The Project Gutenberg EBook of Second Edition of A Discovery Concerning

Ghosts, by George Cruikshank

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Second Edition of A Discovery Concerning Ghosts

With a Rap at the "Spirit-Rappers"

Author: George Cruikshank

Release Date: June 24, 2011 [EBook #36512]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A DISCOVERY CONCERNING GHOSTS ***

Produced by Robert Cicconetti and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

SECOND EDITION

OF A

DISCOVERY

CONCERNING

GHOSTS:

WITH A RAP AT THE "SPIRIT-RAPPERS."

BY

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK.

![]()

TO WHICH IS ADDED

A FEW PARTING RAPS AT THE "RAPPERS,"

AND

QUESTIONS, SUGGESTIONS, AND ADVICE

TO THE

DAVENPORT BROTHERS.

DEDICATED TO THE "GHOST CLUB."

PRICE ONE SHILLING.

LONDON:

PUBLISHED BY ROUTLEDGE, WARNE, AND ROUTLEDGE,

AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS.

1864.

Harrild, Printer, London.

I think it a duty to inform the Public that I have a Nephew whose Christian name is Percy. He is employed by a person of the name of "Read," a Publisher, of Johnson's Court, Fleet Street; who, in Advertising any work executed by my Nephew, announces it as by "Cruikshank," instead of (as it ought to be) illustrated by "Percy Cruikshank." And having been informed by numerous persons that they have purchased these publications under the impression that they were works executed by me, I hereby caution the Public against buying any work as mine with the name of READ, of Johnson's Court, upon it as Publisher. I never did anything for that person, and never shall; and I beg the Public to understand that these observations are not directed against my Nephew, to whom I wish every good, but that they are against the said Read, who, by leaving out my Nephew's Christian name, Percy, deprives him of whatever credit he may deserve for his literary and artistic productions, and thereby creating a confusion of persons, which, if not done for the purpose of Deceiving the Public, appears to be very much like it.

A DISCOVERY CONCERNING GHOSTS.

"Enter Ghost."

Hamlet.—"Thou com'st in such a questionable shape."—

Shakespeare.

Questionable!—ay; so very questionable, in my opinion, is the fact of their coming at all, that I am now going to question whether they ever did, or can come. This opinion I know is opposed to a very general, a long-established, and with some a deeply-rooted belief in supernatural appearances, and is opposed to what may be almost considered as well-authenticated facts, which neither the repeated exposure of very many "ghost tricks," and clearly-proved imposture, nor sound philosophical arguments, have been able to set aside altogether. Most persons, therefore, will no doubt consider that the task of "laying" all the ghosts that have appeared, and putting a stop to any others ever making an appearance, is a most difficult task. This is granted; and although I do not believe, like Owen Glendower, that I can "call the spirits from the vasty deep," but on the contrary agree in this respect with Hotspur, if I did call that they would not come, I nevertheless, although no conjuror, do conjure up for the occasion hosts of ghosts which I see I have to contend against. Yes, I do see before me, "in my mind's eye"—

A vast army, composed of ghost, goblin, and sprite!"

With their eyes full of fire, all gleaming with spite!"

All lurking about in the "dead of the night""

With their faces so pale and their shrouds all so white!"

Or hiding about in dark holes and corners,"

To fright grown-up folk, or little "Jack Horners.""

But though they all stand in this fierce grim array,"

Armed with pen and with pencil, "I'll drive them away."

It is not only, however, against these horrible and ghastly-looking cloud of flimsy foes that one has to deal with in a question like this, but there are numbers of respectable and respected authors, and highly respectable witnesses, on the side of the ghosts; and it must be admitted that it is no easy matter to put aside the testimony of all these respectable persons. They may have thought, and some may still think, that they have done, and are doing, good, by supporting this belief; but I know on the contrary that they have done, and are doing, great harm; and I, therefore, stand forth in the hope of "laying" all the ghosts, and settling this long-disputed question for ever.

The belief in ghost, or apparition, is of course of very early date, originating in what are called the "dark ages," and dark indeed those ages were! as a reference to the early history of the world will show; and although we have in these days a large diffusion of the blessed light of intelligence, nevertheless there is still existing, even amongst civilized people, a fearful amount of ignorance upon the subject of Ghosts, Witchcraft, Fortune-telling, and "Ruling the Stars," besides a vast amount of this sort of imaginary and mischievous nonsense. Now it will be as well here to inquire what good has ever resulted from this belief in what is commonly understood to be a ghost? None that I have ever heard of, and I have been familiar with all the popular ghost stories from boyhood, and have of late waded through almost all the works produced in support of this spiritual visiting theory, but in no one instance have I discovered where any beneficial result has followed from the supernatural or rather unnatural supposed appearances; whereas, on the other hand, we do find unfortunately a large and serious amount of suffering and injury arising from this belief in ghosts, and which I shall have occasion to refer to further on; but I will now proceed to bring forward some of the evidences which have been adduced from time to time, all pretty much in the same style, in support of the probability and truth of the appearance of ghosts—first, in fact, to call up the ghosts, in order that I may put them down.

All the ghost story tellers, or writers upon this subject, seem to consider that one most important point in the appearance of apparitions is, that the ghost should be a most perfect and EXACT RESEMBLANCE, in every respect, to the deceased person—the spirit of whom they are supposed to be. Their faces appear the same, except in some cases where it is described as being rather paler than when they were alive, and the general expression is described as "more in sorrow than in anger," but this varies in some instances according to circumstances; but in all these appearances the countenances are so precisely similar, so minutely so, that in one case mentioned by Mrs. Crowe in her "Night-side of Nature," the very "pock-pits" or "pock-marks" on the face were distinctly visible. The narrators also all agree that the spirits appear in similar, or the same dresses which they were accustomed to wear during their lifetime (please to observe that this is very important), so exactly alike that the ghost-seer could not possibly be mistaken as to the identity of the individual, in face, figure, manner, and dress; and on the same authority in some cases the same spirit has appeared at the same moment to different persons in different places, although perhaps 15,000 miles apart, in precisely the same dress.

In referring to the play of "Hamlet," it will be found that Shakespeare has been most particular in describing the general appearance of the Ghost of Hamlet's father, who was

"Doomed for a certain time to walk by night."

For instance, when Marcellus says to Horatio,

"Is it not like the king?"

Horatio replies—

"As thou art to thyself:

Such was the very armour he had on,

When he the ambitious Norway combated;

So frown'd he once, when, in angry parle,

He smote the sledded Polack on the ice."

Horatio also, in describing the Ghost to Hamlet, says—

"A figure like your father,

Armed at all points, exactly, cap-à-pé."

And, in further explanation, it is stated that the Ghost was armed "from top to toe," "from head to foot," that "he wore his beaver up," with "a countenance more in sorrow than in anger," and was "very pale." Then, again, when Hamlet sees his father's spirit, he exclaims—

"What may this mean,

That thou, dead corse, again, in complete steel,

Revisit'st thus the glimpses of the moon."

So also in the play of "Macbeth," when the Ghost of Banquo rises, and takes a seat at the table, Macbeth says to the apparition—

"Never shake

Thy gory locks at me."

And further on he says—

"Thou hast no speculation in those eyes

Which thou dost glare with!"

Daniel de Foe also insists upon, and goes into the most minute details as to the person and dress of a Ghost; and in a work which he published upon apparitions,[1] we may see how careful and circumstantial the author is in his descriptions of apparitions, whose appearance he vouches for in his peculiar narrative and matter-of-fact style. One of these ghost stories is of some robbers who broke into a mansion in the country, and whilst ransacking one of the chambers, they saw, sitting in a chair, "a grave, ancient man, with a long full-bottomed wig and a rich brocaded gown," etc. One of the robbers threatened to tear off his "rich brocaded gown;" another hit at him with a fuzee, and was instantly alarmed at finding it passed through air; and then the old gentleman "changed into the most horrible monster that ever was seen, with eyes like two fiery daggers red hot." They then rushed into another room, and found the same "grave, ancient man" seated there! and so also in another chamber; and he was seen by different robbers in three different rooms at the same moment! Just at this time the servants, who were at the top of the house, threw some "hand grenades" down the chimneys of these rooms. The result altogether was that some of the thieves were badly wounded, the others driven away, and the mansion saved from being plundered. What a capital thing it would be surely, if the police could attach some of these spirits to their force!

