The Project Gutenberg EBook of Four American Naval Heroes, by Mabel Beebe

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Four American Naval Heroes

Paul Jones, Admiral Farragut, Oliver H. Perry, Admiral Dewey

Author: Mabel Beebe

Commentator: James Baldwin

Release Date: July 2, 2011 [EBook #36581]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOUR AMERICAN NAVAL HEROES ***

Produced by Heather Clark, paksenarrion and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

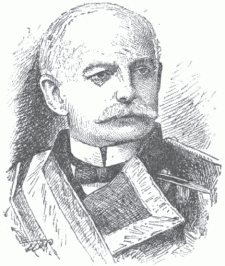

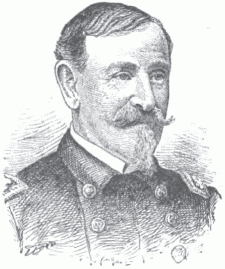

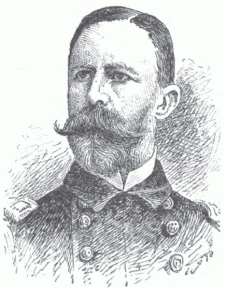

Paul Jones

Oliver H. Perry

Admiral Farragut

Admiral Dewey

A BOOK FOR YOUNG AMERICANS

By MABEL BORTON BEEBE

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY JAMES BALDWIN

WERNER SCHOOL BOOK COMPANY

NEW YORK CHICAGO BOSTON

Four times in the history of our country has the American navy achieved renown and won the gratitude of the nation. These four times correspond, of course, to the four great wars that we have had; and with the mention of each the name of a famous hero of the sea is at once brought to mind. What would the Revolution have been without its Paul Jones; or the War of 1812, without its Perry? How differently might the Civil War have ended but for its Farragut; and the Spanish War, but for its Dewey! The story of the achievements of these four men covers a large part of our naval history.

SEAL OF THE U.S. NAVY.

SEAL OF THE U.S. NAVY.

Six months after the battle of Lexington the Continental Congress decided to raise and equip a fleet to help carry on the war against England. Before the end of the year (1775) seventeen vessels were ready for service, and it was then that Paul Jones began his public career. Many other ships were soon added.

EZEK HOPKINS.

EZEK HOPKINS.

The building and equipping of this first navy was largely intrusted to Ezek Hopkins, whom Congress had appointed Commander-in-Chief, but it does not seem that he did all [Pg 4] that was expected of him, for within less than two years he was dismissed. He was the only person who ever held the title of Commander-in-Chief of the navy. During the war several other vessels were added to the fleet, and over 800 prizes were captured from the British. But before peace was declared twenty-four of our ships had been taken by the enemy, others had been wrecked in storms, and nearly all the rest were disabled. There was no effort to build other vessels, and so, for many years, our country had no navy.

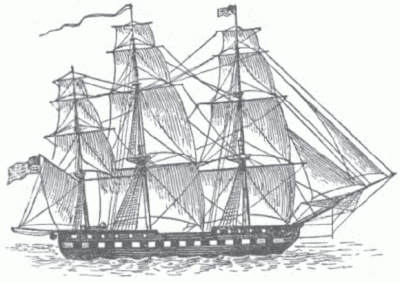

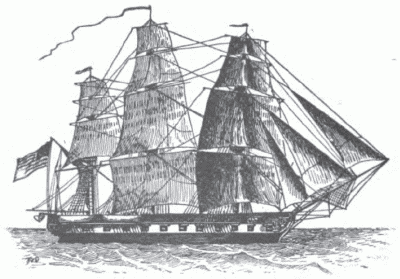

THE FRIGATE CONSTITUTION.

THE FRIGATE CONSTITUTION.

In 1794, when war with the Barbary States was expected, Congress ordered the building of six large frigates. One of these was the famous Constitution, which is still in existence and about which Dr. Holmes wrote the well-known poem called "Old Ironsides."[Pg 5] Through all the earlier years of our history, John Adams used his influence to strengthen our power on the sea; and he was so far successful that he has often been called "The Father of the American Navy." When the War of 1812 began the United States owned a great many gunboats for coast defense, besides seventeen sea-going vessels. It was during this war that the navy especially distinguished itself, and Oliver Hazard Perry made his name famous.

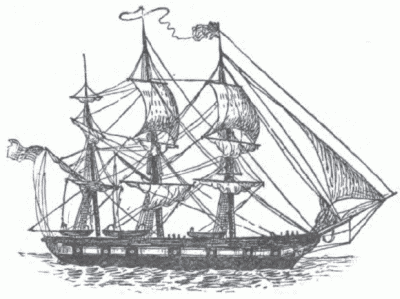

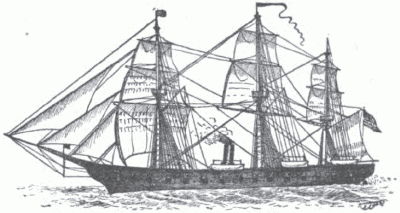

A SLOOP OF WAR.

A SLOOP OF WAR.

The ships of war in those earlier times were wooden sailing vessels, and they were very slow-goers when compared with the swift cruisers which sail the ocean now. The largest of these vessels were called ships of the line, because they formed the line of battle in any general fight at sea. They usually had three decks, with guns on every deck. The upper deck was often covered over, and on the open deck thus formed above there was a fourth tier of guns. This open deck was called the forecastle and quarter-deck. Some of the largest ships of the line carried as many as 120 guns each; the smallest was built to carry 72 guns.[Pg 6]

Next in size to these ships were the frigates. A frigate had only one covered deck and the open forecastle and quarter-deck above it, and therefore had but two tiers of guns. The largest frigate carried sixty guns, besides a large pivot gun at the bow. The American frigates were noted for their speed.

Still smaller than the frigates were the corvettes, or sloops of war, as they are more commonly called. These had but one tier of guns, and that was on the open deck. They were rigged like the larger vessels, with three masts and square sails.

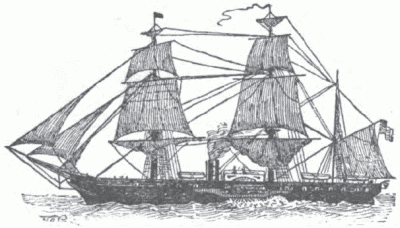

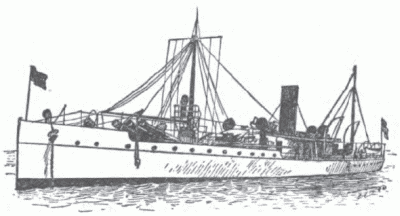

THE STEAM FRIGATE POWHATAN.

THE STEAM FRIGATE POWHATAN.

The fourth class of vessels included the brigs of war, which had but two masts and carried from six to twenty guns. Equal to them in size were the schooners, which also had two masts, but were rigged fore-and-aft. The guns which they carried were commonly much smaller than those on the sloops and frigates.

After Robert Fulton's invention of the steamboat in 1807 there were many attempts to apply steam on vessels of war. But it was a long time before these attempts were [Pg 7] very successful. The earliest war steamships were driven by paddle-wheels, placed at the sides of the vessels. The paddles, besides taking up much valuable space, were exposed to the shots of the enemy, and in any battle were very easily crippled and made useless. But the speed of these vessels was much greater than that of any sailing ship, and this alone made them very desirable. For many years steam frigates were the most formidable vessels in the navy. The first successful steamship of war was the English frigate Penelope, which was built in 1843, and carried forty-six guns. One of the earliest and most noted American vessels of the same type was the Powhatan. The first screw line of battle ship was built by the French in 1849. It was called the Napoleon, and carried one hundred guns. It was so successful that steamships soon began to take the place of sailing vessels in all the navies of the world.

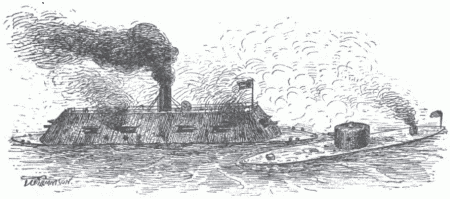

THE MERRIMAC AND THE MONITOR.

THE MERRIMAC AND THE MONITOR.

Up to this time all war vessels were built of wood; but [Pg 8] there had been many experiments to learn whether they might not be protected by iron plating. The first iron-clad ship was built in France in 1858; and not long after that Great Britain added to her navy an entire fleet of iron-clads. All these were built after the same pattern as wooden ships, and were simply covered or protected with iron plates.

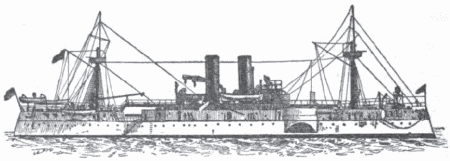

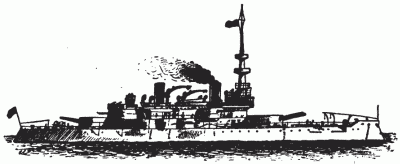

THE BATTLESHIP OREGON.

THE BATTLESHIP OREGON.

