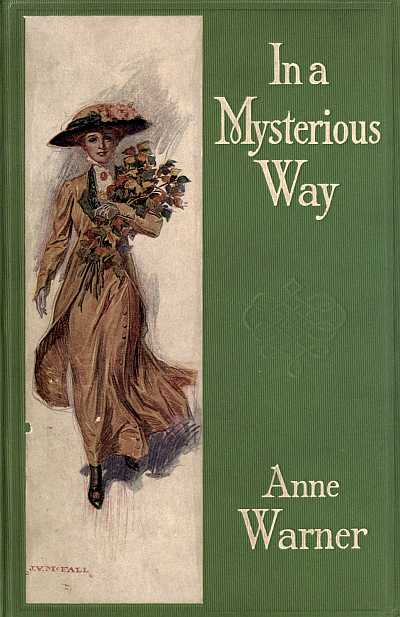

In a Mysterious Way

Anne Warner

IN A MYSTERIOUS WAY

"THE ONLY REAL HOLE IS WHERE HE SAT DOWN ON AN ENGINE SPARK AT THE STATION." (Frontispiece See p. 129)

IN A MYSTERIOUS WAY

BY ANNE WARNER

AUTHOR OF "THE REJUVENATION OF AUNT MARY"

"SUSAN CLEGG AND HER FRIEND MRS. LATHROP"

"AN ORIGINAL GENTLEMAN," ETC.

Illustrated by

J. V. McFALL

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1909

Copyright, 1909,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published April, 1909

Electrotyped and Printed at

THE COLONIAL PRESS:

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, U.S.A.

CONTENTS

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Introducing Mrs. Ray | 1 |

| II. | The Coming of the Lassie | 9 |

| III. | Introducing Lassie to Mrs. Ray | 28 |

| IV. | The Difference | 43 |

| V. | That Dispassionate Observer, Mrs. Ray | 68 |

| VI. | When Differences Lead to What is Ever the Same | 90 |

| VII. | The Lathbuns | 104 |

| VIII. | Miss Lathbun's Story | 112 |

| IX. | Pleasant Converse | 125 |

| X. | The Broader Meaning | 137 |

| XI. | The War-Path | 148 |

| XII. | Another Path | 156 |

| XIII. | And Still Another Path | 161 |

| XIV. | Devoted to Coats and Case-Knives | 170 |

| XV. | Learning Lessons | 181 |

| XVI. | The Walk to the Lower Falls | 195 |

| XVII. | Righteous Justice | 210 |

| XVIII. | In the Hour of Need | 218 |

| XIX. | Doubts | 225 |

| XX. | Shifting Sunshine and Clouds | 238 |

| XXI. | The Post-Office | 250 |

| XXII. | Aftermath | 259 |

| XXIII. | The Darkness Before | 265 |

| XXIV. | Dawn | 274 |

| XXV. | The Breaking of Another Day and Way | 284 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| "The only real hole is where he sat down on an engine spark at the station" | Frontispiece |

| "It's her that bought the old Whittacker house" | 21 |

| "Surely you remember me" | 95 |

| Alva | 166 |

| "If you've lent money to the Lathbuns you're going to lose it" | 224 |

IN A MYSTERIOUS WAY

[1]

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCING MRS. RAY

"'He moves in a mysterious way His wonders to perform,'" sang Mrs. Ray, coming in from the wood-shed and proceeding to fill up the stove, with the energy which characterized her whole person. A short, well-knit, active person it was, too,—a figure of health and compact muscular strength, a well-shaped head with a tight wad of neat hair on top, bright eyes, and a firm mouth.

Mrs. Wiley, a near neighbor, sat by the table and watched her friend with the after-nightfall passivity of a woman who has to be very active during daylight. Mrs. Wiley was not small and well-knit, neither was she energetic. Life for Mrs. Wiley had gone mainly in a minor key composed largely of sharps, and as a consequence she sighed frequently and sighed even now.

Mrs. Ray slammed the stove door and caroled louder than ever, as if to drown even the echo of a sigh in her kitchen. "'He moves in a mysterious way His wonders to perform,'" she sang, and then, folding her arms on top of her bosom in a manner peculiarly her own, she[2] spoke to Mrs. Wiley in that obtrusively cheerful tone which we use to those who sigh when feeling no desire to sigh with them: "That's my motto—that song—yes, indeed. It fits everything and accounts for everything and comes in handy anywhere any time, even if I never have wondered myself, but have been dead sure all along. Yes, indeed."

Mrs. Wiley sighed again, and her eyes moved towards a large, awkward parcel rolled in newspaper, which lay on the end of the table by her. "I'm so glad you feel able to undertake it, Mrs. Ray. I don't know how I ever could have managed it, if you'd said no. Mr. Wiley will have a new pig-pen this year, and the pigs never can pay for it themselves. So you were my only way to a new winter coat. I'm so glad you didn't say no. Besides it's father's suit, and I shall love to wear it for that reason, too."

"I never do say no to any kind of work, do I?" said Mrs. Ray, looking at the clock, and then all over the room; "this would be a nice time of life for me to begin to sit around and say no to work. What with Mr. Ray's second wife's children not all educated yet, and his first wife's children getting along to where they're beginning to be left widows with six apiece and no life insurance, I'm likely to want all the work I can get for some years, as far as I can see. Yes, indeed."

Mrs. Wiley sighed heavily.

"Mr. Wiley thinks we'd ought to insure our lives in favor of Lottie Ann," she said, feeling for her pocket-handkerchief at the thought; "she's so dreadful delicate—but I think it's foolish—she's so dreadful delicate."[3]

"Why don't you insure Lottie Ann, then?" Mrs. Ray glanced at the clock again, frowned a little and puckered her lips. "If you don't mind taking that chair the cat's in, Mrs. Wiley, I believe I've got just about time enough to sprinkle the clothes before the mail comes in; it looks so to me."

Mrs. Wiley slowly and gravely exchanged seats with the cat. "Do you take much washing in now? I shouldn't think you had time."

"Time!" Mrs. Ray was dragging a clothes-basket from under the table and filling a dipper with water. "I never stop to think whether I have time or not, any more. 'He moves in a mysterious way—' there's where my motto comes in again. Yes, indeed. I move just the same way myself. I don't see how I get so much done, but I've no time to stop and study over it, or I'd be behind just that much. There's more than you wonder where I get time from, Mrs. Wiley. They asked me if I had time for the post-office. And I said I had. They asked first if I could read and write, and I said I could; and then they asked me if I had time, and I said I had. And that settled it."

"Why, Mrs. Ray," said Mrs. Wiley, watching the clothes-sprinkling, which was now going forward, attentively, "that's one of the waists from that girl at Nellie O'Neil's, isn't it?"

"Yes, indeed. She asked Nellie for a French laundress, and Nellie put her shawl right over her head and run up and asked me if I had time for that, too. I said I was willing to try, so I'm a French laundress too, now. 'He moves'—"

"What do you think of those two young people at Nellie's, anyway?" Mrs. Wiley dropped her voice[4] confidentially. "I was meaning to ask you that, right at first."

"Well, if you ask me," said Mrs. Ray, "I can't make him out, and I think she's mooney. I'm a great judge of mooney people ever since I first knew Mr. Ray, and that girl looks very mooney to me. Look at her coming here and hiking right over and buying the Whittacker house next day—a house I wouldn't send a rat to buy—not if I had a real liking for the rat. And now the way she's pulling it to pieces and nailing on new improvements, with the trees all boxed up, as though trees weren't free as air—oh, she's mooney, very mooney—yes, indeed."

"Nellie don't think they act loving," said Mrs. Wiley; "and Joey Beall says they don't act loving even when they're alone together. He's been building a culvert for Mr. Ledge, and he's seen 'em alone together twice. Joey knows how people ought to act when they're alone together. He always knows when folks are in love, before they know themselves. He tells by seeing them alone together. Why, he knew when you was going to be married—he saw you and Mr. Ray alone together that day you walked to the Lower Falls."

"But it wasn't through our acting loving that he knew it," said Mrs. Ray, energetically ruminative between the dipper of water and the clothes to be sprinkled; "my, but I was mad that day! It was the first and last time anybody ever fooled me into walking to the Lower Falls. Yes, indeed. I like to of died! If Mr. Ray hadn't asked me to marry him, I'd never have forgiven him getting me to go on that walk. Those flights of steps! And those paths! All the way down[5] I was wanting to turn round and go back. I made up my mind never to take Mr. Ray's word for nothing again. And I never did. He fooled me into that walk, but he never fooled me again. Yes, indeed. Never!"

