The Project Gutenberg EBook of Wolf and Coyote Trapping, by

A. R. (Arthur Robert) Harding

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Wolf and Coyote Trapping

An Up-to-Date Wolf Hunter's Guide, Giving the Most

Successful Methods of Experienced Wolfers for Hunting and

Trapping These Animals, Also Gives Their Habits in Detail.

Author: A. R. (Arthur Robert) Harding

Release Date: November 29, 2010 [EBook #34501]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WOLF AND COYOTE TRAPPING ***

Produced by Linda M. Everhart, Blairstown, Missouri

There are certain wild animals which when hard pressed by severe cold and hunger, will raid the farmers and ranchmen's yards, killing fowls and stock. There however, are no animals that destroy so much stock as wolves and coyotes as they largely live upon the property of farmers, settlers and ranchmen to which they add game as they can get it.

While these animals are trapped, shot, poisoned, hunted with dogs, etc., their numbers, in some states, seem to be on the increase rather than the decrease in face of the fact that heavy bounties are offered.

The fact that wolf and coyote scalps command a bounty, in many states, and in addition their pelts are valuable, makes the hunting and trapping of these animals of no little importance.

One thing that has helped to keep the members of these "howlers" so numerous is the fact that they are among the shrewdest animal in America. The day of their extermination is, no doubt, far in the distance.

This book contains much of value to those who expect to follow the business of catching wolves and coyotes. A great deal of the habits and many of the methods were written by Mr. E. Kreps, who has had experience with these animals upon the Western Plains, in Canada, and the South. Additional information has been secured from Government Bulletins and experienced "wolfers" from various parts of America.

A. R. Harding.

Wolves of all species belong to that class of animals known as the dog family, the members of which are considered to be the most intelligent of brute animals. They are found, in one species or another, in almost every part of the world. They are strictly carnivorous and are beyond all doubt the most destructive of all wild animals.

In general appearance the wolf resembles a large dog having erect ears, elongated muzzle, long heavy fur and bushy tail. The size and color varies considerably as there are many varieties.

The wolves of North America may be divided into two distinct groups, namely, the large timber wolves, and the prairie wolves or coyotes (ki'-yote). Of the timber wolves there are a number of varieties, perhaps species, for there is considerable difference in size and color. For instance there is the small black wolf which is still found in Florida, and the large Arctic wolf which is found in far Northern Canada and Alaska, the color of which is a pure white with a black tip to the tail. Then there is that intermediate variety known as the Grey Wolf, also called "Timber Wolf," "Lobo" and "Wolf," the latter indefinite name being used throughout the West to distinguish the animal from the prairie species. It is the most common of the American wolves, the numbers of this variety being in excess of all of the others combined. In addition to those mentioned, there are others such as the Red Wolf of Texas and the Brindled Wolf of Mexico. All of these, however, belong to the group known to naturalists as the Timber Wolves. Just how many species and how many distinct varieties there are is not known.

As a rule, the largest wolves are found in the North; the Gray Wolves of the western plains being slightly smaller than the white and Dusky Wolves of Northern Canada and Alaska, specimens of which, it is said, sometimes weigh as much as one hundred and fifty pounds. Again the wolves of the southern part of the United States and of Mexico are smaller than the gray variety.

The average full grown wolf will measure about five feet in length, from the end of the nose to the tip of the tail, and will weigh from eighty to one hundred pounds, but specimens have been killed which far exceeded these figures. The prevailing color is gray, being darkest on the back and dusky on the shoulders and hips. The tail is very bushy and the fur of the body is long and shaggy. The ears are erect and pointed, the muzzle long and heavy, the eyes brown and considering the fierce, bloodthirsty nature of the animal, have a very gentle expression.

In early days wolves were found in all parts of the country but they have been exterminated or driven out of the thickly settled portions and their present distribution in the United States is shown by the accompanying map. As will be noted they are found in only a small portion of Nevada and none are found in California, but they are to be met with in all other states west of the Missouri and the lower Mississippi, also all of the most southern tier of states, as well as those parts bordering on Lake Superior. A few are yet found in the Smokey Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. They are probably most abundant in Northern Michigan and Northern Minnesota, Western Wyoming, Montana and New Mexico.

Wyoming is the center of the wolf infested country and they are found in greatest numbers in that state, on the headwaters of the Green River. As to the numbers still found the report of the Biological Survey for the years 1895 to 1906, inclusive, but not including the year 1898, shows that bounties were paid on 20,819 wolves in that state.

In Northern Michigan they are also abundant. In the year 1907, thirty-four wolves were killed in Ontonagon County; in Luce County fifty-four were killed up to November 10th, '07, and in Schoolcraft Co., thirty were killed from October 1st, '07 to April 29th, '08. This gives a total of one hundred and eighteen wolves killed in three out of the sixteen counties of the Upper Peninsula. These statistics are from a pamphlet issued by the Department of Agriculture.

The breeding season of the timber wolves is not as definite as that of many of the furbearing animals, for the young make their appearance from early in March until in May, and an occasional litter will be born during the summer, even as late as August. The mating season of course varies, but is mainly in January and February, the period of gestation being nine weeks. The number in a litter varies from five to thirteen, the usual number being eight or ten.

In early days the wolves of the western plains followed the great buffalo herds and preyed on the young animals, also the old and feeble. After the extermination of that animal they turned their attention to the herds of cattle which soon covered the great western range and their depredations have become a positive nuisance. In the Northern States and throughout Canada they subsist almost entirely on wild game.

Wolves den in the ground or rocks in natural dens if such can be found, but in case natural excavations are rare as in northern portions of the country, they appropriate and enlarge the homes of other animals. In the heavily timbered country they sometimes den in hollow logs.

The wolf is both cowardly and courageous, depending on circumstances. When found singly, and especially in daylight the animal is as much of a coward as any creature could possibly be, and especially does it fear man. But when suffering from the pangs of hunger and when traveling in bands as they usually do, they are bold, fierce and bloodthirsty creatures. In such cases they have been known to attack man.

When hunting large game, wolves always go in bands, usually of three to five but often a larger number. They invariably kill animals by springing on from behind and hamstringing the victim. Small game is hunted by lone animals.

The great losses suffered by stockmen in the West led the Biological Survey, in connection with the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture, to make a special investigation, and later a general campaign against the wolves of the National Forests began. During the year 1907 a large number of wolves and coyotes were captured in and near the forest reserves: the number from the various states being as follows:

| STATE | WOLVES | COYOTES |

|---|---|---|

| Wyoming | 1,009 | 1,983 |

| Montana | 261 | 2.629 |

| Idaho | 14 | 3,881 |

| Washington | 10 | 675 |

| Colorado | 65 | 2,362 |

| Oklahoma | 3 | 15 |

| New Mexico | 232 | 544 |

| Arizona | 127 | 1,424 |

| Utah | 5,001 | |

| Nevada | 500 | |

| California | 224 | |

| Oregon | 2 | 3,290 |

| ------ | ------ | |

| Total | 1,723 | 22,528 |

Many of these animals were captured by the forest guards but in addition the government employed a number of expert trappers. On the Gila National Forest 36 wolves and 30 coyotes were killed by one forest guard, who sent the skulls to the Biological Survey for identification, as well as the skulls of 9 bears, 7 mountain lions, 17 bobcats, and 46 grey foxes. One den of 8 very young wolf pups was taken March 13. These statistics are from Circular 63, issued by the U. S. Department of Agriculture.

Wolves are great ramblers, traveling over a large section of country. Like almost all other animals of rambling habits, they have their regular routes of travel. By this, we mean they follow the same valleys, passes, water courses, etc., but when in pursuit of game they sometimes stray quite a long distance out of their course.

The track of the wolf resembles that of a dog, but is a trifle narrower in proportion to its length. The difference is in the two middle toes, which are somewhat longer on the wolf, however, the difference is so slight that it could easily pass unnoticed. When the wolf is running these toes are spread well apart. The length of step when the animal is walking will be from 18 to 24 inches, and the average footprint will measure about 2 3/4 or 3 inches in width by about 3 1/2 or 4 inches in length. Ernest Thompson Seton, the naturalist claims that he can judge with fair accuracy, the weight of a wolf by the size of the track. He allows twenty pounds for each inch in length, of the foot print.

