The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's Round Table, May 28, 1895, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Harper's Round Table, May 28, 1895 Author: Various Release Date: June 25, 2010 [EBook #32976] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S ROUND TABLE, MAY 28, 1895 *** Produced by Annie McGuire

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| PUBLISHED WEEKLY. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, MAY 28, 1895. | FIVE CENTS A COPY. |

| VOL. XVI.—NO. 813. | TWO DOLLARS A YEAR. |

he battle of Chancellorsville marked the zenith of Confederate good fortune. Immediately afterwards, in June, 1863, Lee led the victorious Army of Northern Virginia north into Pennsylvania. The South was now the invader, not the invaded, and its heart beat proudly with hopes of success; but these hopes went down in bloody wreck on July 4th, when word was sent to the world that the high valor of Virginia had failed at last on the field of Gettysburg, and that in the far West Vicksburg had been taken by the army of the "silent soldier."

At Gettysburg Lee had under him some seventy thousand men, and his opponent, Meade, about ninety thousand. Both armies were composed mainly of seasoned veterans, trained to the highest point by campaign after campaign and battle after battle; and there was nothing to choose between them as to the fighting power of the rank and file. The Union army was the larger, yet most of the time it stood on the defensive; for the difference between the generals, Lee and Meade, was greater than could be bridged by twenty thousand men.

For three days the battle raged. No other battle of recent years has been so obstinate and so bloody. The victorious Union army lost a greater percentage in killed and wounded than the allied armies of England, Germany, and the Netherlands lost at Waterloo. Four of its seven corps suffered each a greater relative loss than befell the world-renowned British infantry on the day that saw the doom of the mighty French Emperor. The defeated Confederates at Gettysburg lost relatively as many men as the defeated French at Waterloo; but whereas the French army became a mere rabble, Lee withdrew his formidable soldiery with their courage unbroken, and their fighting power only diminished by their actual losses in the field.

The decisive moment of the battle, and perhaps of the whole war, was in the afternoon of the third day, when[Pg 546] Lee sent forward his choicest troops in a last effort to break the middle of the Union line. The kernel of the attacking force was Pickett's division, the flower of the Virginian infantry, but many other brigades took part in the assault, and the attacking column, all told, numbered over fifteen thousand men. At the same time Longstreet's Confederate forces attacked the Union left to create a diversion. The attack was preceded by a terrific cannonade, Lee gathering one hundred and fifteen guns, and opening a terrible fire on the centre of the Union line. In response, the Union chief of artillery gathered eighty guns along on the crest of the gently sloping hill where attack was threatened. For two hours, from one to three, there was a terrific cannonade, and the batteries on both sides suffered severely. In both the Union and Confederate lines caissons were blown up by the fire, riderless horses dashed hither and thither, the dead lay in heaps, and throngs of wounded streamed to the rear. Every man lay down and sought what cover he could. It was evident that the Confederate cannonade was but a prelude to a great infantry attack, and at three o'clock Hunt, the Union chief of artillery, ordered the fire to stop, that the guns might cool to be ready for the coming assault. The Confederates thought that they had silenced the Union artillery, and for a few minutes their firing continued; then suddenly it ceased, and there was a lull.

The men on the Union side who were not at the point directly menaced peered anxiously across the space between the lines to watch the next move, while the men in the divisions which it was certain were about to be assaulted lay hugging the ground and gripping their muskets, excited, but confident and resolute. They saw the smoke clouds rise slowly above the opposite crest, where the Confederate army lay, and the sunlight glinted again on the long line of brass and iron guns which had been hidden from view during the cannonade. In another moment, out of the lifting smoke there appeared, beautiful and terrible, the picked thousands of the Southern army advancing to the assault. They advanced in three lines, each over a mile long, and in perfect order. Pickett's Virginians held the centre, with on their left the North Carolinians of Pender and Pettigrew, and on their right the Alabama regiments of Wilcox; and there were also Georgian and Tennessee regiments in the attacking force. Pickett's division, however, was the only one able to press its charge home.

The Confederate lines came on magnificently. As they crossed the Emmetsburg Pike the eighty guns on the Union crest, now cool and in good shape, opened upon them, first with shot and then with shell. Great gaps were made every second in the ranks, but the gray-clad soldiers closed up to the centre, and the color-bearers leaped to the front, shaking and waving the flags. The Union infantry reserved their fire until the Confederates were within easy range, when the musketry crashed out with a roar; the big guns began to fire grape and canister.

On came the Confederates, the men falling by hundreds, the colors fluttering in front like a little forest; for as fast as a color-bearer was shot, some one else seized the flag from his hand before it fell. The North Carolinians were more exposed to the fire than any other portion of the attacking force, and they were broken before they reached the line. There was a gap between the Virginians and the Alabama troops, and this was taken advantage of by Stannard's Vermont brigade and a demi-brigade under Gates of the Twentieth New York, who were thrust forward into it. Stannard changed front with his regiments and attacked Pickett's forces in flank, and Gates continued the attack. When thus struck in the flank the Virginians could not defend themselves, and they crowded off toward the centre to avoid the pressure. Many of them were killed or captured; many of them were driven back: but two of the brigades, headed by General Armistead, forced their way forward to the stone wall on the crest, where the Pennsylvania regiments were posted under Gibbon and Webb.

The Union guns fired to the last moment, until of the two batteries immediately in front of the charging Virginians every officer but one had been struck. One of the mortally wounded officers was young Cushing, a brother of the hero of the Albemarle fight. He was almost cut in two, but holding his body together with one hand, with the other he fired his last gun, and fell dead just as Armistead, pressing forward at the head of his men, leaped the wall, waving his hat on his sword. Immediately afterwards the battle-flags of the foremost Confederate regiments crowned the crest; but their strength was spent. The Union troops moved forward with the bayonet, and the remnant of Pickett's division, attacked on all sides, either surrendered or retreated down the hill again. Armistead fell dying by the body of the dead Cushing. Both Gibbon and Webb were wounded. Of Pickett's command two-thirds were killed, wounded, or captured, and every brigade commander and every field officer save one fell. The Virginians tried to rally, but were broken and driven again by Gates, while Stannard repeated at the expense of the Alabamians the movement he had made against the Virginians, and, reversing his front, attacked them in flank. Their lines were torn by the batteries in front, and they fell back before the Vermonters' attack, and Stannard reaped a rich harvest of prisoners and of battle-flags.

The charge was over. It was the greatest charge in any battle of modern times, and it had failed. It would be impossible to surpass the gallantry of those that made it, or the gallantry of those that withstood it. Had there been in command of the Union army a general like Grant, it would have been followed by a counter-charge, and in all probability the war would have been shortened by nearly two years; but no counter-charge was made.

As the afternoon waned, a fierce cavalry fight took place on the Union right. Stuart, the famous Confederate cavalry commander, had moved forward to turn the Union right, but he was met by Gregg's cavalry, and there followed a contest at close quarters with "the white arm." It closed with a desperate melee, in which the Confederates, charging under Wade Hampton and Fitz-Hugh Lee, were met in mid-career by the Union Generals Custer and McIntosh. All four fought, sabre in hand, at the head of their troopers, and every man on each side was put into the struggle. Custer, his yellow hair flowing, his face aflame with the eager joy of battle, was in the thick of the fight, rising in his stirrups as he called to his famous Michigan swordsmen, "Come on, you Wolverines, come on!" All that the Union infantry, watching eagerly from their lines, could see was a vast dust cloud, where flakes of light shimmered as the sun shone upon the swinging sabres. At last the Confederate horsemen were beaten back, and they did not come forward again or seek to renew the combat; for Pickett's charge had failed, and there was no longer hope of Confederate victory.

When night fell the Union flags waved in triumph over the field of Gettysburg; but over thirty thousand men lay dead or wounded, strewn through wood and meadow, on field and hill, where the three days' fight had surged.

Flutter of flag and beat of drum

And the sound of marching feet,

And in long procession the soldiers come

To the call of the bugles sweet.

And the marching soldiers stop at last

Where their sleeping comrades lie,

The men whose battles have long been fought,

Who dared for the land to die.

Children, quick with your gathered flowers,

Scatter them far and near;

They who were fathers and brothers once

Are peacefully resting here.

Flutter of banner and beat of drum

And the bugle's solemn call,

In grand procession the soldiers come—

And God is over us all!

[Pg 547]

At last the cats have had a show of their own, and for the time being their old enemies, the dogs, have been forced to take a back seat, and sulk at the attention which the 250 and more pussies received from the girls and boys and grown-up people at the Madison Square Garden in New York. It has been a gala-time for the children, especially, and the petting which the different tabbies received would have turned their heads had they not been so well-bred and aristocratic. For the common tramp cat, who knows no better than to give unwelcome concerts on the back fence at night, or the scraggly kitten, whose one ambition is rat-catching, had no place among the cats who made their first public bow and mieuw a week ago. Only those whose great grandpapas or grandmammas were distinguished people in the cat kingdom were allowed to be exhibited.