The first iron-clads used in our own navy were built soon after the beginning of the Civil War (1861), and were designed for use on the large rivers and along the coast. They were called "turtle-backs," and were simply large steamboats covered with thick slabs of iron and carrying thirteen guns each. The iron slabs were joined closely together and laid in such a manner as to inclose the decks with sloping sides and roofs. The first great deviation from old patterns was the Monitor, built by John Ericsson in 1862. She was the strangest looking craft that had ever been seen, and has been likened to a big washtub turned upside down and floating on the water. The Merrimac, which she defeated in Hampton Roads, was a wooden frigate which the Confederates had made into an iron-clad by covering her with railroad rails. They had also, by giving her an iron prow, converted her into a ram. These [Pg 9] two vessels, the Monitor and the Merrimac, were indirectly the cause of a great revolution in naval warfare; they were the forerunners of all the modern ships of war now in existence. The nations of the world saw at once that there would be no more use for ships of the line and wooden frigates and sloops of war.

THE DYNAMITE CRUISER VESUVIUS.

THE DYNAMITE CRUISER VESUVIUS.

The ships that have been built since that time are entirely unlike those with which Paul Jones and Commodore Perry and Admiral Farragut won their great victories. The largest and most formidable of the new vessels are known as battleships, and may be briefly described as floating forts, built of steel and armed with powerful guns. These are named after the states, as the Oregon, the Texas, and the Iowa. Next to them in importance are the great monitors, such as the Monadnock and the Monterey. These are slow sailers but terrible fighters, and are intended chiefly for harbor defense. The cruisers, which rank next, are smaller than battleships and are not so heavily armed; but they are built for speed, and their swiftness makes up for their lack of strength. Among the most noted of these are the Brooklyn, the Columbia, and the Minneapolis. There [Pg 10] are also smaller cruisers, such as the Cincinnati and the Raleigh, that are intended rather for scout duty than for service in battle. Most of the cruisers are named after cities. One of the strangest vessels in the navy is the dynamite cruiser Vesuvius, which is armed with terrible dynamite guns. Then there is the ram Katahdin. She carries no heavy guns, and her only weapon of offense is a powerful ram. Her speed is greater than that of most battleships, and she is protected by a covering of the heaviest steel armor. Besides all these there are a number of smaller vessels, such as torpedo boats and tugs.

A few old-fashioned wooden vessels—steam frigates and sailing vessels—are still to be found in our navy yards, but these would be of no use in a battle.

In reading of the exploits of our great naval heroes it is well to keep in mind these wonderful changes that have taken place in the navy. Think of the slow-going wooden frigates which sailed the seas in the time of Paul Jones or Commodore Perry—how small and insignificant they would be if placed side by side with the tremendous Oregon or with the cruisers which Admiral Dewey led to victory in the Bay of Manila! But if the glory of an achievement is measured by the difficulties that are encountered and overcome, to whom shall we award the greater honor—to our earlier heroes, or to our later?

James Baldwin.

[Pg 11]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| Introduction | 3 | ||

| THE STORY OF PAUL JONES | |||

| I. | The Little Scotch Lad. | 17 | |

| II. | The Young Sailor. | 20 | |

| III. | The Beginning of the American Revolution. | 23 | |

| IV. | Lieutenant Paul Jones. | 26 | |

| V. | The Cruise of the Alfred. | 29 | |

| VI. | Captain Paul Jones. | 32 | |

| VII. | The Cruise of the Ranger. | 35 | |

| VIII. | The Ranger and the Drake. | 41 | |

| IX. | The Bon Homme Richard. | 45 | |

| X. | The Great Fight with the Serapis. | 49 | |

| XI. | Honor to the Hero. | 57 | |

| XII. | The Return to America. | 61 | |

| XIII. | Ambitious Hopes. | 63 | |

| XIV. | Sad Disappointments. | 66 | |

| THE STORY OF OLIVER H. PERRY | |||

| I. | How the Perry Family Came to Rhode Island. | 71 | |

| II. | School Days. | 75 | |

| III. | Plans for the Future. | 81 | |

| IV. | The Cruise in the West Indies. | 83 | |

| V. | The War with the Barbary States. | 87 | |

| VI. | More Trouble with England. | 94 | |

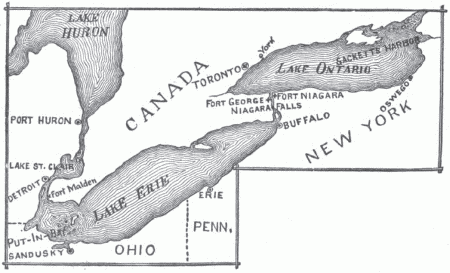

| VII. | War on the Canadian Border. | 100 | |

| VIII. | Oliver Perry Builds a Fleet. | 105 | |

| IX. | "We Have Met the Enemy and They are Ours." | 110 | |

| X. | What Perry's Victory Accomplished. | 117 | |

| XI. | On the Mediterranean again. | 122 | |

| XII. | Captain Perry's Last Cruise. | 126 | |

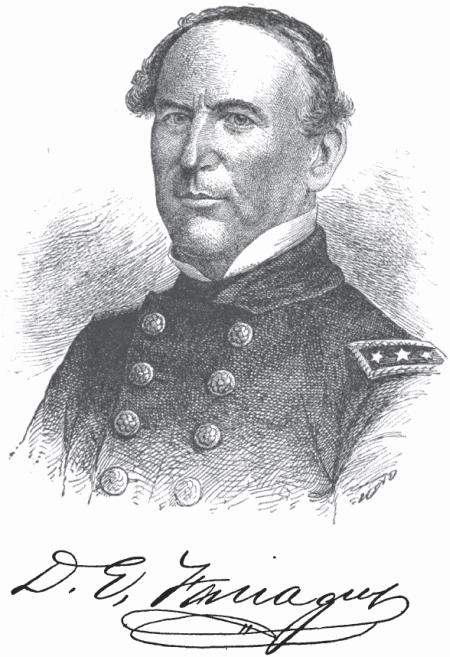

| THE STORY OF ADMIRAL FARRAGUT | |||

| I. | Childhood. | 133 | |

| II. | The Little Midshipman. | 138 | |

| III. | The Loss of the Essex. | 144 | |

| IV. | The Trip on the Mediterranean. | 147 | |

| V. | War with the Pirates. | 150 | |

| VI. | From Lieutenant to Captain. | 155 | |

| VII. | The Question of Allegiance. | 162 | |

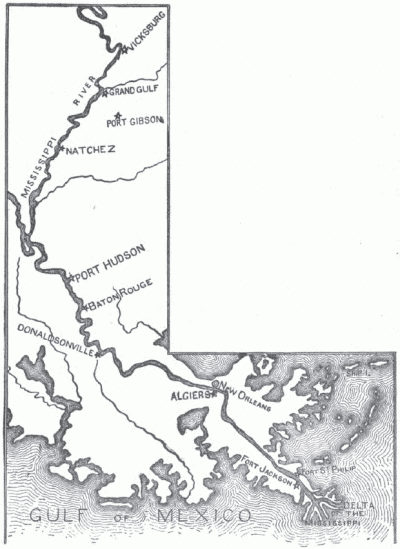

| VIII. | The Capture of New Orleans. | 168 | |

| IX. | The Battle of Mobile Bay. | 177 | |

| X. | Well-Earned Laurels. | 186 | |

| THE STORY OF ADMIRAL DEWEY | |||

| Foreword—Causes of the War with Spain. | 195 | ||

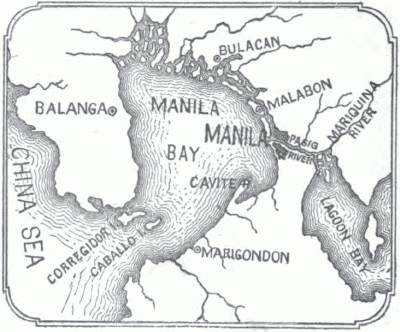

| I. | The Battle of Manila. | 201 | |

| II. | The Boyhood of George Dewey. | 207 | |

| III. | Dewey as a Naval Cadet. | 210 | |

| IV. | From Lieutenant to Commodore. | 212 | |

| V. | The American Navy in Cuban Waters. | 217 | |

| VI. | The Cruise of the Oregon. | 221 | |

| VII. | Lieutenant Hobson and the Merrimac. | 225 | |

| VIII. | The Destruction of Cervera's Fleet. | 230 | |

| IX. | The End of the War. | 236 | |

| X. | Life on an American Man-of-War. | 242 | |

| XI. | Some Facts about the Navy of 1898. | 247 | |

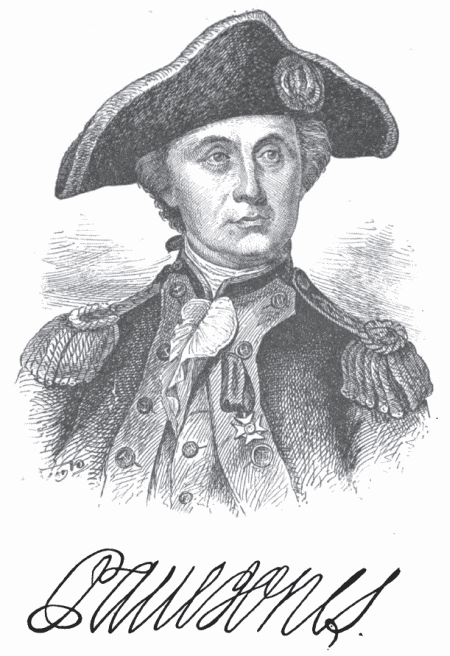

Paul Jones.

Paul Jones.

