Project Gutenberg's Indian Stories Retold From St. Nicholas, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Indian Stories Retold From St. Nicholas

Author: Various

Release Date: January 21, 2011 [EBook #35021]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INDIAN STORIES RETOLD ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Emmy and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[i]

INDIAN STORIES

HISTORICAL STORIES

RETOLD FROM

ST. NICHOLAS MAGAZINE

IN FIVE VOLUMES

| INDIAN STORIES |

| A mirror of Indian ideas, customs, and adventures. |

| COLONIAL STORIES |

| Stirring tales of the rude frontier life of early times. |

| REVOLUTIONARY STORIES |

| Heroic deeds, and especially children's part in them. |

| CIVIL WAR STORIES |

| Thrilling stories of the great struggle, both on land and sea. |

| OUR HOLIDAYS |

| Something of their meaning and spirit. |

—————

Each about 200 pages. Full cloth, 12mo.

THE CENTURY CO.

[ii]

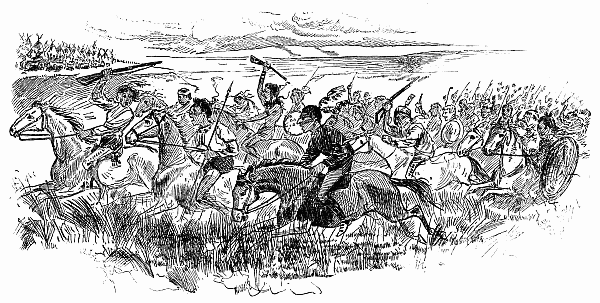

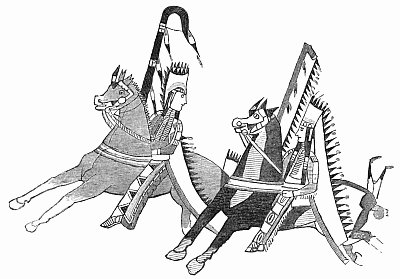

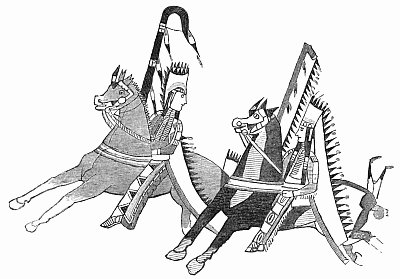

AN INDIAN HORSE-RACE—COMING OVER THE SCRATCH

AN INDIAN HORSE-RACE—COMING OVER THE SCRATCH

Drawing by Frederic Remington

[iv]

INDIAN STORIES

PUBLISHED BY THE CENTURY CO.

NEW YORK MCMVII

[v]

Copyright, 1877, 1878, 1879, by

Scribner & Co.

Copyright, 1884, 1888, 1889, 1893, 1894, 1896, 1899, 1900, 1904, by

The Century Co.

THE DEVINNE PRESS

[vi]

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

This collection of Indian stories is the first in a

series of volumes of historic tales retold from "St.

Nicholas."

The books do not pretend to give anything like

connected history, but by means of the story that

thrills and interests they impart the real spirit of

the times they depict in a way no youthful reader

will be likely to forget.

Most of the stories in this book a boy of eight or

nine can read for himself, and these are the years

of his school life when he is being taught something

of our colonial history and of the myths and

legends of primitive man. Thus these stories,

while delighting many children and tempting

them to read "out of hours," will serve a very useful

[vii]purpose.

CONTENTS

| | | PAGE |

| Onatoga's Sacrifice | John Dimitry | 1 |

| Waukewa's Eagle | James Buckham | 10 |

| A Fourth of July Among the Indians | W. P. Hooper | 22 |

| A Boy's Visit To Chief Joseph | Erskine Wood | 43 |

| Little Moccasin's Ride on The Thunder-Horse | Colonel Guido Ilges | 54 |

| The Little First Man and the Little First Woman | William M. Cary | 74 |

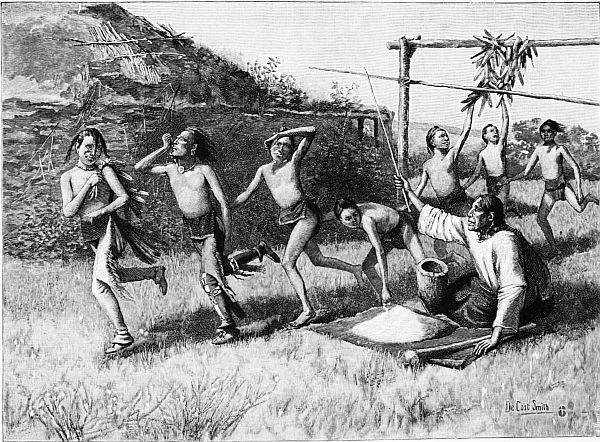

| Fun Among the Red Boys | Julian Ralph | 87 |

| The Children of Zuñi | Maria Brace Kimball | 100 |

| The Indian Girl and Her Messenger-bird | George W. Ranck | 112 |

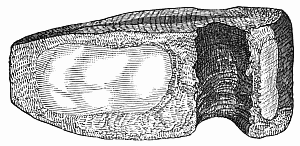

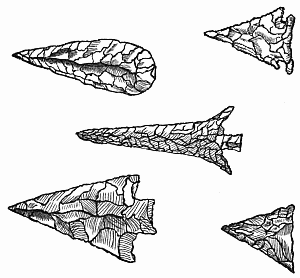

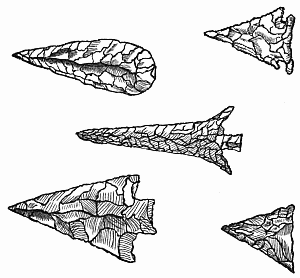

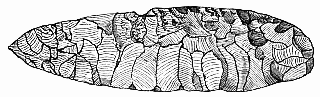

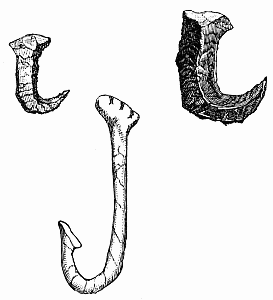

| How the Stone-age Children Played | Charles C. Abbott | 115 |

| Games and Sports of the Indian Boy | Dr. Charles Alexander Eastman | 123 |

| An Old-time Thanksgiving | M. Eloise Talbot | 136 |

| Some Indian Dolls | Olive Thorne Miller | 155 |

| The Walking Purchase | George Wheeler | 159 |

| The First Americans | F. S. Dellenbaugh | 171 |

[viii]

INDIAN STORIES

[ix]

INDIAN LULLABY

Sleep, sleep, my boy; the Chippewas

Are far away—are far away.

Sleep, sleep, my boy; prepare to meet

The foe by day—the foe by day!

The cowards will not dare to fight

Till morning break—till morning break.

Sleep, sleep, my child, while still 'tis night;

Then bravely wake—then bravely wake!

[1]

INDIAN STORIES

ONATOGA'S SACRIFICE

BY JOHN DIMITRY

ONCE, in the long ago, before the white man

had heard of the continent on which we

live, red men, who were brave and knew not what

fear was in battle, trembled at the mention of a

great man-eating bird that had lived before the

time told of in the traditions known of their oldest

chiefs.

This bird, which, according to the Indian legends,

ate men, was known as the Piasau.

The favorite haunt of this terrible bird was a

bluff on the Mississippi River, a short distance

above the site of the present city of Alton, Illinois.

There it was said to lie in wait, and to keep watch

over the broad, open prairies. Whenever some

rash Indian ventured out alone to hunt upon this[2]

fatal ground, he became the monster's prey. The

legend says that the bird, swooping down with the

fierce swiftness of a hawk, seized upon its victim

and bore him to a gloomy cave wherein it

made its horrid feasts. The monster must have

had an insatiable appetite or a prolonged existence,

for tradition declares that it depopulated

whole villages. Then it was that the wise men

began to see visions and to prophesy the speedy

extinction of the tribe. Years of its ravages followed

one upon another, until at length, according

to the legend, was lost all reckoning of the

time when first that strange, foul creature came to

scourge their sunny plains. The aged men, whose

youth was but a dim memory, could say only that

the bird was as it had always been. None like it

had ever been heard of save in vague traditions.

There was one, Onatoga, who began to ponder.

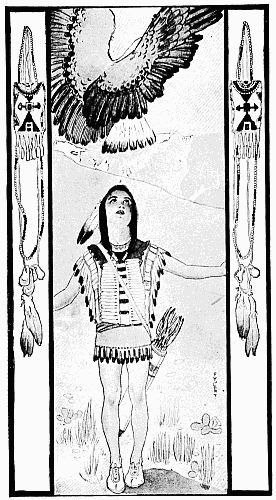

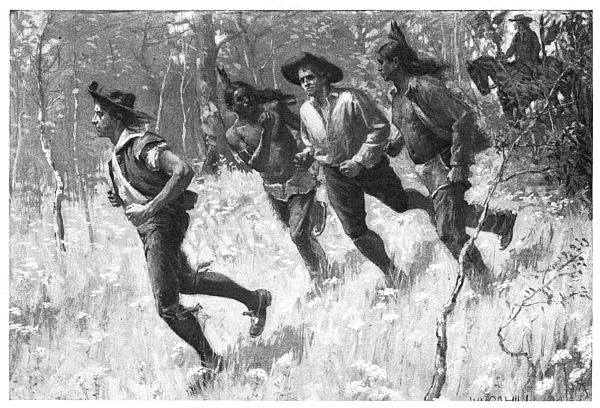

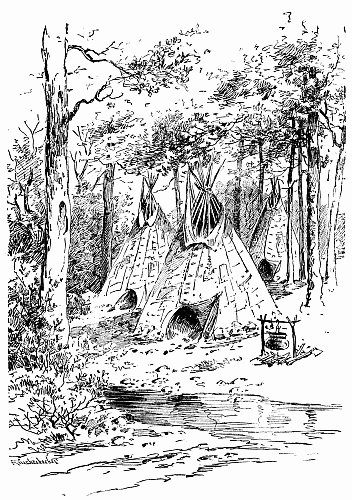

ONATOGA IN THE FOREST

ONATOGA IN THE FOREST

Now, Onatoga was the great leader of the Illini;

one whose name was spoken with awe even in

the distant wigwams north of the Great Lake.

Long had he grieved and wondered over the will

of the Great Spirit; that he should look upon the

men of the Western prairies, not as warriors, but

as deer or bison, only fit to fill the maw of so pestilent

a thing as this monstrous bird! Before the[4]

new moon began to grow upon the face of the sky,

Onatoga's resolve was taken. He would go to

some spot deep in the forest where by fasting and

prayer his spirit would become so pure that the

Great Master of Life would hear him and once

again be kind and turn His face back, in light,

upon the Illini.

Stealing away from his tribe in the night, he

plunged far into the trackless forest. Then,

blackening his face, for a whole moon he fasted.

The moon waxed full and then waned; but no

vision came to assure him that the Great Spirit

had heard his prayers. Only one more night remained.

Wearied and sorrow-worn, he closed his

eyes. But, through the deep sleep that fell upon

him, came the voice of the Great Spirit. And this

is the message that came to Onatoga, as he lay

sleeping in body but, in his soul, awake:

"Arise, Chief of the Illini! Thou shalt save

thy race. Choose thou twenty of thy warriors;

noble-hearted, strong-armed, eagle-eyed. Put in

each warrior's hand a bow. Give to each an

arrow dipped in the venom of the snake. Seek

then the man whose heart loveth the Great Spirit.

Let him not fear to look the Piasau in the face;

but see that the warriors, with ready bows, stand

near in the shadow of the trees."[5]

Onatoga awoke; strong, though he had fasted

a month; happy, though he knew he was soon to

die! Who, but he, the Great Chief of the Illini,

should die for his people—for was it not death to

look on the face of the Piasau?

Binding his moccasins firmly upon his feet, he

washed the marks of grief from his face, and

painted it with the brightest vermilion and blue.

