BURNING SANDS

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Burning Sands

Author: Arthur Weigall

Release Date: January 15, 2011 [EBook #34978]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BURNING SANDS ***

Produced by Darleen Dove, Roger Frank, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

Burning Sands

By

Arthur Weigall

Contents

- CHAPTER I—A STUDY IN BEHAVIOUR

- CHAPTER II—THE FREEDOM OF THE DESERT

- CHAPTER III—THE WORLD AND THE FLESH

- CHAPTER IV—A JACKAL IN A VILLAGE

- CHAPTER V—FAMILY AFFAIRS

- CHAPTER VI—TOWARDS THE SUNSET

- CHAPTER VII—THE DESERT AND THE CITY

- CHAPTER VIII—THE ACCOMPLICE

- CHAPTER IX—ON THE NILE

- CHAPTER X—“FOR TOMORROW WE DIE”

- CHAPTER XI—THE OASIS IN THE DESERT

- CHAPTER XII—THE HELPMATE

- CHAPTER XIII—THE NEW LIFE

- CHAPTER XIV—THE COURT PHILOSOPHER

- CHAPTER XV—A BALL AT THE GENERAL’S

- CHAPTER XVI—AT CHRISTMASTIDE

- CHAPTER XVII—DESTINY

- CHAPTER XVIII—MAN AND WOMAN

- CHAPTER XIX—THE SEEDS OF SORROW

- CHAPTER XX—PRIVATE INTERESTS

- CHAPTER XXI—THE CLASH

- CHAPTER XXII—THE CALL OF THE DESERT

- CHAPTER XXIII—THE NATURE OF WOMEN

- CHAPTER XXIV—THE GREAT ADVENTURE

- CHAPTER XXV—BREAKING LOOSE

- CHAPTER XXVI—THE STOLEN HOUR

- CHAPTER XXVII—THE FLIGHT

- CHAPTER XXVIII—THE SURPRISING FORTNIGHT

- CHAPTER XXIX—IN THE PRESENCE OF DEATH

- CHAPTER XXX—THE REVOLT

- CHAPTER XXXI—PAYING THE PRICE

- CHAPTER XXXII—THINKING THINGS OVER

- CHAPTER XXXIII—THE RETURN

CHAPTER I—A STUDY IN BEHAVIOUR

The music ceased. For a full minute the many dancers stood as the dance had left them, stranded, so to speak, upon the polished floor of the ballroom, clapping their white-gloved hands in what seemed to be an appeal to the tired musicians to release them from their awkward situation. The chef d’orchestre rose from his chair and shook his head, pointing to the beads of moisture upon his sallow forehead. Two or three couples, more merciful than their companions, turned and walked away; and therewith the whole company ceased their vain clapping, and, as though awakened from an hypnotic seizure, hastened to jam themselves into the heated, chattering mass which moved out of the brilliantly lighted room and dispersed into the shadows of the halls and passages beyond.

Lady Muriel Blair, to all appearances the only cool young person in the throng, led her perspiring partner towards a group of elderly women who sat fanning themselves near an open window, beyond which the palms could be seen redundant in the light of the moon. An enormous-bosomed matron, wearing a diamond tiara upon her dyed brown hair, and a rope of pearls about her naked pink shoulders, turned to her as she approached, and smiled upon her in a patronizing manner. She was the wife of Sir Henry Smith-Evered, Commander-in-chief of the British Forces in Egypt; and her smile was highly valued in Cairo society.

“You seem to be enjoying yourself, my dear,” she said, taking hold of the girl’s hand. “But you mustn’t get overtired in this heat. Wait another month, until the weather is cool, and then you can dance all night.”

“Oh, but I don’t feel it at all,” Lady Muriel replied, looking with mild disdain at her partner’s somewhat limp collar. “Father warned me that October in Cairo would be an ordeal, but so far I’ve simply loved it.”

Her voice had that very slight suggestion of husky tiredness in it which has a certain fascination. With her it was habitual.

“You’ve only been in Egypt twenty-four hours,” Lady Smith-Evered reminded her. “You must be careful.”

“Careful!” the girl muttered, with laughing scorn. “I hate the word.”

Her good-looking little partner, Rupert Helsingham, ran his finger around the inside of his collar, and adjusted his eyeglass. “Let’s go and sit on the veranda,” he suggested.

Lady Muriel turned an eye of mocking enquiry upon the General’s lady, who was her official chaperone (though the office had little, if any, meaning); for, in a strange country and in a diplomatic atmosphere, it was as well, she thought, to ascertain the proprieties. Lady Smith-Evered, aware of dear little Rupert’s strict regard on all occasions for his own reputation, nodded acquiescence; and therewith the young couple sauntered out of the room.

“A charming girl!” remarked the stout chaperone, turning her heavily powdered face to her companions.

“She is beautiful,” said Madam Pappadoulopolos, an expansive, black-eyed, black-haired, black-moustached, black-robed figure, wife of the Greek Consul-General.

“She has the sort of monkey-beauty of all the Blairs,” declared Mrs. Froscombe, the gaunt but romantic wife of the British Adviser to the Ministry of Irrigation. She spoke authoritatively. She had recently purchased a richly illustrated volume dealing with the history of that eminent family.

“It is a great responsibility for Lord Blair,” said Lady Smith-Evered. “Now that poor Lady Blair has been dead for over a year, he felt that he ought not to leave his only daughter, his only child, with her relations in England any longer; and, of course, it is very right that she should take her place as mistress here at the Residency, though I could really have acted as hostess for him perfectly well.”

“Indeed yes,” Madam Pappadoulopolos assented, warmly.

“You have a genius for that sort of thing,” murmured Mrs. Froscombe, staring out of the window at the moonlit garden.

“Thank you, Gladys dear,” said Lady Smith-Evered, smiling coldly at her friend’s averted face.

Muriel Blair’s type of beauty was in a way monkey-like, if so ludicrous a term can be employed in a laudatory sense to describe a face of great charm. She was of about the average height; her head was gracefully set upon her excellent neck and shoulders; and there was a sort of airy dignity in her carriage and step. Her enemies called her sullen at times, and named her Moody Muriel; her friends, on the contrary, described her as a personification of the spirit of Youth; while her feminine intimates said that, except for her dislike of the cold, she might have earned her living as a sculptor’s model.

She possessed a much to be envied mane of rather coarse brown hair which she wore coiled high upon her head; and her skin was that of a brunette, though there was some nice colour in her cheeks. Her eyes were good, and she had the habit of staring at her friends, sometimes, in a manner which seemed to indicate a fortuitous mimicry of childlike and incredulous questioning.

It was perhaps the tilt of her small nose and an occasional setting of her jaw which caused her undoubted beauty to be called monkey-like; or possibly it was the occasional defiance of her brown eyes, or the puckering of her eyebrows, or sometimes the sudden and whimsical grimace which she made when she was displeased.

As she seated herself now in the moonlight and leant back in the basket chair, Rupert Helsingham looked at her with admiration; and in the depths of his worldly little twenty-five-year-old mind he anticipated with pleasurably audacious hopes a season tinctured with romance. He held the position of Oriental Secretary at the Residency, and was considered to be a rising young man, something of an Arabic scholar, and an expert on points of native etiquette. She was his chief’s daughter, and heiress to the Blair estates. Every day they would meet; and probably, since she was rather adorable, he would fall in love with her, and perhaps she with him. It was a charming prospect.

His father had recently been created Baron Helsingham of Singleton. The old gentleman was the first of an ancient race of village squires who had ever performed any public service or received any royal recognition; and now he, the son and heir, might very possibly make the first notable matrimonial alliance of his line.

“I wonder what’s happened to my father,” said Muriel, breaking the silence engendered by Rupert’s reflections. “I haven’t seen him since the how-d’you-doing business.”

His whereabouts was only of casual interest to her, for she regarded him with no particular love, nor, indeed, did she know him at all intimately. His duties had taken him abroad a great deal during her childhood, while her education had kept her in England; and for the last three or four years he had passed almost entirely out of her scheme of things.

“He’s working in his study,” her companion replied, pointing to the wing of the house which went to form the angle wherein they were sitting. “He always dictates his telegrams at this time: he says he feels more benevolent after dinner. He’ll come into the ballroom presently, and say the correct thing to the correct people. He’s a paragon of tact, and, I can tell you, tact is needed here in Cairo! There’s such a mixture of nationalities to deal with. What languages do you speak?”

“Only French,” she replied.

“Good!” he laughed. “Speak French to everybody: especially to those who are not French. It makes them think that you think them cosmopolitan. Everybody wants to be thought cosmopolitan in a little place like this: it indicates that they have had the money to travel.”

