The Project Gutenberg EBook of With Rifle and Bayonet, by F.S. Brereton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

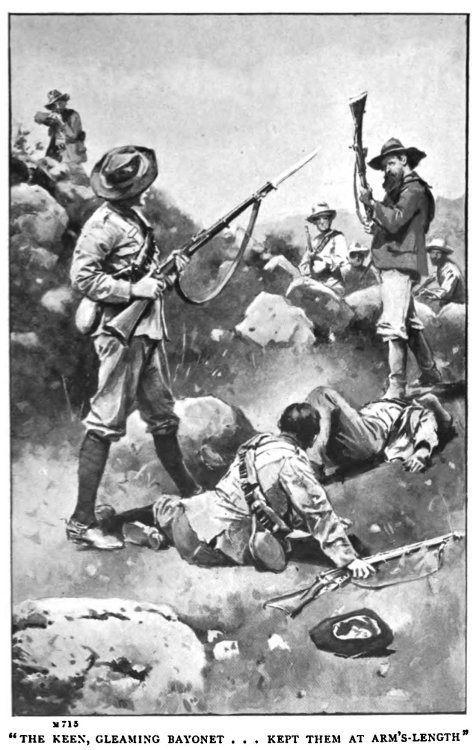

Title: With Rifle and Bayonet

A Story of the Boer War

Author: F.S. Brereton

Illustrator: Wal Paget

Release Date: June 20, 2010 [EBook #32918]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITH RIFLE AND BAYONET ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain F.S. Brereton, R.A.M.C.

"With Rifle and Bayonet"

Chapter One.

A Sad Mistake.

The last few rays of a cold September sunset were streaming through the High Street of a large and populous village called Redford, in the county of Surrey, lighting up the pretty red-brick cottages and casting a deep shadow beyond the quaint and tumble-down old porch which led to the church. A few mellow shafts had slipped by it, and, struggling through the iron bars of a massive gate, travelled up a long gravel drive and cast a ruddy glow on the windows of a fine country mansion.

In one of the rooms facing the sunset, a man and a woman were standing opposite one another, engaged in angry conversation, while outside, on the great staircase, the subject of their dispute, a boy of about eleven, was slowly making his way upward, stopping now and again to let his head drop upon his folded arms against the banisters, and sob as if his heart would break. At last, after many stops, he reached a landing midway up, and was just in the act of succumbing once more to his grief when a jeering and unsympathetic laugh from above caught his ear, and caused him to give a violent start. Instantly the lad dried his eyes, and choked back his sobs. Then, with a sudden gesture, as if of determination to forget his sorrow, he crossed the landing, and with his head now held proudly erect in the air, ran up the remaining stairs and was quickly out of sight.

Meanwhile, in the room below, the man and woman faced one another in the gathering gloom, while angry words passed between them.

The former, Captain Charles Somerton by name and title, a lithe and active man of middle age, was evidently ill at ease. He stood close beside his writing-desk, shuffling restlessly from one foot to another, and toying with a paper-knife. His wife, on the other hand, was apparently calm and self-contained, though a careful scrutiny of her features would have shown that passion had almost mastered her. She was a proud, haughty-looking woman, and now that her temper had almost got the better of her there was a decidedly evil look upon her face. She listened impatiently to what her husband was saying, glaring spitefully at him, and occasionally opening her lips as if on the point of interrupting.

“My dear,” the captain was saying, somewhat nervously, “you really must be more kind to the poor little chap. Scold him if you wish to, for I have no doubt that, like all boys, he is constantly up to some kind of mischief; but if you have occasion to correct him, do so in a more gentle manner. He is quite a young lad, you must remember, and I am sure that his worst deeds cannot merit such punishment. You frighten him out of his life, and you do what I consider an extremely unkind thing—you constantly hurt his feelings, well knowing him to be a thin-skinned boy. Poor little chap! If you are not more careful he will detest you. You say that he and Frank together smashed a piece of valuable china in your boudoir? How then is it that Frank is forgiven, while Jack, who is the younger by more than a year, has his ears boxed and is spoken to so harshly?”

“There you are again, Charles!” was Mrs Somerton’s angry answer. “How often must I tell you that Jack is the ringleader in all the mischief? If it were not for him Frank would never go astray, for he is a quiet and good-mannered boy, and, unless led away by the bad example of the other, always conducts himself as I should wish.”

“I am much inclined to disagree with you there, Julia,” the captain replied, with some show of temper. “It seems to me that there is something of the hypocrite about Frank. His manners may be good, but he can never look one in the face, and he is ready at any moment to snivel and whine. Jack may be a naughty boy, and given to getting into mischief, but I tell you candidly that I would far rather that he were so than a namby-pamby, milk-sop lad, afraid to say boo! to a goose. He’s a plucky little fellow, and all that is wrong with him is that, like the majority of healthy individuals, he has a large stock of animal spirits, which are a tremendous help in getting one along in this world, but which occasionally lead one into trouble. You say he is the ringleader; but to my mind that only shows his pluck. He goes ahead where others are afraid and hang back.

“But there, my dear, do not let us quarrel about this trumpery matter. Remember that when I, a widower with one boy, married you, a widow with an only son, a great object of our union was that the lads might prove good brothers and playfellows. That was three years ago, and now we have the satisfaction of knowing that they are fairly good companions, and our wish is that they should continue so. Treat them alike, Julia, and they will always be firm friends. But make a difference between them, punish one for the other’s faults, and you will surely separate the lads and cause them to dislike one another. As for the bit of china, I am sorry it is broken. Give it to me next time I go to London, and, if possible, I will replace it, or buy you something more valuable.”

Captain Somerton spoke in his kindest and most conciliatory manner, and patted his wife playfully on the arm. But this subject of the two boys was a bitter one to her, and she was far from feeling appeased.

“Yes, it is just like you, Charles, to take Jack’s part!” she exclaimed, with an angry sneer. “It is always the same, and, upon my word, I have no patience with you. Jack is a mischievous little monkey, and if there is to be an unpleasant scene between us whenever he misbehaves himself, then the sooner he is sent away to school the better. If I had had my way he should have gone long ago.”

Mrs Somerton, having delivered a parting shot, glared angrily at her husband, and bounced out of the room, banging the door after her.

As for the captain, he was evidently distressed that his attempt to set matters right had failed so completely. He gave a deep sigh, and, sinking resignedly into a chair, lit a cigar, and smoked furiously till the room was filled with choking clouds, through which the red end of his cheroot glimmered feebly.

He was a soldierly-looking man, tall and upright, and with a kindly expression on his face. Had a stranger seen him he would have taken him at once for what he was. There was no mistaking the moustache and the military air; while, had anyone been in doubt, the manner in which his grooms—who were all old soldiers—saluted him, and his method of responding, would have been convincing to the dullest. A few years before the event just narrated Captain Somerton had belonged to a crack hussar regiment. But, his father dying, he had resigned his commission, in order that he might be able to manage in person the property which had come into his possession.

Then it was that his first wife had died, leaving him with a child of five. Three years later he had married a widow, who also had a boy.

It had been a sad, indeed a fatal, mistake. His second wife was unsuitable in every respect, and was the very last woman he should have selected. She had no sympathy with him, spent much of her time amongst smart people in London, and when at home invariably upset the house, and caused her husband displeasure by her treatment of his boy. Indeed, as time passed, she seemed to take a positive delight in speaking sharply to Jack, knowing well that by doing so she caused Captain Somerton pain and annoyance.

And Jack—poor little fellow!—though at first he had, boy-like, quickly forgotten his scoldings, was now really in terror of his unloving stepmother.

People who knew the Somertons, and were callers at Frampton Grange, soon learnt what kind of a woman its new mistress was. Though outwardly all that was pleasant and entertaining to them, they quickly gauged her character, and knew her to be a source of discord in a house which was, before her arrival there, one of the happiest in the land. They summed her up, noticed the icy looks with which she often greeted Jack, and contrasted them with the tender embraces with which she almost smothered her own son.

Then they discussed the subject by other firesides till it was almost threadbare, and came to the conclusion that jealousy of Jack’s undoubted superior qualities and good looks was the main cause of her unkind treatment of him.

