The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Secret of the League, by Ernest Bramah

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Secret of the League

The Story of a Social War

Author: Ernest Bramah

Release Date: November 30, 2010 [EBook #34522]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SECRET OF THE LEAGUE ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

CHAPTER I. Irene

CHAPTER II. The Period, and the Coming of Wings

CHAPTER III. The Million to One Chance

CHAPTER IV. The Compact

CHAPTER V. The Downtrodden

CHAPTER VI. Miss Lisle tells a Long Pointless Story

CHAPTER VII. "Schedule B"

CHAPTER VIII. Tantroy earns his Wage

CHAPTER IX. Secret History

CHAPTER X. The Order of St. Martin of Tours

CHAPTER XI. Man between Two Masters

CHAPTER XII. By Telescribe

CHAPTER XIII. The Effect of the Bomb

CHAPTER XIV. The Last Chance and the Counsel of Expedience

CHAPTER XV. The Great Fiasco

CHAPTER XVI. The Dark Winter

CHAPTER XVII. The Incident of the 13th of January

CHAPTER XVIII. The Music and the Dance

CHAPTER XIX. The "Finis" Message

CHAPTER XX. Stobalt of Salaveira

CHAPTER XXI. The Bargain of Famine

CHAPTER XXII. "Poor England"

NELSON LIBRARY

"I suppose I am old-fashioned"—there was a murmur of polite dissent from all the ladies present, except the one addressed—"Oh, I take it as a compliment nowadays, I assure you; but when I was a girl a young lady would have no more thought of flying than of"—she paused almost on a note of pained surprise at finding the familiar comparison of a lifetime cut off—"well, of standing on her head."

"No," replied the young lady in point, with the unfeeling candour that marked the youthful spirit of the age, "because it wasn't invented. But you went bicycling, and your mothers were very shocked at first."

"I hardly think that you can say that, Miss Lisle," remarked another of the matrons, "because I can remember that more than twenty years ago one used to see quite elderly ladies bicycling."

"After the others had lived all the ridicule down," retorted Miss Lisle scornfully. "Oh yes; I quite expect that in a few more years you will see quite elderly ladies flying."

The little party of matrons seated on the Hastings promenade regarded each other surreptitiously, and one or two smiled slightly, while one or two shuddered slightly. "Flying is very different, dear," said Mrs Lisle reprovingly. "I often think of what your dear grandfather used to say. He said"—impressively—"that if the Almighty had intended that we should fly, He would have sent us into the world with wings upon our backs."

There was a murmur of approval from all—all except Miss Lisle, that is.

"But do you ever think of what Geoffrey replied to dear grandpapa when he heard him say that once, mother?" said the unimpressed daughter. "He said: 'And don't you think, sir, that if the Almighty had intended us to use railways, He would have sent us into the world with wheels upon our feet?'"

"I do not see any connection at all between the two things," replied her mother distantly. "And such a remark seems to me to be simply irreverent. Birds are born with wings, and insects, and so on, but nothing, as far as I am aware, is born with wheels. Your grandfather used to travel by the South Eastern regularly every day, or how could he have reached his office? and he never saw anything wrong in using trains, I am sure. In fact, when you think of it you will see that what Geoffrey said, instead of being any argument, was supremely silly."

"Perhaps he intended it to be," replied Miss Lisle with suspicious meekness. "You never know, mother."

Such a remark merited no serious attention. Why should any one, least of all a really clever young man like Geoffrey, deliberately intend to be silly? There was too often, her mother had observed, an utter lack of relevance in Irene's remarks.

"I think that it is a great mistake to have white flying costumes as so many do," observed another lady. "They look—but perhaps they wish to."

"Certainly when they use lace as well it really seems as though they do. Oh!"

There was a passing shadow across the group and a slight rustle in the air. Scarcely a dozen yards above the promenade a young lady was flying strongly down the wind with the languid motion of the "swan stroke." She wore white—and lace trimming. Mrs Lisle gazed fixedly out to sea. Even Irene felt that the vision was inopportune.

"There are always some who overdo a thing," she remarked. "There always have been. That was only Velma St Saint of the New Gaiety; she flies about the front every day for the advertisement of the thing: I wonder that she doesn't drop handbills as she goes. There's plenty of room up on the Castle Hill—in fact, you aren't supposed to fly west of the Breakwater—but there will always be some——" A vague resentment closed the period.

"Are you staying at the Palatial this time?" asked the lady who had mentioned lace, feeling it tactful to change the subject. "I think that you used to."

"Oh, haven't you seen?" was the reply. "The Palatial has been closed for the last six months."

"Yes, it's a great pity," remarked another. "It looks so depressing too, right on the front. But they simply could not go on. I suppose that the rates here are something frightful now."

"Oh, enormous, my dear; but it was not that alone. The Palatial has always aimed at being a 'popular' hotel, and so few of the upper middle class can afford hotels now. Then the new tax on every servant above one—calculated as fifty per cent. of their wages, I think, but there are so many new taxes to remember—proved the last straw."

"Yes, it is fifty per cent. I remember because I had to give up my between-maid to pay the cook's tax. But I thought that hotels were to be exempt?"

"Not in the end. It was argued that hotels existed for the convenience of the monied classes, and that they ought to pay for it. So a large number of hotels are closed altogether; others work with a reduced staff, and a great many servants have been thrown out of employment."

Miss Lisle laughed unpleasantly. "A good thing, too," she remarked. "I hate hotel servants. So does everybody. It is the only good thing I have heard of the Labour Government doing."

"I am sure I don't hate them," said Mrs Lisle, looking round with pathetic resignation, "although they certainly had become rather grasping and over-bearing of late. But it was quite an unforeseen development of the scheme that so many should lose their places. Indeed the special object of the tax was to create a fund—'earmarked' I think they call it—out of which to meet the growing pension claim, now that so few of the servant class think it worth while to save."

Miss Lisle laughed again, this time with a note of genuine amusement.

("A most unpleasant girl, I fear," murmured the lady who had raised the white costume question, to her neighbour in a whisper: "so odd.")

"It made a great difference at the registry offices. There are a dozen maids to be had any day where there were really none before. Only one cannot afford to keep them now."

There was a word, a sigh, and an "Ah!" to mark this point of agreement among the four ladies.

"I am afraid that the Government confiscation of all dividends above five per cent. bears very heavily on some," remarked one after a pause. "I know a poor soul of over sixty-five, nearly blind too, whose husband had invested all his savings in the company he had worked for because he knew that it was safe, and, having a good reserve, intended to pay ten per cent. for a long time. When he died it brought her in fifty pounds a year. Now——"

There were little signs of sympathy and commiseration from the group. The sex was beginning to take an unwonted interest in terms financial—per centage, surrender value, trustee stock, unearned increment, and so on. They had reason to do so, for revolutionary finance was very much in the air, or, rather, had come tangibly down to earth at length: not the placid city echoes that were wont to ripple gently across the breakfast-table a few years earlier without leaving any one much better or much worse off, but the galvanic adjustment that by a stroke made the rich well-to-do, the well-to-do just so-so, the struggling poor, and left the poor where they were before. The frenzied effort that in a session strove to tear up the trees of the forest and leave the plants beneath untouched; to pull to pieces the intertwined fabric of a thousand years' growth and to create from it a bundle of straight and equal twigs; in a word, to administer justice on the principle of knocking out one eye in all the sound because a number of people were unfortunately born or fallen blind.

"Five and twenty," mused Mrs Lisle. "I suppose it is just possible."

"It is really less than that," explained the other. "You may have noticed that as it is now no good making more than five per cent., most companies pay even less. There is no incentive to do well."