Many years ago there lived, in the southwestern part of Scotland, on the beautiful bay called Solway Firth, a gentleman whose name was Mr. Craik. In Scotland, a large farm is called an estate. Mr. Craik named his estate Arbigland.

His large house stood high on the shore overlooking the sea. The lawn sloped gradually to the firth.

Mr. Craik's gardener, John Paul, lived in a cottage on the estate. Mr. Craik was very fond of John Paul, for he worked well. He made the grounds like a beautiful park, and planted many trees, some of which are still standing.

One day John Paul married Jean Macduff. She was the daughter of a neighboring farmer. She and John lived very happily in their little [Pg 18] cottage. They had seven children. The fifth child was a boy, named for his father, John Paul. He was born July 6, 1747.

When little John was large enough to run about he liked to play on the beautiful lawn and to wander along the shore of the firth. Sometimes he would sit still for hours watching the waves.

Sometimes he and Mr. Craik's little boy would play with tiny sailboats and paddle about in the water. When they grew tired of this, they would climb among the rocks on the mountains which were back of the estate.

When there were storms at sea, vessels would come into Solway Firth for a safe harbor. The water was very deep near the shore. Because of this the ships could come so near the lawn of Arbigland that their masts seemed to touch the overhanging trees.

Little John Paul and his playmates liked to watch the sailors, and sometimes could even talk to them. They heard many wonderful stories of a land called America, where grew the tobacco that was packed in some of the ships. [Pg 19]

The children would often take their little sailboats to some inlet, where they would play sailor. John Paul was always the captain. He had listened carefully to the commands given by the captains of the large vessels. These he would repeat correctly and with great dignity, though he did not always understand them.

John Paul spent more time in this kind of play than in going to school. In those days there were few schools, and book-learning was not thought to be of much use. At a parish school near by, John learned to spell and to repeat the rules of grammar.

When he was twelve years old he felt that the time had come when he could be a real sailor. So his father allowed him to go across the firth to an English town called Whitehaven. There he was apprenticed to Mr. Younger, a merchant, who owned a ship and traded in goods brought from foreign lands.

He soon went to sea in Mr. Younger's vessel, the Friendship. This ship was bound for America to get tobacco from the Virginia fields. [Pg 20]

At that time the trip across the Atlantic could not be made as quickly as now. There were no steamships, and the sailing vessels had, of course, to depend upon the wind to carry them to their destination. It was several months before the Friendship anchored at the mouth of the Rappahannock River.

Farther inland, on this river, was the town of Fredericksburg. John Paul's eldest brother, William, lived there. He had left his Scottish home many years before, and had come with his wife to Virginia. Here he was now living on his own plantation, where he raised tobacco for the English market.

While the Friendship was in port being loaded for its return voyage, John Paul went to Fredericksburg to stay with his brother. While there he spent the most of his time in hard study. Although he was still young, he had found that he could not succeed as he wished with so little education.

It was during these months in America that he [Pg 21] formed the habit of study. All through the remainder of his life his leisure time was given to the reading of books.

After he returned to Scotland he spent six years in the employ of Mr. Younger. During that time he learned a great deal about good seamanship.

When John Paul was nineteen years of age, the loss of money compelled Mr. Younger to give up his business.

John Paul was soon afterward made mate on a slaver called the Two Friends. This was a vessel whose sole business was the carrying of slaves from Africa to America and other countries.

People at that time did not think there was any wrong in slave-trading. It was a very profitable business. Even the sailors made more money than did those on vessels engaged in any other business.

The Two Friends carried a cargo of slaves to Jamaica, an English possession in the West Indies. As soon as port was reached, John Paul left the vessel. He said that he would never again sail on a slave-trading voyage. He could not endure to [Pg 22] see men and women treated so cruelly, and bought and sold like cattle.

He sailed for home as a passenger on board a small trading vessel. On the voyage both the captain and the mate died of fever, and the ship with all its passengers was in mid-ocean with no one to command.

John Paul took the captain's place, for no one else knew so much about seamanship. This was a daring thing for one so young, as he was not yet twenty years old.

When he brought the vessel safely into port, the owners were so grateful to him that they made him the captain.

Soon afterward he sailed for the West Indies. The carpenter on board was, one day, very disrespectful to the young captain. He was punished by a flogging, and was discharged. Not long after this he died of a fever.

The enemies of John Paul, who were jealous of him, thought this was their chance to do him harm. They said that the flogging had killed the carpenter. [Pg 23]

Many people believed this, and when John Paul again returned to Scotland, he found that his friends had lost their faith in him.

During the next two years he made several voyages, but all the while he remembered the injustice done to him. He finally succeeded, however, in proving to his friends that he was worthy of their confidence.

When John Paul visited his brother in Virginia, America was not much like what it is now. Most of the country was an unexplored wilderness, and there was no United States as we know it to-day.

Some large settlements, known as colonies, had been made in that part of the country which lies between the Atlantic Ocean and the Alleghany Mountains.

Most of the people who lived in these colonies were English, and their governors were appointed by the king of England. [Pg 24]

Each governor, with the help of a few men whom he chose from the people, would make laws for the colony.

Not all the laws were made in this way. Sometimes the king, without caring for the wishes of the colonists, would make laws to suit himself.

Up to this time the people had been obedient and loyal to their king. But when George the Third came to the throne of England, he caused the people a great deal of trouble.

He sent orders to the governors that the colonists should trade with no other country than his own.

All their goods should be bought in England, and, to pay for them, they must send to the same country all the corn, cotton, and tobacco which they had to sell. The colonists wished to build factories and weave their own cloth, but the king would not allow this.

For a long while England had been at war with France. King George said that the colonists should help pay the expenses of that war, and therefore he began to tax them heavily. [Pg 25]

They were obliged to pay a tax on every pound of tea, and stamped paper must be bought for every legal document.

The colonists were much aroused on account of the tea tax and the stamp act, as it was called.

One day startling news came to John Paul in Virginia. A shipload of tea had anchored in Boston harbor. The colonists declared that they would not pay the tax on this tea, and some of them, dressed as Indians, had gone on board the vessel and thrown it all into the harbor.

Later on, came the news that the king had sent his English soldiers to Boston to keep the people quiet. He had also closed the port of Boston and said that no more ships should come in or go out. This aroused the whole country. Everybody felt that something must be done to preserve the freedom of the people.

Each colony chose men as delegates to confer together about what was best to be done. The delegates met in Philadelphia on the 5th of September, 1774. That meeting has since been called the First Continental Congress of America. [Pg 26]

The delegates of the colonies decided to send a petition to the king asking that he would remove the taxes and not make unjust laws.

All winter the people waited for an answer, but as none came, matters grew worse in the spring.

On the 19th of April, 1775, a battle was fought with the king's soldiers at Lexington, in Massachusetts. This was the first battle of the American Revolution.

In the year 1773, soon after the trouble with England had begun, John Paul's brother William died in Virginia. He left some money and his plantation, but had made no will to say who should have them. He had no children, and his wife had been dead for years.

His father had died the year before, and John was the only one of the family now living who could manage the estate.

So he left the sea and went to live on the farm near Fredericksburg, in Virginia. He thought that [Pg 27] he would spend the rest of his life in the quiet country, and never return to the sea.

He soon learned to love America very dearly, even more than he did his own country. He wanted to see the colonists win in their struggle for their rights.

But so good a sailor could not be a good farmer. In two years the farm was in a bad condition and all the money left by his brother had been spent. The agents in Scotland, with whom John Paul had left money for the care of his mother and sisters, had proved to be dishonest, and this money also had been lost.

In the midst of these perplexities, he decided to serve America in the war which every one saw was now inevitable.

Another congress of delegates from the colonies met in 1775, and made preparations for that war. The colonists were organized into an army, with George Washington as the commander in chief.

A fleet of English vessels had been sent across the Atlantic. The swiftest of these sailed up and down the Atlantic coast, forcing the people in the [Pg 28] towns to give provisions to the king's sailors and soldiers. Other vessels were constantly coming over, loaded with arms and ammunition for the English soldiers.

George Washington's army was almost without ammunition. There was very little gunpowder made in this country at that time, and the need of it was very great.

JOHN ADAMS.

JOHN ADAMS.

It was thought that the best way to supply the American army with ammunition was to capture the English vessels. It was for this purpose that the first American navy was organized.

The first navy yard was established at Plymouth. Here a few schooners and merchant vessels were equipped with cannon as warships. These were manned by bold, brave men, who, since boyhood, had been on the sea in fishing or trading vessels. [Pg 29]

No member of the Continental Congress did more to strengthen and enlarge this first navy than John Adams.

In 1775 John Paul settled up his affairs, left the Virginia farm, and went to Philadelphia to offer his services to the naval committee of Congress.

He gave his name as John Paul Jones. Just why he did this, we do not know. Perhaps he did not wish his friends in Scotland to know that he had taken up arms against his native country.

Perhaps he thought that, should he ever be captured by the English, it would go harder with him if they should know his English name. We cannot tell. Hereafter we shall call him Paul Jones, as this is the name by which he was known during the rest of his life.

Congress accepted his offer and he was made first lieutenant on the Alfred, a flag-ship.

The young lieutenant was now twenty-nine years old. His health was excellent and he could [Pg 30] endure great fatigue. His figure was light, graceful, and active. His face was stern and his manner was soldierly. He was a fine seaman and familiar with armed vessels.

