The Project Gutenberg EBook of "I Conquered", by Harold Titus This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: "I Conquered" Author: Harold Titus Illustrator: Charles M. Russell Release Date: April 13, 2011 [EBook #35866] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK "I CONQUERED" *** Produced by Andrew Sly, Al Haines and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

"I Conquered"

By HAROLD TITUS

With Frontispiece in Colors

By CHARLES M. RUSSELL

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by Arrangements with Rand, McNally & Company

Copyright, 1916,

By Rand McNally & Company

THE CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | Denunciation |

| II. | A Young Man Goes West |

| III. | "I've Done My Pickin'" |

| IV. | The Trouble Hunter |

| V. | Jed Philosophizes |

| VI. | Ambition Is Born |

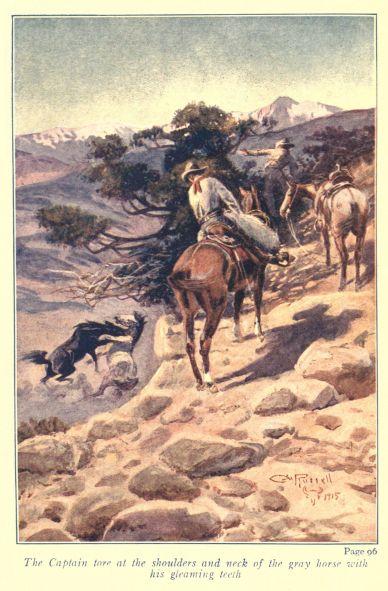

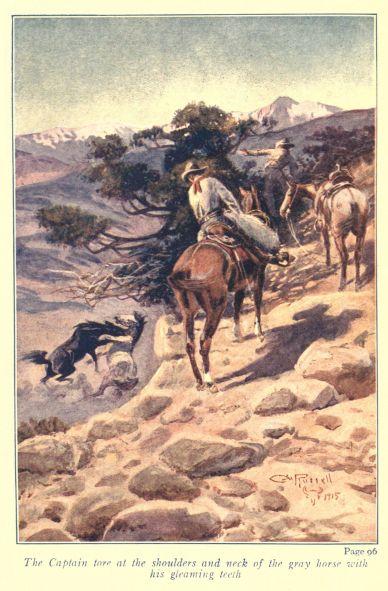

| VII. | With Hoof and Tooth |

| VIII. | A Head of Yellow Hair |

| IX. | Pursuit |

| X. | Capture |

| XI. | A Letter and a Narrative |

| XII. | Woman Wants |

| XIII. | VB Fights |

| XIV. | The Schoolhouse Dance |

| XV. | Murder |

| XVI. | The Candle Burns |

| XVII. | Great Moments |

| XVIII. | The Lie |

| XIX. | Through the Night |

| XX. | The Last Stand |

| XXI. | Guns Crash |

| XXII. | Tables Turn; and Turn Again |

| XXIII. | Life, the Trophy |

| XXIV. | Victory |

| XXV. | "The Light!" |

| XXVI. | To the Victor |

Danny Lenox wanted a drink. The desire came to him suddenly as he stood looking down at the river, burnished by bright young day. It broke in on his lazy contemplation, wiped out the indulgent smile, and made the young face serious, purposeful, as though mighty consequence depended on satisfying the urge that had just come up within him.

He was the sort of chap to whom nothing much had ever mattered, whose face generally bore that kindly, contented smile. His grave consideration had been aroused by only a scant variety of happenings from the time of a pampered childhood up through the gamut of bubbling boyhood, prep school, university, polo, clubs, and a growing popularity with a numerous clan until he had approached a state of established and widely recognized worthlessness.

Economics did not bother him. It mattered not how lavishly he spent; there had always been more forthcoming, because Lenox senior had a world of the stuff. The driver of his taxicab—just now whirling away—seemed surprised when Danny waved back change, but the boy did not bother himself with thought of the bill he had handed over.

Nor did habits which overrode established procedure for men cause him to class himself apart from the mass. He remarked that the cars zipping past between him and the high river embankment were stragglers in the morning flight businessward; but he recognized no difference between himself and those who scooted toward town, intent on the furtherance of serious ends.

What might be said or thought about his obvious deviation from beaten, respected paths was only an added impulse to keep smiling with careless amiability. It might be commented on behind fans in drawing rooms or through mouths full of food in servants' halls, he knew. But it did not matter.

However—something mattered. He wanted a drink.

And it was this thought that drove away the smile and set the lines of his face into seriousness, that sent him up the broad walk with swinging, decisive stride, his eyes glittering, his lips taking moisture from a quick-moving tongue. He needed a drink!

Danny entered the Lenox home up there on the sightly knoll, fashioned from chill-white stone, staring composedly down on the drive from its many black-rimmed windows. The heavy front door shut behind him with a muffled sound like a sigh, as though it had been waiting his coming all through the night, just as it had through so many nights, and let suppressed breath slip out in relief at another return.

A quick step carried him across the vestibule within sight of the dining-room doorway. He flung his soft hat in the general direction of a cathedral bench, loosed the carelessly arranged bow tie, and with an impatient jerk unbuttoned the soft shirt at his full throat. Of all things, from conventions to collars, Danny detested those which bound. And just now his throat seemed to be swelling quickly, to be pulsing; and already the glands of his mouth responded to the thought of that which was on the buffet in a glass decanter—amber—and clear—and—

At the end of the hallway a door stood open, and Danny's glance, passing into the room it disclosed, lighted on the figure of a man stooping over a great expanse of table, fumbling with papers—fumbling a bit slowly, as with age, the boy remarked even in the flash of a second his mind required to register a recognition of his father.

Danny stopped. The yearning of his throat, the call of his tightening nerves, lost potency for the moment; the glitter of desire in his dark eyes softened quickly. He threw back his handsome head with a gesture of affection that was almost girlish, in spite of its muscular strength, and the smile came back, softer, more indulgent.

His brow clouded a scant instant when he turned to look into the dining room as he walked down the long, dark, high-ceilinged hall, and his step hesitated. But he put the impulse off, going on, with shoulders thrown back, rubbing his palms together as though wholesomely happy.

So he passed into the library.

"Well, father, it's a good morning to you!"

At the spontaneous salutation the older man merely ceased moving an instant. He remained bent over the table, one hand arrested in the act of reaching for a document. It was as though he held his breath to listen—or to calculate quickly.

The son walked across to him, approaching from behind, and dropped a hand on the stooping, black-clothed shoulder.

"How go—"

Danny broke his query abruptly, for the other straightened with a half-spoken word that was, at the least, utmost impatience; possibly a word which, fully uttered, would have expressed disgust, perhaps—even loathing! And on Danny was turned such a mask as he had never seen before. The cleanly shaven face was dark. The cold blue eyes flashed a chill fire and the grim slit of a tightly closed mouth twitched, as did the fingers at the skirts of the immaculate coat.

Lenox senior backed away, putting out a hand to the table, edging along until a corner of it was between himself and his heir. Then the hand, fingers stiffly extended, pressed against the table top. It trembled.

The boy flushed, then smiled, then sobered. On the thought of what seemed to him the certain answer to the strangeness of this reception, his voice broke the stillness, filled with solicitude.

"Did I startle you?" he asked, and a smile broke through his concern. "You jumped as though—"

Again he broke short. His father's right hand, palm outward, was raised toward him and moved quickly from side to side. That gesture meant silence! Danny had seen it used twice before—once when a man of political power had let his angered talk rise in the Lenox house until it became disquieting; once when a man came there to plead. And the gesture on those occasions had carried the same quiet, ominous conviction that it now impressed on Danny.

The voice of the old man was cold and hard, almost brittle for lack of feeling.

"How much will you take to go?" he asked, and breathed twice loudly, as though struggling to hold back a bursting emotion.

Danny leaned slightly forward from his hips and wrinkled his face in his inability to understand.

"What?" He drawled out the word. "Once more, please?"

"How much will you take to go?"

Again the crackling, colorless query, by its chill strength narrowing even the thought which must transpire in the presence of the speaker.

"How much will I take to go?" repeated Danny. "How much what? To go where?"

Lenox senior blinked, and his face darkened. His voice lost some of its edge, became a trifle muffled, as though the emotion he had breathed hard to suppress had come up into his throat and adhered gummily to the words.

