Project Gutenberg's An I.D.B. in South Africa, by Louise Vescelius-Sheldon

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: An I.D.B. in South Africa

Author: Louise Vescelius-Sheldon

Illustrator: G.E. Graves and Al Hencke

Release Date: August 29, 2011 [EBook #37265]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN I.D.B. IN SOUTH AFRICA ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Louise Vescelius-Sheldon

"An I.D.B. in South Africa"

Chapter One.

The Marked Diamond.

“Who is that beautiful woman in the box opposite us, Herr Schwatka?”

“Which one, Major? There are two, if my eyes may be trusted.”

“She with the dark hair?”

“That is Mrs Laure, and the gentleman is her husband, Donald Laure.”

“What a beautiful creature, is she not?”

“Yes, beautiful indeed, as many of the Cape women are. But the union of European with African produces, in their descendants, beings endowed with strange and inconsistent natures. These two bloods mingle but will not blend; more prominently are these idiosyncrasies developed where the Zulu parentage can be traced, and naturally so, for the Zulus are the most intelligent of all the African tribes. Now they are all love, tenderness, and devotion, ready to make any sacrifice for those on whom their affections are placed; again revengeful, jealous, vindictive.”

“But surely that woman has no African blood in her veins,” said the major.

“Yes,” replied Schwatka, quietly; “but the fact is not generally known.”

“What eyes! I should like to know such a woman. To analyse character moulded in such a form would be a delightful study. And the lady with her, who may she be?” continued the major.

“Miss Kate Darcy, an American lady now visiting her brother, a director in the Standard Diamond Mining Company. These Americans, turn up everywhere,” and Schwatka lifted his shoulders with an expressive shrug.

“Then the gentleman with her is the brother, eh?” persistently continued the major.

“No, that is Count Telfus, a large dealer in diamonds, said to have made much money. There goes the curtain.”

The preceding conversation between Major Kildare and Herr Schwatka took place in a box of the Theatre Royal on the Kimberley Diamond Fields. As Schwatka looked at Donald Laure, the latter glanced across the house; their eyes met and a sign of recognition passed between them. Presently Mrs Laure turned, disclosing an exquisitely beautiful face, but one apparently unconscious of the effect of its beauty. Her height was slightly below the average, and her form faultless. Her short, black, wavy hair adorned a small but beautifully-shaped head, crowning a swan-like neck, encircled by a necklace of diamonds and rubies sparkling like drops of dew. Her toilet was conspicuous by its elegance—an elegance that well became her unusual style.

Shortly before the end of the first act, while the attention of the audience was riveted on the stage, a man quietly entered the Laure box, and touching Count Telfus on the shoulder whispered a few words in his ear. The Count gave a sudden start, his face blanching perceptibly, but with perfect composure of carriage he arose, and, excusing himself to the ladies, retired from the box. The stranger had entered unnoticed by the other occupants, who were attentively listening to the music of the opera, with the exception of Donald Laure, who had been an observer of the proceeding. As the curtain fell at the end of the act he followed the Count.

Major Kildare, who had been interested in watching the face of Mrs Laure, observed this scene in the box and drew Herr Schwatka’s attention. The latter sprang to his feet, at the same time exclaiming, in a voice low but audible to those in the immediate vicinity, “Detectives.” Drawing the Major’s arm through his, he led him out of the theatre, into the café adjoining, where they found Count Telfus in charge of two men of the detective force. The Count stood silent in the midst of the excited crowd that filled the room; but his pale face and the nervous manner in which he bit on an unlighted cigar plainly showed that he was suffering intensely.

“Count Telfus,” said one of the detectives, “we have an order for your arrest, and you must also permit us to search you. We trust that we have been misinformed, but a marked diamond has been traced to your possession, and our orders are imperative.”

“I have nothing about me not mine by a legitimate ownership,” said the Count, in a cold, clear voice, “and I will not submit to the outrage of a personal search. It is well known that I am a licensed diamond buyer; here is the proof of it.” And he drew a paper from his pocket.

“That you are a licensed buyer is the greater reason why your dealings should be honest,” rejoined one of his captors, proceeding to search him. Even as he spoke he drew a large diamond from the Count’s vest-pocket.

“Fifteen years in the chain-gang,” cried an ex-Judge who had bought many a stone on the sly.

“Father Abraham!” exclaimed a sympathising Israelite, “how could he be so careless with such a blazer.” Similar ejaculations rose from the crowd around him.

In those bitter moments a despair like, death fell on Telfus; for his life was blighted and his family name disgraced. He did not see that excited crowd of which he was the centre; he only saw, in his mind’s eye, his mother’s face filled with an agony of shame. And he heard, with the acuteness that comes only in times of greatest distress, the low contralto tones of a soulful voice floating from the stage of the theatre within, and breathing out the words: “Farewell, farewell, my dear, my happy home.”

Alone he stood, bidding an inward farewell to his own home—condemned to an infamous exposure.

His friends around him were powerless to aid, for the diamond had been found on him. “Sorry for you, old boy,” said Dr Fox, an American, as he wrung the hand above which the detectives put on the bracelets of the law, which shutting with a click, struck on the Count’s consciousness like a knell of doom. He gasped, and stifled a cry that rose to his lips. When his hands were secured, followed by a noisy crowd, he was led to a Cape cart standing in front of the door. He sank into the seat, a brokenhearted man, his thoughts far away in that home in Paris, which on the morrow would be filled with sorrow and anguish.

Suddenly arousing himself he asked to be taken to the telegraph office. Arriving there they found it closed.

“Fortune favours me thus much,” he thought; “the only news they will receive will be that I am dead.”

They reached the prison, and the Count was placed in a cell.

Before the sound of the jailer’s footsteps had died away, the report of a pistol told that Telfus had passed beyond the reach of human law.

Chapter Two.

The Mystic Sign.

Within rifle-shot of the “ninth wonder of the world,” the great Kimberley Mine, stood a pretty one-story cottage nestling among a mass of creepers that shaded a wide veranda. The house, like many others on the Fields, was constructed of corrugated iron, fastened to a framework of wood. Beams were laid on the ground; to these were fastened uprights from four to six inches square.

In place of lath and plastered walls, thick building paper formed the interior covering, leaving a space between the iron outside and the paper within.

The interior of the cottage was in marked contrast with its outer appearance. A wide hall extended through the entire depth, with a door at each end. The walls were artistically hung with shields, assagais, spears, and knob-kerries, and in either corner stood a large elephant’s tusk, mounted on a pedestal of ebony.

A small horned head of the beautiful blesse-bok hung over a door leading into an apartment, the floor of which was covered with India matting, over which was strewn karosses of rarest fur; a piano stood in one corner, while costly furniture, rich lace, and satin hangings were arranged with an artistic sense befitting the mistress of it all.

On a divan, the upholstering of which was hidden by a karosse of leopard skins, reclined Dainty Laure, a woman on whom the South African suns had shone for not more than twenty years. The light, softened by amber curtains, revealed an oval face, with features of that sensuous type seen only in those born in the climes of the sun. This clear, olive-tinted face showed a love of ease and luxury, unless the blood which seemed to sleep beneath its crystal veil should rouse to a purpose, and make this being a dangerous and implacable enemy.

Her eyes were closed; one would have thought she slept, but for the occasional motion of a fan of three ostrich feathers. The reverie into which she had fallen was broken by the striking of the clock. The pencilled eyebrows gave a little electric move, and the lids slowly unveiled those dark languorous eyes, which seemed like hidden founts of love.

So expressive was the play of those delicate eyelids that one forgot the face in watching them, as they would droop and droop, and then slowly open until the great, luminous orbs appeared, and seemed to dilate with an infinite wonder, a sort of childlike fear combined with the look of a caged wild animal. This expression extended to the mouth, with its budding lips over small, white teeth. Should occasion come, she could smile with her eyes, while her mouth looked cruel.

A white robe of fleecy lace clung round her form, and from the hem of her garment peeped a ravishing little foot, encased in silken hose and satin slipper of the same bronze hue.

Bracelets of dewdrop diamonds encircled her wrists, and with the rubies and diamonds at throat and ear, completed a toilet which might have vied with that of some semi-barbaric Eastern princess.

Such was the woman in whose veins ran the blood of European and African races.

