Project Gutenberg's The Go Ahead Boys on Smugglers' Island, by Ross Kay This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Go Ahead Boys on Smugglers' Island Author: Ross Kay Illustrator: R. Emmett Owen Release Date: March 5, 2011 [EBook #35483] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GO AHEAD BOYS ON *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.)

BY

ROSS KAY

Author of “The Search for the Spy,” “The Air Scout,”

“Dodging the North Sea Mines,” “With Joffre

on the Battle Line,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

R. EMMETT OWEN

I leave this rule for others when I’m dead;

Be always sure you’re right—THEN GO AHEAD.

—Davy Crockett’s Motto.

NEW YORK

BARSE & HOPKINS

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1916,

by

BARSE & HOPKINS

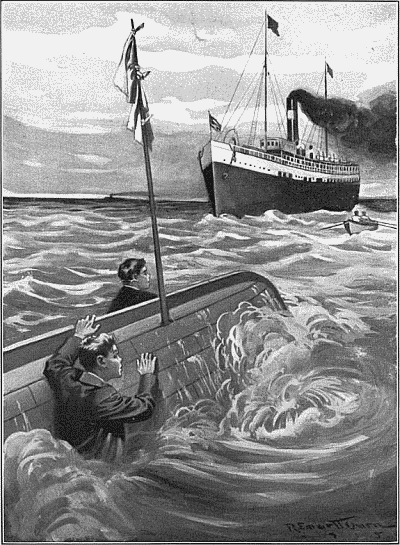

Not long afterward a yawl was lowered from the boat and two men took their places at the oars. (Page 151.)

A basis of fact underlies many of the incidents incorporated in this story. Even the letters are very like those received by one of the official agents of the United States Treasury. Occasional use has been made of the work entitled, “Defrauding the Government.” Out of his material the writer has tried to present a tale that should be stirring and yet wholesome, having plenty of action, but free from sensationalism.

Naturally, changes in characters and localities have been freely made. If his young readers shall be interested in the story and shall draw the conclusion that any attempt to defraud the Government reacts in harsher form upon the one who tried to evade the laws, a part at least of his purpose will have been accomplished.

“I never saw such a morning!”

“I never did either. I am glad I am alive!”

“So am I. It is worth something to be up here where the air is so strong that you can almost bite it off. When we left Mackinac this morning one could hardly tell whether the island was upside down or not. He could see the reflections just as clearly in the water as he could see the island above.”

“I wonder what would happen if a fire should break out on the island?”

“Probably it would burn, just as it does everywhere else. They did have a fire over there once and they say the whole island burned down.”

“This is the place for the simple life!”

“Yes, it is a good place for the simple life, but to my mind there is a great difference between a simple life and an idiotic life.”

It was an hour before sunrise in a morning in July. The conversation which has been recorded occurred on board a beautiful little motor-boat named the Gadabout. Assisting the captain and owner in the management of the fleet little craft was a young man, whose name sounded to the boys very much like Eph, when they heard the owner of the boat address him.

On board the motor-boat were four boys among whom conversation did not lag. The one who had perhaps the most to say was Fred Button. He was a tiny, little fellow, though his round face and rounder body gave him the appearance, as one of his friends described it, of a young bantam. He was familiarly known among his companions sometimes by the nick-name of Stub, or more often was called Peewee, or Pygmy, the last appellation sometimes being affectionately shortened into pyggie, or even pyg.

Seated next to him was John Clemens, a boy already six feet three inches tall, though he had not yet attained his eighteenth birthday. Familiarly he was known as String and frequently, when he and Fred Button, who were warm friends, were together they were referred to as the “long and short of it.”

On the opposite seat was Grant Jones, a clear headed, self-contained boy of the same age as his companions. A leader in his class in school and active on the athletic field, he had won for himself the nickname of Socrates, which frequently was shortened to Soc. The fourth member of the group was George Washington Sanders, a boy whose good-nature and witty remarks had made him a favorite among his friends. In honor of the name which he bore he sometimes had been referred to as the father of his country, which distinction was occasionally shortened to Papa, or even to Pop.

The owner and captain of the swift little craft was an elderly man, whose whiskers and hair formed an unbroken circle about his tanned face. Both he and Eph, when occasion required, served as oarsmen in the two skiffs which the swift Gadabout was towing. The light little boats were far astern, each being held in its place by a long rope made fast to the Gadabout.

“Whew!” said Fred Button, rising and stretching himself, “I hope we’ll get some fish to-day. How far do we have to go?” he added, addressing the captain as he spoke.

“It depends a little upon where you want to go to,” drawled the captain in response, without turning his head as he replied.

“I thought it was understood,” continued Fred, “that we were going to the channel between Drummond Island and Cockburn Island.”

“Ye’ll have to show your papers, if you fish over on the Canadian side,” growled the captain.

“We shan’t fish on the Canadian side,” spoke up Grant Jones. “We’ll leave it to you to keep us in American waters.”

“That’s right,” added John. “If we get caught on the Canadian side, Captain, we’ll hold you responsible for it.”

“Humph,” growled the captain, “we’ll see what we’ll see.”

Meanwhile the sun had risen and like a huge ball of fire was casting its beams across the smooth waters of Lake Huron. Scarcely a ripple was to be seen as the boat sped forward. The day promised to be unusually warm, but as yet the air was cool, and the spirits of the boys, after their early breakfast, were all high.

“We’ve got to get some of these fish to-day,” broke in George Sanders. “We didn’t get many the other day.”

“We weren’t far enough away from Mackinac,” said Fred.

“I’ve usually noticed,” suggested Grant, “that the best fishing grounds are always a good ways away from where you’re staying. The further away they are, the better they are.”

“I’ve noticed that too,” laughed George. “In fact there are a good many funny things in this world. I wonder what people speak of a family jar for.”

“What do you mean?” inquired Fred.

“I mean just what I say. I heard a family jar this morning.”

“I don’t understand you,” persisted Fred.

“Why, there was a family having a jar in the room next to mine. Only I think it was a little more than a family jar, it was more of a family churn, it was such a big one. There seemed to be such a very decided difference of opinion that the jar wouldn’t hold all that they were saying.”

“You shouldn’t listen to such things,” said Fred.

“‘Listen’! ‘Listen’! Why that was the very thing I was trying not to do, but I guess anybody on Mackinac Island could have heard them, if he had stopped.”

“Who were the people?” inquired George.

“I don’t know their names. The man is the one that wears that ice-cream suit when he goes fishing.”

“Oh, yes, I know him,” laughed Grant. “I have observed several times that the immaculateness of his manipulators has not been extremely noticeable.”

“That’s right,” laughed John. “There seems to be a superincrustation of unnecessary geological deposits that doubtless are due to his transcontinental pedestrianism.”

“Why, did he have to tramp across the continent to get here?” laughed George.

“I guess so. I know more about them than I wish I did, but I don’t know enough to know that.”

“I noticed,” said Fred, “yesterday afternoon when he came in that his lips looked like Alkali Pete’s.”

“What was the matter with Alkali Pete’s lips?” demanded George.

“They were seldom closed and there were great crevasses in them, cracked by the alkali.”

“I am taking your word for it,” said John, “but I confess I don’t know what you’re talking about. I’m a good deal more interested in the fish we’re going to get.”

“‘We’re going to get.’ I like that. Does String really think he is going to catch any fish?” said George, turning to his companions as he spoke. “His attenuated form doesn’t look to me as if it would be able to stand the strain of landing the fish some of us are going to catch to-day. About the only thing I think String will ever catch will be a crab.”

“String, how old are you?” demanded Grant abruptly.

“I’m eighteen in October.”

“When will you be ten?”

“I don’t understand your language,” replied John. “In your superlunary efforts to appear intellectual you sometimes state things that are incomprehensible, even to people of my limited intellectual parts.”

“Oh, quit!” broke in Fred, “don’t spoil the day and scare the fish away. I want to tell you about Professor Jackson. You know him, don’t you?”

“Yes,” replied Grant, “he’s the man who came on Monday, isn’t he? The man who is making investigations of the island, digging up all sorts of relics?”

