The Project Gutenberg EBook of The High Heart, by Basil King This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The High Heart Author: Basil King Release Date: March 3, 2011 [EBook #35463] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HIGH HEART *** Produced by Barbara Watson, Ross Cooling and the Online Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

I could not have lived in the Brokenshire circle for nearly a year without recognizing the fact that in the eyes of his family J. Howard, as he was commonly called by the world, was the Great Dispenser; but my first intimation that he meant to act in that capacity toward me came from Larry Strangways, on a bright July morning during the summer of 1913, when we were at Newport.

I was crossing the lawn, going toward the sea, with little Gladys Rossiter, to whom I acted as companion in the hours when she was out of the nursery, with a specific duty to speak French. Larry Strangways was tutor to the Rossiter boy, and in our relative positions we were bound to exercise toward each other a good deal of discretion. We fraternized with constraint. We fraternized because—well, chiefly because we couldn't help it. In the mocking flare of his eye, which contradicted the assumed young gravity of his manner, I read an opinion of the Rossiter household and of the Brokenshire family in general similar to my own. That would have been enough for mutual comprehension had there been no instinctive sympathies between us; but there were. Allowing for the fact that we were of different nationalities, we had the same kind of antecedents; we spoke the same kind of social language; we had the same kind of aims in life. Neither of us regarded the position in the Rossiter establishment as a permanent status. He was a tutor merely for the minute, while feeling his way to that first rung of the ladder which I was convinced would lead him to some high place in American life. I was a nursery governess only on the way to getting married. Matrimony was the continent toward which more or less consciously I had been traveling for five or six years, without having actually descried a port. In this connection I may relate a little incident which had taken place between myself and Mrs. Rossiter after I had accepted my situation in her family. It will retard my meeting with Larry Strangways on the lawn, but it will throw light on it when it comes.

I had met Mrs. Rossiter, who was J. Howard Brokenshire's daughter, in the way that is known as socially. I never understood why she should have taken a house for the summer in our quiet old town of Halifax, unless she was urged to it by the vague restlessness which was one of her characteristics. But there she was in a roomy old brick mansion I had known all my life, with gardens and conservatories and lawns running down to the fiord or back-harbor which we call the Northwest Arm, and a fine English air of seclusion. In our easy, neighborly way she was well received, and made herself agreeable. She flirted with the officers of both Army and Navy enough to create talk without raising scandal; and she was sufficiently good-natured to be civil to us girls, among whom she singled me out for attentions. I attributed this kindness to our recent bereavement and financial crash, which had left me poor after twenty-four years of comfort, and was proportionately grateful. It was partly gratitude, and partly a natural love of children, and partly a special affection for the exquisite thing herself, that drew me to little Gladys Rossiter, to playing with her on the lawns, and rowing her on the Arm, and—as I had been for three or four years at school in Paris—dropping into a habit of lisping French to her. As the child liked me the mother left her more and more to my care, gaining thus the greater scope for her innocuous flirtations.

It was toward the end of the summer that Mrs. Rossiter began to sigh, "I don't know how I shall ever tear Gladys away from you," and, "I do wish you were coming with us."

I wished it in a way myself, since I was rather at a loss as to what to do. I had never expected to have to earn a living; I had expected to get married. My two elder sisters, Louise and Victoria, had married easily enough, the one in the Navy, the other in the Army; but with me suitors seemed to lag. They came and saw—but they never went far enough for conquest. I couldn't understand it. I was not stupid; I was not ugly; and I was generally spoken of as having charm. But there was the fact that I was twenty-four, with scarcely a penny, and drawing nearer and nearer to the end of my expedients. I was not without some social experience, having kept house in a generous way for my widowed father, till his death, some two years before the summer when I met Mrs. Rossiter, brought with it our financial collapse. If he hadn't left a lot of old books—Canadiana, the pamphlets were called—and rare first editions of all kinds, which I took over to London and sold at Sothbey's, I shouldn't have had enough on which to dress. This business being settled, I stayed as long as I decently could with Louise at Southsea and Victoria at Gibraltar; but no man asked me to marry him during the course of either visit. Had there been a sign of any such possibility the sisters would have put themselves out to keep me; but as nothing warranted them in doing so they let me go. An uncle and aunt having offered to give me shelter for a time at Halifax, there was nothing left for it but to go back and renew the search for my fortunes in my native town.

When, therefore, Mrs. Rossiter, in her pretty, helpless way said to me one day, "Why shouldn't you come with me, dear Miss Adare?" I jumped inwardly at the opportunity, though I smiled and replied in an offhand manner, "Oh, that would have to be discussed."

Mrs. Rossiter admitted the truth of this observation somewhat pensively. I know now that I took her up with too much promptitude.

"Yes, of course," she returned, absently, and the subject was dropped.

It was taken up again, however, and our bargain made. On Mrs. Rossiter's part it was made astutely, not in the matter of money, but in the way in which she shifted me from the position of a friend into that of a retainer. It was done with the most perfect tact, but it was done. I had no complaint to make. What she wanted was a nursery governess. My own first preoccupations were food and shelter for which I should not be dependent on my kin. We came to the incident I am about to relate very gradually; but when we did come to it I had no difficulty in seeing that it had been in the back of Mrs. Rossiter's mind from the first. It had been the cause of that second thought on the day when I had taken her up too readily.

She began by telling me about her father. Beyond the fact that some man who seemed to be specially well informed would occasionally say with awe, "She's J. Howard Brokenshire's daughter," I knew nothing whatever about him. But I began to see him now as the central sun round whom all the Brokenshires revolved. They revolved round him, not so much from adoration or even from natural affection as from some tremendous rotary force to which there was no resistance.

Up to this time I had heard no more of American life than American life had heard of me. The great country south of our border was scarcely on my map. The Halifax in which I was born and grew up was not the bustling Canadian port, dependent on its hinterland, it is to-day; it was an outpost of England, with its face always turned to the Atlantic and the east. My own face had been turned the same way. My home had been literally a jumping-off place, in that when we left it we never expected to go in any but the one direction. I had known Americans when they came into our midst as summer visitors, but only in the way one knows the stars which dawn and fade and leave no trace of their passage on actual happenings.

In the course of Mrs. Rossiter's confidences I began to see a vast cosmogony beyond my own personal sun, with J. Howard Brokenshire as the pivot of the new universe. With a curious little shock of surprise I discovered that there could be other solar systems besides the one to which I was accustomed, and that Canada was not the whole of North America. It was like looking through a telescope which Mrs. Rossiter held to my eye, a telescope through which I saw the nebular evidence of an immense society, wealthy, confused, more intellectual than our own, but more provincial too, perhaps; more isolated, more timid, more conservative, less instinct with the great throb of national and international impulse which all of us feel who live on the imperial red line and, therefore, less daring, but interesting all the same. I began to glow with the spirit of adventure. My position as a nursery governess presented the opportunities not merely of a Livingstone or a Stanley, but of a Galileo or a Copernicus.

I learned that Mrs. Rossiter's mother had been a Miss Brew, and that the Brews were a great family in Boston. She was the mother of all Mr. Brokenshire's children. By looks and hints and sighs I gathered from Mrs. Rossiter that her father's second marriage had been a trial to his family. Not that there had been any social descent. On the contrary, the present Mrs. Brokenshire had been Editha Billing, of Philadelphia, and there could be nothing better than that. It was a question of fitness, of necessity, of age. "There was no need for him to marry again at all," Mrs. Rossiter complained. "If she'd only been a middle-aged woman," she said to me later, "we might not have felt. . . . But she's younger than Mildred and only a year or two older than I am." "Oh yes," was another remark, "she's pretty; very pretty . . . but I often—wonder."

She described her brothers and her sister by degrees. One day she told me about Mildred, another about Jack, so coming toward her point. Mildred was the eldest of the family, a great invalid. She had been thrown from her horse years before while hunting in England, and had injured her spine. Jack had just gone into business with his father, and had married Pauline Gray, of Baltimore. Though she didn't say it in so many words I judged that it was not a happy marriage in the highest sense—that Jack was somewhat light of love, while Pauline "went her own way" to a degree that made her talked about. It was not till the day before her departure for New York that Mrs. Rossiter mentioned her younger brother, Hugh.

