The Project Gutenberg EBook of Jack Buntline, by W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Jack Buntline

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Illustrator: Horace Harral

Release Date: August 29, 2011 [EBook #37256]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JACK BUNTLINE ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

WHG Kingston

"Jack Buntline"

Preface.

Look at yon smooth-faced blue-eyed lad; his fair locks escaping from beneath his broad-brimmed hat stuck to the back of his head; his blue shirt collar, let in with white, turned over his neck-handkerchief, which is tied with long streaming ends; his loose jacket, his wide trousers. You know the sailor lad at a glance. He is a well cared for apprentice under a kind captain. He wins your regard by his artless frank manners, and you think all sailor boys are like him. Then see that fine specimen of a man rolling along, with his huge beard and whiskers, his love locks, his dark flashing eyes, his well bronzed countenance, his bare throat, his dress, similar to that of the lad, but of good quality and cut to a nicety. He looks the hero of the sea, and so he is, and so he feels himself.

What will he not dare and do? He will board a foeman’s ship by his captain’s side, however few with him or many against him; storm a battery sending forth showers of deadly shot; leap overboard to rescue a shipmate from a watery grave; will lift in his arms a charged shell with the fuzee yet burning, or will carry on his shoulders a wounded comrade from beneath the very guns of the foe. He loves to fight on shore as well as at sea. He will suffer cold, and hunger, and thirst, and face death in a thousand forms without complaint if his officers set him the example. He is the true man-of-war’s-man, proud of his calling and despising all others.

Now watch yonder nicely dressed old gentleman, with his three cornered hat, white neckcloth, long blue coat with gold lace cuffs. He is a Greenwich pensioner. He has done his duty to his country and done it well, with all his heart; and now his country, whom he served in his strength and manhood, cares for him as she should in his old age.

From these pleasing pictures people are apt to form their notions of sailors and of a sea life, but there exists another numerous class of whom I have a very different sketch to present.

They are as a class, however, gallant fellows. They also will dare and do all that men can accomplish. Many are kind hearted, generous, brave; but others are too often brutal, fierce, vicious, drunkards, blasphemers, thinking only of present gratifications, and utterly regardless of the future or of the world to come.

If such characteristics be theirs, I have a very solemn question to ask. Why are they so? Who has allowed them to become so? What steps have been taken to improve them? The newspapers often give us one reason why they are brutal. Sent ignorant to sea, ignorant they grow up, no one taking thought for the wellbeing of their souls or bodies; placed often under ignorant brutal masters, whose only idea is how to get the most work out of them, whose only argument is a handspike or rope’s end; ill-fed, ill-treated, ill-clothed, ill-lodged (oh what foul, wet, dark holes have thousands of gallant sailors to live in on board ship); ill looked after in sickness; when they return to port, handed over to the tender mercies of crimps and foul harpies of every description, the lives of our merchant seamen are short and hard indeed.

Remember that these are the men who supply us with all the luxuries we enjoy, who have charge of the merchandise which has made England great, glorious, and powerful. Who then, I ask, has an excuse for refusing to support any measure which will benefit them, their souls and their bodies? Can any one deny that our seamen have a claim on the sympathies and aid of every member of the community, whether living in an inland town, in the sequestered village, or on the wild sea side?

Oh could you but behold the merchant seaman on board his ship, the coaster, the trader to neighbouring lands, aye on board some fine looking craft also bound to distant ports; could you see him as he is, day after day toiling on in his tarry, dirty clothes, unshaven, unwashed, with rude companions, obscene in language and habits, in their foul den of a berth; could you hear the expression applied to him by his superiors, his groans of pain, his muttered curses as kicks and blows and cuffs follow after the oaths showered on him; could you see him in port consorting with the vilest of the vile, living in filth and iniquity till his hard-earned gains being spent, his senses steeped in drink, he is put on board another ship, often not knowing where he is going till far out at sea. Could you see and hear, I say, one tenth part of the horrors which take place, unnoticed by man, on the wide ocean, you, my readers, would weep and exclaim, unless your hearts are harder than adamant, “We must, we must do something for that poor fellow’s soul and mortal frame.”

Before, therefore, I begin the life of Jack Buntline, I must tell you how that something may be done. There exists in London a society called The Missions to Seamen, which I was the humble means of establishing there some five years ago. It had before existed at Bristol. It is warmly supported by numerous admirals, and other naval officers and men of influence. The office is at 11, Buckingham Street, Strand, and the Secretary is the Rev. T.A. Walrond, an excellent clergyman, who has devoted himself with the utmost zeal and energy to the interests of sailors. The object of the Society is to supply clergymen and lay missionaries for seamen: but they do not wait till the sailors come to them, they seek them out on board their ships, not only in harbours and rivers, but even in open roadsteads, such as the Downs, the Solent, and Portland Bay, wherever, indeed, any number of vessels are brought up together. The Society possesses several small vessels, on board which seamen are collected and services are held, as also boats for carrying the missionaries on board the ships. They have a flag, the design of which is an angel carrying the open gospel in her hand, on a blue ground.

The work of the chaplains and missionaries is, as I have said, especially to seek out seamen on board their ships, without waiting for them to come to hear them. They visit them in their berths, however close or foul they may be, read and explain the Bible to them, pray with them, collect them for public worship, and preach to them; offer them Bibles, leave tracts with them, and speak to them as friends whose only desire is for their soul’s welfare. Under God’s guidance a very large amount of good has, I believe, by these means been done, not only among British, but foreign seamen who visit our ports. Five years ago I was induced to commence the work by the Rev. T.C. Childs, who had succeeded the Rev. Dr Ashley, as sole chaplain of the Bristol Channel Mission, the only one then existing. We have now eleven chaplains, twelve lay missionaries, and an income which already exceeds 6,000 pounds per annum. God has evidently particularly blessed our work. Still we have calls from all directions for more Chaplains and Scripture Readers, and all who read this little book will, I trust, give their aid to the work by such contributions as they can collect, taking care that they send them to the Society for which I plead.

I should add, that I wrote the following story to read to the pupils of the Rev. J. Thomson, of Blackheath, and also to those of my friend the Rev. T. Langhorne, of Loretta House, Musselburgh, near Edinburgh. Mr Thomson’s boys collected upwards of 10 pounds soon afterwards for the Missions to Seamen. Great will be my satisfaction if all my readers follow their excellent example, and collect similar sums for the same important object.

William H.G. Kingston.

Middle Hill, Wimborne, Dorset.

Dedication.

My dear Mr Walrond,

Allow me to dedicate the following little work to you, that I may have the gratification of expressing my admiration of the judgment, energy, and perseverance with which you have laboured in the great and noble cause we both have at heart—the spiritual welfare of the British seaman, so long unhappily neglected. Nearly twenty of our flags (the angel with the open Bible), waving in as many ports or roadsteads, joyfully proclaim that it is neglected no longer. Should thrice that number be hoisted ere long, as I pray God there may be in various parts of the world, I feel assured that you will be more gratified than you would be by attaining any reward which the whole earth could give you. That you may live to see abundant fruit from your labours, is the earnest wish of

Yours most truly,

William H.G. Kingston.

To the Rev. Theodore A. Walrond, Secretary, Missions to Seamen.

Chapter One.

The sailor boy, as he is described in romances, or when he is made to act the part of a hero on the stage, has run away from school or from his parents, and entered under a feigned name on board a man-of-war; there, instead of being punished for his misconduct, he is placed on the quarter deck, and turns out in the end to be the heir to an earldom or to a baronetcy.

Such was not the origin of poor Jack Buntline. He was the only son of his mother, and while he was yet an infant she was left a widow. His father had been a sailor, a true hearted gallant man. He found Bessie Miller, then neither young nor good looking, in distress and poverty. He married her, saying that she should no longer want to the end of her days. How was he mistaken! He went away to sea. In vain his anxious wife waited his return. He never came back. It was supposed that his vessel was run down, and that he and all hands perished. His poor widow struggled hard to support herself and child: for some years she succeeded. She endeavoured also to impart to him what knowledge she possessed. It was but little. But lessons of piety she instilled into his mind at an early age. The following, among many other quotations from Holy Writ, she taught him: “God is love.” “Behold the Lamb of God which taketh away the sins of the world.” “In God put I my trust, I shall never be brought to confusion.” Deep into the inmost recesses of his memory sunk those blessed words, and though long disregarded, there they remained to bring forth fruit in due season.

