The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Lady of the Mount, by Frederic S. Isham This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Lady of the Mount Author: Frederic S. Isham Illustrator: Lester Ralph Release Date: May 22, 2011 [EBook #36083] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LADY OF THE MOUNT *** Produced by Al Haines

THE LADY OF THE MOUNT

By

FREDERIC S. ISHAM

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

LESTER RALPH

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT 1908

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

FEBRUARY

BY FREDERIC S. ISHAM

BLACK FRIDAY

Illustrated by Harrison Fisher

12mo, Cloth $1.50

UNDER THE ROSE

Illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy

12mo, Cloth $1.50

THE STROLLERS

Illustrated by Harrison Fisher

12mo, Cloth $1.50

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | |

| I | A CHANCE ENCOUNTER |

| II | AN ECHO OF THE PAST |

| III | A SUDDEN RESOLUTION |

| IV | A DANCE ON THE BEACH |

| V | AN INTERRUPTION |

| VI | A MESSAGE FOR MY LADY |

| VII | A DISTANT MENACE |

| VIII | THE OLD WATCH-TOWER |

| IX | A DISCOVERY |

| X | THE CLOISTER IN THE AIR |

| XI | THE GOVERNOR IS SURPRISED |

| XII | AT THE COCKLES |

| XIII | THE SEETHING OF THE SEA |

| XIV | THE PILGRIMAGE |

| XV | THE VOICE FROM THE GROUP |

| XVI | THE MOUNTEBANK AND THE PEOPLE |

| XVII | THE MOUNTEBANK AND THE HUNCHBACK |

| XVIII | THE MOUNTEBANK AND MY LADY |

| XIX | THE MOUNTEBANK AND THE GOVERNOR |

| XX | THE MOUNTEBANK AND THE SOLDIER |

| XXI | THE STAIRWAY OF SILVER |

| XXII | THE WHIRLING OF THE WHEEL |

| XXIII | AT THE VERGE OF THE APERTURE |

| XXIV | THE HALL OF THE CHEVALIERS |

| XXV | THE UNDER WORLD |

| XXVI | A NEW ARRIVAL |

| XXVII | A STROLL ON THE STRAND |

| XXVIII | THE HESITATION OF THE MARQUIS |

| XXIX | THE MARQUIS INTERVENES |

| XXX | A SOUND AFAR |

| XXXI | THE ATTACK ON THE MOUNT |

| XXXII | NEAR THE ALTAR |

| XXXIII | ON THE SANDS |

| XXXIV | SOME TIME LATER |

"Don't you know, boy, you ought not to get in my way?"

The tide was at its ebb; the boats stranded afar, and the lad addressed had started, with a fish—his wage—in one hand, to walk to shore, when, passing into the shadow of the rampart of the Governor's Mount, from the opposite direction a white horse swung suddenly around a corner of the stone masonry and bore directly upon him. He had but time to step aside; as it was, the animal grazed his shoulder, and the boy, about to give utterance to a natural remonstrance, lifted his eyes to the offender. The words were not forthcoming; surprised, he gazed at a tiny girl, of about eleven, perched fairy-like on the broad back of the heavy steed.

"Don't you know you ought not to get in my way?" she repeated imperiously.

The boy, tall, dark, unkempt as a young savage, shifted awkwardly; his black eyes, restless enough ordinarily, expressed a sudden shyness in the presence of this unexpected and dainty creature.

"I—didn't see you," he half stammered.

"Well, you should have!" And again the little lady frowned, shook her disordered golden curls disapprovingly and gazed at him, a look of censure in her brown eyes. "But perhaps you don't know who I am," she went on with a lift of the patrician doll-like features. "I don't think you do, or you wouldn't stand there like a booby, without taking off your hat." More embarrassed, he removed a worn cap while she continued to regard him with the reverse of approval. "I am the Comtesse Elise," she observed; "the daughter of the Governor of the Mount."

"Oh!" said the boy, and his glance shifted to the most important and insistent feature of the landscape.

Carrying its clustered burden of houses and palaces, a great rock reared itself from the monotony of the bare and blinding sands. Now an oasis in the desert, ere night was over he knew the in-rushing waters would convert it into an island; claim it for the sea! A strange kingdom, yet a mighty one, it belonged alternately to the land and to the ocean. With the sky, however, it enjoyed perpetual affiliation, for the heavens were ever wooing it; now winding pretty ribbons of light about its air-drawn castles; then kissing it with the tender, soft red glow of celestial fervor.

"Yes; I live right on top among the clouds, in a castle, with dungeons underneath, where my father puts the bad people who don't like the nobles and King Louis XVI. But where," categorically, "do you live?"

His gaze turned from the points and turrets and the clouds she spoke of—that seemed to linger about the lofty summit—to the mainland, perhaps a mile distant.

"There!" he said, and specifically indicated a dark fringe, like a cloud on the lowlands.

"In the woods! How odd!" She looked at him with faint interest. "And don't the bears bother you? Once when I wanted to see what the woods were like, my nurse told me they were filled with terrible bears who would eat up little girls. I don't have a nurse any more," irrelevantly, "only a governess who came from the court of Versailles, and Beppo. Do you know Beppo?"

"No."

"I don't like him," she confided. "He is always listening. But why do you live in the woods?"

"Because!" The reason failed him.

"And didn't you ever live anywhere else?"

A shadow crossed the dark young face. "Once," he said.

"I suppose the bears know you," she speculated, "and that is the reason they let you alone. Or, perhaps, they are like the wolf in the fairy-tale. Did you ever hear of the kind-hearted wolf?"

He shook his head.

"My nurse used to tell it to me. Well, once there was a boy who was an orphan and everybody hated him. So he went to live in the forest and there he met a wolf. 'Where are you going, little boy?' said the wolf. 'Nowhere,' said the boy; 'I have no home.' 'No home!' said the kind-hearted wolf; 'then come with me, and you shall share my cave.' Isn't that a nice story?"

He looked at her in a puzzled manner. "I don't know," he began, when she tossed her head.

"What a stupid boy!" she exclaimed severely. A moment she studied him tentatively through her curls, from the vantage point of her elevated seat. "That's a big fish," she remarked, after the pause.

"Do you want it?" he asked quickly, his face brightening.

"You can give it to Beppo when he comes," she said, drawing herself up loftily. "He'll be here soon. I've run away from him!" A sudden smile replaced her brief assumption of dignity. "He'll be so angry! He's fat and ugly," more confidentially. "And he's so amusing when he's vexed! But how much do you ask for the fish?"

"I didn't mean—to sell it!"

"Why not?"

"I—don't sell fish."

"Don't sell fish!" She looked at the clothes, frayed and worn, the bare muscular throat, the sunburned legs. "You meant to give it to me?"

"Yes."

The girl laughed. "What a funny boy!"

His cheek flushed; from beneath the matted hair, the disconcerted black eyes met the mocking brown ones.

"Of course I can't take it for nothing," she explained, "and it is very absurd of you to expect it."

"Then," with sudden stubbornness, "I will keep it!"

Her glance grew more severe. "Most people speak to me as 'my Lady.' You seem to have forgotten. Or perhaps you have been listening to some of those silly persons who talk about everybody being born equal. I've heard my father, the Governor, speak of them and how he has put some of them in his dungeons. You'd better not talk that way, or he may shut you up in some terrible dark hole beneath the castle."

"I'm not afraid!" The black eyes shone.

"Then you must be a very wicked boy. It would serve you right if I was to tell."

"You can!"

"Then I won't! Besides, I'm not a telltale!" She tossed her curls and went on. "I've heard my father say these people who want to be called 'gentilhomme' and 'monsieur' are low and ignorant; they can't even read and write."

Again the red hue mantled the boy's cheek. "I don't believe you can!" she exclaimed shrewdly and clapped her hands. "Can you now?" He did not answer. "'Monsieur'! 'Gentilhomme'!" she repeated.

He stepped closer, his face dark; but whatever reply he might have made was interrupted by the sound of a horse's hoofs and the abrupt appearance, from the direction the child had come, of a fat, irascible-looking man of middle age, dressed in livery.

"Oh, here you are, my Lady!" His tone was far from amiable; as he spoke he pulled up his horse with a vicious jerk. "A pretty chase you've led me!"

She regarded him indifferently. "If you will stop at the inn, Beppo—"

The man's irate glance fell. "Who is this?"

"A boy who doesn't want to sell his fish," said the girl merrily.

"Oh!" The man's look expressed a quick recognition. "A fine day's work is this—to bandy words with—" Abruptly he raised his whip. "What do you mean, sirrah, by stopping my Lady?"