Another case, a clergyman (the Rev. Dr. Scot) was seated in his library, with the door closed, when he suddenly saw "an ancient, grave gentleman, in a black velvet gown"—very particular, you observe, as to the material—"and a long wig." This ghost was an entire stranger to Dr. Scot, and came to ask the doctor to do him a favour—asking a favour under such circumstances of course amounts to a command—which was to go to another part of the country, to a house where the ghost's son resided, and point out to the son the place where an important family document was deposited. Dr. Scot complied with this request, and the family property was secured to the son of the ghost in the "black velvet gown and the long wig."

Now one naturally asks here, why did not this old ghost go and point the place out to his son himself? And so also with the well-authenticated story of the ghost of Sir George Villars, who wanted to give a warning to his son, the Duke of Buckingham; which warning, if properly delivered and properly acted upon, might have saved the duke's life; but instead of warning his son himself (take notice), he appeared to one of the duke's domestics, "in the very clothes he used to wear," and commissioned him to deliver the message. After all, this warning was of no use, so this ghost might have saved himself the trouble of coming; but spirits are indeed strange things, and of course act in strange ways.

About the year 1700, a translation from a French book was brought out in London, entitled "Drelincourt on Death;" and after it had been published for some time, Daniel Defoe, at the request of Mr. Midwinter, the publisher, wrote a preface to the work, and therein introduced a short story about the ghost of a lady appearing to her friend. It was headed thus:—"A true Relation of the Apparition of Mrs. Veal, next day after her death, to one Mrs. Bargrave, at Canterbury, on the 8th of September, 1705; which Apparition recommends the perusal of Drelincourt's book of Consolation against the Fears of Death. (Thirteenth edition.)"

Mrs. Veal and Mrs. Bargrave, it appears, were intimate friends. One day at twelve o'clock at noon, when Mrs. B. was sitting alone, Mrs. Veal entered the room, dressed in a "riding habit," hat, etc., as if going a journey. Mrs. Bargrave advanced to welcome her friend, and was going to salute her, and their lips almost touched, but Mrs. V. held back her head and passing her hand before her face, said, "I am not very well to-day;" and avoided the salute. In the course of a long talk which they had, Mrs. Veal strongly recommends Drelincourt's Book on Death to Mrs. Bargrave, and occasionally "claps her hand upon her knee, in great earnestness." Mrs. Veal had been, subject to fits, and she asks if Mrs. Bargrave does not think she is "mightily impaired by her fits?" Mrs. B.'s reply was, "No! I think you look as well as ever I knew you;" and during the conversation she took hold of Mrs. Veal's gown several times, and commended it. Mrs. V. told her it was a "scoured silk" and newly made up. Mrs. Veal at length took her departure, but stood at the street door some short time, in the face of the beast market; this was Saturday the market-day. She then went from Mrs. B., who saw her walk in her view, till a turning interrupted the sight of her; this was three quarters after one o'clock. Mrs. Veal had died that very day at noon!!! at Dover, which is about twenty miles from Canterbury.

Some surprise was expressed to Mrs. Bargrave, about the fact of her feeling the gown, but she said she was quite sure that she felt the gown. It was a striped silk, and Mrs. Veal had never been seen in such a dress; but such a one was found in her wardrobe after her decease.

This story made a great sensation at the time it was published; and "Drelincourt on Death," with the Preface and Defoe's tale, became exceedingly popular.[2]

The absurdities and impossibilities of the foregoing narrative of this apparition of Mrs. Veal need not be pointed out; but the story is introduced here for two reasons; one of which will be explained further on, and the other is to show how the public have been imposed upon with these short stories.

It has all along been known to the literary world that this "true Relation" was a falsehood, and brought forward under the following circumstances:—

Mr. Midwinter, who published the translation of "Drelincourt on Death," finding that the work did not sell, complained of this to Defoe, and asked him if he could not write some preface or introduction to the work for the purpose of calling the attention of the public to this rather uninviting subject. Defoe undertook to do so, and produced this story about the ghost of Mrs. Veal. The gullibility of the public was much greater at that time than now, and they would then swallow anything in the shape of a ghost; a great sensation was created, and the publisher's purpose was answered, as the work had an extraordinary sale; but one cannot help expressing a very deep regret that the author of "Robinson Crusoe" should have so degraded his talent, by thus deliberately foisting upon the public a gross and mischievous falsehood as a veritable truth; and, worse than this, guilty of bringing in the most sacred names upon one of the most solemn subjects which the mind of man can contemplate, for the purpose of supporting and propagating a falsehood for a mercenary purpose.

As the belief in ghosts has long been popular, and considered as an established fact, it may be quite allowable for an author to introduce a ghost into his romance; and it may be argued that authors have thus been enabled "to point a moral" as well as to "adorn a tale," by using this poetical license, or spiritual medium; but in these cases the tales or poems were given out to the world as inventions of the author to amuse the public, or to convey a moral lesson, and were accepted by the public as such.

We find in these foregoing examples that apparitions do appear sometimes to strangers, and sometimes in the dresses in which they had not been seen when alive; but these dresses have been afterwards discovered or accounted for, and it has also been discovered who these strange spirits represented. But it will be seen by the cases cited, and others which are to follow, that this exact appearance, this Vraisemblance is essential, nay, Indispensable, in order that there shall be "no mistake;" for should mistakes be made, it would, in some cases, be perhaps a very serious matter. I fully assent to all this, and to show that I wish to do battle in all fairness, that it shall be a "fair fight and no favour," I am willing even to illustrate my opponents' statements in these particulars, and to do this I here introduce—don't start, reader! not a ghost, but a figure of Napoleon the First, but without a head; not that I mean to imply thereby that this military hero had no head. No, no! quite the contrary, but I have omitted this head and the head of the ghost of Hamlet's father for an especial purpose, as will be explained further on, when I shall have occasion to touch upon these heads again. But if this cut is held at a distance, by any one at all familiar with the portraits or statues of "Napoleon le Grand" in this costume, they will at once recognize who the figure is intended to represent.

Let us now turn to "The Night-side of Nature," and through the dismal gloom which surrounds these apparitions, call up some more spirits, who, according to Mrs. Crowe, and, indeed, on the authority of all other authors who support the ghost doctrine, "generally come in their habits as they lived;" and it appears that there is no difference in this respect between the beggar and the king, for they come

"Some in rags, and some in jags, and some in silken gowns."

At page 289 of this exceedingly cleverly written but most ghastly collection of ghost stories, it is related that the ghost of a beggar-man appeared at the same time in two different apartments (all in his dirty rags, of course), to a young man and a young woman who had allowed this beggar to sleep in their master's barn (unbeknown to their master), where he died in the night, but could not rest after his death until some money of his was found by these young people, who had both suffered in their health in consequence of these visits of the beggar's ghost. They at length consulted and explained all this to a priest, who advised them to distribute the money they had found under the straw (where the beggar had slept and died) between three churches, which advice was accordingly acted upon, and this settled the business, for the dirty ragged ghost never troubled them again.

In contrast to this we have the story of the ghost of a lady of title, who had been in her lifetime Princess Anna of Saxony. She came decked out in "silks and satins," gold lace, embroidery, and jewels, all so grand, and appeared to one of the descendants of her family, Duke Christian of Saxe Eisenburg, requesting him to be so kind as to try and "make it up" between her and her ghost husband, who, it seems, was a bad-tempered man, had quarrelled with her, and had died without being reconciled.

