The Project Gutenberg EBook of Behind the Green Door, by Mildred A. Wirt This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Behind the Green Door Author: Mildred A. Wirt Release Date: December 7, 2010 [EBook #34592] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BEHIND THE GREEN DOOR *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Brenda Lewis and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By

MILDRED A. WIRT

Author of

MILDRED A. WIRT MYSTERY STORIES

TRAILER STORIES FOR GIRLS

Illustrated

CUPPLES AND LEON COMPANY

Publishers

NEW YORK

PENNY PARKER

MYSTERY STORIES

Large 12 mo. Cloth Illustrated

TALE OF THE WITCH DOLL

THE VANISHING HOUSEBOAT

DANGER AT THE DRAWBRIDGE

BEHIND THE GREEN DOOR

CLUE OF THE SILKEN LADDER

THE SECRET PACT

THE CLOCK STRIKES THIRTEEN

THE WISHING WELL

SABOTEURS ON THE RIVER

GHOST BEYOND THE GATE

HOOFBEATS ON THE TURNPIKE

VOICE FROM THE CAVE

GUILT OF THE BRASS THIEVES

SIGNAL IN THE DARK

WHISPERING WALLS

SWAMP ISLAND

THE CRY AT MIDNIGHT

COPYRIGHT, 1940, BY CUPPLES AND LEON CO.

Behind the Green Door

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

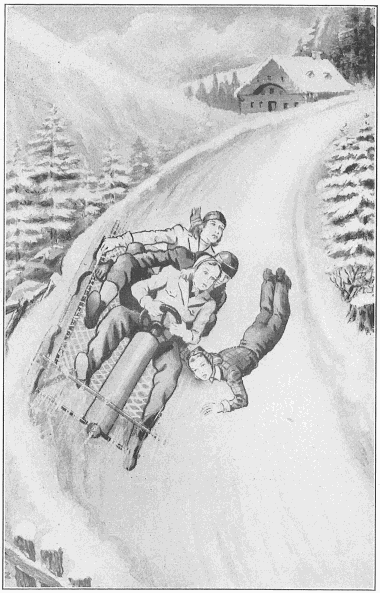

PENNY’S TRAILING BODY, ACTING AS A BRAKE, SLOWED DOWN THE SLED.

“Behind the Green Door” (See Page 124)

“Watch me coming down the mountain, Mrs. Weems! This one is a honey! An open christiana turn with no brakes dragging!”

Penny Parker, clad in a new black and red snowsuit, twisted her agile young body sideways, causing the small rug upon which she stood to skip across the polished floor of the living room. She wriggled her slim hips again, and it slipped in the opposite direction toward Mrs. Weems who was watching from the kitchen doorway.

“Coming down the mountain, my eye!” exclaimed the housekeeper, laughing despite herself. “You’ll be coming down on your head if you don’t stop those antics. I declare, you’ve acted like a crazy person ever since your father rashly agreed to take you to Pine Top for the skiing.”

“I have to break in my new suit and limber up my muscles somehow,” said Penny defensively. “One can’t practice outdoors when there’s no snow. Now watch this one, Mrs. Weems. It’s called a telemark.”

“You’ll reduce that rug to shreds before you’re through,” sighed the housekeeper. “Can’t you think of anything else to do?”

“Yes,” agreed Penny cheerfully, “but it wouldn’t be half as much fun. How do you like my suit?” She darted across the room to preen before the full length mirror.

A red-billed cap pulled at a jaunty angle over her blond curls, Penny made a striking figure in the well tailored suit of dark wool. Her eyes sparkled with the joy of youth and it was easy for her to smile. She was an only child, the daughter of Anthony Parker, editor and publisher of the Riverview Star, and her mother had died when she was very young.

“It looks like a good, practical suit,” conceded the housekeeper.

Penny made a wry face. “Is that the best you can say for it? Louise Sidell and I shopped all over Riverview to get the snappiest number out, and then you call it practical.”

“Oh, you know you look cute in it,” laughed Mrs. Weems. “So what’s the use of telling you?”

Before Penny could reply the telephone rang and the housekeeper went to answer it. She returned to the living room a moment later to say that Penny’s father was in need of free taxi service home from the office.

“Tell him I’ll be down after him in two shakes of a kitten’s tail!” Penny called, making for the stairway.

She took the steps two at a time and had climbed halfway out of the snowsuit by the time she reached the bedroom. A well aimed kick landed the garment on the bed, and then because it was very new and very choice she took time to straighten it out. Seizing a dress blindly from the closet, she wriggled into it and ran downstairs again.

“Some more skiing equipment may come while I’m gone,” she shouted to Mrs. Weems who was in the kitchen. “I bought a new pair of skis, a couple of poles, three different kinds of wax and a pair of red mittens.”

“Why didn’t you order the store sent out and be done with it?” responded the housekeeper dryly.

Penny pulled on her heavy coat and hurried to the garage where two cars stood side by side. One was a shining black sedan of the latest model, the other, a battered, unwashed vehicle whose reputation was as discouraging as its appearance. “Leaping Lena,” as Penny called her car, had an annoying habit of running up repair bills, and then repaying its long suffering owner by refusing to start on cold winter days.

“Lena, you get to stay in your cozy nest this time,” Penny remarked, climbing into her father’s sedan. “Dad can’t stand your rattle and bounce.”

The powerful engine started with a blast. While Mrs. Weems watched anxiously from the kitchen window, Penny shot the car out backwards, wheeling it around the curve of the driveway with speed and ease. She liked to handle her father’s automobile, and since he did not enjoy driving, she frequently called at the newspaper office to take him home.

The Star building occupied a block in the downtown section of Riverview. Penny parked the car beside the loading dock at the rear, and took an elevator to the editorial rooms. Nearly all of the desks were deserted at this late hour of the afternoon. But Jerry Livingston, one of the best reporters on the paper, was still pecking out copy on a noisy typewriter.

“Hi, Penny!” he observed, grinning as she brushed past his desk. “Have you caught any more witch dolls?”

“Not for the front page,” she flung back at him. “My newspaper career is likely to remain in a state of status quo for the next two weeks. Dad and I are heading for Pine Top to dazzle the natives with our particular brand of skiing. Don’t you envy us?”

“I certainly would, if you were going.”

“If!” exclaimed Penny indignantly. “Of course we’re going! We leave Thursday by plane. Dad needs a vacation and this time I know he won’t try to wiggle out of it at the last minute.”

“Well, I hope not,” replied Jerry in a skeptical voice. “Your father needs a good rest, Penny. But I have a sneaking notion you’re in for a disappointment again.”

“What makes you say that, Jerry? Dad promised me faithfully—”

“Sure, I know,” he nodded, “but there have been developments.”

“An important story?”

“No, it’s more serious than that. But you talk with him. I may have the wrong slant on the situation.”

Not without misgiving, Penny went on to her father’s private office and tapped on the door.

“Come in,” he called in a gruff voice, and as she entered, waved her into a chair. “You arrived a little sooner than I expected, Penny. Mind waiting a few minutes?”

“Not at all.”

Studying her father’s lean, tired-looking face, Penny decided that something was wrong. He seemed unusually worried and nervous.

“A hard day, Dad?” she asked.

Mr. Parker finished straightening a sheaf of papers before he glanced up.

“Yes, I hadn’t intended to tell you until later, but I may as well. I’m afraid our trip is off—at least as far as I’m concerned.”

“Oh, Dad!”

“It’s a big disappointment, Penny. The truth is, I’m in a spot of trouble.”

“Isn’t that the usual condition of a newspaper publisher?”

“Yes,” he smiled, “but there are different degrees of trouble, and this is the worst possible. The Star has been sued for libel, a matter of fifty odd thousand.”

“Fifty thousand!” gasped Penny. “But of course you’ll win the suit!”

“I’m not at all sure of it.” Anthony Parker spoke grimly. “My lawyer tells me that Harvey Maxwell has a strong case against the paper.”

“Harvey Maxwell?” repeated Penny thoughtfully. “Isn’t he the man who owns the Riverview Hotel?”

“Yes, and a chain of other hotels and lodges throughout the country. Harvey Maxwell is a rather well known sportsman. He lives lavishly, travels a great deal, and in general is a hard, shrewd business man.”

“He’s made a large amount of money from his hotels, hasn’t he?”

“Maxwell acquired a fortune from some source, but I’ve always had a doubt that it came from the hotel business.”

“Why is he suing the Star for libel, Dad?”

“Early this fall, while I was out of town for a day DeWitt let a story slip through which should have been killed. It was an interview with a football player named Bill Morcrum who was quoted as saying that he had been approached by Maxwell who offered him a bribe to throw an important game.”

