This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Who?

Author: Elizabeth Kent

Release Date: February 7, 2011 [eBook #35205]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHO?***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/whobyelizabethke00kentiala |

CHAPTER I. The Woman in the Compartment

CHAPTER II. "Mrs. Peter Thompkins"

CHAPTER III. The Tribulations of a Liar

CHAPTER IV. On the Scene of the Tragedy

CHAPTER V. The Detective Detects

CHAPTER VI. The Mysterious Maid

CHAPTER VII. The Inquest

CHAPTER VIII. Lady Upton

CHAPTER IX. The Jewels

CHAPTER X. The Two Frenchmen

CHAPTER XI. The Inspector Interviews Cyril

CHAPTER XII. A Perilous Venture

CHAPTER XIII. Campbell Remonstrates

CHAPTER XIV. What Is the Truth?

CHAPTER XV. Finger Prints in the Dust

CHAPTER XVI. The Story of a Wrong

CHAPTER XVII. Guy Relents

CHAPTER XVIII. A Slip of the Tongue

CHAPTER XIX. An Unexpected Visitor

CHAPTER XX. "I Know It, Cousin Cyril"

CHAPTER XXI. The Truth

CHAPTER XXII. Campbell Resigns

A Selection from the Catalogue of G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

It was six o'clock on a raw October morning, and the cross Channel boat had just deposited its cargo of pale and dishevelled passengers at Newhaven. Cyril Crichton, having seen his servant place his bags in a first-class compartment, gazed gloomily at the scene before him.

It was the first time in three years that he had set foot on his native shore and the occasion seemed invested with a certain solemnity.

"What a mess I have made of my life! Yet God knows I meant well!" He muttered in his heart. "If I hadn't been such a good-natured ass, I should never have got into all this trouble. But I won't be made a fool of any longer. I will consult Campbell as to what—" He paused. It suddenly occurred to him that he had forgotten to let the latter know of his impending arrival. "I will send him a wire," he decided.

The telegraph-office was farther off than he expected, and to Crichton's disgust, he found it shut. He had forgotten that in well-regulated England, even matters of life and death have to wait till the offices open at eight A.M.

He was still staring at the closed window, when he was startled by the guard's whistle, and the slamming of the carriage doors. Turning quickly, he ran back, trying to find his compartment, but it was too late; the train was already moving. Flinging off a porter's detaining hand, he jumped on to the foot-board and wrenched open the nearest door. The impetus flung him headlong into the lap of a lady,—the sole occupant of the carriage. To his horror and amazement, instead of listening to his apologies, she uttered a piercing shriek and fell forward into his arms. For a moment Crichton was too dazed to move. There he knelt, tightly clasping her limp form and wondering fearfully what would happen next. At last he managed to pull himself together, and staggering to his feet, laid her gently on the seat near the window. Strangely enough, he had had no idea, so far, as to the appearance, or even the age, of the lady with whom fate had thrown him into such intimate contact: consequently he now looked at her with considerable curiosity. Her slight, graceful figure proclaimed her youth, but her face was completely concealed by a thick, black veil, which prevented him from so much as guessing the outline of her features. As she continued to show no sign of returning consciousness, Crichton looked helplessly around for some means of reviving her. More air was what she needed; so with much trepidation he decided to unfasten her veil. His fingers fumbled clumsily over their unaccustomed task, but finally the last knot was disentangled, the last pin extracted. The unknown proved to be even younger than he expected, and to possess beauty of the kind which admits of no discussion. At present, however, it was sadly marred by a red welt, probably the result of a fall, Crichton decided, which disfigured her left cheek. A minute before he had been cursing his luck, which invariably landed him in strange adventures, but at the sight of her beauty, our hero suddenly ceased to find the situation annoying. His interest, however, increased his alarm. What if she were dead or dying? Heart attacks were not uncommon. Bending over her, he laid his hand on her heart, and as he did so, the long lashes lifted, and a pair of sapphire blue eyes looked straight into his. Before he had time to move, she threw out both hands and cried: "Oh, let me go!"

"Don't be alarmed. Notwithstanding my unceremonious entrance, I assure you, I am a perfectly respectable member of society. My name is Crichton."

The girl staggered to her feet. "Crichton?" she gasped.

He looked at her in surprise.

"Yes, Crichton. Do you know any member of my family by any chance? My cousin, Lord Wilmersley, has a place near here."

"No," she faltered, "I—I am quite a stranger in this part of the country."

He was sure she was lying, but what could be her object in doing so? And why had his name caused her such alarm? What unpleasant connection could she possibly have with it? The only male members of his family who bore it, were, a curate, serving his probation in the East End of London, and a boy at Eton.

"That is a pity," he said. "I hoped we might find some mutual friends who would vouch for my inoffensiveness. I can't tell you how sorry I am to have given you such a fright. It was unpardonably stupid of me. The fact is, I am rather absent-minded, and I should have been left behind if I had not tumbled in on you as I did. Please forgive me."

"On the contrary, it is I who should apologise to you for having made such a fuss about nothing. You must have thought me quite mad." She laughed nervously.

"Madam," he replied, with mock solemnity, "I assure you I never for a moment doubted your sanity, and I am an expert in such matters."

"Are you really?" She shrank farther from him.

"Really what?" he inquired, considerably puzzled.

"A—a brain specialist? That is what they are called, isn't it?"

He laughed heartily.

"No, indeed. But you said——"

"Of course! How stupid of me!"

"Why should you know that I am a soldier?"

She blushed vividly. "You don't look like a civilian."

"At all events I hope I don't look like the keeper of an insane asylum."

"No, indeed. But you said——"

"Oh, as to being an expert. Was that it? I must plead guilty to having attempted a feeble joke, though as a matter of fact, it so happened that I do know something about lunatics."

"Aren't you dreadfully afraid of them?"

"On general principles, of course, I am afraid of nothing, but I fancy a full-grown lunatic, with a carving knife and a hankering for my blood, would have a different tale to tell."

"Oh, don't speak of them!" She covered her eyes with her hands.

"I beg your pardon."

"Why should you beg my pardon?" she asked looking at him suspiciously.

"I really don't know," he acknowledged.

"I know that I am behaving like a hysterical schoolgirl. What must you think of me! But,—but I am just recovering from an illness and am still very nervous, and the mere mention of lunatics always upsets me. I have the greatest horror of them."

"Poor child, she must have been through some terrible experience with one," thought Crichton.

"I trust you may never meet any," he said aloud.

"I don't intend to." She spoke with unexpected vehemence.

"Well, there is not much chance of your doing so. Certified lunatics find it pretty difficult to mingle in general society."

"I know—oh, I know—" Her voice sounded almost regretful.

What an extraordinary girl! Could it be—was it possible that she herself—but no, her behaviour was certainly strange and she seemed hysterical, but mad—no, and yet that would explain everything.

"I am sure it was the horrid crossing which upset you—as much as anything else," he said.

"I didn't cross, I—" She stopped abruptly, and bit her lip.

It was quite obvious that for some reason or other, she had not wished him to know that she had got in at Newhaven. He knew that politeness demanded he should not pursue a subject which was evidently distasteful to her. But his curiosity overcame his scruples.

"Really? It is rather unusual to take this train unless one is coming from the continent."

"Yes. One has to start so frightfully early. I had to get up a little before five." That meant she must live in Newhaven, and not far from the station at that—but was it true? She had about her that indescribable something which only those possess whose social position has never been questioned. No, Newhaven did not seem the background for her. But then, had she not herself told him that she did not live there? She might have gone there on an errand of charity or—After all, what business was it of his? Why should he attempt to pry into her life? It was abominable.

She settled herself in a corner of the carriage, and he fancied that she wished to avoid further conversation. Serve him jolly well right, he thought.

During the rest of the journey his behaviour was almost ostentatiously discreet. If she feared that he was likely to take advantage of the situation, he was determined to show her that he had no intention of doing so. To avoid staring at her he kept his eyes fixed on the rapidly changing landscape; but they might have been suddenly transported to China without his observing the difference. In fact, he had not realised that they were nearing their destination, till he saw his companion readjust her veil. A few minutes later the train stopped at Hearne Hill.

Crichton put his head out of the window.

"There is something up," he said, a moment later turning to her. "There must be a criminal on board. There are a lot of policemen about, and they seem to be searching the train."

