan was perspicacious; he could see anything that was as closely thrust under his nose as is the comparative rarity of the Englishman in Hampstead. He laughed.

"Oh, that! We're used to that. We've all sorts up here.... By Jove, I believe Aunt Grace has been thrown into the arms of a Jap or a nigger or something! Well, if that doesn't put the lid on!... So of course you wondered what I meant by the fore-quarter and Jezebel and the dogs. Those are just some things they used to have.... Well, I'll tell you what you can do about it next time, auntie. You talk to 'em about Ludlow. That shuts 'em up. Sore spot, Ludlow; they're trying to forget about Ye Olde Englysshe Maypole, and that row with old Wynn-Jenkins, and old Griffin letting his hair grow and reciting those poems. They look at you as if it never happened. But they didn't shut me up."

"You seem to have been thoroughly rude," Lady Tasker remarked.

"Well, dash it all, they ask for it. She used to be some sort of a pal of Dorothy's——"[Pg 29]

"She's very clever, and she was always very kind to me," Dorothy interpolated over her sewing.

"When, I should like to know? But never mind. I was going to say, Aunt Grace, that I've had to put my foot down. I won't have the Bits meeting those kids of Pratt's. It's perfectly awful; why, those children know as much as I do—and I know a bit! They'll be wanting latchkeys presently. That day I was up there I heard one of 'em say that little boys weren't the same as little girls. I forget how she put it, but she knew all right; think of that, at about four! I wish I could remember the words, but it was a bit thick for four!——"

A restrained smile, perhaps at the thought of Stan putting his foot down, had crossed Lady Tasker's face; no doubt it was part of the smile that she presently said, toying with the little gold-rimmed glass, "Quite right, Stan.... Anything fresh about Fortune & Brooks? Dorothy told me."

Stan's feelings on any subject were never so strong but that at a word he was quite ready to talk about something else. "Eh? Rather!" he said heartily, and went straightway off at score.—New? Yes. He'd seen old Brooks the day before; not a bad chap at all really; and they quite understood one another, he and old Brooks. He'd told Stan things, old Brooks had, (which Stan wasn't at liberty to disclose) about the commissions they paid for really first-class introductions, things that would astonish Lady Tasker!—[Pg 30]—

"You see," he explained, "as Brooks himself said, they can't afford to advertise in the ordinary way; infra dig. They'd actually lose custom if they put an ad. in the 'Daily Spec.' I don't mean that they don't put a thing now and then into the right kind of paper, but just being mentioned in general conversation, at dinners and tamashas and so on, that's their kind of advertisement! For instance—but just a minute, and I'll show you——"

He jumped up and dashed out of the room. Lady Tasker took advantage of his absence to give a discreet glance at Dorothy, but Dorothy's head remained bent demurely over her work. Stan returned, carrying a small parcel.

"Here we are," he said, unfastening the package: and then suddenly his voice and manner changed remarkably. He took a small pot from the parcel and set it on the palm of his left hand; he pointed at it with the index-finger of his right hand; and a bright and poster-like smile overspread his face. He spoke slightly loudly, and very, very persuasively.

"Now I have here, Aunt Grace, one of our newest lines—Pickled Banyan. Now I'm not going to ask you to take my word for it; I want you to try it for yourself. It isn't what this man says or what that man says; tasting's believing. Give me your teaspoon."

"My dear Stan!" the astonished Lady Tasker gasped.

"We're selling a great many of this particular[Pg 31] article, and are prepared to stake our reputation on it," Stan went on. "Established 1780; more than One Hundred Gold Medals. Those are our credentials. Those are what we lose.—Pass your spoon."

Lady Tasker was rigid. Perhaps Stan would have been better advised to cast his spell over those who were going up in the world, and not on those who, like themselves, were coming down or barely holding their own. Again he went on, pointing engagingly at the small pot.

"But just try it," he urged, pushing the pot under his aunt's nose. "It isn't what this man says or—I mean, it doesn't cost you anything to try it. A free trial invited. Here's the recipe, look, on the bottle—carefully selected Banyans, best cane sugar, lemon-juice refined by a patent process, and a touch of tabasco. The makers' guarantee on every label—none genuine without it—have a go!"

With a "Really, Stan!" Lady Tasker had turned away in her chair, revolted. "And do you expect to go to a house again after an exhibition like that?" she asked over her shoulder.