After all, the cat kingdom isn't nearly so large as the dog kingdom. All of our domestic cats are grouped under two distinct heads—the short-haired European or Western cat, and the long-haired Asiatic or Eastern cat. The tortoise-shell, white, black, blue, or slate-color (Maltese), and the tabbies are embraced in the European, and the Asiatic includes the Persian, Angora, Russian, and Indian. So that it is ever so much easier to learn what class your cat belongs in than to know the different kinds of dogs.

What an attractive sight the long rows of dainty cages, each fitted up in royal fashion for its feline occupant, made! Here at the beginning of the long row of wire houses, "Dick," a miniature tiger, slept with eyes half closed (as every good cat always does), and his right paw outstretched, as if in his dreams some poor little sparrow were within clutching distance. Not far away "Charles Dickens," a very aristocratic Maltese, was purring out his compliments to a little girl who was vainly endeavoring to educate him to eat peanuts.

Then there was "Columbia" and her two kittens, "Yale" and "Harvard." The readers of the Round Table never saw their older brothers wear their college colors more bravely than these wee little kittens. Their fawn-colored mother would get them quieted down after some merry romp, and then they would suddenly begin another friendly fight, and roll over and over again, till it was impossible to tell whether the blue or the red was victorious. Near by was a "happy family" of short-haired spotted cats from Elizabeth, New Jersey, consisting of a great-grandmother, grandmother, mother, and seven kittens. And how proud gentle great-grandmamma was when her granddaughter captured the second prize in her class.

Perhaps our President would feel pleased were he to know how much attention his namesake "Grover Cleveland" had at the show. He is a rich, brown tabby, with wide black stripes, and was given a blue ribbon, the mark of the first prize. He took it all very calmly, as much as to say, "You couldn't do anything less for one with such a name as mine."

But even "Grover Cleveland" was not so aristocratic-looking as "Grover B.," from Philadelphia. His short-haired coat was as white as the stone door-steps of the houses in his native town, and—think of it—his mistress values him at $1000! So well brought up is he that he sits at the table with his master and mistress in a high chair and feeds himself with his paw. His master says that he eats more quietly and gracefully than their little nephew of five years, who, when he spills his bread and milk, is told he can profit by "Grover's" example. So fond of him is his master that his head appears on all his business paper and envelopes, so that "Grover B." is known all over the world, and, through his pictures on his master's envelopes, has travelled more extensively than almost any other cat.

An even more wonderful short-haired cat was "Mittens," who has actually been trained to love and live with birds. "Mittens" is a great deal of a swell. His grandfather was a pure-blooded Maltese, and his great-grandmamma was a very haughty Angora. All the traditions in his family prompted him to consider birds as his natural prey and dogs as his enemies. When he came to his present mistress, Mrs. M. L. Ponchez, the latter had two Yorkshire terriers, a parrot, eight canaries, a red-bird, and several chameleons, and of course she thought it would be pretty difficult for "Mittens" to live in peace with all these other pets. She thought she would try to teach him to be friendly to the birds and dogs, and this is what she did.

She first kept all of her pets a day without food, and then the next day placed the cat between the dogs while she fed him his breakfast. After that the cat and the dogs became such good friends that they all slept together. At the next meal she took one of the canaries, put him on her finger, and petted him while she held "Mittens" in her lap and fed him. This she did several times, and then let all of the birds fly around the cat. The latter never attempted to touch one, and frequently to-day you may see "Mittens" slumbering peacefully before the fire, with a canary nestled on the soft fur of his back.

IN THE LONG-HAIRED CAT-ROOM.

IN THE LONG-HAIRED CAT-ROOM.

While there were many more short-haired cats on exhibition for prizes, the long-haired ones created more attention because they are much less common. They had a separate room to themselves upstairs, and a band of music played for them lest they should forget that many of them were descended from cat emperors and princes in the far-off East. There was "Ajax," a white Angora, with firm mouth and keen eyes, his fluffy white mane looking like a lion's, every inch of him a king. There was "Paderewski," blue-ribboned, with longer and thicker hair than the famous musician whose name he bears. Near by an interested crowd watched "Ellen Terry" and her seven kittens. "Ellen" is a large white and orange Angora, and very cozy were she and her kittens in a basket lined with yellow silk and trimmed with dotted muslin. Her manners were perfect, for whenever her cunning little kittens were caressed she showed no surprise, but looked on with calm maternal pride.

Just to show by contrast how very aristocratic these long-haired cats were, six or eight lost cats from the Shelter for Animals (where lost and homeless cats are cared for) were exhibited near the haughty Angoras. All but one looked sadly out of place. They were thin, their fur was uneven, and the disdainful sniffs which their Persian and Angora neighbors gave them made them feel very miserable indeed. But one of them, though, a short-haired cat, looked as if his grandfather had been a somebody in the cat kingdom, and he seemed to say,

"Though appearances are against me, please don't think that I belong to this vulgar herd of tramp cats."

And he was vindicated, for the third day of the show a little girl came rushing over to the cage with a glad cry of recognition, which the cat immediately responded to by joyful purring. The cat had been lost for over two weeks, and now as his young mistress took him away he looked back at his proud long-haired neighbors with a smile, which meant,

"Ah, you see I'm somebody, after all!"

Perhaps the readers of the Round Table would like to know whether their cats and kittens are "somebody" or not, whether they are pure-blooded examples of the classes to which they belong. It is quite simple. A prominent doctor, who knows more about cats than almost any other man in the United States, says that in judging a cat the first thing to be considered is its general symmetry.

"The body ought to be long and slenderly shaped, like that of a tiger. The eyes should be of a correct shade; for instance, a cat that is white should have blue eyes, a black cat yellow eyes, and so on. The eyes, too, should be round and full. The color of a cat is important, and is the key to its character. A cat of one color should have no other hue in its coat. The most rarely marked cat is the tortoise-shell, uneven patches of red, black, and yellow, equally distributed over the body. In the tabbies the dark markings should be in direct contrast with the light, gray or brown being marked with black, while blue is marked with some darker shade, and yellow with red."

So successful was this first cat show that it is almost settled that another one will be held next fall. A cat club[Pg 548] is to be formed, as exclusive as some of the kennel clubs to which the cats' canine enemies belong. So that hereafter when a proud-looking Angora goes to call on a Maltese friend, the question no longer will be: "How many birds have you killed lately?" or, "How do you find your milk these days?" But as the pussies purr in good-fellowship together, you will hear them ask each other (if you can understand the cat language), "Are you going to the club this evening?" and "Shall I see you at the 'show' next fall?"

The sport of steamship-hunting is the finest I ever enjoyed. It has more excitement in it than any other I have ever heard of. If you catch your ship properly you are happier than the slayer of many lions; if you don't catch her—well, there are some possibilities too shiverish to think about.

Of course the kind of steamship-hunting I mean is the game instituted by the big newspapers in such a case as that of La Gascogne, when recently she was eleven days overdue from Havre because one of her piston-heads broke down. This game is played with a tug-boat, a full equipment of night-glasses, and a great amount of patience. Just think of how important the results are! Within the circuit of New York, Boston, Buffalo, and Washington—the territory wherein New York newspapers are chiefly taken—there are at least ten millions of readers, all anxious for every scrap of news of the missing ship. Hundreds of these people have friends or relatives on board, but every one of the vast number is equally eager to hear of the ship's safe arrival, and all about the reason for her lateness.

If the lion-hunter's rifle misses fire he loses his life, but if the steamship-hunter misses his game he loses most of his good name and all of his employment. Imagine, then, the studious skill he devotes to sweeping the wide field of ocean with his glasses. He knows that half a dozen other tug-loads of reporters are out on the same errand, and that if any of them "beat" him he'd better sail right down into Davy Jones's locker and lock it from the inside.

The tug of a New York paper went down to the Quarantine Station at Staten Island on that very cold Friday evening three days before La Gascogne was heard from. She was then eight days overdue. Three reporters and an artist were aboard the tug. They called at the telegraph office at Quarantine, and learned that nothing had been heard of the French ship from Sandy Hook or Fire Island. The only thing to do was to go down to the entrance of the Harbor and wait and hope—especially hope. Just before the steamship-hunters left the snug warm telegraph office the instruments began to sputter. The operator in the Sandy Hook tower was saying,

"Wind blowing fifty-six miles an hour from the N. W."