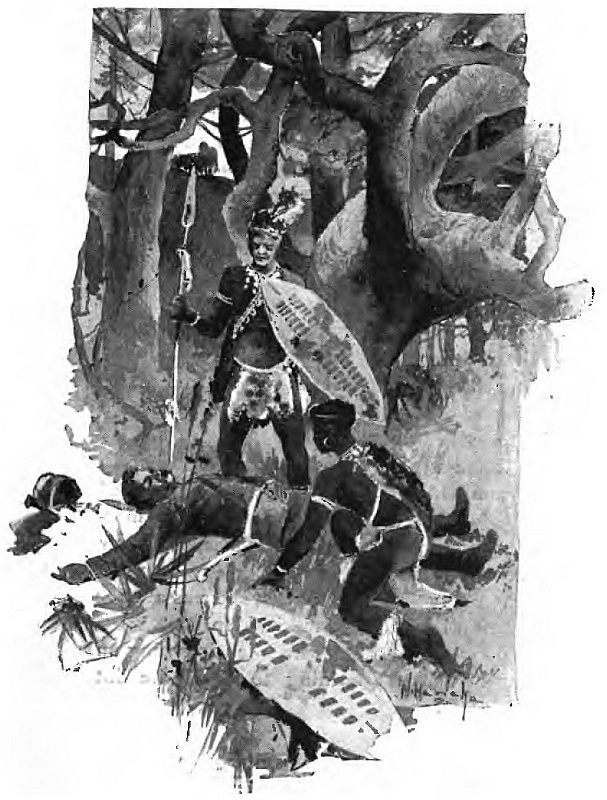

In one of the numerous wars between the native tribes and English soldiers in Africa, Captain Montgomery, pierced by an assegai, fell wounded on the battle-field, and was left for dead. For hours he lay unconscious. Toward night he awoke to a realisation of his perilous situation, in the midst of a dense underbrush infested with reptiles and wild beasts, to which he at any moment might fall a victim. He attempted to rise, but his stiffened limbs refused their office; thirst, that ever-present demon of the wounded, parched his throat.

After many fruitless efforts he succeeded in rising to a sitting posture, but the effort caused his brain to reel, and all again became a blank. For a short time he remained in this condition, when perfect consciousness, like that which with vivid force precedes dissolution, returned, and revealed standing before him an aged Zulu chief, accompanied by an attendant. The supreme moment of his life seemed to have arrived, and with a final effort he summoned all his strength and made a sign—the sign known to the elect of all nations. The sign was recognised—understood—by that savage in the wilderness. There, in that natural temple of the Father of all good, stood one to whom had descended from the ages the mystic token of brotherhood.

At a signal the attendant Zulu bounded away, leaving the chief, who gently placed the soldier’s body in a less painful position. The native soon returned with three others, bringing a litter made of ox-hides, on which, with slow and measured steps, they bore him to their kraal, situated on a hillside, at the foot of which was a running stream.

He was taken to a hut and placed on a bed of soft, sweet-smelling grasses covered with skins. Tenderly the rude Africans moistened his lips, removed his clothing, and bathed his wounds. For hours he lay unconscious; then a sigh welled from his breast, another and another. Gently the attendants raised his head, and administered a cooling drink.

Soon a profuse perspiration covered his body, and the strained look of pain gradually left his face.

The following day the chief, with his principal attendants, visited the Englishman. Forming a circle round his couch, they stood for several moments gazing at the sufferer in profound silence; then, passing before his pallet, they slowly filed out of the hut.

Chapter Three.

Cupid’s Arrow in an African Forest.

For several days Captain Montgomery’s condition was extremely critical, but the careful nursing and devoted attention of the Izinyanga, or native doctor, aided by his simple, yet efficient remedies, soon restored the patient.

One morning he awoke quite free from pain, the fever broken, and with that sense of restful languor that attends convalescence, pervading his being. As he lay in this condition, with his eyes half closed, he saw standing in the opening of the hut a girl of perhaps sixteen years.

A leopard skin was thrown over her right shoulder, which, falling to the knee, draped her form. A necklace of strands of beads encircled her throat. Her arms and ankles were ornamented with bands of gold. For a moment she gazed on him, and then uttered to her two female attendants a few words consisting of vowel sounds and sharp notes made by clicking the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

On hearing her voice Montgomery widely opened his eyes, when, followed by her women, the girl fled with a springing step like a frightened deer.

Often, after that fleeting vision, during his waking moments would Montgomery feel that those dusky eyes were gazing at him, and when he lifted his own it would be to see her swiftly and silently moving away.

In a short time he was able to walk about in the cool shade of the great forests of paardepis and saffron-wood, where he would at times see the face of the Zulu princess peering out, like some dusky dryad, from behind the hanging boughs, only to disappear, when detected, into the depths of the wood.

After a few weeks had passed she grew less shy, and when he spoke to her she would stand a few moments listening to the unknown tongue, whose accents seemed to charm and draw her to the spot; but if he made a motion as if to approach, she would vanish swiftly as a thought flies.

One morning when his health had become fully restored, the chief who had rescued the captain in his hour of extremity, appeared, and by signs made him understand that he was to follow him. They proceeded to the outer edge of the gloomy forest, where speaking a few words in Zuluese, the native disappeared in the direction they had come. Understanding that the parting speech of his guide instructed him to continue in the course he had pointed out, Montgomery pressed forward on his journey. He had walked alone, perhaps an hour, when he was startled by the sight of the Princess, emerging from the shade of a tall boxwood tree, leading two horses. She motioned him to take one, and as he leaped on its back, she quickly mounted the other, and in a few moments they had passed away from the scene forever.

These two beings were the ancestors of Dainty Laure.

Soon after his arrival in Cape Town, Donald Laure had met Dainty. She was little more than a child in years, but matured in form, and being possessed of dangerous beauty was attractive to this impulsive Scotchman from the cold North, where women of her radiant type are never seen.

From the first moment he saw her, he had only one thought, one idea, which grew to a determined purpose, and that was, to possess her. She was a wild bird and knew little of the world’s ways, and as he was the first man who had laid siege to her heart he amused her, and she grew more and more interested in him.

When a few weeks later he asked her to become his wife, she consented with a half wonder, half delight; and when the marriage ceremony had taken place, and they were on their way to Kimberley, she could scarcely realise the fact that she was a wife; it was all so strange and sudden.

Four years after we find her dreaming on her divan, with nothing to do in life but to dream.

Chapter Four.

The Unwelcome Letter.

The morning following the events related in our first chapter, found Kimberley in a high state of excitement.

Every man looked at his neighbour with a face like an interrogation point, as if to ask, “Who next?”

The diamond market was crowded with men, gathered in groups, earnestly discussing the exposé, and the fatal dénouement.

No one had stood higher in the esteem of the people than Count Telfus.

Among the first to engage in the diamond trade in Kimberley, he had enjoyed the confidence of his associates, and, up to the day of his arrest, no breath of suspicion had dimmed the lustre of his name. It was evident that the numerous thefts of precious stones by the Kafirs had aroused the authorities to their highest endeavour, and no one knew on whom the next bolt of discovery might fall.

With Telfus guilty, whose name might not be found on the list of I.D.B.’s?

There were few among those engaged in this unlawful trade whose minds were free from anxiety, for even the guiltless might find his name in the Doomsday book as among the suspected. When Donald reached home that evening he found Dainty anxiously awaiting his return. The excitement caused by the arrest and death of Count Telfus had reached every class, and the unusual stir among the domestics had filled her mind with dire apprehensions. She immediately inquired if there were any further developments.

“The town is greatly excited. Dr Fox has written to the Count’s family in Paris, that the Count was accidentally killed, but carefully avoided any mention of the true cause of his death. Poor Telfus!”

Dainty sighed, for the Count had been a frequent visitor, and his face always brought sunshine into the house.

“Do you think he was guilty?”

“Rumour says the police sold a marked diamond to a Kafir for a song, and then watched him. By some strange fatality it fell into Telfus’ hands.”

He paused, and looking into her eyes, asked:

“What would you do, if some great trouble should come to you?”

“Trouble? Surely no danger threatens us, Donald. You alarm me, what harm can come to us?”

He was about to speak, but checked himself, and turning on his heel, hastily left the room.