In the western parts of the United States, the coyote is far more abundant than the grey, or timber wolf, but its range is more limited as it is found only in those parts lying west of the Mississippi River and in the western portion of the Dominion of Canada. As there are a number of varieties of the timber wolf, so it is with the coyote, but naturalists have never yet been able to agree on the number of types and their distribution. In the Southwest, it appears there are several distinct varieties, showing considerable difference in size and color. Mr. Vasma Brown, a noted coyote trapper of Texas has the following to say on the subject:

"I have lived in Texas nineteen years and have had some years of experience with the coyotes, coons and cats. Some coyotes are of a silver-grey color, others are dark brown. The ends of their hair are jet black and it makes them look brown. Some have black tips on the tail and some white. The dark variety are the most vicious of the two."

With the exception of the southwestern section, it is probable that the coyotes of all portions of the Great Plains and the country to the westward are of the same variety, and a description of this, the most common type will answer for the species. In size, the coyote or prairie wolf is considerably smaller than the timber wolf, the largest specimens of the former being about equal in size to the smallest adult wolves. The average coyote will measure about thirty-six or thirty-eight inches from the end of the nose to the base of the tail, which is about sixteen inches additional length. The fur is of about the same texture as that of the grey fox and the general color is fulvous, black and white hairs being mingled in parts, giving a grizzled appearance. The ears are larger, comparatively than those of the grey wolf, and the muzzle is more pointed. All through the animal appears to be of more delicate build. A larger form of the coyote is found in Minnesota and the adjoining territory and is commonly known as the "brush wolf". Whether this is a distinct variety is not known.

Coyotes are intelligent and cunning animals and their habits and general appearance suggest the fox rather than the wolf. While they are greedy, bloodthirsty creatures, they are sneaking and cowardly and never kill animals larger than deer, in fact they rarely attack such large game. An Arizona trapper writes:

"The coyote bears the same relation to the wolf family that the Apache Indian does to the human race. It is a belief among some of the Apaches that they turn into coyotes when they depart this life, and nothing will induce one of them to kill a coyote. Like the Indian he is sneaky and treacherous, and full of the devil."

While there is no doubt that the animal enjoys its wild, free life, it always has a miserable, distressed expression. It carries its tail in a drooping manner and slinks out of sight like a dog that has been doing wrong and has a troubled conscience.

The high piercing cry of the animal, which is so different from the deep bass note of the timber wolf, is mournful in the extreme. In the morning before the coyotes retire for the day, they stop on the top of some elevation and sound their "reveille", which once heard will never be forgotten. It is a shrill, piercing note, combining a howl with a bark and although in all probability there will be only a pair of the animals, one who does not know would be inclined to think that the number is larger, the notes are so commingled.

Coyotes live in natural dens in the rocks, also in dens of badgers, in the prairie country. In the "Bad Lands" of the West and the foot hills of the mountain ranges, wind worn holes in the rim-rock and buttes are quite common and the animals have no trouble in securing a good den. Naturally, they select the most secluded and inaccessible places for their dens. The food of the coyote consists of small game, such as hares and grouse, prairie dogs and any other small animals that they can capture. In the sheep raising districts of the Western States they are very destructive to sheep and in those parts it is probable that their food consists mostly of mutton. They feed on carrion and have a particular liking for horse flesh. They also kill badgers and when conditions are very favorable may kill an occasional deer or antelope. They also sometimes kill calves and hogs.

Speaking of conditions in Oregon and other parts of the Northwest, one of our friends writes:

"The prairie wolf or coyote in the Western states are becoming so numerous that it looks as though the sheep industry in Idaho and Eastern Oregon would soon be a thing of the past, if something it not done to lesson the number of the destructive coyotes.

"Twenty years ago there were a great many coyotes in Oregon, but the black tail rabbits were so numerous then that the coyote contented himself with them and did not molest the sheep to any great extent. Idaho and Oregon both put a bounty on rabbits, which soon caused them to become scarce, then the coyotes began their depredations among the sheep. The wool growers supplied themselves with plenty of strychnine and kept the coyote reduced to quite an extent. Of late years it seems that poison will not kill a coyote. As soon as he feels the effect of the poison he throws up the bait he has just eaten, and in a few minutes he is all right.

The only way to kill coyotes these days is with the gun, the trap or with dogs. They are so thick here now that hounds would not be much good, as the coyotes would change at any time and run them down. I don't think there was a band of sheep anywhere in this country but what suffered more or less from coyotes last winter. I trapped some last winter for the Munz Brothers, and I saw where 48 sheep had been killed at one camp. They had been camped there about ten days. This is about an average killing if the weather is stormy.

"In Southeastern Oregon there is a desert about one hundred miles square, and thirty or forty bands of sheep feed there every winter. They run from two to three thousand sheep in a band. The sheep men on this desert last winter, 1904-'05, paid $40.00 per month and board for trappers to trap coyotes, and the trappers were allowed to keep the furs they caught. Some of them made very large wages."

It is said that when hunting rabbits, two coyotes will join forces and in this way one animal will drive the game to within reach of the other, thus avoiding the fatigue caused by running down game. Naturalists also claim that the adult animals will sometimes drive the game close to the den, so that the young coyotes may have the opportunity of killing it. They frequently pick up scraps about the camps, and if undisturbed, will in a short time, lose much of their timidity. Old camping places are always inspected in the hopes of finding some morsel of food, and one can always find coyote tracks in the ashes of the campfire.

Though the coyote belongs to the flesh-eating class of animals, it is not strictly carnivorous. In late summer when the wild rose tips are red and sweet and berries are plentiful, its flesh eating propensities forsake it in part and it adds fruit to its "bill of fare". Whether this is caused by hunger or a change of appetite, or whether the fruit acts as a tonic and the animal, instinctively, realizes that it must tone up its system in preparation for the long winter, is not known.

Coyotes have a more regular breeding season than the timber wolves, for practically all of the young make their appearance in the months of April and May. The number of young varies from five to twelve. The young animals are of a yellowish grey color with brown ears and black tail, muzzle tawny or yellowish brown. As they become older they take on a lighter shade and the tail changes to greyish with a black tip. Both wolves and coyotes pair for the breeding season and the males stay with the females during the summer and help take care of the young. It is probable that they do not breed until two years of age. As soon as the young are strong enough, and their eyes are open they commence to play about the mouth of the den and later on the mother leads them to the nearest water and finally allows them to accompany her on hunting excursions. In late summer they start out to shift for themselves.

As before mentioned, the coyote is a wary and cunning animal, especially in the more settled portions of its range; where man is not too much in evidence, they are far less wary. Again the fact that there are several varieties may account for the difference in the nature of the animals of the various sections, anyway those of the southern part of the range are less wary than those of the North. The trappers of Texas, Arizona and New Mexico claim that the coyote is a fool and is easily caught while those of the North and Northwest find them exceedingly cunning and intelligent. Not only does the animal appear to know when you are armed but it also seems to know something of the range of the weapon and will sneak along provokingly close, but just out of reach. When one is unarmed they appear to be more bold and will loaf around in the most unconcerned manner imaginable.

In intelligence and cunning, we consider the northern coyote the equal of the eastern red fox. While the western trappers make very large catches of coyotes, we believe that if foxes were found in equal numbers the catches of those animals would be fully as large. The number of coyotes found in some parts of the West is almost incredible, and in most parts one will find a hundred coyotes to one grey wolf.

The coyote makes a track similar to that of the timber wolf, but considerably smaller. The length of step, when walking, is about sixteen inches and the footprints will measure about two or two and a fourth inches in length by one and a half in width.

Undoubtedly the wolves and coyotes of the United States and Canada destroy more stock and game than all other predatory animals combined. In the Western part of our country where stock raising is one of the principal industries, the ranchmen suffer great losses from the depredation of these animals, and in other sections the wolves destroy large quantities of game. The reason that wolves are more destructive than others of the carnivora is that when they have the opportunity, they kill far more than they can consume for food. Often they only tear a mouthful of flesh from the body of their victim; sometimes they do not even kill the animal but leave it to suffer a slow and painful death. The animals that are only slightly bitten are sure to die from blood poisoning, according to the western ranchmen.