Duke Christian consented to do this. She had walked into the duke's presence, although all the doors were shut, and one day after their first interview she brought her husband to their relative in the same unceremonious manner. Her ghost husband, who had been the Duke Casimer, appeared dressed in his royal robes. They each told their story (these, you will observe were talking ghosts as well as stalking ghosts). Duke Christian most gallantly decided in favour of the lady, and the ghost duke very properly acquiesced in the justice of the decision. Duke Christian then took the "icy cold hand" of the ghost-duke and placed it in the hand of the ghost-wife, whose hand felt of a "natural heat." It appears to be the opinion of the advocates of apparitions that naughty ghosts have cold hands. In this case the husband was the offending party, and was very naughty, and therefore his hands were very cold. It seems strange that his hands should have been cold, for, being naughty, one would suppose he would come from the same place that Hamlet's father did; and from what he said we should conclude that there was a roaring fire there, where the duke might have warmed his cold hands. It further appears that these parties all "prayed and sung together!" after which the now happy ghosts disappeared sans ceremonie, without troubling the servants to open the doors, or allowing Duke Christian to "show them out." One remarkable fact in connection with this story is, that, upon referring to the portraits of these ghosts which hung in the castle, was, that they had appeared in exactly the same dresses which they had on, when these portraits were painted—one hundred years before this time.

Duke Christian died two years after the ghosts' visits, and by his own orders was buried in "quicklime," to prevent, it is supposed, his ghost from walking the earth! He must indeed have been a poor ignorant creature, although a duke, to suppose that "quicklime," or "slow lime," or any other kind of lime, or anything else that would destroy the body, could make any difference with respect to the appearance of the spirit.

The next case, then, is of the ghost of a soldier's wife, who appeared to a "Corporal Q——" who was lying ill in bed, and also to a comrade who was an invalid lying in the next bed. This was in the night, but the corporal could see that she was dressed in a "flannel gown, edged with a black ribbon," exactly like the grave-clothes which he had helped to put on her twelve months before. It appears, however, that he could see through her, flannel gown and all. This female ghost came to the bed-side of the sick man to ask him to write to her husband, who was in Ireland, to communicate something to him which was to be kept a "profound secret."

This is certainly a strange story, but is it not still more strange that this ghost did not go to her husband and tell him the important secret herself, instead of trusting a stranger to do so? It will be observed that there are different classes of ghosts, as there are of living people—the princely, the aristocratic, the genteel, and the common. The vulgar classes delight to haunt in graveyards, dreary lanes, ruins, and all sorts of dirty dark holes and corners, and in cellars. Yes, dark cellars seem to be a favourite abode of these common ghosts. This fact raises the question whether the lower class of spirits are obliged to keep to the lower parts of the house—to the "lower regions"—and are not allowed to go into the parlours or the drawing-rooms, and not allowed to mix with the higher order of ghosts! Can this be a law or regulation amongst the ghosts? If so, is it not most extraordinary that these spirits should not be allowed to choose their own place of residence, and take to the most comfortable apartments, instead of grovelling amongst the rats and mice, the slugs, the crickets, and the blackbeetles? 'Tis strange, 'tis passing strange; but so it appears to be. By the by, some few of these poor spirits of the humble class of ghosts do sometimes, it appears, mount up to the bed-rooms, in the hope, I suppose, of getting occasionally now and then a "comfortable lodging" and a "good night's rest."

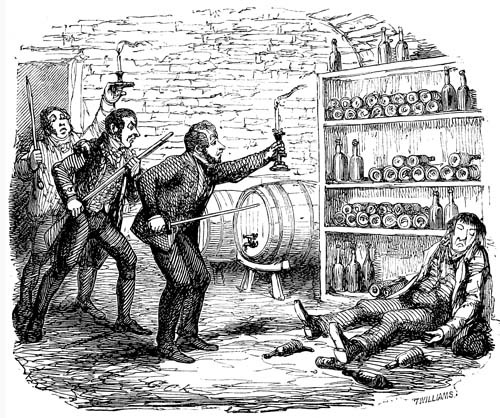

At page 310 of this same work we have an account of a haunted cellar in a gentleman's house, out of town, in which were heard "loud knockings," "a voice crying," "heavy feet walking," etc. The old butler, with his "acolytes," descended to the cellar (wine cellar) armed with sword, blunderbuss, and other offensive weapons, but the ghosts put them all to flight, and they "turned tail" in a fright. Yes, they all ran up-stairs again, followed by the "sound of feet" and "a visible shadow!" This, of course, is a fact; and it so happens that I know another fact about a haunted wine-cellar, which, however, had quite a different result to the foregoing.

In a wine-cellar of a gentleman's house, somewhere near Blackheath, it was found that strange noises were sometimes heard in the evenings and in the night time, in this "wine vault," similar to those described above, such as knocking, groaning, footsteps, etc., so that the servants were afraid to go into the cellar, particularly at a late hour. The master at length determined to "lay" this ghost, if possible, and one evening when these noises had been heard, arming himself with a sword, and the servants with a fowling-piece and a poker, they cautiously descended into the cellar (with lighted candles, of course). Nothing was to be seen there, and all was quiet except a strange, smothered kind of sound, like the hard breathing of an animal, something like snoring, that seemed to proceed out of the earth in one of the dark corners of the vault, when, lo and behold! in turning their lights in the direction from which the sounds came, and advancing carefully, they discovered—what do you think? Don't be alarmed. Why, the ghost lying on the ground, dead—drunk! Yes, the ghost had laid himself, not with "Bell, Book, and Candle," but by swallowing the spirit of alcohol, the spirit of wine, beer, and brandy. Most disgraceful; in fact, this ghost had taken a "drop too much."

Upon looking a little closer, they found that this ghost was one Tom Brown, an under-gardener; and it was discovered that he had tunnelled a hole from the "tool-house" through the wall into the cellar. This spirit was so over-charged with spirit, that he was unable to walk, so was doomed to be carried in a cart to the "cage;" and all the people living round about came next morning to look at the ghost that had been haunting the squire's wine cellar. Oh! what a fortune it would be to any one who could catch a ghost—a real, right down, "'arnest" ghost, and put him in a cage to show him round the country! I wish I had one.[3] It would cost little or nothing to keep such a thing; only the lodging, as he would require neither food, fire, clothing, nor washing!

At page 118, we find an account of an apparition appearing to a gentleman, who was staying at a friend's house at Sarratt, in Hertfordshire, and was awoke in the middle of the night by a pressure on his feet, and, looking up, saw, by the light that was burning in the fire-place, a "well-dressed gentleman," in a "blue coat and bright gilt buttons," leaning on the foot of the bed, without a head! It appears that this was reported to be the ghost of a poor gentleman of that neighbourhood who had been murdered, and whose head had been cut off! and could therefore only be recognized by his "blue coat and bright gilt buttons."

Under any real circumstance this would indeed be too horrible and too serious a subject to turn into ridicule; but in this case, such an evident falsehood, it is surely allowable to "lay" such a ghost as this, such a senseless ghost, in any possible way; in fact, to laugh such a ghost out of countenance—

I, therefore, with my rod of double H. blacklead,

Hold up to scorn this well-dressed ghost without a head.

Any one looking at this figure will clearly see that he does not belong to this world, and has therefore no business here; for, although there may be some persons in this world who, perhaps, go about with a very small allowance of brain, yet every body here must have some sort of a head upon his shoulders, no matter how handsome, or queer-looking it may be. Now I am sorry to be rude to any "well-dressed gentleman," or, indeed, to any body or soul; but as it appears (from the story) that this ghost had really no real business upon earth, what "on earth" does he come here for? Why, for no other object, it appears, but to "show himself off;" so, in my opinion, the sooner he "walks off" the better. By the by, perhaps we ought not to be too severe upon the poor fellow, for, upon consideration, he is placed in rather an awkward position, as his head may be on the look out for the body, and know where it is, but having no legs it cannot get to the body. On the other hand, although the body has legs and could walk to the head, yet, having no eyes, cannot see where the head is; so some excuse may be made upon this head, particularly if he is not a talking ghost.

