This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Art Principles

With Special Reference to Painting Together with Notes on the Illusions Produced by the Painter

Author: Ernest Govett

Release Date: June 14, 2011 [eBook #36427]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ART PRINCIPLES***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/artprincipleswit00goverich |

This book is put forward with much diffidence, for I am well aware of its insufficiencies. My original idea was to produce a work covering all the principles of painting, but after many years spent in considering the various recorded theories relating to æsthetic problems, and in gathering materials to indicate how the accepted principles have been applied, I came to the conclusion that a single life is scarcely long enough for the preparation of an exhaustive treatise on the subject. Nevertheless, I planned a work of much wider scope than the one now presented, but various circumstances, and principally the hindrance to research caused by the war, impelled me to curtail my ambition. Time was fading, and my purpose seemed to be growing very old. I felt that if one has something to say, it is better to say it incompletely than to run the risk of compulsory silence. The book will be found little more than a skeleton, and some of its sections, notably those dealing with illusions in the art, contain only a few suggestions and instances, but perhaps enough is said to induce a measure of further inquiry into the subject.

That part of the work dealing with the fine arts generally is the result of long consideration of the [Pg iv] apparent contradictions involved in the numerous suggested standards of art. In a little book on The Position of Landscape in Art (published under a nom de plume a few years ago), I threw out, as a ballon d'essai, an idea of the proposition now elaborated as the Law of General Assent, and I have been encouraged to affirm this proposition more strongly by the fact that its validity was not questioned in any of the published criticism of the former work; nor do I find reason to vary it after years of additional deliberation. I have not before dealt with the other propositions now put forward.

The notes being voluminous I have relegated them to the end of the book, leaving the feet of the text pages for references only.

Where foreign works quoted have been translated into English, the English titles are recorded, and foreign quotations are given in English, save in one or two minor instances where the sense could not be precisely rendered in translation.

E. G.

New York, January, 1919.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Definitions of "Art" and "Beauty"—Æsthetic systems—The earliest Art—Art periods—The Grecian and Italian developments—National and individual "Inspiration"—Powers of imagination and execution—Nature of "Genius"—The Impressionist Movement—Sprezzatura—The broad manner—Position in art of Rembrandt and Velasquez—Position of Landscape in art. | |

| BOOK I | |

| CHAPTER | |

| I.—Classification of the Fine Arts | 52 |

| The Arts imitative of Nature—Classified according to the character of their signs—Relative value of form in Poetry—Scope of the Arts in the production of beauty. | |

| II.—Law of Recognition in the Associated Arts | 59 |

| Explanation of the Law—Its application to Poetry—To Sculpture—To Painting—To Fiction. | |

| III.—Law of General Assent | 72 |

| General opinion the test of beauty in the Associated Arts. | |

| IV.—Limitations of the Associated Arts | 78 |

| Production of beauty in the respective Arts—Their limitations. | |

| V.—Degrees of Beauty in the Painter's Art[Pg vi] | 83 |

| VI.—Expression. Part 1.—The Ideal | 86 |

| VII.—Expression. Part 2.—Christian Ideals | 91 |

| The Deity—Christ—The Madonna—Madonna and Child. | |

| VIII.—Expression. Part 3.—Classical Ideals | 106 |

| Ideals of the Greeks—Use of the ancient divinities by the Painter. | |

| IX.—Expression. Part 4.—General Ideals | 135 |

| X.—Expression. Part 5.—Portraiture | 141 |

| Limitations of the Portrait Painter—Emphasis and addition of qualities in portrait painting—Practice of the ancient Greeks—Dignity—Importance of Simplicity—Some of the great masters—Portraiture of women—The English masters—The quality of Grace—The necessity for Repose. | |

| XI.—Expression. Part 6.—Miscellaneous | 167 |

| Grief—The Smile—The Open Mouth—Contrasts—Representation of Death. | |

| XII.—Landscape | 192 |

| Limitations of the Landscape Painter—Illusion of opening distance—Illusion of motion in Landscape—Moonlight scenes—Transient conditions. | |

| XIII.—Still-life | 214 |

| XIV.—Secondary Art | 219 |

| Paintings of record—Scenes from the Novel—From the written drama—From the acted drama—Humorous subjects—Allegorical paintings. | |

| XV.—Colour[Pg vii] | 228 |

| BOOK II | |

| Introductory.—Illusion in the Painter's Art | 236 |

| CHAPTER | |

| I.—Illusion of Relief | 239 |

| II.—Illusion of Motion with Men and Animals | 249 |

| III.—Illusion of Suspension and Motion in the Air | 259 |

| Notes | 273 |

| Index of Artists and Works of Art Mentioned in this Book | 357 |

| General Index | 369 |

| PAGE | |

| Frontispiece.—Detail from Fragonard's The Pursuit (Frick Collection, New York). | |

| This work, which is one of the celebrated Grasse series of panels, offers a very fine example of the use of an ideal head in a romantic subject. (See Page 139.) | |

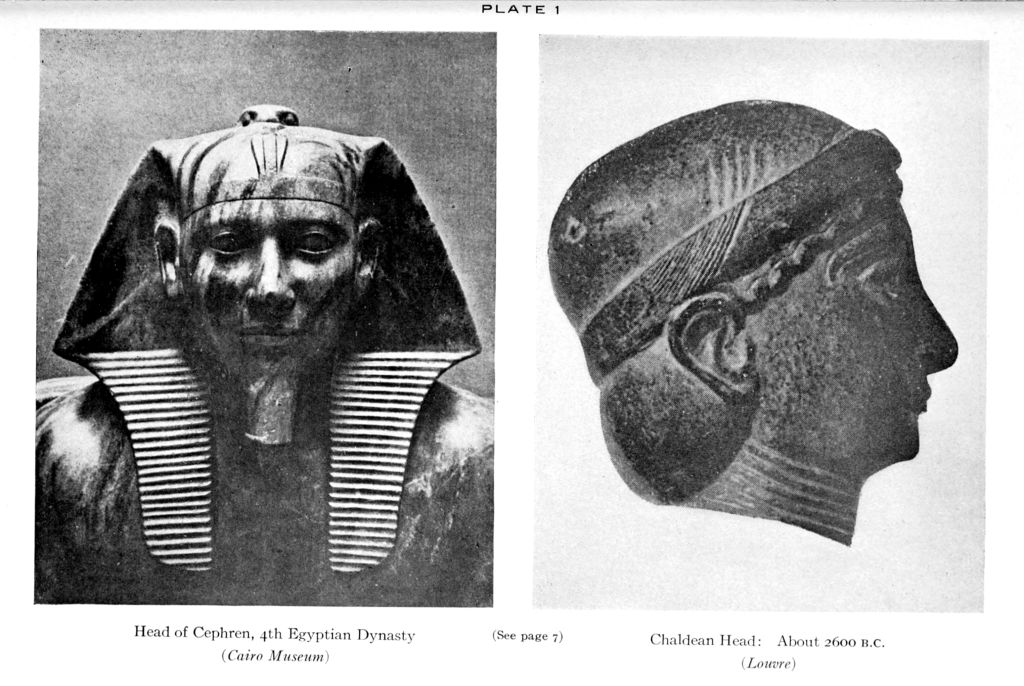

| Plate 1.—The Earliest Great Sculptures | 6 |

| (a). Head from a statue of Chefren, a king of the 4th Egyptian Dynasty, about 3000 B.C. (Cairo Museum.) | |

| (b). Head from a fragmentary statuette of Babylonia, dating about 2600 B.C. (Louvre: from Spearing's "Childhood of Art.") | |

| The first head is generally regarded as the finest example of Egyptian art extant, and certainly there was nothing executed in Egypt to equal it during the thirty centuries following the 5th Dynasty. The Babylonian head is the best work of Chaldean art known to us, though there are some fine fragments remaining from the period of about a thousand years later. It will be observed that the tendency of the art in both examples is towards the aims achieved by the Greeks. (See Page 7.) | |

| Plate 2.—"Le Bon Dieu d'Amiens", in the North Porch, Amiens Cathedral | 18 |

| This figure by a French sculptor of the thirteenth century, was considered by Ruskin to be the finest ideal of Christ in existence. It is another example of the universality of ideals, for the head from the front view might well have been modelled from a Grecian work of the late fourth or early third century B.C. (See Page 319.) | |

| Plate 3.—After an Ancient Copy of the Cnidian Venus of Praxiteles. (Vatican)[Pg x] | 30 |

| It is commonly agreed that this is the finest model in existence after the great work of Praxiteles, which itself has long disappeared. The figure as it now stands at the Vatican, has the right arm restored, and the hand is made to hold up some metallic drapery with which the legs are covered, the beauty of the form being thus seriously weakened. (See Pages 111 et seq.) | |

| Plate 4.—Venus Anadyomene | 42 |

| (a). Ancient Greek sculpture from the design of Venus in the celebrated picture of Apelles. (Formerly Chessa Collection, now in New York.) | |

| The immense superiority of the sculpture over the painting (Plate 5), from the point of view of pure art, is visible at a glance. It is an indication of the far-reaching scope of the sculptor when executing ideals. (See Page 113.) | |

| Plate 5.—Venus Anadyomene, from the Painting by Titian. (Bridgewater Collection.) | 42 |

| Compare with the Sculpture on Plate 4. (See Page 115) | |

| Plate 6.—Venus Reposing, by Giorgione. (Dresden Gallery) | 54 |

| This is the finest reposing Venus in existence in painting. It was the model for the representation of the goddess in repose used by Titian, and many other artists who came after him. (See Page 116.) | |

