The Project Gutenberg EBook of Benjamin Franklin, by

Frank Luther Mott and Chester E. Jorgenson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Benjamin Franklin

Representative selections, with introduction, bibliograpy, and notes

Author: Frank Luther Mott

Chester E. Jorgenson

Release Date: March 6, 2011 [EBook #35508]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BENJAMIN FRANKLIN ***

Produced by Mark C. Orton, Christine Aldridge and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Notes:

1. This text uses UTF-8 (unicode) file encoding. If the apostrophes

and quotation marks in this paragraph appear as garbage, you may

have an incompatible browser or unavailable fonts. First, make sure

that your browser’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set to

Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change the default font.

2. The editor of the original book marked some mispelled words with

[sic], and these have been retained as written, uncorrected.

Additional words found to be mispelled have been corrected and are

listed under "Spelling Corrections" at the end of this e-text.

Additionally this work contains a large number of word spelling

variations found to be valid in Webster's English Dictionary as well

as several unverified spellings that appear multiple times,

inconsistant word capitalization and hyphenation, all of which have

been retained as printed. The interested reader will find an

alphabetic "Word Variations" list at the end of this e-text.

3. Numbered footnotes in Sections I-VII of the Introduction have been

relocated to the end of the Introduction and marked with an "i-".

Lettered footnotes in the "Selections" have been relocated directly

under the paragraph they pertain to.

4 Additional Transcriber's Notes are located at the end of this e-text.

*

AMERICAN WRITERS SERIES

*

HARRY HAYDEN CLARK

General Editor

*

* AMERICAN WRITERS SERIES *

Volumes of representative selections, prepared by American scholars under

the general editorship of Harry Hayden Clark, University of Wisconsin.

Volumes now ready are starred.

American Transcendentalists, Raymond Adams, University of North

Carolina

*William Cullen Bryant, Tremaine McDowell, University of Minnesota

*James Fenimore Cooper, Robert E. Spiller, Swarthmore College

*Jonathan Edwards, Clarence H. Faust, University of Chicago, and

Thomas H. Johnson, Hackley School

*Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederic I. Carpenter, Harvard University

*Benjamin Franklin, Frank Luther Mott and Chester E. Jorgenson,

University of Iowa

*Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, Frederick C. Prescott,

Cornell University

Bret Harte

*Nathaniel Hawthorne, Austin Warren, Boston University

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Robert Shafer, University of Cincinnati

*Washington Irving, Henry A. Pochmann, Mississippi State College

Henry James, Lyon Richardson, Western Reserve University

Abraham Lincoln

*Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Odell Shepard, Trinity College

James Russell Lowell, Norman Foerster, University of Iowa, and Harry

H. Clark, University of Wisconsin

Herman Melville, Willard Thorp, Princeton University

John Lothrop Motley

Thomas Paine, Harry H. Clark, University of Wisconsin

Francis Parkman, Wilbur L. Schramm, University of Iowa

*Edgar Allan Poe, Margaret Alterton, University of Iowa, and Hardin

Craig, Stanford University

William Hickling Prescott, Claude Jones, Johns Hopkins University

*Southern Poets, Edd Winfield Parks, University of Georgia

Southern Prose, Gregory Paine, University of North Carolina

*Henry David Thoreau, Bartholow Crawford, University of Iowa

*Mark Twain, Fred Lewis Pattee, Rollins College

*Walt Whitman, Floyd Stovall, University of Texas

John Greenleaf Whittier

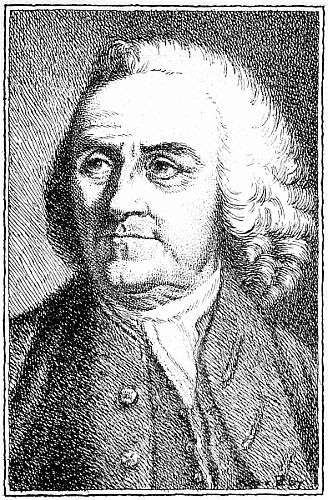

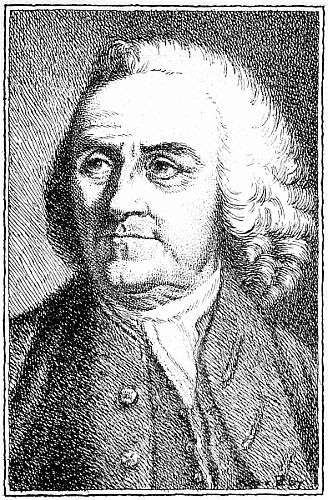

Pen drawing by Kerr Eby, after an

engraving by Mason Chamberlin

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

ÆT. 56

REPRESENTATIVE SELECTIONS, WITH

INTRODUCTION, BIBLIOGRAPHY, AND NOTES

BY

Frank Luther Mott

Director, School of Journalism

University of Iowa

AND

Chester E. Jorgenson

Instructor in English

University of Iowa

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

New York · Cincinnati · Chicago

Boston · Atlanta

Copyright, 1936, by

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

All rights reserved

Mott and Jorgenson's Franklin

W.P.I.

Made in U.S.A.

[v]

PREFACE

Benjamin Franklin's reputation in America has been singularly

distorted by the neglect of his works other than his

Autobiography and his most utilitarian aphorisms. If America

has contented herself with appraising him as "the earliest incarnation

of 'David Harum,'" as "the first high-priest of the

religion of efficiency," as "the first Rotarian," it may be that

this aspect of Franklin is all that an America plagued by growing

pains, by peopling and mechanizing three thousand miles

of frontier, has been able to see. That facet of Franklin's mind

and mien which allowed Carlyle to describe him as "the Father

of all Yankees" was appreciated by Sinclair Lewis's George F.

Babbitt: "Once in a while I just naturally sit back and size up

this Solid American Citizen, with a whale of a lot of satisfaction."

But this is not the Franklin of "imperturbable common-sense"

honored by Matthew Arnold as "the very incarnation of

sanity and clear-sense, a man the most considerable ... whom

America has yet produced." Nor is this the Franklin who

emerges from his collected works (and the opinions of his

notable contemporaries) as an economist, political theorist,

educator, journalist, scientific deist, and disinterested scientist.

If he wrote little that is narrowly belles-lettres, he need not be

ashamed of his voluminous correspondence, in an age which

saw the fruition of the epistolary art. The Franklin found in

his collected and uncollected writings is, as the following

Introduction may suggest, not the Franklin who too commonly

is synchronized exclusively with the wisdom and wit of Poor

Richard.

Since the present interpretation of the growth of Franklin's

mind, with stress upon its essential unity in the light of scientific

deism, tempered by his debt to Puritanism, classicism, and neoclassicism,[vi]

may seem somewhat novel, the editors have felt it

desirable to document their interpretation with considerable

fullness. It is hoped that the reader will withhold judgment as

to the validity of this interpretation until the documentary

evidence has been fully considered in its genetic significance,

and that he will feel able to incline to other interpretations only

in proportion as they can be equally supported by other evidence.

The present interpretation is also supported by the

Selections following—the fullest collection hitherto available

in one volume—which offer, the editors believe, the essential

materials for a reasonable acquaintance with the growth of

Franklin's mind, from youth to old age, in its comprehensive

interests—educational, literary, journalistic, economic, political,

scientific, humanitarian, and religious.

With the exception of the selections from the Autobiography,

the works are arranged in approximate chronological order,

hence inviting a necessarily genetic study of Franklin's mind.

The Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain,

never before printed in an edition of Franklin's works or in a

book of selections, is here printed from the London edition of

1725, retaining his peculiarities of italics, capitalization, and

punctuation. Attention is also drawn to the photographically

reproduced complete text of Poor Richard Improved (1753),

graciously furnished by Mr. William Smith Mason. The Way

to Wealth is from an exact reprint made by Mr. Mason, and

with his permission here reproduced. One of the editors is

grateful for the privilege of consulting Mr. Mason's magnificent

collection of Franklin correspondence (original MSS), especially

the Franklin-Galloway and Franklin-Jonathan Shipley

(Bishop of St. Asaph) unpublished correspondence. With Mr.

Mason's generous permission the editors reproduce fragments

of this correspondence in the Introduction.

