This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Calavar

or The Knight of The Conquest, A Romance of Mexico

Author: Robert Montgomery Bird

Release Date: October 23, 2010 [eBook #34121]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CALAVAR***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/calavartheknight00birdrich |

PREFACE TO THE NEW EDITION.

INTRODUCTION.

CALAVAR.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

CHAPTER XXIX.

CHAPTER XXX.

CHAPTER XXXI.

CHAPTER XXXII.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

CHAPTER XXXIV.

CHAPTER XXXV.

CHAPTER XXXVI.

CHAPTER XXXVII.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

CHAPTER XXXIX.

CHAPTER XL.

CHAPTER XLI.

CHAPTER XLII.

CHAPTER XLIII.

CHAPTER XLIV.

CHAPTER XLV.

CHAPTER XLVI.

CHAPTER XLVII.

CHAPTER XLVIII.

CHAPTER XLIX.

CHAPTER L.

CHAPTER LI.

CHAPTER LII.

CHAPTER LIII.

CHAPTER LIV.

CHAPTER LV.

CHAPTER LVI.

CHAPTER LVII.

CHAPTER LVIII.

CHAPTER LIX.

CHAPTER LX.

CHAPTER LXI.

CHAPTER LXII.

CHAPTER LXIII.

CHAPTER LXIV.

CHAPTER LXV.

CONCLUSION.

It is now thirteen years since the first publication of "Calavar," which, apart from the ordinary objects of an author, was written chiefly with a view of illustrating what was deemed the most romantic and poetical chapter in the history of the New World; but partly, also, with the hope of calling the attention of Americans to a portion of the continent which it required little political forecast to perceive must, before many years, assume a new and particular interest to the people of the United States. It was a part of the original design to prepare the way for a history of Mexico, which the author meditated; a design which was, however, soon abandoned. There was then little interest really felt in Mexican affairs, which presented, as they have always done since the first insurrection of Hidalgo, a scene of desperate confusion, not calculated to elevate republican institutions in the opinions of the world. Even the events in Texas had not, at that time, attracted much attention. Mexico was, in the popular notion, regarded as a part of South America, the alter ego almost of Peru,—beyond the world, and the concerns of Americans. There was little thought, and less talk, of "the halls of the Montezumas;" and the ancient Mexican history was left to entertain school-boys, in the pages of Robertson.

"Calavar" effected its more important purpose, as far as could be expected of a mere work of fiction. The revolution of Texas, which dismembered from the mountain republic the finest and fairest portion of her territory, attracted the eyes and speculations of the world; and from that moment, Mexico has been an object of regard. The admirable history of Prescott has rendered all readers familiar with the ancient annals of the Conquest; and now, with an American army thundering at the gates of the capital, and an American general resting his republican limbs on the throne of Guatimozin and the Spanish Viceroys, it may be believed that a more earnest and universal attention is directed towards Mexico than was ever before bestowed, since the time when Cortes conquered upon the same field of fame where Scott is now victorious. There is, indeed, a remarkable parallel between the invasions of the two great captains. There is the same route up the same difficult and lofty mountains; the same city, in the same most magnificent of valleys, as the object of attack; the same petty forces, and the same daring intrepidity leading them against millions of enemies, fighting in the heart of their own country; and finally, the same desperate fury of unequal armies contending in mortal combat on the causeways and in the streets of Mexico. We might say, perhaps, that there is the same purpose of conquest: but we do not believe that the American people aim at, or desire, the subjugation of Mexico.

"Calavar" was designed to describe the first campaign, or first year, of Cortes in Mexico. It was written with an attempt at the strictest historical accuracy compatible with the requisitions of romance; and as it embraces, in a narrow compass, and—what was at least meant to be—a popular form, a picture of the war of 1520, which so many will like to contrast with that of 1847, the publishers have thought that its revival, in a cheap edition, would prove acceptable to the reading community. The republication has, indeed, been suggested and called for by numerous persons desirous to obtain copies of the book, which has been for some time out of print.

The revival of the romance might have furnished its author an opportunity to remove many faults which, he is sensible, exist in it. Long dialogues might have been contracted, heavy descriptions lightened or expunged, and antiquated phraseology modernized, with undoubted benefit. But, after a respectful consideration of all critical suggestions, friendly or unfriendly, the author has not thought it of consequence to attempt the improvement of a work of so trivial and evanescent a character; and he accordingly commits it again to the world precisely as it was first committed, with all its faults—would he could say, its merits—unchanged; satisfied with any fate that may befall it, or any reception it may meet, which should either imply its having given some little pleasure, or imparted some little information, to its readers.

R. M. B.

Philadelphia.

Nature, and the memory of strange deeds of renown have flung over the valley of Mexico a charm more romantic than is attached to many of the vales of the olden world for though historic association and the spell of poetry have consecrated the borders of Leman and the laurel groves of Tempe, and Providence has touched both with the finger of beauty, yet does our fancy, in either, dwell upon objects which are not so much the adjuvants of romance as of sentiment; in both, we gather food rather for feeling than imagination,—we live over thoughts which are generated by memory, and our conceptions are the reproductions of experience. But poetry has added no plenary charm, history has cast no over-sufficient light on the haunts of Montezuma; on the Valley of Lakes, though filled with the hum of life, the mysteries of backward years are yet brooding; and the marvels of human destiny are whispered to our ears, in the sigh of every breeze,—in the rustling of every tree which it stirs on the shore, and in the sound of every ripple it curls up on the lake. One chapter only of its history (and that how full of marvels!) has been written, or preserved; the rest is a blank: a single chain of vicissitudes,—a few consecutive links in the concatenation of events,—have escaped; the rest is a secret, strange, captivating, and pregnant of possibilities. This is the proper field for romantic musings.

So, at least, thought a traveller,—or, to speak more strictly, a rambler, whose idle wanderings from place to place, directed by ennui or whim, did not deserve the name of travels,—who sat, one pleasant evening of October, 183-, on the hill of Chapoltepec, regarding the spectacle which is disclosed from the summit of that fair promontory.

The hum of the city came faintly to his ear; the church-towers flung their long shadows over the gardened roofs; the wildfowl flapped the white wing over the distant sheets of water, which stretched, in a chain, from Chalco to San Cristobal; the shouts of Indian boatmen were heard, at a distance, on the canal of La Viga, and the dark forms of others, trotting along the causeway that borders it, were seen returning to their huts among the Chinampas. Quiet stole over the valley; the lizard crept to his hole; the bat woke up in the ruined chambers of the viceroy's palace, that crowns the hill of Chapoltepec, or started away from his den among the leaves of those mossy, majestic, and indeed colossal, cypresses, which, at its base, overshadow the graves of Aztec kings and sultanas. At last, the vesper-bells sounded in the city, and the sun stooped under the western hills, leaving his rays still glittering, with such hues as are only seen in a land of mountains, on the grand peaks of Popocatepetl and the White Woman, the farthest but yet the noblest summits of all in that girdle of mountain magnificence, which seems to shut out Mexico from the rest of the world.

As these bright tints faded into a mellow and harmonious lustre, casting a sort of radiant obscurity over vale and mountain, lake and steeple, the thoughts of the wanderer (for the romance of the spectacle and the hour had pervaded his imagination,) crept back to the ages of antiquity and to those mystic races of men, the earliest of the land, who had built their cities and dug their graves in this Alpine paradise, now possessed by a race of whom their world had not dreamed. He gazed and mused, until fancy peopled the scene around him with spectral life, and his spirit's eye was opened on spectacles never more to be revealed to the corporeal organ. It opened on the day when the land was a wilderness, shaking for the first time under the foot of a stranger; and he beheld, as in a vision, the various emigrations and irruptions into the vale, of men born in other climates. They came like the tides of ocean, and, as such, passed away,—like shadows, and so departed; the history of ages was compressed into the representation of a moment, and an hundred generations, assembled together as one people, rushed by in successive apparitions.