There is a story, somewhere in the Roman Catholic chronicles, of a martyr, who, after being beheaded, picked up his head, and walked away with it under his arm; but our ghost here, in the "blue coat and bright gilt buttons," is not allowed to do this sort of thing, and the question naturally arises, what has become of, or where is the spirit of this unfortunate gentleman's head? Can the believers in ghosts tell us that? and surely we shall all feel obliged if they can inform us whether the apparitions of all decapitated persons appear without their heads; and, if not, what becomes of their heads? and, further, whether the mutilation of the body can in any way affect the spirit—the soul?

I shall not in this case "pause for a reply," because I know I shall have a very long time to wait for an answer; but in proceeding to bring to the light of day some more facts about ghosts from the dark side of nature, I feel as if some inquisitive spirit was irresistibly compelling me to put questions as I go on writing; and therefore, under these circumstances, present my compliments to those persons who know about ghosts, and the various authors who support this belief, and I shall feel greatly obliged if they will answer my queries at their earliest convenience.—N.B. Shall be glad to hear the replies from the ghosts themselves, provided they pay the postage.

In the first place, then, from the authority quoted above, it appears that a widow lady had, strange to say, married a second time! and that the ghost of her first husband paid her "constant visits." Query, What did the ghost come for, and was the second husband at all jealous of his coming? With respect to a celebrated actor, who had married a second wife, we find that the apparition of his first wife appeared to him, and which appearance unfortunately threw him into a fit, and at the same moment this ghost appeared to the second wife, although they were several hundred miles apart at the time. I can understand why the ghost of his first wife came to visit him who once was hers, that is, because he was such a great actor, and such a good fellow; but why did it appear to the second wife? and how is it that the same spirit can appear in several places at the same instant? I should like to know that. At page 274 we find a dog frightened at the ghost of a soldier! But this is not the only "unlucky dog" that has been terrified by apparitions; several instances are given in different works. Query, How do the "poor dogs" know a ghost is a ghost when they see one, particularly as they appear in the same dresses which they had on when "in the flesh;" and even, suppose they know that they are in the presence of a ghost, what makes them "turn tail?" Yes, why should a dog, especially if he is a spirited dog, do so? for almost in the same page we are told of a horse who recognized his old master, who appeared in the same dress he wore when alive, a "sky-blue coat." This horse did not "turn tail." No! but followed the phantom of his dear old master, who was walking about the farm, and no doubt wanted to give him a ride. Query, If a horse is not frightened at a ghost, why should dogs be frightened at the sight of them? And also, if a goose would be frightened if it saw a ghost? Asses, we know, are sometimes frightened at nothing, and as a ghost is "next to nothing," they must of course be frightened at ghosts. At page 459 we are told of the ghost of a "horse and cart," and also of the "ghosts of sheep." If this be so, doubtless there must likewise be the ghosts of dogs (what "droll dogs" they must be), also of puppies, and asses.

What an interesting subject of inquiry is this for the zoologist!

We find, as we dive into the dark mysteries of apparitions, that there are ghosts of all sorts and sizes, and that there are even lame ghosts, as is proved by the following true tale of the apparition of an officer in India, as related by several of his brother officers, whose words dare not be doubted:—One Major R——, who was presumed to be of about fifty or sixty years of age, was with some young officers, proceeding up a river in a barge; and as they came to a considerable bend in the river, the major and the other officers went ashore, in order to cross the neck of land, taking their fowling-pieces and powder and shot with them, in the hopes of meeting some game; and they also took something to refresh themselves on the road. At one part of their journey they took their "tiffing," and after this they had to jump across a ditch, which the young officers cleared, but the major "jumped short." He told his companions to march on, and he would follow after he had dried and put himself a little in marching order. They saw him lay down his fowling-piece and his hat, and they moved on. After marching some time, they came in sight of the barge, and were wondering why the major did not follow, when, on a sudden, they were surprised to see him (the major) at some distance from them making towards the barge, "without his hat or gun," limping hastily along in his top boots, and he did not appear to observe them. When they arrived at the barge, he was not there. They returned to the spot where they had left him, and found his hat and his fowling-piece, and with the assistance of some natives they discovered the body of the major in a pit dug for trapping wild animals!

I defer asking any questions upon the foregoing for the present, for a reason, but as the next case related is that of the ghost of a young man who had been drowned, and the poor old mother saw her son "dripping with water," we may surely inquire here if there is or can be such a wonderful sight as an apparition of "dripping water!" or ghosts of tears! for we find at page 387 an account of a weeping ghost, who let his tears fall on the face of a female, who "often felt the tears on her cheek; icy cold, but burn afterwards, and leave a blue mark!" And on the same authority we find that there is the ghost of dirt, for the ghost of the old beggar-man was "dirty." And then if the ghost of a chimney-sweep were to appear—and why not the spirit of a sweep as well as anybody else? But if he came, he must also appear "in his habits as he lived." In that case there must be the ghost of soot! Thus there are not only the apparitions of fluids, and dust and dirt, but also of hard substances, as in the case of a ghost who was seen in a garden with the ghost of a "spade in his hand!"

And not only have we, then, ghosts of all these matters, but also a ghost of the "rustling of silk," "creaking of shoes," and "sounds of footsteps," many instances of which will be found in "Footfalls on the Boundary of another World," by Robert Dale Owen, a work most elaborately compiled, and sincerely do I wish that such talent and such research had been engaged and directed to illustrate and assist with light, instead of darkness, the present progressive state of society, instead of striving and endeavouring, as it does, to drive us back into the "outer darkness" of the ignorance of the "dark ages," to endeavour to support and to bring back the mind of man to a belief in the visits of ghosts, of necromancy, bewitching, and all the "black arts;" all of which it was hoped, in the progress of time, would ultimately be swept away from the face of the earth, by pure and sound Christian religion, education and science, all of which go clearly to prove that "black arts" are matters contrary to the natural laws of the creation and the laws of God.

In one of the tales brought forward by this author is an account of the haunting of an old manor-house near Leigh, in Kent, called Ramhurst, where there was heard "knockings and sounds of footsteps," more especially voices which could not be accounted for, usually in an unoccupied room; "sometimes as if talking in a loud tone, sometimes as if reading aloud, occasionally screaming." The servants never saw anything, but the cook told her mistress that on one occasion, in broad daylight, hearing the rustling of a silk dress behind her, and which seemed to touch her, she turned suddenly round, supposing it to be her mistress, but to her great surprise and terror could not see anybody.

Mr. Owen is so thoroughly master of this spirit subject that he must be able to tell us all about this "rustling" of the "silk dresses" of ghosts, and surely every one will be curious to learn the secret of such a curious fact.

The lady of the house, a Mrs. R——, drove over one day to the railway station at Tunbridge to fetch a young lady friend who was coming to stay with her for some weeks. This was a Miss S——, who "had been in the habit of seeing apparitions from early childhood," and when, upon their return, they drove up to the entrance of the manor-house, Miss S—— perceived on the threshold the appearance of two figures, apparently an elderly couple, habited in the costume of the time of Queen Anne. They appeared as if standing on the ground. Miss S—— saw the same apparition several times after this, and held conversations with them, and they told her that they were husband and wife, and that their name was "Children;" and she informed the lady of the house, Mrs. R——, of what she had seen and heard; and as Mrs. R—— was dressing hurriedly one day for dinner, "and not dreaming of anything spiritual, as she hastily turned to leave her bed-chamber, there, in the doorway, stood the same female figure Miss S—— had described! identical in appearance and costume—even to the old 'point-lace' on her 'brocaded silk dress'—while beside her, on the left, but less distinctly visible, was the figure of the old squire, her husband; they uttered no sound, but above the figure of the lady, as if written in phosphoric light in the dusk atmosphere that surrounded her, were the words, 'Dame Children,' together with some other words intimating that having never aspired beyond the joys and sorrows of this world, she had remained 'earth bound.' These last, however, Mrs. R—— scarcely paused to decipher, as her brother (who was very hungry) called out to know if they were 'going to have any dinner that day?'" There was no time for hesitation; "she closed her eyes, rushed through the apparition and into the dining-room, throwing up her hands, and exclaiming to Miss S——, 'Oh, my dear, I've walked through Mrs. Children!'" Only think of that, "gentle reader!" Only think of Mrs. R—— walking right through "Dame Children"—"old point-lace, brocaded silk dress," and all—and as old "Squire Children" was standing by the side of his "dame," Mrs. R—— must either have upset the old ghost or have walked through him also.