Two wise men, who had been to sea a few times, insisted on staying several miles inside of Sandy Hook, but the other man insisted a great deal harder on going. Off we went after a very short debate. The wind rattled the pilot-house windows, and if the door fell ajar a moment the breeze nearly whipped it off and blew it away. The bay was covered with floating ice. There were some cakes almost as big as a city block, and some looked tiny enough to put in a glass of water; but most of them were as long and wide as the deck of a big canal-boat. Every time one of the big fellows crunched against our bow we couldn't help wondering whether it was coming through. The moon flooded the vast field of white, and made it look as if we were sailing over a great prairie. Now and then we came to patches of clear blue water, and these danced in the moon's rays like giant turquoises. The tug's condensed steam rolled and bounded along, seeming like great masses of ivory. The intense cold caused this curious effect. Everything was fairylike, except the harsh grinding and cannonlike thumps of the ice.

Off the point of Sandy Hook we were almost clear of ice. Nobody could see anything that looked like a steamship coming from the eastward. The ice had kept the water quiet, but here in the open it was heaving and pitching under the lash of the gale. We ran into the Horseshoe inside of Sandy Hook, trying to get up to the landing, so that if we had very late news to send we could telegraph it from Sandy Hook, instead of Quarantine, which was an hour to the north of us. Ice was packed and jammed so thick and tight inside the Horseshoe that not even an icicle could be pushed into it. After our tug narrowly escaped being caught and held fast for the night we backed out. No use trying to land.[Pg 549]

"Mast-head light to the east'd!" sang out our skipper as we rounded the point of the Hook. Has your heart ever begun to dance at the sight of a school of bluefish when you were running down toward them with four squids trailing from your cat-boat? Have you ever heard a deer come crashing through the thicket toward your rifle? Imagine us, then, when we heard those words. Every man whipped out a night-glass, or waited eagerly for his neighbor's. A speck of yellow light on the horizon crawled slowly up the blue sky.

"She's a liner," said our captain. "The ice and the hurricane have sent all the channel buoys adrift" (you know the ship channel is lighted with electric lamps like Fifth Avenue), "so her pilot will anchor outside."

Away went the tug at full speed. The yellow mast-head light kept growing higher, like a meteor going backward. Soon we could distinguish the dim white shape of a giant steamship. As she came nearer we saw that she was ice-coated from the water-line to one hundred feet above the deck. The lights glowed and twinkled out of the cabin ports like the candles shining out of the white churches we used to have when we were little boys. The big ship anchored not far from the Sandy Hook Lightship (six miles out on the Atlantic). Our Captain knew her for the Teutonic as readily as you would know your father in the street. On account of the high waves we dared not go within one hundred feet, for fear of being dashed against the steamship's side. Our tug's bow swung up in the wind, and we began a conversation with the officer on the Teutonic's bridge, our words shooting back and forth across fifty yards of icy wind that sped between us at the rate of fifty-six miles an hour. The Teutonic had no news of La Gascogne.

On that Monday afternoon when the telegraph-operator in Fire Island tower reported the missing Gascogne approaching his station, our tug started out again. The many weary and fruitless nights of watching and cruising were all forgotten. The searchers hurried through dinner in the galley, and drank big mugs of coffee in gulps. Every one was too happy to stay long at anything. I never knew the distance between the Battery and the outer light-ship to be so long. From here, at last, we spied a glimmer of red on the sky-line. If enthusiasm burned, there wouldn't have been a lens left in one of those glasses. Men perched on the top of the pilot-house to see better.

"That's the Gascogne—three red lights at the mast-head—going under repairs," cried the mate, from the loftiest perch.

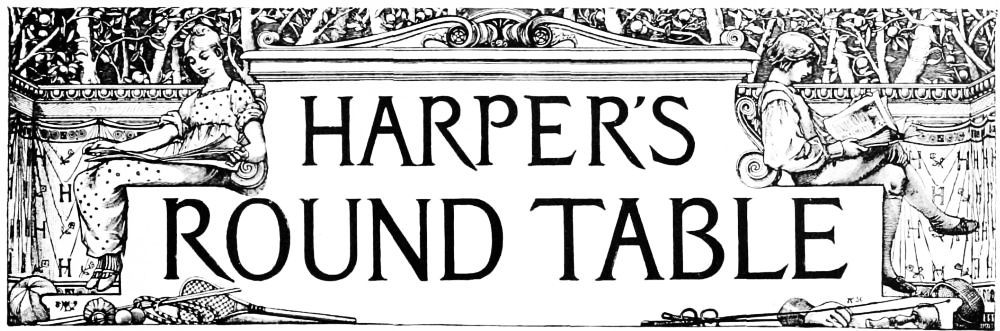

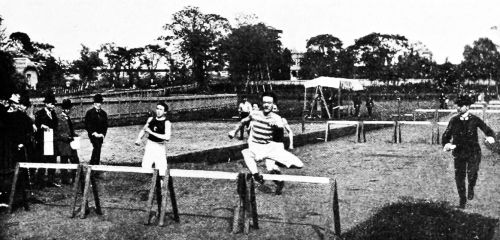

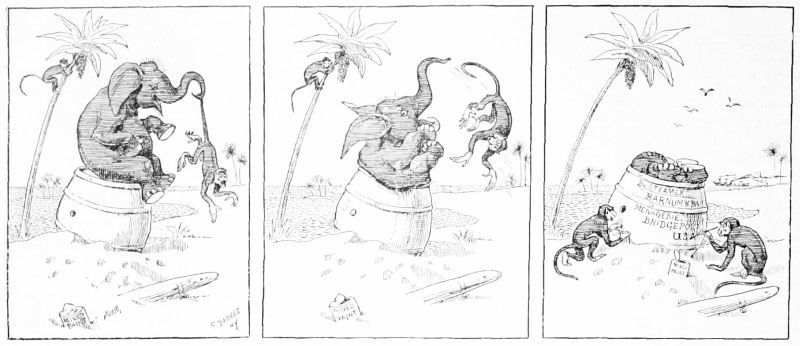

ONE OF THE NERVE-TICKLING DETAILS OF THE HUNT.

ONE OF THE NERVE-TICKLING DETAILS OF THE HUNT.

Every minute dragged outrageously until we got alongside of the steamship. Nothing in her appearance except the three red lights indicated that anything was wrong. She was moving slowly—only eight miles an hour. We ran under her stern, and got alongside her lee bow. Groups of passengers gathered along the rails, although it was now very near midnight. They cheered the men who came so far to welcome them. An officer on the bridge told of the accident in a dozen words. Through one of the ports we could see a blue-jacketed steward polishing a plate.

"Has Faure formed a cabinet yet?" shouted one passenger.

The answer we gave him was lost in the chorus of cheers. Some one weighted a copy of the ship's log, and threw it aboard our tug.

But while all this was very pleasant, it was not enough. The ship's officers promised to lower a companion-ladder for our men to go aboard.

A long wait. No ladder. Our own skipper solved the problem by ordering his men to throw up a twenty-foot wooden ladder—a fragile thing. Such roars in English and counter-roars in French as there were while that ladder was being arranged!

"Take a couple of bights of that line, and make it fast on the third rung, you three-fingered blacksmith!" yelled our mate.

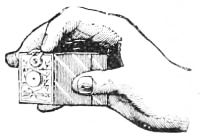

The Frenchmen guessed what he meant. At last the ladder was up, resting on our deck, and its end scraping the Gascogne's side. There was great danger that at any moment the top end might catch on an iron plate as our rolling tug pushed it upward. Then the great weight of the tug would crush the ladder into matchwood. No matter; that was one of the nerve-tickling details of the newspaper steamship hunt. Up ran two reporters and an artist, one after the other, while men stood by to throw them life-buoys if the ladder should be smashed.

But they got aboard all right. Afterward came the interviewing, the hurried writing of copy, the telegraphing from a secret place in Staten Island out of the reach of news thieves; but all that is the mere recital of how we carried home our game.[Pg 550]

"I say he sha'n't come in!"

"And I tell you he shall!"

The boys' voices rose high and angry; their attitude was threatening; and at the sound of contention a bevy of other barefooted urchins came scampering over the damp sand, shouting, "Hi! a scrap, a scrap!" and eager to see fair play.

"What's it all about?" inquired Ned Eaton, a good-looking youth, rather better dressed than his companions.

"It's about little Jem Ferguson," spoke up the shorter and stockier of the belligerents. "Kit Bandy here says he oughtn't to be let into the beach-combing, and I hold it's mean as cramp-fish to bar him out just because he's weak and pindlin' and no account in a boat."

"So it is, so it is," chorused the listening youngsters.

But Kit put in quickly, "All right, let him in then; but if you do he'll hoodoo every mother's son of us. Who killed the luck bird last June?"

"Not Jem," cried Herbert Woolley.