Donald was naturally of a buoyant disposition, and extremely popular in business and social circles: but of late he had grown moody and taciturn, and there was a marked change in his demeanour toward Dainty.

She believed that her husband adored her, and if his preoccupied and distracted manner sometimes raised a query in her mind, it was too short-lived to warrant any serious thought, and she quickly banished it. She was fond of her husband in a childlike, cooing way, and it was her delight to wind her arms about his neck, and, with a gentle twittering sound, like a dove caressing its mate, ask the question that every woman asks (who is sure of the answer): “Do you love me?”—and wait to hear the low, responsive sigh, or receive a fond embrace. This unusual question of Donald’s alarmed her, and she stole softly into the adjoining room where she found Donald nervously pacing the floor.

His face was pale and his eyes glistened with a hunted expression. Laying her hand on his arm, she said:

“What is it that worries you, Donald?” He started and stammered: “Nothing—except a little business annoyance.”

She saw a letter in his hand, bearing a foreign postmark, and gave it a questioning glance, to which he replied:

“A letter I have received from Amsterdam. There is a heavy decline in the diamond market.”

“Don’t worry about that; you have now more than enough of this world’s goods to take care of yourself and your little wife as long as you live,” said Dainty, as she laughingly rubbed her cheek on his arm with an action suggestive of a purring kitten. Without looking up, she continued:

“Why don’t you take me to England?”

He shut his eyes, and bit his lips, but oblivious to his emotion she went on.

“You have so often promised, and I so want a change. I long to visit the land you have told me of.”

“Some day, my dear, you will see that great country of mine, but not just now,” rejoined Donald, gently.

“Ah, Donald, why do you always feed my curiosity with the shadow of promises?”

Donald watched her with an idolatrous look until she passed from the room, and then with a groan sank into a chair, and buried his face in his hands. For a moment he sat in silence, then re-opened the letter. It was dated “London” and the passage in it that he had read and re-read, was this:

“The person you inquire about is in the city, and has learned—I know not how—that you are in South Africa, and is determined to hunt you down.”

Striking a match, he set fire to the letter, and watched it slowly burn, and crisply curl in his fingers. He then threw it on the floor, and crushed it with his foot, with the unspoken wish that this act could blot out its menace from his memory.

Growing calmer he arose, and passing his hand over his face as if putting on a mask, went out of the room to join his wife at dinner.

The dinner was served by a black dwarf named Bela, who in his fantastic proportions resembled a heathen idol in bronze.

After they had eaten sometime in silence, Dainty asked.

“Are you going out this evening?”

“I must go to the club, but I will return early.”

“I am often lonely, Donald, when I am left with only my thoughts for company,” said Dainty, somewhat mournfully.

“You must be lonely sometimes,” replied Donald. “Let us try a small diversion. Why not invite in a few friends for an evening? Make out your list, and send the invitations to-morrow. Don’t get the blues while I am away,” and kissing her, he hurried into the street.

Chapter Five.

Impressions.

There are women who have no power of attraction until you meet them in their homes, surrounded by evidences of an individuality which belies your first impression. Then for the first time you discover new traits of character, and evidences of thought that fascinate and hold you; then for the first time they surprise and delight you with their real selves.

Again, there are those who shine abroad, but darken their homes. In the chilling atmosphere surrounding them, no life can expand. These women are dwarfed souls. Affecting the semblance, they know not the real. The lifeless imitation of their surroundings betrays them, and chills the sensibilities of their guests.

The wife of Donald Laure, was a woman whose surroundings seemed a part of herself—a bright, light creature, glorifying the materialities about her with a certain radiance, and none could enter her home without feeling the charm that pervaded it. With her warm heart and generous impulses she seemed born but to make beholders happy.

She was, as yet, unconscious of the powers that lay dormant in her; under her childlike exterior was a soul of which even her husband knew nothing. All her knowledge of the world was like the knowledge of a maiden, far from its busy actualities.

She mused upon its wonders as they were presented to her mind by her husband, but he would have been amazed at the panorama of her thoughts.

Greater amazement would have been his, had he known the strange truth of which she herself was entirely oblivious, that the great pulsating power of Love had not yet inspired her. To be loved, caressed, cared for, had so far made her content. But, born of the English soldier and the daughter of a savage warrior, there slumbered in her soul a possibility of passion that needed only to be roused to burst into flame.

The life of excitement that society offers, brings little contentment to a woman with Dainty’s nature. She only beats the bars raised by its cold, formal laws, and sufficient unto herself, living a life within that soothes, she becomes a fascinating siren to the energetic nineteenth century man, who comes with his beliefs in materialism, and his doubts of any goodness that he cannot prove.

Such a woman is to him a creature to be tested by his methods, and broken on the wheels of his unfeeling Juggernaut of selfishness and animalism.

Being a delightfully untutored, trusting soul, she is not looking for this monster evil—self, that he has raised up and worships. At first attracted to him by a warmth of manner which has every appearance of generosity, she at last becomes interested in him so deeply, that the winning of her perfect trust, her whole heart, is an easy pastime, undertaken at seemingly accidental moments, but in reality pursued as steps in a long and carefully laid plan.

The evening set apart for receiving the “few friends” was a memorable one.

Herr Schwatka, accompanied by Major Kildare, was the first to arrive. Herr Schwatka was a tall, fair-haired Austrian, of distinguished appearance, and engaging manners. He was a cool-headed, strong-willed materialist, to whom human nature was a congenial study, who never allowed anything to thwart his purpose, and whose spirit of determination dominated most of those with whom he came in contact. To him, women had been but playthings; he laughed at such an idea as the grand passion—a figment of the brain for the misleading of boys!

As the two men entered the salon, Kildare, with all his English coolness, started with surprise at the beauty of his surroundings. Accustomed to the society which his rank as an officer in the British army gave him, he had seen much that was rich and alluring in many countries; but here, in an African desert, many hundred miles from the sea, to find such taste and elegance displayed, was to him surprising.

The crimson and gold hangings reflected from mirrors in the opal light, made a fitting background to a picture, in which stood as its central figure, the Queen of this home, Dainty Laure—a highly gifted woman, possessing that rarest of all gifts, perfect naturalness. Donald, standing by her side, presented the two gentlemen.

Had she been the daughter of a duke, she could not have done the honours with more grace.

The European in Africa has a deep-seated antipathy to the faintest trace of mixed blood. Yet, as Herr Schwatka bowed to Mrs Laure in his elegant way, he was conscious of receiving a pleasant impression entirely new to him.

As for Major Kildare, he was altogether charmed with her, and speedily opened conversation with the common-place question:

“Mrs Laure, how do you amuse yourself in this dusty town of Kimberley?”

“I do not amuse myself, but let what I see amuse me,” replied Dainty. “My horses and my dogs are company; everything that is beautiful pleases me; I make friends of the pleasant people I meet, and avoid the unhappy ones who carry their woes pictured on their faces.”

“But what do you do for a confidential friend? Woman must have them, you know, and you hardly find any congenial woman here!”

“You forget Kate Darcy,” replies Dainty. “She is a being to admire. I look at no one else when Kate is by.”

“Would it be wrong to be glad she is not here then?” said the major, gallantly.

“I think you will be pleased to meet her, you cannot fail to admire her,” answered Dainty. “She is not like me.”

Herr Schwatka smiled at the last assertion.

“Do you expect us to admire her when she is not like you?”

Dainty looked at the Austrian with a little deprecatory smile, as she said: “You will admire her for what she is, rather than what she is not.”

“It is pleasant to hear a woman praise a woman,” said Herr Schwatka. “All women do it sometimes, for they all must have some intimate whom they can love, caress, and lavish themselves upon.”

“Yes,” said Dainty, “that may be true, but Kate is not the style of woman you imagine. She is strong and noble, though gentle withal—wait till you meet her.”

Herr Schwatka felt a warm thrill at the enthusiasm and loyalty of the heart that loved its friends so wholly.

“It were well to gain you for a friend,” he said.

Chapter Six.

Kate.

The conversation was interrupted by the arrival of Miss Kate Darcy, and Doctor Fox. They were a very handsome couple, at least so thought Major Kildare, for turning to Mrs Laure he said:

“I believe all you have said of your friend is true, and without the slightest exaggeration.”

