The Project Gutenberg EBook of Four Afloat, by Ralph Henry Barbour

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

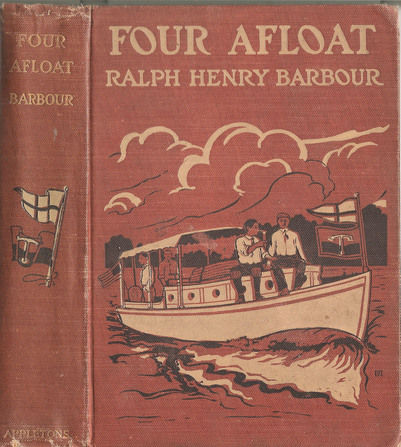

Title: Four Afloat

Being the Adventures of the Big Four on the Water

Author: Ralph Henry Barbour

Release Date: August 10, 2011 [EBook #37021]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOUR AFLOAT ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

BY RALPH HENRY BARBOUR.

Each 12mo, Cloth.

|

Four Afoot. Illustrated. $1.50.

Four in Camp. Illustrated. $1.50.

On Your Mark. Illustrated in Colors. $1.50.

The Arrival of Jimpson. Illustrated. $1.50.

The Book of School and College Sports. Illustrated. $1.75 net.

Weatherby’s Inning. Illustrated in Colors. $1.50.

Behind the Line. A Story of School and Football. $1.50.

Captain of the Crew. $1.50.

For the Honor of the School. A Story of School Life and Interscholastic Sport. $1.50.

The Half-Back. A Story of School, Football, and Golf. $1.50. |

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY, NEW YORK.

FOUR AFLOAT

BEING THE ADVENTURES OF THE

BIG FOUR ON THE WATER

By RALPH HENRY BARBOUR

Author of “Four in Camp,”

“Four Afoot,” etc.

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1907

Copyright, 1907, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Published, September, 1907

TO

J. W. A.

SKIPPER OF MANY

CRAFT

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introduces a Gasoline Launch, Four Boys and a Dog | 1 |

| II. | Starts the Vagabond on its Cruise | 11 |

| III. | Wherein Dan Practices Steering | 21 |

| IV. | Is Largely Concerned with Salt Water and Salt Fish | 34 |

| V. | Wherein Tom Buys Lobsters and Dan Disapproves | 43 |

| VI. | In Which They Follow a Race | 57 |

| VII. | In Which Nelson Discovers a Stowaway | 69 |

| VIII. | Tells How They Outwitted the Captain of the Henry Nellis | 86 |

| IX. | Proves that a Stern Chase is not Always a Long Chase | 95 |

| X. | Shows The Crew Of the Vagabond Under Fire | 108 |

| XI. | Records A Mysterious Disappearance | 118 |

| XII. | Wherein Nelson Solves the Mystery | 130 |

| XIII. | Wherein Dan Tells a Story and Tom is Incredulous | 138 |

| XIV. | In Which Tom Disappears from Sight | 152 |

| XV. | Tells of Adventures in the Fog | 163 |

| XVI. | Witnesses a Defeat for the Vagabond | 172 |

| XVII. | In Which Dan Plays a Joke | 186 |

| XVIII. | In Which Tom Puts Up at the Seamont Inn | 200 |

| XIX. | Narrates a Midnight Adventure | 209 |

| XX. | Wherein Tom Appears and the Launch Disappears | 225 |

| XXI. | Tells of the Search for the Vagabond | 235 |

| XXII. | Wherein the Vagabond is Recovered and the Thief is Captured | 245 |

| XXIII. | Tells How The Four Encountered Old Acquaintances | 256 |

| XXIV. | Wherein Spencer Floyd Leaves the Henry Nellis | 265 |

| XXV. | Wherein the Vagabond Starts for Home and the Story Ends | 273 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| “The Vagabond started after the other craft with a rush” | Frontispiece |

| “Captain Sander ... raised his revolver and fired” | 116 |

| “‘I would like to see the manager, if you please’” | 208 |

| “At the top of the sandy road he turned and waved them farewell” | 274 |

“She’s a pu-pu-pu-pu——!”

“Quite so, Tommy,” said Dan soothingly, “but don’t excite yourself.”

“——pu-pu-peach!”

“Oh, all right!” laughed Nelson. “I thought you were trying to call her a puppy. What do you think of her, Bob?”

“Best ever,” answered Bob promptly and quietly.

They were standing, the four of them—“to say nothing of the dog,” which in this case was a wide-awake wire-haired terrier—on the edge of a wharf overlooking a small slip in which, in spite of the fact that it was the last week in June and many of the winter tenants had been hauled out and placed in commission, a dozen or more boats lay huddled. There were many kinds of pleasure craft there, from an eighty-foot yawl, still housed over, to a tiny sixteen-foot launch which rejoiced in the somewhat inappropriate name of Formidable. Beyond the slip was another wharf, a marine railway, masts and spars, and, finally, the distant rise of Beacon Hill, crowned with 2 the glittering, golden dome of the State House. To their right, beyond the end of the jutting wharf, Boston Harbor lay blue and inviting in the morning sunlight. From the boat yard came the sound of mallet and caulking iron, and the steady puff-puff, puff-puff of the machine-shop exhaust. Nearer at hand a graceful sloop was being hurriedly overhauled, and the slap-slap of the paint brush and the rasp of the scraper were mingled. The air was pleasantly redolent of fresh paint and new wood—oak and cedar and pine—and the salty breath of the ocean. And to the four boys all these things appealed strongly, since they were on the verge of a summer cruise and were beginning to feel quite nautical.

The object of their enthusiasm lay below them at the edge of the wharf—a handsome gasoline cruising launch, bright with freshly polished brass work, gleaming with new varnish, and immaculate in scarcely dry paint. She was thirty-six feet long over all, nine feet in extreme breadth, and had a draught of three feet. A hunting cabin began five feet from the bow, and extended eighteen feet to the beginning of the cockpit. The sides of the cabin were mahogany and the roof was covered with canvas. A shining brass hand rail ran around the edge of the roof, a brass steering wheel protruded through it at the sternmost end, and toward the bow a search light stood like a gleaming sentinel above a small whistle. Between wheel and search light rested, inverted and securely lashed to the roof, a ten-foot cedar tender. The cockpit was nine feet long, and, like the deck fore and aft, was floored with narrow 3 strips of white pine which, since the scrapers had just left it, looked, under its new coat of varnish, as white and clean as a kitchen table. There were iron stanchions to support an awning which, when in place, extended from well forward of the steering wheel to the stern of the cockpit, where a curved seat, with a locker beneath it, ran across the end. (“There are some wicker chairs that go in the cockpit,” Nelson was explaining, “but we won’t need more than a couple of them.”) Below the water-line the boat was painted green. Above that the hull was aglisten with white to the upper strake save where a slender gold line started at the bow and terminated at the graceful canoe stern just short of the gold letters which spelled the boat’s name.

“Vagabond,” said Dan. “That’s a dandy name.”

“Mighty appropriate for a boat that you’re in,” added Bob unkindly. “Come on, Nel; I’m dying to see inside of her.”

“All right. Here’s the ladder over here.”

“What’s the matter with jumping?” asked Tom.

“Remember your weight, Tommy,” counseled Dan.

They followed Nelson to the ladder, Dan bearing the terrier, whose name was Barry, and scrambled into the cockpit.

“I don’t see that we need any chairs,” said Dan. “This seat here will hold three of us easily.”

“Oh, we’ve got to have some place for Tommy to take his naps,” answered Nelson as he produced a key, unlocked a padlock, and pushed back a hatch. 4

“Hope you choke!” muttered Tom good-naturedly.

Nelson opened the folding doors and led the way down three steps into the engine room. This compartment, like that beyond, was well lighted by oval port lights above the level of the deck. On the left, a narrow seat ran along the side. Here were the tool box and the batteries, and a frame of piping was made to pull out and form a berth when required. In the center was the engine—a three-cylinder fifteen horse-power New Century, looking to the uninitiated eyes of Dan and Bob and Tom very complicated. On the starboard side was, first of all, a cupboard well filled with dishes and cooking utensils; next, an ice box; then a very capable-looking stove and sink, and, against the forward partition, a well-fitted lavatory. The floor was covered with linoleum of black and white squares, and the woodwork was of mahogany and white pine. A brass ship’s clock pointed to twelve minutes after nine, and two brass lamps promised to afford plenty of light.

A swinging door admitted to the forward cabin, or, as Nelson called it, the stateroom. Here there were four berths, which in the daytime occupied but little room, but at night could be pulled out to make comfortable if not overwide couches. Dan observed Nelson’s demonstration of the extension feature with an anxious face.

“That’s all very well,” he said, “for you and Bob and me, maybe, but you don’t suppose for a minute, do you, that Tommy could get into one of those?”

