The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rambles and Studies in Greece by J. P. Mahaffy

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Rambles and Studies in Greece Author: J. P. Mahaffy Release Date: February 16, 2011 [Ebook #35298] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAMBLES AND STUDIES IN GREECE***

HUNC LIBRUM

Edmundo Wyatt Edgell

OB INSIGNEM

INTER CASTRA ITINERA OTIA NEGOTIA LITTERARUM AMOREM

OLIM DEDICATUM

NUNC CARISSIMI AMICI MEMORIAE

CONSECRAT AUCTOR

PREFACE.

Few men there are who having once visited Greece do not contrive to visit it again. And yet when the returned traveller meets the ordinary friend who asks him where he has been, the next remark is generally, “Dear me! have you not been there before? How is it you are so fond of going to Greece?” There are even people who imagine a trip to America far more interesting, and who at all events look upon a trip to Spain as the same kind of thing—southern climate, bad food, dirty inns, and general discomfort, odious to bear, though pleasant to describe afterward in a comfortable English home.

This is a very ignorant way of looking at the matter, for excepting Southern Italy, there is no country which can compare with Greece in beauty and interest to the intelligent traveller. It is not a land for creature comforts, though the climate is splendid, and though the hotels in Athens are as good as those in most European towns. It is not a land for society, though the society at Athens is excellent, and far easier of access than that of most European capitals. But if a man is fond of the large [pg viii]effects of natural scenery, he will find in the Southern Alps and fiords of Greece a variety and a richness of color which no other part of Europe affords. If he is fond of the details of natural scenery, flowers, shrubs, and trees, he will find the wild-flowers and flowering-trees of Greece more varied than anything he has yet seen. If he desires to study national character, and peculiar manners and customs, he will find in the hardy mountaineers of Greece one of the most unreformed societies, hardly yet affected by the great tide of sameness which is invading all Europe in dress, fabrics, and usages. And yet, in spite of the folly still talked in England about brigands, he will find that without troops, or police, or patrols, or any of those melancholy safeguards which are now so obtrusive in England and Ireland, life and property are as secure as they ever were in our most civilized homes. Let him not know a word of history, or of art, and he will yet be rewarded by all this natural enjoyment; perhaps also, if he be a politician, he may study the unsatisfactory results of a constitution made to order, and of a system of free education planted in a nation of no political training, but of high intelligence.

Need I add that as to Cicero the whole land was one vast shrine of hallowed memories—quocunque incedis, historia est—so to the man of culture this splendor of associations has only increased with the lapse of time and the greater appreciation of human [pg ix]perfection. Even were such a land dead to all further change, and a mere record in its ruins of the past, I know not that any man of reflection could satisfy himself with contemplating it. Were he to revisit the Parthenon, as it stands, every year of his life, it would always be fresh, it would always be astonishing. But Greece is a growing country, both in its youth and in its age. The rapid development of the nation is altering the face of the country, establishing new roads and better communications, improving knowledge among the people, and making many places accessible which were before beyond the reach of brief holiday visits. The insecurity which haunted the Turkish frontier has been pushed back to the north; new Alps and new monasteries are brought within the range of Greece. And this is nothing to what has been done in recovering the past. Every year there are new excavations made, new treasures found, new problems in archæology raised, old ones solved; and so at every visit there is a whole mass of new matter for the student who feels he had not yet grasped what was already there.

The traveller who revisits the country now after a lapse of four or five years will find at Athens the Schliemann museum set up and in order, where the unmatched treasures of Mycenæ are now displayed before his astonished eyes. He will find an Egyptian museum of extraordinary merit—the gift of a patriotic merchant of Alexandria—in which there [pg x]are two figures—that of a queen, in bronze and silver, and that of a slave kneading bread, in wood—which alone would make the reputation of any collection throughout Europe. In the Parthenon museum he will find the famous statuette, copied from Phidias’s Athene, and the recent wonder, archaic statues on which the brightness of the colors is not more astonishing than the moulding of the figures.

And these are only the most salient novelties. It is indeed plain that were not the new city covering the site of the old, discoveries at Athens might be made perhaps every year, which would reform and enlarge our knowledge of Greek life and history.

But Athens is rapidly becoming a great and rich city. It already numbers 110,000, without counting the Peiræus; accordingly, except in digging foundations for new houses, it is not possible to find room for any serious excavations. House rent is enormously high, and building is so urgent that the ordinary mason receives eight to ten francs per day. This rapid increase ought to be followed by an equal increase in the wealth of the surrounding country, where all the little proprietors ought to turn their land into market-gardens. I found that either they could not, or (as I was told) they would not, keep pace with the increased wants of the city. They are content with a little, and allow the city to be supplied—badly and at great cost—from Salonica, [pg xi]Syra, Constantinople, and the islands, while meat comes in tons from America. How different is the country round Paris and London!

But this is a digression into vulgar matters, when I had merely intended to inform the reader what intellectual novelties he would find in revisiting Athens. For nothing is more slavish in modern travel than the inability the student feels, for want of time in long journeys, or want of control over his conveyance, to stop and examine something which strikes him beside his path. And that is the main reason why Oriental—and as yet Greek—travelling is the best and most instructive of all.

You can stop your pony or mule, you can turn aside from the track which is called your road, you are not compelled to catch a train or a steamer at a fixed moment. When roads and rails have been brought into Greece, hundreds of people will go to see its beauty and its monuments, and will congratulate themselves that the country is at last accessible. But the real charm will be gone. There will be no more riding at dawn through orchards of oranges and lemons, with the rich fruit lying on the ground, and the nightingales, that will not end their exuberant melody, still outsinging from the deep-green gloom the sounds of opening day. There will be no more watching the glowing east cross the silver-gray glitter of dewy meadows; no more wandering along grassy slopes, where the scarlet anemones, all [pg xii]drenched with the dews of night, are striving to raise their drooping heads and open their splendid eyes to meet the rising sun. There will be no more watching the serpent and the tortoise, the eagle and the vulture, and all the living things whose ways and habits animate the sunny solitudes of the south. The Greek people now talk of going to Europe, and coming from Europe, justly too, for Greece is still, as it always was, part of the East. But the day is coming when enlightened politicians, like Mr. Tricoupi, will insist on introducing through all the remotest glens the civilization of Europe, with all its benefits forsooth, but with all its shocking ugliness, its stupid hurry, and its slavish uniformity.

I will conclude with a warning to the archæologist, and one which applies to all amateurs who go to visit excavations, and cannot see what has been reported by the actual excavators. As no one is able to see what the evidences of digging are, except the trained man, who knows not only archæology, but architecture, and who has studied the accumulation of soil in various places and forms, so the observer who comes to the spot after some years, and expects to find all the evidences unchanged, commits a blunder of the gravest kind. As Dr. Dörpfeld, now one of the highest living authorities on such matters, observed to me, if you went to Hissarlik expecting to find there clearly marked the various strata of successive occupations, you would show that you were [pg xiii]ignorant of the first elements of practical knowledge. For in any climate, but especially in these southern lands, Nature covers up promptly what has been exposed by man; all sorts of plants spring up along and across the lines which in the cutting when freshly made were clear and precise. In a few years the whole place turns back again into a brake, or a grassy slope, and the report of the actual diggers remains the only evidence till the soil is cut open again in the same way. I saw myself, at Olympia, important lines disappearing in this way. Dr. Purgold showed me where the line marking the embankment of the stadium—it was never surrounded with any stone seats—was rapidly becoming effaced, and where the plan of the foundations was being covered with shrubs and grass. The day for visiting and verifying the Trojan excavations is almost gone by. That of all the excavations will pass away, if they are not carefully kept clear by some permanent superintendence; and to expect this of the Greek nation, who know they have endless more treasures to find in new places, is more than could reasonably be expected. The proper safeguard is to do what Dr. Schliemann does, to have with him not only the Greek ephoros or superintendent—generally a very competent scholar, and sometimes not a very friendly witness of foreign triumphs—but also a first-rate architect, whose joint observation will correct any hastiness or misprision, [pg xiv]and so in the mouth of two or more witnesses every word will be confirmed.

In passing on I cannot but remark how strange it is that among the many rich men in the world who profess an interest in archæology, not one can be found to take up the work as Dr. Schliemann did, to enrich science with splendid fields of new evidence, and illustrate art, not only with the naïve efforts of its infancy, but with forgotten models of perfect and peerless form.

This New Edition is framed with a view of still satisfying the demand for the book as a traveller’s handbook, somewhat less didactic than the official guide-books, somewhat also, I hope, more picturesque. For that purpose I have added a new chapter on mediæval Greece, as well as many paragraphs with new information, especially the ride over Mount Erymanthus, pp. 343, sqq. I have corrected many statements which are now antiquated by recent discoveries, and I have obliterated the traces of controversy borne by the Second Edition. For the criticisms on the book are dead, while the book survives. To me it is very pleasant to know that many visitors to Greece have found it an agreeable companion.

February, 1892.