And below stairs, in the kitchen of Frampton Grange, the captain’s servants put their heads together many a time, with the result that all sympathised secretly with their master and his son, and cordially disliked the new mistress and the peevish and ill-mannered cub belonging to her.

Even as Captain Somerton and his wife were exchanging their views in the study above, old Banks, the butler, who had been with the Somertons for many years, was holding forth with unusual vehemence to the cook and maids below.

“I calls it just about a shame!” he cried indignantly, bringing his fat fist down upon the table with such a thump as to make his audience start out of their seats and cause himself a twinge of pain.

“Why can’t she let the boy alone? Poor little chap! She’s always a-nagging at him; and to hear her going on at the captain is enough to make yer tear yer hair. And he sits there in front of her as tame as a girl, and gives her back gentle words. Bah! I hates it! Yer wouldn’t think at such times as he’s got a name for miles round here as the daringest rider after hounds; but that’s what he has, as anyone would tell yer. And yet, when he gets in front of her, and she starts to tackle him, he’s as mild as milk, and scarcely dares to answer her. She’s a vixen, that’s what she is, cook, and I can tell yer I ain’t much in love with her. Why don’t he pitch into her a bit? But I dare say he acts all for peace! He dislikes a row, as all gentlemen does, and his motter is ‘Least said the soonest mended’. ’Tain’t the way I’d do it if I was in his shoes! I’d pretty soon make her leave the boy alone and stop her talk, I can assure yer!”

Banks shook his head in a threatening manner, and finding that his outburst of indignation had gained for him the sympathy and admiration of his fellow-servants, gave a deep grunt of satisfaction, and was on the point of launching forth afresh when a bell, rung from Mrs Somerton’s boudoir, sounded in the passage.

With a startled “Oh, lor!” he was himself again. His flushed features at once assumed their accustomed impassiveness, and with a hasty hitch at his tie to place it in the most exact position, he slipped hurriedly from the kitchen to obey the summons.

And now to follow the boy who had been weeping so bitterly on the stairs. Having gained the landing above, he entered a large room which was evidently set aside for the lads to play in. It was carpeted with felt, almost bare of furniture, and had stacks of cricket bats and balls and other implements in its various corners. Encircling the room, and running close to the wall, was a miniature set of rails, with a wonderfully-constructed station near the fireplace; while opposite the door there was a long tunnel, built up with artificial bricks and earth, from the mouth of which a beautiful model locomotive had half emerged, and remained there stationary, waiting for steam to get up again, and hinting gently to its two old playmates that they were sadly neglectful of their one-time friend.

Here, seated on the fire-guard, with his legs dangling some inches from the floor, was a dark, sallow-complexioned lad, with heavy features and shifting eyes, who went by the name of Frank.

“Well, baby!” this pleasant young gentleman remarked as Jack entered the room, “so you’ve been blubbing again, have you? Why, you are always turning the taps on. We shall have a flood soon.”

“If you were anything but a sneak you would take my part, and your own share in the blame,” Jack answered sharply, vainly endeavouring to steady his quivering lip. “You are a coward to leave me to bear it all. Why did you say that I broke the vase, when you know very well that you pushed me against it? I may be a baby, but I’d rather be that than a coward and a sneak.”

Jack blurted out his last words boldly, and glared defiantly at his stepbrother.

“Here, you shut up, baby!” cried Frank, slipping to the floor and looking threateningly at him.

“Sha’n’t,” said Jack stubbornly. “You know it’s the truth.”

“It’s the truth, is it, baby?” repeated the other, lifting his hand menacingly. “Take it back, or I’ll lick you.”

“I won’t take it back. You are a sneak and a coward, and now you are trying to be a bully,” cried Jack sturdily, facing his opponent without a sign of flinching.

“Then take that!” shouted Frank, bringing his hand with a smack across Jack’s face.

Words ended there. Jack might be a baby and give way to tears when he had been treated unkindly, for he was a very sensitive boy, though not wanting in manliness, but for all that it took a considerable amount of physical pain to make him whimper.

On the receipt of the blow from Frank his teeth closed tightly, cutting off the cry he might otherwise have given; his hands shot out in front of him, and moved rapidly backwards and forwards as he guarded the vicious blows aimed at him, while he returned them with due interest whenever there was an opportunity. To anyone who did not know the two boys it looked at first a most unfair encounter, for, despite the fact that little more than twelve months intervened between Jack’s birthday and that of Frank, the latter was at least three inches taller, and correspondingly heavy.

But, though Nature had given him a body which overlapped Jack’s by more than a year’s growth, it had placed within it a meagre stock of courage, which fact was quickly brought to light.

In the first scuffle Frank’s weight and reach gave him an advantage, and in spite of his lack of science, he planted some heavy blows on Jack’s face, which, however, only seemed to increase the latter’s stubbornness. He took his punishment without a murmur, and, blinking to clear the stars from his eyes, attacked his opponent with even more vigour and fierceness than before. Then luck favoured him. He succeeded in stopping an ugly rush with such abruptness as to make Frank stagger, and followed it up with lightning-like rapidity.

That was the turning-point. Frank could no longer face him, but dodged and scuttled round the room in a desperate hurry, vainly endeavouring to avoid the blows. One more settled the matter. With a sharp and most unpleasant thud Jack’s fist struck him on the nose, and next moment the bully was grovelling on the floor, writhing and shrieking as if in agony, while a flood of tears poured down his cheeks.

It was a funny sight, and fat and jovial old Banks, who, at his mistress’s order, had scrambled hurriedly upstairs to learn what the commotion was about, chuckled inwardly, and looked on in great enjoyment. Nor was it the only part of the struggle he had witnessed. He had arrived at the door of the play-room shortly after its commencement, quite unknown to the boys, and there he remained, listening for sounds from below, and waiting for a more opportune time to interfere.

“That’s it! Go it, my lads!” he murmured to himself, as he stood panting on the landing outside. “You’re bound to have it out, and I ain’t a-going to stop yer if I can help it. Best get it settled now. That young Master Frank’s been wanting a licking for a goodish time, and I’ll back Master Jack to give it him.”

And so he stood calmly in the darkness, till Jack had, to the butler’s huge delight, proved victorious, when, having cautiously stolen back to the top of the stairs, he returned, walking heavily across the landing, and burst into the room. He was quickly followed by Mrs Somerton, at whose appearance Frank’s agonised bellows increased tenfold, while Jack went sullenly to the fireplace and waited for the scolding which he knew would undoubtedly be his. He was not disappointed, and a few minutes later he had retired to his room in great disgrace.

On the following morning Captain Somerton called him into his study, and explained with much kindness and sympathy that he had arranged to send him away to school.

“It will be the best place for you, Jack,” he said, patting him on the back. “You are not too young to go to a public school, and I can vouch for it that you will thoroughly enjoy the life. It will give you opportunities of playing games and of making friends that you have never had here. You will be leaving this house in about a week’s time, and till then, my boy, contrive to live on good terms with Frank. Do not quarrel with him. A term at school will make all the difference, and when you return here you two lads will be the best of friends. There, that will do, Jack.”

Captain Somerton had come to a wise determination. His wife was strongly in favour of home education, and for that purpose a tutor attended daily at the Grange. But to the captain’s mind such a bringing up was far from judicious. He himself had had a public-school life, and had rubbed shoulders with hundreds of other boys, and he knew the value of such a training. He argued, and argued rightly, that in the majority of cases a boy who has never left his home becomes either a milk-sop or a conceited youth, and he was strongly of opinion that Jack should go to school. Now, much to his secret delight, there was an opportunity to separate the boys and send Jack away from home, and he seized it promptly.

Within two days of the quarrel between himself and Mrs Somerton, and between Jack and Frank, he had posted off to a popular and high-class public school not forty miles from London, where he arranged that Jack should be sent at once, as the term was about to commence and he was fortunate in obtaining a vacancy.

Meanwhile Jack had received the news of his impending change in life with the greatest pleasure. For the past three years his had been anything but a happy existence, and the knowledge that there was now to be a change was therefore a source of delight to him. He was not a quarrelsome lad; far from it. But for all that he was not the lad to put up with ill-treatment; and his stepbrother’s attempts to presume upon his year of seniority so often approached the verge of ill-treatment that trouble was constantly occurring.