The wolf's method of attack is from the rear, springing on its victim and hamstringing it and literally eating it alive. The bite of the wolf is a succession of quick, savage snaps and there is no salvation for the creature that has no means of defense from a rear attack. This peculiar method of killing prey can not be practiced successfully on horses, owing to the fact that they can defend themselves by kicking, but for all of that, a considerable number of colts and a few full grown horses are killed. For this reason cattle suffer more than horses, but while the horse is, to a certain extent, exempt from attack by wolves, they are frequently killed by mountain lions, because their method of attack, a spring at the head and throat is more successful with these animals than with cattle. As food, however, horse flesh is preferred to beef by both of these animals.

One of the western trappers writes:

"Many times in the past thirty years I have watched wolves catch cows. The wolf is by nature a coward and will not, singly, attack a grown cow, though he will by himself kill a pig, chicken, calf, goat or sheep.

"On the ranges, where the stockmen and settlements are far apart, wolves go in bunches, from three to ten or even more, and when very hungry a bunch of them will attack a grown bull. They frighten him by snapping and playing around him till they get him on the run, when the bunch give full chase and stay close at his heels. While he is running in this way, one or more of them will grab him by the ham strings just above the hock joint. The bull makes, of course, a vigorous effort to free himself from the wolf, but before he can do so, the sharp teeth of the latter have cut or partially cut the ham string. They keep him on the run till they finally cut him down in both ham strings and then he cannot go further or fight the hungry wolves off.

"The whole bunch then eat his hams out while the bull is still alive, and after they get their full they let him rest. When they want to fill up again, they return and eat him till he dies, finishing the carcass as they require food.

"I have seen horses and cattle killed by wolves in this way live for several days with their hams eaten out, and have never seen the wolf make his attack or give chase in any other way. Being cowardly, he always follows behind and keeps out of all danger from the bull's hoofs."

Of cattle, calves and yearlings are generally selected, partly because the flesh of the younger animals is more to the wolf's liking and partly because they cannot defend themselves as readily as full grown animals, but full grown steers are also killed at times. Far more cattle are killed than are eaten. The wolf prefers fresh food always and in summer when their resources are unlimited they seldom return to the carcass for a second meal.

In "Bulletin 72," issued by the United States Department of Agriculture, the author, Mr. Vernon Bailey, has the following to say on the subject:

"The actual number of cattle killed by wolves can not be determined. Comparatively few animals are found by cattlemen and hunters, when freshly killed, with wolf tracks around them and with wolf marks on them. Not all of the adult cattle missing from a herd can surely be charged the depredations of wolves, while missing calves may have been taken by wolves, by mountain lions, or by 'rustlers.'"

Nevertheless there are data enough from which to draw fairly reliable conclusions. In the Green River Basin, Wyoming, on April 2, 1906, Mr. Charles Budd had 8 yearling calves and 4 colts killed in his pasture by wolves within six weeks. At Big Piney a number of cattle and a few horses had been killed around the settlement during the previous fall and winter. At Pinedale, members of the local stockmen's association counted 30 head of cattle killed in the valley around Cora and Pinedale in 1905, between April, when the cattle were turned out on the range, and June 30, when they were driven to the mountains. In 1906, wolves were said to have come into the pastures near Cora and Pinedale and begun killing cattle in January on the "feed grounds," and Mr. George Glover counted up 22 head of cattle killed by them up to April 10. Just north of Cora, Mr. Alexander, a well known ranchman, told me that the wolves killed near his place in June, 1904, a large three year old steer, a cow, 3 yearlings and a horse. On the G O S Ranch, in the Gila Forest Reserve in New Mexico, May 11 to 30, 1906, the cowboys on the round-up reported finding calves or yearlings killed by wolves almost daily, and Mr. Victor Culberson, president of the company, estimated the loss by wolves on the ranch at 10 per cent. of the cattle.

In a letter to the Biological Survey, under date of April 3, 1896, Mr. R. M. Allen, general manager of the Standard Cattle Company, with headquarters at Ames, Neb., and ranches in both Wyoming and Montana, states that in 1894 his company paid a $5.00 bounty at their Wyoming ranch on almost exactly 500 wolves. The total loss to Wyoming through the depredations of wolves Mr. Allen estimated at a million dollars a year.

In an address before the National Live Stock Association at Denver, Col., January 25, 1899, Mr. A. J. Bothwell said: "In central Wyoming my experience has been that these wolves kill from 10 to 20 per cent. of the annual increase of the herds."

Lieut. E. L. Munson, of Chouteau County, Mont., writing in Recreation, says: "It is said that in this country the loss from wolves and coyotes is about 15 per cent. * * * Wolves in this vicinity seldom kill sheep, as the latter are too carefully herded. They get a good many young colts, but prey especially on young cattle."

Mr. J. B. Jennett, of Stanford, Montana, says in Recreation: "A family of wolves will destroy about $3,000 worth of stock per annum."

The loss caused by wolves and coyotes in Big Horn County, Wyo., is estimated at three hundred thousand dollars per year. It has been variously estimated that each grey wolf costs the stockmen from two hundred and fifty to one thousand dollars annually.

Sheep, for some reason, are seldom troubled by timber wolves in the West, but suffer considerably from the attacks of coyotes; in fact, the loss occasioned the sheep men of Wyoming and Montana in this way is enormous. In summer when the sheep are driven up into the mountains, the coyotes migrate to those sections and kill sheep whenever the opportunity is presented. In the fall when the sheep are brought down into the foothills, the coyotes are also to be found in great numbers in those parts. In all probability there is a greater loss occasioned by the depredations of coyotes in the two states mentioned than is caused by wolves and mountain lions combined. Farther south, however, it is the wolf that does the most mischief. Where timber wolves are plentiful and very little stock is raised, as in the northern parts of Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota, sheep are not safe from the attacks of wolves, and for that reason few sheep are raised in those parts. It is probably the fact that the western range is very open and the sheep always carefully guarded by herders that they suffer so little from timber wolves in the Western States.

In the swamps of the Southern States, and especially in the lowlands of Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas, hogs are sometimes killed by wolves. In New Mexico, Texas, Colorado and Mexico where large numbers of goats are raised, these animals are frequently killed.

That an immense amount of game is killed in the wilder and less thickly settled portions of the United States and Canada goes without saying. In the West the wild game does not suffer as much as does the domestic animals, but in the heavily timbered portions of the country where little stock is raised as in the states bordering on Lake Superior and in the greater part of Canada large numbers of deer and other game animals fall victims to these fierce creatures. Regarding the killing of game on the western cattle range, Mr. Bailey has the following to say:

"At Big Piney, Wyoming, I examined wolf dung in probably fifty places around dens and along wolf trails. In about nine-tenths of the cases it was composed mainly or entirely of cattle or horse hair; in all other cases but one, of rabbit fur and bones, and in this one case mainly of antelope hair. A herd of 20 or 30 antelope wintered about 5 or 6 miles from this den, and the old wolves frequently visited the herd, but I could find no other evidence that they destroyed antelope, though I followed wolf tracks for many miles among the antelope tracks on the snow. Jack rabbits were killed and eaten along the trails or brought to the den and eaten near it almost every night, and a half eaten cottontail was found in the den with the little pups. While wolves are usually found around antelope herds, they are probably able to kill only the sick, crippled and young. The following note from Wyoming appeared in the Pinedale Roundup of July 4, 1906:

While riding on the outside circle with the late round-up, Nelse Jorgensen chanced to see a wolf making away with a fawn antelope. He gave chase to the animal, but it succeeded in getting away, never letting loose on its catch.

About a den near Cora, the numerous deposits of wolf dung on the crest of the ridge not far away were found to be composed of horse and cattle hair, though fresh elk tracks were abundant over the side hills on all sides of the den, while cattle and horses were then to be found only in the valley, 8 miles distant. Several jack rabbits had been brought in and eaten and the old wolf on her way to the den had laid down her load, evidently a jack rabbit, gone aside some 20 feet and caught a ruffed grouse eaten it on the spot, and then resumed her load and her journey to the waiting pups. One small carpal bone in this den may have been from a deer or small elk, but no other trace of game was found.