"One hears of even worse cases on every hand," said another of the ladies. "I am trying to interest people in a poor deformed creature whose father left her an annuity derived from ground rents in the City.... As it has been worked out I think that she owes the Incomes Adjustment Department lawyers something a year now. But private charity seems almost to have ceased altogether. Have you heard that 'Jim's' is closed?"

It was true. St James's Hospital, whose unvarnished record was, "Three hundred of the very poor treated freely each day," was a thing of the past, and across its portal, where ten years before a couple of stalwart gentlemen wearing red ties had rested for a moment, while they lit their pipes, a banner with the strange device, "Curse your Charity!" now ran the legend, "Closed for want of Funds."

"I wonder sometimes," mused the last speaker, "why some one doesn't do something."

"But," objected another, "what is there to do? What is there?"

They all agreed that there was nothing—absolutely nothing. Every one else was tacitly making the same admission; that was the fatal symptom.

Miss Lisle jumped up and began to move away unceremoniously.

"Where are you going, dear?" asked her mother in mild reproof.

"Oh, anywhere," replied Irene restlessly.

"But what for?" persisted Mrs Lisle.

"Oh, anything."

"That is 'nothing,' Miss Lisle," smiled the tactful lady of the party, anxious to smooth over the awkwardness of the moment.

"No, it is at least something," flung back the girl brusquely; and with swinging strides she set off at a furious pace towards the open country.

"Irene is a little impulsive at times," apologized her mother, sitting back with placidly folded hands.

An intelligent South Sea Islander, who had been imported into this country to stimulate missionary enterprise, on his return had said that the most marked characteristic of the English of the period was what they called "snap."

The nearest equivalent in his own language signifying literally "quick hot words," he had some difficulty in conveying the impression he desired, and his circle had to rest content that "snap" permeated the journalism, commerce, politics, drama, and social life of the English, had assailed their literature, and was beginning to influence religion, art, and science. It may be admitted that the foreign gentleman's visit had coincided with a period of national stress, for the week in question had embraced the more entertaining half of a general election, seen the advent of two new farthing daily papers, and been marked by the Rev. Sebastian Tauthaul's striking series of addresses from the pulpit of the City Sanctum, entitled "If Christ put up for Battersea." It had also included the launching of a new cocoa, a new soap, and a new concentrated food.

The new food was called "Chip-Chunks." "A name which I venture to think spells success of itself," complacently remarked its inventor. "A very good name indeed," admitted his advertising manager. "It has the great desideratum that it might be anything, and, on the other hand, it might equally well be nothing." "Just so," said the inventor with weighty approval; "just so." A "snap-line" was required that would ineradicably fix Chip-Chunks in the public mind, and "Bow-wow! Feel chippy? Then champ Chip-Chunks" was found in an inspired moment. It was, of course, fully cooked and already quite digested. It was described as the delight of the unweaned infant, the mainstay of the toothless nonagenarian, and so simple and wholesome that it could be safely taken and at once assimilated by the invalid who had undergone the operation of having his principal organ of digestion removed. So little, indeed, remained for nature and the human parts to do in the matter of Chip-Chunks as to raise the doubt whether it might not be simpler and scarcely less nutritive to open the tin and pour the contents down the drain forthwith.

As Chip-Chunks was designed for those who were disinclined to exercise the functions of digestion, so Isabella soap made an appeal to those who disliked work and had something of an antipathy to soap at all. One did not wash with Isabella, it was assured: one sat down and watched it. It had its "snap-lines," too:

"You write it 'wash,' but you call it 'wosh.'

"What is the difference?

"There is 'a' difference.

"There is also 'a' difference between Isabella soap and all other soaps:

"All the difference.

"That's our point. Put it in your washtub and watch it."

Cocoa was approached in a more sober spirit. Soap may blow bubbles of light and airy fancy, pills ricochet from one gay conceit to another, meat extracts gambol with the irresponsible exuberance of bulls in china cups, but cocoa relied upon sincerity and statistics. Kingcup cocoa was the last word of the expert. It won its way into the great heart of the people by driving home the significant fact that it contained .00001 per cent. more phosphorus, and .000002 per cent. less of something fatty, than any other cocoa in existence. When the newspaper reader of the period had been confronted by this assertion, in various guises, seventeen thousand times, he had reached a state of mind in which .00001 per cent. more phosphorus and .000002 per cent. less fat represented the difference between vigorous manhood and drivelling imbecility.

The Rev. Sebastian was all "snap." His topical midday addresses—described by himself as "Seven minutes sandwich-sermonettes"—have already been referred to. Young men who were pressed for time were bidden to bring their bath buns or buttered scones and eat openly and unashamed. Workmen with bread and cheese and pots of beer were welcomed with effusion. This particular series extended over the working days of a week, and was subdivided thus:

Of the new papers, of their sprightliness, their enterprise, their general all-roundness, their almost wicked experience of the ways of the world, from a quite up-to-date fund of junior office witticism to a knowledge of the existence of actresses who do not act, outwardly respectable circles of society who play cards for money on Sunday, and (exclusively for the benefit of their readers) places where quite high-class provisions (only nominally damaged) could be bought cheap on Saturday nights, it is unnecessary to say much. Of their irresponsible cock-sureness, their bristling combativeness, their amazing powers of prophetic penetration, and, it must be confessed, their ineradicable air of somewhat second-rate infant phenomenonship, their crumbling yellow files still bear witness. As a halfpenny is half a penny, so a farthing is half a halfpenny, and the mind that is not too appalled by the possibilities of the development can people for itself this journalistic Eden.

The Whip described its programme as "Vervy and nervy; brainy and champagny." The Broom relied more on solider attractions of the "News of the World in Pin Point Pars" and "Knowledge in Nodules" order. Both claimed to be written exclusively by "brainy" people, and both might have added, with equal truth, read exclusively by brainless. Avowedly appealing "to the great intellect of the nation," neither fell into the easy mistake of aiming too high, and the humblest son of toil might take them up with the fullest confidence of finding nothing from beginning to end that was beyond his simple comprehension.

But the most cursory review of national "snappishness" would be incomplete if it omitted the field of politics, especially when the period in question contained so concentrated an accumulation of "snap" as a general election. Contests had long ceased to be decided on the merits of individuals or of parties, still less to be the occasions for deliberate consideration of policy. Each group had its label and its "snap-cries." The outcome as a whole—the decision of each division with few exceptions—lay in the hands of a class which, while educated to the extent of a little reading and a little writing, was practically illiterate in thought, in experience, and in discrimination. To them a "snap-cry" was eminently suited, as representing a concrete idea and being in fact the next best argument to a decayed egg. That national disaster had never so far been evolved out of this rough-and-ready method could be traced to a variety of saving clauses. At such a time the strict veracity of the cries raised was not to be too closely examined; indeed, there was not the time for contradiction, and therein lay the essence of some of the most successful "snaps."

Misrepresentation, if on a sufficiently large scale, was permissible, but it was advisable to make it wholesale, lurid, and applied not to an individual but to a party—emphasising, of course, the fact that your opponent was irretrievably pledged to that party through thick and thin.

In other words, it was quite legitimate for A to declare that the policy of the party to which his opponent B belonged was a policy of murder, rapine, piracy, black-mail, highway robbery, extermination, and indiscriminate bloodshed; that they had swum to office on a sea of tears racked from the broken hearts of an outraged peasantry, risen to power on the apex of a smoking hecatomb of women and children, and kept their position by methods of ruthless barbarism; that assassination, polygamy, thuggeeism, simony, bureaucracy, and perhaps even an additional penny on the poor man's tea, would very likely be found included in their official programme; that they were definitely pledged to introduce Kalmucks and Ostyaks into the Government Dock-yards, who would work in chained gangs, be content with three farthings for a fourteen hours' day, and live exclusively on engine waste and barley-water.