A fierce gleam in the lad's eyes belied the smile on his lips. "Don't beat me, good Beppo!" he said in a mocking voice, and stood, alert, lithe, like a tiger ready to spring. The man hesitated; his arm dropped to his side. "The very spot!" he said, looking around him.

A moment the boy waited, then turned on his heel and, without a word, walked away. Soon an angle in the sea-wall, girdling the Mount, hid him from view.

"Why didn't you strike him?" Quietly the child regarded the man. "Were you afraid?" Beppo's answering look was not one of affection for his charge. "Who is he?"

"An idle vagabond."

"What is his name?"

"I don't know."

"Don't you?"

A queer expression sprang into his eyes. "One can't remember every peasant brat," he returned evasively.

She considered him silently; then: "Why did you say: 'The very spot'?" she asked.

"Did I? I don't remember. But it's time we were getting back. Come, my Lady!" And Beppo struck his horse smartly.

Immovable on its granite base, the great rock, or "Mount," as it had been called for centuries, stood some distance from the shore in a vast bay on the northwestern coast of France. To the right, a sweep of sward and marsh stretched seaward, until lost in the distance; to the left, lay the dense Desaurac forest, from which an arm of land, thickly wooded, reached out in seeming endeavor to divide the large bay into two smaller basins. But the ocean, jealous of territory already conquered, twice in twenty-four hours rose to beat heavily on this dark promontory, and, in the angry hiss of the waters, was a reminder of a persistent purpose. Here and there, through the ages, had the shore-line of the bay, as well as the neighboring curvatures of the coast, yielded to the assaults of the sea; the Mount alone, solidly indifferent to blandishment or attack, maintained an unvarying aspect.

For centuries a monastery and fortress of the monks, at the time of Louis XVI the Mount had become a stronghold of the government, strongly ruled by one of its most inexorable nobles. Since his appointment many years before to the post, my lord, the Governor of the rock, had ever been regarded as a man who conceded nothing to the people and pursued only the set tenure of his way. During the long period of his reign he committed but one indiscretion; generally regarded as a man confirmed in apathy for the gentler sex, he suddenly, when already past middle age, wedded. Speculation concerning a step so unlooked for was naturally rife.

In hovel and hut was it whispered the bride Claire, only daughter of the Comtesse de la Mart, had wept at the altar, but that her mother had appeared complacent, as well she might; for the Governor of the Mount and the surrounding country was both rich and powerful; his ships swept far and wide, even to the Orient, while the number of métayers, or petty farmers that paid him tribute, constituted a large community. Other gossips, bending over peat fires within mud walls, affirmed—beneath their breath, lest the spies of the well-hated lord of the North might hear them!—that the more popular, though impoverished Seigneur Desaurac had been the favored suitor with the young woman herself, but that the family of the bride had found him undesirable. The Desaurac fortune, once large, had so waned that little remained save the rich, though heavily encumbered lands, and, in the heart of the forest, a time-worn, crumbling castle.

Thus it came to pass the marriage of the lady to the Governor was celebrated in the jeweled Gothic church crowning a medley of palaces, chapels and monastery on the Mount; that the rejected Seigneur Desaurac, gazing across the strip of water—for the tide was at its full—separating the rocky fortress from the land, shrugged his shoulders angrily and contemptuously, and that not many moons later, as if to show disdain of position and title, took to his home an orphaned peasant lass. That a simple church ceremony had preceded this step was both affirmed and denied; hearsay described a marriage at a neighboring village; more malicious gossip discredited it. A man of rank! A woman of the soil! Feudal custom forbade belief that the proper sort of nuptial knot had been tied.

Be this as it may, for a time the sturdy, dark brown young woman presided over the Seigneur's fortunes with exemplary care and patience. She found them in a chaotic condition; lands had either been allowed to run to waste, or were cultivated by peasants that so long had forgotten to pay the métayage, or owner's due, they had come to regard the acres as their own—a delusion this practical helpmate would speedily have dispelled, save that the Seigneur himself pleaded for them and would not permit of the "poor people" being disturbed. Whereupon she made the best of an anomalous situation, and all concerned might have continued to live satisfactorily enough unto themselves, when unfortunately an abrupt break occurred in the chain of circumstances. In presenting the Seigneur with a child, half-peasant, half-lord, the mother gave up her own life for his posterity.

At first, thereafter, the Seigneur remained a recluse; when, however, a year or two had gone by, the peasants—who had settled in greater numbers thereabouts, even to the verge of the forest—noticed that he gradually emerged from his solitude, ventured into the world at large, and occasionally was seen in the vicinity of the Mount. This predilection for lonely walks clearly led to his undoing; one morning he was found stabbed in the back, on the beach at the foot of the Mount.

Carried home, he related how he had been set upon by a band of miscreants, which later, coming to the Governor's ears, led to an attempt to locate the assailants among the rocky isles to the northwest, haunts of privateersmen, rogues and those reformers who already were beginning to undermine the peace of Louis XVI's northern provinces. In the pursuit of these gentry, the Governor showed himself in earnest. Perhaps his own sorrow at the rather sudden death of his lady, occurring about this time, and leaving him, a morose widower, with a child, a little girl, led him to more relentless activities; perhaps the character of the crime—a noble stabbed!—incensed him.

Certainly he revenged himself to the full; not only raked the rocks for runagates, but dragged peasants, inclined to sullenness, from their huts; clapped some in dungeons and hanged the rest. In the popular mind his name became synonymous with cruelty, but, on his high throne, he continued to exercise his autocratic prerogative and cared not what the people thought.

Meanwhile, the Seigneur Desaurac, recovering, became a prey to greater restlessness; no sooner was he able to get about, than, accompanied by a faithful servant, Sanchez, he left the neighborhood, and, for a number of years, led a migratory existence in continental capitals. The revolt of the colonies in America and the news of the contemplated departure of the brave Lafayette for the seat of hostilities, offered, at least, a pretext to break the fetters of a purposeless life. At once, he placed his sword at Lafayette's disposal, and packed himself and servitor—a fellow of dog-like fidelity—across the ocean. There, at the seat of war's alarms, in the great conflict waged in the name of liberty, he met a soldier's end, far from the fief of his ancestors. Sanchez, the man, buried him, and, having dutifully performed this last task, walked away from the grave and out of the army.

During this while, the son by the peasant woman, intrusted to an old fishwife who had been allowed to usurp a patch of his father's lands, received scanty care and attention, even when the stipulated fees for his maintenance had continued to come; but when, at the Seigneur's death, they ceased, any slight solicitude on the caretaker's part soured to acrimony. An offspring of dubious parentage, she begrudged him his bread; kept him from her own precious brood, and taught them to address him as "brat," "pauper," or by terms even more forcible. Thus set upon, frequently he fought; but like young wolves, hunting in packs, they worried him to the earth, and, when he continued to struggle, beat him to unconsciousness, if not submission.

One day, after such an experience at the hands of those who had partaken of the Seigneur's liberality, the boy, all bruised and aching, fled to the woods, and, with the instinct of an animal to hide, buried himself in its deepest recesses. Night came; encompassed by strange sounds, unknown terrors, he crept to the verge of the forest, and lying there, looked out across the distance toward the scattered habitations, visible through the gloom. One tiny yellow dot of light which he located held his glance. Should he return? That small stone hut, squalid as it was, had been his only remembered home. But the thought of the reception that awaited him there made him hesitate; the stars coming out, seemed to lend courage to his resolution, and, with his face yet turned toward the low long strip of land, sprinkled with the faint, receding points of light, he fell asleep.

The earliest shafts of morn, however, awaking him, sent him quickly back into the dark forest, where all day he kept to the most shadowy screens and covers, fearing he should be followed, and, perhaps, captured. But the second night was like the first, the next like the second, and the days continued to pass with no signs of pursuit. Pinched by hunger, certain of the berries and roots he ate poisoned him, until in time he profited by his sufferings and learned to discriminate in his choice of the frugal fare about him. Not that his appetite was ever satisfied, even when he extended his explorations to the beach at night, digging in the sand with his fingers for cockles, or prowling about the rocks for mussels.