First, over the distant ridges of Nochistongo, there stole, or seemed to steal, a multitude of men, worn with travel, yet bearing idols on their backs, in whose honour, for now they had reached their land of promise, they built huge pyramids, to outlive their gods and themselves; and, scattering over the whole plain, covered it at once with cornfields and cities. The historian (for this unknown race brought with it science as well as religion,) sat him in the grove, to trace the pictured annals of his age; the astronomer ascended to the tower, to observe the heavens, and calculate the seasons, of the new land; while the multitude, forgetting the austere climes of their nativity, sat down in peace and joy, under the vines and fruit-trees that made their place of habitation so beautiful. Thus they rested and multiplied, until the barbarians of the hills,—the earlier races, and perhaps the aborigines of the land,—descended to take counsel of their wisdom, and follow in the ways of civilization. Then came a cloud, bringing a pestilence, in whose hot breath the rivers vanished, the lakes turned to dust and the mountains to volcanoes, the trees crackled and fell as before a conflagration, and men lay scorched with the leaves, as thick and as dead, on the plain; and the few who had strength to fly, betook themselves to the hills and the seaside, to forget their miseries and their arts, and become barbarians.—Thus began, and thus ended, in Mexico, the race of Toltecs, the first and the most civilized of which Mexican hieroglyphics,—the legacy of this buried people to their successors,—have preserved the memory.

But the rains fell at last, the lakes filled, the forests grew; and other tribes,—the Chechemecs and Acolhuacans, with others, many in number and strangers to each other,—coming from the same distant North, but bringing not the civilization of the first pilgrims, sat in their seats, and mingling together into one people, began, at last, after long seasons of barbarism, to emerge from the gloom of ignorance, and acquire the arts, and understand the destinies of man.

To these came, by the same trodden path, a herd of men, ruder than any who had yet visited the southern valleys,—Aztecs in family, but called by their neighbours and foes, Nahuatlacas, or People of the Lakes,—consisting of many tribes, the chief of which was that which bore upon a throne of bulrushes an image of the god Mexitli, the Destroyer, from whom, in its days of grandeur, it took its name. From this crew of savages, the most benighted and blood-thirsty, and, at first, the feeblest of all,—so base that history presents them as the only nation of bondmen known to the region of Anahuac, and so sordid that, in the festivals of religion, they could provide for their deity only the poor offering of a knife and flower,—fated now to fight the battles of their task-masters, and now condemned to knead the bread of independence from the fetid plants and foul reptiles of the lake;—from this herd of barbarians, grew, as it seemed, in a moment's space, the vast, the powerful, and, in many respects, the magnificent empire of the Montezumas. In his mind's eye, the stranger could perceive the salt Tezcuco, restored to its ancient limits, beating again upon the porphyry hill on which he sat, and the City of the Island, with her hundred temples and her thousand towers, rising from the shadows, and heaving again with the impulses of nascent civilization. It was at this moment, when the travail of centuries was about to be recompensed, when the carved statue, the work of many successive Pygmalions, was beginning to breathe the breath, and feel the instincts of moral animation, that a mysterious destiny trampled upon the little spark, and crushed to atoms the body it was warming. From the eastern hills came the voice of the Old World—the sound of the battle-trumpet; the smoke of artillery rolled over the lake; and, in a moment more, the shout of conquest and glory was answered by the groan of a dying nation.

As this revery ended in the brain of the stranger, and the conqueror and the captive of the vision vanished away together, he began to contrast in his mind the past condition of the new world with the present, and particularly of those two portions, which, at the time of their invasion, had outlived the barbarism of nature, and were teeming with the evidences of incipient greatness. As for this fair valley of Mexico, there was scarcely an object either of beauty or utility, the creation of Christian wants or Christian taste, to be seen, for which his memory could not trace a rival, or superior, which existed in the day of paganism. The maize fields, the maguey plantations, the orchards and flower-gardens, that beautify the plains and sweeping slopes,—these were here, long ages ago, with the many villages that glisten among them,—all indeed but the white church and steeple; the lakes which are now noisome pools,—were they not lovelier when they covered the pestilential fens, and when the rose-garden floated over their blue surface? The long rows of trees marking the line of the great Calzadas, or causeways, the approaches to Mezico, but poorly supply the place of aboriginal groves, the haunts of the doe and the centzontli, while the calzadas themselves, stretching along over bog and morass, have entirely lost the charm they possessed, when washed, on either side, by rolling surges; even the aqueducts, though they sprang not from arch to arch, over the valley, as at the present time, were not wanting; and where the church spires of the metropolis pierce the heaven, the sacred tabernacles of the gods rose from the summits of pyramids. The changes in the physical spectacle among the valleys of Peru were perhaps not much greater; but what happy mutations in the character and condition of man, what advance of knowledge and virtue, had repaid the havoc and horror which were let loose, three hundred years ago, on the lands of Montezuma and the Incas? The question was one to which the rambler could not conceive an answer without pain.

'The ways of Providence,' he murmured, 'are indeed inscrutable; the designs of Him who layeth the corner-stone and buildeth up the fabric of destiny, unfathomable. Two mighty empires,—the only states which seemed to be leading the new world to civilization,—were broken, and at an expense of millions of lives, barbarously destroyed; and for what purpose? to what good end? How much better or happier are the present races of Peru and Mexico, than the past? Hope speaks in the breath of fancy—time may, perhaps, teach us the lesson of mystery; and these magnificent climates, now given up, a second time, to the sway of man in his darkest mood,—to civilized savages and Christian pagans,—may be made the seats of peace and wisdom; and perhaps, if mankind should again descend into the gloom of the middle ages, their inhabitants will preserve, as did the more barbarous nations in all previous retrogressions, the brands from which to rekindle the torches of knowledge, and thus be made the engines of the reclamation of a world.'

The traveller muttered the conclusion of his speculations aloud, and, insensibly to himself, in the Spanish tongue, totally unconscious of the presence of a second person, until made aware of it by a voice exclaiming suddenly, as if in answer, and in the same language—

"Right! very right! pecador de mi! sinner that I am, that I should not have thought it, for the honour of God and my country!"

The voice was sharp, abrupt, and eager, but very quavering. The stranger turned, and perceived that the words came from a man dressed in a long loose surtout or gown of black texture, none of the newest, with a hat of Manilla grass, umbrageous as an oak-top. He looked old and infirm; his person was very meager; his cheeks were of a mahogany hue, and hollow, and the little hair that stirred over them in the evening breeze, was of a sable silvered: his eyes were large, restless, exceedingly bright, and irascible. He carried swinging in his hand, without seeming to use it much, (for, in truth, his gait was too irregular and capricious to admit such support,) a staff, to the head of which was tied a bunch of flowers; and he bore under his arm, as they seemed to the unpractised eye of the observer, a bundle of books, a cluster of veritable quartos, so antique and worn, that the string knotted round each, seemed necessary to keep together its dilapidated pages. The whole air of the man was unique, but not mean; and the traveller did not doubt, at the first glance, that he belonged to some inferior order of ecclesiastics, and was perhaps the curate of a neighbouring village.

"Right! you have said the truth!" he continued, regarding the traveller eagerly, and, as the latter thought, with profound veneration; "I must speak with you, very learned stranger, for I perceive you are a philosopher. Very great thanks to you! may you live a thousand years! In a single word, you have revealed the secret that has been the enigma of a long life, made good the justice of heaven, and defended the fame of my country. God be thanked! I am grateful to your wisdom: you speak like a saint: you are a philosopher!"

The traveller stared with surprise on the speaker; but though thus moved by the abruptness of the address, and somewhat inclined to doubt its seriousness, there was something so unusual in the mode and quality of the compliment as to mollify any indignation which he might have felt rising in his breast.

"Father," said he, "reverend father—for I perceive you are one of the clergy——"

"The poor licentiate, Cristobal Johualicahuatzin, curate of the parish of San Pablo de Chinchaluca," interrupted the ecclesiastic meekly, and in fact with the greatest humility.

"Then, indeed, very excellent and worthy father Cristobal," resumed the stranger, courteously, "though I do not pretend to understand you——"

The padre raised his head; his meekness vanished; he eyed the traveller with a sharp and indignant frown:

"Gachupin!" he cried; "you are a man with two souls: you are wise and you are foolish, and you speak bad Spanish!—Why do you insult me?"

The stranger stared at his new acquaintance with fresh amazement.