I was helping her to pack—that is, I was helping the maid while Mrs. Rossiter directed. Just at that minute, however, she was standing up, shaking out the folds of an evening dress. She seemed to peep at me round its garnishings as she said, apropos of nothing:

"There's my brother Hugh. He's the youngest of us all—just twenty-six. He has no occupation as yet—he's just studying languages and things. My father wants him to go into diplomacy." As I caught her eye there was a smile in it, but a special kind of smile. It was the smile to go with the sensible, kindly, coaxing inflection with which she said, "You'll leave him alone, won't you?"

I took the dress out of her hand to carry it to the maid in the next room.

"Leave him alone—how?"

She flushed to a lovely pink.

"Oh, you know what I mean. I don't have to explain."

"You mean that in my position in the household it will be for me to—to keep out of his way?"

"It's you who put it like that, dear Miss Adare—"

"But it's the way you want me to put it?"

"Well, if I admit that it is?"

"Then I don't think I care for the place."

"What?"

I stated my position more simply.

"If I'm to have nothing to do with your brother, Mrs. Rossiter, I don't want to go."

In the audacity of this response she saw something that amused her, for, snatching the dress from my hand, she ran with it into the next room, laughing.

During the following winter in New York and the early summer of the next year in Newport I saw a good deal of Mr. Hugh Brokenshire, but never with any violent restriction on the part of Mrs. Rossiter. I say violent with intention, for she did intervene when she could do so. Only once did I hear that she knew he was kind to me, and that was from Larry Strangways. It was an observation he had overheard as it passed from Mrs. Rossiter to her husband, and which, in the spirit of our silent camaraderie, he thought it right to hand along.

"I can't be responsible for Hugh!" Mrs. Rossiter had said. "He's old enough to look after himself. If he wants a row with father he must have it; and he seems to me in a fair way to get it. If he does it will be his own fault; it won't be Miss Adare's."

Fortified by this acquittal, I went on my way as quietly as I could, though I cannot say I was free from perturbation.

Perturbation caught me like a whiff of wind as I saw Larry Strangways deflect from his course across the lawn and come in my direction. I knew he wouldn't have done that unless he felt himself authorized; and nothing could give him the authorization but something in the way of a message or command. To all observers we were strangers. We should have been strangers even to each other had it not been for that freemasonry of caste, that secret mutual comprehension, which transcends speech and opportunities of meeting, and which, on our part, at least, had little expression beyond smiles and flying glances.

Of course he was good-looking. It has often seemed to me the privilege of ineligible men to be tall and slim and straight, with just such a flash in the eye and just such a beam about the mouth as belonged to Larry Strangways. Instinct had told me from the first that it would be wise for me to avoid him, while prudence, as I have hinted, gave him the same indication to keep at a distance from me. Luckily he didn't live in the house, but in lodgings in the town. We hardly ever met face to face, and then only under the eye of Mrs. Rossiter when each of us marshaled a pupil to lunch or to tea.

As the collie at his heels and the wire-haired terrier at ours made a bee-line for each other the children kept them company, which gave us space for those few minutes of privacy the occasion apparently demanded. Though he lifted his hat formally, and did his best to preserve the decorum of our official situations, the prank in his eye flung out that signal to which I could never do anything but respond.

"I've a message for you, Miss Adare."

I managed to stammer out the word "Indeed?" I couldn't be surprised, and yet I could hardly stand erect from fear.

He glanced at the children to make sure they were out of earshot.

"It's from the great man himself—indirectly."

I was so near to collapse that I could only say, "Indeed?" again, though I rallied sufficiently to add, "I didn't know he was aware of my existence."

"Apparently he wasn't—but he is now. He desires you—I give you the verb as Spellman, the secretary, passed it on to me—he desires you to be in the breakfast loggia here at three this afternoon."

I could barely squeak the words out:

"Does he mean that he's coming to see me?"

"That, it seems, isn't necessary for you to know. Your business is to be there. There's quite a subtle point in the limitation. Being there, you'll see what will happen next. It isn't good for you to be told too much at a time."

My spirit began to revive.

"I'm not his servant. I'm Mrs. Rossiter's. If he wants anything of me why doesn't he say so through her?"

"'Sh, 'sh, Miss Adare! You mustn't dictate to God, or say he should act in this way or in that."

"But he's not God."

"Oh, as to that—well, you'll see." He added, with his light laugh, "What will you bet that I don't know what it's all about?"

"Oh, I bet you do."

"Then," he warned, "you're up against it."

I was getting on my mettle.

"Perhaps I am—but I sha'n't be alone."

"No; but you'll be made to feel alone."

"Even so—"

As I was anxious to keep from boasting beforehand, I left the sentence there.

"Yes?" he jogged. "Even so—what?"

"Oh, nothing. I only mean that I'm not afraid of him—that is," I corrected, "I'm not afraid of him fundamentally."

He laughed again. "Not afraid of him fundamentally! That's fine!" Something in his glance seemed to approve of me. "No, I don't believe you are; but I wonder a little why not."

I reflected, gazing beyond his shoulder, down the velvety slopes of the lawn, and across the dancing blue sea to the islets that were mere specks on the horizon. In the end I decided to speak soberly. "I'm not afraid of him," I said at last, "because I've got a sure thing."

"You mean him?"

I knew the reference was to Hugh Brokenshire. "If I mean him," I replied, after a minute's thinking, "it's only as the greater includes the less, or as the universal includes everything."

He whistled under his breath.

"Does that mean anything? Or is it just big talk?"

Half shy and half ashamed of going on with what I had to say, I was obliged to smile ruefully.

"It's big talk because it's a big principle. I don't know how to manage it with anything small." I tried to explain further, knowing that my dark skin flushed to a kind of dahlia-red while I was doing so. "I don't know whether I've read it—or whether I heard it—or whether I've just evolved it—but I seem to have got hold of—of—don't laugh too hard, please—of the secret of success."

"Good for you! I hope you're not going to be stingy with it."

"No; I'll tell you—partly because I want to talk about it to some one, and just at present there's no one else."

"Thanks!"

"The secret of success, as I reason it out, must be something that will protect a weak person against a strong one—me, for instance, against J. Howard Brokenshire—and work everything out all right. There," I cried, "I've said the word."

"You've said a number. Which is the one?"

Anxiety not to seem either young or didactic or a prig made my tone apologetic.

"There's such a thing as Right, written with a capital. If I persist in doing Right—still with a capital—then nothing but right can come of it."

"Oh, can't it!"

"I know it sounds like a platitude—"

"No, it doesn't," he interrupted, rudely, "because a platitude is something obviously true; and this isn't."

I felt some relief.

"Oh, isn't it? Then I'm glad. I thought it must be."

"You won't go on thinking it. Suppose you do right and somebody else does wrong?"

"Then I should be willing to back my way against his. Don't you see? That's the point. That's the secret I'm telling you about. Right works; wrong doesn't."

"That's all very fine—"

"It's all very fine because it's so. Right is—what's the word William James put into the dictionary?"

He suggested pragmatism.

"That's it. Right is pragmatic, which I suppose is the same thing as practical. Wrong must be impractical; it must be—"

"I shouldn't bank too confidently on that in dealing with the great J. Howard."

"But I'm going to bank on it. It's where I'm to have him at a disadvantage. If he does wrong while I do right, why, then I'll get him on the hip."

"How do you know he's going to do wrong?"

"I don't. I merely surmise it. If he does right—"

"He'll get you on the hip."

"No, because there can't be a right for him which isn't a right for me. There can't be two rights, each contrary to the other. That's not in common sense. If he does right then I shall be safe—whichever way I have to take it. Don't you see? That's where the success comes in as well as the secret. It can't be any other way. Please don't think I'm talking in what H. G. Wells calls the tin-pot style—but one must express oneself somehow. I'm not afraid, because I feel as if I'd got something that would hang about me like a magic cloak. Of course for you—a man—a magic cloak may not be necessary; but I assure you that for a girl like me, out in the world on her own—"

He, too, sobered down from his chaffing mood.