As the guests continued to arrive, Dainty appeared radiantly happy. At a request for some music, Miss Darcy moved toward the piano.

“What shall I sing for you?”

“Make your own selection and that will be your best,” said Dainty, as she reclined in the depths of a chair, prepared to be captivated. Herr Schwatka took a seat at her side. Kate touched the keys caressingly for some minutes, striking a few chords here and there, with a little running accompaniment between, which expressed her indecision of selection, until finally striking a decided chord, she began, in a perfectly modulated voice, to sing that recitative and aria by Handel, commencing “Lascia ch’io pianga,” incomparable for opportunity of expression, and for revealing the artistic sense of the singer. Sinking from the triumphant strains into a soft pleading accent, she sang the three stanzas with a pathos that moved her auditors to the depths of their natures.

As she arose from the piano, there was a murmur of regret.

“Don’t rise, Miss Darcy,” said Dainty, pleadingly. “Just think how hungry appreciative South Africans are for good music. We have never heard such singing here before. Please give us another selection.”

Kate never indulged in affectations of reluctance, so resuming her seat, she sang a plaintive old negro melody from the plantations of American slavery, the only original music, some one has said, of which Americans can boast.

Kate’s face was singularly attractive. Her eyes, inherited from an Irish mother, were dark blue shaded by black eyelashes. One might criticise her features, for they were not perfect, and might examine her dimpled face and say it was not pretty, yet it was so expressive, that a stranger on being introduced to her, when she was in a happy mood, would be fascinated, and think her altogether charming.

Major Kildare was attracted to Kate and completely captivated, when he learned in the course of conversation that they had mutual friends in his far away home, in merrie England. But he was not privileged to monopolise Miss Darcy, for others pressed around her, and Doctor Fox stood ever in the background, perhaps discussing some mining operation in the intricacies of which he was well versed, but never far from the sound of her voice. Having speculated in the gold and silver mines of California and Colorado, and being possessed of that sixth sense with which Americans are accredited, and which being evolved becomes, in a few, the gift of invention, Doctor Fox had won, by his knowledge of mining and his improvements in mining machinery, the favourable opinions of the officers of the Diamond Mining Company in which he was a heavy stockholder.

“Herr Schwatka,” said Donald, “have you been down in the mine by the new shaft? It is now completed, and the cage is in perfect operation.”

“I went down yesterday,” replied Schwatka, “and I found it a wonder of mining enterprise. The ladies should visit it. Would you not like to go, Mrs Laure, and you, Miss Darcy?”

“We would be delighted; I will answer for both,” said Kate, smilingly.

This evening was the beginning of a new era in the lives of these two women, who had felt singularly drawn to each other. Dainty realised that she gathered forces new to her from Kate, while the latter was fascinated by this beautiful wildling, who knew nothing of the great world, which the other had but recently left behind her.

As Major Kildare left the house that evening with Herr Schwatka, he enthusiastically remarked:

“By Jove! that Miss Darcy is a fine woman!”

Herr Schwatka took a pull at his cigar, and dreamily watched the rings in the bright moonlight as they slowly curled up into the still air. At last he said:

“She is, indeed, but I feel a little afraid of those fair ‘Américaines!’ I can’t keep pace with them. I met one in Vienna during the Exposition, and she was a revelation. Such a sight-seer! Her mother was with her, but she could do very well without her. If she wanted to go out of an evening, and her mother was tired from her day’s peregrinations, that girl would say: ‘Go to bed, mamma; we are going to the opera?’ or whatever it might be. And off we would go, without protest from the submissive mamma. It was some while before I could comprehend her; her ways were so different from those of my own countrywomen. One evening while we were driving to a fête, emboldened by her unreserved manner, I attempted a little lover-like caress. You should have seen the American then! She sat as straight as a needle, and was equally sharp. ‘You and I are friends, aren’t we?’ she asked.

“‘Doubtless,’ I replied.

“‘Well,’ said she, ‘if you wish us to continue as such, don’t attempt to ditto that. I have come to see Europe, and I haven’t much time to spare. If we commence to make love, I won’t see anything but you, and as there is not the slightest possibility of your being the whole of Europe to me, if you will just be my comrade, I shall like it better.’

“I shall never forget the satisfied expression that stole over her face, as she folded her hands, and looked straight ahead with a gleam in her eyes, and then turned the conversation in the easiest manner imaginable. It amused me immensely, but I didn’t repeat the little indiscretion, and the few weeks she remained in Vienna were among the most delightful ones of my life. We were comrades, and I never understood till then how a woman could be perfectly free in her manners, yet perfectly true to her womanhood.”

“By Jove! Schwatka, it isn’t often that you find your match,” said the major, laughing heartily, as they entered the “Queen’s” Hotel.

That night the picture that only faded from the consciousness of Herr Schwatka, to reappear in his dreams, was that of a graceful woman—the wife of Donald Laure.

Chapter Seven.

The Story of a Singer.

What a charming creature is the enthusiastic talented girl, who is ever trying to solve the riddle of life with a girl’s avidity. How earnestly she follows the light on her pathway! Sometimes deluded, but always in earnest; even leaving the old roof-tree in the search for satisfaction, often returning to it, weary and travel-stained, content to have one little corner by the home fireside, where she finds more happiness and rest in a day, than in her years of wandering and chasing butterflies.

It is the clear-eyed, far-seeing girl, with a singing voice, that can thrill the hearts of her hearers, in whom we are now interested.

What a book could be written on the broken lives, the vanished hopes, and the lost voices, of American girls in Europe!

There, where the life is alluring, and maestros paid in gold; where Americans are looked upon as common prey by the Parisian shop-keeper, the student finds that Art is long, and not only time, but gold is fleeting.

There, many an enthusiastic girl possessed of ordinary talent, and led away by vanity and the flattery of over-zealous friends, is found living in a feverish belief in her ultimate success, and looking to her teacher to promote her interests.

He is more often but a shark, ready to devour her, body and soul. For he panders to her belief in his charlatanry, and flatters her vanity, until the money is nearly gone. Not until then does she realise that no one but herself has been deceived.

Her pride comes to her rescue, and with her voice still undeveloped, she rushes hither and thither in her frantic endeavours to secure the position she desires.

Friendless, moneyless, and alone: what can she do?

A singer’s life is emphatically a mixture of fulfilled hopes and bitter disappointments.

A famous teacher in Paris says to his pupils:

“Before starting out on your career, make for yourself two pockets; one very large, and the other exceedingly small; the large one for the snubs, and the small one for the money.”

Talent is one thing, but management is another, and without the latter, talent goes begging. Art may become a classic in the hands of talent, but the singer must depend largely upon the manager (often ungrammatical of speech, and arbitrary of manner), if she would know practical success and be known of the world. Kate Darcy had both tact and talent, and the gift of knowing how to use them.

Her childhood was passed in the atmosphere of the theatrical world in New York City, where her father was a violinist, and earned his bread by the sweep of his bow.

When yet a child, she developed great musical talent, and possessed that rarest and most delightful of all voices, a rich contralto.

At fifteen the child was a rising artist, studying day and night, until, at the age of seventeen, being graceful and well developed, she became a leading contralto of an English Opera Company. Her voice grew in strength and richness, and with the growth of the voice came ambition to study under the best masters. That will-o’-the-wisp of art drew her on to Italy, to prepare herself to enter the lists of fame and win a high niche in the temple of song.

She felt that she could conquer anything. She believed in herself—a very necessary requisite for youth, when talented and ambitious. There were no “perhaps’s” or “might be’s” crystallised in the amber of her belief. She was vividly conscious that she possessed the great gift of a rare voice, and did not doubt that somewhere in the world it would be appreciated, and made to yield the wealth which Love always wants, in order to bestow gifts and comforts on its beloved.

On her last appearance on the concert platform in her native city, previous to her departure for Italy, she bore herself with such unaffected simplicity, and seemed so earnest in her efforts, that everyone felt like breathing a benediction for her future success; they realised that the goal she aimed at was only to be reached by years of labour, and by the patient pursuit of opportunities.

She sang several numbers, but nothing half so beautiful as the low, entreating tones in which she breathed out “Kathleen Mavourneen.” As the words rolled out, “It may be for years, and it may be forever,” many an eye filled with tears at the tender pathos in which she veiled the uncertainties of the future.