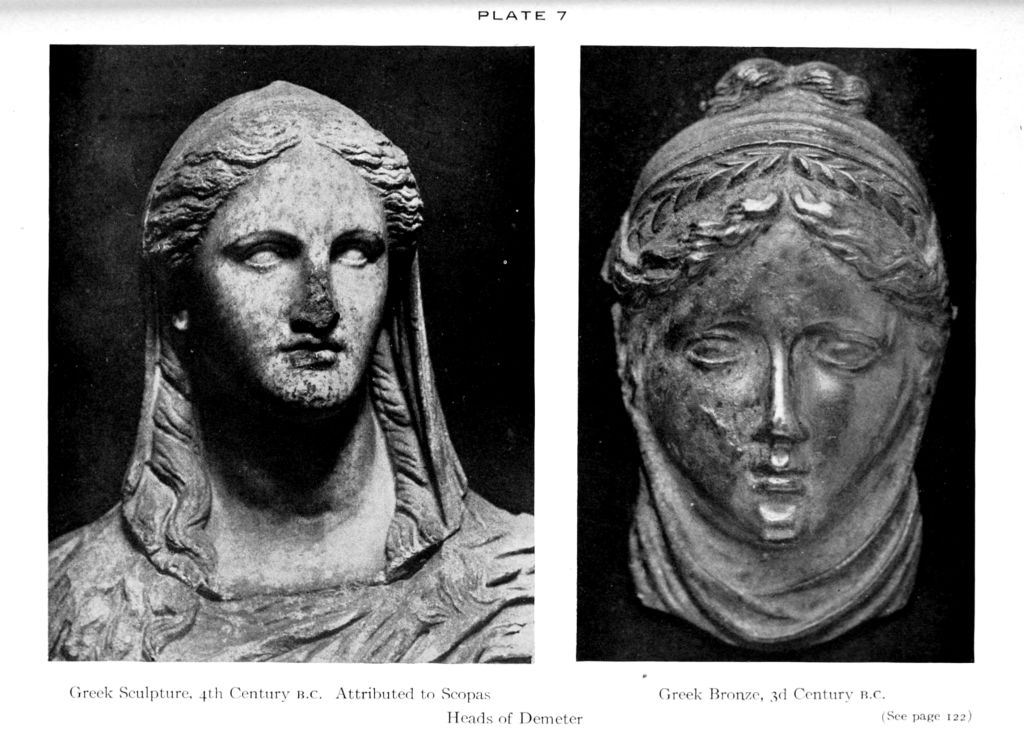

| Plate 7.—Demeter | 66 |

| (a). Head from the Cnidos marble figure of the fourth century B.C., attributed to Scopas. (British Museum.) | |

| (b). Small head in bronze of the third century B.C. (Private Collection.) | |

| In each of these heads the artist has been successful in maintaining the ideal, while indicating a suggestion of the sorrowful resignation with which Grecian legend has enveloped the mind picture of Demeter. Nevertheless, even this slight departure from the established rule tends to lessen the art, though in a very small degree. (See Page 122.) | |

| Plate 8.—Raphael's Sistine Madonna (Dresden Gallery), with the Face of the Central Figure in Fragonard's The Pursuit Substituted for that of the Virgin[Pg xi] | 80 |

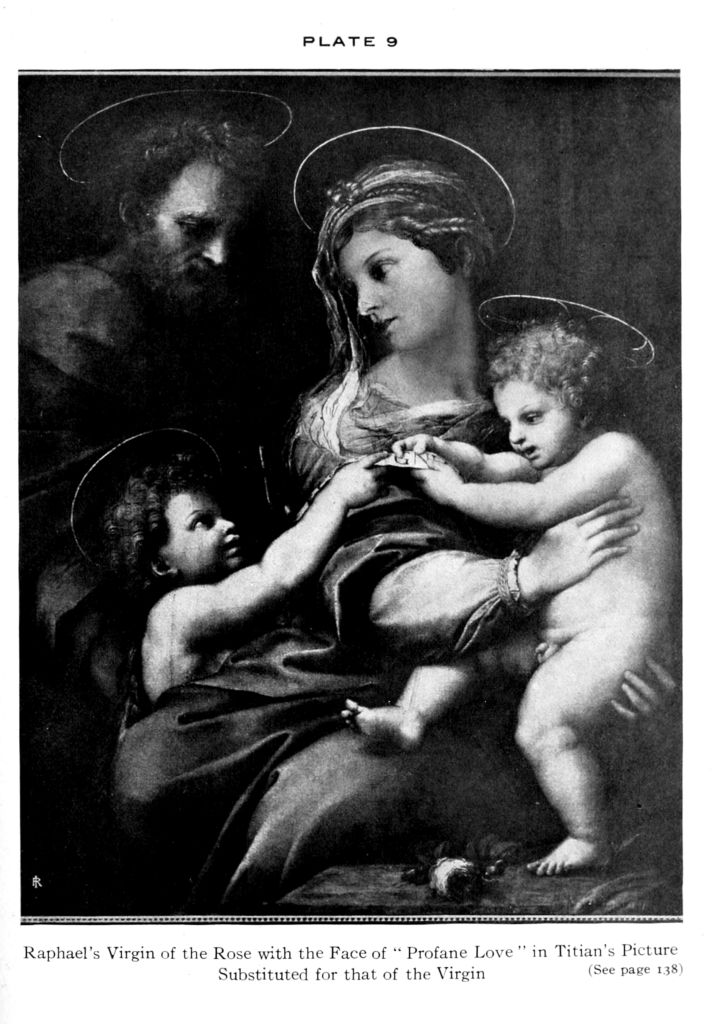

| This and the two following plates show very clearly that in striving for an ideal, artists must necessarily arrive at the same general type. (See Pages 138 et seq.) | |

| Plate 9.—Raphael's Virgin of the Rose (Madrid), with the Face of the Figure Representing Profane Love in Titian's Picture Substituted for that of the Virgin | 92 |

| Plate 10.—Raphael's Holy Family (Madrid), with the Face of Luini's Salome Substituted for that of the Virgin | 102 |

| Plate 11.—The Pursuit, by Fragonard. (Frick Collection, N. Y.) | 114 |

| A detail from this picture forms the Frontispiece. It will be observed that in the complete painting the central figure apparently wears a startled expression, but that this is entirely due to the surroundings and action, is shown by the substitution of the face of the central figure for that of the Virgin in the Sistine Madonna, Plate 8. (See Page 139.) | |

| Plate 12.—Portrait Heads of the Greek Type, Fourth Century, b.c. (See Page 145) | 130 |