"Eh?" said Stan, a little discomfited. "Too much salesman about it, d'you think? Brooks warned me about that. Fact is, he had a chap in as a sort of object-lesson. This chap came in—I didn't know they had schools and classes for this kind of thing, did you?—this chap came in, and I was supposed to be somebody who didn't want the stuff at any price, and he'd got to sell it[Pg 32] to me whether I wanted it or not, and old Brooks said to me, 'Now ask him how much the beastly muck is,' and a lot of facers like that, and so we'd a set-to.... Then, when the fellow had gone, he said he'd had him in just to show me how not to do it.... But he was an ingenious sort of beast, and I can't get his talk out of my head. I'd thought of having a shot at it to-night, but perhaps I'd better practise a bit more first. Thanks awfully for the criticism, Aunt Grace. If you don't mind I'll practise on you as we go along. I'm dining with a man to-night, but I'd better be sure of my ground.—Now what about having the Bits in, Dot?"

"I think I hear them coming," said Dorothy, whose demureness had not given as much as a flicker. Perhaps she was wondering whether she could spare the sovereign His Impudence would presently ask her for.

The door opened, and Noel and Jackie stood there with a nurse behind them. Noel walked stoutly in. Jackie, not yet very firm on his pins, bumbled after him like an overladen bee.

Stan was quite right in supposing that the Cosimo Pratts wished to forget all about the Ludlow experiment that had disturbed the Shropshire country-side a year or more before, but he was wrong in the reason he assigned them. They were not in the least ashamed of it. As a stage in their intellectual development, the experiment had been entirely in its place. Especially in Mrs. Pratt's career—as an old student of the McGrath School of Art, a familiar (for a time) with Poverty in cheap studios, the painter of the famous Feminist picture "Barrage," and so forward—had this been true. Cosimo, in "The Life and Work of Miss Amory Towers," a labour to which he devoted himself intermittently, pointed out the naturalness and inevitability of the sequence with real eloquence. Step had led to step, and the omission of any one step would have ruined the whole.

But nobody with work still in them lingers long over the past. They had dropped the task of regenerating rural England, or rather had handed it over to others, only when it had been pointed out to them that capacity so rare as theirs ought to be directed to larger ends. One evening there[Pg 34] had put in an appearance at one of the Ludlow meetings—a meeting of the Hurdy-gurdy Octette, which afterwards gave instrumental performances with such success at Letchworth, Bushey and Golder's Green—Mr. Strong, the original founder and present editor of the "Novum Organum," or, as it was usually called, the "Novum." Mr. Strong, as it happened, was the man whom the scatter-brained Stan had met at The Witan, and of whom he had expected that impossibility of any man whomsoever—an admission that he did not know what he was talking about. At that time Mr. Strong had been perambulating the country with a Van, holding meetings and distributing literature; and whatever Mr. Strong's other failings might have been, nobody had ever said of him that he did not recognize a good thing when he saw it. The Cause itself had served as an introduction between him and Cosimo; it had also been a sufficient reason for his inviting himself to Cosimo's house for a couple of days and remaining there for three weeks; and then he had got rid of the Van and had come again. He was a rapturous talker, when there was an end to be gained, and he had expressed himself as strongly of the opinion that, magnificent a field for the sowing of the good seed as the country-side was, there was simply stupendous propaganda to be done in London. He knew (he had gone on) that Mrs. Pratt would forgive him (he had a searching blue eye and an actor's smile) if he appeared for a moment to speak disparagingly of what he might call the[Pg 35] mere graces of the Movement, (alluring as these were in Mrs. Pratt's capable and very pretty hands); it was not disparagement really; he only meant that these garlands would burgeon a hundred-fold if the stern and thankless work was got out of the way first. Mr. Strong had a valuable trick of suddenly making those searching blue eyes of his more searching, and of switching off the actor's smile altogether; both of these things had happened as he had gone on to point out that what the Cause was really languishing for was a serious and responsible organ; and then, and only then, when they had got (so to speak) the diapason, there would be time enough for the trills and appoggiaturas of the Hurdy-gurdy Band.

Before the end of Mr. Strong's second visit Cosimo had put up the greater part of the money for the "Novum."