And Tom, who, after all and in spite of his friends’ 5 frequent jokes, was not enormously large, promptly charged Dan and bore him backward on to the berth which Nelson had drawn out. As thirty inches afforded insufficient space whereon to pummel each other, they promptly rolled off to the nice crimson carpet, and had to be parted by the others, much to the regret of Barry, who was enjoying the fracas hugely and taking a hand whenever opportunity offered. The disturbance over, the four sat themselves down and looked admiringly about them. There was a locker under each berth, numerous ingenious little shelves above, and several clothes hooks against the partition. At the extreme forward end of the stateroom there was a handsome mahogany chiffonier built in between the two forward berths.

“Well, I call this pretty swell!” said Dan.

“You bet!” said Tom. “I had no idea it was like this. I thought maybe we slept in hammocks. Say, Nel, your father is a trump to let us have her.”

“That’s so,” Bob assented. “But, seems to me, he’s taking big risks. Supposing something happened to her?”

“Well, don’t you talk that way at the house,” laughed Nelson. “I had trouble enough to get dad to consent. I had to tell him that you were a regular old salt.”

“You shouldn’t lie to your father,” said Dan severely.

“I didn’t. Bob has sailed a lot—haven’t you, Bob?”

“I can sail a boat all right,” answered Bob, “but I don’t know one end of an engine from the other.”

“You won’t have to,” Nelson assured him. “I’ll look after that and you can be navigating officer.” 6

“Whatever that is,” murmured Dan parenthetically.

“Who’s going to cook?” asked Tom.

“You are,” said Bob.

“Heaven help us all!” cried Dan.

“Huh! I’ll bet I can cook better than you can,” Tom replied indignantly.

“Get out! I’ll bet you can’t tell why is a fried egg!”

“Oh, you dry up! What’s he going to do, fellows?”

“Me?” said Dan. “I’m going to be lookout, and sit on the bow and yell ‘Sail ho!’ and ‘There she blows!’”

“Let’s have an election,” suggested Bob. “I nominate Nel for Captain.”

“Make it Admiral,” amended Dan.

“All in favor of Nel for Captain will say——”

“Aye!” cried Dan and Tom.

“You’re elected, Nel.”

Nelson bowed impressively, hand on heart, and Barry barked loudly.

“Then Bob’s first mate,” said Nelson, “and you can be second, Dan. Tom’s going to be cook and purser.”

“How about Barry?” asked Bob.

“He’s the Sea Dog,” said Dan. “But look here, fellows; if we’re really going to get off to-morrow, we’d better be moving. What’s the programme for this afternoon, Nelson?”

“Buy supplies and get them down here. We’ll get dad to tell us what we need. It’s almost twelve o’clock, and we’d better light out now.” 7

“All right,” answered Dan, “but I hate to go. I’m afraid the boat may not be here when we get back. Don’t you think I’d better stay here and watch her?”

They passed out into the engine room, and Bob stopped to look at the engine curiously.

“Where’s the gasoline?” he asked.

“In a tank at the bow,” Nelson answered. “Here’s the supply pipe here.”

“And what’s that thing?”

“Vaporizer. The gasoline enters here and the air here—see?”

“Then what happens?”

“Why, they mix into vapor, which passes up through this pipe to the cylinders.”

“Oh!” said Bob. “Well, it sounds all right, but I don’t see how that makes the boat go. If I were you I’d stick a mast on her and have some sort of a sail.”

“Oh, if the engine gives out,” laughed Nelson, “we’ll put Tommy overboard and let him tow us!”

“I mean to learn all about this thing,” said Bob resolutely with a final look at the engine. “How fast did you say she can go, Nel?”

“She’s supposed to make eleven and a half miles an hour, but she’s done better than that.”

“That doesn’t sound very fast,” said Tom.

“It’s fast enough for cruising,” answered Nelson. “Are we all out? Where’s Barry?” He put his head back into the engine room. “Barry, where are you? Oh, I see; sniffing around the ice chest, eh? Well, you’d 8 better wait until to-morrow, if you want anything to eat out of there. Come on!”

Nelson locked the doors and the four boys climbed back to the wharf, pausing for a parting look at the Vagabond ere they turned toward home.

Possibly you have met these boys before, either at Camp Chicora two summers before, when they came together for the first time and gained the title of the Big Four, or a year later, when in a walking trip on Long Island they met with numerous adventures, pleasant and unpleasant, all of which helped to cement still closer the bonds of friendship, and when they secured an addition to their party in the shape of a wire-haired terrier. If Bob and Nelson and Tom and Dan are already old acquaintances, I advise you to skip the next few paragraphs, wherein, for the benefit of new friends, I am going to introduce my heroes all over again.

First of all—if only because he is the oldest—there is Robert Hethington. I call him Robert, though nobody else does, as a mark of respect. He is seventeen years of age, and a full-fledged freshman at Erskine College; and if that doesn’t call for respect, I’d like to know what does! Bob—there! I’ve forgotten already; but never mind—Bob comes from Portland, Maine. He is a very good-looking chap, tall, broad-shouldered, and healthy. He has nice black eyes, somewhat curly black hair, and is at once quiet and capable.

Then there is Nelson Tilford, of Boston. He, too, is booked for Erskine in the autumn. In fact, they all 9 are, with the possible exception of Tom. (Tom has just taken the examinations, in spite of the fact that he has only finished his third year at Hillton Academy, and has yet to hear the result.) Nelson is fairly tall, slimly built, lithe and muscular. He isn’t nearly so well-behaved as his thoughtful, sober countenance promises. He is sixteen years old, and has just finished at Hillton.

The third member of the quartette is Dan Speede, of New York. Dan has decidedly red hair, the bluest of blue eyes, and is somewhat heavily built. Dan, as the mischievous twinkle in his eyes suggests, is fond of fun—any kind of fun. He is generally on the lookout for it, and generally finds it. Dan is sixteen, and has just finished, not too brilliantly, I fear, his senior year at St. Eustace Academy.

And last, but not least, there is Tom—otherwise Tommy—Ferris. Tom lives in Chicago (but Dan declares that that is his misfortune and not his fault) and is sixteen years old—almost; so nearly sixteen that he gives his age as that when Dan isn’t by to correct him. Tom is inclined toward stoutness; also laziness. But he’s a nice boy, just the same, with gray eyes, light hair, and a cheerful, good-natured disposition which the other members of the party are inclined to take advantage of.

There you have them all—the Big Four. But I am forgetting the little fifth, which Dan wouldn’t approve of at all. The fifth is Barry. I suppose that his last name, since he is Dan’s property, is Speede—Barry Speede in full. Barry is an aristocratic member of the fox terrier 10 family, a one-time prize winner. As to age, he is about two and a half years old; as to looks, he is eminently attractive; as to disposition, he is undoubtedly as well if not better off than any other member of the party. In short, he is a nice, jolly, faithful, and fairly well-behaved little dog, and Dan wouldn’t part with him for any sum of money that has ever been mentioned.

Last summer the four had made up their several minds that this summer they would again be together, and when Nelson announced in May that his father had at last consented to lend them his launch for a cruise along the coast, the manner of doing so was settled. And so, when school was over, Bob and Dan and Tom had joined Nelson at his home in Boston, prepared for the biggest kind of a good time.

They were very busy that afternoon. Armed with a list of necessary supplies, they stormed one of the big grocery stores, and a smaller but very interesting emporium where everything from a sail needle to a half-ton anchor was to be found.

Bob listened to the order at the grocery with misgivings. “I don’t for the life of me see where we’re going to stow all that truck, Nelson,” he said.

“Oh, there’s more room on the Vagabond than you think,” was the cheerful response.

“And he’s not referring to Tommy, either,” added Dan.

“You fellows are having lots of fun with me, aren’t you, this trip?” asked Tom, mildly aggrieved.

“And the trip hasn’t really begun yet,” laughed Nelson. “Don’t you care, Tommy, you’re all right. Let’s see, did we have pepper down? Yep. Well, I guess that’s all, isn’t it?”

“How about oil?” asked Tom.

“Oil? Do we need it? Look here, you don’t think you’re going to feed us on salad, do you?” 12

“If it’s seaweed salad, I pass,” said Bob.

“No,” answered Tom, “but I thought you always carried oil in case of a storm; to pour on the water, you know.”

“Oh, we use gasoline for that,” explained Nelson gravely. “Come on and let’s find the other joint.”

Their way lay through a number of extremely narrow and very crooked streets—only Dan contemptuously called them alleys—and because of the crowds it was usually necessary to proceed in single file. First there was Nelson as guide; then came Bob; then trotted Barry; at the other end of his leash was Dan; and Tom jogged along in the rear.

“Thunder!” exclaimed Bob at last. “The chap who laid out this town must have been crazy! I’ll bet you anything, fellows, this is the same lane we were on five minutes ago. Look here, Nelson, are you plumb certain you’re not lost?”