Still, his father had asked him to be on good terms with Frank till he left for school, and Jack determined to act up to the promise he had given. He told his father he was sorry there had been a quarrel, and retired to the schoolroom again. Frank was there, seated again on the fire-guard, and greeted him with no very friendly looks, made all the more unpleasant by the unnatural size of his nose and lips. But he had had a lesson, and carefully confined himself to grimaces, fearing that Jack might renew the struggle.

The week passed slowly, so that Jack was heartily glad when the carriage drove up to the door, and he and his father were whirled away to the station, together with a couple of large school boxes. The past seven days had been decidedly dull and unpleasant. There had been an obvious coolness between Captain and Mrs Somerton, which affected the whole house, and in addition Frank had been silent and morose, and occasionally inclined to forget his caution and venture upon sarcastic jeers.

But Jack took it all calmly, the knowledge that he was going where he would make many friends helping him to do so. He therefore carefully abstained from answering, and when on the point of leaving, shook hands with his stepbrother heartily. Mrs Somerton gave him a kiss which was as cold as an icicle, and good-natured, fat old Banks squeezed his hand, and huskily wished him good luck and good-bye.

It was not long before they arrived at their destination, and that night Jack was one of the new boys at a large school where there were as many as four hundred. It was a new experience, but he enjoyed it, despite the many jokes which his comrades saw fit to make at his expense. For a few days he put up with them all good-naturedly, and soon felt quite at home; so much so, that before very long, when comparing his present life with the unhappy days he had lately spent at Frampton Grange, he had scarcely sufficient words of praise to bestow upon it.

He quickly fell into the ways of the school, and showed his masters what they might expect of him—which, to tell the truth, was not a great deal at first—and rapidly made friends with all his fellows. As with most popular lads, a nickname was very soon found for him, though why it should have been “Toby” not one of his comrades could have told you. Still, that is what it was, but it was used always in the most friendly way, which showed that he was a favourite.

Before many weeks had passed shouts of “Go it, Toby! Well hit, Toby!” resounded across the playing-fields; while a stranger, looking on at the game, might often have heard a sigh of relief from certain select lads who, like himself, were spectators, as Jack walked out to take his place at the wickets, and “Now we’ll have better luck! Toby’ll give ’em beans!” muttered in very audible tones, and with every sign of satisfaction.

If it was wet, and outdoor games were impossible, Jack was to be found in the gymnasium, or in the workshop, using his hands as best he could, and learning to be dexterous with his fingers.

Thus, in one way and another, he spent his days. The terms rapidly succeeded one another, and almost before he could realise it, he was one of the big boys of the school. At home matters seemed to have improved, and separation had certainly had the effect of making Frank more friendly. But still he was not quite the fellow that Jack was accustomed to. Any attempt to rag or scuffle annoyed him, and sent him upstairs to rearrange his clothing; and as for a rough-and-tumble game of football, he looked on at such a thing with horror, as he also did at Jack’s venturesome attempts to ride a wild young colt which was out to grass in the paddock. Such recklessness was beyond his comprehension; he could not understand Jack’s high spirits, and always endeavoured to curb them as if he were in charge of him.

“Take him easy, Jack!” said Captain Somerton one day, noticing the difference between his sons. “Frank is not used to your rough ways. ’Pon my word, you are like a young bull in a china shop! I hear your shouts and your romping all over the house. But there, don’t let me discourage you. I love to hear it. It wakes the old place up. But be careful, Jack, and if you can, endeavour to copy Frank in politeness. See how well he behaves at meals, and notice how at afternoon-tea he helps your mother when we have callers. Everyone remarks upon his manners, and I can tell you, old boy, you should take a leaf from his book. I like to see you in good spirits, but I also wish you to be well accustomed to the ways of the people you will meet Remember this, politeness is never thrown away; the smallest attention to your elders—the mere opening of a door—is never forgotten, and has before now helped many a man on in the world.”

“Very well, Father, I’ll do my best,” replied Jack heartily. “But I’m an awful bungler, I am afraid. Only yesterday I tried to do as Frank does, and handed round the cream at tea in the drawing-room. I felt just like an elephant; my feet got in the way, and I almost came a cropper on the floor. Then, just as I was helping that old Mrs Tomkins, I caught sight of Spot racing round the house after a cat. By Jove! it was a near shave, and puss only just saved her skin by bolting across the lawn and jumping into the beech-tree. But the worst of it was, that while I was staring through the window old Tomkins was whispering something or other to Miss Brown, and as neither of us was watching her cup it moved a little to one side, and before I knew what was happening the cream was pouring down her dress. Mother says it was a brand-new one on that day, and that’s perhaps why the old lady looked at me so funnily. She said it didn’t matter, but I could see she was just boiling, and felt glad to get away. Then, of course, Mother had something to say to me, and Frank called me a clumsy beggar. That’s all I got for trying to be polite. But I’ll do what I can to learn; see if I don’t, Father!”

“Ha, ha, ha! That was an unfortunate beginning!” laughed Captain Somerton. “I can well imagine poor Mrs Tomkins’ disgust. You must be more careful next time. Stick to it, old boy! There are lots of other ways in which you can show your politeness, and if handing tea or cream is too much for you, you must leave it alone for a while.”

Jack was not discouraged by the want of success which attended his first attempt. He was an observant lad, and quickly picked up his brother’s manners, so much so that when the holidays were over, and he returned to school, his chums noticed that “Toby” was strangely altered. Out in the playing-fields he was still the same jolly, noisy fellow, always ready for a bit of fun. But at meal-times there was something different about him; he was quieter and more polished.

And the change, little as it was valued by his schoolfellows, rapidly caught the attention of his masters, and in consequence they took more notice of him, and became quite attached to the lad.

But in spite of this change in Jack, he led the way in all outdoor games, and indeed was as noisy and high-spirited as ever. So that during holiday times he and Frank still differed vastly from one another. The latter had now donned the very highest of stick-up collars, and his ties were a source of the greatest anxiety to him. In addition, owing to Mrs Somerton’s foolishness, his allowance of ready money enabled him to do as he wished as regards his clothes. And in consequence, he was never happier than when at his tailor’s, trying on some new suit.

To many other boys this is a great pleasure, and indeed it is a gratifying thing to see a lad careful of his personal appearance, and always anxious to appear neat and tidy. But the boy who expends all his time and money in dressing himself, and to whom the rough clothes and boots and the dirt associated with a game of football are distasteful, is a fop, and a fop is the least attractive of all individuals.

This was what Frank was fast becoming. He was selfish and indolent, and gave himself such airs that to a lad of Jack’s breezy nature he was perfectly intolerable. But Jack had promised his father to live peacefully with him, and he kept his promise faithfully, only disagreeing openly when Frank attempted to dictate to him or order him about. Then there was invariably an angry scene, during which Jack pointed out to his brother in plain, matter-of-fact terms that the consequences might be painful if he persisted in trying to rule; and Frank, remembering a struggle, now some years past, in which he had decidedly come off the worse, usually contented himself with some sarcastic remark, and went off to Mrs Somerton to tell her his grievances. So that, altogether, life at Frampton Grange was not so happy as it might have been, and Jack far preferred his school-days. What he did enjoy, however, were the summer holidays, when, by mutual consent, the family divided, and Jack and Captain Somerton went for a trip on the Continent.

At school he was now a prefect, and a most popular boy, and thoroughly appreciated his life. Though, like others of his age, he was looking forward to the time when he would take some position in the world a little more exalted than a school-boy’s, he was yet in no hurry to say “Goodbye!” Cricket and football and his comrades were strong inducements to stay, and when at last the unexpected happened, and misfortune burst like a bomb at his feet, he looked back at the old days with a longing and regret which was never deeper in any boy’s heart.

Chapter Two.

Good-Bye to Home.

Jack Somerton was not given to low spirits; to mope and worry about trifles was a foolish habit to which he had never yielded; but had he done so one beautiful evening in May, a few days before his return to school, he might very well have been excused, for matters had been anything but pleasant.