So you see just where the feather-pated Stan was wrong. The Cosimo Pratts were not outfaced from anything; they had merely seen a new and heralding light. They did not so much recede from the Rural Experiment, and discussions of the Suffrage, and eating buns on the floor at assemblies of the Poets' Club, and a hundred and twenty other such things, as become as it were translated. They still shed over these activities the benignity of their approval, but from on high now. Amory could no longer be expected actually to "run" the Suffrage Shop herself—Dickie Lemesurier did that; nor the "Eden" (the new offshoot off the Lettuce Grill)—that she left to Katie Deedes;[Pg 36] nor the "Lectures on Love" Agency—that was quite safe in the hands of her friends, Walter Wyron and Laura Beamish. Amory merely shed approval down. She was hors concours. She ... but you really must read Cosimo's book. You will find it all there (or at any rate a good deal of it).

For Amory Pratt, in so far as Cosimo was the proprietor of the "Novum," was the proprietor of the proprietor of a high-class weekly review that was presently going to put the two older parties out of business entirely. She had more than a Programme now; she had a Policy. She had crossed the line into the haute politique. Her At Homes were already taking on the character of the political salon, and between herself and the wives of ministers and ambassadors were differences, in degree perhaps, but not in kind. And that even these differences should become diminished she had taken on, ever since her settling-down at The Witan, slight, but significant, new attitudes and condescensions. She was kinder and more gracious to her sometime equals than before. She gave them encouraging looks, as much as to say that they need not be afraid of her. But it was quite definitely understood that when she took Mr. Strong apart under the copper beech or retired with him into the studio at the back of the house, she must on no account be disturbed.—Mr. Strong, by the way, always dressed in the same Norfolk jacket, red tie and soft felt hat, and his first caution to Cosimo and Amory had been that Brimby, the novelist, was an excellent chap, but not always to be taken very seriously.[Pg 37]

Amory did not often put in an appearance at the "Novum's" offices. This was not that she thought it more befitting that Mr. Strong should wait on her, for she went about a good deal with Mr. Strong, and did not always trouble him to come up to The Witan to fetch her. It was, rather, if the truth must be told, that she found the offices rather dingy. Her senses loved the newly-machined smell of each new issue of the paper, but not the mingled odour of dust and stale gum and Virginia cigarettes of the place whence it came. Moreover, the premises were rather difficult to find. They lay at the back of Charing Cross Road. You dodged into an alley between a second-hand bookseller's and a shop where electric-light fittings were sold, entered a narrow yard, and, turning to the right into a gas-lighted cavern where were stacked hundreds and hundreds of sandwich-boards, some back-and-fronts, some with the iron forks for the bearer's shoulders, you ascended by means of a dark staircase to the second floor. There, at the end of a passage which some poster-artist had half papered with the specimens of his art, you came upon the three rooms. The first of these was the general office; the second was Mr. Strong's private office; and the third was a room which, the "Novum" having no need of it, Mr. Strong had thought he might as well use as a rent-free bedroom as not. The door of this room Mr. Strong always kept locked. It was more prudent. He was supposed to live somewhere in South Kentish Town, and gave this address to certain of[Pg 38] his correspondents. The letters of these reached him sooner or later, through the agency of a barber, in whose window was a placard, "Letters may be addressed here."

Perhaps, too, the extraordinary people who visited Mr. Strong in the way of business helped to keep Amory away. For an endless succession of the queerest people came—contributors, and would-be contributors, and friends of the Cause who "were just passing and thought they'd look in," and artists seeking a paper with the courage to print really stinging caricatures, and article-writers who were out of a job only because they dared to tell the truth about things, and Russian political exiles, and Armenians who wanted passages to America, and Eurasians who wanted rifles, and tramps, and poets, and the boy from the milkshop who brought in the bread and butter and eggs for Mr. Strong's breakfast. And out of these strange elements had grown up the paper's literary style. This was unique in London journalism: philosophical, yet homely; horizon-wide of outlook, yet never without hope that the shining thing in the gutter might prove to be a jewel; and, despite its habitual omissions of the prefix "Mr." from the names of statesmen, and its playful allusions to this personage's nose or the waist-measurement of the other, with more than a little of the Revelation of Saint John the Divine about it. "Damn" and "Hell" were words the "Novum" commonly used. Once Amory had demurred at the use of a word stronger still. But Mr. Strong had merely[Pg 39] replied, "If I can say it to you I think I can say it to them." He was no truckler to his proprietors, and anyhow, the man whom the word had encarnadined was only a colliery-owner.