“Yes,” answered the other.

“Well, I’m not,” growled Dan. “I’m lost as anything. I don’t know whether I’m coming or going. I’d just like to——”

But at that moment a dray horse tried to walk up his back, and Dan’s remarks were cut short. When he had reached the other side of the street in safety he half turned his head and addressed himself to Tommy.

“Did you see that blamed horse?” he asked indignantly. “He deliberately tried to walk through me. Guess he mistook me for one of those short cuts that 13 Nelson is always talking about. I’ve a good mind to go back and have him arrested.”

As there was no reply, Dan turned and looked back. Then:

“Whoa! Back up!” he shouted. “We’ve lost Tommy!”

Consternation reigned.

“When did you see him last?” asked Nelson anxiously.

“About five minutes ago, I guess,” said Dan. “It was when we were coming through that three-inch boulevard back there. Poor Tommy!” he said sorrowfully. “We’ll never see him again.”

“I guess we’d better go back and look for him,” said Nelson.

“Have you any idea you know how we came?” asked Dan incredulously.

“If we don’t find him, he’ll make his way home, I guess,” said Bob.

“I’ll bet I can tell you what’s happened to him,” said Dan.

“What?”

“He’s got stuck fast in one of these narrow streets, of course. I only hope they won’t have to tear down a building or two to get him loose.”

“Oh, they’ll probably let him stay there until he is starved thin,” laughed Nelson.

“That’s so. And build a flight of steps over him. Bet you a dollar, though, that when they do pry him loose, they’ll arrest him for stopping the traffic!” 14

“Well, come on,” said Nelson. “We’ll see if we can find him.”

So they turned and retraced their steps, although Dan affirmed positively that they had never come that way.

“The sensible thing to have done,” he grumbled, “was to have stayed just where we were and waited for the streets to come around to us. Then, when one went by with Tommy on the sidewalk, we could have just reached out and plucked him off.”

But no one heard him save a newsboy, who thought he was asking for an afternoon paper.

After five minutes on the “back trail,” they concluded to give it up, agreeing that Tom had probably wandered into one of the side streets, and that he would undoubtedly find some one to direct him to Nelson’s house. So they started again for the yacht-supply store, Dan pretending to be terribly worried.

“Who’s going to break the news to his parents?” he asked lugubriously. But by the time they were in sight of their destination he had acquired a more cheerful frame of mind. “Of course,” he confided to Nelson—the sidewalk here was wide enough to allow them to walk two abreast—“of course, I’m sorry to lose Tommy, but it’s well to look on the bright side of things. You see, Bob will have to be cook now, and you know he’s a heap better cook than Tommy ever was or ever would have been. Oh, yes, every cloud has a silver lining!” In the store he insisted on buying a dory compass for his own use. “You see, Bob, I might get lost myself on the way back,” he 15 explained. Bob, however, convinced him that what he wanted was a chart.

Their purchases here were not many but bulky, and so they decided to call a hack. When it came, they climbed into it and surrounded themselves with bundles of rope, fenders, lubricating oil in gallon cans, and assorted tools and hardware. It was getting toward five o’clock by this time, and they decided to go to the boat yard, put the things on board, and leave the arranging of them until the morning. They dismissed the carriage at the entrance to the wharf and took up their burdens again. Dan, hurried along by the impatient Barry, was the first to reach the edge of the wharf, and——

“Well, I’ll be blowed!” he cried.

Bob and Nelson hurried to his side. There, lolling comfortably in the cockpit seat of the Vagabond and eating caramels, was Tom!

“You’re a nice one!” said Nelson indignantly. “We thought you were lost!”

“So I was,” answered Tom calmly. “Quite lost. So I hired a hansom and came here.”

“Well, you’ve got a great head, Tommy,” said Dan admiringly. “Give you my word, I’d never have thought to do that! I’d have just roamed about and roamed about until overcome by weariness and hunger. What you eating, you pig?”

“Caramels. I stopped to buy them at a store, and when I came out, you fellows were gone and some one had turned the streets around.” 16

“And there we were searching for you for hours, worried half crazy,” said Dan. “Stand up there and catch these bundles, you loafer!”

They went home in the elevated and finished Tom’s caramels on the way. After dinner they got their baggage ready to send to the launch in the morning, studied the charts for the twentieth time, and listened to final directions and cautions from Mr. Tilford.

Nelson’s father was a tall and rather severe-looking man of about fifty, and at first the three visitors had been very much in awe of him. But they had speedily discovered that his severity was, to use Dan’s expression, “only shin deep,” and that in reality he was a very jolly sort in a quiet way. And as they entertained an immense respect for him, they listened very attentively to what he had to say that evening in the library.

“Now there’s just one way in which you boys are going to be able to keep out of trouble,” said Mr. Tilford, “and that’s by using sound common sense. The Vagabond isn’t an ocean liner, and you mustn’t think you can take deep-sea voyages in her. I want you to be in port every evening before dark. I don’t care how early you set out in the morning, but I want you to find your mooring or your anchorage by supper-time. If you take my advice, you’ll have at least one square meal every day on shore. You can’t do much cooking on the launch, even if you know how, and to keep well and happy you’ve got to be well fed on good food.

“I naturally feel a bit anxious about this trip, boys. 17 You’ve all received permission from your parents to take it, but it’s my boat and I don’t want anything to happen to you while you’re on it. You’re all of you getting old enough to look after yourselves pretty well, but I don’t know whether you can all do it. My first idea,” he went on, turning to Bob, “was to send a man along with you. But Nelson didn’t like that, and I realized that it would just about cut your fun in half. So I let him back me down on that proposition. Now it’s up to you to prove that I haven’t made a mistake. Nelson knows that engine about as well as I do, and I don’t think there’ll be any trouble to speak of there. Don’t be sparing of oil, Nelson; half the gas-engine troubles originate with the lubrication. Oil’s cheap and repairs are dear; remember that. And don’t be afraid to throw your anchor out. It’s better to ride out a blow in a stanch boat like the Vagabond than to try to make some port that you don’t know anything about.

“I want to get word from you at least every other day, too; oftener, if you can make it. Just a line will do, so that your mother and I won’t worry. Watch your barometer and the weather flags, and when in doubt hug the harbor. Now, how are you off for money?”

Whereupon the session resolved into a meeting of the Committee on Ways and Means.

The next morning the luggage was dispatched to the wharf, and, after a hurried breakfast had been eaten and they had bade good-by to Nelson’s mother, the four followed. The provisions were there before them, and for 18 an hour they were busy stowing things away. It was wonderful what a lot of supplies and clothing and personal belongings it was possible to pile away in that little cabin. The cushions, mattresses, and awning were brought aboard, and the cockpit was supplied with two of the wicker chairs belonging there. The side lights and riding light were filled, trimmed, and put in place, the searchlight tank recharged, and the ice box filled. Everybody was intensely busy and excited, and Barry was all over the boat and under everyone’s feet. Mr. Tilford hurried over from his office at ten o’clock, looked things over anxiously and hurried off again to attend a meeting at eleven, shaking hands all around and wishing them good luck. Then the launch was hauled around to the head of the wharf to have her gasoline and water tanks filled.

By that time Nelson had invaded the flag locker, and the Vagabond was in holiday trim fore and aft. From the bow fluttered the pennant of the Boston Yacht Club and, beneath it, the owner’s burgee, an inverted anchor in white, forming the letter T, on a divided field of red and blue. Over the stern hung the yachting ensign. Their personal effects were disposed of in the stateroom; underclothing and such apparel in the chiffonier, toilet articles in the lavatory, sweaters and oilskins on the hooks, and shoes in the berth lockers. Tom, to whom had fallen the distribution of the provisions, had completed his task, and the ice box and shelves above were full. Doubtless they had taken aboard a great deal more than they would stand in need of, but that is an error that most inexperienced 19 mariners commit. Save for such things as eggs and butter and bread, their provisions were mostly canned or preserved. At eleven Nelson busied himself with the engine, filling his oil cans and cups, cleaning and polishing. The batteries were brand new and so was the wiring, and when he tried the spark he smiled his satisfaction.

“Fat and purple,” he muttered.

“Who is?” asked Tom resentfully as he slammed down the lid of the ice box.

“The spark, Tommy, my boy,” was the reply. “I was not referring to you; you’re not purple, are you?”

“No, nor fat, either. Say, what’s this? I thought it was something to eat at first.”

“That,” answered Nelson, “is something you’ll become better acquainted with to-morrow, Tommy. That is a nice quart can of metal polish.”

“Huh! I’d like to know what I’ve got to do with it!”

“Oh, the cook always shines the bright-work.”

“Now, look here——”

“Careful,” warned Nelson, “or we’ll put you in irons for mutiny.”

“Guess the iron wouldn’t be any worse than the brass,” said Tom with a grin.