"But Joey Beall saw you that day," said Mrs. Wiley, whose mind was of that strength which is not to be swept beyond its gait by any other mind's rapidity, "and he said right off that night you'd marry him."

"Maybe he saw Mr. Ray take his first and second wife down to the Lower Falls, and knew it from his looks with them—Mr. Ray took 'em both down there, and asked 'em each to marry him coming back. All the way down he was telling me what they each said to everything they saw. And coming back he showed me where he asked 'em each. Mr. Ray never made any secret of his first and second wife to me. I'll say that for him. Yes, indeed. And like enough Joey was around then. He's always round when people are alone together."

"But he doesn't think these young people act loving," Mrs. Wiley went on, recurring to the main issue under discussion. "Joey says they don't have the right way at all. He says they don't disagree right, either. They're on opposite sides of the dam, the same as if they were married folks, but they don't seem to feel interested in their discussing. Nellie says they're real pleasant, but she can't understand them; Nellie's very far from making them out."

"Oh, Nellie can't make nothing out. She and Jack is dead easy. Look at those other boarders they've got. She says she can't make them out, either. I should think not."[6]

Mrs. Wiley's standpoint refused to stretch to the other boarders. She sighed again.

"She seems a very nice girl," she said, sadly.

"Oh, yes, nice enough—but mooney," said Mrs. Ray. "I know the kind as soon as I see 'em. I could almost tell 'em by their legs, when they get down from the train on the side away from me. She's got ideas about souls and scenery, that girl has; but that young man's got his living to earn, and he hasn't no time for any ideas. I like him! We both work for the United States Government, and that's a great bond. Yes, indeed. That young man knows if the dam goes through here, he'll be fixed for life digging it, and the girl's just the kind he wants, for he's practical and she's mooney—she's so mooney she's bought a house to live in while he digs the dam, and yet she's solemnly hoping there won't be no dam. She says so."

"Perhaps she don't mean it," suggested Mrs. Wiley.

"Yes, she does mean it," said Mrs. Ray; "yes, indeed, she means it. I'm a great judge of character and that girl means what she says."

"About the dam?"

"Yes, about everything. She's very friendly with me. She buys lots of stamps, and cancels up like a lady. I'm very fond of her."

"What did she say about the dam?"

"Oh, lots of things. She said it was a desecration for one thing, and then I was singing one day and she said I was very right, for the Lord did move in a very mysterious way, and He would save the falls."

"Was she as sure as that?" asked Mrs. Wiley, appalled.[7]

"She seemed to be. Oh, but she's very mooney."

"She's expecting a friend on to-night's train," said Mrs. Wiley; "Nellie says it's a girl younger than she is."

"There'll be trouble then," said Mrs. Ray, with the calmness of all prophets of evil; "a girl younger than she is is going to make her look awful old."

"I wonder how long they'll stay!"

"I don't know. You never can tell how long any one will stay here. Some come and say 'Oh, it's so quiet,' and the next morning the express has got to be flagged to take 'em right away; and others come and say 'Oh, it's so quiet,' and send for their trunks and paint-boxes that night. You never can tell how this place is going to strike any one. Mr. Ray's first wife cried all the time, till she died of asthma brought on by hay-fever; and his second wife liked to be where she could go without her false teeth, and she just loved it here! Yes, indeed."

"It isn't so very long till the train now," said Mrs. Wiley; "I guess I'll go down to the station. I always like to see the train come in. It's so sort of amusing to think it's going to Buffalo. Lottie Ann says it's so funny to think of something being right here with us, and then going right to Buffalo. I wish Lottie Ann could travel more. Lottie Ann would be a great traveller if she could travel any."

Mrs. Ray took up the lamp. "Well, if you must go," she said, "I'll put the light in the post-office and get down cellar, myself. I'm raising celery odd minutes this year, and getting the beds ready to lay it under is a lot of work."

Mrs. Wiley rose and moved slowly towards the door.[8] "I wonder how long those other two will stay at Nellie's," she said.

Mrs. Ray's lips drew tightly together. "I can't say I'm sure," she said; "I know nothing about them. Folks who never write letters nor get letters don't cut any figure in my life. Good night, Mrs. Wiley,"—she opened the door as she spoke—"good-by."

"They've been there—" murmured Mrs. Wiley, but the door closing behind her ended her speech.[9]

CHAPTER II

THE COMING OF THE LASSIE

On that same evening Alva and Ingram, the main subject of Mrs. Ray's and Mrs. Wiley's discourse, sat in the dining-room of the O'Neil House, waiting for train time. They had the dining-room to themselves, except for occasional vague and interjectional appearances of Mary Cody in the door, to see "if they wanted anything." Ingram had been eating,—he was late, always late,—and Alva sat watching him in the absent-minded way in which she was apt to contemplate the doings of other people, while she talked to him with the earnest interest which she always gave to talking,—when she talked at all. The contrast between her dreamy eyes and the intentness of her tone was as great as the contrast between the first impression wrought by a glance at her colorless face and simple dress, and the second, when, with a start, the onlooker realized that here was some one well worth looking at, well worth studying, and well worth meditating later. Perhaps she was not beautiful—I am not quite sure as to that—but she was surely lovely, with the loveliness which a certain sort of life brings to some faces.

Ingram, on the other side of the table, was just the ordinary good-looking, professional man of thirty to thirty-five. Tall, straight, slightly tanned, as would be[10] natural for a civil engineer who had spent September in the open; especially well-groomed for a man sixty miles from what he called civilization, fine to see in his knickerbockers and laced shoes, genial, jolly, and appreciative to the limit, apparently.

The contrast between the two was very great, and was felt by more than Mrs. Ray, for there had been many who had watched them during the week of Alva's stay. "He's a awful nice man," Mrs. O'Neil had said to Mrs. Ray, "but I don't see how she ever came to fancy him. They seem happy together, but it's such a funny way to be happy together."

This had been the original form of the statement which Mrs. Ray had later repeated to Mrs. Wiley.

It was true that they seemed very far apart, but were nevertheless apparently happy together. The week had been a pleasant week to both. Not, perhaps, as the town supposed, but pleasant anyway.

"I'm selfish enough to wish that it wasn't at an end to-night," Ingram said, as he took his piece of blackberry pie from Mary Cody; "you're a godsend in this place, Alva."

"But you'll like Lassie," his companion replied; "she's a charming little girl,—and I love her so. I always have loved the child, and just now it seemed to me as if it would do both her and me good to be together. Life for me is so wonderful—I don't like to be selfish with these days. My thoughts are too happy to keep to myself. I want some one to share my joy."

Ingram looked at her quizzically. "And I won't do at all?" he asked.

"You,—oh, you're away all day. And then,[11] besides, you're still so material, so awfully material. You can't deny it, Ronald, you're frightfully material—practical—commonplace. Of the world so very worldly."

He laughed lightly. "Just because I don't agree with you about the dam," he said; "there, that's it, you know. Why, my dear girl, suppose all America had been reserved for its beauty, set aside for the perpetual preservation of the buffaloes and the scenery,—where would you and I be now?"

She looked away from him in her curious, contemplative way. "If you knew," she said, after a minute, "how silly and petty and trivial such arguments sound to thinking people, you'd positively blush with shame to use them. It's like arguing with a baby to try to talk Heaven's reason with the ordinary man; he just sees his own little, narrow, earthly standpoint. I wonder whether it's worth while to ever try to be serious with you. You know very well that the most of your brethren would be willing to wreck the Yellowstone from end to end, if they could make their own private and personal fortunes building railways through it."

Ingram laughed again. "Where would the country be without railroads?" he asked.

She withdrew the meaning in her gaze out of the infinite beyond, where it seemed to float easily, and centred it on him.

"Just to think," she said, with deep meaning, "that ten years ago I might have married you, and had to face your system of logic for life!"

"Is it as bad as that?"

"It might have been. We might have made it so before we knew better. That's the rub in marriage.[12] Every one does it before he or she has settled his or her own views. I wasn't much of an idealist ten years ago, and you were not much of anything. But if I could have married any one then, I should have married you."