The "Novum" had hardly been six weeks old when a certain desire on Amory's part to make experiment of her power had, putatively at any rate, lost it money. The little collision of wills had come about over the question of whether the "Novum" should admit advertisements to its columns or not. Now as most people know, that is a question that seldom arises in journalism. A question far more likely to arise is whether the advertisements can be got. But when a journal sets out to do something that hitherto has not only not been done, but has not even been attempted, you will admit that the case is special. The experience of other papers is useless; their economics do not apply. What did apply was the fact that Mrs. Pratt had been an artist, looked on sheets of paper from another angle than that of the mere journalist and literary man, and loved symmetry and could not endure unsightliness. Besides, "No Compromise" was the "Novum's" motto, and what was the good of having a motto like that if you compromised in the very form of your expression?... A "shoulder-piece," "The Little Mary Emollient," had brought out all Mrs. Pratt's finer artistic instincts. Here was a journal consecrated to a great and revolutionary cause, and the very first thing to catch a reader's eye was, not only an advertisement, but a facetious advertisement at[Pg 40] that—a Pill, without a Pill's robust familiarity—a commercial cackle issuing from the "Novum's" august and oracular mouth.... For the first time in her life Mrs. Pratt had wielded the blue pencil, tearing the rubbishy proof-paper in the energy with which she did so. Mr. Strong's blue eyes, bluer for the contrast with his red knot of a tie, had watched her face, but he had said nothing. He was willing to humour her....

But when all was said and done he was an editor, and no sooner was Amory's back turned than he had restored the announcement. The paper had appeared, and there had been a row....

"Then I appeal to Pratt," Mr. Strong had said, with all the good-nature in the world. "I take it the 'Novum's' a serious enterprise, and not just a hobby?"

Cosimo had glanced a little timidly at his wife. Then he had replied thoughtfully.

"I don't know. I'm not so sure. That is, I'm not so sure it oughtn't to be a serious enterprise and a hobby. The world's best work is always done for love—that's another way of calling it a hobby—you see what I mean—Nietzsche has something about it somewhere or other—or if he hasn't Ruskin has——"

Any number of effective replies had been open to Mr. Strong, but he had used none of them. Instead his eyes had given as it were a flick to Amory's face. The proprietor's proprietor had continued indignantly.

"It ruins the whole effect! It's unspeakably[Pg 41] vulgar! After that glowing, that impassioned Foreword—this! Hardly a month ago that lovely apostrophe to Truth Naked—that beautiful image of her stark and innocent on our banners but with a forest of bright bayonets bristling about her—and now this! It's revolting!"

But Mr. Strong had himself written that impassioned Foreword, and knew all about it. Again he had given his proprietor's wife that quietly humouring look.

"Do you mean that the 'Novum's' going to refuse advertisements?"

"I mean that I blue-pencilled that one myself."

"And what about the others—the 'Eden' and the Suffrage Shop and Wyron's Lectures?"

"They're different. They are the Cause. You said yourself that the 'Novum' was going to be a sort of generalissimo, and these the brigades or whatever they're called. They are, at any rate, doing the Work. Is that doing any Work, I should like to know?"

Mr. Strong had refrained from flippancy.—"I see what you mean," he had replied equably. "At the same time, if you're going to refuse advertisements the thing's going to cost a good deal more money."

"Well?" Amory had replied, as who might say, "Has money been refused you yet?"

Strong had given a compliant shrug—"All right. That means I censor the advertisements, I suppose. New industry. Very well. The 'Eden' and Wyron's Lectures and Week-end Cottages and the[Pg 42] Plato Press only, then. I'll strike out that 'Platinum: False Teeth Bought.' But I warn you it will cost more."

"Never mind that."

And so the incident had ended.