Yet, despite all, he hugged to his breast a compensating sense of liberty; the biting tooth of autumn was preferable to the stripes and tongue-lashings of the old life; and, if now frugal repasts were the rule, hunger had often been his lot in the past. So he assimilated with his surroundings; learned not to fear the animals, and they, to know him; indeed, they seemed to recognize him by that sharp unsated glint of the eye as one of their kind. When the days grew bleaker and the nights colder, he took refuge in a corner within the gray walls of the moss-grown castle of his ancestors, the old Seigneurs. No cheerful place, above all at night, when the spirits of the dead seem to walk abroad, and sobs, moans, and fierce voices fill the air! Then, creeping closer to the fire he had started in the giant hearth, wide-eyed he would listen, only at length through sheer weariness to fall asleep. Nevertheless, it was a shelter, and here, throughout the winter, the boy remained.

Here, too, Sanchez, the Seigneur's old servant, returning months later from long wanderings to the vicinity of the Mount—for no especial reason, save the desire once more to see the place—had found him. And at the sight the man frowned.

In the later days, the Seigneur Desaurac had become somewhat unmindful, if not forgetful, of his own flesh and blood. It may be that the absorbing character of the large and chivalrous motives that animated him left little disposition or leisure for private concerns; at any rate, he seemed seldom to have thought, much less spoken of, that "hostage of fortune" he had left behind; an absent-mindedness that in no wise surprised the servant—which, indeed, met the man's full, unspoken approval! The Seigneur, his master, was a nobleman of untarnished ancestry, to be followed and served; the son—Sanchez had never forgiven the mother her low-born extraction. He was, himself, a peasant!

After his chance encounter with my lady, the Governor's daughter, and Beppo, her attendant, the boy walked quickly from the Mount to the forest. His eyes were still bright; his cheeks yet burned, but occasionally the shadow of a smile played about his mouth, and he threw up his head fiercely. At the verge of the wood he looked back, stood for a moment with the reflection of light on his face, then plunged into the shadows of the sylvan labyrinth. Near the east door of the castle, which presently he reached, he stopped for an armful of faggots, and, bending under his load, passed through an entrance, seared and battered, across a great roofless space and up a flight of steps to a room that had once been the kitchen of the vast establishment. As he entered, a man, thin, wizened, though active looking, turned around.

"So you've got back?" he said in a grumbling tone.

"Yes," answered the boy good-naturedly, casting the wood to the flagging near the flame and brushing his coat with his hand; "the storm kept us out last night, Sanchez."

"It'll keep you out for good some day," remarked the man. "You'll be drowned, if you don't have a care."

"Better that than being hanged!" returned the lad lightly.

The other's response, beneath his breath, was lost, as he drew his stool closer to the pot above the blaze, removed the lid and peered within. Apparently his survey was not satisfactory, for he replaced the cover, clasped his fingers over his knees and half closed his eyes.

"Where's the fish?"

The boy, thoughtfully regarding the flames, started; when he had left the child and Beppo, unconsciously he had dropped it, but this he did not now explain. "I didn't bring one."

"Didn't bring one?"

"No," said the boy, flushing slightly.

"And not a bone or scrap in the larder! Niggardly fishermen! A small enough wage—for going to sea and helping them—"

"Oh, I could have had what I wanted. And they are not niggardly! Only—I forgot."

"Forgot!" The man lifted his hands, but any further evidence of surprise or expostulation was interrupted by a sudden ebullition in the pot.

Left to his thoughts, the boy stepped to the window; for some time stood motionless, gazing through a forest rift at the end of which uprose the top of an Aladdin-like structure, by an optical illusion become a part of that locality; a conjuror's castle in the wood!

"The Mount looks near to-night, Sanchez!"

"Near?" The man took from its hook the pot and set it on the table. "Not too near to suit the Governor, perhaps!"

"And why should it suit him?" drawing a stool to the table and sitting down.

"Because he must be so fond of looking at the forest."

"And does that—please him?"

"How could it fail to? Isn't it a nice wood? Oh, yes, I'll warrant you he finds it to his liking. And all the lands about the forest that used to belong to the old Seigneurs, and which the peasants have taken—waste lands they have tilled—he must think them very fine to look at, now! And what a hubbub there would be, if the lazy peasants had to pay their métayage, and fire-tax and road-tax—and all the other taxes—the way the other peasants do—to him—"

"What do you mean?"

"Nothing!" The man's jaw closed like a steel trap. "The porridge is burned."

And with no further word the meal proceeded. The man, first to finish, lighted his pipe, moved again to the fire, and, maintaining a taciturnity that had become more or less habitual, stolidly devoted himself to the solace of the weed and the companionship of his own reflections. Once or twice the boy seemed about to speak and did not; finally, however, he leaned forward, a more resolute light in his sparkling black eyes.

"You never learned to read, Sanchez?"

At the unexpected question, the smoke puffed suddenly from the man's lips. "Not I."

"Nor write?"

The man made a rough gesture. "Nor sail to the moon!" he returned derisively. "Read? Rubbish! Write? What for? Does it bring more fish to your nets?"

"Who—could show me how to read and write?"

"You?" Sanchez stared.

"Why not?"

"Books are the tools of the devil!" declared Sanchez shortly. "There was a black man here to-day with a paper—a 'writ,' I think he called it—or a 'service' of some kind—anyhow, it must have been in Latin," violently, "for such gibberish, I never heard and—"

The boy rose. "People who can't read and write are low and ignorant!"

"Eh? What's come over you?"

"My father was a gentleman."

"Your father!—yes—"

"And a Seigneur!—"

"A Seigneur truly!"

"And I mean to be one!" said the boy suddenly, closing his fists.

"Oh, oh! So that's it?" derisively. "You! A Seigneur? Whose mother—"

"Who could teach me?" Determined, but with a trace of color on his brown cheek, the boy looked down.

"Who?" The man began to recover from his surprise. "That's not so easy to tell. But if you must know—well, there's Gabriel Gabarie, for one, a poet of the people. He might do it—although there's talk of cutting off his head—"

"What for?"

"For knowing how to write."

The lad reached for his hat.

"Where are you going?"

"To the poet's."

"At this late hour! You are in a hurry!"

"If what you say is true, there's no time to lose."

"Well, if you find him writing verses about liberty and equality, don't interrupt him, or you'll lose your head," shouted the man.

But when the sound of the boy's footsteps had ceased, Sanchez's expression changed; more bent, more worn, he got up and walked slowly to and fro. "A fine Seigneur!" The moldering walls seemed to echo the words. "A fine Seigneur!" he muttered, and again sat brooding by the fire.

In the gathering dusk the lad strode briskly on. A squirrel barked to the right; he did not look around. A partridge drummed to the left; usually alert to wood sound or life, to-night he did not heed it. But, fairly out of the forest and making his way with the same air of resolution across the sands toward the lowland beyond, his attention, on a sudden, became forcibly diverted. He had but half completed the distance from the place where he had left the wood to the objective point in the curvature of the shore, when to the left through the gloom, a great vehicle, drawn by six horses, could be seen rapidly approaching. From the imposing equipage gleamed many lamps; the moon, which ere this had begun to assert its place in the heavens, made bright the shining harness and shone on the polished surface of the golden car. Wondering, the boy paused.

"What is that?"

The person addressed, a fisherman belated, bending to the burden on his shoulders, stopped, and, breathing hard, looked around and watched the approaching vehicle intently.

"The Governor's carriage!" he said. "Haven't you ever heard of the Governor's carriage?"

"No."

"That's because he hasn't used it lately; but in her ladyship's day—"

"Her ladyship?"

"The Governor's lady—he bought it for her. But she soon got tired of it—or perhaps didn't like the way the people looked at her!" roughly. "Mon dieu! perhaps they did scowl a little—for it didn't please them, I can tell you!—the sight of all that gold squeezed from the taxes!"

"Where is he going now?"

"Nowhere himself—he never goes far from the Mount. But the Lady Elise, his daughter—some one in the village was saying she was going to Paris—"

"Paris!" The lad repeated the word quickly. "What for?"

"What do all the great lords and nobles send their children there for? To get educated—married, and—to learn the tricks of the court! Bah!" With a coarse laugh the man turned; stooping beneath his load, he moved grumblingly on.

The boy, however, did not stir; as in a dream he looked first at the Mount, a dark triangle against the sky, then at the carriage. Nearer the latter drew, was about to dash by, when suddenly the driver, on his high seat, uttered an exclamation and at the same time tugged hard at the reins. The vehicle took a quick turn, lurched dangerously in its top-heavy pomp, and, almost upsetting, came to a standstill nearly opposite the boy.

"Careless dog!" a shrill voice screamed from the inside. "What are you doing?"

"The lises, your Excellency!" The driver's voice was thick; as he spoke he swayed uncertainly.