"But in this case what is going to be Right—written with a capital?"

I had just time to reply, "Oh, that I shall have to see!" when the children and dogs came scampering up and our conversation was over.

On returning from my walk with Gladys I informed Mrs. Rossiter of the order I had received. I could see her distressed look in the mirror before which she sat doing something to her hair.

"Oh, dear!" she sighed, "it's just what I was afraid of. Now I suppose he'll want you to leave."

"That is, he'll want you to send me away."

"It's the same thing," she said, fretfully, and sat with hands lying idly in her lap.

She stared out of the window. It was a large bow window, with a window-seat cushioned in flowered chintz. Couch, curtains, and easy-chairs reproduced this Enchanted Garden effect, forming a paradisiacal background for her intensely modern and somewhat neurotic prettiness. I had seen her sit by the half-hour like this, gazing over the shrubberies, lawns, and waves, with a yearning in her eyes like that of some twentieth-century Blessed Damozel.

It was her unhappy hour of the day. Between getting up at nine or ten and descending languidly to lunch, life was always a great load to her. It pressed on one too weak to bear its weight and yet too conscientious to throw it off, though, as a matter of fact, this melancholy was only the reaction of her nerves from the mild excitements of the night before. I was generally with her during some portion of this forenoon time, reading her notes and answering them, speaking for her at the telephone, or keeping her company and listening to her confidences while she nibbled without appetite at a bit of toast and sipped her tea.

To put matters on the common footing I said:

"Is there anything you'd like me to do, Mrs. Rossiter?"

She ignored this question, murmuring in a way she had, through half-closed lips, as if mere speech was more than she was equal to: "And just when we were getting on so well—and the way Gladys adores you—"

"And the way I adore Gladys."

"Oh, well, you don't spoil the child, like that Miss Phips. I suppose it's your sensible English bringing up."

"Not English," I interrupted.

"Canadian then. It's almost the same thing." She went on without transition of tone: "Mr. Millinger was there again last night. He was on my left. I do wish they wouldn't keep putting him next to me. It makes everything look so pointed—especially with Harry Scott glowering at me from the other end of the table. He hardly spoke to Daisy Burke, whom he'd taken in. I must say she was a fright. And Mr. Millinger so imprudent! I'm really terrified that Jim will hear gossip when he comes down from New York—or notice something." There was the slightest dropping of the soft fluting voice as she continued: "I've never pretended to love Jim Rossiter more than any man I've ever seen. That was one of papa's matches. He's a born match-maker, you know, just as he's a born everything else. I suppose you didn't think of that. But since I am Jim's wife—"

As I was the confidante of what she called her affairs—a rôle for which I was qualified by residence in British garrison towns—I interposed diplomatically, "But so long as Mr. Millinger hasn't said anything, not any more than Mr. Scott—"

"Oh, if I were to allow men to say things, where should I be? You can go far with a man without letting him come to that. It's something I should think you'd have known—with your sensible bringing up—and the heaps of men you had there in Halifax—and I suppose at Southsea and Gibraltar, too." It was with a hint of helpless complaint that she added, "You remember that I asked you to leave him alone, now don't you?"

"Oh, I remember—quite. And suppose I did—and he didn't leave me alone?"

"Of course there's that, though it won't have any effect on papa. You are unusual, you know. Only one man in five hundred would notice it; but there always is that man. It's what I was afraid of about Hugh from the first. You're different—and it's the sort of thing he'd see."

"Different from what?" I asked, with natural curiosity.

Her reply was indirect.

"Oh, well, we Americans have specialized too much on the girl. You're not half as good-looking as plenty of other girls in Newport, and when it comes to dress—"

"Oh, I'm not in their class, I know."

"No; it's what you seem not to know. You aren't in their class—but it doesn't seem to matter. If it does matter, it's rather to your advantage."

"I'm afraid I don't see that."

"No, you wouldn't. You're not sufficiently subtle. You're really not subtle at all, in the way an American girl would be." She picked up the thread she had dropped. "The fact is we've specialized so much on the girl that our girls are too aware of themselves to be wholly human. They're like things wound up to talk well and dress well and exhibit themselves to advantage and calculate their effects—and lack character. We've developed the very highest thing in exquisite girl-mechanics—a work of art that has everything but a soul." She turned half round to where I stood respectfully, my hands resting on the back of an easy-chair. She was lovely and pathetic and judicial all at once. "The difference about you is that you seem to spring right up out of the soil where you're standing—just like an English country house. You belong to your background. Our girls don't. They're too beautiful for their background, too expensive, too produced. Take any group of girls here in Newport—they're no more in place in this down-at-the-heel old town than a flock of parrakeets in a New England wood. It's really inartistic, though we don't know it. You're more of a woman and less of a lovely figurine. But that won't appeal to papa. He likes figurines. Most American men do. Hugh is an exception, and I was afraid he'd see in you just what I've seen myself. But it won't go down with papa."

"If it goes down with Hugh—" I began, meekly.

"Papa is a born match-maker, which I don't suppose you know. He made my match and he made Jack's. Oh, we're—we're satisfied now—in a way; and I suppose Hugh will be, too, in the long run." I wanted to speak, but she tinkled gently on: "Papa has his designs for him, which I may as well tell you at once. He means him to marry Lady Cissie Boscobel. She's Lord Goldborough's daughter, and papa and he are very intimate. Papa knew him when we lived in England before grandpapa died. Papa has done things for him in the American money-market, and when we're in England he does things for us. Two or three of our men have married earls' daughters during the last few years, and it hasn't turned out so badly. Papa doesn't want not to be in the swim."

"Does"—I couldn't pronounce Hugh's name again—"does your brother know of Mr. Brokenshire's intentions?"

"Yes. I told him so. I told him when I began to see that he was noticing you."

"And may I ask what he said?"

"It would be no use telling you that, because, whatever he said, he'd have to do as papa told him in the end."

"But suppose he doesn't?"

"You can't suppose he doesn't. He will. That's all that can be said about it." She turned fully round on me, gazing at me with the largest and sweetest and tenderest eyes. "As for you, dear Miss Adare," she murmured, sympathetically, "when papa comes to see you this afternoon, as apparently he means to do, he'll grind you to powder. If there's anything smaller than powder he'll grind you to that. After he's gone we sha'n't be able to find you. You'll be dust."

At five minutes to three, precisely, I took my seat in the breakfast loggia.

The front of the house with the garden looked toward Ochre Point Avenue. The so-called breakfast loggia was thrown out from the dining-room in the direction of the sea. Here the family and their guests could gather on warm evenings, and in fine weather eat in the open air. Paved with red tiles, it was furnished with a long oak table, ornately carved, and some heavy old oak chairs that might have come from a monastery. Steamer chairs and wicker easy-chairs were scattered on the grass outside. On the left the loggia was screened from the neighboring property by a hedge of rambler roses that now ran the gamut of shades from crimson to sea-shell pink, while on the right it commanded a view of the two terraces supporting the house, with their long straight lines of flowers. The house itself had been built piecemeal, and was now a low, rambling succession of pavilions or corps de logis, to which a series of rose-colored awnings gave the only unifying principle.

Just now it was a house deserted by every one but the servants and myself. Mrs. Rossiter, having gone out to luncheon, had been careful not to return, and even the children had been sent over to Mrs. Jack Brokenshire, on the pretext of playing with her baby, but really to be out of the way. From Hugh I had had no sign of life since the previous afternoon. As to whether his father was coming as his enemy, his master, or his interpreter I could do nothing but conjecture.