"Insult you, father!" he exclaimed. "I declare to you, I have, this moment, woke out of a revery; and I scarcely know what you have said or what I have answered, or what you are saying and what I am answering. If I have offended you, I ask your pardon."

"Enough! right!" said the curate, with an air of satisfaction; "you are a philosopher; you are right. You were in a revery; you have done me no wrong. I have intruded upon your musings,—I beg your pardon. I thank you very heartily. You have instructed my ignorance, and appeased my repining; you have taught me the answer to a vast and painful riddle; and now I perceive why Providence hath given over my native land to seeming ruin, and permitted it to become a place of dust and sand, of dry-rot and death. The day of darkness shall come again,—it is coming; man merges again into gloom, and now we fall into the age of stone, when the hearts of men shall be as flint. This then shall be the valley of resuscitation, after it is first plenus ossibus, full of skeletons, an ossuary—a place of moral ossification. Here, then, shall the wind blow, the voice sound, the spirit move, the bone unite to his bone, the sinew come with the flesh, and light and knowledge, animating the mass into an army, send it forth to conquer the world;—not as an army of flesh, with drum and trump, sword and spear, banner and cannon, to kill and destroy, to ravage and depopulate; but as a phalanx of angels, with healing on their wings, to harmonize and enlighten, to pacify and adorn. Yes, you have taught me this, excellent sage! and you shall know my gratitude: for great joy is it to the child of Moteuczoma, to know there shall be an end to this desolation, this anarchy, this horror!

Came I into the world to watch in sorrow and fear for ever? Hijo mio! give me thy hand; I love thee. The vale of Anahuac is not deformed for nothing; Christian man has ruined it, but not for a long season!"

The Cura delivered this rhapsody with extreme animation; his eye kindled, he spoke with a rapid and confused vehemence; and the stranger began to doubt the stability of his understanding. He flung his bundle to the earth, and grasped the hand of the philosopher, who, until this moment, was ignorant of the depth of his own wisdom. While still in perplexity, unable to comprehend the strange character, or indeed the strange fancies to which he had given tongue, the padre looked around him with complacency on the scene, over which a tropical moon was rising to replace the luminary of day, and continued, with a gravity which puzzled as much as did his late vivacity,—

"It is very true; I regret it no longer, but it cannot be denied: The cutting through yonder hill of Nochistongo has given the last blow in a system of devastation; the canal of Huehuetoca has emptied the golden pitcher of Moteuczoma. It has converted the valley into a desert, and will depopulate it.—Men cannot live upon salt."

"A desert, father!"

"Hijo mio! do you pretend to deny it?" cried the Cura, picking up his bundle, and thumping it with energy. "I aver, and I will prove it to your satisfaction, out of these books, which—But hold! Are you a spy? will you betray me? No; you are not of Mexico: the cameo on your breast bears the device of stars, the symbol of intellectual as well as political independence. I reverence that flag; I saw it, when your envoy, attacked by an infuriated mob, in his house in yonder very city, (I stole there in spite of them!) sprang upon the balcony, and waved it abroad in the street. Frenzy vanished at the sight: it was the banner of man's friend!—No! you are no fool with a free arm, a licentious tongue, and a soul in chains. Therefore, you shall look into these pages, concealed for years from the jealousy of misconstruction, and the penal fires of intolerance; and they shall convince you, that this hollow of the mountain, as it came from the hands of God, and as it was occupied by the children of nature, was the loveliest of all the vales of the earth; and that, since Christian man has laid upon it his innovating finger, its beauty has vanished, its charm decayed; and it has become a place fitting only for a den of thieves, a refuge for the snake and the water-newt, the wild-hog and the vulture!"

"To my mind, father," said the American, no longer amazed at the extravagant expressions of the ecclesiastic, for he was persuaded his wits were disordered, "to my mind, it is still the most charming of valleys; and were it not that the folly and madness of its inhabitants, the contemptible ambition of its rulers, and the servile supineness of its people,—in fine, the general disorganization of all its elements, both social and political, have made it a sort of Pandemonium,—a spot wherein splendour and grandeur (at least the possibilities and rudiments of grandeur,) are mixed with all the causes of decline and perdition, I should be fain to dream away my life on the borders of its blue lakes, and under the shadow of its volcanic barriers."

"True, true, true! you have said it!" replied the curate, eagerly; "the ambition of public men; the feverish servility of the people, forgetful of themselves, of their own rights and interests, and ever anxious to yoke themselves to the cars of demagogues, to the wires wherewith they may be worked as puppets, and giving their blood to aggrandize these—the natural enemies of order and justice, of reason and tranquillity; is not this enough to demoralize and destroy? What people is like mine? Wo for us! The bondmen of the old world wake from sleep and live, while we, in the blessed light of sunshine, wrap the mantle round our eyes, sleep, and perish! Revolution after revolution, frenzy after frenzy! and what do we gain? By revolution, other nations are liberated, but we, by revolution, are enslaved. 'Nil medium est'—is there no happy mean?"

"It is true," said the American. "But let us not speak of this: it is galling to be able to inveigh against folly without possessing the medicament for its cure."

"Thou art an American of the North," said the Cura; "thy people are wise, thy rulers are servants, and you are happy! Why, then, art thou here? I thought thee a sage, but, I perceive, thou hast the rashness of youth. Art thou here to learn to despise thine own institutions? Why dost thou remain? the death-wind comes from the southern lakes"—(in fact, at this moment, the breeze from the south, rising with the moon, brought with it a mephitic odour, the effluvium of a bog, famous, even in Aztec days, as the breath of pestilence;) "the death-wind breathes on thee: even as this will infect thy blood, when it has entered into thy nostrils, disordering thy body, until thou learnest to loathe all that seems to thee now, in this scenery, to be so goodly and fair; so will the gusts of anarchy, rising from a distempered republic, disease thy imagination, until thou comest to be disgusted with the yet untainted excellence of thine own institutions, because thou perceivest the evils of their perversion. Arise, and begone; remain no longer with us; leave this land, and bear with thee to thine own, these volumes,—the poor remnants of another Sibylline library,—which will teach thee to appreciate and preserve, even as thy soul's ransom, the pure and admirable frame of government, which a beneficent power has suffered you to enjoy."

"And what, then, are these?" demanded the traveller, curiously, laying his hand on the bundle, "which can teach Americans to admire the beauty of a republic, and yet are not given to thine own countrymen?"

"They are," said the curate, "the fruits of years of reflection and toil, of deep research and profound speculation. They contain a history of Mexico, which, when they were perfect, that is, before my countrymen," (and here the Cura began to whisper, and look about him in alarm, as if dreading the approach of listeners,)—"before my countrymen were taught to fear them and to destroy, contained the chronicles of the land, from the time that the Toltecas were exiled from Huehuetapallan, more than twelve hundred years ago, down to the moment when Augustin climbed up to the throne, which Hidalgo tore from the Cachupins. A history wherein," continued the padre, with great complacency, "I flatter myself, though Mexicans have found much to detest, Americans will discover somewhat to approve."

"What is it," said the rambler, "which your people have found so objectionable?"

"Listen," said the padre, "and you shall be informed. In me,"—here he paused, and surveyed his acquaintance with as much majesty as he could infuse into his wasted figure and hollow countenance,—"in me you behold a descendant of Moteuczoma Xocojotzin."

"Moteuczoma what?" exclaimed the traveller.

"Are you so ignorant, then?" demanded the padre, in a heat, "that you must be told who was Moteuczoma Xocojotzin, that is, the younger,—the second of that name who reigned over Mexico?—the very magnificent and unfortunate emperor so basely decoyed into captivity, so ruthlessly oppressed and, as I may say, by a figure of speech, (for, literally, it is not true) so truculently slain, by the illustrious Don Hernan Cortes, the conqueror of Mexico? Perhaps you are also ignorant of the great names of Tizoc, of Xocotzin, and of Ixtlilxochitl?"

"I have no doubt," replied the American, with courteous humility, "that in the histories of Mexico, which I have ever delighted to read,—in the books of De Solis, of Clavigero, of Bernal Diaz del Castillo, and especially in that of Dr. Robertson,—I have met these illustrious names; but you must allow, that, to one ignorant of the language, and of the mode of pronouncing such conglomerated grunts, it must be extremely difficult, if not wholly impossible, to rivet them in the memory."