"How much money—how much money will you take to go away from here? Away from me? Away from New York? Out of my sight—out of my way?"

Once more the fingers pressed the table top and the fighting jaw of the gray-haired man protruded slowly as the younger drew nearer a faltering step, two—three, until he found support against the table.

There across the corner of the heavy piece of furniture they peered at each other; one in silent, mighty rage; the other with eyes widening, quick, confusing lights playing across their depths as he strove to refuse the understanding.

"How much money—to go away from New York—from you? Out of your way?"

Young Danny's voice rose in pitch at each word as with added realization the strain on his emotions increased. His body sagged forward and the hands on the table bore much of its weight; so much that the elbows threatened to give, as had his knees.

"To go away—why? Why—is this?"

In his query was something of the terror of a frightened child; in his eyes something of the look of a wounded beast.

"You ask me why!"

Lenox senior straightened with a jerk and followed the exclamation with something that had been a laugh until, driven through the rage within him, it became only a rattling rasp in his throat.

"You ask me why!" he repeated. "You ask me why!"

His voice dropped to a thin whisper; then, anger carrying it above its normal tone:

"You stand here in this room, your face like suet from months and years of debauchery, your mind unable to catch my idea because of the poison you have forced on it, because of the stultifying thoughts you have let occupy it, because of the ruthless manner in which you have wasted its powers of preception, of judgment, and ask me why!"

In quick gesture he leveled a vibrating finger at the face of his son and with pauses between the words declared: "You—are—why!"

Danny's elbows bent still more under the weight on them, and his lips worked as he tried to force a dry throat through the motions of swallowing. On his face was reflected just one emotion—surprise. It was not rage, not resentment, not shame, not fear—just surprise.

He was utterly confused by the abruptness of his father's attack; he was unable to plumb the depths of its significance, although an inherent knowledge of the other's moods told him that he faced disaster.

Then the older man was saying:

"You have stripped yourself of everything that God and man could give you. You have thrown the gems of your opportunity before your swinish desires. You have degenerated from the son your mother bore to a worthless, ambitionless, idealless, thoughtless—drunkard!"

Danny took a half-step closer to the table, his eyes held on those others with mechanical fixity.

"Father—but, dad—" he tried to protest.

Again the upraised, commanding palm.

"I have stood it as long as I can. I have suggested from time to time that you give serious consideration to things about you and to your future; suggested, when a normal young man would have gone ahead of his own volition to meet the exigencies every individual must face sooner or later.

"But you would have none of it! From your boyhood you have been a waster. I hoped once that all the trouble you gave us was evidence of a spirit that would later be directed toward a good end. But I was never justified in that.

"You wasted your university career. Why, you weren't even a good athlete! You managed to graduate, but only to befog what little hope then remained to me.

"You have had everything you could want; you had money, friends, and your family name. What have you done? Wasted them! You had your polo string and the ability to play a great game, but what came of it? You'd rather sit in the clubhouse and saturate yourself with drink and with the idle, parasitic thoughts of the crowd there!

"You have dropped low and lower until, everything else gone, you are now wasting the last thing that belongs to you, the fundamental thing in life—your vitality!

"Oh, don't try to protest! Those sacks under your eyes! Your shoulders aren't as straight as they were a year ago; you don't think as quickly as you did when making a pretense of playing polo; your hand isn't steady for a man of twenty-five. You're going; you're on the toboggan slide.

"You have wasted yourself, flung yourself away, and not one act or thought of your experience has been worth the candle! Now—what will you take to get out?"

The boy before him moved a slow step backward, and a flush came up over his drawn face.

"You—" he began. Then he stopped and drew a hand across his eyes, beginning the movement slowly and ending with a savage jerk. "You never said a word before! You never intimated you thought this! You never—you—"

He floundered heavily under the stinging conviction that of such was his only defense!

"No!" snapped his father, after waiting for more to come. "I never said anything before—not like this. You smiled away whatever I suggested. Nothing mattered—nothing except debauchery. Now you've passed the limit You're a common drunk!"

His voice rose high and higher; he commenced to gesticulate.

"You live only to wreck yourself. Yours is the fault—and the blame!

"It is natural for me to be concerned. I've hung on now too long, hoping that you would right yourself and justify the hopes people have had in you. I planned, years ago, to have you take up my work where I must soon leave off—to go on in my place, to finish my life for me as I began yours for you! I've had faith that you would do this, but you won't—you can't!

"That isn't all. You're holding me back. I must push on now harder than ever, but with the stench of your misdeeds always in my nostrils it is almost an impossibility."

Danny raised his hands in a half-gesture of pleading, but the old man motioned him back.

"Don't be sorry; don't try to explain. This had to come. It's an accumulation of years. I have no more faith in you. If I thought you could ever rally I'd give up everything and help you, but not once in your life have you shown me that you possessed one impulse to be of use."

His voice dropped with each word, and its return to the cold normal sent a stiffness into the boy's spine. His head went up, his chin out; his hands closed slowly.

"How much money will you take to get out?"

The old man moved from behind the table corner and approached Danny, walking slowly, with his hands behind him. He came to a stop before the boy, slowly unbuttoned his coat, reached to an inner pocket, and drew out a checkbook.

"How much?"

Danny's gesture, carried out, surely would have resulted in a blow strong enough to send the book spinning across the room; but he stopped it halfway.

His eyes were puffed and bloodshot; his pulse hammered loudly under his ears, and the rush of blood made his head roar. Before him floated a mist, fogging thought as it did his vision.

The boy's voice was scarcely recognizable as he spoke. It was hard and cold—somewhat like the one which had so scourged him.

"Keep your money," he said, looking squarely at his father at the cost of a peculiar, unreal effort. "I'll get out—and without your help. Some day I'll—I'll show you what a puny thing this faith of yours is!"

The elder Lenox, buttoning his coat with brisk motions, merely said, "Very well." He left the room.

Danny heard his footsteps cross the hall, heard the big front door sigh when it closed as though it rejoiced at the completion of a distasteful task.

Then he shut his eyes and struck his thighs twice with stiff forearms. He was boiling, blood and brain! At first he thought it anger; perhaps anger had been there, but it was not the chief factor of that tumult.

It was humiliation. The horrid, unanswerable truth had seared Danny's very body—witness the anguished wrinkles on his brow—and his molten consciousness could find no argument to justify himself, even to act as a balm!

"He never said it before," the boy moaned, and in that spoken thought was the nearest thing to comfort that he could conjure.

He stood in the library a long time, gradually cooling, gradually nursing the bitterness that grew up in the midst of conflicting impulses. The look in his eyes changed from bewilderment to a glassy cynicism, and he began to walk back and forth unsteadily.

He paced the long length of the room a dozen times. Then, with a quickened stride, he passed into the hall, crossed it, and entered the dining room, the tip of his tongue caressing his lips.

On the buffet stood a decanter, a heavy affair of finely executed glassworker's art. The dark stuff in it extended halfway up the neck, and as he reached for it Danny's lips parted. He lifted the receptacle and clutched at a whisky glass that stood on the same tray. He picked it up, looked calculatingly at it, set it down, and picked up a tumbler.

The glass stopper of the bottle thudded on the mahogany; his nervous hand held the tumbler under its gurgling mouth. Half full, two-thirds, three-quarters, to within a finger's breadth of the top he filled it.

Then, setting the decanter down, he lifted the glass to look through the amber at the morning light; his breath quick, his eyes glittering, Danny Lenox poised. A smile played about his eager lips—a smile that brightened, and lingered, and faded—and died.

The hand holding the glass trembled, then was still; trembled again, so severely that it spilled some of the liquor; came gradually down from its upraised position, down below his mouth, below his shoulder, and waveringly sought the buffet.

As the glass settled to the firm wood Danny's shoulders slacked forward and his head drooped. He turned slowly from the buffet, the aroma of whisky strong in his dilated nostrils. After the first faltering step he faced about, gazed at his reflection in the mirror, and said aloud:

"And it's not been worth—the candle!"

Savagery was in his step as he entered the hall, snatched up his hat, and strode to the door.

As the heavy portal swung shut behind the hurrying boy it sighed again, as though hopelessly. The future seemed hopeless for Danny. He had gone out to face a powerful foe.