Kate went to Italy with her mother (who had become a widow), and studied under the direction of the great maestro, Lamperti. She had but few faults to overcome, but she applied herself unceasingly. The voice is a jealous mistress, and stands guard over every thought and action, demanding high recompense from the being who possesses the power to soothe or thrill a soul in darkness. Any letting down the bars of stern discipline of the intellect, finds that vigilant sentinel inquiring the cause.

The ear of the lover becomes aware that the divine voice has lost its love tones; those pure heaven-born messages come to him with a harsher sound. Then when the singer’s thoughts have drifted into some dark miasma, the sensitive instrument cannot attune itself in those dreamy poisonous vapours, and the delicate string loses its perfect harmony. The lover again wonders what powers of earth or air have taken possession of that erstwhile melodious instrument, now, “like sweet bells jangled and out of tune.”

Thus it is if, from looking and listening, with hearing keen and heart responsive, the eyes of the soul ever upward turned for inspiration (the only attitude that makes the spirit by and by victorious), she ceases for a moment, and, hearing the jingling of false bells, looks below; she sees the reflection of the sun on some tinsel-robed, fair, but deluded sister, and is attracted to her. The delights of dissipation in the society of thoughtless, undedicated companions allure her from the path where gleams the pure, white light of art. As she turns, thinking to live only for a little hour with her companions, the gates of the lighted realm, where few enter, close behind her. When she has wandered through the pleasures, which prove to be but the shadows of reality, the temple of that beautifully-tuned and soul-inspiring instrument is a wreck, and the angel-voice fled. Such is the result of neglecting that exacting sovereign, the goddess of music.

She demands the consecration of the whole self, in return for the prize she offers. And none realised it better than Kate. So she gained the excellence of real attainment.

After a brilliant career of seven years, she wearied of incessant travel, and longed to make her home in some quiet corner, away from the sound and whirl of the great busy world, and yet near enough to its heartbeats to feel the pulsation. She found such a spot near London, where she took her old mother, for whom she had an idolatrous love, and where she hoped to enjoy her life in semi-seclusion for a season. She furnished her gem of a house with rare taste, and filled it with souvenirs of the world she had conquered. There her mother fell ill, and demanded, in her nervous, irritable state, in which she would allow the service of no other nurse, constant, care from Kate.

Often when Kate returned home late at night from some concert where she had been the idol of the hour, she would sit and hold her mother in her arms until the cold night air had chilled her to the very bone, for the invalid could not endure a fire in the room. No murmur fell from Kate’s lips, and when the dear sufferer succumbed to the disease and passed quietly away, her grief was overwhelming.

But joy trod on the heel of sorrow. A presence had come into her life which grew to be a part of it.

He was one whom everybody admired; a man of culture and refinement, an able musical critic and no mean musician.

He had won her heart, and they were soon to plight their vows sit the marriage altar. Some weeks after her mother’s death, he departed one morning for Paris, with her kiss on his lips. In a few hours came the news that a channel steamer had collided and gone down with all on board. Her lover was among them!

In a week’s time she had left London for the Continent; six months later, she was seen again in the gay world of Paris: but her face was white and wan, and her spirit broken.

Her musical studies were kept up, but her heart was not in her work; and when one night she appeared at the Théâtre des Italiens, and received an ovation, she broke down at the end of the phrase, with stage fright. Without ambition to rise above this misfortune, she left the stage, her career ended.

A few weeks later, impelled by a craving for new sights and surroundings, and a desire for rest far from the scenes of her triumphs and disasters, she arrived in Africa.

Chapter Eight.

Horses and Riders.

Donald Laure grew more and more morose; some grief was silently preying on his mind. He could not sleep, and often walked the floor of his room during the weary hours of the night.

He became at last so restless that he sought the society of a nature stronger than his own. This society he found in the company of Schwatka, who was now a daily visitor at the house.

Dainty observed his altered appearance, but was unable to fathom its cause.

As his manner grew more and more restrained toward her, she unconsciously turned to Schwatka, whose equable temperament seemed to invite her confidence and her friendship.

Gradually the Austrian made himself a necessary factor in the lives of both husband and wife, and he was her constant attendant in her rides and drives over the veldt.

All this time Dainty was only conscious that his presence made her supremely happy. He was always thoughtful of her welfare, always doing little acts of kindness, which, for the first time in his life, were spontaneous.

She was a refreshing rest to his blasé, worldly nature. When a man who has become selfish, and therefore cruel, in satisfying his own vanity, and pandering to his own appetites, meets with a fresh, guileless soul like Dainty’s, he is at once enthralled, and, whether he admits it even to himself, sets about winning a new toy.

Herr Schwatka’s new delight was a constant surprise to him; and as he drew out forces in her nature, of whose latent existence he had been ignorant, she more and more revealed charming little traits of character, which had been hidden from Donald.

She loved to ride, and heretofore Donald had always gladly accompanied her in these equestrian pleasures. But as solitude wrapped him up more and more, Schwatka began to take the place at her side. As soon as the outskirts of the town were reached, she would give rein to her horse, and together they would speed over the veldt. The colour came to her cheeks, and a sparkle to her eye, which made her look like an houri in the rosy morn.

Kate Darcy’s early morning ride was also her chief delight. Seated on her horse “Beauty,” she would leave the camp locked in slumber, and scamper across the barren waste of country, to greet the first rays of the rising sun. Fearless and independent in all her actions, she had learned to rely on her own judgment, and to adapt herself to her surroundings. On several occasions she had seen a couple of equestrians appear on the horizon; and as the outline of their forms became visible, and she recognised Herr Schwatka and Dainty, with a word her horse would shoot away in an opposite direction. She knew human nature, and perceived that the Austrian was gaining a mental ascendency over her friend. Was this to be the beginning of the too-oft repeated story of mistaken love? If so she would avoid seeing a human spider weave his web at that beautiful hour of the day. So she would shake off a sensation of depression, and, in love with dear old Mother Nature, free as air she would bound away, until they were lost to view; only so restored to mental quiet. With swift and graceful motions, “Beauty” flew across the shrubless plain, and when she talked to him caressingly, he would shake his head and lift his ears with as much expression in them as in a coquette’s eyes, and dash forward with a sense of untrammelled delight.

As “Beauty” leaped ditches and hillocks, Kate would laugh aloud with the spirit of freedom which filled her; that spirit which fills the air of old Africa, with its spiky topped mountains and its barbaric elements, which exploration, civilisation, and Christianity have not conquered. The sleeping barbarian within wakens more or less in every human heart, attuned to nature, when in Africa.

At times, the hollowness and baubles of civilisation, with its art and science, its looms, wheels, and fiery engines, its conventionalities and restrictions, contrasted with the sun-baths, health, and ignorance of disease, in the Zulu mind, with its contented pastoral existence, its adherence to the laws of morality, virtue, and cleanliness, suggests the question: “What is gained by civilisation?”

On his arrival in England, old King Cetewayo innocently asked:

“When Queen Victoria has all this, why does she want my poor little corner of the earth?”

Herr Schwatka could have won hearts in his Vienna home, as food for his vanity. Why did he want to mesmerise this little creature? Why must he bring into her life the gewgaws of civilisation, the tales of wonderful cities where she would be happy, and shine like a meteor in a heaven of celestial beauties?

Could he, with his mesmeric mentality, which would at times rouse her to such a pitch that her spirit would become restless almost to agony, could he offer her the tranquillity of a life which would fold its wings in happy security from hidden enemies, and lull her to rest, safe from the cruel shafts of the tongues rooted in the mouths of those hideous moral volcanoes who, with the gusts of their smiles and flatteries, would overturn and wreck her innocent life?

Men sometimes act as if they believed themselves to be gods.

Few men live up to the reflection of their real selves. Few men are godlike; therefore, few are happy.

Chapter Nine.

Poker and Philosophy.

There were few Americans on the Fields, scarcely a score, but you heard from each one of them, as an individual, and soon learned on what footing you must meet him. Were he a gentleman from the “States,” if you had not heard of that country, he had, and could give you information about it, from its present commander-in-chief to the one who in early days first held aloft the screaming eagle—that invincible bird!—a man like himself in one particular—he could not tell a lie. That is to say, if you dared to doubt his word, you could immediately have a chance to choose your weapons.