He knew that the men placed above him in the navy had had less experience than he. But he took the position given him without complaint.

When the commander of the Alfred came on board, Paul Jones hoisted the American flag. This was the first time a flag of our own had ever been raised.

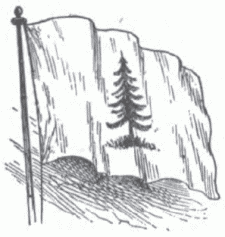

THE PINE TREE FLAG.

THE PINE TREE FLAG.

We do not know just what this flag was like, but some of the earliest naval flags bore the picture of a pine tree; others had a rattlesnake stretched across the stripes, and the words, "Don't tread on me." Our present flag was not adopted until two years later.

On the 17th of February, 1776, the first American squadron sailed for the Bahama Islands.

On the way, two British sloops were captured. The English sailors told the Americans that on the [Pg 31] island of New Providence were forts, which contained a large amount of military supplies. They said that these forts could easily be taken.

The soldiers on a vessel are called marines. A plan was made to hide the American marines in the British sloops. In that way it was thought they could go safely into the harbor of New Providence. Then they could land and take possession of the forts.

THE RATTLESNAKE FLAG.

THE RATTLESNAKE FLAG.

This plan would have been successful, but for one foolish mistake. The squadron sailed so close to the harbor during the night that in the morning all the ships could be seen from the shore. The war vessels should have remained out of sight until the marines had been safely landed from the sloops. The alarm was spread, and the sloops were not allowed to cross the bar.

The commander of the squadron then planned to land on the opposite side of the island and take the forts from the rear, but Paul Jones told him he could not do this. There was no [Pg 32] place to anchor the squadron, and no road to the forts.

However, he had learned from the pilots of a good landing not far from the harbor. When he told the commander of this, he was only rebuked for confiding in pilots.

So Paul Jones undertook, alone, to conduct the Alfred to the landing he had found. He succeeded in doing this and the whole squadron afterwards followed.

The English soldiers abandoned the forts, and the squadron sailed away the same day, carrying a hundred cannon and other military stores.

A short time after this, the American squadron tried to capture a British ship called the Glasgow, but the attempt was not successful.

Because of this failure, one of the captains was dismissed from the navy, and the command of his vessel was given to Lieutenant Jones. This vessel was named the Providence. [Pg 33]

With it and the Alfred, which he also commanded, Captain Jones captured sixteen prizes in six weeks. Among them were cargoes of coal and dry goods.

Best of all, he captured an English vessel bound for Canada, full of warm clothing for the British soldiers. This was a prize that proved of great value to General Washington's poorly clothed army.

In those days there were selfish people just as now. In January, 1777, a jealous commodore succeeded in depriving Paul Jones of his position as captain. He was now without ship or rank. When he appealed to Congress he was put off with promises from time to time. It was not until May that his petitions were heard.

There were three new ships being built for the navy at Boston. Congress gave him permission to choose one of these and have it fitted out as he wished.

While waiting in Boston for these ships to be finished, Paul Jones wrote many wise suggestions about the management of the navy. Congress at [Pg 34] first paid but little attention to these suggestions, but was afterwards glad to act upon them.

These were some of the things he said:

"1. Every officer should be examined before he receives his commission.

"2. The ranks in a navy should correspond to those in an army.

"3. As England has the best navy in the world, we should copy hers."

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN.

Before the ship he had chosen was completed, he was ordered to wait no longer in Boston, but to take the Ranger, an old vessel, and sail at once for France. Through the efforts of Benjamin Franklin, the American Minister to France, the French king had acknowledged the independence of the colonies, and was ready to aid the Americans in the war.

Paul Jones was to carry a letter from Congress to the American commissioners in Paris. [Pg 35]

This letter told the commissioners to buy a new fast-sailing frigate for Captain Jones, and to have it fitted up as he desired. They were then to advise him as to what he should do with it.

When the Ranger sailed out of Boston harbor, the stars and stripes of the American republic waved from the mast head.

Paul Jones was the first naval officer to raise this flag. You remember that two years before, on the Alfred, he had first hoisted the pine tree emblem.

When Jones with his ship entered Quiberon Bay, in France, the French admiral there saluted the American flag. This was the first time that a foreign country had recognized America as an independent nation.

Paul Jones anchored the Ranger at Brest and went to Paris to deliver his letter, and lay his plans before the commissioners. He told them two important things: [Pg 36]

First, that our navy was too small to win in open battle with the fleets of the English.

Second, that the way to keep the English vessels from burning, destroying, and carrying away property on the American coasts, was to send vessels to the English coasts to annoy the English in the same way.

The commissioners thought that these plans should be carried out at once; and since a new frigate could not be purchased for some time, they refitted the Ranger for his use.

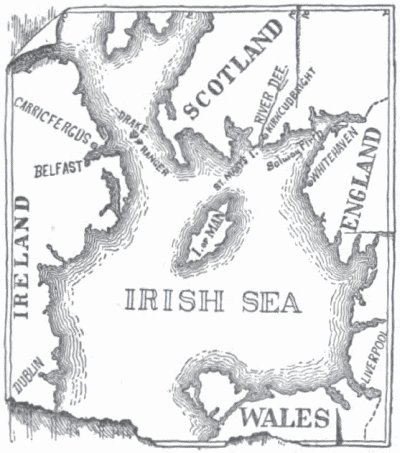

On April 10, 1778, Paul Jones set out on what proved to be a memorable cruise.

You remember that when he first went to sea, as a boy, he sailed from Whitehaven. This town is on the English coast, just across the Solway Firth from John Paul's old home.

He knew there were large shipping yards there, and he determined to set fire to them. He planned to reach the harbor in the night, and burn the ships while the people were asleep.

Because of the wind and tides, it was nearly midnight when he arrived. He found three [Pg 37] hundred vessels of different kinds lying in the harbor. His men were put into two small boats, and each boat was ordered to set fire to half the ships.

It was nearly daylight when they rowed away from the Ranger. Nothing could be heard but the splashing of their oars. Their flickering torches showed to them the old sleeping town, with the many white ships along the shore.

Leaving orders that the fire be speedily kindled, Captain Jones took with him a few men, and scaled the walls of the batteries which protected the harbor. He locked the sleeping sentinels in the guardhouse and spiked the cannon.

Then, sending his men back to the harbor, he went, with one man only, to another fort, which was a quarter of a mile away. Here he also spiked the guns.

After all this had been done he returned to his boats to find that his sailors had done nothing. Not one ship was on fire!

The lieutenant in charge told Paul Jones that their torches had gone out. "Anyway," he said, [Pg 38] "nothing can be gained by burning poor people's property."

Determined that they should not leave the harbor until something was destroyed, Paul Jones ran to a neighboring house and got a light. With this he set fire to the largest ship.

By this time the people had been aroused, and hundreds were running to the shore.

There was no time to do more. The sailors hastened back to the Ranger, taking with them three prisoners, whom Paul Jones said he would show as "samples."

The soldiers tried to shoot the sailors from the forts; but they could do nothing with the spiked guns. The sailors amused themselves by firing back pistol shots.

On reaching the ship they found that a man was missing. Paul Jones was afraid that harm had befallen him. He need not have been troubled, however, for the man was a deserter. He spread the alarm for miles along the shore. The people afterward called him the "Savior of Whitehaven."

Paul Jones was greatly disappointed by the failure [Pg 39] of his plans. He knew that if he had reached the harbor a few hours earlier he could have burned, not only all the ships, but the entire town.

Although the plan to destroy English property to aid the American cause, was a wise one, from a military point of view, yet we cannot understand why Paul Jones should have selected Whitehaven for this destruction. There he had received kindness and employment when a boy. His mother and sisters lived just across the bay, and had he succeeded in burning Whitehaven, the people, in their anger, might have injured the family of the man who had so cruelly harmed them. We wonder if he thought of these things.

The Earl of Selkirk lived near Whitehaven, on St. Mary's Isle. As the Ranger sailed by this island, Paul Jones thought it would be well to take the earl prisoner.

There were many Americans held as prisoners, by the English, and the earl could be exchanged for some of these.

So, with a few men, Paul Jones rowed to the shore, where some fishermen told him that the earl [Pg 40] was away from home. Paul Jones started to go back to his vessel. But his sailors were disappointed and asked his permission to go to the earl's house and take away the silver.

Paul Jones did not like this plan, but at last consented. He did not go with the men, however, but walked up and down the shore until they returned.

The sailors found Lady Selkirk and her family at breakfast. They took all the silver from the table, put it into a bag, and returned to the ship.

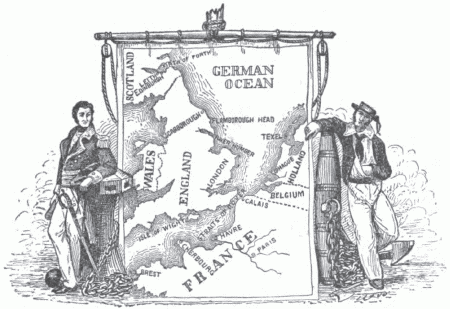

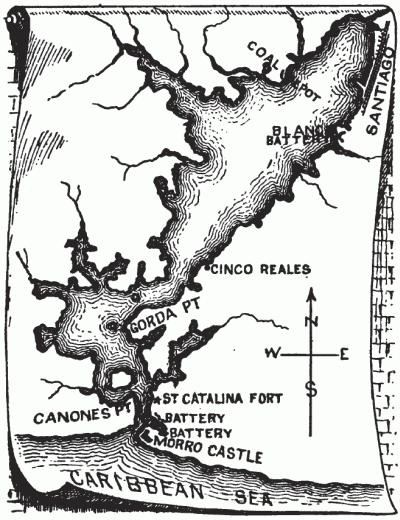

MAP OF THE IRISH SEA, SHOWING THE CRUISE OF THE RANGER.