At half-past eleven all was in readiness. One of the yard hands threw off the mooring rope and Bob took the wheel. Dan and Tom stood at the engine-room door and watched Nelson as he turned on the gasoline, looked to his vaporizer valve, and closed his battery switch.

“All clear!” answered Bob.

Nelson opened the valve at the vaporizer and turned over the fly wheel. The engine hummed, and from without came the steady chug-chug, chug-chug of the exhaust. Then, with Nelson at the lever and moving at half speed, the launch pointed her nose toward the outer harbor. The cruise of the Vagabond had begun.

Never was there a brighter, more perfect June day! Low down in the south a few long cloud-streamers floated, but for the rest the heavens were as clear as though the old lady in the nursery rhyme who swept the cobwebs out of the sky had just finished her task. In the east where sky and sea came together it was hard to tell at first glance where one left off and the other began. Golden sunlight glinted the dancing waves, and a fresh little breeze from the southwest held the Vagabond’s pennants stiffly from the poles.

The grassy slopes of Fort Independence looked startlingly green across the water, and the sails of the yachts and ships which dotted the harbor were never whiter. But, although the sun shone strongly, it was more of a spring day than a summer one, and the four aboard the Vagabond were glad to slip on their sweaters when the point of Deer Island had been rounded and the breeze met them unobstructed. Bob set the boat’s nose northwest and headed for Cape Ann.

So far they had made no definite plans save for the 22 first day’s cruise. They intended to make Gloucester, a matter of twenty-six miles, to-day and lie over there until morning. After that the journey was yet to arrange. There was talk of a run to the Isle of Shoals, and so on up to Portland, Bob’s home; but Dan, for his part, wanted to get to New York for a day. And just now they were too taken up with the present to plan for the future.

The Vagabond was reeling off ten miles an hour, and Nelson had returned to the cockpit, greatly to the alarm of Tom, who was of the opinion that Nelson ought to stay below and keep his eye on the engine. Nelson, however, convinced him that that wasn’t necessary. Bob still held the wheel, and was having a fine time.

“It’s more fun than a circus,” he declared. “It works so dead easy, you know! How long will it take us to make Gloucester, Nelson?”

“Oh, call it three hours at the outside, if nothing happens.”

“If nothing happens!” exclaimed Tom uneasily. “What could happen?” He looked doubtfully at the open water toward which they were speeding.

“Lots of things,” answered Nelson, with a wink at Dan. “The engine might break down, or we might run on a rock or a sand bar, or you might get too near the edge of the boat and tip it over, or——”

“Thought you said we were going to keep near the shore,” Tom objected.

“We’re only a mile out now.” 23

“Yes, bu-bu-bu-but we’re going farther every mi-mi-minute!”

“Tommy’s getting scared,” said Dan. “You didn’t mind that little jaunt in Peconic Bay last summer.”

“Well, that was a pu-pond and this is the ocean,” was the answer.

“It looked mighty little like a pond at one time,” said Bob. “Besides, you could have drowned just as easy there as you can here, Tommy.”

“Anyhow,” added Dan soothingly, “you couldn’t drown if you tried. You’re so fat you can’t sink.”

“I can su-su-swim under water as well as you cu-cu-cu-can!”

“What’s the town over there, Nelson?” Bob interrupted.

“Winthrop; and that’s Nahant ahead. You might head her in a bit more until Tommy gets his sea legs.”

Bob turned the wheel a mite and the launch’s bow swung further inshore.

“What time is it?” asked Dan.

“Just twelve,” answered Nelson, glancing at the clock.

“Well, what time do we feed?”

“About one, I suppose,” answered Nelson. “Who’s hungry?”

Dan groaned. “I, for one. I could eat nails.”

“Same here,” said Bob. “Tommy, you get busy, like a good little cookie, and fry a few thousand eggs.”

“And make some coffee,” added Dan. 24

“All right,” Tom replied. “Only there’s a lot of canned baked beans down there. What’s the matter with those?”

“Search me,” said Dan. “Suppose you heat some up and we’ll find out. Beans sound better than eggs to yours truly.”

“I suppose that, as Tom’s the cook, he had better give us what he thinks best,” said Nelson.

“Maybe,” Dan replied, “only it gives him a terrible power over the rest of us. If he should get a grouch, we might have nothing but pilot bread and water.”

“You’ll have to be good to me,” said Tom with a grin as he started down the steps to the engine room.

“Oh, we will be,” answered Dan earnestly; and to give weight to his words he aided Tom’s descent with a gentle but well-placed kick.

“You get short rations for that,” sung out the cook from below.

“If I do, I’ll go down there and eat up the ice box!”

“Say, Nelson,” sang out Bob, “what about that sloop over there? It looks as though she was trying to cross. Who has the right of way?”

“She has. Keep astern of her,” answered Nelson.

“Say!” came a disgusted voice from below. “We haven’t any can opener!”

“Thunder!” exclaimed Nelson. “Is that so? Have you looked among the knives?”

“Looked everywhere,” answered Tom, “except up on deck.” 25

“Use your teeth, Tommy,” suggested Dan.

“Let the beans go, and fry some eggs,” called Bob.

“Use the potato knife,” said Nelson, “and we’ll get a new one when we go shopping.”

“All right,” answered Tom. “If I bust it—there!”

“Did you?” laughed Dan.

“Short off! Say, Bob, lend me your knife a minute, will you?”

A howl of laughter arose, and Tom’s flushed face appeared at the companion way.

“Well, I’ve got to get the lid off somehow, haven’t I?” he asked with a grin.

“Not necessarily with my new knife,” answered Bob.

“I’ll tell you a way you can do it,” said Dan soberly, and Tom, looking suspicious, asked how.

“Why, you set the can on the stove and get it good and hot all through, and just as soon as it begins to boil hard the lid comes off.”

“Huh! And everything else, I guess,” said Tom.

“And we spend the rest of the cruise picking Boston baked beans off the cabin walls,” supplemented Nelson. “No explosions for me, if you please. I don’t see why we should bother ourselves about the can, anyhow; it’s the cook’s funeral.”

“Well, it’s your luncheon,” Tom replied.

“It’s a job for the ship’s carpenter,” said Bob. “Call the carpenter.”

“I guess I’m it,” said Dan. “Come on, Tommy, and we’ll get the old thing open.” 26

They disappeared together and for a minute or two the sound of merry laughter floated up from below, and the two on deck smiled in sympathy. Then there was a loud and triumphant chorus of “Ah-h-h!” and Dan emerged.

“I want to try steering,” he announced. “Get out of there, Bob.”

“All right, but don’t get gay,” was the response. Dan tried to wither Bob with a glance as he took his place at the wheel. Then——

“Gosh! Don’t she turn easy? Who-oa! Come back here, Mr. Vagabond! Say, Nel, how much does a tub like this cost?”

“Thirty-four hundred, this one. But there’s been a lot of extras since then.”

“Honest? Say, that’s a whole lot, isn’t it? I suppose you could get one cheaper if you didn’t have so much foolish mahogany and so many velvet cushions, eh?”

“Maybe. You thinking of buying a launch?”

“I’d like to. I’m dead stuck on this one, all right. A sailor’s life for me, fellows!” And Dan tried to do a few steps of the hornpipe without letting go of the wheel. Nelson, laughing, disappeared to look after the engine, and with him, when he reappeared, came an appetizing odor of cooking.

“Tommy’s laying the tablecloth,” he announced. “When grub’s ready, you fellows go down and I’ll take a turn at the wheel.”

“Get out!” said Dan. “I’m helmsman or steersman, 27 or whatever you call it. You run along and eat; I’m not hungry yet.”

“How about it, Bob?” asked Nelson. Bob looked doubtful.

“I’m afraid he’ll run us against the rocks over there just for a joke.”

“Honest, I won’t,” exclaimed Dan earnestly. “If I see a rock coming, I’ll call you.”

“All right,” laughed Nelson. “See that you do.”

At that moment there came eight silvery chimes from the clock in the engine room.

“‘Sixteen bells on the Waterbury watch! Yo-ho, my lads, yo-ho!’” sang Dan. “Say, what time is that, anyhow?”

“Twelve,” answered Bob.

“Twelve! Well, that’s the craziest way of telling time I ever heard of! What’s it do when it gets to be one?”

“Strikes two bells.”

“Yes, indeed! Isn’t it simple?” asked Dan sarcastically.

“When you get the hang of it,” Nelson answered. “All you have to do is to remember that it’s eight bells at twelve, four and eight. Then one bell is half-past, two bells one hour later, three bells half-past again, and——”

“That’ll do for you,” interrupted Dan. “I don’t want to learn it all the first lesson. But, look here, now; suppose I wake up in the night and hear the silly thing strike eight. How do I know whether it’s midnight or four in the morning?” 28

“Why,” said Bob, “all you have to do is to lie awake awhile. If the sun comes up it was four, and if it doesn’t it was twelve.”