“I shall look to you for guidance,” said Muriel, opening her mouth to yawn, and shutting it again as though remembering her manners.

“I’ll give you a golden rule to start with,” he answered. “Be very gracious to all foreigners, because every little politeness helps the international situation, but behave how you like to English people, because their social aspirations require them to speak of you as dear Lady Muriel, however fiercely they burn with resentment.”

Muriel smiled. She had a really fascinating smile, and her teeth were worthy of the great care she gave to them. “And how must I treat an Egyptian—I mean an Egyptian gentleman?” she enquired.

“There isn’t such a thing,” he laughed, having very insular ideas as to the meaning of the word.

“Well, a Prince or a Pasha or whatever they’re called?”

“O, that’s simple enough. If his colour is anything lighter than black coffee, ask him if he’s a Frenchman. He will protest vehemently, and cry ‘Mais non!—je suis Egyptien.’ But he’ll love you for ever all the same.”

Muriel gazed before her into the mystery of the garden. For a brief moment she had the feeling that their conversation was at variance with their surroundings, that the sweet night and the moon and the stately trees were bidding them be silent. But the thought was gone almost before it was recorded.

From where she sat she looked across one side of the short circular entrance-drive, and behind the acacias and slender palms, which grew close up to the veranda, she could see the high white wall of the garden, whereon the purple bougainvillea clustered. Through the ornate bars of the great front gates she watched the regular passage to and fro of the kilted sentry, the moonlight gleaming upon the bayonet fixed to his rifle. Beyond, there was an open lamp-lit square, in the middle of which a jet of sparkling water shot up from a marble fountain.

Roses grew in profusion at the edges of the drive, and the gentle night-wind brought their fragrance to her nostrils; while to her ears came the rustling of the trees, the ringing tramp of the sentry’s heavy boots, and the subdued chatter of the resting dancers to whom this part of the veranda was forbidden. In the clear Egyptian atmosphere so strong was the moonlight that every detail of the scene was almost as apparent as it would have been at high noon; and, between the houses on the opposite side of the square, her vision travelled out over the ranges of white buildings which gradually rose towards the towering Citadel and the hills of the desert beyond. Here and there a minaret pierced the sky, so slender that its stability seemed a marvel of balance; and countless domes and cupolas gleamed like great pearls in the silvery light.

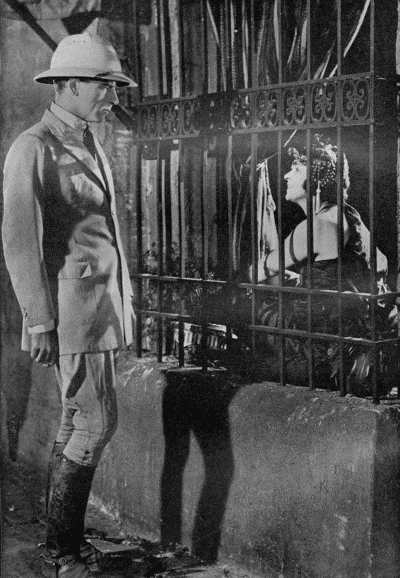

She was about to ask a further languid question of her partner in regard to the ways of Cairene society when her attention was attracted by the appearance of a man wearing a slouch hat, who came suddenly into view beyond the bars of the gates and was at once accosted by the Scotch sentry. He looked something of a ruffian, and the sentry seemed to be acting correctly in barring the way with his rifle held in both hands across his bare knees.

A rapid argument followed, the exact words of which she could not quite catch; but it was evident that the Scotchman was not going to admit any suspicious character or possible anarchist on to the premises until he had consulted with the native policeman who was to be seen hurrying across the square. On the other hand the intruder appeared to be in a hurry, and his voice had clearly to be controlled as he explained to the zealous guardian of the gate that he had business at the Residency. But the sentry was obdurately silent, and the voice of the speaker, in consequence, increased in volume.

“Now don’t be silly,” Muriel heard him say, “or I’ll take your gun away from you.”

At this she laughed outright, and, turning to her companion, suggested that he should go and find out what was the trouble; but he shook his head.

“No,” he said. “We can’t be seen here behind these flower-pots: let’s watch what happens.”

The newcomer made a sudden forward movement; the sentry assumed an attitude as though about to bayonet him, or to pretend to do so; there was a rapid scuffle; and a moment later the rifle was twisted out of its owner’s brawny hands.

The soldier uttered an oath, stepped back a pace, and like a lion, leapt upon his assailant. There was a confused movement; the rifle dropped with a clatter upon the pavement; and the Scotchman seized about the middle in a grip such as he was unlikely ever to have experienced before, turned an amazingly unexpected somersault, landing, like a clown at the circus, in a sitting position in which he appeared to be staring open-mouthed at the beauties of a thousand dazzling stars.

Thereupon the ruffian quietly picked up the rifle, opened the gate, shut it behind him, and walked up the drive; while the Egyptian policeman ran to the soldier’s assistance, blowing the while upon his whistle with all the wind God had given him.

The dazed sentry scrambled to his feet, and, with a curious crouching gait, suggestive of the ring, followed the intruder into the drive.

“Gi’ me ma rifle,” he said, hoarsely. It was evident that he was trying to collect his wits; and his attitude was that of a wrestler looking for an opening.

The ruffian stood still, and in voluble Arabic ordered the policeman to stop his noise, at which the bewildered native, as though impressed by the peremptory words, obediently took the whistle out of his mouth and stood irresolute.

“Gi’ me ma rifle,” repeated the Scot, in injured tones, warily circling around his cool opponent.

Rupert Helsingham suddenly got up from his chair. “Why,” he exclaimed, “it’s Daniel Lane! Excuse me a moment.”

He hurried down the steps of the veranda; and, with breathless interest, Muriel watched the two men shake hands, the one a small dapper ballroom figure, the other a large, muscular brigand, a mighty man from the wilds. He wore a battered, broad-brimmed felt hat, an old jacket of thin tweed, and grey flannel trousers which sagged at the knees and were rolled up above a pair of heavy brown boots, covered with dust.

With an air of complete unconcern he gave the rifle back to the abashed sentry; and, putting his hand on Helsingham’s shoulder, strolled towards the veranda.

“I’ve ridden in at top speed,” he said, and Muriel noticed that his voice was deep and quiet, and that there was a trace of an American accent. “A hundred and fifty miles in under three days. Pretty good going, considering how bad the tracks are up there.” He jerked his thumb in the direction of the western desert.

“The Great Man will be very pleased,” the other replied. ‘The Great Man’ was the designation generally used by the diplomatic staff in speaking of Lord Blair.

As they ascended the steps Daniel Lane cast a pair of searching blue eyes upon the resplendent figure of the girl in the chair. In the sheen of the moon her dress, of flimsy material, seemed to array her as it were in a mist; and the diamonds about her throat and in her hair—for she was wearing family jewels—gleamed like magic points of light.

“Got a party on?” he asked, with somewhat disconcerting directness.

“A dance,” Rupert Helsingham replied, stiffly, “in honour of Lady Muriel’s arrival. But let me introduce you.”

He turned to the girl, and effected the introduction. “Mr. Lane,” he said, “is one of your father’s most trusted friends. I don’t know what we should do sometimes without his counsel and advice. He knows the native mind inside out.”

Now that the man had removed his hat, Lady Muriel felt sure that she had seen him before, but where, she could not recall. The face was unforgettable. The broad forehead from which the rough mud-coloured hair was thrown back; the heavy brows which screened the steady blue eyes; the bronzed skin; the white, regular teeth—these features she had looked at across a drawing-room somewhere. His bulk and figure, too, were not of the kind to be forgotten easily: the powerful neck, the great shoulders, the mighty chest, the strong hands, were all familiar to her.

“I think we’ve met before,” she ventured.

“Yes, I fancy we have,” he replied. “Use’n’t you to wear your hair in two fat pigtails?”

“Four years ago,” she laughed.

“Then I guess it was four years ago that we met,” he said; and without further remark he turned to Rupert Helsingham, asking whether and when he might see Lord Blair. “I was going to ring at the side door there,” he explained, pointing to the door behind them which led directly into the corridor before the Great Man’s study. “That’s my usual way in: I’ve no use for the main entrance and the footman.”

“And not much real use for sentries, either,” Muriel laughed.

“The lad only did his duty,” he answered good-humouredly, pointing to his rough clothes; “but somehow things like fixed bayonets always make me impatient. I must try to get over it.”