MAP OF THE IRISH SEA, SHOWING THE CRUISE OF THE RANGER.

Paul Jones was always troubled about this. He afterwards bought the silver for a large sum of money, and sent it back to Lady Selkirk with a letter of apology.

The people in the neighborhood were frightened when they heard of the earl's silver being taken. [Pg 41] They ran here and there, hiding their valuables. Some of them dragged a cannon to the shore, and spent a night firing at what they supposed in the darkness to be Paul Jones' vessel. In the morning they found they had wasted all their powder on a rock!

The next day the alarm was carried to all the towns along the shore: "Beware of Paul Jones, the pirate!"

An English naval vessel called the Drake was sent out to capture the Ranger. Every one felt sure that she would be successful, and five boatloads of men went out with her to see the fight.

When the Drake came alongside of the Ranger, she hailed and asked what ship it was. Paul Jones replied: "The American Continental ship Ranger! Come on! We are waiting for you!"

After a battle of one hour, the Drake surrendered. The captain and forty-two men had been killed, and the vessel was badly injured. Paul [Pg 42] Jones lost only his lieutenant and one seaman. Six others were wounded, one of whom died.

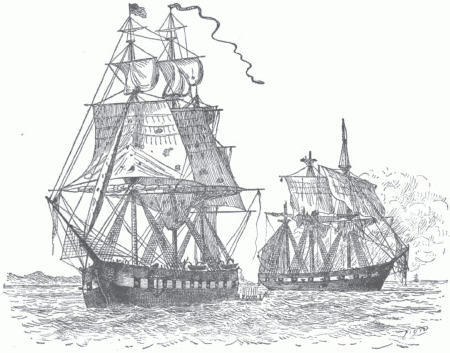

THE RANGER AND THE DRAKE.

THE RANGER AND THE DRAKE.

This was a great victory for Paul Jones. The Drake not only mounted two more guns than the Ranger, but was manned by a crew that was much better drilled. The vessel belonged to the well-established English navy, which was accustomed to victory on the seas. [Pg 43]

Towing the Drake, Paul Jones sailed northward in safety. Then, leaving the Irish Sea, he sailed around the north coast of Ireland and returned to the harbor at Brest, with the Drake and two hundred prisoners. This was just a month from the day he had set out on his cruise.

The French government had now concluded an alliance with the American republic. War had been openly declared between France and England, and all the French people rejoiced over the victory of the Ranger.

Paul Jones was not sorry when Congress sent him an order to bring his vessel to America. It was needed to protect the coasts of New Jersey from the war ships of the British.

The French king did not like brave Paul Jones to return to America. He wished him to remain where he could be of more direct service to France. He therefore caused letters to be sent to him, promising that if he would stay on that side of the Atlantic he should have command of the new frigate he had wished for so long.

Pleased with the prospect of this, he gave up [Pg 44] the command of the Ranger, and it sailed to America under a new captain.

But promises are often more easily made than kept. The French navy was well supplied with ships and officers. These officers were jealous of the success of Paul Jones, and did all they could to prevent him from obtaining his commission.

The summer and most of the winter of 1778 passed away, and Paul Jones was still waiting for his ship. He began to wish he had gone to America.

Some wealthy men offered him a ship if he would take charge of a trading expedition for them. To do this, he must give up his commission in the American navy, and so Paul Jones said, "As a servant of the republic of America, I cannot serve either myself or my best friends, unless the honor of America is the first object."

During these months of waiting, his only weapon was his pen. He wrote letters of appeal to all persons of influence, to Congress, and also to the king of France. [Pg 45]

One day, when Paul Jones was reading "Poor Richard's Almanac," written by Dr. Franklin, he found a paragraph which set him to thinking. It was: "If you would have your business done, go; if not, SEND."

He sent no more letters, but went at once to the French court and pleaded his case there in person. As a result, he was soon after made commander of a vessel which he named the Bon Homme Richard, which means Poor Richard. He did this out of gratitude to Dr. Franklin. [Pg 46]

The Bon Homme Richard was an old trading vessel, poorly fitted out for war. But after his long months of waiting, Paul Jones was thankful even for this.

He was also given command of four smaller vessels. One of these, the Alliance, had, for captain, a Frenchman named Pierre Landais, who was afterwards the cause of much trouble. Paul Jones was ordered to cruise with his small squadron along the west coast of Ireland and to capture all the English merchant vessels he could find.

RICHARD DALE.

RICHARD DALE.

The officer next in command to Paul Jones was Lieutenant Richard Dale, who has since been remembered not only for his bravery during that famous cruise, but for his service to the country at a later period.

On the 14th of August, 1779, the ships put to sea. When they reached the southern point of Ireland, [Pg 47] one of the four small vessels was left behind and deserted.

Cruising northward, the squadron soon captured two valuable prizes. Without asking the permission of Paul Jones, Captain Landais sent these captured vessels to Norway.

On the way, they were taken by the Danes, who returned them to England. The value of these prizes, thus lost through Captain Landais, was about £40,000, or nearly $200,000.

The squadron sailed round the north of Scotland, and down the eastern coast until it came to the Firth of Forth. Here was the town of Leith, and in its harbor lay some English war vessels.

Paul Jones wished to capture these. The winds were favorable, and a landing could easily have been made but for Captain Landais.

Paul Jones spent a whole night persuading this troublesome captain to help him. It was only with a promise of money that he at last succeeded. But in the morning the winds were contrary.

That day the Richard captured an English [Pg 48] merchant ship. The captain promised Paul Jones that if he would allow his vessel to go free, he would pilot the squadron into the harbor.

The people, seeing the fleet piloted by the English vessel, supposed the visit to be a friendly one. So they sent a boat out to the Richard, asking for powder and shot to defend the town from the visit of "Paul Jones the pirate."

Jones sent back a barrel of powder with the message that he had no suitable shot. It was not until the vessels were nearing the harbor that the object of the visit was suspected. The people, in their fright, ran to the house of the minister. He had helped them when in trouble at other times, and could surely do something now.

The good man, with his flock following him, ran to the beach, where he made a strange prayer.

He told the Lord that the people there were very poor, and that the wind was bringing to the shore that "vile pirate," Paul Jones, who would burn their houses and take away even their clothes. "I canna think of it! I canna think of it! I have long been a faithful servant to ye, O Lord. [Pg 49] But gin ye dinna turn the wind aboot and blaw the scoundrel out of our gates, I'll nae stir a foot, but will just sit here till the tide comes in."

Just then a violent gale sprang up, and by the time it had abated the squadron had been driven so far out to sea that the plan was given up.

Long afterward, the good minister would often say, "I prayed, but the Lord sent the wind."

Paul Jones next cruised up and down the eastern coast of England, trying to capture some merchant ships that were bound for London.

About noon, on September 23, 1779, he saw not far from the shore an English fleet, sailing from the north. It was convoyed by two new war ships, the Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough.

Paul Jones at once signaled to his ships to form in line of battle. Captain Landais disobeyed.

The sight of the American squadron seemed to cause confusion in the English fleet. They let fly [Pg 50] their top gallant sails and fired many signals. The Serapis and the Countess drew up in line of battle and waited for the enemy, while the merchant ships ran into port.

It was a clear, calm afternoon. The sea was like a polished mirror, with scarcely a ripple on its surface.

The vessels approached each other so slowly that they scarcely seemed to move. The decks had all been cleared for action, and the captains were full of impatience.

Word had gone from town to town along the shore, that a great battle was soon to be fought. The people along the shore gathered on the high cliffs, eagerly hoping to see the dreaded Paul Jones crushed forever.

The sun had gone down behind the hills before the ships were within speaking distance of each other. The harvest moon came up, full and clear, and shed a soft light over the dreadful battle that followed.

Captain Landais, when he disobeyed Paul Jones' order to join in line of battle, spread the [Pg 51] sails of the Alliance, and went quickly toward the enemy as though to make an attack. But when very near to where the Serapis lay, he changed his course, and sailed away to a place where the battle could be seen without harm.

About half-past seven in the evening, the Richard rounded to on the side of the Serapis within pistol-shot.

Captain Pearson of the Serapis hailed, saying: "What ship is that?" The answer came: "I can't hear what you say."

Captain Pearson repeated: "What ship is that? Answer at once or I shall fire."

Paul Jones' reply was a shot. This was followed by a broadside from each vessel.

At this first fire, two of the guns in the lower battery of the Richard burst. The explosion tore up the decks, and killed many men.

The two vessels now began pouring broadsides into each other. The Richard was old and rotten, and these shots caused her to leak badly. Captain Pearson saw this, and hailed, saying, "Has your ship struck?" [Pg 52]

The bold reply came: "I have not yet begun to fight."

Paul Jones saw, that, as the Serapis was so much the better ship of the two, his only hope lay in getting the vessels so close together that the men could board the Serapis from the Richard.

All this time the vessels had been sailing in the same direction, crossing and re-crossing each other's course.