"No; but his daddy did, and if he had been drinking too much hard cider at the time, that makes no difference, and the whole family has had a powerful sight of bad fortune ever since. Jest two weeks after their cow choked to death with a green apple; Jem's hip trouble grew worse; and Jake Smithers told me that the smack in which Dan Ferguson sails is sure to come back with a light haul. The men all look on him as a Jonah, for fish don't come to the nets of those who take the life of a hawk."

"Well, but ill-luck can't be inherited, like consumption or the shape of one's nose," protested Herbert, "and even if it could, Jem's having a bit of sand to sift couldn't affect the rest of us."

Still the boys glanced at each other doubtfully, and one muttered. "We'll each have more ground, and so more chance, if he isn't there," while Kit clinched his argument by declaring, "Oh, if Bert has his way we all may as well give up all hope of winning that," pointing, as he spoke, to a flaring yellow poster which adorned one of the bathing-houses.

was the heading, in conspicuous capitals two inches long, and below this amount was offered, in smaller type, as a reward for the return of a diamond earring lost by one of the summer visitors in Benton, the pretty New Jersey village where these lads lived, and which was a quasi-fashionable seaside resort for three months of the year. Now, however, the broad white beach was given into the hands of those young natives who in the early fall make a business of going carefully over it, rubbing the iridescent sand between their fingers, and seeking for any articles there lost and hidden during the gay warm season.

In grim silence, then, the boys re-read the advertisement which all knew by heart, and Ned Eaton suggested, "Let's take a vote. Those who want Limpy Jem to have a show drop a white shell in my hat, and those who are for freezing him out a purple one."

"Yes, yes, that is a good way; that will be fair." And the members of this hastily formed Beach-Comber's Union turned aside with relief to select their ballots from the deep-sea treasures cast up by the bobbing foam-capped waves.

Five minutes later, then, the polls were open, and Kit looked triumphant and Bert annoyed as both noted that the majority of the voters were endeavoring to conceal dark mussel-shells in their brown little fists. There was no doubt that Jem's fate was sealed, when suddenly a faint shout attracted their attention, and all started at sight of a slender auburn-haired lassie speeding toward them from the direction of the village. "Gee whizz, but it's Eileen Ferguson!" shrieked small Teddy Todd, "and her temper is as fiery as her curly mop."

Certainly there was a dangerous flash in her big gray eyes and a sharp ring in her young voice as, coming nearer, she cried: "So, Kit Bundy, you are playin' the snake in the grass again, are you? You never did like my brother, and now I hear you are tryin' to have him put out of the beach-combin'. Poor Jemmy, who is too sickly to go to the fishin'-banks, and has so looked forward to the fall in hopes of earnin' a few dollars for the mither! I should think ye'd be ashamed of yourself! Dickson, the bathin'-master tould me how you were talkin' to the others; but you won't mind him, will you, boys?" And there was that in the appealing, half tearful glance which the earnest little sister turned upon them that made most of her hearers look sheepish, and become deeply absorbed in stirring up the sand with their toes.

But Kit, was furious. "What?" he roared; "be dictated to by a girl? Not if I know our combers. Go on, fellows, and vote as you intended; while, Miss Impudence, the sooner you take yourself off the better."

Instinctively, however, Eileen turned to young Woolley. "Oh, Bert, Bert!" she wailed, "don't let them throw my Jemmy out. He has had such a dreadful summer, and this—this will break his heart. We need the money so much, and niver did he dream his old friends could treat him so." Then all at once her wrath dissolved in a girlish burst of tears.

"Pepper me if I can stand that, bad luck or not," growled Ned, hurriedly picking up a white shell and flinging it into the hat; and as boys, like older people, are very much akin to a flock of sheep, the majority followed suit, and Jem Ferguson was, as in former years, numbered with the beach-combers, the three purple shells cast by Kit and two of his chums not being sufficient to rule him out.

"A thousand thanks, boys! You are blissid darlints, ivery one of ye—barrin' that trio," exclaimed Eileen, who, though American born, in moments of excitement sometimes betrayed her ancestry by her speech.

When, then, on the morning of September 18th, the combers gathered to commence operations, one of the happiest faces there was that of little "Limpy," hopping briskly along on his crutches, and nodding gay greetings to his old comrades. They found the beach evenly measured off and divided by stakes. The plan of the lads of Benton was to draw lots for their respective portions, a strict though unwritten law being that no one should poach upon another's grounds.

"See, Kit, you and I are neighbors," said Jem, cordially, to young Bundy. "And such fine sections as we have! right in front of the great Naiad Hotel. We have a good chance for the diamond. Oh, but don't I wish I could find it!"

But Kit only growled something about "luck-bird-killers" under his breath, and strode away to his own preserve. Always rather a leader among his companions, he was chagrined by his defeat, and felt injured and annoyed by the cripple's presence.

As the day wore on, however, he found it difficult to keep up his antagonism to cheery Jem, who ignored all rebuffs, and chatted away in the most friendly as well as quaint manner—now about the sea, wondering why it changed its hue from blue to green and green to gray; and now about the fish-hawks circling overhead, and longing to be one of them, that he too might fly off to some warm Southern land before the cold, biting winter came on.

"What a queer un you are!" remarked Kit at length. "What makes you think of such things? Why, I'd a heap rather be a boy than a bird."

"Yes, 'cause you are so big and strong. You can make your way in the world, and your back isn't crooked, and your legs all drawed up. Now I, you see, am neither flesh nor fowl nor good red herring," and Jem cackled a feeble little laugh, but without a tinge of bitterness. How, too, he enjoyed the lunch eaten on the beach, and insisted that every one must taste the pie Eileen had made for him out of "two pertaties and a bit of a lemon."

For three days the weather was perfect, and the combers "made hay while the sun shone," gathering quite a profitable collection of old iron and nails, children's toys, small coins, and inexpensive pins and pieces of jewelry, while Bert Woolley had the good fortune to come upon a[Pg 551] silver watch little the worse for its sojourn in the damp sand.

But on the fourth morning there came a change. Heavy clouds obscured old Sol from view, the sea roared with a low ominous undertone, and the wind blew raw and chill from the northeast, making the lads shake and shiver, and seeming to freeze weakly Jem to the very marrow and set his limbs to aching. Then in the night the storm broke, one of those fierce September gales which often sweep the coast, and for forty-eight hours roared and raged without, while the impatient urchins grumbled and raged within.

It was an exceedingly wet world that at last emerged, bright and glistening, after the deluge, but Kit Bundy was early astir and down on the shore to see what havoc the tempest had made. Dead fish, drift-wood, portions of wrecks, and other flotsam and jetsam strewed the beach, up which he slowly sauntered, kicking before him a round stone that bounded merrily across the sand. Presently, in front of the Naiad Hotel, a particularly vigorous kick sent it high in air, and then landed it in a deep hollow worn by the waves. Mechanically Kit paused to lift his improvised plaything from the hole, when something beside it caused him to fall on his knees with a low stifled gasp. Not another sound escaped him, but there was a new and curious expression on his face when he finally rose and almost ran to the boarding-house he and his father called "home." Later in the day the long line of beach-combers were electrified by the message that passed from mouth to mouth, "Kit is the lucky one; he has found the diamond earring."

From far and near the boys hastened to behold the jewel, about which there could not have been more interest had it been the Koh-i-noor itself, and the finder had to point out just where he discovered it in his section, deeply buried a foot from the surface.

"Not so dreadfully hoodooed after all, were you, Kit?" Bert could not resist remarking; but most of the lads swallowed their own disappointment, and congratulated him warmly, while Jem threw his hat in the air, piping,

"Hip, hip, hurrah for Bundy, the prize-winner!"

But the hero of the hour did not appear particularly pleased with these attentions. He grew very red, and turned away, muttering, "Oh, shut up, fellows! It isn't worth makin' such a fuss over."

"Just hear the Rothschild," squeaked Teddy Todd. "One would think he picked up gems every day in the year. I shouldn't be so grumpy if I had had his luck."

"Which he don't deserve," said outspoken Eileen, who had come down to gather drift-wood. "Oh dear! how unequal things are in this world! If Jem had but drawn that side of the stake instead of the other, we would be fairly spinnin' with the joy, and whiskin' him off to the best doctor in the county. Poor lamb! he scarce slept a wink last night, with the pain in his hip, and oughtn't to be out here to-day."

And the next morning Jem was missing, his sister coming to fill his place, and, with her ready Irish wit, parrying all the boys' jokes on "the first girl comber of Monmouth." But from that time the interest in the beach-combing flagged, and the work soon came to an end.

One afternoon, not long after, a youth, conspicuously conscious of his Sunday clothes and stiff collar, rang the bell of a handsome New York residence, the shining door-plate of which bore the name, "J. C. Landon, M.D." He was admitted by a supercilious colored boy in buttons, who, ushering him into a luxuriantly furnished office, told him to "Wait, the doctor was engaged at present." And he did wait a full half-hour before the physician emerged from an inner apartment, accompanied by a lady who gently supported a young girl, richly attired, and with long fair hair floating on her shoulders, but who limped painfully, and in whose sweet face was an expression of suffering that somehow reminded Kit—for Kit it was—of Jem Ferguson.