"Oh, what shall I do!" she cried, starting to her feet.

"What is the matter?"

"They will shut me up. Oh, save me—save me!"

For a moment he was too startled to speak.

Was it possible? This girl a criminal—a thief? He couldn't believe it.

"But what have you done?"

"Nothing, nothing I assure you. Oh, believe me, it is all a mistake."

He looked at her again. Innocent or guilty, he would stand by her.

"They will be here directly," he said. "Have you enough self-control to remain perfectly calm and to back up any story I tell?"

"Yes."

"Sit down then, and appear to be talking to me."

"Tickets, please." The guard was at the door, and behind him stood a police inspector.

Crichton having given up his ticket, turned to the girl and said: "You have your ticket, Amy."

She handed it over.

"From Newhaven, I see." The inspector stepped forward:

"I must ask the lady to lift 'er veil, please."

"What do you mean, my man? Are you drunk?

"Steady, sir. Do you know this lady?"

"This lady happens to be my wife, so you will kindly explain your extraordinary behaviour."

The inspector looked a little nonplussed.

"Sorry to hinconvenience you, sir, but we 'ave orders to search this train for a young lady who got in at Newhaven. Now this is the only lady on board whose ticket was not taken in Paris. So you see we have got to make sure that this is not the person we want."

"But, man alive, I tell you this lady is my wife."

"So you say, sir, but you can't prove it, can you, now? You're registered through from Paris, and this lady gets in at Newhaven. How do you explain that?"

"Of course, one doesn't travel about with one's marriage certificate—but as it happens, I can prove that this lady is my wife. Here is my passport; kindly examine it. Mrs. Crichton returned to England several months ago, and went down to Newhaven last night so as to be able to meet me this morning. As to lifting her veil, of course she has no objection to doing so. I thought it idle curiosity on your part, but as it is a question of duty, that alters the case completely."

"Thank you, sir." The inspector opened the passport and read aloud. "Cyril Crichton—Lieutenant in the—Rifles, age 27 years, height 6 ft., 1 inch, weight 12 stone. Hair—fair; complexion—fair, inclined to be ruddy. Eyes—blue. Nose—straight, rather short. Mouth—large. Distinguishing marks: cleft in chin." And as he read each item, he paused to compare the written description with the original.

"Well, that's all right," he said. "And now for the lady's. Will you kindly lift your veil, m'm?"

To Crichton's surprise, the girl did so quite calmly, and her face, although deadly pale, was perfectly composed.

The inspector read: "Amy Crichton, wife of Cyril Crichton, age—26 years—H'm that seems a bit old for the lady."

The girl blushed vividly, but to Crichton's infinite relief she smiled gaily, and with a slight bow to the inspector said: "You flatter me."

Crichton breathed more freely. Her manner had done more to relieve the situation than anything he had said. The inspector continued in quite a different tone.

"'Height—5 ft., 4 inches.' You look a bit shorter than that."

"Measure me, if you doubt it." She challenged him.

"Oh, well, I am sure it is all right. 'Weight—9 stone, 4 lbs.'" He paused again, but this time made no comment, although Crichton felt sure that his companion weighed at least ten pounds less than the amount mentioned. "Hair—black. Complexion—fair. Eyes—blue. Nose—straight. Mouth—small. Oval chin. Distinguishing marks—none. All right, m'm! Sorry to 'ave disturbed you, but you understand we 'ave got to be very careful. We'd never 'ear the last of it if we let the party we're after slip through our fingers."

"What is the woman you are looking for accused of?" asked Crichton.

"Murder," replied the inspector, as he closed the door.

"Murder!"

Crichton looked at the girl. Her eyes were closed and she lay back breathing heavily. He did not know if she had even heard the accusation. Luckily the train was already moving. In a few minutes, however, they would be in London and then what should he do with her? Now that he had declared her to be his wife, it would arouse the suspicion of the police if he parted from her at the station. Besides, he could not desert the poor child in her terrible predicament. For she was innocent, he was sure of that. But here he was wasting precious time worrying about the future, when he ought to be doing something to revive her. It was simply imperative that she should be able to leave the train without exciting remark, as, once outside the station, the immediate danger would be over. His ministrations, however, were quite ineffectual, and, to his dismay, the train came to a standstill before she showed a sign of returning consciousness.

A porter opened the door.

"Bring a glass of water; the lady has fainted," he ordered. The porter returned in a few minutes followed by the police inspector. Crichton's heart sank. He fancied the latter eyed them with reawakened suspicion. As he knelt by the girl's side, her head on his shoulder, his arms around her, he suddenly became aware that a number of people had collected near the door and were watching the scene with unconcealed interest And among them stood Peter, his valet, staring at him with open-mouthed amazement.

Damn! He had completely forgotten him. If he didn't look out, the fellow would be sure to give the situation away.

"Peter," he called.

Peter elbowed his way through the crowd.

"Your mistress has fainted. Get my flask." Crichton spoke slowly and distinctly and looked Peter commandingly in the eye. Would he understand? Would he hold his tongue? Crichton watched him breathlessly. For a moment Peter blinked at him uncomprehendingly. Then the surprise slowly faded from his face, leaving it as stolid as usual.

"Very well, sir," was all he said as he went off automatically to do his master's bidding. An order has a wonderfully steadying effect on a well-trained servant.

The brandy having been brought, Crichton tried to force a few drops of it between the girl's clenched teeth. After a few minutes, however, he had to abandon the attempt.

The situation was desperate.

The inspector stepped forward.

"Don't you think, sir, you ought to send for a doctor? The lady looks bad and she can't stay here, you know. The train has to be backed out in a few minutes. We'll carry her to the waiting-room if you wish, or come to think of it, hadn't you better call an ambulance? Then you could take the lady home and the doctor who comes with them things would know what to do for her."

Crichton almost gasped with relief.

"An ambulance! The very thing. Get one immediately!"

The last passenger was just leaving the station when the ambulance clattered up.

The doctor, although hardly more than a boy, seemed to know his business, and after examining the girl and asking a few questions, he proceeded to administer various remedies, which he took out of a bag he carried.

"I am afraid this case is too serious for me," he said at last.

"What is the trouble?"

"Of course, I can't speak with any certainty, but from what you tell me, I think the lady is in for an attack of brain fever."

Crichton felt his brain reel.

"What shall I do?"

"We will take her home and in the meantime telephone to whatever doctor you wish to have called, so that he can see the patient as soon as possible."

"I have no house in town. I was going into lodgings but I can't take an invalid there."

"Of course not! What do you say to taking her at once to a nursing home?"

"Yes, that would be best. Which one would you recommend? I am ignorant of such matters."

"Well—Dr. Stuart-Smith has one not far from here. You know him by reputation, don't you?"

"Certainly. All right, take her there."

"I had better telephone and prepare them for our arrival. What is the lady's name, please?"

The inspector's eyes were upon him; Peter was at his elbow. Well—there was no help for it.

"Mrs. Cyril Crichton," he said.

The doctor returned in a few minutes.

"It is all right. They have got a room and Doctor Smith will be there almost as soon as we are."

Having lifted her into the ambulance, the doctor turned to Cyril and said: "I suppose you prefer to accompany Mrs. Crichton. You can get in, in front."

Crichton meekly obeyed.

"Take my things to the lodgings and wait for me there, and by the way, be sure to telephone at once to Mr. Campbell and tell him I must see him immediately," he called to Peter as they drove off.

They had apparently got rid of the police—that was something at all events. His own position, however, caused him the gravest concern. It was not only compromising but supremely ridiculous. He must extricate himself from it at once. His only chance, he decided, lay in confiding the truth to Dr. Smith. Great physicians have necessarily an enormous knowledge of life and therefore he would be better able than any other man to understand the situation and advise him as to what should be done. At all events the etiquette of his calling would prevent a doctor from divulging a professional secret, even in the case of his failing to sympathise with his, Cyril's, knight-errantry. Crichton heaved a sigh of satisfaction. His troubles, he foresaw, would soon be over.

The ambulance stopped. The girl was carried into the house and taken possession of by an efficient-looking nurse, and Cyril was requested to wait in the reception-room while she was being put to bed. Dr. Smith, he was told, would communicate with him as soon as he had examined the patient.