“What would be the reason behind that?”

“Maxwell is thought by those in the know to have a finger in nearly every dishonest sports scheme ever pulled off in this town. He places heavy wagers, and seldom comes out on the losing end. But the story never should have been published.”

“It was true though?”

“I’m satisfied it was,” replied Mr. Parker. “However, it always is dangerous to make insinuations against a man.”

“Can’t the story be proven? I should think with the football player’s testimony you would have a good case.”

“That’s the trouble, Penny. This boy, Bill Morcrum, now claims he never made any such accusation against Maxwell. He says the reporter misquoted him and twisted his statements.”

“Who covered the story, Dad?”

“A man named Glower, a very reliable reporter. He swears he made no mistake, and I am inclined to believe him.”

“Then why did the football player change his story?”

“I have no proof, but it’s a fairly shrewd guess that he was approached by Maxwell a second time. Either he was threatened or offered a bribe which was large enough to sway him.”

“With both Maxwell and the football player standing together, it does rather put you on the spot,” Penny acknowledged. “What are you going to do?”

“We’ll fight the case, of course, but unless we can prove that our story was accurate, we’re almost sure to lose. I’ve asked Bill Morcrum to come to my office this afternoon, and he promised he would. He’s overdue now.”

Anthony Parker glanced at his watch and scowled. Getting up from the swivel chair he began to pace to and fro across the room.

A buzzer on his desk gave three sharp, staccato signals.

“Morcrum must be here now!” the editor exclaimed in relief. “I’ll want to see him alone.”

Penny arose to leave. As she went out the doorway she met the receptionist, accompanied by an awkward, oversized youth who shuffled his feet in walking. He grinned at her in a sheepish way and entered the private office.

While Penny waited, she entertained herself by reading all the comic strips she could find in the out-of-town exchange papers. In the adjoining room she could hear the rhythmical thumping, clicking sound of the Star’s teletype machines. She wandered aimlessly into the room to read the copy just as the machines typed it out, a story from Washington, one from Chicago, another from Los Angeles. It was fascinating to watch the print appear like magic upon the long rolls of copy paper.

Presently, the teletype attendant, young Billy Stevens, came dashing into the room.

“Oh, hello, Miss Parker,” he said with a bashful grin.

“Hello, Billy,” Penny answered cordially. She studied the keyboard of the sending teletype machine, running her fingers over the letters. “I wish I could work this thing,” she said.

“There’s nothing to it if you can run a typewriter,” answered Billy. “Just a minute, I’ll throw it off the line on to the test position. Then you can try it.”

At first Penny’s copy was badly garbled, but under Billy’s enthusiastic coaching she was soon doing accurate work.

“Say, this is fun!” she declared. “I’m coming in again one of these days and practice. Thanks a lot, Billy!”

As Penny went back into the editorial room she saw the Morcrum boy leaving her father’s office. His head was downcast and his face was flushed to the ears. Obviously, he had not had a comfortable time with Mr. Parker.

The moment the boy had vanished, Penny hurried into her father’s office to learn the outcome of the interview.

“No luck,” reported Mr. Parker, reaching for his hat and overcoat.

“He wouldn’t change his story?”

“No. He seemed like a fairly decent sort of boy, but he kept insisting he had been misquoted. I couldn’t get anywhere with him. He’ll testify for Maxwell when the case comes to trial.”

Mr. Parker put on his overcoat and hat, and opened the door for Penny. As they left the building he told her more about the interview.

“I asked the boy point-blank if he hadn’t been hired by Maxwell. Naturally, he denied it, but he acted rather alarmed. Oh, I’m satisfied he’s either been bought off or threatened.”

“When does the case come to trial?”

“The last of next month, unless we gain a delay.”

“That gives you quite a bit of time. Don’t you think you could take two weeks off anyhow, Dad? We both planned upon having such a wonderful time at Mrs. Downey’s place.”

Penny and her father had been invited to spend the Christmas holidays at Pine Top, a winter resort which attracted many Riverview persons. They especially had looked forward to the trip since they were to have been the house guests of Mrs. Christopher Downey, an old friend of Mr. Parker’s who operated a skiing lodge on the slopes of the mountain overlooking Silver Valley.

“There’s not much chance of my getting away,” Mr. Parker replied regretfully. “That is, not unless important evidence falls into my hands, or I am able to make a deal with Maxwell.”

“A deal?”

“If he would make reasonable demands I might be willing to settle out of court.”

Penny gazed at her father in blank amazement.

“And admit you were in the wrong when you’re certain you weren’t?”

“Any good general will make a strategic retreat if the situation calls for it. It might be more sensible to settle out of court than to lose the case. Maxwell has me in a tight place and knows it.”

“Then why don’t you see him? He might be fairly reasonable.”

“I suppose I could stop at the Riverview Hotel on our way home,” Mr. Parker said, frowning thoughtfully. “There’s an outside chance Maxwell may come to terms. Drop me off there, Penny.”

While the car threaded its way in and out of dense traffic, the editor remained in a deep study. Penny had never seen him look so worried. Her own disappointment was keen, yet she realized that far more than a vacation trip was at stake. Fifty thousand dollars represented a large sum of money! If Maxwell won his suit it might even mean the loss of the Riverview Star.

Sensing his daughter’s alarm, Mr. Parker reached out to pat her knee.

“Don’t worry,” he said, “we’re not licked yet, Penny! And if there’s any way to arrange it, you shall have your trip to Pine Top just as we planned.”

Penny presently edged the sedan into a parking space across the street from the Riverview Hotel. As she switched off the ignition her father said:

“Better come along with me and wait in the lobby. It’s cold out here.”

Penny followed her father into the building. The hotel was an elegant one with many services available for guests. She noticed a florist shop, a candy store, a dry cleaning establishment, and even a small brokerage office opening off the lobby.

“Oh, yes,” said Mr. Parker as Penny called his attention to the brokerage. “Maxwell hasn’t overlooked anything. The hotel has a special leased wire which I’ve been told gives him a direct connection with his other places.”

Walking over to the desk, Mr. Parker mentioned his name and asked the clerk if he might see Harvey Maxwell.

“Mr. Maxwell is not here,” replied the man with an insolent air.

“When will he be at the hotel?”

“Mr. Maxwell has left the city on business. He does not expect to return until the end of next month.”

Mr. Parker could not hide his annoyance.

“Let me have his address then,” he said in a resigned voice. “I’ll write him.”

The clerk shook his head. “I have been instructed not to give you Mr. Maxwell’s address. If you wish to deal with him you will have to see his lawyer, Gorman S. Railey.”

“So Maxwell was expecting me to come here to make a deal with him?” demanded Mr. Parker. “Well, I’ve changed my mind. I’ll make a deal all right, but it will be in court. Good day!”

Angrily, the newspaper man strode from the lobby. Penny hurried to keep pace with him.

“That settles it,” he said tersely as they climbed into the sedan again. “This libel suit will be a fight to the finish. And maybe my finish at that!”

“Oh, Dad, I’m sure you’ll win. But it’s a pity all this had to come up just when you had planned a fine vacation. Mrs. Downey will be disappointed, too.”

“Yes, she will, Penny. And there’s Mrs. Weems to be thought about. I promised her a two weeks’ trip while we were gone.”

They drove in silence for a few blocks. As the car passed the Sidell residence, Penny’s father said thoughtfully:

“I suppose I could send you out to Pine Top alone, Penny. Or perhaps you might be able to induce your chum, Louise, to go along. Would you like that?”

“It would be more fun if you went also.”

“That’s out of the picture now. If everything goes well I might be able to join you for Christmas weekend.”

“I’m not sure Louise could go,” said Penny doubtfully. “But I can find out right away.”

After dinner that night, she lost no time in running over to the Sidell home. At first Louise was thrown into a state of ecstasy at the thought of making a trip to Pine Top and then her face became gloomy.

“I would love it, Penny! But it’s practically a waste of words to ask Mother. We’re going to my grandmother’s farm in Vermont for the holidays, and I’ll have to tag along.”

Since grade school days the two girls had been inseparable friends. Between them there was perfect understanding and they made an excellent pair, for Louise exerted a subduing effect upon the more impulsive, excitable Penny.

Inactivity bored Penny, and wherever she went she usually managed to start things moving. When nothing better offered, she tried her hand at writing newspaper stories for her father’s paper. Several of these reportorial experiences had satisfied even Penny’s deep craving for excitement.

Three truly “big” stories had rolled from her typewriter through the thundering presses of the Riverview Star: Tale of the Witch Doll, The Vanishing Houseboat, and Danger at the Drawbridge. Even now, months after her last astonishing adventure, friends liked to tease her about a humorous encounter with a certain Mr. Kippenberg’s alligator.