At length a mortal sickness attacked the poor widow, and Jack was left an orphan, houseless and hungry, to druggie with the hard world. The furniture and clothes his mother possessed were seized for rent, and he was carried off to become an inmate of the workhouse. He knew not where he was going, but he thought the people very harsh and unkind. He was let out the next day to follow a coffin to a pauper’s grave. They told him his mother slept beneath that low green mound. When far, far away over the blue ocean, often would his memory fly back to that one solitary spot, to him the oasis in life’s wilderness. No relation, no friend had he. A pauper he lived for many a day, picking oakum and wishing to be free. That workhouse had a master, a stern, hard man.

An old companion, captain of an African trader, came to see him. As they sipped their brandy and water—“I want a boy or two aboard there,” said Captain Gullbeak, “one o’ mine fell overboard last week and was drownded.”

“You may have as many on ’em as you like, perwided you takes care they none on ’em come back again on the parish. The guardians don’t approve of that ere joke.”

“Not much fear of that, I guess,” replied the captain with a grin; “they has a knack of dying uncommon fast out there in Africa. It’s only old hands like me can stand it do ye see.”

So it was settled that little Jack was to be a sailor. Jack was asked if he would like to go to sea. Would a sky-lark in a cage like to be free? He knew also that his father was lost at sea, and he thought he might find him; so he said “Yes.” The guardians were informed of the lad’s strong desire to go to sea. His resolution was highly approved of, and leave was granted him to go. So under the tender care of Captain Gullbeak, of the Tiger brig, poor Jack commenced his career as a seaman—in mind still a child, in stature a big lad. The only thing he regretted was being separated so far from his mother’s grave. Away over the ocean glided the African trader. Hard had been Jack’s life in the workhouse—much harder was it now. Every man’s hand seemed against him. A cuff or a rope’s end was his only reward for every service done his many masters.

Occasionally in the workhouse he did hear prayers said and a discourse uttered, somewhat hard to understand, perhaps. Now, blaspheming, scoffing, and obscenity were in every sentence spoken by those around him. What words can describe the dark foul hole into which Jack had to creep at night to find rest from his grief in sleep. It was in the very head of the vessel. The ceaseless murmur of the waves was ever in his ears, and as the brig plunged into the seas the loud blows the received on her bows made his heart sink within him, and it was long before he could persuade himself that his last hour was not near at hand.

On, on flew the brig. Hitherto the weather had been fine. Jack had sometimes gone aloft, but as yet he was but little accustomed to the rolling and pitching of a ship at sea. One night he was asleep dreaming of the humble cottage by the greenwood side. He was kneeling, as he was wont, by his mother’s knee, uttering a simple prayer to heaven for protection from peril. Now, alas, he has forgotten when awake how to pray. Loud harsh voices sound in his ear. “All hands shorten sail.” He starts up. “Rouse out there, rouse out,” he hears. He dare not evade the summons. He springs on deck. The wind howls fiercely, the waves leap wildly around, and sheets of spray fly over the deck. Lightning flashes, dark clouds obscure every spot, the thunder growls, scarcely can he lift his head to face the storm. But he must go aloft and lay out on the topgallant yard, high up in the darkness, where the masts are bending like willow wands. So rapidly, too, are they turning here and there, that it seems impossible any human being can hold on to them. A rope’s end urges him on. Up he climbs, the lightning almost blinding him, yet serving to show the wild hungry waves which break ever and anon over the labouring vessel. He reaches the topgallant yard. There he clings, swinging aloft, the rain beating in his face, the wind driving fiercely to tear him off—darkness around him, darkness below him. Not a glimpse can he obtain of the deck. It appears as if the ship had already sunk beneath those foaming waves. How desolate, how helpless he feels! How can he expect to hold on to that unstable shaking mast. Now rolling on one side, now on the other, he hangs over the dark threatening abyss. What can he do to conquer that struggling sail? But there is one who sends help to the helpless, who turns not away from the poor in their distress. Jack there hears the first words of kindness addressed to him since he came on board, and a helping hand is stretched out to aid him. The voice is that of a negro. “No say I wid you,” adds Sambo, “or I no help you again.” The sail is furled, and Jack descends safe on deck, his heart lighter with the feeling that there is near at hand a human being who can sympathise with his lot.

Chapter Two.

The storm increased, but the brig, brought under snug canvas, rides buoyantly over seas. “Hillo, youngster, you are afraid of drowning are you?” cried old Joe Growler, as he saw Jack’s eye watching the heavy seas, which came rolling up as if they would engulf the vessel. “This is nothing to what you may have to look out for, let me tell you.” Jack thought the sea rough enough as it was, but he made no reply, for old Joe seldom passed him without giving him the taste of his toe or of a rope’s end. The other sailors laughed and jeered at Jack. He was not, however, afraid of the heavy seas. He soon got accustomed to the look of them. He had a feeling also that God, who had put it into the heart of the negro to help him on the topgallant yard, would not desert him. The other men often reminded him of that awful name, but, alas, they used it only to blaspheme and curse.

During the day the weather appeared finer, though the brig still lay hove to; but at night the wind blew fiercer and fiercer, the sea broke more wildly than ever. Towards morning a loud report was heard, as if a gun had been fired on board: the fore-topsail had been blown from the bolt-ropes. Before another sail could be set a terrific sea struck the ship, washing fore and aft. “Hold on, hold on for your lives,” sung out the master. Jack grasped the main rigging, so did Sambo and others; but two men were forced from their hold by the water and carried overboard. A flash of lightning revealed their countenances full of horror and despair. A shriek—their death wail—reached his ears. Jack never forgot those pale terror-struck faces.

When morning broke, the crew no longer seemed inclined to jeer and laugh at Jack. The ship was labouring heavily. About noon, the carpenter, who had been below, appeared on deck with a countenance which showed that something was the matter. “What’s wrong now?” asked the captain. “Why, the ship’s sprung a leak, and if we don’t look out we shall all go to the bottom,” answered the carpenter gruffly. He and the captain were on bad terms. “All hands man the pumps,” sung out the captain. The men looked sulkily at each other, as if doubting whether or not they would obey the order. “Let’s get some grog aboard; and no matter, then, whether we sink or swim,” said one. “Ay, hoist up a spirit cask, and have one jolly booze before we die,” chimed in another. It was evident that they would if they could break into the spirit room, and steeping their senses in liquor, die like brute beasts. Sambo and Jack, however, rushed to the pumps to help the mates rig them. When the captain saw the hesitation of the rest of the crew, uttering a dreadful oath, he entered his cabin, and immediately returned on deck with a pistol in each hand. “Mutiny—mutiny!” he exclaimed. “You know me, my lads—just understand I’ll shoot the first man who disobeys me.” Strange, that the men who an instant before would not have hesitated to rush into the presence of their Maker, were now afraid of the captain and his pistols. Without another word they went to the pumps. The labour was incessant, but they were able to prevent the water from increasing. All day, and through the next night, they pumped on. In the morning the storm began to break; and soon, the wind shifting, the brig was put on her proper course. Still the water poured in through the leak; but as the sea went down, half the crew were enabled to keep it under. It was hard work though, watch and watch at the pumps. The captain and his mates walked the deck with their pistols in their belts, ready to shoot any man who might refuse to labour. Jack and Sambo were the only ones who pumped away with a will. Several days passed thus. At length the water grew of a yellowish tinge, and a long line of dark-leaved trees appeared, as if growing out of the sea. Jack was told that they were mangrove bushes, and that they were on the coast of Africa. A canoe came off from the shore full of black men. One of them, dressed in a cocked hat and blue shirt, with a pair of top boots on his legs, but no other clothing, stepped on board. He told the captain that he was son to the king of the country; and having begged hard for a quid of tobacco and a tumbler of rum, offered to pilot the brig up the river. The brig’s head was turned in shore, and passing through several heavy rollers which came tumbling in, threatening to sweep her decks, she was quickly in smooth water, and gliding up with the sea breeze between two lines of mangrove bushes. The men required to shorten sail, had slackened at their labours at the pumps. This neglect allowed the water to gain on them; so the captain, instead of ordering the anchor to be let go, when some way up the river, ran the brig on shore. He did this to save her from sinking, which in another ten minutes she would have done. It was now high tide; and the captain hoped when the water fell to get at the leak and repair damages. He was come to trade in palm oil, ivory, and gold dust, besides gums and spices, and any other articles which might sell well at home. He had brought Manchester goods—cottons, and cloths, and ribbons; and also other merchandise from Birmingham, such as carpenters’ tools, and knives and daggers, and swords and pistols and guns, to give in exchange for the productions of the country.