Thus, in the splendid colors of a triumphant warrior,

he returned homeward. All was silent in the

village when, in the gray light of early day, he

entered his lodge. Soon the joyful news was

known. From lodge to lodge it spread until the

last wigwam was reached. Onatoga's quest was

successful!

Then the warriors began to gather. Furtively,

even in their gladness, they sought his lodge, for

the fear of the Piasau was over all. A solemn

awe fell upon them as they gathered around the

chief, who, it was whispered, had heard the voice

of the Great Spirit. Without, on that high bluff,

they knew that the fiend-bird crouched, waiting

for the morning light to reveal its prey. Within,

in sorrowing silence, they heard how the people

could be saved; but the hearts of the warriors

were heavy. All knew the sacrifice demanded—their

bravest and their best![6]

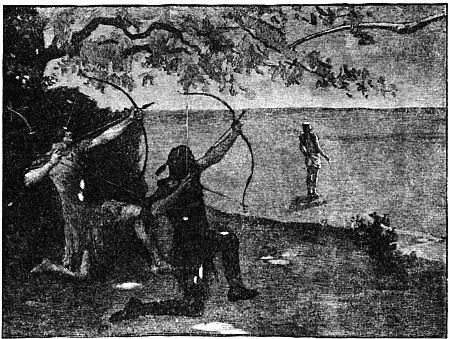

"ONATOGA, NEVER CEASING HIS CHANT, FACED THE PIASAU FEARLESSLY"

"ONATOGA, NEVER CEASING HIS CHANT, FACED THE PIASAU FEARLESSLY"

Onatoga chose his twenty warriors and appointed

them their place, where the rolling prairie

was broken by the edge of the forest. Then, when

the sun shot its first long shafts of light across the

level grasses, the chief walked slowly forth and

stood alone upon the prairie. The world in the

morning light was beautiful to Onatoga's eyes.

The flowers beneath his feet seemed to smile, and

poured forth richest perfumes; the sun was glorious

in its golden breast-plate, to do him honor;

while the lark and the mock-bird sang his praise

in joyous songs.[7]

He had not long to wait. Soon, afar off, the

dreaded Piasau was seen moving heavily through

the clear morning air. Onatoga, drawing himself

to the full measure of his lofty height, raised his

death-song. The dull flutter of huge wings came

nearer, and a great shadow came rushing over the

sunlit fields. Onatoga, never ceasing his chant,

faced the Piasau fearlessly. A sudden fierce

swoop downward! In that very moment, twenty

poisoned arrows, loosed by twenty faithful hands,

sped true to their aim. With a scream that the

bluffs sent rolling back in sharp and deafening

echoes, the foul monster dropped dead! The

Great Spirit loved the man who had been willing

to sacrifice his life for his people. In the very instant

when death seemed sure, he covered the

heart of Onatoga with a shield; and he suffered

not the wind to blow aside a single arrow from its

mark,—the body of the fated Piasau.

"CUNNING CARVERS CUT DEEP INTO THE ROCK THE FORM OF THE PIASAU"

"CUNNING CARVERS CUT DEEP INTO THE ROCK THE FORM OF THE PIASAU"

Great were the rejoicings that followed and

rich were the feasts that were held in honor of

Onatoga. The Illini resolved that the story of the

great deliverance and of the courageous love of

Onatoga should not die, though they themselves

should pass away. The cunning carvers of the

tribe cut deep into the living rock of the bluff the[9]

terrible form of the Piasau. And, in later years,

when young children asked the meaning of this

great figure, so unlike any of the birds that they

knew upon their rivers and their prairies, then the

fathers would tell them the story of the Piasau,

and how the Great Spirit had found, in Onatoga,

a warrior who loved his fellow-men better than he

loved his own life.

[10]

WAUKEWA'S EAGLE

BY JAMES BUCKHAM

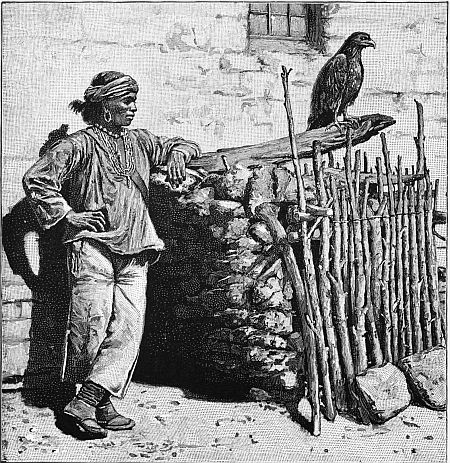

ONE day, when the Indian boy Waukewa was

hunting along the mountain-side, he found

a young eagle with a broken wing, lying at the

base of a cliff. The bird had fallen from an aery

on a ledge high above, and being too young to fly,

had fluttered down the cliff and injured itself so

severely that it was likely to die. When Waukewa

saw it he was about to drive one of his sharp

arrows through its body, for the passion of the

hunter was strong in him, and the eagle plunders

many a fine fish from the Indian's drying-frame.

But a gentler impulse came to him as he saw the

young bird quivering with pain and fright at his

feet, and he slowly unbent his bow, put the arrow

in his quiver, and stooped over the panting eaglet.

For fully a minute the wild eyes of the wounded

bird and the eyes of the Indian boy, growing gentler

and softer as he gazed, looked into one another.

Then the struggling and panting of the

[11]

young eagle ceased; the wild, frightened look

passed out of its eyes, and it suffered Waukewa to

pass his hand gently over its ruffled and draggled

feathers. The fierce instinct to fight, to defend its

threatened life, yielded to the charm of the tenderness

and pity expressed in the boy's eyes; and

from that moment Waukewa and the eagle were

friends.

Waukewa went slowly home to his father's

lodge, bearing the wounded eaglet in his arms.

He carried it so gently that the broken wing gave

no twinge of pain, and the bird lay perfectly still,

never offering to strike with its sharp beak the

hands that clasped it.

Warming some water over the fire at the lodge,

Waukewa bathed the broken wing of the eagle

and bound it up with soft strips of skin. Then

he made a nest of ferns and grass inside the lodge,

and laid the bird in it. The boy's mother looked

on with shining eyes. Her heart was very tender.

From girlhood she had loved all the creatures of

the woods, and it pleased her to see some of her

own gentle spirit waking in the boy.

When Waukewa's father returned from hunting,

he would have caught up the young eagle and

wrung its neck. But the boy pleaded with him so[12]

eagerly, stooping over the captive and defending

it with his small hands, that the stern warrior

laughed and called him his "little squaw-heart."

"Keep it, then," he said, "and nurse it until it is

well. But then you must let it go, for we will not

raise up a thief in the lodges." So Waukewa

promised that when the eagle's wing was healed

and grown so that it could fly, he would carry it

forth and give it its freedom.

It was a month—or, as the Indians say, a moon—before

the young eagle's wing had fully mended

and the bird was old enough and strong enough

to fly. And in the meantime Waukewa cared for

it and fed it daily, and the friendship between the

boy and the bird grew very strong.

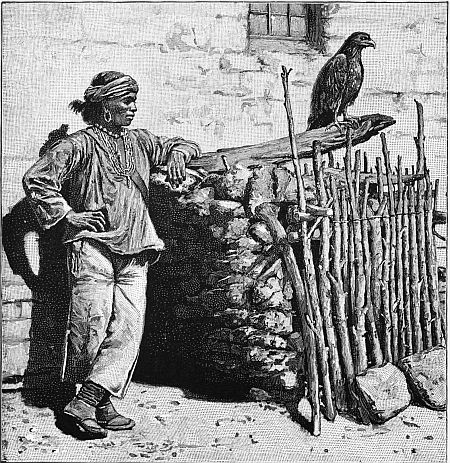

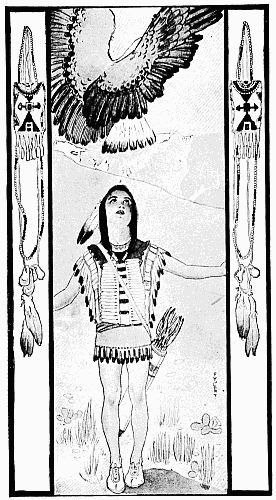

"THE YOUNG EAGLE ROSE TOWARD THE SKY"

"THE YOUNG EAGLE ROSE TOWARD THE SKY"

But at last the time came when the willing captive

must be freed. So Waukewa carried it far

away from the Indian lodges, where none of the

young braves might see it hovering over and be

tempted to shoot their arrows at it, and there he

let it go. The young eagle rose toward the sky in

great circles, rejoicing in its freedom and its

strange, new power of flight. But when Waukewa

began to move away from the spot, it came

swooping down again; and all day long it followed

him through the woods as he hunted. At[15]

dusk, when Waukewa shaped his course for the

Indian lodges, the eagle would have accompanied

him. But the boy suddenly slipped into a hollow

tree and hid, and after a long time the eagle

stopped sweeping about in search of him and flew

slowly and sadly away.

Summer passed, and then winter; and spring

came again, with its flowers and birds and swarming

fish in the lakes and streams. Then it was

that all the Indians, old and young, braves and

squaws, pushed their light canoes out from shore

and with spear and hook waged pleasant war

against the salmon and the red-spotted trout.

After winter's long imprisonment, it was such joy

to toss in the sunshine and the warm wind and

catch savory fish to take the place of dried meats

and corn!

Above the great falls of the Apahoqui the

salmon sported in the cool, swinging current,

darting under the lee of the rocks and leaping full

length in the clear spring air. Nowhere else were

such salmon to be speared as those which lay

among the riffles at the head of the Apahoqui rapids.

But only the most daring braves ventured to

seek them there, for the current was strong, and

should a light canoe once pass the danger-point[16]

and get caught in the rush of the rapids, nothing

could save it from going over the roaring falls.

Very early in the morning of a clear April day,

just as the sun was rising splendidly over the

mountains, Waukewa launched his canoe a half-mile

above the rapids of the Apahoqui, and floated

downward, spear in hand, among the salmon-riffles.

He was the only one of the Indian lads

who dared fish above the falls. But he had been

there often, and never yet had his watchful eye

and his strong paddle suffered the current to

carry his canoe beyond the danger-point. This

morning he was alone on the river, having risen

long before daylight to be first at the sport.

The riffles were full of salmon, big, lusty fellows,

who glided about the canoe on every side

in an endless silver stream. Waukewa plunged

his spear right and left, and tossed one glittering

victim after another into the bark canoe. So absorbed

in the sport was he that for once he did not

notice when the head of the rapids was reached

and the canoe began to glide more swiftly among

the rocks. But suddenly he looked up, caught his

paddle, and dipped it wildly in the swirling water.

The canoe swung sidewise, shivered, held its own

against the torrent, and then slowly, inch by inch,[17]

began to creep upstream toward the shore. But

suddenly there was a loud, cruel snap, and the

paddle parted in the boy's hands, broken just

above the blade! Waukewa gave a cry of despairing

agony. Then he bent to the gunwale of

his canoe and with the shattered blade fought desperately

against the current. But it was useless.

The racing torrent swept him downward; the

hungry falls roared tauntingly in his ears.

Then the Indian boy knelt calmly upright in

the canoe, facing the mist of the falls, and folded

his arms. His young face was stern and lofty.

He had lived like a brave hitherto—now he would

die like one.

Faster and faster sped the doomed canoe toward

the great cataract. The black rocks glided

away on either side like phantoms. The roar of

the terrible waters became like thunder in the

boy's ears. But still he gazed calmly and sternly

ahead, facing his fate as a brave Indian should.

At last he began to chant the death-song, which

he had learned from the older braves. In a few

moments all would be over. But he would come

before the Great Spirit with a fearless hymn upon

his lips.

Suddenly a shadow fell across the canoe.[18]

Waukewa lifted his eyes and saw a great eagle

hovering over, with dangling legs, and a spread

of wings that blotted out the sun. Once more

the eyes of the Indian boy and the eagle met; and

now it was the eagle who was master!