This and much more was held to be fair political warfare which should not offend the keenest patriot. But if A so far descended to vulgar personalities as to accuse B himself of employing an urchin to scare crows at eightpence a day when the trade union rate for crow-scaring was ninepence, he stood a fair chance of having an action for libel or defamation of character on his hands in addition to an election.

Under such a system the least snappy went to the wall. Happy was the man who was armed not necessarily with a just cause, but with a name that lent itself to topical alliteration. Who could resist the appeal to

| Vote for | Frank | Blarney. |

| Fresh | Brooms in Parliament. | |

| Fewer | Bungles during the next five years. | |

| Financial | Betterment at home. | |

| Free | Breakfast-tables for the People. | |

| Flourishing | Businesses all round. |

—especially when it was coupled with the reminder that

Every vote given to A. J. Wallflower is a slice of bread filched from your innocent children's hard-earned loaf.

Of course the schools could not escape the atmosphere. The State-taught children were wonderfully snappy—for the time being. Afterwards, it might be noticed, that when the props were pulled away they were generally either annoyingly dull or objectionably pert, or, perhaps, offensively dully-pert, according to whether their nature was backward or forward, or a mixture of both. The squad-drilled units could remember wonderfully well—for the time; they could apply the rules they learned in just the way they were taught to apply them—for the time. But they could not remember what they had not been drilled to remember; they could not apply the rules in any other way; they could not apply the principles at all; and they could not think.

High and low, children were not allowed to think; with ninety-nine mothers out of a hundred its proper name was "idleness." "I do not like to see you sitting down doing nothing, dear," said every mother to every daughter plaintively. "Is there no sewing you might do?" So the would-be thoughtful child was harried into working, or playing, or eating, or sleeping, as though a mind contentedly occupied with itself was an unworthy or a morbid thing.

Yet it was a too close adherence to the national character that proved to be the undoing of Wynchley Slocombe, who is now generally admitted to have been the father of the form of aerial propulsion so widely enjoyed to-day. Like everybody else, he had read the offer of the Traffic and Locomotion Department of a substantial reward for a satisfactory flying-machine, embracing "any contrivance ... that would by demonstration enable one or more persons, freed from all earth-support or connection (a) to remain stationary at will, at any height between 50 and 1500 feet; (b) at that height to travel between two points one mile apart within a time limit of seven minutes and without deviating more than fifty yards from a straight line connecting the two points; (c) to travel in a circle of not less than three miles in circumference within a time limit of fifteen minutes." Wynchley took an ordinary intelligent interest in the subject, but he had no thought of competing.

It was not until the last day of the period allowed for submitting plans that Wynchley's great idea occurred to him. There was then no time for elaborating the germ or for preparing the requisite specifications, even if he had any ability to do so, which he had not, being, in fact, quite ignorant of the subject. But he remembered hearing in his youth that when a former Government of its day had offered a premium for a convenient method of dividing postage stamps (until that time sold in unperforated sheets and cut up as required by the users), the successful competitor had simply tendered the advice, "Punch rows of little holes between them." In the same spirit Wynchley Slocombe took half a sheet of silurian notepaper (now become famous, and preserved in the South Kensington Museum) and wrote on it, "Fasten on a pair of wings, and practise! practise!! practise!!!" It was to be the aerial counterpart of "Gunnery! Gunnery!! Gunnery!!!"

Unfortunately, the departmental offices were the only places in England where "snap" was not recognised. Wynchley was regarded as a suicidal lunatic—a familiar enough figure in flying-machine circles—and his suggestion was duly pigeon-holed without consideration.

The subsequent career of the unhappy man may be briefly stated. Disappointed in his hopes of an early recognition, and not having sufficient money at his disposal to demonstrate the practicability of his idea, he took to writing letters to the President of the Board, and subsequently to waylaying high officials and demanding interviews with them. Dismissed from his situation for systematic neglect of duty, he became a "poor litigant with a grievance" at the Law Courts, and periodically applied for summonses against the Prime Minister, the Lord Mayor of London, and the Archbishop of Canterbury. Still later his name became a by-word as that of a confirmed window-breaker at the Government offices. A few years afterwards, a brief paragraph in one or two papers announced that Wynchley Slocombe, "who, some time ago, gained an unenviable notoriety on account of his hallucinations," had committed suicide in a Deptford model lodging-house.

In the meanwhile two plans for flying-machines had been selected as displaying the most merit, and their inventors were encouraged to press on with the construction under a monetary grant. Both were finished during the same week, and for the sake of comparison they were submitted to trial on the same day upon Shorncliffe plain. Vimbonne VI., which resembled a much-distended spider with outspread legs, made the first ascent. According to instructions, it was to demonstrate its ability to go in a straight line by descending in a field near the Military Canal, beyond Seabrook, but from the moment of its release it continued to describe short circles with a velocity hitherto unattained in any air-ship, until its frantic constructor was too dizzy to struggle with its mechanism any longer. The Moloch was then unmoored, and took up its position stationary at a height of 1000 feet with absolute precision. It was built on the lines of a gigantic centipede, with two rows of clubby oars beneath, and ranked as the popular favourite. Being instructed, for the sake of variety, to begin with the three mile circle, the Moloch started out to sea on the flash of the gun, the sinuous motion that rippled down its long vertebrate body producing an effect, accidental but so very life-like, that many of the vast concourse assembled on the ground turned pale and could not follow it unmoved....

There have been many plausible theories put forward by experts to account for the subsequent disaster, but for obvious reasons the real explanation can never progress beyond the realms of conjecture, for the Moloch, instead of bending to the east, encircling Folkestone and its suburbs, and descending again in the middle of Shorncliffe Camp, continued its unswerving line towards the coast of France, and never held communication with civilised man again.

So exact was its course, however, that it was easy to trace its passage across Europe. It reached Boulogne about four o'clock in the afternoon, and was cheered vociferously under the pathetic impression that everything was going well. Amiens saw it a little to the east in the fading light of evening, and a few early citizens of Dijon marked it soon after dawn. Its passage over the Alps was accurately timed and noted at several points, and the Italian frontier had a glimpse of it, very high up, it was recorded, at nightfall. A gentleman of Ajaccio, travelling in the interior of the island, thought that he had seen it some time during the next day; and several Tripoli Greeks swore that it had passed a few yards above their heads a week later; but the testimony of the Corsican was deemed the more reliable of the two. A relief expedition was subsequently sent out and traversed a great part of Africa, but although the natives in the district around the Albert Nyanza repeatedly prostrated themselves and smacked their thighs vigorously—the tribal signs of fear and recognition—when shown a small working model of the Moloch, no further trace was ever obtained of it.

The accident had a curious sequel in the House of Commons, which significantly illustrates how unexpected may be the ultimate developments of a chain of circumstance. It so happened that in addition to its complement of hands, the Moloch carried an assistant under-secretary to the Board of Agriculture. This gentleman, who had made entomology a lifelong study, was invaluable to his office, and the lamentable consequence of his absence was that when the President of the Board rose the following night to answer a question respecting the importation of lady-birds to arrest an aphis plague then devastating the orchards of the country, he ingenuously displayed so striking an unfamiliarity with the subject that his resignation was demanded, the Government discredited, and a dissolution forced. In particular, the hon. gentleman convulsed the House by referring throughout to lady-birds as "the female members of the various feathered tribes," and warmly defending their importation as the only satisfactory expedient in the circumstances.

Wynchley's suggestion remained on file for the next few years, and would doubtless have crumbled to dust unfruitfully had it not been for a trivial incident. A junior staff clerk, finding himself to be without matches one morning, and hesitating to mutilate the copy of—let us say, the official Pink Paper which he was reading at the moment, absent-mindedly tore a sheet haphazard from a bundle close at hand. As he lit his cigarette, the name of Wynchley Slocombe caught his eye and stirred a half-forgotten memory, for the unfortunate Wynchley had been a stock jest in the past.