But as far as I could I kept myself from conjecturing; holding my faculties in suspense. I had enough to do in assuring myself that I was not afraid—fundamentally. Superficially I was terrified. I should have been terrified had the great man but passed me in the hall and cast a look at me. He had passed me in the hall on occasions, but as he had never cast the look I had escaped. He had struck me then as a master of that art of seeing without seeing which I had hitherto thought of as feminine. Even when he stopped and spoke to Gladys he seemed not to know that I occupied the ground I stood on. I cannot say I enjoyed this treatment. I was accustomed to being seen. Moreover, I had lived with people who were courteous to inferiors, however cavalier with equals. The great J. Howard was neither courteous nor cavalier toward me, for the reason that where I was he apparently saw nothing but a vacuum.

Out to the loggia I took my work-basket and some sewing. Having no idea from which of the several approaches my visitor would come on me, I drew up one of the heavy arm-chairs and sat facing toward the sea. With the basket on the table beside me and my sewing in my hands I felt indefinably more mistress of myself.

It was a still afternoon and hot, with scarcely a sound but the pounding of the surf on the ledges at the foot of the lawn. Though the sky was blue overhead, a dark low bank rose out of the horizon, foretelling a change of wind with fog. In the air the languorous scent of roses and honeysuckle mingled with the acrid tang of the ocean.

I felt extraordinarily desolate. Not since hearing what the lawyer had told me on the afternoon of my father's funeral had I seemed so entirely alone. The fact that for nearly twenty-four hours Hugh had got no word to me threw me back upon myself. "You'll be made to feel alone," Mr. Strangways had said in the morning; and I was. I didn't blame Hugh. I had purposely left the matter in such a way that there was nothing he could say or do till after his father had spoken. He was probably waiting impatiently; I had, indeed, no doubt about that; but the fact remained that I, a girl, a stranger, in a certain sense a foreigner, was to make the best of my situation without help. J. Howard Brokenshire could grind me to powder—when he had gone away I should be dust.

"If I do right, nothing but right can come of it."

The maxim was my only comfort. By sheer force of repeating it I got strength to thread my needle and go on with my seam, till on the stroke of three the dread personage appeared.

I saw him from the minute he mounted the steps that led up from the Cliff Walk to Mr. Rossiter's lawn. He was accompanied by Mrs. Brokenshire, while a pair of greyhounds followed them. Having reached the lawn, they crossed it diagonally toward the loggia. Because of the heat and the up-hill nature of the way, they advanced slowly, which gave me leisure to observe.

Mrs. Brokenshire's presence had almost caused my heart to stop beating. I could imagine no motive for her coming but one I refused to accept. If the mission was to be unfriendly, she surely would have stayed away; but that it could be other than unfriendly was beyond my strength to hope.

I had never seen her before except in glimpses or at a distance. I noticed now that she was a little thing, looking the smaller for the stalwart six-foot-two beside which she walked. She was in white and carried a white parasol. I saw that her face was one of the most beautiful in features and finish I had ever looked into. Each trait was quite amazingly perfect. The oval was perfect; the coloring was perfect; mouth and nose and forehead might have been made to a measured scale. The finger of personified Art could have drawn nothing more exquisite than the arch of the eyebrows, or more delicately fringed than the lids. It might have been a doll's face, or the face for the cover of an American magazine, had it not been saved by something I hadn't the time to analyze, though I was later to know what it was.

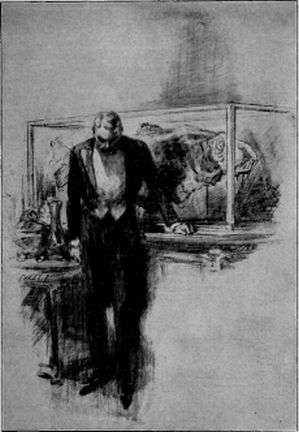

As for him, he was as perfect in his way as she in hers. When I say that he wore white shoes, white-duck trousers, a navy-blue jacket, and a yachting-cap I give no idea of the something noble in his personality. He might have been one of the more ornamental Italian princes of immemorial lineage. A Jove with a Vandyke beard one could have called him, and if you add to that the conception of Jove the Thunderer, Jove with the look that could strike a man dead, perhaps the description would be as good as any. He was straight and held his head high. He walked with a firm setting of his feet that impressed you with the fact that some one of importance was coming.

It is not my purpose to speak of this man from the point of view of the ordinary member of the public. Of that I know next to nothing. I was dimly aware that his wealth and his business interests made him something of a public character; but apart from having heard him mentioned as a financier I could hardly have told what his profession was. So, too, with questions of morals. I have been present when, by hints rather than actual words, he was introduced as a profligate and a hypocrite; and I have also known people of good judgment who upheld him both as man and as citizen. On this subject no opinion of mine would be worth giving. I have always relegated the matter into that limbo of disputed facts with which I have nothing to do. I write of him only as I saw him in daily life, or at least in direct intercourse, and with that my testimony must end. Other people have been curious with regard to those aspects of his character on which I can throw no light. To me he became interesting chiefly because he was one of those men who from a kind of naïve audacity, perhaps an unthinking audacity, don't hesitate to play the part of the Almighty.

When they drew near enough to the loggia I stood up, my sewing in my hand. The two greyhounds, who had outdistanced them, came sniffing to the threshold and stared at me. I felt myself an object to be stared at, though I had taken pains with my appearance and knew that I was neat. Neatness, I may say in passing, is my strong point. Where many other girls can stand expensive dressing I am at my best when meticulously tidy. The shape of my head makes the simplest styles of doing the hair the most distinguished. My figure lends itself to country clothes and the tailor-made. In evening dress I can wear the cheapest and flimsiest thing, so long as it is dependent only on its lines. I was satisfied, therefore, with the way I looked, and when I say I felt myself an object to be stared at I speak only of my consciousness of isolation.

I cannot affirm, however, that J. Howard Brokenshire stared at me. He stared; but only at the general effects in which I was a mere detail. The loggia being open on all sides, he paused for half a second to take it and its contents in. I went with the contents. I looked at him; but nothing in the glance he cast over me recognized me as a human being. I might have been the table; I might have been the floor; for him I was hardly in existence.

I wonder if you have ever stood under the gaze of one who considered you too inferior for notice. The sensation is quite curious. It produces not humiliation or resentment so much as an odd apathy. You sink in your own sight; you go down; you understand that abjection of slaves which kept them from rising against their masters. Negatively at least you concede the right that so treats you. You are meek and humble at once; and yet you can be strong. I think I never felt so strong as when I saw that cold, deep eye, which was steely and fierce and most inconsistently sympathetic all in one quick flash, sweep over me and pay me no attention. Ecce Femina I might have been saying to myself, as a pendant in expression to the Ecce Homo of the Prætorium.

He moved aside punctiliously at the lower of the two steps that led up to the loggia to let his wife precede him. As she came in I think she gave me a salutation that was little more than a quiver of the lids. Having closed her parasol, she slipped into one of the arm-chairs not far from the table.

Now that he was at close quarters, with his work before him, he proceeded to the task at once. In the act of laying his hat and stick on a chair he began with the question, "Your name is—?"

The voice had a crisp gentleness that seemed to come from the effort to despatch business with the utmost celerity and spend no unnecessary strength on words. The fact that he must have heard my name from Hugh was plainly to play no part in our discussion. I was so unutterably frightened that when I tried to whisper the word "Adare" hardly a sound came forth.

As he raised himself from the placing of his cap and stick he was obliged to utter a sharp, "What?"

"Adare."

"Oh. Adare!"

It is not a bad name as names go; we like to fancy ourselves connected with the famous Fighting Adares of the County Limerick; but on J. Howard Brokenshire's lips it had the undiscriminating commonness of Smith or Jones. I had never been ashamed of it before.

"And you're one of my daughter's—"

"I'm her nursery governess."

"Sit down."

As he took the chair at the end of the table I dropped again into that at the side from which I had risen. It was then that something happened which left me for a second in doubt as to whether to take it as comic or catastrophic. His left eye closed; his left nostril quivered; he winked. To avoid having to face this singular phenomenon a second time I lowered my eyes and began mechanically to sew.

"Put that down!"

I placed the work on the table and once more looked at him. The striking eyes were again as striking as ever. In their sympathetic hardness there was nothing either ribald or jocose.