Finally Paul Jones ran the Richard across the bow of the Serapis. The anchor of the Serapis caught in the stern of the Richard and became firmly fastened there. As the vessels were swung around by the tide, the sides came together. The spars and rigging were entangled and remained so until the close of the engagement.

With the muzzles of the guns almost touching, the firing began. The effect was terrible.

Paul Jones, who had only two guns that could be used on the starboard side, grappled with the Serapis. With the help of a few men, he brought over a larboard gun, and these three were all that he used during the rest of the battle. [Pg 53]

Meanwhile the other ships of the American squadron did strange things. The Pallas, alone, did her duty. In a half hour she had captured the Countess of Scarborough. The Vengeance simply sailed for the nearest harbor.

Worst of all was the conduct of Captain Landais and his ship Alliance. For a while he looked quietly on as though he were umpire. At 9:30 o'clock he came along the larboard side of the Richard so that she was between him and the enemy. Then he deliberately fired into her, killing many men.

Many voices cried out that he was firing into the wrong ship. He seemed not to hear, for, until the battle was over, his firing continued. The Poor Richard had an enemy on each side.

Paul Jones sent some men up the masts and into the rigging to throw hand-grenades, or bombs, among the enemy. One of these set fire to some cartridges on the deck of the Serapis. This caused a terrible explosion, disabling all the men at the guns in that part of the ship. Twenty of them were killed outright. [Pg 54]

By this time so much water had leaked into the Richard that she was settling. A sailor, seeing this, set up the cry: "Quarter! quarter! Our ship is sinking!"

Captain Pearson, hearing the cry, sent his men to board the Richard. Paul Jones, with a pike in his hand, headed a party of his men similarly armed, and drove the English back.

Some of the Richard's men ran below and set the prisoners free. There were more than a hundred of them.

One of these prisoners climbed through the port holes into the Serapis. He told Captain Pearson that if he would hold out a little longer, the Richard would either sink or strike.

Poor Paul Jones was now in a hard place. His ship was sinking. More than a hundred prisoners were running about the decks, and they, with the crew, were shouting for quarter. His own ship, the Alliance, was hurling shots at him from the other side. Everywhere was confusion.

But he, alone, was undismayed. He shouted to the prisoners to go below to the pumps or they [Pg 55] would be quickly drowned. He ordered the crew to their places. He himself never left the three guns that could still be fired.

At half-past ten o'clock, the Serapis surrendered.

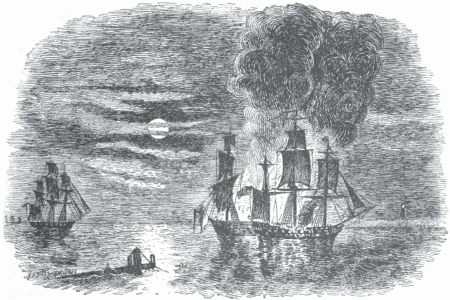

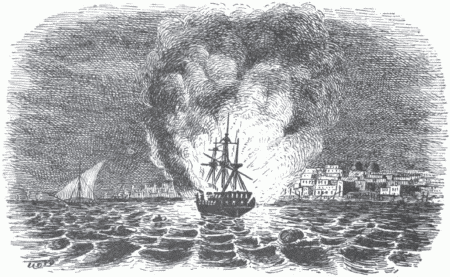

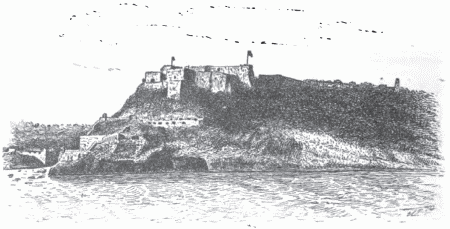

THE SERAPIS AND THE BON HOMME RICHARD.

THE SERAPIS AND THE BON HOMME RICHARD.

When Captain Pearson gave his sword to Paul Jones, he said it was very hard to surrender to a man who had fought "with a halter around his neck." Paul Jones replied, "Sir! You have fought like a hero. I hope your king will reward you."

This battle had lasted for three hours and a half. [Pg 56] It has since been known in history as one of the greatest victories ever won upon the seas. The Serapis and the Countess were both new ships, one of forty guns and the other of twenty. The crews were well-drilled Englishmen.

Everything was against the Richard, and the victory was due alone to the great courage and will of its commander. When the fight was over, Paul Jones separated the ships and set the sails of the Richard. All night every sailor was busy fighting the fire which raged on both ships.

When daylight showed to Captain Pearson the wreck of the Richard, he was sorry he had surrendered. Her rudder was gone and her rotten timbers were split into pieces. Some of the shots had passed entirely through her.

Paul Jones wished to take her into port to show how desperately he had fought, but this was out of the question. By nine o'clock the sailors abandoned her, and at ten she suddenly went down.

Repairing the Serapis as best he could, Paul Jones took her and the Countess of Scarborough, with his unfaithful fleet, to Holland. [Pg 57]

After this great victory, Paul Jones was everywhere received as a hero. The king of France presented him with a gold sword.

He also sent word, through his minister, that, with the consent of Congress, he would make Paul Jones a Knight of the Order of Military Merit. To avoid delay, the gold cross of the order had been sent to the French minister in America, who would present it to Paul Jones when permission to accept it had been received from Congress.

The hero traveled about in Holland and France, from city to city, enjoying his great triumph. Crowds of people were everywhere eager to see him, and a word with him was thought to be a great honor.

The most serious fault in the character of Paul Jones was his vanity. He had always been very fond of praise and glory, and now his longings were partly satisfied by all this homage.

Dr. Franklin wrote him a letter, praising him for his bravery. He thanked him, most of all, for the prisoners he had captured. There were [Pg 58] so many of them that, by exchange, every American, held by the English, could be set at liberty.

While Paul Jones was enjoying this praise, Captain Landais was going about also, claiming for himself the glory for the capture of the Serapis, and trying to make people believe that he was the real hero.

When Dr. Franklin heard from the sailors how he had fired upon the Richard, he ordered him to Paris to be tried.

During the next year, Paul Jones made a few short cruises, but accomplished nothing more than the taking of a few prizes.

At this time the army of George Washington was sorely in need of clothing and military supplies. Word was sent to Dr. Franklin to buy them in France and send them to America by Paul Jones.

Fifteen thousand muskets, with powder, and one hundred and twenty bales of cloth, were bought and stored in the Alliance and the Ariel. Dr. Franklin told Paul Jones to sail with these goods at once. This was early in the year 1780. [Pg 59]

The summer came and passed away, and the ships were still anchored in the French harbor. Paul Jones gave excuse after excuse until the patience of Dr. Franklin was about gone.

Captain Landais had been one cause of the delay. Instead of going to Paris for trial, as Franklin had ordered, he had gone back to the Alliance to stir up mutiny against Paul Jones. He caused one trouble after another and disobeyed every order. Finally, by intrigue, he took command of the Alliance and sailed to America.

But Captain Landais never again troubled Paul Jones. His reception in America was not what he had expected. Instead of being regarded as a hero, he was judged insane, and dismissed from the navy. A small share of prize money was afterward paid to him. On this he lived until eighty-seven years of age, when he died in Brooklyn, New York.

Another reason Paul Jones gave for his delay in France was that he wished to get the prize money due for the capture of the Serapis, and pay the sailors. This gave him an excuse to [Pg 60] linger about the courts where he could receive more of the homage he loved so well.

Then, too, he spent much time in getting letters and certificates of his bravery from the king and the ministers. He wished to show these to Congress when he should arrive in America.

Finally, one day in October, he set sail in the Ariel. He had not gone far when a furious gale forced him to return to port for safety.

For three months longer he waited, hoping still for the prize money that was due. One day he gave a grand fête on his ship. Flags floated from every mast. Pink silk curtains hung from awnings to the decks. These were decorated with mirrors, pictures, and flowers.

The company invited were men and women of high rank. When all was ready, Paul Jones sent his boats ashore to bring them on board.

He, himself, dressed in full uniform, received them and conducted them to their seats on the deck. At three o'clock they sat down to an elaborate dinner which lasted until sunset.

At eight o'clock, as the moon rose, a mock [Pg 61] battle of the Richard and the Serapis was given. There was much noise from the firing of guns, and a great blaze of light from the rockets that were sent up. The effect was beautiful, but the din was such that the ladies were frightened. At the end of an hour this display was ended.

After a dance on the deck, the officers rowed the company back to the shore.

On the 18th of December, 1780, nearly a year after he had received his orders, Jones sailed for America. He arrived in Philadelphia on February 18th, 1781. When Congress inquired into the cause of his long delay, he gave explanations which seemed to be satisfactory. Resolutions of thanks were passed, and permission given to the French minister to present the Cross of Military Merit, which had been sent by the French king.

This cross was presented with great ceremony, and it was ever after a source of much pride to [Pg 62] Paul Jones. He wore it upon all occasions and loved to be called Chevalier.

During the following year Paul Jones superintended the construction of a new war ship, the America, which was being built by Congress.

This was the largest seventy-four gun ship in the world, and he was to be her captain.

Once more Paul Jones was disappointed. Before the America was finished, Congress decided to give her to France. She was to replace a French vessel, which had been lost while in the American service.

Paul Jones was again without a ship. As he could not bear to be idle, he spent the time until the close of the war, with a French fleet, cruising among the West Indies.