He was celebrated for his talent in forming stock companies, then running up the price of shares and quietly selling out; after which, intimating that he needed a vacation, he would return to the States, leaving the bubble to burst after his departure.

Sometimes he was known as a physician who, with his patent medicines, pretended to successfully combat those African fevers which English flesh is heir to; or a surgeon of skill, with instruments acknowledged to be as keen as Damascus blades, compared with those with which his English professional brother was “handicapped.”

He was not less renowned for playing a beautiful hand at the (so-called) American national game of Poker, and for teaching some highly intellectual emissary of Duke of This and Lord That, who had come out to speculate for their Serene Highnesses, how neatly the game could be played, provided they took a few lessons, and paid well for them.

Among the few Americans on the Fields none stood higher in public favour than the really skilful surgeon, Dr Fox, who took a deep interest in all public matters.

Dr Fox was sitting in his office puffing at his briar-wood, and thinking of—nothing; a subject which he made it a point to reflect on daily, at least one hour of his sixteen waking ones.

He had knocked around the world a good deal, and now, among people from everywhere, was “settled” for the time at Kimberley. Strange as it may seem, it was no less a fact, that right here amidst the most intense excitement of an easily excited population he had suddenly stumbled across a thought. That thought was not to think: here where everybody was thinking and thinking, he thought of the thought—not to think. To give his brain a rest, he stopped thinking in the very midst of a deep thought. Great scheme!

This idea came to him something in this wise. He had been walking until he became very tired. Wanting to rest, and not being near a convenient hotel, or at home, or in any place where he could go to bed, he sat down, pulled out his pipe, lit it, and smoked. As he smoked he thought; he had not yet learned how not to think.

“My body rests while sitting: I do not always go to sleep to rest. Why not sit down for an hour, and think of nothing, and rest my brain by vacancy, instead of sleep?”

He did so. While resting his body by keeping still, he rested his brain by not thinking. When the hour expired he said to himself:

“To think constantly on one subject, will relax our hold on it. Given a subject we think and think on it, until all the grip of the brain is lost. I’ll give the grey matter a rest.”

On this evening, his hour for meditating on nothing was interrupted by a visit from Herr Schwatka and Major Kildare.

“Good evening, Doctor.”

“Good evening, gentlemen; glad to see you. Cool night this, after such a hot day. These African nights are glorious. Step inside,” and the doctor led the way to his private room. “Now, with your permission, I will mix you a concoction, the secret of which I learned in New York; ’tis a nectar fit for—men,” and turning to the sideboard loaded with lemons, spices, and cooling beverages, he commenced to prepare the summer drink whose delights he had extolled.

“Do you know,” said Kildare, “I have not tasted a drop of palatable water since I’ve been on the Fields?”

“I have had many encounters with the water question, and have subdued, but not yet conquered it. I had a barrel brought from the Dam yesterday. The brownish liquid you see in that jar is some of it. Don’t look so disgusted, Major, the little water you will drink in the compound I am mixing has been filtered through that Faitje of powdered charcoal,” and the doctor pointed to a bag suspended from the ceiling of an adjoining room.

Major Kildare was a retired English officer, who had been sent, as Agent of his Grace the Duke of Graberg, to purchase from the unsuspecting Boers, at nominal sums, their Transvaal farms on which he knew there was gold. Many of these farms were valueless stone mountains, but if His Grace the Duke allowed his name to appear at the head of the great South African gold mining company, it must be a good thing to invest in.

The Agent had an original idea—so he thought—as to the way a certain game of cards should be played, suggested by an American Diplomat at the Court of Saint James, from whom he had taken several expensive lessons.

He unfolded his scheme to the two gentlemen present, and proposed a practical exhibition of his science. Dr Fox, having limited the game to eleven o’clock, at which hour he had an appointment with two other M.D.’s, for an important consultation, consented, and then proceeded to become initiated in the mysteries of the game of Poker, as taught by an Englishman, and in endeavouring to graduate in it, lost several large sums of money. The three played until Herr Schwatka protested that he was no match for the other two, and withdrew from the game.

The Yankee Doctor soon began to exhibit signs of having known—perhaps in some pre-historic existence which he was just beginning to remember—something of how the game should be played himself.

“Doctor,” said Schwatka, “if I could develop so great a talent as you have, in so short a time, at a game you seemed to know but little of, I should stop giving medicine for a living.”

“Ah! would you,” replied the doctor. “I rarely do give medicine. Five out of every ten physicians give their patients medicine simply to follow traditions. The friend of my boyhood, old Dr Snow, used to say, that giving medicine to a patient, is like going into a dark room where your friend is in mortal combat with an enemy. All is dark, not a ray of light to distinguish friend from foe. You raise a club and strike in the location of the struggle. If you miss your friend and hit his foe, your friend is saved!”

“The deal is with you, Doctor.”

“Excuse me for talking shop, though you’ll have to charge that to Herr Schwatka,” said the doctor, dealing. “How many cards, Major?”

“Two.”

“I’ll chance one.”

“What is it that makes people sick?” continued Schwatka.

“It is often fear that makes people ill. They fear this and fear that; their thoughts dwell upon a dread disease, or they apprehend some danger in business affairs, until their thoughts are so saturated with the dread, that it is impossible to escape from it.”

“This looks good for a pound,” put in the major.

“I’ll see that and raise you five,” said the doctor.

“I’ll see that five and go you five better,” said Kildare.

“I’ll see that and raise you ten,” returned the doctor.

“Call you, Doctor. You can’t scare me with a bob-tail flush.” The doctor threw his cards in the pack. The major smiled as he raked in the stakes, and asked the doctor to continue on his theory.

“Many men,” he observed, “of supposed integrity on the Fields, are illicit diamond buyers. They are constantly haunted by the fear of detection, and they will try to deceive themselves into the belief that the dread that is eating them up is some liver or stomach trouble, and they come to the doctor for relief. That they are tracked by this invisible foe no further proof is needed than the fact that last year six of our leading business men committed suicide. Fear is a ghost which stalks to and fro over the earth, forever haunting the imaginations of men.”

“Raise you a fiver,” called the major.

“See that, and ten better,” replied the doctor.

“Call you, doctor.”

“Queens.”

“Never bet on the women, Doctor; Kings.”

“Heavy betting for so light a hand,” remarked Herr Schwatka.

“I’ve won a thousand with a smaller. It’s sand, not cards, that wins at Poker. Half past ten!—as I have to be present at an interesting surgical operation, within the next hour, I think we had better discontinue our game.”

Chapter Ten.

An Explosion or Two.

“We have time for a game or two yet, Doctor, and let us make it a Jack-pot,” said the major.

“All right. I’ll open it for a pound,” said the doctor, looking at two cards.

“How many cards will you have?”

“I’ll stand pat.”

“I’ll take three.”

“Major, I think these are worth a fiver.”

“Mine are worth ten.”

“Well, let me see. I’ll see that ten and raise you twenty.”

“Kilters won’t work in a Jack-pot. I think you’re bluffing with that pat hand.”

“It will only cost you twenty pounds more to find out.”

“I’ll see that twenty and raise you fifty,” said the major.

“There is your fifty, and one hundred on top. Now your curiosity may be more expensive. I think it will take all that to make me even,” rejoined the doctor. The Englishman hesitated, and raised it another hundred.

“Well, here goes; I’ll call you. I don’t like high play among friends, Major. What have you got?”

The major dropped three kings and two aces. The doctor showed four sixes.

“I thought you played with sand, and not with cards, Doctor,” remarked the major, sarcastically.

“They are both useful in the game of poker,” replied the doctor as he tipped back in his chair.

The major’s face showed signs of annoyance, but with a forced calmness he said:

“It is early yet; shall we not continue?”

“I think we have played long enough for one sitting,” responded the doctor. “It is eleven now; recollect my consultation. I trust you may have better luck next time.”

“I hardly think it quite square to quit, and I so heavy a loser.”

“I am not accustomed to having my squareness questioned, Major. My record here and elsewhere shows no entry of unfair play; but we will not continue this line of conversation. Gentlemen, you are my guests.”

“Herr Schwatka is your friend, and mine. He shall settle the question,” continued the major, turning to Schwatka.