Crichton paced the room in feverish impatience. His doubts revived. What if the doctor should refuse to keep her? Again and again he rehearsed what he intended to say to him, but the oftener he did so, the more incredible did his story appear. It also occurred to him that a physician might not feel himself bound to secrecy when it was a question of concealing facts other than those relating to a patient's physical condition. What if the doctor should consider it his duty to inform the police of her whereabouts?

At last the door opened. Dr. Smith proved to be a short, grey-haired man with piercing, black eyes under beetling, black brows, large nose, and a long upper lip. Cyril's heart sank. The doctor did not look as if he would be likely to sympathise with his adventure.

"Mr. Crichton, I believe." The little man spoke quite fiercely and regarded our friend with evident disfavour.

Crichton was for a moment nonplussed. What had he done to be addressed in such a fashion?

"I hope you can give me good news of the patient?" he said, disregarding the other's manner.

"No," snapped out the doctor. "Mrs. Crichton is very seriously, not to say dangerously, ill."

What an extraordinary way of announcing a wife's illness to a supposed husband! Was every one mad to-day?

"I am awfully sorry—" began Crichton.

"Oh, you are, are you?" interrupted the doctor, and this time there could be no doubt he was intentionally insulting. "Will you then be kind enough to explain how your wife happens to be in the condition she is?"

"What condition?" faltered Cyril.

"Tut, man, don't pretend to be ignorant. Remember I am a doctor and can testify to the facts; yes, facts," he almost shouted.

Poor Crichton sat down abruptly. He really felt he could bear no more.

"For God's sake, doctor, tell me what is the matter with her. I swear I haven't the faintest idea."

His distress was so evidently genuine that the doctor relaxed a little and looked at him searchingly for a moment.

"Your wife has been recently flogged!"

"Flogged! How awful! But I can't believe it."

"Indeed!"

"Certainly not. You must be mistaken. The bruises may be the result of a fall."

"They are not," snapped the doctor.

"Flogged! here in England, in the twentieth century! But who could have done such a thing?"

"That is for you to explain, and I must warn you that unless your explanation is unexpectedly satisfactory, I shall at once notify the police."

Police! Crichton wiped beads of perspiration from his forehead.

"But, doctor, I know no more about it than you do."

"So you think that it will be sufficient for you to deny all knowledge as to how, where, and by whom a woman who is your wife—yes, sir—your wife, has been maltreated? Man, do you take me for a fool?"

What should he do? Was this the moment to tell him the truth? No, it would be useless. The doctor, believing him to be a brute, was not in a frame of mind to attach credence to his story. The truth was too improbable, a convincing lie could alone save the situation.

"My wife and I have not been living together lately," he stammered.

"Indeed!" The piercing eyes seemed to grow more piercing, the long upper lip to become longer.

"Yes," Crichton hesitated—it is so difficult to invent a plausible story on the spur of the moment. "In fact, I met her quite unexpectedly in Newhaven."

"In Newhaven?"

"Yes. I have just arrived from France," continued Crichton more fluently. An idea was shaping itself in his mind. "I was most astonished to meet my wife in England as I had been looking for her in Paris for the last week."

"I don't understand."

"My wife is unfortunately mentally unbalanced. For the last few months she has been confined in an asylum." Crichton spoke with increasing assurance.

"Where was this asylum?"

"In France."

"Yes, but where? France is a big place."

"It is called Charleroi and is about thirty miles from Paris in the direction of Fontainebleau."

"Who is the director of this institution?"

"Dr. Leon Monet."

"And you suggest that it was there that she was ill-treated. Let me tell you——"

Cyril interrupted him.

"I suggest no such thing. My wife escaped from Charleroi over a week ago. We know she went to Paris, but there we lost all trace of her. Imagine my astonishment at finding her on the train this morning. How she got there, I can't think. She seemed very much agitated, but I attributed that to my presence. I have lately had a most unfortunate effect upon her. I did ask her how she got the bruise on her cheek, but she wouldn't tell me. I had no idea she was suffering. If I had been guilty of the condition she is in, is it likely that I should have brought her to a man of your reputation and character? I think that alone proves my innocence."

The doctor stared at him fixedly for a few moments as if weighing the credibility of his explanation.

"You say that the physician under whose care your wife has been is called Monet?"

"Yes, Leon Monet."

The doctor left the room abruptly. When he returned, his bearing had completely changed.

"I have just verified your statement in a French medical directory and I must apologise to you for having jumped at conclusions in the way I did. Pray, forgive me——"

Crichton bowed rather distantly. He didn't feel over-kindly to the man who had forced him into such a quagmire of lies.

"Now as to—" Cyril hesitated a moment; he detested calling the girl by his name. "Now—as to—to—the patient. Have you any idea when she is likely to recover consciousness?"

"Not the faintest. Of course, what you tell me of her mental condition increases the seriousness of the case. With hysterical cases anything and everything is possible."

"But you do not fear the—worst."

"Certainly not. She is young. She will receive the best of care. I see no reason why she should not recover. Now if you would like to remain near her——"

There seemed a conspiracy to keep him forever at the girl's side, but this time he meant to break away even if he had to fight for it.

"I shall, of course, remain near her," Cyril interrupted hastily. "I have taken lodgings in Half Moon Street and shall stay there till she has completely recovered. As she has lately shown the most violent dislike of me, I think I had better not attempt to see her for the present. Don't you agree with me?"

"Certainly. I should not permit it under the circumstances."

"I shall call daily to find out how she is, and if there is any change in her condition, you will, of course, notify me at once." Crichton took out a card and scribbled his address on it. "This will always find me. And now I have a rather delicate request to make. Would you mind not letting any one know the identity of your patient? You see I have every hope that she will eventually recover her reason and therefore I wish her malady to be kept a secret. I have told my friends that my wife is in the south of France undergoing a species of rest cure."

"I think you are very wise. I shall not mention her name to any one."

"But the nurses?"

"It is a rule of all nursing homes that a patient's name is never to be mentioned to an outsider. But if you wish to take extra precautions, you might give her another name while she is here and they need never know that it is not her own."

"Thank you. That is just what I should wish."

"What do you think Mrs. Crichton had better be called?"

Cyril thought a moment.

"Mrs. Peter Thompkins, and I will become Mr. Thompkins. Please address all communications to me under that name; otherwise the truth is sure to leak out."

"But how will you arrange to get your mail?"

"Peter Thompkins is my valet, so that is quite simple."

"Very well. Good-bye, Mr. Thompkins. I trust I shall soon have a better report to give you of Mrs. Thompkins."

A moment later Cyril was in a taxi speeding towards Mayfair, a free man—for the moment.

While Crichton was dressing he glanced from time to time at his valet. Peter had evidently been deeply shocked by the incident at the railway station, for the blunt profile, so persistently presented to him, was austerely remote as well as subtly disapproving. Cyril was fond of the old man, who had been his father's servant and had known him almost from his infancy. He felt that he owed him some explanation, particularly as he had without consulting him made use of his name.

But what should he say to him? Never before had he so fully realised the joy, the comfort, the dignity of truth. It was not a virtue he decided; it was a privilege. If he ever got out of the hole he was in, he meant to wallow in it for the future. That happy time seemed, however, still far distant.

Believing the girl to be innocent, he wanted as few people as possible to know the nature of the cloud which hung over her. Peter's loyalty, he knew, he could count on, that had been often and fully proved; but his discretion was another matter. Peter was no actor. If he had anything to conceal, even his silence became so portentous of mystery that it could not fail to arouse the curiosity of the most unsuspicious. No, he must think of some simple story which would satisfy Peter as to the propriety of his conduct and yet which, if it leaked out, would not be to the girl's discredit.

"You must have been surprised to hear me give my name to the young lady you saw at the station," he began tentatively.

"Yes, sir." Peter's expression relaxed.

"Her story is a very sad one." So much at any rate must be true, thought poor Cyril with some satisfaction.

"Yes, sir." Peter was waiting breathlessly for the sequel.

"I don't feel at liberty to repeat what she told me. You understand that, don't you?"

"Certainly, sir," agreed Peter, but his face fell.

"So all I can tell you is that she was escaping from a brute who horribly ill-treated her. Of course I offered to help her."

"Of course," echoed Peter.