To begin with, he and Frank had fallen out seriously, partly owing to the latter’s selfishness, and also partly, it must be owned, to Jack’s hot-headed impulsiveness, which always caused him to blurt out at once exactly what was on his tongue, before considering the consequences. He was just one of those lads who liked what is called a “row” as little as did anyone, and sooner than sulk, or treasure up a fancied grievance, he preferred to end the matter at once. Not by blows, for he was not pugnacious either, but amicably, if possible, and if not—well in some other way.

Frank, on the other hand, could never forget that he was the elder of the two, and when Jack came home for the holidays a certain amount of friction always arose, because the former attempted to control his brother’s actions.

“You can’t do that,” he would say, as Jack was on the point of saddling his father’s favourite hunter for a canter in the paddock. “You know very well that Father does not allow anyone to ride Prince Charlie but himself.”

“Who told you that?” would be Jack’s answer. “Did Father say so, or ask you to see that no one rode the horse? Of course he didn’t; Prince Charlie’s a bit fresh at times, and that’s why Father does not like anyone to ride him. But I have had him out before, and I am going to do so again.”

Jack was not exactly a wilful boy, but his brother’s attempts to rule him jarred his feelings. Had Captain Somerton told him he was not to ride his horse, Jack would certainly have obeyed him. But when it practically became a question as to whether he was to do as Frank said, and thereby acknowledge a certain amount of authority on his part, it was a different matter, and the opposition to his wishes very often drove him to doing what he would otherwise not have done.

Day by day these petty squabbles were almost certain to occur, and as the holidays neared the end they became even more frequent. One had arisen on the evening in question. It was not a serious one, but had, as usual, been caused by an attempt on Frank’s part to order Jack about.

As a natural consequence Mrs Somerton had been put out, and had made Frampton Grange so exceedingly uncomfortable for Jack that he had at once gone to the stables, saddled his pony, and ridden through the village, out into the country.

“Well, I shall be jolly glad when the 15th comes, and I get back to school again,” he said to himself as his pony walked slowly along the road. “I wish things weren’t quite so wretched at home. It would be ripping if Frank were like Ted Humphreys, always jolly and ready for a bit of fun, and not for ever nagging and advising me, or ordering me not to do this or that. One would think I was a perfect baby still and he was a grown-up man. I’m sorry, that’s all. Father feels the same too, I know. He as good as told me so the other day. Never mind, I won’t let it worry me. I shall be out of the Grange in a few days, and when next term’s done I shall go up to London to coach for the army.”

How long Jack would have soliloquised it would be difficult to state. He was completely lost in the brownest of brown studies, so much so that he did not heed the noise of hoofs clattering up behind him, and only woke with a start when another rider had drawn his steed in close at his side, and given him a smack on the back which almost knocked the breath out of his body.

“Dreaming, eh? Good gracious, the lad’s wool-gathering!” exclaimed the stranger—a dark, dapper little man, with a clean-shaven face,—giving vent to a hearty chuckle. “What in the world’s the matter, lad?”

“Oh, is that you, Dr Hanly?” exclaimed Jack.

“Of course it is!—who else would it be? What’s the matter, my boy?” answered the doctor kindly. “Troubles at home—eh? Well, don’t worry about them. They’ll mend themselves, and you’ll be back at school soon.”

Dr Hanly looked sympathisingly at Jack, and patted him gently on the shoulder. He was an old friend of Captain Somerton, and had known for a long while how matters were at the Grange. Indeed, outside the family no one knew so well what quarrels there were, and what trials the captain and his son had to put up with. Nor was it in his professional capacity alone that the doctor had obtained his information. He had long been an intimate friend of Jack’s father, and had known and appreciated the former mistress of Frampton Grange.

“Well, Jack, when do you leave school?” he continued. “The captain tells me he intends sending you shortly to a crammer’s, who will coach you for the army. Fine profession, my boy; a fine profession! You’ll make one in a long line, for, if I make no mistake, the Somertons have held commissions for years. I’ve no doubt you will enjoy a soldier’s life. From what one hears it is not all so smooth and easy as one would think. There’s a gay uniform and a jolly life on the surface, but behind the scenes there’s sure to be plenty of tough work—marching and drilling and so on. But—halloo!—who’s this! Someone in a desperate hurry evidently. Want me for sure; a doctor never has a moment he can call his own.”

Doctor Hanly’s last words were caused by the sudden appearance of a light cart, which at that moment whirled round a distant bend in the road, and came racing along towards them, behind a galloping horse. In the cart, standing up and using his whip freely, was a man whose cap and clothes showed that he had some connection with the railway.

As he reached Jack and the doctor he pulled in his horse with a jerk, and waving his arms excitedly, shouted: “There’s been an awful smash on the railway, sir, midways between here and Redley. The station-master said as he’d seen you a-riding this way, and told me I was to let yer know that an engine and truck would stop at Harvey’s crossing, and take yer on to where the line is blocked. It’s been an awful smash, sir, and I heard nigh everyone in the London express has been badly hurt!”

“Why, that’s the train in which Father said he should return this evening!” exclaimed Jack, suddenly feeling a chill of fear run through his body.

“Come with me then, lad,” cried the doctor. “This way. It’s only a few hundred yards. Perhaps you will be of use. Go back to the station, my man,” he called out as they were setting off, “and tell the station-master to send out blankets, brandy, and any linen he can get hold of, as quickly as he can. Come along, Jack. I can hear the engine.”

They both put their animals into a gallop, jumped a narrow ditch which flanked the road, dashed across a broad stretch of common land, and finally pulled up at a gate which closed a level crossing over the railway. The engine and truck were already there.

“Hitch your reins on to this post,” said Dr Hanly calmly, making his own horse fast. “Now, on to the engine! Every moment may be of the utmost value. Send her ahead, my man.”

Jack climbed on to the foot-plate of the engine, followed by the doctor, who at once sat down on the driver’s seat and proceeded to inspect sundry instruments and bandages with which two capacious side pockets of his coat were stocked. He was as cool as if on an ordinary journey. Carefully selecting three of his instruments, he put the case back in his pocket, and commenced to cut a sheet of lint into small strips. These he folded up methodically and gave to Jack to hold. Then he rose to his feet, and looked along the line in front, waiting quietly for the moment when the engine should reach the scene of the disaster, and enable him to commence his work of rescuing the injured. What a contrast there was between this dapper little man, cool and collected, with all his wits about him, waiting for his work to begin with a quietness born of long experience, and Jack, standing on the other side of the foot-plate, dodging his head from side to side to obtain a better view of the rails, holding the bundle of lint with fingers which trembled with nervous excitement, whilst his heart thumped against his ribs with a force which almost frightened him!

“Steady, Jack, steady!” exclaimed the doctor, smiling encouragingly at him. “Nothing was ever done well in a hurry. Keep cool, and you will be able to help me considerably. Ah, there it is! We shall be close up in a few seconds.”

As the doctor spoke the engine ran round a wide curve, and came in full sight of the spot where the accident had occurred. The axle of the driving-wheels of the express engine had suddenly snapped, causing the whole train to leave the rails, and plough along on the gravel. Then the heavy engine had suddenly toppled over and come to an abrupt halt, while the carriages had been piled on top of it and on one another in hopeless confusion.

It was indeed a dreadful disaster. The guard’s van and the first passenger truck lay crushed out of all shape on the gravel, while on top of them the others were heaped in disorder, with dangling wheels and shattered woodwork, the whole being surmounted by the last carriage of all, the end of which was thrown up as high as a house in the air.

About twenty men had already collected near, and these at once set to work, at Dr Hanly’s orders, to climb into the carriages and bring out the passengers. Jack joined in the work, feeling giddy and thoroughly upset at the awful sights he saw, and dreading that every body taken from the wreckage would prove to be his father’s.

But the doctor, guessing what his feelings were, called him to help in bandaging up one of the injured passengers, and kept him hard at work for an hour at least; so that when Captain Somerton’s body was at last discovered, crushed almost out of recognition, Jack was not there to see it and be shocked at the sight. Indeed, he did not hear the tidings for some time, for the doctor required his help; and before long Jack was so much absorbed in his work that he had forgotten his nervousness, and was applying splints and bandages together with his friend with a skill and coolness which would have done credit to an older hand. But all the time he was oppressed by a feeling that a calamity had befallen him.