A shadow fell upon his face. He turned his chair a little from the table. "If I was not the right one, I wish that you had married some other man then,—I wish it with all my heart. You would have been so much happier. You're not happy now—you know that. It would have been so much better for you if you had married."

She smiled and shook her head. "Oh, no. It is much better as it is. Infinitely better. It's like coming up against a great granite wall to try and talk to you, Ronald, because you simply cannot understand what I mean when I say words, but nevertheless, believe me, I'm on my knees day and night, figuratively speaking, thanking God that I didn't marry then. I wasn't meant to marry then. I've been needed single."

He took out his cigarette case. "What were you meant for, then, do you think?" he queried; "nothing except as a convenience for others?"

"I was meant to learn, and then later, perhaps, to teach."

"To learn?" He looked his question with a quick intensity. "To teach?—" the question deepened sharply.

She smiled. "Yes. To learn so that I could teach. I feel some days that I was born to teach, and of course no one may hope to teach until he has learned first."

He shrugged his shoulders and laughed a little. She smiled again. "You great, granite wall, you don't[13] understand a bit, do you? Never mind, light your cigarette, and then tell me what time it is. We must not forget Lassie, you know."

He looked at his watch. "Ten minutes yet."

"Dear child, how tired she'll be. Never mind, she'll have a good rest during the next ten days."

"Will she stay ten days? She'll be here as long as you will then, won't she?"

"Yes; I'm going when she does."

"You think that the house will be done by that time?"

"I know that it will be done. It must be done."

He took his cigarette up in his fingers, turned it about a little, and then looked suddenly straight at her. "Alva, tell me the mystery, tell me the story, please. What is the house for?"

She looked at him and was silent.

"Why won't you tell me?"

Still silence. Still she looked at him.

"You'll tell her when she comes. Why not me?"

She spoke then: "She'll be able to understand, perhaps. You couldn't."

Ingram compressed his lips. "And am I so awfully dense?" he asked, half hurt.

"Not so dense, but, as yet, too ignorant. Or else it is that I am still too little myself to be able to rise above some human sentiments. And there is one point where endurance of the world's opinion is such refinement of torture, that only the very strongest and greatest can go willingly forward to meet and suffer the inevitable. The inevitable is close to me these days; it is approaching closer hourly, and there is no possible way for me to make you or the world understand[14] how I feel in regard to it all. And I shrink from facing the kind of thing that I shall soon have to face any sooner than is absolutely necessary. And so I won't tell you."

She stopped. Although her voice was firm, her eyes had again become far away in their expression, and she seemed almost to have forgotten him even while making this explanation for his sake. He was watching her with deepest interest, and the curiosity in his eyes burned more brightly than ever.

"But if it is all as terrible as you make out," he said, "how can you make that young girl understand what you suppose to be so far beyond me?"

"Because I can teach her."

"How?"

"She'll be with me night and day for ten days. We'll have a good deal of time together. And then, too, she is a woman. Women learn some lessons easily. Easier far than men."

"Is it right to teach her such a lesson as this?"

"Why do you ask that, when you do not know what my lesson will be? How can you dare fancy that it could possibly be wrong?"

Ingram paused for a minute, a little staggered. Then he said, bluntly: "The world is made up of reasonable men and women, and it seems to me best that all men and women should be reasonable. What isn't reasonable is wrong. Forgive me, Alva, but you don't sound reasonable."

"You think that I am not reasonable? Therefore I must be wrong. That's your logic?"

He hesitated. "Perhaps I think you wrong. I must confess that to me you often seem so."[15]

She thought a minute, considering his standpoint.

"Ronald," she said then, "'reasonable' is a term that is given its meaning by those in power, isn't that so? 'Reasonable' is what best serves the ends of those who generally seek to serve no ends except their own. It's true that I don't at all care what a few selfish and near-sighted individuals think of me. I have thrown in my lot with the unreasonable majority, the poor, the suffering, and those yet to be born who are being robbed of their birthright. To leave my mystery and go back to our familiar difference, there's the dam to illustrate my exact meaning. The 'reasonable' use of the river out there is to build a dam, and so make a few more millionaires and give employment for a few years to a few thousands of Italians. The 'unreasonable' use to make of the river is to preserve it intact for tired, weary souls to flee to through all the future, so that their bodies may breathe God and life into their being again, and go forth strong. You know you don't agree with me as to that view of that case, so how can I expect you to disagree with the general opinion that the 'reasonable' thing for me to do personally is to take my life and get all the pleasure that I can from it? The 'unreasonable' view, the one I hold myself, is that I have elected to take it and give—not get—all the pleasure that I can with it. Of course you don't understand that unreasonableness, and so you don't agree with me; but I can tell you one thing, Ronald," she leaned forward and suddenly threw intense meaning into her words, "and that is this. My story—my mystery as you call it so often—is at once a very old mystery and a very new one. I have suffered, and I am to suffer, most terribly. The[16] happiness to which I am looking forward is going to be an ordeal for which all that I have undergone until now will be none too much preparation. But in the hour of my keenest agony I shall be happier and more hopeful than you will ever be able to realize in your life. Unless you change completely. Take my word for that."

She rose as she spoke, and he rose, too, looking towards her with eyes that plainly subscribed to Mrs. Ray's opinion as expressed in the simple vernacular.

"Oh, no, I can't understand, and I don't believe," he said: "but I am able to meet trains, anyhow."

A large cape lay on an empty chair near by, and she took it up now.

"But I'm going alone," she said, as she slipped into it.

"What nonsense. Of course I am not going to let you go alone."

She looked at him, buttoning the woolen cross-straps upon the cape as she did so; then she threw one corner back over her forearm and laid that hand on his, speaking decidedly.

"I'm going alone to meet her. You know what I asked you to promise when I came here a week ago, and you know that you gave me your word that you'd never interfere with me. Lassie is almost a stranger to you, and after you have learned to know her as a young lady there will come years for you two to talk together, but for me this meeting is something that I don't want to share. Don't say any more."

"But what will she think," he queried, "when she and you return together, and here sits a cavalier who[17] didn't trouble himself to accompany one lady through the dark night to meet another's train?"

"She will think nothing, because she will not see the cavalier. When we come in, we shall go straight up-stairs."

Ingram more than smiled now. "Forgive me, Alva, but you and I are such old, such near, such dear friends, that I can say to you frankly, as I do say to you frankly over and over again, I don't understand you."

She laughed at that, and turned towards the door.

"I know—I know. I'm very queer, most awfully queer, in the eyes of every one. But I can tell you, as I tell them, that the worst of it is only for a little while. Just a few brief weeks and I shall be again, in most ways, a normal woman. A woman just like all the rest again," her back was towards him now, "in most thing—in most things."

"Never! You never have been like other women,—you've always been different from other women; you always will be."

"Have I? Shall I? Well, perhaps it's so. I'm rather glad of it. Most women are stupid, I think. Poor things!" she sighed.

He followed her as she moved towards the door, half-vexed, half-laughing:

"And men, Alva, and men. Are they all stupid in your eyes?"

She had her hand on the knob, and her great cape was gathered about her in heavy folds.

"Oh, Ronald," she said, looking into his look, "if you had any idea how fearfully stupid they seem to me. Often and often in the last three years. Even yourself.[18] And ten years ago, when we were eighteen and twenty-five, I thought you so interesting, too."

He burst out laughing at that,—it wasn't in him to take her seriously enough to really mind her "ways" long.

"But what are we to do, when we are such mere ordinary creatures? And you know, my dear, that if the transcendentals like to muse on bridges by moonlight, some well-educated, commonplace individuals must build them the bridges first."

"Ah, there you go again. Yes, that's true. One should never forget that, of course. Particularly when talking with a man who uses a man's logic."

Then she opened the door, passed quickly into the hall, and let it close after her.

A lantern was resting on the floor outside, as if in waiting, and she picked it up and went at once into the night—a dark night through which the station lights and signals, red and yellow, sparkled brightly.

It was a brisk October air that filled that outer world, and the superabundant vitality of God's country came glinting, storming, down, up, and across earth, sky, and ether in between.

"This glorious night!" she thought prayerfully. "If one might only realize just all it means to be existing right now." She held the lantern behind her, and saw her shadow spread forth into space and fade away beyond. "The train isn't in the block yet," she thought, glancing at the signal; "that means minutes long to wait." Quickly she ran down the cinder-path beside the tracks, and entered the little station where a crowd of men lounged.