| (a). Head of Plato. (Copenhagen Museum.) | |

| (b). Term of Euripides. (Naples Museum.) | |

| Plate 13.—Portrait Heads of the Time of Imperial Rome. (See Page 145) | 146 |

| (a). Vespasian. (Naples Museum.) | |

| (b). Hadrian. (Athens Museum.) | |

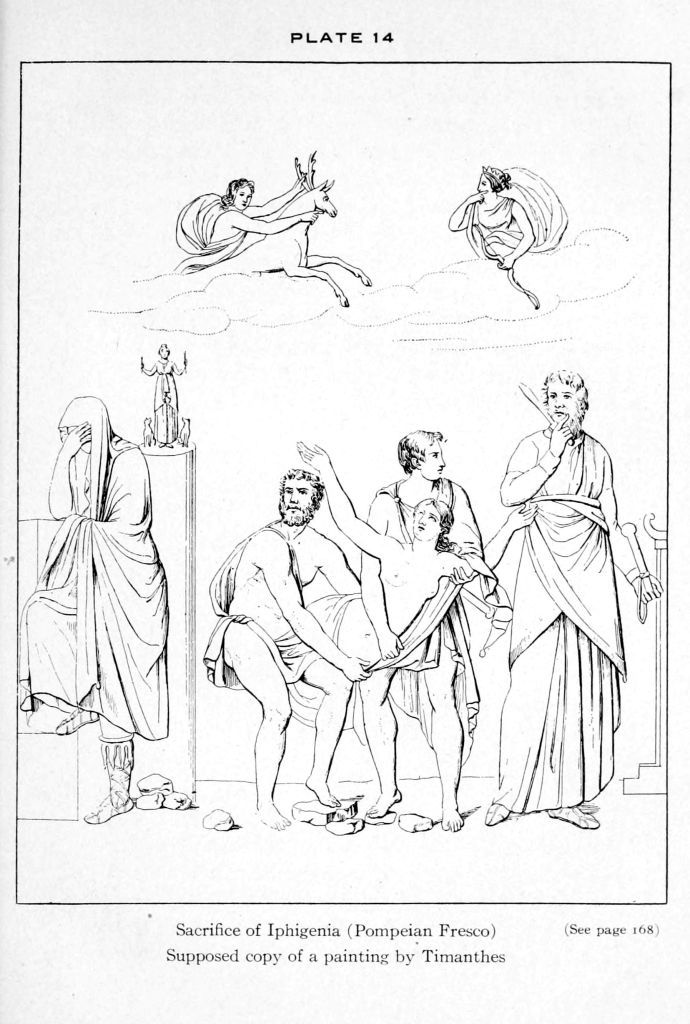

| Plate 14.—Sacrifice of Iphigenia, from a Pompeian Fresco. (Roux Ainé's Herculanum et Pompei, Vol. III)[Pg xii] | 160 |

| This work is presumed to be a copy of the celebrated picture of Timanthes, in which the head of Agamemnon was hidden because the artist could see no other way of expressing extreme grief without distorting the features. (See Pages 168 and 339.) | |

| Plate 15.—All's Well, by Winslow Homer. (Boston Museum, U. S. A.) | 176 |

| An instance where the permanent beauty of a picture is killed by an open mouth. After a few moments' inspection, it will be observed that the mouth appears to be kept open by a wedge. (See Page 176.) | |

| Plate 16.—Hercules Contemplating Death, by A. Pollaiuolo. (Frick Collection, New York.) | 190 |

| The only known design of this nature which appears to exist in any of the arts. (See Pages 190 and 343.) | |

| Plate 17.—Arcadian Landscape, by Claude Lorraine. (National Gallery, London) | 198 |

| A fine illusion of opening distance created by the precise rendering of the aerial perspective. The illusion is of course unobservable in the reproduction owing to its small size and the want of colour. (See Page 198). | |

| Plate 18.—Landscape, by Hobbema. (Met. Museum, New York) | 210 |

| A fine example of Hobbema's work. A strong light is thrown in from the back to enable the artist to multiply his signs for the purpose of deepening the apparent distance. (See Page 202.) | |

| Plate 19.—Landscape, by Jacob Ruysdael, (National Gallery, London) | 220 |

| Example of an illusion of movement in flowing water. (See Page 204.) | |

| Plate 20.—The Storm, by Jacob Ruysdael. (Berlin Gallery)[Pg xiii] | 232 |

| Exhibiting an excellent illusion of motion, due to the faithful representation of a series of consecutive movements of water as the vessel passes through it. The illusion is practically lost in the reproduction, but the details of design may be observed. (See Page 206.) | |

| Plate 21.—The Litta Madonna, by Lionardo da Vinci. (Hermitage) | 240 |

| This is perhaps the best example known of an illusion of relief secured by shading alone. (See Page 240.) | |

| Plate 22.—Christ on the Cross, by Van Dyck. (Antwerp Museum) | 252 |

| A superb example of relief obtained by the exclusion of accessories. Van Dyck took the idea from Rubens, who borrowed it from Titian, this artist improving on Antonella da Messina. The relief of course is not well observed in the reproduction because of its miniature form. The work is usually regarded as the finest of its kind in existence. (See Page 244.) | |

| Plate 23.—Patricia, by Lydia Emmet. (Private Possession, N. Y.) | 264 |

| A very excellent example of the plan of securing relief described in Book II, Chap. I. Here also the relief is not observed in the reproduction, but the original is of life size and provides an illusion as nearly perfect as possible. (See Page 247.) | |

| Plate 24.—The Creation of Adam, by Michelangelo. (Vatican) | 276 |

| Instance of the use of an oval form of drapery to assist in presenting an illusion of suspension in the air. (See Page 260.) | |

| Plate 25.—The Pleiads, by M. Schwind. (Denner Collection.) | 288 |

| One of the finest examples of illusion of motion in the air. (See Page 269.) | |

| Plate 26.—St. Margaret, by Raphael. (Louvre)[Pg xiv] | 302 |

| Perhaps the best example in existence of a painted human figure in action. It will be seen that every part of the body and every fold of the drapery are used to assist in the expression of movement. (See Page 250.) | |

| Plate 27.—Diana and Nymphs Pursued by Satyrs, by Rubens. (Prado) | 318 |

| A good example of an illusion of motion created by showing a number of persons in different stages of a series of consecutive actions. (See Page 254.) | |

| Plate 28.—Automedon with the Horses of Achilles, by H. Regnault. (Boston Museum, U. S. A.) | 334 |

| The extraordinary spirit and action of these horses are above the experience of life, but they do not appear to be beyond the bounds of possibility. In any case the action is perfectly appropriate here, as the animals are presumed to be immortal. (See Page 256.) | |

| Plate 29.—Marble Figure of Ariadne. (Vatican) | 348 |

| This work, of the Hellenistic period, illustrates the possibility of largely varying the regular proportions of the human figure without injury to the art, by the skilful use of drapery. (See Page 329.) |

In view of the many varied definitions of "Art" which have been put forward in recent times, and the equally diverse hypotheses advanced for the solution of æsthetic problems relating to beauty, it is necessary for one who discusses principles of art, to state what he understands by the terms "Art" and "Beauty."

Though having a widely extended general meaning, the term "Art" in common parlance applies to the fine arts only, but the term "Arts" has reference as well to certain industries which have utility for their primary object. This work considers only the fine arts, and when the writer uses the term "Art" or "Arts" he refers to one or more of these arts, unless a particular qualification is added. The definition of "Art" as applied to the fine arts, upon which he relies, is "The production of beauty for the purpose of giving pleasure," or as it is more precisely put, "The beautiful representation of nature for the purpose of giving disinterested pleasure." This is, broadly, the definition generally accepted, and is[Pg 2] certainly the understanding of art which has guided the hands of all the creators of those great works in the various arts before which men have bowed as triumphs of human skill.

There has been no satisfactory definition of "Beauty," nor can the term be shortly interpreted until there is a general agreement as to what it covers. Much of the confusion arising from the contradictory theories of æstheticists in respect of the perception of beauty is apparently due to the want of separate consideration of emotional beauty and beauty of mind, that is to say, the beauty of sensorial effects and beauty of expression respectively.1 There are kinds of sensorial beauty which depend for their perception upon immediately preceding sensory experience, or particular coexistent surroundings which are not necessarily permanent, while in other cases a certain beauty may be recognized and subsequently appear to vanish altogether. From this it is obvious that any æsthetic system based upon the existence of an objectivity of beauty must fall to the ground. On the other hand, without an objectivity there can be no system, because in its absence a line of reasoning explaining cause and effect in the perception of beauty, which is open to demonstration, is naturally impossible. Nor may we properly speak of a philosophy of art.2 We may reasonably consider æsthetics a branch of psychology, but the emotions arising from the recognition of beauty vary only in degree and not in kind, whether the beauty be seen in nature or art. Consequently there can be no separate psychological en[Pg 3]quiry into the perception of beauty created by art as distinguished from that observable in nature.

It must be a natural attraction for the insoluble mysteries of life that has induced so many philosophers during the last two centuries to put forward æsthetic systems. That no two of these systems agree on important points, and that each and every one has crumbled to dust from a touch of the wand of experience administered by a hundred hands, are well-known facts, yet still the systems continue to be calmly presented as if they were valuable contributions to knowledge. Each new critic in the domain of philosophy carefully and gravely sets them up, and then carefully and gravely knocks them down.3 An excuse for the systems has been here and there offered, that the explanations thereof sometimes include valuable philosophical comments or suggestions. This may be, but students cannot reasonably be expected to sift out a few oats from a bushel of husks, even if the supply be from the bin of a Hegel or a Schopenhauer. Is it too much to suggest that these phantom systems be finally consigned to the grave of oblivion which has yawned for them so long and so conspicuously? Bubbles have certain measurements and may brilliantly glow, but they are still bubbles. It is as impossible to build up a system of philosophy upon the perception of beauty, which depends entirely upon physical and physiological laws, as to erect a system of ethics on the law of gravitation, for a feasible connection between superstructure and foundation cannot be presented to the mind.[Pg 4]

We may further note that a proper apprehension of standards of judgment in art cannot be obtained unless the separate and relative æsthetic values of the two forms of beauty are considered, because the beauty of a work may appear greater at one time than at another, according as it is more or less permanent or fleeting, that is to say, according as the balance of the sensorial and intellectual elements therein is more or less uneven; or if the beauty present be almost entirely emotional, according as the observer may be affected by independent sensorial conditions of time or place. Consequent upon these considerations, an endeavour has been made in this work to distinguish between the two forms of beauty in the various arts, and the separate grades thereof.