When all the injured had been seen to, Jack was at liberty to make enquiries, when he soon learnt that his father was among the killed.

“It is a sad thing, my dear boy, a shocking accident,” murmured Dr Hanly, taking him on one side, “and your grief is natural, for you have lost the best friend you ever had in the world. Go home now and break the news. I will come to-morrow, and after that, if you are in any difficulty come to me.”

The next few days were exceedingly trying ones for Jack. Frampton Grange was even more miserable than before, for there was no sympathy amongst the inmates, and therefore no consolation in talking to one another about the terrible accident which had led to Captain Somerton’s death.

Two days were occupied in attending and giving evidence at the inquest; then there was the funeral, after which Mrs Somerton and her two sons returned to the Grange with Dr Hanly, a few relatives of the deceased captain, and two austere gentlemen, who proved to be lawyers. The will of the late owner of the house was then produced.

A quarter of an hour later it had been read, the party had broken up, and Jack found himself the future owner of Frampton Grange and all the wealth his father had possessed, and alone in the world save for a stepmother and stepbrother who cared little for him.

Captain Somerton had made one very big mistake during his life. He had married, for the second time, a woman upon whom his choice should never have fallen. This he recognised too late, but not so late as to prevent him from altering his will accordingly.

“I leave to my son, John Hartly Somerton, all that I possess,” ran the will, “to be held in trust by my wife and Dr Hanly, the former of whom shall have the use of Frampton Grange till the said John Hartly Somerton shall attain the age of twenty-six.”

Mention was made that Mrs Somerton had sufficient means of her own to live in the same style as before. In addition to this, there were various small legacies to the servants, a sum was set aside for Jack’s education and for his expenses in entering the army, and another sum for the upkeep of the Grange until it came into his own management.

“Come over and see me to-morrow, Jack,” whispered the doctor as soon as the will had been read. “I am now a kind of guardian to you, and shall feel it my business to give you advice. I shall be in about tea-time, when we can be sure of a quiet chat.”

“Thanks, Doctor,” replied Jack. “You can expect me at the time you mention.”

On the following afternoon, therefore, Jack mounted his pony and rode through the village and away up the hill to the doctor’s house.

“Now, my boy, what are you going to do with yourself?” asked the doctor, when they had finished their tea and were strolling in the garden.

“Well, first of all, as you know, Doctor, I am not to go back to school. I am awfully sorry, as I have been very happy there, and we hoped to pull off some good cricket matches this term. But now that is all knocked on the head for me. Do you know, I believe Father had some kind of feeling that something was going to happen to him, for he left a letter with the lawyer instructing me to leave school and begin coaching for the army immediately his death occurred. He mentioned that he would like me to read at home with Frank, but really, Doctor, I feel more inclined to go straight up to London, as I had intended all along. You know Frank and I are not too friendly. We don’t get on well together; and I’m afraid I don’t hit it off very well with Mother either.”

“Yes, I know that, my boy. It’s very unfortunate,” remarked Dr Hanly. “Still, it is the case. I believe you will do well to go up to London at an early date, for, if I am any judge, you are still more likely to quarrel at home now that there is no one to keep the peace. Think it over, and if you make up your mind to do as I say, come over and see me again, and we will arrange to go up together. London is a very big place, and it is a good thing to have a friend or two there when you go. I have many, and will ask them to look after you. Take your time about deciding. It would not do to leave home immediately after your father’s death.”

Jack rode slowly back to the Grange, and long before he got there had come to the decision that it would be best for all if he left home and went up to the big city.

“We’re certain to have rows if I stay,” he thought. “Then perhaps Frank will try to boss me, as he has tried before; so, altogether, I shall be doing everyone a good turn by going.”

His conviction was strengthened during the next few days, for the very sight of him seemed to be an annoyance to his stepmother. The truth was, that Mrs Somerton was highly incensed at the contents of her husband’s will. At the least she had expected a third, or perhaps more, of the estate to be left to Frank. But that all should have gone to Jack was a bitter pill which she found too difficult to swallow.

“How your father can have been so unjust I cannot imagine!” she had the bad grace to remark to Jack on the evening after his chat with Dr Hanly. “You and Frank are equally his sons, and should have been treated alike. But it was always the same. You were to have first place, and Frank was to have what was left. It is abominable, and if it were not that your father was always unjust in dealing with Frank, I really should begin to think that he was out of his senses when he made that will.”

Jack listened to his mother’s reproach, and was on the point of indignantly protesting; but better counsel prevailed, and he kept silent.

Two weeks later he and Dr Hanly took the mid-day train for London, leaving Mrs Somerton still in a very sullen mood, and Frank standing in a lordly manner on the steps of Frampton Grange, with an ill-disguised air of triumph about him which seemed to say that now at least he would be head and ruler of the establishment.

Jack had only once before been to London, and when the four-wheeler in which he and his friend were driving to their hotel became jammed in the dense traffic which converges at the Mansion House he was perfectly astounded. Nor was his astonishment lessened when he noticed how the busmen and drivers joked and laughed as they drove their vehicles through the narrowest parts with an accuracy which was wonderful; while tall, powerful-looking policemen stood in the thick of it all, and with a wave of a hand arrested the flow in one direction, while a flood of omnibuses and carriages swept by in the other.

“Fine fellows, aren’t they!” exclaimed Dr Hanly. “And many of them are old soldiers too. I really do not think there is another force in the world that equals them. They are well-trained and disciplined; polite and obliging, especially to country-cousins like ourselves, and with a power which is simply wonderful. I have never seen its equal, though I have known of many attempts to copy. In Paris, for instance, the policeman’s efforts to control the traffic, and make a street-crossing comparatively safe, are simply ludicrous.”

Ten minutes later the cab drew up at the hotel, and their baggage was carried in.

“Now, Jack, you can do as you like for the next hour,” cried the doctor. “I have letters to write, and so will go to my room. You had better get on a bus and go as far as you can in the time. I should advise your taking one which runs through the Strand and on past Charing Cross and Westminster. But wherever you go you will find it interesting.”

Jack had never gone alone through the streets of London before, but he was quite old enough to take care of himself, and having selected a bus, with the words “Strand, Charing Cross, and Victoria” painted on the side, he boarded it while it was running at a respectable pace, just as every boy likes to do, and seated himself in the garden-seat on top, just behind the driver.

“Afternoon, sir!” the latter, a jolly, red-faced individual, exclaimed.

“Good afternoon!” Jack replied. “I’m up in town for the second time in my life, and if you can tell me the names of the various buildings we pass, I shall be much obliged to you.”

“Ah, then you ain’t the first gentleman from the country as I’ve taken round!” answered the busman, grinning with pleasure, for, seated for many hours during the day on his box, an occasional chat came as a treat, which relieved the monotony.

“Well now, sir, that there building’s the Law Courts, and a fine place it is too; and under that funny-looking arch on t’other side is the Temple, where all these lawyer chaps has their lodgings and their church.”

As they drove through the Strand the driver showed him the various theatres, and finally pointed to the National Gallery across Trafalgar Square.

“That’s where all the best pictures go to, sir,” he said, “and if yer was to pass along on the right of it you’d see the sodger-sergeants a-walking up and down a-looking for recruits. And a fine bag they are making nowadays. What with old Kruger and the Transvaal Boers there’s likely to be trouble coming, and that’s what draws recruits. When there’s a chance of active service the young chaps comes up in scores. Funny, ain’t it, when yer think of other countries where pretty well every man has to join the army, whether he likes or not; while here, in free England, it’s left to choice, and no one need belong who doesn’t like!

“Do yer know who it is who’s perched up yonder a-looking down towards Westminster?” he continued, nodding to the Nelson Monument.

“Yes, that’s Nelson, of course,” answered Jack. “I’ve been here once before, I remember, to see the square and the fountains playing.”

“Nelson it is, right enough, sir, but he ain’t the only chap as perches himself up there. There’s a lot of chaps stands on the stonework below at times and spouts to the crowd. Agitators or something of the sort they calls ’em. At any rate they’re fellers as has got too long tongues in their mouths, I should think. Then it’s round that moniment that Englishmen gathers when there’s a row abroad, so as to let everybody know what they thinks about the matter. Ah! Trafalgar Square’s a useful sort of place, if it ain’t so very nice to look at.”