“That’s the man,” acknowledged Fred. “Yesterday he dug up some cannon balls. He said they were relics of the French and Indian war.”

“They were all right,” said George. “I know, for one of the guides told me that they were the same balls that had been dug up by every old fellow for the last twenty-five years.”

“A new crop?” laughed Fred.

“Not at all. They are the same old cannon balls. They plant them every spring and give pleasure to some of these old fellows, who are traveling around the island in their gentle, antiquated gait looking for things that belonged to our grandfathers. They give them the childish pleasure of making ‘discoveries’ every year.”

“I should think they would take the balls away with them,” suggested John.

“No, they leave them for the historical interest they provide for the visitors. You go up to the reception room and you’ll find some there now in the glass case. They are a part of the same crop.”

“That’s all right,” laughed Grant. “It’s an easy way to keep the old people interested.”

By this time the Gadabout had gained the lower point of Drummond Island, thirty-five miles from the place from which they had started more than two hours before this time. Across the narrow channel they saw the shores of Cockburn Island. The latter was within the Canadian boundaries and as the captain of the Gadabout had explained, the boys would not be permitted to fish in the waters along its shore without a special permit from the Canadian officials.

The shore which they were approaching apparently had no buildings of any kind. There were high bluffs and rocky points, but no house was within sight.

“Captain,” called Fred, “why are you taking us to this island?”

“I’m not taking you to this island,” responded the captain. “I’m going to take you past it. I’m not fool enough to try to dodge the Canadian laws.”

Both the captain and his mate were watching the shore of the island, which every moment was becoming more distinct.

Unexpectedly on a bluff far to the left a man was seen standing and suddenly he appeared to become aware of the approaching Gadabout. Turning abruptly about he several times waved a white cloth, which he held in his hand, to parties that apparently were behind him. Then, once more facing the waters, he again waved the cloth. Instantly and with a grin of satisfaction appearing on his face the captain changed the course of his motor boat.

The four boys glanced blankly at one another and for a brief time no one spoke.

It was later when they learned that the signal which they had observed was to mean much, both in excitement and adventure, for all four of the boys on board the Gadabout.

As the course of the Gadabout was sharply changed in response to the call of the captain, the attention of the four boys was quickly drawn in another direction. Not one of them was aware of anything unusual in what really was a signal on the shore of the Canadian island.

In a brief time the party was once more in American waters and as it was still early in the morning, preparations were soon made for the sport of the day.

The Gadabout was anchored in a little cove and the mate, with Fred and John, as the members of his party, took one of the skiffs, while Grant and George together with the captain departed in the other. It was agreed that they should meet at a certain place for luncheon and the rivalry was keen as to which boat should have the bigger catch of fish.

“Look out for us!” called Fred as his boat drew away from that in which his companions were being carried. “Look out for us! If you hear a whistle you’ll know we will need help.”

“To catch your fish?” laughed Grant.

“No, to bring them in. We’ll have a boat-load, anyway.”

In high spirits the boys soon were ready for the sport of the day, and it was not long before neither boat was within sight of the other.

When the noon hour arrived, still excited and hungry, the two boats were landed at the place agreed upon and the captain at once displayed his skill as a cook.

“Isn’t it wonderful!” said George, not long after they were seated about the folding table which the captain had brought in the Gadabout. “Isn’t it wonderful the amount of food a fellow can put himself outside of?”

“It is that,” mumbled John, who was as busy as any of his comrades. “It pays for it all, now.”

“Of course it pays,” laughed Fred. “That’s what we’re here for. Honest, Grant, who caught that big pickerel?”

“I did,” responded Grant proudly. “I cannot tell a lie, I caught it with my little hook and line.”

“I’ll ask the captain about that later. I saw some other boats up there where you were and I am going to ask them how much they charged for the fish they sold you.”

“They didn’t sell us any fish!” retorted George indignantly.

“Another boy that cannot tell a lie. No wonder they call you the papa of your country. What do we do this afternoon?”

“I’m going to take you to another place,” explained the captain, who throughout the meal had been busied in attending to the numerous wants of the boys.

“Shall we get more fish than we did this morning?”

“That depends,” said the captain solemnly. “Some people do and some don’t. It mostly depends on whether they are any good with the rod.”

“Don’t you think we’re good?” demanded Fred.

“Huh!” retorted the captain. “Maybe you will be some day. Most of the fish you got this morning were hooked so that they couldn’t have got off the hook. There’s a big difference between catching a fish that way, and getting one with just a hook through his lip. It takes some skill then.”

“All right, captain, just as you say. You show us the right ground and we’ll do the rest.”

“Maybe you will and maybe you won’t,” retorted the captain as he turned away to prepare dinner for himself and his mate.

When afternoon came, the Gadabout took the two skiffs once more in tow and swiftly carried them seven miles farther, where the wonderful ground described by the captain was located.

As soon as the anchor was dropped, the skiffs, arranged as in the morning, sought the place where the marvelous fishing was to be had.

Apparently the words of the captain were in a measure fulfilled for so busy were the four young fishermen that not one of them was aware of the increasing distance between the boat in which he was fishing and the one which carried his comrades.

It was late in the afternoon when Fred suddenly looked up and said, “It’s getting late, Jack. We ought to be going back to the boat. I don’t see it anywhere, do you?”

“You mean the skiff in which Grant and George are fishing?”

“Yes.”

“No, I don’t see them,” said John slowly, after he had glanced all about him. “I don’t see the Gadabout either.”

“Well, the mate knows where it is,” said Fred easily. “I hope the other fellows won’t get into any trouble, for there’s a storm coming up.”

As he spoke, Fred pointed to some clouds that rapidly were approaching in the sky directly overhead. They were black, angry clouds too, and the frequent flashes of lightning were followed by reports of thunder that at first had been so low as scarcely to be noticed. Now, however, the sounds were threatening and the oarsman, bidding the two boys reel in their lines at once, began to row swiftly toward the point behind which the Gadabout was anchored.

In a few moments, however, the calm waters had become rough. Whitecaps were to be seen all about them and the boys glanced anxiously at each other. The wind too had risen now, but instead of blowing steadily across the waters, it was coming in puffs.

“We’re in for it, Jack,” said Fred anxiously.

His companion made no reply, though the frequent glances he cast at the sky indicated that he too was becoming anxious for their safety.

“Don’t you want me to help?” inquired John as he glanced at the oarsman.

The mate shook his head in response and it was plain that he was exerting all his strength in his efforts to keep the boat headed in the direction in which it had started.

“There comes the rain,” exclaimed John, as some heavy drops fell upon them and the nearby water was becoming more and more disturbed.

“Take one of these oars,” called the mate sharply, as he spoke rising with difficulty from his seat and placing one oar in another oarlock. “We’ll have all we can do to make the point.”

By this time both boys were thoroughly aroused. The rain was falling in torrents and both were drenched to their skins.

Such a plight, however, was hardly to be noticed in the presence of the danger that now beset them. In spite of their efforts the wind was driving them away from the point. More and more the boys did their utmost but their efforts were in vain. At last the mate shouted, “There’s nothing for it, boys, except to run for it. Sit down and we’ll let the gale drive us across to the other shore.”

The Canadian island was nearby and the shore could not be more than two miles distant, as both boys learned from their oarsman. However, it was with white and set faces that they followed his directions and each took his seat as he was bidden.

Swiftly the boat was driven before the wind, the mate exerting himself only to keep the light, little skiff headed in the right direction. So black were the clouds that already the boys were surrounded by darkness almost like that of night. Neither was able to see the shore toward which they were headed. The mate, however, appeared to be more confident than he had been while he was seeking to drive the boat against the wind.

Swiftly and still more swiftly the frail little craft sped forward. No one spoke in the brief interval between the crashes of thunder. The streaks of the lightning seemed to fall directly into the waters of the lake and at times the boys believed themselves to be surrounded by fire. Never had either been in such peril before.