Herbert Baedeker Phipps now becomes a force in the history of aerial conquest. He smoothed out the paper from which he had only torn off a fragment, read the stirring "Practise! Practise!! Practise!!!" (at least it has since been recognised to be stirring—stirring, inspired, and pulsating with the impassioned ardour of neglected genius), and pondered deeply to the accompaniment of three more cigarettes. Was there anything in it? Why could not people fly by means of artificial wings? There had been attempts; how did the enthusiasts begin? Usually by precipitating themselves out of an upper window in the first flush of their self-confidence. They were killed, and wings fell into disfavour; but the same result would attend the unsophisticated novice who made his first essay in swimming by diving off a cliff into ten fathoms deep of water. Here, even in a denser medium, was the admitted necessity for laborious practice before security was assured.

Phipps looked a step further. By nature man is ill-equipped for flying, whereas he possesses in himself all the requisites for successful propulsion through the water. Yet he needs practice in water; more practice therefore in air. For thousands of years mankind has been swimming and thereby lightening the task for his descendants, to such an extent that in certain islands the children swim almost naturally, even before they walk; whereas, with the solitary exception of a certain fabled gentleman who made the attempt so successfully and attained such a height that the sun melted the wax with which he had affixed his wings (Styckiton in convenient tubes not being then procurable), no man has ever flown. More, more practice. The very birds themselves, Phipps remembered, first require parental coaching in the art, while aquatic creatures and even the amphibia take to that element with developed faculties from their birth. Still more need of practice for ungainly man. Here, he was convinced, lay the whole secret of failure and possible success. "Practise! Practise!! Practise!!!" The last word was with Wynchley Slocombe.

So wings came—to stay, every one admitted, although most people complained that after all flying was not so wonderful when one could do it as they thought it would have been. For at the first glance the popular fancy had inclined towards pinning on a pair of gauzy appendages and soaring at once into empyrean heights with the spontaneity of a lark, or of lightly fluttering from point to point with the ease and grace of a butterfly. They found that a pair of wings cost rather more than a high-grade bicycle, and that the novice who could struggle from the stage into a net placed twenty yards away, after a month's course of daily practices, was held to be very promising. There was no more talk of England lying at the mercy of any and every invader; for one man, and one only, had so far succeeded in crossing even the Channel, and that at its narrowest limit. For at least three years after the conversion of Phipps the generality of people gleaned their knowledge of the progress of flying from the pages of the comic papers. To the comic papers wings had been sent as an undiluted blessing.

But if alatics, in their infancy, did not come up to the wider expectation, there were many who found in it a novel and exhilarating sport. There were also those who, discovering something congenial in the new force, set quietly and resolutely to work to develop its possibilities and to raise it above the level of a mere fashionable novelty. There have always been some, a few, not infrequently Englishmen, who have unostentatiously become pre-eminent in every development of science with a fixity of purpose. Their names rarely appear in the pages of history, but they largely write it.

Hastings permitted mixed flying. It was a question that had embittered many a town council. To one section it seemed intolerable that a father, a husband, or a brother should be torn for twenty minutes from the side of his female relatives; to the opposing section it seemed horrible that coatless men should be allowed to spread their wings within a hundred and fifty yards of shoeless women.

"I have no particular convictions," one prominent citizen remarked, "but in view of the existing railway facilities it is worth while considering whether we shall have any visitors at all this season if we stand in the way of families flying down together." The humour of the age was flowing mordaciously, even as the wit of France had done little more than a century before. The readiest jests carried a tang, whether turning upon personal poverty, municipal extravagance, or national incapacity. Opinion being evenly divided, the local rate of seventeen shillings in the pound influenced the casting vote in favour of mixed flying. There were necessary preparations, including a captive balloon in which an ancient mariner, decked out with a pair of wings like a superannuated Cupid, was posted to render assistance to the faltering. The rates at once rose to seventeen shillings and sixpence, but the principle of the enterprise was admitted to be sound.

So on this pleasant summer afternoon—an ideal day for a fly, said every one—the heights above the old town were echoing to the ceaseless gaiety of the watching crowd, for alatics had not yet ceased to be a novelty, while the air above was cleft by a hundred pairs of beating wings.

"A remarkable sight," said an old man who had opened conversation with the sociable craving of the aged; "ten years ago we little expected this."

"Why, no," replied his chance acquaintance on the seat; "if I remember rightly, the tendency was all towards a combination either of a balloon and a motor-car or of a submarine and a band-box."

"You don't fly yourself?"

The young man—and he was a stalwart enough youth—looked at himself critically as if mentally picturing the effect of a pair of wings upon his person. "Well, no," he replied; "one doesn't get the time for practice. Then consider the price of the things. And the annual licence—oh, they won't let you forget that, I assure you. Well, is it worth it?"

The old man shook his head in harmonious agreement; decidedly for him it was not worth it. "Perhaps you are in Somerset House?" he remarked tentatively. It is not the young who are curious; they have the fascinating study of themselves.

"Not exactly," replied the other, veiling by this diplomatic ambiguity an eminent firm of West End drapers; "but I happen to have rather exceptional chances of knowing what is going on behind the scenes in London. I can assure you, sir, that in spite of the last sixpence on the income-tax and the hen-roost tax, the Chancellor of the Exchequer has sent out stringent orders to whip up every penny in the hope of lessening a serious deficit."

"There may possibly be a deficit," admitted the old man with bland assurance; "but what do a few millions, either one way or the other, matter to a country with our inexhaustible resources? We are certainly passing through a period of financial depression, but the unfailing lesson of the past has been that a cycle of bad years is inevitably followed by a cycle of good years, and in the competition with foreign countries our advantage of free trade ensures our pre-eminence." For it is a mistake now to ascribe optimism to youth. Those youths have by this time grown up into old men. Age is the optimist because it has seen so many things "come right," so many difficulties "muddled through." Also because they who would have been pessimistic old men have worried themselves into early graves. Your unquenchable optimist needs no pill to aid digestion. "Then," he concluded, "why trouble yourself unnecessarily on a beautiful day like this!"

"Oh, it doesn't trouble me," laughed the other man; "at least the deficit doesn't; nor the income-tax, I regret to say. But I rather kick at ten per cent. on my season ticket and a few other trifles when I consider that there used to be better national value without them. And I rather think that most others have had about enough of it."

"Patience, patience; you are a young man yet. Look round. I don't think I ever saw the grass greener for the time of the year, and in my front garden I noticed only to-day that the syringa is out a full week earlier than I can remember.... Eh! What is it? Which way? Where?"

The clerk was on his feet suddenly, and standing on the seat. Every one was standing up, and all in a common impulse were pointing to the sky. Some—women—screamed as they stood and watched, but after a gasp of horrified surprise, like a cry of warning cut short because too late, the mingling noises of the crowd seemed to shrink away in a breath. Every one had read of the sickening tragedies of broken cross-rods or of sudden loss of wing-power—ærolanguisis it was called—and one was taking place before their eyes. High up, very high at first, and a little to the east, a female figure was cleaving headlong through the air, and beyond all human power to save.

So one would have said; so every one indeed assumed; and when a second later another figure crossed their range it only heralded a double tragedy. It drew a gasp ... a gasp that lingered, spun out long and turned to one loud, tumultuous shout. The next minute men were shouting incoherently, dancing wildly, shaking hands with all and any, and expressing frantic relief in a hundred frantic ways.

Thus makes his timely entry into this chronicle Gatacre Stobalt, and reviewing the progress of flying as it then immaturely stood, it is not too much to say that no other man could have turned that tragedy. With an instinctive judgment of time, distance, angle, and his own powers, Stobalt, from a hundred feet above, had leapt as a diver often leaps as he leaves the plank, and with rigid outstretched wings was dropping earthward on all but a plummet line. It was the famous "razor-edge" stroke at its narrowest angle, the delight of strong and daring fliers, the terror of those who watched beneath. It may be realised by ascending to the highest point of St Paul's and contemplating a dive into the flooded churchyard.