From the upper four hundreds on Riverside Drive to Broadway where the lower thirties slash through is a long walk. Danny Lenox walked it this June day. As he left the house his stride was long and nervously eager, but before he covered many blocks his gait moderated and the going took hours.

Physical fatigue did not slow down his progress. The demands upon his mental machinery retarded his going. He needed time to think, to plan, to bring order out of the chaos into which he had been plunged. Danny had suddenly found that many things in life are to be considered seriously. An hour ago they could have been numbered on his fingers; now they were legion. It was a newly recognized fact, but one so suddenly obvious that the tardiness of his realization became of portentous significance.

Through all the hurt and shame and rage the great truth that his father had hammered home became crystal clear. He had been merely a waster, and a sharp bitterness was in him as he strode along, hands deep in pockets.

The first flash of his resentment had given birth to the childish desire to "show 'em," and as he crowded his brain against the host of strange facts he found this impulse becoming stronger, growing into a healthy determination to adjust his standard of values so that he could, even with this beginning, justify his existence.

Oh, the will to do was strong in his heart, but about it was a clammy, oppressive something. He wondered at it—then traced it back directly to the place in his throat that cried out for quenching. As he approached a familiar haunt that urge became more insistent and the palms of his hands commenced to sweat. He crossed the street and made on down the other side. He had wasted his ability to do, had let this desire sap his will. He needed every jot of strength now. He would begin at the bottom and call back that frittered vitality. He shut his teeth together and doggedly stuck his head forward just a trifle.

The boy had no plan; there had not been time to become so specific. His whole philosophy had been stood on its head with bewildering suddenness. He knew, though, that the first thing to do was to cut his environment, to get away, off anywhere, to a place where he could build anew. The idea of getting away associated itself with one thing in his mind: means of transportation. So, when his eyes without conscious motive stared at the poster advertising a railroad system that crosses the continent, Danny Lenox stopped and let the crowd surge past him.

A man behind the counter approached the tall, broad-shouldered chap who fumbled in his pockets and dumped out their contents. He looked with a whimsical smile at the stuff produced: handkerchiefs, pocket-knife, gold pencil, tobacco pouch, watch, cigarette case, a couple of hat checks, opened letters, and all through it money—money in bills and in coins.

The operation completed, Danny commenced picking out the money. He tossed the crumpled bills together in a pile and stacked the coins. That done, he swept up the rest of his property, crammed it into his coat pockets, and commenced smoothing the bills.

The other man, meanwhile, stood and smiled.

"Cleaning up a bit?" he asked.

Danny raised his eyes.

"That's the idea," he said soberly. "To clean up—a bit."

The seriousness of his own voice actually startled him.

"How far will that take me over your line?" he asked, indicating the money.

The man stared hard; then smiled.

"You mean you want that much worth of ticket?"

"Yes, ticket and berth—upper berth. Less this." He took out a ten-dollar bill. "I'll eat on the way," he explained gravely.

The other counted the bills, turning them over with the eraser end of his pencil, then counted the silver and made a note of the total.

"Which way—by St. Louis or Chicago?" he asked. "We can send you through either place."

Danny lifted a dollar from the stack on the counter and flipped it in the air. Catching it, he looked at the side which came up and said:

"St. Louis."

Again the clerk calculated, referring to time-tables and a map.

"Denver," he muttered, as though to himself. Then to Danny: "Out of Denver I can give you the Union Pacific, Denver and Rio Grande, or Santa Fé."

"The middle course."

"All right—D. and R.G."

Then more referring to maps and time-tables, more figuring, more glances at the pile of money.

"Let's see—that will land you at—at—" as he ran his finger down the tabulation—"at Colt, Colorado."

Danny moved along the counter to the glass-covered map, a new interest in his face.

"Where's that—Colt, Colorado?" he asked, leaning his elbows on the counter.

"See?" The other indicated with his pencil.

"You go south from Denver to Colorado Springs; then on through Pueblo, through the Royal Gorge here, and right in here—" he put the lead point down on the red line of the railroad and Danny's head came close to his—"is where you get off."

The boy gazed lingeringly at the white dot in the red line and then looked up to meet the other's smile.

"Mountains and more mountains," he said with no hint of lightness. "That's a long way from this place."

He gazed out on to flowing Broadway with a look somewhat akin to pleading, and heard the man mutter: "Yes, beyond easy walking from downtown, at least."

Danny straightened and sighed. That much was settled. He was going to Colt, Colorado. He looked back at the map again, possessed with an uneasy foreboding.

Colt, Colorado!

"Well, when can I leave?" he asked, as he commenced putting his property back into the proper pockets.

"You can scarcely catch the next train," said the clerk, glancing at the clock, "because it leaves the Grand Central in nineteen min—"

"Yes, I can!" broke in Danny. "Get me a ticket and I'll get there!" Then, as though to himself, but still in the normal speaking tone: "I'm through putting things off."

Eighteen and three-quarters minutes later a tall, young man trotted through the Grand Central train shed to where his Pullman waited. The porter looked at the length of the ticket Danny handed the conductor.

"Ain't y'll carryin' nothin', boss?" he asked.

"Yes, George," Danny muttered as he passed into the vestibule, "but nothing you can help me with."

With the grinding of the car wheels under him Danny's mind commenced going round and round his knotty problem. His plan had called for nothing more than a start. And now—Colt, Colorado!

Behind him he was leaving everything of which he was certain, sordid though it might be. He was going into the unknown, ignorant of his own capabilities, realizing only that he was weak. He thought of those burned bridges, of the uncertainty that lay ahead, of the tumbling of the old temple about his ears—

And doubt came up from the ache in his throat, from the call of his nerves. He had not had a drink since early last evening. He needed—No! That was the last thing he needed.

He sat erect in his seat with the determination and strove to fight down the demands which his wasting had made so steely strong. He felt for his cigarette case. It was empty, but the tobacco pouch held a supply, and as he walked toward the smoking compartment he dusted some of the weed into a rice paper.

Danny pushed aside the curtain to enter, and a fat man bumped him with a violent jolt.

"Oh, excuse me!" he begged, backing off. "Sorry. I'll be back in a jiffy with more substantial apologies."

Three others in the compartment made room for Danny, who lighted his cigarette and drew a great gasp of smoke into his lungs.

In a moment the fat man was back, his eyes dancing. In his hand was a silver whisky flask.

"Now if you don't say this is the finest booze ever turned out of a gin mill, I'll go plumb!" he declared. "Drink, friend, drink!"

He handed the flask to one of the others.

"Here's to you!" the man saluted, raising the flask high and then putting its neck to his mouth.

Danny's tongue went again to his lips; his breath quickened and the light in his eyes became a greedy glitter. He could hear the gurgle of the liquid; his own throat responded in movement as he watched the swallowing. He squeezed his cigarette until the thin paper burst and the tobacco sifted out.

"Great!" declared the man with a sigh as he lowered the flask. "Great!"

He smacked his lips and winked. "Ah! No whisky's bad, but this's better'n most of it!"

Then, extending the flask toward Danny, he said: "Try it, brother; it's good for a soul."

But Danny, rising to his feet with a suddenness that was almost a spring, strode past him to the door. His face suddenly had become tight and white and harried. He paused at the entry, holding the curtain aside, and turned to see the other, flask still extended, staring at him in bewilderment.

"I'm not drinking, you know," said Danny weakly, "not drinking."

Then he went out, and the fat man who had produced the liquor said soberly:

"Not drinking, and havin' a time staying off it. But say—ain't that some booze?"

Long disuse of the power to plan concretely, to think seriously of serious facts, had left it weak. Danny strove to route himself through to that new life he knew was so necessary, but he could not call back the ability of tense thinking with a word or a wish. And while he tried for that end the boy commenced to realize that perhaps he had not so far to seek for his fresh start. Perhaps it was not waiting for him in Colt, Colorado. Perhaps it was right here in his throat, in his nerves. Perhaps the creature in him was not a thing to be cleared away before he could begin to fight—perhaps it was the proper object at which to direct his whole attack.

Enforced idleness was an added handicap. Physical activity would have made the beginning much easier, for before he realized it Danny was in the thick of battle. A system that had been stimulated by poison in increasing proportion to its years almost from boyhood began to make unequivocal demands for the stuff that had held it to high pitch. Tantalizingly at first, with the thirsting throat and jumping muscles; then with thundering assertions that warped the vision and numbed the intellect and toyed with the will. He gave up trying to think ahead. His entire mental force went into the grapple with that desire. Where he had thought to find possible distress in the land out yonder, it had come to meet him—and of a sort more fearful, more tremendous, than any which he had been able to conceive.