The curate snatched up his bundle, and surveyed the stranger with a look in which it was hard to tell whether anger or contempt bore the greater sway.

"De Solis! Diaz! Clavigero! Robertson!" he at last exclaimed, irefully. "Basta! demasiado? What a niño, a little child, a pobre Yankee, have I fallen upon! That I should waste my words on a man who studies Mexican history out of the books of these jolterheads!"

The padre was about to depart, without bestowing another word on the offender. The American was amused at the ready transition of the curate from deep reverence to the most unbounded contempt. He was persuaded the wits of the poor father were unsettled, and felt there was the greater need to humour and appease him: and, besides, he was curious to discover what would be the end of the adventure.

"Father," said he, with composure, "before you condemn me for acquiring my little knowledge from these books, you should put it in my power to read better."—The padre looked back.—"What information should be expected from incompetent writers? from jolterheads? When I have perused the histories of father Cristobal, it will then be my fault, if I am found ignorant of the names of his imperial ancestors."

"Ay de mi!" said the curate, striking his forehead; "why did I not think of that before? Santos santísimos! I am not so quick-witted as I was before. I could forgive you more readily, had you not named to me that infidel Scotchman, who calls the superb Moteuczoma a savage, and all the Tlatoani, the great princes, and princesses, the people and all, barbarians! But what more could you expect of a heretic? I forgive you, my son—you are a Christian?"

"A Christian, father; but not of the Catholic faith."

"You will be damned!" said the curate, hastily.

"A point of mere creed, perhaps I should say, mere form—"

"Say nothing about it; form or creed, ceremony or canon, you are in the way to be lost. Open your ears, unbind your eyes—hear, see, and believe!—Poor, miserable darkened creature! how can your heretical understanding be made to conceive and profit by the great principles of philosophy, when it is blind to the truths of religion?"

"Reverend padre," said the traveller, drily, "my people are a people of heretics, and yours of Catholic believers. Which has better understood, or better practised, the principles of the philosophy you affect to admire?"

The padre smote his forehead a second time: "The sneer is, in this case, just! The sin of the enlightened is greater than the crime of the ignorant, and so is the punishment: the chosen people of God were chastised with frequent bondage, and finally with expatriation and entire dispersion, for crimes, which, in heathen nations, were punished only with wars and famine. But let us not waste time in argument: as babes may be made the organs of wisdom, so may heretics be suffered as the instruments of worldly benefaction. What thou sayest, is true; unbelievers as ye are, ye will comprehend and be instructed by truths, which, in this land, would be misconceived and opposed; and from you may the knowledge you gain, be reflected back on my own people. In these books, which I commit to you for a great purpose, you will learn who were those worthies of whom I spoke. You will perceive how Ixtlilxochitl, the king of Tezcuco, was descended from the house that gave birth to Moteuczoma. This illustrious name inherit I from my mother. With its glory, it has conferred the penalty to be suspected, opposed, and trampled. Three historians of the name, my ancestors, have already written in vain; jealousy has locked up their works in darkness, in the veil of manuscript; the privilege of chronicling and perverting the history of the land is permitted only to Spaniards, to strangers, to Gachupins. Twenty years since, and more, the books I composed, wherein the truth was told, and the injustice of Spanish writers made manifest, were condemned by ignorance and bigotry to such flames as consumed, at Tezcuco, all the native chronicles of Anahuac. But what was written in my books, was also recorded in the brain; fire could not be put to my memory. Twenty years of secret labour have repaired the loss. Behold! here is my history; I give it to you.—My enemies must be content with the ashes!"

The padre rubbed his hands with exultation, as the traveller surveyed the bundle.

"Why should you fear a similar fate for these volumes, now?" said the latter. "Times are changed."

"The times, but not the people. Hide them, let no man see them; or the pile will be kindled again; all will be lost—I cannot repair the loss a second time, for now I am old! Five years have I borne them with me, night and day, seeking for some one cunning and faithful, wise like thyself, to whom to commit them. I have found thee; thou art the man; I am satisfied: buen provecho, much good may they do you,—not you only, but your people,—not your people alone, but the world! Affection for country is love of mankind; true patriotism is philanthropy.—Five years have I borne them with me, by night and by day."

"Really, I think that this betokened no great fear for their safety."

The padre laughed. "Though the Gachupin and the bigot would rob me of a Spanish dissertation, yet neither would envy me the possession of a few rolls of hieroglyphics."

As he spoke, he knelt upon the ground, untied the string that secured one of the apparent volumes, and, beginning to unfold the MS., as one would a very nicely secured traveller's map, displayed, in the moonlight, a huge sheet of maguey paper, emblazoned in gaudy colours with all kinds of inexplicable devices. As he exhibited his treasure, he looked up for approbation to the American. The 'pobre Yankee' surveyed him with a humorous look:

"Father," said he, "you have succeeded to admiration, under this goodly disguise, not only in concealing your wisdom from the penetration of your countrymen, but, as I think, the whole world."

The padre raised his finger to his nose very significantly, saying, with a chuckle of delight,—the delight of a diseased brain in the success of its cunning,—

"This time, I knew I should throw dust in their eyes, even though they might demand, for their satisfaction, to look into my work. You perceive, that this volume, done up after the true manner of ancient Mexican books, unrolls from either end. The first pages, and the last, of each volume, contain duplicates of the first and the last chapters, done in Mexican characters: the rest is in Spanish, and, I flatter myself, in very choice Spanish. Hoc ego rectè—I knew what I was about.—One does not smuggle diamonds in sausages, without stuffing in some of the minced meat.—Here is the jewel!"

So saying, and spreading the sheet at its full length, so as to discover his hidden records, the padre rose to his feet, and began to dance about with exultation.

"And what am I to do with these volumes?" said the traveller, after pondering awhile over the manuscripts.

"What are you to do with them? Dios mio! are you so stupid? Take them, hide them in your bosom, as you would the soul of some friend you were smuggling into paradise. Leave this land forthwith, on any pretence; bear them with you; translate them into your own tongue, and let them be given to the world. If they do not, after they have received the seal of your approbation, make their way back to this land, they will, at least, serve some few of the many objects, for which they were written: they will set the character of my great ancestors in its true light, and teach the world to think justly of the unfortunate people from whom I have the honour to be descended; and, in addition, they will open the eyes of men to some of the specks of barbarism which yet sully their own foreheads. As for my countrymen, were it even possible they could be persuaded to spare these pages, and to read them, they would read them in vain. They are a thousand years removed from civilization, and the wisdom of this book would be to them as folly. The barbaric romance which loiters about the brains even of European nations, is the pith and medulla of a Mexican head. The poetry of bloodshed, the sentiment of renown,—the first and last passion, and the true test, of the savage state,—are not yet removed from us. We are not yet civilized up to the point of seeing that reason reprobates, human happiness denounces, and God abhors, the splendour of contention. Your own people—the happiest and most favoured of modern days,—are, perhaps, not so backward."

The heretic sighed.—The padre went on, and with the smile of generosity,—tying, at the same time, the string that secured the volume, and knotting it again into the bundle.

"The profits which may accrue from the publication, I freely make over to you, as some recompense for the trouble of translation, and the danger you run in assuming the custody. Danger, I say,—heaven forbid I should not acquaint you, that the discovery of these volumes on your person, besides insuring their speedy and irretrievable destruction, will expose you to punishment, perhaps to the flames which will be kindled for them; and this the more readily, that you are an unbeliever.—Pray, my son, listen to me; suffer me to convert you. Alas! you shake your head!—What a pity, I am compelled to entrust this great commission to a man who refuses to be a Christian!"

"Buen padre, let us say nothing about that: judge me not by the creed I profess, but by the acts I perform. Let us despatch this business: the moon is bright, but the air is raw and unwholesome. I would willingly do your bidding, not doubting that the world will be greatly advantaged thereby. But, father, here is the difficulty:—To do justice to your composition, I should, myself, possess the skill of an author; but, really, I feel my incompetency—I am no bookmaker."

"And am I?" said the descendant of Moteuczoma, indignantly; "I am an historian!"

