The Project Gutenberg EBook of Palm Tree Island, by Herbert Strang

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Palm Tree Island

Author: Herbert Strang

Illustrator: Archibald Webb

Alan Wright

Release Date: September 19, 2011 [EBook #37418]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PALM TREE ISLAND ***

Produced by Al Haines

PALM TREE ISLAND

BEING THE NARRATIVE OF HARRY BRENT SHOWING HOW HE IN COMPANY WITH WILLIAM BOBBIN OF LIMEHOUSE WAS LEFT ON AN ISLAND IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE, AND THE ACCIDENTS AND ADVENTURES THAT SPRANG THEREFROM, THE WHOLE FAITHFULLY SET FORTH

BY

HERBERT STRANG

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

ARCHIBALD WEBB AND ALAN WRIGHT

LONDON

HENRY FROWDE

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

1910

Copyright 1909, by the G. H. Doran Company, in the

United States of America.

CONTENTS

OF MY UNCLE AND HIS HOBBY, AND WHAT CAME OF HIS CONVERSATIONS WITH TWO MARINERS

OF THE VOYAGE OF THE LOVEY SUSAN AND OF MY CONCERN THEREIN, ALSO THE DISTRESSFUL CASE OF WILLIAM BOBBIN

OF THE NAVIGATION OF STRANGE SEAS; OF MUTTERINGS AND DISCONTENTS, OF DESERTION, OF MUTINY AND OF SHIPWRECK

OF THE MEANS WHEREBY WE CHEATED NEPTUNE AND CAME WITHIN THE GRIP OF VULCAN; AND OF THE INHUMANITY OF THE MARINERS

OF CLAMS AND COCOA-NUTS AND SUNDRY OUR DISCOVERIES; AND OF OUR REFLECTIONS ON OUR FORLORN STATE

OF OUR SEARCH FOR SUSTENANCE AND SHELTER; WITH VARIOUS MATTERS OF MORE CONSEQUENCE TO THE CASTAWAY THAN EXCITEMENT TO THE READER

OF THE BUILDING OF OUR HUT, TO WHICH WE BRING MORE ENTHUSIASM THAN SKILL

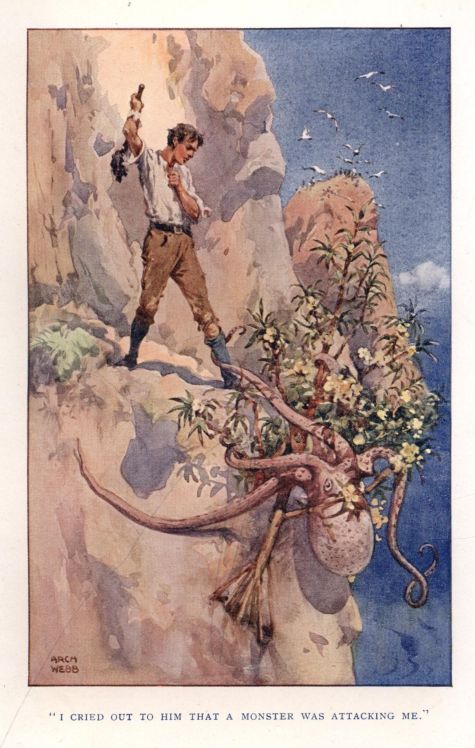

OF MY ENCOUNTER WITH A SEA MONSTER; AND OF THE MEANS WHEREBY WE PROVIDED OURSELVES WITH ARMS

OF PIGS AND POULTRY, AND OF THE DEPREDATIONS OF THE WILD DOGS, UPON WHOM WE MAKE WAR

OF THE NAMING OF OUR ISLAND—OF A FLEET OF CANOES, AND OF THE MEANS WHEREBY WE PREPARE TO STAND A SIEGE

OF OUR SUBTERRANEOUS ADVENTURE, AND THE MANNER IN WHICH THE WILD DOGS PROFITED BY OUR ABSENCE

OF A DIFFERENCE OF OPINION BETWEEN BILLY AND THE NARRATOR—OF AN ENCOUNTER WITH A SHARK, AND THE BUILDING OF A CANOE

OF OUR ENTRENCHMENTS; OF THE LAUNCHING OF OUR CANOE, AND THE DEADLY PERIL THAT ATTENDED OUR FIRST VOYAGE

OF OUR VOYAGE TO A NEIGHBOURING ISLAND, AND OF OUR INHOSPITABLE RECEPTION BY THE SAVAGES

OF THE SEVERAL SURPRISES THAT AWAITED BILLY AND THE NARRATOR AND THE CREW OF THE LOVEY SUSAN; AND OF OUR ADVENTURES IN THE CAVE

OF THE ASSAULT ON THE HUT, IN WHICH BOWS AND ARROWS PROVE SUPERIOR TO MUSKETS

OF THE END OF THE SEA MONSTERS; AND OF THE EVENTS THAT LED US TO RECEIVE THE CREW AS OUR GUESTS

OF THE DISCOMFITURE OF THE SAVAGES, AND THE UNMANNERLY BEHAVIOUR OF OUR GUESTS

OF OUR RETREAT TO THE RED ROCK, AND OF OUR VARIOUS RAIDS UPON OUR PROPERTY

OF ATTACKS BY LAND AND SEA; AND OF THE USES OF HUNGER IN THE MENDING OF MANNERS

OF THE MANNER IN WHICH THE CREW ARE PERSUADED TO AN INDUSTRIOUS AND ORDERLY MODE OF LIFE

OF OUR DEPARTURE FROM PALM TREE ISLAND; OF THOSE WHO WON THROUGH, AND OF THOSE WHO FELL BY THE WAY

ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

BY ARCHIBALD WEBB

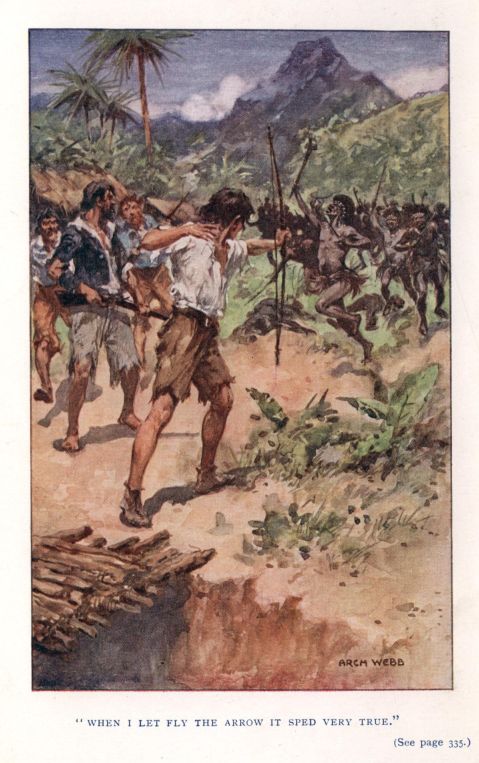

"WHEN I LET FLY THE ARROW IT SPED VERY TRUE . . . . . . Frontispiece

(see p. 335)

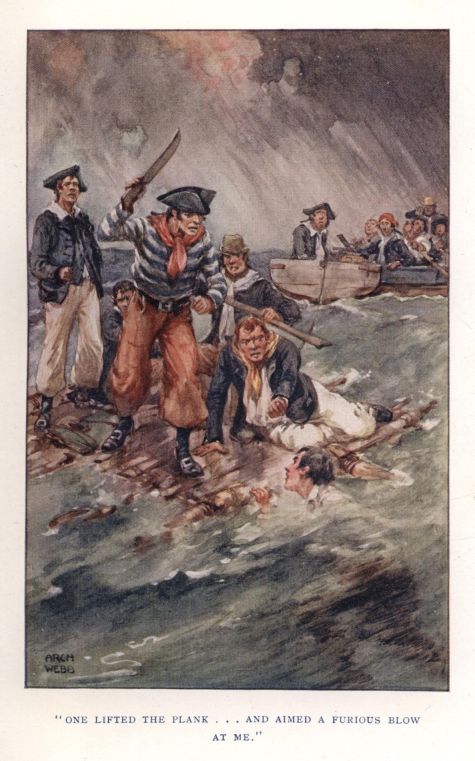

"ONE LIFTED THE PLANK AND AIMED A FURIOUS BLOW AT MY HEAD"

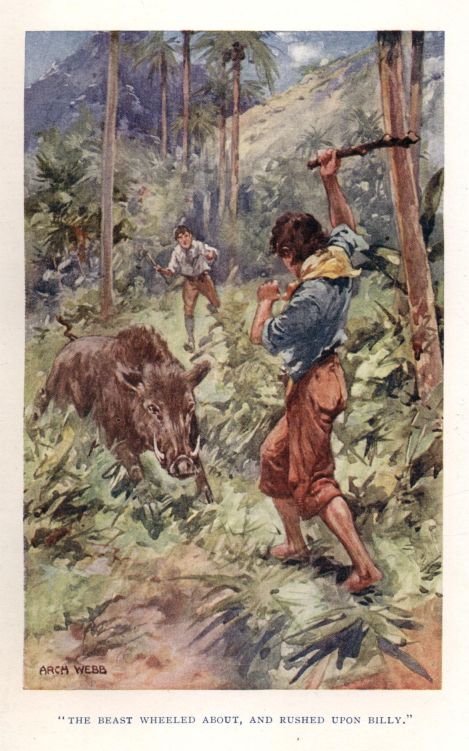

"THE BEAST WHEELED ABOUT, AND RUSHED UPON BILLY"

"I CRIED OUT TO HIM THAT A MONSTER WAS ATTACKING ME"