"Yes, yes, Mrs. Graham," Dr. Landon was saying. "I see no reason why Miss Ethel should not walk without crutches in time. Science works wonders nowadays. She would get on faster if you could consent to let her go to my sanitarium, but since you are unwilling, I will visit her often and do the best I am able; while I can at least promise that there will soon be no more of the neuralgia that causes such excruciating agony." With which he bowed his visitors out, and, returning, asked briskly, "Well, my lad, what can I do for you? You don't look like an invalid."

"No, sir; I'm pretty hearty," responded Kit, with a grin. "I came because—because I have found this," and without further words he produced a small box and opened it.

"My wife's lost earring! Why, she will be overjoyed!" exclaimed the physician. "But I shall have to turn you over to her, as I am due at the hospital, and haven't a moment to spare. Here, Nero, ask Mrs. Landon to step down to the office." And without more ado the busy man hurried off, leaving the confused and stammering Kit to the tender mercies of the mistress of the mansion.

But these proved very delightful, for not only did the lady shower him with graceful thanks, but ordered up a dainty little collation for his refreshment, which he ate to the sound of the surgeon's praises as sung by Nero, who declared his master to be "De berry bestest doctah in all de United States. Why, sah, he kin mos' raise de dead, and I 'low he makes de lame to walk ebery day, and tinks nottin' ob it"; and, when he finally left the house, it was with a fat roll of greenbacks snugly tucked in his pocket.

This was the hour to which Christopher Bundy had been looking forward, and he proceeded to make the most of it. Of course he went to the theatre, and from a high gallery seat glowed and shivered in sympathy with the hero on the boards, and he followed this up with an oyster-stew in a gayly decorated and illuminated restaurant. But, strange to say, he was not as happy as he should have been, and—it was very queer—the features of "Limpy Jem" would keep rising before him, curiously intermingled with those of the lame girl he had seen that day, while he seemed to hear again a weak voice piping, "That's because you are so big and strong, and your back isn't crooked and your legs all drawn up. I must have the vapors," he concluded, as he tumbled into bed.

The following evening, when Kit stepped off the train at Benton, he was met by a delegation of beach-combers, all shouting: "Hullo, old fellow! Did you get the reward, sure enough? Goin' to stand treat now, ain't yer? Ginger-pop and sodas for the crowd!" and insisted upon bearing him off to drink his health at his expense.

"Wish poor Limpy was here too," remarked Ned Eaton, as he drained his glass of sarsaparilla. "Does any one know how he is to-night?"

"Dreadful bad," answered Teddy Todd. "They think he's dyin'."

"What! Is he so sick as that?" and Kit's voice sounded sharp and unnatural.

"Yes; he took cold that day before the storm; fever set in, and the doctor says he won't get well."

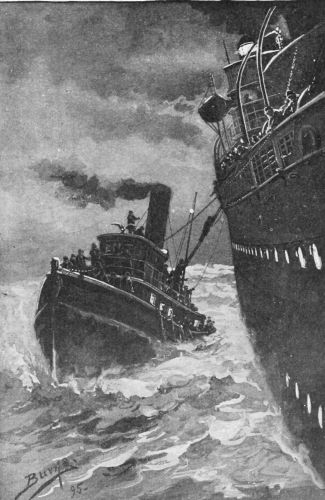

It was nine o'clock, and the little seaside town was settling down to sleepy repose, when a timid knock summoned Eileen to the Fergusons' humble portal. Her eyes were red and swollen, as could be seen by the blazing pine-knot she carried, and her lips quivered as she cried: "Kit Bundy at this hour! What brings you here?"

"To see Jem. Stop, Eileen! Don't say I can't, for I must, indeed I must. I know I've been mean to him and rude to you, but there is something I must tell him before he dies."

There was so much wild anxiety in his manner and imploring in his tone that the curt refusal on the girl's tongue was hushed, and instead she said, "Come, then; only don't stay long," and led the way to the dreary room where Jem lay. A wan smile flitted across his face at sight of his guest, and he murmured:

"Howdy, Kit; do you know, I guess I'll get my wish, after all, and fly away like the luck-birds."

With a low cry, however, the older lad threw himself down beside the bed, and sobbed: "No, no, Limpy; don't say that. You must stop and be comfortable and happy here, for see, this is yours, all yours"; and he flung upon the patchwork quilt the roll of bills paid him by Mrs. Landon.

Jem gasped. "What a big, big lot of money! It's the[Pg 552] reward, isn't it—the reward for the diamond? But you mustn't give it to me."

"It belongs to you. I never had any right to the diamond, for—for I found it on your side of the stake, and buried it in my part of the beach."

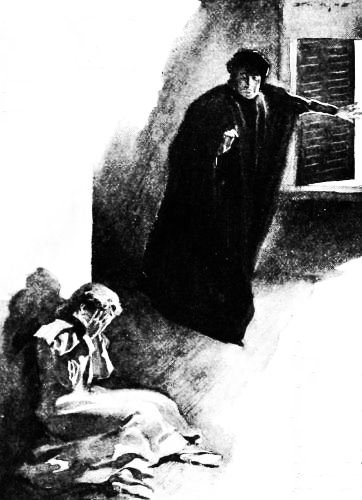

THEN JEM WHISPERED: "POOR KIT! BUT I'M GLAD YOU'VE TOLD

ME."

THEN JEM WHISPERED: "POOR KIT! BUT I'M GLAD YOU'VE TOLD

ME."

After this confession there was dead silence for a moment. Then Jem whispered: "Poor Kit! But I'm glad you've told me."

"So am I; though the beach-combers will hiss me out of their company when they know. Here's the hundred and fifty dollars, however, every penny of it; and you, Eileen, must spend it all for your brother"; and he thrust the greenbacks into that astonished maiden's hands.

But Jemmy protested with all his feeble strength, "I cannot, I will not take it all," he said. "You were the finder, even if it was in my portion of sand. But we will divide, half for you and half for me, and then the other fellows need never know. It shall be our secret." And as he was growing dangerously excited, to this arrangement Kit had to consent.

Before leaving, though, he told the sick boy and his sister of the marvellous cures Dr. Landon was said to have made, and of the fair cripple he had seen in his office, concluding with, "Now, Jem, if you could go to his hospital, mebbe science would work some of those wonders on you."

"Oh, if he could, if he only could!" sighed Eileen.

Hope, however, is a great restorative, and the following day Jem was stronger than he had been for some time, which encouraged Kit to take another trip to New York, where he astonished Dr. Landon by suddenly appearing before him and demanding, "Tell me, sir, is seventy-five dollars enough to put a chap in your hospital and get him cured.'"

"Well, that depends," laughed Dr. Landon, much amused. "Who is this chap, and what is his trouble?"

As concisely as possible the boy told the story of lame Jem, but so interesting the kindly physician that he ran down to Benton expressly to see the case, and the result was the new year found the young invalid established in a great airy ward, where the sunshine sifted in through a beautiful lattice-work of window plants, and cheery, bright-faced attendants were ready to answer every call and supply every want.

"It seems like Paradise," said Jem, nestling among the soft pillows, and that proved a truly blissful winter, in spite of some pain and discomfort he had to endure, while he made life-long friends of Mrs. Landon and Mrs. Graham, who paid him frequent visits, and brought him lovely flowers and delicious fruit from the fair-haired Ethel.

And at length, when the spring-time came over the land, Bert Woolley and Kit Bundy one evening helped off the cars a very pale but very radiant lad, while the former said,

"See, Limpy, there are all the beach-combers coming to welcome you home."

Cordially the rough youths crowded about their young comrade, healed and restored as though by a miracle, and shook him warmly by the hand, wondering to see in a slight limp the only trace of his former lameness. But the throng parted as an auburn head suddenly flashed through their midst, and Eileen, throwing her arms around her brother, cried:

"Oh, Jem, Jem! this is the happy day for sure—to see you walking on your own two feet, while the father has signed the pledge, and a pair of luck-birds are building their nest in the big pine-tree right forninst our door."[Pg 553]

At the point where our travellers had again struck the Yukon, nearly 1500 miles from its mouth, it was still a mighty stream two miles wide. Above this they found it bounded on both sides by mountains that often approached to its very waters, where, in sheer precipices hundreds of feet high, they found gigantic palisades, similar to those of the Hudson, which are known as the "Upper Ramparts." On the lower river the sledge party had journeyed over a smooth surface, on which were few obstructions. Their course from Anvik had at first been due north, then northeast, then east, and was now due south, the source of the Yukon towards which they were now travelling being some ten degrees south of its great arctic bend.