"I crave your pardon;—but I am not."

"And who said you were?" demanded the historian, with contempt. "Do I expect of you the qualifications or the labours of an historian? Do I ask you to write a book? to rake for records in dusty closets and wormy shelves? to decypher crabbed hands and mouldered prints? to wade through the fathers of stupidity, until your brain turns to dough, and your eyes to pots of glue? to gather materials with the labour of a pearl-diver, and then to digest and arrange, to methodise and elucidate, with the patient martyrdom of an almanac-maker? Who asks you this? Do I look for a long head, an inspired brain? a wit, a genius? Ni por sueño,—by no means. I ask you to read and render,—to translate;—to do the tailor's office, and make my work a new coat! Any one can do this!"

"Father," said the traveller, "your arguments are unanswerable; do me the favour to send, or to bring, your production to the city, to the Calle——"

"Send! bring! Se burla vm.?" cried the padre, looking aghast. "Do you want to ruin me? Know, that by the sentence of the archbishop and the command of the viceroy, I am interdicted from the city: and know that I would sooner put my soul into the keeping of a parrot, than my books into the hands of a messenger!"

"A viceroy, did you say, father? It has been many long years since a king's ape has played his delegated antics in Mexico. To please you, however, I will bear the sacred treasure in my own hands; earnestly desiring you, notwithstanding your fears, which are now groundless, and the prohibition, which must be at this period invalid, to do me the favour of a visit, in person, as soon as may suit your conveniency; inasmuch as there are many things I esteem needful to be——"

The padre had seized on the hands of the speaker, in testimony of his delight; but before the latter had concluded his discourse, he was interrupted by a voice at a distance, calling, as it seemed, on the Cura; for this worthy, starting with fear, and listening a moment, suddenly took to his heels, and before the traveller could give vent to his surprise, was hidden among the shadows of the cypress trees.

"May I die," said the philosopher, in no little embarrassment, "but this lunatic Cura has left me to lug away his lucubrations,—his hieroglyphical infants, for which I am to make new coats,—on my own shoulders! Well! I can but carry them to the city, and seek some means of restoring them to his friends, or commit them to a more fitting depository. Pray heaven I meet no drunken Indian, or debauched soldado on my way."

By great good fortune, he was able, in a few days, with the assistance of a friendly Mexican, to solve the secret of the padre's confidence.

"You have seen him then?" said the excellent Señor Don Andres Santa-Maria de Arcaboba, laughing heartily at the grave earnestness with which his heretical friend inquired after the eccentric padre. "He offered you his hieroglyphics? Ah, I perceive! No man passes scot-free the crazy Cura. Ever his books in his hand, much praise with the offer, and seven times seven maledictions when you refuse his bantlings."

"He is crazy, then?"

"Demonios! were you long finding it out? Ever since the old archbishop burned his first heathenish volumes, he has done naught but——"

"I beg your pardon.—Burn his books?—the old archbishop?—Pray enlighten me a little on the subject of the good father's history.

"'Tis done in a moment," said Don Andres; "the only wonder is that he did not himself give you the story; that being, commonly, the prelude to his petition. The mother of Don Cristobal was an Indian damisela, delighting in the euphonical cognomen of Ixtlilxochitl; a name, which, I am told, belonged to some old pagan king or other, the Lord knows who—as for myself, I know nothing about it. But this set the padre mad, or, what's the same thing, it made him an historian.—'Tis a silly thing to trouble one's noddle about the concerns of our granddads: let them sleep! rest to their bones—Asi sea!—They made him a licenciado, and then Cura of some hacienda or other, out among the hills—I know nothing about it. He wrote a book, in which he proved that the old heathen Montezuma, the great Cacique, was a saint, and Hernan Cortes, who conquered the land, a sinner. It may be so—Quien sabe? who knows? who cares? This was before the revolution—that is, before the first: (we have had five hundred since;—I never counted them.) Somehow, the viceroy Vanegas took a dislike to the book, and so did the archbishop. They set their heads together, got the good old fathers of the Brotherhood—(We have no Brotherhood now,—neither religious nor social: every man is his own brother, as the king says in the English play.—Did you ever read Calderon?) They got the old fathers to vote it dangerous,—I suppose, because they did not understand it. So they burned it, and commanded Johualicahuatzin—(that's another Indian king—so he calls himself.—His father was the Señor Marhojo, a creole, a lieutenant in the viceroy's horse, a very worthy Christian, who was hanged somewhere, for sedition. But Cristobal writes after his mother's name, as being more royal.)—What was I saying? Oh, yes!—They ordered the licentiate back to his hacienda. Then, what became of him, the lord knows; I don't.—Then came Hidalgo, the valiant priest of Dolores, with his raggamuffin patriots,—(I don't mean any reflection, being a patriot myself, though no fighter; but Hidalgo had a horrid crew about him!) Where was I? Oh, ay,—Hidalgo came to knock the city about our ears; and Cristobal, being seized with a fit of blood-thirstiness, joins me the gang. They say, he came with an old sabre of flint—I don't know the name; it belonged to some king in the family. Then Calleja, whom they made viceroy—the devil confound him! (He cut my uncle's throat, with some fourteen thousand others, at Guanaxuato, one day, to save powder.)—Calleja chased Hidalgo to Aculco, and, there, he beat him. Cristobal's brother (he had a brother, a very fine young fellow, a patriot major;) was killed at Cristobal's side; Cristobal was knocked on the head,—somebody said, with his own royal weapon:—I don't know,—where's the difference? They broke his skull, and took him prisoner. Y pues? what then? Being a notorious crazy man, and very savagely mauled, they did not hang him. Ever since, he has been madder than ever. He writes histories, and, to save them from viceroys, (he takes all our presidents for viceroys: to my mind, they are; but that's nothing. You know Bustamente? a mighty great man: Santa Anna will beat him—but don't say so!) Well, to save his books from the president-viceroys, or viceroy-presidents, Cristobal offers them to every body he meets, with a petition to take them over the seas and publish them.—That's all!—The Indians at the hacienda love him, and take care of him.—Ha, ha! he caught you, did he? What did he say?"

"He gave me his books," said the traveller.

"Fuego! you took them? Ha, ha! now will the poor padre die happy!"

"I will return them to his relations."

"Relations! they are all in heaven; he is the last of the Ixtlilxochitls! Ha, ha! I beg your pardon, amigo mio! I beg your pardon; but if you offer them to any body, never believe me, but folks will take you for Cristobal the Second, el segundo maniatico, or some one he has hired to do the work of donation. Ha, ha! cielo mio, pity me! say nothing about it;—burn them."

"At least, let us look over them."

"Olla podrida! look over a beggar's back! a pedler's sack! or a dictionary!—Any thing reasonable. Burn them; or take them to America, to your North, and deposit them in a museum, as the commonplace books of Montezuma. Vamos; que me manda vm.? will you ride to the Alameda?—Pobre Cristobal! he will die happy——"

The traveller returned to his own land: he bore with him the books of Cristobal. Twenty times did he essay to make examination of their contents, and twenty times did he yawn, in mental abandonment, over their chaotic pages,—not, indeed, that they seemed so very incoherent in style and manner, but because the cautious historian, as it seemed, with a madman's subtlety, had hit upon the device of so scattering and confusing the pages, that it was next to impossible that any one, after reading the first, should discover the clue to the second. Each volume, as has been hinted, consisted of a single great sheet, folded up in the manner of a pocket map; both sides were very carefully written over, the paragraphs clustered in masses or pages, but without numbers; and, but for the occurrence, here and there, of pages of hideous hieroglyphics, such as were never seen in a Christian book, the whole did not seem unlike to a printed sheet, before it is carried to the binder. The task of collating and methodising the disjointed portions, required, in the words of the padre himself, the devotedness which he had figured as 'the patient martyrdom of an almanac-maker;' it was entirely too much for the traveller. He laid the riddle aside for future investigation: but Cristobal was not forgotten.