Fred had sunk into his seat so that only his head appeared above the gunwale. John, whose seat was in the stern of the skiff, was so tall that he was unable to follow the example of his friend and was clinging tenaciously to the sides of the boat. Meanwhile, the mate successfully keeping the skiff headed for the shore, was watchful of every movement of his passengers.

When ten minutes had elapsed it was manifest that the anxiety of the oarsman was increasing, as they drew near the shore. Without explaining his purpose he did his utmost to change the direction so that they would move in a course parallel to the shore, but, labor as he might, he was unable to accomplish his purpose. Directly upon the rocky border of Cockburn Island the gale was driving the little boat.

Once more the mate exerted his strength to his utmost as he strove to guide the little skiff toward a cove not far away. For a time it seemed as if his efforts were to succeed. But at that moment the wind became even stronger than before and the howling of the tempest increased.

The boys had a sudden vision of an opening in the rocky shore, then there was a crash and both found themselves struggling in the water.

When they arose to the surface they saw that before them the waters were still. The sheltered cove promised a degree of safety such as a moment before they had scarcely dared to hope for. Fishing rods, coats, cooking utensils, tackle, all things had been thrown into the water when the boat had struck the jutting rock. All these facts, however, were ignored in the efforts of both boys to gain the beach before them, for they now could see a sandy stretch not more than forty feet in length that marked the limit of the waters. And it was only twenty yards away.

“All right, Fred?” called John as he swam near his friend.

“All right,” sputtered Fred. “How is it with you?”

“I’m all right here. Have you seen the mate?”

“Yes, he’s ahead of us.”

Even as he spoke the mate could be seen rising to his feet in the shallower waters and a moment later he gained the refuge of the sandy beach.

It was not long before the boys also gained the same place of safety, although before their arrival the oarsman had disappeared from sight.

As soon as the boys stood on the shore they shook themselves much as dogs might do when they come out of the water and then in a moment the thought of the peril of their friends came back to their minds.

“What do you suppose has happened to Grant and George?” said Fred in a low voice.

“I think they must be all right,” replied John, although his expression of confidence was belied by the tones of his voice. “What shall we do?”

“Better go up on the bluff. Perhaps there we’ll see the Gadabout or the skiff. They must have been driven in the same direction that we were.”

“I don’t think so. You see the Gadabout was in the lee of that point. The last I saw of the skiff it was on the other side of the point too. I think that Grant and George probably have gone back to the Gadabout and are all right. Very likely they are talking about us at this very minute and are scared at what may have happened.”

“Can’t we signal them?” inquired Fred anxiously.

“Signal them? No. We haven’t anything to signal with in the first place and they can’t see us in the second.”

“The storm is going down,” suggested Fred. “They say the lake up here gets quiet almost as quickly as it gets stirred up.”

“It can’t get quiet any too soon to suit me,” said John dryly. “Where’s the mate?”

“I don’t know. I don’t see him anywhere.”

Both boys looked carefully along the shore, but no trace of the missing oarsmen was discovered.

The rain had ceased by this time and the sky was clearing. Not a sign of the presence of the Gadabout was to be seen on the waters before them. The oarsmen had disappeared and each boy for a moment gazed anxiously at his companion.

“Look yonder!” said John, suddenly pointing as he spoke to a spot in the direction of the interior of the island.

“What is it?” said Fred.

“Why, there’s a house up yonder. Don’t you see it?”

“You mean a shanty?”

“I don’t care what you call it, but I see smoke coming out of the chimney. We’ll go up there and get somebody to help us.”

Moved by a common impulse both boys started in the direction of the strange house. Neither was aware that they were entering upon an experience that was to be as mysterious as it was trying.

The sun was shining brightly as the boys moved across the island in the direction of the place they were seeking. As they stopped occasionally to look back over the waters of the lake, they saw that the waves still were tipped with white and the waters still were rough.

“I wish I knew where the other fellows are,” said Fred, once more stopping to look out over the waters that now were reflecting the light of the afternoon sun.

“They are all right,” said John, confidently. “I told you both the Gadabout and the other skiff are around the point.”

“I know you told me so, but that doesn’t make it so,” said Fred, still unconvinced by the confident manner of his companion.

“Look yonder, will you!” said John abruptly as he pointed toward the house they were seeking. “I’m sure there is somebody in there.”

“It doesn’t look as if it would hold together long enough to let any one stay very long inside,” laughed Fred.

“We’ll find out anyway pretty quick who it is.”

In a brief time the boys arrived at the rear of the little house, which was not much more than a shanty in its appearance. They found that their surmise that smoke was rising from the chimney was correct. There could be no doubt that some one was within the building.

Once more the boys turned and looked anxiously toward the lake, eager to discover if any trace of their missing friends could be seen. The waters already were becoming smoother and the rays of the sun were almost blinding as they were reflected by the shining waters.

“What shall we do?” said Fred in a low voice. “Shall we rap?”

“Of course we’ll rap,” retorted John. “You talk as if you didn’t know what the customs of civilized countries are.”

“Is knocking one of them?” inquired Fred demurely.

“It certainly is.”

“Well, then, I guess I don’t live in the place you are talking about, for nobody has rapped at our door at home for the last ten years. Not since we have put in electric bells.”

“It’s hard work to keep up with you,” said John, not strongly impressed by the attempt of his friend to be facetious. “But we’ll knock here anyway.”

Advancing to the kitchen door, John rapped loudly to proclaim the presence of visitors.

A silence followed the summons and when several seconds had elapsed John repeated his knocking. Still no one came to welcome them, and then, glancing behind him at his friend, John demurely raised the latch and opened the door.

Fred at once followed and the two boys found themselves in a low, rude kitchen. The stove was in one corner and it was plain now that the smoke they had discovered was rising from it through the chimney. Upon the stove several cooking utensils were to be seen, but as yet no person had announced his presence in the little building.

“There must be somebody here,” whispered Fred.

“Of course there is.”

“Well, why doesn’t he show up?”

“He will be here in a minute.”

But when several minutes passed and still no one made known his presence, John decided to announce their arrival in other ways.

“Hello!” he called, and then as his hail was not answered he repeated the summons in tones still louder. “Hello! Hello!” he shouted again.

While he was speaking both boys were glancing toward the rude stairway that led from the room to the small loft. They had surmised that the occupants of the house might have been caught in the storm as they themselves had been, and were in the upper room changing their clothing.

“Who are you?”

Startled by the unexpected sound both boys turned quickly about and saw standing in the doorway of the kitchen a man plainly puzzled by their unexpected appearance.

Neither of the boys ever had seen him before. He was apparently fifty years of age, strong, and his face bronzed by sun and wind. There was an expression in his face, however, that was puzzling to both boys. He glanced quickly from one to the other and for a moment the boys suspected that he was prepared either to leap upon them or precipitately flee from the spot, they could not decide which.

The man was well-dressed and it was plain that he was not an ordinary inhabitant.

“We got caught in the storm,” explained John hastily. “We landed down here and then we saw this little house and we thought perhaps we could come up here and dry out.”

“Anybody with you?” inquired the other man, still gazing keenly at both his young visitors.

“Nobody but the mate.”

“Mate of what?”

“The Gadabout.”

“Did you come over from Mackinac Island?” demanded the man quickly.

“Yes, sir,” said Fred. “We started this morning about four o’clock.”

“And you came over with Captain Hastings?”

“Yes, sir. We got caught in the storm out here around the point and we couldn’t get back to the Gadabout, so the mate just let our skiff drive before the wind and the boat was stove in when we finally landed in that little cove out yonder.”

“Where is the mate now?”

“We don’t know. He went ahead of us and the first thing we knew he disappeared from sight.”

“Was he on shore here?”

“Yes, sir, we landed, as I told you, in that little cove and while we were getting ashore we lost the mate. We don’t know where he went.”

“And you say there were others with you?”

“Yes, sir,” explained Fred, “there were two other boys and they went out with the captain.”

“What happened to them in the storm?”

“We don’t know. We wish we did,” said John soberly.

“Oh, they’re all right,” broke in Fred. “The Gadabout and the skiff were both beyond the point when the storm broke and they had no trouble in keeping to the lee of the point.”