The moment was a classic one in the history of the wing. The air had claimed its victims as the waters have; and there was a legitimate pride, since the enterprise was no longer foolhardy, that they had never been withheld. But never before had a rescue been effected beyond the limits of the nets; it was not then deemed practicable and the axiom of the sport "A broken wing is a broken neck," so far held good. Yet here was a man, no novice in the art, deliberately pointing sheer to earth on a line that must bring him, if unswervingly maintained, into contact with the falling girl beneath. Up to that point the attempt would have been easy if daring, beyond it nothing but the readiest self-possession and the most consummate skill could avert an irretrievable disaster to himself.

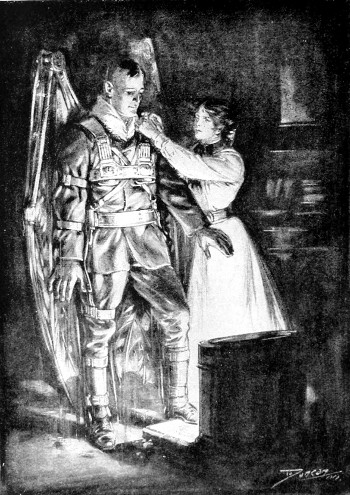

"You have not even had the curiosity to ask if I am hurt yet." Her voice certainly was.

"X = - 4 {C^2} {x^3}," murmured Stobalt abstractedly. "I assure you," he explained, leaving the higher mathematics at her reproach, "that I had quite satisfied myself that you were not.... It all turns on the extra tension thrown on the crank by the additional three feathers. I am convinced that English makers have gone as far as they safely can in that direction." He glanced at her wings as he mused. They were of the familiar detached feather—or "venetian blind," as it was commonly called—pattern, and wonderfully graceful in their long sweep and elegant poise. Made of the purest white celluloid, just tinted with a delicate and deepening pink at the base, they harmonised with her sea-green costume as faultlessly as the lily with the leaves it springs from. Stobalt himself used the more difficult but much more powerful "bat" shape, built up of gold-beaters' skin; he had already folded them in rest, but in those early days the prudish conventions of the air debarred the girl from seeking a like repose.

"I should certainly discard the three outside feathers," he summed up.

"I shall certainly discard the whole thing," she replied. "I do not know which felt the worse—being killed or being saved."

He made a gesture that would seem to say that the personal details of the adventure were better dismissed. He was plainly a man of few words, but the mechanical defect still held his interest.

"One understands that a brave man always dislikes being thanked," she continued a little nervously; "and, indeed, what can I say to thank you? You have saved my life, and I know that it must have been at a tremendous risk to yourself."

"I think," he said, "that the sooner you forget the incident.... That and the removal of those three feathers." His gestures were deliberate and the reverse of vivacious, but when he glanced up and moved a hand, it at once conveyed to the girl that in his opinion nothing else need stand in the way of her recovered powers and confidence.

"And there is," she said timidly, "nothing?" Precisely what there might be had not occurred to her satisfactorily.

"Nothing," he said, without the air of being heroic in his generosity. "Unless," he added, "you care to promise that you will not let——" He stopped with easy self-possession and turned enquiringly to a man in some official dress who had suddenly appeared in the glade.

"Have you a licence?" demanded the official, ignoring Stobalt and addressing himself in a style that at one time would have been deemed objectionably abrupt, to the lady. He was in point of fact a policeman, and from a thong on his wrist swung a truncheon, while the butt of a revolver showed at his belt. He wore no number or identifying mark, for it had long since been agreed that it must be objectionable to their finer feelings to treat policemen as though they were—one cannot say convicts, for a sympathetic Home Secretary had already discontinued the numbering of convicts on the ground that it created a state of things "undistinguishable from slavery," though not really slavery—but as though they were railway bridges or district council lamp-posts. "Treat a man as a dog, and he becomes a dog," had been the invincible argument of the band of humanitarians who had introduced what was known as the "Get-up-when-you-like-and-have-what-you-want" system of prison discipline, and "Treat a man as a lamp-post, and he becomes a lamp-post," had been the logical standpoint of the Amalgamated Union of Policemen and Plain Clothes Detectives.

"Yes," replied the girl, and her voice had not quite that agreeable intonation that members of the force usually hear from the lips of fair young ladies nowadays. "Do you wish to see it?"

"What else should I ask you if you had one for?" he demanded with the innate boorishness of the heavy-witted man. "Of course I want to see it."

She opened the little bag that hung from her girdle and handed him a paper without a word.

"Muriel Ursula Percy Sleigh Hampden?" It would be idle to pretend that the names pleased him, or that he tried to veil his contempt.

"Yes," she replied.

He indicated his private disbelief—or possibly merely took a ready means of exercising his authority in a way that he knew to be offensive—by producing a small tin box from one of his pockets and passing it to her without any explanation. The requirement was so universal in practice, however, that no explanation was necessary, for the signature, as the chief mark of identification, had long been superseded by the simpler and more effective thumb-sign. Miss Hampden made a slight grimace when she saw the condition of the soft wax which the box contained, but she obediently pressed it with her thumb and passed it back again. As her licence bore another thumb-sign, stamped in pigment, it was only necessary for the constable to compare the two (a process simplified by the superimposing glass, a contrivance not unlike a small opera-glass with converging tubes) in order to satisfy himself at once whether the marks were the impress of the same thumb. Apparently they were, for with a careless "Right-O," he proceeded on his way, swinging his truncheon with an easy grace, and occasionally striking off the end of an overhanging branch.

"I wonder," said Stobalt, when at length the zealous officer had quite disappeared in search of other fields for tactful activity, "I wonder if you are a daughter of Sir John Hampden?"

"Yes," she replied, looking at him with renewed interest. "His only daughter. Do you know my father?"

He shook his head. "I have been away, but we see the papers sometimes," he said. "The Sir John I mean," he explained, as though the point were a matter of some moment, "was a few years ago regarded as the one man who might unite our parties and save the position."

"There is only one Sir John Hampden," she replied. "But it was too late."

"Oh yes," he admitted vaguely, dismissing the subject.

Both were silent for a few minutes; it might be noticed that people often became thoughtful when they spoke of the past in those years. Indeed, an optimist might almost have had some ground for believing that a thinking era had begun.

When he spoke again it was with something of an air of constraint. "You asked me just now if there was—anything. Well, I have since thought——"

"Yes?" she said encouragingly.

"I have thought that I should like to meet your father. I hear everywhere that he is the most inaccessible man in London; but perhaps if you could favour me with a line of introduction——"

"Oh yes," she exclaimed gladly. "I am sure that he would wish to thank you. I will write to-morrow."

"I have paper and a pencil here," he suggested. "I have been a sailor," he added, as though that simple statement explained an omnipercipient resourcefulness; as perhaps it did.

"If you prefer it," she said, accepting the proffered stationery. It did not make the least difference, she told herself, but this business-like expedition chilled her generous instincts.

"I leave for town to-night," was all he vouchsafed.

For a few minutes she wrote in silence, while he looked fixedly out to sea. "What name am I to write, please?" she asked presently.

"Oh, Salt—George Salt," he replied in a matter-of-fact voice, and without turning his head.

"Is it 'Mr Salt,' or 'Captain,' or——?"

"Just 'Mr,' please. And"—his voice fell a little flat in spite of himself, but he did not meet her eyes—"and would it be too much if I asked you to mention the circumstances under which we met?"

She bent a little lower over the paper in a shame she could not then define. "I will not fail to let my father know how heroic you have been, and to what an extent we are indebted to you," she replied dispassionately.