But perhaps Mrs. Pratt's sensitiveness of eye was not the only cause of the rejection of that offending advertisement. Another reason might have lain in her present relation with her sometime fellow-student of the McGrath School of Art, Dorothy Tasker. For that relation had suffered a change since the days when the two girls had shared a shabby day-studio in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. At that time, now five years ago, Amory Towers had been thrust by circumstances into a position of ignoble envy of her friend. She had been poor, and Dorothy's people (or so she had supposed) very, very wealthy. True, poor Dorothy, without as much as a single spark of talent, had nevertheless buckled to, and, in various devious ways, had contrived to suck a parasitic living out of the wholesome body of real art; none the less, Amory had conceived her friend to be of the number of those who play at hardship and independence with a fully spread table at home for them to return to when they are tired of the game. But the case was entirely changed now. Amory frankly admitted that she had been mistaken in one thing, namely, that if those people of Dorothy's had more money, they had also more claims upon it, and so were relatively poor. Amory herself was now very comfortably off indeed. By that virtue and good management which the envious[Pg 43] call luck, she had now money, Cosimo's money, to devote to the regeneration of the world. Dorothy, married to the good-tempered and shiftless Stan, sometimes did not know which way to turn for the overdue quarter's rent.

Now among her other ways of making ends meet Dorothy had for some years done rather well out of precisely that kind of work which Amory refused to allow the "Novum" to touch—advertisements. She had wormed herself into the services of this firm and that as an advertisement-adviser. But her contracts had begun in course of time to lapse, one or two fluky successes had not been followed up, and two children had further tightened things. Nor had Stan been of very much help. Amory despised Stan. She thought him, not a man, but a mere mouth to be fed. Real men, like Cosimo, always had money, and Amory was quite sure that, even if Cosimo had not inherited a fortune from his uncle, he would still have contrived to make himself the possessor of money in some other way.

Therefore Amory was even kinder to Dorothy than she was to Dickie Lemesurier of the Suffrage Shop, to Katie Deedes of the "Eden," and to Laura Beamish and Walter Wyron, who ran the "Lectures on Love." But somehow—it was a little difficult to say exactly how, but there it undoubtedly was—Dorothy did not accept her kindnesses in quite the proper spirit. One or two she had even rejected—gently, Amory was bound to admit, but still a rejection. For example, there had been that little rebuff (to call it by its worst name for a moment)[Pg 44] about the governess. Amory had, in Miss Britomart Belchamber, the most highly-qualified governess for Corin and Bonniebell that money and careful search had been able to obtain; Dorothy lived less than a quarter of an hour's walk away; it would have been just as easy for Britomart to teach four children as to teach two; but Dorothy had twisted and turned and had finally said that she had decided that she couldn't put Amory to the trouble. And again, when the twins had had their party, Amory would positively have liked Noel and Jackie to come and dance "Twickenham Ferry" in those spare costumes and to join in those songs from the Book of Caroline Ditties; but again an excuse had been made. And half a dozen similar things had driven Amory to the conclusion, sadly against her will, that the Taskers were taking up that ridiculous, if not actually hostile attitude, of the poor who hug their pride. It was not nice between old friends. Amory could say with a clear conscience that she had not refused Dorothy's help in the days when the boot had been on the other leg. She was not resentful, but really it did look very much like putting on airs.

But of course that stupid Stanhope Tasker was at the bottom of it all. Amory did not so much mind his not having liked her from the first; she would have been sorry to let a trifle like that ruffle her equanimity; but it was evident that he did not in the least realize his position. She was quite sure, in the first place, that he couldn't afford (or rather Dorothy couldn't afford) to pay eighty[Pg 45] pounds for that flat, plus another twenty for the little office they had annexed and used as a nursery. And in the next place he dressed absurdly above his position. Cosimo dressed for hygiene and comfort, in cellular things and things made of non-irritant vegetable fibre; but those absurdly modish jackets and morning-coats of Stan's had, unless Amory was very much mistaken, to be bought at the expense of real necessaries. And so with their hospitality. In that too, they tried to cut a dash and came very near to making themselves ridiculous. Amory didn't want to interfere; she couldn't plan and be wise for everybody; she had her own affairs to attend to; but she was quite sure that the Taskers would have done better to regulate their hospitality as hospitality was regulated at The Witan—that was, to make no special preparation, but to have the door always open to their friends. But no; the Taskers must make a splash. They must needs "invite" people and be a little stand-offish about people coming uninvited. They were "At home" and "Not at home" for all the world as if they had been important people. But Amory would have thought herself very stupid to be taken in by all this ceremony. For example, the last time she and Cosimo had been asked to the flat to dinner she knew that they had been "worked off" only because the Taskers had had the pheasants given by somebody, and very likely the fish too. And it would have been just like Stan Tasker's insolence had he asked them because he knew that the Pratts did not eat poor beasties that should have been[Pg 46] allowed to live because of their lovely plumes, nor the pretty speckled creatures that had done no harm to the destroyer who had taken them with a hook out of their pretty stream.