"Unfortunately she was taken ill before she had told me her name or who the friends were with whom she was seeking refuge. What was I to do? If the police heard that a young girl had been found unconscious on the train, the fact would have been advertised far and wide so as to enable them to establish her identity, in which case the person from whom she was hiding would have taken possession of her, which he has a legal right to do—so she gave me to understand." Crichton paused quite out of breath. He was doing beautifully. Peter was swallowing his tale unquestionably—and really, you know, for an inexperienced liar that was a reasonably probable story. "So you see," he continued, "it was necessary for her to have a name and mine was the only one which would not provoke further inquiry."

"Begging your pardon, sir, but I should 'ave thought that Smith or Jones would 'ave done just as well."

"Certainly not. The authorities would have wanted further particulars and would at once have detected the fraud. No one will ever know that I lent an unfortunate woman for a few hours the protection of my name, and there is no one who has the right to object to my having done so—except the young lady herself."

"Yes, sir, quite so."

"On the other hand, on account of the position I am in at present, it is most important that I should do nothing which could by any possibility be misconstrued."

"Yes, sir, certainly, sir."

"And so I told the doctor that the young lady had better not be called by my name while she is at the home and so—and so—well—in fact—I gave her yours. I hope you don't mind?"

"My name?" gasped Peter in a horrified voice.

"Yes, you see you haven't got a wife, have you?"

"Certainly not, sir!"

"So there couldn't be any possible complications in your case."

"One never can tell, sir—a name's a name and females are sometimes not over-particular."

"Don't be an ass! Why, you ought to feel proud to be able to be of use to a charming lady. Where's your chivalry, Peter?"

"I don't know, sir, but I do 'ope she's respectable," he answered miserably.

"Of course she is. Don't you know a lady when you see one?"

Peter shook his head tragically.

"I'm sorry you feel like that about it," said Crichton. "It never occurred to me you would mind, and I haven't yet told you all. I not only gave the young lady your name but took it myself."

"Took my name!"

"Yes. At the nursing home I am known as Mr. Peter Thompkins. Pray that I don't disgrace you, Peter."

"Oh, sir, a false name! If you get found out, they'll never believe you are hinnocent when you've done a thing like that. Of course, a gentleman like you hought to know his own business best, but it do seem to me most awful risky."

"Well, it's a risk that had to be taken. It was a choice of evils, I grant you. Hah! I sniff breakfast; the bacon and eggs of my country await me. I am famishing, and I say, Peter, do try to take a more cheerful view of this business."

"I'll try, sir."

Crichton was still at breakfast when a short, red-haired young man fairly burst into the room.

"Guy Campbell!" exclaimed Cyril joyfully.

"Hullo, old chap, glad to see you," cried the newcomer, pounding Cyril affectionately on the back. "How goes it? I say, your telephone message gave me quite a turn. What's up? Have you got into a scrape? You look as calm as possible."

"If I look calm, my looks belie me. I assure you I never felt less calm in my life."

"What on earth is the matter?"

"You won't have some breakfast?"

"Breakfast at half-past eleven! No thank you."

"Well, then, take a cigarette, pull up that chair to the fire, and listen—and don't play the fool; this is serious."

"Fire away."

"I want your legal advice, Guy, though I suppose you'll tell me I need a solicitor, not a barrister. I wish to get a divorce."

"A divorce? Why, Cyril, I am awfully sorry. I had heard that your marriage hadn't turned out any too well, but I had no idea it was as bad as that. You have proof, I suppose."

"Ample."

"Tell me the particulars. I never have heard anything against your wife's character."

"You mean that you have never heard that she was unfaithful to me. Bah, it makes me sick the way people talk, as if infidelity were the only vice that damned a woman's character. Guy, her character was rotten through and through. Her infidelity was simply a minor, though culminating, expression of it."

"But how did you come to marry such a person?"

"You know she was the Chalmerses' governess?"

"Yes."

"I had been spending a few weeks with them. Jack, the oldest son, was a friend of mine and she was the daughter of a brother officer of old Chalmers's who had died in India, and consequently her position in the household was different from that of an ordinary governess. I soon got quite friendly with Amy and her two charges, and we used to rag about together a good deal. I liked her, but upon my honour I hadn't a thought of making love to her. Then one day there was an awful row. They accused her of carrying on a clandestine love affair with Freddy, the second son, and with drinking on the sly. They had found empty bottles hidden in her bedroom. She posed as injured innocence—the victim of a vile plot to get her out of the house—had no money, no friends, no hope of another situation. I was young; she was pretty. I was dreadfully sorry for her and so—well, I married her. As the regiment had just been ordered to South Africa, we went there immediately. We had not been married a year, however, when I discovered that she was a confirmed drunkard. I think only the fear of losing her position had kept her within certain bounds. That necessity removed, she seemed unable to put any restraint on herself. I doubt if she even tried to do so."

"Poor Cyril!"

"Later on I found out that she was taking drugs as well as stimulants. She would drink herself into a frenzy and then stupefy herself with opiates. But it is not only weakness I am accusing her of. She was inherently deceitful and cruel—ah, what is the use of talking about it! I have been through Hell."

"You haven't been living together lately, have you?"

"Well, you see, she was disgracing not only herself but the regiment, and so it became a question of either leaving the army or getting her to live somewhere else. So I brought her back to Europe, took a small villa near Pau, and engaged an efficient nurse-companion to look after her. I spent my leave with her, but that was all. Last spring, however, she got so bad that her companion cabled for me. For a few weeks she was desperately ill, and when she partially recovered, the doctor persuaded me to send her to a sanitarium for treatment. Charleroi was recommended to me. It was chiefly celebrated as a lunatic asylum, but it has an annex where dipsomaniacs and drug fiends are cared for. At first, the doctor's reports were very discouraging, but lately her improvement is said to have been quite astonishing, so much so that it was decided that I should take her away for a little trip. I was on my way to Charleroi, when the news reached me that Amy had escaped. We soon discovered that she had fled with a M. de Brissac, who had been discharged as cured the day before my wife's disappearance. We traced them to within a few miles of Paris, but there lost track of them. I have, however, engaged a detective to furnish me with further particulars. I fancy the Frenchman is keeping out of the way for fear I shall kill him. Bah! Why, I pity him, that is all! He'll soon find out what that woman is like. He has given me freedom! Oh, you can't realise what that means to me. I only wish my father were alive to know that I have this chance of beginning life over again."

"I was so sorry to hear of his death. He was always so kind to us boys when we stayed at Lingwood. I wrote you when I heard the sad news, but you never answered any of my letters."

"I know, old chap, but you must forgive me. I have been too miserable—too ashamed. I only wanted to creep away and to be forgotten."

"Your father died in Paris, didn't he?"

"Yes, luckily I was with him. It was just after I had taken Amy to Charleroi. He was a broken-hearted man. He never got over the mess I had made of my life and Wilmersley's marriage was the last straw. He brooded over it continually."

"Why had your father been so sure that Lord Wilmersley would never marry? He was an old bachelor, but not so very old after all. He can't be more than fifty now."

"Well, you see, Wilmersley has a bee in his bonnet. His mother was a Spanish ballet dancer whom my uncle married when he was a mere boy. She was a dreadful old creature. I remember her distinctly, a great, fat woman with a big, white face and enormous, glassy, black eyes. I was awfully afraid of her. She died when Wilmersley was about twenty and my uncle followed her a few months later. His funeral was hardly over when my cousin left Geralton and nothing definite was heard of him for almost twenty-five years. He was supposed to be travelling in the far East, and from time to time some pretty queer rumours drifted back about him. Whether they were true or not, I have never known. One day he returned to Geralton as unexpectedly as he had left it. He sent for me at once. He has immense family pride—the ballet dancer, I fancy, rankles—and having decided for some reason or other not to marry, he wished his heir to cut a dash. He offered me an allowance of £4000 a year, told me to marry as soon as possible, and sent me home."

"Well, that was pretty decent of him. You don't seem very grateful."

"I can't bear him. He's a most repulsive-looking chap, a thorough Spaniard, with no trace of his father's blood that I can see. And as I married soon afterwards and my marriage was not to his liking, he stopped my allowance and swore I should never succeed him if he could help it. So you see I haven't much reason to be grateful to him."

"Beastly shame! He married Miss Mannering, Lady Upton's granddaughter, didn't he?"

"Yes."

"She is a little queer, I believe."