The king’s son remained on board, and acted as interpreter. Numbers of natives came down to the banks of the river, and a brisk trade commenced. No vessel had been there for some time, and the captain congratulated himself on quickly collecting a cargo. The men, meantime, had to work in the mud under the ship’s bottom to stop the leak; and the hot sun came down on their heads, and at night the damp mists rose around them, and soon the dreadful coast-fever made its appearance. One by one they sickened and died. Jack’s heart sank within him when he heard their ravings as the fever was at its height. They died without consolation, without hope, knowing God only as a God of vengeance, whose laws they had systematically outraged. The mates died, and the carpenter and the boatswain, till two men only of the crew besides the captain and Jack’s friend, Sambo, remained alive. The captain thought that he had discovered the means of warding off disease, and always talked of getting the brig afloat, and returning home with a full cargo. He seemed to have no sorrow for the death of his shipmates, and cursed and swore as much as ever. At last Jack felt very ill, and one morning when he tried to get up he could not. Sambo came and looked at him, and telling him not to fear, returned on deck and sent off for a cocoa-nut-bottle full of some cooling liquid. When it came, no mother could have administered the beverage with greater gentleness than did Sambo. Though it cooled his thirst, still Jack thought he was going to die. The fever grew worse and worse, and for many days Jack knew nothing of what was taking place around him.

While he had been well he had never said his prayers; but now the recollection of them came back to his mind, and he kept repeating them and the verses he had learned from his mother over and over again.

Chapter Three.

At last Jack completely recovered his senses. The two men who had remained in the berth were no longer there. Sambo, who nursed him tenderly as before, was the only person he saw. He inquired what had become of the rest. “Captain and all gone. Fis’ eat them,” was the answer. Yes; out of all that crew the negro and the boy were the only survivors. The king’s son and his subjects had carried away all the cargo, and the rigging and stores and the bare hull alone remained.

Jack was still very weak, but his black friend carried him on deck whenever the sea breeze blew up the river, and that refreshed him.

While he lay on his mattress, he bethought him of repeating the verses from the Bible and his prayers to Sambo. The black listened, and soon took pleasure in learning them also. Jack remembered something about the Bible, and how Jesus Christ came on earth to save sinners; and Sambo replied it was very good of him, and that he was just the master he should like to serve.

Thus many weeks and months passed away till Jack was quite strong again, and he wished to go on shore and to see what was beyond all those dark mangrove trees; but Sambo would not let him, telling him that there were bad people who lived there, and that he might come to harm.

But a change in their lives was coming which they little expected. As they were sitting on the deck one evening, a long dark schooner appeared gliding up the river like a snake from among the trees. Sambo pulled Jack immediately under shelter of the bulwarks, and hurried him below. “The slaver—come to take black mans away—berry bad for we.” The slaver, for such she was, dropped her anchor close to the brig. Jack and Sambo lay concealed in the hold, and hoped that they had not been seen. Oh that men would be as active in doing good as they are when engaged in evil pursuits. The slaver’s crew, aided by numerous blacks from the shore, forthwith began to take on board water and provisions, and in the mean time gangs of blacks, tied two and two by the wrists, came down to the river’s banks from various directions. Sambo looked out every now and then, and said that he hoped the schooner would soon get her cargo on board and sail. “She soon go now,” said he one day, “all people in ship.”

While, however, he was speaking, a boat touched the side of the brig, and to their infinite dismay the footsteps of people were heard on deck. Still they hoped that they might escape discovery. “What dis smoke from?” exclaimed Sambo. “Dey put fire to de brig!” So it was. The smoke was almost stifling them. They had not a moment to lose. Up the fore-hatchway they sprung, and as they did so they found themselves confronting three or four white men.

“Ho, ho, who are you?” said one, who turned and spoke a few words to his companions in Spanish.

Jack replied that they were English sailors belonging to the brig, and that they wished to return home.

“That’s neither here nor there, my lads,” was the unsatisfactory answer. “You’ll come with us, so say no more about the matter.”

Thereon Jack and Sambo were seized and hurried on board the schooner. Her hold was crowded with slaves. The anchor was apeak, and with the land breeze filling her sails, she ran over the bar and stood out to sea. “We are short handed and you two will be useful,” said the white man who had spoken to them, and who proved to be the mate; “it’s lucky for you, for we don’t stand on much ceremony with any we find troublesome.” Sambo had advised Jack to say nothing, but to work if he was bid, and the mate seemed satisfied.

What words can describe the horrors of a crowded slave ship, even in those days before the blockade was established. Men, women, and children all huddled together, sitting with their chins on their knees and without the power of moving. A portion only were allowed to come on deck at a time, and the crew attended to their duties with pistols in their belts and cutlasses by their sides ready to suppress an outbreak. Many such outbreaks Jack was told had occurred, when all the white men had been murdered. He was rather less harshly treated than in the brig, but he had plenty of work to do and many masters to make him do it. It was dreadful work—the cries and groans of the slaves—the stench rising from below—the surly looks and fierce oaths of the ruffian crew, outcasts from many different nations, made Jack wish himself safe on shore again.

Thus, the slave ship sailed on across the Atlantic, the officers and men exulting in the thought of the large profit they expected to make by their hapless cargo.