The bulk of the selections have been printed from the latest,

standard edition, The Writings of Benjamin Franklin, collected[vii]

and edited with a Life and Introduction by Albert Henry

Smyth (10 vols., 1905-1907). For permission to use this material

the editors are grateful to The Macmillan Company,

publishers. The editors are indebted to Dr. Max Farrand,

Director of the Henry E. Huntington Library, for permission

to reprint part of Franklin's MS version of the Autobiography.

Chester E. Jorgenson is preparing an analysis and interpretation

of Franklin's brand of scientific deism, its sources and

relation to his economic, political, and literary theories and

practice. Fragments of this projected study are included, especially

in Section VII of the following Introduction. For the

past two years Mr. Jorgenson has enjoyed the kindness and

generosity of Mr. William Smith Mason, and has incurred an

indebtedness which cannot be expressed adequately in print.

The work of the editors has been vastly eased by Beata

Prochnow Jorgenson's assistance in typing, proofreading, et

cetera. They are extremely grateful to Professor Harry Hayden

Clark for incisive suggestions and valuable editorial assistance.

F. L. M.

C. E. J.

[viii]

[ix]

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chronological Table, cxlii

Selected Bibliography

Selections

- From the Autobiography, 3

- Dogood Papers, No. I (1722), 96

- Dogood Papers, No. IV (1722), 98

- Dogood Papers, No. V (1722), 102

- Dogood Papers, No. VII (1722), 105

- Dogood Papers, No. XII (1722), 109

- Editorial Preface to the New England Courant (1723), 111

- A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain (1725), 114

- Rules for a Club Established for Mutual Improvement (1728), 128

- Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion (1728), 130

- The Busy-Body, No. 1 (1728/9), 137

- The Busy-Body, No. 2 (1728/9), 139

- The Busy-Body, No. 3 (1728/9), 141

- The Busy-Body, No. 4 (1728/9), 145

- Preface to the Pennsylvania Gazette (1729), 150

- A Dialogue between Philocles and Horatio (1730), 152

- A Second Dialogue between Philocles and Horatio (1730), 156

- A Witch Trial at Mount Holly (1730), 161

- An Apology for Printers (1731), 163

- Preface to Poor Richard (1733), 169

- A Meditation on a Quart Mugg (1733), 170

- Preface to Poor Richard (1734), 172[x]

- Preface to Poor Richard (1735), 174

- Hints for Those That Would Be Rich (1736), 176

- To Josiah Franklin (April 13, 1738), 177

- Preface to Poor Richard (1739), 179

- A Proposal for Promoting Useful Knowledge among the British Plantations in America (1743), 180

- Shavers and Trimmers (1743), 183

- To the Publick (1743), 186

- Preface to Logan's Translation of "Cato Major" (1743/4), 187

- To John Franklin, at Boston (March 10, 1745), 188

- Preface to Poor Richard (1746), 189

- The Speech of Polly Baker (1747), 190

- Preface to Poor Richard (1747), 193

- To Peter Collinson (August 14, 1747), 194

- Preface to Poor Richard Improved (1748), 195

- Advice to a Young Tradesman (1748), 196

- To George Whitefield (July 6, 1749), 198

- Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania (1749), 199

- Idea of the English School (1751), 206

- To Cadwallader Colden Esq., at New York (1751), 213

- Exporting of Felons to the Colonies (1751), 214

- Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, Etc. (1751), 216

- To Peter Collinson (October 19, 1752), 223

- Poor Richard Improved (1753)—facsimile reproduction, 225

- To Joseph Huey (June 6, 1753), 261

- Three Letters to Governor Shirley (1754), 263

- To Miss Catherine Ray, at Block Island (March 4, 1755), 270

- To Peter Collinson (August 25, 1755), 272

- To Miss Catherine Ray (September 11, 1755), 274

- To Miss Catherine Ray (October 16, 1755), 277

- To Mrs. Jane Mecom (February 12, 1756), 278

- To Miss E. Hubbard (February 23, 1756), 278

- To Rev. George Whitefield (July 2, 1756), 279

- The Way to Wealth (1758), 280

- To Hugh Roberts (September 16, 1758), 289

- To Mrs. Jane Mecom (September 16, 1758), 291

- To Lord Kames (May 3, 1760), 293

- To Miss Mary Stevenson (June 11, 1760), 295

- To Mrs. Deborah Franklin (June 27, 1760), 298

- To Jared Ingersoll (December 11, 1762), 300

- To Miss Mary Stevenson (March 25, 1763), 301

- To John Fothergill, M.D. (March 14, 1764), 304

- To Sarah Franklin (November 8, 1764), 307

- From A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County (1764), 308[xi]

- To the Editor of a Newspaper (May 20, 1765), 315

- To Lord Kames (June 2, 1765), 318

- Letter Concerning the Gratitude of America (January 6, 1766), 321

- To Lord Kames (April 11, 1767), 325

- To Miss Mary Stevenson (September 14, 1767), 330

- On the Labouring Poor (1768), 336

- To Dupont de Nemours (July 28, 1768), 340

- To John Alleyne (August 9, 1768), 341

- To the Printer of the London Chronicle (August 18, 1768), 343

- Positions to be Examined, Concerning National Wealth (1769), 345

- To Miss Mary Stevenson (September 2, 1769), 347

- To Joseph Priestley (September 19, 1772), 348

- To Miss Georgiana Shipley (September 26, 1772), 349

- To Peter Franklin (undated), 351

- On the Price of Corn, and Management of the Poor (undated), 355

- An Edict by the King of Prussia (1773), 358

- Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One (1773), 363

- To William Franklin (October 6, 1773), 371

- Preface to "An Abridgment of the Book of Common Prayer" (1773), 374

- A Parable against Persecution, 379

- A Parable on Brotherly Love, 380

- To William Strahan (July 5, 1775), 381

- To Joseph Priestley (July 7, 1775), 382

- To a Friend in England (October 3, 1775), 383

- To Lord Howe (July 30, 1776), 384

- The Sale of the Hessians (1777), 387

- Model of a Letter of Recommendation (April 2, 1777), 389

- To —— (October 4, 1777), 390

- To David Hartley (October 14, 1777), 390

- A Dialogue between Britain, France, Spain, Holland, Saxony and America, 394

- To Charles de Weissenstein (July 1, 1778), 397

- The Ephemera (1778), 402

- To Richard Bache (June 2, 1779), 404

- Morals of Chess (1779), 406

- To Benjamin Vaughan (November 9, 1779), 410

- The Whistle (1779), 412

- The Lord's Prayer (1779?), 414

- The Levée (1779?), 417

- Proposed New Version of the Bible (1779?), 419

- To Joseph Priestley (February 8, 1780), 420

- To George Washington (March 5, 1780), 421

- To Miss Georgiana Shipley (October 8, 1780), 422[xii]

- To Richard Price (October 9, 1780), 423

- Dialogue between Franklin and the Gout (1780), 424

- The Handsome and Deformed Leg (1780?), 430

- To Miss Georgiana Shipley (undated), 432

- To David Hartley (December 15, 1781), 434

- Supplement to the Boston Independent Chronicle (1782), 434

- To John Thornton (May 8, 1782), 443

- To Joseph Priestley (June 7, 1782), 443

- To Jonathan Shipley (June 10, 1782), 445

- To James Hutton (July 7, 1782), 447

- To Sir Joseph Banks (September 9, 1782), 448

- Information to Those Who Would Remove to America (1782?), 449

- Apologue (1783?), 458

- To Sir Joseph Banks (July 27, 1783), 459

- To Mrs. Sarah Bache (January 26, 1784), 460

- An Economical Project (1784?), 466

- To Samuel Mather (May 12, 1784), 471

- To Benjamin Vaughan (July 26, 1784), 472

- To George Whately (May 23, 1785), 479

- To John Bard and Mrs. Bard (November 14, 1785), 481

- To Jonathan Shipley (February 24, 1786), 481

- To —— (July 3, 1786?), 484

- Speech in the Convention; On the Subject of Salaries (1787), 486

- Motion for Prayers in the Convention (1787), 489

- Speech in the Convention at the Conclusion of Its Deliberations (1787), 491

- To the Editors of the Pennsylvania Gazette (1788), 493

- To Rev. John Lathrop (May 31, 1788), 496

- To the Editor of the Federal Gazette (1788?), 496

- To Charles Carroll (May 25, 1789), 500

- An Account of the Supremest Court of Judicature in Pennsylvania, viz. the Court of the Press (1789), 501