Through the rise of that fevered fighting the words of his father rang constantly in Danny's mind.

"He was right—right, right!" the boy declared over and over. "It was brutal; but he was right! I've wasted, I've gone the limit. And he doesn't think I can come back!"

While faith would have been as a helping hand stretched down to pull him upward, the denial of it served as a stinging goad, driving him on. A chord deep within him had been touched by the raining blows from his father, and the vibrations of that chord became quicker and sharper as the battle crescendoed. The unbelief had stirred a retaliating determination.

It was this that sent a growl of defiance into Danny's throat at sight of a whisky sign; it was the cause of his cursing when, walking up and down a station platform at a stop, he saw men in the buffet car lift glasses to their lips and smile at one other. It was this that drew him away from an unfinished meal in the diner when a man across the table ordered liquor and Danny's eyes ached for the sight of it, his nostrils begged for the smell.

So on every hand came the suggestions that made demands upon his resistance, that made the weakness gnaw the harder at his will. But he fought against it, on and on across a country, out into the mountains, toward the end of his ride.

The unfolding of the marvels of a continent's vitals had a peculiar effect on Danny.

Before that trip he had held the vaguest notions of the West, but with the realization of the grandeur of it all he was torn between a glorified inspiration and a suffocating sense of his own smallness.

He had known only cities, and cities are, by comparison, such puny things. They froth and ferment and clatter and clang and boast, and yet they are merely flecks, despoiled spots, on an expanse so vast that it seems utterly unconscious of their presence. The boy realized this as the big cities were left behind, as the stretches between stations became longer, the towns more flimsy, newer. A species of terror filled him as he gazed moodily from his Pullman window out across that panorama to the north. Why, he could see as far as to the Canadian boundary, it seemed! On and on, rising gently, ever flowing, never ending, went the prairie. Here and there a fence; now a string of telephone poles marching out sturdily, bravely, to reduce distance by countless hours. There a house, alone, unshaded, with a woman standing in the door watching his speeding train. Yonder a man shacking along on a rough little horse, head down, listless—a crawling jot under that endless sky.

Even his train, thing of steel and steam, was such a paltry particle, screaming to a heaven that heard not, driving at a distance that cared not.

Then the mountains!

Danny awoke in Denver, to step from his car and look at noble Evans raising its craggy, hoary head into the salmon pink of morning, defiant, ignoring men who fussed and puttered down there in its eternal shadow; at Long's Peak, piercing the sky as though striving to be away from humans; at Pike, shimmering proudly through its sixty miles of crystal distance, taking a heavy, giant delight in watching beings worry their way through its hundred-mile dooryard.

Then along the foothills the train tore with the might of which men are so proud; yet it only crawled past those mountains.

Stock country now, more and more cattle in sight. Blasé, white-faced Herefords lifted their heads momentarily toward the cars. They heeded little more than did the mountains.

Then, to the right and into the ranges, twisting, turning, climbing, sliding through the narrow defiles at the grace of the towering heights which—so alive did they seem—could have whiffed out that thing, those lives, by a mere stirring on their complacent bases.

And Danny commenced to draw parallels. Just as his life had been artificial, so had his environment. Manhattan—and this! Its complaining cars, its popping pavements, its echoing buildings—it had all seemed so big, so great, so mighty! And yet it was merely a little mud village, the work of a prattling child, as compared with this country. The subway, backed by its millions in bonds, planned by constructive genius, executed by master minds, a thing to write into the history of all time, was a mole-passage compared to this gorge! The Woolworth, labor of years, girders mined on Superior, stones quarried elsewhere, concrete, tiling, cables, woods, all manner of fixtures contributed by continents; donkey engines puffing, petulant whistles screaming, men of a dozen tongues crawling and worming and dying for it; a nation standing agape at its ivory and gold attainments! And what was it? Put it down here and it would be lost in the rolling of the prairie as it swelled upward to meet honest heights!

No wonder Danny Lenox felt inconsequential. And yet he sensed a friendly something in that grandeur, an element which reached down for him like a helping hand and offered to draw him out of his cramped, mean little life and put him up with stalwart men.

"If this rotten carcass of mine, with its dry throat and fluttering hands, will only stick by me I'll show 'em yet!" he declared, and held up one of those hands to watch its uncertainty.

And in the midst of one of those bitter, griping struggles to keep his vagrant mind from running into vinous paths, the brakes clamped down and the porter, superlatively polite, announced:

"This is Colt, sah."

A quick interest fired Danny. He hurried to the platform, stood on the lowest step, and watched the little clump of buildings swell to natural size. He reached into his pocket, grasped the few coins remaining there, and gave them to the colored boy.

The train stopped with a jolt, and Danny stepped off. The conductor, who had dropped off from the first coach as it passed the station, ran out of the depot, waved his hand, and the grind of wheels commenced again.

As the last car passed, Danny Lenox stared at it, and for many minutes his gaze followed its departure. After it had disappeared around the distant curve he retained a picture of the white-clad servant, leaning forward and pouring some liquid from a bottle.

The roar of the cars died to a murmur, a muttering, and was swallowed in the cañon. The sun beat down on the squat, green depot and cinder platform, sending the quivering heat rays back to distort the outlines of objects. Everywhere was a white, blinding light.

From behind came a sound of waters, and Danny turned about to gaze far down into a ragged gorge where a river tumbled and protested through the rocky way.

Beyond the stream was stretching mesa, quiet and flat and smooth looking in the crystal distance, dotted with pine, shimmering under the heat.

For five minutes he stared almost stupidly at that grand sweep of still country, failing to comprehend the fact of arrival. Then he walked to the end of the little station and gazed up at the town.

A dozen buildings with false fronts, some painted, some without pretense of such nicety, faced one another across a thoroughfare four times as wide as Broadway. Sleeping saddle ponies stood, each with a hip slumped and nose low to the yellow ground. A scattering of houses with their clumps of outbuildings and fenced areas straggled off behind the stores.

Scraggly, struggling pine stood here and there among the rocks, but shade was scant.

Behind the station were acres of stock pens, with high and unpainted fences. Desolation! Desolation supreme!

Danny felt a sickening, a revulsion. But lo! his eyes, lifting blindly for hope, for comfort, found the thing which raised him above the depression of the rude little town.

A string of cliffs, ranging in color from the bright pink of the nearest to the soft violet of those which might be ten or a hundred miles away, stretched in mighty columns, their varied pigments telling of the magnificent distances to which they reached. All were plastered up against a sky so blue that it seemed thick, and as though the color must soon begin to drip. Glory! The majesty of the earth's ragged crust, the exquisite harmony of that glorified gaudiness! Danny pulled a great chestful of the rare air into his lungs. He threw up his arms in a little gesture that indicated an acceptance of things as they were, and in his mind flickered the question:

"The beginning—or the end?"

Then he felt his gaze drawn away from those vague, alluring distances. It was one of those pulls which psychologists have failed to explain with any great clarity; but every human being recognizes them. Danny followed the impulse.

He had not seen the figure squatting there on his spurs at the shady end of the little depot, for he had been looking off to the north. But as he yielded to the urge he knew its source—in those other eyes.

The figure was that of a little man, and his doubled-up position seemed to make his frame even more diminutive. The huge white angora chaps, the scarlet kerchief about his neck and against the blue of his shirt, the immense spread of his hat, his drooping gray mustache, all emphasized his littleness.

Yet Danny saw none of those things. He looked straight into the blue eyes squinting up at him—eyes deep and comprehensive, set in a copper-colored face, surrounded by an intricate design of wrinkles in the clear skin; eyes that had looked at incalculably distant horizons for decades, and had learned to look at men with that same long-range gaze. A light was in those eyes—a warm, kindly, human light—that attracted and held and created an atmosphere of stability; it seemed as though that light were tangible, something to which a man could tie—so prompt is the flash from man to man that makes for friendship and devotion; and to Danny there came a sudden comfort. That was why he did not notice the other things about the little man. That was why he wanted to talk.

"Good morning," he said.

"'Mornin'."

Then a pause, while their eyes still held one another.