“This fire feels good anyway,” said John, whose long, attenuated frame was trembling with cold, in spite of the warmth which had followed the shower.

“Sorry, boys, that I cannot give you a change,” said the man, smiling dryly as he spoke. As he was a man who weighed at least 190 pounds, while John’s form towered at least six inches higher and his weight was at least seventy pounds less, the idea of either wearing the clothing of the other was so ludicrous that Fred laughed aloud at the suggestion.

“That’s all right,” said John quickly. “All we want is a chance to dry out before the mate gets back.”

“How are you going to get back to Mackinac?”

“I don’t know,” said John ruefully. “We thought that perhaps the mate could get word to the Gadabout and the motor-boat would stop for us.”

“How can he get word to the Gadabout?”

“I’m sure I don’t know,” said Fred. “We don’t know anything about this part of the country. It’s the first time we ever were here. We thought perhaps the captain might know some point where he could signal. It isn’t more than two or three miles across, is it?”

“Not here,” responded the man. “But you are cold and I shouldn’t be surprised if you were both hungry. I’ve seen fellows at your age who sometimes were afflicted in that manner. I’ll put some more wood on the fire and we’ll dry you out and then we’ll see what we can do.”

Placing his hands together in a peculiar manner the man whistled through them and in response, in an incredibly short time, a little Japanese serving man appeared.

“Mike,” said the man, “see if you can’t find something for these hungry young fellows to eat. They were caught in the storm and their boat was wrecked down here in the cove.”

The Japanese laughed loudly at the explanation and then quickly turning about departed from the house.

“What do you say his name is?” inquired Fred.

“We call him Mike.”

“I never heard of a Japanese with that name.”

“Well, I don’t suppose that is his full name. That’s a mouthful and I don’t often speak it. He has been with me for several years and when he first came some one named him Mikado, that was shortened to Mik, and of late that’s been gradually changing to Mike.”

“Then he wasn’t born in Ireland?” laughed John.

“No, he belongs to the Sunrise Kingdom. He will have something for you to eat very soon. I have been coming here for several years now every summer.”

“Where is your home?” inquired John.

“That’s hard to say. I was born on the ocean when my father and mother were coming from England. My father was French and my mother was Russian. We lived in the States two years after I was born and then we went to Bermuda a year or two and finally we wound up in Brazil. From Brazil we moved to Sweden and then went to Constantinople. After my father and mother died I came to England and then moved to Montreal. Now, if you can tell me where I belong and what I am you’ll do better than I have been able to do for myself.”

“I think you’re a first cousin of the Wandering Jew,” laughed Fred.

“Perhaps I am more like the Man Without a Country,” said the man soberly. “I have come up here from Montreal every summer for the last few years.”

“Why, how do you get here?” inquired Fred.

“I come up the Ottawa River from Montreal and then I leave the river at Mattawa. It is easy going then from Lake Nippising, across the Georgian Bay, and from Georgian Bay into Lake Huron doesn’t take very long. Have you ever been there, boys?”

“Where?” inquired Fred.

“Georgian Bay.”

“No, sir.”

“Then you have missed one of the prettiest spots in America. I never tire—”

The man stopped abruptly as the mate of the Gadabout suddenly appeared in the doorway.

Without waiting for an invitation he at once entered the room and then to the surprise of the two boys extended his hand and received from his host a small package which he quickly thrust into the pocket of his coat.

The action although simple in itself nevertheless was surprising to the boys. It was manifest that the mate already was acquainted with the occupant of the house and also that he was having relations with him. Just what these were neither of the boys understood, but before many days elapsed they both were keenly excited by the recollection of the simple exchange which they had just seen in the kitchen of the old house on the shore of Cockburn Island.

It was quickly manifest to the two interested boys that the mate and their host were well acquainted with each other. Puzzled as they were to account for the familiar greeting it was not long before John whispered to his companion, “I suppose that man has been coming here so many years that he knows all the men on the lake. That must be the reason why they know each other so well.”

“I guess that’s right,” said Fred, who was watching the men with an interest which he was not entirely able to explain even to himself.

The mate was endeavoring to speak in whispers, but his voice was so penetrating that it carried into the remote corners of the house, although no one was able to distinguish the words which he spoke.

By this time the boys were dry once more and as they prepared to depart, the Japanese servant unexpectedly returned. In his hands he was carrying a tray on which there were numerous tempting viands. Both boys watched the lithe little man as he speedily cleared the table and then deposited upon it the plates and food which he had brought.

“You’re not going now,” said their host to the two boys. “You’re just in time for afternoon tea.”

“We didn’t know that you served anything like that,” laughed Fred. “I think we’ll both be glad to stay and accept your invitation, shan’t we?” he added as he turned to John.

“I’m sure we shall,” replied John, with a sigh which caused the others in the room to smile at his eagerness.

The movements of the little Japanese speedily convinced the boys that he had had long experience in the work he then was doing. Deftly and silently he attended to all the wants of the guests and not many minutes had elapsed before, responding to the influence, both Fred and John were in better spirits.

Turning to the mate, John said, “Don’t you think it is time for us to find out what has become of the other boys?”

“Don’t you worry none about them,” said the mate. “I guess the cap knows how to take care of them.”

“But we don’t know where they are,” suggested Fred. “We don’t know how we are going to get back to Mackinac. We’re sure they’ll be anxious about us and I know we are about them.”

“Don’t you worry none,” retorted the mate. “They’ll be coming this way pretty soon. I can tell the toot of the Gadabout if Gabriel was blowing the whistle. They’ll be here very soon, but I think by and by it may be a good thing for us to go down to the shore and watch a little if we don’t hear the whistle calling pretty soon.”

The entire party still was seated about the table. Relieved by the confidence of the mate in the safety of their friends and of the Gadabout, both John and Fred became more intent listeners to the conversation which was occurring between the men.

“That Mackinac Island,” suggested their host after a time, turning to the boys, “is one of the most beautiful spots in the world. Ever been there before?”

“No, sir,” replied Fred. “This is our first visit.”

“Don’t you like it?”

“Very much. There are no two days alike. We have been up the river, down the shore of Lake Michigan and to-day we came over here to Drummond Island to try the fishing.”

“And pretty nearly had a shipwreck, didn’t you?” asked the mate.

“Yes, if you can call a skiff that was smashed a shipwreck.”

“The skiff isn’t smashed,” drawled the sailor. “She’s just stove in. We’ll have her fixed up in no time and she’ll be as good as ever.”

“I’m fond myself of Mackinac Island,” continued the host. “I go over there some days and shut my eyes and try to imagine what it was like so many years ago when it was first discovered by the French.”

“They didn’t hold it very long,” suggested John.

“No, and we didn’t either.”

“Nor did the British in the War of 1812. They got it away from us just as they got it away from the French years ago. But after that war was ended it came back to us and nobody has been able to lay hands on it since.”

“You stay there all winter?” inquired the host, turning to the mate as he spoke.

“I do that.”

“I guess it’s pretty cold,” suggested Fred.

“You don’t need to ‘guess’ and you don’t need to say ‘pretty.’ It’s just cold. It’s so cold that when you toss an egg up into the air it just freezes and stays there.”

“It couldn’t stay there,” said John.

“Why couldn’t it?” declared the mate. “I guess I know what I am talking about.”

“Why, the attraction of gravitation would pull it to the ground.”

“That’s all right,” roared the mate, “but the attraction of gravitation is frozen too. Yes, I’ve seen with my own eyes eggs staying right up in the air and the air itself all froze up and the attraction of gravitation froze too.”

“That must be a great sight,” laughed Fred.

“It is, and you can’t see it anywhere except on Mackinac Island.”

“What do you do with yourself all winter?” demanded John.

“Get ready for summer.”

“And then when summer comes you work all the while getting ready for the winter, don’t you?”

“Yes, that’s just it,” acknowledged the sailor soberly. “It just seems as if all the time nobody had a chance to live, but he just plans to get ready for it.”