Although this story looks very much like as if it were intended as an additional chapter to "Joe Miller's Jest-book," the reader will please to observe that Mr. Owen does not relate this as a joke, but, on the contrary, expects that it will be received as a solemn serious fact; there was a cause for the haunting of this old manor-house, with the talking, screaming, and rustling of silk, and the appearance of the old-fashioned ghosts; there was a secret which these ghosts wished to impart to the persons in the house at that time, and if the gentleman reader will brace up his nerves, and the lady reader will get her "smelling-bottle" ready, I'll let them into the secret. Now, pray, dear madam, don't be terrified! Squire Children had formerly been proprietor of the mansion, and he and his "dame" had taken great delight and interest in the house—when alive—and they were very sorry to find that the property had gone out of the family, and he and his dame had come on purpose to let Mrs. R—— and her friend know all this! There now, there's a secret for you—what do you think of that?

In the year 1854, a baron (of the rather funny name of Guldenstubbé) was residing alone in apartments in the Rue St. Lazare, Paris, and one night there appeared to him in his bed-room the ghost of a stout old gentleman. It seems that he saw a column of "light grayish vapour," or sort of "bluish light," out of which there gradually grew into sight, within it, the figure of a "tall, portly old man, with a fresh colour, blue eyes,[4] snow white hair, thin white whiskers, but without beard or moustache, and dressed with care. He seemed to wear a white cravat and long white waistcoat, high stiff shirt collar, and long black frock coat thrown back from his chest as is wont of corpulent people like him in hot weather. He appeared to lean on a heavy white cane." After the baron had seen this portly ghost, he went to bed and to sleep, and in a dream the same figure appeared to him again, and he thought he heard it say, "Hitherto you have not believed in the reality of apparitions, considering them only as the recallings of memory; now, since you have seen a stranger, you cannot consider it the reproduction of former ideas."

Every one will acknowledge that this was exceedingly kind on the part of the ghost, as he had no doubt to come a long way for the express purpose of setting the baron's mind right upon this point; and had also come from a very warm place, as his frock coat "was thrown from his chest, as is wont with corpulent people in hot weather."

This polite, good-natured, "blue"-eyed apparition, who was "dressed with care," had been the proprietor of the maison—a Monsieur Caron—who had dropped down in an apoplectic fit; and, oh, horror of horrors, had actually "died in the very bed now occupied by the baron!"...

When the daughter heard of the ghost of her papa, appearing thus upon one or two occasions, "she caused masses to be said for the soul of her father," and it is "alleged that the apparition has not been seen in any of the apartments since;" or, to use a vulgarism, we might say here, that this ghost had "cut his stick."

Mr. Robert Dale Owen had this narrative from the baron himself in Paris, on the 11th of May, 1859, and he is of opinion that this "story derives much of its value from the calm and dispassionate manner in which the witness appears to have observed the succession of phenomena, and the exact details which, in consequence, he has been enabled to furnish. It is remarkable also, as well for the electrical influences which preceded the appearance, as on account of the correspondence between the apparition to the baron in his waking state, and that subsequently seen in his dream; the first cognizable by one sense only—that of sight—the second appealing (though in vision of the sight only) to the hearing also. The coincidences as to personal peculiarities and details of dress are too numerous and minutely exact to be fortuitous, let us adopt what theory we may."

As this baron is no doubt a most respectable and well-conducted gentleman, in every respect, I will not say—

That Monsieur the Baron de Guldenstubbe

Had taken too much out of a bottle or tub,

but this I will say, that his account seems to be nothing more or less than a very exact description of some "dissolving view" trick played off upon the baron and others by some clever French neighbour; and as to his dream, it is surely hardly worth while to notice such nonsense, as dreams are now well understood to be only the imperfect operations of the organs of thought, in a semi-dormant state, "half asleep and half awake," and are the effect sometimes of agreeable sensations or painful emotions, during the waking hours, and may be produced to any disagreeable amount by eating a very hearty supper of underdone "pork pies," and going to sleep on the back instead of reclining on the side. We cannot dream of anything of which we have not seen or had something of a similar kind before, nor can we form either awake or in a dream any form whatever—animate or inanimate, which does not partake or form some part of nature's general objects; and in fact we cannot invent an animal form without combining the parts of existing animals either of man or beast. I trust that this fact will be a sufficient answer for Monsieur Caron. And then, as to the "laying" of this ghost, it does seem to me to be extraordinary, that any person possessed of common understanding in these days, let their religion be what it may, should believe that the Almighty God would not let a departed spirit rest, until "masses" had been said for the soul of such person; until some money had been paid to a priest to mumble over a few set forms of prayer. Paid for prayers—prayers at a certain market price! Then, as to the "white cravat," "white waistcoat," "high stiff shirt collar," and "black frock coat," and more particularly the "heavy white cane," is it to be understood that these said "masses" put all these materials to rest, as well as the soul or spirit of the body? If not, where did they go to? Had they to return to purgatory by themselves—had the heavy white walking-stick to walk off without its owner?

In the frame of mind in which this story is written, it is not at all surprising that the author should have taken so much trouble to put these facts together, and that he should evidently be altogether so satisfied with the conclusion which he arrives at. But ghost stories, like many other matters, where a foundation is once laid and established in falsehood or nonsense, such builders may go on, adding any amount of the same materials, upon this false basis. They may go on, working in the dark—piling up one story upon another, until the structure assumes the appearance in the dusk of a well-established and substantial edifice, and looking as if it would stand firm for ever; but undermine this apparently stronghold, with that which is always considered as a great bore, when used in working under the foundations of long-established error or prejudice, namely, Truth, guided by true Religion, and when thus armed and prepared, "spring the mine" with a good "blow-up" of common sense, to let in the light of Heaven and Christian civilized intelligence, and the whole mass of ignorance and superstition is blown and scattered to the winds, "like the baseless fabric of a vision."

It may be said that the truth of this ghost story rests mainly on a stick—leans upon a "heavy white cane." Take away the cane and down comes the ghost! "white waistcoat," "high stiff shirt collar," "black coat," "blue eyes," and all!

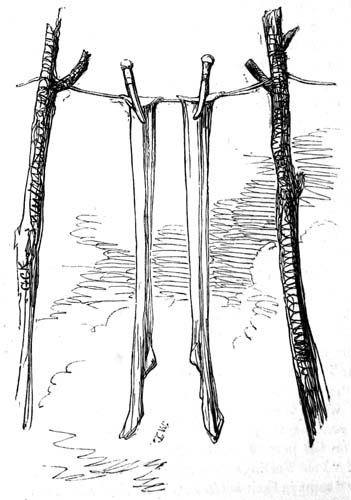

The author of "Footfalls on the Boundary of another World" is evidently a religious man, and had he but thought as deeply upon these matters as I have done, I am sure he would never have been guilty of the impiety of bringing forward such questions as to the spirituality of walking-sticks. But I am well pleased that this "heavy white cane" has been introduced here, because it affords me a handle to cane or to knock down and drive away entirely these hideous and unnatural myths; and also because it enables me to stick to the text, and to introduce here to the public an old friend, as another illustration bearing upon the stick question. This is the apparition of one Tom Straitshank, drawn, as you will see, by your humble servant.