“Huh! I guess I’ll go by my watch. The chap who invented the ship’s clock must have been crazy!”

“Lunch is ready!” called Tom.

“Go ahead, you fellows,” said Dan. “But don’t eat it all up.”

“And you keep a watch where you’re going,” cautioned Nelson. “If you get near a boat or anything, sing out; hear?”

“Aye, aye, sir!”

“Bet you he runs into something,” muttered Bob as they went in.

“No, he won’t,” said Nelson, “because he knows that if he does we won’t let him do any more steering. I’ve got to wash my hands; they’re all over engine grease. You and Tommy sit down.”

The table, which when not in use was stored against the stateroom roof, was set up between the berths and was covered with a clean linen cloth, adorned in one corner with the club flag and the private signal crossed. The napkins were similarly marked, as was the neat china service and the silverware.

“Say, aren’t we swell?” asked Tom admiringly. “And I found a whole bunch of writing paper and envelopes in that locker over there, with the crossed flags and the boat’s name on them. I’m going to write letters to everyone I know after lunch.” 29

The menu this noon wasn’t elaborate, but there was plenty to eat. A big dish of smoking baked beans, a pot of fragrant coffee, a jar of preserves, and the better part of a loaf of bread graced the board. And there was plenty of fresh butter and a can of evaporated cream.

“This is swell!” muttered Tom with his mouth full.

“Tom, if I ever said you couldn’t cook I retract,” said Nelson. “I apologize humbly. Pass the bread, please.”

“Oh, don’t ask me to pass anything,” begged Bob. “I’m starving. I suppose we’ll have to leave a little for Dan, but I hate to do it!”

“Wonder how Dan’s getting on,” said Nelson presently, after a sustained but busy silence. “I should think he’d be hungry by this time.” He raised himself and glanced out of one of the open port lights. Then he flung down his napkin and hurried through the engine room to the cockpit.

“What the dickens!” exclaimed Bob, following.

When Nelson reached the wheel the boat’s head was pointed straight for Boston. But Dan had heard him coming, and was now turning hard on the wheel.

“Where do you think you’re going?” demanded Nelson.

“Who, me? Why, Gloucester.”

“Well, what——”

“Oh, I’ve just been giving myself a few lessons in steering,” answered Dan calmly. “I’ve been turning her around, you know. She works fine, doesn’t she?” 30

“You crazy idiot!” laughed Nelson. “What do you suppose those folks in that sloop over there think of us?”

“Oh, they probably think we’re chasing our tail,” answered Dan with a grin. “Have you eaten all that lunch?”

“No, but we will if you don’t hold her steady.”

“That’s all right, Nel; I’ll keep her as straight as a die; honest Injun!”

The others returned to the table and finished their repast. Then Nelson relieved Dan, and the latter went below in turn. Later he and Tom washed up the few dishes, and when they came up on deck found the Vagabond opposite Marblehead Light. It was after one o’clock and considerably warmer, as the breeze had lessened somewhat. Nelson and Bob had already shed their sweaters, and the others followed suit. Nelson was pointing out the sights.

“That’s Marblehead Rock over there, where they start the races from. The yacht clubs are on the other side of the Neck. Salem and Beverly are in there; see?”

“What’s the light ahead, to the left?” asked Dan.

“Baker’s Island Light,” answered Nelson. “Only you ought to say to port instead of to the left.”

“Sure! Off the port bow is what I meant. A sailor’s life for me!”

“We’ve got all day to make twelve miles,” said Nelson, “so we’ll go inside of Baker’s and keep along the shore.” He turned the wheel and the Vagabond swung her nose toward the green slopes of the Beverly shore. 31 Tom insisted on having a turn at the wheel, and so Nelson relinquished his place and went below to look after his oil cups. Under Bob’s guidance, Tom held the boat about a quarter mile offshore. There was lots to see now, for the water was pretty well dotted with sailing craft and launches, and the wooded coast was pricked out with charming summer residences.

About half-past two the gleaming white lighthouse at the tip of Eastern Point was fairly in sight, and they rounded Magnolia, a cheerful jumble of hotels and cottages. A little farther on Nelson pointed out Norman’s Woe, a small reef just off the shore. Dan had never heard of the “Wreck of the Hesperus,” and Tom spouted two stanzas of it before he could be stopped. Bob had laid the chart out on the cabin roof, and was studying it intently.

“Where do we anchor?” he asked. “According to this thing there are about forty-eleven coves in the harbor.”

“Well, we were in here a couple of years ago,” answered Nelson, “and anchored off one of the hotels to the left of that island with the stumpy lighthouse. I guess we’ll go there to-day. Here’s the bar now.”

The Vagabond was tossing her bow as she slid through the long swells in company with a fishing schooner returning to port.

“‘Adventurer,’” read Dan, his eyes on the bow of the schooner. “That’s a good name for her, isn’t it? I’ll bet she’s had adventures, all right.” 32

“That’s the life for you, Dan,” laughed Bob. But Dan looked doubtful.

“Well, I don’t know,” he answered. “I’d like to try it, though.”

A long granite breakwater stretched out from the end of the point on the starboard, ending in a circular heap of rocks on which an iron frame supported a lantern. Before them stretched the long expanse of Gloucester Harbor, bordered on one side by the high wooded slopes of the mainland and on the other by the low-lying, curving shore of the Point. Far in there was a forest of masts, and, back of it, the town rising from the harborside and creeping back up the face of a hill. Launches and sailboats were at anchor in the coves or crossing the harbor, and a couple of funereal-looking coal barges were lying side by side, their empty black hulls high out of water. At Nelson’s request, Tom turned the boat’s head toward one of the coves, and Nelson went below and reduced the speed of the engine. Then the anchor and cable were hauled out from the stern locker and taken forward. Nelson again stood by the engine and Bob took the wheel. Then——

“All right,” called the latter, and the busy chugging of the engine ceased. Nelson hurried up, and when the Vagabond had floated in to within some forty yards of the shore the anchor was ordered down.

“Aye, aye, sir!” answered Dan promptly, and there was a splash. When the cable was made fast and the Vagabond had swung her nose inquiringly toward the 33 nearest landing, the boys went below to spruce up for a visit ashore. Then the tender was unlashed from the cabin roof and lifted over the side, Dan piled in and took the oars, and the others followed. Near at hand a rambling white building stood behind the protecting branches of two giant elms.

“That’s where we’ll have dinner,” said Nelson. “It’s a jolly old place.”

“Dinner!” cried Tom. “Me for dinner! Give way, Dan!”

“They don’t serve it in the middle of the afternoon, though,” said Nelson.

“Maybe Tommy could get something at the kitchen if he went around there,” Bob suggested. “I don’t believe he’s a real cook, after all; real cooks are never hungry.”

“Huh!” answered Tom. “I’m no cook, I’m a chef; that’s different. Chefs are always hungry.”

“Easy, Dan,” cautioned Bob. “Look where you’re going if you don’t want to run the landing down. Here we are, Barry; out you go!”

And Barry went out and was halfway up the pier before anyone else had set foot on the landing.

“Let’s do the town,” suggested Dan.

Inquiry elicited the information that the town proper was a good two miles by road, although it was in plain sight across the harbor. By walking a block they could take a car—if the cars happened to be running that day; it seemed that in Gloucester one could never tell about the street cars.

“Blow the cars!” said Dan. “Let’s walk.”

So they started out, found the car tracks, and proceeded to follow them along the side of the harbor, past queer little white cottages set in diminutive gardens or nestled in tiny groves of apple trees. To their right a high granite cliff shot up against the blue sky, and was crowned with a few houses which looked as though they might blow off at the first hard wind. After three hours on the boat it felt mighty good to be able to stretch their legs again, and they made fast time. Presently they came to what at first glance seemed to be an acre or so of low white canvas tents, and Tom and Dan, walking ahead, stopped in surprise. Then——

“Blamed if they aren’t fish!” exclaimed Tom. “With 35 little awnings over them to keep them from getting freckled!”

“What are they doing?” asked Bob.

“They dry them like this,” answered Nelson. “They’ve been cleaned and salted, you see, and when they’re dried they are packed in boxes and tubs and casks.” Bob whistled expressively.

“I never knew there were so many fish in the world!” he exclaimed. Nelson laughed.

“This is only one,” he said. “There are lots more fish yards just like it here.”

“What are they?” asked Dan. “Codfish?”

“Oh, all sorts: cod, hake, pollack—everything.”

There was row after row of benches covered with wooden slats on which the fish, still damp with the brine, were spread flat. Above the flakes, as the benches are called, strips of white cotton cloth were stretched, to moderate the heat of the sunlight. There was a strong odor of fish, and a stronger and less pleasant odor from the harbor bottom left exposed by the ebbing tide. Tom sniffed disgustedly.

“I never liked fish cakes, anyhow,” he muttered.