Talking with hunters and trappers who spend much time in the mountains when the snow is on the ground brought little positive information on the destruction of elk or deer by wolves. Mr. George Glover, a forest ranger long familiar with the Wind River Mountains in both winter and summer, said that he had found a large blacktail buck which the wolves had eaten, but he suspected that it had been previously shot by hunters. In many winters of trapping where elk were abundant, Mr. Glover has never found any evidence that elk had been killed by wolves. Coyotes constantly follow the elk herds, especially in spring when the calves are being born, and probably destroy many of the young, but wolves apparently do not share this habit. It seems probably, however, that in summer the young of both elk and deer suffer to some extent while the wolves are among them in the mountains."

In the Northern Peninsula of Michigan, wolves are very plentiful and large numbers of deer are killed during the winter months, the remains being found later by hunters, trappers, and lumbermen. The same conditions exist in Northern Minnesota and Wisconsin, also in parts of Ontario, Canada. In the Rainy River District, wolves have always been abundant and much game has been killed by them. Farther east, they are just making their appearance of late years having followed the deer which are coming into the country from some other section. Farther east, in the eastern portions of New Ontario and in some parts of Quebec wolves are also numerous. One of our friends from Northern Wisconsin writes as follows:

"I have trapped and caught five old female wolves since I came to Iron County, Wisconsin, six years ago. Two of them I got in Michigan, Gogebic County, as I live almost on the line. There are times when you can see six or eight wolf tracks all going down the river or coming up at the same time. You can go again for a week and never see a track. I have followed them for a week, in deep snow on snow shoes, and never left their track, and in one week I set traps at 50 different deer that wolves had killed. I might have gotten a few more wolves but the fox, mink, cats, skunk, owls and "porkys" (porcupines) were bound to butt in. At one set I got a wolf, 3 foxes, 1 skunk, 1 mink and 10 porkys till June.

Two wolves caught a buck that would weigh 150 pounds, within 10 rods of my camp one night. The next morning there was not one pound of meat left on the bones.

I had a tent and one shanty in Gogebic County last winter, and I know the wolves killed 500 deer on the snow. How many fawns and does did they kill in summer time when you cannot see their tracks? The wild cats are not so bad, a fawn, rabbit or partridge makes a meal for them."

In the far north where the barren ground caribou is the principal game animal, and where wolves are plentiful, there can be no doubt that they kill large numbers of those animals. Musk oxen are also killed, and farther south the moose is killed by wolves, but it is our belief that the number is comparatively small. The moose is such a large and powerful animal that even a band of half starved wolves will, as a rule, pass it by, but there can be no doubt of the fact that they do kill them on rare occasions.

The elk is a great enemy of the wolf and it appears that they are seldom molested. Beyond all doubt the deer is the principal prey of the timber wolf.

For many years the state governments of the wolf infested country have been paying bounties on wolves and coyotes, to encourage the hunting and trapping of these animals. It is doubtful, however, whether the bounties offered are sufficient to encourage any, other than the regular trappers, to hunt wolves, and if they are, it has certainly had no definite results, for the wolves and coyotes, taken over the whole country, are practically as plentiful as ever.

Realizing that the state bounties were not a sufficient inducement to trappers, certain of the counties of those states where wolves are most abundant, offer additional bounty. This has the effect of thinning the wolves out of that county alone, but they immediately become more plentiful in the adjoining portions of the country.

In some of the Western States, the stockmen pay a bounty, in addition to that offered by the state. Some of them even offer special inducements, in addition to the bounties paid on the captured animals, and among them may be mentioned, board and lodging for the trapper, bait for the traps and the use of saddle and pack horses.

Such special offers to trappers have the effect of stimulating the hunting and trapping of noxious animals in that immediate vicinity and the result is, a thinning out of the animals for the time being. Usually the trappers drift into those sections where the animals are most plentiful and the bounty is highest.

One of the Government bulletins has the following to say regarding the bounty question:

"Bounties, even when excessively high, have proved ineffective in keeping down the wolves, and the more intelligent ranchmen are questioning whether the bounty system pays. In the past ten years Wyoming has paid out in State bounties over $65,000 on wolves alone, and $160,156 on wolves, coyotes and mountain lions together, and to this must be added still larger sums in local and county bounties on the same animals."

"In many cases three bounties are paid on each wolf. In the upper Green River Valley the local stockmen's association pays a bounty of $10 on each wolf pup, $20 on each grown dog wolf, and $40 on each bitch with pup. Fremont County adds $3 to each of these, and the State of Wyoming $3 more. Many of the large ranchers pay a private bounty of $10 to $20 in addition to the county and state bounty. Gov. Bryant B. Brooks, of Wyoming, paid six years ago, on his ranch in Natrona County, $10 each on 50 wolves in one year, and considered it a good investment, since it practically cleared his range of wolves for the time. It invariably happens, however, that when cleared out of one section the wolves are left undisturbed to breed in neighboring sections, and the depleted country is soon restocked."

"A floating class of hunters and trappers receive most of the bounty money and drift to the sections where the bounty is highest. If extermination is left to these men, it will be a long process. Even some of the small ranch owners support themselves in part from the wolf harvest, and it is not uncommon to hear men boast that they know the location of dens, but are leaving the young to grow up for higher bounty. The frauds, which have frequently wasted the funds appropriated for the destruction of noxious animals almost vitiate the wolf records of some of the States: If bounties resulted in the extermination of the wolves or in an important reduction in their number, the bounty system should be encouraged, but if it merely begets fraud and yields a perpetual harvest for the support of a floating class of citizens, other means should be adopted."

The failure of bounties to accomplish their proposed object was clearly shown by Dr. T. S. Palmer in 1896. Under the heading, "What have bounties accomplished," he says:

"Advocates of the bounty system seem to think that almost any species can be exterminated in a short time if the premiums are only high enough. Extermination, however, is not a question of months, but of years, and it is a mistake to suppose that it can be accomplished rapidly except under extraordinary circumstances, as in the case of the buffalo and the fur seal. Theoretically, a bounty should be high enough to insure the destruction of at least a majority of the individuals during the first season, but it has already been shown that scarcely a single State has been able to maintain a high rate for more than a few months, and it is evident that the higher the rate, the greater the danger of fraud. Although Virginia has encouraged the killing of wolves almost from the first settlement of the colony, and has sometimes paid as high as $25 apiece for their scalps, wolves were not exterminated until about the middle of this (the past) century, or until the rewards had been in force for more than two hundred years. Nor did they become extinct in England until the beginning of the sixteenth century, although efforts toward their extermination had been begun in the reign of King Edgar (959-975). France, which has maintained bounties on these animals for more than a century, found it necessary to increase the rewards to $30 and $40 in 1882, and in twelve years expended no less than $115,000 for nearly 8,000 wolves."

"The larger animals are gradually becoming rare, particularly in the East, but it can not be said that bounties have brought about the extermination of a single species in any State."

"New Hampshire has been paying for bears about as long as Maine, but in 1894 the State treasurer called attention to the large number reported by four or five of the towns, and added that should the other 231 towns 'be equally successful in breeding wild animals for the State market, in proportion to their tax levy, it would require a State tax levy of nearly $2,000,000 to pay the bounty claims' Even New York withdrew the rewards on bears in 1895, not because they had become unnecessary, but because the number of animals killed increased steadily each year."

"Wolf skins are often ruined by the requirements of bounty laws, especially when the head, feet, or ears are cut off. The importance of preserving the skins in condition to bring the highest market price is as great as that of making it impossible to collect bounties twice. A slit in the skin can be sewed up so that it will never show on the fur side, but can not be concealed on the inside. A single longitudinal or vertical slit, or double or cross slits 4 inches long, in the center where the fur is longest, would serve every purpose of the law without seriously impairing the market value of the skin."

One thing that is detrimental to the success of the bounty system, is the invariable "red tape" connected with such laws. In some states the bounty regulations are so complicated and so exacting, that trappers do not care to follow "wolfing" because of the trouble in securing the bounty money.

It would be impossible, in a work of this kind, to give the bounty laws of the different states, also as they are repealed so frequently, detailed information on that subject would be of little value to the prospective hunter or trapper. We give, however, an outline of the regulations in some of the principal wolf states.

The State of Wyoming pays a bounty of five dollars each on timber wolves and mountain lions, and one dollar and twenty-five cents for each coyote. In addition to this, there are both county and stockmen's bounties in certain parts of the state. Some ranchmen offer as much as forty-five dollars each, for grey wolves caught on their ranches.