This was a jolly bold daring spirit, and was seen when on board the Victory at the battle of Trafalgar to emerge, like Monsieur Caron, out of some light bluish vapour, very much like the smoke of gunpowder; and in that battle it appears, like one of the heroes in "Chevy Chase," his "legs were smitten off!" but, unlike that warrior, he found that he could not fight "upon his stumps," so he had a pair of wooden legs made, and having bought two stout walking-sticks, was thus enabled to hobble about on his "timber toes." He almost always appeared in various different parts of "Greenwich Hospital," and very often surrounded by, and sometimes emerging from, a vapour very like the smoke of tobacco. I feel here that I ought to have given Tom his pipe, but the drawing of this tar was done many years since, and until I read Mrs. Crowe's book lately, I was not aware that ghosts smoked their pipes, but it actually appears that they do smoke, for at page 210 of "The Night-side of Nature," a ghost is introduced with a "short pipe," and it was found out that the reason of his "walking by night" was, that he owed "a small debt for tobacco!"

And when this little bacca-bill was paid,

This ghost, with his little bacca-pipe, was "laid;"

and we may suppose the spirit laid down his pipe. This ghost of a tobacco-pipe raises the question of what these spiritual pipes are made—of what clay, or if the Meer Schum are only mere shams; what sort of tobacco-leaves their cigars are made of, and if there are any spiritual "cabbage-leaves" mixed up with them.

Yes, we'd just like to know, what weed 'tis they burns,

Whether "Shortcut," "Shag," "Bird's eye," or "Returns."

As the gents here, light their pipes and cigars with a kind of Lucifer match, we may be pretty sure that they will continue to do so elsewhere; but one would like to know also if ghosts chaw tobacco, if they take a quid of "pig-tail," and if the smokers use spittoons—faugh!—and further, as ghosts do smoke, if they take a pinch of snuff, if there is such a thing as spiritual snuff, if there be such things as the spirit of "Irish blaguard" and "Scotch rappee?"

Some of these "sensation" melodramas, or rather farces, might vie in the number of nights in which the performances took place, with some of the "sensation" or popular theatrical pieces of the present day. Here is one entitled, "The Drummer of Tedworth" (what a capital heading for a "play bill!"), in which the ghost or evil spirit of a drummer, or the ghost of a drum (for it does not appear clearly which of the two it was), performed the principal part in this drama, with slight intervals, for "two entire years."

Oh! this drummer, oh! this drummer,

I'll tell you what he used to do,

He used to beat upon his drum,

The "Old Gentleman's tattoo."

The "plot" runs thus:—In March, 1661, Mr. Mompesson, a magistrate, caused a vagrant drummer to be arrested, who had been annoying the country by noisy demands for charity, and had ordered his drum, "oh that drum!" to be taken from him and left in the bailiff's hands. About the middle of April following (that is in 1661), when Mr. Mompesson was preparing for a journey to London, the bailiff sent the drum to his house. Upon his return home he was informed that noises had been heard, and then he heard the noises himself, which were a "thumping and drumming" accompanied by "a strange noise and hollow sound." The sign of it when it came, was like a hurling in the air, over the house, and at its going off, the beating of a drum, like that at the "breaking up of a guard."

"After a month's disturbance outside the house ('which was most of it of board') it came into the room where the drum lay." "For an hour together it would beat 'Roundheads and cockolds,' the 'tattoo,' and several other points of war, as well as any drummer." Upon one occasion, "when many were present, a gentleman said, 'Satan, if the drummer set thee to work, give three knocks,' which it did very distinctly and no more." And for further trial, he bid it for confirmation, if it were the drummer, to give five knocks and no more that night, which it did, and left the house quiet all the night after.

All this seems very strange, about this drummer and his drum,

But for myself, I really think this drumming ghost was "all a hum."

But strange as it certainly was, is it not still more strange, that educated gentlemen, and even clergymen, as in this case also, should believe that the Almighty would suffer an evil spirit to disturb and affright a whole innocent family, because the head of that family had, in his capacity as magistrate, thought it his duty to take away a drum, from no doubt a drunken drummer, who by his noisy conduct had become a nuisance and an annoyance to the neighbourhood?

The next case of supposed spiritual antics was not the drumming of a drum, but a tune upon a warming-pan, the "clatter" of "a warming-pan," and a vast variety of other earthly sounds, which it was proved to have been heard at the Rev. Samuel Wesley's, who was the father of the celebrated John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, at a place called Epworth, in Lincolnshire. These sounds consisted of "knockings," and "groanings," of "footsteps," and "rustling of silk trailing along" (the "rustling of silk" seems to be a favourite air with the ghosts), "clattering" of the "iron casement," and "clattering" of the "warming-pan," and then as if a "vessel full of silver was poured upon Mrs. Wesley's breast and ran jingling down to her feet;" and all sorts of frightful noises, not only enough to "frighten anybody," but which frightened even a big dog!—a large mastiff, who used at first, when he heard the noises, "to bark and leap and snap on one side and the other, and that frequently before any person in the room heard the noises at all; but after two or three days, he used to tremble and creep away before the noise began. And by this, the family knew it was at hand; nor did the observation ever fail." Poor bow woo! what cruel ghosts to be sure, to go and frighten a poor dog in this way.

Mrs. Wesley at one time thought it was "rats, and sent for a horn to blow them away;" but blowing the horn did not blow the ghosts away. No; for at first it only came at night, but after the horn was blown it came in the daytime as well.

There were many opinions offered as to the cause of these disturbances, by different persons at different times. Dr. Coleridge "considered it to be a contagious nervous disease, the acme or intensest form of which is catalepsy." Mr. Owen here asks if the mastiff was cataleptic also? It is rather curious that a cat is mentioned in this narrative. Now supposing the dog could not have been cataleptic, the cat might perhaps have been so.

Some of the Wesley family believed it to be supernatural hauntings, and give the following reason for it:—It appears that at morning and evening family prayers, "when the Rev. Samuel Wesley, the father, commenced the prayer for the king, a knocking began all round the room, and a thundering knock attended the Amen." Mr. Wesley observed that his wife did not say amen to the prayer for the king. She said she could not, for she did not believe that the Prince of Orange was king. Mr. Wesley vowed he could not live with her until she did. He took his horse and rode away, and she heard nothing of him for a twelvemonth. He then came back and lived with her, as before, and although he did so, they add, that they fear this vow was not forgotten before God.

If any religious persons were asked whether they thought that any law, natural or divine, could be suspended or set aside without the permission or sanction of the Creator, their answer would be, nay, must be, certainly not. Yes, this would be their answer. Then is it not extraordinary that the members of this pious clergyman's family, and from whence sprang the founder of such a large and respectable religious sect, should have such a mean idea of the Supreme Being, as to suppose that He would allow the regular laws of the universe to be suspended or set aside, and whole families (including unoffending innocent children) to be disturbed, terrified, and sometimes seriously injured, for such contemptible, ridiculous, and senseless reasons, or purposes, such as those assigned in the various cases already alluded to. It is indeed to me surprising that any one possessing an atom of sound Christian religion, can suppose and maintain for one moment that these silly, supposed supernatural sounds and appearances can be, as they say, "of God."

We may defy the supporters of this apparition doctrine to bring forward one circumstance in connection with these ghosts, which corresponds in any way with the real character of the Creator, where any real benefit has been known to result from such sounds and such appearances—none, none, none; whereas we know that there has been a large amount of human suffering, illness, folly, and mischief, and in former times, we know, to a large and serious extent, but even now, in this "age of intellect," when we come to investigate the causes of some of the most painful diseases amongst children and young persons, particularly young females, we find, on the authority of the first medical men, that they are occasioned by being frightened by mischievous, thoughtless, or cruel persons, mainly in consequence of being taught in their childhood to believe in ghosts. I know a young lady who, when a child, was placed in a dark closet by her nurse, and so terrified in this way that the poor little girl lost her speech, and has been dumb ever since. Dr. Elliotson, in one of his reports of the Mesmeric Hospital, cites several most distressing and painful cases of "chorea," or St. Vitus's dance, and dreadful fits, brought on through fright; and Dr. Wood, physician to St. Luke's Hospital (for lunatics), assures me that many cases of insanity are produced by terror from these causes; but even supposing that there are not very many cases of positive insanity brought on in this way, still the unnatural excitement thus acting on the brain, or the mind dwelling upon such matters, must have an unhealthy tendency.