“Pine Top won’t be any fun without you, Lou,” Penny complained.

“Oh, yes it will,” contradicted her chum. “I know you’ll manage to stir up plenty of excitement. You’ll probably pull a mysterious Eskimo out of a snow bank or save Santa Claus from being kidnaped! That’s the way you operate.”

“Pine Top is an out of the way place, close to the Canadian border. All one can do there is eat, sleep, and ski.”

“You mean, that’s all one is supposed to do,” corrected Louise with a laugh. “But you’ll run into some big story or else you’re slipping!”

“There isn’t a newspaper within fifty miles. No railroad either. The only way in and out of the valley is by airplane, and bob-sled, of course.”

“That may cramp your style a little, but I doubt it,” declared Louise. “I do wish I could go along.”

The girls talked with Mrs. Sidell, but as they both had expected, it was not practical for Louise to make the trip.

“I’ll come to the airport to see you off on your plane,” Louise promised as Penny left the house. “You’re starting Thursday, aren’t you?”

“Yes, at ten-thirty unless there’s bad weather. But I’ll see you again before that.”

All the next day Penny packed furiously. Mr. Parker was unusually busy at the office, but he bought his daughter’s ticket and made all arrangements for the trip to Pine Top. Since Mrs. Weems also planned to leave Riverview the following day, the house was in a constant state of turmoil.

“I feel sorry for Dad being left here alone,” remarked Penny. “He’ll never make his bed, and he’ll probably exist on strong coffee and those wretched raw beef sandwiches they serve at the beanery across from the Star office.”

“I ought to give up my vacation,” declared Mrs. Weems. “It seems selfish of me not to stay here.”

Mr. Parker would not hear of such an arrangement, and so plans moved forward just as if his own trip had not been postponed.

“Dad, you’ll honestly try to come to Pine Top for Christmas?” Penny pleaded.

“I’ll do my best,” he promised soberly. “I have a hunch that Harvey Maxwell may still be in town, despite what we were told at the hotel. I intend to busy myself making a complete investigation of the man.”

“If I could help, I’d be tickled to stay, Dad.”

“There’s nothing you can do, Penny. Just go out there and have a nice vacation.”

Mr. Parker had not intended to go to the office Thursday morning until after Penny’s plane had departed, but at breakfast time a call came from DeWitt, the city editor, urging his presence at once. Before leaving, he gave his daughter her ticket and travelers checks.

“Now I expect to be at the airport to see you off,” he promised. “Until then, good-bye.”

Mr. Parker kissed Penny and hastened away. Later, Louise Sidell came to the house. Soon after ten o’clock the girls took leave of Mrs. Weems, taxiing to the airport.

“I don’t see Dad anywhere,” Penny remarked as the cabman unloaded her luggage. “He’ll probably come dashing up just as the plane takes off.”

The girls entered the waiting room and learned that the plane was “on time.” Curiously, they glanced at the other passengers. Two travelers Penny immediately tagged as business men. But she was rather interested in a plump, over-painted woman whose nervous manner suggested that she might be making her first airplane trip.

While Penny’s luggage was being weighed, two men entered the waiting room. One was a lean, sharp-faced individual suffering from a bad cold. The other, struck Penny as being vaguely familiar. He was a stout man, expensively dressed, and had a surly, condescending way of speaking to his companion.

“Who are those men?” Penny whispered to Louise. “Do you know them?”

Louise shook her head.

“That one fellow looks like someone I’ve seen,” Penny went on thoughtfully. “Maybe I saw his picture in a newspaper, but I can’t place him.”

The two men went up to the desk and the portly one addressed the clerk curtly:

“You have our reservations for Pine Top?”

“Yes, sir. Just sign your name here.” The clerk pushed forward paper and a pen.

Paying for the tickets from a large roll of greenbacks, the two men went over to the opposite side of the waiting room and sat down. Penny glanced anxiously at the clock. It was twenty minutes past ten.

A uniformed messenger boy entered the room, letting in a blast of cold air as he opened the door. He went over to the desk and the clerk pointed out the two girls.

“Now what?” said Penny in a low voice. “Maybe my trip is called off!”

The message was for her, from her father. But it was less serious than she had expected. Because an important story had “broken” it would be impossible for him to leave the office. He wished her a pleasant trip west and again promised he would bend every effort toward visiting Pine Top for Christmas.

Penny folded the message and slipped it into her purse.

“Dad won’t be able to see me off,” she explained to her chum. “I was afraid when DeWitt called him this morning he would be held up.”

Before Louise could reply the outside door opened once more, and a girl of perhaps twenty-two who walked with a long, masculine gait, came in out of the cold. Penny sat up a bit straighter in her chair.

“Do you see what I see?” she whispered.

“Who is she?” inquired Louise curiously.

“The one and only Francine Sellberg.”

“Which means nothing to me.”

“Don’t tell me you haven’t seen her by-line in the Riverview Record! Francine would die of mortification.”

“Is she a reporter?”

“She covers special assignments. And she is pretty good,” Penny added honestly. “But not quite as good as she believes.”

“Wonder what she’s doing here?”

“I was asking myself that same question.”

As the two girls watched, they saw Francine’s cool gaze sweep the waiting room. She did not immediately notice Penny and Louise whose backs were partly turned to her. Her eyes rested for an instant upon the two men who previously had bought tickets to Pine Top, and a flicker of satisfaction showed upon her face.

Moving directly to the desk she spoke to the ticket agent in a low voice, yet loudly enough for Penny and Louise to hear.

“Is it still possible to make a reservation for Pine Top?”

“Yes, we have one seat left on the plane.”

“I’ll take it,” said Francine.

Penny nudged Louise and whispered in her ear: “Did you hear that?”

“I certainly did. Why do you suppose she’s going to Pine Top? For the skiing?”

“Unless I’m all tangled in a knot, she’s after a big story for the Record. And I just wonder if those two mysterious-looking gentlemen aren’t the reason for her trip!”

Francine Sellberg paid for her ticket and turned so that her gaze fell squarely upon Penny and Louise. Abruptly, she crossed over to where they sat.

“Hello, girls,” she greeted them breezily. “What brings you to the airport?”

As always, the young woman reporter’s manner was brusque and business-like. Without meaning to offend, she gave others an impression of regarding them with an air of condescension.

“I came to see Penny off,” answered Louise before her chum could speak.

“Oh, are you taking this plane?” inquired Francine, staring at Penny with quickening interest.

“I am if it ever gets here.”

“Traveling alone?”

“All by my lonesome,” Penny admitted cheerfully.

“You’re probably only going a short ways?”

“Oh, quite a distance,” returned Penny. She did not like the way Francine was quizzing her.

“Penny is going to Pine Top for the skiing,” declared Louise, never guessing that her chum preferred to withhold the information.

“Pine Top!” The smile left Francine’s face and her eyes roved swiftly toward the two men who sat at the opposite side of the room.

“We are to be traveling companions, I believe,” remarked Penny innocently.

Francine’s attention came back to the younger girl. Her eyes narrowed with suspicion.

“So you’re going out to Pine Top for the skiing,” she said softly.

“And you?” countered Penny.

“Oh, certainly for the skiing,” retorted Francine, mockery in her voice.

“Nice of the Record to give you a vacation.”

By this time the silver-winged transport had wheeled into position on the apron, and passengers were beginning to leave the waiting room. The two men who had attracted Penny’s attention, arose and without appearing to notice the three girls, went outside.

“You don’t deceive me one bit, Penny Parker,” said Francine with a quick change of attitude. “I know very well why you are going to Pine Top, and it’s for the same reason I am!”

“You seem to have divined all my secrets, even when I don’t know them myself,” responded Penny. “Suppose you tell me why I am going to Pine Top mountain?”

“It’s perfectly obvious that your father sent you, But I am afraid he over-estimates your journalistic powers if he thinks you have had enough experience to handle a difficult assignment of this sort. I’ll warn you right now, Penny, don’t come to me for help. On this job we’re rivals. And I won’t tolerate any bungling or interference upon your part!”

“Nice to know just where we stand,” replied Penny evenly. “Then there will be no misunderstanding or tears later on.”

“Exactly. And mind you don’t give any tip-off as to who I am!”

“You mean you don’t care to have those two gentlemen who were here a moment ago know that you are a reporter for the Record.”

“Naturally.”

“And who are these men of mystery?”

“As if you don’t know!” Francine made an impatient gesture. “Oh, why pose, Penny? This innocent act doesn’t go over worth a cent.”

Louise broke indignantly into the conversation. “Penny isn’t posing! It’s true she is going to Pine Top for the skiing and not to get a story. Isn’t it?”