"Really? I didn't know that. I have never seen her, but I hear she is very pretty. Well, I'm sorry for her, brought up by that old curmudgeon of a grandmother and married out of the schoolroom to Wilmersley. She has never had much of a chance, has she?"

"There are no children as yet?"

"No."

"So that now that your father is dead, you are the immediate heir."

The door was flung open and Peter rushed into the room brandishing a paper.

"Oh, sir, it's come at last! I always felt it would!" He stuttered with excitement.

"What on earth is the matter with you?"

"I beg pardon, sir, but I am that hovercome! I heard them crying 'hextras,' so I went out and gets one—just casual-like. Little did I think what would be in it—and there it was."

"There was what?" Both men spoke at once, leaning eagerly forward.

"That Lord Wilmersley is dead; and so, my lord, I wish you much joy and a long life."

"This is very sudden," gasped Crichton. "I hadn't heard he was ill. What did he die of?"

"'E was murdered, my lord."

"When, how, who did it?" cried Cyril incoherently. "Give me the paper."

"Murder of Lord Wilmersley—disappearance of Lady Wilmersley," he read. "Disappearance of Lady Wilmersley," he repeated, as the paper fell from his limp hand.

"Here, get your master some whiskey; the shock has been too much for him," said Camp bell. "Mysterious disappearance of Lady Wilmersley," murmured Crichton, staring blankly in front of him.

"Here, drink this, old man; you'll be all right in a moment," said Campbell, pressing a glass into his hand.

Cyril emptied it automatically.

"The deuce take it!" he cried, covering his face with his hands.

"Shall I read you the particulars?" Campbell asked, taking the paper. Cyril nodded assent.

"'The body of Lord Wilmersley was found at seven o'clock this morning floating in the swimming bath at Geralton. It was at first thought that death had been caused by drowning, but on examination, a bullet wound was discovered over the heart. Search for the pistol with which the crime was committed has so far proved fruitless. The corpse was dressed in a long, Eastern garment frequently worn by the deceased. Lady Wilmersley's bedroom, which adjoins the swimming bath, was empty. The bed had not been slept in. A hurried search of the castle and grounds was at once made, but no trace of her ladyship has been discovered. It is feared that she also has been murdered and her body thrown into the lake, which is only a short distance from the castle. None of her wearing apparel is missing, even the dress and slippers she wore on the previous evening were found in a corner of her room. Robbery was probably the motive of the crime, as a small safe, which stands next to Lady Wilmersley's bed and contained her jewels, has been rifled. Whoever did this must, however, have known the combination, as the lock has not been tampered with. This adds to the mystery of the case. Lady Wilmersley is said to be mentally unbalanced. Arthur Edward Crichton, 9th Baron Wilmersley, was born—' here follows a history of your family, Cyril, you don't want to hear that. Well, what do you think of it?" asked Campbell.

"It's too horrible! I can't think," said Crichton.

"I don't believe Lady Wilmersley was murdered," said Campbell. "Why should a murderer have troubled to remove one body and not the other? Mark my words, it was his wife who killed Wilmersley and opened the safe."

"I don't believe it! I won't believe it!" cried Cyril. "Besides, how could she have got away without a dress or hat? Remember they make a point of the fact that none of her clothes are missing."

"In the first place, you can't believe everything you read in a newspaper; but even granting the correctness of that statement, what was there to prevent her having borrowed a dress from one of her maids? She must have had one, you know."

"No—no! It can't be, I tell you; I—" Cyril stopped abruptly.

"What's the matter with you? You look as guilty as though you had killed him yourself. I can't for the life of me see why you take the thing so terribly to heart. You didn't like your cousin and from what you yourself tell me, I fancy he is no great loss to any one, and you don't know his wife—widow, I mean."

"It is such a shock," stammered Cyril.

"Of course it's a shock, but you ought to think of your new duties. You will have to go to Geralton at once?"

"Yes, I suppose it will be expected of me," Cyril assented gloomily. "Peter, pack my things and find out when the next train leaves."

"Very well, my lord."

"And Guy, you will come with me, won't you? I really can't face this business alone. Besides, your legal knowledge may come in useful."

"I am awfully sorry, but I really can't come to-day. I've got to be in court this afternoon; but I'll come as soon as I can, if you really want me."

"Do!"

"Of course I want to be of use if I can, but a detective is really what you need."

"A detective?" gasped Cyril.

"Well, why not? Don't look as if I had suggested your hiring a camel!"

"Yes, of course not—I mean a detective is—would be—in fact—very useful," stammered Cyril. Why couldn't Guy mind his own business?

"Why not get one and take him down with you?" persisted Campbell.

"Oh, no!" Cyril hurriedly objected, "I don't think I had better do that. They may have one already. Shouldn't like to begin by hurting local feeling and—and all that, you know."

"Rot!"

"At any rate, I'm not going to engage any one till I've looked into the matter myself," said Cyril. "If I find I need a man, I'll wire."

Campbell, grumbling about unnecessary delay, let the matter drop.

Two hours later Cyril was speeding towards Newhaven.

Huddled in a corner of the railway carriage, he gave himself up to the gloomiest reflections. Was ever any one pursued by such persistent ill-luck? It seemed too hard that just as he began to see an end to his matrimonial troubles, he should have tumbled headlong into this terrible predicament. From the moment he heard of Lady Wilmersley's disappearance he had never had the shadow of a doubt but that it was she he had rescued that morning from the police. What was he going to do, now that he knew her identity? He must decide on a course of action at once. Wash his hands of her? No-o. He felt he couldn't do that—at least, not yet. But unless he immediately and voluntarily confessed the truth, who would believe him if it ever came to light? If it were discovered that he, the heir, had helped his cousin's murderess to escape—had posed as her husband, would any one, would any jury believe that chance alone had thrown them together? He might prove an alibi, but that would only save his life—not his honour. He would always be suspected of having instigated, if not actually committed, the murder.

If, however, by some miracle the truth did not leak out, what then? It would mean that from this day forward he would live in constant fear of detection. The very fact of her secret existence must necessarily poison his whole life. Lies, lies, lies would be his future portion. Was he willing to assume such a burden? Was it his duty to take upon himself the charge of a woman who was after all but a homicidal maniac? But was she a maniac? Again and again he went over each incident of their meeting, weighed her every word and action, and again he found it impossible to believe that her mind was unbalanced. Yet if she was not insane, what excuse could he find to explain her crime? Provocation? Yes, she had had that. She had been beaten, flogged. But even so, to kill! He had once been present when a murderer was sentenced: "To hang by the neck until you are dead," the words rang in his ears. That small white neck—no—never. Suddenly he realised that his path was irrevocably chosen. As long as she needed him, he would protect her to the uttermost of his ability. Even if his efforts proved futile, even if he ruined his life without saving hers, he felt he would never regret his decision.

"Newhaven."

It seemed centuries since he had left it that morning. Hiring a fly, he drove out to Geralton, a distance of nine miles. There the door was opened by the same butler who had admitted him five years previously. "It's Mr. Cyril!" he cried, falling back a step. "Why, sir, they all told us as 'ow you were in South Africa. But I bid you welcome, sir."

"Thank you. I am glad to see you again."

"Thank you, sir,—my lord, I mean, and please forgive your being received like this—but every one is so upset, there's no doing nothing with nobody. If you will step in 'ere, I'll call Mrs. Eversley, the 'ousekeeper."

"Is Mrs. Eversley still here? I remember her perfectly. She used to stuff me with doughnuts when I came here as a boy. Tell her I will see her presently."

"Very good, my lord."

"Now I want to hear all the particulars of the tragedy. The newspaper account was very meagre."

"Quite so, my lord," assented the butler.

"Lady Wilmersley has not been found?" asked Cyril.

"No, my lord. We've searched for her ladyship 'igh and low. Not a trace of her. And now every one says as 'ow she did it. But I'll never believe it—never. A gentle little lady, she was, and so easily frightened! Why, if my lord so much as looked at her sometimes, she'd fall a trembling, and 'e always so kind and devoted to 'er. 'E just doted on 'er, 'e did. I never saw nothing like it."

"If you don't believe her ladyship guilty, is there any one else you do suspect?"

"No, my lord, I can't say as I do." He spoke regretfully. "It was a burglar, I believe. I think the detective——"

"What detective?" interrupted Cyril.