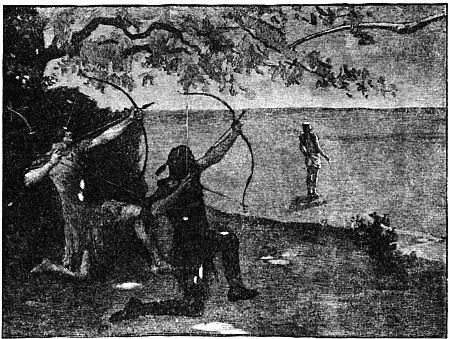

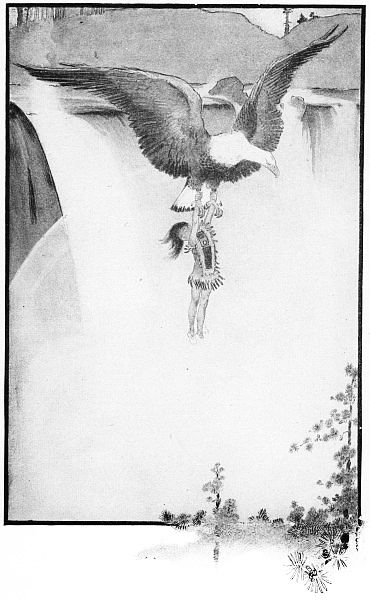

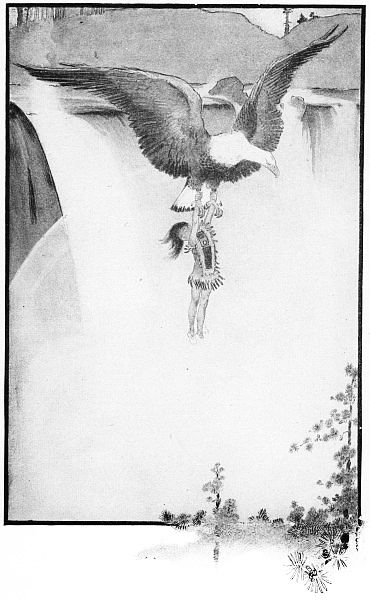

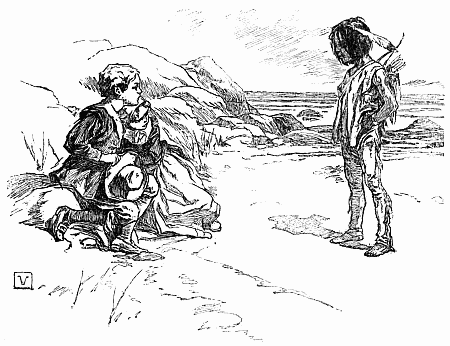

"HE AND THE STRUGGLING EAGLE WERE FLOATING OUTWARD AND DOWNWARD"

"HE AND THE STRUGGLING EAGLE WERE FLOATING OUTWARD AND DOWNWARD"

With a glad cry the Indian boy stood up in his

canoe, and the eagle hovered lower. Now the

canoe tossed up on that great swelling wave that

climbs to the cataract's edge, and the boy lifted his

hands and caught the legs of the eagle. The next

moment he looked down into the awful gulf of

waters from its very verge. The canoe was

snatched from beneath him and plunged down the

black wall of the cataract; but he and the struggling

eagle were floating outward and downward

through the cloud of mist. The cataract roared

terribly, like a wild beast robbed of its prey. The

spray beat and blinded, the air rushed upward as

they fell. But the eagle struggled on with his

burden. He fought his way out of the mist and

the flying spray. His great wings threshed the

air with a whistling sound. Down, down they

sank, the boy and the eagle, but ever farther from

the precipice of water and the boiling whirlpool

below. At length, with a fluttering plunge, the

eagle dropped on a sand-bar below the whirlpool,[21]

and he and the Indian boy lay there a minute,

breathless and exhausted. Then the eagle slowly

lifted himself, took the air under his free wings,

and soared away, while the Indian boy knelt on

the sand, with shining eyes following the great

bird till he faded into the gray of the cliffs.

[22]

A FOURTH OF JULY AMONG THE INDIANS

BY W. P. HOOPER

INDIANS—real Indians—real,

live Indians—were

what we, like all

boys, wanted to

see; and this was

why, after leaving the railroad

on which we had been traveling

for several days and

nights, we found ourselves at

last in a big canvas-covered

wagon lumbering across the

monotonous prairie.

We were on our way to see

a celebration of the Fourth of

July at a Dakota Indian agency.

It was late in the afternoon of a hot summer's

day. We had been riding since early morning,[23]

and had not met a living creature—not even a

bird or a snake. Only those who have experienced

it know how wearying to the eyes it is to

gaze all day long, and see nothing but the sky and

the grass.

However, an hour before sunset we did see

something. At first, it looked like a mere speck

against the sky; then it seemed like a bush or a

shrub; but it rapidly increased in size as we approached.

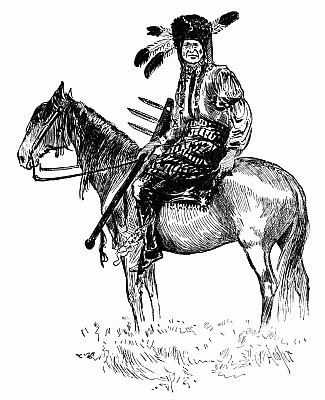

Then, with the aid of our field-glass,

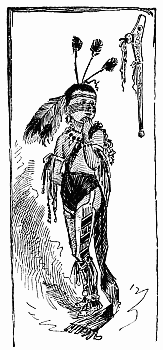

we saw it was a man on horseback. No, not exactly

that, either; it was an Indian chief riding an

Indian pony. Now, I have seen Indians in the

East—"Dime Museum Indians." I have seen

the Indians who travel with the circus—yes, and

I have seen the untutored savages who sell bead-work

at Niagara Falls; but this one was different—he

was quite different. I felt sure that he was

a genuine Indian. He was unlike the Indians I

had seen in the East. The most striking difference

was that this one presented a grand unwashed

effect. It must have required years of

patient industry in avoiding the wash-bowl, and

great good luck in dodging the passing showers,

for him to acquire the rich effect of color which he

displayed. Though it was one of July's hottest[24]

days, he had on his head an arrangement made of

fur, with head trimmings and four black-tipped

feathers; a long braid of his hair, wound with

strips of fur, hung down in front of each ear, and

strings of beads ornamented his neck. He wore

a calico shirt, with tin bands on his arms above

the elbow; a blanket was wrapped around his

waist; his leggings had strips of beautiful bright

bead-work, and his moccasins were ornamented

in the same style. But in his right hand he was

holding a most murderous-looking instrument.

It was a long wooden club, into one end of which

three sharp, shining steel knife-blades were set.

Though I had been complaining of the heat, still I

now felt chilly as I looked at the weapon, and saw

how well it matched the expression of his cruel

mouth and piercing eyes.

He passed on while we were trying to make a

sketch of him. However, the next day, an interpreter

brought him around, and, for a small piece

of tobacco, he was glad to pose while the sketch

was being finished. We learned his name was

"Can-h-des-ka-wan-ji-dan" (One Hoop).

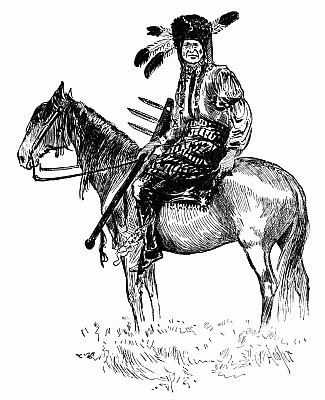

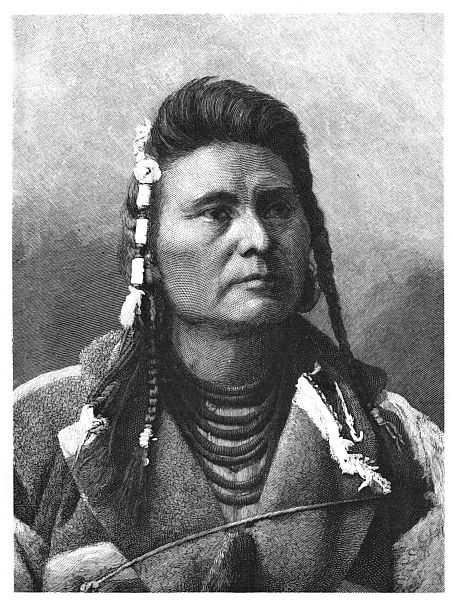

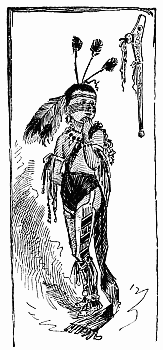

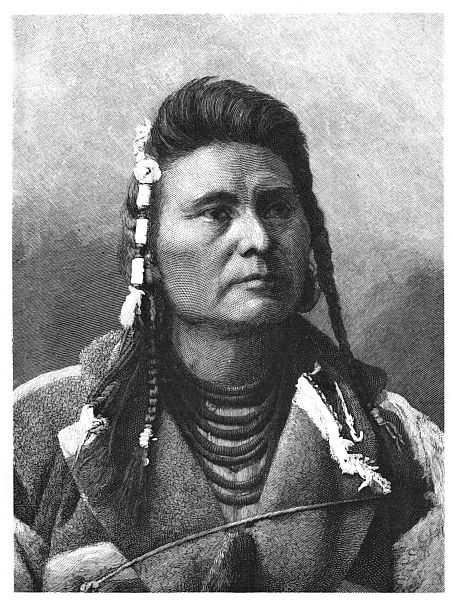

"ONE HOOP" IN HIS SUMMER COSTUME

"ONE HOOP" IN HIS SUMMER COSTUME

A few moments later, we passed an iron post set

firmly into the ground. It marked one of the

boundaries of the Indian Reservation. We were[25]

now on a tract of land set aside by the United

States Government as the living-ground of sixteen

hundred "Santee" Sioux Indians. We soon

saw more Indians, who, like us, seemed to be moving

toward the little village at the Indian agency.

Each group had put their belongings into a big[26]

bundle, and strapped it upon long poles, which

were fastened at one end to the back of a pony.

In this bundle the little papooses rode in great

comfort, looking like blackbirds peering from a

nest. In some cases, an older child would be riding

in great glee on the pony's back among the

poles. The family baggage seemed about equally

distributed between the pony and the squaw who

led him. She was preceded by her lord and master,

the noble red Indian, who carried no load except

his long pipe.

The next thing of interest was what is called a

Red River wagon. It was simply a cart with two

large wheels, the whole vehicle made of wood.

As the axles are never oiled, the Red River carry-all

keeps up a most terrible squeaking. This

charming music-box was drawn by one ox, and

contained an Indian, who was driving with a

whip. His wife and children were seated on the

bottom of this jolting and shrieking cart.