- An Address to the Public (1789), 505

- To David Hartley (December 4, 1789), 506

- To Ezra Stiles (March 9, 1790), 507

- On the Slave-Trade (1790), 510

- Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America, 513

- An Arabian Tale, 519

- A Petition of the Left Hand (date unknown), 520

- Some Good Whig Principles (date unknown), 521

- The Art of Procuring Pleasant Dreams, 523

Notes, 529

[xiii]

INTRODUCTION

I. FRANKLIN'S MILIEU: THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT

Benjamin Franklin's reputation, according to John Adams,

"was more universal than that of Leibnitz or Newton, Frederick

or Voltaire, and his character more beloved and esteemed than

any or all of them."[i-1] The historical critic recognizes increasingly

that Adams was not thinking idly when he doubted

whether Franklin's panegyrical and international reputation

could ever be explained without doing "a complete history of

the philosophy and politics of the eighteenth century." Adams

conceived that an explication of Franklin's mind and activities

integrated with the thought patterns of the epoch which fathered

him "would be one of the most important that ever was written;

much more interesting to this and future ages than the 'Decline

and Fall of the Roman Empire.'" And such a historical and

critical colossus is still among the works hoped for but yet unborn.

Too often, even in the scholarly mind, Franklin has

become a symbol, and it may be confessed, not a winged one,

of the self-made man, of New-World practicality, of the successful

tradesman, of the Sage of Poor Richard with his

penny-saving economy and frugality. In short, the Franklin

legend fails to transcend an allegory of the success of the doer

in an America allegedly materialistic, uncreative, and unimaginative.

It is the purpose of this essay to show that Franklin, the

American Voltaire,—always reasonable if not intuitive, encyclopedic

if not sublimely profound, humane if not saintly,—is

best explained with reference to the Age of Enlightenment, of

which he was the completest colonial representative. Due attention[xiv]

will, however, be paid to other factors. And therefore it is

necessary to begin with a brief survey of the pattern of ideas

of the age to which he was responsive. Not without reason does

one critic name him as "the most complete representative of his

century that any nation can point to."[i-2]

When Voltaire, "the patriarch of the philosophes," in 1726

took refuge in England, he at once discovered minds and an

attitude toward human experience which were to prove the

seminal factors of the Age of Enlightenment. He found that

Englishmen had acclaimed Bacon "the father of experimental

philosophy," and that Newton, "the destroyer of the Cartesian

system," was "as the Hercules of fabulous story, to whom the

ignorant ascribed all the feats of ancient heroes." Voltaire then

paused to praise Locke, who "destroyed innate ideas," Locke,

than whom "no man ever had a more judicious or more methodical

genius, or was a more acute logician." Bacon, Newton,

and Locke brooded over the currents of eighteenth-century

thought and were formative factors of much that is most characteristic

of the Enlightenment.

To Bacon was given the honor of having distinguished between

the fantasies of old wives' tales and the certainty of

empiricism. Moved by the ghost of Bacon, the Royal Society

had for its purpose, according to Hooke, "To improve the

knowledge of naturall things, and all useful Arts, Manufactures,

Mechanick practises, Engynes and Inventions by Experiments."[i-3]

The zeal for experiment was equaled only by its miscellaneousness.

Cheese making, the eclipses of comets, and the intestines[xv]

of gnats were alike the objects of telescopic or microscopic

scrutiny. The full implication of Baconian empiricism came to

fruition in Newton, who in 1672 was elected a Fellow of the

Royal Society. Bacon was not the least of those giants upon

whose shoulders Newton stood. To the experimental tradition

of Kepler, Brahe, Harvey, Copernicus, Galileo, and Bacon,

Newton joined the mathematical genius of Descartes; and as

a result became "as thoroughgoing an empiricist as he was a

consummate mathematician," for whom there was "no a priori

certainty."[i-4] At this time it is enough to note of Newtonianism,

that for the incomparable physicist "science was composed of

laws stating the mathematical behaviour of nature solely—laws

clearly deducible from phenomena and exactly verifiable in

phenomena—everything further is to be swept out of science,

which thus becomes a body of absolutely certain truth about

the doings of the physical world."[i-5] The pattern of ideas known

as Newtonianism may be summarized as embracing a belief in

(1) a universe governed by immutable natural laws, (2) which

laws constitute a sublimely harmonious system, (3) reflecting a

benevolent and all-wise Geometrician; (4) thus man desires to

effect a correspondingly harmonious inner heaven; (5) and feels

assured of the plausibility of an immortal life. Newton was a

believer in scriptural revelation. It is ironical that through his

cosmological system, mathematically demonstrable, he lent reinforcement[xvi]

to deism, the most destructive intellectual solvent

of the authority of the altar.

Deists, as defined by their contemporary, Ephraim Chambers

(in his Cyclopædia ..., London, 1728), are those "whose distinguishing

character it is, not to profess any particular form,

or system of religion; but only to acknowledge the existence of

a God, without rendering him any external worship, or service.

The Deists hold, that, considering the multiplicity of religions,

the numerous pretences to revelation, and the precarious arguments

generally advanced in proof thereof; the best and surest

way is, to return to the simplicity of nature, and the belief of

one God, which is the only truth agreed to by all nations."

They "reject all revelations as an imposition, and believe no

more than what natural light discovers to them...."[i-6] The

"simplicity of nature" signifies "the established order, and

course of natural things; the series of second causes; or the laws

which God has imposed on the motions impressed by him."[i-7]

And attraction, a kind of conatus accedendi, is the crown, according

to the eighteenth century, of the series of secondary causes.

Hence, Newtonian physics became the surest ally of the deist

in his quest for a religion, immutable and universal. The Newtonian

progeny were legion: among them were Boyle, Keill,

Desaguliers, Shaftesbury, Locke, Samuel Clarke, 'sGravesande,

Boerhaave, Diderot, Trenchard and Gordon, Voltaire, Gregory,

Maclaurin, Pemberton, and others. The eighteenth century

echoed Fontenelle's eulogy that Newtonianism was "sublime

geometry." If, as Boyle wrote, mathematical and mechanical

principles were "the alphabet, in which God wrote the world,"

Newtonian science and empiricism were the lexicons which the

deists used to read the cosmic volume in which the universal

laws were inscribed. And the deists and the liberal political

theorists "found the fulcrum for subverting existing institutions[xvii]

and standards only in the laws of nature, discovered, as

they supposed, by mathematicians and astronomers."[i-8]

Complementary to Newtonian science was the sensationalism

of John Locke. Conceiving the mind as tabula rasa, discrediting

innate ideas, Lockian psychology undermined such a theological

dogma as total depravity—man's innate and inveterate

malevolence—and hence was itself a kind of tabula rasa on

which later were written the optimistic opinions of those

who credited man's capacity for altruism. If it remained for

the French philosophes to deify Reason, Locke honored it as the

crowning experience of his sensational psychology.[i-9] Then, too,

as Miss Lois Whitney has ably demonstrated, Lockian psychology

"cleared the ground for either primitivism or a theory of

progress."[i-10] In addition, his social compact theory, augmenting

seventeenth-century liberalism, furnished the political theorists

of the Enlightenment with "the principle of Consent"[i-11] in their[xviii]

antipathy for monarchial obscurantism. Locke has been described

as the "originator of a psychology which provided democratic

government with a scientific basis."[i-12] The full impact of

Locke will be felt when philosophers deduce that if sensations

and reflections are the product of outward stimuli—those of

nature, society, and institutions—then to reform man one

needs only to reform society and institutions, or remove to

some tropical isle. We remember that the French Encyclopedists,

for example, were motivated by their faith in the

"indefinite malleability of human nature by education and

institutions."[i-13]

"With the possible exception of John Locke," C. A. Moore

observes, "Shaftesbury was more generally known in the mid-century

than any other English philosopher."[i-14] Shaftesbury's

a priori "virtuoso theory of benevolence" may be viewed as

complementary to Locke's psychology to the extent that both

have within them the implication that through education and

reform man may become perfectible. Both tend to undermine

social, political, and religious authoritarianism. Shaftesbury's

insistence upon man's innate altruism and compassion, coupled

with the deistic and rationalistic divorce between theology

and morality, resulted in the dogma that the most acceptable

service to God is expressed in kindness to God's other children

and helped to motivate the rise of humanitarianism.