But, kind to her old friend as Amory was always ready to be, she did not feel herself called upon to go out of her way to be very nice to her friend's husband. He had no right to expect it after his rudeness to Edgar Strong about the "Novum." For it had been about the "Novum" that Stan had given Strong that talking-to. Much right (Amory thought hotly) he had to talk! Just because he consorted with men who counted their money in rupees and thought nothing of shouldering their darker-skinned brothers off the pavement, he thought he was entitled to put an editor into his place! But the truth, of course, was, that that very familiarity prevented him from really knowing anything about these questions at all. Because an order was established, he had not imagination enough to see how it could have been anything different. His mind (to give it that name) was of the hidebound, official type, and too many limited intelligences of that kind stopped the cause of Imperial progress to-day. Or rather, they tried to stop it, and perhaps thought they were stopping it; but really, little as they suspected it, they were helping more than they knew. A pig-headed administration does unconsciously help when, out of its own excesses, a divine discontent is bred. Mr. Suwarree Prang had been eloquent on that very subject one afternoon not very long ago. A charming man! Amory[Pg 47] had listened from her hammock, rapt. Mr. Prang did the "Indian Review" for the "Novum," in flowery but earnest prose; and as he actually was Indian, and did not merely hobnob with a few captains and subalterns home on leave, it was to be supposed that he would know rather more of the subject than Mr. Stanhope Tasker!——

And Mr. Stanhope Tasker had had the cheek to tell Mr. Strong that he didn't know what he was talking about!

Amory felt that she could never be sufficiently thankful for the chance that had thrown Mr. Strong in her way. She had always secretly felt that her gifts were being wasted on such minor (but still useful) tasks as the "Eden" Restaurant and the "Love Lectures" Agency. But her personal exaltation over Katie Deedes and the others had caused her no joy. What had given her joy had been the immensely enlarged sphere of her usefulness; that was it, not the odious vanity of leadership, but the calm and responsible envisaging of a task for which not one in ten thousand had the vision and courage and strength. And Edgar Strong had shown her these things. Of course, if he had put them in these words she might have suspected him of trying to flatter her; but as a matter of fact he had not said a single word about it. He had merely allowed her to see for herself. That was his way: to all-but-prove a thing—to take it up to the very threshold of demonstration—and then apparently suddenly to lose interest in it. And that in a way was his weakness as an[Pg 48] editor. Amory, whom three or four wieldings of the blue pencil had sufficed to convince that there was nothing in journalism that an ordinary intelligence could not master in a month, realized this. She herself, it went without saying, always saw at once exactly what Mr. Strong meant; she personally liked those abrupt and smiling stops that left Mr. Strong's meaning as it were hung up in the air; but it was a mistake to suppose that everybody was as clever as she and Mr. Strong. "I's" had to be dotted and "t's" crossed for the multitude. But it was at that point that Mr. Strong always became almost languid.

It was inevitable that the man who had thus revealed to her, after a single glance at her, such splendid and unsuspected capacities within herself, should exercise a powerful fascination over Amory. If he had seen all this in her straight away (as he assured her he had), then he was a man not lightly to be let go. He might be the man to show her even greater things yet. He puzzled her; but he appeared to understand her; and as both of them understood everybody else, she was aware of a challenge in his society that none other of her set afforded her. He could even contradict her and go unsacked. Prudent people, when they sack, want to know what they are sacking, and Amory did not know. Therefore Mr. Strong was quite sure of his job until she should find out.