In order to secure the state bounty, one must present the entire skin to the County Clerk, or Notary Public, of the county in which the animal was killed, and accompanied by affidavit to the effect that the animal was killed in that county, by the person presenting the skin, on or after March 1st, 1909. The skin must have the feet and upper jaw or head, with both upper and lower lips attached. The head will then be cut off and destroyed by the county official. Applicants for bounty must be identified.

With regard to private bounties, one should consult the county officials, but these, and in that case, the state bounty also, are as a rule, paid by the treasurer of the association offering the bounty.

Wisconsin pays twenty dollars on old wolves and eight dollars each on pups. Half of this bounty money is paid by the state and the other half by the county. In order to secure it, the trapper must take the carcass of the animal to the Town Chairman and remove the scalp in his presence. He gives a certificate to that effect and the bounty claimant presents the scalp and certificate to the County Clerk, who destroys the scalp and gives an order to the County Treasurer for one-half of the bounty. The County Clerk also sends an affidavit to the State Treasurer, stating that you have presented the scalp and it has been destroyed and the claimant then receives the balance of the bounty money from the state.

In the State of Washington the bounty is fifteen dollars on timber wolves and one dollar on coyotes. The method of procuring the bounty as given here is copied direct from the game law pamphlet:

"Upon the production to the county auditor of any county of the entire hide or pelt and right fore leg to the knee joint intact of any cougar, lynx, wild cat, coyote or timber wolf, killed in such county, each of which hides or pelts shall show two ears, eye holes, skin to tip of nose, and right fore leg to the knee join intact, the county auditor shall require satisfactory proof that such animal was killed in such county. When the county auditor is satisfied that such animal was killed in his county, he shall cut from such hide or pelt the bone of the right fore leg to the knee as aforesaid which shall be burned in the presence of such auditor and one other county official, who shall certify to the date and place of such burning."

Utah pays a bounty of ten dollars on grey wolves and two dollars and fifty cents on coyotes. The entire skin, with tail, feet and the bones of the leg, to the knee, must be presented to the County Clerk within sixty days of the date on which said animal was killed. The County Clerk must then remove and destroy the bones of the legs and the applicant will sign an affidavit stating that the animal was killed by himself, in that county and within sixty days prior to that date.

The county official will then send a certified statement to the State Auditor, along with the other papers, who, after same have been examined, will transmit the bounty money to the claimant.

No bounty will be paid on the skin of a grey wolf until it has been seen and passed upon by the board of county commissioners at their first regular meeting. Bounty claimants must be identified by a reputable citizen and tax payer of the county.

In Minnesota the bounty on grown wolves is seven dollars and fifty cents and one dollar for wolf pups. The bounty regulations are practically the same as in the other states; the entire skin with head and ears intact must be presented to the Town Clerk within thirty days and the applicant must take affidavit as to the date and place of the killing.

In other states, if our information is correct, the bounties at present (1909) are as follows:

| ADULT WOLVES |

YOUNG WOLVES |

COYOTES |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | $10 00 | $2 00 | |

| Arkansas | 5 00 | ||

| Colorado | 5 00 | 1 00 | |

| Idaho | (?) 10 00 | (?) 1 00 | |

| Kansas | 5 00 | 1 00 | |

| Michigan | 25 00 | $10 00 | |

| Montana | 10 00 | 3 00 | |

| Nebraska | 4 00 | 1 25 | |

| New Mexico | 20 00 | 2 00 | |

| North Dakota | 4 50 | 2 50 | |

| Oregon | 10 00 | 7 00 | |

| South Dakota | 5 00 | 1 50 | |

| THE CANADIAN PROVINCES | |||

| Alberta | 10 00 | 1 00 | 1 00 |

| British Columbia | 15 00 | 2.00 | |

| Ontario | 15 00 | ||

| Quebec | 15 00 | ||

| Saskatchewan | 3 00 | 1 00 |

The fraud so often practiced by unscrupulous parties has always been detrimental to the efficacy of the bounty system. The Bureau of Biological Survey, have issued a special circular on this subject and being of general interest, it is reprinted here.

"The bounty system has everywhere proved an incentive to fraud, and thousands of dollars are wasted annually in paying bounties on coyote scalps offered in place of wolves, and on the scalps of dogs, foxes, coons, badgers, and even cats, which are palmed off for wolves and coyotes. If in all states having the bounty system whole skins, including nose, ears, feet, and tail of both adult and young animals, were required as valid evidence for bounty payments, the possibility of deception would be reduced to a minimum. The common practice of paying bounty on scalps alone, or in some cases merely the ears, is dangerous, as even an expert can not always positively identify such fragments. A satisfactory way of marking skins on which the bounty has been paid is by a slit 4 to 6 inches long between the ears. This does not injure the skins for subsequent use. If all bounty-paying states would adopt such a system, the possibility of collecting more than one bounty on the same skin in different states would be avoided."

"The following directions have been prepared as an aid to county and state officers in identifying scalps, skins, and skulls of wolves and coyotes, the pups of wolves, coyotes, red, grey, and kit foxes, and young bob-cats, coons and badgers."

"The variation in dogs is so great that no one set of characters will always distinguish them from wolves or coyotes, but when there is reason to suspect that dogs are being presented for bounties, their skins and skulls should be sent to the Biological Survey for positive identification. It goes without saying that anyone detected in such fraud should be prosecuted with a view to the suppression of these dishonest practices."

KEY TO ADULT WOLVES AND COYOTES.

| WOLF | COYOTE | |

|---|---|---|

| Width of nose pad | 1 1/4 to 1 1/2 inches | 3/4 to 1 inch |

| Width of heel pad of front foot | 1 1/2 to 2 inches | 1 inch |

| Upper canine tooth — greatest diameter at base |

5/10 to 6/10 inch | 3/10 to 4/10 inch |

These characters will not always hold in Oklahoma and Texas east and south of the Staked Plains, where there is a small wolf in size between the Coyote and Lobo or Plains wolf.

KEY TO WOLF, COYOTE AND FOX PUPS.

Wolf Pups.KEY TO YOUNG CATS, COONS AND BADGERS.

The bounty laws have always been a good thing for the trapper as they have helped much towards making his occupation a lucrative one, but, as before explained, it is doubtful if it has ever, in any marked degree, tended to decrease the numbers of predatory animals.

It is true that continued trapping will cause the numbers of wolves and coyotes to diminish, but would not the trapping be prosecuted practically the same, even if there were no bounties? We believe that it would, for if the bounty offered were any great incentive, there would be more trapping done during the summer when the furs were of no account.

Neither do we believe that it ever induces others, not trappers, to kill these animals, for they will kill them on every opportunity, bounty or no bounty. It is man's nature to kill, for he is the enemy of all animal life.

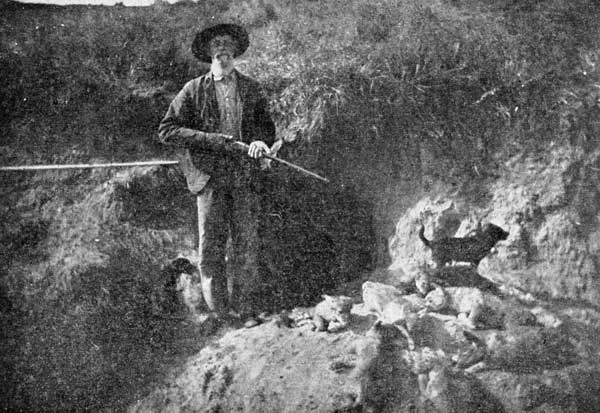

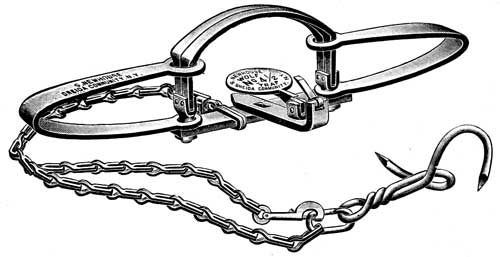

Of the many methods of hunting and otherwise capturing wolves and coyotes, employed by the professional "wolfers" of the west, none is more remunerative than the hunting of the young animals during the spring season. While the fur of the adult animals is of little value at that time and that of the young is not worth saving, the bounty which is usually paid for wolf and coyote pups will fully compensate for all loss from that source. At that time of year (March, April and May) there is very little fur of any value, to be had but the wolf hunter can combine wolf trapping and the hunting of the parent animals with the killing of the young, and the large bounties paid by many of the states and the various provinces of Canada, will alone enable one to do a profitable business.