“Yes,” acknowledged Penny unwillingly. She was sorry that her chum had put an end to the little game with Francine.

The reporter stared at the two girls, scarcely knowing whether or not to believe them.

“Why not break down and tell me the identity of our two fellow passengers?” suggested Penny.

“So you really don’t know their names?” Francine flashed a triumphant smile. “Fancy that! Well, you’ve proven such a clever little reporter in the past, I’ll allow you to figure it out for yourself. See you in Pine Top.”

Turning away, the young woman went back to the desk to speak once more with the ticket man.

“Doesn’t she simply drip conceit!” Louise whispered in disgust. “Did I make a mistake in letting her know that you weren’t on an assignment?”

“It doesn’t matter, Lou. Shall we be going out to the plane before I miss it?”

The huge streamliner stood warming up on the ribbon of cement, long tongues of flame leaping from the exhausts. Nearly all of the passengers already had taken their seats in the warm, cozy cabin.

“Good-bye, Lou,” Penny said, shaking her chum’s hand.

“Good-bye. Have a nice time. And don’t let that know-it-all Francine get ahead of you!”

“Not if I can help it,” laughed Penny.

Francine had left the waiting room and was walking with a brisk step toward the plane. Not wishing to be the last person aboard, Penny stepped quickly into the cabin. All but two seats were taken. One was at the far end of the plane, the other directly behind the two strange men.

Penny slid into the latter chair just as Francine came into the cabin. As she went down the aisle to take the only remaining seat, the reporter shot the younger girl an irritated glance.

“She thinks I took this place just to spite her!” thought Penny. “How silly!”

The stewardess, trim in her blue-green uniform, had closed the heavy metal door. The plane began to move down the ramp, away from the station’s canopied entrance. Penny leaned close to the window and waved a last good-bye to Louise.

As the speed of the engines was increased, the plane raced faster and faster over the smooth runway. A take-off was not especially thrilling to Penny who often had made flights with her father. She shook her head when the stewardess offered her cotton for her ears, but accepted a magazine.

Penny flipped carelessly through the pages. Finding no story worth reading, she turned her attention to her fellow passengers. Beside her, on the right, sat the over-painted woman, her hands gripping the arm rests so hard that her knuckles showed white.

“We—we’re in the air now, aren’t we?” she asked nervously, meeting Penny’s gaze. “I do hope I’m not going to be sick.”

“I am sure you won’t be,” replied Penny. “The air is very quiet today.”

“They tell me flying over the mountains in winter time is dangerous.”

“Not in good weather with a skilful pilot. I am sure we will be in no danger.”

“Just the same I never would have taken a plane if it hadn’t been the only way of reaching Pine Top.”

Penny turned to regard her companion with new interest. The woman was in her early forties, though she had attempted by the lavish use of make-up to appear younger. Her hair was a bleached yellow, dry and brittle from too frequent permanent waving. Her shoes were slightly scuffed, and a tight-fitting black crepe dress, while expensive, was shiny from long use.

“Oh, are you traveling to Pine Top, too?” inquired Penny. “Half the passengers on this plane must be heading for there.”

“Is that where you are going?”

“Yes,” nodded Penny. “I plan to visit an old friend who has an Inn on the mountain side, and try a little skiing.”

“This is strictly a business trip with me,” confided the woman. She had relaxed now that the transport was flying at an even keel. “I am going there to see Mr. Balantine—David Balantine. You’ve heard of him, of course.”

Penny shook her head.

“My dear, everyone in the East is familiar with his name. Mr. Balantine has a large chain of theatres throughout the country. He produces his own shows, too. I hope to get a leading part in a new production which will soon be cast.”

“Oh, I see,” murmured Penny. “You are an actress?”

“I’ve been on the stage since I was twelve years old,” the woman answered proudly. “You must have seen my name on the billboards. I am Miss Miller. Maxine Miller.”

“I should like to see one of your plays,” Penny responded politely.

“The truth is I’ve been ‘at liberty’ for the past year or two,” the actress admitted with an embarrassed laugh. “‘At liberty’ is a word we show people use when we’re temporarily out of work. The movies have practically ruined the stage.”

“Yes, I know.”

“For several weeks I have been trying to get an interview with Mr. Balantine. His secretaries would not make an appointment for me. Then quite by luck I learned that he planned to spend two weeks at Pine Top. I thought if I could meet him out there in his more relaxed moments, he might give me a role in the new production.”

“Isn’t it a rather long chance to take?” questioned Penny. “To go so far just in the hope of seeing this man?”

“Yes, but I like long chances. And I’ve tried every other way to meet him. If I win the part I’ll be well repaid for my time and money.”

“And if you fail?”

Maxine Miller shrugged. “The bread line, perhaps, or burlesque which would be worse. If I stay at Pine Top more than a few days I’ll never have money enough to get back here. They tell me Pine Top is high-priced.”

“I don’t know about that,” answered Penny.

As the plane winged its way in a northwesterly direction, the actress kept the conversational ball rolling at an exhausting pace. She told Penny all about herself, her trials and triumphs on the stage. As first, it was fairly interesting, but as Miss Miller repeated herself, the girl became increasingly bored. She shrewdly guessed that the actress never had been the outstanding stage success she visioned herself.

Penny paid more than ordinary attention to the two men who sat in front of her. However, Miss Miller kept her so busy answering questions that she could not have overheard their talk, even if she had made an effort to do so.

Therefore, when the plane made a brief stop, she was astonished to have Francine sidle over to her as she sat on a high stool at the lunch stand, and say in a cutting tone:

“Well, did you find out everything you wanted to know? I saw you listening hard enough.”

“Eavesdropping isn’t my method,” replied Penny indignantly. “It’s stupid and is employed only by trash fiction writers and possibly Record reporters.”

“Say, are you suggesting—?”

“Yes,” interrupted Penny wearily. “Now please go find yourself a roost!”

Francine ignored the empty stools beside Penny and went to the far side of the lunch room. A moment later the two men, who had caused the young woman reporter such concern, entered and sat down at a counter near Penny, ordering sandwiches and coffee.

Rather ironically, the girl could not avoid hearing their conversation, and almost their first words gave her an unpleasant shock.

“Don’t worry, Ralph,” said the stout one. “Nothing stands in our way now.”

“You’re not forgetting Mrs. Downey’s place?”

“We’ll soon take care of her,” the other boasted. “That’s why I’m going out to Pine Top with you, Ralph. I’ll show you how these little affairs are handled.”

Penny was startled by the remarks of the two men because she felt certain that the Mrs. Downey under discussion must be the woman at whose inn she would spend a two weeks’ vacation. Was it possible that a plot was being hatched against her father’s friend? And what did Francine know about it?

She glanced quickly toward the young woman reporter who was doing battle with a tough steak which threatened to leap off her plate whenever she tried to cut it. Apparently, Francine had not heard any part of the conversation.

Being only human, Penny decided that despite her recent comments, she could not be expected to abandon a perfectly good sandwich in the interests of theoretical honor. She remained at her post and waited for the men to reveal more.

Unobligingly, they began to talk of the weather and politics. Penny finished her sandwich, and sliding down from the stool wandered outdoors.

“I wish I knew who those men are,” she thought. “Francine could tell me if she weren’t so horrid.”

Penny waited until the last possible minute before boarding the plane. As she stepped inside the cabin she was surprised to see that Francine had taken the chair beside Maxine Miller, very coolly moving Penny’s belongings to the seat at the back of the airliner.

“Did you two decide to change places?” inquired the stewardess as Penny hesitated beside the empty chair.

“I didn’t decide. It just seems to be an accomplished fact.”

The stewardess went down the aisle and touched Francine’s arm. “Usually the passengers keep their same seats throughout the journey,” she said with a pleasant smile. “Would you mind?”

Francine did mind for she had cut her lunch short in the hope of obtaining the coveted chair, but she could not refuse to move. Frowning, she went back to her former place.

Actually, Penny was not particular where she sat. There was no practical advantage in being directly behind the two strangers, for their voices were seldom audible above the roar of the plane. On the other hand, Miss Miller talked loudly and with scarcely a halt for breath. Penny was rather relieved when an early stop for dinner enabled her to gain a slight respite.

With flying conditions still favorable, the second half of the journey was begun. Penny curled up in her clean, comfortable bed, and the gentle rocking of the plane soon lulled her to sleep. She did not awaken until morning when the stewardess came to warn her they soon would be at their destination. Penny dressed speedily, and enjoyed a delicious breakfast brought to her on a tray. She had just finished when Francine staggered down the aisle, eyes bloodshot, her straight black hair looking as if it had never been combed.