“If Lady Muriel will excuse me, I’ll go and find out if his Lordship can see you at once,” said Helsingham, in his most official tone of voice. A sentry after all is a sentry, not an acrobat; and if people will wear the garments of a tramp, they must take the consequences.

Daniel Lane thrust his hands into his pockets, and stared out into the garden; while Muriel, left alone with him, was aware of a feeling of awkwardness and a consequent sense of annoyance. His broad back was turned to her—if not wholly, certainly sufficiently to suggest a lack of deference, a lack, almost, of consciousness of her presence.

A minute or two passed. She hoped that her polite little partner would quickly return to take her back to the ballroom, in which the music had again begun. She felt stupid and curiously tongue-tied. She wanted to make some remark, if only as a reminder to him of his manners.

The remark which at length she made, however, was foolish, and unworthy of her: she knew this before the words had passed her lips. “You seem to find the garden very interesting,” she said.

He turned round slowly, a whimsical smile upon his face. “Very,” he answered; and then, after an embarrassing pause, “I haven’t seen any roses for six months: I’m revelling in them.”

“Do you live in the desert?” she asked.

“Yes, most of my time. It’s a fine free life.”

“Oh, one can be free anywhere,” she replied. She felt an indefinable desire to be contrary.

“Nonsense!” he answered, abruptly. “You don’t call yourself free, do you, in those diamonds and those absurd shoes?”

He turned again to the garden and breathed in the scent of the roses, with head thrown back. To Lady Muriel’s joy Rupert Helsingham returned at this moment, followed by a footman.

“Lord Blair will see you at once,” he said.

The girl gave a sigh of relief which she hoped Mr. Lane would observe; but in this she was disappointed, for, with a nod to her partner and a good-natured bow to herself, he strode away.

“A very odd fellow,” remarked Helsingham, when they were alone once more. “His manners are atrocious; but what can one expect from a man who spends his life in the desert?”

“What makes him live there?” she asked.

He shrugged his shoulders. “Being a crank, I suppose. He’s studying Bedouin manners and customs, or something. He’s a great Arabic scholar.”

“He made me feel rather uncomfortable,” she said, as she rose from her chair and laid her fingers on her partner’s arm.

“Yes, he’s boorish,” he replied, smoothing his sleek, dark hair with his disengaged hand.

“It isn’t that, quite,” she corrected him, her eyebrows puckering. “But he made me feel that I was of no importance whatsoever, and, being a woman, I resented it. He brushed me aside, like the sentry.”

“He was probably shy,” her companion suggested, for conciliation was his métier. “And of course he must have been tired after that long ride.”

“No,” she said, as they entered the ballroom, “I don’t think he was in the least bit shy; and, as for being tired, could anything make a man of that kind tired? He looks like a Hercules, or a Samson, or something unconquerable of that sort.”

Rupert Helsingham glanced quickly at her. There was a tone in her voice which suggested that their visitor’s personality had at once imposed itself on her mind. Women, he understood, were often attracted by masculine strength and brutality. He had known cases where an assumption of prehistoric manners had been eminently successful in the seduction of the weaker sex, painfully more successful, indeed, than had been his own well-bred dalliance with romance.

A school-friend had told him once that no girl could resist the man who took her by the throat, or pulled back her head by the hair, or, better still, who picked her up in his arms and bit her in the neck. He wondered whether Lady Muriel was heavy, and, with a sort of timorous audacity, he asked himself whether she would be likely to enjoy being bitten. He would have to be careful of Daniel Lane: he did not want any rivals.

She led him across to the three elderly ladies. He was her partner also for the present dance; but Muriel, throwing herself into a chair beside Lady Smith-Evered, told him that she would prefer not to take the floor. He glanced at the forbidding aspect of the three, and admired what he presumed to be her self-sacrifice in the interests of diplomacy.

“Rupert, my dear,” said the General’s wife, “do be an angel and bring us some ices.”

“What a willing little fellow he is,” murmured Mrs. Froscombe, as he hurried away on his errand, and there was a tone of derision in her voice.

“He’s always very helpful,” Lady Smith-Evered retorted, somewhat sharply, for he was her pet.

“I think he’s a dear,” said Muriel. “Nice manners are a tremendous asset. I hate churlishness.”

“I think you seldom meet with churlishness in Englishmen,” remarked Madam Pappadoulopolos. Her husband had told her to flatter the English whenever she could.

Muriel laughed. “I don’t know so much about that,” she replied. “On the veranda just now I met an Englishman who, to say the least, was not exactly courteous.”

“Oh, who was that?” asked her chaperone, with interest.

“A certain Daniel Lane,” she replied.

Lady Smith-Evered gave a gesture of impatience. “Oh, that man!” she exclaimed. “He’s in Cairo again, is he? He’s an absolute outsider.”

“What is he?—What’s he do?” Muriel asked, desiring further particulars.

“Ah! That’s the mystery,” said Lady Smith-Evered, with a look of profound knowing. “Incidentally, my dear, he is said to keep a harîm of Bedouin women somewhere out in the desert. I shouldn’t be surprised if every night he beat them all soundly and sent them where the rhyme says.”

She laughed nastily, and Muriel made a grimace.

CHAPTER II—THE FREEDOM OF THE DESERT

Lord Blair rose from his chair as the door opened, and removed from his thin, furtive nose a pair of large horn-rimmed spectacles which he always wore when quite alone in his study.

“Come in, come in, my dear Mr. Lane,” he exclaimed, taking a few blithe steps forward and shaking his visitor warmly by the hand. “I’m very well, thank you, very well indeed, and so are you, I see. That’s right, that’s good,—splendid! Dear me, what physique! What a picture of health! How did you get here so quickly?—do take a seat, do be seated. Yes, yes, to be sure! Have a cigar? Now, where did I put my cigars?”

He pushed a leather arm-chair around, so that it faced his own desk chair, and began at once to hunt for his cigar-box, lifting and replacing stacks of papers and books, glancing rapidly, like some sort of rodent, around the room, and then again searching under his papers.

“Thanks,” said Daniel Lane, “I’ll smoke my pipe, if it won’t make you sick.”

“Tut, tut!” Lord Blair laughed, extending his delicate hands in a comprehensive gesture. “I sometimes smoke a pipe myself: I enjoy it. A good, honest, English smoke! Dear me, where are my cigars?”

Lord Blair was a little man of somewhat remarkable appearance—remarkable, that is to say, when considered in relation to his historic name and excellent diplomatic record. In a company of elderly club waiters he would, on superficial observation, have passed unnoticed. He bore very little resemblance to his daughter; and, in fact, he was often disposed to believe his late wife’s declaration, made whenever she desired to taunt him, that Muriel was no child of his. Lady Blair had had many lovers; and it is notorious that twenty odd years ago in Mayfair there was an exceptionally violent epidemic of adultery.

He himself had thin auburn hair, now nearly grey, neatly parted in the middle; nervous, quick-moving brown eyes; closely cut ‘mutton-chop’ whiskers; an otherwise clean-shaven, sharp-featured face; and a wide mouth, furnished with two somewhat apparent rows of false teeth. His smile was kindly and gracious, and his expression, in spite of a certain vigilance, mild.

The evening dress which he was now wearing was noteworthy in four particulars: his collar was so big for him that one might suppose that, in moments of danger, his head totally disappeared into it; his bow-tie was exceptionally wide and large; his links and studs were, as such things go, enormous; and the legs of his trousers were cut so tightly as to be bordering on the comic. In other respects there was nothing striking in his appearance, except, perhaps, a general cleanliness, almost a fastidiousness, especially to be noticed in the polished surface of his chin and jaw, and in his carefully manicured finger-nails.

Daniel Lane pulled out his pipe and began to fill it from a worn old pouch. “Please don’t bother about cigars,” he said, as Lord Blair extended his hand towards the bell. “Tell me why you sent for me. Your letter was brought over from El Homra by a nigger corporal of your precious frontier-patrol, who nearly lamed his camel in trying to do the thirty miles in under four hours. My Bedouin friends thought at the very least that the King of England was dying and wished to give me his blessing.”

“Dear, dear!—it was not so urgent as all that,” his Lordship replied. “I told them to mark the letter ”Express,“ but I trust, I do trust, the message itself was not peremptory.”

“Not at all,” the other replied. “I was mighty glad of an excuse to come into Cairo; I wanted to do some shopping; and there was another reason also. A young cousin of mine—in the Guards—has come to Cairo, with his regiment, and I ought to see him about some family business. I should probably have let it slide if you hadn’t sent for me. Tell me, what’s your trouble?”