Owing to this, they now found themselves confronted by the hardest kind of sledging over rough hummocky ice that was often piled in chaotic ridges twenty and thirty feet high. As the river freezes first at its most northerly point, and this belt of solid ice is gradually extended south, or back toward its source, the floating cakes of its upper reaches, borne by the swift current, are piled on the ever-advancing barrier in confused masses that stretch across the river like windrows.

In the spring, when the ice breaks up and is hurled irresistibly down stream on the swollen current, the same effect is reproduced on a vastly increased scale. Then the upper river breaks first, and a sudden rise of water from some great tributary starts the ice over the still solid barrier below. The huge cakes slide, jam, push, and crash over the still unbroken ice sheet, until they are piled in a vast gleaming mass seventy or eighty feet in height, from a quarter of a mile to one mile in length, and extending from bank to bank.

This mighty gorge must give way at length, and when it does it goes with a roaring fury that is terrifying and grand beyond description. After grinding and tearing onward for several miles, or perhaps less than one, the furious impulse is again checked by another solid barrier, which must in turn be broken down and swept away, its added weight giving increased energy to the mighty force.

So the ice crashes its resistless way down the whole Yukon Valley to Bering Sea, two thousand miles distant, sweeping everything before it, mowing down vast areas of forest, submerging islands, tearing out banks, and leaving everywhere traces of its terrible progress in the shape of huge ice cakes, weighing many tons, stranded high above ordinary water level.

Although Phil Ryder and his companions were not to witness this grand exhibition of one of nature's mightiest forces, they were sadly inconvenienced and delayed by the uncomfortable fashion in which their frozen highway had been constructed some months earlier. If they could have left the river and followed along its banks, they would have done so; but this was out of the question, not only on account of their rugged character, but because on their timbered portions the snow lay many feet in depth, while from the river it had been so blown by strong north winds that for long stretches the ice was barely covered. This enabled the sledge men to walk without snow-shoes, which was a great comfort to all three, but especially to Jalap Coombs, who had not yet learned to use the netted frames with "ease and fluency," as Phil said.

To this light-hearted youth the sight of his sailor friend wrestling with the difficulties of inland navigation as[Pg 554] practised in arctic regions afforded a never-failing source of mirth. A single glance at Jalap's lank figure enveloped in firs, with his weather-beaten face peering from the recesses of a hair-fringed hood, was enough at any time to make Phil laugh. Jalap on snow-shoes that, in spite of all his efforts, would slide in every direction but the one desired, and Jalap gazing at a frosty world through a pair of wooden snow-goggles, were sights that even sober-sided Serge found humorous.

But funniest of all was to see Jalap drive a dog-team. This he was now obliged to do, for, while they still had three sledges, they had been unable to procure any Indians at Forty Mile to take the places of Kurilla and Chitsah. So while Phil, who was now an expert in the art of dog-driving, and could handle a six-yard whip like a native, took turns with Serge in breaking the road, Jalap was always allowed to bring up the rear. His dogs had nothing to fear from the whip, except, indeed, when it tripped him up so that he tell on top of them, but they cringed and whined beneath the torrent of incomprehensible sea terms incessantly poured forth by the strange master, who talked to them as though they were so many lubberly sailors.

"Port your hellum! Hard a-port!" he would roar to the accompaniment of flying chunks of ice that he could throw with amazing certainty of aim. Then, "Steady! So! Start a sheet and give her a rap full. Now keep her so! Keep her so! D'ye hear! Let her fall off a fraction of a p'int and I'll rake ye fore and aft. Now, then, bullies, pull all together. Yo-ho, heave! No sojering! Ah, you will, will ye, ye furry sea-cook! Then take that, and stow it in your bread-locker. Shake your hay-seed and climb—climb, I tell ye. Avast heaving!" And so on, hour after hour, while the dogs would jump and pull and tangle their "running rigging," as Jalap named the trace-thongs, and the two boys would shout with laughter.

But while the journey thus furnished something of merriment, it was also filled with tribulations. So bitter was the cold that their bloodless lips were often too stiff for laughter or even for speech. So rough was the way, that they rarely made more than eight or ten miles in a day of exhausting labor. Several dogs broke their legs amid the chaotic ice blocks of the ever-recurring ridges, and had to be shot. Along the palisaded Ramparts it was difficult to find timbered places in which to camp. Their dog feed was running low, and there was none to be had in the wretched native villages that they passed at long intervals.

At length the setting sun of one evening found them at a point where the river, narrowed to a few hundred yards, was bounded on one side by a lofty precipice of rock, and on the other by a steeply sloping bank that, devoid of timber, seemed to descend from an open plateau. They halted beside a single log of drift that, half embedded in ice, was the only available bit of firewood in sight. It was a bleak and bitter place in which to spend an arctic night, and they shivered in anticipation of what they were to suffer during its long hours.

"I am going to climb to the top of the bank," said Serge, "and see if I can't find some more wood. If I do, I'll roll it down; so look out!"

Suiting his action to his words the active lad started with a run that carried him a few yards up the steep ascent. It was so abrupt that he was on the point of sliding back, and dug his heel sharply into the snow to secure a hold. At the same instant he uttered a cry, threw up his arms, and dropped from the sight of his astonished companions as though he had fallen down a well.

Before they could make a move toward his rescue they were more astounded than ever to hear his voice, somewhat muffled, but apparently close beside them.

"I'm all right!" he cried, cheerily. "That is, I think I am, and I believe I can cut my way out. Don't try to climb the bank. Just wait a minute."

Then the bank began to tremble as though shaken by a gentle earthquake, and suddenly a hand clutching a knife shot out from it so close to Jalap Coombs that the startled sailor leaped back to avoid it, stumbled over a sledge, and plunged headlong among his own team of dogs, who were lying in the snow beyond, patiently waiting to be unharnessed. By the time the yelling, howling mass of man and dogs was disentangled and separated, Serge had emerged from the mysterious bank, and stood looking as though he did not quite understand what had happened. Behind him was a black opening into which Phil was peering with the liveliest curiosity.

"Of all the miracles I ever heard of this is the strangest!" he cried. "What does it mean, old man?"

"I don't exactly know," answered Serge: "but I rather think it is a moss blanket. Anyhow, that's an elegant place to crawl into out of the cold. Seems to be plenty of wood too."

Serge was right in his conjecture. What appeared to be the river-bank was merely a curtain of tough, closely compacted Alaskan moss, closely resembling peat in its structure, one foot thick, and reaching from the crest of an overhanging bank to the edge of the river. It had thus held together, and fallen to its present position when the river undermined and swept away the earth from beneath it. That it presented a sloping surface instead of hanging perpendicular was owing to a great number of timbers, the ends of which projected from the excavated bank behind it. Serge had broken through the moss curtain, fallen between these timbers to the beach, and then cut his way out. Now, as he suggested, what better camping-place could they ask than the warm, dry, moss-enclosed space from which he had just emerged.

"I never saw nor heard of anything so particularly and awfully jolly in all my life," pronounced Phil, after the three travellers had entered this unique cavern, and started a fire by which they were enabled to see something of its strange interior. "And, I say, Serge, what a thoughtful scheme it was on your part to provide a chimney for the fire before you lighted it! See how the smoke draws up? If it wasn't for that hole in the roof I am afraid we should be driven out of here in short order. But, hello, old man! Whew—w! what are you throwing bones on the fire for? It reminds me of your brimstone-and-feather experiment on Oonimak."

"Bones!" repeated Serge in surprise. "Are those bones? I thought they were dry sticks."

"I should say they were bones!" cried Phil, snatching a couple of the offending objects from the fire. "And, sure as I live, this log I am sitting on is a bone too. Why, it's bigger than I am. It begins to look as though this place were some sort of a tomb. But there's plenty of wood. Let's throw on some more and light up."

"Toughest wood to cut I ever see," growled Jalap Coombs, who was hacking away at another half-buried log. "'Pears to be brittle, though, and splits easy," he added, dodging a sliver that broke off and flew by his head.

"Hold on!" cried Phil, picking up the sliver. "You'll ruin the axe. That's another bone you're chopping. This place is a regular giants' cemetery."

So strange and uncanny was the place in which our sledge party thus unexpectedly found themselves, that Phil was for exploring it, and attempting to determine its true character at once; but practical Serge persuaded him to wait until they had performed their regular evening duties, and eaten supper. "After that," he said, "we can explore all night if we choose."

So Phil turned his attention to the dogs, which he unharnessed and fed, while Serge prepared supper, and Jalap Coombs gathered a supply of firewood from the bleached timber ends projecting from the bank behind them. He tested each of these before cutting into it to make certain that it was not a bone, quantities of which were mingled with the timber.