As the conversation continued John became more and more thoughtful and silent. Several times he had been startled by sounds which he had heard in the room directly above that in which they were assembled. Twice he suspected that some one had come to the head of the rude little stairway and was listening to the sounds of conversation below.

On each occasion it had seemed to him that he had heard the sound of a rustle of a woman’s dress. But of all this he could not be certain and even if his surmise had been correct he had no reason to be more suspicious of their host.

Indeed his suspicions might not have been aroused had not he intercepted a look which the man gave his Japanese servant, which caused the latter quickly to go to the head of the stairway.

John was deeply interested and striving to appear indifferent watched keenly the face of the Japanese when the latter returned to the room and was positive that he saw the little, brown man shake his head slightly in response to a question in the eyes of his employer.

Such actions might be entirely natural, and John tried to assure himself that there was no cause for his increasing suspicions that something was not right in the strange house on the shores of Cockburn Island.

He had no opportunity to explain his suspicions to Fred, however, for just then the sailor said, “It is time for us to go back and keep a lookout for the Gadabout.”

Acting at once upon his suggestions the two boys arose from their seats.

Cordially thanking their host for his kindness in receiving them into his house and providing for their wants, they soon departed, following the mate as he led the way to one of the higher bluffs along the shore.

“I don’t know that man’s name yet,” said John to Fred.

“That’s so,” acknowledged Fred. “We don’t know who he is, do we? Well, it’s as broad as it is long, for he doesn’t know our names either.”

“Probably we never shall see him again anyway, so it won’t make any difference, but I should like to know more about him.”

“He seems to have been in several parts of the world, doesn’t he, Jack!”

“He surely does. I don’t wonder that he can’t tell what nationality he is.”

“Look out on the lake,” suggested Fred. “It’s as calm as a mill pond.”

“Yes,” acknowledged John. “It’s so smooth that if one didn’t know, he wouldn’t believe it possible for it to stir up such a gale as we saw there a couple of hours ago.”

“Well, there’s one comfort,” said Fred. “If it doesn’t take very long for a squall to come, it doesn’t take very long for it to go either. So we’re just about as well off as when we started.”

“Except our fish,” suggested John.

“Well, we’re carrying back some fish, though they don’t show. I don’t think I ever ate so much fish in my life as I did this noon. I think the pickerel will hold a revolutionary congress—”

“Look yonder!” interrupted John quickly. “Isn’t that the Gadabout?”

Fred instantly looked in the direction indicated by his companion and far away saw the faint outline of a small boat which plainly was headed in the direction of the bluff. “Yes,” he said after a brief silence. “I believe that’s the Gadabout.”

“Probably they are out looking for us. I hope the boys won’t be worried.”

“You needn’t be afraid of Papa Sanders being worried,” laughed Fred. “As long as he and Grant are in some dry place and don’t have to think of any work they won’t trouble their heads about us, you may be sure about that.”

“They ought to be ashamed of themselves if they are not,” replied John half angrily. “But they certainly are coming this way,” he added a moment later.

“Yes, and they see us, too,” said Fred quickly, as he pointed to the mate, who, in advance of them, had arrived at the bluff and was waving a signal.

This signal consisted of a large piece of cloth that had at one time been white, attached to a long pole. The sailor was waving this back and forth in such a peculiar manner that the attention of the boys at once was drawn to his actions.

“What’s he trying to do?” whispered John to Fred.

“Trying to signal the Gadabout.”

“Yes, but what’s he doing it in that way for?”

“Well, I don’t know, Jack. You’re always suspicious of somebody. Probably the captain doesn’t know that he is doing anything out of the ordinary.”

Whatever the explanation may have been, in a brief time the Gadabout was seen approaching the bluff on which the sailor and the two boys now were standing.

The skiff in which their friends had been seen was in tow and soon after it was discovered both Grant and George were seen in the bow of the swift little motor-boat.

“That’s good. That’s a relief,” said John when he was convinced that his friends were on board.

“Probably they feel the same way now that they have seen us.”

“We’ll know about that very soon.”

It was decided to leave behind them the skiff that had been wrecked and as the boys ran down to the shore they saw that the beautiful little boat had been drawn up on the land.

“That can be fixed all right,” said the mate in response to the question of the boys. “The frame’s all good.”

Neither of the boys, however, heard his words as they both climbed into the skiff, which Grant had rowed ashore.

“Where were you, fellows?” he asked as he grasped the oars and headed the little boat once more for the Gadabout.

“We went ashore. The mate just let us drive before the wind. We couldn’t do anything against it.”

“Yes,” added Fred. “We stove in the boat when we tried to land. The waves were a million feet high.”

“How high?” laughed John.

“Well, they were pretty nearly ten feet anyway.”

“That’s about as near as you get to things, isn’t it?” remarked John.

“Well, you know what I mean.”

“I don’t care what you mean as long as you’re both safe. The captain was afraid you might capsize.”

“You mean he was afraid we would be capsized,” retorted Fred.

“May be that was it. At all events he was afraid you would go into the water and he knew you couldn’t take care of yourselves if you did.”

“Hello,” exclaimed John abruptly. “Here comes our recent host. I wonder what he wants now.”

As he spoke John pointed toward the shore from which the man in whose house they recently found refuge was seen approaching in a skiff. Just where his boat had been kept was not plain to either of the boys. There was no boathouse on the shore and few places where the craft might have been sheltered.

“I guess he has forgotten something,” laughed Fred, “or he’s after us. John, did you take anything from the table when you left the house?”

“Nothing except what I had already taken inside,” retorted John.

In response to the call of the man the departing Gadabout was delayed until he came alongside. There was a whispered conversation between him and the captain, which lasted only a few minutes. What was said could not be heard by the boys, although John was really trying to discover what the subject of the conversation was, at the same time doing his utmost to appear indifferent.

Fred, who understood the peculiarities of his companion, laughed silently as he saw John’s actions and shook his head warningly.

Quickly, however, the captain turning about gave the order to start and almost as if it had been hurled forward by some powerful and unseen hand the graceful little boat suddenly started swiftly on its return to Mackinac Island.

The speed of the motor-boat was much greater than in the morning. Indeed as the time passed and the graceful little craft darted over the surface of the water the boys looked at one another in amazement. The water seemed almost to rise and be parted by the bow. It rushed past them with a noise that was loud and almost confusing. Still the speed of the Gadabout increased. The roaring of the waters and the occasional call of the captain were all that could be heard and in a brief time the boys abandoned all attempts to speak to one another.

Darkness had fallen when at last they arrived at their destination. The lights of the many windowed hotels and of the cottages along the road were shining in the evening darkness. There was yet time, however, for the boys to obtain dinner and in a brief time all four were seated about the table, which had been assigned them when first they had arrived.

Fred was the last to enter the dining-room and as he did so his companions saw that something had greatly amused or pleased him.

“Look here, fellows,” he said as he seated himself at the table. “See what I have got.”

Drawing from his pocket a letter, which he explained he had received from the clerk on his way to the dining-room, he placed the sheet of paper on the table and began to read,—

Sir,—I am one good american Citizen and I will do not

the other Strangers peoples Cheat us My duty Me oblige to

let you know which Cheater the U. S. Secret Contraband the

man is it one British have one store in Chicago and one other

store in Montreal Canada. This man make her Business in

this Way. he order her goods to come from Paris france

to Montreal Canada and ther he pay duty Very Cheap and

then he express her goods to the boarderings of the untied

States and then he took the Said goods and giving to the

Cariage Man and the Cariag Man in the nighte time he Carry

them With other different things eggs and other things lik

that in many Barrel and the goods Mixed With Them So the

goods entre in united States in the Way the dessert.

respectfully yours truly,

American Brother.

“What do you think of that?” demanded John as he extended his hand and received the letter.

“I don’t know what to think of it,” laughed Fred. “What do you think of it?”

“It’s too much for me,” said Grant. “I don’t believe even papa here knows what it means.”

“But it was sent to me,” said Fred. “At least the directions are to Mr. F. Button, and that’s my name.”

The boys were still laughing and talking about the strange epistle which Fred had received when at last they withdrew from the dining-room and selected four chairs near together on the broad piazza.