“Ah, that’s the point!—you always come to the point quickly. It’s capital, capital!” Lord Blair leaned forward and tapped his friend’s knee with a sort of affection. “I don’t know where I should be without your advice, Mr. Lane—Daniel: may I call you Daniel?”

“Sure,” said Daniel, laconically.

“When I came here two years ago, my predecessor said to me ‘When in doubt, send for Daniel Lane.’ Do you remember how worried, indeed how shaken—yes, I may say shaken—I was by the Michael Pasha affair? How you laughed! Dear me, you were positively rude to me; and how right you were! Personally I should have had him deported: it never occurred to me to convert him into a friend.”

His visitor smiled. “ ‘Bind a brave enemy with the chains of absolution,’ ” he said.

“Yes, yes, very true,” replied Lord Blair, still hunting about for the cigars. “Very true, very daring: a policy for brave men.” He started into rigidity, as though at a sudden thought: one might have supposed that he had recollected where he had put the cigars. “Daniel!” he exclaimed, “you bring with you an air of the mediæval! That’s it! One always forgets that Egypt is mediæval.”

Daniel blew a cloud of oriental tobacco-smoke through his nostrils, at which his host frenziedly renewed his search for the less pungent cigars. “About this business you want to ask my advice upon ...?” he asked.

“Ah yes, you must be tired,” his Lordship murmured. “You want to go to bed after your long ride. Let me put you up here. I’ll ring and have a room prepared.”

“No thanks,” said Daniel, firmly. “I’ve left my kit at the Orient Hotel. But fire away, and I’ll give you my opinion either at once or in the morning.”

Lord Blair laid his thin fingers upon a document, and handed it to his friend. “Read that,” he said, and therewith leaned back in his chair, his dark eyes glancing anxiously about the room.

The document was written in Arabic, and beneath the flowing script a secretary had pencilled an English translation. “The translation is appended,” remarked his Lordship, as Daniel bent forward to study the paper in the light of the electric reading-lamp.

“I prefer the original,” he replied, with a smile, “I don’t trust translations: they lose the spirit.”

For some considerable time there was silence. Suddenly Lord Blair rose from his chair, and hurried across to a cupboard, from which he returned bearing in triumph the missing cigars. He proffered them to his visitor, who, without raising his eyes, took one, smelt it, and put it in his breast pocket.

At length, through a cloud of smoke, Daniel looked up. “The man’s a fool,” he said, and laid the paper back upon the table.

“You think I ought to refuse?” asked Lord Blair.

“No, procrastinate. That’s the basis of diplomacy, isn’t it?”

The document in question was a request made by the Egyptian Minister of War that the nomadic Bedouin tribes of the desert should be brought under the Conscription Act, from which, until now, they had been exempt.

“I ventured to ask you to come in,” said his Lordship, “because I am sure, indeed I know, you have the interests of these rascals at heart. I thought you would wish to be consulted; and at the same time I felt that you would be able to tell me just what the consequences would be of any action of this kind.”

Daniel nodded. “Yes, I can tell you the consequences,” he answered. “If you conscribe them, they will evade the law by all possible means, and you will turn honest men into law-breakers.”

“But, as you see, he suggests that it will bring the benefits of discipline into their lives,” Lord Blair argued. “And if some of them escape across the frontiers into Arabia or Tripoli, it will be, surely it will be, no great loss to Egypt.”

Daniel spread out his hands. “What is military discipline?” he asked. “Good Lord!—d’you think the Bedouin will be better men for having learnt to form fours and present arms? Will barrack life in dirty cities bring them some mystic benefit which they have missed in the open spaces of the clean desert? Don’t you realize that it is just their freedom from the taint of what we call civilization that gives them their particular good qualities? Why is it that the man of the desert is faithful and honourable and truthful? Because time and money and power and ambition and success and cunning are nothing to him. Because he is not herded with other men.”

He leant forward earnestly. “Lord Blair,” he said, and his voice was grave, “hasn’t the thought ever come to you that we civilized people, with our rules and regulations, our etiquette and our conventions, have built up a structure which screens us from the face of the sun?”

“Ah, yes, indeed, my dear Daniel,” he replied. “Back to the land: the simple life: Fresh Air Fund—a capital sentiment. But, you know, I am very anxious, most anxious, not to offend this particular minister—most anxious.”

His visitor relapsed into silence, and the volume of smoke which issued from his mouth was some indication that he had much to say which he preferred to leave unsaid.

At length he took the pipe from between his teeth. “You had better fix your frontiers first,” he declared. “There’ll be a fine old row if Egyptian patrols blunder into foreign territory. There’s your chance for procrastination. Send out a commission to settle the desert frontiers definitely. That’ll keep you all wrangling comfortably for five years.”

“Ah!—that is an idea, a very good idea,” replied Lord Blair, bringing the tips of the fingers of one hand against those of the other sharply and repeatedly.

“Write to the minister,” Daniel went on, “and tell him you don’t altogether agree with him, but that you will consent to the preliminary step of fixing the frontiers. Before that’s accomplished you may both be dead.”

“I trust not, I trust not,” murmured Lord Blair.

“Or retired,” said his friend; and his Lordship nodded his thanks for the correction.

It was not long before Daniel rose to take his departure. “Oh, by the way,” he said, with a broad smile, “I have one little favor to ask you....”

“Certainly, certainly,” responded Lord Blair warmly. “Anything I can do, I’m sure—anything. You have put me under a great obligation by coming so promptly to my aid in this matter.”

“Well, will you be so good as to walk as far as your front gate with me? There’s something I want to show you.”

Lord Blair, somewhat mystified, accompanied him on to the veranda; and here they chanced upon Lady Muriel again taking the air with Rupert Helsingham who was once more her partner. The couple were strolling towards them as they came out of the house.

Daniel made for the steps. “What I want you to see is over here,” he said, pointing to the gateway.

“One moment,” Lord Blair interjected, taking hold of his arm. “I want to introduce you to my daughter.”

He called Muriel to him, who replied somewhat coldly that she had already met Mr. Lane.

“Really?” exclaimed his Lordship. “Splendid, capital!”

“Yes,” said Daniel, taking his pipe out of his mouth, “when she was quite a kid; but I’m blest if I know where it was.”

He was standing again almost with his back to Muriel, his pipe between his teeth, and once more a sense of annoyance entered her mind. She would have liked to pinch him, but for all she knew he might turn round and fling her into the middle of the drive. She racked her brains for something to say, something which would show him that she was not to be ignored in this fashion.

“Ah,” she exclaimed suddenly, “now I remember. It was in the Highlands that we met. You came over to tea with us: I was staying with my cousin the Duchess of Strathness.”

Daniel scratched his head. “I’m so bad at names,” he said. “What’s she like?”

Lord Blair uttered a sudden guffaw, but Muriel did not treat the matter so lightly. A man with gentlemanly instincts, she thought to herself, would at any rate pretend he remembered.

“Oh, why bother to think it out?” she answered, her foot ominously tapping the floor. “It’s of no consequence.”

“None,” Daniel replied, looking at her with his steady laughing eyes. “You’re still you, and I’m still I.... But I did like your pigtails.”

Muriel turned to her partner, who stood anxiously fiddling with his eyeglass. “Come along,” she said; “let’s go back. The music’s begun again.”

She nodded with decided coolness to Daniel, and turned away. He gazed after her in silence for a moment; then he put his hand on her father’s arm, and gently propelled him towards the gates.

As they walked down the drive in the moonlight, the sentry peered at them through the iron bars, and, recognizing Lord Blair, suddenly presented arms, becoming thereat a very passable imitation of a waxwork figure.

Lord Blair put his arm in Daniel’s. “What is it you wanted to show me?” he asked, as they passed through the gate and stood upon the pavement outside.

“A good soldier,” said Daniel, indicating the sentry, whose face assumed an expression of mingled anxiety and astonishment. “I wanted to call your attention to this lad. Do you think you could put in a word for him to his colonel? I was very much struck this evening with the way in which he dealt with a ruffianly tramp who apparently wanted to get into the grounds. He showed great self-restraint combined with determination and devotion to duty.” There was not the trace of a smile upon his face.

Lord Blair turned to the rigid Scotchman, whose mouth had fallen open. “What’s your name, my man?” he asked.

“John Macdonald, me Lord,” he answered unsteadily.

“Now, will you make a note of it?” said Daniel. “And if you get a chance, recommend him for his soldierly conduct. Or, better still, send him a little present as a mark of your regard.”

“Certainly, certainly,” replied Lord Blair, still somewhat puzzled.

“Thanks, that’s all,” said Daniel. “Good-night.”