It will be noticed that the writer has adopted the somewhat unusual course of including fiction among the fine arts. Why this practice is not commonly followed is hard to determine, but no definition of a fine art has been or can be given which does not cover fiction. In the definition here accepted, the art is clearly included, for the primary object of fiction is the beautiful representation of nature for the purpose of giving disinterested pleasure.

Art is independent of conditions of peoples or countries. Its germ is unconnected with civilization, politics, religion, laws, manners, or morals. It may appear like a brilliant flower where the mind of man is an intellectual desert, or refuse to bloom in the busiest hive of human energy. Its mother is the imagination, and wherever this has room to[Pg 5] expand, there art will grow, though the ground may be nearly sterile, and the bud wither away from want of nourishment. Every child is born a potential artist, for he comes into the world with sensorial nerves, and a brain which directs the imagination. The primitive peoples made beautiful things long before they could read or write, and the recognition of harmony of form appears to have been one of the first understandings in life after the primal instincts of self-preservation and the continuation of the species. Some of the sketches made by the cave men of France are equal to anything of the kind produced in a thousand years of certain ancient civilizations, commencing countless centuries after the very existence of the cave men had been forgotten; and even if executed now, would be recognized as indicating the possession of considerable talent by the artists. The greatest poem ever written was given birth in a country near which barbaric hordes had recently devastated populous cities, and wrecked a national fabric with which were interwoven centuries of art and culture. That the author of this poem had seen great works of art is certain, or he could not have conceived the shield of Achilles, but the laboured sculpture that had fired his imagination, and the legends which had perhaps been the seed of his masterpieces were doubtless buried with his own records beneath the tramp of numberless mercenaries. Fortunately here and there the human voice could draw from memory's store, and so the magic of Homer was whispered by the dying to the living; but even his time and place are now only[Pg 6] vaguely known, and he remains like the waratah on the bleached pasture of some desert fringe—a solitary blaze of scarlet where all else is drear and desolate.

Head of Cephren, 4th Egyptian Dynasty (Cairo Museum)

Chaldean Head: About 2600 B.C. (Louvre)

Head of Cephren, 4th Egyptian Dynasty (Cairo Museum)

Chaldean Head: About 2600 B.C. (Louvre)

(See page 7)

Strong is the root of art, though frail the flower. Stifled in sun-burnt ground ere it can welcome the smile of light; fading with the first blast of air upon its delicate shoots; shrivelling back to dust when the buds are ready to break; or falling in the struggle to spread its branches after its beautiful blossoms have scattered their fragrance around: whatever condition has brought it low, it ever fights again—ever seeks to assure mankind that while it may droop or disappear, its seed, its heart, its life, are imperishable, and surely it will bloom again in all its majesty. Sometimes with decades it has run a fitful course; sometimes with centuries; sometimes with millenniums. It has heralded every civilization, but its breath is freedom, and it flourishes and sickens only with liberty. Trace its course in the life of every nation, and the track will be found parallel with the line of freedom of thought. A solitary plant may bloom unimpeded far from tyranny's thrall, but the art and soul of a nation live, and throb, and die, together.

Egypt, Babylon, Crete, Greece, Rome, tell their stories through deathless monuments, and all are alike in that they demonstrate the dependence of art expansion upon freedom of action and opinion. An art rises, develops another and another, and they proceed together on their way. Sooner or later comes catastrophe in the shape of crushing [Pg 7]tyranny which curbs the mind with slavery, or steel-bound sacerdotal rules which say to the artist "Thou shalt go no further," or annihilation of nation and life. What imagination can picture the expansion of art throughout the world had its flight been free since the dawn of history? Greece reached the sublime because its mind was unfettered, but twenty or thirty centuries before Phidias, Egyptian art had arrived at a loftier plane than that on which the highest plastic art of Greece was standing but a few decades before the Olympian Zeus uplifted the souls of men, while whole civilizations with their arts had lived and died, and were practically forgotten.

It is to be observed that while in its various isolated developments, art has proceeded from the immature to the mature, there has been no general evolution, as in natural life, but on the other hand there seems to be a limit to its progress. So far as our imagination can divine, no higher reaches in art are attainable than those already achieved. The mind can conceive of nothing higher than the spiritual, and this cannot be represented in art except by means of form; while within the range of human intelligence, no suggestion of spiritual form can rise above the ideals of Phidias. Of the purely human form, nothing greater than the work of Praxiteles and Raphael can be pictured on our brains. There may be poets who will rival Homer and Shakespeare, but it is exceedingly doubtful. In any case we must discard the law of evolution as applicable to the arts, with the one exception of music, which, on[Pg 8] account of the special functioning of its signs, must be put into a division by itself.[a]

But although there has been no general progression in art parallel with the growth of the sciences and civilization, there have been, as already indicated, many separate epochs of art cultivation in various countries, sometimes accompanied by the production of immortal works, which epochs in themselves seem to provide examples of restricted evolution.4 It is desirable to refer to these art periods, as they are commonly called, for the purpose of removing, if possible, a not uncommon apprehension that they are the result of special conditions operating an æsthetic stimulus, and that similar or related conditions must be present in any country if the flame of art there is to burn high and brightly.5 The well-defined periods vary largely both in character and duration, the most important of them—the Grecian development and the Italian Renaissance—covering two or three centuries each, and the others, as the French thirteenth century sculpture expansion, the English literary revival in the sixteenth century,6 and the Dutch development in painting in the seventeenth, lasting only a few decades. These latter periods can be dispensed with at once because they were each concerned with one art only, and therefore can scarcely have resulted from a general æsthetic stimulus. But the Grecian and Italian movements applied to all the arts. They represented natural developments from the crude to the advanced, of which all nations [Pg 9]produce examples, and were only exceptional in that they reached higher levels in art than were attained by other movements. But there is no evidence to show that they were brought about by special circumstances outside of the arts themselves. While there were national crises preceding the one development, there was no trouble of consequence to herald the other, nor was there any parallel between the conditions of the two peoples during the progress of the movements. A short reference to each development will show that its rise and decline were the outcome of simple matter-of-fact conditions of a more or less accidental nature, uninfluenced by an æsthetic impulse in the sense of inspiration.

The most common suggestion advanced to account for the rise in Grecian art, is that it was due to the exaltation of the Greek mind through the victories of Marathon, Platæa, and Salamis. That a people should be so trampled upon as were the Greeks; that their cities should be razed, their country desolated, and their commerce destroyed; that notwithstanding all this they should refuse to give way before enemies outnumbering them twenty, fifty, or even a hundred to one; and that after all they should crush these enemies, was no doubt a great and heroic triumph, likely to exalt the nation and feed the imagination of the people for a long time to come; but that these victories were responsible for the lofty eminence reached by the Greek artists, cannot be maintained. From what we know of Calamis, Myron, and others, it is clear that Grecian art was already on its way to the summit reached[Pg 10] by Phidias when Marathon and Salamis were fought, though the victories of the Greek arms hastened the development for the plain reason that they led to an increased demand for works of art. And the decline in Grecian art resulted purely and simply from a lessened demand. Though this was the reason for the general decay, there was a special cause for the apparent weakening with the commencement of the fourth century B.C. In the fifth century Phidias climbed as high in the accomplishment of ideals as the imagination could soar. He reached the summit of human endeavour. Necessarily then, unless another Phidias arose, whatever in art came after him would appear to mark a decline. But it is scarcely proper to put the case of Phidias forward for comparative purposes. He carried the art of sculpture higher than it is possible for the painter to ascend, and so we should rather use the giants of the fourth century—Scopas, Praxiteles, Lysippus, Apelles—as the standards to be compared with the foremost spirits of the Italian Renaissance—Raphael and Michelangelo—for each of these groups achieved the human ideal, though failing with the spiritual ideal established by Phidias.