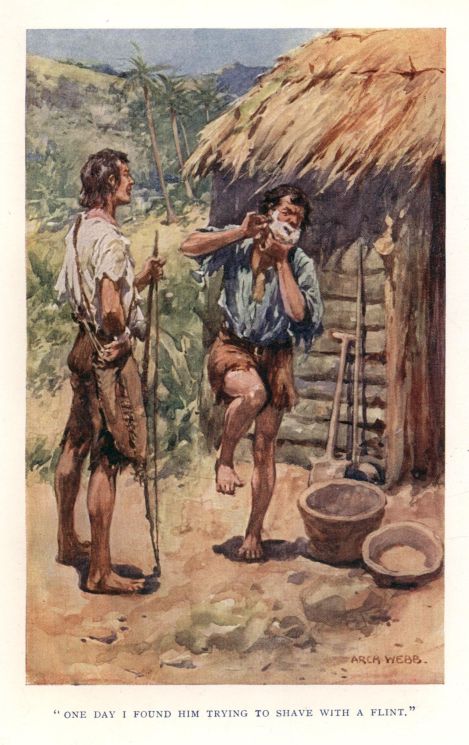

"ONE DAY I FOUND HIM TRYING TO SHAVE WITH A FLINT"

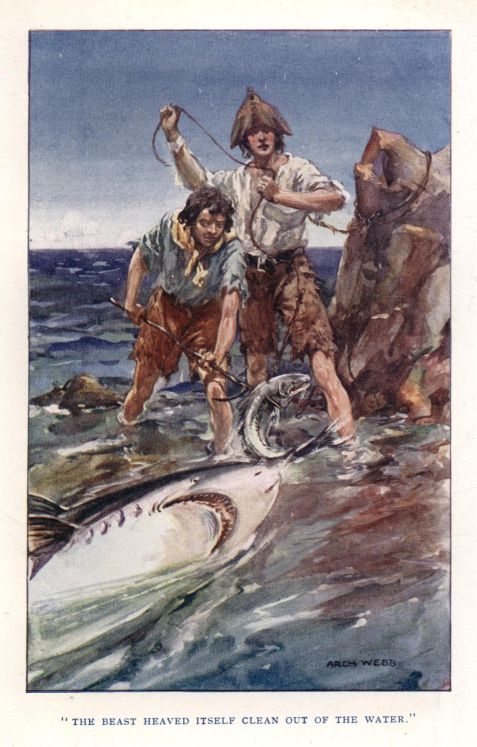

"THE BEAST HEAVED ITSELF CLEAN OUT OF THE WATER"

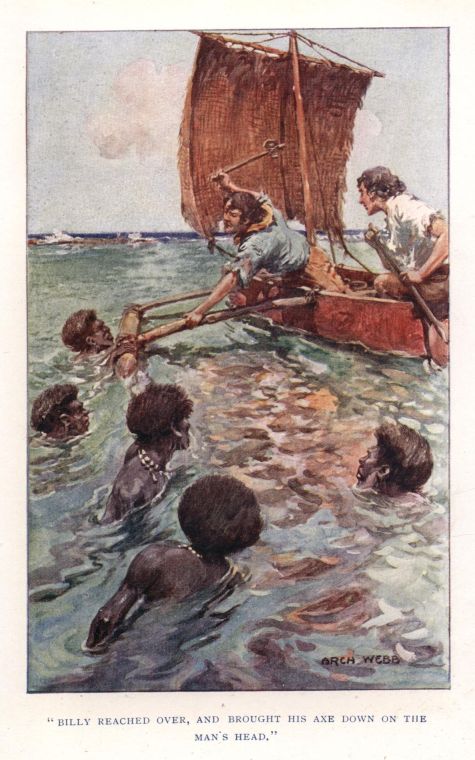

"BILLY REACHED OVER, AND BROUGHT HIS AXE DOWN ON THE MAN'S HEAD"

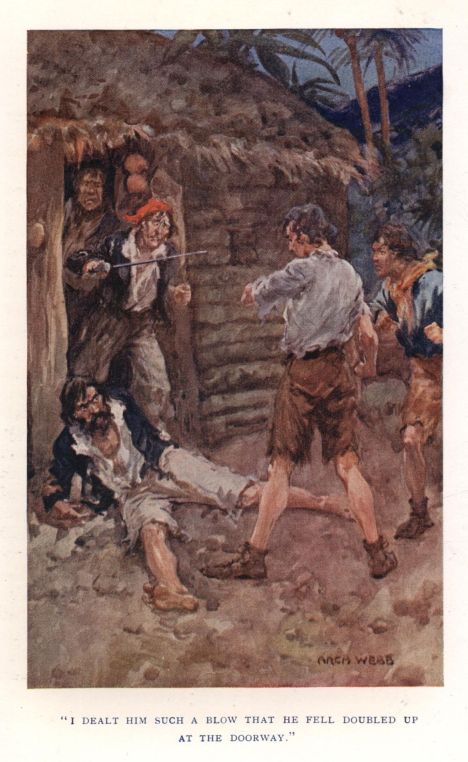

"I DEALT HIM SUCH A BLOW THAT HE FELL DOUBLED UP AT THE DOORWAY"