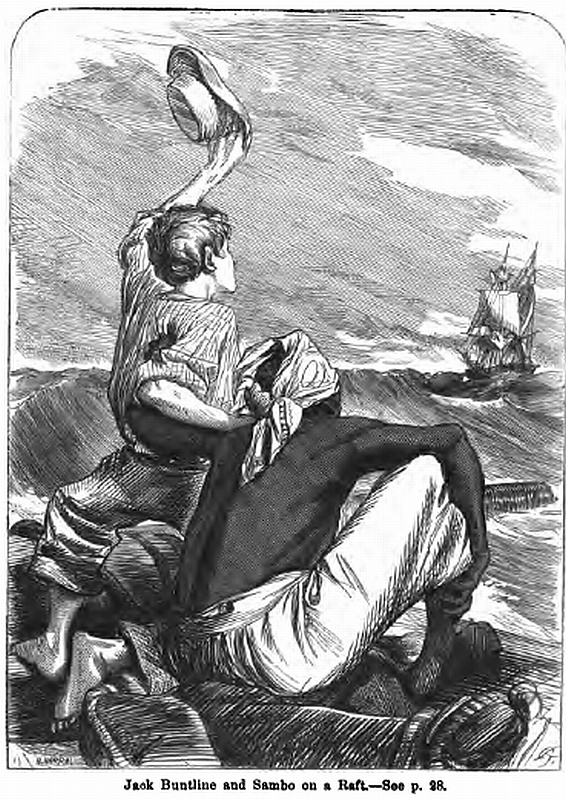

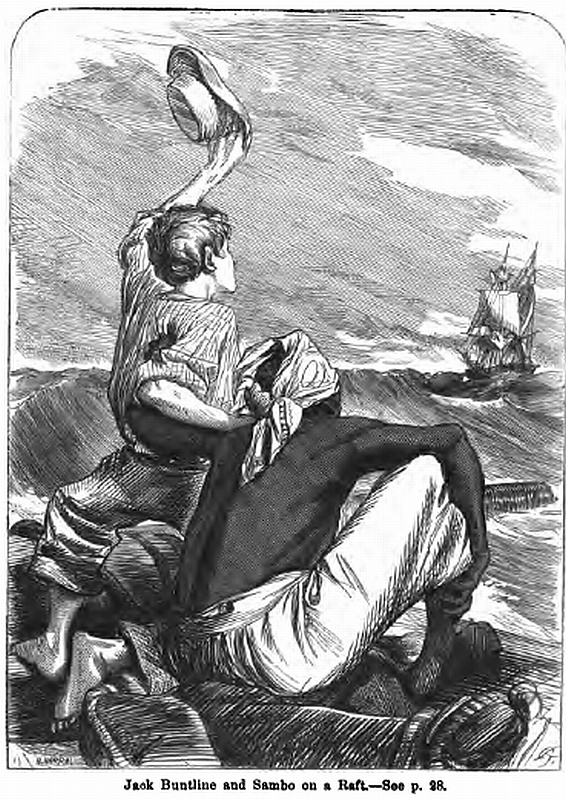

But there was an avenging arm already raised to strike them. No enemy pursued them—the weather had hitherto been fine. Suddenly there came a change. Dark clouds gathered rapidly—thunder roared—lightning flashed vividly. It was night—Jack was standing on deck near Sambo—“Oh! what is dat?” exclaimed Sambo, as a large ball of fire struck the main-topmast head. Down it came with a crash, riving the mast into a thousand fragments. Wild, wild shrieks of horror and dismay arose. Bright flames burst forth, shewing the terror-struck countenances of the crew. Down—down sank the ship, the fierce waves washed over her decks. Jack thought his last moment had come as the waters closed over his head, while he was drawn in by the vortex of the foundering vessel; but he struck out boldly, and once more rose to the surface. He found himself among several spars with a few fathom of thin rope attached to them. He contrived to get hold of these spars, and by lashing them together to form a frail raft. This was the work of a minute. He listened for the sound of a human voice, yet he feared that he himself was the sole survivor of those who lately lived on board the slave ship. Not a sound did he hear, nothing could he see. How solitary and sad did he feel thus floating in darkness and alone on the wide ocean. Oh picture the young sailor boy, tossing about on a few spars in the middle of the Atlantic, hundreds of miles away from any land, thick gloom above him, thick gloom on every side. What hope could he have of ultimately escaping? Still he remembered that God, who had before been so merciful to him, might yet preserve his life. He had not been many minutes on his raft when he shouted again, in the hopes that some one might have escaped to bear him company. With what breathless anxiety did he listen! A voice in return came faintly over the waters towards him from no great distance. He was sure he knew it. “Is that you, Sambo?” he exclaimed.—“Yes, Jack, me. Got hold of two oars. Come to you,” answered Sambo, for it was the black who spoke. After some time Sambo swam up to him, and together they made the raft more secure. It was a great consolation to Jack to have his friend with him; yet forlorn, indeed, was their condition.

Chapter Four.

At length the night passed away, and the sun rose and struck down on their unprotected heads. They had no food and no water. Anxiously they gazed around. Not a sail was in fight. Death—a miserable death—was the fate they had in prospect. Their condition has been that of many a poor seaman, and oh, if we did but think what consolation, what support, would a saving knowledge of religion present to men thus situated, we should rejoice at finding any opportunity of affording it to them. The day wore on, Jack felt as if he could not endure another. He could hold very little conversation with his companion. The night came. He had to secure himself to the raft to save himself from falling off, so drowsy had he become.

The sun was once more shining down on his head, when an exclamation from Sambo roused him up. Not a quarter of a mile from them was a large ship passing by them. But, oh, what agony of suspense was theirs, lest no one on board should see them! They shouted—they waved their hands. Jack had a handkerchief round his neck,—he flew it eagerly above his head,—he almost fainted with joy. The ship’s lighter sails were clewed up. She was brought to the wind, a boat was lowered and pulled towards them. They were saved. The ship was an outward bound Indiaman. Humane people tended the poor sufferers. A little liquid was poured down their throats: a little food was given them: they were put into clean hammocks. For many a day Jack had not enjoyed so much luxury. He had hitherto been accustomed only to kicks and blows. He thought Sambo the only good man alive. Kindness won his heart, and he learned to love others of his race.

The voyage was prosperous. India was reached in safety. With a fresh cargo the ship then sailed for China. What wonders Jack saw in that strange land I cannot stop to describe. Laden with tea the good ship, the Belvoir Castle, returned to England, and Jack’s first and eventful voyage was ended.

Chapter Five.

Jack’s Second Voyage.

Jack had behaved so well when on board the Indiaman, that Captain Hudson, her commander, kept him on to assist in looking after the ship while she was refitting for sea, and once more he sailed in her. Nearly all the crew had been shipped when Sambo made his appearance and got a berth on board. Away rolled the old Belvoir Castle laden with a rich cargo, and full of passengers hoping to gain fortune and fame in the distant land of the East. None of them, however, took notice of the young sailor lad, nor did it ever occur to Jack that such grand people would think of speaking to such as he. How vast was the gap between them!

It was war time. One morning a strange sail was seen bearing down on them, but whether friend or foe no one could tell. To escape by flight was impossible, so the ship was prepared for action. Jack, like the rest, stripped himself to the waist, and went to his gun with alacrity. The old hands said they should have a tough job to beat off the enemy, but they would do their best. An enemy’s frigate the stranger proved to be, but so well were the old Indiaman’s guns fought, that she beat off the frigate with the loss of her foremast. It was an achievement of which all on board might justly have been proud, though several similar acts of gallantry were performed during the war. Jack’s coolness had been remarked, and he was called aft, and thanked by Captain Hudson on the quarter deck for the way in which he had stood to his gun.

Chapter Six.

India was reached at last, the nabobs and the Griffins and the young ladies were safely landed, and the ship, as before, proceeded to China. There she took in a cargo of tea, and the time of year being suitable the captain resolved to return home by Cape Horn. The Pacific was true to its character, and the Indiaman had a smooth run across it. Cape Horn was almost doubled. It was a fine night. The passengers tripped it gaily on the quarter deck to the sound of music, the crew amused themselves by singing forward. No one thought of danger. The moon’s bright beams played on the surface of the dark mysterious deep. So passed the evening away. The passengers retired to rest; the first watch was set; silence reigned over the ship. Before the watch was out dark clouds collected in the horizon and came rolling up overhead. Every instant they grew thicker and thicker, the wind whistled louder and louder, the sea rose higher and higher. A heavy gale was blowing; such a sea Jack had never before witnessed. Suddenly a cry arose from below, a cry the dread import of which a sailor too well knows—“Fire! Fire! Fire!” The crew in a moment sprung on deck. The passengers, pale with terror, rushed from their cabins.

Jack listened for the orders of one on whom he knew all must depend—their venerable captain. Quick as lightning all flew to obey them. The courses were brailed up, the ship’s head was brought to the wind. All hands were stationed to pass buckets along the decks, to deluge the hold with water, but a fiercer element was at work. Upward darted the bright flames, grappling savagely with everything they encountered. On—on they fought their way, vanquishing the utmost efforts of the crew. Those who had never before felt fear now trembled at the rapid progress of the devouring element. Already had the flames gained the foremast and were mounting the rigging. Their bright glare fell on the terror-stricken countenances of the passengers and the figures of some of the crew labouring to lower the boats into the water. Others were endeavouring hastily to construct a raft by which, perchance, some few more of those on board might have their lives prolonged. Provisions, water, blankets, compasses, and other articles were collected in haste, and thrown into the boats, as they were got into the water and dropped under the counter. Then the order was given to lower the women and children into them. Rapidly were the flames making their way aft. Still the generous seamen obeyed the call of duty, and endeavoured to see the most helpless rescued from immediate destruction before they attempted to seek their own safety. The frail raft was launched: one by one the people descended on it: still many remained on board.

There was a loud explosion! Fragments of the wreck flew high into the air. Bright hungry flames enveloped the whole ship. Jack felt his arm seized, and in another moment he was struggling in the waves supported by Sambo, who then struck out for the nearest boat, the ship’s launch. They were taken on board. Sad and solemn was the sight as Jack watched the burning ship, casting its ruddy glare on the tossing foam-crested waves, the tossing boats and helpless raft. The launch, already crowded, could take no more people in, and the second officer, who had charge of her, judged it necessary to keep her before the wind. So hoisting sail they soon left their companions in misfortune and the burning wreck far astern. Yet how miserable was the condition of the people in that storm-tossed boat. Great also were their fears as to the fate of those from whom they had just parted. What hope also could they have for themselves? No sail in sight, land far far away, with small supply of provisions or water. The mate, Mr Collins, was a man of decision and judgment. The scanty store was husbanded to the utmost, grumblers were silenced, discipline was maintained.

Still the sufferings of all were great. Exposed to the sun by day, to the cold at night, wet to the skin, with but little food, one after the other they died.