As soon as he heard that peace was declared between England and America, he left the French fleet and returned to America. He arrived in Philadelphia in May, 1783.

Now that the war was over, and there was no more fighting to be done, Paul Jones thought that the best thing for him to do was to get the [Pg 63] prize money still due from the French government for the vessels he had captured.

For this purpose, he soon returned to France. After many delays the money, amounting to nearly $30,000, was paid to him. It was to be divided among the officers and crews of the ships which he had commanded.

Paul Jones came again to America in 1787 to attend to the final division of this money.

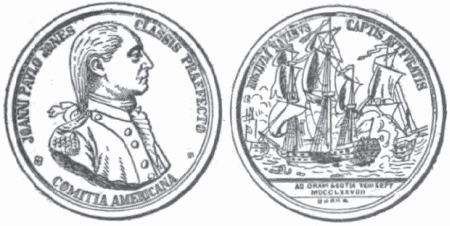

While in this country, Congress ordered a gold medal to be presented to him for his services during the war.

You remember that, during the war, Captain Landais had sent two valuable ships to Norway, and so caused the loss of much prize money. [Pg 64] Denmark had taken these ships, by force, and given them back to England.

Paul Jones determined to go to Denmark to try to induce that country to pay for these ships. In November, 1787, he left America for the last time.

On the way to Denmark, he stopped in Paris. Here he heard some news which pleased him very much.

For some time Russia had been at war with Turkey, and the Russian navy had lately met with several disasters on the Black Sea.

The Russian minister in Paris had heard a great deal about the hero, Paul Jones. So he sent word to the Empress Catherine, who was then the ruler of Russia, that if she would give Paul Jones the command of the Russian fleet, "all Constantinople would tremble in less than a year."

When Paul Jones heard that this message had gone to Russia, he was sure that a chance would come to win still more glory and fame.

He was more anxious than before to go to Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. He would [Pg 65] then be nearer to Russia and could more quickly answer the summons of the empress.

He was not disappointed in this. He was in Copenhagen but a few weeks, when he received the offer of a position in the Russian navy, with the rank of rear-admiral.

He gave up the hope of the prize money, and started in April, 1788, for St. Petersburg.

The story of his trip to Russia shows what a fearless man he was. No danger was too great for him to brave, in order to accomplish any purpose he had in mind.

In order to reach St. Petersburg with the least delay, he went to Stockholm, Sweden. Here he took an open boat and crossed the Baltic Sea, which was full of floating ice.

He did not let the boatmen know of his intentions until they were well out at sea. Then, pistol in hand, he compelled the unwilling men to steer for the Russian shore.

For four days and nights they were out in the open boats, carefully steering through the ice, and many times barely escaping death. [Pg 66]

When, at last, they arrived safely at a Russian port on the Gulf of Finland, he rewarded the boatmen and gave them a new boat and provisions for their return. Scarcely would any one believe the story, as such a trip had never been made before, and was thought to be impossible.

He hurried on to St. Petersburg, where he was warmly welcomed. The story of his trip across the Baltic, added to other tales of his bravery, caused the empress to show him many favors.

After a few days in St. Petersburg, Paul Jones hurried on to the Black Sea to take command of his fleet. But he again met with disappointments. He was not given the command of the whole fleet, as he had expected. Instead, he was given only half, Prince Nassau commanding the remainder. Both of these men were under a still higher authority, Prince Potemkin.

Potemkin was as fond of glory as was Paul [Pg 67] Jones. He and Nassau were both jealous of the foreigner, and Potemkin finally succeeded in having Paul Jones recalled to St. Petersburg.

He arrived there, full of sorrow, because he had achieved no fame. More trouble was in store for him. Some jealous conspirators so blackened his character that the empress would not allow him to appear at court.

Even after proving his innocence to the satisfaction of the empress, he could not regain his former position.

About this time his health began to fail. Sick, both in body and mind, he went back to Paris in 1790, having been in Russia about eighteen months.

It was nearly a year afterward, before he gave up all hope of regaining a position in the Russian service. When the empress refused him this, he quietly waited for death.

This occurred on the 18th of July, 1792, in his lodgings in Paris. His pride and love of titles had left him. He told his friends that he wished no longer to be called Admiral or Chevalier. [Pg 68]

He wished to be simply a "citizen of the United States."

The National Assembly of France decreed him a public funeral, and many of the greatest men of the time followed his body to the tomb. The place of his burial has been forgotten.

The most enduring monument to his memory is to be found in the grateful recollections of his countrymen. The name of Paul Jones, the first naval hero of America, will not be forgotten so long as the stars and stripes float over the sea. [Pg 69]

Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry

A very long time ago, there lived in England a [Pg 71] young Quaker whose name was Edmund Perry.

At that time the Quakers were much persecuted. They were a quiet and peace-loving people, and would not serve in the army. They had their own religious meetings, and refused to pay money for the support of the Church of England. For these reasons, they were imprisoned, beaten, and driven from their homes.

Edmund Perry believed that the Quakers were right, and he could not endure these persecutions. So, in 1650, he came to America to live.

Thirty years before that time, a company of Pilgrims had left England because they also wished to be free to worship God as they chose. [Pg 72] They had founded a colony at Plymouth, which is now in the state of Massachusetts.

Edmund Perry thought that in this settlement of Pilgrims he could surely live peaceably in the enjoyment of his own belief. He did not stay long in Plymouth, however. His Quaker religion was hated there, as it had been in England; and the Pilgrims did not wish to have any one in their colony who did not agree with them.

Not far from Plymouth was the colony of Rhode Island, which had been founded by Roger Williams. Roger Williams declared that a man is responsible for his opinions only to God and his own conscience, and that no one has any right to punish him for his belief.

The people in the Rhode Island colony did not quarrel with one another about religion, but lived together in peace.

Edmund Perry thought that this was the place where he could make a home for himself and his family. He therefore purchased a large tract of land on the shores of Narragansett Bay, near what is now the site of South Kingston. [Pg 73]

Here he lived for the rest of his life, at peace with all about him, even his Indian neighbors. His descendants also lived in this neighborhood. Among them were judges, lawyers, and doctors, as well as farmers and mechanics; and they were always highly respected in the colony.

Christopher Raymond Perry, a great-great-grandson of Edmund Perry, was born in December, 1761.

At that time there were thirteen colonies or great settlements of English people at different places along the Atlantic coast of what is now the United States. But troubles had already begun to brew between the people of these colonies and the king of England. These troubles finally led to the Revolutionary War.

Christopher Perry, although a mere boy, was one of the first persons in Rhode Island to offer himself for this war. He joined a company of volunteers known as the "Kingston Reds"; but soon afterwards left the army and entered the navy. Here he served, having many adventures, until the close of the war, in 1783. [Pg 74]

He had become very fond of a sailor's life, and when there was no more use for him in the navy he obtained a place on a merchant vessel, and went on a cruise to Ireland.

During the homeward voyage he became acquainted with one of the passengers, a beautiful girl of Scotch descent, whose name was Sara Alexander. Soon after their arrival in America, their friendship ripened into love, and in 1784 they were married in Philadelphia.

Christopher Perry, though but twenty-three years of age, was then the captain of a vessel. The young couple went to live with Christopher's father, on the old Perry estate in South Kingston.

This was then a farm of two hundred acres. The old homestead stood at the foot of a hill not far from the Narragansett shore.

Through the trees in a neighboring wood, shone the white stones which marked the graves of the Quaker, Edmund Perry, and many of his children and grandchildren.

The Perry family were glad to welcome Christopher's young wife into their home. She was as [Pg 75] intelligent as she was beautiful; and her sweet and happy disposition made every one love her.

Christopher Perry gave up his life on the sea for a time, and many happy months were spent in the old home.

On the 23d of August, 1785, their first baby boy was born. He was named for an uncle and a great-great-grandfather, Oliver Hazard Perry.

Oliver was a winsome baby and he grew strong and beautiful very fast. Every one loved him, for he thought all strangers were friends, and was never afraid of them.

Indeed he was not afraid of anything, for to him there was no danger. We shall see that he kept this same fearlessness all through his life.

When he was three years old, he was playing one day with an older child, in the road near his grandfather's house. A man was seen coming rapidly towards them on horseback. The elder [Pg 76] child ran out of the way, calling to Oliver to do the same.

The little fellow sat quite still, however, until the horse was nearly upon him. As the horseman drew rein, Oliver looked up into his face and said, "Man, you will not ride over me, will you?"

CHILDHOOD HOME OF OLIVER PERRY.

CHILDHOOD HOME OF OLIVER PERRY.

The gentleman, who was a friend of the family's, carried him into the house, and told the story.

When scarcely more than a baby, Oliver sat [Pg 77] upon his mother's knee, while she taught him letters and words. It was not long before he could read quite well. By the time he was five years old, there were two other babies to keep the beautiful, loving mother busy. So it was thought best to send Oliver to school.

Not far from the Perrys', there lived an old gentleman whom the people loved because of his goodness of heart. As there was no school near by, he had often been asked to teach the neighborhood children.

The good old man was notoriously lazy, and consented upon one condition—that he should be allowed to have a bed in the schoolroom.

Teachers were few in those days, and, since there was no one else, the bed was set up. How amusing it must have been to see the children standing about the master's bed and reciting their lessons!