“Will I be glad to get off this plane!” she moaned. “What a night!”

“I didn’t notice anything wrong with it,” said Penny. “I take it you didn’t sleep well.”

“Sleep? I never closed my eyes all night, not with this roller-coaster sliding down one mountain and up another. I thought every minute we were going to crash.”

Maxine Miller likewise seemed to have spent an uncomfortable night, for her face was haggard and worn. She looked five years older and her make-up was smeared.

“Tell me, do I look too dreadful?” she asked Penny anxiously. “I want to appear my best when I meet Mr. Balantine.”

“You’ll have time to rest up before you see him,” the girl replied kindly.

“How long before we reach Pine Top?”

“We should be approaching there now.” Penny studied the terrain below with deep interest, noting mountain ranges and beautiful snowy valleys.

At last the plane circled and swept down on a small landing field which had been cleared of snow. Passengers began to pour from the cabin, grateful that the long journey was finally at an end.

“I hope I see you again,” said Penny, extending her hand to Miss Miller. “And the best of luck with Mr. Balantine.”

Eagerly, she gathered together her possessions and stepped out of the plane into blinding sunlight. The air was crisp and cold, but there was a quality to it which made her take long, deep breaths. Beyond the landing field stood a tall row of pine trees, each topped with a layer of snow like the white icing of a cake. From somewhere far away she could hear the merry jingle of sleigh bells.

“So this is Pine Top!” thought Penny. “It’s as pretty as a Christmas card!”

A small group of persons were at the field to meet the plane. Catching sight of a short, sober-looking little woman who was bundled in furs, Penny hastened toward her.

“Mrs. Downey!” she cried.

“Penny, my dear! How glad I am to see you!” The woman clasped her firmly, planting a kiss on either cheek. “But your father shouldn’t have disappointed me. Why didn’t he come along?”

“He wanted to, but he’s up to his eyebrows in trouble. A man is suing him for libel.”

“Oh, that is bad,” murmured Mrs. Downey. “I know what legal trouble means because I’ve had an unpleasant taste of it myself lately. But come, let’s get your luggage and be starting up the mountain.”

“Just a minute,” said Penny in a low tone. With a slight inclination of her head, she indicated the two male passengers who had made the long journey from Riverview to Pine Top. “You don’t by any chance know either of those men?”

Mrs. Downey’s face lost its kindliness and she said, in a grim voice: “I certainly do!”

Before Penny could urge the woman to reveal their identity, Francine walked over to where she and Mrs. Downey stood.

“Did you wish to see me?” inquired the hotel woman as Francine looked at her with an inquiring gaze.

“Are you Mrs. Downey?”

“Yes, I am.”

“I am looking for a place to stay,” said Francine. “I was told that you keep an inn.”

“Yes, we have a very nice lodge up the mountain about a mile from here. The rooms are comfortable, and I do most of the cooking myself. We’re located on the best ski slopes in the valley. But if you’re looking for a place with plenty of style and corresponding prices you might prefer the Fergus place.”

“Your lodge will exactly suit me, I think,” declared Francine. “How do I get there?”

“In my bob-sled,” offered Mrs. Downey. “I may have a few other guests.”

“It won’t take me a minute to get my luggage,” said Francine, moving away.

Penny was none too pleased to know that the girl reporter would make her headquarters at the Downey Inn. Her face must have mirrored her misgiving, for Mrs. Downey said apologetically:

“Business hasn’t been any too good this season. I have to pick up an extra tourist whenever I can.”

“Of course,” agreed Penny hastily. “One can’t run a hotel without guests.”

“I do believe Jake has snared another victim,” Mrs. Downey laughed. “That woman with the bleached hair.”

“And who is Jake?” inquired Penny.

Mrs. Downey nodded her head toward a spry man with leathery skin who was talking with Maxine Miller.

“He does odd jobs for me at the Inn,” she explained. “When he has no other occupation he tries to entice guests into our den.”

“You make it sound like a very wicked business,” chuckled Penny.

“Since the Fergus hotel was built it’s become a struggle, to the death,” replied Mrs. Downey soberly. “I truly believe this will be my last year at Pine Top.”

“Why, you’ve had your home here for years,” said Penny in astonishment. “You were at Pine Top long before anyone thought of it as a great skiing resort. You’re an institution here, Mrs. Downey. Surely you aren’t serious about giving up your lodge?”

“Yes, I am, Penny. But I shouldn’t start telling my troubles the moment you arrive. I never would have said a word if you hadn’t asked me about those two men yonder.”

She gazed scornfully toward the strangers whose identity Penny hoped to learn.

“Who are they?” Penny asked quickly.

“The slim fellow with the sharp face is Ralph Fergus,” answered Mrs. Downey, her voice filled with bitterness. “He manages the hotel and is supposed to be the owner. Actually, the other man is the one who provides all the money.”

“And who is he?”

“Why, you should know,” replied Mrs. Downey. “He has a hotel in Riverview. His name is Harvey Maxwell. He only comes here now and then.”

“Harvey Maxwell!” repeated Penny. “Wait until Dad hears about this!”

“Your father has had dealings with him?”

“Has he?” murmured Penny. “Maxwell is the man who is suing Dad for libel!”

“Well, of all things!”

“I believe I understand why Francine came out here too,” Penny said thoughtfully.

“Francine?”

“The girl who just engaged a room at your place. I think she went to your Inn for the sole purpose of keeping an eye on me.”

“Why should she wish to do that?”

“Francine is a reporter for the Riverview Record. Dad’s story about Maxwell bribing a football player served as a tip-off to other editors. Now the Record may hope to get evidence against him which they can build up into a big story.”

“I should think that would help your father’s case.”

“It might,” agreed Penny, “all depending upon how the evidence was used. But somehow, I don’t trust Francine. If there’s any fancy newspaper work to be done at Pine Top, I aim to look after it myself!”

Mrs. Downey laughed at Penny’s remark, not taking it very seriously.

“I wish someone could uncover damaging evidence against Harvey Maxwell,” she declared. “But I fear he’s far too clever a man to be caught in anything dishonest. Sometime when you’re in the mood to hear a tale of woe, I’ll tell you how he is running things at Pine Top.”

“I’d like to learn everything I can about him,” responded Penny eagerly.

Mrs. Downey led the girl across the field to the road where the bob-sled and team of horses had been hitched. Jake, the handy man, appeared a moment later, loaded down with skis and luggage. Maxine Miller, Francine, and a well-dressed business man soon arrived and were helped into the sled.

“This is unique taxi service to say the least,” declared Francine, none too well pleased. “It must take ages to get up the mountain.”

“Not very long,” replied Mrs. Downey cheerfully.

Jake drove, with the hotel woman and her guests sitting on the floor of the sled, covered by warm blankets.

“Is it always so cold here?” shivered Miss Miller.

“Always at this time of year,” returned Mrs. Downey. “You’ll not mind it in a day or two. And the skiing is wonderful. We had six more inches of snow last night.”

Penny thoroughly enjoyed the novel experience of gliding swiftly over the hard-packed snow. The bobsled presently passed a large rustic building at the base of the mountain which Mrs. Downey pointed out as the Fergus hotel.

“I suppose all the rich people stay there,” commented Miss Miller. “Do you know if they have a guest named David Balantine?”

“The producer? Yes, I believe he is staying at the Fergus hotel.”

At the next bend Jake stopped the horses so that the girls might obtain a view of the valley.

“Over to the right is the village of Pine Top,” indicated Mrs. Downey. “Just beyond the Fergus hotel is the site of an old silver mine, abandoned many years ago. And when we reach the next curve you’ll be able to look north and see into Canada.”

A short ride on up the mountain brought the party to the Downey Lodge, a small but comfortable log building amid the pines. On the summit of a slope not far away they could see the figure of a skier, poised for a swift, downward flight.

Mrs. Downey assigned the guests to their rooms, tactfully establishing Penny and Francine at opposite ends of a long hall.

“Luncheon will be served at one o’clock,” she told them. “If you feel equal to it you’ll have time for a bit of skiing.”

“I believe I’ll walk down to the village and send a wire to Dad,” said Penny. “Then this afternoon I’ll try my luck on the slopes.”

“Just follow the road and you’ll not get lost,” instructed Mrs. Downey.

Penny unpacked her suitcase, and then set forth at a brisk walk for the village. She found the telegraph station without difficulty and dispatched a message to her father, telling him of Harvey Maxwell’s presence in Pine Top.

The town itself, consisting of half a dozen stores and twice as many houses, was soon explored. Before starting back up the mountain Penny thought she would buy a morning newspaper. But as she made inquiry at a drug store, the owner shook his head.