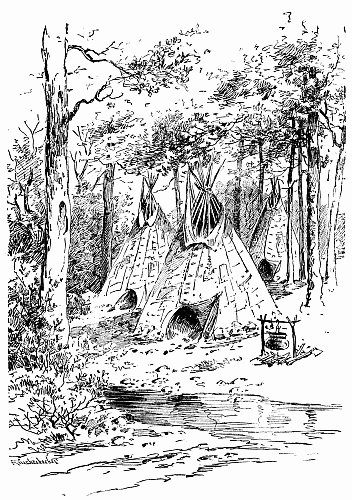

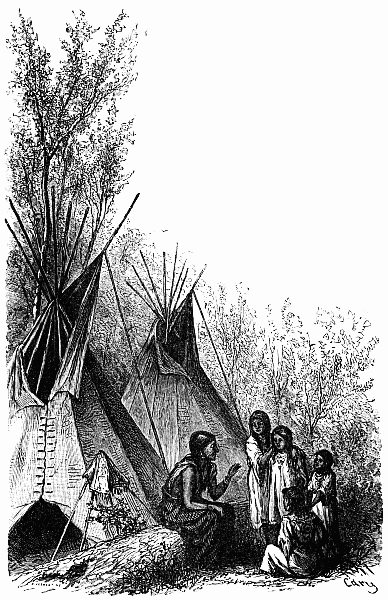

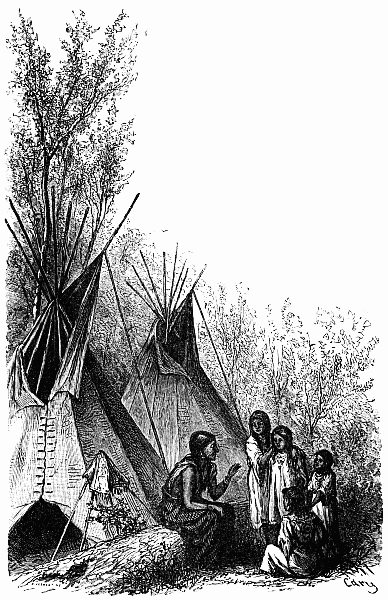

AN INDIAN ENCAMPMENT FOR THE NIGHT

AN INDIAN ENCAMPMENT FOR THE NIGHT

As we neared the agency buildings, we passed

many Indians who had settled for the night.

They chose the wooded ravines, near streams, by

which to put up their tents, or "tepees," which

consisted of long poles covered with patched and

smoke-stained canvas, with two openings, one at[28]

the top for a "smoke-hole" and the other for a

door, through which any one must crawl in order

to enter the domestic circle of the gentle savage.

We entered several tepees, making ourselves welcome

by gifts of tobacco to every member of the

family. That night, after reaching the agency

and retiring to our beds, we dreamed of smoking

great big pipes, with stems a mile long, which

were passed to us by horrible-looking black

witches. But morning came at last,—and such

a morning!

That Fourth of July morning I shall never forget.

We were awakened by the most blood-curdling

yells that ever pierced the ears of three white

boys. It was the Indian war-whoop. I found

myself instinctively feeling for my back hair, and

regretting the distance to the railroad. We lingered

indoors in a rather terrified condition, until

we found out that this was simply the beginning

of the day's celebration. It was the "sham-fight,"

but it looked real enough when the Indians

came tearing by, their ponies seeming to enter

into the excitement as thoroughly as their riders.

There were some five hundred, in full frills and

war-paint, and all giving those terrible yells.

Their costumes were simple, but gay in color—paint,[29]

feathers, and more paint, with an occasional

shirt.

For weapons they carried guns, rifles, and long

spears. Bows and arrows seemed to be out of

style. A few had round shields on their left arms.

Most of the tepees had been collected together

and pitched so as to form a large circle, and their

wagons were placed outside this circle so as to

make a sort of protection for the defending party.

The attacking party, brandishing their weapons

in the air with increased yells, rushed their excited

and panting ponies up the slope toward the

tepees, where they were met by a rapid discharge

of blank cartridges and powder. Some of the ponies

became frightened and unmanageable, several

riders were unhorsed, and general confusion

prevailed. The intrenched party, in the meantime,

rushed out from behind their defenses,

climbing on top of their wagons, yelling and

dancing around like demons. Added to this, the

sight of several riderless ponies flying wildly from

the tumult made the sham-fight have a terribly

realistic look.

After the excitement was over, the regular

games which had been arranged for the day

began.[30]

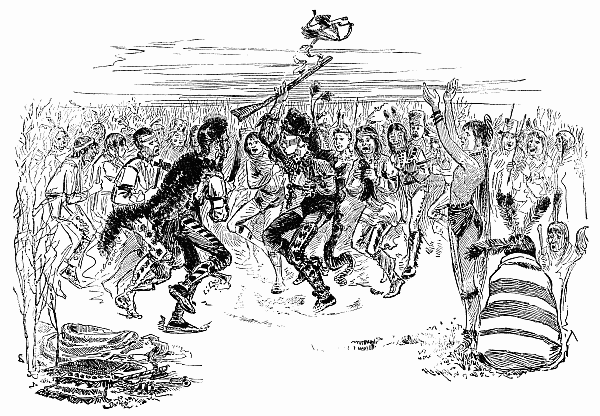

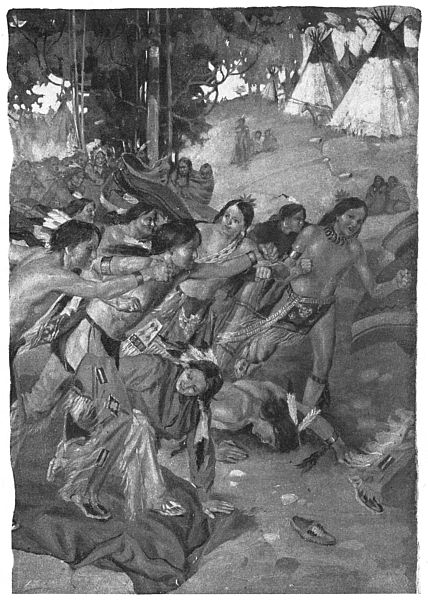

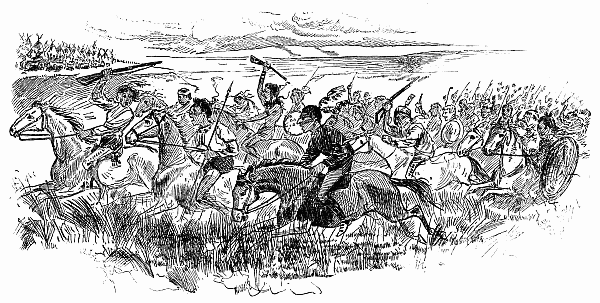

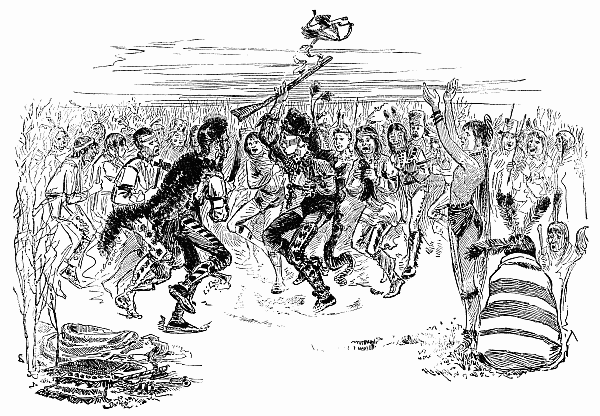

THE SHAM-FIGHT

THE SHAM-FIGHT

[31]

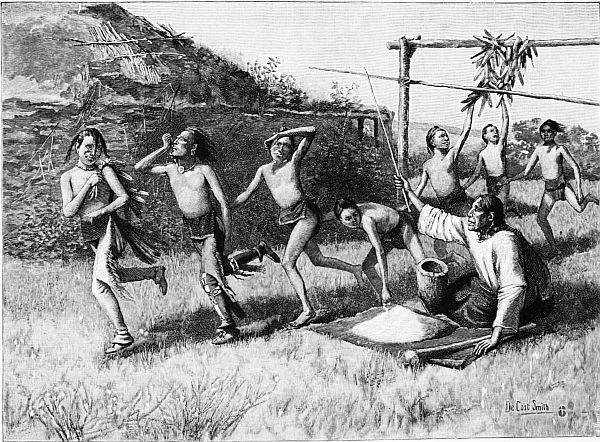

In the foot-races, the costumes were so slight

that there was nothing to describe—simply paint

in fancy patterns, moccasins, and a girdle of red

flannel. But how they could run! I did not suppose

anything on two legs could go so fast. The

lacrosse costumes were bright and attractive.

The leader of one side wore a shirt of soft, tanned

buck-skin, bead-work and embroidery on the

front, long fringe on the shoulders, bands around

the arms, and deep fringe on the bottom of the

skirt. The legs were bare to the knee, and from

there down to the toes was one mass of fine glittering

bead-work. In the game, there were a

hundred Indians engaged on each side. The

game was long, but exciting, being skilfully

played. The grounds extended about a mile in

length. The ball was the size of a common baseball,

and felt almost as solid as a rock, the center

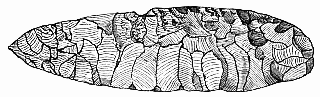

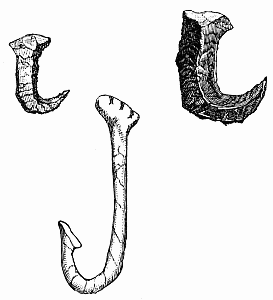

being of lead. The shape of the Indian lacrosse

stick is shown in the sketch.

SHA-KE-TO-PA, A YOUNG BRAVE

SHA-KE-TO-PA, A YOUNG BRAVE

Then came games on horseback. But the most

interesting performance of the whole day, and one

in which they all manifested an absorbing interest,

was the dinner.

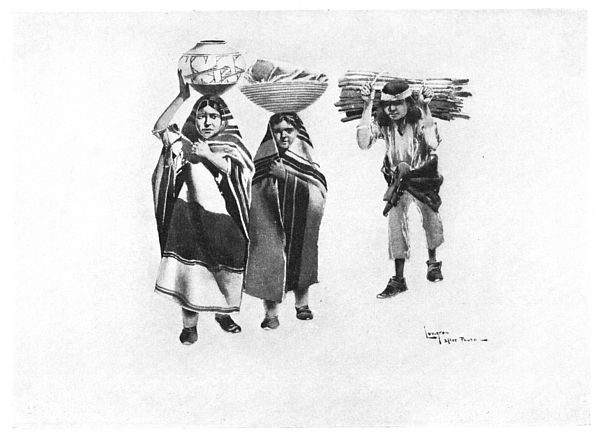

At 3 a.m. several oxen had been butchered, and

from that time till the dinner was served all the[32]

old squaws had their hands

full. Fires were made in long

lines, poles placed over them,

and high black pots, kettles,

and zinc pails filled with a

combination of things, including

beef and water, were suspended

there and carefully

tended by ancient Indian ladies

in picturesque, witch-like

costumes, who gently stirred

the boiling bouillion with

pieces of wood, while other

seemingly more ancient and

worn-out-looking squaws

brought great bundles of wood from the ravines,

tied up in blankets and swung over their shoulders.

Think of a dinner for sixteen hundred noble

chiefs and braves, stalwart head-men, young

bucks, old squaws, girls, and children! And such

queer-looking children—some dressed in full war

costume, some in the most approved dancing

dresses.

"TAKING A SPOONFUL OF THE SOUP, HE POURED IT UPON THE GROUND."

"TAKING A SPOONFUL OF THE SOUP, HE POURED IT UPON THE GROUND."

One little boy, whose name was Sha-ke-to-pa

(Four Nails), had five feathers—big ones, too—in

his hair. His face was painted; he wore great

round ear-rings, and rows of beads and claws[33]

around his neck; bands of beads on his little bare

brown arms; embroidered leggings and beautiful

moccasins, and a long piece of red cloth hanging

from his waist. In fact, he was as gaily dressed

as a grown-up Indian man, and he had a cunning

little war-club, all ornamented and painted.

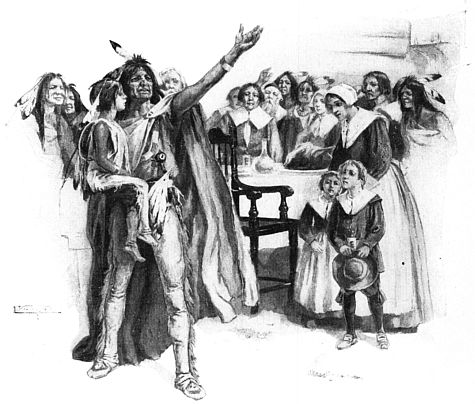

When the dinner was nearly ready, the men began[34]

to seat themselves in a long curved line.