I suppose my scrutiny annoyed him, though I was unconscious of more than a mute asking for orders. He pointed to a distant chair, a chair in a corner, just within the loggia as you come from the direction of the dining-room.

"Sit there."

I know now that his wink distressed him. It was something which at that time had come upon him recently, and that he could neither control nor understand. A less imposing man, a man to whom personal impressiveness was less of an asset in daily life and work, would probably have been less disturbed by it; but to J. Howard Brokenshire it was a trial in more ways than one. Curiously, too, when the left eye winked the right grew glassy and quite terrible.

Not knowing that he was sensitive in this respect, I took my retreat to the corner as a kind of symbolic banishment.

"Hadn't I better stand up?" I asked, proudly, when I had reached my chair.

"Be good enough to sit down."

I seemed to fall backward. The tone had the effect of a shot. If I had ever felt small and foolish in my life it was then. I flushed to my darkest crimson. Angry and humiliated, I was obliged to rush to my maxim in order not to flash back in some indignant retort.

And then another thing happened of which I was unable at the minute to get the significance. Mrs. Brokenshire sprang up with the words:

"You're quite right, Howard. It's ever so much cooler over here by the edge. I never felt anything so stuffy as the middle of this place. It doesn't seem possible for air to get into it."

While speaking she moved with incomparable daintiness to a chair corresponding to mine and diagonally opposite. With the length and width of the loggia between us we exchanged glances. In hers she seemed to say, "If you are banished I shall be banished too"; in mine I tried to express gratitude. And yet I was aware that I might have misunderstood both movement and look entirely.

My next surprise was in the words Mr. Brokenshire addressed to me. He spoke in the soft, slightly nasal staccato which I am told had on his business associates the effect of a whip-lash.

"We've come over to tell you, Miss—Miss Adare, how much we appreciate your attitude toward our boy, Hugh. I understand from him that he's offered to marry you, and that very properly in your situation you've declined. The boy is foolish, as you evidently see. He meant nothing; he could do nothing. You're probably not without experience of a similar kind among the sons of your other employers. At the same time, as you doubtless expect, we sha'n't let you suffer by your prudence—"

It was a bad beginning. Had he made any sort of appeal to me, however unkindly worded, I should probably have yielded. But the tradition of the Fighting Adares was not in me for nothing, and after a smothering sensation which rendered me speechless I managed to stammer out:

"Won't you allow me to say that—"

The way in which his large, white, handsome hand went up was meant to impose silence upon me while he himself went on:

"In order that you may not be annoyed by my son's folly in the future you will leave my daughter's employ, you'll leave Newport—you'll be well advised, indeed, in going back to your own country, which I understand to be the British provinces. You will lose nothing, however, by this conduct, as I've given you to understand. Three—four—five thousand dollars—I think five ought to be sufficient—generous, in fact—"

"But I've not refused him," I was able at last to interpose. "I—I mean to accept him."

There was an instant of stillness during which one could hear the pounding of the sea.

"Does that mean that you want me to raise your price?"

"No, Mr. Brokenshire. I have no price. If it means anything at all that has to do with you, it's to tell you that I'm mistress of my acts and that I consider your son—he's twenty-six—to be master of his."

There was a continuation of the stillness. His voice when he spoke was the gentlest sound I had ever heard in the way of human utterance. If it were not for the situation it could have been considered kind:

"Anything at all that has to do with me? You seem to attach no importance to the fact that Hugh is my son."

I do not know how words came to me. They seemed to flow from my lips independently of thought.

"I attach importance only to the fact that he's a man. Men who are never anything but their father's sons aren't men."

"And yet a father has some rights."

"Yes, sir; some. He has the right to follow where his grown-up children lead. He hasn't the right to lead and require his grown-up children to follow."

He shifted his ground. "I'm obliged to you for your opinion, but at present it's not to the point—"

I broke in breathlessly: "Pardon me, sir; it's exactly to the point. I'm a woman; Hugh's a man. We're—we're in love with each other; it's all we have to be concerned with."

"Not quite; you've got to be concerned—with me."

"Which is what I deny."

"Oh, denial won't do you any good. I didn't come to hear your denials, or your affirmations, either. I've come to tell you what to do."

"But if I know that already?"

"That's quite possible—if you mean to play your game as doubtless you've played it before. I only want to warn you—"

I looked toward Mrs. Brokenshire for help, but her eyes were fixed on the floor, on which she was drawing what seemed like a design with the tip of her parasol. The greyhounds were stretched at her feet. I could do nothing but speak for myself, which I did with a calmness that surprised me.

"Mr. Brokenshire," I interrupted, "you are a man and I'm a woman. What's more, you're a strong man, while I'm a woman with no protection at all. I ask you—do you think you're playing a man's part in insulting me?"

His tone grew kind almost to affection. "My dear young lady, you misunderstand me. Insult couldn't be further from my thoughts. I'm speaking entirely for your own sake. You're young; you're very pretty; I won't say you've no knowledge of the world because I see you have—"

"I've a good deal of knowledge of the world."

"Only not such knowledge as would warrant you in pitting yourself against me."

"But I don't. If you'd leave me alone—"

"Let us keep to what we're talking of. I'm sorry for you; I really am. You're at the beginning of what might euphemistically—do you know the meaning of the word?—be called a career. I should like to save you from it; that's all. It's why I'm speaking to you very plainly and using language that can't be misunderstood. There's nothing original in your proceeding, believe me. Nearly every family of the standing of mine has had to reckon with something of the sort. Where there are young men, and young women of—what do you want me to say?—young women who mean to do the best they can for themselves—let us put it in that way—"

"I'm a gentleman's daughter," I broke in, weakly.

He smiled. "Oh yes; you're all gentlemen's daughters. Neither is there anything original in that."

"Mrs. Rossiter will tell you that my father was a judge in Canada—"

"The detail doesn't interest me."

"No, but it interests me. It gives me a sense of being equal to—"

"If you please! We'll not go into that."

"But I must speak. If I'm to marry Hugh you must let me tell you who I am."

"It's not necessary. You're not to marry Hugh. Let that be absolutely understood. Once you've accepted the fact—"

"I could only accept it from Hugh himself."

"That's foolish. Hugh will do as I tell him."

"But why should he in this case?"

"That again is something we needn't discuss. All that matters, my dear young lady, is your own interest. I'm working for that, don't you see, against yourself—"

I burst out, "But why shouldn't I marry him?"

He leaned on the table, tapping gently with his hand. "Because we don't want you to. Isn't that enough?"

I ignored this. "If it's because you don't know anything about me I could tell you."

"Oh, but we do know something about you. We know, for example, since you compel me to say it, that you're a little person of no importance whatever."

"My family is one of the best in Canada."

"And admitting that that's so, who would care what constituted a good family in Canada? To us here it means nothing; in England it would mean still less. I've had opportunities of judging how Canadians are regarded in England, and I assure you it's nothing to make you proud."

Of the several things he had said to sting me I was most sensitive to this. I, too, had had opportunities of judging, and knew that if anything could make one ashamed of being a British colonial of any kind it would be British opinion of colonials.

"My father used to say—"

He put up his large, white hand. "Another time. Let us keep to the subject before us."

I omitted the mention of my father to insist on a theory as to which I had often heard him express himself: "If it's part of the subject before us that I'm a Canadian and that Canadians are ground between the upper and lower millstones of both English and American contempt—"

"Isn't that another digression?"

"Not really," I hurried on, determined to speak, "because if I'm a sufferer by it, you are, too, in your degree. It's part of the Anglo-Saxon tradition for those who stay behind to despise those who go out as pioneers. The race has always done it. It isn't only the British who've despised their colonists. The people of the Eastern States despised those who went out and peopled the Middle West; those in the Middle West despised those who went farther West." I was still quoting my father. "It's something that defies reason and eludes argument. It's a base strain in the blood. It's like that hierarchy among servants by which the lady's maid disdains the cook, and the cook disdains the kitchen-maid, and the proudest are those who've nothing to be proud of. For you to look down on me because I'm a Canadian, when the commonest of Englishmen, with precisely the same justification, looks down on you—"

"Dear young lady," he broke in, soothingly, "you're talking wildly. You're speaking of things you know nothing about. Let us get back to what we began with. My son has offered to marry you—"

"He didn't offer to marry me. He asked me—he begged me—to marry him."