It must be remembered that all good art means slow work—long thinking, much experiment, tedious attention to detail in plan, and careful execution. Meanwhile men have to live, even immortal artists, and rarely indeed does one undertake a work of importance on his own account. It is true that in the greater days of Greece the best artists were almost entirely employed by a State, or at least to[Pg 11] execute works for public exhibition, and doubtless the payment they received was quite a secondary matter with them, but nevertheless few could practise their art without remuneration. During the fifth and fourth centuries great events were constantly happening in Greece, and in consequence there were numberless temples to build and adorn, groves to decorate, men to honour, and monumental tombs to erect. Innumerable statues of gods and goddesses were wanted, and we must not forget the wholesale destruction of Athenian and other temples and sculptures during the Persian invasion. In fact for a century and a half after Platæa, there was practically an unlimited demand for works of art, and it was only when the empire of Alexander began to crumble away that conditions changed. While Greece was weakening Rome was growing and her lengthening shadows were approaching the walls of Athens. Greece could build no more temples when her people were becoming slaves of Rome; she could order no more monuments when defeat was the certain end of struggle. And so the decline was brought about, not by want of artists, but through the dearth of orders and the consequent neglect of competition.

In the case of the Italian Renaissance the decadence was not due to the same cause. The art of Greece declined gradually in respect of quantity as well as quality, while in Italy after the decay in quality set in, art was as nourishing as ever from the point of view of demand. The change in the character of the art was due entirely to Raphael's[Pg 12] achievements. As with the early Greek, nearly the whole of the early Italian art was concerned with religion, though in this case there were very few ideals. The numerous ancient gods of Greece and Rome were long gone, to become only classical heroes with the Italians, and their places were taken by twenty or thirty personages from the New Testament. Incidents from the Old Testament were sometimes painted, but nearly all the greater work dealt with the life of Christ and the Saints. The painters of the first century of the Renaissance distributed their attention fairly equally among these personages, but as time went on and the art became of a superior order, artists aimed at the highest development of beauty that their imaginations could conceive, and hence the severe beauty that might be shown in a picture of Christ or a prominent Saint, had commonly to give way to a more earthly perfection of feature and form, which, suggesting an ideal, could only be given to the figure of the Virgin. And so the test of the power of an artist came to be instinctively decided by his representation of the Madonna. No doubt there were many persons living in the fifteenth century who watched the gradually increasing beauty of the Madonna as depicted by the succession of great painters then working, and wondered when and where the summit would be reached—when an artist would appear beyond whose work the imagination could not pass, for there is a limit to human powers.

The genius arose in Raphael, and when he produced in the last ten or twelve years of his life,[Pg 13] Madonna after Madonna, so far in advance of anything that had hitherto been done, so great in beauty as to leave his fellow artists lost in wonder, so lofty in conception that the term "divine" was applied to him in his lifetime, it was inevitable that a decadence should set in, for so far as the intelligence could see, whatever came after him must be inferior. He did not ascend to the height of Phidias, for a pure ideal of spiritual form is beyond the power of the painter,[b] but as with Praxiteles he reached a perfect human ideal, and so gained the supreme pinnacle of his art. But while there was an inevitable decadence after him, as after Praxiteles, it was, as already indicated, only in the character of the art, for in Italy artists generally were as busy for a hundred years after Raphael, as during his time. Michelangelo, Titian, and the other giants who were working when Raphael died, kept up the renown of the period for half a century or so, but it seemed impossible for artists who came on the scene after Raphael's death, to enter upon an entirely original course. The whole of the new generation seemed to cling to the models put forward by the great Urbino painter, save some of the Venetians who had a model of their own in Titian.

Thus it is clear that the rise and decline of the Grecian and Italian movements were due to well ascertained causes which had nothing to do with a national æsthetic impulse; nor is there evidence of such an impulse connected with other art developments.

The suggestion that a nation may be assisted in its art by emotional or psychological influences arising from patriotic exaltation, is only an extension of an opinion commonly held, that the individual artist is subject to similar influences, though due to personal exaltation connected with his art. It is as well to point out that there is only one way to produce a work of art, and that is to combine the exercise of the imagination with skill in execution. The artist conceives an idea and puts it into form. He does nothing more. He can rely upon no extraneous influence. It is suggested that to bring about a supreme accomplishment in art, the imagination must be associated with something outside of our power of control—some impulse which acts upon the brain but is independent of it. This unmeasured force or lever is usually known by the term "Inspiration." It is supposed that this force comes to certain persons when they have particular moods upon them, and gives them a great idea which they may use in a painting, a poem, or a musical composition. The suggestion is attractive, but in the long range of historical record there is no evidence that accident, in the shape of inspiration or other psychological lever, has been responsible in the slightest degree for the production of a work of art. The writer of a sublime poem, or the painter of a perfect Madonna, uses the same kind of mental and material labour as the man who chisels a lion's head on a chair, or adds a filigree ornament to a bangle. The difference is one of degree only. The poet or painter is gifted with a vivid imagination which he has[Pg 15] cultivated by study; and by diligence has acquired superlative facility in execution, which he uses to the best advantage. The work of the furniture carver or jeweller does not require such high powers, and he climbs only a few steps of the ladder whose uppermost rungs have been scaled by the greater artists.

If in the course of the five and twenty centuries during which works of high art have been produced, some of them had been executed with the assistance of a psychological impulse directed independently of the will, there would certainly have been references to the phenomenon by the artists concerned, or the very numerous art historians, but without a known exception, all the great artists who have left any record of the cause of their success, or whose views on the subject are to be gained by indirect references, have attributed this success to hard study, or manual industry, or both together. We know little of the opinion of the ancient Greeks on the matter, but the few anecdotes we have, indicate that their artists were very practical men indeed, and hardly likely to expect mysterious psychological influences to help them in their work. So with the Romans, and it is noticeable that the key to the production of beauty in poetry, in the opinion of Virgil and Horace, is careful preparation and unlimited revision. This appears to be the view of some modern poets, and if Dante, Shakespeare, and Milton, had experienced visionary inspiration, we should surely have heard of it. Fortunately some of the most eminent painters of modern times have[Pg 16] expressed themselves definitely upon the point. Lionardo observed that the painter arrives at perfection by manual operation; and Michelangelo asserted that Raphael acquired his excellence by study and application. Rubens praised his brushes, by which he meant his acquired facility, as the instruments of his fortune; and Nicholas Poussin attributed his success to the fact that he neglected nothing, referring of course to his studies. According to his biographers, the triumphs of Claude were due to his untiring industry, while Reynolds held that nothing is denied to well directed labour. And so with many others down to Turner, whose secret according to Ruskin, was sincerity and toil.

It would seem to be possible for an artist to work himself into a condition of emotional excitement,7 either involuntarily when a great thought comes to him, or voluntarily when he seeks ideas wherewith to execute a brilliant conception; and it is comprehensible that when in this condition, which is practically an extreme concentration of his mental energy upon the purpose in hand, images or other æsthetic suggestions suitable for his work may present themselves to his mind. These he might regard as the result of inspiration, but in reality they would be the product of a trained imagination operating under advantageous conditions.

Nor can any rule be laid down that the character or temperament of an artist influences his work, for if instances can be given in support of such an assertion, at least an equal number may be adduced which directly oppose it. If we might approximately[Pg 17] gauge the true characters of Fra Angelico and Michelangelo from a study of their work, it is certain that no imagination could conjure up the actual personalities of Perugino and Cellini, from an examination of the paintings of the one and the sculptures of the other. What can be said on the subject when assassins of the nature of Corenzio and Caravaggio painted so many beautiful things, and evil-minded men like Ribera and Battistello adorned great churches with sacred compositions? If the work of Claude appears to harmonize with his character, that of Turner does not. "Friendless in youth: loveless in manhood; hopeless in death." Such was Turner according to Ruskin, but is there any sign of this in his works? Not a trace. If any conclusion as to his character and temperament can be drawn from Turner's paintings, it is that he was a gay, light-hearted thinker, with all the optimism and high spirits that come from a delight in beautiful things. The element of mood is unquestionably of importance in the work of an artist, but it is not uncommon to find the character of his designs contrary to his mood. Poets, as in the case of Hood, or painters as with Tassaert, may execute the most lively pieces while in moods verging on despair. With some men adversity quickens the imagination with fancies; with others it benumbs their faculties.

The tendency of popular criticism to search for psychological phenomena in paintings, apparently arises largely from the difficulty in comprehending how it is that certain artists of high repute vary[Pg 18] their styles of painting after many years of good work, and produce pictures without the striking beauty characterizing their former efforts. Sometimes when age is beginning to tell upon them, they broaden their manner considerably, as with Rembrandt and others of the seventeenth century, and many recent artists of lesser fame. The critic, very naturally perhaps, is chary of condemning work from the hand of one who has given evidence of consummate skill, and so seeks for hidden beauties in lieu of those to which he has been accustomed. A simple enquiry into the matter will show that the change of style in these cases has a commonplace natural cause.