"His name is Judson; 'e comes from London and they say as 'e can find a murderer just by looking at the chair 'e sat in."

"Who sent for him? The police?"

"No, it was Mr. Twombley of Crofton. He said we owed it to 'er ladyship to hemploy the best talent."

"Where is the detective now?"

"'E's in the long drawing-room with Mr. Twombley."

"Has the inquest been held?"

"No, the corpse won't be sat on till to-morrow morning."

"Show me the way to the drawing-room. I don't quite remember it."

The butler preceded him across the hall and throwing open a door announced in a loud voice:

"Lord Wilmersley."

The effect was electrical. Four men who had been deep in conversation turned and stared open-mouthed at Cyril, and one of them, a short fat man in clerical dress, dropped his teacup in his agitation.

"Who?" bellowed a tall, florid old gentleman.

The butler, secretly delighted at having produced such a sensation, closed the door discreetly after him.

"I don't wonder you are surprised to see me. You thought I was with my regiment."

"So you're the little shaver I knew as a boy? Well, you've grown a bit since then. Hah, hah." Then, recollecting the solemnity of the occasion, he subdued his voice. "I'm Twombley, friend of your father's, you know, and this is Mr. James, your vicar, and this is Mr. Tinker, the coroner, and this is Judson, celebrated detective, you know. I sent for him. Hope you approve? Terrible business, what?"

"It has been a great shock to me, and I am very glad to have Judson's assistance," replied Cyril, casting a searching and apprehensive glance at the detective.

He was a small, clean-shaven man with short, grey hair, grey eyebrows, grey complexion, dressed in a grey tweed suit. His features were peculiarly indefinite. His half-closed eyes, lying in the shadow of the overhanging brows, were fringed with light eyelashes and gave no accent to his expressionless face.

At all events, thought Cyril, he doesn't look very alarming, but then, you never can tell.

"I must condole with you on the unexpected loss of a relative, who was in every way an honour to his name and his position," said the vicar, holding out a podgy hand.

Cyril was so taken aback at this unexpected tribute to his cousin's memory that he was only able to murmur a discreet "Thank you."

"The late Lord Wilmersley," said the coroner, "was a most public-spirited man and is a loss to the county."

"Quite so, quite so," assented Mr. Twombley. "Gave a good bit to the hunt, though he never hunted. Pretty decent of him, you know. You hunt, of course?"

"I haven't done much of it lately, but I shall certainly do so in future."

"Your cousin," interrupted the vicar, "was a man of deep religious convictions. His long stay in heathen lands had only strengthened his devotion to the true faith. His pew was never empty and he subscribed liberally to many charities."

By Jove, thought poor Cyril, his cousin had evidently been a paragon. It seemed incredible.

"I see it will be difficult to fill his place," he said aloud. "But I will do my best."

Twombley clapped him heartily on the back. "Oh, you'll do all right, my boy, and then, you know, you'll open the castle. The place has been like a prison since Wilmersley's marriage."

"No one regretted that as much as Lord Wilmersley," said the vicar. "He often spoke to me about it. But he had the choice between placing Lady Wilmersley in an institution or turning the castle into an asylum. He chose the latter alternative, although it was a great sacrifice. I have rarely known so agreeable a man or one so suited to shine in any company. It was unpardonable of Lady Upton to have allowed him to marry without warning him of her granddaughter's condition. But he never had a word of blame for her."

"It was certainly a pity he did not have Lady Wilmersley put under proper restraint. If he had only done so, he would be alive now," said the coroner.

"So you believe that she murdered his lordship?"

"Undoubtedly. Who else could have done it? Who else had a motive for doing it. My theory is that her ladyship wanted to escape, that his lordship tried to prevent her, and so she shot him. Don't you agree with me, Mr. Judson?"

"It is impossible for me to express an opinion at present. I have not had time to collect enough data," replied the detective pompously.

"He puts on such a lot of side, I believe he's an ass," thought Cyril, heaving a sigh of relief. "But what about the missing jewels?" he said aloud. "Their disappearance certainly provides a motive for the crime?"

"Yes, but only Lord and Lady Wilmersley knew the combination of the safe."

"Who says so?"

"All the servants are agreed as to that. Besides, a burglar would hardly have overlooked the drawers of Lord Wilmersley's desk, which contained about £300 in notes."

"The thief may not have got as far as the library. Lady Wilmersley occupied the blue room, I suppose."

"Not at all. At the time of his marriage Lord Wilmersley ordered a suite of rooms on the ground floor prepared for his bride's reception," replied the vicar.

"And this swimming-bath? Where is that? There was none when I was here as a child."

"No, it was built for Lady Wilmersley and adjoins her private apartments," said the vicar.

"But all these rooms are on the ground floor. It must be an easy matter to enter them. Consequently——"

"Easy!" interrupted Twombley; "not a bit of it! But come and see for yourself."

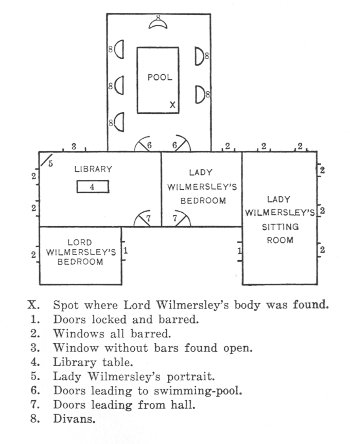

Crossing the hall they paused at a door. "Now this door and that one next to it, which is the door of Lady Wilmersley's bedroom," said the coroner, "are the only ones in this wing which communicate with the rest of the castle, and both were usually kept locked, not only at night, but during the daytime. You will please notice, my lord," continued the coroner, as they entered the library, "that both doors are fitted with an ingenious device, by means of which they can be bolted and unbolted from several seats in this room and from the divans in the swimming-bath. Only in the early morning were the housemaids admitted to these rooms; after that no one but Mustapha, Lord Wilmersley's Turkish valet, ever crossed the threshold, unless with his lordship's express permission."

Twombley hurried him through the library.

"You can look this room over later; I want you first to see the swimming-bath."

Cyril found himself in an immense and lofty hall, constructed entirely of white marble and lighted by innumerable jewelled lamps, whose multi-coloured lights were reflected in the transparent waters of a pool, from the middle of which rose and splashed a fountain. Divans covered with soft cushions and several small tables laden with pipes, houkahs, cigarettes, etc., were placed at intervals around the sides of the bath. On one of the tables, Cyril noticed that two coffee-cups were still standing and by the side of a divan lay a long Turkish pipe. The floor was strewn with rare skins. A profusion of tropical plants imparted a heavy perfume to the air, which was warm and moist. Cyril blinked his eyes; he felt as if he had suddenly been transported to the palace of Aladdin.

"Rum place, what?" said Twombley, looking about him with evident disfavour. "To be shut in here for three years would be enough to drive any one crazy, I say."

"You will notice," said the coroner, "that the only entrance to the bath is through the library or her ladyship's bedroom. No one could have let himself down through the skylight, as it is protected by iron bars."

"I see."

"It was here and in the library that Lord Wilmersley spent his time, and it was here in the right-hand corner of the bath that his body was discovered this morning by one of the housemaids. The spot, as you see, is exactly opposite her ladyship's door and that door was found open, just as it stands at present. Now the housemaids swear that they always found it closed and it is their belief that his lordship used to lock her ladyship in her rooms before retiring to his own quarters for the night. At all events they were never allowed to see her ladyship or enter her apartments unless his lordship or her ladyship's maid was also present."

"At about what time is Lord Wilmersley supposed to have been killed?" asked Cyril after a slight pause.

"Judging from the condition of the body, the doctor thinks that the murder was committed between eleven and twelve P.M.," replied the coroner; "and whoever fired the shot must have stood five or six feet from Lord Wilmersley; in all probability, therefore, in the doorway of the bedroom. This is the room. Nothing has been touched, and you see that neither here nor in the swimming-bath are there signs of a struggle."

"The door leading into the hall was found locked?"

"Yes, my lord."

"Then how did the house-man enter?"

"By means of a pass-key."

"Where does that other door lead to?" asked Cyril, pointing to a door to his left.

"Into the sitting-room," replied the coroner, throwing it open. "It was here, I am told, that Lady Wilmersley usually spent the morning."