"Is the train on time to-night?" she asked one.[19]

He shook his head. "Half an hour late," he said; "wreck on the road. Wheel off a car of thrashing-machines at Kent's."

"A whole half hour?"

"Well, I heard Joey Beall say they was making it up," said the man; "the station agent's gone home to supper, or you could ask him."

"Thank you very much," Alva said, and turned and went out.

The night appeared even fairer than before. Her eyes roamed widely. She thought for a minute of going back to the hotel and bidding Ingram come out with her, but then her own mood cried for relief from the labor of his companionship. We do not give our spirits credit for what they learn through adapting themselves to uncongenial companionship. Alva felt hers craved a rest. "I'll go out on the bridge and wait there," she told herself; "that will be the right thing,—to stand above the gorge and say my evening prayers."

So, stepping carefully over the switch impedimenta, she walked on, following the embankment that led out to the Long Bridge.

It is very long—that Long Bridge—and very high as well. I believe that the first bridge, the wooden one, was close to a world's wonder in its days. Even now the skilfully combined network of iron, steel, joist and cable seems a species of marvel, as it springs across the great cleft that the glacier sawed through several million layers of Devonian stratum several million years ago. I forget how many tons of metal went into its structure, but so intricate and delicately poised is the whole, that while trains roar forth upon its length and find no danger, yet does it echo quick and responsive[20] to the light step of a lithe treading woman or even of the littlest child. On this night Alva, wrapped close in her cape, fared fearlessly out into the black beyond. The high braces and beams creaked all along its vanishing length, and she smiled at the sound. "I wonder if sometime, years from now, I shall return and walk out here again, and find the bridge crying me a welcome!" she thought; "I wonder!" A narrow, boarded way led to the right of the rails, and she was soon directly over the gorge. It was far too dark to see the ribbon of river hundreds and hundreds of feet below, or the steep picture-crevasse that encased the water's way. Beyond and below, to the left, she could have seen the windows of Ledgeville, had she turned that way, but she did not do so. It was the gorge that always claimed her, whether by day or by night, and now she leaned upon the steel guard and stared below. "I can see it plainly, even in the dark," she murmured to herself. "I can see every rock and eddy down there, the great curve of whirlpool, and the place where the water slides so smoothly off and then goes mad and foams below. It is all distinct to me. I remember the day that I first saw it, years ago, when—right here, where I stand to-night—he came to me for the first time, and we knew one another directly. And I shall see it just so plainly in the years to come, when it will never enter into my daily life any more, and yet will be the background of all my living."

She stood there for a long time, wrapped in the depth of her own thoughts. The shadows below seemed to shift and drift in their variations of intensity, and her eyes found rest in their profundity. "It's like drawing water out of a well when one is very thirsty," she said, [21]at last, straightening herself and sighing; "it's unexplainable, but oh, it's so good,—the lesson of darkness and water and trees and sky. How grateful I am to be able to spell out a little in that primer!"

Then she clasped her hands and said a prayer, and as she finished the signal flashed the train's entrance within the block. That meant only two minutes until its arrival, and so she turned herself back at once. The crowd at the station had perceptibly increased and began now to surge forth upon the platform. Mrs. Dunstall was there and Pinkie, and Joey Beall and Mrs. Wiley, and Clay Wright Benton, and old Sammy Adams, and Lucia Cosby.

"Been out on the Bridge, I suppose?" Mrs. Dunstall said pleasantly to Alva.

"Yes; it's lovely to-night," the latter replied.

Every one smiled. They all felt that any one who would go out on the bridge on a pitch black night must be mildly insane, but they looked upon Alva as mildly insane anyhow. Mrs. Ray had many beside Ingram to uphold her opinion.

"It's her that bought the old Whittacker house and is putting a bath-tub in it," Joey Beall whispered to a man who was waiting to leave by the last train out.

"IT'S HER THAT BOUGHT THE OLD WHITTACKER HOUSE."

"I know it," said the man; he was one of those men who never let Joey or anybody else feel that he had any advantage of him, in even the slightest way.

Just then the train charged madly in beside them.

Lassie, out on the Pullman's rear platform, preparatory to climbing down the steep steps the instant that it should be allowable, saw a well-known figure wrapped in a dark cloak, and gave a little cry of joy—

"Alva! Here I am—all safe."[22]

Then she was enwrapped in the same dark cloak herself, for the space of one warm, all-embracing hug, her friend repeating over and over, "I'm so happy to have you—so happy to have you." And then they moved away through the little group of bystanders, and started up the cinder-path towards the hotel.

"I'm so happy to have you!" Alva exclaimed again, when they were alone. She did not even seem to know that she had said so before.

"It was so good of you to ask me! How did you come to think of it? And oh, Alva, what are you doing here, in this lonely place?"

"It will take me all your visit to properly answer those questions, dear; but I'll tell you this much at once. I asked you because I wanted to have you with me, and because I thought that you and I could help one another a great deal right now. And I am here, dear, because I am the happiest woman that the world has ever seen, and because the greatest happiness that the world has ever known is to be here in a few weeks."

Lassie stopped short, astonished.

Alva went on, laughing gaily: "Yes, it is so! Come on,—or you will stumble without my lantern to guide you. I'm going to tell you all about everything when we get alone in our room, but now, little girl, hurry, hurry. Don't stop behind."

So Lassie swallowed her astonishment for the time being, and followed.

The hotel stood on the crest of the hill above the station and the railway's path curved by it. They were there in a minute, and in another minute alone up-stairs in their room—or rather, rooms—for there were two bedrooms, opening one into the other.[23]

"Why, how pretty you have made them," the young girl cried; "pictures, and a real live tea-table. And a work-stand! How cosy and dear! It's just as if you meant to live here always."

Her face glowed, as she absorbed the surprising charm of her new abode. One does not need to be very old or to have travelled very extensively to recognize some comforts as pleasingly surprising in the country.

Alva was hanging up her cloak, and now she came and began to undo the traveller's with a loving touch.

"Why, in one way I do mean to live here always, dear. I never am anywhere that I do not—in a certain sense—live there ever after. People and places never fade out of my life. Wherever I have once been is forever near and dear to me, so dear that I can't bear to remember anybody or anything there as ugly. The difference between a pretty room and an ugly one is only a little money and a few minutes, after all, and I'm beginning to learn to apply the same rule to people. It only takes a little to find something interesting about each. We'll be so happy here, Lassie; how we will talk and sew and drink tea in these two tiny rooms! I've been just feasting on the thought of it every minute since you wrote that you could come."

Lassie hugged her again. "I can't tell you how overjoyed I was to think of coming and having a whole fortnight of you to myself. Every one thought it was droll, my running off like this when I ought to be deep in preparations for my début, but mamma said that the rest and change would do me good. And I was so glad!"

Alva had gone to hang up the second cloak and now[24] she turned, smiling her usual quiet sweet smile as she did so.

"It's a great thing for me to have you, dear; I haven't been lonely, but my life has been so happy here that I have felt selfish over keeping so much rare, sweet, unutterable joy all to myself,—I wanted to share it."

She seated herself on the side of the bed, and held out her hand in invitation, and Lassie accepted the invitation and went and perched beside her.

"Tell me all about it," she said, nestling childishly close; "how long have you been here anyway?"

"A week to-day."

"Only a week! Why, you wrote me a week ago."

"No, dear, six days ago."

"But you spoke as if you had been here ever so long then."

"Did I? It seemed to me that I had been here a long time, I suppose. Time doesn't go with me as regularly as it should, I believe. Some years are days, and the first day here was a year."

"And why are you here, Alva?"

"Oh, that's a long story."

"But tell it me, can't you?"

"Wait till to-morrow, dearest; wait until to-morrow, until you see my house."

"Your house!"

"I've bought a house here,—a dear little old Colonial dwelling hidden behind a high evergreen wall."

"A house here—in Ledge?"

"No, dear, not in Ledge—in Ledgeville. Across the bridge—"[25]

"But when—"

"A week ago—the day I came."

"But why—"

Alva leaned her face down against the bright brown head.

"I wanted a home of my own, Lassie."

"But I thought that you couldn't leave your father and mother?"

"I can't, dear."

"Are they coming here to live?"

"No, dear."