A year afterwards, in reading a Mexican gazette, which had fallen into his hands, his eye wandered to the little corner which appeals so placidly to the feelings of the contemplative,—the place of obituaries. His attention was instantly captivated by a name in larger characters than the others. Was it? could it be? Pobre Cristobal!—'El Licenciado Cristobal Santiago Marhojo y Ixtlilxochitl, Cura de la Hacienda de Chinchaluca, ordinariamente llamado El Maniatico Historiador'——. The same! But what is this? the common immortality of a long paragraph?—The heretic rubbed his eyes. "Several MSS., historical memoirs, relating to the earlier ages of the Aztec monarchy, the work of his own hand, have been discovered; and a lucky accident revealing the expedient which he adopted to render them illegible, or at least inexplicable to common readers, they have been found to be in all respects sane and coherent, the work less of a madman than an eccentric but profound scholar. The pages are arranged like those in the form of the printer; and, being cut by a knife without unfolding——" The heretic started up, and drew forth the long-neglected tomes.—"It is said that a North American, a year ago, received, and carried away, many of the volumes, which the eccentric clergyman was accustomed to offer to strangers. It is hoped, if this should meet his eye——" 'Enough! if thy work be at all readable, departed padre, it shall have the new coat!'

Great was the surprise of the philosopher, when having, at the suggestion of the gazetteer, cut the folded sheet of a volume, he beheld the chaos of history reduced to order. There they were, the annals of Aztecs and Toltecs, of Chechemecs and Chiapanecs, and a thousand other Ecs, from the death of Nezahualcojotl, the imperial poet, up to the confusion of tongues. "Here's a nut for the philosophers," quoth the traveller; "but now for a peep at Montezuma!—Poor Cristobal! what a wonderful big book you have made of it!"

How many days and nights were given to the examination of the history, we do not think fit to record. It is enough, that the inheritor of this treasure discovered with satisfaction, that, if Cristobal had been mad, he had been mad after a rule,—dramatically so: he was sane in the right places. A thousand eccentricities were, indeed, imbodied in his work, the result, doubtless, of a single aberration, in which he persuaded himself that men were yet barbarians, and that civilization, even to the foremost of nations, was yet unknown. Under the influence of this conceit, he was constantly betrayed, for he was a philanthropist, into sharp animadversion upon popular morals; and he stigmatized as vices of the most brutal character, many of those human peculiarities which the world has consented to esteem the highest virtues. In other respects, he was sane, somewhat judicious, and, as far as could be expected in an historian, a teller of the truth.

His work consisted of several divisions; it was, in fact, a series of annals, relating to different epochs. Of these, that volume which treated of the Conquest of Mexico, had the most charms for the traveller; and he thought it would possess the most interest for the world. It was this which he determined to introduce to the public. It differed greatly from common histories in one particular; it descended to minutiæ of personal adventure, and was, indeed, as much a general memoir of the great Conquistadores as a history of the fall of Tenochtitlan. Of this the writer was himself sensible; the running title of the division, as recorded in his own hand, being, "Una Cronica de la Conquista de Megico, y Historia verdadera de los Conquistadores, particularmente de esos Caballeros á quienes descuidaron celebrar los Escritores Antiguos. Por Cristobal Johualicahuatzin Santiago Marhojo y Ixtlilxochitl;"—that is to say, 'A Chronicle of the Conquest of Mexico, and true History of the Conquerors, especially of those Cavaliers who were neglected by the ancient authors.'

The first portion of this,—for there were several,—treated of those events which occurred between the departure of the first army of invasion from Cuba, and its expulsion from Mexico, and this portion the executor of Cristobal resolved to present to the world.

In pursuance of this resolution, he instituted a long and laborious comparison of the MS. with the most authentic printed histories; the result of which was a conviction, (which we beg the reader constantly to bear in mind,) that, although the good padre had introduced, and upon authority which his editor could not discover, the characters of certain worthy cavaliers, of whom he had never heard, the relation, in all other particulars, corresponded precisely with the narratives of the most esteemed writers. The events—the great and the minute alike—of the whole campaign were, in point of fact, identical with those chronicled by the best authors; and in no way did this history differ from others, except in the introduction of the above-mentioned forgotten or neglected cavaliers, such as the knight of Calavar and his faithful esquire, and in the recital of events strictly personal to them. It is true, the narrative was more diffuse, perhaps we should say, verbose; but Cristobal lived in an age of amplification. It was here alone that the traveller felt himself bound to take liberties with the original; for though the march of mind and the general augmentation of ideas, have made prolixity a common characteristic of each man in his own person, they have not made him more tolerant of it in another. He shaved, therefore, and he cut, he amputated and he compressed; and he felt the joy of an editor, when exercising the hydraulic press of the mind.

This will be excused in him. He expunged as much of the philosophy as he could. The few principles at variance with worldly propensities, which he left in the book, must be referred to another responsibility.—The hallucinations of philanthropy are, at the worst, harmless.

For the title adopted in this, the initial chronicle, he confesses himself answerable. The peculiar appetites of the literary community, the result of intellectual dyspepsia, require and justify empiricism in nomenclature. A good name is sugar and sweetmeats to a bad book. If it should be objected, that he has called the Historia Verdadera a romance, let it be remembered, that the world likes romance better than truth, as the booksellers can testify; and that the history of Mexico, under all aspects but that of fiction, is itself——a romance.

Note.—It was said by the learned Scaliger, of the Basque language, 'that those who spoke it were thought to understand one another,—a thing which he did not himself believe.' For fear that the reader, from the specimens of Mexican words he will meet in this history, should imagine that the Mexican tongue was not meant even to be spoken, we think fit to apprise him, that all such words are to be pronounced as they would be uttered by a Spaniard. In his language, for example, the G, when before the vowels E and I, the J always, and, in certain cases, the X, have the value of the aspirate. Thus, the name of the city, the chief scene of our history, has been spelled, at different times, Mexico, Mejico, and Megico; yet is always pronounced May-he-co. The sound of our W he represents by HU,—as Huascar, for Wascar; and, indeed, JU has nearly the same sound, as in Juan. The names Johualicahuatzin, Anahuac, Xocojotzin, Mexitli, and Chihuahua, pronounced Howalicawatzin, Anawac, Hocohotzin, Meheetlee, and Chewawa, will serve for examples. But this is a thing not to be insisted on, so much as the degree of belief which should be accorded to the relation.

Esto importa poco á nuestro cuento: basta que en la narracion de el, no se salga un punto de la verdad.—Don Quijote.

In the year of Grace fifteen hundred and twenty, upon a day in the month of May thereof, the sun rose over the islands of the new deep, and the mountains that divided it from an ocean yet unknown, and looked upon the havoc, which, in the name of God, a Christian people were working upon the loveliest of his regions. He had seen, in the revolution of a day, the strange transformations which a few years had brought upon all the climes and races of his love. The standard of Portugal waved from the minarets of the east; a Portuguese admiral swept the Persian Gulf, and bombarded the walls of Ormuz; a Portuguese viceroy held his court on the shores of the Indian ocean; the princes of the eastern continent had exchanged their bracelets of gold for the iron fetters of the invader; and among the odours of the Spice Islands, the fumes of frankincense ascended to the God of their new masters. He passed on his course: the breakers that dashed upon the sands of Africa, were not whiter than the squadrons that rolled among them; the chapel was built on the shore, and under the shadow of the crucifix was fastened the first rivet in the slavery of her miserable children. Then rose he over the blue Atlantic: the new continent emerged from the dusky deep; the ships of discoverers were penetrating its estuaries and straits, from the Isles of Fire even to the frozen promontories of Labrador; and the roar of cannon went up to heaven, mingled with the groans and blood of naked savages. But peace had descended upon the islands of America; the gentle tribes of these paradises of ocean wept in subjection over the graves of more than half their race; hamlets and cities were springing up in their valleys and on their coasts; the culverin bellowed from the fortress, the bell pealed from the monastery; and the civilization and vices of Europe had supplanted the barbarism and innocence of the feeble native. Still, as he careered to the west, new spectacles were displayed before him; the followers of Balboa had built a proud city on the shores, and were launching their hasty barks on the surges of the New Ocean; the hunter of the Fountain of Youth was perishing under the arrows of the wild warriors of Florida, and armed Spaniards were at last retreating before a pagan multitude. One more sight of pomp and of grief awaited him: he rose on the mountains of Mexico; the trumpet of the Spaniards echoed among the peaks; he looked upon the bay of Ulua, and, as his beams stole tremblingly over the swelling current, they fell upon the black hulls and furled canvas of a great fleet riding tranquilly at its moorings. The fate of Mexico was in the scales of destiny; the second army of invaders had been poured upon her shores. In truth, it was a goodly sight to look upon the armed vessels that thronged this unfrequented bay; for peacefully and majestically they slept on the tide, and as the morning hymn of the mariners swelled faintly on the air, one would have thought they bore with them to the heathen the tidings of great joy, and the good-will and grace of their divine faith, instead of the earthly passions which were to cover the land with lamentation and death.