It was a large, pleasant room panelled in white. A few faded pastels of by-gone beauties ornamented the walls. A gilt cage in which slumbered a canary hung in one of the windows. Cyril looked eagerly about him for some traces of its late occupant's personality; but except for a piece of unfinished needlework, lying on a small table near the fireplace, there was nothing to betray the owner's taste or occupations.

"And there is no way out of this room except through the bedroom?"

"None."

"No secret door?"

"No, my lord. Mr. Judson thought of that and has tapped the walls."

"But the windows?"

"These windows as well as those in the bedroom are fitted with heavy iron bars. Look," he said.

"Who was the last person known to have seen Lord Wilmersley alive?"

"Mustapha. He carried coffee into the swimming-bath at a quarter past nine, as was his daily custom."

"And he noticed nothing unusual?"

"Nothing. And he swears that in passing out through the library he heard the bolt click behind him."

"What sort of a person is Mustapha?"

"Lord Wilmersley brought him back with him when he returned from the East. He had the greatest confidence in him," said the vicar.

"Do you know what his fellow-servants think of him," inquired Cyril, addressing the coroner.

"He kept very much to himself. I fancy he is not a favourite, but no one has actually said anything against him."

"Insular prejudice!" cried the vicar. "How few of us are able to overcome our inborn British suspicion of the foreigner!"

"Now will you examine the library?" asked the coroner. "See, here is his lordship's desk. There are the drawers in which the £300 were found, and yet any one could have picked that lock."

"Where does that door lead to?"

"Into Lord Wilmersley's bedroom, the window of which is also provided with iron bars."

"And that room has no exit but this?"

"None, my lord. If the murderer came from outside, he must have got in through one of these windows, which are the only ones in this wing which have no protection, and this one was found ajar—but it may have been used only as an exit, not as an entrance."

Cyril looked out. Even a woman would have no difficulty in jumping to the ground.

"But it couldn't have been a burglar," said the vicar, "for what object could a thief have for destroying a portrait?"

"Destroying what portrait?" inquired Cyril.

"Oh, didn't you know that her ladyship's portrait was found cut into shreds?" said the coroner.

"And a pair of Lady Wilmersley's scissors lay on the floor in front of it," added the vicar.

"Let me see it," cried Cyril.

Going to a corner of the room the vicar pulled aside a velvet curtain behind which hung the wreck of a picture. The canvas was slashed from top to bottom. No trace of the face was left; only a small piece of fair hair was still distinguishable.

Cyril grasped Twombley's arm. Fair! And his mysterious protégée was dark!

"What—what was the colour of Lady Wilmersley's hair?" He almost stuttered with excitement.

"A very pale yellow," replied the coroner.

"Why do you ask?" inquired the detective.

For the convenience of my readers I give a diagram of Lord and Lady Wilmersley's apartments.

| X. | Spot where Lord Wilmersley's body was found. |

| 1. | Doors locked and barred. |

| 2. | Windows all barred. |

| 3. | Window without bars found open. |

| 4. | Library table. |

| 5. | Lady Wilmersley's portrait. |

| 6. | Doors leading to swimming-pool. |

| 7. | Doors leading from hall. |

| 8. | Divans. |

"A very pale yellow!" Cyril was dumb-founded.

Every fact, every inference had seemed to prove beyond the shadow of a doubt that his protégée and Lady Wilmersley were one and the same person. Was it possible that she could have worn a wig? No, for he remembered that in lifting her veil, he had inadvertently pulled her hair a little and had admired the way it grew on her temples.

"Why does the colour of her ladyship's hair interest you, my lord?" again inquired the detective.

Cyril blushed with confusion as he realised that all three men were watching him with evident astonishment. What a fool he was not to have been able to conceal his surprise! What answer could he give them? However, as it was not his cousin's murderess he was hiding, he felt he had nothing to fear from the detective, so ignoring him he turned to Mr. Twombley and said with a forced laugh:

"I must be losing my mind, for I distinctly remember hearing a friend of mine rave about Lady Wilmersley's dark beauty." Rather a fishy explanation, thought poor Cyril; but really his powers of invention were exhausted. Would it satisfy them?

He glanced sharply at the detective. The latter was no longer looking at him, but was contemplating his watch-chain with absorbed attention.

"Hah, hah! Rather a joke, what?" laughed Twombley. "Never had seen her, I suppose; no one ever did, you know, except out driving."

"It was either a silly joke or my memory is in a bad shape," said Cyril. "Luckily it is a matter of no consequence. What is of vital importance, however," he continued, turning to the detective, "is that her ladyship should be secured immediately. No one is safe while she is still at large."

"It is unfortunate," replied the detective, "that no photograph of her ladyship can be found, but we have telegraphed her description all over the country."

"What is her description, by the way?"

"Here it is, my lord," said Judson, handing Cyril a printed sheet.

"Height, 5 feet 3; weight, about 9 stone 2; hair, very fair, inclined to be wavy; nose, straight; mouth, small; eyes, blue; face, oval," read Cyril. "Well, I suppose that will have to do, but of course that description would fit half the women in England."

"That's the trouble, my lord."

"Mr. Twombley, when you said just now that no one knew her, did you mean that literally?"

"Nobody in the county did; I'm sure of that."

"And you, Mr. James? Is it possible that even you never saw her?"

"I have never spoken to her."

"Then so far as you know, the only person outside the castle she could communicate with was the doctor. What sort of a man is he?"

"What doctor are you speaking of?" inquired the vicar.

"Why, the doctor who had charge of her case, of course," replied Cyril impatiently.

"I never heard of her having a doctor."

"Do you mean to say that Wilmersley kept her in confinement without orders from a physician?"

"No, I suppose not. Of course not. There must have been some one," faltered the vicar a trifle abashed.

"You never, however, inquired by what authority he kept his wife shut up?"

"I never insulted Lord Wilmersley by questioning the wisdom of his conduct or the integrity of his motives, and I repeat that there was undoubtedly some physician in attendance on Lady Wilmersley, only I do not happen to know who he is."

"Well, I must clear this matter up at once. Please ring the bell, Judson."

A minute later the butler appeared.

"Who was her ladyship's physician?" demanded Cyril.

"My lady never 'ad one; leastways not till yesterday."

"Yesterday?"

"Yes, my lord, yesterday afternoon two gentlemen drove up in a fly and one of them says 'is name is Dr. Brown and that 'e was expected, and 'is lordship said as how I was to show them in here, and so I did."

"You think they came to see her ladyship?"

"Yes, my lord, and at dinner her ladyship seemed very much upset. She didn't eat a morsel, though 'is lordship urged 'er ever so."

"But why should a doctor's visit upset her ladyship?"

The butler pursed his lips and looked mysterious. "I can't say, my lord."

"Nonsense, you've some idea in your head. Out with it!"

"Well, my lord, me and Charles, we thought as she was afraid they were going to lock 'er up."

Cyril started slightly.

"Ah! If they had done so long ago!" exclaimed the vicar, clasping his hands.

"But, sir, her ladyship wasn't crazy! They all say so, but it isn't true. Me and Charles 'ave watched 'er at table day in and day out and we're willing to swear that she isn't any more crazy than—than me! Please excuse the liberty, but I never thought 'er ladyship was treated right, I never did."

"Why, you told me yourself that his lordship was devoted to her."

"So 'e was, my lord, so 'e was." The man shuffled uneasily.

"If her ladyship is not insane, why do you think his lordship kept her a prisoner here?"

"Well, my lord, some people 'ave thought that it was jealousy as made him do it."

"That," exclaimed the vicar, "is a vile calumny, which I have done my best to refute."

"So jealousy was the motive generally ascribed to my cousin's treatment of his wife?"

"Not generally, far from it; but I regret to say that there are people who professed to believe it."

"Did her ladyship have a nurse?" asked Cyril, addressing the butler.

"No, my lord, only a maid."

"Mrs. Valdriguez is a very respectable person, my lord."

"Mrs. What?" demanded Cyril.

"Mrs. Valdriguez."

"What a queer name."

"Perhaps, my lord, I don't pronounce it just right. Mrs. Valdriguez is Spanish."

"Indeed!"

"Yes, my lord, she was here first in the time of Lord Wilmersley's mother, and 'is lordship brought 'er back again when he returned from 'is 'oneymoon. Lady Wilmersley never left these rooms without 'aving either 'is lordship, Mustapha, or Valdriguez with 'er."