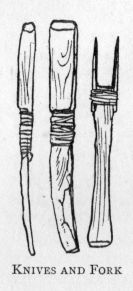

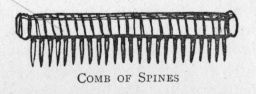

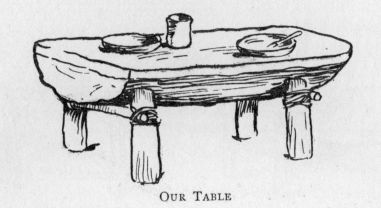

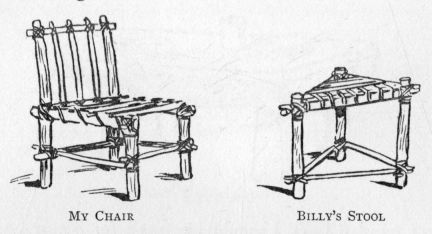

PEN-AND-INK SKETCHES

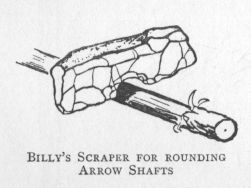

BY ALAN WRIGHT

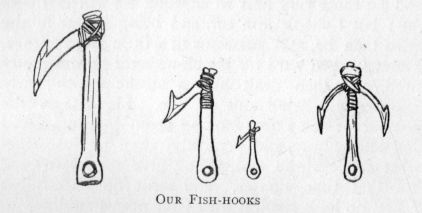

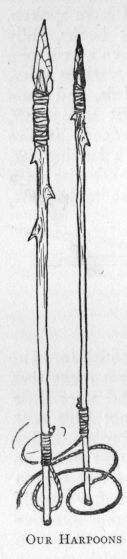

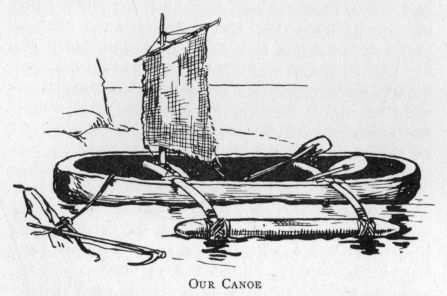

OUR FLINT SCRAPER FOR SHARPENING AXES

BILLY'S SCRAPER FOR ROUNDING ARROW SHAFTS

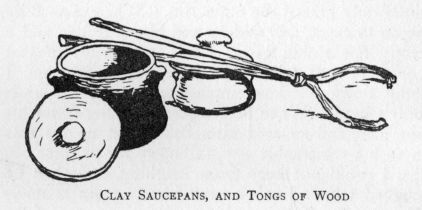

CLAY SAUCEPANS, AND TONGS OF WOOD

CLAY PAIL, THE HANDLE OF A TOUGH ROOT, BOUND ON WITH SHRUNK HIDE

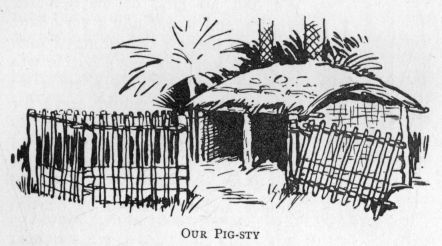

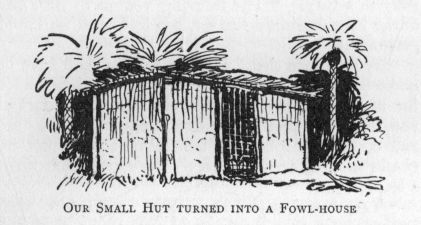

OUR SMALL HUT TURNED INTO A FOWL-HOUSE

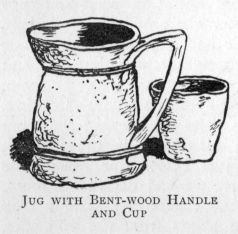

JUG WITH BENT-WOOD HANDLE, AND CUP

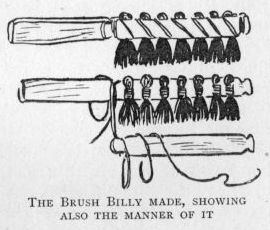

THE BRUSH BILLY MADE, SHOWING ALSO THE MANNER OF IT

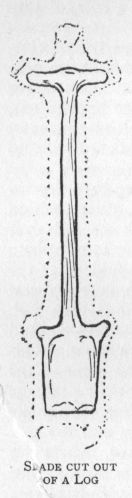

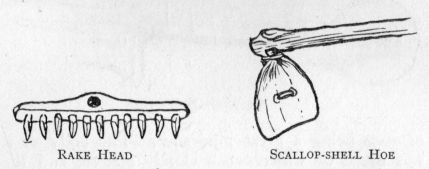

RAKE HEAD AND SCALLOP-SHELL HOE

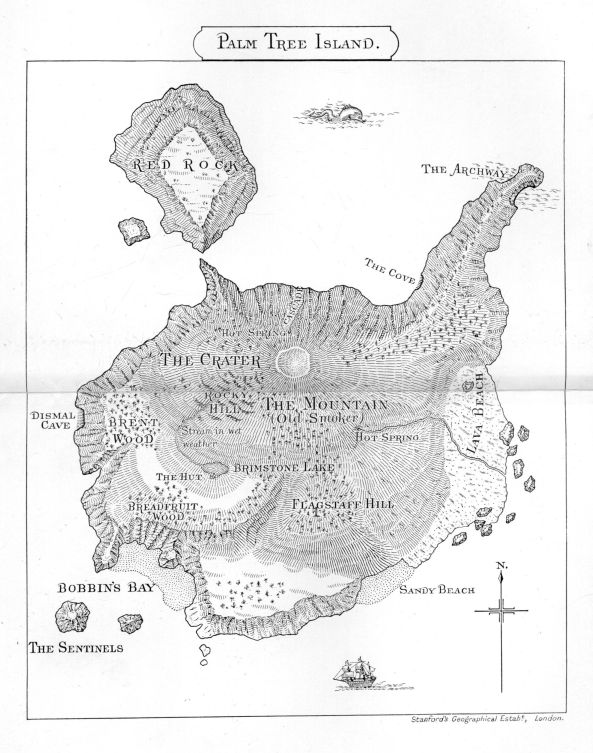

MAP OF PALM TREE ISLAND … … … … facing p. 96

OF MY UNCLE AND HIS OF HIS CONVERSATIONS WITH TWO MARINERS

I was rising four years old when my parents died, both within one week, of the small-pox; and the day of their funeral is the furthermost of my recollections. My nurse, having tied up the sleeves of my pinafore with black, held me with her in the great room down-stairs as the mourners assembled. Their solemn faces and whispered words, and the dreadful black garments, drove me into a state of terror, and I was not far from screaming among them when there entered a big man with a jolly red face, at whom the company rose and bowed very respectfully. The moment he was within the room his eye lit on me, and seeing at a glance how matters stood, he thrust one hand into his great pocket, and drew it forth full of sugar-plums, which he laid in my pinafore, and then bade the nurse take me away.

'Twas my uncle Stephen, said Nurse, and a kind good man. Certainly I liked him well enough, and when, two or three days thereafter, he set me before him on his saddle, and rode away humming the rhyme of "Banbury Cross," I laughed very joyously, never believing but that after I had seen the lady with the tinkling toes, Uncle Stephen would bring me home again, and that by that time my mother would have returned from heaven, whither they told me she had gone.

I did not see my childhood's home again for near thirty years.

My uncle took me to live with him, in his own house not a great way from Stafford. He was an elder brother of my father's, and till then had been a bachelor; but having now a small nephew to nourish and breed up, he did not delay to seek a wife, and wed a fine young woman of Burslem. She was very kind to me, and even when there were two boys of her own to engage her affections, her kindness did not alter. So I grew up in great happiness, having had few troubles, the greatest of them being, perhaps, those that beset my first steps to learning in Dame Johnson's little school. As for my subsequent search after knowledge on the benches of the Grammar School at Stafford, the less said the better: the master once declared, in Latin, that I was "only not a fool."

The light esteem in which the pedagogue held my intellects did not give my uncle any concern. He was bad at the books himself, saving in one kind I am to mention hereafter. He was a master potter, in a substantial way of business, and held in some repute among men of his trade. Indeed, it was the belief of many in our parts that he might have become as famous in the world as Mr. Wedgwood himself, had he not been afflicted with a hobby.

I will not follow the example of the ingenious Mr. Sterne, and write here a chapter upon hobby-horses; though I do believe I could say something on that subject, if not with his incomparable humour, yet with a certain truth of observation. Why is a man's hobby often at such variance with other parts of his character? Why did the late Mr. Selwyn, to wit, take the greatest pleasure in life in seeing men hanged, drawn, and quartered? Who that knew John Steer (I knew him well) only as he stood with knife and cleaver in his butcher's shop, would believe that 'twas his delight, after slaughtering his sheep and oxen, to solace his evenings with warbling on the German flute? My uncle's hobby was no less extraordinary. He was inland bred, and I do believe, until the year of his great adventure, had never gone above twenty miles from his native town; yet he had a wondrous passion for the sea and all that pertained to it. I am sure that he never saw the sea until he and I together looked upon it at Tilbury, and there, to be sure, the salt water is much qualified with fresh; yet, after business hours, he was for ever talking of it and reading about it and the doings of sailor men. He would pore for long hours upon the pages of the Sailor's Waggoner, and con by heart the rules and instructions of the Sailor's Vade Mecum. He was deeply learned in the Principal Navigations of Mr. Hakluyt; he could tell you all that befell George Cavendish in the Desire and Sir Richard Hawkins in the Dainty, and would hold me spell-bound as he recited with infinite gusto the stark doings of the Buccaneers. And when Mr. Cadell, the bookseller in the Strand in London, sent him the great volumes containing the discoveries of Commodore Byron, and those gallant captains Carteret, Wallis, and Cook in the southern hemisphere, the days were a weariness to him until he could light his candle and put on his spectacles and feast on those enthralling narratives. Many's the time, as I lay awake in my bed, have I heard my aunt Susan call down the stairs through the open door of her room, "Steve, Steve, when be a-coming to bed, man?" and his jolly voice rolling up, "Yes, my dear, I am near the end of the chapter"; and there he would sit, and finish the chapter, and begin another, and read on and on, until I might be stirred from a doze by the sound of him shuffling past in his stockings, and grumbling because there was but an inch of guttering candle left.

My uncle was a sturdy patriot, and took a great delight in knowing that the most of the navigators of those far-off seas were Englishmen. I remember how he fumed and fretted when his bookseller in London sent him the volume of Monsieur de Bougainville's voyage round the world. What had these French apes, he cried, to do with voyages of discovery? And when he read later, in Dr. Hawkesworth's book, of the trick which Monsieur de Bougainville played on Captain Wallis—how, meeting the captain on his homeward way, he sought with feigning to worm out of him the secrets of his expedition—my uncle smote the table with his great fist, and used such fiery language that my aunt turned pale and my little cousins began to blubber.

At this time I was in my seventeenth year, and had been for some months in my uncle's factory, learning the rudiments of his trade. 'Twas taken for granted that I should become a partner with him when I was of age, for the business was good enough to support both me and my elder cousin Thomas; while as for the younger, James, my aunt had set her heart on making a parson of him. But it was ordained that, in my case, things should fall out quite contrary to the intention, as you shall hear.

One fine Sunday we were walking home from church, my uncle and I, across the fields, as our practice was, when we saw that the last stile before we reached our road was occupied. A big fellow, clad in a dress that was strange to our part of the country, sat athwart the rail of the fence, with his feet on the upper step. Another man sprawled on the grass beside the fence, lying stretched on his back with his hands under his head, and a hat of black glazed straw tilted over his eyes. As we drew nearer, I saw that the man on the stile had a big fat face, his red cheeks so puffed out that his eyes were scarce visible, his mouth loose and watery, with an underhung chin, a thick fringe of black hair encircling it from ear to ear.

Seeing us approach, he began with uncouth and clumsy movements to descend from his perch; but he gave my uncle a hard look as we came up with him, and then, spitting upon the ground, he said,

"Bless my eyes—surely 'tis—ain't your name Stephen Brent, sir?"

My uncle looked at the man in the way of one who is puzzled, and for some while stood thus, the man smiling at him. Then of a sudden his face partly cleared, and he said—

"You are never Nick Wabberley?"

"The same, sir, Nick and Wabberley, as you knowed five and twenty year ago."

"Why, man, I am glad to see you," says my uncle heartily, offering his hand, which the man took, not however before he had rubbed his own hand upon the back of his breeches.

"Same to you, sir, and very glad I am to see you so hearty. After five and twenty year at sea——"

"You have been to sea!" cries my uncle, his jolly face beaming. "Then you must come up to my house to supper and tell me all about it."

"Why, d'ye see, sir, there's my messmate," said the man, with a glance at the prone figure, which had not moved; indeed, there came from beneath the hat a succession of snores, as untuneful as ever I heard. "We're in tow, d'ye see," added the big man.

"Bring him too," says my uncle. "We have plenty of bread and bacon, thank God."

Whereupon the man went to his sleeping comrade, and neatly kicked his hat into the air, bidding him wake, with a strange oath that startled me. The sleeper did not at once open his eyes, but his mouth being already open, he let forth a volley of curses, and demanded his hat, avouching that if he suffered a sunstroke he would "this" and "that" the other: his actual words I cannot write. My uncle's face showing his reprobation of such language, especially on the Sabbath, the big man excused his comrade, saying that 'twas only Joshua Chick's way, and he was really a good soul, and very obliging. At this the prostrate man opened his eyes, and, seeing my uncle, got upon his feet, and when he was told of the invitation to supper, he touched his forelock and said he was always ready to oblige. If the looks of Nick Wabberley did not take my fancy, still less did those of Joshua Chick, who was a small man, very lean and swarthy, and his eyes squinted so dreadfully that he seemed to be looking at my uncle and myself at one and the same time.

After a few more words we parted, the men promising to be at our house prompt at eight o'clock. And as we continued our walk home, my uncle satisfied my curiosity, telling me that the big man, Nick Wabberley, who was, as I had already guessed, the brother of Tom Wabberley, that owned Lowcote Farm some two miles from our door, had been a school-fellow of his, and the idlest boy in the whole countryside. He never got through a day without a flogging. The master birched him; his father leathered him; but neither did him any good: he remained an incorrigible dunce and truant, and no one was very sorry when one morning it was found that he had slipped out of his bedroom window during the night and run away. He had never since been heard of, but now that after twenty-five years he had returned to his native place, my uncle's heart warmed towards him because he had been to sea. Sailors were not often seen in our inland parts, and the prospect of discourse with a man who had actually beheld what he had only read about filled my uncle with delight.

Prompt on the stroke of eight Nick Wabberley arrived, accompanied by his messmate Joshua Chick. They proved to be excellent trenchermen: indeed, they prolonged the meal longer than either my uncle or my aunt liked, the former being impatient to hear stories of the sea, the latter watching with concern the disappearance of her viands. But supper was over at last, and then my uncle bade the visitors draw their chairs to the fire, gave them each a long pipe and a sneaker of punch, and settled himself in his arm-chair to drink in the tale of their adventures. Being near seventeen I was allowed to make one of the company, to the envy of my young cousins, who hung about the room for some time, but being at last detected were bundled off to bed.