Another thing that gave Mr. Strong this apparently off-hand hold over her was the confidential manner in which he had warned her not to take Mr.[Pg 49] Brimby, the novelist, too seriously. For without the warning Amory, like a good many other people, might have committed precisely that error.... But when Mr. Brimby, taking Amory apart one day, had expressed in her ear a gentle doubt whether Mr. Strong was quite "sound" on certain important questions, Amory had suddenly seen. Mr. Strong had "cut" one of Mr. Brimby's poignantly sorrowful sketches of the East End—seen through Balliol eyes—and Mr. Brimby was resentful. She did not conceal from herself that he might even be a little envious of Mr. Strong's position. He might have been wiser to keep his envy to himself, for, while mere details of routine could hardly expect to get Amory's personal attention, there was one point on which Mr. Strong was quite "sound" enough for Amory—his sense of her own worth and of how that worth had hitherto been wasted. And Mr. Strong had not been ill-natured about Mr. Brimby either. He had merely twinkled and put Amory on her guard. And because he appeared to have been right in this instance, Amory was all the more disposed to believe in his rightness when he gave her a second warning. This was about Wilkinson, the Labour Member. He was awfully fond of dear old Wilkie, he said; he didn't know a man more capable in some things than Wilkie was; but it would be foolish to deny that he had his limitations. He wasn't fluid enough; wanted things too much cut-and-dried; was a little inclined to mistake violence for strength; and of course the whole point[Pg 50] about the "Novum" was that it was fluid....

"In fact," Mr. Strong concluded, his wary blue eyes ceasing suddenly to hold Amory's brook-brown ones and taking a reflective flight past her head instead, "for a paper like ours—I'm hazarding this, you understand, and keep my right to reconsider it—I'm not sure that a certain amount of fluidity isn't a Law...."

Amory nodded. She thought it excellently put.

Amory sometimes thought, when she took her bird's-eye-view of the numerous activities that found each its voice in its proper place in the columns of the "Novum," that she would have allowed almost any of them to perish for lack of support rather than the Wyron's "Lectures on Love." She admitted this to be a weakness in herself, a sneaking fondness, no more; but there it was—just that one blind spot that mars even the clearest and most piercing vision. And she always smiled when Mr. Strong tried to show this weakness of hers in the light of a merit.

"No, no," she always said, "I don't defend it. Twenty things are more important really, but I can't help it. I suppose it's because we know all about Laura and Walter themselves."

"Perhaps so," Mr. Strong would musingly concede.

Anybody who was anybody knew all about Laura Beamish and Walter Wyron and a certain noble defeat in their lives that was to be accounted as more than a hundred ordinary victories. That almost historic episode had just shown everybody[Pg 52] who was anybody what the world's standards were really worth. Hitherto the Wyrons have been spoken of both as a married couple and as "Walter Wyron" and "Laura Beamish" separately; let the slight ambiguity now be cleared up.

Mrs. Cosimo Pratt became on occasion Miss Amory Towers for reasons that began and ended in her profession as a painter; and everybody who was anybody was as well aware that Miss Amory Towers, the painter of the famous feminist picture "Barrage," was in reality Mrs. Cosimo Pratt, as the great mass of people who were nobody knew that Miss Elizabeth Thompson, the painter of "The Roll Call," was actually Lady Butler. But not so with the Wyrons. Reasons, not of business, nor yet of fame, but of a burning and inextinguishable faith, had led to their noble equivocation. Deeply seated in the hearts both of Walter and of Laura had lain a passionate non-acceptance of the merely parroted formula of the Wedding Service. So searching and fundamental had this been that by the time their various objections had been disposed of little had remained that had seemed worth bothering about; and in one sense they had not bothered about it. True, in another sense they had bothered, and that was precisely where the defeat came in; but that did not dim the splendour of the attempt. To come without further delay to the point, the Wyrons had married, under strong protest, in the ordinary everyday way, Laura submitting to the momentary indignity of a ring; but thereafter they had magnificently[Pg 53] vindicated the New Movement (in that one aspect of it) by not saying a word about the ceremony of their marriage to anybody—no, not even to the people who were somebody. Then they had flown off to the Latin Quarter.

It had not been in the Latin Quarter, however, that the true character of their revolt had first shown. Perhaps—nobody knows—their relation had not been singular enough there. Perhaps—there were people base enough to whisper this—they had feared the singularity of "letting on." It is easy to do in the Boul' Mich' as the Boul' Mich' does. The real difficulties begin when you try to do in London what London permits only as long as you do it covertly.