After a moment Danny looked away. He had a stabbing idea that the little man was reading him with that penetrating gaze. The look was kindly, sincere, yet—and perhaps because of it—the boy cringed.

The man stirred and spat.

"To be sure, things kind of quiet down when th' train quits this place," he remarked with a nasal twang.

"Yes, indeed. I—I don't suppose much happens here—except trains."

Danny smiled feebly. He took his hat off and wiped the brow on which beads of sweat glistened against the pallor. The little man still looked up, and as he watched Danny's weak, uncertain movements the light in his eyes changed. The smile left them, but the kindliness did not go; a concern came, and a tenderness.

Still, when he spoke his nasal voice was as it had been before.

"Take it you just got in?"

"Yes—just now."

Then another silence, while Danny hung his head as he felt those searching eyes boring through him.

"Long trip this hot weather, ain't it?"

"Yes, very long."

Danny looked quickly at his interrogator then and asked:

"How did you know?"

"Didn't. Just guessed." He chuckled.

"Ever think how many men's been thought wise just guessin'?"

But Danny caught the evasion. He looked down at his clothes, wrinkled, but still crying aloud of his East.

"I suppose," he muttered, "I do look different—am different."

And the association of ideas took him across the stretches to Manhattan, to the life that was, to—

He caught his breath sharply. The call of his throat was maddening!

The little man had risen and, with thumbs hooked in his chap belt, stumped on his high boot heels close to Danny. A curious expression softened the lines of his face, making it seem queerly out of harmony with his garb.

"You lookin' for somebody?" he ventured, and the nasal quality of his voice seemed to be mellowed, seemed to invite, to compel confidence.

"Looking for somebody?"

Danny, only half consciously, repeated the query. Then, throwing his head back and following that range of flat tops off to the north, he muttered: "Yes, looking for somebody—looking for myself!"

The other shifted his chew, reached for his hat brim, and pulled it lower.

"No baggage?" he asked. "To be sure, an' ain't you got no grip?"

Danny looked at him quickly again, and, meeting the honest query in that face, seeing the spark there which meant sympathy and understanding—qualities which human beings can recognize anywhere and to which they respond unhesitatingly—he smiled wanly.

"Grip?" he asked, and paused. "Grip? Not the sign of one! That's what I'm here for—in Colt, Colorado—to get a fresh grip!" After a moment he extended an indicating finger and asked: "Is that all of Colt—Colt, Colorado?"

The old man did not follow the pointing farther than the uncertain finger. And when he answered his eyes had changed again, changed to searching, ferreting points that ran over every puff and seam and hollow in young Danny's face. Then the older man set his chin firmly, as though a grim conclusion had been reached.

"That's th' total o' Colt," he answered. "It ain't exactly astoundin', is it?"

Danny shook his head slowly.

"Not exactly," he agreed. "Let's go up and look it over."

An amused curiosity drove out some of the misery that had been in his pallid countenance.

"Sure, come along an' inspect our metropolis!" invited the little man, and they struck off through the sagebrush.

Danny's long, free stride made the other hustle, and the contrast between them was great; the one tall and broad and athletic of poise in spite of the shoulders, which were not back to their full degree of squareness; the other, short and bowlegged and muscle-bound by years in the saddle, taking two steps to his pacemaker's one.

They attracted attention as they neared the store buildings. A man in riding garb came to the door of a primitive clothing establishment, looked, stepped back, and emerged once more. A moment later two others joined him, and they stared frankly at Danny and his companion.

A man on horseback swung out into the broad street, and as he rode away from them turned in his saddle to look at the pair. A woman ran down the post-office steps and halted her hurried progress for a lingering glance at Danny. The boy noticed it all.

"I'm attracting attention," he said to the little man, and smiled as though embarrassed.

"Aw, these squashies ain't got no manners," the other apologized. "They set out in there dog-gone hills an' look down badger holes so much that they git loco when somethin' new comes along."

Then he stopped, for the tall stranger was not beside him. He looked around. His companion was standing still, lips parted, fingers working slowly. He was gazing at the front of the Monarch saloon.

From within came the sound of an upraised voice. Then another in laughter. The swinging doors opened, and a man lounged out. After him, ever so faint, but insidiously strong and compelling, came an odor!

For a moment, a decade, a generation—time does not matter when a man chokes back temptation to save himself—Danny stood in the yellow street, under the white sunlight, making his feet remain where they were. They would have hurried him on, compelling him to follow those fumes to their source, to push aside the flapping doors and take his throat to the place where that burning spot could be cooled.

In Colt, Colorado! It had been before him all the way, and now he could not be quit of its physical presence! But though his will wavered, it held his feet where they were, because it was stiffened by the dawning knowledge that his battle had only commenced; that the struggle during the long journey across country had been only preliminary maneuvering, only the mobilizing of his forces.

When he moved to face the little Westerner his eyes were filmed. The other drew a hand across his mouth calculatingly and jerked his hat-brim still lower.

"As I was sayin'," he went on a bit awkwardly as they resumed their walk, "these folks ain't got much manners, but they're good hearted."

Danny did not hear. He was casting around for more resources, more reserves to reinforce his front in the battle that was raging.

He looked about quickly, a bit wildly, searching for some object, some idea to engage his thoughts, to divert his mind from that insistent calling. His eyes spelled out the heralding of food stuffs. The sun stood high. It was time. It was not an excuse; it was a Godsend!

"Let's eat," he said abruptly. "I'm starving."

"That's a sound idee," agreed the other, and they turned toward the restaurant, a flat-roofed building of rough lumber. A baby was playing in the dirt before the door and a chained coyote puppy watched them from the shelter of a corner.

On the threshold Danny stopped, confusion possessing him. He stammered a moment, tried to smile, and then muttered:

"Guess I'd better wait a little. It isn't necessary to eat right away, anyhow."

He stepped back from the doorway with its smells of cooking food and the other followed him quickly, blue eyes under brows that now drew down in determination.

"Look here, boy," the man said, stepping close, "you was crazy for chuck a minute ago, an' now you make a bad excuse not to eat. To be sure, it ain't none of my business, but I'm old enough to be your daddy; I ain't afraid to ask you what's wrong. Why don't you want to eat?"

The sincerity of it, the unalloyed interest that precluded any hint of prying or sordid curiosity, went home to Danny and he said simply:

"I'm broke."

"You didn't need to tell me. I knowed it. I ain't, though. You eat with me."

"I can't! I can't do that!"

"Expect to starve, I s'pose?"

"No—not exactly. That is," he hastened to say, "not if I'm worth my keep. I came out here to—to get busy and take care of myself. I'll strike a job of some sort—anything, I don't care what it is or where it takes me. When I'm ready to work, I'll eat. I ought to get work right away, oughtn't I?"

In his voice was a sudden pleading born of the fear awakened by his realization of absolute helplessness, as though he looked for assurance to strengthen his feeble hopes, but hardly dared expect it. The little man looked him over gravely from the heels of his flat shoes to the crown of his rakishly soft hat. He pushed his Stetson far back on his gray hair.

"To be sure, and I guess you won't have to look far for work," he said. "I've been combin' this town dry for a hand all day. If you'd like to take a chance workin' for me I'd be mighty glad to take you on—right off. I'm only waitin' to find a man—can't go home till I do. Consider yourself hired!"

He turned on his heel and started off. But Danny did not follow. He felt distrust; he thought the kindness of the other was going too far; he suspected charity.

"Come on!" the man snapped, turning to look at the loitering Danny. "Have I got to rope an' drag you to grub?"

"But—you see it's—this way," the boy stammered. "Do you really want me? Can I do your work? How do you know I'm worth even a meal?"

A slow grin spread over the Westerner's countenance.

"Friend," he drawled in his high, nasal tone, "it's a pretty poor polecat of a man who ain't worth a meal; an' it's a pretty poor specimen who goes hirin' without makin' up his mind sufficient. They ain't many jobs in this country, but just now they's fewer men. We've got used to bein' careful pickers. I've done my pickin'. Come on."

Only half willingly the boy followed.

They walked through the restaurant, the old man saluting the lone individual who presided over the place, which was kitchen and dining room in one.

"Hello, Jed," the proprietor cried, waving a fork. "How's things?"

"Finer 'n frog's hair!" the other replied, shoving open the broken screen door at the rear.