With the morning sunbeam, stole into the harbour one of those little caravels, wherein the men of those days dared the perils of unknown deeps, and sought out new paths to renown and fortune; and as she drew nigh to the reposing fleet, the hardy adventurers who thronged her deck, gazed with new interest and admiration on the shores of that empire, the fame of whose wild grandeur and wealth had already driven from their minds the dreams of Golconda and the Moluccas. No fortress frowned on the low islands, no city glistened among the sand-hills on shore: the surf rolled on the coast of an uninhabited waste: the tents of the armourer and other artisans, the palm-thatched sheds of the sick, and some heaps of military stores, covered with sails, and glimmering in the sun, were the only evidences of life on a beach which was, in after times, to become the site of a rich and bustling port. But beyond the low desert margin of the sea, and over the rank and lovely belt of verdure, which succeeded the glittering sand-hills, rose a rampart of mountains green with an eternal vegetation, over which again peered chain after chain, and crag after crag, with still the majestic Perote and the colossal Orizaba frowning over all, until those who had dwelt among the Pyrenees, or looked upon the Alps, as some of that adventurous company had done, dreamed what wealth should be in a land, whose first disclosure was so full of grandeur.

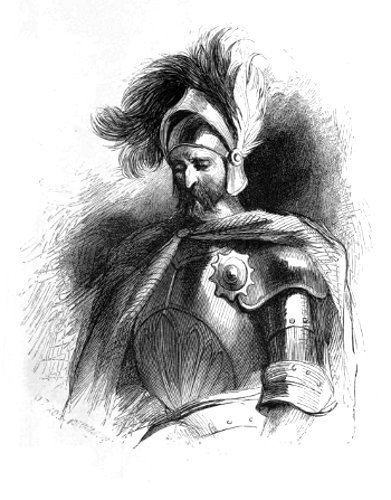

Of the four-score individuals who crowded the decks of the little caravel, there was not one whose countenance, at that spectacle, did not betray a touch of the enthusiasm,—the mingled lust of glory and of lucre,—which had already transformed so many ruffians into heroes. Among this motley throng might be seen all sorts of martial madmen, from the scarred veteran who had fought the Moors under the walls of Oran, to the runagate stripling who had hanselled his sword of lath on the curs of Seville; from the hidalgo who remembered the pride of his ancestors, in the cloak of his grandsire, to the boor who dreamed of the crown of a pagan emperor, in a leather shirt and cork shoes: here was a brigand, who had cursed the Santa Hermandad of all Castile, and now rejoiced over a land where he could cut throats at his leisure; there a gray-haired extortioner, whom roguery had reduced to bankruptcy, but who hoped to repair his fortune by following the pack of man-hunters, and picking up the offals they despised, or cheating them of the prizes they had secured; here too was a holy secular, who came to exult over the confusion and destruction of all barbarians who should see nothing diviner in the crucifix than in their own idols. The greater number, however, was composed of debauched and decayed planters of the islands, who ceased to lament their narrow acres and decreasing bondmen, snatched away by the good fortune of some fellow-profligate, when they thought of territories for an estate, and whole tribes for a household. Indeed, in all the group, however elevated and ennobled, for the moment, by the excitement of the scene, and by the resolute impatience they displayed to rush upon adventures well known to be full of suffering and peril, there was but one whom a truly noble-hearted gentleman would have chosen to regard with respect, or to approach with friendship.

This was a young cavalier, who, in propriety of habiliments, in excellence of person, and in nobleness of carriage, differed greatly from all: and, to say the truth, he himself seemed highly conscious of the difference, since he regarded all his fellow-voyagers, saving only his own particular and armed attendants, with the disdain befitting so distinguished a personage. His frame, tall and moderately athletic, was arrayed in hose and doublet of a dusky brown cloth, slashed with purple: his cap and cloak were of black velvet, and in the band of one, and on the shoulder of the other, were symbols of his faith and his profession,—the first being a plain crucifix of silver, and the second a cross of white cloth of eight points, inserted in the mantle. In addition to these badges of devotion, he wore a cross of gold, pointed like the former, and suspended to his neck by a chain of such length and massiveness, as to imbue his companions with high notions of his rank and affluence.

The only point in which he exhibited any feeling in common with his companions, was in admiration of the noble prospect that stretched before him, and which was every moment disclosing itself with newer and greater beauty, as the wind wafted his little vessel nearer to it. His cheek flushed, his eye kindled, and smiting his hands together, in his ardour, he dropped so much of his dignity as to address many of his exclamations to the obsequious but not ungentle master.

"By St. John! señor Capitan," he cried, with rapture, "this is a most noble land to be wasted upon savages!"

"True, señor Don Amador," replied the thrice-honoured master; "a noble land, a rich land, a most glorious land; and, I warrant me, man has never before looked on its equal."

"For my part," said the youth, proudly, "I have seen some lands, that, in the estimation of those who know better, may be pronounced divine; among which I may mention the Greek islands, the keys of the Nile, the banks of the Hellespont, and the hills of Palestine,—not to speak of Italy, and many divisions of our own country; yet, to be honest, I must allow I have never yet looked upon a land, which, at the first sight, impressed me with such strange ideas of magnificence."

"What then will be your admiration, noble cavalier," said the captain, "when you have passed this sandy shore, and yonder rugged hills, and find yourself among the golden valleys they encompass! for all those who have returned from the interior, thus speak of them, and declare upon the gospels and their honour, no man can conceive properly of paradise, until he has looked upon the valleys of Mexico."

"I long to be among them," said the youth; "and the sooner I am mounted on my good steed, Fogoso, (whom God restore to his legs and his spirit, for this cursed ship has cramped both;) I say, the sooner I am mounted upon my good horse, and scattering this heathen sand from under his hoofs, the better will it be for myself, as well as for him. Hark'ee, good captain: I know not by what sort of miracle I shall surmount yonder tall and majestic pinnacles; but it will be some consolation, while stumbling among them, to be able at least to pronounce their names. What call you yon mountain to the north, with the huge, coffer-like crag on its summit?"

"Your favour has even hit the name, in finding a similitude for the crag," said the captain. "The Indians call it by a name, which signifies the Square Mountain; but poor mariners like myself, who can scarce pronounce their prayers, much less the uncouth and horrible articulations of these barbarians, are content to call it the Coffer Mountain. It lies hard by the route to the great city; and is said to be such a desolate, fire-blasted spot as will sicken a man with horror."

"And yon kingly monster," continued the cavalier, "that raises his snowy cone up to heaven, and mixes his smoke with the morning clouds,—that proudest of all,—what call you him?"

"Spaniards have named him Orizaba," said the master; "but these godless Pagans, who cover every human object with some diabolical superstition, call that peak the Starry Mountain; because the light of his conflagration, seen afar by night, shines like to a planet, and is thought by them to be one of their gods, descending to keep watch over their empire."

"A most heathenish and damning belief!" said the youth, with a devout indignation; "and I do not marvel that heaven has given over to bondage and destruction a race stained with such beastly idolatry. But nevertheless, señor Capitan, and notwithstanding that it is befouled with such impious heresies, I must say, that I have looked upon Mount Olympus, a mountain in Greece, whereon, they say, dwelt the accursed old heathen gods, (whom heaven confound!) before the time that our blessed Saviour hurled them into the Pit; and yet that mountain Olympus is but a hang-dog Turk's head with a turban, compared to this most royal Orizaba, that raiseth up his front like an old patriarch, and smokes with the glory of his Maker."

"And yet they say," continued the captain, "that there is a mountain of fire even taller and nobler than this, and that hard by the great city. But your worship will see this for yourself, with many other wonders, when your worship fights the savages in the interior."