CONTENTS.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Introduction—First Impressions of the Coast | 1 |

| II. | General Impressions of Athens and Attica | 30 |

| III. | Athens—The Museums—The Tombs | 55 |

| IV. | The Acropolis of Athens | 89 |

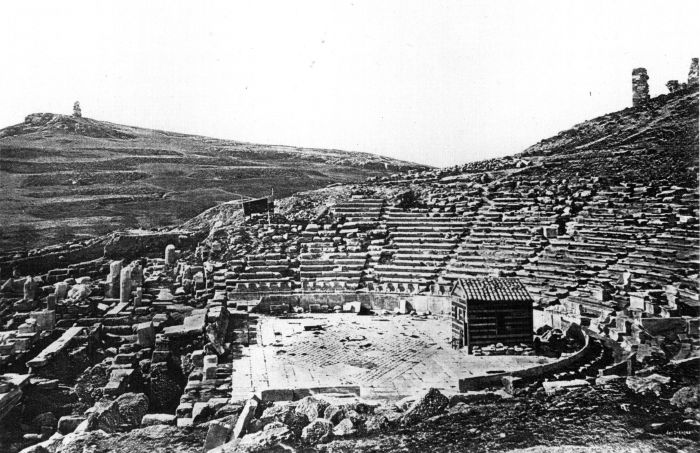

| V. | Athens—The Theatre of Dionysus—The Areopagus | 122 |

| VI. | Excursions in Attica—Colonus—The Harbors—Laurium—Sunium | 152 |

| VII. | Excursions in Attica—Pentelicus—Marathon—Daphne—Eleusis | 184 |

| VIII. | From Athens To Thebes—The Passes of Parnes and of Cithæron, Eleutheræ, Platæa | 215 |

| IX. | The Plain of Orchomenus, Livadia, Chæronea | 248 |

| X. | Arachova—Delphi—The Bay of Kirrha | 274 |

| XI. | Elis—Olympia and Its Games—The Valley of the Alpheus—Mount Erymanthus—Patras | 299 |

| XII. | Arcadia—Andritzena—Bassæ—Megalopolis—Tripolitza | 351 |

| XIII. | Corinth—Tiryns—Argos—Nauplia—Hydra—Ægina—Epidaurus | 388 |

| XIV. | Kynuria—Sparta—Messene | 435 |

| XV. | Mycenæ and Tiryns | 456 |

| XVI. | Mediæval Greece | 492 |

| INDEX | 531 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

Photogravures by A. W. Elson & Co.