"This is where we abolute," he remarked, indicating the dirty wash-basin, the soap which needed a boiling out itself, and the discouraged, service-stiffened towel.

Danny looked dubiously at the array. He had never seen as bad, to say nothing of having used such; but the man with him sloshed water into the basin from a tin pail and said:

"You're next, son, you're next."

And Danny plunged his bared wrists into the water. It was good, it was cool; and he forgot the dirty receptacle in the satisfaction that came with drenching his aching head and dashing the cooling water over his throat. The other stood and watched, his eyes busy, his face reflecting the rapid workings of his mind.

They settled in hard-bottomed, uncertain-legged chairs, and Jed—whoever he might be, Danny thought, as he remembered the name—gave their order to the man, who was, among other things, waiter and cook.

"Make it two sirloins," he said; "one well done an' one—" He lifted his eyebrows at Danny.

"Rare," the boy said.

"An' some light bread an' a pie," concluded the employer-host.

Danny saw that the cook wore a scarf around his neck and down his back, knotted in three places. When he moved on the floor it was evident that he wore riding boots. On his wrists were the leather cuffs of the cowboy.

Danny smiled. A far cry, indeed, this restaurant in Colt, Colorado, from his old haunts along the dark thoroughfare that is misnamed a lighted way! The other was talking: "We'll leave soon's we're through an' make it on up th' road to-night. It'll take us four days to get to th' ranch, probably, an' we might's well commence. Can you ride?"

Danny checked a short affirmative answer on his lips.

"I've ridden considerably," he said. "You people wouldn't call it riding, though. You'll have to teach me."

"Well, that's a good beginnin'. To be sure it is. Them as has opinions is mighty hard to teach—'cause opinions is like as not to be dead wrong."

He smeared butter on a piece of bread and poked it into his mouth. Then:

"I brought out my last hand—I come with him, I mean. Th' sheriff brought him. His saddle an' bed's over to th' stable. You can use 'em."

"Sheriff?" asked Danny. "Get into trouble?"

"Oh, a little. He's a good boy, mostly—except when he gets drinkin'."

Danny shoved his thumb down against the tines of the steel fork he held until they bent to uselessness.

Knee to knee, at a shacking trot, they rode out into the glory of big places, two horses before them bearing the light burden of a Westerner's bed.

"My name's Jed Avery," the little man broke in when they were clear of the town. "I'm located over on Red Mountain—a hundred an' thirty miles from here. I run horses—th' VB stuff. They call me Jed—or Old VB; mostly Jed now, 'cause th' fellers who used to call me Old VB has got past talkin' so you can hear 'em, or else has moved out. Names don't matter, anyhow. It ain't a big outfit, but I have a good time runnin' it. Top hands get thirty-five a month."

Danny felt that there was occasion for answer of some sort. In those few words Avery had given him as much information as he could need, and had given it freely, not as though he expected to open a way for the satisfaction of any curiosity. He wanted to forget the past, to leave it entirely behind him; did not want so much as a remnant to cling to him in this new life. Still, he did not deem it quite courteous to let the volunteered information come to him and respond with merely an acknowledgment.

He cleared his throat. "I'm from Riverside Drive, New York City," he said grimly. "Names don't matter. I don't know how to do a thing except waste time—and strength. If you'll give me a chance, I'll get to be a top hand."

An interval of silence followed.

"I never heard of th' street you mention. I know New York's on th' other slope an' considerable different from this here country. Gettin' to be a top hand's mostly in makin' up your mind—just like gettin' anywhere else."

Then more wordless travel. Behind them Colt dwindled to a bright blotch. The road ran close against the hills, which rose abruptly and in scarred beauty. The way was ever upward, and as they progressed more of the country beyond the river spread out to their view, mesas and mountains stretching away to infinite distance, it seemed.

Even back of the sounds of their travel the magnificent silence impressed itself. It was weird to Danny Lenox, unlike anything his traffic-hardened ears had ever experienced, and it made him uneasy—it, and the ache in his throat.

That ache seemed to be the last real thing left about him, anyhow. Events had come with such unreasonable rapidity in those last few days that his harassed mind could not properly arrange the impressions. Here he was, hired out to do he knew not what, starting a journey that would take him a hundred and thirty miles from a place called Colt, in the state of Colorado, through a country as unknown to him as the regions of mythology, beside a man whose like he had never seen before, traveling in a fashion that on his native Manhattan had worn itself to disuse two generations ago!

Out of the whimsical reverie he came with a jolt. Following the twisting road, coming toward them at good speed, was the last thing he would have associated with this place—an automobile. He reined his horse out of the path, saw the full-figured driver throw up his arm in salutation to Jed, and heard Jed shout an answering greeting. The driver looked keenly at Danny as he passed, and touched his broad hat.

"Who was that?" the boy asked, as he again fell in beside his companion.

"That's Bob Thorpe," the other explained. "He's th' biggest owner in this part of Colorado—mebby in th' whole state. Cattle. S Bar S mostly, but he owns a lot of brands."

"Can he get around through these mountains in a car?"

"He seems to. An' his daughter! My! To be sure, she'd drive that dog-gone bus right up th' side of that cliff! You'll see for yourself. She'll be home 'fore long—college—East somewheres."

The boy looked at him questioningly but said nothing. "College—East—home 'fore long—" Might it not form a link between this new and that old—a peculiar sort of link—as peculiar as this sudden, unwarranted interest in this girl?

Through the long afternoon Danny eagerly awaited the coming of more events, more distractions. When they came—such as informative bursts from Jed or the passing of the automobile—he forgot for the brief passage of time the throb in his throat, that wailing of the creature in him. But when the two rode on at the shambling trot, with the silence and the immense grandeur all about them, the demands of his appetite were made anew, intensified perhaps by a feeling of his own inconsequence, by the knowledge that should he fail once in standing off those assaults it would mean only another beginning, and harder by far than this one he was experiencing.

Every hour of sober reflection, of sordid struggle, added to his estimate of the strength of that self he must subdue. He was going away into the waste places, and a sneaking fear of being removed from the stuff that had kept him keyed commenced to grow, adding to the fleshly wants.

If he should be whipped and a surrender be forced? What then? He realized that that doubting was cowardice. He had come out here to have freedom, a new beginning, and now he found himself begging for a way back should the opposition be too great. It was sheer weakness!

Cautiously Jed Avery had watched Danny's face, and when he saw anxiety show there as doubt rose, he broke into words:

"Yes, sir, Charley was sure a good boy, but th' booze got him."

He looked down at his horse's withers so he could not see the start this assertion gave Danny.

"He didn't want to be bad, but it's so easy to let go. To be sure, it is. Anyhow, Charley never had a chance, never a look-in. He was good hearted an' meant well—but he didn't have th' backbone."

And Danny found that a rage commenced to rise within him, a rage which drove back those queries that had made him weak.

Day waned. The sun slid down behind the string of cliffs which stretched on before them at their left. Distances took on their purple veils, a canopy of virgin silver spread above the earth, and the stillness became more intense.

"Right on here a bit now we'll stop," Jed said. "This's th' Anchor Ranch. They're hayin', an' full up. We'll get somethin' to eat, though, an' feed for th' ponies. Then we'll sleep on th' ground. Ever do it?"

"Never."

"Well, you've got somethin' comin', then. With a sky for a roof a man gets close to whatever he calls his God—an' to himself. Some fellers out here never seem to see th' point. Funny. I been sleepin' out, off an' on, for longer than I like to think about—an' they's a feelin' about it that don't come from nothin' else in th' world."

"You think it's a good thing, then, for a man to get close to himself?"

"To be sure I do."

"What if he's trying to get away from himself?"

Jed tugged at his mustache while the horses took a dozen strides. Then he said:

"That ain't right. When a man thinks he wants to get away from himself, that's th' coyote in him talkin'. Then he wants to get closer'n ever; get down close an' fight again' that streak what's come into him an' got around his heart. Wants to get down an' fight like sin!"

He whispered the last words. Then, before Danny could form an answer, he said, a trifle gruffly:

"Open th' gate. I'll ride on an' turn th' horses back."

They entered the inclosure and rode on toward a clump of buildings a half-mile back from the road.