In those parts of our country where the extermination of the wolves and coyotes is necessary for the protection of stock and game and the authorities and stockmen co-operate for the destruction of predatory animals, the hunting of the young animals during the breeding season should be especially encouraged. In no other way can the number of wolves be so surely reduced. To those who are well acquainted with the habits of the wolf, their time of breeding and the most favored breeding grounds, this mode of hunting is very simple.

Wolves breed much earlier than is commonly supposed, even by stockmen who have resided for a considerable length of time in the wolf country. The majority of young wolves are born in March in the Western States and the young of the coyote make their appearance mainly in April, but occasional litters of both will appear in May, and grey wolves may be born at any time during the summer.

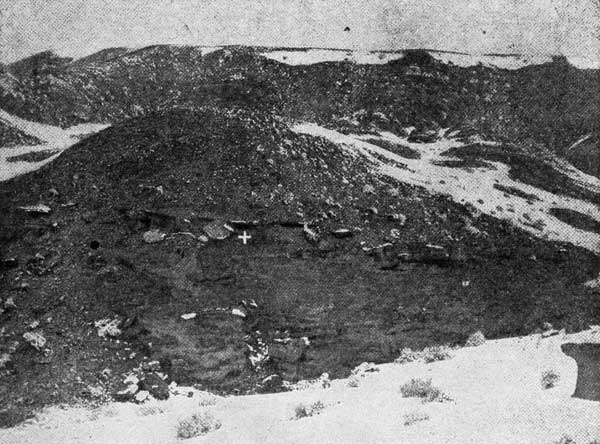

On the western cattle range, the dens of the wolf and coyote are located mainly in the valleys among the foothills of the mountain ranges and among the low mountains, but seldom at any great elevation. The steep side of a hill or canyon facing the south is the most favored location, and the rougher and more broken and brushy the ground, the better it suits the wolves for denning purposes. They especially like knolls, strewn with large boulders, from which the male parent can watch for the approach of enemies.

As before mentioned, the mode of hunting is very simple. All that is necessary is to look carefully over the breeding grounds until tracks are found and these should be followed to the den. It is safe to say that at that time of year, nine out of every ten tracks will lead to a den. On the northern portions of the range, there is almost certain to be good tracking snow during the early part of the breeding season, but even if the ground is bare it is not generally a difficult matter to trail the animals to the den. A track that has been made in the evening should be followed backwards and one made in the morning should be followed forwards, as the wolves do most of their hunting at night and return to the den in the early morning. When the track can not be followed, if one can get the general course of it, the lay of the land will enable one, on many occasions, to locate the den.

Whenever the hunter hears of wolves, or their signs having been seen frequently, he should make a diligent search for the den. As the old mother wolf always goes to the nearest water to drink, the number of tracks at a watering place will often be a dead give-away and a careful search of the locality will usually result in the discovery of the den. As the den is approached, the tracks will become more numerous, and near by there will be well beaten trails. Where tracks are numerous one should keep watch for the male, sentinel wolf, as he will always be on the lookout somewhere near the den and his position will enable one to locate it more readily. As one approaches, the male animal will howl and endeavor to draw the hunter off in pursuit and thus prevent the finding of the den. Their tricks on such occasions show considerable intelligence.

When looking for dens on bare ground, a dog, if he understands the work is very useful. A fox hound that is well trained on fox is good, but if trained for this style of hunting especially, will be found to be better. Unless on the trail of a bachelor wolf, which by the way are occasionally found during the breeding season, the dog will readily trail the wolf to the den. It is best to go early in the morning as the trail will be fresher at that time and the dog is more apt to follow a fresh trail, therefore, more certain of locating the den. In all probability, one of the old wolves will attempt to draw the dog off for a mile or two, but in that case the mother will endeavor to return to her young. Sometimes they find it necessary to fight the dogs and try to keep them from approaching too near the den. Anyway the actions of the animals will show when they are in the vicinity of the den, which may then be readily located.

One hunter who uses a dog for this style of hunting says: "The kind of a dog needed is a good ranger, extra good cold trailer and an everlasting stayer. Then if he will only run a short distance after starting the wolf and come back and hunt the pups and then bark at them when found, you have a good dog that is worth a large price. There are plenty of dogs that will hunt and trail wolves all right, but very few that will hunt the pups."

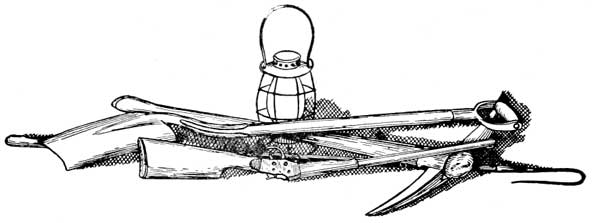

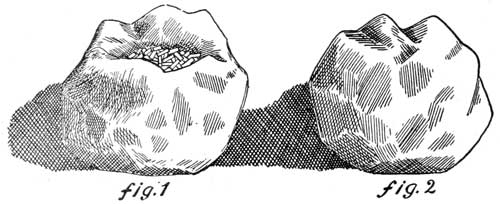

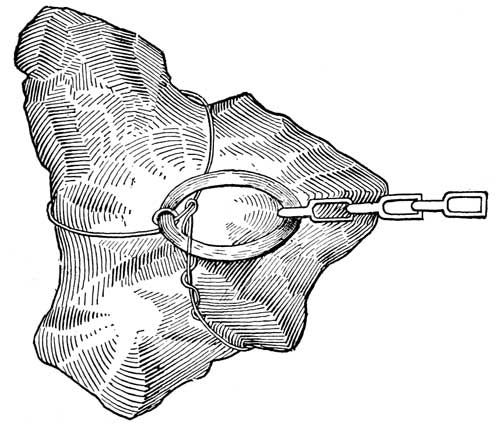

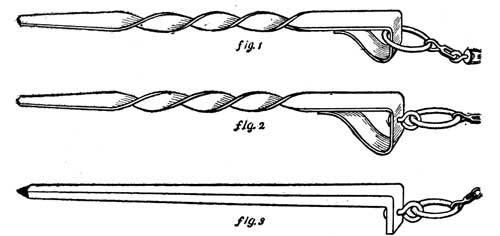

The den is usually a natural one; a hole worn in the rocks by the elements, or in washed out cavities in the hard ground of the bad lands. Down in the valleys they sometimes den in the ground, enlarging the burrow of a badger or other animal. The opening is, as a rule, large enough to allow one to enter and secure the pups, but sometimes it will be necessary to dig the den open. For dens in the rocks, which are too small to allow one to enter, the hunter should provide a hook, something on the order of a gaff hook such as is used by fishermen. The hook should be of fair size, very sharp, and should be attached to a handle about three or four feet in length. A famous western wolf hunter in speaking of his outfit says:

"I will say to the boys who intend to hunt pups, get two or three strong fish hooks and a strong cord and carry them in your pocket. You can usually find a small stick or pole of some kind. When you find a den, tie your hooks on end of stick, wrapping cord very tight. If you use two hooks, put one on each side of stick. Shove your stick in the den among the pups and turn or twist it and you will soon have a pup hooked. This works the best of anything I have ever tried; where pups are small. I have gotten many a bunch or pups this way, when my pick or shovel would be five or six miles away.

When the pups get too large and strong to pull out alive, I put a candle on the stick, shove it into the den and lay on my stomach. With a 22 rifle I shoot the pups in the head and then they are easily pulled out with the fish hooks. I mean this for dens that cannot be dug out, as there are many of them in rock ledges and in holes in the solid rock. Instead of the candles mentioned by this hunter, some prefer to use a lantern and one "wolfer" uses a hunting lamp, attached to his hat. Some sort of firearm should be carried always. A revolver is good for use in the den, but a rifle is best outside.