| PAGE | |

| The Acropolis, Athens | Frontispiece |

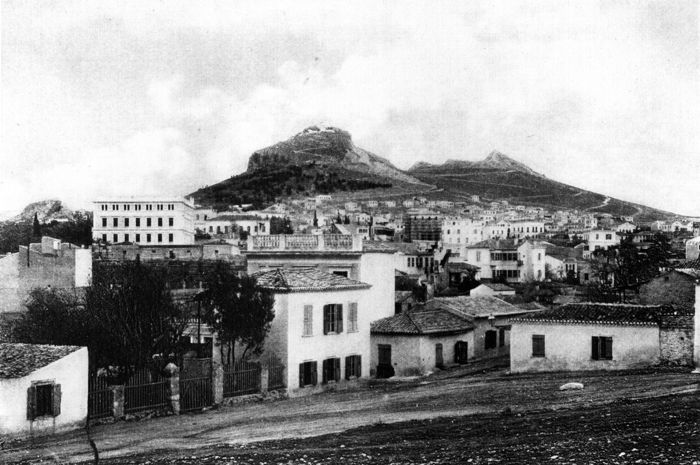

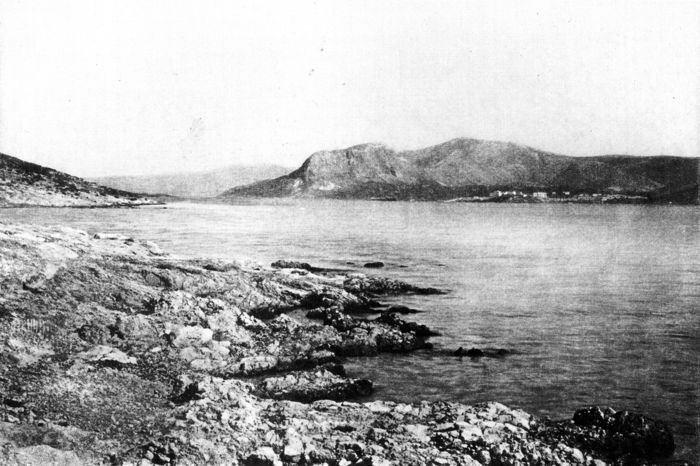

| Along the Coast from the Throne of Xerxes | 30 |

| The Erechtheum from the West, Athens | 36 |

| A Tomb from the Via Sacra, Athens | 78 |

| Part of the West Frieze of the Parthenon, Athens | 110 |

| Theatre of Dionysus, Athens | 122 |

| Mars’ Hill, Athens | 140 |

| The Peiræus | 160 |

| Laurium | 168 |

| Mount Lycabettus, Athens | 188 |

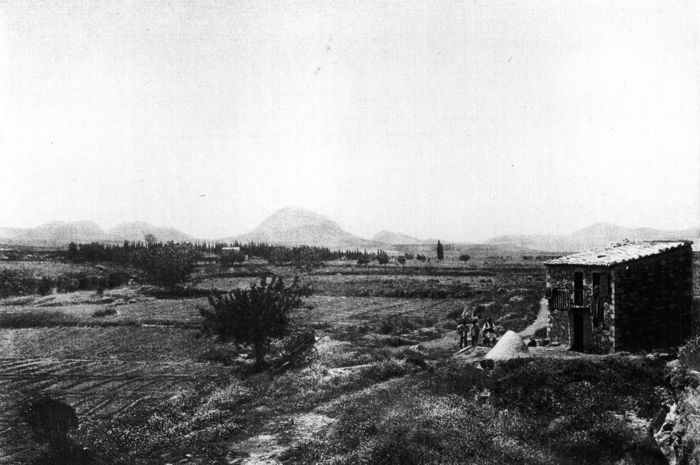

| Looking Toward the Sea from the Soros, Marathon | 198 |

| Salamis, from across the Bay | 206 |

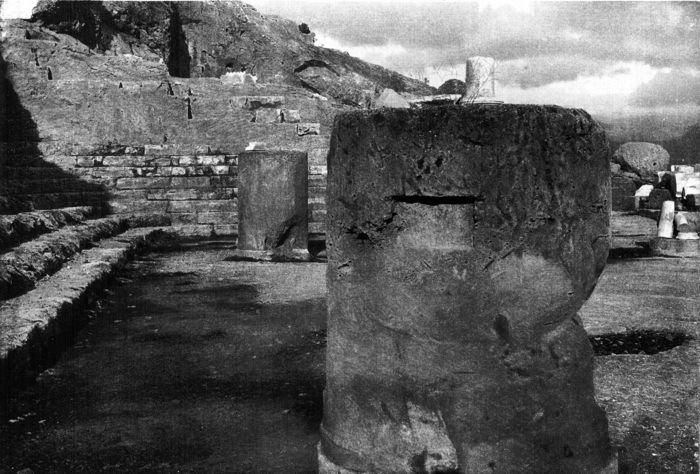

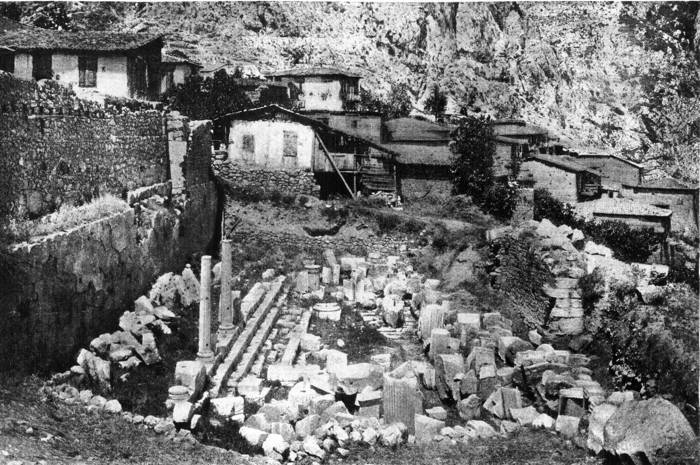

| Temple of Mysteries, Eleusis | 212 |

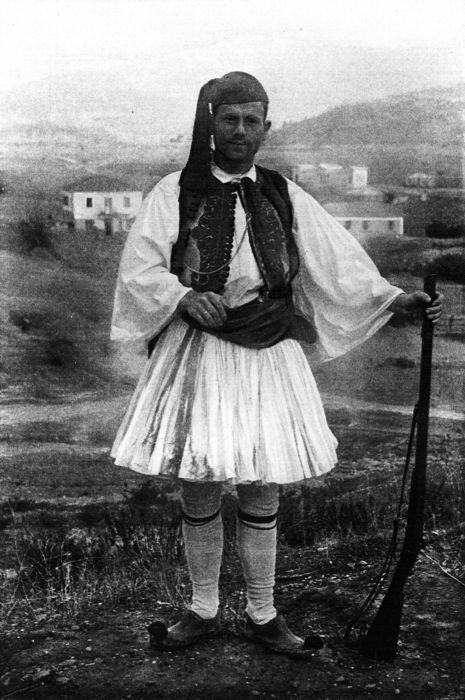

| A Greek Shepherd, Olympia | 274 |

| The Temple of Apollo, Delphi | 284 |

| The Banks of the Kladeus | 302 |

| Statue of Niké, by Pæonius | 306 |

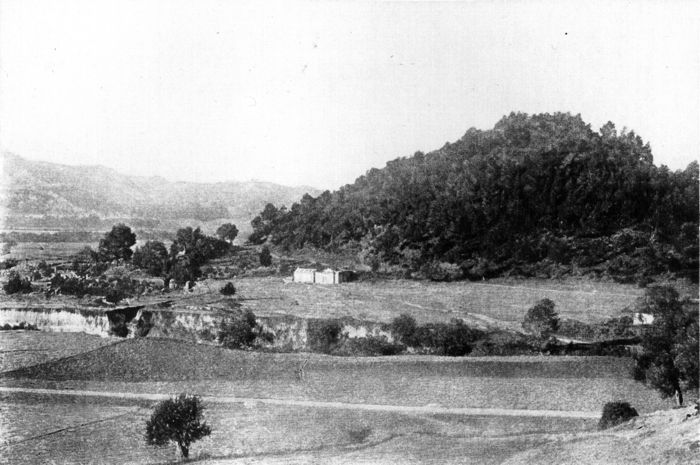

| Kronion Hill, Olympia | 318 |

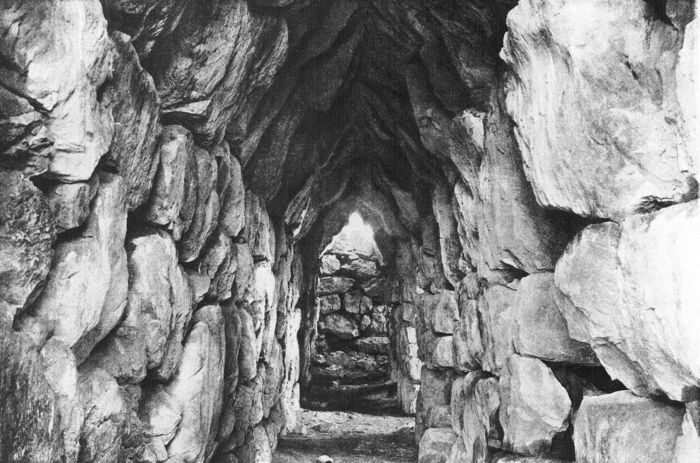

| Entrance to the Stadium, Olympia | 330 |

| The Valley of the Alpheus | 342 |

| A Greek Peasant in National Costume | 380 |

| Temple of Corinth | 392 |

| Scene near Corinth, the Acro-Corinthus in the distance | 395 |

| Gallery at Tiryns | 406 |

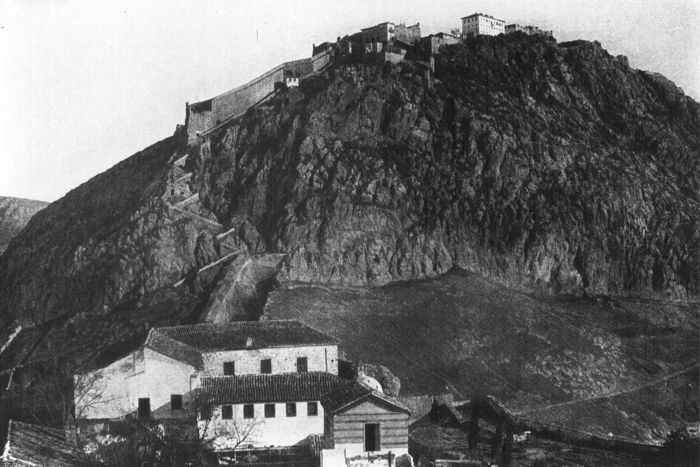

| The Palamedi, Nauplia | 424 |

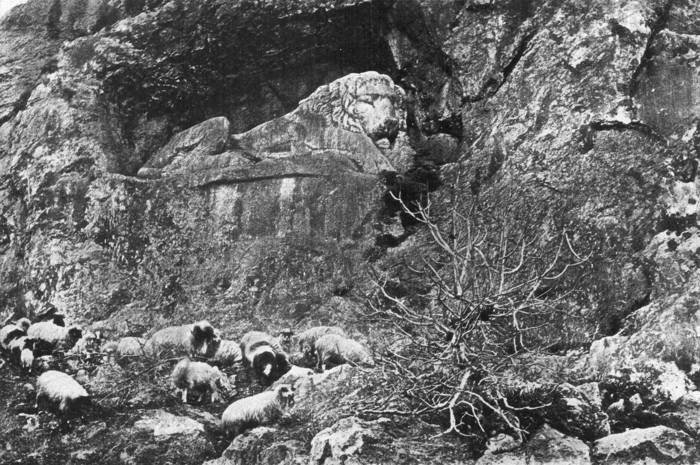

| Sculptured Lion, Nauplia | 428 |

| Langada Pass | 446 |

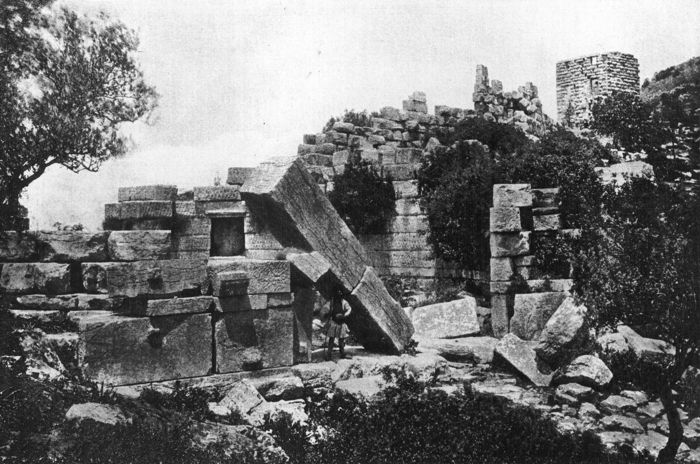

| Arcadian Gateway, Messene | 452 |

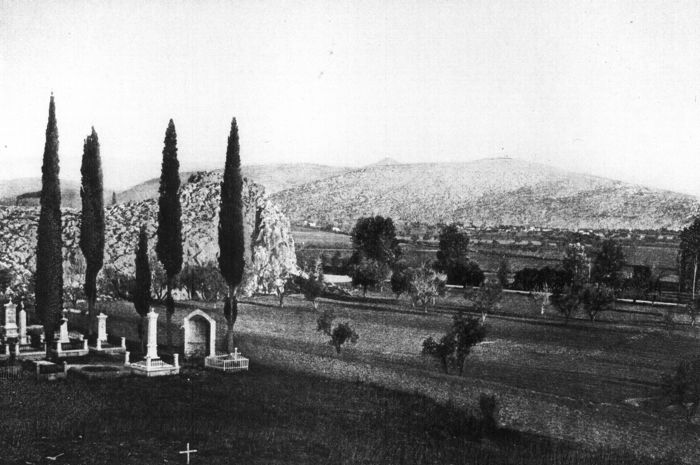

| The Argive Plain | 458 |

| Lion Gate, Mycenæ | 472 |

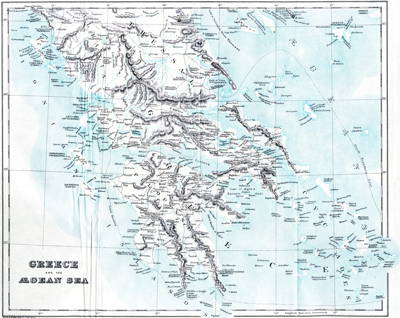

GREECE.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTION—FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF THE COAST.

A voyage to Greece does not at first sight seem a great undertaking. We all go to and fro to Italy as we used to go to France. A trip to Rome, or even to Naples, is now an Easter holiday affair. And is not Greece very close to Italy on the map? What signifies the narrow sea that divides them? This is what a man might say who only considered geography, and did not regard the teaching of history. For the student of history cannot look upon these two peninsulas without being struck with the fact that they are, historically speaking, turned back to back; that while the face of Italy is turned westward, and looks towards France and Spain, and across to us, the face of Greece looks eastward, towards Asia Minor and towards Egypt. Every great city in Italy, except Venice, approaches or borders the Western Sea—Genoa, Pisa, Florence, Rome, Naples. All the older history of Rome, its [pg 2]development, its glories, lie on the west of the Apennines. When you cross them you come to what is called the back of Italy; and you feel that in that flat country, and that straight coast-line, you are separated from its true beauty and charm.1 Contrariwise, in Greece, the whole weight and dignity of its history gravitate towards the eastern coast. All its great cities—Athens, Thebes, Corinth, Argos, Sparta—are on that side. Their nearest neighbors were the coast cities of Asia Minor and of the Cyclades, but the western coasts were to them harborless and strange. If you pass Cape Malea, they said, then forget your home.

So it happens that the coasts of Italy and Greece, which look so near, are outlying and out-of-the way parts of the countries to which they belong; and if you want to go straight from real Italy to real Greece, the longest way is that from Brindisi to Corfu, for you must still journey across Italy to Brindisi, and from Corfu to Athens. The shortest way is to take ship at Naples, and to be carried round Italy and round Greece, from the centres of culture on the west of Italy to the centres of culture (such as they are) on the east of Greece. But this [pg 3]is no trifling passage. When the ship has left the coasts of Calabria, and steers into the open sea, you feel that you have at last left the west of Europe, and are setting sail for the Eastern Seas. You are, moreover, in an open sea—the furious Adriatic—in which I have seen storms which would be creditable to the Atlantic Ocean, and which at times forbid even steam navigation.

I may anticipate for a moment here, and say that even now the face of Athens is turned, as of old, to the East. Her trade and her communications are through the Levant. Her chief intercourse is with Constantinople, and Smyrna, and Syra, and Alexandria.

This curious parallel between ancient and modern geographical attitudes in Greece is, no doubt, greatly due to the now bygone Turkish rule. In addition to other contrasts, Mohammedan rule and Eastern jealousy—long unknown in Western Europe—first jarred upon the traveller when he touched the coasts of Greece; and this dependency was once really part of a great Asiatic Empire, where all the interests and communications gravitated eastward, and away from the Christian and better civilized West. The revolution which expelled the Turks was unable to root out the ideas which their subjects had learned; and so, in spite of Greek hatred of the Turk, his influence still lives through Greece in a thousand ways.