It needs not to tell how late we sat up, nor how many tumblers of brandy-punch the two sailors tossed off between them before they departed, steady enough on their legs, but a trifle thick in their speech. My uncle was abstemious himself, and held a toper to be something less than a man; at an ordinary time he would have avoided to ply his visitors with liquor, but the truth is that on this occasion his whole soul was rapt away into a kind of wonderland by Nick Wabberley's tales, so that the men were able to replenish their glasses at intervals, unperceived. I have heard many a mariner's yarn since, and know them to be works of fancy and imagination as often as not; at that time I was as credulous as a babe, and my uncle scarcely less, and I doubt not we gulped down all the marvels we heard as greedily as the trout gapes at a fly. Certainly Nick Wabberley was a masterly story-teller, spinning yarns, as they say, as easily as a spider spins her web, and never at a loss for a word. Joshua Chick took but a modest part in the conversation, being very well occupied in replenishing the glasses; but every now and again he would slip in a word to correct some statement of his comrade, Nick accepting it with great composure. I noticed that these occasional contributions of Joshua's tended most often towards embellishment, and the level tones in which he related the most astonishing marvels, at the same time fixing one eye on my uncle and the other on me (keeping his hand on the brandy-bottle), made a wonderful impression on us.

It appeared that the two sailors had been members of the company which sailed with Captain Cook (he was then lieutenant) on his first voyage into the southern hemisphere. My uncle knew by heart the story of this voyage as it is given in Dr. Hawkesworth's book, and expressed great surprise that so many of the incidents and particulars related by Nick Wabberley were not mentioned in that worthy doctor's pages. He even ventured at one point to controvert a statement of Nick's, adducing the doctor as his authority, at which Nick waxed mightily indignant. "Why, d'ye see, warn't I there?" he said. "Warn't I there, Josh?"

"You was," says Chick firmly.

"And warn't you there?" says Wabberley, his moist lips quivering with indignation.

"I were," replies Chick, with vehemence.

"Then what the blazes has any landlubber of a doctor got to do with it, what don't know one end of a ship from t'other!"

There was nothing to be said in answer to this, and my uncle afterwards confided to me his opinion that Captain Cook's own journals contained a good many things which Dr. Hawkesworth had not seen fit to print.

My uncle was so well pleased with the conversation of the seamen that he invited them to come and see him again, and before long it became their regular custom to drop in about supper-time, much to the annoyance of Aunt Susan. She called Nick Wabberley a lazy lubber, and as for Joshua Chick, she said his eyes made her feel creepy, and he ate enough for four decent men. But my uncle was fairly mounted on his hobby, and he asked her rather warmly whether she grudged a bite and a sup to worthy mariners who had braved the perils of the deep (not to speak of the appetites of cannibals) in the service of their country. 'Twas in vain she said that she knew Farmer Wabberley wished his brother at Jericho—the great fat lubber lolloping about doing nothing but eat and drink, when there were fields to hoe, and Joshua Chick looking two ways at once, one eye on bacon and the other on beer; 'twas a mercy he hadn't got two mouths as well, she said. My uncle would hear nothing against them; always kindly and indulgent, he reminded her that a gammon rasher and home-baked bread must be the most delectable of dainties to men who for months at a time ate nothing but salt junk and ship's biscuit.

He never tired—nor, I must own, did I—of listening to Nick Wabberley. His face fairly glowed as he heard of those favoured islands of the south where food grew without labour and wealth was to be had almost without lifting a finger. Wabberley described the ease with which pearls might be obtained in the Pacific: how he had seen the natives dive into the water and bring up oysters, every tenth of them containing a gem, so little valued by the finders that the present of a four-penny nail or a glass bead would purchase a handful of them. Wabberley heaved a great sigh as he deplored his desperate bad luck in not being permitted to trade. "The Captain, d'ye see, warn't a trader," he said; "he was always thinking of taking soundings and marking charts and discovering that there southern continent, which I don't believe there ain't no such thing, though they do say as how the world 'ud topple over if there warn't summat over yonder to keep it steady. And as often as not, when we come to a island, we was so desperate pushed for provisions, and vegetables to cure us of the scurvy, that he hadn't no thought except for stocking the ship. Oh! 'twas cruel, when we might all ha' been as rich as lords, and all vittles found in the bargain."

In those days I remarked a certain restlessness in my uncle. He would go to the door of an evening and look down the road for the two seamen, and if they did not appear, which was seldom, he would walk up and down, in and out of the house, with hands in pockets, melancholy whistlings issuing from his lips. He read even more closely than usual the pages of the Vade Mecum, and pored for hours on the maps that embellish Dr. Hawkesworth's volumes. For the most part he was silent and abstracted, but ever and anon he would startle me with some sudden exclamation, some remark or question addressed, it seemed, to himself. "Tugwell is a good man: I can trust him.... What will Susan say? ... A matter of a year or two: what's that? ... I haven't a grey hair in my head." I was somewhat concerned when I listened to these mutterings, and wondered whether much brooding on oversea adventures had turned my uncle's brain. And I was not at all prepared for the revelation that came one night, when, looking up from his book, which lay open on his knees, he waved his long pipe in the air and cried, "I'll do it, as sure as my name is Stephen Brent."

And then he poured out upon my astonished ears the full tale of his imaginings. He was bent on making a voyage round the world. The South Seas had cast a spell upon him. He longed to see the lands of which the sailor-men had spoken; he was athirst for discovery. Perhaps he might light upon this Southern Continent which had eluded the search of others, and if he could forestall the French, what a feather it would be in his cap, and how glorious for old England! And in these dreams he was not less a man of business. There was vast wealth to be had by bold adventurers; why should not he obtain a share of it, and amass a second fortune for his boys?

The greatness of this scheme as he unrolled it before me took my breath away. When I asked how his business would fare in his absence he swept the air with his pipe and declared that Tugwell, his manager, was sober and trustworthy, and he had no fears on that score. I spoke of the perils of shipwreck and pirates, of the Sallee rovers, of the numberless accidents that might befall; but he brushed them all away as things of no account. And then I myself took fire from his own enthusiasm and begged that I might go with him. "No, no, Harry, my boy," he said, kindly enough. "You must stay at home to look after your aunt and the boys. Tugwell is a good man, but growing old; and if anything happens to me you will be at hand to look to things; you are seventeen, and pretty near a man."

That night at supper, with much hemming and hawing, he broached his project to my aunt. You should have heard her laugh! 'twas plain she did not believe him to be serious; she said it was all gammon, and she wondered what next indeed. But when he assured her that he meant every word of it, she was first alarmed and then angry. She talked about a maggot in his head, and asked what she was to do, a widow and not a widow, with two growing boys that would run wild without their father; and she wondered how a respectable man nigh fifty years old should think of such a thing, and there wasn't a woman in the country who would put up with such a pack of nonsense. To which he replied that Captain Cook was a respectable man with a wife and family, and if the captain's lady could part with her husband for a year or two, for the honour and profit of England, surely 'twas not becoming in Mrs. Stephen Brent to make an outcry over such a trifling matter. This made my aunt only the more angry, and, for the first time in all my knowledge of them, the good people looked unkindly upon each other.

That my uncle's mind was firmly made up was plain to us next day. Bidding me say nought of his intentions, which he wished to be kept secret, lest they came to the ears of the French, he set off for London, and was absent for a matter of ten days, much to the displeasure of Nick Wabberley and Joshua Chick, who came to the house evening after evening and went very disconsolate away, my aunt detesting them both, and refusing to feed the men to whom she attributed this mad whimsy of her husband. Her anger somewhat moderated while he was away, and after a week or so she could smile at his rubbish, declaring to me that she was sure he would think better of it: he would be like a fish out of water in London Town, and the sensible folks there would laugh him out of his foolishness, that they would. She smiled and tossed her head even when he came back and told us with great heartiness that he had bought a vessel—a north-country collier of near four hundred tons, stout in her timbers and broad in the beam, built for strength rather than speed—just such a vessel as Captain Cook had sailed in. "Go along with you, Steve," she said. "Don't tell me! You'll never go rampaging over the seas—a man of your age: and 'tis a mercy, I'm sure, that you're a warm man and won't ruin yourself, for you won't get half what you gave for it when you sell your precious vessel again." She told me privately that she was sure, when the time came, the foolish man would never venture himself on a ship; what would he do on a ship, she'd like to know, when he couldn't ride a dozen miles in a coach, as he had told us, without becoming squeamish and feeling as if his inside didn't belong to him! The news that he had engaged a captain—a seasoned skipper, by name Ezekiel Corke—only made her lift her hands and cry out, "Well, did you ever see!" I am sure that her air of disbelief, and amusement mingled with it, was a sore trial to my uncle.

As for him, good man, he was in earnest, if ever a man was. One day after he returned he rode over with me to Lowcote Farm, where we found those two mariners, Chick and Wabberley, gloomily sucking straws on a five-barred gate, and idly looking on at a busy scene of sheep-shearing. Their dull faces brightened at the sight of him, and when he told them what he had been doing, and asked if they would join his crew, they smote each other on the back and swore lustily for very joy. They asked him many questions about the ship and the captain, talked very knowingly of spars and armaments and the various articles it behoved to carry for trading with the natives, and offered to go at once to London—my uncle paying their coach fares—and seek out old messmates who should form the finest crew that ever foregathered in a foc'sle. My uncle showed great pleasure at their willingness, and arranged that they should accompany him when he next went to London to make his preparations for the voyage.