"The way of putting it is of no importance."

"Ah, but it is."

"I mean that, however he expressed it—however you express it—the result must be the same."

I nerved myself to look at him steadily. "I mean to accept him. When he asked me yesterday I said I wouldn't give him either a Yes or a No till I knew what you and his family thought of it. But now that I do know—"

"You're determined to try the impossible."

"It won't be the impossible till he tells me so."

He seemed for a second or two to study me. "Suppose I accepted you as what you say you are—as a young woman of good antecedents and honorable character. Would you still persist in the effort to force yourself on a family that didn't want you?"

I confess that in the language Mr. Strangways and I had used in the morning, he had me here "on the hip." To force myself on a family that didn't want me would normally have been the last of my desires. But I was fighting now for something that went beyond my desires—something larger—something national, as I conceived of nationality—something human—though I couldn't have said exactly what it was. I answered only after long deliberation.

"I couldn't stop to consider a family. My object would be to marry the man who loved me—and whom I loved."

"So that you'd face the humiliation—"

"It wouldn't be humiliation, because it would have nothing to do with me. It would pass into another sphere."

"It wouldn't be another sphere to him."

"I should have to let him take care of that. It's all I can manage to look out for myself—"

There seemed to be some admiration in his tone.

"Which you seem marvelously well fitted to do."

"Thank you."

"In fact, it's one of the ways in which you betray yourself. An innocent girl—"

I strained forward in my chair. "Wouldn't it be fair for you to tell me what you mean by the word innocent?"

"I mean a girl who has no special ax to grind—"

I could hear my foot tapping on the floor, but I was too indignant to restrain myself. "Even that figure of speech leaves too much to the imagination."

He studied me again. "You're very sharp."

"Don't I need to be," I demanded, "with an enemy of your acumen?"

"But I'm not your enemy. It's what you don't seem to see. I'm your friend. I'm trying to keep you out of a situation that would kill you if you got into it."

I think I laughed. "Isn't death preferable to dishonor?" I saw my mistake in the quickness with which Mrs. Brokenshire looked up. "There are more kinds of dishonor than one," I explained, loftily, "and to me the blackest would be in allowing you to dictate to me."

"My dear young woman, I dictate to men—"

"Oh, to men!"

"I see! You presume on your womanhood. It's a common American expedient, and a cheap one. But I don't stop for that."

"You may not stop for womanhood, Mr. Brokenshire; but neither does womanhood stop for you."

He rose with an air of weary patience. "I'm afraid we sha'n't gain anything by talking further—"

"I'm afraid not." I, too, rose, advancing to the table. We confronted each other across it, while one of the dogs came nosing to his master's hand. I had barely the strength to gasp on: "We've had our talk and you see where I am. I ask nothing but the exercise of human liberty—and the measure of respect I conceive to be due to every one. Surely you, an American, a representative of what America is supposed to stand for, can't think of it as too much."

"If America is supposed to stand for your marrying my son—"

"America stands, so I've been told by Americans, for the reasonable freedom of the individual. If Hugh wants to marry me—"

"Hugh will marry the woman I approve of."

"Then that apparently is what we must put to the test."

I was now so near to tears that I suppose he saw an opening to his own advantage. Coming round the table, he stood looking down at me with that expression which I can only describe as sympathetic. With all the dominating aggressiveness which either forced you to give in to him or urged you to fight him till you dropped, there was that about him which left you with a lingering suspicion that he might be right. It was the man who might be right who was presently sitting easily on the edge of the table, so that his face was on a level with my own, and saying in a kindly voice:

"Now look here! Let's be reasonable. I don't want to be unfair to you, or to say anything a man isn't justified in saying to a woman. I'm willing to throw the whole blame on Hugh—"

"I'm not," I declared, hotly.

"That's generous; but I'm speaking of myself. I'm willing to throw the whole blame on Hugh, because he's my son. I'll absolve you, if you like, because you're a stranger and a girl, and consider you a victim—"

"I'm not a victim," I insisted. "I'm only a human being, asking for a human being's rights."

He shrugged his shoulders. "Oh, rights! Who knows what rights are?"

"I do. That is," I corrected, "I know my own."

"Oh, of course! One always knows one's own. One's own rights are everything one can get. Now you can't get Hugh; but you can get five thousand dollars. That's a lot of money. There are men all over the United States who'd cut off a hand for it. You won't have to cut off a hand. You only need to be a good, sensible little girl and—get out." Perhaps he thought I was yielding, for he tapped his side pocket as he went on speaking. "It won't take a minute. I've got a check-book here—a stroke of the pen—"

My work was lying on the table a few inches away. Leaning forward deliberately I put it into the basket, which I tucked under my arm. I looked at Mrs. Brokenshire, who was leaning forward and looking at me. I inclined my head with a slight salutation, to which she did not respond, and turned away. Of him I took no notice.

"So it's war."

I was half-way to the dining-room when I heard him say that. As I paused to look back he was still sitting sidewise on the edge of the table, swinging a leg and staring after me.

"No, sir," I said, quietly. "It takes two to fight, and I should never think of being one."

"You know, of course, that I shall have no mercy on you."

"No, sir; I don't."

"Then you can know it now. I'm sorry for you; but I can't afford to spare you. Bigger things than you have come in my way—and have been blasted."

Mrs. Brokenshire made a quick little movement behind his back. It told me nothing I understood then, though I was able to interpret it later. I could only say, in a voice that shook with the shaking of my whole body:

"You couldn't blast me, sir, because—because—"

"Yes? Because—what? I should like to know."

There was a robin hopping on the lawn outside and I pointed to it. "You couldn't blast a little bird like that with a bombshell."

"Oh, birds have been shot."

"Yes, sir; with a fowling-piece; but not with a howitzer. The one is too big; the other is too small."

I was about to drop him a little courtesy when I saw him wink. It was a grotesque, amusing wink that quivered and twisted till it finally closed the left eye. If he had been a less handsome man the effect would have been less absurd.

I made my courtesy the deeper, bending my head and lowering my eyes so as to spare him the knowledge that I saw.

"He attacked my country. I think I could forgive him everything but that."

It was an hour after Mr. and Mrs. Brokenshire had left me. I was half crying by this time—that is, half crying in the way one cries from rage, and yet laughing nervously, in flashes, at the same time. From the weakness of sheer excitement I had dropped to one of the steps leading down to the Cliff Walk, while Larry Strangways leaned on the stone post. I had met him there as I was going out and he was coming toward the house. We couldn't but stop to exchange a word, especially with his knowledge of the situation. He took what I had to say with the light, gleaming, non-committal smile which he brought to bear on everything. I was glad of that because it kept him detached. I didn't want him any nearer to me than he was.

"Attacked your country? Do you mean England?"

"No; Canada. England is my grandmother; but Canada's my mother. He said you all despised her."

"Oh no, we don't. He was trying to put something over on you."

"Your 'No, we don't' lacks conviction; but I don't mind you. I shouldn't mind him if I hadn't seen so much of it."

"So much of what?"

"Being looked down upon geographically. Of all the ways of being proud," I declared, indignantly, "that which depends on your merely accidental position with regard to land and water strikes me as the most poor-spirited. I can't imagine any one dragging himself down to it who had another rag of a reason for self-respect. As a matter of fact, I don't believe any one ever does. The people I've heard express themselves on the subject—well, I'll give you an illustration: There was a woman at Gibraltar—a major's wife, a big, red-faced woman. Her name was Arbuthnot—her father was a dean or something—a big, red-faced woman, with one of those screechy, twangy English voices that cut you like a saw—you know there are some—a good many—and they don't know it. Well, she was saying something sneering about Canadians. I was sitting opposite—it was at a dinner-party—and so I leaned across the table and asked her why she didn't like them. She said colonials were such dreadful form. I held her with my eye"—I showed him how—"and made myself small and demure as I said, 'But, dear lady, how clever of you! Who would ever have supposed that you'd know that?' My sister Vic pitched into me about it after we got home. She said the Arbuthnot person didn't understand what I meant—nor any one else at the table, they're so awfully thick-skinned—and that it's better to let them alone. But that's the kind of person who—"

He tried to comfort me. "They'll come round in time. One of these days England will see what she owes to her colonists and do them justice."