“We don’t carry them here. The only papers we get come in by plane. They’re all sold out long before this.”

“Oh, I see,” said Penny in disappointment, “well, next time I’ll try to come earlier.”

“I beg your pardon,” ventured a voice directly behind her. “Allow me to offer you my paper.”

Penny turned around to see that Ralph Fergus had entered the drugstore in time to hear her remark. With a most engaging smile, he extended his own newspaper.

“Oh, I don’t like to take your paper,” she protested, wishing to accept no favor however small from the man.

“Please do,” he urged, thrusting it into her hand. “I have finished with it.”

“Thank you,” said Penny.

She took the paper and started to leave the store. Mr. Fergus fell into step with her, following her outside.

“Going back up the mountain?” he inquired casually.

“Yes, I was.”

“I’ll walk along if you don’t mind having company.”

“Not at all.”

Penny studied Ralph Fergus curiously, fairly certain he had a special reason for wishing to walk with her. For a time they trudged along in silence, the snow creaking beneath their boots.

“Staying at the Downey Lodge?” Fergus inquired after awhile.

“Yes, I am.”

“Like it there?”

“Well, I only arrived on the morning plane.”

“Yes, I noticed you aboard,” he nodded. “Mrs. Downey is a very fine woman, a very fine woman, but her lodge isn’t modern. You noticed that, I suppose?”

“I’m not especially critical,” smiled Penny. “It seemed to suit my needs.”

“You’ll be more critical after you have stayed there a few days,” he warned. “The service is very poor. Even this little matter of getting a morning newspaper. Now our hotel sees that every guest has one shoved under his door before breakfast.”

“That would be very nice, I’m sure,” remarked Penny dryly. “You’re the manager of the hotel, aren’t you?”

Ralph Fergus gave her a quick, appraising glance. “Right you are,” he said jovially. “Naturally I think we have the finest hotel at Pine Top and I wish you would try it. I’ll be glad to make you a special rate.”

“You’re very kind.” It was a struggle for Penny to keep her voice casual. “I may drop around sometime and look the hotel over.”

“Do that,” he urged. “Here is my card. Just ask for me and I’ll show you about.”

Penny took the card and dropped it into her pocket. A few minutes later as they passed the Fergus hotel, her companion parted company with her.

“He thought I was an ordinary guest at Mrs. Downey’s,” Penny told herself. “Otherwise, he never would have dared to make such an open bid for my patronage.”

Upon returning to the lodge she told Mrs. Downey of her meeting with Ralph Fergus.

“It doesn’t surprise me one bit,” the woman replied angrily. “Fergus has been using every method he can think of to get my guests away from me. He has runners out all the time, talking up his hotel and talking mine down.”

Penny sat on the edge of the kitchen table, watching Mrs. Downey stir a great kettle of steaming soup.

“While I was coming here on the plane I heard Fergus and Maxwell speaking about you.”

“You did, Penny? What did they have to say? Nothing good, I’ll warrant.”

“I couldn’t understand what they meant at the time, but now I think I do. They said that nothing stood in their way except your place. Maxwell declared he would soon take care of you, and that he was on his way to Pine Top to show Fergus how such affairs were handled.”

Mrs. Downey kept on stirring with the big spoon. “So the screws are to be twisted a bit harder?” she asked grimly.

“Why do they want your place?” Penny inquired.

“Because I take a few of their guests away from them. If my lodge closed up they could raise prices sky high, and they would do it, too!”

“They offered me a special rate, whatever that means.”

“Fergus has been cutting his room rents lately for the sole purpose of getting my customers away from me. He makes up for it by charging three and even four dollars a meal. The guests don’t learn that until after they have moved in.”

“And there’s nothing you can do about it?”

Mrs. Downey shook her head. “I’ve been fighting with my back to the wall this past season. I don’t see how I possibly can make it another year. That is why I wanted you and your father to visit here before I gave up the place.”

“Dad might have helped you,” Penny said regretfully. “I’m sorry he wasn’t able to come.”

At one o’clock Mrs. Downey served a plain but substantial meal to fourteen guests who tramped in out of the snow. They called loudly for second and third helpings which were cheerfully given.

After luncheon Penny sat for a time about the crackling log fire and then she went to her room and changed into her skiing clothes.

“The nursery slopes are at the rear of the lodge,” Mrs. Downey told her as she went out through the kitchen. “But you’re much too experienced for them.”

“I haven’t been on skis for nearly two years.”

“It will come back to you quickly.”

“I thought I might taxi down and look over the Fergus hotel.”

“The trail is well marked. Just be careful as you get about half way down. There is a sharp turn and if you miss it you may find yourself wrapped around an evergreen.”

Penny went outside, and buckling on her skis, glided to the top of a long slope which fell rather sharply through lanes of pine trees to the wide valley below. As she was studying the course, reflecting that the crusted snow would be very fast, Francine came out of the lodge and stood watching her.

“What’s the matter, Penny?” she called. “Can’t you get up your nerve?”

Penny dug in her poles and pushed off. Crouching low, skis running parallel, she tore down the track. Pine trees crowded past on either side in a greenish blur. The wind whistled in her ears. She jabbed her poles into the snow to check her speed.

After the first steep stretch, the course flattened out slightly. From a cautious left traverse, a lifted stem turn gave her time to concentrate her full attention on the route ahead. She swerved to avoid a boulder which would have broken her ski had she crashed into it, and rode out a series of long, undulating hollows.

Gathering speed again, Penny made her decisions with lightning rapidity. There was no time to think. Confronted with a choice of turns, she chose the right hand trail, slashing through in a beautiful christiana. Too late, she realized her error.

Directly ahead loomed a barbed wire fence. There was no opportunity to turn aside. Penny knew that she must jump or take a disastrous fall.

Swinging her poles forward, she let them drop in the snow close to her ski tips. Crouching low she sprang upward with all her strength. The sticks gave her leverage so that she could lift her skis clear of the snow. Momentum carried her forward over the fence.

Penny felt the jar of the runners as they slapped on the snow. Then she lost her balance and tumbled head over heels.

Untangling herself, she sat up and gazed back at the barbed wire fence.

“I wish all my friends at Riverview could have seen that jump!” she thought proudly. “It was a beauty even if I did land wrong side up.”

A large painted sign which had been fastened to the fence, drew her attention. It read: “Skiers Keep Out.”

“I wonder if that means me?” remarked Penny aloud.

“Yes, it means you!” said an angry voice behind her.

Penny rolled over in the snow, waving her skis in the air. She drew in her breath sharply. An old man with a dark beard had stepped from the shadow of the pine trees, a gun grasped in his gnarled hands!

“Can’t you understand signs?” the old man demanded, advancing with cat-like tread from the fringe of pine trees.

“Not when I’m traveling down a mountain side at two hundred miles an hour!” Penny replied. “Please, would you mind pointing that cannon in some other direction? It might go off.”

The old man lowered the shotgun, but the grim lines of his wrinkled, leathery face did not relax.

“Get up!” he commanded, prodding her with the toe of his heavy boot. “Get out of here! I won’t have you or any other skier on my property.”

“Then allow me to make a suggestion,” remarked Penny pleasantly. “Put up another strand of barbed wire and you’ll have them all in the hospital!”

She sat up, gingerly felt of her left ankle and then began to brush snow from her jacket. “Did you see me make the jump?” she asked. “I took it just like a reindeer. Or do I mean a gazelle?”

“You made a very awkward jump!” he retorted. “I could have done better myself.”

Penny glanced up with genuine interest. “Oh, do you ski?”

By this time she no longer was afraid of the old man, if indeed she had ever been.

“No, I don’t ski!” he answered impatiently. “Now hurry up! Get those skis off and start moving! I’ll not wait all day.”

Penny began to unstrap the long hickory runners, but with no undue show of haste. She glanced curiously about the snowy field. An old shed stood not far away. Beside it towered a great stack of wood which reached nearly as high as the roof. Through the trees she caught a glimpse of a weather-stained log cabin with smoke curling lazily from the brick chimney.

As Penny was regarding it, she saw a flash of color at one of the windows. A girl who might have been her own age had her face pressed against the pane. Seeing Penny’s gaze upon her, she began to make motions which could not be understood.

The old man also turned his head to look toward the cabin. Immediately, the girl disappeared from the window.

“Is that where you live?” inquired Penny.

Instead of answering, the old man seized her by the hand and pulled her to her feet.

“Go!” he commanded. “And don’t let me catch you here again!”

Penny shouldered her skis and moved toward the fence.

“So sorry to have damaged your nice snow,” she apologized. “I’ll try not to trespass again.”

Crawling under the barbed wire fence, Penny retraced her way up the slope to the point on the trail where she had taken the wrong turn. There she hesitated and finally decided to walk on to the Fergus hotel.