"Thank you." Suddenly he turned with an arresting gesture, and impulsive speech trembled on his tongue. But the sophistries of explanation, apology, self-extenuation, were foreign to the nature of this strong keen-featured man, whose grey and not unkindly eyes had gained their tranquil depth from long intercourse with sea and sky—those two masters who teach the larger things of life. The words were never spoken, his arm fell down again, and the moment passed.

"I have never," he was known to say with quiet emphasis in later years, "regretted silence. I have never given way to an impulse and spoken hastily without regretting speech."

The London evening papers were being cried in the streets of the old Cinque Port as "George Salt" walked to the station a few hours later. A general election was drawing to its desultory close, but the results seemed to excite curiously little interest among the well-dressed, leisured class that filled the promenades. It was a longer sweep of the pendulum than had ever been anticipated in the days when politics were more or less the pastime of the rich, and the working classes neither understood nor cared to understand them—only understood that whatever else happened nothing ever came their way.

The man who had been a sailor bought two papers of very different views, the Pall Mall Gazette and the orthodox labour organ called The Masses. Neither rejoiced, but to despair The Masses added a note of ingenuous surprise as it summarised the contest as a whole. This was how the matter stood:

| Labour Members | 300 |

| Socialists | 140 |

| Liberals | 112 |

| Unionists | 40 |

| Socialist Gains | 204 |

| Moderate Labour Gains | 5 |

| Imperial Party Gains | 0 |

| Socialists | 344 |

| Moderate Labour Party (all groups) | 179 |

| Combined Imperial Party (Liberals Unionists) | 68 |

| Socialist majority over all possible combinations | 97 |

There is no need to trace the development of political events leading up to this position. It lends itself to summary. The Labour party had come into power by pointing out to voters of the working classes that its members were their brothers, and promising them a great deal of property belonging to other people and a good many privileges which they vehemently denounced in every other class. When in power they had thrown open the doors of election to one and all. The Socialist party had come into power by pointing out to voters of the working classes that its members were even more their brothers, and promising them a still larger share of other people's property (some, indeed, belonging to the more prosperous of the Labour representatives then in office) and still greater privileges. Yet the editor of The Masses was both pained and surprised at the result.

A strong man and a prominent politician, Sir John Hampden had occupied the unfamiliar position in Parliament of belonging to no party. To no party, that is, as the term had then been current in English politics; for, more discerning than most of his contemporaries, he had foreseen the obliteration of the existing boundaries and the phenomenal growth of purely class politics even in the old century. It was, he recognised, to be that development of the franchise with which the world was later to become tolerably familiar: civil war on constitutional lines. His warnings fell on very stony ground. The powers that had never yet prepared for war abroad until the enemy had comfortably occupied all the strategic points, lest they should wound some wily protesting old gentleman's susceptibilities, were scarcely likely to take time by the forelock—or even by a hind fetlock, to enlarge the comparison—at home. While the Labour party was bringing pressure upon the Government of the day to grant an extension of suffrage that made Labour the master of eight out of every ten constituencies, the two great classical parties were quarrelling vehemently whether £5000 should be spent upon a sanatorium at Hai Yang and £5,000,000 upon a dockyard at Pittiescottie, or £5,000,000 upon a dockyard at Hai Yang and £5000 upon a sanatorium at Pittiescottie. When it is added that the Labour party was definitely pledged to the inauguration of universal peace by declining to go to war on any provocation, and looked towards wholesale disarmament as the first means of economy on attaining office, the cataclysmal humour of the situation becomes apparent.

They attained office, as it has been seen, thanks largely to the great Liberal party whom they succeeded. The great Liberal party, like the editor of The Masses some years later, was pained and surprised at this ingratitude. The great Liberal party had never contemplated such a development, and through thick and thin had insisted upon regarding the Labour party as its ally, notwithstanding the fact that the "ally" had always laughed uproariously at the "alliance," and had pleasantly announced its intention of strewing Westminster with the wreckage of all existing capitalistic parties when once it was strong enough to do so.

Little wonder that that great Liberal Administration was destined to pass down to future ages as the "House of Pathetic Fools." Posterity adjudicated that no greater example of servile fatuousness could be produced. This was unjust, for on 20th June 1792, Louis XVI., certainly, let it be admitted, harder pressed, had accepted a red "cap of liberty," and putting it on in obedience to the command of the "extreme party" of his time, had bowed right and left with ingratiating friendliness, while a Labour gentleman, bearing upon a pike a raw cow's heart labelled "The heart of an aristocrat," roared out, with his twenty thousand friends, an amused approval.

It was out of the material of the two great traditional parties that Sir John Hampden tried to create his "class" coalition to meet the new conditions. The spectacle of working men suddenly dropping party differences and merging into a solid phalanx of labour was before their eyes, but the Tories were disintegrated and inert, the Whigs self-satisfied and cock-sure. The years of grace—just so many years as Sir John was before his contemporaries—passed. Then came a brief period, desperate indeed, but not hopeless, while something might yet be done; but the leaders of the historical parties were waiting for some happy chance by which they might retract and yet preserve their dignity. It was during this crisis that the party whose idea of dignity was symbolised by the escort of a brass band on a green-grocer's cart, abolished the House of Lords, suspended the naval programme, and confiscated all ecclesiastical landed property. Panic reigned, but there could be no appeal, for the party in power had never concealed their aims and aspirations, and now that they had been returned, they were only carrying out their promises.

That is putting their position so mildly as to be almost unjust. They were, indeed, among political parties the only one immaculate and beyond reproach. All others had trimmed and whittled, promised and recalled, sworn and forsworn, till political assurances were emptier than libertines' vows. The Socialists had nailed their manifesto to the mast, and no man could charge them with duplicity. On every platform from Caithness to Cornwall they had stood openly and declared: We are the enemies to Capital; we are at war with Society as it is at present constituted; we are for the forcible distribution of wealth, however come by, the abolition of class distinctions, and the levelling of humanity, with the unskilled labourer as the ideal standard.

"Good fellows all," had, in effect, declared their Liberal "allies," "and they do not really mean that—not phraseologically accurately, that is. We go in for a little, say, serpent-charming ourselves at election times, and when these excellent men are in Parliament the refining influence of the surroundings will tone them down wonderfully, and they will turn out thoroughly moderate and conciliatory members."

"Don't you make any error about that, comrades," the Socialistic-Labour candidates had replied; and with a candour unparalleled in the history of electioneering they had not merely hinted this or said it among themselves, but had freely and honourably proclaimed it to the four winds. "If you like to help us just now that's your affair, and we are quite willing to profit by it. But if you knew what you were doing, you would go home and all have the nightmare."

"So naïve!" smiled the great Liberal party. "Suppose they have to talk like that at present to please the unemployed."

Then came the deluge. Sir John Hampden could have every section of the middle and upper class political parties to lead if he so deigned, but wherever else he might lead them there was no possible hope of it being to St. Stephen's. It was, as his daughter had said, then too late. Labour members of one complexion or another had captured three-quarters of the constituencies, and there was not the slightest chance of ousting them.

So it came about that in less than a decade from the first alarm, the extremity of the patriot's hope was that in perhaps twenty years' time, when the country was reduced to bankruptcy and the position of a third class power, and when there was no more property to confiscate in the interest of the working class voter, a popular rising or a foreign invasion might again place a responsible administration in power. But in the meantime the organisations of the old parties fell to pieces, the parties themselves ceased to be powers, their leaders were half forgotten. Sir John Hampden might still be a rallying point if he raised a standard in a time of renewed hope, but there was no hope, and Sir John was reported to have broken his staff, drowned his books, and cut himself off from politics in the bitterness of his indignation and impotent despair.