“Will you come to luncheon tomorrow?” Lord Blair asked, as they shook hands. “I will then show you the draft of my reply to the Minister of War.”

“Thank you,” Daniel answered, knocking the ashes from his pipe. “I’ll be delighted, if it isn’t a party. I haven’t got any respectable clothes with me.”

“Tut, tut!” murmured his Lordship. “Come in anything you like.” And with that he patted his friend on the arm, and hastened with little tripping steps back to the house.

Daniel put his hands in his pockets and faced the sentry, who was once more standing at ease. “John Macdonald,” he said, “is the account square?”

The Scotchman looked at him with a twinkle in his eye. “Ye mus’ na’ speak tae th’ sentry on duty,” he answered.

Daniel uttered a chuckle, and walked off across the square.

CHAPTER III—THE WORLD AND THE FLESH

When a man, in the heyday of his manhood, voluntarily lives the life of a monk or hermit, his friends suppose him to be either religious, defective, or possessed of a secret mistress. Now, nobody supposed Daniel Lane to be religious, for he seldom put his foot inside a church: and people seem to be agreed that religion is, as it were, black kid gloves, handed out with the hymnbooks and, like them, “not to be taken away.” Nor did anybody think him abnormal, for a figure more sane, more healthy, or more robust in its unqualified manhood, could not easily be conjured before the imagination.

Hence the rumour had arisen in Cairo that the daughters of the Bedouin were not strangers to him; but actually, like most rumours, this was entirely incorrect. He did, in very truth, live the life of a celibate in his desert home; and if this manner of existence chanced to be in accord with his ideas of bachelorhood, it was certainly in conformity with the nature of his surroundings. Some men are not attracted by a diet of onions, or by a skin-polish of castor oil.

When he had been commissioned by a well-known scientific institute to make a thorough study of the manners, customs, and folk-lore of the Bedouin tribes of the Egyptian desert, he had entered upon his task in the manner of one dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge; and he found in the life he was called upon to lead the opportunity for the practice of those precepts of the philosophers which, in spite of his impulsive nature, had ever appealed to him in principle during the course of his wide reading.

Almost unwittingly he had cultivated the infinite joys of a mind free from care, free from the desires of the flesh; and, with no apparent, or, at any rate, no great effort, he had established in himself a condition of undisturbed equanimity, by virtue of which he could smile benevolently at the frantic efforts of his fellow men and women to make life amusing. To him his existence in the desert was a continuous pleasure, for the great secret of human life had been revealed to him—that a mind at peace in itself is happiness.

But here in Cairo circumstances were different; and as he walked from the Residency through the moonlit streets to the Orient Hotel his thoughts were by no means tranquil. He did not feel any very noticeable fatigue after his long ride; for a series of recent expeditions through the desert had hardened him to such a point that the hundred and fifty miles which he had covered in the last three days had in no way strained his always astonishing physical resources. His senses were alert and active, and, indeed, were near to a riotous invasion of the placid palace of his mind, where his soul was wont to sit enthroned above the clamour of his mighty body.

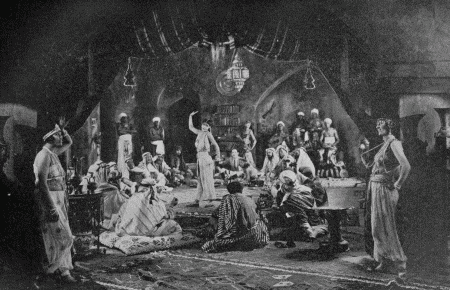

He took the road which led him past the Semiramis Hotel, and through its brilliantly illuminated windows he could see the richly dressed throng of visitors, and could hear the strains of the orchestra which was playing selections from a popular musical comedy. He turned his head away, and gazed across the Nile which lay on his other hand; but here too the lights of the gay city glittered and were reflected in the water, while from a dahabiyah moored against the opposite bank there came the sound of tambourines and the rhythmic beating of the feet of native dancers.

In the main streets of the city the light of the lamps seemed strangely bright to his unaccustomed eyes; and the great square in front of the Orient Hotel presented an animated scene. Crowds of people were here streaming out of the Opera House, and carriages and automobiles were moving in all directions. The trees of the Esbekieh gardens were illuminated by the neighbouring arc lamps, and rich clusters of exotic flowers hung down towards the dazzling globes. The cafés on the other side of the square were crowded, and hundreds of small tables, standing in the open, were occupied by the native and continental inhabitants of the city. The murmur of many voices and the continuous rattle of dice upon the marble table-tops could be heard above the many sounds of the traffic; and somewhere a Neapolitan orchestra was playing a lilting tune.

The terrace and façade of the hotel were illuminated by numerous rows of small electric globes, and as Daniel ascended the steps to the brilliantly lighted main entrance he was met by a throng of men and women in evening dress pouring out on to the terrace. Evidently the weekly ball was in progress, and the couples were emerging into the cool night air to rest for a few brief moments from their exertions.

For some time he wandered about the hotel, furtively watching the dancers; but in his rough clothes he did not feel quite at his ease, and he was conscious that many pairs of eyes looked at him from time to time with wonder, while those of the hall-porter and the waiters, so he thought, expressed frank disapproval, if not disgust. He had no wish, however, to retire to his room; for the music of the orchestra would undoubtedly prevent sleep for yet some time to come. Moreover, he felt excited and disturbed by the brilliant scenes around him; and the seclusion of his desert home seemed very far away.

At length he found a seat upon a sofa at the end of a passage near the American Bar, where, except during the intervals between the dances, he was more or less alone; and here he settled himself down to enjoy the cigar which he had pocketed at the Residency. He wanted to be quiet; his mind was disturbed by his sudden incursion into the world, and he was aware of a number of emotions which he had not experienced for many months.

Suddenly the swinging doors of the Bar were burst open and a red-headed young man, muffled in an overcoat, sprang through and darted down the passage. He was clutching at a lady’s gold bag; and for a moment Daniel supposed him to be a thief. An instant later, however, he was followed by a girl, wearing an evening cloak and a large black hat, who called after him in broken English, telling him to behave himself. At this the man paused, tossed the bag to her, and, with a wave of his hand, disappeared round the corner.

The bag fell at Daniel’s feet. He therefore stooped down, and, picking it up, returned it to her.

“A silly boy—that one,” she smiled. “He like always the rag.”

“I nearly shot him for a thief,” said Daniel, placing his hand significantly upon his hip-pocket, where he still carried the revolver which had accompanied him on his journey.

The girl fixed her large dark eyes upon him in amazement. “Mais non!” she exclaimed. “He has the red hair: he like joking and running about.”

She sat herself down beside him, and made a pretence to touch his hip-pocket.

“Why you carry a pistol?” she asked.

Daniel looked at her with mild amusement. Her profession was evident, but it did not shock him.

“Because I’m a wild man,” he answered, with a smile.

“You not live in Cairo?” she queried.

“No fear!” he replied.

There was silence for some moments, while Daniel, smoking his cigar, endeavoured to ignore her existence. Once or twice she looked expectantly at him: it was evident that she could not quite classify him. Then she rose to her feet, and, with a little friendly nod to him, walked towards the swinging doors.

Daniel suddenly felt lonely, felt that he would like to have somebody to talk to, felt that he could keep any situation within bounds, felt that he did not much mind whether he could do so or not. He took the cigar out of his mouth, forming an instant resolution: “Hi!” he called out.

She turned round. “Why you call me ‘Hi’?” she asked. “I’m Lizette.”

“I beg your pardon,” he answered, gravely. “Will you have supper with me, Lizette?”

“Have you got enough money?” she asked.

“Plenty,” he laughed. “Shall we have supper here?”

She shook her head, “Oh, no,” she replied frankly. “The Manager not like me, because I’m not good girl. Everybody know Lizette—very bad, very wicked girl. Everybody are shocked for Lizette.”

“I’m not shocked,” said Daniel. “I like your face. You look truthful.”

He got up, and followed her into the bar, and, crossing it, made for the street-entrance.

“You give me supper at Berto’s?” she said, putting her hand lightly upon his arm, and looking up at him, as they stood upon the pavement outside.

“Anywhere you like,” he answered; and thus it came about that a few minutes later he found himself seated before her at a small table in a quiet restaurant. She was decidedly attractive. Her grey eyes were tender and sympathetic; the expression of her mouth was kindly; and her dark hair, which was drawn down over her ears, was soft and alluring. She was wearing a low-necked black-velvet dress, and her slender throat and shoulders by contrast seemed to be very white.