The omnibus now turned down Parliament Street, swept past Whitehall and the Horse Guards, and finally drew up at Westminster.

With a cheery “Thank you, and good-bye” to the genial driver, Jack jumped off and walked towards Westminster Bridge, where he stopped for a quarter of an hour or more, looking at the swarm of vehicles crossing, and at the panting tugs and the lazy barges floating on the river. Then he walked along the Embankment, back into the Strand, and so returned to his hotel.

“Well, Jack, to-morrow we will have a good run round the place,” exclaimed the doctor as they finished their dinner, “and after that we must find rooms for you somewhere, and introduce you to the crammer. As regards the rooms, I think it will be a good plan for you to board with someone. It is very lonely for a lad of your age in lodgings by himself, as I remember well, for I spent four years of that kind of life when I was a student. To-night, if you are not too tired, we will go to some place of amusement; a theatre for choice.”

Accordingly they went to Drury Lane, and thoroughly enjoyed the piece and the wonders of modern stage scenery.

On the following day they went to various other places, and in the evening looked up an old friend of the doctor’s, a barrister, who lived near Victoria Station.

“Look here, Jackson,” said Dr Hanly as soon as he had introduced his young friend, “I am on the look-out for rooms for this lad. He is to go to a crammer’s and work up for the army. The next examination takes place in about six months, and, if possible, I want to get him into some comfortable place where he will not be too much alone.”

“Why not try this house, then?” answered Mr Jackson. “I have been here for five years now, and have found it comfortable and reasonable. The people who run the place are most respectable, in fact they are gentlefolks who have been compelled to let rooms owing to reduced circumstances. I have two rooms, and so have Clarke and another man. I know there are two more vacant ones, for Franklin left for India last week. We generally breakfast and dine with the Eltons (the people who let the rooms), and we usually lunch outside.”

“What do you say, Jack?” asked the doctor. “You are the one chiefly concerned.”

“It seems to be just the very thing, Doctor,” Jack answered. “It is close to the address of the crammer, and therefore suitable in that way. Could we look at the rooms now, and come to a decision?”

Accordingly the vacant accommodation was inspected, and at once engaged. A week later Jack had quite settled down, the doctor had returned home, and work at the crammer’s had begun.

Jack enjoyed the life. The allowance which he was entitled to draw was a comfortable one, which enabled him to meet all his current expenses and still find something in his pocket with which to pay for amusements. His work usually kept him engaged from ten in the morning till four in the afternoon, and every night except Saturday and Sunday he did a couple of hours’ reading.

Between tea-time and dinner-time he generally went for a long walk, as to a boy of his habits constant exercise was essential. Sometimes he would make his way along the Embankment and on past Chelsea, for the river always had an attraction for him; while at other times he would go in the opposite direction.

One Saturday evening, just after dark, he was slowly returning towards Victoria, when a shrill whistle suddenly sounded in front of him, followed by a loud shout. Rain was pouring down at the time, so that the streets were practically deserted, while on the Embankment there was not a soul about.

Again the shrill whistle sounded, followed by a shout, this time less loud and decidedly muffled.

Jack’s suspicions were at once aroused, and, dropping his umbrella, he took to his heels and ran along the pavement. A few yards farther on scuffling and the sound of heavy blows reached his ears, while, almost at the same moment, a flickering gas lamp cast a feeble light across the damp pavement, showing the base of Cleopatra’s Needle, close to which was a group of struggling figures.

A minute later Jack had reached the spot, to find that four roughs had set upon two well-dressed gentlemen, one a man of some forty years of age, while the younger was no older than himself.

As Jack reached them the latter was leaning half-stunned against the stonework, where he had been knocked by a staggering blow, while at his feet rolled a police whistle with which he had made a brave attempt to call assistance.

The older gentleman stood with his back to the lamppost, and as Jack reached his side knocked one of the ruffians flat on his back on the pavement.

Jack made up his mind instantly as to what he ought to do. Without stopping he dashed up to the feet of the younger man, picked up the whistle, and next moment was at the side of the older man. Then he placed the whistle to his lips and blew with all his might.

“Come on! What are yer standing there for?” exclaimed one of the ruffians, turning fiercely on his companions, who had drawn away as Jack arrived upon the scene. “He ain’t a peeler! He’s only some clerk as don’t know when to keep himself to himself. Now, let’s do for ’em all, and clear away with the swag!”

A second later Jack was forced to drop his whistle and defend himself, for the three roughs rushed at them. The gentleman sent one of them reeling back with a tremendous blow on the chest, and was instantly engaged with the second; while the leader of the gang, a burly, brutal-looking fellow, singled Jack out and struck at his head with both fists in quick succession.

To attempt to guard was hopeless. It would have required a far stronger young fellow than Jack to break the blows. But he escaped by ducking rapidly, rising the next moment to strike fiercely at the man, and then throw himself upon him and drag him to the ground.

They fell heavily, the jar shaking the breath out of their bodies, and causing a sudden pain to shoot through Jack’s thigh. But though his left leg was now useless to him, he stuck to his man in spite of the excruciating pain it caused him, and, shifting his grasp for a moment, threw his arms round his antagonist and pinned him to the ground.

A few seconds passed, and just as his strength was giving way, and the ruffian was on the point of wrenching himself free, a policeman’s helmet appeared above them, a powerful hand grasped his opponent’s neck, and the man was dragged away.

What happened afterwards was a complete blank to Jack.

Chapter Three.

Off To Africa.

When Jack came to his senses again he was astonished to find himself tucked up in a cosy bed, with clean white sheets and a red counterpane. It was placed in the centre of a row of beds which were precisely similar, and which ran down one side of a large and comfortable-looking ward, on the opposite side of which there was a fire burning brightly, and a table round which sat three neatly-dressed nurses.

Jack slowly ran his eyes round the ward, noted that most of the other beds had occupants, and that the three nurses looked decidedly pretty in their white caps and aprons. And all the while he wondered mildly what it all meant, why he was there, and what sort of a place it was. Then, like others who have been seriously ill for a considerable time and are almost too weak to move a hand, he closed his eyes again and fell into a deep sleep.

When he awoke he lay quite still, with closed eyelids, listening to voices near his bedside.

“He’ll do well now, Nurse,” he heard someone say, “and I am glad to be able to tell you that the worst is over. It was a difficult job to get the thigh in satisfactory position, and nicely put upon the splint. But it’s done, and done well, I think I may say. Your young friend will make steady progress now, sir,” the voice continued, “and from what I have learnt I am sure you will be very pleased to hear it. Good-day! I must be going now, as I have several other patients to look to.”

“Good-day!” was repeated heartily by someone else, and then the owner of the first voice moved away.

“I am delighted to hear the doctor’s report,” somebody else exclaimed, in tones which were unmistakably those of Dr Hanly. “He has met with a very nasty accident, and it takes quite a load from my mind to hear he is doing well. By all accounts he must have increased the severity of the injury by sticking to that fellow as he did. He’s a plucky lad.”

“Plucky, my dear sir! I should think so indeed!” answered a third voice. “Why, I owe a lot to your young ward. There was really no call for him to come to our help; but he did so without hesitation, with the result that he got badly smashed, while Wilfred and I were merely a little bruised and knocked about.”

“I’m glad to hear you say so, Mr Hunter,” was the doctor’s reply. “It is just like the lad to get into a mess in an attempt to help others who were in a tight corner. But we had better be moving away, I think, or we may disturb him.”

“Don’t go, Doctor,” Jack feebly murmured at this moment, opening his eyes and looking up at his friend. “Tell me how I came to be here, and all about it. It’s awfully rummy! I cannot understand why I should be lying in bed, when only a minute ago I was well and strong and walking along the Embankment.”

“Why, good gracious me! that was a week ago, Jack! This is a hospital in London, and you are in bed because your thigh is broken. But you must get to sleep. Mr Hunter and I will come again to-morrow.”

Jack obediently closed his eyes, wondered in a dreamy kind of way who Mr Hunter might be, and who was the plucky lad he had been talking about, and promptly fell asleep.