Behind them, the women and children were gathered.

When everything was ready, a chief wearing

a long arrangement of feathers hanging from

his back hair and several bead pouches across his

shoulders, with a long staff in his

left hand, walked into the center

of the circle. Taking a spoonful

of the soup, he held it high

in the air, and then, turning

slowly around, chanting a song,

he poured the contents of the

spoon upon the ground. This,

an interpreter explained to us,

was done to appease the spirits

of the air. After this, the old squaws limped

nimbly around with the pails of soup and other

food, serving the men. After they were all

bountifully and repeatedly helped, the women and

children, who had been patiently waiting, were

allowed to gather about the fragments and half-empty

pots and finish the repast, which they did

with neatness and despatch.

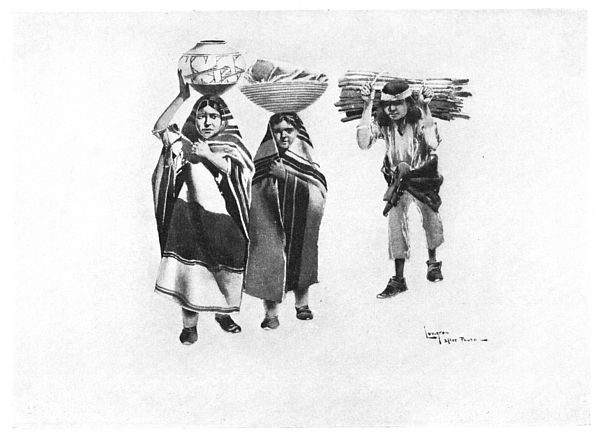

A WAITRESS

A WAITRESS

Then the warriors lay around and smoked their

long-stem pipes, while the young men prepared

for the pony races.[35]

The first of the races was "open to all," and

more than a hundred ponies and their riders were

arranged in a row. Some of the ponies were very

spirited, and seemed fully to realize what was

going to take place, and they would persist in

pushing ahead of the line. Then the other riders

would start their ponies; then the whole line

would have to be reformed. But finally they

were all started, and such shouting, and such

waving of whips in the air!—and how the little

ponies did jump! When the race was over, how

we all crowded around the winner, and how proud

the pony as well as the rider seemed to feel!

Now we had a better chance to examine the ponies

than ever before, and some were very handsome.

And such prices! Think of buying a beautiful

three-year-old cream-colored pony for twenty dollars!

But as the hour of sunset approached, the interest

in the races vanished, and so did most of

the braves. They sought the seclusion of their

bowers, to adorn themselves for the grand "grass

dance," which was to begin at sunset.

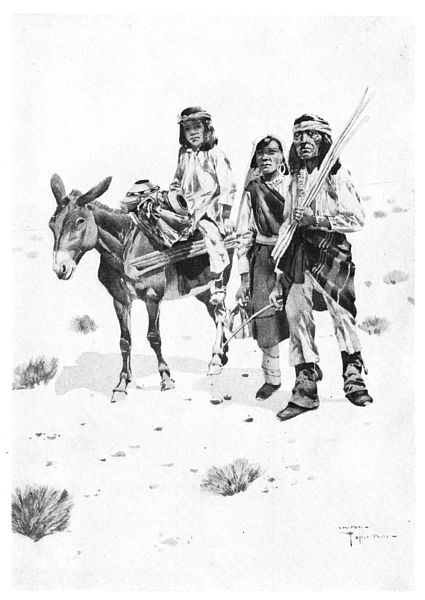

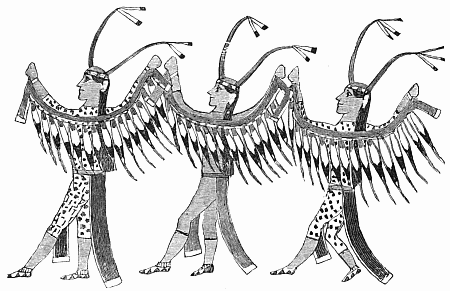

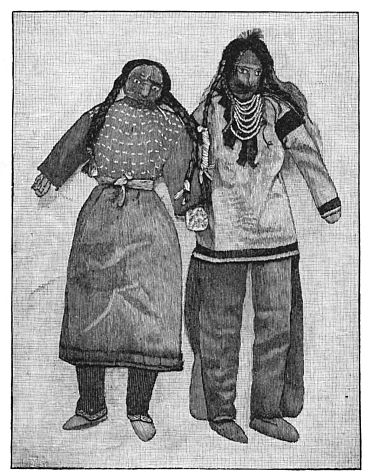

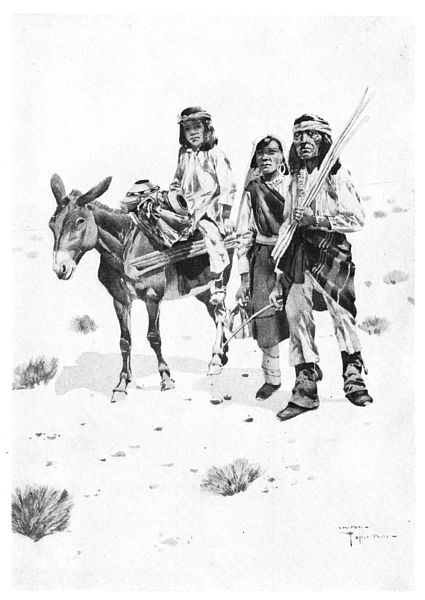

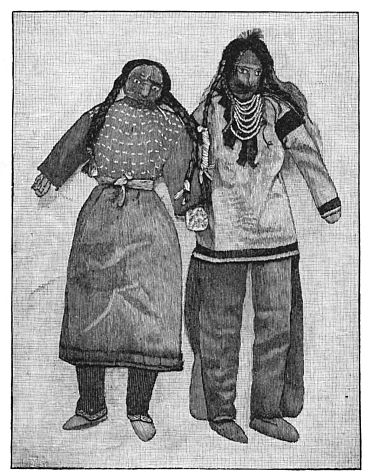

HOLIDAY CLOTHES AND EVERY-DAY CLOTHES

HOLIDAY CLOTHES AND EVERY-DAY CLOTHES

What a contrast between their every-day dress

and their dancing costumes! The former consists

of a blanket more or less tattered and torn, while[36]

the gorgeousness of the latter discourages a description

in words; so I refer you to the pictures.

Of course, we were eager to purchase some of the

Indian finery, but it was

a bad time to trade successfully

with the Indians.

They were too much taken

up with the pleasures of the

day to care to turn an honest

penny by parting with

any of their ornaments.

However, we succeeded in

buying a big war-club set

with knives, some pipes

with carved stems a yard

long, a few knife-sheaths

and pouches, glittering with

beads, and several pairs of

beautiful moccasins,—most

of which now adorn a New

York studio.

Soon the highly decorated

red men silently assembled

inside a large space inclosed by bushes

stuck into the ground. This was their dance-hall.

The squaws were again shut out, as, according to[37]

Santee Sioux custom, they are not allowed to join

in the dances with the men. The Indians, as they

came in, sat quietly down around the sides of the

inclosure. The musicians were gathered around

a big drum, on which they pounded with short

sticks, while they sang a sort of wild, weird chant.

The effect, to an uneducated white man's ear, was

rather depressing, but it seemed very pleasing to

the Indians.

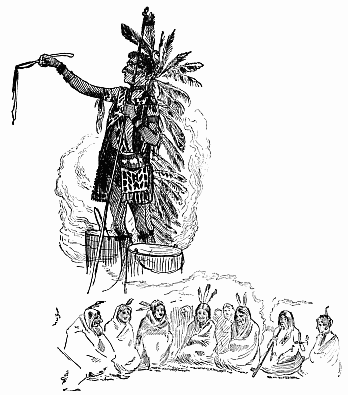

The ball was opened by an old chief, who, rising

slowly, beckoned the others to follow him. In

his right hand the leader carried a wooden gun,

ornamented with eagles' feathers; in the left he

held a short stick, with bells attached to it. He

wore a cap of otter skin, from which hung a long

train. His face was carefully painted in stripes

of blue and yellow.

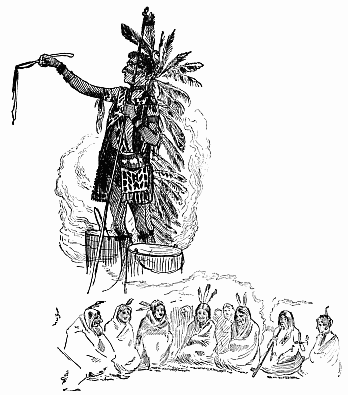

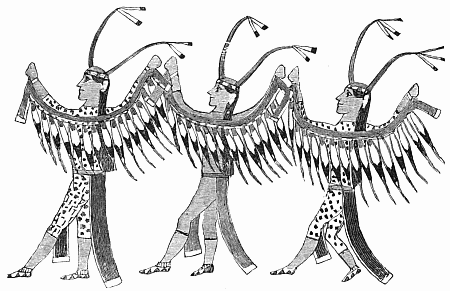

THE DANCE

THE DANCE

At first, they all moved slowly, jumping twice

on each foot; then, as the musicians struck up a

more lively pounding and a more inspiring song,

the dancers moved with more rapidity, giving an

occasional shout and waving their arms in the air.

As they grew warmer and more excited, the musicians

redoubled their exertions on the drum and

changed their singing into prolonged howls; then

one of them, dropping his drumsticks, sprang to[38]

his feet, and, waving his hands over his head, he

yelled till he was breathless, urging on the dancers.

This seemed to be the finishing touch. The

orchestra and dancers seemed to vie with each

other as to who should make the greater noise.

Their yells were deafening, and, brandishing

their knives and tomahawks, they sprang around

with wonderful agility. Of course, this intense

excitement could last but a short time; the voices

of the musicians began to fail, and, finally, with

one last grand effort, they all gave a terrible

shout, and then all was silence. The dancers

crawled back to their places around the inclosure,

and sank exhausted on the grass. But soon some

supple brave regained enough strength to rise.

The musicians slowly recommenced, other dancers

came forward, and the "mad dance" was

again in full blast. And thus the revels went on,

hour after hour, all night, and continued even

through the following day. But there was a curious

fascination about it, and, tired as we were

after the long day, we stood there looking on hour

after hour. Finally, after midnight had passed,

we gathered our Indian purchases about us, including

two beautiful ponies, and began our return

trip toward the railroad and civilization.[40]

But the monotonous sound of the Indian drum

followed us mile after mile over the prairie; in

fact, it followed us much better than my new

spotted pony.

My arm aches now, as I remember how that

pony hung back.

[42]

CHIEF JOSEPH

CHIEF JOSEPH

[43]

A BOY'S VISIT TO CHIEF JOSEPH

BY ERSKINE WOOD

[Note: The author of the sketch "A Boy's Visit to Chief Joseph"

was Erskine Wood, a boy thirteen years old. He was then

an expert shot with the rifle, and had brought down not only

small game, but bear, wolves, and deer. A true woodsman, he

was also a skilled archer and angler, having camped alone in

the woods, and lived upon the game secured by shooting and

fishing.

When Chief Joseph, of the Nez Percé Indians, went to the

national capital, he met Erskine, and invited the young hunter to

visit his camp some summer. So in July, 1892, the boy started

alone from Portland, Oregon, carrying his guns, bows, rods, and

blanket, and made his own way to Chief Joseph's camp on the

Nespilem River.

The Indians received him hospitably, and he took part in their

annual fall hunt. He was even adopted into the tribe by the chief,

and, according to their custom, received an Indian name, Ishem-tux-il-pilp,—"Red Moon."

Chief Joseph's band was the remnant of the tribe which, under his

leadership, fought the United States army so gallantly in 1877;

they carried on a running fight of about eleven hundred miles in

one summer.

When Erskine visited him, the chief was in every way most

kind and hospitable to his young guest.