To be in the front rank an artist must have acquired a vast knowledge of the technique of his art, and have a powerful imagination which has been highly cultivated. But the qualifications must be balanced. Commonly when this balance is not present the deficiency is in the imagination, but there are instances where, though the power of execution is supreme, the imagination has so far exceeded all bounds as to render this power of comparatively small practical value. The most conspicuous example of this want of balance is Lionardo, who accomplished little though he was scarcely surpassed in execution by Raphael or Michelangelo. His imagination invariably ran beyond his execution; his ideas were always above the works he completed or partly finished: he saw in fact far beyond anything he could accomplish, and so was never satisfied with the result of his labour. At the same time[Pg 19] he was filled with ideas in the sciences, and investigated every branch of knowledge without bringing his conclusions to fruition. During the latter part of his life, Michelangelo showed a similar defect in a lesser degree, for his unfinished works of the period exceed in number those he completed. Naturally such intellectual giants, whose imaginations cannot be levelled with the highest ability in execution, are few, but the lesser luminaries who fail, or who constantly fail, in carrying out their conceptions, are legion, though they may have absorbed the limit of knowledge which they are capable of acquiring in respect of execution. It is common for a painter to turn out a few masterpieces and nothing else of permanent value. This was the case with numerous Italian artists of the seventeenth century, and it is indeed a question whether there is one of them, except perhaps Domenichino, whose works have not a considerable range in æsthetic value.

There have been still more artists whose powers of execution were far beyond the flights of their imaginations. They include the whole of the seventeenth century Dutch school with Rembrandt at their head, and the whole of the Spanish school of the same period, except El Greco, Zurbaran, and Murillo. When an artist is in the first rank in respect of execution, but is distinctly inferior in imaginative scope, his work in all grades of his art, except the highest, where ideals are possible, seems to have a greater value than it really possesses because we are insensibly cognizant that the accomplishment[Pg 20] rises above the idea upon which it is founded. On the other hand his work in the highest plane appears to possess a lower value, because we are surprised that ideals have not been attempted, and that the types of the spiritual and classical personages represented are of the same class of men and women as those exhibited in works dealing with ordinary human occupations or actions. This is why the sacred and classical pictures of Rembrandt, Vermeer of Delft, and the other leading Dutch artists, appear to be below their portrait and genre work in power.

The course of variation in the work of a great painter follows the relative power of his imagination and his execution. Where there is a fair balance between the two, the work of the artist increases in æsthetic value with his age and experience; but when his facility in execution rises above the force of his imagination, then his middle period is invariably the best, his later work showing a gradual depreciation in quality. The reason is obvious. The surety of the hand and eye diminishes more rapidly than the power of the mind, which in fact is commonly enhanced with experience till old age comes on. Great artists who rely mostly upon their powers of execution, and exhibit limited fertility in invention, such as Rembrandt, have often a manner which is so interwoven with the effects they seek, that they are seldom or never able to avail themselves of the assistance of others in the lesser important parts of their work. A man with the fertile mind of a Rubens may gather around him a troupe of artists nearly as good as himself in execution,[Pg 21] who will carry out his designs completely save for certain details. Thus he is not occupied with laborious toil, and the decreasing accuracy of his handiwork troubles him but little. On the other hand a Rembrandt, whose merits lie chiefly in the delicate manipulation of light effects and intricate shades in expression, remains tied to his canvas. He feels intensely the decreasing facility in the use of his brush which necessarily accompanies his advancing years, and his only recourse from a stoppage of work is an alteration in manner involving a reduction of labour and a lessened strain upon the eyesight. With few exceptions the great masterpieces of Rembrandt were produced in his middle period. During the last ten or fifteen years of his life he gradually increased his breadth of manner. He was still magnificent in general expression, but the intimate details which produced such glorious effects in the great Amsterdam picture, and fifty or more of his single portraits, could not be obtained with hog's hair.8

Disconnecting then the work of the artist with inspiration or other psychological force, we may now enquire what is mean by "Genius," "Natural gift," or other term used to explain the power of an artist to produce a great work? It would appear that the answer is closely concerned with the condition of the sensorial nerves at birth, and the precocity or otherwise of the infantile imagination. From the fact that we can cultivate the eye and ear so as to recognize forms of harmony which we could not before perceive, and seeing that the effect of[Pg 22] this cultivation is permanent, it follows that exercise must bring about direct changes in the nerves associated with these organs, attuning them so to speak, and enabling them to respond to newer harmonies arising from increased complexity of the signs used.9 It is matter of common knowledge that the structure of the sensorial nerves varies largely in different persons at birth, and when a boy at a very early age shows precocious ability in music or drawing, we may properly infer that the condition of his optic or aural nerves is comparatively advanced, that is to say, it is much less rudimentary than that of the average person at the same age; in other words accident has given him a nerve regularity which can only be gained by the average boy after long exercise. The precocious youth has not a nerve structure superior in kind, but it is abnormally developed, and so he is ahead of his confreres in the matter of time, for under equal conditions of study he is sooner able to arrive at a given degree of skill.

But early appreciation of complex harmony, and skill in execution, are not enough to produce a great artist, for there must be associated with these things a powerful imagination. While the particular nerves or vessels of the brain with which the imagination is concerned have not been identified, we know by analogy and experience that the exercise of the imagination like that of any other function, is necessary for its development, and according as we allow it to remain in abeyance so we reduce its active value. Clearly also, the seat of the imagination[Pg 23] at birth is less rudimentary in some persons than in others. From these facts it would appear that when both the sensory nerve structure and the seat of the imagination are advanced at birth, then we have the basis upon which the precocious genius is built up. With such conditions, patient toil and deep study are alone necessary to produce a sublime artist. Evidently it is extremely rare for the imagination and nerve structure to be together so advanced naturally, but commonly one is more than rudimentary, and the deficiency in the other is compensated for by study.10

Of course these observations are general, for there arises the question, to what extent can the senses and imagination be trained? We may well conceive that there is a limit to the development of the sense organs. There must come a period when the optic or aural nerves can be attuned no further; and is the limit equal in all persons? The probability is that it is not. The physical character of the nerves almost certainly varies in different persons, some being able to appreciate more complex harmonies than others, granted the limit of development. This is a point which has to be considered, particularly in the case of music wherein as a rule, the higher the beauty the more complex the combinations of signs. There is a parallel problem to solve in respect of the imagination. We can well believe that there was something abnormal in the imagination of Shakespeare, beyond the probability that in his case the physiological system controlling the seat of the imagination was unusually advanced at birth.[Pg 24] It is quite certain that with such a man a given training would result in a far greater advance in the functioning capacity of the imagination, than in the vast majority of persons who might commence the training on apparently equal terms; and he would be able to go further—to surpass the point which might be the limit of development with most persons.

These questions are of the highest importance, but they cannot be determined. We are acquainted with certain facts relating to the general development of the sense organs, and of the imagination; and in regard to the former we know that there is a limit within comprehensible bounds, but we see only very dimly anything finite in the scope of the imagination. With what other term than "limitless" can we describe the imagination of a Shakespeare? But in all cases, whatever the natural conditions at birth, it is clear that hard work is the key to success in art, and though some must work harder than others to arrive at an equal result, it is satisfactory to know that generally Carlyle was right when he described "genius" as the transcendent capacity for taking trouble, and we are not surprised that Cicero should have come to the conclusion that diligence is a virtue that seems to include all the others.

Seeing that the conclusions above defined (and some to be later drawn), are not entirely in accord with a large part of modern criticism based upon what are commonly described as new and improved forms of the painter's art, it is necessary to refer[Pg 25] to these forms, which are generally comprehended under what is known as Impressionism.[c] Alas, to the frailty of man must we ascribe the spread of this movement, which has destroyed so many bright young intellects, and is at this moment leading thousands of gentle spirits along the level path which ends in despair. For the real road of art is steep, and difficult, and long. Year upon year of patient thought, patient observation, and patient toil, lie ahead of every man who covets a crown of success as a painter. He must seek to accumulate vast stores of knowledge of the human form and its anatomy, of nature in her prolific variety, of linear and aerial perspective, of animals which move on land or through the air, of the laws of colours and their combinations. He must sound the depths of poetry, and sculpture, and architecture; absorb the cream of sacred and profane history; and with all these things and many more, he must saturate his mind with the practical details of his art. Every artist whose work the world has learned to admire has done his best to gain this knowledge, and certainly no great design was ever produced by one whose youth and early manhood were not worn with ardent study. For knowledge and experience are the only foundations upon which the imagination can build. Every new conception is a rearrangement of known [Pg 26]signs, and the imagination is powerless to arrange them appropriately without a thorough comprehension of their character and significance.