Off to their right ran a strip of flat, cleared land. It was dotted with new haystacks, and beyond them they could see waving grass that remained to be cut. At the corral the two dismounted, Danny stiffly and with necessary deliberation. As they commenced unsaddling, a trio of hatless men, bearing evidences of a strenuous day's labor, came from the door of one of the log houses to talk with Jed. That is, they came ostensibly to talk with Jed; in reality, they came to look at the Easterner who fumbled awkwardly with his cinch.

Danny looked at them, one after the other, then resumed his work. Soon a new voice came to his ears, speaking to Avery. He noticed that where the little man's greeting to the others had been full-hearted and buoyant, it was now curt, almost unkind.

Curious, Danny looked up again—looked up to meet a leer from a pair of eyes that appeared to be only half opened; green eyes, surrounded by inflamed lids, under protruding brows that boasted but little hair, above high, sunburned cheek bones; eyes that reflected all the small meanness that lived in the thin lips and short chin. As he looked, the eyes leered more ominously. Then the man spoke:

"Long ways from home, ain't you?"

Although he looked directly at Danny, although he put the question to him and to him alone, the boy pretended to misunderstand—chose to do so because in the counter question he could express a little of the quick contempt, the instinctive loathing that sprang up for this man who needed not to speak to show his crude, unreasoning, militant dislike for the stranger, and whose words only gave vent to the spirit of the bully.

"Are you speaking to me?" Danny asked, and the cool simplicity of his expression carried its weight to those who stood waiting to hear his answer.

The other grinned, his mouth twisting at an angle.

"Who else round here'd be far from home?" he asked.

Danny turned to Jed.

"How far is it?" he asked.

"A hundred an' ten," Jed answered, a swift pleasure lighting his serious face.

Danny turned back to his questioner.

"I'm a hundred and ten miles from home," he said with the same simplicity, and lifted the saddle from his horse's back.

It was the sort of clash that mankind the world over recognizes. No angry word was spoken, no hostile movement made. But the spirit behind it could not be misunderstood.

The man turned away with a forced laugh which showed his confusion. He had been worsted, he knew. The smiles of those who watched and listened told him that. It stung him to be so easily rebuffed, and his laugh boded ugly things.

"Don't have anything to do with him," cautioned Jed as they threw their saddles under a shed. "His name's Rhues, an' he's a nasty, snaky cuss. He'll make trouble every chance he gets. Don't give him a chance!"

They went in to eat with the ranch hands. A dozen men sat at one long table and bolted immense quantities of food.

The boiled beef, the thick, lumpy gravy, the discolored potatoes, the coarse biscuit were as strange to Danny as was his environment. His initiation back at Colt had not brought him close to such crudity as this. He tasted gingerly, and then condemned himself for being surprised to find the food good.

"You're a fool!" he told himself. "This is the real thing; you've been dabbling in unrealities so long that you've lost sense of the virtue of fundamentals. No frills here, but there's substance!"

He looked up and down at the low-bent faces, and a new joy came to him. He was out among men! Crude, genuine, real men! It was an experience, new and refreshing.

But in the midst of his contemplation it was as though fevered fingers clutched his throat. He dropped his fork, lifted the heavy cup, and drank the coffee it contained in scorching gulps.

Once more his big problem had pulled him back, and he wrestled with it—alone among men!

After the gorging the men pushed back their chairs and yawned. A desultory conversation waxed to lively banter. A match flared, and the talk came through fumes of tobacco smoke.

"Anybody got th' makin's?" asked Jed.

"Here," muttered Danny beside him, and thrust pouch and papers into his hand.

Danny followed Jed in the cigarette rolling, and they lighted from the same match with an interchange of smiles that added another strand to the bond between them.

"That's good tobacco," Jed pronounced, blowing out a whiff of smoke.

"Ought to be; it cost two dollars a pound."

Jed laughed queerly.

"Yes, it ought to," he agreed, "but we've got a tobacco out here they call Satin. Ten cents a can. It tastes mighty good to us."

Danny sensed a gentle rebuke, but he somehow knew that it was given in all kindliness, that it was given for his own good.

"While I fight up one way," he thought, "I must fight down another." And then aloud: "We'll stock up with your tobacco. What's liked by one ought to be good enough for—" He let the sentence trail off.

Jed answered with: "Both."

And the spirit behind that word added more strength to their uniting tie.

The day had been a hard one. Darkness came quickly, and the workers straggled off toward the bunk house. Tossing away the butt of his cigarette, Jed proposed that they turn in.

"I'm tired, and you've got a right to be," he declared.

They walked out into the cool of evening. A light flared in the bunk house, and the sound of voices raised high came to them.

"Like to look in?" Avery asked, and Danny thought he would.

Men were in all stages of undress. Some were already in their beds; others, in scant attire, stood in mid-floor and talked loudly. From one to another passed Rhues. In his hand he held a bottle, and to the lips of each man in turn he placed the neck. He faced Jed and Danny as they entered. At sight of the stranger a quick hush fell. Rhues stood there, bottle in hand, leering again.

"Jed, you don't drink," he said in his drawling, insinuating voice, "but mebby yer friend here 'uld like a nightcap."

He advanced to Danny, bottle extended, an evil smile on his face. Jed raised a hand as though to interfere; then dropped it. His jaw settled in grim resolution, his nostrils dilated, and his eyes fixed themselves fast on Danny's face.

Oh, the wailing eagerness of those abused nerves! The cracking of that tortured throat! All the weariness of the day, of the week; all the sagging of spirit under the assault of the demon in him were concentrated now. A hot wave swept his body. The fumes set the blood rushing to his eyes, to his ears; made him reel. His hand wavered up, half daring to reach for the bottle, and the strain of his drawn face dissolved in a weak smile.

Why hold off? Why battle longer? Why delay? Why? Why? Why?

Of a sudden his ears rang with memory of his father's brittle voice in cold denunciation, and the quick passing of that illusion left another talking there, in nasal twang, carrying a great sympathy.

"No, thanks," he said just above a whisper. "I'm not drinking."

He turned quickly and stepped out the door.

Through the confusion of sounds and ideas he heard the rasping laughter of Rhues, and the tone of it, the nasty, jeering note, did much to clear his brain and bring him back to the fighting.

Jed walked beside him and they crossed to where their rolls of bedding had been dropped, speaking no word. As they stooped to pick up the stuff the older man's hand fell on the boy's shoulder. His fingers squeezed, and then the palm smote Danny between the shoulder blades, soundly, confidently. Oh, that assurance! This man understood. And he had faith in this wreck of a youth that he had seen for the first time ten hours before!

Shaken, tormented though he was, weakened by the sharp struggle of a moment ago, Danny felt keenly and with something like pride that it had been worth the candle. He knew, too, with a feeling of comfort, that an explanation to Jed would never be necessary.

Silently they spread the blankets and, with a simple "Good night," crawled in between.

Danny had never before slept with his clothes on—when sober. He had never snuggled between coarse blankets in the open. But somehow it did not seem strange; it was all natural, as though it should be so.

His mind went round and round, fighting away the tingling odor that still clung in his nostrils, trying to blot out the wondering looks on the countenances of those others as they watched his struggle to refuse the stuff his tormentor held out to him.

He did not care about forgetting how Rhues's laughter sounded. Somehow the feeling of loathing for the man for a time distracted his thought from the pleading of his throat, augmented the singing of that chord his father had set in motion, bolstered his will to do, to conquer this thing!

But the effect was not enduring. On and on through the narrow channels that the fevered condition made went his thinking; forever and forever it must be so—the fighting, fighting, fighting; the searching for petty distractions that would make him forget for the moment!

Suddenly he saw that there were stars—millions upon countless millions of them dusted across the dome of the pale heavens as carelessly as a baker might dust silvered sugar over the icing of a festal cake. Big stars and tiny stars and mere little diffusive glows of light that might come from a thousand worlds, clustering together out there in infinite void. Blue stars and white stars, orange stars, and stars that glowed red. Stars that sent beams through incalculable space and stars that swung low, that seemed almost attainable. Stars that blinked sleepily and stars that stared without wavering, purposeful, attentive. Stars alone and lonely; stars in bunches. Stars in rows and patterns, as though put there with design.

Danny breathed deeply, as though the pure air were stuffy and he needed more of it, for the vagary of his wandering mind had carried him back to the place where light points were arranged by plan. He saw again the electric-light kitten and the spool of thread, the mineral-water clock, the cigarette sign with flowing border, the—

Whisky again! He moved his throbbing head from side to side.