Her broken English, however, was her chiefest charm; and Daniel listened with pleasure as she talked away, candidly answering his somewhat direct questions in regard to her early life and adventures. She hailed originally, she told him, from Marseilles; but when her widowed mother had died she had found herself at the age of seventeen, alone and penniless. She had got into bad company, and at length had been advised by a well-meaning young British guardsman, on his way to Egypt, to ply her trade in Cairo. Here she had become a great favourite with his particular battalion, and in fact, was so monopolized by them that when she was seen in the company of a civilian her action was said to be “by kind permission of the Colonel and officers” of the regiment in question.

“Good Lord, what a life!” said Daniel.

“But what else can a girl do,” she asked, “after the little first mistake, eh? I get plenty good food; I not work eight hours, ten hours, every day to get thirty francs the week; I not live in the little top one room and cry: no, I have the beautiful appartements au premier étage, and I laugh always—plenty friends, plenty dresses, plenty sun.”

At a table at the other side of the room, Daniel had noticed, while she was talking, a heavy-jowled, red-faced young officer who was seated alone, and whose sullen eyes appeared to be fixed upon him. The girl’s back was turned to this man; but presently she observed that her companion was not paying attention to her remarks, and, wondering what had attracted his attention, she looked behind her. Immediately she uttered a little angry exclamation, and made an impatient shrug with her shoulders.

“That is a beast,” she said.

“He’s drunk, I think,” Daniel remarked. “Is he a friend of yours?”

She made a gesture of denial. “He hate me because I not let him come home with me ever.”

“Why not?” he asked.

“Because he very cruel pig-man. He beat his dog. I see him beat his dog.”

They rose presently to leave the restaurant, and as they did so the objectionable officer floundered unsteadily to his feet, and placed himself across the doorway. As in the case of most men of gigantic physical strength, Daniel’s nature was gentle, and wanting in all bellicose tendencies; and, moreover, he had already once that evening used his muscles in a manner which did not conform to his principles. He therefore made an attempt to take no notice of the obstruction; but finding the way entirely barred, he was obliged to request the man to stand aside. The officer, however, stood his ground stolidly.

Daniel raised his voice very slightly. “Will you kindly get out of the way,” he said.

For answer the man shot out his hand, and made an ineffectual grab at the girl’s arm. She darted aside, and by a quick manœuvre slipped out through the glass doorway, standing thereafter in the entrance passage, watching the two men with an expression of anger in her alert eyes.

It was now Daniel’s turn to bar the way, whereat his opponent thrust his red face forward and uttered a string of oaths, his fists clenched.

“I don’t stand any nonsense from a damned civilian,” he roared. “Let me pass, or I’ll put my fist through your face.”

Suddenly Daniel’s self-control for the second time deserted him. He blushed with shame for his countryman; he burnt with indignation at the arrogance of this product of a militaristic age; he felt like an exasperated schoolmaster dealing with a bully. With a quick movement he gripped the man’s raised arm, and seizing with his other hand the collar of his tunic, shook him so that his head was bumped violently against the wall behind him.

“I don’t believe in violence,” he said, shaking him till the teeth rattled in his head, “or I’d really hurt you. I don’t believe in it.”

In his tremendous grip the wretched man was, in spite of his bulk, as entirely powerless as the sentry at the Residency had been. His eyes grew round and frightened: he had never before come up against strength such as Daniel possessed.

“Let me go,” he gasped.

“Shut your mouth, or you’ll bite your tongue,” said Daniel, a grim smile upon his face, as he administered another shattering shake. Then with a contemptuous movement he flung him backwards, so that he fell to the floor at the feet of an amazed waiter who had hurried across the room.

Daniel turned upon his heel, and, taking the girl’s arm, conducted her out of the building. She appeared to be too enthralled by the discomfiture of her enemy to utter a word.

An empty taxi-cab was passing, and this he hailed.

“Where d’you want to go to?” he asked.

She gave him her address. “You are coming home with me?” she asked. “Please do.” Her expression was eloquent.

“I’ll drive you as far as your door,” he replied.

“But...?” There was a question in her eyes.

He sat himself down beside her, and she put her arm in his, looking up into his face with admiration.

“I never see a one so strong,” she whispered, with a kind of awe. “I think you very great man, very to be loved.”

Daniel laughed ironically, “Oh, yes, of course you’re filled with admiration because you’ve seen me handle a poor drunken fellow-creature roughly. My girl, that is not the thing for which you should admire a man. I’m ashamed of myself.”

“Ashamed?” she exclaimed, incredulously.

“Yes,” he answered, shortly. “D’you think I’m proud that I can master any man in a fair fight? What I want to be able to do is to master myself!”

There was silence between them, but he was aware that she did not take her eyes from him. At length he turned and looked at her and, seeing the admiration in her face, laughed aloud.

“Why you laugh?” she asked.

“I’m laughing at you women,” he answered. “How you love a little show of muscle! Good God, we might be living in the year one!”

“I not understand,” she said.

“No, I don’t suppose you do,” he answered. “But here we are: is this where you live?”

They had stopped before some large buildings in the vicinity of the main station. She nodded her head.

“Please don’t go away,” she said.

“No,” he answered. “I’ve had enough of the world, the flesh, and the devil for one day. I guess we’ll meet again some time or other. Good night, my girl; and thank you for your company.”

She held her hand in his. “Thank you,” she said, “for fighting that pig-man, Barthampton.”

“Barthampton? Lord Barthampton?” he repeated. “Was that the man?”

She nodded. “Why?” she asked, as he uttered a low whistle.

“Gee!” he laughed. “He’s my own cousin.”

CHAPTER IV—A JACKAL IN A VILLAGE

Tired after the dance, Lady Muriel stayed upstairs next day until the luncheon hour. The long windows of her room led out on to a balcony which, being on the west side of the house, remained in the shade for most of the morning; and here in a comfortable basket chair, she lay back idly glancing at the week-old magazines and illustrated papers which the mail had just brought from England. While the sun was not yet high in the heavens the shadow cast by the house was broad enough to mitigate to the eyes the glare of the Egyptian day; and every now and then she laid down her literature to gaze at the brilliant scene before her.

The grounds of the Residency, with the rare flowering trees and imported varieties of palm, the masses of variegated flowers and the fresh-sown lawns of vivid grass, looked like well-kept Botanical Gardens, and appealed more to her cultivated tastes than to the original emotions of her nature. It was all very elegant and civilized and pleasing, and seemed correspondent to the charming new garment—all silk and lace and ribbons—which she was wearing, and to the fashionable literature which she was reading. She, the balcony, the garden, and the deep blue sky might have been a picture on the cover of a society journal.

But when she raised her eyes, and looked over the Nile, which flowed past the white terrace at the bottom of the lawn, and allowed her gaze to rest upon the long line of the distant desert on the opposite bank, the aspect of things, outward and inward, was altered; and momentarily she felt the play of disused or wholly novel sensations lightly touching upon her heart.

So far she was delighted with her experience of Egypt. She enjoyed the heat; she was charmed by the somewhat luxurious life at the Residency; and the deference paid to her as the Great Man’s daughter amused and pleased her. At the dance the previous night she had met half a dozen very possible young officers; and the secretaries whom she saw every day were pleasant enough, little Rupert Helsingham being quite amusing. That afternoon she was going to ride with him, which would be jolly....

There was, however, one small and almost insignificant source of unease in her mind, one little blot upon the enjoyment of the last two or three days. A ruffianly fellow had treated her in a manner bordering on rudeness, and in his presence she had felt stupid. He had shown at first complete indifference to her, and later he had spoken with a sort of easy familiarity which suggested a long experience in dealing with her sex, but no ability to discriminate between the bondwoman and the free. And she had behaved as a bondwoman.

The recollection caused her now to tap her foot angrily upon the tiled floor, and to draw the delicate line of her eyebrows into a puckered frown. The thought which lay at the root of her discomfort was this: she had pretended that their previous meeting had been at the house of the Duchess of Strathness simply because she had been lashed into a desire to assert her own standing in response to his lack of respect. The Duchess was her most exalted relative: she was a Royal Princess who had married the Duke, and the Duke was cousin to her mother. She knew quite well that she had not met Mr. Lane there: she had uttered the words before her nicer instincts had had time to prevail.

She had said it in self-defence—to make an impression; and his reply, whether he had meant it as a snub or not, had stung her. “I’m so bad at names: what’s she like?” Her Royal Highness Princess Augusta Maria, Duchess of Strathness! Of course it was a snub; and she had deserved it. He couldn’t have made a more shattering reply: he couldn’t have said more plainly to her “Now, no airs with me, please!—to me you are just you.”