[pg 4]For many hours after the coasts of Calabria had faded into the night, and even after the snowy dome of Etna was lost to view, our ship steamed through the open sea, with no land in sight; but we were told that early in the morning, at the very break of dawn, the coasts of Greece would be visible. So, while others slept, I started up at half-past three, eager to get the earliest possible sight of the land which still occupies so large a place in our thoughts. It was a soft gray morning; the sky was covered with light, broken clouds; the deck was wet with a passing shower, of which the last drops were still flying in the air; and before us, some ten miles away, the coasts and promontories of the Peloponnesus were reaching southward into the quiet sea. These long serrated ridges did not look lofty, in spite of their snow-clad peaks, nor did they look inhospitable, in spite of their rough outline, but were all toned in harmonious color—a deep purple blue, with here and there, on the far Arcadian peaks, and on the ridge of Mount Taygetus, patches of pure snow. In contrast to the large sweeps of the Italian coast, its open seas, its long waves of mountain, all was here broken, and rugged, and varied. The sea was studded with rocky islands, and the land indented with deep, narrow bays. I can never forget the strong and peculiar impression of that first sight of Greece; nor can I cease to wonder at the strange likeness which rose in my mind, and which [pg 5]made me think of the bays and rocky coasts of the west and south-west of Ireland. There was the same cloudy, showery sky, which is so common there; there was the same serrated outline of hills, the same richness in promontories, and rocky islands, and land-locked bays. Nowhere have I seen a light purple color, except in the wilds of Kerry and Connemara; and though the general height of the Greek mountains, as the snow in May testified, was far greater than that of the Irish hills, yet on that morning, and in that light, they looked low and homely, not displaying their grandeur, or commanding awe and wonder, but rather attracting the sight by their wonderful grace, and by their variety and richness of outline and color.

I stood there, I know not how long—without guide or map—telling myself the name of each mountain and promontory, and so filling out the idle names and outlines of many books with the fresh reality itself. There was the west coast of Elis, as far north as the eye could reach—the least interesting part of the view, as it was of the history, of Greece; then the richer and more varied outline of Messene, with its bay, thrice famous at great intervals, and yet for long ages feeding idly on that fame; Pylos, Sphacteria, Navarino—each a foremost name in Hellenic history. Above the bay could be seen those rich slopes which the Spartans coveted of [pg 6]old, and which, as I saw them, were covered with golden corn. The three headlands which give to the Peloponnesus “its plane-leaf form,”2 were as yet lying parallel before us, and their outline confused; but the great crowd of heights and intersecting chains, which told at once the Alpine character of the peninsula, called to mind the other remark of the geographer, in which he calls it the Acropolis of Greece. The words of old Herodotus, too, rise in the mind with new reality, when he talks of the poor and stony soil of the country as a “rugged nurse of liberty.”

For the nearer the ship approaches, the more this feature comes out; increased, no doubt, greatly in later days by depopulation and general decay, when many arable tracts have lain desolate, but still at all times necessary, when a large proportion of the country consists of rocky peaks and precipices, where a goat may graze, but where the eagle builds secure from the hand of man. The coast, once teeming with traffic, is now lonely and deserted. A single sail in the large gulf of Koron, and a few miserable huts, discernible with a telescope, only added to the feeling of solitude. It was, indeed, “Greece, but living Greece no more.” Even the pirates, who sheltered in these creeks and moun[pg 7]tains, have abandoned this region, in which there is nothing now to plunder.3

But as we crossed the mouth of the gulf, the eye fastened with delight on distant white houses along the high ground of the eastern side—in other words, along the mountain slopes which run out into the promontory of Tainaron; and a telescope soon brought them into distinctness, and gave us the first opportunity of discussing modern Greek life. We stood off the coast of Maina—the home of those Mainotes whom Byron has made so famous as pirates, as heroes, as lovers, as murderers; and even now, when the stirring days of war and of piracy have passed away, the whole district retains the aspect of a country in a state of siege or of perpetual danger. Instead of villages surrounded by peaceful homesteads, each Mainote house, though standing alone, was walled in, and in the centre was a high square tower, in which, according to trustworthy travellers, the Mainote men used to spend their day watching their enemies, while only the women and children ventured out to till the fields. For these fierce mountaineers were not only perpetually defying the [pg 8]Turkish power, which was never able to subdue them thoroughly, but they were all engaged at home with internecine feuds, of which the origin was often forgotten, but of which the consequences remained in the form of vengeance due for the life of a kinsman. When this was exacted on one side, the obligation changed to the other; and so for generation after generation they spent their lives in either seeking or avoiding vengeance. This more than Corsican vendetta4 was, by a sort of mediæval chivalry, prohibited to the women and children, who were thus in perfect safety, while their husbands and fathers were in daily and deadly danger.

They are considered the purest in blood of all the Greeks, though it does not appear that their dialect approaches old Greek nearer than those of their neighbors; but for beauty of person, and independence of spirit, they rank first among the inhabitants of the Peloponnesus, and most certainly they must have among them a good deal of the old Messenian blood. Most of the country is barren, but there are orange woods, which yield the most delicious fruit—a fruit so large and rich that it makes all other oranges appear small and tasteless. The country is now perfectly safe for visitors, and the people extremely hospitable, though the diet is not very palatable to the northern traveller.

[pg 9]So with talk and anecdote about the Mainotes—for every one was now upon deck and sight-seeing—we neared the classic headland of Tainaron, almost the southern point of Europe, once the site of a great temple of Poseidon—not preserved to us, like its sister monument on Sunium—and once, too, the entry to the regions of the dead. And, as if to remind us of its most beautiful legend, the dolphins, which had befriended Arion of old, and carried him here to land, rose in the calm summer sea, and came playing round the ship, showing their quaint forms above the water, and keeping with our course, as it were an escort into the homely seas and islands of truer Greece. Strangely enough, in many other journeys through Greek waters, once again only did we see these dolphins; and here as elsewhere, the old legend, I suppose, based itself upon the fact that this, of all their wide domain, was the favorite resort of these creatures, with which the poets of old felt so strong a sympathy.

But, while the dolphins have been occupying our attention, we have cleared Cape Matapan, and the deep Gulf of Asine and Gythium—in fact, the Gulf of Sparta is open to our view. We strained our eyes to discover the features of “hollow Lacedæmon,” and to take in all the outline of this famous bay, through which so many Spartans had held their course in the days of their greatness. The site of Sparta is far from the sea, probably twelve or fifteen [pg 10]miles; but the place is marked for every spectator, throughout all the Peloponnesus and its coasts, by the jagged top of Mount Taygetus, even in June covered with snow. Through the forests upon its slopes the young Spartans would hunt all day with their famous Laconian hounds, and after a rude supper beguile the evening with stories of their dangers and their success. But, as might be expected, of the five villages which made up the famous city, few vestiges remain. The old port of Gythium is still a port; but here, too, the “wet ways,” and that sea once covered with boats, which a Greek comic poet has called the “ants of the sea,” have been deserted.

We were a motley company on board—Russians, Greeks, Turks, French, English; and it was not hard to find pleasant companions and diverting conversation among them all. I turned to a Turkish gentleman, who spoke French indifferently. “Is it not,” said I, “a great pity to see this fair coast so desolate?” “A great pity, indeed,” said he; “but what can you expect from these Greeks? They are all pirates and robbers; they are all liars and knaves. Had the Turks been allowed to hold possession of the country they would have improved it and developed its resources; but since the Greeks became independent everything has gone to ruin. Roads are broken up, communications abandoned; [pg 11]the people emigrate and disappear—in fact, nothing prospers.”

Presently, I got beside a Greek gentleman, from whom I was anxiously picking up the first necessary phrases and politenesses of modern Greek, and, by way of amusement, put to him the same question. I got the answer I expected. “Ah!” said he, “the Turks, the Turks! When I think how these miscreants have ruined our beautiful country! How could a land thrive or prosper under such odious tyranny?” I ventured to suggest that the Turks were now gone five and forty years, and that it was high time to see the fruits of recovered liberty in the Greeks. No, it was still too soon. The Turks had cut down all the woods, and so ruined the climate; they had destroyed the cities, broken up the roads, encouraged the bandits—in fact, they had left the country in such a state that centuries would not cure it.

The verdict of Europe is in favor of the Greek gentleman; but it might have been suggested, had we been so disposed, that the greatest and the most hopeless of all these sorrows—the utter depopulation of the country—is not due to either modern Greeks or Turks, nor even to the Slav hordes of the Middle Ages. It was a calamity which came upon Greece almost suddenly, immediately after the loss of her independence, and which historians and phys[pg 12]iologists have as yet been only partially able to explain.5

Of this very coast upon which we were then gazing, the geographer Strabo, about the time of Christ, says, “that of old, Lacedæmon had numbered one hundred cities; in his day there were but ten remaining.” So, then, the sum of the crimes of both Greeks and Turks may be diminished by one. But I, perceiving that each of them would have been extremely indignant at this historical palliation of the other’s guilt, “kept silence, even from good words.”

These dialogues beguiled us till we found ourselves, almost suddenly, facing the promontory of Malea, with the island of Cythera (Cerigo) on our right. The island is little celebrated in history. The Phœnicians seem, in very old times, to have had a settlement there for the working of their purple shell-fishery, for which the coasts of Laconia were celebrated; and they doubtless founded there the worship of the Sidonian goddess, who was transformed by the Greeks into Aphrodite (Venus). During the Peloponnesian War we hear of the Athenians using it as a station for their fleet, when they were ravaging the adjacent coasts. It was, in fact, used by their naval power as the same sort of [pg 13]blister (ἐπιτείχισις) on Sparta that Dekelea was when occupied by the Spartans in Attica.

Cape Malea is more famous. It was in olden days the limit of the homely Greek waters, the bar to all fair weather and regular winds—a place of storms and wrecks, and the portal to an inhospitable open sea; and we can well imagine the delight of the adventurous trader who had dared to cross the Western Seas, to gather silver and lead in the mines of Spain, when he rounded the dreaded Cape, homeward bound in his heavy-laden ship, and looked back from the quiet Ægean. The barren and rocky Cape has its new feature now. On the very extremity there is a little platform, at some elevation over the water, and only accessible with great difficulty from the land by a steep goat-path. Here a hermit built himself a tiny hut, cultivated his little plot of corn, and lived out in the lone seas, with no society but stray passing ships.6 When Greece was thickly peopled he might well have been compelled to seek loneliness here; but now, when in almost any mountain chain he could find solitude and desolation enough, it seems as if that poetic instinct which so often guides the ignorant and unconscious anchorite had sent him to this spot, which combines, in a strange way, solitude and publicity, and which ex[pg 14]cites the curiosity, but forbids the intrusion, of every careless passenger to the East.