"Lises—quicksands—"

"There, your Excellency," indicating a gleaming place right in their path; a small bright spot that looked as if it might have been polished, while elsewhere on the surrounding sands tiny rippling parallels caressed the eye with streaks of black and silver. "I saw it in time!"

"In time!" angrily. "Imbecile! Didn't you know it was there?"

"Of course, your Excellency! Only I had misjudged a little, and—" The man's manner showed he was frightened.

"Falsehoods! You have been drinking! Don't answer. You shall hear of this later. Drive around the spot."

"Yes, your Excellency," was the now sober and subdued answer.

Ere he obeyed, however, the carriage door, from which the Governor had been leaning, swung open. "Wait!" he called out impatiently, and tried to close it, but the catch—probably from long disuse—would not hold, and, before the liveried servant perched on the lofty carriage behind had fully perceived the fact and had recovered himself sufficiently to think of his duties, the boy on the beach had sprung forward.

"Slam it!" commanded an irate voice.

The lad complied, and as he did so, peered eagerly into the capacious depths of the vehicle.

"The boy with the fish!" exclaimed at the same time a girlish treble within.

"Eh?" my lord turned sharply.

"An impudent lad who stopped the Lady Elise!" exclaimed the fat man—surely Beppo—on the front seat.

"Stopped the Lady Elise!" The Governor repeated the words slowly; an ominous pause was followed by an abrupt movement on the part of the child.

"He did not stop me; it was I who nearly ran over him, and it was my fault. Beppo does not tell the truth—he's a wicked man!—and I'm glad I'm not going to see him any more! And the boy wasn't impudent; at least until Beppo offered to strike him, and then, Beppo didn't! Beppo," derisively, "was afraid!"

"My lady," Beppo's voice was soft and unctuous, "construes forbearance for fear."

"Step nearer, boy!"

Partly blinded by the lamps, the lad obeyed; was cognizant of a piercing scrutiny; two hard, steely eyes that seemed to read his inmost thoughts; a face, indistinguishable but compelling; beyond, something white—a girl's dress—that moved and fluttered!

"Who is he?"

"A poor boy who lives in the woods, papa!"

But Beppo bent forward and whispered, his words too low for the lad to catch. Whatever his information, the Governor started; the questioning glance on an instant brightened, and his head was thrust forward close to the boy's. A chill seemed to pass over the lad, yet he did not quail.

"Good-by, boy!" said the child, and, leaning from the window, smiled down at him.

He tried to answer, when a hand pulled her in somewhat over-suddenly.

"Drive on!" Again the shrill tones cut the air. "Drive on, I tell you! Diable! What are you standing here for!"

A whip lashed the air and the horses leaped forward. The back wheels of the vehicle almost struck the lad, but, motionless, he continued staring after it. Farther it drew away, and, as he remained thus he discerned, or fancied he discerned, a girl's face at the back—a ribbon that waved for a moment in the moonlight, and then was gone.

Eight years elapsed before next he saw her.

The great vernal equinox of April 178-, was the cause of certain unusual movements of the tide, which made old mariners and coast-fishermen shake their heads and gaze seaward, out of all reckoning. At times, after a tempest, on this strange coast, the waters would rise in a manner and at an hour out of the ordinary, and then among the dwellers on the shore, there were those who prognosticated dire unhappiness, telling how the sea had once devoured two villages overnight, and how, beneath the sands, were homes intact, with the people yet in their beds.

Concerned with a disordered social system and men in and out of dungeons, the Governor had little time and less inclination to note the caprices of the tide or the vagaries of the strand. The people! The menacing and mercurial ebb and flow of their moods! The maintenance of autocratic power on the land, and, a more difficult task, on the sea—these were matters of greater import than the phenomena of nature whose purposes man is powerless to shape or curb. My lady, his daughter, however, who had just returned from seven years' schooling at a convent and one year at court where the Queen, Marie Antoinette, set the fashion of gaiety, found in the conduct of their great neighbor, the ocean, a source of both entertainment and instruction for her guests, a merry company transported from Versailles.

"Is it not a sight well worth seeing after your tranquil Seine, my Lords?" she would say with a wave of her white hand toward the restless sea. "Here, perched in mid air like eagles, you have watched the 'grand tide,' as we call it, come in—like no other tide—faster than a horse can gallop! Where else could you witness the like?"

"Nowhere. And when it goes out—"

"It goes out so far, you can no longer see it; only a vast beach that reaches to the horizon, and—"

"Must be very dangerous?"

"For a few days, perhaps; later, not at all, when the petites tides are the rule, and can be depended on. Then are the sands, except for one or two places very well-known, as safe as your gardens at Versailles. But remain, and—you shall see."

Which they did—finding the place to their liking—or their hostess; for the Governor, who cared not for guests, but must needs entertain them for reasons of state, left them as much as might be to his daughter. She, brimming with the ardor and effervescence of eighteen years, accepted these responsibilities gladly; pending that period she had referred to, turned the monks' great refectory into a ball-room, and then, when the gales had swept away, proposed the sands themselves as a scene for diversion both for her guests and the people. This, despite the demur of his Excellency, her father.

"Is it wise," he had asked, "to court the attention of the people?"

"Oh, I am not afraid!" she had answered. "And they are going to dance, too!"

"They!" He frowned.

"Why not? It is the Queen's own idea. 'Let the people dance,' she has said, 'and they will keep out of mischief.' Besides," with a prouder poise of the bright head, "why shouldn't they see, and—like me?"

"They like nothing except themselves, and," dryly, "to attempt to evade their just obligations."

"Can you blame them?" She made a light gesture. "Obligations, mon père, are so tiresome!"

"Well, well," hastily, "have your own way!" Although he spoke rather shortly, on the whole he was not displeased with his daughter; her betrothal with the Marquis de Beauvillers, a nobleman of large estates,—arranged while she was yet a child!—promised a brilliant marriage and in a measure offered to his Excellency some compensation for that old and long-cherished disappointment—the birth of a girl when his ambition had looked so strongly for an heir to his name as well as to his estate.

And so my lady and her guests danced and made merry on the sands below, and the people came out from the mainland, or down from the houses in the town at the base of the rock, to watch. A varied assemblage of gaunt-looking men and bent, low-browed women, for the most part they stood sullen and silent; though exchanging meaning glances now and then as if to say: "Do you note all this ostentation—all this glitter and display? Yes; and some day—" Upon brooding brows, in deep-set eyes, on furrowed faces a question and an answer seemed to gleam and pass. Endowed with natural optimism and a vivacity somewhat heedless, my lady appeared unconscious of all this latent enmity until an unlooked-for incident, justifying in a measure the Governor's demur, broke in upon the evening's festivities and claimed her attention.

On the beach, lighted by torches, a dainty minuet was proceeding gaily, when through the throng of onlookers, a young man with dark head set on a frame tall and powerful, worked his way carefully to a point where he was afforded at least a restricted view of the animated spectacle. Absorbed each in his or her way in the scene before them, no one noticed him, and, with hat drawn over his brow, and standing in the shadow of the towering head-dresses of several peasant women, he seemed content to attract as little attention to himself as possible. His look, at first quick and alert, that of a man taking stock of his surroundings, suddenly became intent and piercing, as, passing in survey over the lowly spectators to the glittering company, it centered itself on the young mistress of festivities.

In costume white and shining, the Lady Elise moved through the graceful numbers, her slender supple figure now poised, now swaying, from head to foot responsive to the rhythm of that "pastime of little steps." Her lips, too, were busy, but such was the witchery of her motion—all fire and life!—the silk-stockinged cavaliers whom she thus regaled with wit, mockery, or jest, could, for the most part, respond only with admiring glances or weakly protesting words.

"That pretty fellow, her partner," with a contemptuous accent on the adjective, "is the Marquis de Beauvillers, a kinsman of the King!" said one of the women in the throng.

"Ma foi! They're well matched. A dancing doll for a popinjay!"

The young man behind the head-dresses, now nodding viciously, moved nearer the front. Dressed in the rough though not unpicturesque fashion of the northern fisherman, a touch of color in his apparel lent to his bearing a note of romance the bold expression of his swarthy face did not belie. For a few moments he watched the girl; the changing eyes and lips, shadowed by hair that shone and flashed like bright burnished gold; then catching her gaze, the black eyes gleamed. An instant their eyes lingered; hers startled, puzzled.

"Where have I seen him?" My lady, in turning, paused to swing over her shoulders a glance.

"Whom?" asked her companion in the dance—a fair, handsome nobleman of slim figure and elegant bearing.

"That's just what I can't tell you," she answered, sweeping a courtesy that fitted the rhythm of the music. "Only a face I should remember!"