A fortnight passed away. Still no ship appeared in sight, no land was made. Scarcely could any of those in the boat have been recognised by their dearest friends, so sad was the change wrought by those days of suffering. The wind now shifting, the mate determined to steer for the Falkland Islands, the nearest land he could expect to make. There, at all events, they could obtain water and fresh meat. Still it was a hundred leagues or more away: could any hope to live to reach that resting place for their feet? Alas, their hollow voices, their haggard countenances as in despair they looked into each other’s faces, told them that such hope was vain. Jack and Sambo sat side by side, others talked of home and friends, and entreated those who might survive to bear their last messages to those friends in their far, far-off homes; but Jack and the black had no homes, no friends to mourn their loss. Much anguish were they saved. It might have been the reason that they retained their strength while others sunk under their trials. Jack remembered also how he and Sambo had before been preserved, and did not despair.

Day after day passed away, the boat sailed on, her track marked by the bodies of those committed to their uncoffined graves. Strong men, as well as women and children, young as well as old, sank and died. At length six only remained, the mate, and Jack, and Sambo, and three others of the crew. They had no water—no food. The three men had drawn together and had been holding consultation forward. “It must be done,” muttered one, in a low ominous voice.

“We are not all going to die,” growled out another, looking towards the mate who was steering; “we’ve made up our minds, sir, to draw lots.”

“For what?” exclaimed the mate with startling energy; “for what, I ask, fellow?”

The man did not answer. There was something in the mate’s tone which silenced him.

“No more of that while I live,” added Mr Collins, drawing a pistol from his bosom and laying it beside him. For many hours after this not a word was spoken.

Chapter Seven.

On sailed the boat. The black was the only person who kept his eyes constantly moving about him. He might have suspected treachery. Suddenly his whole manner seemed changed. He jumped to his feet clapping his hands. “A sail—a sail,” he cried. Then he sat down and wept. All looked eagerly in the direction towards which he pointed. A large barque was crossing their course, but how could they hope that a small boat could be seen by the people on board at that great distance? They got out the oars, but their strength was insufficient to go through the movements of rowing, much less to urge on the boat. All they could do was to sit still and wait, watching with intense eagerness every movement of the stranger. Picture them at this juncture. On, on they sailed. Every one felt that if they missed the vessel their fate was sealed. A simultaneous groan escaped their bosom. She altered her course, and was standing away from them. One of the men threw himself down into the bottom of the boat, prepared to die. Still Jack kept his eye on the barque. “See—see dere!” exclaimed Sambo. The barque had hove to. Why, they could not tell, at the distance she was away. She had done so without reference to them. Perhaps some one had fallen overboard. How anxiously did they wait!

As they were looking a spout of water rose in the air. “Whales! whales!” cried Sambo. “See dere is anoder.” Ere long they descried a boat rapidly approaching, urged on by some unseen power. She dashed by them, her bows covered with foam.

Well might her crew look with surprise and horror at the hapless beings in the Indiaman’s boat. Jack and Sambo and the mate waved their hands, their voices were too weak and hollow to be heard. “We’ll come to you—we’ll come to you, poor fellows!” shouted the crew of the whale boat. It was long, however, before the whale to which the boat was fast rose to the surface, and lashing the sea with its tremendous tail, spouted out its life blood and died. The whaler had made sail after her boat, and now seeing the Indiaman’s boat, took Jack and his companions on board.

“Who sent that whale towards us when we were almost dead?” thought Jack; as often as he asked the question the answer came: “It was God in His great mercy guided the senseless fish that we might be saved.”

There were but five survivors. One man, he whose ominous looks had made the mate draw his pistol, had not lived to see the approach of the whale boat. Jack and his companions were treated not unkindly on board, though their life was a rough one. The whaler was an American, outward bound, and five fresh hands when their strength returned were no unwelcome addition to her crew. Their early success put all hands in good humour, and several sperm whales were killed before they reached their usual cruising ground on the borders of the Antarctic ice fields. Jack was soon initiated into the mysteries of blubber cutting and boiling, and as the dirt and oil-begrimed countenances of the men were seen as they moved around their seething cauldrons, amid bright flames and dense masses of smoke, they looked like spirits of evil summoned to labour by some diabolical agency.

Several weeks thus passed by, when the whaler with a full cargo was once more steered northward. All hands were exulting in their success. The weather had been fine. There was every prospect of a prosperous voyage. Cape Horn had been rounded, and they were at no great distance from the coast of South America. Before long, however, a change took place; thick weather came on, and for many days not a glimpse of the sun was obtained. The master too was taken ill, and the first mate had proved himself a bad navigator. The result was that the ship was out of her reckoning. A gale sprung up, which, shifting to the eastward, increased to a hurricane.

The belief was that the ship was a long way from the coast.

It was night. The darkness was intense, such as can be felt. The gale had somewhat abated, and it was hoped that canvas might soon be got on the ship to take her off the land, when that terror-inspiring cry arose from forward:—“Breakers ahead!” In tones of dismay it was repeated along the decks. “There’s a watery grave for most of us then,” exclaimed the old boatswain, near whom Jack was standing. Scarcely had he spoken when the ship struck, and the wild sea made a clean breach over her, washing many poor fellows to destruction. Groans of horror, shrieks of despair rose on every side; but the sounds were quickly silenced by the roar of the waves, the crashing of the falling sails, and the wrenching asunder of the stout timbers. Jack clung to the bulwarks, and as they gave way he found himself borne onward with them through the foaming breakers into comparatively smooth water. The force of the wind still drove him on till he felt his feet touching the hard sand. Disengaging himself from the pieces of wreck, before the waters returned, he was beyond their reach.

He sat down—he thought—how good God had been again to save him, and he tried to shape his thoughts into prayer; but there had been nothing like prayer on board the whaler, and he could not pray. For some time he sat almost stupified; then he roused himself and listened for the sound of some human voice to tell him that others had escaped from the wreck. “I should go and help them if they have,” he exclaimed, starting to his feet. He ran along the beach calling out: a voice replied. He at the same moment came across a coil of light rope. Carrying it on his arm he hove the end of it towards the spot whence the voice came. Twice he hove, and had again to haul it in. The third time it was seized. He dragged on shore one of the whaler’s crew. Jack placed him out of the reach of the waves and ran on, for he thought that he heard another person calling. Again his rope was of use. He discerned through the darkness a large piece of the wreck. Three men were clinging to it. One of them was Sambo. Together they continued their search for others, venturing as far into the water as they dared. Another man was found struggling to gain the shore. He was almost exhausted. By himself he could not have succeeded. Jack was truly glad to find his old friend Mr Collins, the mate of the Indiaman. After a little time he also recovered, and together the survivors continued their search. In vain they searched during the night. The next morning not a particle of the wreck was found hanging together. Some dead bodies were washed on shore, and several articles also of which the shipwrecked mariners stood much in need were picked up, casks of provisions, clothing, tools, and some arms and powder and shot. They had thus no fear of starving. As soon as they had collected whatever the waves threw up they climbed to the top of the cliffs to look around them. They were evidently in an uncivilised part of the country, though it was well wooded and watered. Their great fear was from the Indians, a fierce race thereabouts. The mate, who naturally took the lead, told them that they might be able probably to reach some of the Spanish settlements, and they resolved to set off in search of them. It was necessary, however, that they should lay in a store of provisions, and recover their strength for the journey. There were numerous large trees and rocks scattered about the shore, and the shipwrecked seamen soon discovered a cave in one of the rocks, where they could shelter themselves from the wind and rain, and in which they might lay up their stores.

Chapter Eight.

Several days passed quietly away, most of the party going out for a few hours at a time to endeavour to shoot any animals or birds which might serve to vary their diet. At length, however, they fancied themselves strong enough to prosecute their journey, and a day was fixed on which to commence it. One morning the party, as was their custom, went out in pairs to hunt. Jack accompanied Sambo. They were later than usual, but on their return they saw no signs of a fire at their hut, nor any sounds from their companions. Jack’s heart sunk within him. On reaching the hut his apprehensions were verified. It was stripped almost of everything. The articles too bulky to be carried off were broken in pieces. What had become of their companions? “Me fear killed,” said Sambo, who had been looking anxiously about. He beckoned to Jack, and penetrating through the wood to a short distance they found the dead bodies of two of their late companions. Sambo, after examining the marks on the ground, declared it his belief that their other two companions had been carried off by the Indians, Jack’s first impulse was to run away from the fatal spot, but on consulting with Sambo they agreed that the Indians, having carried off every thing, were not likely to return: besides, without the mate to guide them, they were unable to find their way to the European settlements. He, with the other man, had probably been carried away by the Indians. All they could hope for was that some vessel might visit that part of the coast and take them off.