The news of my uncle's enterprise soon spread through our town, and it became a nine days' wonder among our neighbours and the townsfolk. His friends accosted him in the streets; some poked fun at him for entering on a new branch of business at his time of life; others, with the best intentions in the world, addressed to him the most solemn warnings, taking him by the buttonhole and expatiating on the risks he was about to run, doubting whether any money was to be made at sea, and advising him very earnestly to stick to the clay. He bore their pleasantries and their counsels with great good nature, declaring that he knew what he was about, and they would see if they lived long enough. But I could not help feeling sometimes that he was not quite so confident as he liked to appear, and that the drawbacks and dangers he had shut his eyes to in the first flush of his enthusiasm were now looming larger in the prospect. Yet, whatever his qualms may have been, he pushed on his preparations with vigour. He spent another fortnight in London, collecting a crew with the aid of Wabberley and Chick, purchasing stores, and laying in a cargo, and then he returned to take leave of his family and friends.

All this time I was beset with a great longing. The making of pottery in a quiet town seemed to me a very tame and spiritless occupation: I felt an immense stirring towards a life of activity and adventure, and wished with all my heart that my uncle would change his mind and take me with him. Against this, however, he was resolute, and the utmost he would concede was that I should accompany him when he departed finally from Stafford, and see the vessel in which he was to sail forth. Accordingly, one fine August day ('twas the year 1775), I took passage with him in the London coach. All Stafford had gathered to speed him. He parted from my aunt and his boys at the inn door: up to the very last she had held to the belief that he would draw back; and even when he left her side and mounted into the coach she whispered to me, "I don't believe it. I won't believe it! He'll never go. He never will!" But the coach rumbled off, the crowd cheered, some one flung an old shoe after us for luck, and I had never a doubt that before the month was out my uncle would be afloat on the wide ocean, fairly committed to his wonderful adventure in the southern seas.

OF THE VOYAGE OF THE LOVEY SUSAN AND OF MY CONCERN THEREIN; ALSO THE DISTRESSFUL CASE OF WILLIAM BOBBIN

The Lovey Susan—for so my uncle had named his vessel—lay at Deptford, and as we walked from our inn, the Cod and Lobster in Great Tower Street, to see how her fitting out was proceeding, I was amazed (this being the first time I had come to London) at the smells and the noises of the narrow streets, and at the number of rough seamen whom we met. How much greater was my amazement when we came to the docks, and I saw the multitude of shipping—the forests of masts, the great black hulls, the crowds of lighters that moved in and out among them. I remember the fond air of pride with which my uncle pointed to his vessel, and the smile upon his face when the captain spied him and touched his hat. Captain Corke did not in the least resemble the idea I had formed of a sea-captain. He was a little man, with lean cheeks, and a brown wig a world too small for his head, so that I could see the grey stubble of his own hair showing beneath it. My uncle presented me to him and to the first mate, Mr. Lummis, whose hand, when I shook it, left a strange pattern of tar on mine. Mr. Lummis was a rough-looking man, with a square face and a tight mouth, who broke off his talk with us very frequently to roar at one or other of the crew as they went to and fro about their duties. The captain took us over the vessel, which was all very strange to a landsman, and showed me his own quarters in the round house, and when we came to my uncle's cabin, which was certainly not so big as Aunt Susan's larder, nor half so sweet, I thought of what she had said, and for the first time I felt some pity for my uncle, and wondered how he would endure the being cooped up in so narrow a compass. I was presented also to Mr. Bodger, the second mate, who seemed a very shy and timid fellow, always looking away when he spoke. I did not see either Wabberley or Chick, but learnt by and by that they were on shore beating up for a few men to make up the ship's full complement.

Things were in a very forward state, and the captain said that the Lovey Susan would be ready to set sail in a week's time. We spent that week in going to and fro between the ship and our inn. I own I should have liked to see the sights of London, but my uncle was so much in love with his vessel that he could not bear to be away from her, and he would not let me go sight-seeing alone, saying that London was a terrible wicked place for a boy. The utmost he would consent to was to ride out to Tilbury and ride in again, which was a very paltry expedition. When the end of the week came, there were still some berths vacant, a number of the men having been seized for the king's ships, the press being then very active. This put my uncle in a desperate state of annoyance. He declared it was monstrous that his men should be stolen when he was embarking on an adventure which might bring great honour to the country. Since it was plain that his departure must be delayed, he said it was sinful for me to waste any more time in London when I might be useful at the works, and so took passage for me in the coach and dispatched me home. Knowing that the business would not suffer a jot by my absence, I wondered whether my uncle dreaded a scene of parting; and for my part I was so sore at not being allowed to accompany him that I thought it would save me an extra pang if I did not take my farewell of him at the ship's side.

I found my aunt wonderfully cheerful. She smiled when I told her of the hindrances my uncle had met with, and declared that we should even yet see him give up his whimsy and return to his proper business. This opinion, however, I scouted, and when, after about a week, we received a letter from him, I felt sure as I broke the seal that it was a last message penned on the eve of sailing. It proved otherwise, being a brief note to say that the crew was complete, through the good offices of the obliging Chick, but that the departure was once more delayed, my uncle being confined to his room at the Cod and Lobster by a slight attack of the gout. My aunt was for starting at once to attend upon her husband, but this I dissuaded her from, saying that by the time she arrived in London the attack might have passed and the ship sailed, and she would have made the long journey for nothing, besides wasting money. However, within three days comes another letter, in which my uncle wrote that he was much worse, and desired me to come to him post haste. This letter gave my aunt much concern, but on the whole pleased her mightily, for she was sure I had been sent for to bring my uncle home, and she went about with that triumphant look which a good lady wears when she sees events answer to her predictions.

I set off by the coach next morning. When I opened the door of my uncle's room he fairly screamed at me: "Take care! for mercy's sake take care!" I stepped back and looked about me in alarm, seeking for some great peril against which I must be on my guard. But I saw nothing but my uncle sitting in a big chair, with one leg propped on a stool, and his foot swathed in huge wrappings of flannel. "Take care!" he cried again with a groan as I approached. "Mind my toe! Keep a yard away; not an inch nearer, or I shall yell the house down." At that time I was astonished beyond measure at my uncle's vehemence; but having since then suffered from the gout myself—'tis in our family: my grandfather was a martyr to it, I have been told—I know the terror which a movement, even a gust of air, inspires in the sufferer.

My uncle told me, amid groans, that his heart was broken. The Lovey Susan was ready; he had as good a captain and crew as any man could wish to have, but he himself would never make the voyage. Three physicians, the best in London, were attending him, and their opinion was that not only might he be some considerable time in recovering of it, but that, being of a gouty habit of body, a new attack might seize him at any moment and without warning. "Suppose it took me on the voyage, Harry!" he said, groaning deeply. "Suppose I was like this on board! You saw my cabin; no room to swing a kitten. What if a storm blew up! What if I was tossed about!" Here he groaned again. "No doctors! No comforts! I must go home to Susan, my boy—if I can ever stand the journey—— Oh!" he shouted, as a twinge took him. "A thousand plagues! Give me my draught, Harry; take care! Mind my toe!"

I was distressed at my uncle's pitiful plight. 'Twas plain that his agony of mind was as great as that of his body, because of his disappointment in the check to his cherished design. For some while he did nothing but groan; presently, when he was a little easier, he announced the resolution he had come to, which was a great surprise to me, but a still greater joy. 'Twas nothing less than that I should take his place. He could not abide that his plans should be brought to nought. He had weighed the matter carefully as he lay awake o' nights; I was seventeen and nearly a man, and though no doubt I had gout in my blood, I need not fear that enemy for some years to come. Being sober-minded (he was pleased to say), and well acquainted with his purposes, I could very well represent him, and though this responsibility was great for one of my years, yet it would teach me self-reliance and strengthen my character. He spoke to me long and earnestly of the manner in which I should bear myself, with respect to the captain and kindliness to the seamen; and I must never lose sight of the object of the expedition, which was to discover the southern continent, if it were the will of Providence, and so forestall the French.

I fear I paid less heed than I ought to my uncle's solemn admonitions, so overjoyed was I at the wonderful prospect opening before me. Having taken his resolution, my uncle was not the man to delay in executing it. He sent for Captain Corke, and acquainted him with his design, adjuring him to regard me in all things as his deputy, and to take me fully into his counsels. He summoned before him Mr. Lummis and Mr. Bodger, and Chick, who was made boatswain of the vessel, and addressed them in my presence very solemnly, enlarging on the service they would do their country if they assisted Captain Corke and me to bring the expedition to a successful issue. And then, having dismissed them, he bade me fall on my knees (at a yard's distance from his toe), and besought the blessing of the Almighty on the voyage. A lump came into my throat as I listened to his prayer, and when at its conclusion I muttered my "Amen!" it expressed my earnest desire to do all that in me lay to fulfil my uncle's behests, and, in God's good time, to give him an account of my stewardship which should bring him comfort and happiness.

Next day, it being Friday the 22nd of August and a fair day, we loosed our moorings at four o'clock in the morning and fell down with the tide. We were lucky in encountering a favouring breeze when we came out into the broad estuary of the river, and rounding the Foreland, we set our course down channel. The movements of the sailors in working the ship gave me much entertainment, and the gentle motion of the vessel, the sea being calm, caused not the least discomfort, though it was the first time I had sailed upon the deep.

About eight o'clock in the evening, the time which mariners call eight-bells, I was standing beside the captain on the main deck, and he was pointing out a cluster of houses on the shore which he told me was the fishing village of Margate, when we were aware of a commotion in the fore-part of the vessel. I distinguished the rough voice of Mr. Lummis, shouting abuse with many oaths that were new and shocking to my ears. Presently the first mate comes up, hauling by the neck a boy of some fifteen years, a short and sturdy fellow in dirty and ragged garments, and with the grimiest face I ever did see. Up comes Mr. Lummis, I say, lugging this boy along, cuffing him about the head, and still rating him with the utmost vehemence. He hauls him in front of the captain, and, shaking him as a terrier shakes a rat, says, "Here's a young devil, sir, a —— stowaway. Found him on the strakes in the bilge, sir, the —— little swipe."