"Should?" The Marquis' look followed hers.

But the subject of their conversation, as if divining the trend of their talk, had drawn back.

"Oh, he is gone now," she answered.

"A malcontent, perhaps! One meets them nowadays."

"No, no! He did not look—"

"Some poor fellow, then, your beauty has entrapped?" he insinuated. "Humble admirer!"

"Then I would remember him!" she laughed as the dance came to an end.

Now in a tented pavilion, servants, richly garbed in festal costume, passed among the guests, circulating trays, bright with golden dishes and goblets, stamped with the ancient insignia of the Mount, and once the property of the affluent monks, early rulers of the place. Other attendants followed, bearing light delicacies, confections and marvelous frosted towers and structures from the castle kitchen.

"The patron saint in sugar!" Merry exclamations greeted these examples of skill and cunning. "Are we to devour the saint?"

"Ah, no; he is only to look at!"

"But the Mount in cake—?"

"You may cut into that—though beware!—not so deep as the dungeons!"

"A piece of the cloister!"

"A bit of the abbey!"

"And you, Elise?"

The girl reached gaily. "A little of the froth of the sea!"

Meanwhile, not far distant, a barrel had been broached and wine was being circulated among the people. There, master of ceremonies, Beppo dispensed advice with the beverage, his grumbling talk heard above the light laughter and chatter of the lords and ladies.

"Drink to his Excellency!" As he spoke, the Governor's man, from the elevated stand upon which he stood, gazed arrogantly around him. "Clods! Sponges that sop without a word of thanks! Who only think of your stomachs! Drink to the Governor, I say!"

"To the Governor!" exclaimed a few, but it might have been noticed they were men from the town, directly beneath the shadow of his Excellency's castle, and now close within reach of the fat factotum's arm.

"Once more! Had I the ordering of wine, the barrels would all be empty ones, but her ladyship would be generous, and—"

Beppo broke abruptly off, his wandering glance, on a sudden, arrested.

"Hein!" he exclaimed, with eyes protruding.

A moment he stammered a few words of surprise and incredulity, the while he continued to search eagerly—but now in vain! The object of his startled attention, illumined, for an instant, on the outskirts of the throng, by the glare of a torch, was no more to be descried. As questioning the reality of a fleeting impression, his gaze fixed itself again near the edge of flickering lights; shifted uncertainly to the pavilion where servants from the Mount hurried to and fro; then back to the people around him. His jaw which had dropped grew suddenly firm.

"Clear a space for the dance!" he called out in tones impatient, excited. "It is her ladyship's command—so see you step blithely! And you fellows there, with the tambourin and hautbois, come forward!"

Two men, clad in sheepskin and carrying rude instruments, obediently advanced, and at once, in marked contrast to the recent tinkling measures of the orchestra, a wild, half-barbaric concord rang out.

But the Governor's man, having thus far executed the orders he had received, did not linger to see whether or not his own injunction, "to step blithely," was observed; some concern, remote from gaillarde, gavotte or bourrée of the people, caused him hastily to dismount from his stand and make his way from the throng. As he started at a rapid pace across the sands, his eyes, now shining with anticipation, looked back.

"What could have brought him here? Him!" he repeated. "Ah, my fine fellow, this should prove a lucky stroke for me!" And quickening his step, until he almost ran, Beppo hurried toward the tower gate of the Mount.

"They seem not to appreciate your fête champêtre, my Lady!" At the verge of the group of peasant dancers, the Lady Elise and the Marquis de Beauvillers, who had left the other guests to the enjoyment of fresh culinary surprises, paused to survey a scene, intended, yet failing, to be festal. For whether these people were too sodden to avail themselves of the opportunity for merrymaking, or liked not the notion of tripping together at Beppo's command, their movements, which should have been free and untrammeled as the vigorous swing of the music, were characterized only by painful monotony and lagging. In the half-gloom they came together like shadows; separated aimlessly and cast misshapen silhouettes—caricatures of frolicking peasants—on the broad surface of the sands beyond. These bobbing, black spots my lady disapprovingly regarded.

"They seem not in the mood, truly!" tapping her foot on the beach.

"Here—and elsewhere!" he laughed.

But the Governor's daughter made an impatient movement; memories of the dance, as she had often seen it, when she was a child at the Mount, recurred to her. "They seem to have forgotten!" Her eyes flashed. "I should like to show them."

"You? My Lady!"

She did not answer; pressing her red lips, she glanced sharply around. "Stupid people! Half of them are only looking on! When they can dance, they won't, and—" She gave a slight start, for near her, almost at her elbow, stood the young seaman she had observed only a short time before, when the minuet was in progress. His dark eyes were bent on her and she surprised on his face an expression half derisory, half quizzical. Her look changed to one of displeasure.

"You are not dancing?" severely.

"No, my Lady." Too late, perhaps, he regretted his temerity—that too unveiled and open regard.

"Why not?" more imperiously.

"I—" he began and stopped.

"You can dance?"

"A little, perhaps—"

"As well as they?" looking at the people.

"Wooden fantoccini!" said the man, a flicker of bold amusement returning to his face.

"Fantoccini?" spoke the girl impatiently. "What know you of them?"

"We Breton seamen sail far, on occasion."

"Far enough to gain in assurance!" cried my lady, with golden head high, surveying him disdainfully through half-closed, sweeping lashes. "But you shall prove your right."

"Right?" asked the fellow, his eyes fixed intently upon her.

"The right of one who does not dance—to criticize those who do!" she said pointedly, and made, on the sudden, an imperious gesture.

He gave a start of surprise; audacious though he was, he looked as if he would draw back. "What? With you, my Lady?"

A gleam of satisfaction, a little cold and scornful, shone from the girl's eyes at this evidence of his discomfiture. "Unless," she added maliciously, "you fear you—can not?"

"Fear?" His look shot around; a moment he seemed to hesitate; then a more reckless expression swept suddenly over his dark features and he sprang to her side.

"At your Ladyship's command!"

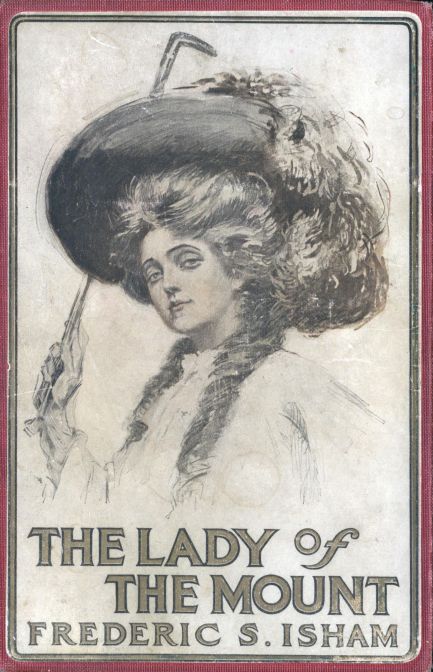

My lady's white chin lifted. The presumptuous fellow knew the dance of the Mount—danced it well, no doubt!—else why such ease and assurance? Her lids veiled a look of disappointment; she was half-minded curtly to dismiss him, when a few words of low remonstrance and the sight of my lord's face decided her. She drew aside her skirts swiftly; flashed back at the nobleman a smile, capricious and wilful.

"They," indicating the peasants, "must have an example, my Lord!" she exclaimed, and stood, with eyes sparkling, waiting the instant to catch up the rhythm.

But the Marquis, not finding the reason sufficient to warrant such condescension, gazed with mute protest and disapproval on the two figures, so ill-assorted: my lady, in robe of satin, fastened with tassels of silver—the sleeves, wide and short, trimmed at the elbow with fine lace of Brussels and drawn up at the shoulder with glistening knots of diamonds; the other, clad in the rough raiment of a seaman! The nice, critical sense of the Marquis suffered from this spectacle of the incongruous; his eyes, seeking in vain those of the Governor's daughter, turned and rested querulously on the heavy-browed peasants, most of whom, drawing nearer, viewed the scene with stolid indifference. In the gaze of only a few did that first stupid expression suffer any change; then it varied to one of vague wonder, half-apathetic inquiry!

"Is he mad?" whispered a clod of this class to a neighbor.

"Not so loud!" breathed the other in a low tone.

"But he," regarding with dull awe the young fisherman, "doesn't care! Look! What foolhardiness! He's going to dance with her!"

"Witchcraft! That's what I call it!"

"Hush!"