So we passed into the Ægean, the real thoroughfare of the Greeks, the mainstay of their communication—a sea, and yet not a sea, but the frame of countless headlands and islands, which are ever in view to give confidence to the sailor in the smallest boat. The most striking feature in our view was the serrated outline of the mountains of Crete, far away to the S. E. Though the day was gray and cloudy, the atmosphere was perfectly clear, and allowed us to see these very distant Alps, on which the snow still lay in great fields. The chain of Ida brought back to us the old legends of Minos and his island kingdom, nor could any safer seat of empire be imagined for a power coming from the south than this great long bar of mountains, to which half the islands of the Ægean could pass a fire signal in times of war or piracy.7 The legends preserved to us of Minos—the human sacrifices to the Minotaur—the hostility to Theseus—the identification of Ariadne with the legends of Bacchus, so eastern and orgiastic in character—make us feel, with a sort of instinctive certainty, that the power of Minos was [pg 15]no Hellenic empire, but one of Phœnicians, from which, as afterwards from Carthage, they commanded distant coasts and islands, for the purposes of trade. They settled, as we know, at Corinth, at Thebes, and probably at Athens, in the days of their greatness, but they seem always to have been strangers and sojourners there, while in Crete they kept the stronghold of their power. Thucydides thinks that Minos’s main object was to put down piracy, and protect commerce; and this is probably the case, though we are without evidence on the point. The historian evidently regards this old Cretan empire as the older model of the Athenian, but settled in a far more advantageous place, and not liable to the dangers which proved the ruin of Athens.

The nearer islands were small, and of no reputation, but each like a mountain top reaching out of a submerged valley, stony and bare. Melos was farther off, but quite distinct—the old scene of Athenian violence and cruelty, to Thucydides so impressive, that he dramatizes the incidents, and passes from cold narrative and set oration to a dialogue between the oppressors and the oppressed. Melian starvation was long proverbial among the Greeks, and there the fashionable and aristocratic Alcibiades applied the arguments and carried out the very policy which the tanner Cleon could not propose without being pilloried by the great histo[pg 16]rian whom he made his foe. This and other islands, which were always looked upon by the mainland Greeks with some contempt, have of late days received special attention from archæologists. It is said that the present remains of the old Greek type are now to be found among the islanders—an observation which I found fully justified by a short sojourn at Ægina, where the very types of the Parthenon frieze can be found among the inhabitants, if the traveller will look for them diligently. The noblest and most perfect type of Greek beauty has, indeed, come to us from Melos, but not in real life. It is the celebrated Venus of Melos—the most pure and perfect image we know of that goddess, and one which puts to shame the lower ideals so much admired in the museums of Italy.8

Another remark should be made in justice to the islands, that the groups of Therasia and Santorin, which lie round the crater of a great active volcano, have supplied us not only with the oldest forms of the Greek alphabet in their inscriptions, but with far the oldest vestiges of inhabitants in any part of Greece. In these, beneath the lava slopes formed by a great eruption—an eruption earlier than any history, except, perhaps, Egyptian—have been found the dwellings, the implements, and the bones of men who cannot have lived there much later than 2000 [pg 17]B. C. The arts, as well as the implements, of these old dwellers in their Stone Age, have shown us how very ancient Greek forms, and even Greek decorations, are in the world’s history: and we may yet from them and from further researches, such as Schliemann’s, be able to reconstruct the state of things in Greece before the Greeks came from their Eastern homes. The special reason why these inquiries seem to me likely to lead to good result is this, that what is called neo-barbarism is less likely to mislead us here than elsewhere. Neo-barbarism means the occurrence in later times of the manners and customs which generally mark very old and primitive times. Some few things of this kind survive everywhere; thus, in the Irish Island of Arran, a group of famous savants mistook a stone donkey-shed of two years’ standing for the building of an extinct race in gray antiquity: as a matter of fact, the construction had not changed from the oldest type. But the spread of culture, and the fulness of population in the good days of Greece, make it certain that every spot about the thoroughfares was improved and civilized; and so, as I have said, there is less chance here than anywhere of our being deceived into mistaking rudeness for oldness, and raising a modern savage to the dignity of a primæval man.

But we must not allow speculations to spoil our observations, nor waste the precious moments given [pg 18]us to take in once for all the general outline of the Greek coasts. While the long string of islands, from Melos up to the point of Attica, framed in our view to the right, to the left the great bay of Argolis opened far into the land, making a sort of vista into the Peloponnesus, so that the mountains of Arcadia could be seen far to the west standing out against the setting sun; for the day was now clearer—the clouds began to break, and let us feel touches of the sun’s heat towards evening. As we passed Hydra, the night began to close about us, and we were obliged to make out the rest of our geography with the aid of a rich full moon.

But these Attic waters, if I may so call them, will be mentioned again and again in the course of our voyage, and need not now be described in detail. The reader will, I think, get the clearest notion of the size of Greece by reflecting upon the time required to sail round the Peloponnesus in a good steamer. The ship in which we made the journey—the Donnai, of the French Messagerie Company,—made about eight miles an hour. Coming within close range of the coast of Messene, about five o’clock in the morning, we rounded all the headlands, and arrived at the Peiræus about eleven o’clock the same night. So, then, the Peloponnesus is a small peninsula, but even to an outside view “very large for its size;” for the actual climbing up and down of constant mountains, in any land [pg 19]journey from place to place, makes the distance in miles very much greater than the line as the crow flies. If I said that every ordinary distance, as measured on the map, is doubled in the journey, I believe I should be under the mark.

It may be well to add a word here upon the other route into Greece, that by Brindisi and the Ionian Islands. It is fully as picturesque, in some respects more so, for there is no more beautiful bay than the long fiord leading up to Corinth, which passes Patras, Vostitza, and Itea, the port of Delphi. The Akrokeraunian mountains, which are the first point of the Albanian coast seen by the traveller, are also very striking, and no one can forget the charms and beauties of Corfu. I think a market-day in Corfu, with those royal-looking peasant lads, who come clothed in sheepskins from the coast, and spend their day handling knives and revolvers with peculiar interest at the stalls, is among the most picturesque sights to be seen in Europe. The lofty mountains of Ithaca and its greater sister, and then the rich belt of verdure along the east side of Zante—all these features make this journey one of surpassing beauty and interest. Yet notwithstanding all these advantages, there is not the same excitement in first approaching semi-Greek or outlying Greek settlements, and only gradually arriving at the real centres of historic interest. Such at least was the feeling (shared by other observers) which I had in approach[pg 20]ing Greece by this more varied route. No traveller, however, is likely to miss either, as it is obviously best to enter by one route and depart by the other, in a voyage not intended to reach beyond Greece. But from what I have said, it may be seen that I prefer to enter by the direct route from Naples, and to leave by the Gulf of Corinth and the Ionian Islands. I trust that ere long arrangements may be made for permitting travellers who cross the isthmus to make an excursion to the Akrokorinthus—the great citadel of Corinth—which they are now compelled to hurry past, in order to catch the boat for Athens.

The modern Patras, still a thriving port, is now the main point of contact between Greece and the rest of Europe. For, as a railway has now been opened from Patras to Athens, all the steamers from Brindisi, Venice, and Trieste put in there, and from thence the stream of travellers proceeds by the new line to the capital. The old plan of steaming up the long fiord to Corinth is abandoned; still more the once popular route round the Morea, which, if somewhat slower, at least saved the unshipping at Lechæum, the drive in omnibuses across the isthmus, and reshipment at Cenchreæ—all done with much confusion, and with loss and damage to luggage and temper. Not that there is no longer confusion. The railway station at Patras, and that at Athens, are the most curious bear-gardens in which business ever was [pg 21]done. The traveller (I speak of the year of our Lord 1889) is informed that unless he is there an hour before the time he will not get his luggage weighed and despatched. And when he comes down from his comfortable hotel to find out what it all means, he meets the whole population of the town in possession of the station. Everybody who has nothing to do gets in the way of those who have; everything is full of noise and confusion.

At last the train steams out of the station, and takes its deliberate way along the coast, through woods of fir trees, bushes of arbutus and mastic, and the many flowers which stud the earth. And here already the traveller, looking out of the window, can form an idea of the delights of real Greek travel, by which he must understand mounting a mule or pony, and making his way along woody paths, or beside the quiet sea, or up the steep side of a rocky defile. Every half-hour the train crosses torrents coming from the mountains, which in flood times color the sea for some distance with the brilliant brick-red of the clay they carry with them from their banks. The peacock blue of the open sea bounds this red water with a definite line, and the contrast in the bright sun is something very startling. Shallow banks of sand also reflect their pale yellow in many places, so that the brilliancy of this gulf exceeds anything I had ever seen in sea or lake. We pass the sites of Ægion, now Vostitza, [pg 22]once famous as the capital or centre (politically) of the Achæan League. We pass Sicyon, the home of Aratus, the great regenerator, the mean destroyer of that League, as you can still read in Plutarch’s fascinating life of the man. But these places, like so many others in Greece, once famous, have now no trace of their greatness left above ground. The day may, however, still come when another Schliemann will unearth the records and fragments of a civilization distinguished even in Greece for refinement. Sicyon was a famous school of art. Painting and sculpture flourished there, and there was a special school of Sicyon, whose features we can still recognize in extant copies of the famous statues they produced. There is a statue known as the Canon Statue, a model of human proportions, which was the work of the famous Polycleitus of Sicyon, and which we know from various imitations preserved at Rome and elsewhere. But we shall return in due time to Greek sculpture as a whole, and shall not interrupt our journey at this moment.