The idea of progress[i-15] was popularized (if not born) in the

eighteenth century. It has been recently shown that not only[xix]

the results of scientific investigations but also Anglican defenses

of revealed religion served to accelerate a belief in progress.

In answer to the atheists and deists who indicted revealed

religion because revelation was given so late in the growth of

the human family and hence was not eternal, universal, and immutable,

the Anglican apologists were forced into the position

of asserting that man enjoyed a progressive ascent, that the religious

education of mankind is like that of the individual. If,

as the deists charged, Christ appeared rather belatedly, the

apologists countered that he was sent only when the race was

prepared to profit by his coming. God's revelations thus were

adjusted to progressive needs and capacities.[i-16]

Carl Becker has suggestively dissected the Enlightenment in

a series of antitheses between its credulity and its skepticism.

If the eighteenth-century philosopher renounced Eden, he discovered

Arcadia in distant isles and America. Rejecting the

authority of the Bible and church, he accepted the authority

of "nature," natural law, and reason. Although scorning metaphysics,

he desired to be considered philosophical. If he denied

miracles, he yet had a fond faith in the perfectibility of the

species.[i-17]

Even as Voltaire had his liberal tendencies stoutly reinforced

by contact with English rationalism and deism,[i-18] so were the

other French philosophes, united in their common hatred of the

Roman Catholic church, also united in their indebtedness to

exponents of English liberalism, dominated by Locke and Newton.

If, as Madame de Lambert wrote in 1715, Bayle more than

others of his age shook "the Yoke of authority and opinion,"

English free thought powerfully reinforced the native French

revolt against authoritarianism. After 1730 English was the[xx]

model for French thought.[i-19] Nearly all of Locke's works had

been translated in France before 1700. Voltaire's affinity for the

English mind has already been touched on. D'Alembert comments,

"When we measure the interval between a Scotus and a

Newton, or rather between the works of Scotus and those of

Newton, we must cry out with Terence, Homo homini quid

præstat."[i-20]

Any doctrine was intensely welcome which would allow

the Frenchman to regain his natural rights curtailed by the

revocation of the Edict of Nantes, by the inequalities of a state

vitiated by privileges, by an economic structure tottering because

of bankruptcy attending unsuccessful wars and the upkeep

of a Versailles with its dazzling ornaments, and by a religious

program dominated by a Jesuit rather than a Gallican

church.[i-21] Economic, political, and religious abuses were inextricably

united; the spirit of revolt did not feel obliged to

discriminate between the authority of the crown and nobles and

the authority of the altar. Graphic is Diderot's vulgar vituperation:

he would draw out the entrails of a priest to strangle a king!

Let us now turn to the American backgrounds. The bibliolatry

of colonial New England is expressed in William

Bradford's resolve to study languages so that he could "see with

his own eyes the ancient oracles of God in all their native

beauty."[i-22] In addition to furnishing the new Canaan with[xxi]

ecclesiastical and political precedent, Scripture provided "not

a partiall, but a perfect rule of Faith, and manners." Any dogma

contravening the "ancient oracle" was a weed sown by Satan

and fit only to be uprooted and thrown in the fire. The colonial

seventeenth century was one which, like John Cotton, regularly

sweetened its mouth "with a piece of Calvin." One need not

be reminded that Calvinism was inveterately and completely

antithetical to the dogma of the Enlightenment.[i-23] Calvinistic

bibliolatry contended with "the sacred book of nature." Its

wrathful though just Deity was unlike the compassionate, virtually

depersonalized Deity heralded in the eighteenth century,

in which the Trinity was dissolved. The redemptive Christ became

the amiable philosopher. Adam's universally contagious

guilt was transferred to social institutions, especially the tyrannical

forms of kings and priests. Calvin's forlorn and depraved

man became a creature naturally compassionate. If once man

worshipped the Deity through seeking to parallel the divine

laws scripturally revealed, in the eighteenth century he honored

his benevolent God, who was above demanding worship,

through kindnesses shown God's other children. The individual

was lost in society, self-perfection gave way to humanitarianism,

God to Man, theology to morality, and faith to reason.

The colonial seventeenth century was politically oligarchical:[xxii]

when Thomas Hooker heckled Winthrop on the lack of suffrage,

Winthrop with no compromise asserted that "the best

part is always the least, and of that best part the wiser part is

always the lesser."[i-24] If the seventeenth-century college was a

cloister for clerical education, the Enlightenment sought to

train the layman for citizenship.

With the turn of the seventeenth century several forces came

into prominence, undermining New England's Puritan heritage.

Among those relevant for our study are: the ubiquitous frontier,

and the rise of Quakerism, deism, Methodism, and science. The

impact of the frontier was neglected until Professor Turner

called attention to its existence; he writes that "the most important

effect of the frontier has been in the promotion of

democracy here and in Europe.... It produces antipathy to

control, and particularly to any direct control.... The frontier

conditions prevalent in the colonies are important factors in

the explanation of the American Revolution...."[i-25] In the

period included in our survey the frontier receded from the coast

to the fall line to the Alleghenies: at each stage it "did indeed

furnish a new field of opportunity, a gate of escape from the

bondage of the past; and freshness, and confidence, and scorn

of older society, impatience of its restraints and its ideas, and

indifference to its lessons, have accompanied the frontier."[i-26]

One recalls the spirited satire on frontier conditions, as the above

aspects give birth to violence and disregard for law, in Hugh

Brackenridge's Modern Chivalry. Under the satire one feels the

justness of the attack, intensified by our knowledge that Brackenridge

grew up "in a democratic Scotch-Irish back-country

settlement." If the frontiersmen during the eighteenth century

did not place their dirty boots on their governors' desks, they

were partially responsible for an inveterate spirit of revolt,[xxiii]

shown so brutally in the "massacres" provoked by the "Paxton

boys" of Pennsylvania. One is not unprepared to discover

resentment against the forms of authority in a territory in

which a strong back is more immediately important than a

knowledge of debates on predestination. Granting the importance

of the frontier in opposing the theocratic Old Way, it

must be considered in terms of other and more complex factors.

Reinforcing Edwards's Great Awakening, George Whitefield,

especially in the Middle Colonies, challenged the growing

complacence of colonial religious thought with his insistence

that man "is by nature half-brute and half-devil." It has been

suggested that Methodism in effect allied itself with the attitudes

of Hobbes and Mandeville in attacking man's nature, and hence

by reaction tended to provoke "a primitivism based on the

doctrine of natural benevolence."[i-27]

The "New English Israel" was harried by the Quakers,[i-28]

who preached the priesthood of all believers and the right of

private judgment. They denied the total depravity of the natural

man and the doctrine of election; they gloried in a loving

Father, and scourged the ecclesiastical pomp and ceremony of

other religions. They were possessed by a blunt enthusiasm

which held the immediate private revelation anterior to scriptural

revelation. Faithful to the inner light, the Quakers seemed to

neglect Scripture. Although the less extreme Quakers, such as

John Woolman, did not blind themselves to the need for personal

introspection and self-conquest, Quakerism as a movement

tended to place the greater emphasis on morality articulate in

terms of fellow-service, and lent momentum to the rise of

humanitarianism expressed in prison reform and anti-slavery

agitation. Also one may wonder to what extent colonial Quakerism

tended to lend sanction to the rising democratic spirit.