It was to this strange school that little Oliver was first sent. Some girl cousins lived on the adjoining farm. Though they were all older than he, it was Oliver's duty, each day, to take them to [Pg 78] and from school. No one, not even the other scholars, thought this at all strange. His dignified manners always made him seem older than he really was.

One day his mother told him that he was old enough to go to school at Tower Hill, a place four miles away. Boys and girls would now think that a long way to go to school; but Oliver and his cousins did not mind the walk through the woods and over the hills.

The master of this school was so old that he had once taught Oliver's grandfather. He was not lazy, however, and was never known to lose his temper.

It was not long until a change was made and Oliver was taken away from "old master Kelly."

For several years past, Oliver's father had been again on the sea. He had commanded vessels on successful voyages to Europe and South America, and now he had a large income. He was therefore able to pay for better teaching for Oliver and the younger children.

So the family moved from South Kingston to Newport, a larger town, with better schools. [Pg 79]

At first Oliver did not like the change. The discipline was much more strict than it had been in the little country schools.

His teacher, Mr. Frazer, had one serious fault. He had a violent temper which was not always controlled.

One day he became angry at Oliver and broke a ruler over his head. Without a word, Oliver took his hat and went home. He told his mother that he would never go back.

The wise mother said nothing until the next morning. Then, giving him a note for Mr. Frazer, she told him to go to school as usual. The proud boy's lip quivered and tears were in his eyes, but he never thought of disobeying his mother.

The note he carried was a kind one, telling Mr. Frazer that she intrusted Oliver to his care again and hoped that she would not have cause to regret it.

After this Oliver had no better friend than Mr. Frazer. On holidays they walked together to the seashore and spent many hours wandering along [Pg 80] the beach. The schoolmaster took great delight in teaching Oliver the rules of navigation, and the use of the instruments necessary for sailing a vessel.

Oliver learned these things so readily that it was not long until Mr. Frazer said he was the best navigator in Rhode Island. This, of course, was not strictly true, but it showed what an apt scholar the boy was.

Oliver made many friends in Newport. Among them was the Frenchman, Count Rochambeau. The father of this man was a great general, and had once commanded some French troops who helped the Americans in the Revolutionary War.

Count Rochambeau often invited Oliver to dine with him, and one day he gave him a beautiful little watch.

When Oliver was twelve years old, his father gave up his life on the sea. The family then moved to Westerly, a little village in the southwestern part of Rhode Island.

For five years Oliver had been a faithful pupil of Mr. Frazer's, and he was now far advanced for his years. [Pg 81]

About this time some unexpected troubles arose in our country.

France and England had been at war for years. The French were anxious that America should join in the quarrel; and when they could not bring this about by persuasion, they tried to use force.

French cruisers were sent to the American shores to capture merchant vessels while on their way to foreign ports.

You may be sure that this roused the people from one end of the United States to the other. Preparations for war with France were begun; and the first great need was a better navy.

At the close of the Revolutionary War, all work on government vessels had been stopped. Those that were unfinished were sold to shipping merchants. Even the ships of war that had done such good service, were sold to foreign countries. In this way, the entire American navy passed out of existence. [Pg 82]

But now the President, John Adams, went to work to establish a navy that should give protection to American commerce.

In the spring of 1798, a naval department was organized, with Benjamin Stoddert as the first Secretary of the Navy. The following summer was busy with active preparations. Six new frigates were built, and to these were added a number of other vessels of various kinds.

Captain Christopher Perry was given command of one of the new frigates that were being built at Warren, a small town near Bristol, Rhode Island. This vessel was to be called the General Greene.

In order to superintend the building of this vessel, Captain Perry, with his wife, left his quiet home in Westerly, and went to stay in Warren.

Oliver, then not quite thirteen years old, remained at home to take charge of the family.

He saw that his sister and brothers went to school regularly. He bought all the family provisions. Each day he wrote to his father and mother, telling them about home affairs. In the [Pg 83] meantime, he was busily planning what his work in life should be.

His mother had taught him that a man must be brave, and always ready to serve his country. She had told him many stories of battles fought long ago in her native land across the sea.

Oliver had lived most of his life in sight of the sea, and had spent many hours with seamen. It is not strange, therefore, that he should decide,—"I wish to be a captain like my father."

He had heard of the troubles with France, and he longed to help defend his country. And so at last he wrote to his father, asking permission to enter the navy. It was a manly letter, telling all his reasons for his choice.

The consent was readily given, and Oliver soon afterward received an appointment as midshipman on his father's vessel, the General Greene.

In the meantime, the people grew more eager for war. An army had been raised to drive back [Pg 84] the French, should they attempt to invade the land. George Washington, though nearly sixty-seven years of age, had been appointed commander in chief of the American forces.

In February, 1799, one of the new frigates, the Constellation, under Captain Truxton, defeated and captured a French frigate of equal size. By spring the General Greene was completed, and Captain Perry was ordered to sail for the West Indies.

CAPT. THOMAS TRUXTON.

CAPT. THOMAS TRUXTON.

America had large trading interests with those islands. Many of our merchant vessels brought from there large cargoes of fruits, coffee, and spices. The General Greene was ordered to protect these cargoes from the French cruisers, and bring them safely into port.

For several months Captain Perry's vessel convoyed ships between Cuba and the United States. In July, some of the sailors on board were sick [Pg 85] with yellow fever. So Captain Perry brought the vessel back to Newport.

Oliver went at once to see his mother. The tall lad in his bright uniform was a hero to all the children in the neighborhood.

His brothers and sister considered it an honor to wait upon him. They would go out in the early morning and pick berries for his breakfast, so that he might have them with the dew upon them.

While on shipboard he had learned to play a little on the flute. The children loved to sit about him, and listen to his music.

By the autumn of 1799, the crew of the General Greene were well again, and Captain Perry sailed back to Havana.

It was during the following winter months of cruising with his father, that Oliver was taught his lessons of naval honor. He also applied the lessons in navigation which he had learned from Mr. Frazer.

He read and studied very carefully, and could not have had a better teacher than his father.

While the General Greene was cruising among [Pg 86] the West Indies, Captain Truxton had won another victory with his Constellation. This time he captured a French frigate which carried sixteen guns more than the Constellation.

The French, dismayed at these victories of the Americans, began to be more civil. They even seemed anxious for peace.

THE CONSTELLATION.

THE CONSTELLATION.

War had been carried on for about a year, though it had never been formally declared.

In May, 1800, the General Greene came back to Newport, and remained in harbor until the terms of peace were concluded.

The trouble with France being settled, it was [Pg 87] decided by the government to dispose of nearly all the naval vessels. As a result, many of the captains and midshipmen were dismissed, Captain Perry being one of the number.

Fortunately for the country, young Oliver was retained as midshipman.

On the northern coast of Africa, bordering on the Mediterranean Sea, are four countries known as the Barbary States. These are Tunis, Algiers, Tripoli, and Morocco.

For more than four hundred years, these countries had been making a business of sea-robbery. Their pirate vessels had seized and plundered the ships of other nations, and the captured officers and men were sold into slavery.

Instead of resisting these robbers, most of the nations had found it easier to pay vast sums of money to the Barbary rulers to obtain protection for their commerce.

The Americans had begun in this way, and had [Pg 88] made presents of money and goods to Algiers and Tunis.

Then the ruler of Tripoli, called the Bashaw, informed our government that he would wait six months for a handsome present from us. If it did not come then, he would declare war against the United States.

COMMODORE CHARLES MORRIS.

COMMODORE CHARLES MORRIS.

This did not frighten the Americans at all. Their only reply was to send a fleet of four ships to the Mediterranean. The intention was to force the Bashaw to make a treaty which should insure safety for our ships.

This squadron did not do much but blockade the ports of Tripoli.

A year later, in 1802, a larger squadron was fitted out to bring the Bashaw to terms. Commodore Morris was the commander. On one of the vessels, the Adams, was Oliver Perry as midshipman. [Pg 89]

Soon after the arrival of his ship in the Mediterranean, Oliver celebrated his seventeenth birthday.

The captain of the Adams was very fond of him, and succeeded in having him appointed lieutenant on that day.

For a year and a half, the squadron of Commodore Morris cruised about the Mediterranean. No great battles were fought and no great victories were won.

The Adams stopped at the coast towns of Spain, France, and Italy. Through the kindness of the captain, Oliver was often allowed to go on shore and visit the places of interest.

Commodore Morris, being recalled to America, sailed thither in the Adams; and so it happened that in November, 1803, Oliver Perry arrived again in America.

His father was then living in Newport, and Oliver remained at home until July of the next year.

He spent much of his time in studying mathematics and astronomy. He liked to go out among the young people, and his pleasing manners [Pg 90] and good looks made him a general favorite.

He was fond of music and could play the flute very skillfully. When not studying, he liked most of all to ride horses, and fence with a sword.

While Lieutenant Perry was spending this time at home, the war in the Mediterranean was still being carried on. Commodore Preble, who had succeeded Commodore Morris, had won many brilliant victories.

The most daring feat of all this war was accomplished by Stephen Decatur, a young lieutenant only twenty-three years old.

One of the largest of the American vessels, the Philadelphia, had, by accident, been grounded on a reef. Taking advantage of her helpless condition, the whole Tripolitan fleet opened fire upon her.

Captain Bainbridge, the commander of the Philadelphia, was obliged to surrender. The Tripolitans managed to float the vessel off the reef, and towed her into the harbor.