It was in something very like this mood that George Salt found him, and it was an issue of the mood that would have made him inaccessible to a less resourceful man. Day after day he had denied himself to his old associates, and little disappointed hucksters who were anxious to betray their party for their conscience' sake—provided there was a definite offer of a more lucrative position in a new party—vainly shadowed his doorway with ready-made cabals in their pocket-books. But the man who had been a sailor and spoke few words had an air that carried where fluency and self-assurance failed. Even then, almost at his first words, Sir John would have closed the subject, definitely and without discussion.

"Politics do not concern me, Mr Salt," he said, rising, with an angry flash in the eyes whose fighting light gave the lie to the story of abandoned hope. "If that is your business you have reached me by a subterfuge."

"Having reached you," replied Salt, unmoved, "will you allow me to put my suggestions before you?"

"I have no doubt that they are interesting," replied the baronet, falling into smooth indifference, "but, as you may see, I am exclusively devoted to Euplexoptera now." It might be true, for the table before him was covered with specimens, scientific instruments and entomological works, while not even a single newspaper betrayed an interest in the day; but a world of bitterness smouldered beneath his half-scornful admission. "If," he continued in the same vein, "you have an idea for an effective series of magic lantern slides, you will find the offices of the Union of Imperial Agencies in Whitehall."

The first act to which the new Government was pledged was the evacuation of Egypt, and the mighty counterblast from the headquarters of the remnant of the great opposing organisation was, it should be explained, a travelling magic lantern van, designed to satisfy rural voters as to the present happy condition of the fellahin!

"Possibly you would hardly complain that I am not prepared to go far enough," replied the visitor. "But in order to discuss that, I must have your serious attention."

"I have already expressed myself," replied Sir John formally. "I am not interested."

"If you will hear me out and then repeat that, I will go," urged Salt with desperate calmness. "Yet I have thrown up the profession of my life because I hold that there is a certain remedy. And I have come a hundred miles to-night to offer it to you: for you are the man. Realise that I am vitally concerned."

"I am very sorry," replied Sir John courteously, but without the faintest encouragement, "but the matter is beyond me. Leave me, and try some younger, less disillusionised man."

"There is no other man who will serve my purpose." Sir John stared hard, as well he might: others had not been in the habit of appealing to him to serve their purposes. "You are the natural leader of our classes. You alone can inspire them; you alone have the authority to call them to any effort."

"I have been invited to lead a hundred forlorn hopes," replied Sir John. "A dozen years—nine years—aye, perhaps even six years ago any one of them might have been sufficient. Now—I have my earwigs. Good night, Mr Salt."

The dismissal was so unmistakably final that the most stubborn persistence could scarcely ignore it. Mr Salt rose, but only to approach the table by which Sir John was standing.

"I wished to have you with me on the bare merits of my plan," he said in a low voice, "but you would not. But you shall save England in spite of your dead heart. Read this letter."

For a moment it seemed doubtful how Hampden would take so brusque a demand. Another second and he might have imperiously ordered Salt to leave the house, when his eyes fell with a start upon the writing thrust before him, and taking the letter in his hand he read it through, read it twice.

"Little fool!" he said, so low that it sounded tenderly; "poor little fool!" Then aloud: "Am I to understand that you have saved my daughter's life?"

"Yes," replied George Salt, and even the tropical sunburn could not cover his hot shame.

"At great personal risk to yourself?"

Again the reply was, "Yes," without an added word.

"Why did you not let me know of this before?"

"Does that matter now?" It had been his master card, but a very humiliating one to play throughout: to trade upon that moment's instinctive heroism, to assert his bravery, to apprise it at its worth, and to claim a fit return.

"No," admitted Sir John with intuition, "I don't suppose it does. The position then is, that instead of exchanging the usual compliments applicable to the occasion, I express my gratitude by listening to your views on the political situation? And further," he continued, with the same gentle air of irony, accepting Salt's silent acquiescence, "that I proceed to liquidate my obligation fully by identifying myself with a scheme which you have in your pocket for averting national disaster?"

"No," replied Salt sharply. "That is for you to accept or reject unconditionally on your own judgment."

"Very well. I am entirely at your service now."

"In the first place, then, I ask you to admit that a state of civil war morally exists, and that the only possible hope for our existence lies in adopting the methods of covert civil war to secure our ends."

"Admit! Good God! I have been shrieking it into deaf ears for half my life, it seems," cried Sir John, suddenly stirred despite himself. "They called me the Phantom Storm-petrel—'Wolf-cry' Hampden, Heaven knows what not—through an entire decade. Admit! Go on, Mr Salt. I accept your first clause more easily than Lord Stirling swallowed Socialistic amendments to his own Bills, and that is saying a great deal."

"Then," continued Salt, taking a bundle of papers from an inner pocket and selecting a docket of half a dozen typewritten sheets from it, "I propose for your acceptance the following plan of campaign."

He looked round the littered desk for a vacant space on which to lay the document. With an impetuous movement of his arm Sir John swept books, trays, and insects into one chaotic heap, and spreading the summary before him plunged into it forthwith.

"Kumreds," announced Mr Tubes with winning familiarity, "I may say now and once and for all that you've thoroughly convinced me of the justice of your claims. But that isn't saying that the thing's as good as done, so don't go slinging it broadcast in the next pub you come to. There's our good kumred the Chancellor of the Exchequer to be taken into account, and while I'm about it let me tell you straight that these Cabinet jobs, whether at twenty, fifty, or a hundred quid a week, aren't the softest things going, as some of you chaps seem to imagine."

"Swap you, mate, then," called out a facetious L. & N. W. fireman. "Yus, and throw the missis and kids into the bargain. Call it a deal?"

In his modest little house the Right Hon. James Tubes, M.P., Secretary of State for the Home Department, was receiving a deputation. Success, said his friends, had not spoiled him; others admitted that success had not changed him. From the time of his first appearance in Parliament he had been dubbed "Honest Jim" (perhaps a somewhat empty compliment in view of the fact that every Labour constituency had barbed unconscious satire at its own expense by distinguishing its representative as "Honest" Tom, Dick, or Harry), and after his elevation to Cabinet rank he still remained honest. More to the point, because more apparent, he remained unpretentious. It is true that he ceased to wear, as a personal concession to the Prime Minister, by whose side he sat, the grimy coal miner's suit in which he had first appeared in the House to the captivating of all hearts; but, more fortunate than Caractacus, he escaped envy by continuing to occupy his humble villa in Kilburn. The expenses of a Cabinet Minister, even in a Socialist Government, must inevitably be heavier than those of a private member, but this admirable man illustrated the uselessness of riches by continuing to live frugally but comfortably upon a tenth of his official income. According to intimate rumour he prudently invested the superfluous nine-tenths against a rainy day in the gilt-edged securities of countries where Socialism was least rampant.

Mr Tubes never refused to see a deputation, and when their views had been laid before him it was rare indeed that he was not able to declare a warm personal interest in their objects. True, he could not always undertake to carry their recommendations into effect; as a Minister he could not always express official approval of them, but they were rarely sent away without the moral support of that wink which is proverbially as significant as a more compromising form of agreement. Whether the particular expression of the great voice of the people was in the direction of the State adoption of Zulu orphans, or the compulsory removal of park palings from around private estates, the deputation could always go away with the inward satisfaction that however his words might read to outsiders on the morrow, they knew that as a man and a comrade, he, Jim Tubes, was with them heart and soul. "It costs nothing," he was wont to remark broad-mindedly to his home circle—referring, of course, to his own sympathetic attitude; for some of the ingenuous proposals which he countenanced were found in practice to prove very costly indeed—"and who knows what may happen next?"

But on this occasion, as far as compliance lay within his power, there had been no need for mental reservation. The railway-men had been patient under capitalistic oppression in the past; they were convincing now in argument; and they were moderate in their demands for the future. It was no "Væ victis!" that these sturdy wearers of green corduroy trousers held out to their employers, but a cheery "Come now, mates. Fair does and we'll mess along somehow till the next strike."