“I beg you, gentlemen,” said Schwatka, “to arrange this matter without any quarrel.”

“Herr Schwatka,” said the doctor, slowly, “there will be no quarrel. It takes two to make one, and I shall not be a party. I merely say, that long play, and high play, tends to mar friendship, and we cannot afford to be other than friends.”

“Dr Fox, I regret that I have met a card sharper, instead of a gentleman,” cried the major, choking with rage.

“Major, do not lose your temper so cheaply. Name your loss and I will return the sum to you.”

The brow of Kildare clouded as black as night, and he fiercely exclaimed:

“Do you mean to insult me, sir? I am no beggar to ask alms. You add insult to injury, and shall answer for it.”

He and Schwatka had risen to their feet during this heated colloquy. The doctor alone remained seated.

Leaning his arm on the table he said, in a low and firm voice:

“Major, you and I cannot afford to fight. All know you are a brave man. Your courage, as the world interprets that sentiment, no one would question.”

The quiet, unimpassioned tone of Dr Fox seemed to subdue the fiery major, who resumed his seat as the doctor proceeded: “My definition of the word ‘courage’ differs widely from the general acceptation of its meaning. Why does the commander of a regiment rush to the front, and lead his men to the charge? Paradoxical as it may seem, fear, fear is the impelling force; fear lest he be thought a coward. I have looked down the barrel of a shot-gun, in a country where men go gunning for men, as you do for chance hits at fledgelings at the game of poker.”

Here the doctor rose, and proceeded to the sideboard; as he mixed a drink, he continued:

“I am alone in the world, with no family ties. You have a wife and family. Would it he a heroic act for me to accept a challenge from you and perchance kill you? No, Major, I confess I am too much of a coward to meet the anguished looks of those whom my hand had widowed and orphaned. If you will drop in here any evening, I shall be pleased to give you the opportunity of getting even.”

Before Kildare could reply, a terrific roar and cannonading smote the air. The three men gazed in silence at each other, with astonishment depicted on their faces. As the cannonading continued, they rushed to the door, and there in the bright moonlight perceived a column of smoke rising to the height of near a thousand feet.

Looking at it, Schwatka exclaimed: “The unexpected is constantly occurring in this town. Earthquakes shake the mine, causing the reef to fall, thereby covering up valuable ground which must be laboriously unearthed again. Explosions in the mines follow on the heels of some accident caused by machinery giving way, and so it goes on, ad infinitum. What’s this last infernal noise about, I wonder?”

This disturbance was beyond the understanding of those men, who had forgotten all their differences of the evening, in gazing at that strange and monstrous cloud rising in the air, and hanging over them with threatening aspect, as if it would descend upon the town and destroy it.

As the noise continued, they went out into the compound, and walked in the direction of the sound.

The midnight hour is devoted to blasting in the mines, but it was not yet midnight. Hastening on their way to the scene of the cannonading, a man approached, leading Mrs Laure’s favourite servant, Bela. He was covered with blood, and, holding his hand to his face, moaned piteously. The doctor perceived that the boy’s face had been terribly torn by a flying missile.

“What is the cause of all this noise?” asked the doctor.

“The powder magazines are blown up,” replied the man.

“Which ones?”

“The whole thirty.”

“What do you say? Not thirty tons of dynamite?”

“Yes, together with the gelatine and the cartridges. You needn’t go any further, this boy needs your attention. I will leave him in your care, Doctor, and return to the scene of the disaster.”

“I will go with you,” said Kildare. Dr Fox, accompanied by Herr Schwatka, returned to his office with Bela. On examining the boy, the doctor found it necessary to use his surgical skill on the boy’s eye, which had been torn from its socket.

“Well, Bela,” said Schwatka, “this is a sorry piece of business, but as one of your most interesting characteristics is lack of beauty, your value may be enhanced by the loss of an optic! Your mistress will be sorry to lose you, for she could not endure to see you around her disfigured in this way.” He left Bela with the doctor, and sauntered out. After Schwatka had gone, Dr Fox gazed some time at Bela, then sat down and wrote a letter to a London oculist, ready for that day’s English mail, ordering a glass eye for Bela, to be sent to him immediately.

“Yes,” mused the doctor, “I can place an artificial eye in that socket, that will make you again presentable,” and taking the boy by the hand, accompanied him to the hospital, and placed him in charge of those self-sacrificing women, who devote their lives to the alleviation of human pain, utterly forgetful of self, in the divine love which shines through them.

Although Bela was called “boy” by many, he was nearly forty years of age. It is the custom of the white men to call the blacks “boys,” in speaking to them.

Bela was a “Bosjesman” or Bushman, with features of the negro type, and short crispy black hair. He was about four feet in height, being one of a race of pigmies, now nearly extinct. They are the oldest race known in Africa. Though living in the midst of foreign tribes of warriors of large stature, their traditions tell of a mighty nation who dwelt in caves and holes in the ground, who were great elephant hunters, and who used poisoned arrows in warfare.

Chapter Eleven.

A Visit to a Diamond Mine.

As Dainty Laure and Kate Darcy stood on the edge of the Kimberley Mine, it was with a feeling of awe that Kate looked down into its depths filled with Kafirs and their white overseers, and saw those endless cable wires extending from the brink to the bottom of the mine. The huge buckets resembled spiders at work, ascending until they reached the edge of the bowl, when they would drop their spoils into cars which stood waiting for them, and which in turn would crawl off and away to the “floor,” where they deposited their load, leaving the spiders to return to their task in the bottom of the mine.

On the arrival of Donald, Schwatka, and the ladies at the Company’s office, they were conducted to the brink of the shaft sunk by a countryman of Kate’s, which was the first successful attempt made in that direction.

Entering an elevator about six feet square, which was waiting to receive them, they slowly descended to the depth of two hundred feet. The earth had been probed to three times that depth, but the shaft had not as yet been sunk deeper. From the bottom of the shaft was a tunnel reaching to the mine, a distance of two hundred feet. It seemed like looking through an inverted telescope.

In this tunnel was laid a tramway, on which cars were constantly going to and from the mine.

They walked through the tunnel until an opening was reached, then stepped out on a ledge, and found themselves in the mine, on the precious blue soil; with hundreds of Kafirs working below, under the inspection of overseers, who would occasionally draw a gem from under the spade of one of the delvers. From there they looked upward to the sun, glaring hot and bright over them, and then to the brink of the mine, where men seemed like small boys moving about.

It was a strange sensation to stand and gaze around on this comparatively recent discovery, and contemplate what had been accomplished, and reflect on the strange chance that had unearthed so much magnificent wealth.

“Mr Laure, how has this bed of diamonds been formed?” asked Miss Darcy.

“The mine is thought to be the ‘pipe’ of an extinct volcano, and it is supposed that the diamondiferous soil containing garnets, ironstone, crystals, and diamonds, has been thrown up by the action of the great heat of this volcano,” replied Donald, “and there seems to be no end of the glorious riches of this bed of diamonds.”

“Well,” continued Kate, “it is difficult to realise that this monster pit has been hewn out in so short a time by man. Nothing daunts him in his frantic search for wealth.”

“Those white men you see are overseers. Each overseer has from ten to fifteen Kafirs under his eye, to see that they do not conceal diamonds, as they turn over the ‘blue stuff’ as we call it,” said Schwatka. “Notwithstanding the utmost watchfulness, they contrive to steal and secrete the gems about their persons in inconceivable ways. As an incentive to his vigilance each overseer is given a portion of the profits on all diamonds found under his watchful eyes. An overseer picked up the Porter Rhodes diamond, and his share of the profits made him a wealthy man.”

“Do these overseers detect many Kafirs in the act of stealing?”

“No, Miss Darcy. A Kafir’s countenance is so immovable, that it is unreadable. Looking right at the overseer he will work a diamond in between his toes, and thus convey it out of the mine. He eludes the keenest vigilance by concealing the gems in his woolly hair, and under his tongue, and even by swallowing them. A stray dog will receive into his shaggy back, a valuable stone, and carry it around with him, until relieved of it by the Kafir.”

“The working of the mine must be attended with great expense, and these natives must seem like vampires to the claim-holders,” said Kate.