C. E. S. Wood.]

I LEFT Portland on the third of July, 1892,

to visit Chief Joseph, who was chief of the

Nez Percé Indians. They lived on the Colville

Agency, two or three hundred miles north of the

city of Spokane, in the State of Washington.

I arrived at Davenport, Washington, on the

fourth of July. There was no stage, so I had to

stay all night. I left for Fort Spokane next day,

arriving at about seven in the evening. As we

did not start for Nespilem until the seventh, I

went and visited Colonel Cook, commanding officer

at the fort. I stayed all night, and next morning[44]

I helped the soldiers load cartridges at the

magazine. That afternoon I watched the soldiers

shooting volleys at the target range. We started

for Nespilem in a wagon at three o'clock in the

morning.

The next day I went fishing in the morning,

and in the afternoon I went up the creek again,

fishing with Doctor Latham. He was doctor at

the Indian agency. The next day I went down to

Joseph's camp, where I stayed the rest of the time—about

five months—alone with the Indians.

The doctor and the teamster returned to the

agency. During my first day in the camp, I wrote[45]

a letter to my mother, and bought a beaded leather

belt from one of the squaws. I stayed about camp

most of the first day; but in the afternoon I went

fishing, and caught a nice string of trout.

The Indian camp is usually in two or more long

rows of tepees. Sometimes two or three families

occupy one lodge. When they are hunting and

drying meat for their winter supply, several

lodges are put together, making one big lodge

about thirty feet long, in which are two or three

fires instead of one. They say that it dries the

meat better.

When game gets scarce, camp is broken and

moved to a different place. The men and boys

catch the horses, and then the squaws have to put

on the pack-saddles (made of bone and covered

with untanned deer-hide) and pack them. The

men sit around smoking and talking. When all

is ready, the different families set out, driving

their spare horses and pack-horses in front of

them. The men generally hunt in the early morning;

they get up at about two o'clock, take a vapor

bath, get breakfast, and start to hunt at about

three. Sometimes they hunt on horseback, and

sometimes on foot. They come back at about ten

or eleven o'clock, and if they have been on foot[46]

and have been successful they take a horse and

go and bring in the game. The meat is always

divided. If Chief Joseph is there, he divides it;

and if he is not there, somebody is chosen to fill

his place. They believe that if the heads or horns

of the slain deer are left on the ground, the other

deer feel insulted and will go away, and that

would spoil the hunting in that neighborhood. So

the heads and horns are hung up in trees. They

think, too, that when anybody dies, his spirit hovers

around the spot for several days afterward,

and so they always move the lodge. I was sitting

with Joseph in the tepee once, when a lizard

crawled in. I discovered it, and showed it to Joseph.

He was very solemn, and I asked him what

was the matter. "A medicine-man sent it here to

do me harm. You have very good eyes to discover

the tricks of the medicine-men." I was

going to throw it into the fire, but he stopped me,

saying: "If you burn it, it will make the medicine-men

angry. You must kill it some other way."

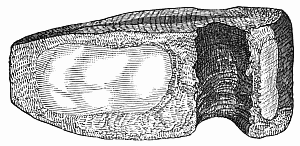

The Indians' calendars are little square sticks

of wood about eight inches long. Every day they

file a little notch, and on Sunday a little hole is

made. When any one dies, the notch is painted

red or black. When they are home at Nespilem,[47]

they all meet out on the prairie on certain days,

and have horse-racing. They run for about two

miles. When they are on the home-stretch, about

half a mile from the goal, a lot of men get behind

them and fire pistols and whip the horses.

I was out grouse-hunting with Niky Mowitz,

my Indian companion, and we started a deer. We

were near the camp, and he proposed to run

around in front of the deer and head it for camp.

So we started, and the way he got over those rocks

was a wonder! If we had not had the dogs, we

might have succeeded; but as soon as they caught

sight of the deer, they went after it like mad, and

we did not see it again. Niky Mowitz is a nephew

and adopted son of Chief Joseph; his father was

killed in the Nez Percé war of 1877. In the fall

hunt the boys are not allowed to go grouse- or

pheasant-hunting without first getting permission

of the chief in command. And it is never granted

to them until the boys have driven the horses to

water and counted them to see if any are missing.

The game that the boys play most has to be

played out in open country, where there are no

sticks or underbrush. They get a little hoop, or

some of them have a little iron ring, about two

inches across. Then they range themselves in[48]

rows, and one rolls the ring on the ground, and

the others try to throw spears through it. The

spears are straight sticks about three feet and a

half long, with two or three little branches cut

short at the end, to keep the spear from going

clear through the ring.

The Indians take "Turkish," or vapor, baths.

They have a little house in the shape of a half

globe, made of willow sticks, covered with sods

and dirt until it is about a foot thick and perfectly

tight. A hole is dug in the house and filled with

hot rocks. The Indians (usually about four)

crowd in, and then one pours hot water on the hot

rocks, making a lot of steam. They keep this up

until one's back commences to burn, and then he

gives a little yell, and somebody outside tilts up

the door (a blanket), and they all come out and

jump at once into the cold mountain-stream.

This bath is taken just before going hunting, as

they think that the deer cannot scent them after it.

Only the boys indulge in wrestling. They fold

their hands behind each other's backs, and try to

throw each other by force, or by bending the back

backward. Tripping is unfair, in their opinion.

The country is full of game, and we killed

many deer and a cinnamon bear. In the evening,[49]

when they come home, they talk about the day's

hunt, and what they saw and did. The one that

killed the bear said that when he first saw the bear

it was about fifteen yards off, and coming for him

with open jaws, and growling and roaring like

everything. He fired and wounded it. It stopped

and stood on its hind legs, roaring worse than

ever. While this was going on, the Indian slipped

around and shot it through the heart. I cut off

the claws and made a necklace out of them. The

next day they dug a hole nine feet in diameter and

built a big fire in it, and piled rocks all over the fire

to heat them. In the meantime the squaws had

cut a lot of fir-boughs and brought the bear-meat.

When the fire had burned down, and the rocks

were red hot, all the coals and things that would

smoke were raked out, and sticks laid across the

hole (it was about three feet deep). Then the fir-boughs

were dipped in water and laid over the

sticks. And then meat was laid on, and then more

fir-boughs, and then the fat (the fat between the

hide and flesh of a bear is taken off whole) is laid

on, and then more fir-boughs dipped and sprinkled

with water. Then come two or three blankets,

and, last of all, the whole thing is covered with

earth until it is perfectly tight. After about two[50]

hours everything is removed, and the water that

has been put on the boughs has steamed the meat

thoroughly. Then Chief Joseph comes and cuts

it up, and every family gets a portion. I helped

the squaws cook some wild carrots once (they

cook them just as they do the bear, except that

they let them cook all night), and Joseph said that

I must not do squaws' work: that a brave must

hunt, fish, fight, and take care of the horses; but

a squaw must put up the tepees, cook, sew, make

moccasins and clothes, tan the hides, and take care

of the household goods.

The boys take care of the horses. They catch

them and drive them to and from their watering-places;

and the rest of the time they hunt with

bows and arrows (the boys don't have guns), and

fish and play games. The Indian dogs are fine

grouse- and pheasant-hunters, scenting the game

from a long distance, and going and treeing them;

and they will stay there and bark until the men

come. The dogs are exactly like coyotes, except

that they are smaller.

ERSKINE WOOD—NAMED BY CHIEF JOSEPH "ISHEM-TUX-IL-PILP" OR "RED MOON"

ERSKINE WOOD—NAMED BY CHIEF JOSEPH "ISHEM-TUX-IL-PILP" OR "RED MOON"

Many people have said that the Indian is lazy.

In the summer he takes care of his horses, hunts

enough to keep fresh meat, fishes, and plays games.

But in the fall, when they are getting their winter[53]

meat, they get up regularly every morning at two

o'clock and start to hunt. And if the Indian has

been successful, as he usually is, he seldom gets

home before five o'clock. And the next morning

it is the same thing, while hoar-frost is all over

the ground. In the Fall Hunt, I was out in the

mountains with them seventy-five miles from

Nespilem (where Joseph's camp was, and about

one hundred and fifty miles from the agency), and

it was about the 15th of November; and if I had

not gone home then, I would not have been able

to go until spring. So Niky Mowitz brought me

in to Nespilem, and we made the trip (seventy-six

miles) in one day. We started at about eight

o'clock in the morning, on our ponies. We had

not been gone more than an hour when the dogs

started a deer; we rode very fast, and tried to get

a sight of it, but we couldn't.

Chief Joseph did not go to the mountains with

us on this hunt, and we reached his tent in Nespilem

at about ten o'clock. When we got to the

tent, one of Joseph's squaws cooked us some supper;

and on the third day after that, I went to

Wilbur, a little town on the railroad, and from

there to Portland, where papa met me at the train.

[54]

LITTLE MOCCASIN'S RIDE ON THE THUNDER-HORSE

BY COLONEL GUIDO ILGES

"LITTLE MOCCASIN" was, at the time we

speak of, fourteen years old, and about as

mischievous a boy as could be found anywhere in

the Big Horn mountains. Unlike his comrades

of the same age, who had already killed buffaloes

and stolen horses from the white men and the

Crow Indians, with whom Moccasin's tribe, the

Uncapapas, were at war, he preferred to lie under

a shady tree in the summer, or around the campfire

in winter, listening to the conversation of the

old men and women, instead of going upon expeditions

with the warriors and the hunters.

The Uncapapas are a very powerful and numerous

tribe of the great Sioux Nation, and before

Uncle Sam's soldiers captured and removed

them, and before the Northern Pacific Railroad[55]

entered the territory of Montana, they occupied

the beautiful valleys of the Rosebud, Big and Little

Horn, Powder and Redstone rivers, all of

which empty into the grand Yellowstone Valley.

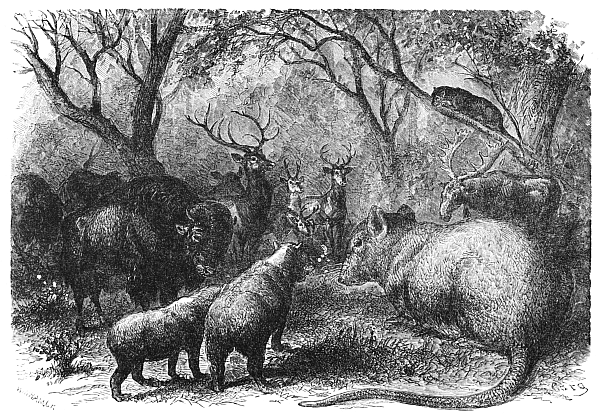

In those days, before the white man had set foot

upon these grounds, there was plenty of game,

such as buffalo, elk, antelope, deer, and bear; and,

as the Uncapapas were great hunters and good

shots, the camp of Indians to which Little Moccasin

belonged always had plenty of meat to eat

and plenty of robes and hides to sell and trade for

horses and guns, for powder and ball, for sugar

and coffee, and for paint and flour. Little Moccasin

showed more appetite than any other Indian

in camp. In fact, he was always hungry, and used

to eat at all hours, day and night. Buffalo meat

he liked the best, particularly the part taken from

the hump, which is so tender that it almost melts

in the mouth.

When Indian boys have had a hearty dinner of

good meat, they generally feel very happy and

very lively. When hungry, they are sad and dull.

This was probably the reason why Little Moccasin

was always so full of mischief, and always

inventing tricks to play upon the other boys. He

was a precocious and observing youngster, full of[56]

quaint and original ideas—never at a loss for expedients.

But he was once made to feel very sorry for

having played a trick, and I must tell my young

readers how it happened.

"Running Antelope," one of the great warriors

and the most noted orator of the tribe, had returned

from a hunt, and Mrs. Antelope was frying

for him a nice buffalo steak—about as large

as two big fists—over the coals. Little Moccasin,

who lived in the next street of tents, smelled the

feast, and concluded that he would have some of

it. In the darkness of the night he slowly and

carefully crawled toward the spot where Mistress

Antelope sat holding in one hand a long stick, at

the end of which the steak was frying. Little

Moccasin watched her closely, and, seeing that

she frequently placed her other hand upon the

ground beside her and leaned upon it for support,

he soon formed a plan for making her drop the

steak.