The firewood that he thus collected exhibited several puzzling peculiarities. To begin with, it was so very tough and thoroughly lifeless that, as Jalap Coombs remarked, he didn't know but what bones would cut just as easy. When laid on the fire it was slow to ignite, and finally only smouldered,[Pg 555] giving out little light, but yielding a great heat. As Serge said, it made one of the poorest fires to see by and one of the best to cook over that he had ever known.

Although in all their experience they had never enjoyed a more comfortable and thoroughly protected camping-place than this one, the lack of their usual cheerful blaze and their mysterious surroundings created a feeling of depression that caused them to eat supper in unusual silence. At its conclusion Serge picked up a freshly cut bit of the wood, and, holding it in as good a light as he could get, examined it closely.

"I never saw nor heard of any wood like this in all Alaska," he said at length. "Do you suppose this can be part of a buried forest that grew thousands of years ago?"

"I believe that's exactly what it is," replied Phil. "I expect it was some awfully prehistoric forest that was blown down by a prehistoric cyclone, and got covered with mud, somehow, and was just beginning to turn into coal when the ice age set in. Thus it has been preserved in cold storage ever since. It must have grown in one of the ages that one always likes to hear of, but hates to study about, a paleozoic or Silurian or post-tertiary, or one of those times. At any rate I expect it was a tropical forest, for they all were in those days."

"Then like as not these here is elephant's bones," remarked Jalap Coombs. "I were jest thinking as how this one had a look of ivory about it."

"They may be," assented Phil, dubiously, "but they must have belonged to pretty huge old elephants; for I don't believe Jumbo's bones would look like more than toothpicks alongside some of these. It is more likely that they belonged to hairy mammoths, or mastodons, or megatheriums, or plesiosauruses, or fellows like that."

"I don't know as I ever met up with any of them, nor yet heerd tell of 'em," replied Jalap Coombs, simply, "onless what you've just said is the Latin names of rhinocerosses or hoponthomases or giraffees, of which my old friend Kite Roberson useter speak quite frequent. He allus said consarning 'em, though, that they'd best be let alone, for lions nor yet taggers warn't a sarcumstance to 'em. Now if these here bones belonged to any sich critters as them, he sartainly knowed what he were talking about, and I for one are well pleased that they all went dead afore we hove in sight."

"I don't know but what I am too," assented Phil, "for at close range I expect it would be safer to meet one of Mr. Robinson's taggers. Still, I would like to have seen them from a safe place, like the top of Groton Monument or behind the bars of a bank vault. Where are you going, Serge?"

"Going for some wood that isn't quite so prehistoric and will blaze," answered the other lad, who had picked up an axe and was stepping toward the entrance to the cavern.

"That's a scheme! Come on, Mr. Coombs. Let's help him tackle that up-to-date log outside, and see if we can't get a modern illumination out of it," suggested Phil.

So they chopped vigorously at the ice-bound drift-log that had induced them to halt at that point, and half an hour later the gloom of their cavern was dispelled by a roaring, snapping, up-to-date blaze. By its cheerful light they examined with intense interest the great fossil bones that lay scattered about them.

"I should think a whole herd of mammoths must have perished at once," said Phil. "Probably they were being hunted by some antediluvian Siwash and got bogged in a quicksand. How I wish we could see a whole one! But, great Scott! Now we have gone and done it!"

Phil's final exclamation was caused by a crackling sound overhead. The sloping moss roof had caught fire from the leaping blaze, and for a moment the dismayed spectators of this catastrophe imagined that their snug camping-place was about to be destroyed. They quickly saw, however, that the body of the moss was not burning; it was too thoroughly permeated with ice for that, and that the fire was only flashing over its dry under surface.

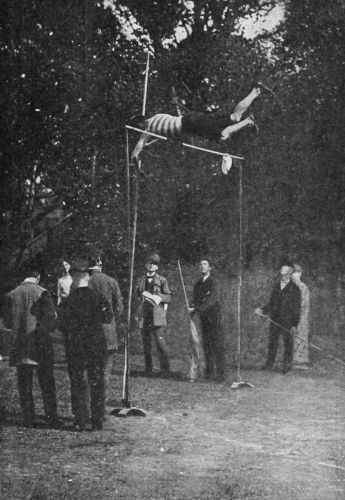

FOR A SINGLE MINUTE THEY GAZED IN BREATHLESS AWE.

FOR A SINGLE MINUTE THEY GAZED IN BREATHLESS AWE.

As they watched these fitful flames running along the roof and illuminating remote recesses of the cavern, all three suddenly uttered cries of amazement, and each called the attention of the others to the most wonderful sight he had ever seen. Brilliantly lighted and distinctly outlined against the dark background of a clay bank, that held it intact, was a gigantic skeleton complete in every detail, even to a huge tusk that curved outward from a massive skull. For a single minute they gazed in breathless awe. Then the illuminating flame died out, and like a dissolving picture the vast outline slowly faded from view and was lost in the blackness.

"Was that one of 'em?" gasped Jalap Coombs.

"I expect it was," answered Phil.

"Waal, then, old Kite didn't make no mistake when he said a tagger warn't a sarcumstance."

"It must have been all of twenty feet high," remarked Serge, reflectively.

For more than an hour they talked of the wonderful sight, and Phil told what he could remember of the gigantic hairy mammoth discovered frozen in a Siberian glacier, and so perfectly preserved that sledge-dogs were fed for weeks on its flesh.

As they talked their fire burned low, and the outside cold creeping stealthily into camp turned their thoughts to fur-lined sleeping-bags. So they slept, and dreamed of prehistoric monsters; while Musky, Luvtuk, Amook, and their comrades restlessly sniffed and gnawed at the ancient bones of this strange encampment, and wondered at finding them so void of flavor.

Glad as our sledge travellers would have been to linger for days and fully explore the mysteries of that great moss-hidden cavern, they dared not take the necessary time. It was already two weeks since they had left the mining-camp, winter was waning, and they must leave the river ere spring destroyed its icy highway. So they were off again with the first gray light of morning, and two days later found them at the mouth of the Pelly River, the upper Yukon's largest tributary, and two hundred and fifteen miles from Forty Mile.

One evening they spent in the snug quarters of Harper, the Pelly River trader, who was the last white man they could hope to meet before reaching the coast.

From the Pelly River trader our travellers gained much valuable information concerning the routes they might pursue and the difficulties they had yet to encounter. They had indeed heard vaguely of the great cañon of the Yukon, through which the mad waters are poured with such fury that they can never freeze, of the rocky Five Fingers that obstruct its channel, the Rink and White Horse rapids, and the turbulent open streams connecting its upper chain of lakes; but until this time they had given these dangers little thought. Now they became real, while some of them, according to the trailer, were impassable save by weary detours through dense forests and deep snows that they feared would delay them beyond the time of the river's breaking up.

"What, then, can we do?" asked Phil.

"I'll tell you," replied the trader. "Leave the Yukon at this point; go about fifty miles up the Pelly, and turn to your right into the Fox. Ascend this to its head, cross Fox Lake, Indian Trail Lake, Lost Lake, and three other small lakes. Then go down a creek that empties into the Little Salmon, and a few miles down that river to the Yukon. In this way you will have avoided the Five Fingers and the Rink Rapids, and found good ice all the way. After that keep on up the main river till you pass Lake Le Barge. There again leave the Yukon, this time for good by the first stream that flows in on your right. It is the Tahkeena, and will lead you to the Chilkat Pass, which is some longer, but no worse than the Chilkoot. Thus you will avoid most of the rough ice, the great cañon, and all the rapids."

"But we shall surely get lost," objected Phil.

"Not if you can hire Cree Jim who lives somewhere up on the Fox River to go with you, for he is the best guide in the country."

So the next morning Phil and his companions again set forth, this time up the Pelly River, with all their hopes for safety and a successful termination to their journey centred upon the finding and hiring of Cree Jim, the guide.

| Blanche Howe, President of the Ninepin Club. |

| Felicia Deforest, Secretary of the Ninepin Club. |

Morna Rowland, Lucille Taylor, Christabel Mason, Sophia Pratt, Annette Simpson, Helen Fairchild, Agnes Stowe.

Alice Trowbridge, a classmate, not a member of the Club; an Old Woman; a Maid; Birds.

| Eight Blue Birds | { four little girls } | |

| { four little boys } | ||

| Six Yellow Birds | { three little girls } | The Kindergarten Class. |

| { three little boys } | ||

| Six Red Birds | { three little girls } | |

| { three little boys. } |

Scene.—A drawing-room in Mrs. Ames's private boarding-school. The Ninepin Club is holding one of its regular meetings. The question for discussion is A Summer Fête. The President is in the chair.

Time.—The 30th of May.