"Very good, Douglas, you can go now."

"A pretty state of things!" cried Cyril when the door closed behind the butler. "Here in civilised England a poor young creature is kept in confinement with a Spanish woman and a Turk to watch over her, and no one thinks of demanding an investigation! It's monstrous!"

"My boy, you're right. Never liked the man myself—confess it now—but I didn't know anything against him. Pretty difficult to interfere, what? Never occurred to me to do so."

"I am deeply pained by your attitude to your unfortunate cousin, who paid with his life for his devotion to an afflicted woman. I feel it my duty to say that your suspicions are unworthy of you. I must go now; I have some parochial duties to attend to." And with scant ceremony the vicar stalked out of the room.

"It's getting late, I see. Must be off too. Can't be late for dinner—wife, you know. Why don't you come with me—gloomy here—delighted to put you up. Do come," urged Twombley.

"Thanks awfully, not to-night. I'm dead beat. It's awfully good of you to suggest it, though."

"Not at all; sorry you won't come. See you at the inquest," said Twombley as he took his departure followed by the coroner.

Cyril remained where they left him. He was too weary to move. Before him on the desk lay his cousin's blotter. Its white surface still bore the impress of the latter's thick, sprawling handwriting. That chair not so many hours ago had held his unwieldy form. The murdered man's presence seemed to permeate the room. Cyril shuddered involuntarily. The heavy, perfume-laden air stifled him. What was that? He could hear nothing but the tumultuous beating of his own heart. Yet he was sure, warned by some mysterious instinct, that he was not alone. Behind him stood—something. He longed to move, but terror riveted him to the spot. A vision of his cousin's baleful eyes rose before him with horrible vividness. He could feel their vindictive glare scorching him. Was he going mad? Was he a coward? No, he must face the—thing—come what might. Throwing back his head defiantly, he wheeled around—the detective was at his elbow! Cyril gave a gasp of relief and wiped the tell-tale perspiration from his forehead. He had completely forgotten the fellow. What a shocking state his nerves were in!

"Can you spare me a few minutes, my lord?" Whenever the detective spoke, Cyril had the curious impression as of a voice issuing from a fog. So grey, so effaced, so absolutely characterless was the man's exterior! His voice, on the other hand, was excessively individual. There lurked in it a suggestion of assertiveness, of aggressiveness even. Cyril was conscious of a sudden dread of this strong, insistent personality, lying as it were at ambush within that envelope of a body, that envelope which he felt he could never penetrate, which gave no indication whether it concealed a friend or enemy, a saint or villain.

"I shall not detain you long," Judson added, as Cyril did not answer immediately.

"Come into the drawing-room," said Cyril, leading the way there.

Thank God, he could breathe freely once more, thought Cyril, as he flung himself into the comfortable depths of a chintz-covered sofa. How delightfully wholesome and commonplace was this room! The air, a trifle chill, notwithstanding the coal fire burning on the hearth, was like balm to his fevered senses. His very soul felt cleansed and refreshed. He no longer understood the terror which had so lately possessed him. He looked at Judson. How could he ever have dignified this remarkably unremarkable little man with his pompous manner into a mysterious and possibly hostile force. The thing was absurd.

"Sit down, Judson," said Cyril carelessly.

"My lord, am I not right in supposing that I am unknown to you? By reputation, I mean."

"Quite," Cyril candidly acknowledged.

"Ah! I thought so. Let me tell you then, my lord, that I am the receptacle of the secrets of most, if not all, of the aristocracy."

"Indeed!" said Cyril. I'll take good care, he thought, that mine don't swell the number.

"That being the case, it is clear that my reputation for discretion is unassailable. You see the force of that argument, my lord?"

"Certainly," replied Cyril wearily.

"Anything, therefore, which I may discover during the course of this investigation, you may rest assured will be kept absolutely secret." He paused a moment. "You can, therefore, confide in me without fear," continued the detective.

Cyril was surprised and a little startled. What did the man know?

"What makes you think I have anything to confide?" he asked.

"It is quite obvious, my lord, that you are holding something back—something which would explain your attitude towards Lady Wilmersley."

"I don't follow you," replied Cyril, on his guard.

"You have given every one to understand that you have never seen her ladyship. You take up a stranger's cause very warmly, my lord."

"I trust I shall always espouse the cause of every persecuted woman."

"But how are you sure that she was persecuted? Every one praises his lordship's devotion to her. He gave her everything she could wish for except liberty. If she was insane, his conduct deserves great praise."

"But I am sure she is not."

"But you yourself urged me to secure her as soon as possible because you were afraid she might do further harm," Judson reminded him.

"That was before I heard Douglas's testimony. He has seen her daily for three years and swears she is sane."

"And the opinion of an ignorant servant is sufficient to make you condemn his lordship without further proof?"

Cyril moved uneasily.

"If Lady Wilmersley is perfectly sane, it seems to me incredible that she did not manage to escape years ago. A note dropped out of her carriage would have brought the whole countryside to her rescue. Why, she had only to appeal to this very same butler, who is convinced of her sanity, and Lord Wilmersley could not have prevented her from leaving the castle. Public opinion would have protected her."

"That is true," acknowledged Cyril, "but her spirit may have been broken."

"What was there to break it? We hear only of his lordship's almost excessive devotion. No, my lord, I can't help thinking that you are judging both Lord and Lady Wilmersley by facts of which I am ignorant."

Cyril did not know what to answer. He had at first championed Lady Wilmersley because he had believed her to be his protégée, but now that it had been proved that she was not, why was he still convinced that she had in some way been a victim of her husband's cruelty? He had to acknowledge that beyond a vague distrust of his cousin he had not only no adequate reason, but no reason at all, for his suspicions.

"You are mistaken," he said at last; "I am withholding nothing that could in any way assist you to unravel this mystery. I confess I neither liked nor trusted my cousin. I had no special reason. It was simply a case of Dr. Fell. I know no more than you do of his treatment of her ladyship. But doesn't the choice of a Turk and a Spaniard as attendants on Lady Wilmersley seem to you open to criticism?"

"Not necessarily, my lord. We trust most those we know best. Lord Wilmersley had spent the greater part of his life with Turks and Spaniards. It therefore seems to me quite natural that when it came to selecting guardians for her ladyship, he should have chosen a man and a woman he had presumably known for some years, whose worth he had proved, whose fidelity he could rely on."

"That sounds plausible," agreed Cyril; "still I can't help thinking it very peculiar, to say the least, that Lady Wilmersley was not under a doctor's care."

"Her ladyship may have been too unbalanced to mingle with people, and yet not in a condition to require medical attention. Such cases are not uncommon."

"True, and yet I have a feeling that Douglas was right, when he assured us that her ladyship is not insane. You discredit his testimony on the ground that he is an ignorant man. But if a man of sound common-sense has the opportunity of observing a woman daily during three years, it seems to me that his opinion cannot be lightly ignored. You never knew my cousin. Well, I did, and as I said before, he was a man who inspired me with the profoundest distrust, although I cannot cite one fact to justify my aversion. I cannot believe that he ever sacrificed himself for any one and am much more inclined to credit Douglas's suggestion that it was jealousy which led him to keep her ladyship in such strict seclusion. But why waste our time in idle conjectures when it is so easy to find out the truth? Those two doctors who saw her yesterday must be found. If they are men of good reputation, of course I shall accept their report as final."

"Very good, my lord, I will at once have an advertisement inserted in all the papers asking them to communicate with us. If that does not fetch them, I shall employ other means of tracing them."

"Has Lady Upton, her ladyship's grandmother, been heard from?"

"She wired this morning asking for further particulars. Mr. Twombley answered her, I believe."

A slight pause ensued during which Judson watched Cyril as if expecting him to speak.

"And you have still nothing to say to me, my lord?" The detective spoke with evident disappointment.

"No, what else should I have to say?" replied Cyril with some surprise.

"That is, of course, for you to judge, my lord." His meaning was unmistakable. Cyril flushed angrily. Was it possible that the man dared to doubt his word? Dared to disbelieve his positive assertion that he knew nothing whatsoever about the murder? The damnable—suddenly he remembered! Remembered the lies he had been so glibly telling all day. Why should any one believe him in future? His ignominy was probably already stamped on his face.

"I have nothing more to say," replied Cyril in a strangely meek voice.