The captain looked at the boy, who stood with his shoulders hunched to defend his head from the mate's blows, and then bidding Mr. Lummis loose him, he asked him in a mild voice what he did aboard the vessel. The boy rubbed his hand across his eyes, thereby spreading a black smudge, and then answered in a tearful mumble that he didn't know.

"What's your name?" says the captain.

"Bobbin, sir," says the boy.

"Bobbin what?" says the captain.

"William, sir," says the boy.

"Bobbin William?" says the captain.

"William Bobbin," says the boy.

The captain looked sternly on William Bobbin for the space of a minute or two, but I do not remember that he said anything more to him at that time. Mr. Lummis lugged him away and set him to some task, the captain telling me that he would either put him ashore at some port in the Channel or keep him if he gave promise of making himself useful. I may as well say here that Billy Bobbin, as we called him, was not sent ashore when contrary winds made us put in at Plymouth. It had come out that his father was a blacksmith, of Limehouse, and the boy had run away from the cruelties of his stepmother, and being strong of his arms, and with some skill in smith's work, he proved a handy fellow. I often wondered whether his stepmother used him any worse than he was used aboard our vessel. The crew, as I was not long in finding out, were a rough set of men, and seemed to look on Billy, being a stowaway, as fair game. He was a good deal knocked about among them, and the officers, so far as I could see, did nothing to defend him from their ill-usage. When I spoke of it to the captain, he only said that was the way at sea; and, indeed, Mr. Lummis himself was very free in cuffing any of the seamen who displeased him, and once I saw him fell a man to the deck with a marlin-spike, so that it was not to be wondered at, when the men were thus treated, that they should deal in like manner with the boy. I did speak of it once to Wabberley, thinking he might perhaps put in a word for Billy, and he promised to speak to Chick, who would do anything to oblige; but I never observed that anything came of it.

We had fair weather for a week or more, with light breezes, and I was not the least incommoded by the motion of the vessel, whereby I began to think that I should escape the sea-sickness of which I had heard some speak. But when we had passed the Lizard the wind freshened, and the ship rolled so heavily that I turned very sick, and lay for several days in my bunk a prey to the most horrible sufferings I ever endured, so that I wished I was dead, and did nothing but groan. During this time I was left much to myself, the captain coming now and then to see me, and ordering Clums the cook to give me a little biscuit soaked in rum. However, the sickness passed, and when I went on deck again the captain told me that I had now found my sea-legs and should suffer no more, a prediction which to my great thankfulness came true.

We proceeded without any remarkable incident until the 14th of September, when we came to an anchor in Madeira road. The captain sent a party of men on shore to replenish our water-casks, Mr. Lummis going with them carrying three pistols stuck in his belt. I supposed that he went thus armed for fear of some opposition from the natives of that island, but the captain told me 'twas only to prevent the men from deserting, it being not uncommon for such incidents to happen. We sailed again on the 17th, and for two months never saw land, until the 6th of November, when we anchored off Cape Virgin Mary in the country named Patagonia. There we perceived a great number of people on the shore, who ran up and down both on foot and on horseback, hallooing to us as if inviting us to land. This the captain was resolved not to do, somewhat to my disappointment, for I should have liked to see the Indians more nearly, especially as I had heard many things about them from Wabberley when he related his voyages to my uncle. I had to content myself with gazing at them through the captain's perspective glass, and observed that all were tall and swarthy, and had a circle of white painted round one eye, and a black ring about the other, the rest of the face being streaked with divers colours, and their bodies almost naked. One man, who seemed to be a chief, was of a gigantic stature, and painted so as to make the most hideous appearance I ever beheld, with the skin of some wild beast thrown over his shoulders.

The captain questioned whether we should proceed through the Straits of Magellan or attempt to double Cape Horn. He decided for the latter course, and having heard somewhat of the violent storms that were to be encountered in that latitude, I was not a little apprehensive of our safety. However, having taken in water at a retired part of the coast, we doubled the Cape after a voyage of rather more than two months, having sustained no damage, and the Lovey Susan sailed into the South Sea. Here the calm weather which had favoured us broke up, and for several weeks we had strong gales and heavy seas, so that we were frequently brought under our courses, and there was not a dry place in the ship for weeks together. Our upper works being open, and our clothes and beds continually wet, as well from the heavy mists and rains as from the washing of the seas, many of the crew sickened with fever, and the captain kept his bed for several days. On the first fair day our clothes were spread on the rigging to dry, and the sick were taken on deck and dosed with salop, which, with portable soup boiled in their pease and oatmeal, and as much vinegar and mustard as they could use, brought them in a fair way to recovery.

We proceeded on our voyage, the weather being variable, and I observed that many strange birds came about the ship on squally days, which the captain took for a sign that land was not far off. He was anxious now to make land, for the men began to fall with the scurvy, and even those who were not seized by that plague looked pale and sickly. We were greatly rejoiced one day when the man at the masthead called out that he saw land in the N.N.W., and within a little we sighted an island, which approaching, we brought to, and the captain sent Mr. Lummis with a boat fully manned and armed to the shore. After some hours the boat returned, bearing a number of cocoa-nuts and a great quantity of scurvy-grass, which proved an inestimable comfort to our sick. Mr. Lummis reported that he had seen none of the inhabitants, who had all fled away, it was plain, at the sight of our vessel. It being evening, we stood off all night, and in the morning the captain sent two boats to find a place where the ship might come to an anchor. But this was found to be impossible, by reason of the reef surrounding the island. The captain marked it down on his chart, and called it Brent Island after my uncle; but I learnt many years afterward that it had already been named Whitsun Island by Captain Wallis, having discovered it on Whitsun Eve. We sailed away, hoping for better fortune. There was none of us but longed to stretch our legs on the solid earth again, and I think maybe it had been better for us if the captain had permitted the men to stay for a while at Cape Virgin Mary or some other spot on the coast of Patagonia, for the being cooped up for so many months within the compass of a vessel of no great size must needs be trying to the spirits even of men accustomed to it.

However, within a few days of our leaving Brent Island we made another, that afforded a safe anchorage. Here we went ashore by turns, and the native people being very friendly, we stayed for upwards of a fortnight among them. It was an inestimable blessing, after living so long on ship's fare—salt junk and pease and hard sea-biscuit (much of it rotten and defiled by weevils)—to please our appetites with fresh meat and fruits, and these the natives very willingly provided in exchange for knives and beads and looking-glasses and other such trifles. It was now I tasted for the first time many vegetable things of which I had known nothing save from the reports of Wabberley and Chick and the books I had heard my uncle read—yams (a great fibrous tuber that savoured of potatoes sweetened), bananas (a fruit shaped like a sausage and tasting like a pear, though not so sweet), and bread-fruit, a marvellous fruit that grows on a tree about the size of a middling oak, and is the nearest in flavour to good wheaten bread that ever I ate. As for flesh meat and poultry, we had that in plenty, the island being perfectly overrun with pigs (rather boars than our English swine) and fowls no different from our own, except that they were more active on the wing. In this place, I say, we stayed for a fortnight or more, and were marvellously invigorated by the change of food, so that our men recovered the ruddy look of health, and the scurvy wholly left us.

During this time the captain and I lodged in a hut obligingly lent us by the chief of the island. We talked frequently of the main purpose of our adventure, the discovery of a southern continent, the captain intending, when we left the island, to sail southwards by west, into latitudes to which his charts gave him very little guide. After we had spent some time in diligent search, whether we made the discovery or not, he proposed sailing north again, and visiting Otaheite and other islands whereon Captain Cook had landed, for another part of my uncle's purpose, though lesser, was to find what opportunities for trading there were in these seas. It was the first part that engaged my fancy the most, pleasing myself with the thought of my uncle's pride if we should succeed where so many navigators before us had failed.

When we left the island and sailed away, I remarked that the crew were very loath to quit this land of ease and plenty. Indeed, when we mustered the crew before embarking, we found that Wabberley and Hoggett the sailmaker were amissing, and the captain in a great rage sent Mr. Lummis with a party to find them. Chick offered to lead another party, so as to scour the whole island (which was only a few miles across) more expeditiously; but this the captain would not permit, for what reason I knew not then, though I afterwards had cause to suspect it. Half-a-day was wasted before the truants were brought back, and though they pretended that they had lost their way in the woods that covered the centre of the island, they looked so glum when they came that I conceived a notion that Wabberley, a lazy fellow at all times, would not have been much put about if we had sailed without him. It came into my head that in the play of The Tempest, when the sailors are cast upon an island, one of them proposes to make himself its king and the other his minister, and I was amused to think how Wabberley and Hoggett would have disputed about the allotment of those dignities, even as Stephano and Trinculo.

We took on board a good store of the fruits of the island, and sailed for many days without dropping our anchor, though we passed several islands both large and small. Then on a sudden the wind failed us, our sails hung idle, and for many days we lay becalmed, the vessel being so close wrapt about by mist that we could not see beyond a fathom line. This had a bad effect on the temper of the men, who, being perforce idle, had the more time for quarrelling, which is ever apt to break out, even among good folk, when there is little to do. Some lay in a kind of sullen stupor about the deck; others cast the dice and wrangled with oaths and much foul talk; and when they tired even of this, they took a cruel delight in tormenting poor Billy Bobbin in many ingenious ways. So long did the calm endure that our store of fresh provision gave out, and the men were put on short allowance, at which, although the need of it was plain, they murmured as much as they dared. Having always in mind my uncle's counsel to deal kindly with them, I had been treated hitherto with respect; but I now observed that some of them looked askance at me as I went about the ship, and once or twice after I had passed I heard a muttering behind me, and then a burst of coarse laughter. To make matters worse, the captain again fell sick of a kind of calenture, and took to his bed. For all he was a quiet man, he exercised a considerable authority over the crew, much greater than Mr. Lummis, though the first mate was rougher, and sparing neither of oaths nor of blows. With the captain always in his cabin the men became the more unruly, and I longed very fervently for a breeze to spring up, so that the need for work might effect a betterment in their tempers.