My lady extended the tips of her fingers. "Attack well!" runs the old Gallic injunction to dancers; the partner she had chosen apparently understood its significance. A lithe muscular hand closed on the small one; whirled my lady swiftly; half back again. It took away her breath a little, so forcible and unceremonious that beginning! Then, obeying the mad rhythm of the movement, she yielded to the infectious measure. An arm quickly encircled her waist; swept the slender form here,—there. Never had she had partner so vigorous, yet graceful. One who understood so well this song of the soil; its wild symbolism; the ancient music of the hardy Scandinavians who first brought the dance to these shores.

More stirring, the melodies resounded—faster—faster. In a rapid turn, the golden hair just brushed the dark, glowing face. He bent lower; as if she had been but a peasant maid, the bold eyes looked now down into hers; nay, more—in their depths she might fancy almost a warmer sparkle—of mute admiration! And her face, on a sudden, changed; grew cold.

"Certes, your Ladyship sets them an example!" murmured the audacious fellow. "Though, pardi!—one not easy to imitate!"

She threw back her head, proudly, imperiously; the brown eyes gleamed, and certain sharp words of reproof were about to spring from her lips, when abruptly, above the sound of the music, a trumpet call, afar, rang out. My lady—not sorry perhaps of the pretext—at once stopped.

"I thank your Ladyship," said the man and bowed low.

But the Governor's daughter seemed, or affected, not to hear, regarding the other dancers, who likewise had come to a standstill—the two musicians looking up from instruments now silent. A moment yet the young fisherman lingered; seemed about once more to voice his acknowledgments, but, catching the dull eye of a peasant, stepped back instead.

"Sapristi! They might, at least, have waited until the end of the dance!" he muttered, and, with a final look over his shoulder and a low laugh, disappeared in the crowd.

"Where are the enemy?" It was the Marquis who spoke—in accents he strove to make light and thereby conceal, perhaps, possible annoyance. Coming forward, he looked around toward the point whence the sound had proceeded. "If I mistake not," a note of inquiry in his tone, "it means—a call to arms!"

My lady bit her lips; her eyes still gleamed with the bright cold light of a topaz. "Why—a call to arms?" she asked somewhat petulantly, raising her hand to her hair, a little disarranged in the dance.

"Perhaps, as a part of the military discipline?" murmured the Marquis dubiously. "See!" With sudden interest, he indicated a part of the Mount that had been black against the star-spangled sky, now showing sickly points of light. "It does mean something! They are coming down!"

And even as the Marquis spoke, a clatter of hoofs on the stone pavement leading from the Mount to the sand ushered a horseman into view. He was followed by another and yet another, until in somewhat desultory fashion, owing to the tortuous difficulties of the narrow way that had separated them above, an array of mounted men was gathered at the base of the rock. But only for a moment; a few words from one of their number, evidently in command, and they dispersed; some to ride around the Mount to the left, others to the right.

"Perhaps Elise will enlighten us?" Of one accord her guests now crowded around the girl.

"Does the Governor intend to take us prisoners?"

"You imply it is necessary to do that—to keep you?" answered my lady.

"Then why—"

Her expression, as perplexed as theirs, answered.

"Beppo!" She waved her hand.

The Governor's servitor, who was passing, with an anxious, inquiring look upon his face, glanced around.

"Beppo!" she repeated, and beckoned again.

The man approached. "Your Ladyship wishes to speak with me?" he asked in a voice he endeavored to make unconcerned.

"I do." In her manner the old antipathy she had felt toward him as a child again became manifest. "What do the soldiers want? Why have they come down?"

His eyes shifted. "I—my Lady—" he stammered.

The little foot struck the strand. "Why don't you answer? You heard my question?"

"I am sorry, my Lady—" Again he hesitated: "Le Seigneur Noir has been seen on the beach!"

"Le Seigneur Noir?" she repeated.

"Yes, my Lady. He was caught sight of among the peasants, at the time the barrels were opened, in accordance with your Ladyship's command. I assure your Ladyship," with growing eagerness, "there can be no mistake, as—"

"Who," interrupted my lady sharply, "is this Black Seigneur?"

Beppo's manner changed. "A man," he said solemnly, "his Excellency, the Governor, has long been most anxious to capture."

The girl's eyes flashed with impatience, and then she began to laugh. "Saw you ever, my Lords and Ladies, his equal for equivocation? You put to him the question direct, and he answers—"

The loud report of a carbine from the other side of the Mount, followed by a desultory volley, interrupted her. The laughter died on her lips; the color left her cheek.

"What—" The startled look in her eyes completed the sentence.

Beppo rubbed his hands softly. "His Excellency takes no chances!" he murmured.

"So you failed to capture him, Monsieur le Commandant?"

The speaker, the Marquis de Beauvillers, leaned more comfortably back in his chair in the small, rather barely furnished barracks' sitting-room in which he found himself later that night and languidly surveyed the florid, irate countenance of the man in uniform before him.

"No, Monsieur le Marquis," said the latter, endeavoring to conceal any evidence of mortification or ill humor in the presence of a visitor so distinguished; "we didn't. But," as if to turn the conversation, with a gesture toward a well-laden table, "I should feel honored if—"

"Thank you, no! After our repast on the beach—however, stand on no ceremony yourself. Nay, I insist—"

"If Monsieur le Marquis insists!—" The commandant drew up his chair; then, reaching for a bottle, poured out a glass of wine, which he offered his guest.

"No, no!" said the Marquis. "But as I remarked before, stand on no ceremony!" And daintily opening a snuff-box, he watched his host with an expression half-amused, half-ironical.

That person ate and drank with little relish; the wine—so he said—had spoiled; and the dishes were without flavor; it was fortunate Monsieur le Marquis had no appetite—

Whereupon the Marquis smiled; but, considering the circumstances, in his own mind excused the commandant, who had only just come from the Governor's palace, and who, after the interview that undoubtedly had ensued, could hardly be expected to find the pâté palatable, or the wine to his liking. This, despite the complaisance of the young nobleman whom the commandant had encountered, while descending from the Governor's abode, and who, adapting his step to the other's had accompanied the officer back to his quarters, and graciously accepted an invitation to enter.

"Well, you know the old saying," the Marquis closed the box with a snap, "'There's many a slip'—but how," airily brushing with his handkerchief imaginary particles from a long lace cuff, "did he get away?"

"He had got away before we were down on the beach. It was a wild-goose chase, at best. And so I told his Excellency, the Governor—"

"A thankless task, no doubt! But the shots we heard—"

"An imbecile soldier saw a shadow; fired at it, and—"

"The others followed suit?" laughed the visitor.

"Exactly!" The commandant's face grew red; fiercely he pulled at his mustache. "What can one expect, when they make soldiers out of every dunderpate that comes along?"

"True!" assented the Marquis. "But this fellow, this Black Seigneur—why is the Governor so anxious to lay hands on him? Who is he, and what has he done? I confess," languidly, "to a mild curiosity."

"He's a privateersman and an outlaw, and has done enough to hang himself a dozen times—"

"When you capture him!" interposed the visitor lightly. A moment he studied the massive oak beams of the ceiling. "Why do they call him the Black Seigneur? An odd sobriquet!"

"His father was a Seigneur—the last of the fief of Desaurac. The Seigneurs have all been fair men for generations, while this fellow—"

"Then he has noble blood in him?" The Marquis showed surprise. "Where is the fief?"

"The woods on the shore mark the beginning of it."

"But—I don't understand. The father was a Seigneur; the son—"

Bluntly the commandant explained; the son was a natural child; the mother, a common peasant woman whom the former Seigneur had taken to his house—

"I see!" The young nobleman tapped his knee. "And that being the case—"

"Under the terms of the ancient grant, there being no legal heir, the lands were confiscated to the crown. His Excellency, however, had already bought many of the incumbrances against the property, and, in view of this, and his services to the King, the fief, declared forfeited by the courts, was subsequently granted and deeded, without condition, to the Governor."

"To the Governor!" repeated the Marquis.

"Who at once began a rare clearing-out; forcing the peasants who for years had not been paying métayage, to meet this just requirement, or—move away!"

"And did not some of them object?"

"They did; but his Excellency found means. The most troublesome were arrested and taken to the Mount, where they have had time to reflect—his Excellency believes in no half-way measures with peasants."

"A rich principality, no doubt!" half to himself spoke the Marquis.

"I have heard," blurted the commandant, "he's going to give it to the Lady Elise; restore the old castle and turn the grounds surrounding it into a noble park."

The visitor frowned, as if little liking the introduction of the lady's name into the conversation. "And what did the Black Seigneur do then," he asked coldly, "when he found his lands gone?"