Beyond the flakes were the wharves and sheds, the masts of several schooners showing above the roofs. As they came to one of the open doors they stopped and looked in. Dried fish were piled here and there on the salt-encrusted floor, and men were hard at work packing them into casks.

“Will they let you go through the place?” asked Dan. 36

“Yes,” Nelson answered.

“Let’s go, then. I’d like to see how they do it.”

“All right,” said Nelson, “but I’ve seen it once, and I’d rather go to town. You fellows go, if you want to.”

Finally Dan and Tom decided to go through the fish house and Bob and Nelson to continue on to town.

“You’ll have to shed your clothes and take a bath when you come out,” Nelson warned them.

There wasn’t much to see in the town, and after making a few small purchases—that of a new potato knife being one of them—they boarded a car and, after the trials and tribulations usually falling to the lot of the person so rash as to patronize the Gloucester street railway, returned to the hotel and found Dan and Tom awaiting them on the porch.

Nelson and Bob halted at a respectful distance.

“Have you had your baths yet?” they asked.

“Not yet, but soon,” answered Tom.

“Then we’ll stay here, if you don’t mind,” said Bob.

“Oh, get out! It wasn’t very smelly,” declared Dan.

“But you are, I’ll bet!” Nelson took a few cautious steps toward them, and then turned as though in panic and raced for the landing. Bob followed, and after him came Tom and Dan and Barry. Despite the frantic efforts of the first two to cast off the tender before the others arrived, they were unsuccessful, and Dan, Tom, and the dog piled into the boat. Bob rowed with an expression of deep disgust, and Nelson ostentatiously kept his nose into the wind all the way to the launch. 37

“I was thinking of taking a dip myself,” he said as he climbed out and took the painter, “but I don’t know about going into the same ocean as you chaps.”

But a few minutes later they were standing, all four of them, on the after deck of the Vagabond, clad in their bathing suits.

“I’ll bet it’ll be as cold as thunder!” said Dan with a shudder.

“Bound to,” agreed Bob. “All in when I say three.” The rest assented.

“One!” counted Bob.

“Go slow, please!” Nelson begged.

“Two!” They all threw their hands over their heads and poised for the dive.

“Four!”

Three bodies splashed simultaneously into the water. Bob, grinning like the Cheshire cat, seated himself on the bench in the cockpit and awaited their reappearance. Dan’s head came up first, and he shook his fist.

“You just wait till I get you in the water!” he threatened.

“He ch-ch-ch-cheated!” sputtered Tom. Tom could talk as straight as anyone until he became excited; then, to quote Dan, “it was all off.” At this moment Tom was excited and indignant.

“That was one on us,” called Nelson as his head came up. “To think of getting fooled by such an old trick as that! Come out of that boat, now, or we’ll throw you out!” 38

“Try it!” taunted Bob. There was a concerted rush, but it was no easy matter to climb over the side; and, as Bob’s first act was to haul the steps in, that was what they had to do. Dan was almost over when Bob caught him and sent him back into the water. Then Nelson got one knee over, only to meet with the same treatment. As for Tom—well, Tom wouldn’t have got aboard without assistance in a week of Sundays. Thrice repelled, Dan and Nelson hit on strategy. They climbed into the tender, seized the oars, and shot it to the side of the launch. Nelson and Bob grappled, and in that instant Dan jumped on deck. After that the conquest was easy. With Dan on one side and Nelson on the other, and Tom screaming encouragement from the water, Bob was hustled, struggling, to the side and ignominiously pushed over.

“Three!” he yelled. Then the waters closed over him. When he came up he brushed the drops from his eyes and exclaimed:

“Pshaw! It isn’t cold at all!”

“We knew that,” answered Dan, “but we weren’t going to tell you, you faker!”

They had a jolly time there in the water until the sun, settling down above the wooded hills in the west, warned them that it was time to think of dinner. They got out of their dripping suits in the engine room and dressed again in their shore togs. Afterwards they hung their bathing suits over the awning frame and pulled the tender alongside. At that moment the clock struck four bells. 39

“Wait!” cried Dan. “I know! It’s six o’clock!”

“Right!” laughed Nelson. From the hotel came a loud booming of a gong or bell.

“What’s that?” asked Tom, startled.

“Dinner bell at the hotel,” said Nelson.

“Sounded like a riot call,” observed Dan. Then they piled into the tender and went ashore, to be ushered, four very sedate and well-behaved young gentlemen, into the dining room.

It was all of an hour later when Tom was finally separated from the table and led protestingly back to the porch.

“But I wanted some more frozen pudding!” he explained.

“Of course you did,” answered Bob soothingly. “But you must remember that we’re only paying for one dinner apiece, Tommy. Don’t bankrupt the hotel right at the beginning of the season.”

“Hope you ch-choke!” said Tom.

Later they rowed back to the launch over the peaceful cove, which was shot with all sorts of steel-blue and purple lights and shadows. Across the cove Rocky Neck was a blurred promontory of darkness, with here and there a yellow gleam lighting some window and finding reflection in the water below. Seaward, the harbor was still alight with the afterglow, and the lantern at the end of the breakwater showed coldly white in the gathering darkness. It had grown chilly since sunset, and so, after making all fast for the night, the boys went below and closed the doors and hatch behind them. With the lamps going, 40 the cabin soon warmed up. Bob, by request, had brought his mandolin, and now, also by request, he produced it and they had what Nelson called a “sing-song,” Tom alternately attempting bass and soprano, and not meeting with much success at either. Finally Bob tossed the mandolin onto the bunk and said he was going to bed. That apparently casual remark seemed to remind Dan of something, for he suddenly sat up on the edge of the berth and grabbed Tom by the arm.

“We haven’t given them our stunt yet, Tommy,” he said.

“Eh? What stunt? Oh, yes; that’s so! Come on!” And Tom climbed to his feet. Dan joined him, and they stood very stiffly at attention.

“What’s this?” asked Bob.

“It’s called—it’s called ‘The Dirge of the Salt Codfish,’” answered Dan soberly. “Are you ready, Tommy?”

“All ready.”

“Let her go!”

Whereupon they began to recite with serious faces and ludicrous lack of vocal expression, illustrating the “dirge” with wooden gestures.

“They come in three-pound, five-pound, and ten-pound packages,” chanted the pair, “also in glass jars. A rubber band is placed around the top, the air is forced out by a vacuum machine, and the cover is clamped on. To remove the cover, you puncture the lid!”

“Where’d you get that?” laughed Nelson. 41

“The fellow that showed us around the fish shop told it to us. It’s the way they put up their codfish. Isn’t it great? Want us to say it again?”

“Yes, and say it slow.”

For the next ten minutes “The Dirge of the Salt Codfish” had things its own way, Nelson and Bob insisting on learning it by heart. When they could all four say it in unison, standing in a row like a quartet of idiots, they were satisfied. Then the berths were made up and, after Dan had satisfied himself which was the strongest one and therefore best suited to Tom, they undressed and put out the lights. Of course they didn’t go to sleep very soon; things were still too novel for that. They talked and laughed, quieted down and woke up again, recited “The Dirge of the Salt Codfish,” and—well, finally went to sleep. Some time later—no one ever knew just when, since the clock refused to ring out any information—Bob and Dan were awakened by the sound of some one blundering around the stateroom.

“Who—who’s that?” asked Dan in startled tones, sitting up in his berth with a jerk.

“It’s me, you idiot!” growled a voice.

“Who’s ‘me’?” questioned Dan sharply.

“Nelson. We forgot to set the riding light, and I’ve bumped into everything here. I’d like to know where that door’s got to!”

“Well, keep off of me,” groaned Bob. “The door’s behind you, of course. Can’t you find a match?”

“No, I can’t. If I could I’d light it, you silly fool!” 42

“There are some in the engine room, on top of the ice box,” laughed Dan.

Then they heard the door swing back and heard Nelson’s bare feet go scraping over the cold oilcloth and his teeth chattering. Presumably the riding light was fixed as the law demands, but neither Dan nor Bob could have sworn to it. They turned over in their berths, and by the time Nelson was picking his way along the side of the launch by the light of the flickering lantern they were sound asleep again.

Perhaps it was because Tom had slept undisturbedly through Nelson’s prowling that he was the first to awake the next morning. When he opened his eyes the early sunlight was streaming through the ports, and from the other side of the planking came the gentle swish of the lapping waves. Tom stuck one foot outside the covers tentatively, then drew it quickly back again; the air outside, since most of the ports had been left open all night, was decidedly chill. But the sunlight and the breeze and the lapping water called loudly, and pretty soon Tom was out on the floor, scurrying around for his clothes. Now and then the others stirred uneasily, but none awoke. Washed, and dressed in the white duck trousers and jumpers with which the four had provided themselves, Tom glanced at the clock, pushed back the hatch, and opened the doors to the cockpit. It was only a little after half-past six, and the cove and harbor were deserted. From the houses on the Neck thin streamers of blue smoke were twisting upward from the kitchen chimneys, and from the Harborside House, where they had eaten dinner 44 the night before, came the cheerful sound of rattling tins and the thud of cleaver on block.