"Never!" I declared, vehemently. "It will be always the same—till we knock the Empire to pieces. Then they'll respect us. Look at the Boer War. Didn't our men sacrifice everything to go out that long distance—and win battles—and lay down their lives—only to have the English say afterward—especially the army people—that they were more trouble than they were worth? It will be always the same. When we've given our last penny and shed our last drop of blood they'll still tell us we've been nothing but a nuisance. You may live to see it and remember that I said so. If when Shakespeare wrote that it's sharper than a serpent's tooth to have a thankless child he'd gone on to add that it's the very dickens to have a picturesque, self-satisfied old grandmother who thinks her children's children should give her everything and take kicks instead of ha'pence for their pay, he'd have been up to date. Mind you, we don't object to giving our last penny and shedding our last drop of blood; we only hate being abused and sneered at for doing it."

I warmed to my subject as I dabbed fiercely at my eyes.

"I'll tell you what the typical John Bull is like. He's like those men—big, flabby men they generally are—who'll be brutes to you so long as you're civil to them, but will climb down the minute you begin to hit back. Look at the way they treat you Americans! They can't do enough for you—because you snap your fingers in their faces and show them you don't care a hang about them. They come over here, and give you lectures, and marry your girls, and pocket your money, and adopt your bad form as delightful originality—and respect you. Now that earls' daughters are beginning to cast an eye on your millionaires—Mrs. Rossiter told me that—they won't leave you a rag to your back. But with us who've been faithful and loyal they're all the other way. I can hardly tell you the small pin-pricking indignities to which my sisters and I have been subjected for being Canadians. And they'll never change. It will never be otherwise, no matter what we do, no matter what we become, no matter if we give our bodies to be burned, as the Bible says. It will never be otherwise—not till we imitate you and strike them in the face. Then you'll see how they'll come round."[1]

He still smiled, with an aloofness in which there was a beam of sweetness. "I had no idea that you were such a little rebel."

"I'm not a rebel. I'm loyal to the King. That is, I'm loyal to the great Anglo-Saxon ideal of which the King is the symbol—and I suppose he's as good a symbol as any other, especially as he's already there. The English are only partly Anglo-Saxon. 'Saxon and Norman and Dane are they'—didn't Tennyson say that? Well, there's a lot that's Norman, and a lot that's Dane, and a lot that's Scotch and Irish and rag-tag in them. But they're saved by the pure Anglo-Saxon ideal in so far as they hold to it—just as you'll be, with all your mixed bloods—and just as we shall be ourselves. It's like salt in the meat, it's like grace in the Christian religion—it's the thing that saves, and I'm loyal to that. My father used to say that it's the fact that English and Canadians and Australians are all devoted to the same principle that holds us together as an Empire, and not the subservience of distant lands to a Parliament sitting at Westminster. And so it is. We don't always like each other; but that doesn't matter. What does matter is that we should betray the fact that we don't like each other to outsiders—and so give them a handle against us."

"You mean that J. Howard should be in a position to side with the English in looking down on you as a Canadian?"

"Yes, and that the English should give him that position. He's an American and an enemy—every American is an enemy to England au fond. Oh yes, he is! You needn't deny it! It's something fundamental, deeper down than anything you understand. Even those of you who like England are hostile to her at heart and would be glad to see her in trouble. So, I say, he's an American and an enemy, and yet they hand me, their child and their friend, over to him to be trampled on. He's had opportunities of judging how Canadians are regarded in England, he says—and he assures me it's nothing to be proud of. That's it. I've had opportunities too—and I have to admit that he's right. Don't you see? That's what enrages me. As far as their liking us and our not liking them is concerned, why, it's all in the family. So long as it's kept in the family it's like the pick that Louise and Vic have always had on me. I'm the youngest and the plainest—"

"Oh, you're the plainest, are you? What on earth are they like?"

"They're quite good-looking, and they're awfully chic. But that's in parentheses. What I mean is that they're always hectoring me because I'm not attractive—"

"Really?"

"I'm not fishing for compliments. I'm too busy and too angry for that. I want to go on talking about what we're talking about."

"But I want to know why they said you were unattractive."

"Well, perhaps they didn't say it. What they have said is this, and it's what Mrs. Rossiter says—she said it to-day—that I'm only attractive to one man in five hundred—"

"But very attractive to him?"

"No; she didn't say that. She merely admitted that her brother Hugh was that man—"

He interrupted with something I wished at the time he hadn't said, and which I tried to ignore:

"He's the man in that five hundred—and I know another in another five hundred, which makes two in a thousand. You'd soon get up to a high percentage, when you think of all the men there are in the world."

As he had never hinted at anything of the kind before, it gave me—how shall I put it?—I can only think of the word fright—it gave me a little fright. It made me uneasy. It was nothing, really. It was spoken with that gleaming smile of his which seemed to put distance between him and me—between him and everything else that was serious—and yet subconsciously I felt as one feels on hearing the first few notes, in an opera or a symphony, of that arresting phrase which is to work up into a great motive. I tried to get back to my original theme, rising to move on as I did so.

"Good gracious!" I cried. "Isn't the world big enough for us all? Why should we go about saying unkind and untrue things of one other, when each of us is an essential part of a composite whole? Isn't it the foot saying to the hand I have no need of thee, and the eye saying the same thing to the nose? We've got something you haven't got, and you've got something we haven't got. Why shouldn't we be appreciative toward each other, and make our exchange with mutual respect as we do with trade commodities?"

It was probably to urge me on to talk that he said, with a challenging smile: "What have you Canadians got that we haven't? Why, we could buy and sell you."

"Oh no, you couldn't; because our special contribution toward the civilization of the American continent isn't a thing for sale. It can be given; it can be inherited; it can be caught; but it can't be purchased."

"Indeed? What is this elusive endowment?"

I answered frankly enough: "I don't know. It's there—and I can't tell you what it is. Ever since I've been living among you I've felt how much we resemble each other—what a difference. I think—mind you, I only think—that what it consists in is a sense of the comme il faut. We're simpler than you; and less intellectual; and poorer, of course; and less, much less, self-analytical; and yet we've got a knowledge of what's what that you couldn't command with money. None of the Brokenshires have it at all, and, as far as I can see, none of their friends. They command it with money, and the difference is like having a copy of a work of art instead of the original. It gives them the air of being—I'm using Mrs. Rossiter's word—of being produced. Now we Canadians are not produced. We just come—but we come the right way—without any hooting or tooting or beating of tin pans or self-advertisement. We just are—and we say nothing about it. Let me make an example of what Mrs. Rossiter was discussing this morning. There are lots of pretty girls in my country—as many to the hundred as you have here—but we don't make a fuss about them or talk as if we'd ordered a special brand from the Creator. We grow them as you grow flowers in a garden, at the mercy of the air and sunshine. You grow yours like plants in a hothouse, to be exhibited in horticultural shows. Please don't think I'm bragging—"

He laughed aloud. "Oh no!"

"Well, I'm not," I insisted. "You asked me a question and I'm trying to answer it—and incidentally to justify my own existence, which J. Howard has called into question. You've got lots to offer us, and many of us come and take it thankfully. What we can offer to you is a simpler and healthier and less self-conscious standard of life, with a great deal less talk about it—with no talk about it at all, if you could get yourselves down to that—and a willingness to be instead of an everlasting striving to become. You won't recognize it or take it, of course. No one ever does. Nations seem to me insane, and ruled by insane governments. Don't the English need the Germans, and the Germans the French, and the French the Austrians, and the Austrians the Russians, and so on? Why on earth should the foot be jealous of the nose? But there! You're simply making me say things—and laughing at me all the while—so I'm off to take my walk. We'll get even with J. Howard and all the first-class powers some day, and till then—au revoir."