When he became conscious again a nurse was bending over him, and, feeling stronger and more lively, he was propped up in bed as far as his splint would allow, and given a cup of tea. From that day he rapidly improved. The pain, which had been severe at first after he had recovered consciousness, had now entirely gone, and about three weeks after his accident his bed was lifted on to a long wheeled chair, and he was able to get about the ward and chat with the other patients.

Almost daily Mr Hunter and his son Wilfred came to see Jack, and very soon the two lads, who were within a few days of the same age, had become fast friends.

“By Jove!” Wilfred exclaimed one day as he was sitting by Jack’s side, “it was touch and go for us when those four blackguards attacked us, and you were a perfect brick to come up in time to lend us a helping hand.”

“Oh, humbug! What else could I have done?” answered Jack. “I heard your whistle and shouts, and guessed there was a row on. I couldn’t stand still, could I? so of course I came along to see what was up. Then, when I found it was an uneven fight, I tacked myself on to the side which wanted me most.”

“It’s all very well your talking like that, Jack, but you know as well as I do that you might just as well have run in the opposite direction, especially when you saw what brutes the men were who were attacking us. But we’ll say no more about it just now. I’ll get even with you though, old chap, if I can manage it, one of these fine days.”

“Then that’s agreed,” answered Jack; “but before you drop the subject, tell me what the row was really about. I suppose those fellows were after your money!”

“Money! Yes, but in a different form from that in which you usually see it. You know, Father runs a big store out in Johannesburg, and deals in everything. You can get anything, from a bag of peas or a tin tack to Kimberley diamonds of the first water, from his shop, and it’s the last that those ruffians were after. But here is Father. Ask him, and he will tell you all about it.”

“Well, Jack, getting along nicely, are you?” exclaimed the latter heartily. “And you want to know how it was we were attacked by those ruffians? It’s very simple. I have come over from South Africa for a holiday, and to see the old home. My wife and Wilfred came too, and during our stay here I have managed to combine business and pleasure. I brought over some diamonds, and on the day you came so opportunely to our aid I had been to a stone merchant in the city, and was returning with all those he had not bought from me; I should say some fifteen thousand pounds’ worth. It would have been a good haul if they had managed to get away with the bag. No doubt they knew all about me, and had tracked me all the way from the hotel. But they made a little mistake. You see in my younger days I had to rough it pretty well, and of recent years, while living in the Transvaal, life has not been altogether smooth. Every Boer’s hand there is against the Englishman, Uitlanders as they call us, and so one has to be particularly wary.

“Immediately I caught sight of those rascals I guessed their game, but I can tell you, my lad, it would have been all U P if it hadn’t been for you and the whistle. Well, we came out of it pretty comfortably, save for your fractured thigh, and as soon as you are fit to go out those fellows will be tried and, I trust, will get heavily sentenced.

“By the way, my boy, have you thought about the future? You know it will be at least three months before that leg of yours is really strong again; at least that is what the surgeon says.”

“No, I haven’t given it a thought, Mr Hunter. I suppose I shall go home to the Grange for a month or so, and then return to the crammer’s. Not that that would be much good, for I cannot possibly go up for the next exam. I haven’t done nearly enough reading, and should certainly get ploughed if I attempted it.”

“Why not come out to Africa with us?” said Mr Hunter earnestly. “We go as soon as those ruffians are tried, and we should be good companions on the way. Besides, it would be a splendid ‘pick-me-up’ for you; you would get the air on the voyage, and still be able to keep your leg in splints, or whatever is found necessary.”

“Mr Hunter, it’s awfully kind of you, and I should enjoy it immensely!” Jack suddenly blurted out, and then stopped abruptly as the thought of the expense entailed flashed across his mind.

“Then it’s settled,” exclaimed Mr Hunter. “I thought you’d jump at the idea. I’ve spoken to Dr Hanly about it, and he and your mother are quite willing for you to go. It will be the best thing you could possibly do under the circumstances, and besides, you may find that the experience will be of real service to you later on; for if you join the army it is more than probable that you will find yourself out in Africa with your regiment before many years are gone. I expect we shall sail in about a month’s time. It will be another four weeks before we reach Johnny’s Burg, as we call it, and then you can stay with us just as long as you please.”

Jack was delighted at the prospect before him, and made up his mind to get his leg sound again as quickly as possible. Save for a trip on the Continent with his father he had never left the shores of old England, and now the knowledge that in a short time he would be on board a huge ocean-going vessel bound for Africa, the land of gold and diamonds, Zulus, ostriches, and lions, filled him with the highest spirits, and served, to no small extent, to relieve the tedium of his long stay in hospital.

A month afterwards he was staying with the Hunters at a fine hotel near Piccadilly, and a week later had been able to give evidence at the Old Bailey—where he was complimented for his pluck by the judge,—and had seen the four ruffians who had attempted to obtain possession of the bag of diamonds condemned to heavy sentences.

In a fortnight they had set sail from Southampton, and were well in the Channel. It was a lovely summer’s day, and Jack enjoyed the change immensely. Reclining in a long cane chair, propped up with cushions and wrapped in a rug, he was a subject of interest to the passengers, and before many days had passed was on the best of terms with all. Indeed, had he but known it, he was thought a deal of by them, for Mr Hunter and Wilfred had not failed, when they joined the gentlemen in the smoking-room, to tell how his leg became damaged; while Mrs Hunter confided it to the ladies after dinner in the drawing-room.

Day by day Jack’s leg grew stronger and more firmly knit, and very soon, when the sea was quite smooth, he was able to hobble about the deck with the help of a crutch. Before the voyage was over he had discarded the plaster splint with which his thigh had been encased, and by the time the big ship steamed into Table Bay and whistled for the authorities to come off and give instructions as to where it was to berth, he had become quite an ordinary individual once more, and there was nothing noticeable about this strong, broad-shouldered young Englishman save the fact that he walked with a slight limp. It was a glorious morning when Mr and Mrs Hunter and the two boys landed, and as they were not to take the train for Johannesburg till the following day, Wilfred was able to escort Jack round the town and out into the country.

Jack enjoyed it all immensely. The streets were much the same as in London, and in many respects it reminded him of home. But the people walking about were different; Englishmen were certainly in evidence, but there was a good sprinkling of other nationalities, French, German, Kafir, and especially Dutch.

The country outside, however, was very different. The vegetation, of a semi-tropical nature, was more luxuriant and green, while the scorching sun overhead, and the dusty roads underfoot, which reflected the dazzling rays, were a complete change from what he had known in this country.

Still, in spite of the glaring sun there was no doubt of the picturesqueness of Cape Town, backed as it was by its green slopes and fields, and frowned over by the sharply-cut summit of Table Mountain.

Two days later the party arrived in Johannesburg, tired and weary after their long railway journey.

“Now, Jack, you must do just as you like while you are here,” said Mr Hunter a few days after they had reached this modern city in which the Uitlander population of the Transvaal had, for the most part, taken up its residence. “Of course you will want to see Pretoria, and get a peep at his honour, dear old Kruger, whom we Englishmen love so much. Then, perhaps, you would like to accompany me to Kimberley. I go there about twice a month, and though it is a dusty, uninteresting sort of place at first sight, yet I think I can promise to open your eyes when I show you the mines. You have heard of them, of course, and are aware that they are valued at millions of pounds. On our way there, or on our return, we could take a peep at Bloemfontein, the capital of the Orange Free State, where President Steyn has his residence. It will be all new to you, and, I dare say, sufficiently interesting.”

“Thank you very much, Mr Hunter!” Jack replied. “I am already awfully interested, and should certainly like to see all there is in the country. I wonder whether you would object to my helping sometimes in the store. I am quite strong enough for that now, and I should very much like to learn how you manage matters, and particularly how your books are kept. I am sorry to say I am a terribly poor hand at accounts. Mine never came out right at the end of the month in London.”