Blanch (raps for order). The Club will come to order, and hear the minutes of the last meeting. The Secretary will please rise.

Felicia (rises and reads). The Ninepin Club met in the drawing-room for its usual weekly meeting. After the minutes of the last meeting had been read and approved, there being no business on hand, and no question to discuss, one of the members produced a box of cake and fruit just received from home, and the Club enjoyed a fine feast. The box was the more appreciated, as the members had dined that day off corned beef and cabbage, which bill of fare, it was voted, should never be allowed in the members' future homes. It was voted that thanks should be sent to the member's mother for the box. Lucille announced that she was expecting a box soon, and would treat the Club at their next meeting.

Blanche. You have heard the report. As many as approve will say aye.

All. Aye!

Blanche. The President would like to inquire if the member who was expecting the box to-day has received said box.

Lucille. I am sorry to say, Miss President, and members of the Club, that the box has been unaccountably delayed.

Blanche. It may come to-day?

Lucille. It may. And if it does, the members will be notified to attend a midnight meeting in my room.

Blanche. That is satisfactory. The Club accepts with thanks Lucille's invitation. Girls, you must put on your bedroom slippers, and come in perfect silence. If any member is absent, on account of not being able to pass the section teacher's open door, she shall be commiserated, and her share of cake and fruit shall be sent to her next day. Is there any other business?

Morna. I think we ought to consider whether Alice shall be asked to join the Club. Not that I want her, goodness knows, but yesterday Miss Foster spoke to me about her. She said we didn't seem to associate with her much.

Annette. Miss Foster spoke to me too. She thought Alice was a good girl, and only needed to be brought out.

[Several of the girls speak at once, excitedly.]

Helen. Oh no, we don't want her.

Christabel. She would just spoil the Club.

Sophia. To me she is positively disagreeable.

Felicia. She dresses so plainly.

Helen. And does up her hair horridly.

Christabel. She is scared out of her wits if we just speak to her. I asked her the other day where her home was, and she looked awfully funny, and didn't answer a word.

Morna. I don't exactly like her face. I wouldn't trust her.

Sophia. That's it. I don't believe she is sincere.

Annette. And she hasn't had a box since she came.

Blanche. Order! You know Alice wouldn't be a bit congenial to me. But we will take a vote. Somebody make a motion.

Felicia. I move that Alice Trowbridge be not admitted to this Club.

Helen. I second the motion.

Blanche. All in favor say aye.

All. Aye!

Blanche. There, that is settled. But, girls, I advise you to pay a little attention to Alice outside of the Club, just so that the teachers won't notice. Miss Foster is awfully sharp. She pries about a good deal more than there's any call for her to. I shall ask Alice to walk with me pretty soon.

Agnes. Noble, self-sacrificing president! I will follow your example.

Lucille. I too.

Sophia. Suppose we all walk with her. Then Miss Foster can't say anything.

Christabel. I wish Miss Foster would mind her own business.

Blanche. Well, do not let's talk about this disagreeable subject any more. We were to have a paper on "Summer." Is the member prepared?

Morna (rises and reads). I must beg pardon for having no paper prepared, but I have had so many headaches lately I have been warned by Dr. Louise not to work so hard. Instead of a paper, I have a proposal. The Doctor says we ought to live out-of-doors more than we do. Let us have a summer fête—something that is quaint and original.

Blanche. It occurs to me that we might have a picnic and dress in peasant costume.

Lucille. How would you like a mountain laurel party?

Agnes. Oh, Lucille! just the thing. Girls, we could ask for a hall-holiday, and have a Queen, and cover her with lovely pink and white blossoms.

Blanche. How many would like a laurel party? Raise your hands.

[All raise their hands.]

Sophia. Let's appoint a committee to get it up.

Christabel. Do you suppose we could let Alice in on that?

Annette. Oh, bother that tiresome girl! No, we can't.

[A knock on the door. All hush, and sit up very straight. Helen unlocks and opens the door. An Old Woman enters. She stoops, leans heavily on a cane, and limps. She has on a long black cloak, and wears a large poke bonnet. Adjusting glasses on her nose, she scans the club members, then hobbles up to the President.]

Old Woman. Good-afternoon. Might I sit down and visit you a few minutes? (Helen places a chair.) Thank you,[Pg 557] dearie. You see, it's hard for me to stand. I'm pretty lame. But I can get about very well. Oh yes; very well, considering. You don't know me, I suppose?

Blanche. I think not. Perhaps you have got into the wrong place?

Old Woman. Isn't this the Ninepin Club?

Blanche. Yes.

Old Woman (chuckling). It's the right place. Oh yes, it's the right place. The Ninepin Club is where I was bound for.

Christabel. A most extraordinary person.

Old Woman. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine. Oh, I see, nine of you. That's why you are the Ninepin Club. Quite a coincidence. (Shakes her head gravely.) But I thought there were ten in your class. How does it happen that you're one short?

Blanche. If you please, we would like to know what right you have to question our Club. Who are you, please?

Old Woman. Certainly, certainly. What's my name and where's my home? My name is Granny Playfair, and I am the general Club regulator. Whenever a Club is established, I look after it, d'ye see?

[The girls appear much mystified.]

Blanche. Well, Granny Playfair?

Granny. And knowing about the Ninepin Club, I have come to regulate it.

Blanche. But how did you know about our Club? The members are pledged to secrecy.

Granny. How did I know? Well, there's where I am pledged to secrecy. It's a mighty good thing for Clubs that I regulate them, though. Little birds of the air sometimes tell me things.

Blanche. But, are you sure that our Club needs regulating?

Granny. Quite sure. Your Club is wrong all through.

Blanche. I have made a special study of Cushing's Manual, and we are quite parliamentary.

Granny. Well, I'm glad of that. (Shakes her head.) Oh, but you do need regulating. And I shall do it. Never fear. Now let me see, you were talking about summer. Would you like to see how the birds keep summer? That would help you a little.

Several of the Girls. Oh yes, indeed.

Granny (knocks on the floor. Door opens, and enter two little children dressed in blue). Come in, my birds. Are all the other birds assembled to do my bidding?

Blue Birds:

We heard you call, yes, one and all,

And we were sent, we two;

So now, dear Lady, tell us, please,

What you would have us do;

For every little blue bird is

Devoted quite to you.

Granny. Then fly, and find us the wood where the laurel grows thickest.

[Exeunt birds.]

Helen (aside). This is an interesting Old Woman, but I can't make her out.

Agnes. Nor I, one bit.

Granny. Shall I tell you my dream, young ladies?

Girls. Oh! do tell us your dream.

I SAW A FIGURE HUDDLED IN A CORNER.

I SAW A FIGURE HUDDLED IN A CORNER.

Granny. I was passing through a long, deserted hall, when I heard sounds as of some one sobbing. In a side room, whose door was just ajar, entering, I saw a small figure huddled in a corner. The room was dark, and I drew a shutter, letting the light in upon a young girl. Yes, she was crying. I went softly to her, and touched her on the shoulder. "What ails you, dearie?" I said. "Oh, I am not in it," she wailed. I took a seat, and drew the poor child to me, and stroked her forehead, and chafed her little cold hands. "Not in what, sweetheart?" I said. "Not in the Club," she answered. "They are all in it but me." "But why are you not in it?" I said. And she answered. "Because my dresses are sober and old-fashioned. I am not bright and witty. I am plain. I believe I am dull in my studies, because the girls look at me so. I am frightened, and can't recite even when I know the lesson. Oh, I have not one friend in the class." My little dear fell to crying again, and I had to take her in my arms, and kiss her, and comfort her a long time before she could tell me all of her story. "My mamma is dead," she said. "Those girls don't know how dreadful it is to lose their mammas. My uncle takes care of me, and he won't send me boxes of sweets, because he thinks they are hurtful. And he thinks girls ought to dress plainly and inexpensively. He has money enough. I have some money of my own, which my mother told my uncle to take care of for me till I was of age. If only I could make my uncle understand that I can't bear to be different from the rest of the girls. When the other girls go home in vacations, I stay here with the housekeeper. My uncle says I ought to be thankful for so good a home. But I'm not thankful. Oh, Granny, I want my mamma!"[Pg 558]

Well girls, you may believe me, this poor child's story touched me very much, and I thought how I could help her. I asked her uncle's address and kissed her, and told her that Granny would be her friend, and we went out of that lonely dark room, her little heart comforted. Then I wrote to that uncle, and the result was— But here come the Birds.

Blanche (to the other girls). It begins to dawn on me what Granny's dream means.

Morna. It's Alice, of course.

Granny. Hush!

[Enter Birds. Eight blue birds, six red birds, six yellow birds. Each carries a cluster or wreath or basket of pink laurel.]

Granny. Go back, little birds, and find Flora, your Queen.