"But I don't understand—"

"But you will to-morrow; I'll tell you everything to-morrow; I'd tell you to-night, only that I promised myself that we would go to a certain dear spot, and sit there alone in the woods while I told you."

"Why in the woods?"

"Ah, Lassie, because I love the woods; I've gotten so fond of woods, you don't know how fond; trees and grass have come to be such friends to me; I'll tell you about it all later. It's all part of the story."

"But why did you come here, Alva,—here of all places, where you don't know any one. For you don't know any one here, do you?"

"I know a man named Ronald Ingram here; he is the chief of the engineering party that is surveying for the dam."

"Is he an old friend?"

"Oh, yes, from my childhood."

Lassie turned quickly, her eyes shining:

"Alva, are you going to marry him?"

Her face was so bright and eager that something veiled the eyes of the other with tears as she answered:[26]

"No, dear; he's nothing but a friend. I was looking for a house—a house in the wilderness—and he sent for me to come and see one here. And I came and saw it and bought it at once; I expect to see it in order in less than a fortnight."

"Then you're going to spend this winter here?"

Alva nodded. "Part of it at any rate."

"Alone?"

Alva shook her head.

Lassie's big eyes grew yet more big. "Do you mean—you don't mean—oh, what do you mean?"

She leaned forward, looking eagerly up into the other's face. "Alva, Alva, it isn't—it can't be—oh, then you are really—"

Two great tears rolled down that other woman's face. She simply bowed her head and said nothing.

Lassie stared speechless for a minute; then—"I'm so glad—so glad," she stammered, "so glad. And you'll tell me all about it to-morrow?"

"Yes, dear," Alva whispered, "I'll tell you all to-morrow. I'll be glad to tell it all to you. The truth is, Lassie, that I thought that I was strong enough to live these days alone, but I learned that I am weaker than I thought. You see how weak I am. I am weeping now, but they are tears of joy, believe me—they are tears of joy; I am the happiest and most blessed woman in the whole wide world. And yet, it is your coming that leads me to weep. I had to have some outlet, dear, some one to whom to speak. And I want to live, Lassie, and be strong, very, very strong—for God."

Lassie sat staring.

"You don't understand, do you?" Alva said to[27] her, with the same smile with which she had put the same question to Ingram.

But Lassie did not answer the question as Ingram had answered it.

"You will teach me and I shall learn to understand," she said.[28]

CHAPTER III

INTRODUCING LASSIE TO MRS. RAY

The next morning dawned gorgeous.

When Lassie, in her little gray kimono, stole gently in to wake her friend, she found Alva already up and dressed, standing at the window, looking out over the October beauty that spread afar before her. It was a wonderful sight, all the trees bright and yet brighter in their autumn gladness, while the grass sparkled green through the dew that had been frost an hour before. The view showed the radiance fading off into the distant blue, where bare brown fields told of the harvest garnered and the ground made ready for another spring.

Lassie pressed Alva's arm as she peeped over her shoulder, and the other turned in silence and kissed her tenderly.

Side by side they looked forth together for some minutes longer, and then Lassie whispered:

"I could hardly get to sleep last night—for thinking of it all, you know. You don't guess how interested I am. I do so want to know everything."

Alva turned to regard her with her calm smile.

"But when you did get to sleep, you slept well, didn't you?" she asked; "tell me that, first of all."

"Why, is it late? Did I sleep too awfully long? Why didn't you call me?"[29]

"Oh, my dear, why? It's barely nine, and that isn't late at all for a girl who spent all yesterday on the train. I let you sleep on purpose. What's the use of waking up before the mail comes? And that isn't in till half-past under the most favorable circumstances; and even then it never is distributed until quarter to ten. I thought we'd get our letters after our breakfast, and then carry them across the bridge with us. Would you like to do that? I have to cross the bridge every morning."

"Cross the bridge? That means to go to your house?"

"Yes, dear."

"How nice! I'm crazy to see your house. Is it far from here to the post-office? Will that be on our way?"

"That is the post-office there—by the trees." Alva pointed to a brown, two-story, cottage-like structure three hundred yards further up the track.

"The little house with the box nailed to the gate-post?"

"It isn't such a little house, Lassie; it's quite a mansion. The lady who lives in it rents the upper part for a flat and takes boarders down-stairs."

"Does she take many?"

Alva laughed. "She told me that she only had a double-bed and a half-bed, so she was limited to eight."

"Oh!"

"I know, my dear, I thought that very same 'Oh' myself; but that's what she said. And that really is as naught compared to the rest of her capabilities."

"What else does she do?"

"I'm afraid I can't remember it all at once, but among other things she runs a farm, raises chickens,[30] takes in sewing, cuts hair, canes chairs and is sexton of the church. She's postmistress, too, and does several little things around town."

Lassie drew back in amazement. "You're joking."

"No, dear, I'm not joking. She's the eighth wonder in the world, in my opinion."

"She must be quite a character."

"Every one's quite a character in the country. Country life develops character. I expect to become a character myself, very soon; indeed I'm not very positive but that I am one already."

"But how does the woman find time to do so much?"

"There is more time in the country than in the city; you'll soon discover that. One gets up and dresses and breakfasts and goes for the mail, and reads the letters and answers them, and then its only quarter past ten,—in the country."

Lassie withdrew from the arm that held her. "It won't be so with me to-day, at all events," she laughed. "What will they think of me if every one here is as prompt as that?"

"It doesn't matter to-day; we'll be prompt ourselves to-morrow. But you'd better run now. I'm in a hurry to get to my house; I'm as silly over that house as a little child with a new toy,—sillier, in fact, for my interest is in ratio with my growth, and I've wanted a home for so long."

"But you've had a home."

"Not of my very ownest own, not such as this will be."

The young girl looked up into her face. "I'm so very curious," she said, with emphasis; "I want so to know the story."[31]

Alva touched her cheek caressingly, "I'll tell you soon," she promised, "after you've seen the house."

Lassie went back into her room and proceeded to make her toilet, which was soon finished.

They went down into the little hotel dining-room then for breakfast, and found it quite deserted, but neat and sweet, and pleasantly odorous of bacon.

"Such a dolls' house of a hotel," said Lassie.

"It's a cozy place," Alva answered. "I like this kind of hotel. It's sweet and informal. If they forget you, you can step to the kitchen and ask for more coffee. I'm tired of the world and the world's conventionality. I told Mrs. Lathbun yesterday that Ledge would spoil me for civilization hereafter. I like to live in out-of-the-way places."

"Mrs. Lathbun is the hostess, I suppose?"

"No, Mrs. O'Neil is the hostess, or rather, she's the host's wife. You must meet her to-day. Such a pretty, brown-eyed, girlish creature,—the last woman in the world to bring into a country hotel. She says herself that when you've been raised with a faucet and a sewer, it's terrible to get used to a cistern and a steep bank. She was born and brought up in Buffalo."

By this time Mary Cody had entered, beaming good morning, and placed the hot bacon and eggs, toast and coffee, before them.

"I'm going for the mail after breakfast, Mary," Alva said; "shall I bring yours?"

"Can't I bring yours?" said Mary Cody. "I can run up there just as well as not." Mary Cody was all smiles at the mere idea.

"No, I'll have to go myself to-day, I think. I'm expecting a registered letter."[32]

"I'll be much obliged then if you will bring mine."

"If there are any for the house, I'll bring them all," Alva said; "will you tell Mrs. Lathbun that?"

"I'll tell her if I see her, but they're both gone. They went out early—off chestnutting, I suppose."

"Oh!"

"Who is Mrs. Lathbun?" Lassie asked, when Mary Cody had gone out of the room.

"I spoke of her before and you asked about her then, didn't you? And I meant to tell you and forgot. She's another boarder, a lady who is here with her daughter. Such nice, plain, simple people. You'll like them both."

"I thought that we were to be here all alone."

"We are, to all intents and purposes. The Lathbuns won't trouble us. They are not intrusive, only interesting when we meet at table or by accident."

"Every one interests you, Alva; but I don't like strangers."

Alva sighed and smiled together.

"I learned to fill my life with interest in people long ago," she said simply; "it's the only way to keep from getting narrow sometimes."

Lassie looked at her earnestly.

"Does every one that you meet interest you really?" she asked.

"I think so; I hope so, anyway."

"Don't you ever find any one dull?"