He had once or twice in his life seen a pin, but

he had never owned one, and he could not have

known what use is sometimes made of them by

bad white boys. He had noticed, however, that

some of the leaves of the larger varieties of the[57]

prickly-pear cactus-plant are covered with many

thorns, as long and as sharp as an ordinary pin.

So when Mrs. Antelope again sat down and

looked at the meat to see if it was done, he slyly

placed half-a-dozen of the cactus leaves upon the

very spot of ground upon which Mrs. Antelope

had before rested her left hand.

Then the young mischief crawled noiselessly

into the shade and waited for his opportunity,

which came immediately.

When the unsuspecting Mrs. Antelope again

leaned upon the ground, and felt the sharp points

of the cactus leaves, she uttered a scream, and

dropped from her other hand the stick and the

steak, thinking only of relief from the sharp pain.

Then, on the instant, the young rascal seized

the stick and tried to run away with it. But Running

Antelope caught him by his long hair, and

gave him a severe whipping, declaring that he

was a good-for-nothing boy, and calling him a

"coffee-cooler" and a "squaw."

The other boys, hearing the rumpus, came running

up to see the fun, and they laughed and

danced over poor Little Moccasin's distress.

Often afterward they called him "coffee-cooler";

which meant that he was cowardly and faint-hearted,[58]

and that he preferred staying in camp

around the fire, drinking coffee, to taking part in

the manly sports of hunting and stealing expeditions.

The night after the whipping, Little Moccasin

could not sleep. The disgrace of the whipping

and the name applied to him were too much for

his vanity. He even lost his appetite, and refused

some very nice prairie-dog stew which his mother

offered him.

He was thinking of something else. He must

do something brave—perform some great deed

which no other Indian had ever performed—in

order to remove this stain upon his character.

But what should it be? Should he go out alone

and kill a bear? He had never fired a gun, and

was afraid that the bear might eat him. Should

he attack the Crow camp single-handed? No, no—not

he; they would catch him and scalp him

alive.

All night long he was thinking and planning;

but when daylight came, he had reached no conclusion.

He must wait for the Great Spirit to

give him some ideas.

During the following day he refused all food

and kept drawing his belt tighter and tighter[59]

around his waist every hour, till, by evening, he

had reached the last notch. This method of appeasing

the pangs of hunger, adopted by the Indians

when they have nothing to eat, is said to be

very effective.

In a week's time Little Moccasin had grown

almost as thin as a bean-pole, but no inspiration

had yet revealed what he could do to redeem himself.

About this time a roving band of Cheyennes,

who had been down to the mouth of the Little

Missouri, and beyond, entered the camp upon a

friendly visit. Feasting and dancing were kept

up day and night, in honor of the guests; but

Little Moccasin lay hidden in the woods nearly all

the time.

During the night of the second day of their

stay, he quietly stole to the rear of the great council-tepee,

to listen to the pow-wow then going on.

Perhaps he would there learn some words of wisdom

which would give him an idea how to carry

out his great undertaking.

After "Black Catfish," the great Cheyenne

warrior, had related in the flowery language of

his tribe some reminiscences of his many fights

and brave deeds, "Strong Heart" spoke. Then[60]

there was silence for many minutes, during which

the pipe of peace made the rounds, each warrior

taking two or three puffs, blowing the smoke

through the nose, pointing toward heaven, and

then handing the pipe to his left-hand neighbor.

"Strong Heart," "Crazy Dog," "Bow-String,"

"Dog-Fox," and "Smooth Elkhorn" spoke of the

country they had just passed through.

Then again the pipe of peace was handed

round, amid profound silence.

"Black Pipe," who was bent and withered with

the wear and exposure of seventy-nine winters,

and who trembled like some leafless tree shaken

by the wind, but who was sound in mind and

memory, then told the Uncapapas, for the first

time, of the approach of a great number of white

men, who were measuring the ground with long

chains, and who were being followed by "Thundering

Horses" and "Houses on Wheels." (He

was referring to the surveying parties of the

Northern Pacific Railway Company, who were

just then at work on the crossing of the Little

Missouri.)

With heart beating wildly, Little Moccasin listened

to this strange story and then retired to his

own blankets in his father's tepee.[61]

Now he had found the opportunity he so long

had sought! He would go across the mountains,

all by himself, look at the thundering horses and

the houses on wheels. He then would know more

than any one in the tribe, and return to the camp,—a

hero!

At early morn, having provided himself with a

bow and a quiver full of arrows, without informing

any one of his plan he stole out of camp, and,

running at full speed, crossed the nearest mountain

to the East.

Allowing himself little time for rest, pushing

forward by day and night, and after fording

many of the smaller mountain-streams, on the

evening of the third day of his travel he came

upon what he believed to be a well-traveled road.

But—how strange!—there were two endless iron

rails lying side by side upon the ground. Such a

curious sight he had never beheld. There were

also large poles, with glass caps, and connected

by wire, standing along the roadside. What

could all this mean?

Poor Little Moccasin's brain became so bewildered

that he hardly noticed the approach of a

freight-train drawn by the "Thundering Horse."

There was a shrill, long-drawn whistle, and immense[62]

clouds of black smoke; and the Thundering

Horse was sniffing and snorting at a great

rate, emitting from its nostrils large streams of

steaming vapor. Besides all this, the earth, in the

neighborhood of where Little Moccasin stood,

shook and trembled as if in great fear; and to him

the terrible noises the horse made were perfectly

appalling.

Gradually the snorts, and the puffing, and the

terrible noise lessened, until, all at once, they entirely

ceased. The train had come to a stand-still

at a watering tank, where the Thundering Horse

was given its drink.

The rear car, or "House on Wheels," as old

Black Pipe had called it, stood in close proximity

to Little Moccasin,—who, in his bewilderment

and fright at the sight of these strange moving

houses, had been unable to move a step.

But as no harm had come to him from the terrible

monster, Moccasin's heart, which had sunk

down to the region of his toes, began to rise

again; and the curiosity inherent in every Indian

boy mastered fear.

He moved up, and down, and around the great

House on Wheels; then he touched it in many

places, first with the tip-end of one finger, and[63]

finally with both hands. If he could only detach

a small piece from the house to take back to camp

with him as a trophy and as a proof of his daring

achievement! But it was too solid, and all made

of heavy wood and iron.

At the rear end of the train there was a ladder,

which the now brave Little Moccasin ascended

with the quickness of a squirrel to see what there

was on top.

It was gradually growing dark, and suddenly

he saw (as he really believed) the full moon approaching

him. He did not know that it was

the headlight of a locomotive coming from the

opposite direction.

Absorbed in this new and glorious sight, he did

not notice the starting of his own car, until it was

too late, for, while the car moved, he dared not let

go his hold upon the brake-wheel.

There he was, being carried with lightning

speed into a far-off, unknown country, over

bridges, by the sides of deep ravines, and along

the slopes of steep mountains.

But the Thundering Horse never tired nor

grew thirsty again during the entire night.

At last, soon after the break of day, there came

the same shrill whistle which had frightened him[64]

so much on the previous day; and, soon after, the

train stopped at Miles City.

But, unfortunately for our little hero, there

were a great many white people in sight; and he

was compelled to lie flat upon the roof of his car,

in order to escape notice. He had heard so much

of the cruelty of the white men that he dared not

trust himself among them.

Soon they started again, and Little Moccasin

was compelled to proceed on his involuntary journey,

which took him away from home and into

unknown dangers.

At noon, the cars stopped on the open prairie to

let Thundering Horse drink again. Quickly, and

without being detected by any of the trainmen, he

dropped to the ground from his high and perilous

position. Then the train left him—all alone in

an unknown country.

Alone? Not exactly; for, within a few minutes,

half a dozen Crow Indians, mounted on

swift ponies, are by his side, and are lashing him

with whips and lassoes.

He has fallen into the hands of the deadliest

enemies of his tribe, and has been recognized by

the cut of his hair and the shape of his moccasins.

When they tired of their sport in beating poor[65]

Little Moccasin so cruelly, they dismounted and

tied his hands behind his back.

Then they sat down upon the ground to have a

smoke and to deliberate about the treatment of

the captive.

During the very severe whipping, and while

they were tying his hands, though it gave him

great pain, Little Moccasin never uttered a groan.

Indian-like, he had made up his mind to "die

game," and not to give his enemies the satisfaction

of gloating over his sufferings. This, as will

be seen, saved his life.

The leader of the Crows, "Iron Bull," was in

favor of burning the hated Uncapapa at a stake,

then and there; but "Spotted Eagle," "Blind

Owl," and "Hungry Wolf" called attention to

the youth and bravery of the captive, who had

endured the lashing without any sign of fear.

Then the two other Crows took the same view.

This decided poor Moccasin's fate; and he understood

it all, although he did not speak the Crow

language, for he was a great sign-talker, and had

watched them very closely during their council.

Blind Owl, who seemed the most kind-hearted

of the party, lifted the boy upon his pony, Blind

Owl himself getting up in front, and they rode at[66]

full speed westward to their large encampment,

where they arrived after sunset.

Little Moccasin was then relieved of his bonds,

which had benumbed his hands during the long

ride, and a large dish of boiled meat was given

to him. This, in his famished condition, he relished

very much. An old squaw, one of the wives

of Blind Owl, and a Sioux captive, took pity on

him, and gave him a warm place with plenty of

blankets in her own tepee, where he enjoyed a

good rest.

During his stay with the Crows, Little Moccasin

was made to do the work, which usually falls

to the lot of the squaws; and which was imposed

upon him as a punishment upon a brave enemy,

designed to break his proud spirit. He was

treated as a slave, made to haul wood and draw

water, do the cooking, and clean game. Many of

the Crow boys wanted to kill him, but his foster-mother,

"Old Looking-Glass," protected him;

and, besides, they feared that the soldiers of Fort

Custer might hear of it, if he was killed, and punish

them.

Many weeks thus passed, and the poor little

captive grew more despondent and weaker in

body every day. Often his foster-mother would[67]

talk to him in his own language, and tell him to

be of good cheer; but he was terribly homesick

and longed to get back to the mountains on the

Rosebud, to tell the story of his daring and become

the hero which he had started out to be.

One night, after everybody had gone to sleep

in camp, and the fires had gone out, Old Looking-Glass,

who had seemed to be soundly sleeping, approached

his bed and gently touched his face.

Looking up, he saw that she held a forefinger

pressed against her lips, intimating that he must

keep silence, and that she was beckoning him to

go outside.

There she soon joined him; then, putting her

arm around his neck, she hastened out of the camp

and across the nearest hills.

When they had gone about five miles away

from camp, they came upon a pretty little mouse-colored

pony, which Old Looking-Glass had hidden

there for Little Moccasin on the previous day.

She made him mount the pony, which she called

"Blue Wing," and bade him fly toward the rising

sun, where he would find white people who would

protect and take care of him.