“Mind! Of course not, Jack! I am glad to think you would care to do it. Place yourself in Wilfred’s hands. He knows all about it, and will show you how the business is carried on. Who knows? One of these days you may find shopkeeping more congenial than army life. Out here there are lots of young fellows who come from the best of houses in the old country, and yet are not ashamed to pull off their coats and put their shoulders to the wheel. Why, one man of my acquaintance, who is in a very prosperous way of business just now, in spite of the exorbitant taxation with which we have to put up, owns to a title in England, and when he was there would have no more thought of turning out in the streets of London without the time-honoured tail-coat and topper than he would have thought of flying. And here he is now, not too proud to make his living by honest means, simply because he happened to be born a lord. And there are lots more like him too. Dear me, what a shock their parents would have if they could see them now, working behind their counters with sleeves rolled up, and selling groceries or ironware as if they had been at it all their lives!”

On the following day Jack took the train for Pretoria, and had the good fortune to catch a glimpse of Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal Republic, as he drove by in his carriage.

“Father says he’s the deepest and cleverest schemer that ever was!” exclaimed Wilfred, nodding after the carriage, “and from all one hears there can be little doubt about it. They say, too, that he is a religious man, and is something like the Puritans of old. Whatever he is, however, he is certainly one of our bitterest enemies. He simply loathes the sight of an Englishman, and won’t speak our language. He forgets all we have done for him, for I can tell you, there would have been no Kruger and no Boers in the Transvaal if it hadn’t been for our country.”

“He’s a funny-looking fellow at any rate,” answered Jack; “and why in the name of all that’s rummy he should want to wear a topper in this outlandish place is more than I can guess. If I met him at home I should take him for some dissenting minister, a trifle hard-up and out-at-elbow.”

“Hard-up!” exclaimed Wilfred in disgust. “Don’t make that mistake, Jack. Paul Kruger is no pauper. He is certainly one of the wealthiest of the Boers.”

And this was exactly the case. President Kruger was a man who had for many years not only managed the affairs of this particular country, but had also contrived to look well after his own. It was only a glimpse that Jack caught of him, but it was quite sufficient to impress the features on his mind.

Paul Kruger was a heavily-built man, arrayed in black from head to foot, which shone as all threadbare and worn-out clothing does. On his head was a fairly presentable top hat, and in his fat, ungainly hands he held a pair of black kid gloves.

But his face was the part which riveted one’s attention.

In anyone else’s case but the president’s it would have passed without comment, especially amongst a gathering of typical Boers. But, holding the position he did, one looked a second time, and noticed the wrinkled, jowly cheeks, fringed with a belt of straggly hair; the heavy, sleepy-looking eyes, overhung by bushy brows, and the general appearance of obtuseness.

And yet it was this man who, for the sake of a boundless ambition, was destined to defy the might of England, ay, and stagger it with his blows; and he it was, this sheepish-looking Boer, who for years and years had been secretly dreaming and planning—planning to oust the Britishers from their fair colonies, and claim for himself the proud position and title of President—perhaps King—of the United States of Africa.

Shortly after his return from Pretoria, Jack settled down to life in Johannesburg, and soon found himself quite one of the Uitlanders. His leg was now practically strong again, though he had not yet got rid of the limp. Still, for all that, he was able to get about, and even enjoy a game of cricket.

Soon, too, he became accustomed to life in the store conducted by Mr Hunter, and made it a regular custom to help wherever he could during the morning hours. It was really a large shop, with several departments, and with a big storehouse behind. The main entrance was quite an imposing one, and a common place for friends to meet, while just inside was a large office in which the books were kept.

Jack was often here, and did not take long to master the intricacies of book-keeping, so much so that he soon became of real help to Mr Hunter.

In the afternoon he played cricket or drove out with Wilfred, and in the evening he and his friend frequently sauntered into the town, and played billiards at a large restaurant which was a popular rendezvous. Here he met numbers of Englishmen, and in addition several Boers, some of whom he learnt to like. But the younger men were for the most part odious, and gave themselves such airs that the Uitlanders held aloof from them.

Now it happened that Jack and Wilfred frequently played with two other young fellows, one of whom was a delicate lad about Jack’s age, who had come to Africa for the sake of his health. His name was Mathews, and Jack took a great fancy to him. He was quiet and dignified, seldom spoke unless asked a question, and was as inoffensive and harmless a being as anyone could have wished to meet.

But this very mildness was to be the cause of trouble, as Jack was soon to learn.

Amongst the young Boers who visited the restaurant was one tall young man of about twenty-five, who made himself more objectionable than any of the others. He was bumptious to a degree, and openly expressed his hatred of all Englishmen. Even in the billiard saloon his sneers were loudly uttered, so that Jack itched to thrash him on several occasions. But Wilfred dissuaded him.

“Be careful, Jack,” he exclaimed earnestly, one evening, when the Boer had been more than usually hostile. “Don’t take any notice of the brute, or it will lead you into trouble. I know him well, and so does Father, and I can tell you that Piet Maartens, as he calls himself, is a scoundrel, and a most dangerous man to have anything to do with. He is thickly in with the Kruger gang, and if all is true that has been said of him, he has a reputation that would hang a man in England. I have no wish to blacken his character. I merely tell the truth when I say that he has treated more than one of the Kaffirs on his father’s farm so brutally as to cause death. Keep clear of him, Jack!”

“I’ll do my best, Wilfred,” Jack answered slowly, “but he’d better look out. I’m not going to stand quietly by much longer and listen to his sneers. One would think we Englishmen were dirt beneath his feet. Up to the present his remarks have been general, but I’ll tell you this, if he shouts any of his names at me, I’ll show him that an Englishman is as good as, and perhaps better than, a Boer. I’ve got a game leg, but that won’t prevent me from tackling him if it’s necessary.”

“Take my advice; keep clear of him,” repeated Wilfred. “After all, if you had lived all your life here you would have become accustomed to the doings of these young Boers. Ever since Majuba they have been brought up to think of us and our soldiers as cowards, and their absolute ignorance prevents them from seeing their mistake. I never take any notice of them.”

“Yes, I dare say that is the best plan,” Jack answered stubbornly; “but when I was at school a fellow had to take the consequences of what he said. If he called another chap names there was safe to be a row, and someone got a licking. That’s what happens in ordinary life, and it’s going to be the same here if that Piet Maartens doesn’t look out. Perhaps he could lick me if we had a fight, but I’d rather get knocked about and teach the fellow manners than sit down quietly and be insulted.”

Jack meant every word he said. Himself a kind-hearted and polite young fellow, to hurt the feelings of a comrade, or of a foreigner who happened to be anywhere within hearing of him, was the last thing he would have thought of doing. And to be forced to listen to sneers which were meant for any Englishman who might happen to hear them was so galling that it set his blood on fire. Just as his stepbrother’s attempts to control his actions had raised his ire, so did the behaviour of this young Boer irritate him and stir him to anger. Jack was not pugnacious, but the mere suspicion that he was in the presence of a bully ruffled him, and his meetings with Piet Maartens had so convinced him that this was what he was at heart, that Jack, in his own quiet dogged way, determined to discomfit him at the very first opportunity.

“He’s a bully,” he muttered to himself after Wilfred’s warning, “and I’m not going to put up with his sneers any longer.”

A few nights later the four lads were playing billiards in the restaurant, and the opposite table was occupied by Piet Maartens and a friend, while a number of Uitlanders and Boers were looking on. Jack had completely forgotten his determination, and, wrapped up in the game, had scarcely noticed the other players. Mathews was his partner, and, suddenly getting the balls into a favourable position, was adding rapidly to the score. The onlookers became interested, and all stood up to watch the game. Even Piet Maartens stepped over, and, rudely pushing Jack aside, craned his head and watched as Mathews played a stroke.

“Come here, Fritz,” he cried loudly. “Come and see this Uitlander. See, after all one of these Britishers is some good. Well, there is room for improvement, but whatever happens they will never make brave men.”

Instantly the whole of the occupants of the room became silent, while Mathews turned round and faced the Boer.

“You look after your own game, Maartens,” he said nervously.

“Thank you, little man, but perhaps I prefer to look on at you,” Piet Maartens answered, while his companion gave vent to a sniggering laugh which set Jack’s pulses thumping.

“Then you’ll have to wait a little,” cried Mathews angrily. “I’m going to stay here till you are out of the way.”

“Don’t get angry, my friend,” the Boer answered tauntingly. “Here, this will cool you.” And snatching up a tumbler of iced water which stood on a table near at hand, he deliberately poured it over Mathews, drenching him to the skin.