This then is the programme of work which must be adopted by any serious aspirant to fame in the art of the painter, and it is perhaps not surprising that the number of artists who survive the ordeal is strictly limited. In any walk of life where years of struggle are necessary for success, how small the proportion of men who persevere to the end; who present a steel wall to misfortune and despair, and with an indomitable will, overcome care, and worry, and fatigue, for year after year, till at last the clouds disappear, and they are able to front the world with an all-powerful shield of radiant knowledge! But unfortunately in the painter's art it is difficult to convince students of the necessity for long and hard study, because there is no definite standard for measuring success or failure which they can grasp without long experience. In industries where knowledge is applied to improvement in appliances, or methods with definite ends, or to the realization of projects having a fixed scope, failure is determined by material results measured commonly by mathematical processes of one kind or another. A man produces a new alloy which he claims will fulfil a certain purpose. It is tested by recognized means: all concerned admit the validity of the test, and there the matter ends. But in the arts, while the relative value of the respective grades is equally capable of demonstration, the test is of a different kind. Instead of weights and measures which every man[Pg 27] can apply, general experience must be brought in. The individual may be right in his judgment, and commonly is, but he is unable to measure the evidence of his senses by material demonstration, and as he has no means of judging whether his senses are normal, except by comparison, he is liable to doubt his own experience if it clash with that of others. Thus, he may find but little beauty in a given picture, and then may read or hear that the work has a high æsthetic value, and without calling to mind the fact that no evidence in the matter is conclusive unless it be based on general experience, he is liable to believe that his own perception is in some way deficient.

Thus in the arts, and particularly in painting, there is ample scope for the spread of false principles. Poetry has an advantage in that the intellect must first be exercised before the simplest pictures are thrown on the brain, so feeble or eccentric verse appeals to very few persons, and seldom has a clientèle, if one may use the word, outside of small coteries of weak thinkers. It is difficult also in sculpture to put forward poor works as of a high order, because this art deals almost entirely with simple human and animal forms in respect of which the knowledge is universal, and so as signs they cannot be varied except in the production of what would be immediately recognized as monstrosities. But in painting an immense variety in kind of beauty may be produced, from a simple colour harmony to the representation of ideal forms involving the highest sensorial and intellectual reaches, and there[Pg 28] is ample scope for the misrepresentation of æsthetic effects—for the suggestion that a work yielding a momentary appeal to the senses is superior to a high form of permanent beauty.

It is to the ease with which simple forms of ephemeral beauty may be produced in painting that is due the large number of artists who should never have entered upon the profession. Nearly every person of average intelligence is capable with a few lessons of producing excellent imitations of natural things in colour, as for instance, flowers, bits of landscape, and so on, and great numbers of young men and women, surprised at the facility with which this work can be done, erroneously suppose that nature has endowed them with special gifts, and so take up the art of painting as a career. Hence for every sculptor there are twenty painters. Now these youthful aspirants usually start with determination and hope, but although they know the value of studious toil, they rarely comprehend that this toil, long continued, is the only key to success. Most of them seem under the impression that inspiration will come to their assistance, and that their genius will enable them to dispense with much of the labour which others, less fortunate, must undertake. They do not understand that all painters, even a Raphael, must go through long years of hard application.

We need not be surprised that there should be occasional eruptions in art circles tending to the exaltation of the immature at the expense of the superior, or even the sublime, for we have always[Pg 29] with us the undiligent man of talent, and the "unrecognized genius." But hitherto, movements of the kind have not been serious, for with one exception they are lost in oblivion, and the exception is little more than a vague memory. That the present movement should have lasted so long is not difficult to understand when we remember the modern advantages for the spread of new sensations—the exhibitions, the unlimited advertising scope, and above all the new criticism, with its extended vocabulary, its original philosophy, and its boundless discoveries as to the psychological and musical qualities of paint. That history is silent as to previous eruptions of the kind before the seventeenth century is a matter of regret. It is unlikely that the greatest of all art epochs experienced an impressionist fever, for one cannot imagine the spread of spurious principles within measurable distance of a State (Thebes) which went so far as to prohibit the representation of unbeautiful things. In respect of poetry we know that the Greeks stood no nonsense, for did not Zoilus suffer an ignominious death for venturing upon childish criticism of Homer? In Rome eccentric painters certainly found some means to thrive, for where "Bohemian" poets gathered, who neglected the barber and the bath, and pretended an æsthetic exclusiveness, there surely would painters of "isms" be found in variety. Naturally in the early stages of the Renaissance, when patronage of the arts was almost confined to the Church, and so went hand in hand with learning, inferior art stood small chance of recognition; and a little[Pg 30] later when Lorenzo gathered around him the intellectual cream of Italy; when the pupils of Donatello were spreading the light of his genius; when the patrician beauties of Florence were posing for Ghirlandaio and his brilliant confrères, and when the minds of Lionardo and Michelangelo were blooming; who would have dared to talk of the psychological qualities of paint, or suggest the composition of a fresco "symphony"?

But another century and more passed away. The blaze of the Renaissance had gone down, but the embers were kept alive, for Italy still seemed to vibrate with a desire to paint. Simultaneously in Flanders, in Holland, in France, and in England, private citizens appeared to develop a sudden demand for pictures, and quite naturally artists multiplied and fed the flame. Outside of Italy the hustle and bustle in the art world were novelties to the general public, though pleasant ones withal, and for half a century or more they delighted in the majestic designs of Rubens and Van Dyck, the intimate scenes of the Dutch artists, and the delicate landscapes of Claude and Poussin and their followers, which were continually finding their way from Rome. The simplicity of the people protected the arts. They knew the hard labour involved in the production of a picture; the worries, the struggles, the joys of the painters; and daily saw beautiful imitations of every-day life in the shops and markets. They must have been proud of them—insensibly proud of the value of human endeavour. For them the sham and immature had no place: there is not a single example of [Pg 31]spurious art of the first three quarters of the seventeenth century that has come down to us from Holland or Flanders. But while the Dutch school was at the height of its fame, a change was marking Italian art conditions. The half score of academies scattered through the country were still in a state of activity, carrying on, as far as they could, the traditions of the Renaissance: from all parts of Europe students were still pouring in, endeavouring to glean the secrets of the immortals; and there was no apparent decrease in the demand for pictures from the religious foundations and private buyers. But the character of the art produced was rapidly declining: the writing on the wall was being done by the hand that wielded the brush. As a necessary consequence the trader was called in and art began to be commercialized. Worse still, fashions appeared, guided by successive masters in the various centres, often with an influence quite out of proportion with their merits.

By the middle of the century a general fall in activity and enthusiasm was noticeable. The disciples of the Roman school, largely through the pernicious influence of Bernini, had nearly forgotten the great lessons taught by the followers of Raphael, and later by the three Carracci, and were fast descending below mediocrity; the Florentine school included half a dozen good painters, mostly students of Berritini: Venice was falling into a stagnation in which she remained till the appearance of Longhi and Tiepolo and their brethren; Bologna was living on the reputation of the Carracci, and had yet to[Pg 32] recover with the aid of Cignani: Milan and Genoa as separate schools had practically faded away; and the Neapolitan school was relying on Salvator Rosa, though Luca Giordano was growing into an inexhaustible hive of invention. This was the condition of Italian art, while political and other troubles were further complicating the position of artists. For most of them the time was gloomy and the future dark. A few turned to landscape; others extended the practice of copying the early masters for the benefit of foreign capitals, while some sought for novelty in still-life, or in the then newly practised pastel work. But there was a considerable number who would have none of these things; some of them with talent but lacking industry, and others with industry but void of imagination. What were these to do at a time when at the best the outlook was poor?

An answer came to this question. A new taste must be cultivated, and for an art that required less study and trouble to produce than the sublime forms with which the Renaissance culminated. So whispers went round that Raphael was not really so great a master as was supposed, and that with Michelangelo he was out of date and did not comprehend the real meaning of art—very similar conclusions with which the modern impressionist movement was heralded.11 The discovery was made in Rome, but the news expanded to Florence and Naples, and Venice, and behold the result—Sprezzatura, or to use the modern word, Impressionism, that is to say, the substitution of sketches for finished pictures,[Pg 33] though this is not the definition usually given to it. But fortunately for the art of the time the innovation was chiefly confined to coteries. All that could be said or done failed to convince the principal patrons of the period that a half finished work is so beautiful as a completed one, and so the novelties rarely found entrance into great collections, nor were they used to adorn the interiors of public buildings. But a good many of them were executed though they have long ceased to interest anybody. Now and again one comes across an example in a sleepy Italian village, or in the smaller shops of Rome or Florence, but it is quickly put aside as a melancholy memento of a disordered period of art when talented painters had to struggle for fame, and the untalented for bread.