They had guns, but a very small supply of powder, and this they determined to keep to make a signal should it be necessary. As, however, Sambo knew a variety of methods of trapping both birds and beasts and of catching fish, and also what roots and fruits were wholesome and unwholesome, they were not likely to want food. Day after day, and week after week, and month after month passed away, till Jack lost all count of time and began to fear that no vessel would ever come to take them off. Several times in the summer they met with traces of Indians, but Sambo was always able to avoid them. Numberless were the adventures they met with and the risks they ran. Jack had reason to be thankful that he had so intelligent a companion and faithful a friend as Sambo, though they had not much power of interchanging ideas. “What matters the colour of our skin?” thought Jack. “The same God made us both, and I love him as a brother.” At length Jack began to be very anxious to get away. He thought that he might have to live there for ever. Sambo was much more contented with his lot.

Some twenty months or so had passed away since the shipwreck, when one morning, as Jack went to the top of a cliff to take his usual look for a vessel, he saw a large brig standing along the shore about a mile to the northward. He hurried back to the cave to call Sambo, and to get their musket with the few rounds of ammunition they had left. The two returned to the shore. Jack’s heart beat quicker than it had ever before done. Off he set, followed by Sambo along the beach in the direction of the brig. He was afraid she might stand off shore again without any on board observing them. At length they came abreast of the brig. They shouted and waved their handkerchiefs; still no notice was taken of them. “We must fire,” said Jack. But the powder flashed in the pan. He tried again. “Make haste! make haste!” shouted Sambo. They were standing on the summit of a rock which lay on the beach, with a wide extent of open country which sloped up from the shore behind them. There, galloping towards them at full speed, were a band of mounted Indians. Jack again primed the musket. It went off. He loaded and fired again. The signal was observed on board the brig, and a gun was fired in return. The reports of the firearms had the effect of making the Indians rein in their steeds and look about them. At the same time a boat put off from the brig. She was immediately perceived by the Indians, and again they advanced, but more cautiously than before. Jack and Sambo looked anxiously at the boat. It was doubtful whether she or the Indians would reach them first. They rushed down to the beach and waded into the water. The crew of the boat saw their danger. On came the Indians with terrific yells, flourishing their lassoes high above their heads. Jack and Sambo saw that narrow indeed was their chance of escape. The brig had been standing in shore. Just then she brought her broadside to bear, and opening her ports sent a shower of round shot among the Indians. Two or three of their saddles were emptied and they again halted. The delay enabled Jack and Sambo to spring into the boat. Scarcely had her head been pulled round, when the Indians, again galloping on, dashed into the water and endeavoured to throw their lassoes over their heads. One man was very nearly caught, but he had a sharp knife ready to cut the rope as it reached his neck. Others among the Indians shot arrows at them, but the boat’s crew having no arms could not retaliate, and Jack’s musket had got wet. By smart pulling they were soon safe on board the brig.

Chapter Nine.

Jack and his companion found the brig was in search of a spot further to the south where good water could be got. Having visited it, Jack and Sambo were able to pilot her there, and thus at once obtained favour with their captain. They had not been many days on board before Jack became suspicious of the character of the Sea Hawk, such was the name of the brig. “Don’t ask questions,” was the only answer he got when he inquired under what flag she sailed. He found that she was neither English nor American; still she was strongly armed, and from the bandages which decked the heads and arms of several of the crew, and the marks of shot in her hull and rigging, it was evident she had only lately been engaged. The people also were of all nations and colours, and dressed in every variety of costume. Watching his opportunity he mentioned his doubts to Sambo. The black shook his head. “Berry bad, me fear,” he replied. “This brig one big pirate—nothin’ else.” Jack had once seen some pirates hanging in chains, and had a wholesome fear of their character. He was therefore not a little anxious to get out of their company. He, however, said nothing, and went about his duty cheerfully.

In spite of the lawless manners of the crew, there was strict discipline maintained on board, and a sharp look out kept. From their conversation, Jack guessed that they were on the watch for some of the homeward-bound Spanish ships from Peru or Mexico, supposed to be freighted with gold and other valuable commodities. No one was more constantly on the alert than the captain. Every one paid him the greatest respect. Jack at first could not tell why. His outward appearance had nothing about it of the ferocious pirate. Captain John was a little man, somewhat sunburnt and wizened, and no beauty certainly, but with usually a calm, rather benignant expression of countenance, and a gentle soft voice. If, however, any thing went wrong or in any way displeased him, his eye kindled up, and his voice gave out a note between the roar of a lion and the croak of a raven, and on these occasions Jack always felt inclined to get away from him as far as he could.

Several weeks passed away and no prize had been made. A thick fog had hung over the sea since daybreak, shrouding every thing near or far from sight. A breeze springing up soon after noon, the fog lifted, when away dead to leeward a ship was descried, her maintop just appearing above the horizon. Instantly all sail was made in chase. No one doubted but that at length a prize long waited for was to be theirs. They rapidly overhauled the stranger, who, apparently unsuspicious of danger, was holding her course to the northward. As the Sea Hawk neared her, she seemed to be a large ship, her build, her paint and rigging shewing her to be a merchantman. At the same time, as a Spanish ship of her size would certainly carry guns, and as her crew might possibly fight them to defend their freight, the pirates went to their quarters to be prepared for the strife. However, when the brig drew still nearer she seemed in no way inclined to begin the combat. This made the pirates fancy that she would not fight at all, and that they would obtain an easy victory. “We must not let one of the people escape to bear witness against us,” said the mild-looking Captain John as he eyed the stranger. Sad was the fate awaiting all on board the merchantman. Nearer and nearer drew the two vessels. So completely did the pirate brig outsail the other that the Sea Hawk might be likened to a spider with a fly in his toils.

The brig, hoisting her accursed black flag, sure harbinger of death and destruction, was about to pour in her broadside, when an exclamation escaped the pirate captain. Large folds of canvas were drawn up from the ship’s sides, down came tumbling sundry other bits from aloft, the muzzles of twenty guns looked grinning out of her ports, up went the glorious British ensign at her peak, and at the same moment the frigate, for such she was, sent forth a terrific shower of round shot and langrage, which made the pirate brig tremble to her keel, and struck down many a fierce desperado never to rise again.

The pirate captain now seemed in his element, though he must have known his case to be desperate. Ordering his man to fire high, wishing to disable his opponent, he braced up his yards in the hopes of getting off to windward; but the hitherto slow sailing frigate showed that she had a quick pair of heels of her own, and was immediately after him. Jack was endeavouring to get away, that he might not fire on his countrymen; but the pirates drove him back to his gun, with the threat of shooting him if he attempted to desert them again. Sambo, on account of his general intelligence, had been made captain of his gun, and he seemed to be as eager in working it as any one else; but he gave Jack a hint that no one on board the frigate would be the worse for any shot he fired. Now began a scene of the most terrific carnage. The pirates fought like demons; but were struck down by numbers at a time, till the deck became a complete shambles. Still Jack and Sambo were unhurt. Some of the pirates gave signs of a desire to haul down their flag; but their captain shot a man who was attempting the operation, and that made the others desist. At length Captain John received a wound and fell to the deck, and the crew rushing aft struck to the frigate. After giving them a couple of extra broadsides—for pirates are seldom treated with courtesy—the victor sent his boats, well armed, to take possession. No further opposition was made, though the little captain, as he lay writhing on the deck, urged his crew to heave cold shot into the boats as they came alongside. The British seamen climbed up the sides with their cutlasses in their teeth, and took possession of their prize.

Chapter Ten.

Some dozen men only of the pirates remained unhurt. They, with Jack and Sambo, were forthwith transferred to the frigate and placed in irons below. “I’m no pirate,” said Jack to the men who were handcuffing him. “Oh, no,” they answered with a laugh; “you looks like a lamb, and that ’ere craft there with the black flag flying is just an honest trader.” Poor fellow, he was begrimed with powder and smoke and blood, and looked very unattractive. He felt very wretched, for he saw no means of proving that he was innocent. His only comfort was that Sambo was near him. They could thus carry on a conversation in an undertone. Sambo had been so knocked about the world, and had been in so many strange positions, that he was not easily cast down. “Neber mind, Jack—something save us dis time too—we trust in God.”