In the person of Cotton Mather, until recently considered a[xxiv]

bigoted incarnation of the "Puritan spirit ... become ossified,"

are discovered forces which, when divorced from Puritan theology,

were to become the sharpest wedges splintering the deep-rooted

oak of the Old Way. These forces were the authority

of reason and science. In The Christian Philosopher,[i-29] basing

his attitude on the works of Ray, Derham, Cheyne, and Grew,[i-30]

Mather attempted to shatter the Calvinists' antithesis between

science and theology, asserting "that [Natural] Philosophy is no

Enemy, but a mighty and wondrous Incentive to Religion."[i-31]

He warned that since even Mahomet with the aid of reason

found the Workman in his Work, Christian theologians should

fear "lest a Mahometan be called in for thy Condemnation!"[i-32]

Studying nature's sublime order, one must be blind if his

thoughts are not carried heavenward to "admire that Wisdom

itself!" Although Mather mistrusted Reason, he accepted it as

"the voice of God"—an experience which enabled him to discover

the workmanship of the Deity in nature. Magnetism, the

vegetable kingdom, the stars infer a harmonious order, so wondrous

that only a God could have created it. If Reason is no

complete substitute for Scripture it offers enough evidence to

hiss atheism out of the world: "A Being that must be superior

to Matter, even the Creator and Governor of all Matter, is

everywhere so conspicuous, that there can be nothing more

monstrous than to deny the God that is above."[i-33] Sir Isaac

Newton with his mathematical and experimental proof of the

sublime universal order strung on invariable secondary causes,

Mather confessed, is "our perpetual Dictator."[i-34] Conceiving of

science as a rebuke to the atheist, and a natural ally to scriptural[xxv]

theology, Mather, like a Newton himself, juxtaposed rationalism

and faith in one pyramidal confirmation of the existence,

omnipotence, and benevolence of God. Here were

variations from Calvinism's common path which, when augmented

by English and French liberalism, by the influence of

Quakerism and the frontier, were to give rise to democracy,

rationalism, and scientific deism. The Church of England

through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had "pursued

a liberal latitudinarian policy which, as a mode of thought,

tended to promote deism by emphasizing rational religion and

minimizing revelation."[i-35] It was to be expected that in colonies

created by Puritans (or even Quakers), deism would have

a less spectacular and extensive success than it appears to have

had in the mother country. If militant deism remained an

aristocratic cult until the Revolution,[i-36] scientific rationalism

(Newtonianism) long before this, from the time of Mather,

became a common ally of orthodoxy. If a "religion of nature"

may be defined with Tillotson as "obedience to Natural Law,

and the performance of such duties as Natural Light, without

any express and supernatural revelation, doth dictate to man,"

then it was in the colonies, prior to the Revolution, more commonly

a buttress to revealed religion than an equivalent to it.

Lockian sensism and Newtonian science were the chief

sources of that brand of colonial rationalism which at first complemented

orthodoxy, and finally buried it among lost causes.

The Marquis de Chastellux was astounded when he found on a

center table in a Massachusetts inn an "Abridgment of Newton's

Philosophy"; whereupon he "put some questions" to his

host "on physics and geometry," with which he "found him

well acquainted."[i-37] Now, even a superficial reading of the eighteenth

century discloses countless allusions to Newton, his[xxvi]

popularizers, and the implications of his physics and cosmology.

As Mr. Brasch suggests, "From the standpoint of the

history of science," the extent of the vogue of Newtonianism

"is yet very largely unknown history."[i-38]

In Samuel Johnson's retrospective view, the Yale of 1710 at

Saybrook was anything but progressive with its "scholastic

cobwebs of a few little English and Dutch systems."[i-39] The year

of Johnson's graduation (1714), however, Mr. Dummer, Yale's

agent in London, collected seven hundred volumes, including

works of Norris, Barrow, Tillotson, Boyle, Halley, and the

second edition (1713) of the Principia and a copy of the Optics,

presented by Newton himself. After the schism of 1715/6 the

collection was moved to New Haven, at the time of Johnson's

election to a tutorship. It was then, writes Johnson, that the

trustees "introduced the study of Mr. Locke and Sir Isaac

Newton as fast as they could and in order to this the study of

mathematics. The Ptolemaic system was hitherto as much believed

as the Scriptures, but they soon cleared up and established

the Copernican by the help of Whiston's Lectures, Derham,

etc."[i-40] Johnson studied Euclid, algebra, and conic

sections "so as to read Sir Isaac with understanding." He

gloomily reviews the "infidelity and apostasy" resulting from

the study of the ideas of Locke, Tindal, Bolingbroke, Mandeville,

Shaftesbury, and Collins. That Newtonianism and even

deism made progress at Yale is the tenor of Johnson's backward

glance. About 1716 Samuel Clarke's edition of Rohault was introduced

at Yale: Clarke's Rohault[i-41] was an attack upon this[xxvii]

standard summary of Cartesianism. Ezra Stiles was not certain

that Clarke was honest in heaping up notes "not so much to illustrate

Rohault as to make him the Vehicle of conveying the

peculiarities of the sublimer Newtonian Philosophy."[i-42] This

work was used until 1743 when 'sGravesande's Natural Philosophy

was wisely substituted. Rector Thomas Clap used Wollaston's

Religion of Nature Delineated as a favorite text. That

there was no dearth of advanced natural science and philosophy,

even suggestive of deism, is fairly evident.

Measured by the growth of interest in science in the English

universities, Harvard's awareness of new discoveries was not

especially backward in the seventeenth century. Since Copernicanism

at the close of the sixteenth century had few adherents,[i-43]

it is almost startling to learn that probably by 1659 the

Copernican system was openly avowed at Harvard.[i-44] In 1786

Nathaniel Mather wrote from Dublin: "I perceive the Cartesian

philosophy begins to obteyn in New England, and if I conjecture

aright the Copernican system too."[i-45] John Barnard,

who was graduated from Harvard in 1710, has written that no

algebra was then taught, and wistfully suggests that he had been

born too soon, since "now" students "have the great Sir Isaac

Newton and Dr. Halley and some other mathematicians for their

guides."[i-46] Although Thomas Robie and Nathan Prince are

thought to have known Newton's physics through secondary

sources,[i-47] and, as Harvard tutors, indoctrinated their charges

with Newtonianism, it was left to Isaac Greenwood[i-48] to transplant[xxviii]

from London the popular expositions of Newtonian

philosophy. A Harvard graduate in 1721, Greenwood continued

his theological studies in London where he attended

Desaguliers's lectures on experimental philosophy, based essentially

on Newtonianism. From Desaguliers Greenwood learned

how

By Newton's help, 'tis evidently seen

Attraction governs all the World's machine.[i-49]

He learned that Scripture is "to teach us Morality, and our

Articles of Faith" but not to serve as an instructor in natural

philosophy.[i-50] In fine, Greenwood became devoted to science,

and science as it might serve to augment avenues to the religious

experience. In London he had come to know Hollis, who in

1727 suggested to Harvard authorities that Greenwood be

elected Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural and Experimental

Philosophy.[i-51] Greenwood accepted, and until 1737

was at Harvard a propagandist of the new science. In 1727 he

advertised in the Boston News-Letter[i-52] that he would give

scientific lectures, revolving primarily around "the Discoveries

of the incomparable Sir Isaac Newton." From 1727 through

1734 he was a prominent popularizer of Newtonianism in

Boston.[i-53]

It remained for Greenwood's pupil John Winthrop to be the

first to teach Newton at Harvard with adequate mechanical and

textual materials. Elected in 1738 to the Hollis professorship

formerly held by Greenwood, Winthrop adopted 'sGravesande's

Natural Philosophy, at which time, Cajori observes, "the teachings[xxix]

of Newton had at last secured a firm footing there."[i-54]

The year after his election he secured a copy of the Principia

(the third edition, 1726, edited by Dr. Henry Pemberton, friend

of Franklin in 1725-1726). According to the astute Ezra Stiles,

Winthrop became a "perfect master of Newton's Principia—which

cannot be said of many Professors of Philosophy in

Europe."[i-55] That he did not allow Newtonianism to draw him

to deism may be seen in Stiles's gratification that Winthrop

"was a Firm friend to Revelation in opposition to Deism."