If all rational and religious persons will give this subject the attention which it demands, they will, I feel confident, see, that this belief in ghosts should not only be discountenanced, but put an end to altogether, if possible, as such notions not only have an injurious effect upon the health and comfort of many persons, particularly those of tender age, but it also debases the proper ideas which man ought to have of the Creator; and not only so, but it also interferes with and trenches upon that mysterious and sacred question, the immortality of the soul; that it disturbs that belief which, with a firm trust and reliance upon the goodness and mercy of God, is the only consolation the afflicted mind can have, when mourning for the loss of those they have loved dearer than themselves.

These hauntings of drumming and knocking, and thumping and bumping, with thundering noises, almost shaking the houses down, accompanied by the delicate rustlings of silk and trailing of gowns, etc., were at the time suspected of being tricks; and by the perusal of the following cases the reader will see that such tricks can and have been played, and such imposture carried on so successfully as to deceive clergymen and others; and but for the severe natural tests brought to bear upon the supposed supernatural actors, would no doubt have been quoted by Mr. Owen and others as well-attested, well-established, veritable spiritual performances.

At the corner of a street which runs from Snow Hill into Smithfield, stands what I consider a public nuisance, commonly called a "public-house," the sign of "The Cock," and that which is now a street was formerly a rustic lane, and took its name from the sign of that house, and therefore called to this day "Cock Lane," which locality, in about the years 1754 to 1756, became one of the most celebrated places in London, in consequence, as it was believed, of one of the houses therein being taken possession of by a female ghost, who was designated "the Cock Lane ghost."

A man of the name of Parsons kept the house, and in which lodged a gentleman and his wife of the name of Kempe. This lady died at this house, and after her death it was given out by Parsons that his daughter, then eleven years of age (who used to sleep with Mrs. Kempe when her husband was out of town), was "possessed" with the spirit of the deceased lady, and that the spirit had informed the little girl that she had been murdered by her husband—that she had been "poisoned!" A vast number of respectable ladies and gentlemen, including clergymen, were "taken in"—but happily for themselves not "done for"—by this ghost; and it is said that even the celebrated Dr. Samuel Johnson was convinced of the spirituality of the "knocks" which the ghost gave in answer to questions, for it kept up conversations in precisely the same manner—that is, by "knocks" or "raps"—as the "spirit-rappers" do at the present day. The "scratchings" and "knocks" were only heard when Parson's little daughter was in bed.

After this sort of thing had gone on for a considerable time, and a post-mortem examination of the body of the supposed murdered lady, which had been deposited in the vaults of St. John's, Clerkenwell Close, Mr. Kempe found it necessary to take steps to defend his character. The child was removed to the house of a highly-respectable lady, where "not a sound was heard," no "scratchings" or "knocks," for several nights; but the girl Parsons, who was now a year or two older, upon going to bed one night informed the watchers that the ghost would pay a visit the following morning; but the servants of the house informed the watchers that the young lady had taken a bit of wood, six inches long by four inches broad, into bed with her, which she had concealed in her stays. This bit of wood was used to "stand the kettle on." The imposture was discovered, and the poor girl confessed to the wicked trickery which her parents had taught her to practise!

Mr. Kempe indicted Parsons and others for conspiracy against his life and character, the case was tried before Lord Mansfield at Guildhall, July 10th, 1756, and all the parties convicted. The Rev. Mr. More and a printer, with others, were heavily fined. Parsons was set in the pillory three times in one month and imprisoned for two years, his wife for one year, and Mary Eraser, the "Medium," for six months in Bridewell, and kept to hard labour. It came out in the course of investigation that Master Parsons had borrowed some money of Mr. Kempe, and it was rather suspected that he did not want to pay it back again.

Another celebrated spiritual farce was enacted in 1810, entitled "The Sampford Ghost." This is a village near Tiverton, in Devonshire, and the following striking performances were "attested by affidavit of the Rev. C. Cotton," who, by the by, was of opinion that "a belief in ghosts is favourable to virtue."

Imprimis, "stamping on the boards answered by similar sounds underneath the flooring, and these sounds followed the persons through the upper apartments and answered the stamping of the feet. The servant women were beaten in bed 'with a fist,' a candlestick thrown at the master's head but did not hit him, heard footsteps, no one could be seen walking round, candles were alight but could see no one, but steps were heard 'like a man's foot in a slipper,' with rapping at the doors, etc. etc. After this the servants were slapped, pushed, and buffeted. The bed was more than once stuck full of pins, loud repeated knockings were heard in all the upper rooms, the house shook, the windows rattled in their casements, and all the horrors of the most horrible of romances were accumulated in this devoted habitation." Amongst other things it was declared by a man, of the rather suspicious name of "Dodge," that the prentice boy had seen "an old woman descend through the ceiling."

The house was tenanted by a man of the name of Chave, a huckster. The landlord was a Mr. Tully, who determined to investigate this matter himself, and went to sleep, or rather to pass the night, at the house for this purpose. The account says that "he took with him a reasonable degree of scepticism, a considerable share of common sense;" and I believe a good thick stick, which is, in my opinion, a much more powerful instrument in laying these kinds of ghosts than the old-fashioned remedy of "bell, book, and candle."

When Mr. Tully went to the house he saw "Dodge" speaking to Mrs. Chave in the shop, and also saw him leave the house; but when he went up stairs by himself who should he see but this same "Dodge," who had got up stairs by a private entrance, but who could not dodge out of Mr. Tully's way. So Mr. Tully pounced upon him and locked him in the room, where he also found a mopstick "battered at the end into splinters and covered with whitewash," and this was the ghost that answered the stamping on the floors. Mr. Tully went to bed, and as no ghosts thumped he went to sleep and had a good night's rest; and upon examining the house the next day, found the ceilings below in "a state of mutilation," from the ghostly thumps it had received.

Tho cause of the house being haunted was a conspiracy on the part of Chave and his friends to get the house at a very low rent, as he would not mind living on the promises, but other persons would not, of course, be likely to take a "haunted house."

A drunken mob one day met and assaulted Chave after this trick was exposed, and he took refuge in his "haunted house," from whence he fired a pistol and shot one man dead. Another man was also killed at the same time, thus two lives were sacrificed to this "Sampford ghost." The Rev. C. Cotton died shortly after this ghost was discovered to be a flam, or sham ghost; it was supposed of chagrin and vexation at being made a butt of by the vulgar for his simplicity and credulity.

Another sensation farce was "The Stockwell Ghost," which performed its tricks very cleverly and successfully at a farm-house in that place in the year 1772. It broke nearly every bit of glass, china, and crockery in the house, and no discovery was made at the time of the how, the why, or the wherefore. But in "The Every Day Book," edited and published by W. Hone, the whole matter is explained in the confession of a woman who lived at the house as servant girl at the time, and who played the part of the ghost so well, that she escaped detection, and came off, only suspected by a few.

The inutility of attempting to do away entirely with this popular belief in ghosts by arguments, however well founded on reason and science, has already been hinted at; but it will be only fair that science should just put a word in, as it can do no harm and may do good.

In "Sketches of the Philosophy of Apparition, or an Attempt to Trace such Illusions to their Physical Causes, by Samuel Hibbert, M.D., F.R.S.E.," the author states his opinion to be that "Apparitions are nothing more than ideas or recollected images of the mind, which have been rendered more vivid than actual impressions," perhaps by morbid affections. It is also pointed out that "in ghost stories of a supposed supernatural character which by disease are rendered so unduly intense as to induce spectral illusions, may be traced to such fantastical objects of prior belief as are incorporated in the various systems of superstition which for ages have possessed the minds of the vulgar." "Spectral illusions arise from a highly excited state of the nervous irritability acting generally upon the system, or from inflammation of the brain."

"The effect induced on the brain by intoxication from ardent spirits, which have a strong tendency to inflame this organ, is attended with very remarkable effects. These have lately been described as symptoms of 'delirium tremens.' Many cases are recorded which show the liability of the patient to long-continued spectral impressions."

Sir David Brewster represents these phenomena as images projected on the retina—from the brain, and seen with the eyes open or shut.