“That is true. Two years ago there were one million carats of diamonds taken out of the Kimberley Mine, while those of Dutoits Pan and Bultfontein yielded no less than seven hundred thousand carats. About one quarter of this enormous product was stolen by the Kafirs employed in the mines, and sold by them to the I.D.B.’s, who are often respected and licensed diamond buyers. The large number of jewels stolen by the blacks while working in the mines has led the Government to make stringent laws to regulate their purchase and sale.”

“How do these Kafirs know to whom to sell their booty?” asked Kate.

“Most of the natives who work in the mines have friends in service in the town; and it is through their assistance that they dispose of the stolen diamonds. These house servants form the acquaintance of some illicit diamond buyer, or I.D.B., as he is pithily called, to whom they sell the precious stones. There is a fascination to some men engaged in this traffic which far excels that of any other species of gambling. If they win, they leave for Europe comparatively rich men in a few years, but they run such risks of detection that it makes life unbearable to a man troubled with a conscience.”

“Are the diamonds from this soil as fine as those taken from the Brazilian mines?”

“That is a question that is raised by many, but there is no doubt that the South African or Cape diamond is as pure and brilliant as any from Brazil. Most of the crown jewels of Europe, renowned for their history no less than their intrinsic worth, came from India. The Koh-i-noor was owned by an East Indian chief, five thousand years ago. The Indian mines were eclipsed by the Brazilian, which in their turn have yielded to the fame of those of South Africa—the largest in the world.”

Chapter Twelve.

Strolling among Riches.

As Kate watched the Kafirs fill the buckets with the diamondiferous soil, she understood the fascination which kept men tarrying in that hot climate, hoping that some lucky turn of the pick or spade might unearth for them a fortune.

While they were standing on the ledge of blue stuff extending from the tunnel, Donald moved a short distance from them when a stone fell at his feet. It was thrown in such a manner, that he knew it was not accidental. His countenance never changed, and he stood perfectly still for several minutes, then strolled leisurely back to the mouth of the tunnel. As he did so, a Kafir’s voice in a low tone said: “Ba-a-as!”

Donald wheeled, and there in a dark angle of the excavation where it led into an inner chamber, stood a native who had been pushing the cars through the tunnel as the party entered it.

He held up between his thumb and finger something white, like a large lump of alum. Donald stood a few seconds with his hands in his pockets, eyeing him intently, then took a few steps, looked down the tunnel and listened attentively for any sound in the opposite direction; the next moment he had made three strides toward the boy and taken the diamond from his hand, when two shadows fell across his pathway. He glanced up and beheld Dainty and Schwatka. He closed his hand over the gem and put it in his pocket. The two men looked at each other without speaking, and then as Herr Schwatka’s eyes filled with a fine scorn they fell on Dainty, and there was an instantaneous change of expression in them, which he concealed by turning his face. Speaking in a bantering tone, he said:

“Donald prefers darkness to light! I think, Mrs Laure, that if he does not regain his sunny disposition, you will have to take him away from the camp for a vacation.”

Dainty had observed the look which passed between her husband and Schwatka, but did not understand its meaning.

She had not perceived the diamond in Donald’s hand, for she had been picking her way to the entrance of the tunnel, and had approached it with her eyes cast down, until her companion came to a standstill.

She understood the meaning of that look later. How often a cloud passes over us surcharged with power, to which we are indifferent, until it is revealed to us by some lightning flash of memory.

The Kafir had immediately taken hold of his car, and wheeled it into an inner chamber, but not before Dainty had noted that he was a Fingo boy, who often came to the house on errands for Donald. The beads, earrings, and ornaments with which the natives adorn themselves, and also the style of wearing the hair, distinguish one tribe of Kafirs from another; and these peculiarities were well known to Dainty.

As Miss Darcy joined them, they returned to the shaft, entered the elevator, and soon arrived at the Company’s office.

The day’s “wash-up” of the diamonds was next seen, and the assorting of them on the “sorting” table (which is very agreeable work to those who are looking for a prize—and find it, but a little tedious if the labours result in failure) was gone through, and some fine brilliants found.

It was about five o’clock in the afternoon on their return home that they strolled through the diamond market, a street of one-story houses built of corrugated iron, with the interiors very simply finished. They visited the offices of several diamond buyers, representing Parisian, English, Viennese, and Holland houses in this branch of trade. They were of all nations, those of Jewish origin predominating, and the visitors were received with the utmost courtesy.

The contents of their safes, stored with precious stones awaiting the departure of the English mail, packets of gems containing from ten to one hundred carats weight, were freely exhibited; and Kate almost wished that she too might enter the fascinating trade of buying and selling diamonds.

Proceeding on their way to the hotel, they passed through the market square which was strewn with the merchandise of the country. It was difficult to say whether the mine they had recently left was even as interesting as the exhibit of wealth lying before them, brought from a great distance in the interior; that delightful unknown country, with its lions, leopards, ivory, and impregnable strongholds of savage chiefs and adventurous traders.

The life of this latter class is as interesting to contemplate as are the fruits of their labour and skill. They go into the strange country where the ’Tse fly stings their horses to death, and where they must fight the still more deadly fevers. If they survive and manage to crawl out yellow and wan, the fervid life still holds out its charms for them, and they return to it again with the same eagerness; the voice of adventure drowns the admonitory tones of ease and safety.

On the corner of the market square, sat a Coolie woman, about thirty years of age, of diminutive form. In her native costume of many bright-hued silk handkerchiefs draped around her limbs, neck, and head, with the gold ring hanging from the nose, the earrings surrounding the entire outer edge of the ear, bracelets, anklets, and armlets, she presented a perfect type of this semi-barbaric country.

Sitting there beside her basket of oranges and melons, she fitted like a mosaic into the strange scene before them.

A little farther on was a trader’s wagon, about fourteen feet long, and four and a half feet wide, piled high with skins of the leopard, silver jackal, tiger, hyena, and rare black fox. These skins, or karosses, as they are called, were as soft to the touch as a velvet robe, and had none of that hard thickness which characterise the cured skins of our wild animals. The natives are experts in the curing of these skins, and deliver them to the traders sewed together as neatly as a Parisian kid-glove, with thread made from the sinews of wild animals.

As they strolled along, the next objects which attracted their attention were the large-sized oxen with their enormously long and graceful horns.

These animals are the especial pride of the Boer farmer, who cares more for his span of sixteen handsomely-matched oxen than for any other object, animate or inanimate, on his farm. The particular cattle which attracted their notice were beautifully spotted black and white, with hides shining like satin. As Kate approached one of them, and reached out her hand, she could not touch the line of his back-bone, even when standing on tip-toe.

They stood there, huge creatures, with their horns towering in the air.

They would have made a fortune for the brush of a Bonheur.

It can hardly excite wonder that such animals gain so much affection. The trader’s wagon to which they were yoked was loaded with ivory tusks, valuable furs, ostrich feathers, and other rich and singular merchandise. One feather, a yard long and half a yard wide from tip to tip, passed into Kate’s possession. It was a plume no less beautiful than rare.

“These feathers,” said Kate, regarding the gift with admiration, “do not look like the flossy, saucy, flirty things which appear on ladies’ hats, strewing coquettish shadows over the face. They resemble those ugly awkward trailing bits of vanity which weep from their hats after a heavy rain, when they have neglected to carry that everyday English article of dress, an umbrella! They are as ugly as the bird from which they are plucked, until some unconscionable merchant brings the tempting merchandise to town, and places it in the hands of the milliner. Then the great play of ‘My Milliner’s Bill’ is enacted, husbands and fathers are ruined by its representation, while the women, pretty pieces of vanity, get free tickets to the show.”

Chapter Thirteen.

A Morning Ride.

One bright summer’s morning in the latter part of November, as Dr Fox was on his way to visit a patient living in Dutoits Pan, he turned his horses’ heads into the street where lived Miss Kate Darcy.

As he neared the house of his countrywoman, in whom he had recently come to take a deep interest, she appeared descending the steps of the verandah which surrounded the house. He spoke to his horses, and they increased their speed, reaching the curbstone as Miss Darcy opened the gate.

“Good-morning, Miss Darcy,” said he, “out for a walk? Would that I were also walking!”

Kate looked up brightly and smiled. “Good-morning,” said she, “would that I were also riding!”