All that we have passed through hitherto may be classed under the title of “first impressions.” The wild northern coast shows us but one inlet, of the Gulf of Salona, with a little port of Itea at its mouth. This was the old highway to ascend to the oracle of Delphi on the snowy Parnassus, which we shall approach better from the Bœotian side. But now we strain our eyes to behold the great rock of [pg 23]Corinth, and to invade this, the first great centre of Greek life, which closes the long bay at its westernmost end.

I will add a word upon the form and scope of the following work. My aim is to bring the living features of Greece home to the student, by connecting them, as far as possible, with the facts of older history, which are so familiar to most of us. I shall also have a good deal to say about the modern politics of Greece, and the character of the modern population. A long and careful survey of the extant literature of ancient Greece has convinced me that the pictures usually drawn of the old Greeks are idealized, and that the real people were of a very different—if you please, of a much lower—type. I may mention, as a very remarkable confirmation of my judgment, that intelligent people at Athens, who had read my opinions elsewhere set forth upon the subject,9 were so much struck with the close resemblance of my pictures of the old Greeks to the present inhabitants, that they concluded that I must have visited the country before writing these opinions, and that I was, in fact, drawing my classical people from the life of the moderns. If this is not a proof of the justice of these views, it at least strongly suggests that they may be true, and is a powerful support in arguing the matter on the perfectly independent ground of the inferences from old literature. After [pg 24]all, national characteristics are very permanent, and very hard to shake off, and it would seem strange, indeed, if both these and the Greek language should have remained almost intact, and yet the race have either changed, or been saturated with foreign blood. Foreign invasions and foreign conquests of Greece were common enough; but here, as elsewhere, the climate and circumstances which have formed a race seem to conspire to preserve it, and to absorb foreign types and features, rather than to permit the extinction or total change of the older race.

I feel much fortified in my judgment of Greek character by finding that a very smart, though too sarcastic, observer, M. E. About, in his well-known Grèce contemporaine, estimates the people very nearly as I am disposed to estimate the common people of ancient Greece. He notices, in the second and succeeding chapters of his book, a series of features which make this nationality a very distinct one in Europe. Starting from the question of national beauty, and holding rightly that the beauty of the men is greater than that of the women, he touches on a point which told very deeply upon all the history of Greek art. At the present day, the Greek men are much more particular about their appearance, and more vain of it, than the women. The most striking beauty among them is that of young men; and as to the care of figure, as About well observes, in Greece it is the men who pinch [pg 25]their waists—a fashion unknown among Greek women. Along with this handsome appearance, the people are, without doubt, a very temperate people; although they make a great deal of strong wine, they seldom drink much, and are far more critical about good water than wine. Indeed, in so warm a climate, wine is disagreeable even to the northern traveller; and, as Herodotus remarked long ago, very likely to produce insanity, the rarest form of disease among the Greeks. In fact, they are not a passionate race—having at all ages been gifted with a very bright intellect, and a great reasonableness; they have an intellectual insight into things, which is inconsistent with the storms of wilder passion.

They are, probably, as clever a people as can be found in the world, and fit for any mental work whatever. This they have proved, not only by getting into their hands all the trade of the Eastern Mediterranean, but by holding their own perfectly among English merchants in England. As yet they have not found any encouragement in other directions; but there can be no doubt that, if settled among a great people, and weaned from the follies and jealousies of Greek politics, they would (like the Jews) outrun many of us, both in politics and in science. However that may be—and perhaps such a development requires moral qualities in which they seem deficient—it is certain that their work[pg 26]men learn trades with extraordinary quickness; while their young commercial or professional men acquire languages, and the amount of knowledge necessary for making money, with the most singular aptness. But as yet they are stimulated chiefly by the love of gain.

Besides this, they have great national pride, and, as M. About remarks, we need never despair of a people who are at the same time intelligent and proud. They are very fond of displaying their knowledge on all points—I noted especially their pride in exhibiting their acquaintance with old Greek history and legend. When I asked them whether they believed the old mythical stories which they repeated, they seemed afraid of being thought simple if they confessed that they did, and of injuring the reputation of their ancestors if they declared they did not. So they used to preserve a discreet neutrality.

The instinct of liberty appears to me as strong in the nation now as it ever was. In fact, the people have never been really enslaved. The eternal refuge for liberty afforded by the sea and the mountains has saved them from this fate; and, even beneath the heavy yoke of the Turks, a large part of the nation was not subdued, but, in the guise of bandits and pirates, enjoyed the great privilege for which their ancestors had contended so earnestly. The Mainotes, for example, of whom I have just [pg 27]spoken as occupying the coast of Messene, never tolerated any resident Turkish magistrate among them, but “handed to a trembling tax-collector a little purse of gold pieces, hung on the end of a naked sword.”10 Now, the whole nation is more intensely and thoroughly democratic than any other in Europe. They acknowledge no nobility save that of descent from the chiefs who fought in the war of liberation; they will allow no distinction of classes; every common mule-boy is a gentleman (κύριος), and fully your equal. He sits in the room at meals, and joins in the conversation at dinner. They only tolerate a king because they cannot endure one of themselves as their superior. This jealousy is, unfortunately, a mainspring of Greek politics, and when combined with a dislike of agriculture, as a stupid and unintellectual occupation, fills all the country with politicians, merchants, and journalists. Moreover, they want the spirit of subordination of their great ancestors, and are often accused of lack of honesty—a very grave feature, and the greatest obstacle to progress in all ages. It is better, however, to let points of character come out gradually in the course of our studies than to bring them together into an official portrait. It is impossible to wander through the country without seeing and understanding the inhabitants; for the traveller is [pg 28]in constant contact with them, and they have no scruple in displaying all their character.

M. About has earned the profound hatred and contempt of the nation by his picture, and I do not wonder at it, seeing that the tone in which he writes is flippant and ill-natured, and seems to betoken certain private animosities, of which the Greeks tell numerous anecdotes.

I have no such excuse for being severe or ill-natured, as I found nothing but kindness and hospitality everywhere, and sincerely hope that my free judgments may not hurt any sensitive Greek who may chance to see them. Even the great Finlay—one of their best friends—is constantly censured by them for his writings about Modern Greece.

But, surely, any real lover of Greece must feel that plain speaking about the faults of the nation is much wanted. The worship lavished upon them by Byron and his school has done its good, and can now only do harm. On the other hand, I must confess that a longer and more intimate intercourse with the Greeks of the interior and of the mountains leads a fair observer to change his earlier estimate, and think more highly of the nation than at first acquaintance. Unfortunately, the Greeks known to most of us are sailors—mongrel villains from the ports of the Levant, having very little in common with the bold, honest, independent peasant who lives under his vine and his fig-tree in the valleys of Arcadia [pg 29]or of Phocis. It was, no doubt, an intimate knowledge of the sound core of the nation which inspired Byron with that enthusiasm which many now think extravagant and misplaced. But here, as elsewhere, the folly of a great genius has more truth in it than the wisdom of his feebler critics.

CHAPTER II.

GENERAL IMPRESSIONS OF ATHENS AND ATTICA.

There is probably no more exciting voyage, to any educated man, than the approach to Athens from the sea. Every promontory, every island, every bay, has its history. If he knows the map of Greece, he needs no guide-book or guide to distract him; if he does not, he needs little Greek to ask of any one near him the name of this or that object; and the mere names are sufficient to stir up all his classical recollections. But he must make up his mind not to be shocked at Ægina or Phalerum, and even to be told that he is utterly wrong in his way of pronouncing them.

It was our fortune to come into Greece by night, with a splendid moon shining upon the summer sea. The varied outlines of Sunium on the one side, and Ægina on the other, were very clear, but in the deep shadows there was mystery enough to feed the burning impatience to see it all in the light of common day; and though we had passed Ægina, and had come over against the rocky Salamis, as yet there was no sign of Peiræus. Then came the light on Psyttalea, and they told us that the harbor was right [pg 31]opposite. Yet we came nearer and nearer, and no harbor could be seen. The barren rocks of the coast seemed to form one unbroken line, and nowhere was there a sign of indentation or of break in the land. But, suddenly, as we turned from gazing on Psyttalea, where the flower of the Persian nobles had once stood in despair, looking upon their fate gathering about them, the vessel had turned eastward, and discovered to us the crowded lights and thronging ships of the famous harbor. Small it looked, very small, but evidently deep to the water’s edge, for great ships seemed touching the shore; and so narrow is the mouth that we almost wondered how they had made their entrance in safety. But we saw it some weeks later, with nine men-of-war towering above all its merchant shipping and its steamers, and among them crowds of ferry-boats skimming about in the breeze with their wing-like sails. Then we found out that, like the rest of Greece, the Peiræus was far larger than it looked.

It differed little, alas! from more vulgar harbors in the noise and confusion of disembarking; in the delays of its custom house; in the extortion and insolence of its boatmen. It is still, as in Plato’s day, “the haunt of sailors, where good manners are unknown.” But when we had escaped the turmoil, and were seated silently on the way to Athens, almost along the very road of classical days, all our [pg 32]classical notions, which had been scared away by vulgar bargaining and protesting, regained their sway. We had sailed in through the narrow passage where almost every great Greek that ever lived had sometime passed; now we went along the line, hardly less certain, which had seen all these great ones going to and fro between the city and the port. The present road is shaded with great silver poplars and plane trees, and the moon had set, so that our approach to Athens was even more mysterious than our approach to the Peiræus. We were, moreover, perplexed at our carriage stopping under some large plane trees, though we had driven but two miles, and the night was far spent. Our coachman would listen to no advice or persuasion. We learned afterwards that every carriage going to and from the Peiræus stops at this half-way house, that the horses may drink, and the coachman take “Turkish delight” and water. There is no exception made to this custom, and the traveller is bound to submit. At last we entered the unpretending ill-built streets at the west of Athens.