The recollection of the incident was unpleasant; it made her feel small. She had behaved no better than the servants and shopkeepers who delight to speak in familiar terms of duchesses and dukes. However!... she did not suppose that she would see the man again: he belonged to the desert, not to Cairo; and with this consolation, she dismissed the matter from her mind.

When at last she descended the stairs at the sound of the gong, she came upon General Smith-Evered, who had called to see Lord Blair upon some matter of business, and was just stumping across the hall on his way out. He was a very martial little man. He greeted her with jocularity tempered by deference; he kissed her hand in what he believed to be a very charming old-world manner; he told her what a radiant vision she made as she walked down the great staircase in her pretty summer dress; he described himself as a bluff old soldier fairly bowled over by her youthful grace; and he slapped his leggings with his cane and gloves and kissed his fingers to England, home and beauty.

Muriel knew the type well—in real life, on the stage, and in the comic papers; nevertheless, she felt pleased with the rotund compliments, and there was a pleasurable sense of well-being in her mind as she entered the drawing-room. Here the sun-blinds shaded the long French windows, and the light in the room was so subdued that she did not observe at once that she was not alone. She had paused to rearrange a vase of flowers which stood upon a small table, when a movement behind her caused her to turn; and she found herself face to face with Daniel Lane, who had just risen from the sofa.

“Good morning!” he said, gravely looking at her with his deep-set blue eyes.

Her heart sank: she felt like a schoolgirl in the presence of a master who had lately punished her. “Oh, good morning,” she answered, but she did not offer him her hand.

She turned again to the flowers. “Are you waiting to see my father?” she asked, as she aimlessly withdrew a rose from the bunch and inserted it again at another angle.

“I’ve come to lunch,” he said. “I’m early, I suppose. My watch is busted.”

Deeper sank her heart. “No, you’re not early,” she replied, “the gong’s gone.”

“Good!” he exclaimed; “then you haven’t got a party. I was shy about my clothes.”

He was wearing the same clothes in which she had seen him the night before, except that he appeared to have a clean collar and shirt, his hair was carefully combed back, and he had evidently visited a barber.

“Do sit down,” she said.

“Thanks,” he answered, and remained where he was, his hands deep in the pockets of his jacket, and his eyes fixed upon her.

There was an awkward pause, awkward, that is to say, to Muriel, who could not for the life of her think what to talk about.

“Will you smoke a cigarette?” she asked, handing him the box as a preliminary to an escape from the room.

He took it from her unthinkingly, and, without opening it, put it down upon a table.

“I’ve remembered where it was we met,” he remarked suddenly, as she moved towards the door.

“Really?” There was a note of assumed indifference in her voice; and, as she turned and came back to him, she made a desperate attempt to emulate the cucumber. She felt that there was a challenge in his words, in face of which she could not honourably run away.

“Yes,” he said. “It was at Eastbourne, at your school. I came down to see your head mistress, who was a friend of mine; and they let you come into the drawing-room to tea.”

A wave of recollection passed over her mind. “Of course,” she exclaimed, “that was it.”

They had let her, they had allowed her, to come into the drawing-room to have the honour of making his acquaintance! She paused: the scene of their meeting developed in her mind. A girl had rushed into the schoolroom where she was reading, and had told her that she and one or two others were to go into the drawing-room to make themselves polite to this man, who was described as a great scholar and explorer. She had gone in shyly, and had shaken hands with him, and he had stared at her and, later, had turned his back on her; and, after he had gone, the headmistress had commended her manners as having been quiet, ladylike, and respectful. Respectful!

He was smiling at her when she looked up at him once more. “You were wrong about it being at your cousin’s,” he said.

Muriel felt as though she had been smacked. “Oh, I only suggested that,” she replied, witheringly, “to help you out. I didn’t really suppose that you knew her.”

“I know very few people,” he answered, unmoved. “I can’t afford the time. Life is such a ‘brief candle’ that a man has to choose one of its two pleasures—sociability or study: he can’t enjoy both.”

She looked at him curiously. He must have a tough hide, she thought, to be unruffled by a remark so biting as that she had made. For a moment she stared straight at him, her hand resting on her hip. Then she caught sight of herself in the great mirror against the wall, and her hand slipped hastily from its resting-place: her attitude had been that of a common Spanish dancing-girl. Her eyes fell before his.

“I’ll go and find the others,” she said, and turned from him.

As she did so Lord Blair hurried into the room. He was wearing a hot-weather suit of some sort of drab-coloured silk, straight from the laundry, where, one might have supposed, the trousers had been accidentally shrunk. His stiff and spacious collar, and his expansive tie, folded in the four-in-hand manner and fastened with a large gold pin, detracted from the sense of coolness suggested by his suit; but a rose in his buttonhole gave a comfortable touch of nature to an otherwise artificial figure.

“Ah, good morning, Muriel dear,” he exclaimed, giving her cheek a friendly but quite unaffectionate kiss. “You’ve had a lazy morning, eh? Feel the heat, no doubt. Yes? No? Ah, that’s good, that’s capital! Good morning Mr. Lane, or Daniel, I should say, since you permit it. I hope Muriel has been amusing you.”

“She has,” said Daniel, and Muriel blushed.

Rupert Helsingham entered the room; and, when he had made his salutations, Muriel turned to him with relief, strolling with him across to the windows through which the warm scented air of the garden drifted, bringing with it the drone of the flies and the incessant rustle of the palms.

“Please see that I don’t sit next to that horrible man at lunch,” she whispered.

“There’s no choice,” he answered. “The four of us are alone today.”

“Shall we go in?” said Lord Blair, nodding vigorously to Muriel; and the three men followed her into the dining-room.

The meal proved to be less of an ordeal than she had expected. Their visitor talked at first almost exclusively to his host, who showed him, and discussed, the draft of his reply to the Minister of War; and Muriel made herself quite entrancing to Rupert Helsingham. Under ordinary circumstances she was, in spite of occasional lapses into bored silence, a quick and witty talker; one who speedily established a sympathetic connection with the person with whom she was conversing; and her laughter was frequent and infectious. It was only this Daniel Lane who had such a disturbing effect upon her equanimity; but here, at the opposite side of a large table, she seemed to be out of range of his influence, and she rejoiced in her unimpaired power to captivate the little Diplomatic secretary.

“I am going to call you Rupert at once,” she said to him; and, breaking in on the opposite conversation, “Father,” she demanded, “d’you mind if I call this man by his Christian name? Everybody seems to.”

Lord Blair laughed, holding out his hands in a gesture which indicated that he took no responsibility, and turned to Daniel. “Do you think I ought to let her?” he asked.

To Muriel his remark could hardly have been more unfortunate, and a momentary frown gathered upon her face.

“I think it’s a good idea,” replied Daniel, looking quietly at her. “Then if you quarrel you can revert to ‘Mr. Helsingham’ with telling effect.”

Muriel made a slight movement, not far removed from a toss of her head, and, without giving any reply, continued her conversation to Rupert.

The meal was nearly finished when she became aware that her friend was not paying full attention to her remarks, but was listening to Daniel Lane, whose tongue a glass of wine had loosened, and who was speaking in a low vibrating voice, describing some phases of his life in the desert. At this she, too, began to listen, at first with some irritation, but soon with genuine interest. She had supposed him to be more or less monosyllabic, and she was astonished at his command of languages.

As she fixed her eyes upon him he glanced at her for a moment, and there was a pause in his words. For the first time he was conscious of a look of friendship in her face; and his heart responded to the expression. The pause was hardly noticeable, but to him it was as though something of importance had happened; and when he turned again to continue to address himself to his host, there was a warm impulse behind his words. Muriel thereafter made no further remark to Rupert; but leaning her elbow upon the table, and fingering some grapes, gave her undivided attention to the speaker.

“It’s always a matter of surprise to me,” he was saying, “that people don’t come out more often into the desert. You all sit here in this garden of Egypt, this little strip of fertile land on the banks of the Nile, and you look up at the great wall of the hills to east and west; but you don’t ever seem to think of climbing over and running away into the wonderful country beyond.”

Was it, he asked, that they were afraid of the roads that led nowhere-in-particular, and the tracks that wandered like meandering dreams? Why, those were the best kind of roads, because they merely took your feet wherever your heart suggested—to shady places where you could sprawl on the cool sand; or up to rocks where the sun beat on you and the invigorating wind blew on your face; or down to wells of good water where you could drink your fill and take your rest in the shade of the tamarisks; or along echoing valleys where there was always an interesting turning just ahead; or into the flat plains where the mirage receded before you.