Mr Drugget, M.P., introduced the deputation. It consisted of railway workers of all the lower grades with the exception of clerks. After many ineffectual attempts to get clerks to enter the existing Labour ring, it had been seriously proposed by the Labour wirepullers (who loved them in spite of their waywardness, and would have saved them, and their votes and their weekly contribution, from themselves) that they should form a Union of their own in conjunction with shop assistants and domestic servants. When the clerks (of whom the majority employed domestic servants directly or indirectly in their homes or in their lodgings) laughed slightly at the proposal; when the shop assistants smiled self-consciously, and when the domestic servants giggled openly, the promoters of this amusing triple alliance cruelly left them to their fate thenceforward, pettishly declaring that all three were a set of snobs—a designation which they impartially applied to every class of society except their own, and among themselves to every minute subdivision of Labour except the one which they adorned.

It devolved upon a rising young "greaser" in the service of the Great Northern to explain, as spokesman, the object of the visit. Under the existing unfair conditions the directors of the various companies were elected at large salaries by that unnecessary and parasitic group, the shareholders, while the workmen—the true creators of every penny of income—had no direct hand in the management of affairs. When they wished to approach the chief authorities it was necessary for them to send delegates from their Union, who were frequently kept waiting ten minutes in an ante-room; and although of late years their demands were practically always conceded without demur, the position was anomalous and humiliating. What seemed only reasonable to them, then, was that they should have the right to elect an equal number of directors from among themselves, who should sit on the Board with the other directors, have equal powers, and receive similar salaries.

"To be, in fact, your permanent deputation to the Board," suggested the Home Secretary.

"That's it—with powers," replied the G. N. man.

"There'll be some soft jobs going—then," murmured a shunter, who was getting on in years, reflectively.

"No need for the missis to take in young men lodgers if you get one, eh, Bill?" said his neighbour jocosely.

Whether it was the extreme unlikelihood of his ever being made a director, or some other deeper cause, the secret history of the period does not say, but Bill turned upon his innocent friend in a very aggressive mood.

"What d'yer mean—young men lodgers?" he demanded warmly. "What call have you to bring that up? Come now!"

"Why, mate," expostulated the offending one mildly, "no one said anything to give any offence. What's the 'arm? Your missis does take in lodgers, same as plenty more, don't she? Well, then!"

"I can take a 'int along the lines as well as any other," replied Bill darkly. "It's gone far enough between pals. See? I never said anything about your sister leaving that there laundry, did I? Never, I didn't."

"And what about it if you did?" demanded the neighbour, growing hot in his turn. "I should think you'd have enough——"

"Gentlemen, gentlemen," expostulated the glib young spokesman, as the voices rose above the conversational whisper, "let us have absolute unanimity, if you please—expressed in the usual way, by all saying nothing together."

"Wha's matter with Bill?" murmured the next delegate with polite curiosity.

"Seems to me the little man is troubled with his teef," replied the unfortunate cause of the ill-feeling, with smouldering passion. "Strike me if he isn't. Ah!" And seeing the impropriety of relieving his feelings in the usual way in a Cabinet Minister's private study, he relapsed into bitter silence.

Mr Tubes having expressed his absolute approval of this detail of the programme, the second point was explained. Why, it was demanded, should the provisions of the Employers' Liability Act apply only to the hours during which a man was at work? Furthermore, why should they apply only to accidents? Supposing, said Mr William Mulch, the spokesman in question, that a bloke went out in a social way among his friends, as any bloke might, caught the small-pox, and got laid up for life with after-effects, or died? Or suppose the bloke, after sweating through a day's work, went home dog-tired to his miserable hovel, and broke his leg falling over the carpet, or poisoned his hand opening a tin of sardines? They looked to the present Government to extend the working of the Act so as to cover the disablement or death of employés from every cause whatever, natural death included, and wherever they might be at the time. Under the present unfair and artificial conditions of labour, the work-people were nothing but the slaves and chattels of capitalists, and it was manifestly unfair that the latter should escape their responsibilities after exploiting a man's labour for their own greedy ends, simply because he happened to die of hydrophobia or senile decay, or because the injury that disabled him was received outside the fœtid, insanitary den where in exchange for a bare sordid pittance his flesh was ground from his bones for eight hours daily.

The Right Hon. gentleman expressed his entire concurrence with this provision also, and roused considerable enthusiasm by mentioning that some time ago he had independently arrived at the conclusion that such a clause was urgently required.

Before the next point was considered, Comrade Tintwistle asked permission to say a few words. He explained that he had no intention of introducing a discordant note. On the contrary, he heartily supported the proposal as far as it went, but—and here he wished to say that though he only voiced the demands of a minority, it was a large, a growing, and a noisy minority—it did not go far enough. The contention of those he represented was that the responsibility of employers ought to extend to the wives and families of their work-people. Many a poor comrade was sadly harassed by having to keep a crippled child who would never be a bread-winner, or an ailing wife who was incapable of looking after his home comfort properly. They were fighting over again the battle that they had won in the matter of free meals for school children. It had taken years to convince people that it was equally necessary that children who did not happen to be attending school should have meals provided for them, and even more necessary to see that their mothers should be well nourished; it had taken even longer to arrive at the logical conclusion that if free meals were requisite, free clothes were not a whit less necessary. No one nowadays doubted the soundness of that policy, yet here they were again timorously contemplating half-measures, while the insatiable birds of prey who sucked their blood laughed in their sleeve at the spectacle of the British working men hiding their heads ostrich-like in the shifting quicksand of a fool's paradise.

The signs of approval that greeted this proposal showed clearly enough that other members of the deputation had sympathetic leanings towards the larger policy of the minority. Mr Tubes himself more than hinted at the possibility of a personal conversion in the near future. "In the meantime," he remarked, "everything is on your side. Your position is logical, moderate, and just. All can admit that, although we may not all exactly agree as to whether the time is ripe for the measure. With every temptation to wipe off some of the arrears of injustice of the past, we must not go so far as to kill the goose that lays the golden egg."

"How do you make that out?" demanded an unsophisticated young signalman. "It's the work of the people that produces every penny that circulates."

"Oh, just so," replied Tubes readily. "That is the real point of the story. It was the grains of corn that made the eggs, and the goose did nothing but sit and lay them. We must always have our geese." He turned to the subject in hand again with a laugh, and approved a few more modest suggestions for abolishing "privileges."

"The last point," continued the spokesman, "is one that closely concerns the principles that we all profess. I refer to the obsolete and humiliating anachronism that with a Government pledged to the maintenance of social equality in office, at any hour of the day, at practically every railway station throughout the land you will still see trains subdivided as regards designation and accommodation into first, second, and third classes. It is a distinction which to us, as the representatives of the so-called third class, is nothing more or less than insulting. Why should me and my missis when we travel be compelled to sit where the accidents generally happen and have to put up with eighteen in a compartment, when smug clerks and saucy ladies' maids, who are no better than us, enjoy the comparative luxury of only fifteen in a compartment away from the collisions, and snide financiers and questionable duchesses, who are certainly a good deal worse, sit in padded rooms, well protected front and rear, and never know what it is to be packed more than six a-side? If that isn't class distinction I should like to know what is. It isn't—Gawd help us!—that we wish to mix with these people, or that we envy their position or covet their wealth. Such motives have never entered into the calculations of those who have been foremost in Socialistic propaganda. But as thoughtful and self-respecting units of an integral community we object to being segregated by the imposition of obsolete and arbitrary barriers, we do resent the artificial creation of social grades, and we regard with antagonism and distrust the unjust accumulation of labour-created wealth in the hands of the idle and incapable few.