I had waved my hand to him and gone some paces into the fog that had begun to blow in when he called to me.

"Wait a minute. I've something to tell you."

I turned, without going back.

"I'm—I'm leaving."

I was so amazed that I retraced a step or two toward him. "What?"

His smile underwent a change. It grew frozen and steely instead of being bright with a continuous play suggesting summer lightning, which had been its usual quality.

"My time is up at the end of the month—and I've asked Mr. Rossiter not to expect me to go on."

I was looking for something of the sort sooner or later, but now that it had come I saw how lonely I should be.

"Oh! Where are you going? Have you got anything in particular?"

"I'm going as secretary to Stacy Grainger."

"I've some connection with that name," I said, absently, "though I can't remember what it is."

"You've probably heard of him. He's a good deal in the public eye."

"Have you known him long?" I asked, for the sake of speaking, though I was only thinking of myself.

"Never knew him at all." He came nearer to me. "I've a confession to make, though it won't be of interest to you. All the while I've been here, playing with little Broke Rossiter, I've been—don't laugh—I've been contributing to the press—moi qui vous parle!"

"What about?"

"Oh, politics and finance and foreign policy and public things in general. Always had a taste that way. Now it seems that something I wrote for the Providence Express—people read it a good deal—has attracted the attention of the great Stacy. Yes, he's great, too—J. Howard's big rival for—"

I began to recall something I had heard. "Wasn't there a story about him and Mr. Brokenshire and Mrs. Brokenshire?"

"That's the man. Well, he's noticed my stuff, and written to the editor—and to me, and I'm to go to him."

I was still thinking of myself and the loss of his camaraderie. "I hope he's going to pay you well."

"Oh, for me it will be wealth."

"It will probably be more than that. It will be the first long step up."

He nodded confidently. "I hope so."

I had again begun to move away when he stopped me the second time.

"Miss Adare, what's your first name? Mine's Lawrence, as you know."

If I laughed a little it was to conceal my discomfort at this abrupt approach to the intimate.

"I'm rather sorry for my name," I said, apologetically. "You see my father was one of those poetically loyal Canadians who rather overdo the thing. My eldest sister should have been Victoria, because Victoria was the queen. But the Duchess of Argyll was in Canada at that time—and very nice to father and mother—and so the first of us had to be Louise. He couldn't begin on the queens till there was a second one. That's poor Vic; while I'm—I know you'll shout—I'm Alexandra. If there'd been a fourth she'd have been a Mary; but poor mother died and the series stopped."

He shook hands rather gravely. "Then I shall think of you as Alexandra."

"If you are going to think of me at all," I managed to say, with a little moue, "put me down as Alix. That's what I've always been called."

I was glad of the fog. It was cool and refreshing; it was also concealing. I could tramp along under its protection with little or no fear of being seen. Wearing tweeds, thick boots, and a felt hat, I was prepared for wet, and as a Canadian girl I was used to open air in all weathers. The few stragglers generally to be seen on the Cliff Walk having rushed to their houses for shelter, I had the rocks and the breakers, the honeysuckle and the patches of dog-roses, to myself. In the back of my mind I was fortified, too, by the knowledge that dampness curls my hair into pretty little tendrils, so that if I did meet any one I should be looking at my best.

The path is like no other in the world. I have often wondered why the American writer-up of picturesque bits didn't make more of it. Trouville has its Plage, and Brighton its King's Road, and Nice its Promenade des Anglais, but in no other kingdom of leisure that I know anything about will you find the combination of qualities, wild and subdued, that mark this ocean-front of the island of Aquidneck. Neither will you easily come elsewhere so near to a sense of the primitive human struggle, of the crude social clash, of the war of the rights of man—Fisherman's Rights, as this coast historically knows them—against encroachment, privilege, and seclusion. As you crunch the gravel, and press the well-rolled turf, and sniff the scent of the white and red clover and Queen Anne's lace that fringe the precipice leaning over the sea, you feel in the air those elements of conflict that make drama.

In clinging to the edge of the cliff, in twisting round every curve of the shore line, in running up hill and down dale, under crags and over them, the path is, of course, not the only one of its kind. You will find the same thing anywhere on the south coast of England or the north coast of France. But in the sum of human interest it sucks into the three miles of its course I can think of nothing else that resembles it. As guaranteeing the rights of the fisherman it is, so I believe, inalienable public property. The fisherman can walk on it, sit on it, fish from it, right into eternity. So much he has secured from the past history of colony and state; but he has done it at the cost of making himself offensive to the gentlemen whose lawns he hems as a seamstress hems a skirt.

It is a hem like a serpent, with a serpent's sinuosity and grace, but also with a serpent's hatefulness to those who can do nothing but accept it as a fact. Since, as a fact, it cannot be abolished it has to be put up with; and since it has to be put up with the means must needs be found to deal with it effectively. Effectively it has been dealt with. Money, skill, and imagination have been spent on it, to adorn it, or disguise it, or sink it out of sight. The architect, the landscape gardener, and the engineer have all been called into counsel. On Fisherman's Rights the smile and the frown are exercised by turns, each with its phase of ingenuity. Along one stretch of a hundred yards bland recognition borders the way with roses or spans the miniature chasms with decorative bridges; along the next shuddering refinement grows a hedge or digs a trench behind which the obtrusive wayfarer may pass unseen. But shuddering refinement and bland recognition alike withdraw into themselves as far as broad lawns and lofty terraces permit them to retire, leaving to the owner of Fisherman's Rights the enjoyment of ocher and umber rocks and sea and sky and grain-fields yellowing on far headlands.

It gave me the nearest thing to glee I ever felt in Newport. It was bracing and open and free. It suggested comparisons with scrambles along Nova-Scotian shores or tramps on the moors in Scotland. I often hated the fine weather; it was oppressive; it was strangling. But a day like this, with its whiffs of wild wind and its handfuls of salt slashing against eyes and mouth and nostrils, was not only exhilarating, it was glorious. I was glad, too, that the prim villas and pretentious châteaux, most of them out of proportion to any scale of housekeeping of which America is capable, could only be descried like castles in a dream through the swirling, diaphanous drift. I could be alone to rage and fume—or fly onward with a speed that was in itself a relief.

I could be alone till, on climbing the slope of a shorn and wind-swept bluff, I saw a square-shouldered figure looming on the crest. It was no more than a deepening of the texture of the fog, but I knew its lines. Skimming up the ascent with a little cry, I was in Hugh's arms, my head on his burly breast.

I think it was his burliness that made the most definite appeal to me. He was so sturdy and strong, and I was so small and desolate. From the beginning, when he first used to come near me, I felt his presence, as the Bible says, like the shadow of a rock in a thirsty land. That was in my early homesick time, before I had seized the new way of living and the new national point of view. The fact, too, that, as I expressed it to myself, I was in the second cabin when I had always been accustomed to the first, inspired a discomfort for which unwittingly I sought consolation. Nobody thought of me as other than Mrs. Rossiter's retainer, but this one kindly man.

I noticed his kindliness almost before I noticed him, just as, I think, he noticed my loneliness almost before he noticed me. He opened doors for me when I went in or out; he served me with things if he happened to be there at tea; he dropped into a chair beside me when I was the only member of a group whom no one spoke to. If Gladys was of the company I was of it too, with a nominal footing but a virtual exclusion. The men in the Rossiter circle were of the four hundred and ninety-nine to whom I wasn't attractive; the women were all civil—from a distance. Occasionally some nice old lady would ask me where I came from and if I liked my work, or talk to me of new educational methods in a way which, with my bringing up, was to me as so much Greek; but I never got any other sign of friendliness. Only this short, stockily built young fellow, with the small, blue eyes, ever recognized me as a human being with the average yearning for human intercourse.