“You soon grow desert-wise,” he said: “you can’t get lost; and at last the tracks will always bring you to some Abraham’s tent, and he’ll lift up his eyes and see you, and come running to you to bid you welcome. And there’s bread for you, and honey, and curds, and camel’s milk, and maybe venison; and tobacco; and quiet, courteous talk far into the night, under the stars; and perhaps a boy’s full-throated song.... I can’t think how you can live your crabbed life here in Cairo, when there’s all that vast liberty so near at hand.”

Muriel sipped her coffee, and listened, with a kind of excitement. His voice had some quality in it which seemed to arouse a response deep in the unfrequented places of her mind. It was as though she saw with her own eyes the scenes which he was describing. With him she ascended the bridlepath over the wall of the hills, and ran laughing down into the valleys beyond, the wind in her face and the sun at her back; with him she went sliding down the golden drifts of sand, or sprang from rock to rock along the course of forgotten torrents; and with him she sat at the camp fire and listened to the far-off cry of the little jackals.

He told of warm moonlight nights spent in the open, when the drowsy eye looks up at the Milky Way, and the mind drifts into sleep, rocked, as it were, in a cradle slung between the planets. He spoke of the first sweet vision of the opalescent dawn, when sleep ends in quiet wakefulness, without a middle period of stupor; and of the rising sun over the low horizon, when every pebble casts a liquid blue shadow and the shallowest footprints in the sand look like little pools of water.

He told of blazing days; of long journeys across hills and plains; of the drumming of the pads of the camels upon the hard tracks; of deep, shadowed gorges, and precipices touched only at the summit by the glare of the sun; of the endless waves of the sand drifts, their sharp ridges seen against the sky, like gold against blue enamel; of flaming sunsets, and mysterious dusks, when, by creeping over the top of a hillock, one might look down at ghostly gazelle drinking from a pool, and might listen to the sucking in of the water.

And more especially he spoke of the freedom of the desert. “Ah, there’s liberty for you!” he exclaimed, and his eyes seemed to be alight with his enthusiasm. “That’s the life for a man! There are no clocks out there, no miserable appointments to keep, no laying of foolish foundation stones, or inspecting of sweating troops, no diplomatic speeches, no wordy documents signifying nothing. Out there the men that you meet speak the truth openly, and do all that they have to do without cunning, and without fuss or frills. If you are wandering and hungry they give you shelter and feed you; if they like you they treat you as a brother; and when they wish to kill you they tell you so, and give you four-and-twenty hours in which to quit. They are free men, and to them all men have the status of the free; all partake, so to speak, of the liberty of the desert.”

He stopped rather abruptly: it was as though suddenly he had become conscious that he had engaged the attention of the company, and was abashed.

“You make me quite restless,” said Lord Blair, as they rose from the table. “Some day you will find me, even conservative me, setting out into that happy playground beyond the horizon. Aha! I grow lyrical, too!”

“I’ve stayed too long,” said Daniel. “I must say good-bye at once. I have a lot of shopping to do, and I told my men to meet me with the camels at five o’clock at Mena House.”

“What!—are you going back at once?” exclaimed Rupert Helsingham, adjusting his eyeglass.

“Yes, I’ve had enough of Cairo,” he laughed. “I feel like a fish out of water here, or rather, I feel like a jackal that has ventured into a village and must make tracks over the wall and away. I’ve stolen a square meal and I’m off again.”

He stood at the door smiling at them. He seemed now to radiate imperturbable and rather disconcerting happiness: it was as though he regarded life as a quiet, good-natured comedy, and the friends before him as participators in the fun. His talking about the desert had, as it were, softened his uncouthness, and had made him of a sudden surprisingly intelligible.

“I’m immensely obliged to you for coming,” said Lord Blair, warmly clasping his hand. “In fact I can’t tell you how highly I value your advice and friendship.”

Muriel held out her hand. She saw this man in a new light, and her hostility was temporarily checked. His words had aroused in her a number of perplexing sensations: it was like tasting a new fruit, in part sweet, in part bitter.

“I’ve enjoyed listening to you,” she said, frankly.

“I’ve enjoyed talking to you,” he replied, his voice sinking, but his eyes fixed powerfully upon her.

There was something dominating in his manner which again caused her to be perverse. “I thought you were talking to my father,” she answered casually.

“No,” he said, “I was speaking to you.”

CHAPTER V—FAMILY AFFAIRS

Daniel Lane left the Residency with curiously mixed feelings; and as he made his way through the sun-scorched streets, he found some difficulty in bringing his thoughts to bear upon the afternoon’s business. He felt that he had talked too much: it was almost as though he had faithlessly given away secrets that were sacred. Lord Blair and young Helsingham were hardly possessed of ears in which to repeat the confidences of the desert; and as for Lady Muriel, he was not in a position to say whether she had received his words with real understanding or not.

He had enjoyed his luncheon, and he was obliged to confess to himself that dainty dishes and a handsome table were by no means to be despised. On the other hand, he had been conscious of an artificiality, a sort of pose in much that was said or done at the Residency. His long absences from his countrymen had made him rather critical, and seemed now to reveal what might otherwise have passed undetected.

On the previous evening Muriel Blair had appeared to him—in her diamonds and frills and high-heeled shoes—to constitute as artificial a picture as could well be imagined; and he was disconcerted by the fact that nevertheless she had looked delightful. And today he had overheard fragments of her conversation with Rupert Helsingham, and had been alternately charmed and distressed by the manner in which they exhibited to one another their familiarity with all that was thought to represent modern culture and refinement of taste. It had seemed to be such empty wit; and yet the effect was often, as though by accident, quite close to the truth.

“Epstein is plain-spoken by implication”; ... “dear Augustus John! He’s a striking instance of the power of matter over mind”; ... “I always enjoy the Russian dancers: they are so stupid”; ... “the trouble with English Art is that it is so Scotch”; ... and so forth.

It was the wit of a certain section of London society, and it troubled him because it was restless and superficial; and he did not want to find an attractive girl, such as Muriel Blair, to be a kind of dragon-fly of a summer’s day. He would like to take her right out of her environment; and yet—oh, he could not be bothered with her!

With an effort he collected his thoughts, and, standing still at the street corner, studied his notebook and his watch. The first thing to be done was to go to find his cousin, to whom he had already sent a note saying that he would call upon him in the early afternoon, a time of day when at this season of the year most reasonable people remained within doors. He had long dreaded the visit to this unknown relative; and now after the tussle of the previous night, he felt keenly the awkwardness of the situation. However, the painful family duty could not be shirked, and the sooner it was over the better.

He turned off to his left, and walked quickly over to the barracks, which were not far distant; and at the gates he enquired his way to the officers’ quarters.

“Who d’you want to see, mate?” said a young corporal who sat in the shadow of the archway, picking his teeth.

Daniel told him.

“Oh, ’im!” chuckled the soldier. “Are you the man from Kodak’s? I ’eard him a-cursin’ and a-swearin’ this morning when ’e smashed ’is camera. Just ’ere, it was. ’E’ll give you ’Ell!—’e says the strap broke. It’s always somebody else’s fault with ’is Lordship.”

Daniel smiled. “A bit impatient like, is he?” he asked. He saw no point in explaining his identity.

“Impatient!” laughed the corporal. “Twice already ’e’s sent for the whole shop. You’ll catch it, mate, I warn yer!”

Daniel followed the direction indicated to him, and crossing the flaming compound, soon reached the entrance of his cousin’s rooms. Here a soldier-servant took in his name, and, quickly returning, ushered him through the inner doorway.

Lord Barthampton had risen from his chair, and was standing in what appeared to be interested expectation of the meeting with his unknown relation. His tunic was unfastened, and his collarless shirt was open at the neck, revealing a pink, hairy chest. His heavy red face was damp with perspiration, and it was evident that he was feeling the effects of a large luncheon. He had a big lighted cigar in his hand, and on a table beside him there were glasses, a decanter, and a syphon. The Sporting Times and Referee lay on the floor at his feet.

As Daniel appeared in the doorway his manner suddenly changed, and his bloodshot blue eyes opened wide under frowning eyebrows. He slowly replaced the cigar in his mouth and thrust his hands into his pockets.

“What d’you want?” he muttered.

“Well, Cousin Charles ...” said Daniel. He held out his hand, but Lord Barthampton made no responding movement.

“So you are Daniel, are you!” he ejaculated. “I might have guessed it. I’d heard that you were a sort of prize-fighting vagabond. What d’you want to see me for?”

“First of all,” the visitor replied, “to say I’m sorry about last night. I didn’t know till afterwards who you were.”