"Claimed it was a plot!—that his mother was an honest woman, though neither the priest who performed the ceremony nor the marriage records could be found. He even resisted at first—refused to be turned out—and, skulking about the forest with his gun, kept the deputies at bay. But they surrounded him at last; drove him to the castle, and would have captured him, only he escaped that night, and took to the high seas, where he has been making trouble ever since!"

"Trouble?"

"He has seriously hampered his Excellency's commerce; interfered with his ships, and crippled his trade with the Orient."

"But—the Governor has many boats, many men. Why have they failed to capture him?"

"For a number of reasons. In the first place he is one of the most skilful pilots on the coast; when hard pressed, he does not hesitate to use even the Isles des Rochers as a place of refuge."

"The Isles des Rochers?" queried the nobleman.

"A chevaux-de-frise on the sea, my Lord!" continued the commandant; "where fifty barren isles are fortified by a thousand rocks; frothing fangs when the tide is low; sharp teeth that lie in wait to bite when the smiling lips of the treacherous waters have closed above! There, the Governor's ships have followed him on several occasions, and—few of them have come back!"

"But surely there must be times when he can not depend on that retreat?"

"There are, my Lord. His principal harbor and resort is a little isle farther north—English, they call it—that offers refuge at any time to miscreants from France. There may they lie peacefully, as in a cradle; or go ashore with impunity, an they like. Oh, he is safe enough there. Home for French exiles, they designate the place. Exiles! Bah! It was there he first found means to get his ship—sharing his profits, no doubt, with the islander who built her. There, too, he mustered his crew—savage peasants who had been turned off the lands of the old Seigneur; fisher-folk who had become outlaws rather than pay to the Governor just dues from the sea; men fled from the banalité of the mill, of the oven, of the wine-press—"

"Still must he be a redoubtable fellow, to have done what he did to-night; to have dared mingle with the people, under the Governor's very guns!"

"The people! He has nothing to fear from them. An ignorant, low, disloyal lot! They look upon this fellow as a hero. He has played his cards well; sends money to the lazy, worthless ones, under pretext that they are poor, over-taxed, over-burdened. In his company is one Gabriel Gabarie, a poet of the people, as he is styled, who keeps in touch with those stirring trouble in Paris. Perhaps they hope for an insurrection there, and then—"

"An insurrection?" The Marquis' delicate features expressed ironical protest; he dismissed the possibility with an airy wave of the hand. "One should never anticipate trouble, Monsieur le Commandant," he said lightly and rose. "Good night."

"Good night, Monsieur le Marquis," returned the officer with due deference, and accompanied his noble visitor to the door.

At first, without the barracks, the Marquis walked easily on, but soon the steepness of the narrow road, becoming more marked as it approached the commanding structures at the top of the Mount, caused his gait gradually to slacken; then he paused altogether, at an upper platform.

From where he stood, by day could be seen, almost directly beneath, the tiny habitations of men clinging like limpets to the precipitous sides of the rocks at the base; now was visible only a void, an abysm, out of which swam the sea; so far below, a boat looked no larger than a gull on its silver surface; so immense, the dancing waves seemed receding to a limit beyond the reach of the heavens.

"You found him?" A girl's clear voice broke suddenly upon him. He wheeled.

"Elise! You!"

"Yes! why not? You found him? The commandant?"

"At your command, but—"

"And learned all?"

"All he could tell."

"It is reported at the castle that the man escaped!" quickly.

"It is true. But," in a voice of languid surprise, "I believe you are glad—"

"No, no!" She shook her head. "Only," a smile curved her lips, "Beppo will be so disappointed! Now," seating herself lightly on the low wall of the giant rampart, "tell me all you have learned about this Black Seigneur."

The Marquis, considered; with certain reservations obeyed. At the conclusion of his narrative, she spoke no word and he turned to her inquiringly. Her brows were knit; her eyes down-bent. A moment he regarded her in silence; then she looked up at him suddenly.

"I wonder," she said, her face bathed in the moonlight, "if—if it was this Black Seigneur I danced with?"

"The Black Seigneur!" My lord started; frowned. "Nonsense! What an absurd fancy! He would not have dared!"

"True," said the girl quickly. "You are right, my Lord. It is absurd. He would not have dared."

But guests come and guests go; pastimes draw to a close, and the hour arrives when the curtain falls on the masque. The friends of my lady, however reluctantly, were obliged at last to forgo further holiday-making, depart from the Mount, and return to the court. An imposing cavalcade, gleaming in crimson and gold, they wended down the dark rock; laughing ladies, pranked-out cavaliers who waved their perfumed hands with farewell kisses to the grim stronghold in the desert, late their palace of pleasure, and to the young mistress thereof.

"Good-by, Elise!" The Marquis was last to go.

"Good-by."

He took her hand; held it to his lips. On the whole, he was not ill-pleased. His wooing had apparently prospered; for, although the marriage had been long arranged, my lady's beauty and capriciousness had fanned in him the desire to appear a successful suitor for her heart as well as her hand. If sometimes she laughed and thus failed to receive his delicate gallantries in the mood in which they were tendered, the Marquis' vanity only allowed him to conclude that a woman does not laugh if she is displeased. It was enough that she found him diverting; he served her; they were friends and had danced and ridden through the spring days in amicable fashion.

"Good-by," he repeated. "When are you coming to court again? The Queen is sure to ask. I understand her Majesty is planning all manner of brilliant entertainments, yet Versailles—without you, Elise!"

"Me?" arching her finely penciled brows. "Oh, I'm thinking of staying here, becoming a nun, and restoring the Mount to its old religious prestige."

"Then I'll come back a monk," he returned in the same tone.

"If you come back at all!" provokingly. "There, go! The others will soon be out of sight!"

"I, too—alas, Elise!"

He touched his horse; rode on, but soon looked back to where, against a great, grim wall, stood a figure all in white gleaming in the sunshine. The Marquis stopped; drew from his breast a deep red rose, and, gazing upward, gracefully kissed the glowing token. Beneath the aureole of golden hair my lady's proud face rewarded him with a faint smile, and something—a tiny handkerchief—fluttered like a dove above the frowning, time-worn rock. At that, with the eloquent gesture of a troubadour, he threw his arm backward, as if to launch the impress on the rose to the crimson lips of the girl, and then, plying his spurs, galloped off.

And as he went at a pace, headlong if not dangerous and fitting the exigencies of the moment, my lord smiled. Truly had he presented a perfect, dainty and gallant figure for any woman's eyes, and the Lady Elise, he fancied, was not the least discerning of her sex. And had he seen the girl, when an unkind angle of the wall hid him from sight, his own nice estimate of the situation would have suffered no change. The Mount, which formerly had resounded to the life and merriment of the people from the court, on a sudden to her looked cold, barren, empty.

"Heigh-ho!" she murmured, stretching her arms toward that point where he—they—had vanished. "I shall die of ennui, I am sure!" And thoughtfully retraced her steps to her own room.

But she did not long stay there; by way of makeshift for gaiety, substituted activity. The Mount, full of early recollections and treasure-house mystery, furnished an incentive for exploration, and for several days she devoted herself to its study; now pausing for an instant's contemplation of a sculptured thing of beauty, then before some closed door that held her, as at the threshold of a Bluebeard's forbidden chamber.

One day, such a door stood open and her curiosity became cured. She had passed beneath a machicolated gateway, and climbing a stairway that began in a watch-tower, found herself unexpectedly on a great platform. Here several men, unkempt, pale, like creatures from another world, were walking to and fro; but at sight of her, an order was issued and they vanished through a trap—all save one, a misshapen dwarf who remained to shut the iron door, adjust the fastening and turn a ponderous key. For a moment she stood staring.

"Why did you do that?" she asked angrily.

"The Governor's orders," said the man, bowing hideously. "They are to see no one."

"Then let them up at once! Do you hear? At once!"

And as he began to unlock the door, walked off. After that, her interest in the rock waned; the Mount seemed but a prison; she, herself, desired only to escape from it.

"Have my saddle put on Saladin," she said to Beppo the next day, toward the end of a long afternoon.

"Very well, my Lady. Who accompanies your Ladyship?"

"No one!" With slight emphasis. "I ride alone."

Beppo discretely suppressed his surprise. "Is your Ladyship going far? If so, I beg to remind that to-night is the change of the moon, and the 'grand,' not the 'little' tide may be coming in."

"I was already aware of it, and shall keep between the Mount and the shore. Have my horse sent to the upper gate," she added, and soon afterward rode down.