The cult of Sprezzatura faded to a glimmer before the end of the seventeenth century. Bernini was dead, and Carlo Maratta with a few others led the way in re-establishing the health if not the brilliancy and renown of Italian art. Nor did a recurrence of the movement occur in the next century. During this period there was comparatively little call for art in Italy, and at the end of it, when political disturbances made havoc with academies and artists, the principal occupation of Italian painters with talent was precisely that of their skilled brethren in Holland and Flanders—the manufacture of "old" masterpieces. It was reserved for the second half of the nineteenth century for Sprezzatura to make its reappearance, and this time Italy followed the lead of France.[Pg 34]

There are many methods and mannerisms which go under the name of Impressionism, but they are mostly suggestions in design or experiments in tones which were formerly produced solely as studies to assist artists in executing their complete works, or else eccentricities which are obviously mere camouflage for lack of skill.12 Sometimes the sketches are slightly amplified with more or less finished signs, and now and then novelties are present in the shape of startling colour effects; but in all cases the impartial observer sees in the pictures only sensorial beauty of a kind which is inevitably short lived, while his understanding is oppressed with the thought, firstly that the picture is probably the result of a want of diligence on the part of the artist, and secondly that its exhibition as a serious work is somewhat of a reflection upon the intelligence of the public.

Obviously the fundamental basis of Impressionism is weak and illogical, for in our conception of nature it invites us to eliminate the understanding. What the impressionist practically says is: "We do not see solid form; we see only flat surface in which objects are distinguished by colours. The artist should reproduce these colours irrespective of the nature of the objects." But the objects are distinguished by our knowledge and experience, and if we are to eliminate these in one art, why not in another? Why trouble about carving in the round when we only actually see in the human figure a flat surface defined by colour? There is no scene in nature such as the impressionist paints, nor can[Pg 35] such a scene be thrown upon the mind of the painter as a natural scene. Except in absolute deserts there are no scenes without many signs which are clearly defined to the eye, and which the artist can paint. He cannot of course produce all the signs in a view, but he can indicate sufficient of them to make a beautiful picture apart from the tones, and there can be no valid æsthetic reason for substituting for these signs vague suggestions of colour infinitely less definite than the signs as they appear in nature. Nor is there any such atmosphere in nature as the impressionist usually paints. We do not see blotched outlines of human figures, but the outlines in nature, except at a considerable distance, appear to us clear and decisive though delicately shaded, and not as seen through a veil of steam. Nor has any valid reason been advanced for juxtaposing pure colours instead of blending them before use.13 Why should the eye have to seek a particular distance from a painting in order that the colours might naturally blend, when the artist can himself blend them and present a harmony which is observable at any reasonable distance? We do not carve a statue with blurred and broken edges, and then tell the observer that the outlines will appear correct if he travel a certain distance away before examining them.

In giving nearly his whole attention to colour the impressionist limits his art to the feeblest form, and produces a quickly tiring, ephemeral thing, as if unconscious of natural beauty. Sylvan glades and fairy dales, where the brooks ripple pleasantly as they moisten the roots of the violet, and gently lave[Pg 36] the feet of the lark and the robin; where shady trees bow welcome to the wanderer; where the grassy carpet is sprinkled with flowers, and every bush can tell of lovers' sighs! Does the impressionist see these things? Offer him the sweetest beauties of nature, and he shows you in return a shake of a kaleidoscope. Mountain peaks towering one above the other till their snowy crests sparkle the azure sky; mighty rivers dividing the hills, crumbling the granite cliffs, or thundering their course over impeding rocks; cascades of flowing crystal falling into seething seas of foam and mist; the angry ocean convulsively defying human power with its heaving walls and fearsome caverns! Nature in her grandest form: sublime forces which kindle the spirit of man: exhibit them to the impressionist, and he presents to you a flat experiment in the juxtaposition of pure colours! And the majesty of the human form, with its glorious attributes; the noble woman and courageous man; incidents of self-sacrifice; the realms of spiritual beauty, and the great ideals which expand the mind to the bounds of space and lift the soul to Heaven! What of these? Ask the impressionist, and he knows nothing of them. For his pencil they are but relics of the past, like the bones of the men who immortalized them in art.

This is perhaps an overstatement of impressionism as applied to the works of a large number of artists, who although commonly sacrificing form to colour, infuse more or less interest in the human poses and actions which are nominally the subjects of their pictures. But one can only deal generally with[Pg 37] such a matter. The evil of Impressionism does not lie in the presentation of colour harmonies as beautiful things, for they are unquestionably pleasing, though the beauty is purely sensorial and of an ephemeral character. The mischief arises from the declaration, overt or implied, that these harmonies represent the higher reaches of the painter's art, and that form or design therein is of secondary importance. Let something false in thought or activity be propagated in any domain where the trader can make use of it, then surely will the evil grow, each new weed being more rank than its predecessor. Impressionism is not a spurious form of art, but seeing that its spurious claims were widely accepted, with substantial results, there soon appeared innumerable other forms inferior to it. There is no necessity to deal here with these forms, with the crude experiments of Cézanne, the vagaries of Van Gogh,14 the puerilities of Matisse, or the awful sequence of "isms," commencing with "Post-Impressionism," and ending in the lowest depths of art degradation; but it is proper to point out that so long as Impressionism puts forward its extravagant pretensions, these corrupt forms will continue to taint the realm of art to the detriment of both artists and public.

The significance of Impressionism is alleged by its advocates to be of such considerable import that in the public interest they should have brought forward the most cogent arguments for its support. But we have no such arguments, nor has any logical reason been advanced to offset the obvious practical[Pg 38] defects of the innovation, namely, that in the general opinion the art is incomplete and decidedly inferior, and that the leading critics of every country have ignored or directly condemned it as an immature form of art. Nevertheless, although there has been no determined attempt to upset the basis of art criticism as this basis has been understood for more than twenty centuries; although the whole of the arguments in support of the various forms of Impressionism have failed to indicate any comprehensible basis at all, but have dealt entirely with vague sensorial theories, and psychological suggestions which have no general meaning; although it has never been remotely advanced that the beauty produced by means of Impressionism is connected with intellectual activity, as any high form of art must necessarily be: notwithstanding all this, there has been gradually growing up in the public mind, a vague and uncertain signification of the comparative forms of art, which tends to the general confusion of thought amongst the public, and a chaos of ideas in the minds of young artists.

The root of these spreading branches of mysticism is to be found in the insistent affirmation that the broad manner of painting is necessary for the production of great work, and that only those old masters who used this manner are worthy of study. It is, as if the advocates of the new departure declare, "If we cannot demonstrate the superiority of our work, we can at least affirm that our methods are the best." Where a small minority is persistent in advocating certain views, and the great majority[Pg 39] do not trouble about replying thereto, false principles are likely to find considerable area for permeation among the rising generation, who are easily impressed with the appearance of undisputed authority. In the matter we are discussing, the limited authority is particularly likely to be recognized by the inexperienced of those mostly concerned, that is to say, young artists, because it sanctions a method of work which reduces to a minimum the labour involved in arriving at excellence by the regular channels.

Now the artist is at liberty to use any method of painting in producing his picture providing he presents something beautiful. There is no special virtue in a broad manner, a fine manner, or any other manner, and the public, for whom the artist toils, is not concerned with the point. It is as indifferent to the kind of brushwork used by the painter, as to the variety of chisel handled by the sculptor. The observer of the picture judges it for its beauty, and if it be well painted, then the character of the brushwork is unconsidered. If, however, the brushwork is so broad that the manner of painting protrudes itself upon the observer at first sight, then the work cannot be of a high class. All the paintings which we recognize as great works of art are pictured upon the brain as complete things immediately they are brought within the compass of the eye, and to this rule there is no exception. If, when encompassed by the sight we find that a picture is so broadly painted that we must move backwards to an unknown point before the character of the work can be thoroughly comprehended as a complete whole, then it[Pg 40] is distinctly inferior as a work of art, because, being incomprehensible on first inspection, it is necessarily unbeautiful, and the act of converting it into a thing of beauty, by means of a mechanical operation, complicates the picture on the brain and so weakens its æsthetic value.15 This is axiomatic. There are proportions and propriety in all the arts, and the good artist is quite aware of the lines to be drawn in respect of the manner he adopts. Jan Van Eyck's picture of Arnolfini and his Wife, and Holbein's Ambassadors, both painted in the fine manner, are equally great works of art with Titian's portraits; and Raphael's portrait of Julius II. (the Pitti Palace example),16 which is in a manner midway between that of Holbein and Titian, is superior to the work of all other portrait artists.