One day when I was in the fore part of the ship, I heard a great hubbub in the forecastle, and looking down through the scuttle, I saw a big ruffian of a fellow—it was that same Hoggett whom I have mentioned before—I saw him, I say, very brutally thrashing Billy Bobbin, dealing him such savage blows on the bare back with a rope-end that his flesh stood up in great livid weals, the rest of the men laughing and jeering. The boy was so willing and good-tempered that I knew there could be no just cause for such heavy punishment, and he was withal of a brave spirit, bearing the stripes with little outcry until one stroke of especial fierceness caused him to shriek with the pain. I had a liking for Billy, and when I saw him thus ill-used I could no longer contain myself, but springing down through the scuttle, I seized Hoggett's arm and so prevented the rope from falling. Hoggett held the boy with his left hand, but when I caught him and commanded him to cease, he loosed Billy and turned upon me, dealing me a blow with the rope before I was aware of it, and demanding with a string of oaths what I meant by interfering, and crying that I had no business in the forecastle. At this I got into a fury, and without thinking of the odds against me I smote him in the face with my fist, an exceedingly foolish thing to do with a man of his size. In a moment I lay stretched on the deck, with the fellow above me, belabouring me with his great fist so that I was like to be battered to a jelly, and I doubt not would have been but that Mr. Lummis chanced to come by. Seeing what was afoot he sprang down after me and immediately felled Hoggett with a hand-spike. I was very much bruised, and felt sore for a week after, and withal greatly distressed in mind, for none of the men, not even Wabberley, who was among them, had offered to help me, and I could not but look on this as a very clear proof that a dangerous spirit was growing up among the crew. True, I was not an officer of the ship, and was not in my rights in giving orders, as Hoggett said when Mr. Lummis sentenced him to the loss of half his rum for the week. But being nephew of the owner of the vessel, I considered, and justly, that my position was as good as an officer's; and as for my striking the man, Mr. Lummis did as much every day.

It was on the day after this that Billy Bobbin came to me with a tale that disturbed me mightily. He had been for some time uneasy in his mind, he said, but owned that he would still have kept silence but for my intervention in his behalf. He sought me after sunset (in those latitudes it falls dark about seven o'clock), when the men were at their supper, and he might talk to me unobserved. He said that the men had been grumbling ever since we left the island where we had stayed. They had a hearty dislike to the purpose of our expedition, and a great scorn as well, deeming the search for a southern continent to be merely a fool's quest. I own it caused me vast surprise to learn that Wabberley was the most scornful of them all, saying that, having been with Captain Cook on his first voyage, he knew there was no such continent, or the captain would have found it, and telling the others dreadful particulars of the tribulations they suffered: how some of them spent a night of terror and freezing cold (though 'twas midsummer) on a hillside of Tierra del Fuego, and how, out of a company of eighty, the half died of fever or scurvy. And in contrast to these ills he told us of the lovely island of Savu, and of Otaheite, where there was everything that man could wish for—a genial climate, the earth yielding its fruits without labour, or at least with the little labour that a man might demand of his wives (for he could have as many wives as he listed); in a word, a paradise where men might live at their ease and never do a hand's turn more. Furthermore, Billy told me (and this was the most serious part) that he had overheard the men talking, a night or two before, of deserting in a body when we next went ashore (provided the island was one of the fruitful sort, for there were some barren), and leave the officers to navigate the vessel as best they might. Great as my surprise had been to hear that Wabberley was one of the moving spirits of this conspiracy, still greater was it when Billy told me that this purpose of deserting was mooted by Joshua Chick the boatswain. I had never been drawn to that obliging person; nay, his very obligingness had annoyed me, just as sometimes I am nowadays annoyed by a person over-officious in handing cups of tea; and when I came to put two and two together, I could not doubt that this scheme had been in the man's mind from the first. In short, he and Wabberley had taken advantage of my uncle's hobby to beguile him upon setting this expedition on foot, for no other reason than to find a means of returning to these southern islands, where they might live in sloth and luxurious ease.

Bidding Billy to be silent on what he had told me, I went to the captain, who, as I have said, was ill in his bunk, and acquainted him with this pretty plot that was a-hatching. He was in a mighty taking, I warrant you, and swore that he would hang the mutineers at the yard-arm, at the same time handing me a sixpence to give to Billy Bobbin for his fidelity. He called Mr. Lummis and Mr. Bodger into council, and could hardly prevail on the former not to fling the ringleaders into irons at once. Mr. Bodger, whom I had always regarded as a man of mild disposition, suggested that they should be put ashore among cannibals, and so be disposed of in the cook-pot (the natives, for the most part, boiling their meat), which led Mr. Lummis to declare, with a volley of oaths, that if the calm lasted much longer they would want food aboard the vessel, and Wabberley would cut up well. I own such talk as this seemed to me very ill-suited to the occasion, though when it came to the point the officers were not barren of practicable schemes for dealing with the mutineers, as will be seen hereafter.

OF THE NAVIGATION OF STRANGE SEAS; OF MUTTERINGS AND DISCONTENTS, OF DESERTION, OF MUTINY AND OF SHIPWRECK.

We lay becalmed for several days longer, during which time there was no further outbreak among the men, for the captain bestirred himself and came on deck, though in truth he was not fit for it. His mere presence seemed to make for peace and quietness. He had counselled the officers to alter nothing in their conduct, yet to be watchful; and I think he never feared a mutiny on board the ship, expecting no danger until we should set foot to land again.

At length the mist cleared, the sails once more filled, and we set our courses again towards the south-west. The men went about their duties at first cheerfully, for the mere pleasure of action after so long idleness; but when, after about a week, they perceived that the captain held steadily on his course, without offering to touch at any of the islands we sighted, their looks fell gloomy again, and there was some grumbling, though subdued. Though our fresh food was now all gone, we still had great stores of the common victuals—biscuit and pease and oatmeal, besides salt junk, a sufficiency of rum, and water for two months. This was sparingly used, every man of us washing in salt water, which made my skin smart very much until I was used to it.

Day by day, as we approached the high latitudes, the air became sensibly colder, and in the morning we sometimes saw icicles on the rigging. The sky was for the most part gloomy; showers of sleet and hail beat upon us, and I own I felt a pity for the sailors at these times, having to spend so many long hours below decks in darkness and stench. For days at a stretch we crept through thick fogs, and by and by came among icefloes, and then among icebergs, against which we ran some risk of being shipwrecked, so that we had to keep a very careful look-out. When I marked the growing discontent of the men, I feared lest they should rise in mutiny and take the navigation of the vessel into their own hands, and I verily believe we were only saved from this by the captain's change of mind. He made it a point of honour to fulfil the desires of my uncle so far as he might, and would have continued the search for the southern continent against all risks; but when the ice grew constantly thicker, and our fresh water began to lie perilously low, he concluded that it was folly to try any more for that season, and so steered north.

Our men were greatly rejoiced at this resolution, and their cheerfulness was such that I began to lose my fear of untoward happenings. When I said as much to the captain, however, he observed that our particular danger would arise when we came to a land of plenty. It was his ill hap again to be seized with sickness at this time, and he seldom left his bunk in the roundhouse.

The South Seas

One fair day—I think it was about a year after our sailing from Deptford—we sighted an island which did not appear on our chart, but which, on our nearer approach, gave promise of furnishing that refreshment of which we were in need. It was very well wooded, and we knew while still a great way off that it was inhabited, seeing through our perspective glass a good number of canoes about its shore. When we came within a little distance of it some of the canoes put off towards us, and a crowd of people stood on the beach, inviting us as well by their gestures as their loud cries to land. The captain, who had come out of the roundhouse and sat on a stool by the door, considering that the fertility of the place and the friendliness of the natives favoured us, ordered the vessel to be hove to, and a boat to be made ready, with casks for bringing back a supply of water. He then appointed a dozen of the crew to man the boat, calling them before him, and commanding them very strictly that they should not stray far from the neighbourhood of the beach, but fill their casks at the nearest spring or freshet, and purchase what vegetables and fruit they could in exchange for such trifles as I have before mentioned. I observed that the captain had not chosen Wabberley and Hoggett, or any other of the men whom we certainly knew to be disaffected: indeed, both Hoggett and Chick, with several more, were then sick of the scurvy. The captain set Mr. Bodger over the boat's crew, and he went with a cutlass and two pistols in his belt, but the men were without arms.

As soon as they set off, being accompanied by two canoes which had by this time reached our vessel, Mr. Lummis, at a word from the captain, commanded the men that remained on board to collect all the arms that were in the ship and bring them into the roundhouse. It was plain from their looks that they were amazed and confounded at this order, which they obeyed very sullenly, Mr. Lummis having in sight of them all stuck a pistol in his belt. As they went to and fro they eyed the captain suspiciously, and cast many a glance towards the shore, where their fellows were beginning their task amid a great uproar of the natives. It had been arranged between the captain and Mr. Lummis that this precaution regarding the arms should be taken when the crew was thus divided, so that we should have the means of coping with any mutinous outbreak. The captain also insisted that I should take a pistol, which I was loath to do, having never fired one in my life.

The arms had all been bestowed in the roundhouse before the boat returned with its first cargo. When the men came aboard they began to tell their messmates of the exceeding richness of the island, as far as they had seen it, but they had gone but a little way in their tale before the other men broke in with an account of what had been done in their absence, which made them dumb with astonishment. Being conscious of their guilty designs, they perceived that we knew them too, though they were not able in their first surprise to divine the means by which we had obtained our knowledge. However, it was not a time to take counsel together, with the officers about them, and as they had performed but a small part of their task on shore, they went back into the boat with as meek a look as ever I saw.