Stiles "wish[es] the evangelical Doctors of Grace had made a

greater figure in his Ideal System of divinity," thus inferring that

Winthrop was a rationalist in theology, however orthodox.[i-56]

A cursory view of the eighteenth-century pulpit discloses

that if the clergy did not become deistic they were not blind

to a natural religion, and often employed its arguments to augment

scriptural authority. Aware of the writings of Samuel

Clarke, Wollaston, Whiston, Cudworth, Butler, Hutcheson,[i-57]

Voltaire, and Locke, Mayhew revolts against total depravity[i-58]

and the doctrines of election and the Trinity, arraigns himself

against authoritarianism and obscurantism, and though he draws

upon reason for revelation of God's will, he does not seem to

have been latitudinarian in respect to the holy oracles. Although

he often wrote ambiguously concerning the nature of Christ,

he asserted: "That I ever denied, or treated in a bold or ludicrous

manner, the divinity of the Son of God, as revealed in scripture,[xxx]

I absolutely deny."[i-59] He is antagonistic toward the mystical in

Calvinism, convinced that "The love of God is a calm and

rational thing, the result of thought and consideration."[i-60] His

biographer thinks that Mayhew was "the first clergyman in New

England who expressly and openly opposed the scholastic doctrine

of the trinity."[i-61] Coupling "natural and revealed religion,"

he does not threaten but he urges that one "ought not to leave

the clear light of revelation.... It becomes us to adhere to the

holy Scriptures as our only rule of faith and practice, discipline

and worship."[i-62] In Mayhew one finds an impotent compromise

between Calvinism and the demands of reason, fostered by

the Enlightenment. Like Mayhew's, in the main, are the views

of Dr. Charles Chauncy, who reconciled the demands of reason

and revelation, concluding that "the voice of reason is the voice

of God."[i-63] Jason Haven and Jonas Clarke are typical of the

orthodox rationalists who were alive to the implications of

science, and to such rationalists as Tillotson and Locke. Haven

affirms that "by the light of reason and nature, we are led to

believe in, and adore God, not only as the maker, but also as

the governor of all things."[i-64] "Revelation comes in to the assistance

of reason, and shews them to us in a clearer light than

we could see them without its aid." Clarke observes that "the

light of nature teaches, which revelation confirms."[i-65] Rev.

Henry Cumings, illustrating his indebtedness to scientific rationalism,

honors "the gracious Parent of the universe, whose[xxxi]

tender mercies are over all his works ...,"[i-66] a Deity "whose

providence governs the world; whose voice all nature obeys;

to whose controul all second causes and subordinate agents are

subject; and whose sole prerogative it is to dispense blessings

or calamities, as to his wisdom seems best."[i-67] Simeon Howard

discovers the "perfections of the Deity, as displayed in the

Creation" as well as in the "government and redemption of the

world."[i-68] Both Phillips Payson[i-69] and Andrew Eliot[i-70] affirm the

identity of "the voice of reason, and the voice of God."

No clergyman of the eighteenth century was more terribly

conscious of the polarity of colonial thought than was Ezra

Stiles. Abiel Holmes has told the graphic story of Stiles's

struggles with deism after reading Pope, Whiston, Boyle,

Trenchard and Gordon, Butler, Tindal, Collins, Bolingbroke,

and Shaftesbury.[i-71] If he finally, as a result of his trembling and

fearful doubt, reaffirmed zealously his faith in the bibliolatry and

relentless dogma of Calvinism,[i-72] Newtonian rationalism was a

means to his recovery, and throughout his life a complement to

his Calvinism.[i-73] Turning from his well-worn Bible, the chief

source of his faith, he also kindled his "devotion at the stars."

It should be remembered, however, that this tendency among

Puritan clergy to call science to the support of theology had

been inaugurated by Cotton Mather as early as 1693,[i-74] and that

it was the Puritan Mather whom Franklin acknowledged as

having started him on his career and influenced him, by his

Essays to do Good, throughout life.

[xxxii]

Only against this complex and as yet inadequately integrated

background of physical conditions and ideas (the dogmas of

Puritanism, Quakerism, Methodism, rationalism, scientific

deism, economic and political liberalism[i-75]—against a cosmic,

social, and individual attitude, the result of Old-World thought

impinging on colonial thought and environment) can one attempt

to appraise adequately the mind and achievements of

Franklin, whose life was coterminous with the decay of Puritan

theocracy and the rise of rationalism, democracy, and science.

II. FRANKLIN'S THEORIES OF EDUCATION

Franklin's penchant for projects manifests itself nowhere more

fully than in his schemes of education, both self and formal. One

may deduce a pattern of educational principles not undeservedly

called Franklin's theories of education, theories which he successfully

institutionalized, from an examination of his Junto

("the best school of philosophy, morality, and politics that then

existed in the province"[i-76]), his Philadelphia Library Company

(his "first project of a public nature"[i-77]), his[xxxiii]

Proposal for Promoting Useful Knowledge among the British Plantations in

America, calling for a scientific society of ingenious men or

virtuosi, his Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in

Pensilvania and Idea of the English School, which eventually

fathered the University of Pennsylvania, and from his fragmentary

notes in his correspondence.

Variously apotheosized, patronized, or damned for his practicality,

expediency, and opportunism, dramatized for his allegiance

to materiality, Franklin has commonly been viewed

(and not only through the popular imagination) as one fostering

in the American mind an unimaginative, utilitarian prudence,

motivated by the pedestrian virtues of industry, frugality, and

thrift. Whatever the educational effect of Franklin's life and

writings on American readers, we shall find that his works contain

schemes and theories which transcend the more mundane

habits and utilitarian biases ascribed to him.

Franklin progressively felt "the loss of the learned education"

his father had planned for him, as he realized in his

hunger for knowledge that he must repair the loss through assiduous

reading, accomplished during hours stolen from recreation

and sleep.[i-78] Proudly he confessed that reading was his

"only amusement."[i-79] In 1727 he formed the Junto, or Leather

Apron Club, his first educational project. Franklin was never

more eclectic than when founding the Junto. To prevent Boston

homes from becoming "the porches of hell,"[i-80] Cotton Mather

had created mutual improvement societies through which

neighbors would help one another "with a rapturous assiduity."[i-81]

Mather in his Essays to do Good proposed:[xxxiv]

That a proper number of persons in a neighborhood, whose

hearts God hath touched with a zeal to do good, should form

themselves into a society, to meet when and where they shall

agree, and to consider—"what are the disorders that we may

observe rising among us; and what may be done, either by

ourselves immediately, or by others through our advice, to

suppress those disorders?"[i-82]

Since Franklin's father was a member of one of Mather's "Associated

Families" and since Franklin as a boy read Mather's

Essays with rapt attention,[i-83] and since his Rules for a Club

Established for Mutual Improvement are amazingly congruent

with Mather's rules proposed for his neighborly societies, it is

not improbable that Franklin in part copied the plans of this

older club. One also wonders whether Franklin remembered

Defoe's suggestions in Essays upon Several Projects (1697) for

the formation of "Friendly Societies" in which members covenanted

to aid one another.[i-84] In addition, M. Faÿ has observed

that the "ideal which this society [the Junto] adopted was the

same that Franklin had discovered in the Masonic lodges of

England."[i-85] Then, too, in London during the period of

Desaguliers, Sir Hans Sloane, and Sir Isaac Newton, he would

have heard much of the ideals and utility of the Royal Society.

Many of the questions discussed by the Junto are suggestive

of the calendar of the Royal Society:

Is sound an entity or body?

How may the phenomena of vapors be explained?

What is the reason that the tides rise higher in the Bay of

Fundy, than the Bay of Delaware?

[xxxv]

How may smoky chimneys be best cured?

Why does the flame of a candle tend upwards in a spire?[i-86]

The Junto members, like Renaissance gentlemen, were determined

to convince themselves that nothing valuable to the

several powers of life should be alien to them. They were urged

to communicate to one another anything significant "in history,

morality, poetry, physic, travels, mechanic arts, or other parts

of knowledge."[i-87] Surely a humanistic catholicity of interest!

Schemes for getting on materially, suggestions for improving

the laws and protecting the "just liberties of the people,"[i-88]

efforts to aid the strangers in Philadelphia (an embryonic association

of commerce), curiosity in the latest remedies used for

the sick and wounded: all were to engage the minds of this assiduously

curious club. Above all, the members must be "serviceable

to mankind, to their country, to their friends, or to

themselves."[i-89] The intensity of the Junto's utilitarian purpose

was matched only by its humanitarian bias. Members must swear

that they "love mankind in general, of what profession or religion

soever,"[i-90] and that they believe no man should be persecuted

"for mere speculative opinions, or his external way of

worship." Also they must profess to "love truth for truth's

sake," to search diligently for it and to communicate it to

others. Tolerance, the empirical method, scientific disinterestedness,

and humanitarianism had hardly gained a foothold in

the colonies in 1728. On the other hand, the Junto members

were urged, when throwing a kiss to the world, not to neglect

their individual ethical development.[i-91] Franklin's humanitarian[xxxvi]

neighborliness is associated with a rigorous ethicism. The

members were invited to report "unhappy effects of intemperance,"

of "imprudence, of passion, or of any other vice

or folly," and also "happy effects of temperance, of prudence,

of moderation." Franklin reflects sturdily here, and boundlessly

elsewhere, the Greek and English emphasis on the Middle Way.