The Lion frigate, which had captured the pirate, had been dispatched from the West India squadron expressly to look for him, and now shaped a course for Jamaica with her prize. From what Jack heard from the pirates and from the crew of the frigate, he had no doubt that all of them would be hung, as a warning to other evildoers. Uncomfortable as he was, he was in no hurry to have the voyage over. He did not like the prospect at its termination. He tried in vain to get the ear of some of the officers of the ship that he might tell his tale. There was no chaplain, or he would have spoken to him.

At length the frigate reached Jamaica, and Jack and his companions were transferred to the prison on shore. They were there constantly visited by a minister of the gospel, and Jack seized an early opportunity of telling him how he had come to be on board the pirate brig. The clergyman listened attentively to his tale, and cross-questioned both him and Sambo on the subject. He often spoke to them, losing no opportunity of turning their minds to eternal things. Still they were left in doubt whether or not he believed their story.

The day of the trial arrived; Jack and Sambo and the other prisoners were brought into the court of justice. The evidence against them was so clear that their counsel had little to plead in their defence. Jack simply repeated his story, describing how he and others, escaping from the burning Indiaman, had been picked up by the whaler, and afterwards wrecked on the coast of South America.

“I can corroborate one part of the story,” said a gentleman, rising in the court, “I was on board the Indiaman, and remember that young seaman and the black, who both at different times performed some service for me.”

“I felt sure, also, that they were innocent,” added the chaplain of the prison; “they were the only two of all the pirate crew who from the first knelt in prayer, and were resigned to the will of God, acknowledging his justice and goodness.”

“There’s no doubt about their innocence,” exclaimed a sunburnt, broad-shouldered man from the crowd, whom Jack recognised as his friend Mr Collins. “I was second officer of the Indiaman,” he continued; “I was wrecked in the whaler, carried off by the Indians, and have only just escaped from them, and found my way here.”

Still as Jack and Sambo had been found on board a pirate, and the frigate wanted hands, though their lives were spared, it was on condition that they should enter on board her. Three days afterwards the survivors of the pirate crew were seen swinging on gibbets,—a punishment they richly deserved.

This event having taken place, the Lion frigate put to sea. Jack soon found himself rated as an able seaman, and well able was he to do his duty, to hand and reef and steer with any man in the ship. No one would have recognised in the active, well-built, intelligent, sunburnt seaman the poor little spirit-cowed workhouse lad, who a few years before had left the shores of England.

After serving for some months on board the frigate, Sambo was raised to the dignity of ship’s cook, his chief qualification being his power of enduring heat. For a better reason Jack was made captain of the mizen-top, whence he might hopefully aspire to become captain of the maintop. War, which had only lately been concluded by a peace, again broke out, and the frigate was sent to cruise in search of an enemy. Jack’s heart beat high at the thought of meeting one. The last time he had stood at his gun in action, its muzzle was turned against the very ship on board which he now served, and he longed to show how he could fight in a rightful cause.

He had not long to wait. The frigate, having the island of Barbadoes some fifty leagues or so to the westward, caught sight of a stranger, her topsails just showing above the horizon to the eastward. Sail was made in chase, and as they rose her courses, she was pronounced to be an enemy’s cruiser of about equal force. The private signals were unanswered, and as soon as the ships got within range of each other’s guns the action commenced. As the wind was from the westward, the British frigate had the weather-gauge,—an advantage she kept,—and so well were her guns served, that it was soon evident the enemy were getting the worst of it. Still the enemy fought well, and many of the Lion’s crew lost the number of their mess. At length it was resolved to close, and carry her by boarding, for the night coming on it was feared she might escape in the dark. Jack buckled on his cutlass with no little glee, and, following the first lieutenant, as the ships’ sides touched each other, was one of the first on board the enemy. The decks were slippery with blood; oaths, and cries, and shrieks, and groans, and clashing of steel, and flashing and rattling of pistols, resounded on every side, interrupted by loud roars, as both ships continued to work their heavy guns as they could be brought to bear. Numbers were falling on both sides; but the intrepid courage of the English bore down all opposition, and the enemy being driven below or overboard at last cried out for quarter. It was granted, and their flag being hauled down, the well-won prize was taken possession of.

A violent south-westerly gale springing up soon afterwards, the frigate and her prize were driven so far to the north-east that the captain ordered a course to be shaped for England. There, in seven weeks or so, they arrived, and the ship being shortly afterwards paid off, Jack found himself in possession of no small amount of prize money.

Chapter Eleven.

Jack knew less of the world, if possible, than most of his shipmates, and not being much wiser, his wealth very rapidly disappeared. How it went he could scarcely tell. He had just enough left to pay for an outfit, when he found himself pressed on board the Tribune sloop of war, fitting out for the East Indies. This time, greatly to his sorrow, he was parted from Sambo, who had got his old rating as cook on board a large frigate. Away sailed the Tribune for the lands of pearls and pagodas, diamonds and marble temples, elephants and ivory palaces, scorching suns and wealth unbounded; but what cared Jack whether he went to the tropics or the poles, provided he had a stout ship under his foot and trusty companions by his side.

India was reached, and over those bright calm seas the frigate glided, visiting many a port, where many a strange scene was beheld, and where communication was opened with many strange people. The Tribune was continuing her voyage towards the rising sun—shortening each day in her progress—when, as she was sailing by some spice-bearing isle, a soft breeze wafting the sweet odours of many a fragrant flower from off the land, a change came over the smiling face of the blue deep,—sudden—terrific—like the work of magic. A loud, tremendous roar was heard, with a milling, hurtling, crashing sound. The tall palm-trees bent low before the blast, torn up by the roots, with roofs of houses, entire cottages, and whole crops, the produce of rich lands and days of wearying toil: they were swept like chaff before it. All hands were called, quick aloft they flew to shorten sail, tacks, sheets, and halliards quickly were let go. The topsail yards were speedily lowered, but the gale was down upon them before the sails could be handed. Wildly they fluttered, bursting all restraint, and then flew in tattered shreds from the bolt-ropes. Not a sail remained entire. Fluttering wildly in the gale the strips of canvas twisted and turned, flapping loudly, driving the hardy seamen from the yards, till it had formed thick, folds and knots which no human power could untie. Not till then could it be cut from the yards. On, on flew the ship, what could stop her now? The fierce typhoon howled and whistled through the rigging. A yard parted; away it was carried; two brave men were on it. Both together were hurled into the seething, hissing, foaming water, through which the ship was madly rushing. Could any human aid avail them? Alas! the cry was heard of a strong swimmer in his agony. He turned his longing eyes towards the ship fast leaving him, as still with giant strength he struggled on, cleaving the yielding waters with his brawny arms, his head lifted above the white foam thrown from her eddying wake, in the vain hope—he knows it vain—to overtake her. Yet he had never given in throughout his life’s combat with the world, and would not now till remorseless death had claimed him as his own. His shipmates grazed astern with aching eyes, till his head alone was dimly seen in the far distance amid the snow-white track the ship had left behind.

“Who was it fell?” was asked from the quarter deck.

“Jack Buntline,” many a voice replied. “Alas, ’twas poor Jack Buntline.”

“But two men were carried away with the broken yard,” exclaimed the officer of the watch; “I saw them fall.”

A voice, faint and struggling for utterance, at that moment was heard from alongside. A rope from aloft was trailing overboard, and at the end a human form was clinging. Numbers hurried to assist their shipmate. “Be careful now, my men, or he also will be carried away,” cried the officers. A rope with a bight was hove to him, but the struggling sailor durst not attempt to clutch it, lest on quitting one he might miss the other, and be borne, like his comrade, far away astern. Oh, not another instant could he cling on. If help cannot be sent him he too certainly must let go. Another rope was hove. This time more successfully, the bight fell over his shoulder. He passed an arm through it. “Now haul away,” was the cry. He was hoisted half fainting on the deck. The surgeon was ready to attend him. “Who is it?” was asked. “Jack Buntline,” was the answer.

Once again Jack Buntline was preserved from sudden death, and what death more dreadful than to feel the life blood flowing freely through the veins, with youth, and strength, and many a fancied joy in prospect, friends looking on, eager to save yet powerless, and to be left alone on the cheerless boundless ocean, the stout ship flying fast and far away, and unable to return till long, long after the strongest swimmer must have sunk in the cold grasp of death. Jack knew and acknowledged with a grateful heart the arm which saved him. Away, away flew the ship. The sky overhead a clear deep-dazzling blue, not a cloud but that wind must have blown it from the atmosphere; the sea beneath was one mass of seething, hissing, foaming, madly-leaping waves; not upward, but rushing in frantic haste one over the other, the spray, like thickest snow drifts, following fast astern, torn, as it seemed, from the summit of the seas. Royal masts, and topgallant masts and yards had from the first been struck, top masts were housed,—still frantically onward flew the ship, scudding under bare poles.