It is not often that the mother wolf will be found in the den, as she usually makes her escape before one comes near, but should she be found at home she should be disposed of first. There is no danger, whatever, from the adult wolves. One of our western friends in speaking of this says: "I never hesitate in entering a wolf den, even when I know the mother wolf is with her young, and have never known one to act vicious, but always sneaking and cowardly. A few years ago at the Cypress Hills in Canada I entered a den and took ten pups. The mother crawled as far from me as she could and never raised her head. I set my 30-30 Savage and pulled it off with a rope, shooting her through the heart. It was forty feet from the entrance of the hole to where she lay, and it was midnight when I got her out. I had to move some dirt and rocks and it was a big job.

"I have killed other grown wolves in the den and have never known one to show fight. Of course, I always use a lantern to see what I am doing, and would not enter a den without one." The young wolves should be killed immediately and live pups should never be handled with bare hands, as blood poisoning is likely to result from a bite.

Beyond all doubt wolf chasing as it is practiced in some parts of the country is one of the most fascinating of sports and in a place where the animals are fairly plentiful and the surface of the country is not too rough, is also profitable. In parts of the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, some of the professional wolfers use this method of securing their game and in the states lying west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, also in Western Canada, wolf hunting is a very popular sport among the ranchmen.

Among the dogs that are most approved of by the wolf and coyote hunters, may be mentioned the fox hound, the greyhounds, and stag hounds of various varieties, the bloodhound and crosses of these dogs. The grey hounds are the swiftest of dogs and a pair of them are invariably to be found in a pack, the balance being some heavier and fiercer breed of dog, such as the blood hound, fox hound or a cross of the two. It is the grey hounds that run the game down and hold it until the arrival of the balance of the pack, the heavier dogs doing the actual fighting.

One who has followed wolf hunting extensively gives the following short but interesting description of the sport: "On the open plains of the west, wolves are often hunted with large swift running dogs, grey hounds, stag or wolf hounds or their crosses. The hunters go on horseback and the wolves are usually roused out of some coulee or draw. Sometimes trail hounds are used to start the game, on breaking from cover and being sighted by the running dogs the race is on. Wolf, dogs and horsemen, race across the often rough and dangerous ground at breakneck speed. The wolf, maneuvering to gain the coulee or cover of some sort and get out of sight of the dogs (the running dogs have only slight scenting powers and depend entirely on their sight). The lighter and swifter grey hounds, as a rule, are the first to overtake the wolf and by coming up alongside and snapping at his flanks, force him to turn and face them, thus giving the heavier and fiercer wolf hounds a chance to close in and grapple with and kill the wolf. Unless the dogs are well trained and very courageous, a large timber wolf often proves more than a match for the bunch of four or five dogs."

No matter what kind of dogs are used, they must be good tonguers and good fighters, and must have an abundance of strength and endurance. It is needless to say that the dog must be trained and this must be done at an early age. The young dog should never be run alone, for the wolf is likely to fight it off and once the young dog is driven back it will be spoiled for hunting purposes.

One of our Kansas friends in speaking of wolf dogs says: "We have plenty of wolves (coyotes) and have had for the twenty years we have kept dogs. As to breeding, we used an English greyhound bitch with courage, speed and a special hatred for a wolf, crossed with an English fox hound with all the qualities necessary, except the speed. We then picked the bitch with the most good qualities and crossed her with another fox hound whose ancestry is perfect. Here we get the dog we are using now and with which we have made the most satisfactory of catches. We seldom have a run lasting more than three hours and catch many, when vegetation is not too high, in from one to one and a half hours. Where this dog has the advantage over the fox hound is in speed and the fact that it is ever on the watch ahead for the game."

Evidently the party who used this breed of dog has endeavored to instill into the one type, all of the good qualities of the several breeds that go to make up the regulation pack of wolf dogs. It is surmised, also, that the one breed of dog is used alone, when chasing wolves. In Western Canada, wolf hunting is a favorite sport and one of the hunters from that section in speaking on this subject gives the following method of hunting:

"First, we put a box on the sleigh big enough to hold our dogs and then hook up a lively team, and strike across the country, leaving the dogs run along side. When a wolf is sighted, we get the dogs into the box and drive as close to the wolf as we can — that's usually from three to five hundred yards — then turn the dogs loose and cheer them to victory. The dogs usually run down the wolf within a mile, and we follow as fast as horse flesh can take us. When the leading dog gets alongside, the wolf stops, and in a second the dogs form a circle around him and he is a goner. Some hunters just turn the dogs loose, not knowing when they are ever going to see them again. That plan would not work with me. Good hounds are too expensive to monkey with that way. I have found that letting one or two dogs on a wolf trail spoils them, because one wolf will give two dogs all they can handle, and sometimes a little bit more, especially if they are young dogs. It takes two old dogs at least, to handle one wolf, and I have seen them get the hard end of it. The wolf perhaps would take to running into the scrub and then it wouldn't be long until a pair of wolves would be slashing your dogs or 'fleecing' the stuffing out of them."

Those who make a business of wolf hunting, or in other words, those who hunt for profit, do not always allow the dogs to fight and kill the wolf, but carry a gun with them, on all occasions and if they have an opportunity to shorten the chase by means of a well directed bullet, do not hesitate to do so. A high powered rifle should be used and one should learn to handle it in a business-like way. In the Western States where the large ranches are rapidly disappearing and the farm, with the barbed wire fence is taking its place, wolf hunting will soon be a thing of the past. Mr. Jack Kinsey, one of the most noted wolfers of the West, gives a description of an exciting wolf chase, in which he illustrates this point, and we give the story in his own words:

"While I was in Dakota last winter I had two exciting wolf chases. I was stopping with Mr. Wm. Clanton, a cowman, living seven miles south of Harding, S. D. One day I was in his shop putting a coyote hide on a stretcher, when one of his neighbors drove up and asked Mr. Clanton if he had a rifle. He said, 'Yes, there is a wolfer here who has one.' 'Why,' his friend said, 'there are two big grey wolves just back over that hill.'"

"I waited for no more but ran for my horse and gun. Clanton saw me going to the barn and told me to bring his horse. Now I was not long in getting those horses and we were soon on their trail. We followed their tracks about one and one-half miles when we sighted them. Picking out the largest of the two we both rode after him. The wolf started west towards some bad lands, but Mr. Clanton was riding a good young horse and he soon turned the wolf south, but now he was headed straight for a wire fence.

"Mr. Clanton would have succeeded in turning him again, but he struck a ditch full of snow, so the wolf got inside the pasture but I was fixed for wire fences. I had my trapping axe on my saddle and soon made a gate that we did not stop to fix up. We had run the wolf five or six miles by this time, and our horses were pretty well winded. So we pulled them up and let them take a slower gait until we got through the other side of the pasture.

"As I said before, Mr. Clanton was riding the best horse, so he kept the outside while I took advantage of the cuts. Mr. Clanton was just far enough ahead of me to make one throw at the wolf with his rope, but he missed him. The wolf cut in behind his horse, when I rode in front of him and put a 30-40 soft point in his head. He was a very large grey wolf. His hide stretched 6 1/2 feet long. On the way back we saw three more wolves and two coyotes."

We give the following spirited account of a wolf hunt which occurred in South Dakota:

"Will tell about one of my hunts behind a pair of wolf hounds that are certainly right when it comes to coyotes. I left my home here in Illinois on the 12th of December and arrived at Presho, S. D., early the 14th, where my friends met me, and we started for the ranch, which is about midway between Presho and Pierre.

"When we got to the reservation fence (Brule Reservation), we kept a lookout for coyote signs, and located a place that we thought would be all right, and planned a hunt for the following Saturday.

"The day proved all that could be desired, so we started out at noon. Earl, Claude, Mort, Chas., Sheldon and myself, with the two hounds, Ike and Lucy. A ride of about two miles brought us to the reservation, and the hunt was on.

"Our outfit consisted of our saddled ponies and team and buggy, and by standing up in the buggy seat we located two coyotes on the side hill playing in the high grass. A circle around the hill and Lucy discovered them and was off with Ike a second, as he was not as fast as Lucy.

"Away we all go across the prairie with the team and buggy following the reservation fence to keep the coyote away from the fence. It was a short chase, as Lucy soon had Mr. Coyote by the hind leg and turned him on his back quicker than it can be told, and Ike being close at hand soon had him by the throat, so by the time we could get out horses stopped and turned Mr. Coyote was no more.

"After skinning, we started for the buggy and Sheldon reported coyote No. 2 headed south down the draw, and Earl went after him around the hill and drove him back our way.