If this is prudential, it is an elevated prudence.

The Philadelphia Library Company was born of the Junto

and became "the mother of all the North American subscription

libraries, now so numerous."[i-92] The colonists, "having no publick

amusements to divert their attention from study, became

better acquainted with books, and in a few years were observ'd

by strangers to be better instructed and more intelligent than

people of the same rank generally are in other countries."[i-93] It

is curious that although many articles have been written describing

the Library Company no one seems to include a study

of the climate of ideas represented in its volumes.[i-94] One must

be careful not to credit Franklin with solely presiding over

the ordering of books. At a meeting in 1732 of the company,

Thomas Godfrey, probable inventor of the quadrant and he

who learned Latin to read the Principia, notified the body

that "Mr. Logan had let him know he would willingly give

his advice of the choice of the books ... the Committee esteeming[xxxvii]

Mr. Logan to be a Gentleman of universal learning, and the best

judge of books in these parts, ordered that Mr. Godfrey should

wait on him and request him to favour them with a catalogue

of suitable books."[i-95] The first order included: Puffendorf's

Introduction and Laws of Nature, Hayes upon Fluxions, Keill's

Astronomical Lectures, Sidney on Government, Gordon and

Trenchard's Cato's Letters, the Spectator, Guardian, Tatler,

L'Hospital's Conic Sections, Addison's works, Xenophon's

Memorabilia, Palladio, Evelyn, Abridgement of Philosophical

Transactions, 'sGravesande's Natural Philosophy, Homer's Odyssey

and Iliad, Bayle's Critical Dictionary, and Dryden's Virgil.

As a gift Peter Collinson included Newton's Principia in the

order. The ancient phalanxes were thoroughly routed! Then

there is the MS "List of Books of the Original Philadelphia

Library in Franklin's Handwriting"[i-96] which lends recruits to

the modern battalions. Included in this list are: Fontenelle on

Oracles, Woodward's Natural History of Fossils and Natural

History of the Earth, Keill's Examination of Burnet's Theory of

the Earth, Memoirs of the Royal Academy of Surgery at Paris,

William Petty's Essays, Voltaire's Elements of Sir Isaac Newton's

Philosophy, Halley's Astronomical Tables, Hill's Review of

the Works of the Royal Society, Montesquieu's Spirit of Laws,

Burlamaqui's Principles of Natural Law and Principles of Politic

Law, Bolingbroke's Letters on the Study and Use of History,

and Conyer Middleton's Miscellaneous Works. From the

volumes owned by the Library Company in 1757 it would

have been possible for an alert mind to discover all of the

implications, philosophic and religious, of the rationale of

science. No less could be found here the political speculations

which were later to aid the colonists in unyoking themselves

from England. The Library was an arsenal capable of supplying[xxxviii]

weapons to rationalistic minds intent on besieging the

fortress of Calvinism. Defenders of natural rights could find

ammunition to wound monarchism; here authors could discover

the neoclassic ideals of curiosa felicitas, perspicuity,

order, and lucidity reinforced by the emphasis on clarity and

correctness sponsored by the Royal Society and inherent in

Newtonianism as well as Cartesianism. In short, the volumes

contained the ripest fruition of scientific and rationalistic modernity.

One can only conjecture the extent to which this library

would perplex, astonish, and finally convert men to rationalism

and scientific deism, and release them from bondage to throne

and altar.

In 1743 Franklin wrote and distributed among his correspondents

A Proposal for Promoting Useful Knowledge among

the British Plantations in America. From a letter (Feb. 17,

1735/6) of William Douglass, one-time friend of Franklin's

brother James, to Cadwallader Colden, we learn that some years

before 1736, Colden "proposed the forming a sort of Virtuoso

Society or rather Correspondence."[i-97] I. W. Riley suggests that

Franklin owes Colden thanks for having stimulated him to form

the American Philosophical Society.[i-98] There remains no convincing

evidence, however, to disprove A. H. Smyth's observation

that Franklin's Proposal "appears to contain the first suggestions,

in any public form [editors' italics] for an American

Philosophical Society." P. S. Du Ponceau has noted with compelling

evidence that the philosophical society formed in 1744

was the direct descendant of Franklin's Junto.[i-99] That in part

the Philadelphia Library Company was one of the factors in[xxxix]

the formation of the scientific society may be inferred from

Franklin's request that it be founded in Philadelphia, which,

"having the advantages of a good growing library," can "be the

centre of the Society."[i-100] The most important factor, however,

was obviously the desire to imitate the forms and ideals of the

Royal Society of London. Both societies had as their purpose

the improvement of "the common stock of knowledge"; neither

was to be provincial or national in interests, but was to have in

mind the "benefit of mankind in general." A study of Franklin's

Proposal will suggest the purpose of the Royal Society as

interpreted by Thomas Sprat:

Their purpose is, in short, to make faithful Records, of all

the Works of Nature, or Art, which can come within their

reach: that so the present Age, and posterity, may be able to

put a mark on the Errors, which have been strengthened by

long prescription: to restore the Truths, that have lain neglected:

to push on those, which are already known, to more

various uses: and to make the way more passable, to what

remains unreveal'd.[i-101]

The Royal Society, no less than Franklin's Proposal, stressed

the usefulness of its experimentation. Even as it sought "to overcome

the mysteries of all the Works of Nature"[i-102] through

experimentation and induction, the Baconian empirical method,

so Franklin urged the cultivation of "all philosophical experiments

that let light into the nature of things, tend to increase the

power of man over matter, and multiply the conveniences or

pleasures of life."[i-103] Though Franklin may have stopped short

of theoretical science,[i-104] he was not only interested in making[xl]

devices but also in discovering immutable natural laws on which

he could base his mechanics for making the world more habitable,

less unknown and terrifying. Interpreting natural phenomena

in terms of gravity and the laws of electrical attraction

and repulsion is to detract from the terror in a universe presided

over by a providential Deity, exerting his wrath through portentous

comets, "fire-balls flung by an angry God."

Franklin's program is no more miscellaneous, or seemingly

pedestrian, than the practices of the Royal Society. As a discoverer

of nature's laws and their application to man's use,

Franklin, the Newton of electricity, appealed to fact and experiment

rather than authority and suggested that education in

science may serve, in addition to making the world more comfortable,

to make it more habitable and less terrifying. The

ideals of scientific research and disinterestedness were dramatized

picturesquely by the Tradesman Franklin, who aided the

colonist in becoming unafraid.

Although his Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth

in Pensilvania (1749) furnished the initial suggestion which

created the Philadelphia Academy, later the college, and ultimately

the University of Pennsylvania, it is easy to overestimate

the real significance of Franklin's influence in these

schemes unless we remember that political quarrels separated

him from those who were nurturing the school in the 1750's. In

1759 Franklin wrote from London to his friend, Professor Kinnersley,

concerning the cabal in the Academy against him:

"The Trustees have reap'd the full Advantage of my Head,

Hands, Heart and Purse, in getting through the first Difficulties

of the Design, and when they thought they could do without[xli]

me, they laid me aside."[i-105] After Franklin failed to secure

Samuel Johnson,[i-106] Rev. William Smith was made Provost and

Professor of Natural Philosophy of the Academy in 1754. He

quoted Franklin as saying that the Academy had become "a

narrow, bigoted institution, put into the hands of the Proprietary

party as an engine of government."[i-107]

[xlii]

With Milton, Locke, Fordyce, Walker, Rollin, Turnbull,

and "some others" as his sources, Franklin adapted the works of

these pioneers in education to provincial uses. (One finds it

difficult to discover any original ideas in the Proposals.) Like

Locke and Milton, he urged that education "supply the succeeding

Age with Men qualified to serve the Publick with Honour

to themselves, and to their Country."[i-108] Here he was unlike

President Clap, who in 1754 explained that "the Original End

and design of Colleges was to instruct and train up persons

for the Work of the ministry.... The great design of founding

this school [Yale] was to educate ministers in our own

way."[i-109] As early as 1722, in Dogood Paper No. IV, Franklin

caricatured sardonically the narrow theological curriculum

of Harvard College.[i-110] Existing for the citizenry rather than

the clergy, offering instruction in English as well as Latin and

Greek, in mechanics, physical culture, natural history, gardening,

mathematics, and arithmetic rather than in sectarian theology,

Franklin's Academy was to be more secular and utilitarian

than any other school in the provinces. Indeed, Rev. George

Whitefield lamented the want of "aliquid Christi" in the curriculum,

"to make it as useful as I would desire it might be."