Alva looked at her with a smile, quickly repressed. "No one is really dull, dear, or else every one is dull; it's all in the view-point. The interest is there if we want it there; or it isn't there, if we so prefer. That's all."[33]

There was a little pause, while the young girl thought this over.

"I suppose that one is happiest in always trying to find the interest," she said then slowly; "but do tell me more about the Lathbuns."

"Presupposing them in the dull catalogue?"

Lassie blushed, "Not necessarily," she said, half confusedly.

Alva laughed at her face, "I don't know so very much about them, except that they interest me. The mother is large and rather common looking, but a very fine musician, and the daughter is a pale, delicate girl with a romance."

Lassie's face lit up: "Oh, a romance! Is it a nice romance? Tell me about it."

"It's rather a wonderful romance in my eyes. I'll tell it all to you sometime, but that was the train that came in just now, and I want to get the mail and go on over to the house, so we'll have to put off the romance for the present, I'm afraid."

"I don't hear the train."

"Maybe not—but it went by."

"Went by! And the mail! How does the mail get off by itself?"

"Oh, my dear, I must leave you to learn about the mail from Mrs. Ray. She'll explain to you all about what happens to the Ledge mail when the train rushes by. It's one of her pet subjects."

"Do you know you're really very clever, Alva; you seem to be plotting to fill me full of curiosity about everything and everybody in this little out-of-the-way corner in the world? Nobody could ever be dull where you are."[34]

A sudden shadow fell over the older's face at that; a wistful wonder crept to her eyes.

"I wish I could believe that," she said.

"But you can, dear. You've always seemed to me to be just like that French woman who was the only one who could amuse the king, even after she'd been his wife for forty years. You'd be like that."

Alva rose, laughing a little sadly. "God grant that it may be so," she said, "there are so many people who need amusing after forty years. But, dear, you know I told you last night that I sent for you to come and teach and learn, and you are teaching already."

"What am I teaching?" Lassie's eyes opened widely.

"You are teaching me what I really am, and that's a lesson that I need very much just now. It would be so very easy to forget what I really am these days. My head is so often dizzy."

"Why, dear? What makes you dizzy?"

"Oh, because the world seems slipping from me so fast. I could so easily quit it altogether. And I must not quit it. I have too much to do. And I am to have a great task left me to perform, perhaps. Oh, Lassie, it's hopeless to tell you anything until I have begun by telling you everything. You'll see then why I want to die, and why I can't."

"Alva!"

"Don't be shocked, dear; you don't know what I mean at all now, but later you will. Come, we must be going. No time to waste to-day."

They went up-stairs for hats and wraps, and then came down ready for the October sunshine. It was fine to step into the crispness and breathe the ozone of its[35] glory. On the big stone cistern cover by the door a fat little girl sat, hugging a cat and swinging her feet so as to kick caressingly the brown and white hound that lay in front of her.

"A nice, round, rosy picture of content," Alva said, smiling at the tot. "I love to see babies and animals stretched out in the sun, enjoying just being alive."

"I enjoy just being alive myself," said Lassie.

They went up the path that ran beside the road and, arriving at the post-office, turned in at the gate and climbed the three steps. The post-office door stuck, and Alva jammed it open with her knee. Then she went in, followed by Lassie.

The post-office was just an extremely small room, two thirds of which appeared reserved for groceries, ranged upon shelves or piled in three of its four corners. The fourth corner belonged to the United States Government, and was screened off by a system of nine times nine pigeonholes, all empty. Behind the pigeonholes Mrs. Ray was busy stamping letters for the outgoing mail.

"You never said that she kept a grocery store, too," whispered Lassie.

"No, but I told you that I'd forgotten ever so many things that she did," whispered Alva in return.

The lady behind the counter calmly continued her stamping, and paid not the slightest attention to them.

They sat down upon two of the three wooden chairs that were ranged in front of a pile of sacks of flour and remained there, meekly silent, until some one with a basket came in and took the remaining wooden chair. All three united then in adopting and maintaining the reverential attitude of country folk awaiting the mail's[36] distribution, and Lassie learned for the first time in her life how strong and binding so intangible a force as personal influence and atmosphere may become, even when it be only the personal influence and atmosphere of a country postmistress. It may be remarked in passing, that not one of the letters then being post-marked received an imprint anything like as strong as that frame of mind which the postmistress of Ledge had the power to impress upon those who came under her sceptre. She never needed to speak, she never needed to even glance their way, but her spirit reigned triumphant in her kingdom, and, as she carried her governmental duties forward with as deep a realization of their importance as the most zealous political reformer could wish, no onlooker could fail to feel anything but admiration for her omniscience and omnipotence. Mrs. Ray's governmental attitude towards life showed itself in an added seriousness of expression. Her dress was always plain and severe, and in the post-office she invariably put over her shoulders a little gray shawl with fringe which she had a way of tucking in under her arms from time to time as she moved about.

Lassie had ample time to note all this while the stamping went vigorously forward. Meanwhile the mail-bag which had just arrived lay lean and lank across the counter, appearing as resigned as the three human beings ranged on the chairs opposite. Finally, when the last letter was post-marked, the postmistress turned abruptly, jerked out a drawer, drew therefrom a key which hung by a stout dog-chain to the drawer knob and held it carefully as if for the working up of some magic spell. Lassie, contemplating every move[37] with the closest attention, could not but think just here that if the postal key of Ledge ever had decided to lose its senses and rush madly out into the whirlwind of wickedness which it may have fancied existing beyond, it would assuredly not have gotten far with that chain holding it back, and Mrs. Ray holding the chain. It was a fearfully large and imposing chain, and seemed, in some odd way, to be Mrs. Ray's assistant in maintaining the dignity necessary to their dual position in the world's eyes.

The lady of the post-office now unlocked the bag and, thrusting her hand far in, secured two packets containing nine letters in all from the yawning depths. She carefully examined each letter, and then turned the bag upside down and gave it one hard, severe, and solemn shake. Nothing falling out, she placed it on top of a barrel, took up the nine letters, and went to work upon them next.

When they were all duly stamped, she laid them, address-side up, before her like a pack of fortune-telling cards, folded her arms tightly across her bosom, and, standing immovable, directed her gaze straight ahead.

Now seemed to be the favorable instant for consulting the sacred oracle. Alva and the third lady rose with dignity and approached the layman's side of the counter; Lassie sat still, thrilled in spite of herself.

Alva, being a mere visitor, drew back a little with becoming modesty and gave the native a chance to speak first.

"I s'pose there ain't nothing for me," said that other, almost apologetically, "but if there's anything for Bessie or Edward Griggs or Ellen Scott I can take[38] it; and John is going down the St. Helena road this afternoon, so if there's anything for Judy and Samuel—"

"Here's yours as usual," said Mrs. Ray, rising calmly above the other's speech and handing Alva three letters as she did so; "the regular one, and the one you get daily, and then here's a registered one. I shall require a receipt for the registered one, as the United States Government holds me legally liable otherwise, and after my husband died I made up my mind I was all done being legally liable for anything unless I had a receipt. Yes, indeed. I'd been liable sometimes legally in my married life, but more often just by being let in for it, and I quit then. Yes, indeed. When they tell me I'm legally liable for anything now, I never fail to get a receipt, and I read every word of the President's message over twice every year to be sure I ain't being given any chance to get liable accidentally when I don't know it—when I ain't took in what was being enacted, you know. Here,—here's the things and the ink; you sign 'em all, please."

Alva bent above the counter obediently and proceeded to fill out the forms as according to law. Mrs. Ray watched her sharply until the one protecting her own responsibility had been indorsed, and then she turned to the other inquirer:

"Now, what was you saying, Mrs. Dunstall? Oh, I remember,—no, of course there ain't anything for you. Nor for any of them except the Peterkins, and I daren't give you their mail because they writ me last time not to ever do so again. I told Mrs. Peterkin you meant it kindly, but she don't like that law as lets you open other people's letters and then write[39] on 'Opened by accident.' Mrs. Peterkin makes a point of opening her own letters. She says her husband even don't darst touch 'em. It's nothing against you, Mrs. Dunstall, for she's just the same when I write on 'Received in bad order.' She always comes right down and asks me why I did it. Yes, indeed. I suppose she ain't to blame; some folks is funny; they never will be pleasant over having their letters opened."