"If it please Heaven," said the cavalier, "I will see this mountain, and those other wonders, whereof you speak; but as to fighting the savages, I must give you to know, that I cannot perceive how a man who has used his sword upon raging Mussulmans, with a sultan at their head, can condescend to draw it upon poor trembling barbarians, who fight with flints and fish-bones, and run away, a thousand of them together, from six not over-valiant Christians."

"Your favour," said the captain, "has heard of the miserable poltroonery of the island Indians, who, truth to say, are neither Turks nor Moors of Barbary: but, señor Don Amador de Leste, you will find these dogs of Mexico to be another sort of people, who live in stone cities instead of bowers of palm-leaves; have crowned emperors, in place of feathered caciques; are marshalled into armies, with drums, banners, and generals, like Christian warriors; and, finally, go into battle with a most resolute and commendable good will. They will pierce a cuirass with their copper lances, crush an iron helmet with their hardened war-clubs, and,—as has twice or thrice happened with the men of Hernan Cortez,—they will, with their battle-axes of flint, smite through the neck of a horse, as one would pierce a yam with his dagger. Truly, señor caballero, these Mexicans are a warlike people."

"What you tell me," said Don Amador, "I have heard in the islands; as well as that these same mountain Indians roast their prisoners with pepper and green maize, and think the dish both savoury and wholesome; all which matters, excepting only the last, which is reasonable enough of such children of the devil, I do most firmly disbelieve: for how, were they not cowardly caitiffs, could this rebellious cavalier, the valiant Hernan Cortes, with his six hundred mutineers, have forced his way even to the great city Tenochtitlan, and into the palace of the emperor? By my faith," and here the señor Don Amador twisted his finger into his right mustachio with exceeding great complacency, "these same Mexicans may be brave enemies to the cavaliers of the plantations, who have studied the art of war among the tribes of Santo Domingo and Cuba; but to a soldier who, as I said before, has fought the Turks, and that too at the siege of Rhodes, they must be even such chicken-hearted slaves as it would be shame and disgrace to draw sword upon."

The master of the caravel regarded Don Amador with admiration for a moment, and then said, with much emphasis, "May I die the death of a mule, if I am not of your way of thinking, most noble Don Amador. To tell you the truth, these scurvy Mexicans, of whose ferocity and courage so much is said by those most interested to have them thought so, are even just such poor, spiritless, contemptible creatures as the Arrowauks of the isles, only that there are more of them; and, to be honest, I know nothing that should tempt a soldier and hidalgo to make war on them, except their gold, of which the worst that can be said is, first, that there is not much of it, and secondly, that there are too many hands to share it. There is neither honour nor wealth to be had in Tenochtitlan. But if a true soldier and a right noble gentleman, as the world esteems Don Amador de Leste, should seek a path worthy of himself, he has but to say the word, and there is one to be found from which he may return with more gold than has yet been gathered by any fortunate adventurer, and more renown than has been won by any other man in the new world: ay, by St. James, and diadems may be found there! provided one have the heart to contest for them with men who fight like the wolves of Catalonia, and die with their brows to the battle!"

"Now by St. John of Jerusalem!" said Amador, kindling with enthusiasm, "that is a path which, as I am a true Christian and Castilian, I should be rejoiced to tread. For the gold of which you speak, it might come if it would, for gold is a good thing, even to one who is neither needy nor covetous; but I should be an idle hand to gather it. As for the diadems, I have my doubts whether a man, not born by the grace of God to inherit them, has any right to wear them, unless, indeed, he should marry a king's daughter: but here the kings are all infidels, and, I vow to Heaven, I would sooner burn at a stake, along with a Christian beggar, than sell my soul to perdition in the arms of any infidel princess whatever. But for the renown of subduing a nation of such valiant Pagans as those you speak of, and of converting them to the true faith! that is even such a thought as makes my blood tingle within me; and were I, in all particulars, the master of my own actions, I should say to you, Right worthy and courageous captain, (for truly from those honourable scars on your front and temple, and from your way of thinking, I esteem you such a man,) point me out that path, and, with the blessing of Heaven, I will see to what honour it may lead me."

"Your favour," said the captain, "has heard of the great island, Florida, and of the renowned señor Don Ponce de Leon, its discoverer?"

"I have heard of such names, both of isle and of man, I think," said Don Amador, "but, to say truth, señor comandante, you have here, in this new world, such a multitude of wonderful territories, and of heroic men, that, were I to give a month's labour to the study, I think I should not master the names of all of them. Truly, in Rhodes, where the poor knights of the Hospital stood at bay before Solyman el Magnifico, and did such deeds as the world had not heard of since the days of Leonidas and his brave knights of Sparta,—I say, even in Rhodes, where all men thought of their honour and religion, and never a moment of their blood, we heard not of so many heroes as have risen up here in this corner of the earth, in a few years' chasing of the wild Indians."

"The señor Ponce de Leon," said the captain, without regarding the sneer of the proud soldier, "the señor Ponce de Leon, Adelantado of Bimini and of Florida, in search of the miraculous Fountain of Youth, which, the Indians say, lies somewhere to the north, landed eight years ago, with the crews of three ships, all of them bigger and better than this little rotten Sangre de Cristo, whereof I myself commanded one. Of the extraordinary beauty and fertility of the land of Florida, thus discovered, I will say nothing. Your favour will delight more to hear me speak of its inhabitants. These were men of a noble stature, and full of such resolution, that we were no sooner ashore, than they fell upon us; and I must say, we found we were now at variance with a people in no wise resembling those naked idiots of Cuba, or these cowardly hinds of Mexico. They cared not a jot for swordsman, arcubalister, or musketeer. To our rapiers they opposed their stone battle-axes, which gushed through the brain more like a thunderbolt than a Christian espada; no crossbowman could drive an arrow with more mortal aim and fury than could these wild archers with their horn bows, (for know, señor, they have, in that country of Florida, some prodigious animal, which yields them abundant material for their weapons;) and, what filled us with much surprise, and no little fear, instead of betaking themselves to their heels at the sound of our firelocks, as we looked for them to do, no sooner had they heard the roar of these arms, than they fetched many most loud and frightful yells, to express their contempt of our warlike din, and rushed upon us with such renewed and increasing violence, that, to be honest, as a Christian of my years should be, we were fain to betake ourselves to our ships with what speed and good fortune we could. And now, señor, you will be ashamed to hear that our courage was so much mollified by this repulse, and our fears of engaging further with such desperadoes so urgent and potent, that we straightway set sail, and, in the vain search for the enchanted Fountain, quite forgot the nobler objects of the voyage."

"What you have said," quoth Don Amador, "convinces me that these savages of Florida are a warlike people, and worthy the wrath of a brave soldier; but you have said nothing of the ores and diadems, whereof, I think, you first spake, and which, heaven save the mark! by some strange mutation of mind, have made a deeper impression on my imagination than such trifles should."

"We learned of some wounded captives we carried to the ships," continued the master, "as well, at least, as we could understand by their signs, that there was a vast country to the north-west, where dwelt nations of fire-worshippers, governed by kings, very rich and powerful, on the banks of a great river; and from some things we gathered, it was thought by many that the miraculous Fountain was in that land, and not in the island Bimini; and this think I myself, for, señor, I have seen a man who, with others, had slaked his thirst in every spring that gushes from that island, and, by my faith, he died of an apoplexy the day after his arrival in the Habana. Wherefore, it is clear, that marvellous Fountain must be in the country of the fire-worshippers. But notwithstanding all these things, señor, our commander Don Ponce, would resolve upon naught but to return to the Bahamas, where our ships were divided, each in search of the island called Bimini. It was my fortune to be despatched westward; and here, what with the aid of a tempest that blew from the east, and some little hankering of mine own appetites after that land of the fire-worshippers, I found myself many a league beyond where any Christian had ever navigated before, where a fresh and turbid current rolled through the deep, bearing the trunks of countless great trees, many of them scorched with fire: whereupon I knew that I was near to the object of my desires, which, however, the fears and the discontent of my crew prevented my reaching. I was even compelled to obey them, and conduct them to Cuba."