The town was astir, and many looked after her as she passed; not kindly, but with the varying expressions she had of late begun to notice. Again was she cognizant of that feeling of secret antagonism, even from these people whose houses clung to the very foundations of her own abode, and her lips set tightly. Why did they hate her? What right had they to hate her? A sensation, almost of relief, came over her, when passing through the massive, feudal gate, she found herself on the beach.

Still and languorous was the day; not a breath stirred above the tiny ripples of the sand; a calm, almost unnatural, seemed to wrap the world in its embrace. The girl breathed deeper, feeling the closeness of the air; her impatient eyes looked around; scanned the shore; to the left, low and flat—to the right, marked by the dark fringe of a forest. Which way should she go? Irresolutely she turned in the direction of the wood.

Saladin, her horse, seemed in unusually fine fettle, and the distance separating her from the land was soon covered; but still she continued to follow the shore, swinging around and out toward a point some distance seaward. Not until she had reached that extreme projection of land, where the wooing green crept out from the forest as far as it might, did she draw rein. Saladin stopped, albeit with protest, tossing his great head.

"You might as well make an end of that, sir!" said the girl, and, springing from the saddle, deftly secured him. Then turning her back toward the Mount, a shadowy pyramid in the distance, she seated herself in the grass with her eyes to the woods.

Not long, however, did my lady remain thus; soon rising, she walked toward the shadowy depths. At the verge she paused; her brows grew thoughtful; what was it the woods recalled? Suddenly, she remembered—a boy she had met the night she left for school so long ago, had told her he lived in them. She recalled, too, as a child, how the woman, Marie, who had been maid to her mother, had tried to frighten her about that sequestered domain, with tales of fierce wild animals and unearthly creatures, visible and invisible, that roamed within.

She had no fear now, though faint rustlings and a pulsation of sound held her listening. Then, through the leafy interstice, a gleaming and flashing, as if some one were throwing jewels to the earth, lured her on to the cause of the seeming enchantment—a tiny waterfall!

The moment passed; still she lingered. Around the Mount's high top, her own home, only transcendent silence reigned; here was she surrounded by babbling voices and all manner of merry creatures—lively little squirrels; winged insects, romping in the twilight shade; a portly and well-satisfied appearing green monster who regarded her amicably from a niche of green. A butterfly, poised and waving its wings, held her a long time—until she was suddenly aroused by the wood growing darker. Raising her eyes, she saw through the green foliage overhead that the bright sky had become sunless. At the same time a rumbling detonation, faint, far-off, broke in upon the whisperings and tinklings of that wood nook. Getting up, she stood for a moment listening; then walked away.

Near the verge of the sand, Saladin greeted her with impatience, tossing his head toward the darkening heavens. Nor did he wait until she was fairly seated before starting back at a rapid gait along the shore. But the girl offered no protest; her face showed only enjoyment. A little wild he might be at times, as became one of rugged ancestry, but never vicious, only headstrong! And she didn't mind that—

Already had he begun to slack that first thundering pace when something white—a veil, perhaps, dropped from the cavalcade of lords and ladies some days before on the land and wafted to the beach—fluttered like a live thing suddenly before him. In his tense mood, Saladin, affrighted, sprang to one side; then wheeling outright, madly took the bit in his teeth. Perforce his mistress resigned herself, sitting straight and sure, with little hands hard and firm at the reins. Saladin was behaving very badly, but—at least he was superb, worth conquering, if—

A brief thrill of apprehension seized her as, again drawing near the point of land, he showed no signs of yielding; resisted all her attempts to turn, to direct him to it. With nostrils thrust forward and breathing strong, he continued to choose his own course; to whirl her on; past the promontory; around into the great bay beyond—now a vast expanse, or desert of sand, broken only, about half-way across, by the small isle of Casque. Toward this rocky formation, a pygmy to the great Mount from which it lay concealed by the intervening projection of land, the horse rushed.

On, on! In vain she still endeavored to stop him; thinking uneasily of stories the fishermen told of this neighboring coast; of the sands that often shifted here, setting pitfalls for the unwary. She saw the sky grow yet darker, noted the nearer flashings of light, and heard the louder rumblings that followed. Then presently another danger she had long been conscious of, on a sudden became real.

She saw, or thought she saw, a faint streak, like a silver line drawn across the sky where the yellow sands touched the sombrous horizon. And Saladin seemed to observe it, too; to detect in it cause for wonder; reason for hesitation. At any rate, that headlong speed now showed signs of diminishing; he clipped and tossed the sand less vigorously, and looked around at his mistress with wild, uneasy eyes. Again she spoke to him; pulled with all her strength at the reins, and, at once, he stopped.

None too soon! Great drops of rain had begun to fall, but the girl did not notice them. The white line alone riveted her attention! It seemed to grow broader; to acquire an intangible movement of its own; at the same time to give out a sound—a strange, low droning that filled the air. Heard for the first time, a stranger at the Mount would have found it inexplicable; to the Governor's daughter, the menacing cadence left no room for doubt as to its origin.

The girl's cheek paled; her gaze swung in the opposite direction, toward the point of land, now so distant. Could they reach it? She did not believe they could; indeed, the "grand" tide coming up behind on the verge of the storm, faster than any horse could gallop, would overtake them midway. And Saladin seemed to know it also; beneath her, he trembled. Yet must they try, she thought, and had tightened the reins to turn, when looking ahead once more, she discerned a break in the forbidding cliffs of the little island of Casque, and, back of the fissure, a shining spot which marked a tiny cove.

A moment she hesitated; what should she do? Ride toward the isle and the white danger, or toward the point of mainland and from it? Either alternative was a desperate one, but the isle lay much nearer; and quickly, the brown eyes gleaming with sudden courage, she decided; touched her horse and pressed him forward.

But fast as she went the "grand" tide came faster; struck with a loud, menacing sound the seaward side of the isle and swung hungrily around. My lady cast over her shoulder a quick glance; the cove, however, was near; only a line of small rocks, jutting from the sand, separated her from it. If they could but pass, she thought; they had passed, she told herself joyfully, when of a sudden the horse stumbled; fell. Thrown violently from his back, a moment was she cognizant of a deafening roar; a riotous advance of foam; above, a hundred birds that screamed distractedly; then all these sounds mingled; darkness succeeded, and she remembered no more.

A wall! A window—a prison-like interior! As her eyes opened, the Governor's daughter strove confusedly to decipher her surroundings. The wall seemed real; the narrow window, too, high above, framing, against a darkening background, a slant of fine rain! Again she closed her eyes, only to be conscious of a gentle languor; a heaviness like that of half-sleep; of bodily heat, and also a little bodily pain. For an indefinite period, really a moment or two, she resigned herself to that dreamy torpor; then, with an effort, lifted her lashes once more.

As she gazed before her, something bright seemed leaping back and forth; a flame—that played on the wall; revealing the joints between the stones of massive masonry; casting shadows, but to wipe them out; paling near a small window, the only aperture apparent in the cell-like place. Turning from the flickerings, her glance quickly sought their source—a fire in a hearth, before which she lay—or half-sat, propped against a stone.

But why? The spot was strange; in her ears sounded a buzzing, like the murmur of a waterfall. She remembered now; she had lingered before one—in the woods; and Saladin had run away, madly, across the sands, until—my lady raised her hand to her brow; abruptly let it fall. In the shadow on the other side of the hearth some one moved; some one who had been watching her and who now stepped out into the light.

"Are you better?" said a voice.

She stared. On the bold, swarthy features of a young man now standing and looking down at her, the light flared and gleamed; the open shirt revealed a muscular throat; the down-turned black eyes were steady, solicitous. His appearance was unexpected, yet not quite strange; she had seen him before, but, in the general surprise and perplexity of the moment, did not ask herself where. The interval between what she last remembered on the beach—the rush and swirl of water—and what she woke to, absorbed the hazy workings of her mind.

The young man stopped; stirred the fire, and after a pause, apparently to give her time to collect her thoughts, repeated his question: "Are you better, now?"

"Oh, yes," she said, with an effort, half sitting up. And then irrelevantly, with rather a wild glance about her: "Isn't—isn't it storming outside?"

"A little—not much—" A smile crossed the dark features.

"I remember," she added, as if forcing herself to speak, "it had just begun to, on the beach, when it—the 'grand' tide—" The words died away; mechanically she lifted her hand, brushed back the shining waves of hair.

"Why think of it now?" he interposed gently.

"But," uncertainly she smoothed her skirt; it was damp and warm; "I suppose this is the island of Casque?"

"Yes."

"And this place?"

"The old watch-tower."