Franklin stressed the need for the acquisition of a clear and

concise literary style. He observed: "Reading should also be[xliii]

taught, and pronouncing, properly, distinctly, emphatically; not

with an even Tone, which under-does, nor a theatrical, which

over-does Nature." Hence he reflected the virtues of neoclassic

perspicuity and correctness. (These plans he more fully expressed

in his Idea of the English School, published in 1751.) As

he grew older he apparently became less tolerant of the teaching

of the ancient languages in colonial schools: in Observations

Relative to the Intentions of the Original Founders of the Academy

of Philadelphia (1789), he charged that the Latin school had

swallowed the English and that he was hence "surrounded by the

Ghosts of my dear departed Friends, beckoning and urging me to

use the only Tongue now left us, in demanding that Justice to

our Grandchildren, that our Children has [sic] been denied."[i-111]

The Latin and Greek languages he considered "in no other light

than as the Chapeau bras of modern Literature."[i-112] Like Emerson's,

his opposition was to linguistic study rather than to the

classical ideas.

Although he emphasized the study of science and mechanics,

it is important to observe that he kept his balance. He warned

Miss Mary Stevenson in 1760: "There is ... a prudent Moderation

to be used in Studies of this kind. The Knowledge of Nature

may be ornamental, and it may be useful; but if, to attain

an Eminence in that, we neglect the Knowledge and Practice of

essential Duties, we deserve Reprehension."[i-113] Not without

reserve did he champion the Moderns; remembering several

provocative scientific observations in Pliny, he wrote to William

Brownrigg (Nov. 7, 1773): "It has been of late too much the

mode to slight the learning of the ancients."[i-114] He would not

agree with the enthusiastic and trenchant disciple of the[xliv]

moderns, M. Fontenelle, that "We are under an obligation to

the ancients for having exhausted almost all the false theories

that could be found."[i-115] Although he would agree that the

empirical method of acquiring knowledge is more reasonable

than authoritarianism reared on syllogistic foundations, and

with Cowley that

Bacon has broke that scar-crow Deity ["Authority"],[i-116]

he was not blithely confident that science and the knowledge

gained from experimentation would create a more rigorously

moral race. He wrote to Priestley in 1782: "I should rejoice

much, if I could once more recover the Leisure to search with

you into the Works of Nature; I mean the inanimate, not the

animate or moral part of them, the more I discover'd of the

former, the more I admir'd them; the more I know of the latter,

the more I am disgusted with them."[i-117] He often suggested,

"As Men grow more enlightened," but seldom did this clause

carry more than an intellectual connotation. Progress in knowledge[i-118]

did not on the whole suggest to Franklin progress in

morals or the general progress of mankind.

Essentially classical in morality, extolling a temperance like

that of Xenophon, Epictetus, Cicero, Socrates, and Aristotle,

Franklin could not cheerily champion the moderns without

serious reservations. Considering only progress in knowledge,

man may be considered as pedetentim progredientes, but,

Franklin thought, man seemed to have found it easier to conquer

lightning than himself. If science and other contemporaneous

knowledge detracted from cosmic terror, it did not solve the

problem of the mystery of evil and sin: like Shakespeare, Franklin

was perplexed by the inexplicability and ruthlessness of

Man's potential and actual malevolence.[i-119] Thus in stressing[xlv]

utility and vocational adaptiveness, Franklin did not forget to

stress the need for development of character, man's internal self,

and here he did not find the ancients dispensable.[i-120] If unlike

Socrates in his studies of physical nature, he was like the Athenian

gadfly in his quest for moral perfection in the teeth of "perpetual

temptation," in his strenuous and sober effort to know

himself. Too little attention has been paid Franklin's Hellenic

sobriety—even as it has had too meagre an influence. Let

Molière challenge, "The ancients are the ancients, we are the

people of today"; Franklin, although confident that he could

learn more of physical nature from Newton than from Aristotle,

was not convinced that the wisdom of Epictetus or the

Golden Verses of Pythagoras were less salutary than the wit

of his own age. A modern in his confidence in the progress of

knowledge, Franklin, approaching the problem of morality,

wisely saw the ancients and moderns as complementary. Aware

of the continuity of the mind and race, he was not willing to

dismiss the ancients as fit to be imitated. Yet he failed to discover

in the welter of egoistic men any continuous moral progress,

although, unlike the determinists, he thought that the individual

could improve himself through self-knowledge and

self-control. Unlike contemporary exponents of the "original

genius" cult who scorned industrious rational study and conformity,

Franklin as an educational theorist was the exponent

of reason and of conscious intellectual industry and thrift; he

would mediate between the study of nature and of man, and, like

Aristotle, he would rely not so much upon individualistic self-expression

as upon a purposeful imitation of those men in the

past who had led useful and happy lives.

[xlvi]

III. FRANKLIN'S LITERARY THEORY AND PRACTICE

[i-121]

Uniting the "wit of Voltaire with the simplicity of Rousseau,"

Franklin achieved a style "only surpassed by the unimprovable

Hobbes of Malmesbury, the paragon of perspicuity." Characterized

by simplicity, order, and a trenchant pointedness, his

prose style was "a principal means" of his "advancement."[i-122]

He was "extreamly ambitious ... to be a tolerable English

writer." In the Autobiography he recalls that he read books in

"polemic divinity," Plutarch's Lives (probably Dryden's translation),

Pilgrims Progress, Defoe's Essays upon Several Projects,

Mather's Essays to do Good, Xenophon's Memorabilia,[i-123]

the Spectator papers, and the writings of Shaftesbury and Collins.

Born in Boston, he knew the Bible,[i-124] characterized by[xlvii]

the apostle of Augustan correctness, Jonathan Swift, as possessing

"that simplicity, which is one of the greatest perfections

in any language." If Franklin did not achieve its "sublime

eloquence," he approximated at intervals its directness and

simplicity. In reading Defoe's Essays he learned that Queen

Anne's England urged that writers be "as concise as possible"

and avoid all "superfluous crowding in of insignificant words,

more than are needful to express the thing intended." (It is possible

that Defoe's efforts "to polish and refine the English

tongue," to avoid "all irregular additions that ignorance and

affectation have introduced," influenced Franklin in favor of

"correctness" and against provincialisms.) Defoe's "explicit,

easy, free, and very plain" rhetoric is Franklin's.

After Franklin's father warned him that his arguments were

not well-ordered and trenchantly expressed, he desperately

sought to acquire a convincing prose style. In 1717 James,

Franklin's elder brother, returned from serving a printer's

apprenticeship in London. James had known and been attracted

to Augustan England, the England of the Tatler, Spectator, and

Guardian. Familiar is Franklin's narrative of how he patterned

his fledgling style on the pages of the Spectator papers, and

learned to satisfy his father—and himself. Like the neoclassicists,

Franklin learned to write by imitation, by respectfully

subordinating himself to those he recognized as masters, and

not, like the romanticists, by expressing his own ego in revolt

against convention and conformity to traditional standards. The

group who supplied copy for James's New England Courant,

we are told, were trying to write like the Spectator. "The very

look of an ordinary first page of the Courant is like that of the

Spectator page."[i-125] In the Dogood Papers (1722) and the Busy-Body[xlviii]

series (1728) Franklin's writings show a literal indebtedness

to the style and even substance of the Spectator.[i-126] If, after

the Busy-Body essays, Franklin's writings bear little resemblance

to the elegance and glow of the Spectator, he did learn

from it a long-remembered lesson in orderliness. From the

Spectator he may have learned to temper wit with morality and

morality with wit; he may have learned the neoclassic objection

to the "unhappy Force of an Imagination, unguided by the

Check of Reason and Judgment";[i-127] he may have acquired

his distrust of foreign phrases when English ones were as good,

or better, insisting on the use of native English undefiled. It is

interesting but perhaps futile to conjecture to what degree

Franklin at this time, on reading Spectator No. 160, "On Geniuses"

(warning against a servile imitation of ancient authors,