Alva bent closer over her writing; Lassie was coughing in her handkerchief. Mrs. Dunstall stood before the counter as if nailed there, and continued to receive the whole charge full in her face.

"But I've got your hat done for you; yes, I have. I dyed the flowers according to the Easter egg recipe, and it's in the oven drying now. And I made you that cake, too. And I've got the setting of hens' eggs all ready. Just as soon as the mail is give out, I'll get 'em all for you. It's pretty thick in the kitchen, or you could go out there to wait, but Elmer Haskins run his lawn-mower over his dog's tail yesterday, and the dog's so lost confidence in Elmer in consequence, that Elmer brought him up to me to take care of. He's a nice dog, but he won't let no one but me set foot in the kitchen to-day. I don't blame him, I'm sure. He was sleepin' by Deacon Delmar's grave in the cemetery and woke suddenly to find his tail gone. It's a lesson to me never to leave the grave-cutting to no one else again. I'd feel just as the dog does, if I'd been through a similar experience. Yes, indeed. I was telling Sammy Adams last night and he said the same."

"There, Mrs. Ray," said Alva, in a stifled voice, straightening up as she spoke, "I think that will set you free from all liability; I've signed them all."[40]

"Let me see,—you mustn't take it odd that I'm so particular, because a government position is a responsibility as stands no feeling." She looked at the signatures carefully, one after the other. "Yes, they're right," she said then; "it wasn't that I doubted you, but honesty's the best policy, and I ought to know, for it was the only policy my husband didn't let run out before he died without telling me. He had four when I married him—just as many as he had children by his first wife—he had six by his second—and his name and the fact that it was a honest one, was all he left me to live on and bring up his second wife's children on. Goodness knows what he done with his money; he certainly didn't lay it by for the moths and rust, for I'm like the text in the Bible—wherever are moths and rust there am I, too. Yes, indeed, and with pepper and sapolio into the bargain; but no, the money wasn't there, for if it was where it could rust it would be where I could get it."

Alva smiled sympathetically, and then she and Lassie almost rushed out into the open air. When they were well out of hearing, they dared to laugh.

"Oh, my gracious me," Lassie cried; "how can you stand it and stay sober?"

"I can't, that's the trouble!" Alva gasped. "My dear, she felt strange before you, and was rather reticent, but wait till she knows you well—until to-morrow. Oh, Lassie, she's too amusing! Wait till she gets started about the dam, or about Niagara, or about her views on running a post-office, or anything—" she was stopped by Lassie's seizing her arm.[41]

"Look quick, over there,—who is that? He looks so out of place here, somehow. Don't he? Just like civilization."

Alva looked. "That? Oh, that's Ronald—Ronald Ingram, you know, coming across lots for his letters. You remember him, surely, when you were a little girl. He was always at our house then. You'll meet him again to-night. I'd stop now and introduce you, only I want to hurry."

"I suppose that he knows all about it?"

"All about what?"

"The secret."

"Ronald? Oh, no, dear. No one knows. No one—that is, except—except we two. You will be the only outsider to share that secret."

"For how long?"

"Until I am married."

"Until you are married! Why, when are you to be married?—Soon?"

"In a fortnight."

"And no one is to know!"

"No one."

"Not his family? Not yours?"

"No one."

"How strange!"

Alva put out her hand and stayed the words upon her friend's lips. "Look, dear, this is the Long Bridge. You've heard of it all your life; now we're going to walk across it. Look to the left; all that lovely scene of hill and valley and the little white town with green blinds is Ledgeville; and there to the right is the famous gorge, with its banks of gray and its chain of falls, each lovelier than the last. Stand still and just [42] look; you'll never see anything better worth looking at if you travel the wide world over."

They stopped and leaned on the bridge-rail in silence for several minutes, and then Alva continued softly, almost reverently: "This scene is my existence's prayer. I can't make you understand all that it means to me, because you can't think how life comes when one is crossing the summit—the very highest peak. I've climbed for so long,—I'll be descending upon the other side for so long,—but the hours upon the summit are now, and are wonderful! I should like to be so intensely conscious that not one second of the joy could ever fade out of my memory again. I feel that I want to grave every rock and ripple and branch and bit of color into me forever. Oh, what I'd give if I might only do so. I'd have it all to comfort me afterwards then—afterwards in the long, lonely years to come."

"Why, Alva," said her friend, turning towards her in astonishment, "you speak as if you didn't expect to be happy but for a little while."

A sad, faint smile crept around Alva's mouth, and then it altered instantly into its usual sweet serenity.

"Come, dear," she said; "we'll hurry on to the house, and then after you've seen it we'll go to my own dear forest-seat, and there I'll tell you the whole story."

"Oh, let us hurry!" Lassie said, impetuously; "I can't wait much longer."

So they set quickly forward across the Long Bridge.[43]

CHAPTER IV

THE DIFFERENCE

On the further side of the Long Bridge the railway tracks swept off in a smooth curve to the right, and, as there was a high embankment to adapt the grade to the hillside, a long flight of steps ran down beside it into the glen below.

A pretty glen, dark with shadows, bright with dancing sun-rays. A glen which bore an odd likeness to some lives that we may meet (if we have that happiness), lives that lead their ways in peace and beauty, with the roar and smoke of the world but a stone's throw distant.

Lassie's eyes, looking down, were full of appreciation.

"Is it there that you are going to live?" she asked.

Alva shook her head. "Oh, no, not there; that is Ledge Park, the place that all the hue and cry is being raised over just now."

"Oh, yes," Lassie turned eagerly; "tell me about that. I read something in the papers, but I forgot that it was here."

"It is 'here,' as you say. But it concerns all the country about here, only it's much too big a subject for us to go into now. There are two sides, and then ever so many sides more. I try to see them all, I try to see every one's side of everything as far as I can,[44] but there is one side that overbalances all else in my eyes, and that happens to be the unpopular one."

"That's too bad."

"Yes, dear," Alva spoke very simply; "but what makes you say so?"

"Why? Why, because then you won't get what you want."

Her friend laughed. "Don't say that in such a pitying tone, Lassie. Better to be defeated on the right side, than to win the most glorious of victories for the wrong. Who said that?"

Lassie looked doubtful.

Alva laughed again and touched her cheek with a finger-caress. "I'll tell you just this much now, dear;—all of both the river banks—above, below and surrounding the three falls—belong to Mr. Ledge, and he has always planned to give the whole to the State as a gift, so that there might be one bit of what this country once was like, preserved. He made all his arrangements to that end, and gave the first deeds last winter. What do you think followed? As soon as the State saw herself practically in possession, it appointed a commission to examine into the possibilities of the water power!" Alva paused and looked at her friend.

"But—" Lassie was clearly puzzled.

"The engineers are here surveying now. Ronald Ingram is at the head and the people of all the neighborhood are so excited over the prospect of selling their farms that no one stops to think what it would really mean."

"What would it really mean?"

"A manufacturing district with a huge reservoir above it."[45]

"Where?"

"Back there," she turned and pointed; "they say that there was a great prehistoric lake there once, and they will utilize it again."

"But there's a town down there."

"Yes, my dear, Ledgeville. Ledgeville and six other towns will be submerged."

Lassie stopped short on the railroad track and stared. She had come to a calamity which she could realize now.

"Why, what ever will the people do then?"

"Get damages. They're so pleased over being drowned out. You must talk it over with Mrs. Ray. You must get Mrs. Ray's standpoint, and then get Ronald's standpoint. Theirs are the sensible, practical views, the world's views. My views are never practical. I'm not practical. I'm only heartbroken to think of anything coming in to ruin the valley. Mr. Ledge and I share the same opinions as to this valley; it seems to us too great a good to sell for cash."

"You speak bitterly."

"Yes, dear, I'm afraid that I do speak bitterly. On that subject. But we won't talk of it any more just now. See, here's the wood road that leads to my kingdom; come, take it with me."

They turned into a soft, pine-carpeted way on the left, and in the length of a bow-shot seemed buried in the forest.

"Lassie, wait!"

Turning her head, Lassie saw that Alva had stopped behind, and was standing still beside where a little pine-tree was growing out from under a big glacial boulder. She went back to her.[46]

"Dear, look at this little tree. Here's my daily text."

"How?"

"Do you see how it has grown out and struggled up from under the rock?"

Lassie nodded.