“I wonder who that girl was at the window?” Penny reflected as she trudged along. “She looked too young to be Old Whisker’s daughter. And what was she trying to tell me?”

The problem was too deep for her to solve. But she made up her mind she would ask Mrs. Downey the name of the queer old man as soon as she returned to the lodge.

Reaching the Fergus hotel, Penny parked her skis upright in a snowbank near the front door, and went inside. She found herself in a long lobby at the end of which was a great stone fireplace with a half burned log on the hearth. Bellboys in green uniforms and brass buttons darted to and fro. A general stir of activity pervaded the place.

As Penny was gazing about, she saw Maxine Miller leave an elevator and come slowly across the lobby. The actress would not have seen her had she not spoken.

“How do you do, Miss Miller. I didn’t expect to see you here.”

“Oh, Miss Parker!” The actress’ face was the picture of despair. “I’ve had the most wretched misfortune!”

“Why, what has happened?” inquired Penny, although she thought she knew the answer to her question.

“I’ve just seen Mr. Balantine.” Miss Miller sagged into the depths of a luxuriously upholstered davenport and leaned her head back against the cushion.

“Your interview didn’t turn out as you expected?”

“He wouldn’t give me the part. Hateful old goat! He even refused to allow me to demonstrate how well I could read the lines! And he said some very insulting things to me.”

“That is too bad,” returned Penny sympathetically. “What will you do now? Go back home?”

“I don’t know,” the woman replied in despair. “I would stay if I thought I could change Mr. Balantine’s opinion. Do you think I could?”

“I shouldn’t advise it myself. Of course, I don’t know anything about Mr. Balantine.”

“He’s very temperamental. Perhaps if I kept bothering him he would finally give me a chance.”

“Well, it might be worth trying,” Penny said doubtfully. “But I think if I were you I would return home.”

“All of my friends will laugh at me. They thought it was foolish to come out here as it was. I can’t go back. I am inclined to move down to this hotel so I’ll be able to keep in touch with Mr. Balantine with less difficulty.”

“It’s a very nice looking hotel,” commented Penny. “Expensive, I’ve been told.”

“In the show business one must keep up appearances at all cost,” replied Miss Miller. “I believe I’ll inquire about the rates.”

While Penny waited, the actress crossed over to the desk and talked with a clerk. In a small office close by, Ralph Fergus and Harvey Maxwell could be seen in consultation. They were poring over a ledger, apparently checking business accounts.

Miss Miller returned in a moment. “I’ve taken a room,” she announced. “I can’t afford it, but I am doing it anyway.”

“Will you be able to manage?”

“Oh, I’ll run up a bill and then let them try to collect!”

Penny gazed at the actress with frank amazement.

“You surely don’t mean you would deliberately defraud the hotel?”

“Not so loud or the clerk will hear you,” Miss Miller warned. “And don’t use such an ugly word. If I land the part with Mr. Balantine, of course I’ll pay. If not—the worst they can do is to throw me out.”

Penny said no more but her opinion of Miss Miller had descended several notches.

“What are you doing here?” the actress inquired, quickly changing the subject.

“Oh, I just came down to look over the hotel. It’s very swanky, but I like Mrs. Downey’s place better.”

Miss Miller turned to leave. “I am going back there now to check out,” she declared. “Would you like to walk along?”

“No, thank you, I’ll just stay here and rest for a few minutes.”

Penny had no real purpose in coming to the Fergus hotel. She merely had been curious to see what it was like. Even a casual inspection made it clear that Mrs. Downey’s modest little lodge never could compete with such a luxurious establishment.

She studied the faces of the persons in the lobby. There seemed to be a strange assortment of people, including a large number of men and women who certainly had never been drawn to Pine Top by the skiing. Penny thought whimsically that it would be interesting to see some of the fat, pampered-looking ones take a tumble on the slippery slopes.

“But what is the attraction of this place, if not the skiing?” she puzzled. “There is no other form of entertainment.”

Presently, a well-fed lady in rustling black silk, her hand heavy with diamond rings, paused beside Penny.

“I beg your pardon,” she said, “can you tell me how to find the Green Room?”

“No, I can’t,” replied Penny. “I would need a map to get around in this hotel. You might ask at the desk.”

The woman fluttered over to the clerk and asked the same question.

“You have your card, Madam?” he inquired in a low tone.

“Oh, yes, to be sure. The manager presented it to me this morning.”

“Take the elevator to the second floor wing,” the man instructed. “Room 22. Show your card to the doorman and you will be admitted.”

Penny waited until after the woman had gone away. Then she arose and sauntered across the lobby. She picked up a handful of hotel literature but there was no mention of any Green Room. Pausing by the elevator, she waited until the cage was deserted of passengers before speaking to the attendant, a red headed boy of about seventeen.

“Where is the Green Room, please?”

“Second floor, Miss.”

“And what is it? A dining room?”

The attendant shot her a peculiar glance and gave an answer which was equally strange.

“It’s not a dining room. I can’t tell you what it is.”

“A cocktail room perhaps?”

“Listen, I told you I don’t know,” the boy answered.

“You work here, don’t you?”

“Sure I do,” he said with emphasis. “And I aim to keep my job for awhile. If you want to know anything about the Green Room ask at the desk!”

Before Penny could ask another question, the signal board flashed a summons, and the attendant slammed shut the door of the elevator. He shot the cage up to the fifth floor and did not return.

Hesitating a moment, Penny wandered over to the desk.

“How does one go about obtaining a card for the Green Room?” she inquired casually.

“You’re not a guest here?” questioned the clerk.

“No.”

“You’ll have to talk with the manager. Oh, Mr. Fergus!”

Penny had not meant to have the matter go so far, but there was no retreating. The hotel manager came out of his office, and recognizing her, smiled ingratiatingly.

“Ah, good afternoon, Miss—” He groped for her name but Penny did not supply it. “So you decided to pay us a visit after all.”

“This young lady asked about the Green Room,” said the clerk significantly.

Mr. Fergus bestowed a shrewd, appraising look upon Penny.

“Oh, yes,” he said to give himself more time, “Oh, yes, I see. What was it you wished to know?”

“How does one obtain a card of admission?”

“It is very simple. That is, if you have the proper recommendations and bank credit.”

“Recommendations?” Penny asked blankly. “Just what is the Green Room anyway?”

Ralph Fergus and the clerk exchanged a quick glance which was not lost upon the girl.

“I see you are not familiar with the little service which is offered hotel guests,” Mr. Fergus said suavely. “I shall be most happy to explain it to you at some later time when I am not quite so busy.”

He bowed and went hurriedly back into the office.

“I guess I shouldn’t have inquired about the Green Room,” Penny observed aloud. “There seems to be a deep mystery connected with it.”

“No mystery,” corrected the clerk. “If you will leave your name and address I am sure everything can be arranged within a few days.”

“Thank you, I don’t believe I’ll bother.”

Penny turned and nearly ran into Francine Sellberg. Too late, she realized that the girl reporter probably had been standing by the desk for some time, listening to her conversation.

“Hello, Francine,” she said carelessly.

The girl returned a haughty stare. “I don’t believe I know you, Miss,” she said, and walked on across the lobby.

Penny was rather stunned by the unexpected snub. She took a step as if to follow Francine and demand an explanation, but her sense of humor came to her rescue.

“Who cares?” she asked herself with a shrug. “If she doesn’t care to know me, it’s perfectly all right. I can manage to bear up.”

After Francine had left the hotel, Penny made up her mind that she would try to learn a little more about the Green Room. Her interest was steadily mounting and she could not imagine what “service” might be offered guests in this particular part of the hotel.

Choosing a moment when no one appeared to be watching, Penny mounted the stairway to the second floor. She followed a long corridor to its end but did not locate Room 22. Returning to the elevator, she started in the opposite direction. The numbers ended at 20.

While Penny was trying to figure it out, a group of four men and women came down the hall. They were well dressed individuals but their manner did not stamp them as persons of good breeding. One of the women who carried a jeweled handbag was talking in a loud, excited tone:

“Oh, Herbert, wait until you see it! I shall weep my eyes out if you don’t agree to buy it for me at once. And the price! Ridiculously cheap! We’ll never run into bargains like these in New York.”

“We’ll see, Sally,” replied the man. “I’m not satisfied yet that this isn’t a flim-flam game.”

He opened a door which bore no number, and stood aside for the others to pass ahead of him. Penny caught a glimpse of a long, empty hallway.

“That must be the way to Room 22,” she thought.