Of the many causes assigned for spectral illusions the following may be enumerated:—Holy ecstasies, various diseases of the brain, diseases of the eye, extreme sensibility or nervous excitement from fright, various degrees of fever, effects of opium, delirium tremens, ignorance and superstition, catalepsy, and confused, indistinct, or uncomprehended natural causes. Now all persons who suppose they see ghosts are at liberty to select any of the foregoing causes for their being so deluded, for delusion it is, as I hope presently to prove; but they may rest assured that these supposed spectres are always produced either by disease or by over-excited imagination, which in some cases it may be said amounts to disease.

However, to return to the ghosts. A very common, or rather the common, idea of a ghost is generally a very thin and scraggy figure; but if there are such things there must be fat ghosts as well as thin ghosts; fat or thin people are equally eligible "to put in an appearance" of this sort if they can; and to carry out this idea and make it quite clear, I here introduce an old acquaintance of the public, Mr. Daniel Lambert, as he appeared to my un-excited imagination whilst engaged on this work. Now if Daniel came as an apparition, he must, according to the authorities in these matters, not only "come in his habits as he lived," that is, in the clothes he wore, but must also come in his fat, or he would not be recognized as the fattest man "and the heaviest man that ever lived," and although he weighed "52 stone 11 pounds" (14 lb. to the stone) in the flesh, in the spirit, he would, of course, be "as light as a feather," or rather an "air bubble;" and as he could not dance and jump about when alive, I thought if I brought him in as a ghost, I'd give him a bit of a treat, and let him dance upon the "tight rope."

Most persons will remember a story told by "Pliny the younger" of the apparition of "an old" man appearing to Athenadorous, a Greek scholar. This ghost was "lean, haggard, and dirty," with "dishevelled hair and a long beard." He had "chains on," and came "shaking his chains" at the Greek scholar, who heeded him not, but went on with his studies. The old ghost, however, "came close to him and shook his chains over his head as he sat at the table," whereupon Athenadorous arose and followed the dirty old man in his chains, who went into the courtyard and "stamped his foot upon a stone about the centre of it, and—disappeared." The Greek scholar marked the spot, and next day had the place dug up, when, lo and behold, they found there the skeleton of a human being.

Going back to the days of "Pliny the younger" is going back far enough into early history for my purpose, which is to show that the notions about apparitions which prevailed at that period are the same as those of the present day, that is, of their appearing in the dresses they wore in their life-time, in every minute particular, as to form, colour, and condition, new or old, as the case might be; but to prevent any mistake upon this head, I will just add some few words from that reliable authority, Defoe, who, you will have already remarked, is exceedingly particular as to the exactness of every article of dress; but in what follows he goes far beyond any other writer on this subject, for instance he says, "We see them dressed in the very clothes which we have cut to pieces, and given away, some to one body, some to another, or applied to this or that use, so that we can give an account of every rag of them. We can hear them speaking with the same voice and sound, though the organ which formed their former speech we are sure is perished and gone."

From the various instances of the appearance of apparitions which have been brought before the reader, it will, I presume, be admitted that abundant and sufficient proof has been given that the writers about ghosts, and all those who have professed to have seen ghosts, declare that they appear in the dresses which they wore in their lifetime; but from all I have been able to learn, it does not appear that from the days of Pliny the younger down to the days of Shakespeare, and from thence down to the present time, THAT ANY ONE HAS EVER THOUGHT OF THE GROSS ABSURDITY, AND IMPOSSIBILITY, OF THERE BEING SUCH THINGS AS GHOSTS OF WEARING APPAREL, IRON ARMOUR, WALKING STICKS, AND SHOVELS! NO, NOT ONE, except myself, and this I claim as my DISCOVERY CONCERNING GHOSTS, and that therefore it follows, as a matter of course, that as ghosts cannot, must not, dare not, for decency's sake, appear WITHOUT CLOTHES; and as there can be no such things AS GHOSTS OR SPIRITS OF CLOTHES, why, then, it appears that GHOSTS NEVER DID APPEAR, AND NEVER CAN APPEAR, at any rate not in the way in which they have been hitherto supposed to appear.

And now let us glance at the material question, or question of materialism.

In the year 1828, a work was published, entitled "Past Feelings Renovated; or, Ideas occasioned by the perusal of Dr. Hibbert's Philosophy of Apparitions," which the author says were "written with the view of counteracting any sentiments approaching materialism, which that work, however unintentional on the part of the author, may have a tendency to produce." The author of "Past Feelings Renovated" is a firm believer in apparitions, who generally "come in their habits as they lived;" and in his preface he says, "The general tendency of Dr. Hibbert's work, and evident fallacy of many of the arguments in support of opinions too nearly approaching 'materialism,' induced me to give the subject that serious consideration which it imperatively demands."

This author, it will be perceived, is very much opposed to anything like "materialism" in relation to this question, and is strongly in favour of "spiritualism," but will he be so good as to tell us what "a pair of Buckskins" are made of? and what a pair of Top-boots are made of? and whether these materials are spiritualized by any process, or whether THE CLOTHES WE WEAR ON OUR BODIES BECOME A PART AND PARCEL OF OUR SOULS? And as it is clearly impossible for spirits to wear dresses made of the materials of the earth, we should like to know if there are spiritual-outfitting shops for the clothing of ghosts who pay visits on earth, and if empty, haunted houses are used for this purpose, in the same way as the establishments, and after the manner of "Moses and Son," or "Hyam Brothers," or such like houses of business, or if so, then there must be also the spirit of woollen cloth, the spirit of leather, the spirit of a coat, the spirit of boots and shoes. There must also be the spirit of trousers, spirits of gaiters, waistcoats, neckties, spirits of buckles, for shoes and knees; spirit of buttons, "bright gilt buttons;" spirits of hats, caps, bonnets, gowns, and petticoats; spirits of hoops and crinoline, and ghost's stockings. Yes; only think of the ghosts of stockings, but if the ghost of a lady had to make her appearance here, she could not present herself before company without her shoes and stockings, so there must be

GHOSTS OF STOCKINGS.

Most persons will surely feel some hesitation in accepting the assertions made by Defoe, that ghosts appear in clothes that have been cut up, or distributed in different places, or destroyed, or that they come in the same garments that are being worn at the same moment by living persons, or which are at the time of appearing, in wardrobes or old clothes shops; or, perhaps, thousands of miles away from the spot where the ghost pays his unwelcome visit, or worn or torn into rags, and stuck upon a broomstick "to frighten away the crows." No, no, I think we may rest assured that ghosts could not appear in these dresses, or shreds and patches; in fact, that they could not show themselves in any dress made of the materials of the earth as already suggested; and, therefore, if they did wear any dresses they must have been composed of a spiritual material, if it be possible to unite, in any way, two such opposites. Then comes the question, from whence is this spiritual material obtained, and also if there are spirit manufactories, spirit weavers and spinners, and spirit tanners and "tan pits?"

If this be so, then there must, of course, be ghost tailors, working with ghosts of needles (how sharp they must be!), and ghosts of threads (and how fine they must be!), and the ghost of a "sleeve board," and the ghost of the iron, which the tailors use to flatten the seams, called a "goose" (only think of the ghost of a tailor's "goose!") Then there must be the ghost of a "bootmaker," with the ghost of a "lapstone," and a "last," and the spirit of "cobbler's wax!" Ghost of "button makers," "wig makers," and "hatters;" and, indeed, of every trade necessary to fit out a ghost, either lady or gentleman, in order to make it appear that they really did appear "in their habits as they lived."

There are, I know, many respectable worthy persons even at the present day who believe they sometimes see apparitions, and I would here take the liberty to advise such persons to ponder a little upon the above remarks relative to the clothing of spirits, and, when again they think they see a GHOST, recollect that with the exception of the face and a little bit of the neck perhaps, and also the hands, if without gloves, that all the other parts are CLOTHES. And I would also take the liberty to suggest that he should ask the ghost these questions:—"Who's your tailor?" and "Who's your hatter?"