They had not been seated very long before the clerk of the hotel approached the group and said to Fred, “I think I gave you a letter which belongs to some other man.”

“I guess you did,” laughed Fred. “I don’t think it belongs to me anyway. Is this the letter?” he added, as he held forth the epistle which had been the cause of so much mirth among the boys.

“I don’t know whether it is or not,” replied the clerk. “All I know is that there is another man here, whose name is almost like yours. He is Mr. Ferdinand Button. That letter was directed to Mr. F. Button. As you had been here longer than he I thought it was for you.”

“Well, it isn’t,” said Fred. “If it was my letter I would read it to you, but I guess it belongs to Ferdinand, so you had better take it and give it to him.” Laughingly Fred held out the letter which the clerk took and at once withdrew from the place.

It was not long afterward before a stranger approached the boys who were still seated and said, “One of you, I am afraid had a letter to-night which belonged to me.”

“Yes, I guess we did,” said Fred quickly, rising as he spoke. “My name is Fred Button and the clerk said that this letter was meant for Mr. Ferdinand Button.”

“That’s my name,” explained the stranger, “and the letter was for me. Did you read it?”

“I shall have to acknowledge that I did,” answered Fred. “I didn’t suspect until I had done that that it really belonged to any one else.”

Somewhat confused by his confession Fred noted the bearing of the man before him more carefully.

It was plain to him now that the stranger was quiet in his manner, gentlemanly in his bearing and possessed of a quick intelligence that enabled him to perceive many a thing which his younger companions might have lost. The stranger was about thirty-five years of age and his bronzed face was nearly the color of that of the captain of the Gadabout.

“Have you been here long?” inquired John.

“I came this morning.”

“I thought perhaps you had been on the lake—”

“I have been on the lake,” interrupted the stranger. “Indeed, I spend much of my time on the lake. I am sorry you had the misfortune to receive this letter which apparently was meant for me.”

“What makes you so sure it was for you?” inquired Fred laughingly. “It was signed ‘American Brother’ and was simply addressed ‘Sir.’ Perhaps it was meant for me after all.”

“No, the letter is mine,” said the man quietly and as he spoke the four boys were aware that he intended to retain possession of the perplexing missive.

That he was able to do so was manifest in the breadth of his shoulders and the evidences of strength which were apparent as he turned and walked away.

“Whew!” whispered Grant. “I guess that man could tell some stories if he wanted to.”

“I hope he will want to,” said George. “I know I want to hear them.”

The conversation turned from the stranger who had claimed the letter to plans for the following day and then when two hours had elapsed all four boys, thoroughly tired by their experiences of the day, sought their rooms.

The following morning John was surprised when he first went down to the lobby to discover there his host of the preceding day.

At first John suspected that the man intended to ignore him, for he advanced toward him with outstretched hand to express his surprise at the unexpected meeting. The stranger, however, turned abruptly away. Abashed by the action John’s face flushed and he watched the man when he slowly walked out to the piazza and seated himself near the entrance.

Turning to the clerk John said, “Who is that man?”

“I do not know,” replied the clerk. “I have seen him here several times this summer.”

“How many years have you been coming here?” broke in John.

“Fourteen.”

“And you never saw this man until this summer?”

“No. Why?”

“Oh, nothing much. I just wanted to know. I had an idea somehow that he belonged to this part of the country and that perhaps he was here every summer.”

“No, sir,” answered the clerk. “This is the first summer he has shown up on Mackinac Island.”

“You mean it is the first time he has shown up at your hotel,” suggested John.

“No, I don’t mean anything of the kind. I mean just what I say, that this is the first summer he has been seen on the island.”

John said no more and turned away. He had decided that he would go out to the piazza and see if this mysterious man was still there. Was it possible that he had been mistaken? Was not this the man who had received them in his strange house on Cockburn Island the preceding day? If any questions concerning the identity of the man remained in John’s mind they were quickly dispelled when he glanced toward the dock and there saw the newcomer talking to the captain of the Gadabout.

At that moment the other three boys approached the place where John was standing and declaring that they were hungry demanded that he should at once go with them to the dining-room.

While the boys were seated in the dining-room they found Fred’s namesake, as they now called Mr. Button, seated near them at a small table. Apparently, however, he ignored their presence and paid no attention to what they were saying.

Convinced, that peculiar as the man’s actions were they had nothing to fear from him, the boys soon gave their undivided attention to their breakfast and to discussing their plans for the coming day.

“It is agreed,” said Fred, “that we are to go back to Drummond Island, isn’t it?”

“That’s right,” said George. “We shan’t get as early a start this morning but we ought to do as much as we did yesterday.”

“I hope,” said Grant, “that we shan’t have any such storm.”

“And I hope,” joined in John, “that we don’t have any more of these mysterious events that took us over to Canada and made us afraid there is somebody watching us.”

“It’s only a guilty conscience that is afraid,” retorted Fred, “but we’ll go to Drummond Island and the sooner we can get started the better it will be. We’re late as it is.”

When the boys departed from the dining-room they stopped together on the piazza to discuss one or two further details in connection with their proposed trip.

To their surprise Mr. Ferdinand Button approached the group and said, “Pardon me, but did I understand you to say that you were going to Drummond Island?”

“Yes, sir,” said Fred promptly.

“I chanced to overhear your remarks while I was at breakfast and I thought perhaps you might be willing to give me a lift.”

“Do you want to go there?” asked John.

“Near there,” said the stranger quietly. “I find there isn’t another motor-boat to be had. I am going to take a skiff and my man and if you can find a place for us on board your motor-boat I shall gladly bear my part of the expense and also appreciate your courtesy very much.”

“Of course you can come,” said Fred quickly.

“I shall not trouble you about coming back. I may not be ready to come when you are, or I may want to come before you do. In either event, I want to pay for my share of the Gadabout for the day.”

“We’ll talk about that later,” said Fred. “Are you ready to start?”

“Yes, my man is at the dock with his skiff.”

“All right,” said Fred. “Go right down there and we’ll all be down in a minute.”

“Well, Captain,” said John, when the boys approached the dock and found their boat already at hand. “We’re going to take a couple more passengers.”

“Who are they?” growled the captain.

“Why, this man, Mr. Button. He wants us to take him over to Drummond Island. He doesn’t know whether he will come back again with us or not.”

“My guide says he will ride in the skiff,” suggested Mr. Button.

“That won’t be necessary, unless he wants to,” said Fred.

“That’s the way we’ll go,” said Mr. Button quietly, and at once the five passengers took their places on board the swift, little Gadabout.

“What’s the matter with the captain?” whispered Grant in a low voice to Fred as soon as the motor-boat had put out from the dock.

“I don’t know. Why?”

“Look at him, that’s all. He’s grouchy or else he’s afraid. He looks to me as if he wasn’t very enthusiastic over the addition to the list of passengers.”

“It doesn’t make any difference whether he is or not. We chartered the boat and can do what we please with it.”

Whether or not the captain was suspicious of the newcomer, the boys gave no further attention to him. In a brief time they were drawn to the newcomer, whose knowledge of the region and whose stories of the early days at once appealed strongly to his young listeners.

“Yes, sir,” said Mr. Button. “There have been some stirring scenes up around Mackinac Island. To my mind it is one of the most beautiful spots in the United States, and, standing just as it does where the lakes join, I do not wonder that the Indians did not want to give it up and that the French and English fought over it the way they did. There’s a very interesting story of the defense of the old fort. It is published I believe, in a little pamphlet and my advice to you is to get a copy and read it before you go home.”

“We’ll do that,” said Grant enthusiastically.

“When we get back,” laughed George, “Grant’s head is going to be so full of the information that he has picked up about the lakes and Mackinac Island, that the rest of us won’t have to do any work, except to keep him quiet.”

“By the way, Mr. Button,” said Fred, “did you find out anything more about that letter?”

To the surprise of the boys the captain appeared at that moment, glaring angrily at Fred and turning about several times after he had started back to his place at the wheel.

“It was a strange letter,” said Mr. Button, “but I am accustomed to such things. It is a part of my business.”