“What sea room has she?” was asked with many an anxious look into each others’ eyes.

“Not much on either hand—isles and reefs and rocks on every side abound,” was the whispered answer.

The typhoon howled louder than before. Land could be seen blue and distinct broad on the starboard beam, but though a sheltering port is there, the ship cannot be steered to reach it, but must run on, whatever may be the dangers ahead.

On, on she went: night was approaching. A startling cry was heard, “breakers on the starboard bow—breakers on the port bow—breakers ahead—breakers abeam.” High over the hidden rocks the wild sea leaps. The stoutest ship which ever floated on old ocean, if once amid them but for a moment, would be shattered into a thousand fragments; and not for an instant could a human being struggle among those roaring waters and live. All on board know this. Where can they look for safety? Can they alter their course and beat the frigate out of that dangerous bay of rocks? Impossible! Not a yard of canvas can be stretched to meet that terrific gale. On they must steer; neither on one hand nor the other did an opening appear by which they might escape. The faces of even the bravest of that hardy crew were blanched with dread, as calm and collected they stood contemplating their approaching doom. There were lookouts ahead,—lookouts on the fore-yard-arms with straining eager eyes, endeavouring to find, even against hope itself, some passage among the reefs through which the ship might run.

There was a shout. At one spot, a little on the starboard bow, there appeared to be a break in the line of dancing foam. It was scarcely perceptible among the thickening gloom dealing over the ocean. The helm was put to port. With voice and hand the helmsman was directed how to steer. The frigate rushed towards the spot. In an instant more her fate would be sealed. The breaking waters, in cataracts of foam, leaped up on either side, but on she rushed without impediment. Still all knew that ere another instant the fatal crash may sound, and then masts, spars, and rigging will all come hurtling down; the deck on which they now scarcely stand, the oaken timbers and the stoutest planking will all be wrenched asunder, and wildly tossed amid their mangled bodies, till cast on some lone, far-off shore, or till the sea itself is summoned to give up its dead.

Who, at such a moment, can freely draw a breath? Yet the crash came not. The ship flew plunging on; reef after reef, covered with foaming waves, was passed in safety. What hand, with mercy in its palm, came down to guide that ship? No human knowledge or experience availed the captain or his officers: no chart could help them: in an unknown sea they scudded on. Did any of them believe that chance or Fate stood near the helm and conned the ship? Did any of them dare in that awful moment to pray to chance, or fate, or fortune to preserve them, and steer them clear of all dangers? If any did—and surely many of the bravest lifted up the voice of prayer—it was to Him who made heaven and earth, the sea, and all things in them, and governs them with wisdom infinite.

It was no deceptive passage the frigate had entered. It widened as she advanced, the water becoming smoother; but still before her lay stretched out the moonlit ocean; the stars, also, glittering with an almost dazzling brilliancy in heaven’s dark blue arch. The channel was passed through, but still who could tell the numberless dangers which might yet remain to be encountered. Before another watch was set, “breakers ahead—breakers abeam!” was once more echoed along the decks.

“Then, to my mind, our sand has pretty well run, and we and our brave old ship are doomed,” exclaimed Ned Faintheart, putting his hands in his pockets, with a deep sigh.

“Doomed by whom?” cried Jack. “I tell you what, mate, I haven’t forgotten, and I hope I never may, the saying of an old friend, a black, as good a foul as ever lived, when we both lay expecting little better than a felon’s death, though undeserved, at the hands of our fellow men, ‘Never mind, Jack, something save us this time, too. We trust in God.’”

The breakers roared as loudly as before over the coral reefs, but, still unharmed, the British frigate flew quickly by them. A graze almost from the outer point of the rugged surface of a reef might hurl her to destruction; but neither coral reef, nor rock, nor sandbank stopped her course. Day came at last, and what a wide expanse of troubled waters broke upon the sight of the weary seamen! No one had that night turned in; all kept the deck, steady at their stations, ready to do what men might do to save the ship or their lives; at all events to obey their officers to the last. When the sun with an ensanguined glow shot upward from the ocean, his beams glanced on a dark object which lay ahead. The lookouts soon proclaimed it to be a dismasted ship. As on they rushed in their still headlong course, not only did they see that she was dismasted but was keel upward, the seas constantly breaking over. A turn to starboard of the helm carried the frigate clear, but how their hearts wrung with sorrow and regret—alas! unavailing—when they saw clinging to the keel some eight or more of their fellow creatures. Some, apparently, could scarcely move, their fast waning strength barely enabling them to hold on; but others wildly waved their hats and caps, shouting, though their voices could not be heard, for help. Utterly impossible would it have been to lower a boat. Again the poor wretches shouted in chorus and held out their hands imploringly as the frigate drove onward by them. On, on she went. Many a heart, like Jack Buntline’s, bled for them, and he and others kept their eyes on them; and there they clung and knelt along the keel, holding out their hands till the frigate sailed far beyond their sight. Still on the frigate flew, yet through every danger they passed unharmed. “Messmates,” said Jack, “God has been with us. God dwells on the deep. God is everywhere.”

The typhoon’s fury ceased, and at length in a quiet harbour the frigate rode at anchor. Some, who during the gale had stood with blanched cheek and silent tongue, now began to talk as loud as ever and to boast what they would have done; how they would have swum on shore if the ship had struck some island coast, and how they would have lived a life of ease and indolence among the harmless natives. Among the loudest of the talkers was a man named Richard Random. He was bold, and often seemed to be among the bravest, but in the night just passed scarcely a man appeared to be more unnerved. Religion was his scorn, while the holy name of God he never uttered but to blaspheme. Now, pretending to forget all his late fears, he began openly to deny the existence of a God. Jack urged him to beware lest vengeance should overtake him before long. He laughed all such warnings to scorn. He was a bold, strong swimmer, no man in the ship could compete with him. He boasted that he could swim for many hours, that he feared neither sharks nor any other monsters of the deep. Why then should he be afraid of what spirits of evil or angels of vengeance could do to him? He defied them. He was not afraid of man, angel, or devil. To men of sense, the wickedness he spoke might have done no harm, but there were many youths on board who listened with admiration to whatever Random said. To the ears of such his words were rankest poison. Foolish as himself, they thought his folly wisdom. He was a bully, too, and brawler, and often had he caused a quarrel when a soothing word would have brought peace about. To give him but his due, he was a most pestiferous and dangerous fellow among a crew.

Boasting one day of what he could do; “I’ll undertake,” he said, “to swim a dozen times or more around the ship, or, if you please, a mile away and back, if the water is but calm. Who’ll dare to follow me?”

Jack could no longer bear this boasting. “When young Seaton fell overboard, did you jump overboard to save him? Was it not our gallant first lieutenant, though wounded in the arm and twice your age, while you stood hesitating because you had seen a shark swimming around the ship?”

The question silenced Random for the time. Several days passed away. The frigate bent new sails, set up her rigging, and once more all hands put to sea. Traversing the blue Pacific she steered her course far to the south. A gentle breeze wafted her along, the sea was smooth as polished glass. All sail alow and aloft was set. Some block at the yard-arm required fresh stopping. Random was sent to do the duty. Thoughtless of danger he went aloft and sat carelessly on the yard. Suddenly he lost his balance, a falling form was seen, a splash was heard.

“A man overboard—a man overboard!” cried the sentry at the gangway.

Random rose to the surface. “Never fear me,” he sung out; “I can take good care of myself. Who’s afraid?” He shouted this in bravado. All the officers were looking on he saw, and, vain of his powers, he fought to gain their admiration.

Just ere he fell the breeze had strengthened suddenly, and with all her canvas set the ship was running quickly through the water. The order was promptly given to shorten sail,—the crew as promptly flew aloft to obey it. While studden-sail-sheets, and halliards were let fly, and all the lighter canvas was fluttering loosely in the wind, Random swam bravely on. Still he was dropping fast astern.

A boat was quickly lowered and hastening towards him. “How calm the ocean! what reason can any have for fear?”

“That man swims well,” observed the captain, “I never saw a finer swimmer.”