The stillness of the night is a phenomenon hardly known in that city. No sooner have men and horses gone to rest than all the dogs and cats of the town come out to bark and yell about the thoroughfares. Athens, like all parts of modern Greece, abounds in dogs. You cannot pass a sailing boat in the Levant without seeing a dog looking angrily [pg 33]over the taffrail, and barking at you as you pass. Every ship in the Peiræus has at least one, often a great many, on board. I suppose every house in Athens is provided with one. These creatures seem to make it their business to prevent silence and rest all the night long. They were ably seconded by cats and crowing cocks, as well as by an occasional wakeful donkey; and both cats and donkeys seemed to have voices of almost tropical violence.

So the night wore away under rapidly growing adverse impressions. How is a man to admire art and revere antiquity if he is robbed of his repose? The Greeks sleep so much in the day that they seem indifferent about nightly disturbances; and, perhaps, after many years’ habit, even Athenian caterwauling may fail to rouse the sleeper. But what chance has the passing traveller? Even the strongest ejaculations are but a narrow outlet for his feelings.

In this state of mind, then, I rose at the break of dawn to see whether the window would afford any prospect to serve as a requital for angry sleeplessness. And there, right opposite, stood the rock which of all rocks in the world’s history has done most for literature and art—the rock which poets, and orators, and architects, and historians have ever glorified, and cannot stay their praise—which is ever new and ever old, ever fresh in its decay, ever [pg 34]perfect in its ruin, ever living in its death—the Acropolis of Athens.

When I saw my dream and longing of many years fulfilled, the first rays of the rising sun had just touched the heights, while the town below was still hid in gloom. Rock, and rampart, and ruined fanes—all were colored in uniform tints; the lights were of a deep rich orange, and the shadows of dark crimson, with the deeper lines of purple. There was no variety in color between what nature and what man had set there. No whiteness shone from the marble, no smoothness showed upon the hewn and polished blocks; but the whole mass of orange and crimson stood out together into the pale, pure Attic air. There it stood, surrounded by lanes and hovels, still perpetuating the great old contrast in Greek history, of magnificence and meanness—of loftiness and lowness—as well in outer life as in inward motive. And, as it were in illustration of that art of which it was the most perfect bloom, and which lasted in perfection but a day of history, I saw it again and again, in sunlight and in shade, in daylight and at night, but never again in this perfect and singular beauty.

If we except the Acropolis, there are only two striking buildings of classical antiquity within the modern town of Athens—the Temple of Theseus and the few standing columns of Hadrian’s great temple to Zeus. The latter is, indeed, very remarkable. [pg 35]The pillars stand on a vacant platform, once the site of the gigantic temple; the Acropolis forms a noble background; away towards Phalerum stretch undulating hills which hide the sea; to the left (if we look from the town), Mount Hymettus raises its barren slopes; and in the valley, immediately below the pillars, flows the famous little Ilisus,11 glorified for ever by the poetry of Plato, and in its summer-dry bed the fountain Callirrhoe, from which the Athenian maidens still draw water as of old—water the purest and best in the city. It wells out from under a great limestone rock, all plumed with the rich Capillus Veneris, which seems to find out and frame with its delicate green every natural spring in Greece.

But the pillars of the Temple of Zeus, though very stately and massive, and with their summits bridged together by huge blocks of architrave, are still not Athenian, not Attic, not (if I may say so) genuine Greek work; for the Corinthian capitals, which are here seen perhaps in their greatest perfection, cannot be called pure Greek taste. As is well known, they were hardly ever used, and never used prominently, till the Græco-Roman stage of [pg 36]art. The older Greeks seem to have had a fixed objection to intricate ornamentation in their larger temples. All the greater temples of Greece and Greek Italy are of the Doric Order, with its perfectly plain capital. Groups of figures were admitted upon the pediments and metopes, because these groups formed clear and massive designs visible from a distance. But such intricacies as those of the Corinthian capital were not approved, except in small monuments, which were merely intended for close inspection, and where delicate ornament gave grace to a building which could not lay claim to grandeur. Such is clearly the case with the only purely Greek (as opposed to Græco-Roman) monument of the Corinthian Order, which is still standing—the Choragic monument of Lysicrates at Athens.12 It was also the case with that beautiful little temple, or group of temples, known as the Erechtheum, which, standing beside the great massive Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens, presents [pg 37]the very contrasts upon which I am insisting. It is small and essentially graceful, being built in the Ionic style, with rich ornamentation; while the Parthenon is massive, and, in spite of much ornamentation, very severe in its plainer Doric style.

But to return to the pillars of Hadrian’s Temple. They are about fifty-five feet high, by six and a half feet in diameter, and no Corinthian pillar of this colossal size would ever have been set up by the Greeks in their better days. So, then, in spite of the grandeur of these isolated remains—a grandeur not destroyed, perhaps even not diminished, by coffee tables, and inquiring waiters, and military bands, and a vulgar crowd about their base—to the student of really Greek art they are not of the highest interest; nay, they even suggest to him what the Periclean Greeks would have done had they, with such resources, completed the great temple due to the munificence of the Roman Emperor.

Let us turn, in preference, to the Temple of Theseus, at the opposite extremity of the town, it too standing upon a clear platform, and striking the traveller with its symmetry and its completeness, as he approaches from the Peiræus. It is in every way a contrast to the temple of which we have just spoken. It is very small—in fact so small in comparison with the Parthenon, or the great temple at Pæstum, that we are disappointed with it; and yet it is built, not in the richly-decorated Ionic style of [pg 38]the Erechtheum, but in severe Doric; and though small and plain, it is very perfect—as perfect as any such relic that we have. It is many centuries older than Hadrian’s great temple. It could have been destroyed with one-tenth of the trouble, and yet it still stands almost in its perfection. The reason is simply this. Few of the great classical temples suffered much from wanton destruction till the Middle Ages. Now, in the Middle Ages this temple, as well as the Parthenon, was usurped by the Greek Church, and turned into a place of Christian worship. So, then, the little Temple of Theseus has escaped the ravages which the last few centuries—worse than all that went before—have made in the remains of a noble antiquity. To those who desire to study the effect of the Doric Order this temple appears to me an admirable specimen. From its small size and clear position, all its points are very easily taken in. “Such,” says Bishop Wordsworth, “is the integrity of its structure, and the distinctness of its details, that it requires no description beyond that which a few glances might supply. Its beauty defies all: its solid yet graceful form is, indeed, admirable; and the loveliness of its coloring is such that, from the rich mellow hue which the marble has now assumed, it looks as if it had been quarried, not from the bed of a rocky mountain, but from the golden light of an Athenian sunset.” And in like terms many others have spoken.

[pg 39]I have only one reservation to make. The Doric Order being essentially massive, it seems to me that this beautiful temple lacks one essential feature of that order, and therefore, after the first survey, after a single walk about it, it loses to the traveller who has seen Pæstum, and who presently cannot fail to see the Parthenon, that peculiar effect of massiveness—of almost Egyptian solidity—which is ever present, and ever imposing, in these huger Doric temples. It seems as if the Athenians themselves felt this—that the plain simplicity of its style was not effective without size—and accordingly decorated this structure with colors more richly than their other temples. All the reliefs and raised ornaments seem to have been painted; other decorations were added in color on the flat surfaces, so that the whole temple must have been a mass of rich variegated hues, of which blue, green, and red are still distinguishable—or were in Stuart’s time—and in which bronze and gilding certainly played an important part.

We are thus brought naturally face to face with one of the peculiarities of old Greek art most difficult to realize, and still more to appreciate.13 We can recognize in Egyptian and in Assyrian art the [pg 40]richness and appropriateness of much coloring. Modern painters are becoming so alive to this, that among the most striking pictures in our Royal Academy in London have been seen, for some years back, scenes from old Egyptian and Assyrian life, in which the rich coloring of the architecture has been quite a prominent feature.

But in Greek art—in the perfect symmetry of the Greek temple, in the perfect grace of the Greek statue—we come to think form of such paramount importance, that we look on the beautiful Parian and Pentelic marbles as specially suited for the expression of form apart from color. There is even something in unity of tone that delights the modern eye. Thus, though we feel that the old Greek temples have lost all their original brightness, yet, as I have myself said, and as I have quoted from Bishop Wordsworth, the rich mellow hue which tones all these ruins has to us its peculiar charm. The same rich yellow brown, almost the color of the Roman travertine, is one of the most striking features in the splendid remains which have made Pæstum unique in all Italy. This color contrasts beautifully with the blue sky of southern Europe; it lights up with extraordinary richness in the rising or setting sun. We can easily conceive that were it proposed to restore the Attic temples to their pristine whiteness, we should feel a severe shock, and beg to have these venerable buildings left in the soberness of their [pg 41]acquired color. Still more does it shock us to be told that great sculptors, with Parian marble at hand, preferred to set up images of the gods in gold and ivory, or, still worse, with parts of gold and ivory; and that they thought it right to fill out the eyes with precious stones, and set gilded wreaths upon colored hair.

When we first come to realize these things, we are likely to exclaim against such a jumble, as we should call it, of painting and architecture—still worse, of painting and sculpture. Nor is it possible or reasonable that we should at once submit to such a revolution in our artistic ideas, and bow without criticism to these shocking features in Greek art. But if blind obedience to these our great masters in the laws of beauty is not to be commended, neither is an absolute resistance to all argument on the question to be respected; nor do I acknowledge the good sense or the good taste of that critic who insists that nothing can possibly equal the color and texture of white marble, and that all coloring of such a substance is the mere remains of barbarism. For, say what we will, the Greeks were certainly, as a nation, the best judges of beauty the world has yet seen. And this is not all. The beauty of which they were evidently the most fond was beauty of form—harmony of proportions, symmetry of design. They always hated the tawdry and the extravagant. As to their literature, there is no poetry, no oratory, no [pg 42]history, which is less decorated with the flowers of rhetoric: it is all pure in design, chaste in detail. So with their dress; so with their dwellings. We cannot but feel that, had the effect of painted temples and statues been tawdry, there is no people on earth who would have felt it so keenly, and disliked it so much. There must, then, have been strong reasons why this bright coloring did not strike their eye as it would the eye of sober moderns.