That reminded Tom that, as usual, he was hungry. But there was no use in thinking about breakfast yet. He sat down on the cockpit seat—which proved on close acquaintance to be soaking wet with the dew—and looked about him. The sound of oars creaking in rowlocks drew his attention, and he looked across the quiet cove. From around the point came a man in a pea-green dory, rowing with the short, jerky strokes of the fisherman. Tom watched him. Presently he stopped rowing, dropped his oars, and reached over the side of the dory. When he straightened up he had a line in his hand, and now he got on his feet and began pulling it in. Tom wondered what was on the other end, and when the end appeared was more puzzled than ever. For what the man in the dory hauled into the boat looked for all the world like a hencoop, and Tom didn’t see why the man kept his hens under water, although he remembered having read somewhere of Mother Carey’s Chickens, which, in some way beyond his understanding, were connected with salt water.

The man drew something out of the hencoop and threw it back into the cove. It flashed in the sunlight as it fell, and Tom wondered if it was an egg. Something else was taken out and thrown into the dory. Then, presently, the hencoop was lifted over the side again and sank out of sight. The man took up his oars and started toward the Vagabond, but he hadn’t gone far when he again ceased rowing and prepared to produce another 45 hen-coop from the vasty deep. That was too much for Tom. He seized the oars, drew the tender alongside, and tumbled in. Then he headed for the dory. When he drew near the second hencoop was coming into sight. Tom leaned on his oars and opened conversation.

“Good morning,” he said. The man in the dory looked up and nodded.

“Mornin’,” he answered.

Then the hencoop was pulled over the side of the dory and rested across it, and Tom saw that instead of chickens it contained fish. It was fashioned of laths, was rounding on top, and at one end a funnel of netting took the place of the laths.

“What do you call that?” asked Tom.

“This? That’s a lobster pot. Never see one before?”

Tom shook his head.

“No, I don’t think so. I thought it was a hencoop.”

The lobsterman chuckled as he undid the door of the trap and thrust in his arm. Out came a handful of small fish, which were thrown into a pail in the dory. Then one or two larger fish were tossed overboard, and last of all a fine big greenish-black lobster was produced. Tom paddled nearer and saw that a box in the dory was already half full of lobsters which were shuffling their claws about and blinking their protruding eyes. Another pail held fish for bait, and after the pot was cleared out new bait was placed in it and it was once more let down at the end of a rope. Tom now saw that the surface end of the rope was attached to a white wooden float. 46

“Not much there, was there?” said the fisherman as he took up his oars. “You come over to the next one and I’ll show you some lobsters.”

So Tom rowed after him a hundred yards or so and awaited with interest the appearance of the next pot. The prediction proved true, for when the pot came to the surface it looked to be swarming with lobsters. To Tom’s surprise, the first two or three that were taken out were tossed back into the water.

“Aren’t those any good?” he questioned.

“Best eatin’ there is,” was the reply, “but they’re ‘shorts.’”

“What are ‘shorts,’ please?”

“Young ’uns under ten inches long. Law don’t allow us to keep ’em.”

There were a good many shorts in the trap, but there were also four good-sized lobsters, and the lobsterman seemed well pleased.

“Do you sell them?” asked Tom. The man glanced across at him shrewdly.

“‘Shorts,’ do you mean?”

“Oh, no; the others.”

“Yes; want to buy some?”

“If you could let me have a couple, I’d like it.”

The man held out two medium-sized ones.

“Fifty cents,” he said.

“All right.” Tom dived into his pocket, brought up the money and pulled up to the dory, where the exchange was made. 47

“Guess you never see no hens like them afore,” chuckled the lobsterman as he rowed away. “An’, say, don’t pet ’em much; they might peck yer!”

The lobsters were in the bottom of the tender, and as he rowed back to the launch Tom was careful to keep his feet out of their reach. When he had made fast and carefully lifted the lobsters on board, he put his head into the engine room and listened. Not a sound reached him save the peaceful breathing of his companions. That appeared to put an idea into Tom’s head. With a malicious smile, he tiptoed across to the lobsters, took one gingerly in each hand, and descended to the stateroom. There he placed the lobsters in the middle of the space between the berths, where they would each show to the best advantage, kicked off his sneakers, carefully closed the hatch and the doors, and finally crept back to bed. Once under the covers, he threw his arms out and yawned loudly. That not having the desired effect, he called sleepily to Dan:

“Time to get up, Dan! It’s most half-past seven! Da-a-an!”

“Huh?”

“Time to get up, you lazy chump!”

“Wha-what time is it?” asked Dan fretfully.

“Oh, it’s late; most half-past seven,” answered Tom.

“Is it?” There was quiet for a moment. Then Dan sat up resolutely, stared drowsily about him and tumbled out of bed. As luck would have it, one bare foot landed plump on the cold, slippery back of the nearest lobster. 48 The lobster rolled over, and so did Dan. There was a shriek, and Dan, staring in horrified dismay at the cause of his upset, tried to retreat into Bob’s berth.

That annoyed Bob, who, half awake, struck out at the invader and again sent him sprawling. This time it was the other lobster that Dan came into contact with, and both went rolling up against the locker under Nelson’s berth. But it didn’t take Dan long to pick himself up, and once on his feet he made haste to get off them by sinking into Nelson’s arms and waving them wildly in air.

By that time the stateroom rang with laughter and Barry’s barking. Dan curled his feet up under him and, after making certain that neither of the lobsters had attached themselves to him, joined his laughter with the rest. On the floor the lobsters, justly indignant, or, as Tom remarked, “a bit peeved,” were waving their claws and trying to get back on their feet again. At last Nelson stopped laughing and turned a puzzled countenance to Bob.

“Where’d they come from?” he asked.

“Eh?” asked Bob.

“By Jove!” cried Dan.

Tom only stared his bewilderment.

Nelson looked suspiciously at the others, but Dan and Bob were each in pyjamas, and so, of course, must be Tommy, although the covers still reached to just below his wondering countenance.

“They must have come aboard last night,” said Dan. 49

“But the doors are closed,” said Bob.

“Through the ports, then?”

“Poppycock!” said Nelson. “Lobsters can’t climb. Some one must——”

“Maybe there was a high tide last night,” suggested Tom.

“What’s that got to do with it, I’d like to know?” Bob demanded.

“Why, maybe the water came up to the port lights and the lobsters were swimming on the surface, and they saw Dan and mistook him for a long-lost brother——”

“Tommy, if you call me a lobster, I’ll hammer you! Look at the ugly, crawly things! Ugh! Some one throw ’em overboard!”

“Some smart chump must have opened the door and tossed them in here last night,” said Nelson thoughtfully. “Or maybe this morning.”

“More likely this morning,” said Bob. “And probably the person, whoever he was, dropped them in through the ports.”

“That’s so,” said Tom, a trifle too eagerly. “Bet you that’s just what happened!”

Bob looked at him in dawning suspicion.

“Think that’s the way of it, do you, Tommy?” he asked. Tom nodded, but didn’t seem to care to look at the questioner.

“Maybe a fisherman was going by,” he elaborated, “and saw us all asleep in here, and thought it would be a good joke——” 50

“Is that so?” cried Bob, leaning over and jerking the bedclothes from Tom. “You’re a very smart little boy, aren’t you?”

Dan made a leap and landed astride the culprit.

“You did it, you grinning idiot!” he cried, shaking Tom back and forth.

“Honest, Du-du-du-dan!” gurgled Tom. “I—I——”

“Honest, you what?” demanded Dan, letting up for an instant.

“Did!” squealed Tom. Then chaos reigned and blankets waved as Dan and Tom rolled about the narrow berth. “You’d bu-bu-bu-better lemme up!” panted Tom, “or I won’t cu-cu-cook you any bu-bu-bu-bu-bu-breakfast!”

“Apologize?” asked Dan.

But at that moment a terrific yelping drowned the question. Barry had left the foot of Bob’s berth and proceeded to investigate the visitors on the floor. The natural thing had happened, and Barry was jumping about with a pound and a half of lobster attached to one of his front paws. Hostilities between Dan and Tom were forgotten and everyone rushed to Barry’s rescue. It was Nelson who finally released the dog and tossed the two troublesome guests up into the cockpit. Barry’s paw was badly pinched, but not seriously damaged, and after he had licked it for five minutes steadily he was apparently willing to call the episode closed.

“What did you bring those things in here for,” demanded Nelson, “and where did you get them?” 51

Tom explained the manner of acquiring the prizes, and said that he was going to cook them.

“Cook them!” shrieked Dan. “Why, they aren’t fit to cook; they’re green as grass! They’re probably spoiled!”