All four boys looked at him questioningly, but he smiled slightly without satisfying their curiosity at the time.

“As I was saying,” he continued, “there have been some very exciting adventures around Mackinac Island. Perhaps I will tell you something about them before long. Just now I should like to have you tell me about your trip yesterday. Did you have good luck?”

“It depends upon how you look at it,” said John with a laugh. “We caught all the fish we wanted for our luncheon, but we had a terrific thunder storm out there that drove us ashore in the afternoon. At least Fred and I were driven ashore.”

“You were wise lads to run before the gale.”

“You needn’t charge us with the wisdom,” laughed Fred. “It was the mate that had it. We were lucky enough to have him with us and he took us ashore over at Cockburn Island. We weren’t so lucky when we landed, though, because our skiff was all stove in and we had to leave it when we came away.”

“How did you get away?”

“Why, the other fellows took the Gadabout and began to look for us after the storm died out and then they came ashore for us in their skiff.”

“How far is it between Drummond Island and Cockburn?”

“Two or three miles. That’s about all, isn’t it, Captain?” said John turning abruptly about as the captain’s face once more was seen peering eagerly at the company seated in the stern.

“That’s about it,” drawled the captain. “Have you never been there?” he added, looking directly at Mr. Button as he spoke.

“I’m looking forward with great pleasure to the trip,” replied Mr. Button, quietly, apparently ignoring the question that had been asked. “You don’t think we are likely to have another storm, to-day, do you?”

“No,” said the captain abruptly, as once more he turned to his work.

“Tell me about Cockburn Island,” said Mr. Button, speaking to the boys. “Is it inhabited? Are there many people living there?”

“I don’t know,” said John. “We didn’t see very much of it. We found a little shanty, or shack, not far from the shore and when we saw smoke coming out of the chimney we went up there thinking that we might dry our clothes, for we were wet through.”

“Did you find anybody there?”

“Yes, that’s the strange part of it,” explained John. “The old shanty, that looked almost as if it would fall to pieces, was pretty well fixed up inside. There was a man there and he had a Japanese servant. Indeed, I am sure I saw the man at the harbor this morning. At least I thought it was the same man, but he didn’t speak to me, so I couldn’t be sure after all.”

Conversation ceased for a time and it was not until they had arrived off the shore of Drummond Island that Mr. Button said, “I think I will leave you here. I want to thank you again for your kindness in bringing me.”

“Where are you going?” demanded the captain, who again approached the group.

“I’m going to leave the Gadabout here,” explained Mr. Button.

“Where you going? There’s no good fishing here.”

“I’m going to trust my guide for that,” explained Mr. Button, pointing as he spoke to the man in whose skiff he was to depart. This man was now seated in his little skiff about one hundred feet astern of the Gadabout.

“Fetch him up then,” said the captain. “I’ll stop the Gadabout and let you off.”

In spite of the captain’s manifest effort to appear at ease it was plain to his young passengers that he still was angry or alarmed over the presence of Mr. Ferdinand Button. What the connection was between the two not one of the boys was able to conjecture.

Their attention, however, was speedily drawn to the skiff which Mr. Button now hauled in and as soon as it was drawn alongside he stepped lightly on board.

It was impossible for any of the boys to see the face of the guide, who at the time was bending low over a box which contained the fishing tackle. It was only later when John reminded the other boys of the strange coincidence between the excitement of the captain and the inability of all to see the face of the guide in Mr. Button’s boat, that they recalled it.

“There isn’t any fishing here,” again shouted the captain.

Apparently Mr. Button was not greatly impressed by the knowledge of the captain, for ignoring his words, he seated himself in the stern of the skiff and prepared to begin his trolling.

Meanwhile the Gadabout was belying her name, as now she was only drifting slowly with the current.

“Come on, Captain,” called Fred at last. “We’re ready to start.”

“Better start,” retorted the commander of the motor-boat. “There’s no fishing here and I told that man there wasn’t, but he doesn’t seem to pay no attention.”

“That’s his own fault,” laughed Grant. “Go on with us.”

Still manifestly reluctant the captain at last started the engine but the Gadabout had not gone more than a few yards before he again stopped the boat and said, “We might as well try it here as anywhere.”

“But you said the fishing here wasn’t any good,” protested Fred.

“It’ll do no harm to try it.”

In accordance with the captain’s words the Gadabout was anchored, and as soon as the young fishermen were separated into two parties as they had been the preceding day, the two skiffs were soon prepared for the sport of the morning.

The captain, who now was rowing the boat in which John and Fred were seated, had rowed one hundred yards from the Gadabout and the boys both were trolling. Still the captain watched the skiff in which Mr. Button had departed as long as the little boat could be seen. Even the Gadabout now was soon lost to sight.

“I’ll have to have a fresh bait,” said Fred, who had been the first to have a strike. He reeled in his line and swung the hook around for the captain to bait it. A moment later the captain abruptly changing his position dropped overboard the box which contained the leaders.

“There I’ve gone and done it!” he said. “Lost every leader! There is nothing to do, boys, except to go back to the Gadabout and get some more. I’m sorry, but it won’t take long.”

“Nothing else to be done,” said John, “so the sooner we get back the better.”

No one in the little boat spoke while the captain rowed swiftly back to the motor-boat.

The surprise of the boys was great when they drew near the little Gadabout to discover that a skiff had been made fast alongside the boat.

“Whose skiff is that?” demanded John abruptly. “We didn’t leave any boat here.”

The captain without replying increased the speed at which he was rowing and as he drew near the Gadabout the boys were startled when they saw peering from the companionway the face of Mr. Ferdinand Button.

“Who’s that on board the Gadabout?” roared the captain. “What are you doing there, you lubber?”

“I guess you know who I am,” replied the man on deck, who now the boys were convinced was indeed the mysterious stranger.

Both boys were startled, as they looked into the face of the captain, who was now rowing swiftly toward the little motor-boat. Whether the expression on his face was one of anger or of fear was not known by either. The man, however, was keenly excited and his anxiety to gain his boat became apparent with every stroke of his oars.

In a brief time he swung the skiff alongside the Gadabout and without making any effort to board the boat the captain roared, “What are you doing on board there?”

“I came back to get something that I thought might be here, which I didn’t take with me,” said Mr. Button quietly. It was manifest from his appearance that he was in nowise alarmed by the noisy questions of the captain of the Gadabout.

“Well, did you find it?” demanded the captain.

“I cannot say that I have—as yet.”

“I guess that depends on what you’re looking for,” said the captain, his voice becoming lower, although his excitement was still manifest.

“I didn’t suppose there would be any such feeling over my coming back to your boat. I have known of other men who neglected to take some things with them when they left home, to say nothing about a motor-boat.”

“Did you say you found it?” again demanded the captain.

“I found something that will do me just as well.”

For a moment the two men stared at each other, the captain still keenly suspicious or angry, while the expression on the face of Mr. Button was one which the boys were not able to understand. To all appearances he was unruffled by the noisy queries of the captain, and yet what was behind it all no one could say.

There was nothing, however, more to be done and in a brief time Mr. Button stepped into his skiff in which the man, who was to be his guide, was still seated. Without any delay the guide picked up his oars and resumed his rowing.

Meanwhile the captain remained standing on the deck of the Gadabout, glaring at the departing skiff, although he did not utter any sound until the man of whom he was suspicious or afraid had rounded the nearest point.

“Better get your leaders, captain, because we want to start,” suggested Fred impatient over the long delay.

“Humph,” grunted the captain. Nevertheless he disappeared below and in a brief time came back to the deck with a box in his hands.

“That’s the same box you took out this morning, isn’t it, Captain?” laughed John.

“What’s that you say?” roared the sailor.

“I said, isn’t that the same box of leaders that you took out this morning?”

“Well I’ll have to own up that it is,” said the captain. “I had it in my pocket all the while and I thought I dropped it overboard. We’ll make up for lost time now, so get aboard, both of you.”