"Is it a blank wall?" he asked quite calmly. "Shall I always come up against it? Is there no way out?"

Morning: a flickering in the east that gives again to the black hold of night. Another attempt, a longer glimmer. It recedes, returns stronger; struggles, bursts from the pall of darkness, and blots out the stars before it. And after that first silver white come soft colors—shoots of violet, a wave of pink, then the golden glory of a new day.

Jed Avery yawned loud and lingeringly, pushing the blankets away from his chin with blind, fumbling motions. He thrust both arms from the covers and reached above his head, up and up and—up! until he ended with a satisfied groan. He sat erect, opening and shutting his mouth, rubbed his eyes—and stopped a motion half completed.

Danny Lenox slept with lips parted. His brown hair—the hair that wanted to curl so badly—was well down over the brow, and the skin beneath those locks was damp. One hand rested on the tarpaulin covering of the bed, the fingers in continual motion.

"Poor kid!" Jed muttered under his breath. "Poor son of a gun! He's in a jack-pot, all right, an' it'll take all any man ever had to pull—"

"'Mornin', sonny!" he cried as Danny opened his eyes and raised his head with a start.

For a moment the boy stared at him, evidencing no recognition. Then he smiled and sat up.

"How are you, Mr. Avery?"

"Well," the other began grimly, looking straight before him, "Mr. Avery's in a bad way. He died about thirty year ago."

Danny looked at him with a grin.

"But Old Jed—Old VB," he went on, "he's alive an' happy. Fancy wrappin's is for boxes of candy an' playin' cards," he explained. "They ain't necessary to men."

"I see—all right, Jed!"

Danny stared about him at the freshness of the young day.

"Wouldn't it be slick," Jed wanted to know, "if we was all fixed like th' feller who makes th' days? If yesterday's was a bad job he can start right in on this one an' make it a winner! Now, if this day turns out bad he can forget it an' begin to-morrow at sun-up to try th' job all over again!"

"Yes, it would be fine to have more chances," agreed Danny.

Jed sat silent a moment.

"Mebby so, an' mebby no," he finally recanted. "It would be slick an' easy, all right; but mebby we'd get shiftless. Mebby we'd keep puttin' off tryin' hard until next time. As 'tis, we have to make every chance our only one, an' work ourselves to th' limit. Never let a chance get away! Throw it an' tie it an' hang on!"

"In other words, think it's now or never?"

Jed reached for a boot and declared solemnly:

"It's th' only thing that keeps us onery human bein's on our feet an' movin' along!"

Breakfast was a brief affair, brief but enthusiastic. The gastronomic feats performed at that table were things at which to marvel, and Danny divided his thoughts between wonder at them and recalling the events of the night before. Only once did he catch Rhues's eyes, and then the leer which came from them whipped a flush high in his cheeks.

Jed and Danny rode out into the morning side by side, smoking some of the boy's tobacco. As the sun mounted and the breeze did not rise, the heat became too intense for a coat, and Danny stripped his off and tied it behind the saddle. Jed looked at the pink silk shirt a long time.

"To be sure an' that's a fine piece of goods," he finally declared.

Danny glanced down at the gorgeous garment with a mingled feeling of amusement and guilt. But he merely said:

"I thought so, too, when I bought it."

And even that little tendency toward foppishness which has been handed down to men from those ancestors who paraded in their finest skins and paints before the home of stalwart cave women seemed to draw the two closer to each other.

As though he could sense the young chap's bewilderment and wonder at the life about him, Jed related much that pertained to his own work.

"Yes, I raise some horses," he concluded, "but I sell a lot of wild ones, too. It's fun chasin' 'em, and it gets to be a habit with a feller. I like it an' can make a livin' at it, so why should I go into cattle? Those horses are out there in th' hills, runnin' wild, like some folks, an' doin' nobody no good. I catch 'em an' halter-break 'em an' they go to th' river an' get to be of use to somebody."

"Isn't it a job to catch them?" Danny asked.

"Well, I guess so!" Jed's eyes sparkled.

"Some of 'em are wiser than a bad man. Why, up in our country's a stallion that ain't never had a rope on him. Th' Captain we've got to call him. He's th' wildest an' wisest critter, horse or human, you ever see. Eight years old, an' all his life he's been chased an' never touched. He's big—not so big in weight; big like this here man Napoleon, I mean. He rules th' range. He has th' best mares on th' mountain in his bunch, an' he handles 'em like a king. We've tossed down our whole hand time an' again, but he always beats us out. We're no nearer catchin' him to-day than we was when he run a yearlin'."

The little man's voice rose shrilly and his eyes flashed until Danny, gazing on him, caught some of his fever and felt it run to the ends of his body.

"Oh, but that's a horse!" Jed went on. "Why, just to see him standin' up on the sky line, head up, tail arched-like, ready to run, not scared, just darin' us to come get him—well, it's worth a hard ride. There's somethin' about th' Captain that keeps us from hatin' him. By all natural rights somebody ought to shoot a stallion that'll run wild so long an' drive off bunches of gentle mares an' make 'em crazy wild. But no. Nobody on Red Mountain or nobody who ever chased th' Captain has wanted to harm him; yet I've heard men swear until it would make your hair curl when they was runnin' him! He's that kind. He gets to somethin' that's in real men that makes 'em light headed. I guess it's his strength. He's bigger'n tricks, that horse. He's learned all about traps an' such, an' th' way men generally catch wild horses don't bother him at all. Lordy, boy, but th' Captain's somethin' to set up nights an' talk about!"

His voice dropped on that declaration, almost in reverence.

"Well, he's so wise and strong that he'll just keep right on running free; is that the idea?" asked Danny.

Jed gnawed off a fresh chew and repocketed the plug, shifted in his saddle, and shook his head.

"Nope, I guess not," he said gravely. "I don't reckon so, because it ain't natural; it ain't th' way things is done in this world. Did you ever stop to think that of all th' strong things us men has knowed about somethin' has always turned up to be a little bit stronger? We've been all th' time pattin' ourselves on th' back an' sayin', 'There, we've gone an' done it; that'll last forever!' an' then watchin' a wind or a rain carry off what we've thought was so strong. Either that, I say, or else we've been fallin' down on our knees an' prayin' for help to stop somethin' new an' powerful that's showed up. An' when prayin' didn't do no good up pops somebody with an idea that th' Lord wants us folks to carry th' heavy end of th' load in such matters, an' gets busy workin'. An' his job ends up by makin' somethin' so strong that it satisfied all them prayers—folks bein' that unparticular that they don't mind where th' answer comes from so long as it comes an' they gets th' benefits!

"That's th' way it is all th' time. We wake up in th' mornin' an' see somethin' so discouragin' that we want to crawl back to bed an' quit tryin'; then we stop to think that nothin' has ever been so great or so strong that it kept right on havin' its own way all th' time; an' we get our sand up an' pitch in, an' pretty soon we're on top!

"All we need is th' sand to tackle big jobs; just bein' sure that they's some way of doin' or preventin' an' makin' a reg'lar hunt for that one thing. So 'tis with th' Captain. He's fooled us a long time now, but some day a man'll come along who's wiser than th' Captain, an' he'll get caught.

"Nothin' strange about it. Just th' workin' out of things. 'Course, it'll all depend on th' man. Mebby some of us on th' mountain has th' brains; mebby some others has th' sand, but th' combination ain't been struck yet. We ain't men enough. Th' feller who catches that horse has got to be all man, just like th' feller who beats out anythin' else that's hard; got to be man all th' way through. If he's only part man an' tackles th' job he's likely to get tromped on; if he's all man, he'll do th' ridin'."

Jed stopped talking and gazed dreamily at the far horizon; dreamily, but with an eye which moved a trifle now and then to take into its range the young chap who rode beside him. Danny's head was down, facing the dust which rose from the feet of the horses ahead. The biting particles irritated the membrane of his throat, but for the moment he did not heed. "Am I a man—all the way through?" he kept asking himself. "All the way through?"

And then his nerves stung him viciously, shrieking for the stimulant which had fed them so long and so well. His aching muscles pleaded for it; his heart, miserable and lonely, missed the close, reckless friendships of those days so shortly removed, in spite of his realization of what those relations had meant; he yearned for the warming, heedless thrills; his eyes ached and called out for just the one draft that would make them alert, less hurtful.