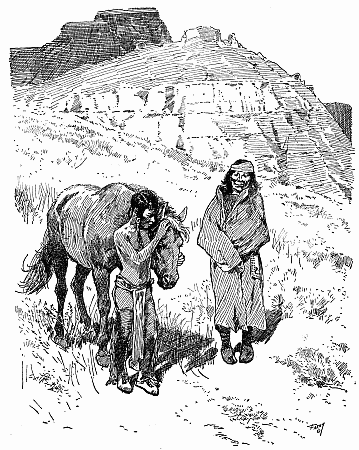

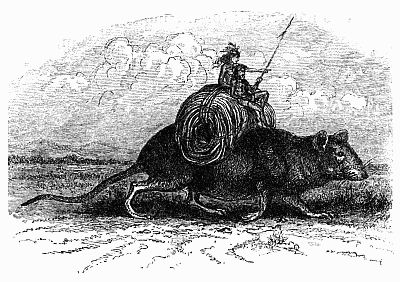

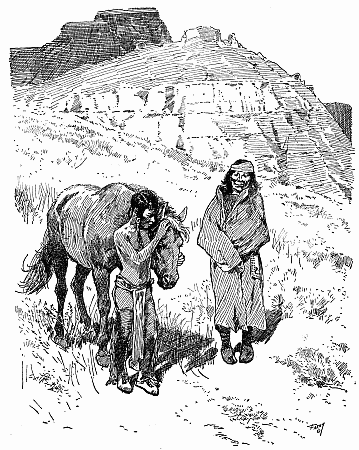

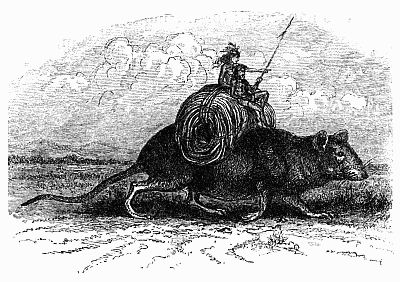

"THEY CAME UPON A PRETTY LITTLE MOUSE-COLORED PONY"

"THEY CAME UPON A PRETTY LITTLE MOUSE-COLORED PONY"

Old Looking-Glass then kissed Little Moccasin

upon both cheeks and the forehead, while the tears[69]

ran down her wrinkled face; she also folded her

hands upon her breast and, looking up to the

heavens, said a prayer, in which she asked the

Great Spirit to protect and save the poor boy in

his flight.

After she had whispered some indistinct words

into the ear of Blue Wing (who seemed to understand

her, for he nodded his head approvingly),

she bade Little Moccasin be off, and advised him

not to rest this side of the white man's settlement,

as the Crows would soon discover his absence,

and would follow him on their fleetest ponies.

"But Blue Wing will save you! He can outrun

them all!"

These were her parting words, as he galloped

away.

In a short time the sun rose over the nearest

hill, and Little Moccasin then knew that he was

going in the right direction. He felt very happy

to be free again, although sorry to leave behind

his kind-hearted foster-mother, Looking-Glass.

He made up his mind that after a few years, when

he had grown big and become a warrior, he would

go and capture her from the hated Crows and

take her to his own tepee.

He was so happy in this thought that he had[70]

not noticed how swiftly time passed, and that already

the sun stood over his head; neither had he

urged Blue Wing to run his swiftest; but that

good little animal kept up a steady dog-trot, without,

as yet, showing the least sign of being tired.

But what was the sudden noise which was

heard behind him? Quickly he turned his head,

and, to his horror, he beheld about fifty mounted

Crows coming toward him at a run, and swinging

in their hands guns, pistols, clubs, and knives!

His old enemy, Iron Bull, was in advance, and

under his right arm he carried a long lance, with

which he intended to spear Little Moccasin.

Moccasin's heart stood still for a moment with

fear; he knew that this time they would surely

kill him if caught. He seemed to have lost all

power of action.

Nearer and nearer came Iron Bull, shouting at

the top of his voice.

But Blue Wing now seemed to understand the

danger of Moccasin's situation; he pricked up his

ears, snorted a few times, made several short

jumps, fully to arouse Moccasin, who remained

paralyzed with fear, and then, like a bird, fairly

flew over the prairie, as if his little hoofs were not

touching the ground.[71]

Little Moccasin, too, was now awakened to his

peril, and he patted and encouraged Blue Wing;

while, from time to time, he looked back over his

shoulder to watch the approach of Iron Bull.

Thus they went, on and on; over ditches and

streams, rocks and hills, through gulches and

valleys. Blue Wing was doing nobly, but the

pace could not last forever.

Iron Bull was now only about five hundred

yards behind and gaining on him.

Little Moccasin felt the cold sweat pouring

down his face. He had no firearm, or he would

have stopped to shoot at Iron Bull.

Blue Wing's whole body seemed to tremble beneath

his young rider, as if the pony was making

a last desperate effort, before giving up from exhaustion.

Unfortunately, Little Moccasin did not know

how to pray, or he might have found some comfort

and help thereby; but in those moments, when

a terrible death was so near to him, he did the

next best thing: he thought of his mother and his

father, of his little sisters and brothers, and also

of Looking-Glass, his kind old foster-mother.

Then he felt better and was imbued with fresh

courage. He again looked back, gave one loud,[72]

defiant yell at Iron Bull, and then went out of

sight over some high ground.

Ki-yi-yi-yi! There is the railroad station just

in front, only about three hundred yards away.

He sees white men around the buildings, who will

protect him.

At this moment Blue Wing utters one deep

groan, stumbles, and falls to the ground. Fortunately,

though, Little Moccasin has received no

hurt. He jumps up, and runs toward the station

as fast as his weary legs can carry him.

At this very moment Iron Bull with several of

his braves came in sight again, and, realizing the

helpless condition of the boy, they all gave a shout

of joy, thinking that in a few minutes they would

capture and kill him.

But their shouting had been heard by some of

the white men, who at once concluded to protect

the boy, if he deserved aid.

Little Moccasin and Iron Bull reached the door

of the station-building at nearly the same moment;

but the former had time enough to dart inside

and hide under the table of the telegraph

operator.

When Iron Bull and several other Crows

rushed in to pull the boy from underneath the[73]

table, the operator quickly took from the table

drawer a revolver, and with it drove the murderous

Crows from the premises.

Then the boy had to tell his story, and he was

believed. All took pity upon his forlorn condition,

and his brave flight made them his friends.

In the evening Blue Wing came up to where

Little Moccasin was resting and awaiting the arrival

of the next train, which was to take him back

to his own home.

Then they both were put aboard a lightning-express

train, which took them to within a short

distance of the old camp on the Rosebud.

When Little Moccasin arrived at his father's

tepee, riding beautiful Blue Wing, now rested and

frisky, the whole camp flocked around him; and

when he told them of his great daring, of his capture

and his escape, Running Antelope, the big

warrior of the Uncapapas and the most noted

orator of the tribe, proclaimed him a true hero,

and then and there begged his pardon for having

called him a "coffee-cooler." In the evening Little

Moccasin was honored by a great feast, and

the name of "Rushing Lightning," Wakee-wata-keepee,

was bestowed upon him—and by that

name he is known to this day.

[74]

THE LITTLE FIRST MAN AND THE LITTLE FIRST WOMAN

AN INDIAN LEGEND

BY WILLIAM M. CARY

[This story has been told to the children of the Dacotah Indians

for very many years, having been handed down from generation

to generation; and it is now listened to by Indian children with as

much interest as it excited in the red-skinned boys and girls of a

thousand years ago.]

ON the bank of one of the many branches of

the Missouri River—or "Big Muddy," as

it is called by the Indians on account of the color

of its waters—there lived a little boy and a little

girl. These children were very small indeed,

being no bigger than a man's finger, but very

handsome, well formed, and also quite strong,

considering their size. There were no men and

women in the world at that time, and none of the

people who told the story knew how these two

small folk came to be living on the banks of the

river. Some persons thought that they might

have been little beavers, or little turtles, who were

[75]

so smart that they turned into a boy and a girl;

but nothing about this is known for certain.

These small people lived in a tiny lodge near the

river, feeding upon the berries that grew along

the shore. These were of great variety and many

delicious flavors. There were wild currants,

raspberries, gooseberries, service-berries, wild

plums and grapes; and of most of these, one was

sufficient to make a meal for both of the children.

The little girl was very fond of the boy, and

watched over and tended him with great care.

She made him a tiny bow from a blade of grass,

with arrows to match, and he hunted grasshoppers,

crickets, butterflies, and many other small

creatures. She then made him a hunting-shirt, or

coat, from the skin of a humming-bird, ornamented

with brilliant little stones and tiny shells

found in the sand. She loved him so dearly that

no work was too much when done for him.

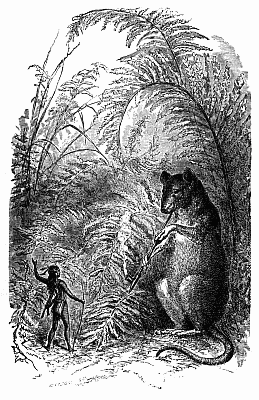

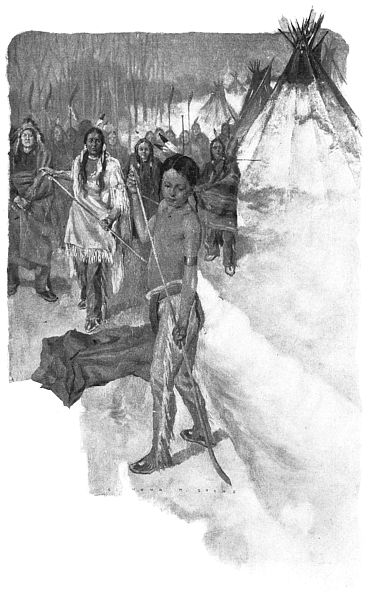

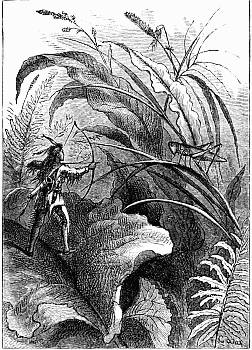

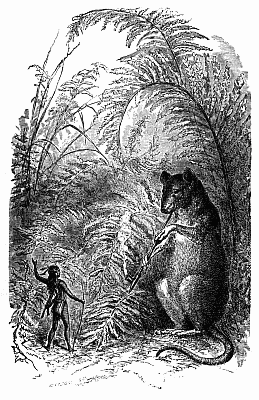

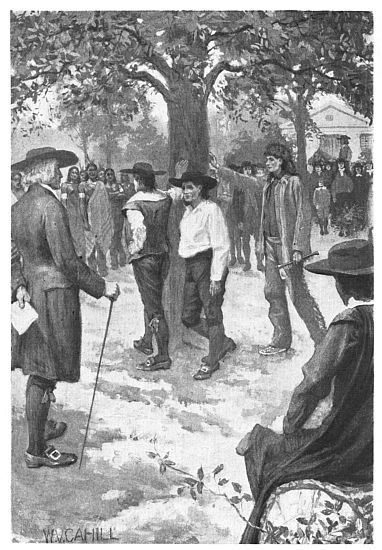

TELLING THE STORY OF THE LITTLE FIRST MAN AND THE LITTLE FIRST WOMAN

TELLING THE STORY OF THE LITTLE FIRST MAN AND THE LITTLE FIRST WOMAN

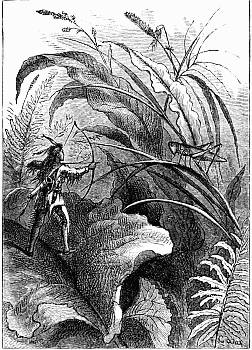

"HE HUNTED GRASSHOPPERS"

"HE HUNTED GRASSHOPPERS"

One day he was out hunting on the prairie; and,

feeling tired from an unusually long tramp, he lay

down to rest and soon fell fast asleep. The wind

began to rise, after the heat of the day; but this

made him sleep the sounder, and he knew nothing

of the storm that was threatening. The clouds

rolled over from the northwestern horizon, like an[76]

army of blankets torn and

ragged. With flashing lightning,

the thunder-god let

loose his powers, and peal

after peal went echoing

loudly through the cañons,

up over the hills, and down

into prairies where the quaking-asp

shivered, the willows

waved, and the tall

blue-grass rolled, as[77]

the wind passed over, like a tempest-tossed sea.

Only the stubborn aloes, the Spanish-bayonet, and

the prickly-pears kept their position. But the

storm was as brief as it was violent; and, gradually

subsiding, it passed to the southeast, leaving

nothing but a bank of clouds behind the horizon.

Everything was drenched by the heavy rain. The

flowers hung their heads, or lay crushed from the