She waited until the men and women had gone ahead, and then cautiously opened the door which had closed behind them. No one questioned her as she moved noiselessly down the corridor. At its very end loomed a green painted door, its top edge gracefully circular. Beside it at a small table sat a man who evidently was stationed there as a guard.

Penny walked slowly, watching the men and women ahead. They paused at the table and showed slips of cardboards. The guard then opened the green door and allowed them to pass through.

It looked so very easy that Penny decided to try her luck. She drew closer.

“Your card please,” requested the doorman.

“I am afraid I haven’t mine with me,” said Penny, flashing her most beguiling smile.

The smile was entirely lost upon the man. “Then I can’t let you in,” he said.

“Not even if I have lost my card?”

“Orders,” he answered briefly. “You’ll have no trouble getting another.”

Penny started to turn away, and then asked with attempted carelessness:

“What’s going on in there anyway? Are they selling something?”

“I really couldn’t tell you,” he responded.

“Everyone in this hotel seems to be blind, deaf and dumb,” Penny muttered to herself as she retraced her way to the main hall. “And definitely, for a purpose. I wonder if maybe I haven’t stumbled into something?”

She still had not the faintest idea what might lie beyond the Green Door, but the very name had an intriguing sound. It suggested mystery. It suggested, too, that Ralph Fergus and his financial backer, Harvey Maxwell, might have developed some special money-making scheme which would not bear exposure.

Into Penny’s mind leaped a remark which her father had made, one to the effect that Harvey Maxwell was thought to have his finger in many dishonest affairs. The Green Room might be a perfectly legitimate place of entertainment for hotel guests, but the remarks she had overheard led Penny to think otherwise. Something was being sold in Room 22. And to a very select clientele!

“If only I could learn facts which would help Dad’s case!” she told herself. “Anything showing that Maxwell is mixed up in a dishonest scheme might turn the trick!”

It occurred to Penny that the editor of the Riverview Record might have had some inkling of a story to be found at Pine Top. Otherwise, why had Francine been sent to the mountain resort? Certainly the rival reporter was working upon an assignment which concerned Harvey Maxwell. She inadvertently had revealed that fact at the Riverview airport.

“Francine thinks I came here for the same purpose,” mused Penny. “If only she weren’t so high-hat we could work together.”

There was almost no real evidence to point to a conclusion that the Fergus hotel was not being operated properly. Penny realized only too well that once more she was depending upon a certain intuition. An investigation of the Green Room might reveal no mystery. But at least there was a slender hope she could learn something which would aid her father in discrediting Harvey Maxwell.

Without attracting attention, Penny descended to the main floor and left the hotel. As she retrieved her skis from the snowbank she was surprised to see Francine standing close by, obviously waiting for her.

“Hello, Penny,” the girl greeted her.

“Goodness! Aren’t you mistaken? I don’t think you know me!”

“Oh, don’t try to be funny,” Francine replied, falling into step. “I’ll explain.”

“I wish you would.”

“You should have known better than to shout out my name there in the lobby.”

“I don’t follow your reasoning at all, Francine. Are you traveling incognito or something?”

“Naturally I don’t care to have it advertised that I am a reporter. I rather imagine you’re not overly anxious to have it known that you are the daughter of Anthony Parker either!”

“It probably wouldn’t be any particular help,” admitted Penny.

“Exactly! Despite your play-acting at the airport, I know you came here to get the low-down on Harvey Maxwell. But the minute he learns who you are you’ll not even get inside the hotel.”

“And that goes double, I take it?”

“No one at Pine Top except you knows I am a reporter,” went on Francine without answering. “So I warn you, don’t pull another boner like you did a few minutes ago. Whenever we’re around Fergus or Maxwell or persons who might report to them, just remember you never saw me before. Is that clear?”

“Moderately so,” drawled Penny.

“I guess that’s all I have to say.” Francine hesitated and started to walk off.

“Wait a minute, Francine,” spoke Penny impulsively. “Why don’t we bury the hatchet and work together on this thing? After all I am more interested in gaining evidence against Maxwell than I am in getting a big story for the paper. How about it?”

Francine smiled in a superior way.

“Thank you, I prefer to lone wolf it. You see, I happen to have a very good lead, and you don’t.”

“Well, I’ve heard about the Green Room,” said Penny, hazarding a shot in the dark. “That’s something.”

Francine stopped short.

“What do you know about it?” she demanded quickly. “Maybe we could work together after all.”

Penny laughed as she bent down to strap on her skis.

“No, thanks,” she declined pleasantly. “You once suggested that a clever reporter finds his own answers. You’ll have to wait until you read it in the Star!”

Penny sat in the kitchen of Mrs. Downey’s lodge, warming her half frozen toes in the oven.

“Well, how did you like the skiing?” inquired her hostess who was busy mixing a huge meat loaf to be served for dinner.

“It was glorious,” answered Penny, “only I took a bad spill. Somehow I missed the turn you told me about, and found myself heading for a barbed wire fence. I jumped it and made a one point landing in a snowbank!”

“You didn’t hurt yourself, thank goodness.”

“No, but an old man with a shotgun came out of the woods and said ‘Scat!’ to me. It seems he doesn’t like skiers.”

“That must have been Peter Jasko.”

“And who is he, Mrs. Downey?”

“One of the oldest settlers on Pine Top Mountain,” sighed Mrs. Downey. “He’s a very pleasant man in some respects, but in others—oh, dear.”

“Skiing must be one of his unpleasant aspects. I noticed he had a ‘Keep Out’ sign posted on his property.”

“Peter Jasko is a great trial to me and other persons on the mountain. He has a hatred of skiing and everything pertaining to it, which amounts to fanaticism. A number of skiers have been injured by running into his barbed wire fence.”

“Then he put it up on purpose?”

“Oh, yes! He has an idea it will keep folks from skiing.”

“He isn’t—?” Penny tapped her forehead significantly.

“No,” smiled Mrs. Downey. “Old Peter is right in his mind, at least in every respect save this one. He owns our best ski slopes, too.”

Penny shifted her foot to a cooler place in the oven.

“Not the slopes connected with this lodge?”

Mrs. Downey nodded as she whipped eggs to a foamy yellow.

“I leased the land from Jasko’s son many years ago, and Jasko can do nothing about it except rage. However, the lease expires soon. He has given me to understand it will not be renewed.”

“Can’t you deal with the son?”

“He is dead, Penny.”

“Oh, I see. That does make it difficult.”

“Decidedly. Jasko’s attitude about the lease is another reason why I think this will be my last year in the hotel business.”

“You don’t think Ralph Fergus or Harvey Maxwell have influenced Jasko?” Penny asked thoughtfully, a frown ridging her forehead.

“I doubt that anyone could influence the old man,” replied Mrs. Downey. “Stubborn isn’t the word to describe his character. Even if I lose the ski slopes, I am quite sure he will never lease them to the Fergus hotel interests.”

“While I was down there I thought I saw a girl standing at the window of the cabin.”

“Probably you did, Penny. Jasko has a granddaughter about your age, named Sara. A very nice girl, too, but she is kept close at home.”

“I feel sorry for her if she has to live with that old man. He seemed like a regular ogre.”

Removing her toasted feet from the oven, Penny pulled on her stiff boots again. Without bothering to lace them, she hobbled toward the door.

“Oh, by the way,” she remarked, pausing. “Did you ever hear of a Green Room at the Fergus hotel?”

“A Green Room?” repeated Mrs. Downey. “No, I can’t say I have. What is it, Penny?”

“I wonder myself. Something funny seems to be going on there.”

Having aroused Mrs. Downey’s curiosity, Penny gave a more complete account of her visit to the Fergus hotel.

“I’ve never heard anyone mention such a place,” declared the woman in a puzzled voice. “But I will say this. The hotel always has attracted a peculiar group of guests.”

“How would you like to have me solve the mystery for you?” joked Penny.

“It would suit me very well indeed,” laughed Mrs. Downey. “And while you’re about it you might put Ralph Fergus out of business, and bring me a new flock of guests.”

“I’m afraid you’re losing one instead. Maxine Miller told me she is moving down to the big hotel.”

“I know. She checked out a half hour ago. Jake made an extra trip to haul her luggage down the mountain.”

“Anyway, I shouldn’t be sorry to see her go if I were you,” comforted Penny. “I am quite sure she hasn’t enough money to pay for a week’s stay at Pine Top.”

Going to her room, Penny changed into more comfortable clothing and busied herself writing a long letter to her father. From her desk by the window she could see skiers trudging up the slopes, some of them making neat herring-bone tracks, others slipping and sliding, losing almost as much distance as they gained.

As she watched, Francine swung into view, poling rhythmically, in perfect timing with her long easy strides.

“She is good,” thought Penny, grudgingly.