To any one who has seen the country, and thought about the question there, many such reasons present themselves. In the first place, all through southern Europe, and more especially in Greece, there is an amount of bright color in nature, which prevents almost any artificial coloring from producing a startling effect. Where all the landscape, the sea, and the air are exceedingly bright, we find the inhabitants increasing the brightness of their dress and houses, as it were to correspond with nature. Thus, in Italy, they paint their houses green, and pink, and yellow, and so give to their towns and villas that rich and warm effect which we miss so keenly among the gray and sooty streets of northern Europe. So also in their dress, these people wear scarlet, and white, and rich blue, not so much in patterns as in large patches, and a festival in Sicily or Greece fills the streets with intense color. We know that the coloring of the old Greek dress was quite of the same character as that of the modern, [pg 43]though in design it has completely changed. We must, therefore, imagine the old Greek crowd before their temples, or in their market-places, a very white crowd, with patches of scarlet and various blue; perhaps altogether white in processions, if we except scarlet shoe-straps and other such slight relief. One cannot but feel that a richly colored temple—that pillars of blue and red—that friezes of gilding, and other ornament, upon a white marble ground, and in white marble framing, must have been a splendid and appropriate background, a genial feature, in such a sky and with such costume. We must get accustomed to such combinations—we must dwell upon them in imagination, or ask our good painters to restore them for us, and let us look upon them constantly and calmly.

But I will not seek to persuade; let us merely state the case fairly, and put the reader in a position to judge for himself. So much for the painted architecture. I will but add, the most remarkable specimen of a richly painted front to which we can now appeal is also really one of the most beautiful in Europe—the front of S. Mark’s at Venice. The rich frescoes and profuse gilding on this splendid front, of which photographs give a very false idea, should be studied by all who desire to judge fairly of this side of Greek taste.

But I must say a word, before passing on, concerning the statues. No doubt, the painting of [pg 44]statues, and the use of gold and ivory upon them, were derived from a rude age, when no images existed but rude wooden work—at first a mere block, then roughly altered and reduced to shape, probably requiring some coloring to produce any effect whatever. To a public accustomed from childhood to such painted, and often richly dressed images, a pure white marble statue must appear utterly cold and lifeless. So it does to us, when we have become accustomed to the mellow tints of old and even weather-stained Greek statues; and it should be here noticed that this mellow skin-surface on antique statues is not the mere result of age, but of an artificial process, whereby they burnt into the surface a composition of wax and oil, which gave a yellowish tone to the marble, as well as also that peculiar surface which so accurately represents the texture of the human skin. But if we imagine all the marble surfaces and reliefs in the temple colored for architectural richness’ sake, we can feel even more strongly how cold and out-of-place would be a perfectly colorless statue in the centre of all this pattern.

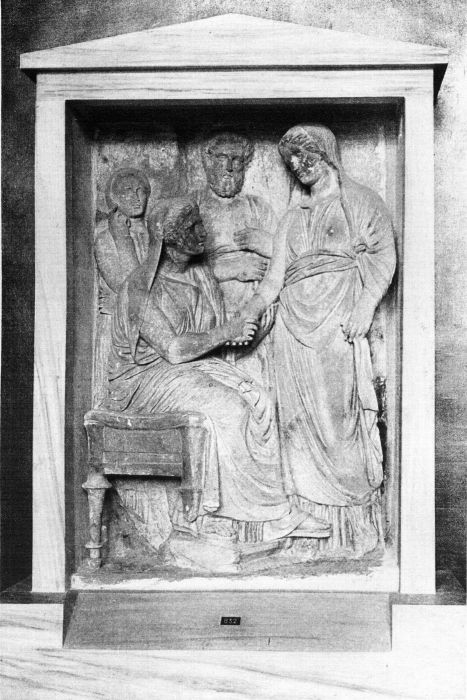

I will go further, and say we can point out cases where coloring greatly heightens the effect and beauty of sculpture. The first is from the bronzes found at Herculaneum, now in the museum at Naples. Though they are not marble, they are suitable for our purpose, being naturally of a single [pg 45]dark brown hue, which is indeed even more unfavorable (we should think) for such treatment. In some of the finest of these bronzes—especially in the two young men starting for a race—the eyeballs are inserted in white, with iris and pupil colored. Nothing can be conceived more striking and lifelike than the effect produced. There is in the Varvakion at Athens a marble mask, found in the Temple of Æsculapius under the south side of the Acropolis, probably an ex voto offered for a recovery from some disease of the eyes. This marble face also has its eyes colored in the most striking and lifelike way, and is one of the most curious objects found in the late excavations.

I will add one remarkable modern example—the monument at Florence to a young Indian prince, who visited England and this country some years ago, and died of fever during his homeward voyage. They have set up to him a richly colored and gilded baldachin, in the open air, and in a quiet, wooded park. Under this covering is a life-sized bust of the prince, in his richest state dress. The whole bust—the turban, the face, the drapery—all is colored to the life, and the dress, of course, of the most gorgeous variety. The turban is chiefly white, striped with gold, in strong contrast to the mahogany complexion and raven hair of the actual head; the robe is gold and green, and covered with ornament. The general effect is, from the very first [pg 46]moment, striking and beautiful. The longer it is studied, the better it appears; and there is hardly a reasonable spectator who will not confess that, were we to replace the present bust with a copy of it in white marble, the beauty and harmony of the monument would be utterly marred. To those who have the opportunity of visiting Greece or Italy, I strongly commend these specimens of colored buildings and sculpture. When they have seen them, they will hesitate to condemn what we still hear called the curiously bad taste of the old Greeks in their use of color in the plastic arts.

But these archæological discussions are truly ἐκβολαὶ λόγου, digressions—in themselves necessary, yet only tolerable if they are not too long. I revert to the general state of the antiquities at Athens, always reserving the Acropolis for a special chapter. As I said, the isolated pillars of Hadrian’s Temple of Zeus, and the so-called Temple of Theseus, are the only very striking objects.14 There are, of [pg 47]course, many other buildings, or remains of buildings. There is the monument of Lysicrates—a small and very graceful round chamber, adorned with Corinthian engaged pillars, and with friezes of the school of Scopas, and intended to carry on its summit the tripod Lysicrates had gained in a musical and dramatic contest (334 B. C.) at Athens. There is the later Temple of the Winds, as it is called—a sort of public clock, with sundials and fine reliefs of the Wind-gods on its outward surfaces, and arrangements for a water-clock within. There are two portals, or gateways—one leading into the old agora, or market-place, the other leading from old Athens into the Athens of Hadrian.

But all these buildings are either miserably defaced, or of such late date and decayed taste as to make them unworthy specimens of pure Greek art. A single century ago there was much to be seen and admired which has since disappeared; and even to-day the majority of the population are careless as to the treatment of ancient monuments, and sometimes even mischievous in wantonly defacing them. Thus, I saw the marble tombs of Ottfried Müller and Charles Lenormant—tombs which, though modern, were yet erected at the cost of the nation to men who were eminent lovers and students of Greek art—I saw these tombs used as common targets by [pg 48]the neighborhood, and all peppered with marks of shot and of bullets. I saw them, too, all but blown up by workmen blasting for building-stones close beside them.15 I saw, also, from the Acropolis, a young gentleman practising with a pistol at a piece of old carved marble work in the Theatre of Dionysus. His object seemed to be to chip off a piece from the edge at every shot. Happily, on this occasion, our vantage ground enabled us to take the law into our own hands; and after in vain appealing to a custodian to interfere, we adopted the tactics of Apollo at Delphi, and by detaching stones from the top of our precipice, we put to flight the wretched barbarian who had come to ravage the treasures of that most sacred place.

These unhappy examples of the defacing of architectural monuments,16 which can hardly be removed, naturally suggest to the traveller in Greece the kindred question how all the smaller and movable antiquities that are found should be distributed so as best to promote the love and knowledge of art.

On this point it seems to me that we have gone to one extreme, and the Greeks to the other, and [pg 49]that neither of us have done our best to make known what we acknowledge ought to be known as widely as possible. The tendency in England, at least of later years, has been to swallow up all lesser and all private collections in the great national Museum in London, which has accordingly become so enormous and so bewildering that no one can profit by it except the trained specialist, who goes in with his eyes shut, and will not open them till he has arrived at the special class of objects he intends to examine. But to the ordinary public, and even the generally enlightened public (if such an expression be not a contradiction in terms), there is nothing so utterly bewildering, and therefore so unprofitable, as a visit to the myriad treasures of that great world of curiosities.

In the last century many private persons—many noblemen of wealth and culture—possessed remarkable collections of antiquities. These have mostly been swallowed up by what is called “the nation,” and new private collections are very rare indeed.

In Greece the very opposite course is being now pursued. By a special law it is forbidden to sell out of the country, or even to remove from a district, any antiquities whatever; and in consequence little museums have been established in every village in Greece—nay, sometimes even in places where there is no village, in order that every district may pos[pg 50]sess its own riches, and become worth a visit from the traveller and the antiquary. I have seen such museums at Eleusis, some fifteen miles from Athens, at Thebes, now an unimportant town, at Livadia, at Chæronea, at Argos, at Olympia, and even in the wild plains of Orchomenus, in a little chapel, with no town within miles.17 If I add to this that most of these museums were mere dark outhouses, only lighted through the door, the reader will have some notion what a task it would be to visit and criticise, with any attempt at completeness, the ever-increasing remnants of classical Greece.