"A shout from that direction and the dogs have discovered No. 2 and we are away with Lucy in the lead, and this time we are not far behind, so that when the dogs got him we were right there, and the coyote not much hurt, so he gets a rope halter and is stowed away alive under the buggy seat.

"The dogs are panting hard and are very thirsty, with no water closer than five miles, so we head for home, but not far away on the hillside another one is seen and the buggy starts toward the left to head him toward the ranch, so the dogs will be running toward home when they jump him.

"This time Ike catches sight and is off, and Lucy cuts across to head him off. It is a short chase, for old Ike soon has his favorite hold and all is over.

"After skinning we started for home and as I hadn't ridden much for over a year you can gamble I was feeling pretty sore, for the pace a pack of hounds set isn't slow by a long shot. On driving into the yard the dogs were not slow about getting into the house and lying down.

"The live coyote we tied to the buggy wheel, and while I was gone after a strap and chain he bit the rope off and 'cut the mustard' for parts unknown with about a foot of rope still hanging to him.

"We have good hunting here in the spring and fall, plenty of chickens and, some ducks and geese, with lots of jack rabbits and (Flicker Tails), prairie dogs, and their side partners, owls and rattlers.

"Our outfit is the bar circle outfit, O and I think our Holstein cattle are among the first herds in the state. Have since this hunt disposed of my interest in the O but still have a bunch of cattle at Presho, which supply the town with milk."

Hunting wolves with dogs, as described in the preceding chapter is certainly exciting sport but it is doubtful if it is as remunerative as still-hunting, especially in the rough sections where hunting with dogs is almost impracticable. In parts of the country where wolves and coyotes are plentiful, as they are in many of the thinly settled portions of the West, they may be still hunted at all times of the year. In the heavily timbered parts of the North, this method is practical only in winter.

The outfit that is needed for still-hunting in the West is one or more good saddle horses and the necessary equipment and a good, high powered rifle. A pair of field glasses will also be useful, but some hunters equip their rifles with telescope sights and the field glass is unnecessary. Hunters differ in their views, and with regard to rifles especially, there is a great difference of opinion. What one believes to be perfect, and which answers his purpose admirably, another has no use for whatever.

The arm selected should, however, have considerable power, and the flight of the bullet should be rapid, with a low trajectory. On the Western Plains the atmosphere is so light and transparent, and there is such a sameness to the surface of the country that one may easily be deceived in distances and with the high powered long-ranged rifle, there is less liability of errors, as the accurate estimating of distances is not necessary.

A gun of rapid action is also to be recommended and beyond all doubt the automatic acting arms are superior for shooting at running game. Personally, if the writer were selecting an arm for this kind of hunting, a high powered automatic rifle would be chosen, and it would be fitted with a small bead front sight and hunting peep rear sight. For use on horse back the shorter barrels are to be preferred.

In speaking of the outfit it is presumed that the wolf hunter would be a resident of the western country and would be hunting from home or anyway, making his headquarters at some ranch and hunting from there. If, however, he wants to go out into virgin territory, or if a stranger, he might find it necessary to camp out and in that case he would require a complete camping outfit. Some of the western wolfers use covered wagons for camps and this style of camp is very convenient as it may be moved easily, but if the surface of the country is very rough, this plan is not practical. In that case a tent would be needed and the hunter would use a pack horse in moving camp.

Speaking of saddle horses, in the more arid parts of the wolf country, the vegetation is scanty and horses require considerable time in which to rustle food. For that reason the same horse can not be used each day and one should have several so that each would have plenty of time to recuperate, after use. If one can obtain horses that will allow one to shoot from the saddle, so much the better. No special knowledge of hunting is required, but one should be expert in the use of the rifle, and should also be a good rider. All that is necessary is to ride over the rougher parts of the country, where wolves are most likely to be seen, and keep a sharp lookout for the game. It is always best to hunt to windward as one can approach closer to the game.

Where the bounty is sufficient to make summer hunting profitable, we would recommend this style of hunting at that time of year. In summer, hunting with dogs is not as simple a matter as in winter and trapping is not as good as during the colder part of the year. For coyotes, still hunting is a very successful method in parts of the country where the animals are plentiful and there is probably no place in which the method could be used to better advantage than in the sheep-raising district of Montana and Wyoming. There coyotes may be sighted every day and if the hunter would make a practice of following up the large herds of sheep to the summer range, he would always be sure of an abundance of game.

One is most likely to sight coyotes by riding along the coulees and over the rougher ground. About prairie dog towns are excellent places, as there they will frequently be found looking for the little inhabitants of the burrows. Other good places are the ragged, craggy parts of the Bad Lands and in the sage brush along the watercourses.

In winter one may follow the tracks in the snow and will stand a better chance of securing the game. While still hunting alone might not prove a very profitable method of hunting if one were hunting for bounty, it should always be used in connection with trapping and den hunting. As mentioned in a previous chapter one will often get shots at the adult animals near the dens and if one knows of the location of a den, he may often get a shot by watching it. Anyway the rifle should always be carried, and it should be used whenever a wolf or coyote is seen within range.

We will conclude this chapter by giving an account of a coyote still-hunt, as recorded by one of our western friends.

"It was one of those bright balmy September mornings, so characteristic of Wyoming, that I drove my horses down to water and noticed some coyote tracks in the mud at the edge of the water hole, and I decided then and there to have a coyote hunt that day. I was at the time in charge of a relay station, midway between two small towns and it was my business to look after the spare stage horses, for the stage driver changed teams here, leaving the tired horses in my care and taking on fresh ones. The northbound stage passed about 8:30 A. M., and the southbound outfit was due at about 6:30 P. M., which left me with practically the entire day at my disposal, to do with as I liked, and having my full quota of the spirit of our savage ancestors, I naturally turned to hunting the coyotes which abounded in that section.

"For some time past I had been doing practically no hunting. I say 'practically none' for I had not been out on a real hunt for several weeks, but I did have a short line of traps set and had been looking at them every second morning. On these trips over the trap line I always carried my 30-30 carbine on the saddle and had surprised and shot three coyotes, besides shooting at several more, one of which was wounded but escaped by crawling into a deep hole in a bad-land butte. Besides the three animals mentioned, I had caught in my traps up to that time, some twenty more.

"On this particular morning the 'Spirit of the Wild' called loudly, for as every hunter knows, there is something in the air of autumn which gets into one's blood at times, and there is no remedy except to go on a hunt. My trap line had been looked at the day before, so I was free for the day. Returning to the little sod house which I called my home, I got my rifle and six shooter, prepared a lunch and as soon as the stage had arrived, changed horses and departed, I mounted my horse and hit the trail for the hills to the westward.

"The section of the country to the west of the station was of the bad-land type, groups of buttes and ridges, radiating in every direction, seamed and honey-combed by the rains of centuries. While the country is very dry, the rains are veritable deluges when they do come, and the ordinarily dry water courses become raging torrents. Along these creek beds, sage and grease wood brush was abundant; in the hills, no vegetation was to be found. It was at all times a paradise for coyotes and occasionally a band of grey wolves strayed through those parts. However, the wolves had been rarely met with since the stockmen had abandoned the cattle industry and gone to sheep raising, but the coyotes had increased in numbers.

"At this time of the year, the sheep were being driven down from the mountains into their winter range and in addition to the coyotes which remained, throughout the summer, in the bad-lands, the still larger number which make a practice of following up the great bands of sheep were also appearing on the scene, and the day promised good sport.

"Riding westward about two and a half miles, I struck the bed of a stream and followed it up towards the hills. Here, I knew there were several prairie dog villages and about such places one is almost certain to find coyotes, so I turned my horse that way in the hope of getting a shot at one of the wary animals. My fond hopes were realized, for on rounding the hill at the edge of the first village I saw a large coyote slinking guiltily over the crest of the nearest ridge, but giving me no chance to draw the gun before he passed out of sight. Hastily riding to the top of the ridge, I saw the animal making his get-away down the draw at the other side and throwing my carbine to my shoulder, I caught a quick aim and fired just as he was rounding a spur of the ridge about a hundred and fifty yards away. Snap-shooting from horseback is uncertain at all times and on this occasion I had barely time to catch a half-hearted aim, so was not very hopeful regarding the results of my shot.