And if there had been a certain covertness about their behaviour when, after a month, they had returned, what a venial and pardonable subterfuge, to what a tremendous end! Amory herself, up to then, had not had a larger conception. For while the Wyrons had secretly married simply and solely in order that their offspring should not lie under a stigma, their overt lives had been one impassioned and beautiful protest against any assumption whatever on the part of the world of a right to make rules for the generation that was to follow. No less a gospel than this formed the substance of those Lectures of Walter's; great as the number of the born was, his mission was the protection of a greater number still. The best aspects both of legitimacy and of illegitimacy were to be stereoscoped in the perfect birth. And[Pg 54] he now had, in quite the strict sense of the word, a following. The same devoted faces followed him from the Lecture at the Putney Baths on the Monday to that at the Caxton Hall on the Thursday, from his ascending the platform at the Hampstead Town Hall on the Tuesday to his addressing of a garden-party from under the copper-beech at The Witan on the Sunday afternoon. And in course of time the faithfulness of the followers was rewarded. They graduated, so to speak, from the seats in the body of the building to the platform itself. There they supported Laura, and gave her a countenance that she no longer needed (for she had earned her right to wear her wedding-ring openly now), and flocked about the lecturer afterwards, not as about a mere man, but rather as seeing in him the physician, the psychologist, the expert, the helper, and the setter of crooked things straight that he was.

As a lecturer—may we say as a prophet?—Walter had a manner original and taking in the extreme. Anybody less sustained by his vision and less upheld by his faith might have been a little tempted to put on "side," but not so Walter. Perhaps his familiarity with the stage—everybody knew his father, Herman Wyron, of the New Greek Theatre—had taught him the value of the large and simple statement of large and simple things; anyhow, he did not so much lecture to his audiences as accompany them, chattily and companionably, through the various windings of his subject. With his hands thrust unaffectedly into the pockets[Pg 55] of his knickers, and a sort of sublimated "Well, here we are again" expression on his face, he allayed his hearers' natural timidity before the magnitude of his mission, and gave them a direct and human confab. on a subject that returned as it were from its cycle of vastness to simple personal experience again. His every sentence seemed to say, "Don't be afraid; it's nothing really; soon you'll be as much at your ease in dealing with these things as I am; just let me tell you an anecdote." No wonder Laura held her long and muscular neck very straight above her hand-embroidered yoke. Everybody understood that unless she adopted some sort of an attitude her proper pride in such a married lover must show, which would have been rather rubbing it in to the rest of her sex. So she booked dates for new lectures almost nonchalantly, and, when the platform was invaded at the end of the Lecture, or Walter stepped down to the level of those below, she was there in person as the final demonstration of how well these things actually would work as soon as Society had decided upon some concerted action.

Corin and Bonniebell, Amory's twins, did not attend Walter's Lectures. It was not deemed advisable to keep them out of bed so late at night. But Miss Britomart Belchamber, the governess, could have passed—had in fact passed—an examination in them. It had been Amory who, so to speak, had set the paper. For it had been at one of the Lectures—the one on "The Future Race: Are We Making Manacles?"—that Miss[Pg 56] Belchamber had first impressed Amory favourably. Amory had singled her out, first because she wore the guarantee of Prince Eadmond's Collegiate Institution—the leather-belted brown sleeveless djibbah with the garment of fine buff fabric showing beneath it as the fruit of a roasted chestnut shows when the rind splits—and secondly because of her admirable physique. She was splendidly fair, straight as an athlete, and could shut up her long and massive limbs in a wicker chair like a clasp-knife; and for her movements alone it was almost a sin that Walter's father could not secure her for the New Greek Society's revival of "Europa" at the Choragus Theatre. And she was not too quick mentally. That is not to say that she was a fool. What made Amory sure that she was not a fool was that she herself was not instinctively attracted by fools, and it was better that Miss Belchamber should be ductile under the influence of Walter's ideas than that she should have just wit enough to ask those stupid and conventional and so-called "practical" questions that Walter always answered at the close of the evening as patiently as if he had never heard them before. And Miss Belchamber told the twins stories, and danced "Rufty Tufty," with them, and "Catching of Quails," and was really cheap at her rather stiff salary. Cosimo loved to watch her at "Catching of Quails." If the children did not grow up with a love of beauty after that, he said, he gave it up. (The twins, by the way, unconsciously served Amory as another example[Pg 57] of Dorothy Tasker's unreasonableness. As the mother of Noel and Jackie, Dorothy seemed rather to fancy herself as an experienced woman. But Amory could afford to smile at this pretension. There was a difference in age of a year and more between Noel and Jackie. No doubt Dorothy knew a little, but she, Amory, could have told her a thing or two).