"You know very little of what makes up life, dear. I've sent for you to teach you." She lifted her eyes earnestly to the face near hers, and her own eyes were full of appeal. "Lassie, try to understand all I say to you these days; try to believe that it's worth learning. See this little tree—" she touched her fingers caressingly to the pine branches as she spoke—"it's a very little tree, but it has taught me daily since I came, and I believe that you can learn of it, too."

Lassie's big eyes were very big indeed. "Learn of a tree!"

Alva lifted one of the little stunted uneven branches tenderly in her fingers. "This is its lesson," she said; "the pine-cone fell between the rocks; it didn't choose where it would fall, it just found itself alive and under the rocks; there wasn't much earth there, but it took root and grew. There was no room to give out branches, so it forced its way crookedly upward; crookedly because there was no room to grow straight, but always upward; there wasn't much sunlight, but it was as bravely green as any other tree; the big rock made it one-sided, but it put out thickly on the side where it had space. My life hasn't been altogether sunlit. I was born between rocks, and I have been forced to grow one-sided, too. But the tree's sermon came home to me the first day that I saw it. Courageous little tree, doing your best in the woods, where [47]no one but God could take note of your efforts,—you'll be straight and have space and air and sunshine in plenty next time—next time! Oh, blessed 'next time' that is to surely right the woes of those who keep up courage and continue fighting. That's the reward of all. That's the lesson."

Lassie listened wonderingly. "Next time!" she repeated questioningly, "what next time? Do you believe in a heaven for trees?"

"I am not sure of a heaven for anything," said Alva, "not an orthodox heaven. But I believe in an endless existence for every atom existing in the universe, and I believe that each atom determines the successive steps of its own future, and so a brave little pine-tree fills me with just as sincere admiration as any other species of bravery. 'Next time'! It will have a beautiful 'next time' in the heaven which means something so different from what we are taught, or here again on earth, or wherever its little growing spirit takes form again. I'm not wise enough to understand much of that, but I'm wise enough to know that there is a next time of so much infinitely greater importance than this time, that this time is really only of any importance at all in comparison just according to how we use it in preparation. That's part of the lesson that the tree teaches. But you can't understand me, Lassie, unless you are able to grasp my belief—my fixed conviction—that this world is only an instant in eternity. I couldn't live at all unless I had this belief and hope, and it's the key to everything with me; so please—please—give me credit for sincerity, at least."

Lassie looked thoroughly awed. "I'll try to see everything just as you do," she said.[48]

Alva pressed her hand. "Thank you, dear."

Then they went on up the road.

Presently the sound of hammer and saw was heard, and the smell of wet plaster and burning rubbish came through the trees.

"Is it from your house?" Lassie asked, with her usual visible relief at the approach of the understandable.

"Yes, from my house," Alva answered. "They are very much occupied with my house; fancy buying a dear, old, dilapidated dwelling in the wilderness, and having to make it new and warm and bright and cheerful in a fortnight! Why, the tale of these two weeks will go down through all the future history of the country, I know. Such a fairy tale was never before. I shall become the Legend of Ledge, I feel sure."

The road, turning here, ended sharply in a large, solid, wooden gate, set deep in a thick hedge of pine trees.

"It is like a fairy tale!" Lassie cried delightedly; "a regular Tourangean porte with a guichet!"

"It is better than any fairy tale," said Alva; "it is Paradise, the lovely, simple-minded, Bible-story Paradise, descending upon earth for a little while." She pushed one half of the great gate-door open, and they went through.

A small, old-fashioned, Colonial dwelling rose up before them in the midst of dire disorder. Shingling, painting, glass-setting, and the like were all going forward at once. Workmen were everywhere; wagons loading and unloading were drawn up at the side; mysterious boxes, bales and bundles lay about; confusion reigned rampant.

"Not exactly evolution, but rather revolution,"[49] laughed Alva, ceasing transcendentalism with great abruptness, and becoming blithely gay. "And oh, Lassie, the joy of it, the downright childish fun of it! Don't you see that I couldn't be alone through these days; they are too grand to be selfish over. I had to have some one to share my fun. We'll come here and help every day after this; the pantries will be ready soon, and you and I will do every bit of the putting them in order. Screw up the little hooks for the cups, you know, and arrange the shelves, and oh, won't we have a good time?"

Lassie's eyes danced. "I just love that kind of work," she said, fully conscious of the pleasant return to earth, "I can fit paper in drawers beautifully."

"Which proves that after all women stay women in spite of many modern encouragements to be men," Alva said. "You know really I'm considered to be most advanced, and people look upon me as quite intellectual; but I'm fairly wild over thinking how we'll scrub the pantries, and put in the china—and then there's a fine linen-closet, too. We'll set that in order afterwards, and put all the little piles straight on the shelves."

By this time they had gone up the plank that bridged over the present hiatus between ground and porch, and entered the living-room, which was being papered in red with a green dado and ceiling.

"How pretty and bright!" Lassie exclaimed.

"It's going to be furnished in the same red and green, with little book-shelves all around and the dining table in the middle," Alva explained. "Oh, I do love this room. It's my ideal sitting-room. It has to be the dining-room, too, but I don't mind that."

"Won't the table have to be very small?"[50]

"Just big enough for two."

"But when you have company?"

"We shall never have any company."

"I mean when you have friends with you here."

"I shall never have any friends with me, dear."

"Alva! Why—I can come—can't I?—Sometime?"

Alva shook her head.

"That's part of the story, Lassie, part of the story that I am going to tell you in a few minutes now. But be a little patient, dear; give me a few minutes more. Come in here first; see—this was the dining-room, but it has been changed into—I don't know what. A sort of bedroom, I suppose one would call it. I've had it done in blue, with little green vines and birds and bees and butterflies painted around it. Birds and bees and butterflies are always so lively and bright, so busy and cheerful. All the pictures here are going to be of animals, either out in the wild, free forest or else in warm, sunshiny farmyards. I have a lovely print of Wouverman's 'Im Stall' to hang in the big space. You know the picture, don't you?—the shadowy barn-room with one whole side open, and the hay dripping from above, and the horses just ridden in, and the chickens scratching, and some little children playing in the corner by the well. It's such a sweet gemuthliche picture—so full of fresh country air—I felt that it was the picture of all others to hang in this room. There will be a big sofa-bed at one side, and my piano, and pots of blooming flowers. And you can't think, little Lassie, of all that I look forward to accomplishing in this room. I expect to learn to be a very different woman, every atom and fibre of my being will[51] be altered here. All of my faults will be atoned for—" she stopped abruptly, and Lassie turned quickly with an odd impression that her voice had broken in tears.

"Alva!" she exclaimed.

"It's nothing, dear, only that side of me that keeps forgetting the lesson of the tree. Don't mind me,—I am so happy that you must not mind anything nor must I mind anything either; but—when I come into this room and think—" her tone suddenly turned dark, full of quivering emotion, and she put her hand to her eyes.

"Alva, tell me what you mean? I feel frightened,—I must know what's back of it all now. Tell me. Tell me!"

"I'm going to tell you in just a minute, as soon as I've shown you all over the house." She took her handkerchief, pressed it to her eyes, made a great, choking effort at self-control, and then managed to go on speaking. "See," pushing open a door, "this is a nice little dressing-room, isn't it? And then around and through this narrow back hall comes the kitchen. There is an up-stairs, but I've done nothing there except make a room comfortable and pleasant for the Japanese servant who will do the work, that is, all that I don't do myself."

"Won't you want but one servant?"

"I think so. A man from outside will take the extras, and really it's a very small house, dear. The laundry will be sent out. Dear me, how I do enjoy hearing that kind of speech from my own lips. 'The laundry will be sent out!' That sounds so delightfully commonplace, so sort of everyday and like other[52] people. I can't express to you what the commonplaces, the little monotonies of ordinary lives, mean to me here. You'll divine later, perhaps. But fancy a married life where nothing is too trivial to be glorified! That is how things will be with us."

"Are you so sure?" Lassie tried to smile and speak archly. Tried very hard to do both, because an intangible atmosphere of sorrow was beginning to press heavily on her spirits.

"Very sure,—really, quite confident. You must not think that, because I sob suddenly as I did just now, I am ever weak or ever doubt myself or any one else. I never doubt or waver. It is only that no matter how hard one tries, one can hardly rise completely out of the thrall of one existence into the freedom of another at only a week's notice."

"Is that what you are trying to do?"