Mutterings

When they came again to the island, they set about their work as before, though more sluggishly; but having filled a cask or two, and brought them to the boat, I observed them, all but one, go up the strand again without another cask to be replenished. I supposed that they were now going to procure vegetables, but Mr. Lummis, who was standing at my side, suddenly let forth a great oath, bidding me observe that the men went empty-handed. And then we saw Mr. Bodger, who had been left at the boat, hastily following them, and though we were too far off to hear any words distinctly (besides, the native people still made a great clamour), we could tell by his motions that the mate was calling after them, and we saw two or three of them turn round and laugh at him, and then go on up the island amid a concourse of the natives. Mr. Lummis cried out to him to use his pistol on the mutinous dogs, but he could not hear, and indeed he was a timid man, besides being apprehensive, perhaps, that the natives, many of whom had long spears, would turn upon him if he offered any violence. This notion of ours had some colour when we saw him return hastily to the boat, and endeavour, with the only man of them all that was left, to launch her. This, however, they were unable to do, the boat being beached high on the sand, and heavy with the full casks already laid in her.

Mr. Lummis went into the roundhouse, whither the captain had retired, to acquaint him with these proceedings. They thought, and so did I, that the men were putting in act the plot of which Billy Bobbin had told us, though it seemed to me strange that they should have gone without the ringleaders, who were still on board the vessel. We were considering of this when Mr. Lummis, with another great oath, cried out that he saw through the rascals' plan, which was, he said, to tempt us to send another boat's crew after them, and then, having both the mates ashore, to overpower them, as they would easily do with the aid of the natives, in spite of the pistols. But he swore that he would prove one too many for them, and having trained on the beach one of the six swivel guns we carried, he commanded two of the men to lower the dinghy, and then to come to the roundhouse for the captain's orders.

This being done, and the men coming in, the captain looked very severely upon them, and said that he was about to send them with Mr. Lummis to bring off the boat with Mr. Bodger in it, and that if they should attempt to join the rascals on shore, who had flatly disobeyed orders, Mr. Lummis would shoot them instantly. This he said in a very loud tone of voice, so as to be heard by the rest of the crew, who had sneaked up out of curiosity to learn what was toward. The two men with Mr. Lummis then descended into the dinghy, Mr. Lummis taking with him a large piece of bright-coloured cloth, two small looking-glasses, and a new sailor's knife.

When they came to the shore, Mr. Lummis stepped out and waved the cloth above his head, at which a number of the people came running to him, making strange and uncouth cries. I had afterwards, as will be seen, to learn how hard it is to communicate with men who have no common speech with us; but even as the beasts are able to hold converse with their kind, so the great Creator of all things has given to man the power to make his thoughts plain to folk sundered in speech by the iniquity of Babel. Mr. Lummis contrived to make these poor savages understand his wishes, and when, with the aid of them and of the seamen, the large boat was launched, and was rowed back to the ship, taking the dinghy in tow, one of their canoes came also, with some of their chief men in it.

At the invitation of Mr. Lummis, the savages came aboard our vessel, and then, with much pains, he acquainted them further with his desires. He pointed to the seamen who were gathered on deck, and then to the island, with gestures signifying that the men of their kind who had first landed must be brought back. He made them understand that a price would be paid for each man that was recovered, either a piece of cloth, or a knife, or a looking-glass like those he showed to them. And then, bethinking him that it were profitable to impress them with a sense of his power, he ordered the gun to be fired with a blank charge, at whose roar the savages fell flat upon their faces, and lay for some while quaking in a great fear. After this they made haste to get into their canoe and paddle to the shore, which was now deserted, all the people having fled away at the sound of our gun; and they ran very fleetly up into the wooded country and disappeared from our view.

We saw nothing more of them or of our seamen that day; but early the next morning, almost as soon as it was light, we heard a great commotion on the shore, and soon perceived a vast throng flocking to the beach, with our men among them. There they were cast with some roughness into three of the canoes, and I perceived by the manner of their falling, like as sheep when they are cast into a cart, that their limbs were tied, which, without doubt, sorely ruffled their tempers, being Englishmen. When the canoes came alongside our vessel, the natives shouting and yelling like mad things, Mr. Lummis let down a sling over the side, in which our men were hoisted one by one to the deck. It was as much as I could do to keep from laughing, so sorry was their look, their faces being scratched and bruised, and their garments very much tattered, and indeed on one or two hanging mere shreds. Mr. Lummis heartily cursed each one as he came up, with many quaint derisive observations which mightily vexed them. We had taken seven or eight aboard when Mr. Lummis, looking over those that were left in the canoes, perceived that there were only ten in all, when there should have been eleven, the party having numbered twelve at the first, of whom one had returned with Mr. Bodger. Mr. Lummis flew into a rage at this, supposing that the natives had kept back one man, with a design to chaffer for a higher price; but when he demanded of the rest where Wilkins was (that being the name of him who was missing), they answered sullenly that he was dead, for he had offered a stout resistance when the savages attempted to tie his hands, and had the temerity to fell the chief himself with his fist. This spirited act, which was in truth worthy of a true-born Englishman, cost him his life, for he was instantly thrust through with spears. I doubt not his death was the means of saving the lives of the rest, for seeing what had befallen their comrade, and being unarmed, they submitted (though surely with an ill grace) to be bound, and were so brought back to their vessel, as I have said. The savages having received the presents promised them returned to the island, where they immediately fell a-quarrelling about the apportionment of their wages, and we saw that the strip of coloured cloth was very soon torn into a hundred little pieces.

Mutiny

As for the seamen, they were by the captain's orders immediately put into irons and laid in the hold. Though we had not taken aboard near as much water or provision as we intended, yet the captain would not risk the sending of another crew to the island, albeit he might safely have done so, I think, the men being for the time sufficiently tamed. We had to wait the best part of the day for a breeze; then we weighed anchor and stood away to the north. While the island was still in sight, the wind suddenly shifted its quarter, and blew first a gale and then a hurricane, so that we had to shorten canvas. While this was a-doing the sea was lashed to a fury, prodigious waves sweeping over the deck and buffeting the vessel so heavily that her timbers shook, and we feared the masts would go by the board. With ten men in irons and about as many weakened by the scurvy, the crew were pretty hard pressed, and though they worked with a will, since their very lives depended on it, they railed without measure against the captain and Mr. Lummis, heedless of what punishment might be dealt to them when the storm abated. Presently a cry arose that the vessel had sprung a leak, and since none of those above could be spared to man the pumps, Mr. Lummis ordered the men in irons to be brought up, and made them work at the pumps in turn. The storm rather increased than diminished in fury, and the seamen were seized with a fear that the vessel would founder, and I heard them mingle prayers and curses in a breath, reviling the captain for taking them from the hospitable island, and crying out "Lord, have mercy on us!" again and again. Darkness fell upon us while we were still battling with the storm, which added to our terrors, for the vessel would not obey the helm, and we knew not but we might be cast upon some coral reef, such as abound in those regions, and there be clean broken up. In this extremity of peril I own I was dreadfully afraid, and prayed very fervently that we might be saved, thinking too of my uncle and aunt, and the happiness I had enjoyed with them, casting my mind back over many things in my past life, almost as a drowning man does, at least I have heard so.

I was inexpressibly relieved when at last the violence of the tempest abated, in the wind first, for it was long before the turbulence of the sea was sensibly diminished. About the middle of the night, however, we were able to stand once more upright on the deck without clinging to the shrouds or other things for support, and then, being utterly worn out, we sought repose, but not before the leak had been discovered and stopped, which took a long time, and the unruly seamen who were in irons once more confined in the hold. I gave hearty thanks to God who had so mercifully delivered us, and went to my bunk in as peaceful a frame of mind as if it were my bed at home.

I was awakened, how long afterwards I know not, by Mr. Bodger breaking into my cabin, which was on the maindeck, and calling on me to come instantly to the quarterdeck, and bring my pistol, for the crew had risen in mutiny, and having made a rush to the hold had liberated the men in irons. I sprang up and cast my coat, which was still dripping wet, about me, and seizing my pistol, followed the man up to where Mr. Lummis and the captain stood in front of the roundhouse. But a moment after I joined them we were aware that the crew were advancing to attack us, judging by the sounds of their shouting, for the night was so black that we could see but little, the men having put out the sole lantern. We were in a very desperate case, being but four against the whole crew, saving some few who were sick, not one of the men having come to our side; the captain, moreover, being very feeble from his illness. But we had all the firearms at our command, and Mr. Lummis trusted by means of these to do such execution among the mutineers that they would lose heart, and while the worst of them would be cowed, the better-disposed would yield to authority. Thus we four stood side by side, and as the men drew near Mr. Lummis called to them in a loud voice, warning them that we had weapons which we would use upon them if they did not instantly return to their duty. There was silence for a space; the shuffling of bare feet on the deck ceased; then a voice called out (I think it was Hoggett's) that the captain should return to the island we had lately left, and let 'em rest and recruit themselves, they being dead sick of sailing without end. He finished by saying that if the captain did not consent to this course, they would slit his weazand and cast him to the sharks, and serve all of us the same, and we had best make our choice without delay. Mr. Lummis, to whom the captain left all this matter, roared out a string of oaths and commanded the men to seize that rascal who had the insolency to order the captain's goings. There was a great laugh, very horrid to hear, being rather the sound that wild beasts would make than men; then there was again silence, or rather we heard the low murmurs of the men talking among themselves. Mr. Lummis cursed again, but this time under his breath, and muttering "They mean mischief," he bade Mr. Bodger in a whisper put out the lantern that swung from the roof of the roundhouse behind us, and so made a light against which our forms, as we stood on the threshold, could be distinctly seen by the men. This was no sooner done than there came a single shrill blast on the sea-pipe, and the men rushed up towards us with fierce shouts that made my flesh creep.

"Fire!" cried Mr. Lummis loud enough to be heard above all the din. As I have said before, I had never in my life fired a pistol, and what with excitement and flurry, my finger fumbled a little at the trigger, so that I was a thought behind the others; but even in that little moment I heard terrible screams as the bullets from the officers' pistols flew among the crew; and though I fired mine immediately after, I could not tell whether 'twas pointed up or down, or in what direction soever, and I was seized with a fit of shuddering when the thought came to me in a flash that peradventure I had slain a fellow-creature. You may think I was a coward, and perhaps I was; but yet I think I was not, but only new at such kind of work, because I do not recollect that ever I felt the same way again when I had to defend myself, as will appear in order.