This feezed Tom until Bob explained that live lobsters were always more or less green, and that it was boiling them that made them red. But Dan remained antagonistic to the plan of eating them.

“I wouldn’t touch one of them for a hundred dollars,” he declared. “I don’t believe they’re lobsters at all.”

Tom was hurt.

“They are, tu-tu-too!” he asserted indignantly. “I gu-gu-got ’em from a lobster fisher, and saw him pu-pu-pu-pull ’em up.”

“Oh, you get out! Who’s going to believe you, Tommy? You run along and get breakfast.”

“That’s so,” said Nelson. “You’re in disgrace, Tommy, and you’ll have to cook us something pretty nice if you expect to be forgiven.”

“Something nice!” growled Tom. “What do you expect? Spanish omelet and sirloin steak?”

“I don’t care what we have,” replied Dan, “but I want mine fried on both sides.”

“Me too,” added Nelson.

Tom left them to their dressing and took himself off to the corner of the engine room where the stove and sink and ice box were located, and which he had nautically dubbed the galley. Here he busied himself, chuckling now 52 and then over the lobster episode, until Barry’s frantic barking took him to the door. He looked out and then called to the others. The lobsters, quite still now, as though wearied by their recent experiences, were lying side by side near the after locker. In front of them, a safe two feet away, stood Barry. His tail—there was only a bare two inches of it—wagged violently, the hair stood up along the middle of his back and neck, and he was daring the lobsters to mortal combat. Finding himself reinforced by the quartet of laughing boys at the door, he grew very brave and began a series of wild dashes at the enemy, barking hysterically.

“Anybody want to eat them?” asked Bob finally.

Nobody seemed enthusiastic, and Bob heaved them over the side. “There goes your fifty cents, Tommy,” he said. Tom glanced at Dan and grinned.

“It was worth it,” he said.

After a breakfast of fried eggs, bacon, toast, and coffee the four went on deck, feeling ready for anything. Nelson and Tom found seats on the edge of the cabin roof, Dan and Bob sat on the after seat, and the subject of destination was discussed. Bob advanced the merits of the Maine coast as a cruising ground, Dan was in favor of heading south toward New York and Long Island Sound, Tom was for staying where they were, and Nelson remained neutral. Thus matters stood when a launch of about the size of the Vagabond chugged around the point and picked up moorings some fifty feet distant. The discussion died away and the boys watched the new arrival 53 with interest. Her name was the Amy, and she was very similar to the Vagabond in build, save that her cabin was much longer and her whole length perhaps two feet greater. She flew the flag of the Knickerbocker Yacht Club of New York, and trailed a tender behind her. She had a crew of five men, and as the tender was drawn alongside one of the number called across.

“Hello, there!” he called. “Are you entered for the race?”

“No,” answered Nelson. “What race do you mean?”

“To-morrow’s. Marblehead to College Point. Saw you had a tender along, and thought maybe you were in it.”

“No; are you?” replied Nelson.

“Yes.” They seemed to lose interest in the Vagabond after that, and piled into their tender and rowed across to the hotel landing.

“Going for breakfast, I guess,” mused Bob. “What race are they talking about, Nel?”

“I don’t know for sure, but seems to me I read something in the paper about a race for cruising launches from Marblehead to New York.”

“College Point, he said,” observed Tom.

“That’s near New York, on the Sound,” said Dan. “Let’s go into it!”

“We couldn’t now,” said Nelson. “It’s probably too late. Besides, it wouldn’t do for us to try it; it would be pretty risky.”

“I don’t see why,” spoke up Tom eagerly. “That 54 boat isn’t any bigger than the Vagabond; at least, not much!”

“Hello!” said Bob. “Tommy must have got over his nervousness!”

“I tell you what we might do,” said Nelson. “We might go over and see the start. That would be fun, wouldn’t it?”

“Let’s do it!” cried Dan. “Then we can decide meanwhile where we’re going.”

The idea suited all hands, and it was agreed that they should spend the forenoon in cleaning up and run over to the scene of the race after luncheon. “And,” said Dan, “let’s find out about the race. It ought to be in the morning paper. If one of you fellows will put me ashore, I’ll go and buy one.”

So Bob rowed him to the landing, and when he returned the three got out the mops and metal polish and rags and set to work cleaning up the woodwork and polishing the brass. They hadn’t nearly finished by the time Dan hailed from the landing. Tom brought him aboard. He had found a paper and was full of the race. All hands stopped work while he read the account of it.

The race was a handicap affair for cruising launches, and there were twelve entries. The start was to be made the next afternoon, at six o’clock, from Marblehead, and the boats were to race to College Point, N.Y., a distance of about three hundred miles.

“But if it isn’t until to-morrow at six,” asked Tom, “what’s the use of going over there this afternoon?” 55

“That’s so,” said Bob. “We might as well wait until to-morrow morning.”

“But what shall we do this afternoon? Run up to Portland and back?” asked Nelson laughingly.

“Let’s cruise around here,” said Bob. “And you can show me how to run the engine. Some one ought to know, Nel, in case anything happened to you.”

“All right. We’ll finish cleaning up, and then take a run around the harbor if there’s time before lunch. If there isn’t, we’ll go afterwards. How’s that?”

All were agreeable and the work went on again. Nelson got into the tender and, armed with a hand mop and a canvas bucket of fresh water, cleaned the white paint-work of the hull. Tom scrubbed the deck, cockpit floor, and cabin roof, Dan cleaned up below, and Bob shined the bright-work. But, try as they might, there was no such thing as finishing before noon. And so they had an early lunch, and very hungry for it they were, too, and then weighed anchor and headed for the inner harbor on a sight-seeing cruise. They chugged in and out of the shipping, read the names on the dozens of fishing schooners which lined the wharves, and finally raced a tugboat out to the breakwater, winning easily.

There the wheel was given to Dan, and Nelson took Bob below and initiated him into the mysteries of the gas engine. Nelson started at the gasoline tank, and traced the flow of the fuel until it had passed through the cylinders and was discharged at the exhaust. Carburetor—or, in the present case, vaporizer—pump, oil 56 cups, spark plug, and clutch were duly explained, and then Nelson took up the ignition, starting at the battery and following the wires to the engine. Finally, the motor was stopped, the gasoline shut off, and Bob was allowed to start things up again. Of course, he didn’t succeed the first time, nor the second, but in the end he did, and was as pleased as could be. For the rest of the afternoon he stayed in the engine room—while Dan and Tom had a beautiful time on deck running the boat to suit themselves—and by the time they reached their anchorage again Bob had qualified, to his own satisfaction at least, as a gas engineer.

“It’s simple enough when you understand it, isn’t it?” he asked earnestly.

“Yes,” laughed Nelson; “there’s nothing to it at all—until the engine stops and you can’t find out why!”

They had dinner at the Harborside again, and in the evening wrote home to their folks on the lovely stationery with the crossed flags. And at half-past nine, everyone having personally assisted at the lighting of the riding light, they turned in and slept like logs until morning.

“Well!” exclaimed Bob. “Look at the boats!”

The Vagabond was cutting her way through the sunlit waters at the best pace of which she was capable—“easily twelve miles an hour, I’ll bet you,” according to Nelson. Bob had the wheel, and was turning to port as the point drew abreast. Once around the lighthouse, the harbor lay before them blue and sparkling in the morning sunshine, and as full of boats as a raisin pie of raisins. Even Tom, eminently matter of fact, drew his breath as the Vagabond dashed across the harbor mouth.

Marblehead Harbor is naturally one of the most beautiful on the coast, and this morning, thronged with yachts of all descriptions, swinging at their moorings, cream-white sails aflutter in the light breeze, flags flying everywhere, paint and varnish glistening and brasswork catching the sunlight on every side, it presented as fair a sight as one is apt to find. Between the white and black and mahogany-red hulls of the yachts busy, cheerful, impertinent 58 launches darted in and out, filling the air with the sharp explosions of their engines.

On one side the quaint old town came tumbling down to the wharves and the dripping seawall, a delightful hodgepodge of weather-stained sheds and whitewashed houses. On the other, green lawns set with summer cottages and shaded by vividly green elms stretched from the distant causeway to where the shore broke into a rocky promontory, from which the stone and shingle house of the Corinthian Yacht Club arose as though a part of the natural scenery.

“By Jove!” said Nelson. “It doesn’t look as though there was room for us anywhere.”

And it didn’t, so closely were the boats packed together. Nelson stopped down the engine to half speed, and, with her bunting flapping in the breeze and her bright-work agleam, the Vagabond nosed her way through the throng until she was opposite the Boston Yacht Club House. Here a space large enough to swing around in was discovered, and as Bob skillfully turned her toward it Dan held the anchor ready. Then there was a splash, and an excited protest from the exhaust as the engine was reversed; then silence, and the Vagabond had come to anchor as neatly as you wish. After that the four gave themselves to a thorough enjoyment of the scene.