To the surprise of the young fishermen, however, the captain did not return to the ground over which he had been fishing at the time of his unexpected return to the Gadabout. Instead, he followed swiftly in the direction in which Mr. Button had disappeared. Both boys questioned him sharply concerning the change in their plans, but the only reply their guide made was to explain that he thought the fishing was likely to be better in the direction in which he was going than where they had been before.

Fred winked slyly at his companion when several times the captain ceasing his efforts took a glass and drank of the waters of the lake and then taking from his pocket a jointed telescope gazed long and earnestly in the direction in which they were moving.

“What’s the trouble, Captain? What are you looking for?” demanded Fred.

“I wanted to see if that man’s got on my ground.”

“Do you see him anywhere?”

“No, I don’t. I wish I did.”

“Who is he, anyway?” inquired John. “You seem to have a pretty wholesome respect for him.”

“What’s that you say? What’s that you say?” demanded the captain sharply, as he glared at John.

“Why, what I said,” explained John, “was that you seem to be very much impressed by him. Do you know who he is?”

“I don’t know nothin’ about him,” retorted the captain, resuming his occupation once more.

When at last the captain declared that they had arrived at the grounds he was seeking the boys renewed their attempts of the morning. For some reason, however, all their efforts were unavailing. Either the fish were not there, or they were not biting.

“I believe, Captain,” said John, at last, “that you were more interested in following that man than you are in getting a good shoal for us to fish over.”

“What’s that you say?” retorted the captain. “It’s no such thing. It’s no such thing. I don’t care about that man any more than I do about—you.”

“You have a strange way of showing it, then,” suggested Fred with a laugh.

“I tell you what I’ll do, boys,” said the captain at last. “If we don’t have any luck here by noon I’ll take you across the channel and we’ll try it ’long Cockburn Island.”

“But we haven’t any right to fish there. That’s in Canadian waters,” said John quickly.

“Well, I have a permit,” explained the captain.

“Good for us, too?” inquired Fred.

“Yes, good for you, too.”

Both boys were somewhat dubious as to the extent of the permission secured by the captain, but they made no protest. Swiftly the little boat was rowed across the intervening waters and in a brief time, under the shelter of the bluffs of the island they were seeking, preparations were made for resuming their sport.

“We don’t want many fish just now,” said the captain.

“That’s lucky for us,” laughed Fred.

“What I mean is, that we want something for dinner, but that’s about all. After dinner we’ll see what we can do with our luck.”

When the time came for landing, the captain turned to the boys and said, “Before I start a fire I want to go up to that house yonder for a minute.”

“We’ll go with you,” suggested Fred, winking at John as he spoke.

“No, no,” said the captain sharply. “You stay right here on the shore. If you want to you can start a fire and have things goin’ so that when I come back everything will be ready.”

“What do you suppose is the matter with the captain?” inquired John after the departure of their guide.

“Why he’s either afraid of or he doesn’t like that Mr. Button. Maybe he’s the man that wrote that letter.”

“More likely he’s the man that the other fellow wrote the letter about,” laughed John. “I think myself that the old fellow will bear watching.”

“I haven’t seen anything in him that I thought was wrong,” said Fred. “Naturally he doesn’t waste very much affection on the officials of the law.”

“I don’t see why he shouldn’t,” broke in John. “Unless there’s something wrong with him.”

“There may be something wrong as far as the law is concerned, but I guess the old fellow himself thinks he’s right. You know there are a good many people that do that.”

“What do you suppose he’s up to?”

“I don’t believe anybody knows, not even the captain himself. I guess it’s his general principles. He’s opposed to everything.”

“Do you think this Mr. Button is anything more than he appears to be?”

“I’m not sure,” said Fred thoughtfully. “It may be that he knows a good deal more than he explains and it may be that letter he got, which was sent to me first, has made him suspicious of the captain. I don’t myself believe there’s anything the matter with the captain anyway.”

“Look yonder!” said John quickly, dropping the fish, which he was cleaning, as he spoke. “Isn’t that Mr. Button himself?”

Hastily looking in the direction indicated by his friend Fred was silent for a moment and then said, “That’s just who it is. What do you suppose he’s doing here on this island?”

“He isn’t on the island yet. I’ll tell you later what he does, that is, if he lands. Don’t let him see us.”

Hastily moving behind the high bushes, though neither boy could explain just why he did so, they watched their fellow-guest, as his skiff was swiftly sent ashore and Mr. Button himself stepped out upon the land.

It was plain that he was not aware of the presence of the boys and that all his movements were being keenly watched.

The interest of the boys, however, was speedily increased and in a brief time both were highly excited when they saw Mr. Button take from his pocket a revolver, which he inspected carefully and after he had returned it to its place he at once started toward the house in the distance.

It was the same rude, little shanty in which the boys had found refuge the preceding day. Now, however the sun was shining brightly and the clear waters of the lake were reflecting its beams. There were no signs of life about the house on the shore, but both boys excitedly watched Mr. Button as he made his way across the fields and after a brief time approached the side door of the house and then entered the little building.

“Let’s go up to the house, too,” suggested Fred quickly.

“What for?”

“Why, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t go and if there’s any fun going on we want to be on hand.”

“I’m with you,” said John cordially, and as soon as they had banked their fire both boys started across the open field toward the house in the distance.

“I’m telling you,” said Fred in a low voice, “there’s something going on up in that house.”

“You always make a mountain out of a mole hill.”

“Well, perhaps I do, but I’m sure there’s something doing and they may need us before long.”

“Yes, probably they are wondering now why we don’t come,” laughed John.

“Just you wait,” retorted Fred. “You’ll see I’m right.”

“If I thought you were, I know of one fellow who wouldn’t go near that house.”

“But you’re going just the same,” said Fred positively.

There was no delay and after the boys had crossed the field they approached the kitchen-door of the rude, little house where Fred made known their presence by his noisy summons.

In response to Fred’s knock the door was opened by the little Japanese servant. He stared blankly at the boys and then broke into another of his loud laughs.

“Is there any one here?” inquired Fred.

The response of the Japanese was another boisterous laugh.

“Why don’t you tell us?” demanded John, irritated by the manner of the little man; but the sole response of the Japanese was a loud burst of laughter after each inquiry.

“Let’s go in anyway,” suggested Fred.

The Japanese offered no opposition to their entrance and when they were within the familiar room they glanced hastily about them, but there were no signs of the man they were seeking.

Abruptly, however, Fred said, “Hush! Listen, Jack! That’s the captain’s voice upstairs.”

Both boys were silent as they listened attentively to the sound of voices which now could be heard from the upper room. Gradually the captain’s voice became louder and it was manifest that he was either in trouble or angry.

To the astonishment of the boys the interview suddenly ended and the captain, rushing down the stairway, abruptly departed from the house. Apparently he had been unaware of the presence of either of the boys. He had glanced neither to the right nor to the left and as the boys looked out of the window they saw that he was walking rapidly toward the shore.

“Let him go,” said John, “he’ll have to wait for us anyway.”

“I wish I was sure that he would wait,” said Fred doubtfully.

“Wait? Of course he’ll wait,” retorted John. “That’s what he’s paid for.”

“I’m not so sure,” said Fred once more. “I think the best thing to do would be for one of us to go back and see that everything is all right.”

“All right,” responded John quickly. “You stay here if you want to and I’ll go down to the shore and see if anything happens there.”

Meanwhile Fred seated himself in the room and watched the Japanese servant, who apparently ignored his presence save occasionally when he stopped and stared blankly at him for a moment and then broke into a noisy laugh.

Not many minutes had elapsed, however, before John came running back to the house.

“The captain has taken the skiff and left the island!” he said excitedly when he burst into the room.

“Oh, I guess not,” said Fred.

“But he has, I tell you. He was rowing like mad. He has taken the skiff and left us here.”

“We’ll go down to see about it,” said Fred, abruptly rising and accompanying his friend as together they ran back to the shore.

“There it is, just as I told you!” said John, when they arrived on the bluff. “The boat has gone and the captain has gone with it.”

For a moment Fred made no reply. He glanced in either direction along the shore, and then peered intently out over the water, but neither the boat nor the captain was to be seen.